User login

Screening for tuberculosis: Updated recommendations

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a significant public health problem worldwide with an estimated 10.4 million new cases and 1.7 million deaths having occurred in 2016.1 In that same year, there were 9287 new cases in the United States—the lowest number of TB cases on record.2

TB appears in one of 2 forms: active disease, which causes symptoms, morbidity, and mortality and is a source of transmission to others; and latent TB infection (LTBI), which is asymptomatic and noninfectious but can progress to active disease. The estimated prevalence of LTBI worldwide is 23%,3 although in the United States it is only about 5%.4 The proportion of those with LTBI who will develop active disease is estimated at 5% to 10% and is highly variable depending on risks.4

In the United States, about two-thirds of active TB cases occur among those who are foreign born, whose rate of active disease is 14.6/100,000.2 Five countries account for more than half of foreign-born cases: Mexico, the Philippines, India, Vietnam, and China.2

Who should be tested?

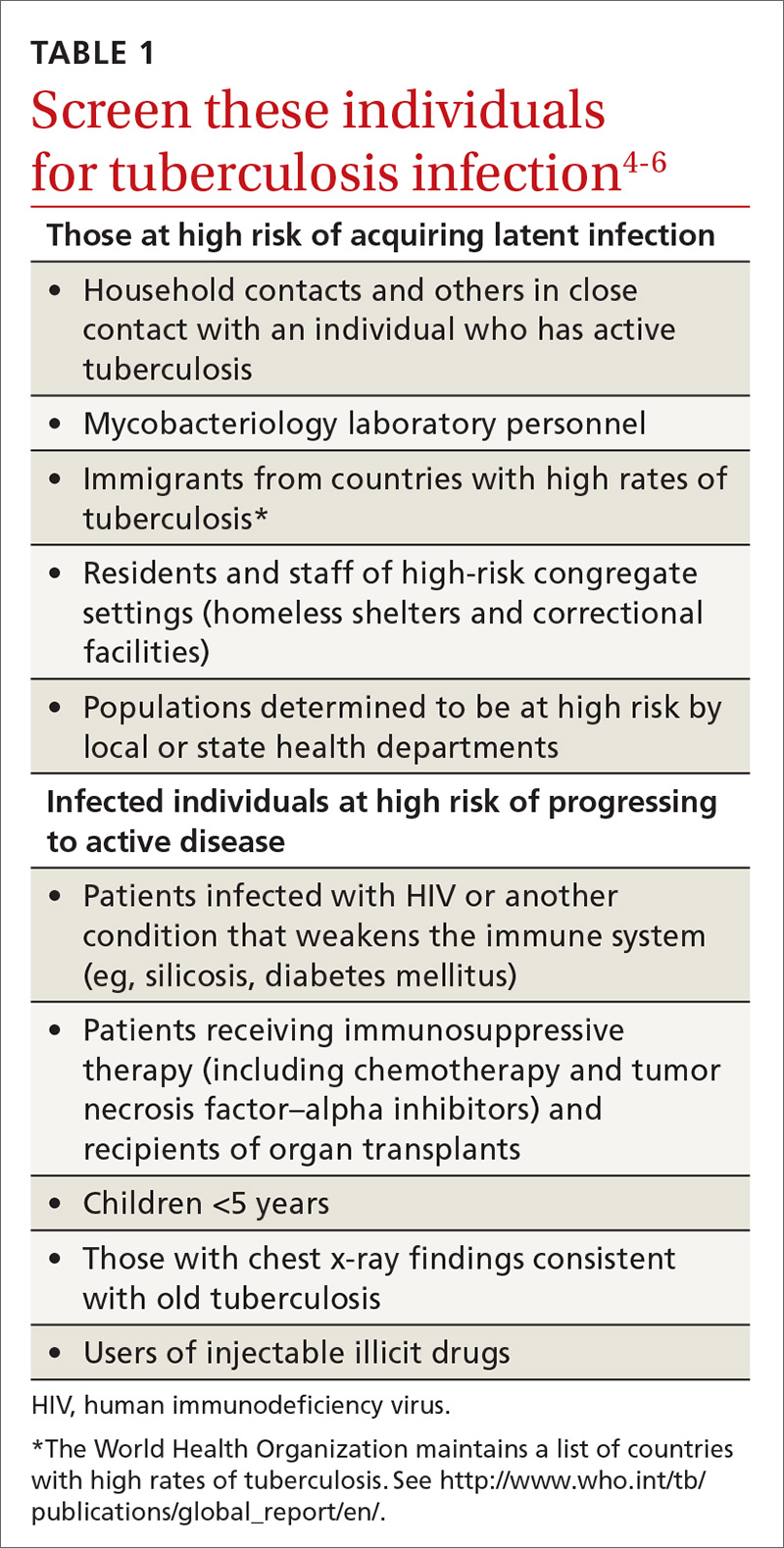

A major public health strategy for controlling TB in the United States is targeted screening for LTBI and treatment to prevent progression to active disease. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening for LTBI in adults age 18 and older who are at high risk of TB infection.4 This is consistent with recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), although the CDC also recommends testing infants and children

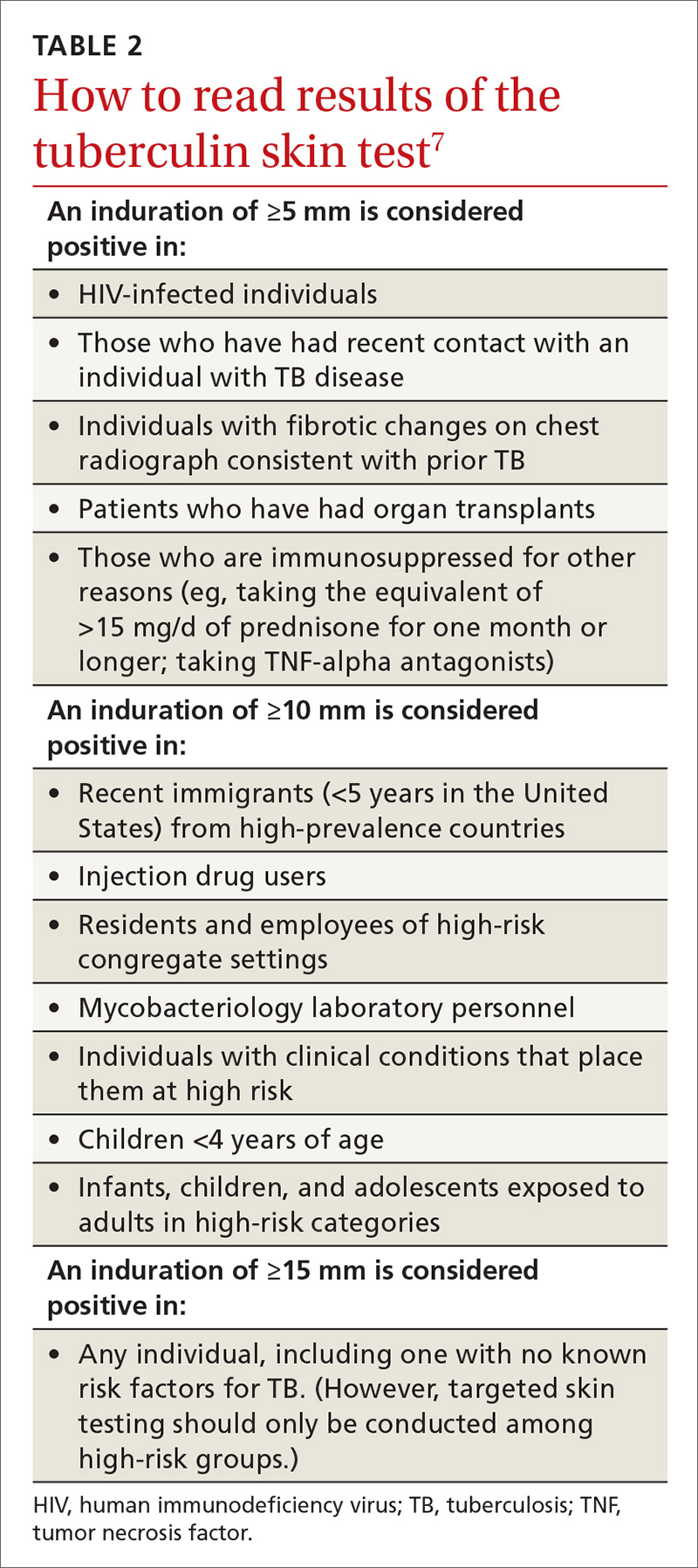

Two types of testing are available for TB screening: the TB skin test (TST) and the interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA). There are 2 IGRA test options: T-SPOT. TB (Oxford Immunotec) and QuantiFERON-TB Gold (Qiagen). The TST and IGRA each has advantages and disadvantages. The TST must be placed intradermally and read correctly, and the patient must return for the interpretation 48 to 72 hours after placement. Test interpretation depends on the patient’s risk category, with either a 5-mm, 10-mm, or 15-mm induration being classified as a positive result (TABLE 27).

