User login

Children’s hospitals grapple with wave of mental illness

Krissy Williams, 15, had attempted suicide before, but never with pills.

The teen was diagnosed with schizophrenia when she was 9. People with this chronic mental health condition perceive reality differently and often experience hallucinations and delusions. She learned to manage these symptoms with a variety of services offered at home and at school.

But the pandemic upended those lifelines. She lost much of the support offered at school. She also lost regular contact with her peers. Her mother lost access to respite care – which allowed her to take a break.

On a Thursday in October, the isolation and sadness came to a head. As Krissy’s mother, Patricia Williams, called a mental crisis hotline for help, she said, Krissy stood on the deck of their Maryland home with a bottle of pain medication in one hand and water in the other.

Before Patricia could react, Krissy placed the pills in her mouth and swallowed.

Efforts to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus in the United States have led to drastic changes in the way children and teens learn, play and socialize. Tens of millions of students are attending school through some form of distance learning. Many extracurricular activities have been canceled. Playgrounds, zoos, and other recreational spaces have closed. Kids like Krissy have struggled to cope and the toll is becoming evident.

Government figures show the proportion of children who arrived in EDs with mental health issues increased 24% from mid-March through mid-October, compared with the same period in 2019. Among preteens and adolescents, it rose by 31%. Anecdotally, some hospitals said they are seeing more cases of severe depression and suicidal thoughts among children, particularly attempts to overdose.

The increased demand for intensive mental health care that has accompanied the pandemic has worsened issues that have long plagued the system. In some hospitals, the number of children unable to immediately get a bed in the psychiatric unit rose. Others reduced the number of beds or closed psychiatric units altogether to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

“It’s only a matter of time before a tsunami sort of reaches the shore of our service system, and it’s going to be overwhelmed with the mental health needs of kids,” said Jason Williams, PsyD, a psychologist and director of operations of the Pediatric Mental Health Institute at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora.

“I think we’re just starting to see the tip of the iceberg, to be honest with you.”

Before COVID, more than 8 million kids between ages 3 and 17 were diagnosed with a mental or behavioral health condition, according to the most recent National Survey of Children’s Health. A separate survey from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found one in three high school students in 2019 reported feeling persistently sad and hopeless – a 40% increase from 2009.

The coronavirus pandemic appears to be adding to these difficulties. A review of 80 studies found forced isolation and loneliness among children correlated with an increased risk of depression.

“We’re all social beings, but they’re [teenagers] at the point in their development where their peers are their reality,” said Terrie Andrews, PhD, a psychologist and administrator of behavioral health at Wolfson Children’s Hospital in Jacksonville, Fla. “Their peers are their grounding mechanism.”

Children’s hospitals in Colorado, Missouri, and New York all reported an uptick in the number of patients who thought about or attempted suicide. Clinicians also mentioned spikes in children with severe depression and those with autism who are acting out.

The number of overdose attempts among children has caught the attention of clinicians at two facilities. Dr. Andrews said the facility gives out lockboxes for weapons and medication to the public – including parents who come in after children attempted to take their life using medication.

Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C., also has experienced an uptick, said Colby Tyson, MD, associate director of inpatient psychiatry. She’s seen children’s mental health deteriorate because of a likely increase in family conflict – often a consequence of the chaos caused by the pandemic. Without school, connections with peers or employment, families don’t have the opportunity to spend time away from one another and regroup, which can add stress to an already tense situation.

“That break is gone,” she said.

The higher demand for child mental health services caused by the pandemic has made finding a bed at an inpatient unit more difficult.

Now, some hospitals report running at full capacity and having more children “boarding,” or sleeping in EDs before being admitted to the psychiatric unit. Among them is the Pediatric Mental Health Institute at Children’s Hospital Colorado. Williams said the inpatient unit has been full since March. Some children now wait nearly 2 days for a bed, up from the 8-10 hours common before the pandemic.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio is also running at full capacity, said clinicians, and had several days in which the unit was above capacity and placed kids instead in the emergency department waiting to be admitted. In Florida, Dr. Andrews said, up to 25 children have been held on surgical floors at Wolfson Children’s while waiting for a spot to open in the inpatient psychiatric unit. Their wait could last as long as 5 days, she said.

Multiple hospitals said the usual summer slump in child psychiatric admissions was missing last year. “We never saw that during the pandemic,” said Andrews. “We stayed completely busy the entire time.”

Some facilities have decided to reduce the number of beds available to maintain physical distancing, further constricting supply. Children’s National in D.C. cut five beds from its unit to maintain single occupancy in every room, said Adelaide Robb, MD, division chief of psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

The measures taken to curb the spread of COVID have also affected the way hospitalized children receive mental health services. In addition to providers wearing protective equipment, some hospitals like Cincinnati Children’s rearranged furniture and placed cues on the floor as reminders to stay 6 feet apart. The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Western Psychiatric Hospital and other facilities encourage children to keep their masks on by offering rewards like extra computer time. Patients at Children’s National now eat in their rooms, a change from when they ate together.

Despite the need for distance, social interaction still represents an important part of mental health care for children, clinicians said. Facilities have come up with various ways to do so safely, including creating smaller pods for group therapy. Children at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital can play with toys, but only with ones that can be wiped clean afterward. No cards or board games, said Suzanne Sampang, MD, clinical medical director for child and adolescent psychiatry at the hospital.

“I think what’s different about psychiatric treatment is that, really, interaction is the treatment,” she said, “just as much as a medication.”

The added infection-control precautions pose challenges to forging therapeutic connections. Masks can complicate the ability to read a person’s face. Online meetings make it difficult to build trust between a patient and a therapist.

“There’s something about the real relationship in person that the best technology can’t give to you,” said Dr. Robb.

For now, Krissy Williams is relying on virtual platforms to receive some of her mental health services. Despite being hospitalized and suffering brain damage due to the overdose, she is now at home and in good spirits. She enjoys geometry, dancing on TikTok, and trying to beat her mother at Super Mario Bros. on the Wii. But being away from her friends, she said, has been a hard adjustment.

“When you’re used to something,” she said, “it’s not easy to change everything.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of Kaiser Family Foundation, which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Krissy Williams, 15, had attempted suicide before, but never with pills.

The teen was diagnosed with schizophrenia when she was 9. People with this chronic mental health condition perceive reality differently and often experience hallucinations and delusions. She learned to manage these symptoms with a variety of services offered at home and at school.

But the pandemic upended those lifelines. She lost much of the support offered at school. She also lost regular contact with her peers. Her mother lost access to respite care – which allowed her to take a break.

On a Thursday in October, the isolation and sadness came to a head. As Krissy’s mother, Patricia Williams, called a mental crisis hotline for help, she said, Krissy stood on the deck of their Maryland home with a bottle of pain medication in one hand and water in the other.

Before Patricia could react, Krissy placed the pills in her mouth and swallowed.

Efforts to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus in the United States have led to drastic changes in the way children and teens learn, play and socialize. Tens of millions of students are attending school through some form of distance learning. Many extracurricular activities have been canceled. Playgrounds, zoos, and other recreational spaces have closed. Kids like Krissy have struggled to cope and the toll is becoming evident.

