User login

Hairless Scalp Lesion

The Diagnosis: Nevus Sebaceus of Jadassohn

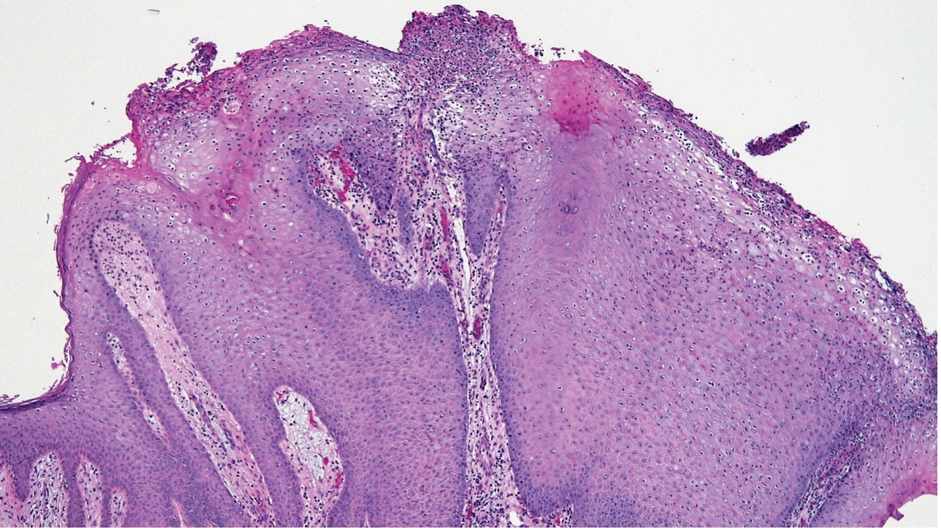

The diagnosis of nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn was made clinically based on the lesion’s appearance and presence since birth as well as the absence of systemic symptoms. Clinically, nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn typically manifests as a well-demarcated, yellow- brown plaque often located on the scalp, as was seen in our patient. The lack of pruritus and pain further supported the diagnosis in our patient. No biopsy was performed, as the presentation was considered classic for this condition. Our patient opted to forgo surgery and will be routinely monitored for any changes, as nevus sebaceus has a potential risk, albeit low, for malignant transformation later in life. No changes have been observed since the initial presentation, and regular follow-ups are planned to monitor for future developments.

Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn is a hamartomatous lesion involving the pilosebaceous follicle and adjacent adnexal structures.1-3 It most commonly forms on the scalp (59.3%) and is accompanied by partial or total alopecia. 3,4 It is seen less often on the face, periauricular area, or neck1,4; thorax or limbs5; and oral or genital mucosae.6 Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn affects approximately 0.3% of newborns,1 usually as a solitary lesion that can form an extensive plaque. The male-to-female occurrence ratio has been reported as equal to slightly more predominant in females; all races and ethnicities are affected.1,5

Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn follows 3 stages of clinical development: infantile, adolescent, and adulthood. It manifests at birth or shortly afterward as a smooth hairless patch or plaque that is yellowish and can be hyperpigmented in Black patients.5 It may have an oval or linear configuration, typically is asymptomatic, and often arises along the Blaschko lines when it occurs as multiple lesions (a rare manifestation).1 During puberty, hormonal changes cause accelerated growth, sebaceous gland maturation, and epidermal hyperplasia. 7 Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn often is not identified until this stage, when its classic wartlike appearance has fully developed.1

Patients with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn have a 10% to 20% risk for tumor development in adulthood.2,7 Trichoblastoma and syringocystadenoma papilliferum are the most frequently described neoplasms.8 Basal cell carcinoma is the most common malignant secondary neoplasm with an occurrence rate of 0.8%.6,9 However, basal cell carcinoma and trichoblastoma may share histopathologic features, which may lead to misdiagnosis and a higher reported incidence of basal cell carcinoma in adults than is accurate.2

Early prophylactic surgical removal of nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn has been recommended; however, surgical management is controversial because the risk for a benign secondary neoplasm remains relatively high while the risk for malignancy is much lower.2,7 Surgical excision remains an acceptable option once the patient is mature enough to tolerate the procedure.1 However, patient education regarding watchful waiting vs a surgical approach— and the risks of each—is critical to ensure shared decision-making and a management plan tailored to the individual.

The differential diagnosis includes hypertrophic lichen planus, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (Letterer-Siwe disease type), epidermal nevus, and seborrheic keratosis. Hypertrophic lichen planus often occurs symmetrically on the dorsal feet and shins with thick, scaly, and extremely pruritic plaques. The lesions often persist for an average of 6 years and may lead to multiple keratoacanthomas or follicular base squamous cell carcinomas. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (Letterer-Siwe disease type) manifests with acute, disseminated, visceral, and cutaneous lesions before 2 years of age. These lesions appear as 1- to 2-mm, pink, seborrheic papules, pustules, or vesicles on the scalp, flexural neck, axilla, perineum, and trunk; they often are associated with petechiae, purpura, scale, crust, erosion, impetiginization, and tender fissures. Epidermal nevus occurs within the first year of life and is a hamartoma of the epidermis and papillary dermis. It manifests as papillomatous pigmented linear lines along the Blaschko lines. Seborrheic keratosis manifests as well-demarcated, waxy/verrucous, brown papules with a “stuck on” appearance on hair-bearing skin sparing the mucosae. They are common benign lesions associated with sun exposure and often manifest in the fourth decade of life.10

- Baigrie D, Troxell T, Cook C. Nevus sebaceus. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 16, 2023. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482493/

- Terenzi V, Indrizzi E, Buonaccorsi S, et al. Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. J Craniofac Surg. 2006;17:1234-1239. doi:10.1097/01 .scs.0000221531.56529.cc

- Kelati A, Baybay H, Gallouj S, et al. Dermoscopic analysis of nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 13 cases. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;3:83-91. doi:10.1159/000460258

- Ugras N, Ozgun G, Adim SB, et al. Nevus sebaceous at unusual location: a rare presentation. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2012;55:419-420. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.101768

- Serpas de Lopez RM, Hernandez-Perez E. Jadassohn’s sebaceous nevus. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1985;11:68-72. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725 .1985.tb02893.x

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2 pt 1):263-268. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(00)90136-1

- Santibanez-Gallerani A, Marshall D, Duarte AM, et al. Should nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn in children be excised? a study of 757 cases, and literature review. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:658-660. doi:10.1097/00001665-200309000-00010

- Chahboun F, Eljazouly M, Elomari M, et al. Trichoblastoma arising from the nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Cureus. 2021;13:E15325. doi:10.7759/cureus.15325

- Cazzato G, Cimmino A, Colagrande A, et al. The multiple faces of nodular trichoblastoma: review of the literature with case presentation. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2021;8:265-270. doi:10.3390 /dermatopathology8030032

- Dandekar MN, Gandhi RK. Neoplastic dermatology. In: Alikhan A, Hocker TLH (eds). Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2016: 321-366.

The Diagnosis: Nevus Sebaceus of Jadassohn

The diagnosis of nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn was made clinically based on the lesion’s appearance and presence since birth as well as the absence of systemic symptoms. Clinically, nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn typically manifests as a well-demarcated, yellow- brown plaque often located on the scalp, as was seen in our patient. The lack of pruritus and pain further supported the diagnosis in our patient. No biopsy was performed, as the presentation was considered classic for this condition. Our patient opted to forgo surgery and will be routinely monitored for any changes, as nevus sebaceus has a potential risk, albeit low, for malignant transformation later in life. No changes have been observed since the initial presentation, and regular follow-ups are planned to monitor for future developments.

Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn is a hamartomatous lesion involving the pilosebaceous follicle and adjacent adnexal structures.1-3 It most commonly forms on the scalp (59.3%) and is accompanied by partial or total alopecia. 3,4 It is seen less often on the face, periauricular area, or neck1,4; thorax or limbs5; and oral or genital mucosae.6 Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn affects approximately 0.3% of newborns,1 usually as a solitary lesion that can form an extensive plaque. The male-to-female occurrence ratio has been reported as equal to slightly more predominant in females; all races and ethnicities are affected.1,5

Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn follows 3 stages of clinical development: infantile, adolescent, and adulthood. It manifests at birth or shortly afterward as a smooth hairless patch or plaque that is yellowish and can be hyperpigmented in Black patients.5 It may have an oval or linear configuration, typically is asymptomatic, and often arises along the Blaschko lines when it occurs as multiple lesions (a rare manifestation).1 During puberty, hormonal changes cause accelerated growth, sebaceous gland maturation, and epidermal hyperplasia. 7 Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn often is not identified until this stage, when its classic wartlike appearance has fully developed.1

Patients with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn have a 10% to 20% risk for tumor development in adulthood.2,7 Trichoblastoma and syringocystadenoma papilliferum are the most frequently described neoplasms.8 Basal cell carcinoma is the most common malignant secondary neoplasm with an occurrence rate of 0.8%.6,9 However, basal cell carcinoma and trichoblastoma may share histopathologic features, which may lead to misdiagnosis and a higher reported incidence of basal cell carcinoma in adults than is accurate.2

Early prophylactic surgical removal of nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn has been recommended; however, surgical management is controversial because the risk for a benign secondary neoplasm remains relatively high while the risk for malignancy is much lower.2,7 Surgical excision remains an acceptable option once the patient is mature enough to tolerate the procedure.1 However, patient education regarding watchful waiting vs a surgical approach— and the risks of each—is critical to ensure shared decision-making and a management plan tailored to the individual.

The differential diagnosis includes hypertrophic lichen planus, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (Letterer-Siwe disease type), epidermal nevus, and seborrheic keratosis. Hypertrophic lichen planus often occurs symmetrically on the dorsal feet and shins with thick, scaly, and extremely pruritic plaques. The lesions often persist for an average of 6 years and may lead to multiple keratoacanthomas or follicular base squamous cell carcinomas. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (Letterer-Siwe disease type) manifests with acute, disseminated, visceral, and cutaneous lesions before 2 years of age. These lesions appear as 1- to 2-mm, pink, seborrheic papules, pustules, or vesicles on the scalp, flexural neck, axilla, perineum, and trunk; they often are associated with petechiae, purpura, scale, crust, erosion, impetiginization, and tender fissures. Epidermal nevus occurs within the first year of life and is a hamartoma of the epidermis and papillary dermis. It manifests as papillomatous pigmented linear lines along the Blaschko lines. Seborrheic keratosis manifests as well-demarcated, waxy/verrucous, brown papules with a “stuck on” appearance on hair-bearing skin sparing the mucosae. They are common benign lesions associated with sun exposure and often manifest in the fourth decade of life.10

The Diagnosis: Nevus Sebaceus of Jadassohn

The diagnosis of nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn was made clinically based on the lesion’s appearance and presence since birth as well as the absence of systemic symptoms. Clinically, nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn typically manifests as a well-demarcated, yellow- brown plaque often located on the scalp, as was seen in our patient. The lack of pruritus and pain further supported the diagnosis in our patient. No biopsy was performed, as the presentation was considered classic for this condition. Our patient opted to forgo surgery and will be routinely monitored for any changes, as nevus sebaceus has a potential risk, albeit low, for malignant transformation later in life. No changes have been observed since the initial presentation, and regular follow-ups are planned to monitor for future developments.

Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn is a hamartomatous lesion involving the pilosebaceous follicle and adjacent adnexal structures.1-3 It most commonly forms on the scalp (59.3%) and is accompanied by partial or total alopecia. 3,4 It is seen less often on the face, periauricular area, or neck1,4; thorax or limbs5; and oral or genital mucosae.6 Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn affects approximately 0.3% of newborns,1 usually as a solitary lesion that can form an extensive plaque. The male-to-female occurrence ratio has been reported as equal to slightly more predominant in females; all races and ethnicities are affected.1,5

Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn follows 3 stages of clinical development: infantile, adolescent, and adulthood. It manifests at birth or shortly afterward as a smooth hairless patch or plaque that is yellowish and can be hyperpigmented in Black patients.5 It may have an oval or linear configuration, typically is asymptomatic, and often arises along the Blaschko lines when it occurs as multiple lesions (a rare manifestation).1 During puberty, hormonal changes cause accelerated growth, sebaceous gland maturation, and epidermal hyperplasia. 7 Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn often is not identified until this stage, when its classic wartlike appearance has fully developed.1

Patients with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn have a 10% to 20% risk for tumor development in adulthood.2,7 Trichoblastoma and syringocystadenoma papilliferum are the most frequently described neoplasms.8 Basal cell carcinoma is the most common malignant secondary neoplasm with an occurrence rate of 0.8%.6,9 However, basal cell carcinoma and trichoblastoma may share histopathologic features, which may lead to misdiagnosis and a higher reported incidence of basal cell carcinoma in adults than is accurate.2

Early prophylactic surgical removal of nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn has been recommended; however, surgical management is controversial because the risk for a benign secondary neoplasm remains relatively high while the risk for malignancy is much lower.2,7 Surgical excision remains an acceptable option once the patient is mature enough to tolerate the procedure.1 However, patient education regarding watchful waiting vs a surgical approach— and the risks of each—is critical to ensure shared decision-making and a management plan tailored to the individual.

