User login

Let’s Dance: A Holistic Approach to Treating Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Dance holds value as a cathartic, therapeutic act.1 Dance and movement therapies may help reduce symptoms of several medical conditions and aid overall motor functioning. Studies have shown that they have been used to improve gait and balance in patients with Parkinson disease.2,3

Many theorists believe in the psychological healing power of dance/movement therapies, and researchers have begun to examine the ability of these therapies to enhance well-being and quality of life. Their findings suggest that dance fosters a sense of well-being, community, mastery, and joy.3-8 Bräuninger found that a 10-week dance/movement intervention reduced stress and improved social relations, general life satisfaction, and physical and psychological health.9 Other research has shown that subjective well-being is maintained through dance in elderly adults.10,11

Dance/movement also has been found helpful in reducing symptoms associated with several psychiatric conditions. Kline and colleagues reported that movement therapy reduced anxiety in populations with severe mental illness.12 Koch and colleagues found larger reductions on depression measures and higher vitality ratings in a dance intervention group compared with music-only and exercise groups.13 An approach integrating yoga and dance/movement was found to improve stress-management skills in people affected by several mental illnesses.14

Compared with the amount of data demonstrating that dance and movement are helpful treatment modalities for psychiatric conditions, there is relatively little empirical evidence that dance or movement is effective in treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This is particularly surprising given the somatic or bodily nature of PTSD. Traumatic events trigger significant bodily reactions—flight, fight, or freeze reactions—and PTSD involves reexperiencing bodily sensations, such as hypervigilance, agitation, and elevated arousal.15 Although dance/movement has consistently been used to treat PTSD, the evidence for its effectiveness comes mainly from case studies.16 Further empirical studies are needed to determine whether dance/movement therapies are effective in treating PTSD.

Recently, as part of the VHA patient-centered, innovative care initiative, efforts have been made to augment treating disease with improving wellness and health. For example, the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS) has supported Dance for Veterans (DFV), a dance/movement program that uses movement, creativity, relaxation, and social cohesion to treat veterans with serious mental illnesses. In a recent VAGLAHS study of the effect of DFV on patients with chronic schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, PTSD, and other serious mental illnesses, Wilbur and colleagues found a 25% decrease in stress, self-rated at the beginning and end of each class; in addition, veterans indicated they received long-term benefits from taking the class.17

This pilot study investigated the effectiveness of DFV as an adjunctive treatment for PTSD. The goal of the study was to assess whether the dance class helped reduce stress symptoms in veterans diagnosed with PTSD. As rates of PTSD are much higher in veterans than in the general population, the VA has taken particular interest in the diagnosis and has prioritized treatment of this disorder.18

Toward that end, the VA began a wide-scale national dissemination of 2 empirically validated PTSD-specific treatments: prolonged exposure therapy and cognitive processing therapy. These evidence-based therapies produce clinically significant reductions in PTSD symptoms among veterans.19,20 Nevertheless, concern exists about the dropout rates and tolerability of these manualized trauma-focused treatments.19,21 Patient-centered, integrative treatments are considered less demanding and more enjoyable, but there is little evidence of their effectiveness in PTSD treatment. The VA Los Angeles Ambulatory Care Center (LAACC) had been using DFV as an adjunct treatment for veterans diagnosed with PTSD. This pilot study examined whether participating in the program reduced veterans’ stress levels.

Methods

Development of DFV was a collaborative effort of members of the department of psychiatry at VAGLAHS, dancers in the community, and graduate students in the department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). The first class, in January 2011, was offered to patients in the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery Program at the West Los Angeles campus of VAGLAHS. The program quickly spread to LAACC, the Sepulveda Ambulatory Care Center, the East Los Angeles Clinic, and other VAGLAHS campuses.

The goals of DFV were to introduce techniques for stress management, enhance participants’ commitment to self-worth, increase participants’ faith in their physical capabilities, encourage focus and self-discipline, build confidence, have participants discover the value of learning new skills, challenge participants to use a variety of learning styles (eg, kinesthetic, aural, musical, visual), create opportunities for active watching and listening, decrease feelings of isolation, improve group (social) and personal awareness, cultivate expressive and emotional range, develop group trust, and improve large and small muscle coordination.22

Class Format

The DFV classes were standardized, and each week followed a consistent structure. Dance for Veterans is a 1-hour class that begins with a greeting and an expression of gratitude as represented by movements developed by individual class members. After listening to an introduction, the seated participants perform yogalike stretches that promote relaxation and improve flexibility. The stretches are followed by rhythm games. Participants repeat and change rhythms to the sounds of upbeat songs, thereby enhancing their observation and listening skills, creativity, and sense of mastery. Then, in Brain Dance, the middle part of the class, memory and coordination are challenged as participants learn a 7-part movement progression.23 Last is a group creative exploration call-and-response activity, usually a game in which the group coordinates participants’ names with their specific individual movements. Each participant says his or her name and creates an individual movement to represent himself or herself; the group then echoes that participant’s name and movement. This activity fosters group cohesion and creativity while improving attention, memory, and a sense of self-worth.

Instructor Training

The 12-week course of DFV classes was led by Dr. Steinberg-Oren and Dr. Krasnova as part of the LAACC general mental health program. The instructors received intensive training in DFV implementation from Sarah Wilbur, a doctoral student in the UCLA department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance and one of the founders of DFV. Training involved written materials and a half-day retreat. Ms. Wilbur modeled the class for 8 weeks. Then she observed the teachers and provided corrective feedback for another 4 weeks. After the 12-week training period, Ms. Wilbur attended class periodically to monitor how closely the instructors were following the prescribed class format and to provide helpful suggestions and new exercises.

Participants

Veterans receiving outpatient psychiatric care for PTSD at LAACC were recruited for the DFV class. They had undergone a thorough psychiatric interview and been found to meet the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM) criteria for PTSD. All underwent physical screening by a primary care provider to rule out preexisting medical conditions that would contraindicate taking the class. Participation was voluntary. Data analysis was approved by the institutional review board of VAGLAHCS.

Data Collection

Sixty-one veterans entered the class on a rolling basis from August 2012 to November 2014. At the participants first class, they completed a demographic questionnaire. For each of the first 12 sessions attended, they were asked to complete the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) form Y before and immediately after class.24 The STAI is a self-report questionnaire that measures short-term state anxiety and long-term trait anxiety as characterized by tension, apprehension, nervousness, and worry. It lists the same 20 items twice, first for state anxiety and then for trait anxiety. This valid and reliable measure of generalized anxiety, which has been used in hundreds of research studies, has test–retest intervals ranging from 1 hour to more than 3 months.24,25 Veterans in the study were also asked to provide qualitative feedback on any mood or sense-of-self changes experienced from the time they entered class to once it was completed.

For data analysis, a final sample of 20 veterans was selected. These veterans had completed at least 12 preclass and postclass STAI ratings within the 4-month period. The other 41 veterans in the study were not included in the data analysis because of inconsistent attendance, tardiness, or leaving class without completing a questionnaire. Further, because a large amount of STAI trait data was missing, only state items were analyzed. The data of the veterans who completed their ratings were double-entered to minimize recording errors.

Of the 20 completers (all men), 7 (35%) were African American, 7 (35%) were Hispanic, 5 (25%) were white, and 1 (5%) declined to report race. Completers’ ages ranged from the 40s to the late 70s; 40% (the largest grouping) were between ages 60 and 69 years. Noncompleters’ demographic data were comparable. Of the 41 noncompleters, 14 (34%) were African American, 15 (37%) were Hispanic, 8 (19%) were white, and 4 (10%) were Asian or Pacific Islander. Noncompleters’ ages also ranged from the 40s to the late 70s, with the largest grouping (58%) between ages 60 and 69 years. Thus, the authors did not find any significant differences between completers and noncompleters.