IGRA is a blood test that needs to be processed within a limited time frame and is more expensive than the TST. The USPSTF lists the sensitivity and specificity of each option as follows: TST, using a 10-mm cutoff, 79%, 97%; T-SPOT, 90%, 95%; QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube, 80%, 97%.4

Which test to use?

Recently the CDC, the American Thoracic Society, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America jointly published revised recommendations on TB testing:8

- For children younger than 5 years, TST is the preferred option, although IGRA is acceptable in children older than 3 years of age.

- For individuals at high risk of infection but not at high risk of disease progression, IGRA is recommended if they have received a bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine or are unlikely to return for TST interpretation.

- For others at high risk of infection but not at high risk of disease progression, IGRA is preferred but TST is acceptable.

- For those who have both a high risk of infection and a high risk of disease progression, evidence is insufficient to recommend one test over another; either type is acceptable.

- For those with neither high risk of infection nor high risk of disease progression, testing is not recommended. However, it may be required by law or for credentialing of some kind (eg, for some health professionals or those who work in schools or nursing homes). If this is the case, IGRA is suggested as the preferred test. If the test result is positive, performing a second test is advised (either TST or an alternative type of IGRA). Consider the individual to be infected only if the second test result is also positive.

If a TB screening result is positive, confirm or rule out active TB by asking about symptoms (cough, fever, weight loss) and performing a chest x-ray. If the radiograph shows signs of active TB, collect 3 sputum samples by induction for analysis by smear microscopy, culture, and, possibly, nucleic acid amplification and rifampin susceptibility testing. Consider consulting your local public health department for advice on, or assistance with, sample collection. Report LTBI to the local health department and seek advice on the appropriate tests and treatments.

Expanded treatment selections

With LTBI there are now 4 treatment options for patients and physicians to consider:9 isoniazid given daily or twice weekly for either 6 or 9 months; isoniazid and rifapentine given once weekly for 3 months; or rifampin given daily for 4 months. Factors influencing treatment selection include a patient’s age, concomitant conditions, and the likelihood of bacterial resistance. Free treatment for LTBI may be available; again, check with your local health department.

1. WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2017. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Accessed November 8, 2017.

2. Schmit KM, Wansaula Z, Pratt R, et al. Tuberculosis—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:289-294.

3. Houben RMGJ, Dodd PJ. The global burden of latent tuberculosis infection: a re-estimation using mathematical modelling. PLoS Med. 2016;13(10):e1002152. Available at: http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1002152. Accessed November 10, 2017.

4. USPSTF. Screening for latent tuberculosis infection in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:962-969.

5. CDC. Tuberculosis. Who should be tested. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/testing/whobetested.htm. Accessed November 8, 2017.

6. CDC. Latent tuberculosis infection: a guide for primary health care providers. Targeted testing for tuberculosis. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/ltbi/targetedtesting.htm#identifyingTBDisease. Accessed November 8, 2017.

7. CDC. TB elimination. Tuberculin skin testing. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/testing/skintesting.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2017.

8. Lewinsohn DM, Leonard MK, LoBue PA, el al. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of tuberculosis in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:111-115.

9. CDC. Treatment regimens for latent TB infection (LTBI). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/ltbi.htm. Accessed November 8, 2017.

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a significant public health problem worldwide with an estimated 10.4 million new cases and 1.7 million deaths having occurred in 2016.1 In that same year, there were 9287 new cases in the United States—the lowest number of TB cases on record.2

TB appears in one of 2 forms: active disease, which causes symptoms, morbidity, and mortality and is a source of transmission to others; and latent TB infection (LTBI), which is asymptomatic and noninfectious but can progress to active disease. The estimated prevalence of LTBI worldwide is 23%,3 although in the United States it is only about 5%.4 The proportion of those with LTBI who will develop active disease is estimated at 5% to 10% and is highly variable depending on risks.4

In the United States, about two-thirds of active TB cases occur among those who are foreign born, whose rate of active disease is 14.6/100,000.2 Five countries account for more than half of foreign-born cases: Mexico, the Philippines, India, Vietnam, and China.2

Who should be tested?

A major public health strategy for controlling TB in the United States is targeted screening for LTBI and treatment to prevent progression to active disease. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening for LTBI in adults age 18 and older who are at high risk of TB infection.4 This is consistent with recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), although the CDC also recommends testing infants and children

Two types of testing are available for TB screening: the TB skin test (TST) and the interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA). There are 2 IGRA test options: T-SPOT. TB (Oxford Immunotec) and QuantiFERON-TB Gold (Qiagen). The TST and IGRA each has advantages and disadvantages. The TST must be placed intradermally and read correctly, and the patient must return for the interpretation 48 to 72 hours after placement. Test interpretation depends on the patient’s risk category, with either a 5-mm, 10-mm, or 15-mm induration being classified as a positive result (TABLE 27).

IGRA is a blood test that needs to be processed within a limited time frame and is more expensive than the TST. The USPSTF lists the sensitivity and specificity of each option as follows: TST, using a 10-mm cutoff, 79%, 97%; T-SPOT, 90%, 95%; QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube, 80%, 97%.4

Which test to use?

Recently the CDC, the American Thoracic Society, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America jointly published revised recommendations on TB testing:8

- For children younger than 5 years, TST is the preferred option, although IGRA is acceptable in children older than 3 years of age.

- For individuals at high risk of infection but not at high risk of disease progression, IGRA is recommended if they have received a bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine or are unlikely to return for TST interpretation.

- For others at high risk of infection but not at high risk of disease progression, IGRA is preferred but TST is acceptable.

- For those who have both a high risk of infection and a high risk of disease progression, evidence is insufficient to recommend one test over another; either type is acceptable.

- For those with neither high risk of infection nor high risk of disease progression, testing is not recommended. However, it may be required by law or for credentialing of some kind (eg, for some health professionals or those who work in schools or nursing homes). If this is the case, IGRA is suggested as the preferred test. If the test result is positive, performing a second test is advised (either TST or an alternative type of IGRA). Consider the individual to be infected only if the second test result is also positive.

If a TB screening result is positive, confirm or rule out active TB by asking about symptoms (cough, fever, weight loss) and performing a chest x-ray. If the radiograph shows signs of active TB, collect 3 sputum samples by induction for analysis by smear microscopy, culture, and, possibly, nucleic acid amplification and rifampin susceptibility testing. Consider consulting your local public health department for advice on, or assistance with, sample collection. Report LTBI to the local health department and seek advice on the appropriate tests and treatments.

Expanded treatment selections

With LTBI there are now 4 treatment options for patients and physicians to consider:9 isoniazid given daily or twice weekly for either 6 or 9 months; isoniazid and rifapentine given once weekly for 3 months; or rifampin given daily for 4 months. Factors influencing treatment selection include a patient’s age, concomitant conditions, and the likelihood of bacterial resistance. Free treatment for LTBI may be available; again, check with your local health department.

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a significant public health problem worldwide with an estimated 10.4 million new cases and 1.7 million deaths having occurred in 2016.1 In that same year, there were 9287 new cases in the United States—the lowest number of TB cases on record.2

TB appears in one of 2 forms: active disease, which causes symptoms, morbidity, and mortality and is a source of transmission to others; and latent TB infection (LTBI), which is asymptomatic and noninfectious but can progress to active disease. The estimated prevalence of LTBI worldwide is 23%,3 although in the United States it is only about 5%.4 The proportion of those with LTBI who will develop active disease is estimated at 5% to 10% and is highly variable depending on risks.4

In the United States, about two-thirds of active TB cases occur among those who are foreign born, whose rate of active disease is 14.6/100,000.2 Five countries account for more than half of foreign-born cases: Mexico, the Philippines, India, Vietnam, and China.2

Who should be tested?

A major public health strategy for controlling TB in the United States is targeted screening for LTBI and treatment to prevent progression to active disease. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening for LTBI in adults age 18 and older who are at high risk of TB infection.4 This is consistent with recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), although the CDC also recommends testing infants and children

Two types of testing are available for TB screening: the TB skin test (TST) and the interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA). There are 2 IGRA test options: T-SPOT. TB (Oxford Immunotec) and QuantiFERON-TB Gold (Qiagen). The TST and IGRA each has advantages and disadvantages. The TST must be placed intradermally and read correctly, and the patient must return for the interpretation 48 to 72 hours after placement. Test interpretation depends on the patient’s risk category, with either a 5-mm, 10-mm, or 15-mm induration being classified as a positive result (TABLE 27).

