User login

The light at the end of the tunnel: Reflecting on a 7-year training journey

Throughout my training, a common refrain from more senior colleagues was that training “goes by quickly.” At the risk of sounding cliché, and even after a 7-year journey spanning psychiatry and preventive medicine residencies as well as a consultation-liaison psychiatry fellowship, I agree without reservations that it does indeed go quickly. In the waning days of my training, reflection and nostalgia have become commonplace, as one might expect after such a meaningful pursuit. In sharing my reflections, I hope others progressing through training will also reflect on elements that added meaning to their experience and how they might improve the journey for future trainees.

Residency is a team sport

One realization that quickly struck me was that residency is a team sport, and finding supportive communities is essential to survival. Other residents, colleagues, and mentors played integral roles in making my experience rewarding. Training might be considered a shared traumatic experience, but having peers to commiserate with at each step has been among its greatest rewards. Residency automatically provided a cohort of colleagues who shared and validated my experiences. Additionally, having mentors who have been through it themselves and find ways to improve the training experience made mine superlative. Mentors assisted me in tailoring my training and developing interests that I could integrate into my future practice. The interpersonal connections I made were critical in helping me survive and thrive during training.

See one, do one, teach one

Residency and fellowship programs might be considered “see one, do one, teach one”1 at large scale. Since their inception, these programs—designed to develop junior physicians—have been inherently educational in nature. The structure is elegant, allowing trainees to continue learning while incrementally gaining more autonomy and teaching responsibility.2 Naively, I did not understand that implicit within my education was an expectation to become an educator and hone my teaching skills. Initially, being a newly minted resident receiving brand-new 3rd-year medical students charged me with apprehension. Thoughts I internalized, such as “these students probably know more than me” or “how can I be responsible for patients and students simultaneously,” may have resulted from a paucity of instruction about teaching available during medical school.3,4 I quickly found, though, that teaching was among the most rewarding facets of training. Helping other learners grow became one of my passions and added to my experience.

Iron sharpens iron

Although my experience was enjoyable, I would be remiss without also considering accompanying trials and tribulations. Seemingly interminable night shifts, sleep deprivation, lack of autonomy, and system inefficiencies frustrated me. Eventually, these frustrations seemed less bothersome. These challenges likely had not vanished with time, but perhaps my capacity to tolerate distress improved—likely corresponding with increasing skill and confidence. These challenges allowed me to hone my clinical decision-making abilities while under duress. My struggles and frustrations were not unique but perhaps lessons themselves.

Residency is not meant to be easy. The crucible of residency taught me that I had resilience to draw upon during challenging times. “Iron sharpens iron,” as the adage goes, and I believe adversity ultimately helped me become a better psychiatrist.

Self-reflection is part of completing training

Reminders that my journey is at an end are everywhere. Seeing notes written by past residents or fellows reminds me that soon I too will merely be a name in the chart to future trainees. Perhaps this line of thought is unfair, reducing my training experience to notes I signed—whereas my training experience was defined by connections made with colleagues and mentors, opportunities to teach junior learners, and confidence gained by overcoming adversity.

While becoming an attending psychiatrist fills me with trepidation, fear need not be an inherent aspect of new beginnings. Reflection has been a powerful practice, allowing me to realize what made my experience so meaningful, and that training is meant to be process-oriented rather than outcome-oriented. My reflection has underscored the realization that challenges are inherent in training, although not without purpose. I believe these struggles were meant to allow me to build meaningful relationships with colleagues, discover joy in teaching, and build resiliency.

The purpose of residencies and fellowships should be to produce clinically excellent psychiatrists, but I feel the journey was as important as the destination. Psychiatrists likely understand this better than most, as we were trained to thoughtfully approach the process of termination with patients.5 While the conclusion of our training journeys may seem unceremonious or anticlimactic, the termination process should include self-reflection on meaningful facets of training. For me, this reflection has itself been invaluable, while also making me hopeful to contribute value to the training journeys of future psychiatrists.

1. Gorrindo T, Beresin EV. Is “See one, do one, teach one” dead? Implications for the professionalization of medical educators in the twenty-first century. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):613-614. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0424-8

2. Wright Jr. JR, Schachar NS. Necessity is the mother of invention: William Stewart Halsted’s addiction and its influence on the development of residency training in North America. Can J Surg. 2020;63(1):E13-E19. doi:10.1503/cjs.003319

3. Dandavino M, Snell L, Wiseman J. Why medical students should learn how to teach. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):558-565. doi:10.1080/01421590701477449

4. Liu AC, Liu M, Dannaway J, et al. Are Australian medical students being taught to teach? Clin Teach. 2017;14(5):330-335. doi:10.1111/tct.12591

5. Vasquez MJ, Bingham RP, Barnett JE. Psychotherapy termination: clinical and ethical responsibilities. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(5):653-665. doi:10.1002/jclp.20478

Throughout my training, a common refrain from more senior colleagues was that training “goes by quickly.” At the risk of sounding cliché, and even after a 7-year journey spanning psychiatry and preventive medicine residencies as well as a consultation-liaison psychiatry fellowship, I agree without reservations that it does indeed go quickly. In the waning days of my training, reflection and nostalgia have become commonplace, as one might expect after such a meaningful pursuit. In sharing my reflections, I hope others progressing through training will also reflect on elements that added meaning to their experience and how they might improve the journey for future trainees.

Residency is a team sport

One realization that quickly struck me was that residency is a team sport, and finding supportive communities is essential to survival. Other residents, colleagues, and mentors played integral roles in making my experience rewarding. Training might be considered a shared traumatic experience, but having peers to commiserate with at each step has been among its greatest rewards. Residency automatically provided a cohort of colleagues who shared and validated my experiences. Additionally, having mentors who have been through it themselves and find ways to improve the training experience made mine superlative. Mentors assisted me in tailoring my training and developing interests that I could integrate into my future practice. The interpersonal connections I made were critical in helping me survive and thrive during training.

See one, do one, teach one

Residency and fellowship programs might be considered “see one, do one, teach one”1 at large scale. Since their inception, these programs—designed to develop junior physicians—have been inherently educational in nature. The structure is elegant, allowing trainees to continue learning while incrementally gaining more autonomy and teaching responsibility.2 Naively, I did not understand that implicit within my education was an expectation to become an educator and hone my teaching skills. Initially, being a newly minted resident receiving brand-new 3rd-year medical students charged me with apprehension. Thoughts I internalized, such as “these students probably know more than me” or “how can I be responsible for patients and students simultaneously,” may have resulted from a paucity of instruction about teaching available during medical school.3,4 I quickly found, though, that teaching was among the most rewarding facets of training. Helping other learners grow became one of my passions and added to my experience.

Iron sharpens iron

Although my experience was enjoyable, I would be remiss without also considering accompanying trials and tribulations. Seemingly interminable night shifts, sleep deprivation, lack of autonomy, and system inefficiencies frustrated me. Eventually, these frustrations seemed less bothersome. These challenges likely had not vanished with time, but perhaps my capacity to tolerate distress improved—likely corresponding with increasing skill and confidence. These challenges allowed me to hone my clinical decision-making abilities while under duress. My struggles and frustrations were not unique but perhaps lessons themselves.

Residency is not meant to be easy. The crucible of residency taught me that I had resilience to draw upon during challenging times. “Iron sharpens iron,” as the adage goes, and I believe adversity ultimately helped me become a better psychiatrist.

Self-reflection is part of completing training

Reminders that my journey is at an end are everywhere. Seeing notes written by past residents or fellows reminds me that soon I too will merely be a name in the chart to future trainees. Perhaps this line of thought is unfair, reducing my training experience to notes I signed—whereas my training experience was defined by connections made with colleagues and mentors, opportunities to teach junior learners, and confidence gained by overcoming adversity.

While becoming an attending psychiatrist fills me with trepidation, fear need not be an inherent aspect of new beginnings. Reflection has been a powerful practice, allowing me to realize what made my experience so meaningful, and that training is meant to be process-oriented rather than outcome-oriented. My reflection has underscored the realization that challenges are inherent in training, although not without purpose. I believe these struggles were meant to allow me to build meaningful relationships with colleagues, discover joy in teaching, and build resiliency.

The purpose of residencies and fellowships should be to produce clinically excellent psychiatrists, but I feel the journey was as important as the destination. Psychiatrists likely understand this better than most, as we were trained to thoughtfully approach the process of termination with patients.5 While the conclusion of our training journeys may seem unceremonious or anticlimactic, the termination process should include self-reflection on meaningful facets of training. For me, this reflection has itself been invaluable, while also making me hopeful to contribute value to the training journeys of future psychiatrists.

Throughout my training, a common refrain from more senior colleagues was that training “goes by quickly.” At the risk of sounding cliché, and even after a 7-year journey spanning psychiatry and preventive medicine residencies as well as a consultation-liaison psychiatry fellowship, I agree without reservations that it does indeed go quickly. In the waning days of my training, reflection and nostalgia have become commonplace, as one might expect after such a meaningful pursuit. In sharing my reflections, I hope others progressing through training will also reflect on elements that added meaning to their experience and how they might improve the journey for future trainees.

Residency is a team sport

One realization that quickly struck me was that residency is a team sport, and finding supportive communities is essential to survival. Other residents, colleagues, and mentors played integral roles in making my experience rewarding. Training might be considered a shared traumatic experience, but having peers to commiserate with at each step has been among its greatest rewards. Residency automatically provided a cohort of colleagues who shared and validated my experiences. Additionally, having mentors who have been through it themselves and find ways to improve the training experience made mine superlative. Mentors assisted me in tailoring my training and developing interests that I could integrate into my future practice. The interpersonal connections I made were critical in helping me survive and thrive during training.

See one, do one, teach one

Residency and fellowship programs might be considered “see one, do one, teach one”1 at large scale. Since their inception, these programs—designed to develop junior physicians—have been inherently educational in nature. The structure is elegant, allowing trainees to continue learning while incrementally gaining more autonomy and teaching responsibility.2 Naively, I did not understand that implicit within my education was an expectation to become an educator and hone my teaching skills. Initially, being a newly minted resident receiving brand-new 3rd-year medical students charged me with apprehension. Thoughts I internalized, such as “these students probably know more than me” or “how can I be responsible for patients and students simultaneously,” may have resulted from a paucity of instruction about teaching available during medical school.3,4 I quickly found, though, that teaching was among the most rewarding facets of training. Helping other learners grow became one of my passions and added to my experience.

Iron sharpens iron

Although my experience was enjoyable, I would be remiss without also considering accompanying trials and tribulations. Seemingly interminable night shifts, sleep deprivation, lack of autonomy, and system inefficiencies frustrated me. Eventually, these frustrations seemed less bothersome. These challenges likely had not vanished with time, but perhaps my capacity to tolerate distress improved—likely corresponding with increasing skill and confidence. These challenges allowed me to hone my clinical decision-making abilities while under duress. My struggles and frustrations were not unique but perhaps lessons themselves.

Residency is not meant to be easy. The crucible of residency taught me that I had resilience to draw upon during challenging times. “Iron sharpens iron,” as the adage goes, and I believe adversity ultimately helped me become a better psychiatrist.

Self-reflection is part of completing training

Reminders that my journey is at an end are everywhere. Seeing notes written by past residents or fellows reminds me that soon I too will merely be a name in the chart to future trainees. Perhaps this line of thought is unfair, reducing my training experience to notes I signed—whereas my training experience was defined by connections made with colleagues and mentors, opportunities to teach junior learners, and confidence gained by overcoming adversity.

While becoming an attending psychiatrist fills me with trepidation, fear need not be an inherent aspect of new beginnings. Reflection has been a powerful practice, allowing me to realize what made my experience so meaningful, and that training is meant to be process-oriented rather than outcome-oriented. My reflection has underscored the realization that challenges are inherent in training, although not without purpose. I believe these struggles were meant to allow me to build meaningful relationships with colleagues, discover joy in teaching, and build resiliency.

