User login

Ulcerated Nodule on the Lip

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastasis

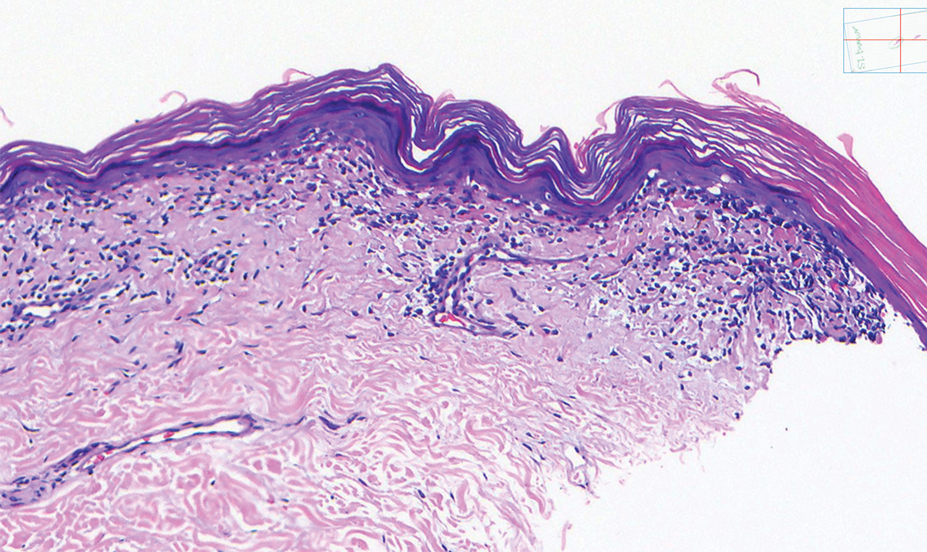

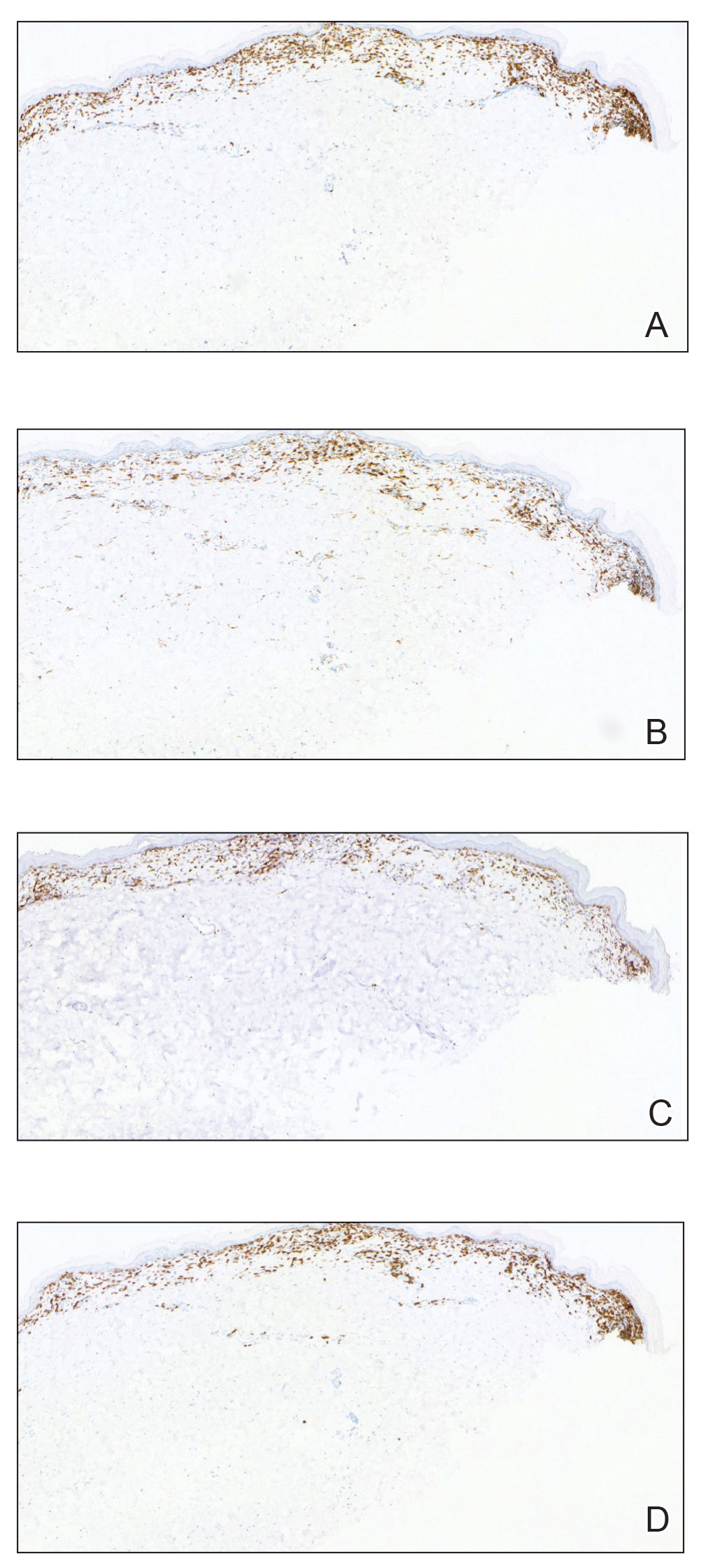

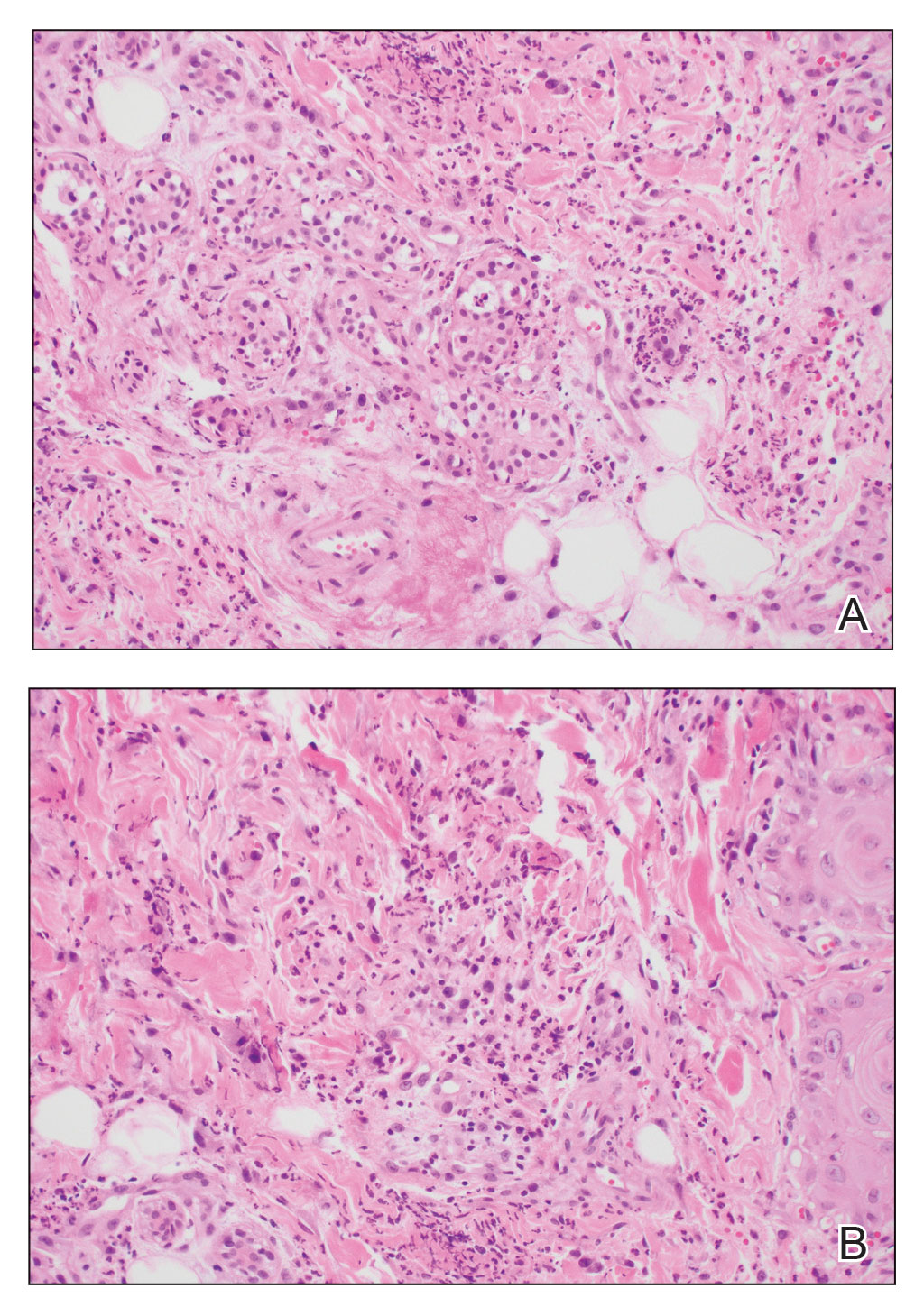

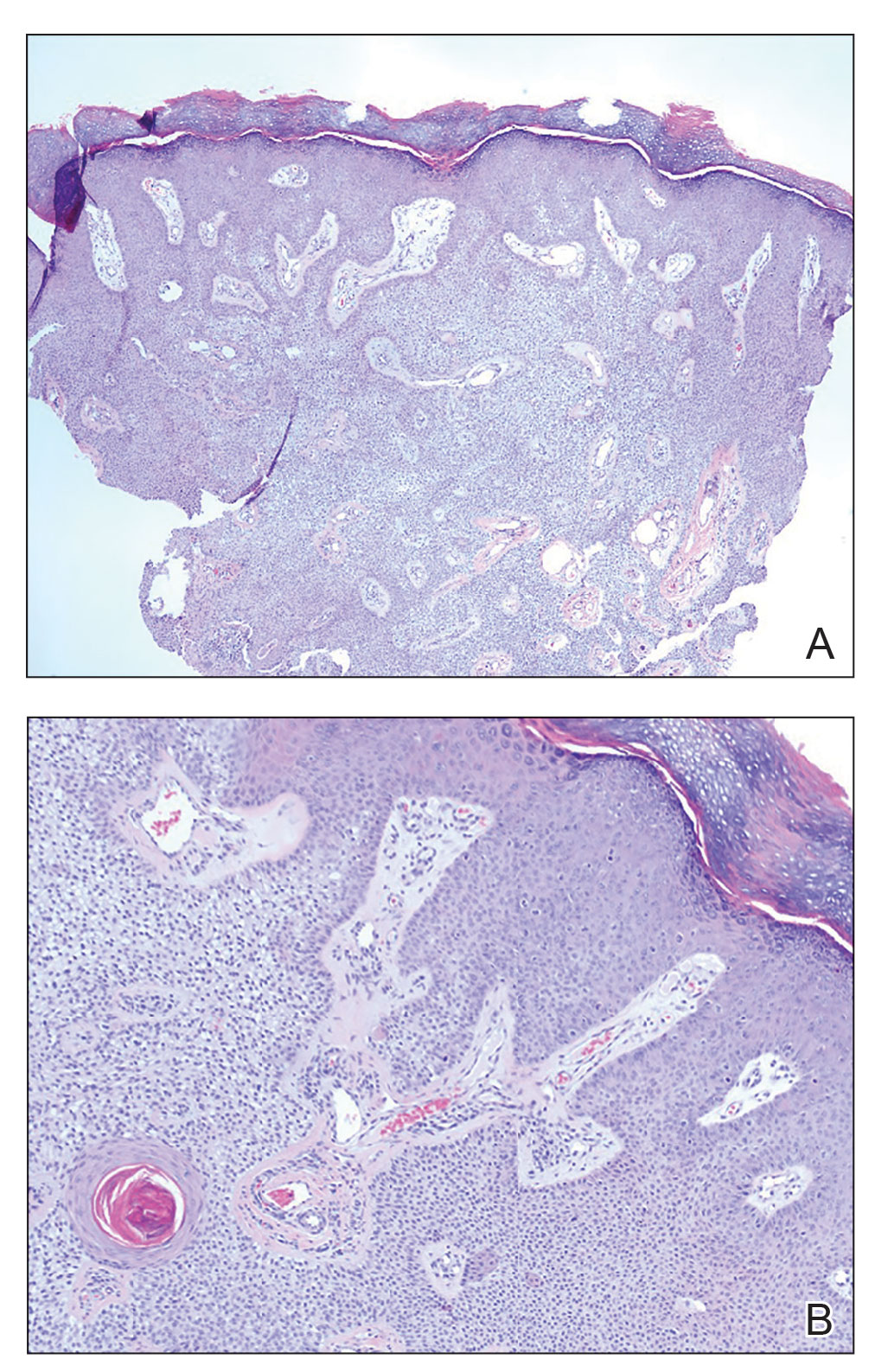

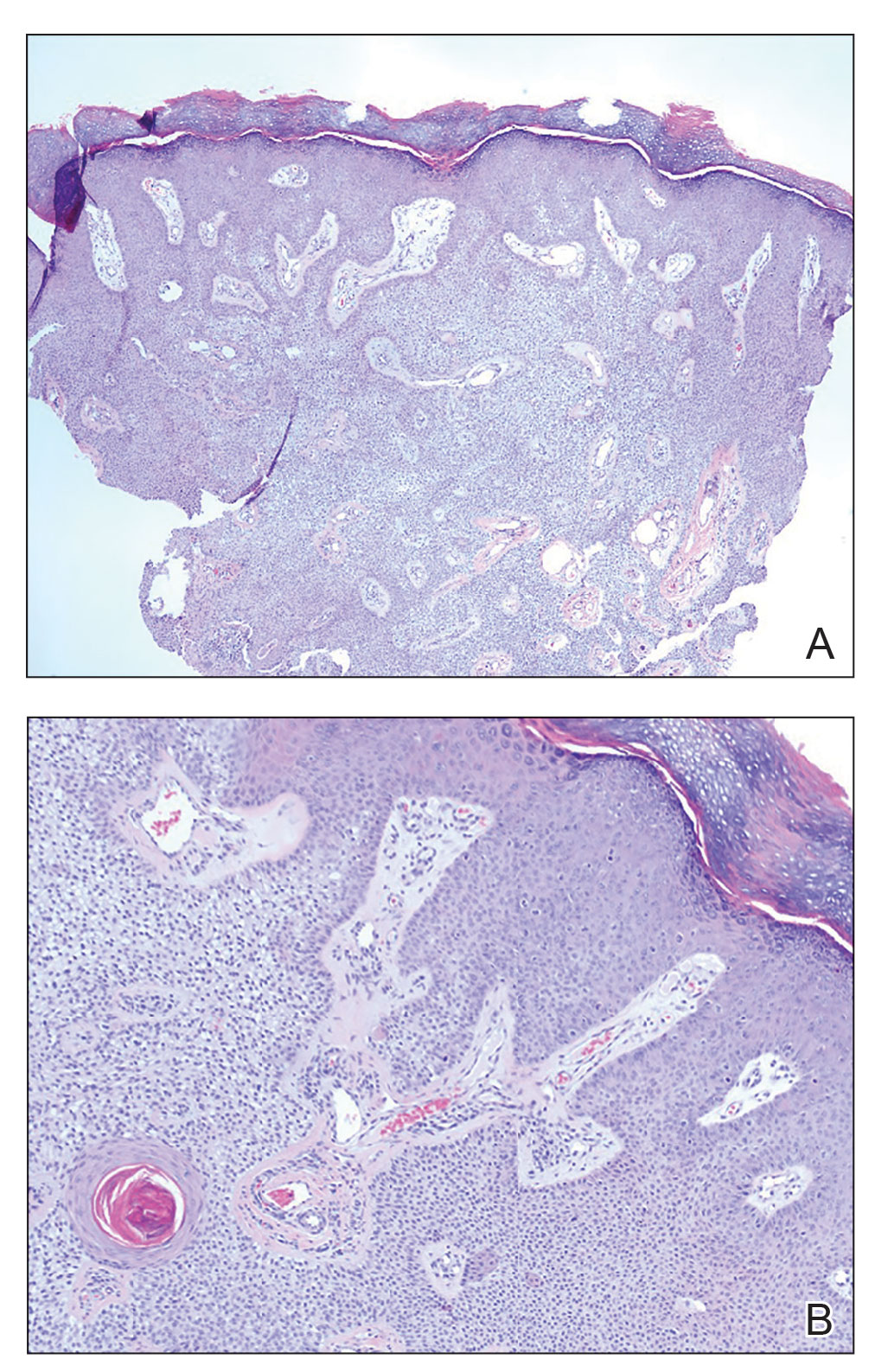

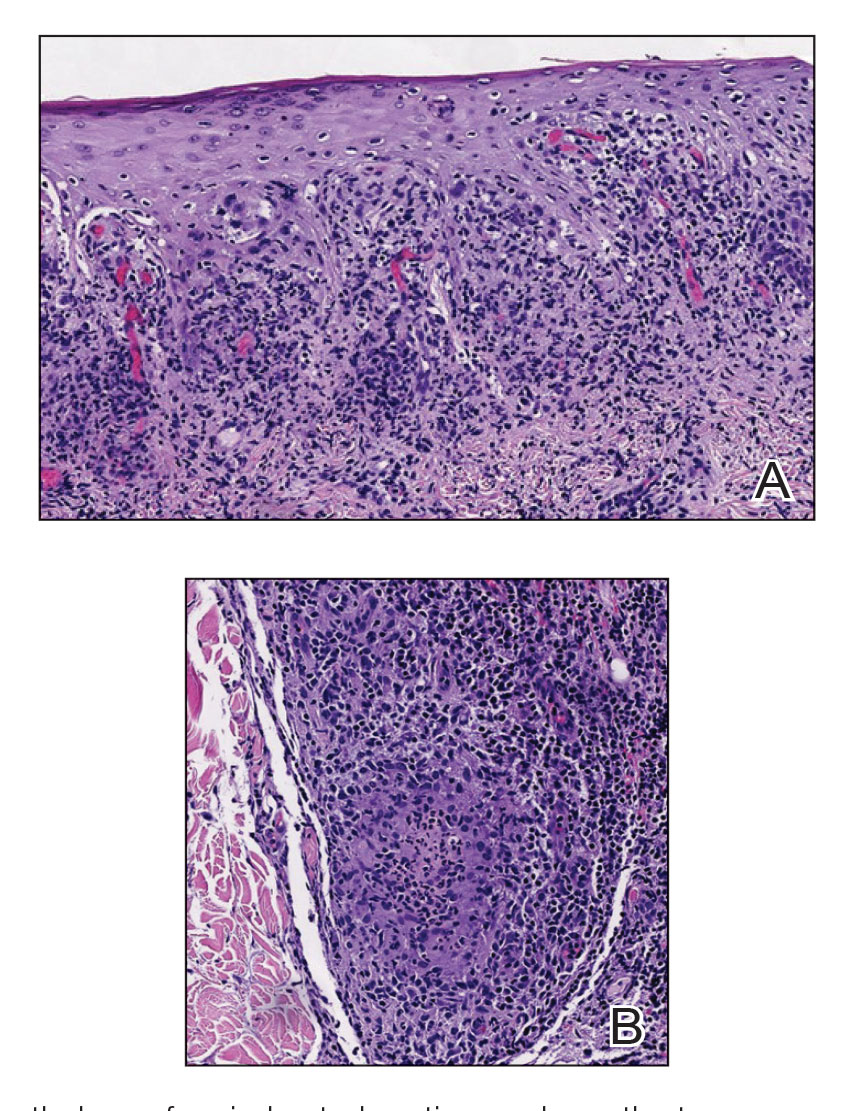

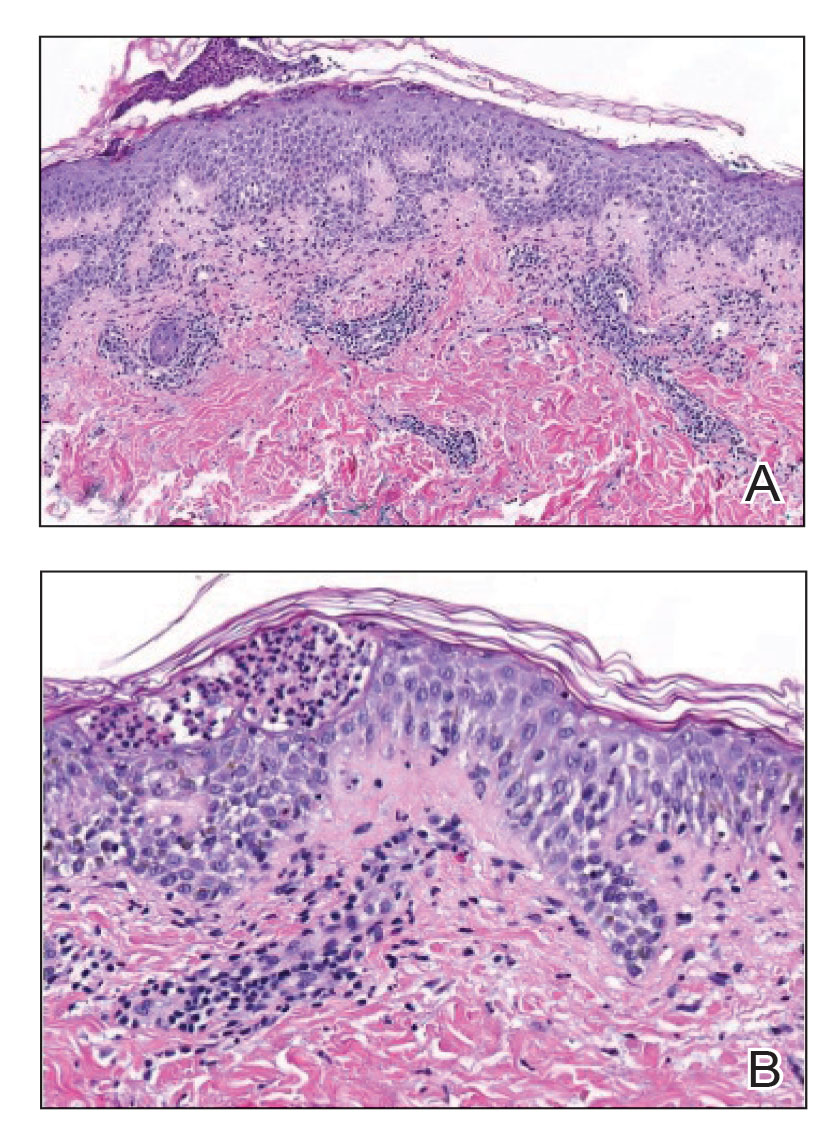

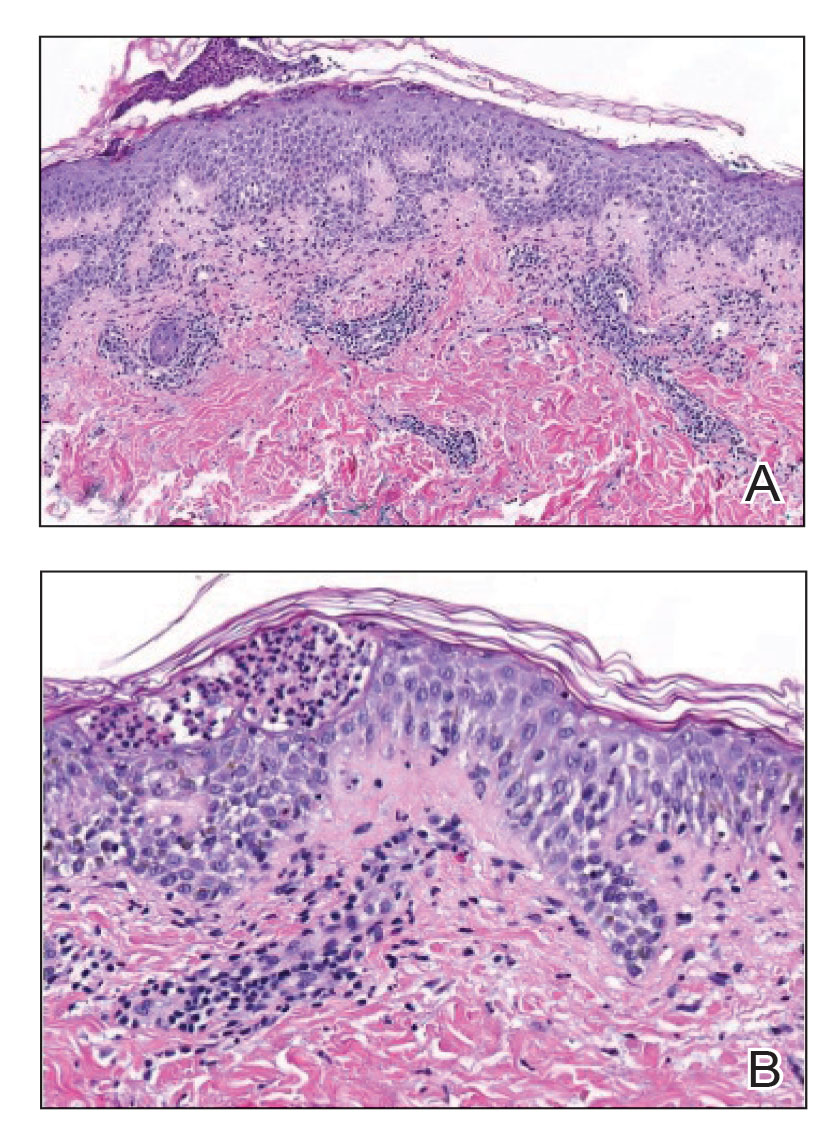

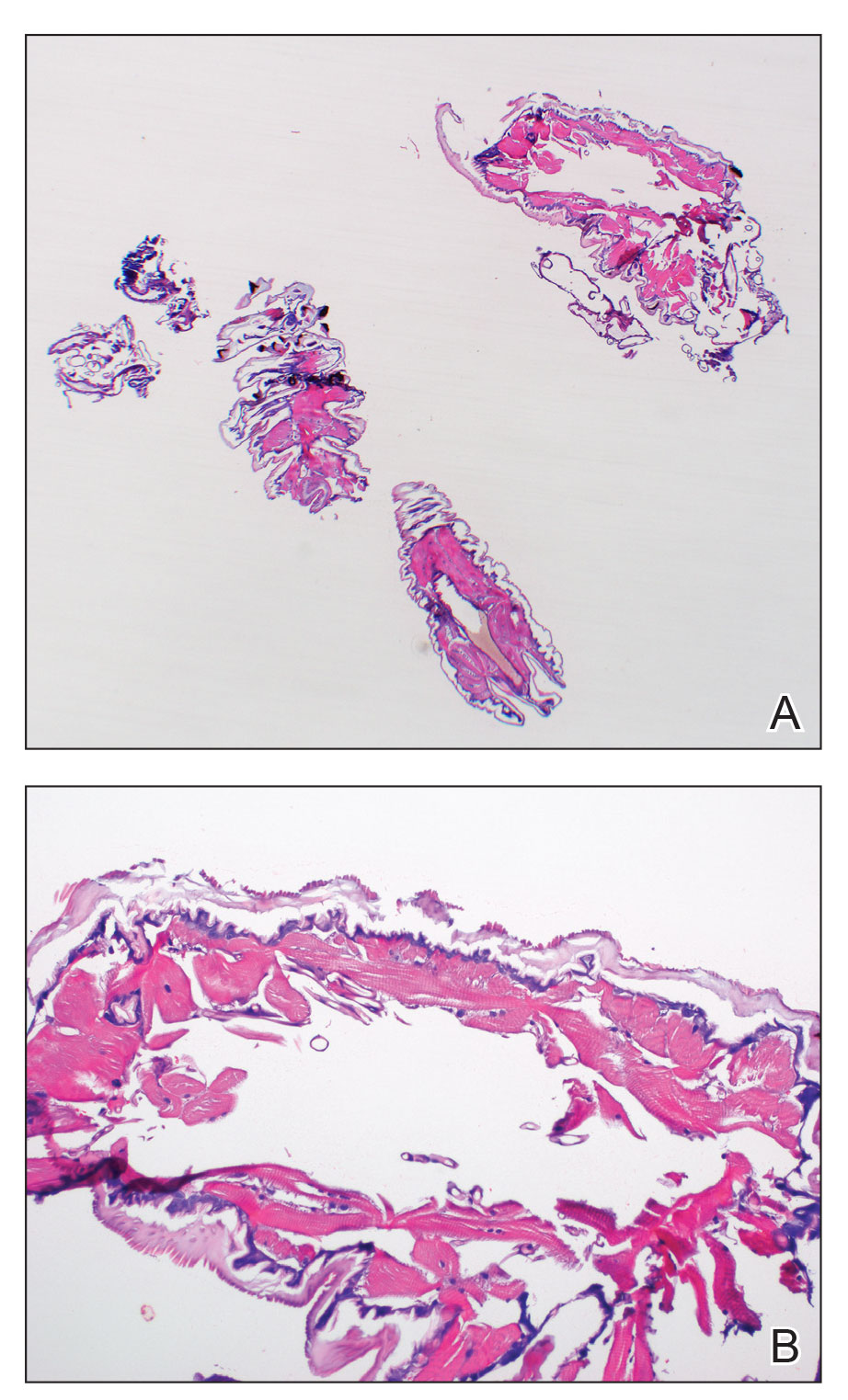

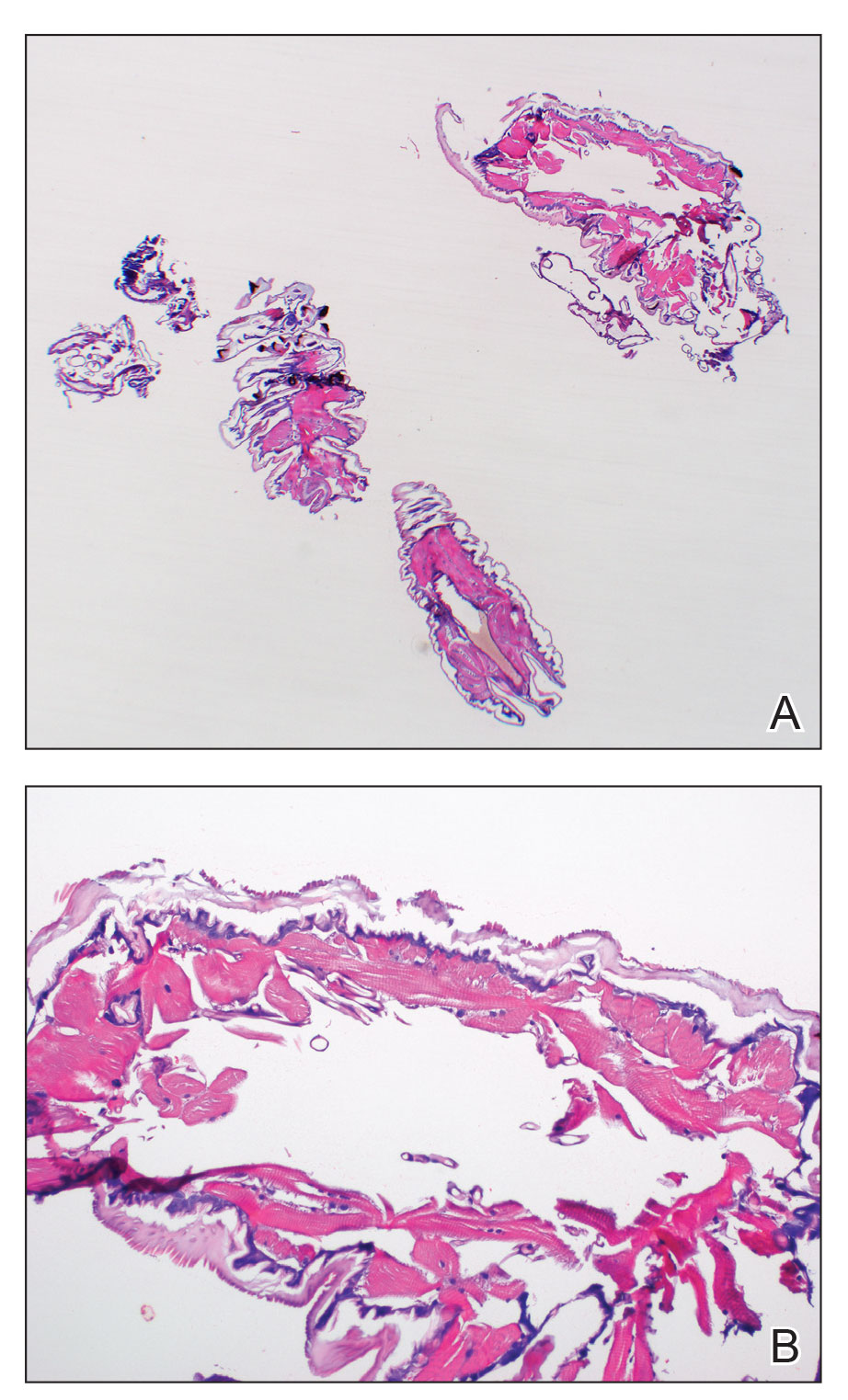

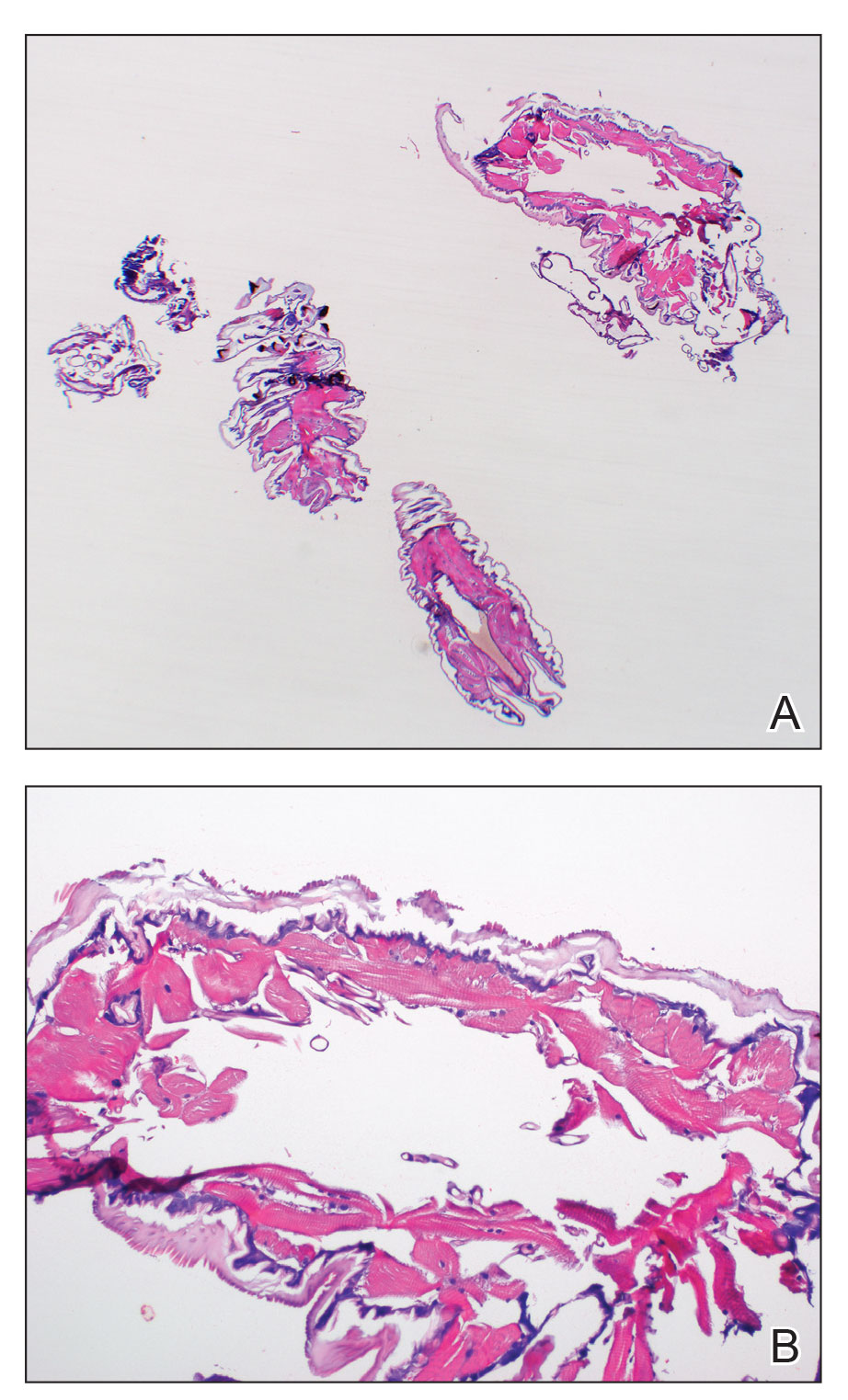

A shave biopsy of the lip revealed a diffuse cellular infiltrate filling the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1A). Morphologically, the cells had abundant clear cytoplasm with eccentrically located, pleomorphic, hyperchromatic nuclei with occasional prominent nucleoli (Figure 1B). The cells stained positive for AE1/ AE3 on immunohistochemistry (Figure 2). A punch biopsy of the nodule in the right axillary vault revealed a morphologically similar proliferation of cells. A colonoscopy revealed a completely obstructing circumferential mass in the distal ascending colon. A biopsy of the mass confirmed invasive adenocarcinoma, supporting a diagnosis of cutaneous metastases from adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient underwent resection of the lip tumor and started multiagent chemotherapy for his newly diagnosed stage IV adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient died, despite therapy.

Cutaneous metastasis from solid malignancies is uncommon, as only 1.3% of them exhibit cutaneous manifestations at presentation.1 Cutaneous metastasis from signet ring cell adenocarcinoma (SRCA) of the colon is uncommon, and cutaneous metastasis of colorectal SRCA rarely precedes the diagnosis of the primary lesion.2 Among the colorectal cancers that metastasize to the skin, metastasis to the face occurs in only 0.5% of patients.3

Signet ring cell adenocarcinomas are poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas histologically characterized by the neoplastic cells’ circular to ovoid appearance with a flattened top.4,5 This distinctive shape is from the displacement of the nucleus to the periphery of the cell due to the accumulation of intracytoplasmic mucin.4 Classically, malignancies are characterized as an SRCA if more than 50% of the cells have a signet ring cell morphology; if the signet ring cells comprise less than 50% of the neoplasm, the tumor is designated as an adenocarcinoma with signet ring morphology.4 The most common cause of cutaneous metastasis with signet ring morphology is gastric cancer, while colorectal carcinoma is less common.1 Colorectal SRCAs usually are found in the right colon or the rectum in comparison to other colonic sites.6

Clinically, cutaneous metastasis can present in a variety of ways. The most common presentation is nodular lesions that may coalesce to become zosteriform in configuration or lesions that mimic inflammatory dermatoses.7 Cutaneous metastasis is more common in breast and lung cancer, and when it occurs secondary to colorectal cancer, cutaneous metastasis rarely predates the detection of the primary neoplasm.2