Results

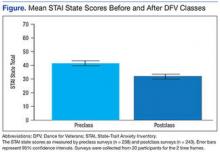

A mixed-effects linear model was used to assess whether participation length (in weeks), testing time (preclass vs postclass), or the interaction of these two variables were significant predictors of state anxiety as measured by STAI. This model included a random intercept by participant to account for differences in baseline stress levels. Analyses revealed a significant main effect of testing time on STAI state scores, t(458) = 7.48, P < .0001, such that class participation appeared to be associated with a mean decrease of 11 points on the state scale (Figure). However, participation length was not a significant predictor of STAI state scores, t(458) = 1.20, P = .233, and there was no interaction effect, t(458) = –0.57, P = .567.

Qualitative Results

Study participants unanimously reported improvements in outlook, well-being, mood, sense of well-being, and interpersonal relationships as a result of taking the DFV class. The most commonly reported preclass–postclass change was an increased sense of camaraderie and belonging. Many participants also expressed reductions in anger and isolation as well as an increase in self/other acceptance. Participants’ comments about the DFV class included, “It makes me forget about everything, and I enjoy myself.” “It relaxes me, makes me smile.” “I’ve made new friends.” “When I came here and tried this group, I felt very nervous. But I came over and over. I am so much more at ease.” “I come to class upset, and I leave with a smile on my face.” “I enjoy the camaraderie. I feel I am part of something.” “The class is helping me by body movement: moving my arms and legs—my attitude just changes.” “It’s a lot of fun!”

Discussion

This hypothesis-generating study examined whether an adjunctive, holistic intervention (dance class) could reduce stress in veterans with PTSD. Results showed significant reductions in state stress levels after DFV class participation. The finding of a significant effect of short-term reduction in state stress levels corroborates the findings from Wilbur and colleagues but with use of a comprehensive, reliable, well-validated measure of stress.17,24,25 This study’s qualitative results are also consistent with the prior qualitative data suggesting improvements in social connection and sense of well-being.

Some experts believe that PTSD-associated symptoms are fairly intractable and that trauma-focused treatments are required to reduce symptoms and promote a sense of well-being. This study did not show sustained reductions in stress levels across class sessions. Nevertheless, the significant state stress reductions that occurred after class suggest that this dance/movement intervention is a helpful adjunctive treatment for enhancing well-being, at least temporarily, in veterans with PTSD. The findings also suggest that veterans can benefit from a single session and need not attend class regularly to see results. Thus, DFV shows promise even on a drop-in basis. Overall, the results of this study provide further impetus to develop and provide more holistic, arts-based programs for veterans diagnosed with PTSD.

Study Limitations

At the beginning of this study, the authors did not expect strong participation of male veterans in a dance class. Surprisingly, 61 veterans enrolled over a period of 2 years 3 months. Nevertheless, the research sample was small, as empirical difficulties were encountered secondary to veterans’ inconsistent attendance and failure to complete ratings in a consistent and timely manner. Therefore, the sample may not have been representative. Research is needed to validate and expand the findings of this study.

Another methodologic concern was lack of a control group. Future studies might use a no-intervention control group and/or comparison groups, including support, meditation, and trauma-focused groups. In addition, veterans were not blinded to the intervention, and the STAI is a self-report survey with face-valid items. Thus, participants may have tried to please the instructors, bringing into question how much social desirability may have accounted for the reductions in stress levels.

The authors also did not examine confounding variables with regard to additional mental health treatments. It would have been helpful to address whether stress reductions were larger for veterans who were also receiving psychiatric medications and/or participating in other mental health groups or individual psychotherapies. The effect of comorbid diagnoses on the reduction in state stress levels also was not examined. Last, the authors did not investigate actual PTSD symptoms (eg, flashbacks, nightmares, hypervigilance, and avoidance). Further studies are needed to measure reductions on the PTSD Checklist for DSM 5 or on other empirical measures of PTSD as a consequence of this class in order to examine its effectiveness in reducing PTSD symptoms.

Qualitative responses from the veterans suggested that DFV promoted quality-of-life and well-being improvements. It would be helpful to assess this quantitatively through control or comparison group studies using measurements that minimize face validity. To understand the mechanism by which this class is effective, research also needs to examine what class-related factors are most effective in promoting positive change. The qualitative data provide glimpses into these factors, but empirical investigation could provide substantive proof of what specific factors are therapeutic.

Conclusion

The VHA has introduced several integrative adjunctive PTSD treatments, including dance, tai chi, mindfulness meditation, breathing/stretching/relaxation, yoga, healing touch, and others with the goal of maximizing veterans’ physical and psychological wellness. Although it seems unlikely that integrative once-a-week treatments lead to sustained reductions in PTSD and other serious psychiatric conditions, it is possible that participating in DFV classes more regularly, as part of adjunctive treatment, could promote a sustained sense of well-being, self-compassion, self-confidence, and sense of belonging. The question still remains whether such programs are effective in promoting well-being. The present study was not conclusive enough to substantiate that claim, but it represents a small step (a dance step) in the right direction, toward a holistic, creative, and well-rounded approach to the treatment of PTSD in veterans.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the many people involved in Dance for Veterans. Robert Rubin, MD, had the creative foresight to assemble the program; Donna Ames, MD, invited her coauthors to undergo training and provided them with research support; Sarah Wilbur, PhD, (program in Culture and Performance, Department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance, University of California, Los Angeles) developed the class and handbook as well as showed the authors how to run it; Sandra Robertson, RN, MSN, PH-CNS, (principal investigator, Integrative Health and Healing Project, VA T21 Center of Innovation Grant for Patient-Centered Care) provided the funding and initiative to develop and implement the class; and (Christine Suarez Suarez Dance Theatre, Santa Monica, California) developed the class and the handbook and trained instructors.

The authors also thank all the VAGLAHS veterans and staff for their help with the class—especially Andrea Serafin, LCSW; Rosie Dominguez, LCSW; Retha de Johnette, LCSW; and Donna Ames, MD, all part of the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery Programs; Dana Melching, LCSW, Mental Health Intensive Case Management; and Vanessa Baumann, PhD (Vet Center).

1. Levy FJ. Dance/Movement Therapy: A Healing Art. Reston, VA: American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance; 1992.

2. Marigold DS, Misiaszek JE. Whole-body responses: neural control and implications for rehabilitation and fall prevention. Neuroscientist. 2009;15(1):36-46.

3. Hackney ME, Kantorovich S, Levin R, Earhart GM. Effects of tango on functional mobility in Parkinson's disease: a preliminary study. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;31(4):173-179.

4. Ravelin T, Kylmä J, Korhonen T. Dance in mental health nursing: a hybrid concept analysis. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2006;27(3):307-317.

5. Hackney ME, Earhart GM. Effects of dance on gait and balance in Parkinson's disease: a comparison of partnered and nonpartnered dance movement. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010;24(4):384-392.

6. Heiberger L, Maurer C, Amtage F, et al. Impact of a weekly dance class on the functional mobility and on the quality of life of individuals with Parkinson's disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2011;3:14.

7. Houston S, McGill A. A mixed-methods study into ballet for people living with Parkinson's. Arts Health. 2013;5(2):103-119.

8. Westheimer O. Why dance for Parkinson's disease. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2008;24(2):127-140.

9. Bräuninger I. Dance movement therapy group intervention in stress treatment: a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Arts Psychother. 2012;39(5):443-450.

10. Kattenstroth, JC, Kalisch T, Holt S, Tegenthoff M, Dinse HR. Six months of dance intervention enhances postural, sensorimotor, and cognitive performance in elderly without affecting cardio-respiratory functions. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:5.

11. Kattenstroth J-C, Kolankowska I, Kalisch T, Dinse HR. Superior sensory, motor, and cognitive performance in elderly individuals with multi-year dancing activities. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010;2:31.

12. Kline F, Burgoyne RW, Staples F, Moredock P, Snyder V, Ioerger M. A report on the use of movement therapy for chronic, severely disabled outpatients. Arts Psychother. 1977;4(4-5):181-183.

