User login

Docs fight back after losing hospital privileges, patients, and income

In April, a group of more than a dozen cardiologists at St. Louis Heart and Vascular (SLHV) lost their privileges at SSM Health, an eight-hospital system in St. Louis.

The physicians did not lose their privileges because of a clinical failure. Rather, it was because of SSM’s decision to enter into an exclusive contract with another set of cardiologists.

“The current situation is economically untenable for us,” said Harvey Serota, MD, founder and medical director of SLHV. “This is an existential threat to the practice.”

Because of the exclusive contract, many of SLHV’s patients are now being redirected to SSM-contracted cardiologists. Volume for the group’s new $15 million catheterization lab has plummeted. SLHV is suing SSM to restore its privileges, claiming lack of due process, restraint of trade, interference with its business, and breach of contract.

Losing privileges because a hospital seeks to increase their profits is becoming all too familiar for many independent specialists in fields such as cardiology, orthopedic surgery, and urology, as the hospitals that hosted them become their competitors and forge exclusive contracts with opposing groups.

What can these doctors do if they’re shut out? File a lawsuit, as SLHV has done? Demand a hearing before the medical staff and try to resolve the problem? Or simply give up their privileges and move on?

Unfortunately, none of these approaches offer a quick or certain solution, and each comes with risks.

Generally, courts have upheld hospitals’ use of exclusive contracts, which is also known as economic credentialing, says Barry F. Rosen, a health law attorney at Gordon Feinblatt, in Baltimore.

“Courts have long recognized exclusive contracts, and challenges by excluded doctors usually fail,” he says.

However, Mr. Rosen can cite several examples in which excluded doctors launched legal challenges that prevailed, owing to nuances in the law. The legal field in this area is tangled, and it varies by state.

Can hospitals make exclusive deals?

Hospitals have long used exclusive contracts for hospital-based specialists – anesthesiologists, radiologists, pathologists, emergency physicians, and hospitalists. They say that restricting patients to one group of anesthesiologists or radiologists enhances operational efficiency and that these contracts do not disrupt patients, because patients have no ties to hospital-based physicians. Such contracts are often more profitable for the hospital because of the negotiated rates.

Exclusive contracts in other specialties, however, are less accepted because they involve markedly different strategies and have different effects. In such cases, the hospital is no longer simply enhancing operational efficiency but is competing with physicians on staff, and the arrangement can disrupt the care of patients of the excluded doctors.

In the courts, these concerns might form the basis of an antitrust action or a claim of tortious interference with physicians’ ability to provide care for their patients, but neither claim is easy to win, Mr. Rosen says.

In antitrust cases, “the issue is not whether the excluded doctor was injured but whether the action harmed competition,” Mr. Rosen says. “Will the exclusion lead to higher prices?”

In the case of interference with patient care, “you will always find interference by one entity in the affairs of another,” he says, “but tortious interference applies to situations where something nefarious is going on, such as the other side was out to destroy your business and create a monopoly.”

Hospitals may try to restrict the privileges of physicians who invest in competing facilities such as cath labs and ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs), says Gregory Mertz, managing director of Physician Strategies Group, a consultancy in Virginia Beach.

“However, any revenge that a hospital might take against the doctors who started an ASC would usually not be publicly admitted,” Mr. Mertz says. “Revenge would be exacted in subtle ways.”

In the St. Louis situation, SSM did not cite SLHV’s cath lab as a reason for its exclusive contract. SSM stated in court documents that the decision was based on the recommendations of an expert panel. Furthermore, SSM said the board created the panel in response to a state report that cited the limited experience of some SLHV cardiologists in treating a rare type of heart attack.

Mr. Mertz says the board’s interest in the state’s concern and then its forming the special panel lent a great deal of legitimacy to SSM’s decision to start an exclusive contract. “SSM can show evidence that the board’s decision was based on a clinical matter and not on trying to squeeze out the cardiologists,” he says.

In SLHV’s defense, Dr. Serota says the practice offered to stop taking calls for the type of heart attack that was cited, but the hospital did not respond to its offer. He says SSM should have consulted the hospital’s medical staff to address the state’s concern and to create the exclusive contract, because these decisions involved clinical issues that the medical staff understands better than the board.

The law, however, does not require a hospital board to consult with its medical staff, says Alice G. Gosfield, a health care attorney in Philadelphia. “The board has ultimate legal control of everything in the hospital,” she says. However, the board often delegates certain functions to the medical staff in the hospital bylaws, and depending on the wording of the bylaws, it is still possible that the board violated the bylaws, Ms. Gosfield adds.

Can excluded physicians get peer review?

Can the hospital medical staff help restore the privileges of excluded physicians? Don’t these physicians have the right to peer review – a hearing before the medical staff?

Indeed, the Joint Commission, which accredits hospitals, states that the hospital must have “mechanisms, including a fair hearing and appeal process, for addressing adverse decisions for existing medical staff members and other individuals holding clinical privileges for renewal, revocation, or revision of clinical privileges.”

However, excluded physicians may not have a right to a hearing if they have not been fully stripped of privileges. SSM discontinued adult cardiology privileges for SLHV doctors but retained some doctors’ internal medicine privileges. Dr. Serota says internal medicine privileges are useless to cardiologists, but because the doctors’ privileges had not been fully removed, they cannot ask for a hearing.

More fundamentally, exclusive contracts are not a good fit for peer review. Mr. Rosen says the hearings were designed to review the physicians’ clinical competence or behavior, but excluded physicians do not have these problems. About all the hearing could focus on is the hospital’s policy, which the board would not want to allow. To avoid this, “the hospital might rule out a hearing as contrary to the intent of the bylaws,” Mr. Rosen says.

Furthermore, even if peer review goes forward, “what the medical staff decides is only advisory, and the hospital board makes the final decision,” Mr. Rosen says. He notes that the doctor could challenge the decision in court, but the hospital might still prevail.

Excluded physicians sometimes prevail

Although it is rare for excluded physicians to win a lawsuit against their hospital, it does happen, says Michael R. Callahan, health lawyer at Katten Muchin Rosenman, in Chicago.

Mr. Callahan cites a 2010 decision by the Arkansas Supreme Court that stopped the state’s largest health system from denying physicians’ privileges. Among other things, the hospital was found to have tortiously interfered with the physicians’ contracts with patients.

In a 2007 decision, a West Virginia court ruled that hospitals that have a mission to serve the public cannot exclude physicians for nonquality issues. In addition, some states, such as Texas, limit the economic factors that can be considered when credentialing decisions are made. Other states, such as Ohio, give hospitals a great deal of leeway to alter credentialing.

Dr. Serota is optimistic about his Missouri lawsuit. Although the judge in the case did not immediately grant SLHV’s request for restoration of privileges while the case proceeds, she did grant expedited discovery – allowing SLHV to obtain documents from SSM that could strengthen the doctors’ case – and she agreed to a hearing on SLHV’s request for a temporary restoration of privileges.

Ms. Gosfield says Dr. Serota’s optimism seems justified, but she adds that such cases cost a lot of money and that they may still not be winnable.

Often plaintiffs can settle lawsuits before they go to trial, but Mr. Callahan says hospitals are loath to restore privileges in a settlement because they don’t want to undermine an exclusivity deal. “The exclusive group expects a certain volume, which can’t be reached if the competing doctors are allowed back in,” he says.

Many physicians don’t challenge the exclusion

Quite often, excluded doctors decide not to challenge the decision. For example, Dr. Serota says groups of orthopedic surgeons and urologists have decided not to challenge similar decisions by SSM. “They wanted to move on,” he says.

Mr. Callahan says many excluded doctors also don’t even ask for a hearing. “They expect that the hospital’s decision will be upheld,” he says.

This was the case for Devendra K. Amin, MD, an independent cardiologist in Easton, Pa. Dr. Amin has not had any hospital privileges since July 2020. Even though he is board certified in interventional cardiology, which involves catheterization, Dr. Amin says he cannot perform these procedures because they can only be performed in a hospital in the area.

In the 1990s, Dr. Amin says, he had invasive cardiology privileges at five hospitals, but then those hospitals consolidated, and the remaining ones started constricting his privileges. First he could no longer work in the emergency department, then he could no longer read echocardiograms and interpret stress test results, because that work was assigned exclusively to employed doctors, he says.

