User login

Women with recurrent UTIs express fear, frustration

Fear of antibiotic overuse and frustration with physicians who prescribe them too freely are key sentiments expressed by women with recurrent urinary tract infections (rUTIs), according to findings from a study involving six focus groups.

“Here in our female pelvic medicine reconstructive urology clinic at Cedars-Sinai and at UCLA, we see many women who are referred for evaluation of rUTIs who are very frustrated with their care,” Victoria Scott, MD, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

“So with these focus groups, we saw an opportunity to explore why women are so frustrated and to try and improve the care delivered,” she added.

Findings from the study were published online Sept. 1 in The Journal of Urology.

“There is a need for physicians to modify management strategies ... and to devote more research efforts to improving nonantibiotic options for the prevention and treatment of recurrent urinary tract infections, as well as management strategies that better empower patients,” the authors wrote.

Six focus groups

Four or five participants were included in each of the six focus groups – a total of 29 women. All participants reported a history of symptomatic, culture-proven UTI episodes. They had experienced two or more infections in 6 months or three or more infections within 1 year. Women were predominantly White. Most were employed part- or full-time and held a college degree.

From a qualitative analysis of all focus group transcripts, two main themes emerged:

- The negative impact of taking antibiotics for the prevention and treatment of rUTIs.

- Resentment of the medical profession for the way it managed rUTIs.

The researchers found that participants had a good understanding of the deleterious effects from inappropriate antibiotic use, largely gleaned from media sources and the Internet. “Numerous women stated that they had reached such a level of concern about antibiotics that they would resist taking them for prevention or treatment of infections,” Dr. Scott and colleagues pointed out.

These concerns centered around the risk of developing resistance to antibiotics and the ill effects that antibiotics can have on the gastrointestinal and genitourinary microbiomes. Several women reported that they had developed Clostridium difficile infections after taking antibiotics; one of the patients required hospitalization for the infection.

Women also reported concerns that they had been given an antibiotic needlessly for symptoms that might have been caused by a genitourinary condition other than a UTI. They also reported feeling resentful toward practitioners, particularly if they felt the practitioner was overprescribing antibiotics. Some had resorted to consultations with alternative practitioners, such as herbalists. “A second concern discussed by participants was the feeling of being ignored by physicians,” the authors observed.

In this regard, the women felt that their physicians underestimated the burden that rUTIs had on their lives and the detrimental effect that repeated infections had on their relationships, work, and overall quality of life. “These perceptions led to a prevalent mistrust of physicians,” the investigators wrote. This prompted many women to insist that the medical community devote more effort to the development of nonantibiotic options for the prevention and treatment of UTIs.

Improved management strategies

Asked how physicians might improve their management of rUTIs, Dr. Scott shared a number of suggestions. Cardinal rule No. 1: Have the patient undergo a urinalysis to make sure she does have a UTI. “There is a subset of patients among women with rUTIs who come in with a diagnosis of an rUTI but who really have not had documentation of more than one positive urine culture,” Dr. Scott noted. Such a history suggests that they do not have an rUTI.

It’s imperative that physicians rule out commonly misdiagnosed disorders, such as overactive bladder, as a cause of the patient’s symptoms. Symptoms of overactive bladder and rUTIs often overlap. While waiting for results from the urinalysis to confirm or rule out a UTI, young and healthy women may be prescribed a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), such as naproxen, which can help ameliorate symptoms.

Because UTIs are frequently self-limiting, Dr. Scott and others have found that for young, otherwise healthy women, NSAIDs alone can often resolve symptoms of the UTI without use of an antibiotic. For relatively severe symptoms, a urinary analgesic, such as phenazopyridine (Pyridium), may soothe the lining of the urinary tract and relieve pain. Cystex is an over-the-counter urinary analgesic that women can procure themselves, Dr. Scott added.

If an antibiotic is indicated, those most commonly prescribed for a single episode of acute cystitis are nitrofurantoin and sulfamethoxazole plus trimethoprim (Bactrim). For recurrent UTIs, “patients are a bit more complicated,” Dr. Scott admitted. “I think the best practice is to look back at a woman’s prior urine culture and select an antibiotic that showed good sensitivity in the last positive urine test,” she said.

Prevention starts with behavioral strategies, such as voiding after sexual intercourse and wiping from front to back following urination to avoid introducing fecal bacteria into the urethra. Evidence suggests that premenopausal women who drink at least 1.5 L of water a day have significantly fewer UTI episodes, Dr. Scott noted. There is also “pretty good” evidence that cranberry supplements (not juice) can prevent rUTIs. Use of cranberry supplements is supported by the American Urological Association (conditional recommendation; evidence level of grade C).

For peri- and postmenopausal women, vaginal estrogen may be effective. It’s use for UTI prevention is well supported by the literature. Although not as well supported by evidence, some women find that a supplement such as D-mannose may prevent or treat UTIs by causing bacteria to bind to it rather than to the bladder wall. Probiotics are another possibility, she noted. Empathy can’t hurt, she added.

“A common theme among satisfied women was the sentiment that their physicians understood their problems and had a system in place to allow rapid diagnosis and treatment for UTI episodes,” the authors emphasized.

“[Such attitudes] highlight the need to investigate each patient’s experience and perceptions to allow for shared decision making regarding the management of rUTIs,” they wrote.

Further commentary

Asked to comment on the findings, editorialist Michelle Van Kuiken, MD, assistant professor of urology, University of California, San Francisco, acknowledged that there is not a lot of good evidence to support many of the strategies recommended by the American Urological Association to prevent and treat rUTIs, but she often follows these recommendations anyway. “The one statement in the guidelines that is the most supported by evidence is the use of cranberry supplements, and I do routinely recommended daily use of some form of concentrated cranberry supplements for all of my patients with rUTIs,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Van Kuiken said that vaginal estrogen is a very good option for all postmenopausal women who suffer from rUTIs and that there is growing acceptance of its use for this and other indications. There is some evidence to support D-mannose as well, although it’s not that robust, she acknowledged.

She said the evidence supporting the use of probiotics for this indication is very thin. She does not routinely recommend them for rUTIs, although they are not inherently harmful. “I think for a lot of women who have rUTIs, it can be pretty debilitating and upsetting for them – it can impact travel plans, work, and social events,” Dr. Van Kuiken said.

“Until we develop better diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, validating women’s experiences and concerns with rUTI while limiting unnecessary antibiotics remains our best option,” she wrote.

Dr. Scott and Dr. Van Kuiken have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fear of antibiotic overuse and frustration with physicians who prescribe them too freely are key sentiments expressed by women with recurrent urinary tract infections (rUTIs), according to findings from a study involving six focus groups.

“Here in our female pelvic medicine reconstructive urology clinic at Cedars-Sinai and at UCLA, we see many women who are referred for evaluation of rUTIs who are very frustrated with their care,” Victoria Scott, MD, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

“So with these focus groups, we saw an opportunity to explore why women are so frustrated and to try and improve the care delivered,” she added.

Findings from the study were published online Sept. 1 in The Journal of Urology.

“There is a need for physicians to modify management strategies ... and to devote more research efforts to improving nonantibiotic options for the prevention and treatment of recurrent urinary tract infections, as well as management strategies that better empower patients,” the authors wrote.

Six focus groups

Four or five participants were included in each of the six focus groups – a total of 29 women. All participants reported a history of symptomatic, culture-proven UTI episodes. They had experienced two or more infections in 6 months or three or more infections within 1 year. Women were predominantly White. Most were employed part- or full-time and held a college degree.

From a qualitative analysis of all focus group transcripts, two main themes emerged:

- The negative impact of taking antibiotics for the prevention and treatment of rUTIs.

- Resentment of the medical profession for the way it managed rUTIs.

The researchers found that participants had a good understanding of the deleterious effects from inappropriate antibiotic use, largely gleaned from media sources and the Internet. “Numerous women stated that they had reached such a level of concern about antibiotics that they would resist taking them for prevention or treatment of infections,” Dr. Scott and colleagues pointed out.

These concerns centered around the risk of developing resistance to antibiotics and the ill effects that antibiotics can have on the gastrointestinal and genitourinary microbiomes. Several women reported that they had developed Clostridium difficile infections after taking antibiotics; one of the patients required hospitalization for the infection.