13. Koch SC, Morlinghaus K, Fuchs T. The joy dance: specific effects of a single dance intervention on psychiatric patients with depression. Arts Psychother. 2007;34(4):340-349.

14. Barton EJ. Movement and mindfulness: a formative evaluation of a dance/movement and yoga therapy program with participants experiencing severe mental illness. Am J Dance Ther. 2011;33(2):157-181.

15. van der Kolk BA, McFarlane AC, Weisaeth L, eds. Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body, and Society. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1996.

16. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA, eds. Effective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines From the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009.

17. Wilbur S, Meyer HB, Baker MR, et al. Dance for Veterans: a complementary health program for veterans with serious mental illness. Arts Health. 2015;7(2):96-108.

18. Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, PTSD: National Center for PTSD website. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp. Published January 30, 2014. Accessed August 20, 2015.

19. Eftekhari A, Ruzek JI, Crowley JJ, Rosen CS, Greenbaum MA, Karlin BE. Effectiveness of national implementation of prolonged exposure therapy in Veterans Affairs care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(9):949-955.

20. Monson CM, Schnurr PP, Resick PA, Friedman MJ, Young-Xu Y, Stevens SP. Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(5):898-907.

21. Schottenbauer MA, Glass CR, Arnkoff DB, Tendick V, Gray SH. Nonresponse and dropout rates in outcome studies on PTSD: review and methodological considerations. Psychiatry. 2008;71(2):134-168.

22. Suarez CA, Wilbur S, Smiarowski K, Rubin RT, Ames D. Dance for Veterans: Music, Movement & Rhythm Manual for Instruction. 2nd ed. Publisher unknown; 2014.

23. Gilbert AG, Gilbert BA, Rossano A. Brain-Compatible Dance Education. Reston, VA: National Dance Association; 2006.

24. Spielberger C. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Rev ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983.

25. Julian LJ. Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(suppl 11):S467-S472.

Dance holds value as a cathartic, therapeutic act.1 Dance and movement therapies may help reduce symptoms of several medical conditions and aid overall motor functioning. Studies have shown that they have been used to improve gait and balance in patients with Parkinson disease.2,3

Many theorists believe in the psychological healing power of dance/movement therapies, and researchers have begun to examine the ability of these therapies to enhance well-being and quality of life. Their findings suggest that dance fosters a sense of well-being, community, mastery, and joy.3-8 Bräuninger found that a 10-week dance/movement intervention reduced stress and improved social relations, general life satisfaction, and physical and psychological health.9 Other research has shown that subjective well-being is maintained through dance in elderly adults.10,11

Dance/movement also has been found helpful in reducing symptoms associated with several psychiatric conditions. Kline and colleagues reported that movement therapy reduced anxiety in populations with severe mental illness.12 Koch and colleagues found larger reductions on depression measures and higher vitality ratings in a dance intervention group compared with music-only and exercise groups.13 An approach integrating yoga and dance/movement was found to improve stress-management skills in people affected by several mental illnesses.14

Compared with the amount of data demonstrating that dance and movement are helpful treatment modalities for psychiatric conditions, there is relatively little empirical evidence that dance or movement is effective in treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This is particularly surprising given the somatic or bodily nature of PTSD. Traumatic events trigger significant bodily reactions—flight, fight, or freeze reactions—and PTSD involves reexperiencing bodily sensations, such as hypervigilance, agitation, and elevated arousal.15 Although dance/movement has consistently been used to treat PTSD, the evidence for its effectiveness comes mainly from case studies.16 Further empirical studies are needed to determine whether dance/movement therapies are effective in treating PTSD.

Recently, as part of the VHA patient-centered, innovative care initiative, efforts have been made to augment treating disease with improving wellness and health. For example, the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS) has supported Dance for Veterans (DFV), a dance/movement program that uses movement, creativity, relaxation, and social cohesion to treat veterans with serious mental illnesses. In a recent VAGLAHS study of the effect of DFV on patients with chronic schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, PTSD, and other serious mental illnesses, Wilbur and colleagues found a 25% decrease in stress, self-rated at the beginning and end of each class; in addition, veterans indicated they received long-term benefits from taking the class.17

This pilot study investigated the effectiveness of DFV as an adjunctive treatment for PTSD. The goal of the study was to assess whether the dance class helped reduce stress symptoms in veterans diagnosed with PTSD. As rates of PTSD are much higher in veterans than in the general population, the VA has taken particular interest in the diagnosis and has prioritized treatment of this disorder.18

Toward that end, the VA began a wide-scale national dissemination of 2 empirically validated PTSD-specific treatments: prolonged exposure therapy and cognitive processing therapy. These evidence-based therapies produce clinically significant reductions in PTSD symptoms among veterans.19,20 Nevertheless, concern exists about the dropout rates and tolerability of these manualized trauma-focused treatments.19,21 Patient-centered, integrative treatments are considered less demanding and more enjoyable, but there is little evidence of their effectiveness in PTSD treatment. The VA Los Angeles Ambulatory Care Center (LAACC) had been using DFV as an adjunct treatment for veterans diagnosed with PTSD. This pilot study examined whether participating in the program reduced veterans’ stress levels.

Methods

Development of DFV was a collaborative effort of members of the department of psychiatry at VAGLAHS, dancers in the community, and graduate students in the department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). The first class, in January 2011, was offered to patients in the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery Program at the West Los Angeles campus of VAGLAHS. The program quickly spread to LAACC, the Sepulveda Ambulatory Care Center, the East Los Angeles Clinic, and other VAGLAHS campuses.

The goals of DFV were to introduce techniques for stress management, enhance participants’ commitment to self-worth, increase participants’ faith in their physical capabilities, encourage focus and self-discipline, build confidence, have participants discover the value of learning new skills, challenge participants to use a variety of learning styles (eg, kinesthetic, aural, musical, visual), create opportunities for active watching and listening, decrease feelings of isolation, improve group (social) and personal awareness, cultivate expressive and emotional range, develop group trust, and improve large and small muscle coordination.22

Class Format

The DFV classes were standardized, and each week followed a consistent structure. Dance for Veterans is a 1-hour class that begins with a greeting and an expression of gratitude as represented by movements developed by individual class members. After listening to an introduction, the seated participants perform yogalike stretches that promote relaxation and improve flexibility. The stretches are followed by rhythm games. Participants repeat and change rhythms to the sounds of upbeat songs, thereby enhancing their observation and listening skills, creativity, and sense of mastery. Then, in Brain Dance, the middle part of the class, memory and coordination are challenged as participants learn a 7-part movement progression.23 Last is a group creative exploration call-and-response activity, usually a game in which the group coordinates participants’ names with their specific individual movements. Each participant says his or her name and creates an individual movement to represent himself or herself; the group then echoes that participant’s name and movement. This activity fosters group cohesion and creativity while improving attention, memory, and a sense of self-worth.

Instructor Training

The 12-week course of DFV classes was led by Dr. Steinberg-Oren and Dr. Krasnova as part of the LAACC general mental health program. The instructors received intensive training in DFV implementation from Sarah Wilbur, a doctoral student in the UCLA department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance and one of the founders of DFV. Training involved written materials and a half-day retreat. Ms. Wilbur modeled the class for 8 weeks. Then she observed the teachers and provided corrective feedback for another 4 weeks. After the 12-week training period, Ms. Wilbur attended class periodically to monitor how closely the instructors were following the prescribed class format and to provide helpful suggestions and new exercises.

Participants

Veterans receiving outpatient psychiatric care for PTSD at LAACC were recruited for the DFV class. They had undergone a thorough psychiatric interview and been found to meet the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM) criteria for PTSD. All underwent physical screening by a primary care provider to rule out preexisting medical conditions that would contraindicate taking the class. Participation was voluntary. Data analysis was approved by the institutional review board of VAGLAHCS.

