User login

Multiple Nodules on the Scrotum

The Diagnosis: Scrotal Calcinosis

Scrotal calcinosis is a rare benign disease that results from the deposition of calcium, magnesium, phosphate, and carbonate within the dermis and subcutaneous layer of the skin in the absence of underlying systemic disease or serum calcium and phosphorus abnormalities.1,2 Lesions usually are asymptomatic but can be mildly painful or pruritic. They usually present in childhood or early adulthood as yellow-white firm nodules ranging in size from a few millimeters to a few centimeters that increase in size and number over time. Additionally, lesions can ulcerate and discharge a chalklike exudative material. Although benign in nature, the quality-of-life impact in patients with this condition can be substantial, specifically regarding cosmesis, which may cause patients to feel embarrassed and even avoid sexual activity. This condition rarely has been associated with infection.1

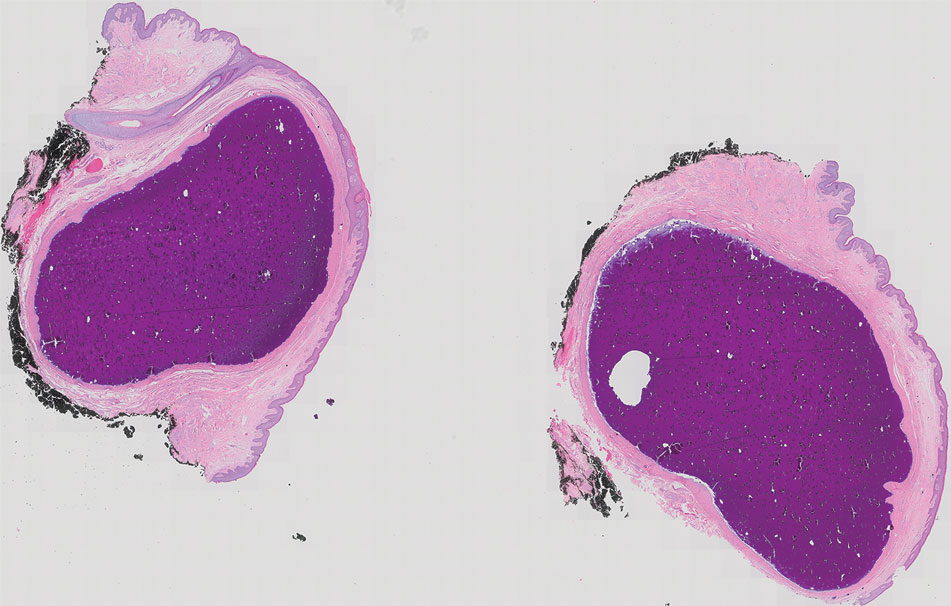

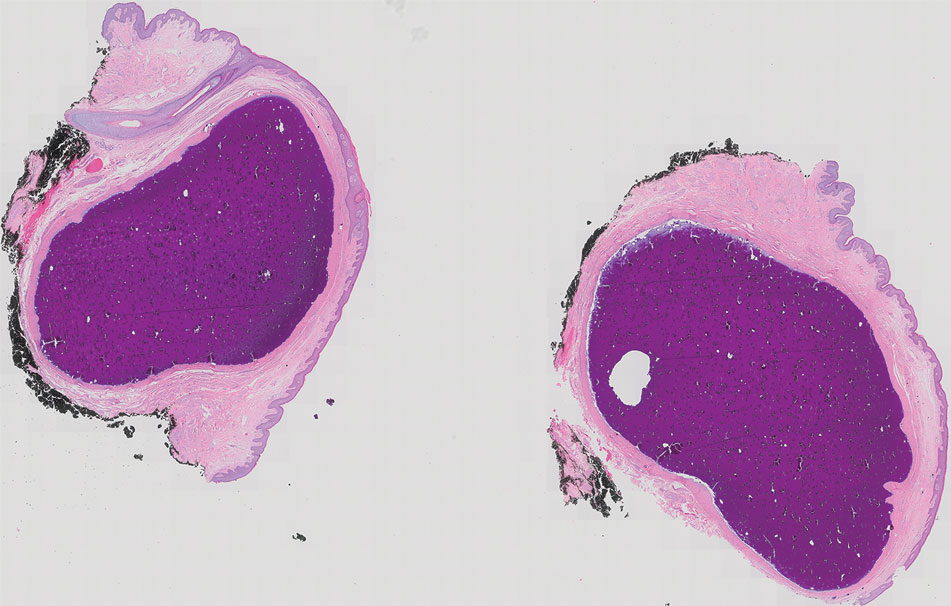

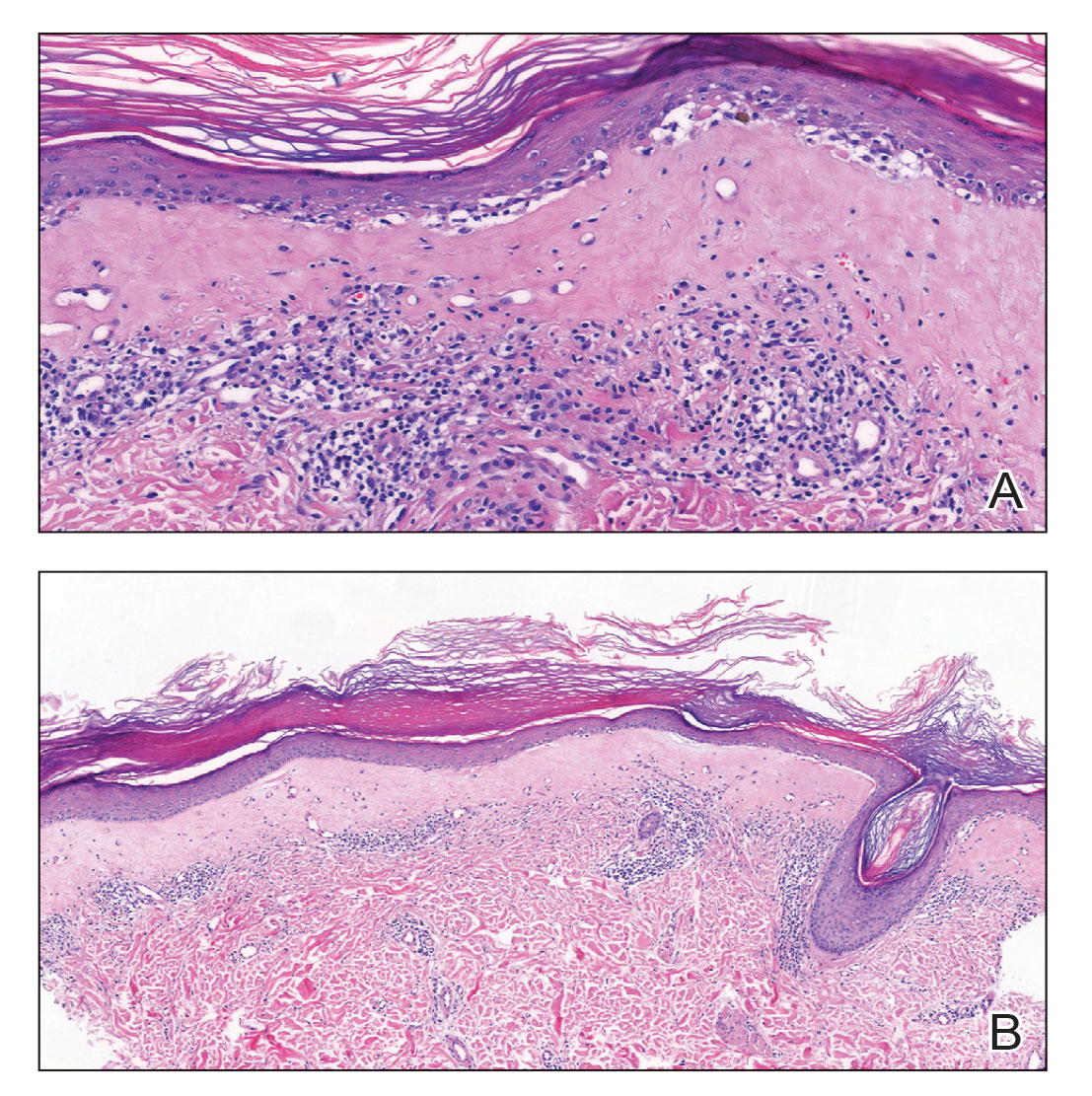

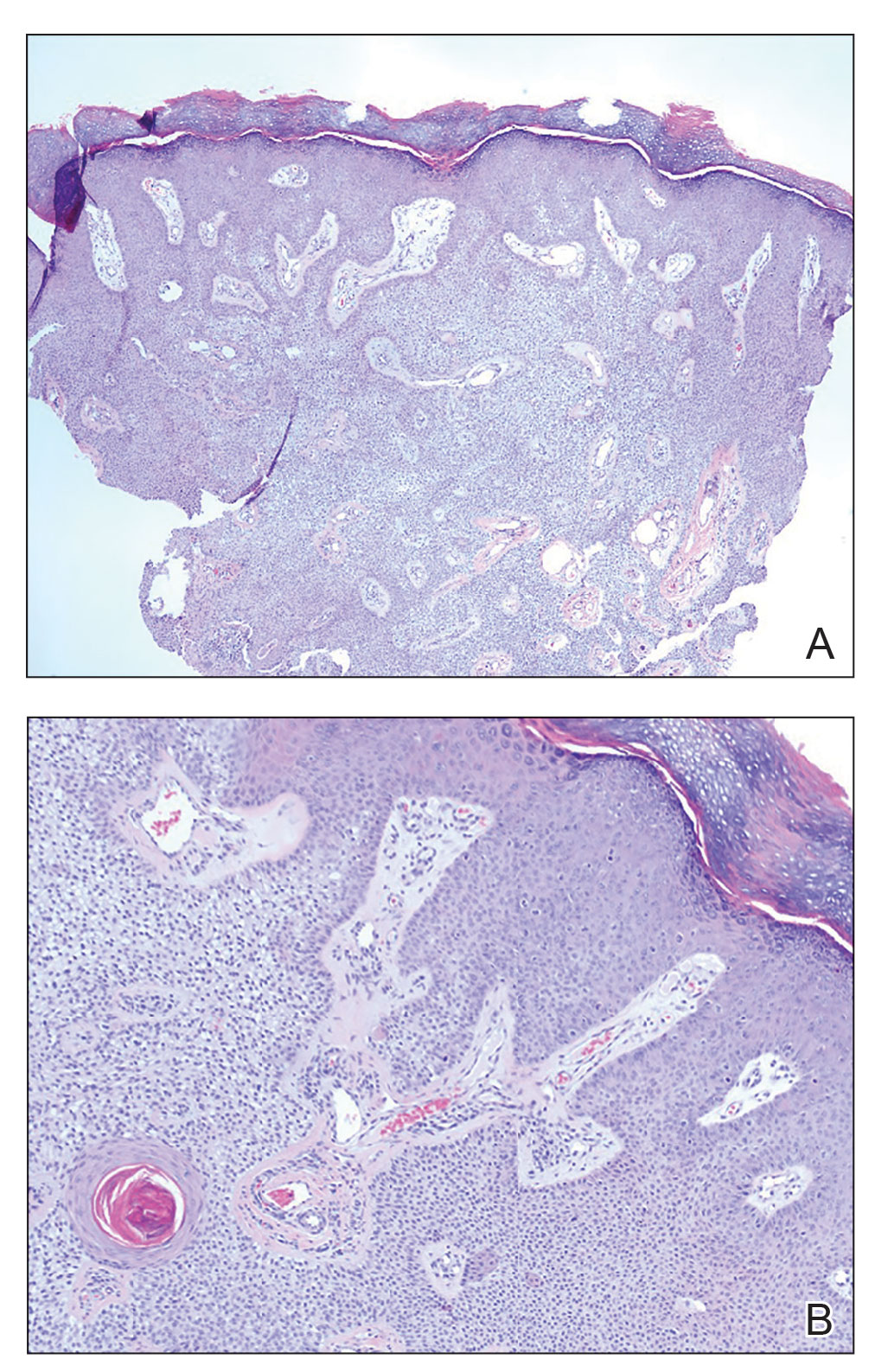

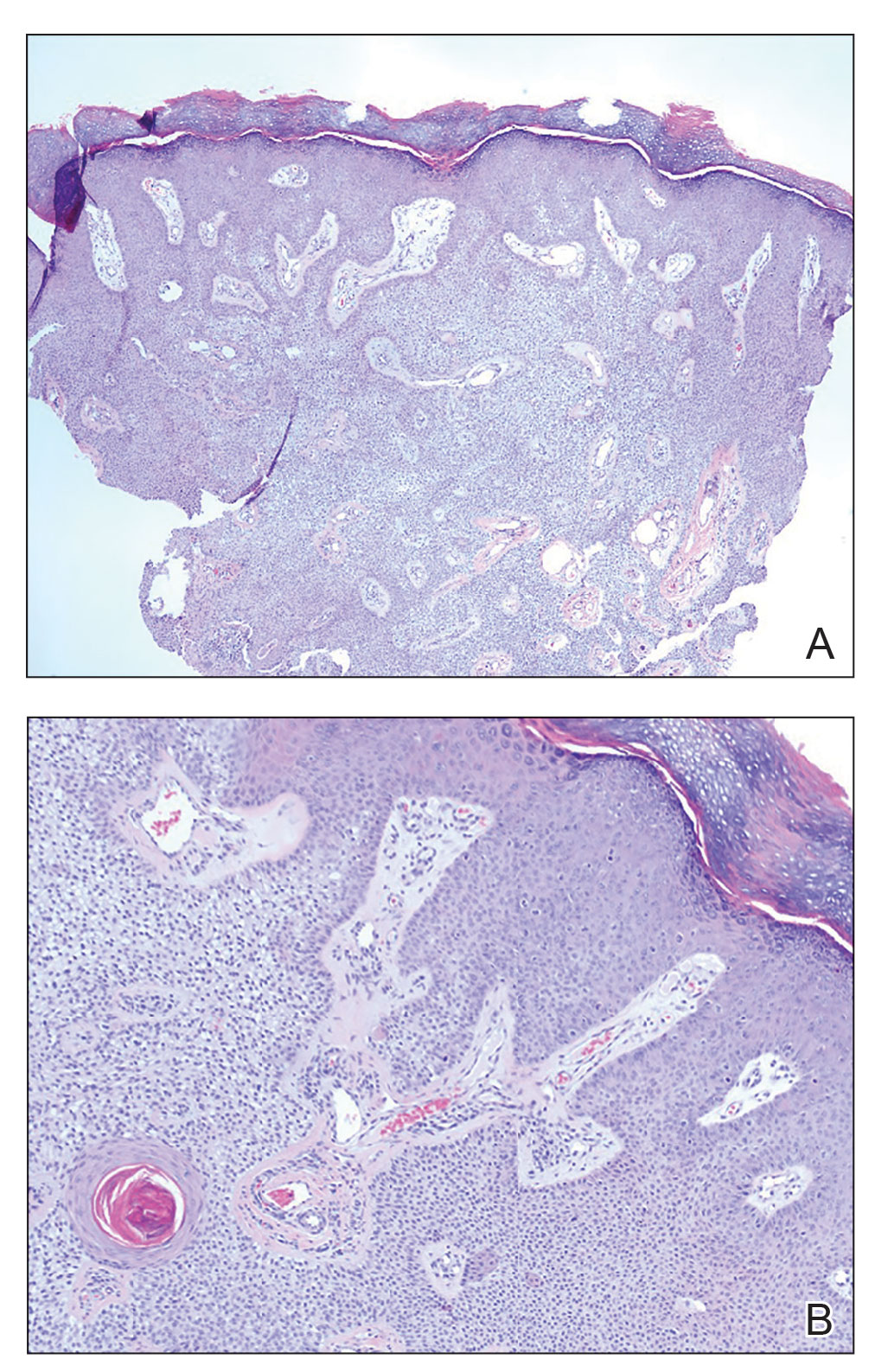

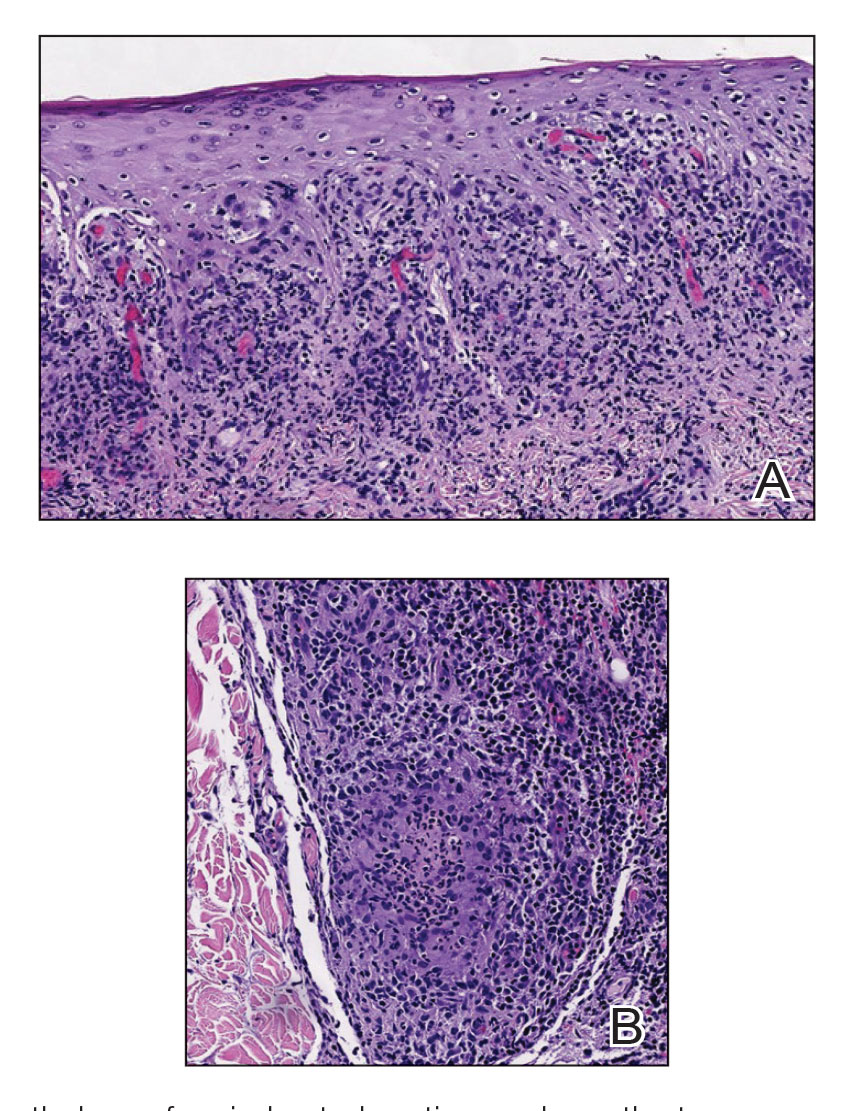

Our patient elected to undergo surgical excision under local anesthesia, and the lesions were sent for histopathologic examination. His postoperative course was unremarkable, and he was pleased with the cosmetic result of the surgery (Figure 1). Histopathology revealed calcified deposits that appeared as intradermal basophilic nodules lacking an epithelial lining (Figure 2), consistent with the diagnosis of scrotal calcinosis.2 No recurrence of the lesions was documented over the course of 18 months.

