User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Lawsuit alleges undisclosed stomach risks from Ozempic, Mounjaro

The two drugs, which are Food and Drug Administration approved to treat type 2 diabetes, have become well known for their weight loss properties. Ozempic is made by Danish drug maker Novo Nordisk, and Mounjaro is made by Indiana-based Eli Lilly and Co.

In the lawsuit, Jaclyn Bjorklund, 44, of Louisiana, asserts that she was “severely injured” after using Ozempic and Mounjaro and that the pharmaceutical companies failed to disclose the drugs’ risk of causing vomiting and diarrhea due to inflammation of the stomach lining, as well as the risk of gastroparesis.

The prescribing labels for Mounjaro and Ozempic state that each “delays gastric emptying” and warn of the risk of severe gastrointestinal adverse reactions. The prescribing labels for both drugs state that the most common side effects include vomiting, diarrhea, and stomach pain. The Ozempic label does not mention gastroparesis, and the Mounjaro label states that the drug has not been studied in people with the condition and is therefore not recommended for people who have it.

Ms. Bjorklund has not been diagnosed with gastroparesis, but her symptoms are “indicative of” the condition, her lawyer, Paul Pennock, told NBC News.

Ms. Bjorklund used Ozempic for more than 1 year, and in July 2023 switched to Mounjaro, the lawsuit states. The document, posted on her law firm’s website, details that using the drugs resulted in “severe vomiting, stomach pain, gastrointestinal burning, being hospitalized for stomach issues on several occasions including visits to the emergency room, [and] teeth falling out due to excessive vomiting, requiring additional medications to alleviate her excessive vomiting, and throwing up whole food hours after eating.”

Novo Nordisk spokesperson Natalia Salomao told NBC News that patient safety is “of utmost importance to Novo Nordisk,” and she also noted that gastroparesis is a known risk for people with diabetes. The Food and Drug Administration declined to comment on the case, and Eli Lilly did not immediately respond to a request for comment, NBC News reported.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The two drugs, which are Food and Drug Administration approved to treat type 2 diabetes, have become well known for their weight loss properties. Ozempic is made by Danish drug maker Novo Nordisk, and Mounjaro is made by Indiana-based Eli Lilly and Co.

In the lawsuit, Jaclyn Bjorklund, 44, of Louisiana, asserts that she was “severely injured” after using Ozempic and Mounjaro and that the pharmaceutical companies failed to disclose the drugs’ risk of causing vomiting and diarrhea due to inflammation of the stomach lining, as well as the risk of gastroparesis.

The prescribing labels for Mounjaro and Ozempic state that each “delays gastric emptying” and warn of the risk of severe gastrointestinal adverse reactions. The prescribing labels for both drugs state that the most common side effects include vomiting, diarrhea, and stomach pain. The Ozempic label does not mention gastroparesis, and the Mounjaro label states that the drug has not been studied in people with the condition and is therefore not recommended for people who have it.

Ms. Bjorklund has not been diagnosed with gastroparesis, but her symptoms are “indicative of” the condition, her lawyer, Paul Pennock, told NBC News.

Ms. Bjorklund used Ozempic for more than 1 year, and in July 2023 switched to Mounjaro, the lawsuit states. The document, posted on her law firm’s website, details that using the drugs resulted in “severe vomiting, stomach pain, gastrointestinal burning, being hospitalized for stomach issues on several occasions including visits to the emergency room, [and] teeth falling out due to excessive vomiting, requiring additional medications to alleviate her excessive vomiting, and throwing up whole food hours after eating.”

Novo Nordisk spokesperson Natalia Salomao told NBC News that patient safety is “of utmost importance to Novo Nordisk,” and she also noted that gastroparesis is a known risk for people with diabetes. The Food and Drug Administration declined to comment on the case, and Eli Lilly did not immediately respond to a request for comment, NBC News reported.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The two drugs, which are Food and Drug Administration approved to treat type 2 diabetes, have become well known for their weight loss properties. Ozempic is made by Danish drug maker Novo Nordisk, and Mounjaro is made by Indiana-based Eli Lilly and Co.

In the lawsuit, Jaclyn Bjorklund, 44, of Louisiana, asserts that she was “severely injured” after using Ozempic and Mounjaro and that the pharmaceutical companies failed to disclose the drugs’ risk of causing vomiting and diarrhea due to inflammation of the stomach lining, as well as the risk of gastroparesis.

The prescribing labels for Mounjaro and Ozempic state that each “delays gastric emptying” and warn of the risk of severe gastrointestinal adverse reactions. The prescribing labels for both drugs state that the most common side effects include vomiting, diarrhea, and stomach pain. The Ozempic label does not mention gastroparesis, and the Mounjaro label states that the drug has not been studied in people with the condition and is therefore not recommended for people who have it.

Ms. Bjorklund has not been diagnosed with gastroparesis, but her symptoms are “indicative of” the condition, her lawyer, Paul Pennock, told NBC News.

Ms. Bjorklund used Ozempic for more than 1 year, and in July 2023 switched to Mounjaro, the lawsuit states. The document, posted on her law firm’s website, details that using the drugs resulted in “severe vomiting, stomach pain, gastrointestinal burning, being hospitalized for stomach issues on several occasions including visits to the emergency room, [and] teeth falling out due to excessive vomiting, requiring additional medications to alleviate her excessive vomiting, and throwing up whole food hours after eating.”

Novo Nordisk spokesperson Natalia Salomao told NBC News that patient safety is “of utmost importance to Novo Nordisk,” and she also noted that gastroparesis is a known risk for people with diabetes. The Food and Drug Administration declined to comment on the case, and Eli Lilly did not immediately respond to a request for comment, NBC News reported.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Higher occurrence of kidney stones with more added sugar

Consuming a higher percentage of calories from added sugars is linked with a higher prevalence of kidney stones, new research suggests.

Though added sugars have been linked with multiple poor health outcomes, their link with kidney stones has been unclear.

Added sugars are sugars or caloric sweeteners added to foods or drinks during processing or preparation to add flavor or shelf life. They do not include natural sugars such as lactose in milk and fructose in fruits.

Researchers, led by Shan Yin, a urologist at Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College, in Nanchong, China, compared the added-sugar intake by quartiles in the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007-2018.

A total of 28,303 adults were included in this study, with an average age of 48. Women who consumed less than 600 or more than 3,500 kcal or men who consumed less than 800 or more than 4,200 kcal were excluded.

Researchers adjusted for factors including age, race, education, income, physical activity, and marital, employment, and smoking status.

Compared with the first quartile of percentage added-sugar calorie intake, the population in the fourth quartile, with the highest added sugar intake, had a higher prevalence of kidney stones (odds ratio, 1.39; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.65).

Compared with the group with fewer than 5% of calories from added sugar, the group that consumed at least 25% of calories from added sugar had nearly twice the prevalence of kidney stones (OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.52-2.32).

Findings were published online in Frontiers in Nutrition.

“By identifying this association, policymakers and health professionals can emphasize the need for public health initiatives to reduce added sugar consumption and promote healthy dietary habits,” the authors write.

Added sugar in the U.S. diet

Sugar-sweetened beverages such as soft drinks and energy and sports drinks account for 34.4% of added sugars in the American diet. Previous studies have shown the relationship between consuming sugar-sweetened beverages and a higher risk of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, diseases that often co-occur with kidney stones.

Researchers note that even though most added sugars in the United States come from sugar-sweetened beverages, it’s unclear whether the association between added sugars and kidney stones is caused by the beverages or other sources. For instance, fructose intake has been found to be independently associated with kidney stones.

How much is too much?

The recommended upper limit on added sugar is controversial and varies widely by health organization. The American Heart Association says daily average intake from added sugars should be no more than 150 kcal for adult males (about 9 teaspoons) and no more than 100 kcal for women (about 6 teaspoons). The Institute of Medicine allows up to 25% of calories to be consumed from added sugars. The 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and World Health Organization set 10% of calories as the recommended upper limit.

