User login

Painful Losses

A 58‐year‐old man presented to the emergency department with a 1‐month history of progressive, severe left hip pain that had become unbearable. The pain was constant and significantly worse with weight‐bearing, and the patient was now confined to bed. He denied back pain, falls, or trauma.

Although hip pain is a common complaint and a frequent manifestation of chronic degenerative joint disease, the debilitating and subacute nature of the pain suggests a potentially more serious underlying cause. Patients and even clinicians may refer to hip pain when the actual symptoms are periarticular, often presenting over the trochanter laterally, or muscular, presenting as posterior pain. The true hip joint is located in the anterior hip and groin area and often causes symptoms that radiate to the buttock. Pain can also be referred to the hip area from the spine, pelvis, or retroperitoneum, so it is crucial not to restrict the differential diagnosis to hip pathology.

Key diagnostic considerations include (1) inflammatory conditions such as trochanteric bursitis or gout; (2) bacterial infection of the hip joint, adjacent bone, or a nearby structure; (3) benign nerve compression (such as meralgia paresthetica); and (4) tumor (particularly myeloma or metastatic disease to the bone, but also potentially a pelvic or spinal mass with nerve compression). Polymyalgia rheumatica and other systemic rheumatologic complaints are a consideration, but because a single joint is involved, these conditions are less likely. The hip would be an unusual location for a first gout flare, and the duration of symptoms would be unusually long for gout. Avascular necrosis should be considered if the patient has received glucocorticoids for his previously diagnosed rheumatologic disease. If the patient is anticoagulated, consideration of spontaneous hematoma is reasonable, but usually this would present over a course of days, not weeks. The absence of trauma makes a fracture of the hip or pelvis less likely, and the insidious progression of symptoms makes a pathologic fracture less likely.

The patient reported 6 months of worsening proximal upper and lower extremity myalgia and weakness, with arthralgia of the hips and shoulders. The weakness was most notable in his proximal lower extremities, although he had remained ambulatory until the hip pain became limiting. He maintained normal use of his arms. The patient denied current rash but noted photosensitivity and a mild facial rash several months earlier. He described having transient mouth sores intermittently for several years. He denied fever, chills, night sweats, weight loss, dyspnea, recent travel, and outdoor exposures. Several months previously, he had been evaluated for these symptoms at another institution and given the diagnoses of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). At that time, he had initiated treatment with weekly dosing of methotrexate and etanercept.

The patient's medical history was also notable for hypertension, Graves' disease treated previously with radioiodine ablation, quiescent ulcerative colitis, and depression. Current medications included methotrexate, etanercept, levothyroxine, enalapril, hydrochlorothiazide, fluoxetine, ibuprofen, and oxycodone‐acetaminophen. He denied tobacco, alcohol, and recreational drug use.

Weakness occurring in the proximal lower extremities is the classic distribution for polymyositis and dermatomyositis. In contrast to polymyalgia rheumatica, dermatomyositis and polymyositis do not generally feature severe muscle pain, but they can be associated with a painful polyarthritis. Oral ulcers, photosensitivity, and facial rash are consistent with SLE, but dermatomyositis can also lead to a symmetrical erythema of the eyelids (commonly referred to as a heliotrope rash, named after the flower bearing that name) and sometimes can be associated with photosensitivity. Oral ulcers, particularly the painful ones known as canker sores, are extraordinarily common in the general population, and patients and providers may miss the mucosal lesions of SLE because they are usually painless. As methotrexate and etanercept are immunosuppressive, opportunistic pathogens such as typical or atypical mycobacteria and disseminated fungal infections should be considered, with special attention to the possibility of infection in or near the left hip. Given that SLE and RA rarely coexist, it would be helpful to seek outside medical records to know what the prior serologic evaluation entailed, but it is unlikely that this presentation is a manifestation of a diffuse connective tissue process.

Physical examination should focus on the features of dermatomyositis including heliotrope rash, truncal erythema, and papules over the knuckles (Gottron's papules); objective proximal muscle weakness in the shoulder and hip girdle; and findings that might suggest antisynthetase syndrome such as hyperkeratotic mechanic hand palmar and digital changes, and interstitial crackles on lung exam. If necrotic skin lesions are found, this would raise concern for a disseminated infection. The joints should be examined for inflammation and effusions.

His temperature was 36.6C, heart rate 74 beats per minute, blood pressure 134/76 mm Hg, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and O2 saturation 97% on room air. He was obese but did not have moon facies or a buffalo hump. There were no rashes or mucosal lesions. Active and passive motion of his left hip joint elicited pain with both flexion/extension and internal/external rotation. Muscle strength was limited by pain in the left hip flexors and extenders, but was 5/5 in all other muscle groups. Palpation of the proximal muscles of his arms and legs did not elicit pain. His extremities were without edema, and examination of his shoulders, elbows, wrists, hands, knees, ankles, and feet did not reveal any erythema, synovial thickening, effusion, or deformity. Examination of the heart, chest, and abdomen was normal.

Given the reassuring strength examination, the absence of rashes or skin lesions, and the reassuring joint exam aside from the left hip, a focal infectious, inflammatory, or malignant process seems most likely. The pain with range of motion of the hip does not definitively localize the pathology to the hip joint, because pathology of the nearby structures can lead to pain when the hip is moved. Laboratory evaluation should include a complete blood count to screen for evidence of infection or marrow suppression, complete metabolic panel, and creatine kinase. The history of ulcerative colitis raises the possibility of an enthesitis (inflammation of tendons or ligaments) occurring near the hip. Enthesitis is sometimes a feature of the seronegative spondyloarthropathy‐associated conditions and can occur in the absence of sacroiliitis or spondyloarthropathy.

The patient's myalgias and arthralgias had recently been evaluated in the rheumatology clinic. Laboratory evaluation from that visit was remarkable only for an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test that was positive at a titer of 1:320 in a homogeneous pattern, creatine phosphokinase 366 IU/L (normal range [NR] 38240), and alkaline phosphatase 203 IU/L (NR 30130). All of the following labs from that visit were within normal ranges: cyclic citrullinated peptide, rheumatoid factor, antidouble stranded DNA, aldolase, complement levels, serum and urine protein electrophoresis, thyroglobulin antibody, thyroid microsomal antibody, thyroid‐stimulating hormone, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (10 mm/h), and C‐reactive protein (0.3 mg/dL).

The patient was admitted to the hospital. Initial blood test results on admission included sodium 139 mEq/L, potassium 3.9 mEq/L, chloride 105 mEq/L, bicarbonate 27 mEq/L, urea nitrogen 16 mg/dL, creatinine 0.6 mg/dL, glucose 85 mg/dL, calcium 9.2 mg/dL (NR 8.810.3), phosphate 1.3 mg/dL (NR 2.74.6), albumin 4.7 g/dL (NR 3.54.9), and alkaline phosphatase 195 IU/L (NR 30130). The remainder of a comprehensive metabolic profile, complete blood count with differential, and coagulation studies were all normal.

The homogeneous ANA titer of 1:320 is high enough to raise eyebrows, but is nonspecific for lupus and other ANA‐associated rheumatologic conditions, and may be a red herring, particularly given the low likelihood of a systemic inflammatory process explaining this new focal hip pain. The alkaline phosphatase is only mildly elevated and could be of bone or liver origin. The reassuringly low inflammatory markers are potentially helpful, because if checked now and substantially increased from the prior outpatient visit, they would be suggestive of a new inflammatory process. However, this would not point to a specific cause of inflammation.

Given the focality of the symptoms, imaging is warranted. As opposed to plain films, contrast‐enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the pelvis or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be an efficient first step, because there is low suspicion for fracture and high suspicion for an inflammatory, neoplastic, or infectious process. MRI is more expensive and usually cannot be obtained as rapidly as CT. There is a chance that CT imaging alone will provide enough information to guide the next diagnostic steps, such as aspiration of an abscess or joint, or biopsy of a suspicious lesion. However, for soft tissue lesions and many bone lesions, including osteomyelitis, MRI offers better delineation of pathology.