The pathogenesis of this condition is not clear. Most research supports scrotal calcinosis resulting from dystrophic calcification of epidermal inclusion cysts.3 There have been cases of scrotal calcinosis coinciding with epidermal inclusion cysts of the scrotum in varying stages of inflammation (some intact and some ruptured).2 Some research also suggests dystrophic calcification of eccrine epithelial cysts and degenerated dartos muscle as the origin of scrotal calcinosis.3

The differential diagnosis for this case included calcified steatocystoma multiplex, eruptive xanthomas, nodular scabies, and epidermal inclusion cysts. Steatocystoma multiplex can be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion or can develop sporadically with mutations in the KRT17 gene.4 It is characterized by multiple sebum-filled, cystic lesions of the pilosebaceous unit that may become calcified. Calcified lesions appear as yellow, firm, irregularly shaped papules or nodules ranging from a few millimeters to centimeters in size. Cysts can develop anywhere on the body with a predilection for the chest, upper extremities, axillae, trunk, groin, and scrotum.4 Histologically, our patient’s lesions were not associated with the pilosebaceous unit. Additionally, our patient denied a family history of similar skin lesions, which made calcified steatocystoma multiplex an unlikely diagnosis.

Eruptive xanthomas result from localized deposition of lipids within the dermis, typically in the setting of dyslipidemia or poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. They commonly appear on the extremities or buttocks as pruritic crops of yellow-red papules or nodules that are a few millimeters in size. Although our patient has a history of hyperlipidemia, his lesions differed substantially from eruptive xanthomas in clinical presentation.

Nodular scabies is a manifestation of classic scabies that presents with intensely pruritic erythematous papules and nodules that are a few millimeters in size and commonly occur on the axillae, groin, and genitalia. Our patient’s skin lesions were not pruritic and differed in appearance from nodular scabies.

Although research indicates scrotal calcinosis may result from dystrophic calcification of epidermal inclusion cysts,2 the latter present as dome-shaped, flesh-colored nodules with central pores representing the opening of hair follicles. Our patient lacked characteristic findings of epidermal inclusion cysts on histology.

The preferred treatment for scrotal calcinosis is surgical excision, which improves the aesthetic appearance, relieves itch, and removes ulcerative lesions.5 Additionally, surgical excision provides histological diagnostic confirmation. Recurrence with incomplete excision is possible; therefore, all lesions should be completely excised to reduce the risk for recurrence.3

- Pompeo A, Molina WR, Pohlman GD, et al. Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis: a rare entity and a review of the literature. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:E439-E441. doi:10.5489/cuaj.1387

- Swinehart JM, Golitz LE. Scrotal calcinosis: dystrophic calcification of epidermoid cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:985-988. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1982.01650240029016

- Khallouk A, Yazami OE, Mellas S, et al. Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis: a nonelucidated pathogenesis and its surgical treatment. Rev Urol. 2011;13:95-97.

- Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:475-480. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02413.x

- Solanki A, Narang S, Kathpalia R, et al. Scrotal calcinosis: pathogenetic link with epidermal cyst. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2015211163. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-211163

The Diagnosis: Scrotal Calcinosis

Scrotal calcinosis is a rare benign disease that results from the deposition of calcium, magnesium, phosphate, and carbonate within the dermis and subcutaneous layer of the skin in the absence of underlying systemic disease or serum calcium and phosphorus abnormalities.1,2 Lesions usually are asymptomatic but can be mildly painful or pruritic. They usually present in childhood or early adulthood as yellow-white firm nodules ranging in size from a few millimeters to a few centimeters that increase in size and number over time. Additionally, lesions can ulcerate and discharge a chalklike exudative material. Although benign in nature, the quality-of-life impact in patients with this condition can be substantial, specifically regarding cosmesis, which may cause patients to feel embarrassed and even avoid sexual activity. This condition rarely has been associated with infection.1

Our patient elected to undergo surgical excision under local anesthesia, and the lesions were sent for histopathologic examination. His postoperative course was unremarkable, and he was pleased with the cosmetic result of the surgery (Figure 1). Histopathology revealed calcified deposits that appeared as intradermal basophilic nodules lacking an epithelial lining (Figure 2), consistent with the diagnosis of scrotal calcinosis.2 No recurrence of the lesions was documented over the course of 18 months.

The pathogenesis of this condition is not clear. Most research supports scrotal calcinosis resulting from dystrophic calcification of epidermal inclusion cysts.3 There have been cases of scrotal calcinosis coinciding with epidermal inclusion cysts of the scrotum in varying stages of inflammation (some intact and some ruptured).2 Some research also suggests dystrophic calcification of eccrine epithelial cysts and degenerated dartos muscle as the origin of scrotal calcinosis.3

The differential diagnosis for this case included calcified steatocystoma multiplex, eruptive xanthomas, nodular scabies, and epidermal inclusion cysts. Steatocystoma multiplex can be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion or can develop sporadically with mutations in the KRT17 gene.4 It is characterized by multiple sebum-filled, cystic lesions of the pilosebaceous unit that may become calcified. Calcified lesions appear as yellow, firm, irregularly shaped papules or nodules ranging from a few millimeters to centimeters in size. Cysts can develop anywhere on the body with a predilection for the chest, upper extremities, axillae, trunk, groin, and scrotum.4 Histologically, our patient’s lesions were not associated with the pilosebaceous unit. Additionally, our patient denied a family history of similar skin lesions, which made calcified steatocystoma multiplex an unlikely diagnosis.

Eruptive xanthomas result from localized deposition of lipids within the dermis, typically in the setting of dyslipidemia or poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. They commonly appear on the extremities or buttocks as pruritic crops of yellow-red papules or nodules that are a few millimeters in size. Although our patient has a history of hyperlipidemia, his lesions differed substantially from eruptive xanthomas in clinical presentation.

Nodular scabies is a manifestation of classic scabies that presents with intensely pruritic erythematous papules and nodules that are a few millimeters in size and commonly occur on the axillae, groin, and genitalia. Our patient’s skin lesions were not pruritic and differed in appearance from nodular scabies.

Although research indicates scrotal calcinosis may result from dystrophic calcification of epidermal inclusion cysts,2 the latter present as dome-shaped, flesh-colored nodules with central pores representing the opening of hair follicles. Our patient lacked characteristic findings of epidermal inclusion cysts on histology.

The preferred treatment for scrotal calcinosis is surgical excision, which improves the aesthetic appearance, relieves itch, and removes ulcerative lesions.5 Additionally, surgical excision provides histological diagnostic confirmation. Recurrence with incomplete excision is possible; therefore, all lesions should be completely excised to reduce the risk for recurrence.3

The Diagnosis: Scrotal Calcinosis

Scrotal calcinosis is a rare benign disease that results from the deposition of calcium, magnesium, phosphate, and carbonate within the dermis and subcutaneous layer of the skin in the absence of underlying systemic disease or serum calcium and phosphorus abnormalities.1,2 Lesions usually are asymptomatic but can be mildly painful or pruritic. They usually present in childhood or early adulthood as yellow-white firm nodules ranging in size from a few millimeters to a few centimeters that increase in size and number over time. Additionally, lesions can ulcerate and discharge a chalklike exudative material. Although benign in nature, the quality-of-life impact in patients with this condition can be substantial, specifically regarding cosmesis, which may cause patients to feel embarrassed and even avoid sexual activity. This condition rarely has been associated with infection.1

Our patient elected to undergo surgical excision under local anesthesia, and the lesions were sent for histopathologic examination. His postoperative course was unremarkable, and he was pleased with the cosmetic result of the surgery (Figure 1). Histopathology revealed calcified deposits that appeared as intradermal basophilic nodules lacking an epithelial lining (Figure 2), consistent with the diagnosis of scrotal calcinosis.2 No recurrence of the lesions was documented over the course of 18 months.

The pathogenesis of this condition is not clear. Most research supports scrotal calcinosis resulting from dystrophic calcification of epidermal inclusion cysts.3 There have been cases of scrotal calcinosis coinciding with epidermal inclusion cysts of the scrotum in varying stages of inflammation (some intact and some ruptured).2 Some research also suggests dystrophic calcification of eccrine epithelial cysts and degenerated dartos muscle as the origin of scrotal calcinosis.3

The differential diagnosis for this case included calcified steatocystoma multiplex, eruptive xanthomas, nodular scabies, and epidermal inclusion cysts. Steatocystoma multiplex can be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion or can develop sporadically with mutations in the KRT17 gene.4 It is characterized by multiple sebum-filled, cystic lesions of the pilosebaceous unit that may become calcified. Calcified lesions appear as yellow, firm, irregularly shaped papules or nodules ranging from a few millimeters to centimeters in size. Cysts can develop anywhere on the body with a predilection for the chest, upper extremities, axillae, trunk, groin, and scrotum.4 Histologically, our patient’s lesions were not associated with the pilosebaceous unit. Additionally, our patient denied a family history of similar skin lesions, which made calcified steatocystoma multiplex an unlikely diagnosis.

Eruptive xanthomas result from localized deposition of lipids within the dermis, typically in the setting of dyslipidemia or poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. They commonly appear on the extremities or buttocks as pruritic crops of yellow-red papules or nodules that are a few millimeters in size. Although our patient has a history of hyperlipidemia, his lesions differed substantially from eruptive xanthomas in clinical presentation.

Nodular scabies is a manifestation of classic scabies that presents with intensely pruritic erythematous papules and nodules that are a few millimeters in size and commonly occur on the axillae, groin, and genitalia. Our patient’s skin lesions were not pruritic and differed in appearance from nodular scabies.

Although research indicates scrotal calcinosis may result from dystrophic calcification of epidermal inclusion cysts,2 the latter present as dome-shaped, flesh-colored nodules with central pores representing the opening of hair follicles. Our patient lacked characteristic findings of epidermal inclusion cysts on histology.

The preferred treatment for scrotal calcinosis is surgical excision, which improves the aesthetic appearance, relieves itch, and removes ulcerative lesions.5 Additionally, surgical excision provides histological diagnostic confirmation. Recurrence with incomplete excision is possible; therefore, all lesions should be completely excised to reduce the risk for recurrence.3

- Pompeo A, Molina WR, Pohlman GD, et al. Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis: a rare entity and a review of the literature. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:E439-E441. doi:10.5489/cuaj.1387

- Swinehart JM, Golitz LE. Scrotal calcinosis: dystrophic calcification of epidermoid cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:985-988. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1982.01650240029016

- Khallouk A, Yazami OE, Mellas S, et al. Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis: a nonelucidated pathogenesis and its surgical treatment. Rev Urol. 2011;13:95-97.

- Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:475-480. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02413.x

- Solanki A, Narang S, Kathpalia R, et al. Scrotal calcinosis: pathogenetic link with epidermal cyst. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2015211163. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-211163

- Pompeo A, Molina WR, Pohlman GD, et al. Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis: a rare entity and a review of the literature. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:E439-E441. doi:10.5489/cuaj.1387

- Swinehart JM, Golitz LE. Scrotal calcinosis: dystrophic calcification of epidermoid cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:985-988. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1982.01650240029016

- Khallouk A, Yazami OE, Mellas S, et al. Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis: a nonelucidated pathogenesis and its surgical treatment. Rev Urol. 2011;13:95-97.

- Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:475-480. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02413.x

- Solanki A, Narang S, Kathpalia R, et al. Scrotal calcinosis: pathogenetic link with epidermal cyst. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2015211163. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-211163

A 33-year-old man presented with progressively enlarging bumps on the scrotum that were present since adolescence. He had a history of hyperlipidemia but no history of systemic or autoimmune disease. The lesions were asymptomatic without associated pruritus, pain, or discharge. No treatments had been administered, and he had no known personal or family history of similar skin conditions or skin cancer. He endorsed a monogamous relationship with his wife. Physical examination revealed 15 firm, yellow-white, subcutaneous nodules on the scrotum that varied in size.

Porcelain White, Crinkled, Violaceous Patches on the Inner Thighs

The Diagnosis: Extragenital Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus

