User login

In geriatric urinary incontinence, think DIAPERS mnemonic

NEW ORLEANS – Neil M. Resnick, MD, has devoted more than 30 years of his career to refining the diagnosis and management of geriatric urinary incontinence. He has found it to be a deeply rewarding area of his medical practice. And he wants primary care physicians to share the joy.

Once you get the hang of it, you’re going to love it,” he promised at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

“There is so much you have to offer, and it’s going to make you one happy, fulfilled, non–burned-out physician,” added Dr. Resnick, professor of medicine and chief of the division of geriatric medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

He insisted that geriatric urinary incontinence belongs squarely in the province of primary care physicians, not just urologic surgeons. That’s because the condition is typically caused or exacerbated by medical diseases and drugs.

“These are things for which we are the experts, because they are conditions outside the bladder that our surgical colleagues aren’t always expert in,” the internist emphasized.

The seven reversible causes of geriatric urinary incontinence, which are categorized as transient urinary incontinence, can easily be remembered by busy primary care practitioners with the aid of a mnemonic of Dr. Resnick’s own devising: DIAPERS. It stands for Delirium, Infection, Atrophic urethritis/vaginitis, Pharmaceuticals, Excess urine output, Restricted mobility, and Stool impaction.

“Treatable causes of urinary incontinence are much more common in older people than in the young,” Dr. Resnick said. “If you just pay attention to these, and you can’t even spell ‘bladder,’ you can cure one-third of older patients. It’s pretty dramatic. And it improves the incontinence in all of the people in whom it’s still persistent, and that means improved responsiveness to further treatment addressing the urinary tract, improvement of other problems related to the incontinence, better quality of life, and it just makes patients better overall. This is really the joy and glory of geriatrics.”

He emphasized that urinary incontinence is never normal, no matter how advanced the patient’s age. The basic geriatric principle is that aging reduces resilience. Bladder sensation and contractility decrease with age. The prostate enlarges. Sphincter strength and urethral length decrease in older women. Involuntary bladder contractions occur in half of all elderly individuals. Nocturnal urine excretion increases. Postvoid urine volume creeps up to 50-100 mL. These are normal changes, but they predispose to tipping over into urinary incontinence in the setting of any additional challenges created by DIAPERS.

The scope of the problem

More than one-third of elderly individuals experience urinary incontinence with daily to weekly frequency. The associated morbidity includes cellulitis, perineal rashes, pressure ulcers, falls, fractures, anxiety, depression, and sexual dysfunction. The economic cost of geriatric urinary incontinence is believed to exceed that of coronary artery bypass surgery and renal dialysis combined.

“The morbidity is huge and the costs are astonishing,” the geriatrician declared.

Fewer than one-fifth and perhaps as few as one-tenth of affected patients actually require surgery.

Less than 20% of elderly patients with urinary incontinence volunteer that information to their primary care physician because of the stigma involved. So, it’s important to ask about it, he noted.

The lowdown on DIAPERS

- Delirium. “The last thing you want to do is refer a patient with urinary incontinence and delirium to a urologist for cystoscopy or urodynamic testing,” according to Dr. Resnick. “It misses the point: The problem is their brain is not working. If you address the causes of delirium, once the delirium subsides, the incontinence will abate.” However, addressing the cause of the acute confusional state can be challenging, he conceded, because delirium can result from virtually any drug or disease anywhere in the body.

- Infection. Acute urinary tract infection (UTI) is the cause of about only 3% of geriatric urinary incontinence. But when present, it’s simple enough to diagnosis and treat. Far more common is asymptomatic bacteriuria, which is present in about 20% of elderly men and 40% of elderly women but does not cause incontinence.

- “The key symptom is dysuria: If the patient [with bacteriuria] has new-onset urinary incontinence or worsened urinary incontinence that’s happened for only the last couple days, that’s an acute UTI that needs to be treated,” Dr. Resnick advised. “Other than that, don’t treat. All you’ll do is select for more virulent organisms, so when the patient does get an acute UTI, it’s tougher to treat.”

- Atrophic vaginitis/urethritis. A common condition when endogenous estrogen goes down. It is characterized by vaginal and urethral erosions and tissue friability. When an affected woman urinates, the acid urine gains exposure to the underlying subendothelial tissue, causing inflammation and irritation that prevent the urethra from closing properly. This condition, frequently mistaken for a UTI, responds well to low-dose topical estrogen in the form of either an easily implantable ring that lasts for 3 months or a topical estrogen cream applied once daily, after establishing the absence of breast or uterine cancer.

- “It takes weeks to months for this condition to remit,” he said. “So, if they’re doing cream, they do it every day for a month. Then every month, they pull back by one day. Eventually, they get to the point where they can be maintained with once- or twice-weekly application.”

- Pharmaceuticals. The list of potential offenders is lengthy. Dr. Resnick focused on six types of medications that are most often linked to increased risk of geriatric urinary incontinence. Those six include long-acting sedative hypnotics, including diazepam (Valium); loop diuretics; and anticholinergic agents, including sedating antihistamines, antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants, and tiotropium bromide (Spiriva).

- They also include adrenergic agents, with alpha-adrenergic blockers causing or contributing to urinary incontinence in women and alpha-adrenergic agonists – present in a vast number of OTC cold, sleep, and cough medications – being responsible for problems in men; drugs causing fluid accumulation, including the dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, NSAIDs, some Parkinson’s agents, and gabapentin/pregabalin; and ACE inhibitors because of their side effect of cough.

- “The most common problem drugs in my practice are calcium channel blockers and gabapentin or pregabalin,” according to the geriatrician.

- Excess urine output. Older people have smaller bladders. Dr. Resnick loathes the popular advice to drink 8 glasses of water per day. Every time that so-called health tip appears in the mass media, he sees a flurry of patients with new-onset geriatric urinary incontinence. Other causes of excess urine output include alcohol, caffeine, metabolic disorders including hyperglycemia, and peripheral edema attributable to heart failure or venous insufficiency.

- Restricted mobility. This often results from overlooked correctable conditions that bedevil older people, including poorly fitting shoes, calluses, bunions, and deformed toenails, as well as readily treatable disorders including depression, orthostatic or postprandial hypotension, and arthritis pain.

- Stool impaction. “The clinical key is new onset of double incontinence associated with bladder distension. One gloved finger will disimpact and cure both,” Dr. Resnick said.

- In patients whose urinary incontinence persists after systematic attention to the DIAPERS details, there are only four possible mechanisms, according to Dr. Resnick: an overactive detrusor or stress incontinence, which can be categorized as storage problems, or an underactive detrusor or a urethral obstruction, which can be considered emptying problems.

Dr. Resnick reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

NEW ORLEANS – Neil M. Resnick, MD, has devoted more than 30 years of his career to refining the diagnosis and management of geriatric urinary incontinence. He has found it to be a deeply rewarding area of his medical practice. And he wants primary care physicians to share the joy.

Once you get the hang of it, you’re going to love it,” he promised at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

“There is so much you have to offer, and it’s going to make you one happy, fulfilled, non–burned-out physician,” added Dr. Resnick, professor of medicine and chief of the division of geriatric medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

He insisted that geriatric urinary incontinence belongs squarely in the province of primary care physicians, not just urologic surgeons. That’s because the condition is typically caused or exacerbated by medical diseases and drugs.

“These are things for which we are the experts, because they are conditions outside the bladder that our surgical colleagues aren’t always expert in,” the internist emphasized.

The seven reversible causes of geriatric urinary incontinence, which are categorized as transient urinary incontinence, can easily be remembered by busy primary care practitioners with the aid of a mnemonic of Dr. Resnick’s own devising: DIAPERS. It stands for Delirium, Infection, Atrophic urethritis/vaginitis, Pharmaceuticals, Excess urine output, Restricted mobility, and Stool impaction.

“Treatable causes of urinary incontinence are much more common in older people than in the young,” Dr. Resnick said. “If you just pay attention to these, and you can’t even spell ‘bladder,’ you can cure one-third of older patients. It’s pretty dramatic. And it improves the incontinence in all of the people in whom it’s still persistent, and that means improved responsiveness to further treatment addressing the urinary tract, improvement of other problems related to the incontinence, better quality of life, and it just makes patients better overall. This is really the joy and glory of geriatrics.”

