User login

Hair Loss in a 12-Year-Old

A mother brings her 12-year-old son to dermatology following a referral from the boy’s pediatrician. Several months ago, she noticed her son’s hair loss. The change had been preceded by a stressful period in which she and her husband divorced and one of the boy’s grandparents died unexpectedly.

Both the mother and other relatives and friends had observed the boy reaching for his scalp frequently and twirling his hair “absentmindedly.” When asked if the area in question bothers him, the boy always answers in the negative. Although he knows he should leave his scalp and hair alone, he says he finds it difficult to do so—even though he acknowledges the social liability of his hair loss. According to the mother, the more his family discourages his behavior, the more it persists.

EXAMINATION

Distinct but incomplete hair loss is noted in an 8 x 10–cm area of his scalp crown. There is neither redness nor any disturbance to the skin there. On palpation, there is no tenderness or increased warmth. No nodes are felt in the adjacent head or neck. Hair pull test is negative.

Closer examination shows hairs of varying lengths in the affected area: many quite short, others of normal length, and many of intermediate length.

Blood work done by the referring pediatrician—including complete blood count, chemistry panel, antinuclear antibody test, and thyroid testing—yielded no abnormal results.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Hair loss, collectively termed alopecia, is a disturbing development, especially in a child. In this case, we had localized hair loss most likely caused by behavior that was not only witnessed by the boy’s parents but also admitted to by the patient. (We’re not always so fortunate.) Thus, it was fairly straightforward to diagnosis trichotillomania, also known as trichotillosis or hair-pulling disorder. This condition can mimic alopecia areata and tinea capitis.

In this case, the lack of epidermal change (scaling, redness, edema) and palpable adenopathy spoke loudly against fungal infection. The hair loss in alopecia areata (AA) is usually sharply defined and complete, which our patient’s hair loss was not. And the blood work that was done effectively ruled out systemic disease (an unlikely cause of localized hair loss in any case).

The jury is still out as to how exactly to classify trichotillomania (TTM). The new DSM-V lists it as an anxiety disorder, in part because it often appears in that context. What we do know is that girls are twice as likely as boys to be affected. And children ages 4 to 13 are seven times more likely than adults to develop TTM.

TTM can involve hair anywhere on the body, though children almost always confine their behavior to their scalp. Actual hair-pulling is not necessarily seen. Manipulation, such as the twirling in this case, is enough to weaken hair follicles, causing hair to fall out. In cases involving hair-pulling, a small percentage of patients actually ingest the hairs they’ve plucked out (trichophagia). Being indigestible, the hairs can accumulate in hairballs (trichobezoars).

Even though TTM is most likely a psychiatric disorder lying somewhere in the obsessive-compulsive spectrum, it is seen more often in primary care and dermatology offices. Scalp biopsy would certainly settle the matter, but a better alternative is simply shaving a dime-sized area of scalp and watching it for normal hair growth.

Most cases eventually resolve with time and persistent but gentle reminders, but a few will require psychiatric intervention. This typically includes habit reversal therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy, plus or minus combinations of psychoactive medications. (The latter decision depends on whether there psychiatric comorbidities.) Despite all these efforts, severe cases of TTM can persist for years or even a lifetime.

It remains to be seen how this particular patient responds to his parents’ efforts. It was an immense relief for them to know the cause of their son’s hair loss and that the condition is likely self-limiting.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Trichotillomania (TTM) is an unusual form of localized hair loss, usually involving children’s scalps.

• TTM affects children ages 4 to 13 and at least twice as many girls as boys.

• TTM does not always involve actual plucking of hairs. Repetitive manipulation, such as twirling, can weaken the hairs enough to cause hair loss.

• Unlike alopecia areata (the main item in the alopecia differential for children), TTM is more likely to cause incomplete, poorly defined hair loss in an area where hairs of varying length can be seen.

• Usually self-limiting, TTM can require psychiatric attention, for which a variety of habit training techniques can be used.

A mother brings her 12-year-old son to dermatology following a referral from the boy’s pediatrician. Several months ago, she noticed her son’s hair loss. The change had been preceded by a stressful period in which she and her husband divorced and one of the boy’s grandparents died unexpectedly.

Both the mother and other relatives and friends had observed the boy reaching for his scalp frequently and twirling his hair “absentmindedly.” When asked if the area in question bothers him, the boy always answers in the negative. Although he knows he should leave his scalp and hair alone, he says he finds it difficult to do so—even though he acknowledges the social liability of his hair loss. According to the mother, the more his family discourages his behavior, the more it persists.

EXAMINATION

Distinct but incomplete hair loss is noted in an 8 x 10–cm area of his scalp crown. There is neither redness nor any disturbance to the skin there. On palpation, there is no tenderness or increased warmth. No nodes are felt in the adjacent head or neck. Hair pull test is negative.

Closer examination shows hairs of varying lengths in the affected area: many quite short, others of normal length, and many of intermediate length.

Blood work done by the referring pediatrician—including complete blood count, chemistry panel, antinuclear antibody test, and thyroid testing—yielded no abnormal results.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Hair loss, collectively termed alopecia, is a disturbing development, especially in a child. In this case, we had localized hair loss most likely caused by behavior that was not only witnessed by the boy’s parents but also admitted to by the patient. (We’re not always so fortunate.) Thus, it was fairly straightforward to diagnosis trichotillomania, also known as trichotillosis or hair-pulling disorder. This condition can mimic alopecia areata and tinea capitis.

In this case, the lack of epidermal change (scaling, redness, edema) and palpable adenopathy spoke loudly against fungal infection. The hair loss in alopecia areata (AA) is usually sharply defined and complete, which our patient’s hair loss was not. And the blood work that was done effectively ruled out systemic disease (an unlikely cause of localized hair loss in any case).

The jury is still out as to how exactly to classify trichotillomania (TTM). The new DSM-V lists it as an anxiety disorder, in part because it often appears in that context. What we do know is that girls are twice as likely as boys to be affected. And children ages 4 to 13 are seven times more likely than adults to develop TTM.

TTM can involve hair anywhere on the body, though children almost always confine their behavior to their scalp. Actual hair-pulling is not necessarily seen. Manipulation, such as the twirling in this case, is enough to weaken hair follicles, causing hair to fall out. In cases involving hair-pulling, a small percentage of patients actually ingest the hairs they’ve plucked out (trichophagia). Being indigestible, the hairs can accumulate in hairballs (trichobezoars).

Even though TTM is most likely a psychiatric disorder lying somewhere in the obsessive-compulsive spectrum, it is seen more often in primary care and dermatology offices. Scalp biopsy would certainly settle the matter, but a better alternative is simply shaving a dime-sized area of scalp and watching it for normal hair growth.

Most cases eventually resolve with time and persistent but gentle reminders, but a few will require psychiatric intervention. This typically includes habit reversal therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy, plus or minus combinations of psychoactive medications. (The latter decision depends on whether there psychiatric comorbidities.) Despite all these efforts, severe cases of TTM can persist for years or even a lifetime.

It remains to be seen how this particular patient responds to his parents’ efforts. It was an immense relief for them to know the cause of their son’s hair loss and that the condition is likely self-limiting.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Trichotillomania (TTM) is an unusual form of localized hair loss, usually involving children’s scalps.

• TTM affects children ages 4 to 13 and at least twice as many girls as boys.

• TTM does not always involve actual plucking of hairs. Repetitive manipulation, such as twirling, can weaken the hairs enough to cause hair loss.

• Unlike alopecia areata (the main item in the alopecia differential for children), TTM is more likely to cause incomplete, poorly defined hair loss in an area where hairs of varying length can be seen.

• Usually self-limiting, TTM can require psychiatric attention, for which a variety of habit training techniques can be used.

A mother brings her 12-year-old son to dermatology following a referral from the boy’s pediatrician. Several months ago, she noticed her son’s hair loss. The change had been preceded by a stressful period in which she and her husband divorced and one of the boy’s grandparents died unexpectedly.