Women also reported concerns that they had been given an antibiotic needlessly for symptoms that might have been caused by a genitourinary condition other than a UTI. They also reported feeling resentful toward practitioners, particularly if they felt the practitioner was overprescribing antibiotics. Some had resorted to consultations with alternative practitioners, such as herbalists. “A second concern discussed by participants was the feeling of being ignored by physicians,” the authors observed.

In this regard, the women felt that their physicians underestimated the burden that rUTIs had on their lives and the detrimental effect that repeated infections had on their relationships, work, and overall quality of life. “These perceptions led to a prevalent mistrust of physicians,” the investigators wrote. This prompted many women to insist that the medical community devote more effort to the development of nonantibiotic options for the prevention and treatment of UTIs.

Improved management strategies

Asked how physicians might improve their management of rUTIs, Dr. Scott shared a number of suggestions. Cardinal rule No. 1: Have the patient undergo a urinalysis to make sure she does have a UTI. “There is a subset of patients among women with rUTIs who come in with a diagnosis of an rUTI but who really have not had documentation of more than one positive urine culture,” Dr. Scott noted. Such a history suggests that they do not have an rUTI.

It’s imperative that physicians rule out commonly misdiagnosed disorders, such as overactive bladder, as a cause of the patient’s symptoms. Symptoms of overactive bladder and rUTIs often overlap. While waiting for results from the urinalysis to confirm or rule out a UTI, young and healthy women may be prescribed a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), such as naproxen, which can help ameliorate symptoms.

Because UTIs are frequently self-limiting, Dr. Scott and others have found that for young, otherwise healthy women, NSAIDs alone can often resolve symptoms of the UTI without use of an antibiotic. For relatively severe symptoms, a urinary analgesic, such as phenazopyridine (Pyridium), may soothe the lining of the urinary tract and relieve pain. Cystex is an over-the-counter urinary analgesic that women can procure themselves, Dr. Scott added.

If an antibiotic is indicated, those most commonly prescribed for a single episode of acute cystitis are nitrofurantoin and sulfamethoxazole plus trimethoprim (Bactrim). For recurrent UTIs, “patients are a bit more complicated,” Dr. Scott admitted. “I think the best practice is to look back at a woman’s prior urine culture and select an antibiotic that showed good sensitivity in the last positive urine test,” she said.

Prevention starts with behavioral strategies, such as voiding after sexual intercourse and wiping from front to back following urination to avoid introducing fecal bacteria into the urethra. Evidence suggests that premenopausal women who drink at least 1.5 L of water a day have significantly fewer UTI episodes, Dr. Scott noted. There is also “pretty good” evidence that cranberry supplements (not juice) can prevent rUTIs. Use of cranberry supplements is supported by the American Urological Association (conditional recommendation; evidence level of grade C).

For peri- and postmenopausal women, vaginal estrogen may be effective. It’s use for UTI prevention is well supported by the literature. Although not as well supported by evidence, some women find that a supplement such as D-mannose may prevent or treat UTIs by causing bacteria to bind to it rather than to the bladder wall. Probiotics are another possibility, she noted. Empathy can’t hurt, she added.

“A common theme among satisfied women was the sentiment that their physicians understood their problems and had a system in place to allow rapid diagnosis and treatment for UTI episodes,” the authors emphasized.

“[Such attitudes] highlight the need to investigate each patient’s experience and perceptions to allow for shared decision making regarding the management of rUTIs,” they wrote.

Further commentary

Asked to comment on the findings, editorialist Michelle Van Kuiken, MD, assistant professor of urology, University of California, San Francisco, acknowledged that there is not a lot of good evidence to support many of the strategies recommended by the American Urological Association to prevent and treat rUTIs, but she often follows these recommendations anyway. “The one statement in the guidelines that is the most supported by evidence is the use of cranberry supplements, and I do routinely recommended daily use of some form of concentrated cranberry supplements for all of my patients with rUTIs,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Van Kuiken said that vaginal estrogen is a very good option for all postmenopausal women who suffer from rUTIs and that there is growing acceptance of its use for this and other indications. There is some evidence to support D-mannose as well, although it’s not that robust, she acknowledged.

She said the evidence supporting the use of probiotics for this indication is very thin. She does not routinely recommend them for rUTIs, although they are not inherently harmful. “I think for a lot of women who have rUTIs, it can be pretty debilitating and upsetting for them – it can impact travel plans, work, and social events,” Dr. Van Kuiken said.

“Until we develop better diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, validating women’s experiences and concerns with rUTI while limiting unnecessary antibiotics remains our best option,” she wrote.

Dr. Scott and Dr. Van Kuiken have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fear of antibiotic overuse and frustration with physicians who prescribe them too freely are key sentiments expressed by women with recurrent urinary tract infections (rUTIs), according to findings from a study involving six focus groups.

“Here in our female pelvic medicine reconstructive urology clinic at Cedars-Sinai and at UCLA, we see many women who are referred for evaluation of rUTIs who are very frustrated with their care,” Victoria Scott, MD, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

“So with these focus groups, we saw an opportunity to explore why women are so frustrated and to try and improve the care delivered,” she added.

Findings from the study were published online Sept. 1 in The Journal of Urology.

“There is a need for physicians to modify management strategies ... and to devote more research efforts to improving nonantibiotic options for the prevention and treatment of recurrent urinary tract infections, as well as management strategies that better empower patients,” the authors wrote.

Six focus groups

Four or five participants were included in each of the six focus groups – a total of 29 women. All participants reported a history of symptomatic, culture-proven UTI episodes. They had experienced two or more infections in 6 months or three or more infections within 1 year. Women were predominantly White. Most were employed part- or full-time and held a college degree.

From a qualitative analysis of all focus group transcripts, two main themes emerged:

- The negative impact of taking antibiotics for the prevention and treatment of rUTIs.

- Resentment of the medical profession for the way it managed rUTIs.

The researchers found that participants had a good understanding of the deleterious effects from inappropriate antibiotic use, largely gleaned from media sources and the Internet. “Numerous women stated that they had reached such a level of concern about antibiotics that they would resist taking them for prevention or treatment of infections,” Dr. Scott and colleagues pointed out.

These concerns centered around the risk of developing resistance to antibiotics and the ill effects that antibiotics can have on the gastrointestinal and genitourinary microbiomes. Several women reported that they had developed Clostridium difficile infections after taking antibiotics; one of the patients required hospitalization for the infection.

Women also reported concerns that they had been given an antibiotic needlessly for symptoms that might have been caused by a genitourinary condition other than a UTI. They also reported feeling resentful toward practitioners, particularly if they felt the practitioner was overprescribing antibiotics. Some had resorted to consultations with alternative practitioners, such as herbalists. “A second concern discussed by participants was the feeling of being ignored by physicians,” the authors observed.

In this regard, the women felt that their physicians underestimated the burden that rUTIs had on their lives and the detrimental effect that repeated infections had on their relationships, work, and overall quality of life. “These perceptions led to a prevalent mistrust of physicians,” the investigators wrote. This prompted many women to insist that the medical community devote more effort to the development of nonantibiotic options for the prevention and treatment of UTIs.

Improved management strategies

Asked how physicians might improve their management of rUTIs, Dr. Scott shared a number of suggestions. Cardinal rule No. 1: Have the patient undergo a urinalysis to make sure she does have a UTI. “There is a subset of patients among women with rUTIs who come in with a diagnosis of an rUTI but who really have not had documentation of more than one positive urine culture,” Dr. Scott noted. Such a history suggests that they do not have an rUTI.

It’s imperative that physicians rule out commonly misdiagnosed disorders, such as overactive bladder, as a cause of the patient’s symptoms. Symptoms of overactive bladder and rUTIs often overlap. While waiting for results from the urinalysis to confirm or rule out a UTI, young and healthy women may be prescribed a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), such as naproxen, which can help ameliorate symptoms.

Because UTIs are frequently self-limiting, Dr. Scott and others have found that for young, otherwise healthy women, NSAIDs alone can often resolve symptoms of the UTI without use of an antibiotic. For relatively severe symptoms, a urinary analgesic, such as phenazopyridine (Pyridium), may soothe the lining of the urinary tract and relieve pain. Cystex is an over-the-counter urinary analgesic that women can procure themselves, Dr. Scott added.