Then the one remaining hospital announced that privileges would only be available to physicians by invitation, and he was not invited. Dr. Amin says he could have regained general cardiology privileges if he had accepted employment at the hospital, but he did not want to do this. A recruiter and the head of the cardiology section at the hospital even took him out to dinner 2 years ago to discuss employment, but there was a stipulation that the hospital would not agree to.

“I wanted to get back my interventional privileges back,” Dr. Amin says, “but they told me that would not be possible because they had an exclusive contract with a group.”

Dr. Amin says that now, he can only work as a general cardiologist with reduced volume. He says primary care physicians in the local hospital systems only refer to cardiologists within their systems. “When these patients do come to me, it is only because they specifically requested to see me,” Dr. Amin says.

He does not want to challenge the decisions regarding privileging. “Look, I am 68 years old,” Dr. Amin says. “I’m not retiring yet, but I don’t want to get into a battle with a hospital that has very deep pockets. I’m not a confrontational person to begin with, and I don’t want to spend the next 10 years of my life in litigation.”

Diverging expectations

The law on exclusive contracts does not provide easy answers for excluded doctors, and often it defies physicians’ conception of their own role in the hospital.

Many physicians expect the hospital to be a haven where they can do their work without being cut out by a competitor. This view is reinforced by organizations such as the American Medical Association.

The AMA Council on Medical Service states that privileges “can only be abridged upon recommendation of the medical staff and only for reason related to professional competence, adherence to standards of care, and other parameters agreed to by the medical staff.”

But the courts don’t tend to agree with that position. “Hospitals have a fiduciary duty to protect their own financial interests,” Mr. Callahan says. “This may involve anything that furthers the hospital’s mission to provide high-quality health care services to its patient community.”

At the same time, however, there are plenty of instances in which courts have ruled that exclusive contracts had gone too far. But usually it takes a lawyer experienced in these cases to know what those exceptions are.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In April, a group of more than a dozen cardiologists at St. Louis Heart and Vascular (SLHV) lost their privileges at SSM Health, an eight-hospital system in St. Louis.

The physicians did not lose their privileges because of a clinical failure. Rather, it was because of SSM’s decision to enter into an exclusive contract with another set of cardiologists.

“The current situation is economically untenable for us,” said Harvey Serota, MD, founder and medical director of SLHV. “This is an existential threat to the practice.”

Because of the exclusive contract, many of SLHV’s patients are now being redirected to SSM-contracted cardiologists. Volume for the group’s new $15 million catheterization lab has plummeted. SLHV is suing SSM to restore its privileges, claiming lack of due process, restraint of trade, interference with its business, and breach of contract.

Losing privileges because a hospital seeks to increase their profits is becoming all too familiar for many independent specialists in fields such as cardiology, orthopedic surgery, and urology, as the hospitals that hosted them become their competitors and forge exclusive contracts with opposing groups.

What can these doctors do if they’re shut out? File a lawsuit, as SLHV has done? Demand a hearing before the medical staff and try to resolve the problem? Or simply give up their privileges and move on?

Unfortunately, none of these approaches offer a quick or certain solution, and each comes with risks.

Generally, courts have upheld hospitals’ use of exclusive contracts, which is also known as economic credentialing, says Barry F. Rosen, a health law attorney at Gordon Feinblatt, in Baltimore.

“Courts have long recognized exclusive contracts, and challenges by excluded doctors usually fail,” he says.

However, Mr. Rosen can cite several examples in which excluded doctors launched legal challenges that prevailed, owing to nuances in the law. The legal field in this area is tangled, and it varies by state.

Can hospitals make exclusive deals?

Hospitals have long used exclusive contracts for hospital-based specialists – anesthesiologists, radiologists, pathologists, emergency physicians, and hospitalists. They say that restricting patients to one group of anesthesiologists or radiologists enhances operational efficiency and that these contracts do not disrupt patients, because patients have no ties to hospital-based physicians. Such contracts are often more profitable for the hospital because of the negotiated rates.

Exclusive contracts in other specialties, however, are less accepted because they involve markedly different strategies and have different effects. In such cases, the hospital is no longer simply enhancing operational efficiency but is competing with physicians on staff, and the arrangement can disrupt the care of patients of the excluded doctors.

In the courts, these concerns might form the basis of an antitrust action or a claim of tortious interference with physicians’ ability to provide care for their patients, but neither claim is easy to win, Mr. Rosen says.

In antitrust cases, “the issue is not whether the excluded doctor was injured but whether the action harmed competition,” Mr. Rosen says. “Will the exclusion lead to higher prices?”

In the case of interference with patient care, “you will always find interference by one entity in the affairs of another,” he says, “but tortious interference applies to situations where something nefarious is going on, such as the other side was out to destroy your business and create a monopoly.”

Hospitals may try to restrict the privileges of physicians who invest in competing facilities such as cath labs and ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs), says Gregory Mertz, managing director of Physician Strategies Group, a consultancy in Virginia Beach.

“However, any revenge that a hospital might take against the doctors who started an ASC would usually not be publicly admitted,” Mr. Mertz says. “Revenge would be exacted in subtle ways.”

In the St. Louis situation, SSM did not cite SLHV’s cath lab as a reason for its exclusive contract. SSM stated in court documents that the decision was based on the recommendations of an expert panel. Furthermore, SSM said the board created the panel in response to a state report that cited the limited experience of some SLHV cardiologists in treating a rare type of heart attack.

Mr. Mertz says the board’s interest in the state’s concern and then its forming the special panel lent a great deal of legitimacy to SSM’s decision to start an exclusive contract. “SSM can show evidence that the board’s decision was based on a clinical matter and not on trying to squeeze out the cardiologists,” he says.

In SLHV’s defense, Dr. Serota says the practice offered to stop taking calls for the type of heart attack that was cited, but the hospital did not respond to its offer. He says SSM should have consulted the hospital’s medical staff to address the state’s concern and to create the exclusive contract, because these decisions involved clinical issues that the medical staff understands better than the board.

The law, however, does not require a hospital board to consult with its medical staff, says Alice G. Gosfield, a health care attorney in Philadelphia. “The board has ultimate legal control of everything in the hospital,” she says. However, the board often delegates certain functions to the medical staff in the hospital bylaws, and depending on the wording of the bylaws, it is still possible that the board violated the bylaws, Ms. Gosfield adds.

Can excluded physicians get peer review?

Can the hospital medical staff help restore the privileges of excluded physicians? Don’t these physicians have the right to peer review – a hearing before the medical staff?

Indeed, the Joint Commission, which accredits hospitals, states that the hospital must have “mechanisms, including a fair hearing and appeal process, for addressing adverse decisions for existing medical staff members and other individuals holding clinical privileges for renewal, revocation, or revision of clinical privileges.”

However, excluded physicians may not have a right to a hearing if they have not been fully stripped of privileges. SSM discontinued adult cardiology privileges for SLHV doctors but retained some doctors’ internal medicine privileges. Dr. Serota says internal medicine privileges are useless to cardiologists, but because the doctors’ privileges had not been fully removed, they cannot ask for a hearing.

More fundamentally, exclusive contracts are not a good fit for peer review. Mr. Rosen says the hearings were designed to review the physicians’ clinical competence or behavior, but excluded physicians do not have these problems. About all the hearing could focus on is the hospital’s policy, which the board would not want to allow. To avoid this, “the hospital might rule out a hearing as contrary to the intent of the bylaws,” Mr. Rosen says.

Furthermore, even if peer review goes forward, “what the medical staff decides is only advisory, and the hospital board makes the final decision,” Mr. Rosen says. He notes that the doctor could challenge the decision in court, but the hospital might still prevail.

Excluded physicians sometimes prevail

Although it is rare for excluded physicians to win a lawsuit against their hospital, it does happen, says Michael R. Callahan, health lawyer at Katten Muchin Rosenman, in Chicago.

Mr. Callahan cites a 2010 decision by the Arkansas Supreme Court that stopped the state’s largest health system from denying physicians’ privileges. Among other things, the hospital was found to have tortiously interfered with the physicians’ contracts with patients.