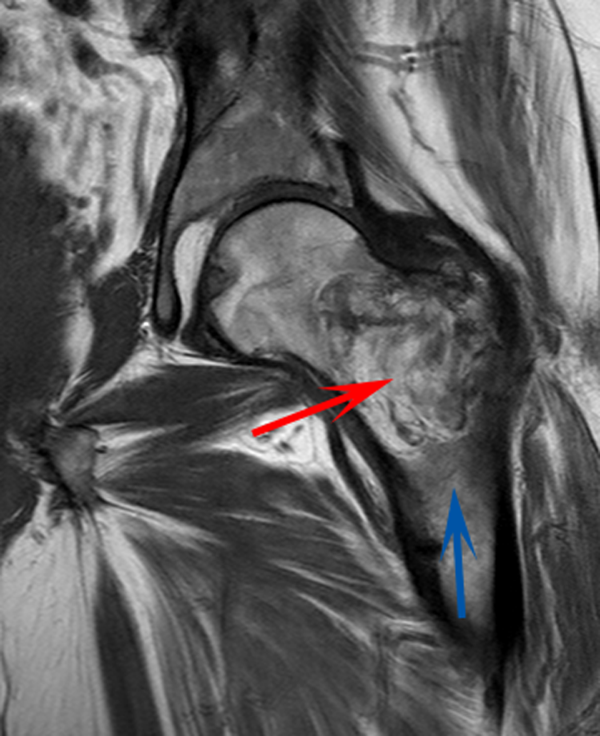

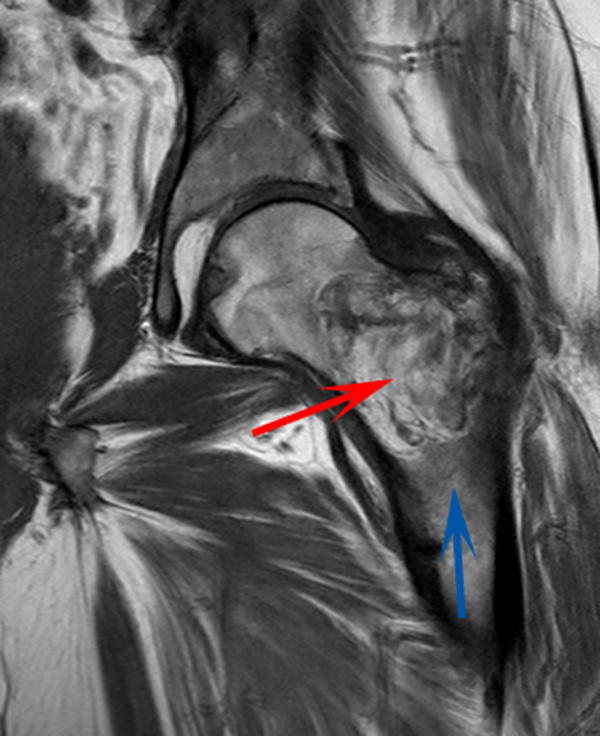

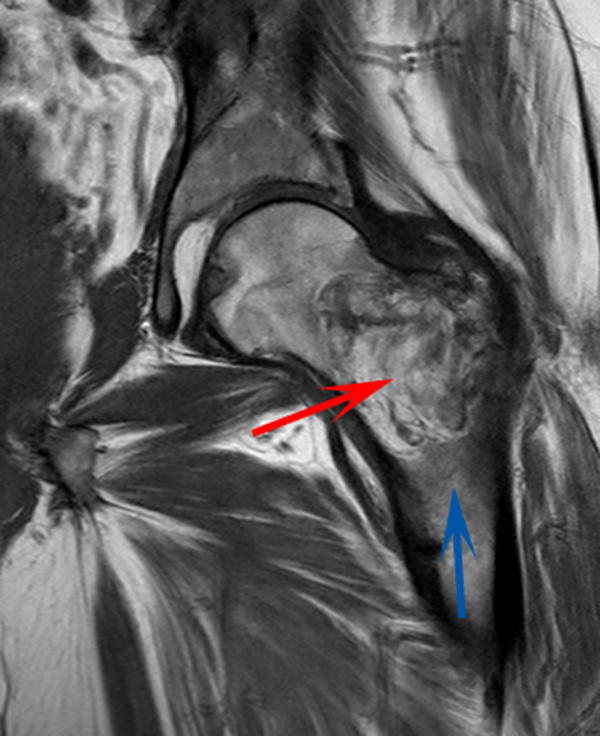

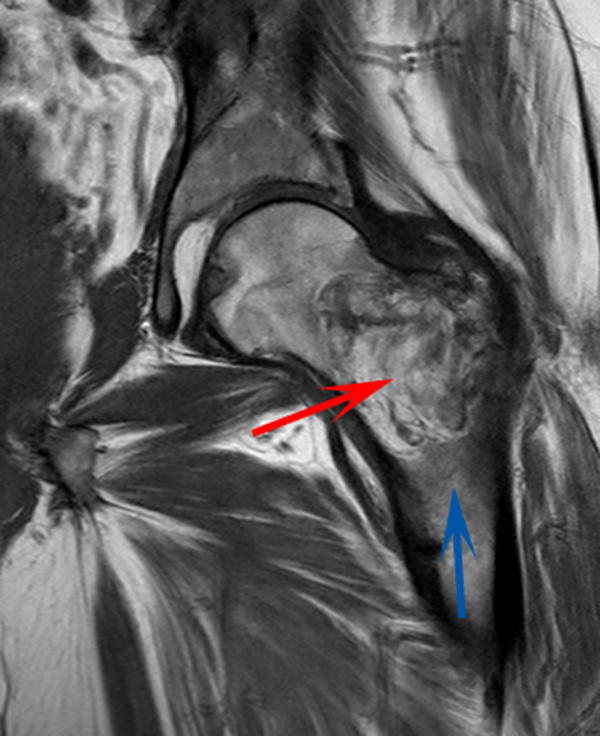

CT scan of the left femur demonstrated a large lytic lesion in the femoral neck that contained macroscopic fat and had an aggressive appearance with significant thinning of the cortex. MRI confirmed these findings and demonstrated a nondisplaced subtrochanteric femur fracture in the proximity of the lesion (Figure 1). Contrast‐enhanced CT scans of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis revealed no other neoplastic lesions. Prostate‐specific antigen level was normal. The patient's significant hypophosphatemia persisted, with levels dropping to as low as 0.9 mg/dL despite aggressive oral phosphate replacement.

Although hypophosphatemia is often a nonspecific finding in hospitalized patients and is usually of little clinical importance, profound hypophosphatemia that is refractory to supplementation suggests an underlying metabolic disorder. Phosphate levels less than 1.0 mg/dL, particularly if prolonged, can lead to decreased adenosine triphosphate production and subsequent weakness of respiratory and cardiac muscles. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) excess and production of parathyroid hormone‐related protein (PTHrP) by a malignancy can cause profound hypophosphatemia, but are generally associated with hypercalcemia, a finding not seen in this case. Occasionally, tumors can lead to renal phosphate wasting via nonPTH‐related mechanisms. The best characterized example of this is the paraneoplastic syndrome oncogenic osteomalacia caused by tumor production of a fibroblast growth factor. Tumors that lead to this syndrome are usually benign mesenchymal tumors. This patient's tumor may be of this type, causing local destruction and metabolic disturbance. The next step would be consultation with orthopedic surgery for resection of the tumor and total hip arthroplasty with aggressive perioperative repletion of phosphate. Assessment of intact PTH, ionized calcium, 24‐hour urinary phosphate excretion, and even PTHrP levels may help to rule out other etiologies of hypophosphatemia, but given that surgery is needed regardless, it might be reasonable to proceed to the operating room without these diagnostics. If the phosphate levels return to normal postoperatively, then the diagnosis is clear and no further metabolic testing is needed.

PTH level was 47 pg/mL (NR 1065), 25‐hydroxyvitamin D level was 25 ng/mL (NR 2580), and 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D level was 18 pg/mL (NR 1872). Urinalysis was normal without proteinuria or glucosuria. A 24‐hour urine collection contained 1936 mg of phosphate (NR 4001200). The ratio of maximum rate of renal tubular reabsorption of phosphate to glomerular filtration rate (TmP/GFR) was 1.3 mg/dL (NR 2.44.2). Tissue obtained by CT‐guided needle biopsy of the femoral mass was consistent with a benign spindle cell neoplasm.

With normal calcium levels, the PTH level is appropriate, and hyperparathyroidism is excluded. The levels of 25‐hydroxyvitamin D and 1‐25‐dihydroxyvitamin D are not low enough to suggest that vitamin D deficiency is driving the impressive hypophosphatemia. What is impressive is the phosphate wasting demonstrated by the 24‐hour urine collection, consistent with paraneoplastic overproduction of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) by the benign bone tumor. Overproduction of this protein can be detected by blood tests or staining of the tumor specimen, but surgery should be performed as soon as possible independent of any further test results. Once the tumor is resected, phosphate metabolism should normalize.

FGF23 level was 266 RU/mL (NR < 180). The patient was diagnosed with tumor‐induced osteomalacia (TIO). He underwent complete resection of the femoral tumor as well as open reduction and internal fixation of the fracture. After surgery, his symptoms of pain and subjective muscle weakness improved, his serum phosphate level normalized, his need for phosphate supplementation resolved, and his blood levels of FGF23 decreased into the normal range (111 RU/mL). The rapid improvement of his symptoms after surgery suggested that they were related to TIO, and not manifestations of SLE or RA. His immunosuppressant medications were discontinued. Surgical pathology demonstrated a heterogeneous tumor consisting of sheets of uniform spindle cells interspersed with mature adipose tissue. This was diagnosed descriptively as a benign spindle cell and lipomatous neoplasm without further classification. Two months later, the patient was ambulating without pain, and muscle strength was subjectively normal.

DISCUSSION

TIO is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome affecting phosphate and vitamin D metabolism, leading to hypophosphatemia and osteomalacia.[1] TIO is caused by the inappropriate tumor secretion of the phosphatonin hormone, FGF23.

