User login

FDA Panel Votes for Limits on Gastric, Esophageal Cancer Immunotherapy

During the meeting, the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) voted in favor of restricting the use of these immunotherapy agents to patients with programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression of 1% or higher.

The agency usually follows the ODAC’s advice.

The FDA had originally approved the two immune checkpoint inhibitors for both indications in combination with chemotherapy, regardless of patients’ PD-L1 status. The FDA had also approved nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab for esophageal cancer, regardless of PD-L1 expression. The approvals were based on overall benefit in intent-to-treat populations, not on specific PD-L1 expression subgroups.

Since then, additional studies — including the agency’s own pooled analyses of the approval trials — have found that overall survival benefits are limited to patients with PD-L1 expression of 1% or higher.

These findings have raised concerns that patients with no or low PD-L1 expression face the risks associated with immunotherapy, which include death, but minimal to no benefits.

In response, the FDA has considered changing the labeling for these indications to require a PD-L1 cutoff point of 1% or higher. The move would mirror guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network that already recommend use with chemotherapy only at certain PD-L1 cutoffs.

Before the agency acts, however, the FDA wanted the advice of the ODAC. It asked the 14-member panel whether the risk-benefit assessment is “favorable for the use of PD-1 inhibitors in first line” for the two indications among patients with PD-L1 expression below 1%.

In two nearly unanimous decisions for each indication, the panel voted that risk-benefit assessment was not favorable. In other words, the risks do outweigh the benefits for this patient population with no or low PD-L1 expression.

The determination also applies to tislelizumab (Tevimbra), an immune checkpoint inhibitor under review by the FDA for the same indications.

Voting came after hours of testimony from FDA scientists and the three drug companies involved in the decisions.

Merck, maker of pembrolizumab, was against any labeling change. Nivolumab’s maker, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), also wanted to stick with the current PD-L1 agnostic indications but said that any indication change should be class-wide to avoid confusion. BeiGene USA, maker of tislelizumab, had no problem with a PD-L1 cutoff of 1% because its approval trial showed benefit only in patients at that level or higher.

In general, Merck and BMS said the drug benefits correspond with higher PD-L1 expression but noted that patients with low or no PD-L1 expression can sometimes benefit from treatment. The companies had several patients testify to the benefits of the agents and noted patients like this would likely lose access. But an ODAC panelist noted that patients who died from immunotherapy complications weren’t there to respond.

The companies also expressed concern about taking treatment decisions out of the hands of oncologists as well as the need for additional biopsies to determine if tumors cross the proposed PD-L1 threshold at some point during treatment. With this potential new restriction, the companies were worried that insurance companies would be even less likely to pay for their checkpoint inhibitors in low or no PD-L1 expressors.

ODAC wasn’t moved. With consistent findings across multiple trials, the strength of the FDA’s data carried the day.

In a pooled analysis of the three companies’ unresectable or metastatic HER2–negative, microsatellite-stable gastric/gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma approval trials across almost 4000 patients, those with PD-L1 levels below 1% did not demonstrate a significant overall survival benefit (hazard ratio [HR], 0.91; 95% CI, 0.75-1.09). The median overall survival with immunotherapy plus chemotherapy was only 1 month more — 13.4 months vs 12.4 months with chemotherapy alone.

FDA’s pooled analysis for unresectable or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma also showed no overall survival benefit (HR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.76-1.58), with a trend suggesting harm. Median overall survival with immunotherapy plus chemotherapy was 14.6 months vs 9.8 months with chemotherapy alone.

Despite the vote on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, panelists had reservations about making decisions based on just over 160 patients with PD-L1 levels below 1% in the three esophageal squamous cell carcinoma trials.

Still, one panelist said, it’s likely “the best dataset we will get.”

The companies all used different methods to test PD-L1 levels, and attendees called for a single standardized PD-L1 test. Richard Pazdur, MD, head of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, said the agency has been working with companies for years to get them to agree to such a test, with no luck.

If the FDA ultimately decides to restrict immunotherapy use in this patient population based on PD-L1 levels, insurance company coverage may become more limited. Pazdur asked the companies if they would be willing to expand their patient assistance programs to provide free coverage of immune checkpoint blockers to patients with low or no PD-L1 expression.

BeiGene and BMS seemed open to the idea. Merck said, “We’ll have to ... think about it.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

During the meeting, the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) voted in favor of restricting the use of these immunotherapy agents to patients with programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression of 1% or higher.

The agency usually follows the ODAC’s advice.

The FDA had originally approved the two immune checkpoint inhibitors for both indications in combination with chemotherapy, regardless of patients’ PD-L1 status. The FDA had also approved nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab for esophageal cancer, regardless of PD-L1 expression. The approvals were based on overall benefit in intent-to-treat populations, not on specific PD-L1 expression subgroups.

Since then, additional studies — including the agency’s own pooled analyses of the approval trials — have found that overall survival benefits are limited to patients with PD-L1 expression of 1% or higher.

These findings have raised concerns that patients with no or low PD-L1 expression face the risks associated with immunotherapy, which include death, but minimal to no benefits.

In response, the FDA has considered changing the labeling for these indications to require a PD-L1 cutoff point of 1% or higher. The move would mirror guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network that already recommend use with chemotherapy only at certain PD-L1 cutoffs.

Before the agency acts, however, the FDA wanted the advice of the ODAC. It asked the 14-member panel whether the risk-benefit assessment is “favorable for the use of PD-1 inhibitors in first line” for the two indications among patients with PD-L1 expression below 1%.

In two nearly unanimous decisions for each indication, the panel voted that risk-benefit assessment was not favorable. In other words, the risks do outweigh the benefits for this patient population with no or low PD-L1 expression.

