User login

Prescribers mostly ignore clopidogrel pharmacogenomic profiling

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – The boxed warning recommending pharmacogenomic testing of patients receiving clopidogrel to identify reduced metabolizers seems to be playing to a largely deaf audience.

Even when handed information on whether each clopidogrel-treated patient was a poor metabolizer of the drug, treating physicians usually did not switch them to a different antiplatelet drug, ticagrelor, that would be fully effective despite the patient’s reduced-metabolizer status. And clinicians who started patients on ticagrelor did not usually switch those with a good clopidogrel-metabolizing profile to the safer drug, clopidogrel, after learning that clopidogrel would be fully effective.

“Routine reporting of pharmacogenomics test results for acute coronary syndrome patients treated with P2Y12-inhibitor therapy had an uncertain yield and little impact on P2Y12-inhibitor switching,” E. Magnus Ohman, MBBS, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The study’s design gave each participating clinician free rein on whether to prescribe clopidogrel or ticagrelor (Brilinta) initially, and switching between the drugs was possible at any time after the initial prescription. At the trial’s start, 1,704 patients (56%) were on ticagrelor and 1,333 (44%) were on clopidogrel.

Pharmacogenomic testing showed that 34% of all patients were ultrametabolizers and 38% were extensive metabolizers. Patients in either of these categories metabolize enough clopidogrel into the active form to get full benefit from the drug and derive no additional efficacy benefit from switching to another P2Y12 inhibitor, such as ticagrelor or prasugrel (Effient) – drugs unaffected by metabolizer status. Testing also identified 25% of patients as intermediate metabolizers, who carry one loss-of-function allele for the CYP2C19 gene, and 3% were reduced metabolizers, who are homozygous for loss-of-function alleles. Standard practice is not to treat intermediate or reduced metabolizers with clopidogrel because they would not get an adequate antiplatelet effect; instead, these patients are usually treated with ticagrelor or with prasugrel when it’s an option.

After receiving the results regarding the clopidogrel-metabolizing status for each patient, attending physicians switched the drugs prescribed for only 7% of all patients: 9% of patients initially on ticagrelor and 4% of those initially on clopidogrel, reported Dr. Ohman, professor of medicine at Duke University in Durham, N.C. In addition, Dr. Ohman and his associates asked each participating physician who made a switch about his or her reasons for doing so. Of the patients who switched from clopidogrel to ticagrelor, only 23 were switched because of their pharmacogenomic results; this represents fewer than half of those who switched and only 2% of all patients who took clopidogrel. Only one patient changed from ticagrelor to clopidogrel based on pharmacogenomic results, representing 0.06% of all patients on ticagrelor.

“We believed the findings do not support the utility of mandatory testing in this context, as most did not act on the information,” Dr. Ohman said.

A major reason for the inertia, Dr. Gurbel suggested, may be the absence of any compelling data proving whether there’s any effect on clinical outcomes for switching reduced metabolizers off of clopidogrel or switching good metabolizers onto it.

“We have no large-scale, prospective data supporting pharmacogenomic-based personalization” of clopidogrel treatment leading to improved outcomes, but “we need to get over that,” he said. “It’s a challenge to get funding for this.” But “the answer is not to give ticagrelor or prasugrel to everyone because then the bleeding rate is too high.”

The findings Dr. Ohman reported came from the Study to Compare the Safety of Rivaroxaban Versus Acetylsalicylic Acid in Addition to Either Clopidogrel or Ticagrelor Therapy in Participants With Acute Coronary Syndrome (GEMINI-ACS-1), which had the primary goal of comparing the safety in acute coronary syndrome patients of a reduced dosage of rivaroxaban plus either clopidogrel or ticagrelor with the safety of aspirin plus one of these P2Y12 inhibitors. The primary endpoint was the rate of clinically significant bleeding events during a year of treatment. The study ran at 371 centers in 21 countries and showed similar bleeding rates in both treatment arms (Lancet. 2017 May 6; 389[10081]:1799-808).

The analysis also showed that patients identified as reduced metabolizers were fivefold more likely to be switched than patients identified as ultra metabolizers, and intermediate metabolizes had a 50% higher switching rate than ultra metabolizers. The rates of both ischemic and major bleeding outcomes were roughly similar across the spectrum of metabolizers, but Dr. Ohman cautioned that the trial was not designed to assess this. Dr. Gurbel urged the investigators to report on outcomes analyzed not just by metabolizer status but also by the treatment they received.

The boxed warning that clopidogrel received in 2010 regarding poor metabolizers led to “regulatory guidance” during design of the GEMINI-ACS-1 trial requiring routine pharmacogenomic testing for clopidogrel-metabolizing status, Dr. Ohman explained.

The trial was funded by Janssen and Bayer, the two companies that jointly market rivaroxaban (Xarelto). Dr. Ohman has been a consultant to Bayer and several other companies including AstraZeneca, the company that markets ticagrelor (Brilinta). He has also received research funding from Janssen, as well as Daiichi Sankyo and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Gurbel holds patents on platelet-function testing methods.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – The boxed warning recommending pharmacogenomic testing of patients receiving clopidogrel to identify reduced metabolizers seems to be playing to a largely deaf audience.

Even when handed information on whether each clopidogrel-treated patient was a poor metabolizer of the drug, treating physicians usually did not switch them to a different antiplatelet drug, ticagrelor, that would be fully effective despite the patient’s reduced-metabolizer status. And clinicians who started patients on ticagrelor did not usually switch those with a good clopidogrel-metabolizing profile to the safer drug, clopidogrel, after learning that clopidogrel would be fully effective.

“Routine reporting of pharmacogenomics test results for acute coronary syndrome patients treated with P2Y12-inhibitor therapy had an uncertain yield and little impact on P2Y12-inhibitor switching,” E. Magnus Ohman, MBBS, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The study’s design gave each participating clinician free rein on whether to prescribe clopidogrel or ticagrelor (Brilinta) initially, and switching between the drugs was possible at any time after the initial prescription. At the trial’s start, 1,704 patients (56%) were on ticagrelor and 1,333 (44%) were on clopidogrel.

Pharmacogenomic testing showed that 34% of all patients were ultrametabolizers and 38% were extensive metabolizers. Patients in either of these categories metabolize enough clopidogrel into the active form to get full benefit from the drug and derive no additional efficacy benefit from switching to another P2Y12 inhibitor, such as ticagrelor or prasugrel (Effient) – drugs unaffected by metabolizer status. Testing also identified 25% of patients as intermediate metabolizers, who carry one loss-of-function allele for the CYP2C19 gene, and 3% were reduced metabolizers, who are homozygous for loss-of-function alleles. Standard practice is not to treat intermediate or reduced metabolizers with clopidogrel because they would not get an adequate antiplatelet effect; instead, these patients are usually treated with ticagrelor or with prasugrel when it’s an option.

After receiving the results regarding the clopidogrel-metabolizing status for each patient, attending physicians switched the drugs prescribed for only 7% of all patients: 9% of patients initially on ticagrelor and 4% of those initially on clopidogrel, reported Dr. Ohman, professor of medicine at Duke University in Durham, N.C. In addition, Dr. Ohman and his associates asked each participating physician who made a switch about his or her reasons for doing so. Of the patients who switched from clopidogrel to ticagrelor, only 23 were switched because of their pharmacogenomic results; this represents fewer than half of those who switched and only 2% of all patients who took clopidogrel. Only one patient changed from ticagrelor to clopidogrel based on pharmacogenomic results, representing 0.06% of all patients on ticagrelor.

“We believed the findings do not support the utility of mandatory testing in this context, as most did not act on the information,” Dr. Ohman said.

A major reason for the inertia, Dr. Gurbel suggested, may be the absence of any compelling data proving whether there’s any effect on clinical outcomes for switching reduced metabolizers off of clopidogrel or switching good metabolizers onto it.

“We have no large-scale, prospective data supporting pharmacogenomic-based personalization” of clopidogrel treatment leading to improved outcomes, but “we need to get over that,” he said. “It’s a challenge to get funding for this.” But “the answer is not to give ticagrelor or prasugrel to everyone because then the bleeding rate is too high.”

