User login

After Rapid Weight Loss, Monitor Antiobesity Drug Dosing

A patient who developed atrial fibrillation resulting from the failure to adjust the levothyroxine dose after rapid, significant weight loss while on the antiobesity drug tirzepatide (Zepbound) serves as a key reminder in managing patients experiencing rapid weight loss, either from antiobesity medications or any other means: Patients taking medications with weight-based dosing need to have their doses closely monitored.

“Failing to monitor and adjust dosing of these [and other] medications during a period of rapid weight loss may lead to supratherapeutic — even toxic — levels, as was seen in this [case],” underscore the authors of an editorial regarding the Teachable Moment case, published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Toxicities from excessive doses can have a range of detrimental effects. In terms of thyroid medicine, the failure to adjust levothyroxine treatment for hypothyroidism in cases of rapid weight loss can lead to thyrotoxicosis, and in older patients in particular, a resulting thyrotropin level < 0.1 mIU/L is associated with as much as a threefold increased risk for atrial fibrillation, as observed in the report.

Case Demonstrates Risks

The case involved a 62-year-old man with obesity, hypothyroidism, and type 1 diabetes who presented to the emergency department with palpitations, excessive sweating, confusion, fever, and hand tremors. Upon being diagnosed with atrial fibrillation, the patient was immediately treated.

His medical history revealed the underlying culprit: Six months earlier, the patient had started treatment with the gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/glucagon-like peptide (GLP) 1 dual agonist tirzepatide. As is typical with the drug, the patient’s weight quickly plummeted, dropping from a starting body mass index of 44.4 down to 31.2 after 6 months and a decrease in body weight from 132 kg to 93 kg (a loss of 39 kg [approximately 86 lb]).

When he was prescribed tirzepatide, 2.5 mg weekly, for obesity, the patient had been recommended to increase the dose every 4 weeks as tolerated and, importantly, to have a follow-up visit in a month. But because he lived in different states seasonally, the follow-up never occurred.

Upon his emergency department visit, the patient’s thyrotropin level had dropped from 1.9 mIU/L at the first visit 6 months earlier to 0.001 mIU/L (well within the atrial fibrillation risk range), and his free thyroxine level (fT4) was 7.26 ng/ dL — substantially outside of the normal range of about 0.9-1.7 ng/dL for adults.

“The patient had 4-times higher fT4 levels of the upper limit,” first author Kagan E. Karakus, MD, of the Barbara Davis Center for Diabetes, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, told this news organization. “That is why he had experienced the adverse event of atrial fibrillation.”

Thyrotoxicosis Symptoms Can Be ‘Insidious,’ Levothyroxine Should Be Monitored

Although tirzepatide has not been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of type 1 diabetes, obesity is on the rise among patients with this disorder and recent research has shown a more than 10% reduction in body weight in 6 months and significant reductions in A1c with various doses.

Of note, in the current case, although the patient’s levothyroxine dose was not adjusted, his insulin dose was gradually self-decreased during his tirzepatide treatment to prevent hypoglycemia.

“If insulin treatment is excessive in diabetes, it causes hypoglycemia, [and] people with type 1 diabetes will recognize the signs of hypoglycemia related to excessive insulin earlier,” Dr. Karakus said.

If symptoms appear, patients can reduce their insulin doses on their own; however, the symptoms of thyrotoxicosis caused by excessive levothyroxine can be more insidious compared with hypoglycemia, he explained.

“Although patients can change their insulin doses, they cannot change the levothyroxine doses since it requires a blood test [thyroid-stimulating hormone; TSH] and a new prescription of the new dose.”

The key lesson is that “following levothyroxine treatment initiation or dose adjustment, 4-6 weeks is the optimal duration to recheck [the] thyrotropin level and adjust the dose as needed,” Dr. Karakus said.

Key Medications to Monitor

Other common outpatient medications that should be closely monitored in patients experiencing rapid weight loss, by any method, range from anticoagulants, anticonvulsants, and antituberculosis drugs to antibiotics and antifungals, the authors note.

Of note, medications with a narrow therapeutic index include phenytoin, warfarin, lithium carbonate, digoxin theophylline, tacrolimus, valproic acid, carbamazepine, and cyclosporine.

The failure to make necessary dose adjustments “is seen more often since the newer antiobesity drugs reduce a great amount of weight within months, almost as rapidly as bariatric surgery,” Dr. Karakus said.

“It is very important for physicians to be aware of the weight-based medications and narrow therapeutic index medications since their doses should be adjusted carefully, especially during weight loss,” he added.

Furthermore, “the patient should also know that weight reduction medication may cause adverse effects like nausea, vomiting and also may affect metabolism of other medications such that some medication doses should be adjusted regularly.”

In the editorial published with the study, Tyrone A. Johnson, MD, of the Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues note that the need for close monitoring is particularly important with older patients, who, in addition to having a higher likelihood of comorbidities, commonly have polypharmacy that could increase the potential for adverse effects.

Another key area concern is the emergence of direct-to-consumer avenues for GLP-1/GIP agonists for the many who either cannot afford or do not have access to the drugs, providing further opportunities for treatment without appropriate clinical oversight, they add.

Overall, the case “highlights the potential dangers underlying under-supervised prescribing of GLP-1/GIP receptor agonists and affirms the need for strong partnerships between patients and their clinicians during their use,” they wrote.

“These medications are best used in collaboration with continuity care teams, in context of a patient’s entire health, and in comprehensive risk-benefit assessment throughout the entire duration of treatment.”

A Caveat: Subclinical Levothyroxine Dosing

Commenting on the study, Matthew Ettleson, MD, a clinical instructor of medicine in the Section of Endocrinology, Diabetes, & Metabolism, University of Chicago, noted the important caveat that patients with hypothyroidism are commonly on subclinical doses, with varying dose adjustment needs.

“The patient in the case was clearly on a replacement level dose. However, many patients are on low doses of levothyroxine (75 µg or lower) for subclinical hypothyroidism, and, in general, I think the risks are lower with patients with subclinical hypothyroidism on lower doses of levothyroxine,” he told this news organization.

Because of that, “frequent TSH monitoring may be excessive in this population,” he said. “I would hesitate to empirically lower the dose with weight loss, unless it was clear that the patient was unlikely to follow up.

“Checking TSH at a more frequent interval and adjusting the dose accordingly should be adequate to prevent situations like this case.”

Dr. Karakus, Dr. Ettleson, and the editorial authors had no relevant disclosures to report.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A patient who developed atrial fibrillation resulting from the failure to adjust the levothyroxine dose after rapid, significant weight loss while on the antiobesity drug tirzepatide (Zepbound) serves as a key reminder in managing patients experiencing rapid weight loss, either from antiobesity medications or any other means: Patients taking medications with weight-based dosing need to have their doses closely monitored.

“Failing to monitor and adjust dosing of these [and other] medications during a period of rapid weight loss may lead to supratherapeutic — even toxic — levels, as was seen in this [case],” underscore the authors of an editorial regarding the Teachable Moment case, published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Toxicities from excessive doses can have a range of detrimental effects. In terms of thyroid medicine, the failure to adjust levothyroxine treatment for hypothyroidism in cases of rapid weight loss can lead to thyrotoxicosis, and in older patients in particular, a resulting thyrotropin level < 0.1 mIU/L is associated with as much as a threefold increased risk for atrial fibrillation, as observed in the report.

Case Demonstrates Risks

The case involved a 62-year-old man with obesity, hypothyroidism, and type 1 diabetes who presented to the emergency department with palpitations, excessive sweating, confusion, fever, and hand tremors. Upon being diagnosed with atrial fibrillation, the patient was immediately treated.

His medical history revealed the underlying culprit: Six months earlier, the patient had started treatment with the gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/glucagon-like peptide (GLP) 1 dual agonist tirzepatide. As is typical with the drug, the patient’s weight quickly plummeted, dropping from a starting body mass index of 44.4 down to 31.2 after 6 months and a decrease in body weight from 132 kg to 93 kg (a loss of 39 kg [approximately 86 lb]).