The determination also applies to tislelizumab (Tevimbra), an immune checkpoint inhibitor under review by the FDA for the same indications.

Voting came after hours of testimony from FDA scientists and the three drug companies involved in the decisions.

Merck, maker of pembrolizumab, was against any labeling change. Nivolumab’s maker, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), also wanted to stick with the current PD-L1 agnostic indications but said that any indication change should be class-wide to avoid confusion. BeiGene USA, maker of tislelizumab, had no problem with a PD-L1 cutoff of 1% because its approval trial showed benefit only in patients at that level or higher.

In general, Merck and BMS said the drug benefits correspond with higher PD-L1 expression but noted that patients with low or no PD-L1 expression can sometimes benefit from treatment. The companies had several patients testify to the benefits of the agents and noted patients like this would likely lose access. But an ODAC panelist noted that patients who died from immunotherapy complications weren’t there to respond.

The companies also expressed concern about taking treatment decisions out of the hands of oncologists as well as the need for additional biopsies to determine if tumors cross the proposed PD-L1 threshold at some point during treatment. With this potential new restriction, the companies were worried that insurance companies would be even less likely to pay for their checkpoint inhibitors in low or no PD-L1 expressors.

ODAC wasn’t moved. With consistent findings across multiple trials, the strength of the FDA’s data carried the day.

In a pooled analysis of the three companies’ unresectable or metastatic HER2–negative, microsatellite-stable gastric/gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma approval trials across almost 4000 patients, those with PD-L1 levels below 1% did not demonstrate a significant overall survival benefit (hazard ratio [HR], 0.91; 95% CI, 0.75-1.09). The median overall survival with immunotherapy plus chemotherapy was only 1 month more — 13.4 months vs 12.4 months with chemotherapy alone.

FDA’s pooled analysis for unresectable or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma also showed no overall survival benefit (HR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.76-1.58), with a trend suggesting harm. Median overall survival with immunotherapy plus chemotherapy was 14.6 months vs 9.8 months with chemotherapy alone.

Despite the vote on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, panelists had reservations about making decisions based on just over 160 patients with PD-L1 levels below 1% in the three esophageal squamous cell carcinoma trials.

Still, one panelist said, it’s likely “the best dataset we will get.”

The companies all used different methods to test PD-L1 levels, and attendees called for a single standardized PD-L1 test. Richard Pazdur, MD, head of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, said the agency has been working with companies for years to get them to agree to such a test, with no luck.

If the FDA ultimately decides to restrict immunotherapy use in this patient population based on PD-L1 levels, insurance company coverage may become more limited. Pazdur asked the companies if they would be willing to expand their patient assistance programs to provide free coverage of immune checkpoint blockers to patients with low or no PD-L1 expression.

BeiGene and BMS seemed open to the idea. Merck said, “We’ll have to ... think about it.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

During the meeting, the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) voted in favor of restricting the use of these immunotherapy agents to patients with programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression of 1% or higher.

The agency usually follows the ODAC’s advice.

The FDA had originally approved the two immune checkpoint inhibitors for both indications in combination with chemotherapy, regardless of patients’ PD-L1 status. The FDA had also approved nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab for esophageal cancer, regardless of PD-L1 expression. The approvals were based on overall benefit in intent-to-treat populations, not on specific PD-L1 expression subgroups.

Since then, additional studies — including the agency’s own pooled analyses of the approval trials — have found that overall survival benefits are limited to patients with PD-L1 expression of 1% or higher.

These findings have raised concerns that patients with no or low PD-L1 expression face the risks associated with immunotherapy, which include death, but minimal to no benefits.

In response, the FDA has considered changing the labeling for these indications to require a PD-L1 cutoff point of 1% or higher. The move would mirror guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network that already recommend use with chemotherapy only at certain PD-L1 cutoffs.

Before the agency acts, however, the FDA wanted the advice of the ODAC. It asked the 14-member panel whether the risk-benefit assessment is “favorable for the use of PD-1 inhibitors in first line” for the two indications among patients with PD-L1 expression below 1%.

In two nearly unanimous decisions for each indication, the panel voted that risk-benefit assessment was not favorable. In other words, the risks do outweigh the benefits for this patient population with no or low PD-L1 expression.

The determination also applies to tislelizumab (Tevimbra), an immune checkpoint inhibitor under review by the FDA for the same indications.

Voting came after hours of testimony from FDA scientists and the three drug companies involved in the decisions.

Merck, maker of pembrolizumab, was against any labeling change. Nivolumab’s maker, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), also wanted to stick with the current PD-L1 agnostic indications but said that any indication change should be class-wide to avoid confusion. BeiGene USA, maker of tislelizumab, had no problem with a PD-L1 cutoff of 1% because its approval trial showed benefit only in patients at that level or higher.

In general, Merck and BMS said the drug benefits correspond with higher PD-L1 expression but noted that patients with low or no PD-L1 expression can sometimes benefit from treatment. The companies had several patients testify to the benefits of the agents and noted patients like this would likely lose access. But an ODAC panelist noted that patients who died from immunotherapy complications weren’t there to respond.

The companies also expressed concern about taking treatment decisions out of the hands of oncologists as well as the need for additional biopsies to determine if tumors cross the proposed PD-L1 threshold at some point during treatment. With this potential new restriction, the companies were worried that insurance companies would be even less likely to pay for their checkpoint inhibitors in low or no PD-L1 expressors.

ODAC wasn’t moved. With consistent findings across multiple trials, the strength of the FDA’s data carried the day.