IGRA is a blood test that needs to be processed within a limited time frame and is more expensive than the TST. The USPSTF lists the sensitivity and specificity of each option as follows: TST, using a 10-mm cutoff, 79%, 97%; T-SPOT, 90%, 95%; QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube, 80%, 97%.4

Which test to use?

Recently the CDC, the American Thoracic Society, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America jointly published revised recommendations on TB testing:8

- For children younger than 5 years, TST is the preferred option, although IGRA is acceptable in children older than 3 years of age.

- For individuals at high risk of infection but not at high risk of disease progression, IGRA is recommended if they have received a bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine or are unlikely to return for TST interpretation.

- For others at high risk of infection but not at high risk of disease progression, IGRA is preferred but TST is acceptable.

- For those who have both a high risk of infection and a high risk of disease progression, evidence is insufficient to recommend one test over another; either type is acceptable.

- For those with neither high risk of infection nor high risk of disease progression, testing is not recommended. However, it may be required by law or for credentialing of some kind (eg, for some health professionals or those who work in schools or nursing homes). If this is the case, IGRA is suggested as the preferred test. If the test result is positive, performing a second test is advised (either TST or an alternative type of IGRA). Consider the individual to be infected only if the second test result is also positive.

If a TB screening result is positive, confirm or rule out active TB by asking about symptoms (cough, fever, weight loss) and performing a chest x-ray. If the radiograph shows signs of active TB, collect 3 sputum samples by induction for analysis by smear microscopy, culture, and, possibly, nucleic acid amplification and rifampin susceptibility testing. Consider consulting your local public health department for advice on, or assistance with, sample collection. Report LTBI to the local health department and seek advice on the appropriate tests and treatments.

Expanded treatment selections

With LTBI there are now 4 treatment options for patients and physicians to consider:9 isoniazid given daily or twice weekly for either 6 or 9 months; isoniazid and rifapentine given once weekly for 3 months; or rifampin given daily for 4 months. Factors influencing treatment selection include a patient’s age, concomitant conditions, and the likelihood of bacterial resistance. Free treatment for LTBI may be available; again, check with your local health department.

1. WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2017. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Accessed November 8, 2017.

2. Schmit KM, Wansaula Z, Pratt R, et al. Tuberculosis—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:289-294.

3. Houben RMGJ, Dodd PJ. The global burden of latent tuberculosis infection: a re-estimation using mathematical modelling. PLoS Med. 2016;13(10):e1002152. Available at: http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1002152. Accessed November 10, 2017.

4. USPSTF. Screening for latent tuberculosis infection in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:962-969.

5. CDC. Tuberculosis. Who should be tested. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/testing/whobetested.htm. Accessed November 8, 2017.

6. CDC. Latent tuberculosis infection: a guide for primary health care providers. Targeted testing for tuberculosis. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/ltbi/targetedtesting.htm#identifyingTBDisease. Accessed November 8, 2017.

7. CDC. TB elimination. Tuberculin skin testing. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/testing/skintesting.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2017.

8. Lewinsohn DM, Leonard MK, LoBue PA, el al. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of tuberculosis in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:111-115.

9. CDC. Treatment regimens for latent TB infection (LTBI). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/ltbi.htm. Accessed November 8, 2017.

1. WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2017. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Accessed November 8, 2017.

2. Schmit KM, Wansaula Z, Pratt R, et al. Tuberculosis—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:289-294.

3. Houben RMGJ, Dodd PJ. The global burden of latent tuberculosis infection: a re-estimation using mathematical modelling. PLoS Med. 2016;13(10):e1002152. Available at: http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1002152. Accessed November 10, 2017.

4. USPSTF. Screening for latent tuberculosis infection in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:962-969.

5. CDC. Tuberculosis. Who should be tested. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/testing/whobetested.htm. Accessed November 8, 2017.

6. CDC. Latent tuberculosis infection: a guide for primary health care providers. Targeted testing for tuberculosis. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/ltbi/targetedtesting.htm#identifyingTBDisease. Accessed November 8, 2017.

7. CDC. TB elimination. Tuberculin skin testing. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/testing/skintesting.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2017.

8. Lewinsohn DM, Leonard MK, LoBue PA, el al. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of tuberculosis in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:111-115.

9. CDC. Treatment regimens for latent TB infection (LTBI). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/ltbi.htm. Accessed November 8, 2017.

From The Journal of Family Practice | 2017;66(12):755-757.

CDC Updates Guidance on Infants With Possible Zika Infection

Infants with possible prenatal exposure to Zika who test positive for the virus should receive an in-depth ophthalmologic exam, intensified hearing testing, and a thorough neurologic evaluation with brain imaging within one month of birth, according to new interim guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The new clinical management guidelines, published in the October 20 issue of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, supersede the CDC guidance issued in August 2016. The update was the product of a forum on the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of Zika in infants that the centers convened with the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practicing clinicians and federal agency representatives reviewed the evolving body of knowledge on how best to care for these infants. Since Zika emerged as a public health concern, clinicians have reported postnatal onset of some symptoms, including eye abnormalities, incident microcephaly in infants with a normal head circumference at birth, EEG abnormalities, and diaphragmatic paralysis.

Infants With Clinical Findings Consistent With Zika Syndrome

Infants with clinical findings consistent with congenital Zika syndrome who are born to mothers with possible Zika virus exposure in pregnancy should be tested for Zika virus with serum and urine tests. If those tests are negative, and there is no other apparent cause of the symptoms, they should have a CSF sample tested for Zika RNA and IgM Zika antibodies.

By one month, these infants should undergo a head ultrasound and a detailed ophthalmologic exam. The eye exam should pick up any anomalies of the anterior and posterior eye, including microphthalmia, coloboma, intraocular calcifications, optic nerve hypoplasia and atrophy, and macular scarring with focal pigmentary retinal mottling.

By one month, these infants also should undergo auditory brainstem response (ABR) audiometry, especially if the initial newborn hearing screen was done by otoacoustic emissions alone. Zika syndrome can include sensorineural hearing loss, although late-onset hearing loss has not been seen. Therefore, the follow-up ABR previously recommended at four to six months is no longer deemed necessary.

A comprehensive neurologic exam also is recommended. Seizures are sometimes part of Zika syndrome, but infants can also have subclinical EEG abnormalities. Advanced neuroimaging can identify obvious and subtle brain abnormalities, such as cortical thinning, corpus callosum abnormalities, calcifications at the junction of white and gray matter, and ventricular enlargement.

As infants grow, clinicians should be alert for signs of increased intracranial pressure that could signal postnatal hydrocephalus. Diaphragmatic paralysis also has been seen; it manifests as respiratory distress. Dysphagia that interferes with feeding can develop as well.

“The follow-up care of [these infants] requires a multidisciplinary team and an established medical home to facilitate the coordination of care and ensure that abnormal findings are addressed,” said Dr. Adebanjo and colleagues.

Asymptomatic Infants of Mothers With Possible Infection

Infants without clinical findings born to mothers with laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection during pregnancy should have the same early head ultrasound, hearing, and eye exams as those with clinical findings. All of these infants also should be tested for Zika virus just as those with clinical findings should be.

If tests are positive, these infants should have all the investigations and follow-up recommended for babies with clinical findings. If laboratory testing is negative, and clinical findings are normal, Zika infection is highly unlikely, and the infants can receive routine care. Clinicians and parents should be on the lookout, however, for new symptoms that might suggest postnatal Zika syndrome.

Asymptomatic Infants Whose Mothers Had Unconfirmed Zika Exposure

Infants without clinical findings consistent with congenital Zika syndrome born to mothers with possible Zika virus exposure in pregnancy, but without laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection during pregnancy, constitute a large group. Some women, for example, are never tested during pregnancy, and others have false negative test results. “Because the latter issues are not easily discerned, all mothers with possible exposure to Zika virus during pregnancy who do not have laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, including those who tested negative with currently available technology, should be considered in this group,” said Dr. Adebanjo and colleagues.

The CDC do not recommend further Zika evaluation for these infants unless additional testing confirms maternal infection. For older infants, parents and clinicians should decide together whether further evaluations would be helpful. “If findings consistent with congenital Zika syndrome are identified at any time, referrals to the appropriate specialists should be made, and subsequent evaluation should follow recommendations for infants with clinical findings consistent with congenital Zika syndrome,” said the authors.

The CDC also reiterated their special recommendations for infants who had a prenatal diagnosis of Zika infection. For now, these recommendations remain unchanged, although “as more data become available, understanding of the diagnostic role of prenatal ultrasound and amniocentesis … will improve, and guidance will be updated.”

