User login

A 71-year-old White female developed erosions after hip replacement surgery 2 months prior to presentation

The patient had been diagnosed with pemphigus vulgaris (PV) 1 year prior to presentation with erosions on the axilla. Biopsy at that time revealed intraepithelial acantholytic blistering with areas of suprabasilar and subcorneal clefting. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for linear/granular IgG deposition throughout the epithelial cell surfaces, as well as linear/granular C3 deposits of the lower two thirds of the epithelial strata, consistent for pemphigus vulgaris.

There is likely a genetic predisposition. Medications that may induce pemphigus include penicillamine, nifedipine, or captopril.

Clinically, PV presents with flaccid blistering lesions that may be cutaneous and/or mucosal. Bullae can progress to erosions and crusting, which then heal with pigment alteration but not scarring. The most commonly affected sites are the mouth, intertriginous areas, face, and neck. Mucosal lesions can involve the lips, esophagus, conjunctiva, and genitals.

Biopsy for histology and direct immunofluorescence is important in distinguishing between PV and other blistering disorders. Up to 75% of patients with active disease also have a positive indirect immunofluorescence with circulating IgG.

There are numerous reports in the literature of PV occurring in previous surgical scars, and areas of friction or trauma. This so-called Koebner’s phenomenon is seen more commonly in several dermatologic conditions, such as psoriasis, lichen planus, verruca vulgaris, and vitiligo.

Treatment for PV is generally immunosuppressive. Systemic therapy usually begins with prednisone and then is transitioned to a steroid sparing agent such as mycophenolate mofetil. Other steroid sparing agents include azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and intravenous immunoglobulin. Secondary infections are possible and should be treated. Topical therapies aimed at reducing pain, especially in mucosal lesions, can be beneficial.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Florida. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Cerottini JP et al. Eur J Dermatol. 2000 Oct-Nov;10(7):546-7.

Reichert-Penetrat S et al. Eur J Dermatol. 1998 Jan-Feb;8(1):60-2.

Saini P et al. Skinmed. 2020 Aug 1;18(4):252-253.

The patient had been diagnosed with pemphigus vulgaris (PV) 1 year prior to presentation with erosions on the axilla. Biopsy at that time revealed intraepithelial acantholytic blistering with areas of suprabasilar and subcorneal clefting. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for linear/granular IgG deposition throughout the epithelial cell surfaces, as well as linear/granular C3 deposits of the lower two thirds of the epithelial strata, consistent for pemphigus vulgaris.

There is likely a genetic predisposition. Medications that may induce pemphigus include penicillamine, nifedipine, or captopril.

Clinically, PV presents with flaccid blistering lesions that may be cutaneous and/or mucosal. Bullae can progress to erosions and crusting, which then heal with pigment alteration but not scarring. The most commonly affected sites are the mouth, intertriginous areas, face, and neck. Mucosal lesions can involve the lips, esophagus, conjunctiva, and genitals.

Biopsy for histology and direct immunofluorescence is important in distinguishing between PV and other blistering disorders. Up to 75% of patients with active disease also have a positive indirect immunofluorescence with circulating IgG.

There are numerous reports in the literature of PV occurring in previous surgical scars, and areas of friction or trauma. This so-called Koebner’s phenomenon is seen more commonly in several dermatologic conditions, such as psoriasis, lichen planus, verruca vulgaris, and vitiligo.

Treatment for PV is generally immunosuppressive. Systemic therapy usually begins with prednisone and then is transitioned to a steroid sparing agent such as mycophenolate mofetil. Other steroid sparing agents include azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and intravenous immunoglobulin. Secondary infections are possible and should be treated. Topical therapies aimed at reducing pain, especially in mucosal lesions, can be beneficial.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Florida. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Cerottini JP et al. Eur J Dermatol. 2000 Oct-Nov;10(7):546-7.

Reichert-Penetrat S et al. Eur J Dermatol. 1998 Jan-Feb;8(1):60-2.

Saini P et al. Skinmed. 2020 Aug 1;18(4):252-253.

The patient had been diagnosed with pemphigus vulgaris (PV) 1 year prior to presentation with erosions on the axilla. Biopsy at that time revealed intraepithelial acantholytic blistering with areas of suprabasilar and subcorneal clefting. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for linear/granular IgG deposition throughout the epithelial cell surfaces, as well as linear/granular C3 deposits of the lower two thirds of the epithelial strata, consistent for pemphigus vulgaris.

There is likely a genetic predisposition. Medications that may induce pemphigus include penicillamine, nifedipine, or captopril.

Clinically, PV presents with flaccid blistering lesions that may be cutaneous and/or mucosal. Bullae can progress to erosions and crusting, which then heal with pigment alteration but not scarring. The most commonly affected sites are the mouth, intertriginous areas, face, and neck. Mucosal lesions can involve the lips, esophagus, conjunctiva, and genitals.

Biopsy for histology and direct immunofluorescence is important in distinguishing between PV and other blistering disorders. Up to 75% of patients with active disease also have a positive indirect immunofluorescence with circulating IgG.

There are numerous reports in the literature of PV occurring in previous surgical scars, and areas of friction or trauma. This so-called Koebner’s phenomenon is seen more commonly in several dermatologic conditions, such as psoriasis, lichen planus, verruca vulgaris, and vitiligo.

Treatment for PV is generally immunosuppressive. Systemic therapy usually begins with prednisone and then is transitioned to a steroid sparing agent such as mycophenolate mofetil. Other steroid sparing agents include azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and intravenous immunoglobulin. Secondary infections are possible and should be treated. Topical therapies aimed at reducing pain, especially in mucosal lesions, can be beneficial.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Florida. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Cerottini JP et al. Eur J Dermatol. 2000 Oct-Nov;10(7):546-7.

Reichert-Penetrat S et al. Eur J Dermatol. 1998 Jan-Feb;8(1):60-2.

Saini P et al. Skinmed. 2020 Aug 1;18(4):252-253.

Hypnosis May Offer Relief During Sharp Debridement of Skin Ulcers

TOPLINE:

Hypnosis reduces pain during sharp debridement of skin ulcers in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, with most patients reporting decreased pain awareness and lasting pain relief for 2-3 days after the procedure.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers reported their experience with the anecdotal use of hypnosis for pain management in debridement of skin ulcers in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases.

- They studied 16 participants (14 women; mean age, 56 years; 14 with systemic sclerosis or morphea) with recurrent skin ulcerations requiring sharp debridement, who presented to a wound care clinic at the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds, United Kingdom. The participants had negative experiences with pharmacologic pain management.

- Participants consented to hypnosis during debridement as the only mode of analgesia, conducted by the same hypnosis-trained, experienced healthcare professional in charge of their ulcer care.

- Ulcer pain scores were recorded using a numerical rating pain scale before and immediately after debridement, with a score of 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating worst pain.

TAKEAWAY:

- Hypnosis reduced the median pre-debridement ulcer pain score from 8 (interquartile range [IQR], 7-10) to 0.5 (IQR, 0-2) immediately after the procedure.

- Of 16 participants, 14 reported being aware of the procedure but not feeling the pain, with only two participants experiencing a brief spike in pain.

- The other two participants reported experiencing reduced awareness and being pain-free during the procedure.

- Five participants reported a lasting decrease in pain perception for 2-3 days after the procedure.

IN PRACTICE:

“These preliminary data underscore the potential for the integration of hypnosis into the management of intervention-related pain in clinical care,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Begonya Alcacer-Pitarch, PhD, Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine, the University of Leeds, and Chapel Allerton Hospital in Leeds, United Kingdom. It was published as a correspondence on September 10, 2024, in The Lancet Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings. The methods used for data collection were not standardized, and the individuals included in the study may have introduced selection bias.

DISCLOSURES:

The study did not have a funding source. The authors declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Hypnosis reduces pain during sharp debridement of skin ulcers in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, with most patients reporting decreased pain awareness and lasting pain relief for 2-3 days after the procedure.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers reported their experience with the anecdotal use of hypnosis for pain management in debridement of skin ulcers in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases.

- They studied 16 participants (14 women; mean age, 56 years; 14 with systemic sclerosis or morphea) with recurrent skin ulcerations requiring sharp debridement, who presented to a wound care clinic at the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds, United Kingdom. The participants had negative experiences with pharmacologic pain management.

- Participants consented to hypnosis during debridement as the only mode of analgesia, conducted by the same hypnosis-trained, experienced healthcare professional in charge of their ulcer care.

- Ulcer pain scores were recorded using a numerical rating pain scale before and immediately after debridement, with a score of 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating worst pain.

TAKEAWAY:

- Hypnosis reduced the median pre-debridement ulcer pain score from 8 (interquartile range [IQR], 7-10) to 0.5 (IQR, 0-2) immediately after the procedure.

- Of 16 participants, 14 reported being aware of the procedure but not feeling the pain, with only two participants experiencing a brief spike in pain.

- The other two participants reported experiencing reduced awareness and being pain-free during the procedure.

- Five participants reported a lasting decrease in pain perception for 2-3 days after the procedure.

IN PRACTICE:

“These preliminary data underscore the potential for the integration of hypnosis into the management of intervention-related pain in clinical care,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Begonya Alcacer-Pitarch, PhD, Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine, the University of Leeds, and Chapel Allerton Hospital in Leeds, United Kingdom. It was published as a correspondence on September 10, 2024, in The Lancet Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings. The methods used for data collection were not standardized, and the individuals included in the study may have introduced selection bias.

DISCLOSURES:

The study did not have a funding source. The authors declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Hypnosis reduces pain during sharp debridement of skin ulcers in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, with most patients reporting decreased pain awareness and lasting pain relief for 2-3 days after the procedure.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers reported their experience with the anecdotal use of hypnosis for pain management in debridement of skin ulcers in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases.

- They studied 16 participants (14 women; mean age, 56 years; 14 with systemic sclerosis or morphea) with recurrent skin ulcerations requiring sharp debridement, who presented to a wound care clinic at the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds, United Kingdom. The participants had negative experiences with pharmacologic pain management.

- Participants consented to hypnosis during debridement as the only mode of analgesia, conducted by the same hypnosis-trained, experienced healthcare professional in charge of their ulcer care.

- Ulcer pain scores were recorded using a numerical rating pain scale before and immediately after debridement, with a score of 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating worst pain.

TAKEAWAY:

- Hypnosis reduced the median pre-debridement ulcer pain score from 8 (interquartile range [IQR], 7-10) to 0.5 (IQR, 0-2) immediately after the procedure.

- Of 16 participants, 14 reported being aware of the procedure but not feeling the pain, with only two participants experiencing a brief spike in pain.

- The other two participants reported experiencing reduced awareness and being pain-free during the procedure.

- Five participants reported a lasting decrease in pain perception for 2-3 days after the procedure.

IN PRACTICE:

“These preliminary data underscore the potential for the integration of hypnosis into the management of intervention-related pain in clinical care,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Begonya Alcacer-Pitarch, PhD, Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine, the University of Leeds, and Chapel Allerton Hospital in Leeds, United Kingdom. It was published as a correspondence on September 10, 2024, in The Lancet Rheumatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings. The methods used for data collection were not standardized, and the individuals included in the study may have introduced selection bias.

DISCLOSURES:

The study did not have a funding source. The authors declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

First Combined Face and Eye Transplant Performed

In a groundbreaking procedure, a team of surgeons from New York University Langone Health successfully performed the first combined face and eye transplant on a patient with extensive craniofacial tissue loss after an electrical accident.

The highly complex surgery lasted for 21 hours and involved more than 140 surgeons, nurses, and other healthcare professionals under the leadership of Eduardo D. Rodriguez. MD. It not only restored the patient’s facial features, but also integrated a functional eyeball, potentially setting a new standard for future treatments in similar cases.

The transplant took place in May 2023, and the case report was published on September 5 this year in JAMA.

The 46-year-old man lost a large part of his craniofacial tissue and his left eyeball. The approach was highly specialized. Advanced microsurgical techniques such as anastomoses of microscopic vessels and delicate suturing techniques were crucial for the transplant’s success.

Moreover, customized surgical devices, specific implants, and tissue manipulation tools were developed specifically for this case, thus ensuring the viability of the transplant and adequate perfusion of the transplanted ocular tissue.

