User login

Borderline personality disorder: Remember empathy and compassion

Oh, great!” a senior resident sardonically remarked with a smirk as they read up on the next patient in the clinic. “A borderline patient. Get ready for a rough one ... Ugh.”

Before ever stepping foot into the patient’s room, this resident had prematurely established and demonstrated an unfortunate dynamic for any student or trainee within earshot. This is an all-too-familiar occurrence when caring for individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD), or any other patients deemed to be “difficult.” The patient, however, likely walked into the room with a traumatic past that they continue to suffer from, in addition to any other issues for which they were seeking care.

Consider what these patients have experienced

A typical profile of these resilient patients with BPD: They were born emotionally sensitive. They grew up in homes with caretakers who knowingly or unknowingly invalidated their complaints about having their feelings hurt, about being abused emotionally, sexually, or otherwise, or about their worries concerning their interactions with peers at school. These caretakers may have been frightening and unpredictable, randomly showing affection or arbitrarily punishing for any perceived misstep, which led these patients to develop (for their own safety’s sake) a hypersensitivity to the affect of others. Their wariness and distrust of their social surroundings may have led to a skeptical view of kindness from others. Over time, without any guidance from prior demonstrations of healthy coping skills or interpersonal outlets from their caregivers, the emotional pressure builds. This pressure finally erupts in the form of impulsivity, self-harm, desperation, and defensiveness—in other words, survival. This is often followed by these patients’ first experience with receiving some degree of appropriate response to their complaints—their first experience with feeling seen and heard by their caretakers. They learn that their needs are met only when they cry out in desperation.1-3

These patients typically bring these maladaptive coping skills with them into adulthood, which often leads to a series of intense, unhealthy, and short-lived interpersonal and professional connections. They desire healthy, lasting connections with others, but through no fault of their own are unable to appropriately manage the normal stressors therein.1 Often, these patients do not know of their eventual BPD diagnosis, or even reject it due to its ever-negative valence. For other patients, receiving a personality disorder diagnosis is incredibly validating because they are no longer alone regarding this type of suffering, and a doctor—a caretaker—is finally making sense of this tumultuous world.

The countertransference of frustration, anxiety, doubt, and annoyance we may feel when caring for patients with BPD pales in comparison to living in their shoes and carrying the weight of what they have had to endure before presenting to our care. As these resilient patients wait in the exam room for the chance to be heard, let this be a reminder to greet them with the patience, understanding, empathy, and compassion that physicians are known to embody.

Suggestions for working with ‘difficult’ patients

The following tips may be helpful for building rapport with patients with BPD or other “difficult” patients:

- validate their complaints, and the difficulties they cause

- be genuine and honest when discussing their complaints

- acknowledge your own mistakes and misunderstandings in their care

- don’t be defensive—accept criticism with an open mind

- practice listening with intent, and reflective listening

- set ground rules and stick to them (eg, time limits, prescribing expectations, patient-physician relationship boundaries)

- educate and support the patient and their loved ones.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:947.

2. Porter C, Palmier-Claus J, Branitsky A, et al. Childhood adversity and borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2020;141(1):6-20.

3. Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Emotional hyper-reactivity in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(9):16-20.

Oh, great!” a senior resident sardonically remarked with a smirk as they read up on the next patient in the clinic. “A borderline patient. Get ready for a rough one ... Ugh.”

Before ever stepping foot into the patient’s room, this resident had prematurely established and demonstrated an unfortunate dynamic for any student or trainee within earshot. This is an all-too-familiar occurrence when caring for individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD), or any other patients deemed to be “difficult.” The patient, however, likely walked into the room with a traumatic past that they continue to suffer from, in addition to any other issues for which they were seeking care.

Consider what these patients have experienced

A typical profile of these resilient patients with BPD: They were born emotionally sensitive. They grew up in homes with caretakers who knowingly or unknowingly invalidated their complaints about having their feelings hurt, about being abused emotionally, sexually, or otherwise, or about their worries concerning their interactions with peers at school. These caretakers may have been frightening and unpredictable, randomly showing affection or arbitrarily punishing for any perceived misstep, which led these patients to develop (for their own safety’s sake) a hypersensitivity to the affect of others. Their wariness and distrust of their social surroundings may have led to a skeptical view of kindness from others. Over time, without any guidance from prior demonstrations of healthy coping skills or interpersonal outlets from their caregivers, the emotional pressure builds. This pressure finally erupts in the form of impulsivity, self-harm, desperation, and defensiveness—in other words, survival. This is often followed by these patients’ first experience with receiving some degree of appropriate response to their complaints—their first experience with feeling seen and heard by their caretakers. They learn that their needs are met only when they cry out in desperation.1-3

These patients typically bring these maladaptive coping skills with them into adulthood, which often leads to a series of intense, unhealthy, and short-lived interpersonal and professional connections. They desire healthy, lasting connections with others, but through no fault of their own are unable to appropriately manage the normal stressors therein.1 Often, these patients do not know of their eventual BPD diagnosis, or even reject it due to its ever-negative valence. For other patients, receiving a personality disorder diagnosis is incredibly validating because they are no longer alone regarding this type of suffering, and a doctor—a caretaker—is finally making sense of this tumultuous world.

The countertransference of frustration, anxiety, doubt, and annoyance we may feel when caring for patients with BPD pales in comparison to living in their shoes and carrying the weight of what they have had to endure before presenting to our care. As these resilient patients wait in the exam room for the chance to be heard, let this be a reminder to greet them with the patience, understanding, empathy, and compassion that physicians are known to embody.

Suggestions for working with ‘difficult’ patients

The following tips may be helpful for building rapport with patients with BPD or other “difficult” patients:

- validate their complaints, and the difficulties they cause

- be genuine and honest when discussing their complaints

- acknowledge your own mistakes and misunderstandings in their care

- don’t be defensive—accept criticism with an open mind

- practice listening with intent, and reflective listening

- set ground rules and stick to them (eg, time limits, prescribing expectations, patient-physician relationship boundaries)

- educate and support the patient and their loved ones.

Oh, great!” a senior resident sardonically remarked with a smirk as they read up on the next patient in the clinic. “A borderline patient. Get ready for a rough one ... Ugh.”

Before ever stepping foot into the patient’s room, this resident had prematurely established and demonstrated an unfortunate dynamic for any student or trainee within earshot. This is an all-too-familiar occurrence when caring for individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD), or any other patients deemed to be “difficult.” The patient, however, likely walked into the room with a traumatic past that they continue to suffer from, in addition to any other issues for which they were seeking care.

Consider what these patients have experienced

A typical profile of these resilient patients with BPD: They were born emotionally sensitive. They grew up in homes with caretakers who knowingly or unknowingly invalidated their complaints about having their feelings hurt, about being abused emotionally, sexually, or otherwise, or about their worries concerning their interactions with peers at school. These caretakers may have been frightening and unpredictable, randomly showing affection or arbitrarily punishing for any perceived misstep, which led these patients to develop (for their own safety’s sake) a hypersensitivity to the affect of others. Their wariness and distrust of their social surroundings may have led to a skeptical view of kindness from others. Over time, without any guidance from prior demonstrations of healthy coping skills or interpersonal outlets from their caregivers, the emotional pressure builds. This pressure finally erupts in the form of impulsivity, self-harm, desperation, and defensiveness—in other words, survival. This is often followed by these patients’ first experience with receiving some degree of appropriate response to their complaints—their first experience with feeling seen and heard by their caretakers. They learn that their needs are met only when they cry out in desperation.1-3

These patients typically bring these maladaptive coping skills with them into adulthood, which often leads to a series of intense, unhealthy, and short-lived interpersonal and professional connections. They desire healthy, lasting connections with others, but through no fault of their own are unable to appropriately manage the normal stressors therein.1 Often, these patients do not know of their eventual BPD diagnosis, or even reject it due to its ever-negative valence. For other patients, receiving a personality disorder diagnosis is incredibly validating because they are no longer alone regarding this type of suffering, and a doctor—a caretaker—is finally making sense of this tumultuous world.

