User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

How to Reduce Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality in Psoriasis and PsA

Patients with psoriatic disease have significantly higher risks of myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality than does the general population, yet research consistently paints what dermatologist Joel M. Gelfand, MD, calls an “abysmal” picture: Only a minority of patients with psoriatic disease know about their increased risks, only a minority of dermatologists and rheumatologists screen for cardiovascular risk factors like lipid levels and blood pressure, and only a minority of patients diagnosed with hyperlipidemia are adequately treated with statin therapy.

In the literature and at medical meetings, Dr. Gelfand and others who have studied cardiovascular disease (CVD) comorbidity and physician practices have been urging dermatologists and rheumatologists to play a more consistent and active role in primary cardiovascular prevention for patients with psoriatic disease, who are up to 50% more likely than patients without it to develop CVD and who tend to have atherosclerosis at earlier ages.

According to the 2019 joint American Academy of Dermatology (AAD)–National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) guidelines for managing psoriasis “with awareness and attention to comorbidities,” this means not only ensuring that all patients with psoriasis receive standard CV risk assessment (screening for hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia), but also recognizing that patients who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy — or who have psoriasis involving > 10% of body surface area — may benefit from earlier and more frequent screening.

CV risk and premature mortality rises with the severity of skin disease, and patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) are believed to have risk levels similar to patients with moderate-severe psoriasis, cardiologist Michael S. Garshick, MD, director of the cardio-rheumatology program at New York University Langone Health, said in an interview.

In a recent survey study of 100 patients seen at NYU Langone Health’s psoriasis specialty clinic, only one-third indicated they had been advised by their physicians to be screened for CV risk factors, and only one-third reported having been told of the connection between psoriasis and CVD risk. Dr. Garshick shared the unpublished findings at the annual research symposium of the NPF in October.

Similarly, data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey shows that just 16% of psoriasis-related visits to dermatology providers from 2007 to 2016 involved screening for CV risk factors. Screening rates were 11% for body mass index, 7.4% for blood pressure, 2.9% for cholesterol, and 1.7% for glucose, Dr. Gelfand and coauthors reported in 2023. .

Such findings are concerning because research shows that fewer than a quarter of patients with psoriasis have a primary care visit within a year of establishing care with their physicians, and that, overall, fewer than half of commercially insured adults under age 65 visit a primary care physician each year, according to John S. Barbieri, MD, of the department of dermatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He included these findings when reporting in 2022 on a survey study on CVD screening.

In many cases, dermatologists and rheumatologists may be the primary providers for patients with psoriatic disease. So, “the question is, how can the dermatologist or rheumatologist use their interactions as a touchpoint to improve the patient’s well-being?” Dr. Barbieri said in an interview.

For the dermatologist, educating patients about the higher CVD risk fits well into conversations about “how there may be inflammation inside the body as well as in the skin,” he said. “Talk about cardiovascular risk just as you talk about PsA risk.” Both specialists, he added, can incorporate blood pressure readings and look for opportunities to measure lipid levels and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). These labs can easily be integrated into a biologic work-up.

“The hard part — and this needs to be individualized — is how do you want to handle [abnormal readings]? Do you want to take on a lot of the ownership and calculate [10-year CVD] risk scores and then counsel patients accordingly?” Dr. Barbieri said. “Or do you want to try to refer, and encourage them to work with their PCP? There a high-touch version and a low-touch version of how you can turn screening into action, into a care plan.”

Beyond traditional risk elevation, the primary care hand-off

Rheumatologists “in general may be more apt to screen for cardiovascular disease” as a result of their internal medicine residency training, and “we’re generally more comfortable prescribing ... if we need to,” said Alexis R. Ogdie, MD, a rheumatologist at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and director of the Penn Psoriatic Arthritis Clinic.

Referral to a preventive cardiologist for management of abnormal lab results or ongoing monitoring and prevention is ideal, but when hand-offs to primary care physicians are made — the more common scenario — education is important. “A common problem is that there is underrecognition of the cardiovascular risk being elevated in our patients,” she said, above and beyond risk posed by traditional risk factors such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and obesity, all of which have been shown to occur more frequently in patients with psoriatic disease than in the general population.

Risk stratification guides CVD prevention in the general population, and “if you use typical scores for cardiovascular risk, they may underestimate risk for our patients with PsA,” said Dr. Ogdie, who has reported on CV risk in patients with PsA. “Relative to what the patient’s perceived risk is, they may be treated similarly (to the general population). But relative to their actual risk, they’re undertreated.”

The 2019 AAD-NPF psoriasis guidelines recommend utilizing a 1.5 multiplication factor in risk score models, such as the American College of Cardiology’s Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) Risk Estimator, when the patient has a body surface area >10% or is a candidate for systemic therapy or phototherapy.

Similarly, the 2018 American Heart Association (AHA)-ACC Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol defines psoriasis, along with RA, metabolic syndrome, HIV, and other diseases, as a “cardiovascular risk enhancer” that should be factored into assessments of ASCVD risk. (The guideline does not specify a psoriasis severity threshold.)

“It’s the first time the specialty [of cardiology] has said, ‘pay attention to a skin disease,’ ” Dr. Gelfand said at the NPF meeting.

Using the 1.5 multiplication factor, a patient who otherwise would be classified in the AHA/ACC guideline as “borderline risk,” with a 10-year ASCVD risk of 5% to <7.5%, would instead have an “intermediate” 10-year ASCVD risk of ≥7.5% to <20%. Application of the AHA-ACC “risk enhancer” would have a similar effect.

For management, the main impact of psoriasis being considered a risk enhancer is that “it lowers the threshold for treatment with standard cardiovascular prevention medications such as statins.”

In general, “we should be taking a more aggressive approach to the management of traditional cardiovascular risk factors” in patients with psoriatic disease, he said. Instead of telling a patient with mildly elevated blood pressure, ‘I’ll see you in a year or two,’ or a patient entering a prediabetic stage to “watch what you eat, and I’ll see you in a couple of years,” clinicians need to be more vigilant.

“It’s about recognizing that these traditional cardiometabolic risk factors, synergistically with psoriasis, can start enhancing CV risk at an earlier age than we might expect,” said Dr. Garshick, whose 2021 review of CV risk in psoriasis describes how the inflammatory milieu in psoriasis is linked to atherosclerosis development.

Cardiologists are aware of this, but “many primary care physicians are not. It takes time for medical knowledge to diffuse,” Dr. Gelfand said. “Tell the PCP, in notes or in a form letter, that there is a higher risk of CV disease, and reference the AHA/ACC guidelines,” he advised. “You don’t want your patient to go to their doctor and the doctor to [be uninformed].”

‘Patients trust us’

Dr. Gelfand has been at the forefront of research on psoriasis and heart disease. A study he coauthored in 2006, for instance, documented an independent risk of MI, with adjusted relative risks of 1.29 and 3.10 for a 30-year-old patient with mild or severe disease, respectively, and higher risks for a 60-year-old. In 2010, he and coinvestigators found that severe psoriasis was an independent risk factor for CV mortality (HR, 1.57) after adjusting for age, sex, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

Today, along with Dr. Barbieri, Dr. Ogdie, and others, he is studying the feasibility and efficacy of a proposed national, “centralized care coordinator” model of care whereby dermatologists and rheumatologists would educate the patient, order lipid and HbA1c measurements as medically appropriate, and then refer patients as needed to a care coordinator. The care coordinator would calculate a 10-year CVD risk score and counsel the patient on possible next steps.

In a pilot study of 85 patients at four sites, 92% of patients followed through on their physician’s recommendations to have labs drawn, and 86% indicated the model was acceptable and feasible. A total of 27% of patients had “newly identified, previously undiagnosed, elevated cardiovascular disease risk,” and exploratory effectiveness results indicated a successful reduction in predicted CVD risk in patients who started statins, Dr. Gelfand reported at the NPF meeting.

With funding from the NPF, a larger, single-arm, pragmatic “CP3” trial (NCT05908240) is enrolling 525 patients with psoriasis at 10-20 academic and nonacademic dermatology sites across the United States to further test the model. The primary endpoint will be the change in LDL cholesterol measured at 6 months among people with a 10-year risk ≥5%. Secondary endpoints will cover improvement in disease severity and quality of life, behavior modification, patient experience, and other issues.

“We have only 10-15 minutes [with patients] ... a care coordinator who is empathetic and understanding and [informed] could make a big difference,” Dr. Gelfand said at the NPF meeting. If findings are positive, the model would be tested in rheumatology sites as well. The hope, he said, is that the NPF would be able to fund an in-house care coordinator(s) for the long-term.

Notably, a patient survey conducted as part of exploratory research leading up to the care coordinator project showed that patients trust their dermatologist or rheumatologist for CVD education and screening. Among 160 patients with psoriasis and 162 patients with PsA, 76% and 90% agreed that “I would like it if my dermatologist/rheumatologist educated me about my risk of heart disease,” and 60% and 75%, respectively, agree that “it would be convenient for me to have my cholesterol checked by my dermatologist/rheumatologist.”

“Patients trust us,” Dr. Gelfand said at the NPF meeting. “And the pilot study shows us that patients are motivated.”

Taking an individualized, holistic, longitudinal approach

“Sometimes you do have to triage bit,” Dr. Gelfand said in an interview. “For a young person with normal body weight who doesn’t smoke and has mild psoriasis, one could just educate and advise that they see their primary care physician” for monitoring.