If an antibiotic is indicated, those most commonly prescribed for a single episode of acute cystitis are nitrofurantoin and sulfamethoxazole plus trimethoprim (Bactrim). For recurrent UTIs, “patients are a bit more complicated,” Dr. Scott admitted. “I think the best practice is to look back at a woman’s prior urine culture and select an antibiotic that showed good sensitivity in the last positive urine test,” she said.

Prevention starts with behavioral strategies, such as voiding after sexual intercourse and wiping from front to back following urination to avoid introducing fecal bacteria into the urethra. Evidence suggests that premenopausal women who drink at least 1.5 L of water a day have significantly fewer UTI episodes, Dr. Scott noted. There is also “pretty good” evidence that cranberry supplements (not juice) can prevent rUTIs. Use of cranberry supplements is supported by the American Urological Association (conditional recommendation; evidence level of grade C).

For peri- and postmenopausal women, vaginal estrogen may be effective. It’s use for UTI prevention is well supported by the literature. Although not as well supported by evidence, some women find that a supplement such as D-mannose may prevent or treat UTIs by causing bacteria to bind to it rather than to the bladder wall. Probiotics are another possibility, she noted. Empathy can’t hurt, she added.

“A common theme among satisfied women was the sentiment that their physicians understood their problems and had a system in place to allow rapid diagnosis and treatment for UTI episodes,” the authors emphasized.

“[Such attitudes] highlight the need to investigate each patient’s experience and perceptions to allow for shared decision making regarding the management of rUTIs,” they wrote.

Further commentary

Asked to comment on the findings, editorialist Michelle Van Kuiken, MD, assistant professor of urology, University of California, San Francisco, acknowledged that there is not a lot of good evidence to support many of the strategies recommended by the American Urological Association to prevent and treat rUTIs, but she often follows these recommendations anyway. “The one statement in the guidelines that is the most supported by evidence is the use of cranberry supplements, and I do routinely recommended daily use of some form of concentrated cranberry supplements for all of my patients with rUTIs,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Van Kuiken said that vaginal estrogen is a very good option for all postmenopausal women who suffer from rUTIs and that there is growing acceptance of its use for this and other indications. There is some evidence to support D-mannose as well, although it’s not that robust, she acknowledged.

She said the evidence supporting the use of probiotics for this indication is very thin. She does not routinely recommend them for rUTIs, although they are not inherently harmful. “I think for a lot of women who have rUTIs, it can be pretty debilitating and upsetting for them – it can impact travel plans, work, and social events,” Dr. Van Kuiken said.

“Until we develop better diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, validating women’s experiences and concerns with rUTI while limiting unnecessary antibiotics remains our best option,” she wrote.

Dr. Scott and Dr. Van Kuiken have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pelvic floor dysfunction imaging: New guidelines provide recommendations

New consensus guidelines from a multispecialty working group of the Pelvic Floor Disorders Consortium (PFDC) clear up inconsistencies in the use of magnetic resonance defecography (MRD) and provide universal recommendations on MRD technique, interpretation, reporting, and other factors.

“The consensus language used to describe pelvic floor disorders is critical, so as to allow the various experts who treat these patients [to] communicate and collaborate effectively with each other,” coauthor Liliana Bordeianou, MD, MPH, an associate professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and chair of the Massachusetts General Hospital Colorectal and Pelvic Floor Centers, told this news organization.

“These diseases do not choose an arbitrary side in the pelvis,” she noted. “Instead, these diseases affect the entire pelvis and require a multidisciplinary and collaborative solution.”

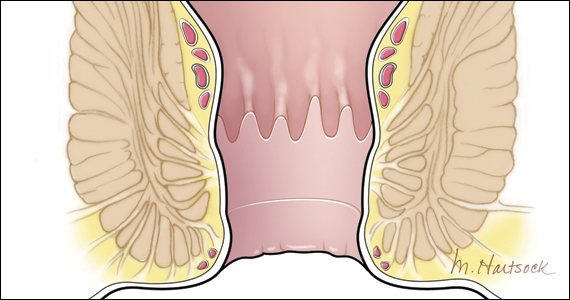

MRD is a key component in that solution, providing dynamic evaluation of pelvic floor function and visualization of the complex interaction in pelvic compartments among patients with defecatory pelvic floor disorders, such as vaginal or uterine prolapse, constipation, incontinence, or other pelvic floor dysfunctions.

However, a key shortcoming has been a lack of consistency in nomenclature and the reporting of MRD findings among institutions and subspecialties.

Clinicians may wind up using different definitions for the same condition and different thresholds for grading severity, resulting in inconsistent communication not only between clinicians across institutions but even within the same institution, the report notes.

To address the situation, radiologists with the Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Disease Focused Panel of the Society of Abdominal Radiology (SAR) published recommendations on MRD protocol and technique in April.

However, even with that guidance, there has been significant variability in the interpretation and utilization of MRD findings among specialties outside of radiology.

The new report was therefore developed to include input from the broad variety of specialists involved in the treatment of patients with pelvic floor disorders, including colorectal surgeons, urogynecologists, urologists, gynecologists, gastroenterologists, radiologists, physiotherapists, and other advanced care practitioners.

“The goal of this effort was to create a universal set of recommendations and language for MRD technique, interpretation, and reporting that can be utilized and carry the same significance across disciplines,” write the authors of the report, published in the American Journal of Roentgenology.

One key area addressed in the report is a recommendation that MRD can be performed in either the upright or supine position, which has been a topic of inconsistency, said Brooke Gurland, MD, medical director of the Pelvic Health Center at Stanford University, California, a co-author on the consensus statement.

“Supine versus upright position was a source of debate, but ultimately there was a consensus that supine position was acceptable,” she told said in an interview.

Regarding positioning, the recommendations conclude that “given the variable results from different studies, consortium members agreed that it is acceptable to perform MRD in the supine position when upright MRD is not available.”

“Importantly, consortium experts stressed that it is very important that this imaging be performed after proper patient education on the purpose of the examination,” they note.

Other recommendations delve into contrast medium considerations, such as the recommendation that MRD does not require the routine use of vaginal contrast medium for adequate imaging of pathology.

And guidance on the technique and grading of relevant pathology include a recommendation to use the pubococcygeal line (PCL) as a point of reference to quantify the prolapse of organs in all compartments of the pelvic floor.

“There is an increasing appreciation that most patients with pelvic organ prolapse experience dual or even triple compartment pathology, making it important to describe the observations in all three compartments to ensure the mobilization of the appropriate team of experts to treat the patient,” the authors note.

The consensus report features an interpretative template providing synopses of the recommendations, which can be adjusted and modified according to additional radiologic information, as well as individualized patient information or clinician preferences.

However, “the suggested verbiage and steps should be advocated as the minimum requirements when performing and interpreting MRD in patients with evacuation disorders of the pelvic floor,” the authors note.

Dr. Gurland added that, in addition to providing benefits in the present utilization of MRD, the clearer guidelines should help advance its use to improve patient care in the future.

“Standardizing imaging techniques, reporting, and language is critical to improving our understanding and then developing therapies for pelvic floor disorders,” she said.

“In the future, correlating MRD with surgical outcomes and identifying modifiable risk factors will improve patient care.”

In addition to being published in the AJR, the report was published concurrently in the journals Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, International Urogynecology Journal, and Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery.

The authors of the guidelines have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New consensus guidelines from a multispecialty working group of the Pelvic Floor Disorders Consortium (PFDC) clear up inconsistencies in the use of magnetic resonance defecography (MRD) and provide universal recommendations on MRD technique, interpretation, reporting, and other factors.

“The consensus language used to describe pelvic floor disorders is critical, so as to allow the various experts who treat these patients [to] communicate and collaborate effectively with each other,” coauthor Liliana Bordeianou, MD, MPH, an associate professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and chair of the Massachusetts General Hospital Colorectal and Pelvic Floor Centers, told this news organization.

“These diseases do not choose an arbitrary side in the pelvis,” she noted. “Instead, these diseases affect the entire pelvis and require a multidisciplinary and collaborative solution.”

MRD is a key component in that solution, providing dynamic evaluation of pelvic floor function and visualization of the complex interaction in pelvic compartments among patients with defecatory pelvic floor disorders, such as vaginal or uterine prolapse, constipation, incontinence, or other pelvic floor dysfunctions.