The clinical appearance of metastasis is not specific and can mimic many entities8; therefore, a high index of suspicion must be employed when managing patients, even those without a history of internal malignancy. In our patient, the smooth nodular lesion appeared similar to a basal cell carcinoma; however, basal cell carcinomas appear more pearly, and arborizing telangiectasia often is seen.9 Merkel cell carcinoma is common on sundamaged skin of the head and neck but clinically appears more violaceous than the lesion seen in our patient.10 Paracoccidioidomycosis may form ulcerated papulonodules or plaques, especially around the nose and mouth. In many of these cases, lesions develop from contiguous lesions of the oral mucosa; therefore, the presence of oral lesions will help distinguish this infectious entity from cutaneous metastasis. Multiple lesions usually are identified when there is hematogenous dissemination.11 Mycosis fungoides is a subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and is characterized by multiple patches, plaques, and nodules on sun-protected areas. Involvement of the head and neck is not common, except in the folliculotropic subtype, which has a separate and distinct clinical morphology.12

The development of signet ring morphology from an adenocarcinoma can be attributed to the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), which leads to downstream activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and the subsequent loss of intercellular tight junctions. The mucin 4 gene, MUC4, also is upregulated by PI3K activation and possesses antiapoptotic and mitogenic effects in addition to its mucin secretory function.13

The neoplastic cells in SRCAs stain positive for mucicarmine, Alcian blue, and periodic acid–Schiff, which highlights the mucinous component of the cells.7 Immunohistochemical stains with CK7, CK20, AE1/AE3, and epithelial membrane antigen can be implemented to confirm an epithelial origin of the primary cancer.7,13 CK20 is a low-molecular-weight cytokeratin normally expressed by Merkel cells and by the epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract and urothelium, whereas CK7 expression typically is expressed in the lungs, ovaries, endometrium, and breasts, but not in the lower gastrointestinal tract.14 Differentiating primary cutaneous adenocarcinoma from cutaneous metastasis can be accomplished with a thorough clinical history; however, p63 positivity supports a primary cutaneous lesion and may be useful in certain situations.7 CDX2 stains can be utilized to aid in localizing the primary neoplasm when it is unknown, and when positive, it suggests a lower gastrointestinal tract origin. However, special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 (SATB2) recently has been proposed as a replacement immunohistochemical marker for CDX2, as it has greater specificity for SRCA of the lower gastrointestinal tract.15 Benign entities with signet ring cell morphology are difficult to distinguish from SRCA; however, malignant lesions are more likely to demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern, frequent mitotic figures, and apoptosis. Immunohistochemistry also can be utilized to support the diagnosis of benign proliferation with signet ring morphology, as benign lesions often will demonstrate E-cadherin positivity and negativity for p53 and Ki-67.13

Cutaneous metastasis usually correlates to advanced disease and generally indicates a worse prognosis.13 Signet ring cell morphology in both gastric and colorectal cancer portends a poor prognosis, and there is a lower overall survival in patients with these malignancies compared to cancers of the same organ with non–signet ring cell morphology.4,8

- Mandzhieva B, Jalil A, Nadeem M, et al. Most common pathway of metastasis of rectal signet ring cell carcinoma to the skin: hematogenous. Cureus. 2020;12:E6890.

