User login

Marijuana during prenatal OUD treatment increases premature birth

BALTIMORE – Marijuana is a not a good idea during pregnancy, and it’s an even worse idea when women are being treated for opioid addiction, according to an investigation from East Tennessee State University, Mountain Home.

Marijuana use may become more common as legalization rolls out across the country, and legalization, in turn, may add to the perception that pot is harmless, and maybe a good way to take the edge off during pregnancy and prevent morning sickness, said neonatologist Darshan Shaw, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the university.

Dr. Shaw wondered how that trend might impact treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD) during pregnancy, which has also become more common. The take-home is that “if you have a pregnant patient on medically assistant therapy” for opioid addition, “you should warn them against use of marijuana. It increases the risk of prematurity and low birth weight,” he said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

He and his team reviewed 2,375 opioid-exposed pregnancies at six hospitals in south-central Appalachia from July 2011 to June 2016. All of the women had used opioids during pregnancy, some illegally and others for opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment or other medical issues; 108 had urine screens that were positive for tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) at the time of delivery.

Infants were born a mean of 3 days earlier in the marijuana group, and a mean of 265 g lighter. They were also more likely to be born before 37 weeks’ gestation (14% versus 6.5%); born weighing less than 2,500 g (17.6% versus 7.3%); and more likely to be admitted to the neonatal ICU (17.5% versus 7.1%).

On logistic regression to control for parity, maternal status, and tobacco and benzodiazepine use, prenatal marijuana exposure more than doubled the risk of prematurity (odds ratio, 2.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.3-4.23); tobacco and benzodiazepines did not increase the risk. Marijuana also doubled the risk of low birth weight (OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.18-3.47), about the same as tobacco and benzodiazepines.

The study had limitations. There was no controlling for a major confounder: the amount of opioids woman took while pregnant. These data were not available, Dr. Shaw said.

Neonatal abstinence syndrome was more common in the marijuana group (33.3% versus 18.1%), so it’s possible that women who used marijuana also used more opioids. “We suspect that opioid exposure was not uniform among all infants,” he said. There were also no data on the amount or way marijuana was used.

Marijuana-positive women were more likely to be unmarried, nulliparous, and use tobacco and benzodiazepines.

There was no industry funding for the work, and Dr. Shaw had no disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Marijuana is a not a good idea during pregnancy, and it’s an even worse idea when women are being treated for opioid addiction, according to an investigation from East Tennessee State University, Mountain Home.

Marijuana use may become more common as legalization rolls out across the country, and legalization, in turn, may add to the perception that pot is harmless, and maybe a good way to take the edge off during pregnancy and prevent morning sickness, said neonatologist Darshan Shaw, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the university.

Dr. Shaw wondered how that trend might impact treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD) during pregnancy, which has also become more common. The take-home is that “if you have a pregnant patient on medically assistant therapy” for opioid addition, “you should warn them against use of marijuana. It increases the risk of prematurity and low birth weight,” he said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

He and his team reviewed 2,375 opioid-exposed pregnancies at six hospitals in south-central Appalachia from July 2011 to June 2016. All of the women had used opioids during pregnancy, some illegally and others for opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment or other medical issues; 108 had urine screens that were positive for tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) at the time of delivery.

Infants were born a mean of 3 days earlier in the marijuana group, and a mean of 265 g lighter. They were also more likely to be born before 37 weeks’ gestation (14% versus 6.5%); born weighing less than 2,500 g (17.6% versus 7.3%); and more likely to be admitted to the neonatal ICU (17.5% versus 7.1%).

On logistic regression to control for parity, maternal status, and tobacco and benzodiazepine use, prenatal marijuana exposure more than doubled the risk of prematurity (odds ratio, 2.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.3-4.23); tobacco and benzodiazepines did not increase the risk. Marijuana also doubled the risk of low birth weight (OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.18-3.47), about the same as tobacco and benzodiazepines.

The study had limitations. There was no controlling for a major confounder: the amount of opioids woman took while pregnant. These data were not available, Dr. Shaw said.

Neonatal abstinence syndrome was more common in the marijuana group (33.3% versus 18.1%), so it’s possible that women who used marijuana also used more opioids. “We suspect that opioid exposure was not uniform among all infants,” he said. There were also no data on the amount or way marijuana was used.

Marijuana-positive women were more likely to be unmarried, nulliparous, and use tobacco and benzodiazepines.

There was no industry funding for the work, and Dr. Shaw had no disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Marijuana is a not a good idea during pregnancy, and it’s an even worse idea when women are being treated for opioid addiction, according to an investigation from East Tennessee State University, Mountain Home.

Marijuana use may become more common as legalization rolls out across the country, and legalization, in turn, may add to the perception that pot is harmless, and maybe a good way to take the edge off during pregnancy and prevent morning sickness, said neonatologist Darshan Shaw, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the university.

Dr. Shaw wondered how that trend might impact treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD) during pregnancy, which has also become more common. The take-home is that “if you have a pregnant patient on medically assistant therapy” for opioid addition, “you should warn them against use of marijuana. It increases the risk of prematurity and low birth weight,” he said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

He and his team reviewed 2,375 opioid-exposed pregnancies at six hospitals in south-central Appalachia from July 2011 to June 2016. All of the women had used opioids during pregnancy, some illegally and others for opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment or other medical issues; 108 had urine screens that were positive for tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) at the time of delivery.

Infants were born a mean of 3 days earlier in the marijuana group, and a mean of 265 g lighter. They were also more likely to be born before 37 weeks’ gestation (14% versus 6.5%); born weighing less than 2,500 g (17.6% versus 7.3%); and more likely to be admitted to the neonatal ICU (17.5% versus 7.1%).

On logistic regression to control for parity, maternal status, and tobacco and benzodiazepine use, prenatal marijuana exposure more than doubled the risk of prematurity (odds ratio, 2.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.3-4.23); tobacco and benzodiazepines did not increase the risk. Marijuana also doubled the risk of low birth weight (OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.18-3.47), about the same as tobacco and benzodiazepines.

The study had limitations. There was no controlling for a major confounder: the amount of opioids woman took while pregnant. These data were not available, Dr. Shaw said.

Neonatal abstinence syndrome was more common in the marijuana group (33.3% versus 18.1%), so it’s possible that women who used marijuana also used more opioids. “We suspect that opioid exposure was not uniform among all infants,” he said. There were also no data on the amount or way marijuana was used.

Marijuana-positive women were more likely to be unmarried, nulliparous, and use tobacco and benzodiazepines.

There was no industry funding for the work, and Dr. Shaw had no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM PAS 2019

Key clinical point: Warn pregnant women being treated for opioid use disorder to stay away from marijuana.

Major finding: Marijuana use more than doubled the risk of prematurity and low birth weight.

Study details: Review of 2,375 opioid-exposed pregnancies at six hospitals

Disclosures: There was no industry funding for the work, and the lead investigator had no disclosures.

EU authorization recommended for buprenorphine implant

The European Medicines Agency announced April 26 that its human medicines committee has recommended granting a marketing authorization for Sixmo, a long-lasting implant delivering buprenorphine as treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD).

This recommendation is a step toward making the product available to patients with OUD in the European Union, according to a press release from the EMA. Safety and efficacy of the implant were studied in three trials with a total of 628 patients.

Standard treatment of OUD includes psychological and social counseling, as well as substitution opioid therapy – such as methadone or buprenorphine. The Sixmo implant involves four small rods implanted in the patient’s upper arm under local anesthetic.

The most common adverse events associated with the medicine were in keeping with the known events associated with buprenorphine – headache, constipation, and insomnia. Insertion and removal were associated with pain, severe itching, and hematoma at the implant site.