The findings Dr. Ohman reported came from the Study to Compare the Safety of Rivaroxaban Versus Acetylsalicylic Acid in Addition to Either Clopidogrel or Ticagrelor Therapy in Participants With Acute Coronary Syndrome (GEMINI-ACS-1), which had the primary goal of comparing the safety in acute coronary syndrome patients of a reduced dosage of rivaroxaban plus either clopidogrel or ticagrelor with the safety of aspirin plus one of these P2Y12 inhibitors. The primary endpoint was the rate of clinically significant bleeding events during a year of treatment. The study ran at 371 centers in 21 countries and showed similar bleeding rates in both treatment arms (Lancet. 2017 May 6; 389[10081]:1799-808).

The analysis also showed that patients identified as reduced metabolizers were fivefold more likely to be switched than patients identified as ultra metabolizers, and intermediate metabolizes had a 50% higher switching rate than ultra metabolizers. The rates of both ischemic and major bleeding outcomes were roughly similar across the spectrum of metabolizers, but Dr. Ohman cautioned that the trial was not designed to assess this. Dr. Gurbel urged the investigators to report on outcomes analyzed not just by metabolizer status but also by the treatment they received.

The boxed warning that clopidogrel received in 2010 regarding poor metabolizers led to “regulatory guidance” during design of the GEMINI-ACS-1 trial requiring routine pharmacogenomic testing for clopidogrel-metabolizing status, Dr. Ohman explained.

The trial was funded by Janssen and Bayer, the two companies that jointly market rivaroxaban (Xarelto). Dr. Ohman has been a consultant to Bayer and several other companies including AstraZeneca, the company that markets ticagrelor (Brilinta). He has also received research funding from Janssen, as well as Daiichi Sankyo and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Gurbel holds patents on platelet-function testing methods.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – The boxed warning recommending pharmacogenomic testing of patients receiving clopidogrel to identify reduced metabolizers seems to be playing to a largely deaf audience.

Even when handed information on whether each clopidogrel-treated patient was a poor metabolizer of the drug, treating physicians usually did not switch them to a different antiplatelet drug, ticagrelor, that would be fully effective despite the patient’s reduced-metabolizer status. And clinicians who started patients on ticagrelor did not usually switch those with a good clopidogrel-metabolizing profile to the safer drug, clopidogrel, after learning that clopidogrel would be fully effective.

“Routine reporting of pharmacogenomics test results for acute coronary syndrome patients treated with P2Y12-inhibitor therapy had an uncertain yield and little impact on P2Y12-inhibitor switching,” E. Magnus Ohman, MBBS, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The study’s design gave each participating clinician free rein on whether to prescribe clopidogrel or ticagrelor (Brilinta) initially, and switching between the drugs was possible at any time after the initial prescription. At the trial’s start, 1,704 patients (56%) were on ticagrelor and 1,333 (44%) were on clopidogrel.

Pharmacogenomic testing showed that 34% of all patients were ultrametabolizers and 38% were extensive metabolizers. Patients in either of these categories metabolize enough clopidogrel into the active form to get full benefit from the drug and derive no additional efficacy benefit from switching to another P2Y12 inhibitor, such as ticagrelor or prasugrel (Effient) – drugs unaffected by metabolizer status. Testing also identified 25% of patients as intermediate metabolizers, who carry one loss-of-function allele for the CYP2C19 gene, and 3% were reduced metabolizers, who are homozygous for loss-of-function alleles. Standard practice is not to treat intermediate or reduced metabolizers with clopidogrel because they would not get an adequate antiplatelet effect; instead, these patients are usually treated with ticagrelor or with prasugrel when it’s an option.

After receiving the results regarding the clopidogrel-metabolizing status for each patient, attending physicians switched the drugs prescribed for only 7% of all patients: 9% of patients initially on ticagrelor and 4% of those initially on clopidogrel, reported Dr. Ohman, professor of medicine at Duke University in Durham, N.C. In addition, Dr. Ohman and his associates asked each participating physician who made a switch about his or her reasons for doing so. Of the patients who switched from clopidogrel to ticagrelor, only 23 were switched because of their pharmacogenomic results; this represents fewer than half of those who switched and only 2% of all patients who took clopidogrel. Only one patient changed from ticagrelor to clopidogrel based on pharmacogenomic results, representing 0.06% of all patients on ticagrelor.

“We believed the findings do not support the utility of mandatory testing in this context, as most did not act on the information,” Dr. Ohman said.

A major reason for the inertia, Dr. Gurbel suggested, may be the absence of any compelling data proving whether there’s any effect on clinical outcomes for switching reduced metabolizers off of clopidogrel or switching good metabolizers onto it.

“We have no large-scale, prospective data supporting pharmacogenomic-based personalization” of clopidogrel treatment leading to improved outcomes, but “we need to get over that,” he said. “It’s a challenge to get funding for this.” But “the answer is not to give ticagrelor or prasugrel to everyone because then the bleeding rate is too high.”

The findings Dr. Ohman reported came from the Study to Compare the Safety of Rivaroxaban Versus Acetylsalicylic Acid in Addition to Either Clopidogrel or Ticagrelor Therapy in Participants With Acute Coronary Syndrome (GEMINI-ACS-1), which had the primary goal of comparing the safety in acute coronary syndrome patients of a reduced dosage of rivaroxaban plus either clopidogrel or ticagrelor with the safety of aspirin plus one of these P2Y12 inhibitors. The primary endpoint was the rate of clinically significant bleeding events during a year of treatment. The study ran at 371 centers in 21 countries and showed similar bleeding rates in both treatment arms (Lancet. 2017 May 6; 389[10081]:1799-808).

The analysis also showed that patients identified as reduced metabolizers were fivefold more likely to be switched than patients identified as ultra metabolizers, and intermediate metabolizes had a 50% higher switching rate than ultra metabolizers. The rates of both ischemic and major bleeding outcomes were roughly similar across the spectrum of metabolizers, but Dr. Ohman cautioned that the trial was not designed to assess this. Dr. Gurbel urged the investigators to report on outcomes analyzed not just by metabolizer status but also by the treatment they received.

The boxed warning that clopidogrel received in 2010 regarding poor metabolizers led to “regulatory guidance” during design of the GEMINI-ACS-1 trial requiring routine pharmacogenomic testing for clopidogrel-metabolizing status, Dr. Ohman explained.

The trial was funded by Janssen and Bayer, the two companies that jointly market rivaroxaban (Xarelto). Dr. Ohman has been a consultant to Bayer and several other companies including AstraZeneca, the company that markets ticagrelor (Brilinta). He has also received research funding from Janssen, as well as Daiichi Sankyo and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Gurbel holds patents on platelet-function testing methods.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Physicians switched P2Y12 inhibitors for only 2% of patients on clopidogrel and only 0.06% on ticagrelor on the basis of their pharmacogenomic results.

Data source: GEMINI-ACS-1, a multicenter, prospective trial with 3,037 patients.

Disclosures: The GEMINI-ACS-1 trial was funded by Janssen and Bayer, the two companies that jointly market rivaroxaban (Xarelto). Dr. Ohman has been a consultant to Bayer and several other companies, including AstraZeneca, the company that markets ticagrelor (Brilinta). He has also received research funding from Janssen, as well as Daiichi Sankyo and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Gurbel holds patents on platelet-function testing methods.

Keep PCI patients on aspirin for noncardiac surgery

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – For every 1,000 patients with a history of percutaneous coronary intervention undergoing noncardiac surgery, perioperative aspirin would prevent 59 myocardial infarctions but cause 8 major/life-threatening bleeds, according to a substudy of the POISE-2 trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

For patients with previous PCI undergoing noncardiac surgery, “I think aspirin will be more likely to benefit them than harm them,” so long as they are not having an operation where bleeding would be devastating.” These include “delicate neurosurgery in which, if you bleed into your spine, you end up paralyzed,” said lead investigator Michelle Graham, MD, an interventional cardiologist and professor of cardiology at the University of Alberta, Edmonton.