The differential diagnosis includes hypertrophic lichen planus, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (Letterer-Siwe disease type), epidermal nevus, and seborrheic keratosis. Hypertrophic lichen planus often occurs symmetrically on the dorsal feet and shins with thick, scaly, and extremely pruritic plaques. The lesions often persist for an average of 6 years and may lead to multiple keratoacanthomas or follicular base squamous cell carcinomas. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (Letterer-Siwe disease type) manifests with acute, disseminated, visceral, and cutaneous lesions before 2 years of age. These lesions appear as 1- to 2-mm, pink, seborrheic papules, pustules, or vesicles on the scalp, flexural neck, axilla, perineum, and trunk; they often are associated with petechiae, purpura, scale, crust, erosion, impetiginization, and tender fissures. Epidermal nevus occurs within the first year of life and is a hamartoma of the epidermis and papillary dermis. It manifests as papillomatous pigmented linear lines along the Blaschko lines. Seborrheic keratosis manifests as well-demarcated, waxy/verrucous, brown papules with a “stuck on” appearance on hair-bearing skin sparing the mucosae. They are common benign lesions associated with sun exposure and often manifest in the fourth decade of life.10

- Baigrie D, Troxell T, Cook C. Nevus sebaceus. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 16, 2023. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482493/

- Terenzi V, Indrizzi E, Buonaccorsi S, et al. Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. J Craniofac Surg. 2006;17:1234-1239. doi:10.1097/01 .scs.0000221531.56529.cc

- Kelati A, Baybay H, Gallouj S, et al. Dermoscopic analysis of nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 13 cases. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;3:83-91. doi:10.1159/000460258

- Ugras N, Ozgun G, Adim SB, et al. Nevus sebaceous at unusual location: a rare presentation. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2012;55:419-420. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.101768

- Serpas de Lopez RM, Hernandez-Perez E. Jadassohn’s sebaceous nevus. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1985;11:68-72. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725 .1985.tb02893.x

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2 pt 1):263-268. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(00)90136-1

- Santibanez-Gallerani A, Marshall D, Duarte AM, et al. Should nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn in children be excised? a study of 757 cases, and literature review. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:658-660. doi:10.1097/00001665-200309000-00010

- Chahboun F, Eljazouly M, Elomari M, et al. Trichoblastoma arising from the nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Cureus. 2021;13:E15325. doi:10.7759/cureus.15325

- Cazzato G, Cimmino A, Colagrande A, et al. The multiple faces of nodular trichoblastoma: review of the literature with case presentation. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2021;8:265-270. doi:10.3390 /dermatopathology8030032

- Dandekar MN, Gandhi RK. Neoplastic dermatology. In: Alikhan A, Hocker TLH (eds). Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2016: 321-366.

- Baigrie D, Troxell T, Cook C. Nevus sebaceus. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 16, 2023. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482493/

- Terenzi V, Indrizzi E, Buonaccorsi S, et al. Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. J Craniofac Surg. 2006;17:1234-1239. doi:10.1097/01 .scs.0000221531.56529.cc

- Kelati A, Baybay H, Gallouj S, et al. Dermoscopic analysis of nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 13 cases. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;3:83-91. doi:10.1159/000460258

- Ugras N, Ozgun G, Adim SB, et al. Nevus sebaceous at unusual location: a rare presentation. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2012;55:419-420. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.101768

- Serpas de Lopez RM, Hernandez-Perez E. Jadassohn’s sebaceous nevus. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1985;11:68-72. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725 .1985.tb02893.x

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2 pt 1):263-268. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(00)90136-1

- Santibanez-Gallerani A, Marshall D, Duarte AM, et al. Should nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn in children be excised? a study of 757 cases, and literature review. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:658-660. doi:10.1097/00001665-200309000-00010

- Chahboun F, Eljazouly M, Elomari M, et al. Trichoblastoma arising from the nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Cureus. 2021;13:E15325. doi:10.7759/cureus.15325

- Cazzato G, Cimmino A, Colagrande A, et al. The multiple faces of nodular trichoblastoma: review of the literature with case presentation. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2021;8:265-270. doi:10.3390 /dermatopathology8030032

- Dandekar MN, Gandhi RK. Neoplastic dermatology. In: Alikhan A, Hocker TLH (eds). Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2016: 321-366.

A 23-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with hair loss on the scalp of several years’ duration. The patient reported persistent pigmented bumps on the back of the scalp. He denied any pruritus or pain and had no systemic symptoms or comorbidities. Physical examination revealed a 1×1.5-cm, yellow-brown, hairless plaque on the left parietal scalp.

Purpuric Lesions on the Leg

THE DIAGNOSIS: Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever

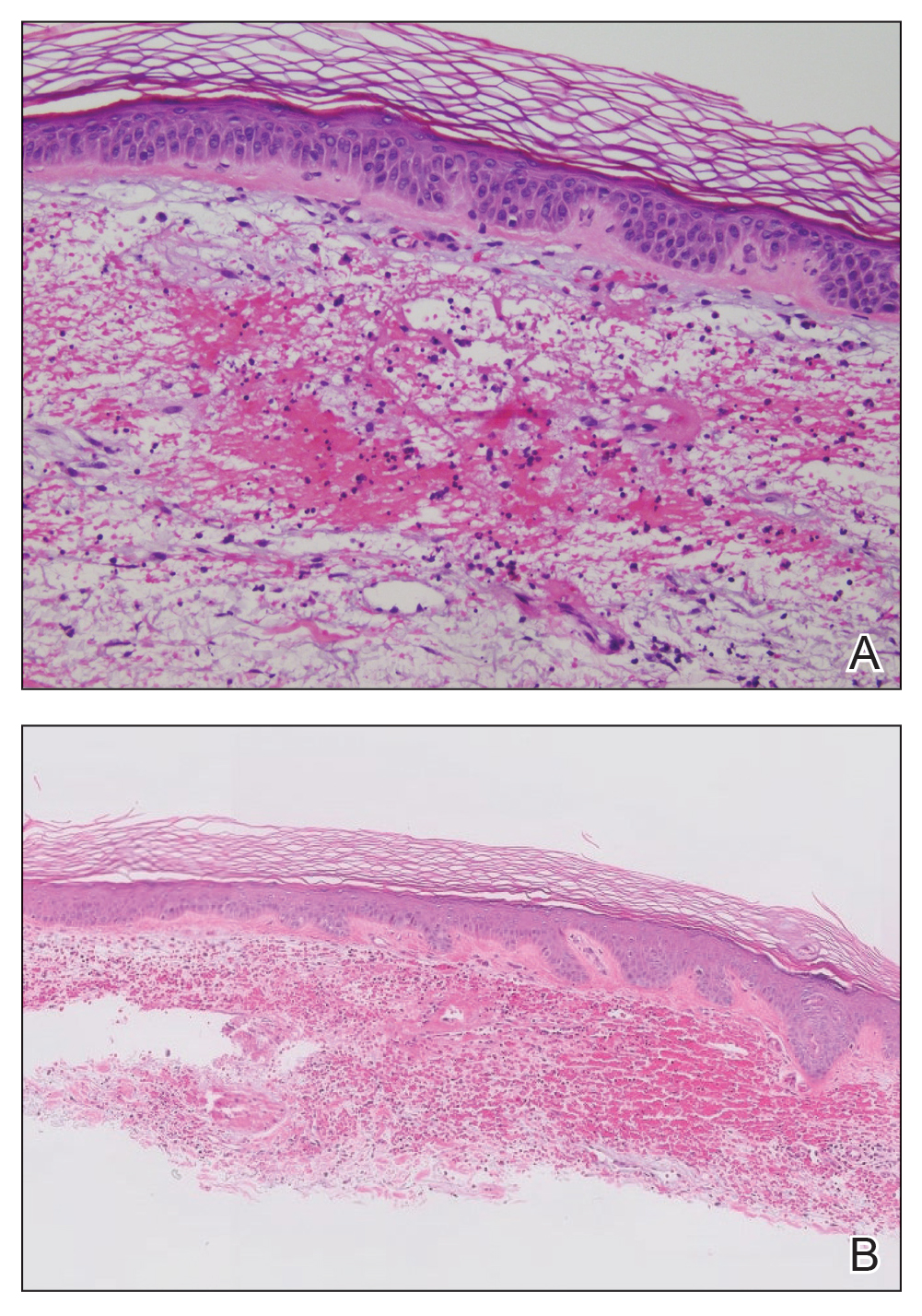

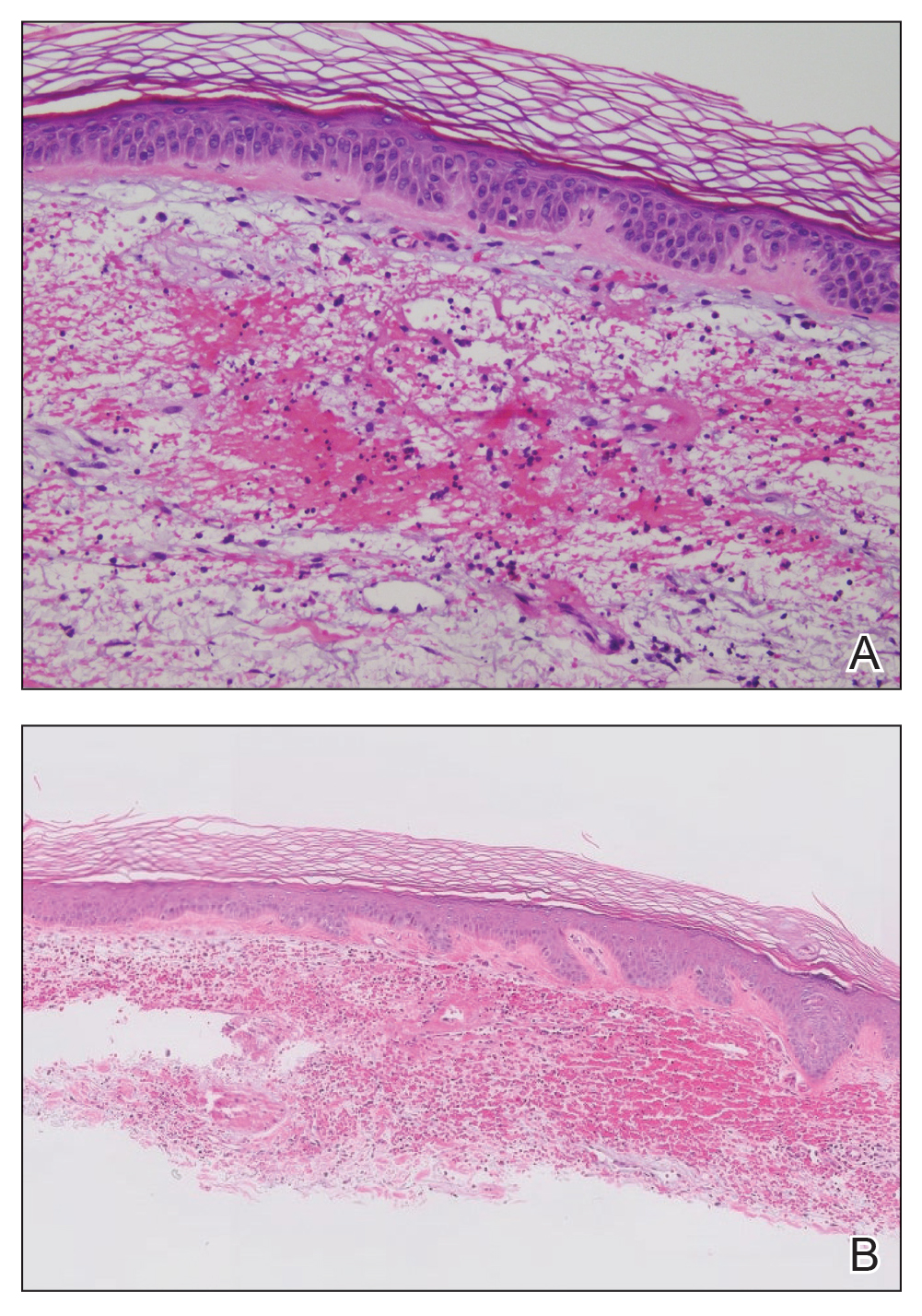

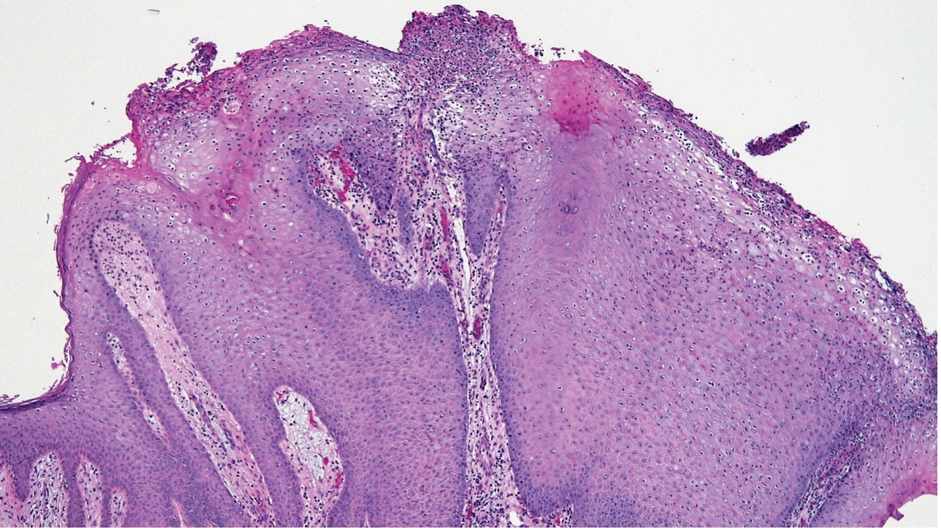

The retiform purpura observed in our patient was suggestive of a vasculitic, thrombotic, or embolic etiology. Dengue IgM serologic testing performed based on her extensive travel history and recent return from a dengue-endemic area was positive, indicating acute infection. A clinical diagnosis of dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) was made based on the hemorrhagic appearance of the lesion. Histopathology revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure). Anti–double-stranded DNA, antideoxyribonuclease, C3 and C4, CH50 (total hemolytic complement), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, HIV, and hepatitis B virus tests were normal. Direct immunofluorescence was negative.