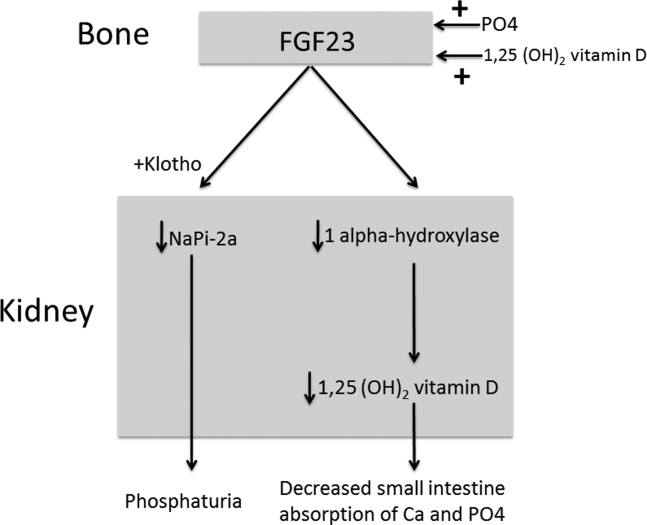

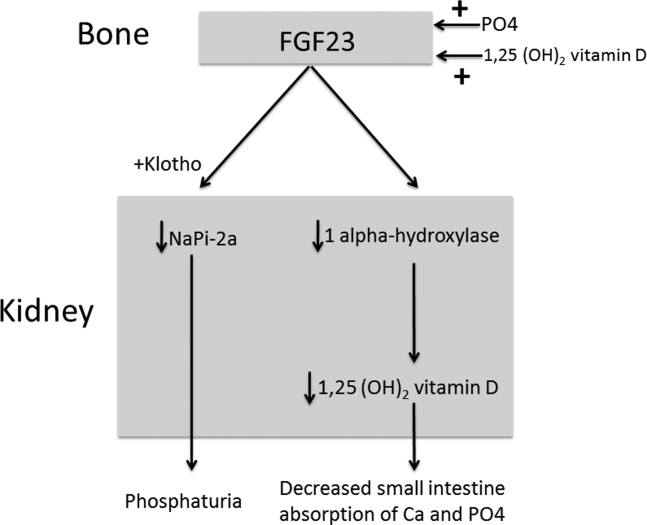

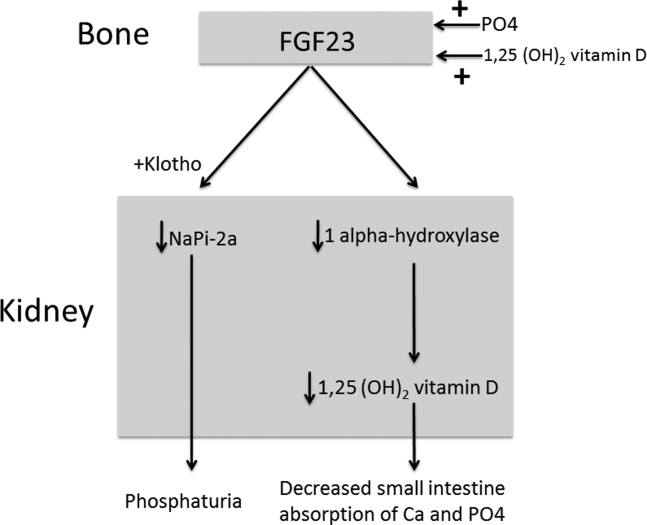

The normal physiology of FGF23 is illustrated in Figure 2. Osteocytes appear to be the primary source of FGF23, but the regulation of FGF23 production is not completely understood. FGF23 production may be influenced by several factors, including 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D levels, and serum phosphate and PTH concentrations. This hormone binds to the FGF receptor and its coreceptor, Klotho,[2] causing 2 major physiological effects. First, it decreases the expression of the sodium‐phosphate cotransporters in the renal proximal tubular cells,[3, 4] resulting in increased tubular phosphate wasting. This effect appears to be partly PTH dependent.[5] Second, it has effects on vitamin D metabolism, decreasing renal production of activated vitamin D.[3, 4, 6]

In overproduction states, the elevated FGF23 leads to chronically low serum phosphate levels (with renal phosphate wasting) and the clinical syndrome of osteomalacia, manifested by bone pain, fractures, and deformities. Hypophosphatemia can also lead to painful proximal myopathy, cardiorespiratory dysfunction, and a spectrum of neuropsychiatric findings. The clinical findings in TIO are similar to those seen in genetic diseases in which hypophosphatemia results from the same mechanism.[3, 4]

In this case, measurement of the serum phosphate level was important in reaching the diagnosis. Although hypophosphatemia in the hospitalized patient is often easily explained, severe or persistent hypophosphatemia requires a focused evaluation. Causes of hypophosphatemia are categorized in Table 1.[7, 8, 9] In patients with hypophosphatemia that is not explained by the clinical situation (eg, osmotic diuresis, insulin treatment, refeeding syndrome, postparathyroidectomy, chronic diarrhea), measurement of serum calcium, PTH, and 25‐hydroxyvitamin D are used to investigate possible primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism. In addition, low‐normal or low serum 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D with normal PTH, normal 25‐hydroxyvitamin D stores, and normal renal function are clues to the presence of TIO. Urine phosphate wasting can be measured by collecting a 24‐hour urine sample. Calculation of the TmP/GFR (a measure of the maximum tubular resorption of phosphate relative to the glomerular filtration rate), as described by the nomogram of Walton and Bijvoet, may improve the accuracy of this assessment and confirm a renal source of the hypophosphatemia.[10]

|

| Internal redistribution |

| Insulin or catecholamine effect (including that related to refeeding syndrome, and infusion of glucose or TPN) |

| Acute respiratory alkalosis |

| Accelerated bone formation or rapid cell proliferation (eg, hungry bone syndrome, leukemic blast crisis, erythropoietin, or granulocyte colony stimulating factor administration) |

| Decreased absorption |

| Poor intake (including that seen in alcoholism*) |

| Vitamin D deficiency |

| Gastrointestinal losses (eg, chronic diarrhea) |

| Malabsorption (eg, phosphate‐binding antacids) |

| Urinary losses |

| Osmotic diuresis (eg, poorly controlled diabetes, acetazolamide) or volume expansion |

| Other diuretics: thiazides, indapamide |

| Hyperparathyroidism |

| Primary |

| Secondary (including vitamin D or calcium deficiency) |

| Parathyroid hormone‐related peptide |

| Renal tubular disease |

| Medications (eg, ethanol,* high‐dose glucocorticoids, cisplatin, bisphosphonates, estrogens, imatinib, acyclovir) |

| Fanconi syndrome |

| Medications inducing Fanconi syndrome: tenofovir, cidofovir, adefovir, aminoglycosides, ifosfamide, tetracyclines, valproic acid |

| Other (eg, postrenal transplant) |

| Excessive phosphatonin hormone activity (eg, hereditary syndromes [rickets], tumor‐induced osteomalacia) |

| Multifactorial causes |

| Alcoholism* |

| Acetaminophen toxicity |

| Parenteral iron administration |

The patient presented here had inappropriate urinary phosphate losses, and laboratory testing ruled out primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism and Fanconi syndrome. The patient was not taking medications known to cause tubular phosphate wasting. The patient's age and clinical history made hereditary syndromes unlikely. Therefore, the urinary phosphate wasting had to be related to an acquired defect in phosphate metabolism. The diagnostic characteristics of TIO are summarized in Table 2.

|

| Patients may present with symptoms of osteomalacia (eg, bone pain, fractures), hypophosphatemia (eg, proximal myopathy), and/or neoplasm. |

| Hypophosphatemia with urinary phosphate wasting. |

| Serum calcium level is usually normal. |

| Serum 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D level is usually low or low‐normal. |

| Parathyroid hormone is usually normal. |

| Plasma FGF23 level is elevated. |

| A neoplasm with the appropriate histology is identified, although the osteomalacia syndrome may precede identification of the tumor, which may be occult. |

| The syndrome resolves after complete resection of the tumor. |

The presence of a known neoplasm makes the diagnosis of TIO considerably easier. However, osteomalacia often precedes the tumor diagnosis. In these cases, the discovery of this clinical syndrome necessitates a search for the tumor. The tumors can be small, occult, and often located in the extremities. In addition to standard cross‐sectional imaging, specialized diagnostic modalities can be helpful in localizing culprit tumors. These include F‐18 flourodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography with computed tomography, 111‐Indium octreotide single photon emission CT/CT, 68‐Gallium‐DOTA‐octreotide positron emission tomography with computed tomography, and even selective venous sampling for FGF23 levels.[1, 11] The octreotide tests capitalize on the fact that culprit tumors often express somatostatin receptors.

TIO is most often associated with mesenchymal tumors of the bone or soft tissue. It has also been reported in association with several malignancies (small cell carcinoma, hematologic malignancies, prostate cancer), and with polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, neurofibromatosis, and the epidermal nevus syndrome. The mesenchymal tumors are heterogeneous in appearance and can be variably classified as hemangiopericytomas, hemangiomas, sarcomas, ossifying fibromas, granulomas, giant cell tumors, or osteoblastomas.[1] However, 1 review suggests that most of these tumors actually represent a distinct but heterogeneous, under‐recognized entity that is best classified as a phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor.[11]

TIO is only cured by complete resection of the tumor.[1] Local recurrences have been described, as have rare occurrences of metastatic disease.[1, 12] Medical treatment can be used to normalize serum phosphate levels in patients who are unable to be cured by surgery. The goal is to bring serum phosphate into the low‐normal range via phosphate supplementation (typically 13 g/day of elemental phosphorus is required) and treatment with either calcitriol or alfacalcidol. Due to the inhibition of 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D activation in TIO, relatively large doses of calcitriol are needed. A reasonable starting dose of calcitriol is 1.5 g/day, and most patients require 15 to 60 ng/kg per day. Because PTH action is involved in FGF23‐mediated hypophosphatemia, suppression of PTH may also be useful in these patients.[13]

This patient presented with a painful femoral tumor in the setting of muscle and joint pain that had been erroneously attributed to connective tissue disease. However, recognition and thorough evaluation of the patient's hypophosphatemia led to a unifying diagnosis of TIO. This diagnosis altered the surgical approach (emphasizing complete resection to eradicate the FGF23 production) and helped alleviate the patient's painful losses of phosphate.

TEACHING POINTS

- Hypophosphatemia, especially if severe or persistent, should not be dismissed as an unimportant laboratory finding. A focused evaluation should be performed to determine the etiology.

- In patients with unexplained hypophosphatemia, the measurement of serum calcium, parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D levels can identify primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism.