The full release can be found on the EMA website.

The European Medicines Agency announced April 26 that its human medicines committee has recommended granting a marketing authorization for Sixmo, a long-lasting implant delivering buprenorphine as treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD).

This recommendation is a step toward making the product available to patients with OUD in the European Union, according to a press release from the EMA. Safety and efficacy of the implant were studied in three trials with a total of 628 patients.

Standard treatment of OUD includes psychological and social counseling, as well as substitution opioid therapy – such as methadone or buprenorphine. The Sixmo implant involves four small rods implanted in the patient’s upper arm under local anesthetic.

The most common adverse events associated with the medicine were in keeping with the known events associated with buprenorphine – headache, constipation, and insomnia. Insertion and removal were associated with pain, severe itching, and hematoma at the implant site.

The full release can be found on the EMA website.

The European Medicines Agency announced April 26 that its human medicines committee has recommended granting a marketing authorization for Sixmo, a long-lasting implant delivering buprenorphine as treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD).

This recommendation is a step toward making the product available to patients with OUD in the European Union, according to a press release from the EMA. Safety and efficacy of the implant were studied in three trials with a total of 628 patients.

Standard treatment of OUD includes psychological and social counseling, as well as substitution opioid therapy – such as methadone or buprenorphine. The Sixmo implant involves four small rods implanted in the patient’s upper arm under local anesthetic.

The most common adverse events associated with the medicine were in keeping with the known events associated with buprenorphine – headache, constipation, and insomnia. Insertion and removal were associated with pain, severe itching, and hematoma at the implant site.

The full release can be found on the EMA website.

Medical cannabis relieved pain, decreased opioid use in elderly

results of a recent retrospective chart review suggest. Treatment with medical cannabis improved pain, sleep, anxiety, and neuropathy in patients aged 75 years of age and older, and was associated with reduced use of opioids in about one-third of cases, according to authors of the study, which will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“Our findings are promising and can help fuel further research into medical marijuana as an additional option for this group of people who often have chronic conditions,” said lead investigator Laszlo Mechtler, MD, of Dent Neurologic Institute in Buffalo, N.Y., in a news release. However, additional randomized, placebo-controlled studies are needed to confirm results of this study, Dr. Mechtler added.

The chart review focused on 204 elderly patients who participated in New York State’s medical marijuana program and were followed in a neurologic outpatient setting. The cohort included 129 female and 75 male patients, ranging in age from 75 to 102 years, with a mean age of 81 years. The medical marijuana was taken by mouth as a liquid extract tincture, capsule, or in an electronic vaporizer.

With an average exposure time of 16.8 weeks, 69% of patients experienced symptomatic benefit, according to patient self-report. The most commonly reported benefit was relief of chronic pain in 49%, while improvements in sleep, neuropathy, and anxiety were reported in 18%, 15%, and 10%, respectively. Reductions in opioid pain medication were noted in about one-third of cases, they found.

While 34% of patients had adverse effects on medical marijuana, only 21% reported adverse effects after cannabinoid doses were adjusted, investigators said. Adverse effects led to discontinuation of medical cannabis in seven patients, or 3.4% of the overall cohort. Somnolence, disequilibrium, and gastrointestinal disturbance were the most common adverse effects, occurring in 13%, 7%, and 7% of patients, respectively. Euphoria was reported in 3% of patients.

Among patients who had no reported adverse effects, the most commonly used formulation was a balanced 1:1 tincture of tetrahydrocannabinol to cannabidiol, investigators said.

Further trials could explore optimal dosing of medical cannabis in elderly patients and shed more light on adverse effects such as somnolence and disequilibrium, according to Dr. Mechtler and colleagues.

The study was supported by the Dent Family Foundation.

SOURCE: Bargnes V et al. AAN 2019, Abstract P4.1-014.

results of a recent retrospective chart review suggest. Treatment with medical cannabis improved pain, sleep, anxiety, and neuropathy in patients aged 75 years of age and older, and was associated with reduced use of opioids in about one-third of cases, according to authors of the study, which will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“Our findings are promising and can help fuel further research into medical marijuana as an additional option for this group of people who often have chronic conditions,” said lead investigator Laszlo Mechtler, MD, of Dent Neurologic Institute in Buffalo, N.Y., in a news release. However, additional randomized, placebo-controlled studies are needed to confirm results of this study, Dr. Mechtler added.

The chart review focused on 204 elderly patients who participated in New York State’s medical marijuana program and were followed in a neurologic outpatient setting. The cohort included 129 female and 75 male patients, ranging in age from 75 to 102 years, with a mean age of 81 years. The medical marijuana was taken by mouth as a liquid extract tincture, capsule, or in an electronic vaporizer.

With an average exposure time of 16.8 weeks, 69% of patients experienced symptomatic benefit, according to patient self-report. The most commonly reported benefit was relief of chronic pain in 49%, while improvements in sleep, neuropathy, and anxiety were reported in 18%, 15%, and 10%, respectively. Reductions in opioid pain medication were noted in about one-third of cases, they found.

While 34% of patients had adverse effects on medical marijuana, only 21% reported adverse effects after cannabinoid doses were adjusted, investigators said. Adverse effects led to discontinuation of medical cannabis in seven patients, or 3.4% of the overall cohort. Somnolence, disequilibrium, and gastrointestinal disturbance were the most common adverse effects, occurring in 13%, 7%, and 7% of patients, respectively. Euphoria was reported in 3% of patients.

Among patients who had no reported adverse effects, the most commonly used formulation was a balanced 1:1 tincture of tetrahydrocannabinol to cannabidiol, investigators said.

Further trials could explore optimal dosing of medical cannabis in elderly patients and shed more light on adverse effects such as somnolence and disequilibrium, according to Dr. Mechtler and colleagues.

The study was supported by the Dent Family Foundation.

SOURCE: Bargnes V et al. AAN 2019, Abstract P4.1-014.

results of a recent retrospective chart review suggest. Treatment with medical cannabis improved pain, sleep, anxiety, and neuropathy in patients aged 75 years of age and older, and was associated with reduced use of opioids in about one-third of cases, according to authors of the study, which will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“Our findings are promising and can help fuel further research into medical marijuana as an additional option for this group of people who often have chronic conditions,” said lead investigator Laszlo Mechtler, MD, of Dent Neurologic Institute in Buffalo, N.Y., in a news release. However, additional randomized, placebo-controlled studies are needed to confirm results of this study, Dr. Mechtler added.

The chart review focused on 204 elderly patients who participated in New York State’s medical marijuana program and were followed in a neurologic outpatient setting. The cohort included 129 female and 75 male patients, ranging in age from 75 to 102 years, with a mean age of 81 years. The medical marijuana was taken by mouth as a liquid extract tincture, capsule, or in an electronic vaporizer.

With an average exposure time of 16.8 weeks, 69% of patients experienced symptomatic benefit, according to patient self-report. The most commonly reported benefit was relief of chronic pain in 49%, while improvements in sleep, neuropathy, and anxiety were reported in 18%, 15%, and 10%, respectively. Reductions in opioid pain medication were noted in about one-third of cases, they found.

While 34% of patients had adverse effects on medical marijuana, only 21% reported adverse effects after cannabinoid doses were adjusted, investigators said. Adverse effects led to discontinuation of medical cannabis in seven patients, or 3.4% of the overall cohort. Somnolence, disequilibrium, and gastrointestinal disturbance were the most common adverse effects, occurring in 13%, 7%, and 7% of patients, respectively. Euphoria was reported in 3% of patients.

Among patients who had no reported adverse effects, the most commonly used formulation was a balanced 1:1 tincture of tetrahydrocannabinol to cannabidiol, investigators said.

