User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss soars after NYT article

.

The weekly rate of first-time low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) prescriptions per 10,000 outpatient encounters was “significantly higher 8 weeks after vs. 8 weeks before article publication,” at 0.9 prescriptions, compared with 0.5 per 10,000, wrote the authors of the research letter, published in JAMA Network Open. There was no similar bump for first-time finasteride or hypertension prescriptions, wrote the authors, from Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Truveta, a company that provides EHR data from U.S. health care systems.

The New York Times article noted that LDOM was relatively unknown to patients and doctors – and not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating hair loss – but that it was inexpensive, safe, and very effective for many individuals. “The article did not report new research findings or large-scale randomized evidence,” wrote the authors of the JAMA study.

Rodney Sinclair, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of Melbourne, who conducted the original research on LDOM and hair loss and was quoted in the Times story, told this news organization that “the sharp uplift after the New York Times article was on the back of a gradual increase.” He added that “the momentum for minoxidil prescriptions is increasing,” so much so that it has led to a global shortage of LDOM. The drug appears to still be widely available in the United States, however. It is not on the ASHP shortages list.

“There has been growing momentum for minoxidil use since I first presented our data about 6 years ago,” Dr. Sinclair said. He noted that 2022 International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery survey data found that 26% of treating physicians always or often prescribed off-label oral minoxidil, up from 10% in 2019 and 0% in 2017, while another 20% said they prescribed it sometimes.

The authors of the new study looked at prescriptions for patients at eight health care systems before and after the Times article was published in August 2022. They calculated the rate of first-time oral minoxidil prescriptions for 2.5 mg and 5 mg tablets, excluding 10 mg tablets, which are prescribed for hypertension.

Among those receiving first-time prescriptions, 2,846 received them in the 7 months before the article and 3,695 in the 5 months after publication. Men (43.6% after vs. 37.7% before publication) and White individuals (68.6% after vs. 60.8% before publication) accounted for a higher proportion of prescriptions after the article was published. There was a 2.4-fold increase in first-time prescriptions among men, and a 1.7-fold increase among females, while people with comorbidities accounted for a smaller proportion after the publication.

“Socioeconomic factors, such as access to health care and education and income levels, may be associated with individuals seeking low-dose oral minoxidil after article publication,” wrote the authors.

In an interview, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said that he was not surprised to see an uptick in prescriptions after the Times article.

He and his colleagues were curious as to whether the article might have prompted newfound interest in LDOM. They experienced an uptick at George Washington, which Dr. Friedman thought could have been because he was quoted in the Times story. He and colleagues conducted a national survey of dermatologists asking if more patients had called, emailed, or come in to the office asking about LDOM after the article’s publication. “Over 85% said yes,” Dr. Friedman said in the interview. He and his coauthors also found a huge increase in Google searches for terms such as hair loss, alopecia, and minoxidil in the weeks after the article, he said.

The results are expected to published soon in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

“I think a lot of people know about [LDOM] and it’s certainly has gained a lot more attention and acceptance in recent years,” said Dr. Friedman, but he added that “there’s no question” that the Times article increased interest.

That is not necessarily a bad thing, he said. “With one article, education on a common disease was disseminated worldwide in a way that no one doctor can do,” he said. The article was truthful, evidence-based, and included expert dermatologists, he noted.

“It probably got people who never thought twice about their hair thinning to actually think that there’s hope,” he said, adding that it also likely prompted them to seek care, and, more importantly, “to seek care from the person who should be taking care of this, which is the dermatologist.”

However, the article might also inspire some people to think LDOM can help when it can’t, or they might insist on a prescription when another medication is more appropriate, said Dr. Friedman.

Both he and Dr. Sinclair expect demand for LDOM to continue increasing.

“Word of mouth will drive the next wave of prescriptions,” said Dr. Sinclair. “We are continuing to do work to improve safety, to understand its mechanism of action, and identify ways to improve equity of access to treatment for men and women who are concerned about their hair loss and motivated to treat it,” he said.

Dr. Sinclair and Dr. Friedman report no relevant financial relationships.

.

The weekly rate of first-time low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) prescriptions per 10,000 outpatient encounters was “significantly higher 8 weeks after vs. 8 weeks before article publication,” at 0.9 prescriptions, compared with 0.5 per 10,000, wrote the authors of the research letter, published in JAMA Network Open. There was no similar bump for first-time finasteride or hypertension prescriptions, wrote the authors, from Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Truveta, a company that provides EHR data from U.S. health care systems.

The New York Times article noted that LDOM was relatively unknown to patients and doctors – and not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating hair loss – but that it was inexpensive, safe, and very effective for many individuals. “The article did not report new research findings or large-scale randomized evidence,” wrote the authors of the JAMA study.

Rodney Sinclair, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of Melbourne, who conducted the original research on LDOM and hair loss and was quoted in the Times story, told this news organization that “the sharp uplift after the New York Times article was on the back of a gradual increase.” He added that “the momentum for minoxidil prescriptions is increasing,” so much so that it has led to a global shortage of LDOM. The drug appears to still be widely available in the United States, however. It is not on the ASHP shortages list.

“There has been growing momentum for minoxidil use since I first presented our data about 6 years ago,” Dr. Sinclair said. He noted that 2022 International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery survey data found that 26% of treating physicians always or often prescribed off-label oral minoxidil, up from 10% in 2019 and 0% in 2017, while another 20% said they prescribed it sometimes.

The authors of the new study looked at prescriptions for patients at eight health care systems before and after the Times article was published in August 2022. They calculated the rate of first-time oral minoxidil prescriptions for 2.5 mg and 5 mg tablets, excluding 10 mg tablets, which are prescribed for hypertension.

Among those receiving first-time prescriptions, 2,846 received them in the 7 months before the article and 3,695 in the 5 months after publication. Men (43.6% after vs. 37.7% before publication) and White individuals (68.6% after vs. 60.8% before publication) accounted for a higher proportion of prescriptions after the article was published. There was a 2.4-fold increase in first-time prescriptions among men, and a 1.7-fold increase among females, while people with comorbidities accounted for a smaller proportion after the publication.

“Socioeconomic factors, such as access to health care and education and income levels, may be associated with individuals seeking low-dose oral minoxidil after article publication,” wrote the authors.

In an interview, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said that he was not surprised to see an uptick in prescriptions after the Times article.

He and his colleagues were curious as to whether the article might have prompted newfound interest in LDOM. They experienced an uptick at George Washington, which Dr. Friedman thought could have been because he was quoted in the Times story. He and colleagues conducted a national survey of dermatologists asking if more patients had called, emailed, or come in to the office asking about LDOM after the article’s publication. “Over 85% said yes,” Dr. Friedman said in the interview. He and his coauthors also found a huge increase in Google searches for terms such as hair loss, alopecia, and minoxidil in the weeks after the article, he said.

The results are expected to published soon in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

“I think a lot of people know about [LDOM] and it’s certainly has gained a lot more attention and acceptance in recent years,” said Dr. Friedman, but he added that “there’s no question” that the Times article increased interest.

That is not necessarily a bad thing, he said. “With one article, education on a common disease was disseminated worldwide in a way that no one doctor can do,” he said. The article was truthful, evidence-based, and included expert dermatologists, he noted.

“It probably got people who never thought twice about their hair thinning to actually think that there’s hope,” he said, adding that it also likely prompted them to seek care, and, more importantly, “to seek care from the person who should be taking care of this, which is the dermatologist.”

However, the article might also inspire some people to think LDOM can help when it can’t, or they might insist on a prescription when another medication is more appropriate, said Dr. Friedman.