Further investigating what causes kidney stones is critical as kidney stones are common worldwide, affecting about 1 in 10 people in the United States alone, and occurrence is increasing. Kidney stones have a high recurrence rate – about half of people who get them have a second episode within 10 years, the authors note.

The researchers acknowledge that because participants self-reported food intake, there is the potential for recall bias. Additionally, because of the cross-sectional design, the researchers were not able to determine whether sugar intake or kidney stone occurrence came first.

This work was supported by the Doctoral Fund Project of North Sichuan Medical College. The authors declare no relevant financial relationships.

Consuming a higher percentage of calories from added sugars is linked with a higher prevalence of kidney stones, new research suggests.

Though added sugars have been linked with multiple poor health outcomes, their link with kidney stones has been unclear.

Added sugars are sugars or caloric sweeteners added to foods or drinks during processing or preparation to add flavor or shelf life. They do not include natural sugars such as lactose in milk and fructose in fruits.

Researchers, led by Shan Yin, a urologist at Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College, in Nanchong, China, compared the added-sugar intake by quartiles in the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007-2018.

A total of 28,303 adults were included in this study, with an average age of 48. Women who consumed less than 600 or more than 3,500 kcal or men who consumed less than 800 or more than 4,200 kcal were excluded.

Researchers adjusted for factors including age, race, education, income, physical activity, and marital, employment, and smoking status.

Compared with the first quartile of percentage added-sugar calorie intake, the population in the fourth quartile, with the highest added sugar intake, had a higher prevalence of kidney stones (odds ratio, 1.39; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.65).

Compared with the group with fewer than 5% of calories from added sugar, the group that consumed at least 25% of calories from added sugar had nearly twice the prevalence of kidney stones (OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.52-2.32).

Findings were published online in Frontiers in Nutrition.

“By identifying this association, policymakers and health professionals can emphasize the need for public health initiatives to reduce added sugar consumption and promote healthy dietary habits,” the authors write.

Added sugar in the U.S. diet

Sugar-sweetened beverages such as soft drinks and energy and sports drinks account for 34.4% of added sugars in the American diet. Previous studies have shown the relationship between consuming sugar-sweetened beverages and a higher risk of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, diseases that often co-occur with kidney stones.

Researchers note that even though most added sugars in the United States come from sugar-sweetened beverages, it’s unclear whether the association between added sugars and kidney stones is caused by the beverages or other sources. For instance, fructose intake has been found to be independently associated with kidney stones.

How much is too much?

The recommended upper limit on added sugar is controversial and varies widely by health organization. The American Heart Association says daily average intake from added sugars should be no more than 150 kcal for adult males (about 9 teaspoons) and no more than 100 kcal for women (about 6 teaspoons). The Institute of Medicine allows up to 25% of calories to be consumed from added sugars. The 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and World Health Organization set 10% of calories as the recommended upper limit.

Further investigating what causes kidney stones is critical as kidney stones are common worldwide, affecting about 1 in 10 people in the United States alone, and occurrence is increasing. Kidney stones have a high recurrence rate – about half of people who get them have a second episode within 10 years, the authors note.

The researchers acknowledge that because participants self-reported food intake, there is the potential for recall bias. Additionally, because of the cross-sectional design, the researchers were not able to determine whether sugar intake or kidney stone occurrence came first.

This work was supported by the Doctoral Fund Project of North Sichuan Medical College. The authors declare no relevant financial relationships.

Consuming a higher percentage of calories from added sugars is linked with a higher prevalence of kidney stones, new research suggests.

Though added sugars have been linked with multiple poor health outcomes, their link with kidney stones has been unclear.

Added sugars are sugars or caloric sweeteners added to foods or drinks during processing or preparation to add flavor or shelf life. They do not include natural sugars such as lactose in milk and fructose in fruits.

Researchers, led by Shan Yin, a urologist at Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College, in Nanchong, China, compared the added-sugar intake by quartiles in the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007-2018.

A total of 28,303 adults were included in this study, with an average age of 48. Women who consumed less than 600 or more than 3,500 kcal or men who consumed less than 800 or more than 4,200 kcal were excluded.

Researchers adjusted for factors including age, race, education, income, physical activity, and marital, employment, and smoking status.

Compared with the first quartile of percentage added-sugar calorie intake, the population in the fourth quartile, with the highest added sugar intake, had a higher prevalence of kidney stones (odds ratio, 1.39; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.65).

Compared with the group with fewer than 5% of calories from added sugar, the group that consumed at least 25% of calories from added sugar had nearly twice the prevalence of kidney stones (OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.52-2.32).

Findings were published online in Frontiers in Nutrition.

“By identifying this association, policymakers and health professionals can emphasize the need for public health initiatives to reduce added sugar consumption and promote healthy dietary habits,” the authors write.

Added sugar in the U.S. diet

Sugar-sweetened beverages such as soft drinks and energy and sports drinks account for 34.4% of added sugars in the American diet. Previous studies have shown the relationship between consuming sugar-sweetened beverages and a higher risk of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, diseases that often co-occur with kidney stones.

Researchers note that even though most added sugars in the United States come from sugar-sweetened beverages, it’s unclear whether the association between added sugars and kidney stones is caused by the beverages or other sources. For instance, fructose intake has been found to be independently associated with kidney stones.

How much is too much?

The recommended upper limit on added sugar is controversial and varies widely by health organization. The American Heart Association says daily average intake from added sugars should be no more than 150 kcal for adult males (about 9 teaspoons) and no more than 100 kcal for women (about 6 teaspoons). The Institute of Medicine allows up to 25% of calories to be consumed from added sugars. The 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and World Health Organization set 10% of calories as the recommended upper limit.

Further investigating what causes kidney stones is critical as kidney stones are common worldwide, affecting about 1 in 10 people in the United States alone, and occurrence is increasing. Kidney stones have a high recurrence rate – about half of people who get them have a second episode within 10 years, the authors note.

The researchers acknowledge that because participants self-reported food intake, there is the potential for recall bias. Additionally, because of the cross-sectional design, the researchers were not able to determine whether sugar intake or kidney stone occurrence came first.

This work was supported by the Doctoral Fund Project of North Sichuan Medical College. The authors declare no relevant financial relationships.

FROM FRONTIERS IN NUTRITION

Using Ozempic for ‘minor’ weight loss: Fair or foul?

Ashley Raibick is familiar with the weight loss yo-yo. She’s bounced through the big names: Weight Watchers, Jenny Craig, and so on. She drops 10 pounds and then slides off the plan only to see her weight pop back up.

But a day at her local med spa – where she gets facials, Botox, and fillers – changed all that for the 28-year-old hairstylist who just wanted to lose 18 pounds.

During one of her visits, she noticed that the spa’s owner was thinner. When Ms. Raibick asked her how she did it, the owner explained that she was on semaglutide and talked Ms. Raibick through the process. Ms. Raibick was convinced. That same day, she got a prescription from a doctor at the spa and got her first shot.

“Are people going to think I’m crazy for doing this?” she recalls thinking.

At 5 foot 4, her starting weight before the drug was 158, which would put her in the overweight, but not obese, category based on body mass index (BMI). And she really just wanted to get down to 140 and stop there.

Ozempic is part of an ever-growing group of GLP-1 receptor agonists that contain a peptide called semaglutide as its main ingredient. Although first meant to treat type 2 diabetes, the reputation of Ozempic and its siblings picked up when already-thin celebrities were suspected of using the injectable drugs to become even slimmer.

The FDA approved Ozempic’s cousin, Wegovy, for “weight management” in patients with obesity a few years ago, whereas Ozempic is currently approved only for diabetes treatment. Curious patients who don’t fit the criteria can – and do – get off-label prescriptions if they can afford to pay out of pocket, often to the tune of more than $1,400 a month.

For many – mainly those who have been on the drug for a couple of months and have lost weight as a result – taking Ozempic has not only helped them shed stubborn weight, but has also freed them from the constant internal chatter around eating, commonly called “food noise.” But experts do not all agree that semaglutide is the right path for those who aren’t technically obese – especially in the long term.

