User login

A Double‐Edged Sword

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant.

A 40‐year‐old man with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and a CD4 count of 58 cells/L was admitted to the hospital with 1 month of fevers, night sweats, a 5‐kg weight loss, several weeks of progressive dyspnea on exertion, and a nonproductive cough. He denied headaches, vision changes, odynophagia, diarrhea, or rash. He had no history of opportunistic infections, HIV‐associated neoplasms, or other relevant past medical history. He was diagnosed with HIV 3 years ago and had been off antiretroviral therapy (ART) for the last 10 months. Two weeks prior to this presentation, he was seen in clinic but did not report his symptoms. He was prescribed trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) for prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP). He had recently moved from New York City to San Francisco, had quit smoking within the last month, and denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

At a CD4 cell count of 58 cells/L, the patient is at risk for the entire spectrum of HIV‐associated opportunistic infections and neoplasms. The presence of fevers, night sweats, and weight loss suggests the possibility of a disseminated infection, although a neoplastic process with accompanying B symptoms should also be considered. Dyspnea and nonproductive cough indicate cardiopulmonary involvement. The duration of these complaints is more suggestive of a nonbacterial infectious etiology (e.g., PCP, mycobacterial or fungal disease) than a bacterial etiology (e.g., Streptococcus pneumoniae). Irrespective of CD4 count, patients with HIV are at increased risk for cardiovascular events and pulmonary arterial hypertension, although the time course and presence of constitutional symptoms makes these diagnoses less likely. Similarly, patients with HIV are at increased risk for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and the patient does have a history of cigarette smoking, but the clinical history and systemic involvement make COPD unlikely.

On physical examination, the patient was in no acute distress. The temperature was 36C, the blood pressure 117/68 mm Hg, the heart rate 106 beats per minute, the respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, and the oxygen saturation 100% on ambient air. No oral lesions were noted, and his neck was supple with nontender bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy measuring up to 1.5 cm. There was no jugular venous distension or peripheral edema. The cardiovascular exam revealed tachycardia with a regular rhythm and no murmurs or gallops. His lungs were clear to auscultation. The spleen tipwas palpable. No rashes were identified. The neurological examination, including mental status, was normal.

The white blood cell count was 2400/mm3, the hemoglobin 7 g/dL with mean corpuscular volume of 86 fL, and the platelet count 162,000/mm3. Basic chemistry, liver, and glucose‐6‐phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) tests were within the laboratory's normal range. The HIV viral load was 150,000 copies/mL. Chest radiography revealed bibasilar hazy opacities, and computerized tomography (CT) of the chest revealed a focal nodular consolidation in the right middle lobe along with subcentimeter bilateral axillary and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. There were no ground‐glass opacities.

The patient's physical examination does not support a cardiac disorder. Lymphadenopathy is nonspecific, but it is consistent with a potential infectious or neoplastic process. Leukopenia and anemia suggest potential bone‐marrow infiltration or suppression by TMP/SMX. Although the pulmonary exam was nonfocal, chest imaging is the cornerstone of the evaluation of suspected pulmonary disease in persons with HIV. The focal nodular consolidation on chest CT is nonspecific but is more characteristic of typical or atypical bacterial pneumonia, mycobacterial disease such as tuberculosis, or fungal pneumonia than PCP or viral pneumonia. A lack of ground‐glass opacities also makes PCP and interstitial lung diseases less likely.

The patient was treated for community‐acquired pneumonia with ceftriaxone and doxycycline with improvement in dyspnea. Antiretroviral therapy with darunavir, ritonavir, tenofovir, and emtricitabine was initiated. Azithromycin was started for prophylaxis against Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). The TMP/SMX was changed to dapsone, given concern for bone‐marrow suppression. Blood cultures for bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria were negative. Polymerase chain reaction from pharyngeal swab for influenza A and B, parainfluenza types 13, rhinovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus were negative. Several attempts to obtain sputum for acid‐fast bacillus staining and culture were unsuccessful because the patient was unable to expectorate sputum. Serum interferon‐gamma release assay for M. tuberculosis and thefollowing serologic studies were also negative: cytomegalovirus, Epstein‐Barr virus, parvovirus, Bartonella species, Coccidioides immitis, and Cryptococcus neoformans antigen. Given his improvement, the patient was discharged from the hospital on ART, doxycycline for community‐acquired pneumonia, and prophylactic azithromycin and dapsone with scheduled outpatient follow‐up.

Ten days later, he was seen in clinic. Though his dyspnea had improved after completing the doxycycline, he noted a persistent dry cough and daily fevers to 40C. The physical exam was unchanged, including persistent cervical lymphadenopathy. Laboratories revealed a white blood cell count of 2400/mm3, hemoglobin of 4.8 g/dL, and a platelet count of 122,000/mm3. The absolute reticulocyte count was 21,000/L (normal value, 20,000100,000/L). A peripheral blood smear was unremarkable, and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was within normal limits. The direct antiglobulin test (DAT) was negative. The patient was readmitted to the hospital.

The initial improvement in dyspnea but persistent fevers and cough and worsening pancytopenia are suggestive of multiple processes occurring simultaneously. Dapsone can cause both hemolytic anemia and aplastic anemia, although the peripheral smear, normal LDH and G6PD, and negative DAT are not consistent with the former. Bone‐marrow suppression from a combination of ART medications and dapsone cannot be ruled out. An infiltrative process involving the bone marrow, including tuberculosis, MAC, disseminated fungal infection, or malignancy, remains a possibility. Repeat chest imaging is warranted to assess the prior right middle lobe consolidation and to further evaluate the persistent respiratory complaints.

Prophylaxis of PCP with dapsone was switched to atovaquone due to persistent anemia. A repeat CT of the chest and a concurrent abdominal CT revealed interval enlargement of mediastinal lymph nodes with multiple periportal, retroperitoneal, and hilar nodes not present on prior chest imaging, in addition to new bilateral centrilobular nodules and interval development of small bilateral pleural effusions. The abdominal CT also showed hepatosplenomegaly with splenic‐vein engorgement. Empiric treatment for disseminated MAC infection with clarithromycin and ethambutol was initiated in addition to vancomycin and cefepime for possible healthcare‐associated pneumonia. Over the next several days, the patient continued to have daily fevers up to 39.8C. A repeat CD4 count 3 weeks after starting ART was 121 cells/L. The HIV RNA level had decreased to 854 copies/mL.

The patient has developed progressive, generalized lymphadenopathy, worsening pancytopenia, and persistent fevers in the setting of negative cultures and serologic studies and despite treatment for MAC. This constellation, along with the radiographic findings of hilar lymphadenopathy and pleural effusions, is suggestive of non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Alternatively, Kaposi sarcoma (KS) or tuberculosis can have a similar radiographic and clinical presentation, although pancytopenia from KS seems unusual. The lymphadenopathy could be consistent with multicentric Castleman disease or bacillary angiomatosis (BA), although the latter diagnosis would be unlikely given recent antibiotic therapy. At this time, a careful search for other manifestations and reasonable targets for biopsy is warranted. An appropriate suppression of the HIV viral load after initiation of ART, with improvement in CD4 count, is the proper context for the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), which is characterized by paradoxical worsening or unmasking of a disseminated process.

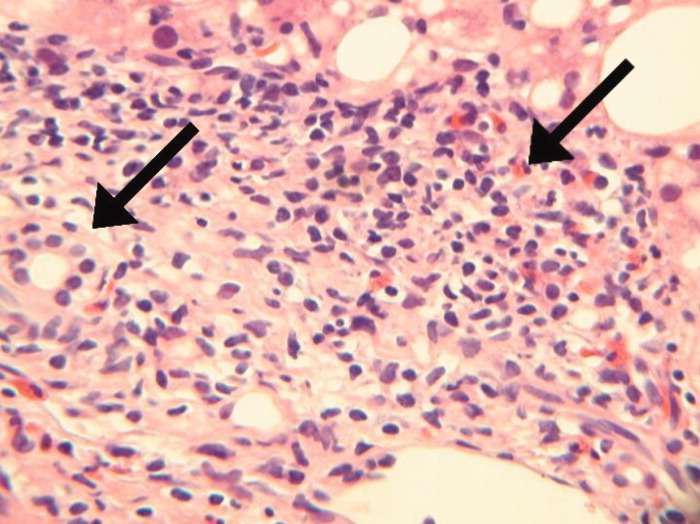

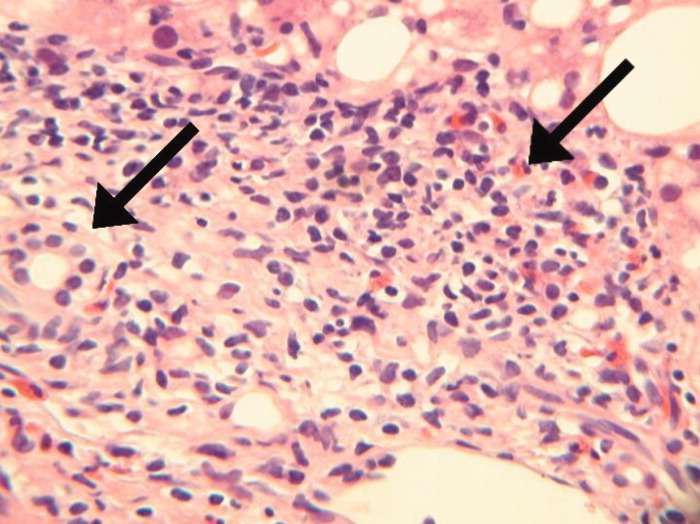

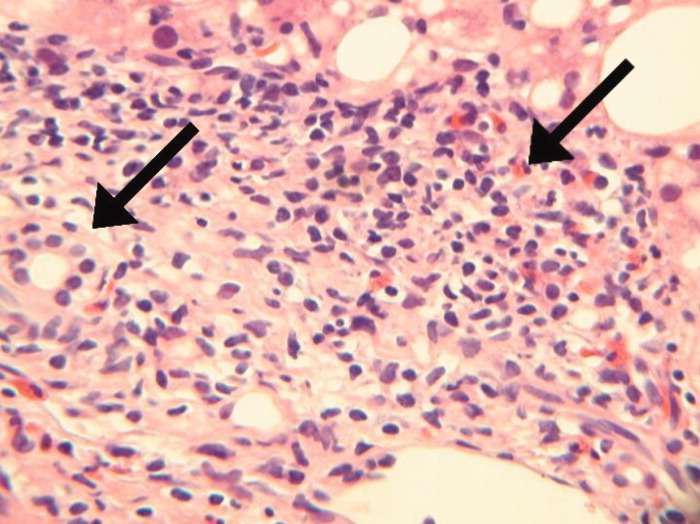

A bone‐marrow biopsy revealed marked dysmegakaryopoiesis and mild dyserythropoiesis, but no other abnormalities. Flow cytometry and histoimmunochemical staining did not show evidence of lymphoproliferative disorder in the marrow. Smears and cultures of the bone marrow for bacteria, acid‐fast bacilli, and fungi were negative. A right cervical lymph node biopsy was performed, with multiple fine‐needle aspiration and core samples taken. Bacterial, fungal, and acid‐fast bacilli tissue cultures were without growth, and initial pathology results were concerning for high‐grade lymphoma. A monoclonal proliferation of lymphocytes was noted on flow cytometry of the tissue sample. The patient developed progressive dyspnea, tachypnea, and hypoxemia. A chest x‐ray revealed worsening perihilar and basilar opacities.