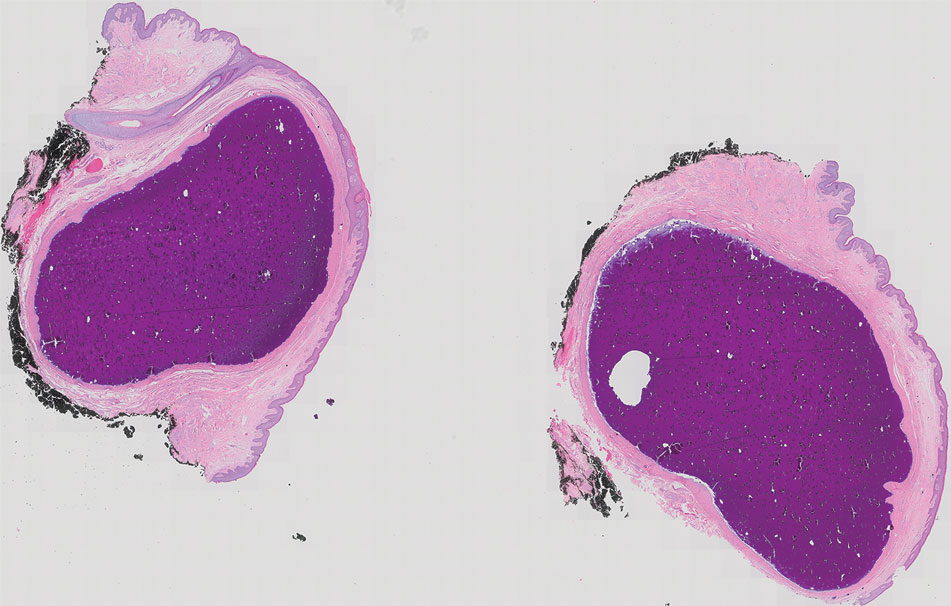

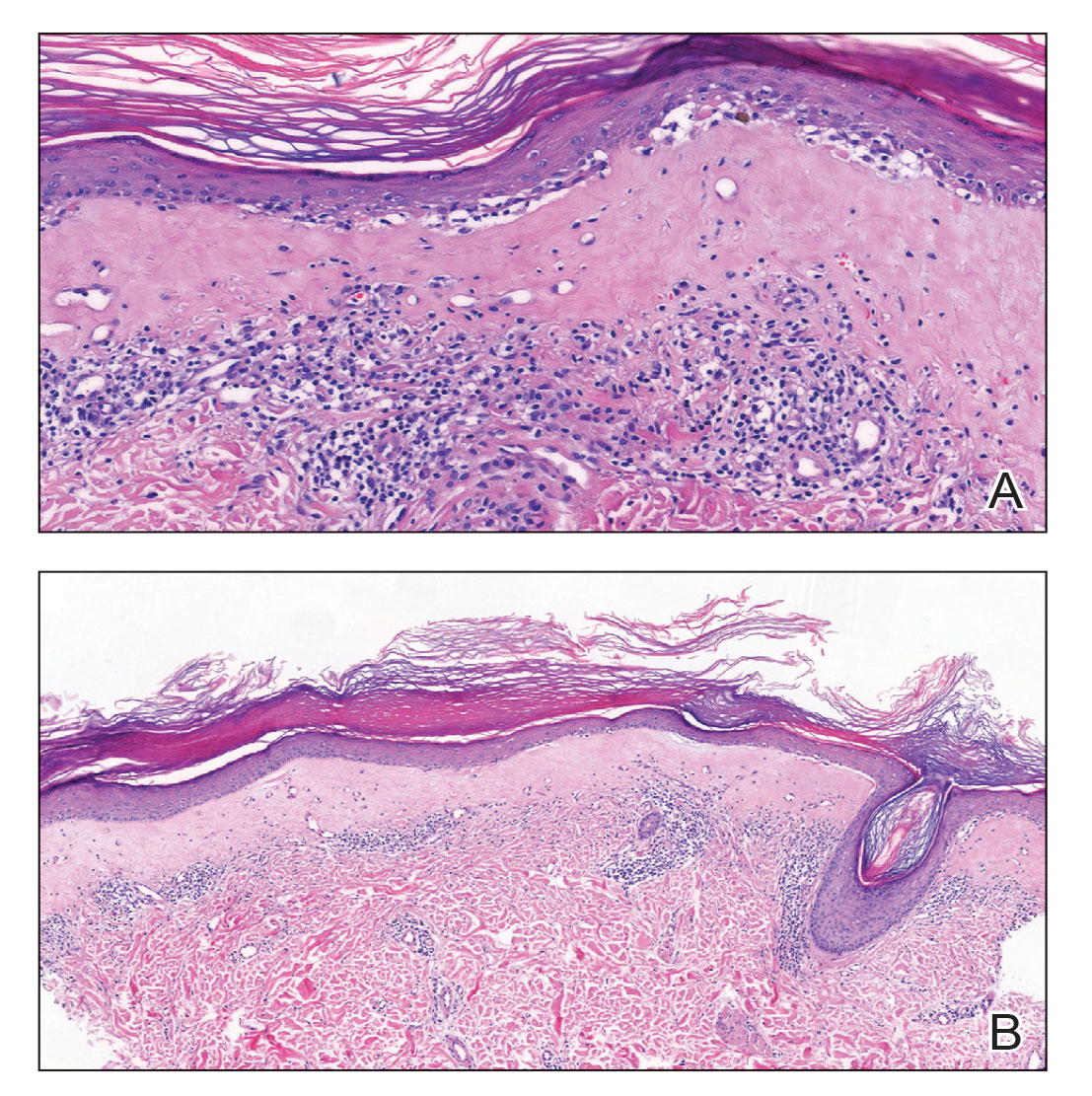

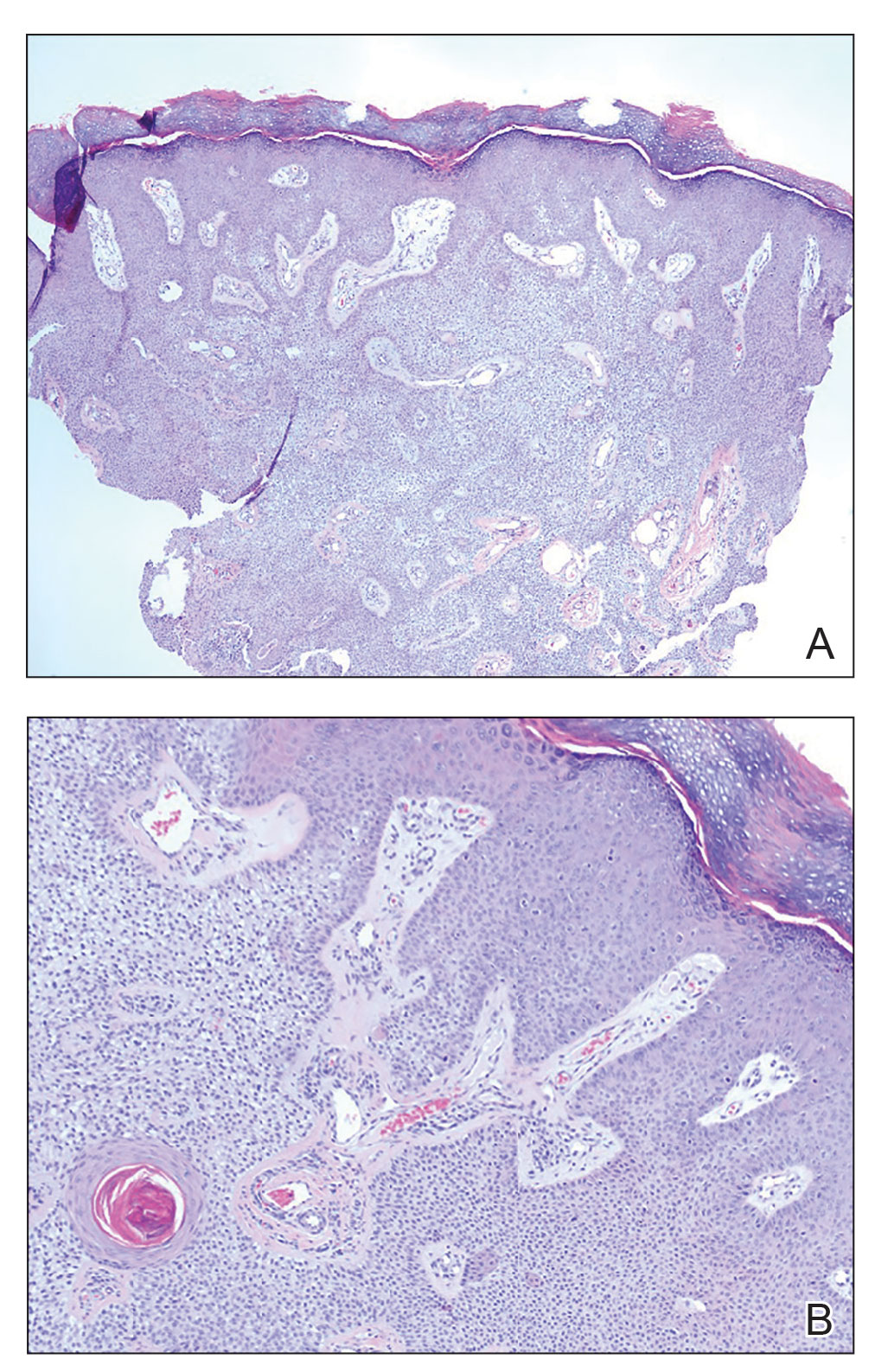

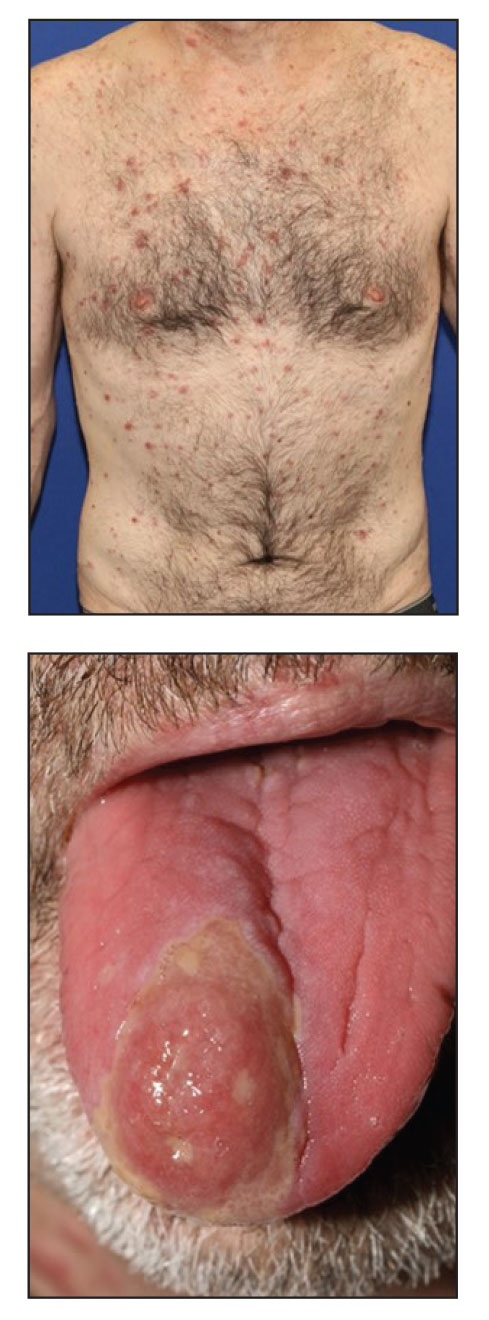

A punch biopsy of the lesion revealed epidermal hyperkeratosis, atrophy, follicular plugs with basal vacuolar degeneration, and homogenous dense fibrosis in the papillary dermis with a dense lymphocytic infiltrate beneath the fibrosis (Figure 1). Dermoscopic examination was remarkable for a distinctive rainbow pattern. Clinical, histopathologic, and dermoscopic findings led to the diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSEA). A potent corticosteroid cream was prescribed twice daily for 2 months, after which the lesions completely resolved. At 2-year follow-up, a relapse was not observed (Figure 2).

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an inflammatory dermatosis that clinically presents as atrophic or hypertrophic plaques that may show pigmentation changes with anogenital and extragenital involvement. It is common among females and predominantly occurs in prepubescent girls and postmenopausal women. The exact etiology is unclear; however, it is hypothesized to occur secondary to autoimmunity with an underlying genetic predisposition. Local trauma, hormonal influences, and infections are other suspected etiologic factors. Genital lesions often lead to itching, pain, and dyspareunia, whereas extragenital lesions predominantly are asymptomatic. When symptomatic, itching usually is the main concern. Unlike genital LSEA, extragenital lesions are not associated with squamous cell carcinoma development. Reported dermoscopic features of LSEA are white structureless areas with scaling, comedolike openings, follicular plugs, white shiny streaks, blue-gray peppering, pigment network, and red-purple globules.1 In our case, the dermoscopic finding of a rainbow pattern in LSEA is rare.2 Although the mechanism behind this appearance unclear, it can be the result of the birefringence effect—local variations in refractive index—influenced by the direction of structures within the dermis such as collagen. In this case, there was diffuse and dense homogenous fibrosis in the superficial dermis that corresponded to dermoscopic white polygonal clods.

Extragenital LSEA commonly is located on the neck, shoulders, wrists, and upper trunk and manifests clinically as whitish papules coalescing into scarlike plaques. Of all patients who have LSEA, 20% have extragenital lesions, and most of these lesions are seen in patients who also have genital LSEA. Approximately 6% of all LSEA patients have extragenital LSEA without genital involvement.3

For experienced dermatologists, clinical symptoms and lesion characteristics usually are sufficient for diagnosis; however, a differential diagnosis of atypical lesions and isolated extragenital presentations such as morphea, lichen simplex chronicus, lichen planus, and vitiligo requires the correlation of clinical findings with histopathology and dermoscopy. Morphea, known as localized scleroderma, is an idiopathic inflammatory skin disease with sclerotic changes. It manifests as inflammatory plaques that vary in color from red to purple. If there is moderate sclerosis in the center of this plaque, the color progressively fades to white, leaving a purplish ring around the edges. Dermoscopic features of morphea are reported as areas of erythema; red-focused vessels of linear, irregular, or dotted morphology; white fibrotic beams; and pigmentary structures.2 Lichen simplex chronicus is characterized by single or multiple dry and patchy skin lesions that are intensely pruritic. It commonly occurs on the neck, scalp, extremities, genital areas, and buttocks. Scratching the lesions leads to scarring, thickening of the skin, and increased frequency of itching. Histopathology of lichen simplex chronicus most frequently demonstrates a thickening of the epidermis and papillary dermis, irregularly elongated rete ridges, and fibroplasia with stellate or multinucleated fibroblasts completed by perivascular lymphocytic inflammation.4 Lichen planus presents with pruritic, polygonal, purple papules and/or plaques that can present in a variety of clinical forms, including atrophic and hypertrophic lichen planus.5 Lichen planus was an unlikely diagnosis for our patient due to the presence of patchy scarlike lesions and dermoscopic features that are well described in patients with LSEA. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus presents with hypopigmented and/or hyperpigmented patches and plaques, distinguishing itself from vitiligo, which has flat lesions.

Topical steroids are the first-line therapeutic agents in the treatment of LSEA.6 Despite frequent use in this setting, common side effects such as localized scarring and atrophic degenerations have led to debate about their use. In our patient, the lesions resolved almost completely in 2 months, and no relapse was observed in the following 2 years. In the setting of topical steroid resistance, topical calcineurin inhibitors, UVA/UVB phototherapy, and topical tacrolimus can be used for treatment.6

The diagnosis of isolated extragenital LSEA may be a clinical challenge and generally requires further workup. When evaluating extragenital lesions, dermatologists should keep in mind extragenital LSEA as a differential diagnosis in the presence of a dermoscopic rainbow pattern arranged over white polygonal clods.

- Wang Y-K, Hao J-C, Liu J, et al. Dermoscopic features of morphea and extragenital lichen sclerosus in Chinese patients. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133:2109-2111.

- Errichetti E, Lallas A, Apalla Z, et al. Dermoscopy of morphea and cutaneous lichen sclerosus: clinicopathological correlation study and comparative analysis. Dermatology. 2017;233:462-470.

- Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:9-30.

- Balan R, Grigoras¸ A, Popovici D, et al. The histopathological landscape of the major psoriasiform dermatoses. Arch Clin Cases. 2021;6:59-68.

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149.

- Kirtschig G, Becker K, Günthert A, et al. Evidence-based (S3) guideline on (anogenital) lichen sclerosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:E1-E43.

The Diagnosis: Extragenital Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus

A punch biopsy of the lesion revealed epidermal hyperkeratosis, atrophy, follicular plugs with basal vacuolar degeneration, and homogenous dense fibrosis in the papillary dermis with a dense lymphocytic infiltrate beneath the fibrosis (Figure 1). Dermoscopic examination was remarkable for a distinctive rainbow pattern. Clinical, histopathologic, and dermoscopic findings led to the diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSEA). A potent corticosteroid cream was prescribed twice daily for 2 months, after which the lesions completely resolved. At 2-year follow-up, a relapse was not observed (Figure 2).

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an inflammatory dermatosis that clinically presents as atrophic or hypertrophic plaques that may show pigmentation changes with anogenital and extragenital involvement. It is common among females and predominantly occurs in prepubescent girls and postmenopausal women. The exact etiology is unclear; however, it is hypothesized to occur secondary to autoimmunity with an underlying genetic predisposition. Local trauma, hormonal influences, and infections are other suspected etiologic factors. Genital lesions often lead to itching, pain, and dyspareunia, whereas extragenital lesions predominantly are asymptomatic. When symptomatic, itching usually is the main concern. Unlike genital LSEA, extragenital lesions are not associated with squamous cell carcinoma development. Reported dermoscopic features of LSEA are white structureless areas with scaling, comedolike openings, follicular plugs, white shiny streaks, blue-gray peppering, pigment network, and red-purple globules.1 In our case, the dermoscopic finding of a rainbow pattern in LSEA is rare.2 Although the mechanism behind this appearance unclear, it can be the result of the birefringence effect—local variations in refractive index—influenced by the direction of structures within the dermis such as collagen. In this case, there was diffuse and dense homogenous fibrosis in the superficial dermis that corresponded to dermoscopic white polygonal clods.

Extragenital LSEA commonly is located on the neck, shoulders, wrists, and upper trunk and manifests clinically as whitish papules coalescing into scarlike plaques. Of all patients who have LSEA, 20% have extragenital lesions, and most of these lesions are seen in patients who also have genital LSEA. Approximately 6% of all LSEA patients have extragenital LSEA without genital involvement.3

For experienced dermatologists, clinical symptoms and lesion characteristics usually are sufficient for diagnosis; however, a differential diagnosis of atypical lesions and isolated extragenital presentations such as morphea, lichen simplex chronicus, lichen planus, and vitiligo requires the correlation of clinical findings with histopathology and dermoscopy. Morphea, known as localized scleroderma, is an idiopathic inflammatory skin disease with sclerotic changes. It manifests as inflammatory plaques that vary in color from red to purple. If there is moderate sclerosis in the center of this plaque, the color progressively fades to white, leaving a purplish ring around the edges. Dermoscopic features of morphea are reported as areas of erythema; red-focused vessels of linear, irregular, or dotted morphology; white fibrotic beams; and pigmentary structures.2 Lichen simplex chronicus is characterized by single or multiple dry and patchy skin lesions that are intensely pruritic. It commonly occurs on the neck, scalp, extremities, genital areas, and buttocks. Scratching the lesions leads to scarring, thickening of the skin, and increased frequency of itching. Histopathology of lichen simplex chronicus most frequently demonstrates a thickening of the epidermis and papillary dermis, irregularly elongated rete ridges, and fibroplasia with stellate or multinucleated fibroblasts completed by perivascular lymphocytic inflammation.4 Lichen planus presents with pruritic, polygonal, purple papules and/or plaques that can present in a variety of clinical forms, including atrophic and hypertrophic lichen planus.5 Lichen planus was an unlikely diagnosis for our patient due to the presence of patchy scarlike lesions and dermoscopic features that are well described in patients with LSEA. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus presents with hypopigmented and/or hyperpigmented patches and plaques, distinguishing itself from vitiligo, which has flat lesions.

Topical steroids are the first-line therapeutic agents in the treatment of LSEA.6 Despite frequent use in this setting, common side effects such as localized scarring and atrophic degenerations have led to debate about their use. In our patient, the lesions resolved almost completely in 2 months, and no relapse was observed in the following 2 years. In the setting of topical steroid resistance, topical calcineurin inhibitors, UVA/UVB phototherapy, and topical tacrolimus can be used for treatment.6

The diagnosis of isolated extragenital LSEA may be a clinical challenge and generally requires further workup. When evaluating extragenital lesions, dermatologists should keep in mind extragenital LSEA as a differential diagnosis in the presence of a dermoscopic rainbow pattern arranged over white polygonal clods.

The Diagnosis: Extragenital Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus

A punch biopsy of the lesion revealed epidermal hyperkeratosis, atrophy, follicular plugs with basal vacuolar degeneration, and homogenous dense fibrosis in the papillary dermis with a dense lymphocytic infiltrate beneath the fibrosis (Figure 1). Dermoscopic examination was remarkable for a distinctive rainbow pattern. Clinical, histopathologic, and dermoscopic findings led to the diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSEA). A potent corticosteroid cream was prescribed twice daily for 2 months, after which the lesions completely resolved. At 2-year follow-up, a relapse was not observed (Figure 2).