He emphasized that urinary incontinence is never normal, no matter how advanced the patient’s age. The basic geriatric principle is that aging reduces resilience. Bladder sensation and contractility decrease with age. The prostate enlarges. Sphincter strength and urethral length decrease in older women. Involuntary bladder contractions occur in half of all elderly individuals. Nocturnal urine excretion increases. Postvoid urine volume creeps up to 50-100 mL. These are normal changes, but they predispose to tipping over into urinary incontinence in the setting of any additional challenges created by DIAPERS.

The scope of the problem

More than one-third of elderly individuals experience urinary incontinence with daily to weekly frequency. The associated morbidity includes cellulitis, perineal rashes, pressure ulcers, falls, fractures, anxiety, depression, and sexual dysfunction. The economic cost of geriatric urinary incontinence is believed to exceed that of coronary artery bypass surgery and renal dialysis combined.

“The morbidity is huge and the costs are astonishing,” the geriatrician declared.

Fewer than one-fifth and perhaps as few as one-tenth of affected patients actually require surgery.

Less than 20% of elderly patients with urinary incontinence volunteer that information to their primary care physician because of the stigma involved. So, it’s important to ask about it, he noted.

The lowdown on DIAPERS

- Delirium. “The last thing you want to do is refer a patient with urinary incontinence and delirium to a urologist for cystoscopy or urodynamic testing,” according to Dr. Resnick. “It misses the point: The problem is their brain is not working. If you address the causes of delirium, once the delirium subsides, the incontinence will abate.” However, addressing the cause of the acute confusional state can be challenging, he conceded, because delirium can result from virtually any drug or disease anywhere in the body.

- Infection. Acute urinary tract infection (UTI) is the cause of about only 3% of geriatric urinary incontinence. But when present, it’s simple enough to diagnosis and treat. Far more common is asymptomatic bacteriuria, which is present in about 20% of elderly men and 40% of elderly women but does not cause incontinence.

- “The key symptom is dysuria: If the patient [with bacteriuria] has new-onset urinary incontinence or worsened urinary incontinence that’s happened for only the last couple days, that’s an acute UTI that needs to be treated,” Dr. Resnick advised. “Other than that, don’t treat. All you’ll do is select for more virulent organisms, so when the patient does get an acute UTI, it’s tougher to treat.”

- Atrophic vaginitis/urethritis. A common condition when endogenous estrogen goes down. It is characterized by vaginal and urethral erosions and tissue friability. When an affected woman urinates, the acid urine gains exposure to the underlying subendothelial tissue, causing inflammation and irritation that prevent the urethra from closing properly. This condition, frequently mistaken for a UTI, responds well to low-dose topical estrogen in the form of either an easily implantable ring that lasts for 3 months or a topical estrogen cream applied once daily, after establishing the absence of breast or uterine cancer.

- “It takes weeks to months for this condition to remit,” he said. “So, if they’re doing cream, they do it every day for a month. Then every month, they pull back by one day. Eventually, they get to the point where they can be maintained with once- or twice-weekly application.”

- Pharmaceuticals. The list of potential offenders is lengthy. Dr. Resnick focused on six types of medications that are most often linked to increased risk of geriatric urinary incontinence. Those six include long-acting sedative hypnotics, including diazepam (Valium); loop diuretics; and anticholinergic agents, including sedating antihistamines, antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants, and tiotropium bromide (Spiriva).

- They also include adrenergic agents, with alpha-adrenergic blockers causing or contributing to urinary incontinence in women and alpha-adrenergic agonists – present in a vast number of OTC cold, sleep, and cough medications – being responsible for problems in men; drugs causing fluid accumulation, including the dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, NSAIDs, some Parkinson’s agents, and gabapentin/pregabalin; and ACE inhibitors because of their side effect of cough.

- “The most common problem drugs in my practice are calcium channel blockers and gabapentin or pregabalin,” according to the geriatrician.

- Excess urine output. Older people have smaller bladders. Dr. Resnick loathes the popular advice to drink 8 glasses of water per day. Every time that so-called health tip appears in the mass media, he sees a flurry of patients with new-onset geriatric urinary incontinence. Other causes of excess urine output include alcohol, caffeine, metabolic disorders including hyperglycemia, and peripheral edema attributable to heart failure or venous insufficiency.

- Restricted mobility. This often results from overlooked correctable conditions that bedevil older people, including poorly fitting shoes, calluses, bunions, and deformed toenails, as well as readily treatable disorders including depression, orthostatic or postprandial hypotension, and arthritis pain.

- Stool impaction. “The clinical key is new onset of double incontinence associated with bladder distension. One gloved finger will disimpact and cure both,” Dr. Resnick said.

- In patients whose urinary incontinence persists after systematic attention to the DIAPERS details, there are only four possible mechanisms, according to Dr. Resnick: an overactive detrusor or stress incontinence, which can be categorized as storage problems, or an underactive detrusor or a urethral obstruction, which can be considered emptying problems.

Dr. Resnick reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

NEW ORLEANS – Neil M. Resnick, MD, has devoted more than 30 years of his career to refining the diagnosis and management of geriatric urinary incontinence. He has found it to be a deeply rewarding area of his medical practice. And he wants primary care physicians to share the joy.

Once you get the hang of it, you’re going to love it,” he promised at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

“There is so much you have to offer, and it’s going to make you one happy, fulfilled, non–burned-out physician,” added Dr. Resnick, professor of medicine and chief of the division of geriatric medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

He insisted that geriatric urinary incontinence belongs squarely in the province of primary care physicians, not just urologic surgeons. That’s because the condition is typically caused or exacerbated by medical diseases and drugs.

“These are things for which we are the experts, because they are conditions outside the bladder that our surgical colleagues aren’t always expert in,” the internist emphasized.

The seven reversible causes of geriatric urinary incontinence, which are categorized as transient urinary incontinence, can easily be remembered by busy primary care practitioners with the aid of a mnemonic of Dr. Resnick’s own devising: DIAPERS. It stands for Delirium, Infection, Atrophic urethritis/vaginitis, Pharmaceuticals, Excess urine output, Restricted mobility, and Stool impaction.

“Treatable causes of urinary incontinence are much more common in older people than in the young,” Dr. Resnick said. “If you just pay attention to these, and you can’t even spell ‘bladder,’ you can cure one-third of older patients. It’s pretty dramatic. And it improves the incontinence in all of the people in whom it’s still persistent, and that means improved responsiveness to further treatment addressing the urinary tract, improvement of other problems related to the incontinence, better quality of life, and it just makes patients better overall. This is really the joy and glory of geriatrics.”

He emphasized that urinary incontinence is never normal, no matter how advanced the patient’s age. The basic geriatric principle is that aging reduces resilience. Bladder sensation and contractility decrease with age. The prostate enlarges. Sphincter strength and urethral length decrease in older women. Involuntary bladder contractions occur in half of all elderly individuals. Nocturnal urine excretion increases. Postvoid urine volume creeps up to 50-100 mL. These are normal changes, but they predispose to tipping over into urinary incontinence in the setting of any additional challenges created by DIAPERS.

The scope of the problem

More than one-third of elderly individuals experience urinary incontinence with daily to weekly frequency. The associated morbidity includes cellulitis, perineal rashes, pressure ulcers, falls, fractures, anxiety, depression, and sexual dysfunction. The economic cost of geriatric urinary incontinence is believed to exceed that of coronary artery bypass surgery and renal dialysis combined.

“The morbidity is huge and the costs are astonishing,” the geriatrician declared.

Fewer than one-fifth and perhaps as few as one-tenth of affected patients actually require surgery.

Less than 20% of elderly patients with urinary incontinence volunteer that information to their primary care physician because of the stigma involved. So, it’s important to ask about it, he noted.

The lowdown on DIAPERS

- Delirium. “The last thing you want to do is refer a patient with urinary incontinence and delirium to a urologist for cystoscopy or urodynamic testing,” according to Dr. Resnick. “It misses the point: The problem is their brain is not working. If you address the causes of delirium, once the delirium subsides, the incontinence will abate.” However, addressing the cause of the acute confusional state can be challenging, he conceded, because delirium can result from virtually any drug or disease anywhere in the body.