Both the mother and other relatives and friends had observed the boy reaching for his scalp frequently and twirling his hair “absentmindedly.” When asked if the area in question bothers him, the boy always answers in the negative. Although he knows he should leave his scalp and hair alone, he says he finds it difficult to do so—even though he acknowledges the social liability of his hair loss. According to the mother, the more his family discourages his behavior, the more it persists.

EXAMINATION

Distinct but incomplete hair loss is noted in an 8 x 10–cm area of his scalp crown. There is neither redness nor any disturbance to the skin there. On palpation, there is no tenderness or increased warmth. No nodes are felt in the adjacent head or neck. Hair pull test is negative.

Closer examination shows hairs of varying lengths in the affected area: many quite short, others of normal length, and many of intermediate length.

Blood work done by the referring pediatrician—including complete blood count, chemistry panel, antinuclear antibody test, and thyroid testing—yielded no abnormal results.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Hair loss, collectively termed alopecia, is a disturbing development, especially in a child. In this case, we had localized hair loss most likely caused by behavior that was not only witnessed by the boy’s parents but also admitted to by the patient. (We’re not always so fortunate.) Thus, it was fairly straightforward to diagnosis trichotillomania, also known as trichotillosis or hair-pulling disorder. This condition can mimic alopecia areata and tinea capitis.

In this case, the lack of epidermal change (scaling, redness, edema) and palpable adenopathy spoke loudly against fungal infection. The hair loss in alopecia areata (AA) is usually sharply defined and complete, which our patient’s hair loss was not. And the blood work that was done effectively ruled out systemic disease (an unlikely cause of localized hair loss in any case).

The jury is still out as to how exactly to classify trichotillomania (TTM). The new DSM-V lists it as an anxiety disorder, in part because it often appears in that context. What we do know is that girls are twice as likely as boys to be affected. And children ages 4 to 13 are seven times more likely than adults to develop TTM.

TTM can involve hair anywhere on the body, though children almost always confine their behavior to their scalp. Actual hair-pulling is not necessarily seen. Manipulation, such as the twirling in this case, is enough to weaken hair follicles, causing hair to fall out. In cases involving hair-pulling, a small percentage of patients actually ingest the hairs they’ve plucked out (trichophagia). Being indigestible, the hairs can accumulate in hairballs (trichobezoars).

Even though TTM is most likely a psychiatric disorder lying somewhere in the obsessive-compulsive spectrum, it is seen more often in primary care and dermatology offices. Scalp biopsy would certainly settle the matter, but a better alternative is simply shaving a dime-sized area of scalp and watching it for normal hair growth.

Most cases eventually resolve with time and persistent but gentle reminders, but a few will require psychiatric intervention. This typically includes habit reversal therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy, plus or minus combinations of psychoactive medications. (The latter decision depends on whether there psychiatric comorbidities.) Despite all these efforts, severe cases of TTM can persist for years or even a lifetime.

It remains to be seen how this particular patient responds to his parents’ efforts. It was an immense relief for them to know the cause of their son’s hair loss and that the condition is likely self-limiting.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Trichotillomania (TTM) is an unusual form of localized hair loss, usually involving children’s scalps.

• TTM affects children ages 4 to 13 and at least twice as many girls as boys.

• TTM does not always involve actual plucking of hairs. Repetitive manipulation, such as twirling, can weaken the hairs enough to cause hair loss.

• Unlike alopecia areata (the main item in the alopecia differential for children), TTM is more likely to cause incomplete, poorly defined hair loss in an area where hairs of varying length can be seen.

• Usually self-limiting, TTM can require psychiatric attention, for which a variety of habit training techniques can be used.

Slowly Spreading Hand Lesions

Several months ago, lesions appeared on both of this 48-year-old woman’s hands. They have been completely unresponsive to any of the treatments prescribed by her primary care provider, including oral (terbinafine) and topical antifungal medications.

The lesions, which are asymptomatic, manifested slowly. They first appeared on the dorsa of her hands and then gradually spread until they covered the central portion of both hands. The lesions wax and wane in terms of thickness and extent but never disappear.

The patient denies similar lesions elsewhere. She also denies contact with animals or children. She has never been immunosuppressed and is quite healthy aside from her skin problems. She has a family history but no personal history of diabetes.

EXAMINATION

The condition affects both hands equally. It is composed of intradermal reddish brown papules and plaques that cover the metacarpal areas and extend onto the proximal interphalangeal skin and the distal dorsa. No epidermal component (scale or other broken skin surface) is seen.

The margins of the lesions are arciform, slightly raised, and smooth. The centers of several are concave.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is the classic presentation of granuloma annulare (GA), in terms of morphology, distribution, and patient gender. Though this common condition can manifest in a number of locations and in men, it tends to favor the extensor surfaces of the extremities of women. The dorsum of the foot, anterior tibial skin, and elbows are typical locations that make it a relatively easy condition to recognize.

GA can be more difficult to identify, however, when it is generalized or deeper in the dermis. The latter, termed subcutaneous GA, is most common in children, who present with large dark annular patches of discoloration too deep in the dermis to produce any palpable surface changes. The more rare generalized GA can be difficult to diagnose and treat. Biopsy of suspected generalized or subcutaneous GA is necessary to differentiate it from its lookalikes, such as secondary syphilis, lichen planus, sarcoidosis, and tinea.

The annular borders of GA lesions are notorious for deceiving the unwary practitioner into diagnosing fungal infection. But the latter is, by definition, an infection of the outermost layers of the skin on which fungal organisms feed. That process almost invariably produces significant scaling, especially on the periphery of the lesions. Such scaling is completely absent on GA lesions, which also have a papularity and induration rarely seen with superficial fungal infections. In this particular case, the patient denied any potential source for a fungal infection (animals, children) and denied the itching we would expect with one.

The cause of GA is unknown, but it appears to represent a reaction to an unknown antigen. One previous hypothesis held that it was connected to diabetes, but this was proved false.

Ordinary GA resolves on its own (though this can take months)—which is fortunate, since there is no uniformly successful treatment. Many things have been tried, including topical or intralesional steroids and cryotherapy, with varying levels of success. Generalized GA is even more difficult to treat, can linger for years, and can be highly pruritic. Treatments have included hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, potassium iodide, isotretinoin, and PUVA. More recently, biologics are being used with some success.

The bigger problem with GA is simply to consider it in the differential for odd, annular, or generalized lesions.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Granuloma annulare (GA) is often mistaken for fungal infection, but it is an intradermal rather than epidermal process.

• The extensor surfaces of the extremities of women are favored sites for GA lesions.

• Biopsy of suspected GA lesions confirms the diagnosis while ruling out other items in the differential (eg, sarcoidosis and lichen planus).

• GA has no connection to diabetes.

Several months ago, lesions appeared on both of this 48-year-old woman’s hands. They have been completely unresponsive to any of the treatments prescribed by her primary care provider, including oral (terbinafine) and topical antifungal medications.

The lesions, which are asymptomatic, manifested slowly. They first appeared on the dorsa of her hands and then gradually spread until they covered the central portion of both hands. The lesions wax and wane in terms of thickness and extent but never disappear.

The patient denies similar lesions elsewhere. She also denies contact with animals or children. She has never been immunosuppressed and is quite healthy aside from her skin problems. She has a family history but no personal history of diabetes.

EXAMINATION

The condition affects both hands equally. It is composed of intradermal reddish brown papules and plaques that cover the metacarpal areas and extend onto the proximal interphalangeal skin and the distal dorsa. No epidermal component (scale or other broken skin surface) is seen.

The margins of the lesions are arciform, slightly raised, and smooth. The centers of several are concave.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is the classic presentation of granuloma annulare (GA), in terms of morphology, distribution, and patient gender. Though this common condition can manifest in a number of locations and in men, it tends to favor the extensor surfaces of the extremities of women. The dorsum of the foot, anterior tibial skin, and elbows are typical locations that make it a relatively easy condition to recognize.

