User login

EDs saw more benzodiazepine overdoses, but fewer patients overall, in 2020

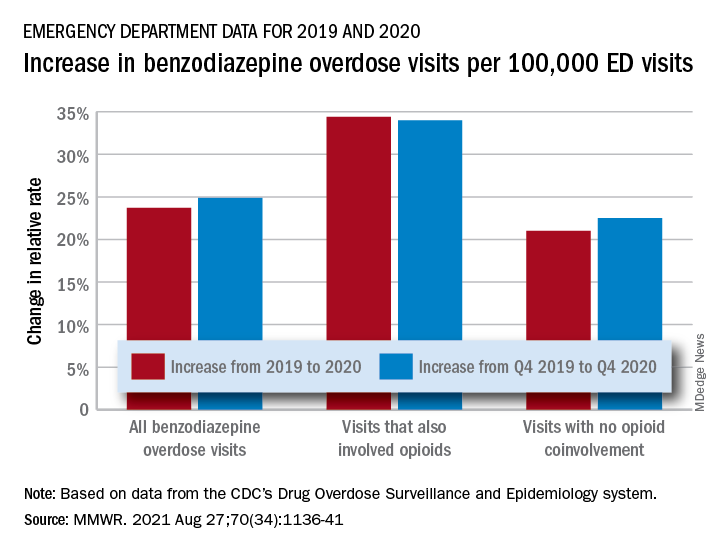

In a year when emergency department visits dropped by almost 18%, visits for benzodiazepine overdoses did the opposite, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The actual increase in the number of overdose visits for benzodiazepine overdoses was quite small – from 15,547 in 2019 to 15,830 in 2020 (1.8%) – but the 11 million fewer ED visits magnified its effect, Stephen Liu, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The rate of benzodiazepine overdose visits to all visits increased by 23.7% from 2019 (24.22 per 100,000 ED visits) to 2020 (29.97 per 100,000), with the larger share going to those involving opioids, which were up by 34.4%, compared with overdose visits not involving opioids (21.0%), the investigators said, based on data reported by 32 states and the District of Columbia to the CDC’s Drug Overdose Surveillance and Epidemiology system. All of the rate changes are statistically significant.

The number of overdose visits without opioid coinvolvement actually dropped, from 2019 (12,276) to 2020 (12,218), but not by enough to offset the decline in total visits, noted Dr. Liu, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and associates.

The number of deaths from benzodiazepine overdose, on the other hand, did not drop in 2020. Those data, coming from 23 states participating in the CDC’s State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, were available only for the first half of the year.

In those 6 months, The first quarter of 2020 also showed an increase, but exact numbers were not provided in the report. Overdose deaths rose by 22% for prescription forms of benzodiazepine and 520% for illicit forms in Q2 of 2020, compared with 2019, the researchers said.

Almost all of the benzodiazepine deaths (93%) in the first half of 2020 also involved opioids, mostly in the form of illicitly manufactured fentanyls (67% of all deaths). Between Q2 of 2019 and Q2 of 2020, involvement of illicit fentanyls in benzodiazepine overdose deaths increased from almost 57% to 71%, Dr. Liu and associates reported.

“Despite progress in reducing coprescribing [of opioids and benzodiazepines] before 2019, this study suggests a reversal in the decline in benzodiazepine deaths from 2017 to 2019, driven in part by increasing involvement of [illicitly manufactured fentanyls] in benzodiazepine deaths and influxes of illicit benzodiazepines,” they wrote.

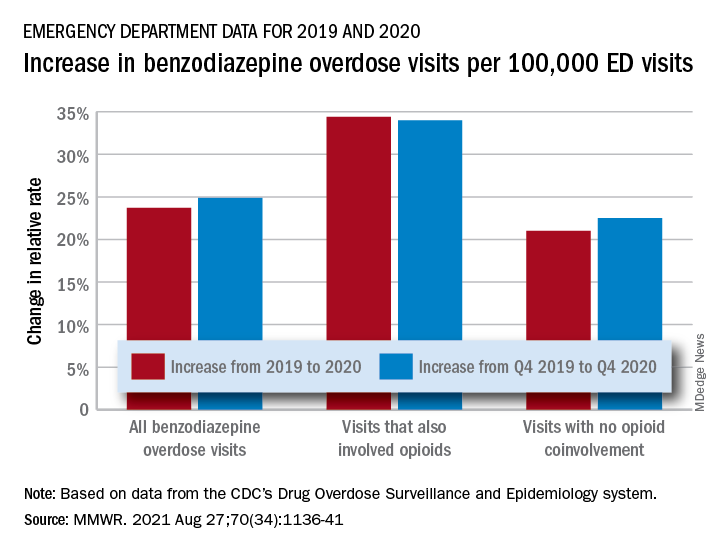

In a year when emergency department visits dropped by almost 18%, visits for benzodiazepine overdoses did the opposite, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The actual increase in the number of overdose visits for benzodiazepine overdoses was quite small – from 15,547 in 2019 to 15,830 in 2020 (1.8%) – but the 11 million fewer ED visits magnified its effect, Stephen Liu, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The rate of benzodiazepine overdose visits to all visits increased by 23.7% from 2019 (24.22 per 100,000 ED visits) to 2020 (29.97 per 100,000), with the larger share going to those involving opioids, which were up by 34.4%, compared with overdose visits not involving opioids (21.0%), the investigators said, based on data reported by 32 states and the District of Columbia to the CDC’s Drug Overdose Surveillance and Epidemiology system. All of the rate changes are statistically significant.

The number of overdose visits without opioid coinvolvement actually dropped, from 2019 (12,276) to 2020 (12,218), but not by enough to offset the decline in total visits, noted Dr. Liu, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and associates.

The number of deaths from benzodiazepine overdose, on the other hand, did not drop in 2020. Those data, coming from 23 states participating in the CDC’s State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, were available only for the first half of the year.

In those 6 months, The first quarter of 2020 also showed an increase, but exact numbers were not provided in the report. Overdose deaths rose by 22% for prescription forms of benzodiazepine and 520% for illicit forms in Q2 of 2020, compared with 2019, the researchers said.

Almost all of the benzodiazepine deaths (93%) in the first half of 2020 also involved opioids, mostly in the form of illicitly manufactured fentanyls (67% of all deaths). Between Q2 of 2019 and Q2 of 2020, involvement of illicit fentanyls in benzodiazepine overdose deaths increased from almost 57% to 71%, Dr. Liu and associates reported.

“Despite progress in reducing coprescribing [of opioids and benzodiazepines] before 2019, this study suggests a reversal in the decline in benzodiazepine deaths from 2017 to 2019, driven in part by increasing involvement of [illicitly manufactured fentanyls] in benzodiazepine deaths and influxes of illicit benzodiazepines,” they wrote.

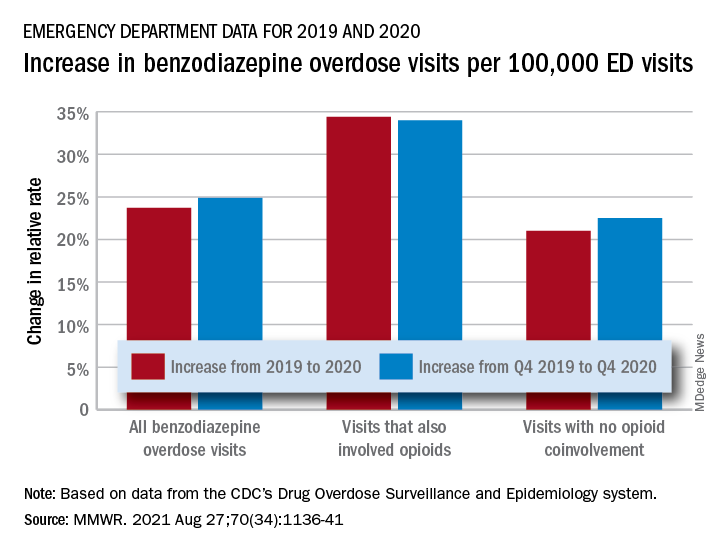

In a year when emergency department visits dropped by almost 18%, visits for benzodiazepine overdoses did the opposite, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The actual increase in the number of overdose visits for benzodiazepine overdoses was quite small – from 15,547 in 2019 to 15,830 in 2020 (1.8%) – but the 11 million fewer ED visits magnified its effect, Stephen Liu, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The rate of benzodiazepine overdose visits to all visits increased by 23.7% from 2019 (24.22 per 100,000 ED visits) to 2020 (29.97 per 100,000), with the larger share going to those involving opioids, which were up by 34.4%, compared with overdose visits not involving opioids (21.0%), the investigators said, based on data reported by 32 states and the District of Columbia to the CDC’s Drug Overdose Surveillance and Epidemiology system. All of the rate changes are statistically significant.