- The differential diagnosis of hypophosphatemia is narrowed if there is clinical evidence of inappropriate urinary phosphate wasting (ie, urinary phosphate levels remain high, despite low serum levels).

- TIO is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome caused by FGF23, a phosphatonin hormone that causes renal phosphate wasting, hypophosphatemia, and osteomalacia.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- , , , . Tumor‐induced osteomalacia. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011;18:R53–R77.

- . The FGF23‐Klotho axis: endocrine regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5:611–619.

- , . Genetic disorders of renal phosphate transport. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2399–2409.

- . The expanding family of hypophosphatemic syndromes. J Bone Miner Metab. 2012;30:1–9.

- , , , , . FGF‐23 is elevated by chronic hyperphosphatemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4489–4492.

- , , , et al. FGF‐23 is a potent regulator of vitamin D metabolism and phosphate homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:429–435.

- , . Hypophosphatemia: an update on its etiology and treatment. Am J Med. 2005;118:1094–1101.

- , , . In: Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:1237–1304.

- , , . Medication‐induced hypophosphatemia: a review. QJM. 2010;103:449–459.

- , . Nomogram for derivation of renal threshold phosphate concentration. Lancet. 1975;2:309–310.

- , , , et al. Improving diagnosis of tumor‐induced osteomalacia with gallium‐68 DOTATATE PET/CT. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013; 98:687–694.

- , , , et al. Most osteomalacia‐associated mesenchymal tumors are a single histopathologic entity: an analysis of 32 cases and a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1–30.

- , , , , , . Cinacalcet in the management of tumor‐induced osteomalacia. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:931–937.

A 58‐year‐old man presented to the emergency department with a 1‐month history of progressive, severe left hip pain that had become unbearable. The pain was constant and significantly worse with weight‐bearing, and the patient was now confined to bed. He denied back pain, falls, or trauma.

Although hip pain is a common complaint and a frequent manifestation of chronic degenerative joint disease, the debilitating and subacute nature of the pain suggests a potentially more serious underlying cause. Patients and even clinicians may refer to hip pain when the actual symptoms are periarticular, often presenting over the trochanter laterally, or muscular, presenting as posterior pain. The true hip joint is located in the anterior hip and groin area and often causes symptoms that radiate to the buttock. Pain can also be referred to the hip area from the spine, pelvis, or retroperitoneum, so it is crucial not to restrict the differential diagnosis to hip pathology.

Key diagnostic considerations include (1) inflammatory conditions such as trochanteric bursitis or gout; (2) bacterial infection of the hip joint, adjacent bone, or a nearby structure; (3) benign nerve compression (such as meralgia paresthetica); and (4) tumor (particularly myeloma or metastatic disease to the bone, but also potentially a pelvic or spinal mass with nerve compression). Polymyalgia rheumatica and other systemic rheumatologic complaints are a consideration, but because a single joint is involved, these conditions are less likely. The hip would be an unusual location for a first gout flare, and the duration of symptoms would be unusually long for gout. Avascular necrosis should be considered if the patient has received glucocorticoids for his previously diagnosed rheumatologic disease. If the patient is anticoagulated, consideration of spontaneous hematoma is reasonable, but usually this would present over a course of days, not weeks. The absence of trauma makes a fracture of the hip or pelvis less likely, and the insidious progression of symptoms makes a pathologic fracture less likely.

The patient reported 6 months of worsening proximal upper and lower extremity myalgia and weakness, with arthralgia of the hips and shoulders. The weakness was most notable in his proximal lower extremities, although he had remained ambulatory until the hip pain became limiting. He maintained normal use of his arms. The patient denied current rash but noted photosensitivity and a mild facial rash several months earlier. He described having transient mouth sores intermittently for several years. He denied fever, chills, night sweats, weight loss, dyspnea, recent travel, and outdoor exposures. Several months previously, he had been evaluated for these symptoms at another institution and given the diagnoses of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). At that time, he had initiated treatment with weekly dosing of methotrexate and etanercept.

The patient's medical history was also notable for hypertension, Graves' disease treated previously with radioiodine ablation, quiescent ulcerative colitis, and depression. Current medications included methotrexate, etanercept, levothyroxine, enalapril, hydrochlorothiazide, fluoxetine, ibuprofen, and oxycodone‐acetaminophen. He denied tobacco, alcohol, and recreational drug use.

Weakness occurring in the proximal lower extremities is the classic distribution for polymyositis and dermatomyositis. In contrast to polymyalgia rheumatica, dermatomyositis and polymyositis do not generally feature severe muscle pain, but they can be associated with a painful polyarthritis. Oral ulcers, photosensitivity, and facial rash are consistent with SLE, but dermatomyositis can also lead to a symmetrical erythema of the eyelids (commonly referred to as a heliotrope rash, named after the flower bearing that name) and sometimes can be associated with photosensitivity. Oral ulcers, particularly the painful ones known as canker sores, are extraordinarily common in the general population, and patients and providers may miss the mucosal lesions of SLE because they are usually painless. As methotrexate and etanercept are immunosuppressive, opportunistic pathogens such as typical or atypical mycobacteria and disseminated fungal infections should be considered, with special attention to the possibility of infection in or near the left hip. Given that SLE and RA rarely coexist, it would be helpful to seek outside medical records to know what the prior serologic evaluation entailed, but it is unlikely that this presentation is a manifestation of a diffuse connective tissue process.

Physical examination should focus on the features of dermatomyositis including heliotrope rash, truncal erythema, and papules over the knuckles (Gottron's papules); objective proximal muscle weakness in the shoulder and hip girdle; and findings that might suggest antisynthetase syndrome such as hyperkeratotic mechanic hand palmar and digital changes, and interstitial crackles on lung exam. If necrotic skin lesions are found, this would raise concern for a disseminated infection. The joints should be examined for inflammation and effusions.

His temperature was 36.6C, heart rate 74 beats per minute, blood pressure 134/76 mm Hg, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and O2 saturation 97% on room air. He was obese but did not have moon facies or a buffalo hump. There were no rashes or mucosal lesions. Active and passive motion of his left hip joint elicited pain with both flexion/extension and internal/external rotation. Muscle strength was limited by pain in the left hip flexors and extenders, but was 5/5 in all other muscle groups. Palpation of the proximal muscles of his arms and legs did not elicit pain. His extremities were without edema, and examination of his shoulders, elbows, wrists, hands, knees, ankles, and feet did not reveal any erythema, synovial thickening, effusion, or deformity. Examination of the heart, chest, and abdomen was normal.

Given the reassuring strength examination, the absence of rashes or skin lesions, and the reassuring joint exam aside from the left hip, a focal infectious, inflammatory, or malignant process seems most likely. The pain with range of motion of the hip does not definitively localize the pathology to the hip joint, because pathology of the nearby structures can lead to pain when the hip is moved. Laboratory evaluation should include a complete blood count to screen for evidence of infection or marrow suppression, complete metabolic panel, and creatine kinase. The history of ulcerative colitis raises the possibility of an enthesitis (inflammation of tendons or ligaments) occurring near the hip. Enthesitis is sometimes a feature of the seronegative spondyloarthropathy‐associated conditions and can occur in the absence of sacroiliitis or spondyloarthropathy.

The patient's myalgias and arthralgias had recently been evaluated in the rheumatology clinic. Laboratory evaluation from that visit was remarkable only for an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test that was positive at a titer of 1:320 in a homogeneous pattern, creatine phosphokinase 366 IU/L (normal range [NR] 38240), and alkaline phosphatase 203 IU/L (NR 30130). All of the following labs from that visit were within normal ranges: cyclic citrullinated peptide, rheumatoid factor, antidouble stranded DNA, aldolase, complement levels, serum and urine protein electrophoresis, thyroglobulin antibody, thyroid microsomal antibody, thyroid‐stimulating hormone, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (10 mm/h), and C‐reactive protein (0.3 mg/dL).

The patient was admitted to the hospital. Initial blood test results on admission included sodium 139 mEq/L, potassium 3.9 mEq/L, chloride 105 mEq/L, bicarbonate 27 mEq/L, urea nitrogen 16 mg/dL, creatinine 0.6 mg/dL, glucose 85 mg/dL, calcium 9.2 mg/dL (NR 8.810.3), phosphate 1.3 mg/dL (NR 2.74.6), albumin 4.7 g/dL (NR 3.54.9), and alkaline phosphatase 195 IU/L (NR 30130). The remainder of a comprehensive metabolic profile, complete blood count with differential, and coagulation studies were all normal.

The homogeneous ANA titer of 1:320 is high enough to raise eyebrows, but is nonspecific for lupus and other ANA‐associated rheumatologic conditions, and may be a red herring, particularly given the low likelihood of a systemic inflammatory process explaining this new focal hip pain. The alkaline phosphatase is only mildly elevated and could be of bone or liver origin. The reassuringly low inflammatory markers are potentially helpful, because if checked now and substantially increased from the prior outpatient visit, they would be suggestive of a new inflammatory process. However, this would not point to a specific cause of inflammation.

Given the focality of the symptoms, imaging is warranted. As opposed to plain films, contrast‐enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the pelvis or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be an efficient first step, because there is low suspicion for fracture and high suspicion for an inflammatory, neoplastic, or infectious process. MRI is more expensive and usually cannot be obtained as rapidly as CT. There is a chance that CT imaging alone will provide enough information to guide the next diagnostic steps, such as aspiration of an abscess or joint, or biopsy of a suspicious lesion. However, for soft tissue lesions and many bone lesions, including osteomyelitis, MRI offers better delineation of pathology.