In a pooled analysis of the three companies’ unresectable or metastatic HER2–negative, microsatellite-stable gastric/gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma approval trials across almost 4000 patients, those with PD-L1 levels below 1% did not demonstrate a significant overall survival benefit (hazard ratio [HR], 0.91; 95% CI, 0.75-1.09). The median overall survival with immunotherapy plus chemotherapy was only 1 month more — 13.4 months vs 12.4 months with chemotherapy alone.

FDA’s pooled analysis for unresectable or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma also showed no overall survival benefit (HR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.76-1.58), with a trend suggesting harm. Median overall survival with immunotherapy plus chemotherapy was 14.6 months vs 9.8 months with chemotherapy alone.

Despite the vote on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, panelists had reservations about making decisions based on just over 160 patients with PD-L1 levels below 1% in the three esophageal squamous cell carcinoma trials.

Still, one panelist said, it’s likely “the best dataset we will get.”

The companies all used different methods to test PD-L1 levels, and attendees called for a single standardized PD-L1 test. Richard Pazdur, MD, head of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, said the agency has been working with companies for years to get them to agree to such a test, with no luck.

If the FDA ultimately decides to restrict immunotherapy use in this patient population based on PD-L1 levels, insurance company coverage may become more limited. Pazdur asked the companies if they would be willing to expand their patient assistance programs to provide free coverage of immune checkpoint blockers to patients with low or no PD-L1 expression.

BeiGene and BMS seemed open to the idea. Merck said, “We’ll have to ... think about it.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Melanoma: Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy Provides Optimal Survival Results

BARCELONA, SPAIN — with immunotherapy or a targeted agent or targeted therapy plus immunotherapy, according to a large-scale pooled analysis from the International Neoadjuvant Melanoma Consortium.

Importantly, the analysis — presented at the annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology — showed that achieving a major pathological response to neoadjuvant therapy is a key indicator of survival outcomes.

After 3 years of follow-up, the results showed that neoadjuvant therapy is not delaying melanoma recurrence, “it’s actually preventing it,” coinvestigator Hussein A. Tawbi, MD, PhD, Department of Melanoma Medical Oncology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, said in an interview. That’s “a big deal.”

Since 2010, the introduction of novel adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapies for high-risk stage III resectable melanoma has led to incremental gains for patients, said Georgina V. Long, MD, PhD, BSc, chair of Melanoma Medical Oncology and Translational Research at the University of Sydney in Australia, who presented the results.

The first pooled analysis of neoadjuvant therapy in 189 patients, published in 2021, indicated that those who achieved a major pathological response — defined as either a pathological complete response (with no remaining vital tumor) or a near-complete pathological response (with vital tumor ≤ 10%) — had the best recurrence-free survival rates.

In the current study, the researchers expanded their cohort to include 818 patients from 18 centers. Patients received at least one dose of neoadjuvant therapy — either combination immunotherapy, combination of targeted and immunotherapy agents, or monotherapy with either an immune checkpoint inhibitor or a targeted agent.

The median age was 59 years, and 38% of patients were women. The median follow-up so far is 38.8 months.

Overall, the 3-year event-free survival was 74% in patients who received any immunotherapy, 72% in those who received immunotherapy plus a targeted BRAF/MEK therapy, and just 37% in those who received targeted therapy alone. Similarly, 3-year recurrence-free survival rates were highest in patients who received immunotherapy at 77% vs 73% in those who received immunotherapy plus a targeted BRAF/MEK therapy and just 37% in those who received targeted therapy alone.

Looking specifically at progressive death 1 (PD-1)–based immunotherapy regimens, combination therapy led to a 3-year event-free survival rate between 77% and 95%, depending on the specific combinations, vs 64% with PD-1 monotherapy and 37% with combination targeted therapy.

Overall, patients who had a major pathological response were more likely to be recurrence free at 3 years. The 3-year recurrence-free survival was 88% in patients with a complete response, 68% in those with a partial pathological response, and 40% in those without a response.

Patients who received immunotherapy were more likely to have major pathological response. The 3-year recurrence-free survival was about 94% in patients who received combination or monotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibition, and about 87% in those who received immunotherapy plus targeted therapy. The recurrence-free survival rate was much lower in patients given only BRAF/MEK inhibitors.

The current overall survival data, which are still immature, suggested a few differences when stratifying the patients by treatment. Almost all patients with a major pathological response were alive at 3 years, compared with 86% of those with a partial pathological response and 70% of those without a pathological response.

Overall, the results showed that immunotherapy — as either combination or monotherapy — is “quite a bit” better than targeted therapy with BRAF/MEK agents, which offers no substantial benefit, said Dr. Twabi.

“When you see the same pattern happening in study after study, in a very clear, robust way, it actually becomes very powerful,” he explained.

Rebecca A. Dent, MD, MSc, chair of the ESMO Scientific Committee who was not involved in the study, told a press conference that the introduction of immunotherapy and combination immunotherapy has dramatically changed outcomes in melanoma.

Commenting on the current study results, Dr. Dent said that “combination immunotherapy is clearly showing exceptional stability in terms of long-term benefits.”

The question now is what are the toxicities and costs that come with combination immunotherapy, said Dr. Dent, from National Cancer Centre Singapore and Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore.

No funding source was declared. Dr. Long declared relationships with a variety of companies, including AstraZeneca UK Limited, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, and Regeneron. Dr. Twabi declared relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Merck, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Eisai, and others. Dr. Dent declared relationships with AstraZeneca, Roche, Eisai, Gilead Sciences, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Pfizer.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

BARCELONA, SPAIN — with immunotherapy or a targeted agent or targeted therapy plus immunotherapy, according to a large-scale pooled analysis from the International Neoadjuvant Melanoma Consortium.