Government figures show the proportion of children who arrived in EDs with mental health issues increased 24% from mid-March through mid-October, compared with the same period in 2019. Among preteens and adolescents, it rose by 31%. Anecdotally, some hospitals said they are seeing more cases of severe depression and suicidal thoughts among children, particularly attempts to overdose.

The increased demand for intensive mental health care that has accompanied the pandemic has worsened issues that have long plagued the system. In some hospitals, the number of children unable to immediately get a bed in the psychiatric unit rose. Others reduced the number of beds or closed psychiatric units altogether to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

“It’s only a matter of time before a tsunami sort of reaches the shore of our service system, and it’s going to be overwhelmed with the mental health needs of kids,” said Jason Williams, PsyD, a psychologist and director of operations of the Pediatric Mental Health Institute at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora.

“I think we’re just starting to see the tip of the iceberg, to be honest with you.”

Before COVID, more than 8 million kids between ages 3 and 17 were diagnosed with a mental or behavioral health condition, according to the most recent National Survey of Children’s Health. A separate survey from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found one in three high school students in 2019 reported feeling persistently sad and hopeless – a 40% increase from 2009.

The coronavirus pandemic appears to be adding to these difficulties. A review of 80 studies found forced isolation and loneliness among children correlated with an increased risk of depression.

“We’re all social beings, but they’re [teenagers] at the point in their development where their peers are their reality,” said Terrie Andrews, PhD, a psychologist and administrator of behavioral health at Wolfson Children’s Hospital in Jacksonville, Fla. “Their peers are their grounding mechanism.”

Children’s hospitals in Colorado, Missouri, and New York all reported an uptick in the number of patients who thought about or attempted suicide. Clinicians also mentioned spikes in children with severe depression and those with autism who are acting out.

The number of overdose attempts among children has caught the attention of clinicians at two facilities. Dr. Andrews said the facility gives out lockboxes for weapons and medication to the public – including parents who come in after children attempted to take their life using medication.

Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C., also has experienced an uptick, said Colby Tyson, MD, associate director of inpatient psychiatry. She’s seen children’s mental health deteriorate because of a likely increase in family conflict – often a consequence of the chaos caused by the pandemic. Without school, connections with peers or employment, families don’t have the opportunity to spend time away from one another and regroup, which can add stress to an already tense situation.

“That break is gone,” she said.

The higher demand for child mental health services caused by the pandemic has made finding a bed at an inpatient unit more difficult.

Now, some hospitals report running at full capacity and having more children “boarding,” or sleeping in EDs before being admitted to the psychiatric unit. Among them is the Pediatric Mental Health Institute at Children’s Hospital Colorado. Williams said the inpatient unit has been full since March. Some children now wait nearly 2 days for a bed, up from the 8-10 hours common before the pandemic.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio is also running at full capacity, said clinicians, and had several days in which the unit was above capacity and placed kids instead in the emergency department waiting to be admitted. In Florida, Dr. Andrews said, up to 25 children have been held on surgical floors at Wolfson Children’s while waiting for a spot to open in the inpatient psychiatric unit. Their wait could last as long as 5 days, she said.

Multiple hospitals said the usual summer slump in child psychiatric admissions was missing last year. “We never saw that during the pandemic,” said Andrews. “We stayed completely busy the entire time.”

Some facilities have decided to reduce the number of beds available to maintain physical distancing, further constricting supply. Children’s National in D.C. cut five beds from its unit to maintain single occupancy in every room, said Adelaide Robb, MD, division chief of psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

The measures taken to curb the spread of COVID have also affected the way hospitalized children receive mental health services. In addition to providers wearing protective equipment, some hospitals like Cincinnati Children’s rearranged furniture and placed cues on the floor as reminders to stay 6 feet apart. The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Western Psychiatric Hospital and other facilities encourage children to keep their masks on by offering rewards like extra computer time. Patients at Children’s National now eat in their rooms, a change from when they ate together.

Despite the need for distance, social interaction still represents an important part of mental health care for children, clinicians said. Facilities have come up with various ways to do so safely, including creating smaller pods for group therapy. Children at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital can play with toys, but only with ones that can be wiped clean afterward. No cards or board games, said Suzanne Sampang, MD, clinical medical director for child and adolescent psychiatry at the hospital.

“I think what’s different about psychiatric treatment is that, really, interaction is the treatment,” she said, “just as much as a medication.”

The added infection-control precautions pose challenges to forging therapeutic connections. Masks can complicate the ability to read a person’s face. Online meetings make it difficult to build trust between a patient and a therapist.

“There’s something about the real relationship in person that the best technology can’t give to you,” said Dr. Robb.

For now, Krissy Williams is relying on virtual platforms to receive some of her mental health services. Despite being hospitalized and suffering brain damage due to the overdose, she is now at home and in good spirits. She enjoys geometry, dancing on TikTok, and trying to beat her mother at Super Mario Bros. on the Wii. But being away from her friends, she said, has been a hard adjustment.

“When you’re used to something,” she said, “it’s not easy to change everything.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of Kaiser Family Foundation, which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Krissy Williams, 15, had attempted suicide before, but never with pills.

The teen was diagnosed with schizophrenia when she was 9. People with this chronic mental health condition perceive reality differently and often experience hallucinations and delusions. She learned to manage these symptoms with a variety of services offered at home and at school.

But the pandemic upended those lifelines. She lost much of the support offered at school. She also lost regular contact with her peers. Her mother lost access to respite care – which allowed her to take a break.

On a Thursday in October, the isolation and sadness came to a head. As Krissy’s mother, Patricia Williams, called a mental crisis hotline for help, she said, Krissy stood on the deck of their Maryland home with a bottle of pain medication in one hand and water in the other.

Before Patricia could react, Krissy placed the pills in her mouth and swallowed.

Efforts to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus in the United States have led to drastic changes in the way children and teens learn, play and socialize. Tens of millions of students are attending school through some form of distance learning. Many extracurricular activities have been canceled. Playgrounds, zoos, and other recreational spaces have closed. Kids like Krissy have struggled to cope and the toll is becoming evident.

Government figures show the proportion of children who arrived in EDs with mental health issues increased 24% from mid-March through mid-October, compared with the same period in 2019. Among preteens and adolescents, it rose by 31%. Anecdotally, some hospitals said they are seeing more cases of severe depression and suicidal thoughts among children, particularly attempts to overdose.

The increased demand for intensive mental health care that has accompanied the pandemic has worsened issues that have long plagued the system. In some hospitals, the number of children unable to immediately get a bed in the psychiatric unit rose. Others reduced the number of beds or closed psychiatric units altogether to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

“It’s only a matter of time before a tsunami sort of reaches the shore of our service system, and it’s going to be overwhelmed with the mental health needs of kids,” said Jason Williams, PsyD, a psychologist and director of operations of the Pediatric Mental Health Institute at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora.

“I think we’re just starting to see the tip of the iceberg, to be honest with you.”