The number of overdose visits without opioid coinvolvement actually dropped, from 2019 (12,276) to 2020 (12,218), but not by enough to offset the decline in total visits, noted Dr. Liu, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and associates.

The number of deaths from benzodiazepine overdose, on the other hand, did not drop in 2020. Those data, coming from 23 states participating in the CDC’s State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, were available only for the first half of the year.

In those 6 months, The first quarter of 2020 also showed an increase, but exact numbers were not provided in the report. Overdose deaths rose by 22% for prescription forms of benzodiazepine and 520% for illicit forms in Q2 of 2020, compared with 2019, the researchers said.

Almost all of the benzodiazepine deaths (93%) in the first half of 2020 also involved opioids, mostly in the form of illicitly manufactured fentanyls (67% of all deaths). Between Q2 of 2019 and Q2 of 2020, involvement of illicit fentanyls in benzodiazepine overdose deaths increased from almost 57% to 71%, Dr. Liu and associates reported.

“Despite progress in reducing coprescribing [of opioids and benzodiazepines] before 2019, this study suggests a reversal in the decline in benzodiazepine deaths from 2017 to 2019, driven in part by increasing involvement of [illicitly manufactured fentanyls] in benzodiazepine deaths and influxes of illicit benzodiazepines,” they wrote.

FROM MMWR

Opioid prescribing laws having an impact

State laws capping initial opioid prescriptions to 7 days or less have led to a reduction in opioid prescribing, a new analysis of Medicare data shows.

While overall opioid prescribing has decreased, the reduction in states with legislation restricting opioid prescribing was “significantly greater than in states without such legislation,” study investigator Michael Brenner, MD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said in an interview.

The study was published online August 9 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Significant but limited effect

Because of rising concern around the opioid crisis, 23 states representing 43% of the U.S. population passed laws from 2016 through 2018 limiting initial opioid prescription to 7 days or less.

Using Medicare data from 2013 through 2018, Dr. Brenner and colleagues conducted a before-and-after study to assess the effect of these laws.

They found that on average, the number of days an opioid was prescribed for each Medicare beneficiary decreased by 11.6 days (from 44.2 days in 2013 to 32.7 days in 2018) in states that imposed duration limits, compared with 10.1 days in states without these laws (from 43.4 days in 2013 to 33.3 days in 2018).

Prior to the start of duration limits in 2016, days an opioid was prescribed were comparable among states.

After adjusting for state-level differences in race, urbanization, median income, tobacco and alcohol use, serious mental illness, and other factors, state laws limiting opioid prescriptions to 7 days or less were associated with a reduction in prescribing of 1.7 days per enrollee, “suggesting a significant but limited outcome” for these laws, the researchers note.

, but this was not significantly different in states with limit laws versus those without. However, state laws limiting duration led to a significant reduction in days of opioid prescribed among surgeons, dentists, pain specialists, and other specialists.

Inadequate pain control?

The researchers note the study was limited to Medicare beneficiaries; however, excess opioid prescribing is prevalent across all patient populations.

In addition, it’s not possible to tell from the data whether acute pain was adequately controlled with fewer pills.

“The question of adequacy of pain control is a crucial one that has been investigated extensively in prior work but was not possible to evaluate in this particular study,” said Dr. Brenner.

However, “ample evidence supports a role for reducing opioid prescribing and that such reduction can be achieved while ensuring that pain is adequately controlled with fewer pills,” he noted.

“A persistent misconception is that opioids are uniquely powerful and effective for controlling pain. Patients may perceive that effective analgesia is being withheld when opioids are not included in a regimen,” Dr. Brenner added.

“Yet, the evidence from meta-analyses derived from large numbers of randomized clinical trials finds that [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs] NSAIDS combined with acetaminophen provide similar or improved acute pain when compared to commonly prescribed opioid regimens, based on number-needed-to-treat analyses,” he added.

In a related editorial, Deborah Grady, MD, MPH, with University of California, San Francisco, and Mitchell H. Katz, MD, president and CEO of NYC Health + Hospitals, say the decrease in opioid prescribing with duration limits was “small but probably meaningful.”

Restricting initial prescriptions to seven or fewer days is “reasonable because patients with new onset of pain should be re-evaluated in a week if the pain continues,” they write.

However, Dr. Grady and Dr. Katz “worry” that restricting initial prescriptions to shorter periods, such as 3 or 5 days, as has occurred in six states, “may result in patients with acute pain going untreated or having to go to extraordinary effort to obtain adequate pain relief.”

In their view, the data from this study suggest that limiting initial prescriptions to seven or fewer days is “helpful, but we would not restrict any further given that we do not know how it affected patients with acute pain.”

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Brenner, Dr. Grady, and Dr. Katz have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

State laws capping initial opioid prescriptions to 7 days or less have led to a reduction in opioid prescribing, a new analysis of Medicare data shows.

While overall opioid prescribing has decreased, the reduction in states with legislation restricting opioid prescribing was “significantly greater than in states without such legislation,” study investigator Michael Brenner, MD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said in an interview.

The study was published online August 9 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Significant but limited effect

Because of rising concern around the opioid crisis, 23 states representing 43% of the U.S. population passed laws from 2016 through 2018 limiting initial opioid prescription to 7 days or less.

Using Medicare data from 2013 through 2018, Dr. Brenner and colleagues conducted a before-and-after study to assess the effect of these laws.

They found that on average, the number of days an opioid was prescribed for each Medicare beneficiary decreased by 11.6 days (from 44.2 days in 2013 to 32.7 days in 2018) in states that imposed duration limits, compared with 10.1 days in states without these laws (from 43.4 days in 2013 to 33.3 days in 2018).

Prior to the start of duration limits in 2016, days an opioid was prescribed were comparable among states.

After adjusting for state-level differences in race, urbanization, median income, tobacco and alcohol use, serious mental illness, and other factors, state laws limiting opioid prescriptions to 7 days or less were associated with a reduction in prescribing of 1.7 days per enrollee, “suggesting a significant but limited outcome” for these laws, the researchers note.

, but this was not significantly different in states with limit laws versus those without. However, state laws limiting duration led to a significant reduction in days of opioid prescribed among surgeons, dentists, pain specialists, and other specialists.

Inadequate pain control?

The researchers note the study was limited to Medicare beneficiaries; however, excess opioid prescribing is prevalent across all patient populations.

In addition, it’s not possible to tell from the data whether acute pain was adequately controlled with fewer pills.

“The question of adequacy of pain control is a crucial one that has been investigated extensively in prior work but was not possible to evaluate in this particular study,” said Dr. Brenner.

However, “ample evidence supports a role for reducing opioid prescribing and that such reduction can be achieved while ensuring that pain is adequately controlled with fewer pills,” he noted.

“A persistent misconception is that opioids are uniquely powerful and effective for controlling pain. Patients may perceive that effective analgesia is being withheld when opioids are not included in a regimen,” Dr. Brenner added.

“Yet, the evidence from meta-analyses derived from large numbers of randomized clinical trials finds that [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs] NSAIDS combined with acetaminophen provide similar or improved acute pain when compared to commonly prescribed opioid regimens, based on number-needed-to-treat analyses,” he added.

In a related editorial, Deborah Grady, MD, MPH, with University of California, San Francisco, and Mitchell H. Katz, MD, president and CEO of NYC Health + Hospitals, say the decrease in opioid prescribing with duration limits was “small but probably meaningful.”