However, a key shortcoming has been a lack of consistency in nomenclature and the reporting of MRD findings among institutions and subspecialties.

Clinicians may wind up using different definitions for the same condition and different thresholds for grading severity, resulting in inconsistent communication not only between clinicians across institutions but even within the same institution, the report notes.

To address the situation, radiologists with the Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Disease Focused Panel of the Society of Abdominal Radiology (SAR) published recommendations on MRD protocol and technique in April.

However, even with that guidance, there has been significant variability in the interpretation and utilization of MRD findings among specialties outside of radiology.

The new report was therefore developed to include input from the broad variety of specialists involved in the treatment of patients with pelvic floor disorders, including colorectal surgeons, urogynecologists, urologists, gynecologists, gastroenterologists, radiologists, physiotherapists, and other advanced care practitioners.

“The goal of this effort was to create a universal set of recommendations and language for MRD technique, interpretation, and reporting that can be utilized and carry the same significance across disciplines,” write the authors of the report, published in the American Journal of Roentgenology.

One key area addressed in the report is a recommendation that MRD can be performed in either the upright or supine position, which has been a topic of inconsistency, said Brooke Gurland, MD, medical director of the Pelvic Health Center at Stanford University, California, a co-author on the consensus statement.

“Supine versus upright position was a source of debate, but ultimately there was a consensus that supine position was acceptable,” she told said in an interview.

Regarding positioning, the recommendations conclude that “given the variable results from different studies, consortium members agreed that it is acceptable to perform MRD in the supine position when upright MRD is not available.”

“Importantly, consortium experts stressed that it is very important that this imaging be performed after proper patient education on the purpose of the examination,” they note.

Other recommendations delve into contrast medium considerations, such as the recommendation that MRD does not require the routine use of vaginal contrast medium for adequate imaging of pathology.

And guidance on the technique and grading of relevant pathology include a recommendation to use the pubococcygeal line (PCL) as a point of reference to quantify the prolapse of organs in all compartments of the pelvic floor.

“There is an increasing appreciation that most patients with pelvic organ prolapse experience dual or even triple compartment pathology, making it important to describe the observations in all three compartments to ensure the mobilization of the appropriate team of experts to treat the patient,” the authors note.

The consensus report features an interpretative template providing synopses of the recommendations, which can be adjusted and modified according to additional radiologic information, as well as individualized patient information or clinician preferences.

However, “the suggested verbiage and steps should be advocated as the minimum requirements when performing and interpreting MRD in patients with evacuation disorders of the pelvic floor,” the authors note.

Dr. Gurland added that, in addition to providing benefits in the present utilization of MRD, the clearer guidelines should help advance its use to improve patient care in the future.

“Standardizing imaging techniques, reporting, and language is critical to improving our understanding and then developing therapies for pelvic floor disorders,” she said.

“In the future, correlating MRD with surgical outcomes and identifying modifiable risk factors will improve patient care.”

In addition to being published in the AJR, the report was published concurrently in the journals Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, International Urogynecology Journal, and Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery.

The authors of the guidelines have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New consensus guidelines from a multispecialty working group of the Pelvic Floor Disorders Consortium (PFDC) clear up inconsistencies in the use of magnetic resonance defecography (MRD) and provide universal recommendations on MRD technique, interpretation, reporting, and other factors.

“The consensus language used to describe pelvic floor disorders is critical, so as to allow the various experts who treat these patients [to] communicate and collaborate effectively with each other,” coauthor Liliana Bordeianou, MD, MPH, an associate professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and chair of the Massachusetts General Hospital Colorectal and Pelvic Floor Centers, told this news organization.

“These diseases do not choose an arbitrary side in the pelvis,” she noted. “Instead, these diseases affect the entire pelvis and require a multidisciplinary and collaborative solution.”

MRD is a key component in that solution, providing dynamic evaluation of pelvic floor function and visualization of the complex interaction in pelvic compartments among patients with defecatory pelvic floor disorders, such as vaginal or uterine prolapse, constipation, incontinence, or other pelvic floor dysfunctions.

However, a key shortcoming has been a lack of consistency in nomenclature and the reporting of MRD findings among institutions and subspecialties.

Clinicians may wind up using different definitions for the same condition and different thresholds for grading severity, resulting in inconsistent communication not only between clinicians across institutions but even within the same institution, the report notes.

To address the situation, radiologists with the Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Disease Focused Panel of the Society of Abdominal Radiology (SAR) published recommendations on MRD protocol and technique in April.

However, even with that guidance, there has been significant variability in the interpretation and utilization of MRD findings among specialties outside of radiology.

The new report was therefore developed to include input from the broad variety of specialists involved in the treatment of patients with pelvic floor disorders, including colorectal surgeons, urogynecologists, urologists, gynecologists, gastroenterologists, radiologists, physiotherapists, and other advanced care practitioners.

“The goal of this effort was to create a universal set of recommendations and language for MRD technique, interpretation, and reporting that can be utilized and carry the same significance across disciplines,” write the authors of the report, published in the American Journal of Roentgenology.

One key area addressed in the report is a recommendation that MRD can be performed in either the upright or supine position, which has been a topic of inconsistency, said Brooke Gurland, MD, medical director of the Pelvic Health Center at Stanford University, California, a co-author on the consensus statement.

“Supine versus upright position was a source of debate, but ultimately there was a consensus that supine position was acceptable,” she told said in an interview.

Regarding positioning, the recommendations conclude that “given the variable results from different studies, consortium members agreed that it is acceptable to perform MRD in the supine position when upright MRD is not available.”

“Importantly, consortium experts stressed that it is very important that this imaging be performed after proper patient education on the purpose of the examination,” they note.

Other recommendations delve into contrast medium considerations, such as the recommendation that MRD does not require the routine use of vaginal contrast medium for adequate imaging of pathology.

And guidance on the technique and grading of relevant pathology include a recommendation to use the pubococcygeal line (PCL) as a point of reference to quantify the prolapse of organs in all compartments of the pelvic floor.

“There is an increasing appreciation that most patients with pelvic organ prolapse experience dual or even triple compartment pathology, making it important to describe the observations in all three compartments to ensure the mobilization of the appropriate team of experts to treat the patient,” the authors note.

The consensus report features an interpretative template providing synopses of the recommendations, which can be adjusted and modified according to additional radiologic information, as well as individualized patient information or clinician preferences.

However, “the suggested verbiage and steps should be advocated as the minimum requirements when performing and interpreting MRD in patients with evacuation disorders of the pelvic floor,” the authors note.

Dr. Gurland added that, in addition to providing benefits in the present utilization of MRD, the clearer guidelines should help advance its use to improve patient care in the future.

“Standardizing imaging techniques, reporting, and language is critical to improving our understanding and then developing therapies for pelvic floor disorders,” she said.

“In the future, correlating MRD with surgical outcomes and identifying modifiable risk factors will improve patient care.”

In addition to being published in the AJR, the report was published concurrently in the journals Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, International Urogynecology Journal, and Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery.

The authors of the guidelines have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

2021 Update on pelvic floor disorders

With the increasing prevalence of pelvic floor disorders among our aging population, women’s health clinicians should be prepared to counsel patients on treatment options and posttreatment expectations. In this Update, we will review recent literature on surgical treatments for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI). We also include our review of an award-winning and practice-changing study on office-based pessary care. Lastly, we will finish with a summary of a recent Society of Gynecologic Surgeons collaborative systematic review on sexual function after surgery.

5-year RCT data on hysteropexy vs hysterectomy for POP

Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:153. e1-153.e31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.012.

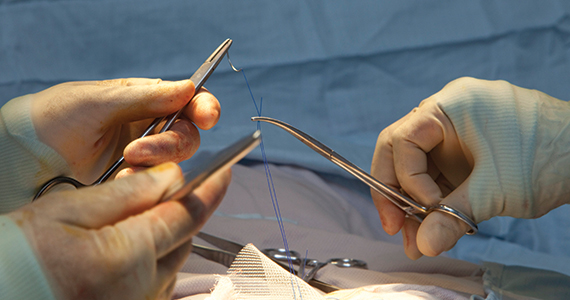

The Pelvic Floor Disorders Network conducted a multisite randomized superiority trial comparing sacrospinous hysteropexy with mesh graft to vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension for POP.

