User login

Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES) Following Bevacizumab and Atezolizumab Therapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

Background

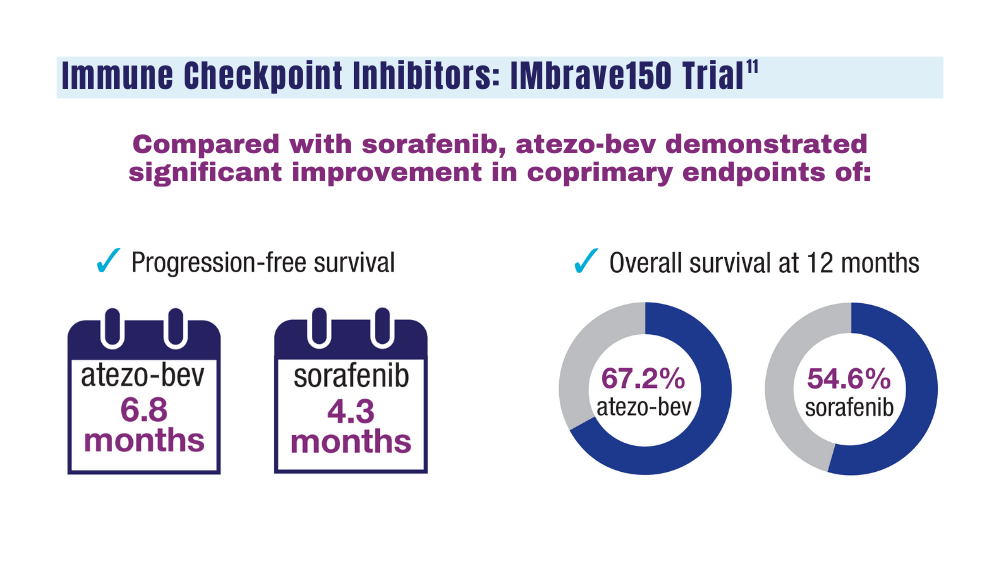

Bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody, is known to inhibit angiogenesis and prevent carcinogenesis. Recent evidence from the IMbrave050 trial indicates that combining bevacizumab with atezolizumab enhances recurrence-free survival (RFS) in high-risk HCC patients undergoing curative treatments. Bevacizumab is notorious for causing endothelial dysfunction that may provoke vasospasm, leading to central hypoperfusion, hypertension, and, albeit rarely, PRES. Similarly, immunotherapy, including atezolizumab, has been implicated in PRES, underscoring a potential risk when these therapies are administered concurrently.

Case Presentation

A 64-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C and alcoholic cirrhosis was diagnosed with stage II (T2 N0 M0) HCC. Following partial hepatectomy, we proceeded with adjuvant systemic therapy with atezolizumab and bevacizumab (per the IMbrave050 trial). After her 2nd treatment, she developed altered mental status, seizures, and severe hypertension. Labs revealed acute kidney injury and elevated creatinine kinase levels suggesting rhabdomyolysis. Computed tomography head showed no acute findings, but magnetic resonance imaging of the brain identified increased flair attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) signal in the brain’s posterior regions, indicating PRES. Symptomatic management with anti-hypertensives and intravenous fluids led to the recovery of mental status to baseline. Further therapy with bevacizumab and atezolizumab was then held off.

Discussion

Therapeutic advances in HCC management through the IMbrave050 trial demonstrate the efficacy of bevacizumab and atezolizumab in reducing RFS, without highlighting the serious side effects like PRES. To our knowledge, this is the first case reported where PRES occurred with the simultaneous use of atezolizumab and bevacizumab. Since both drugs can individually cause PRES, there might be a heightened risk with the co-administration, signaling a critical need for vigilant monitoring and further research into this treatment modality’s long-term safety profile.

Background

Bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody, is known to inhibit angiogenesis and prevent carcinogenesis. Recent evidence from the IMbrave050 trial indicates that combining bevacizumab with atezolizumab enhances recurrence-free survival (RFS) in high-risk HCC patients undergoing curative treatments. Bevacizumab is notorious for causing endothelial dysfunction that may provoke vasospasm, leading to central hypoperfusion, hypertension, and, albeit rarely, PRES. Similarly, immunotherapy, including atezolizumab, has been implicated in PRES, underscoring a potential risk when these therapies are administered concurrently.

Case Presentation

A 64-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C and alcoholic cirrhosis was diagnosed with stage II (T2 N0 M0) HCC. Following partial hepatectomy, we proceeded with adjuvant systemic therapy with atezolizumab and bevacizumab (per the IMbrave050 trial). After her 2nd treatment, she developed altered mental status, seizures, and severe hypertension. Labs revealed acute kidney injury and elevated creatinine kinase levels suggesting rhabdomyolysis. Computed tomography head showed no acute findings, but magnetic resonance imaging of the brain identified increased flair attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) signal in the brain’s posterior regions, indicating PRES. Symptomatic management with anti-hypertensives and intravenous fluids led to the recovery of mental status to baseline. Further therapy with bevacizumab and atezolizumab was then held off.

Discussion

Therapeutic advances in HCC management through the IMbrave050 trial demonstrate the efficacy of bevacizumab and atezolizumab in reducing RFS, without highlighting the serious side effects like PRES. To our knowledge, this is the first case reported where PRES occurred with the simultaneous use of atezolizumab and bevacizumab. Since both drugs can individually cause PRES, there might be a heightened risk with the co-administration, signaling a critical need for vigilant monitoring and further research into this treatment modality’s long-term safety profile.

Background

Bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody, is known to inhibit angiogenesis and prevent carcinogenesis. Recent evidence from the IMbrave050 trial indicates that combining bevacizumab with atezolizumab enhances recurrence-free survival (RFS) in high-risk HCC patients undergoing curative treatments. Bevacizumab is notorious for causing endothelial dysfunction that may provoke vasospasm, leading to central hypoperfusion, hypertension, and, albeit rarely, PRES. Similarly, immunotherapy, including atezolizumab, has been implicated in PRES, underscoring a potential risk when these therapies are administered concurrently.

Case Presentation

A 64-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C and alcoholic cirrhosis was diagnosed with stage II (T2 N0 M0) HCC. Following partial hepatectomy, we proceeded with adjuvant systemic therapy with atezolizumab and bevacizumab (per the IMbrave050 trial). After her 2nd treatment, she developed altered mental status, seizures, and severe hypertension. Labs revealed acute kidney injury and elevated creatinine kinase levels suggesting rhabdomyolysis. Computed tomography head showed no acute findings, but magnetic resonance imaging of the brain identified increased flair attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) signal in the brain’s posterior regions, indicating PRES. Symptomatic management with anti-hypertensives and intravenous fluids led to the recovery of mental status to baseline. Further therapy with bevacizumab and atezolizumab was then held off.

Discussion

Therapeutic advances in HCC management through the IMbrave050 trial demonstrate the efficacy of bevacizumab and atezolizumab in reducing RFS, without highlighting the serious side effects like PRES. To our knowledge, this is the first case reported where PRES occurred with the simultaneous use of atezolizumab and bevacizumab. Since both drugs can individually cause PRES, there might be a heightened risk with the co-administration, signaling a critical need for vigilant monitoring and further research into this treatment modality’s long-term safety profile.

Cancer Data Trends 2024: Hepatocellular Carcinoma

1. Pinheiro PS, Jones PD, Medina H, et al. Incidence of etiology-specific hepatocellular carcinoma: diIverging trends and significant heterogeneity by race and ethnicity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Published online September 6, 2023. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2023.08.016

2. Ju MR, Karalis JD, Chansard M, et al. Variation of hepatocellular carcinoma treatment patterns and survival across geographic regions in a veteran population. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29(13):8413-8420. doi:10.1245/s10434-022-12390-7

3. Veterans Health Administration. VA collaborative consensus on a pathway for the development of a multidisciplinary team to manage hepatocellular carcinoma. VA Liver Cancer Summit; March 8, 2019; Miami, FL. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.hepatitis.va.gov/pdf/HCC-multidisciplinary-management-best-practices.pdf

4. Emerson L. Hepatocellular carcinoma treatment, survival varies among VA regions. US Medicine. Published June 12, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.usmedicine.com/clinical-topics/cancer/hepatocellular-carcinoma/hepatocellular-carcinoma-treatment-survival-varies-among-va-regions/