When he was prescribed tirzepatide, 2.5 mg weekly, for obesity, the patient had been recommended to increase the dose every 4 weeks as tolerated and, importantly, to have a follow-up visit in a month. But because he lived in different states seasonally, the follow-up never occurred.

Upon his emergency department visit, the patient’s thyrotropin level had dropped from 1.9 mIU/L at the first visit 6 months earlier to 0.001 mIU/L (well within the atrial fibrillation risk range), and his free thyroxine level (fT4) was 7.26 ng/ dL — substantially outside of the normal range of about 0.9-1.7 ng/dL for adults.

“The patient had 4-times higher fT4 levels of the upper limit,” first author Kagan E. Karakus, MD, of the Barbara Davis Center for Diabetes, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, told this news organization. “That is why he had experienced the adverse event of atrial fibrillation.”

Thyrotoxicosis Symptoms Can Be ‘Insidious,’ Levothyroxine Should Be Monitored

Although tirzepatide has not been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of type 1 diabetes, obesity is on the rise among patients with this disorder and recent research has shown a more than 10% reduction in body weight in 6 months and significant reductions in A1c with various doses.

Of note, in the current case, although the patient’s levothyroxine dose was not adjusted, his insulin dose was gradually self-decreased during his tirzepatide treatment to prevent hypoglycemia.

“If insulin treatment is excessive in diabetes, it causes hypoglycemia, [and] people with type 1 diabetes will recognize the signs of hypoglycemia related to excessive insulin earlier,” Dr. Karakus said.

If symptoms appear, patients can reduce their insulin doses on their own; however, the symptoms of thyrotoxicosis caused by excessive levothyroxine can be more insidious compared with hypoglycemia, he explained.

“Although patients can change their insulin doses, they cannot change the levothyroxine doses since it requires a blood test [thyroid-stimulating hormone; TSH] and a new prescription of the new dose.”

The key lesson is that “following levothyroxine treatment initiation or dose adjustment, 4-6 weeks is the optimal duration to recheck [the] thyrotropin level and adjust the dose as needed,” Dr. Karakus said.

Key Medications to Monitor

Other common outpatient medications that should be closely monitored in patients experiencing rapid weight loss, by any method, range from anticoagulants, anticonvulsants, and antituberculosis drugs to antibiotics and antifungals, the authors note.

Of note, medications with a narrow therapeutic index include phenytoin, warfarin, lithium carbonate, digoxin theophylline, tacrolimus, valproic acid, carbamazepine, and cyclosporine.

The failure to make necessary dose adjustments “is seen more often since the newer antiobesity drugs reduce a great amount of weight within months, almost as rapidly as bariatric surgery,” Dr. Karakus said.

“It is very important for physicians to be aware of the weight-based medications and narrow therapeutic index medications since their doses should be adjusted carefully, especially during weight loss,” he added.

Furthermore, “the patient should also know that weight reduction medication may cause adverse effects like nausea, vomiting and also may affect metabolism of other medications such that some medication doses should be adjusted regularly.”

In the editorial published with the study, Tyrone A. Johnson, MD, of the Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues note that the need for close monitoring is particularly important with older patients, who, in addition to having a higher likelihood of comorbidities, commonly have polypharmacy that could increase the potential for adverse effects.

Another key area concern is the emergence of direct-to-consumer avenues for GLP-1/GIP agonists for the many who either cannot afford or do not have access to the drugs, providing further opportunities for treatment without appropriate clinical oversight, they add.

Overall, the case “highlights the potential dangers underlying under-supervised prescribing of GLP-1/GIP receptor agonists and affirms the need for strong partnerships between patients and their clinicians during their use,” they wrote.

“These medications are best used in collaboration with continuity care teams, in context of a patient’s entire health, and in comprehensive risk-benefit assessment throughout the entire duration of treatment.”

A Caveat: Subclinical Levothyroxine Dosing

Commenting on the study, Matthew Ettleson, MD, a clinical instructor of medicine in the Section of Endocrinology, Diabetes, & Metabolism, University of Chicago, noted the important caveat that patients with hypothyroidism are commonly on subclinical doses, with varying dose adjustment needs.

“The patient in the case was clearly on a replacement level dose. However, many patients are on low doses of levothyroxine (75 µg or lower) for subclinical hypothyroidism, and, in general, I think the risks are lower with patients with subclinical hypothyroidism on lower doses of levothyroxine,” he told this news organization.

Because of that, “frequent TSH monitoring may be excessive in this population,” he said. “I would hesitate to empirically lower the dose with weight loss, unless it was clear that the patient was unlikely to follow up.

“Checking TSH at a more frequent interval and adjusting the dose accordingly should be adequate to prevent situations like this case.”

Dr. Karakus, Dr. Ettleson, and the editorial authors had no relevant disclosures to report.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A patient who developed atrial fibrillation resulting from the failure to adjust the levothyroxine dose after rapid, significant weight loss while on the antiobesity drug tirzepatide (Zepbound) serves as a key reminder in managing patients experiencing rapid weight loss, either from antiobesity medications or any other means: Patients taking medications with weight-based dosing need to have their doses closely monitored.

“Failing to monitor and adjust dosing of these [and other] medications during a period of rapid weight loss may lead to supratherapeutic — even toxic — levels, as was seen in this [case],” underscore the authors of an editorial regarding the Teachable Moment case, published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Toxicities from excessive doses can have a range of detrimental effects. In terms of thyroid medicine, the failure to adjust levothyroxine treatment for hypothyroidism in cases of rapid weight loss can lead to thyrotoxicosis, and in older patients in particular, a resulting thyrotropin level < 0.1 mIU/L is associated with as much as a threefold increased risk for atrial fibrillation, as observed in the report.

Case Demonstrates Risks

The case involved a 62-year-old man with obesity, hypothyroidism, and type 1 diabetes who presented to the emergency department with palpitations, excessive sweating, confusion, fever, and hand tremors. Upon being diagnosed with atrial fibrillation, the patient was immediately treated.

His medical history revealed the underlying culprit: Six months earlier, the patient had started treatment with the gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/glucagon-like peptide (GLP) 1 dual agonist tirzepatide. As is typical with the drug, the patient’s weight quickly plummeted, dropping from a starting body mass index of 44.4 down to 31.2 after 6 months and a decrease in body weight from 132 kg to 93 kg (a loss of 39 kg [approximately 86 lb]).

When he was prescribed tirzepatide, 2.5 mg weekly, for obesity, the patient had been recommended to increase the dose every 4 weeks as tolerated and, importantly, to have a follow-up visit in a month. But because he lived in different states seasonally, the follow-up never occurred.

Upon his emergency department visit, the patient’s thyrotropin level had dropped from 1.9 mIU/L at the first visit 6 months earlier to 0.001 mIU/L (well within the atrial fibrillation risk range), and his free thyroxine level (fT4) was 7.26 ng/ dL — substantially outside of the normal range of about 0.9-1.7 ng/dL for adults.

“The patient had 4-times higher fT4 levels of the upper limit,” first author Kagan E. Karakus, MD, of the Barbara Davis Center for Diabetes, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, told this news organization. “That is why he had experienced the adverse event of atrial fibrillation.”

Thyrotoxicosis Symptoms Can Be ‘Insidious,’ Levothyroxine Should Be Monitored

Although tirzepatide has not been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of type 1 diabetes, obesity is on the rise among patients with this disorder and recent research has shown a more than 10% reduction in body weight in 6 months and significant reductions in A1c with various doses.

Of note, in the current case, although the patient’s levothyroxine dose was not adjusted, his insulin dose was gradually self-decreased during his tirzepatide treatment to prevent hypoglycemia.

“If insulin treatment is excessive in diabetes, it causes hypoglycemia, [and] people with type 1 diabetes will recognize the signs of hypoglycemia related to excessive insulin earlier,” Dr. Karakus said.

If symptoms appear, patients can reduce their insulin doses on their own; however, the symptoms of thyrotoxicosis caused by excessive levothyroxine can be more insidious compared with hypoglycemia, he explained.