The purpose of residencies and fellowships should be to produce clinically excellent psychiatrists, but I feel the journey was as important as the destination. Psychiatrists likely understand this better than most, as we were trained to thoughtfully approach the process of termination with patients.5 While the conclusion of our training journeys may seem unceremonious or anticlimactic, the termination process should include self-reflection on meaningful facets of training. For me, this reflection has itself been invaluable, while also making me hopeful to contribute value to the training journeys of future psychiatrists.

1. Gorrindo T, Beresin EV. Is “See one, do one, teach one” dead? Implications for the professionalization of medical educators in the twenty-first century. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):613-614. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0424-8

2. Wright Jr. JR, Schachar NS. Necessity is the mother of invention: William Stewart Halsted’s addiction and its influence on the development of residency training in North America. Can J Surg. 2020;63(1):E13-E19. doi:10.1503/cjs.003319

3. Dandavino M, Snell L, Wiseman J. Why medical students should learn how to teach. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):558-565. doi:10.1080/01421590701477449

4. Liu AC, Liu M, Dannaway J, et al. Are Australian medical students being taught to teach? Clin Teach. 2017;14(5):330-335. doi:10.1111/tct.12591

5. Vasquez MJ, Bingham RP, Barnett JE. Psychotherapy termination: clinical and ethical responsibilities. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(5):653-665. doi:10.1002/jclp.20478

1. Gorrindo T, Beresin EV. Is “See one, do one, teach one” dead? Implications for the professionalization of medical educators in the twenty-first century. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):613-614. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0424-8

2. Wright Jr. JR, Schachar NS. Necessity is the mother of invention: William Stewart Halsted’s addiction and its influence on the development of residency training in North America. Can J Surg. 2020;63(1):E13-E19. doi:10.1503/cjs.003319

3. Dandavino M, Snell L, Wiseman J. Why medical students should learn how to teach. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):558-565. doi:10.1080/01421590701477449

4. Liu AC, Liu M, Dannaway J, et al. Are Australian medical students being taught to teach? Clin Teach. 2017;14(5):330-335. doi:10.1111/tct.12591

5. Vasquez MJ, Bingham RP, Barnett JE. Psychotherapy termination: clinical and ethical responsibilities. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(5):653-665. doi:10.1002/jclp.20478

Younger doctors call for more attention to patients with disabilities

As an undergraduate student at Northeastern University in Boston, Meghan Chin spent her summers working for a day program in Rhode Island. Her charges were adults with various forms of intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD).

“I was very much a caretaker,” Ms. Chin, now 29, said. “It was everything from helping them get dressed in the morning to getting them to medical appointments.”

During one such visit Ms. Chin got a lesson about how health care looks from the viewpoint of someone with an IDD.

The patient was a woman in her 60s and she was having gastrointestinal issues; symptoms she could have articulated, if asked. “She was perfectly capable of telling a clinician where it hurt, how long she had experienced the problem, and what she had done or not done to alleviate it,” Ms. Chin said.

And of comprehending a response. But she was not given the opportunity.

“She would explain what was going on to the clinician,” Ms. Chin recalled. “And the clinician would turn to me and answer. It was this weird three-way conversation – as if she wasn’t even there in the room with us.”

Ms. Chin was incensed at the rude and disrespectful way the patient had been treated. But her charge didn’t seem upset or surprised. Just resigned. “Sadly, she had become used to this,” Ms. Chin said.

For the young aide, however, the experience was searing. “It didn’t seem right to me,” Ms. Chin said. “That’s why, when I went to medical school, I knew I wanted to do better for this population.”

Serendipity led her to Georgetown University, Washington, where she met Kim Bullock, MD, one of the country’s leading advocates for improved health care delivery to those with IDDs.

Dr. Bullock, an associate professor of family medicine, seeks to create better training and educational opportunities for medical students who will likely encounter patients with these disabilities in their practices.

When Dr. Bullock heard Ms. Chin’s story about the patient being ignored, she was not surprised.

“This is not an unusual or unique situation,” said Dr. Bullock, who is also director of Georgetown’s community health division and a faculty member of the university’s Center for Excellence for Developmental Disabilities. “In fact, it’s quite common and is part of what spurred my own interest in educating pre-med and medical students about effective communication techniques, particularly when addressing neurodiverse patients.”

More than 13% of Americans, or roughly 44 million people, have some form of disability, according to the National Institute on Disability at the University of New Hampshire, a figure that does not include those who are institutionalized. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 17% of children aged 3-17 years have a developmental disability.

Even so, many physicians feel ill-prepared to care for disabled patients. A survey of physicians, published in the journal Health Affairs, found that some lacked the resources and training to properly care for patients with disabilities, or that they struggled to coordinate care for such individuals. Some said they did not know which types of accessible equipment, like adjustable tables and chair scales, were needed or how to use them. And some said they actively try to avoid treating patients with disabilities.

Don’t assume

The first step at correcting the problem, Dr. Bullock said, is to not assume that all IDD patients are incapable of communicating. By talking not to the patient but to their caregiver or spouse or child, as the clinician did with Ms. Chin years ago, “we are taking away their agency, their autonomy to speak for and about themselves.”

Change involves altering physicians’ attitudes and assumptions toward this population, through education. But how?

“The medical school curriculum is tight as it is,” Dr. Bullock acknowledged. “There’s a lot of things students have to learn. People wonder: where we will add this?”

Her suggestion: Incorporate IDD all along the way, through programs or experiences that will enable medical students to see such patients “not as something separate, but as people that have special needs just as other populations have.”

Case in point: Operation House Call, a program in Massachusetts designed to support young health care professionals, by building “confidence, interest, and sensitivity” toward individuals with IDD.

Eight medical and allied health schools, including those at Harvard Medical School and Yale School of Nursing, participate in the program, the centerpiece of which is time spent by teams of medical students in the homes of families with neurodiverse members. “It’s transformational,” said Susan Feeney, DNP, NP-C, director of adult gerontology and family nurse practitioner programs at the graduate school of nursing at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester. “They spend a few hours at the homes of these families, have this interaction with them, and journal about their experiences.”

Dr. Feeney described as “transformational” the experience of the students after getting to know these families. “They all come back profoundly changed,” she told this news organization. “As a medical or health care professional, you meet people in an artificial environment of the clinic and hospital. Here, they become human, like you. It takes the stigma away.”

One area of medicine in which this is an exception is pediatrics, where interaction with children with IDD and their families is common – and close. “They’re going to be much more attuned to this,” Dr. Feeney said. “The problem is primary care or internal medicine. Once these children get into their mid and later 20s, and they need a practitioner to talk to about adult concerns.”

And with adulthood come other medical needs, as the physical demands of age fall no less heavily on individuals with IDDs than those without. For example: “Neurodiverse people get pregnant,” Dr. Bullock said. They also can get heart disease as they age; or require the care of a rheumatologist, a neurologist, an orthopedic surgeon, or any other medical specialty.

Generation gap

Fortunately, the next generation of physicians may be more open to this more inclusionary approach toward a widely misunderstood population.

Like Ms. Chin, Sarah Bdeir had experience with this population prior to beginning her training in medicine. She had volunteered at a school for people with IDD.

“It was one of the best experiences I’ve ever had,” Ms. Bdeir, now 23 and a first-year medical student at Wayne State University, Detroit, said. She found that the neurodiverse individuals she worked with had as many abilities as disabilities. “They are capable of learning, but they do it differently,” she said. “You have to adjust to the way they learn. And you have to step out of your own box.”

Ms. Bdeir also heard about Dr. Bullock’s work and is assisting her in a research project on how to better improve nutritional education for people with IDDs. And although she said it may take time for curriculum boards at medical schools to integrate this kind of training into their programs, she believes they will, in part because the rising cohort of medical students today have an eagerness to engage with and learn more about IDD patients.

As does Ms. Chin.

“When I talk to my peers about this, they’re very receptive,” Ms. Chin said. “They want to learn how to better support the IDD population. And they will learn. I believe in my generation of future doctors.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As an undergraduate student at Northeastern University in Boston, Meghan Chin spent her summers working for a day program in Rhode Island. Her charges were adults with various forms of intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD).

“I was very much a caretaker,” Ms. Chin, now 29, said. “It was everything from helping them get dressed in the morning to getting them to medical appointments.”

During one such visit Ms. Chin got a lesson about how health care looks from the viewpoint of someone with an IDD.

The patient was a woman in her 60s and she was having gastrointestinal issues; symptoms she could have articulated, if asked. “She was perfectly capable of telling a clinician where it hurt, how long she had experienced the problem, and what she had done or not done to alleviate it,” Ms. Chin said.

And of comprehending a response. But she was not given the opportunity.

“She would explain what was going on to the clinician,” Ms. Chin recalled. “And the clinician would turn to me and answer. It was this weird three-way conversation – as if she wasn’t even there in the room with us.”

Ms. Chin was incensed at the rude and disrespectful way the patient had been treated. But her charge didn’t seem upset or surprised. Just resigned. “Sadly, she had become used to this,” Ms. Chin said.

For the young aide, however, the experience was searing. “It didn’t seem right to me,” Ms. Chin said. “That’s why, when I went to medical school, I knew I wanted to do better for this population.”

Serendipity led her to Georgetown University, Washington, where she met Kim Bullock, MD, one of the country’s leading advocates for improved health care delivery to those with IDDs.

Dr. Bullock, an associate professor of family medicine, seeks to create better training and educational opportunities for medical students who will likely encounter patients with these disabilities in their practices.

When Dr. Bullock heard Ms. Chin’s story about the patient being ignored, she was not surprised.

“This is not an unusual or unique situation,” said Dr. Bullock, who is also director of Georgetown’s community health division and a faculty member of the university’s Center for Excellence for Developmental Disabilities. “In fact, it’s quite common and is part of what spurred my own interest in educating pre-med and medical students about effective communication techniques, particularly when addressing neurodiverse patients.”

More than 13% of Americans, or roughly 44 million people, have some form of disability, according to the National Institute on Disability at the University of New Hampshire, a figure that does not include those who are institutionalized. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 17% of children aged 3-17 years have a developmental disability.

Even so, many physicians feel ill-prepared to care for disabled patients. A survey of physicians, published in the journal Health Affairs, found that some lacked the resources and training to properly care for patients with disabilities, or that they struggled to coordinate care for such individuals. Some said they did not know which types of accessible equipment, like adjustable tables and chair scales, were needed or how to use them. And some said they actively try to avoid treating patients with disabilities.

Don’t assume

The first step at correcting the problem, Dr. Bullock said, is to not assume that all IDD patients are incapable of communicating. By talking not to the patient but to their caregiver or spouse or child, as the clinician did with Ms. Chin years ago, “we are taking away their agency, their autonomy to speak for and about themselves.”

Change involves altering physicians’ attitudes and assumptions toward this population, through education. But how?

“The medical school curriculum is tight as it is,” Dr. Bullock acknowledged. “There’s a lot of things students have to learn. People wonder: where we will add this?”

Her suggestion: Incorporate IDD all along the way, through programs or experiences that will enable medical students to see such patients “not as something separate, but as people that have special needs just as other populations have.”

Case in point: Operation House Call, a program in Massachusetts designed to support young health care professionals, by building “confidence, interest, and sensitivity” toward individuals with IDD.

Eight medical and allied health schools, including those at Harvard Medical School and Yale School of Nursing, participate in the program, the centerpiece of which is time spent by teams of medical students in the homes of families with neurodiverse members. “It’s transformational,” said Susan Feeney, DNP, NP-C, director of adult gerontology and family nurse practitioner programs at the graduate school of nursing at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester. “They spend a few hours at the homes of these families, have this interaction with them, and journal about their experiences.”