“But for the same patient who is obese, maybe smokes, and doesn’t have a primary care physician, I’d order labs,” he said. “You don’t want a patient walking out the door with an [undiagnosed] LDL of 160 or hypertension.”

Age is also an important consideration, as excess CVD risk associated with autoimmune diseases like psoriasis rises with age, Dr. Gelfand said during a seminar on psoriasis and PsA held at NYU Langone in December. For a young person, typically, “I need to focus on education and lifestyle … setting them on a healthy lifestyle trajectory,” he said. “Once they get to 40, from 40 to 75 or so, that’s a sweet spot for medical intervention to lower cardiovascular risk.”

Even at older ages, however, lipid management is not the be-all and end-all, he said in the interview. “We have to be holistic.”

One advantage of having highly successful therapies for psoriasis, and to a lesser extent PsA, is the time that becomes available during follow-up visits — once disease is under control — to “focus on other things,” he said. Waiting until disease is under control to discuss diet, exercise, or smoking, for instance, makes sense anyway, he said. “You don’t want to overwhelm patients with too much to do at once.”

Indeed, said dermatologist Robert E. Kalb, MD, of the Buffalo Medical Group in Buffalo, NY, “patients have an open mind [about discussing cardiovascular disease risk], but it is not high on their radar. Most of them just want to get their skin clear.” (Dr. Kalb participated in the care coordinator pilot study, and said in an interview that since its completion, he has been more routinely ordering relevant labs.)

Rheumatologists are less fortunate with highly successful therapies, but “over the continuum of care, we do have time in office visits” to discuss issues like smoking, exercise, and lifestyle, Dr. Ogdie said. “I think of each of those pieces as part of our job.”

In the future, as researchers learn more about the impact of psoriasis and PsA treatments on CVD risk, it may be possible to tailor treatments or to prescribe treatments knowing that the therapies could reduce risk. Observational and epidemiologic data suggest that tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor therapy over 3 years reduces the risk of MI, and that patients whose psoriasis is treated have reduced aortic inflammation, improved myocardial strain, and reduced coronary plaque burden, Dr. Garshick said at the NPF meeting.

“But when we look at the randomized controlled trials, they’re actually inconclusive that targeting inflammation in psoriatic disease reduces surrogates of cardiovascular disease,” he said. Dr. Garshick’s own research focuses on platelet and endothelial biology in psoriasis.

Dr. Barbieri reported he had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Garshick reported consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Kiniksa, Horizon Therapeutics, and Agepha. Dr. Ogdie reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Takeda, and UCB. Dr. Gelfand reported serving as a consultant for AbbVie, Artax, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, and other companies.

Patients with psoriatic disease have significantly higher risks of myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality than does the general population, yet research consistently paints what dermatologist Joel M. Gelfand, MD, calls an “abysmal” picture: Only a minority of patients with psoriatic disease know about their increased risks, only a minority of dermatologists and rheumatologists screen for cardiovascular risk factors like lipid levels and blood pressure, and only a minority of patients diagnosed with hyperlipidemia are adequately treated with statin therapy.

In the literature and at medical meetings, Dr. Gelfand and others who have studied cardiovascular disease (CVD) comorbidity and physician practices have been urging dermatologists and rheumatologists to play a more consistent and active role in primary cardiovascular prevention for patients with psoriatic disease, who are up to 50% more likely than patients without it to develop CVD and who tend to have atherosclerosis at earlier ages.

According to the 2019 joint American Academy of Dermatology (AAD)–National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) guidelines for managing psoriasis “with awareness and attention to comorbidities,” this means not only ensuring that all patients with psoriasis receive standard CV risk assessment (screening for hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia), but also recognizing that patients who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy — or who have psoriasis involving > 10% of body surface area — may benefit from earlier and more frequent screening.

CV risk and premature mortality rises with the severity of skin disease, and patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) are believed to have risk levels similar to patients with moderate-severe psoriasis, cardiologist Michael S. Garshick, MD, director of the cardio-rheumatology program at New York University Langone Health, said in an interview.

In a recent survey study of 100 patients seen at NYU Langone Health’s psoriasis specialty clinic, only one-third indicated they had been advised by their physicians to be screened for CV risk factors, and only one-third reported having been told of the connection between psoriasis and CVD risk. Dr. Garshick shared the unpublished findings at the annual research symposium of the NPF in October.

Similarly, data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey shows that just 16% of psoriasis-related visits to dermatology providers from 2007 to 2016 involved screening for CV risk factors. Screening rates were 11% for body mass index, 7.4% for blood pressure, 2.9% for cholesterol, and 1.7% for glucose, Dr. Gelfand and coauthors reported in 2023. .

Such findings are concerning because research shows that fewer than a quarter of patients with psoriasis have a primary care visit within a year of establishing care with their physicians, and that, overall, fewer than half of commercially insured adults under age 65 visit a primary care physician each year, according to John S. Barbieri, MD, of the department of dermatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He included these findings when reporting in 2022 on a survey study on CVD screening.

In many cases, dermatologists and rheumatologists may be the primary providers for patients with psoriatic disease. So, “the question is, how can the dermatologist or rheumatologist use their interactions as a touchpoint to improve the patient’s well-being?” Dr. Barbieri said in an interview.

For the dermatologist, educating patients about the higher CVD risk fits well into conversations about “how there may be inflammation inside the body as well as in the skin,” he said. “Talk about cardiovascular risk just as you talk about PsA risk.” Both specialists, he added, can incorporate blood pressure readings and look for opportunities to measure lipid levels and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). These labs can easily be integrated into a biologic work-up.

“The hard part — and this needs to be individualized — is how do you want to handle [abnormal readings]? Do you want to take on a lot of the ownership and calculate [10-year CVD] risk scores and then counsel patients accordingly?” Dr. Barbieri said. “Or do you want to try to refer, and encourage them to work with their PCP? There a high-touch version and a low-touch version of how you can turn screening into action, into a care plan.”

Beyond traditional risk elevation, the primary care hand-off

Rheumatologists “in general may be more apt to screen for cardiovascular disease” as a result of their internal medicine residency training, and “we’re generally more comfortable prescribing ... if we need to,” said Alexis R. Ogdie, MD, a rheumatologist at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and director of the Penn Psoriatic Arthritis Clinic.

Referral to a preventive cardiologist for management of abnormal lab results or ongoing monitoring and prevention is ideal, but when hand-offs to primary care physicians are made — the more common scenario — education is important. “A common problem is that there is underrecognition of the cardiovascular risk being elevated in our patients,” she said, above and beyond risk posed by traditional risk factors such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and obesity, all of which have been shown to occur more frequently in patients with psoriatic disease than in the general population.

Risk stratification guides CVD prevention in the general population, and “if you use typical scores for cardiovascular risk, they may underestimate risk for our patients with PsA,” said Dr. Ogdie, who has reported on CV risk in patients with PsA. “Relative to what the patient’s perceived risk is, they may be treated similarly (to the general population). But relative to their actual risk, they’re undertreated.”

The 2019 AAD-NPF psoriasis guidelines recommend utilizing a 1.5 multiplication factor in risk score models, such as the American College of Cardiology’s Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) Risk Estimator, when the patient has a body surface area >10% or is a candidate for systemic therapy or phototherapy.

Similarly, the 2018 American Heart Association (AHA)-ACC Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol defines psoriasis, along with RA, metabolic syndrome, HIV, and other diseases, as a “cardiovascular risk enhancer” that should be factored into assessments of ASCVD risk. (The guideline does not specify a psoriasis severity threshold.)

“It’s the first time the specialty [of cardiology] has said, ‘pay attention to a skin disease,’ ” Dr. Gelfand said at the NPF meeting.

Using the 1.5 multiplication factor, a patient who otherwise would be classified in the AHA/ACC guideline as “borderline risk,” with a 10-year ASCVD risk of 5% to <7.5%, would instead have an “intermediate” 10-year ASCVD risk of ≥7.5% to <20%. Application of the AHA-ACC “risk enhancer” would have a similar effect.

For management, the main impact of psoriasis being considered a risk enhancer is that “it lowers the threshold for treatment with standard cardiovascular prevention medications such as statins.”

In general, “we should be taking a more aggressive approach to the management of traditional cardiovascular risk factors” in patients with psoriatic disease, he said. Instead of telling a patient with mildly elevated blood pressure, ‘I’ll see you in a year or two,’ or a patient entering a prediabetic stage to “watch what you eat, and I’ll see you in a couple of years,” clinicians need to be more vigilant.

“It’s about recognizing that these traditional cardiometabolic risk factors, synergistically with psoriasis, can start enhancing CV risk at an earlier age than we might expect,” said Dr. Garshick, whose 2021 review of CV risk in psoriasis describes how the inflammatory milieu in psoriasis is linked to atherosclerosis development.

Cardiologists are aware of this, but “many primary care physicians are not. It takes time for medical knowledge to diffuse,” Dr. Gelfand said. “Tell the PCP, in notes or in a form letter, that there is a higher risk of CV disease, and reference the AHA/ACC guidelines,” he advised. “You don’t want your patient to go to their doctor and the doctor to [be uninformed].”