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an inflammatory dermatosis that clinically presents as atrophic or hypertrophic plaques that may show pigmentation changes with anogenital and extragenital involvement. It is common among females and predominantly occurs in prepubescent girls and postmenopausal women. The exact etiology is unclear; however, it is hypothesized to occur secondary to autoimmunity with an underlying genetic predisposition. Local trauma, hormonal influences, and infections are other suspected etiologic factors. Genital lesions often lead to itching, pain, and dyspareunia, whereas extragenital lesions predominantly are asymptomatic. When symptomatic, itching usually is the main concern. Unlike genital LSEA, extragenital lesions are not associated with squamous cell carcinoma development. Reported dermoscopic features of LSEA are white structureless areas with scaling, comedolike openings, follicular plugs, white shiny streaks, blue-gray peppering, pigment network, and red-purple globules.1 In our case, the dermoscopic finding of a rainbow pattern in LSEA is rare.2 Although the mechanism behind this appearance unclear, it can be the result of the birefringence effect—local variations in refractive index—influenced by the direction of structures within the dermis such as collagen. In this case, there was diffuse and dense homogenous fibrosis in the superficial dermis that corresponded to dermoscopic white polygonal clods.

Extragenital LSEA commonly is located on the neck, shoulders, wrists, and upper trunk and manifests clinically as whitish papules coalescing into scarlike plaques. Of all patients who have LSEA, 20% have extragenital lesions, and most of these lesions are seen in patients who also have genital LSEA. Approximately 6% of all LSEA patients have extragenital LSEA without genital involvement.3

For experienced dermatologists, clinical symptoms and lesion characteristics usually are sufficient for diagnosis; however, a differential diagnosis of atypical lesions and isolated extragenital presentations such as morphea, lichen simplex chronicus, lichen planus, and vitiligo requires the correlation of clinical findings with histopathology and dermoscopy. Morphea, known as localized scleroderma, is an idiopathic inflammatory skin disease with sclerotic changes. It manifests as inflammatory plaques that vary in color from red to purple. If there is moderate sclerosis in the center of this plaque, the color progressively fades to white, leaving a purplish ring around the edges. Dermoscopic features of morphea are reported as areas of erythema; red-focused vessels of linear, irregular, or dotted morphology; white fibrotic beams; and pigmentary structures.2 Lichen simplex chronicus is characterized by single or multiple dry and patchy skin lesions that are intensely pruritic. It commonly occurs on the neck, scalp, extremities, genital areas, and buttocks. Scratching the lesions leads to scarring, thickening of the skin, and increased frequency of itching. Histopathology of lichen simplex chronicus most frequently demonstrates a thickening of the epidermis and papillary dermis, irregularly elongated rete ridges, and fibroplasia with stellate or multinucleated fibroblasts completed by perivascular lymphocytic inflammation.4 Lichen planus presents with pruritic, polygonal, purple papules and/or plaques that can present in a variety of clinical forms, including atrophic and hypertrophic lichen planus.5 Lichen planus was an unlikely diagnosis for our patient due to the presence of patchy scarlike lesions and dermoscopic features that are well described in patients with LSEA. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus presents with hypopigmented and/or hyperpigmented patches and plaques, distinguishing itself from vitiligo, which has flat lesions.

Topical steroids are the first-line therapeutic agents in the treatment of LSEA.6 Despite frequent use in this setting, common side effects such as localized scarring and atrophic degenerations have led to debate about their use. In our patient, the lesions resolved almost completely in 2 months, and no relapse was observed in the following 2 years. In the setting of topical steroid resistance, topical calcineurin inhibitors, UVA/UVB phototherapy, and topical tacrolimus can be used for treatment.6

The diagnosis of isolated extragenital LSEA may be a clinical challenge and generally requires further workup. When evaluating extragenital lesions, dermatologists should keep in mind extragenital LSEA as a differential diagnosis in the presence of a dermoscopic rainbow pattern arranged over white polygonal clods.

- Wang Y-K, Hao J-C, Liu J, et al. Dermoscopic features of morphea and extragenital lichen sclerosus in Chinese patients. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133:2109-2111.

- Errichetti E, Lallas A, Apalla Z, et al. Dermoscopy of morphea and cutaneous lichen sclerosus: clinicopathological correlation study and comparative analysis. Dermatology. 2017;233:462-470.

- Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:9-30.

- Balan R, Grigoras¸ A, Popovici D, et al. The histopathological landscape of the major psoriasiform dermatoses. Arch Clin Cases. 2021;6:59-68.

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149.

- Kirtschig G, Becker K, Günthert A, et al. Evidence-based (S3) guideline on (anogenital) lichen sclerosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:E1-E43.

- Wang Y-K, Hao J-C, Liu J, et al. Dermoscopic features of morphea and extragenital lichen sclerosus in Chinese patients. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133:2109-2111.

- Errichetti E, Lallas A, Apalla Z, et al. Dermoscopy of morphea and cutaneous lichen sclerosus: clinicopathological correlation study and comparative analysis. Dermatology. 2017;233:462-470.

- Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:9-30.

- Balan R, Grigoras¸ A, Popovici D, et al. The histopathological landscape of the major psoriasiform dermatoses. Arch Clin Cases. 2021;6:59-68.

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149.

- Kirtschig G, Becker K, Günthert A, et al. Evidence-based (S3) guideline on (anogenital) lichen sclerosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:E1-E43.

A 50-year-old woman presented with multiple pruritic lesions on the right inner thigh of 2 years’ duration. Physical examination revealed porcelain white, crinkled, violaceous patches extending from the right inner thigh to the inguinal fold (top). Dermoscopic examination revealed follicular plugs, white structureless areas, white lines, and a rainbow pattern arranged over white polygonal clods on polarized mode (bottom).

Genital Ulcerations With Swelling

The Diagnosis: Mpox (Monkeypox)

Tests for active herpes simplex virus (HHV), gonorrhea, chlamydia, HIV, and syphilis were negative. Swabs from the penile lesion demonstrated positivity for the West African clade of mpox (monkeypox) virus (MPXV) by polymerase chain reaction. The patient was treated supportively without the addition of antiviral therapy, and he experienced a complete recovery.

Mpox virus was first isolated in 1958 in a research facility and was named after the laboratory animals that were housed there. The first human documentation of the disease occurred in 1970, and it was first documented in the United States in 2003 in an infection that was traced to a shipment of small mammals from Ghana to Texas.1 The disease has always been endemic to Africa; however, the incidence has been increasing.2 A new MPXV outbreak was reported in many countries in early 2022, including the United States.1

The MPXV is a double-stranded DNA virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus, and 2 genetic clades have been identified: clade I (formerly the Central African clade) and clade II (formerly the West African clade). The virus has the capability to infect many mammals; however, its host remains unidentified.1 The exact mechanism of transmission from infected animals to humans largely is unknown; however, direct or indirect contact with infected animals likely is responsible. Human-to-human transmission can occur by many mechanisms including contact with large respiratory droplets, bodily fluids, and contaminated surfaces. The incubation period is 5 to 21 days, and the symptoms last 2 to 5 weeks.1

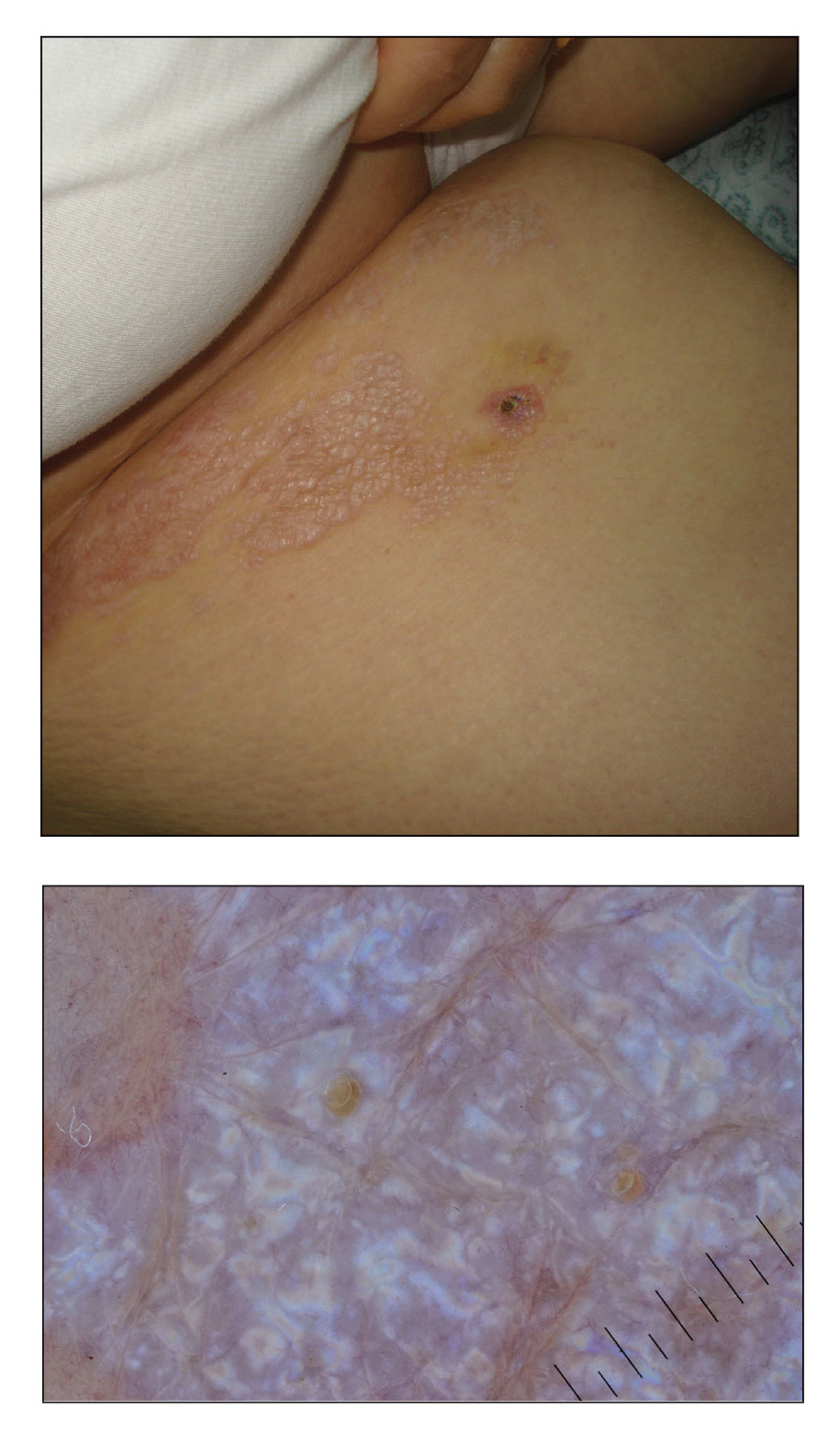

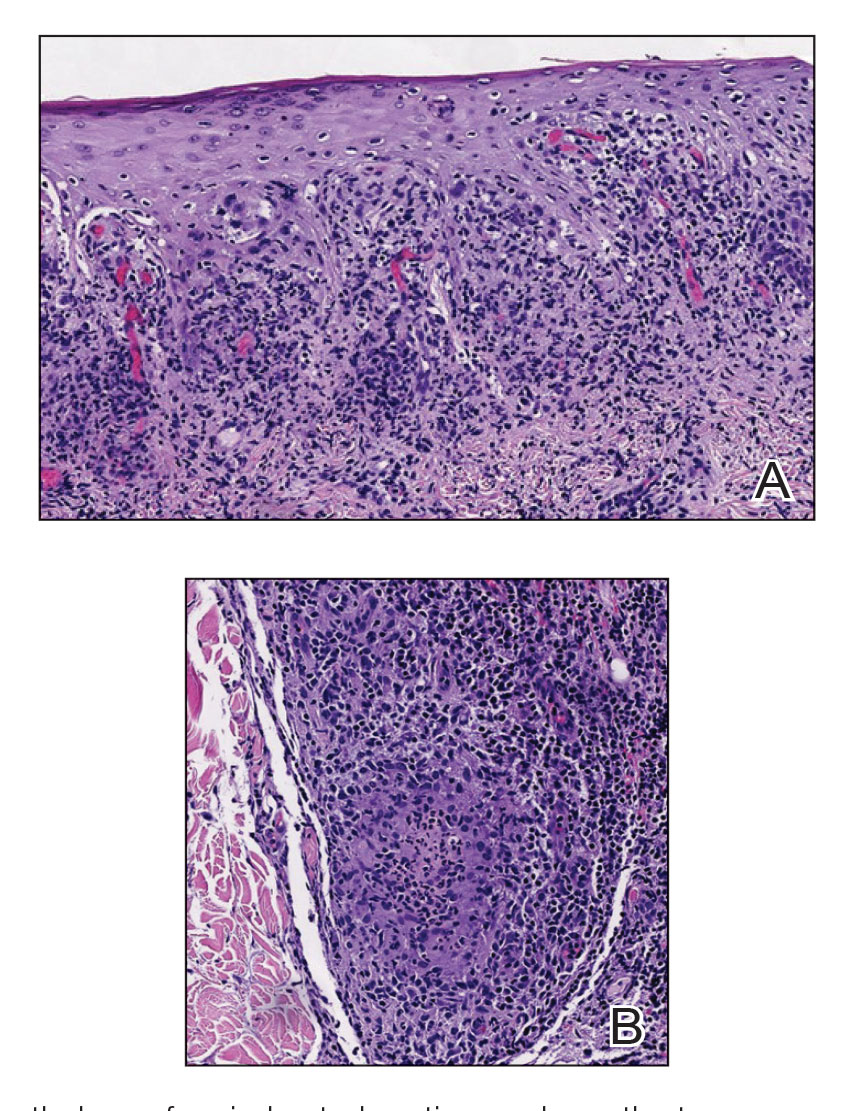

The clinical manifestations of MPXV during the most recent outbreak differ from prior outbreaks. Patients are more likely to experience minimal to no systemic symptoms, and cutaneous lesions can be few and localized to a focal area, especially on the face and in the anogenital region,3 similar to the presentation in our patient (Figure 1). Cutaneous lesions of the most recent MPXV outbreak also include painless ulcerations similar to syphilitic chancres and lesions that are in various stages of healing.3 Lesions often begin as pseudopustules, which are firm white papules with or without a necrotic center that resemble pustules; unlike true pustules, there is no identifiable purulent material within it. Bacterial superinfection of the lesions is not uncommon.4 Over time, a secondary pustular eruption resembling folliculitis also may occur,4 as noted in our patient (Figure 2).

Although we did not have a biopsy to support the diagnosis of associated erythema multiforme (EM) in our patient, features supportive of this diagnosis included the classic clinical appearance of typical, well-defined, targetoid plaques with 3 distinct zones (Figure 3); the association with a known infection; the distribution on the arms with truncal sparing; and self-limited lesions. More than 90% of EM cases are associated with infection, with HHV representing the most common culprit5; therefore, the relationship with a different virus is not an unreasonable suggestion. Additionally, there have been rare reports of EM in association with MPXV.4

Histopathology of MPXV may have distinctive features. Lesions often demonstrate keratinocytic necrosis and basal layer vacuolization with an associated superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. When the morphology of the lesion is vesicular, histopathology reveals spongiosis and ballooning degeneration with epidermal necrosis. Viral inclusion bodies within keratinocytes may be identified.1 Death rates from MPXV has been reported from 1% to 11%, with increased mortality among high-risk populations including children and immunocompromised individuals. Treatment of the disease largely consists of supportive care and management of any associated complications including bacterial infection, pneumonia, and encephalitis.1

The differential diagnosis of MPXV includes other ulcerative lesions that can occur on the genital skin. Fixed drug eruptions often present on the penis,6 but there was no identifiable inciting drug in our patient. Herpes simplex virus infection was very high on the differential given our patient’s history of recurrent infections and association with a targetoid rash, but HHV type 1 and HHV type 2 testing of the lesion was negative. A syphilitic chancre also may present with the nontender genital ulceration7 that was seen in our patient, but serology did not support this diagnosis. Cutaneous Crohn disease also may manifest with genital ulceration even before a diagnosis of Crohn disease is made, but these lesions often present as linear knife-cut ulcerations of the anogenital region.8

Our case further supports a clinical presentation that diverges from the more traditional cases of MPXV. Additionally, associated EM may be a clue to infection, especially in cases of negative HHV and other sexually transmitted infection testing.

- Bunge EM, Hoet B, Chen L, et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—a potential threat? a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16:E0010141.

- Kumar N, Acharya A, Gendelman HE, et al. The 2022 outbreak and the pathobiology of the monkeypox virus. J Autoimmun. 2022;131:102855.

- Eisenstadt R, Liszewski WJ, Nguyen CV. Recognizing minimal cutaneous involvement or systemic symptoms in monkeypox. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1457-1458.

- Català A, Clavo-Escribano P, Riera-Monroig J, et al. Monkeypox outbreak in Spain: clinical and epidemiological findings in a prospective cross-sectional study of 185 cases [published online August 2, 2022]. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:765-772.

- Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:889-902.

- Waleryie-Allanore L, Obeid G, Revuz J. Drug reactions. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:348-375.

- Stary G, Stary A. Sexually transmitted infections. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:1447-1469.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:1644-1663.

The Diagnosis: Mpox (Monkeypox)

Tests for active herpes simplex virus (HHV), gonorrhea, chlamydia, HIV, and syphilis were negative. Swabs from the penile lesion demonstrated positivity for the West African clade of mpox (monkeypox) virus (MPXV) by polymerase chain reaction. The patient was treated supportively without the addition of antiviral therapy, and he experienced a complete recovery.