Dr. Feeney described as “transformational” the experience of the students after getting to know these families. “They all come back profoundly changed,” she told this news organization. “As a medical or health care professional, you meet people in an artificial environment of the clinic and hospital. Here, they become human, like you. It takes the stigma away.”

One area of medicine in which this is an exception is pediatrics, where interaction with children with IDD and their families is common – and close. “They’re going to be much more attuned to this,” Dr. Feeney said. “The problem is primary care or internal medicine. Once these children get into their mid and later 20s, and they need a practitioner to talk to about adult concerns.”

And with adulthood come other medical needs, as the physical demands of age fall no less heavily on individuals with IDDs than those without. For example: “Neurodiverse people get pregnant,” Dr. Bullock said. They also can get heart disease as they age; or require the care of a rheumatologist, a neurologist, an orthopedic surgeon, or any other medical specialty.

Generation gap

Fortunately, the next generation of physicians may be more open to this more inclusionary approach toward a widely misunderstood population.

Like Ms. Chin, Sarah Bdeir had experience with this population prior to beginning her training in medicine. She had volunteered at a school for people with IDD.

“It was one of the best experiences I’ve ever had,” Ms. Bdeir, now 23 and a first-year medical student at Wayne State University, Detroit, said. She found that the neurodiverse individuals she worked with had as many abilities as disabilities. “They are capable of learning, but they do it differently,” she said. “You have to adjust to the way they learn. And you have to step out of your own box.”

Ms. Bdeir also heard about Dr. Bullock’s work and is assisting her in a research project on how to better improve nutritional education for people with IDDs. And although she said it may take time for curriculum boards at medical schools to integrate this kind of training into their programs, she believes they will, in part because the rising cohort of medical students today have an eagerness to engage with and learn more about IDD patients.

As does Ms. Chin.

“When I talk to my peers about this, they’re very receptive,” Ms. Chin said. “They want to learn how to better support the IDD population. And they will learn. I believe in my generation of future doctors.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As an undergraduate student at Northeastern University in Boston, Meghan Chin spent her summers working for a day program in Rhode Island. Her charges were adults with various forms of intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD).

“I was very much a caretaker,” Ms. Chin, now 29, said. “It was everything from helping them get dressed in the morning to getting them to medical appointments.”

During one such visit Ms. Chin got a lesson about how health care looks from the viewpoint of someone with an IDD.

The patient was a woman in her 60s and she was having gastrointestinal issues; symptoms she could have articulated, if asked. “She was perfectly capable of telling a clinician where it hurt, how long she had experienced the problem, and what she had done or not done to alleviate it,” Ms. Chin said.

And of comprehending a response. But she was not given the opportunity.

“She would explain what was going on to the clinician,” Ms. Chin recalled. “And the clinician would turn to me and answer. It was this weird three-way conversation – as if she wasn’t even there in the room with us.”

Ms. Chin was incensed at the rude and disrespectful way the patient had been treated. But her charge didn’t seem upset or surprised. Just resigned. “Sadly, she had become used to this,” Ms. Chin said.

For the young aide, however, the experience was searing. “It didn’t seem right to me,” Ms. Chin said. “That’s why, when I went to medical school, I knew I wanted to do better for this population.”

Serendipity led her to Georgetown University, Washington, where she met Kim Bullock, MD, one of the country’s leading advocates for improved health care delivery to those with IDDs.

Dr. Bullock, an associate professor of family medicine, seeks to create better training and educational opportunities for medical students who will likely encounter patients with these disabilities in their practices.

When Dr. Bullock heard Ms. Chin’s story about the patient being ignored, she was not surprised.

“This is not an unusual or unique situation,” said Dr. Bullock, who is also director of Georgetown’s community health division and a faculty member of the university’s Center for Excellence for Developmental Disabilities. “In fact, it’s quite common and is part of what spurred my own interest in educating pre-med and medical students about effective communication techniques, particularly when addressing neurodiverse patients.”

More than 13% of Americans, or roughly 44 million people, have some form of disability, according to the National Institute on Disability at the University of New Hampshire, a figure that does not include those who are institutionalized. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 17% of children aged 3-17 years have a developmental disability.

Even so, many physicians feel ill-prepared to care for disabled patients. A survey of physicians, published in the journal Health Affairs, found that some lacked the resources and training to properly care for patients with disabilities, or that they struggled to coordinate care for such individuals. Some said they did not know which types of accessible equipment, like adjustable tables and chair scales, were needed or how to use them. And some said they actively try to avoid treating patients with disabilities.

Don’t assume

The first step at correcting the problem, Dr. Bullock said, is to not assume that all IDD patients are incapable of communicating. By talking not to the patient but to their caregiver or spouse or child, as the clinician did with Ms. Chin years ago, “we are taking away their agency, their autonomy to speak for and about themselves.”

Change involves altering physicians’ attitudes and assumptions toward this population, through education. But how?

“The medical school curriculum is tight as it is,” Dr. Bullock acknowledged. “There’s a lot of things students have to learn. People wonder: where we will add this?”

Her suggestion: Incorporate IDD all along the way, through programs or experiences that will enable medical students to see such patients “not as something separate, but as people that have special needs just as other populations have.”

Case in point: Operation House Call, a program in Massachusetts designed to support young health care professionals, by building “confidence, interest, and sensitivity” toward individuals with IDD.

Eight medical and allied health schools, including those at Harvard Medical School and Yale School of Nursing, participate in the program, the centerpiece of which is time spent by teams of medical students in the homes of families with neurodiverse members. “It’s transformational,” said Susan Feeney, DNP, NP-C, director of adult gerontology and family nurse practitioner programs at the graduate school of nursing at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester. “They spend a few hours at the homes of these families, have this interaction with them, and journal about their experiences.”

Dr. Feeney described as “transformational” the experience of the students after getting to know these families. “They all come back profoundly changed,” she told this news organization. “As a medical or health care professional, you meet people in an artificial environment of the clinic and hospital. Here, they become human, like you. It takes the stigma away.”

One area of medicine in which this is an exception is pediatrics, where interaction with children with IDD and their families is common – and close. “They’re going to be much more attuned to this,” Dr. Feeney said. “The problem is primary care or internal medicine. Once these children get into their mid and later 20s, and they need a practitioner to talk to about adult concerns.”

And with adulthood come other medical needs, as the physical demands of age fall no less heavily on individuals with IDDs than those without. For example: “Neurodiverse people get pregnant,” Dr. Bullock said. They also can get heart disease as they age; or require the care of a rheumatologist, a neurologist, an orthopedic surgeon, or any other medical specialty.

Generation gap

Fortunately, the next generation of physicians may be more open to this more inclusionary approach toward a widely misunderstood population.

Like Ms. Chin, Sarah Bdeir had experience with this population prior to beginning her training in medicine. She had volunteered at a school for people with IDD.

“It was one of the best experiences I’ve ever had,” Ms. Bdeir, now 23 and a first-year medical student at Wayne State University, Detroit, said. She found that the neurodiverse individuals she worked with had as many abilities as disabilities. “They are capable of learning, but they do it differently,” she said. “You have to adjust to the way they learn. And you have to step out of your own box.”

Ms. Bdeir also heard about Dr. Bullock’s work and is assisting her in a research project on how to better improve nutritional education for people with IDDs. And although she said it may take time for curriculum boards at medical schools to integrate this kind of training into their programs, she believes they will, in part because the rising cohort of medical students today have an eagerness to engage with and learn more about IDD patients.

As does Ms. Chin.

“When I talk to my peers about this, they’re very receptive,” Ms. Chin said. “They want to learn how to better support the IDD population. And they will learn. I believe in my generation of future doctors.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transitioning From an Intern to a Dermatology Resident

The transition from medical school to residency is a rewarding milestone but involves a steep learning curve wrought with new responsibilities, new colleagues, and a new schedule, often all within a new setting. This transition period has been a longstanding focus of graduate medical education research, and a recent study identified 6 key areas that residency programs need to address to better facilitate this transition: (1) a sense of community within the residency program, (2) relocation resources, (3) residency preparation courses in medical school, (4) readiness to address racism and bias, (5) connecting with peers, and (6) open communication with program leadership.1 There is considerable interest in ensuring that this transition is smooth for all graduates, as nearly all US medical schools feature some variety of a residency preparation course during the fourth year of medical school, which, alongside the subinternships, serves to better prepare their graduates for the healthcare workforce.2

What about the transition from intern to dermatology resident? Near the end of intern year, my categorical medicine colleagues experienced a crescendo of responsibilities, all in preparation for junior year. The senior medicine residents, themselves having previously experienced the graduated responsibilities, knew to ease their grip on the reins and provide the late spring interns an opportunity to lead rounds or run a code. This was not the case for the preliminary interns for whom there was no preview available for what was to come; little guidance exists on how to best transform from a preliminary or transitional postgraduate year (PGY) 1 to a dermatology PGY-2. A survey of 44 dermatology residents and 33 dermatology program directors found electives such as rheumatology, infectious diseases, and allergy and immunology to be helpful for this transition, and residents most often cited friendly and supportive senior and fellow residents as the factor that eased their transition to PGY-2.3 Notably, less than half of the residents (40%) surveyed stated that team-building exercises and dedicated time to meet colleagues were helpful for this transition. They identified studying principles of dermatologic disease, learning new clinical duties, and adjusting to new coworkers and supervisors as the greatest work-related stressors during entry to PGY-2.3

My transition from intern year to dermatology was shrouded in uncertainty, and I was fortunate to have supportive seniors and co-residents to ease the process. There is much about starting dermatology residency that cannot be prepared for by reading a book, and a natural metamorphosis into the new role is hard to articulate. Still, the following are pieces of information I wish I knew as a graduating intern, which I hope will prove useful for those graduating to their PGY-2 dermatology year.

The Pace of Outpatient Dermatology

If the preliminary or transitional year did not have an ambulatory component, the switch from wards to clinic can be jarring. An outpatient encounter can be as short as 10 to 15 minutes, necessitating an efficient interview and examination to avoid a backup of patients. Unlike a hospital admission where the history of present illness can expound on multiple concerns and organ systems, the general dermatology visit must focus on the chief concern, with priority given to the clinical examination of the skin. For total-body skin examinations, a formulaic approach to assessing all areas of the body, with fluent transitions and minimal repositioning of the patient, is critical for patient comfort and to save time. Of course, accuracy and thoroughness are paramount, but the constant mindfulness of time and efficiency is uniquely emphasized in the outpatient setting.

Continuity of Care

On the wards, patients are admitted with an acute problem and discharged with the aim to prevent re-admission. However, in the dermatology clinic, the conditions encountered often are chronic, requiring repeated follow-ups that involve dosage tapers, laboratory monitoring, and trial and error. Unlike the rigid algorithm-based treatments utilized in the inpatient setting, the management of the same chronic disease can vary, as it is tailored to the patient based on their comorbidities and response. This longitudinal relationship with patients, whereby many disorders are managed rather than treated, stands in stark contrast to inpatient medicine, and learning to value symptom management rather than focusing on a cure is critical in a largely outpatient specialty such as dermatology.

Consulter to Consultant

Calling a consultation as an intern is challenging and requires succinct delivery of pertinent information while fearing pushback from the consultant. In a survey of 50 hospitalist attendings, only 11% responded that interns could be entrusted to call an effective consultation without supervision.4 When undertaking the role of a consultant, the goals should be to identify the team’s main question and to obtain key information necessary to formulate a differential diagnosis. The quality of the consultation will inevitably fluctuate; try to remember what it was like for you as a member of the primary team and remain patient and courteous during the exchange.5 In 1983, Goldman et al6 published a guideline on effective consultations that often is cited to this day, dubbed the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultations,” which consists of the following: (1) determine the question that is being asked, (2) establish the urgency of the consultation, (3) gather primary data, (4) communicate as briefly as appropriate, (5) make specific recommendations, (6) provide contingency plans, (7) understand your own role in the process, (8) offer educational information, (9) communicate recommendations directly to the requesting physician, and (10) provide appropriate follow-up.