In a 2007 decision, a West Virginia court ruled that hospitals that have a mission to serve the public cannot exclude physicians for nonquality issues. In addition, some states, such as Texas, limit the economic factors that can be considered when credentialing decisions are made. Other states, such as Ohio, give hospitals a great deal of leeway to alter credentialing.

Dr. Serota is optimistic about his Missouri lawsuit. Although the judge in the case did not immediately grant SLHV’s request for restoration of privileges while the case proceeds, she did grant expedited discovery – allowing SLHV to obtain documents from SSM that could strengthen the doctors’ case – and she agreed to a hearing on SLHV’s request for a temporary restoration of privileges.

Ms. Gosfield says Dr. Serota’s optimism seems justified, but she adds that such cases cost a lot of money and that they may still not be winnable.

Often plaintiffs can settle lawsuits before they go to trial, but Mr. Callahan says hospitals are loath to restore privileges in a settlement because they don’t want to undermine an exclusivity deal. “The exclusive group expects a certain volume, which can’t be reached if the competing doctors are allowed back in,” he says.

Many physicians don’t challenge the exclusion

Quite often, excluded doctors decide not to challenge the decision. For example, Dr. Serota says groups of orthopedic surgeons and urologists have decided not to challenge similar decisions by SSM. “They wanted to move on,” he says.

Mr. Callahan says many excluded doctors also don’t even ask for a hearing. “They expect that the hospital’s decision will be upheld,” he says.

This was the case for Devendra K. Amin, MD, an independent cardiologist in Easton, Pa. Dr. Amin has not had any hospital privileges since July 2020. Even though he is board certified in interventional cardiology, which involves catheterization, Dr. Amin says he cannot perform these procedures because they can only be performed in a hospital in the area.

In the 1990s, Dr. Amin says, he had invasive cardiology privileges at five hospitals, but then those hospitals consolidated, and the remaining ones started constricting his privileges. First he could no longer work in the emergency department, then he could no longer read echocardiograms and interpret stress test results, because that work was assigned exclusively to employed doctors, he says.

Then the one remaining hospital announced that privileges would only be available to physicians by invitation, and he was not invited. Dr. Amin says he could have regained general cardiology privileges if he had accepted employment at the hospital, but he did not want to do this. A recruiter and the head of the cardiology section at the hospital even took him out to dinner 2 years ago to discuss employment, but there was a stipulation that the hospital would not agree to.

“I wanted to get back my interventional privileges back,” Dr. Amin says, “but they told me that would not be possible because they had an exclusive contract with a group.”

Dr. Amin says that now, he can only work as a general cardiologist with reduced volume. He says primary care physicians in the local hospital systems only refer to cardiologists within their systems. “When these patients do come to me, it is only because they specifically requested to see me,” Dr. Amin says.

He does not want to challenge the decisions regarding privileging. “Look, I am 68 years old,” Dr. Amin says. “I’m not retiring yet, but I don’t want to get into a battle with a hospital that has very deep pockets. I’m not a confrontational person to begin with, and I don’t want to spend the next 10 years of my life in litigation.”

Diverging expectations

The law on exclusive contracts does not provide easy answers for excluded doctors, and often it defies physicians’ conception of their own role in the hospital.

Many physicians expect the hospital to be a haven where they can do their work without being cut out by a competitor. This view is reinforced by organizations such as the American Medical Association.

The AMA Council on Medical Service states that privileges “can only be abridged upon recommendation of the medical staff and only for reason related to professional competence, adherence to standards of care, and other parameters agreed to by the medical staff.”

But the courts don’t tend to agree with that position. “Hospitals have a fiduciary duty to protect their own financial interests,” Mr. Callahan says. “This may involve anything that furthers the hospital’s mission to provide high-quality health care services to its patient community.”

At the same time, however, there are plenty of instances in which courts have ruled that exclusive contracts had gone too far. But usually it takes a lawyer experienced in these cases to know what those exceptions are.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In April, a group of more than a dozen cardiologists at St. Louis Heart and Vascular (SLHV) lost their privileges at SSM Health, an eight-hospital system in St. Louis.

The physicians did not lose their privileges because of a clinical failure. Rather, it was because of SSM’s decision to enter into an exclusive contract with another set of cardiologists.

“The current situation is economically untenable for us,” said Harvey Serota, MD, founder and medical director of SLHV. “This is an existential threat to the practice.”

Because of the exclusive contract, many of SLHV’s patients are now being redirected to SSM-contracted cardiologists. Volume for the group’s new $15 million catheterization lab has plummeted. SLHV is suing SSM to restore its privileges, claiming lack of due process, restraint of trade, interference with its business, and breach of contract.

Losing privileges because a hospital seeks to increase their profits is becoming all too familiar for many independent specialists in fields such as cardiology, orthopedic surgery, and urology, as the hospitals that hosted them become their competitors and forge exclusive contracts with opposing groups.

What can these doctors do if they’re shut out? File a lawsuit, as SLHV has done? Demand a hearing before the medical staff and try to resolve the problem? Or simply give up their privileges and move on?

Unfortunately, none of these approaches offer a quick or certain solution, and each comes with risks.

Generally, courts have upheld hospitals’ use of exclusive contracts, which is also known as economic credentialing, says Barry F. Rosen, a health law attorney at Gordon Feinblatt, in Baltimore.

“Courts have long recognized exclusive contracts, and challenges by excluded doctors usually fail,” he says.

However, Mr. Rosen can cite several examples in which excluded doctors launched legal challenges that prevailed, owing to nuances in the law. The legal field in this area is tangled, and it varies by state.

Can hospitals make exclusive deals?

Hospitals have long used exclusive contracts for hospital-based specialists – anesthesiologists, radiologists, pathologists, emergency physicians, and hospitalists. They say that restricting patients to one group of anesthesiologists or radiologists enhances operational efficiency and that these contracts do not disrupt patients, because patients have no ties to hospital-based physicians. Such contracts are often more profitable for the hospital because of the negotiated rates.

Exclusive contracts in other specialties, however, are less accepted because they involve markedly different strategies and have different effects. In such cases, the hospital is no longer simply enhancing operational efficiency but is competing with physicians on staff, and the arrangement can disrupt the care of patients of the excluded doctors.

In the courts, these concerns might form the basis of an antitrust action or a claim of tortious interference with physicians’ ability to provide care for their patients, but neither claim is easy to win, Mr. Rosen says.

In antitrust cases, “the issue is not whether the excluded doctor was injured but whether the action harmed competition,” Mr. Rosen says. “Will the exclusion lead to higher prices?”

In the case of interference with patient care, “you will always find interference by one entity in the affairs of another,” he says, “but tortious interference applies to situations where something nefarious is going on, such as the other side was out to destroy your business and create a monopoly.”

Hospitals may try to restrict the privileges of physicians who invest in competing facilities such as cath labs and ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs), says Gregory Mertz, managing director of Physician Strategies Group, a consultancy in Virginia Beach.

“However, any revenge that a hospital might take against the doctors who started an ASC would usually not be publicly admitted,” Mr. Mertz says. “Revenge would be exacted in subtle ways.”

In the St. Louis situation, SSM did not cite SLHV’s cath lab as a reason for its exclusive contract. SSM stated in court documents that the decision was based on the recommendations of an expert panel. Furthermore, SSM said the board created the panel in response to a state report that cited the limited experience of some SLHV cardiologists in treating a rare type of heart attack.

Mr. Mertz says the board’s interest in the state’s concern and then its forming the special panel lent a great deal of legitimacy to SSM’s decision to start an exclusive contract. “SSM can show evidence that the board’s decision was based on a clinical matter and not on trying to squeeze out the cardiologists,” he says.

In SLHV’s defense, Dr. Serota says the practice offered to stop taking calls for the type of heart attack that was cited, but the hospital did not respond to its offer. He says SSM should have consulted the hospital’s medical staff to address the state’s concern and to create the exclusive contract, because these decisions involved clinical issues that the medical staff understands better than the board.