Further trials could explore optimal dosing of medical cannabis in elderly patients and shed more light on adverse effects such as somnolence and disequilibrium, according to Dr. Mechtler and colleagues.

The study was supported by the Dent Family Foundation.

SOURCE: Bargnes V et al. AAN 2019, Abstract P4.1-014.

FROM AAN 2019

Deadly overlap of fentanyl and stimulants on the rise

Rates of a potentially deadly overlap between use of nonprescribed fentanyl and use of either cocaine or methamphetamine have been increasing, a cross-sectional study of 1 million urine drug tests shows.

Leah LaRue, PharmD, of Millennium Health in San Diego, and colleagues performed the study, which sampled 1 million urine drug tests submitted by health care professionals “as part of routine care” during Jan. 1, 2013–Sept. 30, 2018. They isolated tests that were positive for either cocaine or methamphetamine – but not positive for both – and then determined how many in each group were also positive for nonprescribed fentanyl. Their analyses showed that the rate of cocaine-positive tests that also were positive for nonprescribed fentanyl increased from 0.9% in 2013 (n = 84; 95% confidence interval, 0.7%-1.1%) to 17.6% in 2018 (n = 427; 95% CI, 16.1%-19.1%), an increase of 1,850% (P less than .001). The rate of methamphetamine-positive tests that also were positive for nonprescribed fentanyl also started at 0.9% in 2013 (n = 29; 95% CI, 0.6%-1.2%) but rose to 7.9% in 2018 (n = 344; 95% CI, 7.1%-8.7%, a 798% increase (P less than .001). The study was published in JAMA Network Open.

The investigators suggested two explanations for these increases: intentional combination of drugs for “speedball effects” of combining stimulants and depressants and/or unintentional exposure on the part of users through contamination of substances. There have been increases in both cocaine-related and methamphetamine-related deaths, and the investigators of this study suspect these increases could be explained in part by overlap with opioids such as fentanyl. Part of the overdose risk inherent in these combinations is that, as the stimulant wears off, the fentanyl increasingly depresses the respiratory system, according to investigators; alternatively, opioid-naive stimulant users might be exposed to high levels of fentanyl with no opioid tolerance, which also can lead to overdose.

The study’s limitations include how samples were submitted – by health care professionals as part of routine care – and the possibility that individuals’ list of prescribed medications could have been incomplete or inaccurate such that the presence of prescribed fentanyl was counted as nonprescribed.

“The combination of nonprescribed fentanyl with cocaine or methamphetamine places an individual at increased risk of overdose,” they concluded.

cpalmer@mdedge.com

SOURCE: LaRue L et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Apr 26. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2851.

Rates of a potentially deadly overlap between use of nonprescribed fentanyl and use of either cocaine or methamphetamine have been increasing, a cross-sectional study of 1 million urine drug tests shows.

Leah LaRue, PharmD, of Millennium Health in San Diego, and colleagues performed the study, which sampled 1 million urine drug tests submitted by health care professionals “as part of routine care” during Jan. 1, 2013–Sept. 30, 2018. They isolated tests that were positive for either cocaine or methamphetamine – but not positive for both – and then determined how many in each group were also positive for nonprescribed fentanyl. Their analyses showed that the rate of cocaine-positive tests that also were positive for nonprescribed fentanyl increased from 0.9% in 2013 (n = 84; 95% confidence interval, 0.7%-1.1%) to 17.6% in 2018 (n = 427; 95% CI, 16.1%-19.1%), an increase of 1,850% (P less than .001). The rate of methamphetamine-positive tests that also were positive for nonprescribed fentanyl also started at 0.9% in 2013 (n = 29; 95% CI, 0.6%-1.2%) but rose to 7.9% in 2018 (n = 344; 95% CI, 7.1%-8.7%, a 798% increase (P less than .001). The study was published in JAMA Network Open.

The investigators suggested two explanations for these increases: intentional combination of drugs for “speedball effects” of combining stimulants and depressants and/or unintentional exposure on the part of users through contamination of substances. There have been increases in both cocaine-related and methamphetamine-related deaths, and the investigators of this study suspect these increases could be explained in part by overlap with opioids such as fentanyl. Part of the overdose risk inherent in these combinations is that, as the stimulant wears off, the fentanyl increasingly depresses the respiratory system, according to investigators; alternatively, opioid-naive stimulant users might be exposed to high levels of fentanyl with no opioid tolerance, which also can lead to overdose.

The study’s limitations include how samples were submitted – by health care professionals as part of routine care – and the possibility that individuals’ list of prescribed medications could have been incomplete or inaccurate such that the presence of prescribed fentanyl was counted as nonprescribed.

“The combination of nonprescribed fentanyl with cocaine or methamphetamine places an individual at increased risk of overdose,” they concluded.

cpalmer@mdedge.com

SOURCE: LaRue L et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Apr 26. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2851.

Rates of a potentially deadly overlap between use of nonprescribed fentanyl and use of either cocaine or methamphetamine have been increasing, a cross-sectional study of 1 million urine drug tests shows.

Leah LaRue, PharmD, of Millennium Health in San Diego, and colleagues performed the study, which sampled 1 million urine drug tests submitted by health care professionals “as part of routine care” during Jan. 1, 2013–Sept. 30, 2018. They isolated tests that were positive for either cocaine or methamphetamine – but not positive for both – and then determined how many in each group were also positive for nonprescribed fentanyl. Their analyses showed that the rate of cocaine-positive tests that also were positive for nonprescribed fentanyl increased from 0.9% in 2013 (n = 84; 95% confidence interval, 0.7%-1.1%) to 17.6% in 2018 (n = 427; 95% CI, 16.1%-19.1%), an increase of 1,850% (P less than .001). The rate of methamphetamine-positive tests that also were positive for nonprescribed fentanyl also started at 0.9% in 2013 (n = 29; 95% CI, 0.6%-1.2%) but rose to 7.9% in 2018 (n = 344; 95% CI, 7.1%-8.7%, a 798% increase (P less than .001). The study was published in JAMA Network Open.

The investigators suggested two explanations for these increases: intentional combination of drugs for “speedball effects” of combining stimulants and depressants and/or unintentional exposure on the part of users through contamination of substances. There have been increases in both cocaine-related and methamphetamine-related deaths, and the investigators of this study suspect these increases could be explained in part by overlap with opioids such as fentanyl. Part of the overdose risk inherent in these combinations is that, as the stimulant wears off, the fentanyl increasingly depresses the respiratory system, according to investigators; alternatively, opioid-naive stimulant users might be exposed to high levels of fentanyl with no opioid tolerance, which also can lead to overdose.

The study’s limitations include how samples were submitted – by health care professionals as part of routine care – and the possibility that individuals’ list of prescribed medications could have been incomplete or inaccurate such that the presence of prescribed fentanyl was counted as nonprescribed.

“The combination of nonprescribed fentanyl with cocaine or methamphetamine places an individual at increased risk of overdose,” they concluded.

cpalmer@mdedge.com

SOURCE: LaRue L et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Apr 26. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2851.

FROM jama network open

CDC warns against misuse of opioid-prescribing guideline

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are warning against the misapplication of the agency’s 2016 guidelines on opioid prescribing, as well as clarifying dosage recommendations for patients starting or stopping pain medications.

In a perspective published in the New England Journal of Medicine on April 24, lead author Deborah Dowell, MD, chief medical officer for the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, conveyed concern that some policies and practices derived from the 2016 CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain are inconsistent with the recommendations and often go beyond their scope.

Misapplication examples include inappropriately applying the guideline to patients in active cancer treatment, patients experiencing acute sickle cell crises, or patients experiencing postsurgical pain, Dr. Dowell wrote.