“Although patients can change their insulin doses, they cannot change the levothyroxine doses since it requires a blood test [thyroid-stimulating hormone; TSH] and a new prescription of the new dose.”

The key lesson is that “following levothyroxine treatment initiation or dose adjustment, 4-6 weeks is the optimal duration to recheck [the] thyrotropin level and adjust the dose as needed,” Dr. Karakus said.

Key Medications to Monitor

Other common outpatient medications that should be closely monitored in patients experiencing rapid weight loss, by any method, range from anticoagulants, anticonvulsants, and antituberculosis drugs to antibiotics and antifungals, the authors note.

Of note, medications with a narrow therapeutic index include phenytoin, warfarin, lithium carbonate, digoxin theophylline, tacrolimus, valproic acid, carbamazepine, and cyclosporine.

The failure to make necessary dose adjustments “is seen more often since the newer antiobesity drugs reduce a great amount of weight within months, almost as rapidly as bariatric surgery,” Dr. Karakus said.

“It is very important for physicians to be aware of the weight-based medications and narrow therapeutic index medications since their doses should be adjusted carefully, especially during weight loss,” he added.

Furthermore, “the patient should also know that weight reduction medication may cause adverse effects like nausea, vomiting and also may affect metabolism of other medications such that some medication doses should be adjusted regularly.”

In the editorial published with the study, Tyrone A. Johnson, MD, of the Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues note that the need for close monitoring is particularly important with older patients, who, in addition to having a higher likelihood of comorbidities, commonly have polypharmacy that could increase the potential for adverse effects.

Another key area concern is the emergence of direct-to-consumer avenues for GLP-1/GIP agonists for the many who either cannot afford or do not have access to the drugs, providing further opportunities for treatment without appropriate clinical oversight, they add.

Overall, the case “highlights the potential dangers underlying under-supervised prescribing of GLP-1/GIP receptor agonists and affirms the need for strong partnerships between patients and their clinicians during their use,” they wrote.

“These medications are best used in collaboration with continuity care teams, in context of a patient’s entire health, and in comprehensive risk-benefit assessment throughout the entire duration of treatment.”

A Caveat: Subclinical Levothyroxine Dosing

Commenting on the study, Matthew Ettleson, MD, a clinical instructor of medicine in the Section of Endocrinology, Diabetes, & Metabolism, University of Chicago, noted the important caveat that patients with hypothyroidism are commonly on subclinical doses, with varying dose adjustment needs.

“The patient in the case was clearly on a replacement level dose. However, many patients are on low doses of levothyroxine (75 µg or lower) for subclinical hypothyroidism, and, in general, I think the risks are lower with patients with subclinical hypothyroidism on lower doses of levothyroxine,” he told this news organization.

Because of that, “frequent TSH monitoring may be excessive in this population,” he said. “I would hesitate to empirically lower the dose with weight loss, unless it was clear that the patient was unlikely to follow up.

“Checking TSH at a more frequent interval and adjusting the dose accordingly should be adequate to prevent situations like this case.”

Dr. Karakus, Dr. Ettleson, and the editorial authors had no relevant disclosures to report.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Could a Fungal Infection Cause a Future Pandemic?

The principle of resilience and survival is crucial for medically significant fungi. These microorganisms are far from creating the postapocalyptic scenario depicted in TV series like The Last of Us, and much work is necessary to learn more about them. Accurate statistics on fungal infections, accompanied by clinical histories, simple laboratory tests, new antifungals, and a necessary One Health approach are lacking.

The entomopathogenic fungus Ophiocordyceps unilateralis was made notorious by the TV series, but for now, it only manages to control the brains of some ants at will. Luckily, there are no signs that fungi affecting humans are inclined to create zombies.

What is clear is that the world belongs to the kingdom of fungi and that fungi are everywhere. There are already close to 150,000 described species, but millions remain to be discovered. They abound in decomposing organic matter, soil, or animal excrement, including that of bats and pigeons. Some fungi have even managed to find a home in hospitals. Lastly, we must not forget those that establish themselves in the human microbiome.

Given such diversity, it is legitimate to ask whether any of them could be capable of generating new pandemics. Could the forgotten Cryptococcus neoformans, Aspergillus fumigatus, or Histoplasma species, among others, trigger new health emergencies on the scale of the one generated by SARS-CoV-2?

We cannot forget that a coronavirus has already confirmed that reality can surpass fiction. However, Edith Sánchez Paredes, a biologist, doctor in biomedical sciences, and specialist in medical mycology, provided a reassuring response to Medscape Spanish Edition on this point.

“That would be very difficult to see because the way fungal infections are acquired is not from person to person, in most cases,” said Dr. Sánchez Paredes, from the Mycology Unit of the Faculty of Medicine at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

Close to 300 species have already been classified as pathogenic in humans. Although the numbers are not precise and are increasing, it is estimated that around 1,500,000 people worldwide die each year of systemic fungal infections.

“However, it is important to emphasize that establishment of an infection depends not only on the causal agent. A crucial factor is the host, in this case, the human. Generally, these types of infections will develop in individuals with some deficiency in their immune system. The more deficient the immune response, the more likely a fungal infection may occur,” stated Dr. Sánchez Paredes.

The possibility of a pandemic like the one experienced with SARS-CoV-2 in the short term is remote, but the threat posed by fungal infections persists.

In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined a priority list of pathogenic fungi, with the aim of guiding actions to control them. It is mentioned there that invasive fungal diseases are on the rise worldwide, particularly in immunocompromised populations.

“Despite the growing concern, fungal infections receive very little attention and resources, leading to a paucity of quality data on fungal disease distribution and antifungal resistance patterns. Consequently, it is impossible to estimate their exact burden,” as stated in the document.

In line with this, an article published in Mycoses in 2022 concluded that fungal infections are neglected diseases in Latin America. Among other difficulties, deficiencies in access to tests such as polymerase chain reaction or serum detection of beta-1,3-D-glucan have been reported there.

In terms of treatments, most countries encounter problems with access to liposomal amphotericin B and new azoles, such as posaconazole and isavuconazole.

“Unfortunately, in Latin America, we suffer from a poor infrastructure for diagnosing fungal infections; likewise, we have limited access to antifungals available in the global market. What’s more, we lack reliable data on the epidemiology of fungal infections in the region, so many times governments are unaware of the true extent of the problem,” said Rogelio de Jesús Treviño Rangel, PhD, a medical microbiologist and expert in clinical mycology, professor, and researcher at the Faculty of Medicine of the Autonomous University of Nuevo León in Mexico.

