User login

When should an indwelling pleural catheter be considered for malignant pleural effusion?

An indwelling pleural catheter should be considered when a malignant pleural effusion causes symptoms and recurs after thoracentesis, especially in patients with short to intermediate life expectancy or trapped lung, or who underwent unsuccessful pleurodesis.1

MALIGNANT PLEURAL EFFUSION

Malignant pleural effusion affects about 150,000 people in the United States each year. It occurs in 15% of patients with advanced malignancies, most often lung cancer, breast cancer, lymphoma, and ovarian cancer, which account for more than 50% of cases.2

In most patients with malignant pleural effusion, disabling dyspnea causes poor quality of life. The prognosis is unfavorable, with life expectancy of 3 to 12 months. Patients with poor performance status and lower glucose concentrations in the pleural fluid face a worse prognosis and a shorter life expectancy.2

In general, management focuses on relieving symptoms rather than on cure. Symptoms can be controlled by thoracentesis, but if the effusion recurs, the patient needs repeated visits to the emergency room or clinic or a hospital admission to drain the fluid. Frequent hospital visits can be grueling for a patient with a poor functional status, and so can the adverse effects of repeated thoracentesis. For that reason, an early palliative approach to malignant pleural effusion in patients with cancer and a poor prognosis leads to better symptom control and a better quality of life.3 Multiple treatments can be offered to control the symptoms in patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion (Table 1).

PLEURODESIS HAS BEEN THE TREATMENT OF CHOICE

Pleurodesis has been the treatment of choice for malignant pleural effusion for decades. In this procedure, adhesion of the visceral and parietal pleura is achxieved by inducing inflammation either mechanically or chemically between the pleural surfaces. Injection of a sclerosant into the pleural space generates the inflammation. The sclerosant can be introduced through a chest tube or thoracoscope such as in video-assisted thoracic surgery or medical pleuroscopy. The use of talc is associated with a higher success rate than other sclerosing agents such as bleomycin and doxycycline.4

The downside of this procedure is that pleural effusion recurs in 10% to 40% of cases, and patients require 2 to 4 days in the hospital. Also, the use of talc can lead to acute lung injury–acute respiratory distress syndrome, a rare but potentially life-threatening complication. The incidence of this complication may be related to particle size, with small particles posing a higher risk than large ones.5,6

PLACEMENT OF AN INDWELLING PLEURAL CATHETER

Indwelling pleural catheters are currently used as palliative therapy for patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion who suffer from respiratory distress due to rapid reaccumulation of pleural fluids that require multiple thoracentesis procedures.

An indwelling pleural catheter is contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled coagulopathy, multiloculated pleural effusions, or extensive malignancy in the skin.3 Other factors that need to be considered are the patient’s social circumstances: ie, the patient must be in a clean and safe environment and must have insurance coverage for the supplies.

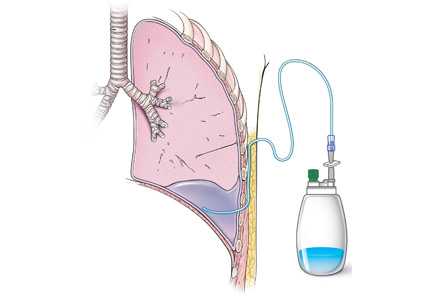

Catheters are 66 cm long and 15.5F and are made of silicone rubber with fenestrations along the distal 24 cm. They have a one-way valve at the proximal end that allows fluids and air to go out but not in (Figure 1).1 Several systems are commercially available in the United States.

The catheter is inserted and tunneled percutaneously with the patient under local anesthesia and conscious sedation (Figure 2). Insertion is a same-day outpatient procedure, and intermittent pleural fluid drainage can be done at home by a home heathcare provider or a trained family member.7

In a meta-analysis, insertion difficulties were reported in only 4% of cases, particularly in patients who underwent prior pleural interventions. Spontaneous pleurodesis occurred in 45% of patients at a mean of 52 days after insertion.8

After catheter insertion, the pleural space should be drained three times a week. No more than 1,000 mL of fluid should be removed at a time—or less if drainage causes chest pain or cough secondary to trapped lung (see below). When the drainage declines to 150 mL per session, the sessions can be reduced to twice a week. If the volume drops to less than 50 mL per session, imaging (computed tomography or bedside thoracic ultrasonography) is recommended to ensure the achievement of pleurodesis and to rule out catheter blockage.

A large multicenter randomized controlled trial9 compared indwelling pleural catheter therapy and chest tube insertion with talc pleurodesis. Both procedures relieved symptoms for the first 42 days, and there was no significant difference in quality of life. However, the median length of hospital stay was 4 days for the talc pleurodesis group compared with 0 days for the indwelling pleural catheter group. Twenty-two percent of the talc group required a further pleural procedure such as a video-assisted thoracic surgery or thoracoscopy, compared with 6% of the indwelling catheter group. On the other hand, 36% of those in the indwelling catheter group experienced nonserious adverse events such as pleural infections that mandated outpatient oral antibiotic therapy, cellulitis, and catheter blockage, compared with 7% of the talc group.9

Symptomatic, inoperable trapped lung is another condition for which an indwelling pleural catheter is a reasonable strategy compared with pleurodesis. Trapped lung is a condition in which the lung fails to fully expand despite proper pleural fluid removal, creating a vacuum space between the parietal and visceral pleura (Figure 3).

Patients with trapped lung complain of severe dull or sharp pain during drainage of pleural fluids due to stretching of the visceral pleura against the intrathoracic vacuum space. Trapped lung can be detected objectively by using intrathoracic manometry while draining fluids, looking for more than a 20-cm H2O drop in the intrathoracic pressure. Radiographically, this may be identified as a pneumothorax ex vacuo10 (ie, caused by inability of the lung to expand to fill the thoracic cavity after pleural fluid has been drained) and is not a procedure complication.

Placement of an indwelling pleural catheter is the treatment of choice for trapped lung, since chemical pleurodesis is not feasible without the potential of parietal and visceral pleural apposition. In a retrospective study of indwelling catheter placement for palliative symptom control, a catheter relieved symptoms, improved quality of life, and afforded a substantial increase in mobility.1,11

In another multicenter pilot study,12 rapid pleurodesis was achieved in 30 patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion by combining chemical pleurodesis and indwelling catheter placement. Both were done under direct vision with medical thoracoscopy. Pleurodesis succeeded in 92% of patients by day 8 after the procedure. The hospital stay was reduced to a mean of 2 days after the procedure. In the catheter group, fluids were drained three times in the first day after the procedure and twice a day on the second and third days. Of the 30 patients in this study, 2 had fever, 1 needed to have the catheter replaced, and 1 contracted empyema.

AN EFFECTIVE INITIAL TREATMENT

Placement of an indwelling pleural catheter is an effective initial treatment for recurrent malignant pleural effusion. Compared with chemical pleurodesis, it has a comparable success rate and complication rate. It offers the advantages of being a same-day surgical procedure entailing a shorter hospital stay and less need for further pleural intervention. This treatment should be considered for patients with symptomatic malignant pleural effusion, especially those in whom symptomatic malignant pleural effusion recurred after thoracentesis.8

- Roberts ME, Neville E, Berrisford RG, Antunes G, Ali NJ; BTS Pleural Disease Guideline Group. Management of a malignant pleural effusion: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax 2010; 65(suppl 2):ii32–ii40.

- Thomas JM, Musani AI. Malignant pleural effusions: a review. Clin Chest Med 2013; 34:459–471.

- Thomas R, Francis R, Davies HE, Lee YC. Interventional therapies for malignant pleural effusions: the present and the future. Respirology 2014; 19:809–822.

- Rodriguez-Panadero F, Montes-Worboys A. Mechanisms of pleurodesis. Respiration 2012; 83:91–98.

- Gonzalez AV, Bezwada V, Beamis JF Jr, Villanueva AG. Lung injury following thoracoscopic talc insufflation: experience of a single North American center. Chest 2010; 137:1375–1381.

- Rossi VF, Vargas FS, Marchi E, et al. Acute inflammatory response secondary to intrapleural administration of two types of talc. Eur Respir J 2010; 35:396–401.

- Fysh ET, Waterer GW, Kendall PA, et al. Indwelling pleural catheters reduce inpatient days over pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusion. Chest 2012; 142:394–400.

- Kheir F, Shawwa K, Alokla K, Omballi M, Alraiyes AH. Tunneled pleural catheter for the treatment of malignant pleural effusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ther 2015 Feb 2. [Epub ahead of print]

- Davies HE, Mishra EK, Kahan BC, et al. Effect of an indwelling pleural catheter vs chest tube and talc pleurodesis for relieving dyspnea in patients with malignant pleural effusion: the TIME2 randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012; 307:2383–2389.