The possibility of bone‐marrow sampling error must be considered in a patient that has such a high pretest probability for lymphoma or infection, but staining, immunological assays, cultures, and direct assessment by pathologists generally give some suggestion of an alternative diagnosis. The bone‐marrow findings are compatible with HIV‐related changes, but continued vigilance for infection and malignancy is warranted. Although the diagnosis of NHL based on the cervical biopsy result is only preliminary, the patient's rapidly deteriorating clinical status warrants initiation of treatment with steroids while awaiting definitive results, particularly given his poor response to aggressive management of potential infectious causes. A bronchoscopy should be considered given the predominance of pulmonary symptoms and his rapid respiratory decline.

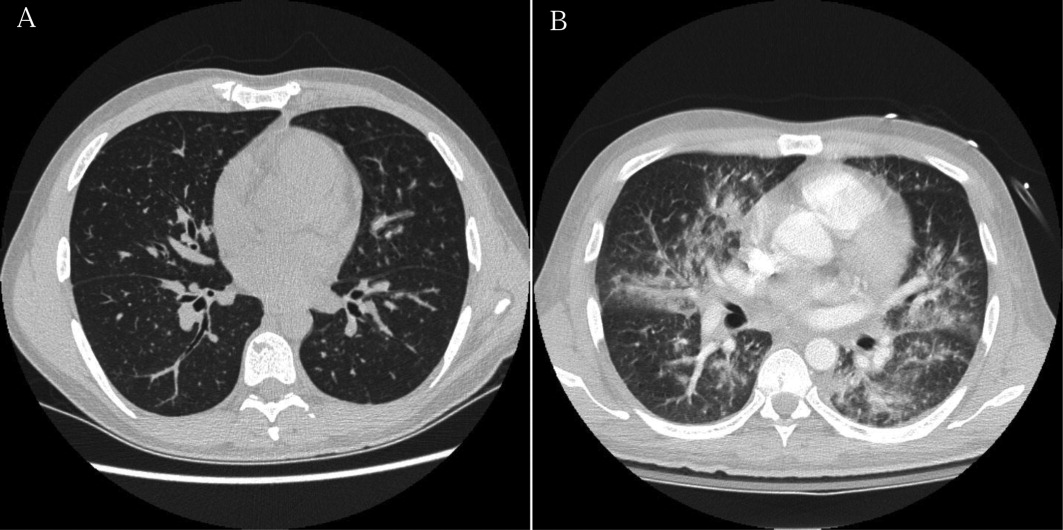

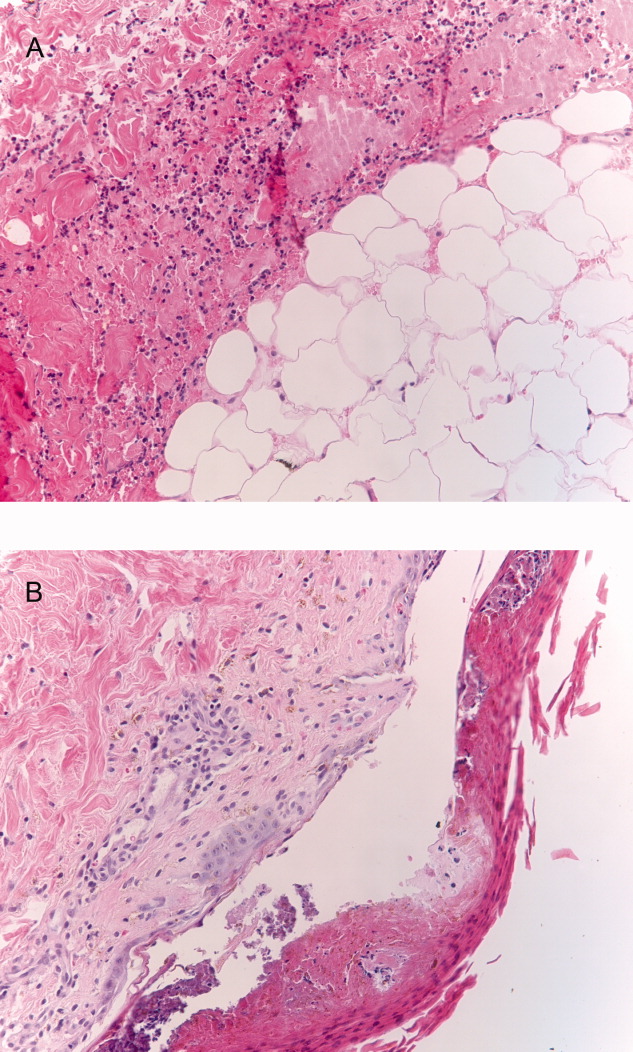

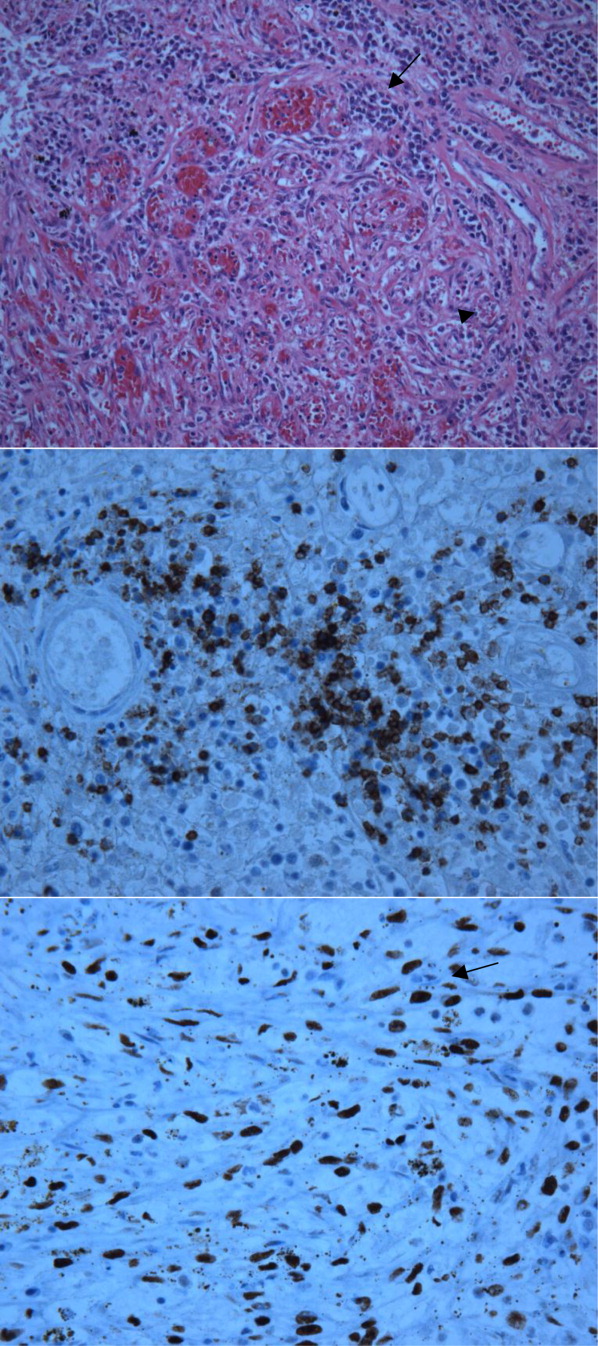

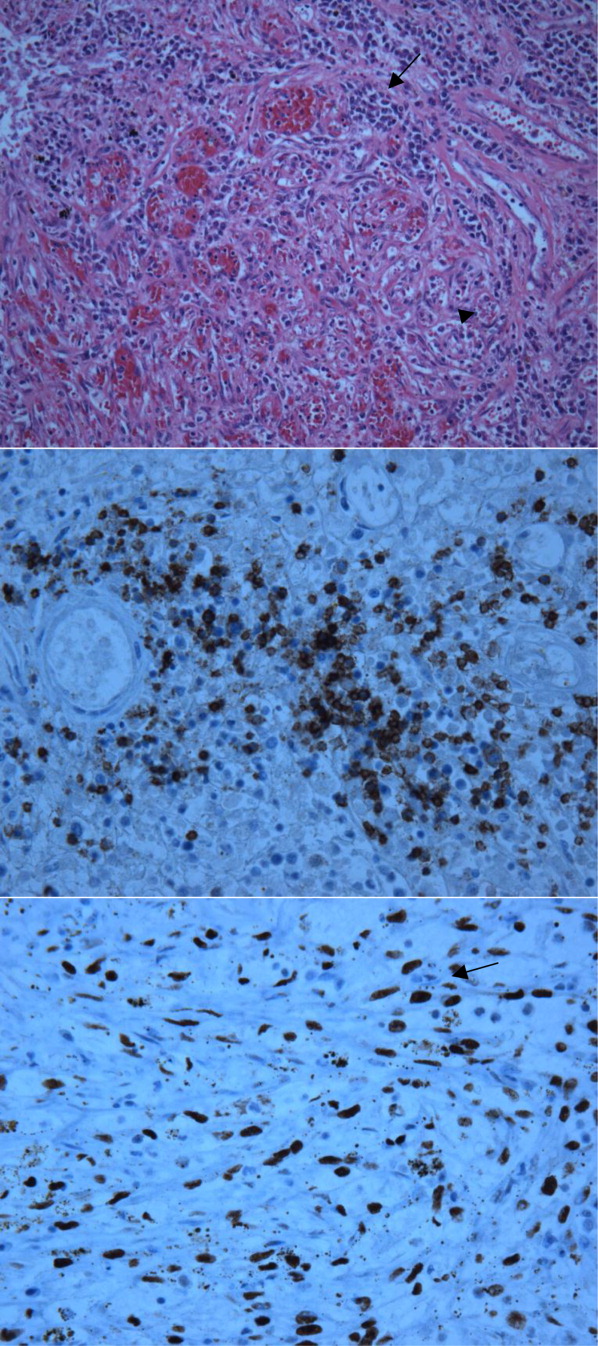

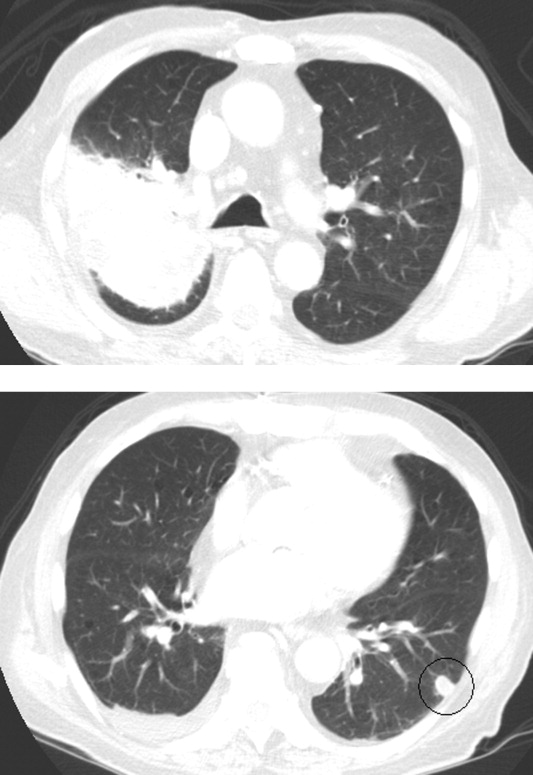

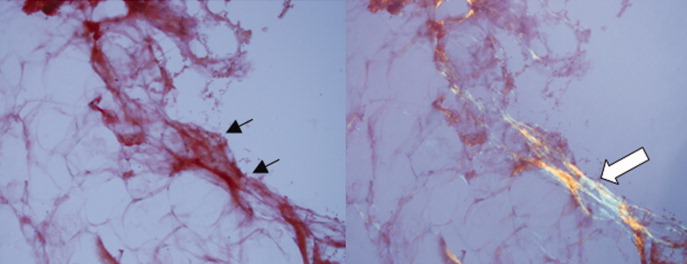

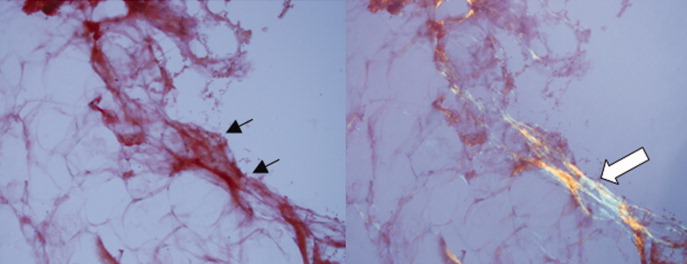

Approximately 1 week after admission, high‐dose systemic corticosteroids were administered for presumed aggressive lymphoma. Over the next 48 hours, the patient's hypoxemia worsened, and he was intubated for hypoxemic respiratory failure. A repeat chest CT (see Fig. 1) showed bilateral peribronchovascular patchy consolidations and pleural effusions without evidence of pulmonary embolism. The patient was also noted to have a single, discrete violaceous nodule on the hard palate as well as a nodule with similar appearance on his upper chest (neither lesion was present on admission). A skin biopsy was obtained. Despite steroids, antibiotic therapy, and aggressive critical‐care management, severe acidosis, progressive acute kidney injury, and anuria ensued. Continuous venovenous hemodialysis was initiated.

Discrete violaceous nodules with mucocutaneous localization in the context of AIDS are virtually pathognomonic for KS. Rarely, BA may be misdiagnosed as KS, or they may occur concurrently. The patient's current clinical deterioration, radiographic findings, and development of new skin lesions in the setting of response to ART are concerning for KS‐related IRIS with visceral involvement. It is likely that systemic corticosteroids are potentiating KS‐related IRIS. At this point, there is compelling evidence of 2 distinct systemic disease processes: lymphoma and KS‐related IRIS, both of which may be contributing to respiratory failure. Steroids can be highly effective in the treatment of high‐grade lymphoma but can be harmful in patients with KS, where they have been shown to potentially exacerbate underlying disease. Given the patient's worsening respiratory status, discontinuation of corticosteroids and initiation of chemotherapy against both opportunistic malignancies should be considered.