Importantly, the analysis — presented at the annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology — showed that achieving a major pathological response to neoadjuvant therapy is a key indicator of survival outcomes.

After 3 years of follow-up, the results showed that neoadjuvant therapy is not delaying melanoma recurrence, “it’s actually preventing it,” coinvestigator Hussein A. Tawbi, MD, PhD, Department of Melanoma Medical Oncology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, said in an interview. That’s “a big deal.”

Since 2010, the introduction of novel adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapies for high-risk stage III resectable melanoma has led to incremental gains for patients, said Georgina V. Long, MD, PhD, BSc, chair of Melanoma Medical Oncology and Translational Research at the University of Sydney in Australia, who presented the results.

The first pooled analysis of neoadjuvant therapy in 189 patients, published in 2021, indicated that those who achieved a major pathological response — defined as either a pathological complete response (with no remaining vital tumor) or a near-complete pathological response (with vital tumor ≤ 10%) — had the best recurrence-free survival rates.

In the current study, the researchers expanded their cohort to include 818 patients from 18 centers. Patients received at least one dose of neoadjuvant therapy — either combination immunotherapy, combination of targeted and immunotherapy agents, or monotherapy with either an immune checkpoint inhibitor or a targeted agent.

The median age was 59 years, and 38% of patients were women. The median follow-up so far is 38.8 months.

Overall, the 3-year event-free survival was 74% in patients who received any immunotherapy, 72% in those who received immunotherapy plus a targeted BRAF/MEK therapy, and just 37% in those who received targeted therapy alone. Similarly, 3-year recurrence-free survival rates were highest in patients who received immunotherapy at 77% vs 73% in those who received immunotherapy plus a targeted BRAF/MEK therapy and just 37% in those who received targeted therapy alone.

Looking specifically at progressive death 1 (PD-1)–based immunotherapy regimens, combination therapy led to a 3-year event-free survival rate between 77% and 95%, depending on the specific combinations, vs 64% with PD-1 monotherapy and 37% with combination targeted therapy.

Overall, patients who had a major pathological response were more likely to be recurrence free at 3 years. The 3-year recurrence-free survival was 88% in patients with a complete response, 68% in those with a partial pathological response, and 40% in those without a response.

Patients who received immunotherapy were more likely to have major pathological response. The 3-year recurrence-free survival was about 94% in patients who received combination or monotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibition, and about 87% in those who received immunotherapy plus targeted therapy. The recurrence-free survival rate was much lower in patients given only BRAF/MEK inhibitors.

The current overall survival data, which are still immature, suggested a few differences when stratifying the patients by treatment. Almost all patients with a major pathological response were alive at 3 years, compared with 86% of those with a partial pathological response and 70% of those without a pathological response.

Overall, the results showed that immunotherapy — as either combination or monotherapy — is “quite a bit” better than targeted therapy with BRAF/MEK agents, which offers no substantial benefit, said Dr. Twabi.

“When you see the same pattern happening in study after study, in a very clear, robust way, it actually becomes very powerful,” he explained.

Rebecca A. Dent, MD, MSc, chair of the ESMO Scientific Committee who was not involved in the study, told a press conference that the introduction of immunotherapy and combination immunotherapy has dramatically changed outcomes in melanoma.

Commenting on the current study results, Dr. Dent said that “combination immunotherapy is clearly showing exceptional stability in terms of long-term benefits.”

The question now is what are the toxicities and costs that come with combination immunotherapy, said Dr. Dent, from National Cancer Centre Singapore and Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore.

No funding source was declared. Dr. Long declared relationships with a variety of companies, including AstraZeneca UK Limited, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, and Regeneron. Dr. Twabi declared relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Merck, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Eisai, and others. Dr. Dent declared relationships with AstraZeneca, Roche, Eisai, Gilead Sciences, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Pfizer.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

BARCELONA, SPAIN — with immunotherapy or a targeted agent or targeted therapy plus immunotherapy, according to a large-scale pooled analysis from the International Neoadjuvant Melanoma Consortium.

Importantly, the analysis — presented at the annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology — showed that achieving a major pathological response to neoadjuvant therapy is a key indicator of survival outcomes.

After 3 years of follow-up, the results showed that neoadjuvant therapy is not delaying melanoma recurrence, “it’s actually preventing it,” coinvestigator Hussein A. Tawbi, MD, PhD, Department of Melanoma Medical Oncology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, said in an interview. That’s “a big deal.”

Since 2010, the introduction of novel adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapies for high-risk stage III resectable melanoma has led to incremental gains for patients, said Georgina V. Long, MD, PhD, BSc, chair of Melanoma Medical Oncology and Translational Research at the University of Sydney in Australia, who presented the results.

The first pooled analysis of neoadjuvant therapy in 189 patients, published in 2021, indicated that those who achieved a major pathological response — defined as either a pathological complete response (with no remaining vital tumor) or a near-complete pathological response (with vital tumor ≤ 10%) — had the best recurrence-free survival rates.

In the current study, the researchers expanded their cohort to include 818 patients from 18 centers. Patients received at least one dose of neoadjuvant therapy — either combination immunotherapy, combination of targeted and immunotherapy agents, or monotherapy with either an immune checkpoint inhibitor or a targeted agent.

The median age was 59 years, and 38% of patients were women. The median follow-up so far is 38.8 months.

Overall, the 3-year event-free survival was 74% in patients who received any immunotherapy, 72% in those who received immunotherapy plus a targeted BRAF/MEK therapy, and just 37% in those who received targeted therapy alone. Similarly, 3-year recurrence-free survival rates were highest in patients who received immunotherapy at 77% vs 73% in those who received immunotherapy plus a targeted BRAF/MEK therapy and just 37% in those who received targeted therapy alone.