After her first 9 weeks on semaglutide, Ms. Raibick had already lost 18 pounds. That’s when she decided to post about it on TikTok, and her videos on GLP-1s were viewed hundreds of thousands of times.

For the time being, there is no data on how many semaglutide takers are using the drug for diabetes and/or obesity, and how many are using it off-label for weight loss alone. But the company that makes Ozempic, Novo Nordisk, has reported sharp increases in sales and projects more profits down the road.

Ms. Raibick knows of others like her, who sought out the drug for more minor weight loss but aren’t as candid about their journeys. Some feel a stigma about having to resort to a weight-loss drug intended to treat obesity, rather than achieving their goals with diet and lifestyle change alone.

Another reason for the secrecy is the guilt some who take Ozempic feel about using their financial privilege to get a drug that had serious shortages, which made it harder for some patients who need the drug for diabetes or obesity treatment to get their doses.

That’s what Diana Thiara, MD, the medical director of the University of California, San Francisco’s weight management program, has been seeing on the ground.

“It’s one of the most depressing things I’ve experienced as a physician,” she said. In her practice, she has seen patients who have finally been able to access GLP-1s and have started to lose weight, only for them to regain the weight in the time it takes to find another prescription under their insurance coverage.

“It’s just horrible, there are patients spending all day calling dozens of pharmacies. I’ve never had a situation like this in my career,” said Dr. Thiara.

Ann, 48, a mom who works from home full-time, has been taking Ozempic since the end of January. (Ann is not her real name; she asked that we use a pseudonym in order to feel comfortable speaking publicly about her use of Ozempic). Like Ms. Raibick, she has been paying out of pocket for her shots. At first, she was going to have to pay $1,400 a month, but she found a pharmacy in Canada that offers the medication for $350. It’s sourced globally, she said, so sometimes her Ozempic boxes will be in Czech or another foreign language.

Unlike a lot of women, Ann never had any qualms with her weight or the way her body looked. She was never big on exercise, but it wasn’t until the pandemic that she started to gain weight. She noticed the changes in her body once places started opening back up, and her clothes didn’t fit anymore.

She tried moving more and eating healthier. She tried former Real Housewives of Beverly Hills cast member Teddi Mellencamp’s controversial weight-loss program, infamous for its incredibly restrictive dietary plan and excessive cardio recommendations. Nothing worked until another mom at her daughter’s school mentioned that she was on Ozempic.

Ann also started to get hot flashes and missed periods. The doctor who prescribed her Ozempic confirmed that she was perimenopausal and that, for women in this stage of life, losing weight can be harder than ever.

Ann, who is 5 foot 7, started out at 176 pounds (considered overweight) and now weighs in at 151, which is considered a normal weight by BMI measurements. She’s still on Ozempic but continues to struggle with the shame around the idea she’s potentially taking the drug away from someone else who might desperately need it. And she doesn’t know how long she’ll have to stay on Ozempic to maintain her weight loss.

Ann has reason for concern. A 2022 study found that most people regain the weight they lost within a year of stopping Ozempic.

Once Ms. Raibick hit her initial goal weight, she felt that she could keep going and lose a little more. It wasn’t until she got into the 120-pound range that she decided it was time to wean off the dose of semaglutide she had been taking.

“I got to the point where my mom was like, ‘All right, you’re a little too thin.’ But I’m just so happy where I’m at. I’m not mentally stressed out about fitting into clothes or getting into a bathing suit,” said Ms. Raibick, who has now lost around 30 pounds in total since she started the shots.

At one point, she stopped taking the drug altogether, and all of the hunger cravings and food noise semaglutide had suppressed came back to the surface. She didn’t gain any weight that month, she said, but the internal chatter around food was enough to make her start back on a lower dose, geared toward weight maintenance.

There’s also the issue of side effects. Ms. Raibick says she never had the overwhelming nausea and digestive problems that so many on the drug – including Ann – have reported. But Dr. Thiara said that even beyond these more common side effects, there are a number of other concerns – like the long-lasting effects on thyroid and reproductive health, especially for women – that we still don’t know enough about. And just recently, CNN reported that some Ozempic users have developed stomach paralysis due to the drug’s ability to slow down the passage of food through the digestive tract.

For Ms. Raibick, the out-of-pocket cost for the drug is around $600 a month. It’s an expense she’s willing to keep paying for, even just for the peace of mind the drug provides. She doesn’t have any plans to stop her semaglutide shots soon.

“There is nothing stopping me from – a year from now, when I’ve put a little weight back on – looking back at photos from this time and thinking I was way too skinny.”

Dan Azagury, MD, a bariatric surgeon and associate professor of surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University, tries GLP-1s for patients with obesity before considering bariatric surgery. For his patient population, it’s possible that drugs like Ozempic will be part of their lifelong treatment plans.

“We’re not doing it for the cosmetic part of it, we’re doing it for health,” he said. “What I tell my patients is, if you’re planning to start on this medication, you should be OK with the idea of staying on it forever.”

For doctors like Dr. Thiara who specialize in weight management, using Ozempic long-term for patients in a healthy weight range is the wrong approach.

“It’s not about the way people look, it’s about health. If you’re a normal weight or even in an overweight category, but not showing signs of risk of having elevated cardiometabolic disease ... You don’t need to be taking medications for weight loss,” she said. “This idea of using medications for aesthetic reasons is really more related to societal ills around how we value fitness above anything else. That’s not the goal, and it’s not safe.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Ashley Raibick is familiar with the weight loss yo-yo. She’s bounced through the big names: Weight Watchers, Jenny Craig, and so on. She drops 10 pounds and then slides off the plan only to see her weight pop back up.

But a day at her local med spa – where she gets facials, Botox, and fillers – changed all that for the 28-year-old hairstylist who just wanted to lose 18 pounds.

During one of her visits, she noticed that the spa’s owner was thinner. When Ms. Raibick asked her how she did it, the owner explained that she was on semaglutide and talked Ms. Raibick through the process. Ms. Raibick was convinced. That same day, she got a prescription from a doctor at the spa and got her first shot.

“Are people going to think I’m crazy for doing this?” she recalls thinking.

At 5 foot 4, her starting weight before the drug was 158, which would put her in the overweight, but not obese, category based on body mass index (BMI). And she really just wanted to get down to 140 and stop there.

Ozempic is part of an ever-growing group of GLP-1 receptor agonists that contain a peptide called semaglutide as its main ingredient. Although first meant to treat type 2 diabetes, the reputation of Ozempic and its siblings picked up when already-thin celebrities were suspected of using the injectable drugs to become even slimmer.

The FDA approved Ozempic’s cousin, Wegovy, for “weight management” in patients with obesity a few years ago, whereas Ozempic is currently approved only for diabetes treatment. Curious patients who don’t fit the criteria can – and do – get off-label prescriptions if they can afford to pay out of pocket, often to the tune of more than $1,400 a month.

For many – mainly those who have been on the drug for a couple of months and have lost weight as a result – taking Ozempic has not only helped them shed stubborn weight, but has also freed them from the constant internal chatter around eating, commonly called “food noise.” But experts do not all agree that semaglutide is the right path for those who aren’t technically obese – especially in the long term.

After her first 9 weeks on semaglutide, Ms. Raibick had already lost 18 pounds. That’s when she decided to post about it on TikTok, and her videos on GLP-1s were viewed hundreds of thousands of times.

For the time being, there is no data on how many semaglutide takers are using the drug for diabetes and/or obesity, and how many are using it off-label for weight loss alone. But the company that makes Ozempic, Novo Nordisk, has reported sharp increases in sales and projects more profits down the road.

Ms. Raibick knows of others like her, who sought out the drug for more minor weight loss but aren’t as candid about their journeys. Some feel a stigma about having to resort to a weight-loss drug intended to treat obesity, rather than achieving their goals with diet and lifestyle change alone.

Another reason for the secrecy is the guilt some who take Ozempic feel about using their financial privilege to get a drug that had serious shortages, which made it harder for some patients who need the drug for diabetes or obesity treatment to get their doses.

That’s what Diana Thiara, MD, the medical director of the University of California, San Francisco’s weight management program, has been seeing on the ground.