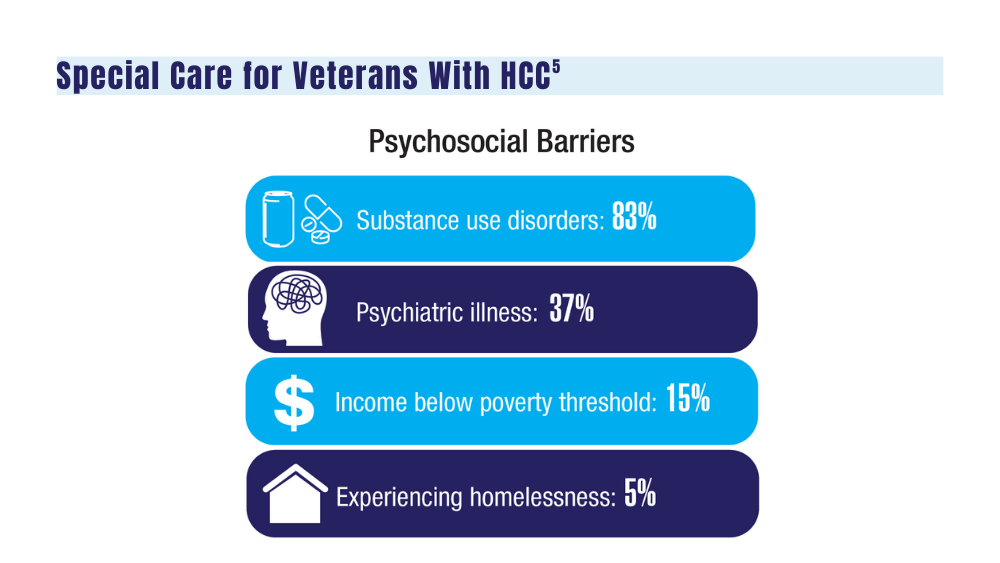

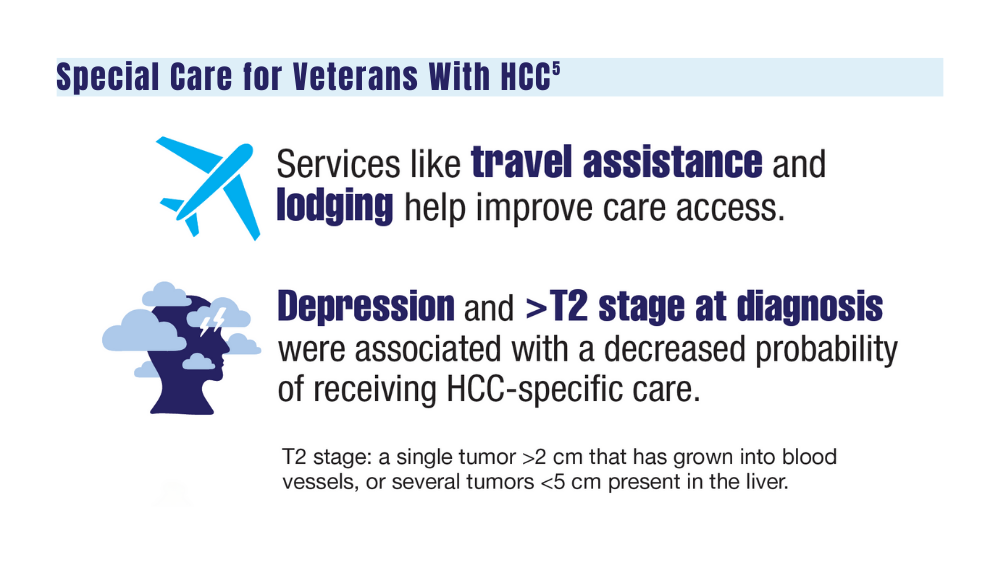

5. Agarwal PD, Haftoglou BA, Ziemlewicz TJ, Lucey MR, Said A. Psychosocial barriers and their impact on hepatocellular carcinoma care in US veterans: tumor board model of care. Fed Pract. 2022;39(suppl 2):S32-S36. doi:10.12788/fp.0272

6. Ito T, Nguyen MH. Perspectives on the underlying etiology of HCC and its effects on treatment outcomes. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2023;10:413-428. doi:10.2147/JHC.S347959

7. Garren P, Serper M. Chronic hepatitis B in US veterans. Curr Hepatol Rep. 2019;18(3):310-315. doi:10.1007/s11901-019-00479-9

8. US Department of Veteran Affairs. Hepatitis C: information for veterans. Published November 2022. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.hepatitis.va.gov/pdf/Hepatitis-C-Factsheet-Veterans.pdf

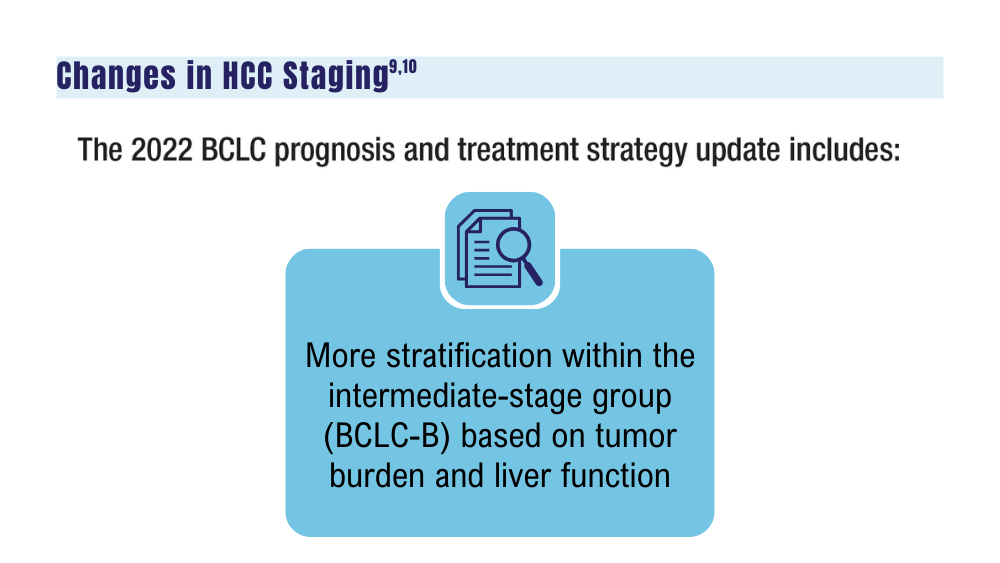

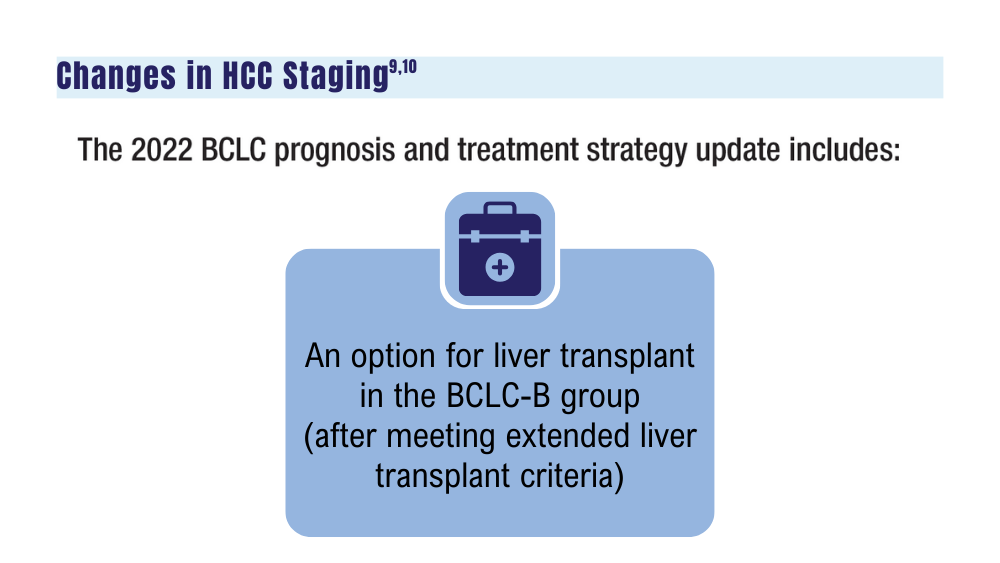

9. Janevska D, Chaloska-Ivanova V, Janevski V. Hepatocellular carcinoma: risk factors, diagnosis and treatment. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2015;3(4):732-736. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2015.111

10. Elderkin J, Al Hallak N, Azmi AS, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: surveillance, diagnosis, evaluation and management. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(21):5118. doi:http://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15215118

11. Wei H, Yang J, Lu R, et al. m6A modification of AC026356.1 facilitates hepatocellular carcinoma progression by regulating the IGF2BP1-IL11 axis. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):19124. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-45449-w

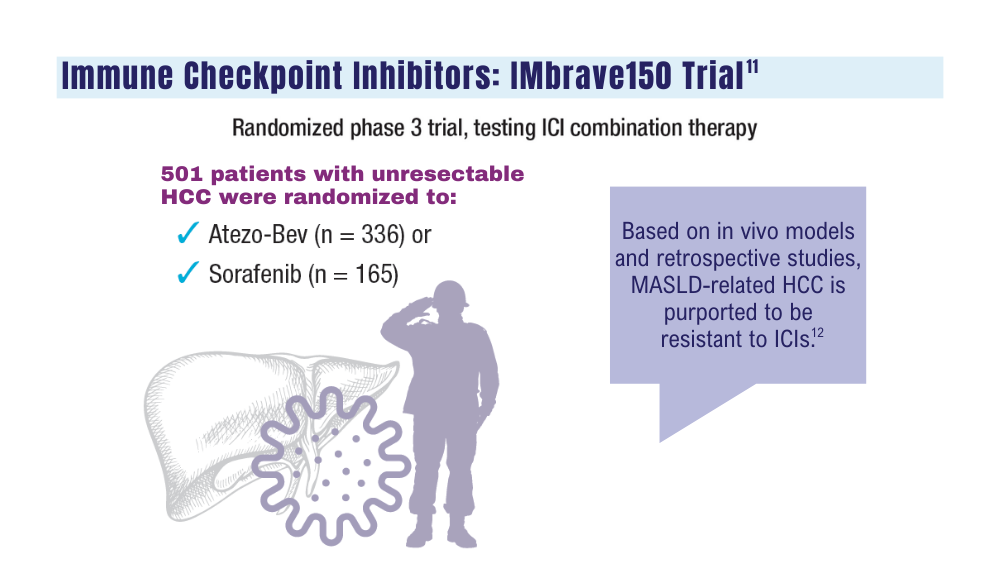

12. Espinoza M, Muquith M, Lim M, Zhu H, Singal AG, Hsiehchen D. Disease etiology and outcomes after atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in hepatocellular carcinoma: post-hoc analysis of IMbrave150. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(1):286-288.e4. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.02.042

13. Zhang H, Zhang W, Jiang L, Chen Y. Recent advances in systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomark Res. 2022;10(1):3. doi:10.1186/s40364-021-00350-4