The optimal timing for a Zika diagnostic ultrasound is uncertain. The CDC recommend that serial ultrasounds be performed every three to four weeks for women with laboratory-confirmed prenatal Zika exposure. Women with possible exposure need only routine ultrasound screenings.

While Zika RNA has been identified in amniotic fluid, there is no consensus on the value of amniocentesis as a prenatal diagnostic tool. Investigations of serial amniocentesis suggest that viral shedding into the amniotic fluid might be transient. If amniocentesis is performed for other reasons, Zika nucleic acid testing can be incorporated.

A shared decision-making process about screening is key, said Dr. Adebanjo and colleagues. “For example, serial ultrasound examinations might be inconvenient, unpleasant, and expensive, and might prompt unnecessary interventions; amniocentesis carries additional known risks such as fetal loss. These potential harms of prenatal screening for congenital Zika syndrome might outweigh the clinical benefits for some patients; therefore, these decisions should be individualized.”

—Michele G. Sullivan

Suggested Reading

Adebanjo T, Godfred-Cato S, Viens L, et al. Update: Interim guidance for the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of infants with possible congenital Zika virus infection - United States, October 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(41):1089-1099.

Infants with possible prenatal exposure to Zika who test positive for the virus should receive an in-depth ophthalmologic exam, intensified hearing testing, and a thorough neurologic evaluation with brain imaging within one month of birth, according to new interim guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The new clinical management guidelines, published in the October 20 issue of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, supersede the CDC guidance issued in August 2016. The update was the product of a forum on the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of Zika in infants that the centers convened with the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practicing clinicians and federal agency representatives reviewed the evolving body of knowledge on how best to care for these infants. Since Zika emerged as a public health concern, clinicians have reported postnatal onset of some symptoms, including eye abnormalities, incident microcephaly in infants with a normal head circumference at birth, EEG abnormalities, and diaphragmatic paralysis.

Infants With Clinical Findings Consistent With Zika Syndrome

Infants with clinical findings consistent with congenital Zika syndrome who are born to mothers with possible Zika virus exposure in pregnancy should be tested for Zika virus with serum and urine tests. If those tests are negative, and there is no other apparent cause of the symptoms, they should have a CSF sample tested for Zika RNA and IgM Zika antibodies.

By one month, these infants should undergo a head ultrasound and a detailed ophthalmologic exam. The eye exam should pick up any anomalies of the anterior and posterior eye, including microphthalmia, coloboma, intraocular calcifications, optic nerve hypoplasia and atrophy, and macular scarring with focal pigmentary retinal mottling.

By one month, these infants also should undergo auditory brainstem response (ABR) audiometry, especially if the initial newborn hearing screen was done by otoacoustic emissions alone. Zika syndrome can include sensorineural hearing loss, although late-onset hearing loss has not been seen. Therefore, the follow-up ABR previously recommended at four to six months is no longer deemed necessary.

A comprehensive neurologic exam also is recommended. Seizures are sometimes part of Zika syndrome, but infants can also have subclinical EEG abnormalities. Advanced neuroimaging can identify obvious and subtle brain abnormalities, such as cortical thinning, corpus callosum abnormalities, calcifications at the junction of white and gray matter, and ventricular enlargement.

As infants grow, clinicians should be alert for signs of increased intracranial pressure that could signal postnatal hydrocephalus. Diaphragmatic paralysis also has been seen; it manifests as respiratory distress. Dysphagia that interferes with feeding can develop as well.

“The follow-up care of [these infants] requires a multidisciplinary team and an established medical home to facilitate the coordination of care and ensure that abnormal findings are addressed,” said Dr. Adebanjo and colleagues.

Asymptomatic Infants of Mothers With Possible Infection

Infants without clinical findings born to mothers with laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection during pregnancy should have the same early head ultrasound, hearing, and eye exams as those with clinical findings. All of these infants also should be tested for Zika virus just as those with clinical findings should be.

If tests are positive, these infants should have all the investigations and follow-up recommended for babies with clinical findings. If laboratory testing is negative, and clinical findings are normal, Zika infection is highly unlikely, and the infants can receive routine care. Clinicians and parents should be on the lookout, however, for new symptoms that might suggest postnatal Zika syndrome.

Asymptomatic Infants Whose Mothers Had Unconfirmed Zika Exposure

Infants without clinical findings consistent with congenital Zika syndrome born to mothers with possible Zika virus exposure in pregnancy, but without laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection during pregnancy, constitute a large group. Some women, for example, are never tested during pregnancy, and others have false negative test results. “Because the latter issues are not easily discerned, all mothers with possible exposure to Zika virus during pregnancy who do not have laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, including those who tested negative with currently available technology, should be considered in this group,” said Dr. Adebanjo and colleagues.

The CDC do not recommend further Zika evaluation for these infants unless additional testing confirms maternal infection. For older infants, parents and clinicians should decide together whether further evaluations would be helpful. “If findings consistent with congenital Zika syndrome are identified at any time, referrals to the appropriate specialists should be made, and subsequent evaluation should follow recommendations for infants with clinical findings consistent with congenital Zika syndrome,” said the authors.

The CDC also reiterated their special recommendations for infants who had a prenatal diagnosis of Zika infection. For now, these recommendations remain unchanged, although “as more data become available, understanding of the diagnostic role of prenatal ultrasound and amniocentesis … will improve, and guidance will be updated.”

The optimal timing for a Zika diagnostic ultrasound is uncertain. The CDC recommend that serial ultrasounds be performed every three to four weeks for women with laboratory-confirmed prenatal Zika exposure. Women with possible exposure need only routine ultrasound screenings.

While Zika RNA has been identified in amniotic fluid, there is no consensus on the value of amniocentesis as a prenatal diagnostic tool. Investigations of serial amniocentesis suggest that viral shedding into the amniotic fluid might be transient. If amniocentesis is performed for other reasons, Zika nucleic acid testing can be incorporated.

A shared decision-making process about screening is key, said Dr. Adebanjo and colleagues. “For example, serial ultrasound examinations might be inconvenient, unpleasant, and expensive, and might prompt unnecessary interventions; amniocentesis carries additional known risks such as fetal loss. These potential harms of prenatal screening for congenital Zika syndrome might outweigh the clinical benefits for some patients; therefore, these decisions should be individualized.”

—Michele G. Sullivan

Suggested Reading

Adebanjo T, Godfred-Cato S, Viens L, et al. Update: Interim guidance for the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of infants with possible congenital Zika virus infection - United States, October 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(41):1089-1099.

Infants with possible prenatal exposure to Zika who test positive for the virus should receive an in-depth ophthalmologic exam, intensified hearing testing, and a thorough neurologic evaluation with brain imaging within one month of birth, according to new interim guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The new clinical management guidelines, published in the October 20 issue of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, supersede the CDC guidance issued in August 2016. The update was the product of a forum on the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of Zika in infants that the centers convened with the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practicing clinicians and federal agency representatives reviewed the evolving body of knowledge on how best to care for these infants. Since Zika emerged as a public health concern, clinicians have reported postnatal onset of some symptoms, including eye abnormalities, incident microcephaly in infants with a normal head circumference at birth, EEG abnormalities, and diaphragmatic paralysis.

Infants With Clinical Findings Consistent With Zika Syndrome

Infants with clinical findings consistent with congenital Zika syndrome who are born to mothers with possible Zika virus exposure in pregnancy should be tested for Zika virus with serum and urine tests. If those tests are negative, and there is no other apparent cause of the symptoms, they should have a CSF sample tested for Zika RNA and IgM Zika antibodies.

By one month, these infants should undergo a head ultrasound and a detailed ophthalmologic exam. The eye exam should pick up any anomalies of the anterior and posterior eye, including microphthalmia, coloboma, intraocular calcifications, optic nerve hypoplasia and atrophy, and macular scarring with focal pigmentary retinal mottling.

By one month, these infants also should undergo auditory brainstem response (ABR) audiometry, especially if the initial newborn hearing screen was done by otoacoustic emissions alone. Zika syndrome can include sensorineural hearing loss, although late-onset hearing loss has not been seen. Therefore, the follow-up ABR previously recommended at four to six months is no longer deemed necessary.

A comprehensive neurologic exam also is recommended. Seizures are sometimes part of Zika syndrome, but infants can also have subclinical EEG abnormalities. Advanced neuroimaging can identify obvious and subtle brain abnormalities, such as cortical thinning, corpus callosum abnormalities, calcifications at the junction of white and gray matter, and ventricular enlargement.

As infants grow, clinicians should be alert for signs of increased intracranial pressure that could signal postnatal hydrocephalus. Diaphragmatic paralysis also has been seen; it manifests as respiratory distress. Dysphagia that interferes with feeding can develop as well.