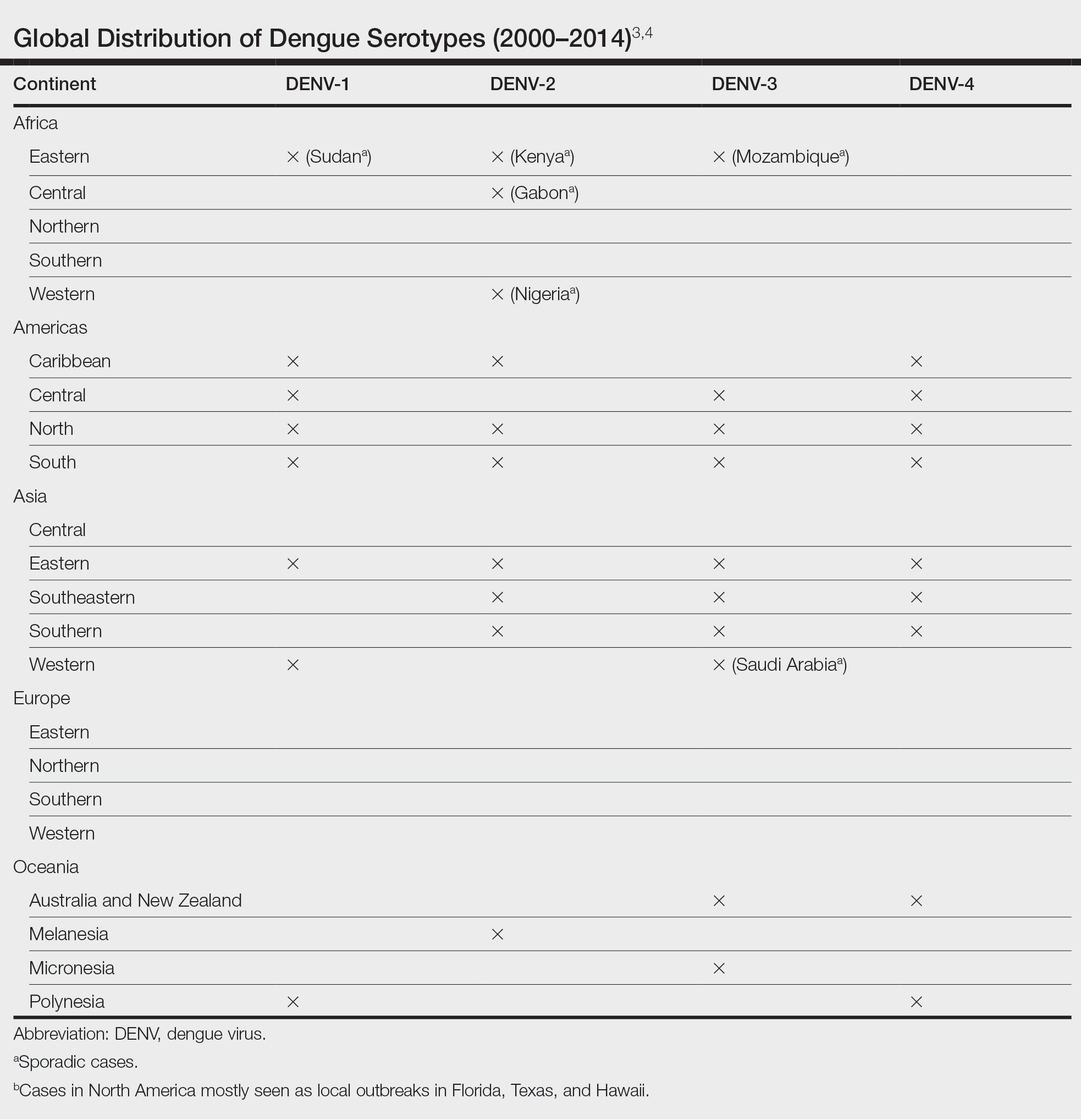

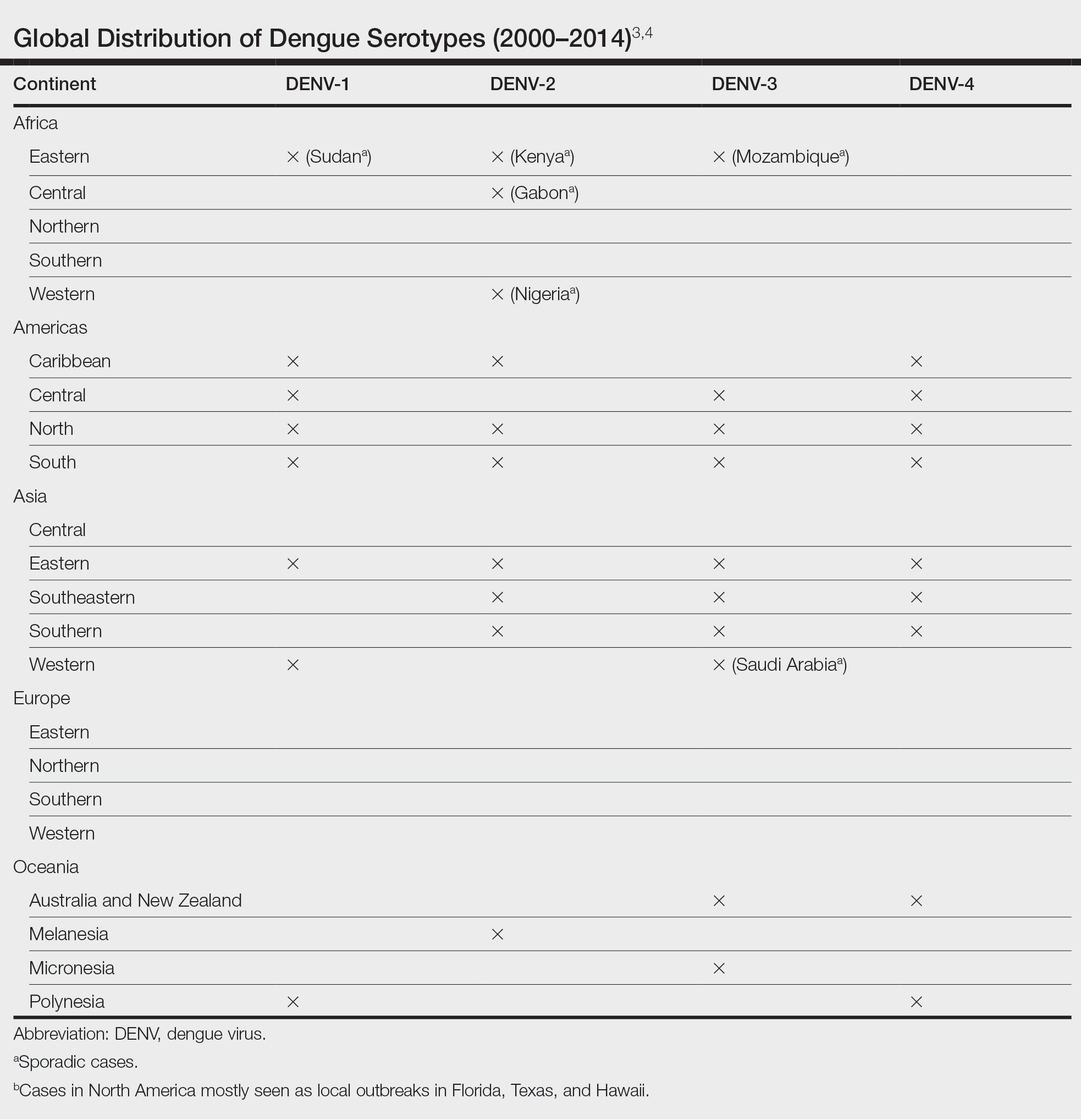

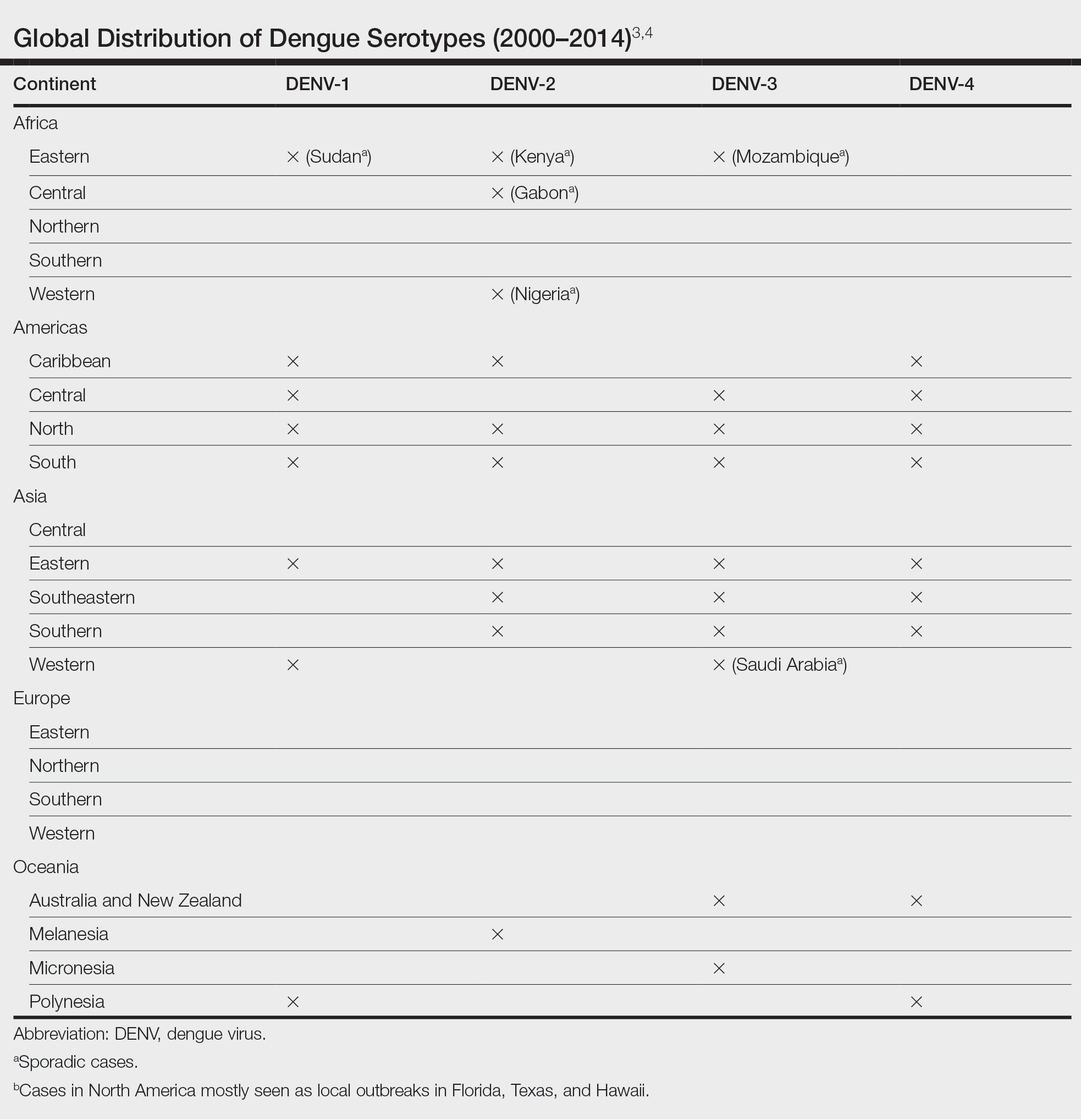

Dengue virus is a single-stranded RNA virus transmitted by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes and is one of the most prevalent arthropod-borne viruses affecting humans today.1,2 Infection with the dengue virus generally is seen in travelers visiting tropical regions of Africa, Mexico, South America, South and Central Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Caribbean.1 The Table shows the global distribution of dengue serotypes from 2000 to 2014.3,4 There are 4 serotypes of the dengue virus: DENV-1 to DENV-4. Infection with 1 strain elicits longlasting immunity to that strain, but subsequent infection with another strain can result in severe DHF due to antibody cross-reaction.1

Dengue virus infection ranges from mildly symptomatic to a spectrum of increasingly severe conditions that comprise dengue fever (DF) and DHF, as well as dengue shock syndrome and brain stem hemorrhage, which may be fatal.2,5 Dengue fever manifests as severe myalgia, fever, headache (usually retro-orbital), arthralgia, erythema, and rubelliform exanthema.6 The frequency of skin eruptions in patients with DF varies with the virus strain and outbreaks.7 The lesions initially develop with the onset of fever and manifest as flushing or erythematous mottling of the face, neck, and chest areas.1,7 The morbilliform eruption develops 2 to 6 days after the onset of the fever, beginning on the trunk and spreading to the face and extremities.1,7 The rash may become confluent with characteristic sparing of small round areas of normal skin described as white islands in a sea of red.2 Verrucous papules on the ears also have been described and may resemble those seen in Cowden syndrome. In patients with prior infection with a different strain of the virus, hemorrhagic lesions may develop, including characteristic retiform purpura, a positive tourniquet test, and the appearance of petechiae on the lower legs. Pruritus and desquamation, especially on the palms and soles, may follow the termination of the eruption.7

The differential diagnosis of DF includes measles, rubella, enteroviruses, and influenza. Chikungunya and West Nile viruses in Asia and Africa and the O’nyong-nyong virus in Africa are also arboviruses that cause a clinical picture similar to DF but not DHF. Other diagnostic considerations include phases of scarlet fever, typhoid, malaria, leptospirosis, hepatitis A, and trypanosomal and rickettsial diseases.7 The differential diagnosis of DHF includes antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis, rheumatoid vasculitis, and bacterial septic vasculitis.