Need for More Medical Mycology Training

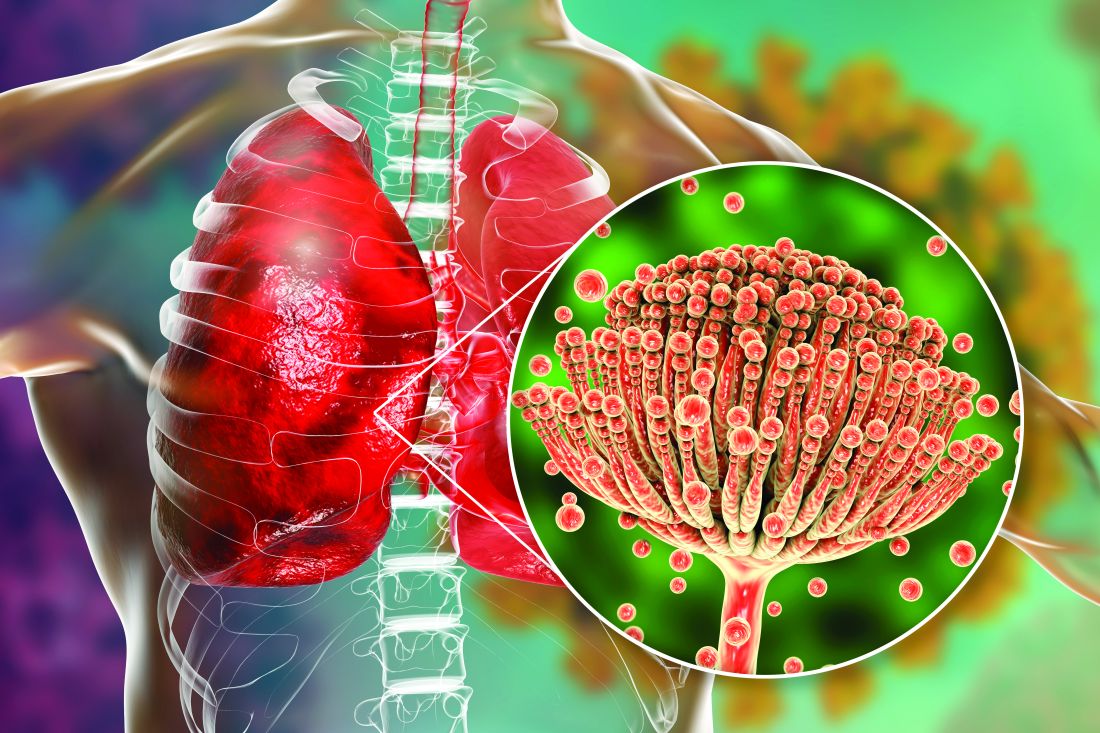

Dr. Fernando Messina is a medical mycologist with the Mycology Unit of the Francisco Javier Muñiz Infectious Diseases Hospital in Buenos Aires, Argentina. He has noted an increase in the number of cases of cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, and aspergillosis in his daily practice.

“Particularly, pulmonary aspergillosis is steadily increasing. This is because many patients have structural lung alterations that favor the appearance of this mycosis. This is related to the increase in cases of tuberculosis and the rise in life expectancy of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or other pulmonary or systemic diseases,” Dr. Messina stated.

For Dr. Messina, the main obstacle in current clinical practice is the low level of awareness among nonspecialist physicians regarding the presence of systemic fungal infections, and because these infections are more common than realized, it is vital to consider fungal etiology before starting empirical antibiotic therapy.

“Health professionals usually do not think about mycoses because mycology occupies a very small space in medical education at universities. As the Venezuelan mycologist Gioconda Cunto de San Blas once said, ‘Mycology is the Cinderella of microbiology.’ To change this, we need to give more space to mycoses in undergraduate and postgraduate studies,” Dr. Messina asserted.

He added, “The main challenge is to train professionals with an emphasis on the clinical interpretation of cases. Current medicine has a strong trend toward molecular biology and the use of rapid diagnostic methods, without considering the clinical symptoms or the patient’s history. Determinations are very useful, but it is necessary to interpret the results.”

Dr. Messina sees it as unlikely in the short term for a pandemic to be caused by fungi, but if it were to occur, he believes it would happen in healthcare systems in regions that are not prepared in terms of infrastructure. However, as seen in the health emergency resulting from SARS-CoV-2, he thinks the impact would be mitigated by the performance of healthcare professionals.

“In general, we have the ability to adapt to any adverse situation or change — although it is clear that we need more doctors, biochemists, and microbiologists trained in mycology,” emphasized Dr. Messina.

More than 40 interns pass through Muñiz Hospital each year. They are doctors and biochemists from Argentina, other countries in the region, or even Europe, seeking to enhance their training in mycology. Regarding fungal infection laboratory work, the interest lies in learning to use traditional techniques and innovative molecular methods.

“Rapid diagnostic methods, especially the detection of circulating antigens, have marked a change in the prognosis of deep mycosis in immunocompromised hosts. The possibility of screening and monitoring in this group of patients is very important and has a great benefit,” said Gabriela Santiso, PhD, a biochemist and head of the Mycology Unit of the Francisco Javier Muñiz Infectious Diseases Hospital.

According to Dr. Santiso, the current landscape includes the ability to identify genus and species, which can help in understanding resistance to antifungals. Furthermore, conducting sensitivity tests to these drugs, using standardized commercial methods, also provides timely information for treatment.

But Dr. Santiso warns that Latin America is a vast region with great disparity in human and technological resources. Although most countries in the region have networks facilitating access to timely diagnosis, resources are generally more available in major urban centers.

This often clashes with the epidemiology of most fungal infections. “Let’s not forget that many fungal pathologies affect low-income people who have difficulties accessing health centers, which sometimes turns them into chronic diseases that are hard to treat,” Dr. Santiso pointed out.

In mycology laboratories, the biggest cost is incurred by new diagnostic tests, such as those allowing molecular identification. Conventional methods are not usually expensive, but they require time and effort to train human resources to handle them.

Because new methodologies are not always available or easily accessible throughout the region, Dr. Santiso recommended not neglecting traditional mycological techniques. “Molecular methods, rapid diagnostic methods, and conventional mycology techniques are complementary and not mutually exclusive tests. Continuous training and updating are needed in this area,” she emphasized.

Why Are Resistant Fungal Infections Becoming Increasingly Common?

The first barrier for fungi to cause infection in humans is body temperature; most of them cannot withstand 37 °C. However, they also struggle to evade the immune response that is activated when they try to enter the body.

“We are normally exposed to many of these fungi, almost all the time, but if our immune system is adequate, it may not go beyond a mild infection, in most cases subclinical, which will resolve quickly,” Dr. Sánchez Paredes stated.

However, according to Dr. Sánchez Paredes, if the immune response is weak, “the fungus will have no trouble establishing itself in our organs. Some are even part of our microbiota, such as Candida albicans, which in the face of an imbalance or immunocompromise, can lead to serious infections.”

It is clear that the population at risk for immunosuppression has increased. According to the WHO, this is due to the high prevalence of such diseases as tuberculosis, cancer, and HIV infection, among others.

But the WHO also believes that the increase in fungal infections is related to greater population access to critical care units, invasive procedures, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy treatments.

Furthermore, factors related to the fungus itself and the environment play a role. “These organisms have enzymes, proteins, and other molecules that allow them to survive in the environment in which they normally inhabit. When they face a new and stressful one, they must express other molecules that will allow them to survive. All of this helps them evade elements of the immune system, antifungals, and, of course, body temperature,” according to Dr. Sánchez Paredes.

It is possible that climate change is also behind the noticeable increase in fungal infections and that this crisis may have an even greater impact in the future. The temperature of the environment has increased, and fungi will have to adapt to the planet’s temperature, to the point where body temperature may no longer be a significant barrier for them.

Environmental changes would also be responsible for modifications in the distribution of endemic mycoses, and it is believed that fungi will more frequently find new ecological niches, be able to survive in other environments, and alter distribution zones.

This is what is happening between Mexico and the United States with coccidioidomycosis, or valley fever. “We will begin to see cases of some mycoses where they were not normally seen, so we will have to conduct more studies to confirm that the fungus is inhabiting these new areas or is simply appearing in new sites owing to migration and the great mobility of populations,” Dr. Sánchez Paredes said.

Finally, exposure to environmental factors would partly be responsible for the increasing resistance to first-line antifungals observed in these microorganisms. This seems to be the case with A. fumigatus when exposed to azoles used as fungicides in agriculture.

One Health in Fungal Infections

The increasing resistance to antifungals is a clear testament that human, animal, and environmental health are interconnected. This is why a multidisciplinary approach that adopts the perspective of One Health is necessary for its management.

“The use of fungicides in agriculture, structurally similar to the azoles used in clinics, generates resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus found in the environment. These fungi in humans can be associated with infections that do not respond to first-line treatment,” explained Carlos Arturo Álvarez, an infectious diseases physician and professor at the Faculty of Medicine at the National University of Colombia.

According to Dr. Álvarez, the approach to control them should not only focus on the search for diagnostic methods that allow early detection of antifungal resistance or research on new antifungal treatments. He believes that progress must also be made with strategies that allow for the proper use of antifungals in agriculture.

“Unfortunately, the One Health approach is not yet well implemented in the region, and in my view, there is a lack of articulation in the different sectors. That is, there is a need for true coordination between government offices of agriculture, animal and human health, academia, and international organizations. This is not happening yet, and I believe we are in the initial stage of visibility,” Dr. Álvarez opined.