“The follow-up care of [these infants] requires a multidisciplinary team and an established medical home to facilitate the coordination of care and ensure that abnormal findings are addressed,” said Dr. Adebanjo and colleagues.

Asymptomatic Infants of Mothers With Possible Infection

Infants without clinical findings born to mothers with laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection during pregnancy should have the same early head ultrasound, hearing, and eye exams as those with clinical findings. All of these infants also should be tested for Zika virus just as those with clinical findings should be.

If tests are positive, these infants should have all the investigations and follow-up recommended for babies with clinical findings. If laboratory testing is negative, and clinical findings are normal, Zika infection is highly unlikely, and the infants can receive routine care. Clinicians and parents should be on the lookout, however, for new symptoms that might suggest postnatal Zika syndrome.

Asymptomatic Infants Whose Mothers Had Unconfirmed Zika Exposure

Infants without clinical findings consistent with congenital Zika syndrome born to mothers with possible Zika virus exposure in pregnancy, but without laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection during pregnancy, constitute a large group. Some women, for example, are never tested during pregnancy, and others have false negative test results. “Because the latter issues are not easily discerned, all mothers with possible exposure to Zika virus during pregnancy who do not have laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, including those who tested negative with currently available technology, should be considered in this group,” said Dr. Adebanjo and colleagues.

The CDC do not recommend further Zika evaluation for these infants unless additional testing confirms maternal infection. For older infants, parents and clinicians should decide together whether further evaluations would be helpful. “If findings consistent with congenital Zika syndrome are identified at any time, referrals to the appropriate specialists should be made, and subsequent evaluation should follow recommendations for infants with clinical findings consistent with congenital Zika syndrome,” said the authors.

The CDC also reiterated their special recommendations for infants who had a prenatal diagnosis of Zika infection. For now, these recommendations remain unchanged, although “as more data become available, understanding of the diagnostic role of prenatal ultrasound and amniocentesis … will improve, and guidance will be updated.”

The optimal timing for a Zika diagnostic ultrasound is uncertain. The CDC recommend that serial ultrasounds be performed every three to four weeks for women with laboratory-confirmed prenatal Zika exposure. Women with possible exposure need only routine ultrasound screenings.

While Zika RNA has been identified in amniotic fluid, there is no consensus on the value of amniocentesis as a prenatal diagnostic tool. Investigations of serial amniocentesis suggest that viral shedding into the amniotic fluid might be transient. If amniocentesis is performed for other reasons, Zika nucleic acid testing can be incorporated.

A shared decision-making process about screening is key, said Dr. Adebanjo and colleagues. “For example, serial ultrasound examinations might be inconvenient, unpleasant, and expensive, and might prompt unnecessary interventions; amniocentesis carries additional known risks such as fetal loss. These potential harms of prenatal screening for congenital Zika syndrome might outweigh the clinical benefits for some patients; therefore, these decisions should be individualized.”

—Michele G. Sullivan

Suggested Reading

Adebanjo T, Godfred-Cato S, Viens L, et al. Update: Interim guidance for the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of infants with possible congenital Zika virus infection - United States, October 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(41):1089-1099.

VIDEO: U.S. hypertension guidelines reset threshold to 130/80 mm Hg

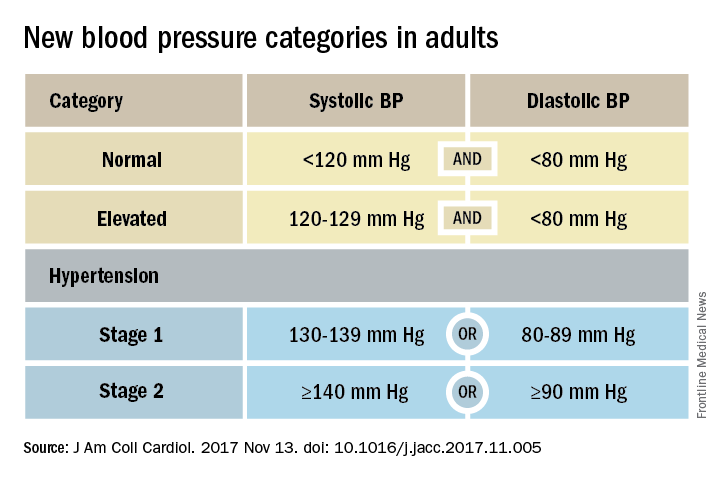

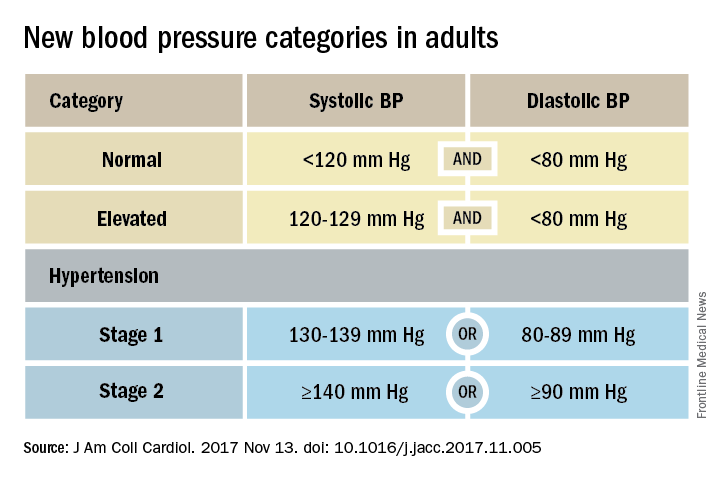

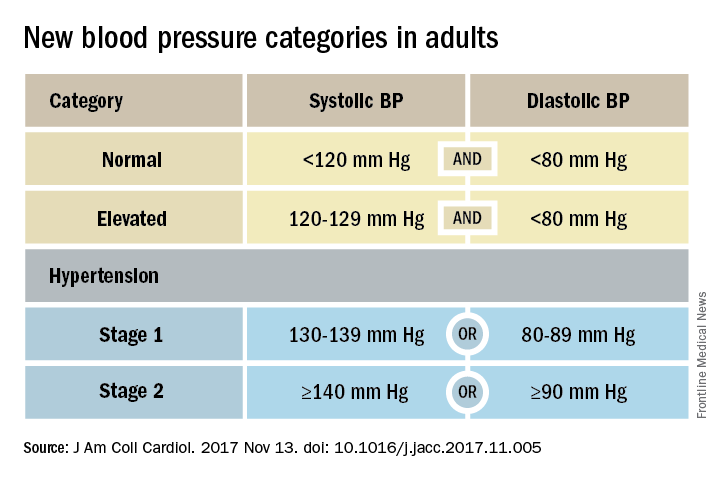

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Thirty million Americans became hypertensive overnight on Nov. 13 with the introduction of new high blood pressure guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

That happened by resetting the definition of adult hypertension from the long-standing threshold of 140/90 mm Hg to a blood pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, a change that jumps the U.S. adult prevalence of hypertension from roughly 32% to 46%. Nearly half of all U.S. adults now have hypertension, bringing the total national hypertensive population to a staggering 103 million.

Goal is to transform care

But the new guidelines (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.005) for preventing, detecting, evaluating, and managing adult hypertension do lots more than just shake up the epidemiology of high blood pressure. With 106 total recommendations, the guidelines seek to transform every aspect of blood pressure in American medical practice, starting with how it’s measured and stretching to redefine applications of medical systems to try to ensure that every person with a blood pressure that truly falls outside the redefined limits gets a comprehensive package of interventions.

Many of these are “seismic changes,” said Lawrence J. Appel, MD. He particularly cited as seismic the new classification of stage 1 hypertension as a pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, the emphasis on using some form of out-of-office blood pressure measurement to confirm a diagnosis, the use of risk assessment when deciding whether to treat certain patients with drugs, and the same blood pressure goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg for all hypertensives, regardless of age, as long as they remain ambulatory and community dwelling.

One goal for all adults

“The systolic blood pressure goal for older people has gone from 140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg and now to 130 mm Hg in the space of 2-3 years,” commented Dr. Appel, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and not involved in the guideline-writing process.

In fact, the guidelines simplified the treatment goal all around, to less than 130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes, those with chronic kidney disease, and the elderly; that goal remains the same for all adults.

“It will be clearer and easier now that everyone should be less than 130/80 mm Hg. You won’t need to remember a second target,” said Sandra J. Taler, MD, a nephrologist and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a member of the guidelines task force.

“Some people may be upset that we changed the rules on them. They had normal blood pressure yesterday, and today it’s high. But it’s a good awakening, especially for using lifestyle interventions,” Dr. Taler said in an interview.