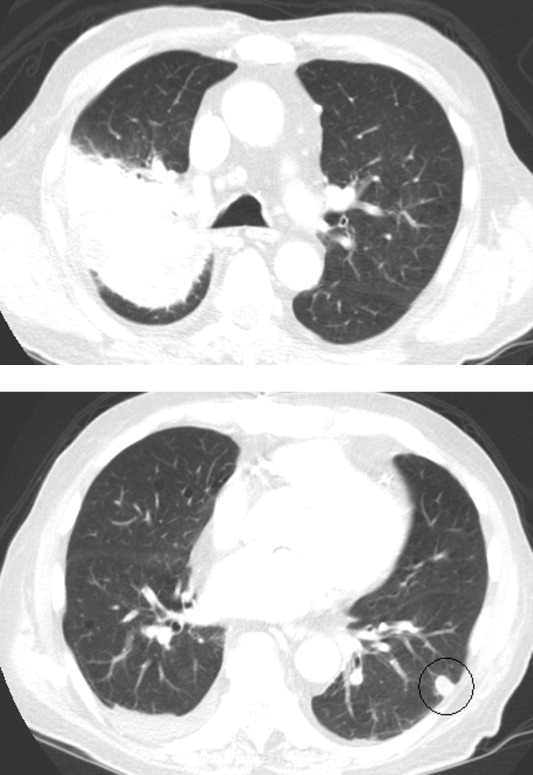

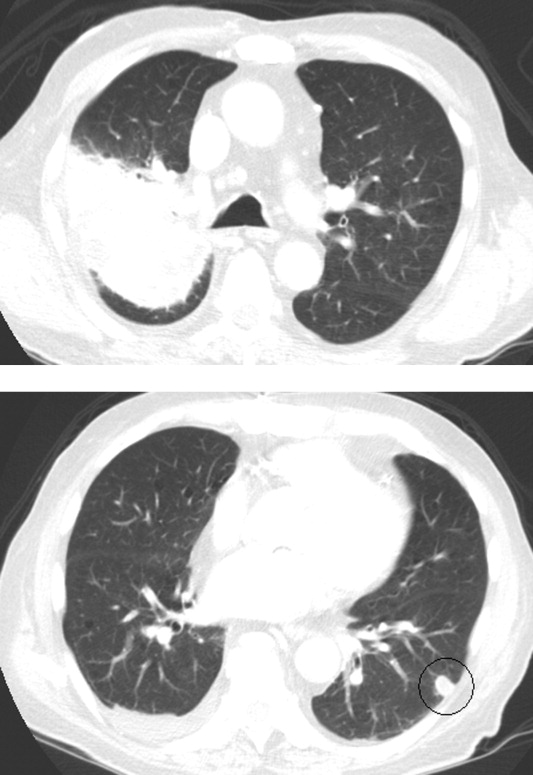

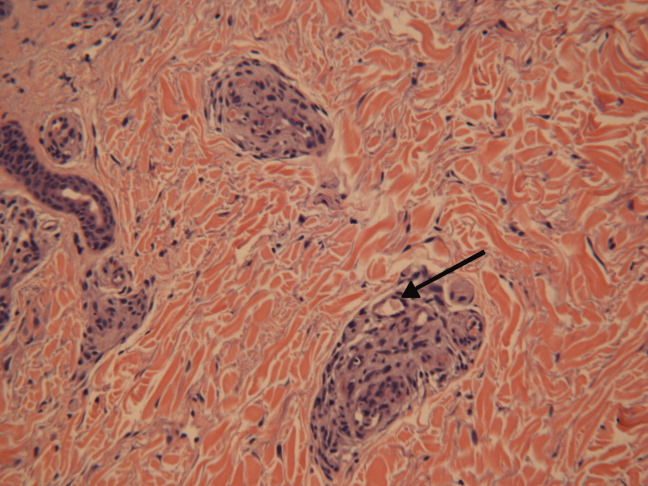

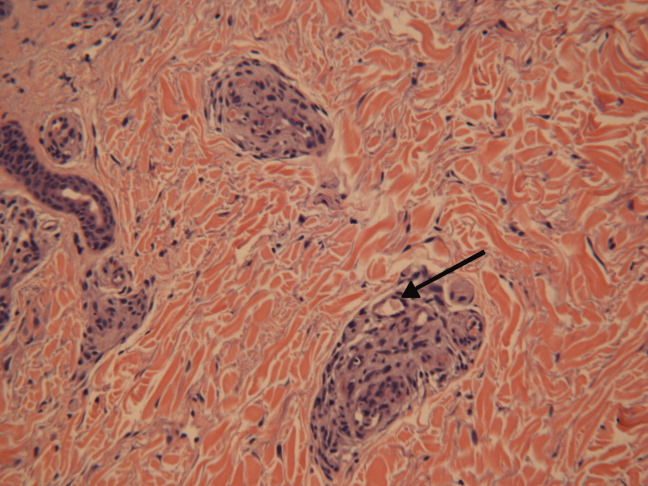

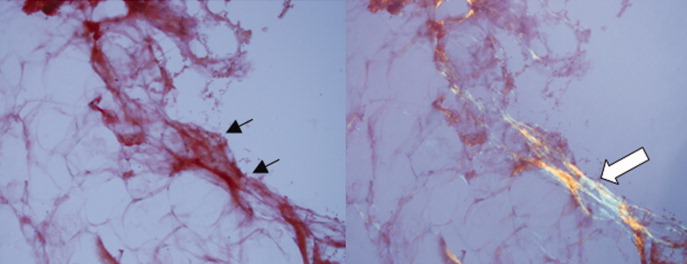

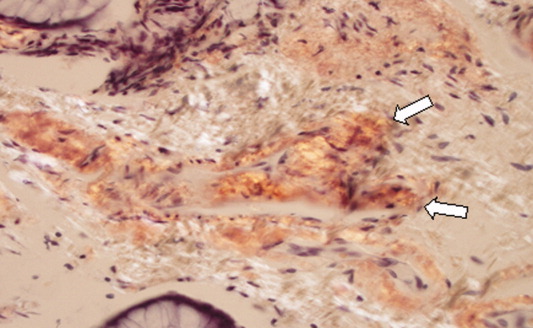

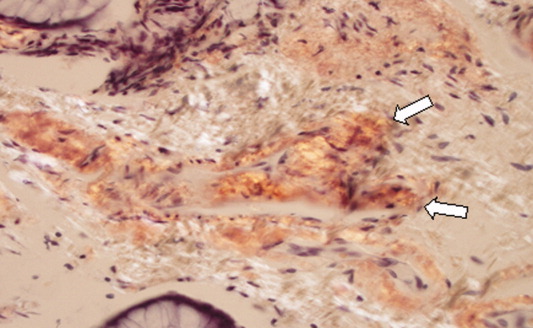

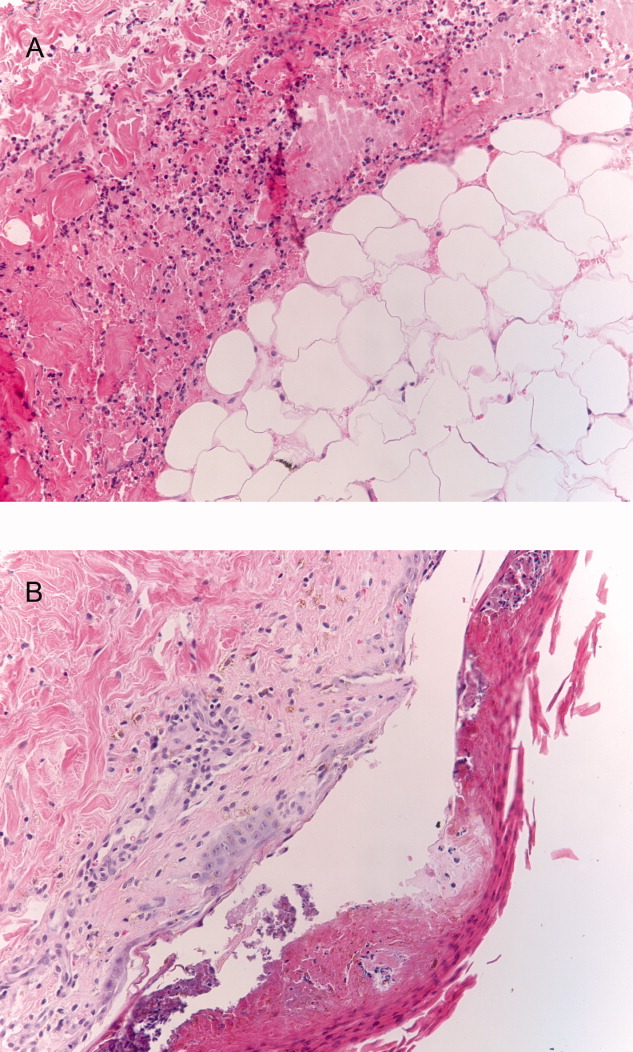

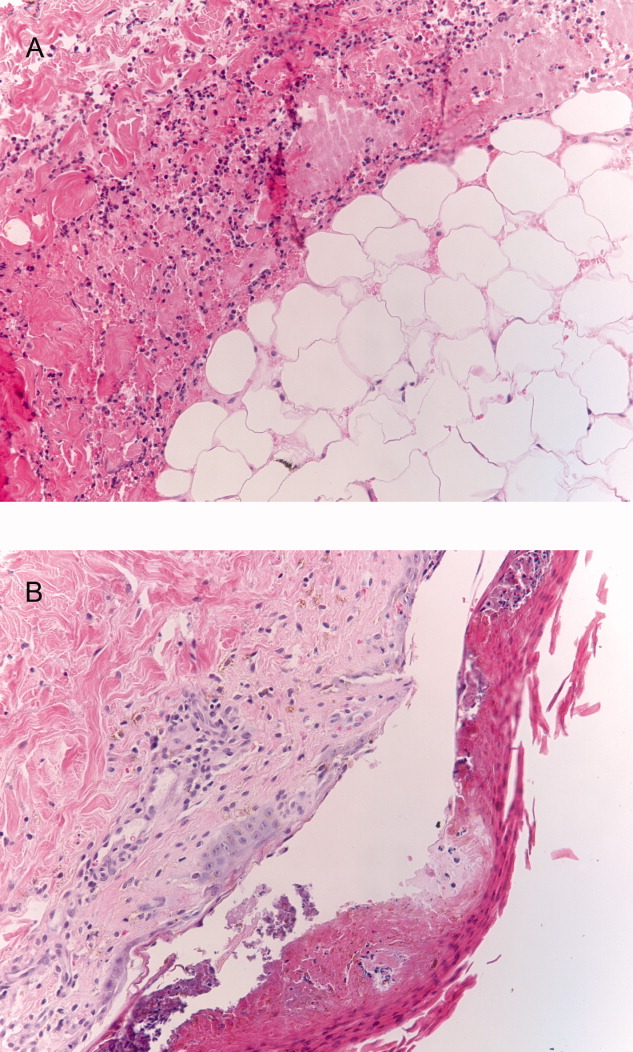

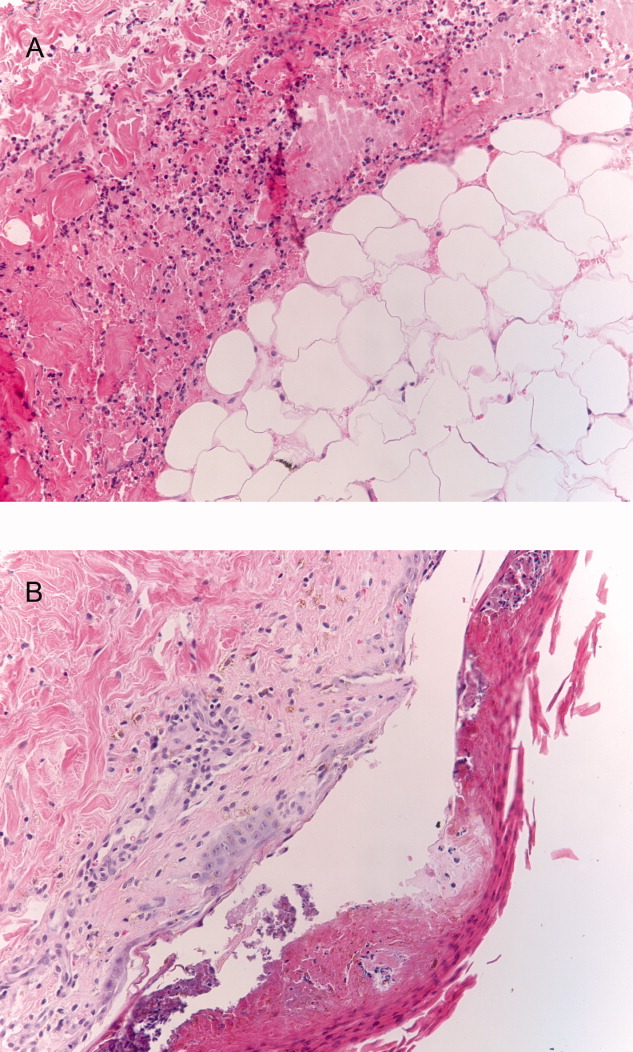

The patient's condition deteriorated with progressive acidosis and hypoxemia, and he died shortly after being transitioned to comfort‐care measures. Review of the skin biopsy revealed KS. Autopsy revealed disseminated KS involving the skin, lymph nodes, and lungs, and high‐grade anaplastic plasmablastic lymphoma infiltrating multiple lymph nodes and organs, including the lungs (see Fig. 2). There was no evidence of infection.

COMMENTARY

This case demonstrates the simultaneous fatal progression of 2 treatable HIV‐associated malignancies in an era in which the end‐stage manifestations of untreated HIV are becoming less common, particularly in developed countries. Modern ARTthe centerpiece of progress with HIVhas yielded dramatic improvements in prognosis, but in this case, by precipitating KS‐IRIS, ART paradoxically contributed to this patient's demise. Similarly, high‐dose systemic corticosteroids, which were deemed necessary to stabilize the progression of his high‐grade lymphoma, likely accelerated his KS. This corticosteroid‐mediated worsening appears to be unique to KS given that corticosteroids are often recommended to treat severe presentations of IRIS in other diseases (eg, tuberculosis, MAC, PCP).

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome is the paradoxical worsening of well‐controlled disease or progression of previously occult disease after initiation of ART.1

Although infectious diseasesincluding mycobacteria, cytomegalovirus, cryptococcosis, or PCPare best known for their ability to recrudesce or manifest with a recovering immune system, opportunistic malignancies such as KS can do the same. Risk factors for development of IRIS are low pre‐ART CD4 count, high pre‐ART viral load, and rapid response to ART.2 In 1 large series, the median time to diagnosis of IRIS was 33 days.2 Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome is a clinical diagnosis without specific pathologic findings. Because IRIS is a diagnosis of exclusion, other explanations for worsening disease, including drug resistance, drug reactions (eg, abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome), and poor adherence to medications, should be ruled out before making the diagnosis.

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular tumor associated with infection by human herpesvirus 8 (HHV‐8). The incidence of AIDS‐related KS has declined substantially in the post‐ART era.2, 4 The classic radiographic presentation of pulmonary KS includes central bilateral opacities with a peribronchovascular distribution as well as pulmonary nodules, intraseptal thickening, mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and associated pleural effusions.5, 6 Kaposi sarcomarelated IRIS has been described as developing within weeks of ART initiation and is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly in the context of pulmonary involvement, with 1 recent series showing 100% mortality in patients who did not receive chemotherapy.79