The original multisite POISE-2 trial (Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation 2) evaluated the effect of perioperative aspirin for noncardiac surgery. Patients were randomized to receive 200 mg aspirin or placebo within 4 hours of surgery and then 100 mg aspirin or placebo in the early postoperative period. There was no significant effect on the composite rate of death or myocardial infarction, but an increased risk of serious bleeding (N Engl J Med. 2014 Apr 17;370[16]:1494-503).

The new substudy focused on the 470 patients with previous PCIs, because such patients are known to have a higher risk for postop complications. More than half received bare-metal stents and a quarter got drug-eluting stents; in most of the rest, the stent type was not known. The median duration from PCI to noncardiac surgery was 64 months, ranging from 34 to 113 months. Patients with bare-metal stents placed within 6 weeks or drug-eluting stents within a year, were excluded.

Overall, 234 patients were randomized to the aspirin group, and 236 to placebo. Among those who came in on chronic, daily aspirin therapy – as almost all of the PCI subjects did – those who were randomized to perioperative aspirin stayed on daily 100 mg aspirin for a week postop, and then flipped back to whatever dose they were on at home. Likewise, placebo patients resumed their home aspirin after 1 week.

The results were very different from the main trial. At 30 days’ follow-up, just 6% of patients in the aspirin arm reached the primary endpoint of death or MI, versus 11.5% in the placebo group, a statistically significant 50% reduction.

This difference was driven almost entirely by a reduction in MIs. Whereas 5.1% of patients in the aspirin arm had MIs, 11% of the placebo group did, a significant 64% reduction. Meanwhile, the risk of major or life-threatening bleeding was not only similar between groups, but also to the overall trial, noted in 5.6% of aspirin and 4.2% of placebo subjects.

Over 75% of the participants were men, almost 60% were undergoing a major surgery, 30% had diabetes, and many had hypertension. Very few were on direct oral anticoagulants. The two arms were well matched, with a median age of about 68 years.

Simultaneously with Dr. Graham’s presentation, the results were published online (Ann Intern Med. 2017 Nov 14; doi: 10.7326/M17-2341)

The work was funded mostly by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Bayer supplied the aspirin. Dr. Graham has no industry disclosures.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – For every 1,000 patients with a history of percutaneous coronary intervention undergoing noncardiac surgery, perioperative aspirin would prevent 59 myocardial infarctions but cause 8 major/life-threatening bleeds, according to a substudy of the POISE-2 trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

For patients with previous PCI undergoing noncardiac surgery, “I think aspirin will be more likely to benefit them than harm them,” so long as they are not having an operation where bleeding would be devastating.” These include “delicate neurosurgery in which, if you bleed into your spine, you end up paralyzed,” said lead investigator Michelle Graham, MD, an interventional cardiologist and professor of cardiology at the University of Alberta, Edmonton.

The original multisite POISE-2 trial (Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation 2) evaluated the effect of perioperative aspirin for noncardiac surgery. Patients were randomized to receive 200 mg aspirin or placebo within 4 hours of surgery and then 100 mg aspirin or placebo in the early postoperative period. There was no significant effect on the composite rate of death or myocardial infarction, but an increased risk of serious bleeding (N Engl J Med. 2014 Apr 17;370[16]:1494-503).

The new substudy focused on the 470 patients with previous PCIs, because such patients are known to have a higher risk for postop complications. More than half received bare-metal stents and a quarter got drug-eluting stents; in most of the rest, the stent type was not known. The median duration from PCI to noncardiac surgery was 64 months, ranging from 34 to 113 months. Patients with bare-metal stents placed within 6 weeks or drug-eluting stents within a year, were excluded.

Overall, 234 patients were randomized to the aspirin group, and 236 to placebo. Among those who came in on chronic, daily aspirin therapy – as almost all of the PCI subjects did – those who were randomized to perioperative aspirin stayed on daily 100 mg aspirin for a week postop, and then flipped back to whatever dose they were on at home. Likewise, placebo patients resumed their home aspirin after 1 week.

The results were very different from the main trial. At 30 days’ follow-up, just 6% of patients in the aspirin arm reached the primary endpoint of death or MI, versus 11.5% in the placebo group, a statistically significant 50% reduction.

This difference was driven almost entirely by a reduction in MIs. Whereas 5.1% of patients in the aspirin arm had MIs, 11% of the placebo group did, a significant 64% reduction. Meanwhile, the risk of major or life-threatening bleeding was not only similar between groups, but also to the overall trial, noted in 5.6% of aspirin and 4.2% of placebo subjects.

Over 75% of the participants were men, almost 60% were undergoing a major surgery, 30% had diabetes, and many had hypertension. Very few were on direct oral anticoagulants. The two arms were well matched, with a median age of about 68 years.

Simultaneously with Dr. Graham’s presentation, the results were published online (Ann Intern Med. 2017 Nov 14; doi: 10.7326/M17-2341)

The work was funded mostly by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Bayer supplied the aspirin. Dr. Graham has no industry disclosures.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – For every 1,000 patients with a history of percutaneous coronary intervention undergoing noncardiac surgery, perioperative aspirin would prevent 59 myocardial infarctions but cause 8 major/life-threatening bleeds, according to a substudy of the POISE-2 trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

For patients with previous PCI undergoing noncardiac surgery, “I think aspirin will be more likely to benefit them than harm them,” so long as they are not having an operation where bleeding would be devastating.” These include “delicate neurosurgery in which, if you bleed into your spine, you end up paralyzed,” said lead investigator Michelle Graham, MD, an interventional cardiologist and professor of cardiology at the University of Alberta, Edmonton.

The original multisite POISE-2 trial (Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation 2) evaluated the effect of perioperative aspirin for noncardiac surgery. Patients were randomized to receive 200 mg aspirin or placebo within 4 hours of surgery and then 100 mg aspirin or placebo in the early postoperative period. There was no significant effect on the composite rate of death or myocardial infarction, but an increased risk of serious bleeding (N Engl J Med. 2014 Apr 17;370[16]:1494-503).

The new substudy focused on the 470 patients with previous PCIs, because such patients are known to have a higher risk for postop complications. More than half received bare-metal stents and a quarter got drug-eluting stents; in most of the rest, the stent type was not known. The median duration from PCI to noncardiac surgery was 64 months, ranging from 34 to 113 months. Patients with bare-metal stents placed within 6 weeks or drug-eluting stents within a year, were excluded.

Overall, 234 patients were randomized to the aspirin group, and 236 to placebo. Among those who came in on chronic, daily aspirin therapy – as almost all of the PCI subjects did – those who were randomized to perioperative aspirin stayed on daily 100 mg aspirin for a week postop, and then flipped back to whatever dose they were on at home. Likewise, placebo patients resumed their home aspirin after 1 week.

The results were very different from the main trial. At 30 days’ follow-up, just 6% of patients in the aspirin arm reached the primary endpoint of death or MI, versus 11.5% in the placebo group, a statistically significant 50% reduction.

This difference was driven almost entirely by a reduction in MIs. Whereas 5.1% of patients in the aspirin arm had MIs, 11% of the placebo group did, a significant 64% reduction. Meanwhile, the risk of major or life-threatening bleeding was not only similar between groups, but also to the overall trial, noted in 5.6% of aspirin and 4.2% of placebo subjects.

Over 75% of the participants were men, almost 60% were undergoing a major surgery, 30% had diabetes, and many had hypertension. Very few were on direct oral anticoagulants. The two arms were well matched, with a median age of about 68 years.

Simultaneously with Dr. Graham’s presentation, the results were published online (Ann Intern Med. 2017 Nov 14; doi: 10.7326/M17-2341)

The work was funded mostly by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Bayer supplied the aspirin. Dr. Graham has no industry disclosures.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: For every 1,000 patients with a history of percutaneous coronary intervention undergoing noncardiac surgery, perioperative aspirin would prevent 59 myocardial infarctions but cause 8 major/life-threatening bleeds.

Data source: POISE-2, a randomized trial of 470 PCI patients.

Disclosures: The work was funded mostly by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Bayer supplied the aspirin. The lead investigator has no industry disclosures.