Restricting initial prescriptions to seven or fewer days is “reasonable because patients with new onset of pain should be re-evaluated in a week if the pain continues,” they write.

However, Dr. Grady and Dr. Katz “worry” that restricting initial prescriptions to shorter periods, such as 3 or 5 days, as has occurred in six states, “may result in patients with acute pain going untreated or having to go to extraordinary effort to obtain adequate pain relief.”

In their view, the data from this study suggest that limiting initial prescriptions to seven or fewer days is “helpful, but we would not restrict any further given that we do not know how it affected patients with acute pain.”

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Brenner, Dr. Grady, and Dr. Katz have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

State laws capping initial opioid prescriptions to 7 days or less have led to a reduction in opioid prescribing, a new analysis of Medicare data shows.

While overall opioid prescribing has decreased, the reduction in states with legislation restricting opioid prescribing was “significantly greater than in states without such legislation,” study investigator Michael Brenner, MD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said in an interview.

The study was published online August 9 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Significant but limited effect

Because of rising concern around the opioid crisis, 23 states representing 43% of the U.S. population passed laws from 2016 through 2018 limiting initial opioid prescription to 7 days or less.

Using Medicare data from 2013 through 2018, Dr. Brenner and colleagues conducted a before-and-after study to assess the effect of these laws.

They found that on average, the number of days an opioid was prescribed for each Medicare beneficiary decreased by 11.6 days (from 44.2 days in 2013 to 32.7 days in 2018) in states that imposed duration limits, compared with 10.1 days in states without these laws (from 43.4 days in 2013 to 33.3 days in 2018).

Prior to the start of duration limits in 2016, days an opioid was prescribed were comparable among states.

After adjusting for state-level differences in race, urbanization, median income, tobacco and alcohol use, serious mental illness, and other factors, state laws limiting opioid prescriptions to 7 days or less were associated with a reduction in prescribing of 1.7 days per enrollee, “suggesting a significant but limited outcome” for these laws, the researchers note.

, but this was not significantly different in states with limit laws versus those without. However, state laws limiting duration led to a significant reduction in days of opioid prescribed among surgeons, dentists, pain specialists, and other specialists.

Inadequate pain control?

The researchers note the study was limited to Medicare beneficiaries; however, excess opioid prescribing is prevalent across all patient populations.

In addition, it’s not possible to tell from the data whether acute pain was adequately controlled with fewer pills.

“The question of adequacy of pain control is a crucial one that has been investigated extensively in prior work but was not possible to evaluate in this particular study,” said Dr. Brenner.

However, “ample evidence supports a role for reducing opioid prescribing and that such reduction can be achieved while ensuring that pain is adequately controlled with fewer pills,” he noted.

“A persistent misconception is that opioids are uniquely powerful and effective for controlling pain. Patients may perceive that effective analgesia is being withheld when opioids are not included in a regimen,” Dr. Brenner added.

“Yet, the evidence from meta-analyses derived from large numbers of randomized clinical trials finds that [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs] NSAIDS combined with acetaminophen provide similar or improved acute pain when compared to commonly prescribed opioid regimens, based on number-needed-to-treat analyses,” he added.

In a related editorial, Deborah Grady, MD, MPH, with University of California, San Francisco, and Mitchell H. Katz, MD, president and CEO of NYC Health + Hospitals, say the decrease in opioid prescribing with duration limits was “small but probably meaningful.”

Restricting initial prescriptions to seven or fewer days is “reasonable because patients with new onset of pain should be re-evaluated in a week if the pain continues,” they write.

However, Dr. Grady and Dr. Katz “worry” that restricting initial prescriptions to shorter periods, such as 3 or 5 days, as has occurred in six states, “may result in patients with acute pain going untreated or having to go to extraordinary effort to obtain adequate pain relief.”

In their view, the data from this study suggest that limiting initial prescriptions to seven or fewer days is “helpful, but we would not restrict any further given that we do not know how it affected patients with acute pain.”

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Brenner, Dr. Grady, and Dr. Katz have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sharp decrease in opioid access for dying U.S. cancer patients

There has been a sharp decrease in access to opioids during the past decade, and many patients are going to emergency departments for pain treatment.

Overall, during the study period (2007-2017), there was a 34% reduction in the number of opioid prescriptions filled per patient and a 38% reduction in the total dose of opioids filled near the end of life.

There was a dramatic drop in the use of long-acting opioids, which can provide patients with more consistent pain relief and are important for managing severe cancer pain. The investigators’ results show that during the study period, the number of long-acting opioid prescriptions filled per patient fell by 50%.

“We do believe that the decline in cancer patients’ access to opioids near the end of life is likely attributable to the efforts to curtail opioid misuse,” commented lead author Andrea Enzinger, MD, a medical oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston.

The study was published online July 22 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“The study provides fascinating data that support our clinical observations,” said Marcin Chwistek, MD, FAAHPM, director of the supportive oncology and palliative care program at Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, who was asked for comment. “Primarily, we have noticed a heightened reluctance on the parts of patients with cancer, including those with advanced cancer, to take opioids in general.”

Many factors involved

The crisis of opioid misuse and abuse led to the implementation of regulations to curb inappropriate prescribing. But these restrictions on opioid prescribing may have unintended consequences for patients with advanced, incurable malignancies who are experiencing pain.

“Many but not all opioid regulations specifically exclude cancer patients,” said Dr. Enzinger. “However, the cumulative effect of these regulations may have had a chilling effect on providers’ comfort or willingness to prescribe opioids, even for cancer pain.”

She said in an interview that the prescribing of opioids has become much more difficult. Prescribers are often required to sign an opioid agreement with patients prior to providing them with opioids. Health care professionals may need to use a two-factor authentication to prescribe, and prescribers in 49 of 50 U.S. states are required to check electronic prescription drug monitoring programs prior to providing the prescription.

“After the medications are prescribed, insurance companies require prior-authorization paperwork before filling the medications, particularly for long-acting opioids or high-dose opioids,” Dr. Enzinger said. “These barriers pile up and make the whole process onerous and time consuming.”

Patient factors may also have contributed to the decline in use.

“Cancer patients are often very hesitant to use opioids to treat their pain, as they worry about becoming addicted or being labeled a ‘pill seeker,’” she explained. “Also, the added regulations, such as requirements for prior authorization paperwork, signing opioid agreements, and so on, may add to the stigma of opioid therapy and send a message to patients that these medications are inherently dangerous.”

Dr. Enzinger added that there are legitimate reasons why patients may not want to use opioids and that these should be respected. “But addiction risk should really not weigh into the decisions about pain management for patients who are dying from cancer,” she said.

Decline in opioid dose and prescriptions

Dr. Enzinger and colleagues used administrative data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to identify 270,632 Medicare fee-for-service patients who had cancers that were associated with poor prognoses and who died from 2007 to 2017. During this period, the opioid crisis was first recognized. There followed legislative reforms and subsequent declines in population-based opioid prescribing.

Among the patients in the study, the most common cancers were lung, colorectal, pancreatic, prostate, and breast cancers; 166,962 patients (61.7%) were enrolled in hospice before death. This percentage increased from 57.1% in 2007 to 66.2% in 2017 (P for trend < .001).

From 2007 to 2017, the proportion of patients filling greater than or equal to 1 opioid prescriptions declined from 42.0% to 35.5%. The proportion declined faster from 2012-2017 than from 2007-2011.

The proportion of patients who filled prescriptions for long-acting opioids dropped from 18.1% to 11.5%. Here again, the decline was faster from 2012-2017 than from 2007-2011. Prescriptions for strong short-acting opioids declined from 31.7% to 28.5%. Prescribing was initially stable from 2007-2011 and began to decline in 2012. Conversely, prescriptions for weak short-acting opioids dropped from 8.4% to 6.5% from 2007-2011 and then stabilized after 2012.

The mean daily dose fell 24.5%, from 85.6 morphine milligram equivalents per day (MMED) to 64.6 MMED. Overall, the total amount of opioids prescribed per decedent fell 38.0%, from 1,075 MMEs per person to 666 MMEs.

At the same time, the proportion of patients who visited EDs increased 50.8%, from 13.2% to 19.9%.