Human immunodeficiency virusassociated KS can respond well to ART alone. Indications for systemic chemotherapy for KS include extensive mucocutaneous disease, symptomatic visceral disease, or KS‐related IRIS.10 The main chemotherapeutic agents used systemically for KS are liposomal anthracyclines such as doxorubicin or daunorubicin, or taxanes such as paclitaxel.11 An association between corticosteroids and progression of KS has been previously described, even as early as several days after steroid administration.1214 Recently, revised diagnostic criteria for corticosteroid‐associated KS‐IRIS have been proposed; this patient met those criteria.15

Plasmablastic lymphoma is a highly aggressive systemic NHL seen predominantly in HIV‐positive patients. There is a strong association with Epstein‐Barr virus; HHV‐8 is more variably associated and is of unclear significance.16 Most HIV‐infected patients have extranodal involvement at diagnosis; in a series of 53 HIV‐positive patients, the oral cavity was the most frequent site, and lung involvement was seen in 12%. The prognosis is poor, with a mean survival of approximately 1 year.17

Treatment for systemic NHL in HIV‐positive patients generally consists of a chemotherapy regimen while ART is continued or initiated.18 The most commonly used chemotherapy combination is cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone, often supplemented with the anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab. In the case of aggressive systemic NHL, more intensive treatment regimens are often utilized, though it remains unclear if they are associated with improved outcomes.17, 19 Antiretroviral therapy is continued, as it has been shown to reduce the rate of opportunistic infections and decrease mortality.20

Despite the remarkable progress that has been made in the past 30 years, HIV/AIDS remains a devastating and remarkably complex disease. As the landscape of HIV/AIDS evolves, clinicians will continue to be faced with new challenging and vexing decisions. Perhaps no greater challenge exists than the presence of 2 simultaneous, rapidly fatal malignancies with directly competing therapeutic strategies, as in this case, where the ART and steroids employed to address NHL fostered widespread KS‐IRIS. This case reminds us that a single unifying diagnosis can often be the exception rather than the rule in the care of patients with advanced HIV. It also illustrates how the mainstay of HIV treatment, ART, can be a double‐edged sword.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

-

In HIV/AIDS patients receiving ART who become paradoxically more ill despite improvements in their CD4 counts, consider IRIS.