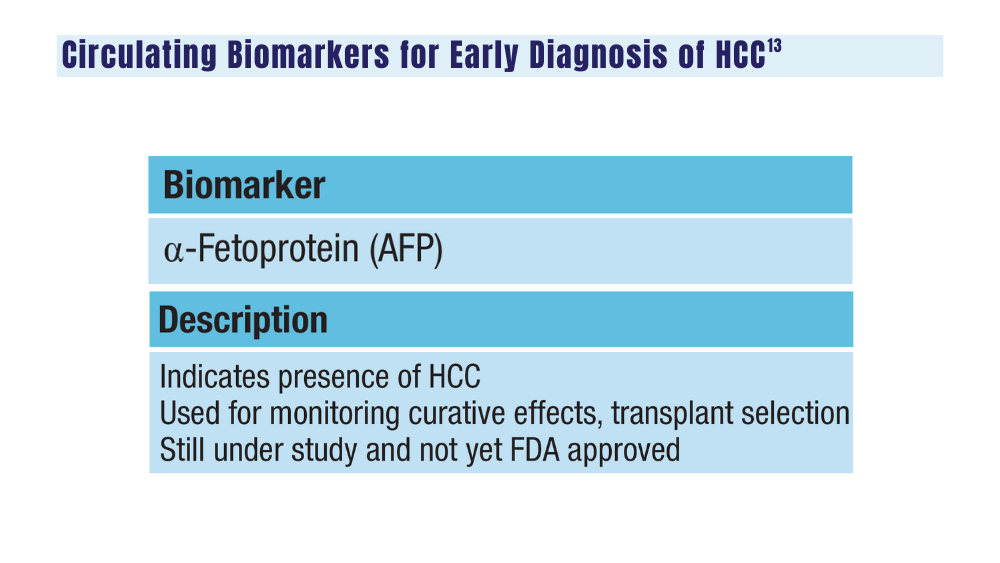

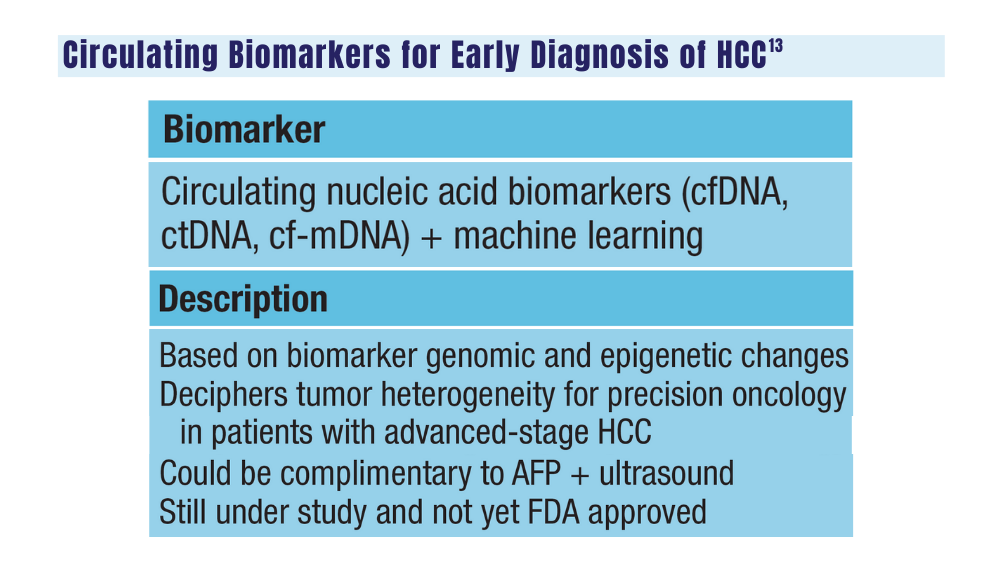

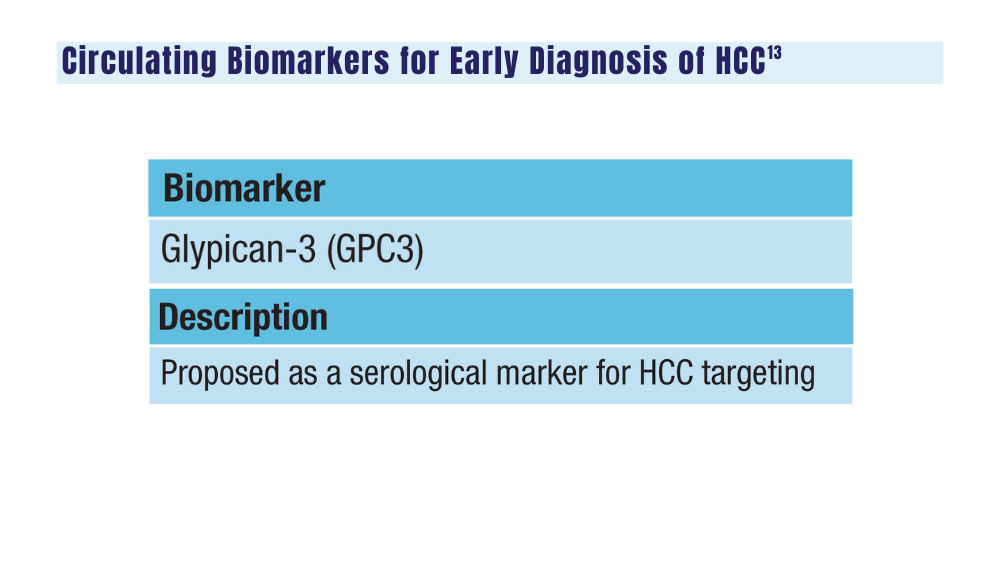

14. Johnson P, Zhou Q, Dao DY, Lo YMD. Circulating biomarkers in the diagnosis and management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19(10):670-681. doi:10.1038/s41575-022-00620-y

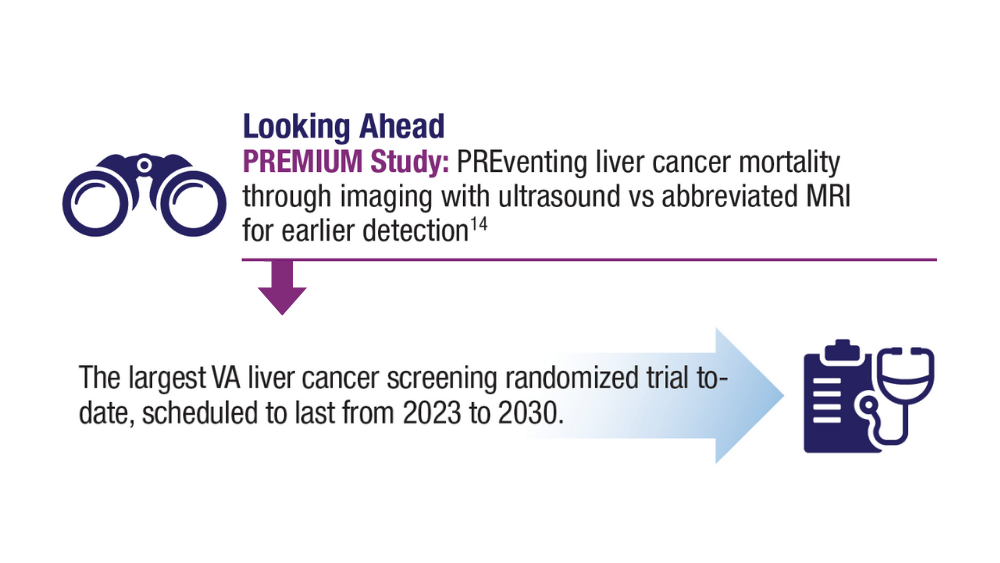

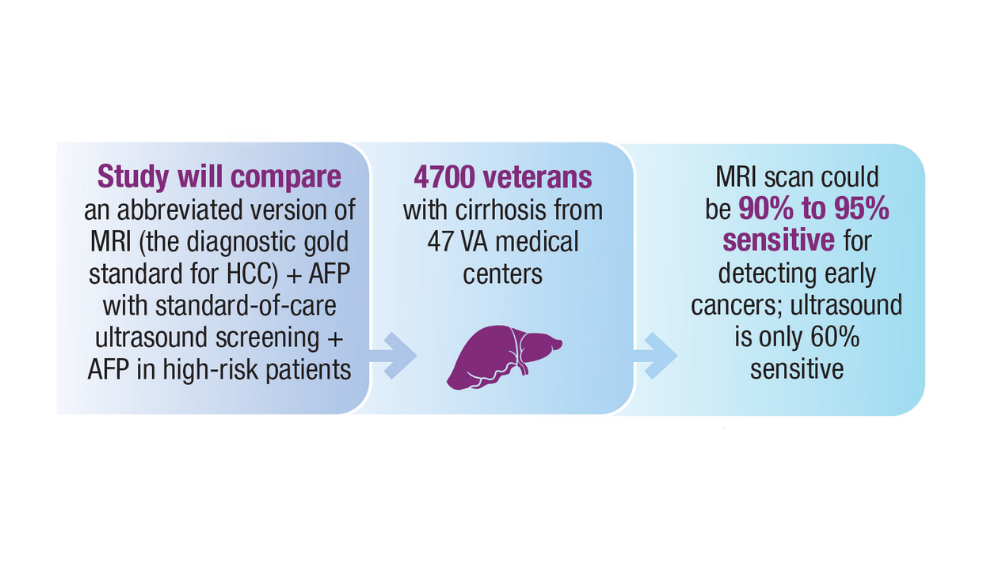

15. US Department of Veteran Affairs. VA Cooperative Studies Program (CSP). CSP #2023 PREventing liver cancer Mortality through Imaging with Ultrasound vs MRI (PREMIUM STUDY). Updated July 2022. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.vacsp.research.va.gov /CSP_2023/CSP_2023.asp

1. Pinheiro PS, Jones PD, Medina H, et al. Incidence of etiology-specific hepatocellular carcinoma: diIverging trends and significant heterogeneity by race and ethnicity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Published online September 6, 2023. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2023.08.016

2. Ju MR, Karalis JD, Chansard M, et al. Variation of hepatocellular carcinoma treatment patterns and survival across geographic regions in a veteran population. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29(13):8413-8420. doi:10.1245/s10434-022-12390-7

3. Veterans Health Administration. VA collaborative consensus on a pathway for the development of a multidisciplinary team to manage hepatocellular carcinoma. VA Liver Cancer Summit; March 8, 2019; Miami, FL. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.hepatitis.va.gov/pdf/HCC-multidisciplinary-management-best-practices.pdf

4. Emerson L. Hepatocellular carcinoma treatment, survival varies among VA regions. US Medicine. Published June 12, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.usmedicine.com/clinical-topics/cancer/hepatocellular-carcinoma/hepatocellular-carcinoma-treatment-survival-varies-among-va-regions/

5. Agarwal PD, Haftoglou BA, Ziemlewicz TJ, Lucey MR, Said A. Psychosocial barriers and their impact on hepatocellular carcinoma care in US veterans: tumor board model of care. Fed Pract. 2022;39(suppl 2):S32-S36. doi:10.12788/fp.0272

6. Ito T, Nguyen MH. Perspectives on the underlying etiology of HCC and its effects on treatment outcomes. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2023;10:413-428. doi:10.2147/JHC.S347959

7. Garren P, Serper M. Chronic hepatitis B in US veterans. Curr Hepatol Rep. 2019;18(3):310-315. doi:10.1007/s11901-019-00479-9

8. US Department of Veteran Affairs. Hepatitis C: information for veterans. Published November 2022. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.hepatitis.va.gov/pdf/Hepatitis-C-Factsheet-Veterans.pdf

9. Janevska D, Chaloska-Ivanova V, Janevski V. Hepatocellular carcinoma: risk factors, diagnosis and treatment. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2015;3(4):732-736. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2015.111

10. Elderkin J, Al Hallak N, Azmi AS, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: surveillance, diagnosis, evaluation and management. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(21):5118. doi:http://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15215118