- Ponrartana S, Laberge JM, Kerlan RK, Wilson MW, Gordon RL. Management of patients with “ex vacuo” pneumothorax after thoracentesis. Acad Radiol 2005; 12:980–986.

- Efthymiou CA, Masudi T, Thorpe JA, Papagiannopoulos K. Malignant pleural effusion in the presence of trapped lung. Five-year experience of PleurX tunnelled catheters. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2009; 9:961–964.

- Reddy C, Ernst A, Lamb C, Feller-Kopman D. Rapid pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusions: a pilot study. Chest 2011; 139:1419–1423.

An indwelling pleural catheter should be considered when a malignant pleural effusion causes symptoms and recurs after thoracentesis, especially in patients with short to intermediate life expectancy or trapped lung, or who underwent unsuccessful pleurodesis.1

MALIGNANT PLEURAL EFFUSION

Malignant pleural effusion affects about 150,000 people in the United States each year. It occurs in 15% of patients with advanced malignancies, most often lung cancer, breast cancer, lymphoma, and ovarian cancer, which account for more than 50% of cases.2

In most patients with malignant pleural effusion, disabling dyspnea causes poor quality of life. The prognosis is unfavorable, with life expectancy of 3 to 12 months. Patients with poor performance status and lower glucose concentrations in the pleural fluid face a worse prognosis and a shorter life expectancy.2

In general, management focuses on relieving symptoms rather than on cure. Symptoms can be controlled by thoracentesis, but if the effusion recurs, the patient needs repeated visits to the emergency room or clinic or a hospital admission to drain the fluid. Frequent hospital visits can be grueling for a patient with a poor functional status, and so can the adverse effects of repeated thoracentesis. For that reason, an early palliative approach to malignant pleural effusion in patients with cancer and a poor prognosis leads to better symptom control and a better quality of life.3 Multiple treatments can be offered to control the symptoms in patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion (Table 1).

PLEURODESIS HAS BEEN THE TREATMENT OF CHOICE

Pleurodesis has been the treatment of choice for malignant pleural effusion for decades. In this procedure, adhesion of the visceral and parietal pleura is achxieved by inducing inflammation either mechanically or chemically between the pleural surfaces. Injection of a sclerosant into the pleural space generates the inflammation. The sclerosant can be introduced through a chest tube or thoracoscope such as in video-assisted thoracic surgery or medical pleuroscopy. The use of talc is associated with a higher success rate than other sclerosing agents such as bleomycin and doxycycline.4

The downside of this procedure is that pleural effusion recurs in 10% to 40% of cases, and patients require 2 to 4 days in the hospital. Also, the use of talc can lead to acute lung injury–acute respiratory distress syndrome, a rare but potentially life-threatening complication. The incidence of this complication may be related to particle size, with small particles posing a higher risk than large ones.5,6

PLACEMENT OF AN INDWELLING PLEURAL CATHETER

Indwelling pleural catheters are currently used as palliative therapy for patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion who suffer from respiratory distress due to rapid reaccumulation of pleural fluids that require multiple thoracentesis procedures.

An indwelling pleural catheter is contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled coagulopathy, multiloculated pleural effusions, or extensive malignancy in the skin.3 Other factors that need to be considered are the patient’s social circumstances: ie, the patient must be in a clean and safe environment and must have insurance coverage for the supplies.

Catheters are 66 cm long and 15.5F and are made of silicone rubber with fenestrations along the distal 24 cm. They have a one-way valve at the proximal end that allows fluids and air to go out but not in (Figure 1).1 Several systems are commercially available in the United States.

The catheter is inserted and tunneled percutaneously with the patient under local anesthesia and conscious sedation (Figure 2). Insertion is a same-day outpatient procedure, and intermittent pleural fluid drainage can be done at home by a home heathcare provider or a trained family member.7

In a meta-analysis, insertion difficulties were reported in only 4% of cases, particularly in patients who underwent prior pleural interventions. Spontaneous pleurodesis occurred in 45% of patients at a mean of 52 days after insertion.8

After catheter insertion, the pleural space should be drained three times a week. No more than 1,000 mL of fluid should be removed at a time—or less if drainage causes chest pain or cough secondary to trapped lung (see below). When the drainage declines to 150 mL per session, the sessions can be reduced to twice a week. If the volume drops to less than 50 mL per session, imaging (computed tomography or bedside thoracic ultrasonography) is recommended to ensure the achievement of pleurodesis and to rule out catheter blockage.

A large multicenter randomized controlled trial9 compared indwelling pleural catheter therapy and chest tube insertion with talc pleurodesis. Both procedures relieved symptoms for the first 42 days, and there was no significant difference in quality of life. However, the median length of hospital stay was 4 days for the talc pleurodesis group compared with 0 days for the indwelling pleural catheter group. Twenty-two percent of the talc group required a further pleural procedure such as a video-assisted thoracic surgery or thoracoscopy, compared with 6% of the indwelling catheter group. On the other hand, 36% of those in the indwelling catheter group experienced nonserious adverse events such as pleural infections that mandated outpatient oral antibiotic therapy, cellulitis, and catheter blockage, compared with 7% of the talc group.9

Symptomatic, inoperable trapped lung is another condition for which an indwelling pleural catheter is a reasonable strategy compared with pleurodesis. Trapped lung is a condition in which the lung fails to fully expand despite proper pleural fluid removal, creating a vacuum space between the parietal and visceral pleura (Figure 3).

Patients with trapped lung complain of severe dull or sharp pain during drainage of pleural fluids due to stretching of the visceral pleura against the intrathoracic vacuum space. Trapped lung can be detected objectively by using intrathoracic manometry while draining fluids, looking for more than a 20-cm H2O drop in the intrathoracic pressure. Radiographically, this may be identified as a pneumothorax ex vacuo10 (ie, caused by inability of the lung to expand to fill the thoracic cavity after pleural fluid has been drained) and is not a procedure complication.

Placement of an indwelling pleural catheter is the treatment of choice for trapped lung, since chemical pleurodesis is not feasible without the potential of parietal and visceral pleural apposition. In a retrospective study of indwelling catheter placement for palliative symptom control, a catheter relieved symptoms, improved quality of life, and afforded a substantial increase in mobility.1,11

In another multicenter pilot study,12 rapid pleurodesis was achieved in 30 patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion by combining chemical pleurodesis and indwelling catheter placement. Both were done under direct vision with medical thoracoscopy. Pleurodesis succeeded in 92% of patients by day 8 after the procedure. The hospital stay was reduced to a mean of 2 days after the procedure. In the catheter group, fluids were drained three times in the first day after the procedure and twice a day on the second and third days. Of the 30 patients in this study, 2 had fever, 1 needed to have the catheter replaced, and 1 contracted empyema.

AN EFFECTIVE INITIAL TREATMENT

Placement of an indwelling pleural catheter is an effective initial treatment for recurrent malignant pleural effusion. Compared with chemical pleurodesis, it has a comparable success rate and complication rate. It offers the advantages of being a same-day surgical procedure entailing a shorter hospital stay and less need for further pleural intervention. This treatment should be considered for patients with symptomatic malignant pleural effusion, especially those in whom symptomatic malignant pleural effusion recurred after thoracentesis.8

An indwelling pleural catheter should be considered when a malignant pleural effusion causes symptoms and recurs after thoracentesis, especially in patients with short to intermediate life expectancy or trapped lung, or who underwent unsuccessful pleurodesis.1

MALIGNANT PLEURAL EFFUSION

Malignant pleural effusion affects about 150,000 people in the United States each year. It occurs in 15% of patients with advanced malignancies, most often lung cancer, breast cancer, lymphoma, and ovarian cancer, which account for more than 50% of cases.2

In most patients with malignant pleural effusion, disabling dyspnea causes poor quality of life. The prognosis is unfavorable, with life expectancy of 3 to 12 months. Patients with poor performance status and lower glucose concentrations in the pleural fluid face a worse prognosis and a shorter life expectancy.2

In general, management focuses on relieving symptoms rather than on cure. Symptoms can be controlled by thoracentesis, but if the effusion recurs, the patient needs repeated visits to the emergency room or clinic or a hospital admission to drain the fluid. Frequent hospital visits can be grueling for a patient with a poor functional status, and so can the adverse effects of repeated thoracentesis. For that reason, an early palliative approach to malignant pleural effusion in patients with cancer and a poor prognosis leads to better symptom control and a better quality of life.3 Multiple treatments can be offered to control the symptoms in patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion (Table 1).