Mpox virus was first isolated in 1958 in a research facility and was named after the laboratory animals that were housed there. The first human documentation of the disease occurred in 1970, and it was first documented in the United States in 2003 in an infection that was traced to a shipment of small mammals from Ghana to Texas.1 The disease has always been endemic to Africa; however, the incidence has been increasing.2 A new MPXV outbreak was reported in many countries in early 2022, including the United States.1

The MPXV is a double-stranded DNA virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus, and 2 genetic clades have been identified: clade I (formerly the Central African clade) and clade II (formerly the West African clade). The virus has the capability to infect many mammals; however, its host remains unidentified.1 The exact mechanism of transmission from infected animals to humans largely is unknown; however, direct or indirect contact with infected animals likely is responsible. Human-to-human transmission can occur by many mechanisms including contact with large respiratory droplets, bodily fluids, and contaminated surfaces. The incubation period is 5 to 21 days, and the symptoms last 2 to 5 weeks.1

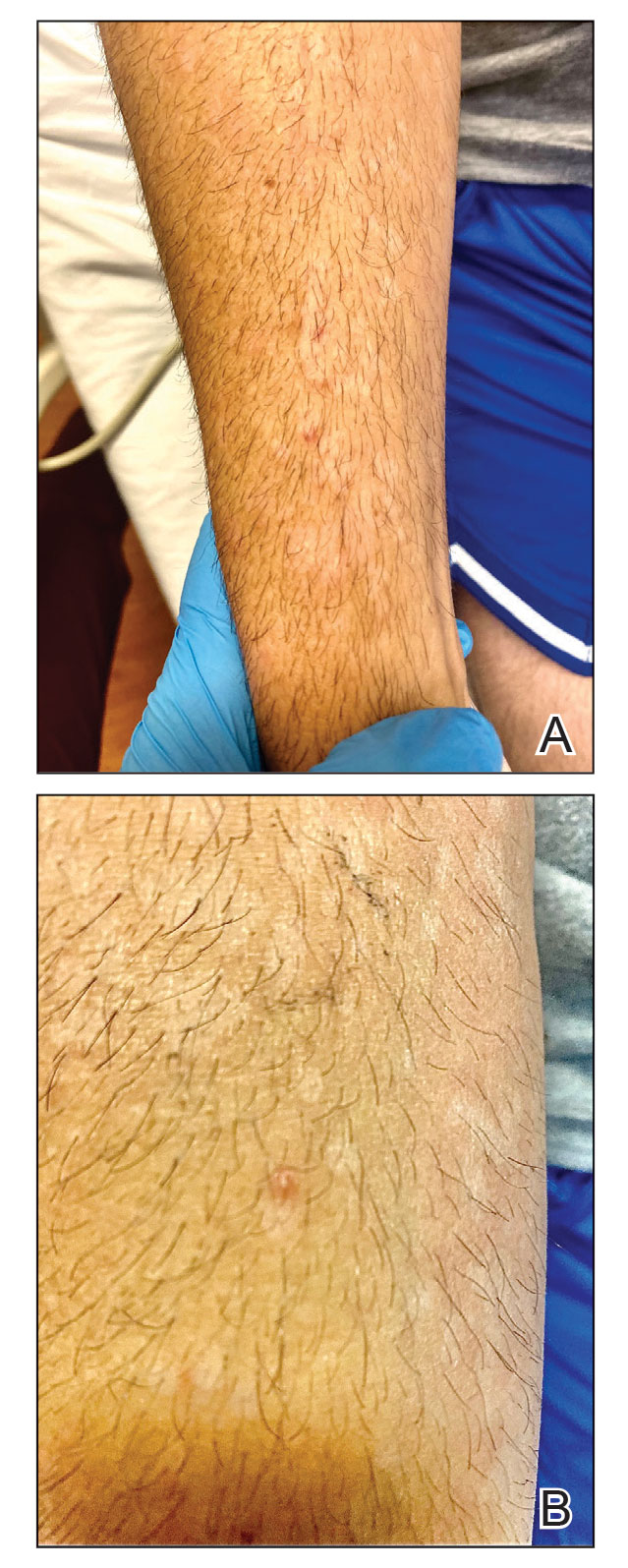

The clinical manifestations of MPXV during the most recent outbreak differ from prior outbreaks. Patients are more likely to experience minimal to no systemic symptoms, and cutaneous lesions can be few and localized to a focal area, especially on the face and in the anogenital region,3 similar to the presentation in our patient (Figure 1). Cutaneous lesions of the most recent MPXV outbreak also include painless ulcerations similar to syphilitic chancres and lesions that are in various stages of healing.3 Lesions often begin as pseudopustules, which are firm white papules with or without a necrotic center that resemble pustules; unlike true pustules, there is no identifiable purulent material within it. Bacterial superinfection of the lesions is not uncommon.4 Over time, a secondary pustular eruption resembling folliculitis also may occur,4 as noted in our patient (Figure 2).

Although we did not have a biopsy to support the diagnosis of associated erythema multiforme (EM) in our patient, features supportive of this diagnosis included the classic clinical appearance of typical, well-defined, targetoid plaques with 3 distinct zones (Figure 3); the association with a known infection; the distribution on the arms with truncal sparing; and self-limited lesions. More than 90% of EM cases are associated with infection, with HHV representing the most common culprit5; therefore, the relationship with a different virus is not an unreasonable suggestion. Additionally, there have been rare reports of EM in association with MPXV.4

Histopathology of MPXV may have distinctive features. Lesions often demonstrate keratinocytic necrosis and basal layer vacuolization with an associated superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. When the morphology of the lesion is vesicular, histopathology reveals spongiosis and ballooning degeneration with epidermal necrosis. Viral inclusion bodies within keratinocytes may be identified.1 Death rates from MPXV has been reported from 1% to 11%, with increased mortality among high-risk populations including children and immunocompromised individuals. Treatment of the disease largely consists of supportive care and management of any associated complications including bacterial infection, pneumonia, and encephalitis.1

The differential diagnosis of MPXV includes other ulcerative lesions that can occur on the genital skin. Fixed drug eruptions often present on the penis,6 but there was no identifiable inciting drug in our patient. Herpes simplex virus infection was very high on the differential given our patient’s history of recurrent infections and association with a targetoid rash, but HHV type 1 and HHV type 2 testing of the lesion was negative. A syphilitic chancre also may present with the nontender genital ulceration7 that was seen in our patient, but serology did not support this diagnosis. Cutaneous Crohn disease also may manifest with genital ulceration even before a diagnosis of Crohn disease is made, but these lesions often present as linear knife-cut ulcerations of the anogenital region.8

Our case further supports a clinical presentation that diverges from the more traditional cases of MPXV. Additionally, associated EM may be a clue to infection, especially in cases of negative HHV and other sexually transmitted infection testing.

The Diagnosis: Mpox (Monkeypox)

Tests for active herpes simplex virus (HHV), gonorrhea, chlamydia, HIV, and syphilis were negative. Swabs from the penile lesion demonstrated positivity for the West African clade of mpox (monkeypox) virus (MPXV) by polymerase chain reaction. The patient was treated supportively without the addition of antiviral therapy, and he experienced a complete recovery.

Mpox virus was first isolated in 1958 in a research facility and was named after the laboratory animals that were housed there. The first human documentation of the disease occurred in 1970, and it was first documented in the United States in 2003 in an infection that was traced to a shipment of small mammals from Ghana to Texas.1 The disease has always been endemic to Africa; however, the incidence has been increasing.2 A new MPXV outbreak was reported in many countries in early 2022, including the United States.1

The MPXV is a double-stranded DNA virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus, and 2 genetic clades have been identified: clade I (formerly the Central African clade) and clade II (formerly the West African clade). The virus has the capability to infect many mammals; however, its host remains unidentified.1 The exact mechanism of transmission from infected animals to humans largely is unknown; however, direct or indirect contact with infected animals likely is responsible. Human-to-human transmission can occur by many mechanisms including contact with large respiratory droplets, bodily fluids, and contaminated surfaces. The incubation period is 5 to 21 days, and the symptoms last 2 to 5 weeks.1

The clinical manifestations of MPXV during the most recent outbreak differ from prior outbreaks. Patients are more likely to experience minimal to no systemic symptoms, and cutaneous lesions can be few and localized to a focal area, especially on the face and in the anogenital region,3 similar to the presentation in our patient (Figure 1). Cutaneous lesions of the most recent MPXV outbreak also include painless ulcerations similar to syphilitic chancres and lesions that are in various stages of healing.3 Lesions often begin as pseudopustules, which are firm white papules with or without a necrotic center that resemble pustules; unlike true pustules, there is no identifiable purulent material within it. Bacterial superinfection of the lesions is not uncommon.4 Over time, a secondary pustular eruption resembling folliculitis also may occur,4 as noted in our patient (Figure 2).

Although we did not have a biopsy to support the diagnosis of associated erythema multiforme (EM) in our patient, features supportive of this diagnosis included the classic clinical appearance of typical, well-defined, targetoid plaques with 3 distinct zones (Figure 3); the association with a known infection; the distribution on the arms with truncal sparing; and self-limited lesions. More than 90% of EM cases are associated with infection, with HHV representing the most common culprit5; therefore, the relationship with a different virus is not an unreasonable suggestion. Additionally, there have been rare reports of EM in association with MPXV.4

Histopathology of MPXV may have distinctive features. Lesions often demonstrate keratinocytic necrosis and basal layer vacuolization with an associated superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. When the morphology of the lesion is vesicular, histopathology reveals spongiosis and ballooning degeneration with epidermal necrosis. Viral inclusion bodies within keratinocytes may be identified.1 Death rates from MPXV has been reported from 1% to 11%, with increased mortality among high-risk populations including children and immunocompromised individuals. Treatment of the disease largely consists of supportive care and management of any associated complications including bacterial infection, pneumonia, and encephalitis.1

The differential diagnosis of MPXV includes other ulcerative lesions that can occur on the genital skin. Fixed drug eruptions often present on the penis,6 but there was no identifiable inciting drug in our patient. Herpes simplex virus infection was very high on the differential given our patient’s history of recurrent infections and association with a targetoid rash, but HHV type 1 and HHV type 2 testing of the lesion was negative. A syphilitic chancre also may present with the nontender genital ulceration7 that was seen in our patient, but serology did not support this diagnosis. Cutaneous Crohn disease also may manifest with genital ulceration even before a diagnosis of Crohn disease is made, but these lesions often present as linear knife-cut ulcerations of the anogenital region.8

Our case further supports a clinical presentation that diverges from the more traditional cases of MPXV. Additionally, associated EM may be a clue to infection, especially in cases of negative HHV and other sexually transmitted infection testing.

- Bunge EM, Hoet B, Chen L, et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—a potential threat? a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16:E0010141.

- Kumar N, Acharya A, Gendelman HE, et al. The 2022 outbreak and the pathobiology of the monkeypox virus. J Autoimmun. 2022;131:102855.

- Eisenstadt R, Liszewski WJ, Nguyen CV. Recognizing minimal cutaneous involvement or systemic symptoms in monkeypox. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1457-1458.

- Català A, Clavo-Escribano P, Riera-Monroig J, et al. Monkeypox outbreak in Spain: clinical and epidemiological findings in a prospective cross-sectional study of 185 cases [published online August 2, 2022]. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:765-772.

- Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:889-902.

- Waleryie-Allanore L, Obeid G, Revuz J. Drug reactions. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:348-375.

- Stary G, Stary A. Sexually transmitted infections. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:1447-1469.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:1644-1663.

- Bunge EM, Hoet B, Chen L, et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—a potential threat? a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16:E0010141.

- Kumar N, Acharya A, Gendelman HE, et al. The 2022 outbreak and the pathobiology of the monkeypox virus. J Autoimmun. 2022;131:102855.

- Eisenstadt R, Liszewski WJ, Nguyen CV. Recognizing minimal cutaneous involvement or systemic symptoms in monkeypox. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1457-1458.

- Català A, Clavo-Escribano P, Riera-Monroig J, et al. Monkeypox outbreak in Spain: clinical and epidemiological findings in a prospective cross-sectional study of 185 cases [published online August 2, 2022]. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:765-772.

- Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:889-902.

- Waleryie-Allanore L, Obeid G, Revuz J. Drug reactions. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:348-375.

- Stary G, Stary A. Sexually transmitted infections. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:1447-1469.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:1644-1663.

A 50-year-old man with a history of recurrent genital herpes simplex virus infections presented to the hospital with genital lesions and swelling of 5 days’ duration. Prior to admission, the patient was treated with a course of valacyclovir by an urgent care physician without improvement. Physical examination revealed a 3-cm, nontender, shallow, ulcerative plaque with irregular borders and a purulent yellow base distributed on the distal shaft of the penis with extension into the coronal sulcus. A few other scattered erosions were noted on the distal penile shaft. He had associated diffuse nonpitting edema of the penis and scrotum as well as tender bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy. Three days after the genital ulcerations began, the patient developed a nontender erythematous papule with a necrotic center on the right jaw followed by an eruption of erythematous papulopustules on the arms and trunk. The patient denied dysuria, purulent penile discharge, fevers, chills, headaches, myalgia, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. The patient was sexually active exclusively with females and had more than 10 partners in the prior year. Shortly after hospital admission, the patient developed red targetoid plaques on the groin, trunk, and arms. No oral mucosal lesions were identified.