Data Collection

Sixty-one veterans entered the class on a rolling basis from August 2012 to November 2014. At the participants first class, they completed a demographic questionnaire. For each of the first 12 sessions attended, they were asked to complete the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) form Y before and immediately after class.24 The STAI is a self-report questionnaire that measures short-term state anxiety and long-term trait anxiety as characterized by tension, apprehension, nervousness, and worry. It lists the same 20 items twice, first for state anxiety and then for trait anxiety. This valid and reliable measure of generalized anxiety, which has been used in hundreds of research studies, has test–retest intervals ranging from 1 hour to more than 3 months.24,25 Veterans in the study were also asked to provide qualitative feedback on any mood or sense-of-self changes experienced from the time they entered class to once it was completed.

For data analysis, a final sample of 20 veterans was selected. These veterans had completed at least 12 preclass and postclass STAI ratings within the 4-month period. The other 41 veterans in the study were not included in the data analysis because of inconsistent attendance, tardiness, or leaving class without completing a questionnaire. Further, because a large amount of STAI trait data was missing, only state items were analyzed. The data of the veterans who completed their ratings were double-entered to minimize recording errors.

Of the 20 completers (all men), 7 (35%) were African American, 7 (35%) were Hispanic, 5 (25%) were white, and 1 (5%) declined to report race. Completers’ ages ranged from the 40s to the late 70s; 40% (the largest grouping) were between ages 60 and 69 years. Noncompleters’ demographic data were comparable. Of the 41 noncompleters, 14 (34%) were African American, 15 (37%) were Hispanic, 8 (19%) were white, and 4 (10%) were Asian or Pacific Islander. Noncompleters’ ages also ranged from the 40s to the late 70s, with the largest grouping (58%) between ages 60 and 69 years. Thus, the authors did not find any significant differences between completers and noncompleters.

Results

A mixed-effects linear model was used to assess whether participation length (in weeks), testing time (preclass vs postclass), or the interaction of these two variables were significant predictors of state anxiety as measured by STAI. This model included a random intercept by participant to account for differences in baseline stress levels. Analyses revealed a significant main effect of testing time on STAI state scores, t(458) = 7.48, P < .0001, such that class participation appeared to be associated with a mean decrease of 11 points on the state scale (Figure). However, participation length was not a significant predictor of STAI state scores, t(458) = 1.20, P = .233, and there was no interaction effect, t(458) = –0.57, P = .567.

Qualitative Results

Study participants unanimously reported improvements in outlook, well-being, mood, sense of well-being, and interpersonal relationships as a result of taking the DFV class. The most commonly reported preclass–postclass change was an increased sense of camaraderie and belonging. Many participants also expressed reductions in anger and isolation as well as an increase in self/other acceptance. Participants’ comments about the DFV class included, “It makes me forget about everything, and I enjoy myself.” “It relaxes me, makes me smile.” “I’ve made new friends.” “When I came here and tried this group, I felt very nervous. But I came over and over. I am so much more at ease.” “I come to class upset, and I leave with a smile on my face.” “I enjoy the camaraderie. I feel I am part of something.” “The class is helping me by body movement: moving my arms and legs—my attitude just changes.” “It’s a lot of fun!”

Discussion

This hypothesis-generating study examined whether an adjunctive, holistic intervention (dance class) could reduce stress in veterans with PTSD. Results showed significant reductions in state stress levels after DFV class participation. The finding of a significant effect of short-term reduction in state stress levels corroborates the findings from Wilbur and colleagues but with use of a comprehensive, reliable, well-validated measure of stress.17,24,25 This study’s qualitative results are also consistent with the prior qualitative data suggesting improvements in social connection and sense of well-being.

Some experts believe that PTSD-associated symptoms are fairly intractable and that trauma-focused treatments are required to reduce symptoms and promote a sense of well-being. This study did not show sustained reductions in stress levels across class sessions. Nevertheless, the significant state stress reductions that occurred after class suggest that this dance/movement intervention is a helpful adjunctive treatment for enhancing well-being, at least temporarily, in veterans with PTSD. The findings also suggest that veterans can benefit from a single session and need not attend class regularly to see results. Thus, DFV shows promise even on a drop-in basis. Overall, the results of this study provide further impetus to develop and provide more holistic, arts-based programs for veterans diagnosed with PTSD.

Study Limitations

At the beginning of this study, the authors did not expect strong participation of male veterans in a dance class. Surprisingly, 61 veterans enrolled over a period of 2 years 3 months. Nevertheless, the research sample was small, as empirical difficulties were encountered secondary to veterans’ inconsistent attendance and failure to complete ratings in a consistent and timely manner. Therefore, the sample may not have been representative. Research is needed to validate and expand the findings of this study.

Another methodologic concern was lack of a control group. Future studies might use a no-intervention control group and/or comparison groups, including support, meditation, and trauma-focused groups. In addition, veterans were not blinded to the intervention, and the STAI is a self-report survey with face-valid items. Thus, participants may have tried to please the instructors, bringing into question how much social desirability may have accounted for the reductions in stress levels.

The authors also did not examine confounding variables with regard to additional mental health treatments. It would have been helpful to address whether stress reductions were larger for veterans who were also receiving psychiatric medications and/or participating in other mental health groups or individual psychotherapies. The effect of comorbid diagnoses on the reduction in state stress levels also was not examined. Last, the authors did not investigate actual PTSD symptoms (eg, flashbacks, nightmares, hypervigilance, and avoidance). Further studies are needed to measure reductions on the PTSD Checklist for DSM 5 or on other empirical measures of PTSD as a consequence of this class in order to examine its effectiveness in reducing PTSD symptoms.

Qualitative responses from the veterans suggested that DFV promoted quality-of-life and well-being improvements. It would be helpful to assess this quantitatively through control or comparison group studies using measurements that minimize face validity. To understand the mechanism by which this class is effective, research also needs to examine what class-related factors are most effective in promoting positive change. The qualitative data provide glimpses into these factors, but empirical investigation could provide substantive proof of what specific factors are therapeutic.

Conclusion

The VHA has introduced several integrative adjunctive PTSD treatments, including dance, tai chi, mindfulness meditation, breathing/stretching/relaxation, yoga, healing touch, and others with the goal of maximizing veterans’ physical and psychological wellness. Although it seems unlikely that integrative once-a-week treatments lead to sustained reductions in PTSD and other serious psychiatric conditions, it is possible that participating in DFV classes more regularly, as part of adjunctive treatment, could promote a sustained sense of well-being, self-compassion, self-confidence, and sense of belonging. The question still remains whether such programs are effective in promoting well-being. The present study was not conclusive enough to substantiate that claim, but it represents a small step (a dance step) in the right direction, toward a holistic, creative, and well-rounded approach to the treatment of PTSD in veterans.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the many people involved in Dance for Veterans. Robert Rubin, MD, had the creative foresight to assemble the program; Donna Ames, MD, invited her coauthors to undergo training and provided them with research support; Sarah Wilbur, PhD, (program in Culture and Performance, Department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance, University of California, Los Angeles) developed the class and handbook as well as showed the authors how to run it; Sandra Robertson, RN, MSN, PH-CNS, (principal investigator, Integrative Health and Healing Project, VA T21 Center of Innovation Grant for Patient-Centered Care) provided the funding and initiative to develop and implement the class; and (Christine Suarez Suarez Dance Theatre, Santa Monica, California) developed the class and the handbook and trained instructors.

The authors also thank all the VAGLAHS veterans and staff for their help with the class—especially Andrea Serafin, LCSW; Rosie Dominguez, LCSW; Retha de Johnette, LCSW; and Donna Ames, MD, all part of the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery Programs; Dana Melching, LCSW, Mental Health Intensive Case Management; and Vanessa Baumann, PhD (Vet Center).