- Parente P, Ciardiello D, Reggiani Bonetti L, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from colorectal cancer: making light on an unusual and misdiagnosed event. Life. 2021;11:954.

- Picciariello A, Tomasicchio G, Lantone G, et al. Synchronous “skip” facial metastases from colorectal adenocarcinoma: a case report and review of literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:68.

- Benesch MGK, Mathieson A. Epidemiology of signet ring cell adenocarcinomas. Cancers. 2020;12:1544.

- Xu Q, Karouji Y, Kobayashi M, et al. The PI 3-kinase-Rac-p38 MAP kinase pathway is involved in the formation of signet-ring cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2003;22:5537-5544.

- Morales-Cruz M, Salgado-Nesme N, Trolle-Silva AM, et al. Signet ring cell carcinoma of the rectum: atypical metastatic presentation. BMJ Case Rep CP. 2019;12:E229135.

- Demirciog˘lu D, Öztürk Durmaz E, Demirkesen C, et al. Livedoid cutaneous metastasis of signet‐ring cell gastric carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:785-788.

- Dong X, Sun G, Qu H, et al. Prognostic significance of signet-ring cell components in patients with gastric carcinoma of different stages. Front Surg. 2021;8:642468.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Nguyen AH, Tahseen AI, Vaudreuil AM, et al. Clinical features and treatment of vulvar Merkel cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017;4:2.

- Marques, SA. Paracoccidioidomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:610-615.

- Larocca C, Kupper T. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Hematol Oncol Clin. 2019;33:103-120.

- Gündüz Ö, Emeksiz MC, Atasoy P, et al. Signet-ring cells in the skin: a case of late-onset cutaneous metastasis of gastric carcinoma and a brief review of histological approach. Dermatol Rep. 2017;8:6819.

- Al-Taee A, Almukhtar R, Lai J, et al. Metastatic signet ring cell carcinoma of unknown primary origin: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:283.

- Ma C, Lowenthal BM, Pai RK. SATB2 is superior to CDX2 in distinguishing signet ring cell carcinoma of the upper gastrointestinal tract and lower gastrointestinal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018; 42:1715-1722.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastasis

A shave biopsy of the lip revealed a diffuse cellular infiltrate filling the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1A). Morphologically, the cells had abundant clear cytoplasm with eccentrically located, pleomorphic, hyperchromatic nuclei with occasional prominent nucleoli (Figure 1B). The cells stained positive for AE1/ AE3 on immunohistochemistry (Figure 2). A punch biopsy of the nodule in the right axillary vault revealed a morphologically similar proliferation of cells. A colonoscopy revealed a completely obstructing circumferential mass in the distal ascending colon. A biopsy of the mass confirmed invasive adenocarcinoma, supporting a diagnosis of cutaneous metastases from adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient underwent resection of the lip tumor and started multiagent chemotherapy for his newly diagnosed stage IV adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient died, despite therapy.

Cutaneous metastasis from solid malignancies is uncommon, as only 1.3% of them exhibit cutaneous manifestations at presentation.1 Cutaneous metastasis from signet ring cell adenocarcinoma (SRCA) of the colon is uncommon, and cutaneous metastasis of colorectal SRCA rarely precedes the diagnosis of the primary lesion.2 Among the colorectal cancers that metastasize to the skin, metastasis to the face occurs in only 0.5% of patients.3

Signet ring cell adenocarcinomas are poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas histologically characterized by the neoplastic cells’ circular to ovoid appearance with a flattened top.4,5 This distinctive shape is from the displacement of the nucleus to the periphery of the cell due to the accumulation of intracytoplasmic mucin.4 Classically, malignancies are characterized as an SRCA if more than 50% of the cells have a signet ring cell morphology; if the signet ring cells comprise less than 50% of the neoplasm, the tumor is designated as an adenocarcinoma with signet ring morphology.4 The most common cause of cutaneous metastasis with signet ring morphology is gastric cancer, while colorectal carcinoma is less common.1 Colorectal SRCAs usually are found in the right colon or the rectum in comparison to other colonic sites.6

Clinically, cutaneous metastasis can present in a variety of ways. The most common presentation is nodular lesions that may coalesce to become zosteriform in configuration or lesions that mimic inflammatory dermatoses.7 Cutaneous metastasis is more common in breast and lung cancer, and when it occurs secondary to colorectal cancer, cutaneous metastasis rarely predates the detection of the primary neoplasm.2

The clinical appearance of metastasis is not specific and can mimic many entities8; therefore, a high index of suspicion must be employed when managing patients, even those without a history of internal malignancy. In our patient, the smooth nodular lesion appeared similar to a basal cell carcinoma; however, basal cell carcinomas appear more pearly, and arborizing telangiectasia often is seen.9 Merkel cell carcinoma is common on sundamaged skin of the head and neck but clinically appears more violaceous than the lesion seen in our patient.10 Paracoccidioidomycosis may form ulcerated papulonodules or plaques, especially around the nose and mouth. In many of these cases, lesions develop from contiguous lesions of the oral mucosa; therefore, the presence of oral lesions will help distinguish this infectious entity from cutaneous metastasis. Multiple lesions usually are identified when there is hematogenous dissemination.11 Mycosis fungoides is a subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and is characterized by multiple patches, plaques, and nodules on sun-protected areas. Involvement of the head and neck is not common, except in the folliculotropic subtype, which has a separate and distinct clinical morphology.12

The development of signet ring morphology from an adenocarcinoma can be attributed to the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), which leads to downstream activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and the subsequent loss of intercellular tight junctions. The mucin 4 gene, MUC4, also is upregulated by PI3K activation and possesses antiapoptotic and mitogenic effects in addition to its mucin secretory function.13

The neoplastic cells in SRCAs stain positive for mucicarmine, Alcian blue, and periodic acid–Schiff, which highlights the mucinous component of the cells.7 Immunohistochemical stains with CK7, CK20, AE1/AE3, and epithelial membrane antigen can be implemented to confirm an epithelial origin of the primary cancer.7,13 CK20 is a low-molecular-weight cytokeratin normally expressed by Merkel cells and by the epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract and urothelium, whereas CK7 expression typically is expressed in the lungs, ovaries, endometrium, and breasts, but not in the lower gastrointestinal tract.14 Differentiating primary cutaneous adenocarcinoma from cutaneous metastasis can be accomplished with a thorough clinical history; however, p63 positivity supports a primary cutaneous lesion and may be useful in certain situations.7 CDX2 stains can be utilized to aid in localizing the primary neoplasm when it is unknown, and when positive, it suggests a lower gastrointestinal tract origin. However, special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 (SATB2) recently has been proposed as a replacement immunohistochemical marker for CDX2, as it has greater specificity for SRCA of the lower gastrointestinal tract.15 Benign entities with signet ring cell morphology are difficult to distinguish from SRCA; however, malignant lesions are more likely to demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern, frequent mitotic figures, and apoptosis. Immunohistochemistry also can be utilized to support the diagnosis of benign proliferation with signet ring morphology, as benign lesions often will demonstrate E-cadherin positivity and negativity for p53 and Ki-67.13

Cutaneous metastasis usually correlates to advanced disease and generally indicates a worse prognosis.13 Signet ring cell morphology in both gastric and colorectal cancer portends a poor prognosis, and there is a lower overall survival in patients with these malignancies compared to cancers of the same organ with non–signet ring cell morphology.4,8

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastasis

A shave biopsy of the lip revealed a diffuse cellular infiltrate filling the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1A). Morphologically, the cells had abundant clear cytoplasm with eccentrically located, pleomorphic, hyperchromatic nuclei with occasional prominent nucleoli (Figure 1B). The cells stained positive for AE1/ AE3 on immunohistochemistry (Figure 2). A punch biopsy of the nodule in the right axillary vault revealed a morphologically similar proliferation of cells. A colonoscopy revealed a completely obstructing circumferential mass in the distal ascending colon. A biopsy of the mass confirmed invasive adenocarcinoma, supporting a diagnosis of cutaneous metastases from adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient underwent resection of the lip tumor and started multiagent chemotherapy for his newly diagnosed stage IV adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient died, despite therapy.

Cutaneous metastasis from solid malignancies is uncommon, as only 1.3% of them exhibit cutaneous manifestations at presentation.1 Cutaneous metastasis from signet ring cell adenocarcinoma (SRCA) of the colon is uncommon, and cutaneous metastasis of colorectal SRCA rarely precedes the diagnosis of the primary lesion.2 Among the colorectal cancers that metastasize to the skin, metastasis to the face occurs in only 0.5% of patients.3

Signet ring cell adenocarcinomas are poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas histologically characterized by the neoplastic cells’ circular to ovoid appearance with a flattened top.4,5 This distinctive shape is from the displacement of the nucleus to the periphery of the cell due to the accumulation of intracytoplasmic mucin.4 Classically, malignancies are characterized as an SRCA if more than 50% of the cells have a signet ring cell morphology; if the signet ring cells comprise less than 50% of the neoplasm, the tumor is designated as an adenocarcinoma with signet ring morphology.4 The most common cause of cutaneous metastasis with signet ring morphology is gastric cancer, while colorectal carcinoma is less common.1 Colorectal SRCAs usually are found in the right colon or the rectum in comparison to other colonic sites.6

Clinically, cutaneous metastasis can present in a variety of ways. The most common presentation is nodular lesions that may coalesce to become zosteriform in configuration or lesions that mimic inflammatory dermatoses.7 Cutaneous metastasis is more common in breast and lung cancer, and when it occurs secondary to colorectal cancer, cutaneous metastasis rarely predates the detection of the primary neoplasm.2

The clinical appearance of metastasis is not specific and can mimic many entities8; therefore, a high index of suspicion must be employed when managing patients, even those without a history of internal malignancy. In our patient, the smooth nodular lesion appeared similar to a basal cell carcinoma; however, basal cell carcinomas appear more pearly, and arborizing telangiectasia often is seen.9 Merkel cell carcinoma is common on sundamaged skin of the head and neck but clinically appears more violaceous than the lesion seen in our patient.10 Paracoccidioidomycosis may form ulcerated papulonodules or plaques, especially around the nose and mouth. In many of these cases, lesions develop from contiguous lesions of the oral mucosa; therefore, the presence of oral lesions will help distinguish this infectious entity from cutaneous metastasis. Multiple lesions usually are identified when there is hematogenous dissemination.11 Mycosis fungoides is a subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and is characterized by multiple patches, plaques, and nodules on sun-protected areas. Involvement of the head and neck is not common, except in the folliculotropic subtype, which has a separate and distinct clinical morphology.12

The development of signet ring morphology from an adenocarcinoma can be attributed to the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), which leads to downstream activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and the subsequent loss of intercellular tight junctions. The mucin 4 gene, MUC4, also is upregulated by PI3K activation and possesses antiapoptotic and mitogenic effects in addition to its mucin secretory function.13

The neoplastic cells in SRCAs stain positive for mucicarmine, Alcian blue, and periodic acid–Schiff, which highlights the mucinous component of the cells.7 Immunohistochemical stains with CK7, CK20, AE1/AE3, and epithelial membrane antigen can be implemented to confirm an epithelial origin of the primary cancer.7,13 CK20 is a low-molecular-weight cytokeratin normally expressed by Merkel cells and by the epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract and urothelium, whereas CK7 expression typically is expressed in the lungs, ovaries, endometrium, and breasts, but not in the lower gastrointestinal tract.14 Differentiating primary cutaneous adenocarcinoma from cutaneous metastasis can be accomplished with a thorough clinical history; however, p63 positivity supports a primary cutaneous lesion and may be useful in certain situations.7 CDX2 stains can be utilized to aid in localizing the primary neoplasm when it is unknown, and when positive, it suggests a lower gastrointestinal tract origin. However, special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 (SATB2) recently has been proposed as a replacement immunohistochemical marker for CDX2, as it has greater specificity for SRCA of the lower gastrointestinal tract.15 Benign entities with signet ring cell morphology are difficult to distinguish from SRCA; however, malignant lesions are more likely to demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern, frequent mitotic figures, and apoptosis. Immunohistochemistry also can be utilized to support the diagnosis of benign proliferation with signet ring morphology, as benign lesions often will demonstrate E-cadherin positivity and negativity for p53 and Ki-67.13

Cutaneous metastasis usually correlates to advanced disease and generally indicates a worse prognosis.13 Signet ring cell morphology in both gastric and colorectal cancer portends a poor prognosis, and there is a lower overall survival in patients with these malignancies compared to cancers of the same organ with non–signet ring cell morphology.4,8

- Mandzhieva B, Jalil A, Nadeem M, et al. Most common pathway of metastasis of rectal signet ring cell carcinoma to the skin: hematogenous. Cureus. 2020;12:E6890.

- Parente P, Ciardiello D, Reggiani Bonetti L, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from colorectal cancer: making light on an unusual and misdiagnosed event. Life. 2021;11:954.

- Picciariello A, Tomasicchio G, Lantone G, et al. Synchronous “skip” facial metastases from colorectal adenocarcinoma: a case report and review of literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:68.

- Benesch MGK, Mathieson A. Epidemiology of signet ring cell adenocarcinomas. Cancers. 2020;12:1544.

- Xu Q, Karouji Y, Kobayashi M, et al. The PI 3-kinase-Rac-p38 MAP kinase pathway is involved in the formation of signet-ring cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2003;22:5537-5544.

- Morales-Cruz M, Salgado-Nesme N, Trolle-Silva AM, et al. Signet ring cell carcinoma of the rectum: atypical metastatic presentation. BMJ Case Rep CP. 2019;12:E229135.

- Demirciog˘lu D, Öztürk Durmaz E, Demirkesen C, et al. Livedoid cutaneous metastasis of signet‐ring cell gastric carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:785-788.

- Dong X, Sun G, Qu H, et al. Prognostic significance of signet-ring cell components in patients with gastric carcinoma of different stages. Front Surg. 2021;8:642468.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Nguyen AH, Tahseen AI, Vaudreuil AM, et al. Clinical features and treatment of vulvar Merkel cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017;4:2.

- Marques, SA. Paracoccidioidomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:610-615.

- Larocca C, Kupper T. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Hematol Oncol Clin. 2019;33:103-120.

- Gündüz Ö, Emeksiz MC, Atasoy P, et al. Signet-ring cells in the skin: a case of late-onset cutaneous metastasis of gastric carcinoma and a brief review of histological approach. Dermatol Rep. 2017;8:6819.

- Al-Taee A, Almukhtar R, Lai J, et al. Metastatic signet ring cell carcinoma of unknown primary origin: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:283.

- Ma C, Lowenthal BM, Pai RK. SATB2 is superior to CDX2 in distinguishing signet ring cell carcinoma of the upper gastrointestinal tract and lower gastrointestinal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018; 42:1715-1722.

- Mandzhieva B, Jalil A, Nadeem M, et al. Most common pathway of metastasis of rectal signet ring cell carcinoma to the skin: hematogenous. Cureus. 2020;12:E6890.

- Parente P, Ciardiello D, Reggiani Bonetti L, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from colorectal cancer: making light on an unusual and misdiagnosed event. Life. 2021;11:954.

- Picciariello A, Tomasicchio G, Lantone G, et al. Synchronous “skip” facial metastases from colorectal adenocarcinoma: a case report and review of literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:68.

- Benesch MGK, Mathieson A. Epidemiology of signet ring cell adenocarcinomas. Cancers. 2020;12:1544.

- Xu Q, Karouji Y, Kobayashi M, et al. The PI 3-kinase-Rac-p38 MAP kinase pathway is involved in the formation of signet-ring cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2003;22:5537-5544.

- Morales-Cruz M, Salgado-Nesme N, Trolle-Silva AM, et al. Signet ring cell carcinoma of the rectum: atypical metastatic presentation. BMJ Case Rep CP. 2019;12:E229135.

- Demirciog˘lu D, Öztürk Durmaz E, Demirkesen C, et al. Livedoid cutaneous metastasis of signet‐ring cell gastric carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:785-788.

- Dong X, Sun G, Qu H, et al. Prognostic significance of signet-ring cell components in patients with gastric carcinoma of different stages. Front Surg. 2021;8:642468.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Nguyen AH, Tahseen AI, Vaudreuil AM, et al. Clinical features and treatment of vulvar Merkel cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017;4:2.

- Marques, SA. Paracoccidioidomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:610-615.

- Larocca C, Kupper T. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Hematol Oncol Clin. 2019;33:103-120.

- Gündüz Ö, Emeksiz MC, Atasoy P, et al. Signet-ring cells in the skin: a case of late-onset cutaneous metastasis of gastric carcinoma and a brief review of histological approach. Dermatol Rep. 2017;8:6819.

- Al-Taee A, Almukhtar R, Lai J, et al. Metastatic signet ring cell carcinoma of unknown primary origin: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:283.

- Ma C, Lowenthal BM, Pai RK. SATB2 is superior to CDX2 in distinguishing signet ring cell carcinoma of the upper gastrointestinal tract and lower gastrointestinal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018; 42:1715-1722.