The initial results are encouraging. Retinal arterial perfusion has been maintained, and retinal architecture has been preserved, as demonstrated by optical coherence tomography. Electroretinography confirmed retinal responses to light, suggesting that the transplanted eye may eventually contribute to the patient’s visual perception. These results are comparable to those of previous facial tissue transplants, but with the significant addition of ocular functionality, which is a notable advance.

“The successful revascularization of the transplanted eye achieved in this study may serve as a step toward the goal of globe transplant for restoration of vision,” wrote the authors.

The complexity of the combined transplant required a deep understanding of facial and ocular anatomy, as well as tissue preservation techniques. The surgical team reported significant challenges, including the need to align delicate anatomical structures and ensure immunological compatibility between the donor and recipient. Meticulous planning from donor selection to postoperative follow-up was considered essential to maximize the likelihood of success and minimize the risk for allograft rejection.

The patient will now be continuously monitored and receive treatment with immunosuppressants such as tacrolimus and prednisone, adjusted according to his response to the transplant. According to the researchers, further studies will be needed to assess the long-term functionality of the transplanted eye and its integration with the central nervous system.

Despite being the fifth facial transplant surgery performed under Dr. Rodriguez’s leadership, this is the first record of a whole-eye transplant. “The mere fact that we have successfully performed the first whole-eye transplant along with a face transplant is a tremendous achievement that many believed to be impossible,” the doctor said in a statement. “We have taken a giant step forward and paved the way for the next chapter in vision restoration.”

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In a groundbreaking procedure, a team of surgeons from New York University Langone Health successfully performed the first combined face and eye transplant on a patient with extensive craniofacial tissue loss after an electrical accident.

The highly complex surgery lasted for 21 hours and involved more than 140 surgeons, nurses, and other healthcare professionals under the leadership of Eduardo D. Rodriguez. MD. It not only restored the patient’s facial features, but also integrated a functional eyeball, potentially setting a new standard for future treatments in similar cases.

The transplant took place in May 2023, and the case report was published on September 5 this year in JAMA.

The 46-year-old man lost a large part of his craniofacial tissue and his left eyeball. The approach was highly specialized. Advanced microsurgical techniques such as anastomoses of microscopic vessels and delicate suturing techniques were crucial for the transplant’s success.

Moreover, customized surgical devices, specific implants, and tissue manipulation tools were developed specifically for this case, thus ensuring the viability of the transplant and adequate perfusion of the transplanted ocular tissue.

The initial results are encouraging. Retinal arterial perfusion has been maintained, and retinal architecture has been preserved, as demonstrated by optical coherence tomography. Electroretinography confirmed retinal responses to light, suggesting that the transplanted eye may eventually contribute to the patient’s visual perception. These results are comparable to those of previous facial tissue transplants, but with the significant addition of ocular functionality, which is a notable advance.

“The successful revascularization of the transplanted eye achieved in this study may serve as a step toward the goal of globe transplant for restoration of vision,” wrote the authors.

The complexity of the combined transplant required a deep understanding of facial and ocular anatomy, as well as tissue preservation techniques. The surgical team reported significant challenges, including the need to align delicate anatomical structures and ensure immunological compatibility between the donor and recipient. Meticulous planning from donor selection to postoperative follow-up was considered essential to maximize the likelihood of success and minimize the risk for allograft rejection.

The patient will now be continuously monitored and receive treatment with immunosuppressants such as tacrolimus and prednisone, adjusted according to his response to the transplant. According to the researchers, further studies will be needed to assess the long-term functionality of the transplanted eye and its integration with the central nervous system.

Despite being the fifth facial transplant surgery performed under Dr. Rodriguez’s leadership, this is the first record of a whole-eye transplant. “The mere fact that we have successfully performed the first whole-eye transplant along with a face transplant is a tremendous achievement that many believed to be impossible,” the doctor said in a statement. “We have taken a giant step forward and paved the way for the next chapter in vision restoration.”

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In a groundbreaking procedure, a team of surgeons from New York University Langone Health successfully performed the first combined face and eye transplant on a patient with extensive craniofacial tissue loss after an electrical accident.

The highly complex surgery lasted for 21 hours and involved more than 140 surgeons, nurses, and other healthcare professionals under the leadership of Eduardo D. Rodriguez. MD. It not only restored the patient’s facial features, but also integrated a functional eyeball, potentially setting a new standard for future treatments in similar cases.

The transplant took place in May 2023, and the case report was published on September 5 this year in JAMA.

The 46-year-old man lost a large part of his craniofacial tissue and his left eyeball. The approach was highly specialized. Advanced microsurgical techniques such as anastomoses of microscopic vessels and delicate suturing techniques were crucial for the transplant’s success.

Moreover, customized surgical devices, specific implants, and tissue manipulation tools were developed specifically for this case, thus ensuring the viability of the transplant and adequate perfusion of the transplanted ocular tissue.

The initial results are encouraging. Retinal arterial perfusion has been maintained, and retinal architecture has been preserved, as demonstrated by optical coherence tomography. Electroretinography confirmed retinal responses to light, suggesting that the transplanted eye may eventually contribute to the patient’s visual perception. These results are comparable to those of previous facial tissue transplants, but with the significant addition of ocular functionality, which is a notable advance.

“The successful revascularization of the transplanted eye achieved in this study may serve as a step toward the goal of globe transplant for restoration of vision,” wrote the authors.

The complexity of the combined transplant required a deep understanding of facial and ocular anatomy, as well as tissue preservation techniques. The surgical team reported significant challenges, including the need to align delicate anatomical structures and ensure immunological compatibility between the donor and recipient. Meticulous planning from donor selection to postoperative follow-up was considered essential to maximize the likelihood of success and minimize the risk for allograft rejection.

The patient will now be continuously monitored and receive treatment with immunosuppressants such as tacrolimus and prednisone, adjusted according to his response to the transplant. According to the researchers, further studies will be needed to assess the long-term functionality of the transplanted eye and its integration with the central nervous system.

Despite being the fifth facial transplant surgery performed under Dr. Rodriguez’s leadership, this is the first record of a whole-eye transplant. “The mere fact that we have successfully performed the first whole-eye transplant along with a face transplant is a tremendous achievement that many believed to be impossible,” the doctor said in a statement. “We have taken a giant step forward and paved the way for the next chapter in vision restoration.”

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Study Identifies Oral Antibiotics Linked to Severe Cutaneous Reactions

according to a large, population-based, nested case-control study of older adults, spanning two decades.

The findings, published online in JAMA, “underscore the importance of judicious prescribing, with preferential use of antibiotics associated with a lower risk when clinically appropriate,” noted senior author David Juurlink, MD, PhD, professor of medicine; pediatrics; and health policy, management and evaluation at the University of Toronto, and head of the Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology Division at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, also in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and coauthors.

“We hope our study raises awareness about the importance of drug allergy and gains support for future studies to improve drug allergy care,” lead author Erika Lee, MD, clinical immunology and allergy lecturer at the University of Toronto’s Drug Allergy Clinic, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, said in an interview. “It is important to recognize symptoms and signs of a severe drug rash and promptly stop culprit drugs to prevent worsening reaction.”

Serious cADRs are “a group of rare but potentially life-threatening drug hypersensitivity reactions involving the skin and, frequently, internal organs,” the authors wrote. “Typically delayed in onset, these reactions include drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) — the most severe cADR, which has a reported mortality of 20%-40%,” they noted.

Speculation Without Data

Although it has been speculated that some oral antibiotics are more likely than others to be associated with serious cADRs, there have been no population-based studies examining this, they added.

The study included adults aged 66 years or older and used administrative health databases in Ontario, spanning from April 1, 2002, to March 31, 2022. Data on antibiotic use were taken from the Ontario Drug Benefit database. The Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) National Ambulatory Care Reporting System was used to obtain data on emergency department (ED) visits for cADRs, while the CIHI Discharge Abstract Database was used to identify hospitalizations for cADRs. Finally, demographic information and outpatient healthcare utilization data were obtained from the Registered Persons Database and the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database, respectively.

A cohort of 21,758 older adults (median age, 75 years; 64.1% women) who had an ED visit or hospitalization for serious cADRs within 60 days of receiving antibiotic therapy was matched by age and sex with 87,025 antibiotic-treated controls who did not have a cutaneous reaction.

The median duration of antibiotic prescription was 7 days among cases and controls, and among the cases, the median latency period between antibiotic prescriptions and hospital visits for cADRs was 14 days. Most of the case patients went to the ED only (86.9%), and the rest were hospitalized.

The most commonly prescribed antibiotic class was penicillins (28.9%), followed by cephalosporins (18.2%), fluoroquinolones (16.5%), macrolides (14.8%), nitrofurantoin (8.6%), and sulfonamides (6.2%). Less commonly used antibiotics (“other” antibiotics) accounted for 6.9%.

Macrolide antibiotics were used as the reference because they are rarely associated with serious cADRs, noted the authors, and the multivariable analysis, adjusted for risk factors associated with serious cADRs, including malignancy, chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease, and HIV.

After multivariable adjustment, relative to macrolides, sulfonamides were most strongly associated with serious cADRs (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.9) but so were all other antibiotic classes, including cephalosporins (aOR, 2.6), “other” antibiotics (aOR, 2.3), nitrofurantoin (aOR, 2.2), penicillins (aOR, 1.4), and fluoroquinolones (aOR,1.3).

In the secondary analysis, the crude rate of ED visits or hospitalizations for cADRs was highest for cephalosporins (4.92 per 1000 prescriptions), followed by sulfonamides (3.22 per 1000 prescriptions). Among hospitalized patients, the median length of stay was 6 days, with 9.6% requiring transfer to a critical care unit and 5.3% dying in the hospital.

Hospitalizations, ED Visits Not Studied Previously

“Notably, the rate of antibiotic-associated serious cADRs leading to an ED visit or hospitalization has not been previously studied,” noted the authors. “We found that at least two hospital encounters for serious cADRs ensued for every 1000 antibiotic prescriptions. This rate is considerably higher than suggested by studies that examine only SJS/TEN and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms.”

Dr. Lee also emphasized the previously unreported findings about nitrofurantoin. “It is surprising to find that nitrofurantoin, a commonly prescribed antibiotic for urinary tract infection, is also associated with an increased risk of severe drug rash,” she said in an interview.

“This finding highlights a potential novel risk at a population-based level and should be further explored in other populations to verify this association,” the authors wrote.

Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore, Maryland, and a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America, who was not involved in the study, agreed that the nitrofurantoin finding was surprising, but he was not surprised that sulfonamides were high on the list.

“The study reinforces that antibiotics are not benign medications to be dispensed injudiciously,” he said in an interview. “Antibiotics have risks, including serious skin reactions, as well as the fostering of antibiotic resistance. Clinicians should always first ask themselves if their patient actually merits an antibiotic and then assess what is the safest antibiotic for the purpose, bearing in mind that certain antibiotics are more likely to result in adverse reactions than others.”

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The study was conducted at ICES, which is funded in part by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. One coauthor reported receiving compensation from the British Journal of Dermatology as reviewer and section editor, the American Academy of Dermatology as guidelines writer, Canadian Dermatology Today as manuscript writer, and the National Eczema Association and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health as consultant; as well as receiving research grants to the coauthor’s institution from the National Eczema Association, Eczema Society of Canada, Canadian Dermatology Foundation, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, US National Institutes of Health, and PSI Foundation. Another coauthor reported receiving grants from AbbVie, Bausch Health, Celgene, Lilly, Incyte, Janssen, LEO Pharma, L’Oréal, Novartis, Organon, Pfizer, Sandoz, Amgen, and Boehringer Ingelheim; receiving payment or honoraria for speaking from Sanofi China; participating on advisory boards for LEO Pharma, Novartis, Sanofi, and Union Therapeutics; and receiving equipment donation from L’Oréal. Dr. Adalja reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a large, population-based, nested case-control study of older adults, spanning two decades.

The findings, published online in JAMA, “underscore the importance of judicious prescribing, with preferential use of antibiotics associated with a lower risk when clinically appropriate,” noted senior author David Juurlink, MD, PhD, professor of medicine; pediatrics; and health policy, management and evaluation at the University of Toronto, and head of the Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology Division at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, also in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and coauthors.

“We hope our study raises awareness about the importance of drug allergy and gains support for future studies to improve drug allergy care,” lead author Erika Lee, MD, clinical immunology and allergy lecturer at the University of Toronto’s Drug Allergy Clinic, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, said in an interview. “It is important to recognize symptoms and signs of a severe drug rash and promptly stop culprit drugs to prevent worsening reaction.”