-

Though corticosteroids are a hallmark of treatment for most types of IRIS‐and for aggressive lymphomas‐they can worsen KS.

- , , , et al. Defining immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: evaluation of expert opinion versus 2 case definitions in a South African cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1424–1432.

- , , , et al. Risk factor analyses for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a randomized study of early vs. deferred ART during an opportunistic infection. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11416.

- , . Kaposi's sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1027–1038.

- , , , et al. The changing pattern of Kaposi sarcoma in patients with HIV, 1994–2003: the EuroSIDA Study. Cancer. 2004;100:2644–2654.

- , , , , , . Imaging features of pulmonary Kaposi sarcoma–associated immune reconstitution syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:956–965.

- , , , et al. Pulmonary involvement in Kaposi sarcoma: correlation between imaging and pathology. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:18.

- , , , et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome associated with Kaposi's sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5224–5228.

- , . Recrudescent Kaposi's sarcoma after initiation of HAART: a manifestation of immune reconstitution syndrome. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005;19:635–644.

- , , , , , . Paradoxical immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV‐infected patients treated with combination antiretroviral therapy after AIDS‐defining opportunistic infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:424–433.

- , , , et al. British HIV Association guidelines for HIV‐associated malignancies 2008. HIV Med. 2008;9:336–388.

- , , , , . HIV/AIDS: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus disease: Kaposi sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(9):1209–1215.

- , , . A 36‐year‐old man with AIDS and relapsing, nonproductive cough. Chest. 2007;131:1929–1931.

- , , , , . Life‐threatening exacerbation of Kaposi's sarcoma after prednisone treatment for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. AIDS. 2008;22:663–665.

- , , , , , . Clinical effect of glucocorticoids on Kaposi sarcoma related to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:937–940.

- , , , . Kaposi sarcoma–associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: in need of a specific case definition. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(1):157–158.

- , , , , , . Plasmablastic lymphoma in HIV‐positive patients: an aggressive Epstein‐Barr virus–associated extramedullary plasmacytic neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1633–1641.

- , , , et al. Human immunodeficiency virus–associated plasmablastic lymphoma: poor prognosis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Cancer. 2012;118:5270–5277.

- , , . Modern management of non‐Hodgkin lymphoma in HIV‐infected patients. Br J Haematol. 2007;136(5):685–698.

- , , , et al. CD20‐negative large‐cell lymphoma with plasmablastic features: a clinically heterogeneous spectrum in both HIV‐positive and ‐negative patients. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(11):1673–1679.

- , , , et al. Concomitant cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone chemotherapy plus highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus–related, non‐Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 2001;91(1):155–163.

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant.

A 40‐year‐old man with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and a CD4 count of 58 cells/L was admitted to the hospital with 1 month of fevers, night sweats, a 5‐kg weight loss, several weeks of progressive dyspnea on exertion, and a nonproductive cough. He denied headaches, vision changes, odynophagia, diarrhea, or rash. He had no history of opportunistic infections, HIV‐associated neoplasms, or other relevant past medical history. He was diagnosed with HIV 3 years ago and had been off antiretroviral therapy (ART) for the last 10 months. Two weeks prior to this presentation, he was seen in clinic but did not report his symptoms. He was prescribed trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) for prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP). He had recently moved from New York City to San Francisco, had quit smoking within the last month, and denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

At a CD4 cell count of 58 cells/L, the patient is at risk for the entire spectrum of HIV‐associated opportunistic infections and neoplasms. The presence of fevers, night sweats, and weight loss suggests the possibility of a disseminated infection, although a neoplastic process with accompanying B symptoms should also be considered. Dyspnea and nonproductive cough indicate cardiopulmonary involvement. The duration of these complaints is more suggestive of a nonbacterial infectious etiology (e.g., PCP, mycobacterial or fungal disease) than a bacterial etiology (e.g., Streptococcus pneumoniae). Irrespective of CD4 count, patients with HIV are at increased risk for cardiovascular events and pulmonary arterial hypertension, although the time course and presence of constitutional symptoms makes these diagnoses less likely. Similarly, patients with HIV are at increased risk for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and the patient does have a history of cigarette smoking, but the clinical history and systemic involvement make COPD unlikely.

On physical examination, the patient was in no acute distress. The temperature was 36C, the blood pressure 117/68 mm Hg, the heart rate 106 beats per minute, the respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, and the oxygen saturation 100% on ambient air. No oral lesions were noted, and his neck was supple with nontender bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy measuring up to 1.5 cm. There was no jugular venous distension or peripheral edema. The cardiovascular exam revealed tachycardia with a regular rhythm and no murmurs or gallops. His lungs were clear to auscultation. The spleen tipwas palpable. No rashes were identified. The neurological examination, including mental status, was normal.

The white blood cell count was 2400/mm3, the hemoglobin 7 g/dL with mean corpuscular volume of 86 fL, and the platelet count 162,000/mm3. Basic chemistry, liver, and glucose‐6‐phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) tests were within the laboratory's normal range. The HIV viral load was 150,000 copies/mL. Chest radiography revealed bibasilar hazy opacities, and computerized tomography (CT) of the chest revealed a focal nodular consolidation in the right middle lobe along with subcentimeter bilateral axillary and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. There were no ground‐glass opacities.

The patient's physical examination does not support a cardiac disorder. Lymphadenopathy is nonspecific, but it is consistent with a potential infectious or neoplastic process. Leukopenia and anemia suggest potential bone‐marrow infiltration or suppression by TMP/SMX. Although the pulmonary exam was nonfocal, chest imaging is the cornerstone of the evaluation of suspected pulmonary disease in persons with HIV. The focal nodular consolidation on chest CT is nonspecific but is more characteristic of typical or atypical bacterial pneumonia, mycobacterial disease such as tuberculosis, or fungal pneumonia than PCP or viral pneumonia. A lack of ground‐glass opacities also makes PCP and interstitial lung diseases less likely.

The patient was treated for community‐acquired pneumonia with ceftriaxone and doxycycline with improvement in dyspnea. Antiretroviral therapy with darunavir, ritonavir, tenofovir, and emtricitabine was initiated. Azithromycin was started for prophylaxis against Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). The TMP/SMX was changed to dapsone, given concern for bone‐marrow suppression. Blood cultures for bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria were negative. Polymerase chain reaction from pharyngeal swab for influenza A and B, parainfluenza types 13, rhinovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus were negative. Several attempts to obtain sputum for acid‐fast bacillus staining and culture were unsuccessful because the patient was unable to expectorate sputum. Serum interferon‐gamma release assay for M. tuberculosis and thefollowing serologic studies were also negative: cytomegalovirus, Epstein‐Barr virus, parvovirus, Bartonella species, Coccidioides immitis, and Cryptococcus neoformans antigen. Given his improvement, the patient was discharged from the hospital on ART, doxycycline for community‐acquired pneumonia, and prophylactic azithromycin and dapsone with scheduled outpatient follow‐up.

Ten days later, he was seen in clinic. Though his dyspnea had improved after completing the doxycycline, he noted a persistent dry cough and daily fevers to 40C. The physical exam was unchanged, including persistent cervical lymphadenopathy. Laboratories revealed a white blood cell count of 2400/mm3, hemoglobin of 4.8 g/dL, and a platelet count of 122,000/mm3. The absolute reticulocyte count was 21,000/L (normal value, 20,000100,000/L). A peripheral blood smear was unremarkable, and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was within normal limits. The direct antiglobulin test (DAT) was negative. The patient was readmitted to the hospital.

The initial improvement in dyspnea but persistent fevers and cough and worsening pancytopenia are suggestive of multiple processes occurring simultaneously. Dapsone can cause both hemolytic anemia and aplastic anemia, although the peripheral smear, normal LDH and G6PD, and negative DAT are not consistent with the former. Bone‐marrow suppression from a combination of ART medications and dapsone cannot be ruled out. An infiltrative process involving the bone marrow, including tuberculosis, MAC, disseminated fungal infection, or malignancy, remains a possibility. Repeat chest imaging is warranted to assess the prior right middle lobe consolidation and to further evaluate the persistent respiratory complaints.

Prophylaxis of PCP with dapsone was switched to atovaquone due to persistent anemia. A repeat CT of the chest and a concurrent abdominal CT revealed interval enlargement of mediastinal lymph nodes with multiple periportal, retroperitoneal, and hilar nodes not present on prior chest imaging, in addition to new bilateral centrilobular nodules and interval development of small bilateral pleural effusions. The abdominal CT also showed hepatosplenomegaly with splenic‐vein engorgement. Empiric treatment for disseminated MAC infection with clarithromycin and ethambutol was initiated in addition to vancomycin and cefepime for possible healthcare‐associated pneumonia. Over the next several days, the patient continued to have daily fevers up to 39.8C. A repeat CD4 count 3 weeks after starting ART was 121 cells/L. The HIV RNA level had decreased to 854 copies/mL.

The patient has developed progressive, generalized lymphadenopathy, worsening pancytopenia, and persistent fevers in the setting of negative cultures and serologic studies and despite treatment for MAC. This constellation, along with the radiographic findings of hilar lymphadenopathy and pleural effusions, is suggestive of non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Alternatively, Kaposi sarcoma (KS) or tuberculosis can have a similar radiographic and clinical presentation, although pancytopenia from KS seems unusual. The lymphadenopathy could be consistent with multicentric Castleman disease or bacillary angiomatosis (BA), although the latter diagnosis would be unlikely given recent antibiotic therapy. At this time, a careful search for other manifestations and reasonable targets for biopsy is warranted. An appropriate suppression of the HIV viral load after initiation of ART, with improvement in CD4 count, is the proper context for the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), which is characterized by paradoxical worsening or unmasking of a disseminated process.

A bone‐marrow biopsy revealed marked dysmegakaryopoiesis and mild dyserythropoiesis, but no other abnormalities. Flow cytometry and histoimmunochemical staining did not show evidence of lymphoproliferative disorder in the marrow. Smears and cultures of the bone marrow for bacteria, acid‐fast bacilli, and fungi were negative. A right cervical lymph node biopsy was performed, with multiple fine‐needle aspiration and core samples taken. Bacterial, fungal, and acid‐fast bacilli tissue cultures were without growth, and initial pathology results were concerning for high‐grade lymphoma. A monoclonal proliferation of lymphocytes was noted on flow cytometry of the tissue sample. The patient developed progressive dyspnea, tachypnea, and hypoxemia. A chest x‐ray revealed worsening perihilar and basilar opacities.