Both he and Dr. Sinclair expect demand for LDOM to continue increasing.

“Word of mouth will drive the next wave of prescriptions,” said Dr. Sinclair. “We are continuing to do work to improve safety, to understand its mechanism of action, and identify ways to improve equity of access to treatment for men and women who are concerned about their hair loss and motivated to treat it,” he said.

Dr. Sinclair and Dr. Friedman report no relevant financial relationships.

.

The weekly rate of first-time low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) prescriptions per 10,000 outpatient encounters was “significantly higher 8 weeks after vs. 8 weeks before article publication,” at 0.9 prescriptions, compared with 0.5 per 10,000, wrote the authors of the research letter, published in JAMA Network Open. There was no similar bump for first-time finasteride or hypertension prescriptions, wrote the authors, from Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Truveta, a company that provides EHR data from U.S. health care systems.

The New York Times article noted that LDOM was relatively unknown to patients and doctors – and not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating hair loss – but that it was inexpensive, safe, and very effective for many individuals. “The article did not report new research findings or large-scale randomized evidence,” wrote the authors of the JAMA study.

Rodney Sinclair, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of Melbourne, who conducted the original research on LDOM and hair loss and was quoted in the Times story, told this news organization that “the sharp uplift after the New York Times article was on the back of a gradual increase.” He added that “the momentum for minoxidil prescriptions is increasing,” so much so that it has led to a global shortage of LDOM. The drug appears to still be widely available in the United States, however. It is not on the ASHP shortages list.

“There has been growing momentum for minoxidil use since I first presented our data about 6 years ago,” Dr. Sinclair said. He noted that 2022 International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery survey data found that 26% of treating physicians always or often prescribed off-label oral minoxidil, up from 10% in 2019 and 0% in 2017, while another 20% said they prescribed it sometimes.

The authors of the new study looked at prescriptions for patients at eight health care systems before and after the Times article was published in August 2022. They calculated the rate of first-time oral minoxidil prescriptions for 2.5 mg and 5 mg tablets, excluding 10 mg tablets, which are prescribed for hypertension.

Among those receiving first-time prescriptions, 2,846 received them in the 7 months before the article and 3,695 in the 5 months after publication. Men (43.6% after vs. 37.7% before publication) and White individuals (68.6% after vs. 60.8% before publication) accounted for a higher proportion of prescriptions after the article was published. There was a 2.4-fold increase in first-time prescriptions among men, and a 1.7-fold increase among females, while people with comorbidities accounted for a smaller proportion after the publication.

“Socioeconomic factors, such as access to health care and education and income levels, may be associated with individuals seeking low-dose oral minoxidil after article publication,” wrote the authors.

In an interview, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said that he was not surprised to see an uptick in prescriptions after the Times article.

He and his colleagues were curious as to whether the article might have prompted newfound interest in LDOM. They experienced an uptick at George Washington, which Dr. Friedman thought could have been because he was quoted in the Times story. He and colleagues conducted a national survey of dermatologists asking if more patients had called, emailed, or come in to the office asking about LDOM after the article’s publication. “Over 85% said yes,” Dr. Friedman said in the interview. He and his coauthors also found a huge increase in Google searches for terms such as hair loss, alopecia, and minoxidil in the weeks after the article, he said.

The results are expected to published soon in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

“I think a lot of people know about [LDOM] and it’s certainly has gained a lot more attention and acceptance in recent years,” said Dr. Friedman, but he added that “there’s no question” that the Times article increased interest.

That is not necessarily a bad thing, he said. “With one article, education on a common disease was disseminated worldwide in a way that no one doctor can do,” he said. The article was truthful, evidence-based, and included expert dermatologists, he noted.

“It probably got people who never thought twice about their hair thinning to actually think that there’s hope,” he said, adding that it also likely prompted them to seek care, and, more importantly, “to seek care from the person who should be taking care of this, which is the dermatologist.”

However, the article might also inspire some people to think LDOM can help when it can’t, or they might insist on a prescription when another medication is more appropriate, said Dr. Friedman.

Both he and Dr. Sinclair expect demand for LDOM to continue increasing.

“Word of mouth will drive the next wave of prescriptions,” said Dr. Sinclair. “We are continuing to do work to improve safety, to understand its mechanism of action, and identify ways to improve equity of access to treatment for men and women who are concerned about their hair loss and motivated to treat it,” he said.

Dr. Sinclair and Dr. Friedman report no relevant financial relationships.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Cuffless blood pressure monitors: Still a numbers game

Medscape’s Editor-in-Chief Eric Topol, MD, referred to continual noninvasive, cuffless, accurate blood pressure devices as “a holy grail in sensor technology.”

He personally tested a cuff-calibrated, over-the-counter device available in Europe that claims to monitor daily blood pressure changes and produce data that can help physicians titrate medications.

Dr. Topol does not believe that it is ready for prime time. Yes, cuffless devices are easy to use, and generate lots of data. But are those data accurate?

Many experts say not yet, even as the market continues to grow and more devices are introduced and highlighted at high-profile consumer events.

Burned before

Limitations of cuffed devices are well known, including errors related to cuff size, patient positioning, patient habits or behaviors (for example, caffeine/nicotine use, acute meal digestion, full bladder, very recent physical activity) and clinicians’ failure to take accurate measurements.

Like many clinicians, Timothy B. Plante, MD, MHS, assistant professor at the University of Vermont Medical Center thrombosis & hemostasis program in Burlington, is very excited about cuffless technology. However, “we’ve been burned by it before,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Plante’s 2016 validation study of an instant blood pressure smartphone app found that its measurements were “highly inaccurate,” with such low sensitivity that more than three-quarters of individuals with hypertensive blood levels would be falsely reassured that their blood pressure was in the normal range.

His team’s 2023 review of the current landscape, which includes more sophisticated devices, concluded that accuracy remains an issue: “Unfortunately, the pace of regulation of these devices has failed to match the speed of innovation and direct availability to patient consumers. There is an urgent need to develop a consensus on standards by which cuffless BP devices can be tested for accuracy.”

Devices, indications differ

Cuffless devices estimate blood pressure indirectly. Most operate based on pulse wave analysis and pulse arrival time (PWA-PAT), explained Ramakrishna Mukkamala, PhD, in a commentary. Dr. Mukkamala is a professor in the departments of bioengineering and anesthesiology and perioperative medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

PWA involves measuring a peripheral arterial waveform using an optical sensor such as the green lights on the back of a wrist-worn device, or a ‘force sensor’ such as a finger cuff or pressing on a smartphone. Certain features are extracted from the waveform using machine learning and calibrated to blood pressure values.

PAT techniques work together with PWA; they record the ECG and extract features from that signal as well as the arterial waveform for calibration to blood pressure values.

The algorithm used to generate the BP numbers comprises a proprietary baseline model that may include demographics and other patient characteristics. A cuff measurement is often part of the baseline model because most cuffless devices require periodic (typically weekly or monthly) calibration using a cuffed device.

Cuffless devices that require cuff calibration compare the estimate they get to the cuff-calibrated number. In this scenario, the cuffless device may come up with the same blood pressure numbers simply because the baseline model – which is made up of thousands of data points relevant to the patient – has not changed.

This has led some experts to question whether PWA-PAT cuffless device readings actually add anything to the baseline model.

They don’t, according to Microsoft Research in what Dr. Mukkamala and coauthors referred to (in a review published in Hypertension) as “a complex article describing perhaps the most important and highest resource project to date (Aurora Project) on assessing the accuracy of PWA and PWA devices.”