The law, however, does not require a hospital board to consult with its medical staff, says Alice G. Gosfield, a health care attorney in Philadelphia. “The board has ultimate legal control of everything in the hospital,” she says. However, the board often delegates certain functions to the medical staff in the hospital bylaws, and depending on the wording of the bylaws, it is still possible that the board violated the bylaws, Ms. Gosfield adds.

Can excluded physicians get peer review?

Can the hospital medical staff help restore the privileges of excluded physicians? Don’t these physicians have the right to peer review – a hearing before the medical staff?

Indeed, the Joint Commission, which accredits hospitals, states that the hospital must have “mechanisms, including a fair hearing and appeal process, for addressing adverse decisions for existing medical staff members and other individuals holding clinical privileges for renewal, revocation, or revision of clinical privileges.”

However, excluded physicians may not have a right to a hearing if they have not been fully stripped of privileges. SSM discontinued adult cardiology privileges for SLHV doctors but retained some doctors’ internal medicine privileges. Dr. Serota says internal medicine privileges are useless to cardiologists, but because the doctors’ privileges had not been fully removed, they cannot ask for a hearing.

More fundamentally, exclusive contracts are not a good fit for peer review. Mr. Rosen says the hearings were designed to review the physicians’ clinical competence or behavior, but excluded physicians do not have these problems. About all the hearing could focus on is the hospital’s policy, which the board would not want to allow. To avoid this, “the hospital might rule out a hearing as contrary to the intent of the bylaws,” Mr. Rosen says.

Furthermore, even if peer review goes forward, “what the medical staff decides is only advisory, and the hospital board makes the final decision,” Mr. Rosen says. He notes that the doctor could challenge the decision in court, but the hospital might still prevail.

Excluded physicians sometimes prevail

Although it is rare for excluded physicians to win a lawsuit against their hospital, it does happen, says Michael R. Callahan, health lawyer at Katten Muchin Rosenman, in Chicago.

Mr. Callahan cites a 2010 decision by the Arkansas Supreme Court that stopped the state’s largest health system from denying physicians’ privileges. Among other things, the hospital was found to have tortiously interfered with the physicians’ contracts with patients.

In a 2007 decision, a West Virginia court ruled that hospitals that have a mission to serve the public cannot exclude physicians for nonquality issues. In addition, some states, such as Texas, limit the economic factors that can be considered when credentialing decisions are made. Other states, such as Ohio, give hospitals a great deal of leeway to alter credentialing.

Dr. Serota is optimistic about his Missouri lawsuit. Although the judge in the case did not immediately grant SLHV’s request for restoration of privileges while the case proceeds, she did grant expedited discovery – allowing SLHV to obtain documents from SSM that could strengthen the doctors’ case – and she agreed to a hearing on SLHV’s request for a temporary restoration of privileges.

Ms. Gosfield says Dr. Serota’s optimism seems justified, but she adds that such cases cost a lot of money and that they may still not be winnable.

Often plaintiffs can settle lawsuits before they go to trial, but Mr. Callahan says hospitals are loath to restore privileges in a settlement because they don’t want to undermine an exclusivity deal. “The exclusive group expects a certain volume, which can’t be reached if the competing doctors are allowed back in,” he says.

Many physicians don’t challenge the exclusion

Quite often, excluded doctors decide not to challenge the decision. For example, Dr. Serota says groups of orthopedic surgeons and urologists have decided not to challenge similar decisions by SSM. “They wanted to move on,” he says.

Mr. Callahan says many excluded doctors also don’t even ask for a hearing. “They expect that the hospital’s decision will be upheld,” he says.

This was the case for Devendra K. Amin, MD, an independent cardiologist in Easton, Pa. Dr. Amin has not had any hospital privileges since July 2020. Even though he is board certified in interventional cardiology, which involves catheterization, Dr. Amin says he cannot perform these procedures because they can only be performed in a hospital in the area.

In the 1990s, Dr. Amin says, he had invasive cardiology privileges at five hospitals, but then those hospitals consolidated, and the remaining ones started constricting his privileges. First he could no longer work in the emergency department, then he could no longer read echocardiograms and interpret stress test results, because that work was assigned exclusively to employed doctors, he says.

Then the one remaining hospital announced that privileges would only be available to physicians by invitation, and he was not invited. Dr. Amin says he could have regained general cardiology privileges if he had accepted employment at the hospital, but he did not want to do this. A recruiter and the head of the cardiology section at the hospital even took him out to dinner 2 years ago to discuss employment, but there was a stipulation that the hospital would not agree to.

“I wanted to get back my interventional privileges back,” Dr. Amin says, “but they told me that would not be possible because they had an exclusive contract with a group.”

Dr. Amin says that now, he can only work as a general cardiologist with reduced volume. He says primary care physicians in the local hospital systems only refer to cardiologists within their systems. “When these patients do come to me, it is only because they specifically requested to see me,” Dr. Amin says.

He does not want to challenge the decisions regarding privileging. “Look, I am 68 years old,” Dr. Amin says. “I’m not retiring yet, but I don’t want to get into a battle with a hospital that has very deep pockets. I’m not a confrontational person to begin with, and I don’t want to spend the next 10 years of my life in litigation.”

Diverging expectations

The law on exclusive contracts does not provide easy answers for excluded doctors, and often it defies physicians’ conception of their own role in the hospital.

Many physicians expect the hospital to be a haven where they can do their work without being cut out by a competitor. This view is reinforced by organizations such as the American Medical Association.

The AMA Council on Medical Service states that privileges “can only be abridged upon recommendation of the medical staff and only for reason related to professional competence, adherence to standards of care, and other parameters agreed to by the medical staff.”

But the courts don’t tend to agree with that position. “Hospitals have a fiduciary duty to protect their own financial interests,” Mr. Callahan says. “This may involve anything that furthers the hospital’s mission to provide high-quality health care services to its patient community.”

At the same time, however, there are plenty of instances in which courts have ruled that exclusive contracts had gone too far. But usually it takes a lawyer experienced in these cases to know what those exceptions are.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

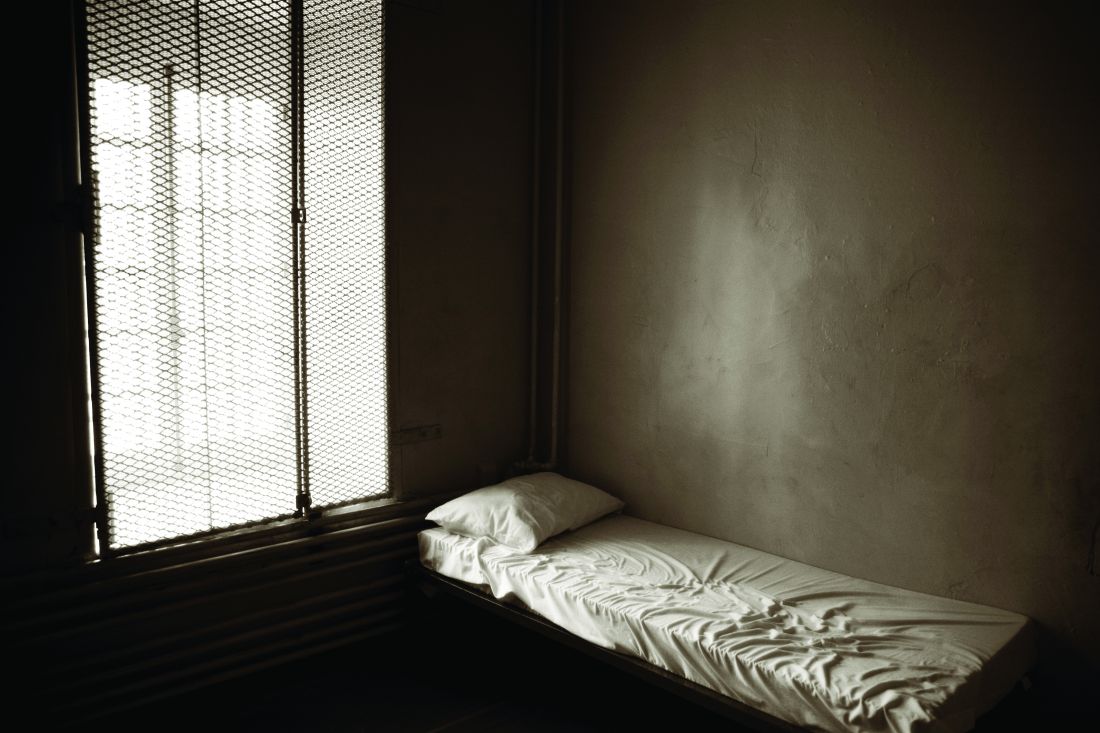

Heart doc offering ‘fountain of youth’ jailed for 6 1/2 years

Cardiologist Samirkumar J. Shah, MD, was sentenced to 78 months in prison after his conviction on two counts of federal health care fraud involving more than $13 million.