Looking specifically at progressive death 1 (PD-1)–based immunotherapy regimens, combination therapy led to a 3-year event-free survival rate between 77% and 95%, depending on the specific combinations, vs 64% with PD-1 monotherapy and 37% with combination targeted therapy.

Overall, patients who had a major pathological response were more likely to be recurrence free at 3 years. The 3-year recurrence-free survival was 88% in patients with a complete response, 68% in those with a partial pathological response, and 40% in those without a response.

Patients who received immunotherapy were more likely to have major pathological response. The 3-year recurrence-free survival was about 94% in patients who received combination or monotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibition, and about 87% in those who received immunotherapy plus targeted therapy. The recurrence-free survival rate was much lower in patients given only BRAF/MEK inhibitors.

The current overall survival data, which are still immature, suggested a few differences when stratifying the patients by treatment. Almost all patients with a major pathological response were alive at 3 years, compared with 86% of those with a partial pathological response and 70% of those without a pathological response.

Overall, the results showed that immunotherapy — as either combination or monotherapy — is “quite a bit” better than targeted therapy with BRAF/MEK agents, which offers no substantial benefit, said Dr. Twabi.

“When you see the same pattern happening in study after study, in a very clear, robust way, it actually becomes very powerful,” he explained.

Rebecca A. Dent, MD, MSc, chair of the ESMO Scientific Committee who was not involved in the study, told a press conference that the introduction of immunotherapy and combination immunotherapy has dramatically changed outcomes in melanoma.

Commenting on the current study results, Dr. Dent said that “combination immunotherapy is clearly showing exceptional stability in terms of long-term benefits.”

The question now is what are the toxicities and costs that come with combination immunotherapy, said Dr. Dent, from National Cancer Centre Singapore and Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore.

No funding source was declared. Dr. Long declared relationships with a variety of companies, including AstraZeneca UK Limited, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, and Regeneron. Dr. Twabi declared relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Merck, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Eisai, and others. Dr. Dent declared relationships with AstraZeneca, Roche, Eisai, Gilead Sciences, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Pfizer.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESMO 2024

Cancer Treatment 101: A Primer for Non-Oncologists

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

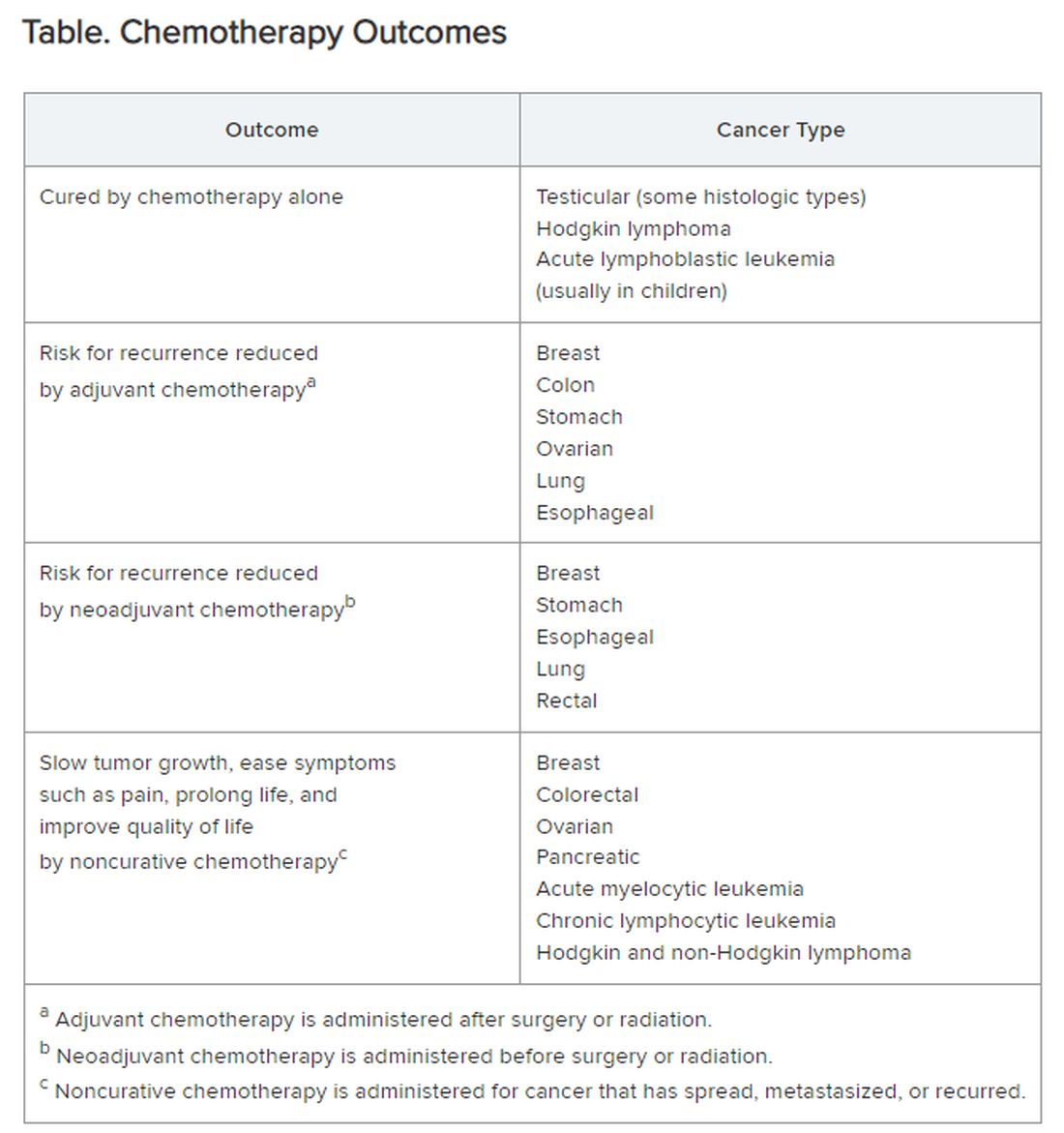

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Diagnosing, Treating Rashes In Patients on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

WASHINGTON, DC — and with judicious usage and dosing of prednisone when deemed necessary, Blair Allais, MD, said during a session on supportive oncodermatology at the ElderDerm conference on dermatology in the older patient hosted by the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC.