Experts weigh in

Approached for an independent comment, Amit Barochia, MD, a hematologist/oncologist with Health First Medical Group, Titusville, Fla., commented that the decline could be due, in part, to greater vigilance and awareness by physicians in light of more stringent requirements and of federal and state regulations. “Some physicians are avoiding prescribing opioids due to more regulations and requirements as well, which is routing patients to the ER for pain relief,” he said.

Dr. Barochia agreed that some of the decline could be due to patient factors. “I do think that some of the patients are hesitant about considering opioid use for better pain relief, in part due to fear of addiction as well as complications arising from their use,” he said. “This is likely resulting from more awareness in the community about their adverse effects.

“That awareness could come from aggressive media coverage as well as social media,” he continued. “It is also true that there is a difficulty in getting authorization for certain opioid products, which is delaying the onset of a proper pain regimen that would help to provide adequate pain relief early on.”

For patients with advanced cancer, earlier referral to palliative care would be beneficial, Dr. Barochia pointed out, because this would allow for a more in-depth discussion about pain in addition to addressing the physical and mental symptoms associated with cancer.

Fox Chase Cancer Center’s Dr. Chwistek noted that patients and their caregivers are often apprehensive about the potential adverse effects of opioids, because they often hear about community-based opioid overdoses and are fearful of taking the medications. “Additionally, it has become increasingly challenging to fill opioid prescriptions at local pharmacies, due to quantity limitations, ubiquitous need for prior authorizations, and stigma,” he said.

The fear of addiction is often brought up by the patients during clinic visits, and insurers and pharmacies have imposed many limits on opioid prescribing. “Most of these can be overcome with prior authorizations, but not always, and prior authorizations are time consuming, confusing, and very frustrating for patients,” he said in an interview.

These findings suggest that not enough patients are getting optimal palliative care. “One of the primary tenets of palliative care is optimal symptom control, including pain,” said Dr. Chwistek. “Palliative care teams have the experience and insight needed to help patients overcome the barriers to appropriate pain control. Education, support, and advocacy are critical to ensure that patients’ pain is appropriately addressed.”

The study was funded by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There has been a sharp decrease in access to opioids during the past decade, and many patients are going to emergency departments for pain treatment.

Overall, during the study period (2007-2017), there was a 34% reduction in the number of opioid prescriptions filled per patient and a 38% reduction in the total dose of opioids filled near the end of life.

There was a dramatic drop in the use of long-acting opioids, which can provide patients with more consistent pain relief and are important for managing severe cancer pain. The investigators’ results show that during the study period, the number of long-acting opioid prescriptions filled per patient fell by 50%.

“We do believe that the decline in cancer patients’ access to opioids near the end of life is likely attributable to the efforts to curtail opioid misuse,” commented lead author Andrea Enzinger, MD, a medical oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston.

The study was published online July 22 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“The study provides fascinating data that support our clinical observations,” said Marcin Chwistek, MD, FAAHPM, director of the supportive oncology and palliative care program at Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, who was asked for comment. “Primarily, we have noticed a heightened reluctance on the parts of patients with cancer, including those with advanced cancer, to take opioids in general.”

Many factors involved

The crisis of opioid misuse and abuse led to the implementation of regulations to curb inappropriate prescribing. But these restrictions on opioid prescribing may have unintended consequences for patients with advanced, incurable malignancies who are experiencing pain.

“Many but not all opioid regulations specifically exclude cancer patients,” said Dr. Enzinger. “However, the cumulative effect of these regulations may have had a chilling effect on providers’ comfort or willingness to prescribe opioids, even for cancer pain.”

She said in an interview that the prescribing of opioids has become much more difficult. Prescribers are often required to sign an opioid agreement with patients prior to providing them with opioids. Health care professionals may need to use a two-factor authentication to prescribe, and prescribers in 49 of 50 U.S. states are required to check electronic prescription drug monitoring programs prior to providing the prescription.

“After the medications are prescribed, insurance companies require prior-authorization paperwork before filling the medications, particularly for long-acting opioids or high-dose opioids,” Dr. Enzinger said. “These barriers pile up and make the whole process onerous and time consuming.”

Patient factors may also have contributed to the decline in use.

“Cancer patients are often very hesitant to use opioids to treat their pain, as they worry about becoming addicted or being labeled a ‘pill seeker,’” she explained. “Also, the added regulations, such as requirements for prior authorization paperwork, signing opioid agreements, and so on, may add to the stigma of opioid therapy and send a message to patients that these medications are inherently dangerous.”

Dr. Enzinger added that there are legitimate reasons why patients may not want to use opioids and that these should be respected. “But addiction risk should really not weigh into the decisions about pain management for patients who are dying from cancer,” she said.

Decline in opioid dose and prescriptions

Dr. Enzinger and colleagues used administrative data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to identify 270,632 Medicare fee-for-service patients who had cancers that were associated with poor prognoses and who died from 2007 to 2017. During this period, the opioid crisis was first recognized. There followed legislative reforms and subsequent declines in population-based opioid prescribing.

Among the patients in the study, the most common cancers were lung, colorectal, pancreatic, prostate, and breast cancers; 166,962 patients (61.7%) were enrolled in hospice before death. This percentage increased from 57.1% in 2007 to 66.2% in 2017 (P for trend < .001).

From 2007 to 2017, the proportion of patients filling greater than or equal to 1 opioid prescriptions declined from 42.0% to 35.5%. The proportion declined faster from 2012-2017 than from 2007-2011.

The proportion of patients who filled prescriptions for long-acting opioids dropped from 18.1% to 11.5%. Here again, the decline was faster from 2012-2017 than from 2007-2011. Prescriptions for strong short-acting opioids declined from 31.7% to 28.5%. Prescribing was initially stable from 2007-2011 and began to decline in 2012. Conversely, prescriptions for weak short-acting opioids dropped from 8.4% to 6.5% from 2007-2011 and then stabilized after 2012.

The mean daily dose fell 24.5%, from 85.6 morphine milligram equivalents per day (MMED) to 64.6 MMED. Overall, the total amount of opioids prescribed per decedent fell 38.0%, from 1,075 MMEs per person to 666 MMEs.

At the same time, the proportion of patients who visited EDs increased 50.8%, from 13.2% to 19.9%.

Experts weigh in

Approached for an independent comment, Amit Barochia, MD, a hematologist/oncologist with Health First Medical Group, Titusville, Fla., commented that the decline could be due, in part, to greater vigilance and awareness by physicians in light of more stringent requirements and of federal and state regulations. “Some physicians are avoiding prescribing opioids due to more regulations and requirements as well, which is routing patients to the ER for pain relief,” he said.

Dr. Barochia agreed that some of the decline could be due to patient factors. “I do think that some of the patients are hesitant about considering opioid use for better pain relief, in part due to fear of addiction as well as complications arising from their use,” he said. “This is likely resulting from more awareness in the community about their adverse effects.

“That awareness could come from aggressive media coverage as well as social media,” he continued. “It is also true that there is a difficulty in getting authorization for certain opioid products, which is delaying the onset of a proper pain regimen that would help to provide adequate pain relief early on.”

For patients with advanced cancer, earlier referral to palliative care would be beneficial, Dr. Barochia pointed out, because this would allow for a more in-depth discussion about pain in addition to addressing the physical and mental symptoms associated with cancer.

Fox Chase Cancer Center’s Dr. Chwistek noted that patients and their caregivers are often apprehensive about the potential adverse effects of opioids, because they often hear about community-based opioid overdoses and are fearful of taking the medications. “Additionally, it has become increasingly challenging to fill opioid prescriptions at local pharmacies, due to quantity limitations, ubiquitous need for prior authorizations, and stigma,” he said.

The fear of addiction is often brought up by the patients during clinic visits, and insurers and pharmacies have imposed many limits on opioid prescribing. “Most of these can be overcome with prior authorizations, but not always, and prior authorizations are time consuming, confusing, and very frustrating for patients,” he said in an interview.

These findings suggest that not enough patients are getting optimal palliative care. “One of the primary tenets of palliative care is optimal symptom control, including pain,” said Dr. Chwistek. “Palliative care teams have the experience and insight needed to help patients overcome the barriers to appropriate pain control. Education, support, and advocacy are critical to ensure that patients’ pain is appropriately addressed.”