As part of his sentence, Dr. Shah, 58, of Fox Chapel, Pa., must pay $1.7 million in restitution and other penalties and undergo 3 years of supervised release after prison.

“Dr. Shah risked the health of his patients so he could make millions of dollars through unnecessary procedures, and lied and fabricated records for years to perpetuate his fraud scheme,” acting U.S. Attorney Stephen R. Kaufman said in an Aug. 5 statement from the Department of Justice.

As previously reported, Dr. Shah was convicted June 14, 2019, of submitting fraudulent claims to private and federal insurance programs between 2008 and 2013 for external counterpulsation (ECP) therapy, a lower limb compression treatment approved for patients with coronary artery disease and refractory angina.

Dr. Shah, however, advertised ECP as the “fountain of youth,” claimed it made patients “younger and smarter,” and offered the treatment for conditions such as obesity, hypertension, hypotension, diabetes, and erectile dysfunction.

Patients were required to undergo diagnostic ultrasounds as a precautionary measure prior to starting ECP, but witness testimony established that Dr. Shah did not review any of the imaging before approving new patients for ECP, placing his patients at risk for serious injury or even death, the DOJ stated.

The evidence also showed that Dr. Shah double-billed insurers, routinely submitted fabricated patient files, and made false statements concerning his practice, patient population, recording keeping, and compliance with coverage guidelines, the government said.

During the scheme, Dr. Shah submitted ECP-related claims for Medicare Part B, UPMC Health Plan, Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield, and Gateway Health Plan beneficiaries totalling more than $13 million and received reimbursement payments in excess of $3.5 million.

“Rather than upholding the oath he swore and providing care for patients who trusted him, this defendant misled patients and drained critical Medicaid funds from families who needed it,” said Attorney General Josh Shapiro. “We will not let anyone put their patients’ lives at risk for a profit.”

“Today’s sentence holds Mr. Shah accountable for his appalling actions,” said FBI Pittsburgh Special Agent in Charge Mike Nordwall. “Mr. Shah used his position as a doctor to illegally profit from a health care program paid for by taxpayers. Fraud of this magnitude will not be tolerated.”

Dr. Shah has been in custody since July 15, 2021, after skipping out on his original July 14 sentencing date. The Tribune-Review reported that Dr. Shah filed a last-minute request for a continuance, claiming he had an adverse reaction to the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination and was advised by his doctor that he needed “strict bedrest for at least 6 weeks.”

Dr. Shah reportedly turned himself after presiding U.S. District Judge David S. Cercone denied the motion and issued an arrest warrant.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiologist Samirkumar J. Shah, MD, was sentenced to 78 months in prison after his conviction on two counts of federal health care fraud involving more than $13 million.

As part of his sentence, Dr. Shah, 58, of Fox Chapel, Pa., must pay $1.7 million in restitution and other penalties and undergo 3 years of supervised release after prison.

“Dr. Shah risked the health of his patients so he could make millions of dollars through unnecessary procedures, and lied and fabricated records for years to perpetuate his fraud scheme,” acting U.S. Attorney Stephen R. Kaufman said in an Aug. 5 statement from the Department of Justice.

As previously reported, Dr. Shah was convicted June 14, 2019, of submitting fraudulent claims to private and federal insurance programs between 2008 and 2013 for external counterpulsation (ECP) therapy, a lower limb compression treatment approved for patients with coronary artery disease and refractory angina.

Dr. Shah, however, advertised ECP as the “fountain of youth,” claimed it made patients “younger and smarter,” and offered the treatment for conditions such as obesity, hypertension, hypotension, diabetes, and erectile dysfunction.

Patients were required to undergo diagnostic ultrasounds as a precautionary measure prior to starting ECP, but witness testimony established that Dr. Shah did not review any of the imaging before approving new patients for ECP, placing his patients at risk for serious injury or even death, the DOJ stated.

The evidence also showed that Dr. Shah double-billed insurers, routinely submitted fabricated patient files, and made false statements concerning his practice, patient population, recording keeping, and compliance with coverage guidelines, the government said.

During the scheme, Dr. Shah submitted ECP-related claims for Medicare Part B, UPMC Health Plan, Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield, and Gateway Health Plan beneficiaries totalling more than $13 million and received reimbursement payments in excess of $3.5 million.

“Rather than upholding the oath he swore and providing care for patients who trusted him, this defendant misled patients and drained critical Medicaid funds from families who needed it,” said Attorney General Josh Shapiro. “We will not let anyone put their patients’ lives at risk for a profit.”

“Today’s sentence holds Mr. Shah accountable for his appalling actions,” said FBI Pittsburgh Special Agent in Charge Mike Nordwall. “Mr. Shah used his position as a doctor to illegally profit from a health care program paid for by taxpayers. Fraud of this magnitude will not be tolerated.”

Dr. Shah has been in custody since July 15, 2021, after skipping out on his original July 14 sentencing date. The Tribune-Review reported that Dr. Shah filed a last-minute request for a continuance, claiming he had an adverse reaction to the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination and was advised by his doctor that he needed “strict bedrest for at least 6 weeks.”

Dr. Shah reportedly turned himself after presiding U.S. District Judge David S. Cercone denied the motion and issued an arrest warrant.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiologist Samirkumar J. Shah, MD, was sentenced to 78 months in prison after his conviction on two counts of federal health care fraud involving more than $13 million.

As part of his sentence, Dr. Shah, 58, of Fox Chapel, Pa., must pay $1.7 million in restitution and other penalties and undergo 3 years of supervised release after prison.

“Dr. Shah risked the health of his patients so he could make millions of dollars through unnecessary procedures, and lied and fabricated records for years to perpetuate his fraud scheme,” acting U.S. Attorney Stephen R. Kaufman said in an Aug. 5 statement from the Department of Justice.

As previously reported, Dr. Shah was convicted June 14, 2019, of submitting fraudulent claims to private and federal insurance programs between 2008 and 2013 for external counterpulsation (ECP) therapy, a lower limb compression treatment approved for patients with coronary artery disease and refractory angina.

Dr. Shah, however, advertised ECP as the “fountain of youth,” claimed it made patients “younger and smarter,” and offered the treatment for conditions such as obesity, hypertension, hypotension, diabetes, and erectile dysfunction.

Patients were required to undergo diagnostic ultrasounds as a precautionary measure prior to starting ECP, but witness testimony established that Dr. Shah did not review any of the imaging before approving new patients for ECP, placing his patients at risk for serious injury or even death, the DOJ stated.

The evidence also showed that Dr. Shah double-billed insurers, routinely submitted fabricated patient files, and made false statements concerning his practice, patient population, recording keeping, and compliance with coverage guidelines, the government said.

During the scheme, Dr. Shah submitted ECP-related claims for Medicare Part B, UPMC Health Plan, Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield, and Gateway Health Plan beneficiaries totalling more than $13 million and received reimbursement payments in excess of $3.5 million.

“Rather than upholding the oath he swore and providing care for patients who trusted him, this defendant misled patients and drained critical Medicaid funds from families who needed it,” said Attorney General Josh Shapiro. “We will not let anyone put their patients’ lives at risk for a profit.”

“Today’s sentence holds Mr. Shah accountable for his appalling actions,” said FBI Pittsburgh Special Agent in Charge Mike Nordwall. “Mr. Shah used his position as a doctor to illegally profit from a health care program paid for by taxpayers. Fraud of this magnitude will not be tolerated.”