“It’s one of the most depressing things I’ve experienced as a physician,” she said. In her practice, she has seen patients who have finally been able to access GLP-1s and have started to lose weight, only for them to regain the weight in the time it takes to find another prescription under their insurance coverage.

“It’s just horrible, there are patients spending all day calling dozens of pharmacies. I’ve never had a situation like this in my career,” said Dr. Thiara.

Ann, 48, a mom who works from home full-time, has been taking Ozempic since the end of January. (Ann is not her real name; she asked that we use a pseudonym in order to feel comfortable speaking publicly about her use of Ozempic). Like Ms. Raibick, she has been paying out of pocket for her shots. At first, she was going to have to pay $1,400 a month, but she found a pharmacy in Canada that offers the medication for $350. It’s sourced globally, she said, so sometimes her Ozempic boxes will be in Czech or another foreign language.

Unlike a lot of women, Ann never had any qualms with her weight or the way her body looked. She was never big on exercise, but it wasn’t until the pandemic that she started to gain weight. She noticed the changes in her body once places started opening back up, and her clothes didn’t fit anymore.

She tried moving more and eating healthier. She tried former Real Housewives of Beverly Hills cast member Teddi Mellencamp’s controversial weight-loss program, infamous for its incredibly restrictive dietary plan and excessive cardio recommendations. Nothing worked until another mom at her daughter’s school mentioned that she was on Ozempic.

Ann also started to get hot flashes and missed periods. The doctor who prescribed her Ozempic confirmed that she was perimenopausal and that, for women in this stage of life, losing weight can be harder than ever.

Ann, who is 5 foot 7, started out at 176 pounds (considered overweight) and now weighs in at 151, which is considered a normal weight by BMI measurements. She’s still on Ozempic but continues to struggle with the shame around the idea she’s potentially taking the drug away from someone else who might desperately need it. And she doesn’t know how long she’ll have to stay on Ozempic to maintain her weight loss.

Ann has reason for concern. A 2022 study found that most people regain the weight they lost within a year of stopping Ozempic.

Once Ms. Raibick hit her initial goal weight, she felt that she could keep going and lose a little more. It wasn’t until she got into the 120-pound range that she decided it was time to wean off the dose of semaglutide she had been taking.

“I got to the point where my mom was like, ‘All right, you’re a little too thin.’ But I’m just so happy where I’m at. I’m not mentally stressed out about fitting into clothes or getting into a bathing suit,” said Ms. Raibick, who has now lost around 30 pounds in total since she started the shots.

At one point, she stopped taking the drug altogether, and all of the hunger cravings and food noise semaglutide had suppressed came back to the surface. She didn’t gain any weight that month, she said, but the internal chatter around food was enough to make her start back on a lower dose, geared toward weight maintenance.

There’s also the issue of side effects. Ms. Raibick says she never had the overwhelming nausea and digestive problems that so many on the drug – including Ann – have reported. But Dr. Thiara said that even beyond these more common side effects, there are a number of other concerns – like the long-lasting effects on thyroid and reproductive health, especially for women – that we still don’t know enough about. And just recently, CNN reported that some Ozempic users have developed stomach paralysis due to the drug’s ability to slow down the passage of food through the digestive tract.

For Ms. Raibick, the out-of-pocket cost for the drug is around $600 a month. It’s an expense she’s willing to keep paying for, even just for the peace of mind the drug provides. She doesn’t have any plans to stop her semaglutide shots soon.

“There is nothing stopping me from – a year from now, when I’ve put a little weight back on – looking back at photos from this time and thinking I was way too skinny.”

Dan Azagury, MD, a bariatric surgeon and associate professor of surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University, tries GLP-1s for patients with obesity before considering bariatric surgery. For his patient population, it’s possible that drugs like Ozempic will be part of their lifelong treatment plans.

“We’re not doing it for the cosmetic part of it, we’re doing it for health,” he said. “What I tell my patients is, if you’re planning to start on this medication, you should be OK with the idea of staying on it forever.”

For doctors like Dr. Thiara who specialize in weight management, using Ozempic long-term for patients in a healthy weight range is the wrong approach.

“It’s not about the way people look, it’s about health. If you’re a normal weight or even in an overweight category, but not showing signs of risk of having elevated cardiometabolic disease ... You don’t need to be taking medications for weight loss,” she said. “This idea of using medications for aesthetic reasons is really more related to societal ills around how we value fitness above anything else. That’s not the goal, and it’s not safe.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Ashley Raibick is familiar with the weight loss yo-yo. She’s bounced through the big names: Weight Watchers, Jenny Craig, and so on. She drops 10 pounds and then slides off the plan only to see her weight pop back up.

But a day at her local med spa – where she gets facials, Botox, and fillers – changed all that for the 28-year-old hairstylist who just wanted to lose 18 pounds.

During one of her visits, she noticed that the spa’s owner was thinner. When Ms. Raibick asked her how she did it, the owner explained that she was on semaglutide and talked Ms. Raibick through the process. Ms. Raibick was convinced. That same day, she got a prescription from a doctor at the spa and got her first shot.

“Are people going to think I’m crazy for doing this?” she recalls thinking.

At 5 foot 4, her starting weight before the drug was 158, which would put her in the overweight, but not obese, category based on body mass index (BMI). And she really just wanted to get down to 140 and stop there.

Ozempic is part of an ever-growing group of GLP-1 receptor agonists that contain a peptide called semaglutide as its main ingredient. Although first meant to treat type 2 diabetes, the reputation of Ozempic and its siblings picked up when already-thin celebrities were suspected of using the injectable drugs to become even slimmer.

The FDA approved Ozempic’s cousin, Wegovy, for “weight management” in patients with obesity a few years ago, whereas Ozempic is currently approved only for diabetes treatment. Curious patients who don’t fit the criteria can – and do – get off-label prescriptions if they can afford to pay out of pocket, often to the tune of more than $1,400 a month.

For many – mainly those who have been on the drug for a couple of months and have lost weight as a result – taking Ozempic has not only helped them shed stubborn weight, but has also freed them from the constant internal chatter around eating, commonly called “food noise.” But experts do not all agree that semaglutide is the right path for those who aren’t technically obese – especially in the long term.

After her first 9 weeks on semaglutide, Ms. Raibick had already lost 18 pounds. That’s when she decided to post about it on TikTok, and her videos on GLP-1s were viewed hundreds of thousands of times.

For the time being, there is no data on how many semaglutide takers are using the drug for diabetes and/or obesity, and how many are using it off-label for weight loss alone. But the company that makes Ozempic, Novo Nordisk, has reported sharp increases in sales and projects more profits down the road.

Ms. Raibick knows of others like her, who sought out the drug for more minor weight loss but aren’t as candid about their journeys. Some feel a stigma about having to resort to a weight-loss drug intended to treat obesity, rather than achieving their goals with diet and lifestyle change alone.

Another reason for the secrecy is the guilt some who take Ozempic feel about using their financial privilege to get a drug that had serious shortages, which made it harder for some patients who need the drug for diabetes or obesity treatment to get their doses.

That’s what Diana Thiara, MD, the medical director of the University of California, San Francisco’s weight management program, has been seeing on the ground.

“It’s one of the most depressing things I’ve experienced as a physician,” she said. In her practice, she has seen patients who have finally been able to access GLP-1s and have started to lose weight, only for them to regain the weight in the time it takes to find another prescription under their insurance coverage.

“It’s just horrible, there are patients spending all day calling dozens of pharmacies. I’ve never had a situation like this in my career,” said Dr. Thiara.

Ann, 48, a mom who works from home full-time, has been taking Ozempic since the end of January. (Ann is not her real name; she asked that we use a pseudonym in order to feel comfortable speaking publicly about her use of Ozempic). Like Ms. Raibick, she has been paying out of pocket for her shots. At first, she was going to have to pay $1,400 a month, but she found a pharmacy in Canada that offers the medication for $350. It’s sourced globally, she said, so sometimes her Ozempic boxes will be in Czech or another foreign language.