The Microsoft article was written for bioengineers. The review in Hypertension explains the project for clinicians, and concludes that, “Cuffless BP devices based on PWA and PWA-PAT, which are similar to some regulatory-cleared devices, were of no additional value in measuring auscultatory or 24-hour ambulatory cuff BP when compared with a baseline model in which BP was predicted without an actual measurement.”

IEEE and FDA validation

Despite these concerns, several cuffless devices using PWA and PAT have been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration.

Validating cuffless devices is no simple matter. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers published a validation protocol for cuffless blood pressure devices in 2014 that was amended in 2019 to include a requirement to evaluate performance in different positions and in the presence of motion with varying degrees of noise artifact.

However, Daichi Shimbo, MD, codirector of the Columbia Hypertension Center in New York and vice chair of the American Heart Association Statement on blood pressure monitoring, and colleagues point out limitations, even in the updated standard. These include not requiring evaluation for drift over time; lack of specific dynamic testing protocols for stressors such as exercise or environmental temperatures; and an unsuitable reference standard (oscillometric cuff-based devices) during movement.

Dr. Shimbo said in an interview that, although he is excited about them, “these cuffless devices are not aligned with regulatory bodies. If a device gives someone a wrong blood pressure, they might be diagnosed with hypertension when they don’t have it or might miss the fact that they’re hypertensive because they get a normal blood pressure reading. If there’s no yardstick by which you say these devices are good, what are we really doing – helping, or causing a problem?”

“The specifics of how a device estimates blood pressure can determine what testing is needed to ensure that it is providing accurate performance in the intended conditions of use,” Jeremy Kahn, an FDA press officer, said in an interview. “For example, for cuffless devices that are calibrated initially with a cuff-based blood pressure device, the cuffless device needs to specify the period over which it can provide accurate readings and have testing to demonstrate that it provides accurate results over that period of use.”

The FDA said its testing is different from what the Microsoft Aurora Project used in their study.

“The intent of that testing, as the agency understands it, is to evaluate whether the device is providing useful input based on the current physiology of the patient rather than relying on predetermined values based on calibration or patient attributes. We evaluate this clinically in two separate tests: an induced change in blood pressure test and tracking of natural blood pressure changes with longer term device use,” Mr. Kahn explained.

Analyzing a device’s performance on individuals who have had natural changes in blood pressure as compared to a calibration value or initial reading “can also help discern if the device is using physiological data from the patient to determine their blood pressure accurately,” he said.

Experts interviewed for this article who remain skeptical about cuffless BP monitoring question whether the numbers that appear during the induced blood pressure change, and with the natural blood pressure changes that may occur over time, accurately reflect a patient’s blood pressure.

“The FDA doesn’t approve these devices; they clear them,” Dr. Shimbo pointed out. “Clearing them means they can be sold to the general public in the U.S. It’s not a strong statement that they’re accurate.”

Moving toward validation, standards

Ultimately, cuffless BP monitors may require more than one validation protocol and standard, depending on their technology, how and where they will be used, and by whom.

And as Dr. Plante and colleagues write, “Importantly, validation should be performed in diverse and special populations, including pregnant women and individuals across a range of heart rates, skin tones, wrist sizes, common arrhythmias, and beta-blocker use.”

Organizations that might be expected to help move validation and standards forward have mostly remained silent. The American Medical Association’s US Blood Pressure Validated Device Listing website includes only cuffed devices, as does the website of the international scientific nonprofit STRIDE BP.

The European Society of Hypertension 2022 consensus statement on cuffless devices concluded that, until there is an internationally accepted accuracy standard and the devices have been tested in healthy people and those with suspected or diagnosed hypertension, “cuffless BP devices should not be used for the evaluation or management of hypertension in clinical practice.”

This month, ESH published recommendations for “specific, clinically meaningful, and pragmatic validation procedures for different types of intermittent cuffless devices” that will be presented at their upcoming annual meeting June 26.

Updated protocols from IEEE “are coming out soon,” according to Dr. Shimbo. The FDA says currently cleared devices won’t need to revalidate according to new standards unless the sponsor makes significant modifications in software algorithms, device hardware, or targeted patient populations.

Device makers take the initiative

In the face of conflicting reports on accuracy and lack of a robust standard, some device makers are publishing their own tests or encouraging validation by potential customers.

For example, institutions that are considering using the Biobeat cuffless blood pressure monitor watch “usually start with small pilots with our devices to do internal validation,” Lior Ben Shettrit, the company’s vice president of business development, said in an interview. “Only after they complete the internal validation are they willing to move forward to full implementation.”

Cardiologist Dean Nachman, MD, is leading validation studies of the Biobeat device at the Hadassah Ein Kerem Medical Center in Jerusalem. For the first validation, the team recruited 1,057 volunteers who did a single blood pressure measurement with the cuffless device and with a cuffed device.

“We found 96.3% agreement in identifying hypertension and an interclass correlation coefficient of 0.99 and 0.97 for systolic and diastolic measurements, respectively,” he said. “Then we took it to the next level and compared the device to ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure monitoring and found comparable measurements.”

The investigators are not done yet. “We need data from thousands of patients, with subgroups, to not have any concerns,” he says. “Right now, we are using the device as a general monitor – as an EKG plus heart rate plus oxygen saturation level monitor – and as a blood pressure monitor for 24-hour blood pressure monitoring.”

The developers of the Aktiia device, which is the one Dr. Topol tested, take a different perspective. “When somebody introduces a new technology that is disrupting something that has been in place for over 100 years, there will always be some grumblings, ruffling of feathers, people saying it’s not ready, it’s not ready, it’s not ready,” Aktiia’s chief medical officer Jay Shah, MD, noted.

“But a lot of those comments are coming from the isolation of an ivory tower,” he said.

Aktiia cofounder and chief technology officer Josep Solà said that “no device is probably as accurate as if you have an invasive catheter,” adding that “we engage patients to look at their blood pressure day by day. … If each individual measurement of each of those patient is slightly less accurate than a cuff, who cares? We have 40 measurements per day on each patient. The accuracy and precision of each of those is good.”

Researchers from the George Institute for Global Health recently compared the Aktiia device to conventional ambulatory monitoring in 41 patients and found that “it did not accurately track night-time BP decline and results suggested it was unable to track medication-induced BP changes.”

“In the context of 24/7 monitoring of hypertensive patients,” Mr. Solà said, “whatever you do, if it’s better than a sham device or a baseline model and you track the blood pressure changes, it’s a hundred times much better than doing nothing.”

Dr. Nachman and Dr. Plante reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Shimbo reported that he received funding from NIH and has consulted for Abbott Vascular, Edward Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Tryton Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medscape’s Editor-in-Chief Eric Topol, MD, referred to continual noninvasive, cuffless, accurate blood pressure devices as “a holy grail in sensor technology.”

He personally tested a cuff-calibrated, over-the-counter device available in Europe that claims to monitor daily blood pressure changes and produce data that can help physicians titrate medications.

Dr. Topol does not believe that it is ready for prime time. Yes, cuffless devices are easy to use, and generate lots of data. But are those data accurate?

Many experts say not yet, even as the market continues to grow and more devices are introduced and highlighted at high-profile consumer events.

Burned before

Limitations of cuffed devices are well known, including errors related to cuff size, patient positioning, patient habits or behaviors (for example, caffeine/nicotine use, acute meal digestion, full bladder, very recent physical activity) and clinicians’ failure to take accurate measurements.