Veterinary public health is another pillar of the aforementioned approach. For various reasons, animals experience a higher frequency of fungal infections. A few carry and transmit true zoonoses that affect human health, but most often, animals act only as sentinels indicating a potential source of transmission.

Carolina Segundo Zaragoza, PhD, has worked in veterinary mycology for 30 years. She currently heads the veterinary mycology laboratory at the Animal Production Teaching, Research, and Extension Center in Altiplano, under the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Husbandry at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Because she has frequent contact with specialists in human mycology, during her professional career she has received several patient consultations, most of which were for cutaneous mycoses.

“They detect some dermatomycosis and realize that the common factor is owning a companion animal or a production animal with which the patient has contact. Both animals and humans present the same type of lesions, and then comes the question: Who infected whom? I remind them that the main source of infection is the soil and that animals should not be blamed in the first instance,” Dr. Segundo Zaragoza clarified.

She is currently collaborating on a research project analyzing the presence of Coccidioides immitis in the soil. This pathogen is responsible for coccidioidomycosis in dogs and humans, and she sees with satisfaction how these types of initiatives, which include some components of the One Health vision, are becoming more common in Mexico.

“Fortunately, human mycologists are increasingly providing more space for the dissemination of veterinary mycology. So I have had the opportunity to be invited to different forums on medical mycology to present the clinical cases we can have in animals and talk about the research projects we carry out. I have more and more opportunities to conduct joint research with human mycologists and veterinary doctors,” she said.

Dr. Segundo Zaragoza believes that to better implement the One Health vision, standardizing the criteria for detecting, diagnosing, and treating mycoses is necessary. She considers that teamwork will be key to achieving the common goal of safeguarding the well-being and health of humans and animals.

Alarms Sound for Candida auris

The WHO included the yeast Candida auris in its group of pathogens with critical priority, and since 2009, it has raised alarm owing to the ease with which it grows in hospitals. In that setting, C auris is known for its high transmissibility, its ability to cause outbreaks, and the high mortality rate from disseminated infections.

“It has been a concern for the mycological community because it shows resistance to most antifungals used clinically, mainly azoles, but also for causing epidemic outbreaks,” emphasized Dr. Sánchez Paredes.

Its mode of transmission is not very clear, but it has been documented to be present on the skin and persist in hospital materials and furniture. It causes nosocomial infections in critically ill patients, such as those in intensive care, and those with cancer or who have received a transplant.

Risk factors for its development include renal insufficiency, hospital stays of more than 15 days, mechanical ventilation, central lines, use of parenteral nutrition, and presence of sepsis.

As for other mycoses, there are no precise studies reporting global incidence rates, but the trend indicates an increase in the detection of outbreaks in various countries lately — something that began to be visible during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Mexico, Dr. Treviño Rangel and colleagues from Nuevo León reported the first case of candidemia caused by this agent. It occurred in May 2020 and involved a 58-year-old woman with a history of severe endometriosis and multiple complications in the gastrointestinal tract. The patient’s condition improved favorably thanks to antifungal therapy with caspofungin and liposomal amphotericin B.

However, 3 months after that episode, the group reported an outbreak of C. auris at the same hospital in 12 critically ill patients co-infected with SARS-CoV-2. All were on mechanical ventilation, had peripherally inserted central catheters and urinary catheters, and had a prolonged hospital stay (20-70 days). The mortality in patients with candidemia in this cohort was 83.3%.

Open Ending

As seen in some science fiction series, fungal infections in the region still have an open ending, and Global Action For Fungal Infections (GAFFI) has estimated that with better diagnostics and treatments, deaths caused by fungi could decrease to less than 750,000 per year worldwide.

But if everything continues as is, some aspects of what is to come may resemble the dystopia depicted in The Last of Us. No zombies, but emerging and reemerging fungi in a chaotic distribution, and resistant to all established treatments.

“The risk factors of patients and their immune status, combined with the behavior of mycoses, bring a complicated scenario. But therapeutic failure resulting from multidrug resistance to antifungals could make it catastrophic,” Dr. Sánchez Paredes summarized.

At the moment, there are only four families of drugs capable of counteracting fungal infections — and as mentioned, some are already scarce in Latin America’s hospital pharmacies.

“Historically, fungal infections have been given less importance than those caused by viruses or bacteria. Even in some developed countries, the true extent of morbidity and mortality they present is unknown. This results in less investment in the development of new antifungal molecules because knowledge is lacking about the incidence and prevalence of these diseases,” Dr. Treviño Rangel pointed out.

He added that the main limitation for the development of new drugs is economic. “Unfortunately, not many pharmaceutical companies are willing to invest in the development of new antifungals, and there are no government programs specifically promoting and supporting research into new therapeutic options against these neglected diseases,” he asserted.

Development of vaccines to prevent fungal infections faces the same barriers. Although, according to Dr. Treviño Rangel, the difficulties are compounded by the great similarity between fungal cells and human cells. This makes it possible for harmful cross-reactivity to occur. In addition, because most severe fungal infections occur in individuals with immunosuppression, a vaccine would need to trigger an adequate immune response despite this issue.

Meanwhile, fungi quietly continue to do what they do best: resist and survive. For millions of years, they have mutated and adapted to new environments. Some theories even blame them for the extinction of dinosaurs and the subsequent rise of mammals. They exist on the edge of life and death, decomposing and creating. There is consensus that at the moment, it does not seem feasible for them to generate a pandemic like the one due to SARS-CoV-2, given their transmission mechanism. But who is willing to rule out that this may not happen in the long or medium term?

Dr. Sánchez Paredes, Dr. Treviño Rangel, Dr. Messina, Dr. Santiso, Dr. Álvarez, and Dr. Segundo Zaragoza have declared no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

This story was translated from Medscape Spanish Edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The principle of resilience and survival is crucial for medically significant fungi. These microorganisms are far from creating the postapocalyptic scenario depicted in TV series like The Last of Us, and much work is necessary to learn more about them. Accurate statistics on fungal infections, accompanied by clinical histories, simple laboratory tests, new antifungals, and a necessary One Health approach are lacking.

The entomopathogenic fungus Ophiocordyceps unilateralis was made notorious by the TV series, but for now, it only manages to control the brains of some ants at will. Luckily, there are no signs that fungi affecting humans are inclined to create zombies.

What is clear is that the world belongs to the kingdom of fungi and that fungi are everywhere. There are already close to 150,000 described species, but millions remain to be discovered. They abound in decomposing organic matter, soil, or animal excrement, including that of bats and pigeons. Some fungi have even managed to find a home in hospitals. Lastly, we must not forget those that establish themselves in the human microbiome.

Given such diversity, it is legitimate to ask whether any of them could be capable of generating new pandemics. Could the forgotten Cryptococcus neoformans, Aspergillus fumigatus, or Histoplasma species, among others, trigger new health emergencies on the scale of the one generated by SARS-CoV-2?

We cannot forget that a coronavirus has already confirmed that reality can surpass fiction. However, Edith Sánchez Paredes, a biologist, doctor in biomedical sciences, and specialist in medical mycology, provided a reassuring response to Medscape Spanish Edition on this point.

“That would be very difficult to see because the way fungal infections are acquired is not from person to person, in most cases,” said Dr. Sánchez Paredes, from the Mycology Unit of the Faculty of Medicine at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

Close to 300 species have already been classified as pathogenic in humans. Although the numbers are not precise and are increasing, it is estimated that around 1,500,000 people worldwide die each year of systemic fungal infections.

“However, it is important to emphasize that establishment of an infection depends not only on the causal agent. A crucial factor is the host, in this case, the human. Generally, these types of infections will develop in individuals with some deficiency in their immune system. The more deficient the immune response, the more likely a fungal infection may occur,” stated Dr. Sánchez Paredes.

The possibility of a pandemic like the one experienced with SARS-CoV-2 in the short term is remote, but the threat posed by fungal infections persists.

In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined a priority list of pathogenic fungi, with the aim of guiding actions to control them. It is mentioned there that invasive fungal diseases are on the rise worldwide, particularly in immunocompromised populations.