‘Patients trust us’

Dr. Gelfand has been at the forefront of research on psoriasis and heart disease. A study he coauthored in 2006, for instance, documented an independent risk of MI, with adjusted relative risks of 1.29 and 3.10 for a 30-year-old patient with mild or severe disease, respectively, and higher risks for a 60-year-old. In 2010, he and coinvestigators found that severe psoriasis was an independent risk factor for CV mortality (HR, 1.57) after adjusting for age, sex, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

Today, along with Dr. Barbieri, Dr. Ogdie, and others, he is studying the feasibility and efficacy of a proposed national, “centralized care coordinator” model of care whereby dermatologists and rheumatologists would educate the patient, order lipid and HbA1c measurements as medically appropriate, and then refer patients as needed to a care coordinator. The care coordinator would calculate a 10-year CVD risk score and counsel the patient on possible next steps.

In a pilot study of 85 patients at four sites, 92% of patients followed through on their physician’s recommendations to have labs drawn, and 86% indicated the model was acceptable and feasible. A total of 27% of patients had “newly identified, previously undiagnosed, elevated cardiovascular disease risk,” and exploratory effectiveness results indicated a successful reduction in predicted CVD risk in patients who started statins, Dr. Gelfand reported at the NPF meeting.

With funding from the NPF, a larger, single-arm, pragmatic “CP3” trial (NCT05908240) is enrolling 525 patients with psoriasis at 10-20 academic and nonacademic dermatology sites across the United States to further test the model. The primary endpoint will be the change in LDL cholesterol measured at 6 months among people with a 10-year risk ≥5%. Secondary endpoints will cover improvement in disease severity and quality of life, behavior modification, patient experience, and other issues.

“We have only 10-15 minutes [with patients] ... a care coordinator who is empathetic and understanding and [informed] could make a big difference,” Dr. Gelfand said at the NPF meeting. If findings are positive, the model would be tested in rheumatology sites as well. The hope, he said, is that the NPF would be able to fund an in-house care coordinator(s) for the long-term.

Notably, a patient survey conducted as part of exploratory research leading up to the care coordinator project showed that patients trust their dermatologist or rheumatologist for CVD education and screening. Among 160 patients with psoriasis and 162 patients with PsA, 76% and 90% agreed that “I would like it if my dermatologist/rheumatologist educated me about my risk of heart disease,” and 60% and 75%, respectively, agree that “it would be convenient for me to have my cholesterol checked by my dermatologist/rheumatologist.”

“Patients trust us,” Dr. Gelfand said at the NPF meeting. “And the pilot study shows us that patients are motivated.”

Taking an individualized, holistic, longitudinal approach

“Sometimes you do have to triage bit,” Dr. Gelfand said in an interview. “For a young person with normal body weight who doesn’t smoke and has mild psoriasis, one could just educate and advise that they see their primary care physician” for monitoring.

“But for the same patient who is obese, maybe smokes, and doesn’t have a primary care physician, I’d order labs,” he said. “You don’t want a patient walking out the door with an [undiagnosed] LDL of 160 or hypertension.”

Age is also an important consideration, as excess CVD risk associated with autoimmune diseases like psoriasis rises with age, Dr. Gelfand said during a seminar on psoriasis and PsA held at NYU Langone in December. For a young person, typically, “I need to focus on education and lifestyle … setting them on a healthy lifestyle trajectory,” he said. “Once they get to 40, from 40 to 75 or so, that’s a sweet spot for medical intervention to lower cardiovascular risk.”

Even at older ages, however, lipid management is not the be-all and end-all, he said in the interview. “We have to be holistic.”

One advantage of having highly successful therapies for psoriasis, and to a lesser extent PsA, is the time that becomes available during follow-up visits — once disease is under control — to “focus on other things,” he said. Waiting until disease is under control to discuss diet, exercise, or smoking, for instance, makes sense anyway, he said. “You don’t want to overwhelm patients with too much to do at once.”

Indeed, said dermatologist Robert E. Kalb, MD, of the Buffalo Medical Group in Buffalo, NY, “patients have an open mind [about discussing cardiovascular disease risk], but it is not high on their radar. Most of them just want to get their skin clear.” (Dr. Kalb participated in the care coordinator pilot study, and said in an interview that since its completion, he has been more routinely ordering relevant labs.)

Rheumatologists are less fortunate with highly successful therapies, but “over the continuum of care, we do have time in office visits” to discuss issues like smoking, exercise, and lifestyle, Dr. Ogdie said. “I think of each of those pieces as part of our job.”

In the future, as researchers learn more about the impact of psoriasis and PsA treatments on CVD risk, it may be possible to tailor treatments or to prescribe treatments knowing that the therapies could reduce risk. Observational and epidemiologic data suggest that tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor therapy over 3 years reduces the risk of MI, and that patients whose psoriasis is treated have reduced aortic inflammation, improved myocardial strain, and reduced coronary plaque burden, Dr. Garshick said at the NPF meeting.

“But when we look at the randomized controlled trials, they’re actually inconclusive that targeting inflammation in psoriatic disease reduces surrogates of cardiovascular disease,” he said. Dr. Garshick’s own research focuses on platelet and endothelial biology in psoriasis.

Dr. Barbieri reported he had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Garshick reported consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Kiniksa, Horizon Therapeutics, and Agepha. Dr. Ogdie reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Takeda, and UCB. Dr. Gelfand reported serving as a consultant for AbbVie, Artax, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, and other companies.

Patients with psoriatic disease have significantly higher risks of myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality than does the general population, yet research consistently paints what dermatologist Joel M. Gelfand, MD, calls an “abysmal” picture: Only a minority of patients with psoriatic disease know about their increased risks, only a minority of dermatologists and rheumatologists screen for cardiovascular risk factors like lipid levels and blood pressure, and only a minority of patients diagnosed with hyperlipidemia are adequately treated with statin therapy.

In the literature and at medical meetings, Dr. Gelfand and others who have studied cardiovascular disease (CVD) comorbidity and physician practices have been urging dermatologists and rheumatologists to play a more consistent and active role in primary cardiovascular prevention for patients with psoriatic disease, who are up to 50% more likely than patients without it to develop CVD and who tend to have atherosclerosis at earlier ages.

According to the 2019 joint American Academy of Dermatology (AAD)–National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) guidelines for managing psoriasis “with awareness and attention to comorbidities,” this means not only ensuring that all patients with psoriasis receive standard CV risk assessment (screening for hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia), but also recognizing that patients who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy — or who have psoriasis involving > 10% of body surface area — may benefit from earlier and more frequent screening.

CV risk and premature mortality rises with the severity of skin disease, and patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) are believed to have risk levels similar to patients with moderate-severe psoriasis, cardiologist Michael S. Garshick, MD, director of the cardio-rheumatology program at New York University Langone Health, said in an interview.

In a recent survey study of 100 patients seen at NYU Langone Health’s psoriasis specialty clinic, only one-third indicated they had been advised by their physicians to be screened for CV risk factors, and only one-third reported having been told of the connection between psoriasis and CVD risk. Dr. Garshick shared the unpublished findings at the annual research symposium of the NPF in October.

Similarly, data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey shows that just 16% of psoriasis-related visits to dermatology providers from 2007 to 2016 involved screening for CV risk factors. Screening rates were 11% for body mass index, 7.4% for blood pressure, 2.9% for cholesterol, and 1.7% for glucose, Dr. Gelfand and coauthors reported in 2023. .

Such findings are concerning because research shows that fewer than a quarter of patients with psoriasis have a primary care visit within a year of establishing care with their physicians, and that, overall, fewer than half of commercially insured adults under age 65 visit a primary care physician each year, according to John S. Barbieri, MD, of the department of dermatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He included these findings when reporting in 2022 on a survey study on CVD screening.

In many cases, dermatologists and rheumatologists may be the primary providers for patients with psoriatic disease. So, “the question is, how can the dermatologist or rheumatologist use their interactions as a touchpoint to improve the patient’s well-being?” Dr. Barbieri said in an interview.

For the dermatologist, educating patients about the higher CVD risk fits well into conversations about “how there may be inflammation inside the body as well as in the skin,” he said. “Talk about cardiovascular risk just as you talk about PsA risk.” Both specialists, he added, can incorporate blood pressure readings and look for opportunities to measure lipid levels and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). These labs can easily be integrated into a biologic work-up.

“The hard part — and this needs to be individualized — is how do you want to handle [abnormal readings]? Do you want to take on a lot of the ownership and calculate [10-year CVD] risk scores and then counsel patients accordingly?” Dr. Barbieri said. “Or do you want to try to refer, and encourage them to work with their PCP? There a high-touch version and a low-touch version of how you can turn screening into action, into a care plan.”

Beyond traditional risk elevation, the primary care hand-off

Rheumatologists “in general may be more apt to screen for cardiovascular disease” as a result of their internal medicine residency training, and “we’re generally more comfortable prescribing ... if we need to,” said Alexis R. Ogdie, MD, a rheumatologist at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and director of the Penn Psoriatic Arthritis Clinic.

Referral to a preventive cardiologist for management of abnormal lab results or ongoing monitoring and prevention is ideal, but when hand-offs to primary care physicians are made — the more common scenario — education is important. “A common problem is that there is underrecognition of the cardiovascular risk being elevated in our patients,” she said, above and beyond risk posed by traditional risk factors such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and obesity, all of which have been shown to occur more frequently in patients with psoriatic disease than in the general population.