Like many clinicians, Timothy B. Plante, MD, MHS, assistant professor at the University of Vermont Medical Center thrombosis & hemostasis program in Burlington, is very excited about cuffless technology. However, “we’ve been burned by it before,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Plante’s 2016 validation study of an instant blood pressure smartphone app found that its measurements were “highly inaccurate,” with such low sensitivity that more than three-quarters of individuals with hypertensive blood levels would be falsely reassured that their blood pressure was in the normal range.

His team’s 2023 review of the current landscape, which includes more sophisticated devices, concluded that accuracy remains an issue: “Unfortunately, the pace of regulation of these devices has failed to match the speed of innovation and direct availability to patient consumers. There is an urgent need to develop a consensus on standards by which cuffless BP devices can be tested for accuracy.”

Devices, indications differ

Cuffless devices estimate blood pressure indirectly. Most operate based on pulse wave analysis and pulse arrival time (PWA-PAT), explained Ramakrishna Mukkamala, PhD, in a commentary. Dr. Mukkamala is a professor in the departments of bioengineering and anesthesiology and perioperative medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

PWA involves measuring a peripheral arterial waveform using an optical sensor such as the green lights on the back of a wrist-worn device, or a ‘force sensor’ such as a finger cuff or pressing on a smartphone. Certain features are extracted from the waveform using machine learning and calibrated to blood pressure values.

PAT techniques work together with PWA; they record the ECG and extract features from that signal as well as the arterial waveform for calibration to blood pressure values.

The algorithm used to generate the BP numbers comprises a proprietary baseline model that may include demographics and other patient characteristics. A cuff measurement is often part of the baseline model because most cuffless devices require periodic (typically weekly or monthly) calibration using a cuffed device.

Cuffless devices that require cuff calibration compare the estimate they get to the cuff-calibrated number. In this scenario, the cuffless device may come up with the same blood pressure numbers simply because the baseline model – which is made up of thousands of data points relevant to the patient – has not changed.

This has led some experts to question whether PWA-PAT cuffless device readings actually add anything to the baseline model.

They don’t, according to Microsoft Research in what Dr. Mukkamala and coauthors referred to (in a review published in Hypertension) as “a complex article describing perhaps the most important and highest resource project to date (Aurora Project) on assessing the accuracy of PWA and PWA devices.”

The Microsoft article was written for bioengineers. The review in Hypertension explains the project for clinicians, and concludes that, “Cuffless BP devices based on PWA and PWA-PAT, which are similar to some regulatory-cleared devices, were of no additional value in measuring auscultatory or 24-hour ambulatory cuff BP when compared with a baseline model in which BP was predicted without an actual measurement.”

IEEE and FDA validation

Despite these concerns, several cuffless devices using PWA and PAT have been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration.

Validating cuffless devices is no simple matter. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers published a validation protocol for cuffless blood pressure devices in 2014 that was amended in 2019 to include a requirement to evaluate performance in different positions and in the presence of motion with varying degrees of noise artifact.

However, Daichi Shimbo, MD, codirector of the Columbia Hypertension Center in New York and vice chair of the American Heart Association Statement on blood pressure monitoring, and colleagues point out limitations, even in the updated standard. These include not requiring evaluation for drift over time; lack of specific dynamic testing protocols for stressors such as exercise or environmental temperatures; and an unsuitable reference standard (oscillometric cuff-based devices) during movement.

Dr. Shimbo said in an interview that, although he is excited about them, “these cuffless devices are not aligned with regulatory bodies. If a device gives someone a wrong blood pressure, they might be diagnosed with hypertension when they don’t have it or might miss the fact that they’re hypertensive because they get a normal blood pressure reading. If there’s no yardstick by which you say these devices are good, what are we really doing – helping, or causing a problem?”

“The specifics of how a device estimates blood pressure can determine what testing is needed to ensure that it is providing accurate performance in the intended conditions of use,” Jeremy Kahn, an FDA press officer, said in an interview. “For example, for cuffless devices that are calibrated initially with a cuff-based blood pressure device, the cuffless device needs to specify the period over which it can provide accurate readings and have testing to demonstrate that it provides accurate results over that period of use.”

The FDA said its testing is different from what the Microsoft Aurora Project used in their study.

“The intent of that testing, as the agency understands it, is to evaluate whether the device is providing useful input based on the current physiology of the patient rather than relying on predetermined values based on calibration or patient attributes. We evaluate this clinically in two separate tests: an induced change in blood pressure test and tracking of natural blood pressure changes with longer term device use,” Mr. Kahn explained.

Analyzing a device’s performance on individuals who have had natural changes in blood pressure as compared to a calibration value or initial reading “can also help discern if the device is using physiological data from the patient to determine their blood pressure accurately,” he said.

Experts interviewed for this article who remain skeptical about cuffless BP monitoring question whether the numbers that appear during the induced blood pressure change, and with the natural blood pressure changes that may occur over time, accurately reflect a patient’s blood pressure.

“The FDA doesn’t approve these devices; they clear them,” Dr. Shimbo pointed out. “Clearing them means they can be sold to the general public in the U.S. It’s not a strong statement that they’re accurate.”

Moving toward validation, standards

Ultimately, cuffless BP monitors may require more than one validation protocol and standard, depending on their technology, how and where they will be used, and by whom.

And as Dr. Plante and colleagues write, “Importantly, validation should be performed in diverse and special populations, including pregnant women and individuals across a range of heart rates, skin tones, wrist sizes, common arrhythmias, and beta-blocker use.”

Organizations that might be expected to help move validation and standards forward have mostly remained silent. The American Medical Association’s US Blood Pressure Validated Device Listing website includes only cuffed devices, as does the website of the international scientific nonprofit STRIDE BP.

The European Society of Hypertension 2022 consensus statement on cuffless devices concluded that, until there is an internationally accepted accuracy standard and the devices have been tested in healthy people and those with suspected or diagnosed hypertension, “cuffless BP devices should not be used for the evaluation or management of hypertension in clinical practice.”

This month, ESH published recommendations for “specific, clinically meaningful, and pragmatic validation procedures for different types of intermittent cuffless devices” that will be presented at their upcoming annual meeting June 26.

Updated protocols from IEEE “are coming out soon,” according to Dr. Shimbo. The FDA says currently cleared devices won’t need to revalidate according to new standards unless the sponsor makes significant modifications in software algorithms, device hardware, or targeted patient populations.

Device makers take the initiative

In the face of conflicting reports on accuracy and lack of a robust standard, some device makers are publishing their own tests or encouraging validation by potential customers.

For example, institutions that are considering using the Biobeat cuffless blood pressure monitor watch “usually start with small pilots with our devices to do internal validation,” Lior Ben Shettrit, the company’s vice president of business development, said in an interview. “Only after they complete the internal validation are they willing to move forward to full implementation.”

Cardiologist Dean Nachman, MD, is leading validation studies of the Biobeat device at the Hadassah Ein Kerem Medical Center in Jerusalem. For the first validation, the team recruited 1,057 volunteers who did a single blood pressure measurement with the cuffless device and with a cuffed device.

“We found 96.3% agreement in identifying hypertension and an interclass correlation coefficient of 0.99 and 0.97 for systolic and diastolic measurements, respectively,” he said. “Then we took it to the next level and compared the device to ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure monitoring and found comparable measurements.”

The investigators are not done yet. “We need data from thousands of patients, with subgroups, to not have any concerns,” he says. “Right now, we are using the device as a general monitor – as an EKG plus heart rate plus oxygen saturation level monitor – and as a blood pressure monitor for 24-hour blood pressure monitoring.”