VIDEO: Regionalized STEMI care slashes in-hospital mortality

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – An American Heart Association program aimed at streamlining care of patients with ST-elevation MI resulted in a dramatic near-halving of in-hospital mortality, compared with STEMI patients treated in hospitals not participating in the project, James G. Jollis, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented the results of the STEMI ACCELERATOR 2 study, which involved 12 participating metropolitan regions across the United States, 132 percutaneous coronary intervention–capable hospitals, and 946 emergency medical services agencies. The ACCELERATOR 2 program entailed regional implementation of a structured STEMI care plan in which EMS personnel were trained to obtain prehospital ECGs and to activate cardiac catheterization labs prior to hospital arrival, bypassing the emergency department when appropriate.

Key elements of the project, which was part of the AHA’s Mission: Lifeline program, included having participating hospitals measure their performance of key processes and send that information as well as patient outcome data to the National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s ACTION–Get With The Guidelines registry. The hospitals in turn received quarterly feedback reports containing blinded hospital comparisons.

Dr. Jollis and his coinvestigators worked to obtain buy-in from local stakeholders, organize regional leadership, and help in drafting a central regional STEMI plan featuring prespecified treatment protocols.

The STEMI ACCELERATOR 2 study was carried out in 2015-2017, during which 10,730 patients with STEMI were transported directly to participating hospitals with PCI capability.

The primary study outcome was the change from the first to the final quarter of the study in the proportion of EMS-transported patients with a time from first medical contact to treatment in the cath lab of 90 minutes or less. This improved significantly, from 67% at baseline to 74% in the final quarter. Nine of the 12 participating regions reduced their time from first medical contact to treatment in the cath lab, and eight reached the national of goal of having 75% of STEMI patients treated within 90 minutes.

The other key time-to-care measures improved, too: At baseline, only 38% of patients had a time from first medical contact to cath lab activation of 20 minutes or less; by the final quarter, this figure had climbed to 56%. That’s an important metric, as evidenced by the study finding that in-hospital mortality occurred in 4.5% of patients with a time from first medical contact to cath lab activation of more than 20 minutes, compared with 2.2% in those with a time of 20 minutes or less.

Also, the proportion of patients who spent 20 minutes or less in the emergency department improved from 33% to 43%.

In-hospital mortality improved from 4.4% in the baseline quarter to 2.3% in the final quarter. No similar improvement in in-hospital mortality occurred in a comparison group of 22,651 STEMI patients treated at hospitals not involved in ACCELERATOR 2.

A significant reduction in the rate of in-hospital congestive heart failure occurred in the ACCELERATOR 2 centers, from 7.4% at baseline to 5.0%. In contrast, stroke, cardiogenic shock, and major bleeding rates were unchanged over time.

The ACCELERATOR 2 model of emergency cardiovascular care is designed to be highly generalizable, according to Dr. Jollis.

“This study supports the implementation of regionally coordinated systems across the United States to abort heart attacks, save lives, and enable heart attack victims to return to their families and productive lives,” he said.

The ACCELERATOR 2 operations manual – essentially a blueprint for organizing a regional STEMI system of care – is available gratis.

Dr. Allen, a cardiologist at the University of Colorado, Denver, said the ACCELERATOR 2 model has been successful because it is consistent with a fundamental principle of implementation science as described by Carolyn Clancy, MD, Executive in Charge at the Veterans Health Affairs Administration, who has said it’s a matter of making the right thing to do the easy thing to do.

Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, founder of the Get With the Guidelines program, predicted that the success of this program will lead to a ramping up of efforts to regionalize and coordinate STEMI care across the country. “I hope and anticipate that the AHA will take and run with the ACCELERATOR 2 model and adopt this into Mission: Lifeline, hoping to make this the standard approach to further improving care and outcomes in these patients,” said Dr. Fonarow, professor and cochief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, in a video interview.

Simultaneous with his presentation at the AHA conference, the results of STEMI ACCELERATOR 2 were published online in Circulation (2017 Nov 14; doi: 0.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032446).

The trial was sponsored by research and educational grants from AstraZeneca and The Medicines Company. Dr. Jollis reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – An American Heart Association program aimed at streamlining care of patients with ST-elevation MI resulted in a dramatic near-halving of in-hospital mortality, compared with STEMI patients treated in hospitals not participating in the project, James G. Jollis, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented the results of the STEMI ACCELERATOR 2 study, which involved 12 participating metropolitan regions across the United States, 132 percutaneous coronary intervention–capable hospitals, and 946 emergency medical services agencies. The ACCELERATOR 2 program entailed regional implementation of a structured STEMI care plan in which EMS personnel were trained to obtain prehospital ECGs and to activate cardiac catheterization labs prior to hospital arrival, bypassing the emergency department when appropriate.

Key elements of the project, which was part of the AHA’s Mission: Lifeline program, included having participating hospitals measure their performance of key processes and send that information as well as patient outcome data to the National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s ACTION–Get With The Guidelines registry. The hospitals in turn received quarterly feedback reports containing blinded hospital comparisons.

Dr. Jollis and his coinvestigators worked to obtain buy-in from local stakeholders, organize regional leadership, and help in drafting a central regional STEMI plan featuring prespecified treatment protocols.

The STEMI ACCELERATOR 2 study was carried out in 2015-2017, during which 10,730 patients with STEMI were transported directly to participating hospitals with PCI capability.

The primary study outcome was the change from the first to the final quarter of the study in the proportion of EMS-transported patients with a time from first medical contact to treatment in the cath lab of 90 minutes or less. This improved significantly, from 67% at baseline to 74% in the final quarter. Nine of the 12 participating regions reduced their time from first medical contact to treatment in the cath lab, and eight reached the national of goal of having 75% of STEMI patients treated within 90 minutes.

The other key time-to-care measures improved, too: At baseline, only 38% of patients had a time from first medical contact to cath lab activation of 20 minutes or less; by the final quarter, this figure had climbed to 56%. That’s an important metric, as evidenced by the study finding that in-hospital mortality occurred in 4.5% of patients with a time from first medical contact to cath lab activation of more than 20 minutes, compared with 2.2% in those with a time of 20 minutes or less.

Also, the proportion of patients who spent 20 minutes or less in the emergency department improved from 33% to 43%.

In-hospital mortality improved from 4.4% in the baseline quarter to 2.3% in the final quarter. No similar improvement in in-hospital mortality occurred in a comparison group of 22,651 STEMI patients treated at hospitals not involved in ACCELERATOR 2.

A significant reduction in the rate of in-hospital congestive heart failure occurred in the ACCELERATOR 2 centers, from 7.4% at baseline to 5.0%. In contrast, stroke, cardiogenic shock, and major bleeding rates were unchanged over time.

The ACCELERATOR 2 model of emergency cardiovascular care is designed to be highly generalizable, according to Dr. Jollis.

“This study supports the implementation of regionally coordinated systems across the United States to abort heart attacks, save lives, and enable heart attack victims to return to their families and productive lives,” he said.

The ACCELERATOR 2 operations manual – essentially a blueprint for organizing a regional STEMI system of care – is available gratis.

Dr. Allen, a cardiologist at the University of Colorado, Denver, said the ACCELERATOR 2 model has been successful because it is consistent with a fundamental principle of implementation science as described by Carolyn Clancy, MD, Executive in Charge at the Veterans Health Affairs Administration, who has said it’s a matter of making the right thing to do the easy thing to do.

Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, founder of the Get With the Guidelines program, predicted that the success of this program will lead to a ramping up of efforts to regionalize and coordinate STEMI care across the country. “I hope and anticipate that the AHA will take and run with the ACCELERATOR 2 model and adopt this into Mission: Lifeline, hoping to make this the standard approach to further improving care and outcomes in these patients,” said Dr. Fonarow, professor and cochief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, in a video interview.

Simultaneous with his presentation at the AHA conference, the results of STEMI ACCELERATOR 2 were published online in Circulation (2017 Nov 14; doi: 0.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032446).