Acute clinical diagnosis of DF can be challenging because of the nonspecific symptoms that can be seen in almost every infectious disease. Clinical presentation assessment should be confirmed with laboratory testing.6 Dengue virus infection usually is confirmed by the identification of viral genomic RNA, antigens, or the antibodies it elicits. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay–based serologic tests are cost-effective and easy to perform.5 IgM antibodies usually show cross-reactivity with platelets, but the antibody levels are not positively correlated with the severity of DF.8 Primary infection with the dengue virus is characterized by the elevation of specific IgM levels that usually occurs 3 to 5 days after symptom onset and persists during the postfebrile stage (up to 30 to 60 days). In secondary infections, the IgM levels usually rise more slowly and reach a lower level than in primary infections.9 For both primary and secondary infections, testing IgM levels after the febrile stage may be helpful with the laboratory diagnosis.

Currently, there is no antiviral drug available for dengue. Treatment of dengue infection is symptomatic and supportive.2

Dengue hemorrhagic fever is indicated by a rising hematocrit (≥20%) and a falling platelet count (>100,000/mm3) accompanying clinical signs of hemorrhage. Treatment includes intravenous fluid replacement and careful clinical monitoring of hematocrit levels, platelet count, vitals, urine output, and other signs of shock.5 For patients with a history of dengue infection, travel to areas with other serotypes is not recommended.

If any travel to a high-risk area is planned, countryspecific travel recommendations and warnings should be reviewed from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s website (https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/level1/dengue-global). Use of an Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellent to avoid mosquito bites and acetaminophen for managing symptoms is advised. During travel, staying in places with window and door screens and using a bed net during sleep are suggested. Long-sleeved shirts and long pants also are preferred. Travelers should see a health care provider if they have symptoms of dengue.10

African tick bite fever (ATBF) is caused by Rickettsia africae transmitted by Amblyomma ticks. Skin findings in ATBF include erythematous, firm, tender papules with central eschars consistent with the feeding patterns of ticks.11 Histopathology of ATBF usually includes fibrinoid necrosis of vessels in the dermis with a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate and coagulation necrosis of the surrounding dermis consistent with eschar formation.12 The lack of an eschar weighs against this diagnosis.

African trypanosomiasis (also known as sleeping sickness) is caused by protozoa transmitted by the tsetse fly. A chancrelike, circumscribed, rubbery, indurated red or violaceous nodule measuring 2 to 5 cm in diameter often develops as the earliest cutaneous sign of the disease.13 Nonspecific histopathologic findings, such as infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages and proliferation of endothelial cells and fibroblasts, may be observed.14 Extravascular parasites have been noted in skin biopsies.15 In later stages, skin lesions called trypanids may be observed as macular, papular, annular, targetoid, purpuric, and erythematous lesions, and histopathologic findings consistent with vasculitis also may be seen.13

Chikungunya virus infection is an acute-onset, mosquito-borne viral disease. Skin manifestations may start with nonspecific, generalized, morbilliform, maculopapular rashes coinciding with fever, which also may be seen initially with DHF. Skin hyperpigmentation, mostly centrofacial and involving the nose (chik sign); purpuric and ecchymotic lesions over the trunk and flexors of limbs in adults, often surmounted by subepidermal bullae and lesions resembling toxic epidermal necrolysis; and nonhealing ulcers in the genital and groin areas are common skin manifestations of chikungunya infection.16 Intraepithelial splitting with acantholysis and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltration may be observed in the histopathology of blistering lesions, which are not consistent with DHF.17

Zika virus infection is caused by an arbovirus within the Flaviviridae family, which also includes the dengue virus. Initial mucocutaneous findings of the Zika virus include nonspecific diffuse maculopapular eruptions. The eruption generally spares the palms and soles; however, various manifestations including involvement of the palms and soles have been reported.18 The morbilliform eruption begins on the face and extends to the trunk and extremities. Mild hemorrhagic manifestations, including petechiae and bleeding gums, may be observed. Distinguishing between dengue and Zika virus infection relies on the severity of symptoms and laboratory tests, including polymerase chain reaction or IgM antibody testing.19 The other conditions listed do not produce hemorrhagic fever.

- Pincus LB, Grossman ME, Fox LP. The exanthem of dengue fever: clinical features of two US tourists traveling abroad. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:308-316. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.08.042

- Radakovic-Fijan S, Graninger W, Müller C, et al. Dengue hemorrhagic fever in a British travel guide. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:430-433. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.111904

- Yamashita A, Sakamoto T, Sekizuka T, et al. DGV: dengue genographic viewer. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:875. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00875

- Centers for Disease and Prevention. Dengue in the US states and territories. Updated October 7, 2020. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/data-research/facts-stats/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/areaswithrisk/in-the-us.html

- Khetarpal N, Khanna I. Dengue fever: causes, complications, and vaccine strategies. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:6803098. doi:10.1155/2016/6803098

- Muller DA, Depelsenaire AC, Young PR. Clinical and laboratory diagnosis of dengue virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(suppl 2):S89-S95. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiw649

- Waterman SH, Gubler DJ. Dengue fever. Clin Dermatol. 1989;7:117-122. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(89)90034-5

- Lin CF, Lei HY, Liu CC, et al. Generation of IgM anti-platelet autoantibody in dengue patients. J Med Virol. 2001;63:143-149. doi:10.1002/1096- 9071(20000201)63:2<143::AID-JMV1009>3.0.CO;2-L

- Tripathi NK, Shrivastava A, Dash PK, et al. Detection of dengue virus. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;665:51-64. doi:10.1007/978-1-60761-817-1_4

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Plan for travel. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel

- Mack I, Ritz N. African tick-bite fever. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:960. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1810093

- Lepidi H, Fournier PE, Raoult D. Histologic features and immunodetection of African tick-bite fever eschar. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1332- 1337. doi:10.3201/eid1209.051540

- McGovern TW, Williams W, Fitzpatrick JE, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of African trypanosomiasis. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1178-1182.

- Kristensson K, Bentivoglio M. Pathology of African trypanosomiasis. In: Dumas M, Bouteille B, Buguet A, eds. Progress in Human African Trypanosomiasis, Sleeping Sickness. Springer; 1999:157-181.

- Capewell P, Cren-Travaillé C, Marchesi F, et al. The skin is a significant but overlooked anatomical reservoir for vector-borne African trypanosomes. Elife. 2016;5:e17716. doi:10.7554/eLife.17716

- Singal A. Chikungunya and skin: current perspective. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:307-309. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_93_17

- Robin S, Ramful D, Zettor J, et al. Severe bullous skin lesions associated with chikungunya virus infection in small infants. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;169:67-72. doi:10.1007/s00431-009-0986-0

- Hussain A, Ali F, Latiwesh OB, et al. A comprehensive review of the manifestations and pathogenesis of Zika virus in neonates and adults. Cureus. 2018;10:E3290. doi:10.7759/cureus.3290

- Farahnik B, Beroukhim K, Blattner CM, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of the Zika virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1286-1287. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1232

THE DIAGNOSIS: Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever

The retiform purpura observed in our patient was suggestive of a vasculitic, thrombotic, or embolic etiology. Dengue IgM serologic testing performed based on her extensive travel history and recent return from a dengue-endemic area was positive, indicating acute infection. A clinical diagnosis of dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) was made based on the hemorrhagic appearance of the lesion. Histopathology revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure). Anti–double-stranded DNA, antideoxyribonuclease, C3 and C4, CH50 (total hemolytic complement), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, HIV, and hepatitis B virus tests were normal. Direct immunofluorescence was negative.

Dengue virus is a single-stranded RNA virus transmitted by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes and is one of the most prevalent arthropod-borne viruses affecting humans today.1,2 Infection with the dengue virus generally is seen in travelers visiting tropical regions of Africa, Mexico, South America, South and Central Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Caribbean.1 The Table shows the global distribution of dengue serotypes from 2000 to 2014.3,4 There are 4 serotypes of the dengue virus: DENV-1 to DENV-4. Infection with 1 strain elicits longlasting immunity to that strain, but subsequent infection with another strain can result in severe DHF due to antibody cross-reaction.1

Dengue virus infection ranges from mildly symptomatic to a spectrum of increasingly severe conditions that comprise dengue fever (DF) and DHF, as well as dengue shock syndrome and brain stem hemorrhage, which may be fatal.2,5 Dengue fever manifests as severe myalgia, fever, headache (usually retro-orbital), arthralgia, erythema, and rubelliform exanthema.6 The frequency of skin eruptions in patients with DF varies with the virus strain and outbreaks.7 The lesions initially develop with the onset of fever and manifest as flushing or erythematous mottling of the face, neck, and chest areas.1,7 The morbilliform eruption develops 2 to 6 days after the onset of the fever, beginning on the trunk and spreading to the face and extremities.1,7 The rash may become confluent with characteristic sparing of small round areas of normal skin described as white islands in a sea of red.2 Verrucous papules on the ears also have been described and may resemble those seen in Cowden syndrome. In patients with prior infection with a different strain of the virus, hemorrhagic lesions may develop, including characteristic retiform purpura, a positive tourniquet test, and the appearance of petechiae on the lower legs. Pruritus and desquamation, especially on the palms and soles, may follow the termination of the eruption.7

The differential diagnosis of DF includes measles, rubella, enteroviruses, and influenza. Chikungunya and West Nile viruses in Asia and Africa and the O’nyong-nyong virus in Africa are also arboviruses that cause a clinical picture similar to DF but not DHF. Other diagnostic considerations include phases of scarlet fever, typhoid, malaria, leptospirosis, hepatitis A, and trypanosomal and rickettsial diseases.7 The differential diagnosis of DHF includes antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis, rheumatoid vasculitis, and bacterial septic vasculitis.

Acute clinical diagnosis of DF can be challenging because of the nonspecific symptoms that can be seen in almost every infectious disease. Clinical presentation assessment should be confirmed with laboratory testing.6 Dengue virus infection usually is confirmed by the identification of viral genomic RNA, antigens, or the antibodies it elicits. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay–based serologic tests are cost-effective and easy to perform.5 IgM antibodies usually show cross-reactivity with platelets, but the antibody levels are not positively correlated with the severity of DF.8 Primary infection with the dengue virus is characterized by the elevation of specific IgM levels that usually occurs 3 to 5 days after symptom onset and persists during the postfebrile stage (up to 30 to 60 days). In secondary infections, the IgM levels usually rise more slowly and reach a lower level than in primary infections.9 For both primary and secondary infections, testing IgM levels after the febrile stage may be helpful with the laboratory diagnosis.

Currently, there is no antiviral drug available for dengue. Treatment of dengue infection is symptomatic and supportive.2

Dengue hemorrhagic fever is indicated by a rising hematocrit (≥20%) and a falling platelet count (>100,000/mm3) accompanying clinical signs of hemorrhage. Treatment includes intravenous fluid replacement and careful clinical monitoring of hematocrit levels, platelet count, vitals, urine output, and other signs of shock.5 For patients with a history of dengue infection, travel to areas with other serotypes is not recommended.

If any travel to a high-risk area is planned, countryspecific travel recommendations and warnings should be reviewed from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s website (https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/level1/dengue-global). Use of an Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellent to avoid mosquito bites and acetaminophen for managing symptoms is advised. During travel, staying in places with window and door screens and using a bed net during sleep are suggested. Long-sleeved shirts and long pants also are preferred. Travelers should see a health care provider if they have symptoms of dengue.10

African tick bite fever (ATBF) is caused by Rickettsia africae transmitted by Amblyomma ticks. Skin findings in ATBF include erythematous, firm, tender papules with central eschars consistent with the feeding patterns of ticks.11 Histopathology of ATBF usually includes fibrinoid necrosis of vessels in the dermis with a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate and coagulation necrosis of the surrounding dermis consistent with eschar formation.12 The lack of an eschar weighs against this diagnosis.

African trypanosomiasis (also known as sleeping sickness) is caused by protozoa transmitted by the tsetse fly. A chancrelike, circumscribed, rubbery, indurated red or violaceous nodule measuring 2 to 5 cm in diameter often develops as the earliest cutaneous sign of the disease.13 Nonspecific histopathologic findings, such as infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages and proliferation of endothelial cells and fibroblasts, may be observed.14 Extravascular parasites have been noted in skin biopsies.15 In later stages, skin lesions called trypanids may be observed as macular, papular, annular, targetoid, purpuric, and erythematous lesions, and histopathologic findings consistent with vasculitis also may be seen.13

Chikungunya virus infection is an acute-onset, mosquito-borne viral disease. Skin manifestations may start with nonspecific, generalized, morbilliform, maculopapular rashes coinciding with fever, which also may be seen initially with DHF. Skin hyperpigmentation, mostly centrofacial and involving the nose (chik sign); purpuric and ecchymotic lesions over the trunk and flexors of limbs in adults, often surmounted by subepidermal bullae and lesions resembling toxic epidermal necrolysis; and nonhealing ulcers in the genital and groin areas are common skin manifestations of chikungunya infection.16 Intraepithelial splitting with acantholysis and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltration may be observed in the histopathology of blistering lesions, which are not consistent with DHF.17

Zika virus infection is caused by an arbovirus within the Flaviviridae family, which also includes the dengue virus. Initial mucocutaneous findings of the Zika virus include nonspecific diffuse maculopapular eruptions. The eruption generally spares the palms and soles; however, various manifestations including involvement of the palms and soles have been reported.18 The morbilliform eruption begins on the face and extends to the trunk and extremities. Mild hemorrhagic manifestations, including petechiae and bleeding gums, may be observed. Distinguishing between dengue and Zika virus infection relies on the severity of symptoms and laboratory tests, including polymerase chain reaction or IgM antibody testing.19 The other conditions listed do not produce hemorrhagic fever.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever

The retiform purpura observed in our patient was suggestive of a vasculitic, thrombotic, or embolic etiology. Dengue IgM serologic testing performed based on her extensive travel history and recent return from a dengue-endemic area was positive, indicating acute infection. A clinical diagnosis of dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) was made based on the hemorrhagic appearance of the lesion. Histopathology revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure). Anti–double-stranded DNA, antideoxyribonuclease, C3 and C4, CH50 (total hemolytic complement), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, HIV, and hepatitis B virus tests were normal. Direct immunofluorescence was negative.

