Case

A 62-year-old man with known adenocarcinoma of the lung with metastasis to the liver and bones presented to the ED complaining of nonproductive cough and progressively worsening shortness of breath for 2 weeks. He was started on crizotinib a week prior to presentation, and had also received multiple courses of oral antibiotics and steroids for presumed exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In addition to COPD, the patient had a history of degenerative joint disease, and was previously a chronic smoker. His current medications included tiotropium, inhaled daily; albuterol, two inhalations as needed; and hydrocodone/acetaminophen as needed for pain.

His vital signs on physical examination were: heart rate, 98 beats/minute; blood pressure 138/89 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/minute; temperature, 99.3°F. Oxygen saturation was 84% on room air, which improved to 92% with 2 L of oxygen. He had mild rhonchi on chest auscultation, but normal heart sounds and normal neurological, gastrointestinal, and extremity examination. Laboratory data revealed persistent elevation of leukocytes ranging between 12 and 15 x 109/L; hemoglobin, 9.2 g/dL; and platelet count, 220 x 109/L. A basic metabolic panel was within the normal range. The chest radiograph showed no evidence of pulmonary or cardiac abnormalities.

The patient was given nebulizer therapy with albuterol, along with oral prednisone. He improved with treatment and was discharged with oral prednisone daily for 4 days and oral doxycycline daily for 7 days. A week later, however, the patient had a cardiorespiratory arrest at home and could not be revived. A postmortem examination confirmed bilateral massive pulmonary embolism (PE).

Cancer Prevalence

According to the Cancer Facts & Figures 2014 published by the American Cancer Society, approximately 13.7 million Americans with a history of cancer were alive on January 1, 2012.1 In 2014, there will be an estimated 1,665,540 new cancer diagnoses and 585,720 cancer deaths in the United States.1 Cancer remains the second most common cause of death in the United States, accounting for nearly one out of every four deaths.

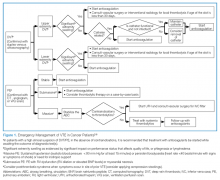

As seen in the above case presentation, cancer patients are at an increased risk for developing venous thromboembolism (VTE), the symptoms of which may not always be overt. Thus, with the increasing incidence and prevalence of cancer, enhanced vision and emphasis on education of emergency physicians—especially in relation to comorbidities associated with the disease—will improve care for this unique population. (See Figure 1 for an algorithm outlining the appropriate emergency management of VTE in cancer patients.)

Venous Thromboembolism

Symptoms

Classic clinical symptoms of acute VTE may not be seen in all patients. Therefore, a high level of clinical suspicion should be made on cancer patients presenting with any clinically overt signs or symptoms that could represent acute VTE. Symptoms of DVT include pain or tenderness and swelling of one or more extremities. On physical examination, increased warmth, edema, and erythema are often found. The most common signs and symptoms of PE include dyspnea, tachypnea, and pleuritic chest pain. Tachycardia, hypoxia, cough, and syncope are not present in all cases of acute PE.2

Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism

Deep vein thrombosis and PE are manifestations of a single disease entity, namely, VTE. The association between VTE and cancer has been well established since it was first recognized by the French internist Armand Trousseau more than 150 years ago.

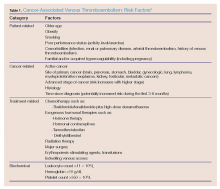

Deep vein thrombosis is characterized by a thrombus, usually in one of the deep venous conduits that return blood to the heart from the lower extremities, proximal to and including the popliteal veins. However, emboli can also originate from the pelvic veins, the inferior vena cava, and the upper extremities. Pulmonary embolism is characterized by a fully or partially occluding thrombus in one or more arteries of the lungs. Patients with cancer carry an increased risk of developing VTE because of tumor- and treatment-mediated hypercoagulability.6-8 Table 1 provides a summary of the risk factors associated with cancer-related VTE.

Venous thromboembolism is the second leading noncancer-related cause of death in oncology patients, with infection being the first.9-11 Mortality from an acute thrombotic event is four to eight times greater in patients with cancer than in those without cancer.12-14 Based on its high prevalence (in part due to prothrombotic effects of oncologic therapies) and high mortality rate, awareness of VTE diagnostic approaches and treatment is particularly important in the ED patient with cancer.