PLEURODESIS HAS BEEN THE TREATMENT OF CHOICE

Pleurodesis has been the treatment of choice for malignant pleural effusion for decades. In this procedure, adhesion of the visceral and parietal pleura is achxieved by inducing inflammation either mechanically or chemically between the pleural surfaces. Injection of a sclerosant into the pleural space generates the inflammation. The sclerosant can be introduced through a chest tube or thoracoscope such as in video-assisted thoracic surgery or medical pleuroscopy. The use of talc is associated with a higher success rate than other sclerosing agents such as bleomycin and doxycycline.4

The downside of this procedure is that pleural effusion recurs in 10% to 40% of cases, and patients require 2 to 4 days in the hospital. Also, the use of talc can lead to acute lung injury–acute respiratory distress syndrome, a rare but potentially life-threatening complication. The incidence of this complication may be related to particle size, with small particles posing a higher risk than large ones.5,6

PLACEMENT OF AN INDWELLING PLEURAL CATHETER

Indwelling pleural catheters are currently used as palliative therapy for patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion who suffer from respiratory distress due to rapid reaccumulation of pleural fluids that require multiple thoracentesis procedures.

An indwelling pleural catheter is contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled coagulopathy, multiloculated pleural effusions, or extensive malignancy in the skin.3 Other factors that need to be considered are the patient’s social circumstances: ie, the patient must be in a clean and safe environment and must have insurance coverage for the supplies.

Catheters are 66 cm long and 15.5F and are made of silicone rubber with fenestrations along the distal 24 cm. They have a one-way valve at the proximal end that allows fluids and air to go out but not in (Figure 1).1 Several systems are commercially available in the United States.

The catheter is inserted and tunneled percutaneously with the patient under local anesthesia and conscious sedation (Figure 2). Insertion is a same-day outpatient procedure, and intermittent pleural fluid drainage can be done at home by a home heathcare provider or a trained family member.7

In a meta-analysis, insertion difficulties were reported in only 4% of cases, particularly in patients who underwent prior pleural interventions. Spontaneous pleurodesis occurred in 45% of patients at a mean of 52 days after insertion.8

After catheter insertion, the pleural space should be drained three times a week. No more than 1,000 mL of fluid should be removed at a time—or less if drainage causes chest pain or cough secondary to trapped lung (see below). When the drainage declines to 150 mL per session, the sessions can be reduced to twice a week. If the volume drops to less than 50 mL per session, imaging (computed tomography or bedside thoracic ultrasonography) is recommended to ensure the achievement of pleurodesis and to rule out catheter blockage.

A large multicenter randomized controlled trial9 compared indwelling pleural catheter therapy and chest tube insertion with talc pleurodesis. Both procedures relieved symptoms for the first 42 days, and there was no significant difference in quality of life. However, the median length of hospital stay was 4 days for the talc pleurodesis group compared with 0 days for the indwelling pleural catheter group. Twenty-two percent of the talc group required a further pleural procedure such as a video-assisted thoracic surgery or thoracoscopy, compared with 6% of the indwelling catheter group. On the other hand, 36% of those in the indwelling catheter group experienced nonserious adverse events such as pleural infections that mandated outpatient oral antibiotic therapy, cellulitis, and catheter blockage, compared with 7% of the talc group.9

Symptomatic, inoperable trapped lung is another condition for which an indwelling pleural catheter is a reasonable strategy compared with pleurodesis. Trapped lung is a condition in which the lung fails to fully expand despite proper pleural fluid removal, creating a vacuum space between the parietal and visceral pleura (Figure 3).

Patients with trapped lung complain of severe dull or sharp pain during drainage of pleural fluids due to stretching of the visceral pleura against the intrathoracic vacuum space. Trapped lung can be detected objectively by using intrathoracic manometry while draining fluids, looking for more than a 20-cm H2O drop in the intrathoracic pressure. Radiographically, this may be identified as a pneumothorax ex vacuo10 (ie, caused by inability of the lung to expand to fill the thoracic cavity after pleural fluid has been drained) and is not a procedure complication.

Placement of an indwelling pleural catheter is the treatment of choice for trapped lung, since chemical pleurodesis is not feasible without the potential of parietal and visceral pleural apposition. In a retrospective study of indwelling catheter placement for palliative symptom control, a catheter relieved symptoms, improved quality of life, and afforded a substantial increase in mobility.1,11

In another multicenter pilot study,12 rapid pleurodesis was achieved in 30 patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion by combining chemical pleurodesis and indwelling catheter placement. Both were done under direct vision with medical thoracoscopy. Pleurodesis succeeded in 92% of patients by day 8 after the procedure. The hospital stay was reduced to a mean of 2 days after the procedure. In the catheter group, fluids were drained three times in the first day after the procedure and twice a day on the second and third days. Of the 30 patients in this study, 2 had fever, 1 needed to have the catheter replaced, and 1 contracted empyema.

AN EFFECTIVE INITIAL TREATMENT

Placement of an indwelling pleural catheter is an effective initial treatment for recurrent malignant pleural effusion. Compared with chemical pleurodesis, it has a comparable success rate and complication rate. It offers the advantages of being a same-day surgical procedure entailing a shorter hospital stay and less need for further pleural intervention. This treatment should be considered for patients with symptomatic malignant pleural effusion, especially those in whom symptomatic malignant pleural effusion recurred after thoracentesis.8

- Roberts ME, Neville E, Berrisford RG, Antunes G, Ali NJ; BTS Pleural Disease Guideline Group. Management of a malignant pleural effusion: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax 2010; 65(suppl 2):ii32–ii40.

- Thomas JM, Musani AI. Malignant pleural effusions: a review. Clin Chest Med 2013; 34:459–471.

- Thomas R, Francis R, Davies HE, Lee YC. Interventional therapies for malignant pleural effusions: the present and the future. Respirology 2014; 19:809–822.

- Rodriguez-Panadero F, Montes-Worboys A. Mechanisms of pleurodesis. Respiration 2012; 83:91–98.

- Gonzalez AV, Bezwada V, Beamis JF Jr, Villanueva AG. Lung injury following thoracoscopic talc insufflation: experience of a single North American center. Chest 2010; 137:1375–1381.

- Rossi VF, Vargas FS, Marchi E, et al. Acute inflammatory response secondary to intrapleural administration of two types of talc. Eur Respir J 2010; 35:396–401.

- Fysh ET, Waterer GW, Kendall PA, et al. Indwelling pleural catheters reduce inpatient days over pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusion. Chest 2012; 142:394–400.

- Kheir F, Shawwa K, Alokla K, Omballi M, Alraiyes AH. Tunneled pleural catheter for the treatment of malignant pleural effusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ther 2015 Feb 2. [Epub ahead of print]

- Davies HE, Mishra EK, Kahan BC, et al. Effect of an indwelling pleural catheter vs chest tube and talc pleurodesis for relieving dyspnea in patients with malignant pleural effusion: the TIME2 randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012; 307:2383–2389.

- Ponrartana S, Laberge JM, Kerlan RK, Wilson MW, Gordon RL. Management of patients with “ex vacuo” pneumothorax after thoracentesis. Acad Radiol 2005; 12:980–986.

- Efthymiou CA, Masudi T, Thorpe JA, Papagiannopoulos K. Malignant pleural effusion in the presence of trapped lung. Five-year experience of PleurX tunnelled catheters. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2009; 9:961–964.

- Reddy C, Ernst A, Lamb C, Feller-Kopman D. Rapid pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusions: a pilot study. Chest 2011; 139:1419–1423.

- Roberts ME, Neville E, Berrisford RG, Antunes G, Ali NJ; BTS Pleural Disease Guideline Group. Management of a malignant pleural effusion: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax 2010; 65(suppl 2):ii32–ii40.

- Thomas JM, Musani AI. Malignant pleural effusions: a review. Clin Chest Med 2013; 34:459–471.

- Thomas R, Francis R, Davies HE, Lee YC. Interventional therapies for malignant pleural effusions: the present and the future. Respirology 2014; 19:809–822.

- Rodriguez-Panadero F, Montes-Worboys A. Mechanisms of pleurodesis. Respiration 2012; 83:91–98.

- Gonzalez AV, Bezwada V, Beamis JF Jr, Villanueva AG. Lung injury following thoracoscopic talc insufflation: experience of a single North American center. Chest 2010; 137:1375–1381.

- Rossi VF, Vargas FS, Marchi E, et al. Acute inflammatory response secondary to intrapleural administration of two types of talc. Eur Respir J 2010; 35:396–401.

- Fysh ET, Waterer GW, Kendall PA, et al. Indwelling pleural catheters reduce inpatient days over pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusion. Chest 2012; 142:394–400.