Before COVID, more than 8 million kids between ages 3 and 17 were diagnosed with a mental or behavioral health condition, according to the most recent National Survey of Children’s Health. A separate survey from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found one in three high school students in 2019 reported feeling persistently sad and hopeless – a 40% increase from 2009.

The coronavirus pandemic appears to be adding to these difficulties. A review of 80 studies found forced isolation and loneliness among children correlated with an increased risk of depression.

“We’re all social beings, but they’re [teenagers] at the point in their development where their peers are their reality,” said Terrie Andrews, PhD, a psychologist and administrator of behavioral health at Wolfson Children’s Hospital in Jacksonville, Fla. “Their peers are their grounding mechanism.”

Children’s hospitals in Colorado, Missouri, and New York all reported an uptick in the number of patients who thought about or attempted suicide. Clinicians also mentioned spikes in children with severe depression and those with autism who are acting out.

The number of overdose attempts among children has caught the attention of clinicians at two facilities. Dr. Andrews said the facility gives out lockboxes for weapons and medication to the public – including parents who come in after children attempted to take their life using medication.

Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C., also has experienced an uptick, said Colby Tyson, MD, associate director of inpatient psychiatry. She’s seen children’s mental health deteriorate because of a likely increase in family conflict – often a consequence of the chaos caused by the pandemic. Without school, connections with peers or employment, families don’t have the opportunity to spend time away from one another and regroup, which can add stress to an already tense situation.

“That break is gone,” she said.

The higher demand for child mental health services caused by the pandemic has made finding a bed at an inpatient unit more difficult.

Now, some hospitals report running at full capacity and having more children “boarding,” or sleeping in EDs before being admitted to the psychiatric unit. Among them is the Pediatric Mental Health Institute at Children’s Hospital Colorado. Williams said the inpatient unit has been full since March. Some children now wait nearly 2 days for a bed, up from the 8-10 hours common before the pandemic.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio is also running at full capacity, said clinicians, and had several days in which the unit was above capacity and placed kids instead in the emergency department waiting to be admitted. In Florida, Dr. Andrews said, up to 25 children have been held on surgical floors at Wolfson Children’s while waiting for a spot to open in the inpatient psychiatric unit. Their wait could last as long as 5 days, she said.

Multiple hospitals said the usual summer slump in child psychiatric admissions was missing last year. “We never saw that during the pandemic,” said Andrews. “We stayed completely busy the entire time.”

Some facilities have decided to reduce the number of beds available to maintain physical distancing, further constricting supply. Children’s National in D.C. cut five beds from its unit to maintain single occupancy in every room, said Adelaide Robb, MD, division chief of psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

The measures taken to curb the spread of COVID have also affected the way hospitalized children receive mental health services. In addition to providers wearing protective equipment, some hospitals like Cincinnati Children’s rearranged furniture and placed cues on the floor as reminders to stay 6 feet apart. The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Western Psychiatric Hospital and other facilities encourage children to keep their masks on by offering rewards like extra computer time. Patients at Children’s National now eat in their rooms, a change from when they ate together.

Despite the need for distance, social interaction still represents an important part of mental health care for children, clinicians said. Facilities have come up with various ways to do so safely, including creating smaller pods for group therapy. Children at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital can play with toys, but only with ones that can be wiped clean afterward. No cards or board games, said Suzanne Sampang, MD, clinical medical director for child and adolescent psychiatry at the hospital.

“I think what’s different about psychiatric treatment is that, really, interaction is the treatment,” she said, “just as much as a medication.”

The added infection-control precautions pose challenges to forging therapeutic connections. Masks can complicate the ability to read a person’s face. Online meetings make it difficult to build trust between a patient and a therapist.

“There’s something about the real relationship in person that the best technology can’t give to you,” said Dr. Robb.

For now, Krissy Williams is relying on virtual platforms to receive some of her mental health services. Despite being hospitalized and suffering brain damage due to the overdose, she is now at home and in good spirits. She enjoys geometry, dancing on TikTok, and trying to beat her mother at Super Mario Bros. on the Wii. But being away from her friends, she said, has been a hard adjustment.

“When you’re used to something,” she said, “it’s not easy to change everything.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of Kaiser Family Foundation, which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Good health goes beyond having a doctor and insurance, says AMA’s equity chief

Part of Dr. Aletha Maybank’s medical training left a sour taste in her mouth.

Her superiors told her not to worry about nonmedical issues affecting her patients’ quality of life, she said, because social workers would handle it. But she didn’t understand how physicians could divorce medical advice from the context of patients’ lives.

“How can you offer advice as recommendations that’s not even relevant to how their day to day plays out?” Dr. Maybank asked.

Today, Dr. Maybank is continuing to question that medical school philosophy. She was recently named the first chief health equity officer for the American Medical Association. In that job, she is responsible for implementing practices among doctors across the country to help end disparities in care. She has a full agenda, including launching the group’s Center for Health Equity and helping the Chicago-based doctors association reach out to people in poor neighborhoods in the city.

A pediatrician, Dr. Maybank previously worked for the New York City government as deputy commissioner for the health department and founding director of the city’s health equity center.

Carmen Heredia Rodriguez of Kaiser Health News recently spoke with Dr. Maybank about her new role and how health inequities affect Americans. This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Can you tell me what health equity means to you, and what are some of the main drivers that are keeping health inequitable in this country?

The AMA policy around health equity is optimal health for all people.

But it’s not just an outcome; there’s a process to get there. How do we engage with people? How do we look at and collect our data to make sure our practices and processes are equitable? How do we hire differently to ensure diversity? All these things are processes to achieve health equity.

In order to understand what produces inequities, we have to understand what creates health. Health is created outside of the walls of the doctor’s office and at the hospital. What are patients’ jobs and employment like? The kind of education they have. Income. Their ability to build wealth. All of these are conditions that impact health.

Q: Is there anything along your career path that really surprised you about the state of health care in the United States?

There’s the perception that all of our health is really determined by whether you have a doctor or not, or if you have insurance. What creates health is much beyond that.

So if we really want to work on health and equity, we have to partner with people who are in the education space and the economic space and the housing spaces, because that’s where health inequities are produced. You could have insurance coverage. You could have a primary care doctor. But it doesn’t mean that you’re not going to experience health inequities.

Q: Discrimination based on racial lines is one obvious driver of health inequities. What are some of the other populations that are affected by health inequity?

I think structural racism is a system that affects us all.

It’s not just the black-white issue. So, whether it’s discrimination or inequities that exist among LGBT youth and transgender [or] nonconforming people, or if it’s folks who are immigrants or women, a lot of that is contextualized under the umbrella of white supremacy within the country.

Q: And what are some of your priorities?

A large part of my work will be how I build the organizational capacity to better understand health equity. The reality in this country is folks aren’t comfortable talking about those issues. So, we have to destigmatize talking about all of this.

Q: Are there any particular populations or relationships that you plan to focus on?

The AMA excluded black physicians until the 1960s. So one question is: How do we work to heal relationships as well as understand the impact of our past actions? The AMA definitely issued an apology in the early 2000s, and my new role is also a step in the right direction. However, there is more that we can and should do.