The developers of the Aktiia device, which is the one Dr. Topol tested, take a different perspective. “When somebody introduces a new technology that is disrupting something that has been in place for over 100 years, there will always be some grumblings, ruffling of feathers, people saying it’s not ready, it’s not ready, it’s not ready,” Aktiia’s chief medical officer Jay Shah, MD, noted.

“But a lot of those comments are coming from the isolation of an ivory tower,” he said.

Aktiia cofounder and chief technology officer Josep Solà said that “no device is probably as accurate as if you have an invasive catheter,” adding that “we engage patients to look at their blood pressure day by day. … If each individual measurement of each of those patient is slightly less accurate than a cuff, who cares? We have 40 measurements per day on each patient. The accuracy and precision of each of those is good.”

Researchers from the George Institute for Global Health recently compared the Aktiia device to conventional ambulatory monitoring in 41 patients and found that “it did not accurately track night-time BP decline and results suggested it was unable to track medication-induced BP changes.”

“In the context of 24/7 monitoring of hypertensive patients,” Mr. Solà said, “whatever you do, if it’s better than a sham device or a baseline model and you track the blood pressure changes, it’s a hundred times much better than doing nothing.”

Dr. Nachman and Dr. Plante reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Shimbo reported that he received funding from NIH and has consulted for Abbott Vascular, Edward Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Tryton Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medscape’s Editor-in-Chief Eric Topol, MD, referred to continual noninvasive, cuffless, accurate blood pressure devices as “a holy grail in sensor technology.”

He personally tested a cuff-calibrated, over-the-counter device available in Europe that claims to monitor daily blood pressure changes and produce data that can help physicians titrate medications.

Dr. Topol does not believe that it is ready for prime time. Yes, cuffless devices are easy to use, and generate lots of data. But are those data accurate?

Many experts say not yet, even as the market continues to grow and more devices are introduced and highlighted at high-profile consumer events.

Burned before

Limitations of cuffed devices are well known, including errors related to cuff size, patient positioning, patient habits or behaviors (for example, caffeine/nicotine use, acute meal digestion, full bladder, very recent physical activity) and clinicians’ failure to take accurate measurements.

Like many clinicians, Timothy B. Plante, MD, MHS, assistant professor at the University of Vermont Medical Center thrombosis & hemostasis program in Burlington, is very excited about cuffless technology. However, “we’ve been burned by it before,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Plante’s 2016 validation study of an instant blood pressure smartphone app found that its measurements were “highly inaccurate,” with such low sensitivity that more than three-quarters of individuals with hypertensive blood levels would be falsely reassured that their blood pressure was in the normal range.

His team’s 2023 review of the current landscape, which includes more sophisticated devices, concluded that accuracy remains an issue: “Unfortunately, the pace of regulation of these devices has failed to match the speed of innovation and direct availability to patient consumers. There is an urgent need to develop a consensus on standards by which cuffless BP devices can be tested for accuracy.”

Devices, indications differ

Cuffless devices estimate blood pressure indirectly. Most operate based on pulse wave analysis and pulse arrival time (PWA-PAT), explained Ramakrishna Mukkamala, PhD, in a commentary. Dr. Mukkamala is a professor in the departments of bioengineering and anesthesiology and perioperative medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

PWA involves measuring a peripheral arterial waveform using an optical sensor such as the green lights on the back of a wrist-worn device, or a ‘force sensor’ such as a finger cuff or pressing on a smartphone. Certain features are extracted from the waveform using machine learning and calibrated to blood pressure values.

PAT techniques work together with PWA; they record the ECG and extract features from that signal as well as the arterial waveform for calibration to blood pressure values.

The algorithm used to generate the BP numbers comprises a proprietary baseline model that may include demographics and other patient characteristics. A cuff measurement is often part of the baseline model because most cuffless devices require periodic (typically weekly or monthly) calibration using a cuffed device.

Cuffless devices that require cuff calibration compare the estimate they get to the cuff-calibrated number. In this scenario, the cuffless device may come up with the same blood pressure numbers simply because the baseline model – which is made up of thousands of data points relevant to the patient – has not changed.

This has led some experts to question whether PWA-PAT cuffless device readings actually add anything to the baseline model.

They don’t, according to Microsoft Research in what Dr. Mukkamala and coauthors referred to (in a review published in Hypertension) as “a complex article describing perhaps the most important and highest resource project to date (Aurora Project) on assessing the accuracy of PWA and PWA devices.”

The Microsoft article was written for bioengineers. The review in Hypertension explains the project for clinicians, and concludes that, “Cuffless BP devices based on PWA and PWA-PAT, which are similar to some regulatory-cleared devices, were of no additional value in measuring auscultatory or 24-hour ambulatory cuff BP when compared with a baseline model in which BP was predicted without an actual measurement.”

IEEE and FDA validation

Despite these concerns, several cuffless devices using PWA and PAT have been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration.

Validating cuffless devices is no simple matter. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers published a validation protocol for cuffless blood pressure devices in 2014 that was amended in 2019 to include a requirement to evaluate performance in different positions and in the presence of motion with varying degrees of noise artifact.

However, Daichi Shimbo, MD, codirector of the Columbia Hypertension Center in New York and vice chair of the American Heart Association Statement on blood pressure monitoring, and colleagues point out limitations, even in the updated standard. These include not requiring evaluation for drift over time; lack of specific dynamic testing protocols for stressors such as exercise or environmental temperatures; and an unsuitable reference standard (oscillometric cuff-based devices) during movement.

Dr. Shimbo said in an interview that, although he is excited about them, “these cuffless devices are not aligned with regulatory bodies. If a device gives someone a wrong blood pressure, they might be diagnosed with hypertension when they don’t have it or might miss the fact that they’re hypertensive because they get a normal blood pressure reading. If there’s no yardstick by which you say these devices are good, what are we really doing – helping, or causing a problem?”

“The specifics of how a device estimates blood pressure can determine what testing is needed to ensure that it is providing accurate performance in the intended conditions of use,” Jeremy Kahn, an FDA press officer, said in an interview. “For example, for cuffless devices that are calibrated initially with a cuff-based blood pressure device, the cuffless device needs to specify the period over which it can provide accurate readings and have testing to demonstrate that it provides accurate results over that period of use.”

The FDA said its testing is different from what the Microsoft Aurora Project used in their study.

“The intent of that testing, as the agency understands it, is to evaluate whether the device is providing useful input based on the current physiology of the patient rather than relying on predetermined values based on calibration or patient attributes. We evaluate this clinically in two separate tests: an induced change in blood pressure test and tracking of natural blood pressure changes with longer term device use,” Mr. Kahn explained.

Analyzing a device’s performance on individuals who have had natural changes in blood pressure as compared to a calibration value or initial reading “can also help discern if the device is using physiological data from the patient to determine their blood pressure accurately,” he said.

Experts interviewed for this article who remain skeptical about cuffless BP monitoring question whether the numbers that appear during the induced blood pressure change, and with the natural blood pressure changes that may occur over time, accurately reflect a patient’s blood pressure.

“The FDA doesn’t approve these devices; they clear them,” Dr. Shimbo pointed out. “Clearing them means they can be sold to the general public in the U.S. It’s not a strong statement that they’re accurate.”

Moving toward validation, standards

Ultimately, cuffless BP monitors may require more than one validation protocol and standard, depending on their technology, how and where they will be used, and by whom.

And as Dr. Plante and colleagues write, “Importantly, validation should be performed in diverse and special populations, including pregnant women and individuals across a range of heart rates, skin tones, wrist sizes, common arrhythmias, and beta-blocker use.”