GA can be more difficult to identify, however, when it is generalized or deeper in the dermis. The latter, termed subcutaneous GA, is most common in children, who present with large dark annular patches of discoloration too deep in the dermis to produce any palpable surface changes. The more rare generalized GA can be difficult to diagnose and treat. Biopsy of suspected generalized or subcutaneous GA is necessary to differentiate it from its lookalikes, such as secondary syphilis, lichen planus, sarcoidosis, and tinea.

The annular borders of GA lesions are notorious for deceiving the unwary practitioner into diagnosing fungal infection. But the latter is, by definition, an infection of the outermost layers of the skin on which fungal organisms feed. That process almost invariably produces significant scaling, especially on the periphery of the lesions. Such scaling is completely absent on GA lesions, which also have a papularity and induration rarely seen with superficial fungal infections. In this particular case, the patient denied any potential source for a fungal infection (animals, children) and denied the itching we would expect with one.

The cause of GA is unknown, but it appears to represent a reaction to an unknown antigen. One previous hypothesis held that it was connected to diabetes, but this was proved false.

Ordinary GA resolves on its own (though this can take months)—which is fortunate, since there is no uniformly successful treatment. Many things have been tried, including topical or intralesional steroids and cryotherapy, with varying levels of success. Generalized GA is even more difficult to treat, can linger for years, and can be highly pruritic. Treatments have included hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, potassium iodide, isotretinoin, and PUVA. More recently, biologics are being used with some success.

The bigger problem with GA is simply to consider it in the differential for odd, annular, or generalized lesions.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Granuloma annulare (GA) is often mistaken for fungal infection, but it is an intradermal rather than epidermal process.

• The extensor surfaces of the extremities of women are favored sites for GA lesions.

• Biopsy of suspected GA lesions confirms the diagnosis while ruling out other items in the differential (eg, sarcoidosis and lichen planus).

• GA has no connection to diabetes.

Several months ago, lesions appeared on both of this 48-year-old woman’s hands. They have been completely unresponsive to any of the treatments prescribed by her primary care provider, including oral (terbinafine) and topical antifungal medications.

The lesions, which are asymptomatic, manifested slowly. They first appeared on the dorsa of her hands and then gradually spread until they covered the central portion of both hands. The lesions wax and wane in terms of thickness and extent but never disappear.

The patient denies similar lesions elsewhere. She also denies contact with animals or children. She has never been immunosuppressed and is quite healthy aside from her skin problems. She has a family history but no personal history of diabetes.

EXAMINATION

The condition affects both hands equally. It is composed of intradermal reddish brown papules and plaques that cover the metacarpal areas and extend onto the proximal interphalangeal skin and the distal dorsa. No epidermal component (scale or other broken skin surface) is seen.

The margins of the lesions are arciform, slightly raised, and smooth. The centers of several are concave.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is the classic presentation of granuloma annulare (GA), in terms of morphology, distribution, and patient gender. Though this common condition can manifest in a number of locations and in men, it tends to favor the extensor surfaces of the extremities of women. The dorsum of the foot, anterior tibial skin, and elbows are typical locations that make it a relatively easy condition to recognize.

GA can be more difficult to identify, however, when it is generalized or deeper in the dermis. The latter, termed subcutaneous GA, is most common in children, who present with large dark annular patches of discoloration too deep in the dermis to produce any palpable surface changes. The more rare generalized GA can be difficult to diagnose and treat. Biopsy of suspected generalized or subcutaneous GA is necessary to differentiate it from its lookalikes, such as secondary syphilis, lichen planus, sarcoidosis, and tinea.

The annular borders of GA lesions are notorious for deceiving the unwary practitioner into diagnosing fungal infection. But the latter is, by definition, an infection of the outermost layers of the skin on which fungal organisms feed. That process almost invariably produces significant scaling, especially on the periphery of the lesions. Such scaling is completely absent on GA lesions, which also have a papularity and induration rarely seen with superficial fungal infections. In this particular case, the patient denied any potential source for a fungal infection (animals, children) and denied the itching we would expect with one.

The cause of GA is unknown, but it appears to represent a reaction to an unknown antigen. One previous hypothesis held that it was connected to diabetes, but this was proved false.

Ordinary GA resolves on its own (though this can take months)—which is fortunate, since there is no uniformly successful treatment. Many things have been tried, including topical or intralesional steroids and cryotherapy, with varying levels of success. Generalized GA is even more difficult to treat, can linger for years, and can be highly pruritic. Treatments have included hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, potassium iodide, isotretinoin, and PUVA. More recently, biologics are being used with some success.

The bigger problem with GA is simply to consider it in the differential for odd, annular, or generalized lesions.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Granuloma annulare (GA) is often mistaken for fungal infection, but it is an intradermal rather than epidermal process.

• The extensor surfaces of the extremities of women are favored sites for GA lesions.

• Biopsy of suspected GA lesions confirms the diagnosis while ruling out other items in the differential (eg, sarcoidosis and lichen planus).

• GA has no connection to diabetes.

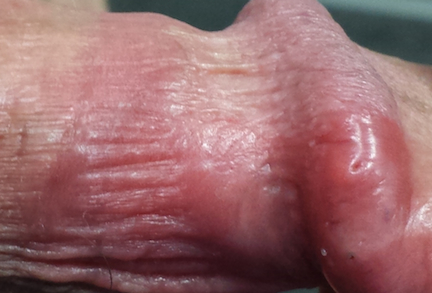

Penile Rash Worries Man (And Wife)

A 61-year-old man presents with an asymptomatic but worrisome (to him) penile rash that manifested over a two-day period several weeks ago. OTC miconazole cream, triple-antibiotic creams, and most recently, a two-day course of fluconazole (200 mg bid) have not helped.

The patient denies any sexual exposure outside his marriage, as does his wife. Both are in good health in other respects, although the wife has been treated for lymphoma (long since declared cured).

At first, the patient denies any other skin problems. However, with specific questioning, he admits to having a chronic scaly and slightly itchy rash that periodically appears in the same places: bilateral brows, nasolabial folds, various spots in his beard, and both external ear canals.

Additional history taking reveals that the patient has been under a great deal of stress lately. His father recently died, leaving him to deal with a number of issues, and his work shift changed, requiring him to sleep during the day and work at night.

EXAMINATION

The penile rash is macular, smooth, strikingly red, and shiny. It covers the dorsal, distal penile shaft, spilling onto the glans. It looks wet but is quite dry. His groin, upper intergluteal area, and axillae are free of any changes.

A fine pink rash is seen in the glabella, extending into both brows. Similar areas of focal scaling on pink bases are also noted in the beard area and in both external auditory meati.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is the way seborrheic dermatitis (SD) acts: It sits around for years, causing minor problems in common areas (eg, face, scalp, ears, and beard). Then the stress of life intrudes, the candle is being burnt from both ends, and SD blossoms, appearing in places such as the chest, groin, suprapubic area, axillae, and genitals.

On the genitals, SD is often bright red, with little if any scale. Why? The moisture and friction particular to the genital and intertriginous (skin on skin) areas prevent scale from accumulating.

Penile rashes generally get everyone’s attention, including that of the patient’s sexual partner(s). For the average nonclinician, the list of possible explanations is infinite—and worrisome. The situation is, in some ways, worse for the average primary care provider, who will almost always decree such a rash a “yeast infection” (though it seldom responds to anti-yeast medications—for good reason: Otherwise healthy circumcised men almost never develop yeast infections anywhere, let alone on the penis).

If you remove “yeast” from the differential, the average primary care provider will be lost. An abbreviated differential list for penile rashes and conditions includes:

• Psoriasis

• Seborrhea

• Contact vs irritant dermatitis

• Eczema/lichen simplex chronicus

• Lichen sclerosis et atrophicus (traditionally termed balanitis xerotica obliterans or BXO when it occurs on the penis)

• Lichen planus

• Reiter syndrome

• Scabies

• Erythroplasia of Queyrat (superficial squamous cell carcinoma)

• Melanoma

• Herpes simplex

• Molluscum

• Pearly penile papules

• Tyson’s glands (prominent pilosebaceous glands on the penile shaft)

• Angiokeratoma of Fordyce

• Condyloma accuminata

• Primary syphilis chancre

• Fixed-drug eruption

(Note that while yeast is not on this list, it certainly could be considered in an uncircumcised hyperglycemic patient.)