- Infection. Acute urinary tract infection (UTI) is the cause of about only 3% of geriatric urinary incontinence. But when present, it’s simple enough to diagnosis and treat. Far more common is asymptomatic bacteriuria, which is present in about 20% of elderly men and 40% of elderly women but does not cause incontinence.

- “The key symptom is dysuria: If the patient [with bacteriuria] has new-onset urinary incontinence or worsened urinary incontinence that’s happened for only the last couple days, that’s an acute UTI that needs to be treated,” Dr. Resnick advised. “Other than that, don’t treat. All you’ll do is select for more virulent organisms, so when the patient does get an acute UTI, it’s tougher to treat.”

- Atrophic vaginitis/urethritis. A common condition when endogenous estrogen goes down. It is characterized by vaginal and urethral erosions and tissue friability. When an affected woman urinates, the acid urine gains exposure to the underlying subendothelial tissue, causing inflammation and irritation that prevent the urethra from closing properly. This condition, frequently mistaken for a UTI, responds well to low-dose topical estrogen in the form of either an easily implantable ring that lasts for 3 months or a topical estrogen cream applied once daily, after establishing the absence of breast or uterine cancer.

- “It takes weeks to months for this condition to remit,” he said. “So, if they’re doing cream, they do it every day for a month. Then every month, they pull back by one day. Eventually, they get to the point where they can be maintained with once- or twice-weekly application.”

- Pharmaceuticals. The list of potential offenders is lengthy. Dr. Resnick focused on six types of medications that are most often linked to increased risk of geriatric urinary incontinence. Those six include long-acting sedative hypnotics, including diazepam (Valium); loop diuretics; and anticholinergic agents, including sedating antihistamines, antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants, and tiotropium bromide (Spiriva).

- They also include adrenergic agents, with alpha-adrenergic blockers causing or contributing to urinary incontinence in women and alpha-adrenergic agonists – present in a vast number of OTC cold, sleep, and cough medications – being responsible for problems in men; drugs causing fluid accumulation, including the dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, NSAIDs, some Parkinson’s agents, and gabapentin/pregabalin; and ACE inhibitors because of their side effect of cough.

- “The most common problem drugs in my practice are calcium channel blockers and gabapentin or pregabalin,” according to the geriatrician.

- Excess urine output. Older people have smaller bladders. Dr. Resnick loathes the popular advice to drink 8 glasses of water per day. Every time that so-called health tip appears in the mass media, he sees a flurry of patients with new-onset geriatric urinary incontinence. Other causes of excess urine output include alcohol, caffeine, metabolic disorders including hyperglycemia, and peripheral edema attributable to heart failure or venous insufficiency.

- Restricted mobility. This often results from overlooked correctable conditions that bedevil older people, including poorly fitting shoes, calluses, bunions, and deformed toenails, as well as readily treatable disorders including depression, orthostatic or postprandial hypotension, and arthritis pain.

- Stool impaction. “The clinical key is new onset of double incontinence associated with bladder distension. One gloved finger will disimpact and cure both,” Dr. Resnick said.

- In patients whose urinary incontinence persists after systematic attention to the DIAPERS details, there are only four possible mechanisms, according to Dr. Resnick: an overactive detrusor or stress incontinence, which can be categorized as storage problems, or an underactive detrusor or a urethral obstruction, which can be considered emptying problems.

Dr. Resnick reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

REPORTING FROM ACP INTERNAL MEDICINE

New Valsalva maneuver for SVT beats all others

NEW ORLEANS – , according to Jeet Mehta, MD, a resident in the combined medicine/pediatrics program at the University of Kansas, Wichita.

The 2015 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines recommended vagal maneuvers as first-line treatment of supraventricular tachycardia, but added that there was no gold standard method. Since then, the situation has changed. Two well-conducted randomized clinical trials have been published that bring clarity as to the vagal maneuver of choice, Dr. Mehta reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

He and his coinvestigators performed a meta-analysis of the three pre-2000 randomized controlled trials that compared the standard Valsalva maneuver to carotid sinus massage plus the two newer studies, both of which systematically compared a modified Valsalva maneuver with the standard version.

The clear winner in terms of efficacy was the modified Valsalva maneuver, in which patients with supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) performed a standardized strain while in a semirecumbent position, then immediately laid flat and had their legs raised to 45 degrees for 15 seconds before returning to the semirecumbent position. The purpose of this postural modification is to boost relaxation phase venous return and vagal stimulation.

In the 433-patient multicenter REVERT trial in the United Kingdom, 43% of those assigned to the modified Valsalva maneuver returned to sinus rhythm 1 minute after completing the task, compared with 17% of those randomized to the standard semirecumbent Valsalva maneuver. This resulted in significantly less need for adenosine and other treatments. Although REVERT investigators had the patients blow into a manometer at 40 mm Hg for 15 seconds, they noted that the same intensity of strain can be achieved more practically by blowing into a 10-mL syringe sufficient to just move the plunger (Lancet. 2015 Oct 31;386[10005]:1747-53).

The REVERT findings were confirmed by a second trial conducted by Turkish investigators, in which the modified Valsalva maneuver was successful in 43% of patients, compared with 11% in the standard Valsalva maneuver group (Am J Emerg Med. 2017 Nov;35[11]:1662-5).

Extrapolating from the published evidence, including a Cochrane Collaboration review (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Feb 18;[2]:CD009502. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009502.pub3), Dr. Mehta and his coinvestigators ranked the likelihood of successful conversion of SVT to sinus rhythm from a high of 48% for the modified Valsalva maneuver, descending to 43% for a supine Valsalva maneuver, 36% for a standard semirecumbent Valsalva, 21% for a seated Valsalva, 19% for a standing one, and just 11% for carotid sinus massage.

“Based on evidence of high quality, we encourage that the modified Valsalva maneuver be done due its safety and low cost,” Dr. Mehta concluded.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, conducted free of commercial support.

NEW ORLEANS – , according to Jeet Mehta, MD, a resident in the combined medicine/pediatrics program at the University of Kansas, Wichita.

The 2015 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines recommended vagal maneuvers as first-line treatment of supraventricular tachycardia, but added that there was no gold standard method. Since then, the situation has changed. Two well-conducted randomized clinical trials have been published that bring clarity as to the vagal maneuver of choice, Dr. Mehta reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

He and his coinvestigators performed a meta-analysis of the three pre-2000 randomized controlled trials that compared the standard Valsalva maneuver to carotid sinus massage plus the two newer studies, both of which systematically compared a modified Valsalva maneuver with the standard version.

The clear winner in terms of efficacy was the modified Valsalva maneuver, in which patients with supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) performed a standardized strain while in a semirecumbent position, then immediately laid flat and had their legs raised to 45 degrees for 15 seconds before returning to the semirecumbent position. The purpose of this postural modification is to boost relaxation phase venous return and vagal stimulation.

In the 433-patient multicenter REVERT trial in the United Kingdom, 43% of those assigned to the modified Valsalva maneuver returned to sinus rhythm 1 minute after completing the task, compared with 17% of those randomized to the standard semirecumbent Valsalva maneuver. This resulted in significantly less need for adenosine and other treatments. Although REVERT investigators had the patients blow into a manometer at 40 mm Hg for 15 seconds, they noted that the same intensity of strain can be achieved more practically by blowing into a 10-mL syringe sufficient to just move the plunger (Lancet. 2015 Oct 31;386[10005]:1747-53).

The REVERT findings were confirmed by a second trial conducted by Turkish investigators, in which the modified Valsalva maneuver was successful in 43% of patients, compared with 11% in the standard Valsalva maneuver group (Am J Emerg Med. 2017 Nov;35[11]:1662-5).

Extrapolating from the published evidence, including a Cochrane Collaboration review (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Feb 18;[2]:CD009502. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009502.pub3), Dr. Mehta and his coinvestigators ranked the likelihood of successful conversion of SVT to sinus rhythm from a high of 48% for the modified Valsalva maneuver, descending to 43% for a supine Valsalva maneuver, 36% for a standard semirecumbent Valsalva, 21% for a seated Valsalva, 19% for a standing one, and just 11% for carotid sinus massage.