The countertransference of frustration, anxiety, doubt, and annoyance we may feel when caring for patients with BPD pales in comparison to living in their shoes and carrying the weight of what they have had to endure before presenting to our care. As these resilient patients wait in the exam room for the chance to be heard, let this be a reminder to greet them with the patience, understanding, empathy, and compassion that physicians are known to embody.

Suggestions for working with ‘difficult’ patients

The following tips may be helpful for building rapport with patients with BPD or other “difficult” patients:

- validate their complaints, and the difficulties they cause

- be genuine and honest when discussing their complaints

- acknowledge your own mistakes and misunderstandings in their care

- don’t be defensive—accept criticism with an open mind

- practice listening with intent, and reflective listening

- set ground rules and stick to them (eg, time limits, prescribing expectations, patient-physician relationship boundaries)

- educate and support the patient and their loved ones.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:947.

2. Porter C, Palmier-Claus J, Branitsky A, et al. Childhood adversity and borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2020;141(1):6-20.

3. Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Emotional hyper-reactivity in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(9):16-20.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:947.

2. Porter C, Palmier-Claus J, Branitsky A, et al. Childhood adversity and borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2020;141(1):6-20.

3. Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Emotional hyper-reactivity in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(9):16-20.

Borderline personality disorder: Is there an optimal therapy?

Schema is a form of psychotherapy that focuses on experiential approaches rather than on behavior change.

The findings from an international randomized controlled trial underscore the importance of offering both individual and group approaches to patients with BPD, study investigator Arnoud Arntz, PhD, professor in the department of clinical psychology at the University of Amsterdam, told this news organization.

“In the Netherlands, there’s a big push from mental health institutes to deliver treatments in group therapy [only] because people think it’s more cost-effective; but these findings question that idea,” Dr. Arntz said.

The findings were published online March 2 in JAMA Psychiatry.

Early childhood experiences

Patients with BPD exhibit extreme sensitivity to interpersonal slights, intense and volatile emotions, and impulsive behaviors. Many abuse drugs, self-harm, or attempt suicide.

Evidence-based guidelines recommend psychotherapy as the primary treatment for BPD.

Schema therapy uses techniques from traditional psychotherapy but focuses on an experiential strategy. It also delves into early childhood experiences, which is relevant because patients with BPD often experienced abuse or neglect early in life.

As well, with this approach, therapists take on a sort of parenting role with patients to try to meet needs “that were frustrated in childhood,” said Dr. Arntz.

Previous research has suggested both individual and group schema therapy help reduce BPD symptoms, but the effectiveness of combining these two approaches has been unclear.

The current study included 495 adult patients (mean age, 33.6 years; 86.2% women) enrolled at 15 sites in five countries: the Netherlands, England, Greece, Germany, and Australia. All participants had a Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index IV (BPDSI-IV) score of more than 20.

The BPDSI-IV score ranges from 0 to 90, with a score of 15 being the cutoff for a BPD diagnosis.

Investigators randomly assigned participants to one of three arms: predominantly group schema therapy, combined individual and group schema therapy, and treatment as usual – which was the optimal psychological treatment available at the site.

The two schema therapy arms, whether group or individual, involved a similar number of sessions each week. However, the frequency was gradually reduced over the course of the study.

Improved severity

The primary outcome was change in BPD severity as assessed at baseline, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, 24 months, and 36 months with the BPDSI-IV total score.

Researchers first compared both the group therapy and the combination therapy with treatment as usual and found that together, the two schema arms were superior for reducing total BPDSI-IV score, with a medium to large effect size (Cohen d, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, .29-1.18; P = .001).

The difference was significant at 1.5 years (mean difference, 2.38; 95% CI, .27-4.49; P = .03).

When the treatment arms were compared separately, the combination therapy was superior to both the group therapy (Cohen d, 0.84; 95% CI, .09-1.59; P = .03) and to treatment as usual (Cohen d, 1.14; 95% CI, .57-1.71; P < .001).

The effectiveness of the predominantly group therapy did not differ significantly from that of treatment as usual.

The difference in effectiveness of combined therapy compared with treatment as usual became significant at 1 year. It became significant at 2.5 years compared with predominantly group therapy.

Treatment retention

In both schema arms, session frequency was tapered to only once a month; and in year 3, no further treatment was offered. However, symptom improvement continued during years 2 and 3.

Dr. Arntz explained this could be because patients realized they could apply what they learned after therapy was discontinued, which boosted their self-confidence.

Treatment retention was greater with combined therapy compared to the other options.

There was also improvement in several secondary outcomes, including happiness and quality of life, in most patients. However, patterns of outcomes for societal and work functioning improved more for those in either arm that received schema therapy.

“Group therapy seems to offer something that is important for learning to cooperate with other people. At work, you often have to collaborate with people who are not necessarily your friends,” Dr. Arntz noted.

The number of suicide attempts declined over time, with the combination arm being significantly superior to treatment as usual. During the study period, three patients died from suicide: one from each treatment arm. Another death had an unknown cause.

Overall, the results suggest that group and individual sessions address different needs of patients, the investigators noted.

While patients may learn to get along with others in a group setting, they may be more comfortable discussing severe trauma or suicidal thoughts in one-on-one sessions with a therapist, they added.

Strengths, weaknesses

Commenting for this news organization, John M. Oldham, MD, Distinguished Emeritus Professor, Menninger Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said the study had a number of strengths, including its size and “good, solid” methodology.

“This is another big study that demonstrates a well-established form of psychotherapy leads to effective improvement in patients with borderline,” said Dr. Oldham, who was not involved in the research.

However, he noted a number of study limitations. First, training for therapists to deliver schema therapy is not always readily available. In addition, schema therapists in the study “were pretty junior,” with some appearing to be “trained on the job,” he said.

Dr. Oldham noted that cost may be another deterrent to implementing this therapeutic approach. Only those with substantial financial resources could afford once-a-week group therapy and once-a-week individual therapy for 2 years, at least in the United States, he said.

Because patients had to be willing to undergo therapy for 2 years to be enrolled in the study, the results may not be generalizable to the entire BPD population, Dr. Oldham added. “Many borderline patients would turn around and walk out the door if asked to commit to that,” he said.

So the study population may be “better attuned and receptive to therapy” and less impaired compared to many patients with this condition, Dr. Oldham said.

He also said the study did not compare individual schema therapy alone with group schema alone.

Study sites were supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development and the Netherlands Foundation for Mental Health Study; Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung; Australian Rotary Health; Greek Society of Schema Therapy, First Department of Psychiatry of the Medical School of the University of Athens, and Institut für Verhaltenstherapie Ausbildung Hamburg; South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and the Research Center Experimental Psychopathology, Maastricht University and Bradford District Care NHS Foundation Trust. Dr. Arntz has received grants from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development and the Netherlands Foundation for Mental Health. Dr. Oldham reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Schema is a form of psychotherapy that focuses on experiential approaches rather than on behavior change.

The findings from an international randomized controlled trial underscore the importance of offering both individual and group approaches to patients with BPD, study investigator Arnoud Arntz, PhD, professor in the department of clinical psychology at the University of Amsterdam, told this news organization.

“In the Netherlands, there’s a big push from mental health institutes to deliver treatments in group therapy [only] because people think it’s more cost-effective; but these findings question that idea,” Dr. Arntz said.

The findings were published online March 2 in JAMA Psychiatry.

Early childhood experiences

Patients with BPD exhibit extreme sensitivity to interpersonal slights, intense and volatile emotions, and impulsive behaviors. Many abuse drugs, self-harm, or attempt suicide.

Evidence-based guidelines recommend psychotherapy as the primary treatment for BPD.

Schema therapy uses techniques from traditional psychotherapy but focuses on an experiential strategy. It also delves into early childhood experiences, which is relevant because patients with BPD often experienced abuse or neglect early in life.

As well, with this approach, therapists take on a sort of parenting role with patients to try to meet needs “that were frustrated in childhood,” said Dr. Arntz.

Previous research has suggested both individual and group schema therapy help reduce BPD symptoms, but the effectiveness of combining these two approaches has been unclear.