CT scan of the left femur demonstrated a large lytic lesion in the femoral neck that contained macroscopic fat and had an aggressive appearance with significant thinning of the cortex. MRI confirmed these findings and demonstrated a nondisplaced subtrochanteric femur fracture in the proximity of the lesion (Figure 1). Contrast‐enhanced CT scans of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis revealed no other neoplastic lesions. Prostate‐specific antigen level was normal. The patient's significant hypophosphatemia persisted, with levels dropping to as low as 0.9 mg/dL despite aggressive oral phosphate replacement.

Although hypophosphatemia is often a nonspecific finding in hospitalized patients and is usually of little clinical importance, profound hypophosphatemia that is refractory to supplementation suggests an underlying metabolic disorder. Phosphate levels less than 1.0 mg/dL, particularly if prolonged, can lead to decreased adenosine triphosphate production and subsequent weakness of respiratory and cardiac muscles. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) excess and production of parathyroid hormone‐related protein (PTHrP) by a malignancy can cause profound hypophosphatemia, but are generally associated with hypercalcemia, a finding not seen in this case. Occasionally, tumors can lead to renal phosphate wasting via nonPTH‐related mechanisms. The best characterized example of this is the paraneoplastic syndrome oncogenic osteomalacia caused by tumor production of a fibroblast growth factor. Tumors that lead to this syndrome are usually benign mesenchymal tumors. This patient's tumor may be of this type, causing local destruction and metabolic disturbance. The next step would be consultation with orthopedic surgery for resection of the tumor and total hip arthroplasty with aggressive perioperative repletion of phosphate. Assessment of intact PTH, ionized calcium, 24‐hour urinary phosphate excretion, and even PTHrP levels may help to rule out other etiologies of hypophosphatemia, but given that surgery is needed regardless, it might be reasonable to proceed to the operating room without these diagnostics. If the phosphate levels return to normal postoperatively, then the diagnosis is clear and no further metabolic testing is needed.

PTH level was 47 pg/mL (NR 1065), 25‐hydroxyvitamin D level was 25 ng/mL (NR 2580), and 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D level was 18 pg/mL (NR 1872). Urinalysis was normal without proteinuria or glucosuria. A 24‐hour urine collection contained 1936 mg of phosphate (NR 4001200). The ratio of maximum rate of renal tubular reabsorption of phosphate to glomerular filtration rate (TmP/GFR) was 1.3 mg/dL (NR 2.44.2). Tissue obtained by CT‐guided needle biopsy of the femoral mass was consistent with a benign spindle cell neoplasm.

With normal calcium levels, the PTH level is appropriate, and hyperparathyroidism is excluded. The levels of 25‐hydroxyvitamin D and 1‐25‐dihydroxyvitamin D are not low enough to suggest that vitamin D deficiency is driving the impressive hypophosphatemia. What is impressive is the phosphate wasting demonstrated by the 24‐hour urine collection, consistent with paraneoplastic overproduction of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) by the benign bone tumor. Overproduction of this protein can be detected by blood tests or staining of the tumor specimen, but surgery should be performed as soon as possible independent of any further test results. Once the tumor is resected, phosphate metabolism should normalize.

FGF23 level was 266 RU/mL (NR < 180). The patient was diagnosed with tumor‐induced osteomalacia (TIO). He underwent complete resection of the femoral tumor as well as open reduction and internal fixation of the fracture. After surgery, his symptoms of pain and subjective muscle weakness improved, his serum phosphate level normalized, his need for phosphate supplementation resolved, and his blood levels of FGF23 decreased into the normal range (111 RU/mL). The rapid improvement of his symptoms after surgery suggested that they were related to TIO, and not manifestations of SLE or RA. His immunosuppressant medications were discontinued. Surgical pathology demonstrated a heterogeneous tumor consisting of sheets of uniform spindle cells interspersed with mature adipose tissue. This was diagnosed descriptively as a benign spindle cell and lipomatous neoplasm without further classification. Two months later, the patient was ambulating without pain, and muscle strength was subjectively normal.

DISCUSSION

TIO is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome affecting phosphate and vitamin D metabolism, leading to hypophosphatemia and osteomalacia.[1] TIO is caused by the inappropriate tumor secretion of the phosphatonin hormone, FGF23.

The normal physiology of FGF23 is illustrated in Figure 2. Osteocytes appear to be the primary source of FGF23, but the regulation of FGF23 production is not completely understood. FGF23 production may be influenced by several factors, including 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D levels, and serum phosphate and PTH concentrations. This hormone binds to the FGF receptor and its coreceptor, Klotho,[2] causing 2 major physiological effects. First, it decreases the expression of the sodium‐phosphate cotransporters in the renal proximal tubular cells,[3, 4] resulting in increased tubular phosphate wasting. This effect appears to be partly PTH dependent.[5] Second, it has effects on vitamin D metabolism, decreasing renal production of activated vitamin D.[3, 4, 6]

In overproduction states, the elevated FGF23 leads to chronically low serum phosphate levels (with renal phosphate wasting) and the clinical syndrome of osteomalacia, manifested by bone pain, fractures, and deformities. Hypophosphatemia can also lead to painful proximal myopathy, cardiorespiratory dysfunction, and a spectrum of neuropsychiatric findings. The clinical findings in TIO are similar to those seen in genetic diseases in which hypophosphatemia results from the same mechanism.[3, 4]

In this case, measurement of the serum phosphate level was important in reaching the diagnosis. Although hypophosphatemia in the hospitalized patient is often easily explained, severe or persistent hypophosphatemia requires a focused evaluation. Causes of hypophosphatemia are categorized in Table 1.[7, 8, 9] In patients with hypophosphatemia that is not explained by the clinical situation (eg, osmotic diuresis, insulin treatment, refeeding syndrome, postparathyroidectomy, chronic diarrhea), measurement of serum calcium, PTH, and 25‐hydroxyvitamin D are used to investigate possible primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism. In addition, low‐normal or low serum 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D with normal PTH, normal 25‐hydroxyvitamin D stores, and normal renal function are clues to the presence of TIO. Urine phosphate wasting can be measured by collecting a 24‐hour urine sample. Calculation of the TmP/GFR (a measure of the maximum tubular resorption of phosphate relative to the glomerular filtration rate), as described by the nomogram of Walton and Bijvoet, may improve the accuracy of this assessment and confirm a renal source of the hypophosphatemia.[10]

|

| Internal redistribution |

| Insulin or catecholamine effect (including that related to refeeding syndrome, and infusion of glucose or TPN) |

| Acute respiratory alkalosis |

| Accelerated bone formation or rapid cell proliferation (eg, hungry bone syndrome, leukemic blast crisis, erythropoietin, or granulocyte colony stimulating factor administration) |

| Decreased absorption |

| Poor intake (including that seen in alcoholism*) |

| Vitamin D deficiency |

| Gastrointestinal losses (eg, chronic diarrhea) |

| Malabsorption (eg, phosphate‐binding antacids) |

| Urinary losses |

| Osmotic diuresis (eg, poorly controlled diabetes, acetazolamide) or volume expansion |

| Other diuretics: thiazides, indapamide |

| Hyperparathyroidism |

| Primary |

| Secondary (including vitamin D or calcium deficiency) |

| Parathyroid hormone‐related peptide |

| Renal tubular disease |

| Medications (eg, ethanol,* high‐dose glucocorticoids, cisplatin, bisphosphonates, estrogens, imatinib, acyclovir) |

| Fanconi syndrome |

| Medications inducing Fanconi syndrome: tenofovir, cidofovir, adefovir, aminoglycosides, ifosfamide, tetracyclines, valproic acid |

| Other (eg, postrenal transplant) |

| Excessive phosphatonin hormone activity (eg, hereditary syndromes [rickets], tumor‐induced osteomalacia) |

| Multifactorial causes |

| Alcoholism* |

| Acetaminophen toxicity |

| Parenteral iron administration |

The patient presented here had inappropriate urinary phosphate losses, and laboratory testing ruled out primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism and Fanconi syndrome. The patient was not taking medications known to cause tubular phosphate wasting. The patient's age and clinical history made hereditary syndromes unlikely. Therefore, the urinary phosphate wasting had to be related to an acquired defect in phosphate metabolism. The diagnostic characteristics of TIO are summarized in Table 2.

|

| Patients may present with symptoms of osteomalacia (eg, bone pain, fractures), hypophosphatemia (eg, proximal myopathy), and/or neoplasm. |

| Hypophosphatemia with urinary phosphate wasting. |

| Serum calcium level is usually normal. |

| Serum 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D level is usually low or low‐normal. |

| Parathyroid hormone is usually normal. |

| Plasma FGF23 level is elevated. |

| A neoplasm with the appropriate histology is identified, although the osteomalacia syndrome may precede identification of the tumor, which may be occult. |

| The syndrome resolves after complete resection of the tumor. |

The presence of a known neoplasm makes the diagnosis of TIO considerably easier. However, osteomalacia often precedes the tumor diagnosis. In these cases, the discovery of this clinical syndrome necessitates a search for the tumor. The tumors can be small, occult, and often located in the extremities. In addition to standard cross‐sectional imaging, specialized diagnostic modalities can be helpful in localizing culprit tumors. These include F‐18 flourodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography with computed tomography, 111‐Indium octreotide single photon emission CT/CT, 68‐Gallium‐DOTA‐octreotide positron emission tomography with computed tomography, and even selective venous sampling for FGF23 levels.[1, 11] The octreotide tests capitalize on the fact that culprit tumors often express somatostatin receptors.