Risk stratification guides CVD prevention in the general population, and “if you use typical scores for cardiovascular risk, they may underestimate risk for our patients with PsA,” said Dr. Ogdie, who has reported on CV risk in patients with PsA. “Relative to what the patient’s perceived risk is, they may be treated similarly (to the general population). But relative to their actual risk, they’re undertreated.”

The 2019 AAD-NPF psoriasis guidelines recommend utilizing a 1.5 multiplication factor in risk score models, such as the American College of Cardiology’s Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) Risk Estimator, when the patient has a body surface area >10% or is a candidate for systemic therapy or phototherapy.

Similarly, the 2018 American Heart Association (AHA)-ACC Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol defines psoriasis, along with RA, metabolic syndrome, HIV, and other diseases, as a “cardiovascular risk enhancer” that should be factored into assessments of ASCVD risk. (The guideline does not specify a psoriasis severity threshold.)

“It’s the first time the specialty [of cardiology] has said, ‘pay attention to a skin disease,’ ” Dr. Gelfand said at the NPF meeting.

Using the 1.5 multiplication factor, a patient who otherwise would be classified in the AHA/ACC guideline as “borderline risk,” with a 10-year ASCVD risk of 5% to <7.5%, would instead have an “intermediate” 10-year ASCVD risk of ≥7.5% to <20%. Application of the AHA-ACC “risk enhancer” would have a similar effect.

For management, the main impact of psoriasis being considered a risk enhancer is that “it lowers the threshold for treatment with standard cardiovascular prevention medications such as statins.”

In general, “we should be taking a more aggressive approach to the management of traditional cardiovascular risk factors” in patients with psoriatic disease, he said. Instead of telling a patient with mildly elevated blood pressure, ‘I’ll see you in a year or two,’ or a patient entering a prediabetic stage to “watch what you eat, and I’ll see you in a couple of years,” clinicians need to be more vigilant.

“It’s about recognizing that these traditional cardiometabolic risk factors, synergistically with psoriasis, can start enhancing CV risk at an earlier age than we might expect,” said Dr. Garshick, whose 2021 review of CV risk in psoriasis describes how the inflammatory milieu in psoriasis is linked to atherosclerosis development.

Cardiologists are aware of this, but “many primary care physicians are not. It takes time for medical knowledge to diffuse,” Dr. Gelfand said. “Tell the PCP, in notes or in a form letter, that there is a higher risk of CV disease, and reference the AHA/ACC guidelines,” he advised. “You don’t want your patient to go to their doctor and the doctor to [be uninformed].”

‘Patients trust us’

Dr. Gelfand has been at the forefront of research on psoriasis and heart disease. A study he coauthored in 2006, for instance, documented an independent risk of MI, with adjusted relative risks of 1.29 and 3.10 for a 30-year-old patient with mild or severe disease, respectively, and higher risks for a 60-year-old. In 2010, he and coinvestigators found that severe psoriasis was an independent risk factor for CV mortality (HR, 1.57) after adjusting for age, sex, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

Today, along with Dr. Barbieri, Dr. Ogdie, and others, he is studying the feasibility and efficacy of a proposed national, “centralized care coordinator” model of care whereby dermatologists and rheumatologists would educate the patient, order lipid and HbA1c measurements as medically appropriate, and then refer patients as needed to a care coordinator. The care coordinator would calculate a 10-year CVD risk score and counsel the patient on possible next steps.

In a pilot study of 85 patients at four sites, 92% of patients followed through on their physician’s recommendations to have labs drawn, and 86% indicated the model was acceptable and feasible. A total of 27% of patients had “newly identified, previously undiagnosed, elevated cardiovascular disease risk,” and exploratory effectiveness results indicated a successful reduction in predicted CVD risk in patients who started statins, Dr. Gelfand reported at the NPF meeting.

With funding from the NPF, a larger, single-arm, pragmatic “CP3” trial (NCT05908240) is enrolling 525 patients with psoriasis at 10-20 academic and nonacademic dermatology sites across the United States to further test the model. The primary endpoint will be the change in LDL cholesterol measured at 6 months among people with a 10-year risk ≥5%. Secondary endpoints will cover improvement in disease severity and quality of life, behavior modification, patient experience, and other issues.

“We have only 10-15 minutes [with patients] ... a care coordinator who is empathetic and understanding and [informed] could make a big difference,” Dr. Gelfand said at the NPF meeting. If findings are positive, the model would be tested in rheumatology sites as well. The hope, he said, is that the NPF would be able to fund an in-house care coordinator(s) for the long-term.

Notably, a patient survey conducted as part of exploratory research leading up to the care coordinator project showed that patients trust their dermatologist or rheumatologist for CVD education and screening. Among 160 patients with psoriasis and 162 patients with PsA, 76% and 90% agreed that “I would like it if my dermatologist/rheumatologist educated me about my risk of heart disease,” and 60% and 75%, respectively, agree that “it would be convenient for me to have my cholesterol checked by my dermatologist/rheumatologist.”

“Patients trust us,” Dr. Gelfand said at the NPF meeting. “And the pilot study shows us that patients are motivated.”

Taking an individualized, holistic, longitudinal approach

“Sometimes you do have to triage bit,” Dr. Gelfand said in an interview. “For a young person with normal body weight who doesn’t smoke and has mild psoriasis, one could just educate and advise that they see their primary care physician” for monitoring.

“But for the same patient who is obese, maybe smokes, and doesn’t have a primary care physician, I’d order labs,” he said. “You don’t want a patient walking out the door with an [undiagnosed] LDL of 160 or hypertension.”

Age is also an important consideration, as excess CVD risk associated with autoimmune diseases like psoriasis rises with age, Dr. Gelfand said during a seminar on psoriasis and PsA held at NYU Langone in December. For a young person, typically, “I need to focus on education and lifestyle … setting them on a healthy lifestyle trajectory,” he said. “Once they get to 40, from 40 to 75 or so, that’s a sweet spot for medical intervention to lower cardiovascular risk.”

Even at older ages, however, lipid management is not the be-all and end-all, he said in the interview. “We have to be holistic.”

One advantage of having highly successful therapies for psoriasis, and to a lesser extent PsA, is the time that becomes available during follow-up visits — once disease is under control — to “focus on other things,” he said. Waiting until disease is under control to discuss diet, exercise, or smoking, for instance, makes sense anyway, he said. “You don’t want to overwhelm patients with too much to do at once.”

Indeed, said dermatologist Robert E. Kalb, MD, of the Buffalo Medical Group in Buffalo, NY, “patients have an open mind [about discussing cardiovascular disease risk], but it is not high on their radar. Most of them just want to get their skin clear.” (Dr. Kalb participated in the care coordinator pilot study, and said in an interview that since its completion, he has been more routinely ordering relevant labs.)

Rheumatologists are less fortunate with highly successful therapies, but “over the continuum of care, we do have time in office visits” to discuss issues like smoking, exercise, and lifestyle, Dr. Ogdie said. “I think of each of those pieces as part of our job.”

In the future, as researchers learn more about the impact of psoriasis and PsA treatments on CVD risk, it may be possible to tailor treatments or to prescribe treatments knowing that the therapies could reduce risk. Observational and epidemiologic data suggest that tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor therapy over 3 years reduces the risk of MI, and that patients whose psoriasis is treated have reduced aortic inflammation, improved myocardial strain, and reduced coronary plaque burden, Dr. Garshick said at the NPF meeting.

“But when we look at the randomized controlled trials, they’re actually inconclusive that targeting inflammation in psoriatic disease reduces surrogates of cardiovascular disease,” he said. Dr. Garshick’s own research focuses on platelet and endothelial biology in psoriasis.

Dr. Barbieri reported he had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Garshick reported consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Kiniksa, Horizon Therapeutics, and Agepha. Dr. Ogdie reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Takeda, and UCB. Dr. Gelfand reported serving as a consultant for AbbVie, Artax, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, and other companies.