- Kheir F, Shawwa K, Alokla K, Omballi M, Alraiyes AH. Tunneled pleural catheter for the treatment of malignant pleural effusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ther 2015 Feb 2. [Epub ahead of print]

- Davies HE, Mishra EK, Kahan BC, et al. Effect of an indwelling pleural catheter vs chest tube and talc pleurodesis for relieving dyspnea in patients with malignant pleural effusion: the TIME2 randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012; 307:2383–2389.

- Ponrartana S, Laberge JM, Kerlan RK, Wilson MW, Gordon RL. Management of patients with “ex vacuo” pneumothorax after thoracentesis. Acad Radiol 2005; 12:980–986.

- Efthymiou CA, Masudi T, Thorpe JA, Papagiannopoulos K. Malignant pleural effusion in the presence of trapped lung. Five-year experience of PleurX tunnelled catheters. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2009; 9:961–964.

- Reddy C, Ernst A, Lamb C, Feller-Kopman D. Rapid pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusions: a pilot study. Chest 2011; 139:1419–1423.

Does stenting of severe renal artery stenosis improve outomes compared with medical therapy alone?

No. In patients with severe atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis and hypertension or chronic kidney disease, renal artery stenting offers no additional benefit when added to comprehensive medical therapy.

In these patients, renal artery stenting in addition to antihypertensive drug therapy can improve blood pressure control modestly but has no significant effect on outcomes such as adverse cardiovascular events and death. And because renal artery stenting carries a risk of complications, medical management should continue to be the first-line therapy.

RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS

Renal artery stenosis is a common form of peripheral artery disease. Atherosclerosis is the most common cause, but it can also be caused by fibromuscular dysplasia or vasculitis (eg, Takayasu arteritis). It is most often unilateral, but bilateral disease has also been reported.

The prevalence of atherosclerotic renal vascular disease in the US Medicare population is 0.5%, and 5.5% in those with chronic kidney disease.1 Furthermore, renal artery stenosis is found in 6.8% of adults over age 65.2 The prevalence increases with age and is higher in patients with hyperlipidemia, peripheral arterial disease, and hypertension. The prevalence of renal artery stenosis in patients with atherosclerotic disease and renal dysfunction is as high as 50%.3

Patients with peripheral artery disease may be five times more likely to develop renal artery stenosis than people without peripheral artery disease.4 Significant stenosis can result in resistant arterial hypertension, renal insufficiency, left ventricular hypertrophy, and congestive heart failure.5

Nephropathy due to renal artery stenosis is complex and is caused by hypoperfusion and chronic microatheroembolism. Renal artery stenosis leads to oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrosis in the stenotic kidney, and, over time, loss of kidney function. Hypoperfusion also leads to activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, which plays a role in development of left ventricular hypertrophy.5,6

Adequate blood pressure control, goal-directed lipid-lowering therapy, smoking cessation, and other preventive measures are the foundation of management.

RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS AND HYPERTENSION

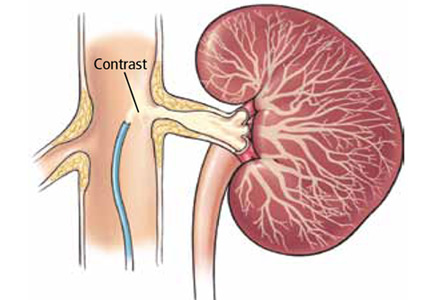

Renal artery stenosis is a cause of secondary hypertension. The stenosis decreases renal perfusion pressure, activating the release of renin and the production of angiotensin II, which in turn raises the blood pressure by two mechanisms (Figure 1): directly, by causing generalized vasoconstriction, and indirectly, by stimulating the release of aldosterone, which in turn increases the reabsorption of sodium and causes hypervolemia. These two mechanisms play a major role in renal vascular hypertension when renal artery stenosis is bilateral. In unilateral renal artery stenosis, pressure diuresis in the unaffected kidney compensates for the reabsorption of sodium in the affected kidney, keeping the blood pressure down. However, with time, the unaffected kidney will develop hypertensive nephropathy, and pressure diuresis will be lost.7,8 In addition, the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system results in structural heart disease, such as left ventricular hypertrophy,5 and may shorten survival.

STENTING PLUS ANTIHYPERTENSIVE DRUG THERAPY

Because observational studies showed improvement in blood pressure control after endovascular stenting of atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis,9,10 this approach became a treatment option for uncontrolled hypertension in these patients. The 2005 joint guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association11 considered percutaneous revascularization a reasonable option (level of evidence B) for patients who meet one of the following criteria:

- Hemodynamically significant stenosis and accelerated, resistant, or malignant hypertension, hypertension with an unexplained unilateral small kidney, or hypertension with intolerance to medication

- Renal artery stenosis and progressive chronic kidney disease with bilateral stenosis or stenosis in a solitary functioning kidney

- Hemodynamically significant stenosis and recurrent, unexplained congestive heart failure or sudden, unexplained pulmonary edema or unstable angina.11

However, no randomized study has shown a direct benefit of renal artery stenting on rates of cardiovascular events or renal function compared with drug therapy alone.

TRIALS OF STENTING VS MEDICAL THERAPY ALONE

Technical improvements have led to more widespread use of diagnostic and interventional endovascular tools for renal artery revascularization. Studies over the past 10 years examined the impact of stenting in patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

The STAR trial

In the Stent Placement and Blood Pressure and Lipid-lowering for the Prevention of Progression of Renal Dysfunction Caused by Atherosclerotic Ostial Stenosis of the Renal Artery (STAR) trial,9 patients with creatinine clearance less than 80 mL/min/1.73 m2, renal artery stenosis greater than 50%, and well-controlled blood pressure were randomized to either renal artery stenting plus medical therapy or medical therapy alone. The authors concluded that stenting had no effect on the progression of renal dysfunction but led to a small number of significant, procedure-related complications. The study was criticized for including patients with mild stenosis (< 50% stenosis) and for being underpowered for the primary end point.

The ASTRAL study

The Angioplasty and Stenting for Renal Artery Lesions (ASTRAL) study10 was a similar comparison with similar results, showing no benefit from stenting with respect to renal function, systolic blood pressure control, cardiovascular events, or death.

HERCULES

The Herculink Elite Cobalt Chromium Renal Stent Trial to Demonstrate Efficacy and Safety (HERCULES)12 was a prospective multicenter study of the effects of renal artery stenting in 202 patients with significant renal artery stenosis and uncontrolled hypertension. It showed a reduction in systolic blood pressure from baseline (P < .0001). However, follow-up was only 9 months, which was insufficient to show a significant effect on long-term cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes.

The CORAL trial

The Cardiovascular Outcomes in Renal Atherosclerotic Lesions (CORAL) trial13 used more stringent definitions and longer follow-up. It randomized 947 patients to either stenting plus medical therapy or medical therapy alone. Patients had atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis, defined as stenosis of at least 80% or stenosis of 60% to 80% with a gradient of at least 20 mm Hg in the systolic pressure), and either systolic hypertension while taking two or more antihypertensive drugs or stage 3 or higher chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 as calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula).

Participants were followed for 43 months to detect the occurrence of adverse cardiovascular and renal events. There was no significant difference in primary outcome between stenting plus drug therapy and drug therapy alone (35.1% and 35.8%, respectively; P = .58). However, stenting plus drug therapy was associated with modestly lower systolic pressures compared with drug therapy alone (−2.3 mm Hg, 95% confidence interval −4.4 to −0.2 mm Hg, P = .03).13 This study provided strong evidence that renal artery stenting offers no significant benefit to patients with moderately severe atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis, and that stenting may actually pose an unnecessary risk.

COMPLICATIONS OF RENAL ARTERY STENTING

Complications of renal artery stenting are a limiting factor compared with drug therapy alone, especially since the procedure offers no significant benefit in outcome. Procedural complication rates of 10% to 15% have been reported.9,10,12 The CORAL trial reported arterial dissection in 2.2%, branch-vessel occlusion in 1.2%, and distal embolization in 1.2% of patients undergoing stenting.13 Other reported complications have included stent misplacement requiring an additional stent, access-vessel damage, stent embolization, renal artery thrombosis or occlusion, and death.10,12

- Kalra PA, Guo H, Kausz AT, et al. Atherosclerotic renovascular disease in United States patients aged 67 years or older: risk factors, revascularization, and prognosis. Kidney Int 2005; 68:293–301.

- Hansen KJ, Edwards MS, Craven TE, et al. Prevalence of renovascular disease in the elderly: a population-based study. J Vasc Surg 2002; 36:443–451.

- Uzu T, Takeji M, Yamada N, et al. Prevalence and outcome of renal artery stenosis in atherosclerotic patients with renal dysfunction. Hypertens Res 2002; 25:537–542.

- Benjamin MM, Fazel P, Filardo G, Choi JW, Stoler RC. Prevalence of and risk factors of renal artery stenosis in patients with resistant hypertension. Am J Cardiol 2014; 113:687–690.