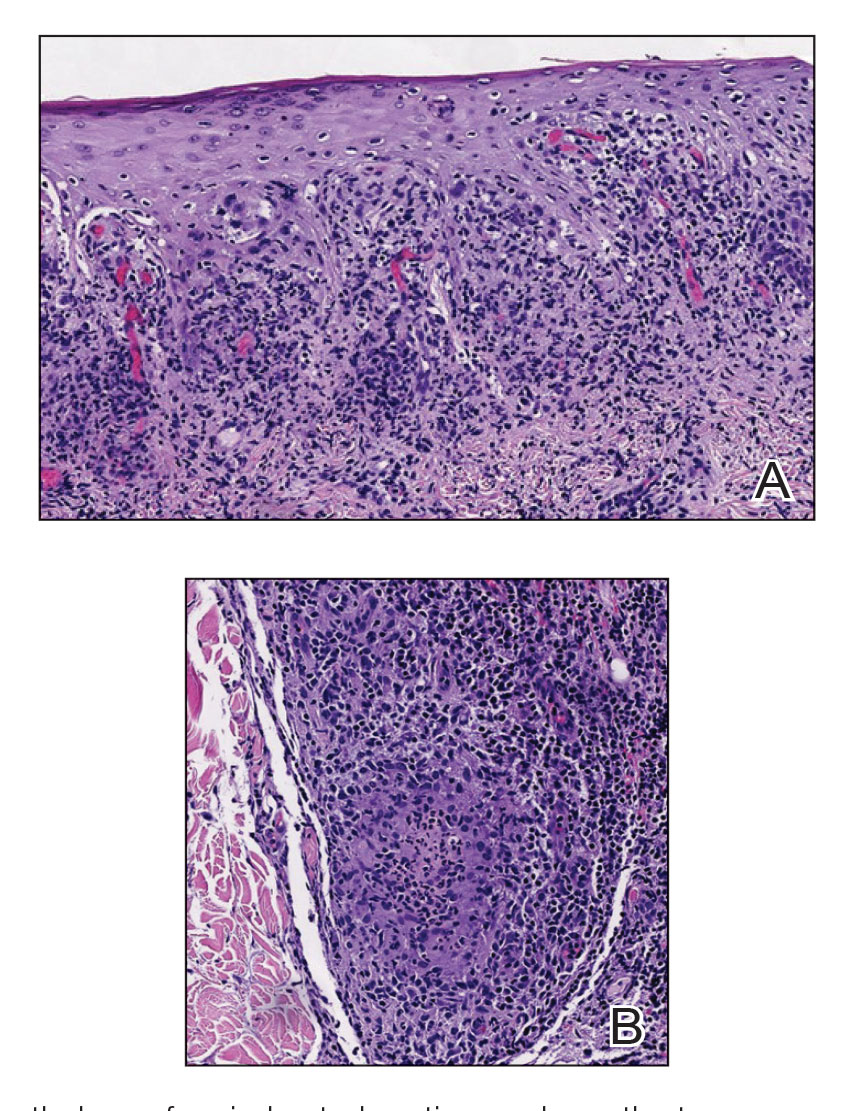

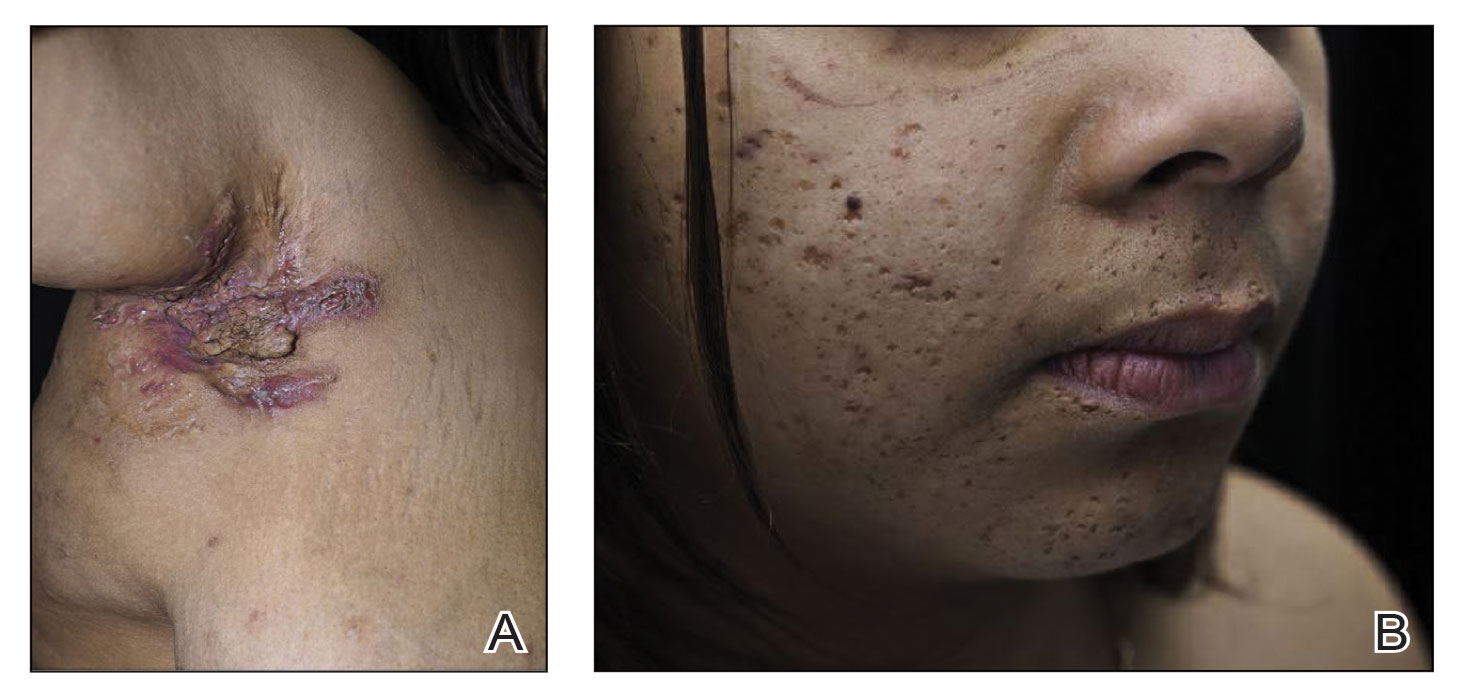

A 79-year-old man with a medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and atrial fibrillation presented with an enlarging lesion on the right side of the upper cutaneous lip of 5 weeks’ duration. He had no personal history of skin cancer or other malignancy and was up to date on all routine cancer screenings. He reported associated lip and oral cavity tenderness, weakness, and a 13.6-kg (30-lb) unintentional weight loss over the last 6 months. He had used over-the-counter bacitracin ointment on the lesion without relief. A full-body skin examination revealed a firm, mobile, flesh-colored, nondraining nodule in the right axillary vault.