Another priority now is: How do we work, and who do we work with, in our own backyard of Chicago? What can we do to work directly with people experiencing the greatest burden of disease? How do we ensure that we acknowledge the power, assets and expertise of communities so that we have the process and solutions driven and led by communities? To that end, we’ve begun working with West Side United via a relationship at Rush Medical Center. West Side United is a community-driven, collective neighborhood planning, implementation and investment effort geared toward optimizing economic well-being and improved health outcomes.

Q: Is there anything else you feel is important to understand about health equity?

Health equity and social determinants of health have become jargon. But we are talking about people’s lives. We were all born equal. We are clearly not all treated equal, but we all deserve equity. I don’t live outside of it, and none of us really do. I am one of those women who were three to four times more likely to die at childbirth because I’m black. So I don’t live outside of this experience. I’m talking about my own life.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Part of Dr. Aletha Maybank’s medical training left a sour taste in her mouth.

Her superiors told her not to worry about nonmedical issues affecting her patients’ quality of life, she said, because social workers would handle it. But she didn’t understand how physicians could divorce medical advice from the context of patients’ lives.

“How can you offer advice as recommendations that’s not even relevant to how their day to day plays out?” Dr. Maybank asked.

Today, Dr. Maybank is continuing to question that medical school philosophy. She was recently named the first chief health equity officer for the American Medical Association. In that job, she is responsible for implementing practices among doctors across the country to help end disparities in care. She has a full agenda, including launching the group’s Center for Health Equity and helping the Chicago-based doctors association reach out to people in poor neighborhoods in the city.

A pediatrician, Dr. Maybank previously worked for the New York City government as deputy commissioner for the health department and founding director of the city’s health equity center.

Carmen Heredia Rodriguez of Kaiser Health News recently spoke with Dr. Maybank about her new role and how health inequities affect Americans. This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Can you tell me what health equity means to you, and what are some of the main drivers that are keeping health inequitable in this country?

The AMA policy around health equity is optimal health for all people.

But it’s not just an outcome; there’s a process to get there. How do we engage with people? How do we look at and collect our data to make sure our practices and processes are equitable? How do we hire differently to ensure diversity? All these things are processes to achieve health equity.

In order to understand what produces inequities, we have to understand what creates health. Health is created outside of the walls of the doctor’s office and at the hospital. What are patients’ jobs and employment like? The kind of education they have. Income. Their ability to build wealth. All of these are conditions that impact health.

Q: Is there anything along your career path that really surprised you about the state of health care in the United States?

There’s the perception that all of our health is really determined by whether you have a doctor or not, or if you have insurance. What creates health is much beyond that.

So if we really want to work on health and equity, we have to partner with people who are in the education space and the economic space and the housing spaces, because that’s where health inequities are produced. You could have insurance coverage. You could have a primary care doctor. But it doesn’t mean that you’re not going to experience health inequities.

Q: Discrimination based on racial lines is one obvious driver of health inequities. What are some of the other populations that are affected by health inequity?

I think structural racism is a system that affects us all.

It’s not just the black-white issue. So, whether it’s discrimination or inequities that exist among LGBT youth and transgender [or] nonconforming people, or if it’s folks who are immigrants or women, a lot of that is contextualized under the umbrella of white supremacy within the country.

Q: And what are some of your priorities?

A large part of my work will be how I build the organizational capacity to better understand health equity. The reality in this country is folks aren’t comfortable talking about those issues. So, we have to destigmatize talking about all of this.

Q: Are there any particular populations or relationships that you plan to focus on?

The AMA excluded black physicians until the 1960s. So one question is: How do we work to heal relationships as well as understand the impact of our past actions? The AMA definitely issued an apology in the early 2000s, and my new role is also a step in the right direction. However, there is more that we can and should do.

Another priority now is: How do we work, and who do we work with, in our own backyard of Chicago? What can we do to work directly with people experiencing the greatest burden of disease? How do we ensure that we acknowledge the power, assets and expertise of communities so that we have the process and solutions driven and led by communities? To that end, we’ve begun working with West Side United via a relationship at Rush Medical Center. West Side United is a community-driven, collective neighborhood planning, implementation and investment effort geared toward optimizing economic well-being and improved health outcomes.

Q: Is there anything else you feel is important to understand about health equity?

Health equity and social determinants of health have become jargon. But we are talking about people’s lives. We were all born equal. We are clearly not all treated equal, but we all deserve equity. I don’t live outside of it, and none of us really do. I am one of those women who were three to four times more likely to die at childbirth because I’m black. So I don’t live outside of this experience. I’m talking about my own life.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Part of Dr. Aletha Maybank’s medical training left a sour taste in her mouth.

Her superiors told her not to worry about nonmedical issues affecting her patients’ quality of life, she said, because social workers would handle it. But she didn’t understand how physicians could divorce medical advice from the context of patients’ lives.

“How can you offer advice as recommendations that’s not even relevant to how their day to day plays out?” Dr. Maybank asked.

Today, Dr. Maybank is continuing to question that medical school philosophy. She was recently named the first chief health equity officer for the American Medical Association. In that job, she is responsible for implementing practices among doctors across the country to help end disparities in care. She has a full agenda, including launching the group’s Center for Health Equity and helping the Chicago-based doctors association reach out to people in poor neighborhoods in the city.

A pediatrician, Dr. Maybank previously worked for the New York City government as deputy commissioner for the health department and founding director of the city’s health equity center.

Carmen Heredia Rodriguez of Kaiser Health News recently spoke with Dr. Maybank about her new role and how health inequities affect Americans. This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Can you tell me what health equity means to you, and what are some of the main drivers that are keeping health inequitable in this country?

The AMA policy around health equity is optimal health for all people.

But it’s not just an outcome; there’s a process to get there. How do we engage with people? How do we look at and collect our data to make sure our practices and processes are equitable? How do we hire differently to ensure diversity? All these things are processes to achieve health equity.

In order to understand what produces inequities, we have to understand what creates health. Health is created outside of the walls of the doctor’s office and at the hospital. What are patients’ jobs and employment like? The kind of education they have. Income. Their ability to build wealth. All of these are conditions that impact health.

Q: Is there anything along your career path that really surprised you about the state of health care in the United States?

There’s the perception that all of our health is really determined by whether you have a doctor or not, or if you have insurance. What creates health is much beyond that.

So if we really want to work on health and equity, we have to partner with people who are in the education space and the economic space and the housing spaces, because that’s where health inequities are produced. You could have insurance coverage. You could have a primary care doctor. But it doesn’t mean that you’re not going to experience health inequities.

Q: Discrimination based on racial lines is one obvious driver of health inequities. What are some of the other populations that are affected by health inequity?

I think structural racism is a system that affects us all.

It’s not just the black-white issue. So, whether it’s discrimination or inequities that exist among LGBT youth and transgender [or] nonconforming people, or if it’s folks who are immigrants or women, a lot of that is contextualized under the umbrella of white supremacy within the country.

Q: And what are some of your priorities?

A large part of my work will be how I build the organizational capacity to better understand health equity. The reality in this country is folks aren’t comfortable talking about those issues. So, we have to destigmatize talking about all of this.