Dance holds value as a cathartic, therapeutic act.1 Dance and movement therapies may help reduce symptoms of several medical conditions and aid overall motor functioning. Studies have shown that they have been used to improve gait and balance in patients with Parkinson disease.2,3

Many theorists believe in the psychological healing power of dance/movement therapies, and researchers have begun to examine the ability of these therapies to enhance well-being and quality of life. Their findings suggest that dance fosters a sense of well-being, community, mastery, and joy.3-8 Bräuninger found that a 10-week dance/movement intervention reduced stress and improved social relations, general life satisfaction, and physical and psychological health.9 Other research has shown that subjective well-being is maintained through dance in elderly adults.10,11

Dance/movement also has been found helpful in reducing symptoms associated with several psychiatric conditions. Kline and colleagues reported that movement therapy reduced anxiety in populations with severe mental illness.12 Koch and colleagues found larger reductions on depression measures and higher vitality ratings in a dance intervention group compared with music-only and exercise groups.13 An approach integrating yoga and dance/movement was found to improve stress-management skills in people affected by several mental illnesses.14

Compared with the amount of data demonstrating that dance and movement are helpful treatment modalities for psychiatric conditions, there is relatively little empirical evidence that dance or movement is effective in treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This is particularly surprising given the somatic or bodily nature of PTSD. Traumatic events trigger significant bodily reactions—flight, fight, or freeze reactions—and PTSD involves reexperiencing bodily sensations, such as hypervigilance, agitation, and elevated arousal.15 Although dance/movement has consistently been used to treat PTSD, the evidence for its effectiveness comes mainly from case studies.16 Further empirical studies are needed to determine whether dance/movement therapies are effective in treating PTSD.

Recently, as part of the VHA patient-centered, innovative care initiative, efforts have been made to augment treating disease with improving wellness and health. For example, the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS) has supported Dance for Veterans (DFV), a dance/movement program that uses movement, creativity, relaxation, and social cohesion to treat veterans with serious mental illnesses. In a recent VAGLAHS study of the effect of DFV on patients with chronic schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, PTSD, and other serious mental illnesses, Wilbur and colleagues found a 25% decrease in stress, self-rated at the beginning and end of each class; in addition, veterans indicated they received long-term benefits from taking the class.17

This pilot study investigated the effectiveness of DFV as an adjunctive treatment for PTSD. The goal of the study was to assess whether the dance class helped reduce stress symptoms in veterans diagnosed with PTSD. As rates of PTSD are much higher in veterans than in the general population, the VA has taken particular interest in the diagnosis and has prioritized treatment of this disorder.18

Toward that end, the VA began a wide-scale national dissemination of 2 empirically validated PTSD-specific treatments: prolonged exposure therapy and cognitive processing therapy. These evidence-based therapies produce clinically significant reductions in PTSD symptoms among veterans.19,20 Nevertheless, concern exists about the dropout rates and tolerability of these manualized trauma-focused treatments.19,21 Patient-centered, integrative treatments are considered less demanding and more enjoyable, but there is little evidence of their effectiveness in PTSD treatment. The VA Los Angeles Ambulatory Care Center (LAACC) had been using DFV as an adjunct treatment for veterans diagnosed with PTSD. This pilot study examined whether participating in the program reduced veterans’ stress levels.

Methods

Development of DFV was a collaborative effort of members of the department of psychiatry at VAGLAHS, dancers in the community, and graduate students in the department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). The first class, in January 2011, was offered to patients in the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery Program at the West Los Angeles campus of VAGLAHS. The program quickly spread to LAACC, the Sepulveda Ambulatory Care Center, the East Los Angeles Clinic, and other VAGLAHS campuses.

The goals of DFV were to introduce techniques for stress management, enhance participants’ commitment to self-worth, increase participants’ faith in their physical capabilities, encourage focus and self-discipline, build confidence, have participants discover the value of learning new skills, challenge participants to use a variety of learning styles (eg, kinesthetic, aural, musical, visual), create opportunities for active watching and listening, decrease feelings of isolation, improve group (social) and personal awareness, cultivate expressive and emotional range, develop group trust, and improve large and small muscle coordination.22

Class Format

The DFV classes were standardized, and each week followed a consistent structure. Dance for Veterans is a 1-hour class that begins with a greeting and an expression of gratitude as represented by movements developed by individual class members. After listening to an introduction, the seated participants perform yogalike stretches that promote relaxation and improve flexibility. The stretches are followed by rhythm games. Participants repeat and change rhythms to the sounds of upbeat songs, thereby enhancing their observation and listening skills, creativity, and sense of mastery. Then, in Brain Dance, the middle part of the class, memory and coordination are challenged as participants learn a 7-part movement progression.23 Last is a group creative exploration call-and-response activity, usually a game in which the group coordinates participants’ names with their specific individual movements. Each participant says his or her name and creates an individual movement to represent himself or herself; the group then echoes that participant’s name and movement. This activity fosters group cohesion and creativity while improving attention, memory, and a sense of self-worth.

Instructor Training

The 12-week course of DFV classes was led by Dr. Steinberg-Oren and Dr. Krasnova as part of the LAACC general mental health program. The instructors received intensive training in DFV implementation from Sarah Wilbur, a doctoral student in the UCLA department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance and one of the founders of DFV. Training involved written materials and a half-day retreat. Ms. Wilbur modeled the class for 8 weeks. Then she observed the teachers and provided corrective feedback for another 4 weeks. After the 12-week training period, Ms. Wilbur attended class periodically to monitor how closely the instructors were following the prescribed class format and to provide helpful suggestions and new exercises.

Participants

Veterans receiving outpatient psychiatric care for PTSD at LAACC were recruited for the DFV class. They had undergone a thorough psychiatric interview and been found to meet the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM) criteria for PTSD. All underwent physical screening by a primary care provider to rule out preexisting medical conditions that would contraindicate taking the class. Participation was voluntary. Data analysis was approved by the institutional review board of VAGLAHCS.

Data Collection

Sixty-one veterans entered the class on a rolling basis from August 2012 to November 2014. At the participants first class, they completed a demographic questionnaire. For each of the first 12 sessions attended, they were asked to complete the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) form Y before and immediately after class.24 The STAI is a self-report questionnaire that measures short-term state anxiety and long-term trait anxiety as characterized by tension, apprehension, nervousness, and worry. It lists the same 20 items twice, first for state anxiety and then for trait anxiety. This valid and reliable measure of generalized anxiety, which has been used in hundreds of research studies, has test–retest intervals ranging from 1 hour to more than 3 months.24,25 Veterans in the study were also asked to provide qualitative feedback on any mood or sense-of-self changes experienced from the time they entered class to once it was completed.

For data analysis, a final sample of 20 veterans was selected. These veterans had completed at least 12 preclass and postclass STAI ratings within the 4-month period. The other 41 veterans in the study were not included in the data analysis because of inconsistent attendance, tardiness, or leaving class without completing a questionnaire. Further, because a large amount of STAI trait data was missing, only state items were analyzed. The data of the veterans who completed their ratings were double-entered to minimize recording errors.

Of the 20 completers (all men), 7 (35%) were African American, 7 (35%) were Hispanic, 5 (25%) were white, and 1 (5%) declined to report race. Completers’ ages ranged from the 40s to the late 70s; 40% (the largest grouping) were between ages 60 and 69 years. Noncompleters’ demographic data were comparable. Of the 41 noncompleters, 14 (34%) were African American, 15 (37%) were Hispanic, 8 (19%) were white, and 4 (10%) were Asian or Pacific Islander. Noncompleters’ ages also ranged from the 40s to the late 70s, with the largest grouping (58%) between ages 60 and 69 years. Thus, the authors did not find any significant differences between completers and noncompleters.