The possibility of bone‐marrow sampling error must be considered in a patient that has such a high pretest probability for lymphoma or infection, but staining, immunological assays, cultures, and direct assessment by pathologists generally give some suggestion of an alternative diagnosis. The bone‐marrow findings are compatible with HIV‐related changes, but continued vigilance for infection and malignancy is warranted. Although the diagnosis of NHL based on the cervical biopsy result is only preliminary, the patient's rapidly deteriorating clinical status warrants initiation of treatment with steroids while awaiting definitive results, particularly given his poor response to aggressive management of potential infectious causes. A bronchoscopy should be considered given the predominance of pulmonary symptoms and his rapid respiratory decline.

Approximately 1 week after admission, high‐dose systemic corticosteroids were administered for presumed aggressive lymphoma. Over the next 48 hours, the patient's hypoxemia worsened, and he was intubated for hypoxemic respiratory failure. A repeat chest CT (see Fig. 1) showed bilateral peribronchovascular patchy consolidations and pleural effusions without evidence of pulmonary embolism. The patient was also noted to have a single, discrete violaceous nodule on the hard palate as well as a nodule with similar appearance on his upper chest (neither lesion was present on admission). A skin biopsy was obtained. Despite steroids, antibiotic therapy, and aggressive critical‐care management, severe acidosis, progressive acute kidney injury, and anuria ensued. Continuous venovenous hemodialysis was initiated.

Discrete violaceous nodules with mucocutaneous localization in the context of AIDS are virtually pathognomonic for KS. Rarely, BA may be misdiagnosed as KS, or they may occur concurrently. The patient's current clinical deterioration, radiographic findings, and development of new skin lesions in the setting of response to ART are concerning for KS‐related IRIS with visceral involvement. It is likely that systemic corticosteroids are potentiating KS‐related IRIS. At this point, there is compelling evidence of 2 distinct systemic disease processes: lymphoma and KS‐related IRIS, both of which may be contributing to respiratory failure. Steroids can be highly effective in the treatment of high‐grade lymphoma but can be harmful in patients with KS, where they have been shown to potentially exacerbate underlying disease. Given the patient's worsening respiratory status, discontinuation of corticosteroids and initiation of chemotherapy against both opportunistic malignancies should be considered.

The patient's condition deteriorated with progressive acidosis and hypoxemia, and he died shortly after being transitioned to comfort‐care measures. Review of the skin biopsy revealed KS. Autopsy revealed disseminated KS involving the skin, lymph nodes, and lungs, and high‐grade anaplastic plasmablastic lymphoma infiltrating multiple lymph nodes and organs, including the lungs (see Fig. 2). There was no evidence of infection.

COMMENTARY

This case demonstrates the simultaneous fatal progression of 2 treatable HIV‐associated malignancies in an era in which the end‐stage manifestations of untreated HIV are becoming less common, particularly in developed countries. Modern ARTthe centerpiece of progress with HIVhas yielded dramatic improvements in prognosis, but in this case, by precipitating KS‐IRIS, ART paradoxically contributed to this patient's demise. Similarly, high‐dose systemic corticosteroids, which were deemed necessary to stabilize the progression of his high‐grade lymphoma, likely accelerated his KS. This corticosteroid‐mediated worsening appears to be unique to KS given that corticosteroids are often recommended to treat severe presentations of IRIS in other diseases (eg, tuberculosis, MAC, PCP).

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome is the paradoxical worsening of well‐controlled disease or progression of previously occult disease after initiation of ART.1

Although infectious diseasesincluding mycobacteria, cytomegalovirus, cryptococcosis, or PCPare best known for their ability to recrudesce or manifest with a recovering immune system, opportunistic malignancies such as KS can do the same. Risk factors for development of IRIS are low pre‐ART CD4 count, high pre‐ART viral load, and rapid response to ART.2 In 1 large series, the median time to diagnosis of IRIS was 33 days.2 Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome is a clinical diagnosis without specific pathologic findings. Because IRIS is a diagnosis of exclusion, other explanations for worsening disease, including drug resistance, drug reactions (eg, abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome), and poor adherence to medications, should be ruled out before making the diagnosis.

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular tumor associated with infection by human herpesvirus 8 (HHV‐8). The incidence of AIDS‐related KS has declined substantially in the post‐ART era.2, 4 The classic radiographic presentation of pulmonary KS includes central bilateral opacities with a peribronchovascular distribution as well as pulmonary nodules, intraseptal thickening, mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and associated pleural effusions.5, 6 Kaposi sarcomarelated IRIS has been described as developing within weeks of ART initiation and is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly in the context of pulmonary involvement, with 1 recent series showing 100% mortality in patients who did not receive chemotherapy.79

Human immunodeficiency virusassociated KS can respond well to ART alone. Indications for systemic chemotherapy for KS include extensive mucocutaneous disease, symptomatic visceral disease, or KS‐related IRIS.10 The main chemotherapeutic agents used systemically for KS are liposomal anthracyclines such as doxorubicin or daunorubicin, or taxanes such as paclitaxel.11 An association between corticosteroids and progression of KS has been previously described, even as early as several days after steroid administration.1214 Recently, revised diagnostic criteria for corticosteroid‐associated KS‐IRIS have been proposed; this patient met those criteria.15

Plasmablastic lymphoma is a highly aggressive systemic NHL seen predominantly in HIV‐positive patients. There is a strong association with Epstein‐Barr virus; HHV‐8 is more variably associated and is of unclear significance.16 Most HIV‐infected patients have extranodal involvement at diagnosis; in a series of 53 HIV‐positive patients, the oral cavity was the most frequent site, and lung involvement was seen in 12%. The prognosis is poor, with a mean survival of approximately 1 year.17

Treatment for systemic NHL in HIV‐positive patients generally consists of a chemotherapy regimen while ART is continued or initiated.18 The most commonly used chemotherapy combination is cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone, often supplemented with the anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab. In the case of aggressive systemic NHL, more intensive treatment regimens are often utilized, though it remains unclear if they are associated with improved outcomes.17, 19 Antiretroviral therapy is continued, as it has been shown to reduce the rate of opportunistic infections and decrease mortality.20

Despite the remarkable progress that has been made in the past 30 years, HIV/AIDS remains a devastating and remarkably complex disease. As the landscape of HIV/AIDS evolves, clinicians will continue to be faced with new challenging and vexing decisions. Perhaps no greater challenge exists than the presence of 2 simultaneous, rapidly fatal malignancies with directly competing therapeutic strategies, as in this case, where the ART and steroids employed to address NHL fostered widespread KS‐IRIS. This case reminds us that a single unifying diagnosis can often be the exception rather than the rule in the care of patients with advanced HIV. It also illustrates how the mainstay of HIV treatment, ART, can be a double‐edged sword.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

-

In HIV/AIDS patients receiving ART who become paradoxically more ill despite improvements in their CD4 counts, consider IRIS.

-

Though corticosteroids are a hallmark of treatment for most types of IRIS‐and for aggressive lymphomas‐they can worsen KS.

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant.

A 40‐year‐old man with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and a CD4 count of 58 cells/L was admitted to the hospital with 1 month of fevers, night sweats, a 5‐kg weight loss, several weeks of progressive dyspnea on exertion, and a nonproductive cough. He denied headaches, vision changes, odynophagia, diarrhea, or rash. He had no history of opportunistic infections, HIV‐associated neoplasms, or other relevant past medical history. He was diagnosed with HIV 3 years ago and had been off antiretroviral therapy (ART) for the last 10 months. Two weeks prior to this presentation, he was seen in clinic but did not report his symptoms. He was prescribed trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) for prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP). He had recently moved from New York City to San Francisco, had quit smoking within the last month, and denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

At a CD4 cell count of 58 cells/L, the patient is at risk for the entire spectrum of HIV‐associated opportunistic infections and neoplasms. The presence of fevers, night sweats, and weight loss suggests the possibility of a disseminated infection, although a neoplastic process with accompanying B symptoms should also be considered. Dyspnea and nonproductive cough indicate cardiopulmonary involvement. The duration of these complaints is more suggestive of a nonbacterial infectious etiology (e.g., PCP, mycobacterial or fungal disease) than a bacterial etiology (e.g., Streptococcus pneumoniae). Irrespective of CD4 count, patients with HIV are at increased risk for cardiovascular events and pulmonary arterial hypertension, although the time course and presence of constitutional symptoms makes these diagnoses less likely. Similarly, patients with HIV are at increased risk for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and the patient does have a history of cigarette smoking, but the clinical history and systemic involvement make COPD unlikely.

On physical examination, the patient was in no acute distress. The temperature was 36C, the blood pressure 117/68 mm Hg, the heart rate 106 beats per minute, the respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, and the oxygen saturation 100% on ambient air. No oral lesions were noted, and his neck was supple with nontender bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy measuring up to 1.5 cm. There was no jugular venous distension or peripheral edema. The cardiovascular exam revealed tachycardia with a regular rhythm and no murmurs or gallops. His lungs were clear to auscultation. The spleen tipwas palpable. No rashes were identified. The neurological examination, including mental status, was normal.

The white blood cell count was 2400/mm3, the hemoglobin 7 g/dL with mean corpuscular volume of 86 fL, and the platelet count 162,000/mm3. Basic chemistry, liver, and glucose‐6‐phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) tests were within the laboratory's normal range. The HIV viral load was 150,000 copies/mL. Chest radiography revealed bibasilar hazy opacities, and computerized tomography (CT) of the chest revealed a focal nodular consolidation in the right middle lobe along with subcentimeter bilateral axillary and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. There were no ground‐glass opacities.

The patient's physical examination does not support a cardiac disorder. Lymphadenopathy is nonspecific, but it is consistent with a potential infectious or neoplastic process. Leukopenia and anemia suggest potential bone‐marrow infiltration or suppression by TMP/SMX. Although the pulmonary exam was nonfocal, chest imaging is the cornerstone of the evaluation of suspected pulmonary disease in persons with HIV. The focal nodular consolidation on chest CT is nonspecific but is more characteristic of typical or atypical bacterial pneumonia, mycobacterial disease such as tuberculosis, or fungal pneumonia than PCP or viral pneumonia. A lack of ground‐glass opacities also makes PCP and interstitial lung diseases less likely.

The patient was treated for community‐acquired pneumonia with ceftriaxone and doxycycline with improvement in dyspnea. Antiretroviral therapy with darunavir, ritonavir, tenofovir, and emtricitabine was initiated. Azithromycin was started for prophylaxis against Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). The TMP/SMX was changed to dapsone, given concern for bone‐marrow suppression. Blood cultures for bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria were negative. Polymerase chain reaction from pharyngeal swab for influenza A and B, parainfluenza types 13, rhinovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus were negative. Several attempts to obtain sputum for acid‐fast bacillus staining and culture were unsuccessful because the patient was unable to expectorate sputum. Serum interferon‐gamma release assay for M. tuberculosis and thefollowing serologic studies were also negative: cytomegalovirus, Epstein‐Barr virus, parvovirus, Bartonella species, Coccidioides immitis, and Cryptococcus neoformans antigen. Given his improvement, the patient was discharged from the hospital on ART, doxycycline for community‐acquired pneumonia, and prophylactic azithromycin and dapsone with scheduled outpatient follow‐up.