“Despite the growing concern, fungal infections receive very little attention and resources, leading to a paucity of quality data on fungal disease distribution and antifungal resistance patterns. Consequently, it is impossible to estimate their exact burden,” as stated in the document.

In line with this, an article published in Mycoses in 2022 concluded that fungal infections are neglected diseases in Latin America. Among other difficulties, deficiencies in access to tests such as polymerase chain reaction or serum detection of beta-1,3-D-glucan have been reported there.

In terms of treatments, most countries encounter problems with access to liposomal amphotericin B and new azoles, such as posaconazole and isavuconazole.

“Unfortunately, in Latin America, we suffer from a poor infrastructure for diagnosing fungal infections; likewise, we have limited access to antifungals available in the global market. What’s more, we lack reliable data on the epidemiology of fungal infections in the region, so many times governments are unaware of the true extent of the problem,” said Rogelio de Jesús Treviño Rangel, PhD, a medical microbiologist and expert in clinical mycology, professor, and researcher at the Faculty of Medicine of the Autonomous University of Nuevo León in Mexico.

Need for More Medical Mycology Training

Dr. Fernando Messina is a medical mycologist with the Mycology Unit of the Francisco Javier Muñiz Infectious Diseases Hospital in Buenos Aires, Argentina. He has noted an increase in the number of cases of cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, and aspergillosis in his daily practice.

“Particularly, pulmonary aspergillosis is steadily increasing. This is because many patients have structural lung alterations that favor the appearance of this mycosis. This is related to the increase in cases of tuberculosis and the rise in life expectancy of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or other pulmonary or systemic diseases,” Dr. Messina stated.

For Dr. Messina, the main obstacle in current clinical practice is the low level of awareness among nonspecialist physicians regarding the presence of systemic fungal infections, and because these infections are more common than realized, it is vital to consider fungal etiology before starting empirical antibiotic therapy.

“Health professionals usually do not think about mycoses because mycology occupies a very small space in medical education at universities. As the Venezuelan mycologist Gioconda Cunto de San Blas once said, ‘Mycology is the Cinderella of microbiology.’ To change this, we need to give more space to mycoses in undergraduate and postgraduate studies,” Dr. Messina asserted.

He added, “The main challenge is to train professionals with an emphasis on the clinical interpretation of cases. Current medicine has a strong trend toward molecular biology and the use of rapid diagnostic methods, without considering the clinical symptoms or the patient’s history. Determinations are very useful, but it is necessary to interpret the results.”

Dr. Messina sees it as unlikely in the short term for a pandemic to be caused by fungi, but if it were to occur, he believes it would happen in healthcare systems in regions that are not prepared in terms of infrastructure. However, as seen in the health emergency resulting from SARS-CoV-2, he thinks the impact would be mitigated by the performance of healthcare professionals.

“In general, we have the ability to adapt to any adverse situation or change — although it is clear that we need more doctors, biochemists, and microbiologists trained in mycology,” emphasized Dr. Messina.

More than 40 interns pass through Muñiz Hospital each year. They are doctors and biochemists from Argentina, other countries in the region, or even Europe, seeking to enhance their training in mycology. Regarding fungal infection laboratory work, the interest lies in learning to use traditional techniques and innovative molecular methods.

“Rapid diagnostic methods, especially the detection of circulating antigens, have marked a change in the prognosis of deep mycosis in immunocompromised hosts. The possibility of screening and monitoring in this group of patients is very important and has a great benefit,” said Gabriela Santiso, PhD, a biochemist and head of the Mycology Unit of the Francisco Javier Muñiz Infectious Diseases Hospital.

According to Dr. Santiso, the current landscape includes the ability to identify genus and species, which can help in understanding resistance to antifungals. Furthermore, conducting sensitivity tests to these drugs, using standardized commercial methods, also provides timely information for treatment.

But Dr. Santiso warns that Latin America is a vast region with great disparity in human and technological resources. Although most countries in the region have networks facilitating access to timely diagnosis, resources are generally more available in major urban centers.

This often clashes with the epidemiology of most fungal infections. “Let’s not forget that many fungal pathologies affect low-income people who have difficulties accessing health centers, which sometimes turns them into chronic diseases that are hard to treat,” Dr. Santiso pointed out.

In mycology laboratories, the biggest cost is incurred by new diagnostic tests, such as those allowing molecular identification. Conventional methods are not usually expensive, but they require time and effort to train human resources to handle them.

Because new methodologies are not always available or easily accessible throughout the region, Dr. Santiso recommended not neglecting traditional mycological techniques. “Molecular methods, rapid diagnostic methods, and conventional mycology techniques are complementary and not mutually exclusive tests. Continuous training and updating are needed in this area,” she emphasized.

Why Are Resistant Fungal Infections Becoming Increasingly Common?

The first barrier for fungi to cause infection in humans is body temperature; most of them cannot withstand 37 °C. However, they also struggle to evade the immune response that is activated when they try to enter the body.

“We are normally exposed to many of these fungi, almost all the time, but if our immune system is adequate, it may not go beyond a mild infection, in most cases subclinical, which will resolve quickly,” Dr. Sánchez Paredes stated.

However, according to Dr. Sánchez Paredes, if the immune response is weak, “the fungus will have no trouble establishing itself in our organs. Some are even part of our microbiota, such as Candida albicans, which in the face of an imbalance or immunocompromise, can lead to serious infections.”

It is clear that the population at risk for immunosuppression has increased. According to the WHO, this is due to the high prevalence of such diseases as tuberculosis, cancer, and HIV infection, among others.

But the WHO also believes that the increase in fungal infections is related to greater population access to critical care units, invasive procedures, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy treatments.

Furthermore, factors related to the fungus itself and the environment play a role. “These organisms have enzymes, proteins, and other molecules that allow them to survive in the environment in which they normally inhabit. When they face a new and stressful one, they must express other molecules that will allow them to survive. All of this helps them evade elements of the immune system, antifungals, and, of course, body temperature,” according to Dr. Sánchez Paredes.

It is possible that climate change is also behind the noticeable increase in fungal infections and that this crisis may have an even greater impact in the future. The temperature of the environment has increased, and fungi will have to adapt to the planet’s temperature, to the point where body temperature may no longer be a significant barrier for them.

Environmental changes would also be responsible for modifications in the distribution of endemic mycoses, and it is believed that fungi will more frequently find new ecological niches, be able to survive in other environments, and alter distribution zones.

This is what is happening between Mexico and the United States with coccidioidomycosis, or valley fever. “We will begin to see cases of some mycoses where they were not normally seen, so we will have to conduct more studies to confirm that the fungus is inhabiting these new areas or is simply appearing in new sites owing to migration and the great mobility of populations,” Dr. Sánchez Paredes said.

Finally, exposure to environmental factors would partly be responsible for the increasing resistance to first-line antifungals observed in these microorganisms. This seems to be the case with A. fumigatus when exposed to azoles used as fungicides in agriculture.

One Health in Fungal Infections

The increasing resistance to antifungals is a clear testament that human, animal, and environmental health are interconnected. This is why a multidisciplinary approach that adopts the perspective of One Health is necessary for its management.

“The use of fungicides in agriculture, structurally similar to the azoles used in clinics, generates resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus found in the environment. These fungi in humans can be associated with infections that do not respond to first-line treatment,” explained Carlos Arturo Álvarez, an infectious diseases physician and professor at the Faculty of Medicine at the National University of Colombia.

According to Dr. Álvarez, the approach to control them should not only focus on the search for diagnostic methods that allow early detection of antifungal resistance or research on new antifungal treatments. He believes that progress must also be made with strategies that allow for the proper use of antifungals in agriculture.

“Unfortunately, the One Health approach is not yet well implemented in the region, and in my view, there is a lack of articulation in the different sectors. That is, there is a need for true coordination between government offices of agriculture, animal and human health, academia, and international organizations. This is not happening yet, and I believe we are in the initial stage of visibility,” Dr. Álvarez opined.

Veterinary public health is another pillar of the aforementioned approach. For various reasons, animals experience a higher frequency of fungal infections. A few carry and transmit true zoonoses that affect human health, but most often, animals act only as sentinels indicating a potential source of transmission.