Organizations that might be expected to help move validation and standards forward have mostly remained silent. The American Medical Association’s US Blood Pressure Validated Device Listing website includes only cuffed devices, as does the website of the international scientific nonprofit STRIDE BP.

The European Society of Hypertension 2022 consensus statement on cuffless devices concluded that, until there is an internationally accepted accuracy standard and the devices have been tested in healthy people and those with suspected or diagnosed hypertension, “cuffless BP devices should not be used for the evaluation or management of hypertension in clinical practice.”

This month, ESH published recommendations for “specific, clinically meaningful, and pragmatic validation procedures for different types of intermittent cuffless devices” that will be presented at their upcoming annual meeting June 26.

Updated protocols from IEEE “are coming out soon,” according to Dr. Shimbo. The FDA says currently cleared devices won’t need to revalidate according to new standards unless the sponsor makes significant modifications in software algorithms, device hardware, or targeted patient populations.

Device makers take the initiative

In the face of conflicting reports on accuracy and lack of a robust standard, some device makers are publishing their own tests or encouraging validation by potential customers.

For example, institutions that are considering using the Biobeat cuffless blood pressure monitor watch “usually start with small pilots with our devices to do internal validation,” Lior Ben Shettrit, the company’s vice president of business development, said in an interview. “Only after they complete the internal validation are they willing to move forward to full implementation.”

Cardiologist Dean Nachman, MD, is leading validation studies of the Biobeat device at the Hadassah Ein Kerem Medical Center in Jerusalem. For the first validation, the team recruited 1,057 volunteers who did a single blood pressure measurement with the cuffless device and with a cuffed device.

“We found 96.3% agreement in identifying hypertension and an interclass correlation coefficient of 0.99 and 0.97 for systolic and diastolic measurements, respectively,” he said. “Then we took it to the next level and compared the device to ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure monitoring and found comparable measurements.”

The investigators are not done yet. “We need data from thousands of patients, with subgroups, to not have any concerns,” he says. “Right now, we are using the device as a general monitor – as an EKG plus heart rate plus oxygen saturation level monitor – and as a blood pressure monitor for 24-hour blood pressure monitoring.”

The developers of the Aktiia device, which is the one Dr. Topol tested, take a different perspective. “When somebody introduces a new technology that is disrupting something that has been in place for over 100 years, there will always be some grumblings, ruffling of feathers, people saying it’s not ready, it’s not ready, it’s not ready,” Aktiia’s chief medical officer Jay Shah, MD, noted.

“But a lot of those comments are coming from the isolation of an ivory tower,” he said.

Aktiia cofounder and chief technology officer Josep Solà said that “no device is probably as accurate as if you have an invasive catheter,” adding that “we engage patients to look at their blood pressure day by day. … If each individual measurement of each of those patient is slightly less accurate than a cuff, who cares? We have 40 measurements per day on each patient. The accuracy and precision of each of those is good.”

Researchers from the George Institute for Global Health recently compared the Aktiia device to conventional ambulatory monitoring in 41 patients and found that “it did not accurately track night-time BP decline and results suggested it was unable to track medication-induced BP changes.”

“In the context of 24/7 monitoring of hypertensive patients,” Mr. Solà said, “whatever you do, if it’s better than a sham device or a baseline model and you track the blood pressure changes, it’s a hundred times much better than doing nothing.”

Dr. Nachman and Dr. Plante reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Shimbo reported that he received funding from NIH and has consulted for Abbott Vascular, Edward Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Tryton Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

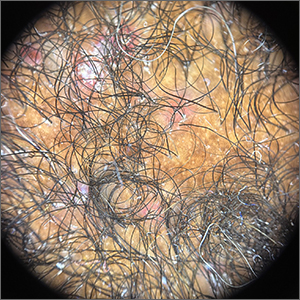

Crusted scalp rash

Dermoscopy showed not only the erythema, inflammation, and crusting visible during the initial examination, but it also revealed that each lesion had a hair growing through it. This pointed to a diagnosis of superficial folliculitis of the scalp.

The physician ruled out tinea capitis, acne keloidalis nuchae, and scarring alopecia based on the dermoscopic exam. There were no broken hairs that one would expect with tinea capitis. Also, there was no polytrichia (multiple hairs pushed into a single follicular opening due to scarring of the skin) that would be expected with acne keloidalis nuchae and scarring alopecias.

There are multiple types of scalp folliculitis. This patient had superficial folliculitis, in which pustules develop at the ostium of the hair follicles. Deep folliculitis is more severe and includes furuncles and carbuncles.1

Folliculitis is usually caused by a bacterial infection and, less commonly, fungal infection. In addition to superficial and deep folliculitis, inflammation with scarring of the follicles occurs with folliculitis decalvans, which is one of the scarring alopecias.1

Mild cases of superficial bacterial folliculitis are treated with topical antibiotics (eg, topical clindamycin 1% applied twice daily). Depending on the severity, oral antibiotics including doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days or trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg (double strength) twice daily for 7 days may be used. There is also a chronic nonscarring form of scalp folliculitis that often responds initially to antibiotics but then recurs. This has been treated with longer courses of oral antibiotics and, if the lesions don’t respond or continue to recur, with low-dose isotretinoin.2

Due to the amount of scalp involvement, crusting, and inflammation seen on this patient’s scalp, he was treated with trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg twice daily for 7 days. After 1 week, he reported that he was doing much better and that the lesions had nearly resolved. He was told to return for reevaluation if the lesions did not completely resolve.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Lugović-Mihić L, Barisić F, Bulat V, et al. Differential diagnosis of the scalp hair folliculitis. Acta Clin Croat. 2011;50:395-402.

2. Romero-Maté A, Arias-Palomo D, Hernández-Núñez A, et al. Chronic nonscarring scalp folliculitis: retrospective case series study of 34 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:1023-1024. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.065

Dermoscopy showed not only the erythema, inflammation, and crusting visible during the initial examination, but it also revealed that each lesion had a hair growing through it. This pointed to a diagnosis of superficial folliculitis of the scalp.

The physician ruled out tinea capitis, acne keloidalis nuchae, and scarring alopecia based on the dermoscopic exam. There were no broken hairs that one would expect with tinea capitis. Also, there was no polytrichia (multiple hairs pushed into a single follicular opening due to scarring of the skin) that would be expected with acne keloidalis nuchae and scarring alopecias.

There are multiple types of scalp folliculitis. This patient had superficial folliculitis, in which pustules develop at the ostium of the hair follicles. Deep folliculitis is more severe and includes furuncles and carbuncles.1

Folliculitis is usually caused by a bacterial infection and, less commonly, fungal infection. In addition to superficial and deep folliculitis, inflammation with scarring of the follicles occurs with folliculitis decalvans, which is one of the scarring alopecias.1

Mild cases of superficial bacterial folliculitis are treated with topical antibiotics (eg, topical clindamycin 1% applied twice daily). Depending on the severity, oral antibiotics including doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days or trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg (double strength) twice daily for 7 days may be used. There is also a chronic nonscarring form of scalp folliculitis that often responds initially to antibiotics but then recurs. This has been treated with longer courses of oral antibiotics and, if the lesions don’t respond or continue to recur, with low-dose isotretinoin.2

Due to the amount of scalp involvement, crusting, and inflammation seen on this patient’s scalp, he was treated with trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg twice daily for 7 days. After 1 week, he reported that he was doing much better and that the lesions had nearly resolved. He was told to return for reevaluation if the lesions did not completely resolve.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

Dermoscopy showed not only the erythema, inflammation, and crusting visible during the initial examination, but it also revealed that each lesion had a hair growing through it. This pointed to a diagnosis of superficial folliculitis of the scalp.