“It’s important when you see these patients to be as specific as possible” based on morphology and histopathology, and to treat the rashes in a similar way as in the non-ICI setting,” said Dr. Allais, a dermato-oncologist at the Inova Schar Cancer Institute, Fairfax, Virginia.

cirAEs are the most frequently reported and most visible adverse effects of checkpoint inhibition — a treatment that has emerged as a standard therapy for many malignancies since the first ICI was approved in 2011 for metastatic melanoma.

And contrary to what the phenomenon of immunosenescence might suggest, older patients are no less prone to cirAEs than younger patients. “You’d think you’d have fewer rashes and side effects as you age, but that’s not true,” said Dr. Allais, who completed a fellowship in cutaneous oncology after her dermatology residency.

A 2021 multicenter international cohort study of over 900 patients aged ≥ 80 years treated with single-agent ICIs for cancer did not find any significant differences in the development of immune-related adverse events among those younger than 85, those aged 85-89 years, and those 90 and older. Neither did the ELDERS study in the United Kingdom; this prospective observational study found similar rates of high-grade and low-grade immune toxicity in its two cohorts of patients ≥ 70 and < 70 years of age.

At the meeting, Dr. Allais, who coauthored a 2023 review of cirAEs from ICIs, reviewed recent developments and provided the following advice:

New diagnostic criteria: “Really exciting” news for more precise diagnosis and optimal therapy of cirAEs, Dr. Allais said, is a position paper published in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer that offers consensus-based diagnostic criteria for the 10 most common types of dermatologic immune-related adverse events and an overall diagnostic framework. “Luckily, through the work of a Delphi consensus group, we can now have [more diagnostic specificity],” which is important for both clinical care and research, she said.

Most cirAEs have typically been reported nonspecifically as “rash,” but diagnosing a rash subtype is “critical in tailoring appropriate therapy that it is both effective and the least detrimental to the oncology treatment plan for patients with cancer,” the group’s coauthors wrote.

The 10 core diagnoses include psoriasis, eczematous dermatitis, vitiligo, Grover disease, eruptive atypical squamous proliferation, and bullous pemphigoid. Outside of the core diagnoses are other nonspecific presentations that require evaluation to arrive at a diagnosis, if possible, or to reveal data that can allow for targeted therapy and severity grading, the group explains in its paper.

“To prednisone or not to prednisone”: The development of cirAEs is associated with reduced mortality and improved cancer outcomes, making the use of immunosuppressants such as corticosteroids a therapeutic dilemma. “Patients who get these rashes usually do better with respect to their cancer, so the concern has been, if we affect how they respond to their immunotherapy, we may minimize that improvement in mortality,” said Dr. Allais, also assistant professor at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, and clinical assistant professor of dermatology at George Washington University.

A widely discussed study published in 2015 reported on 254 patients with melanoma who developed an immune-related adverse event during treatment with ipilimumab — approximately one third of whom required systemic corticosteroids — and concluded that systemic corticosteroids did not affect overall survival or time to (cancer) treatment failure. This study from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York City, “was the first large study looking at this question,” she said, and the subsequent message for several years in conferences and the literature was that steroids do not affect the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors.

“But the study was not without limitations,” Dr. Allais said, “because the patients who got prednisone were mainly those with higher-grade toxicities,” while those not treated with corticosteroids had either no toxicities or low-grade toxicities. “If higher-grade toxicities were associated with better (antitumor) response, the steroids may have just [blunted] that benefit.”

The current totality of data available in the literature suggests that corticosteroids may indeed have an impact on the efficacy of ICI therapy. “Subsequent studies have come out in the community that have shown that we should probably think twice about giving prednisone to some patients, particularly within the first 50 days of ICI treatment, and that we should be mindful of the dose,” Dr. Allais said.

The takeaways from these studies — all published in the past few years — are to use prednisone early and liberally for life-threatening toxicity, to use it at the lowest dose and for the shortest course when there is not an appropriate alternative, to avoid it for diagnoses that are not treated with prednisone outside the ICI setting, and to “have a plan” for a steroid-sparing agent to use after prednisone, she said.

Dr. Allais recommends heightened consideration during the first 50 days of ICI treatment based on a multicenter retrospective study that found a significant association between use of high-dose glucocorticoids (≥ 60 mg prednisone equivalent once a day) within 8 weeks of anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) monotherapy initiation and poorer progression-free and overall survival. The study covered a cohort of 947 patients with advanced melanoma treated with anti–PD-1 monotherapy between 2009 and 2019, 54% of whom developed immune-related adverse events.

This study and other recent studies addressing the association between steroids and survival outcomes in patients with immune-related adverse events during ICI therapy are described in Dr. Allais’ 2023 review of cirAEs from ICIs.

Approach to morbilliform eruptions: This rash is “super common” in patients on ICIs, occurring generally within 2-3 weeks of starting treatment. “It tends to be self-limited and can recur with future infusions,” Dr. Allais said.