Unlike a lot of women, Ann never had any qualms with her weight or the way her body looked. She was never big on exercise, but it wasn’t until the pandemic that she started to gain weight. She noticed the changes in her body once places started opening back up, and her clothes didn’t fit anymore.

She tried moving more and eating healthier. She tried former Real Housewives of Beverly Hills cast member Teddi Mellencamp’s controversial weight-loss program, infamous for its incredibly restrictive dietary plan and excessive cardio recommendations. Nothing worked until another mom at her daughter’s school mentioned that she was on Ozempic.

Ann also started to get hot flashes and missed periods. The doctor who prescribed her Ozempic confirmed that she was perimenopausal and that, for women in this stage of life, losing weight can be harder than ever.

Ann, who is 5 foot 7, started out at 176 pounds (considered overweight) and now weighs in at 151, which is considered a normal weight by BMI measurements. She’s still on Ozempic but continues to struggle with the shame around the idea she’s potentially taking the drug away from someone else who might desperately need it. And she doesn’t know how long she’ll have to stay on Ozempic to maintain her weight loss.

Ann has reason for concern. A 2022 study found that most people regain the weight they lost within a year of stopping Ozempic.

Once Ms. Raibick hit her initial goal weight, she felt that she could keep going and lose a little more. It wasn’t until she got into the 120-pound range that she decided it was time to wean off the dose of semaglutide she had been taking.

“I got to the point where my mom was like, ‘All right, you’re a little too thin.’ But I’m just so happy where I’m at. I’m not mentally stressed out about fitting into clothes or getting into a bathing suit,” said Ms. Raibick, who has now lost around 30 pounds in total since she started the shots.

At one point, she stopped taking the drug altogether, and all of the hunger cravings and food noise semaglutide had suppressed came back to the surface. She didn’t gain any weight that month, she said, but the internal chatter around food was enough to make her start back on a lower dose, geared toward weight maintenance.

There’s also the issue of side effects. Ms. Raibick says she never had the overwhelming nausea and digestive problems that so many on the drug – including Ann – have reported. But Dr. Thiara said that even beyond these more common side effects, there are a number of other concerns – like the long-lasting effects on thyroid and reproductive health, especially for women – that we still don’t know enough about. And just recently, CNN reported that some Ozempic users have developed stomach paralysis due to the drug’s ability to slow down the passage of food through the digestive tract.

For Ms. Raibick, the out-of-pocket cost for the drug is around $600 a month. It’s an expense she’s willing to keep paying for, even just for the peace of mind the drug provides. She doesn’t have any plans to stop her semaglutide shots soon.

“There is nothing stopping me from – a year from now, when I’ve put a little weight back on – looking back at photos from this time and thinking I was way too skinny.”

Dan Azagury, MD, a bariatric surgeon and associate professor of surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University, tries GLP-1s for patients with obesity before considering bariatric surgery. For his patient population, it’s possible that drugs like Ozempic will be part of their lifelong treatment plans.

“We’re not doing it for the cosmetic part of it, we’re doing it for health,” he said. “What I tell my patients is, if you’re planning to start on this medication, you should be OK with the idea of staying on it forever.”

For doctors like Dr. Thiara who specialize in weight management, using Ozempic long-term for patients in a healthy weight range is the wrong approach.

“It’s not about the way people look, it’s about health. If you’re a normal weight or even in an overweight category, but not showing signs of risk of having elevated cardiometabolic disease ... You don’t need to be taking medications for weight loss,” she said. “This idea of using medications for aesthetic reasons is really more related to societal ills around how we value fitness above anything else. That’s not the goal, and it’s not safe.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

How soybean oil could lead to gut inflammation

A popular ingredient in the American diet has been linked to ulcerative colitis. The ingredient is soybean oil, which is very common in processed foods. In fact, U.S. per capita consumption of soybean oil increased more than 1,000-fold during the 20th century.

In a study from the University of California, Riverside, and UC Davis, published in Gut Microbes, mice fed a diet high in soybean oil were more at risk of developing colitis.

The likely culprit? Linoleic acid, an omega-6 fatty acid that composes up to 60% of soybean oil.

Small amounts of linoleic acid help maintain the body’s water balance. But Americans derive as much as 10% of their daily energy from linoleic acid, when they need only 1%-2%, the researchers say.

The findings build on earlier research linking a high-linoleic acid diet with inflammatory bowel disease, or IBD, in humans. (Previous research in mice has also linked high consumption of the oil with obesity and diabetes in the rodents.)

For the new study, the researchers wanted to drill down into how linoleic acid affects the gut.

How linoleic acid may promote inflammation

In mice, the soybean oil diet upset the ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids in the gut. This led to a decrease in endocannabinoids, lipid-based molecules that help block inflammation.

Enzymes that metabolize fatty acids are “shared between two pathways,” said study coauthor Frances Sladek, PhD, professor of cell biology at UC Riverside. “If you swamp the system with linoleic acid, you’ll have less enzymes available to metabolize omega-3s into good endocannabinoids.”

The endocannabinoid system has been linked to “visceral pain” in the gut, said Punyanganie de Silva, MD, MPH, an assistant professor at Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, who was not involved in the study. But the relationship between the endocannabinoid system and inflammation has yet to be fully explored.

“This is one of the first papers that has looked at the association between linoleic acid and the endocannabinoid system,” Dr. de Silva said.

Changes in the gut microbiome

The gut microbiome of the mice also showed increased amounts of adherent invasive E. coli, a type of bacteria that grows by using linoleic acid as a carbon source. A “very close relative” of this bacteria has been linked to IBD in humans, Dr. Sladek said.

Using a method known as metabolomics, the researchers studied 3,000 metabolites in the intestinal cells of both the mice and the bacteria. Endocannabinoids decreased in both.

“We were actually quite surprised. I didn’t realize that bacteria made endocannabinoids,” Dr. Sladek said.

Helpful bacteria, such as the probiotic lactobacillus species, died off. The mice also had increased levels of oxylipins, which are correlated with obesity in mice and colitis in humans.

A high–linoleic acid diet could mean a leaky gut

Linoleic acid binds to a protein known as HNF-4 alpha. Disrupting the expression of this protein can weaken the intestinal barrier, letting toxins flow into the body – more commonly known as leaky gut. Mice on the soybean oil diet had decreased levels of the protein and more porous intestinal barriers, raising the risk for inflammation and colitis. “The HNF-4 alpha protein is conserved from mouse to human, so whatever’s happening to it in the context of the mouse gut, there’s a very high chance that a similar effect could be seen in humans as well,” said study coauthor Poonamjot Deol, PhD, an assistant professional researcher at UC Riverside.

Still, Dr. de Silva urges “some caution when interpreting these results,” given that “this is still experimental and needs to be reproduced in clinical studies as humans have a far more varied microbiome and more variable environmental exposures than these very controlled mouse model studies.”

Dr. de Silva says cooking with olive oil can “help increase omega-3 to omega-6 ratios” and advises eating a varied diet that includes omega-3 fats, such as flaxseed and walnuts, and minimal amounts of processed foods and saturated fats.

Looking ahead, endocannabinoids are being explored as “a potential therapy for treating IBD symptoms,” said Dr. Deol. She hopes to delve further into how linoleic acid affects the endocannabinoid system.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

A popular ingredient in the American diet has been linked to ulcerative colitis. The ingredient is soybean oil, which is very common in processed foods. In fact, U.S. per capita consumption of soybean oil increased more than 1,000-fold during the 20th century.

In a study from the University of California, Riverside, and UC Davis, published in Gut Microbes, mice fed a diet high in soybean oil were more at risk of developing colitis.

The likely culprit? Linoleic acid, an omega-6 fatty acid that composes up to 60% of soybean oil.

Small amounts of linoleic acid help maintain the body’s water balance. But Americans derive as much as 10% of their daily energy from linoleic acid, when they need only 1%-2%, the researchers say.

The findings build on earlier research linking a high-linoleic acid diet with inflammatory bowel disease, or IBD, in humans. (Previous research in mice has also linked high consumption of the oil with obesity and diabetes in the rodents.)