White Spots on the Extremities

The Diagnosis: Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

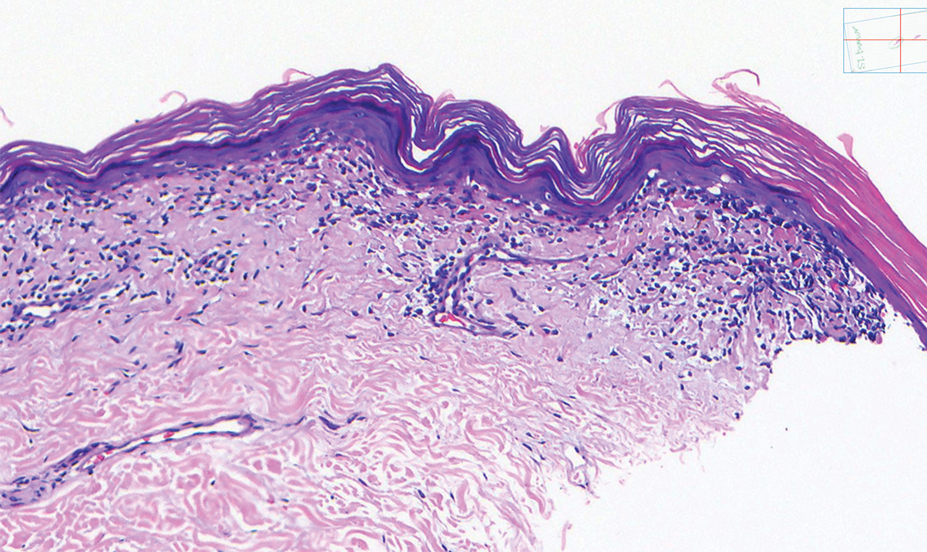

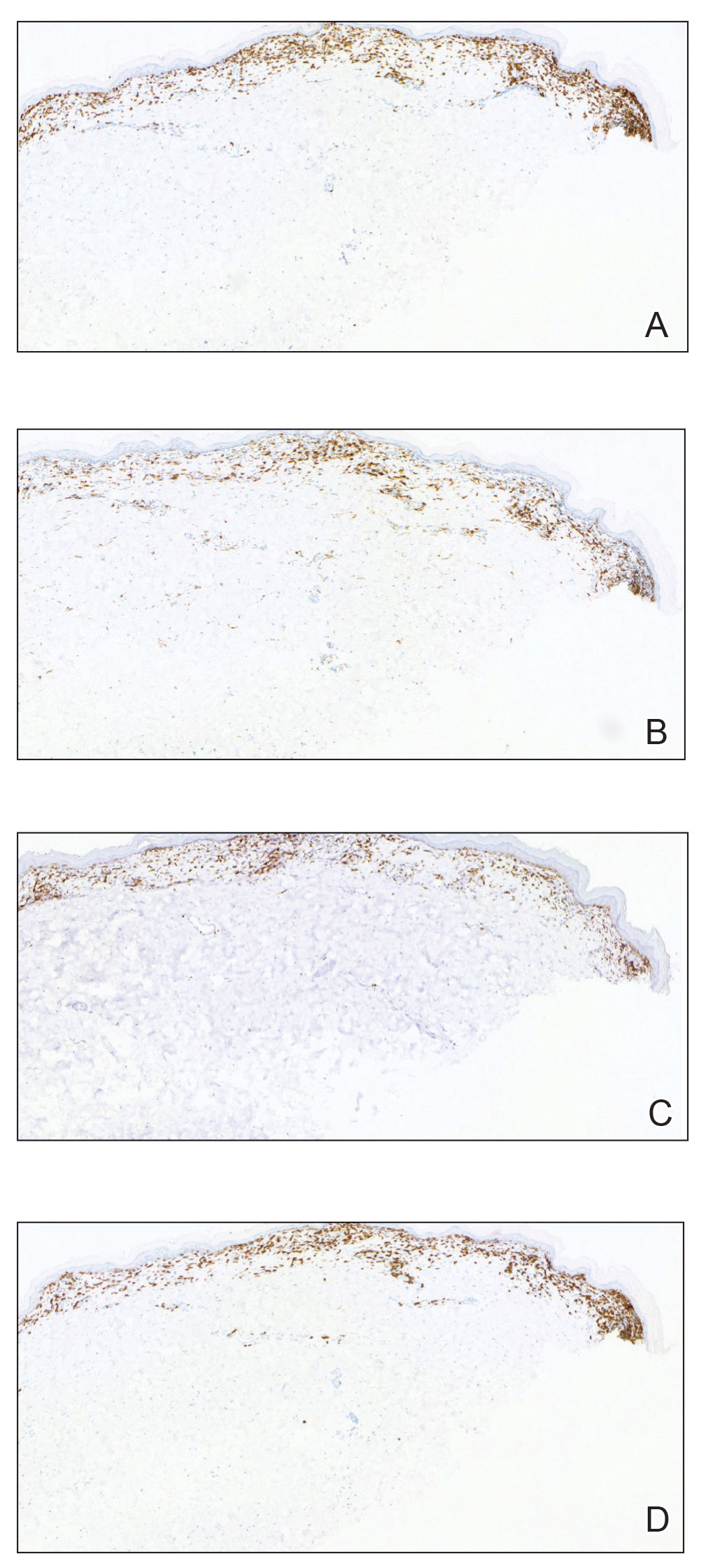

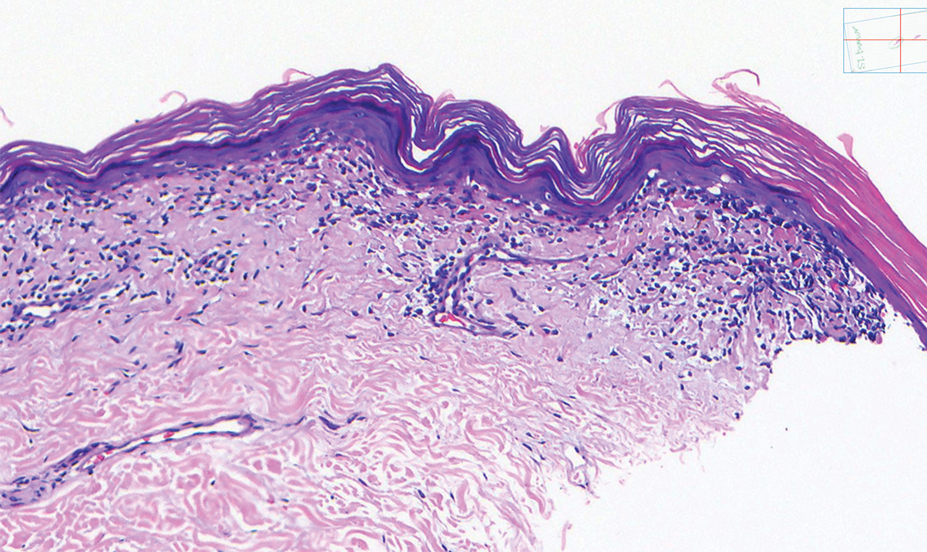

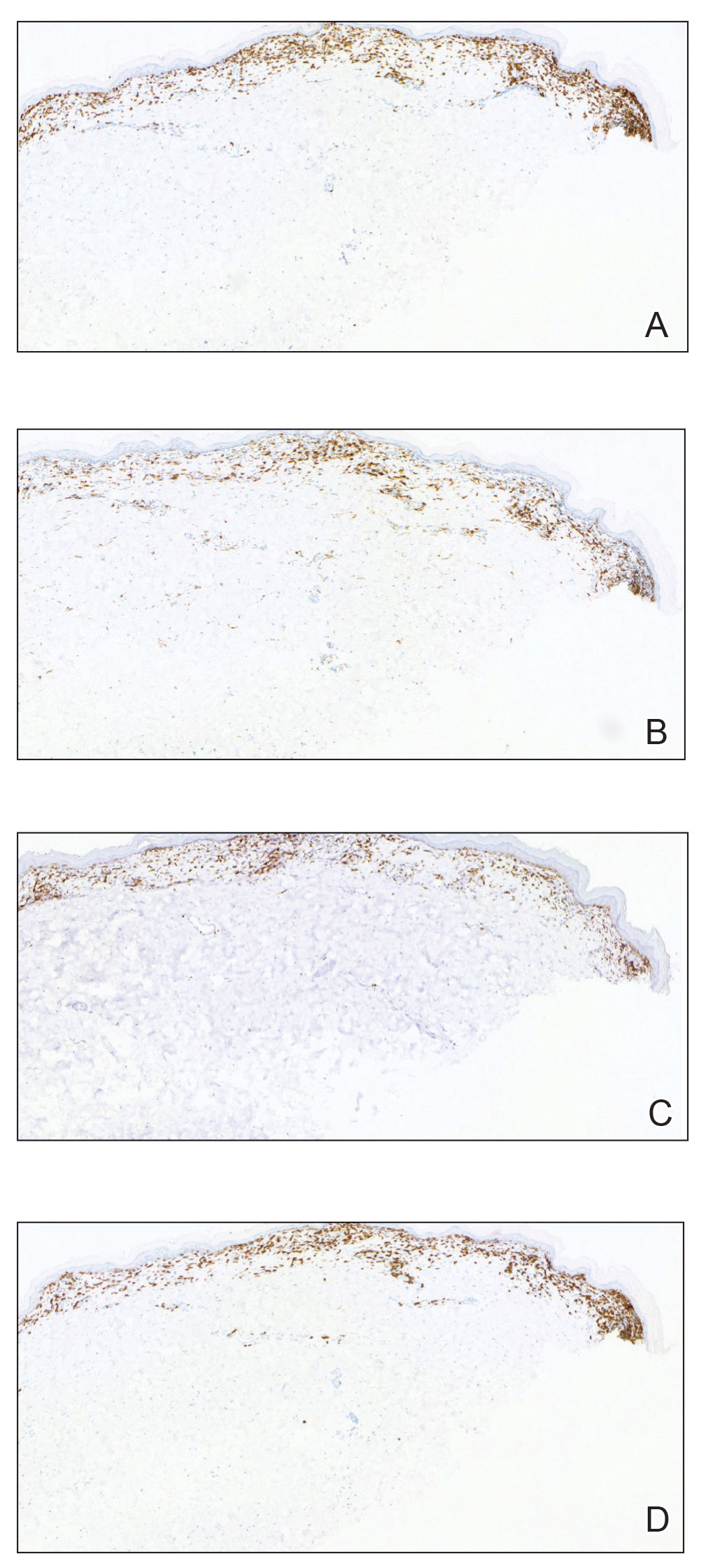

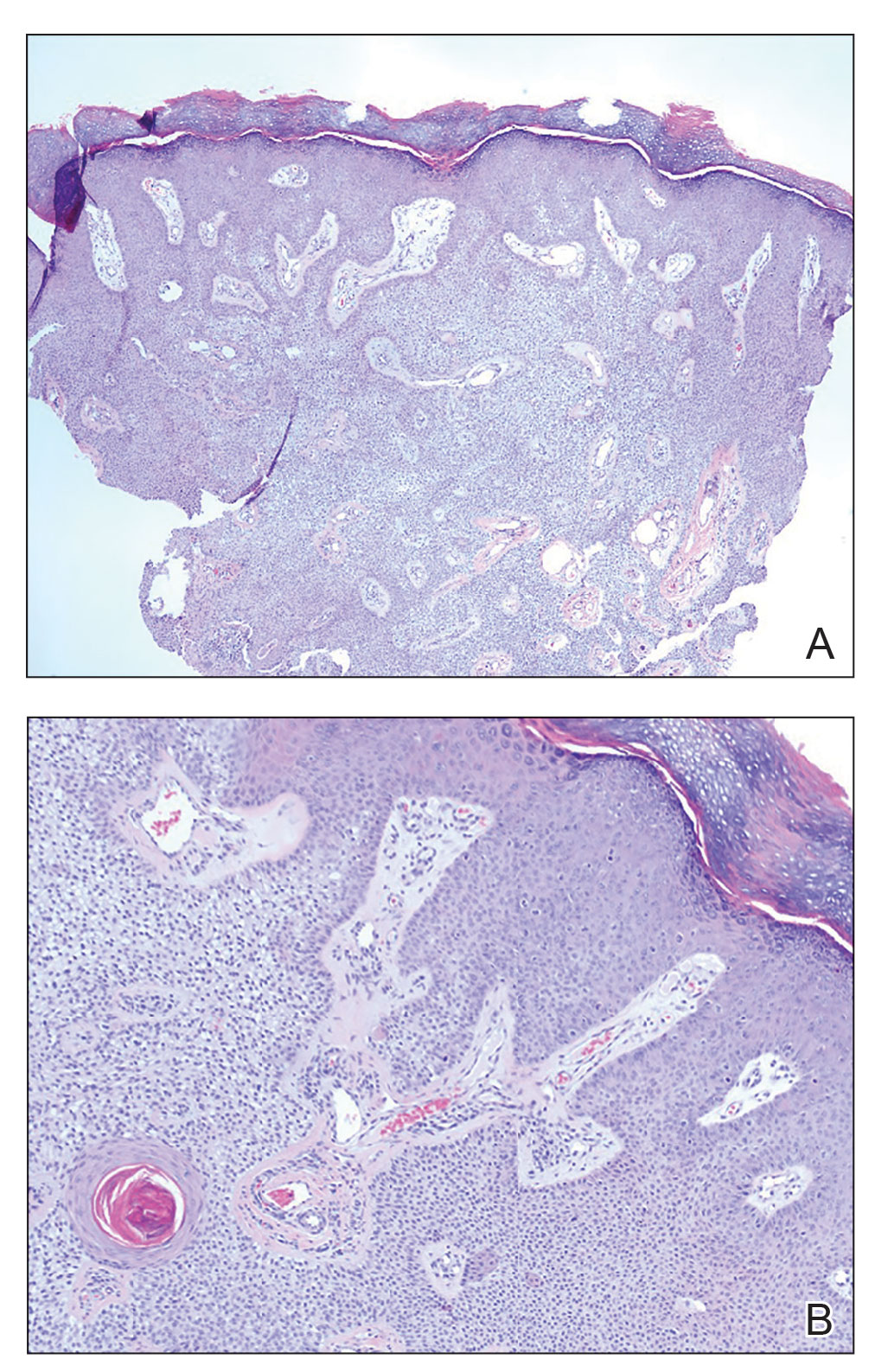

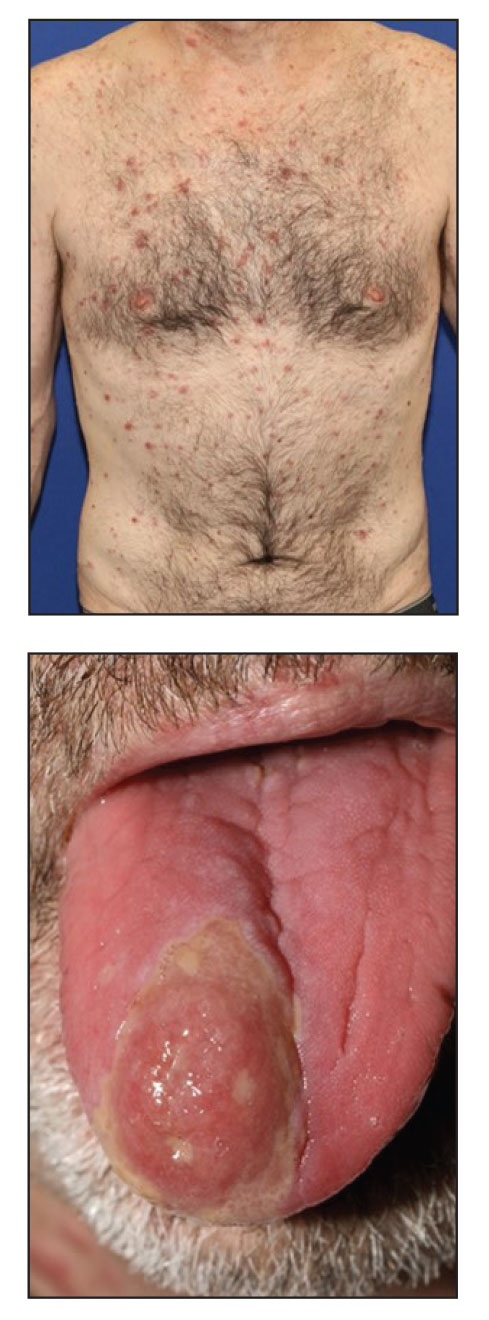

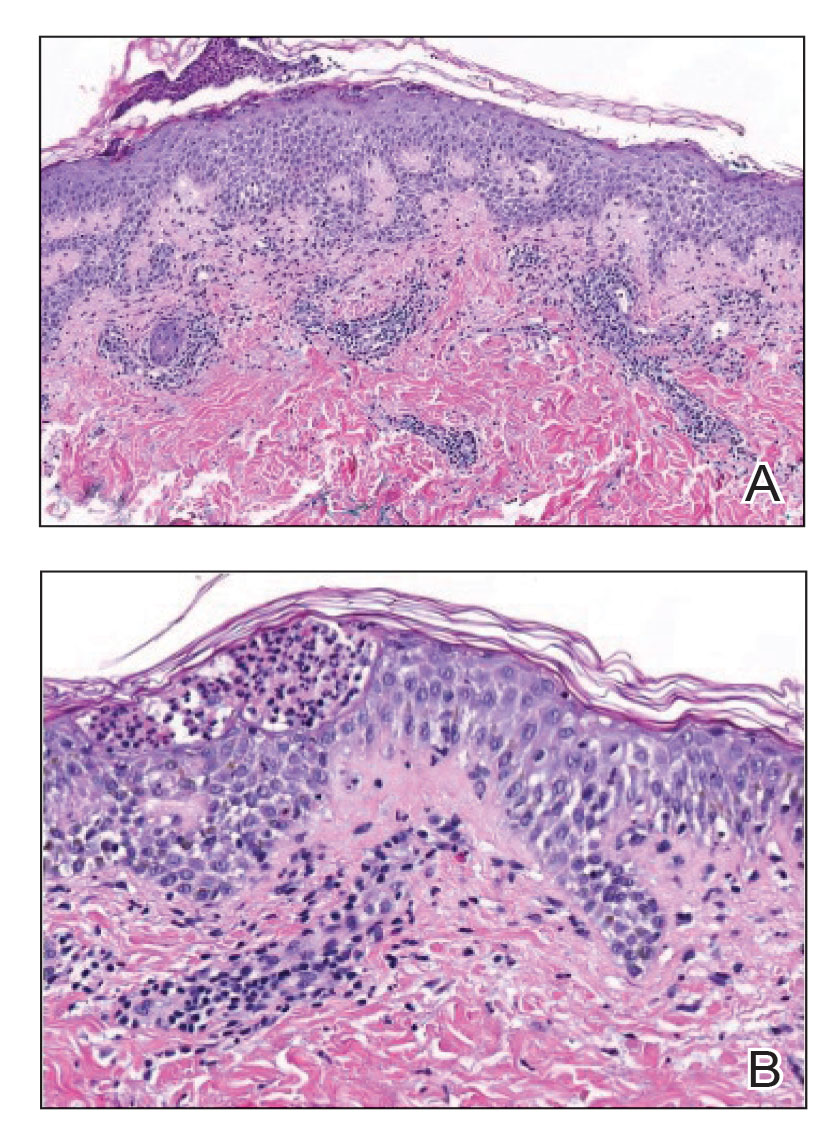

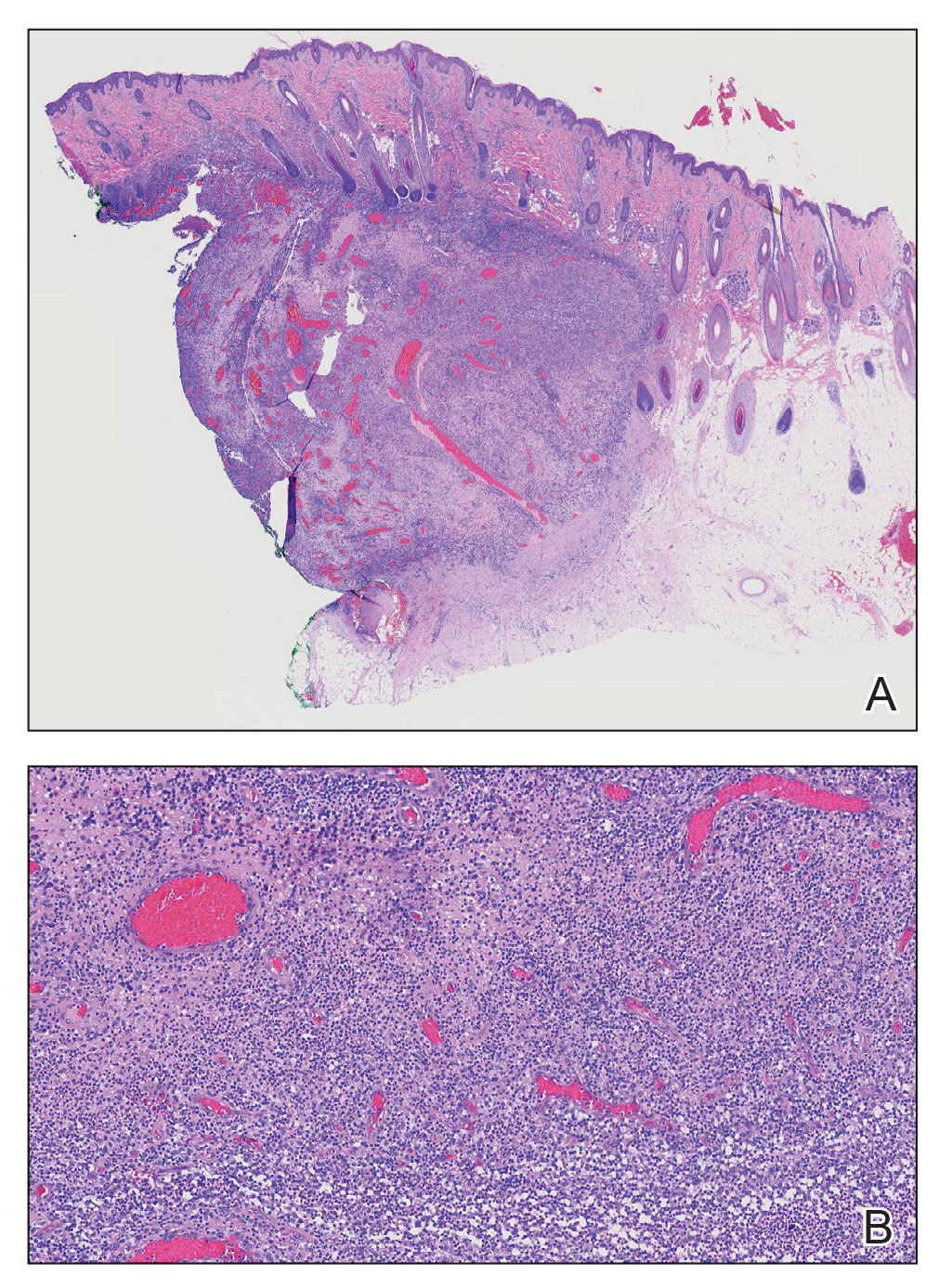

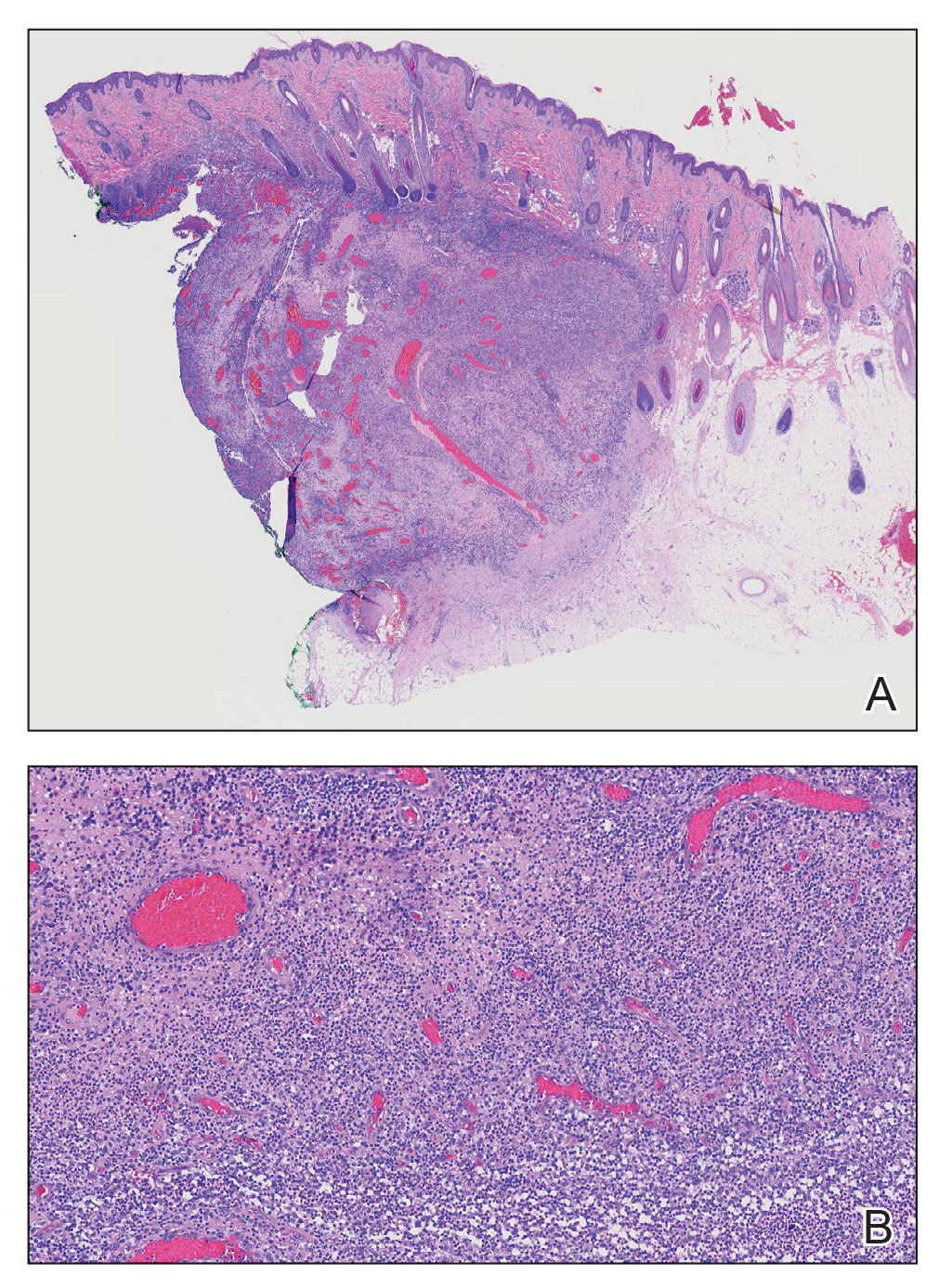

Histopathology showed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with expanded cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei of irregular contours in the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical stains of atypical lymphocytes demonstrated the presence of CD3, CD8, and CD5, as well as the absence of CD7 and CD4 lymphocytes (Figure 2). The T-cell γ rearrangement showed polyclonal lymphocytes with 5% tumor cells. The histologic and clinical findings along with our patient’s medical history led to a diagnosis of stage IA (<10% body surface area involvement) hypopigmented mycosis fungoides (hMF).1 Our patient was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1%; she noted an improvement in her symptoms at 2-month follow-up.

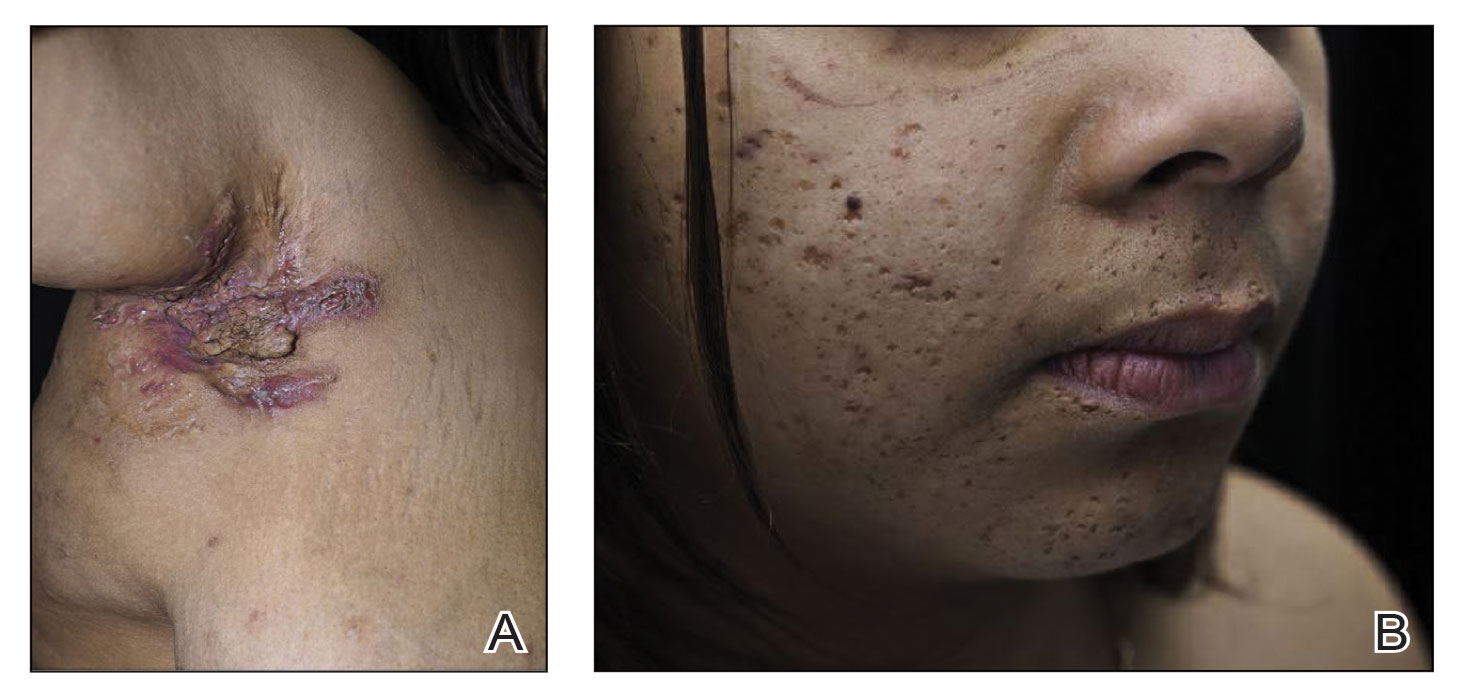

Hypopigmented MF is an uncommon manifestation of MF with unknown prevalence and incidence rates. Mycosis fungoides is considered the most common subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that classically presents as a chronic, indolent, hypopigmented or depigmented macule or patch, commonly with scaling, in sunprotected areas such as the trunk and proximal arms and legs. It predominantly affects younger adults with darker skin tones and may be present in the pediatric population within the first decade of life.1 Classically, MF affects White patients aged 55 to 60 years. Disease progression is slow, with an incidence rate of 10% of tumor or extracutaneous involvement in the early stages of disease. A lack of specificity on the clinical and histopathologic findings in the initial stage often contributes to the diagnostic delay of hMF. As seen in our patient, this disease can be misdiagnosed as tinea versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, vitiligo, pityriasis alba, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, or Hansen disease due to prolonged hypopigmented lesions.2 The clinical findings and histopathologic results including immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of hMF and ruled out pityriasis alba, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, and vitiligo.

The etiology and pathophysiology of hMF are not fully understood; however, it is hypothesized that melanocyte degeneration, abnormal melanogenesis, and disturbance of melanosome transfer result from the clonal expansion of T helper memory cells. T-cell dyscrasia has been reported to evolve into hMF during etanercept therapy.3 Clinically, hMF presents as hypopigmented papulosquamous, eczematous, or erythrodermic patches, plaques, and tumors with poorly defined atrophied borders. Multiple biopsies of steroid-naive lesions are needed for the diagnosis, as the initial hMF histologic finding cannot be specific for diagnostic confirmation. Common histopathologic findings include a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with epidermotropism, intraepidermal nests of atypical cells, or cerebriform nuclei lymphocytes on hematoxylin and eosin staining. In comparison to classical MF epidermotropism, CD4− and CD8+ atypical cells aid in the diagnosis of hMF. Although hMF carries a good prognosis and a benign clinical course,4 full-body computed tomography or positron emission tomography/computed tomography as well as laboratory analysis for lactate dehydrogenase should be pursued if lymphadenopathy, systemic symptoms, or advancedstage hMF are present.

Treatment of hMF depends on the disease stage. Psoralen plus UVA and narrowband UVB can be utilized for the initial stages with a relatively fast response and remission of lesions as early as the first 2 months of treatment. In addition to phototherapy, stage IA to IIA mycosis fungoides with localized skin lesions can benefit from topical steroids, topical retinoids, imiquimod, nitrogen mustard, and carmustine. For advanced stages of mycosis fungoides, combination therapy consisting of psoralen plus UVA with an oral retinoid, interferon alfa, and systemic chemotherapy commonly are prescribed. Maintenance therapy is used for prolonging remission; however, long-term phototherapy is not recommended due to the risk for skin cancer. Unfortunately, hMF requires long-term treatment due to its waxing and waning course, and recurrence may occur after complete resolution.5

- Furlan FC, Sanches JA. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a review of its clinical features and pathophysiology. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:954-960.

- Lambroza E, Cohen SR, Lebwohl M, et al. Hypopigmented variant of mycosis fungoides: demography, histopathology, and treatment of seven cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:987-993.

- Chuang GS, Wasserman DI, Byers HR, et al. Hypopigmented T-cell dyscrasia evolving to hypopigmented mycosis fungoides during etanercept therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(5 suppl):S121-S122.

- Agar NS, Wedgeworth E, Crichton S, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome: validation of the revised International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/ European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer staging proposal. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4730-4739.

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014; 70:223.e1-17; quiz 240-242.

The Diagnosis: Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

Histopathology showed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with expanded cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei of irregular contours in the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical stains of atypical lymphocytes demonstrated the presence of CD3, CD8, and CD5, as well as the absence of CD7 and CD4 lymphocytes (Figure 2). The T-cell γ rearrangement showed polyclonal lymphocytes with 5% tumor cells. The histologic and clinical findings along with our patient’s medical history led to a diagnosis of stage IA (<10% body surface area involvement) hypopigmented mycosis fungoides (hMF).1 Our patient was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1%; she noted an improvement in her symptoms at 2-month follow-up.

Hypopigmented MF is an uncommon manifestation of MF with unknown prevalence and incidence rates. Mycosis fungoides is considered the most common subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that classically presents as a chronic, indolent, hypopigmented or depigmented macule or patch, commonly with scaling, in sunprotected areas such as the trunk and proximal arms and legs. It predominantly affects younger adults with darker skin tones and may be present in the pediatric population within the first decade of life.1 Classically, MF affects White patients aged 55 to 60 years. Disease progression is slow, with an incidence rate of 10% of tumor or extracutaneous involvement in the early stages of disease. A lack of specificity on the clinical and histopathologic findings in the initial stage often contributes to the diagnostic delay of hMF. As seen in our patient, this disease can be misdiagnosed as tinea versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, vitiligo, pityriasis alba, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, or Hansen disease due to prolonged hypopigmented lesions.2 The clinical findings and histopathologic results including immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of hMF and ruled out pityriasis alba, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, and vitiligo.

The etiology and pathophysiology of hMF are not fully understood; however, it is hypothesized that melanocyte degeneration, abnormal melanogenesis, and disturbance of melanosome transfer result from the clonal expansion of T helper memory cells. T-cell dyscrasia has been reported to evolve into hMF during etanercept therapy.3 Clinically, hMF presents as hypopigmented papulosquamous, eczematous, or erythrodermic patches, plaques, and tumors with poorly defined atrophied borders. Multiple biopsies of steroid-naive lesions are needed for the diagnosis, as the initial hMF histologic finding cannot be specific for diagnostic confirmation. Common histopathologic findings include a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with epidermotropism, intraepidermal nests of atypical cells, or cerebriform nuclei lymphocytes on hematoxylin and eosin staining. In comparison to classical MF epidermotropism, CD4− and CD8+ atypical cells aid in the diagnosis of hMF. Although hMF carries a good prognosis and a benign clinical course,4 full-body computed tomography or positron emission tomography/computed tomography as well as laboratory analysis for lactate dehydrogenase should be pursued if lymphadenopathy, systemic symptoms, or advancedstage hMF are present.

Treatment of hMF depends on the disease stage. Psoralen plus UVA and narrowband UVB can be utilized for the initial stages with a relatively fast response and remission of lesions as early as the first 2 months of treatment. In addition to phototherapy, stage IA to IIA mycosis fungoides with localized skin lesions can benefit from topical steroids, topical retinoids, imiquimod, nitrogen mustard, and carmustine. For advanced stages of mycosis fungoides, combination therapy consisting of psoralen plus UVA with an oral retinoid, interferon alfa, and systemic chemotherapy commonly are prescribed. Maintenance therapy is used for prolonging remission; however, long-term phototherapy is not recommended due to the risk for skin cancer. Unfortunately, hMF requires long-term treatment due to its waxing and waning course, and recurrence may occur after complete resolution.5

The Diagnosis: Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

Histopathology showed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with expanded cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei of irregular contours in the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical stains of atypical lymphocytes demonstrated the presence of CD3, CD8, and CD5, as well as the absence of CD7 and CD4 lymphocytes (Figure 2). The T-cell γ rearrangement showed polyclonal lymphocytes with 5% tumor cells. The histologic and clinical findings along with our patient’s medical history led to a diagnosis of stage IA (<10% body surface area involvement) hypopigmented mycosis fungoides (hMF).1 Our patient was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1%; she noted an improvement in her symptoms at 2-month follow-up.