The top five items on the list would cover 90% of patients with penile rashes. Seborrheic dermatitis is utterly common but only rarely recognized when it occurs in unusual areas (as in this case).

For this patient, I prescribed topical hydrocortisone 2.5% cream (to be applied bid to all affected areas) and advised him to shampoo the areas daily with ketoconazole-containing shampoo. But the main thing I did for him, and his wife, was provide peace of mind about all the terrible conditions he didn’t have. With treatment, his penile lesions resolved within two weeks.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is common in the scalp, on the face, and in the ears, but it can also appear on the chest, axillae, or genitals.

• Yeast infections are quite uncommon in otherwise healthy men.

• Stress is often a triggering factor with worsening SD.

• Asking about and finding corroborative areas of involvement (face, ears, brows, scalp) can help in diagnosing atypical cases of SD.

A 61-year-old man presents with an asymptomatic but worrisome (to him) penile rash that manifested over a two-day period several weeks ago. OTC miconazole cream, triple-antibiotic creams, and most recently, a two-day course of fluconazole (200 mg bid) have not helped.

The patient denies any sexual exposure outside his marriage, as does his wife. Both are in good health in other respects, although the wife has been treated for lymphoma (long since declared cured).

At first, the patient denies any other skin problems. However, with specific questioning, he admits to having a chronic scaly and slightly itchy rash that periodically appears in the same places: bilateral brows, nasolabial folds, various spots in his beard, and both external ear canals.

Additional history taking reveals that the patient has been under a great deal of stress lately. His father recently died, leaving him to deal with a number of issues, and his work shift changed, requiring him to sleep during the day and work at night.

EXAMINATION

The penile rash is macular, smooth, strikingly red, and shiny. It covers the dorsal, distal penile shaft, spilling onto the glans. It looks wet but is quite dry. His groin, upper intergluteal area, and axillae are free of any changes.

A fine pink rash is seen in the glabella, extending into both brows. Similar areas of focal scaling on pink bases are also noted in the beard area and in both external auditory meati.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is the way seborrheic dermatitis (SD) acts: It sits around for years, causing minor problems in common areas (eg, face, scalp, ears, and beard). Then the stress of life intrudes, the candle is being burnt from both ends, and SD blossoms, appearing in places such as the chest, groin, suprapubic area, axillae, and genitals.

On the genitals, SD is often bright red, with little if any scale. Why? The moisture and friction particular to the genital and intertriginous (skin on skin) areas prevent scale from accumulating.

Penile rashes generally get everyone’s attention, including that of the patient’s sexual partner(s). For the average nonclinician, the list of possible explanations is infinite—and worrisome. The situation is, in some ways, worse for the average primary care provider, who will almost always decree such a rash a “yeast infection” (though it seldom responds to anti-yeast medications—for good reason: Otherwise healthy circumcised men almost never develop yeast infections anywhere, let alone on the penis).

If you remove “yeast” from the differential, the average primary care provider will be lost. An abbreviated differential list for penile rashes and conditions includes:

• Psoriasis

• Seborrhea

• Contact vs irritant dermatitis

• Eczema/lichen simplex chronicus

• Lichen sclerosis et atrophicus (traditionally termed balanitis xerotica obliterans or BXO when it occurs on the penis)

• Lichen planus

• Reiter syndrome

• Scabies

• Erythroplasia of Queyrat (superficial squamous cell carcinoma)

• Melanoma

• Herpes simplex

• Molluscum

• Pearly penile papules

• Tyson’s glands (prominent pilosebaceous glands on the penile shaft)

• Angiokeratoma of Fordyce

• Condyloma accuminata

• Primary syphilis chancre

• Fixed-drug eruption

(Note that while yeast is not on this list, it certainly could be considered in an uncircumcised hyperglycemic patient.)

The top five items on the list would cover 90% of patients with penile rashes. Seborrheic dermatitis is utterly common but only rarely recognized when it occurs in unusual areas (as in this case).

For this patient, I prescribed topical hydrocortisone 2.5% cream (to be applied bid to all affected areas) and advised him to shampoo the areas daily with ketoconazole-containing shampoo. But the main thing I did for him, and his wife, was provide peace of mind about all the terrible conditions he didn’t have. With treatment, his penile lesions resolved within two weeks.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is common in the scalp, on the face, and in the ears, but it can also appear on the chest, axillae, or genitals.

• Yeast infections are quite uncommon in otherwise healthy men.

• Stress is often a triggering factor with worsening SD.

• Asking about and finding corroborative areas of involvement (face, ears, brows, scalp) can help in diagnosing atypical cases of SD.

A 61-year-old man presents with an asymptomatic but worrisome (to him) penile rash that manifested over a two-day period several weeks ago. OTC miconazole cream, triple-antibiotic creams, and most recently, a two-day course of fluconazole (200 mg bid) have not helped.

The patient denies any sexual exposure outside his marriage, as does his wife. Both are in good health in other respects, although the wife has been treated for lymphoma (long since declared cured).

At first, the patient denies any other skin problems. However, with specific questioning, he admits to having a chronic scaly and slightly itchy rash that periodically appears in the same places: bilateral brows, nasolabial folds, various spots in his beard, and both external ear canals.

Additional history taking reveals that the patient has been under a great deal of stress lately. His father recently died, leaving him to deal with a number of issues, and his work shift changed, requiring him to sleep during the day and work at night.

EXAMINATION

The penile rash is macular, smooth, strikingly red, and shiny. It covers the dorsal, distal penile shaft, spilling onto the glans. It looks wet but is quite dry. His groin, upper intergluteal area, and axillae are free of any changes.

A fine pink rash is seen in the glabella, extending into both brows. Similar areas of focal scaling on pink bases are also noted in the beard area and in both external auditory meati.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is the way seborrheic dermatitis (SD) acts: It sits around for years, causing minor problems in common areas (eg, face, scalp, ears, and beard). Then the stress of life intrudes, the candle is being burnt from both ends, and SD blossoms, appearing in places such as the chest, groin, suprapubic area, axillae, and genitals.

On the genitals, SD is often bright red, with little if any scale. Why? The moisture and friction particular to the genital and intertriginous (skin on skin) areas prevent scale from accumulating.

Penile rashes generally get everyone’s attention, including that of the patient’s sexual partner(s). For the average nonclinician, the list of possible explanations is infinite—and worrisome. The situation is, in some ways, worse for the average primary care provider, who will almost always decree such a rash a “yeast infection” (though it seldom responds to anti-yeast medications—for good reason: Otherwise healthy circumcised men almost never develop yeast infections anywhere, let alone on the penis).

If you remove “yeast” from the differential, the average primary care provider will be lost. An abbreviated differential list for penile rashes and conditions includes:

• Psoriasis

• Seborrhea

• Contact vs irritant dermatitis

• Eczema/lichen simplex chronicus

• Lichen sclerosis et atrophicus (traditionally termed balanitis xerotica obliterans or BXO when it occurs on the penis)

• Lichen planus

• Reiter syndrome

• Scabies

• Erythroplasia of Queyrat (superficial squamous cell carcinoma)

• Melanoma

• Herpes simplex

• Molluscum

• Pearly penile papules

• Tyson’s glands (prominent pilosebaceous glands on the penile shaft)

• Angiokeratoma of Fordyce

• Condyloma accuminata

• Primary syphilis chancre

• Fixed-drug eruption

(Note that while yeast is not on this list, it certainly could be considered in an uncircumcised hyperglycemic patient.)

The top five items on the list would cover 90% of patients with penile rashes. Seborrheic dermatitis is utterly common but only rarely recognized when it occurs in unusual areas (as in this case).