Results

A mixed-effects linear model was used to assess whether participation length (in weeks), testing time (preclass vs postclass), or the interaction of these two variables were significant predictors of state anxiety as measured by STAI. This model included a random intercept by participant to account for differences in baseline stress levels. Analyses revealed a significant main effect of testing time on STAI state scores, t(458) = 7.48, P < .0001, such that class participation appeared to be associated with a mean decrease of 11 points on the state scale (Figure). However, participation length was not a significant predictor of STAI state scores, t(458) = 1.20, P = .233, and there was no interaction effect, t(458) = –0.57, P = .567.

Qualitative Results

Study participants unanimously reported improvements in outlook, well-being, mood, sense of well-being, and interpersonal relationships as a result of taking the DFV class. The most commonly reported preclass–postclass change was an increased sense of camaraderie and belonging. Many participants also expressed reductions in anger and isolation as well as an increase in self/other acceptance. Participants’ comments about the DFV class included, “It makes me forget about everything, and I enjoy myself.” “It relaxes me, makes me smile.” “I’ve made new friends.” “When I came here and tried this group, I felt very nervous. But I came over and over. I am so much more at ease.” “I come to class upset, and I leave with a smile on my face.” “I enjoy the camaraderie. I feel I am part of something.” “The class is helping me by body movement: moving my arms and legs—my attitude just changes.” “It’s a lot of fun!”

Discussion

This hypothesis-generating study examined whether an adjunctive, holistic intervention (dance class) could reduce stress in veterans with PTSD. Results showed significant reductions in state stress levels after DFV class participation. The finding of a significant effect of short-term reduction in state stress levels corroborates the findings from Wilbur and colleagues but with use of a comprehensive, reliable, well-validated measure of stress.17,24,25 This study’s qualitative results are also consistent with the prior qualitative data suggesting improvements in social connection and sense of well-being.

Some experts believe that PTSD-associated symptoms are fairly intractable and that trauma-focused treatments are required to reduce symptoms and promote a sense of well-being. This study did not show sustained reductions in stress levels across class sessions. Nevertheless, the significant state stress reductions that occurred after class suggest that this dance/movement intervention is a helpful adjunctive treatment for enhancing well-being, at least temporarily, in veterans with PTSD. The findings also suggest that veterans can benefit from a single session and need not attend class regularly to see results. Thus, DFV shows promise even on a drop-in basis. Overall, the results of this study provide further impetus to develop and provide more holistic, arts-based programs for veterans diagnosed with PTSD.

Study Limitations

At the beginning of this study, the authors did not expect strong participation of male veterans in a dance class. Surprisingly, 61 veterans enrolled over a period of 2 years 3 months. Nevertheless, the research sample was small, as empirical difficulties were encountered secondary to veterans’ inconsistent attendance and failure to complete ratings in a consistent and timely manner. Therefore, the sample may not have been representative. Research is needed to validate and expand the findings of this study.

Another methodologic concern was lack of a control group. Future studies might use a no-intervention control group and/or comparison groups, including support, meditation, and trauma-focused groups. In addition, veterans were not blinded to the intervention, and the STAI is a self-report survey with face-valid items. Thus, participants may have tried to please the instructors, bringing into question how much social desirability may have accounted for the reductions in stress levels.

The authors also did not examine confounding variables with regard to additional mental health treatments. It would have been helpful to address whether stress reductions were larger for veterans who were also receiving psychiatric medications and/or participating in other mental health groups or individual psychotherapies. The effect of comorbid diagnoses on the reduction in state stress levels also was not examined. Last, the authors did not investigate actual PTSD symptoms (eg, flashbacks, nightmares, hypervigilance, and avoidance). Further studies are needed to measure reductions on the PTSD Checklist for DSM 5 or on other empirical measures of PTSD as a consequence of this class in order to examine its effectiveness in reducing PTSD symptoms.

Qualitative responses from the veterans suggested that DFV promoted quality-of-life and well-being improvements. It would be helpful to assess this quantitatively through control or comparison group studies using measurements that minimize face validity. To understand the mechanism by which this class is effective, research also needs to examine what class-related factors are most effective in promoting positive change. The qualitative data provide glimpses into these factors, but empirical investigation could provide substantive proof of what specific factors are therapeutic.

Conclusion

The VHA has introduced several integrative adjunctive PTSD treatments, including dance, tai chi, mindfulness meditation, breathing/stretching/relaxation, yoga, healing touch, and others with the goal of maximizing veterans’ physical and psychological wellness. Although it seems unlikely that integrative once-a-week treatments lead to sustained reductions in PTSD and other serious psychiatric conditions, it is possible that participating in DFV classes more regularly, as part of adjunctive treatment, could promote a sustained sense of well-being, self-compassion, self-confidence, and sense of belonging. The question still remains whether such programs are effective in promoting well-being. The present study was not conclusive enough to substantiate that claim, but it represents a small step (a dance step) in the right direction, toward a holistic, creative, and well-rounded approach to the treatment of PTSD in veterans.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the many people involved in Dance for Veterans. Robert Rubin, MD, had the creative foresight to assemble the program; Donna Ames, MD, invited her coauthors to undergo training and provided them with research support; Sarah Wilbur, PhD, (program in Culture and Performance, Department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance, University of California, Los Angeles) developed the class and handbook as well as showed the authors how to run it; Sandra Robertson, RN, MSN, PH-CNS, (principal investigator, Integrative Health and Healing Project, VA T21 Center of Innovation Grant for Patient-Centered Care) provided the funding and initiative to develop and implement the class; and (Christine Suarez Suarez Dance Theatre, Santa Monica, California) developed the class and the handbook and trained instructors.

The authors also thank all the VAGLAHS veterans and staff for their help with the class—especially Andrea Serafin, LCSW; Rosie Dominguez, LCSW; Retha de Johnette, LCSW; and Donna Ames, MD, all part of the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery Programs; Dana Melching, LCSW, Mental Health Intensive Case Management; and Vanessa Baumann, PhD (Vet Center).

1. Levy FJ. Dance/Movement Therapy: A Healing Art. Reston, VA: American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance; 1992.

2. Marigold DS, Misiaszek JE. Whole-body responses: neural control and implications for rehabilitation and fall prevention. Neuroscientist. 2009;15(1):36-46.

3. Hackney ME, Kantorovich S, Levin R, Earhart GM. Effects of tango on functional mobility in Parkinson's disease: a preliminary study. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;31(4):173-179.

4. Ravelin T, Kylmä J, Korhonen T. Dance in mental health nursing: a hybrid concept analysis. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2006;27(3):307-317.

5. Hackney ME, Earhart GM. Effects of dance on gait and balance in Parkinson's disease: a comparison of partnered and nonpartnered dance movement. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010;24(4):384-392.

6. Heiberger L, Maurer C, Amtage F, et al. Impact of a weekly dance class on the functional mobility and on the quality of life of individuals with Parkinson's disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2011;3:14.

7. Houston S, McGill A. A mixed-methods study into ballet for people living with Parkinson's. Arts Health. 2013;5(2):103-119.

8. Westheimer O. Why dance for Parkinson's disease. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2008;24(2):127-140.

9. Bräuninger I. Dance movement therapy group intervention in stress treatment: a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Arts Psychother. 2012;39(5):443-450.

10. Kattenstroth, JC, Kalisch T, Holt S, Tegenthoff M, Dinse HR. Six months of dance intervention enhances postural, sensorimotor, and cognitive performance in elderly without affecting cardio-respiratory functions. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:5.

11. Kattenstroth J-C, Kolankowska I, Kalisch T, Dinse HR. Superior sensory, motor, and cognitive performance in elderly individuals with multi-year dancing activities. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010;2:31.

12. Kline F, Burgoyne RW, Staples F, Moredock P, Snyder V, Ioerger M. A report on the use of movement therapy for chronic, severely disabled outpatients. Arts Psychother. 1977;4(4-5):181-183.

13. Koch SC, Morlinghaus K, Fuchs T. The joy dance: specific effects of a single dance intervention on psychiatric patients with depression. Arts Psychother. 2007;34(4):340-349.