Dr. Shah has been in custody since July 15, 2021, after skipping out on his original July 14 sentencing date. The Tribune-Review reported that Dr. Shah filed a last-minute request for a continuance, claiming he had an adverse reaction to the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination and was advised by his doctor that he needed “strict bedrest for at least 6 weeks.”

Dr. Shah reportedly turned himself after presiding U.S. District Judge David S. Cercone denied the motion and issued an arrest warrant.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite retraction, study using fraudulent Surgisphere data still cited

A retracted study on the safety of blood pressure medications in patients with COVID-19 continues to be cited nearly a year later, new research shows.

The study in question, published on May 1, 2020, in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed no increased risk for in-hospital death with the use of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Concerns about the veracity of the Surgisphere database used for the study, however, led to a June 4 retraction and to the June 13 retraction of a second study, published in the Lancet, that focused on hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 treatment.

Although the Surgisphere scandal caused a global reckoning of COVID-19 scientific studies, the new analysis identified 652 citations of the NEJM article as of May 31.

More than a third of the citations occurred in the first 2 months after the retraction, 54% were at least 3 months later, and 2.8% at least 6 months later. In May, 11 months after the article was retracted, it was cited 21 times, senior author Emily G. McDonald, MD, MSc, McGill University, Montreal, and colleagues reported in a research letter in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“In early May and June there were already more than 200 citations in one of the world’s leading scientific journals, so I do believe it was a highly influential article early on and had an impact on different types of studies or research taking place,” she said in an interview.

Dr. McDonald said she’s also “certain that it impacted patient care,” observing that when there are no guidelines available on how to manage patients, physicians will turn to the most recent evidence in the most reputable journals.

“In the case of ACE [inhibitors] and ARBs, although the study was based on fraudulent data, we were lucky that the overall message was in the end probably correct, but that might not have been the case for another study or dataset,” she said.

Early in the pandemic, concerns existed that ACE inhibitors and ARBs could be harmful, increasing the expression of ACE2 receptors, which the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to gain entry into cells. The first randomized trial to examine the issue, BRACE CORONA, showed no clinical benefit to interrupting use of the agents in hospitalized patients. An observational study suggested ACE inhibitors may even be protective.

Of two high-profile retractions, McDonald said they chose to bypass the hydroxychloroquine study, which had an eye-popping Altmetric attention score of 23,084, compared with 3,727 for the NEJM paper, because it may have been cited for “other” reasons. “We wanted to focus less on the politics and more on the problem of retracted work.”

The team found that researchers across the globe were citing the retracted ACE/ARB paper (18.7% in the United States, 8.1% in Italy, and 44% other countries). Most citations were used to support a statement in the main text of a study, but in nearly 3% of cases, the data were incorporated into new analyses.

Just 17.6% of the studies cited or noted the retraction. “For sure, that was surprising to us. We suspected it, but our study confirmed it,” Dr. McDonald said.

Although retracted articles can be identified by a watermark or line of text, in some cases that can be easily missed, she noted. What’s more, not all citation software points out when a study has been retracted, a fate shared by the copyediting process.

“There are a lot of mechanisms in place and, in general, what’s happening is rare but there isn’t a perfect automated system solution to absolutely prevent this from happening,” she said. “It’s still subject to human error.”

The findings also have to be taken in the context of a rapidly emerging pandemic and the unprecedented torrent of scientific papers released over the past year.

“That might have contributed to why this happened, but the takeaway message is that this can happen despite our best efforts, and we need to challenge ourselves to come up with a system solution to prevent this from happening in the future,” Dr. McDonald said. “Current mechanisms are probably capturing 95% of it, but we need to do better.”

Limitations of the present analysis are that it was limited to the single retracted study; used only a single search engine, Google Scholar, to identify the citing works; and that additional citations may have been missed, the authors noted.

McDonald and coauthor Todd C. Lee, MD, report being signatories on a public letter calling for the retraction of the Surgisphere papers. Dr. Lee also reported receiving research support from Fonds De Recherche du Quebec-Sante during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A retracted study on the safety of blood pressure medications in patients with COVID-19 continues to be cited nearly a year later, new research shows.

The study in question, published on May 1, 2020, in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed no increased risk for in-hospital death with the use of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Concerns about the veracity of the Surgisphere database used for the study, however, led to a June 4 retraction and to the June 13 retraction of a second study, published in the Lancet, that focused on hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 treatment.

Although the Surgisphere scandal caused a global reckoning of COVID-19 scientific studies, the new analysis identified 652 citations of the NEJM article as of May 31.

More than a third of the citations occurred in the first 2 months after the retraction, 54% were at least 3 months later, and 2.8% at least 6 months later. In May, 11 months after the article was retracted, it was cited 21 times, senior author Emily G. McDonald, MD, MSc, McGill University, Montreal, and colleagues reported in a research letter in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“In early May and June there were already more than 200 citations in one of the world’s leading scientific journals, so I do believe it was a highly influential article early on and had an impact on different types of studies or research taking place,” she said in an interview.

Dr. McDonald said she’s also “certain that it impacted patient care,” observing that when there are no guidelines available on how to manage patients, physicians will turn to the most recent evidence in the most reputable journals.

“In the case of ACE [inhibitors] and ARBs, although the study was based on fraudulent data, we were lucky that the overall message was in the end probably correct, but that might not have been the case for another study or dataset,” she said.

Early in the pandemic, concerns existed that ACE inhibitors and ARBs could be harmful, increasing the expression of ACE2 receptors, which the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to gain entry into cells. The first randomized trial to examine the issue, BRACE CORONA, showed no clinical benefit to interrupting use of the agents in hospitalized patients. An observational study suggested ACE inhibitors may even be protective.

Of two high-profile retractions, McDonald said they chose to bypass the hydroxychloroquine study, which had an eye-popping Altmetric attention score of 23,084, compared with 3,727 for the NEJM paper, because it may have been cited for “other” reasons. “We wanted to focus less on the politics and more on the problem of retracted work.”

The team found that researchers across the globe were citing the retracted ACE/ARB paper (18.7% in the United States, 8.1% in Italy, and 44% other countries). Most citations were used to support a statement in the main text of a study, but in nearly 3% of cases, the data were incorporated into new analyses.

Just 17.6% of the studies cited or noted the retraction. “For sure, that was surprising to us. We suspected it, but our study confirmed it,” Dr. McDonald said.

Although retracted articles can be identified by a watermark or line of text, in some cases that can be easily missed, she noted. What’s more, not all citation software points out when a study has been retracted, a fate shared by the copyediting process.

“There are a lot of mechanisms in place and, in general, what’s happening is rare but there isn’t a perfect automated system solution to absolutely prevent this from happening,” she said. “It’s still subject to human error.”

The findings also have to be taken in the context of a rapidly emerging pandemic and the unprecedented torrent of scientific papers released over the past year.

“That might have contributed to why this happened, but the takeaway message is that this can happen despite our best efforts, and we need to challenge ourselves to come up with a system solution to prevent this from happening in the future,” Dr. McDonald said. “Current mechanisms are probably capturing 95% of it, but we need to do better.”

Limitations of the present analysis are that it was limited to the single retracted study; used only a single search engine, Google Scholar, to identify the citing works; and that additional citations may have been missed, the authors noted.

McDonald and coauthor Todd C. Lee, MD, report being signatories on a public letter calling for the retraction of the Surgisphere papers. Dr. Lee also reported receiving research support from Fonds De Recherche du Quebec-Sante during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A retracted study on the safety of blood pressure medications in patients with COVID-19 continues to be cited nearly a year later, new research shows.

The study in question, published on May 1, 2020, in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed no increased risk for in-hospital death with the use of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Concerns about the veracity of the Surgisphere database used for the study, however, led to a June 4 retraction and to the June 13 retraction of a second study, published in the Lancet, that focused on hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 treatment.

Although the Surgisphere scandal caused a global reckoning of COVID-19 scientific studies, the new analysis identified 652 citations of the NEJM article as of May 31.

More than a third of the citations occurred in the first 2 months after the retraction, 54% were at least 3 months later, and 2.8% at least 6 months later. In May, 11 months after the article was retracted, it was cited 21 times, senior author Emily G. McDonald, MD, MSc, McGill University, Montreal, and colleagues reported in a research letter in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“In early May and June there were already more than 200 citations in one of the world’s leading scientific journals, so I do believe it was a highly influential article early on and had an impact on different types of studies or research taking place,” she said in an interview.