The study was funded by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There has been a sharp decrease in access to opioids during the past decade, and many patients are going to emergency departments for pain treatment.

Overall, during the study period (2007-2017), there was a 34% reduction in the number of opioid prescriptions filled per patient and a 38% reduction in the total dose of opioids filled near the end of life.

There was a dramatic drop in the use of long-acting opioids, which can provide patients with more consistent pain relief and are important for managing severe cancer pain. The investigators’ results show that during the study period, the number of long-acting opioid prescriptions filled per patient fell by 50%.

“We do believe that the decline in cancer patients’ access to opioids near the end of life is likely attributable to the efforts to curtail opioid misuse,” commented lead author Andrea Enzinger, MD, a medical oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston.

The study was published online July 22 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“The study provides fascinating data that support our clinical observations,” said Marcin Chwistek, MD, FAAHPM, director of the supportive oncology and palliative care program at Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, who was asked for comment. “Primarily, we have noticed a heightened reluctance on the parts of patients with cancer, including those with advanced cancer, to take opioids in general.”

Many factors involved

The crisis of opioid misuse and abuse led to the implementation of regulations to curb inappropriate prescribing. But these restrictions on opioid prescribing may have unintended consequences for patients with advanced, incurable malignancies who are experiencing pain.

“Many but not all opioid regulations specifically exclude cancer patients,” said Dr. Enzinger. “However, the cumulative effect of these regulations may have had a chilling effect on providers’ comfort or willingness to prescribe opioids, even for cancer pain.”

She said in an interview that the prescribing of opioids has become much more difficult. Prescribers are often required to sign an opioid agreement with patients prior to providing them with opioids. Health care professionals may need to use a two-factor authentication to prescribe, and prescribers in 49 of 50 U.S. states are required to check electronic prescription drug monitoring programs prior to providing the prescription.

“After the medications are prescribed, insurance companies require prior-authorization paperwork before filling the medications, particularly for long-acting opioids or high-dose opioids,” Dr. Enzinger said. “These barriers pile up and make the whole process onerous and time consuming.”

Patient factors may also have contributed to the decline in use.

“Cancer patients are often very hesitant to use opioids to treat their pain, as they worry about becoming addicted or being labeled a ‘pill seeker,’” she explained. “Also, the added regulations, such as requirements for prior authorization paperwork, signing opioid agreements, and so on, may add to the stigma of opioid therapy and send a message to patients that these medications are inherently dangerous.”

Dr. Enzinger added that there are legitimate reasons why patients may not want to use opioids and that these should be respected. “But addiction risk should really not weigh into the decisions about pain management for patients who are dying from cancer,” she said.

Decline in opioid dose and prescriptions

Dr. Enzinger and colleagues used administrative data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to identify 270,632 Medicare fee-for-service patients who had cancers that were associated with poor prognoses and who died from 2007 to 2017. During this period, the opioid crisis was first recognized. There followed legislative reforms and subsequent declines in population-based opioid prescribing.

Among the patients in the study, the most common cancers were lung, colorectal, pancreatic, prostate, and breast cancers; 166,962 patients (61.7%) were enrolled in hospice before death. This percentage increased from 57.1% in 2007 to 66.2% in 2017 (P for trend < .001).

From 2007 to 2017, the proportion of patients filling greater than or equal to 1 opioid prescriptions declined from 42.0% to 35.5%. The proportion declined faster from 2012-2017 than from 2007-2011.

The proportion of patients who filled prescriptions for long-acting opioids dropped from 18.1% to 11.5%. Here again, the decline was faster from 2012-2017 than from 2007-2011. Prescriptions for strong short-acting opioids declined from 31.7% to 28.5%. Prescribing was initially stable from 2007-2011 and began to decline in 2012. Conversely, prescriptions for weak short-acting opioids dropped from 8.4% to 6.5% from 2007-2011 and then stabilized after 2012.

The mean daily dose fell 24.5%, from 85.6 morphine milligram equivalents per day (MMED) to 64.6 MMED. Overall, the total amount of opioids prescribed per decedent fell 38.0%, from 1,075 MMEs per person to 666 MMEs.

At the same time, the proportion of patients who visited EDs increased 50.8%, from 13.2% to 19.9%.

Experts weigh in

Approached for an independent comment, Amit Barochia, MD, a hematologist/oncologist with Health First Medical Group, Titusville, Fla., commented that the decline could be due, in part, to greater vigilance and awareness by physicians in light of more stringent requirements and of federal and state regulations. “Some physicians are avoiding prescribing opioids due to more regulations and requirements as well, which is routing patients to the ER for pain relief,” he said.

Dr. Barochia agreed that some of the decline could be due to patient factors. “I do think that some of the patients are hesitant about considering opioid use for better pain relief, in part due to fear of addiction as well as complications arising from their use,” he said. “This is likely resulting from more awareness in the community about their adverse effects.

“That awareness could come from aggressive media coverage as well as social media,” he continued. “It is also true that there is a difficulty in getting authorization for certain opioid products, which is delaying the onset of a proper pain regimen that would help to provide adequate pain relief early on.”

For patients with advanced cancer, earlier referral to palliative care would be beneficial, Dr. Barochia pointed out, because this would allow for a more in-depth discussion about pain in addition to addressing the physical and mental symptoms associated with cancer.

Fox Chase Cancer Center’s Dr. Chwistek noted that patients and their caregivers are often apprehensive about the potential adverse effects of opioids, because they often hear about community-based opioid overdoses and are fearful of taking the medications. “Additionally, it has become increasingly challenging to fill opioid prescriptions at local pharmacies, due to quantity limitations, ubiquitous need for prior authorizations, and stigma,” he said.

The fear of addiction is often brought up by the patients during clinic visits, and insurers and pharmacies have imposed many limits on opioid prescribing. “Most of these can be overcome with prior authorizations, but not always, and prior authorizations are time consuming, confusing, and very frustrating for patients,” he said in an interview.

These findings suggest that not enough patients are getting optimal palliative care. “One of the primary tenets of palliative care is optimal symptom control, including pain,” said Dr. Chwistek. “Palliative care teams have the experience and insight needed to help patients overcome the barriers to appropriate pain control. Education, support, and advocacy are critical to ensure that patients’ pain is appropriately addressed.”

The study was funded by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Record number of U.S. drug overdoses in 2020

More Americans died from drug overdoses in 2020 than in any other year, the CDC said July 14.

, according to the provisional data the National Center for Health Statistics reported.

The spikes are largely attributed to the rise in use of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids.

The Washington Post reported that more than 69,000 overdose deaths involved opioids, up from 50,963 in 2019.

Amid the crush of overdoses, the White House announced that President Joe Biden has nominated Rahul Gupta, MD, to lead the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy.

Dr. Gupta is a former health commissioner of West Virginia, and is chief medical and health officer for the March of Dimes.

“Dr. Gupta led efforts in West Virginia to address the opioid crisis, gaining national prominence as a leader in tackling this issue,” March of Dimes President and CEO Stacey Stewart said in a statement. “At March of Dimes, he has advocated for policies and programs to prevent and treat substance use, with a focus on the safety and care of pregnant women and infants.”

Healthday contributed to this report. A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

More Americans died from drug overdoses in 2020 than in any other year, the CDC said July 14.

, according to the provisional data the National Center for Health Statistics reported.

The spikes are largely attributed to the rise in use of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids.

The Washington Post reported that more than 69,000 overdose deaths involved opioids, up from 50,963 in 2019.

Amid the crush of overdoses, the White House announced that President Joe Biden has nominated Rahul Gupta, MD, to lead the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy.

Dr. Gupta is a former health commissioner of West Virginia, and is chief medical and health officer for the March of Dimes.

“Dr. Gupta led efforts in West Virginia to address the opioid crisis, gaining national prominence as a leader in tackling this issue,” March of Dimes President and CEO Stacey Stewart said in a statement. “At March of Dimes, he has advocated for policies and programs to prevent and treat substance use, with a focus on the safety and care of pregnant women and infants.”