The current study included 495 adult patients (mean age, 33.6 years; 86.2% women) enrolled at 15 sites in five countries: the Netherlands, England, Greece, Germany, and Australia. All participants had a Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index IV (BPDSI-IV) score of more than 20.

The BPDSI-IV score ranges from 0 to 90, with a score of 15 being the cutoff for a BPD diagnosis.

Investigators randomly assigned participants to one of three arms: predominantly group schema therapy, combined individual and group schema therapy, and treatment as usual – which was the optimal psychological treatment available at the site.

The two schema therapy arms, whether group or individual, involved a similar number of sessions each week. However, the frequency was gradually reduced over the course of the study.

Improved severity

The primary outcome was change in BPD severity as assessed at baseline, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, 24 months, and 36 months with the BPDSI-IV total score.

Researchers first compared both the group therapy and the combination therapy with treatment as usual and found that together, the two schema arms were superior for reducing total BPDSI-IV score, with a medium to large effect size (Cohen d, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, .29-1.18; P = .001).

The difference was significant at 1.5 years (mean difference, 2.38; 95% CI, .27-4.49; P = .03).

When the treatment arms were compared separately, the combination therapy was superior to both the group therapy (Cohen d, 0.84; 95% CI, .09-1.59; P = .03) and to treatment as usual (Cohen d, 1.14; 95% CI, .57-1.71; P < .001).

The effectiveness of the predominantly group therapy did not differ significantly from that of treatment as usual.

The difference in effectiveness of combined therapy compared with treatment as usual became significant at 1 year. It became significant at 2.5 years compared with predominantly group therapy.

Treatment retention

In both schema arms, session frequency was tapered to only once a month; and in year 3, no further treatment was offered. However, symptom improvement continued during years 2 and 3.

Dr. Arntz explained this could be because patients realized they could apply what they learned after therapy was discontinued, which boosted their self-confidence.

Treatment retention was greater with combined therapy compared to the other options.

There was also improvement in several secondary outcomes, including happiness and quality of life, in most patients. However, patterns of outcomes for societal and work functioning improved more for those in either arm that received schema therapy.

“Group therapy seems to offer something that is important for learning to cooperate with other people. At work, you often have to collaborate with people who are not necessarily your friends,” Dr. Arntz noted.

The number of suicide attempts declined over time, with the combination arm being significantly superior to treatment as usual. During the study period, three patients died from suicide: one from each treatment arm. Another death had an unknown cause.

Overall, the results suggest that group and individual sessions address different needs of patients, the investigators noted.

While patients may learn to get along with others in a group setting, they may be more comfortable discussing severe trauma or suicidal thoughts in one-on-one sessions with a therapist, they added.

Strengths, weaknesses

Commenting for this news organization, John M. Oldham, MD, Distinguished Emeritus Professor, Menninger Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said the study had a number of strengths, including its size and “good, solid” methodology.

“This is another big study that demonstrates a well-established form of psychotherapy leads to effective improvement in patients with borderline,” said Dr. Oldham, who was not involved in the research.

However, he noted a number of study limitations. First, training for therapists to deliver schema therapy is not always readily available. In addition, schema therapists in the study “were pretty junior,” with some appearing to be “trained on the job,” he said.

Dr. Oldham noted that cost may be another deterrent to implementing this therapeutic approach. Only those with substantial financial resources could afford once-a-week group therapy and once-a-week individual therapy for 2 years, at least in the United States, he said.

Because patients had to be willing to undergo therapy for 2 years to be enrolled in the study, the results may not be generalizable to the entire BPD population, Dr. Oldham added. “Many borderline patients would turn around and walk out the door if asked to commit to that,” he said.

So the study population may be “better attuned and receptive to therapy” and less impaired compared to many patients with this condition, Dr. Oldham said.

He also said the study did not compare individual schema therapy alone with group schema alone.

Study sites were supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development and the Netherlands Foundation for Mental Health Study; Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung; Australian Rotary Health; Greek Society of Schema Therapy, First Department of Psychiatry of the Medical School of the University of Athens, and Institut für Verhaltenstherapie Ausbildung Hamburg; South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and the Research Center Experimental Psychopathology, Maastricht University and Bradford District Care NHS Foundation Trust. Dr. Arntz has received grants from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development and the Netherlands Foundation for Mental Health. Dr. Oldham reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Schema is a form of psychotherapy that focuses on experiential approaches rather than on behavior change.

The findings from an international randomized controlled trial underscore the importance of offering both individual and group approaches to patients with BPD, study investigator Arnoud Arntz, PhD, professor in the department of clinical psychology at the University of Amsterdam, told this news organization.

“In the Netherlands, there’s a big push from mental health institutes to deliver treatments in group therapy [only] because people think it’s more cost-effective; but these findings question that idea,” Dr. Arntz said.

The findings were published online March 2 in JAMA Psychiatry.

Early childhood experiences

Patients with BPD exhibit extreme sensitivity to interpersonal slights, intense and volatile emotions, and impulsive behaviors. Many abuse drugs, self-harm, or attempt suicide.

Evidence-based guidelines recommend psychotherapy as the primary treatment for BPD.

Schema therapy uses techniques from traditional psychotherapy but focuses on an experiential strategy. It also delves into early childhood experiences, which is relevant because patients with BPD often experienced abuse or neglect early in life.

As well, with this approach, therapists take on a sort of parenting role with patients to try to meet needs “that were frustrated in childhood,” said Dr. Arntz.

Previous research has suggested both individual and group schema therapy help reduce BPD symptoms, but the effectiveness of combining these two approaches has been unclear.

The current study included 495 adult patients (mean age, 33.6 years; 86.2% women) enrolled at 15 sites in five countries: the Netherlands, England, Greece, Germany, and Australia. All participants had a Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index IV (BPDSI-IV) score of more than 20.

The BPDSI-IV score ranges from 0 to 90, with a score of 15 being the cutoff for a BPD diagnosis.

Investigators randomly assigned participants to one of three arms: predominantly group schema therapy, combined individual and group schema therapy, and treatment as usual – which was the optimal psychological treatment available at the site.

The two schema therapy arms, whether group or individual, involved a similar number of sessions each week. However, the frequency was gradually reduced over the course of the study.

Improved severity

The primary outcome was change in BPD severity as assessed at baseline, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, 24 months, and 36 months with the BPDSI-IV total score.

Researchers first compared both the group therapy and the combination therapy with treatment as usual and found that together, the two schema arms were superior for reducing total BPDSI-IV score, with a medium to large effect size (Cohen d, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, .29-1.18; P = .001).

The difference was significant at 1.5 years (mean difference, 2.38; 95% CI, .27-4.49; P = .03).

When the treatment arms were compared separately, the combination therapy was superior to both the group therapy (Cohen d, 0.84; 95% CI, .09-1.59; P = .03) and to treatment as usual (Cohen d, 1.14; 95% CI, .57-1.71; P < .001).

The effectiveness of the predominantly group therapy did not differ significantly from that of treatment as usual.

The difference in effectiveness of combined therapy compared with treatment as usual became significant at 1 year. It became significant at 2.5 years compared with predominantly group therapy.

Treatment retention

In both schema arms, session frequency was tapered to only once a month; and in year 3, no further treatment was offered. However, symptom improvement continued during years 2 and 3.

Dr. Arntz explained this could be because patients realized they could apply what they learned after therapy was discontinued, which boosted their self-confidence.

Treatment retention was greater with combined therapy compared to the other options.

There was also improvement in several secondary outcomes, including happiness and quality of life, in most patients. However, patterns of outcomes for societal and work functioning improved more for those in either arm that received schema therapy.

“Group therapy seems to offer something that is important for learning to cooperate with other people. At work, you often have to collaborate with people who are not necessarily your friends,” Dr. Arntz noted.

The number of suicide attempts declined over time, with the combination arm being significantly superior to treatment as usual. During the study period, three patients died from suicide: one from each treatment arm. Another death had an unknown cause.

Overall, the results suggest that group and individual sessions address different needs of patients, the investigators noted.

While patients may learn to get along with others in a group setting, they may be more comfortable discussing severe trauma or suicidal thoughts in one-on-one sessions with a therapist, they added.