11. Wei H, Yang J, Lu R, et al. m6A modification of AC026356.1 facilitates hepatocellular carcinoma progression by regulating the IGF2BP1-IL11 axis. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):19124. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-45449-w

12. Espinoza M, Muquith M, Lim M, Zhu H, Singal AG, Hsiehchen D. Disease etiology and outcomes after atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in hepatocellular carcinoma: post-hoc analysis of IMbrave150. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(1):286-288.e4. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.02.042

13. Zhang H, Zhang W, Jiang L, Chen Y. Recent advances in systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomark Res. 2022;10(1):3. doi:10.1186/s40364-021-00350-4

14. Johnson P, Zhou Q, Dao DY, Lo YMD. Circulating biomarkers in the diagnosis and management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19(10):670-681. doi:10.1038/s41575-022-00620-y

15. US Department of Veteran Affairs. VA Cooperative Studies Program (CSP). CSP #2023 PREventing liver cancer Mortality through Imaging with Ultrasound vs MRI (PREMIUM STUDY). Updated July 2022. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.vacsp.research.va.gov /CSP_2023/CSP_2023.asp

1. Pinheiro PS, Jones PD, Medina H, et al. Incidence of etiology-specific hepatocellular carcinoma: diIverging trends and significant heterogeneity by race and ethnicity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Published online September 6, 2023. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2023.08.016

2. Ju MR, Karalis JD, Chansard M, et al. Variation of hepatocellular carcinoma treatment patterns and survival across geographic regions in a veteran population. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29(13):8413-8420. doi:10.1245/s10434-022-12390-7

3. Veterans Health Administration. VA collaborative consensus on a pathway for the development of a multidisciplinary team to manage hepatocellular carcinoma. VA Liver Cancer Summit; March 8, 2019; Miami, FL. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.hepatitis.va.gov/pdf/HCC-multidisciplinary-management-best-practices.pdf

4. Emerson L. Hepatocellular carcinoma treatment, survival varies among VA regions. US Medicine. Published June 12, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.usmedicine.com/clinical-topics/cancer/hepatocellular-carcinoma/hepatocellular-carcinoma-treatment-survival-varies-among-va-regions/

5. Agarwal PD, Haftoglou BA, Ziemlewicz TJ, Lucey MR, Said A. Psychosocial barriers and their impact on hepatocellular carcinoma care in US veterans: tumor board model of care. Fed Pract. 2022;39(suppl 2):S32-S36. doi:10.12788/fp.0272

6. Ito T, Nguyen MH. Perspectives on the underlying etiology of HCC and its effects on treatment outcomes. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2023;10:413-428. doi:10.2147/JHC.S347959

7. Garren P, Serper M. Chronic hepatitis B in US veterans. Curr Hepatol Rep. 2019;18(3):310-315. doi:10.1007/s11901-019-00479-9

8. US Department of Veteran Affairs. Hepatitis C: information for veterans. Published November 2022. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.hepatitis.va.gov/pdf/Hepatitis-C-Factsheet-Veterans.pdf

9. Janevska D, Chaloska-Ivanova V, Janevski V. Hepatocellular carcinoma: risk factors, diagnosis and treatment. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2015;3(4):732-736. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2015.111

10. Elderkin J, Al Hallak N, Azmi AS, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: surveillance, diagnosis, evaluation and management. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(21):5118. doi:http://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15215118

11. Wei H, Yang J, Lu R, et al. m6A modification of AC026356.1 facilitates hepatocellular carcinoma progression by regulating the IGF2BP1-IL11 axis. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):19124. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-45449-w

12. Espinoza M, Muquith M, Lim M, Zhu H, Singal AG, Hsiehchen D. Disease etiology and outcomes after atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in hepatocellular carcinoma: post-hoc analysis of IMbrave150. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(1):286-288.e4. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.02.042

13. Zhang H, Zhang W, Jiang L, Chen Y. Recent advances in systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomark Res. 2022;10(1):3. doi:10.1186/s40364-021-00350-4

14. Johnson P, Zhou Q, Dao DY, Lo YMD. Circulating biomarkers in the diagnosis and management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19(10):670-681. doi:10.1038/s41575-022-00620-y

15. US Department of Veteran Affairs. VA Cooperative Studies Program (CSP). CSP #2023 PREventing liver cancer Mortality through Imaging with Ultrasound vs MRI (PREMIUM STUDY). Updated July 2022. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.vacsp.research.va.gov /CSP_2023/CSP_2023.asp

Cancer Data Trends 2024

Click to view the Digital Edition.

In this issue:

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Special care for veterans, changes in staging, and biomarkers for early diagnosis

Lung Cancer

Guideline updates and racial disparities in veterans

Multiple Myeloma

Improving survival in the VA

Colorectal Cancer

Barriers to follow-up colonoscopies after FIT testing

B-Cell Lymphomas

Findings from the VA's National TeleOncology Program and recent therapy updates

Breast Cancer

A look at the VA's Risk Assessment Pipeline and incidence among veterans vs the general population

Genitourinary Cancers

Molecular testing in prostate cancer, improving survival for metastatic RCC, and links between bladder cancer and Agent Orange exposure

Click to view the Digital Edition.

In this issue:

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Special care for veterans, changes in staging, and biomarkers for early diagnosis

Lung Cancer

Guideline updates and racial disparities in veterans

Multiple Myeloma

Improving survival in the VA

Colorectal Cancer

Barriers to follow-up colonoscopies after FIT testing

B-Cell Lymphomas

Findings from the VA's National TeleOncology Program and recent therapy updates

Breast Cancer

A look at the VA's Risk Assessment Pipeline and incidence among veterans vs the general population

Genitourinary Cancers

Molecular testing in prostate cancer, improving survival for metastatic RCC, and links between bladder cancer and Agent Orange exposure

Click to view the Digital Edition.

In this issue:

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Special care for veterans, changes in staging, and biomarkers for early diagnosis

Lung Cancer

Guideline updates and racial disparities in veterans

Multiple Myeloma

Improving survival in the VA

Colorectal Cancer

Barriers to follow-up colonoscopies after FIT testing

B-Cell Lymphomas

Findings from the VA's National TeleOncology Program and recent therapy updates

Breast Cancer

A look at the VA's Risk Assessment Pipeline and incidence among veterans vs the general population

Genitourinary Cancers

Molecular testing in prostate cancer, improving survival for metastatic RCC, and links between bladder cancer and Agent Orange exposure

Fewer than 1 out of 4 patients with HCV-related liver cancer receive antivirals

, and rates aren’t much better for patients seen by specialists, based on a retrospective analysis of private insurance claims.

The study also showed that patients receiving DAAs lived significantly longer, emphasizing the importance of prescribing these medications to all eligible patients, reported principal investigator Mindie H. Nguyen, MD, AGAF,, of Stanford University Medical Center, Palo Alto, California, and colleagues.

“Prior studies have shown evidence of improved survival among HCV-related HCC patients who received DAA treatment, but not much is known about the current DAA utilization among these patients in the general US population,” said lead author Leslie Y. Kam, MD, a postdoctoral scholar in gastroenterology at Stanford Medicine, who presented the findings in November at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

To generate real-world data, the investigators analyzed medical records from 3922 patients in Optum’s Clinformatics Data Mart Database. All patients had private medical insurance and received care for HCV-related HCC between 2015 and 2021.

“Instead of using institutional databases which tend to bias toward highly specialized tertiary care center patients, our study uses a large, national sample of HCV-HCC patients that represents real-world DAA treatment rates and survival outcomes,” Dr. Kam said in a written comment.

Within this cohort, fewer than one out of four patients (23.5%) received DAA, a rate that Dr. Kam called “dismally low.”

Patients with either compensated or decompensated cirrhosis had higher treatment rates than those without cirrhosis (24.2% or 24.5%, respectively, vs. 16.2%; P = .001). The investigators noted that more than half of the patients had decompensated cirrhosis, suggesting that HCV-related HCC was diagnosed late in the disease course.

Receiving care from a gastroenterologist or infectious disease physician also was associated with a higher treatment rate. Patients managed by a gastroenterologist alone had a treatment rate of 27.0%, while those who received care from a gastroenterologist or infectious disease doctor alongside an oncologist had a treatment rate of 25.6%, versus just 9.4% for those who received care from an oncologist alone, and 12.4% among those who did not see a specialist of any kind (P = .005).

These findings highlight “the need for a multidisciplinary approach to care in this population,” Dr. Kam suggested.

Echoing previous research, DAAs were associated with extended survival. A significantly greater percentage of patients who received DAA were alive after 5 years, compared with patients who did not receive DAA (47.2% vs. 35.2%; P less than .001). After adjustment for comorbidities, HCC treatment, race/ethnicity, sex, and age, DAAs were associated with a 39% reduction in risk of death (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.61; 0.53-0.69; P less than .001).

“There were also racial ethnic disparities in patient survival whether patients received DAA or not, with Black patients having worse survival,” Dr. Kam said. “As such, our study highlights that awareness of HCV remains low as does the use of DAA treatment. Therefore, culturally appropriate efforts to improve awareness of HCV must continue among the general public and health care workers as well as efforts to provide point of care accurate and rapid screening tests for HCV so that DAA treatment can be initiated in a timely manner for eligible patients. Continual education on the use of DAA treatment is also needed.”

Robert John Fontana, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, described the findings as “frustrating,” and “not the kind of stuff I like to hear about.

“Treatment rates are so low,” Dr. Fontana said, noting that even among gastroenterologists and infectious disease doctors, who should be well-versed in DAAs, antivirals were prescribed less than 30% of the time.

In an interview, Dr. Fontana highlighted the benefits of DAAs, including their ease-of-use and effectiveness.

“Hepatitis C was the leading reason that we had to do liver transplants in the United States for years,” he said. “Then once these really amazing drugs called direct-acting antivirals came out, they changed the landscape very quickly. It really was a game changer for my whole practice, and, nationally, the practice of transplant.”

Yet, this study and others suggest that these practice-altering agents are being underutilized, Dr. Fontana said. A variety of reasons could explain suboptimal usage, he suggested, including lack of awareness among medical professionals and the public, the recency of DAA approvals, low HCV testing rates, lack of symptoms in HCV-positive patients, and medication costs.

This latter barrier, at least, is dissolving, Dr. Fontana said. Some payers initially restricted which providers could prescribe DAAs, but now the economic consensus has swung in their favor, since curing patients of HCV brings significant health care savings down the line. This financial advantage—theoretically multiplied across 4-5 million Americans living with HCV—has bolstered a multi-institutional effort toward universal HCV screening, with testing recommended at least once in every person’s lifetime.