The physician ruled out tinea capitis, acne keloidalis nuchae, and scarring alopecia based on the dermoscopic exam. There were no broken hairs that one would expect with tinea capitis. Also, there was no polytrichia (multiple hairs pushed into a single follicular opening due to scarring of the skin) that would be expected with acne keloidalis nuchae and scarring alopecias.

There are multiple types of scalp folliculitis. This patient had superficial folliculitis, in which pustules develop at the ostium of the hair follicles. Deep folliculitis is more severe and includes furuncles and carbuncles.1

Folliculitis is usually caused by a bacterial infection and, less commonly, fungal infection. In addition to superficial and deep folliculitis, inflammation with scarring of the follicles occurs with folliculitis decalvans, which is one of the scarring alopecias.1

Mild cases of superficial bacterial folliculitis are treated with topical antibiotics (eg, topical clindamycin 1% applied twice daily). Depending on the severity, oral antibiotics including doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days or trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg (double strength) twice daily for 7 days may be used. There is also a chronic nonscarring form of scalp folliculitis that often responds initially to antibiotics but then recurs. This has been treated with longer courses of oral antibiotics and, if the lesions don’t respond or continue to recur, with low-dose isotretinoin.2

Due to the amount of scalp involvement, crusting, and inflammation seen on this patient’s scalp, he was treated with trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg twice daily for 7 days. After 1 week, he reported that he was doing much better and that the lesions had nearly resolved. He was told to return for reevaluation if the lesions did not completely resolve.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Lugović-Mihić L, Barisić F, Bulat V, et al. Differential diagnosis of the scalp hair folliculitis. Acta Clin Croat. 2011;50:395-402.

2. Romero-Maté A, Arias-Palomo D, Hernández-Núñez A, et al. Chronic nonscarring scalp folliculitis: retrospective case series study of 34 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:1023-1024. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.065

1. Lugović-Mihić L, Barisić F, Bulat V, et al. Differential diagnosis of the scalp hair folliculitis. Acta Clin Croat. 2011;50:395-402.

2. Romero-Maté A, Arias-Palomo D, Hernández-Núñez A, et al. Chronic nonscarring scalp folliculitis: retrospective case series study of 34 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:1023-1024. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.065

Persistent scaling rash

The clinical pattern of a scaly herald patch predating the eruption of multiple scaly macules is the hallmark of pityriasis rosea (PR). This patient’s severe itching is also classic for PR.

PR’s etiology is believed to be a reactivation of infection from human herpes viruses 6 and 7.1 Prodromal viral symptoms of malaise, sore throat, myalgias, and fever are common.2 Along with the prodromal symptoms, there is often a several-centimeter herald patch that occurs on the trunk. It is often confused with eczema or tinea due to its erythema and scale. (Secondary syphilis is also in the differential.) Sometimes PR can be differentiated by the scale pattern being a collarette instead of diffuse. The diagnosis becomes clearer 1 to 2 weeks later with the onset of multiple small scaly macules across the trunk following the Langer’s skin lines. The course is self-limited but takes several weeks to months to resolve.

If severe, PR may be treated with acyclovir 800 mg orally 5 times daily for 5 days; this is the same regimen for treating varicella zoster (shingles).1,2 Estimated recurrence rates are 4% to 24%.1,3

At age 49 years, this woman was older than the average patient with PR, as the usual age range is 10 to 35 years.1 Her physician advised her that the outbreak might recur. She was also given a prescription for oral hydroxyzine 25 mg to be taken at bedtime if the itching was interfering with her sleep. Her physician told her to return for reevaluation if the rash did not resolve in 3 months. She did not return for reevaluation.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Drago F, Ciccarese G, Parodi A. Commentary on: "pityriasis rosea recurrence is much higher than previously known: a prospective study." Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:1053-1054. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3265

2. Villalon-Gomez JM. Pityriasis rosea: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:38-44.

3. Yüksel M. Pityriasis rosea recurrence is much higher than previously known: a prospective study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:664-667. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3169

The clinical pattern of a scaly herald patch predating the eruption of multiple scaly macules is the hallmark of pityriasis rosea (PR). This patient’s severe itching is also classic for PR.

PR’s etiology is believed to be a reactivation of infection from human herpes viruses 6 and 7.1 Prodromal viral symptoms of malaise, sore throat, myalgias, and fever are common.2 Along with the prodromal symptoms, there is often a several-centimeter herald patch that occurs on the trunk. It is often confused with eczema or tinea due to its erythema and scale. (Secondary syphilis is also in the differential.) Sometimes PR can be differentiated by the scale pattern being a collarette instead of diffuse. The diagnosis becomes clearer 1 to 2 weeks later with the onset of multiple small scaly macules across the trunk following the Langer’s skin lines. The course is self-limited but takes several weeks to months to resolve.

If severe, PR may be treated with acyclovir 800 mg orally 5 times daily for 5 days; this is the same regimen for treating varicella zoster (shingles).1,2 Estimated recurrence rates are 4% to 24%.1,3

At age 49 years, this woman was older than the average patient with PR, as the usual age range is 10 to 35 years.1 Her physician advised her that the outbreak might recur. She was also given a prescription for oral hydroxyzine 25 mg to be taken at bedtime if the itching was interfering with her sleep. Her physician told her to return for reevaluation if the rash did not resolve in 3 months. She did not return for reevaluation.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

The clinical pattern of a scaly herald patch predating the eruption of multiple scaly macules is the hallmark of pityriasis rosea (PR). This patient’s severe itching is also classic for PR.

PR’s etiology is believed to be a reactivation of infection from human herpes viruses 6 and 7.1 Prodromal viral symptoms of malaise, sore throat, myalgias, and fever are common.2 Along with the prodromal symptoms, there is often a several-centimeter herald patch that occurs on the trunk. It is often confused with eczema or tinea due to its erythema and scale. (Secondary syphilis is also in the differential.) Sometimes PR can be differentiated by the scale pattern being a collarette instead of diffuse. The diagnosis becomes clearer 1 to 2 weeks later with the onset of multiple small scaly macules across the trunk following the Langer’s skin lines. The course is self-limited but takes several weeks to months to resolve.

If severe, PR may be treated with acyclovir 800 mg orally 5 times daily for 5 days; this is the same regimen for treating varicella zoster (shingles).1,2 Estimated recurrence rates are 4% to 24%.1,3

At age 49 years, this woman was older than the average patient with PR, as the usual age range is 10 to 35 years.1 Her physician advised her that the outbreak might recur. She was also given a prescription for oral hydroxyzine 25 mg to be taken at bedtime if the itching was interfering with her sleep. Her physician told her to return for reevaluation if the rash did not resolve in 3 months. She did not return for reevaluation.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Drago F, Ciccarese G, Parodi A. Commentary on: "pityriasis rosea recurrence is much higher than previously known: a prospective study." Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:1053-1054. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3265

2. Villalon-Gomez JM. Pityriasis rosea: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:38-44.

3. Yüksel M. Pityriasis rosea recurrence is much higher than previously known: a prospective study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:664-667. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3169

1. Drago F, Ciccarese G, Parodi A. Commentary on: "pityriasis rosea recurrence is much higher than previously known: a prospective study." Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:1053-1054. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3265

2. Villalon-Gomez JM. Pityriasis rosea: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:38-44.

3. Yüksel M. Pityriasis rosea recurrence is much higher than previously known: a prospective study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:664-667. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3169

Could semaglutide treat addiction as well as obesity?