Ulcerated Nodule on the Lip

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastasis

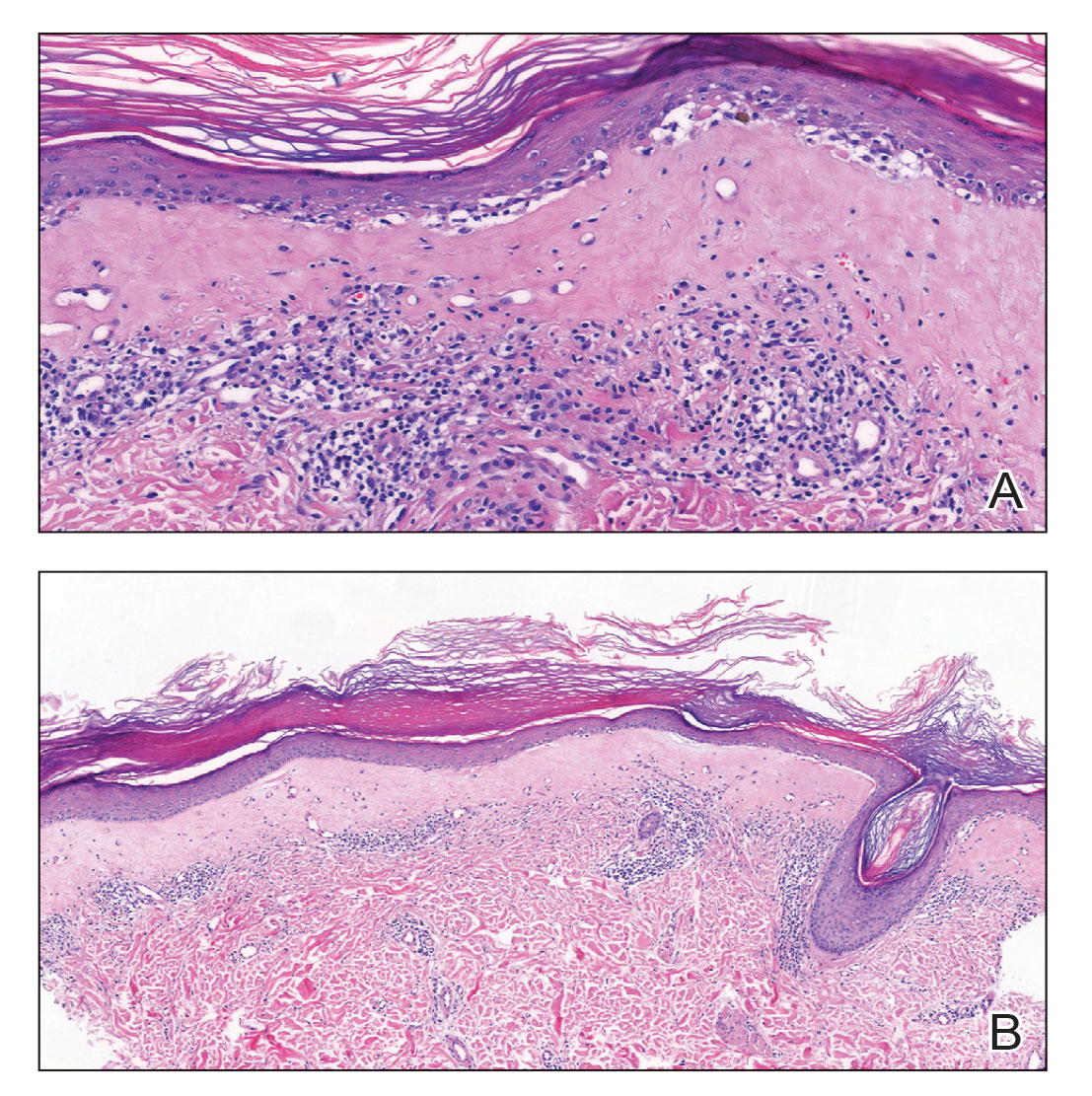

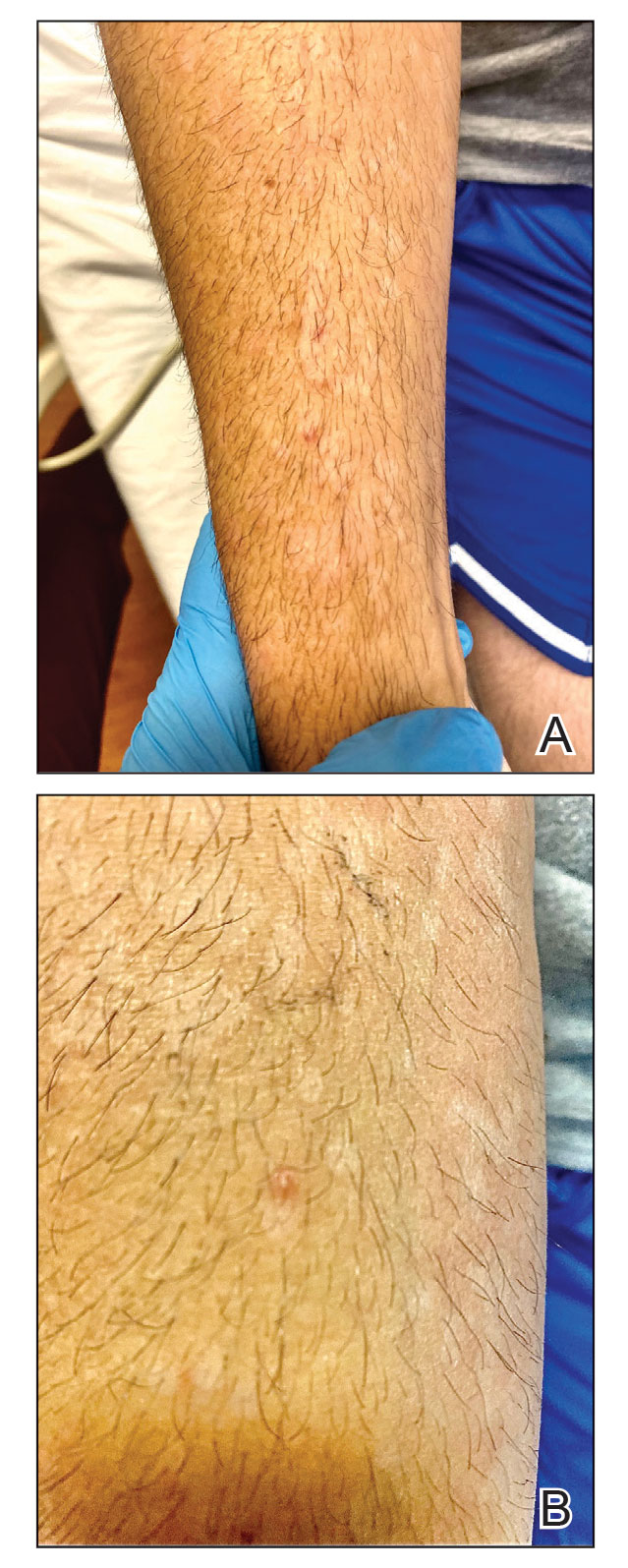

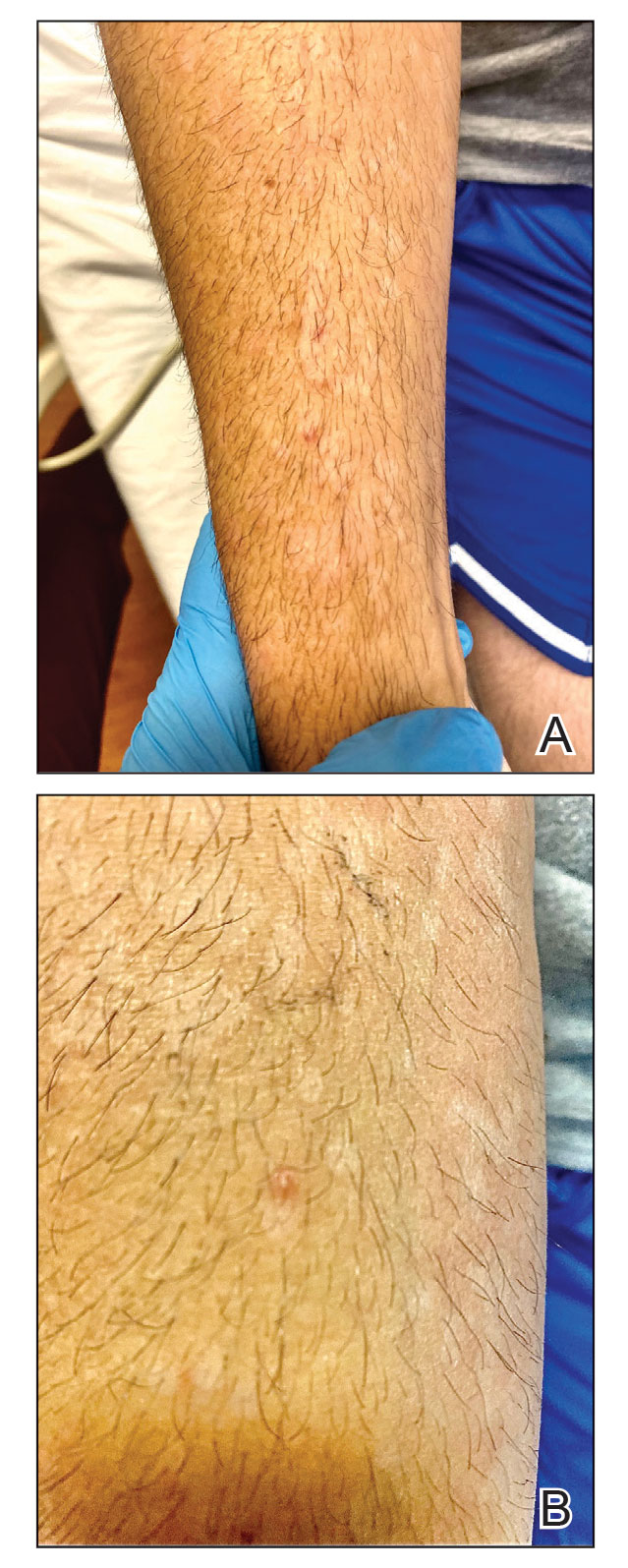

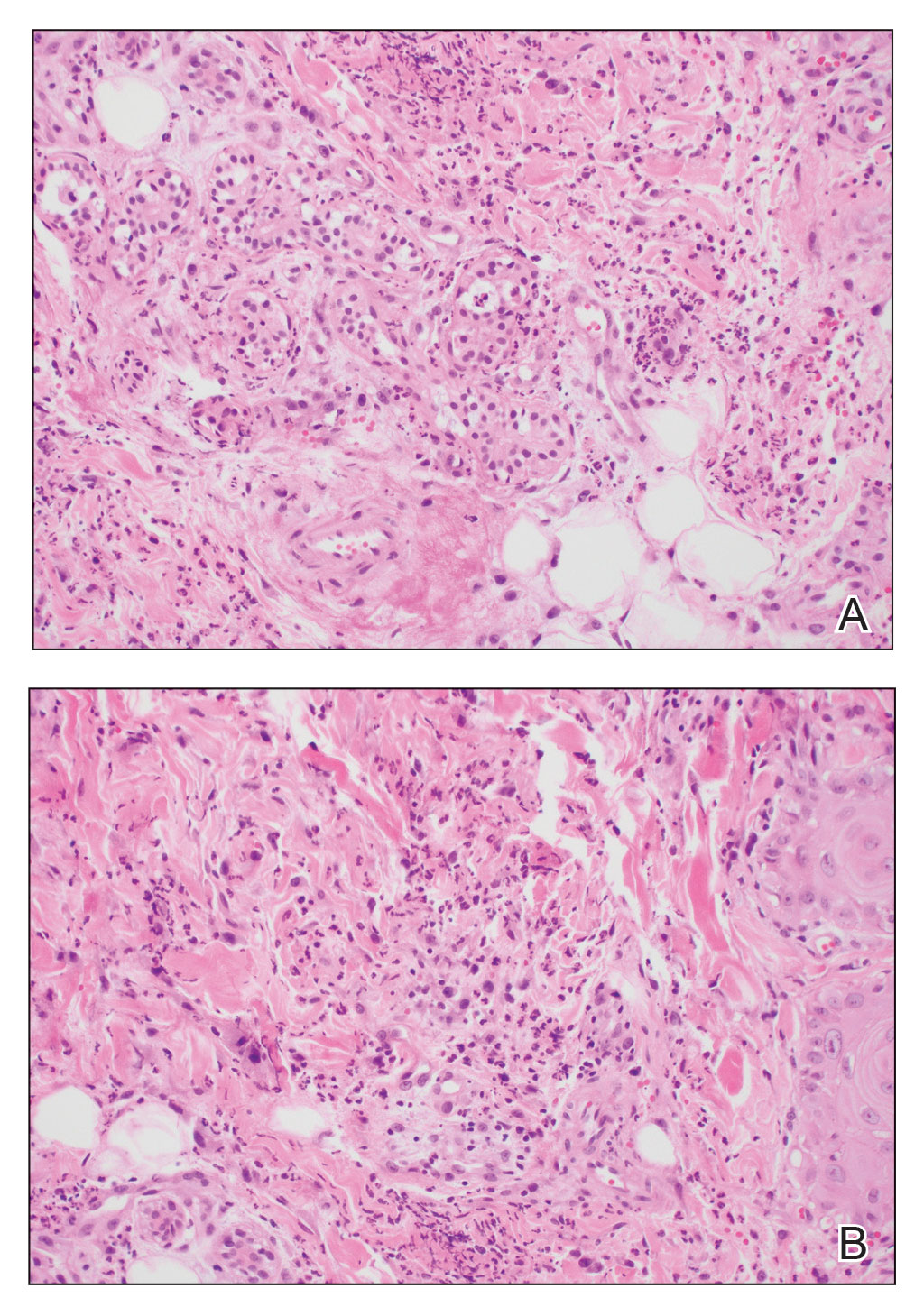

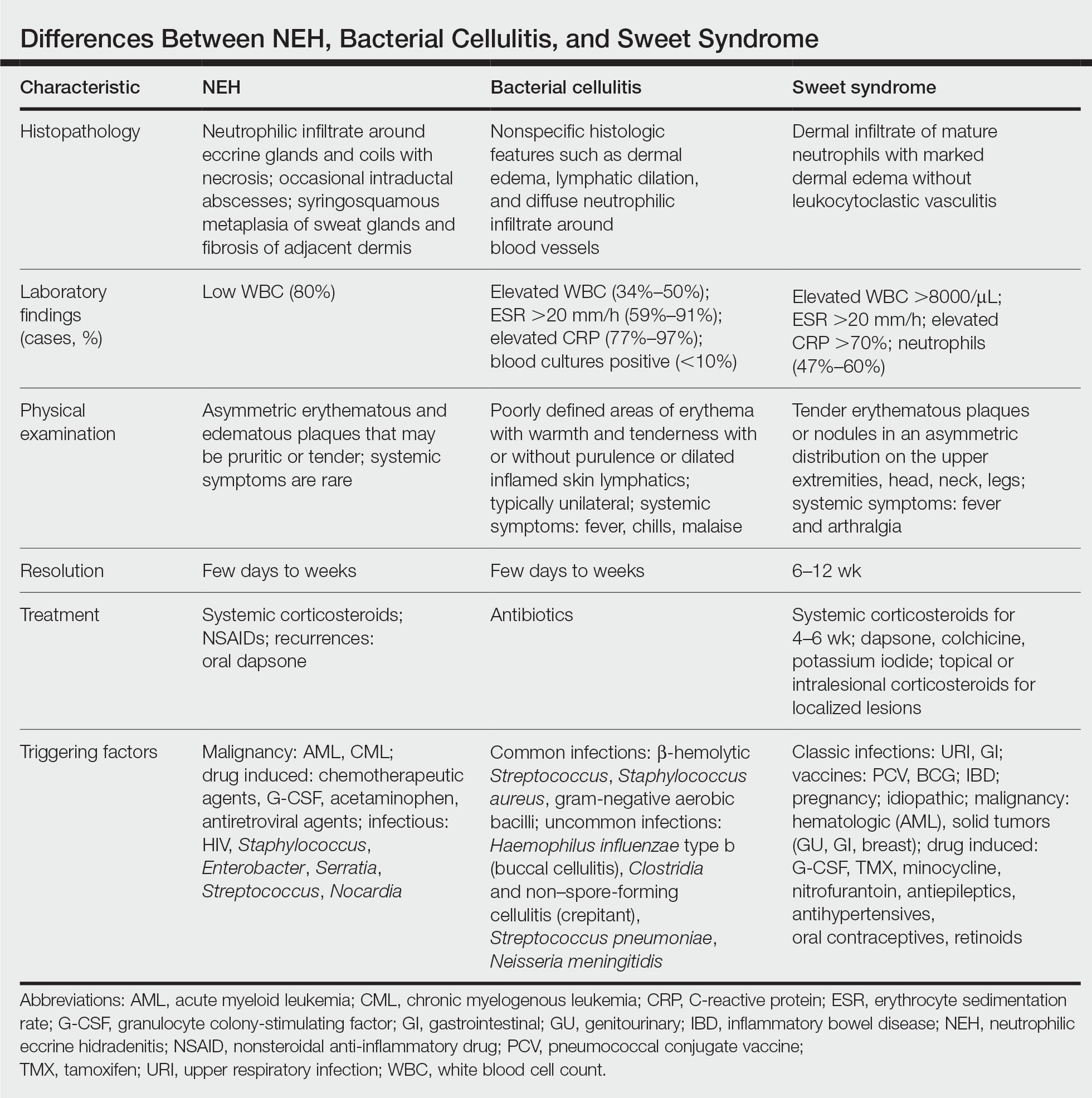

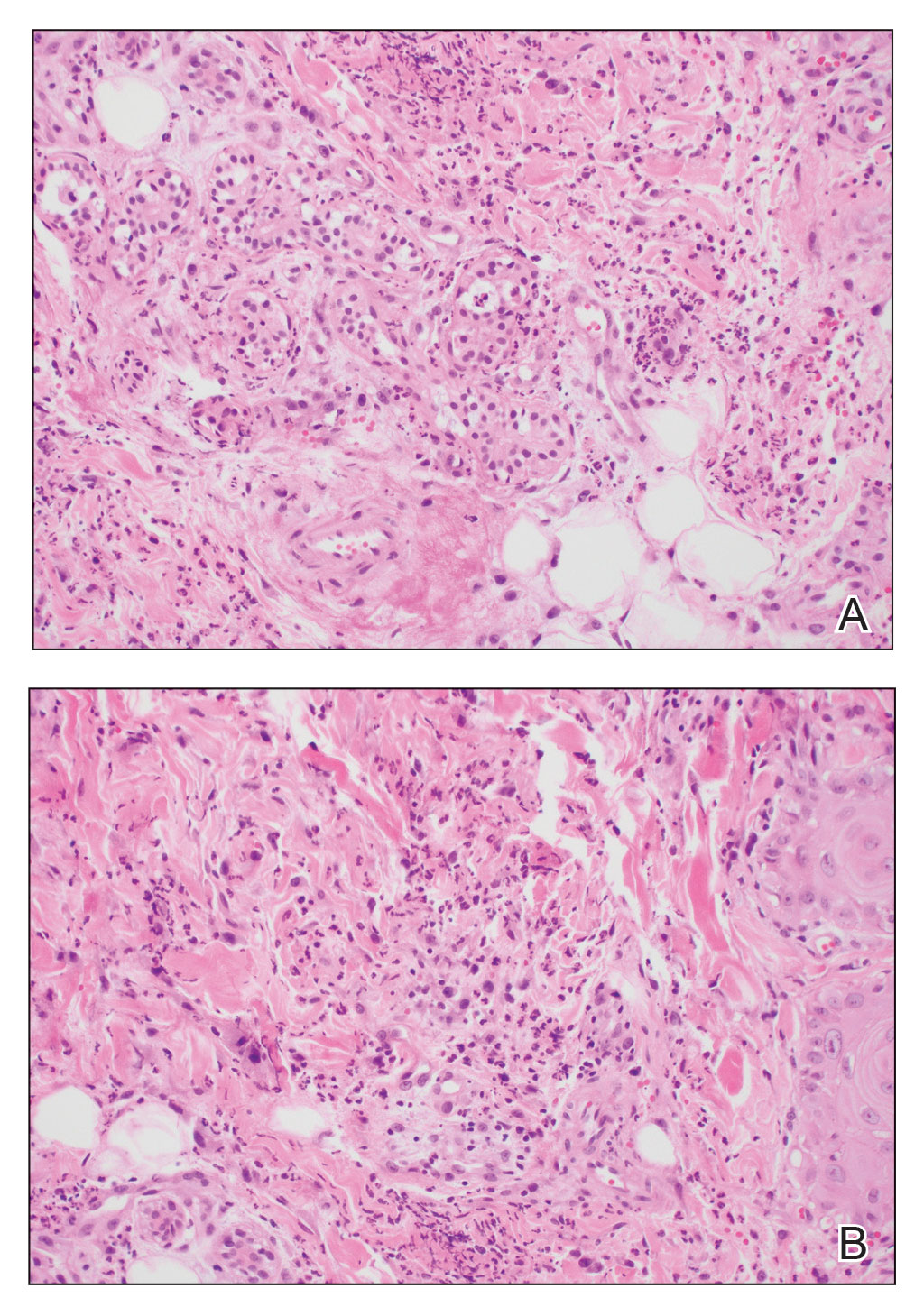

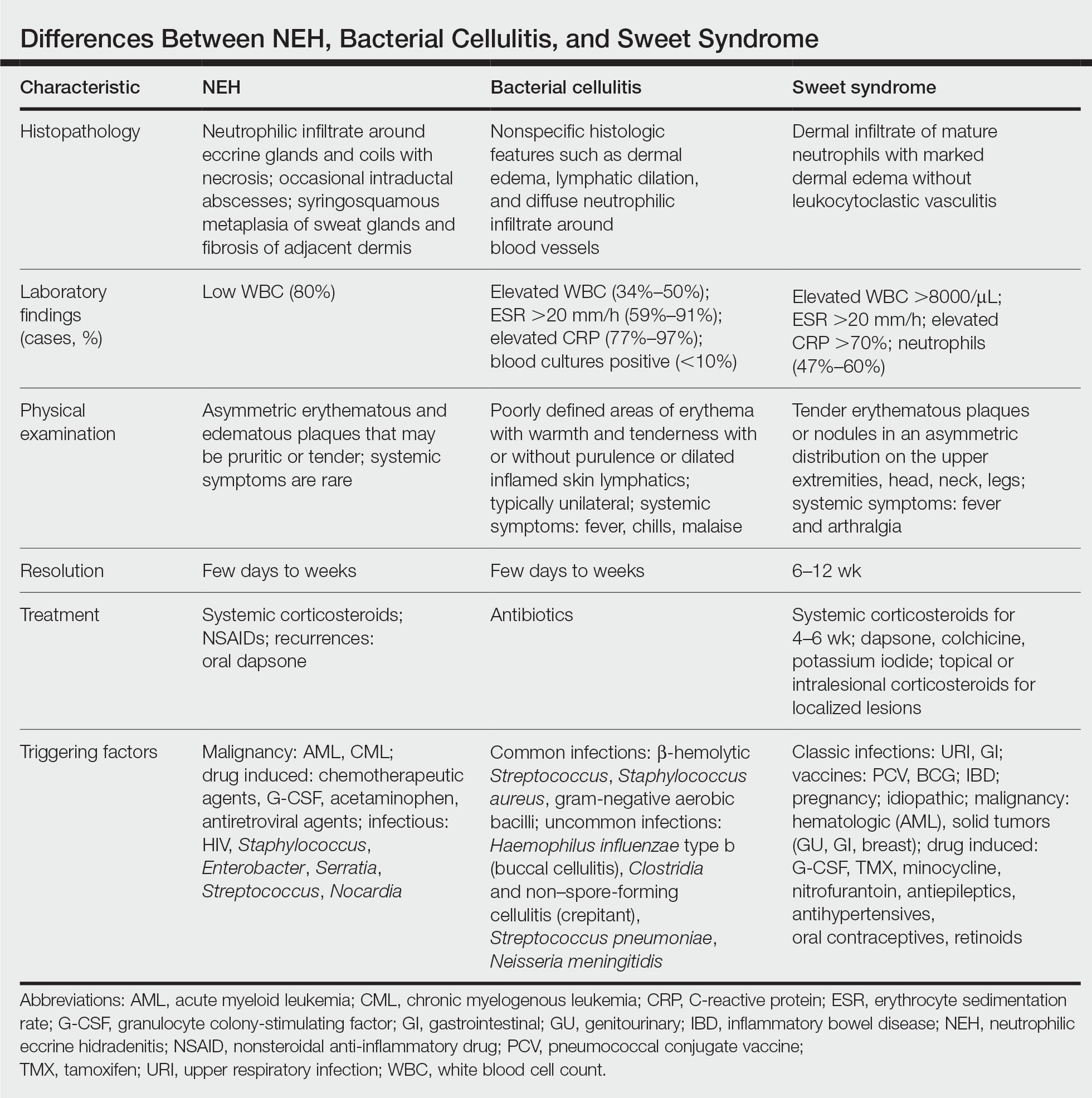

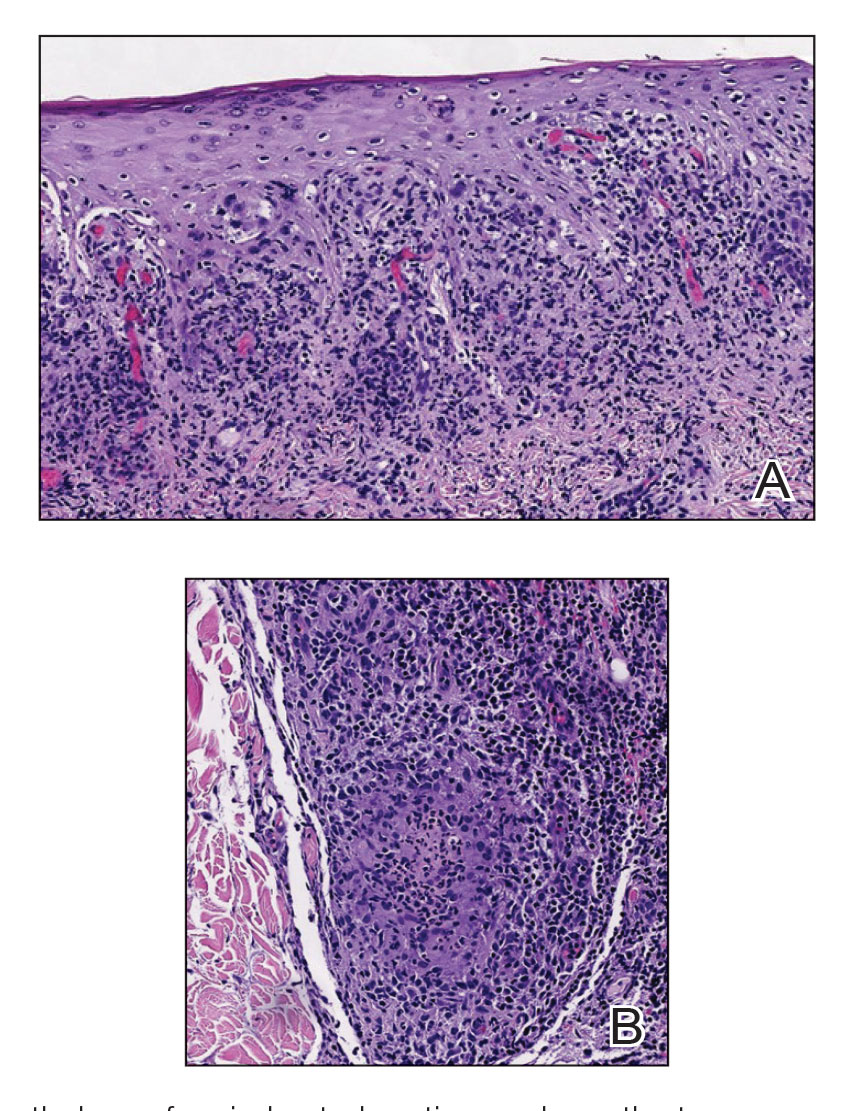

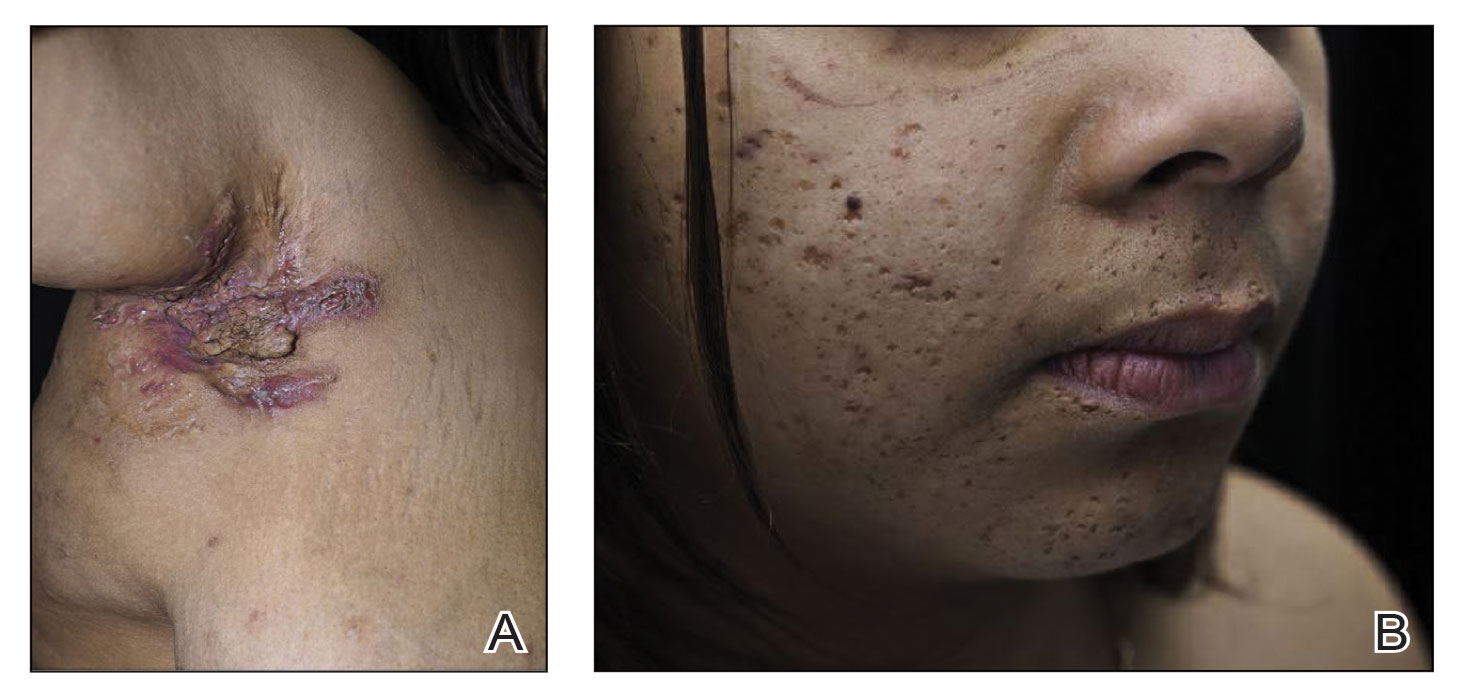

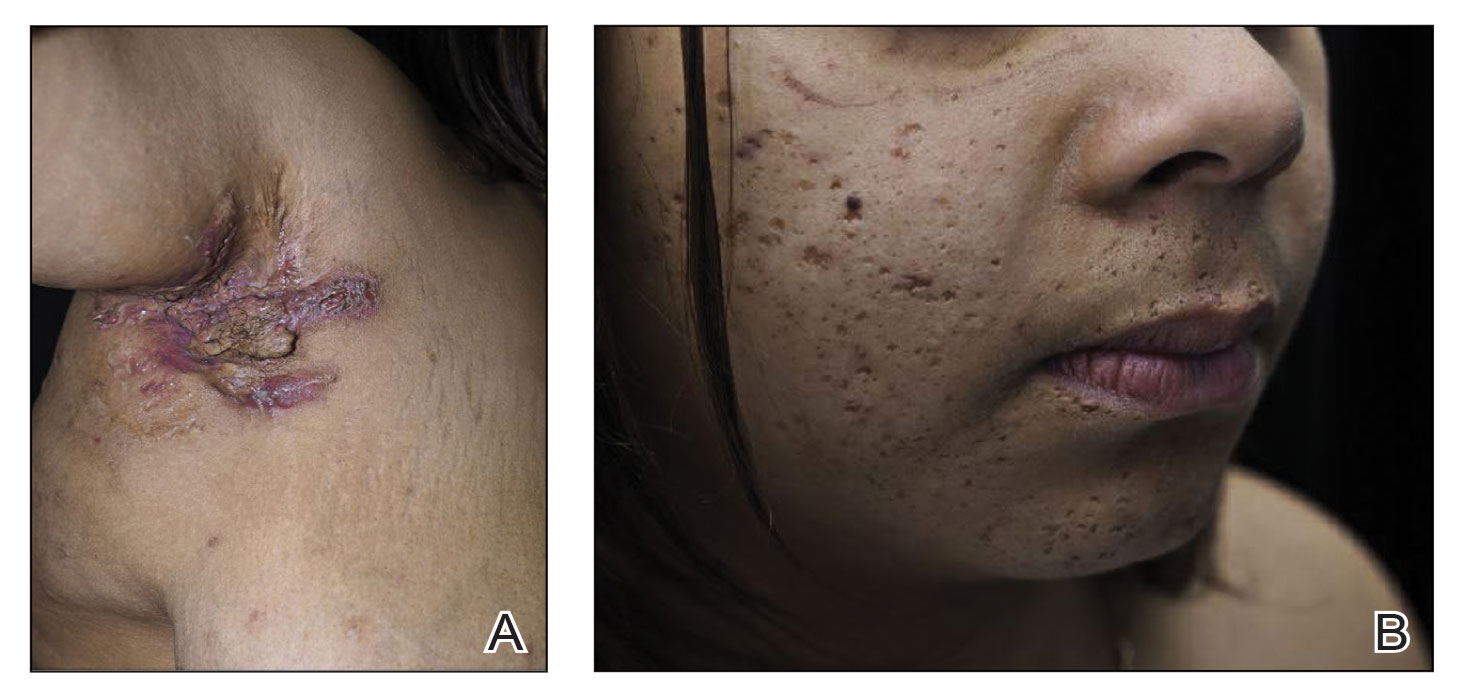

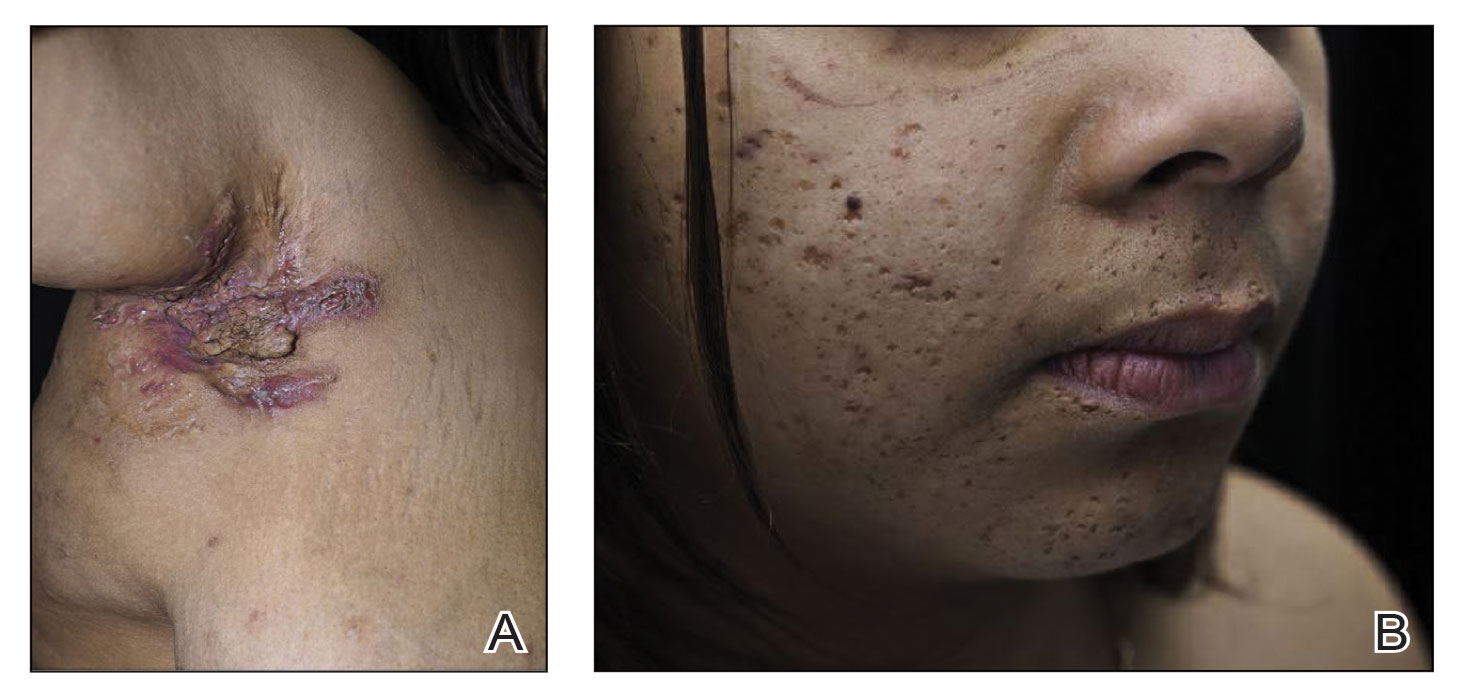

A shave biopsy of the lip revealed a diffuse cellular infiltrate filling the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1A). Morphologically, the cells had abundant clear cytoplasm with eccentrically located, pleomorphic, hyperchromatic nuclei with occasional prominent nucleoli (Figure 1B). The cells stained positive for AE1/ AE3 on immunohistochemistry (Figure 2). A punch biopsy of the nodule in the right axillary vault revealed a morphologically similar proliferation of cells. A colonoscopy revealed a completely obstructing circumferential mass in the distal ascending colon. A biopsy of the mass confirmed invasive adenocarcinoma, supporting a diagnosis of cutaneous metastases from adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient underwent resection of the lip tumor and started multiagent chemotherapy for his newly diagnosed stage IV adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient died, despite therapy.