The trial was sponsored by research and educational grants from AstraZeneca and The Medicines Company. Dr. Jollis reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – An American Heart Association program aimed at streamlining care of patients with ST-elevation MI resulted in a dramatic near-halving of in-hospital mortality, compared with STEMI patients treated in hospitals not participating in the project, James G. Jollis, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented the results of the STEMI ACCELERATOR 2 study, which involved 12 participating metropolitan regions across the United States, 132 percutaneous coronary intervention–capable hospitals, and 946 emergency medical services agencies. The ACCELERATOR 2 program entailed regional implementation of a structured STEMI care plan in which EMS personnel were trained to obtain prehospital ECGs and to activate cardiac catheterization labs prior to hospital arrival, bypassing the emergency department when appropriate.

Key elements of the project, which was part of the AHA’s Mission: Lifeline program, included having participating hospitals measure their performance of key processes and send that information as well as patient outcome data to the National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s ACTION–Get With The Guidelines registry. The hospitals in turn received quarterly feedback reports containing blinded hospital comparisons.

Dr. Jollis and his coinvestigators worked to obtain buy-in from local stakeholders, organize regional leadership, and help in drafting a central regional STEMI plan featuring prespecified treatment protocols.

The STEMI ACCELERATOR 2 study was carried out in 2015-2017, during which 10,730 patients with STEMI were transported directly to participating hospitals with PCI capability.

The primary study outcome was the change from the first to the final quarter of the study in the proportion of EMS-transported patients with a time from first medical contact to treatment in the cath lab of 90 minutes or less. This improved significantly, from 67% at baseline to 74% in the final quarter. Nine of the 12 participating regions reduced their time from first medical contact to treatment in the cath lab, and eight reached the national of goal of having 75% of STEMI patients treated within 90 minutes.

The other key time-to-care measures improved, too: At baseline, only 38% of patients had a time from first medical contact to cath lab activation of 20 minutes or less; by the final quarter, this figure had climbed to 56%. That’s an important metric, as evidenced by the study finding that in-hospital mortality occurred in 4.5% of patients with a time from first medical contact to cath lab activation of more than 20 minutes, compared with 2.2% in those with a time of 20 minutes or less.

Also, the proportion of patients who spent 20 minutes or less in the emergency department improved from 33% to 43%.

In-hospital mortality improved from 4.4% in the baseline quarter to 2.3% in the final quarter. No similar improvement in in-hospital mortality occurred in a comparison group of 22,651 STEMI patients treated at hospitals not involved in ACCELERATOR 2.

A significant reduction in the rate of in-hospital congestive heart failure occurred in the ACCELERATOR 2 centers, from 7.4% at baseline to 5.0%. In contrast, stroke, cardiogenic shock, and major bleeding rates were unchanged over time.

The ACCELERATOR 2 model of emergency cardiovascular care is designed to be highly generalizable, according to Dr. Jollis.

“This study supports the implementation of regionally coordinated systems across the United States to abort heart attacks, save lives, and enable heart attack victims to return to their families and productive lives,” he said.

The ACCELERATOR 2 operations manual – essentially a blueprint for organizing a regional STEMI system of care – is available gratis.

Dr. Allen, a cardiologist at the University of Colorado, Denver, said the ACCELERATOR 2 model has been successful because it is consistent with a fundamental principle of implementation science as described by Carolyn Clancy, MD, Executive in Charge at the Veterans Health Affairs Administration, who has said it’s a matter of making the right thing to do the easy thing to do.

Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, founder of the Get With the Guidelines program, predicted that the success of this program will lead to a ramping up of efforts to regionalize and coordinate STEMI care across the country. “I hope and anticipate that the AHA will take and run with the ACCELERATOR 2 model and adopt this into Mission: Lifeline, hoping to make this the standard approach to further improving care and outcomes in these patients,” said Dr. Fonarow, professor and cochief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, in a video interview.

Simultaneous with his presentation at the AHA conference, the results of STEMI ACCELERATOR 2 were published online in Circulation (2017 Nov 14; doi: 0.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032446).

The trial was sponsored by research and educational grants from AstraZeneca and The Medicines Company. Dr. Jollis reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The in-hospital mortality rate of STEMI patients dropped from 4.4% in the baseline quarter to 2.3% in the final quarter of a study that examined the impact of introducing regionalized STEMI care.

Data source: This was a prospective study of an intervention that involved implementation of regionalized STEMI care in a dozen U.S. metropolitan areas.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by research and educational grants from AstraZeneca and The Medicines Company. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Bicarb, acetylcysteine during angiography don’t protect kidneys

Periprocedural administration of intravenous sodium bicarbonate did not improve outcomes compared with standard sodium chloride in patients with impaired kidney function undergoing angiography, according to results of a randomized study of 5,177 patients.

In addition, there was no benefit for oral acetylcysteine administration over placebo for mitigating those same postangiography risks, Steven D. Weisbord, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions in Anaheim, Calif.

Hypothetically, both sodium bicarbonate and acetylcysteine could help prevent acute kidney injury associated with contrast material used during angiography, said Dr. Weisbord of the University of Pittsburgh.

However, multiple studies of the two agents have yielded “inconsistent results … consequently, equipoise exists regarding these interventions, despite their widespread use in clinical practice,” Dr. Weisbord said.

To provide more definitive evidence, Dr. Weisbord and his colleagues conducted PRESERVE, a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial comprising 5,177 patients scheduled for angiography who were at high risk of renal complications. Using a 2-by-2 factorial design, patients were randomized to receive intravenous 1.26% sodium bicarbonate or intravenous 0.9% sodium chloride, and to 5 days of oral acetylcysteine or oral placebo.

They found no significant differences between arms in the study’s composite primary endpoint of death, need for dialysis, or persistent increase in serum creatinine by 50% or more.

That composite endpoint occurred in 4.4% of patients receiving sodium bicarbonate, and similarly in 4.7% of patients receiving sodium chloride.

Likewise, the endpoint occurred in 4.6% of patients in the acetylcysteine group and 4.5% of the placebo group, Dr. Weisbord reported.

The investigators had planned to enroll 7,680 patients, but the sponsor of the trial stopped the study after enrollment of 5,177 based on the results showing no significant benefit of either treatment, he noted.

There are a few reasons why results of PRESERVE might show a lack of benefit for these agents, in contrast to some previous studies suggesting both the treatments might reduce risk of contrast-associated renal complications in high-risk patients.

Notably, “most of these interventions have been underpowered,” Dr. Weisbord noted.

Also, most previous trials used a primary endpoint of increase in blood creatinine level within days of the angiography. By contrast, the primary endpoint of the current study was a composite of serious adverse events “that are recognized sequelae of acute kidney injury,” he added.

Although subsequent investigations could shed new light on the controversy, the findings of PRESERVE support the “strong likelihood that these interventions are not clinically effective” in preventing acute kidney injury or longer-term adverse outcomes after angiography, he concluded.

The PRESERVE results were published simultaneously with Dr. Weisbord’s presentation (N Engl J Med. 2017 Nov 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710933).

The study was supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Dr. Weisbord reported receiving personal fees from Durect outside the submitted work.

Periprocedural administration of intravenous sodium bicarbonate did not improve outcomes compared with standard sodium chloride in patients with impaired kidney function undergoing angiography, according to results of a randomized study of 5,177 patients.

In addition, there was no benefit for oral acetylcysteine administration over placebo for mitigating those same postangiography risks, Steven D. Weisbord, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions in Anaheim, Calif.

Hypothetically, both sodium bicarbonate and acetylcysteine could help prevent acute kidney injury associated with contrast material used during angiography, said Dr. Weisbord of the University of Pittsburgh.

However, multiple studies of the two agents have yielded “inconsistent results … consequently, equipoise exists regarding these interventions, despite their widespread use in clinical practice,” Dr. Weisbord said.

To provide more definitive evidence, Dr. Weisbord and his colleagues conducted PRESERVE, a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial comprising 5,177 patients scheduled for angiography who were at high risk of renal complications. Using a 2-by-2 factorial design, patients were randomized to receive intravenous 1.26% sodium bicarbonate or intravenous 0.9% sodium chloride, and to 5 days of oral acetylcysteine or oral placebo.

They found no significant differences between arms in the study’s composite primary endpoint of death, need for dialysis, or persistent increase in serum creatinine by 50% or more.

That composite endpoint occurred in 4.4% of patients receiving sodium bicarbonate, and similarly in 4.7% of patients receiving sodium chloride.