14. Barton EJ. Movement and mindfulness: a formative evaluation of a dance/movement and yoga therapy program with participants experiencing severe mental illness. Am J Dance Ther. 2011;33(2):157-181.

15. van der Kolk BA, McFarlane AC, Weisaeth L, eds. Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body, and Society. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1996.

16. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA, eds. Effective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines From the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009.

17. Wilbur S, Meyer HB, Baker MR, et al. Dance for Veterans: a complementary health program for veterans with serious mental illness. Arts Health. 2015;7(2):96-108.

18. Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, PTSD: National Center for PTSD website. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp. Published January 30, 2014. Accessed August 20, 2015.

19. Eftekhari A, Ruzek JI, Crowley JJ, Rosen CS, Greenbaum MA, Karlin BE. Effectiveness of national implementation of prolonged exposure therapy in Veterans Affairs care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(9):949-955.

20. Monson CM, Schnurr PP, Resick PA, Friedman MJ, Young-Xu Y, Stevens SP. Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(5):898-907.

21. Schottenbauer MA, Glass CR, Arnkoff DB, Tendick V, Gray SH. Nonresponse and dropout rates in outcome studies on PTSD: review and methodological considerations. Psychiatry. 2008;71(2):134-168.

22. Suarez CA, Wilbur S, Smiarowski K, Rubin RT, Ames D. Dance for Veterans: Music, Movement & Rhythm Manual for Instruction. 2nd ed. Publisher unknown; 2014.

23. Gilbert AG, Gilbert BA, Rossano A. Brain-Compatible Dance Education. Reston, VA: National Dance Association; 2006.

24. Spielberger C. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Rev ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983.

25. Julian LJ. Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(suppl 11):S467-S472.

1. Levy FJ. Dance/Movement Therapy: A Healing Art. Reston, VA: American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance; 1992.

2. Marigold DS, Misiaszek JE. Whole-body responses: neural control and implications for rehabilitation and fall prevention. Neuroscientist. 2009;15(1):36-46.

3. Hackney ME, Kantorovich S, Levin R, Earhart GM. Effects of tango on functional mobility in Parkinson's disease: a preliminary study. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;31(4):173-179.

4. Ravelin T, Kylmä J, Korhonen T. Dance in mental health nursing: a hybrid concept analysis. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2006;27(3):307-317.

5. Hackney ME, Earhart GM. Effects of dance on gait and balance in Parkinson's disease: a comparison of partnered and nonpartnered dance movement. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010;24(4):384-392.

6. Heiberger L, Maurer C, Amtage F, et al. Impact of a weekly dance class on the functional mobility and on the quality of life of individuals with Parkinson's disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2011;3:14.

7. Houston S, McGill A. A mixed-methods study into ballet for people living with Parkinson's. Arts Health. 2013;5(2):103-119.

8. Westheimer O. Why dance for Parkinson's disease. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2008;24(2):127-140.

9. Bräuninger I. Dance movement therapy group intervention in stress treatment: a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Arts Psychother. 2012;39(5):443-450.

10. Kattenstroth, JC, Kalisch T, Holt S, Tegenthoff M, Dinse HR. Six months of dance intervention enhances postural, sensorimotor, and cognitive performance in elderly without affecting cardio-respiratory functions. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:5.

11. Kattenstroth J-C, Kolankowska I, Kalisch T, Dinse HR. Superior sensory, motor, and cognitive performance in elderly individuals with multi-year dancing activities. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010;2:31.

12. Kline F, Burgoyne RW, Staples F, Moredock P, Snyder V, Ioerger M. A report on the use of movement therapy for chronic, severely disabled outpatients. Arts Psychother. 1977;4(4-5):181-183.

13. Koch SC, Morlinghaus K, Fuchs T. The joy dance: specific effects of a single dance intervention on psychiatric patients with depression. Arts Psychother. 2007;34(4):340-349.

14. Barton EJ. Movement and mindfulness: a formative evaluation of a dance/movement and yoga therapy program with participants experiencing severe mental illness. Am J Dance Ther. 2011;33(2):157-181.

15. van der Kolk BA, McFarlane AC, Weisaeth L, eds. Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body, and Society. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1996.

16. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA, eds. Effective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines From the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009.

17. Wilbur S, Meyer HB, Baker MR, et al. Dance for Veterans: a complementary health program for veterans with serious mental illness. Arts Health. 2015;7(2):96-108.

18. Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, PTSD: National Center for PTSD website. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp. Published January 30, 2014. Accessed August 20, 2015.

19. Eftekhari A, Ruzek JI, Crowley JJ, Rosen CS, Greenbaum MA, Karlin BE. Effectiveness of national implementation of prolonged exposure therapy in Veterans Affairs care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(9):949-955.

20. Monson CM, Schnurr PP, Resick PA, Friedman MJ, Young-Xu Y, Stevens SP. Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(5):898-907.

21. Schottenbauer MA, Glass CR, Arnkoff DB, Tendick V, Gray SH. Nonresponse and dropout rates in outcome studies on PTSD: review and methodological considerations. Psychiatry. 2008;71(2):134-168.

22. Suarez CA, Wilbur S, Smiarowski K, Rubin RT, Ames D. Dance for Veterans: Music, Movement & Rhythm Manual for Instruction. 2nd ed. Publisher unknown; 2014.

23. Gilbert AG, Gilbert BA, Rossano A. Brain-Compatible Dance Education. Reston, VA: National Dance Association; 2006.

24. Spielberger C. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Rev ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983.

25. Julian LJ. Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(suppl 11):S467-S472.

Yoga-Based Classes for Veterans With Severe Mental Illness: Development, Dissemination, and Assessment

There is growing interest in developing a holistic and integrative approach for the treatment of severe mental illnesses (SMI), such as schizophrenia, major depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety disorders. Western medicine has traditionally focused on the direct treatment of symptoms and separated the management of physical and mental health, but increasing attention is being given to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for patients with SMI.

Recognizing the connectedness of the mind and body, these complementary or alternative approaches incorporate nontraditional therapeutic techniques with mainstream treatment methods, including psychopharmacology and psychotherapy.1 Patients with SMI may particularly benefit from a mind-body therapeutic approach, because they often experience psychological symptoms such as stress, anxiety, depression and psychosis, as well as a preponderance of medical comorbidities, including obesity, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease, some of which are compounded by adverse effects (AEs) of essential pharmacologic treatments.2-4 Mind-body interventions might also be particularly advantageous for veterans, who often experience a range of interconnected physical and psychological difficulties due to trauma exposure and challenges transitioning from military to civilian life.5

Related: Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain

In 2002, the White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy issued a report supporting CAM research and integration into existing medical systems.6 The DoD later established Total Force Fitness, a holistic health care program for active-duty military personnel.7 The VA has also incorporated mind-body and holistic strategies into veteran care.8 One such mind-body intervention, yoga, is becoming increasingly popular within the health care field.

Recent research has documented the effectiveness of yoga, underscoring its utility as a mind-body therapeutic approach. Yoga is associated with improvement in balance and flexibility,9 fatigue,10 blood pressure,11 sleep,12 strength,13 and pain14 in both healthy individuals and patients with medical and psychiatric disorders.15 The literature also illustrates that yoga has led to significant improvements in stress and psychiatric symptoms in individuals with PTSD, schizophrenia, depression, and anxiety.16-22 A previous meta-analysis conducted by the authors, which considered studies of the effectiveness of yoga as an adjunctive treatment for patients with mental illness, found that 212 studies with null results would need to be located and incorporated to negate the positive effects of yoga found in the literature.17

Because yoga emphasizes the practice of mindfulness and timing movement with breath awareness, it is a calming practice that may decrease stress and relieve psychiatric symptoms not treated through psychopharmacology and psychotherapy.17,21 Recent research has postulated that the physiological mechanisms by which this occurs may include (a) reduction in sympathetic and increase in parasympathetic activity23,24; (b) increases in heart-rate variability and respiratory sinus arrhythmia, low levels of which are associated with anxiety, panic disorder, and depression23,24; (c) increases in melatonin and serotonin 25-27; and (d) decrease in cortisol.28,29

Related: Enhancing Patient Satisfaction Through the Use of Complementary Therapies

As yoga may calm the autonomic nervous system and reduce stress, it may benefit patients with SMI, whose symptoms are often aggravated by stress.30 In addition, veterans experience both acute stressors and high levels of chronic stress.5 Therefore, because they experience mind-body comorbid illnesses as well as high levels of stress, the authors believe that veterans with SMI could benefit greatly from a tailored yoga-based program as part of a holistic approach that includes necessary medication and evidence-based therapies.