The guideline offers guidance to clinicians treating chronic pain in adults who are already receiving opioids long-term at high dosages, she noted. It includes advice on maximizing nonopioid treatment, reviewing risks associated with continuing high-dose opioids, and collaborating with patients who agree to taper dosage, among other guidance.

Any application of the guideline’s dosage recommendation that results in hard limits or “cutting off” opioids is also an incorrect use of the recommendations, according to Dr. Dowell.

While the guideline advises clinicians to start opioids at the lowest effective dosage and avoid increasing dosage to 90 morphine milligram equivalents per day or more, that statement does not suggest discontinuation of opioids already prescribed at high dosages, according to the CDC’s clarification.

The guidance also does not apply to patients receiving or starting medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder.

The commentary comes after a trio of organizations raised concerns that insurers are inappropriately applying the recommendations to active cancer patients when making coverage determinations.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the American Society of Hematology, raised the issue in a letter to the CDC in February. In response, Dr. Dowell clarified that the recommendations are not intended to deny clinically appropriate opioid therapy to any patients who suffer chronic pain, but rather to ensure that physicians and patients consider all safe and effective treatment options.

In the perspective, Dr. Dowell wrote that the CDC is evaluating the intended and unintended impact of the 2016 opioid-prescribing guideline on clinician and patient outcomes and that the agency is committed to updating the recommendations when new evidence is available.

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are warning against the misapplication of the agency’s 2016 guidelines on opioid prescribing, as well as clarifying dosage recommendations for patients starting or stopping pain medications.

In a perspective published in the New England Journal of Medicine on April 24, lead author Deborah Dowell, MD, chief medical officer for the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, conveyed concern that some policies and practices derived from the 2016 CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain are inconsistent with the recommendations and often go beyond their scope.

Misapplication examples include inappropriately applying the guideline to patients in active cancer treatment, patients experiencing acute sickle cell crises, or patients experiencing postsurgical pain, Dr. Dowell wrote.

The guideline offers guidance to clinicians treating chronic pain in adults who are already receiving opioids long-term at high dosages, she noted. It includes advice on maximizing nonopioid treatment, reviewing risks associated with continuing high-dose opioids, and collaborating with patients who agree to taper dosage, among other guidance.

Any application of the guideline’s dosage recommendation that results in hard limits or “cutting off” opioids is also an incorrect use of the recommendations, according to Dr. Dowell.

While the guideline advises clinicians to start opioids at the lowest effective dosage and avoid increasing dosage to 90 morphine milligram equivalents per day or more, that statement does not suggest discontinuation of opioids already prescribed at high dosages, according to the CDC’s clarification.

The guidance also does not apply to patients receiving or starting medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder.

The commentary comes after a trio of organizations raised concerns that insurers are inappropriately applying the recommendations to active cancer patients when making coverage determinations.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the American Society of Hematology, raised the issue in a letter to the CDC in February. In response, Dr. Dowell clarified that the recommendations are not intended to deny clinically appropriate opioid therapy to any patients who suffer chronic pain, but rather to ensure that physicians and patients consider all safe and effective treatment options.

In the perspective, Dr. Dowell wrote that the CDC is evaluating the intended and unintended impact of the 2016 opioid-prescribing guideline on clinician and patient outcomes and that the agency is committed to updating the recommendations when new evidence is available.

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are warning against the misapplication of the agency’s 2016 guidelines on opioid prescribing, as well as clarifying dosage recommendations for patients starting or stopping pain medications.

In a perspective published in the New England Journal of Medicine on April 24, lead author Deborah Dowell, MD, chief medical officer for the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, conveyed concern that some policies and practices derived from the 2016 CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain are inconsistent with the recommendations and often go beyond their scope.

Misapplication examples include inappropriately applying the guideline to patients in active cancer treatment, patients experiencing acute sickle cell crises, or patients experiencing postsurgical pain, Dr. Dowell wrote.

The guideline offers guidance to clinicians treating chronic pain in adults who are already receiving opioids long-term at high dosages, she noted. It includes advice on maximizing nonopioid treatment, reviewing risks associated with continuing high-dose opioids, and collaborating with patients who agree to taper dosage, among other guidance.

Any application of the guideline’s dosage recommendation that results in hard limits or “cutting off” opioids is also an incorrect use of the recommendations, according to Dr. Dowell.

While the guideline advises clinicians to start opioids at the lowest effective dosage and avoid increasing dosage to 90 morphine milligram equivalents per day or more, that statement does not suggest discontinuation of opioids already prescribed at high dosages, according to the CDC’s clarification.

The guidance also does not apply to patients receiving or starting medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder.

The commentary comes after a trio of organizations raised concerns that insurers are inappropriately applying the recommendations to active cancer patients when making coverage determinations.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the American Society of Hematology, raised the issue in a letter to the CDC in February. In response, Dr. Dowell clarified that the recommendations are not intended to deny clinically appropriate opioid therapy to any patients who suffer chronic pain, but rather to ensure that physicians and patients consider all safe and effective treatment options.

In the perspective, Dr. Dowell wrote that the CDC is evaluating the intended and unintended impact of the 2016 opioid-prescribing guideline on clinician and patient outcomes and that the agency is committed to updating the recommendations when new evidence is available.

FDA approves generic naloxone spray for opioid overdose treatment

The Food and Drug Administration on April 19 approved the first generic naloxone hydrochloride nasal spray (Narcan) as treatment for stopping or reversing an opioid overdose.

“In the wake of the opioid crisis, a number of efforts are underway to make this emergency overdose reversal treatment more readily available and more accessible,” said Douglas Throckmorton, MD, deputy center director for regulatory programs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, in a press release. “In addition to this approval of the first generic naloxone nasal spray, moving forward, we will prioritize our review of generic drug applications for naloxone.”

The agency said the naloxone nasal spray does not need assembly and can be used by anyone, regardless of medical training. If the spray is administered quickly after the overdose begins, the effect of the opioid will be countered, often within minutes. However, patients should still seek immediate medical attention.

The FDA cautioned that, when used on a patient with an opioid dependence, naloxone can cause severe opioid withdrawal, characterized by symptoms such as body aches, diarrhea, tachycardia, fever, runny nose, sneezing, goose bumps, sweating, yawning, nausea or vomiting, nervousness, restlessness or irritability, shivering or trembling, abdominal cramps, weakness, and increased blood pressure.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

lfranki@mdedge.com

The Food and Drug Administration on April 19 approved the first generic naloxone hydrochloride nasal spray (Narcan) as treatment for stopping or reversing an opioid overdose.

“In the wake of the opioid crisis, a number of efforts are underway to make this emergency overdose reversal treatment more readily available and more accessible,” said Douglas Throckmorton, MD, deputy center director for regulatory programs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, in a press release. “In addition to this approval of the first generic naloxone nasal spray, moving forward, we will prioritize our review of generic drug applications for naloxone.”

The agency said the naloxone nasal spray does not need assembly and can be used by anyone, regardless of medical training. If the spray is administered quickly after the overdose begins, the effect of the opioid will be countered, often within minutes. However, patients should still seek immediate medical attention.

The FDA cautioned that, when used on a patient with an opioid dependence, naloxone can cause severe opioid withdrawal, characterized by symptoms such as body aches, diarrhea, tachycardia, fever, runny nose, sneezing, goose bumps, sweating, yawning, nausea or vomiting, nervousness, restlessness or irritability, shivering or trembling, abdominal cramps, weakness, and increased blood pressure.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

lfranki@mdedge.com

The Food and Drug Administration on April 19 approved the first generic naloxone hydrochloride nasal spray (Narcan) as treatment for stopping or reversing an opioid overdose.