Consider Your Future

Frequently reflect on what you most enjoy about your job. Although it can be easy to passively engage with intern year as a mere stepping-stone to dermatology residency, the years in PGY-2 and onward require active introspection to find a future niche. What made you gravitate to the specialty of dermatology? Try to identify your predilections for dermatopathology, pediatric dermatology, dermatologic surgery, cosmetic dermatology, and academia. Be consistently cognizant of your life after residency, as some fellowships such as dermatopathology require applications to be submitted at the conclusion of the PGY-2 year. Seek out faculty mentors or alumni who are walking a path similar to the one you want to embark on, as the next stop after graduation may be your forever job.

Depth, Not Breadth

The practice of medicine changes when narrowing the focus to one organ system. In both medical school and intern year, my study habits and history-taking of patients cast a wide net across multiple organ systems, aiming to know just enough about any one specialty to address all chief concerns and to know when it was appropriate to consult a specialist. This paradigm inevitably shifts in dermatology residency, as residents are tasked with memorizing the endless number of diagnoses of the skin alone, comprehending the many shades of “erythematous,” including pink, salmon, red, and purple. Both on the wards and in clinics, I had to grow comfortable with telling patients that I did not have an answer for many of their nondermatologic concerns and directing them to the right specialist. As medicine continues trending to specialization, subspecialization, and sub-subspecialization, the scope of any given physician likely will continue to narrow,7 as evidenced by specialty clinics within dermatology such as those focusing on hair loss or immunobullous disease. In this health care system, it is imperative to remember that you are only one physician within a team of care providers—understand your own role in the process and become comfortable with not having the answer to all the questions.

Final Thoughts

In a study of 44 dermatology residents, 35 (83%) indicated zero to less than 1 hour per week of independent preparation for dermatology residency during PGY-1.3 Although the usefulness of preparing is debatable, this figure likely reflects the absence of any insight on how to best prepare for the transition. Recognizing the many contrasts between internal medicine and dermatology and embracing the changes will enable a seamless promotion from a medicine PGY-1 to a dermatology PGY-2.

- Staples H, Frank S, Mullen M, et al. Improving the medical school to residency transition: narrative experiences from first-year residents.J Surg Educ. 2022;S1931-7204(22)00146-5. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2022.06.001

- Heidemann LA, Walford E, Mack J, et al. Is there a role for internal medicine residency preparation courses in the fourth year curriculum? a single-center experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:2048-2050.

- Hopkins C, Jalali O, Guffey D, et al. A survey of dermatology residents and program directors assessing the transition to dermatology residency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;34:59-62.

- Marcus CH, Winn AS, Sectish TC, et al. How much supervision is required is the beginning of intern year? Acad Pediatr. 2016;16:E3-E4.

- Bly RA, Bly EG. Consult courtesy. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:533-534.

- Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:1753-1755.

- Oren O, Gersh BJ, Bhatt DL. On the pearls and perils of sub-subspecialization. Am J Med. 2020;133:158-159.

The transition from medical school to residency is a rewarding milestone but involves a steep learning curve wrought with new responsibilities, new colleagues, and a new schedule, often all within a new setting. This transition period has been a longstanding focus of graduate medical education research, and a recent study identified 6 key areas that residency programs need to address to better facilitate this transition: (1) a sense of community within the residency program, (2) relocation resources, (3) residency preparation courses in medical school, (4) readiness to address racism and bias, (5) connecting with peers, and (6) open communication with program leadership.1 There is considerable interest in ensuring that this transition is smooth for all graduates, as nearly all US medical schools feature some variety of a residency preparation course during the fourth year of medical school, which, alongside the subinternships, serves to better prepare their graduates for the healthcare workforce.2

What about the transition from intern to dermatology resident? Near the end of intern year, my categorical medicine colleagues experienced a crescendo of responsibilities, all in preparation for junior year. The senior medicine residents, themselves having previously experienced the graduated responsibilities, knew to ease their grip on the reins and provide the late spring interns an opportunity to lead rounds or run a code. This was not the case for the preliminary interns for whom there was no preview available for what was to come; little guidance exists on how to best transform from a preliminary or transitional postgraduate year (PGY) 1 to a dermatology PGY-2. A survey of 44 dermatology residents and 33 dermatology program directors found electives such as rheumatology, infectious diseases, and allergy and immunology to be helpful for this transition, and residents most often cited friendly and supportive senior and fellow residents as the factor that eased their transition to PGY-2.3 Notably, less than half of the residents (40%) surveyed stated that team-building exercises and dedicated time to meet colleagues were helpful for this transition. They identified studying principles of dermatologic disease, learning new clinical duties, and adjusting to new coworkers and supervisors as the greatest work-related stressors during entry to PGY-2.3

My transition from intern year to dermatology was shrouded in uncertainty, and I was fortunate to have supportive seniors and co-residents to ease the process. There is much about starting dermatology residency that cannot be prepared for by reading a book, and a natural metamorphosis into the new role is hard to articulate. Still, the following are pieces of information I wish I knew as a graduating intern, which I hope will prove useful for those graduating to their PGY-2 dermatology year.

The Pace of Outpatient Dermatology

If the preliminary or transitional year did not have an ambulatory component, the switch from wards to clinic can be jarring. An outpatient encounter can be as short as 10 to 15 minutes, necessitating an efficient interview and examination to avoid a backup of patients. Unlike a hospital admission where the history of present illness can expound on multiple concerns and organ systems, the general dermatology visit must focus on the chief concern, with priority given to the clinical examination of the skin. For total-body skin examinations, a formulaic approach to assessing all areas of the body, with fluent transitions and minimal repositioning of the patient, is critical for patient comfort and to save time. Of course, accuracy and thoroughness are paramount, but the constant mindfulness of time and efficiency is uniquely emphasized in the outpatient setting.

Continuity of Care

On the wards, patients are admitted with an acute problem and discharged with the aim to prevent re-admission. However, in the dermatology clinic, the conditions encountered often are chronic, requiring repeated follow-ups that involve dosage tapers, laboratory monitoring, and trial and error. Unlike the rigid algorithm-based treatments utilized in the inpatient setting, the management of the same chronic disease can vary, as it is tailored to the patient based on their comorbidities and response. This longitudinal relationship with patients, whereby many disorders are managed rather than treated, stands in stark contrast to inpatient medicine, and learning to value symptom management rather than focusing on a cure is critical in a largely outpatient specialty such as dermatology.

Consulter to Consultant

Calling a consultation as an intern is challenging and requires succinct delivery of pertinent information while fearing pushback from the consultant. In a survey of 50 hospitalist attendings, only 11% responded that interns could be entrusted to call an effective consultation without supervision.4 When undertaking the role of a consultant, the goals should be to identify the team’s main question and to obtain key information necessary to formulate a differential diagnosis. The quality of the consultation will inevitably fluctuate; try to remember what it was like for you as a member of the primary team and remain patient and courteous during the exchange.5 In 1983, Goldman et al6 published a guideline on effective consultations that often is cited to this day, dubbed the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultations,” which consists of the following: (1) determine the question that is being asked, (2) establish the urgency of the consultation, (3) gather primary data, (4) communicate as briefly as appropriate, (5) make specific recommendations, (6) provide contingency plans, (7) understand your own role in the process, (8) offer educational information, (9) communicate recommendations directly to the requesting physician, and (10) provide appropriate follow-up.

Consider Your Future

Frequently reflect on what you most enjoy about your job. Although it can be easy to passively engage with intern year as a mere stepping-stone to dermatology residency, the years in PGY-2 and onward require active introspection to find a future niche. What made you gravitate to the specialty of dermatology? Try to identify your predilections for dermatopathology, pediatric dermatology, dermatologic surgery, cosmetic dermatology, and academia. Be consistently cognizant of your life after residency, as some fellowships such as dermatopathology require applications to be submitted at the conclusion of the PGY-2 year. Seek out faculty mentors or alumni who are walking a path similar to the one you want to embark on, as the next stop after graduation may be your forever job.

Depth, Not Breadth

The practice of medicine changes when narrowing the focus to one organ system. In both medical school and intern year, my study habits and history-taking of patients cast a wide net across multiple organ systems, aiming to know just enough about any one specialty to address all chief concerns and to know when it was appropriate to consult a specialist. This paradigm inevitably shifts in dermatology residency, as residents are tasked with memorizing the endless number of diagnoses of the skin alone, comprehending the many shades of “erythematous,” including pink, salmon, red, and purple. Both on the wards and in clinics, I had to grow comfortable with telling patients that I did not have an answer for many of their nondermatologic concerns and directing them to the right specialist. As medicine continues trending to specialization, subspecialization, and sub-subspecialization, the scope of any given physician likely will continue to narrow,7 as evidenced by specialty clinics within dermatology such as those focusing on hair loss or immunobullous disease. In this health care system, it is imperative to remember that you are only one physician within a team of care providers—understand your own role in the process and become comfortable with not having the answer to all the questions.

Final Thoughts

In a study of 44 dermatology residents, 35 (83%) indicated zero to less than 1 hour per week of independent preparation for dermatology residency during PGY-1.3 Although the usefulness of preparing is debatable, this figure likely reflects the absence of any insight on how to best prepare for the transition. Recognizing the many contrasts between internal medicine and dermatology and embracing the changes will enable a seamless promotion from a medicine PGY-1 to a dermatology PGY-2.

The transition from medical school to residency is a rewarding milestone but involves a steep learning curve wrought with new responsibilities, new colleagues, and a new schedule, often all within a new setting. This transition period has been a longstanding focus of graduate medical education research, and a recent study identified 6 key areas that residency programs need to address to better facilitate this transition: (1) a sense of community within the residency program, (2) relocation resources, (3) residency preparation courses in medical school, (4) readiness to address racism and bias, (5) connecting with peers, and (6) open communication with program leadership.1 There is considerable interest in ensuring that this transition is smooth for all graduates, as nearly all US medical schools feature some variety of a residency preparation course during the fourth year of medical school, which, alongside the subinternships, serves to better prepare their graduates for the healthcare workforce.2

What about the transition from intern to dermatology resident? Near the end of intern year, my categorical medicine colleagues experienced a crescendo of responsibilities, all in preparation for junior year. The senior medicine residents, themselves having previously experienced the graduated responsibilities, knew to ease their grip on the reins and provide the late spring interns an opportunity to lead rounds or run a code. This was not the case for the preliminary interns for whom there was no preview available for what was to come; little guidance exists on how to best transform from a preliminary or transitional postgraduate year (PGY) 1 to a dermatology PGY-2. A survey of 44 dermatology residents and 33 dermatology program directors found electives such as rheumatology, infectious diseases, and allergy and immunology to be helpful for this transition, and residents most often cited friendly and supportive senior and fellow residents as the factor that eased their transition to PGY-2.3 Notably, less than half of the residents (40%) surveyed stated that team-building exercises and dedicated time to meet colleagues were helpful for this transition. They identified studying principles of dermatologic disease, learning new clinical duties, and adjusting to new coworkers and supervisors as the greatest work-related stressors during entry to PGY-2.3

My transition from intern year to dermatology was shrouded in uncertainty, and I was fortunate to have supportive seniors and co-residents to ease the process. There is much about starting dermatology residency that cannot be prepared for by reading a book, and a natural metamorphosis into the new role is hard to articulate. Still, the following are pieces of information I wish I knew as a graduating intern, which I hope will prove useful for those graduating to their PGY-2 dermatology year.