Hypopigmented MF is an uncommon manifestation of MF with unknown prevalence and incidence rates. Mycosis fungoides is considered the most common subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that classically presents as a chronic, indolent, hypopigmented or depigmented macule or patch, commonly with scaling, in sunprotected areas such as the trunk and proximal arms and legs. It predominantly affects younger adults with darker skin tones and may be present in the pediatric population within the first decade of life.1 Classically, MF affects White patients aged 55 to 60 years. Disease progression is slow, with an incidence rate of 10% of tumor or extracutaneous involvement in the early stages of disease. A lack of specificity on the clinical and histopathologic findings in the initial stage often contributes to the diagnostic delay of hMF. As seen in our patient, this disease can be misdiagnosed as tinea versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, vitiligo, pityriasis alba, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, or Hansen disease due to prolonged hypopigmented lesions.2 The clinical findings and histopathologic results including immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of hMF and ruled out pityriasis alba, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, and vitiligo.

The etiology and pathophysiology of hMF are not fully understood; however, it is hypothesized that melanocyte degeneration, abnormal melanogenesis, and disturbance of melanosome transfer result from the clonal expansion of T helper memory cells. T-cell dyscrasia has been reported to evolve into hMF during etanercept therapy.3 Clinically, hMF presents as hypopigmented papulosquamous, eczematous, or erythrodermic patches, plaques, and tumors with poorly defined atrophied borders. Multiple biopsies of steroid-naive lesions are needed for the diagnosis, as the initial hMF histologic finding cannot be specific for diagnostic confirmation. Common histopathologic findings include a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with epidermotropism, intraepidermal nests of atypical cells, or cerebriform nuclei lymphocytes on hematoxylin and eosin staining. In comparison to classical MF epidermotropism, CD4− and CD8+ atypical cells aid in the diagnosis of hMF. Although hMF carries a good prognosis and a benign clinical course,4 full-body computed tomography or positron emission tomography/computed tomography as well as laboratory analysis for lactate dehydrogenase should be pursued if lymphadenopathy, systemic symptoms, or advancedstage hMF are present.

Treatment of hMF depends on the disease stage. Psoralen plus UVA and narrowband UVB can be utilized for the initial stages with a relatively fast response and remission of lesions as early as the first 2 months of treatment. In addition to phototherapy, stage IA to IIA mycosis fungoides with localized skin lesions can benefit from topical steroids, topical retinoids, imiquimod, nitrogen mustard, and carmustine. For advanced stages of mycosis fungoides, combination therapy consisting of psoralen plus UVA with an oral retinoid, interferon alfa, and systemic chemotherapy commonly are prescribed. Maintenance therapy is used for prolonging remission; however, long-term phototherapy is not recommended due to the risk for skin cancer. Unfortunately, hMF requires long-term treatment due to its waxing and waning course, and recurrence may occur after complete resolution.5

- Furlan FC, Sanches JA. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a review of its clinical features and pathophysiology. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:954-960.

- Lambroza E, Cohen SR, Lebwohl M, et al. Hypopigmented variant of mycosis fungoides: demography, histopathology, and treatment of seven cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:987-993.

- Chuang GS, Wasserman DI, Byers HR, et al. Hypopigmented T-cell dyscrasia evolving to hypopigmented mycosis fungoides during etanercept therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(5 suppl):S121-S122.

- Agar NS, Wedgeworth E, Crichton S, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome: validation of the revised International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/ European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer staging proposal. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4730-4739.

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014; 70:223.e1-17; quiz 240-242.

- Furlan FC, Sanches JA. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a review of its clinical features and pathophysiology. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:954-960.

- Lambroza E, Cohen SR, Lebwohl M, et al. Hypopigmented variant of mycosis fungoides: demography, histopathology, and treatment of seven cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:987-993.

- Chuang GS, Wasserman DI, Byers HR, et al. Hypopigmented T-cell dyscrasia evolving to hypopigmented mycosis fungoides during etanercept therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(5 suppl):S121-S122.

- Agar NS, Wedgeworth E, Crichton S, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome: validation of the revised International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/ European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer staging proposal. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4730-4739.

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014; 70:223.e1-17; quiz 240-242.

A 52-year-old Black woman presented with self-described whitened spots on the arms and legs of 2 years’ duration. She experienced no improvement with ketoconazole cream and topical calcineurin inhibitors prescribed during a prior dermatology visit at an outside institution. She denied pain or pruritus. A review of systems as well as the patient’s medical history were noncontributory. A prior biopsy at an outside institution revealed an interface dermatitis suggestive of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The patient noted social drinking and denied tobacco use. She had no known allergies to medications and currently was on tamoxifen for breast cancer following a right mastectomy. Physical examination showed hypopigmented macules and patches on the left upper arm and right proximal leg. The center of the lesions was not erythematous or scaly. Palpation did not reveal enlarged lymph nodes, and laboratory analyses ruled out low levels of red blood cells, white blood cells, or platelets. Punch biopsies from the left arm and right thigh were performed.