Systemic steroids should be reserved for severe or refractory eruptions. “Usually, I treat the patients with topical steroids, and I manage their expectations (that the rash may recur with subsequent infusions), but I closely follow them up” within 2-3 weeks, she said. It’s important to rule out a severe cutaneous adverse drug eruption, of course, and to start high-dose systemic steroids immediately if necessary. “Antibiotics are a big culprit” and often can be discontinued.

Soak and smear: “I’m obsessed” with this technique of a 20-minute soak in plain water followed by application of steroid ointment, said Dr. Allais, referring to a small study published in 2005 that reported a complete response after 2 weeks in 60% of patients with psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and other inflammatory skin conditions (none had cancer), who had failed prior systemic therapy. All patients had at least a 75% response.

The method offers a way to “avoid the systemic immunosuppression we’d get with prednisone,” she said. One just needs to make sure the older patient can get in and out of their tub safely.

ICI-induced bullous pemphigoid (BP): BP occurs more frequently in the ICI setting, compared with the general population, with a median time to development of 8.5 months after ICI initiation. It is associated in this setting with improved tumor response, but “many oncologists stop anticancer treatment because of this diagnosis,” she said.

In the supportive oncodermatology space, however, ICI-induced BP exemplifies the value of tailored treatment regimens, she said. A small multi-institutional retrospective cohort study published in 2023 identified 35 cases of ICI-BP among 5636 ICI-treated patients and found that 8 out of 11 patients who received biologic therapy (rituximab, omalizumab, or dupilumab) had a complete response to ICI-BP without flares following subsequent ICI cycles. And while statistical significance was not reached, the study showed that no cancer-related outcomes were worsened.

“If you see someone with ICI-induced BP and they have a lot of involvement, you could start them on steroids and get that steroid-sparing agent initiated for approval. ... And if IgE is elevated, you might reach for omalizumab,” said Dr. Allais, noting that her favored treatment overall is dupilumab.

Risk factors for the development of ICI-induced BP include age > 70, skin cancer, and having an initial response to ICI on first imaging, the latter of which “I find fascinating ... because imaging occurs within the first 12 weeks of treatment, but we don’t see BP popping up until 8.5 months into treatment,” she noted. “So maybe there’s a baseline risk factor that could predispose them.”

Caution with antibiotics: “I try to avoid antibiotics in the ICI setting,” Dr. Allais said, in deference to the “ever-important microbiome.” Studies have demonstrated that the microbiomes of responders to ICI treatment are different from those of nonresponders, she said.

And a “fascinating” study of patients with melanoma undergoing ICI therapy showed not only a higher abundance of Ruminococcaceae bacteria in responders vs nonresponders but a significant impact of dietary fiber. High dietary fiber was associated with significantly improved overall survival in the patients on ICI, with the most pronounced benefit in patients with good fiber intake and no probiotic use. “Even wilder, their T cells changed,” she said. “They had a high expression of genes related to T-cell activation ... so more tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.”

A retrospective study of 568 patients with stages III and IV melanoma treated with ICI showed that those exposed to antibiotics prior to ICI had significantly worse overall survival than those not exposed to antibiotics. “Think before you give them,” Dr. Allais said. “And try to tell your older patients to eat beans and greens.”

Dr. Allais reported having no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON, DC — and with judicious usage and dosing of prednisone when deemed necessary, Blair Allais, MD, said during a session on supportive oncodermatology at the ElderDerm conference on dermatology in the older patient hosted by the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC.

“It’s important when you see these patients to be as specific as possible” based on morphology and histopathology, and to treat the rashes in a similar way as in the non-ICI setting,” said Dr. Allais, a dermato-oncologist at the Inova Schar Cancer Institute, Fairfax, Virginia.

cirAEs are the most frequently reported and most visible adverse effects of checkpoint inhibition — a treatment that has emerged as a standard therapy for many malignancies since the first ICI was approved in 2011 for metastatic melanoma.

And contrary to what the phenomenon of immunosenescence might suggest, older patients are no less prone to cirAEs than younger patients. “You’d think you’d have fewer rashes and side effects as you age, but that’s not true,” said Dr. Allais, who completed a fellowship in cutaneous oncology after her dermatology residency.

A 2021 multicenter international cohort study of over 900 patients aged ≥ 80 years treated with single-agent ICIs for cancer did not find any significant differences in the development of immune-related adverse events among those younger than 85, those aged 85-89 years, and those 90 and older. Neither did the ELDERS study in the United Kingdom; this prospective observational study found similar rates of high-grade and low-grade immune toxicity in its two cohorts of patients ≥ 70 and < 70 years of age.

At the meeting, Dr. Allais, who coauthored a 2023 review of cirAEs from ICIs, reviewed recent developments and provided the following advice:

New diagnostic criteria: “Really exciting” news for more precise diagnosis and optimal therapy of cirAEs, Dr. Allais said, is a position paper published in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer that offers consensus-based diagnostic criteria for the 10 most common types of dermatologic immune-related adverse events and an overall diagnostic framework. “Luckily, through the work of a Delphi consensus group, we can now have [more diagnostic specificity],” which is important for both clinical care and research, she said.

Most cirAEs have typically been reported nonspecifically as “rash,” but diagnosing a rash subtype is “critical in tailoring appropriate therapy that it is both effective and the least detrimental to the oncology treatment plan for patients with cancer,” the group’s coauthors wrote.

The 10 core diagnoses include psoriasis, eczematous dermatitis, vitiligo, Grover disease, eruptive atypical squamous proliferation, and bullous pemphigoid. Outside of the core diagnoses are other nonspecific presentations that require evaluation to arrive at a diagnosis, if possible, or to reveal data that can allow for targeted therapy and severity grading, the group explains in its paper.