The Pace of Outpatient Dermatology

If the preliminary or transitional year did not have an ambulatory component, the switch from wards to clinic can be jarring. An outpatient encounter can be as short as 10 to 15 minutes, necessitating an efficient interview and examination to avoid a backup of patients. Unlike a hospital admission where the history of present illness can expound on multiple concerns and organ systems, the general dermatology visit must focus on the chief concern, with priority given to the clinical examination of the skin. For total-body skin examinations, a formulaic approach to assessing all areas of the body, with fluent transitions and minimal repositioning of the patient, is critical for patient comfort and to save time. Of course, accuracy and thoroughness are paramount, but the constant mindfulness of time and efficiency is uniquely emphasized in the outpatient setting.

Continuity of Care

On the wards, patients are admitted with an acute problem and discharged with the aim to prevent re-admission. However, in the dermatology clinic, the conditions encountered often are chronic, requiring repeated follow-ups that involve dosage tapers, laboratory monitoring, and trial and error. Unlike the rigid algorithm-based treatments utilized in the inpatient setting, the management of the same chronic disease can vary, as it is tailored to the patient based on their comorbidities and response. This longitudinal relationship with patients, whereby many disorders are managed rather than treated, stands in stark contrast to inpatient medicine, and learning to value symptom management rather than focusing on a cure is critical in a largely outpatient specialty such as dermatology.

Consulter to Consultant

Calling a consultation as an intern is challenging and requires succinct delivery of pertinent information while fearing pushback from the consultant. In a survey of 50 hospitalist attendings, only 11% responded that interns could be entrusted to call an effective consultation without supervision.4 When undertaking the role of a consultant, the goals should be to identify the team’s main question and to obtain key information necessary to formulate a differential diagnosis. The quality of the consultation will inevitably fluctuate; try to remember what it was like for you as a member of the primary team and remain patient and courteous during the exchange.5 In 1983, Goldman et al6 published a guideline on effective consultations that often is cited to this day, dubbed the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultations,” which consists of the following: (1) determine the question that is being asked, (2) establish the urgency of the consultation, (3) gather primary data, (4) communicate as briefly as appropriate, (5) make specific recommendations, (6) provide contingency plans, (7) understand your own role in the process, (8) offer educational information, (9) communicate recommendations directly to the requesting physician, and (10) provide appropriate follow-up.

Consider Your Future

Frequently reflect on what you most enjoy about your job. Although it can be easy to passively engage with intern year as a mere stepping-stone to dermatology residency, the years in PGY-2 and onward require active introspection to find a future niche. What made you gravitate to the specialty of dermatology? Try to identify your predilections for dermatopathology, pediatric dermatology, dermatologic surgery, cosmetic dermatology, and academia. Be consistently cognizant of your life after residency, as some fellowships such as dermatopathology require applications to be submitted at the conclusion of the PGY-2 year. Seek out faculty mentors or alumni who are walking a path similar to the one you want to embark on, as the next stop after graduation may be your forever job.

Depth, Not Breadth

The practice of medicine changes when narrowing the focus to one organ system. In both medical school and intern year, my study habits and history-taking of patients cast a wide net across multiple organ systems, aiming to know just enough about any one specialty to address all chief concerns and to know when it was appropriate to consult a specialist. This paradigm inevitably shifts in dermatology residency, as residents are tasked with memorizing the endless number of diagnoses of the skin alone, comprehending the many shades of “erythematous,” including pink, salmon, red, and purple. Both on the wards and in clinics, I had to grow comfortable with telling patients that I did not have an answer for many of their nondermatologic concerns and directing them to the right specialist. As medicine continues trending to specialization, subspecialization, and sub-subspecialization, the scope of any given physician likely will continue to narrow,7 as evidenced by specialty clinics within dermatology such as those focusing on hair loss or immunobullous disease. In this health care system, it is imperative to remember that you are only one physician within a team of care providers—understand your own role in the process and become comfortable with not having the answer to all the questions.

Final Thoughts

In a study of 44 dermatology residents, 35 (83%) indicated zero to less than 1 hour per week of independent preparation for dermatology residency during PGY-1.3 Although the usefulness of preparing is debatable, this figure likely reflects the absence of any insight on how to best prepare for the transition. Recognizing the many contrasts between internal medicine and dermatology and embracing the changes will enable a seamless promotion from a medicine PGY-1 to a dermatology PGY-2.

- Staples H, Frank S, Mullen M, et al. Improving the medical school to residency transition: narrative experiences from first-year residents.J Surg Educ. 2022;S1931-7204(22)00146-5. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2022.06.001

- Heidemann LA, Walford E, Mack J, et al. Is there a role for internal medicine residency preparation courses in the fourth year curriculum? a single-center experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:2048-2050.

- Hopkins C, Jalali O, Guffey D, et al. A survey of dermatology residents and program directors assessing the transition to dermatology residency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;34:59-62.

- Marcus CH, Winn AS, Sectish TC, et al. How much supervision is required is the beginning of intern year? Acad Pediatr. 2016;16:E3-E4.

- Bly RA, Bly EG. Consult courtesy. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:533-534.

- Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:1753-1755.

- Oren O, Gersh BJ, Bhatt DL. On the pearls and perils of sub-subspecialization. Am J Med. 2020;133:158-159.

- Staples H, Frank S, Mullen M, et al. Improving the medical school to residency transition: narrative experiences from first-year residents.J Surg Educ. 2022;S1931-7204(22)00146-5. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2022.06.001

- Heidemann LA, Walford E, Mack J, et al. Is there a role for internal medicine residency preparation courses in the fourth year curriculum? a single-center experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:2048-2050.

- Hopkins C, Jalali O, Guffey D, et al. A survey of dermatology residents and program directors assessing the transition to dermatology residency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;34:59-62.

- Marcus CH, Winn AS, Sectish TC, et al. How much supervision is required is the beginning of intern year? Acad Pediatr. 2016;16:E3-E4.

- Bly RA, Bly EG. Consult courtesy. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:533-534.

- Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:1753-1755.

- Oren O, Gersh BJ, Bhatt DL. On the pearls and perils of sub-subspecialization. Am J Med. 2020;133:158-159.

Resident Pearl

- There is surprisingly little information on what to expect when transitioning from intern year to dermatology residency. Recognizing the unique aspects of a largely outpatient specialty and embracing the role of a specialist will help facilitate this transition.

Learning Experiences in LGBT Health During Dermatology Residency

Approximately 4.5% of adults within the United States identify as members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) community.1 This is an umbrella term inclusive of all individuals identifying as nonheterosexual or noncisgender. Although the LGBT community has increasingly become more recognized and accepted by society over time, health care disparities persist and have been well documented in the literature.2-4 Dermatologists have the potential to greatly impact LGBT health, as many health concerns in this population are cutaneous, such as sun-protection behaviors, side effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy and gender-affirming procedures, and cutaneous manifestations of sexually transmitted infections.5-7

An education gap has been demonstrated in both medical students and resident physicians regarding LGBT health and cultural competency. In a large-scale, multi-institutional survey study published in 2015, approximately two-thirds of medical students rated their schools’ LGBT curriculum as fair, poor, or very poor.8 Additional studies have echoed these results and have demonstrated not only the need but the desire for additional training on LGBT issues in medical school.9-11 The Association of American Medical Colleges has begun implementing curricular and institutional changes to fulfill this need.12,13

The LGBT education gap has been shown to extend into residency training. Multiple studies performed within a variety of medical specialties have demonstrated that resident physicians receive insufficient training in LGBT health issues, lack comfort in caring for LGBT patients, and would benefit from dedicated curricula on these topics.14-18 Currently, the 2022 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) guidelines related to LGBT health are minimal and nonspecific.19

Ensuring that dermatology trainees are well equipped to manage these issues while providing culturally competent care to LGBT patients is paramount. However, research suggests that dedicated training on these topics likely is insufficient. A survey study of dermatology residency program directors (N=90) revealed that although 81% (72/89) viewed training in LGBT health as either very important or somewhat important, 46% (41/90) of programs did not dedicate any time to this content and 37% (33/90) only dedicated 1 to 2 hours per year.20

To further explore this potential education gap, we surveyed dermatology residents directly to better understand LGBT education within residency training, resident preparedness to care for LGBT patients, and outness/discrimination of LGBT-identifying residents. We believe this study should drive future research on the development and implementation of LGBT-specific curricula in dermatology training programs.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey study of dermatology residents in the United States was conducted. The study was deemed exempt from review by The Ohio State University (Columbus, Ohio) institutional review board. Survey responses were collected from October 7, 2020, to November 13, 2020. Qualtrics software was used to create the 20-question survey, which included a combination of categorical, dichotomous, and optional free-text questions related to patient demographics, LGBT training experiences, perceived areas of curriculum improvement, comfort level managing LGBT health issues, and personal experiences. Some questions were adapted from prior surveys.15,21 Validated survey tools used included the 2020 US Census to collect information regarding race and ethnicity, the Mohr and Fassinger Outness Inventory to measure outness regarding sexual orientation, and select questions from the 2020 Association of American Medical Colleges Medical School Graduation Questionnaire regarding discrimination.22-24

The survey was distributed to current allopathic and osteopathic dermatology residents by a variety of methods, including emails to program director and program coordinator listserves. The survey also was posted in the American Academy of Dermatology Expert Resource Group on LGBTQ Health October 2020 newsletter, as well as dermatology social media groups, including a messaging forum limited to dermatology residents, a Facebook group open to dermatologists and dermatology residents, and the Facebook group of the Gay and Lesbian Dermatology Association. Current dermatology residents, including those in combined dermatology and internal medicine programs, were included. Individuals who had been accepted to dermatology training programs but had not yet started were excluded. A follow-up email was sent to the program director listserve approximately 3 weeks after the initial distribution.

Statistical Analysis—The data were analyzed in Qualtrics and Microsoft Excel using descriptive statistics. Stata software (Stata 15.1, StataCorp) was used to perform a Kruskal-Wallis equality-of-populations rank test to compare the means of education level and feelings of preparedness.