Preferred intervention: Lifestyle, not drugs

Lifestyle optimization is repeatedly cited as the cornerstone of intervention for everyone, including those with elevated blood pressure with a systolic pressure of 120-129 mm Hg, and as the only endorsed intervention for patients with hypertension of 130-139 mm Hg but below a 10% risk for a cardiovascular disease event during the next 10 years on the American College of Cardiology’s online risk calculator. The guidelines list six lifestyle goals: weight loss, following a DASH diet, reducing sodium, enhancing potassium, 90-150 min/wk of physical activity, and moderate alcohol intake.

Team-based care essential

The guidelines also put unprecedented emphasis on using a team-based management approach, which means having nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, dietitians, and other clinicians, allowing for more frequent and focused care. Dr. Whelton and others cited in particular the VA Health System and Kaiser-Permanente as operating team-based and system-driven blood pressure management programs that have resulted in control rates for more than 90% of hypertensive patients. The team-based approach is also a key in the Target:BP program that the American Heart Association and American Medical Association founded. Target:BP will be instrumental in promoting implementation of the new guidelines, Dr. Carey said. Another systems recommendation is that every patient with hypertension should have a “clear, detailed, and current evidence-based plan of care.”

“Using nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists has been shown to improve blood pressure levels,” and health systems that use this approach have had “great success,” commented Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor and chairman of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago and not part of the guidelines task force. Some systems have used this approach to achieve high levels of blood pressure control. Now that financial penalties and incentives from payers also exist to push for higher levels of blood pressure control, the alignment of financial and health incentives should result in big changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones predicted in a video interview.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Thirty million Americans became hypertensive overnight on Nov. 13 with the introduction of new high blood pressure guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

That happened by resetting the definition of adult hypertension from the long-standing threshold of 140/90 mm Hg to a blood pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, a change that jumps the U.S. adult prevalence of hypertension from roughly 32% to 46%. Nearly half of all U.S. adults now have hypertension, bringing the total national hypertensive population to a staggering 103 million.

Goal is to transform care

But the new guidelines (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.005) for preventing, detecting, evaluating, and managing adult hypertension do lots more than just shake up the epidemiology of high blood pressure. With 106 total recommendations, the guidelines seek to transform every aspect of blood pressure in American medical practice, starting with how it’s measured and stretching to redefine applications of medical systems to try to ensure that every person with a blood pressure that truly falls outside the redefined limits gets a comprehensive package of interventions.

Many of these are “seismic changes,” said Lawrence J. Appel, MD. He particularly cited as seismic the new classification of stage 1 hypertension as a pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, the emphasis on using some form of out-of-office blood pressure measurement to confirm a diagnosis, the use of risk assessment when deciding whether to treat certain patients with drugs, and the same blood pressure goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg for all hypertensives, regardless of age, as long as they remain ambulatory and community dwelling.

One goal for all adults

“The systolic blood pressure goal for older people has gone from 140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg and now to 130 mm Hg in the space of 2-3 years,” commented Dr. Appel, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and not involved in the guideline-writing process.

In fact, the guidelines simplified the treatment goal all around, to less than 130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes, those with chronic kidney disease, and the elderly; that goal remains the same for all adults.

“It will be clearer and easier now that everyone should be less than 130/80 mm Hg. You won’t need to remember a second target,” said Sandra J. Taler, MD, a nephrologist and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a member of the guidelines task force.

“Some people may be upset that we changed the rules on them. They had normal blood pressure yesterday, and today it’s high. But it’s a good awakening, especially for using lifestyle interventions,” Dr. Taler said in an interview.

Preferred intervention: Lifestyle, not drugs

Lifestyle optimization is repeatedly cited as the cornerstone of intervention for everyone, including those with elevated blood pressure with a systolic pressure of 120-129 mm Hg, and as the only endorsed intervention for patients with hypertension of 130-139 mm Hg but below a 10% risk for a cardiovascular disease event during the next 10 years on the American College of Cardiology’s online risk calculator. The guidelines list six lifestyle goals: weight loss, following a DASH diet, reducing sodium, enhancing potassium, 90-150 min/wk of physical activity, and moderate alcohol intake.

Team-based care essential

The guidelines also put unprecedented emphasis on using a team-based management approach, which means having nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, dietitians, and other clinicians, allowing for more frequent and focused care. Dr. Whelton and others cited in particular the VA Health System and Kaiser-Permanente as operating team-based and system-driven blood pressure management programs that have resulted in control rates for more than 90% of hypertensive patients. The team-based approach is also a key in the Target:BP program that the American Heart Association and American Medical Association founded. Target:BP will be instrumental in promoting implementation of the new guidelines, Dr. Carey said. Another systems recommendation is that every patient with hypertension should have a “clear, detailed, and current evidence-based plan of care.”

“Using nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists has been shown to improve blood pressure levels,” and health systems that use this approach have had “great success,” commented Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor and chairman of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago and not part of the guidelines task force. Some systems have used this approach to achieve high levels of blood pressure control. Now that financial penalties and incentives from payers also exist to push for higher levels of blood pressure control, the alignment of financial and health incentives should result in big changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones predicted in a video interview.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Thirty million Americans became hypertensive overnight on Nov. 13 with the introduction of new high blood pressure guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

That happened by resetting the definition of adult hypertension from the long-standing threshold of 140/90 mm Hg to a blood pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, a change that jumps the U.S. adult prevalence of hypertension from roughly 32% to 46%. Nearly half of all U.S. adults now have hypertension, bringing the total national hypertensive population to a staggering 103 million.

Goal is to transform care

But the new guidelines (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.005) for preventing, detecting, evaluating, and managing adult hypertension do lots more than just shake up the epidemiology of high blood pressure. With 106 total recommendations, the guidelines seek to transform every aspect of blood pressure in American medical practice, starting with how it’s measured and stretching to redefine applications of medical systems to try to ensure that every person with a blood pressure that truly falls outside the redefined limits gets a comprehensive package of interventions.

Many of these are “seismic changes,” said Lawrence J. Appel, MD. He particularly cited as seismic the new classification of stage 1 hypertension as a pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, the emphasis on using some form of out-of-office blood pressure measurement to confirm a diagnosis, the use of risk assessment when deciding whether to treat certain patients with drugs, and the same blood pressure goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg for all hypertensives, regardless of age, as long as they remain ambulatory and community dwelling.

One goal for all adults

“The systolic blood pressure goal for older people has gone from 140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg and now to 130 mm Hg in the space of 2-3 years,” commented Dr. Appel, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and not involved in the guideline-writing process.

In fact, the guidelines simplified the treatment goal all around, to less than 130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes, those with chronic kidney disease, and the elderly; that goal remains the same for all adults.

“It will be clearer and easier now that everyone should be less than 130/80 mm Hg. You won’t need to remember a second target,” said Sandra J. Taler, MD, a nephrologist and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a member of the guidelines task force.

“Some people may be upset that we changed the rules on them. They had normal blood pressure yesterday, and today it’s high. But it’s a good awakening, especially for using lifestyle interventions,” Dr. Taler said in an interview.

Preferred intervention: Lifestyle, not drugs

Lifestyle optimization is repeatedly cited as the cornerstone of intervention for everyone, including those with elevated blood pressure with a systolic pressure of 120-129 mm Hg, and as the only endorsed intervention for patients with hypertension of 130-139 mm Hg but below a 10% risk for a cardiovascular disease event during the next 10 years on the American College of Cardiology’s online risk calculator. The guidelines list six lifestyle goals: weight loss, following a DASH diet, reducing sodium, enhancing potassium, 90-150 min/wk of physical activity, and moderate alcohol intake.

Team-based care essential

The guidelines also put unprecedented emphasis on using a team-based management approach, which means having nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, dietitians, and other clinicians, allowing for more frequent and focused care. Dr. Whelton and others cited in particular the VA Health System and Kaiser-Permanente as operating team-based and system-driven blood pressure management programs that have resulted in control rates for more than 90% of hypertensive patients. The team-based approach is also a key in the Target:BP program that the American Heart Association and American Medical Association founded. Target:BP will be instrumental in promoting implementation of the new guidelines, Dr. Carey said. Another systems recommendation is that every patient with hypertension should have a “clear, detailed, and current evidence-based plan of care.”

“Using nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists has been shown to improve blood pressure levels,” and health systems that use this approach have had “great success,” commented Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor and chairman of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago and not part of the guidelines task force. Some systems have used this approach to achieve high levels of blood pressure control. Now that financial penalties and incentives from payers also exist to push for higher levels of blood pressure control, the alignment of financial and health incentives should result in big changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones predicted in a video interview.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

VIDEO: New PsA guideline expected in 2018

SAN DIEGO – For the first time, a forthcoming evidence-based guideline for the management of psoriatic arthritis recommends tumor necrosis factor inhibitor biologics as first-line therapy.