Study details

Postmenopausal women who desired surgery for symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse were randomly assigned to sacrospinous hysteropexy with polypropylene mesh graft using the Uphold-LITE device (Boston Scientific) versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Participants were masked to treatment allocation and completed study visits at 6-month intervals through 60 months. Quantitative prolapse POP-Q exams were performed and patients completed multiple validated questionnaires regarding the presence; severity; and impact of prolapse, urinary, bowel, and pelvic pain symptoms.

Results

A total of 183 postmenopausal women were randomized, and 156 (81 hysteropexy and 75 hysterectomy) patients completed 5-year follow up with no demographic differences between the 2 intervention groups. Operative time was statistically less in the hysteropexy group (111.5 min vs 156.7 min). There were fewer treatment failures (a composite including retreatment for prolapse, prolapse beyond the hymen, and/or bothersome bulge symptoms) in the hysteropexy than in the hysterectomy group (37% vs 54%, respectively) at 5 years of follow up. However, most patients with treatment failure were classified as an intermittent failure, with only 16% of hysteropexy patients and 22% of hysterectomy patients classified as persistent failures. There were no meaningful differences between patient-reported outcomes. Hysteropexy had an 8% mesh exposure risk, with none requiring surgical management.

This study represents the highest quality randomized trial design and boasts high patient retention rates and 5-year follow up. Findings support further investigation on the use of polypropylene mesh for POP. In April of 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration halted the selling and distribution of vaginal mesh products for prolapse repair given the lack of safety outcomes, concerns about mesh exposure rates, and possible increased rates of pelvic pain and adverse events. This study invites pelvic reconstructive surgeons to revisit the debate of hysteropexy versus hysterectomy and synthetic mesh versus native tissue repairs. The 8% mesh exposure rate represents a challenge for the future design and development of vaginal implant materials, weighing the balancing of improved long-term efficacy with the safety and complication concerns.

Continue to: Preliminary 12-month data for a single-incision sling for surgical management of SUI...

Preliminary 12-month data for a single-incision sling for surgical management of SUI

Erickson T, Roovers JP, Gheiler E, et al. A multicenter prospective study evaluating efficacy and safety of a single-incision sling procedure for stress urinary incontinence. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:93-99. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.04.014.

In this industry-sponsored study, researchers compared a novel single-incision sling to currently available midurethral slings for SUI with 12-month outcomes and adverse event details. However, results are primarily descriptive with no statistical testing.

Study details

Patients were eligible for inclusion in this prospective, nonrandomized cohort study if SUI was their primary incontinence symptom, with confirmatory office testing. Exclusion criteria included POP greater than stage 2, prior SUI surgery, plans for future pregnancy, elevated postvoid residuals, or concomitant surgical procedures. The single-incision Altis (Coloplast) sling was compared to all commercially available transobturator and retropubic midurethral slings. The primary outcome of this study was reduction in 24-hour pad weights, and secondary outcomes included negative cough-stress test and subjective patient-reported outcomes via validated questionnaires.

Results

A total of 184 women were enrolled in the Altis group and 171 in the comparator other sling group. Symptom severity was similar between groups, but more patients in the comparator group had mixed urinary incontinence, and more patients in the Altis group had intrinsic sphincter deficiency. The Altis group had a higher proportion of “dry patients,” but otherwise the outcomes were similar between the 2 groups, including negative cough-stress test and patientreported outcomes. Two patients in the Altis group and 7 patients in the comparator group underwent device revisions. Again, statistical analysis was not performed.

Single-incision slings may reduce the risk of groin pain associated with transobturator slings and may be a good option for patients who desire less mesh burden than the traditional retropubic slings or who are not good candidates. This trial suggests that the Altis single-incision sling may be similar in outcomes and adverse events to currently available midurethral slings, but further, more rigorous trials are underway to fully evaluate this—including a US-based multicenter randomized trial of Altis single-incision slings versus retropubic slings (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03520114).

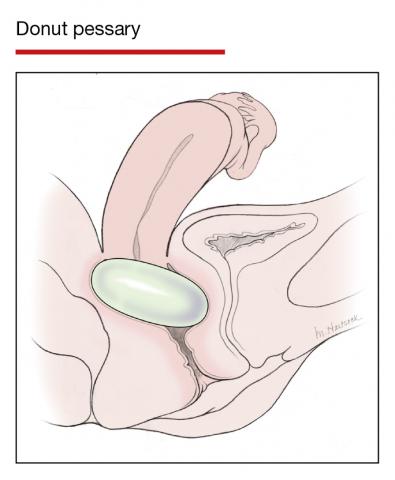

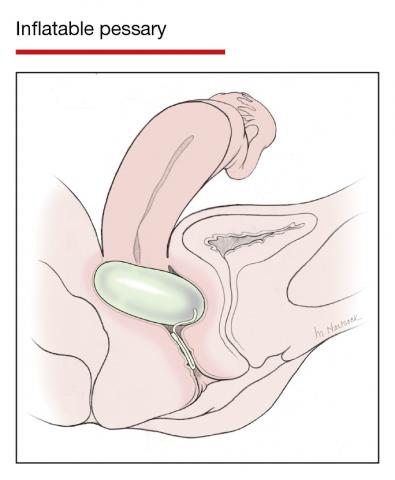

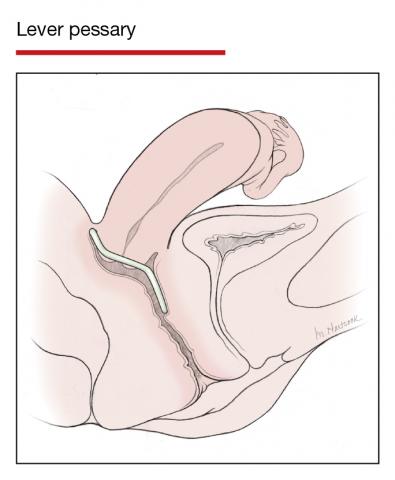

Office-based pessary care can be safely spaced out to 24 weeks without an increase in erosions

Propst K, Mellen C, O’Sullivan DM, et al. Timing of office-based pessary care: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:100-105. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000003580.

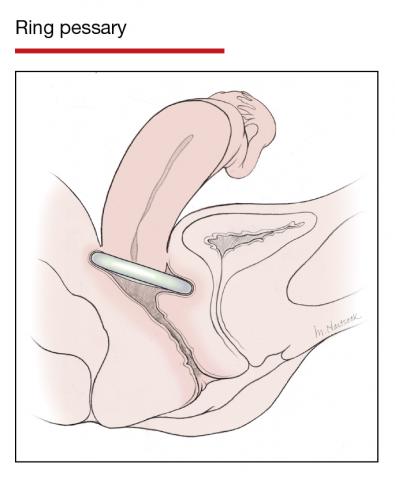

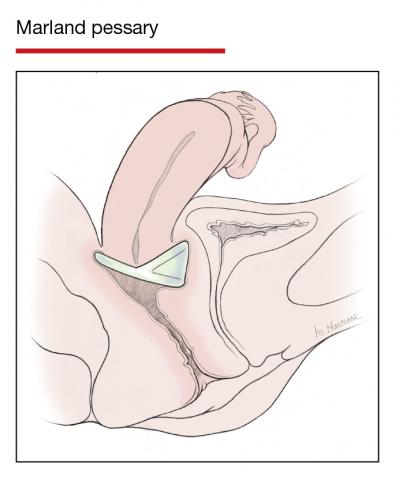

For women already using a pessary without issues, extending office visits to every 6 months does not increase rates of vaginal epithelial abnormalities, according to results of this randomized controlled trial.