“It’s highly cost effective,” Dr. Fontana said. “Even though the drugs are super expensive, you will reduce cost by preventing the people streaming towards liver cancer or streaming towards liver transplant. That’s why all the professional societies—the USPSTF, the CDC—they all say, ‘OK, screen everyone.’ ”

Screening may be getting easier soon, Dr. Fontana predicted, as at-home HCV-testing kits are on the horizon, with development and adoption likely accelerated by the success of at-home viral testing during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Beyond broader screening, Dr. Fontana suggested that greater awareness of DAAs is needed both within and beyond the medical community.

He advised health care providers who don’t yet feel comfortable diagnosing or treating HCV to refer to their local specialist.

“That’s the main message,” Dr. Fontana said. “I’m always eternally hopeful that every little message helps.”

The investigators and Dr. Fontana disclosed no conflicts of interest.

, and rates aren’t much better for patients seen by specialists, based on a retrospective analysis of private insurance claims.

The study also showed that patients receiving DAAs lived significantly longer, emphasizing the importance of prescribing these medications to all eligible patients, reported principal investigator Mindie H. Nguyen, MD, AGAF,, of Stanford University Medical Center, Palo Alto, California, and colleagues.

“Prior studies have shown evidence of improved survival among HCV-related HCC patients who received DAA treatment, but not much is known about the current DAA utilization among these patients in the general US population,” said lead author Leslie Y. Kam, MD, a postdoctoral scholar in gastroenterology at Stanford Medicine, who presented the findings in November at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

To generate real-world data, the investigators analyzed medical records from 3922 patients in Optum’s Clinformatics Data Mart Database. All patients had private medical insurance and received care for HCV-related HCC between 2015 and 2021.

“Instead of using institutional databases which tend to bias toward highly specialized tertiary care center patients, our study uses a large, national sample of HCV-HCC patients that represents real-world DAA treatment rates and survival outcomes,” Dr. Kam said in a written comment.

Within this cohort, fewer than one out of four patients (23.5%) received DAA, a rate that Dr. Kam called “dismally low.”

Patients with either compensated or decompensated cirrhosis had higher treatment rates than those without cirrhosis (24.2% or 24.5%, respectively, vs. 16.2%; P = .001). The investigators noted that more than half of the patients had decompensated cirrhosis, suggesting that HCV-related HCC was diagnosed late in the disease course.

Receiving care from a gastroenterologist or infectious disease physician also was associated with a higher treatment rate. Patients managed by a gastroenterologist alone had a treatment rate of 27.0%, while those who received care from a gastroenterologist or infectious disease doctor alongside an oncologist had a treatment rate of 25.6%, versus just 9.4% for those who received care from an oncologist alone, and 12.4% among those who did not see a specialist of any kind (P = .005).

These findings highlight “the need for a multidisciplinary approach to care in this population,” Dr. Kam suggested.

Echoing previous research, DAAs were associated with extended survival. A significantly greater percentage of patients who received DAA were alive after 5 years, compared with patients who did not receive DAA (47.2% vs. 35.2%; P less than .001). After adjustment for comorbidities, HCC treatment, race/ethnicity, sex, and age, DAAs were associated with a 39% reduction in risk of death (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.61; 0.53-0.69; P less than .001).

“There were also racial ethnic disparities in patient survival whether patients received DAA or not, with Black patients having worse survival,” Dr. Kam said. “As such, our study highlights that awareness of HCV remains low as does the use of DAA treatment. Therefore, culturally appropriate efforts to improve awareness of HCV must continue among the general public and health care workers as well as efforts to provide point of care accurate and rapid screening tests for HCV so that DAA treatment can be initiated in a timely manner for eligible patients. Continual education on the use of DAA treatment is also needed.”

Robert John Fontana, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, described the findings as “frustrating,” and “not the kind of stuff I like to hear about.

“Treatment rates are so low,” Dr. Fontana said, noting that even among gastroenterologists and infectious disease doctors, who should be well-versed in DAAs, antivirals were prescribed less than 30% of the time.

In an interview, Dr. Fontana highlighted the benefits of DAAs, including their ease-of-use and effectiveness.

“Hepatitis C was the leading reason that we had to do liver transplants in the United States for years,” he said. “Then once these really amazing drugs called direct-acting antivirals came out, they changed the landscape very quickly. It really was a game changer for my whole practice, and, nationally, the practice of transplant.”

Yet, this study and others suggest that these practice-altering agents are being underutilized, Dr. Fontana said. A variety of reasons could explain suboptimal usage, he suggested, including lack of awareness among medical professionals and the public, the recency of DAA approvals, low HCV testing rates, lack of symptoms in HCV-positive patients, and medication costs.

This latter barrier, at least, is dissolving, Dr. Fontana said. Some payers initially restricted which providers could prescribe DAAs, but now the economic consensus has swung in their favor, since curing patients of HCV brings significant health care savings down the line. This financial advantage—theoretically multiplied across 4-5 million Americans living with HCV—has bolstered a multi-institutional effort toward universal HCV screening, with testing recommended at least once in every person’s lifetime.

“It’s highly cost effective,” Dr. Fontana said. “Even though the drugs are super expensive, you will reduce cost by preventing the people streaming towards liver cancer or streaming towards liver transplant. That’s why all the professional societies—the USPSTF, the CDC—they all say, ‘OK, screen everyone.’ ”

Screening may be getting easier soon, Dr. Fontana predicted, as at-home HCV-testing kits are on the horizon, with development and adoption likely accelerated by the success of at-home viral testing during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Beyond broader screening, Dr. Fontana suggested that greater awareness of DAAs is needed both within and beyond the medical community.

He advised health care providers who don’t yet feel comfortable diagnosing or treating HCV to refer to their local specialist.

“That’s the main message,” Dr. Fontana said. “I’m always eternally hopeful that every little message helps.”

The investigators and Dr. Fontana disclosed no conflicts of interest.

, and rates aren’t much better for patients seen by specialists, based on a retrospective analysis of private insurance claims.

The study also showed that patients receiving DAAs lived significantly longer, emphasizing the importance of prescribing these medications to all eligible patients, reported principal investigator Mindie H. Nguyen, MD, AGAF,, of Stanford University Medical Center, Palo Alto, California, and colleagues.

“Prior studies have shown evidence of improved survival among HCV-related HCC patients who received DAA treatment, but not much is known about the current DAA utilization among these patients in the general US population,” said lead author Leslie Y. Kam, MD, a postdoctoral scholar in gastroenterology at Stanford Medicine, who presented the findings in November at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

To generate real-world data, the investigators analyzed medical records from 3922 patients in Optum’s Clinformatics Data Mart Database. All patients had private medical insurance and received care for HCV-related HCC between 2015 and 2021.

“Instead of using institutional databases which tend to bias toward highly specialized tertiary care center patients, our study uses a large, national sample of HCV-HCC patients that represents real-world DAA treatment rates and survival outcomes,” Dr. Kam said in a written comment.

Within this cohort, fewer than one out of four patients (23.5%) received DAA, a rate that Dr. Kam called “dismally low.”

Patients with either compensated or decompensated cirrhosis had higher treatment rates than those without cirrhosis (24.2% or 24.5%, respectively, vs. 16.2%; P = .001). The investigators noted that more than half of the patients had decompensated cirrhosis, suggesting that HCV-related HCC was diagnosed late in the disease course.

Receiving care from a gastroenterologist or infectious disease physician also was associated with a higher treatment rate. Patients managed by a gastroenterologist alone had a treatment rate of 27.0%, while those who received care from a gastroenterologist or infectious disease doctor alongside an oncologist had a treatment rate of 25.6%, versus just 9.4% for those who received care from an oncologist alone, and 12.4% among those who did not see a specialist of any kind (P = .005).

These findings highlight “the need for a multidisciplinary approach to care in this population,” Dr. Kam suggested.

Echoing previous research, DAAs were associated with extended survival. A significantly greater percentage of patients who received DAA were alive after 5 years, compared with patients who did not receive DAA (47.2% vs. 35.2%; P less than .001). After adjustment for comorbidities, HCC treatment, race/ethnicity, sex, and age, DAAs were associated with a 39% reduction in risk of death (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.61; 0.53-0.69; P less than .001).

“There were also racial ethnic disparities in patient survival whether patients received DAA or not, with Black patients having worse survival,” Dr. Kam said. “As such, our study highlights that awareness of HCV remains low as does the use of DAA treatment. Therefore, culturally appropriate efforts to improve awareness of HCV must continue among the general public and health care workers as well as efforts to provide point of care accurate and rapid screening tests for HCV so that DAA treatment can be initiated in a timely manner for eligible patients. Continual education on the use of DAA treatment is also needed.”

Robert John Fontana, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, described the findings as “frustrating,” and “not the kind of stuff I like to hear about.

“Treatment rates are so low,” Dr. Fontana said, noting that even among gastroenterologists and infectious disease doctors, who should be well-versed in DAAs, antivirals were prescribed less than 30% of the time.

In an interview, Dr. Fontana highlighted the benefits of DAAs, including their ease-of-use and effectiveness.

“Hepatitis C was the leading reason that we had to do liver transplants in the United States for years,” he said. “Then once these really amazing drugs called direct-acting antivirals came out, they changed the landscape very quickly. It really was a game changer for my whole practice, and, nationally, the practice of transplant.”

Yet, this study and others suggest that these practice-altering agents are being underutilized, Dr. Fontana said. A variety of reasons could explain suboptimal usage, he suggested, including lack of awareness among medical professionals and the public, the recency of DAA approvals, low HCV testing rates, lack of symptoms in HCV-positive patients, and medication costs.

This latter barrier, at least, is dissolving, Dr. Fontana said. Some payers initially restricted which providers could prescribe DAAs, but now the economic consensus has swung in their favor, since curing patients of HCV brings significant health care savings down the line. This financial advantage—theoretically multiplied across 4-5 million Americans living with HCV—has bolstered a multi-institutional effort toward universal HCV screening, with testing recommended at least once in every person’s lifetime.

“It’s highly cost effective,” Dr. Fontana said. “Even though the drugs are super expensive, you will reduce cost by preventing the people streaming towards liver cancer or streaming towards liver transplant. That’s why all the professional societies—the USPSTF, the CDC—they all say, ‘OK, screen everyone.’ ”

Screening may be getting easier soon, Dr. Fontana predicted, as at-home HCV-testing kits are on the horizon, with development and adoption likely accelerated by the success of at-home viral testing during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Beyond broader screening, Dr. Fontana suggested that greater awareness of DAAs is needed both within and beyond the medical community.