“In the wake of the opioid crisis, a number of efforts are underway to make this emergency overdose reversal treatment more readily available and more accessible,” said Douglas Throckmorton, MD, deputy center director for regulatory programs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, in a press release. “In addition to this approval of the first generic naloxone nasal spray, moving forward, we will prioritize our review of generic drug applications for naloxone.”

The agency said the naloxone nasal spray does not need assembly and can be used by anyone, regardless of medical training. If the spray is administered quickly after the overdose begins, the effect of the opioid will be countered, often within minutes. However, patients should still seek immediate medical attention.

The FDA cautioned that, when used on a patient with an opioid dependence, naloxone can cause severe opioid withdrawal, characterized by symptoms such as body aches, diarrhea, tachycardia, fever, runny nose, sneezing, goose bumps, sweating, yawning, nausea or vomiting, nervousness, restlessness or irritability, shivering or trembling, abdominal cramps, weakness, and increased blood pressure.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

lfranki@mdedge.com

CDC clarifies opioid prescribing guidelines in cancer, sickle cell disease

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have clarified the agency’s guidelines on opioid prescribing after a trio of organizations raised concerns that insurers were inappropriately applying the recommendations to active cancer patients when making coverage determinations.

The CDC guidelines, released in March 2016, address when to initiate or continue opioids for chronic pain, opioid selection, dosage, duration, follow-up, and discontinuation, and assess risk and harms of opioid use. Although the guidelines clearly state they are intended for clinicians prescribing opioids outside of active cancer treatment, insurance companies are still applying the guidelines to opioid coverage decisions for patients with active cancer, according to a Feb. 13, 2019, letter sent to the CDC from leaders at the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the American Society of Hematology.

Additionally, the associations wrote that the CDC’s recommendations pose coverage problems for sickle cell patients and select groups of cancer survivors who may benefit from opioids for pain management. The groups asked the CDC to issue a clarification to ensure appropriate implementation of the opioid recommendations.

In a Feb. 28, 2019, letter to ASCO, NCCN, and ASH, Deborah Dowell, MD, chief medical officer for the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control took note of the concerns, clarifying that the recommendations are not intended to deny clinically appropriate opioid therapy to any patients who suffer chronic pain, but rather to ensure that physicians and patients consider all safe and effective treatment options.

The CDC guidance may apply to cancer survivors in certain conditions, Dr. Dowell wrote, namely when survivors experience chronic pain after cancer treatment completion, are in clinical remission, and are under cancer surveillance only. However, she agreed that, for select groups of cancer survivors with persistent pain caused by past cancer, the ratio of opioid benefits to risks for chronic pain is unique. She referred health providers to guidelines by ASCO on chronic pain management for adult cancer survivors and NCCN guidance on managing adult cancer pain when considering opioids for pain control in such populations.

Special considerations in sickle cell disease may also change the balance of opioid risks to benefits for pain management, Dr. Dowell wrote, referring providers and insurers to additional guidance on sickle cell disease from the National Institute of Health when making treatment and reimbursement decisions.

“Clinical decision making should be based on the relationship between the clinician and patient, with an understanding of the patient’s clinical situation, functioning, and life context, as well as careful consideration of the benefits and risk of all treatment options, including opioid therapy,” Dr. Dowell wrote. “CDC encourages physicians to continue using their clinical judgment and base treatment on what they know about their patients, including the use of opioids if determined to be the best course of treatment.”

Clifford A. Hudis, MD, CEO of ASCO, praised the clarification, calling the letter necessary to clear up confusion and prevent inappropriate coverage decisions.

“This clarification from CDC is critically important because, while the agency’s guideline clearly states that it is not intended to apply to patients during active cancer and sickle cell disease treatment, many payers have been inappropriately using it to make opioid coverage determinations for those exact populations,” Dr. Hudis said in a statement.

Sickle cell patients suffer from severe, chronic pain, which is debilitating on its own without the added burden of having to constantly appeal coverage denials, added ASH President Roy Silverstein, MD.

“We appreciate CDC’s acknowledgment that the challenges of managing severe and chronic pain in conditions, such as sickle cell disease, require special consideration, and we hope payers will take the CDC’s clarification into account to ensure that patients’ pain management needs are covered,” he said in the same statement.

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have clarified the agency’s guidelines on opioid prescribing after a trio of organizations raised concerns that insurers were inappropriately applying the recommendations to active cancer patients when making coverage determinations.

The CDC guidelines, released in March 2016, address when to initiate or continue opioids for chronic pain, opioid selection, dosage, duration, follow-up, and discontinuation, and assess risk and harms of opioid use. Although the guidelines clearly state they are intended for clinicians prescribing opioids outside of active cancer treatment, insurance companies are still applying the guidelines to opioid coverage decisions for patients with active cancer, according to a Feb. 13, 2019, letter sent to the CDC from leaders at the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the American Society of Hematology.

Additionally, the associations wrote that the CDC’s recommendations pose coverage problems for sickle cell patients and select groups of cancer survivors who may benefit from opioids for pain management. The groups asked the CDC to issue a clarification to ensure appropriate implementation of the opioid recommendations.

In a Feb. 28, 2019, letter to ASCO, NCCN, and ASH, Deborah Dowell, MD, chief medical officer for the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control took note of the concerns, clarifying that the recommendations are not intended to deny clinically appropriate opioid therapy to any patients who suffer chronic pain, but rather to ensure that physicians and patients consider all safe and effective treatment options.

The CDC guidance may apply to cancer survivors in certain conditions, Dr. Dowell wrote, namely when survivors experience chronic pain after cancer treatment completion, are in clinical remission, and are under cancer surveillance only. However, she agreed that, for select groups of cancer survivors with persistent pain caused by past cancer, the ratio of opioid benefits to risks for chronic pain is unique. She referred health providers to guidelines by ASCO on chronic pain management for adult cancer survivors and NCCN guidance on managing adult cancer pain when considering opioids for pain control in such populations.

Special considerations in sickle cell disease may also change the balance of opioid risks to benefits for pain management, Dr. Dowell wrote, referring providers and insurers to additional guidance on sickle cell disease from the National Institute of Health when making treatment and reimbursement decisions.

“Clinical decision making should be based on the relationship between the clinician and patient, with an understanding of the patient’s clinical situation, functioning, and life context, as well as careful consideration of the benefits and risk of all treatment options, including opioid therapy,” Dr. Dowell wrote. “CDC encourages physicians to continue using their clinical judgment and base treatment on what they know about their patients, including the use of opioids if determined to be the best course of treatment.”

Clifford A. Hudis, MD, CEO of ASCO, praised the clarification, calling the letter necessary to clear up confusion and prevent inappropriate coverage decisions.

“This clarification from CDC is critically important because, while the agency’s guideline clearly states that it is not intended to apply to patients during active cancer and sickle cell disease treatment, many payers have been inappropriately using it to make opioid coverage determinations for those exact populations,” Dr. Hudis said in a statement.

Sickle cell patients suffer from severe, chronic pain, which is debilitating on its own without the added burden of having to constantly appeal coverage denials, added ASH President Roy Silverstein, MD.

“We appreciate CDC’s acknowledgment that the challenges of managing severe and chronic pain in conditions, such as sickle cell disease, require special consideration, and we hope payers will take the CDC’s clarification into account to ensure that patients’ pain management needs are covered,” he said in the same statement.

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have clarified the agency’s guidelines on opioid prescribing after a trio of organizations raised concerns that insurers were inappropriately applying the recommendations to active cancer patients when making coverage determinations.