Serious cADRs are “a group of rare but potentially life-threatening drug hypersensitivity reactions involving the skin and, frequently, internal organs,” the authors wrote. “Typically delayed in onset, these reactions include drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) — the most severe cADR, which has a reported mortality of 20%-40%,” they noted.

Speculation Without Data

Although it has been speculated that some oral antibiotics are more likely than others to be associated with serious cADRs, there have been no population-based studies examining this, they added.

The study included adults aged 66 years or older and used administrative health databases in Ontario, spanning from April 1, 2002, to March 31, 2022. Data on antibiotic use were taken from the Ontario Drug Benefit database. The Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) National Ambulatory Care Reporting System was used to obtain data on emergency department (ED) visits for cADRs, while the CIHI Discharge Abstract Database was used to identify hospitalizations for cADRs. Finally, demographic information and outpatient healthcare utilization data were obtained from the Registered Persons Database and the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database, respectively.

A cohort of 21,758 older adults (median age, 75 years; 64.1% women) who had an ED visit or hospitalization for serious cADRs within 60 days of receiving antibiotic therapy was matched by age and sex with 87,025 antibiotic-treated controls who did not have a cutaneous reaction.

The median duration of antibiotic prescription was 7 days among cases and controls, and among the cases, the median latency period between antibiotic prescriptions and hospital visits for cADRs was 14 days. Most of the case patients went to the ED only (86.9%), and the rest were hospitalized.

The most commonly prescribed antibiotic class was penicillins (28.9%), followed by cephalosporins (18.2%), fluoroquinolones (16.5%), macrolides (14.8%), nitrofurantoin (8.6%), and sulfonamides (6.2%). Less commonly used antibiotics (“other” antibiotics) accounted for 6.9%.

Macrolide antibiotics were used as the reference because they are rarely associated with serious cADRs, noted the authors, and the multivariable analysis, adjusted for risk factors associated with serious cADRs, including malignancy, chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease, and HIV.

After multivariable adjustment, relative to macrolides, sulfonamides were most strongly associated with serious cADRs (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.9) but so were all other antibiotic classes, including cephalosporins (aOR, 2.6), “other” antibiotics (aOR, 2.3), nitrofurantoin (aOR, 2.2), penicillins (aOR, 1.4), and fluoroquinolones (aOR,1.3).

In the secondary analysis, the crude rate of ED visits or hospitalizations for cADRs was highest for cephalosporins (4.92 per 1000 prescriptions), followed by sulfonamides (3.22 per 1000 prescriptions). Among hospitalized patients, the median length of stay was 6 days, with 9.6% requiring transfer to a critical care unit and 5.3% dying in the hospital.

Hospitalizations, ED Visits Not Studied Previously

“Notably, the rate of antibiotic-associated serious cADRs leading to an ED visit or hospitalization has not been previously studied,” noted the authors. “We found that at least two hospital encounters for serious cADRs ensued for every 1000 antibiotic prescriptions. This rate is considerably higher than suggested by studies that examine only SJS/TEN and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms.”

Dr. Lee also emphasized the previously unreported findings about nitrofurantoin. “It is surprising to find that nitrofurantoin, a commonly prescribed antibiotic for urinary tract infection, is also associated with an increased risk of severe drug rash,” she said in an interview.

“This finding highlights a potential novel risk at a population-based level and should be further explored in other populations to verify this association,” the authors wrote.

Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore, Maryland, and a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America, who was not involved in the study, agreed that the nitrofurantoin finding was surprising, but he was not surprised that sulfonamides were high on the list.

“The study reinforces that antibiotics are not benign medications to be dispensed injudiciously,” he said in an interview. “Antibiotics have risks, including serious skin reactions, as well as the fostering of antibiotic resistance. Clinicians should always first ask themselves if their patient actually merits an antibiotic and then assess what is the safest antibiotic for the purpose, bearing in mind that certain antibiotics are more likely to result in adverse reactions than others.”

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The study was conducted at ICES, which is funded in part by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. One coauthor reported receiving compensation from the British Journal of Dermatology as reviewer and section editor, the American Academy of Dermatology as guidelines writer, Canadian Dermatology Today as manuscript writer, and the National Eczema Association and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health as consultant; as well as receiving research grants to the coauthor’s institution from the National Eczema Association, Eczema Society of Canada, Canadian Dermatology Foundation, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, US National Institutes of Health, and PSI Foundation. Another coauthor reported receiving grants from AbbVie, Bausch Health, Celgene, Lilly, Incyte, Janssen, LEO Pharma, L’Oréal, Novartis, Organon, Pfizer, Sandoz, Amgen, and Boehringer Ingelheim; receiving payment or honoraria for speaking from Sanofi China; participating on advisory boards for LEO Pharma, Novartis, Sanofi, and Union Therapeutics; and receiving equipment donation from L’Oréal. Dr. Adalja reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a large, population-based, nested case-control study of older adults, spanning two decades.

The findings, published online in JAMA, “underscore the importance of judicious prescribing, with preferential use of antibiotics associated with a lower risk when clinically appropriate,” noted senior author David Juurlink, MD, PhD, professor of medicine; pediatrics; and health policy, management and evaluation at the University of Toronto, and head of the Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology Division at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, also in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and coauthors.

“We hope our study raises awareness about the importance of drug allergy and gains support for future studies to improve drug allergy care,” lead author Erika Lee, MD, clinical immunology and allergy lecturer at the University of Toronto’s Drug Allergy Clinic, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, said in an interview. “It is important to recognize symptoms and signs of a severe drug rash and promptly stop culprit drugs to prevent worsening reaction.”

Serious cADRs are “a group of rare but potentially life-threatening drug hypersensitivity reactions involving the skin and, frequently, internal organs,” the authors wrote. “Typically delayed in onset, these reactions include drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) — the most severe cADR, which has a reported mortality of 20%-40%,” they noted.

Speculation Without Data

Although it has been speculated that some oral antibiotics are more likely than others to be associated with serious cADRs, there have been no population-based studies examining this, they added.

The study included adults aged 66 years or older and used administrative health databases in Ontario, spanning from April 1, 2002, to March 31, 2022. Data on antibiotic use were taken from the Ontario Drug Benefit database. The Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) National Ambulatory Care Reporting System was used to obtain data on emergency department (ED) visits for cADRs, while the CIHI Discharge Abstract Database was used to identify hospitalizations for cADRs. Finally, demographic information and outpatient healthcare utilization data were obtained from the Registered Persons Database and the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database, respectively.

A cohort of 21,758 older adults (median age, 75 years; 64.1% women) who had an ED visit or hospitalization for serious cADRs within 60 days of receiving antibiotic therapy was matched by age and sex with 87,025 antibiotic-treated controls who did not have a cutaneous reaction.

The median duration of antibiotic prescription was 7 days among cases and controls, and among the cases, the median latency period between antibiotic prescriptions and hospital visits for cADRs was 14 days. Most of the case patients went to the ED only (86.9%), and the rest were hospitalized.

The most commonly prescribed antibiotic class was penicillins (28.9%), followed by cephalosporins (18.2%), fluoroquinolones (16.5%), macrolides (14.8%), nitrofurantoin (8.6%), and sulfonamides (6.2%). Less commonly used antibiotics (“other” antibiotics) accounted for 6.9%.

Macrolide antibiotics were used as the reference because they are rarely associated with serious cADRs, noted the authors, and the multivariable analysis, adjusted for risk factors associated with serious cADRs, including malignancy, chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease, and HIV.

After multivariable adjustment, relative to macrolides, sulfonamides were most strongly associated with serious cADRs (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.9) but so were all other antibiotic classes, including cephalosporins (aOR, 2.6), “other” antibiotics (aOR, 2.3), nitrofurantoin (aOR, 2.2), penicillins (aOR, 1.4), and fluoroquinolones (aOR,1.3).

In the secondary analysis, the crude rate of ED visits or hospitalizations for cADRs was highest for cephalosporins (4.92 per 1000 prescriptions), followed by sulfonamides (3.22 per 1000 prescriptions). Among hospitalized patients, the median length of stay was 6 days, with 9.6% requiring transfer to a critical care unit and 5.3% dying in the hospital.

Hospitalizations, ED Visits Not Studied Previously

“Notably, the rate of antibiotic-associated serious cADRs leading to an ED visit or hospitalization has not been previously studied,” noted the authors. “We found that at least two hospital encounters for serious cADRs ensued for every 1000 antibiotic prescriptions. This rate is considerably higher than suggested by studies that examine only SJS/TEN and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms.”

Dr. Lee also emphasized the previously unreported findings about nitrofurantoin. “It is surprising to find that nitrofurantoin, a commonly prescribed antibiotic for urinary tract infection, is also associated with an increased risk of severe drug rash,” she said in an interview.

“This finding highlights a potential novel risk at a population-based level and should be further explored in other populations to verify this association,” the authors wrote.

Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore, Maryland, and a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America, who was not involved in the study, agreed that the nitrofurantoin finding was surprising, but he was not surprised that sulfonamides were high on the list.

“The study reinforces that antibiotics are not benign medications to be dispensed injudiciously,” he said in an interview. “Antibiotics have risks, including serious skin reactions, as well as the fostering of antibiotic resistance. Clinicians should always first ask themselves if their patient actually merits an antibiotic and then assess what is the safest antibiotic for the purpose, bearing in mind that certain antibiotics are more likely to result in adverse reactions than others.”

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The study was conducted at ICES, which is funded in part by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. One coauthor reported receiving compensation from the British Journal of Dermatology as reviewer and section editor, the American Academy of Dermatology as guidelines writer, Canadian Dermatology Today as manuscript writer, and the National Eczema Association and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health as consultant; as well as receiving research grants to the coauthor’s institution from the National Eczema Association, Eczema Society of Canada, Canadian Dermatology Foundation, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, US National Institutes of Health, and PSI Foundation. Another coauthor reported receiving grants from AbbVie, Bausch Health, Celgene, Lilly, Incyte, Janssen, LEO Pharma, L’Oréal, Novartis, Organon, Pfizer, Sandoz, Amgen, and Boehringer Ingelheim; receiving payment or honoraria for speaking from Sanofi China; participating on advisory boards for LEO Pharma, Novartis, Sanofi, and Union Therapeutics; and receiving equipment donation from L’Oréal. Dr. Adalja reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

Epidermal Tumors Arising on Donor Sites From Autologous Skin Grafts: A Systematic Review

Skin grafting is a surgical technique used to cover skin defects resulting from the removal of skin tumors, ulcers, or burn injuries.1-3 Complications can occur at both donor and recipient sites and may include bleeding, hematoma/seroma formation, postoperative pain, infection, scarring, paresthesia, skin pigmentation, graft contracture, and graft failure.1,2,4,5 The development of epidermal tumors is not commonly reported among the complications of skin grafting; however, cases of epidermal tumor development on skin graft donor sites during the postoperative period have been reported.6-12

We performed a systematic review of the literature for cases of epidermal tumor development on skin graft donor sites in patients undergoing autologous skin graft surgery. We present the clinical characteristics of these cases and discuss the nature of these tumors.

Methods

Search Strategy and Study Selection—A literature search was conducted by 2 independent researchers (Z.P. and V.P.) for articles published before December 2022 in the following databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Cochrane Library, OpenGrey, Google Scholar, and WorldCat. Search terms included all possible combinations of the following: keratoacanthoma, molluscum sebaceum, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, acanthoma, wart, Merkel cell carcinoma, verruca, Bowen disease, keratosis, skin cancer, cutaneous cancer, skin neoplasia, cutaneous neoplasia, and skin tumor. The literature search terms were selected based on the World Health Organization classification of skin tumors.13 Manual bibliography checks were performed on all eligible search results for possible relevant studies. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and, if needed, mediation by a third researcher (N.C.). To be included, a study had to report a case(s) of epidermal tumor(s) that was confirmed by histopathology and arose on a graft donor site in a patient receiving autologous skin grafts for any reason. No language, geographic, or report date restrictions were set.