Bilateral Burning Palmoplantar Lesions

The Diagnosis: Lichen Sclerosus

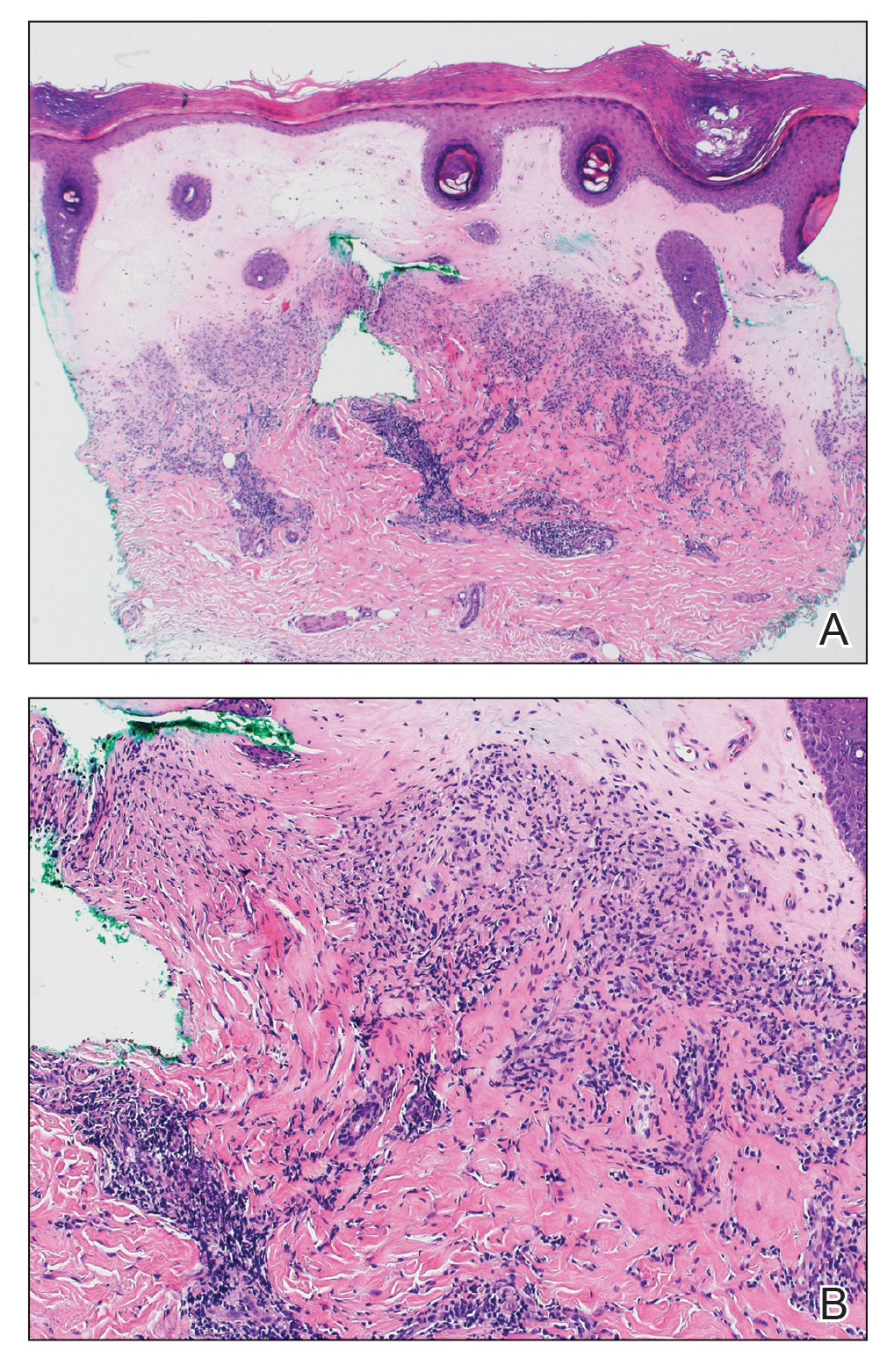

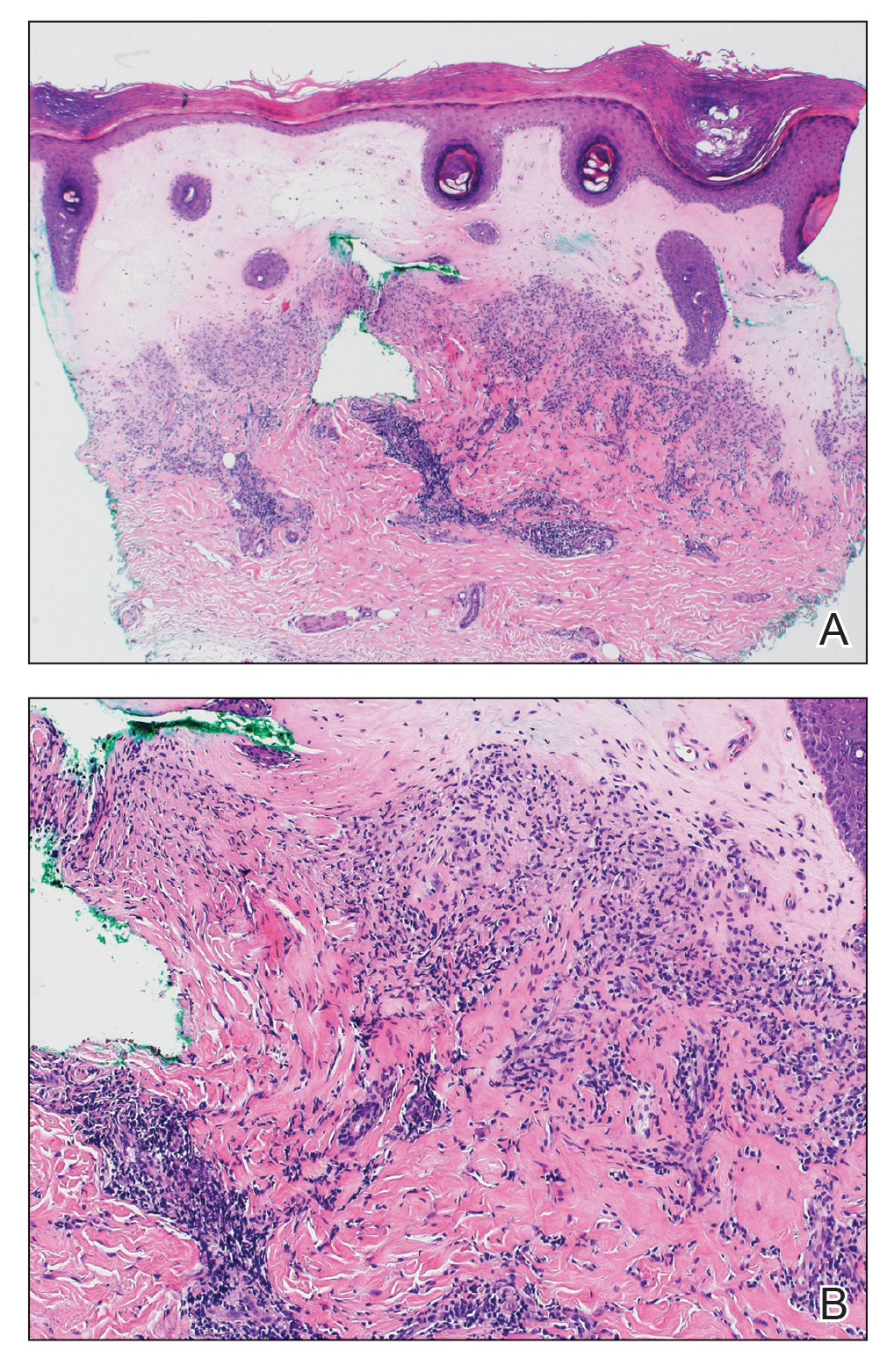

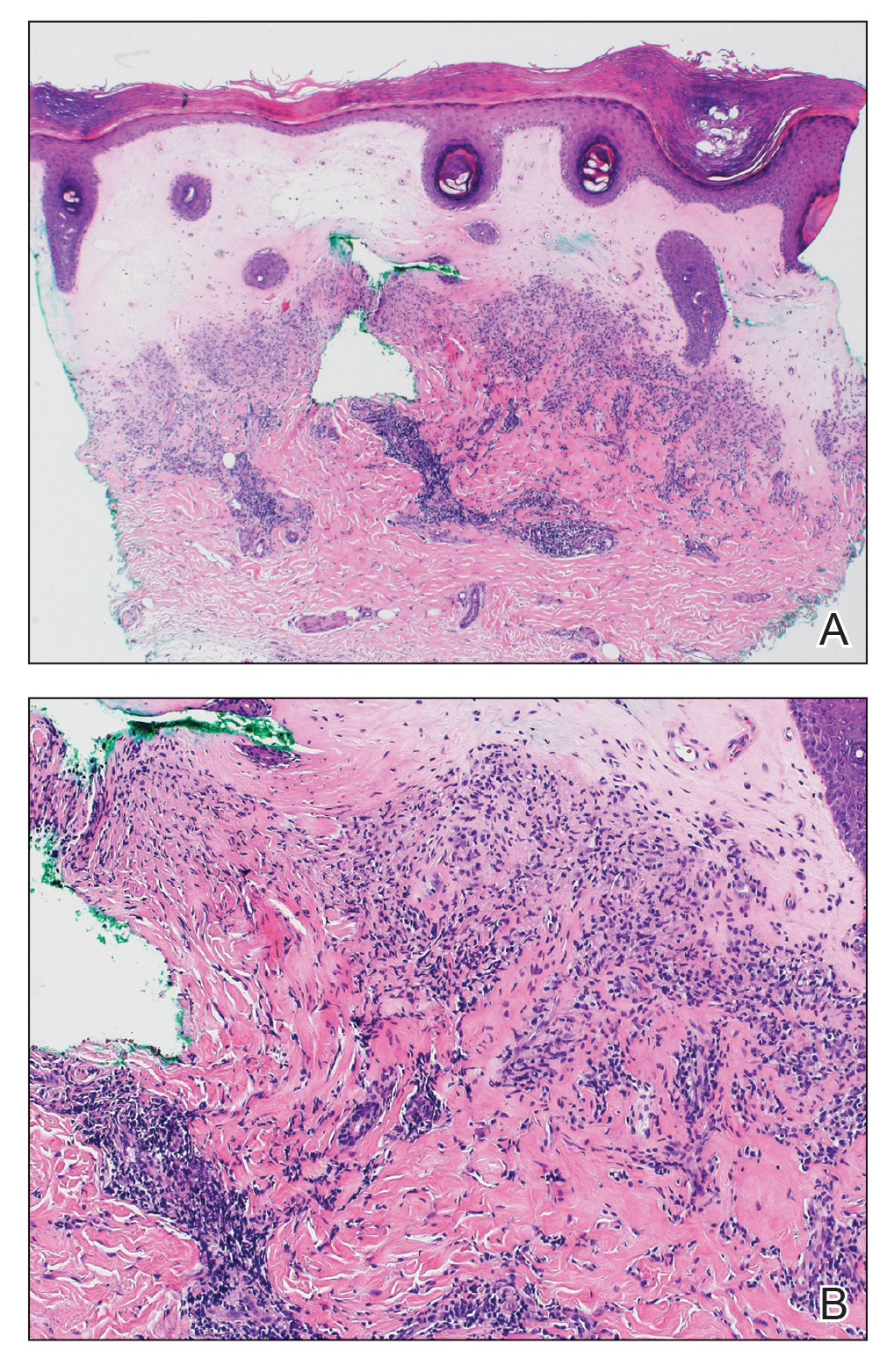

Histopathology revealed a thin epidermis with homogenization of the upper dermal collagen. By contrast, the lower dermis was sclerotic with patchy chronic dermal infiltrate (Figure). Ultimately, the patient’s clinical presentation and histopathologic findings led to a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus (LS).

Lichen sclerosus is a rare chronic inflammatory skin condition that typically is characterized by porcelainwhite atrophic plaques on the skin, most often involving the external female genitalia including the vulva and perianal area.1 It is thought to be underdiagnosed and underreported.2 Extragenital manifestations may occur, though some cases are characterized by concomitant genital involvement.3,4 Our patient presented with palmoplantar distribution of plaques without genitalia involvement. Approximately 6% to 10% of patients with extragenital LS do not have genital involvement at the time of diagnosis.3,5 Furthermore, LS involving the palms and soles is exceedingly rare.2 Although extragenital LS may be asymptomatic, patients can experience debilitating pruritus; bullae with hemorrhage and erosion; plaque thickening with repeated excoriations; and painful fissuring, especially if lesions are in areas that are susceptible to friction or tension.3,6 New lesions on previously unaffected skin also may develop secondary to trauma through the Koebner phenomenon.1,6

Histologically, LS is characterized by epidermal hyperkeratosis accompanied by follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy with flattened rete ridges, vacuolization of the basal epidermis, marked edema in the superficial dermis (in early lesions) or homogenized collagen in the upper dermis (in established lesions), and a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate beneath the homogenized collagen. Although the pathogenesis of LS is unclear, purported etiologic factors from studies in genital disease include immune dysfunction, genetic predisposition, infection, and trauma.6 Lichen sclerosus is associated strongly with autoimmune diseases including alopecia areata, vitiligo, autoimmune thyroiditis, diabetes mellitus, and pernicious anemia, indicating its potential multifactorial etiology and linkage to T-lymphocyte dysfunction.1 Early LS lesions often appear as flat-topped and slightly scaly, hypopigmented, white or mildly erythematous, polygonal papules that coalesce to form larger plaques with peripheral erythema. With time, the inflammation subsides, and lesions become porcelain-white with varying degrees of palpable sclerosis, resembling thin paperlike wrinkles indicative of epidermal atrophy.6

The differential diagnosis of LS includes lichen planus (LP), morphea, discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), and vitiligo.3 Lesions of LP commonly are described as flat-topped, polygonal, pink-purple papules localized mostly along the volar wrists, shins, presacral area, and hands.7 Lichen planus is considered to be more pruritic3 than LS and can be further distinguished by biopsy through identifying a well-formed granular layer and numerous cytoid bodies. Unlike LS, LP is not characterized by basement membrane thickening or epidermal atrophy.8

Skin lesions seen in morphea may resemble the classic atrophic white lesions of extragenital LS; however, it is unclear if the appearance of LS-like lesions with morphea is a simultaneous occurrence of 2 separate disorders or the development of clinical findings resembling LS in lesions of morphea.6 Furthermore, morphea involves deep inflammation and sclerosis of the dermis that may extend into subcutaneous fat without follicular plugging of the epidermis.3,9 In contrast, LS primarily affects the epidermis and dermis with the presence of epidermal follicular plugging.6

Lesions seen in DLE are characterized as well-defined, annular, erythematous patches and plaques followed by follicular hyperkeratosis with adherent scaling. Upon removal of the scale, follicle-sized keratotic spikes (carpet tacks) are present.10 Scaling of lesions and the carpet tack sign were absent in our patient. In addition, DLE typically reveals surrounding pigmentation and scarring over plaques,3 which were not observed in our patient.

Vitiligo commonly is associated with extragenital LS. As with LS, vitiligo can be explained by mechanisms of immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced cytotoxicity as well as perforin and granzyme-B expression.11 Although vitiligo resembles the late hypopigmented lesions of extragenital LS, there are no plaques or surface changes, and a larger, more generalized area of the skin typically is involved.3

- Chamli A, Souissi A. Lichen sclerosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538246/

- Gaddis KJ, Huang J, Haun PL. An atrophic and spiny eruption of the palms. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1344-1345. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2018.1265

- Arif T, Fatima R, Sami M. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: a comprehensive review [published online August 11, 2022]. Australas J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ajd.13890

- Heibel HD, Styles AR, Cockerell CJ. A case of acral lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;8:26-27. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.12.008