Ten days later, he was seen in clinic. Though his dyspnea had improved after completing the doxycycline, he noted a persistent dry cough and daily fevers to 40C. The physical exam was unchanged, including persistent cervical lymphadenopathy. Laboratories revealed a white blood cell count of 2400/mm3, hemoglobin of 4.8 g/dL, and a platelet count of 122,000/mm3. The absolute reticulocyte count was 21,000/L (normal value, 20,000100,000/L). A peripheral blood smear was unremarkable, and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was within normal limits. The direct antiglobulin test (DAT) was negative. The patient was readmitted to the hospital.

The initial improvement in dyspnea but persistent fevers and cough and worsening pancytopenia are suggestive of multiple processes occurring simultaneously. Dapsone can cause both hemolytic anemia and aplastic anemia, although the peripheral smear, normal LDH and G6PD, and negative DAT are not consistent with the former. Bone‐marrow suppression from a combination of ART medications and dapsone cannot be ruled out. An infiltrative process involving the bone marrow, including tuberculosis, MAC, disseminated fungal infection, or malignancy, remains a possibility. Repeat chest imaging is warranted to assess the prior right middle lobe consolidation and to further evaluate the persistent respiratory complaints.

Prophylaxis of PCP with dapsone was switched to atovaquone due to persistent anemia. A repeat CT of the chest and a concurrent abdominal CT revealed interval enlargement of mediastinal lymph nodes with multiple periportal, retroperitoneal, and hilar nodes not present on prior chest imaging, in addition to new bilateral centrilobular nodules and interval development of small bilateral pleural effusions. The abdominal CT also showed hepatosplenomegaly with splenic‐vein engorgement. Empiric treatment for disseminated MAC infection with clarithromycin and ethambutol was initiated in addition to vancomycin and cefepime for possible healthcare‐associated pneumonia. Over the next several days, the patient continued to have daily fevers up to 39.8C. A repeat CD4 count 3 weeks after starting ART was 121 cells/L. The HIV RNA level had decreased to 854 copies/mL.

The patient has developed progressive, generalized lymphadenopathy, worsening pancytopenia, and persistent fevers in the setting of negative cultures and serologic studies and despite treatment for MAC. This constellation, along with the radiographic findings of hilar lymphadenopathy and pleural effusions, is suggestive of non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Alternatively, Kaposi sarcoma (KS) or tuberculosis can have a similar radiographic and clinical presentation, although pancytopenia from KS seems unusual. The lymphadenopathy could be consistent with multicentric Castleman disease or bacillary angiomatosis (BA), although the latter diagnosis would be unlikely given recent antibiotic therapy. At this time, a careful search for other manifestations and reasonable targets for biopsy is warranted. An appropriate suppression of the HIV viral load after initiation of ART, with improvement in CD4 count, is the proper context for the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), which is characterized by paradoxical worsening or unmasking of a disseminated process.

A bone‐marrow biopsy revealed marked dysmegakaryopoiesis and mild dyserythropoiesis, but no other abnormalities. Flow cytometry and histoimmunochemical staining did not show evidence of lymphoproliferative disorder in the marrow. Smears and cultures of the bone marrow for bacteria, acid‐fast bacilli, and fungi were negative. A right cervical lymph node biopsy was performed, with multiple fine‐needle aspiration and core samples taken. Bacterial, fungal, and acid‐fast bacilli tissue cultures were without growth, and initial pathology results were concerning for high‐grade lymphoma. A monoclonal proliferation of lymphocytes was noted on flow cytometry of the tissue sample. The patient developed progressive dyspnea, tachypnea, and hypoxemia. A chest x‐ray revealed worsening perihilar and basilar opacities.

The possibility of bone‐marrow sampling error must be considered in a patient that has such a high pretest probability for lymphoma or infection, but staining, immunological assays, cultures, and direct assessment by pathologists generally give some suggestion of an alternative diagnosis. The bone‐marrow findings are compatible with HIV‐related changes, but continued vigilance for infection and malignancy is warranted. Although the diagnosis of NHL based on the cervical biopsy result is only preliminary, the patient's rapidly deteriorating clinical status warrants initiation of treatment with steroids while awaiting definitive results, particularly given his poor response to aggressive management of potential infectious causes. A bronchoscopy should be considered given the predominance of pulmonary symptoms and his rapid respiratory decline.

Approximately 1 week after admission, high‐dose systemic corticosteroids were administered for presumed aggressive lymphoma. Over the next 48 hours, the patient's hypoxemia worsened, and he was intubated for hypoxemic respiratory failure. A repeat chest CT (see Fig. 1) showed bilateral peribronchovascular patchy consolidations and pleural effusions without evidence of pulmonary embolism. The patient was also noted to have a single, discrete violaceous nodule on the hard palate as well as a nodule with similar appearance on his upper chest (neither lesion was present on admission). A skin biopsy was obtained. Despite steroids, antibiotic therapy, and aggressive critical‐care management, severe acidosis, progressive acute kidney injury, and anuria ensued. Continuous venovenous hemodialysis was initiated.

Discrete violaceous nodules with mucocutaneous localization in the context of AIDS are virtually pathognomonic for KS. Rarely, BA may be misdiagnosed as KS, or they may occur concurrently. The patient's current clinical deterioration, radiographic findings, and development of new skin lesions in the setting of response to ART are concerning for KS‐related IRIS with visceral involvement. It is likely that systemic corticosteroids are potentiating KS‐related IRIS. At this point, there is compelling evidence of 2 distinct systemic disease processes: lymphoma and KS‐related IRIS, both of which may be contributing to respiratory failure. Steroids can be highly effective in the treatment of high‐grade lymphoma but can be harmful in patients with KS, where they have been shown to potentially exacerbate underlying disease. Given the patient's worsening respiratory status, discontinuation of corticosteroids and initiation of chemotherapy against both opportunistic malignancies should be considered.

The patient's condition deteriorated with progressive acidosis and hypoxemia, and he died shortly after being transitioned to comfort‐care measures. Review of the skin biopsy revealed KS. Autopsy revealed disseminated KS involving the skin, lymph nodes, and lungs, and high‐grade anaplastic plasmablastic lymphoma infiltrating multiple lymph nodes and organs, including the lungs (see Fig. 2). There was no evidence of infection.

COMMENTARY

This case demonstrates the simultaneous fatal progression of 2 treatable HIV‐associated malignancies in an era in which the end‐stage manifestations of untreated HIV are becoming less common, particularly in developed countries. Modern ARTthe centerpiece of progress with HIVhas yielded dramatic improvements in prognosis, but in this case, by precipitating KS‐IRIS, ART paradoxically contributed to this patient's demise. Similarly, high‐dose systemic corticosteroids, which were deemed necessary to stabilize the progression of his high‐grade lymphoma, likely accelerated his KS. This corticosteroid‐mediated worsening appears to be unique to KS given that corticosteroids are often recommended to treat severe presentations of IRIS in other diseases (eg, tuberculosis, MAC, PCP).

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome is the paradoxical worsening of well‐controlled disease or progression of previously occult disease after initiation of ART.1

Although infectious diseasesincluding mycobacteria, cytomegalovirus, cryptococcosis, or PCPare best known for their ability to recrudesce or manifest with a recovering immune system, opportunistic malignancies such as KS can do the same. Risk factors for development of IRIS are low pre‐ART CD4 count, high pre‐ART viral load, and rapid response to ART.2 In 1 large series, the median time to diagnosis of IRIS was 33 days.2 Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome is a clinical diagnosis without specific pathologic findings. Because IRIS is a diagnosis of exclusion, other explanations for worsening disease, including drug resistance, drug reactions (eg, abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome), and poor adherence to medications, should be ruled out before making the diagnosis.

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular tumor associated with infection by human herpesvirus 8 (HHV‐8). The incidence of AIDS‐related KS has declined substantially in the post‐ART era.2, 4 The classic radiographic presentation of pulmonary KS includes central bilateral opacities with a peribronchovascular distribution as well as pulmonary nodules, intraseptal thickening, mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and associated pleural effusions.5, 6 Kaposi sarcomarelated IRIS has been described as developing within weeks of ART initiation and is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly in the context of pulmonary involvement, with 1 recent series showing 100% mortality in patients who did not receive chemotherapy.79

Human immunodeficiency virusassociated KS can respond well to ART alone. Indications for systemic chemotherapy for KS include extensive mucocutaneous disease, symptomatic visceral disease, or KS‐related IRIS.10 The main chemotherapeutic agents used systemically for KS are liposomal anthracyclines such as doxorubicin or daunorubicin, or taxanes such as paclitaxel.11 An association between corticosteroids and progression of KS has been previously described, even as early as several days after steroid administration.1214 Recently, revised diagnostic criteria for corticosteroid‐associated KS‐IRIS have been proposed; this patient met those criteria.15

Plasmablastic lymphoma is a highly aggressive systemic NHL seen predominantly in HIV‐positive patients. There is a strong association with Epstein‐Barr virus; HHV‐8 is more variably associated and is of unclear significance.16 Most HIV‐infected patients have extranodal involvement at diagnosis; in a series of 53 HIV‐positive patients, the oral cavity was the most frequent site, and lung involvement was seen in 12%. The prognosis is poor, with a mean survival of approximately 1 year.17

Treatment for systemic NHL in HIV‐positive patients generally consists of a chemotherapy regimen while ART is continued or initiated.18 The most commonly used chemotherapy combination is cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone, often supplemented with the anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab. In the case of aggressive systemic NHL, more intensive treatment regimens are often utilized, though it remains unclear if they are associated with improved outcomes.17, 19 Antiretroviral therapy is continued, as it has been shown to reduce the rate of opportunistic infections and decrease mortality.20

Despite the remarkable progress that has been made in the past 30 years, HIV/AIDS remains a devastating and remarkably complex disease. As the landscape of HIV/AIDS evolves, clinicians will continue to be faced with new challenging and vexing decisions. Perhaps no greater challenge exists than the presence of 2 simultaneous, rapidly fatal malignancies with directly competing therapeutic strategies, as in this case, where the ART and steroids employed to address NHL fostered widespread KS‐IRIS. This case reminds us that a single unifying diagnosis can often be the exception rather than the rule in the care of patients with advanced HIV. It also illustrates how the mainstay of HIV treatment, ART, can be a double‐edged sword.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

-

In HIV/AIDS patients receiving ART who become paradoxically more ill despite improvements in their CD4 counts, consider IRIS.

-

Though corticosteroids are a hallmark of treatment for most types of IRIS‐and for aggressive lymphomas‐they can worsen KS.