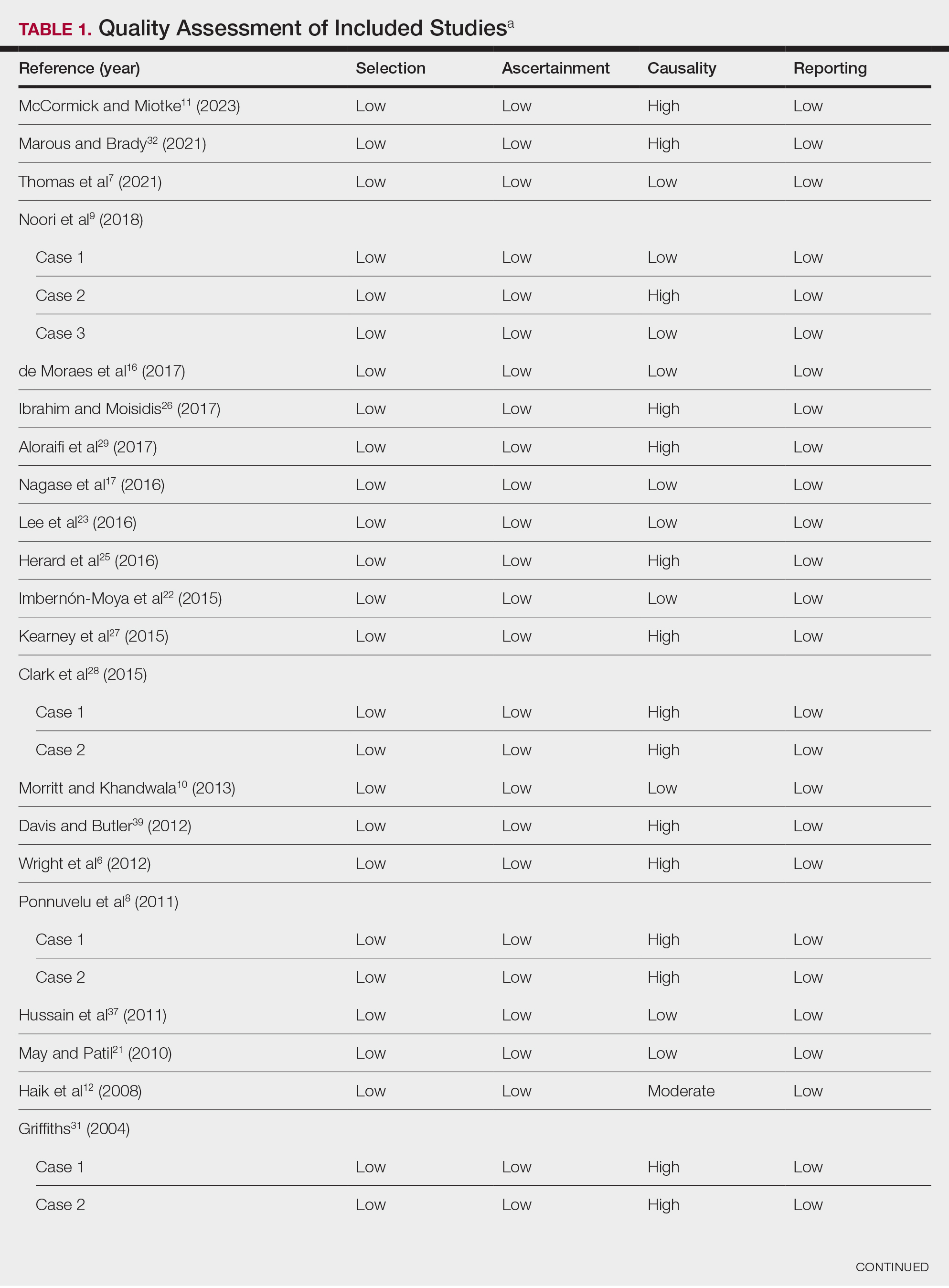

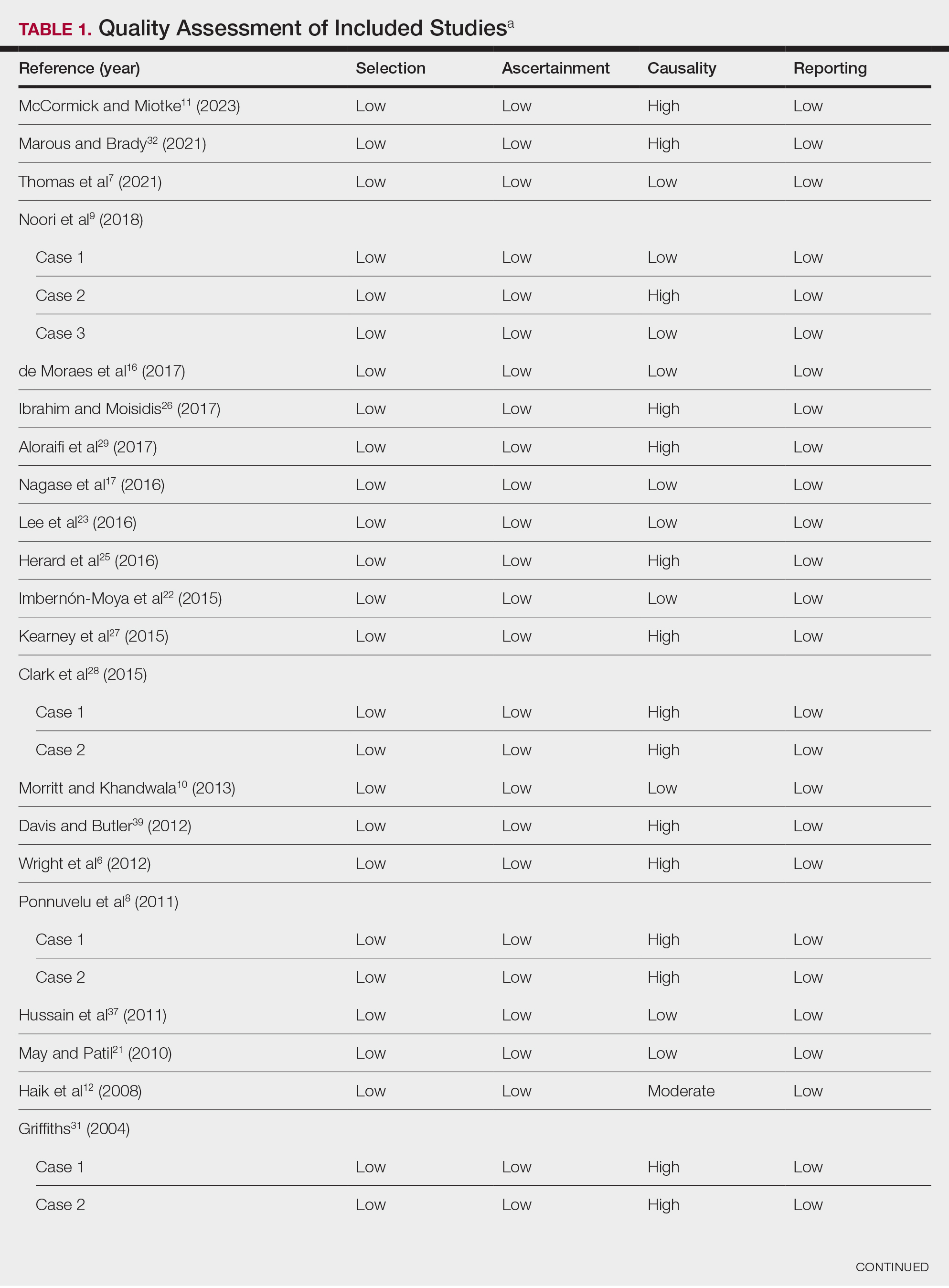

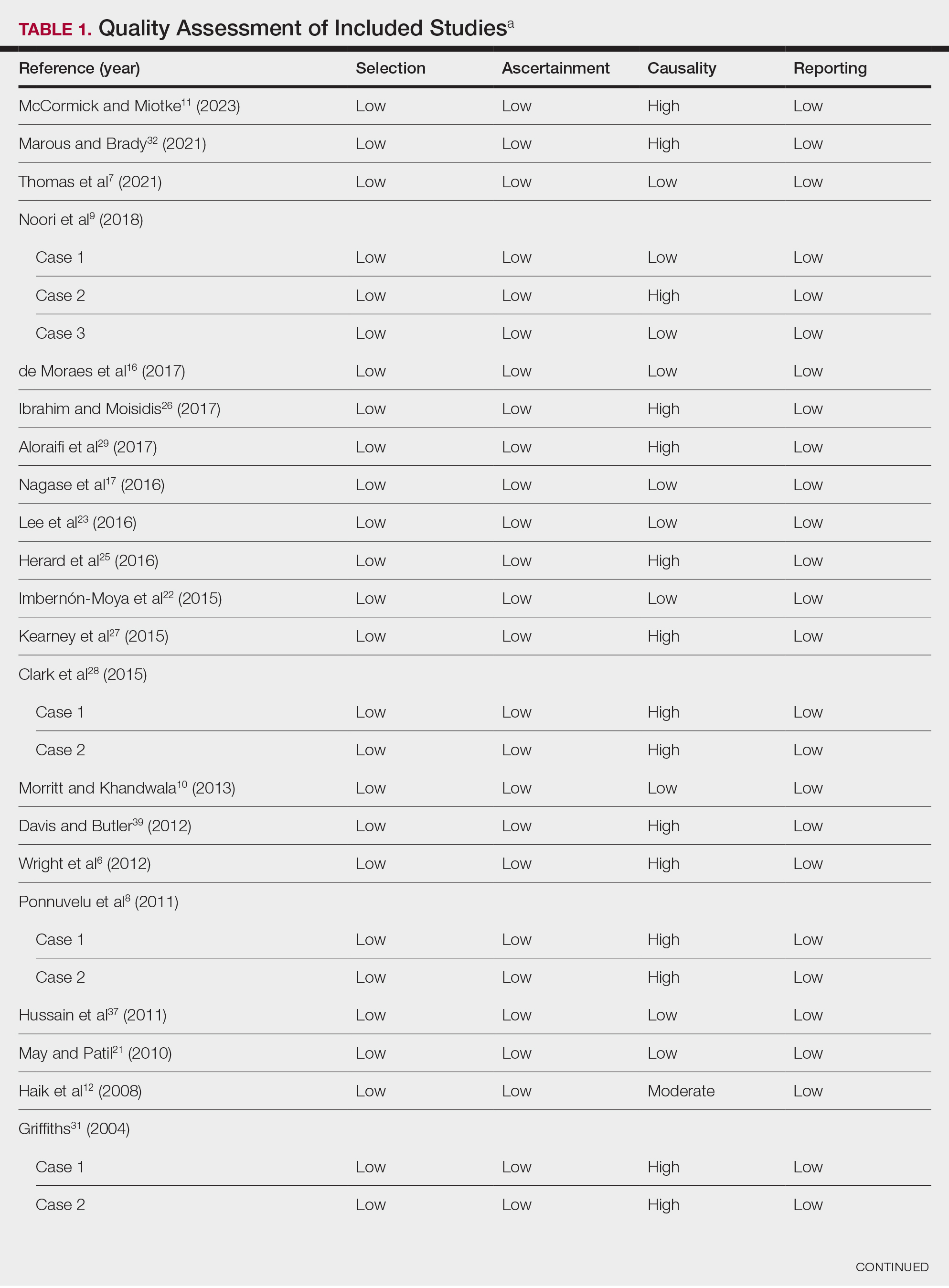

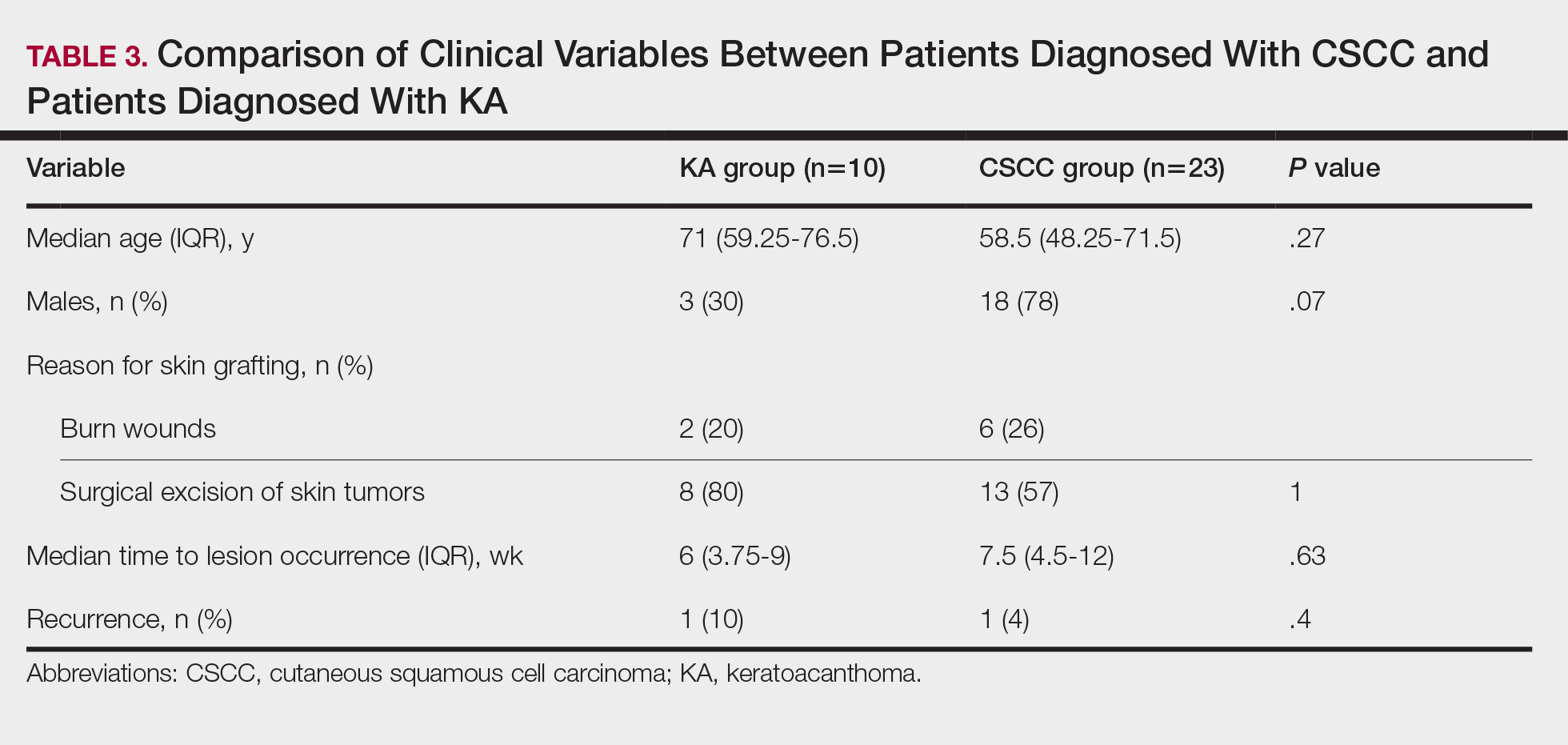

Data Extraction, Quality Assessment, and Statistical Analysis—We adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.14 Two independent researchers (Z.P. and V.P.) retrieved the data from the included studies. We have used the terms case and patient interchangeably, and 1 month was measured as 4 weeks for simplicity. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and mediation by a third researcher (N.C.). The quality of the included studies was assessed by 2 researchers (M.P. and V.P.) using the tool proposed by Murad et al.15

We used descriptive statistical analysis to analyze clinical characteristics of the included cases. We performed separate descriptive analyses based on the most frequently reported types of epidermal tumors and compared the differences between different groups using the Mann-Whitney U test, χ2 test, and Fisher exact test. The level of significance was set at P<.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 29).

Results

Literature Search and Characteristics of Included Studies—The initial literature search identified 1378 studies, which were screened based on title and abstract. After removing duplicate and irrelevant studies and evaluating the full text of eligible studies, 31 studies (4 case series and 27 case reports) were included in the systematic review (Figure).6-12,16-39 Quality assessment of the included studies is presented in Table 1.