Strengths, weaknesses

Commenting for this news organization, John M. Oldham, MD, Distinguished Emeritus Professor, Menninger Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said the study had a number of strengths, including its size and “good, solid” methodology.

“This is another big study that demonstrates a well-established form of psychotherapy leads to effective improvement in patients with borderline,” said Dr. Oldham, who was not involved in the research.

However, he noted a number of study limitations. First, training for therapists to deliver schema therapy is not always readily available. In addition, schema therapists in the study “were pretty junior,” with some appearing to be “trained on the job,” he said.

Dr. Oldham noted that cost may be another deterrent to implementing this therapeutic approach. Only those with substantial financial resources could afford once-a-week group therapy and once-a-week individual therapy for 2 years, at least in the United States, he said.

Because patients had to be willing to undergo therapy for 2 years to be enrolled in the study, the results may not be generalizable to the entire BPD population, Dr. Oldham added. “Many borderline patients would turn around and walk out the door if asked to commit to that,” he said.

So the study population may be “better attuned and receptive to therapy” and less impaired compared to many patients with this condition, Dr. Oldham said.

He also said the study did not compare individual schema therapy alone with group schema alone.

Study sites were supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development and the Netherlands Foundation for Mental Health Study; Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung; Australian Rotary Health; Greek Society of Schema Therapy, First Department of Psychiatry of the Medical School of the University of Athens, and Institut für Verhaltenstherapie Ausbildung Hamburg; South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and the Research Center Experimental Psychopathology, Maastricht University and Bradford District Care NHS Foundation Trust. Dr. Arntz has received grants from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development and the Netherlands Foundation for Mental Health. Dr. Oldham reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

DSM-5 update: What’s new?

Ahead of its official release on March 18, the new Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which is in the form of a textbook, is already drawing some criticism.

It also includes symptom codes for suicidal behavior and nonsuicidal self-injury, clarifying modifications to criteria sets for more than 70 disorders, including autism spectrum disorder; changes in terminology for gender dysphoria; and a comprehensive review of the impact of racism and discrimination on the diagnosis and manifestations of mental disorders.

The Text Revision is a compilation of iterative changes that have been made online on a rolling basis since the DSM-5 was first published in 2013.

“The goal of the Text Revision was to allow a thorough revision of the text, not the criteria,” Paul Appelbaum, MD, chair of the APA’s DSM steering committee, told this news organization.

For the Text Revision, some 200 experts across a variety of APA working groups recommended changes to the text based on a comprehensive literature review, said Appelbaum, who is the Elizabeth K. Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine and Law, and director of the division of law, ethics and psychiatry at Columbia University, New York.

However, there’s not a lot that’s new, in part, because there have been few therapeutic advances.

Money maker?

Allen Frances, MD, chair of the DSM-4 task force and professor and chair emeritus of psychiatry at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said the APA is publishing the Text Revision “just to make money. They’re very anxious to do anything that will increase sales and having a revision forces some people, especially in institutions, to buy the book, even though it may not have anything substantive to add to the original.”

Dr. Frances told this news organization that when the APA published the first DSM in the late 1970s, “it became an instantaneous best-seller, to everyone’s surprise.”

The APA would not comment on how many of the $170 (list price) volumes it sells or how much those sales contribute to its budget.

Dr. Appelbaum acknowledged, “at any point in time, the canonical version is the online version.” However, it’s clear from DSM-5 sales “that many people still value having a hard copy of the DSM available to them.”

Prolonged grief: Timely or overkill?

Persistent complex bereavement disorder (PCBD) was listed as a “condition for further study” in DSM-5. After a 2019 workshop aimed at getting consensus for diagnosis criteria, the APA board approved the new prolonged grief disorder in October 2020, and the APA assembly approved the new disorder in November 2020.

Given the 950,000 deaths from COVID-19 over the past 2 years, inclusion of prolonged grief disorder in the DSM-5 may arrive at just the right time.

The diagnostic criteria for PCBD include:

- The development of a persistent grief response (longer than a year for adults and 6 months for children and adolescents) characterized by one or both of the following symptoms, which have been present most days to a clinically significant degree, and have occurred nearly every day for at least the last month: intense yearning/longing for the deceased person; preoccupation with thoughts or memories of the deceased person.

- Since the death, at least three symptoms present most days to a clinically significant degree, and occurring nearly every day for at least the last month, including identity disruption, marked sense of disbelief about the death, avoidance of reminders that the person is dead, intense emotional pain related to the death, difficulty reintegrating into one’s relationships and activities after the death, emotional numbness, feeling that life is meaningless as a result of the death, and intense loneliness as a result of the death.

- The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

- The duration and severity of the bereavement reaction clearly exceed expected social, cultural, or religious norms for the individual’s culture and context.

- The symptoms are not better explained by another mental disorder, such as major depressive disorder (MDD) or PTSD, and are not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition.

Dr. Frances said he believes creating a new diagnosis pathologizes grief. In DSM-3 and DSM-4, an exception was made under the diagnosis of MDD for individuals who had recently lost a loved one. “We wanted to have at least an opportunity for people to grieve without being stigmatized, mislabeled, and overtreated with medication.”

DSM-5 removed the bereavement exclusion. After 2 weeks, people who are grieving and have particular symptoms could receive a diagnosis of MDD, said Dr. Frances. He believes the exclusion should have been broadened to cover anyone experiencing a major loss – such as a job loss or divorce. If someone is having prolonged symptoms that interfere with functioning, they should get an MDD diagnosis.

The new disorder “doesn’t solve anything, it just adds to the confusion and stigmatization, and it’s part of a kind of creeping medical imperialization of everyday life, where everything has to have a mental disorder label,” Dr. Frances said.

However, Dr. Appelbaum countered that “the criteria for prolonged grief disorder are constructed in such a way as to make every effort to exclude people who are going through a normal grieving process.”

“Part of the purpose of the data analyses was to ensure the criteria that were adopted would, in fact, effectively distinguish between what anybody goes through, say when someone close to you dies, and this unusual prolonged grieving process without end that affects a much smaller number of people but which really can be crippling for them,” he added.

The Text Revision adds new symptom codes for suicidal behavior and nonsuicidal self-injury, which appear in the chapter, “Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention,” said Dr. Appelbaum.

“Both suicidal behavior and nonsuicidal self-injury seem pretty persuasively to fall into that category – something a clinician would want to know about, pay attention to, and factor into treatment planning, although they are behaviors that cross many diagnostic categories,” he added.

Codes also provide a systematic way of ascertaining the incidence and prevalence of such behaviors, said Dr. Appelbaum.

Changes to gender terminology

The Text Revision also tweaks some terminology with respect to transgender individuals. The term “desired gender” is now “experienced gender”, the term “cross-sex medical procedure” is now “gender-affirming medical procedure”, and the terms “natal male/natal female” are now “individual assigned male/female at birth”.

Dr. Frances said that the existence of gender dysphoria as a diagnosis has been a matter of controversy ever since it was first included.

“The transgender community has had mixed feelings on whether there should be anything at all in the manual,” he said. On one hand is the argument that gender dysphoria should be removed because it’s not really a psychiatric issue.

“We seriously considered eliminating it altogether in DSM-4,” said Dr. Frances.

However, an argument in favor of keeping it was that if the diagnosis was removed, it would mean that people could not receive treatment. “There’s no right argument for this dilemma,” he said.

Dr. Frances, who has been a frequent critic of DSM-5, said he believes the manual continues to miss opportunities to tighten criteria for many diagnoses, including ADHD and autism spectrum disorder.

“There’s a consistent pattern of taking behaviors and symptoms of behaviors that are on the border with normality and expanding the definition of mental disorder and reducing the realm of normality,” he said.

That has consequences, Dr. Frances added. “When someone gets a diagnosis that they need to get, it’s the beginning of a much better future. When someone gets a diagnosis that’s a mislabel that they don’t need, it has all harms and no benefits. It’s stigmatizing, leads to too much treatment, the wrong treatment, and it’s much more harmful than helpful.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ahead of its official release on March 18, the new Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which is in the form of a textbook, is already drawing some criticism.