Healthday contributed to this report. A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

More Americans died from drug overdoses in 2020 than in any other year, the CDC said July 14.

, according to the provisional data the National Center for Health Statistics reported.

The spikes are largely attributed to the rise in use of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids.

The Washington Post reported that more than 69,000 overdose deaths involved opioids, up from 50,963 in 2019.

Amid the crush of overdoses, the White House announced that President Joe Biden has nominated Rahul Gupta, MD, to lead the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy.

Dr. Gupta is a former health commissioner of West Virginia, and is chief medical and health officer for the March of Dimes.

“Dr. Gupta led efforts in West Virginia to address the opioid crisis, gaining national prominence as a leader in tackling this issue,” March of Dimes President and CEO Stacey Stewart said in a statement. “At March of Dimes, he has advocated for policies and programs to prevent and treat substance use, with a focus on the safety and care of pregnant women and infants.”

Healthday contributed to this report. A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Opioid addiction meds may curb growing problem of kratom dependence

Medications typically used to treat opioid use disorder (OUD) may* also be effective for the growing public health problem of kratom addiction, new research shows.

Results of a comprehensive literature review and an expert survey suggest buprenorphine, naltrexone, and methadone may be effective for patients seeking help for kratom addiction, and if further research confirms these findings, the indication for OUD medications could potentially be expanded to include moderate-to-severe kratom addiction, study investigator Saeed Ahmed, MD, medical director of West Ridge Center at Rutland Regional Medical Center, Rutland, Vermont, said in an interview.

Dr. Ahmed, who practices general psychiatry and addiction psychiatry, presented the findings at the virtual American Psychiatric Association 2021 Annual Meeting.

Emerging public health problem

Kratom can be ingested in pill or capsule form or as an extract. Its leaves can be chewed or dried and powdered to make a tea. It can also be incorporated into topical creams, balms, or tinctures.

Products containing the substance are “readily available and legal for sale in many states and cities in the U.S.,” said Dr. Ahmed, adding that it can be purchased online or at local smoke shops and is increasingly used by individuals to self-treat a variety of conditions including pain, anxiety, and mood conditions and as an opioid substitute.

As reported by this news organization, a 2018 analysis conducted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration showed kratom is, in fact, an opioid, a finding that garnered significant push-back from the American Kratom Association.

Kratom addiction is an “emerging public health problem,” said Dr. Ahmed, adding that in recent years the number of calls to poison control centers across the country has increased 52-fold – from one per month to two per day. He believes misinformation through social media has helped fuel its use.

Kratom use, the investigators note, can lead to muscle pain, weight loss, insomnia, hallucinations and, in some cases (particularly when combined with synthetic opioids or benzodiazepines), it can lead to respiratory depression, seizures, coma, and death.

In addition,

To investigate, the researchers conducted a systematic literature search for cases pertaining to maintenance treatment for kratom dependence. They also tapped into case reports and scientific posters from reliable online sources and conference proceedings. In addition, they conducted a survey of members from the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM).

The researchers found 14 reports of long-term management of kratom addiction, half of which did not involve an OUD. It’s important to exclude OUDs to avoid possible confounding.

In most cases, buprenorphine was used, but in a few cases naltrexone or methadone were prescribed. All cases had a favorable outcome. Dr. Ahmed noted that buprenorphine maintenance doses appear to be lower than those required to effectively treat OUD.

With a response rate of 11.5% (82 respondents) the ASAM survey results showed 82.6% of respondents (n = 57) had experience managing KUD, including 27.5% (n = 19) who had kratom addiction only. Of these, 89.5% (n = 17-19), used buprenorphine to manage KUD and of these, 6 combined it with talk therapy.

Dr. Ahmed cautioned that the included cases varied significantly in terms of relevant data, including kratom dose and route of administration, toxicology screening used to monitor abstinence, and duration of maintenance follow-up.

Despite these limitations, the review and survey underscore the importance of including moderate to severe kratom dependence as an indication for current OUD medications, the researchers note.

Including kratom addiction as an indication for these medications is important, especially for patients who are heavily addicted, to meet DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for moderate or severe SUD, they add.

In addition, the researchers recommend that clinicians consider referring patients with moderate to severe kratom dependence for counseling or enrollment in 12-step addiction treatment programs.

A separate diagnosis?

Dr. Ahmed said he would like to see kratom dependence included in the DSM-5 as a separate entity because it is a botanical with properties similar to, but different from, traditional opioids.

“This will not only help to better inform clinicians about a diagnostic criteria encompassing problematic use and facilitate screening, but it will also pave the way for treatments to be explored for this diagnosable condition,” he said. Dr. Ahmed pointed to a review published in the Wisconsin Medical Journal earlier this year that explored potential treatments for kratom dependence.

Commenting on the study for an interview, Petros Levounis, MD, professor and chair, department of psychiatry, and associate dean for professional development, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, said the authors “have done a great job reviewing the literature and asking experts” about kratom addiction treatment.

“The punchline of their study is that kratom behaves very much like an opioid and is treated like an opioid.”

Dr. Levounis noted that kratom dependence is so new that experts don’t know much about it. However, he added, emerging evidence suggests that kratom “should be considered an opioid more than anything else,” but specified that he does not believe it warrants its own diagnosis.

He noted that individual opioids don’t have their own diagnostic category and that opioid use disorder is an umbrella term that covers all of these drugs.

Dr. Ahmed and Dr. Levounis have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*Updated 5/18/2021

Medications typically used to treat opioid use disorder (OUD) may* also be effective for the growing public health problem of kratom addiction, new research shows.

Results of a comprehensive literature review and an expert survey suggest buprenorphine, naltrexone, and methadone may be effective for patients seeking help for kratom addiction, and if further research confirms these findings, the indication for OUD medications could potentially be expanded to include moderate-to-severe kratom addiction, study investigator Saeed Ahmed, MD, medical director of West Ridge Center at Rutland Regional Medical Center, Rutland, Vermont, said in an interview.

Dr. Ahmed, who practices general psychiatry and addiction psychiatry, presented the findings at the virtual American Psychiatric Association 2021 Annual Meeting.

Emerging public health problem

Kratom can be ingested in pill or capsule form or as an extract. Its leaves can be chewed or dried and powdered to make a tea. It can also be incorporated into topical creams, balms, or tinctures.

Products containing the substance are “readily available and legal for sale in many states and cities in the U.S.,” said Dr. Ahmed, adding that it can be purchased online or at local smoke shops and is increasingly used by individuals to self-treat a variety of conditions including pain, anxiety, and mood conditions and as an opioid substitute.

As reported by this news organization, a 2018 analysis conducted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration showed kratom is, in fact, an opioid, a finding that garnered significant push-back from the American Kratom Association.

Kratom addiction is an “emerging public health problem,” said Dr. Ahmed, adding that in recent years the number of calls to poison control centers across the country has increased 52-fold – from one per month to two per day. He believes misinformation through social media has helped fuel its use.

Kratom use, the investigators note, can lead to muscle pain, weight loss, insomnia, hallucinations and, in some cases (particularly when combined with synthetic opioids or benzodiazepines), it can lead to respiratory depression, seizures, coma, and death.

In addition,

To investigate, the researchers conducted a systematic literature search for cases pertaining to maintenance treatment for kratom dependence. They also tapped into case reports and scientific posters from reliable online sources and conference proceedings. In addition, they conducted a survey of members from the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM).

The researchers found 14 reports of long-term management of kratom addiction, half of which did not involve an OUD. It’s important to exclude OUDs to avoid possible confounding.

In most cases, buprenorphine was used, but in a few cases naltrexone or methadone were prescribed. All cases had a favorable outcome. Dr. Ahmed noted that buprenorphine maintenance doses appear to be lower than those required to effectively treat OUD.

With a response rate of 11.5% (82 respondents) the ASAM survey results showed 82.6% of respondents (n = 57) had experience managing KUD, including 27.5% (n = 19) who had kratom addiction only. Of these, 89.5% (n = 17-19), used buprenorphine to manage KUD and of these, 6 combined it with talk therapy.