He advised health care providers who don’t yet feel comfortable diagnosing or treating HCV to refer to their local specialist.

“That’s the main message,” Dr. Fontana said. “I’m always eternally hopeful that every little message helps.”

The investigators and Dr. Fontana disclosed no conflicts of interest.

AT THE LIVER MEETING

More than one-third of adults in the US could have NAFLD by 2050

, according to investigators.

These findings suggest that health care systems should prepare for “large increases” in cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and need for liver transplants, reported lead author Phuc Le, PhD, MPH, of the Cleveland Clinic, and colleagues.

“Following the alarming rise in prevalence of obesity and diabetes, NAFLD is projected to become the leading indication for liver transplant in the United States in the next decade,” Dr. Le and colleagues wrote in their abstract for the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “A better understanding of the clinical burden associated with NAFLD will enable health systems to prepare to meet this imminent demand from patients.”

To this end, Dr. Le and colleagues developed an agent-based state transition model to predict future prevalence of NAFLD and associated outcomes.

In the first part of the model, the investigators simulated population growth in the United States using Census Bureau data, including new births and immigration, from the year 2000 onward. The second part of the model simulated natural progression of NAFLD in adults via 14 associated conditions and events, including steatosis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), HCC, liver transplants, liver-related mortality, and others.

By first comparing simulated findings with actual findings between 2000 and 2018, the investigators confirmed that their model could reliably predict the intended epidemiological parameters.

Next, they turned their model toward the future.

It predicted that the prevalence of NAFLD among US adults will rise from 27.8% in 2020 to 34.3% in 2050. Over the same timeframe, prevalence of NASH is predicted to increase from 20.0% to 21.8%, proportion of NAFLD cases developing cirrhosis is expected to increase from 1.9% to 3.1%, and liver-related mortality is estimated to rise from 0.4% to 1% of all deaths.

The model also predicted that the burden of HCC will increase from 10,400 to 19,300 new cases per year, while liver transplant burden will more than double, from 1,700 to 4,200 transplants per year.

“Our model forecasts substantial clinical burden of NAFLD over the next three decades,” Dr. Le said in a virtual press conference. “And in the absence of effective treatments, health systems should plan for large increases in the number of liver cancer cases and the need for liver transplant.”

During the press conference, Norah Terrault, MD, president of the AASLD from the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, noted that all of the reported outcomes, including increasing rates of liver cancer, cirrhosis, and transplants are “potentially preventable.”

Dr. Terrault went on to suggest ways of combating this increasing burden of NAFLD, which she referred to as metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), the name now recommended by the AASLD.

“There’s no way we’re going to be able to transplant our way out of this,” Dr. Terrault said. “We need to be bringing greater awareness both to patients, as well as to providers about how we seek out the diagnosis. And we need to bring greater awareness to the population around the things that contribute to MASLD.”

Rates of obesity and diabetes continue to rise, Dr. Terrault said, explaining why MASLD is more common than ever. To counteract these trends, she called for greater awareness of driving factors, such as dietary choices and sedentary lifestyle.

“These are all really important messages that we want to get out to the population, and are really the cornerstones for how we approach the management of patients who have MASLD,” Dr. Terrault said.

In discussion with Dr. Terrault, Dr. Le agreed that increased education may help stem the rising tide of disease, while treatment advances could also increase the odds of a brighter future.

“If we improve our management of NAFLD, or NAFLD-related comorbidities, and if we can develop an effective treatment for NAFLD, then obviously the future would not be so dark,” Dr. Le said, noting promising phase 3 data that would be presented at the meeting. “We are hopeful that the future of disease burden will not be as bad as our model predicts.”

The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

, according to investigators.

These findings suggest that health care systems should prepare for “large increases” in cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and need for liver transplants, reported lead author Phuc Le, PhD, MPH, of the Cleveland Clinic, and colleagues.

“Following the alarming rise in prevalence of obesity and diabetes, NAFLD is projected to become the leading indication for liver transplant in the United States in the next decade,” Dr. Le and colleagues wrote in their abstract for the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “A better understanding of the clinical burden associated with NAFLD will enable health systems to prepare to meet this imminent demand from patients.”

To this end, Dr. Le and colleagues developed an agent-based state transition model to predict future prevalence of NAFLD and associated outcomes.

In the first part of the model, the investigators simulated population growth in the United States using Census Bureau data, including new births and immigration, from the year 2000 onward. The second part of the model simulated natural progression of NAFLD in adults via 14 associated conditions and events, including steatosis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), HCC, liver transplants, liver-related mortality, and others.

By first comparing simulated findings with actual findings between 2000 and 2018, the investigators confirmed that their model could reliably predict the intended epidemiological parameters.

Next, they turned their model toward the future.

It predicted that the prevalence of NAFLD among US adults will rise from 27.8% in 2020 to 34.3% in 2050. Over the same timeframe, prevalence of NASH is predicted to increase from 20.0% to 21.8%, proportion of NAFLD cases developing cirrhosis is expected to increase from 1.9% to 3.1%, and liver-related mortality is estimated to rise from 0.4% to 1% of all deaths.

The model also predicted that the burden of HCC will increase from 10,400 to 19,300 new cases per year, while liver transplant burden will more than double, from 1,700 to 4,200 transplants per year.

“Our model forecasts substantial clinical burden of NAFLD over the next three decades,” Dr. Le said in a virtual press conference. “And in the absence of effective treatments, health systems should plan for large increases in the number of liver cancer cases and the need for liver transplant.”

During the press conference, Norah Terrault, MD, president of the AASLD from the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, noted that all of the reported outcomes, including increasing rates of liver cancer, cirrhosis, and transplants are “potentially preventable.”

Dr. Terrault went on to suggest ways of combating this increasing burden of NAFLD, which she referred to as metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), the name now recommended by the AASLD.

“There’s no way we’re going to be able to transplant our way out of this,” Dr. Terrault said. “We need to be bringing greater awareness both to patients, as well as to providers about how we seek out the diagnosis. And we need to bring greater awareness to the population around the things that contribute to MASLD.”

Rates of obesity and diabetes continue to rise, Dr. Terrault said, explaining why MASLD is more common than ever. To counteract these trends, she called for greater awareness of driving factors, such as dietary choices and sedentary lifestyle.

“These are all really important messages that we want to get out to the population, and are really the cornerstones for how we approach the management of patients who have MASLD,” Dr. Terrault said.

In discussion with Dr. Terrault, Dr. Le agreed that increased education may help stem the rising tide of disease, while treatment advances could also increase the odds of a brighter future.

“If we improve our management of NAFLD, or NAFLD-related comorbidities, and if we can develop an effective treatment for NAFLD, then obviously the future would not be so dark,” Dr. Le said, noting promising phase 3 data that would be presented at the meeting. “We are hopeful that the future of disease burden will not be as bad as our model predicts.”

The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

, according to investigators.

These findings suggest that health care systems should prepare for “large increases” in cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and need for liver transplants, reported lead author Phuc Le, PhD, MPH, of the Cleveland Clinic, and colleagues.

“Following the alarming rise in prevalence of obesity and diabetes, NAFLD is projected to become the leading indication for liver transplant in the United States in the next decade,” Dr. Le and colleagues wrote in their abstract for the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “A better understanding of the clinical burden associated with NAFLD will enable health systems to prepare to meet this imminent demand from patients.”

To this end, Dr. Le and colleagues developed an agent-based state transition model to predict future prevalence of NAFLD and associated outcomes.

In the first part of the model, the investigators simulated population growth in the United States using Census Bureau data, including new births and immigration, from the year 2000 onward. The second part of the model simulated natural progression of NAFLD in adults via 14 associated conditions and events, including steatosis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), HCC, liver transplants, liver-related mortality, and others.

By first comparing simulated findings with actual findings between 2000 and 2018, the investigators confirmed that their model could reliably predict the intended epidemiological parameters.

Next, they turned their model toward the future.

It predicted that the prevalence of NAFLD among US adults will rise from 27.8% in 2020 to 34.3% in 2050. Over the same timeframe, prevalence of NASH is predicted to increase from 20.0% to 21.8%, proportion of NAFLD cases developing cirrhosis is expected to increase from 1.9% to 3.1%, and liver-related mortality is estimated to rise from 0.4% to 1% of all deaths.

The model also predicted that the burden of HCC will increase from 10,400 to 19,300 new cases per year, while liver transplant burden will more than double, from 1,700 to 4,200 transplants per year.

“Our model forecasts substantial clinical burden of NAFLD over the next three decades,” Dr. Le said in a virtual press conference. “And in the absence of effective treatments, health systems should plan for large increases in the number of liver cancer cases and the need for liver transplant.”

During the press conference, Norah Terrault, MD, president of the AASLD from the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, noted that all of the reported outcomes, including increasing rates of liver cancer, cirrhosis, and transplants are “potentially preventable.”

Dr. Terrault went on to suggest ways of combating this increasing burden of NAFLD, which she referred to as metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), the name now recommended by the AASLD.

“There’s no way we’re going to be able to transplant our way out of this,” Dr. Terrault said. “We need to be bringing greater awareness both to patients, as well as to providers about how we seek out the diagnosis. And we need to bring greater awareness to the population around the things that contribute to MASLD.”

Rates of obesity and diabetes continue to rise, Dr. Terrault said, explaining why MASLD is more common than ever. To counteract these trends, she called for greater awareness of driving factors, such as dietary choices and sedentary lifestyle.

“These are all really important messages that we want to get out to the population, and are really the cornerstones for how we approach the management of patients who have MASLD,” Dr. Terrault said.

In discussion with Dr. Terrault, Dr. Le agreed that increased education may help stem the rising tide of disease, while treatment advances could also increase the odds of a brighter future.

“If we improve our management of NAFLD, or NAFLD-related comorbidities, and if we can develop an effective treatment for NAFLD, then obviously the future would not be so dark,” Dr. Le said, noting promising phase 3 data that would be presented at the meeting. “We are hopeful that the future of disease burden will not be as bad as our model predicts.”

The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

AT THE LIVER MEETING

New biomarker tests could reduce need for liver biopsy

(NASH, now known as metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis or MASH), laying the groundwork for noninvasive alternatives to liver biopsy, new research suggests.

The blood-based tests could expand diagnostic options at health care facilities and facilitate enrollment in NASH clinical trials, which now require a biopsy for inclusion.