For this patient, I prescribed topical hydrocortisone 2.5% cream (to be applied bid to all affected areas) and advised him to shampoo the areas daily with ketoconazole-containing shampoo. But the main thing I did for him, and his wife, was provide peace of mind about all the terrible conditions he didn’t have. With treatment, his penile lesions resolved within two weeks.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is common in the scalp, on the face, and in the ears, but it can also appear on the chest, axillae, or genitals.

• Yeast infections are quite uncommon in otherwise healthy men.

• Stress is often a triggering factor with worsening SD.

• Asking about and finding corroborative areas of involvement (face, ears, brows, scalp) can help in diagnosing atypical cases of SD.

Baby Has Rash; Parents Feel Itchy

A 5-month-old baby is brought in by his parents for evaluation of a rash that manifested on his hands several weeks ago. It then spread to his arms and trunk and is now essentially everywhere except his face. Despite a number of treatment attempts, including use of oral antibiotics (cephalexin suspension 125/5 cc) and OTC topical steroid creams, the problem has persisted.

Prior to dermatology, they had consulted a pediatrician. He suggested the child might have scabies, for which he prescribed permethrin cream. The parents tried it, but it made little if any difference.

Neither the child nor his parents are atopic. However, both parents have recently started to feel itchy.

EXAMINATION

The child is afebrile and in no acute distress. Hundreds of tiny papules are scattered on his trunk, arms, and legs, with a particular concentration on his palms. Several of the papules, on closer examination, prove to be vesicles (ie, filled with clear fluid).

One of these lesions, on the child’s volar wrist, is scraped and the sample examined under the microscope. Magnification at 10x power reveals an adult scabies organism and a number of rugby ball–shaped eggs.

Both parents are also examined and found to have probable scabies as well. The mother’s lesions are concentrated around the anterior axillary areas and waistline. The father’s are on his volar wrists and penis.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case nicely illustrates several issues revolving around the diagnosis of scabies. One might think this would be a simple matter: Diagnose, then treat. Alas, it is seldom so.

For one thing, the diagnosis of scabies needs to be confirmed, whenever possible, with microscopic findings of scabetic elements. Without this, patient and provider confidence are lacking—a situation that often leads to shotgun treatment.

In addition, had the diagnosis been confirmed prior to presentation to dermatology, the previously consulted providers might have considered treating the whole family and trying to identify the source of the infestation. Both of these are absolutely crucial to successful treatment.

Several factors make the diagnosis of scabies difficult in infants. Any part of an infant’s thin, soft, relatively hairless skin is fair game (whereas, in adults, scabies rarely affects skin above the neck). Furthermore, although infants with scabies undoubtedly itch—probably just as much as adults—they are totally inept excoriators and even worse historians. In contrast, adults with scabies will scratch continuously while in the exam room and complain bitterly 24/7.

Once the diagnosis is established, a crucial element of dealing effectively with scabies is education—in this case, of the parents. They must understand the nature of the problem in specific terms. For example, scabies cannot be caught from or given to nonhuman hosts (eg, animals). And while I advise affected families to clean areas such as beds, sofas, and bathrooms, I also emphasize that the organism does not reside in or multiply on inanimate objects. Despite my best efforts, though, some families become almost hysterical: steam-cleaning every surface, calling pest control, washing bedding and towels multiple times, and calling me three times a day.

Families must also understand that treatment of all household members must be coordinated and done twice, seven to 10 days apart, in order to kill freshly hatched organisms. This child was treated with permethrin 5% cream, applied to the entire body and left on overnight, then washed off the next morning (twice per the schedule outlined above). In addition to permethrin, the adults were treated with ivermectin (200 mcg/kg) on the same schedule. Even with these extensive measures, recurrence would not be surprising.

Most often, when treatment “fails,” it is because the diagnosis was not scabies in the first place. In confirmed cases, treatment will be unsuccessful if all family members are not adequately (and concurrently) treated. Another problem occurs when the actual source is outside the home (daycare, sleepovers, sexual partner) and remains unidentified—dooming the family to recurrence. (Institutional scabies—from nursing homes, group living, etc—can be far more difficult to deal with and is beyond the scope of this article.)

The differential for scabies includes—most significantly—atopic dermatitis, which it can closely resemble.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Scabies can show up almost anywhere on an infant’s body, because the skin is so thin, hairless, and soft.

• If the baby has scabies, chances are the parents and siblings have it too.

• Someone brings scabies into the family, and unless the source is identified and treated, the problem will recur.

• Microscopic examination (KOH) for scabetic elements is a crucial component of diagnosis and treatment.

• Scabies sarcoptes var humani is species-specific and cannot be given to or caught from an animal.

• Permethrin cream 5% is considered safe for infants ages 2 months and older.

A 5-month-old baby is brought in by his parents for evaluation of a rash that manifested on his hands several weeks ago. It then spread to his arms and trunk and is now essentially everywhere except his face. Despite a number of treatment attempts, including use of oral antibiotics (cephalexin suspension 125/5 cc) and OTC topical steroid creams, the problem has persisted.

Prior to dermatology, they had consulted a pediatrician. He suggested the child might have scabies, for which he prescribed permethrin cream. The parents tried it, but it made little if any difference.

Neither the child nor his parents are atopic. However, both parents have recently started to feel itchy.

EXAMINATION

The child is afebrile and in no acute distress. Hundreds of tiny papules are scattered on his trunk, arms, and legs, with a particular concentration on his palms. Several of the papules, on closer examination, prove to be vesicles (ie, filled with clear fluid).

One of these lesions, on the child’s volar wrist, is scraped and the sample examined under the microscope. Magnification at 10x power reveals an adult scabies organism and a number of rugby ball–shaped eggs.

Both parents are also examined and found to have probable scabies as well. The mother’s lesions are concentrated around the anterior axillary areas and waistline. The father’s are on his volar wrists and penis.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case nicely illustrates several issues revolving around the diagnosis of scabies. One might think this would be a simple matter: Diagnose, then treat. Alas, it is seldom so.

For one thing, the diagnosis of scabies needs to be confirmed, whenever possible, with microscopic findings of scabetic elements. Without this, patient and provider confidence are lacking—a situation that often leads to shotgun treatment.

In addition, had the diagnosis been confirmed prior to presentation to dermatology, the previously consulted providers might have considered treating the whole family and trying to identify the source of the infestation. Both of these are absolutely crucial to successful treatment.

Several factors make the diagnosis of scabies difficult in infants. Any part of an infant’s thin, soft, relatively hairless skin is fair game (whereas, in adults, scabies rarely affects skin above the neck). Furthermore, although infants with scabies undoubtedly itch—probably just as much as adults—they are totally inept excoriators and even worse historians. In contrast, adults with scabies will scratch continuously while in the exam room and complain bitterly 24/7.

Once the diagnosis is established, a crucial element of dealing effectively with scabies is education—in this case, of the parents. They must understand the nature of the problem in specific terms. For example, scabies cannot be caught from or given to nonhuman hosts (eg, animals). And while I advise affected families to clean areas such as beds, sofas, and bathrooms, I also emphasize that the organism does not reside in or multiply on inanimate objects. Despite my best efforts, though, some families become almost hysterical: steam-cleaning every surface, calling pest control, washing bedding and towels multiple times, and calling me three times a day.

Families must also understand that treatment of all household members must be coordinated and done twice, seven to 10 days apart, in order to kill freshly hatched organisms. This child was treated with permethrin 5% cream, applied to the entire body and left on overnight, then washed off the next morning (twice per the schedule outlined above). In addition to permethrin, the adults were treated with ivermectin (200 mcg/kg) on the same schedule. Even with these extensive measures, recurrence would not be surprising.

Most often, when treatment “fails,” it is because the diagnosis was not scabies in the first place. In confirmed cases, treatment will be unsuccessful if all family members are not adequately (and concurrently) treated. Another problem occurs when the actual source is outside the home (daycare, sleepovers, sexual partner) and remains unidentified—dooming the family to recurrence. (Institutional scabies—from nursing homes, group living, etc—can be far more difficult to deal with and is beyond the scope of this article.)