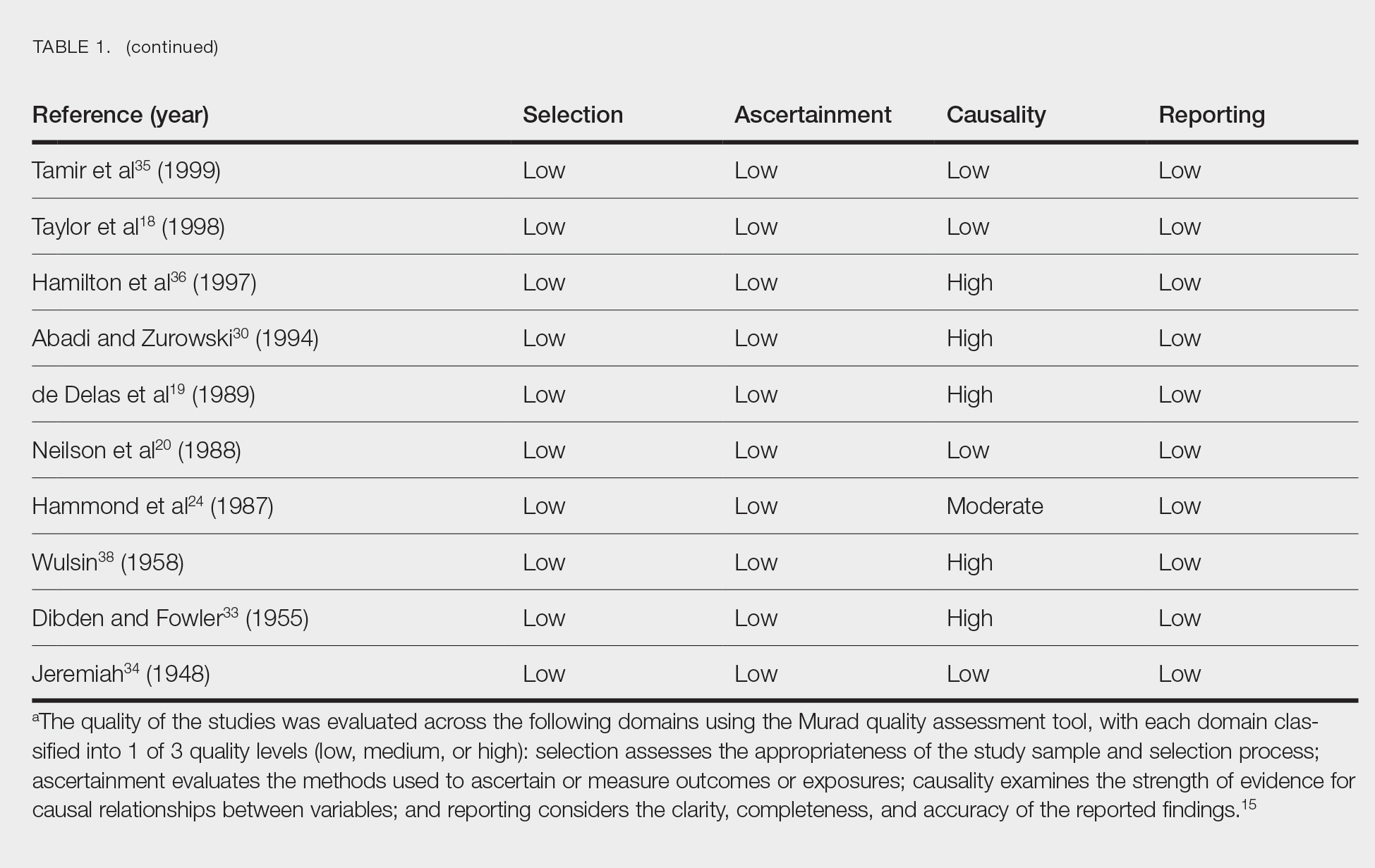

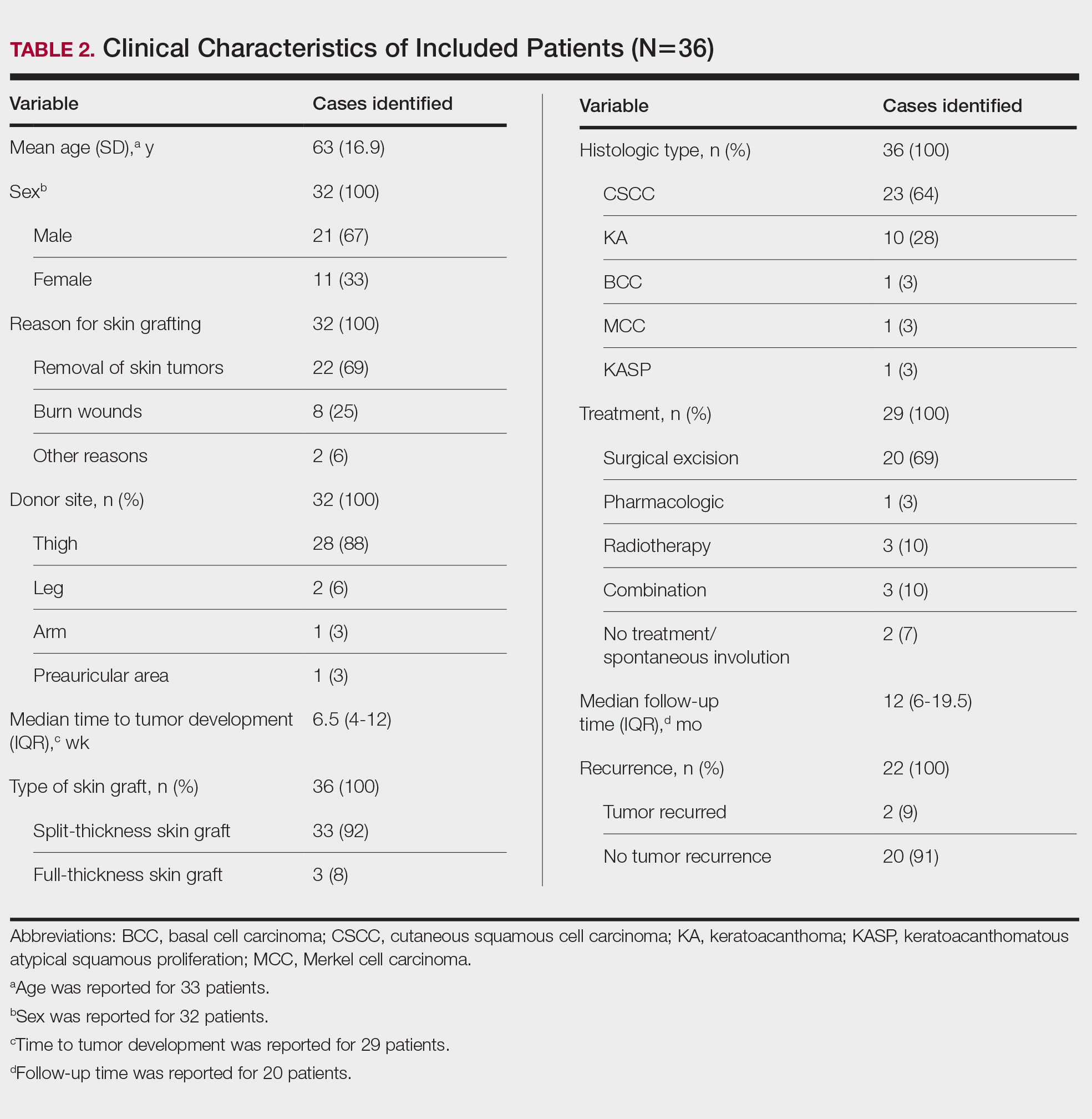

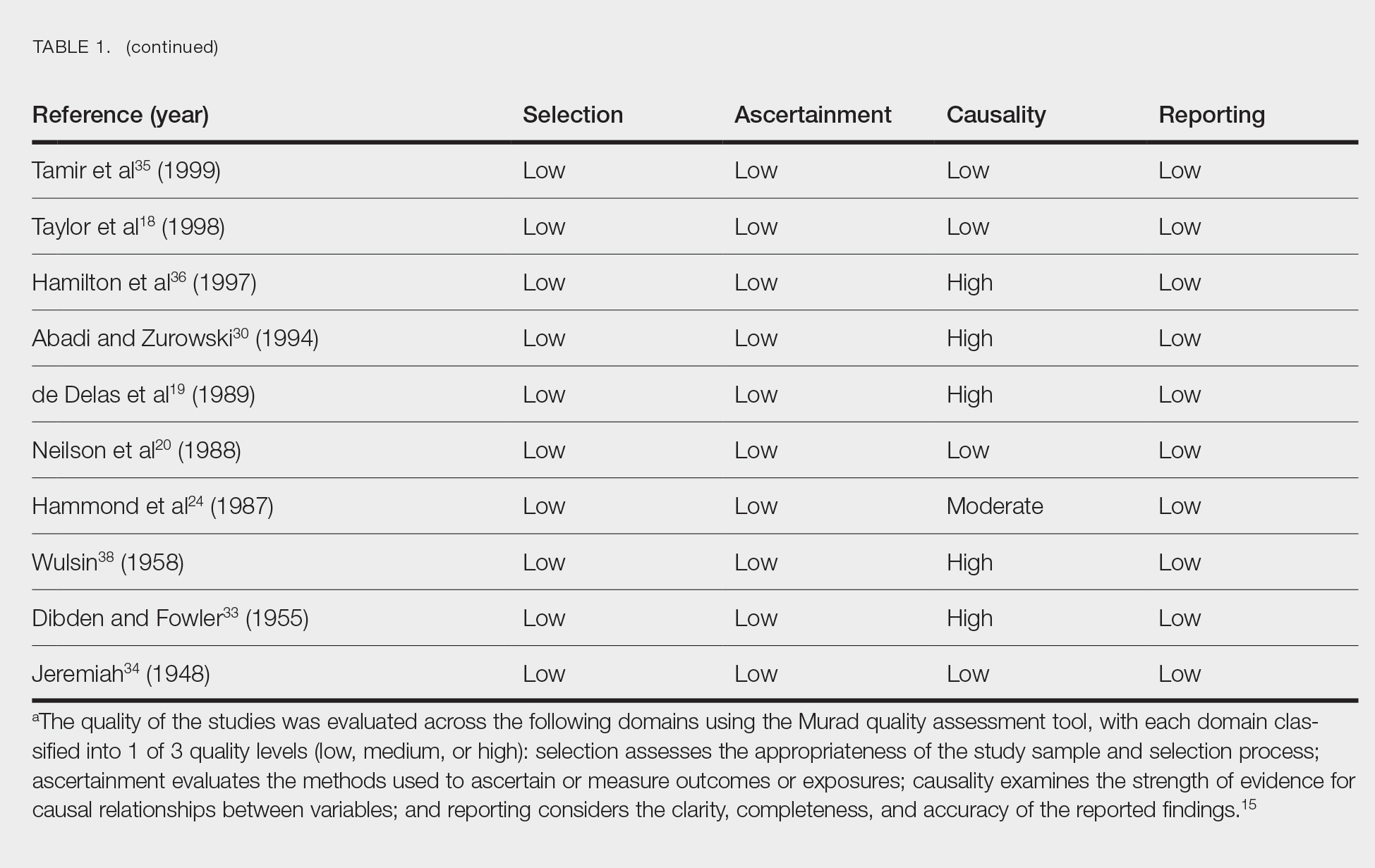

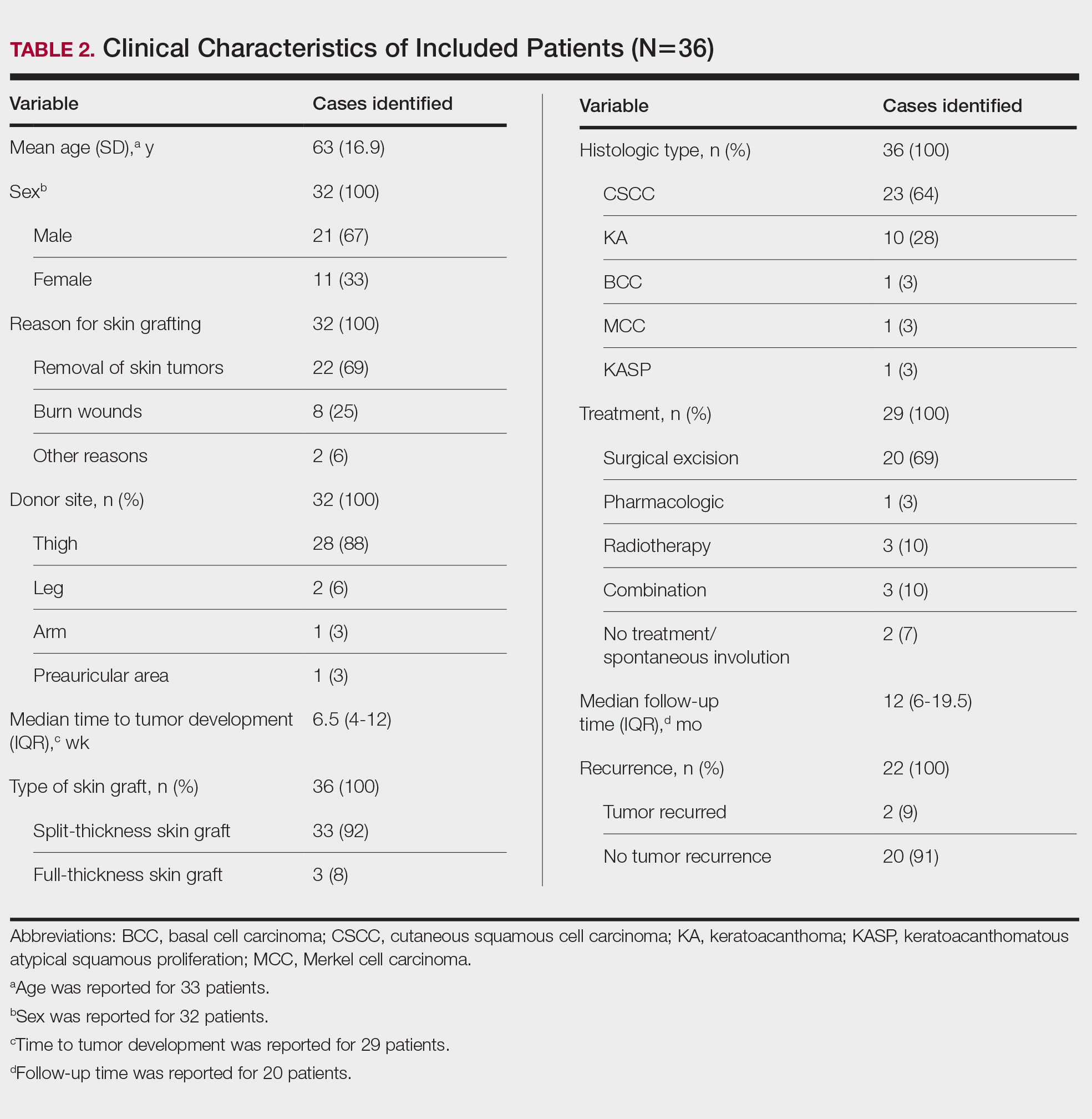

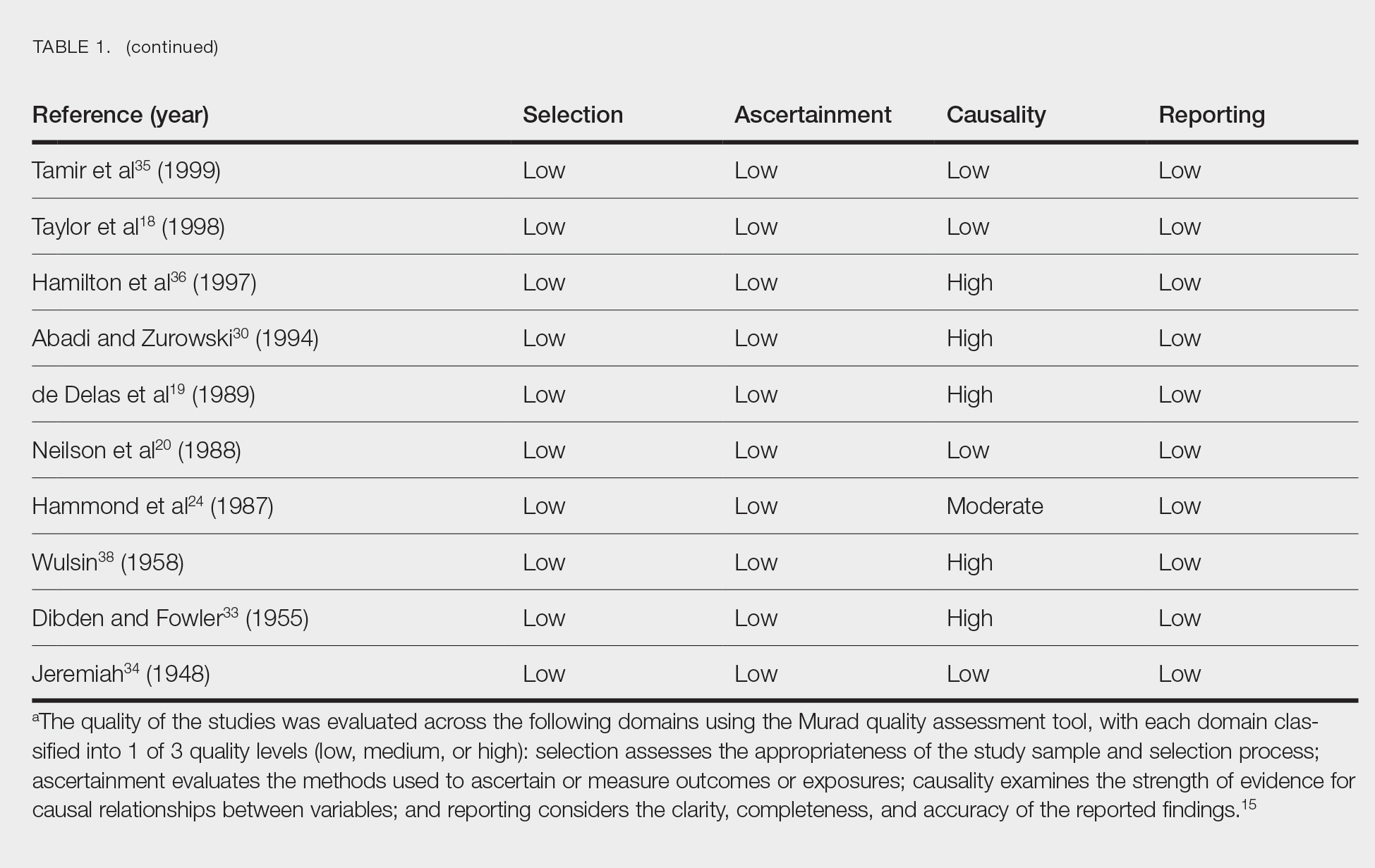

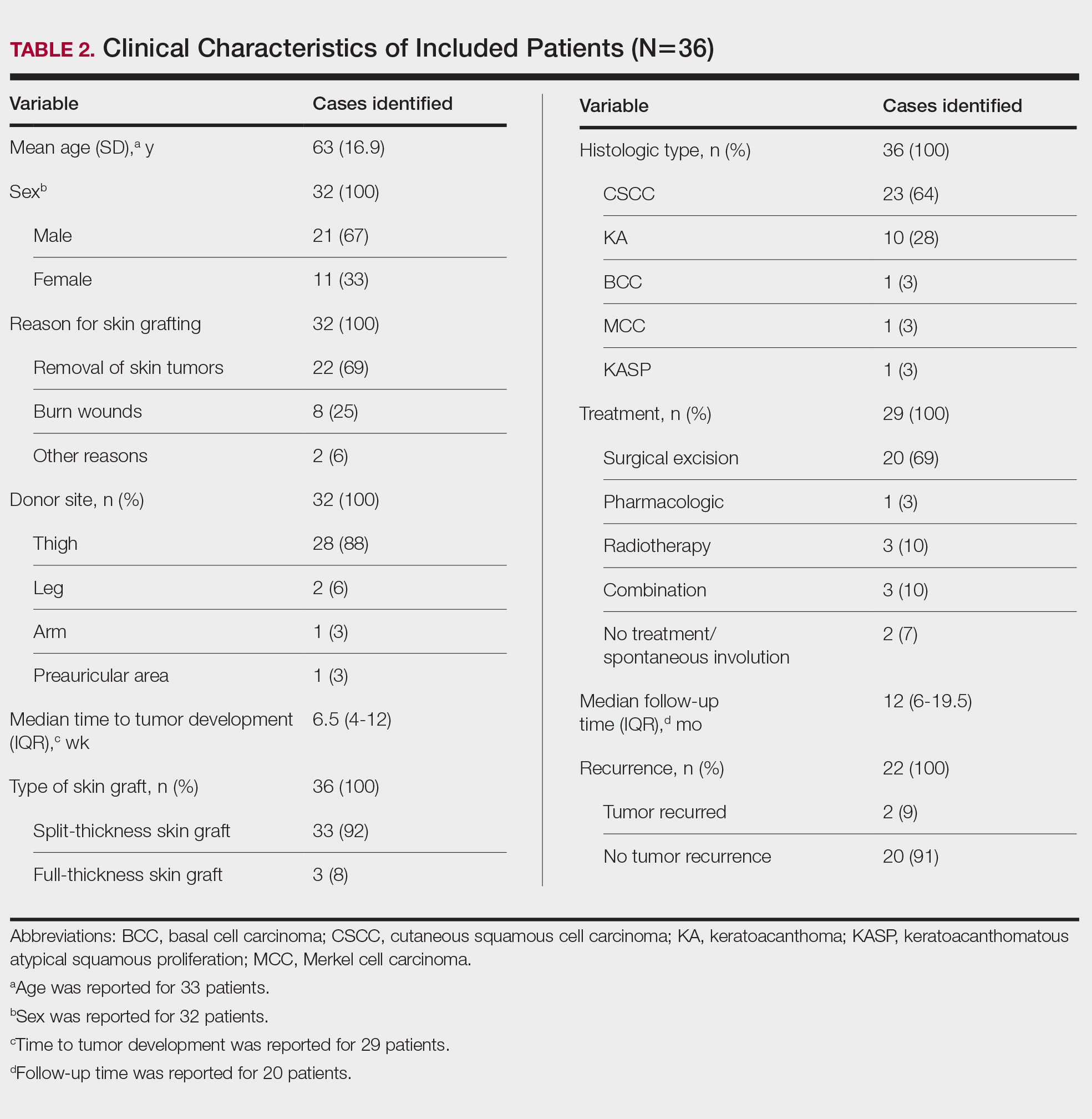

Clinical Characteristics of Included Patients—Our systematic review included 36 patients with a mean age of 63 years and a male to female ratio of 2:1. The 2 most common causes for skin grafting were burn wounds and surgical excision of skin tumors. Most grafts were harvested from the thighs. The development of a solitary lesion on the donor area was reported in two-thirds of the patients, while more than 1 lesion developed in the remaining one-third of patients. The median time to tumor development was 6.5 weeks. In most cases, a split-thickness skin graft was used.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (CSCCs) were found in 23 patients, with well-differentiated CSCCs in 19 of these cases. Additionally, keratoacanthomas (KAs) were found in 10 patients. The majority of patients underwent surgical excision of the tumor. The median follow-up time was 12 months, during which recurrences were noted in a small percentage of cases. Clinical characteristics of included patients are presented in Table 2.

Comment

Reasons for Tumor Development on Skin Graft Donor Sites—The etiology behind epidermal tumor development on graft donor sites is unclear. According to one theory, iatrogenic contamination of the donor site during the removal of a primary epidermal tumor could be responsible. However, contemporary surgical procedures dictate the use of different sets of instruments for separate surgical sites. Moreover, this theory cannot explain the occurrence of epidermal tumors on donor sites in patients who have undergone skin grafting for the repair of burn wounds.37

Another theory suggests that hematogenous and/or lymphatic spread can occur from the site of the primary epidermal tumor to the donor site, which has increased vascularization.16,37 However, this theory also fails to provide an explanation for the development of epidermal tumors in patients who receive skin grafts for burn wounds.

A third theory states that the microenvironment of the donor site is key to tumor development. The donor site undergoes acute inflammation due to the trauma from harvesting the skin graft. According to this theory, acute inflammation could promote neoplastic growth and thus explain the development of epidermal tumors on the donor site.8,26 However, the relationship between acute inflammation and carcinogenesis remains unclear. What is known to date is that the development of CSCC has been documented primarily in chronically inflamed tissues, whereas the development of KA—a variant of CSCC with distinctive and more benign clinical characteristics—can be expected in the setting of acute trauma-related inflammation.13,40,41

Based on our systematic review, we propose that well-differentiated CSCC on graft donor sites might actually be misdiagnosed KA, given that the histopathologic differential diagnosis between CSCC and KA is extremely challenging.42 This hypothesis could explain the development of well-differentiated CSCC and KA on graft donor sites.

Conclusion

Development of CSCC and KA on graft donor sites can be listed among the postoperative complications of autologous skin grafting. Patients and physicians should be aware of this potential complication, and donor sites should be monitored for the occurrence of epidermal tumors.

- Adams DC, Ramsey ML. Grafts in dermatologic surgery: review and update on full- and split-thickness skin grafts, free cartilage grafts, and composite grafts. Dermatologic Surg. 2005;31(8, pt 2):1055-1067. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31831

- Shimizu R, Kishi K. Skin graft. Plast Surg Int. 2012;2012:563493. doi:10.1155/2012/563493

- Reddy S, El-Haddawi F, Fancourt M, et al. The incidence and risk factors for lower limb skin graft failure. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:582080. doi:10.1155/2014/582080

- Coughlin MJ, Dockery GD, Crawford ME, et al. Lower Extremity Soft Tissue & Cutaneous Plastic Surgery. 2nd ed. Saunders Ltd; 2012.