Q: Are there any particular populations or relationships that you plan to focus on?

The AMA excluded black physicians until the 1960s. So one question is: How do we work to heal relationships as well as understand the impact of our past actions? The AMA definitely issued an apology in the early 2000s, and my new role is also a step in the right direction. However, there is more that we can and should do.

Another priority now is: How do we work, and who do we work with, in our own backyard of Chicago? What can we do to work directly with people experiencing the greatest burden of disease? How do we ensure that we acknowledge the power, assets and expertise of communities so that we have the process and solutions driven and led by communities? To that end, we’ve begun working with West Side United via a relationship at Rush Medical Center. West Side United is a community-driven, collective neighborhood planning, implementation and investment effort geared toward optimizing economic well-being and improved health outcomes.

Q: Is there anything else you feel is important to understand about health equity?

Health equity and social determinants of health have become jargon. But we are talking about people’s lives. We were all born equal. We are clearly not all treated equal, but we all deserve equity. I don’t live outside of it, and none of us really do. I am one of those women who were three to four times more likely to die at childbirth because I’m black. So I don’t live outside of this experience. I’m talking about my own life.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Meth’s resurgence spotlights lack of meds to combat the addiction

In 2016, news reports warned the public of an opioid epidemic gripping the nation.

But Madeline Vaughn, then a lead clinical intake coordinator at the Houston-based addiction treatment organization Council on Recovery, sensed something different was going on with the patients she checked in from the street.

Their behavior, marked by twitchy suspicion, a poor memory, and the feeling that someone was following them, signaled that the people coming through the center’s doors were increasingly hooked on a different drug: methamphetamine.

“When you’re in the boots on the ground,” Ms. Vaughn said, “what you see may surprise you, because it’s not in the headlines.”

In the time since, it’s become increasingly clear that, even as the opioid epidemic continues, the toll of methamphetamine use, also known as meth or crystal meth, is on the rise, too.

The rate of overdose deaths involving the stimulant more than tripled from 2011 to 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

But unlike the opioid epidemic – for which medications exist to help combat addiction – medical providers have few such tools to help methamphetamine users survive and recover. A drug such as naloxone, which can reverse an opioid overdose, does not exist for meth. And there are no drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration that can treat a meth addiction.

“We’re realizing that we don’t have everything we might wish we had to address these different kinds of drugs,” said Margaret Jarvis, MD, a psychiatrist and distinguished fellow for the American Society of Addiction Medicine.

Meth revs up the human body, causing euphoria, elevated blood pressure, and energy that enables users to go for days without sleeping or eating. In some cases, long-term use alters the user’s brain and causes psychotic symptoms that can take up to one year after the person has stopped using it to dissipate.

Overdosing can trigger heart attacks, strokes, and seizures, which can make pinpointing the drug’s involvement difficult.

Meth users also tend to abuse other substances, which complicates first responders’ efforts to treat a patient in the event of an overdose, said David Persse, MD, EMS physician director for Houston. With multiple drugs in a patient’s system, overdose symptoms may not neatly fit under the description for one substance.

“If we had five or six miracle drugs,” Dr. Persse said, to use immediately on the scene of the overdose, “it’s still gonna be difficult to know which one that patient needs.”

Research is underway to develop a medication that helps those with methamphetamine addiction overcome their condition. The National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network is testing a combination of naltrexone, a medication typically used to treat opioid and alcohol use disorders, and an antidepressant called bupropion.

And a team from the Universities of Kentucky and Arkansas created a molecule called lobeline that shows promise in blocking meth’s effects in the brain.

For now, though, existing treatments, such as the Matrix Model, a drug counseling technique, and contingency management, which offers patients incentives to stay away from drugs, are key options for what appears to be a meth resurgence, said Dr. Jarvis.

Illegal drugs never disappear from the street, she said. Their popularity waxes and wanes with demand. And as the demand for methamphetamine use increases, the gaps in treatment become more apparent.

Dr. Persse said he hasn’t seen a rise in the number of calls related to methamphetamine overdoses in his area. However, the death toll in Texas from meth now exceeds that of heroin.

Provisional death counts for 2017 showed methamphetamine claimed 813 lives in the Lone Star State. By comparison, 591 people died because of heroin.

The Drug Enforcement Administration reported that the price of meth is the lowest the agency has seen in years. It is increasingly available in the eastern region of the United States. Primary suppliers are Mexican drug cartels. And the meth on the streets is now more than 90% pure.

“The new methods [of making methamphetamine] have really altered the potency,” said Jane Maxwell, PhD, research professor at the University of Texas at Austin’s social work school. “So the meth we’re looking at today is much more potent than it was 10 years ago.”

For Ms. Vaughn, who works as an outpatient therapist and treatment coordinator, these variables are a regular part of her daily challenge. So until the research arms her with something new, her go-to strategy is to use the available tools to tackle her patients’ methamphetamine addiction in layers.

She starts with writing assignments, then coping skills until they are capable of unpacking their trauma. Addiction is rarely the sole demon patients wrestle with, Ms. Vaughn said.

“Substance use is often a symptom for what’s really going on with someone,” she said.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

In 2016, news reports warned the public of an opioid epidemic gripping the nation.

But Madeline Vaughn, then a lead clinical intake coordinator at the Houston-based addiction treatment organization Council on Recovery, sensed something different was going on with the patients she checked in from the street.

Their behavior, marked by twitchy suspicion, a poor memory, and the feeling that someone was following them, signaled that the people coming through the center’s doors were increasingly hooked on a different drug: methamphetamine.

“When you’re in the boots on the ground,” Ms. Vaughn said, “what you see may surprise you, because it’s not in the headlines.”

In the time since, it’s become increasingly clear that, even as the opioid epidemic continues, the toll of methamphetamine use, also known as meth or crystal meth, is on the rise, too.

The rate of overdose deaths involving the stimulant more than tripled from 2011 to 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

But unlike the opioid epidemic – for which medications exist to help combat addiction – medical providers have few such tools to help methamphetamine users survive and recover. A drug such as naloxone, which can reverse an opioid overdose, does not exist for meth. And there are no drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration that can treat a meth addiction.

“We’re realizing that we don’t have everything we might wish we had to address these different kinds of drugs,” said Margaret Jarvis, MD, a psychiatrist and distinguished fellow for the American Society of Addiction Medicine.

Meth revs up the human body, causing euphoria, elevated blood pressure, and energy that enables users to go for days without sleeping or eating. In some cases, long-term use alters the user’s brain and causes psychotic symptoms that can take up to one year after the person has stopped using it to dissipate.

Overdosing can trigger heart attacks, strokes, and seizures, which can make pinpointing the drug’s involvement difficult.

Meth users also tend to abuse other substances, which complicates first responders’ efforts to treat a patient in the event of an overdose, said David Persse, MD, EMS physician director for Houston. With multiple drugs in a patient’s system, overdose symptoms may not neatly fit under the description for one substance.

“If we had five or six miracle drugs,” Dr. Persse said, to use immediately on the scene of the overdose, “it’s still gonna be difficult to know which one that patient needs.”