“The current study meets a key milestone for qualification of the biomarker panels studied for identification of at-risk NASH,” Arun Sanyal, MD, of the Stravitz-Sanyal Institute for Liver Disease and Metabolic Health at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, told this news organization.

“It sets the stage for further validation of these outcomes,” he said. “These data will inform development of full qualification plans for these biomarker panels that will be submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Once these are accepted by the FDA, the final steps toward qualification can be initiated.”

The study, published online in Nature Medicine, was conducted as part of the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health – Biomarkers Consortium’s Noninvasive Biomarkers of Metabolic Liver Disease (FNIH-NIMBLE), a multistakeholder project to support regulatory approval of NASH-related biomarkers.

Multiple biomarkers move forward

The investigators evaluated the diagnostic performance of five blood-based panels in an observational cohort derived from the NASH Clinical Research Network study, which included 4,094 participants; 2,479 individuals were excluded from the current study because of age, lack of samples, or lack of evaluable liver biopsies.

The remaining 1,073 patients (mean age, 52.5 years; 62% women) represented the full spectrum of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD, now known as metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease or MASLD). In total, 225 individuals had NAFLD, 835 had NASH, and 13 had cirrhosis with an indeterminate NAFLD phenotype.

Those without fibrosis were younger and had mainly fatty liver, not steatohepatitis. They also had a lower NAFLD activity score, compared with those with stage 2 or higher fibrosis.

The study population for one of the five tests, FibroMeter VCTE, was a smaller subset (n = 396) of the larger population, with baseline features similar to the larger cohort.

The biomarker panels were intended to diagnose at-risk NASH (NIS4), presence of NASH (OWLiver), or fibrosis stages greater than 2, greater than 3, or 4 (enhanced liver fibrosis [ELF] test, PROC3, and FibroMeter VCTE). At-risk NASH was defined by the presence of NASH, high histologic activity, and fibrosis stage greater than or equal to 2.

The performance metric was an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) greater than or equal to 0.7 and superiority over alanine aminotransferase (ALT) for disease activity and the FIB-4 test for fibrosis severity.

Multiple biomarkers met the required metrics. For example, NIS4 had an AUROC of 0.81 for at-risk NASH. AUROCs for the ELF test (for clinically significant fibrosis, ≥ stage 2), PROC3 (advanced fibrosis, ≥ stage 3), and FibroMeter VCTE (cirrhosis, stage 4) were all greater than or equal to 0.8.

For all fibrosis endpoints, ELF and FibroMeter VCTE also outperformed FIB-4.

“The current study was a first step to determine if the biomarker panels not only identified the relevant phenotypes based on their intended use but also if they were superior to some commonly used clinical laboratory tools, such as ALT and FIB-4,” the authors write. “These will serve as criteria, to be finalized with feedback from the FDA, to move the panels with the most promising performance metrics to the final qualification steps.”

“Individual developers of specific biomarker panels will need to determine their strategy; that is, have separate rule-in and rule-out cutoffs or a single optimized cutoff as they [formulate] the full qualification plans,” Dr. Sanyal noted. “Also, it may be necessary to validate these cutoffs and performance in independent cohorts reflecting the populations where these are planned to be used.”

“We hope that by 2025, the first wave of biomarkers will have enough data to support approval for diagnostic purposes, and the data for prognostic biomarkers will follow within 1-2 years after that,” Dr. Sanyal added.

Are practice changes ahead?

“Findings from this study and subsequent planned studies have the potential to redefine our approach to MASH and fibrosis diagnosis and staging, both in clinical practice and as part of clinical trials for the multiple new therapeutics being evaluated for MASLD/MASH,” Tatyana Kushner, MD, gastroenterologist/hepatologist and associate professor of medicine in the Division of Liver Diseases at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, told this news organization.

Dr. Kushner noted that the study population “may not represent the diverse population affected by MASH in the United States, or even the clinical trial population.” The cohort was predominantly White, with relatively low representation from people of Hispanic ethnicity, who are known to have a higher prevalence of MASH.

“Furthermore, the study population was specifically curated to have representative numbers across liver disease/fibrosis stages, and this may have biased the results,” she added.

In addition, other MASH-related biomarkers were developed after the current study started, including the FAST, Agile, and ADAPT scores, she said. “After validation of the biomarkers in this study, it will also be important to see how this newer wave of biomarkers performs.”

“If subsequent efforts validate the current findings, and there is buy-in from all of the stakeholders, including the FDA, NIH, industry, and academic leaders, this can truly lead to practice-changing approaches to the clinical management and study of MASLD/MASH,” Dr. Kushner concluded.

The study was partially funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The NIMBLE project is sponsored by the FNIH and is a public-private partnership supported by numerous entities. Support was also provided by the Global Liver Institute and FDA. Dr. Sanyal has disclosed financial relationships with multiple companies. He recused himself from the analysis and interpretation of NIS4. Dr. Kushner has declared being an adviser for Gilead, AbbVie, Eiger, and Bausch, and receiving research support from Gilead. None are MASH/NASH-related.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(NASH, now known as metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis or MASH), laying the groundwork for noninvasive alternatives to liver biopsy, new research suggests.

The blood-based tests could expand diagnostic options at health care facilities and facilitate enrollment in NASH clinical trials, which now require a biopsy for inclusion.

“The current study meets a key milestone for qualification of the biomarker panels studied for identification of at-risk NASH,” Arun Sanyal, MD, of the Stravitz-Sanyal Institute for Liver Disease and Metabolic Health at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, told this news organization.

“It sets the stage for further validation of these outcomes,” he said. “These data will inform development of full qualification plans for these biomarker panels that will be submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Once these are accepted by the FDA, the final steps toward qualification can be initiated.”

The study, published online in Nature Medicine, was conducted as part of the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health – Biomarkers Consortium’s Noninvasive Biomarkers of Metabolic Liver Disease (FNIH-NIMBLE), a multistakeholder project to support regulatory approval of NASH-related biomarkers.

Multiple biomarkers move forward

The investigators evaluated the diagnostic performance of five blood-based panels in an observational cohort derived from the NASH Clinical Research Network study, which included 4,094 participants; 2,479 individuals were excluded from the current study because of age, lack of samples, or lack of evaluable liver biopsies.

The remaining 1,073 patients (mean age, 52.5 years; 62% women) represented the full spectrum of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD, now known as metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease or MASLD). In total, 225 individuals had NAFLD, 835 had NASH, and 13 had cirrhosis with an indeterminate NAFLD phenotype.

Those without fibrosis were younger and had mainly fatty liver, not steatohepatitis. They also had a lower NAFLD activity score, compared with those with stage 2 or higher fibrosis.

The study population for one of the five tests, FibroMeter VCTE, was a smaller subset (n = 396) of the larger population, with baseline features similar to the larger cohort.

The biomarker panels were intended to diagnose at-risk NASH (NIS4), presence of NASH (OWLiver), or fibrosis stages greater than 2, greater than 3, or 4 (enhanced liver fibrosis [ELF] test, PROC3, and FibroMeter VCTE). At-risk NASH was defined by the presence of NASH, high histologic activity, and fibrosis stage greater than or equal to 2.

The performance metric was an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) greater than or equal to 0.7 and superiority over alanine aminotransferase (ALT) for disease activity and the FIB-4 test for fibrosis severity.

Multiple biomarkers met the required metrics. For example, NIS4 had an AUROC of 0.81 for at-risk NASH. AUROCs for the ELF test (for clinically significant fibrosis, ≥ stage 2), PROC3 (advanced fibrosis, ≥ stage 3), and FibroMeter VCTE (cirrhosis, stage 4) were all greater than or equal to 0.8.

For all fibrosis endpoints, ELF and FibroMeter VCTE also outperformed FIB-4.

“The current study was a first step to determine if the biomarker panels not only identified the relevant phenotypes based on their intended use but also if they were superior to some commonly used clinical laboratory tools, such as ALT and FIB-4,” the authors write. “These will serve as criteria, to be finalized with feedback from the FDA, to move the panels with the most promising performance metrics to the final qualification steps.”

“Individual developers of specific biomarker panels will need to determine their strategy; that is, have separate rule-in and rule-out cutoffs or a single optimized cutoff as they [formulate] the full qualification plans,” Dr. Sanyal noted. “Also, it may be necessary to validate these cutoffs and performance in independent cohorts reflecting the populations where these are planned to be used.”

“We hope that by 2025, the first wave of biomarkers will have enough data to support approval for diagnostic purposes, and the data for prognostic biomarkers will follow within 1-2 years after that,” Dr. Sanyal added.

Are practice changes ahead?

“Findings from this study and subsequent planned studies have the potential to redefine our approach to MASH and fibrosis diagnosis and staging, both in clinical practice and as part of clinical trials for the multiple new therapeutics being evaluated for MASLD/MASH,” Tatyana Kushner, MD, gastroenterologist/hepatologist and associate professor of medicine in the Division of Liver Diseases at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, told this news organization.

Dr. Kushner noted that the study population “may not represent the diverse population affected by MASH in the United States, or even the clinical trial population.” The cohort was predominantly White, with relatively low representation from people of Hispanic ethnicity, who are known to have a higher prevalence of MASH.

“Furthermore, the study population was specifically curated to have representative numbers across liver disease/fibrosis stages, and this may have biased the results,” she added.

In addition, other MASH-related biomarkers were developed after the current study started, including the FAST, Agile, and ADAPT scores, she said. “After validation of the biomarkers in this study, it will also be important to see how this newer wave of biomarkers performs.”

“If subsequent efforts validate the current findings, and there is buy-in from all of the stakeholders, including the FDA, NIH, industry, and academic leaders, this can truly lead to practice-changing approaches to the clinical management and study of MASLD/MASH,” Dr. Kushner concluded.

The study was partially funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The NIMBLE project is sponsored by the FNIH and is a public-private partnership supported by numerous entities. Support was also provided by the Global Liver Institute and FDA. Dr. Sanyal has disclosed financial relationships with multiple companies. He recused himself from the analysis and interpretation of NIS4. Dr. Kushner has declared being an adviser for Gilead, AbbVie, Eiger, and Bausch, and receiving research support from Gilead. None are MASH/NASH-related.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(NASH, now known as metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis or MASH), laying the groundwork for noninvasive alternatives to liver biopsy, new research suggests.

The blood-based tests could expand diagnostic options at health care facilities and facilitate enrollment in NASH clinical trials, which now require a biopsy for inclusion.

“The current study meets a key milestone for qualification of the biomarker panels studied for identification of at-risk NASH,” Arun Sanyal, MD, of the Stravitz-Sanyal Institute for Liver Disease and Metabolic Health at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, told this news organization.