For the new study, the researchers wanted to drill down into how linoleic acid affects the gut.

How linoleic acid may promote inflammation

In mice, the soybean oil diet upset the ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids in the gut. This led to a decrease in endocannabinoids, lipid-based molecules that help block inflammation.

Enzymes that metabolize fatty acids are “shared between two pathways,” said study coauthor Frances Sladek, PhD, professor of cell biology at UC Riverside. “If you swamp the system with linoleic acid, you’ll have less enzymes available to metabolize omega-3s into good endocannabinoids.”

The endocannabinoid system has been linked to “visceral pain” in the gut, said Punyanganie de Silva, MD, MPH, an assistant professor at Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, who was not involved in the study. But the relationship between the endocannabinoid system and inflammation has yet to be fully explored.

“This is one of the first papers that has looked at the association between linoleic acid and the endocannabinoid system,” Dr. de Silva said.

Changes in the gut microbiome

The gut microbiome of the mice also showed increased amounts of adherent invasive E. coli, a type of bacteria that grows by using linoleic acid as a carbon source. A “very close relative” of this bacteria has been linked to IBD in humans, Dr. Sladek said.

Using a method known as metabolomics, the researchers studied 3,000 metabolites in the intestinal cells of both the mice and the bacteria. Endocannabinoids decreased in both.

“We were actually quite surprised. I didn’t realize that bacteria made endocannabinoids,” Dr. Sladek said.

Helpful bacteria, such as the probiotic lactobacillus species, died off. The mice also had increased levels of oxylipins, which are correlated with obesity in mice and colitis in humans.

A high–linoleic acid diet could mean a leaky gut

Linoleic acid binds to a protein known as HNF-4 alpha. Disrupting the expression of this protein can weaken the intestinal barrier, letting toxins flow into the body – more commonly known as leaky gut. Mice on the soybean oil diet had decreased levels of the protein and more porous intestinal barriers, raising the risk for inflammation and colitis. “The HNF-4 alpha protein is conserved from mouse to human, so whatever’s happening to it in the context of the mouse gut, there’s a very high chance that a similar effect could be seen in humans as well,” said study coauthor Poonamjot Deol, PhD, an assistant professional researcher at UC Riverside.

Still, Dr. de Silva urges “some caution when interpreting these results,” given that “this is still experimental and needs to be reproduced in clinical studies as humans have a far more varied microbiome and more variable environmental exposures than these very controlled mouse model studies.”

Dr. de Silva says cooking with olive oil can “help increase omega-3 to omega-6 ratios” and advises eating a varied diet that includes omega-3 fats, such as flaxseed and walnuts, and minimal amounts of processed foods and saturated fats.

Looking ahead, endocannabinoids are being explored as “a potential therapy for treating IBD symptoms,” said Dr. Deol. She hopes to delve further into how linoleic acid affects the endocannabinoid system.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

A popular ingredient in the American diet has been linked to ulcerative colitis. The ingredient is soybean oil, which is very common in processed foods. In fact, U.S. per capita consumption of soybean oil increased more than 1,000-fold during the 20th century.

In a study from the University of California, Riverside, and UC Davis, published in Gut Microbes, mice fed a diet high in soybean oil were more at risk of developing colitis.

The likely culprit? Linoleic acid, an omega-6 fatty acid that composes up to 60% of soybean oil.

Small amounts of linoleic acid help maintain the body’s water balance. But Americans derive as much as 10% of their daily energy from linoleic acid, when they need only 1%-2%, the researchers say.

The findings build on earlier research linking a high-linoleic acid diet with inflammatory bowel disease, or IBD, in humans. (Previous research in mice has also linked high consumption of the oil with obesity and diabetes in the rodents.)

For the new study, the researchers wanted to drill down into how linoleic acid affects the gut.

How linoleic acid may promote inflammation

In mice, the soybean oil diet upset the ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids in the gut. This led to a decrease in endocannabinoids, lipid-based molecules that help block inflammation.

Enzymes that metabolize fatty acids are “shared between two pathways,” said study coauthor Frances Sladek, PhD, professor of cell biology at UC Riverside. “If you swamp the system with linoleic acid, you’ll have less enzymes available to metabolize omega-3s into good endocannabinoids.”

The endocannabinoid system has been linked to “visceral pain” in the gut, said Punyanganie de Silva, MD, MPH, an assistant professor at Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, who was not involved in the study. But the relationship between the endocannabinoid system and inflammation has yet to be fully explored.

“This is one of the first papers that has looked at the association between linoleic acid and the endocannabinoid system,” Dr. de Silva said.

Changes in the gut microbiome

The gut microbiome of the mice also showed increased amounts of adherent invasive E. coli, a type of bacteria that grows by using linoleic acid as a carbon source. A “very close relative” of this bacteria has been linked to IBD in humans, Dr. Sladek said.

Using a method known as metabolomics, the researchers studied 3,000 metabolites in the intestinal cells of both the mice and the bacteria. Endocannabinoids decreased in both.

“We were actually quite surprised. I didn’t realize that bacteria made endocannabinoids,” Dr. Sladek said.

Helpful bacteria, such as the probiotic lactobacillus species, died off. The mice also had increased levels of oxylipins, which are correlated with obesity in mice and colitis in humans.

A high–linoleic acid diet could mean a leaky gut

Linoleic acid binds to a protein known as HNF-4 alpha. Disrupting the expression of this protein can weaken the intestinal barrier, letting toxins flow into the body – more commonly known as leaky gut. Mice on the soybean oil diet had decreased levels of the protein and more porous intestinal barriers, raising the risk for inflammation and colitis. “The HNF-4 alpha protein is conserved from mouse to human, so whatever’s happening to it in the context of the mouse gut, there’s a very high chance that a similar effect could be seen in humans as well,” said study coauthor Poonamjot Deol, PhD, an assistant professional researcher at UC Riverside.

Still, Dr. de Silva urges “some caution when interpreting these results,” given that “this is still experimental and needs to be reproduced in clinical studies as humans have a far more varied microbiome and more variable environmental exposures than these very controlled mouse model studies.”

Dr. de Silva says cooking with olive oil can “help increase omega-3 to omega-6 ratios” and advises eating a varied diet that includes omega-3 fats, such as flaxseed and walnuts, and minimal amounts of processed foods and saturated fats.

Looking ahead, endocannabinoids are being explored as “a potential therapy for treating IBD symptoms,” said Dr. Deol. She hopes to delve further into how linoleic acid affects the endocannabinoid system.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM GUT MICROBES

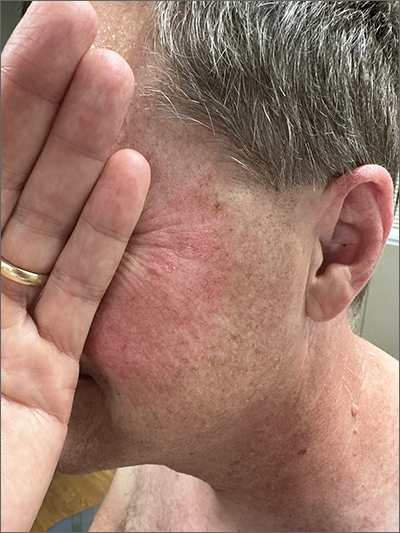

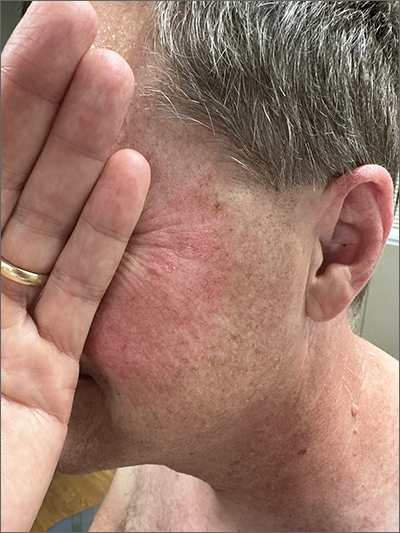

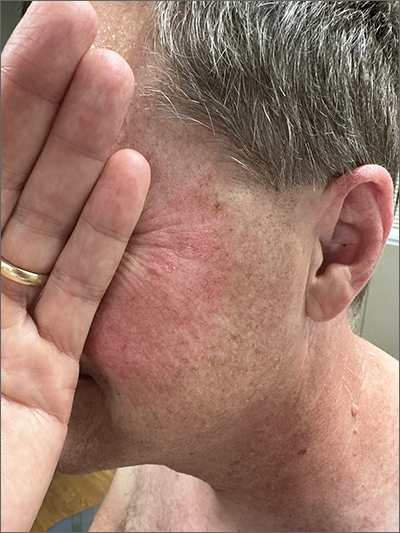

Rosacea look-alike

Although it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that facial erythema is rosacea, there are multiple other conditions that can lead to reddening of the face. In this case, excessive sun exposure had resulted in a diffuse actinic change of the malar and lateral aspects of this patient’s face. The palpably rough lesions were actinic keratoses.