The differential for scabies includes—most significantly—atopic dermatitis, which it can closely resemble.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Scabies can show up almost anywhere on an infant’s body, because the skin is so thin, hairless, and soft.

• If the baby has scabies, chances are the parents and siblings have it too.

• Someone brings scabies into the family, and unless the source is identified and treated, the problem will recur.

• Microscopic examination (KOH) for scabetic elements is a crucial component of diagnosis and treatment.

• Scabies sarcoptes var humani is species-specific and cannot be given to or caught from an animal.

• Permethrin cream 5% is considered safe for infants ages 2 months and older.

A 5-month-old baby is brought in by his parents for evaluation of a rash that manifested on his hands several weeks ago. It then spread to his arms and trunk and is now essentially everywhere except his face. Despite a number of treatment attempts, including use of oral antibiotics (cephalexin suspension 125/5 cc) and OTC topical steroid creams, the problem has persisted.

Prior to dermatology, they had consulted a pediatrician. He suggested the child might have scabies, for which he prescribed permethrin cream. The parents tried it, but it made little if any difference.

Neither the child nor his parents are atopic. However, both parents have recently started to feel itchy.

EXAMINATION

The child is afebrile and in no acute distress. Hundreds of tiny papules are scattered on his trunk, arms, and legs, with a particular concentration on his palms. Several of the papules, on closer examination, prove to be vesicles (ie, filled with clear fluid).

One of these lesions, on the child’s volar wrist, is scraped and the sample examined under the microscope. Magnification at 10x power reveals an adult scabies organism and a number of rugby ball–shaped eggs.

Both parents are also examined and found to have probable scabies as well. The mother’s lesions are concentrated around the anterior axillary areas and waistline. The father’s are on his volar wrists and penis.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case nicely illustrates several issues revolving around the diagnosis of scabies. One might think this would be a simple matter: Diagnose, then treat. Alas, it is seldom so.

For one thing, the diagnosis of scabies needs to be confirmed, whenever possible, with microscopic findings of scabetic elements. Without this, patient and provider confidence are lacking—a situation that often leads to shotgun treatment.

In addition, had the diagnosis been confirmed prior to presentation to dermatology, the previously consulted providers might have considered treating the whole family and trying to identify the source of the infestation. Both of these are absolutely crucial to successful treatment.

Several factors make the diagnosis of scabies difficult in infants. Any part of an infant’s thin, soft, relatively hairless skin is fair game (whereas, in adults, scabies rarely affects skin above the neck). Furthermore, although infants with scabies undoubtedly itch—probably just as much as adults—they are totally inept excoriators and even worse historians. In contrast, adults with scabies will scratch continuously while in the exam room and complain bitterly 24/7.

Once the diagnosis is established, a crucial element of dealing effectively with scabies is education—in this case, of the parents. They must understand the nature of the problem in specific terms. For example, scabies cannot be caught from or given to nonhuman hosts (eg, animals). And while I advise affected families to clean areas such as beds, sofas, and bathrooms, I also emphasize that the organism does not reside in or multiply on inanimate objects. Despite my best efforts, though, some families become almost hysterical: steam-cleaning every surface, calling pest control, washing bedding and towels multiple times, and calling me three times a day.

Families must also understand that treatment of all household members must be coordinated and done twice, seven to 10 days apart, in order to kill freshly hatched organisms. This child was treated with permethrin 5% cream, applied to the entire body and left on overnight, then washed off the next morning (twice per the schedule outlined above). In addition to permethrin, the adults were treated with ivermectin (200 mcg/kg) on the same schedule. Even with these extensive measures, recurrence would not be surprising.

Most often, when treatment “fails,” it is because the diagnosis was not scabies in the first place. In confirmed cases, treatment will be unsuccessful if all family members are not adequately (and concurrently) treated. Another problem occurs when the actual source is outside the home (daycare, sleepovers, sexual partner) and remains unidentified—dooming the family to recurrence. (Institutional scabies—from nursing homes, group living, etc—can be far more difficult to deal with and is beyond the scope of this article.)

The differential for scabies includes—most significantly—atopic dermatitis, which it can closely resemble.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Scabies can show up almost anywhere on an infant’s body, because the skin is so thin, hairless, and soft.

• If the baby has scabies, chances are the parents and siblings have it too.

• Someone brings scabies into the family, and unless the source is identified and treated, the problem will recur.

• Microscopic examination (KOH) for scabetic elements is a crucial component of diagnosis and treatment.

• Scabies sarcoptes var humani is species-specific and cannot be given to or caught from an animal.

• Permethrin cream 5% is considered safe for infants ages 2 months and older.

Itch–Scratch–Itch: Can the Cycle Be Broken?

A 67-year-old woman has had a very itchy rash on the dorsa of both feet for almost a year. In addition to consulting her primary care provider, she has presented to a number of medical venues, including urgent care clinics. Different products have been prescribed—including clotrimazole cream, nystatin powder, and OTC hydrocortisone 1% cream—none of which produced any beneficial effect. So the patient finally self-refers to dermatology.

She reports that at one point, she was convinced her shoes were the source of the problem. But trying new shoes and even going entirely barefoot during a two-week vacation at the beach made no difference.

The patient admits that it is “impossible” to leave the lesions alone, because they are so itchy. She knows that “scratching can’t be good,” so she tries to just rub them, often with a wet washcloth.

Aside from the foot rash, her health is excellent. Her only medications are NSAIDs for mild arthritis.

EXAMINATION

The lesions are confined to the forefeet. There are about five on the right foot and three on the left. The lesions are dark purplish round plaques with planar surfaces that are shiny but have a white frosting-like finish. On average, they measure 1.8 cm in diameter. No surrounding inflammation is appreciated. The patient has otherwise unremarkable type IV skin.

What is the diagnosis?

DIAGNOSIS

Punch biopsy confirms the expected diagnosis of lichen planus.

DISCUSSION

Lichen planus (LP) is a very common problem seen in dermatology offices worldwide. LP represents an immune response of unknown origin and may be found in association with other diseases of altered immunity (eg, dermatomyositis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, morphea, and myasthenia gravis). Some studies support the theory that LP is caused by hepatitis C.

The most common forms of LP lend themselves to a useful mnemonic device that uses the letter “P” to describe common features of the disease: purple, papular or plaquish, planar (flat) surfaces, polygonal shapes, pruritic, penile (frequent location), and finally, “puzzling” to the clinician.

In contrast to this particular case, LP commonly affects flexural surfaces, such as the volar wrist. LP can also affect nails (with dystrophy or onycholysis), the scalp, and, most notoriously, the oral mucosae, where it can cause ulcerations and intense burning. Oral lesions often present with a lacy white look on the buccal mucosal surfaces.

LP is only one of a number of skin diseases that “koebnerize” (ie, form along lines of trauma, such as a scratch). The resulting linear collection of planar purple papules—known as the Koebner phenomenon—is useful for diagnosis.

Biopsy is often needed to confirm the diagnosis. It will show hyperkeratotic epidermis with irregular acanthosis. In the upper dermis, there is often an infiltrating band of lymphocytic and histiocytic cells, along with many Langerhans cells, that effectively obliterates the dermo-epidermal junction (a pathognomic finding of LP).

Most cases of LP eventually resolve, usually within months, though some can persist for years. Treatment can be problematic, especially when the disease is widespread or manifests in difficult areas, such as the mouth or scalp. This particular patient’s problem was relatively simple to treat with topical clobetasol cream under occlusion (bid for three weeks). Had that not worked, we could have tried intralesional injection of triamcinolone (10 mg per cc).

This case was typical of LP seen on the legs of older patients with darker skin. In these patients, the lesions tend to become hypertrophic and darker than the usual light pink to purple seen in those with fairer skin.

The differential for LP includes psoriasis, fixed-drug eruption, granuloma annulare, and nummular eczema.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Lichen planus (LP) is a commonly encountered inflammatory condition that classically affects flexural skin, such as the volar wrist.