“It sets the stage for further validation of these outcomes,” he said. “These data will inform development of full qualification plans for these biomarker panels that will be submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Once these are accepted by the FDA, the final steps toward qualification can be initiated.”

The study, published online in Nature Medicine, was conducted as part of the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health – Biomarkers Consortium’s Noninvasive Biomarkers of Metabolic Liver Disease (FNIH-NIMBLE), a multistakeholder project to support regulatory approval of NASH-related biomarkers.

Multiple biomarkers move forward

The investigators evaluated the diagnostic performance of five blood-based panels in an observational cohort derived from the NASH Clinical Research Network study, which included 4,094 participants; 2,479 individuals were excluded from the current study because of age, lack of samples, or lack of evaluable liver biopsies.

The remaining 1,073 patients (mean age, 52.5 years; 62% women) represented the full spectrum of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD, now known as metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease or MASLD). In total, 225 individuals had NAFLD, 835 had NASH, and 13 had cirrhosis with an indeterminate NAFLD phenotype.

Those without fibrosis were younger and had mainly fatty liver, not steatohepatitis. They also had a lower NAFLD activity score, compared with those with stage 2 or higher fibrosis.

The study population for one of the five tests, FibroMeter VCTE, was a smaller subset (n = 396) of the larger population, with baseline features similar to the larger cohort.

The biomarker panels were intended to diagnose at-risk NASH (NIS4), presence of NASH (OWLiver), or fibrosis stages greater than 2, greater than 3, or 4 (enhanced liver fibrosis [ELF] test, PROC3, and FibroMeter VCTE). At-risk NASH was defined by the presence of NASH, high histologic activity, and fibrosis stage greater than or equal to 2.

The performance metric was an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) greater than or equal to 0.7 and superiority over alanine aminotransferase (ALT) for disease activity and the FIB-4 test for fibrosis severity.

Multiple biomarkers met the required metrics. For example, NIS4 had an AUROC of 0.81 for at-risk NASH. AUROCs for the ELF test (for clinically significant fibrosis, ≥ stage 2), PROC3 (advanced fibrosis, ≥ stage 3), and FibroMeter VCTE (cirrhosis, stage 4) were all greater than or equal to 0.8.

For all fibrosis endpoints, ELF and FibroMeter VCTE also outperformed FIB-4.

“The current study was a first step to determine if the biomarker panels not only identified the relevant phenotypes based on their intended use but also if they were superior to some commonly used clinical laboratory tools, such as ALT and FIB-4,” the authors write. “These will serve as criteria, to be finalized with feedback from the FDA, to move the panels with the most promising performance metrics to the final qualification steps.”

“Individual developers of specific biomarker panels will need to determine their strategy; that is, have separate rule-in and rule-out cutoffs or a single optimized cutoff as they [formulate] the full qualification plans,” Dr. Sanyal noted. “Also, it may be necessary to validate these cutoffs and performance in independent cohorts reflecting the populations where these are planned to be used.”

“We hope that by 2025, the first wave of biomarkers will have enough data to support approval for diagnostic purposes, and the data for prognostic biomarkers will follow within 1-2 years after that,” Dr. Sanyal added.

Are practice changes ahead?

“Findings from this study and subsequent planned studies have the potential to redefine our approach to MASH and fibrosis diagnosis and staging, both in clinical practice and as part of clinical trials for the multiple new therapeutics being evaluated for MASLD/MASH,” Tatyana Kushner, MD, gastroenterologist/hepatologist and associate professor of medicine in the Division of Liver Diseases at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, told this news organization.

Dr. Kushner noted that the study population “may not represent the diverse population affected by MASH in the United States, or even the clinical trial population.” The cohort was predominantly White, with relatively low representation from people of Hispanic ethnicity, who are known to have a higher prevalence of MASH.

“Furthermore, the study population was specifically curated to have representative numbers across liver disease/fibrosis stages, and this may have biased the results,” she added.

In addition, other MASH-related biomarkers were developed after the current study started, including the FAST, Agile, and ADAPT scores, she said. “After validation of the biomarkers in this study, it will also be important to see how this newer wave of biomarkers performs.”

“If subsequent efforts validate the current findings, and there is buy-in from all of the stakeholders, including the FDA, NIH, industry, and academic leaders, this can truly lead to practice-changing approaches to the clinical management and study of MASLD/MASH,” Dr. Kushner concluded.

The study was partially funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The NIMBLE project is sponsored by the FNIH and is a public-private partnership supported by numerous entities. Support was also provided by the Global Liver Institute and FDA. Dr. Sanyal has disclosed financial relationships with multiple companies. He recused himself from the analysis and interpretation of NIS4. Dr. Kushner has declared being an adviser for Gilead, AbbVie, Eiger, and Bausch, and receiving research support from Gilead. None are MASH/NASH-related.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE MEDICINE

Drug combo improves recurrence-free survival after HCC resection

ORLANDO – Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who undergo surgery or thermal ablation with curative intent are at high risk for recurrence, but currently, no adjuvant therapy standard of care exists for these patients.

New findings signal a promising option for these patients. The combination of the immune checkpoint inhibitor atezolizumab (Tecentriq) and the angiogenesis inhibitor bevacizumab (Avastin) was associated with a significant improvement in recurrence-free survival, compared with active surveillance, and represents the first option to show efficacy in the adjuvant setting following surgical resection of HCCs for patients at high risk for recurrence.

among patients who received the combination therapy in comparison with active surveillance. However, the overall survival data remain immature.

The data come from an interim analysis of the IMbrave050 trial, which was presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

“Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab may be a practice-changing adjuvant treatment options for patients with high-risk HCC,” said lead investigator Pierce Chow, MBBS, PhD, codirector of the National Cancer Centre Singapore Comprehensive Liver Cancer Clinic. He presented the results in an oral abstract session at the meeting. The combination “may also change clinical indications for surgical resection” because clinicians may be more likely to consider resection for patients at extremely high risk for recurrence if the risk of recurrence can be reduced with this combination.

In the previous IMbrave150 trial, the combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab significantly improved outcomes for patients with high-risk and non–high-risk unresectable HCC, compared with the standard of care sorafenib (Nexavar).

In that trial, the median overall survival in the intention-to-treat population was 19.2 months for patients who received atezolizumab-bevacizumab versus 13.4 months for patients who received sorafenib (P = .0009).

The combination was also associated with improvements in progression-free survival and objective response rates, compared with sorafenib.

On the basis of these results, the IMbrave050 investigators explored whether the same benefits would occur for patients with resectable disease considered to be at high risk for recurrence owing to tumor size, vascular invasion, or poor tumor differentiation. The trial compared the combination for 334 patients with active surveillance, also for 334 patients, in the adjuvant setting.

Patients were considered good candidates for thermal ablation if they had a single tumor greater than 2 cm, but not larger than 5 cm in its longest dimension, or if they had four or fewer tumors, all of which were no larger than 5 cm. For all other patients, surgical resection was recommended.

The median age of the patients was 60. For about half of patients in each arm, the expression level of programmed death–ligand-1 (PD-L1) was 1% or higher.

After a median follow-up of 17.4 months, the 12-month recurrence-free survival rate, as assessed by independent review, was 78% for patients in the treatment arm, compared with 65% for patients who were assigned to active surveillance (hazard ratio, 0.72; P = .012). This finding was generally consistent across clinical subgroups, including groups based on age, sex, race/ethnicity, performance status, PD-L1 expression, number of high-risk features, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage, cancer etiology, procedure type, microvascular invasion, or tumor numbers and size.

Of 133 patients on active surveillance who experienced a protocol-defined recurrence event, 81 (61%) crossed over to the atezolizumab/bevacizumab arm.

The overall survival benefit of the combination therapy was less clear. Dr. Chow called the overall survival data “highly immature” at the time of data cutoff.

Overall, 47 patients died – 7 more in the combination arm (27 vs. 20). More specifically, 17 patients in the combination arm and 16 on active surveillance died from progressive disease; 6 patients in the treatment arm versus 1 on surveillance died from adverse events. The remaining deaths were attributed to other causes. Two deaths in the combination arm were considered treatment related, one from esophageal varices hemorrhage, and the other from ischemic stroke.

Dr. Chow said a number of deaths attributed to HCC recurrence was similar between the groups. There were three COVID-19–related deaths within 1 year of randomization, all in the combination arm.

As for adverse events, the safety of the combination was largely consistent with that reported in the IMbrave150 trial. Nearly all patients experienced at least one adverse event. Treatment-related grade 3 or 4 adverse events occurred in 34.9% of patients in the combination group, and serious treatment-related events occurred in 13.3%.

The most common adverse events of any grade were proteinuria, hypertension, decreased platelet count, increases in liver enzyme level, hypothyroidism, arthralgia, pruritus, rash, increase in serum bilirubin level, and fever.

Invited discussant Stephen L. Chan, MD, from the Chinese University of Hong Kong, said the study was “definitely” relevant to clinicians and addresses “a very important unmet need.”

Dr. Chan noted that he thinks this combination will “likely” be practice changing, given the improvement in recurrence-free survival, but “certainly we need more data to guide us in patient selection.”

The study was funded by F. Hoffman–La Roche. Dr. Chow has consulting for and has received honoraria and grant/research support from Roche and others. Dr. Chan has received honoraria from Roche and consulting fees and grant/research support from others.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ORLANDO – Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who undergo surgery or thermal ablation with curative intent are at high risk for recurrence, but currently, no adjuvant therapy standard of care exists for these patients.

New findings signal a promising option for these patients. The combination of the immune checkpoint inhibitor atezolizumab (Tecentriq) and the angiogenesis inhibitor bevacizumab (Avastin) was associated with a significant improvement in recurrence-free survival, compared with active surveillance, and represents the first option to show efficacy in the adjuvant setting following surgical resection of HCCs for patients at high risk for recurrence.

among patients who received the combination therapy in comparison with active surveillance. However, the overall survival data remain immature.

The data come from an interim analysis of the IMbrave050 trial, which was presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

“Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab may be a practice-changing adjuvant treatment options for patients with high-risk HCC,” said lead investigator Pierce Chow, MBBS, PhD, codirector of the National Cancer Centre Singapore Comprehensive Liver Cancer Clinic. He presented the results in an oral abstract session at the meeting. The combination “may also change clinical indications for surgical resection” because clinicians may be more likely to consider resection for patients at extremely high risk for recurrence if the risk of recurrence can be reduced with this combination.