Actinic keratoses are caused by exposure to ultraviolet radiation. These lesions are premalignant and common. Areas of the body at greatest risk include those not typically covered by clothing (eg, face, hands, arms, ears, forehead, and top of the scalp—especially in individuals with hair loss). There is a range of estimates regarding the percentage of actinic keratoses that will progress to squamous cell carcinoma in situ, and then invasive squamous cell carcinoma. One study determined that 10% of actinic keratoses progress to squamous cell carcinoma over the course of 2 years.1

In patients with broad areas of multiple clinically palpable lesions with rough sandpapery texture or visible white scale, there are likely preclinical lesions in the same areas. With so many lesions, field therapy of the entire region is often performed instead of treating the lesions 1 at a time.

There are multiple topical agents for field therapy, including 5-fluorouracil, diclofenac gel, and imiquimod gel.2 Since significant erythema and inflammation usually follow application of the topical agent, clinicians may want to have patients treat in segments to make the process more tolerable.

5-fluorouracil has a complete clearance rate (CCR) of 75% to 90% and is usually applied twice daily for 2 weeks, although there are multiple different protocols. Diclofenac has a CCR of 58% over a 60- to 90-day course, and imiquimod has a CCR of 54% after a 120-day course. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has the advantage of a single treatment but a CCR of 38%. PDT may be advantageous for a patient who has difficulty applying topical medication over a period of weeks.

Niacinamide has been shown to help with skin repair and reduce the risk of additional nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC) by 23% and additional actinic keratoses by about 15% in individuals with a history of actinic keratoses or NMSC.3 In contrast to niacin, niacinamide does not cause flushing. Niacinamide is used long term; if discontinued, it no longer confers benefit in helping the skin repair itself.

The patient in this case was prescribed topical 5% fluorouracil cream to be applied twice daily to the malar regions bilaterally for 2 weeks and, if not inflamed by 2 weeks, to extend the treatment until there is robust inflammation (but not to exceed 3 weeks). He was scheduled to follow up in 3 months for reexamination. He was also advised to start taking niacinamide 500 mg twice daily to reduce his risk of additional precancerous and cancerous skin lesions and counseled on the importance of sunscreen, hats, and sun-protective clothing.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

- Fuchs A, Marmur E. The kinetics of skin cancer: progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1099-1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33224.x

- Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Randomized trial of four treatment approaches for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-946. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811850

- Starr P. Oral nicotinamide prevents common skin cancers in high-risk patients, reduces costs. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(spec issue):13-14.

Although it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that facial erythema is rosacea, there are multiple other conditions that can lead to reddening of the face. In this case, excessive sun exposure had resulted in a diffuse actinic change of the malar and lateral aspects of this patient’s face. The palpably rough lesions were actinic keratoses.

Actinic keratoses are caused by exposure to ultraviolet radiation. These lesions are premalignant and common. Areas of the body at greatest risk include those not typically covered by clothing (eg, face, hands, arms, ears, forehead, and top of the scalp—especially in individuals with hair loss). There is a range of estimates regarding the percentage of actinic keratoses that will progress to squamous cell carcinoma in situ, and then invasive squamous cell carcinoma. One study determined that 10% of actinic keratoses progress to squamous cell carcinoma over the course of 2 years.1

In patients with broad areas of multiple clinically palpable lesions with rough sandpapery texture or visible white scale, there are likely preclinical lesions in the same areas. With so many lesions, field therapy of the entire region is often performed instead of treating the lesions 1 at a time.

There are multiple topical agents for field therapy, including 5-fluorouracil, diclofenac gel, and imiquimod gel.2 Since significant erythema and inflammation usually follow application of the topical agent, clinicians may want to have patients treat in segments to make the process more tolerable.

5-fluorouracil has a complete clearance rate (CCR) of 75% to 90% and is usually applied twice daily for 2 weeks, although there are multiple different protocols. Diclofenac has a CCR of 58% over a 60- to 90-day course, and imiquimod has a CCR of 54% after a 120-day course. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has the advantage of a single treatment but a CCR of 38%. PDT may be advantageous for a patient who has difficulty applying topical medication over a period of weeks.

Niacinamide has been shown to help with skin repair and reduce the risk of additional nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC) by 23% and additional actinic keratoses by about 15% in individuals with a history of actinic keratoses or NMSC.3 In contrast to niacin, niacinamide does not cause flushing. Niacinamide is used long term; if discontinued, it no longer confers benefit in helping the skin repair itself.

The patient in this case was prescribed topical 5% fluorouracil cream to be applied twice daily to the malar regions bilaterally for 2 weeks and, if not inflamed by 2 weeks, to extend the treatment until there is robust inflammation (but not to exceed 3 weeks). He was scheduled to follow up in 3 months for reexamination. He was also advised to start taking niacinamide 500 mg twice daily to reduce his risk of additional precancerous and cancerous skin lesions and counseled on the importance of sunscreen, hats, and sun-protective clothing.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

Although it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that facial erythema is rosacea, there are multiple other conditions that can lead to reddening of the face. In this case, excessive sun exposure had resulted in a diffuse actinic change of the malar and lateral aspects of this patient’s face. The palpably rough lesions were actinic keratoses.

Actinic keratoses are caused by exposure to ultraviolet radiation. These lesions are premalignant and common. Areas of the body at greatest risk include those not typically covered by clothing (eg, face, hands, arms, ears, forehead, and top of the scalp—especially in individuals with hair loss). There is a range of estimates regarding the percentage of actinic keratoses that will progress to squamous cell carcinoma in situ, and then invasive squamous cell carcinoma. One study determined that 10% of actinic keratoses progress to squamous cell carcinoma over the course of 2 years.1

In patients with broad areas of multiple clinically palpable lesions with rough sandpapery texture or visible white scale, there are likely preclinical lesions in the same areas. With so many lesions, field therapy of the entire region is often performed instead of treating the lesions 1 at a time.

There are multiple topical agents for field therapy, including 5-fluorouracil, diclofenac gel, and imiquimod gel.2 Since significant erythema and inflammation usually follow application of the topical agent, clinicians may want to have patients treat in segments to make the process more tolerable.

5-fluorouracil has a complete clearance rate (CCR) of 75% to 90% and is usually applied twice daily for 2 weeks, although there are multiple different protocols. Diclofenac has a CCR of 58% over a 60- to 90-day course, and imiquimod has a CCR of 54% after a 120-day course. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has the advantage of a single treatment but a CCR of 38%. PDT may be advantageous for a patient who has difficulty applying topical medication over a period of weeks.

Niacinamide has been shown to help with skin repair and reduce the risk of additional nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC) by 23% and additional actinic keratoses by about 15% in individuals with a history of actinic keratoses or NMSC.3 In contrast to niacin, niacinamide does not cause flushing. Niacinamide is used long term; if discontinued, it no longer confers benefit in helping the skin repair itself.