Dr. McDonald said she’s also “certain that it impacted patient care,” observing that when there are no guidelines available on how to manage patients, physicians will turn to the most recent evidence in the most reputable journals.

“In the case of ACE [inhibitors] and ARBs, although the study was based on fraudulent data, we were lucky that the overall message was in the end probably correct, but that might not have been the case for another study or dataset,” she said.

Early in the pandemic, concerns existed that ACE inhibitors and ARBs could be harmful, increasing the expression of ACE2 receptors, which the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to gain entry into cells. The first randomized trial to examine the issue, BRACE CORONA, showed no clinical benefit to interrupting use of the agents in hospitalized patients. An observational study suggested ACE inhibitors may even be protective.

Of two high-profile retractions, McDonald said they chose to bypass the hydroxychloroquine study, which had an eye-popping Altmetric attention score of 23,084, compared with 3,727 for the NEJM paper, because it may have been cited for “other” reasons. “We wanted to focus less on the politics and more on the problem of retracted work.”

The team found that researchers across the globe were citing the retracted ACE/ARB paper (18.7% in the United States, 8.1% in Italy, and 44% other countries). Most citations were used to support a statement in the main text of a study, but in nearly 3% of cases, the data were incorporated into new analyses.

Just 17.6% of the studies cited or noted the retraction. “For sure, that was surprising to us. We suspected it, but our study confirmed it,” Dr. McDonald said.

Although retracted articles can be identified by a watermark or line of text, in some cases that can be easily missed, she noted. What’s more, not all citation software points out when a study has been retracted, a fate shared by the copyediting process.

“There are a lot of mechanisms in place and, in general, what’s happening is rare but there isn’t a perfect automated system solution to absolutely prevent this from happening,” she said. “It’s still subject to human error.”

The findings also have to be taken in the context of a rapidly emerging pandemic and the unprecedented torrent of scientific papers released over the past year.

“That might have contributed to why this happened, but the takeaway message is that this can happen despite our best efforts, and we need to challenge ourselves to come up with a system solution to prevent this from happening in the future,” Dr. McDonald said. “Current mechanisms are probably capturing 95% of it, but we need to do better.”

Limitations of the present analysis are that it was limited to the single retracted study; used only a single search engine, Google Scholar, to identify the citing works; and that additional citations may have been missed, the authors noted.

McDonald and coauthor Todd C. Lee, MD, report being signatories on a public letter calling for the retraction of the Surgisphere papers. Dr. Lee also reported receiving research support from Fonds De Recherche du Quebec-Sante during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Myocarditis tied to COVID-19 shots more common than reported?

While cases of pericarditis or myocarditis temporally linked to COVID-19 vaccination remain rare, they may happen more often than reported, according to a large review of electronic medical records (EMRs).

They also appear to represent two “distinct syndromes,” George Diaz, MD, Providence Regional Medical Center Everett (Washington), said in an interview.

Myocarditis typically occurs soon after vaccination in younger patients and mostly after the second dose, while pericarditis occurs later in older patients, after the first or second dose.

Dr. Diaz and colleagues reported their analysis in a research letter published online August 4 in JAMA.

They reviewed the records of 2,000,287 people who received at least one COVID-19 vaccination at 40 hospitals in Washington, Oregon, Montana, and California that are part of the Providence health care system and use the same EMRs.

The median age of the cohort was 57 years and 59% were women.

A little more than three quarters (77%) received more than one dose; most received the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer (53%) and Moderna (44%); 3% received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

The records showed that 20 people had vaccine-related myocarditis (1.0 per 100,000) and 37 had pericarditis (1.8 per 100,000).

A recent report, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System, suggested an incidence of myocarditis of about 4.8 cases per 1 million following receipt of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine.

The new study shows a “similar pattern, although at higher incidence, suggesting vaccine adverse event underreporting. In addition, pericarditis may be more common than myocarditis among older patients,” the study team wrote.

“Our study resulted in higher numbers of cases probably because we searched the EMR, and VAERS requires doctors to report suspected cases voluntarily,” Dr. Diaz said in an interview.

Also, in the governments’ statistics, pericarditis and myocarditis were “lumped together,” he noted.

Myocarditis cases

The 20 myocarditis cases occurred a median of 3.5 days after vaccination (11 after the Moderna vaccine and 9 after the Pfizer vaccine), 15 of the patients (75%) were men, and the median age was 36 years.

Four individuals (20%) developed myocarditis symptoms after the first vaccination and 16 (80%) after the second dose. Nineteen of the patients (95%) were admitted to the hospital and all were discharged after a median of 2 days.

None of the 20 patients were readmitted or died. Two received a second vaccination after onset of myocarditis; neither had worsening of symptoms. At last available follow-up (median, 23.5 days after symptom onset), 13 patients (65%) had a resolution of their myocarditis symptoms and seven (35%) were improving.

Pericarditis cases

The 37 pericarditis cases occurred a median of 20 days after the most recent COVID-19 vaccination: 23 (62%) with Pfizer, 12 (32%) with Moderna, and 2 (5%) with the J&J vaccine. Fifteen developed pericarditis after the first vaccine dose (41%) and 22 (59%) after the second.

Twenty-seven (73%) of the cases occurred in men; the median age was 59 years.

Thirteen patients (35%) were admitted to the hospital, none to intensive care. The median hospital stay was 1 day. Seven patients with pericarditis received a second vaccination. No patient died.

At last available follow-up (median, 28 days), 7 patients (19%) had resolved symptoms and 23 (62%) were improving.

The researchers also calculate that the average monthly number of cases of myocarditis or myopericarditis during the prevaccine period of January 2019 through January 2021 was 16.9 (95% confidence interval, 15.3-18.6) compared with 27.3 (95% CI, 22.4-32.9) during the vaccine period of February through May 2021 (P < .001).

The mean numbers of pericarditis cases during the same periods were 49.1 (95% CI, 46.4-51.9) and 78.8 (95% CI, 70.3-87.9), respectively (P < .001).

The authors say limitations of their analysis include potential missed cases outside care settings and missed diagnoses of myocarditis or pericarditis, which would underestimate the incidence, as well as inaccurate EMR vaccination information.

“Temporal association does not prove causation, although the short span between vaccination and myocarditis onset and the elevated incidence of myocarditis and pericarditis in the study hospitals lend support to a possible relationship,” they wrote.

In late June, the Food and Drug Administration added a warning to the fact sheets accompanying the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, flagging the rare risk of heart inflammation after their use.

Dr. Diaz cautioned that myocarditis and pericarditis events remain “a rare occurrence” after COVID-19 vaccination.

“When discussing vaccination with patients, [health care providers] can advise them that patients generally recover in the rare event they get pericarditis or myocarditis and no deaths were found, and that the vaccines are safe and effective,” Dr. Diaz said.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Diaz reported receipt of clinical trial research support from Gilead Sciences, Regeneron, Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Edesa Biotech and scientific advisory board membership for Safeology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While cases of pericarditis or myocarditis temporally linked to COVID-19 vaccination remain rare, they may happen more often than reported, according to a large review of electronic medical records (EMRs).

They also appear to represent two “distinct syndromes,” George Diaz, MD, Providence Regional Medical Center Everett (Washington), said in an interview.

Myocarditis typically occurs soon after vaccination in younger patients and mostly after the second dose, while pericarditis occurs later in older patients, after the first or second dose.

Dr. Diaz and colleagues reported their analysis in a research letter published online August 4 in JAMA.

They reviewed the records of 2,000,287 people who received at least one COVID-19 vaccination at 40 hospitals in Washington, Oregon, Montana, and California that are part of the Providence health care system and use the same EMRs.

The median age of the cohort was 57 years and 59% were women.

A little more than three quarters (77%) received more than one dose; most received the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer (53%) and Moderna (44%); 3% received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

The records showed that 20 people had vaccine-related myocarditis (1.0 per 100,000) and 37 had pericarditis (1.8 per 100,000).