- Wu S, Polavarapu N, Stouffer GA. Left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with renal artery stenosis. Am J Med Sci 2006; 332:334–338.

- Lerman LO, Textor SC, Grande JP. Mechanisms of tissue injury in renal artery stenosis: ischemia and beyond. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2009; 52:196–203.

- Black HR, Glickman MG, Schiff M Jr, Pingoud EG. Renovascular hypertension: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Yale J Biol Med 1978; 51:635–654.

- Tobe SW, Burgess E, Lebel M. Atherosclerotic renovascular disease. Can J Cardiol 2006; 22:623–628.

- Bax L, Mali WP, Buskens E, et al; STAR Study Group. The benefit of stent placement and blood pressure and lipid-lowering for the prevention of progression of renal dysfunction caused by atherosclerotic ostial stenosis of the renal artery. The STAR-study: rationale and study design. J Nephrol 2003; 16:807–812.

- ASTRAL Investigators; Wheatley K, Ives N, Gray R, et al. Revascularization versus medical therapy for renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1953–1962.

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47:1239–1312.

No. In patients with severe atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis and hypertension or chronic kidney disease, renal artery stenting offers no additional benefit when added to comprehensive medical therapy.

In these patients, renal artery stenting in addition to antihypertensive drug therapy can improve blood pressure control modestly but has no significant effect on outcomes such as adverse cardiovascular events and death. And because renal artery stenting carries a risk of complications, medical management should continue to be the first-line therapy.

RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS

Renal artery stenosis is a common form of peripheral artery disease. Atherosclerosis is the most common cause, but it can also be caused by fibromuscular dysplasia or vasculitis (eg, Takayasu arteritis). It is most often unilateral, but bilateral disease has also been reported.

The prevalence of atherosclerotic renal vascular disease in the US Medicare population is 0.5%, and 5.5% in those with chronic kidney disease.1 Furthermore, renal artery stenosis is found in 6.8% of adults over age 65.2 The prevalence increases with age and is higher in patients with hyperlipidemia, peripheral arterial disease, and hypertension. The prevalence of renal artery stenosis in patients with atherosclerotic disease and renal dysfunction is as high as 50%.3

Patients with peripheral artery disease may be five times more likely to develop renal artery stenosis than people without peripheral artery disease.4 Significant stenosis can result in resistant arterial hypertension, renal insufficiency, left ventricular hypertrophy, and congestive heart failure.5

Nephropathy due to renal artery stenosis is complex and is caused by hypoperfusion and chronic microatheroembolism. Renal artery stenosis leads to oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrosis in the stenotic kidney, and, over time, loss of kidney function. Hypoperfusion also leads to activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, which plays a role in development of left ventricular hypertrophy.5,6

Adequate blood pressure control, goal-directed lipid-lowering therapy, smoking cessation, and other preventive measures are the foundation of management.

RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS AND HYPERTENSION

Renal artery stenosis is a cause of secondary hypertension. The stenosis decreases renal perfusion pressure, activating the release of renin and the production of angiotensin II, which in turn raises the blood pressure by two mechanisms (Figure 1): directly, by causing generalized vasoconstriction, and indirectly, by stimulating the release of aldosterone, which in turn increases the reabsorption of sodium and causes hypervolemia. These two mechanisms play a major role in renal vascular hypertension when renal artery stenosis is bilateral. In unilateral renal artery stenosis, pressure diuresis in the unaffected kidney compensates for the reabsorption of sodium in the affected kidney, keeping the blood pressure down. However, with time, the unaffected kidney will develop hypertensive nephropathy, and pressure diuresis will be lost.7,8 In addition, the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system results in structural heart disease, such as left ventricular hypertrophy,5 and may shorten survival.

STENTING PLUS ANTIHYPERTENSIVE DRUG THERAPY

Because observational studies showed improvement in blood pressure control after endovascular stenting of atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis,9,10 this approach became a treatment option for uncontrolled hypertension in these patients. The 2005 joint guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association11 considered percutaneous revascularization a reasonable option (level of evidence B) for patients who meet one of the following criteria:

- Hemodynamically significant stenosis and accelerated, resistant, or malignant hypertension, hypertension with an unexplained unilateral small kidney, or hypertension with intolerance to medication

- Renal artery stenosis and progressive chronic kidney disease with bilateral stenosis or stenosis in a solitary functioning kidney

- Hemodynamically significant stenosis and recurrent, unexplained congestive heart failure or sudden, unexplained pulmonary edema or unstable angina.11

However, no randomized study has shown a direct benefit of renal artery stenting on rates of cardiovascular events or renal function compared with drug therapy alone.

TRIALS OF STENTING VS MEDICAL THERAPY ALONE

Technical improvements have led to more widespread use of diagnostic and interventional endovascular tools for renal artery revascularization. Studies over the past 10 years examined the impact of stenting in patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

The STAR trial

In the Stent Placement and Blood Pressure and Lipid-lowering for the Prevention of Progression of Renal Dysfunction Caused by Atherosclerotic Ostial Stenosis of the Renal Artery (STAR) trial,9 patients with creatinine clearance less than 80 mL/min/1.73 m2, renal artery stenosis greater than 50%, and well-controlled blood pressure were randomized to either renal artery stenting plus medical therapy or medical therapy alone. The authors concluded that stenting had no effect on the progression of renal dysfunction but led to a small number of significant, procedure-related complications. The study was criticized for including patients with mild stenosis (< 50% stenosis) and for being underpowered for the primary end point.

The ASTRAL study

The Angioplasty and Stenting for Renal Artery Lesions (ASTRAL) study10 was a similar comparison with similar results, showing no benefit from stenting with respect to renal function, systolic blood pressure control, cardiovascular events, or death.

HERCULES

The Herculink Elite Cobalt Chromium Renal Stent Trial to Demonstrate Efficacy and Safety (HERCULES)12 was a prospective multicenter study of the effects of renal artery stenting in 202 patients with significant renal artery stenosis and uncontrolled hypertension. It showed a reduction in systolic blood pressure from baseline (P < .0001). However, follow-up was only 9 months, which was insufficient to show a significant effect on long-term cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes.

The CORAL trial

The Cardiovascular Outcomes in Renal Atherosclerotic Lesions (CORAL) trial13 used more stringent definitions and longer follow-up. It randomized 947 patients to either stenting plus medical therapy or medical therapy alone. Patients had atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis, defined as stenosis of at least 80% or stenosis of 60% to 80% with a gradient of at least 20 mm Hg in the systolic pressure), and either systolic hypertension while taking two or more antihypertensive drugs or stage 3 or higher chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 as calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula).

Participants were followed for 43 months to detect the occurrence of adverse cardiovascular and renal events. There was no significant difference in primary outcome between stenting plus drug therapy and drug therapy alone (35.1% and 35.8%, respectively; P = .58). However, stenting plus drug therapy was associated with modestly lower systolic pressures compared with drug therapy alone (−2.3 mm Hg, 95% confidence interval −4.4 to −0.2 mm Hg, P = .03).13 This study provided strong evidence that renal artery stenting offers no significant benefit to patients with moderately severe atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis, and that stenting may actually pose an unnecessary risk.

COMPLICATIONS OF RENAL ARTERY STENTING

Complications of renal artery stenting are a limiting factor compared with drug therapy alone, especially since the procedure offers no significant benefit in outcome. Procedural complication rates of 10% to 15% have been reported.9,10,12 The CORAL trial reported arterial dissection in 2.2%, branch-vessel occlusion in 1.2%, and distal embolization in 1.2% of patients undergoing stenting.13 Other reported complications have included stent misplacement requiring an additional stent, access-vessel damage, stent embolization, renal artery thrombosis or occlusion, and death.10,12

No. In patients with severe atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis and hypertension or chronic kidney disease, renal artery stenting offers no additional benefit when added to comprehensive medical therapy.

In these patients, renal artery stenting in addition to antihypertensive drug therapy can improve blood pressure control modestly but has no significant effect on outcomes such as adverse cardiovascular events and death. And because renal artery stenting carries a risk of complications, medical management should continue to be the first-line therapy.

RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS

Renal artery stenosis is a common form of peripheral artery disease. Atherosclerosis is the most common cause, but it can also be caused by fibromuscular dysplasia or vasculitis (eg, Takayasu arteritis). It is most often unilateral, but bilateral disease has also been reported.