Results

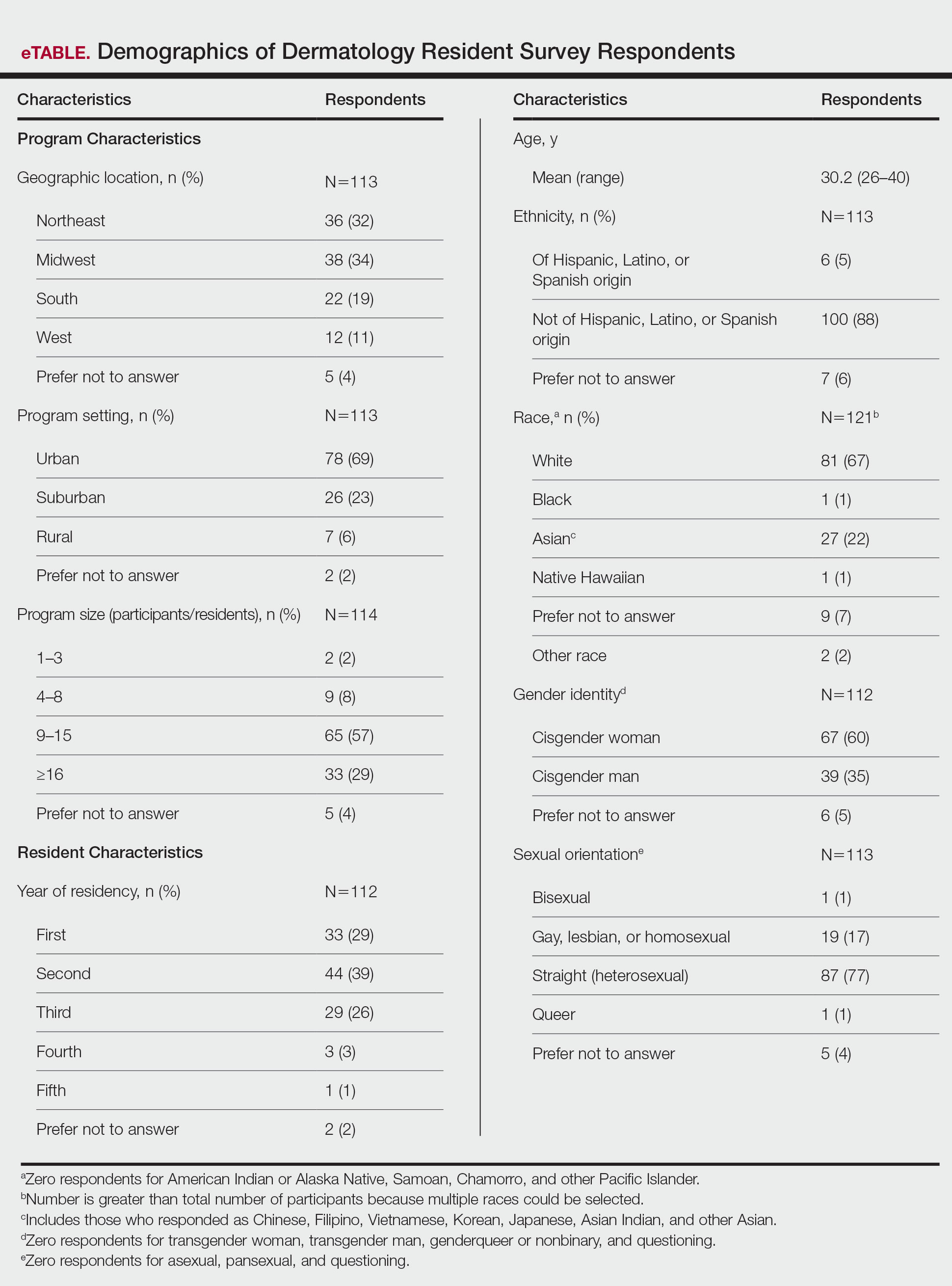

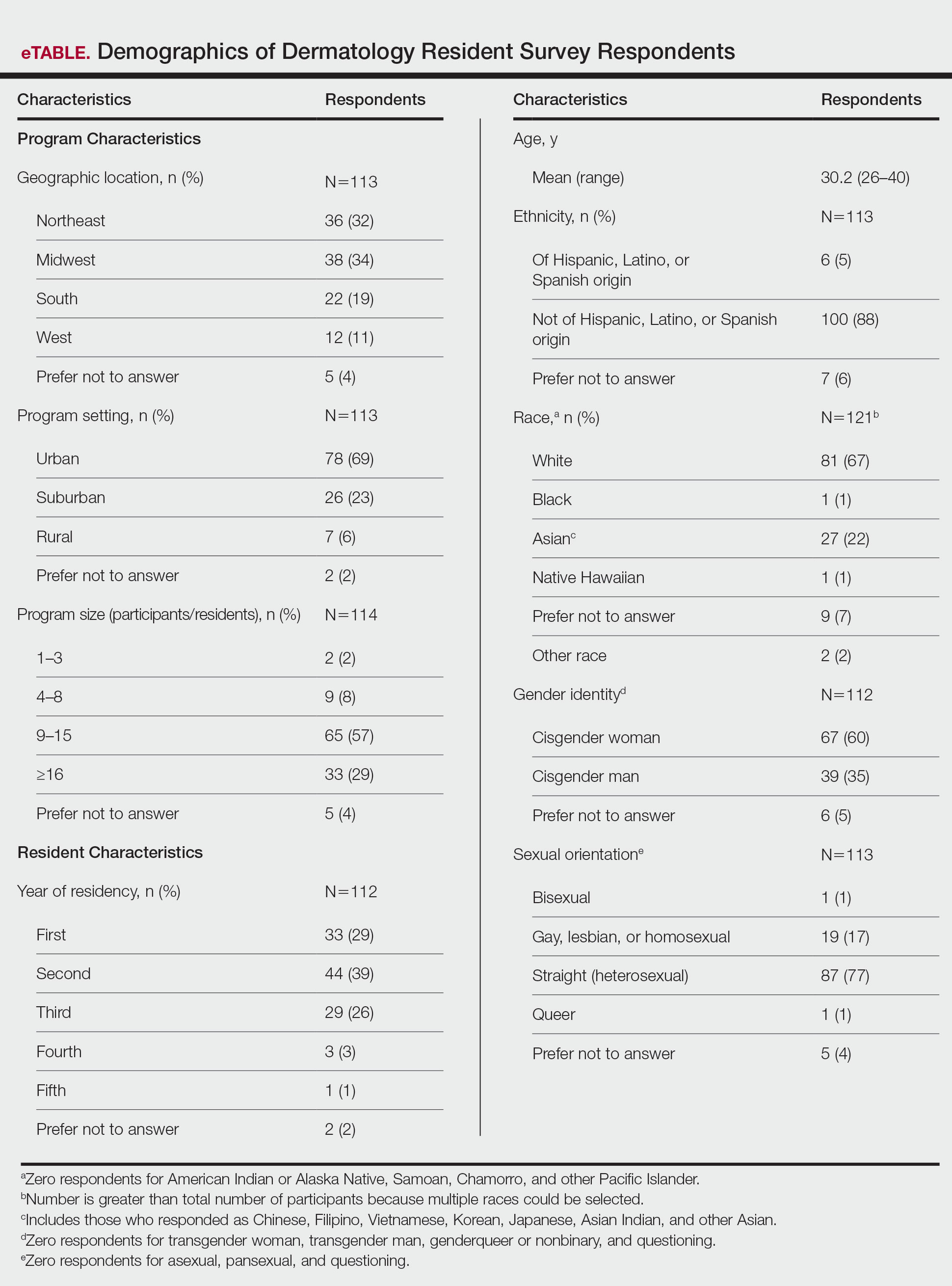

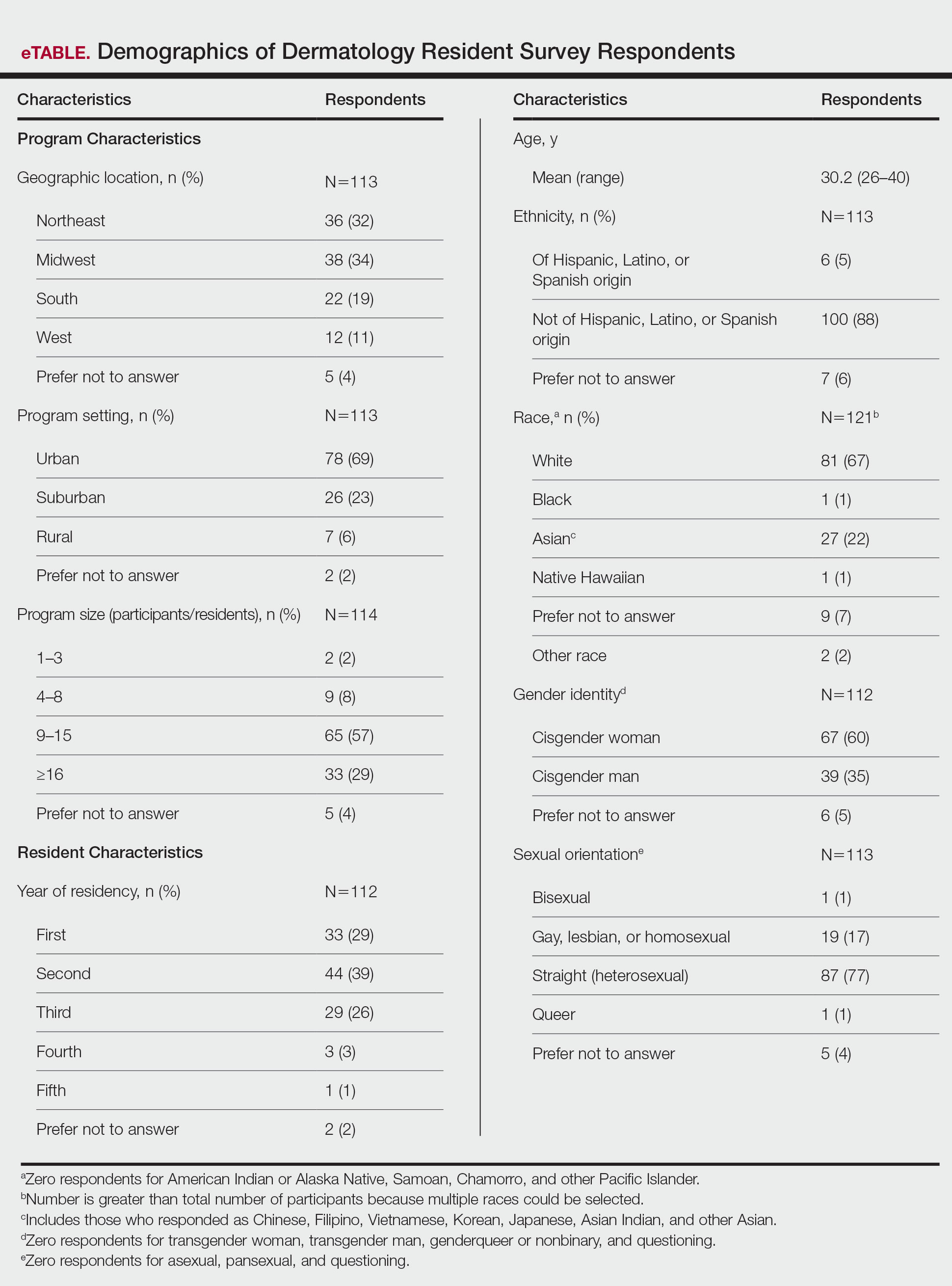

Demographics of Respondents—A total of 126 responses were recorded, 12 of which were blank and were removed from the database. A total of 114 dermatology residents’ responses were collected in Qualtrics and analyzed; 91 completed the entire survey (an 80% completion rate). Based on the 2020-2021 ACGME data listing, there were 1612 dermatology residents in the United States, which is an estimated response rate of 7% (114/1612).25 The eTable outlines the demographics of the survey respondents. Most were cisgender females (60%), followed by cisgender males (35%); the remainder preferred not to answer. Regarding sexual orientation, 77% identified as straight or heterosexual; 17% as gay, lesbian, or homosexual; 1% as queer; and 1% as bisexual. The training programs were in 26 states, the majority of which were in the Midwest (34%) and in urban settings (69%). A wide range of postgraduate levels and residency sizes were represented in the survey.