Erythematous Dermal Facial Plaques in a Neutropenic Patient

THE DIAGNOSIS: Neutrophilic Eccrine Hidradenitis

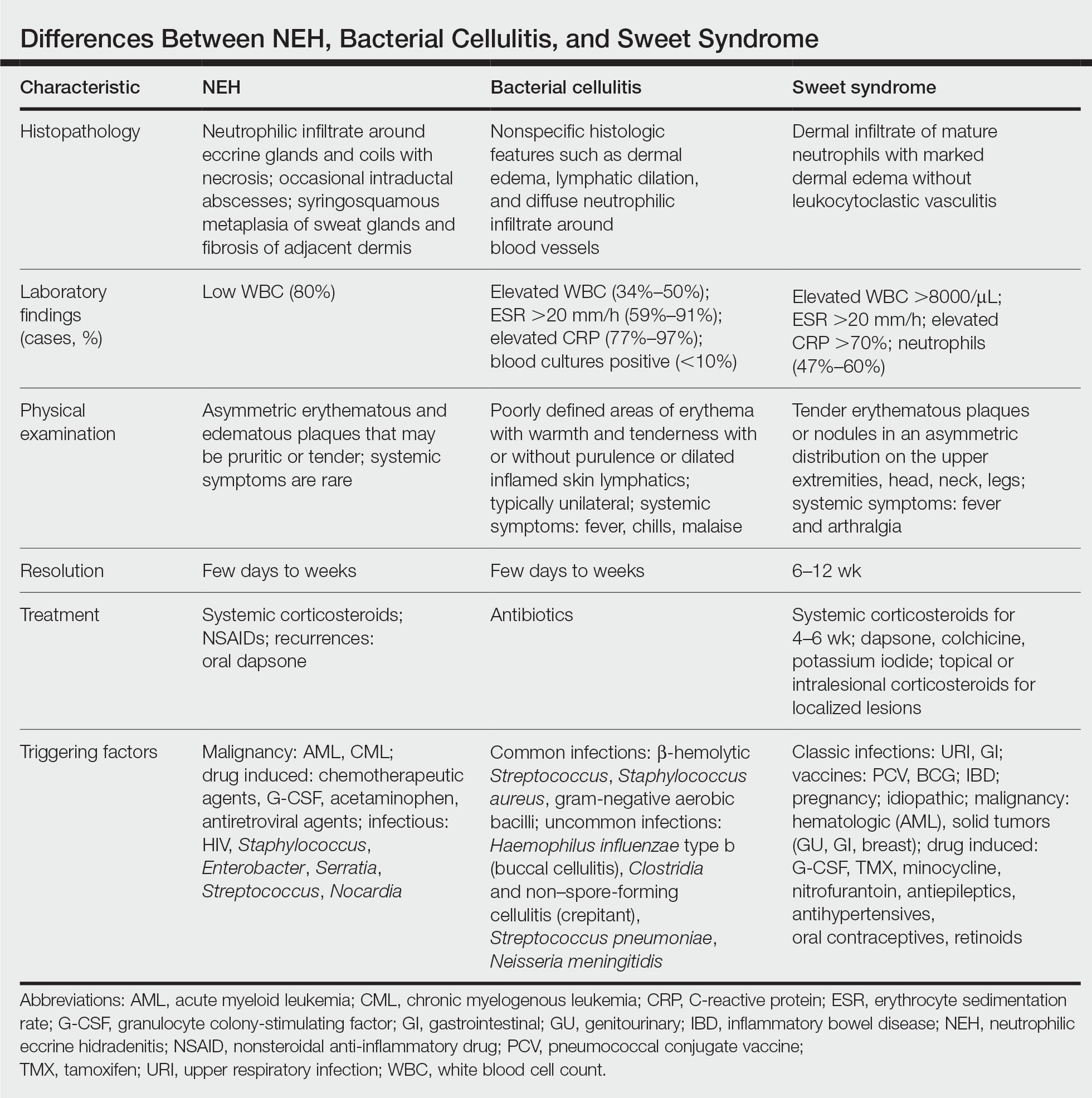

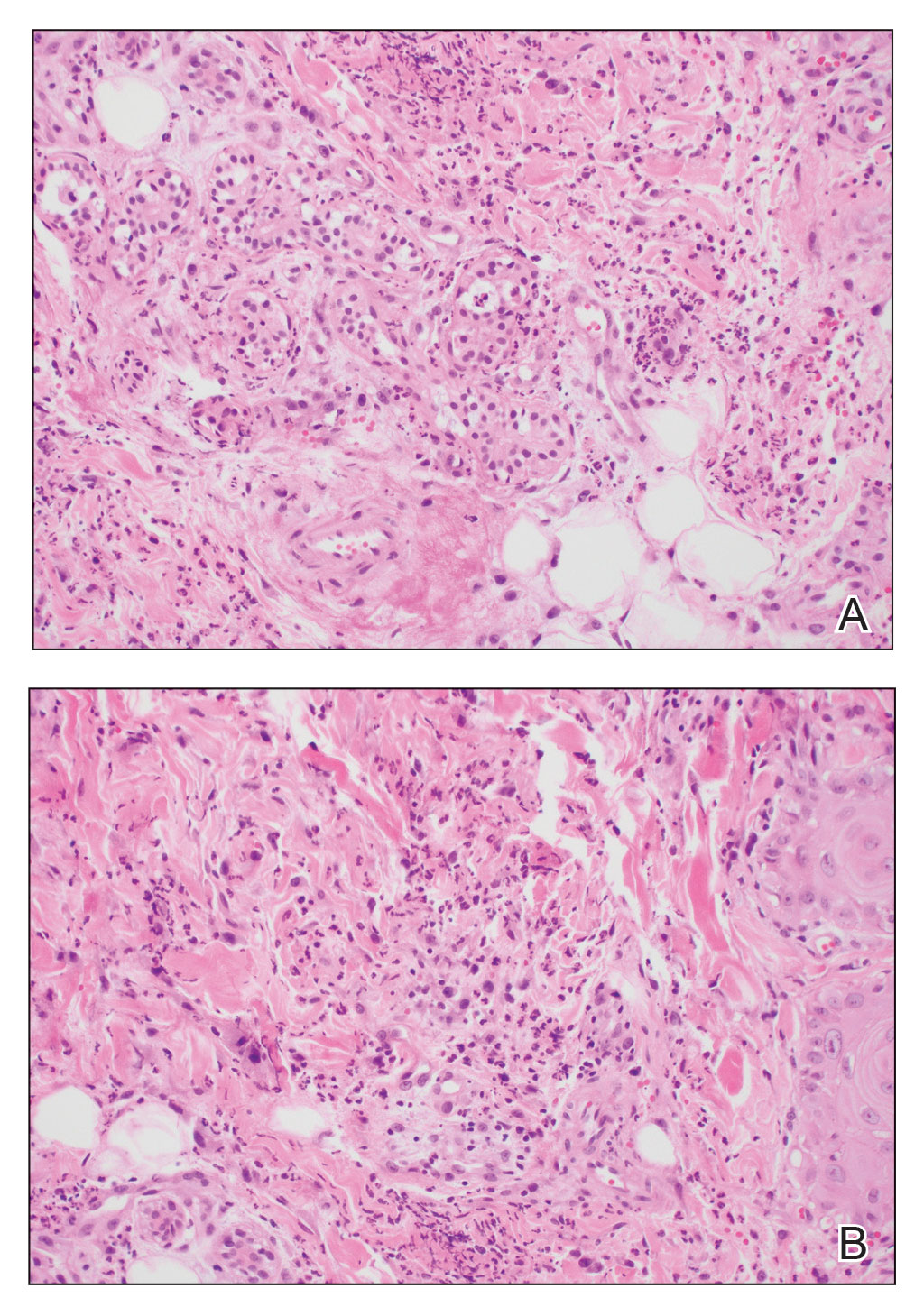

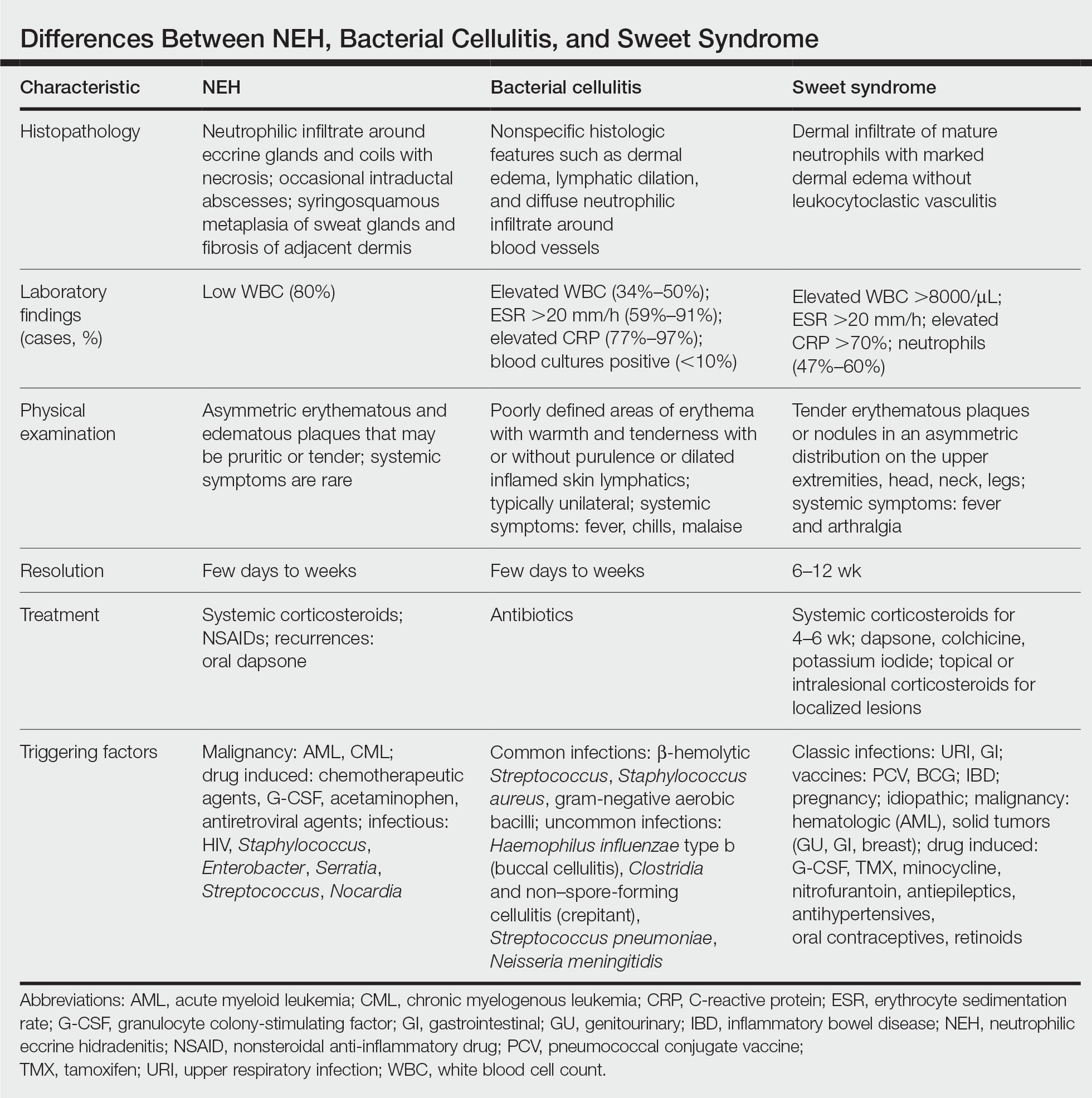

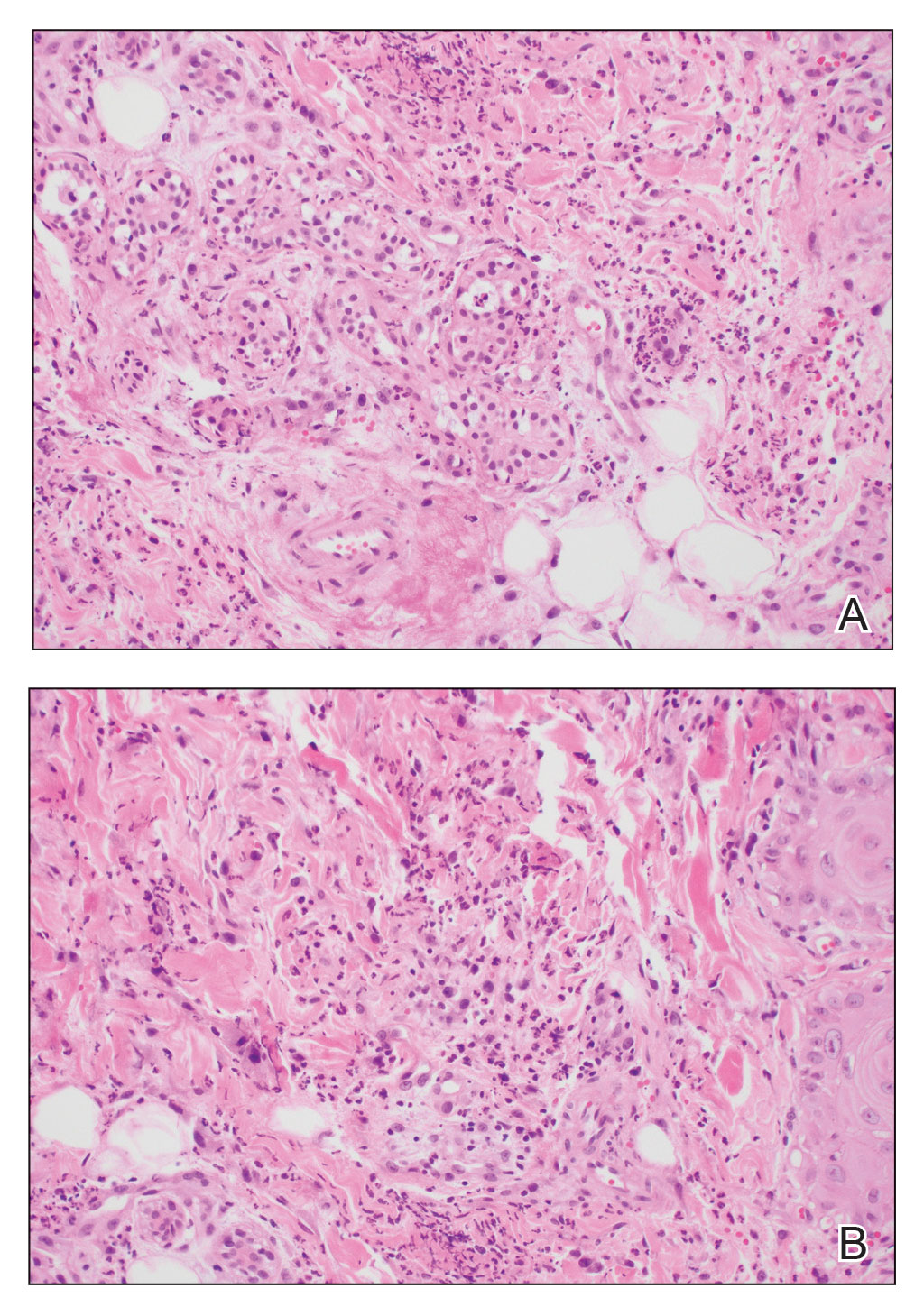

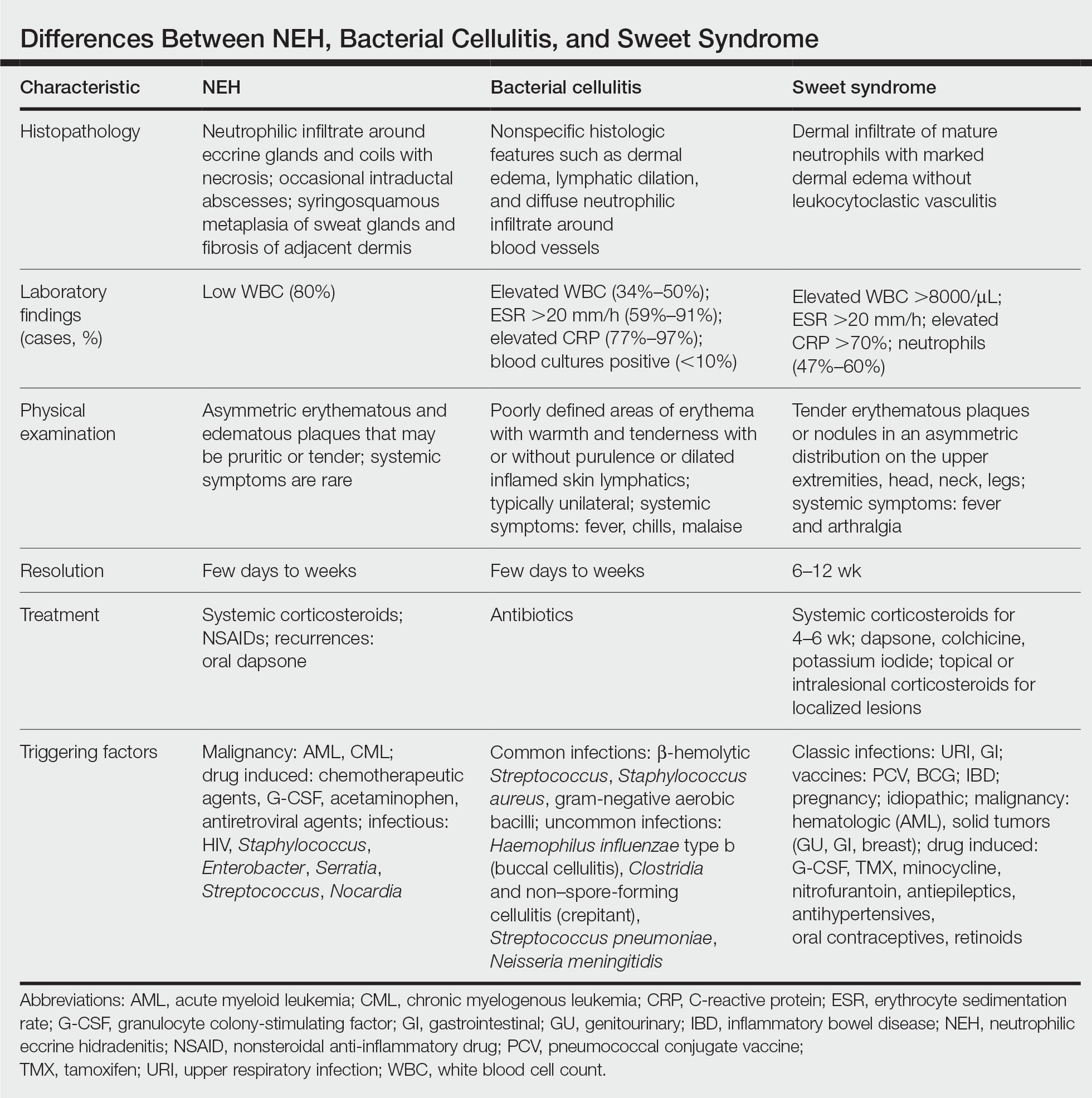

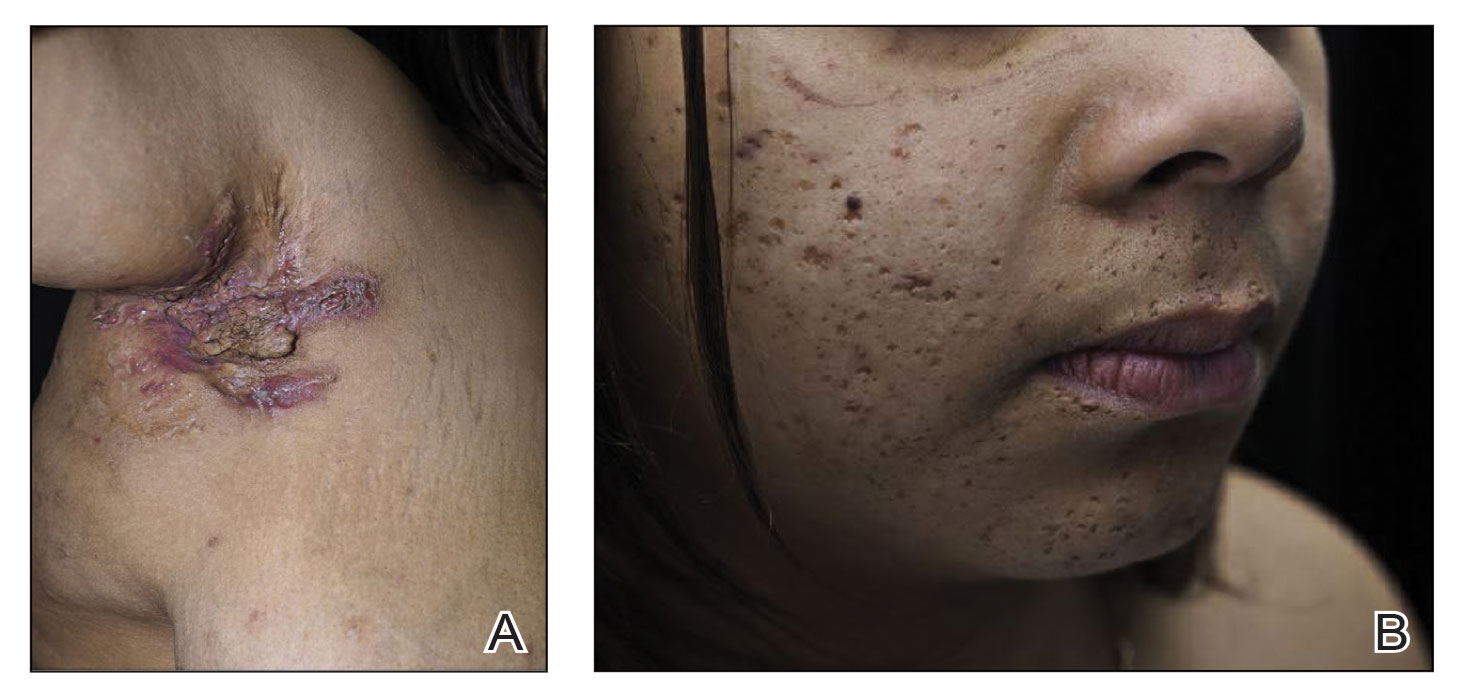

A biopsy from the left preauricular cheek demonstrated dermal neutrophilic inflammation around eccrine coils with focal necrosis (Figure). No notable diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate was present, ruling out Sweet syndrome, and no notable interstitial neutrophilic infiltrate was present, making cellulitis and erysipelas less likely; panculture of tissue also was negative.1,2 Atypical cells in the deep dermis were positive for CD163 and negative for CD117, CD34, CD123, and myeloperoxidase, consistent with a diagnosis of neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis (NEH) and reactive histiocytes.3 Treatment with oral prednisone resulted in rapid improvement of symptoms.

Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis is a rare reactive neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by eccrine gland involvement. This benign and self-limited condition presents as asymmetric erythematous papules and plaques.2 Among 8 granulocytopenic patients with neutrophilic dermatoses, 5 were diagnosed with NEH.4 Although first identified in 1982, NEH remains poorly understood.2 Initial theories suggested that NEH developed due to cytotoxic substances secreted in sweat glands causing necrosis and neutrophil chemotaxis; however, chemotherapy exposure cannot be linked to every case of NEH. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis can be extremely difficult to differentiate clinically from conditions such as cellulitis and Sweet syndrome.

A patient history can be helpful in identifying triggering factors. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis most commonly is associated with malignant, drug-induced, or infectious triggers, while Sweet syndrome has a broad range of associations including infections, vaccines, inflammatory bowel disease, pregnancy, malignancy, and drug-induced etiologies (Table).1 On average, NEH presents 10 days after chemotherapy induction, with 70% of cases presenting after the first chemotherapy cycle.5 Bacterial cellulitis or erysipelas have an infectious etiology, and patients may report symptoms such as fever, chills, or malaise. Immunosuppressed patients are at greater risk for infection; therefore, clinical signs of infection in a granulocytopenic patient should be addressed urgently.

Physical examination may have limited value in differentiating between these diagnoses, as neutrophilic dermatoses notoriously mimic infection. Cutaneous lesions can appear as pruritic or tender erythematous plaques, papules, or nodules in these conditions, though cellulitis and erysipelas tend to be unilateral and may have associated purulence or inflamed skin lymphatics. Given the potential for misdiagnosis, approaching patients with a broad differential can be helpful. In our patient, the differential diagnosis included Sweet syndrome, NEH, bacterial cellulitis, erysipelas, leukemia cutis, sarcoid, and eosinophilic cellulitis.

Leukemia cutis refers to the infiltration of neoplastic leukocytes in the skin and often occurs in patients with peripheral leukemia, most often acute myeloid leukemia or chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Patients with leukemia cutis often have a worse prognosis, as this finding signifies extramedullary spread of disease.6 Clinically, lesions can appear similar to those seen in our patient, though they typically are not symptomatic, can be nodular, tend to exhibit a violaceous hue, and occasionally may be hemorrhagic. Wells syndrome (also known as eosinophilic cellulitis) is an inflammatory dermatosis that presents as painful or pruritic, edematous and erythematous plaques.7,8 A green hue on resolution is present in some cases and may help clinicians differentiate this disease from mimickers.7 Often, eosinophilic cellulitis is misdiagnosed as bacterial cellulitis and treated with antibiotics. The presence of systemic symptoms such as fever or arthralgia is more typical of bacterial cellulitis, erysipelas, eosinophilic cellulitis, or Sweet syndrome than of NEH.1 Additionally, inflammatory markers (ie, C-reactive protein) and white blood cell counts tend to be elevated in bacterial cellulitis and Sweet syndrome, while leukopenia often is seen in NEH.

Histopathology is crucial in distinguishing these disease etiologies. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis is diagnosed by the characteristic neutrophilic infiltrate and necrosis surrounding eccrine glands and coils. There also may be occasional intraductal abscesses and syringosquamous metaplasia of the sweat glands along with fibrosis of the adjacent dermis. In contrast, histologic sections of Sweet syndrome show numerous mature neutrophils infiltrating the dermis with marked papillary dermal edema. The histopathology of bacterial cellulitis and erysipelas is less specific, but common features include dermal edema, lymphatic dilation, and a diffuse neutrophilic infiltrate surrounding blood vessels. Pathogenic organisms may be seen on histopathology but are not required for the diagnosis of bacterial cellulitis or erysipelas.2 Additionally, blood and tissue culture can assist in identification of both the source of infection and the causative organism, but cultures may not always be positive.

Comparatively, the histopathologic features of eosinophilic cellulitis include dermal edema, eosinophilic infiltration, and flame figures that form when eosinophils degranulate and coat collagen fibers with major basic protein. Flame figures are characteristic but not pathognomonic for eosinophilic cellulitis.7 The histopathology of leukemia cutis varies based on the leukemia classification; generally, in acute myeloid leukemia the infiltrate is composed of neoplastic cells in the early stages of development that are positive for myeloid markers such as myeloperoxidase. Atypical and immature granulocytes within the leukocytic infiltrate differentiate this condition from the other diagnoses. Treatment may entail chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and this diagnosis generally carries the worst prognosis of all the conditions in the differential.6

Differentiating between these conditions is important in guiding treatment, especially in patients with febrile neutropenia. Unnecessary steroids in immunosuppressed patients can be dangerous, especially if the patient has an infection such as bacterial cellulitis. Furthermore, unwarranted antibiotic use for noninfectious conditions may expose patients to substantial side effects and not improve the condition. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis typically is self-limited and treated symptomatically with systemic corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.3 Sweet syndrome often requires a longer course of oral steroids. Leukemia cutis worsens as the leukemia advances, and treatment of the underlying malignancy is the most effective treatment.9

Early and accurate recognition of the diagnosis can prevent harmful diagnostic delay, unnecessary antibiotic use, or extended steroid taper in neutropenic patients. Appreciating the differences between these diagnoses can assist clinicians in investigating and tailoring a broad differential to specific patient presentations, which is especially critical when considering common mimickers for life-threatening conditions.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.0642

- Srivastava M, Scharf S, Meehan SA, et al. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis masquerading as facial cellulitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:693-696. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.07.032

- Copaescu AM, Castilloux JF, Chababi-Atallah M, et al. A classic clinical case: neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013; 5:340-346. doi:10.1159/000356229

- Aractingi S, Mallet V, Pinquier L, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses during granulocytopenia. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1141-1145.

- Cohen PR. Neutrophilic dermatoses occurring in oncology patients. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:106-111. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02605.x

- Wang CX, Pusic I, Anadkat MJ. Association of leukemia cutis with survival in acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:826. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0052

- Chung CL, Cusack CA. Wells syndrome: an enigmatic and therapeutically challenging disease. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:908-911.

- Räßler F, Lukács J, Elsner P. Treatment of eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells syndrome): a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1465-1479. doi:10.1111/jdv.13706

- Hobbs LK, Carr PC, Gru AA, et al. Case and review: cutaneous involvement by chronic neutrophilic leukemia vs Sweet syndrome: a diagnostic dilemma. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:644-649. doi:10.1111 /cup.13925

THE DIAGNOSIS: Neutrophilic Eccrine Hidradenitis

A biopsy from the left preauricular cheek demonstrated dermal neutrophilic inflammation around eccrine coils with focal necrosis (Figure). No notable diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate was present, ruling out Sweet syndrome, and no notable interstitial neutrophilic infiltrate was present, making cellulitis and erysipelas less likely; panculture of tissue also was negative.1,2 Atypical cells in the deep dermis were positive for CD163 and negative for CD117, CD34, CD123, and myeloperoxidase, consistent with a diagnosis of neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis (NEH) and reactive histiocytes.3 Treatment with oral prednisone resulted in rapid improvement of symptoms.

Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis is a rare reactive neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by eccrine gland involvement. This benign and self-limited condition presents as asymmetric erythematous papules and plaques.2 Among 8 granulocytopenic patients with neutrophilic dermatoses, 5 were diagnosed with NEH.4 Although first identified in 1982, NEH remains poorly understood.2 Initial theories suggested that NEH developed due to cytotoxic substances secreted in sweat glands causing necrosis and neutrophil chemotaxis; however, chemotherapy exposure cannot be linked to every case of NEH. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis can be extremely difficult to differentiate clinically from conditions such as cellulitis and Sweet syndrome.

A patient history can be helpful in identifying triggering factors. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis most commonly is associated with malignant, drug-induced, or infectious triggers, while Sweet syndrome has a broad range of associations including infections, vaccines, inflammatory bowel disease, pregnancy, malignancy, and drug-induced etiologies (Table).1 On average, NEH presents 10 days after chemotherapy induction, with 70% of cases presenting after the first chemotherapy cycle.5 Bacterial cellulitis or erysipelas have an infectious etiology, and patients may report symptoms such as fever, chills, or malaise. Immunosuppressed patients are at greater risk for infection; therefore, clinical signs of infection in a granulocytopenic patient should be addressed urgently.

Physical examination may have limited value in differentiating between these diagnoses, as neutrophilic dermatoses notoriously mimic infection. Cutaneous lesions can appear as pruritic or tender erythematous plaques, papules, or nodules in these conditions, though cellulitis and erysipelas tend to be unilateral and may have associated purulence or inflamed skin lymphatics. Given the potential for misdiagnosis, approaching patients with a broad differential can be helpful. In our patient, the differential diagnosis included Sweet syndrome, NEH, bacterial cellulitis, erysipelas, leukemia cutis, sarcoid, and eosinophilic cellulitis.

Leukemia cutis refers to the infiltration of neoplastic leukocytes in the skin and often occurs in patients with peripheral leukemia, most often acute myeloid leukemia or chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Patients with leukemia cutis often have a worse prognosis, as this finding signifies extramedullary spread of disease.6 Clinically, lesions can appear similar to those seen in our patient, though they typically are not symptomatic, can be nodular, tend to exhibit a violaceous hue, and occasionally may be hemorrhagic. Wells syndrome (also known as eosinophilic cellulitis) is an inflammatory dermatosis that presents as painful or pruritic, edematous and erythematous plaques.7,8 A green hue on resolution is present in some cases and may help clinicians differentiate this disease from mimickers.7 Often, eosinophilic cellulitis is misdiagnosed as bacterial cellulitis and treated with antibiotics. The presence of systemic symptoms such as fever or arthralgia is more typical of bacterial cellulitis, erysipelas, eosinophilic cellulitis, or Sweet syndrome than of NEH.1 Additionally, inflammatory markers (ie, C-reactive protein) and white blood cell counts tend to be elevated in bacterial cellulitis and Sweet syndrome, while leukopenia often is seen in NEH.

Histopathology is crucial in distinguishing these disease etiologies. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis is diagnosed by the characteristic neutrophilic infiltrate and necrosis surrounding eccrine glands and coils. There also may be occasional intraductal abscesses and syringosquamous metaplasia of the sweat glands along with fibrosis of the adjacent dermis. In contrast, histologic sections of Sweet syndrome show numerous mature neutrophils infiltrating the dermis with marked papillary dermal edema. The histopathology of bacterial cellulitis and erysipelas is less specific, but common features include dermal edema, lymphatic dilation, and a diffuse neutrophilic infiltrate surrounding blood vessels. Pathogenic organisms may be seen on histopathology but are not required for the diagnosis of bacterial cellulitis or erysipelas.2 Additionally, blood and tissue culture can assist in identification of both the source of infection and the causative organism, but cultures may not always be positive.

Comparatively, the histopathologic features of eosinophilic cellulitis include dermal edema, eosinophilic infiltration, and flame figures that form when eosinophils degranulate and coat collagen fibers with major basic protein. Flame figures are characteristic but not pathognomonic for eosinophilic cellulitis.7 The histopathology of leukemia cutis varies based on the leukemia classification; generally, in acute myeloid leukemia the infiltrate is composed of neoplastic cells in the early stages of development that are positive for myeloid markers such as myeloperoxidase. Atypical and immature granulocytes within the leukocytic infiltrate differentiate this condition from the other diagnoses. Treatment may entail chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and this diagnosis generally carries the worst prognosis of all the conditions in the differential.6

Differentiating between these conditions is important in guiding treatment, especially in patients with febrile neutropenia. Unnecessary steroids in immunosuppressed patients can be dangerous, especially if the patient has an infection such as bacterial cellulitis. Furthermore, unwarranted antibiotic use for noninfectious conditions may expose patients to substantial side effects and not improve the condition. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis typically is self-limited and treated symptomatically with systemic corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.3 Sweet syndrome often requires a longer course of oral steroids. Leukemia cutis worsens as the leukemia advances, and treatment of the underlying malignancy is the most effective treatment.9

Early and accurate recognition of the diagnosis can prevent harmful diagnostic delay, unnecessary antibiotic use, or extended steroid taper in neutropenic patients. Appreciating the differences between these diagnoses can assist clinicians in investigating and tailoring a broad differential to specific patient presentations, which is especially critical when considering common mimickers for life-threatening conditions.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Neutrophilic Eccrine Hidradenitis

A biopsy from the left preauricular cheek demonstrated dermal neutrophilic inflammation around eccrine coils with focal necrosis (Figure). No notable diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate was present, ruling out Sweet syndrome, and no notable interstitial neutrophilic infiltrate was present, making cellulitis and erysipelas less likely; panculture of tissue also was negative.1,2 Atypical cells in the deep dermis were positive for CD163 and negative for CD117, CD34, CD123, and myeloperoxidase, consistent with a diagnosis of neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis (NEH) and reactive histiocytes.3 Treatment with oral prednisone resulted in rapid improvement of symptoms.

Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis is a rare reactive neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by eccrine gland involvement. This benign and self-limited condition presents as asymmetric erythematous papules and plaques.2 Among 8 granulocytopenic patients with neutrophilic dermatoses, 5 were diagnosed with NEH.4 Although first identified in 1982, NEH remains poorly understood.2 Initial theories suggested that NEH developed due to cytotoxic substances secreted in sweat glands causing necrosis and neutrophil chemotaxis; however, chemotherapy exposure cannot be linked to every case of NEH. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis can be extremely difficult to differentiate clinically from conditions such as cellulitis and Sweet syndrome.

A patient history can be helpful in identifying triggering factors. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis most commonly is associated with malignant, drug-induced, or infectious triggers, while Sweet syndrome has a broad range of associations including infections, vaccines, inflammatory bowel disease, pregnancy, malignancy, and drug-induced etiologies (Table).1 On average, NEH presents 10 days after chemotherapy induction, with 70% of cases presenting after the first chemotherapy cycle.5 Bacterial cellulitis or erysipelas have an infectious etiology, and patients may report symptoms such as fever, chills, or malaise. Immunosuppressed patients are at greater risk for infection; therefore, clinical signs of infection in a granulocytopenic patient should be addressed urgently.