- Herskovitz I, Hughes OB, Macquhae F, et al. Epidermal skin grafting. Int Wound J. 2016;13(suppl 3):52-56. doi:10.1111/iwj.12631

- Wright H, McKinnell TH, Dunkin C. Recurrence of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma at remote limb donor site. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:1265-1266. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2012.01.022

- Thomas W, Rezzadeh K, Rossi K, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising at a skin graft donor site: case report and review of the literature. Plast Surg Case Stud. 2021;7:2513826X211008425. doi:10.1177/2513826X211008425

- Ponnuvelu G, Ng MFY, Connolly CM, et al. Inflammation to skin malignancy, time to rethink the link: SCC in skin graft donor sites. Surgeon. 2011;9:168-169. doi:10.1016/j.surge.2010.08.006

- Noori VJ, Trehan K, Savetamal A, et al. New onset squamous cell carcinoma in previous split-thickness skin graft donor site. Int J Surg. 2018;52:16-19. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.01.047

- Morritt DG, Khandwala AR. The development of squamous cell carcinomas in split-thickness skin graft donor sites. Eur J Plast Surg. 2013;36:377-380.

- McCormick M, Miotke S. Squamous cell carcinoma at split thickness skin graft donor site: a case report and review of the literature. J Burn Care Res. 2023;44:210-213. doi:10.1093/jbcr/irac137

- Haik J, Georgiou I, Farber N, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a split-thickness skin graft donor site. Burns. 2008;34:891-893. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2007.06.006

- Elder DE, Massi D, Scolyer RA WR. WHO Classification of Skin Tumours. 4th ed. IARC Press; 2018.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264-269, W64. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

- Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, et al. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ. 2018;23:60-63. doi:10.1136/bmjebm-2017-110853

- de Moraes LPB, Burchett I, Nicholls S, et al. Large solitary distant metastasis of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma to skin graft site with complete response following definitive radiotherapy. Int J Bioautomation. 2017;21:103-108.

- Nagase K, Suzuki Y, Misago N, et al. Acute development of keratoacanthoma at a full-thickness skin graft donor site shortly after surgery. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1232-1233. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13368

- Taylor CD, Snelling CF, Nickerson D, et al. Acute development of invasive squamous cell carcinoma in a split-thickness skin graft donor site. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1998;19:382-385. doi:10.1097/00004630-199809000-00004

- de Delas J, Leache A, Vazquez Doval J, et al. Keratoacanthoma over the donor site of a laminar skin graft. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1989;17:225-228.

- Neilson D, Emerson DJ, Dunn L. Squamous cell carcinoma of skin developing in a skin graft donor site. Br J Plast Surg. 1988;41:417-419. doi:10.1016/0007-1226(88)90086-0

- May JT, Patil YJ. Keratoacanthoma-type squamous cell carcinoma developing in a skin graft donor site after tumor extirpation at a distant site. Ear Nose Throat J. 2010;89:E11-E13.

- Imbernón-Moya A, Vargas-Laguna E, Lobato-Berezo A, et al. Simultaneous onset of basal cell carcinoma over skin graft and donor site. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:244-246. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2015.05.004

- Lee S, Coutts I, Ryan A, et al. Keratoacanthoma formation after skin grafting: a brief report and pathophysiological hypothesis. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:e117-e119. doi:10.1111/ajd.12501

- Hammond JS, Thomsen S, Ward CG. Scar carcinoma arising acutelyin a skin graft donor site. J Trauma. 1987;27:681-683. doi:10.1097/00005373-198706000-00017

- Herard C, Arnaud D, Goga D, et al. Rapid onset of squamous cell carcinoma in a thin skin graft donor site. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2016;143:457-461. doi:10.1016/j.annder.2015.03.027

- Ibrahim A, Moisidis E. Case series: rapidly growing squamous cell carcinoma after cutaneous surgical intervention. JPRAS Open. 2017;14:27-32. doi:10.1016/j.jpra.2017.08.004