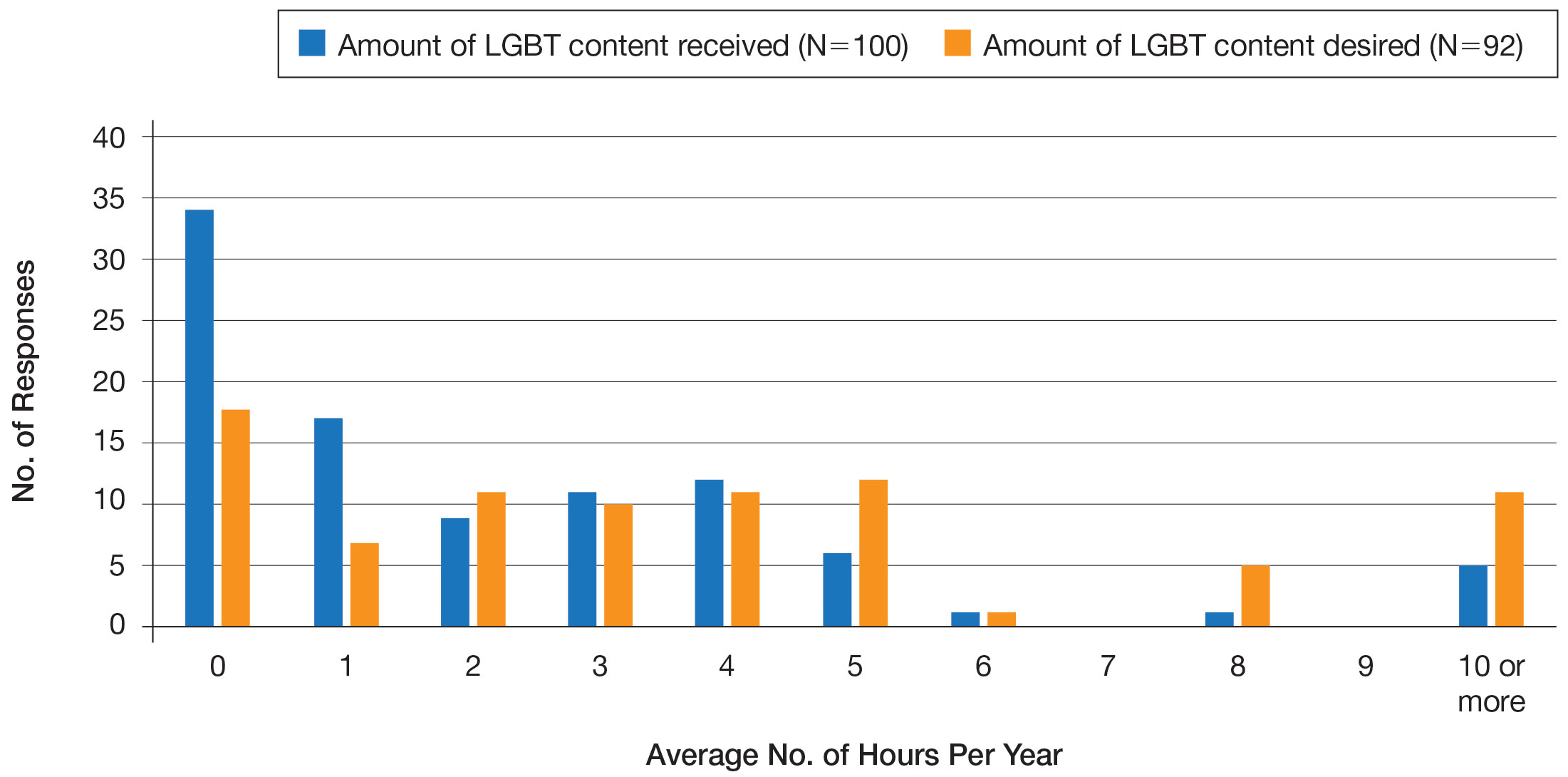

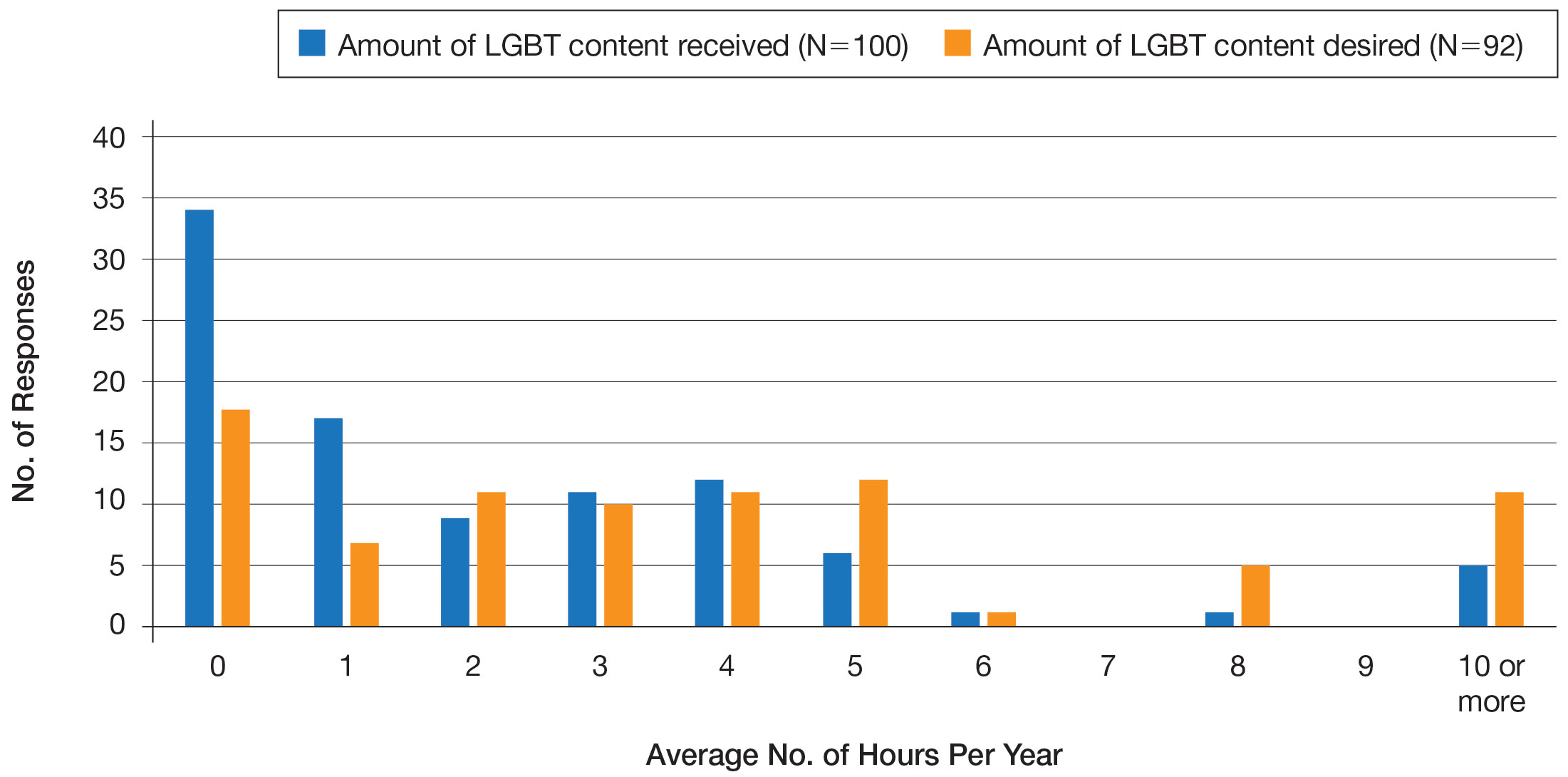

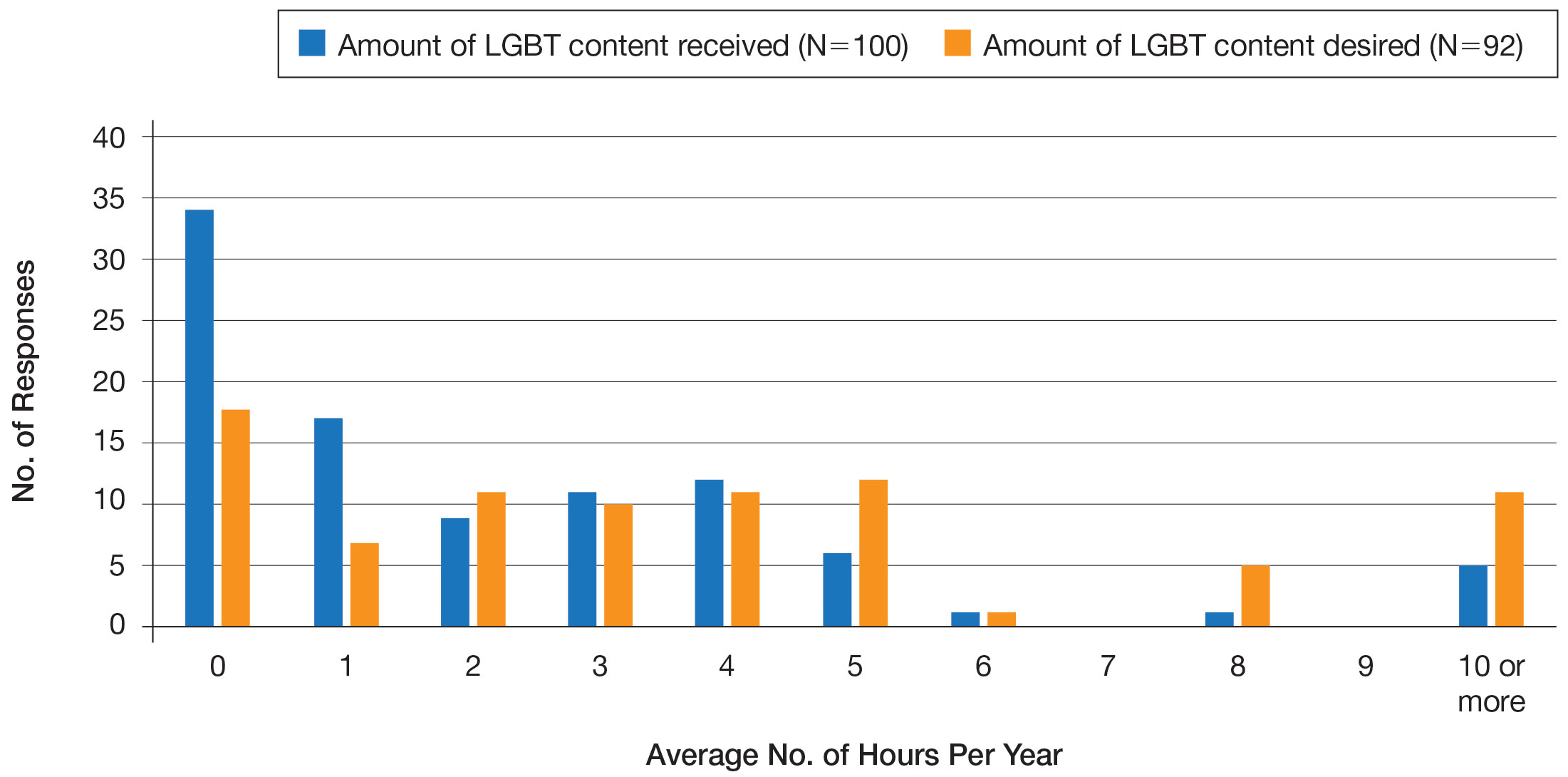

LGBT Education—Fifty-one percent of respondents reported that their programs offer 1 hour or less of LGBT-related curricula per year; 34% reported no time dedicated to this topic. A small portion of residents (5%) reported 10 or more hours of LGBT education per year. Residents also were asked the average number of hours of LGBT education they thought they should receive. The discrepancy between these measures can be visualized in Figure 1. The median hours of education received was 1 hour (IQR, 0–4 hours), whereas the median hours of education desired was 4 hours (IQR, 2–5 hours). The most common and most helpful methods of education reported were clinical experiences with faculty or patients and live lectures.