Cutaneous metastasis from solid malignancies is uncommon, as only 1.3% of them exhibit cutaneous manifestations at presentation.1 Cutaneous metastasis from signet ring cell adenocarcinoma (SRCA) of the colon is uncommon, and cutaneous metastasis of colorectal SRCA rarely precedes the diagnosis of the primary lesion.2 Among the colorectal cancers that metastasize to the skin, metastasis to the face occurs in only 0.5% of patients.3

Signet ring cell adenocarcinomas are poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas histologically characterized by the neoplastic cells’ circular to ovoid appearance with a flattened top.4,5 This distinctive shape is from the displacement of the nucleus to the periphery of the cell due to the accumulation of intracytoplasmic mucin.4 Classically, malignancies are characterized as an SRCA if more than 50% of the cells have a signet ring cell morphology; if the signet ring cells comprise less than 50% of the neoplasm, the tumor is designated as an adenocarcinoma with signet ring morphology.4 The most common cause of cutaneous metastasis with signet ring morphology is gastric cancer, while colorectal carcinoma is less common.1 Colorectal SRCAs usually are found in the right colon or the rectum in comparison to other colonic sites.6

Clinically, cutaneous metastasis can present in a variety of ways. The most common presentation is nodular lesions that may coalesce to become zosteriform in configuration or lesions that mimic inflammatory dermatoses.7 Cutaneous metastasis is more common in breast and lung cancer, and when it occurs secondary to colorectal cancer, cutaneous metastasis rarely predates the detection of the primary neoplasm.2

The clinical appearance of metastasis is not specific and can mimic many entities8; therefore, a high index of suspicion must be employed when managing patients, even those without a history of internal malignancy. In our patient, the smooth nodular lesion appeared similar to a basal cell carcinoma; however, basal cell carcinomas appear more pearly, and arborizing telangiectasia often is seen.9 Merkel cell carcinoma is common on sundamaged skin of the head and neck but clinically appears more violaceous than the lesion seen in our patient.10 Paracoccidioidomycosis may form ulcerated papulonodules or plaques, especially around the nose and mouth. In many of these cases, lesions develop from contiguous lesions of the oral mucosa; therefore, the presence of oral lesions will help distinguish this infectious entity from cutaneous metastasis. Multiple lesions usually are identified when there is hematogenous dissemination.11 Mycosis fungoides is a subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and is characterized by multiple patches, plaques, and nodules on sun-protected areas. Involvement of the head and neck is not common, except in the folliculotropic subtype, which has a separate and distinct clinical morphology.12

The development of signet ring morphology from an adenocarcinoma can be attributed to the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), which leads to downstream activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and the subsequent loss of intercellular tight junctions. The mucin 4 gene, MUC4, also is upregulated by PI3K activation and possesses antiapoptotic and mitogenic effects in addition to its mucin secretory function.13

The neoplastic cells in SRCAs stain positive for mucicarmine, Alcian blue, and periodic acid–Schiff, which highlights the mucinous component of the cells.7 Immunohistochemical stains with CK7, CK20, AE1/AE3, and epithelial membrane antigen can be implemented to confirm an epithelial origin of the primary cancer.7,13 CK20 is a low-molecular-weight cytokeratin normally expressed by Merkel cells and by the epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract and urothelium, whereas CK7 expression typically is expressed in the lungs, ovaries, endometrium, and breasts, but not in the lower gastrointestinal tract.14 Differentiating primary cutaneous adenocarcinoma from cutaneous metastasis can be accomplished with a thorough clinical history; however, p63 positivity supports a primary cutaneous lesion and may be useful in certain situations.7 CDX2 stains can be utilized to aid in localizing the primary neoplasm when it is unknown, and when positive, it suggests a lower gastrointestinal tract origin. However, special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 (SATB2) recently has been proposed as a replacement immunohistochemical marker for CDX2, as it has greater specificity for SRCA of the lower gastrointestinal tract.15 Benign entities with signet ring cell morphology are difficult to distinguish from SRCA; however, malignant lesions are more likely to demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern, frequent mitotic figures, and apoptosis. Immunohistochemistry also can be utilized to support the diagnosis of benign proliferation with signet ring morphology, as benign lesions often will demonstrate E-cadherin positivity and negativity for p53 and Ki-67.13

Cutaneous metastasis usually correlates to advanced disease and generally indicates a worse prognosis.13 Signet ring cell morphology in both gastric and colorectal cancer portends a poor prognosis, and there is a lower overall survival in patients with these malignancies compared to cancers of the same organ with non–signet ring cell morphology.4,8

- Mandzhieva B, Jalil A, Nadeem M, et al. Most common pathway of metastasis of rectal signet ring cell carcinoma to the skin: hematogenous. Cureus. 2020;12:E6890.

- Parente P, Ciardiello D, Reggiani Bonetti L, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from colorectal cancer: making light on an unusual and misdiagnosed event. Life. 2021;11:954.

- Picciariello A, Tomasicchio G, Lantone G, et al. Synchronous “skip” facial metastases from colorectal adenocarcinoma: a case report and review of literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:68.

- Benesch MGK, Mathieson A. Epidemiology of signet ring cell adenocarcinomas. Cancers. 2020;12:1544.

- Xu Q, Karouji Y, Kobayashi M, et al. The PI 3-kinase-Rac-p38 MAP kinase pathway is involved in the formation of signet-ring cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2003;22:5537-5544.

- Morales-Cruz M, Salgado-Nesme N, Trolle-Silva AM, et al. Signet ring cell carcinoma of the rectum: atypical metastatic presentation. BMJ Case Rep CP. 2019;12:E229135.

- Demirciog˘lu D, Öztürk Durmaz E, Demirkesen C, et al. Livedoid cutaneous metastasis of signet‐ring cell gastric carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:785-788.

- Dong X, Sun G, Qu H, et al. Prognostic significance of signet-ring cell components in patients with gastric carcinoma of different stages. Front Surg. 2021;8:642468.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Nguyen AH, Tahseen AI, Vaudreuil AM, et al. Clinical features and treatment of vulvar Merkel cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017;4:2.

- Marques, SA. Paracoccidioidomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:610-615.

- Larocca C, Kupper T. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Hematol Oncol Clin. 2019;33:103-120.

- Gündüz Ö, Emeksiz MC, Atasoy P, et al. Signet-ring cells in the skin: a case of late-onset cutaneous metastasis of gastric carcinoma and a brief review of histological approach. Dermatol Rep. 2017;8:6819.

- Al-Taee A, Almukhtar R, Lai J, et al. Metastatic signet ring cell carcinoma of unknown primary origin: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:283.

- Ma C, Lowenthal BM, Pai RK. SATB2 is superior to CDX2 in distinguishing signet ring cell carcinoma of the upper gastrointestinal tract and lower gastrointestinal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018; 42:1715-1722.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastasis

A shave biopsy of the lip revealed a diffuse cellular infiltrate filling the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1A). Morphologically, the cells had abundant clear cytoplasm with eccentrically located, pleomorphic, hyperchromatic nuclei with occasional prominent nucleoli (Figure 1B). The cells stained positive for AE1/ AE3 on immunohistochemistry (Figure 2). A punch biopsy of the nodule in the right axillary vault revealed a morphologically similar proliferation of cells. A colonoscopy revealed a completely obstructing circumferential mass in the distal ascending colon. A biopsy of the mass confirmed invasive adenocarcinoma, supporting a diagnosis of cutaneous metastases from adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient underwent resection of the lip tumor and started multiagent chemotherapy for his newly diagnosed stage IV adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient died, despite therapy.

Cutaneous metastasis from solid malignancies is uncommon, as only 1.3% of them exhibit cutaneous manifestations at presentation.1 Cutaneous metastasis from signet ring cell adenocarcinoma (SRCA) of the colon is uncommon, and cutaneous metastasis of colorectal SRCA rarely precedes the diagnosis of the primary lesion.2 Among the colorectal cancers that metastasize to the skin, metastasis to the face occurs in only 0.5% of patients.3

Signet ring cell adenocarcinomas are poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas histologically characterized by the neoplastic cells’ circular to ovoid appearance with a flattened top.4,5 This distinctive shape is from the displacement of the nucleus to the periphery of the cell due to the accumulation of intracytoplasmic mucin.4 Classically, malignancies are characterized as an SRCA if more than 50% of the cells have a signet ring cell morphology; if the signet ring cells comprise less than 50% of the neoplasm, the tumor is designated as an adenocarcinoma with signet ring morphology.4 The most common cause of cutaneous metastasis with signet ring morphology is gastric cancer, while colorectal carcinoma is less common.1 Colorectal SRCAs usually are found in the right colon or the rectum in comparison to other colonic sites.6

Clinically, cutaneous metastasis can present in a variety of ways. The most common presentation is nodular lesions that may coalesce to become zosteriform in configuration or lesions that mimic inflammatory dermatoses.7 Cutaneous metastasis is more common in breast and lung cancer, and when it occurs secondary to colorectal cancer, cutaneous metastasis rarely predates the detection of the primary neoplasm.2

The clinical appearance of metastasis is not specific and can mimic many entities8; therefore, a high index of suspicion must be employed when managing patients, even those without a history of internal malignancy. In our patient, the smooth nodular lesion appeared similar to a basal cell carcinoma; however, basal cell carcinomas appear more pearly, and arborizing telangiectasia often is seen.9 Merkel cell carcinoma is common on sundamaged skin of the head and neck but clinically appears more violaceous than the lesion seen in our patient.10 Paracoccidioidomycosis may form ulcerated papulonodules or plaques, especially around the nose and mouth. In many of these cases, lesions develop from contiguous lesions of the oral mucosa; therefore, the presence of oral lesions will help distinguish this infectious entity from cutaneous metastasis. Multiple lesions usually are identified when there is hematogenous dissemination.11 Mycosis fungoides is a subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and is characterized by multiple patches, plaques, and nodules on sun-protected areas. Involvement of the head and neck is not common, except in the folliculotropic subtype, which has a separate and distinct clinical morphology.12

The development of signet ring morphology from an adenocarcinoma can be attributed to the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), which leads to downstream activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and the subsequent loss of intercellular tight junctions. The mucin 4 gene, MUC4, also is upregulated by PI3K activation and possesses antiapoptotic and mitogenic effects in addition to its mucin secretory function.13

The neoplastic cells in SRCAs stain positive for mucicarmine, Alcian blue, and periodic acid–Schiff, which highlights the mucinous component of the cells.7 Immunohistochemical stains with CK7, CK20, AE1/AE3, and epithelial membrane antigen can be implemented to confirm an epithelial origin of the primary cancer.7,13 CK20 is a low-molecular-weight cytokeratin normally expressed by Merkel cells and by the epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract and urothelium, whereas CK7 expression typically is expressed in the lungs, ovaries, endometrium, and breasts, but not in the lower gastrointestinal tract.14 Differentiating primary cutaneous adenocarcinoma from cutaneous metastasis can be accomplished with a thorough clinical history; however, p63 positivity supports a primary cutaneous lesion and may be useful in certain situations.7 CDX2 stains can be utilized to aid in localizing the primary neoplasm when it is unknown, and when positive, it suggests a lower gastrointestinal tract origin. However, special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 (SATB2) recently has been proposed as a replacement immunohistochemical marker for CDX2, as it has greater specificity for SRCA of the lower gastrointestinal tract.15 Benign entities with signet ring cell morphology are difficult to distinguish from SRCA; however, malignant lesions are more likely to demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern, frequent mitotic figures, and apoptosis. Immunohistochemistry also can be utilized to support the diagnosis of benign proliferation with signet ring morphology, as benign lesions often will demonstrate E-cadherin positivity and negativity for p53 and Ki-67.13

Cutaneous metastasis usually correlates to advanced disease and generally indicates a worse prognosis.13 Signet ring cell morphology in both gastric and colorectal cancer portends a poor prognosis, and there is a lower overall survival in patients with these malignancies compared to cancers of the same organ with non–signet ring cell morphology.4,8

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastasis

A shave biopsy of the lip revealed a diffuse cellular infiltrate filling the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1A). Morphologically, the cells had abundant clear cytoplasm with eccentrically located, pleomorphic, hyperchromatic nuclei with occasional prominent nucleoli (Figure 1B). The cells stained positive for AE1/ AE3 on immunohistochemistry (Figure 2). A punch biopsy of the nodule in the right axillary vault revealed a morphologically similar proliferation of cells. A colonoscopy revealed a completely obstructing circumferential mass in the distal ascending colon. A biopsy of the mass confirmed invasive adenocarcinoma, supporting a diagnosis of cutaneous metastases from adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient underwent resection of the lip tumor and started multiagent chemotherapy for his newly diagnosed stage IV adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient died, despite therapy.

Cutaneous metastasis from solid malignancies is uncommon, as only 1.3% of them exhibit cutaneous manifestations at presentation.1 Cutaneous metastasis from signet ring cell adenocarcinoma (SRCA) of the colon is uncommon, and cutaneous metastasis of colorectal SRCA rarely precedes the diagnosis of the primary lesion.2 Among the colorectal cancers that metastasize to the skin, metastasis to the face occurs in only 0.5% of patients.3

Signet ring cell adenocarcinomas are poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas histologically characterized by the neoplastic cells’ circular to ovoid appearance with a flattened top.4,5 This distinctive shape is from the displacement of the nucleus to the periphery of the cell due to the accumulation of intracytoplasmic mucin.4 Classically, malignancies are characterized as an SRCA if more than 50% of the cells have a signet ring cell morphology; if the signet ring cells comprise less than 50% of the neoplasm, the tumor is designated as an adenocarcinoma with signet ring morphology.4 The most common cause of cutaneous metastasis with signet ring morphology is gastric cancer, while colorectal carcinoma is less common.1 Colorectal SRCAs usually are found in the right colon or the rectum in comparison to other colonic sites.6

Clinically, cutaneous metastasis can present in a variety of ways. The most common presentation is nodular lesions that may coalesce to become zosteriform in configuration or lesions that mimic inflammatory dermatoses.7 Cutaneous metastasis is more common in breast and lung cancer, and when it occurs secondary to colorectal cancer, cutaneous metastasis rarely predates the detection of the primary neoplasm.2

The clinical appearance of metastasis is not specific and can mimic many entities8; therefore, a high index of suspicion must be employed when managing patients, even those without a history of internal malignancy. In our patient, the smooth nodular lesion appeared similar to a basal cell carcinoma; however, basal cell carcinomas appear more pearly, and arborizing telangiectasia often is seen.9 Merkel cell carcinoma is common on sundamaged skin of the head and neck but clinically appears more violaceous than the lesion seen in our patient.10 Paracoccidioidomycosis may form ulcerated papulonodules or plaques, especially around the nose and mouth. In many of these cases, lesions develop from contiguous lesions of the oral mucosa; therefore, the presence of oral lesions will help distinguish this infectious entity from cutaneous metastasis. Multiple lesions usually are identified when there is hematogenous dissemination.11 Mycosis fungoides is a subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and is characterized by multiple patches, plaques, and nodules on sun-protected areas. Involvement of the head and neck is not common, except in the folliculotropic subtype, which has a separate and distinct clinical morphology.12

The development of signet ring morphology from an adenocarcinoma can be attributed to the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), which leads to downstream activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and the subsequent loss of intercellular tight junctions. The mucin 4 gene, MUC4, also is upregulated by PI3K activation and possesses antiapoptotic and mitogenic effects in addition to its mucin secretory function.13

The neoplastic cells in SRCAs stain positive for mucicarmine, Alcian blue, and periodic acid–Schiff, which highlights the mucinous component of the cells.7 Immunohistochemical stains with CK7, CK20, AE1/AE3, and epithelial membrane antigen can be implemented to confirm an epithelial origin of the primary cancer.7,13 CK20 is a low-molecular-weight cytokeratin normally expressed by Merkel cells and by the epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract and urothelium, whereas CK7 expression typically is expressed in the lungs, ovaries, endometrium, and breasts, but not in the lower gastrointestinal tract.14 Differentiating primary cutaneous adenocarcinoma from cutaneous metastasis can be accomplished with a thorough clinical history; however, p63 positivity supports a primary cutaneous lesion and may be useful in certain situations.7 CDX2 stains can be utilized to aid in localizing the primary neoplasm when it is unknown, and when positive, it suggests a lower gastrointestinal tract origin. However, special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 (SATB2) recently has been proposed as a replacement immunohistochemical marker for CDX2, as it has greater specificity for SRCA of the lower gastrointestinal tract.15 Benign entities with signet ring cell morphology are difficult to distinguish from SRCA; however, malignant lesions are more likely to demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern, frequent mitotic figures, and apoptosis. Immunohistochemistry also can be utilized to support the diagnosis of benign proliferation with signet ring morphology, as benign lesions often will demonstrate E-cadherin positivity and negativity for p53 and Ki-67.13

Cutaneous metastasis usually correlates to advanced disease and generally indicates a worse prognosis.13 Signet ring cell morphology in both gastric and colorectal cancer portends a poor prognosis, and there is a lower overall survival in patients with these malignancies compared to cancers of the same organ with non–signet ring cell morphology.4,8

- Mandzhieva B, Jalil A, Nadeem M, et al. Most common pathway of metastasis of rectal signet ring cell carcinoma to the skin: hematogenous. Cureus. 2020;12:E6890.

- Parente P, Ciardiello D, Reggiani Bonetti L, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from colorectal cancer: making light on an unusual and misdiagnosed event. Life. 2021;11:954.

- Picciariello A, Tomasicchio G, Lantone G, et al. Synchronous “skip” facial metastases from colorectal adenocarcinoma: a case report and review of literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:68.

- Benesch MGK, Mathieson A. Epidemiology of signet ring cell adenocarcinomas. Cancers. 2020;12:1544.

- Xu Q, Karouji Y, Kobayashi M, et al. The PI 3-kinase-Rac-p38 MAP kinase pathway is involved in the formation of signet-ring cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2003;22:5537-5544.

- Morales-Cruz M, Salgado-Nesme N, Trolle-Silva AM, et al. Signet ring cell carcinoma of the rectum: atypical metastatic presentation. BMJ Case Rep CP. 2019;12:E229135.

- Demirciog˘lu D, Öztürk Durmaz E, Demirkesen C, et al. Livedoid cutaneous metastasis of signet‐ring cell gastric carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:785-788.

- Dong X, Sun G, Qu H, et al. Prognostic significance of signet-ring cell components in patients with gastric carcinoma of different stages. Front Surg. 2021;8:642468.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Nguyen AH, Tahseen AI, Vaudreuil AM, et al. Clinical features and treatment of vulvar Merkel cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017;4:2.

- Marques, SA. Paracoccidioidomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:610-615.

- Larocca C, Kupper T. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Hematol Oncol Clin. 2019;33:103-120.

- Gündüz Ö, Emeksiz MC, Atasoy P, et al. Signet-ring cells in the skin: a case of late-onset cutaneous metastasis of gastric carcinoma and a brief review of histological approach. Dermatol Rep. 2017;8:6819.

- Al-Taee A, Almukhtar R, Lai J, et al. Metastatic signet ring cell carcinoma of unknown primary origin: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:283.

- Ma C, Lowenthal BM, Pai RK. SATB2 is superior to CDX2 in distinguishing signet ring cell carcinoma of the upper gastrointestinal tract and lower gastrointestinal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018; 42:1715-1722.

- Mandzhieva B, Jalil A, Nadeem M, et al. Most common pathway of metastasis of rectal signet ring cell carcinoma to the skin: hematogenous. Cureus. 2020;12:E6890.