It also includes symptom codes for suicidal behavior and nonsuicidal self-injury, clarifying modifications to criteria sets for more than 70 disorders, including autism spectrum disorder; changes in terminology for gender dysphoria; and a comprehensive review of the impact of racism and discrimination on the diagnosis and manifestations of mental disorders.

The Text Revision is a compilation of iterative changes that have been made online on a rolling basis since the DSM-5 was first published in 2013.

“The goal of the Text Revision was to allow a thorough revision of the text, not the criteria,” Paul Appelbaum, MD, chair of the APA’s DSM steering committee, told this news organization.

For the Text Revision, some 200 experts across a variety of APA working groups recommended changes to the text based on a comprehensive literature review, said Appelbaum, who is the Elizabeth K. Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine and Law, and director of the division of law, ethics and psychiatry at Columbia University, New York.

However, there’s not a lot that’s new, in part, because there have been few therapeutic advances.

Money maker?

Allen Frances, MD, chair of the DSM-4 task force and professor and chair emeritus of psychiatry at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said the APA is publishing the Text Revision “just to make money. They’re very anxious to do anything that will increase sales and having a revision forces some people, especially in institutions, to buy the book, even though it may not have anything substantive to add to the original.”

Dr. Frances told this news organization that when the APA published the first DSM in the late 1970s, “it became an instantaneous best-seller, to everyone’s surprise.”

The APA would not comment on how many of the $170 (list price) volumes it sells or how much those sales contribute to its budget.

Dr. Appelbaum acknowledged, “at any point in time, the canonical version is the online version.” However, it’s clear from DSM-5 sales “that many people still value having a hard copy of the DSM available to them.”

Prolonged grief: Timely or overkill?

Persistent complex bereavement disorder (PCBD) was listed as a “condition for further study” in DSM-5. After a 2019 workshop aimed at getting consensus for diagnosis criteria, the APA board approved the new prolonged grief disorder in October 2020, and the APA assembly approved the new disorder in November 2020.

Given the 950,000 deaths from COVID-19 over the past 2 years, inclusion of prolonged grief disorder in the DSM-5 may arrive at just the right time.

The diagnostic criteria for PCBD include:

- The development of a persistent grief response (longer than a year for adults and 6 months for children and adolescents) characterized by one or both of the following symptoms, which have been present most days to a clinically significant degree, and have occurred nearly every day for at least the last month: intense yearning/longing for the deceased person; preoccupation with thoughts or memories of the deceased person.

- Since the death, at least three symptoms present most days to a clinically significant degree, and occurring nearly every day for at least the last month, including identity disruption, marked sense of disbelief about the death, avoidance of reminders that the person is dead, intense emotional pain related to the death, difficulty reintegrating into one’s relationships and activities after the death, emotional numbness, feeling that life is meaningless as a result of the death, and intense loneliness as a result of the death.

- The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

- The duration and severity of the bereavement reaction clearly exceed expected social, cultural, or religious norms for the individual’s culture and context.

- The symptoms are not better explained by another mental disorder, such as major depressive disorder (MDD) or PTSD, and are not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition.

Dr. Frances said he believes creating a new diagnosis pathologizes grief. In DSM-3 and DSM-4, an exception was made under the diagnosis of MDD for individuals who had recently lost a loved one. “We wanted to have at least an opportunity for people to grieve without being stigmatized, mislabeled, and overtreated with medication.”

DSM-5 removed the bereavement exclusion. After 2 weeks, people who are grieving and have particular symptoms could receive a diagnosis of MDD, said Dr. Frances. He believes the exclusion should have been broadened to cover anyone experiencing a major loss – such as a job loss or divorce. If someone is having prolonged symptoms that interfere with functioning, they should get an MDD diagnosis.

The new disorder “doesn’t solve anything, it just adds to the confusion and stigmatization, and it’s part of a kind of creeping medical imperialization of everyday life, where everything has to have a mental disorder label,” Dr. Frances said.

However, Dr. Appelbaum countered that “the criteria for prolonged grief disorder are constructed in such a way as to make every effort to exclude people who are going through a normal grieving process.”

“Part of the purpose of the data analyses was to ensure the criteria that were adopted would, in fact, effectively distinguish between what anybody goes through, say when someone close to you dies, and this unusual prolonged grieving process without end that affects a much smaller number of people but which really can be crippling for them,” he added.

The Text Revision adds new symptom codes for suicidal behavior and nonsuicidal self-injury, which appear in the chapter, “Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention,” said Dr. Appelbaum.

“Both suicidal behavior and nonsuicidal self-injury seem pretty persuasively to fall into that category – something a clinician would want to know about, pay attention to, and factor into treatment planning, although they are behaviors that cross many diagnostic categories,” he added.

Codes also provide a systematic way of ascertaining the incidence and prevalence of such behaviors, said Dr. Appelbaum.

Changes to gender terminology

The Text Revision also tweaks some terminology with respect to transgender individuals. The term “desired gender” is now “experienced gender”, the term “cross-sex medical procedure” is now “gender-affirming medical procedure”, and the terms “natal male/natal female” are now “individual assigned male/female at birth”.

Dr. Frances said that the existence of gender dysphoria as a diagnosis has been a matter of controversy ever since it was first included.

“The transgender community has had mixed feelings on whether there should be anything at all in the manual,” he said. On one hand is the argument that gender dysphoria should be removed because it’s not really a psychiatric issue.

“We seriously considered eliminating it altogether in DSM-4,” said Dr. Frances.

However, an argument in favor of keeping it was that if the diagnosis was removed, it would mean that people could not receive treatment. “There’s no right argument for this dilemma,” he said.

Dr. Frances, who has been a frequent critic of DSM-5, said he believes the manual continues to miss opportunities to tighten criteria for many diagnoses, including ADHD and autism spectrum disorder.

“There’s a consistent pattern of taking behaviors and symptoms of behaviors that are on the border with normality and expanding the definition of mental disorder and reducing the realm of normality,” he said.

That has consequences, Dr. Frances added. “When someone gets a diagnosis that they need to get, it’s the beginning of a much better future. When someone gets a diagnosis that’s a mislabel that they don’t need, it has all harms and no benefits. It’s stigmatizing, leads to too much treatment, the wrong treatment, and it’s much more harmful than helpful.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ahead of its official release on March 18, the new Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which is in the form of a textbook, is already drawing some criticism.

It also includes symptom codes for suicidal behavior and nonsuicidal self-injury, clarifying modifications to criteria sets for more than 70 disorders, including autism spectrum disorder; changes in terminology for gender dysphoria; and a comprehensive review of the impact of racism and discrimination on the diagnosis and manifestations of mental disorders.

The Text Revision is a compilation of iterative changes that have been made online on a rolling basis since the DSM-5 was first published in 2013.

“The goal of the Text Revision was to allow a thorough revision of the text, not the criteria,” Paul Appelbaum, MD, chair of the APA’s DSM steering committee, told this news organization.

For the Text Revision, some 200 experts across a variety of APA working groups recommended changes to the text based on a comprehensive literature review, said Appelbaum, who is the Elizabeth K. Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine and Law, and director of the division of law, ethics and psychiatry at Columbia University, New York.

However, there’s not a lot that’s new, in part, because there have been few therapeutic advances.

Money maker?

Allen Frances, MD, chair of the DSM-4 task force and professor and chair emeritus of psychiatry at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said the APA is publishing the Text Revision “just to make money. They’re very anxious to do anything that will increase sales and having a revision forces some people, especially in institutions, to buy the book, even though it may not have anything substantive to add to the original.”

Dr. Frances told this news organization that when the APA published the first DSM in the late 1970s, “it became an instantaneous best-seller, to everyone’s surprise.”

The APA would not comment on how many of the $170 (list price) volumes it sells or how much those sales contribute to its budget.

Dr. Appelbaum acknowledged, “at any point in time, the canonical version is the online version.” However, it’s clear from DSM-5 sales “that many people still value having a hard copy of the DSM available to them.”

Prolonged grief: Timely or overkill?