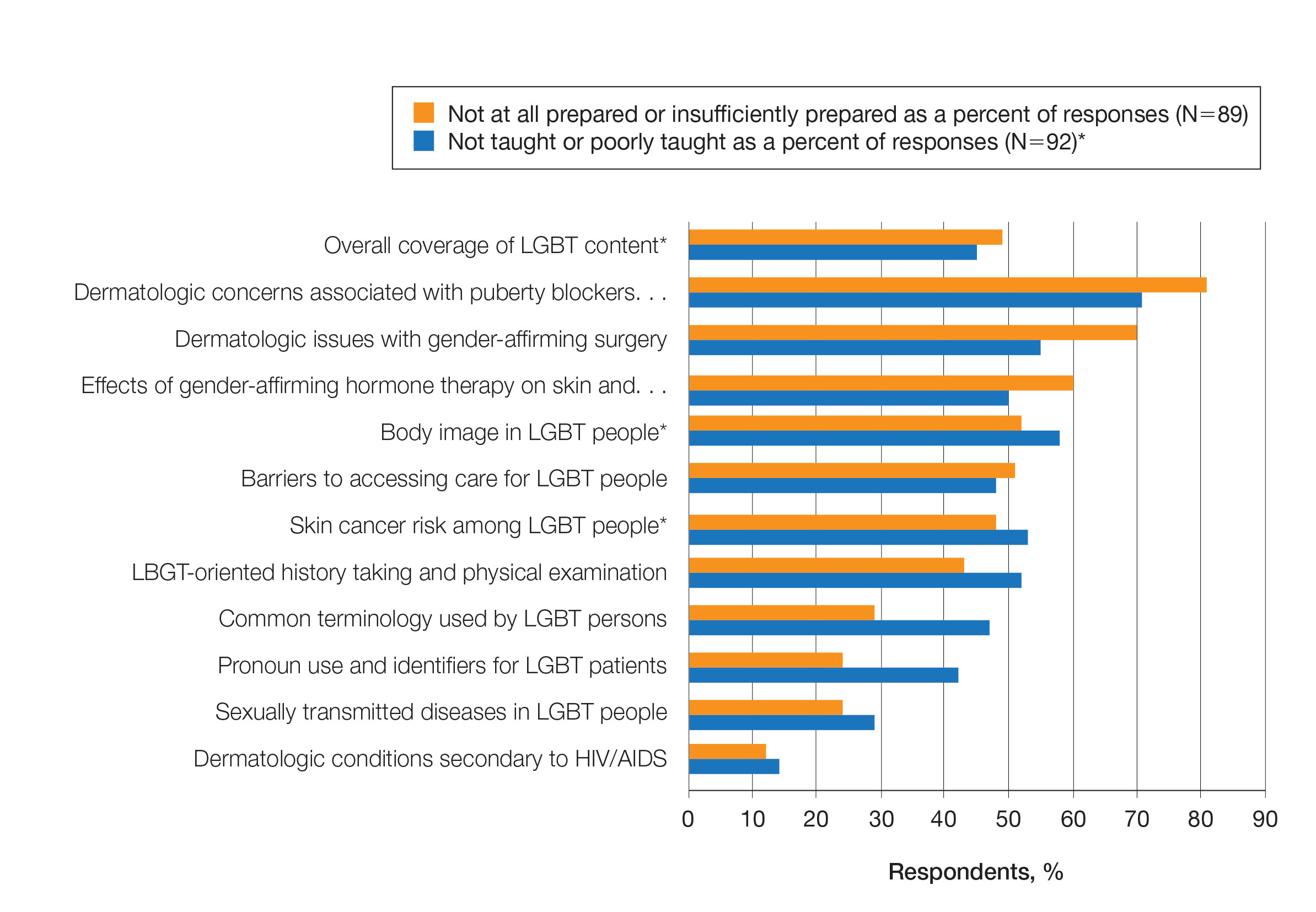

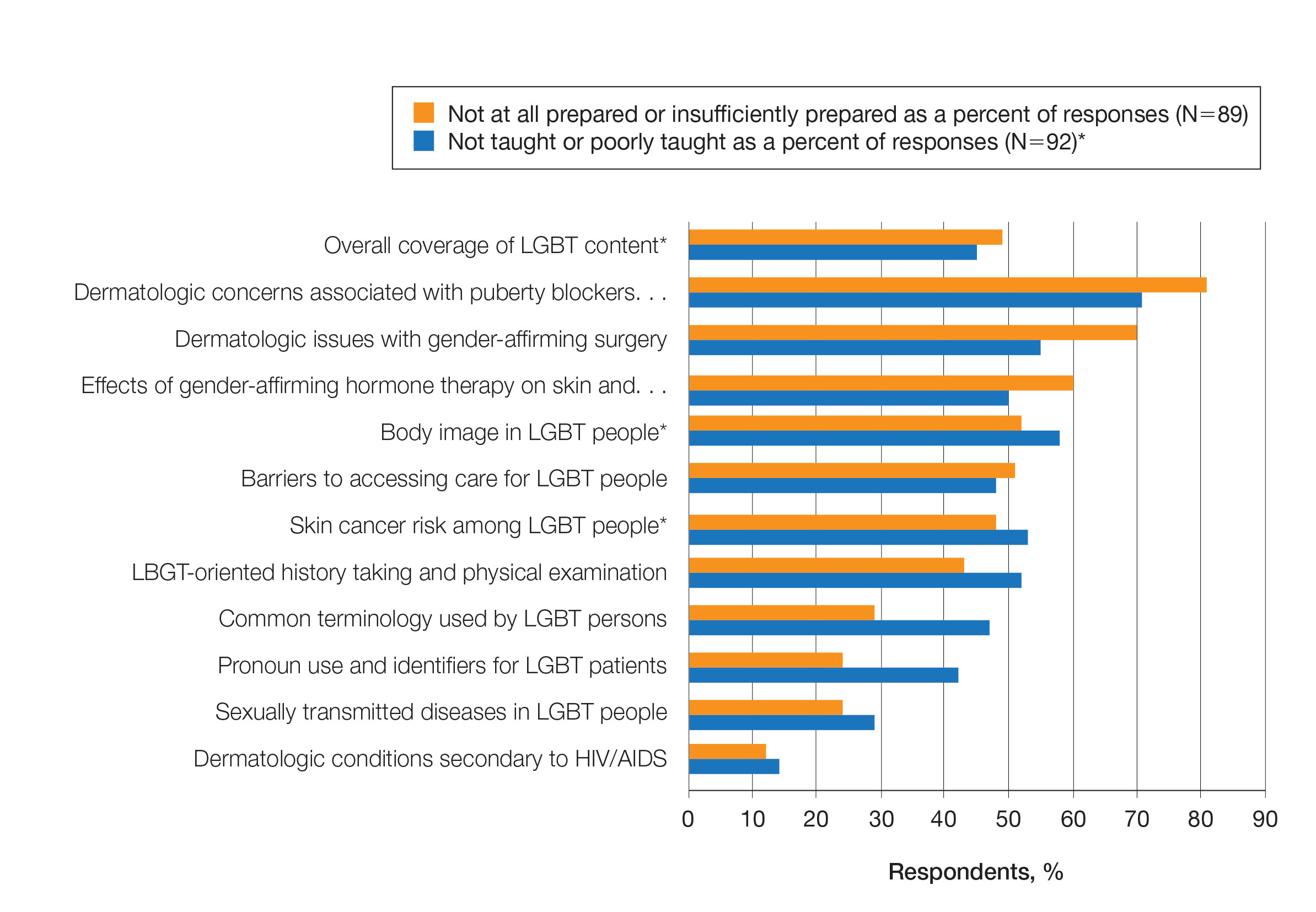

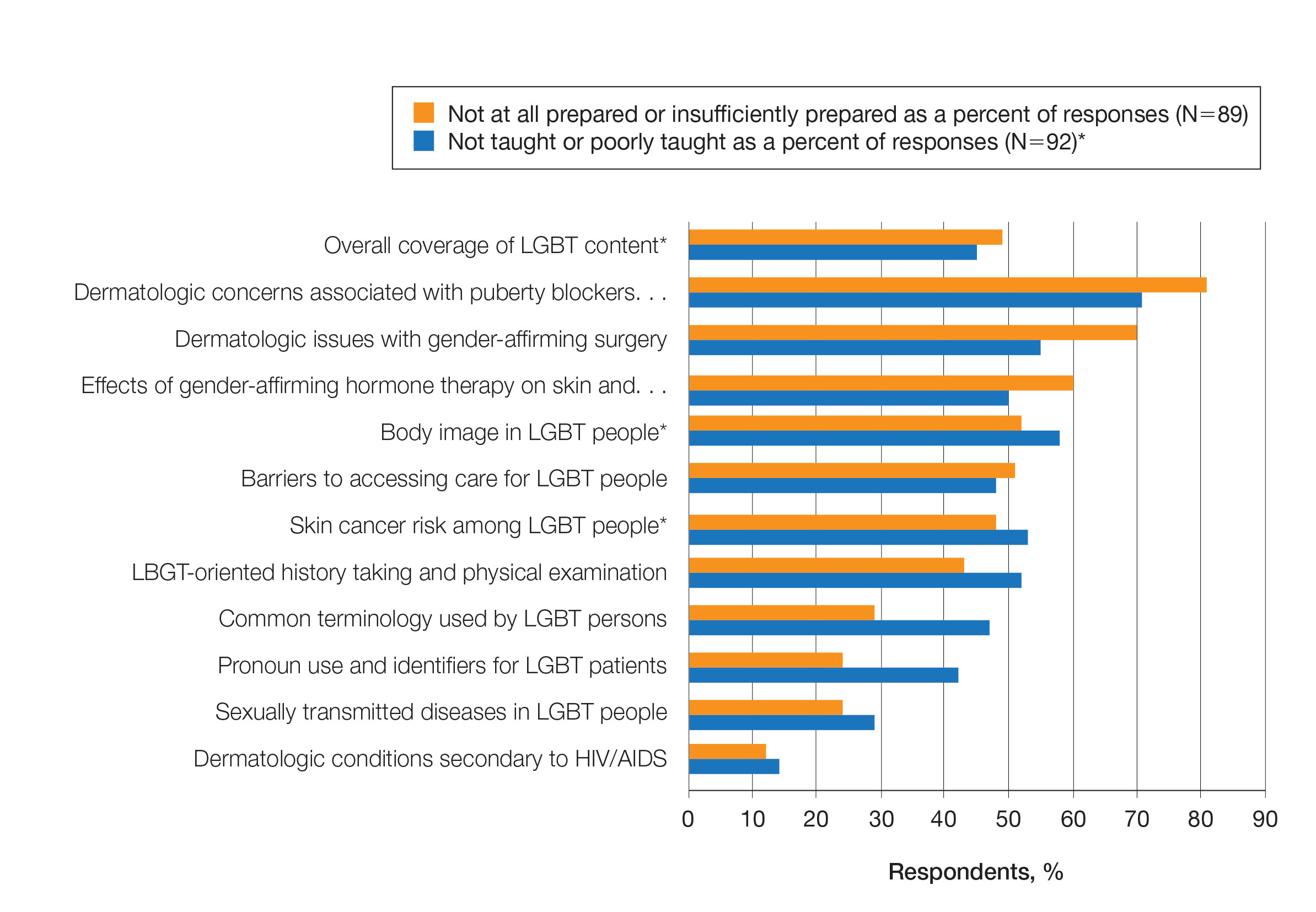

Overall, 45% of survey respondents felt that LGBT topics were covered poorly or not at all in dermatology residency, whereas 26% thought the coverage was good or excellent. The topics that residents were most likely to report receiving good or excellent coverage were dermatologic manifestations of HIV/AIDS (70%) and sexually transmitted diseases in LGBT patients (48%). The topics that were most likely to be reported as not taught or poorly taught included dermatologic concerns associated with puberty blockers (71%), body image (58%), dermatologic concerns associated with gender-affirming surgery (55%), skin cancer risk (53%), taking an LGBT-oriented history and physical examination (52%), and effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy on the skin (50%). A detailed breakdown of coverage level by topic can be found in Figure 2.

Preparedness to Care for LGBT Patients—Only 68% of survey respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they feel comfortable treating LGBT patients. Furthermore, 49% of dermatology residents reported that they feel not at all prepared or insufficiently prepared to provide care to LGBT individuals (Figure 2), and 60% believed that LGBT training needed to be improved at their residency programs.

There was a significant association between reported level of education and feelings of preparedness. A high ranking of provided education was associated with higher levels of feeling prepared to care for LGBT patients (Kruskal-Wallis rank test, P<.001).