The CDC guidelines, released in March 2016, address when to initiate or continue opioids for chronic pain, opioid selection, dosage, duration, follow-up, and discontinuation, and assess risk and harms of opioid use. Although the guidelines clearly state they are intended for clinicians prescribing opioids outside of active cancer treatment, insurance companies are still applying the guidelines to opioid coverage decisions for patients with active cancer, according to a Feb. 13, 2019, letter sent to the CDC from leaders at the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the American Society of Hematology.

Additionally, the associations wrote that the CDC’s recommendations pose coverage problems for sickle cell patients and select groups of cancer survivors who may benefit from opioids for pain management. The groups asked the CDC to issue a clarification to ensure appropriate implementation of the opioid recommendations.

In a Feb. 28, 2019, letter to ASCO, NCCN, and ASH, Deborah Dowell, MD, chief medical officer for the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control took note of the concerns, clarifying that the recommendations are not intended to deny clinically appropriate opioid therapy to any patients who suffer chronic pain, but rather to ensure that physicians and patients consider all safe and effective treatment options.

The CDC guidance may apply to cancer survivors in certain conditions, Dr. Dowell wrote, namely when survivors experience chronic pain after cancer treatment completion, are in clinical remission, and are under cancer surveillance only. However, she agreed that, for select groups of cancer survivors with persistent pain caused by past cancer, the ratio of opioid benefits to risks for chronic pain is unique. She referred health providers to guidelines by ASCO on chronic pain management for adult cancer survivors and NCCN guidance on managing adult cancer pain when considering opioids for pain control in such populations.

Special considerations in sickle cell disease may also change the balance of opioid risks to benefits for pain management, Dr. Dowell wrote, referring providers and insurers to additional guidance on sickle cell disease from the National Institute of Health when making treatment and reimbursement decisions.

“Clinical decision making should be based on the relationship between the clinician and patient, with an understanding of the patient’s clinical situation, functioning, and life context, as well as careful consideration of the benefits and risk of all treatment options, including opioid therapy,” Dr. Dowell wrote. “CDC encourages physicians to continue using their clinical judgment and base treatment on what they know about their patients, including the use of opioids if determined to be the best course of treatment.”

Clifford A. Hudis, MD, CEO of ASCO, praised the clarification, calling the letter necessary to clear up confusion and prevent inappropriate coverage decisions.

“This clarification from CDC is critically important because, while the agency’s guideline clearly states that it is not intended to apply to patients during active cancer and sickle cell disease treatment, many payers have been inappropriately using it to make opioid coverage determinations for those exact populations,” Dr. Hudis said in a statement.

Sickle cell patients suffer from severe, chronic pain, which is debilitating on its own without the added burden of having to constantly appeal coverage denials, added ASH President Roy Silverstein, MD.

“We appreciate CDC’s acknowledgment that the challenges of managing severe and chronic pain in conditions, such as sickle cell disease, require special consideration, and we hope payers will take the CDC’s clarification into account to ensure that patients’ pain management needs are covered,” he said in the same statement.

Treating the pregnant patient with opioid addiction

OBG Management : How has the opioid crisis affected women in general?

Mishka Terplan, MD: Everyone is aware that we are experiencing a massive opioid crisis in the United States, and from a historical perspective, this is at least the third or fourth significant opioid epidemic in our nation’s history.1 It is similar in some ways to the very first one, which also featured a large proportion of women and also was driven initially by physician prescribing practices. However, the magnitude of this crisis is unparalleled compared with prior opioid epidemics.

There are lots of reasons why women are overrepresented in this crisis. There are gender-based differences in pain—chronic pain syndromes are more common in women. In addition, we have a gender bias in prescribing opioids and prescribe more opioids to women (especially older women) than to men. Cultural differences also contribute. As providers, we tend not to think of women as people who use drugs or people who develop addictions the same way as we think of these risks and behaviors for men. Therefore, compared with men, we are less likely to screen, assess, or refer women for substance use, misuse, and addiction. All of this adds up to creating a crisis in which women are increasingly the face of the epidemic.

OBG Management : What are the concerns about opioid addiction and pregnant women specifically?

Dr. Terplan: Addiction is a chronic condition, just like diabetes or depression, and the same principles that we think of in terms of optimizing maternal and newborn health apply to addiction. Ideally, we want, for women with chronic diseases to have stable disease at the time of conception and through pregnancy. We know this maximizes birth outcomes.

Unfortunately, there is a massive treatment gap in the United States. Most people with addiction receive no treatment. Only 11% of people with a substance use disorder report receipt of treatment. By contrast, more than 70% of people with depression, hypertension, or diabetes receive care. This treatment gap is also present in pregnancy. Among use disorders, treatment receipt is highest for opioid use disorder; however, nationally, at best, 25% of pregnant women with opioid addiction receive any care.

In other words, when we encounter addiction clinically, it is often untreated addiction. Therefore, many times providers will have women presenting to care who are both pregnant and have untreated addiction. From both a public health and a clinical practice perspective, the salient distinction is not between people with addiction and those without but between people with treated disease and people with untreated disease.

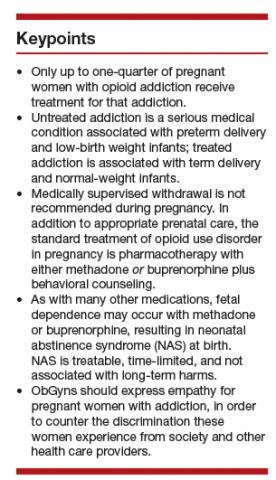

Untreated addiction is a serious medical condition. It is associated with preterm delivery and low birth weight infants. It is associated with acquisition and transmission of HIV and hepatitis C. It is associated with overdose and overdose death. By contrast, treated addiction is associated with term delivery and normal weight infants. Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder stabilize the intrauterine environment and allow for normal fetal growth. Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder help to structure and stabilize the mom’s social circumstance, providing a platform to deliver prenatal care and essential social services. And pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder protect women and their fetuses from overdose and from overdose deaths. The goal of management of addiction in pregnancy is treatment of the underlying condition, treating the addiction.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : What should the ObGyn do when faced with a patient who might have an addiction?

Dr. Terplan: The good news is that there are lots of recently published guidance documents from the World Health Organization,2 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG),3 and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA),4 and there have been a whole series of trainings throughout the United States organized by both ACOG and SAMHSA.

There is also a collaboration between ACOG and the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) to provide buprenorphine waiver trainings specifically designed for ObGyns. Check both the ACOG and ASAM pages for details. I encourage every provider to get a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine. There are about 30 ObGyns who are also board certified in addiction medicine in the United States, and all of us are more than happy to help our colleagues in the clinical care of this population, a population that all of us really enjoy taking care of.

Although care in pregnancy is important, we must not forget about the postpartum period. Generally speaking, women do quite well during pregnancy in terms of treatment. Postpartum, however, is a vulnerable period, where relapse happens, where gaps in care happen, where child welfare involvement and sometimes child removal happens, which can be very stressful for anyone much less somebody with a substance use disorder. Recent data demonstrate that one of the leading causes of maternal mortality in the US in from overdose, and most of these deaths occur in the postpartum period.5 Regardless of what happens during pregnancy, it is essential that we be able to link and continue care for women with opioid use disorder throughout the postpartum period.

OBG Management : How do you treat opioid use disorder in pregnancy?