Persistent complex bereavement disorder (PCBD) was listed as a “condition for further study” in DSM-5. After a 2019 workshop aimed at getting consensus for diagnosis criteria, the APA board approved the new prolonged grief disorder in October 2020, and the APA assembly approved the new disorder in November 2020.

Given the 950,000 deaths from COVID-19 over the past 2 years, inclusion of prolonged grief disorder in the DSM-5 may arrive at just the right time.

The diagnostic criteria for PCBD include:

- The development of a persistent grief response (longer than a year for adults and 6 months for children and adolescents) characterized by one or both of the following symptoms, which have been present most days to a clinically significant degree, and have occurred nearly every day for at least the last month: intense yearning/longing for the deceased person; preoccupation with thoughts or memories of the deceased person.

- Since the death, at least three symptoms present most days to a clinically significant degree, and occurring nearly every day for at least the last month, including identity disruption, marked sense of disbelief about the death, avoidance of reminders that the person is dead, intense emotional pain related to the death, difficulty reintegrating into one’s relationships and activities after the death, emotional numbness, feeling that life is meaningless as a result of the death, and intense loneliness as a result of the death.

- The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

- The duration and severity of the bereavement reaction clearly exceed expected social, cultural, or religious norms for the individual’s culture and context.

- The symptoms are not better explained by another mental disorder, such as major depressive disorder (MDD) or PTSD, and are not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition.

Dr. Frances said he believes creating a new diagnosis pathologizes grief. In DSM-3 and DSM-4, an exception was made under the diagnosis of MDD for individuals who had recently lost a loved one. “We wanted to have at least an opportunity for people to grieve without being stigmatized, mislabeled, and overtreated with medication.”

DSM-5 removed the bereavement exclusion. After 2 weeks, people who are grieving and have particular symptoms could receive a diagnosis of MDD, said Dr. Frances. He believes the exclusion should have been broadened to cover anyone experiencing a major loss – such as a job loss or divorce. If someone is having prolonged symptoms that interfere with functioning, they should get an MDD diagnosis.

The new disorder “doesn’t solve anything, it just adds to the confusion and stigmatization, and it’s part of a kind of creeping medical imperialization of everyday life, where everything has to have a mental disorder label,” Dr. Frances said.

However, Dr. Appelbaum countered that “the criteria for prolonged grief disorder are constructed in such a way as to make every effort to exclude people who are going through a normal grieving process.”

“Part of the purpose of the data analyses was to ensure the criteria that were adopted would, in fact, effectively distinguish between what anybody goes through, say when someone close to you dies, and this unusual prolonged grieving process without end that affects a much smaller number of people but which really can be crippling for them,” he added.

The Text Revision adds new symptom codes for suicidal behavior and nonsuicidal self-injury, which appear in the chapter, “Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention,” said Dr. Appelbaum.

“Both suicidal behavior and nonsuicidal self-injury seem pretty persuasively to fall into that category – something a clinician would want to know about, pay attention to, and factor into treatment planning, although they are behaviors that cross many diagnostic categories,” he added.

Codes also provide a systematic way of ascertaining the incidence and prevalence of such behaviors, said Dr. Appelbaum.

Changes to gender terminology

The Text Revision also tweaks some terminology with respect to transgender individuals. The term “desired gender” is now “experienced gender”, the term “cross-sex medical procedure” is now “gender-affirming medical procedure”, and the terms “natal male/natal female” are now “individual assigned male/female at birth”.

Dr. Frances said that the existence of gender dysphoria as a diagnosis has been a matter of controversy ever since it was first included.

“The transgender community has had mixed feelings on whether there should be anything at all in the manual,” he said. On one hand is the argument that gender dysphoria should be removed because it’s not really a psychiatric issue.

“We seriously considered eliminating it altogether in DSM-4,” said Dr. Frances.

However, an argument in favor of keeping it was that if the diagnosis was removed, it would mean that people could not receive treatment. “There’s no right argument for this dilemma,” he said.

Dr. Frances, who has been a frequent critic of DSM-5, said he believes the manual continues to miss opportunities to tighten criteria for many diagnoses, including ADHD and autism spectrum disorder.

“There’s a consistent pattern of taking behaviors and symptoms of behaviors that are on the border with normality and expanding the definition of mental disorder and reducing the realm of normality,” he said.

That has consequences, Dr. Frances added. “When someone gets a diagnosis that they need to get, it’s the beginning of a much better future. When someone gets a diagnosis that’s a mislabel that they don’t need, it has all harms and no benefits. It’s stigmatizing, leads to too much treatment, the wrong treatment, and it’s much more harmful than helpful.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

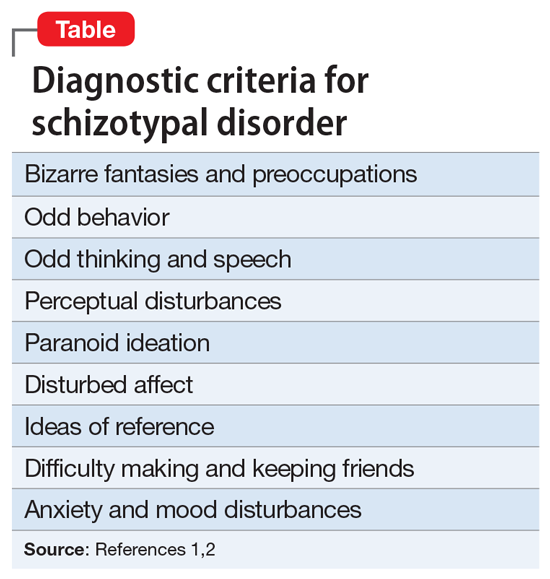

Differentiating pediatric schizotypal disorder from schizophrenia and autism

Schizotypal disorder is a complex condition that is characterized by cognitive-perceptual impairments, oddness, disorganization, and interpersonal difficulties. It often is unrecognized or underdiagnosed. In DSM-5, schizotypal disorder is categorized a personality disorder, but it is also considered part of the schizophrenia spectrum disorders.1 The diagnostic criteria for schizotypal disorder are outlined in the Table.1,2

Although schizotypal disorder has a lifetime prevalence of approximately 4% in the general population of the United States,2 it can present during childhood or adolescence and may be overlooked in the differential diagnosis for psychotic symptoms in pediatric patients.3 Schizotypal disorder of childhood (SDC) can present with significant overlap with several pediatric diagnoses, including schizophrenia spectrum disorders and autism spectrum disorder (ASD), all of which may include psychotic symptoms and difficulties in interpersonal relationships. This overlap, combined with the lack of awareness of schizotypal disorder, can pose a diagnostic challenge. Better recognition of SDC could result in earlier and more effective treatment. In this article, we provide tips for differentiating SDC from childhood-onset schizophrenia and from ASD.

Differentiating SDC from schizophrenia

SDC may be mistaken for childhood-onset schizophrenia due to its perceptual disturbances (which may be interpreted as visual or auditory hallucinations), bizarre fantasies (which may be mistaken for overt delusions), paranoia, and odd behavior. Two ways to distinguish SDC from childhood schizophrenia are by clinical course and by severity of negative psychotic symptoms.

SDC tends to have an overall stable clinical course,4 with patients experiencing periods of time when they exhibit a more normal mental status complemented by fluctuations in symptom severity, which are exacerbated by stressors and followed by a return to baseline.3 SDC psychotic symptoms are predominantly positive, and patients typically do not demonstrate negative features beyond social difficulties. Childhood-onset schizophrenia is typically progressive and disabling, with worsening severity over time, and is much more likely to incorporate prominent negative symptoms.3

Differentiating SDC from ASD

SDC also demonstrates considerable diagnostic overlap with ASD, especially with regards to inappropriate affect; odd thinking, behavior, and speech; and social difficulties. Further complicating the diagnosis, ASD and SDC are comorbid in approximately 40% of ASD cases.3,5 The Melbourne Assessment of Schizotypy in Kids demonstrates validity in diagnosing schizotypal disorder in patients with comorbid ASD.5,6 For clinicians without easy access to advanced testing, 2 ways to distinguish SDC from ASD are the content of the odd behavior and thoughts, and the patient’s reaction to social deficits.