• LP lesions can often be seen in a linear configuration, following the line of a scratch or other trauma, a phenomenon known as the Koebner phenomenon (the isomorphic linear response), which can be helpful diagnostically.

• The “Ps” of LP include papular, purple, planar, plaquish, pruritic, penile, polygonal, and puzzling.

• LP can also affect hair follicles, nails, and oral mucosa.

• LP can present with hypertrophic plaques, especially on legs and feet.

A 67-year-old woman has had a very itchy rash on the dorsa of both feet for almost a year. In addition to consulting her primary care provider, she has presented to a number of medical venues, including urgent care clinics. Different products have been prescribed—including clotrimazole cream, nystatin powder, and OTC hydrocortisone 1% cream—none of which produced any beneficial effect. So the patient finally self-refers to dermatology.

She reports that at one point, she was convinced her shoes were the source of the problem. But trying new shoes and even going entirely barefoot during a two-week vacation at the beach made no difference.

The patient admits that it is “impossible” to leave the lesions alone, because they are so itchy. She knows that “scratching can’t be good,” so she tries to just rub them, often with a wet washcloth.

Aside from the foot rash, her health is excellent. Her only medications are NSAIDs for mild arthritis.

EXAMINATION

The lesions are confined to the forefeet. There are about five on the right foot and three on the left. The lesions are dark purplish round plaques with planar surfaces that are shiny but have a white frosting-like finish. On average, they measure 1.8 cm in diameter. No surrounding inflammation is appreciated. The patient has otherwise unremarkable type IV skin.

What is the diagnosis?

DIAGNOSIS

Punch biopsy confirms the expected diagnosis of lichen planus.

DISCUSSION

Lichen planus (LP) is a very common problem seen in dermatology offices worldwide. LP represents an immune response of unknown origin and may be found in association with other diseases of altered immunity (eg, dermatomyositis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, morphea, and myasthenia gravis). Some studies support the theory that LP is caused by hepatitis C.

The most common forms of LP lend themselves to a useful mnemonic device that uses the letter “P” to describe common features of the disease: purple, papular or plaquish, planar (flat) surfaces, polygonal shapes, pruritic, penile (frequent location), and finally, “puzzling” to the clinician.

In contrast to this particular case, LP commonly affects flexural surfaces, such as the volar wrist. LP can also affect nails (with dystrophy or onycholysis), the scalp, and, most notoriously, the oral mucosae, where it can cause ulcerations and intense burning. Oral lesions often present with a lacy white look on the buccal mucosal surfaces.

LP is only one of a number of skin diseases that “koebnerize” (ie, form along lines of trauma, such as a scratch). The resulting linear collection of planar purple papules—known as the Koebner phenomenon—is useful for diagnosis.

Biopsy is often needed to confirm the diagnosis. It will show hyperkeratotic epidermis with irregular acanthosis. In the upper dermis, there is often an infiltrating band of lymphocytic and histiocytic cells, along with many Langerhans cells, that effectively obliterates the dermo-epidermal junction (a pathognomic finding of LP).

Most cases of LP eventually resolve, usually within months, though some can persist for years. Treatment can be problematic, especially when the disease is widespread or manifests in difficult areas, such as the mouth or scalp. This particular patient’s problem was relatively simple to treat with topical clobetasol cream under occlusion (bid for three weeks). Had that not worked, we could have tried intralesional injection of triamcinolone (10 mg per cc).

This case was typical of LP seen on the legs of older patients with darker skin. In these patients, the lesions tend to become hypertrophic and darker than the usual light pink to purple seen in those with fairer skin.

The differential for LP includes psoriasis, fixed-drug eruption, granuloma annulare, and nummular eczema.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Lichen planus (LP) is a commonly encountered inflammatory condition that classically affects flexural skin, such as the volar wrist.

• LP lesions can often be seen in a linear configuration, following the line of a scratch or other trauma, a phenomenon known as the Koebner phenomenon (the isomorphic linear response), which can be helpful diagnostically.

• The “Ps” of LP include papular, purple, planar, plaquish, pruritic, penile, polygonal, and puzzling.

• LP can also affect hair follicles, nails, and oral mucosa.

• LP can present with hypertrophic plaques, especially on legs and feet.

A 67-year-old woman has had a very itchy rash on the dorsa of both feet for almost a year. In addition to consulting her primary care provider, she has presented to a number of medical venues, including urgent care clinics. Different products have been prescribed—including clotrimazole cream, nystatin powder, and OTC hydrocortisone 1% cream—none of which produced any beneficial effect. So the patient finally self-refers to dermatology.

She reports that at one point, she was convinced her shoes were the source of the problem. But trying new shoes and even going entirely barefoot during a two-week vacation at the beach made no difference.

The patient admits that it is “impossible” to leave the lesions alone, because they are so itchy. She knows that “scratching can’t be good,” so she tries to just rub them, often with a wet washcloth.

Aside from the foot rash, her health is excellent. Her only medications are NSAIDs for mild arthritis.

EXAMINATION

The lesions are confined to the forefeet. There are about five on the right foot and three on the left. The lesions are dark purplish round plaques with planar surfaces that are shiny but have a white frosting-like finish. On average, they measure 1.8 cm in diameter. No surrounding inflammation is appreciated. The patient has otherwise unremarkable type IV skin.

What is the diagnosis?

DIAGNOSIS

Punch biopsy confirms the expected diagnosis of lichen planus.

DISCUSSION

Lichen planus (LP) is a very common problem seen in dermatology offices worldwide. LP represents an immune response of unknown origin and may be found in association with other diseases of altered immunity (eg, dermatomyositis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, morphea, and myasthenia gravis). Some studies support the theory that LP is caused by hepatitis C.

The most common forms of LP lend themselves to a useful mnemonic device that uses the letter “P” to describe common features of the disease: purple, papular or plaquish, planar (flat) surfaces, polygonal shapes, pruritic, penile (frequent location), and finally, “puzzling” to the clinician.

In contrast to this particular case, LP commonly affects flexural surfaces, such as the volar wrist. LP can also affect nails (with dystrophy or onycholysis), the scalp, and, most notoriously, the oral mucosae, where it can cause ulcerations and intense burning. Oral lesions often present with a lacy white look on the buccal mucosal surfaces.

LP is only one of a number of skin diseases that “koebnerize” (ie, form along lines of trauma, such as a scratch). The resulting linear collection of planar purple papules—known as the Koebner phenomenon—is useful for diagnosis.

Biopsy is often needed to confirm the diagnosis. It will show hyperkeratotic epidermis with irregular acanthosis. In the upper dermis, there is often an infiltrating band of lymphocytic and histiocytic cells, along with many Langerhans cells, that effectively obliterates the dermo-epidermal junction (a pathognomic finding of LP).

Most cases of LP eventually resolve, usually within months, though some can persist for years. Treatment can be problematic, especially when the disease is widespread or manifests in difficult areas, such as the mouth or scalp. This particular patient’s problem was relatively simple to treat with topical clobetasol cream under occlusion (bid for three weeks). Had that not worked, we could have tried intralesional injection of triamcinolone (10 mg per cc).

This case was typical of LP seen on the legs of older patients with darker skin. In these patients, the lesions tend to become hypertrophic and darker than the usual light pink to purple seen in those with fairer skin.

The differential for LP includes psoriasis, fixed-drug eruption, granuloma annulare, and nummular eczema.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Lichen planus (LP) is a commonly encountered inflammatory condition that classically affects flexural skin, such as the volar wrist.

• LP lesions can often be seen in a linear configuration, following the line of a scratch or other trauma, a phenomenon known as the Koebner phenomenon (the isomorphic linear response), which can be helpful diagnostically.

• The “Ps” of LP include papular, purple, planar, plaquish, pruritic, penile, polygonal, and puzzling.

• LP can also affect hair follicles, nails, and oral mucosa.

• LP can present with hypertrophic plaques, especially on legs and feet.