In order to evaluate the effects of a yoga program on veterans receiving mental health treatment across the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS), the authors developed a set of yoga-based wellness classes called Breathing, Stretching, Relaxation (BSR) classes. This article describes the process of developing these classes and outlines the procedures and results of a study to assess their effects.

BSR Classes

The development of BSR classes took place at the West Los Angeles VA Medical Center (WLAVAMC), within the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery Center (PRRC) program. The PRRC is a psychoeducational program that focuses on the biological, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects of life in order to help veterans with SMI rehabilitate and reintegrate into the community. The program allows veterans to create their own recovery curriculum by selecting from diverse classes led by program staff members, including physicians, psychologists, nurses, social workers, nutritionists, and recreational therapists.

Development of BSR Protocols

The primary goal of this project was to develop a yoga-based program tailored to the specific needs of veterans with SMI. To the authors’ knowledge, BSR is the first yoga-based program customized for SMI. The BSR classes were developed within interdisciplinary focus groups that included professional yoga teachers, the director of the PRRC, psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, occupational therapists, and physical therapists. Drawing on their experience with SMI and yoga, members of the focus groups identified 3 aspects of yoga that would be most beneficial to veterans with SMI, and the program was designed to optimize these effects. Because SMI can both create and be exacerbated by stress, BSR classes were designed to reduce stress and provide veterans with the tools to monitor and manage their stress.

Breathing and meditative techniques were adapted from yoga in order to facilitate stress reduction. In addition, aerobic elements of yoga have the potential to help veterans manage their incidence of medical diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, obesity, and diabetes. Patients with SMI are at a greater risk for developing these diseases, so classes were designed to incorporate physical stretching elements to promote overall health.4,31-33 Finally BSR was designed to improve veteran self- efficacy and self-esteem, and to place veterans at the center of their care by equipping them with skills to practice BSR independently.

Related: Mindfulness to Reduce Stress

The focus groups also identified the logistic requirements when implementing a yoga-based program for veterans with SMI, including (a) obtaining participant or conservator consent; (b) obtaining medical clearance from care providers, given the high prevalence of medical comorbidities; (c) removing the traditional yoga terms, taking a secular approach, and naming the class “Breathing, Stretching, Relaxation” without directly referencing yoga; (d) asking veterans’ permission before incorporating physical contact into demonstrations, because veterans with SMI, especially those with PTSD, might be uncomfortable with touching from instructors; (e) creating protocols of varying duration and intensity so that BSR was approachable for veterans with diverse levels of physical ability; and (f) ensuring that a clinician who regularly works with SMI patients be present to supervise classes for the safety of patients and instructors.

Yoga instructors and clinicians collaborated to create adaptable 30- and 50-minute protocols that reflected best practices for an SMI population. The 30-minute seated BSR class protocol is included in eAppendix A. Once protocols were finalized, a Train the Trainer program was established to facilitate dissemination of BSR to clinicians working with veterans with SMI throughout the VAGLAHS.

Interested clinicians were given protocols and trained to lead BSR classes on their own. Subsequently, clinician-led BSR classes of various lengths (depending on clinician preference and program scheduling) were established at PRRCs and other mental health programs, such as Mental Health Recovery and Intensive Treatment and Dual Diagnosis Treatment Program, throughout the VAGLAHS. These programs were selected, because they are centered on recovery and improvements in symptoms of SMI. The adoption of a Train the Trainer model, through which VA clinicians were trained by professional yoga instructors, allowed for seamless integration of BSR into VA usual care for veterans with SMI.

Assessment of Classes

The authors conducted a study to assess the quality and effectiveness of BSR classes. This survey research was approved by the VAGLAHS institutional review board for human subjects. The authors hypothesized that there would be significant improvements in veterans’ stress, pain, well-being, and perception of the benefits of BSR over 8 weeks of participation in classes. Also hypothesized was that there would be greater benefits in veterans who participated in longer classes and who attended classes more frequently.

Methods

A total of 120 veterans completed surveys after participating in clinician- and yoga instructor-led BSR classes at the 3 sites within the VAGLAHS: WLAVAMC, Los Angeles Ambulatory Care Center (LAACC), and Sepulveda Ambulatory Care Center (SACC). At the WLAVAMC, surveys were collected at 10-, 30-, 60-, and 90-minute classes. At LAACC, surveys were collected at 30- and 60-minute classes. At SACC, surveys were collected at 20- and 45-minute classes. A researcher noted the duration of the class and was available to assist with comprehension. Veterans completed identical surveys after classes at a designated week 0 (baseline), week 4, and week 8. Of the 120 patients with an initial survey, 82 completed at least 1 follow-up survey and 49 completed both follow-up surveys.

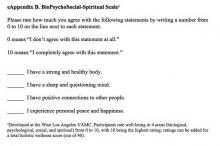

Survey packets included (a) demographic questions, including age, gender, and ethnicity; (b) class participation questions, including frequency of class attendance, patients’ favorite aspect of class, and dura tion of class attendance (in months of prior participation); (c) a pain rating from 0 (no pain) to 10 (the worst pain imaginable); (d) the BioPsychoSocial-Spiritual (BPSS) Scale (eAppendix B), developed at the WLAVAMC, which provides wellness scores from 0 (low) to 10 (high) in 4 areas as well as a holistic wellness score from 0 (low) to 40 (high); (e) the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), developed by Cohen and colleagues, which generates a stress score for the past month from 0 (low) to 40 (high)34; and (f) the Perceived Benefits of Yoga Questionnaire (PBYQ) (eAppendix C), which rates participants’ opinions about the benefits of yoga from 12 (low) to 60 (high) and is based on the Perceived Benefits of Dance Questionnaire.35

Statistical Analysis

Pearson’s r correlation coefficients were calculated between PBYQ scores and quantitative survey items at each time point (weeks 0, 4, and 8). Linear mixed-effects models were used to test for effects of multiple predictor variables on individual outcomes. Each model had a random intercept by participant, and regressors included main effects for the following: survey week (0, 4, or 8), class duration (in minutes), age, sex, ethnicity, frequency of attendance (in days per week), and duration of attendance (in months). For all statistical analyses, a 2-tailed significance criterion of α = .05 was used.

Results

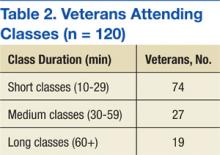

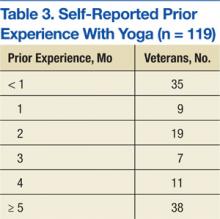

Veterans who completed surveys were predominantly male (90.8%) and averaged 61.4 years of age. Table 1 shows demographic information. Table 2 displays the number of participants who were involved in short (< 30 min), medium (30-59 min), and long (> 60 min) classes. Veteran participants also had a wide range of prior BSR experience (Table 3).

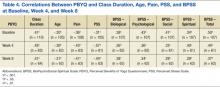

At all time points, PBYQ scores were significantly positively correlated with class duration and biological, psychological, social, spiritual, and total well-being as measured by the BPSS. The PBYQ scores at all time points were also significantly negatively correlated with age, pain ratings, and PSS scores. Table 4 includes specific Pearson’s r values.