The prevalence of atherosclerotic renal vascular disease in the US Medicare population is 0.5%, and 5.5% in those with chronic kidney disease.1 Furthermore, renal artery stenosis is found in 6.8% of adults over age 65.2 The prevalence increases with age and is higher in patients with hyperlipidemia, peripheral arterial disease, and hypertension. The prevalence of renal artery stenosis in patients with atherosclerotic disease and renal dysfunction is as high as 50%.3

Patients with peripheral artery disease may be five times more likely to develop renal artery stenosis than people without peripheral artery disease.4 Significant stenosis can result in resistant arterial hypertension, renal insufficiency, left ventricular hypertrophy, and congestive heart failure.5

Nephropathy due to renal artery stenosis is complex and is caused by hypoperfusion and chronic microatheroembolism. Renal artery stenosis leads to oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrosis in the stenotic kidney, and, over time, loss of kidney function. Hypoperfusion also leads to activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, which plays a role in development of left ventricular hypertrophy.5,6

Adequate blood pressure control, goal-directed lipid-lowering therapy, smoking cessation, and other preventive measures are the foundation of management.

RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS AND HYPERTENSION

Renal artery stenosis is a cause of secondary hypertension. The stenosis decreases renal perfusion pressure, activating the release of renin and the production of angiotensin II, which in turn raises the blood pressure by two mechanisms (Figure 1): directly, by causing generalized vasoconstriction, and indirectly, by stimulating the release of aldosterone, which in turn increases the reabsorption of sodium and causes hypervolemia. These two mechanisms play a major role in renal vascular hypertension when renal artery stenosis is bilateral. In unilateral renal artery stenosis, pressure diuresis in the unaffected kidney compensates for the reabsorption of sodium in the affected kidney, keeping the blood pressure down. However, with time, the unaffected kidney will develop hypertensive nephropathy, and pressure diuresis will be lost.7,8 In addition, the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system results in structural heart disease, such as left ventricular hypertrophy,5 and may shorten survival.

STENTING PLUS ANTIHYPERTENSIVE DRUG THERAPY

Because observational studies showed improvement in blood pressure control after endovascular stenting of atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis,9,10 this approach became a treatment option for uncontrolled hypertension in these patients. The 2005 joint guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association11 considered percutaneous revascularization a reasonable option (level of evidence B) for patients who meet one of the following criteria:

- Hemodynamically significant stenosis and accelerated, resistant, or malignant hypertension, hypertension with an unexplained unilateral small kidney, or hypertension with intolerance to medication

- Renal artery stenosis and progressive chronic kidney disease with bilateral stenosis or stenosis in a solitary functioning kidney

- Hemodynamically significant stenosis and recurrent, unexplained congestive heart failure or sudden, unexplained pulmonary edema or unstable angina.11

However, no randomized study has shown a direct benefit of renal artery stenting on rates of cardiovascular events or renal function compared with drug therapy alone.

TRIALS OF STENTING VS MEDICAL THERAPY ALONE

Technical improvements have led to more widespread use of diagnostic and interventional endovascular tools for renal artery revascularization. Studies over the past 10 years examined the impact of stenting in patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

The STAR trial

In the Stent Placement and Blood Pressure and Lipid-lowering for the Prevention of Progression of Renal Dysfunction Caused by Atherosclerotic Ostial Stenosis of the Renal Artery (STAR) trial,9 patients with creatinine clearance less than 80 mL/min/1.73 m2, renal artery stenosis greater than 50%, and well-controlled blood pressure were randomized to either renal artery stenting plus medical therapy or medical therapy alone. The authors concluded that stenting had no effect on the progression of renal dysfunction but led to a small number of significant, procedure-related complications. The study was criticized for including patients with mild stenosis (< 50% stenosis) and for being underpowered for the primary end point.

The ASTRAL study

The Angioplasty and Stenting for Renal Artery Lesions (ASTRAL) study10 was a similar comparison with similar results, showing no benefit from stenting with respect to renal function, systolic blood pressure control, cardiovascular events, or death.

HERCULES

The Herculink Elite Cobalt Chromium Renal Stent Trial to Demonstrate Efficacy and Safety (HERCULES)12 was a prospective multicenter study of the effects of renal artery stenting in 202 patients with significant renal artery stenosis and uncontrolled hypertension. It showed a reduction in systolic blood pressure from baseline (P < .0001). However, follow-up was only 9 months, which was insufficient to show a significant effect on long-term cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes.

The CORAL trial

The Cardiovascular Outcomes in Renal Atherosclerotic Lesions (CORAL) trial13 used more stringent definitions and longer follow-up. It randomized 947 patients to either stenting plus medical therapy or medical therapy alone. Patients had atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis, defined as stenosis of at least 80% or stenosis of 60% to 80% with a gradient of at least 20 mm Hg in the systolic pressure), and either systolic hypertension while taking two or more antihypertensive drugs or stage 3 or higher chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 as calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula).

Participants were followed for 43 months to detect the occurrence of adverse cardiovascular and renal events. There was no significant difference in primary outcome between stenting plus drug therapy and drug therapy alone (35.1% and 35.8%, respectively; P = .58). However, stenting plus drug therapy was associated with modestly lower systolic pressures compared with drug therapy alone (−2.3 mm Hg, 95% confidence interval −4.4 to −0.2 mm Hg, P = .03).13 This study provided strong evidence that renal artery stenting offers no significant benefit to patients with moderately severe atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis, and that stenting may actually pose an unnecessary risk.

COMPLICATIONS OF RENAL ARTERY STENTING

Complications of renal artery stenting are a limiting factor compared with drug therapy alone, especially since the procedure offers no significant benefit in outcome. Procedural complication rates of 10% to 15% have been reported.9,10,12 The CORAL trial reported arterial dissection in 2.2%, branch-vessel occlusion in 1.2%, and distal embolization in 1.2% of patients undergoing stenting.13 Other reported complications have included stent misplacement requiring an additional stent, access-vessel damage, stent embolization, renal artery thrombosis or occlusion, and death.10,12

- Kalra PA, Guo H, Kausz AT, et al. Atherosclerotic renovascular disease in United States patients aged 67 years or older: risk factors, revascularization, and prognosis. Kidney Int 2005; 68:293–301.

- Hansen KJ, Edwards MS, Craven TE, et al. Prevalence of renovascular disease in the elderly: a population-based study. J Vasc Surg 2002; 36:443–451.

- Uzu T, Takeji M, Yamada N, et al. Prevalence and outcome of renal artery stenosis in atherosclerotic patients with renal dysfunction. Hypertens Res 2002; 25:537–542.

- Benjamin MM, Fazel P, Filardo G, Choi JW, Stoler RC. Prevalence of and risk factors of renal artery stenosis in patients with resistant hypertension. Am J Cardiol 2014; 113:687–690.

- Wu S, Polavarapu N, Stouffer GA. Left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with renal artery stenosis. Am J Med Sci 2006; 332:334–338.

- Lerman LO, Textor SC, Grande JP. Mechanisms of tissue injury in renal artery stenosis: ischemia and beyond. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2009; 52:196–203.

- Black HR, Glickman MG, Schiff M Jr, Pingoud EG. Renovascular hypertension: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Yale J Biol Med 1978; 51:635–654.

- Tobe SW, Burgess E, Lebel M. Atherosclerotic renovascular disease. Can J Cardiol 2006; 22:623–628.

- Bax L, Mali WP, Buskens E, et al; STAR Study Group. The benefit of stent placement and blood pressure and lipid-lowering for the prevention of progression of renal dysfunction caused by atherosclerotic ostial stenosis of the renal artery. The STAR-study: rationale and study design. J Nephrol 2003; 16:807–812.

- ASTRAL Investigators; Wheatley K, Ives N, Gray R, et al. Revascularization versus medical therapy for renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1953–1962.

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47:1239–1312.

- Kalra PA, Guo H, Kausz AT, et al. Atherosclerotic renovascular disease in United States patients aged 67 years or older: risk factors, revascularization, and prognosis. Kidney Int 2005; 68:293–301.

- Hansen KJ, Edwards MS, Craven TE, et al. Prevalence of renovascular disease in the elderly: a population-based study. J Vasc Surg 2002; 36:443–451.

- Uzu T, Takeji M, Yamada N, et al. Prevalence and outcome of renal artery stenosis in atherosclerotic patients with renal dysfunction. Hypertens Res 2002; 25:537–542.

- Benjamin MM, Fazel P, Filardo G, Choi JW, Stoler RC. Prevalence of and risk factors of renal artery stenosis in patients with resistant hypertension. Am J Cardiol 2014; 113:687–690.

- Wu S, Polavarapu N, Stouffer GA. Left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with renal artery stenosis. Am J Med Sci 2006; 332:334–338.

- Lerman LO, Textor SC, Grande JP. Mechanisms of tissue injury in renal artery stenosis: ischemia and beyond. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2009; 52:196–203.

- Black HR, Glickman MG, Schiff M Jr, Pingoud EG. Renovascular hypertension: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Yale J Biol Med 1978; 51:635–654.