“To prednisone or not to prednisone”: The development of cirAEs is associated with reduced mortality and improved cancer outcomes, making the use of immunosuppressants such as corticosteroids a therapeutic dilemma. “Patients who get these rashes usually do better with respect to their cancer, so the concern has been, if we affect how they respond to their immunotherapy, we may minimize that improvement in mortality,” said Dr. Allais, also assistant professor at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, and clinical assistant professor of dermatology at George Washington University.

A widely discussed study published in 2015 reported on 254 patients with melanoma who developed an immune-related adverse event during treatment with ipilimumab — approximately one third of whom required systemic corticosteroids — and concluded that systemic corticosteroids did not affect overall survival or time to (cancer) treatment failure. This study from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York City, “was the first large study looking at this question,” she said, and the subsequent message for several years in conferences and the literature was that steroids do not affect the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors.

“But the study was not without limitations,” Dr. Allais said, “because the patients who got prednisone were mainly those with higher-grade toxicities,” while those not treated with corticosteroids had either no toxicities or low-grade toxicities. “If higher-grade toxicities were associated with better (antitumor) response, the steroids may have just [blunted] that benefit.”

The current totality of data available in the literature suggests that corticosteroids may indeed have an impact on the efficacy of ICI therapy. “Subsequent studies have come out in the community that have shown that we should probably think twice about giving prednisone to some patients, particularly within the first 50 days of ICI treatment, and that we should be mindful of the dose,” Dr. Allais said.

The takeaways from these studies — all published in the past few years — are to use prednisone early and liberally for life-threatening toxicity, to use it at the lowest dose and for the shortest course when there is not an appropriate alternative, to avoid it for diagnoses that are not treated with prednisone outside the ICI setting, and to “have a plan” for a steroid-sparing agent to use after prednisone, she said.

Dr. Allais recommends heightened consideration during the first 50 days of ICI treatment based on a multicenter retrospective study that found a significant association between use of high-dose glucocorticoids (≥ 60 mg prednisone equivalent once a day) within 8 weeks of anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) monotherapy initiation and poorer progression-free and overall survival. The study covered a cohort of 947 patients with advanced melanoma treated with anti–PD-1 monotherapy between 2009 and 2019, 54% of whom developed immune-related adverse events.

This study and other recent studies addressing the association between steroids and survival outcomes in patients with immune-related adverse events during ICI therapy are described in Dr. Allais’ 2023 review of cirAEs from ICIs.

Approach to morbilliform eruptions: This rash is “super common” in patients on ICIs, occurring generally within 2-3 weeks of starting treatment. “It tends to be self-limited and can recur with future infusions,” Dr. Allais said.

Systemic steroids should be reserved for severe or refractory eruptions. “Usually, I treat the patients with topical steroids, and I manage their expectations (that the rash may recur with subsequent infusions), but I closely follow them up” within 2-3 weeks, she said. It’s important to rule out a severe cutaneous adverse drug eruption, of course, and to start high-dose systemic steroids immediately if necessary. “Antibiotics are a big culprit” and often can be discontinued.

Soak and smear: “I’m obsessed” with this technique of a 20-minute soak in plain water followed by application of steroid ointment, said Dr. Allais, referring to a small study published in 2005 that reported a complete response after 2 weeks in 60% of patients with psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and other inflammatory skin conditions (none had cancer), who had failed prior systemic therapy. All patients had at least a 75% response.

The method offers a way to “avoid the systemic immunosuppression we’d get with prednisone,” she said. One just needs to make sure the older patient can get in and out of their tub safely.

ICI-induced bullous pemphigoid (BP): BP occurs more frequently in the ICI setting, compared with the general population, with a median time to development of 8.5 months after ICI initiation. It is associated in this setting with improved tumor response, but “many oncologists stop anticancer treatment because of this diagnosis,” she said.

In the supportive oncodermatology space, however, ICI-induced BP exemplifies the value of tailored treatment regimens, she said. A small multi-institutional retrospective cohort study published in 2023 identified 35 cases of ICI-BP among 5636 ICI-treated patients and found that 8 out of 11 patients who received biologic therapy (rituximab, omalizumab, or dupilumab) had a complete response to ICI-BP without flares following subsequent ICI cycles. And while statistical significance was not reached, the study showed that no cancer-related outcomes were worsened.

“If you see someone with ICI-induced BP and they have a lot of involvement, you could start them on steroids and get that steroid-sparing agent initiated for approval. ... And if IgE is elevated, you might reach for omalizumab,” said Dr. Allais, noting that her favored treatment overall is dupilumab.

Risk factors for the development of ICI-induced BP include age > 70, skin cancer, and having an initial response to ICI on first imaging, the latter of which “I find fascinating ... because imaging occurs within the first 12 weeks of treatment, but we don’t see BP popping up until 8.5 months into treatment,” she noted. “So maybe there’s a baseline risk factor that could predispose them.”

Caution with antibiotics: “I try to avoid antibiotics in the ICI setting,” Dr. Allais said, in deference to the “ever-important microbiome.” Studies have demonstrated that the microbiomes of responders to ICI treatment are different from those of nonresponders, she said.

And a “fascinating” study of patients with melanoma undergoing ICI therapy showed not only a higher abundance of Ruminococcaceae bacteria in responders vs nonresponders but a significant impact of dietary fiber. High dietary fiber was associated with significantly improved overall survival in the patients on ICI, with the most pronounced benefit in patients with good fiber intake and no probiotic use. “Even wilder, their T cells changed,” she said. “They had a high expression of genes related to T-cell activation ... so more tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.”