- Seyffert J, Bibliowicz N, Harding T, et al. Palmar lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:697-699. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.06.005

- Jacobe H. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: clinical features and diagnosis. UpToDate. Updated July 11, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/extragenital-lichen-sclerosus?search=Lichen%20sclerosus&source =search_result&selectedTitle=2~66&usage_type=default&display_ rank=2

- Goldstein BG, Goldstein AO, Mostow E. Lichen planus. UpToDate. Updated October 25, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lichen-planus?search=lichen%20 sclerosus&topicRef=15838&source=see_link

- Tallon B. Lichen sclerosus pathology. DermNet NZ website. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/lichen-sclerosus-pathology

- Jacobe H. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of morphea (localized scleroderma) in adults. UpToDate. Updated November 15, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://medilib.ir/uptodate/show/13776

- McDaniel B, Sukumaran S, Koritala T, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 28, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493145/

- Veronesi G, Scarfì F, Misciali C, et al. An unusual skin reaction in uveal melanoma during treatment with nivolumab: extragenital lichen sclerosus. Anticancer Drugs. 2019;30:969-972. doi:10.1097/ CAD.0000000000000819

The Diagnosis: Lichen Sclerosus

Histopathology revealed a thin epidermis with homogenization of the upper dermal collagen. By contrast, the lower dermis was sclerotic with patchy chronic dermal infiltrate (Figure). Ultimately, the patient’s clinical presentation and histopathologic findings led to a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus (LS).

Lichen sclerosus is a rare chronic inflammatory skin condition that typically is characterized by porcelainwhite atrophic plaques on the skin, most often involving the external female genitalia including the vulva and perianal area.1 It is thought to be underdiagnosed and underreported.2 Extragenital manifestations may occur, though some cases are characterized by concomitant genital involvement.3,4 Our patient presented with palmoplantar distribution of plaques without genitalia involvement. Approximately 6% to 10% of patients with extragenital LS do not have genital involvement at the time of diagnosis.3,5 Furthermore, LS involving the palms and soles is exceedingly rare.2 Although extragenital LS may be asymptomatic, patients can experience debilitating pruritus; bullae with hemorrhage and erosion; plaque thickening with repeated excoriations; and painful fissuring, especially if lesions are in areas that are susceptible to friction or tension.3,6 New lesions on previously unaffected skin also may develop secondary to trauma through the Koebner phenomenon.1,6

Histologically, LS is characterized by epidermal hyperkeratosis accompanied by follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy with flattened rete ridges, vacuolization of the basal epidermis, marked edema in the superficial dermis (in early lesions) or homogenized collagen in the upper dermis (in established lesions), and a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate beneath the homogenized collagen. Although the pathogenesis of LS is unclear, purported etiologic factors from studies in genital disease include immune dysfunction, genetic predisposition, infection, and trauma.6 Lichen sclerosus is associated strongly with autoimmune diseases including alopecia areata, vitiligo, autoimmune thyroiditis, diabetes mellitus, and pernicious anemia, indicating its potential multifactorial etiology and linkage to T-lymphocyte dysfunction.1 Early LS lesions often appear as flat-topped and slightly scaly, hypopigmented, white or mildly erythematous, polygonal papules that coalesce to form larger plaques with peripheral erythema. With time, the inflammation subsides, and lesions become porcelain-white with varying degrees of palpable sclerosis, resembling thin paperlike wrinkles indicative of epidermal atrophy.6

The differential diagnosis of LS includes lichen planus (LP), morphea, discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), and vitiligo.3 Lesions of LP commonly are described as flat-topped, polygonal, pink-purple papules localized mostly along the volar wrists, shins, presacral area, and hands.7 Lichen planus is considered to be more pruritic3 than LS and can be further distinguished by biopsy through identifying a well-formed granular layer and numerous cytoid bodies. Unlike LS, LP is not characterized by basement membrane thickening or epidermal atrophy.8

Skin lesions seen in morphea may resemble the classic atrophic white lesions of extragenital LS; however, it is unclear if the appearance of LS-like lesions with morphea is a simultaneous occurrence of 2 separate disorders or the development of clinical findings resembling LS in lesions of morphea.6 Furthermore, morphea involves deep inflammation and sclerosis of the dermis that may extend into subcutaneous fat without follicular plugging of the epidermis.3,9 In contrast, LS primarily affects the epidermis and dermis with the presence of epidermal follicular plugging.6

Lesions seen in DLE are characterized as well-defined, annular, erythematous patches and plaques followed by follicular hyperkeratosis with adherent scaling. Upon removal of the scale, follicle-sized keratotic spikes (carpet tacks) are present.10 Scaling of lesions and the carpet tack sign were absent in our patient. In addition, DLE typically reveals surrounding pigmentation and scarring over plaques,3 which were not observed in our patient.