Dr. Ahmed cautioned that the included cases varied significantly in terms of relevant data, including kratom dose and route of administration, toxicology screening used to monitor abstinence, and duration of maintenance follow-up.

Despite these limitations, the review and survey underscore the importance of including moderate to severe kratom dependence as an indication for current OUD medications, the researchers note.

Including kratom addiction as an indication for these medications is important, especially for patients who are heavily addicted, to meet DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for moderate or severe SUD, they add.

In addition, the researchers recommend that clinicians consider referring patients with moderate to severe kratom dependence for counseling or enrollment in 12-step addiction treatment programs.

A separate diagnosis?

Dr. Ahmed said he would like to see kratom dependence included in the DSM-5 as a separate entity because it is a botanical with properties similar to, but different from, traditional opioids.

“This will not only help to better inform clinicians about a diagnostic criteria encompassing problematic use and facilitate screening, but it will also pave the way for treatments to be explored for this diagnosable condition,” he said. Dr. Ahmed pointed to a review published in the Wisconsin Medical Journal earlier this year that explored potential treatments for kratom dependence.

Commenting on the study for an interview, Petros Levounis, MD, professor and chair, department of psychiatry, and associate dean for professional development, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, said the authors “have done a great job reviewing the literature and asking experts” about kratom addiction treatment.

“The punchline of their study is that kratom behaves very much like an opioid and is treated like an opioid.”

Dr. Levounis noted that kratom dependence is so new that experts don’t know much about it. However, he added, emerging evidence suggests that kratom “should be considered an opioid more than anything else,” but specified that he does not believe it warrants its own diagnosis.

He noted that individual opioids don’t have their own diagnostic category and that opioid use disorder is an umbrella term that covers all of these drugs.

Dr. Ahmed and Dr. Levounis have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*Updated 5/18/2021

Medications typically used to treat opioid use disorder (OUD) may* also be effective for the growing public health problem of kratom addiction, new research shows.

Results of a comprehensive literature review and an expert survey suggest buprenorphine, naltrexone, and methadone may be effective for patients seeking help for kratom addiction, and if further research confirms these findings, the indication for OUD medications could potentially be expanded to include moderate-to-severe kratom addiction, study investigator Saeed Ahmed, MD, medical director of West Ridge Center at Rutland Regional Medical Center, Rutland, Vermont, said in an interview.

Dr. Ahmed, who practices general psychiatry and addiction psychiatry, presented the findings at the virtual American Psychiatric Association 2021 Annual Meeting.

Emerging public health problem

Kratom can be ingested in pill or capsule form or as an extract. Its leaves can be chewed or dried and powdered to make a tea. It can also be incorporated into topical creams, balms, or tinctures.

Products containing the substance are “readily available and legal for sale in many states and cities in the U.S.,” said Dr. Ahmed, adding that it can be purchased online or at local smoke shops and is increasingly used by individuals to self-treat a variety of conditions including pain, anxiety, and mood conditions and as an opioid substitute.

As reported by this news organization, a 2018 analysis conducted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration showed kratom is, in fact, an opioid, a finding that garnered significant push-back from the American Kratom Association.

Kratom addiction is an “emerging public health problem,” said Dr. Ahmed, adding that in recent years the number of calls to poison control centers across the country has increased 52-fold – from one per month to two per day. He believes misinformation through social media has helped fuel its use.

Kratom use, the investigators note, can lead to muscle pain, weight loss, insomnia, hallucinations and, in some cases (particularly when combined with synthetic opioids or benzodiazepines), it can lead to respiratory depression, seizures, coma, and death.

In addition,

To investigate, the researchers conducted a systematic literature search for cases pertaining to maintenance treatment for kratom dependence. They also tapped into case reports and scientific posters from reliable online sources and conference proceedings. In addition, they conducted a survey of members from the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM).

The researchers found 14 reports of long-term management of kratom addiction, half of which did not involve an OUD. It’s important to exclude OUDs to avoid possible confounding.

In most cases, buprenorphine was used, but in a few cases naltrexone or methadone were prescribed. All cases had a favorable outcome. Dr. Ahmed noted that buprenorphine maintenance doses appear to be lower than those required to effectively treat OUD.

With a response rate of 11.5% (82 respondents) the ASAM survey results showed 82.6% of respondents (n = 57) had experience managing KUD, including 27.5% (n = 19) who had kratom addiction only. Of these, 89.5% (n = 17-19), used buprenorphine to manage KUD and of these, 6 combined it with talk therapy.

Dr. Ahmed cautioned that the included cases varied significantly in terms of relevant data, including kratom dose and route of administration, toxicology screening used to monitor abstinence, and duration of maintenance follow-up.

Despite these limitations, the review and survey underscore the importance of including moderate to severe kratom dependence as an indication for current OUD medications, the researchers note.

Including kratom addiction as an indication for these medications is important, especially for patients who are heavily addicted, to meet DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for moderate or severe SUD, they add.

In addition, the researchers recommend that clinicians consider referring patients with moderate to severe kratom dependence for counseling or enrollment in 12-step addiction treatment programs.

A separate diagnosis?

Dr. Ahmed said he would like to see kratom dependence included in the DSM-5 as a separate entity because it is a botanical with properties similar to, but different from, traditional opioids.

“This will not only help to better inform clinicians about a diagnostic criteria encompassing problematic use and facilitate screening, but it will also pave the way for treatments to be explored for this diagnosable condition,” he said. Dr. Ahmed pointed to a review published in the Wisconsin Medical Journal earlier this year that explored potential treatments for kratom dependence.

Commenting on the study for an interview, Petros Levounis, MD, professor and chair, department of psychiatry, and associate dean for professional development, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, said the authors “have done a great job reviewing the literature and asking experts” about kratom addiction treatment.

“The punchline of their study is that kratom behaves very much like an opioid and is treated like an opioid.”

Dr. Levounis noted that kratom dependence is so new that experts don’t know much about it. However, he added, emerging evidence suggests that kratom “should be considered an opioid more than anything else,” but specified that he does not believe it warrants its own diagnosis.

He noted that individual opioids don’t have their own diagnostic category and that opioid use disorder is an umbrella term that covers all of these drugs.

Dr. Ahmed and Dr. Levounis have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*Updated 5/18/2021

Adulterants in street drugs could increase susceptibility to COVID

The composition of street drugs like heroin and cocaine are changing. According to a new analysis, almost all contain at least one toxic adulterant, and many contain a plethora. Most adulterants have pharmacologic activities and toxicities. Their presence has added impact in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, since some may cause a drastic drop in white blood cells that could leave drug users more vulnerable to infection.

“It’s remarkable that we just forgot to notice, in the horrendous transition from prescription opioid epidemic to the illicit opioid and psychostimulant epidemics, that we would have to pay special attention to what the medications are in the drugs that the person was exposed to – and for how long,” said Mark S. Gold, MD, a coauthor of the review.

The analysis showed that adulterants include new psychoactive substances, industrial compounds, fungicides, veterinary medications, and various impurities. In addition, other various medications are being found in street drugs, such as antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, antihistamines, anthelmintics, anesthetics, anti-inflammatory agents, antipyretics, analgesics, antispasmodics, antiarrhythmics, antimalarials, bronchodilators, decongestants, expectorants, muscle relaxers, natural/synthetic hallucinogens, and sedatives.

Illicit drugs are by nature manufactured without Food and Drug Administration oversight, and it is becoming increasingly common that substances like leftover medicines and other active drugs are added to illicit drug batches to add weight, said Dr. Gold, a professor at Washington University,St. Louis. The study appeared in Current Psychopharmacology.

Effects of adulterants ‘terrifying’

The findings of adulterants and their consequences are concerning, according to Jean Lud Cadet, MD, who was asked to comment on the findings. “The blood dysplasia, the pulmonary problems that some of those adulterants can cause – it’s actually terrifying, to put it bluntly,” said Dr. Cadet, who is a senior investigator and chief of the Molecular Neuropsychiatry Research Branch at the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Before 2000, street drugs were generally diluted with comparatively benign substances such as caffeine, sugars, or lidocaine. Drugs like phenacetin, levamisole, acetaminophen, and diltiazem began to appear in heroin and cocaine in the late 1990s, and by 2010, more powerful adulterants like fentanyl, ketamine, and quetiapine became common.