Dengue virus is a single-stranded RNA virus transmitted by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes and is one of the most prevalent arthropod-borne viruses affecting humans today.1,2 Infection with the dengue virus generally is seen in travelers visiting tropical regions of Africa, Mexico, South America, South and Central Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Caribbean.1 The Table shows the global distribution of dengue serotypes from 2000 to 2014.3,4 There are 4 serotypes of the dengue virus: DENV-1 to DENV-4. Infection with 1 strain elicits longlasting immunity to that strain, but subsequent infection with another strain can result in severe DHF due to antibody cross-reaction.1

Dengue virus infection ranges from mildly symptomatic to a spectrum of increasingly severe conditions that comprise dengue fever (DF) and DHF, as well as dengue shock syndrome and brain stem hemorrhage, which may be fatal.2,5 Dengue fever manifests as severe myalgia, fever, headache (usually retro-orbital), arthralgia, erythema, and rubelliform exanthema.6 The frequency of skin eruptions in patients with DF varies with the virus strain and outbreaks.7 The lesions initially develop with the onset of fever and manifest as flushing or erythematous mottling of the face, neck, and chest areas.1,7 The morbilliform eruption develops 2 to 6 days after the onset of the fever, beginning on the trunk and spreading to the face and extremities.1,7 The rash may become confluent with characteristic sparing of small round areas of normal skin described as white islands in a sea of red.2 Verrucous papules on the ears also have been described and may resemble those seen in Cowden syndrome. In patients with prior infection with a different strain of the virus, hemorrhagic lesions may develop, including characteristic retiform purpura, a positive tourniquet test, and the appearance of petechiae on the lower legs. Pruritus and desquamation, especially on the palms and soles, may follow the termination of the eruption.7

The differential diagnosis of DF includes measles, rubella, enteroviruses, and influenza. Chikungunya and West Nile viruses in Asia and Africa and the O’nyong-nyong virus in Africa are also arboviruses that cause a clinical picture similar to DF but not DHF. Other diagnostic considerations include phases of scarlet fever, typhoid, malaria, leptospirosis, hepatitis A, and trypanosomal and rickettsial diseases.7 The differential diagnosis of DHF includes antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis, rheumatoid vasculitis, and bacterial septic vasculitis.

Acute clinical diagnosis of DF can be challenging because of the nonspecific symptoms that can be seen in almost every infectious disease. Clinical presentation assessment should be confirmed with laboratory testing.6 Dengue virus infection usually is confirmed by the identification of viral genomic RNA, antigens, or the antibodies it elicits. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay–based serologic tests are cost-effective and easy to perform.5 IgM antibodies usually show cross-reactivity with platelets, but the antibody levels are not positively correlated with the severity of DF.8 Primary infection with the dengue virus is characterized by the elevation of specific IgM levels that usually occurs 3 to 5 days after symptom onset and persists during the postfebrile stage (up to 30 to 60 days). In secondary infections, the IgM levels usually rise more slowly and reach a lower level than in primary infections.9 For both primary and secondary infections, testing IgM levels after the febrile stage may be helpful with the laboratory diagnosis.

Currently, there is no antiviral drug available for dengue. Treatment of dengue infection is symptomatic and supportive.2

Dengue hemorrhagic fever is indicated by a rising hematocrit (≥20%) and a falling platelet count (>100,000/mm3) accompanying clinical signs of hemorrhage. Treatment includes intravenous fluid replacement and careful clinical monitoring of hematocrit levels, platelet count, vitals, urine output, and other signs of shock.5 For patients with a history of dengue infection, travel to areas with other serotypes is not recommended.

If any travel to a high-risk area is planned, countryspecific travel recommendations and warnings should be reviewed from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s website (https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/level1/dengue-global). Use of an Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellent to avoid mosquito bites and acetaminophen for managing symptoms is advised. During travel, staying in places with window and door screens and using a bed net during sleep are suggested. Long-sleeved shirts and long pants also are preferred. Travelers should see a health care provider if they have symptoms of dengue.10

African tick bite fever (ATBF) is caused by Rickettsia africae transmitted by Amblyomma ticks. Skin findings in ATBF include erythematous, firm, tender papules with central eschars consistent with the feeding patterns of ticks.11 Histopathology of ATBF usually includes fibrinoid necrosis of vessels in the dermis with a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate and coagulation necrosis of the surrounding dermis consistent with eschar formation.12 The lack of an eschar weighs against this diagnosis.

African trypanosomiasis (also known as sleeping sickness) is caused by protozoa transmitted by the tsetse fly. A chancrelike, circumscribed, rubbery, indurated red or violaceous nodule measuring 2 to 5 cm in diameter often develops as the earliest cutaneous sign of the disease.13 Nonspecific histopathologic findings, such as infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages and proliferation of endothelial cells and fibroblasts, may be observed.14 Extravascular parasites have been noted in skin biopsies.15 In later stages, skin lesions called trypanids may be observed as macular, papular, annular, targetoid, purpuric, and erythematous lesions, and histopathologic findings consistent with vasculitis also may be seen.13

Chikungunya virus infection is an acute-onset, mosquito-borne viral disease. Skin manifestations may start with nonspecific, generalized, morbilliform, maculopapular rashes coinciding with fever, which also may be seen initially with DHF. Skin hyperpigmentation, mostly centrofacial and involving the nose (chik sign); purpuric and ecchymotic lesions over the trunk and flexors of limbs in adults, often surmounted by subepidermal bullae and lesions resembling toxic epidermal necrolysis; and nonhealing ulcers in the genital and groin areas are common skin manifestations of chikungunya infection.16 Intraepithelial splitting with acantholysis and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltration may be observed in the histopathology of blistering lesions, which are not consistent with DHF.17

Zika virus infection is caused by an arbovirus within the Flaviviridae family, which also includes the dengue virus. Initial mucocutaneous findings of the Zika virus include nonspecific diffuse maculopapular eruptions. The eruption generally spares the palms and soles; however, various manifestations including involvement of the palms and soles have been reported.18 The morbilliform eruption begins on the face and extends to the trunk and extremities. Mild hemorrhagic manifestations, including petechiae and bleeding gums, may be observed. Distinguishing between dengue and Zika virus infection relies on the severity of symptoms and laboratory tests, including polymerase chain reaction or IgM antibody testing.19 The other conditions listed do not produce hemorrhagic fever.

- Pincus LB, Grossman ME, Fox LP. The exanthem of dengue fever: clinical features of two US tourists traveling abroad. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:308-316. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.08.042

- Radakovic-Fijan S, Graninger W, Müller C, et al. Dengue hemorrhagic fever in a British travel guide. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:430-433. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.111904

- Yamashita A, Sakamoto T, Sekizuka T, et al. DGV: dengue genographic viewer. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:875. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00875

- Centers for Disease and Prevention. Dengue in the US states and territories. Updated October 7, 2020. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/data-research/facts-stats/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/areaswithrisk/in-the-us.html

- Khetarpal N, Khanna I. Dengue fever: causes, complications, and vaccine strategies. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:6803098. doi:10.1155/2016/6803098

- Muller DA, Depelsenaire AC, Young PR. Clinical and laboratory diagnosis of dengue virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(suppl 2):S89-S95. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiw649

- Waterman SH, Gubler DJ. Dengue fever. Clin Dermatol. 1989;7:117-122. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(89)90034-5

- Lin CF, Lei HY, Liu CC, et al. Generation of IgM anti-platelet autoantibody in dengue patients. J Med Virol. 2001;63:143-149. doi:10.1002/1096- 9071(20000201)63:2<143::AID-JMV1009>3.0.CO;2-L

- Tripathi NK, Shrivastava A, Dash PK, et al. Detection of dengue virus. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;665:51-64. doi:10.1007/978-1-60761-817-1_4

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Plan for travel. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel

- Mack I, Ritz N. African tick-bite fever. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:960. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1810093

- Lepidi H, Fournier PE, Raoult D. Histologic features and immunodetection of African tick-bite fever eschar. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1332- 1337. doi:10.3201/eid1209.051540

- McGovern TW, Williams W, Fitzpatrick JE, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of African trypanosomiasis. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1178-1182.

- Kristensson K, Bentivoglio M. Pathology of African trypanosomiasis. In: Dumas M, Bouteille B, Buguet A, eds. Progress in Human African Trypanosomiasis, Sleeping Sickness. Springer; 1999:157-181.

- Capewell P, Cren-Travaillé C, Marchesi F, et al. The skin is a significant but overlooked anatomical reservoir for vector-borne African trypanosomes. Elife. 2016;5:e17716. doi:10.7554/eLife.17716

- Singal A. Chikungunya and skin: current perspective. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:307-309. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_93_17

- Robin S, Ramful D, Zettor J, et al. Severe bullous skin lesions associated with chikungunya virus infection in small infants. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;169:67-72. doi:10.1007/s00431-009-0986-0

- Hussain A, Ali F, Latiwesh OB, et al. A comprehensive review of the manifestations and pathogenesis of Zika virus in neonates and adults. Cureus. 2018;10:E3290. doi:10.7759/cureus.3290

- Farahnik B, Beroukhim K, Blattner CM, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of the Zika virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1286-1287. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1232

- Pincus LB, Grossman ME, Fox LP. The exanthem of dengue fever: clinical features of two US tourists traveling abroad. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:308-316. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.08.042

- Radakovic-Fijan S, Graninger W, Müller C, et al. Dengue hemorrhagic fever in a British travel guide. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:430-433. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.111904

- Yamashita A, Sakamoto T, Sekizuka T, et al. DGV: dengue genographic viewer. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:875. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00875

- Centers for Disease and Prevention. Dengue in the US states and territories. Updated October 7, 2020. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/data-research/facts-stats/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/areaswithrisk/in-the-us.html

- Khetarpal N, Khanna I. Dengue fever: causes, complications, and vaccine strategies. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:6803098. doi:10.1155/2016/6803098

- Muller DA, Depelsenaire AC, Young PR. Clinical and laboratory diagnosis of dengue virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(suppl 2):S89-S95. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiw649

- Waterman SH, Gubler DJ. Dengue fever. Clin Dermatol. 1989;7:117-122. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(89)90034-5

- Lin CF, Lei HY, Liu CC, et al. Generation of IgM anti-platelet autoantibody in dengue patients. J Med Virol. 2001;63:143-149. doi:10.1002/1096- 9071(20000201)63:2<143::AID-JMV1009>3.0.CO;2-L

- Tripathi NK, Shrivastava A, Dash PK, et al. Detection of dengue virus. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;665:51-64. doi:10.1007/978-1-60761-817-1_4

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Plan for travel. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel

- Mack I, Ritz N. African tick-bite fever. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:960. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1810093

- Lepidi H, Fournier PE, Raoult D. Histologic features and immunodetection of African tick-bite fever eschar. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1332- 1337. doi:10.3201/eid1209.051540

- McGovern TW, Williams W, Fitzpatrick JE, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of African trypanosomiasis. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1178-1182.

- Kristensson K, Bentivoglio M. Pathology of African trypanosomiasis. In: Dumas M, Bouteille B, Buguet A, eds. Progress in Human African Trypanosomiasis, Sleeping Sickness. Springer; 1999:157-181.

- Capewell P, Cren-Travaillé C, Marchesi F, et al. The skin is a significant but overlooked anatomical reservoir for vector-borne African trypanosomes. Elife. 2016;5:e17716. doi:10.7554/eLife.17716

- Singal A. Chikungunya and skin: current perspective. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:307-309. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_93_17

- Robin S, Ramful D, Zettor J, et al. Severe bullous skin lesions associated with chikungunya virus infection in small infants. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;169:67-72. doi:10.1007/s00431-009-0986-0

- Hussain A, Ali F, Latiwesh OB, et al. A comprehensive review of the manifestations and pathogenesis of Zika virus in neonates and adults. Cureus. 2018;10:E3290. doi:10.7759/cureus.3290

- Farahnik B, Beroukhim K, Blattner CM, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of the Zika virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1286-1287. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1232

A 74-year-old woman who frequently traveled abroad presented to the dermatology department with retiform purpura of the lower leg along with gastrointestinal cramps, fatigue, and myalgia. The patient reported that the symptoms had started 10 days after returning from a recent trip to Africa.