Vitiligo commonly is associated with extragenital LS. As with LS, vitiligo can be explained by mechanisms of immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced cytotoxicity as well as perforin and granzyme-B expression.11 Although vitiligo resembles the late hypopigmented lesions of extragenital LS, there are no plaques or surface changes, and a larger, more generalized area of the skin typically is involved.3

The Diagnosis: Lichen Sclerosus

Histopathology revealed a thin epidermis with homogenization of the upper dermal collagen. By contrast, the lower dermis was sclerotic with patchy chronic dermal infiltrate (Figure). Ultimately, the patient’s clinical presentation and histopathologic findings led to a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus (LS).

Lichen sclerosus is a rare chronic inflammatory skin condition that typically is characterized by porcelainwhite atrophic plaques on the skin, most often involving the external female genitalia including the vulva and perianal area.1 It is thought to be underdiagnosed and underreported.2 Extragenital manifestations may occur, though some cases are characterized by concomitant genital involvement.3,4 Our patient presented with palmoplantar distribution of plaques without genitalia involvement. Approximately 6% to 10% of patients with extragenital LS do not have genital involvement at the time of diagnosis.3,5 Furthermore, LS involving the palms and soles is exceedingly rare.2 Although extragenital LS may be asymptomatic, patients can experience debilitating pruritus; bullae with hemorrhage and erosion; plaque thickening with repeated excoriations; and painful fissuring, especially if lesions are in areas that are susceptible to friction or tension.3,6 New lesions on previously unaffected skin also may develop secondary to trauma through the Koebner phenomenon.1,6

Histologically, LS is characterized by epidermal hyperkeratosis accompanied by follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy with flattened rete ridges, vacuolization of the basal epidermis, marked edema in the superficial dermis (in early lesions) or homogenized collagen in the upper dermis (in established lesions), and a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate beneath the homogenized collagen. Although the pathogenesis of LS is unclear, purported etiologic factors from studies in genital disease include immune dysfunction, genetic predisposition, infection, and trauma.6 Lichen sclerosus is associated strongly with autoimmune diseases including alopecia areata, vitiligo, autoimmune thyroiditis, diabetes mellitus, and pernicious anemia, indicating its potential multifactorial etiology and linkage to T-lymphocyte dysfunction.1 Early LS lesions often appear as flat-topped and slightly scaly, hypopigmented, white or mildly erythematous, polygonal papules that coalesce to form larger plaques with peripheral erythema. With time, the inflammation subsides, and lesions become porcelain-white with varying degrees of palpable sclerosis, resembling thin paperlike wrinkles indicative of epidermal atrophy.6

The differential diagnosis of LS includes lichen planus (LP), morphea, discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), and vitiligo.3 Lesions of LP commonly are described as flat-topped, polygonal, pink-purple papules localized mostly along the volar wrists, shins, presacral area, and hands.7 Lichen planus is considered to be more pruritic3 than LS and can be further distinguished by biopsy through identifying a well-formed granular layer and numerous cytoid bodies. Unlike LS, LP is not characterized by basement membrane thickening or epidermal atrophy.8

Skin lesions seen in morphea may resemble the classic atrophic white lesions of extragenital LS; however, it is unclear if the appearance of LS-like lesions with morphea is a simultaneous occurrence of 2 separate disorders or the development of clinical findings resembling LS in lesions of morphea.6 Furthermore, morphea involves deep inflammation and sclerosis of the dermis that may extend into subcutaneous fat without follicular plugging of the epidermis.3,9 In contrast, LS primarily affects the epidermis and dermis with the presence of epidermal follicular plugging.6

Lesions seen in DLE are characterized as well-defined, annular, erythematous patches and plaques followed by follicular hyperkeratosis with adherent scaling. Upon removal of the scale, follicle-sized keratotic spikes (carpet tacks) are present.10 Scaling of lesions and the carpet tack sign were absent in our patient. In addition, DLE typically reveals surrounding pigmentation and scarring over plaques,3 which were not observed in our patient.

Vitiligo commonly is associated with extragenital LS. As with LS, vitiligo can be explained by mechanisms of immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced cytotoxicity as well as perforin and granzyme-B expression.11 Although vitiligo resembles the late hypopigmented lesions of extragenital LS, there are no plaques or surface changes, and a larger, more generalized area of the skin typically is involved.3

- Chamli A, Souissi A. Lichen sclerosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538246/

- Gaddis KJ, Huang J, Haun PL. An atrophic and spiny eruption of the palms. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1344-1345. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2018.1265

- Arif T, Fatima R, Sami M. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: a comprehensive review [published online August 11, 2022]. Australas J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ajd.13890

- Heibel HD, Styles AR, Cockerell CJ. A case of acral lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;8:26-27. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.12.008

- Seyffert J, Bibliowicz N, Harding T, et al. Palmar lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:697-699. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.06.005

- Jacobe H. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: clinical features and diagnosis. UpToDate. Updated July 11, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/extragenital-lichen-sclerosus?search=Lichen%20sclerosus&source =search_result&selectedTitle=2~66&usage_type=default&display_ rank=2

- Goldstein BG, Goldstein AO, Mostow E. Lichen planus. UpToDate. Updated October 25, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lichen-planus?search=lichen%20 sclerosus&topicRef=15838&source=see_link

- Tallon B. Lichen sclerosus pathology. DermNet NZ website. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/lichen-sclerosus-pathology

- Jacobe H. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of morphea (localized scleroderma) in adults. UpToDate. Updated November 15, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://medilib.ir/uptodate/show/13776

- McDaniel B, Sukumaran S, Koritala T, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 28, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493145/

- Veronesi G, Scarfì F, Misciali C, et al. An unusual skin reaction in uveal melanoma during treatment with nivolumab: extragenital lichen sclerosus. Anticancer Drugs. 2019;30:969-972. doi:10.1097/ CAD.0000000000000819

- Chamli A, Souissi A. Lichen sclerosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538246/

- Gaddis KJ, Huang J, Haun PL. An atrophic and spiny eruption of the palms. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1344-1345. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2018.1265

- Arif T, Fatima R, Sami M. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: a comprehensive review [published online August 11, 2022]. Australas J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ajd.13890

- Heibel HD, Styles AR, Cockerell CJ. A case of acral lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;8:26-27. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.12.008

- Seyffert J, Bibliowicz N, Harding T, et al. Palmar lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:697-699. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.06.005

- Jacobe H. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: clinical features and diagnosis. UpToDate. Updated July 11, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/extragenital-lichen-sclerosus?search=Lichen%20sclerosus&source =search_result&selectedTitle=2~66&usage_type=default&display_ rank=2

- Goldstein BG, Goldstein AO, Mostow E. Lichen planus. UpToDate. Updated October 25, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lichen-planus?search=lichen%20 sclerosus&topicRef=15838&source=see_link

- Tallon B. Lichen sclerosus pathology. DermNet NZ website. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/lichen-sclerosus-pathology

- Jacobe H. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of morphea (localized scleroderma) in adults. UpToDate. Updated November 15, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://medilib.ir/uptodate/show/13776

- McDaniel B, Sukumaran S, Koritala T, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 28, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493145/

- Veronesi G, Scarfì F, Misciali C, et al. An unusual skin reaction in uveal melanoma during treatment with nivolumab: extragenital lichen sclerosus. Anticancer Drugs. 2019;30:969-972. doi:10.1097/ CAD.0000000000000819

A 59-year-old woman presented with atrophic, hypopigmented, ivory papules and plaques localized to the central palms and soles of 3 years’ duration. The lesions were associated with burning that was most notable after extended periods of ambulation. The lesions initially were diagnosed as plaque psoriasis by an external dermatology clinic. At the time of presentation to our clinic, treatment with several highpotency topical steroids and biologics approved for plaque psoriasis had failed. Her medical history and concurrent medical workup were notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus, liver dysfunction, thyroid nodules overseen by an endocrinologist, vitamin B12 and vitamin D deficiencies managed with supplementation, and diffuse androgenic alopecia with suspected telogen effluvium. Physical examination revealed no plaque fissuring, pruritus, or scaling. She had no history of radiation therapy or organ transplantation. A punch biopsy of the left palm was performed.

Alcohol and CV Risk: Both Beneficial and Harmful Effects?

with evidence emerging that alcohol use may both increase and decrease the risk for CVD.

The answer may depend on the presence of circulating metabolites of alcohol, some of which may be beneficial while others may be harmful, new research suggests.