TIO is most often associated with mesenchymal tumors of the bone or soft tissue. It has also been reported in association with several malignancies (small cell carcinoma, hematologic malignancies, prostate cancer), and with polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, neurofibromatosis, and the epidermal nevus syndrome. The mesenchymal tumors are heterogeneous in appearance and can be variably classified as hemangiopericytomas, hemangiomas, sarcomas, ossifying fibromas, granulomas, giant cell tumors, or osteoblastomas.[1] However, 1 review suggests that most of these tumors actually represent a distinct but heterogeneous, under‐recognized entity that is best classified as a phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor.[11]

TIO is only cured by complete resection of the tumor.[1] Local recurrences have been described, as have rare occurrences of metastatic disease.[1, 12] Medical treatment can be used to normalize serum phosphate levels in patients who are unable to be cured by surgery. The goal is to bring serum phosphate into the low‐normal range via phosphate supplementation (typically 13 g/day of elemental phosphorus is required) and treatment with either calcitriol or alfacalcidol. Due to the inhibition of 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D activation in TIO, relatively large doses of calcitriol are needed. A reasonable starting dose of calcitriol is 1.5 g/day, and most patients require 15 to 60 ng/kg per day. Because PTH action is involved in FGF23‐mediated hypophosphatemia, suppression of PTH may also be useful in these patients.[13]

This patient presented with a painful femoral tumor in the setting of muscle and joint pain that had been erroneously attributed to connective tissue disease. However, recognition and thorough evaluation of the patient's hypophosphatemia led to a unifying diagnosis of TIO. This diagnosis altered the surgical approach (emphasizing complete resection to eradicate the FGF23 production) and helped alleviate the patient's painful losses of phosphate.

TEACHING POINTS

- Hypophosphatemia, especially if severe or persistent, should not be dismissed as an unimportant laboratory finding. A focused evaluation should be performed to determine the etiology.

- In patients with unexplained hypophosphatemia, the measurement of serum calcium, parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D levels can identify primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism.

- The differential diagnosis of hypophosphatemia is narrowed if there is clinical evidence of inappropriate urinary phosphate wasting (ie, urinary phosphate levels remain high, despite low serum levels).

- TIO is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome caused by FGF23, a phosphatonin hormone that causes renal phosphate wasting, hypophosphatemia, and osteomalacia.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

A 58‐year‐old man presented to the emergency department with a 1‐month history of progressive, severe left hip pain that had become unbearable. The pain was constant and significantly worse with weight‐bearing, and the patient was now confined to bed. He denied back pain, falls, or trauma.

Although hip pain is a common complaint and a frequent manifestation of chronic degenerative joint disease, the debilitating and subacute nature of the pain suggests a potentially more serious underlying cause. Patients and even clinicians may refer to hip pain when the actual symptoms are periarticular, often presenting over the trochanter laterally, or muscular, presenting as posterior pain. The true hip joint is located in the anterior hip and groin area and often causes symptoms that radiate to the buttock. Pain can also be referred to the hip area from the spine, pelvis, or retroperitoneum, so it is crucial not to restrict the differential diagnosis to hip pathology.

Key diagnostic considerations include (1) inflammatory conditions such as trochanteric bursitis or gout; (2) bacterial infection of the hip joint, adjacent bone, or a nearby structure; (3) benign nerve compression (such as meralgia paresthetica); and (4) tumor (particularly myeloma or metastatic disease to the bone, but also potentially a pelvic or spinal mass with nerve compression). Polymyalgia rheumatica and other systemic rheumatologic complaints are a consideration, but because a single joint is involved, these conditions are less likely. The hip would be an unusual location for a first gout flare, and the duration of symptoms would be unusually long for gout. Avascular necrosis should be considered if the patient has received glucocorticoids for his previously diagnosed rheumatologic disease. If the patient is anticoagulated, consideration of spontaneous hematoma is reasonable, but usually this would present over a course of days, not weeks. The absence of trauma makes a fracture of the hip or pelvis less likely, and the insidious progression of symptoms makes a pathologic fracture less likely.

The patient reported 6 months of worsening proximal upper and lower extremity myalgia and weakness, with arthralgia of the hips and shoulders. The weakness was most notable in his proximal lower extremities, although he had remained ambulatory until the hip pain became limiting. He maintained normal use of his arms. The patient denied current rash but noted photosensitivity and a mild facial rash several months earlier. He described having transient mouth sores intermittently for several years. He denied fever, chills, night sweats, weight loss, dyspnea, recent travel, and outdoor exposures. Several months previously, he had been evaluated for these symptoms at another institution and given the diagnoses of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). At that time, he had initiated treatment with weekly dosing of methotrexate and etanercept.

The patient's medical history was also notable for hypertension, Graves' disease treated previously with radioiodine ablation, quiescent ulcerative colitis, and depression. Current medications included methotrexate, etanercept, levothyroxine, enalapril, hydrochlorothiazide, fluoxetine, ibuprofen, and oxycodone‐acetaminophen. He denied tobacco, alcohol, and recreational drug use.

Weakness occurring in the proximal lower extremities is the classic distribution for polymyositis and dermatomyositis. In contrast to polymyalgia rheumatica, dermatomyositis and polymyositis do not generally feature severe muscle pain, but they can be associated with a painful polyarthritis. Oral ulcers, photosensitivity, and facial rash are consistent with SLE, but dermatomyositis can also lead to a symmetrical erythema of the eyelids (commonly referred to as a heliotrope rash, named after the flower bearing that name) and sometimes can be associated with photosensitivity. Oral ulcers, particularly the painful ones known as canker sores, are extraordinarily common in the general population, and patients and providers may miss the mucosal lesions of SLE because they are usually painless. As methotrexate and etanercept are immunosuppressive, opportunistic pathogens such as typical or atypical mycobacteria and disseminated fungal infections should be considered, with special attention to the possibility of infection in or near the left hip. Given that SLE and RA rarely coexist, it would be helpful to seek outside medical records to know what the prior serologic evaluation entailed, but it is unlikely that this presentation is a manifestation of a diffuse connective tissue process.

Physical examination should focus on the features of dermatomyositis including heliotrope rash, truncal erythema, and papules over the knuckles (Gottron's papules); objective proximal muscle weakness in the shoulder and hip girdle; and findings that might suggest antisynthetase syndrome such as hyperkeratotic mechanic hand palmar and digital changes, and interstitial crackles on lung exam. If necrotic skin lesions are found, this would raise concern for a disseminated infection. The joints should be examined for inflammation and effusions.

His temperature was 36.6C, heart rate 74 beats per minute, blood pressure 134/76 mm Hg, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and O2 saturation 97% on room air. He was obese but did not have moon facies or a buffalo hump. There were no rashes or mucosal lesions. Active and passive motion of his left hip joint elicited pain with both flexion/extension and internal/external rotation. Muscle strength was limited by pain in the left hip flexors and extenders, but was 5/5 in all other muscle groups. Palpation of the proximal muscles of his arms and legs did not elicit pain. His extremities were without edema, and examination of his shoulders, elbows, wrists, hands, knees, ankles, and feet did not reveal any erythema, synovial thickening, effusion, or deformity. Examination of the heart, chest, and abdomen was normal.

Given the reassuring strength examination, the absence of rashes or skin lesions, and the reassuring joint exam aside from the left hip, a focal infectious, inflammatory, or malignant process seems most likely. The pain with range of motion of the hip does not definitively localize the pathology to the hip joint, because pathology of the nearby structures can lead to pain when the hip is moved. Laboratory evaluation should include a complete blood count to screen for evidence of infection or marrow suppression, complete metabolic panel, and creatine kinase. The history of ulcerative colitis raises the possibility of an enthesitis (inflammation of tendons or ligaments) occurring near the hip. Enthesitis is sometimes a feature of the seronegative spondyloarthropathy‐associated conditions and can occur in the absence of sacroiliitis or spondyloarthropathy.

The patient's myalgias and arthralgias had recently been evaluated in the rheumatology clinic. Laboratory evaluation from that visit was remarkable only for an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test that was positive at a titer of 1:320 in a homogeneous pattern, creatine phosphokinase 366 IU/L (normal range [NR] 38240), and alkaline phosphatase 203 IU/L (NR 30130). All of the following labs from that visit were within normal ranges: cyclic citrullinated peptide, rheumatoid factor, antidouble stranded DNA, aldolase, complement levels, serum and urine protein electrophoresis, thyroglobulin antibody, thyroid microsomal antibody, thyroid‐stimulating hormone, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (10 mm/h), and C‐reactive protein (0.3 mg/dL).

The patient was admitted to the hospital. Initial blood test results on admission included sodium 139 mEq/L, potassium 3.9 mEq/L, chloride 105 mEq/L, bicarbonate 27 mEq/L, urea nitrogen 16 mg/dL, creatinine 0.6 mg/dL, glucose 85 mg/dL, calcium 9.2 mg/dL (NR 8.810.3), phosphate 1.3 mg/dL (NR 2.74.6), albumin 4.7 g/dL (NR 3.54.9), and alkaline phosphatase 195 IU/L (NR 30130). The remainder of a comprehensive metabolic profile, complete blood count with differential, and coagulation studies were all normal.

The homogeneous ANA titer of 1:320 is high enough to raise eyebrows, but is nonspecific for lupus and other ANA‐associated rheumatologic conditions, and may be a red herring, particularly given the low likelihood of a systemic inflammatory process explaining this new focal hip pain. The alkaline phosphatase is only mildly elevated and could be of bone or liver origin. The reassuringly low inflammatory markers are potentially helpful, because if checked now and substantially increased from the prior outpatient visit, they would be suggestive of a new inflammatory process. However, this would not point to a specific cause of inflammation.