Nonscaly Red-Brown Macules on the Feet and Ankles

THE DIAGNOSIS: Secondary Syphilis

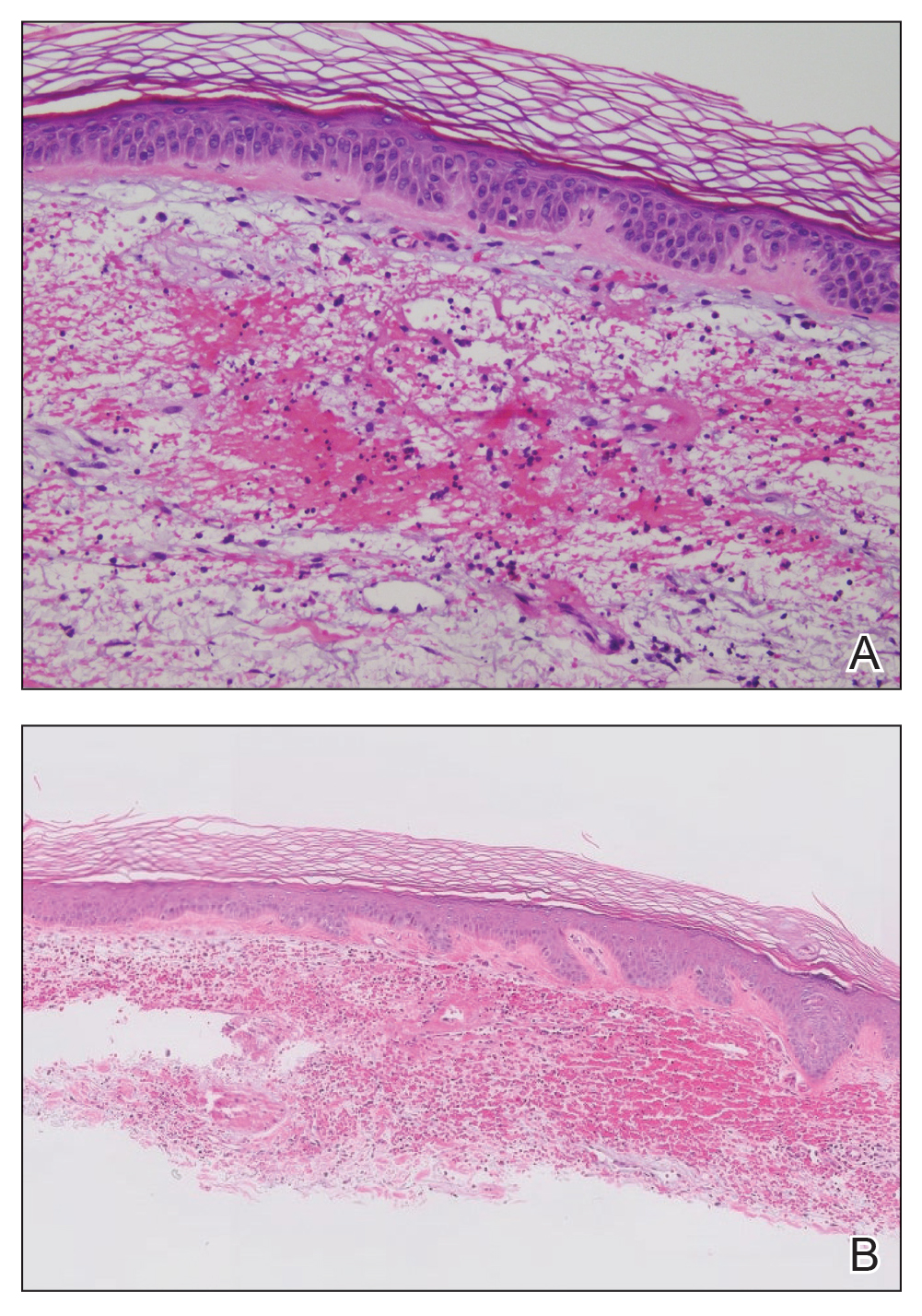

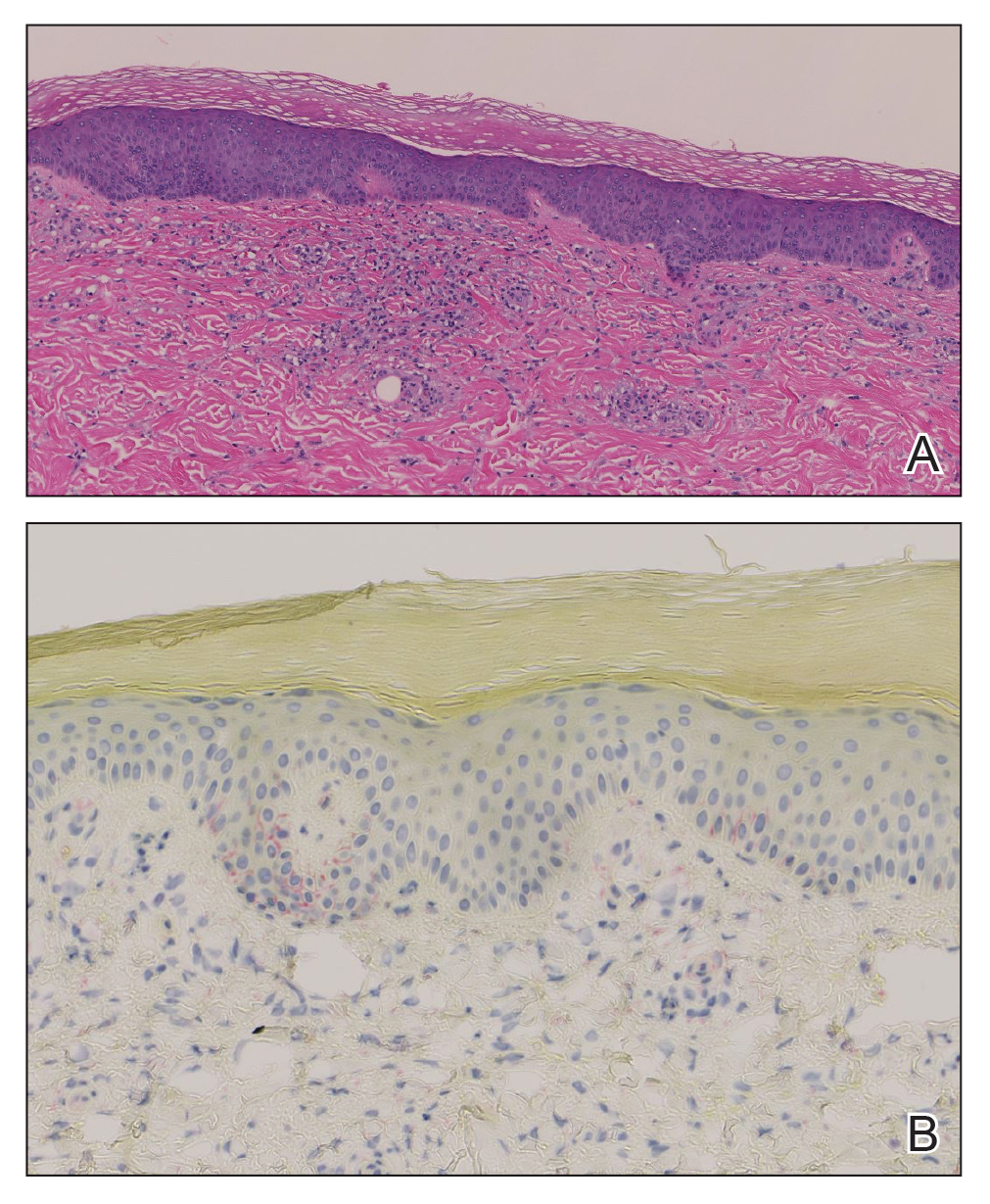

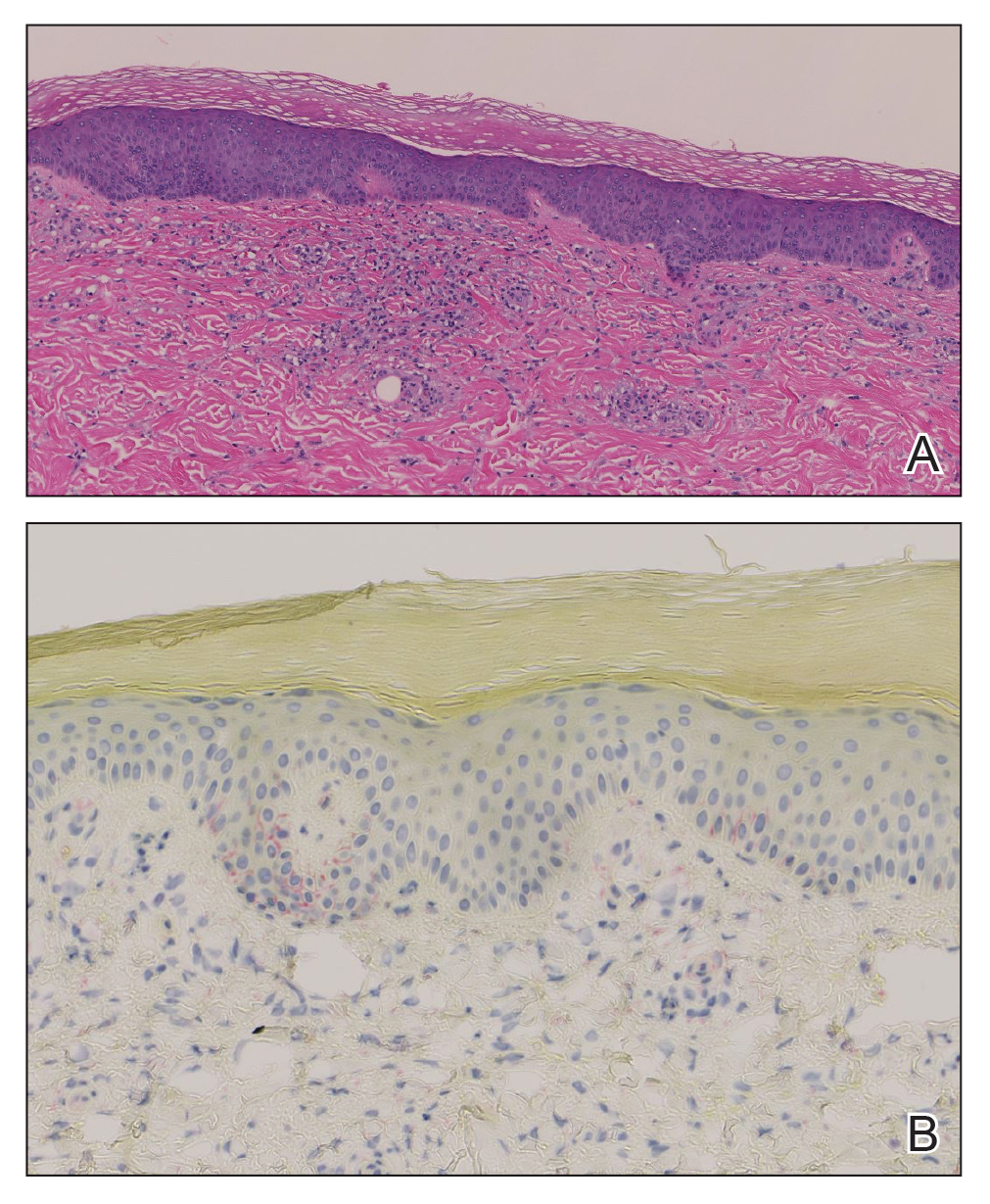

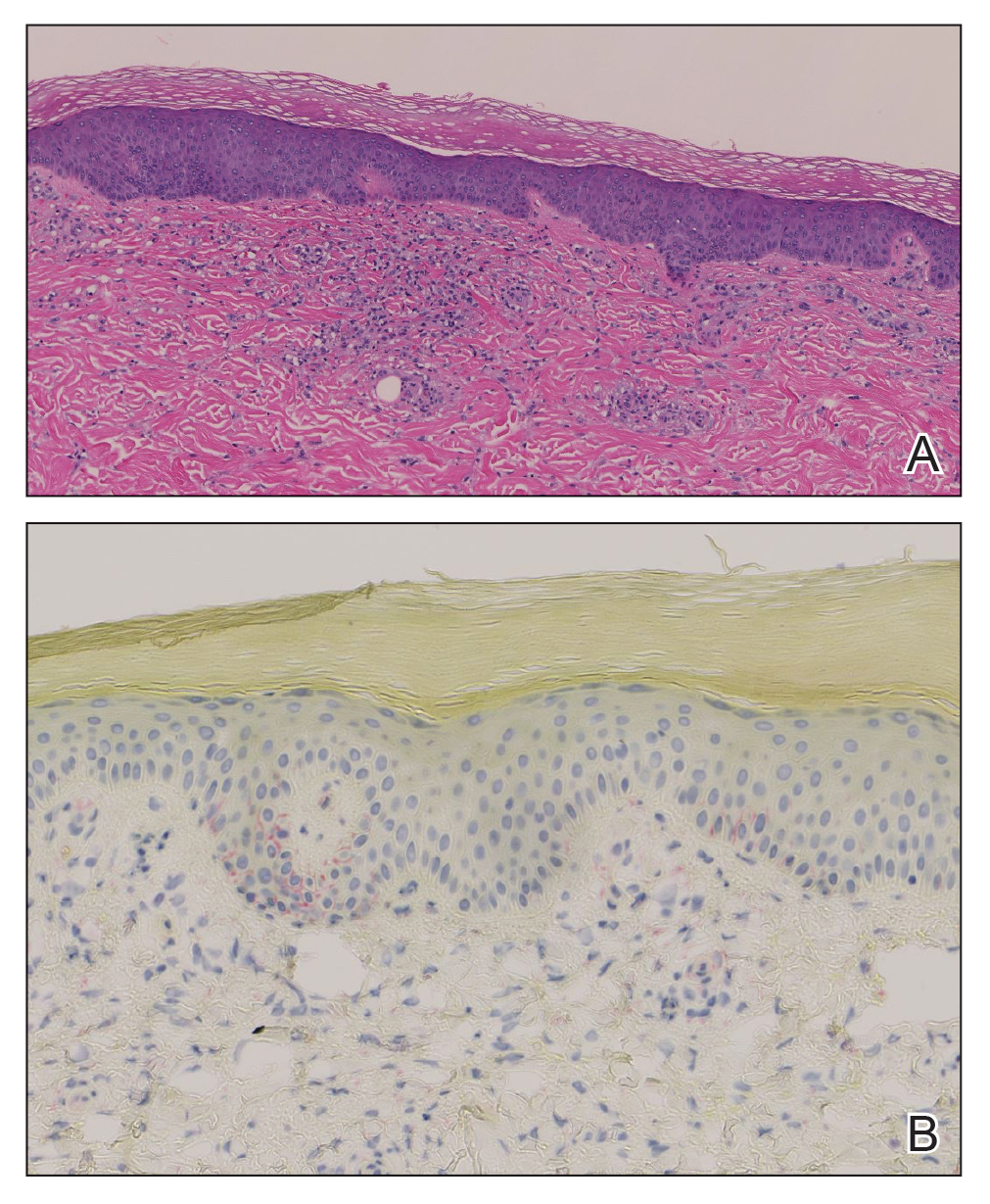

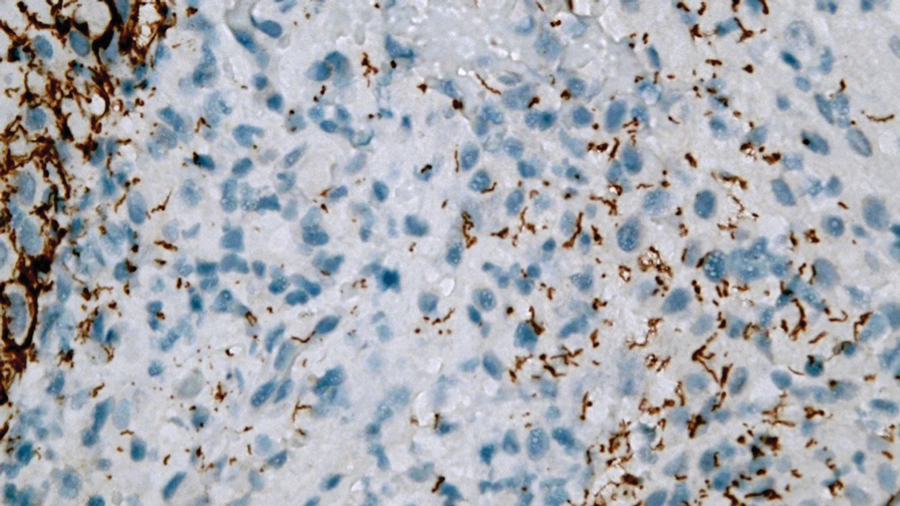

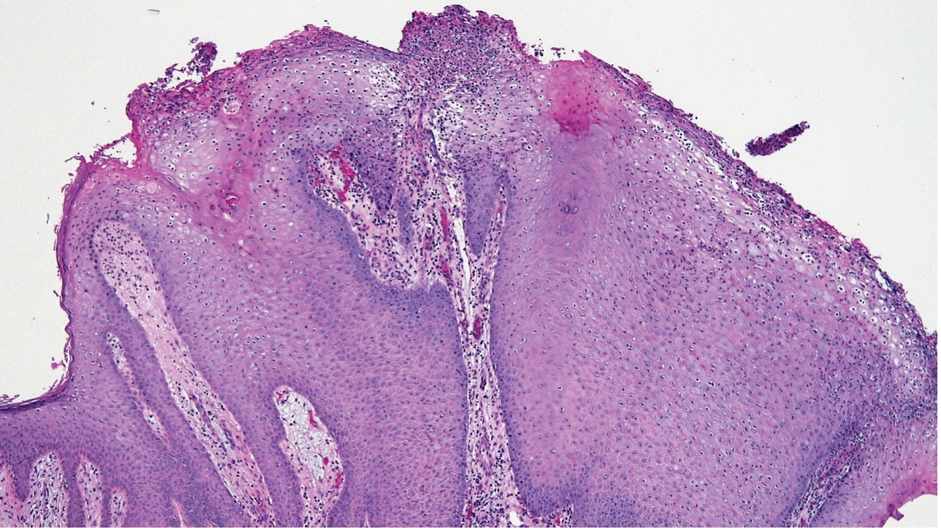

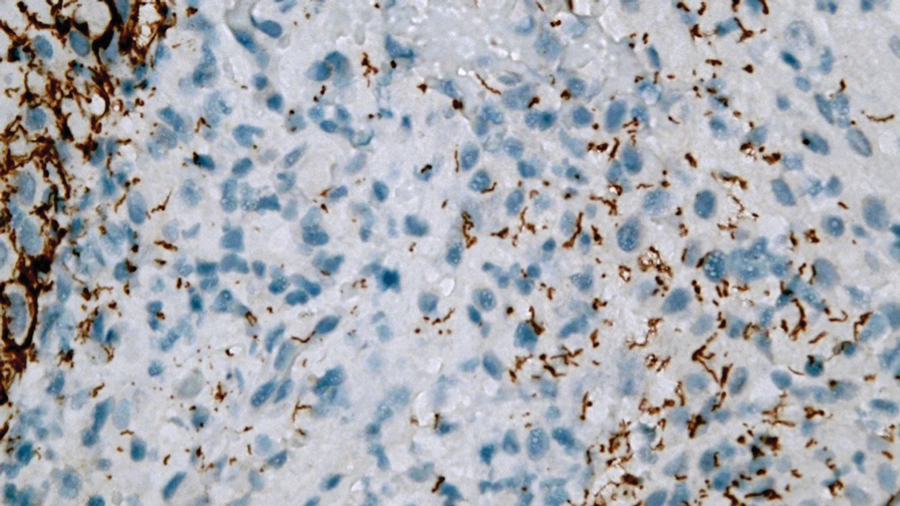

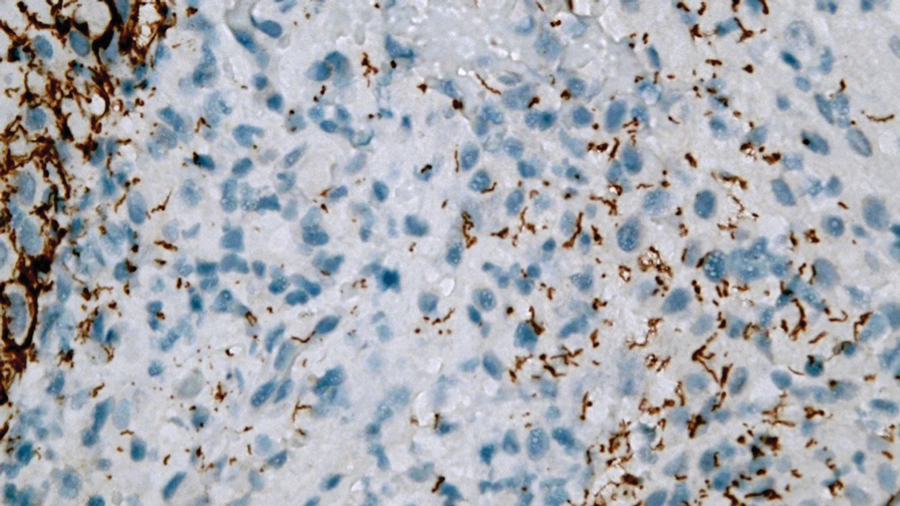

Histopathology demonstrated a mild superficial perivascular and interstitial infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and rare plasma cells with a background of extravasated erythrocytes (Figure, A). Treponema pallidum staining highlighted multiple spirochetes along the dermoepidermal junction and in the superficial dermis (Figure, B). Direct immunofluorescence was negative. Laboratory workup revealed a reactive rapid plasma reagin screen with a titer of 1:16 and positive IgG and IgM treponemal antibodies. The patient was diagnosed with secondary syphilis and was treated with a single dose of 2.4 million U of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G, with notable improvement of the rash and arthritis symptoms at 2-week follow-up.

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the spirochete T pallidum that progresses through active and latent stages. The incidence of both the primary and secondary stages of syphilis was at a historic low in the year 2000 and has increased annually since then.1 Syphilis is more common in men, and men who have sex with men (MSM) are disproportionately affected. Although the incidence of syphilis in MSM has increased since 2000, rates have slowed, with slight decreases in this population between 2019 and 2020.1 Conversely, rates among women have increased substantially in recent years, suggesting a more recent epidemic affecting heterosexual men and women.2

Classically, the primary stage of syphilis manifests as an asymptomatic papule followed by a painless ulcer (chancre) that heals spontaneously. The secondary stage of syphilis results from dissemination of T pallidum and is characterized by a wide range of mucocutaneous manifestations and prodromal symptoms. The most common cutaneous manifestation is a diffuse, nonpruritic, papulosquamous rash with red-brown scaly macules or papules on the trunk and extremities.3 The palms and soles commonly are involved. Mucosal patches, “snail-track” ulcers in the mouth, and condylomata lata are the characteristic mucosal lesions of secondary syphilis. Mucocutaneous findings typically are preceded by systemic signs including fever, malaise, myalgia, and generalized lymphadenopathy. However, syphilis is considered “the great mimicker,” with new reports of unusual presentations of the disease. In addition to papulosquamous morphologies, pustular, targetoid, psoriasiform, and noduloulcerative (also known as lues maligna) forms of syphilis have been reported.3-5

The histopathologic features of secondary syphilis also are variable. Classically, secondary syphilis demonstrates vacuolar interface dermatitis and acanthosis with slender elongated rete ridges. Other well-known features include endothelial swelling and the presence of plasma cells in most cases.6 However, the histopathologic features of secondary syphilis may vary depending on the morphology of the skin eruption and when the biopsy is taken. Our patient lacked the classic histopathologic features of secondary syphilis. However, because syphilis was in the clinical differential diagnosis, a treponemal stain was ordered and confirmed the diagnosis. Immunohistochemical stains using antibodies to treponemal antigens have a reported sensitivity of 71% to 100% and are highly specific.7 Although the combination of endothelial swelling, interstitial inflammation, irregular acanthosis, and elongated rete ridges should raise the possibility of syphilis, a treponemal stain may be useful to identify spirochetes if clinical suspicion exists.8