Likewise, the endpoint occurred in 4.6% of patients in the acetylcysteine group and 4.5% of the placebo group, Dr. Weisbord reported.

The investigators had planned to enroll 7,680 patients, but the sponsor of the trial stopped the study after enrollment of 5,177 based on the results showing no significant benefit of either treatment, he noted.

There are a few reasons why results of PRESERVE might show a lack of benefit for these agents, in contrast to some previous studies suggesting both the treatments might reduce risk of contrast-associated renal complications in high-risk patients.

Notably, “most of these interventions have been underpowered,” Dr. Weisbord noted.

Also, most previous trials used a primary endpoint of increase in blood creatinine level within days of the angiography. By contrast, the primary endpoint of the current study was a composite of serious adverse events “that are recognized sequelae of acute kidney injury,” he added.

Although subsequent investigations could shed new light on the controversy, the findings of PRESERVE support the “strong likelihood that these interventions are not clinically effective” in preventing acute kidney injury or longer-term adverse outcomes after angiography, he concluded.

The PRESERVE results were published simultaneously with Dr. Weisbord’s presentation (N Engl J Med. 2017 Nov 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710933).

The study was supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Dr. Weisbord reported receiving personal fees from Durect outside the submitted work.

Periprocedural administration of intravenous sodium bicarbonate did not improve outcomes compared with standard sodium chloride in patients with impaired kidney function undergoing angiography, according to results of a randomized study of 5,177 patients.

In addition, there was no benefit for oral acetylcysteine administration over placebo for mitigating those same postangiography risks, Steven D. Weisbord, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions in Anaheim, Calif.

Hypothetically, both sodium bicarbonate and acetylcysteine could help prevent acute kidney injury associated with contrast material used during angiography, said Dr. Weisbord of the University of Pittsburgh.

However, multiple studies of the two agents have yielded “inconsistent results … consequently, equipoise exists regarding these interventions, despite their widespread use in clinical practice,” Dr. Weisbord said.

To provide more definitive evidence, Dr. Weisbord and his colleagues conducted PRESERVE, a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial comprising 5,177 patients scheduled for angiography who were at high risk of renal complications. Using a 2-by-2 factorial design, patients were randomized to receive intravenous 1.26% sodium bicarbonate or intravenous 0.9% sodium chloride, and to 5 days of oral acetylcysteine or oral placebo.

They found no significant differences between arms in the study’s composite primary endpoint of death, need for dialysis, or persistent increase in serum creatinine by 50% or more.

That composite endpoint occurred in 4.4% of patients receiving sodium bicarbonate, and similarly in 4.7% of patients receiving sodium chloride.

Likewise, the endpoint occurred in 4.6% of patients in the acetylcysteine group and 4.5% of the placebo group, Dr. Weisbord reported.

The investigators had planned to enroll 7,680 patients, but the sponsor of the trial stopped the study after enrollment of 5,177 based on the results showing no significant benefit of either treatment, he noted.

There are a few reasons why results of PRESERVE might show a lack of benefit for these agents, in contrast to some previous studies suggesting both the treatments might reduce risk of contrast-associated renal complications in high-risk patients.

Notably, “most of these interventions have been underpowered,” Dr. Weisbord noted.

Also, most previous trials used a primary endpoint of increase in blood creatinine level within days of the angiography. By contrast, the primary endpoint of the current study was a composite of serious adverse events “that are recognized sequelae of acute kidney injury,” he added.

Although subsequent investigations could shed new light on the controversy, the findings of PRESERVE support the “strong likelihood that these interventions are not clinically effective” in preventing acute kidney injury or longer-term adverse outcomes after angiography, he concluded.

The PRESERVE results were published simultaneously with Dr. Weisbord’s presentation (N Engl J Med. 2017 Nov 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710933).

The study was supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Dr. Weisbord reported receiving personal fees from Durect outside the submitted work.

FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The composite primary endpoint of death, need for dialysis, or persistent increase in serum creatinine was similar regardless of which treatments the patients received.

Data source: PRESERVE, a randomized study using a 2-by-2 factorial design to evaluate intravenous sodium bicarbonate versus sodium chloride and acetylcysteine versus placebo in 5,177 patients at high risk of renal complications.

Disclosures: PRESERVE was supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Dr. Weisbord reported receiving personal fees from Durect outside the submitted work.

ACA repeal could mean financial ruin for many MI, stroke patients

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Before the Affordable Care Act, over 1 in 8 people under 60 years old hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction or stroke had no insurance, and it ruined most of them financially, according to an analysis presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The importance of the study is that it shows what could happen if the ACA goes away. Debate over its future is “all about pushing people off insurance.” Plans floated in early 2017 “would have increased the uninsured rate to 49 million people,” said lead investigators Rohan Khera, MD, a cardiology fellow at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

And even under the ACA, there are still about 27 million people in the United States, about 8.6% of the population, who don’t have health insurance. Although that’s down from about 44 million people (14.5%) before the ACA, a considerable number of people still face financial ruin if they have a serious medical problem. “Until there is universal coverage for those without resources, catastrophic illness will remain a disabling financial threat to many Americans,” Dr. Khera said.

In a review of the National Inpatient Sample, the investigators identified 39,296 acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and 29,182 stroke hospitalizations among people aged 18-60 years with no insurance from 2008 to 2012, which corresponded to 188,192 AMI and 139,687 stroke hospitalizations nationwide. Overall, the uninsured made up 15% of AMI and stroke hospitalizations among the nonelderly.

By using U.S. Census data to estimate annual income, and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data to estimate food costs, the team found that the median hospital charge for AMI – $53,384 – exceeded 40% of the annual income left after food costs in 85% of uninsured subjects. The median stroke bill – $31,218 – exceeded 40% of what was left over after food in 75%. The situation was deemed “catastrophic” in both instances.

It’s true that hospitalization costs might have been reduced or waived in some cases, but the analysis did not consider missed work, disability, and outpatient costs. If anything, the financial burden on the uninsured was underestimated, Dr. Khera said.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, and published in Circulation (2018 Nov 13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030128) to coincide with the presentation. Dr. Khera had no disclosures.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Before the Affordable Care Act, over 1 in 8 people under 60 years old hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction or stroke had no insurance, and it ruined most of them financially, according to an analysis presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The importance of the study is that it shows what could happen if the ACA goes away. Debate over its future is “all about pushing people off insurance.” Plans floated in early 2017 “would have increased the uninsured rate to 49 million people,” said lead investigators Rohan Khera, MD, a cardiology fellow at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

And even under the ACA, there are still about 27 million people in the United States, about 8.6% of the population, who don’t have health insurance. Although that’s down from about 44 million people (14.5%) before the ACA, a considerable number of people still face financial ruin if they have a serious medical problem. “Until there is universal coverage for those without resources, catastrophic illness will remain a disabling financial threat to many Americans,” Dr. Khera said.

In a review of the National Inpatient Sample, the investigators identified 39,296 acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and 29,182 stroke hospitalizations among people aged 18-60 years with no insurance from 2008 to 2012, which corresponded to 188,192 AMI and 139,687 stroke hospitalizations nationwide. Overall, the uninsured made up 15% of AMI and stroke hospitalizations among the nonelderly.

By using U.S. Census data to estimate annual income, and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data to estimate food costs, the team found that the median hospital charge for AMI – $53,384 – exceeded 40% of the annual income left after food costs in 85% of uninsured subjects. The median stroke bill – $31,218 – exceeded 40% of what was left over after food in 75%. The situation was deemed “catastrophic” in both instances.