Research is underway to develop a medication that helps those with methamphetamine addiction overcome their condition. The National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network is testing a combination of naltrexone, a medication typically used to treat opioid and alcohol use disorders, and an antidepressant called bupropion.

And a team from the Universities of Kentucky and Arkansas created a molecule called lobeline that shows promise in blocking meth’s effects in the brain.

For now, though, existing treatments, such as the Matrix Model, a drug counseling technique, and contingency management, which offers patients incentives to stay away from drugs, are key options for what appears to be a meth resurgence, said Dr. Jarvis.

Illegal drugs never disappear from the street, she said. Their popularity waxes and wanes with demand. And as the demand for methamphetamine use increases, the gaps in treatment become more apparent.

Dr. Persse said he hasn’t seen a rise in the number of calls related to methamphetamine overdoses in his area. However, the death toll in Texas from meth now exceeds that of heroin.

Provisional death counts for 2017 showed methamphetamine claimed 813 lives in the Lone Star State. By comparison, 591 people died because of heroin.

The Drug Enforcement Administration reported that the price of meth is the lowest the agency has seen in years. It is increasingly available in the eastern region of the United States. Primary suppliers are Mexican drug cartels. And the meth on the streets is now more than 90% pure.

“The new methods [of making methamphetamine] have really altered the potency,” said Jane Maxwell, PhD, research professor at the University of Texas at Austin’s social work school. “So the meth we’re looking at today is much more potent than it was 10 years ago.”

For Ms. Vaughn, who works as an outpatient therapist and treatment coordinator, these variables are a regular part of her daily challenge. So until the research arms her with something new, her go-to strategy is to use the available tools to tackle her patients’ methamphetamine addiction in layers.

She starts with writing assignments, then coping skills until they are capable of unpacking their trauma. Addiction is rarely the sole demon patients wrestle with, Ms. Vaughn said.

“Substance use is often a symptom for what’s really going on with someone,” she said.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

In 2016, news reports warned the public of an opioid epidemic gripping the nation.

But Madeline Vaughn, then a lead clinical intake coordinator at the Houston-based addiction treatment organization Council on Recovery, sensed something different was going on with the patients she checked in from the street.

Their behavior, marked by twitchy suspicion, a poor memory, and the feeling that someone was following them, signaled that the people coming through the center’s doors were increasingly hooked on a different drug: methamphetamine.

“When you’re in the boots on the ground,” Ms. Vaughn said, “what you see may surprise you, because it’s not in the headlines.”

In the time since, it’s become increasingly clear that, even as the opioid epidemic continues, the toll of methamphetamine use, also known as meth or crystal meth, is on the rise, too.

The rate of overdose deaths involving the stimulant more than tripled from 2011 to 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

But unlike the opioid epidemic – for which medications exist to help combat addiction – medical providers have few such tools to help methamphetamine users survive and recover. A drug such as naloxone, which can reverse an opioid overdose, does not exist for meth. And there are no drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration that can treat a meth addiction.

“We’re realizing that we don’t have everything we might wish we had to address these different kinds of drugs,” said Margaret Jarvis, MD, a psychiatrist and distinguished fellow for the American Society of Addiction Medicine.

Meth revs up the human body, causing euphoria, elevated blood pressure, and energy that enables users to go for days without sleeping or eating. In some cases, long-term use alters the user’s brain and causes psychotic symptoms that can take up to one year after the person has stopped using it to dissipate.

Overdosing can trigger heart attacks, strokes, and seizures, which can make pinpointing the drug’s involvement difficult.

Meth users also tend to abuse other substances, which complicates first responders’ efforts to treat a patient in the event of an overdose, said David Persse, MD, EMS physician director for Houston. With multiple drugs in a patient’s system, overdose symptoms may not neatly fit under the description for one substance.

“If we had five or six miracle drugs,” Dr. Persse said, to use immediately on the scene of the overdose, “it’s still gonna be difficult to know which one that patient needs.”

Research is underway to develop a medication that helps those with methamphetamine addiction overcome their condition. The National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network is testing a combination of naltrexone, a medication typically used to treat opioid and alcohol use disorders, and an antidepressant called bupropion.

And a team from the Universities of Kentucky and Arkansas created a molecule called lobeline that shows promise in blocking meth’s effects in the brain.

For now, though, existing treatments, such as the Matrix Model, a drug counseling technique, and contingency management, which offers patients incentives to stay away from drugs, are key options for what appears to be a meth resurgence, said Dr. Jarvis.

Illegal drugs never disappear from the street, she said. Their popularity waxes and wanes with demand. And as the demand for methamphetamine use increases, the gaps in treatment become more apparent.

Dr. Persse said he hasn’t seen a rise in the number of calls related to methamphetamine overdoses in his area. However, the death toll in Texas from meth now exceeds that of heroin.

Provisional death counts for 2017 showed methamphetamine claimed 813 lives in the Lone Star State. By comparison, 591 people died because of heroin.

The Drug Enforcement Administration reported that the price of meth is the lowest the agency has seen in years. It is increasingly available in the eastern region of the United States. Primary suppliers are Mexican drug cartels. And the meth on the streets is now more than 90% pure.

“The new methods [of making methamphetamine] have really altered the potency,” said Jane Maxwell, PhD, research professor at the University of Texas at Austin’s social work school. “So the meth we’re looking at today is much more potent than it was 10 years ago.”

For Ms. Vaughn, who works as an outpatient therapist and treatment coordinator, these variables are a regular part of her daily challenge. So until the research arms her with something new, her go-to strategy is to use the available tools to tackle her patients’ methamphetamine addiction in layers.

She starts with writing assignments, then coping skills until they are capable of unpacking their trauma. Addiction is rarely the sole demon patients wrestle with, Ms. Vaughn said.

“Substance use is often a symptom for what’s really going on with someone,” she said.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Mysterious polio-like illness baffles medical experts while frightening parents

A spike in the number of children with a rare neurological disease that causes polio-like symptoms has health officials across the country scrambling to understand the illness. Yet, more than 4 years after health officials first recorded the most recent uptick in cases, much about the national outbreak remains a mystery.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) affects the gray matter in the spinal cord, causing sudden muscle weakness and a loss of reflexes. The illness can lead to serious complications – including paralysis or respiratory failure – and requires immediate medical attention.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is investigating 127 cases of possible AFM, including 62 that have been confirmed in 22 states this year. At least 90% of the cases are among patients 18 years old and younger. The average age of a patient is 4 years old.

AFM remains extremely rare, even with the recent increase. The CDC estimates fewer than 1 in a million Americans will get the disease. Officials advised parents not to panic but remain vigilant for any sudden onset of symptoms. They also suggested that children stay up to date with their vaccines and practice good hand washing habits.