“We adopted an association analysis, looking at 60 metabolites produced during or after alcohol has been metabolized, to see whether those metabolites can link alcohol consumption with CVD,” senior author Jiantao Ma, PhD, MBBS, assistant professor, Division of Nutrition Epidemiology and Data Science, Friedman School, Tufts University, Boston, Massachusetts, said in an interview.

“We found that the relationship is quite complex, with some metabolites showing protective effects against CVD and others showing harmful effects,” said Dr. Ma. “This opens the door for future research because we think that these molecules can help [us] understand the mechanism of the relationship between alcohol and CVD.”

The study was published online in BMC Medicine.

J-Shaped Relationship?

Previous research has painted a confusing picture of the relationship between alcohol consumption and CVD. For example, some studies have suggested that moderate levels of drinking may be hazardous to cardiac health, while others have pointed to potential cardioprotective effects.

Nevertheless, “according to the latest ACC/AHA guidelines regarding alcohol consumption and its relationship to CVD, there is no level of alcohol use that is deemed safe and considered acceptable,” Saurabh Sharma, MD, program director, Internal Medicine Residency Program, and clinical assistant professor of cardiology, Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine, Scranton, Pennsylvania, said in an interview.

Older observational data suggested a “J-shaped” relationship between alcohol consumption and cardiovascular risk, such that a low to moderate amount might reduce risk, while higher amounts increase it, said Dr. Sharma, a member of the American College of Cardiology (ACC) Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases Council.

“But it’s essential to note that these findings were based on observational studies. No randomized controlled trials have provided conclusive evidence supporting the idea that moderate alcohol consumption actively reduces cardiovascular risk,” he said.

The current study is also observational, but it shines a somewhat different spotlight on the subject by examining alcohol consumption–related metabolites, said Dr. Ma — that is, small molecules that are the intermediates or end-products of metabolism in many cellular processes.

Some recent research “shows that alcohol may be harmful or at least has no beneficial effect in CVD prevention,” he said. “Our motivation was to analyze the association using metabolites, genetics, and epigenetics, because we think that these molecules may help us understand some of the mechanisms that underlie the relationship between alcohol consumption and CVD, and partially answer the question of whether alcohol may be harmful or helpful.”

Caution Warranted

Although some previous studies have looked at metabolites, most analyzed alcohol consumption measured at a single time point, “which may not represent habitual or long-term alcohol consumption,” the researchers note.

The team used data derived from 2458 Framingham Heart Study Offspring participants (mean age, 56 ± 9.3 years at the fifth examination; 52% female), calculating the cumulative average alcohol consumption from total intake of beer, wine, and liquor over an average 20-year period. Most participants were overweight, close to one fifth were current smokers, and 636 developed CVD over the study period.

Participants were assessed every 4-8 years, with metabolites measured during the fifth examination.

Linear models were used to investigate the association of alcohol consumption with 211 plasma metabolites, adjusting for a variety of potential confounders, including age, sex, batch, smoking, diet, physical activity, body mass index, and familial relationship.

Sixty metabolites associated with cumulative average alcohol consumption were identified (P < .00024), after adjustment for confounders. Of these, 40 displayed positive associations with the cumulative average alcohol consumption, with the most significant metabolite being cholesteryl palmitoleate (CE16:1), a plasma cholesteryl ester involved with cholesterol metabolism.

One gram per day of higher alcohol consumption was associated with a higher-level CE16:1 in the blood (b = .023). Several other phosphatidylcholine metabolites were also positively associated with alcohol consumption.

On the other hand, 20 metabolites were negatively associated with alcohol consumption, with triacylglycerol 54:4 (TAG 54:4) displaying the most significant association (b = –.017).

The alcoholic beverages were not equal when it came to association with metabolites: 19 metabolites were significantly associated with the cumulative average consumption of beer, 30 with wine, and 32 with liquor. Seven were significantly associated with the cumulative consumption of all three types of drinks.

The researchers conducted survival analysis that identified 10 alcohol-associated metabolites associated with differential CVD risks, after adjusting for confounders. They also built two alcohol consumption–weighted metabolite scores using these 10 metabolites. After adjustment for confounders including CVD risk factors, the two scores had “comparable but opposite” associations with incident CVD, HR 1.11 (95% CI, 1.02-1.21) vs 0.88 (0.78-0.98; both P values = .02).

“We found that seven metabolites were harmful, while three were beneficial, “ Dr. Ma reported.

Dr. Ma cautioned that association “doesn’t represent causation.” On the basis of the findings, however, “we can hypothesize that if you drink a moderate amount of alcohol, you can either increase or decrease your risk of CVD.”

For people with cardiac conditions, “it would be [wise to be] cautious in recommending alcohol consumption,” he said. “For people without cardiac conditions, I would follow the recommendations of the AHA. If people don’t already drink alcohol, we don’t recommend that you start drinking it; and if you already drink, we’d recommend keeping it minimal.”

He cautioned that this is “only one study and we need more research if we are to generate a clearer message to the patient.” At present, perhaps the best message to patients is “to be cautious and warn them that there are potentially harmful effects,” he said.

Mendelian Randomization?

Dr. Sharma, who was not involved in the study, emphasized that it’s “crucial” to recognize that the study “does not alter the established understanding that any level of alcohol consumption poses harm to the heart,” and that “any amount of alcohol consumption has the potential to elevate triglyceride levels, thereby contributing to the increased risk of cardiovascular complications.”

Previously reported cardioprotective benefits “are likely influenced by confounding factors, such as lifestyle and sociodemographic elements,” he speculated.

He noted that observational studies “encounter challenges in disentangling the influence of factors like obesity, lack of exercise, and tobacco use” as well as reverse causality.

“To overcome these limitations, Mendelian randomization emerges as a robust method,” he suggested. “This approach utilizes measured genetic variations with known functions to investigate the causal effect of a modifiable exposure on disease within the framework of observational studies.”

Notably, certain studies using this approach, including one by Larsson and colleagues, and another by Biddinger and associates, “have provided valuable insights by establishing a clear and causal relationship between alcohol consumption and CVD,” he said.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Health’s National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Data collection in the Framingham Heart Study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Ma and coauthors and Dr. Sharma disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

with evidence emerging that alcohol use may both increase and decrease the risk for CVD.

The answer may depend on the presence of circulating metabolites of alcohol, some of which may be beneficial while others may be harmful, new research suggests.

“We adopted an association analysis, looking at 60 metabolites produced during or after alcohol has been metabolized, to see whether those metabolites can link alcohol consumption with CVD,” senior author Jiantao Ma, PhD, MBBS, assistant professor, Division of Nutrition Epidemiology and Data Science, Friedman School, Tufts University, Boston, Massachusetts, said in an interview.

“We found that the relationship is quite complex, with some metabolites showing protective effects against CVD and others showing harmful effects,” said Dr. Ma. “This opens the door for future research because we think that these molecules can help [us] understand the mechanism of the relationship between alcohol and CVD.”

The study was published online in BMC Medicine.

J-Shaped Relationship?

Previous research has painted a confusing picture of the relationship between alcohol consumption and CVD. For example, some studies have suggested that moderate levels of drinking may be hazardous to cardiac health, while others have pointed to potential cardioprotective effects.

Nevertheless, “according to the latest ACC/AHA guidelines regarding alcohol consumption and its relationship to CVD, there is no level of alcohol use that is deemed safe and considered acceptable,” Saurabh Sharma, MD, program director, Internal Medicine Residency Program, and clinical assistant professor of cardiology, Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine, Scranton, Pennsylvania, said in an interview.

Older observational data suggested a “J-shaped” relationship between alcohol consumption and cardiovascular risk, such that a low to moderate amount might reduce risk, while higher amounts increase it, said Dr. Sharma, a member of the American College of Cardiology (ACC) Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases Council.

“But it’s essential to note that these findings were based on observational studies. No randomized controlled trials have provided conclusive evidence supporting the idea that moderate alcohol consumption actively reduces cardiovascular risk,” he said.

The current study is also observational, but it shines a somewhat different spotlight on the subject by examining alcohol consumption–related metabolites, said Dr. Ma — that is, small molecules that are the intermediates or end-products of metabolism in many cellular processes.

Some recent research “shows that alcohol may be harmful or at least has no beneficial effect in CVD prevention,” he said. “Our motivation was to analyze the association using metabolites, genetics, and epigenetics, because we think that these molecules may help us understand some of the mechanisms that underlie the relationship between alcohol consumption and CVD, and partially answer the question of whether alcohol may be harmful or helpful.”

Caution Warranted

Although some previous studies have looked at metabolites, most analyzed alcohol consumption measured at a single time point, “which may not represent habitual or long-term alcohol consumption,” the researchers note.

The team used data derived from 2458 Framingham Heart Study Offspring participants (mean age, 56 ± 9.3 years at the fifth examination; 52% female), calculating the cumulative average alcohol consumption from total intake of beer, wine, and liquor over an average 20-year period. Most participants were overweight, close to one fifth were current smokers, and 636 developed CVD over the study period.

Participants were assessed every 4-8 years, with metabolites measured during the fifth examination.

Linear models were used to investigate the association of alcohol consumption with 211 plasma metabolites, adjusting for a variety of potential confounders, including age, sex, batch, smoking, diet, physical activity, body mass index, and familial relationship.