Given our patient’s known history of GPA, leukocytoclastic vasculitis was high on the list of differential diagnoses. However, leukocytoclastic vasculitis most classically manifests as petechiae and palpable purpura, and unlike in secondary syphilis, the palms and soles are less commonly involved. Because our patient’s rash was mainly localized to the lower limbs, the differential also included 2 pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPDs): progressive pigmentary purpura (Schamberg disease) and purpura annularis telangiectodes (Majocchi disease). Progressive pigmentary purpura is the most common manifestation of PPD and appears as cayenne pepper–colored macules that coalesce into golden brown–pigmented patches on the legs.9 Purpura annularis telangiectodes is another variant of PPD that manifests as pinpoint telangiectatic macules that progress to annular hyperpigmented patches with central clearing. Although PPDs frequently occur on the lower extremities, reports of plantar involvement are rare.10 Annular lichen planus manifests as violaceous papules with a clear center; however, it would be atypical for these lesions to be restricted to the feet and ankles. Palmoplantar lichen planus can mimic secondary syphilis clinically, but these cases manifest as hyperkeratotic pruritic papules on the palms and soles in contrast to the faint brown asymptomatic macules noted in our case.11

Our case highlights an unusual presentation of secondary syphilis and demonstrates the challenge of diagnosing this entity on clinical presentation alone. Because this patient lacked the classic clinical and histopathologic features of secondary syphilis, a skin biopsy with positive immunohistochemical staining for treponemal antigens was necessary to make the diagnosis. Given the variability in presentation of secondary syphilis, a biopsy or serologic testing may be necessary to make a proper diagnosis.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2020. Accessed September 4, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2020/2020-SR-4-10-2023.pdf

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1901593

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: historical aspects, microbiology, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1-14. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.073

- Wu MC, Hsu CK, Lee JY, et al. Erythema multiforme-like secondary syphilis in a HIV-positive bisexual man. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:647-648. doi:10.2340/00015555-0920

- Kopelman H, Lin A, Jorizzo JL. A pemphigus-like presentation of secondary syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:861-864. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.07.021

- Liu XK, Li J. Histologic features of secondary syphilis. Dermatology. 2020;236:145-150. doi:10.1159/000502641

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: laboratory diagnosis, management, and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:17-28. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.074

- Flamm A, Parikh K, Xie Q, et al. Histologic features of secondary syphilis: a multicenter retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:1025-1030. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.08.062

- Kim DH, Seo SH, Ahn HH, et al. Characteristics and clinical manifestations of pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:404-410. doi:10.5021/ad.2015.27.4.404

- Sivendran M, Mowad C. Hyperpigmented patches on shins, palms, and soles. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:223. doi:10.1001/2013.jamadermatol.652a

- Kim YS, Kim MH, Kim CW, et al. A case of palmoplantar lichen planus mimicking secondary syphilis. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:429-431.doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.4.429

THE DIAGNOSIS: Secondary Syphilis

Histopathology demonstrated a mild superficial perivascular and interstitial infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and rare plasma cells with a background of extravasated erythrocytes (Figure, A). Treponema pallidum staining highlighted multiple spirochetes along the dermoepidermal junction and in the superficial dermis (Figure, B). Direct immunofluorescence was negative. Laboratory workup revealed a reactive rapid plasma reagin screen with a titer of 1:16 and positive IgG and IgM treponemal antibodies. The patient was diagnosed with secondary syphilis and was treated with a single dose of 2.4 million U of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G, with notable improvement of the rash and arthritis symptoms at 2-week follow-up.