In 2015, the U.S. Department of State partnered with the Colombo Plan, an international organization based in Sri Lanka, to use field spectroscopy to detect toxins directly in cocaine and heroin samples found in Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, Peru, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico, Colombia, and South Africa. They found a range of adulterants such as aminopyrine, diltiazem, metamizole, levamisole, and phenacetin.

A similar project with 431 heroin and cocaine samples from Vermont and Kentucky found that 69% of samples had five or more controlled drugs, toxic adulterants, or impurities. About 15% had nine or more, and 95% of samples had at least one toxic adulterant.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, these adulterants take on even greater significance. Individuals with substance use disorders often have other health conditions that can make them more vulnerable to viral infections, and this could be exacerbated by the effects of adulterants on white blood cells or other systems. The pandemic has also had an indirect effect by causing a shortage of street drugs. During production shortages, traffickers might boost potency by adding more cutting agents and adulterants. As a result, COVID-19 and opioid addiction tend to reinforce each other.

“The clinical message would be that our [substance use] patients will contract infectious disease and need to be prioritized for [COVID-19] vaccination,” said Dr. Gold.

The findings came as a surprise to Dr. Cadet, and that illustrates a need to publicize the presence of adulterants in street drugs.

“If I wasn’t aware of many of these, then the general public is also not going to be aware of them,” Dr. Cadet said. “Scientists, including myself, and government agencies need to do a better job [of communicating this issue].”

The study references individuals with substance use disorder, but Dr. Cadet cautioned that anyone who uses street drugs, even once or twice, could be a victim of adulterants. “You don’t need to have met criteria for diagnosis in order to suffer the consequences.”

The study had no funding. Dr. Gold and Dr. Cadet have no relevant financial disclosures.

The composition of street drugs like heroin and cocaine are changing. According to a new analysis, almost all contain at least one toxic adulterant, and many contain a plethora. Most adulterants have pharmacologic activities and toxicities. Their presence has added impact in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, since some may cause a drastic drop in white blood cells that could leave drug users more vulnerable to infection.

“It’s remarkable that we just forgot to notice, in the horrendous transition from prescription opioid epidemic to the illicit opioid and psychostimulant epidemics, that we would have to pay special attention to what the medications are in the drugs that the person was exposed to – and for how long,” said Mark S. Gold, MD, a coauthor of the review.

The analysis showed that adulterants include new psychoactive substances, industrial compounds, fungicides, veterinary medications, and various impurities. In addition, other various medications are being found in street drugs, such as antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, antihistamines, anthelmintics, anesthetics, anti-inflammatory agents, antipyretics, analgesics, antispasmodics, antiarrhythmics, antimalarials, bronchodilators, decongestants, expectorants, muscle relaxers, natural/synthetic hallucinogens, and sedatives.

Illicit drugs are by nature manufactured without Food and Drug Administration oversight, and it is becoming increasingly common that substances like leftover medicines and other active drugs are added to illicit drug batches to add weight, said Dr. Gold, a professor at Washington University,St. Louis. The study appeared in Current Psychopharmacology.

Effects of adulterants ‘terrifying’

The findings of adulterants and their consequences are concerning, according to Jean Lud Cadet, MD, who was asked to comment on the findings. “The blood dysplasia, the pulmonary problems that some of those adulterants can cause – it’s actually terrifying, to put it bluntly,” said Dr. Cadet, who is a senior investigator and chief of the Molecular Neuropsychiatry Research Branch at the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Before 2000, street drugs were generally diluted with comparatively benign substances such as caffeine, sugars, or lidocaine. Drugs like phenacetin, levamisole, acetaminophen, and diltiazem began to appear in heroin and cocaine in the late 1990s, and by 2010, more powerful adulterants like fentanyl, ketamine, and quetiapine became common.

In 2015, the U.S. Department of State partnered with the Colombo Plan, an international organization based in Sri Lanka, to use field spectroscopy to detect toxins directly in cocaine and heroin samples found in Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, Peru, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico, Colombia, and South Africa. They found a range of adulterants such as aminopyrine, diltiazem, metamizole, levamisole, and phenacetin.

A similar project with 431 heroin and cocaine samples from Vermont and Kentucky found that 69% of samples had five or more controlled drugs, toxic adulterants, or impurities. About 15% had nine or more, and 95% of samples had at least one toxic adulterant.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, these adulterants take on even greater significance. Individuals with substance use disorders often have other health conditions that can make them more vulnerable to viral infections, and this could be exacerbated by the effects of adulterants on white blood cells or other systems. The pandemic has also had an indirect effect by causing a shortage of street drugs. During production shortages, traffickers might boost potency by adding more cutting agents and adulterants. As a result, COVID-19 and opioid addiction tend to reinforce each other.

“The clinical message would be that our [substance use] patients will contract infectious disease and need to be prioritized for [COVID-19] vaccination,” said Dr. Gold.

The findings came as a surprise to Dr. Cadet, and that illustrates a need to publicize the presence of adulterants in street drugs.

“If I wasn’t aware of many of these, then the general public is also not going to be aware of them,” Dr. Cadet said. “Scientists, including myself, and government agencies need to do a better job [of communicating this issue].”

The study references individuals with substance use disorder, but Dr. Cadet cautioned that anyone who uses street drugs, even once or twice, could be a victim of adulterants. “You don’t need to have met criteria for diagnosis in order to suffer the consequences.”

The study had no funding. Dr. Gold and Dr. Cadet have no relevant financial disclosures.

The composition of street drugs like heroin and cocaine are changing. According to a new analysis, almost all contain at least one toxic adulterant, and many contain a plethora. Most adulterants have pharmacologic activities and toxicities. Their presence has added impact in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, since some may cause a drastic drop in white blood cells that could leave drug users more vulnerable to infection.

“It’s remarkable that we just forgot to notice, in the horrendous transition from prescription opioid epidemic to the illicit opioid and psychostimulant epidemics, that we would have to pay special attention to what the medications are in the drugs that the person was exposed to – and for how long,” said Mark S. Gold, MD, a coauthor of the review.

The analysis showed that adulterants include new psychoactive substances, industrial compounds, fungicides, veterinary medications, and various impurities. In addition, other various medications are being found in street drugs, such as antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, antihistamines, anthelmintics, anesthetics, anti-inflammatory agents, antipyretics, analgesics, antispasmodics, antiarrhythmics, antimalarials, bronchodilators, decongestants, expectorants, muscle relaxers, natural/synthetic hallucinogens, and sedatives.

Illicit drugs are by nature manufactured without Food and Drug Administration oversight, and it is becoming increasingly common that substances like leftover medicines and other active drugs are added to illicit drug batches to add weight, said Dr. Gold, a professor at Washington University,St. Louis. The study appeared in Current Psychopharmacology.

Effects of adulterants ‘terrifying’

The findings of adulterants and their consequences are concerning, according to Jean Lud Cadet, MD, who was asked to comment on the findings. “The blood dysplasia, the pulmonary problems that some of those adulterants can cause – it’s actually terrifying, to put it bluntly,” said Dr. Cadet, who is a senior investigator and chief of the Molecular Neuropsychiatry Research Branch at the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Before 2000, street drugs were generally diluted with comparatively benign substances such as caffeine, sugars, or lidocaine. Drugs like phenacetin, levamisole, acetaminophen, and diltiazem began to appear in heroin and cocaine in the late 1990s, and by 2010, more powerful adulterants like fentanyl, ketamine, and quetiapine became common.

In 2015, the U.S. Department of State partnered with the Colombo Plan, an international organization based in Sri Lanka, to use field spectroscopy to detect toxins directly in cocaine and heroin samples found in Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, Peru, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico, Colombia, and South Africa. They found a range of adulterants such as aminopyrine, diltiazem, metamizole, levamisole, and phenacetin.

A similar project with 431 heroin and cocaine samples from Vermont and Kentucky found that 69% of samples had five or more controlled drugs, toxic adulterants, or impurities. About 15% had nine or more, and 95% of samples had at least one toxic adulterant.