Carolina Segundo Zaragoza, PhD, has worked in veterinary mycology for 30 years. She currently heads the veterinary mycology laboratory at the Animal Production Teaching, Research, and Extension Center in Altiplano, under the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Husbandry at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Because she has frequent contact with specialists in human mycology, during her professional career she has received several patient consultations, most of which were for cutaneous mycoses.

“They detect some dermatomycosis and realize that the common factor is owning a companion animal or a production animal with which the patient has contact. Both animals and humans present the same type of lesions, and then comes the question: Who infected whom? I remind them that the main source of infection is the soil and that animals should not be blamed in the first instance,” Dr. Segundo Zaragoza clarified.

She is currently collaborating on a research project analyzing the presence of Coccidioides immitis in the soil. This pathogen is responsible for coccidioidomycosis in dogs and humans, and she sees with satisfaction how these types of initiatives, which include some components of the One Health vision, are becoming more common in Mexico.

“Fortunately, human mycologists are increasingly providing more space for the dissemination of veterinary mycology. So I have had the opportunity to be invited to different forums on medical mycology to present the clinical cases we can have in animals and talk about the research projects we carry out. I have more and more opportunities to conduct joint research with human mycologists and veterinary doctors,” she said.

Dr. Segundo Zaragoza believes that to better implement the One Health vision, standardizing the criteria for detecting, diagnosing, and treating mycoses is necessary. She considers that teamwork will be key to achieving the common goal of safeguarding the well-being and health of humans and animals.

Alarms Sound for Candida auris

The WHO included the yeast Candida auris in its group of pathogens with critical priority, and since 2009, it has raised alarm owing to the ease with which it grows in hospitals. In that setting, C auris is known for its high transmissibility, its ability to cause outbreaks, and the high mortality rate from disseminated infections.

“It has been a concern for the mycological community because it shows resistance to most antifungals used clinically, mainly azoles, but also for causing epidemic outbreaks,” emphasized Dr. Sánchez Paredes.

Its mode of transmission is not very clear, but it has been documented to be present on the skin and persist in hospital materials and furniture. It causes nosocomial infections in critically ill patients, such as those in intensive care, and those with cancer or who have received a transplant.

Risk factors for its development include renal insufficiency, hospital stays of more than 15 days, mechanical ventilation, central lines, use of parenteral nutrition, and presence of sepsis.

As for other mycoses, there are no precise studies reporting global incidence rates, but the trend indicates an increase in the detection of outbreaks in various countries lately — something that began to be visible during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Mexico, Dr. Treviño Rangel and colleagues from Nuevo León reported the first case of candidemia caused by this agent. It occurred in May 2020 and involved a 58-year-old woman with a history of severe endometriosis and multiple complications in the gastrointestinal tract. The patient’s condition improved favorably thanks to antifungal therapy with caspofungin and liposomal amphotericin B.

However, 3 months after that episode, the group reported an outbreak of C. auris at the same hospital in 12 critically ill patients co-infected with SARS-CoV-2. All were on mechanical ventilation, had peripherally inserted central catheters and urinary catheters, and had a prolonged hospital stay (20-70 days). The mortality in patients with candidemia in this cohort was 83.3%.

Open Ending

As seen in some science fiction series, fungal infections in the region still have an open ending, and Global Action For Fungal Infections (GAFFI) has estimated that with better diagnostics and treatments, deaths caused by fungi could decrease to less than 750,000 per year worldwide.

But if everything continues as is, some aspects of what is to come may resemble the dystopia depicted in The Last of Us. No zombies, but emerging and reemerging fungi in a chaotic distribution, and resistant to all established treatments.

“The risk factors of patients and their immune status, combined with the behavior of mycoses, bring a complicated scenario. But therapeutic failure resulting from multidrug resistance to antifungals could make it catastrophic,” Dr. Sánchez Paredes summarized.

At the moment, there are only four families of drugs capable of counteracting fungal infections — and as mentioned, some are already scarce in Latin America’s hospital pharmacies.

“Historically, fungal infections have been given less importance than those caused by viruses or bacteria. Even in some developed countries, the true extent of morbidity and mortality they present is unknown. This results in less investment in the development of new antifungal molecules because knowledge is lacking about the incidence and prevalence of these diseases,” Dr. Treviño Rangel pointed out.

He added that the main limitation for the development of new drugs is economic. “Unfortunately, not many pharmaceutical companies are willing to invest in the development of new antifungals, and there are no government programs specifically promoting and supporting research into new therapeutic options against these neglected diseases,” he asserted.

Development of vaccines to prevent fungal infections faces the same barriers. Although, according to Dr. Treviño Rangel, the difficulties are compounded by the great similarity between fungal cells and human cells. This makes it possible for harmful cross-reactivity to occur. In addition, because most severe fungal infections occur in individuals with immunosuppression, a vaccine would need to trigger an adequate immune response despite this issue.

Meanwhile, fungi quietly continue to do what they do best: resist and survive. For millions of years, they have mutated and adapted to new environments. Some theories even blame them for the extinction of dinosaurs and the subsequent rise of mammals. They exist on the edge of life and death, decomposing and creating. There is consensus that at the moment, it does not seem feasible for them to generate a pandemic like the one due to SARS-CoV-2, given their transmission mechanism. But who is willing to rule out that this may not happen in the long or medium term?

Dr. Sánchez Paredes, Dr. Treviño Rangel, Dr. Messina, Dr. Santiso, Dr. Álvarez, and Dr. Segundo Zaragoza have declared no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

This story was translated from Medscape Spanish Edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The principle of resilience and survival is crucial for medically significant fungi. These microorganisms are far from creating the postapocalyptic scenario depicted in TV series like The Last of Us, and much work is necessary to learn more about them. Accurate statistics on fungal infections, accompanied by clinical histories, simple laboratory tests, new antifungals, and a necessary One Health approach are lacking.

The entomopathogenic fungus Ophiocordyceps unilateralis was made notorious by the TV series, but for now, it only manages to control the brains of some ants at will. Luckily, there are no signs that fungi affecting humans are inclined to create zombies.

What is clear is that the world belongs to the kingdom of fungi and that fungi are everywhere. There are already close to 150,000 described species, but millions remain to be discovered. They abound in decomposing organic matter, soil, or animal excrement, including that of bats and pigeons. Some fungi have even managed to find a home in hospitals. Lastly, we must not forget those that establish themselves in the human microbiome.

Given such diversity, it is legitimate to ask whether any of them could be capable of generating new pandemics. Could the forgotten Cryptococcus neoformans, Aspergillus fumigatus, or Histoplasma species, among others, trigger new health emergencies on the scale of the one generated by SARS-CoV-2?

We cannot forget that a coronavirus has already confirmed that reality can surpass fiction. However, Edith Sánchez Paredes, a biologist, doctor in biomedical sciences, and specialist in medical mycology, provided a reassuring response to Medscape Spanish Edition on this point.

“That would be very difficult to see because the way fungal infections are acquired is not from person to person, in most cases,” said Dr. Sánchez Paredes, from the Mycology Unit of the Faculty of Medicine at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

Close to 300 species have already been classified as pathogenic in humans. Although the numbers are not precise and are increasing, it is estimated that around 1,500,000 people worldwide die each year of systemic fungal infections.

“However, it is important to emphasize that establishment of an infection depends not only on the causal agent. A crucial factor is the host, in this case, the human. Generally, these types of infections will develop in individuals with some deficiency in their immune system. The more deficient the immune response, the more likely a fungal infection may occur,” stated Dr. Sánchez Paredes.

The possibility of a pandemic like the one experienced with SARS-CoV-2 in the short term is remote, but the threat posed by fungal infections persists.

In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined a priority list of pathogenic fungi, with the aim of guiding actions to control them. It is mentioned there that invasive fungal diseases are on the rise worldwide, particularly in immunocompromised populations.

“Despite the growing concern, fungal infections receive very little attention and resources, leading to a paucity of quality data on fungal disease distribution and antifungal resistance patterns. Consequently, it is impossible to estimate their exact burden,” as stated in the document.