“Guidelines that have been around for the last several years have been skirting around the fact that there’s really no evidence that methotrexate works for PsA,” Dafna D. Gladman, MD, said during a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “So it’s refreshing and reassuring that when you do an appropriate, evidence-based approach, you finally find the truth in front of you, and you have TNF inhibitors as the first-line treatment. Obviously, they’re not for everybody. There are patients in whom we cannot use TNF inhibitors, either because they don’t like needles, or because they have contraindications to getting these particular needles, but at least we have a recommendation for the use of these drugs as a first-line treatment.”

“At first, I wasn’t a big fan of the idea of the GRADE guidelines because the number of questions blows up so fast, [but] it really makes you focus on what the most common [clinical] settings are,” said another core oversight team member, Alexis Ogdie, MD, a rheumatologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “These guidelines also reveal the major gap of no head-to-head studies. I think we’ve known that, but this really called that out as important. When we’re making a treatment decision between [drugs] A and B, we need those studies to be able to better understand how to treat our patients, rather than using the data from one trial to make a decision. ... For my patients, I’m excited that I can now use a TNF inhibitor as a first-line agent. When we have patients come in with very severe disease, occasionally they also have severe psoriasis, so we’ve been able to use TNF inhibitors as first-line treatment in some of our patients in Pennsylvania. This differs state by state. But the exciting thing is that they get better so fast and you don’t have to tell them to wait 12 weeks for methotrexate to work.”

The ACR/NPF guideline is currently under peer review and is expected to be published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, Arthritis Care & Research, and the Journal of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis in the spring or summer of 2018. It focuses on common PsA patients, not exceptional cases. It includes recommendations on the management of patients with active PsA that is defined by the patients’ self-report and judged by the examining clinician to be caused by PsA, based on the on the presence of at least one of the following: actively inflamed joints; dactylitis; enthesitis; axial disease; active skin and/or nail involvement; and/or extra-articular manifestations such as uveitis or inflammatory bowel disease. Authors of the guideline considered cost as one of many possible factors affecting the use of the recommendations, but explicit cost-effectiveness analyses were not conducted. Also, since the NPF and the American Academy of Dermatology are concurrently developing a psoriasis treatment guideline, the treatment of skin psoriasis was not included in the guideline.

According to the guideline’s principal investigator Jasvinder Singh, MD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, the guideline will include 80 recommendations, 75 (94%) that are rated as “conditional,” and 5 (6%) that are rated as “strong,” based on the quality of evidence in the existing medical literature. “Most of our treatment guidelines rely on very low-to-moderate quality evidence, which means that there needs to be an active discussion between the physician and the patient with regard to which treatment to choose,” said Dr. Singh, who is also a staff rheumatologist at the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center and who led development of the 2012 and 2015 ACR treatment guidelines for RA. “When you’re not choosing the preferred treatment, there are defined specific recommendations under which that second treatment may be preferred over the first treatment.”

During a separate session at the meeting, Dr. Singh unveiled a few of the draft recommendations. One calls for using a treat-to-target strategy over not using one. In the setting of immunizing patients who are receiving a biologic, another recommendation calls for clinicians to start the indicated biologic and administer killed vaccines (as indicated) in patients with active PsA rather than delaying the biologic to give the killed vaccines. In addition, delaying the start of the indicated biologic is recommended over not delaying in order to administer a live attenuated vaccine in patients with active PsA. When patients continue to have with active PsA despite being on a TNF inhibitor, the draft guideline recommends switching to a different TNF inhibitor rather than an IL-17 inhibitor, an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor, abatacept (Orencia), tofacitinib (Xeljanz), or adding methotrexate. If PsA is still active, the guideline recommends switching to an IL-17 inhibitor instead of an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor, abatacept, or tofacitinib. If PsA is still active, the guideline recommends switching to an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor over abatacept or tofacitinib.

The guideline also includes suggestions for nonpharmacologic treatments, including recommending low-impact exercise over high-impact exercise, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and weight loss. It also includes a strong recommendation to provide smoking cessation advice to patients.

Dr. Singh acknowledged significant research gaps in the current PsA medical literature, including no head-to-head comparisons of treatments. He said that the field also could benefit from specific studies for enthesitis, axial disease, and arthritis mutilans; randomized trials of nonpharmacologic interventions; more trials of monotherapy vs. combination therapy; vaccination trials for live attenuated vaccines; trials and registry studies of patients with common comorbidities, and studies of NSAIDs and glucocorticoids, to define their role.

Possible topics for future PsA guidelines, he continued, include treatment options for patients for whom biologic medication is not an option; use of therapies in pregnancy and conception; incorporation of high-quality cost or cost-effectiveness analysis into recommendations; and the role of other comorbidities, such as fibromyalgia, hepatitis, depression/anxiety, malignancy, and cardiovascular disease.

“Evidence-based medicine needs to be practiced, even in situations where it’s difficult to get a drug,” Dr. Gladman said. “One of the things we hope will happen in the near future is that companies will start doing head-to-head studies, to help us support evidence-based recommendations in the future.”

None of the speakers reported having relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – For the first time, a forthcoming evidence-based guideline for the management of psoriatic arthritis recommends tumor necrosis factor inhibitor biologics as first-line therapy.

“Guidelines that have been around for the last several years have been skirting around the fact that there’s really no evidence that methotrexate works for PsA,” Dafna D. Gladman, MD, said during a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “So it’s refreshing and reassuring that when you do an appropriate, evidence-based approach, you finally find the truth in front of you, and you have TNF inhibitors as the first-line treatment. Obviously, they’re not for everybody. There are patients in whom we cannot use TNF inhibitors, either because they don’t like needles, or because they have contraindications to getting these particular needles, but at least we have a recommendation for the use of these drugs as a first-line treatment.”

“At first, I wasn’t a big fan of the idea of the GRADE guidelines because the number of questions blows up so fast, [but] it really makes you focus on what the most common [clinical] settings are,” said another core oversight team member, Alexis Ogdie, MD, a rheumatologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “These guidelines also reveal the major gap of no head-to-head studies. I think we’ve known that, but this really called that out as important. When we’re making a treatment decision between [drugs] A and B, we need those studies to be able to better understand how to treat our patients, rather than using the data from one trial to make a decision. ... For my patients, I’m excited that I can now use a TNF inhibitor as a first-line agent. When we have patients come in with very severe disease, occasionally they also have severe psoriasis, so we’ve been able to use TNF inhibitors as first-line treatment in some of our patients in Pennsylvania. This differs state by state. But the exciting thing is that they get better so fast and you don’t have to tell them to wait 12 weeks for methotrexate to work.”

The ACR/NPF guideline is currently under peer review and is expected to be published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, Arthritis Care & Research, and the Journal of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis in the spring or summer of 2018. It focuses on common PsA patients, not exceptional cases. It includes recommendations on the management of patients with active PsA that is defined by the patients’ self-report and judged by the examining clinician to be caused by PsA, based on the on the presence of at least one of the following: actively inflamed joints; dactylitis; enthesitis; axial disease; active skin and/or nail involvement; and/or extra-articular manifestations such as uveitis or inflammatory bowel disease. Authors of the guideline considered cost as one of many possible factors affecting the use of the recommendations, but explicit cost-effectiveness analyses were not conducted. Also, since the NPF and the American Academy of Dermatology are concurrently developing a psoriasis treatment guideline, the treatment of skin psoriasis was not included in the guideline.

According to the guideline’s principal investigator Jasvinder Singh, MD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, the guideline will include 80 recommendations, 75 (94%) that are rated as “conditional,” and 5 (6%) that are rated as “strong,” based on the quality of evidence in the existing medical literature. “Most of our treatment guidelines rely on very low-to-moderate quality evidence, which means that there needs to be an active discussion between the physician and the patient with regard to which treatment to choose,” said Dr. Singh, who is also a staff rheumatologist at the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center and who led development of the 2012 and 2015 ACR treatment guidelines for RA. “When you’re not choosing the preferred treatment, there are defined specific recommendations under which that second treatment may be preferred over the first treatment.”