Physical examination may have limited value in differentiating between these diagnoses, as neutrophilic dermatoses notoriously mimic infection. Cutaneous lesions can appear as pruritic or tender erythematous plaques, papules, or nodules in these conditions, though cellulitis and erysipelas tend to be unilateral and may have associated purulence or inflamed skin lymphatics. Given the potential for misdiagnosis, approaching patients with a broad differential can be helpful. In our patient, the differential diagnosis included Sweet syndrome, NEH, bacterial cellulitis, erysipelas, leukemia cutis, sarcoid, and eosinophilic cellulitis.

Leukemia cutis refers to the infiltration of neoplastic leukocytes in the skin and often occurs in patients with peripheral leukemia, most often acute myeloid leukemia or chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Patients with leukemia cutis often have a worse prognosis, as this finding signifies extramedullary spread of disease.6 Clinically, lesions can appear similar to those seen in our patient, though they typically are not symptomatic, can be nodular, tend to exhibit a violaceous hue, and occasionally may be hemorrhagic. Wells syndrome (also known as eosinophilic cellulitis) is an inflammatory dermatosis that presents as painful or pruritic, edematous and erythematous plaques.7,8 A green hue on resolution is present in some cases and may help clinicians differentiate this disease from mimickers.7 Often, eosinophilic cellulitis is misdiagnosed as bacterial cellulitis and treated with antibiotics. The presence of systemic symptoms such as fever or arthralgia is more typical of bacterial cellulitis, erysipelas, eosinophilic cellulitis, or Sweet syndrome than of NEH.1 Additionally, inflammatory markers (ie, C-reactive protein) and white blood cell counts tend to be elevated in bacterial cellulitis and Sweet syndrome, while leukopenia often is seen in NEH.

Histopathology is crucial in distinguishing these disease etiologies. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis is diagnosed by the characteristic neutrophilic infiltrate and necrosis surrounding eccrine glands and coils. There also may be occasional intraductal abscesses and syringosquamous metaplasia of the sweat glands along with fibrosis of the adjacent dermis. In contrast, histologic sections of Sweet syndrome show numerous mature neutrophils infiltrating the dermis with marked papillary dermal edema. The histopathology of bacterial cellulitis and erysipelas is less specific, but common features include dermal edema, lymphatic dilation, and a diffuse neutrophilic infiltrate surrounding blood vessels. Pathogenic organisms may be seen on histopathology but are not required for the diagnosis of bacterial cellulitis or erysipelas.2 Additionally, blood and tissue culture can assist in identification of both the source of infection and the causative organism, but cultures may not always be positive.

Comparatively, the histopathologic features of eosinophilic cellulitis include dermal edema, eosinophilic infiltration, and flame figures that form when eosinophils degranulate and coat collagen fibers with major basic protein. Flame figures are characteristic but not pathognomonic for eosinophilic cellulitis.7 The histopathology of leukemia cutis varies based on the leukemia classification; generally, in acute myeloid leukemia the infiltrate is composed of neoplastic cells in the early stages of development that are positive for myeloid markers such as myeloperoxidase. Atypical and immature granulocytes within the leukocytic infiltrate differentiate this condition from the other diagnoses. Treatment may entail chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and this diagnosis generally carries the worst prognosis of all the conditions in the differential.6

Differentiating between these conditions is important in guiding treatment, especially in patients with febrile neutropenia. Unnecessary steroids in immunosuppressed patients can be dangerous, especially if the patient has an infection such as bacterial cellulitis. Furthermore, unwarranted antibiotic use for noninfectious conditions may expose patients to substantial side effects and not improve the condition. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis typically is self-limited and treated symptomatically with systemic corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.3 Sweet syndrome often requires a longer course of oral steroids. Leukemia cutis worsens as the leukemia advances, and treatment of the underlying malignancy is the most effective treatment.9

Early and accurate recognition of the diagnosis can prevent harmful diagnostic delay, unnecessary antibiotic use, or extended steroid taper in neutropenic patients. Appreciating the differences between these diagnoses can assist clinicians in investigating and tailoring a broad differential to specific patient presentations, which is especially critical when considering common mimickers for life-threatening conditions.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.0642

- Srivastava M, Scharf S, Meehan SA, et al. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis masquerading as facial cellulitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:693-696. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.07.032

- Copaescu AM, Castilloux JF, Chababi-Atallah M, et al. A classic clinical case: neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013; 5:340-346. doi:10.1159/000356229

- Aractingi S, Mallet V, Pinquier L, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses during granulocytopenia. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1141-1145.

- Cohen PR. Neutrophilic dermatoses occurring in oncology patients. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:106-111. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02605.x

- Wang CX, Pusic I, Anadkat MJ. Association of leukemia cutis with survival in acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:826. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0052

- Chung CL, Cusack CA. Wells syndrome: an enigmatic and therapeutically challenging disease. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:908-911.

- Räßler F, Lukács J, Elsner P. Treatment of eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells syndrome): a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1465-1479. doi:10.1111/jdv.13706

- Hobbs LK, Carr PC, Gru AA, et al. Case and review: cutaneous involvement by chronic neutrophilic leukemia vs Sweet syndrome: a diagnostic dilemma. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:644-649. doi:10.1111 /cup.13925

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.0642

- Srivastava M, Scharf S, Meehan SA, et al. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis masquerading as facial cellulitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:693-696. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.07.032

- Copaescu AM, Castilloux JF, Chababi-Atallah M, et al. A classic clinical case: neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013; 5:340-346. doi:10.1159/000356229

- Aractingi S, Mallet V, Pinquier L, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses during granulocytopenia. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1141-1145.

- Cohen PR. Neutrophilic dermatoses occurring in oncology patients. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:106-111. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02605.x

- Wang CX, Pusic I, Anadkat MJ. Association of leukemia cutis with survival in acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:826. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0052

- Chung CL, Cusack CA. Wells syndrome: an enigmatic and therapeutically challenging disease. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:908-911.

- Räßler F, Lukács J, Elsner P. Treatment of eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells syndrome): a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1465-1479. doi:10.1111/jdv.13706

- Hobbs LK, Carr PC, Gru AA, et al. Case and review: cutaneous involvement by chronic neutrophilic leukemia vs Sweet syndrome: a diagnostic dilemma. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:644-649. doi:10.1111 /cup.13925

A 50-year-old woman undergoing cytarabine induction therapy for acute myeloid leukemia developed tender, erythematous, dermal plaques on the nasal dorsum, left medial eyebrow, left preauricular cheek, and right cheek. The rash erupted 7 days after receiving the cytarabine induction regimen. She had a fever (temperature, 39.9 °C [103.8 °F]) and also was neutropenic.

Oval Brown Plaque on the Palm

The Diagnosis: Poroma

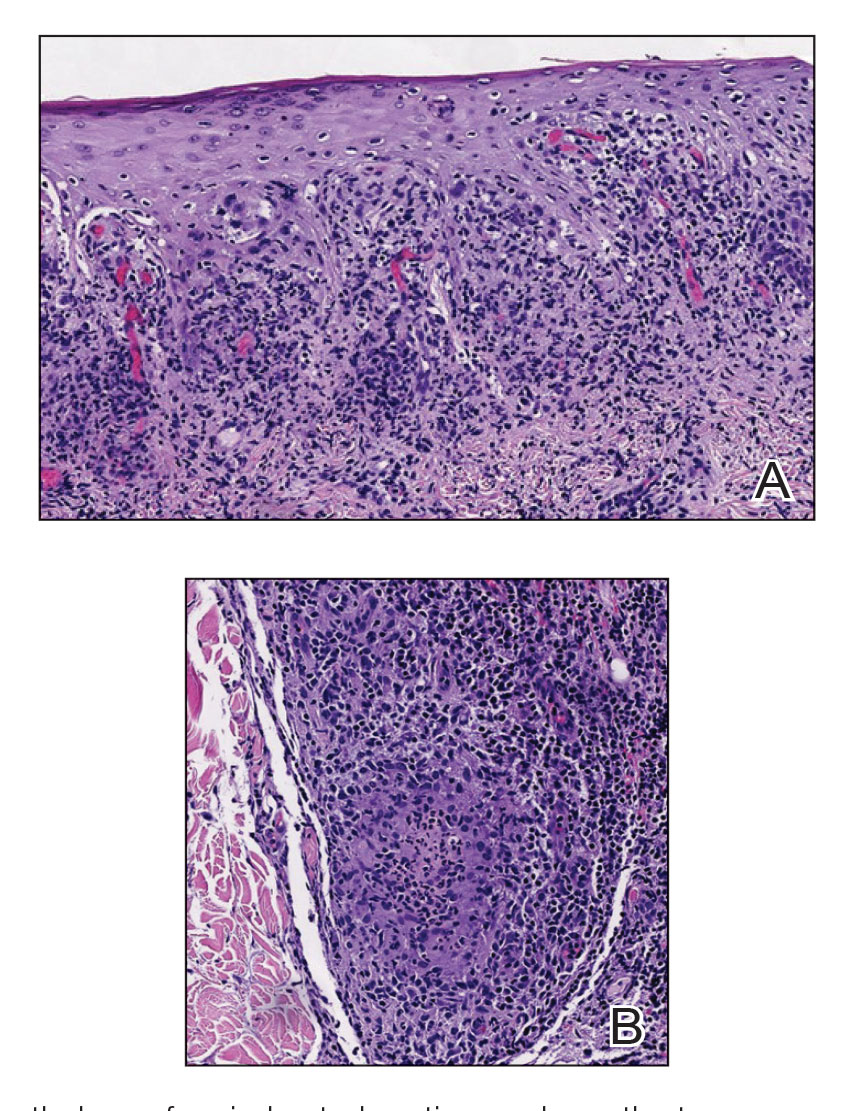

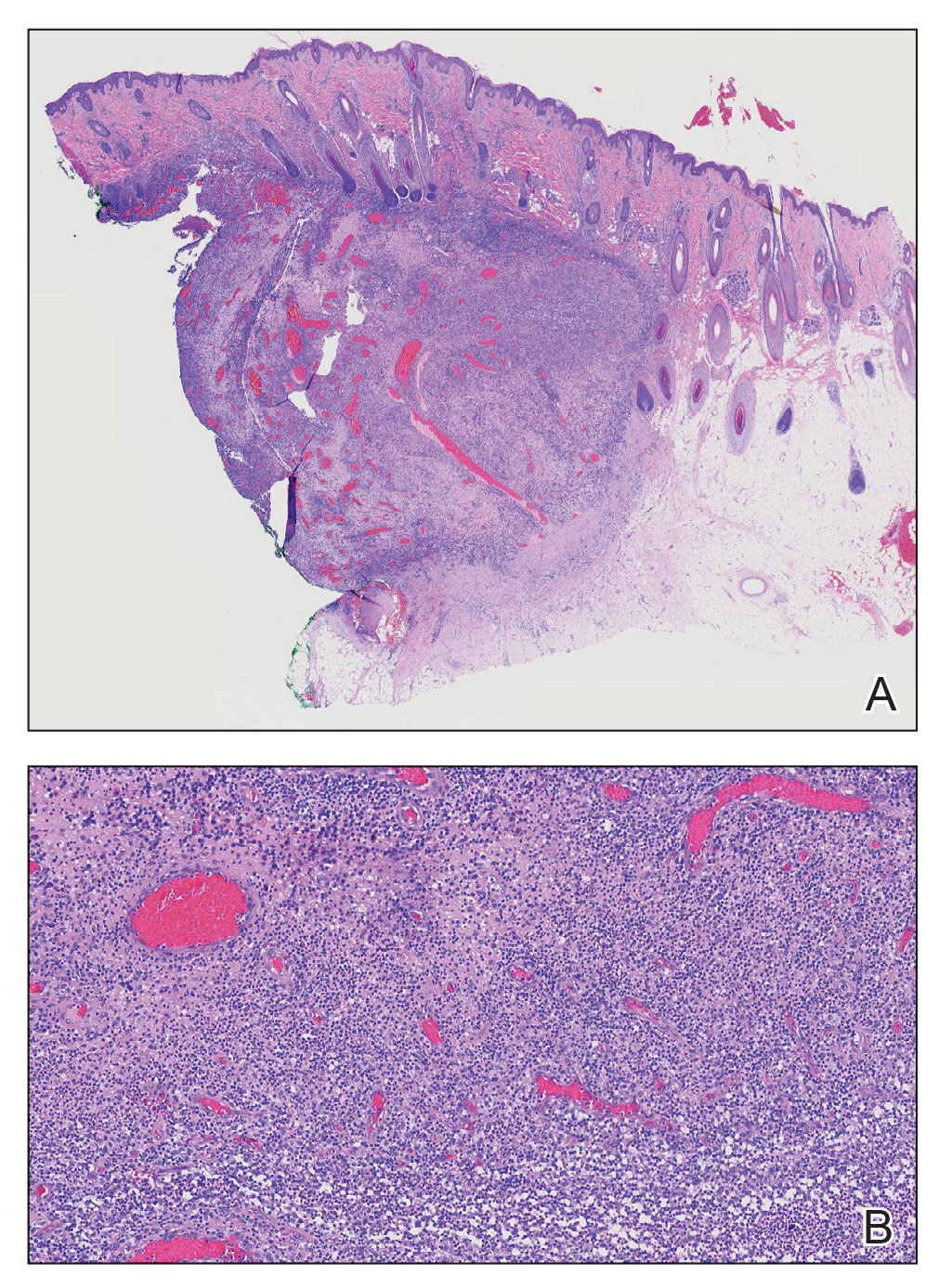

Histopathology showed an endophytic expansion of the epidermis by bland, uniform, basaloid epithelial cells with focal ductal differentiation and an abrupt transition with surrounding epidermal keratinocytes (Figure), consistent with a diagnosis of poroma. The patient elected to monitor the lesion rather than to have it excised.

Eccrine poroma, used interchangeably with the term poroma, is a rare benign adnexal tumor of the eccrine sweat glands resulting from proliferation of the acrosyringium.1,2 It often occurs on the palms or soles, though it also can arise anywhere sweat glands are present.1 Eccrine poromas often appear in middle-aged individuals as singular, well-circumscribed, red-brown papules or nodules.3 A characteristic feature is a shallow, cup-shaped depression within the larger papule or nodule.1

Because the condition is benign and often asymptomatic, it can be safely monitored for progression.1 However, if the lesion is symptomatic or located in a sensitive area, complete excision is curative.4 Eccrine poromas can recur, making close monitoring following excision important.5 The development of bleeding, itching, or pain in a previously asymptomatic lesion may indicate possible malignant transformation, which occurs in only 18% of cases.6

The differential diagnosis includes basal cell carcinoma, circumscribed acral hypokeratosis, Kaposi sarcoma, and pyogenic granuloma. Basal cell carcinoma is the most common type of skin cancer.7 In rare cases it has been shown to present on the palms or soles as a slowgrowing, reddish-pink papule or plaque with central ulceration. It typically is asymptomatic. Histopathology shows dermal nests of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading, stromal mucin, and peritumoral clefts. Treatment is surgical excision.7

Circumscribed acral hypokeratosis presents on the palms or soles as a solitary, shallow, well-defined lesion with a flat base and raised border.8 It often is red-pink in color and most frequently occurs in middle-aged women. Although the cause of the condition is unknown, it is thought to be the result of trauma or human papillomavirus infection.8 Biopsy results characteristically show hypokeratosis demarcated by a sharp and frayed cutoff from uninvolved acral skin with discrete hypogranulosis, dilated blood vessels in the papillary dermis, and slightly thickened collagen fibers in the reticular dermis.9 Surgical excision is a potential treatment option, as topical corticosteroids, retinoids, and calcipotriene have not been shown to be effective; spontaneous resolution has been reported.8

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm that is associated with human herpesvirus 8 infection.10 It typically presents on mucocutaneous sites and the lower extremities. Palmar involvement has been reported in rare cases, occurring as a solitary, well-demarcated, violaceous macule or patch that may be painful.10-12 Characteristic histopathologic features include a proliferation in the dermis of slitlike vascular spaces and spindle cell proliferation.13 Treatment options include cryosurgery; pulsed dye laser; and topical, intralesional, or systemic chemotherapy agents, depending on the stage of the patient’s disease. Antiretroviral therapy is indicated for patients with Kaposi sarcoma secondary to AIDS.14

Pyogenic granuloma presents as a solitary red-brown or bluish-black papule or nodule that bleeds easily when manipulated.15 It commonly occurs following trauma, typically on the fingers, feet, and lips.6 Although benign, potential complications include ulceration and blood loss. Pyogenic granulomas can be treated via curettage and cautery, excision, cryosurgery, or pulsed dye laser.15

- Wankhade V, Singh R, Sadhwani V, et al. Eccrine poroma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:304-305.

- Yorulmaz A, Aksoy GG, Ozhamam EU. A growing mass under the nail: subungual eccrine poroma. Skin Appendage Disord. 2020;6:254-257.

- Wang Y, Liu M, Zheng Y, et al. Eccrine poroma presented as spindleshaped plaque: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:E25971. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000025971

- Sharma M, Singh M, Gupta K, et al. Eccrine poroma of the eyelid. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68:2522.

- Rasool MN, Hawary MB. Benign eccrine poroma in the palm of the hand. Ann Saudi Med. 2004;24:46-47.

- Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms [published online April 2, 2014]. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1053-1061. doi:10.1111/ijd.12448

- López-Sánchez C, Ferguson P, Collgros H. Basal cell carcinoma of the palm: an unusual presentation of a common tumour [published online August 6, 2019]. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:69-70. doi:10.1111/ajd.13129

- Berk DR, Böer A, Bauschard FD, et al. Circumscribed acral hypokeratosis [published online April 6, 2007]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:292-296. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.02.022

- Majluf-Cáceres P, Vera-Kellet C, González-Bombardiere S. New dermoscopic keys for circumscribed acral hypokeratosis: report of four cases. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2021;11:E2021010. doi:10.5826/dpc.1102a10

- Simonart T, De Dobbeleer G, Stallenberg B. Classic Kaposi’s sarcoma of the palm in a metallurgist: role of iron filings in its development? Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:1061-1063. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05331.x

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294. doi:10.5858/arpa.2012-0101-RS

- Al Zolibani AA, Al Robaee AA. Primary palmoplantar Kaposi’s sarcoma: an unusual presentation. Skinmed. 2006;5:248-249. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2006.04662.x

- Cesarman E, Damania B, Krown SE, et al. Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:9. doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0060-9

- Etemad SA, Dewan AK. Kaposi sarcoma updates [published online July 10, 2019]. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:505-517. doi:10.1016/j. det.2019.05.008

- Murthy SC, Nagaraj A. Pyogenic granuloma. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:855. doi:10.1007/s13312-012-0184-4

The Diagnosis: Poroma

Histopathology showed an endophytic expansion of the epidermis by bland, uniform, basaloid epithelial cells with focal ductal differentiation and an abrupt transition with surrounding epidermal keratinocytes (Figure), consistent with a diagnosis of poroma. The patient elected to monitor the lesion rather than to have it excised.

Eccrine poroma, used interchangeably with the term poroma, is a rare benign adnexal tumor of the eccrine sweat glands resulting from proliferation of the acrosyringium.1,2 It often occurs on the palms or soles, though it also can arise anywhere sweat glands are present.1 Eccrine poromas often appear in middle-aged individuals as singular, well-circumscribed, red-brown papules or nodules.3 A characteristic feature is a shallow, cup-shaped depression within the larger papule or nodule.1

Because the condition is benign and often asymptomatic, it can be safely monitored for progression.1 However, if the lesion is symptomatic or located in a sensitive area, complete excision is curative.4 Eccrine poromas can recur, making close monitoring following excision important.5 The development of bleeding, itching, or pain in a previously asymptomatic lesion may indicate possible malignant transformation, which occurs in only 18% of cases.6

The differential diagnosis includes basal cell carcinoma, circumscribed acral hypokeratosis, Kaposi sarcoma, and pyogenic granuloma. Basal cell carcinoma is the most common type of skin cancer.7 In rare cases it has been shown to present on the palms or soles as a slowgrowing, reddish-pink papule or plaque with central ulceration. It typically is asymptomatic. Histopathology shows dermal nests of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading, stromal mucin, and peritumoral clefts. Treatment is surgical excision.7

Circumscribed acral hypokeratosis presents on the palms or soles as a solitary, shallow, well-defined lesion with a flat base and raised border.8 It often is red-pink in color and most frequently occurs in middle-aged women. Although the cause of the condition is unknown, it is thought to be the result of trauma or human papillomavirus infection.8 Biopsy results characteristically show hypokeratosis demarcated by a sharp and frayed cutoff from uninvolved acral skin with discrete hypogranulosis, dilated blood vessels in the papillary dermis, and slightly thickened collagen fibers in the reticular dermis.9 Surgical excision is a potential treatment option, as topical corticosteroids, retinoids, and calcipotriene have not been shown to be effective; spontaneous resolution has been reported.8