“Based on evidence of high quality, we encourage that the modified Valsalva maneuver be done due its safety and low cost,” Dr. Mehta concluded.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, conducted free of commercial support.

NEW ORLEANS – , according to Jeet Mehta, MD, a resident in the combined medicine/pediatrics program at the University of Kansas, Wichita.

The 2015 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines recommended vagal maneuvers as first-line treatment of supraventricular tachycardia, but added that there was no gold standard method. Since then, the situation has changed. Two well-conducted randomized clinical trials have been published that bring clarity as to the vagal maneuver of choice, Dr. Mehta reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

He and his coinvestigators performed a meta-analysis of the three pre-2000 randomized controlled trials that compared the standard Valsalva maneuver to carotid sinus massage plus the two newer studies, both of which systematically compared a modified Valsalva maneuver with the standard version.

The clear winner in terms of efficacy was the modified Valsalva maneuver, in which patients with supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) performed a standardized strain while in a semirecumbent position, then immediately laid flat and had their legs raised to 45 degrees for 15 seconds before returning to the semirecumbent position. The purpose of this postural modification is to boost relaxation phase venous return and vagal stimulation.

In the 433-patient multicenter REVERT trial in the United Kingdom, 43% of those assigned to the modified Valsalva maneuver returned to sinus rhythm 1 minute after completing the task, compared with 17% of those randomized to the standard semirecumbent Valsalva maneuver. This resulted in significantly less need for adenosine and other treatments. Although REVERT investigators had the patients blow into a manometer at 40 mm Hg for 15 seconds, they noted that the same intensity of strain can be achieved more practically by blowing into a 10-mL syringe sufficient to just move the plunger (Lancet. 2015 Oct 31;386[10005]:1747-53).

The REVERT findings were confirmed by a second trial conducted by Turkish investigators, in which the modified Valsalva maneuver was successful in 43% of patients, compared with 11% in the standard Valsalva maneuver group (Am J Emerg Med. 2017 Nov;35[11]:1662-5).

Extrapolating from the published evidence, including a Cochrane Collaboration review (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Feb 18;[2]:CD009502. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009502.pub3), Dr. Mehta and his coinvestigators ranked the likelihood of successful conversion of SVT to sinus rhythm from a high of 48% for the modified Valsalva maneuver, descending to 43% for a supine Valsalva maneuver, 36% for a standard semirecumbent Valsalva, 21% for a seated Valsalva, 19% for a standing one, and just 11% for carotid sinus massage.

“Based on evidence of high quality, we encourage that the modified Valsalva maneuver be done due its safety and low cost,” Dr. Mehta concluded.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, conducted free of commercial support.

REPORTING FROM ACP INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: A simple postural modification to the standard Valsalva maneuver boosts conversion rate.

Major finding: Nearly half of patients in SVT converted to sinus rhythm in response to a modified Valsalva maneuver.

Study details: This was a meta-analysis of five randomized clinical trials of vagal maneuvers for conversion of supraventricular tachycardia to sinus rhythm.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, conducted free of commercial support.

A new, simple, inexpensive DVT diagnostic aid

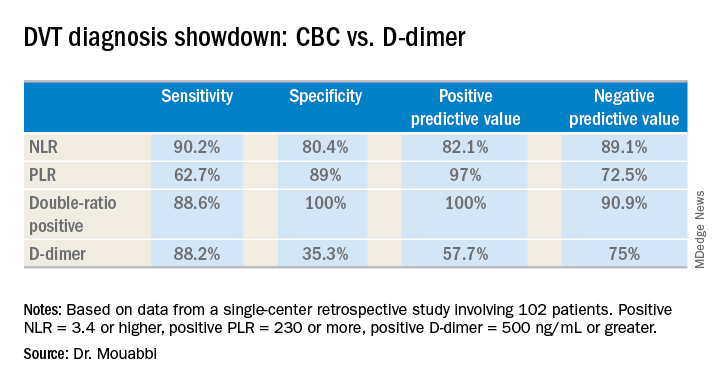

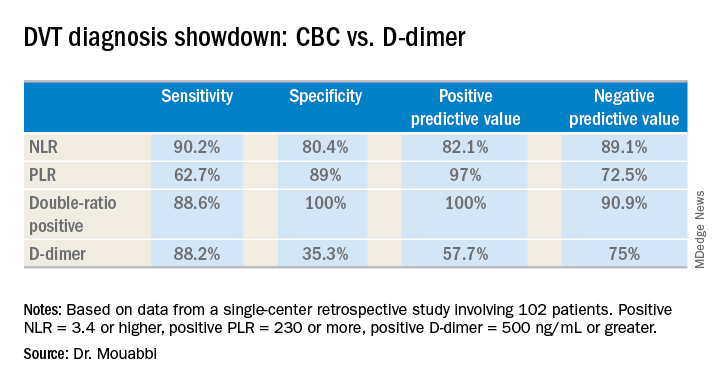

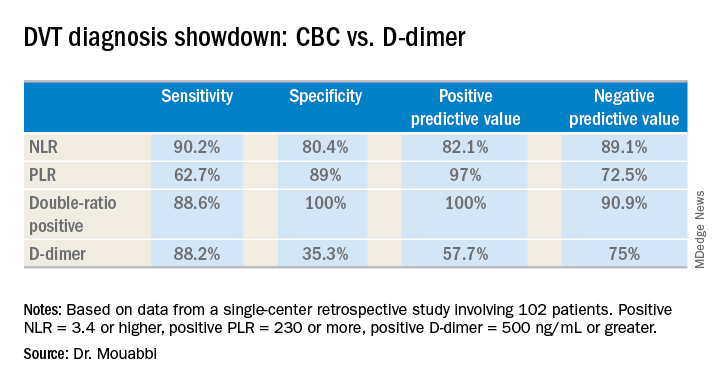

NEW ORLEANS – Both the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio proved to be better predictors of the presence or absence of deep vein thrombosis than the ubiquitous D-dimer test in a retrospective study, Jason Mouabbi, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

What’s more, both the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) can be readily calculated from the readout of a complete blood count (CBC) with differential. A CBC costs an average of $16, and everybody that comes through a hospital emergency department gets one. In contrast, the average charge for a D-dimer test is about $231 nationwide, and depending upon the specific test used the results can take up to a couple of hours to come back, noted Dr. Mouabbi of St. John Hospital and Medical Center in Detroit.

“The NLR and PLR ratios offer a new, powerful, affordable, simple, and readily available tool in the hands of clinicians to help them in the diagnosis of DVT,” he said. “The NLR can be useful to rule out DVT when it’s negative, whereas PLR can be useful in ruling DVT when positive.”

Investigators in a variety of fields are looking at the NLR and PLR as emerging practical, easily obtainable biomarkers for systemic inflammation. And DVT is thought to be an inflammatory process, he explained.

Dr. Mouabbi presented a single-center retrospective study of 102 matched patients who presented with lower extremity swelling and had a CBC drawn, as well as a D-dimer test, on the same day they underwent a lower extremity Doppler ultrasound evaluation. In 51 patients, the ultrasound revealed the presence of DVT and anticoagulation was started. In the other 51 patients, the ultrasound exam was negative and they weren’t anticoagulated. Since the study purpose was to assess the implications of a primary elevation of NLR and/or PLR, patients with rheumatic diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, recent surgery, chronic renal or liver disease, inherited thrombophilia, infection, or other possible secondary causes of altered ratios were excluded from the study.

A positive NLR was considered 3.4 or higher, a positive PLR was a ratio of 230 or more, and a positive D-dimer level was 500 ng/mL or greater. The NLR and PLR collectively outperformed the D-dimer test in terms of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value.

In addition, 89% of the DVT group were classified as “double-positive,” meaning they were both NLR and PLR positive. That combination provided the best diagnostic value of all, since none of the controls were double-positive and only 2% were PLR positive.