Given the focality of the symptoms, imaging is warranted. As opposed to plain films, contrast‐enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the pelvis or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be an efficient first step, because there is low suspicion for fracture and high suspicion for an inflammatory, neoplastic, or infectious process. MRI is more expensive and usually cannot be obtained as rapidly as CT. There is a chance that CT imaging alone will provide enough information to guide the next diagnostic steps, such as aspiration of an abscess or joint, or biopsy of a suspicious lesion. However, for soft tissue lesions and many bone lesions, including osteomyelitis, MRI offers better delineation of pathology.

CT scan of the left femur demonstrated a large lytic lesion in the femoral neck that contained macroscopic fat and had an aggressive appearance with significant thinning of the cortex. MRI confirmed these findings and demonstrated a nondisplaced subtrochanteric femur fracture in the proximity of the lesion (Figure 1). Contrast‐enhanced CT scans of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis revealed no other neoplastic lesions. Prostate‐specific antigen level was normal. The patient's significant hypophosphatemia persisted, with levels dropping to as low as 0.9 mg/dL despite aggressive oral phosphate replacement.

Although hypophosphatemia is often a nonspecific finding in hospitalized patients and is usually of little clinical importance, profound hypophosphatemia that is refractory to supplementation suggests an underlying metabolic disorder. Phosphate levels less than 1.0 mg/dL, particularly if prolonged, can lead to decreased adenosine triphosphate production and subsequent weakness of respiratory and cardiac muscles. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) excess and production of parathyroid hormone‐related protein (PTHrP) by a malignancy can cause profound hypophosphatemia, but are generally associated with hypercalcemia, a finding not seen in this case. Occasionally, tumors can lead to renal phosphate wasting via nonPTH‐related mechanisms. The best characterized example of this is the paraneoplastic syndrome oncogenic osteomalacia caused by tumor production of a fibroblast growth factor. Tumors that lead to this syndrome are usually benign mesenchymal tumors. This patient's tumor may be of this type, causing local destruction and metabolic disturbance. The next step would be consultation with orthopedic surgery for resection of the tumor and total hip arthroplasty with aggressive perioperative repletion of phosphate. Assessment of intact PTH, ionized calcium, 24‐hour urinary phosphate excretion, and even PTHrP levels may help to rule out other etiologies of hypophosphatemia, but given that surgery is needed regardless, it might be reasonable to proceed to the operating room without these diagnostics. If the phosphate levels return to normal postoperatively, then the diagnosis is clear and no further metabolic testing is needed.

PTH level was 47 pg/mL (NR 1065), 25‐hydroxyvitamin D level was 25 ng/mL (NR 2580), and 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D level was 18 pg/mL (NR 1872). Urinalysis was normal without proteinuria or glucosuria. A 24‐hour urine collection contained 1936 mg of phosphate (NR 4001200). The ratio of maximum rate of renal tubular reabsorption of phosphate to glomerular filtration rate (TmP/GFR) was 1.3 mg/dL (NR 2.44.2). Tissue obtained by CT‐guided needle biopsy of the femoral mass was consistent with a benign spindle cell neoplasm.

With normal calcium levels, the PTH level is appropriate, and hyperparathyroidism is excluded. The levels of 25‐hydroxyvitamin D and 1‐25‐dihydroxyvitamin D are not low enough to suggest that vitamin D deficiency is driving the impressive hypophosphatemia. What is impressive is the phosphate wasting demonstrated by the 24‐hour urine collection, consistent with paraneoplastic overproduction of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) by the benign bone tumor. Overproduction of this protein can be detected by blood tests or staining of the tumor specimen, but surgery should be performed as soon as possible independent of any further test results. Once the tumor is resected, phosphate metabolism should normalize.

FGF23 level was 266 RU/mL (NR < 180). The patient was diagnosed with tumor‐induced osteomalacia (TIO). He underwent complete resection of the femoral tumor as well as open reduction and internal fixation of the fracture. After surgery, his symptoms of pain and subjective muscle weakness improved, his serum phosphate level normalized, his need for phosphate supplementation resolved, and his blood levels of FGF23 decreased into the normal range (111 RU/mL). The rapid improvement of his symptoms after surgery suggested that they were related to TIO, and not manifestations of SLE or RA. His immunosuppressant medications were discontinued. Surgical pathology demonstrated a heterogeneous tumor consisting of sheets of uniform spindle cells interspersed with mature adipose tissue. This was diagnosed descriptively as a benign spindle cell and lipomatous neoplasm without further classification. Two months later, the patient was ambulating without pain, and muscle strength was subjectively normal.

DISCUSSION

TIO is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome affecting phosphate and vitamin D metabolism, leading to hypophosphatemia and osteomalacia.[1] TIO is caused by the inappropriate tumor secretion of the phosphatonin hormone, FGF23.

The normal physiology of FGF23 is illustrated in Figure 2. Osteocytes appear to be the primary source of FGF23, but the regulation of FGF23 production is not completely understood. FGF23 production may be influenced by several factors, including 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D levels, and serum phosphate and PTH concentrations. This hormone binds to the FGF receptor and its coreceptor, Klotho,[2] causing 2 major physiological effects. First, it decreases the expression of the sodium‐phosphate cotransporters in the renal proximal tubular cells,[3, 4] resulting in increased tubular phosphate wasting. This effect appears to be partly PTH dependent.[5] Second, it has effects on vitamin D metabolism, decreasing renal production of activated vitamin D.[3, 4, 6]

In overproduction states, the elevated FGF23 leads to chronically low serum phosphate levels (with renal phosphate wasting) and the clinical syndrome of osteomalacia, manifested by bone pain, fractures, and deformities. Hypophosphatemia can also lead to painful proximal myopathy, cardiorespiratory dysfunction, and a spectrum of neuropsychiatric findings. The clinical findings in TIO are similar to those seen in genetic diseases in which hypophosphatemia results from the same mechanism.[3, 4]

In this case, measurement of the serum phosphate level was important in reaching the diagnosis. Although hypophosphatemia in the hospitalized patient is often easily explained, severe or persistent hypophosphatemia requires a focused evaluation. Causes of hypophosphatemia are categorized in Table 1.[7, 8, 9] In patients with hypophosphatemia that is not explained by the clinical situation (eg, osmotic diuresis, insulin treatment, refeeding syndrome, postparathyroidectomy, chronic diarrhea), measurement of serum calcium, PTH, and 25‐hydroxyvitamin D are used to investigate possible primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism. In addition, low‐normal or low serum 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D with normal PTH, normal 25‐hydroxyvitamin D stores, and normal renal function are clues to the presence of TIO. Urine phosphate wasting can be measured by collecting a 24‐hour urine sample. Calculation of the TmP/GFR (a measure of the maximum tubular resorption of phosphate relative to the glomerular filtration rate), as described by the nomogram of Walton and Bijvoet, may improve the accuracy of this assessment and confirm a renal source of the hypophosphatemia.[10]

|

| Internal redistribution |

| Insulin or catecholamine effect (including that related to refeeding syndrome, and infusion of glucose or TPN) |

| Acute respiratory alkalosis |

| Accelerated bone formation or rapid cell proliferation (eg, hungry bone syndrome, leukemic blast crisis, erythropoietin, or granulocyte colony stimulating factor administration) |

| Decreased absorption |

| Poor intake (including that seen in alcoholism*) |

| Vitamin D deficiency |

| Gastrointestinal losses (eg, chronic diarrhea) |

| Malabsorption (eg, phosphate‐binding antacids) |

| Urinary losses |

| Osmotic diuresis (eg, poorly controlled diabetes, acetazolamide) or volume expansion |

| Other diuretics: thiazides, indapamide |

| Hyperparathyroidism |

| Primary |

| Secondary (including vitamin D or calcium deficiency) |

| Parathyroid hormone‐related peptide |

| Renal tubular disease |

| Medications (eg, ethanol,* high‐dose glucocorticoids, cisplatin, bisphosphonates, estrogens, imatinib, acyclovir) |

| Fanconi syndrome |

| Medications inducing Fanconi syndrome: tenofovir, cidofovir, adefovir, aminoglycosides, ifosfamide, tetracyclines, valproic acid |

| Other (eg, postrenal transplant) |

| Excessive phosphatonin hormone activity (eg, hereditary syndromes [rickets], tumor‐induced osteomalacia) |

| Multifactorial causes |

| Alcoholism* |

| Acetaminophen toxicity |

| Parenteral iron administration |

The patient presented here had inappropriate urinary phosphate losses, and laboratory testing ruled out primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism and Fanconi syndrome. The patient was not taking medications known to cause tubular phosphate wasting. The patient's age and clinical history made hereditary syndromes unlikely. Therefore, the urinary phosphate wasting had to be related to an acquired defect in phosphate metabolism. The diagnostic characteristics of TIO are summarized in Table 2.

|

| Patients may present with symptoms of osteomalacia (eg, bone pain, fractures), hypophosphatemia (eg, proximal myopathy), and/or neoplasm. |

| Hypophosphatemia with urinary phosphate wasting. |

| Serum calcium level is usually normal. |

| Serum 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D level is usually low or low‐normal. |

| Parathyroid hormone is usually normal. |

| Plasma FGF23 level is elevated. |

| A neoplasm with the appropriate histology is identified, although the osteomalacia syndrome may precede identification of the tumor, which may be occult. |

| The syndrome resolves after complete resection of the tumor. |

The presence of a known neoplasm makes the diagnosis of TIO considerably easier. However, osteomalacia often precedes the tumor diagnosis. In these cases, the discovery of this clinical syndrome necessitates a search for the tumor. The tumors can be small, occult, and often located in the extremities. In addition to standard cross‐sectional imaging, specialized diagnostic modalities can be helpful in localizing culprit tumors. These include F‐18 flourodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography with computed tomography, 111‐Indium octreotide single photon emission CT/CT, 68‐Gallium‐DOTA‐octreotide positron emission tomography with computed tomography, and even selective venous sampling for FGF23 levels.[1, 11] The octreotide tests capitalize on the fact that culprit tumors often express somatostatin receptors.