In SDC, odd behavior and thoughts most often revolve around daydreaming and a focus on “elaborate inner fantasies.”3,6 Unlike in ASD, in patients with SDC, behaviors don’t typically involve stereotyped mannerisms, the patient is unlikely to have rigid interests (apart from their fantasies), and there is not a particular focus on detail in the external world.3,6 Notably, imaginary companions are common in SDC; children with ASD are less likely to have an imaginary companion compared with children with SDC or those with no psychiatric diagnosis.6 Patients with SDC have social difficulties (often due to social anxiety stemming from their paranoia) but usually seek out interaction and are bothered by alienation, while patients with ASD may have less interest in social engagement.6

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Pulay AJ, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV schizotypal personality disorder: results from the wave 2 national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11(2):53-67. doi:10.4088/pcc.08m00679

3. Tonge BJ, Testa R, Díaz-Arteche C, et al. Schizotypal disorder in children—a neglected diagnosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin Open. 2020;1(1):sgaa048. doi:10.1093/schizbullopen/sgaa048

4. Asarnow JR. Childhood-onset schizotypal disorder: a follow-up study and comparison with childhood-onset schizophrenia. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15(3):395-402.

5. Jones HP, Testa RR, Ross N, et al. The Melbourne Assessment of Schizotypy in Kids: a useful measure of childhood schizotypal personality disorder. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:635732. doi:10.1155/2015/635732

6. Poletti M, Raballo A. Childhood schizotypal features vs. high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: developmental overlaps and phenomenological differences. Schizophr Res. 2020;223:53-58. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2020.09.027

Schizotypal disorder is a complex condition that is characterized by cognitive-perceptual impairments, oddness, disorganization, and interpersonal difficulties. It often is unrecognized or underdiagnosed. In DSM-5, schizotypal disorder is categorized a personality disorder, but it is also considered part of the schizophrenia spectrum disorders.1 The diagnostic criteria for schizotypal disorder are outlined in the Table.1,2

Although schizotypal disorder has a lifetime prevalence of approximately 4% in the general population of the United States,2 it can present during childhood or adolescence and may be overlooked in the differential diagnosis for psychotic symptoms in pediatric patients.3 Schizotypal disorder of childhood (SDC) can present with significant overlap with several pediatric diagnoses, including schizophrenia spectrum disorders and autism spectrum disorder (ASD), all of which may include psychotic symptoms and difficulties in interpersonal relationships. This overlap, combined with the lack of awareness of schizotypal disorder, can pose a diagnostic challenge. Better recognition of SDC could result in earlier and more effective treatment. In this article, we provide tips for differentiating SDC from childhood-onset schizophrenia and from ASD.

Differentiating SDC from schizophrenia

SDC may be mistaken for childhood-onset schizophrenia due to its perceptual disturbances (which may be interpreted as visual or auditory hallucinations), bizarre fantasies (which may be mistaken for overt delusions), paranoia, and odd behavior. Two ways to distinguish SDC from childhood schizophrenia are by clinical course and by severity of negative psychotic symptoms.

SDC tends to have an overall stable clinical course,4 with patients experiencing periods of time when they exhibit a more normal mental status complemented by fluctuations in symptom severity, which are exacerbated by stressors and followed by a return to baseline.3 SDC psychotic symptoms are predominantly positive, and patients typically do not demonstrate negative features beyond social difficulties. Childhood-onset schizophrenia is typically progressive and disabling, with worsening severity over time, and is much more likely to incorporate prominent negative symptoms.3

Differentiating SDC from ASD

SDC also demonstrates considerable diagnostic overlap with ASD, especially with regards to inappropriate affect; odd thinking, behavior, and speech; and social difficulties. Further complicating the diagnosis, ASD and SDC are comorbid in approximately 40% of ASD cases.3,5 The Melbourne Assessment of Schizotypy in Kids demonstrates validity in diagnosing schizotypal disorder in patients with comorbid ASD.5,6 For clinicians without easy access to advanced testing, 2 ways to distinguish SDC from ASD are the content of the odd behavior and thoughts, and the patient’s reaction to social deficits.

In SDC, odd behavior and thoughts most often revolve around daydreaming and a focus on “elaborate inner fantasies.”3,6 Unlike in ASD, in patients with SDC, behaviors don’t typically involve stereotyped mannerisms, the patient is unlikely to have rigid interests (apart from their fantasies), and there is not a particular focus on detail in the external world.3,6 Notably, imaginary companions are common in SDC; children with ASD are less likely to have an imaginary companion compared with children with SDC or those with no psychiatric diagnosis.6 Patients with SDC have social difficulties (often due to social anxiety stemming from their paranoia) but usually seek out interaction and are bothered by alienation, while patients with ASD may have less interest in social engagement.6

Schizotypal disorder is a complex condition that is characterized by cognitive-perceptual impairments, oddness, disorganization, and interpersonal difficulties. It often is unrecognized or underdiagnosed. In DSM-5, schizotypal disorder is categorized a personality disorder, but it is also considered part of the schizophrenia spectrum disorders.1 The diagnostic criteria for schizotypal disorder are outlined in the Table.1,2

Although schizotypal disorder has a lifetime prevalence of approximately 4% in the general population of the United States,2 it can present during childhood or adolescence and may be overlooked in the differential diagnosis for psychotic symptoms in pediatric patients.3 Schizotypal disorder of childhood (SDC) can present with significant overlap with several pediatric diagnoses, including schizophrenia spectrum disorders and autism spectrum disorder (ASD), all of which may include psychotic symptoms and difficulties in interpersonal relationships. This overlap, combined with the lack of awareness of schizotypal disorder, can pose a diagnostic challenge. Better recognition of SDC could result in earlier and more effective treatment. In this article, we provide tips for differentiating SDC from childhood-onset schizophrenia and from ASD.

Differentiating SDC from schizophrenia

SDC may be mistaken for childhood-onset schizophrenia due to its perceptual disturbances (which may be interpreted as visual or auditory hallucinations), bizarre fantasies (which may be mistaken for overt delusions), paranoia, and odd behavior. Two ways to distinguish SDC from childhood schizophrenia are by clinical course and by severity of negative psychotic symptoms.

SDC tends to have an overall stable clinical course,4 with patients experiencing periods of time when they exhibit a more normal mental status complemented by fluctuations in symptom severity, which are exacerbated by stressors and followed by a return to baseline.3 SDC psychotic symptoms are predominantly positive, and patients typically do not demonstrate negative features beyond social difficulties. Childhood-onset schizophrenia is typically progressive and disabling, with worsening severity over time, and is much more likely to incorporate prominent negative symptoms.3

Differentiating SDC from ASD

SDC also demonstrates considerable diagnostic overlap with ASD, especially with regards to inappropriate affect; odd thinking, behavior, and speech; and social difficulties. Further complicating the diagnosis, ASD and SDC are comorbid in approximately 40% of ASD cases.3,5 The Melbourne Assessment of Schizotypy in Kids demonstrates validity in diagnosing schizotypal disorder in patients with comorbid ASD.5,6 For clinicians without easy access to advanced testing, 2 ways to distinguish SDC from ASD are the content of the odd behavior and thoughts, and the patient’s reaction to social deficits.

In SDC, odd behavior and thoughts most often revolve around daydreaming and a focus on “elaborate inner fantasies.”3,6 Unlike in ASD, in patients with SDC, behaviors don’t typically involve stereotyped mannerisms, the patient is unlikely to have rigid interests (apart from their fantasies), and there is not a particular focus on detail in the external world.3,6 Notably, imaginary companions are common in SDC; children with ASD are less likely to have an imaginary companion compared with children with SDC or those with no psychiatric diagnosis.6 Patients with SDC have social difficulties (often due to social anxiety stemming from their paranoia) but usually seek out interaction and are bothered by alienation, while patients with ASD may have less interest in social engagement.6

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Pulay AJ, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV schizotypal personality disorder: results from the wave 2 national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11(2):53-67. doi:10.4088/pcc.08m00679

3. Tonge BJ, Testa R, Díaz-Arteche C, et al. Schizotypal disorder in children—a neglected diagnosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin Open. 2020;1(1):sgaa048. doi:10.1093/schizbullopen/sgaa048

4. Asarnow JR. Childhood-onset schizotypal disorder: a follow-up study and comparison with childhood-onset schizophrenia. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15(3):395-402.