While the results are encouraging, before NLR and PLR can supplant D-dimer in patients with suspected DVT in clinical practice a confirmatory prospective study should be carried out, according to Dr. Mouabbi. Ideally it should include the use of the Wells score, which is part of most diagnostic algorithms as a preliminary means of categorizing DVT probability as low, moderate, or high. However, the popularity of the Wells score has fallen off in the face of reports that the results are subjective and variable. Indeed, the Wells score was included in the electronic medical record of so few participants in Dr. Mouabbi’s study that he couldn’t evaluate its utility.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

NEW ORLEANS – Both the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio proved to be better predictors of the presence or absence of deep vein thrombosis than the ubiquitous D-dimer test in a retrospective study, Jason Mouabbi, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

What’s more, both the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) can be readily calculated from the readout of a complete blood count (CBC) with differential. A CBC costs an average of $16, and everybody that comes through a hospital emergency department gets one. In contrast, the average charge for a D-dimer test is about $231 nationwide, and depending upon the specific test used the results can take up to a couple of hours to come back, noted Dr. Mouabbi of St. John Hospital and Medical Center in Detroit.

“The NLR and PLR ratios offer a new, powerful, affordable, simple, and readily available tool in the hands of clinicians to help them in the diagnosis of DVT,” he said. “The NLR can be useful to rule out DVT when it’s negative, whereas PLR can be useful in ruling DVT when positive.”

Investigators in a variety of fields are looking at the NLR and PLR as emerging practical, easily obtainable biomarkers for systemic inflammation. And DVT is thought to be an inflammatory process, he explained.

Dr. Mouabbi presented a single-center retrospective study of 102 matched patients who presented with lower extremity swelling and had a CBC drawn, as well as a D-dimer test, on the same day they underwent a lower extremity Doppler ultrasound evaluation. In 51 patients, the ultrasound revealed the presence of DVT and anticoagulation was started. In the other 51 patients, the ultrasound exam was negative and they weren’t anticoagulated. Since the study purpose was to assess the implications of a primary elevation of NLR and/or PLR, patients with rheumatic diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, recent surgery, chronic renal or liver disease, inherited thrombophilia, infection, or other possible secondary causes of altered ratios were excluded from the study.

A positive NLR was considered 3.4 or higher, a positive PLR was a ratio of 230 or more, and a positive D-dimer level was 500 ng/mL or greater. The NLR and PLR collectively outperformed the D-dimer test in terms of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value.

In addition, 89% of the DVT group were classified as “double-positive,” meaning they were both NLR and PLR positive. That combination provided the best diagnostic value of all, since none of the controls were double-positive and only 2% were PLR positive.

While the results are encouraging, before NLR and PLR can supplant D-dimer in patients with suspected DVT in clinical practice a confirmatory prospective study should be carried out, according to Dr. Mouabbi. Ideally it should include the use of the Wells score, which is part of most diagnostic algorithms as a preliminary means of categorizing DVT probability as low, moderate, or high. However, the popularity of the Wells score has fallen off in the face of reports that the results are subjective and variable. Indeed, the Wells score was included in the electronic medical record of so few participants in Dr. Mouabbi’s study that he couldn’t evaluate its utility.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

NEW ORLEANS – Both the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio proved to be better predictors of the presence or absence of deep vein thrombosis than the ubiquitous D-dimer test in a retrospective study, Jason Mouabbi, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

What’s more, both the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) can be readily calculated from the readout of a complete blood count (CBC) with differential. A CBC costs an average of $16, and everybody that comes through a hospital emergency department gets one. In contrast, the average charge for a D-dimer test is about $231 nationwide, and depending upon the specific test used the results can take up to a couple of hours to come back, noted Dr. Mouabbi of St. John Hospital and Medical Center in Detroit.

“The NLR and PLR ratios offer a new, powerful, affordable, simple, and readily available tool in the hands of clinicians to help them in the diagnosis of DVT,” he said. “The NLR can be useful to rule out DVT when it’s negative, whereas PLR can be useful in ruling DVT when positive.”

Investigators in a variety of fields are looking at the NLR and PLR as emerging practical, easily obtainable biomarkers for systemic inflammation. And DVT is thought to be an inflammatory process, he explained.

Dr. Mouabbi presented a single-center retrospective study of 102 matched patients who presented with lower extremity swelling and had a CBC drawn, as well as a D-dimer test, on the same day they underwent a lower extremity Doppler ultrasound evaluation. In 51 patients, the ultrasound revealed the presence of DVT and anticoagulation was started. In the other 51 patients, the ultrasound exam was negative and they weren’t anticoagulated. Since the study purpose was to assess the implications of a primary elevation of NLR and/or PLR, patients with rheumatic diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, recent surgery, chronic renal or liver disease, inherited thrombophilia, infection, or other possible secondary causes of altered ratios were excluded from the study.

A positive NLR was considered 3.4 or higher, a positive PLR was a ratio of 230 or more, and a positive D-dimer level was 500 ng/mL or greater. The NLR and PLR collectively outperformed the D-dimer test in terms of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value.

In addition, 89% of the DVT group were classified as “double-positive,” meaning they were both NLR and PLR positive. That combination provided the best diagnostic value of all, since none of the controls were double-positive and only 2% were PLR positive.

While the results are encouraging, before NLR and PLR can supplant D-dimer in patients with suspected DVT in clinical practice a confirmatory prospective study should be carried out, according to Dr. Mouabbi. Ideally it should include the use of the Wells score, which is part of most diagnostic algorithms as a preliminary means of categorizing DVT probability as low, moderate, or high. However, the popularity of the Wells score has fallen off in the face of reports that the results are subjective and variable. Indeed, the Wells score was included in the electronic medical record of so few participants in Dr. Mouabbi’s study that he couldn’t evaluate its utility.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

REPORTING FROM ACP INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio was better than the D-dimer test at helping to rule out DVT, while the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio bested the D-dimer at ruling in DVT.

Study details: A retrospective study of 102 patients with suspected DVT.

Disclosures: Dr. Mouabbi reported no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

Prepare for ‘the coming tsunami’ of NAFLD

NEW ORLEANS – Zobair M. Younossi, MD, declared at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The massive growth in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is being fueled to a great extent by the related epidemics of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. While the overall prevalence of NAFLD worldwide is 24%, almost three-quarters of patients with NAFLD are obese. And the prevalence of NAFLD in individuals with T2DM was 58% in a recent meta-analysis of studies from 20 countries conducted by Dr. Younossi and his coinvestigators.

“The prevalence of NAFLD in U.S. kids is about 10%. This is of course part of the coming tsunami because our kids are getting obese, diabetic, and they’re going to have problems with NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis],” said Dr. Younossi, a gastroenterologist who is professor and chairman of the department of medicine at the Inova Fairfax (Va.) campus of Virginia Commonwealth University.

NASH is the form of NAFLD that has the strongest prognostic implications. It can progress to cirrhosis, liver failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma. As Dr. Younossi and his coworkers have shown (Hepat Commun. 2017 Jun 6;1[5]:421-8), it is associated with a significantly greater risk of both liver-related and all-cause mortality than that of non-NASH NAFLD, although NAFLD also carries an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death in that population.

In addition to highlighting the enormous clinical, economic, and quality-of-life implications of the NAFLD epidemic, Dr. Younossi offered practical tips on how busy primary care physicians can identify patients in their practice who have high-risk NAFLD. They have not done a very good job of this to date. That’s possibly due to lack of incentive, since in 2018 there is no approved drug for the treatment of NASH. He cited one representative retrospective study in which only about 15% of patients identified as having NAFLD received a recommendation for lifestyle modification involving diet and exercise, which is the standard evidence-based treatment, albeit admittedly difficult to sustain. And only 3% of patients with advanced liver fibrosis were referred to a specialist for management.

“So NAFLD is common, but its recognition and doing something about it is quite a challenge,” Dr. Younossi observed.

He argued that patients who have NASH deserve to know it because of its prognostic implications and also so they can have the chance to participate in one of the roughly two dozen ongoing clinical trials of potential therapies, some of which look quite promising. All of the trials required a liver biopsy as a condition for enrollment. Plus, once a patient is known to have stage 3 fibrosis, it’s time to start screening for hepatocellular carcinoma and esophageal varices.

The scope of the epidemic

NASH is the most rapidly growing indication for liver transplantation in the United States, with most of the increase coming from the baby boomer population. NASH is now the second most common indication for placement on the wait list. Meanwhile, liver transplantation due to the consequences of hepatitis C, the No. 1 indication, is declining as a result of the spectacular advances in medical treatment introduced a few years ago. It’s likely that in coming years NASH will take over the top spot, according to Dr. Younossi.