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the spirochete T pallidum that progresses through active and latent stages. The incidence of both the primary and secondary stages of syphilis was at a historic low in the year 2000 and has increased annually since then.1 Syphilis is more common in men, and men who have sex with men (MSM) are disproportionately affected. Although the incidence of syphilis in MSM has increased since 2000, rates have slowed, with slight decreases in this population between 2019 and 2020.1 Conversely, rates among women have increased substantially in recent years, suggesting a more recent epidemic affecting heterosexual men and women.2

Classically, the primary stage of syphilis manifests as an asymptomatic papule followed by a painless ulcer (chancre) that heals spontaneously. The secondary stage of syphilis results from dissemination of T pallidum and is characterized by a wide range of mucocutaneous manifestations and prodromal symptoms. The most common cutaneous manifestation is a diffuse, nonpruritic, papulosquamous rash with red-brown scaly macules or papules on the trunk and extremities.3 The palms and soles commonly are involved. Mucosal patches, “snail-track” ulcers in the mouth, and condylomata lata are the characteristic mucosal lesions of secondary syphilis. Mucocutaneous findings typically are preceded by systemic signs including fever, malaise, myalgia, and generalized lymphadenopathy. However, syphilis is considered “the great mimicker,” with new reports of unusual presentations of the disease. In addition to papulosquamous morphologies, pustular, targetoid, psoriasiform, and noduloulcerative (also known as lues maligna) forms of syphilis have been reported.3-5

The histopathologic features of secondary syphilis also are variable. Classically, secondary syphilis demonstrates vacuolar interface dermatitis and acanthosis with slender elongated rete ridges. Other well-known features include endothelial swelling and the presence of plasma cells in most cases.6 However, the histopathologic features of secondary syphilis may vary depending on the morphology of the skin eruption and when the biopsy is taken. Our patient lacked the classic histopathologic features of secondary syphilis. However, because syphilis was in the clinical differential diagnosis, a treponemal stain was ordered and confirmed the diagnosis. Immunohistochemical stains using antibodies to treponemal antigens have a reported sensitivity of 71% to 100% and are highly specific.7 Although the combination of endothelial swelling, interstitial inflammation, irregular acanthosis, and elongated rete ridges should raise the possibility of syphilis, a treponemal stain may be useful to identify spirochetes if clinical suspicion exists.8

Given our patient’s known history of GPA, leukocytoclastic vasculitis was high on the list of differential diagnoses. However, leukocytoclastic vasculitis most classically manifests as petechiae and palpable purpura, and unlike in secondary syphilis, the palms and soles are less commonly involved. Because our patient’s rash was mainly localized to the lower limbs, the differential also included 2 pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPDs): progressive pigmentary purpura (Schamberg disease) and purpura annularis telangiectodes (Majocchi disease). Progressive pigmentary purpura is the most common manifestation of PPD and appears as cayenne pepper–colored macules that coalesce into golden brown–pigmented patches on the legs.9 Purpura annularis telangiectodes is another variant of PPD that manifests as pinpoint telangiectatic macules that progress to annular hyperpigmented patches with central clearing. Although PPDs frequently occur on the lower extremities, reports of plantar involvement are rare.10 Annular lichen planus manifests as violaceous papules with a clear center; however, it would be atypical for these lesions to be restricted to the feet and ankles. Palmoplantar lichen planus can mimic secondary syphilis clinically, but these cases manifest as hyperkeratotic pruritic papules on the palms and soles in contrast to the faint brown asymptomatic macules noted in our case.11

Our case highlights an unusual presentation of secondary syphilis and demonstrates the challenge of diagnosing this entity on clinical presentation alone. Because this patient lacked the classic clinical and histopathologic features of secondary syphilis, a skin biopsy with positive immunohistochemical staining for treponemal antigens was necessary to make the diagnosis. Given the variability in presentation of secondary syphilis, a biopsy or serologic testing may be necessary to make a proper diagnosis.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Secondary Syphilis

Histopathology demonstrated a mild superficial perivascular and interstitial infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and rare plasma cells with a background of extravasated erythrocytes (Figure, A). Treponema pallidum staining highlighted multiple spirochetes along the dermoepidermal junction and in the superficial dermis (Figure, B). Direct immunofluorescence was negative. Laboratory workup revealed a reactive rapid plasma reagin screen with a titer of 1:16 and positive IgG and IgM treponemal antibodies. The patient was diagnosed with secondary syphilis and was treated with a single dose of 2.4 million U of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G, with notable improvement of the rash and arthritis symptoms at 2-week follow-up.

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the spirochete T pallidum that progresses through active and latent stages. The incidence of both the primary and secondary stages of syphilis was at a historic low in the year 2000 and has increased annually since then.1 Syphilis is more common in men, and men who have sex with men (MSM) are disproportionately affected. Although the incidence of syphilis in MSM has increased since 2000, rates have slowed, with slight decreases in this population between 2019 and 2020.1 Conversely, rates among women have increased substantially in recent years, suggesting a more recent epidemic affecting heterosexual men and women.2

Classically, the primary stage of syphilis manifests as an asymptomatic papule followed by a painless ulcer (chancre) that heals spontaneously. The secondary stage of syphilis results from dissemination of T pallidum and is characterized by a wide range of mucocutaneous manifestations and prodromal symptoms. The most common cutaneous manifestation is a diffuse, nonpruritic, papulosquamous rash with red-brown scaly macules or papules on the trunk and extremities.3 The palms and soles commonly are involved. Mucosal patches, “snail-track” ulcers in the mouth, and condylomata lata are the characteristic mucosal lesions of secondary syphilis. Mucocutaneous findings typically are preceded by systemic signs including fever, malaise, myalgia, and generalized lymphadenopathy. However, syphilis is considered “the great mimicker,” with new reports of unusual presentations of the disease. In addition to papulosquamous morphologies, pustular, targetoid, psoriasiform, and noduloulcerative (also known as lues maligna) forms of syphilis have been reported.3-5

The histopathologic features of secondary syphilis also are variable. Classically, secondary syphilis demonstrates vacuolar interface dermatitis and acanthosis with slender elongated rete ridges. Other well-known features include endothelial swelling and the presence of plasma cells in most cases.6 However, the histopathologic features of secondary syphilis may vary depending on the morphology of the skin eruption and when the biopsy is taken. Our patient lacked the classic histopathologic features of secondary syphilis. However, because syphilis was in the clinical differential diagnosis, a treponemal stain was ordered and confirmed the diagnosis. Immunohistochemical stains using antibodies to treponemal antigens have a reported sensitivity of 71% to 100% and are highly specific.7 Although the combination of endothelial swelling, interstitial inflammation, irregular acanthosis, and elongated rete ridges should raise the possibility of syphilis, a treponemal stain may be useful to identify spirochetes if clinical suspicion exists.8

Given our patient’s known history of GPA, leukocytoclastic vasculitis was high on the list of differential diagnoses. However, leukocytoclastic vasculitis most classically manifests as petechiae and palpable purpura, and unlike in secondary syphilis, the palms and soles are less commonly involved. Because our patient’s rash was mainly localized to the lower limbs, the differential also included 2 pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPDs): progressive pigmentary purpura (Schamberg disease) and purpura annularis telangiectodes (Majocchi disease). Progressive pigmentary purpura is the most common manifestation of PPD and appears as cayenne pepper–colored macules that coalesce into golden brown–pigmented patches on the legs.9 Purpura annularis telangiectodes is another variant of PPD that manifests as pinpoint telangiectatic macules that progress to annular hyperpigmented patches with central clearing. Although PPDs frequently occur on the lower extremities, reports of plantar involvement are rare.10 Annular lichen planus manifests as violaceous papules with a clear center; however, it would be atypical for these lesions to be restricted to the feet and ankles. Palmoplantar lichen planus can mimic secondary syphilis clinically, but these cases manifest as hyperkeratotic pruritic papules on the palms and soles in contrast to the faint brown asymptomatic macules noted in our case.11

Our case highlights an unusual presentation of secondary syphilis and demonstrates the challenge of diagnosing this entity on clinical presentation alone. Because this patient lacked the classic clinical and histopathologic features of secondary syphilis, a skin biopsy with positive immunohistochemical staining for treponemal antigens was necessary to make the diagnosis. Given the variability in presentation of secondary syphilis, a biopsy or serologic testing may be necessary to make a proper diagnosis.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2020. Accessed September 4, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2020/2020-SR-4-10-2023.pdf

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1901593

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: historical aspects, microbiology, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1-14. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.073

- Wu MC, Hsu CK, Lee JY, et al. Erythema multiforme-like secondary syphilis in a HIV-positive bisexual man. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:647-648. doi:10.2340/00015555-0920

- Kopelman H, Lin A, Jorizzo JL. A pemphigus-like presentation of secondary syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:861-864. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.07.021

- Liu XK, Li J. Histologic features of secondary syphilis. Dermatology. 2020;236:145-150. doi:10.1159/000502641

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: laboratory diagnosis, management, and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:17-28. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.074

- Flamm A, Parikh K, Xie Q, et al. Histologic features of secondary syphilis: a multicenter retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:1025-1030. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.08.062

- Kim DH, Seo SH, Ahn HH, et al. Characteristics and clinical manifestations of pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:404-410. doi:10.5021/ad.2015.27.4.404

- Sivendran M, Mowad C. Hyperpigmented patches on shins, palms, and soles. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:223. doi:10.1001/2013.jamadermatol.652a

- Kim YS, Kim MH, Kim CW, et al. A case of palmoplantar lichen planus mimicking secondary syphilis. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:429-431.doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.4.429

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2020. Accessed September 4, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2020/2020-SR-4-10-2023.pdf

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1901593

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: historical aspects, microbiology, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1-14. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.073

- Wu MC, Hsu CK, Lee JY, et al. Erythema multiforme-like secondary syphilis in a HIV-positive bisexual man. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:647-648. doi:10.2340/00015555-0920

- Kopelman H, Lin A, Jorizzo JL. A pemphigus-like presentation of secondary syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:861-864. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.07.021

- Liu XK, Li J. Histologic features of secondary syphilis. Dermatology. 2020;236:145-150. doi:10.1159/000502641

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: laboratory diagnosis, management, and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:17-28. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.074

- Flamm A, Parikh K, Xie Q, et al. Histologic features of secondary syphilis: a multicenter retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:1025-1030. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.08.062

- Kim DH, Seo SH, Ahn HH, et al. Characteristics and clinical manifestations of pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:404-410. doi:10.5021/ad.2015.27.4.404

- Sivendran M, Mowad C. Hyperpigmented patches on shins, palms, and soles. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:223. doi:10.1001/2013.jamadermatol.652a

- Kim YS, Kim MH, Kim CW, et al. A case of palmoplantar lichen planus mimicking secondary syphilis. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:429-431.doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.4.429

A 59-year-old man presented with a nontender nonpruritic rash on the feet of 2 days’ duration. The patient had a several-year history of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and was taking methotrexate and prednisone. The rash appeared suddenly—first on the right foot and then on the left foot—and was preceded by 1 week of worsening polyarthralgia, most notably in the ankles. He denied any fever, chills, sore throat, or weight loss. His typical GPA symptoms included inflammatory arthritis, scleritis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and sinonasal and renal involvement. He recently experienced exacerbation of inflammatory arthritis that required an increase in the prednisone dosage (from 40 mg to 60 mg daily), but there were no other GPA symptoms. He had a history of multiple female sexual partners but no known history of HIV and no recent testing for sexually transmitted infections. Hepatitis C antibody testing performed 5 years earlier was nonreactive. He denied any illicit drug use, recent travel, sick contacts, or new medications.

Dermatologic examination revealed nonscaly, clustered, red-brown macules, some with central clearing, on the medial and lateral aspects of the feet and ankles with a few faint copper-colored macules on the palms and soles. The ankles had full range of motion with no edema or effusion. There were no oral or genital lesions. The remainder of the skin examination was normal. Punch biopsies of skin on the left foot were obtained for histopathology and direct immunofluorescence.

Multiple Draining Sinus Tracts on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterial Infection

An injury sustained in a wet environment that results in chronic indolent abscesses, nodules, or draining sinus tracts suggests a mycobacterial infection. In our patient, a culture revealed MycobacteriuM fortuitum, which is classified in the rapid grower nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) group, along with Mycobacterium chelonae and Mycobacterium abscessus.1 The patient’s history of skin injury while cutting wet grass and the common presence of M fortuitum in the environment suggested that the organism entered the wound. The patient healed completely following surgical excision and a 2-month course of clarithromycin 1 g daily and rifampin 600 mg daily.

MycobacteriuM fortuitum was first isolated from an amphibian source in 1905 and later identified in a human with cutaneous infection in 1938. It commonly is found in soil and water.2 Skin and soft-tissue infections with M fortuitum usually are acquired from direct entry of the organism through a damaged skin barrier from trauma, medical injection, surgery, or tattoo placement.2,3