Study details

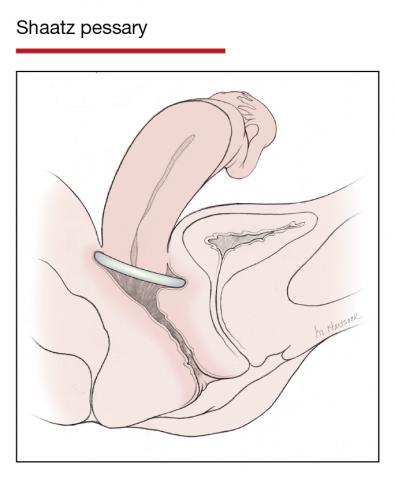

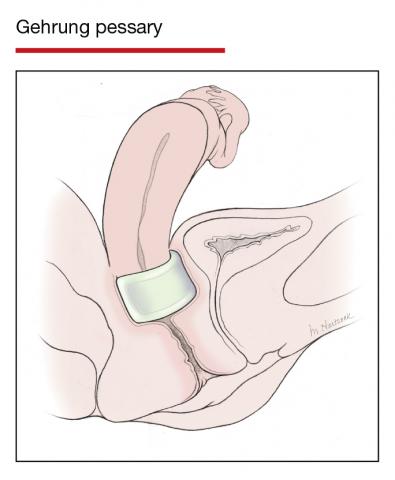

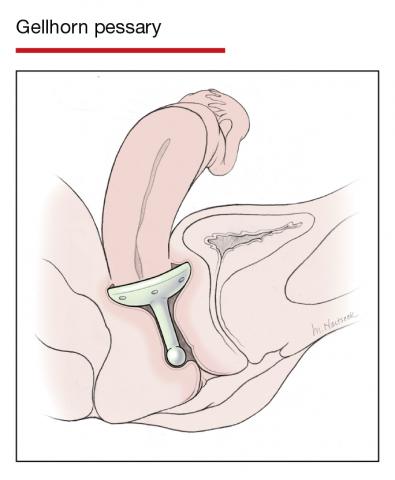

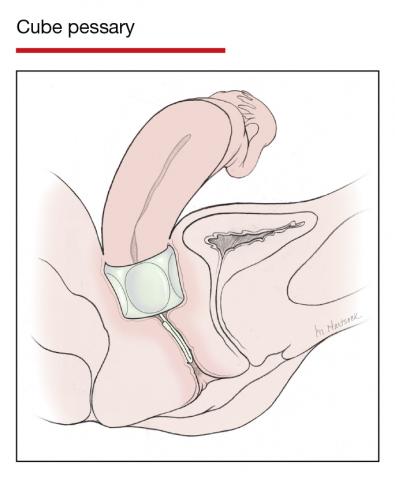

Women already using a Gelhorn, ring, or incontinence dish pessary for POP, SUI, or both were randomized to continue routine care with office evaluation every 12 weeks versus the extended-care cohort (with office evaluation every 24 weeks). Women were excluded if they removed and replaced the pessary themselves or if there was a presence of vaginal epithelial abnormalities, such as erosion or granulation tissue.

Results

The rate of vaginal epithelium erosion was 7.4% in the routine arm and 1.7% in the extended-care arm, meeting criteria for noninferiority of extended care. The majority of patients with office visits every 24 weeks preferred the less frequent examinations, and there was no difference in degree of bother due to vaginal discharge. There was also no difference in the percentage of patients with unscheduled visits. The only factors associated with vaginal epithelium abnormalities were prior abnormalities and lifetime duration of pessary use.

As there are currently no evidenced-based guidelines for pessary care, this study contributes data to support extended office-based care up to 24 weeks, a common practice in the United Kingdom. During the COVID-19 pandemic, with reduced health care access, these findings should be reassuring to clinicians and patients.

Continue to: How can we counsel patients regarding changes in sexual activity and function after surgery for POP?...

How can we counsel patients regarding changes in sexual activity and function after surgery for POP?

Antosh DD, Dieter AA, Balk EM, et al. Sexual function after pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review comparing different approaches to pelvic floor repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;2:S0002-9378(21)00610-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.042.

A secondary analysis of a recent systematic review found overall moderate- to high-quality evidence that were no differences in total dyspareunia, de novo dyspareunia, and scores on a validated sexual function questionnaire (PISQ12) when comparing postoperative sexual function outcomes of native tissue repair to sacrocolpopexy, transvaginal mesh, or biologic graft. Rates of postoperative dyspareunia were higher for transvaginal mesh than for sacrocolpopexy.

Study details

The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group identified 43 original prospective, comparative studies of reconstructive prolapse surgery that reported sexual function outcomes when comparing 2 different types of POP procedures. Thirty-seven of those studies were randomized controlled trials. Specifically, they looked at data comparing outcomes for native tissue versus sacrocolpopexy, native tissue versus transvaginal mesh, native tissue versus biologic graft, and transvaginal mesh versus sacrocolpopexy.

Results

Overall, the prevalence of postoperative dyspareunia was lower than preoperatively after all surgery types. The only statistical difference in this review demonstrated higher postoperative prevalence of dyspareunia after transvaginal mesh than sacrocolpopexy, based on 2 studies. When comparing native tissue prolapse repair to transvaginal mesh, sacrocolpopexy, or biologic grafts, there were no significant differences in sexual activity, baseline, or postoperative total dyspareunia, de-novo dyspareunia, or sexual function changes as measured by the PISQ12 validated questionnaire. ●

This systematic review further contributes to the growing evidence that, regardless of surgical approach to POP, sexual function generally improves and dyspareunia rates generally decrease postoperatively, with overall low rates of de novo dyspareunia. This will help patients and providers select the best-fit surgical approach without concern for worsened sexual function. It also underscores the need for inclusion of standardized sexual function terminology use and sexual health outcomes in future prolapse surgery research.

With the increasing prevalence of pelvic floor disorders among our aging population, women’s health clinicians should be prepared to counsel patients on treatment options and posttreatment expectations. In this Update, we will review recent literature on surgical treatments for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI). We also include our review of an award-winning and practice-changing study on office-based pessary care. Lastly, we will finish with a summary of a recent Society of Gynecologic Surgeons collaborative systematic review on sexual function after surgery.

5-year RCT data on hysteropexy vs hysterectomy for POP

Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:153. e1-153.e31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.012.

The Pelvic Floor Disorders Network conducted a multisite randomized superiority trial comparing sacrospinous hysteropexy with mesh graft to vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension for POP.

Study details

Postmenopausal women who desired surgery for symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse were randomly assigned to sacrospinous hysteropexy with polypropylene mesh graft using the Uphold-LITE device (Boston Scientific) versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Participants were masked to treatment allocation and completed study visits at 6-month intervals through 60 months. Quantitative prolapse POP-Q exams were performed and patients completed multiple validated questionnaires regarding the presence; severity; and impact of prolapse, urinary, bowel, and pelvic pain symptoms.

Results

A total of 183 postmenopausal women were randomized, and 156 (81 hysteropexy and 75 hysterectomy) patients completed 5-year follow up with no demographic differences between the 2 intervention groups. Operative time was statistically less in the hysteropexy group (111.5 min vs 156.7 min). There were fewer treatment failures (a composite including retreatment for prolapse, prolapse beyond the hymen, and/or bothersome bulge symptoms) in the hysteropexy than in the hysterectomy group (37% vs 54%, respectively) at 5 years of follow up. However, most patients with treatment failure were classified as an intermittent failure, with only 16% of hysteropexy patients and 22% of hysterectomy patients classified as persistent failures. There were no meaningful differences between patient-reported outcomes. Hysteropexy had an 8% mesh exposure risk, with none requiring surgical management.

This study represents the highest quality randomized trial design and boasts high patient retention rates and 5-year follow up. Findings support further investigation on the use of polypropylene mesh for POP. In April of 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration halted the selling and distribution of vaginal mesh products for prolapse repair given the lack of safety outcomes, concerns about mesh exposure rates, and possible increased rates of pelvic pain and adverse events. This study invites pelvic reconstructive surgeons to revisit the debate of hysteropexy versus hysterectomy and synthetic mesh versus native tissue repairs. The 8% mesh exposure rate represents a challenge for the future design and development of vaginal implant materials, weighing the balancing of improved long-term efficacy with the safety and complication concerns.

Continue to: Preliminary 12-month data for a single-incision sling for surgical management of SUI...

Preliminary 12-month data for a single-incision sling for surgical management of SUI

Erickson T, Roovers JP, Gheiler E, et al. A multicenter prospective study evaluating efficacy and safety of a single-incision sling procedure for stress urinary incontinence. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:93-99. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.04.014.

In this industry-sponsored study, researchers compared a novel single-incision sling to currently available midurethral slings for SUI with 12-month outcomes and adverse event details. However, results are primarily descriptive with no statistical testing.