He was coauthor of a recent study that modeled the estimated trends for the NAFLD epidemic in the United States through 2030. The forecast is that the prevalence of NAFLD among adults will climb to 33.5% and the proportion of NAFLD categorized as NASH will increase from 20% at present to 27%. Moreover, this will result in a 168% jump in the incidence of decompensated cirrhosis, a 137% increase in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma, and a 178% increase in liver-related mortality, which will account for an estimated 78,300 deaths in 2030 (Hepatology. 2018 Jan;67[1]:123-33).

Practical ways to identify high-risk patients

The best noninvasive means of detecting NAFLD is by ultrasound showing a fatty liver. Often the condition is detected as an incidental finding on abdominal ultrasound ordered for another reason. Elevated liver enzymes can be a tipoff as well. Of course, alcoholic liver disease and other causes must be excluded.

But what’s most important is to identify patients with NASH. It’s a diagnosis made by biopsy. However, it is unthinkable to perform liver biopsies in the entire vast population with NAFLD, so there is a great deal of interest in developing noninvasive diagnostic modalities that can help zero in on the subset of high-risk NAFLD patients who should be considered for referral for liver biopsy.

One useful clue is the presence of comorbid metabolic syndrome in patients with NAFLD. It confers a substantially higher mortality risk – especially cardiovascular mortality – than does NAFLD without metabolic syndrome. Dr. Younossi and his coinvestigators have shown in a study of 3,613 NAFLD patients followed long-term that those with one component of the metabolic syndrome – either hypertension, central obesity, increased fasting plasma glucose, or hyperlipidemia – had 8- and 16-year all-cause mortality rates of 4.7% and 11.9%, nearly double the 2.6% and 6% rates in NAFLD patients with no elements of the metabolic syndrome.

Moreover, the magnitude of risk increased with each additional metabolic syndrome condition: a 3.57-fold increased mortality risk in NAFLD patients with two components of metabolic syndrome, a 5.87-fold increase in those with three, and a 13.09-fold increase in NAFLD patients with all four elements of metabolic syndrome (Medicine [Baltimore]. 2018 Mar;97[13]:e0214. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010214).

Dr. Younossi was a member of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease expert panel that developed the latest practice guidance regarding the diagnosis and management of NAFLD (Hepatology. 2018 Jan;67[1]:328-57). He said that probably the best simple noninvasive scoring system for the detection of NASH with advanced fibrosis is the NAFLD fibrosis score, which is easily calculated using laboratory values and clinical parameters already in a patient’s chart.

A more sophisticated serum biomarker test known as ELF, or the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis test, combines serum levels of hyaluronic acid, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase I, and procollagen amino terminal peptide.

“ELF is a very, very good test. It’s approved in Europe and I suspect it will be in the U.S. within the next year or so,” said Dr. Younossi.

The most exciting noninvasive tests, however, involve imaging that measures liver stiffness, which provides a fairly accurate indication of the degree of scarring in the organ. There are two methods available: vibration wave transient elastography and magnetic resonance elastography.

Transient elastography using the FibroScan device is commercially available in the United States. “It’s a good test, very easy to do, noninvasive. I have a couple of these machines, and we use them all the time,” the gastroenterologist said.

MR elastography provides superior accuracy, but access is an issue.

“At our institution you sometimes have to wait for weeks to get an outpatient MRI, so if you have hundreds of patients with fatty liver disease it makes things difficult. So in our practice we use transient elastography,” he explained.

Both imaging modalities also measure the amount of fat in the liver.

Dr. Younossi uses transient elastography in patients who don’t have type 2 diabetes or frank insulin resistance. If the FibroScan score is 7 kiloPascals or more, he considers liver biopsy, since that’s the threshold for detection of earlier, potentially reversible stage 2 fibrosis. If, however, a patient has diabetes or insulin resistance along with a NAFLD fibrosis score suggesting a high possibility of fibrosis, he sends that patient for liver biopsy, since those endocrinologic disorders are known to be independent risk factors for mortality in the setting of NAFLD.

Dr. Younossi reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

NEW ORLEANS – Zobair M. Younossi, MD, declared at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The massive growth in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is being fueled to a great extent by the related epidemics of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. While the overall prevalence of NAFLD worldwide is 24%, almost three-quarters of patients with NAFLD are obese. And the prevalence of NAFLD in individuals with T2DM was 58% in a recent meta-analysis of studies from 20 countries conducted by Dr. Younossi and his coinvestigators.

“The prevalence of NAFLD in U.S. kids is about 10%. This is of course part of the coming tsunami because our kids are getting obese, diabetic, and they’re going to have problems with NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis],” said Dr. Younossi, a gastroenterologist who is professor and chairman of the department of medicine at the Inova Fairfax (Va.) campus of Virginia Commonwealth University.

NASH is the form of NAFLD that has the strongest prognostic implications. It can progress to cirrhosis, liver failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma. As Dr. Younossi and his coworkers have shown (Hepat Commun. 2017 Jun 6;1[5]:421-8), it is associated with a significantly greater risk of both liver-related and all-cause mortality than that of non-NASH NAFLD, although NAFLD also carries an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death in that population.

In addition to highlighting the enormous clinical, economic, and quality-of-life implications of the NAFLD epidemic, Dr. Younossi offered practical tips on how busy primary care physicians can identify patients in their practice who have high-risk NAFLD. They have not done a very good job of this to date. That’s possibly due to lack of incentive, since in 2018 there is no approved drug for the treatment of NASH. He cited one representative retrospective study in which only about 15% of patients identified as having NAFLD received a recommendation for lifestyle modification involving diet and exercise, which is the standard evidence-based treatment, albeit admittedly difficult to sustain. And only 3% of patients with advanced liver fibrosis were referred to a specialist for management.

“So NAFLD is common, but its recognition and doing something about it is quite a challenge,” Dr. Younossi observed.

He argued that patients who have NASH deserve to know it because of its prognostic implications and also so they can have the chance to participate in one of the roughly two dozen ongoing clinical trials of potential therapies, some of which look quite promising. All of the trials required a liver biopsy as a condition for enrollment. Plus, once a patient is known to have stage 3 fibrosis, it’s time to start screening for hepatocellular carcinoma and esophageal varices.

The scope of the epidemic

NASH is the most rapidly growing indication for liver transplantation in the United States, with most of the increase coming from the baby boomer population. NASH is now the second most common indication for placement on the wait list. Meanwhile, liver transplantation due to the consequences of hepatitis C, the No. 1 indication, is declining as a result of the spectacular advances in medical treatment introduced a few years ago. It’s likely that in coming years NASH will take over the top spot, according to Dr. Younossi.

He was coauthor of a recent study that modeled the estimated trends for the NAFLD epidemic in the United States through 2030. The forecast is that the prevalence of NAFLD among adults will climb to 33.5% and the proportion of NAFLD categorized as NASH will increase from 20% at present to 27%. Moreover, this will result in a 168% jump in the incidence of decompensated cirrhosis, a 137% increase in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma, and a 178% increase in liver-related mortality, which will account for an estimated 78,300 deaths in 2030 (Hepatology. 2018 Jan;67[1]:123-33).

Practical ways to identify high-risk patients

The best noninvasive means of detecting NAFLD is by ultrasound showing a fatty liver. Often the condition is detected as an incidental finding on abdominal ultrasound ordered for another reason. Elevated liver enzymes can be a tipoff as well. Of course, alcoholic liver disease and other causes must be excluded.

But what’s most important is to identify patients with NASH. It’s a diagnosis made by biopsy. However, it is unthinkable to perform liver biopsies in the entire vast population with NAFLD, so there is a great deal of interest in developing noninvasive diagnostic modalities that can help zero in on the subset of high-risk NAFLD patients who should be considered for referral for liver biopsy.