During a separate session at the meeting, Dr. Singh unveiled a few of the draft recommendations. One calls for using a treat-to-target strategy over not using one. In the setting of immunizing patients who are receiving a biologic, another recommendation calls for clinicians to start the indicated biologic and administer killed vaccines (as indicated) in patients with active PsA rather than delaying the biologic to give the killed vaccines. In addition, delaying the start of the indicated biologic is recommended over not delaying in order to administer a live attenuated vaccine in patients with active PsA. When patients continue to have with active PsA despite being on a TNF inhibitor, the draft guideline recommends switching to a different TNF inhibitor rather than an IL-17 inhibitor, an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor, abatacept (Orencia), tofacitinib (Xeljanz), or adding methotrexate. If PsA is still active, the guideline recommends switching to an IL-17 inhibitor instead of an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor, abatacept, or tofacitinib. If PsA is still active, the guideline recommends switching to an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor over abatacept or tofacitinib.

The guideline also includes suggestions for nonpharmacologic treatments, including recommending low-impact exercise over high-impact exercise, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and weight loss. It also includes a strong recommendation to provide smoking cessation advice to patients.

Dr. Singh acknowledged significant research gaps in the current PsA medical literature, including no head-to-head comparisons of treatments. He said that the field also could benefit from specific studies for enthesitis, axial disease, and arthritis mutilans; randomized trials of nonpharmacologic interventions; more trials of monotherapy vs. combination therapy; vaccination trials for live attenuated vaccines; trials and registry studies of patients with common comorbidities, and studies of NSAIDs and glucocorticoids, to define their role.

Possible topics for future PsA guidelines, he continued, include treatment options for patients for whom biologic medication is not an option; use of therapies in pregnancy and conception; incorporation of high-quality cost or cost-effectiveness analysis into recommendations; and the role of other comorbidities, such as fibromyalgia, hepatitis, depression/anxiety, malignancy, and cardiovascular disease.

“Evidence-based medicine needs to be practiced, even in situations where it’s difficult to get a drug,” Dr. Gladman said. “One of the things we hope will happen in the near future is that companies will start doing head-to-head studies, to help us support evidence-based recommendations in the future.”

None of the speakers reported having relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – For the first time, a forthcoming evidence-based guideline for the management of psoriatic arthritis recommends tumor necrosis factor inhibitor biologics as first-line therapy.

“Guidelines that have been around for the last several years have been skirting around the fact that there’s really no evidence that methotrexate works for PsA,” Dafna D. Gladman, MD, said during a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “So it’s refreshing and reassuring that when you do an appropriate, evidence-based approach, you finally find the truth in front of you, and you have TNF inhibitors as the first-line treatment. Obviously, they’re not for everybody. There are patients in whom we cannot use TNF inhibitors, either because they don’t like needles, or because they have contraindications to getting these particular needles, but at least we have a recommendation for the use of these drugs as a first-line treatment.”

“At first, I wasn’t a big fan of the idea of the GRADE guidelines because the number of questions blows up so fast, [but] it really makes you focus on what the most common [clinical] settings are,” said another core oversight team member, Alexis Ogdie, MD, a rheumatologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “These guidelines also reveal the major gap of no head-to-head studies. I think we’ve known that, but this really called that out as important. When we’re making a treatment decision between [drugs] A and B, we need those studies to be able to better understand how to treat our patients, rather than using the data from one trial to make a decision. ... For my patients, I’m excited that I can now use a TNF inhibitor as a first-line agent. When we have patients come in with very severe disease, occasionally they also have severe psoriasis, so we’ve been able to use TNF inhibitors as first-line treatment in some of our patients in Pennsylvania. This differs state by state. But the exciting thing is that they get better so fast and you don’t have to tell them to wait 12 weeks for methotrexate to work.”

The ACR/NPF guideline is currently under peer review and is expected to be published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, Arthritis Care & Research, and the Journal of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis in the spring or summer of 2018. It focuses on common PsA patients, not exceptional cases. It includes recommendations on the management of patients with active PsA that is defined by the patients’ self-report and judged by the examining clinician to be caused by PsA, based on the on the presence of at least one of the following: actively inflamed joints; dactylitis; enthesitis; axial disease; active skin and/or nail involvement; and/or extra-articular manifestations such as uveitis or inflammatory bowel disease. Authors of the guideline considered cost as one of many possible factors affecting the use of the recommendations, but explicit cost-effectiveness analyses were not conducted. Also, since the NPF and the American Academy of Dermatology are concurrently developing a psoriasis treatment guideline, the treatment of skin psoriasis was not included in the guideline.

According to the guideline’s principal investigator Jasvinder Singh, MD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, the guideline will include 80 recommendations, 75 (94%) that are rated as “conditional,” and 5 (6%) that are rated as “strong,” based on the quality of evidence in the existing medical literature. “Most of our treatment guidelines rely on very low-to-moderate quality evidence, which means that there needs to be an active discussion between the physician and the patient with regard to which treatment to choose,” said Dr. Singh, who is also a staff rheumatologist at the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center and who led development of the 2012 and 2015 ACR treatment guidelines for RA. “When you’re not choosing the preferred treatment, there are defined specific recommendations under which that second treatment may be preferred over the first treatment.”

During a separate session at the meeting, Dr. Singh unveiled a few of the draft recommendations. One calls for using a treat-to-target strategy over not using one. In the setting of immunizing patients who are receiving a biologic, another recommendation calls for clinicians to start the indicated biologic and administer killed vaccines (as indicated) in patients with active PsA rather than delaying the biologic to give the killed vaccines. In addition, delaying the start of the indicated biologic is recommended over not delaying in order to administer a live attenuated vaccine in patients with active PsA. When patients continue to have with active PsA despite being on a TNF inhibitor, the draft guideline recommends switching to a different TNF inhibitor rather than an IL-17 inhibitor, an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor, abatacept (Orencia), tofacitinib (Xeljanz), or adding methotrexate. If PsA is still active, the guideline recommends switching to an IL-17 inhibitor instead of an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor, abatacept, or tofacitinib. If PsA is still active, the guideline recommends switching to an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor over abatacept or tofacitinib.

The guideline also includes suggestions for nonpharmacologic treatments, including recommending low-impact exercise over high-impact exercise, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and weight loss. It also includes a strong recommendation to provide smoking cessation advice to patients.

Dr. Singh acknowledged significant research gaps in the current PsA medical literature, including no head-to-head comparisons of treatments. He said that the field also could benefit from specific studies for enthesitis, axial disease, and arthritis mutilans; randomized trials of nonpharmacologic interventions; more trials of monotherapy vs. combination therapy; vaccination trials for live attenuated vaccines; trials and registry studies of patients with common comorbidities, and studies of NSAIDs and glucocorticoids, to define their role.

Possible topics for future PsA guidelines, he continued, include treatment options for patients for whom biologic medication is not an option; use of therapies in pregnancy and conception; incorporation of high-quality cost or cost-effectiveness analysis into recommendations; and the role of other comorbidities, such as fibromyalgia, hepatitis, depression/anxiety, malignancy, and cardiovascular disease.

“Evidence-based medicine needs to be practiced, even in situations where it’s difficult to get a drug,” Dr. Gladman said. “One of the things we hope will happen in the near future is that companies will start doing head-to-head studies, to help us support evidence-based recommendations in the future.”

None of the speakers reported having relevant financial disclosures.

AT ACR 2017

ACOG: VBAC is safe for many women

Women and their , according to an updated practice bulletin from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Trial of labor after cesarean delivery (TOLAC) results in a successful birth in 60%-80% of cases, sparing mothers from major abdominal surgery and reducing the risk of hemorrhage, thromboses, and infection, the authors of the practice bulletin wrote. “The preponderance of evidence suggests that most women with one previous cesarean delivery with a low-transverse incision are candidates for and should be counseled about and offered TOLAC,” they said (Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Nov;130[5]:e217-33. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002398).

Rates of cesarean delivery in the United States jumped from 5% to nearly 32% between 1970 and 2016. Although rates of VBAC rose between the mid-1980s and the mid-1990s, cases of uterine rupture and other complications spurred fears of malpractice litigation and reversed this trend. VBAC rates were more than 28% in 1996 but fell to 8.5% by 2006, according to the practice bulletin.

To reduce the risk of uterine rupture, avoid misoprostol for cervical ripening and labor induction in women with a prior cesarean delivery, ACOG recommended.

“No evidence suggests that epidural analgesia is a causal risk factor for unsuccessful TOLAC,” the authors added. “Therefore, epidural analgesia for labor may be used as part of TOLAC, and adequate pain relief may encourage more women to choose TOLAC.”

Women with two prior low-transverse cesareans also are potential candidates for TOLAC, depending on other predictors of successful VBAC. Factors that reduce the chances of a successful TOLAC include advanced maternal age, high body mass index, high birth weight, gestational age of more than 40 weeks at delivery, and preeclampsia at the time of delivery, according to the practice bulletin.

To reduce the risk of adverse outcomes of complications, TOLAC should not occur at home and should only occur at level I facilities (or higher) that can perform an emergency cesarean delivery if the mother or fetus is in jeopardy.