Study details

Patients were eligible for inclusion in this prospective, nonrandomized cohort study if SUI was their primary incontinence symptom, with confirmatory office testing. Exclusion criteria included POP greater than stage 2, prior SUI surgery, plans for future pregnancy, elevated postvoid residuals, or concomitant surgical procedures. The single-incision Altis (Coloplast) sling was compared to all commercially available transobturator and retropubic midurethral slings. The primary outcome of this study was reduction in 24-hour pad weights, and secondary outcomes included negative cough-stress test and subjective patient-reported outcomes via validated questionnaires.

Results

A total of 184 women were enrolled in the Altis group and 171 in the comparator other sling group. Symptom severity was similar between groups, but more patients in the comparator group had mixed urinary incontinence, and more patients in the Altis group had intrinsic sphincter deficiency. The Altis group had a higher proportion of “dry patients,” but otherwise the outcomes were similar between the 2 groups, including negative cough-stress test and patientreported outcomes. Two patients in the Altis group and 7 patients in the comparator group underwent device revisions. Again, statistical analysis was not performed.

Single-incision slings may reduce the risk of groin pain associated with transobturator slings and may be a good option for patients who desire less mesh burden than the traditional retropubic slings or who are not good candidates. This trial suggests that the Altis single-incision sling may be similar in outcomes and adverse events to currently available midurethral slings, but further, more rigorous trials are underway to fully evaluate this—including a US-based multicenter randomized trial of Altis single-incision slings versus retropubic slings (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03520114).

Office-based pessary care can be safely spaced out to 24 weeks without an increase in erosions

Propst K, Mellen C, O’Sullivan DM, et al. Timing of office-based pessary care: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:100-105. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000003580.

For women already using a pessary without issues, extending office visits to every 6 months does not increase rates of vaginal epithelial abnormalities, according to results of this randomized controlled trial.

Study details

Women already using a Gelhorn, ring, or incontinence dish pessary for POP, SUI, or both were randomized to continue routine care with office evaluation every 12 weeks versus the extended-care cohort (with office evaluation every 24 weeks). Women were excluded if they removed and replaced the pessary themselves or if there was a presence of vaginal epithelial abnormalities, such as erosion or granulation tissue.

Results

The rate of vaginal epithelium erosion was 7.4% in the routine arm and 1.7% in the extended-care arm, meeting criteria for noninferiority of extended care. The majority of patients with office visits every 24 weeks preferred the less frequent examinations, and there was no difference in degree of bother due to vaginal discharge. There was also no difference in the percentage of patients with unscheduled visits. The only factors associated with vaginal epithelium abnormalities were prior abnormalities and lifetime duration of pessary use.

As there are currently no evidenced-based guidelines for pessary care, this study contributes data to support extended office-based care up to 24 weeks, a common practice in the United Kingdom. During the COVID-19 pandemic, with reduced health care access, these findings should be reassuring to clinicians and patients.

Continue to: How can we counsel patients regarding changes in sexual activity and function after surgery for POP?...

How can we counsel patients regarding changes in sexual activity and function after surgery for POP?

Antosh DD, Dieter AA, Balk EM, et al. Sexual function after pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review comparing different approaches to pelvic floor repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;2:S0002-9378(21)00610-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.042.

A secondary analysis of a recent systematic review found overall moderate- to high-quality evidence that were no differences in total dyspareunia, de novo dyspareunia, and scores on a validated sexual function questionnaire (PISQ12) when comparing postoperative sexual function outcomes of native tissue repair to sacrocolpopexy, transvaginal mesh, or biologic graft. Rates of postoperative dyspareunia were higher for transvaginal mesh than for sacrocolpopexy.

Study details

The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group identified 43 original prospective, comparative studies of reconstructive prolapse surgery that reported sexual function outcomes when comparing 2 different types of POP procedures. Thirty-seven of those studies were randomized controlled trials. Specifically, they looked at data comparing outcomes for native tissue versus sacrocolpopexy, native tissue versus transvaginal mesh, native tissue versus biologic graft, and transvaginal mesh versus sacrocolpopexy.

Results

Overall, the prevalence of postoperative dyspareunia was lower than preoperatively after all surgery types. The only statistical difference in this review demonstrated higher postoperative prevalence of dyspareunia after transvaginal mesh than sacrocolpopexy, based on 2 studies. When comparing native tissue prolapse repair to transvaginal mesh, sacrocolpopexy, or biologic grafts, there were no significant differences in sexual activity, baseline, or postoperative total dyspareunia, de-novo dyspareunia, or sexual function changes as measured by the PISQ12 validated questionnaire. ●

This systematic review further contributes to the growing evidence that, regardless of surgical approach to POP, sexual function generally improves and dyspareunia rates generally decrease postoperatively, with overall low rates of de novo dyspareunia. This will help patients and providers select the best-fit surgical approach without concern for worsened sexual function. It also underscores the need for inclusion of standardized sexual function terminology use and sexual health outcomes in future prolapse surgery research.

With the increasing prevalence of pelvic floor disorders among our aging population, women’s health clinicians should be prepared to counsel patients on treatment options and posttreatment expectations. In this Update, we will review recent literature on surgical treatments for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI). We also include our review of an award-winning and practice-changing study on office-based pessary care. Lastly, we will finish with a summary of a recent Society of Gynecologic Surgeons collaborative systematic review on sexual function after surgery.

5-year RCT data on hysteropexy vs hysterectomy for POP

Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:153. e1-153.e31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.012.

The Pelvic Floor Disorders Network conducted a multisite randomized superiority trial comparing sacrospinous hysteropexy with mesh graft to vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension for POP.

Study details

Postmenopausal women who desired surgery for symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse were randomly assigned to sacrospinous hysteropexy with polypropylene mesh graft using the Uphold-LITE device (Boston Scientific) versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Participants were masked to treatment allocation and completed study visits at 6-month intervals through 60 months. Quantitative prolapse POP-Q exams were performed and patients completed multiple validated questionnaires regarding the presence; severity; and impact of prolapse, urinary, bowel, and pelvic pain symptoms.

Results

A total of 183 postmenopausal women were randomized, and 156 (81 hysteropexy and 75 hysterectomy) patients completed 5-year follow up with no demographic differences between the 2 intervention groups. Operative time was statistically less in the hysteropexy group (111.5 min vs 156.7 min). There were fewer treatment failures (a composite including retreatment for prolapse, prolapse beyond the hymen, and/or bothersome bulge symptoms) in the hysteropexy than in the hysterectomy group (37% vs 54%, respectively) at 5 years of follow up. However, most patients with treatment failure were classified as an intermittent failure, with only 16% of hysteropexy patients and 22% of hysterectomy patients classified as persistent failures. There were no meaningful differences between patient-reported outcomes. Hysteropexy had an 8% mesh exposure risk, with none requiring surgical management.

This study represents the highest quality randomized trial design and boasts high patient retention rates and 5-year follow up. Findings support further investigation on the use of polypropylene mesh for POP. In April of 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration halted the selling and distribution of vaginal mesh products for prolapse repair given the lack of safety outcomes, concerns about mesh exposure rates, and possible increased rates of pelvic pain and adverse events. This study invites pelvic reconstructive surgeons to revisit the debate of hysteropexy versus hysterectomy and synthetic mesh versus native tissue repairs. The 8% mesh exposure rate represents a challenge for the future design and development of vaginal implant materials, weighing the balancing of improved long-term efficacy with the safety and complication concerns.

Continue to: Preliminary 12-month data for a single-incision sling for surgical management of SUI...

Preliminary 12-month data for a single-incision sling for surgical management of SUI

Erickson T, Roovers JP, Gheiler E, et al. A multicenter prospective study evaluating efficacy and safety of a single-incision sling procedure for stress urinary incontinence. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:93-99. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.04.014.

In this industry-sponsored study, researchers compared a novel single-incision sling to currently available midurethral slings for SUI with 12-month outcomes and adverse event details. However, results are primarily descriptive with no statistical testing.