It’s true that hospitalization costs might have been reduced or waived in some cases, but the analysis did not consider missed work, disability, and outpatient costs. If anything, the financial burden on the uninsured was underestimated, Dr. Khera said.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, and published in Circulation (2018 Nov 13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030128) to coincide with the presentation. Dr. Khera had no disclosures.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Before the Affordable Care Act, over 1 in 8 people under 60 years old hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction or stroke had no insurance, and it ruined most of them financially, according to an analysis presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The importance of the study is that it shows what could happen if the ACA goes away. Debate over its future is “all about pushing people off insurance.” Plans floated in early 2017 “would have increased the uninsured rate to 49 million people,” said lead investigators Rohan Khera, MD, a cardiology fellow at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

And even under the ACA, there are still about 27 million people in the United States, about 8.6% of the population, who don’t have health insurance. Although that’s down from about 44 million people (14.5%) before the ACA, a considerable number of people still face financial ruin if they have a serious medical problem. “Until there is universal coverage for those without resources, catastrophic illness will remain a disabling financial threat to many Americans,” Dr. Khera said.

In a review of the National Inpatient Sample, the investigators identified 39,296 acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and 29,182 stroke hospitalizations among people aged 18-60 years with no insurance from 2008 to 2012, which corresponded to 188,192 AMI and 139,687 stroke hospitalizations nationwide. Overall, the uninsured made up 15% of AMI and stroke hospitalizations among the nonelderly.

By using U.S. Census data to estimate annual income, and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data to estimate food costs, the team found that the median hospital charge for AMI – $53,384 – exceeded 40% of the annual income left after food costs in 85% of uninsured subjects. The median stroke bill – $31,218 – exceeded 40% of what was left over after food in 75%. The situation was deemed “catastrophic” in both instances.

It’s true that hospitalization costs might have been reduced or waived in some cases, but the analysis did not consider missed work, disability, and outpatient costs. If anything, the financial burden on the uninsured was underestimated, Dr. Khera said.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, and published in Circulation (2018 Nov 13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030128) to coincide with the presentation. Dr. Khera had no disclosures.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The median hospital charge for AMI – $53,384 – exceeded 40% of the annual income left after food costs in 85% of uninsured subjects.

Data source: Modeling study using the National Impatient Sample, U.S. Census data, and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

Disclosures: The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The lead investigator didn’t have any disclosures.

VIDEO: U.S. hypertension guidelines reset threshold to 130/80 mm Hg

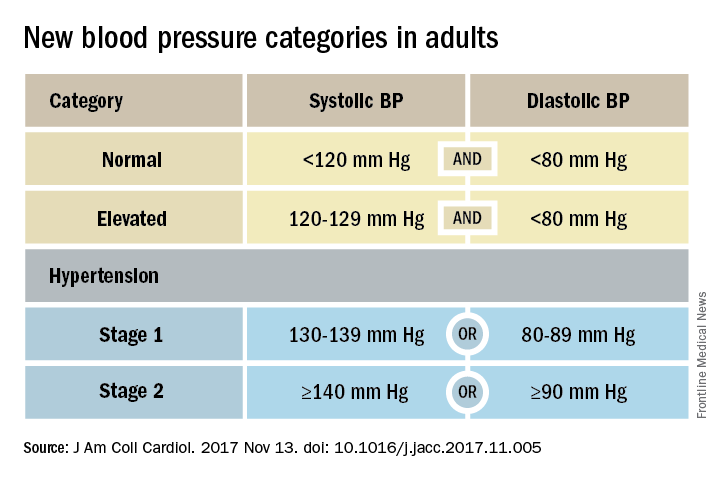

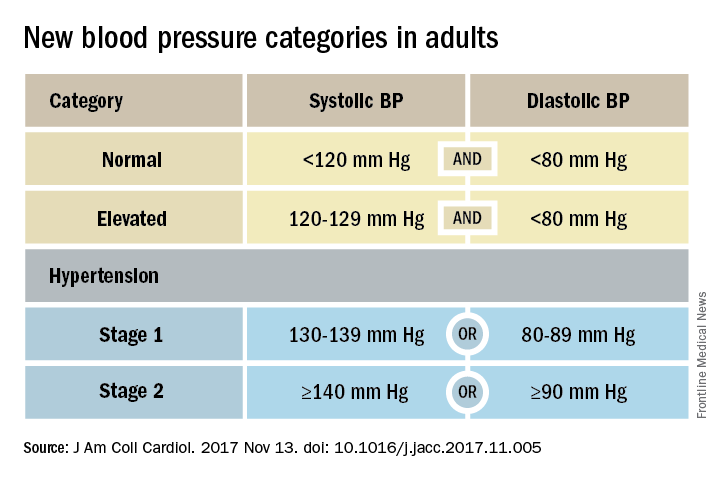

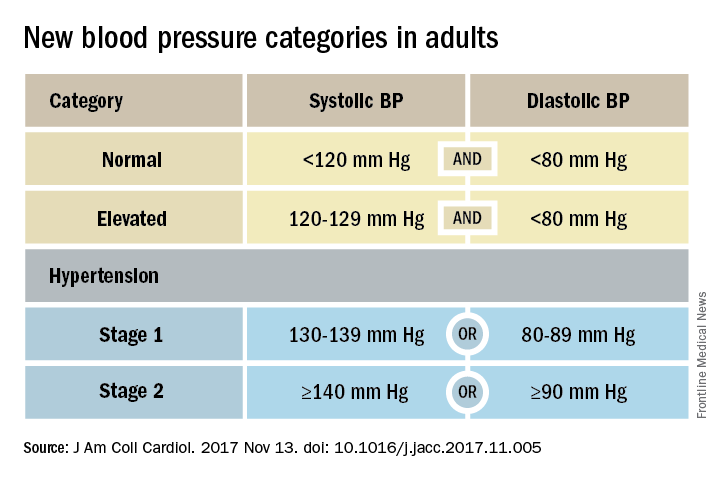

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Thirty million Americans became hypertensive overnight on Nov. 13 with the introduction of new high blood pressure guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

That happened by resetting the definition of adult hypertension from the long-standing threshold of 140/90 mm Hg to a blood pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, a change that jumps the U.S. adult prevalence of hypertension from roughly 32% to 46%. Nearly half of all U.S. adults now have hypertension, bringing the total national hypertensive population to a staggering 103 million.

Goal is to transform care

But the new guidelines (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.005) for preventing, detecting, evaluating, and managing adult hypertension do lots more than just shake up the epidemiology of high blood pressure. With 106 total recommendations, the guidelines seek to transform every aspect of blood pressure in American medical practice, starting with how it’s measured and stretching to redefine applications of medical systems to try to ensure that every person with a blood pressure that truly falls outside the redefined limits gets a comprehensive package of interventions.

Many of these are “seismic changes,” said Lawrence J. Appel, MD. He particularly cited as seismic the new classification of stage 1 hypertension as a pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, the emphasis on using some form of out-of-office blood pressure measurement to confirm a diagnosis, the use of risk assessment when deciding whether to treat certain patients with drugs, and the same blood pressure goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg for all hypertensives, regardless of age, as long as they remain ambulatory and community dwelling.

One goal for all adults

“The systolic blood pressure goal for older people has gone from 140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg and now to 130 mm Hg in the space of 2-3 years,” commented Dr. Appel, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and not involved in the guideline-writing process.

In fact, the guidelines simplified the treatment goal all around, to less than 130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes, those with chronic kidney disease, and the elderly; that goal remains the same for all adults.

“It will be clearer and easier now that everyone should be less than 130/80 mm Hg. You won’t need to remember a second target,” said Sandra J. Taler, MD, a nephrologist and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a member of the guidelines task force.

“Some people may be upset that we changed the rules on them. They had normal blood pressure yesterday, and today it’s high. But it’s a good awakening, especially for using lifestyle interventions,” Dr. Taler said in an interview.

Preferred intervention: Lifestyle, not drugs

Lifestyle optimization is repeatedly cited as the cornerstone of intervention for everyone, including those with elevated blood pressure with a systolic pressure of 120-129 mm Hg, and as the only endorsed intervention for patients with hypertension of 130-139 mm Hg but below a 10% risk for a cardiovascular disease event during the next 10 years on the American College of Cardiology’s online risk calculator. The guidelines list six lifestyle goals: weight loss, following a DASH diet, reducing sodium, enhancing potassium, 90-150 min/wk of physical activity, and moderate alcohol intake.