- Tobe SW, Burgess E, Lebel M. Atherosclerotic renovascular disease. Can J Cardiol 2006; 22:623–628.

- Bax L, Mali WP, Buskens E, et al; STAR Study Group. The benefit of stent placement and blood pressure and lipid-lowering for the prevention of progression of renal dysfunction caused by atherosclerotic ostial stenosis of the renal artery. The STAR-study: rationale and study design. J Nephrol 2003; 16:807–812.

- ASTRAL Investigators; Wheatley K, Ives N, Gray R, et al. Revascularization versus medical therapy for renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1953–1962.

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47:1239–1312.

Does massive hemoptysis always merit diagnostic bronchoscopy?

Yes, all patients with massive hemoptysis should undergo diagnostic bronchoscopy. The procedure plays an important role in protecting the airway, maintaining ventilation, finding the site and underlying cause of the bleeding, and in some cases stopping the bleeding, either temporarily or definitively.

Frightening to patients, massive hemoptysis is a medical emergency and demands immediate attention by an experienced pulmonary team.1 Hemoptysis can be the initial presentation of an underlying infectious, autoimmune, or malignant disorder (Table 1).2 Fortunately, most cases of hemoptysis are not massive or life-threatening.1

WHAT IS ‘MASSIVE’ HEMOPTYSIS?

Numerous studies have defined massive hemoptysis on the basis of the volume of blood lost over time, eg, more than 1 L in 24 hours or more than 400 mL in 6 hours.

Ibrahim3 has proposed that we move away from using the word “massive,” which is not useful, and instead think in terms of “life-threatening” hemoptysis, defined as any of the following:

- More than 100 mL of blood lost in 24 hours (a low number, but blood loss is hard to estimate accurately)

- Causing abnormal gas exchange due to airway obstruction

- Causing hemodynamic instability.

In this article, we use the traditional “massive” terminology.

BRONCHOSCOPY IS SUPERIOR TO IMAGING FOR DIAGNOSIS

Radiography can help identify the side or the site of bleeding in 33% to 82% of patients, and computed tomography can in 70% to 88.5%.4 Magnetic resonance imaging may also have a role; one study found it useful in cases of thoracic endometriosis during the quiescent stage.5 However, transferring a patient who is actively bleeding out of the intensive care unit for imaging can be challenging.

Flexible bronchoscopy is superior to radiographic imaging in evaluating massive hemoptysis: it can be performed at the bed-side and can include therapeutic procedures to control the bleeding until the patient can undergo a definitive therapeutic procedure.6 It has been found helpful in identifying the side of bleeding in 73% to 93% of cases of massive hemoptysis.6

However, one should consider starting the procedure with a rigid bronchoscope, which protects the airway better and allows for better ventilation during the procedure than a flexible one. One can use it to isolate the nonbleeding lung and to apply pressure to the bleeding site if it is in the main bronchus.7 Measuring 12 mm in diameter, a rigid scope cannot go as far into the lung as a flexible bronchoscope (measuring 6.4 mm), but a flexible bronchoscope can be introduced through the rigid bronchoscope to go further in.

MANAGEMENT OPTIONS

The management team should include an anesthesiologist, an intensivist, a thoracic surgeon, an interventional radiologist, and an interventional pulmonologist.

In the intensive care unit, the patient should be placed in the lateral decubitus position on the bleeding side. To maintain ventilation, the nonbleeding lung should be intubated with a large-bore endotracheal tube (internal diameter 8.5–9.0 mm) or, ideally, with a rigid bronchoscope.6 Meanwhile, the patient’s circulatory status should be stabilized with adequate fluid resuscitation and transfusion of blood products, with close monitoring.

Once the bleeding site is found, a bronchoscopic treatment is selected based on the cause of the bleeding. Massive hemoptysis usually arises from high-pressure bronchial vessels (90%) or, less commonly, from non-bronchial vessels or capillaries (10%).8 A variety of agents (eg, cold saline lavage, epinephrine 1:20,000) can be instilled through the bronchoscope to slow the bleeding and offer better visualization of the airway.6

If a bleeding intrabronchial lesion is identified, such as a malignant tracheobronchial tumor, local coagulation therapy can be applied through the bronchoscope. Options include laser treatment, argon plasma coagulation, cryotherapy, and electrocautery (Figure 1).9,10

If the bleeding persists or cannot be localized to a particular subsegment, an endobronchial balloon plug can be placed proximally (Figure 2). This can be left in place to isolate the bleeding and apply tamponade until a definitive procedure can be performed, such as bronchial artery embolization, radiation therapy, or surgery.

- Jean-Baptiste E. Clinical assessment and management of massive hemoptysis. Crit Care Med 2000; 28:1642–1647.

- Abi Khalil S, Gourdier AL, Aoun N, et al. Cystic and cavitary lesions of the lung: imaging characteristics and differential diagnosis [in French]. J Radiol 2010; 91:465–473.

- Ibrahim WH. Massive haemoptysis: the definition should be revised. Eur Respir J 2008; 32:1131–1132.

- Khalil A, Soussan M, Mangiapan G, Fartoukh M, Parrot A, Carette MF. Utility of high-resolution chest CT scan in the emergency management of haemoptysis in the intensive care unit: severity, localization and aetiology. Br J Radiol 2007; 80:21–25.

- Cassina PC, Hauser M, Kacl G, Imthurn B, Schröder S, Weder W. Catamenial hemoptysis. Diagnosis with MRI. Chest 1997; 111:1447–1450.

- Sakr L, Dutau H. Massive hemoptysis: an update on the role of bronchoscopy in diagnosis and management. Respiration 2010; 80:38–58.

- Conlan AA, Hurwitz SS. Management of massive haemoptysis with the rigid bronchoscope and cold saline lavage. Thorax 1980; 35:901–904.

- Deffebach ME, Charan NB, Lakshminarayan S, Butler J. The bronchial circulation. Small, but a vital attribute of the lung. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987; 135:463–481.

- Morice RC, Ece T, Ece F, Keus L. Endobronchial argon plasma coagulation for treatment of hemoptysis and neoplastic airway obstruction. Chest 2001; 119:781–787.

- Sheski FD, Mathur PN. Cryotherapy, electrocautery, and brachytherapy. Clin Chest Med 1999; 20:123–138.

Yes, all patients with massive hemoptysis should undergo diagnostic bronchoscopy. The procedure plays an important role in protecting the airway, maintaining ventilation, finding the site and underlying cause of the bleeding, and in some cases stopping the bleeding, either temporarily or definitively.

Frightening to patients, massive hemoptysis is a medical emergency and demands immediate attention by an experienced pulmonary team.1 Hemoptysis can be the initial presentation of an underlying infectious, autoimmune, or malignant disorder (Table 1).2 Fortunately, most cases of hemoptysis are not massive or life-threatening.1

WHAT IS ‘MASSIVE’ HEMOPTYSIS?

Numerous studies have defined massive hemoptysis on the basis of the volume of blood lost over time, eg, more than 1 L in 24 hours or more than 400 mL in 6 hours.

Ibrahim3 has proposed that we move away from using the word “massive,” which is not useful, and instead think in terms of “life-threatening” hemoptysis, defined as any of the following:

- More than 100 mL of blood lost in 24 hours (a low number, but blood loss is hard to estimate accurately)

- Causing abnormal gas exchange due to airway obstruction

- Causing hemodynamic instability.

In this article, we use the traditional “massive” terminology.

BRONCHOSCOPY IS SUPERIOR TO IMAGING FOR DIAGNOSIS

Radiography can help identify the side or the site of bleeding in 33% to 82% of patients, and computed tomography can in 70% to 88.5%.4 Magnetic resonance imaging may also have a role; one study found it useful in cases of thoracic endometriosis during the quiescent stage.5 However, transferring a patient who is actively bleeding out of the intensive care unit for imaging can be challenging.

Flexible bronchoscopy is superior to radiographic imaging in evaluating massive hemoptysis: it can be performed at the bed-side and can include therapeutic procedures to control the bleeding until the patient can undergo a definitive therapeutic procedure.6 It has been found helpful in identifying the side of bleeding in 73% to 93% of cases of massive hemoptysis.6

However, one should consider starting the procedure with a rigid bronchoscope, which protects the airway better and allows for better ventilation during the procedure than a flexible one. One can use it to isolate the nonbleeding lung and to apply pressure to the bleeding site if it is in the main bronchus.7 Measuring 12 mm in diameter, a rigid scope cannot go as far into the lung as a flexible bronchoscope (measuring 6.4 mm), but a flexible bronchoscope can be introduced through the rigid bronchoscope to go further in.