As demand for semaglutide for weight loss grew following approval of Wegovy by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2021, anecdotal reports of unexpected potential added benefits also began to surface.

Some patients taking these drugs for type 2 diabetes or weight loss also lost interest in addictive and compulsive behaviors such as drinking alcohol, smoking, shopping, nail biting, and skin picking, as reported in articles in the New York Times and The Atlantic, among others.

There is also some preliminary research to support these observations.

This news organization invited three experts to weigh in.

Recent and upcoming studies

The senior author of a recent randomized controlled trial of 127 patients with alcohol use disorder (AUD), Anders Fink-Jensen, MD, said: “I hope that GLP-1 analogs in the future can be used against AUD, but before that can happen, several GLP-1 trials [are needed to] prove an effect on alcohol intake.”

His study involved patients who received exenatide (Byetta, Bydureon, AstraZeneca), the first-generation GLP-1 agonist approved for type 2 diabetes, over 26 weeks, but treatment did not reduce the number of heavy drinking days (the primary outcome), compared with placebo.

However, in post hoc, exploratory analyses, heavy drinking days and total alcohol intake were significantly reduced in the subgroup of patients with AUD and obesity (body mass index > 30 kg/m2).

The participants were also shown pictures of alcohol or neutral subjects while they underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging. Those who had received exenatide, compared with placebo, had significantly less activation of brain reward centers when shown the pictures of alcohol.

“Something is happening in the brain and activation of the reward center is hampered by the GLP-1 compound,” Dr. Fink-Jensen, a clinical psychologist at the Psychiatric Centre Copenhagen, remarked in an email.

“If patients with AUD already fulfill the criteria for semaglutide (or other GLP-1 analogs) by having type 2 diabetes and/or a BMI over 30 kg/m2, they can of course use the compound right now,” he noted.

His team is also beginning a study in patients with AUD and a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 to investigate the effects on alcohol intake of semaglutide up to 2.4 mg weekly, the maximum dose currently approved for obesity in the United States.

“Based on the potency of exenatide and semaglutide,” Dr. Fink-Jensen said, “we expect that semaglutide will cause a stronger reduction in alcohol intake” than exenatide.

Animal studies have also shown that GLP-1 agonists suppress alcohol-induced reward, alcohol intake, motivation to consume alcohol, alcohol seeking, and relapse drinking of alcohol, Elisabet Jerlhag Holm, PhD, noted.

Interestingly, these agents also suppress the reward, intake, and motivation to consume other addictive drugs like cocaine, amphetamine, nicotine, and some opioids, Jerlhag Holm, professor, department of pharmacology, University of Gothenburg, Sweden, noted in an email.

In a recently published preclinical study, her group provides evidence to help explain anecdotal reports from patients with obesity treated with semaglutide who claim they also reduced their alcohol intake. In the study, semaglutide both reduced alcohol intake (and relapse-like drinking) and decreased body weight of rats of both sexes.

“Future research should explore the possibility of semaglutide decreasing alcohol intake in patients with AUD, particularly those who are overweight,” said Prof. Holm.

“AUD is a heterogenous disorder, and one medication is most likely not helpful for all AUD patients,” she added. “Therefore, an arsenal of different medications is beneficial when treating AUD.”

Janice J. Hwang, MD, MHS, echoed these thoughts: “Anecdotally, there are a lot of reports from patients (and in the news) that this class of medication [GLP-1 agonists] impacts cravings and could impact addictive behaviors.”

“I would say, overall, the jury is still out,” as to whether anecdotal reports of GLP-1 agonists curbing addictions will be borne out in randomized controlled trials.

“I think it is much too early to tell” whether these drugs might be approved for treating addictions without more solid clinical trial data, noted Dr. Hwang, who is an associate professor of medicine and chief, division of endocrinology and metabolism, at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Meanwhile, another research group at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, led by psychiatrist Christian Hendershot, PhD, is conducting a clinical trial in 48 participants with AUD who are also smokers.

They aim to determine if patients who receive semaglutide at escalating doses (0.25 mg to 1.0 mg per week via subcutaneous injection) over 9 weeks will consume less alcohol (the primary outcome) and smoke less (a secondary outcome) than those who receive a sham placebo injection. Results are expected in October 2023.

Dr. Fink-Jensen has received an unrestricted research grant from Novo Nordisk to investigate the effects of GLP-1 receptor stimulation on weight gain and metabolic disturbances in patients with schizophrenia treated with an antipsychotic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As demand for semaglutide for weight loss grew following approval of Wegovy by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2021, anecdotal reports of unexpected potential added benefits also began to surface.

Some patients taking these drugs for type 2 diabetes or weight loss also lost interest in addictive and compulsive behaviors such as drinking alcohol, smoking, shopping, nail biting, and skin picking, as reported in articles in the New York Times and The Atlantic, among others.

There is also some preliminary research to support these observations.

This news organization invited three experts to weigh in.

Recent and upcoming studies

The senior author of a recent randomized controlled trial of 127 patients with alcohol use disorder (AUD), Anders Fink-Jensen, MD, said: “I hope that GLP-1 analogs in the future can be used against AUD, but before that can happen, several GLP-1 trials [are needed to] prove an effect on alcohol intake.”

His study involved patients who received exenatide (Byetta, Bydureon, AstraZeneca), the first-generation GLP-1 agonist approved for type 2 diabetes, over 26 weeks, but treatment did not reduce the number of heavy drinking days (the primary outcome), compared with placebo.

However, in post hoc, exploratory analyses, heavy drinking days and total alcohol intake were significantly reduced in the subgroup of patients with AUD and obesity (body mass index > 30 kg/m2).

The participants were also shown pictures of alcohol or neutral subjects while they underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging. Those who had received exenatide, compared with placebo, had significantly less activation of brain reward centers when shown the pictures of alcohol.

“Something is happening in the brain and activation of the reward center is hampered by the GLP-1 compound,” Dr. Fink-Jensen, a clinical psychologist at the Psychiatric Centre Copenhagen, remarked in an email.

“If patients with AUD already fulfill the criteria for semaglutide (or other GLP-1 analogs) by having type 2 diabetes and/or a BMI over 30 kg/m2, they can of course use the compound right now,” he noted.

His team is also beginning a study in patients with AUD and a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 to investigate the effects on alcohol intake of semaglutide up to 2.4 mg weekly, the maximum dose currently approved for obesity in the United States.

“Based on the potency of exenatide and semaglutide,” Dr. Fink-Jensen said, “we expect that semaglutide will cause a stronger reduction in alcohol intake” than exenatide.

Animal studies have also shown that GLP-1 agonists suppress alcohol-induced reward, alcohol intake, motivation to consume alcohol, alcohol seeking, and relapse drinking of alcohol, Elisabet Jerlhag Holm, PhD, noted.

Interestingly, these agents also suppress the reward, intake, and motivation to consume other addictive drugs like cocaine, amphetamine, nicotine, and some opioids, Jerlhag Holm, professor, department of pharmacology, University of Gothenburg, Sweden, noted in an email.

In a recently published preclinical study, her group provides evidence to help explain anecdotal reports from patients with obesity treated with semaglutide who claim they also reduced their alcohol intake. In the study, semaglutide both reduced alcohol intake (and relapse-like drinking) and decreased body weight of rats of both sexes.

“Future research should explore the possibility of semaglutide decreasing alcohol intake in patients with AUD, particularly those who are overweight,” said Prof. Holm.

“AUD is a heterogenous disorder, and one medication is most likely not helpful for all AUD patients,” she added. “Therefore, an arsenal of different medications is beneficial when treating AUD.”