One useful clue is the presence of comorbid metabolic syndrome in patients with NAFLD. It confers a substantially higher mortality risk – especially cardiovascular mortality – than does NAFLD without metabolic syndrome. Dr. Younossi and his coinvestigators have shown in a study of 3,613 NAFLD patients followed long-term that those with one component of the metabolic syndrome – either hypertension, central obesity, increased fasting plasma glucose, or hyperlipidemia – had 8- and 16-year all-cause mortality rates of 4.7% and 11.9%, nearly double the 2.6% and 6% rates in NAFLD patients with no elements of the metabolic syndrome.

Moreover, the magnitude of risk increased with each additional metabolic syndrome condition: a 3.57-fold increased mortality risk in NAFLD patients with two components of metabolic syndrome, a 5.87-fold increase in those with three, and a 13.09-fold increase in NAFLD patients with all four elements of metabolic syndrome (Medicine [Baltimore]. 2018 Mar;97[13]:e0214. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010214).

Dr. Younossi was a member of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease expert panel that developed the latest practice guidance regarding the diagnosis and management of NAFLD (Hepatology. 2018 Jan;67[1]:328-57). He said that probably the best simple noninvasive scoring system for the detection of NASH with advanced fibrosis is the NAFLD fibrosis score, which is easily calculated using laboratory values and clinical parameters already in a patient’s chart.

A more sophisticated serum biomarker test known as ELF, or the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis test, combines serum levels of hyaluronic acid, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase I, and procollagen amino terminal peptide.

“ELF is a very, very good test. It’s approved in Europe and I suspect it will be in the U.S. within the next year or so,” said Dr. Younossi.

The most exciting noninvasive tests, however, involve imaging that measures liver stiffness, which provides a fairly accurate indication of the degree of scarring in the organ. There are two methods available: vibration wave transient elastography and magnetic resonance elastography.

Transient elastography using the FibroScan device is commercially available in the United States. “It’s a good test, very easy to do, noninvasive. I have a couple of these machines, and we use them all the time,” the gastroenterologist said.

MR elastography provides superior accuracy, but access is an issue.

“At our institution you sometimes have to wait for weeks to get an outpatient MRI, so if you have hundreds of patients with fatty liver disease it makes things difficult. So in our practice we use transient elastography,” he explained.

Both imaging modalities also measure the amount of fat in the liver.

Dr. Younossi uses transient elastography in patients who don’t have type 2 diabetes or frank insulin resistance. If the FibroScan score is 7 kiloPascals or more, he considers liver biopsy, since that’s the threshold for detection of earlier, potentially reversible stage 2 fibrosis. If, however, a patient has diabetes or insulin resistance along with a NAFLD fibrosis score suggesting a high possibility of fibrosis, he sends that patient for liver biopsy, since those endocrinologic disorders are known to be independent risk factors for mortality in the setting of NAFLD.

Dr. Younossi reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

NEW ORLEANS – Zobair M. Younossi, MD, declared at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The massive growth in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is being fueled to a great extent by the related epidemics of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. While the overall prevalence of NAFLD worldwide is 24%, almost three-quarters of patients with NAFLD are obese. And the prevalence of NAFLD in individuals with T2DM was 58% in a recent meta-analysis of studies from 20 countries conducted by Dr. Younossi and his coinvestigators.

“The prevalence of NAFLD in U.S. kids is about 10%. This is of course part of the coming tsunami because our kids are getting obese, diabetic, and they’re going to have problems with NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis],” said Dr. Younossi, a gastroenterologist who is professor and chairman of the department of medicine at the Inova Fairfax (Va.) campus of Virginia Commonwealth University.

NASH is the form of NAFLD that has the strongest prognostic implications. It can progress to cirrhosis, liver failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma. As Dr. Younossi and his coworkers have shown (Hepat Commun. 2017 Jun 6;1[5]:421-8), it is associated with a significantly greater risk of both liver-related and all-cause mortality than that of non-NASH NAFLD, although NAFLD also carries an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death in that population.

In addition to highlighting the enormous clinical, economic, and quality-of-life implications of the NAFLD epidemic, Dr. Younossi offered practical tips on how busy primary care physicians can identify patients in their practice who have high-risk NAFLD. They have not done a very good job of this to date. That’s possibly due to lack of incentive, since in 2018 there is no approved drug for the treatment of NASH. He cited one representative retrospective study in which only about 15% of patients identified as having NAFLD received a recommendation for lifestyle modification involving diet and exercise, which is the standard evidence-based treatment, albeit admittedly difficult to sustain. And only 3% of patients with advanced liver fibrosis were referred to a specialist for management.

“So NAFLD is common, but its recognition and doing something about it is quite a challenge,” Dr. Younossi observed.

He argued that patients who have NASH deserve to know it because of its prognostic implications and also so they can have the chance to participate in one of the roughly two dozen ongoing clinical trials of potential therapies, some of which look quite promising. All of the trials required a liver biopsy as a condition for enrollment. Plus, once a patient is known to have stage 3 fibrosis, it’s time to start screening for hepatocellular carcinoma and esophageal varices.

The scope of the epidemic

NASH is the most rapidly growing indication for liver transplantation in the United States, with most of the increase coming from the baby boomer population. NASH is now the second most common indication for placement on the wait list. Meanwhile, liver transplantation due to the consequences of hepatitis C, the No. 1 indication, is declining as a result of the spectacular advances in medical treatment introduced a few years ago. It’s likely that in coming years NASH will take over the top spot, according to Dr. Younossi.

He was coauthor of a recent study that modeled the estimated trends for the NAFLD epidemic in the United States through 2030. The forecast is that the prevalence of NAFLD among adults will climb to 33.5% and the proportion of NAFLD categorized as NASH will increase from 20% at present to 27%. Moreover, this will result in a 168% jump in the incidence of decompensated cirrhosis, a 137% increase in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma, and a 178% increase in liver-related mortality, which will account for an estimated 78,300 deaths in 2030 (Hepatology. 2018 Jan;67[1]:123-33).

Practical ways to identify high-risk patients

The best noninvasive means of detecting NAFLD is by ultrasound showing a fatty liver. Often the condition is detected as an incidental finding on abdominal ultrasound ordered for another reason. Elevated liver enzymes can be a tipoff as well. Of course, alcoholic liver disease and other causes must be excluded.

But what’s most important is to identify patients with NASH. It’s a diagnosis made by biopsy. However, it is unthinkable to perform liver biopsies in the entire vast population with NAFLD, so there is a great deal of interest in developing noninvasive diagnostic modalities that can help zero in on the subset of high-risk NAFLD patients who should be considered for referral for liver biopsy.

One useful clue is the presence of comorbid metabolic syndrome in patients with NAFLD. It confers a substantially higher mortality risk – especially cardiovascular mortality – than does NAFLD without metabolic syndrome. Dr. Younossi and his coinvestigators have shown in a study of 3,613 NAFLD patients followed long-term that those with one component of the metabolic syndrome – either hypertension, central obesity, increased fasting plasma glucose, or hyperlipidemia – had 8- and 16-year all-cause mortality rates of 4.7% and 11.9%, nearly double the 2.6% and 6% rates in NAFLD patients with no elements of the metabolic syndrome.

Moreover, the magnitude of risk increased with each additional metabolic syndrome condition: a 3.57-fold increased mortality risk in NAFLD patients with two components of metabolic syndrome, a 5.87-fold increase in those with three, and a 13.09-fold increase in NAFLD patients with all four elements of metabolic syndrome (Medicine [Baltimore]. 2018 Mar;97[13]:e0214. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010214).

Dr. Younossi was a member of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease expert panel that developed the latest practice guidance regarding the diagnosis and management of NAFLD (Hepatology. 2018 Jan;67[1]:328-57). He said that probably the best simple noninvasive scoring system for the detection of NASH with advanced fibrosis is the NAFLD fibrosis score, which is easily calculated using laboratory values and clinical parameters already in a patient’s chart.

A more sophisticated serum biomarker test known as ELF, or the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis test, combines serum levels of hyaluronic acid, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase I, and procollagen amino terminal peptide.

“ELF is a very, very good test. It’s approved in Europe and I suspect it will be in the U.S. within the next year or so,” said Dr. Younossi.

The most exciting noninvasive tests, however, involve imaging that measures liver stiffness, which provides a fairly accurate indication of the degree of scarring in the organ. There are two methods available: vibration wave transient elastography and magnetic resonance elastography.