MANAGEMENT OPTIONS

The management team should include an anesthesiologist, an intensivist, a thoracic surgeon, an interventional radiologist, and an interventional pulmonologist.

In the intensive care unit, the patient should be placed in the lateral decubitus position on the bleeding side. To maintain ventilation, the nonbleeding lung should be intubated with a large-bore endotracheal tube (internal diameter 8.5–9.0 mm) or, ideally, with a rigid bronchoscope.6 Meanwhile, the patient’s circulatory status should be stabilized with adequate fluid resuscitation and transfusion of blood products, with close monitoring.

Once the bleeding site is found, a bronchoscopic treatment is selected based on the cause of the bleeding. Massive hemoptysis usually arises from high-pressure bronchial vessels (90%) or, less commonly, from non-bronchial vessels or capillaries (10%).8 A variety of agents (eg, cold saline lavage, epinephrine 1:20,000) can be instilled through the bronchoscope to slow the bleeding and offer better visualization of the airway.6

If a bleeding intrabronchial lesion is identified, such as a malignant tracheobronchial tumor, local coagulation therapy can be applied through the bronchoscope. Options include laser treatment, argon plasma coagulation, cryotherapy, and electrocautery (Figure 1).9,10

If the bleeding persists or cannot be localized to a particular subsegment, an endobronchial balloon plug can be placed proximally (Figure 2). This can be left in place to isolate the bleeding and apply tamponade until a definitive procedure can be performed, such as bronchial artery embolization, radiation therapy, or surgery.

Yes, all patients with massive hemoptysis should undergo diagnostic bronchoscopy. The procedure plays an important role in protecting the airway, maintaining ventilation, finding the site and underlying cause of the bleeding, and in some cases stopping the bleeding, either temporarily or definitively.

Frightening to patients, massive hemoptysis is a medical emergency and demands immediate attention by an experienced pulmonary team.1 Hemoptysis can be the initial presentation of an underlying infectious, autoimmune, or malignant disorder (Table 1).2 Fortunately, most cases of hemoptysis are not massive or life-threatening.1

WHAT IS ‘MASSIVE’ HEMOPTYSIS?

Numerous studies have defined massive hemoptysis on the basis of the volume of blood lost over time, eg, more than 1 L in 24 hours or more than 400 mL in 6 hours.

Ibrahim3 has proposed that we move away from using the word “massive,” which is not useful, and instead think in terms of “life-threatening” hemoptysis, defined as any of the following:

- More than 100 mL of blood lost in 24 hours (a low number, but blood loss is hard to estimate accurately)

- Causing abnormal gas exchange due to airway obstruction

- Causing hemodynamic instability.

In this article, we use the traditional “massive” terminology.

BRONCHOSCOPY IS SUPERIOR TO IMAGING FOR DIAGNOSIS

Radiography can help identify the side or the site of bleeding in 33% to 82% of patients, and computed tomography can in 70% to 88.5%.4 Magnetic resonance imaging may also have a role; one study found it useful in cases of thoracic endometriosis during the quiescent stage.5 However, transferring a patient who is actively bleeding out of the intensive care unit for imaging can be challenging.

Flexible bronchoscopy is superior to radiographic imaging in evaluating massive hemoptysis: it can be performed at the bed-side and can include therapeutic procedures to control the bleeding until the patient can undergo a definitive therapeutic procedure.6 It has been found helpful in identifying the side of bleeding in 73% to 93% of cases of massive hemoptysis.6

However, one should consider starting the procedure with a rigid bronchoscope, which protects the airway better and allows for better ventilation during the procedure than a flexible one. One can use it to isolate the nonbleeding lung and to apply pressure to the bleeding site if it is in the main bronchus.7 Measuring 12 mm in diameter, a rigid scope cannot go as far into the lung as a flexible bronchoscope (measuring 6.4 mm), but a flexible bronchoscope can be introduced through the rigid bronchoscope to go further in.

MANAGEMENT OPTIONS

The management team should include an anesthesiologist, an intensivist, a thoracic surgeon, an interventional radiologist, and an interventional pulmonologist.

In the intensive care unit, the patient should be placed in the lateral decubitus position on the bleeding side. To maintain ventilation, the nonbleeding lung should be intubated with a large-bore endotracheal tube (internal diameter 8.5–9.0 mm) or, ideally, with a rigid bronchoscope.6 Meanwhile, the patient’s circulatory status should be stabilized with adequate fluid resuscitation and transfusion of blood products, with close monitoring.

Once the bleeding site is found, a bronchoscopic treatment is selected based on the cause of the bleeding. Massive hemoptysis usually arises from high-pressure bronchial vessels (90%) or, less commonly, from non-bronchial vessels or capillaries (10%).8 A variety of agents (eg, cold saline lavage, epinephrine 1:20,000) can be instilled through the bronchoscope to slow the bleeding and offer better visualization of the airway.6

If a bleeding intrabronchial lesion is identified, such as a malignant tracheobronchial tumor, local coagulation therapy can be applied through the bronchoscope. Options include laser treatment, argon plasma coagulation, cryotherapy, and electrocautery (Figure 1).9,10

If the bleeding persists or cannot be localized to a particular subsegment, an endobronchial balloon plug can be placed proximally (Figure 2). This can be left in place to isolate the bleeding and apply tamponade until a definitive procedure can be performed, such as bronchial artery embolization, radiation therapy, or surgery.

- Jean-Baptiste E. Clinical assessment and management of massive hemoptysis. Crit Care Med 2000; 28:1642–1647.

- Abi Khalil S, Gourdier AL, Aoun N, et al. Cystic and cavitary lesions of the lung: imaging characteristics and differential diagnosis [in French]. J Radiol 2010; 91:465–473.

- Ibrahim WH. Massive haemoptysis: the definition should be revised. Eur Respir J 2008; 32:1131–1132.

- Khalil A, Soussan M, Mangiapan G, Fartoukh M, Parrot A, Carette MF. Utility of high-resolution chest CT scan in the emergency management of haemoptysis in the intensive care unit: severity, localization and aetiology. Br J Radiol 2007; 80:21–25.

- Cassina PC, Hauser M, Kacl G, Imthurn B, Schröder S, Weder W. Catamenial hemoptysis. Diagnosis with MRI. Chest 1997; 111:1447–1450.

- Sakr L, Dutau H. Massive hemoptysis: an update on the role of bronchoscopy in diagnosis and management. Respiration 2010; 80:38–58.

- Conlan AA, Hurwitz SS. Management of massive haemoptysis with the rigid bronchoscope and cold saline lavage. Thorax 1980; 35:901–904.

- Deffebach ME, Charan NB, Lakshminarayan S, Butler J. The bronchial circulation. Small, but a vital attribute of the lung. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987; 135:463–481.

- Morice RC, Ece T, Ece F, Keus L. Endobronchial argon plasma coagulation for treatment of hemoptysis and neoplastic airway obstruction. Chest 2001; 119:781–787.

- Sheski FD, Mathur PN. Cryotherapy, electrocautery, and brachytherapy. Clin Chest Med 1999; 20:123–138.

- Jean-Baptiste E. Clinical assessment and management of massive hemoptysis. Crit Care Med 2000; 28:1642–1647.

- Abi Khalil S, Gourdier AL, Aoun N, et al. Cystic and cavitary lesions of the lung: imaging characteristics and differential diagnosis [in French]. J Radiol 2010; 91:465–473.

- Ibrahim WH. Massive haemoptysis: the definition should be revised. Eur Respir J 2008; 32:1131–1132.

- Khalil A, Soussan M, Mangiapan G, Fartoukh M, Parrot A, Carette MF. Utility of high-resolution chest CT scan in the emergency management of haemoptysis in the intensive care unit: severity, localization and aetiology. Br J Radiol 2007; 80:21–25.

- Cassina PC, Hauser M, Kacl G, Imthurn B, Schröder S, Weder W. Catamenial hemoptysis. Diagnosis with MRI. Chest 1997; 111:1447–1450.

- Sakr L, Dutau H. Massive hemoptysis: an update on the role of bronchoscopy in diagnosis and management. Respiration 2010; 80:38–58.

- Conlan AA, Hurwitz SS. Management of massive haemoptysis with the rigid bronchoscope and cold saline lavage. Thorax 1980; 35:901–904.

- Deffebach ME, Charan NB, Lakshminarayan S, Butler J. The bronchial circulation. Small, but a vital attribute of the lung. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987; 135:463–481.

- Morice RC, Ece T, Ece F, Keus L. Endobronchial argon plasma coagulation for treatment of hemoptysis and neoplastic airway obstruction. Chest 2001; 119:781–787.

- Sheski FD, Mathur PN. Cryotherapy, electrocautery, and brachytherapy. Clin Chest Med 1999; 20:123–138.

In reply: Stress ulcer prophylaxis