5. Jones HP, Testa RR, Ross N, et al. The Melbourne Assessment of Schizotypy in Kids: a useful measure of childhood schizotypal personality disorder. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:635732. doi:10.1155/2015/635732

6. Poletti M, Raballo A. Childhood schizotypal features vs. high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: developmental overlaps and phenomenological differences. Schizophr Res. 2020;223:53-58. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2020.09.027

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Pulay AJ, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV schizotypal personality disorder: results from the wave 2 national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11(2):53-67. doi:10.4088/pcc.08m00679

3. Tonge BJ, Testa R, Díaz-Arteche C, et al. Schizotypal disorder in children—a neglected diagnosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin Open. 2020;1(1):sgaa048. doi:10.1093/schizbullopen/sgaa048

4. Asarnow JR. Childhood-onset schizotypal disorder: a follow-up study and comparison with childhood-onset schizophrenia. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15(3):395-402.

5. Jones HP, Testa RR, Ross N, et al. The Melbourne Assessment of Schizotypy in Kids: a useful measure of childhood schizotypal personality disorder. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:635732. doi:10.1155/2015/635732

6. Poletti M, Raballo A. Childhood schizotypal features vs. high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: developmental overlaps and phenomenological differences. Schizophr Res. 2020;223:53-58. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2020.09.027

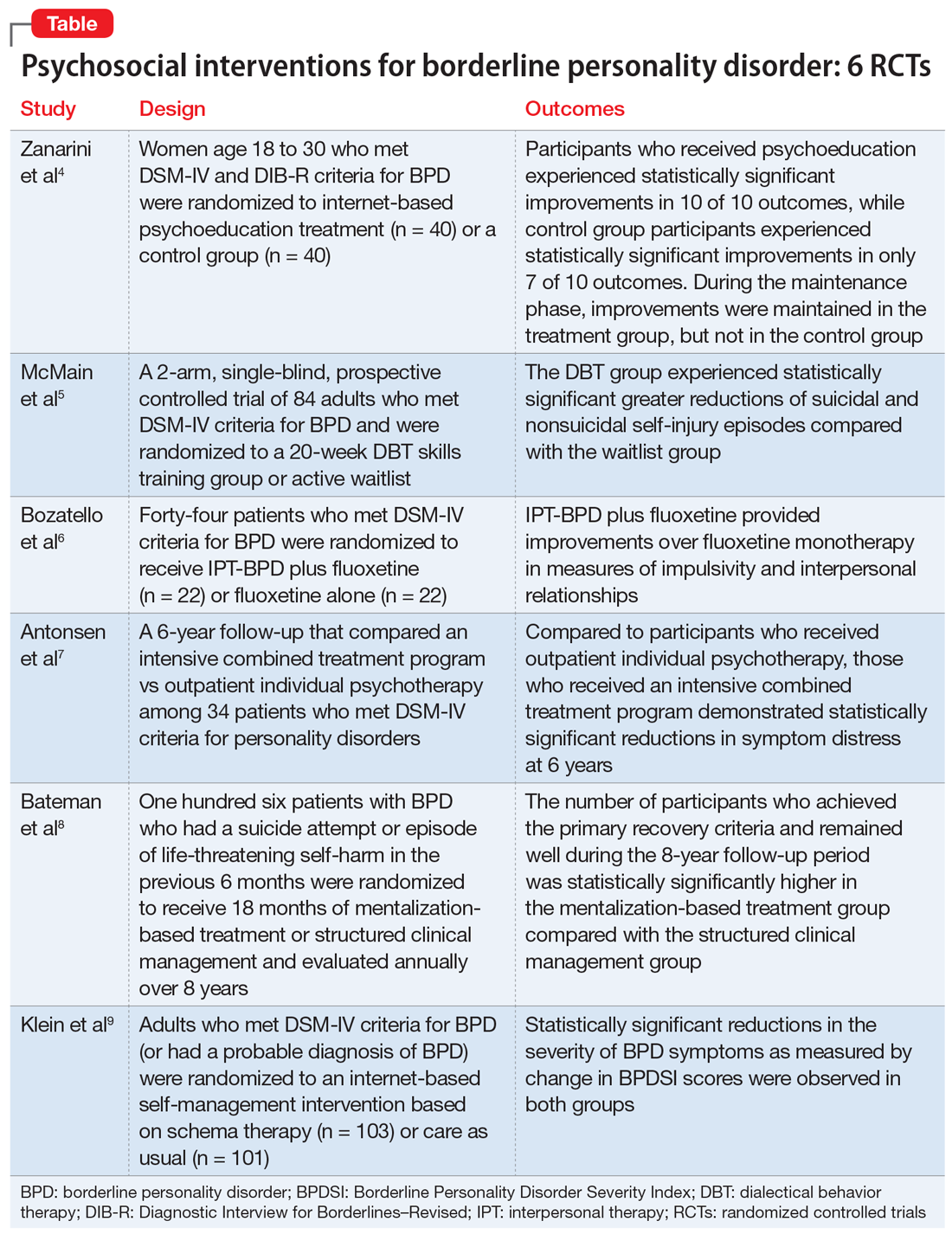

Borderline personality disorder: 6 studies of psychosocial interventions

SECOND OF 2 PARTS

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with serious impairment in psychosocial functioning.1 It is characterized by an ongoing pattern of mood instability, cognitive distortions, problems with self-image, and impulsive behavior that often results in problems in relationships. As a result, patients with BPD tend to utilize more mental health services than patients with other personality disorders or major depressive disorder.2

Some clinicians believe BPD is difficult to treat. While historically there has been little consensus on the best treatments for this disorder, current options include both pharmacologic and psychological interventions. In Part 1 of this 2-part article, we focused on 6 studies that evaluated biological interventions.3 Here in Part 2, we focus on findings from 6 recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of psychosocial interventions for BPD

1. Zanarini MC, Conkey LC, Temes CM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of web-based psychoeducation for women with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(3):16m11153. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m11153

Research has shown that BPD is a treatable illness with a more favorable prognosis than previously believed. Despite this, patients often experience difficulty accessing the most up-to-date information on BPD, which can impede their treatment. A 2008 study by Zanarini et al10 of younger female patients with BPD demonstrated that immediate, in-person psychoeducation improved impulsivity and relationships. Widespread implementation of this program proved problematic, however, due to cost and personnel constraints. To resolve this issue, researchers developed an internet-based version of the program. In a 2018 follow-up study, Zanarini et al4 examined the effect of this internet-based psychoeducation program on symptoms of BPD.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- Women (age 18 to 30) who met DSM-IV and Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines–Revised criteria for BPD were randomized to an internet-based psychoeducation treatment group (n = 40) or a control group (n = 40).

- Ten outcomes concerning symptom severity and psychosocial functioning were assessed during weeks 1 to 12 (acute phase) and at months 6, 9, and 12 (maintenance phase) using the self-report version of the Zanarini Rating Scale for BPD (ZAN-BPD), the Borderline Evaluation of Severity over Time, the Sheehan Disability Scale, the Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale, the Clinically Useful Anxiety Outcome Scale, and Weissman’s Social Adjustment Scale (SAS).

Outcomes

- In the acute phase, treatment group participants experienced statistically significant improvements in all 10 outcomes. Control group participants demonstrated similar results, achieving statistically significant improvements in 7 of 10 outcomes.

- Compared to the control group, the treatment group experienced a more significant reduction in impulsivity and improvement in psychosocial functioning as measured by the ZAN-BPD and SAS.

- In the maintenance phase, treatment group participants achieved statistically significant improvements in 9 of 10 outcomes, whereas control group participants demonstrated statistically significant improvements in only 3 of 10 outcomes.

- Compared to the control group, the treatment group also demonstrated a significantly greater improvement in all 4 sector scores and the total score of the ZAN-BP

Conclusions/limitations