Transient elastography using the FibroScan device is commercially available in the United States. “It’s a good test, very easy to do, noninvasive. I have a couple of these machines, and we use them all the time,” the gastroenterologist said.

MR elastography provides superior accuracy, but access is an issue.

“At our institution you sometimes have to wait for weeks to get an outpatient MRI, so if you have hundreds of patients with fatty liver disease it makes things difficult. So in our practice we use transient elastography,” he explained.

Both imaging modalities also measure the amount of fat in the liver.

Dr. Younossi uses transient elastography in patients who don’t have type 2 diabetes or frank insulin resistance. If the FibroScan score is 7 kiloPascals or more, he considers liver biopsy, since that’s the threshold for detection of earlier, potentially reversible stage 2 fibrosis. If, however, a patient has diabetes or insulin resistance along with a NAFLD fibrosis score suggesting a high possibility of fibrosis, he sends that patient for liver biopsy, since those endocrinologic disorders are known to be independent risk factors for mortality in the setting of NAFLD.

Dr. Younossi reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

REPORTING FROM ACP INTERNAL MEDICINE

Next-gen sputum PCR panel boosts CAP diagnostics

NEW ORLEANS – A next-generation lower respiratory tract sputum polymerase chain reaction (PCR) film array panel identified etiologic pathogens in 100% of a group of patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia, Kathryn Hendrickson, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The investigational new diagnostic assay, the BioFire Pneumonia Panel, is now under Food and Drug Administration review for marketing clearance. (CAP), observed Dr. Hendrickson, an internal medicine resident at Providence Portland (Ore.) Medical Center. The new product is designed to complement the currently available respiratory panels from BioFire.

“Rapid-detection results in less empiric antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. When it’s FDA approved, this investigational sputum PCR panel will simplify the diagnostic bundle while improving antibiotic stewardship,” she observed.

She presented a prospective study of 63 patients with CAP hospitalized at the medical center, all of whom were evaluated by two laboratory methods: the hospital’s standard bundle of diagnostic tests and the new BioFire film array panel. The purpose was to determine if there was a difference between the two tests in the detection rate of viral and/or bacterial pathogens as well as the clinical significance of any such differences; that is, was there an impact on days of treatment and length of hospital stay?

Traditional diagnostic methods detect an etiologic pathogen in at best half of hospitalized CAP patients, and the results take too much time. So Providence Portland Medical Center adopted as its standard diagnostic bundle a nasopharyngeal swab and a BioFire film array PCR that’s currently on the market and can detect nine viruses and three bacteria, along with urine antigens for Legionella sp. and Streptococcus pneumoniae, nucleic acid amplification testing for S. pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus, and blood and sputum cultures. In contrast, the investigational panel probes for 17 viruses, 18 bacterial pathogens, and seven antibiotic-resistant genes; it also measures procalcitonin levels in order to distinguish between bacterial colonization and invasion.

The new BioFire Pneumonia Panel detected a mean of 1.4 species of pathogenic bacteria in 79% of patients, while the standard diagnostic bundle detected 0.7 species in 59% of patients. The investigational panel identified a mean of 1.0 species of viral pathogens in 86% of the CAP patients; the standard bundle detected a mean of 0.6 species in 56%.

All told, any CAP pathogen was detected in 100% of patients using the new panel, with a mean of 2.5 different pathogens identified. The standard bundle detected any pathogen in 84% of patients, with half as many different pathogens found, according to Dr. Hendrickson.

A peak procalcitonin level of 0.25 ng/mL or less, which was defined as bacterial colonization, was associated with a mean 7 days of treatment, while a level above that threshold was associated with 11.3 days of treatment. Patients with a peak procalcitonin of 0.25 ng/mL or less had an average hospital length of stay of 5.9 days, versus 7.8 days for those with a higher procalcitonin indicative of bacterial invasion.

The new biofilm assay reports information about the abundance of 15 of the 18 bacterial targets in the sample. However, in contrast to peak procalcitonin, Dr. Hendrickson and her coinvestigators didn’t find this bacterial quantitation feature to be substantially more useful than a coin flip in distinguishing bacterial colonization from invasion.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding the head-to-head comparative study, which was supported by BioFire Diagnostics.

NEW ORLEANS – A next-generation lower respiratory tract sputum polymerase chain reaction (PCR) film array panel identified etiologic pathogens in 100% of a group of patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia, Kathryn Hendrickson, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The investigational new diagnostic assay, the BioFire Pneumonia Panel, is now under Food and Drug Administration review for marketing clearance. (CAP), observed Dr. Hendrickson, an internal medicine resident at Providence Portland (Ore.) Medical Center. The new product is designed to complement the currently available respiratory panels from BioFire.

“Rapid-detection results in less empiric antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. When it’s FDA approved, this investigational sputum PCR panel will simplify the diagnostic bundle while improving antibiotic stewardship,” she observed.

She presented a prospective study of 63 patients with CAP hospitalized at the medical center, all of whom were evaluated by two laboratory methods: the hospital’s standard bundle of diagnostic tests and the new BioFire film array panel. The purpose was to determine if there was a difference between the two tests in the detection rate of viral and/or bacterial pathogens as well as the clinical significance of any such differences; that is, was there an impact on days of treatment and length of hospital stay?

Traditional diagnostic methods detect an etiologic pathogen in at best half of hospitalized CAP patients, and the results take too much time. So Providence Portland Medical Center adopted as its standard diagnostic bundle a nasopharyngeal swab and a BioFire film array PCR that’s currently on the market and can detect nine viruses and three bacteria, along with urine antigens for Legionella sp. and Streptococcus pneumoniae, nucleic acid amplification testing for S. pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus, and blood and sputum cultures. In contrast, the investigational panel probes for 17 viruses, 18 bacterial pathogens, and seven antibiotic-resistant genes; it also measures procalcitonin levels in order to distinguish between bacterial colonization and invasion.

The new BioFire Pneumonia Panel detected a mean of 1.4 species of pathogenic bacteria in 79% of patients, while the standard diagnostic bundle detected 0.7 species in 59% of patients. The investigational panel identified a mean of 1.0 species of viral pathogens in 86% of the CAP patients; the standard bundle detected a mean of 0.6 species in 56%.

All told, any CAP pathogen was detected in 100% of patients using the new panel, with a mean of 2.5 different pathogens identified. The standard bundle detected any pathogen in 84% of patients, with half as many different pathogens found, according to Dr. Hendrickson.

A peak procalcitonin level of 0.25 ng/mL or less, which was defined as bacterial colonization, was associated with a mean 7 days of treatment, while a level above that threshold was associated with 11.3 days of treatment. Patients with a peak procalcitonin of 0.25 ng/mL or less had an average hospital length of stay of 5.9 days, versus 7.8 days for those with a higher procalcitonin indicative of bacterial invasion.

The new biofilm assay reports information about the abundance of 15 of the 18 bacterial targets in the sample. However, in contrast to peak procalcitonin, Dr. Hendrickson and her coinvestigators didn’t find this bacterial quantitation feature to be substantially more useful than a coin flip in distinguishing bacterial colonization from invasion.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding the head-to-head comparative study, which was supported by BioFire Diagnostics.

NEW ORLEANS – A next-generation lower respiratory tract sputum polymerase chain reaction (PCR) film array panel identified etiologic pathogens in 100% of a group of patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia, Kathryn Hendrickson, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The investigational new diagnostic assay, the BioFire Pneumonia Panel, is now under Food and Drug Administration review for marketing clearance. (CAP), observed Dr. Hendrickson, an internal medicine resident at Providence Portland (Ore.) Medical Center. The new product is designed to complement the currently available respiratory panels from BioFire.

“Rapid-detection results in less empiric antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. When it’s FDA approved, this investigational sputum PCR panel will simplify the diagnostic bundle while improving antibiotic stewardship,” she observed.

She presented a prospective study of 63 patients with CAP hospitalized at the medical center, all of whom were evaluated by two laboratory methods: the hospital’s standard bundle of diagnostic tests and the new BioFire film array panel. The purpose was to determine if there was a difference between the two tests in the detection rate of viral and/or bacterial pathogens as well as the clinical significance of any such differences; that is, was there an impact on days of treatment and length of hospital stay?