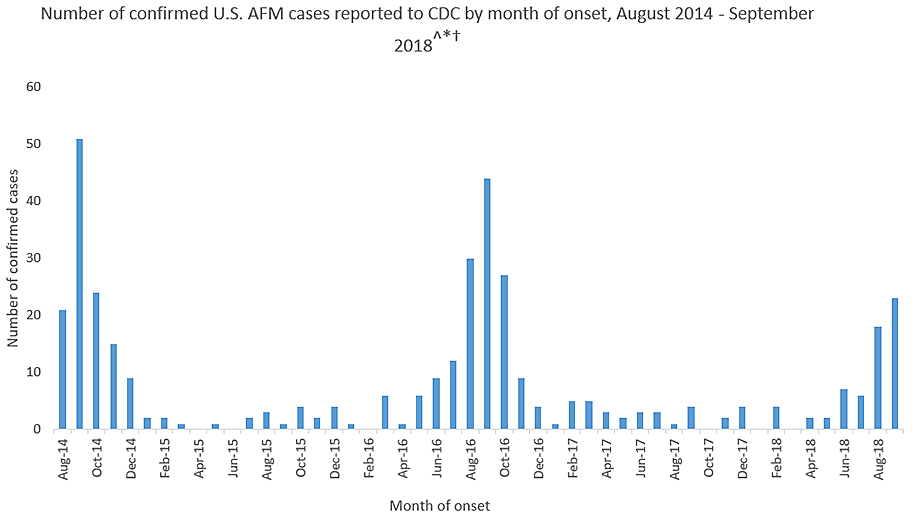

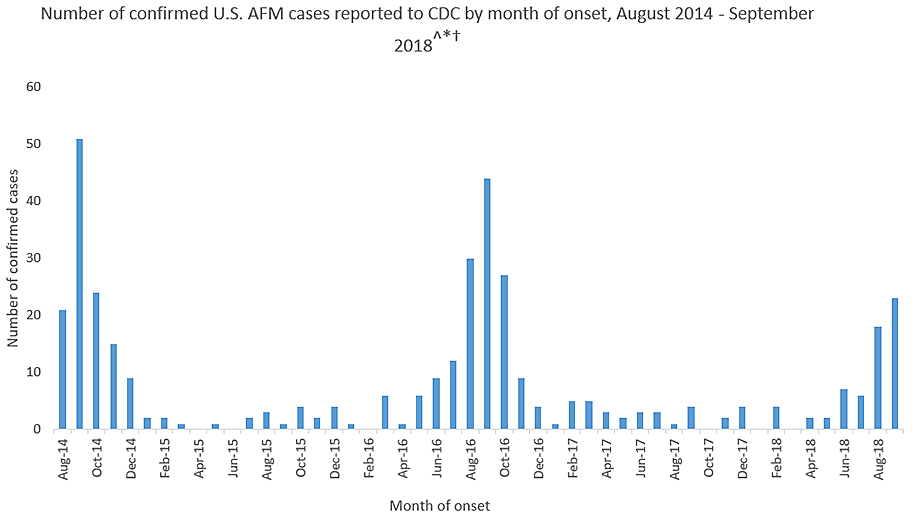

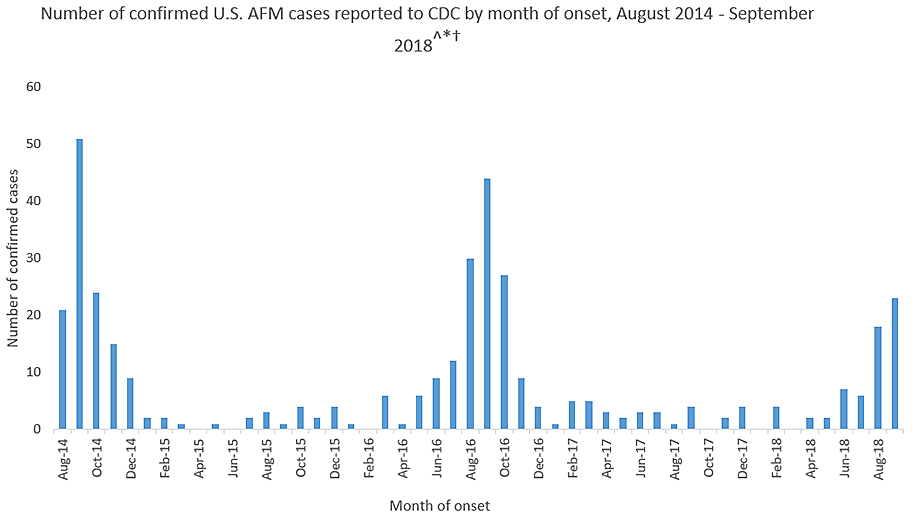

This year’s outbreak marks the third spike of AFM in 4 years. From August 2014 to September 2018, 386 cases have been confirmed. Yet, experts still do not understand crucial aspects of the disease, including its origins and who is most at risk.

“There is a lot we don’t know about AFM,” said Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. Here’s what puzzles health officials about AFM:

The cause is still unknown

Acute flaccid myelitis can be caused by viruses, such as polio or West Nile. But federal officials said that those viruses have not been linked to the U.S. outbreak over the past 4 years. They have not isolated the cause of these cases.

Despite symptoms reminiscent of polio, no AFM cases have tested positive for that virus, according to the CDC. Investigators have also ruled out a variety of germs. Environmental agents, viruses, and other pathogens are still being considered.

The 2014 outbreak of AFM coincided with a surge of another virus that caused severe respiratory problems, called EV-D68. However, the CDC could not establish a causal link between AFM and the virus. Since then, no large outbreaks of the virus have occurred, according to the CDC.

Carlos Pardo-Villamizar, MD, a neurologist and director of the Johns Hopkins Transverse Myelitis Center, said that the mystery lies in whether the damage seen in AFM is caused by an external agent or the body’s own defenses.

“At this moment, we don’t know if it’s a virus that is coming and producing direct damage of the gray matter in the spinal cord,” he said, “or if a virus is triggering immunological responses that produce a secondary damage in the spinal cord.”

It’s not clear who is at risk

Although the disease appears to target a certain age group, federal disease experts do not know who is likely to get acute flaccid myelitis.

Dr. Pardo-Villamizar said identifying vulnerable populations is “a work in progress.”

Mary Anne Jackson, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist and interim dean of the school of medicine at the University of Missouri–Kansas City, said many of the patients she saw were healthy children before falling ill with the disease. She suspects that a host of factors play a role in the likelihood of getting AFM, but more cases must be reviewed in order to find an answer.

The long-term effects are unknown

The CDC said it doesn’t know how long symptoms of the disease will last for patients. However, experts say that initial indications from a small number of cases suggest a grim outlook.

A study published last year found six of eight children in Colorado with acute flaccid myelitis still struggled with motor skills 1 year after their diagnosis. Nonetheless, the researchers found that the patients and families “demonstrated a high degree of resilience and recovery.”

“The majority of these patients are left with extensive problems,” said Dr. Pardo-Villamizar, who was not involved in the study.

Dr. Jackson, who also saw persistent muscle weakness in her patients, said she believes the CDC may be hesitant to specify the long-term effects of the disease because existing studies have included only small numbers of patients. More studies that include a larger proportion of confirmed cases are needed to better understand long-term outcomes, she said.