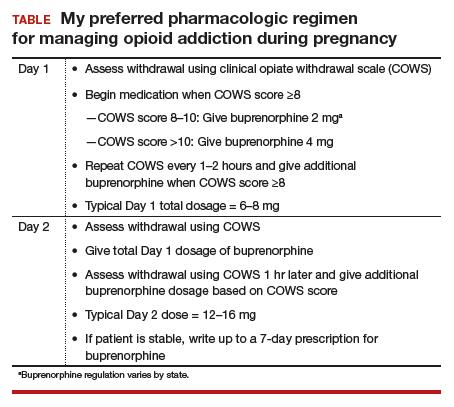

Dr. Terplan: The standard of care for treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy is pharmacotherapy with either methadone or buprenorphine (TABLE) plus behavioral counseling—ideally, co-located with prenatal care. The evidence base for pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder in pregnancy is supported by every single professional society that has ever issued guidance on this, from the World Health Organization to ACOG, to ASAM, to the Royal College in the UK as well as Canadian and Australian obstetrics and gynecology societies; literally every single professional society supports medication.

The core principle of maternal fetal medicine rests upon the fact that chronic conditions need to be treated and that treated illness improves birth outcomes. For both maternal and fetal health, treated addiction is way better than untreated addiction. One concern people have regarding methadone and buprenorphine is the development of dependence. Dependence is a physiologic effect of medication and occurs with opioids, as well as with many other medications, such as antidepressants and most hypertensive agents. For the fetus, dependence means that at the time of delivery, the infant may go into withdrawal, which is also called neonatal abstinence syndrome. Neonatal abstinence syndrome is an expected outcome of in-utero opioid exposure. It is a time-limited and treatable condition. Prospective data do not demonstrate any long-term harms among infants whose mothers received pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder during pregnancy.6

The treatment for neonatal abstinence syndrome is costly, especially when in a neonatal intensive care unit. It can be quite concerning to a new mother to have an infant that has to spend extra time in the hospital and sometimes be medicated for management of withdrawal.

There has been a renewed interest amongst ObGyns in investigating medically-supervised withdrawal during pregnancy. Although there are remaining questions, overall, the literature does not support withdrawal during pregnancy—mostly because withdrawal is associated with relapse, and relapse is associated with cessation of care (both prenatal care and addiction treatment), acquisition and transmission of HIV and Hepatitis C, and overdose and overdose death. The pertinent clinical and public health goal is the treatment of the chronic condition of addiction during pregnancy. The standard of care remains pharmacotherapy plus behavioral counseling for the treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy.

Clinical care, however, is both evidence-based and person-centered. All of us who have worked in this field, long before there was attention to the opioid crisis, all of us have provided medically-supervised withdrawal of a pregnant person, and that is because we understand the principles of care. When evidence-based care conflicts with person-centered care, the ethical course is the provision of person-centered care. Patients have the right of refusal. If someone wants to discontinue medication, I have tapered the medication during pregnancy, but continued to provide (and often increase) behavioral counseling and prenatal care.

Treated addiction is better for the fetus than untreated addiction. Untreated opioid addiction is associated with preterm birth and low birth weight. These obstetric risks are not because of the opioid per se, but because of the repeated cycles of withdrawal that an individual with untreated addiction experiences. People with untreated addiction are not getting “high” when they use, they are just becoming a little bit less sick. It is this repeated cycle of withdrawal that stresses the fetus, which leads to preterm delivery and low birth weight.

Medications for opioid use disorder are long-acting and dosed daily. In contrast to the repeated cycles of fetal withdrawal in untreated addiction, pharmacotherapy stabilizes the intrauterine environment. There is no cyclic, repeated, stressful withdrawal, and consequentially, the fetus grows normally and delivers at term. Obstetric risk is from repeated cyclic withdrawal more than from opioid exposure itself.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : Research reports that women are not using all of the opioids that are prescribed to them after a cesarean delivery. What are the risks for addiction in this setting?

Dr. Terplan: I mark a distinction between use (ie, using something as prescribed) and misuse, which means using a prescribed medication not in the manner in which it was prescribed, or using somebody else’s medications, or using an illicit substance. And I differentiate use and misuse from addiction, which is a behavioral condition, a disease. There has been a lot of attention paid to opioid prescribing in general and in particular postdelivery and post–cesarean delivery, which is one of the most common operative procedures in the United States.

It seems clear from the literature that we have overprescribed opioids postdelivery, and a small number of women, about 1 in 300 will continue an opioid script.7 This means that 1 in 300 women who received an opioid prescription following delivery present for care and get another opioid prescription filled. Now, that is a small number at the level of the individual, but because we do so many cesarean deliveries, this is a large number of women at the level of the population. This does not mean, however, that 1 in 300 women who received opioids after cesarean delivery are going to become addicted to them. It just means that 1 in 300 will continue the prescription. Prescription continuation is a risk factor for opioid misuse, and opioid misuse is on the pathway toward addiction.

Most people who use substances do not develop an addiction to that substance. We know from the opioid literature that at most only 10% of people who receive chronic opioid therapy will meet criteria for opioid use disorder.8 Now 10% is not 100%, nor is it 0%, but because we prescribed so many opioids to so many people for so long, the absolute number of people with opioid use disorder from physician opioid prescribing is large, even though the risk at the level of the individual is not as large as people think.

OBG Management : From your experience in treating addiction during pregnancy, are there clinical pearls you would like to share with ObGyns?

Dr. Terplan: There are a couple of takeaways. One is that all women are motivated to maximize their health and that of their baby to be, and every pregnant woman engages in behavioral change; in fact most women quit or cutback substance use during pregnancy. But some can’t. Those that can’t likely have a substance use disorder. We think of addiction as a chronic condition, centered in the brain, but the primary symptoms of addiction are behaviors. The salient feature of addiction is continued use despite adverse consequences; using something that you know is harming yourself and others but you can’t stop using it. In other words, continuing substance use during pregnancy. When we see clinically a pregnant woman who is using a substance, 99% of the time we are seeing a pregnant woman who has the condition of addiction, and what she needs is treatment. She does not need to be told that injecting heroin is unsafe for her and her fetus, she knows that. What she needs is treatment.

The second point is that pregnant women who use drugs and pregnant women with addiction experience a real specific and strong form of discrimination by providers, by other people with addiction, by the legal system, and by their friends and families. Caring for people who have substance use disorder is grounded in human rights, which means treating people with dignity and respect. It is important for providers to have empathy, especially for pregnant people who use drugs, to counter the discrimination they experience from society and from other health care providers.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : Are there specific ways in which ObGyns can show empathy when speaking with a pregnant woman who likely has addiction?

Dr. Terplan: In general when we talk to people about drug use, it is important to ask their permission to talk about it. For example, “Is it okay if I ask you some questions about smoking, drinking, and other drugs?” If someone says, “No, I don’t want you to ask those questions,” we have to respect that. Assessment of substance use should be a universal part of all medical care, as substance use, misuse, and addiction are essential domains of wellness, but I think we should ask permission before screening.

One of the really good things about prenatal care is that people come back; we have multiple visits across the gestational period. The behavioral work of addiction treatment rests upon a strong therapeutic alliance. If you do not respect your patient, then there is no way you can achieve a therapeutic alliance. Asking permission, and then respecting somebody’s answers, I think goes a really long way to establishing a strong therapeutic alliance, which is the basis of any medical care.

- Terplan M. Women and the opioid crisis: historical context and public health solutions. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:195-199.

- Management of substance abuse. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/activities/treatment_opioid_dependence/en/. Accessed March 20, 2019.

- Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 711: Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):e81-e94.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Clinical guidance for treating pregnant and parenting women with opioid use disorder and their infants. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 18-5054. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2018.

- Metz TD, Royner P, Hoffman MC, et al. Maternal deaths from suicide and overdose in Colorado, 2004-2012. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:1233-1240.

- Kaltenbach K, O’Grady E, Heil SH, et al. Prenatal exposure to methadone or buprenorphine: early childhood developmental outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;185:40-49.

- Bateman BT, Franklin JM, Bykov K, et al. Persistent opioid use following cesarean delivery: patterns and predictors among opioid-naive women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:353.e1-353.e18.