- Kearney L, Dolan RT, Parfrey NA, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a skin graft donor site following melanoma extirpation at a distant site: a case report and review of the literature. JPRAS Open. 2015;3:35-38. doi:10.1016/j.jpra.2015.02.002

- Clark MA, Guitart J, Gerami P, et al. Eruptive keratoacanthomatous atypical squamous proliferations (KASPs) arising in skin graft sites. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:274-276. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2015.06.009

- Aloraifi F, Mulgrew S, James NK. Secondary Merkel cell carcinoma arising from a graft donor site. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:167-169. doi:10.1177/1203475416676805

- Abadir R, Zurowski S. Case report: squamous cell carcinoma of the skin in both palms, axillary node, donor skin graft site and both soles—associated hyperkeratosis and porokeratosis. Br J Radiol. 1994;67:507-510. doi:10.1259/0007-1285-67-797-507

- Griffiths RW. Keratoacanthoma observed. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57:485-501. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2004.05.007

- Marous M, Brady K. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma arising in a split thickness skin graft donor site in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatologic Surg. 2021;47:1106-1107. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002955

- Dibden FA, Fowler M. The multiple growth of molluscum sebaceum in donor and recipient sites of skin graft. Aust N Z J Surg. 1955;25:157-159. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.1955.tb05122.x

- Jeremiah BS. Squamous cell carcinoma development on donor area following removal of a split thickness skin graft. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1948;3:718-721.

- Tamir G, Morgenstern S, Ben-Amitay D, et al. Synchronous appearance of keratoacanthomas in burn scar and skin graft donor site shortly after injury. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(5, pt 2):870-871. doi:10.1053/jd.1999.v40.a94419

- Hamilton SA, Dickson WA, O’Brien CJ. Keratoacanthoma developing in a split skin graft donor site. Br J Plast Surg. 1997;50:560-561. doi:10.1016/s0007-1226(97)91308-4

- Hussain A, Ekwobi C, Watson S. Metastatic implantation squamous cell carcinoma in a split-thickness skin graft donor site. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:690-692. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2010.06.004

- Wulsin JH. Keratoacanthoma: a benign cutaneous tumors arising in a skin graft donor site. Am Surg. 1958;24:689-692.

- Davis L, Butler D. Acute development of squamous cell carcinoma in a split-thickness skin graft donor site [abstract]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:AB208. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.11.874

- Shacter E, Weitzman SA. Chronic inflammation and cancer. Oncology (Williston Park). 2002;16:217-226, 229; discussion 230-232.

- Piotrowski I, Kulcenty K, Suchorska W. Interplay between inflammation and cancer. Reports Pract Oncol Radiother. 2020;25:422-427. doi:10.1016/j.rpor.2020.04.004

- Carr RA, Houghton JP. Histopathologists’ approach to keratoacanthoma: a multisite survey of regional variation in Great Britain and Ireland. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:637-638. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202255

Skin grafting is a surgical technique used to cover skin defects resulting from the removal of skin tumors, ulcers, or burn injuries.1-3 Complications can occur at both donor and recipient sites and may include bleeding, hematoma/seroma formation, postoperative pain, infection, scarring, paresthesia, skin pigmentation, graft contracture, and graft failure.1,2,4,5 The development of epidermal tumors is not commonly reported among the complications of skin grafting; however, cases of epidermal tumor development on skin graft donor sites during the postoperative period have been reported.6-12

We performed a systematic review of the literature for cases of epidermal tumor development on skin graft donor sites in patients undergoing autologous skin graft surgery. We present the clinical characteristics of these cases and discuss the nature of these tumors.