Study details

Patients were eligible for inclusion in this prospective, nonrandomized cohort study if SUI was their primary incontinence symptom, with confirmatory office testing. Exclusion criteria included POP greater than stage 2, prior SUI surgery, plans for future pregnancy, elevated postvoid residuals, or concomitant surgical procedures. The single-incision Altis (Coloplast) sling was compared to all commercially available transobturator and retropubic midurethral slings. The primary outcome of this study was reduction in 24-hour pad weights, and secondary outcomes included negative cough-stress test and subjective patient-reported outcomes via validated questionnaires.

Results

A total of 184 women were enrolled in the Altis group and 171 in the comparator other sling group. Symptom severity was similar between groups, but more patients in the comparator group had mixed urinary incontinence, and more patients in the Altis group had intrinsic sphincter deficiency. The Altis group had a higher proportion of “dry patients,” but otherwise the outcomes were similar between the 2 groups, including negative cough-stress test and patientreported outcomes. Two patients in the Altis group and 7 patients in the comparator group underwent device revisions. Again, statistical analysis was not performed.

Single-incision slings may reduce the risk of groin pain associated with transobturator slings and may be a good option for patients who desire less mesh burden than the traditional retropubic slings or who are not good candidates. This trial suggests that the Altis single-incision sling may be similar in outcomes and adverse events to currently available midurethral slings, but further, more rigorous trials are underway to fully evaluate this—including a US-based multicenter randomized trial of Altis single-incision slings versus retropubic slings (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03520114).

Office-based pessary care can be safely spaced out to 24 weeks without an increase in erosions

Propst K, Mellen C, O’Sullivan DM, et al. Timing of office-based pessary care: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:100-105. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000003580.

For women already using a pessary without issues, extending office visits to every 6 months does not increase rates of vaginal epithelial abnormalities, according to results of this randomized controlled trial.

Study details

Women already using a Gelhorn, ring, or incontinence dish pessary for POP, SUI, or both were randomized to continue routine care with office evaluation every 12 weeks versus the extended-care cohort (with office evaluation every 24 weeks). Women were excluded if they removed and replaced the pessary themselves or if there was a presence of vaginal epithelial abnormalities, such as erosion or granulation tissue.

Results

The rate of vaginal epithelium erosion was 7.4% in the routine arm and 1.7% in the extended-care arm, meeting criteria for noninferiority of extended care. The majority of patients with office visits every 24 weeks preferred the less frequent examinations, and there was no difference in degree of bother due to vaginal discharge. There was also no difference in the percentage of patients with unscheduled visits. The only factors associated with vaginal epithelium abnormalities were prior abnormalities and lifetime duration of pessary use.

As there are currently no evidenced-based guidelines for pessary care, this study contributes data to support extended office-based care up to 24 weeks, a common practice in the United Kingdom. During the COVID-19 pandemic, with reduced health care access, these findings should be reassuring to clinicians and patients.

Continue to: How can we counsel patients regarding changes in sexual activity and function after surgery for POP?...

How can we counsel patients regarding changes in sexual activity and function after surgery for POP?

Antosh DD, Dieter AA, Balk EM, et al. Sexual function after pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review comparing different approaches to pelvic floor repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;2:S0002-9378(21)00610-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.042.

A secondary analysis of a recent systematic review found overall moderate- to high-quality evidence that were no differences in total dyspareunia, de novo dyspareunia, and scores on a validated sexual function questionnaire (PISQ12) when comparing postoperative sexual function outcomes of native tissue repair to sacrocolpopexy, transvaginal mesh, or biologic graft. Rates of postoperative dyspareunia were higher for transvaginal mesh than for sacrocolpopexy.

Study details

The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group identified 43 original prospective, comparative studies of reconstructive prolapse surgery that reported sexual function outcomes when comparing 2 different types of POP procedures. Thirty-seven of those studies were randomized controlled trials. Specifically, they looked at data comparing outcomes for native tissue versus sacrocolpopexy, native tissue versus transvaginal mesh, native tissue versus biologic graft, and transvaginal mesh versus sacrocolpopexy.

Results

Overall, the prevalence of postoperative dyspareunia was lower than preoperatively after all surgery types. The only statistical difference in this review demonstrated higher postoperative prevalence of dyspareunia after transvaginal mesh than sacrocolpopexy, based on 2 studies. When comparing native tissue prolapse repair to transvaginal mesh, sacrocolpopexy, or biologic grafts, there were no significant differences in sexual activity, baseline, or postoperative total dyspareunia, de-novo dyspareunia, or sexual function changes as measured by the PISQ12 validated questionnaire. ●

This systematic review further contributes to the growing evidence that, regardless of surgical approach to POP, sexual function generally improves and dyspareunia rates generally decrease postoperatively, with overall low rates of de novo dyspareunia. This will help patients and providers select the best-fit surgical approach without concern for worsened sexual function. It also underscores the need for inclusion of standardized sexual function terminology use and sexual health outcomes in future prolapse surgery research.

A multidisciplinary approach to gyn care: A single center’s experience

In her book The Silo Effect: The Peril of Expertise and the Promise of Breaking Down Barriers, Gillian Tett wrote that “the word ‘silo’ does not just refer to a physical structure or organization (such as a department). It can also be a state of mind. Silos exist in structures. But they exist in our minds and social groups too. Silos breed tribalism. But they can also go hand in hand with tunnel vision.”

Tertiary care referral centers seem to be trending toward being more and more “un-siloed” and collaborative within their own departments and between departments in order to care for patients. The terms multidisciplinary and intradisciplinary have become popular in medicine, and teams are joining forces to create care paths for patients that are intended to improve the efficiency of and the quality of care that is rendered. There is no better example of the move to improve collaboration in medicine than the theme of the 2021 Society of Gynecologic Surgeons annual meeting, “Working Together: How Collaboration Enables Us to Better Help Our Patients.”

In this article, we provide examples of how collaborating with other specialties—within and outside of an ObGyn department—should become the standard of care. We discuss how to make this team approach easier and provide evidence that patients experience favorable outcomes. While data on combined care remain sparse, the existing literature on this topic helps us to guide and counsel patients about what to expect when a combined approach is taken.

Addressing pelvic floor disorders in women with gynecologic malignancy

In 2018, authors of a systematic review that looked at concurrent pelvic floor disorders in gynecologic oncologic survivors found that the prevalence of these disorders was high enough to warrant evaluation and management of these conditions to help improve quality of life for patients.1 Furthermore, it is possible that the prevalence of urinary incontinence is higher in patients who have undergone surgery for a gynecologic malignancy compared with controls, which has been reported in previous studies.2,3 At Cleveland Clinic, we recognize the need to evaluate our patients receiving oncologic care for urinary, fecal, and pelvic organ prolapse symptoms. Our oncologists routinely inquire about these symptoms once their patients have undergone surgery with them, and they make referrals for all their symptomatic patients. They have even learned about our own counseling, and they pre-emptively let patients know what our counseling may encompass.

For instance, many patients who received radiation therapy have stress urinary incontinence that is likely related to a hypomobile urethra, and they may benefit more from transurethral bulking than an anti-incontinence procedure in the operating room. Reassuring patients ahead of time that they do not need major interventions for their symptoms is helpful, as these patients are already experiencing tremendous burden from their oncologic conditions. We have made our referral patterns easy for these patients, and most patients are seen within days to weeks of the referral placed, depending on the urgency of the consult and the need to proceed with their oncologic treatment plan.

Gynecologic oncology patients who present with preoperative stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse also are referred to a urogynecology specialist for concurrent care. Care paths have been created to help inform both the urogynecologists and the oncologists about options for patients depending on their respective conditions, as both their malignancy and their pelvic floor disorder(s) are considered in treatment planning. There is agreement in this planning that the oncologic surgery takes priority, and the urogynecologic approach is based on the oncologic plan.

Our urogynecologists routinely ask if future radiation is in the treatment plan, as this usually precludes us from placing a midurethral sling at the time of any surgery. Surgical approach (vaginal versus abdominal; open or minimally invasive) also is determined by the oncologic team. At the time of surgery, patient positioning is considered to optimize access for all of the surgeons. For instance, having the oncologist know that the patient needs to be far down on the bed as their steep Trendelenburg positioning during laparoscopy or robotic surgery may cause the patient to slide cephalad during the case may make a vaginal repair or sling placement at the end of the case challenging. All these small nuances are important, and a collaborative team develops the right plan for each patient in advance.