OBG Management : How has the opioid crisis affected women in general?

Mishka Terplan, MD: Everyone is aware that we are experiencing a massive opioid crisis in the United States, and from a historical perspective, this is at least the third or fourth significant opioid epidemic in our nation’s history.1 It is similar in some ways to the very first one, which also featured a large proportion of women and also was driven initially by physician prescribing practices. However, the magnitude of this crisis is unparalleled compared with prior opioid epidemics.

There are lots of reasons why women are overrepresented in this crisis. There are gender-based differences in pain—chronic pain syndromes are more common in women. In addition, we have a gender bias in prescribing opioids and prescribe more opioids to women (especially older women) than to men. Cultural differences also contribute. As providers, we tend not to think of women as people who use drugs or people who develop addictions the same way as we think of these risks and behaviors for men. Therefore, compared with men, we are less likely to screen, assess, or refer women for substance use, misuse, and addiction. All of this adds up to creating a crisis in which women are increasingly the face of the epidemic.

OBG Management : What are the concerns about opioid addiction and pregnant women specifically?

Dr. Terplan: Addiction is a chronic condition, just like diabetes or depression, and the same principles that we think of in terms of optimizing maternal and newborn health apply to addiction. Ideally, we want, for women with chronic diseases to have stable disease at the time of conception and through pregnancy. We know this maximizes birth outcomes.

Unfortunately, there is a massive treatment gap in the United States. Most people with addiction receive no treatment. Only 11% of people with a substance use disorder report receipt of treatment. By contrast, more than 70% of people with depression, hypertension, or diabetes receive care. This treatment gap is also present in pregnancy. Among use disorders, treatment receipt is highest for opioid use disorder; however, nationally, at best, 25% of pregnant women with opioid addiction receive any care.

In other words, when we encounter addiction clinically, it is often untreated addiction. Therefore, many times providers will have women presenting to care who are both pregnant and have untreated addiction. From both a public health and a clinical practice perspective, the salient distinction is not between people with addiction and those without but between people with treated disease and people with untreated disease.

Untreated addiction is a serious medical condition. It is associated with preterm delivery and low birth weight infants. It is associated with acquisition and transmission of HIV and hepatitis C. It is associated with overdose and overdose death. By contrast, treated addiction is associated with term delivery and normal weight infants. Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder stabilize the intrauterine environment and allow for normal fetal growth. Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder help to structure and stabilize the mom’s social circumstance, providing a platform to deliver prenatal care and essential social services. And pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder protect women and their fetuses from overdose and from overdose deaths. The goal of management of addiction in pregnancy is treatment of the underlying condition, treating the addiction.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : What should the ObGyn do when faced with a patient who might have an addiction?

Dr. Terplan: The good news is that there are lots of recently published guidance documents from the World Health Organization,2 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG),3 and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA),4 and there have been a whole series of trainings throughout the United States organized by both ACOG and SAMHSA.

There is also a collaboration between ACOG and the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) to provide buprenorphine waiver trainings specifically designed for ObGyns. Check both the ACOG and ASAM pages for details. I encourage every provider to get a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine. There are about 30 ObGyns who are also board certified in addiction medicine in the United States, and all of us are more than happy to help our colleagues in the clinical care of this population, a population that all of us really enjoy taking care of.

Although care in pregnancy is important, we must not forget about the postpartum period. Generally speaking, women do quite well during pregnancy in terms of treatment. Postpartum, however, is a vulnerable period, where relapse happens, where gaps in care happen, where child welfare involvement and sometimes child removal happens, which can be very stressful for anyone much less somebody with a substance use disorder. Recent data demonstrate that one of the leading causes of maternal mortality in the US in from overdose, and most of these deaths occur in the postpartum period.5 Regardless of what happens during pregnancy, it is essential that we be able to link and continue care for women with opioid use disorder throughout the postpartum period.

OBG Management : How do you treat opioid use disorder in pregnancy?

Dr. Terplan: The standard of care for treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy is pharmacotherapy with either methadone or buprenorphine (TABLE) plus behavioral counseling—ideally, co-located with prenatal care. The evidence base for pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder in pregnancy is supported by every single professional society that has ever issued guidance on this, from the World Health Organization to ACOG, to ASAM, to the Royal College in the UK as well as Canadian and Australian obstetrics and gynecology societies; literally every single professional society supports medication.

The core principle of maternal fetal medicine rests upon the fact that chronic conditions need to be treated and that treated illness improves birth outcomes. For both maternal and fetal health, treated addiction is way better than untreated addiction. One concern people have regarding methadone and buprenorphine is the development of dependence. Dependence is a physiologic effect of medication and occurs with opioids, as well as with many other medications, such as antidepressants and most hypertensive agents. For the fetus, dependence means that at the time of delivery, the infant may go into withdrawal, which is also called neonatal abstinence syndrome. Neonatal abstinence syndrome is an expected outcome of in-utero opioid exposure. It is a time-limited and treatable condition. Prospective data do not demonstrate any long-term harms among infants whose mothers received pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder during pregnancy.6

The treatment for neonatal abstinence syndrome is costly, especially when in a neonatal intensive care unit. It can be quite concerning to a new mother to have an infant that has to spend extra time in the hospital and sometimes be medicated for management of withdrawal.

There has been a renewed interest amongst ObGyns in investigating medically-supervised withdrawal during pregnancy. Although there are remaining questions, overall, the literature does not support withdrawal during pregnancy—mostly because withdrawal is associated with relapse, and relapse is associated with cessation of care (both prenatal care and addiction treatment), acquisition and transmission of HIV and Hepatitis C, and overdose and overdose death. The pertinent clinical and public health goal is the treatment of the chronic condition of addiction during pregnancy. The standard of care remains pharmacotherapy plus behavioral counseling for the treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy.

Clinical care, however, is both evidence-based and person-centered. All of us who have worked in this field, long before there was attention to the opioid crisis, all of us have provided medically-supervised withdrawal of a pregnant person, and that is because we understand the principles of care. When evidence-based care conflicts with person-centered care, the ethical course is the provision of person-centered care. Patients have the right of refusal. If someone wants to discontinue medication, I have tapered the medication during pregnancy, but continued to provide (and often increase) behavioral counseling and prenatal care.

Treated addiction is better for the fetus than untreated addiction. Untreated opioid addiction is associated with preterm birth and low birth weight. These obstetric risks are not because of the opioid per se, but because of the repeated cycles of withdrawal that an individual with untreated addiction experiences. People with untreated addiction are not getting “high” when they use, they are just becoming a little bit less sick. It is this repeated cycle of withdrawal that stresses the fetus, which leads to preterm delivery and low birth weight.

Medications for opioid use disorder are long-acting and dosed daily. In contrast to the repeated cycles of fetal withdrawal in untreated addiction, pharmacotherapy stabilizes the intrauterine environment. There is no cyclic, repeated, stressful withdrawal, and consequentially, the fetus grows normally and delivers at term. Obstetric risk is from repeated cyclic withdrawal more than from opioid exposure itself.

Continue to: OBG Management...

OBG Management : Research reports that women are not using all of the opioids that are prescribed to them after a cesarean delivery. What are the risks for addiction in this setting?

Dr. Terplan: I mark a distinction between use (ie, using something as prescribed) and misuse, which means using a prescribed medication not in the manner in which it was prescribed, or using somebody else’s medications, or using an illicit substance. And I differentiate use and misuse from addiction, which is a behavioral condition, a disease. There has been a lot of attention paid to opioid prescribing in general and in particular postdelivery and post–cesarean delivery, which is one of the most common operative procedures in the United States.