In line with this, an article published in Mycoses in 2022 concluded that fungal infections are neglected diseases in Latin America. Among other difficulties, deficiencies in access to tests such as polymerase chain reaction or serum detection of beta-1,3-D-glucan have been reported there.

In terms of treatments, most countries encounter problems with access to liposomal amphotericin B and new azoles, such as posaconazole and isavuconazole.

“Unfortunately, in Latin America, we suffer from a poor infrastructure for diagnosing fungal infections; likewise, we have limited access to antifungals available in the global market. What’s more, we lack reliable data on the epidemiology of fungal infections in the region, so many times governments are unaware of the true extent of the problem,” said Rogelio de Jesús Treviño Rangel, PhD, a medical microbiologist and expert in clinical mycology, professor, and researcher at the Faculty of Medicine of the Autonomous University of Nuevo León in Mexico.

Need for More Medical Mycology Training

Dr. Fernando Messina is a medical mycologist with the Mycology Unit of the Francisco Javier Muñiz Infectious Diseases Hospital in Buenos Aires, Argentina. He has noted an increase in the number of cases of cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, and aspergillosis in his daily practice.

“Particularly, pulmonary aspergillosis is steadily increasing. This is because many patients have structural lung alterations that favor the appearance of this mycosis. This is related to the increase in cases of tuberculosis and the rise in life expectancy of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or other pulmonary or systemic diseases,” Dr. Messina stated.

For Dr. Messina, the main obstacle in current clinical practice is the low level of awareness among nonspecialist physicians regarding the presence of systemic fungal infections, and because these infections are more common than realized, it is vital to consider fungal etiology before starting empirical antibiotic therapy.

“Health professionals usually do not think about mycoses because mycology occupies a very small space in medical education at universities. As the Venezuelan mycologist Gioconda Cunto de San Blas once said, ‘Mycology is the Cinderella of microbiology.’ To change this, we need to give more space to mycoses in undergraduate and postgraduate studies,” Dr. Messina asserted.

He added, “The main challenge is to train professionals with an emphasis on the clinical interpretation of cases. Current medicine has a strong trend toward molecular biology and the use of rapid diagnostic methods, without considering the clinical symptoms or the patient’s history. Determinations are very useful, but it is necessary to interpret the results.”

Dr. Messina sees it as unlikely in the short term for a pandemic to be caused by fungi, but if it were to occur, he believes it would happen in healthcare systems in regions that are not prepared in terms of infrastructure. However, as seen in the health emergency resulting from SARS-CoV-2, he thinks the impact would be mitigated by the performance of healthcare professionals.

“In general, we have the ability to adapt to any adverse situation or change — although it is clear that we need more doctors, biochemists, and microbiologists trained in mycology,” emphasized Dr. Messina.

More than 40 interns pass through Muñiz Hospital each year. They are doctors and biochemists from Argentina, other countries in the region, or even Europe, seeking to enhance their training in mycology. Regarding fungal infection laboratory work, the interest lies in learning to use traditional techniques and innovative molecular methods.

“Rapid diagnostic methods, especially the detection of circulating antigens, have marked a change in the prognosis of deep mycosis in immunocompromised hosts. The possibility of screening and monitoring in this group of patients is very important and has a great benefit,” said Gabriela Santiso, PhD, a biochemist and head of the Mycology Unit of the Francisco Javier Muñiz Infectious Diseases Hospital.

According to Dr. Santiso, the current landscape includes the ability to identify genus and species, which can help in understanding resistance to antifungals. Furthermore, conducting sensitivity tests to these drugs, using standardized commercial methods, also provides timely information for treatment.

But Dr. Santiso warns that Latin America is a vast region with great disparity in human and technological resources. Although most countries in the region have networks facilitating access to timely diagnosis, resources are generally more available in major urban centers.

This often clashes with the epidemiology of most fungal infections. “Let’s not forget that many fungal pathologies affect low-income people who have difficulties accessing health centers, which sometimes turns them into chronic diseases that are hard to treat,” Dr. Santiso pointed out.

In mycology laboratories, the biggest cost is incurred by new diagnostic tests, such as those allowing molecular identification. Conventional methods are not usually expensive, but they require time and effort to train human resources to handle them.

Because new methodologies are not always available or easily accessible throughout the region, Dr. Santiso recommended not neglecting traditional mycological techniques. “Molecular methods, rapid diagnostic methods, and conventional mycology techniques are complementary and not mutually exclusive tests. Continuous training and updating are needed in this area,” she emphasized.

Why Are Resistant Fungal Infections Becoming Increasingly Common?

The first barrier for fungi to cause infection in humans is body temperature; most of them cannot withstand 37 °C. However, they also struggle to evade the immune response that is activated when they try to enter the body.

“We are normally exposed to many of these fungi, almost all the time, but if our immune system is adequate, it may not go beyond a mild infection, in most cases subclinical, which will resolve quickly,” Dr. Sánchez Paredes stated.

However, according to Dr. Sánchez Paredes, if the immune response is weak, “the fungus will have no trouble establishing itself in our organs. Some are even part of our microbiota, such as Candida albicans, which in the face of an imbalance or immunocompromise, can lead to serious infections.”

It is clear that the population at risk for immunosuppression has increased. According to the WHO, this is due to the high prevalence of such diseases as tuberculosis, cancer, and HIV infection, among others.

But the WHO also believes that the increase in fungal infections is related to greater population access to critical care units, invasive procedures, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy treatments.

Furthermore, factors related to the fungus itself and the environment play a role. “These organisms have enzymes, proteins, and other molecules that allow them to survive in the environment in which they normally inhabit. When they face a new and stressful one, they must express other molecules that will allow them to survive. All of this helps them evade elements of the immune system, antifungals, and, of course, body temperature,” according to Dr. Sánchez Paredes.

It is possible that climate change is also behind the noticeable increase in fungal infections and that this crisis may have an even greater impact in the future. The temperature of the environment has increased, and fungi will have to adapt to the planet’s temperature, to the point where body temperature may no longer be a significant barrier for them.

Environmental changes would also be responsible for modifications in the distribution of endemic mycoses, and it is believed that fungi will more frequently find new ecological niches, be able to survive in other environments, and alter distribution zones.

This is what is happening between Mexico and the United States with coccidioidomycosis, or valley fever. “We will begin to see cases of some mycoses where they were not normally seen, so we will have to conduct more studies to confirm that the fungus is inhabiting these new areas or is simply appearing in new sites owing to migration and the great mobility of populations,” Dr. Sánchez Paredes said.

Finally, exposure to environmental factors would partly be responsible for the increasing resistance to first-line antifungals observed in these microorganisms. This seems to be the case with A. fumigatus when exposed to azoles used as fungicides in agriculture.

One Health in Fungal Infections

The increasing resistance to antifungals is a clear testament that human, animal, and environmental health are interconnected. This is why a multidisciplinary approach that adopts the perspective of One Health is necessary for its management.

“The use of fungicides in agriculture, structurally similar to the azoles used in clinics, generates resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus found in the environment. These fungi in humans can be associated with infections that do not respond to first-line treatment,” explained Carlos Arturo Álvarez, an infectious diseases physician and professor at the Faculty of Medicine at the National University of Colombia.

According to Dr. Álvarez, the approach to control them should not only focus on the search for diagnostic methods that allow early detection of antifungal resistance or research on new antifungal treatments. He believes that progress must also be made with strategies that allow for the proper use of antifungals in agriculture.

“Unfortunately, the One Health approach is not yet well implemented in the region, and in my view, there is a lack of articulation in the different sectors. That is, there is a need for true coordination between government offices of agriculture, animal and human health, academia, and international organizations. This is not happening yet, and I believe we are in the initial stage of visibility,” Dr. Álvarez opined.

Veterinary public health is another pillar of the aforementioned approach. For various reasons, animals experience a higher frequency of fungal infections. A few carry and transmit true zoonoses that affect human health, but most often, animals act only as sentinels indicating a potential source of transmission.