Years of Gardening, and Now a Facial Lesion

The lesion on the face of this 72-year-old woman has slowly grown over a period of years but has never caused pain. On several occasions, she has consulted primary care providers (PCPs), most of whom prescribed oral antibiotics for possible infection. However, these medications never helped.

She recently developed oral health problems and established care with a new PCP, who insisted she see a dermatologist about the facial lesion. The patient, who is “terrified” of needles, resisted this advice at first but finally agreed once her family got involved.

The patient reports a history of extensive sun exposure in childhood, when she worked in the fields, that continued into adulthood; she maintained a garden until recently. Her response to the sun is invariably a deep tan, which lasts all summer.

EXAMINATION

The lesion, almost 6 cm wide and more than 4 cm long, is located in the right infraorbital facial cheek area, well below the eyelid margin. It is focally eroded, peripherally erythematous, and quite firm to the touch. Fortunately, it is still mobile and not fixed to the underlying tissue. There are no palpable lymph nodes in the area and no change in sensation from one side of the face to the other.

A punch biopsy is performed under local infiltrate with 1% lidocaine with epinephrine. The 4-mm defect is closed with 2 x 5-0 nylon sutures and the specimen submitted to pathology. The report confirms the clinical suspicion of basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

Continue for Joe Monroe's discussion >>

DISCUSSION

When they are allowed to reach this size, BCCs can become a real problem. In extreme instances, they can erode into the face and even into bone. Patients can lose ears, noses, or even their entire face to this relentless but “safe” cancer. Given enough time and bad luck, BCC can metastasize to local lymph nodes and even to the brain or lung; it is even occasionally a cause of death.

Patients often ask why we have to remove BCCs if they’re usually “safe.” Without trying to scare them, we describe cases such as this one as the inevitable outcome of prolonged neglect and/or an aggressive tumor. BCCs almost never heal without treatment and almost always grow wider and deeper over time. Some are extremely indolent, taking 20 years to become noticeable, while others are more aggressive. In addition to the clinical behavior of any given BCC, there are also histologic clues to how aggressive a particular BCC might be.

This patient was referred to a Mohs surgeon, who will be able to do two things that require specialized training:

1. He’ll remove the biopsy-proven cancer with scalpel surgery, and while the patient is still present, check the margins for residual cancer. If the margins are positive, he’ll go back to the area and remove more, repeating this step until clear wide and deep microscopic margins are visualized by frozen section technique. (It’s important to note that the exact way the frozen specimen is processed and examined permits evaluation of the entire margin—top, bottom, sides—making it considerably different from ordinary frozen sections.)

2. Then, the Mohs surgeon will have the skill to close the defect in an acceptable way: usually by primary closure, sometimes with flaps or with grafts. All of this is typically done on an outpatient basis, on the same visit, although it may take most of a morning or afternoon.

Mohs surgery was pioneered in the 1930s by Frederic Mohs, MD, a general surgeon, as a way to address large and/or aggressive cancers located in difficult areas (eg, face or genitals). It is not indicated for ordinary, relatively small skin cancers on the arms, legs, or trunk.

Some BCCs and squamous cell carcinomas develop in especially difficult areas, such as the eyelids, or involve large areas of the ear. These lesions may require the attention of relevant surgical specialists, such as oculoplastic or head and neck surgeons.

This patient will undergo Mohs surgery in the near future, and her defect will probably be closed primarily. The depth and histologic markers indicating exceptional aggression may dictate a further step: Radiation therapy may be required to minimize the likelihood of recurrence. Her chances of a complete cure are 95% to 97% with Mohs surgery alone.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) are often mistaken for infection.

• BCCs almost never heal on their own, grow slowly but steadily, and can reach prodigious size and depth.

• BCCs can metastasize to local nodes or even to the brain and lung.

• Ordinary excision is adequate for most BCCs, but Mohs surgery is indicated for larger lesions located in difficult areas (eg, face, scalp or groin).

• Simple shave biopsy is adequate to diagnose most BCCs.

The lesion on the face of this 72-year-old woman has slowly grown over a period of years but has never caused pain. On several occasions, she has consulted primary care providers (PCPs), most of whom prescribed oral antibiotics for possible infection. However, these medications never helped.

She recently developed oral health problems and established care with a new PCP, who insisted she see a dermatologist about the facial lesion. The patient, who is “terrified” of needles, resisted this advice at first but finally agreed once her family got involved.

The patient reports a history of extensive sun exposure in childhood, when she worked in the fields, that continued into adulthood; she maintained a garden until recently. Her response to the sun is invariably a deep tan, which lasts all summer.

EXAMINATION

The lesion, almost 6 cm wide and more than 4 cm long, is located in the right infraorbital facial cheek area, well below the eyelid margin. It is focally eroded, peripherally erythematous, and quite firm to the touch. Fortunately, it is still mobile and not fixed to the underlying tissue. There are no palpable lymph nodes in the area and no change in sensation from one side of the face to the other.

A punch biopsy is performed under local infiltrate with 1% lidocaine with epinephrine. The 4-mm defect is closed with 2 x 5-0 nylon sutures and the specimen submitted to pathology. The report confirms the clinical suspicion of basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

Continue for Joe Monroe's discussion >>

DISCUSSION

When they are allowed to reach this size, BCCs can become a real problem. In extreme instances, they can erode into the face and even into bone. Patients can lose ears, noses, or even their entire face to this relentless but “safe” cancer. Given enough time and bad luck, BCC can metastasize to local lymph nodes and even to the brain or lung; it is even occasionally a cause of death.

Patients often ask why we have to remove BCCs if they’re usually “safe.” Without trying to scare them, we describe cases such as this one as the inevitable outcome of prolonged neglect and/or an aggressive tumor. BCCs almost never heal without treatment and almost always grow wider and deeper over time. Some are extremely indolent, taking 20 years to become noticeable, while others are more aggressive. In addition to the clinical behavior of any given BCC, there are also histologic clues to how aggressive a particular BCC might be.

This patient was referred to a Mohs surgeon, who will be able to do two things that require specialized training:

1. He’ll remove the biopsy-proven cancer with scalpel surgery, and while the patient is still present, check the margins for residual cancer. If the margins are positive, he’ll go back to the area and remove more, repeating this step until clear wide and deep microscopic margins are visualized by frozen section technique. (It’s important to note that the exact way the frozen specimen is processed and examined permits evaluation of the entire margin—top, bottom, sides—making it considerably different from ordinary frozen sections.)

2. Then, the Mohs surgeon will have the skill to close the defect in an acceptable way: usually by primary closure, sometimes with flaps or with grafts. All of this is typically done on an outpatient basis, on the same visit, although it may take most of a morning or afternoon.

Mohs surgery was pioneered in the 1930s by Frederic Mohs, MD, a general surgeon, as a way to address large and/or aggressive cancers located in difficult areas (eg, face or genitals). It is not indicated for ordinary, relatively small skin cancers on the arms, legs, or trunk.

Some BCCs and squamous cell carcinomas develop in especially difficult areas, such as the eyelids, or involve large areas of the ear. These lesions may require the attention of relevant surgical specialists, such as oculoplastic or head and neck surgeons.

This patient will undergo Mohs surgery in the near future, and her defect will probably be closed primarily. The depth and histologic markers indicating exceptional aggression may dictate a further step: Radiation therapy may be required to minimize the likelihood of recurrence. Her chances of a complete cure are 95% to 97% with Mohs surgery alone.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) are often mistaken for infection.

• BCCs almost never heal on their own, grow slowly but steadily, and can reach prodigious size and depth.

• BCCs can metastasize to local nodes or even to the brain and lung.

• Ordinary excision is adequate for most BCCs, but Mohs surgery is indicated for larger lesions located in difficult areas (eg, face, scalp or groin).

• Simple shave biopsy is adequate to diagnose most BCCs.

The lesion on the face of this 72-year-old woman has slowly grown over a period of years but has never caused pain. On several occasions, she has consulted primary care providers (PCPs), most of whom prescribed oral antibiotics for possible infection. However, these medications never helped.