The patient in this case was prescribed topical 5% fluorouracil cream to be applied twice daily to the malar regions bilaterally for 2 weeks and, if not inflamed by 2 weeks, to extend the treatment until there is robust inflammation (but not to exceed 3 weeks). He was scheduled to follow up in 3 months for reexamination. He was also advised to start taking niacinamide 500 mg twice daily to reduce his risk of additional precancerous and cancerous skin lesions and counseled on the importance of sunscreen, hats, and sun-protective clothing.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

- Fuchs A, Marmur E. The kinetics of skin cancer: progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1099-1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33224.x

- Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Randomized trial of four treatment approaches for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-946. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811850

- Starr P. Oral nicotinamide prevents common skin cancers in high-risk patients, reduces costs. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(spec issue):13-14.

- Fuchs A, Marmur E. The kinetics of skin cancer: progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1099-1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33224.x

- Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Randomized trial of four treatment approaches for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-946. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811850

- Starr P. Oral nicotinamide prevents common skin cancers in high-risk patients, reduces costs. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(spec issue):13-14.

Skin reactions common at insulin pump infusion sites

new research suggests.

Insulin pump use is increasingly common, but many patients experience infusion-site failure that in some cases leads to discontinuation. In a novel investigation, researchers at the University of Washington, Seattle, used biopsies and noninvasive imaging to compare insulin pump sites with control sites in 30 patients. Several differences were found at pump sites in comparison with control sites, including fibrosis, inflammation, eosinophils, and increased vessel density.

“These findings support allergic sensitization as a potentially common reaction at [insulin pump] sites. The leading candidates causing this include insulin preservatives, plastic materials, and adhesive glue used in device manufacturing,” wrote Andrea Kalus, MD, of the university’s dermatology division, and colleagues. The findings were published recently in Diabetes Care.

The inflammatory response, they wrote, “may result in tissue changes responsible for the infusion-site failures seen frequently in clinical practice.”

Such infusion site problems represent an “Achilles heel” of these otherwise highly beneficial devices, lead author Irl Hirsch, MD, professor of medicine in the division of metabolism, endocrinology, and nutrition, said in a statement. “It doesn’t really matter how good the technology is. We still don’t understand what is happening with the infusion sites, much less to [be able to] fix it.”

Significant differences between pump and nonpump sites

In the cross-sectional study, Dr. Kalus and colleagues used noninvasive optical coherence tomography (OCT) immediately prior to performing punch biopsies at three sites: the site currently in active use, the “recovery site” used 3-5 days prior to the procedures, and control sites never used for pump infusion. Punch biopsies were also performed at those sites.

The mean age of the patients was 48.3 years, the mean diabetes duration was 30.4 years, and the mean duration of pump use was 15.8 years. Nearly all patients (93.3%) reported itchiness at the site, and 76.7% reported skin redness.

Of the 25 patients for whom OCT imaging was successful, statistical analysis showed significant differences in vascular area density and the optical attenuation coefficient, a surrogate for skin inflammation, between the pump and control sites and between recovery sites and current pump sites. The greater vessel density is likely a result of injury and repair related to catheter insertion, the authors said.

In the biopsy samples, both current and recovery sites showed increased fibrosis, fibrin, inflammation, fat necrosis, vascularity, and eosinophils, compared with the control sites, but no significant differences were found between current and recovery sites.

Eosinophils: ‘The most surprising histologic finding’

Eosinophils were found in 73% of skin biopsy specimens from current sites and in 75% of specimens from recovery sites, compared with none from the control sites (for both, P < .01). In all study participants, eosinophils were found in at least one current and/or recovery infusion site deep in the dermis near the interface with fat. The number of eosinophils ranged from 0 to 31 per high-power field, with a median of 4.

The number of eosinophils didn’t vary by type of insulin or brand of pump, but higher counts were seen in those who had used pumps for less than 10 years, compared with more than 20 years (P = .02).

The prevalence and degree of eosinophils were “the most surprising histologic finding,” the authors wrote, adding that “eosinophils are not typically present as a component of resident inflammatory cells in the skin.”

While eosinophils may be present in normal wound healing, “the absolute number and density of eosinophil in these samples support a delayed-type hypersensitivity response, which is typically observed between 2 and 7 days after exposure to an allergen. ... Eosinophils are often correlated with symptoms of itchiness and likely explain the high percentage of participants who reported itchiness in this study,” Dr. Kalus and colleagues wrote.

Correlation found between inflammation and glycemic control

All participants used the Dexcom G6 continuous glucose monitor as part of their usual care. Inflammation scores were positively correlated with insulin dose (P = .009) and were negatively correlated with time in range (P = .01).

No other OCT or biopsy findings differed by duration of pump use, previous use of animal insulin, or type of insulin.

The reason for these findings is unclear, Dr. Hirsch said. “How much was the catheter or the insulin causing the irritation around the sites? How much was it from the preservatives, or is this because of the insulin pump itself? All these questions need to be answered in future studies. ... The real goal of all of this is to minimize skin damage and improve the experience for our patients.”

The study was funded by the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust. Dr. Hirsch reported grants and contracts from Insulet, Medtronic, and Dexcom outside the submitted work; consulting fees from Abbott Diabetes Care, Lifescan, and Hagar outside the submitted work; and honoraria for lectures, presentations, participation on speaker’s bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events as section editor for UpToDate outside the submitted work. Dr. Kalus has no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Insulin pump use is increasingly common, but many patients experience infusion-site failure that in some cases leads to discontinuation. In a novel investigation, researchers at the University of Washington, Seattle, used biopsies and noninvasive imaging to compare insulin pump sites with control sites in 30 patients. Several differences were found at pump sites in comparison with control sites, including fibrosis, inflammation, eosinophils, and increased vessel density.

“These findings support allergic sensitization as a potentially common reaction at [insulin pump] sites. The leading candidates causing this include insulin preservatives, plastic materials, and adhesive glue used in device manufacturing,” wrote Andrea Kalus, MD, of the university’s dermatology division, and colleagues. The findings were published recently in Diabetes Care.

The inflammatory response, they wrote, “may result in tissue changes responsible for the infusion-site failures seen frequently in clinical practice.”

Such infusion site problems represent an “Achilles heel” of these otherwise highly beneficial devices, lead author Irl Hirsch, MD, professor of medicine in the division of metabolism, endocrinology, and nutrition, said in a statement. “It doesn’t really matter how good the technology is. We still don’t understand what is happening with the infusion sites, much less to [be able to] fix it.”

Significant differences between pump and nonpump sites

In the cross-sectional study, Dr. Kalus and colleagues used noninvasive optical coherence tomography (OCT) immediately prior to performing punch biopsies at three sites: the site currently in active use, the “recovery site” used 3-5 days prior to the procedures, and control sites never used for pump infusion. Punch biopsies were also performed at those sites.

The mean age of the patients was 48.3 years, the mean diabetes duration was 30.4 years, and the mean duration of pump use was 15.8 years. Nearly all patients (93.3%) reported itchiness at the site, and 76.7% reported skin redness.

Of the 25 patients for whom OCT imaging was successful, statistical analysis showed significant differences in vascular area density and the optical attenuation coefficient, a surrogate for skin inflammation, between the pump and control sites and between recovery sites and current pump sites. The greater vessel density is likely a result of injury and repair related to catheter insertion, the authors said.

In the biopsy samples, both current and recovery sites showed increased fibrosis, fibrin, inflammation, fat necrosis, vascularity, and eosinophils, compared with the control sites, but no significant differences were found between current and recovery sites.

Eosinophils: ‘The most surprising histologic finding’

Eosinophils were found in 73% of skin biopsy specimens from current sites and in 75% of specimens from recovery sites, compared with none from the control sites (for both, P < .01). In all study participants, eosinophils were found in at least one current and/or recovery infusion site deep in the dermis near the interface with fat. The number of eosinophils ranged from 0 to 31 per high-power field, with a median of 4.

The number of eosinophils didn’t vary by type of insulin or brand of pump, but higher counts were seen in those who had used pumps for less than 10 years, compared with more than 20 years (P = .02).

The prevalence and degree of eosinophils were “the most surprising histologic finding,” the authors wrote, adding that “eosinophils are not typically present as a component of resident inflammatory cells in the skin.”