KHN’s coverage of children’s health care issues is supported in part by the Heising-Simons Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

A spike in the number of children with a rare neurological disease that causes polio-like symptoms has health officials across the country scrambling to understand the illness. Yet, more than 4 years after health officials first recorded the most recent uptick in cases, much about the national outbreak remains a mystery.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) affects the gray matter in the spinal cord, causing sudden muscle weakness and a loss of reflexes. The illness can lead to serious complications – including paralysis or respiratory failure – and requires immediate medical attention.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is investigating 127 cases of possible AFM, including 62 that have been confirmed in 22 states this year. At least 90% of the cases are among patients 18 years old and younger. The average age of a patient is 4 years old.

AFM remains extremely rare, even with the recent increase. The CDC estimates fewer than 1 in a million Americans will get the disease. Officials advised parents not to panic but remain vigilant for any sudden onset of symptoms. They also suggested that children stay up to date with their vaccines and practice good hand washing habits.

This year’s outbreak marks the third spike of AFM in 4 years. From August 2014 to September 2018, 386 cases have been confirmed. Yet, experts still do not understand crucial aspects of the disease, including its origins and who is most at risk.

“There is a lot we don’t know about AFM,” said Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. Here’s what puzzles health officials about AFM:

The cause is still unknown

Acute flaccid myelitis can be caused by viruses, such as polio or West Nile. But federal officials said that those viruses have not been linked to the U.S. outbreak over the past 4 years. They have not isolated the cause of these cases.

Despite symptoms reminiscent of polio, no AFM cases have tested positive for that virus, according to the CDC. Investigators have also ruled out a variety of germs. Environmental agents, viruses, and other pathogens are still being considered.

The 2014 outbreak of AFM coincided with a surge of another virus that caused severe respiratory problems, called EV-D68. However, the CDC could not establish a causal link between AFM and the virus. Since then, no large outbreaks of the virus have occurred, according to the CDC.

Carlos Pardo-Villamizar, MD, a neurologist and director of the Johns Hopkins Transverse Myelitis Center, said that the mystery lies in whether the damage seen in AFM is caused by an external agent or the body’s own defenses.

“At this moment, we don’t know if it’s a virus that is coming and producing direct damage of the gray matter in the spinal cord,” he said, “or if a virus is triggering immunological responses that produce a secondary damage in the spinal cord.”

It’s not clear who is at risk

Although the disease appears to target a certain age group, federal disease experts do not know who is likely to get acute flaccid myelitis.

Dr. Pardo-Villamizar said identifying vulnerable populations is “a work in progress.”

Mary Anne Jackson, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist and interim dean of the school of medicine at the University of Missouri–Kansas City, said many of the patients she saw were healthy children before falling ill with the disease. She suspects that a host of factors play a role in the likelihood of getting AFM, but more cases must be reviewed in order to find an answer.

The long-term effects are unknown

The CDC said it doesn’t know how long symptoms of the disease will last for patients. However, experts say that initial indications from a small number of cases suggest a grim outlook.

A study published last year found six of eight children in Colorado with acute flaccid myelitis still struggled with motor skills 1 year after their diagnosis. Nonetheless, the researchers found that the patients and families “demonstrated a high degree of resilience and recovery.”

“The majority of these patients are left with extensive problems,” said Dr. Pardo-Villamizar, who was not involved in the study.

Dr. Jackson, who also saw persistent muscle weakness in her patients, said she believes the CDC may be hesitant to specify the long-term effects of the disease because existing studies have included only small numbers of patients. More studies that include a larger proportion of confirmed cases are needed to better understand long-term outcomes, she said.

KHN’s coverage of children’s health care issues is supported in part by the Heising-Simons Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

A spike in the number of children with a rare neurological disease that causes polio-like symptoms has health officials across the country scrambling to understand the illness. Yet, more than 4 years after health officials first recorded the most recent uptick in cases, much about the national outbreak remains a mystery.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) affects the gray matter in the spinal cord, causing sudden muscle weakness and a loss of reflexes. The illness can lead to serious complications – including paralysis or respiratory failure – and requires immediate medical attention.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is investigating 127 cases of possible AFM, including 62 that have been confirmed in 22 states this year. At least 90% of the cases are among patients 18 years old and younger. The average age of a patient is 4 years old.

AFM remains extremely rare, even with the recent increase. The CDC estimates fewer than 1 in a million Americans will get the disease. Officials advised parents not to panic but remain vigilant for any sudden onset of symptoms. They also suggested that children stay up to date with their vaccines and practice good hand washing habits.

This year’s outbreak marks the third spike of AFM in 4 years. From August 2014 to September 2018, 386 cases have been confirmed. Yet, experts still do not understand crucial aspects of the disease, including its origins and who is most at risk.

“There is a lot we don’t know about AFM,” said Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. Here’s what puzzles health officials about AFM:

The cause is still unknown

Acute flaccid myelitis can be caused by viruses, such as polio or West Nile. But federal officials said that those viruses have not been linked to the U.S. outbreak over the past 4 years. They have not isolated the cause of these cases.

Despite symptoms reminiscent of polio, no AFM cases have tested positive for that virus, according to the CDC. Investigators have also ruled out a variety of germs. Environmental agents, viruses, and other pathogens are still being considered.

The 2014 outbreak of AFM coincided with a surge of another virus that caused severe respiratory problems, called EV-D68. However, the CDC could not establish a causal link between AFM and the virus. Since then, no large outbreaks of the virus have occurred, according to the CDC.

Carlos Pardo-Villamizar, MD, a neurologist and director of the Johns Hopkins Transverse Myelitis Center, said that the mystery lies in whether the damage seen in AFM is caused by an external agent or the body’s own defenses.

“At this moment, we don’t know if it’s a virus that is coming and producing direct damage of the gray matter in the spinal cord,” he said, “or if a virus is triggering immunological responses that produce a secondary damage in the spinal cord.”

It’s not clear who is at risk

Although the disease appears to target a certain age group, federal disease experts do not know who is likely to get acute flaccid myelitis.

Dr. Pardo-Villamizar said identifying vulnerable populations is “a work in progress.”

Mary Anne Jackson, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist and interim dean of the school of medicine at the University of Missouri–Kansas City, said many of the patients she saw were healthy children before falling ill with the disease. She suspects that a host of factors play a role in the likelihood of getting AFM, but more cases must be reviewed in order to find an answer.

The long-term effects are unknown

The CDC said it doesn’t know how long symptoms of the disease will last for patients. However, experts say that initial indications from a small number of cases suggest a grim outlook.

A study published last year found six of eight children in Colorado with acute flaccid myelitis still struggled with motor skills 1 year after their diagnosis. Nonetheless, the researchers found that the patients and families “demonstrated a high degree of resilience and recovery.”

“The majority of these patients are left with extensive problems,” said Dr. Pardo-Villamizar, who was not involved in the study.

Dr. Jackson, who also saw persistent muscle weakness in her patients, said she believes the CDC may be hesitant to specify the long-term effects of the disease because existing studies have included only small numbers of patients. More studies that include a larger proportion of confirmed cases are needed to better understand long-term outcomes, she said.

KHN’s coverage of children’s health care issues is supported in part by the Heising-Simons Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.