TIO is most often associated with mesenchymal tumors of the bone or soft tissue. It has also been reported in association with several malignancies (small cell carcinoma, hematologic malignancies, prostate cancer), and with polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, neurofibromatosis, and the epidermal nevus syndrome. The mesenchymal tumors are heterogeneous in appearance and can be variably classified as hemangiopericytomas, hemangiomas, sarcomas, ossifying fibromas, granulomas, giant cell tumors, or osteoblastomas.[1] However, 1 review suggests that most of these tumors actually represent a distinct but heterogeneous, under‐recognized entity that is best classified as a phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor.[11]

TIO is only cured by complete resection of the tumor.[1] Local recurrences have been described, as have rare occurrences of metastatic disease.[1, 12] Medical treatment can be used to normalize serum phosphate levels in patients who are unable to be cured by surgery. The goal is to bring serum phosphate into the low‐normal range via phosphate supplementation (typically 13 g/day of elemental phosphorus is required) and treatment with either calcitriol or alfacalcidol. Due to the inhibition of 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D activation in TIO, relatively large doses of calcitriol are needed. A reasonable starting dose of calcitriol is 1.5 g/day, and most patients require 15 to 60 ng/kg per day. Because PTH action is involved in FGF23‐mediated hypophosphatemia, suppression of PTH may also be useful in these patients.[13]

This patient presented with a painful femoral tumor in the setting of muscle and joint pain that had been erroneously attributed to connective tissue disease. However, recognition and thorough evaluation of the patient's hypophosphatemia led to a unifying diagnosis of TIO. This diagnosis altered the surgical approach (emphasizing complete resection to eradicate the FGF23 production) and helped alleviate the patient's painful losses of phosphate.

TEACHING POINTS

- Hypophosphatemia, especially if severe or persistent, should not be dismissed as an unimportant laboratory finding. A focused evaluation should be performed to determine the etiology.

- In patients with unexplained hypophosphatemia, the measurement of serum calcium, parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D levels can identify primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism.

- The differential diagnosis of hypophosphatemia is narrowed if there is clinical evidence of inappropriate urinary phosphate wasting (ie, urinary phosphate levels remain high, despite low serum levels).

- TIO is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome caused by FGF23, a phosphatonin hormone that causes renal phosphate wasting, hypophosphatemia, and osteomalacia.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- , , , . Tumor‐induced osteomalacia. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011;18:R53–R77.

- . The FGF23‐Klotho axis: endocrine regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5:611–619.

- , . Genetic disorders of renal phosphate transport. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2399–2409.

- . The expanding family of hypophosphatemic syndromes. J Bone Miner Metab. 2012;30:1–9.

- , , , , . FGF‐23 is elevated by chronic hyperphosphatemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4489–4492.

- , , , et al. FGF‐23 is a potent regulator of vitamin D metabolism and phosphate homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:429–435.

- , . Hypophosphatemia: an update on its etiology and treatment. Am J Med. 2005;118:1094–1101.

- , , . In: Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:1237–1304.

- , , . Medication‐induced hypophosphatemia: a review. QJM. 2010;103:449–459.

- , . Nomogram for derivation of renal threshold phosphate concentration. Lancet. 1975;2:309–310.

- , , , et al. Improving diagnosis of tumor‐induced osteomalacia with gallium‐68 DOTATATE PET/CT. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013; 98:687–694.

- , , , et al. Most osteomalacia‐associated mesenchymal tumors are a single histopathologic entity: an analysis of 32 cases and a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1–30.

- , , , , , . Cinacalcet in the management of tumor‐induced osteomalacia. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:931–937.

- , , , . Tumor‐induced osteomalacia. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011;18:R53–R77.

- . The FGF23‐Klotho axis: endocrine regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5:611–619.

- , . Genetic disorders of renal phosphate transport. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2399–2409.

- . The expanding family of hypophosphatemic syndromes. J Bone Miner Metab. 2012;30:1–9.

- , , , , . FGF‐23 is elevated by chronic hyperphosphatemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4489–4492.

- , , , et al. FGF‐23 is a potent regulator of vitamin D metabolism and phosphate homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:429–435.

- , . Hypophosphatemia: an update on its etiology and treatment. Am J Med. 2005;118:1094–1101.

- , , . In: Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:1237–1304.

- , , . Medication‐induced hypophosphatemia: a review. QJM. 2010;103:449–459.

- , . Nomogram for derivation of renal threshold phosphate concentration. Lancet. 1975;2:309–310.

- , , , et al. Improving diagnosis of tumor‐induced osteomalacia with gallium‐68 DOTATATE PET/CT. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013; 98:687–694.

- , , , et al. Most osteomalacia‐associated mesenchymal tumors are a single histopathologic entity: an analysis of 32 cases and a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1–30.

- , , , , , . Cinacalcet in the management of tumor‐induced osteomalacia. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:931–937.

Perioperative statins: More than lipid-lowering?

Soon, the checklist for internists seeing patients about to undergo surgery may include prescribing one of the lipid-lowering hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors, also called statins.

Statins? Not long ago, we were debating whether patients who take statins should stop taking them before surgery, based on the manufacturers’ recommendations.1 The discussion, however, has changed to whether patients who have never received a statin should be started on one before surgery to provide immediate prophylaxis against cardiac morbidity, and how much harm long-term statin users face if these drugs are withheld perioperatively.

The evidence is still very preliminary and based mostly on studies in animals and retrospective studies in people. However, an expanding body of indirect evidence suggests that these drugs are beneficial in this situation.

In this review, we discuss the mechanisms by which statins may protect the heart in the short term, drawing on data from animal and human studies of acute myocardial infarction, and we review the current (albeit limited) data from the perioperative setting.

FEW INTERVENTIONS DECREASE RISK

Each year, approximately 50,000 patients suffer a perioperative cardiovascular event; the incidence of myocardial infarction during or after noncardiac surgery is 2% to 3%.2 The primary goal of preoperative cardiovascular risk assessment is to predict and avert these events.

But short of canceling surgery, few interventions have been found to reduce a patient’s risk. For example, a landmark study in 2004 cast doubt on the efficacy of preoperative coronary revascularization.3 Similarly, although early studies of beta-blockers were promising4,5 and although most internists prescribe these drugs before surgery, more recent studies have cast doubt on their efficacy, particularly in patients at low risk undergoing intermediate-risk (rather than vascular) surgery.6–8

This changing clinical landscape has prompted a search for new strategies for perioperative risk-reduction. Several recent studies have placed statins in the spotlight.

POTENTIAL MECHANISMS OF SHORT-TERM BENEFIT

Statins have been proven to save lives when used long-term, but how could this class of drugs, designed to prevent the accumulation of arterial plaques by lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels, have any short-term impact on operative outcomes? Although LDL-C reduction is the principal mechanism of action of statins, not all of the benefit can be ascribed to this mechanism.9 The answer may lie in their “pleiotropic” effects—ie, actions other than LDL-C reduction.

The more immediate pleiotropic effects of statins in the proinflammatory and prothrombotic environment of the perioperative period are thought to include improved endothelial function (both antithrombotic function and vasomotor function in response to ischemic stress), enhanced stability of atherosclerotic plaques, decreased oxidative stress, and decreased vascular inflammation.10–12

EVIDENCE FROM ANIMAL STUDIES

Experiments in animals suggest that statins, given shortly before or after a cardiovascular event, confer benefit before any changes in LDL-C are measurable.

Lefer et al13 found that simvastatin (Zocor), given 18 hours before an ischemic episode in rats, blunted the inflammatory response in cardiac reperfusion injury. Not only was reperfusion injury significantly less in the hearts of the rats that received simvastatin than in the saline control group, but the simvastatin-treated hearts also expressed fewer neutrophil adhesion molecules such as P-selectin, and they had more basal release of nitric oxide, the potent endothelial-derived vasodilator with antithrombotic, anti-inflammatory, and antiproliferative effects.14 These results suggest that statins may improve endothelial function acutely, particularly during ischemic stress.

Osborne et al15 fed rabbits a cholesterol-rich diet plus either lovastatin (Mevacor) or placebo. After 2 weeks, the rabbits underwent either surgery to induce a myocardial infarction or a sham procedure. Regardless of the pretreatment, biopsies of the aorta did not reveal any atherosclerosis; yet the lovastatin-treated rabbits sustained less myocardial ischemic damage and they had more endothelium-mediated vasodilatation.

Statin therapy also may improve cerebral ischemia outcomes in animal models.14,16

Sironi et al16 induced strokes in rats by occluding the middle cerebral artery. The rats received either simvastatin or vehicle for 3 days before the stroke or immediately afterwards. Even though simvastatin did not have enough time to affect the total cholesterol level, rats treated with simvastatin had smaller infarcts (as measured by magnetic resonance imaging) and produced more nitric oxide.

Comment. Taken together, these studies offer tantalizing evidence that statins have short-term, beneficial nonlipid effects and may reduce not only the likelihood of an ischemic event, but—should one occur—the degree of tissue damage that ensues.

EFFECTS OF STATINS IN ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROME

The National Registry of Myocardial Infarction17 is a prospective, observational database of all patients with acute myocardial infarction admitted to 1,230 participating hospitals throughout the United States. In an analysis from this cohort, patients were divided into four groups: those receiving statins before and after admission, those receiving statins only before admission, those receiving statins only after admission, and those who never received statins.