Methods

Search Strategy and Study Selection—A literature search was conducted by 2 independent researchers (Z.P. and V.P.) for articles published before December 2022 in the following databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Cochrane Library, OpenGrey, Google Scholar, and WorldCat. Search terms included all possible combinations of the following: keratoacanthoma, molluscum sebaceum, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, acanthoma, wart, Merkel cell carcinoma, verruca, Bowen disease, keratosis, skin cancer, cutaneous cancer, skin neoplasia, cutaneous neoplasia, and skin tumor. The literature search terms were selected based on the World Health Organization classification of skin tumors.13 Manual bibliography checks were performed on all eligible search results for possible relevant studies. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and, if needed, mediation by a third researcher (N.C.). To be included, a study had to report a case(s) of epidermal tumor(s) that was confirmed by histopathology and arose on a graft donor site in a patient receiving autologous skin grafts for any reason. No language, geographic, or report date restrictions were set.

Data Extraction, Quality Assessment, and Statistical Analysis—We adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.14 Two independent researchers (Z.P. and V.P.) retrieved the data from the included studies. We have used the terms case and patient interchangeably, and 1 month was measured as 4 weeks for simplicity. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and mediation by a third researcher (N.C.). The quality of the included studies was assessed by 2 researchers (M.P. and V.P.) using the tool proposed by Murad et al.15

We used descriptive statistical analysis to analyze clinical characteristics of the included cases. We performed separate descriptive analyses based on the most frequently reported types of epidermal tumors and compared the differences between different groups using the Mann-Whitney U test, χ2 test, and Fisher exact test. The level of significance was set at P<.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 29).

Results

Literature Search and Characteristics of Included Studies—The initial literature search identified 1378 studies, which were screened based on title and abstract. After removing duplicate and irrelevant studies and evaluating the full text of eligible studies, 31 studies (4 case series and 27 case reports) were included in the systematic review (Figure).6-12,16-39 Quality assessment of the included studies is presented in Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Included Patients—Our systematic review included 36 patients with a mean age of 63 years and a male to female ratio of 2:1. The 2 most common causes for skin grafting were burn wounds and surgical excision of skin tumors. Most grafts were harvested from the thighs. The development of a solitary lesion on the donor area was reported in two-thirds of the patients, while more than 1 lesion developed in the remaining one-third of patients. The median time to tumor development was 6.5 weeks. In most cases, a split-thickness skin graft was used.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (CSCCs) were found in 23 patients, with well-differentiated CSCCs in 19 of these cases. Additionally, keratoacanthomas (KAs) were found in 10 patients. The majority of patients underwent surgical excision of the tumor. The median follow-up time was 12 months, during which recurrences were noted in a small percentage of cases. Clinical characteristics of included patients are presented in Table 2.

Comment

Reasons for Tumor Development on Skin Graft Donor Sites—The etiology behind epidermal tumor development on graft donor sites is unclear. According to one theory, iatrogenic contamination of the donor site during the removal of a primary epidermal tumor could be responsible. However, contemporary surgical procedures dictate the use of different sets of instruments for separate surgical sites. Moreover, this theory cannot explain the occurrence of epidermal tumors on donor sites in patients who have undergone skin grafting for the repair of burn wounds.37

Another theory suggests that hematogenous and/or lymphatic spread can occur from the site of the primary epidermal tumor to the donor site, which has increased vascularization.16,37 However, this theory also fails to provide an explanation for the development of epidermal tumors in patients who receive skin grafts for burn wounds.

A third theory states that the microenvironment of the donor site is key to tumor development. The donor site undergoes acute inflammation due to the trauma from harvesting the skin graft. According to this theory, acute inflammation could promote neoplastic growth and thus explain the development of epidermal tumors on the donor site.8,26 However, the relationship between acute inflammation and carcinogenesis remains unclear. What is known to date is that the development of CSCC has been documented primarily in chronically inflamed tissues, whereas the development of KA—a variant of CSCC with distinctive and more benign clinical characteristics—can be expected in the setting of acute trauma-related inflammation.13,40,41

Based on our systematic review, we propose that well-differentiated CSCC on graft donor sites might actually be misdiagnosed KA, given that the histopathologic differential diagnosis between CSCC and KA is extremely challenging.42 This hypothesis could explain the development of well-differentiated CSCC and KA on graft donor sites.

Conclusion

Development of CSCC and KA on graft donor sites can be listed among the postoperative complications of autologous skin grafting. Patients and physicians should be aware of this potential complication, and donor sites should be monitored for the occurrence of epidermal tumors.

Skin grafting is a surgical technique used to cover skin defects resulting from the removal of skin tumors, ulcers, or burn injuries.1-3 Complications can occur at both donor and recipient sites and may include bleeding, hematoma/seroma formation, postoperative pain, infection, scarring, paresthesia, skin pigmentation, graft contracture, and graft failure.1,2,4,5 The development of epidermal tumors is not commonly reported among the complications of skin grafting; however, cases of epidermal tumor development on skin graft donor sites during the postoperative period have been reported.6-12

We performed a systematic review of the literature for cases of epidermal tumor development on skin graft donor sites in patients undergoing autologous skin graft surgery. We present the clinical characteristics of these cases and discuss the nature of these tumors.

Methods

Search Strategy and Study Selection—A literature search was conducted by 2 independent researchers (Z.P. and V.P.) for articles published before December 2022 in the following databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Cochrane Library, OpenGrey, Google Scholar, and WorldCat. Search terms included all possible combinations of the following: keratoacanthoma, molluscum sebaceum, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, acanthoma, wart, Merkel cell carcinoma, verruca, Bowen disease, keratosis, skin cancer, cutaneous cancer, skin neoplasia, cutaneous neoplasia, and skin tumor. The literature search terms were selected based on the World Health Organization classification of skin tumors.13 Manual bibliography checks were performed on all eligible search results for possible relevant studies. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and, if needed, mediation by a third researcher (N.C.). To be included, a study had to report a case(s) of epidermal tumor(s) that was confirmed by histopathology and arose on a graft donor site in a patient receiving autologous skin grafts for any reason. No language, geographic, or report date restrictions were set.

Data Extraction, Quality Assessment, and Statistical Analysis—We adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.14 Two independent researchers (Z.P. and V.P.) retrieved the data from the included studies. We have used the terms case and patient interchangeably, and 1 month was measured as 4 weeks for simplicity. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and mediation by a third researcher (N.C.). The quality of the included studies was assessed by 2 researchers (M.P. and V.P.) using the tool proposed by Murad et al.15

We used descriptive statistical analysis to analyze clinical characteristics of the included cases. We performed separate descriptive analyses based on the most frequently reported types of epidermal tumors and compared the differences between different groups using the Mann-Whitney U test, χ2 test, and Fisher exact test. The level of significance was set at P<.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 29).

Results

Literature Search and Characteristics of Included Studies—The initial literature search identified 1378 studies, which were screened based on title and abstract. After removing duplicate and irrelevant studies and evaluating the full text of eligible studies, 31 studies (4 case series and 27 case reports) were included in the systematic review (Figure).6-12,16-39 Quality assessment of the included studies is presented in Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Included Patients—Our systematic review included 36 patients with a mean age of 63 years and a male to female ratio of 2:1. The 2 most common causes for skin grafting were burn wounds and surgical excision of skin tumors. Most grafts were harvested from the thighs. The development of a solitary lesion on the donor area was reported in two-thirds of the patients, while more than 1 lesion developed in the remaining one-third of patients. The median time to tumor development was 6.5 weeks. In most cases, a split-thickness skin graft was used.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (CSCCs) were found in 23 patients, with well-differentiated CSCCs in 19 of these cases. Additionally, keratoacanthomas (KAs) were found in 10 patients. The majority of patients underwent surgical excision of the tumor. The median follow-up time was 12 months, during which recurrences were noted in a small percentage of cases. Clinical characteristics of included patients are presented in Table 2.

Comment

Reasons for Tumor Development on Skin Graft Donor Sites—The etiology behind epidermal tumor development on graft donor sites is unclear. According to one theory, iatrogenic contamination of the donor site during the removal of a primary epidermal tumor could be responsible. However, contemporary surgical procedures dictate the use of different sets of instruments for separate surgical sites. Moreover, this theory cannot explain the occurrence of epidermal tumors on donor sites in patients who have undergone skin grafting for the repair of burn wounds.37

Another theory suggests that hematogenous and/or lymphatic spread can occur from the site of the primary epidermal tumor to the donor site, which has increased vascularization.16,37 However, this theory also fails to provide an explanation for the development of epidermal tumors in patients who receive skin grafts for burn wounds.

A third theory states that the microenvironment of the donor site is key to tumor development. The donor site undergoes acute inflammation due to the trauma from harvesting the skin graft. According to this theory, acute inflammation could promote neoplastic growth and thus explain the development of epidermal tumors on the donor site.8,26 However, the relationship between acute inflammation and carcinogenesis remains unclear. What is known to date is that the development of CSCC has been documented primarily in chronically inflamed tissues, whereas the development of KA—a variant of CSCC with distinctive and more benign clinical characteristics—can be expected in the setting of acute trauma-related inflammation.13,40,41

Based on our systematic review, we propose that well-differentiated CSCC on graft donor sites might actually be misdiagnosed KA, given that the histopathologic differential diagnosis between CSCC and KA is extremely challenging.42 This hypothesis could explain the development of well-differentiated CSCC and KA on graft donor sites.

Conclusion

Development of CSCC and KA on graft donor sites can be listed among the postoperative complications of autologous skin grafting. Patients and physicians should be aware of this potential complication, and donor sites should be monitored for the occurrence of epidermal tumors.

- Adams DC, Ramsey ML. Grafts in dermatologic surgery: review and update on full- and split-thickness skin grafts, free cartilage grafts, and composite grafts. Dermatologic Surg. 2005;31(8, pt 2):1055-1067. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31831

- Shimizu R, Kishi K. Skin graft. Plast Surg Int. 2012;2012:563493. doi:10.1155/2012/563493

- Reddy S, El-Haddawi F, Fancourt M, et al. The incidence and risk factors for lower limb skin graft failure. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:582080. doi:10.1155/2014/582080

- Coughlin MJ, Dockery GD, Crawford ME, et al. Lower Extremity Soft Tissue & Cutaneous Plastic Surgery. 2nd ed. Saunders Ltd; 2012.

- Herskovitz I, Hughes OB, Macquhae F, et al. Epidermal skin grafting. Int Wound J. 2016;13(suppl 3):52-56. doi:10.1111/iwj.12631

- Wright H, McKinnell TH, Dunkin C. Recurrence of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma at remote limb donor site. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:1265-1266. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2012.01.022

- Thomas W, Rezzadeh K, Rossi K, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising at a skin graft donor site: case report and review of the literature. Plast Surg Case Stud. 2021;7:2513826X211008425. doi:10.1177/2513826X211008425

- Ponnuvelu G, Ng MFY, Connolly CM, et al. Inflammation to skin malignancy, time to rethink the link: SCC in skin graft donor sites. Surgeon. 2011;9:168-169. doi:10.1016/j.surge.2010.08.006

- Noori VJ, Trehan K, Savetamal A, et al. New onset squamous cell carcinoma in previous split-thickness skin graft donor site. Int J Surg. 2018;52:16-19. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.01.047

- Morritt DG, Khandwala AR. The development of squamous cell carcinomas in split-thickness skin graft donor sites. Eur J Plast Surg. 2013;36:377-380.

- McCormick M, Miotke S. Squamous cell carcinoma at split thickness skin graft donor site: a case report and review of the literature. J Burn Care Res. 2023;44:210-213. doi:10.1093/jbcr/irac137

- Haik J, Georgiou I, Farber N, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a split-thickness skin graft donor site. Burns. 2008;34:891-893. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2007.06.006

- Elder DE, Massi D, Scolyer RA WR. WHO Classification of Skin Tumours. 4th ed. IARC Press; 2018.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264-269, W64. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

- Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, et al. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ. 2018;23:60-63. doi:10.1136/bmjebm-2017-110853

- de Moraes LPB, Burchett I, Nicholls S, et al. Large solitary distant metastasis of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma to skin graft site with complete response following definitive radiotherapy. Int J Bioautomation. 2017;21:103-108.