A recent report, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System, suggested an incidence of myocarditis of about 4.8 cases per 1 million following receipt of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine.

The new study shows a “similar pattern, although at higher incidence, suggesting vaccine adverse event underreporting. In addition, pericarditis may be more common than myocarditis among older patients,” the study team wrote.

“Our study resulted in higher numbers of cases probably because we searched the EMR, and VAERS requires doctors to report suspected cases voluntarily,” Dr. Diaz said in an interview.

Also, in the governments’ statistics, pericarditis and myocarditis were “lumped together,” he noted.

Myocarditis cases

The 20 myocarditis cases occurred a median of 3.5 days after vaccination (11 after the Moderna vaccine and 9 after the Pfizer vaccine), 15 of the patients (75%) were men, and the median age was 36 years.

Four individuals (20%) developed myocarditis symptoms after the first vaccination and 16 (80%) after the second dose. Nineteen of the patients (95%) were admitted to the hospital and all were discharged after a median of 2 days.

None of the 20 patients were readmitted or died. Two received a second vaccination after onset of myocarditis; neither had worsening of symptoms. At last available follow-up (median, 23.5 days after symptom onset), 13 patients (65%) had a resolution of their myocarditis symptoms and seven (35%) were improving.

Pericarditis cases

The 37 pericarditis cases occurred a median of 20 days after the most recent COVID-19 vaccination: 23 (62%) with Pfizer, 12 (32%) with Moderna, and 2 (5%) with the J&J vaccine. Fifteen developed pericarditis after the first vaccine dose (41%) and 22 (59%) after the second.

Twenty-seven (73%) of the cases occurred in men; the median age was 59 years.

Thirteen patients (35%) were admitted to the hospital, none to intensive care. The median hospital stay was 1 day. Seven patients with pericarditis received a second vaccination. No patient died.

At last available follow-up (median, 28 days), 7 patients (19%) had resolved symptoms and 23 (62%) were improving.

The researchers also calculate that the average monthly number of cases of myocarditis or myopericarditis during the prevaccine period of January 2019 through January 2021 was 16.9 (95% confidence interval, 15.3-18.6) compared with 27.3 (95% CI, 22.4-32.9) during the vaccine period of February through May 2021 (P < .001).

The mean numbers of pericarditis cases during the same periods were 49.1 (95% CI, 46.4-51.9) and 78.8 (95% CI, 70.3-87.9), respectively (P < .001).

The authors say limitations of their analysis include potential missed cases outside care settings and missed diagnoses of myocarditis or pericarditis, which would underestimate the incidence, as well as inaccurate EMR vaccination information.

“Temporal association does not prove causation, although the short span between vaccination and myocarditis onset and the elevated incidence of myocarditis and pericarditis in the study hospitals lend support to a possible relationship,” they wrote.

In late June, the Food and Drug Administration added a warning to the fact sheets accompanying the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, flagging the rare risk of heart inflammation after their use.

Dr. Diaz cautioned that myocarditis and pericarditis events remain “a rare occurrence” after COVID-19 vaccination.

“When discussing vaccination with patients, [health care providers] can advise them that patients generally recover in the rare event they get pericarditis or myocarditis and no deaths were found, and that the vaccines are safe and effective,” Dr. Diaz said.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Diaz reported receipt of clinical trial research support from Gilead Sciences, Regeneron, Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Edesa Biotech and scientific advisory board membership for Safeology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While cases of pericarditis or myocarditis temporally linked to COVID-19 vaccination remain rare, they may happen more often than reported, according to a large review of electronic medical records (EMRs).

They also appear to represent two “distinct syndromes,” George Diaz, MD, Providence Regional Medical Center Everett (Washington), said in an interview.

Myocarditis typically occurs soon after vaccination in younger patients and mostly after the second dose, while pericarditis occurs later in older patients, after the first or second dose.

Dr. Diaz and colleagues reported their analysis in a research letter published online August 4 in JAMA.

They reviewed the records of 2,000,287 people who received at least one COVID-19 vaccination at 40 hospitals in Washington, Oregon, Montana, and California that are part of the Providence health care system and use the same EMRs.

The median age of the cohort was 57 years and 59% were women.

A little more than three quarters (77%) received more than one dose; most received the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer (53%) and Moderna (44%); 3% received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

The records showed that 20 people had vaccine-related myocarditis (1.0 per 100,000) and 37 had pericarditis (1.8 per 100,000).

A recent report, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System, suggested an incidence of myocarditis of about 4.8 cases per 1 million following receipt of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine.

The new study shows a “similar pattern, although at higher incidence, suggesting vaccine adverse event underreporting. In addition, pericarditis may be more common than myocarditis among older patients,” the study team wrote.

“Our study resulted in higher numbers of cases probably because we searched the EMR, and VAERS requires doctors to report suspected cases voluntarily,” Dr. Diaz said in an interview.

Also, in the governments’ statistics, pericarditis and myocarditis were “lumped together,” he noted.

Myocarditis cases

The 20 myocarditis cases occurred a median of 3.5 days after vaccination (11 after the Moderna vaccine and 9 after the Pfizer vaccine), 15 of the patients (75%) were men, and the median age was 36 years.

Four individuals (20%) developed myocarditis symptoms after the first vaccination and 16 (80%) after the second dose. Nineteen of the patients (95%) were admitted to the hospital and all were discharged after a median of 2 days.

None of the 20 patients were readmitted or died. Two received a second vaccination after onset of myocarditis; neither had worsening of symptoms. At last available follow-up (median, 23.5 days after symptom onset), 13 patients (65%) had a resolution of their myocarditis symptoms and seven (35%) were improving.

Pericarditis cases

The 37 pericarditis cases occurred a median of 20 days after the most recent COVID-19 vaccination: 23 (62%) with Pfizer, 12 (32%) with Moderna, and 2 (5%) with the J&J vaccine. Fifteen developed pericarditis after the first vaccine dose (41%) and 22 (59%) after the second.

Twenty-seven (73%) of the cases occurred in men; the median age was 59 years.

Thirteen patients (35%) were admitted to the hospital, none to intensive care. The median hospital stay was 1 day. Seven patients with pericarditis received a second vaccination. No patient died.

At last available follow-up (median, 28 days), 7 patients (19%) had resolved symptoms and 23 (62%) were improving.

The researchers also calculate that the average monthly number of cases of myocarditis or myopericarditis during the prevaccine period of January 2019 through January 2021 was 16.9 (95% confidence interval, 15.3-18.6) compared with 27.3 (95% CI, 22.4-32.9) during the vaccine period of February through May 2021 (P < .001).

The mean numbers of pericarditis cases during the same periods were 49.1 (95% CI, 46.4-51.9) and 78.8 (95% CI, 70.3-87.9), respectively (P < .001).

The authors say limitations of their analysis include potential missed cases outside care settings and missed diagnoses of myocarditis or pericarditis, which would underestimate the incidence, as well as inaccurate EMR vaccination information.

“Temporal association does not prove causation, although the short span between vaccination and myocarditis onset and the elevated incidence of myocarditis and pericarditis in the study hospitals lend support to a possible relationship,” they wrote.

In late June, the Food and Drug Administration added a warning to the fact sheets accompanying the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, flagging the rare risk of heart inflammation after their use.

Dr. Diaz cautioned that myocarditis and pericarditis events remain “a rare occurrence” after COVID-19 vaccination.

“When discussing vaccination with patients, [health care providers] can advise them that patients generally recover in the rare event they get pericarditis or myocarditis and no deaths were found, and that the vaccines are safe and effective,” Dr. Diaz said.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Diaz reported receipt of clinical trial research support from Gilead Sciences, Regeneron, Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Edesa Biotech and scientific advisory board membership for Safeology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Thousands of patients were implanted with heart pumps that the FDA knew could be dangerous

John Winkler II was dying of heart failure when doctors came to his hospital bedside, offering a chance to prolong his life. The HeartWare Ventricular Assist Device, or HVAD, could be implanted in Winkler’s chest until a transplant was possible. The heart pump came with disclaimers of risk, but Winkler wanted to fight for time. He was only 46 and had a loving wife and four children, and his second grandchild was on the way.