Team-based care essential

The guidelines also put unprecedented emphasis on using a team-based management approach, which means having nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, dietitians, and other clinicians, allowing for more frequent and focused care. Dr. Whelton and others cited in particular the VA Health System and Kaiser-Permanente as operating team-based and system-driven blood pressure management programs that have resulted in control rates for more than 90% of hypertensive patients. The team-based approach is also a key in the Target:BP program that the American Heart Association and American Medical Association founded. Target:BP will be instrumental in promoting implementation of the new guidelines, Dr. Carey said. Another systems recommendation is that every patient with hypertension should have a “clear, detailed, and current evidence-based plan of care.”

“Using nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists has been shown to improve blood pressure levels,” and health systems that use this approach have had “great success,” commented Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor and chairman of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago and not part of the guidelines task force. Some systems have used this approach to achieve high levels of blood pressure control. Now that financial penalties and incentives from payers also exist to push for higher levels of blood pressure control, the alignment of financial and health incentives should result in big changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones predicted in a video interview.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Thirty million Americans became hypertensive overnight on Nov. 13 with the introduction of new high blood pressure guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

That happened by resetting the definition of adult hypertension from the long-standing threshold of 140/90 mm Hg to a blood pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, a change that jumps the U.S. adult prevalence of hypertension from roughly 32% to 46%. Nearly half of all U.S. adults now have hypertension, bringing the total national hypertensive population to a staggering 103 million.

Goal is to transform care

But the new guidelines (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.005) for preventing, detecting, evaluating, and managing adult hypertension do lots more than just shake up the epidemiology of high blood pressure. With 106 total recommendations, the guidelines seek to transform every aspect of blood pressure in American medical practice, starting with how it’s measured and stretching to redefine applications of medical systems to try to ensure that every person with a blood pressure that truly falls outside the redefined limits gets a comprehensive package of interventions.

Many of these are “seismic changes,” said Lawrence J. Appel, MD. He particularly cited as seismic the new classification of stage 1 hypertension as a pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, the emphasis on using some form of out-of-office blood pressure measurement to confirm a diagnosis, the use of risk assessment when deciding whether to treat certain patients with drugs, and the same blood pressure goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg for all hypertensives, regardless of age, as long as they remain ambulatory and community dwelling.

One goal for all adults

“The systolic blood pressure goal for older people has gone from 140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg and now to 130 mm Hg in the space of 2-3 years,” commented Dr. Appel, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and not involved in the guideline-writing process.

In fact, the guidelines simplified the treatment goal all around, to less than 130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes, those with chronic kidney disease, and the elderly; that goal remains the same for all adults.

“It will be clearer and easier now that everyone should be less than 130/80 mm Hg. You won’t need to remember a second target,” said Sandra J. Taler, MD, a nephrologist and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a member of the guidelines task force.

“Some people may be upset that we changed the rules on them. They had normal blood pressure yesterday, and today it’s high. But it’s a good awakening, especially for using lifestyle interventions,” Dr. Taler said in an interview.

Preferred intervention: Lifestyle, not drugs

Lifestyle optimization is repeatedly cited as the cornerstone of intervention for everyone, including those with elevated blood pressure with a systolic pressure of 120-129 mm Hg, and as the only endorsed intervention for patients with hypertension of 130-139 mm Hg but below a 10% risk for a cardiovascular disease event during the next 10 years on the American College of Cardiology’s online risk calculator. The guidelines list six lifestyle goals: weight loss, following a DASH diet, reducing sodium, enhancing potassium, 90-150 min/wk of physical activity, and moderate alcohol intake.

Team-based care essential

The guidelines also put unprecedented emphasis on using a team-based management approach, which means having nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, dietitians, and other clinicians, allowing for more frequent and focused care. Dr. Whelton and others cited in particular the VA Health System and Kaiser-Permanente as operating team-based and system-driven blood pressure management programs that have resulted in control rates for more than 90% of hypertensive patients. The team-based approach is also a key in the Target:BP program that the American Heart Association and American Medical Association founded. Target:BP will be instrumental in promoting implementation of the new guidelines, Dr. Carey said. Another systems recommendation is that every patient with hypertension should have a “clear, detailed, and current evidence-based plan of care.”

“Using nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists has been shown to improve blood pressure levels,” and health systems that use this approach have had “great success,” commented Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor and chairman of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago and not part of the guidelines task force. Some systems have used this approach to achieve high levels of blood pressure control. Now that financial penalties and incentives from payers also exist to push for higher levels of blood pressure control, the alignment of financial and health incentives should result in big changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones predicted in a video interview.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Thirty million Americans became hypertensive overnight on Nov. 13 with the introduction of new high blood pressure guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

That happened by resetting the definition of adult hypertension from the long-standing threshold of 140/90 mm Hg to a blood pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, a change that jumps the U.S. adult prevalence of hypertension from roughly 32% to 46%. Nearly half of all U.S. adults now have hypertension, bringing the total national hypertensive population to a staggering 103 million.

Goal is to transform care

But the new guidelines (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.005) for preventing, detecting, evaluating, and managing adult hypertension do lots more than just shake up the epidemiology of high blood pressure. With 106 total recommendations, the guidelines seek to transform every aspect of blood pressure in American medical practice, starting with how it’s measured and stretching to redefine applications of medical systems to try to ensure that every person with a blood pressure that truly falls outside the redefined limits gets a comprehensive package of interventions.

Many of these are “seismic changes,” said Lawrence J. Appel, MD. He particularly cited as seismic the new classification of stage 1 hypertension as a pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, the emphasis on using some form of out-of-office blood pressure measurement to confirm a diagnosis, the use of risk assessment when deciding whether to treat certain patients with drugs, and the same blood pressure goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg for all hypertensives, regardless of age, as long as they remain ambulatory and community dwelling.

One goal for all adults

“The systolic blood pressure goal for older people has gone from 140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg and now to 130 mm Hg in the space of 2-3 years,” commented Dr. Appel, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and not involved in the guideline-writing process.

In fact, the guidelines simplified the treatment goal all around, to less than 130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes, those with chronic kidney disease, and the elderly; that goal remains the same for all adults.

“It will be clearer and easier now that everyone should be less than 130/80 mm Hg. You won’t need to remember a second target,” said Sandra J. Taler, MD, a nephrologist and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a member of the guidelines task force.

“Some people may be upset that we changed the rules on them. They had normal blood pressure yesterday, and today it’s high. But it’s a good awakening, especially for using lifestyle interventions,” Dr. Taler said in an interview.

Preferred intervention: Lifestyle, not drugs

Lifestyle optimization is repeatedly cited as the cornerstone of intervention for everyone, including those with elevated blood pressure with a systolic pressure of 120-129 mm Hg, and as the only endorsed intervention for patients with hypertension of 130-139 mm Hg but below a 10% risk for a cardiovascular disease event during the next 10 years on the American College of Cardiology’s online risk calculator. The guidelines list six lifestyle goals: weight loss, following a DASH diet, reducing sodium, enhancing potassium, 90-150 min/wk of physical activity, and moderate alcohol intake.

Team-based care essential

The guidelines also put unprecedented emphasis on using a team-based management approach, which means having nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, dietitians, and other clinicians, allowing for more frequent and focused care. Dr. Whelton and others cited in particular the VA Health System and Kaiser-Permanente as operating team-based and system-driven blood pressure management programs that have resulted in control rates for more than 90% of hypertensive patients. The team-based approach is also a key in the Target:BP program that the American Heart Association and American Medical Association founded. Target:BP will be instrumental in promoting implementation of the new guidelines, Dr. Carey said. Another systems recommendation is that every patient with hypertension should have a “clear, detailed, and current evidence-based plan of care.”

“Using nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists has been shown to improve blood pressure levels,” and health systems that use this approach have had “great success,” commented Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor and chairman of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago and not part of the guidelines task force. Some systems have used this approach to achieve high levels of blood pressure control. Now that financial penalties and incentives from payers also exist to push for higher levels of blood pressure control, the alignment of financial and health incentives should result in big changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones predicted in a video interview.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Targeting PCSK9 inhibitors to reap most benefit

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease or a high-risk history of MI got the biggest bang for the buck from aggressive LDL cholesterol lowering with evolocumab in two new prespecified subgroup analyses from the landmark FOURIER trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.