- , , , et al. Defining immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: evaluation of expert opinion versus 2 case definitions in a South African cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1424–1432.

- , , , et al. Risk factor analyses for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a randomized study of early vs. deferred ART during an opportunistic infection. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11416.

- , . Kaposi's sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1027–1038.

- , , , et al. The changing pattern of Kaposi sarcoma in patients with HIV, 1994–2003: the EuroSIDA Study. Cancer. 2004;100:2644–2654.

- , , , , , . Imaging features of pulmonary Kaposi sarcoma–associated immune reconstitution syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:956–965.

- , , , et al. Pulmonary involvement in Kaposi sarcoma: correlation between imaging and pathology. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:18.

- , , , et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome associated with Kaposi's sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5224–5228.

- , . Recrudescent Kaposi's sarcoma after initiation of HAART: a manifestation of immune reconstitution syndrome. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005;19:635–644.

- , , , , , . Paradoxical immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV‐infected patients treated with combination antiretroviral therapy after AIDS‐defining opportunistic infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:424–433.

- , , , et al. British HIV Association guidelines for HIV‐associated malignancies 2008. HIV Med. 2008;9:336–388.

- , , , , . HIV/AIDS: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus disease: Kaposi sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(9):1209–1215.

- , , . A 36‐year‐old man with AIDS and relapsing, nonproductive cough. Chest. 2007;131:1929–1931.

- , , , , . Life‐threatening exacerbation of Kaposi's sarcoma after prednisone treatment for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. AIDS. 2008;22:663–665.

- , , , , , . Clinical effect of glucocorticoids on Kaposi sarcoma related to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:937–940.

- , , , . Kaposi sarcoma–associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: in need of a specific case definition. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(1):157–158.

- , , , , , . Plasmablastic lymphoma in HIV‐positive patients: an aggressive Epstein‐Barr virus–associated extramedullary plasmacytic neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1633–1641.

- , , , et al. Human immunodeficiency virus–associated plasmablastic lymphoma: poor prognosis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Cancer. 2012;118:5270–5277.

- , , . Modern management of non‐Hodgkin lymphoma in HIV‐infected patients. Br J Haematol. 2007;136(5):685–698.

- , , , et al. CD20‐negative large‐cell lymphoma with plasmablastic features: a clinically heterogeneous spectrum in both HIV‐positive and ‐negative patients. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(11):1673–1679.

- , , , et al. Concomitant cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone chemotherapy plus highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus–related, non‐Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 2001;91(1):155–163.

- , , , et al. Defining immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: evaluation of expert opinion versus 2 case definitions in a South African cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1424–1432.

- , , , et al. Risk factor analyses for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a randomized study of early vs. deferred ART during an opportunistic infection. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11416.

- , . Kaposi's sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1027–1038.

- , , , et al. The changing pattern of Kaposi sarcoma in patients with HIV, 1994–2003: the EuroSIDA Study. Cancer. 2004;100:2644–2654.

- , , , , , . Imaging features of pulmonary Kaposi sarcoma–associated immune reconstitution syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:956–965.

- , , , et al. Pulmonary involvement in Kaposi sarcoma: correlation between imaging and pathology. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:18.

- , , , et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome associated with Kaposi's sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5224–5228.

- , . Recrudescent Kaposi's sarcoma after initiation of HAART: a manifestation of immune reconstitution syndrome. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005;19:635–644.

- , , , , , . Paradoxical immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV‐infected patients treated with combination antiretroviral therapy after AIDS‐defining opportunistic infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:424–433.

- , , , et al. British HIV Association guidelines for HIV‐associated malignancies 2008. HIV Med. 2008;9:336–388.

- , , , , . HIV/AIDS: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus disease: Kaposi sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(9):1209–1215.

- , , . A 36‐year‐old man with AIDS and relapsing, nonproductive cough. Chest. 2007;131:1929–1931.

- , , , , . Life‐threatening exacerbation of Kaposi's sarcoma after prednisone treatment for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. AIDS. 2008;22:663–665.

- , , , , , . Clinical effect of glucocorticoids on Kaposi sarcoma related to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:937–940.

- , , , . Kaposi sarcoma–associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: in need of a specific case definition. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(1):157–158.

- , , , , , . Plasmablastic lymphoma in HIV‐positive patients: an aggressive Epstein‐Barr virus–associated extramedullary plasmacytic neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1633–1641.

- , , , et al. Human immunodeficiency virus–associated plasmablastic lymphoma: poor prognosis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Cancer. 2012;118:5270–5277.

- , , . Modern management of non‐Hodgkin lymphoma in HIV‐infected patients. Br J Haematol. 2007;136(5):685–698.

- , , , et al. CD20‐negative large‐cell lymphoma with plasmablastic features: a clinically heterogeneous spectrum in both HIV‐positive and ‐negative patients. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(11):1673–1679.

- , , , et al. Concomitant cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone chemotherapy plus highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus–related, non‐Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 2001;91(1):155–163.

Overcome by Weakness

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant.

This icon represents the patient's case. Each paragraph that follows represents the discussant's thoughts.

An 89‐year‐old man presented to the emergency department with progressive fatigue, confusion, and generalized weakness over 2 months, worsening in the prior few days.

Four categories of disease account for most cases of confusion in the elderly: metabolic derangements; infection (both within and outside of the central nervous system); structural brain disorder (eg, bleed or tumor); and toxins (generally medications). It will be important early on to determine if weakness refers to true loss of motor function, reflecting a neuromuscular lesion.

At baseline, the patient had normal cognition, ambulated without assistance, and was independent in activities of daily living. Over the preceding 2 months, general functional decline, unsteady gait, balance problems, and word‐finding difficulty developed. He also needed a front‐wheel walker to avoid falling. One month prior to presentation, the patient's children noticed he was markedly fatigued and was requiring a nightly sedative‐hypnotic in order to fall asleep.

He denied any recent travel, sick contacts, or recent illness. He denied vertigo, dizziness, or syncope. He reported occasional urinary incontinence which he attributed to being too weak to get to the bathroom promptly.

This rapid progression over 2 months is not consistent with the time course of the more common neurodegenerative causes of dementia, such as Alzheimer's or Parkinson's disease. In Parkinson's, cognitive impairment is a late feature, occurring years after gait and motor disturbances develop. Normal pressure hydrocephalus, which causes the classic triad of incontinence, ataxia, and confusion, would also be unlikely to develop so abruptly. Although we do not think of vascular (multi‐infarct) dementia as having such a short time course, on occasion a seemingly rapid presentation is the postscript to a more insidious progression that has been underway for years. A subdural hematoma, which may have occurred with any of his falls, must also be considered, as should neoplastic and paraneoplastic processes.

His past medical history included paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease complicated by prior myocardial infarction for which he underwent coronary artery bypass grafting 7 years prior, mild aortic sclerosis and insufficiency, mild mitral regurgitation, anemia, recurrent low‐grade bladder cancer treated with serial local resections over the last 8 years, low‐grade prostate cancer which had not required treatment, hypothyroidism, chronic kidney disease, and lumbar spinal stenosis.

His atrial fibrillation and valvular disease put him at risk for thrombotic and infective embolic phenomena causing multiple cerebral infarcts. He has all the requisite underlying conditions for vascular dementia. Untreated hypothyroidism could explain his decline and sedation. Prostate and bladder cancers would be unusual causes of subacute central nervous system (CNS) disease. Finally, his chronic kidney disease may have progressed to uremia.

One year prior to admission, the patient developed bilateral shoulder pain, right‐sided headache with loss of vision in his right eye, fevers, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Although temporal artery biopsy specimens did not reveal arterial inflammation, he was started on high‐dose prednisone for polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis (GCA); he experienced improvement in his ESR and in all symptoms, with the exception of permanent right eye blindness. Maintenance prednisone was continued for disease suppression.

Even without confirmatory biopsy results, the clinical case for GCA was compelling and the rationale for starting steroids strong; his sustained response over 1 year further supports the diagnosis. GCA is almost always confined to extracranial vessels, and altered sensorium would be an unusual manifestation. His extended treatment with prednisone expands the list of CNS and systemic infections, particularly opportunistic ones, for which he is now at risk.

Outpatient medications were prednisone at doses fluctuating between 10 and 20 mg daily, furosemide 20 mg daily, amiodarone 200 mg daily, levothyroxine 50 mcg daily, alendronate 70 mg weekly, eszopiclone 1 mg nightly, losartan 50 mg daily, and warfarin. The patient was an accomplished professor and had published a book 1 year prior to admission. He quit smoking over 30 years ago, and he occasionally drank wine. He denied any drug use.

Three months prior to the current presentation, the patient was hospitalized for right upper‐lobe pneumonia for which he received a course of doxycycline, and his symptoms improved. Follow‐up chest x‐ray, 4 weeks later (2 months prior to admission), showed only slight improvement of the right upper‐lobe opacity.

Leading possibilities for the persistent lung opacity are cancer and untreated infection. After 3 decades of being tobacco‐free, his smoking‐related risk of cancer is low, but remains above baseline population risk. There are at least 4 ways untreated lung cancer may render patients confused: direct metastases to the brain, carcinomatous or lymphomatous meningitis, paraneoplastic phenomenon (eg, limbic encephalitis), and metabolic derangements (eg, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, hypercalcemia).

The upper‐lobe infiltrate that failed to improve with doxycycline could also reflect an aspiration pneumonia that evolved into an abscess, or an infection with mycobacteria or endemic fungi.

In the emergency department, the patient's temperature was 38.5C, blood pressure 139/56 mmHg, heart rate 92 beats per minute, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation while breathing ambient room air was 98%.

He was alert and well‐appearing. Jugular venous pressure was normal. The thyroid was normal. He had rhonchi in his right anterior upper chest and right lower lung base. Cardiac exam demonstrated a regular rhythm, with a 3/6 systolic murmur at the second right intercostal space that radiated to the carotids, and a 2/6 nonradiating holosystolic murmur at the apex. Abdomen was soft with no organomegaly or masses. There was no lymphadenopathy, and his extremities showed no clubbing or edema. There were multiple contusions in various stages of healing on his legs.

He was confused, had word‐finding difficulty, and frequently would lose his train of thought, stopping in mid‐sentence. He had no dysarthria. Cranial nerves were normal, except for reduced visual acuity and diminished pupillary response to light in his right pupil, which had been previously documented. Finger‐to‐nose testing was slow bilaterally, but was more sluggish on the right. Rapid alternating hand movements were intact. He was unable to perform heel‐to‐shin testing. Sensation was intact. Plantar reflexes were flexor bilaterally. Strength in his limbs was preserved both distally and proximally, and deep tendon reflexes were normal. However, he was unable to sit up or stand on his own due to weakness.

The fever on prednisone is a red flag for infection. The infection may be the primary diagnosis (eg, meningoencephalitis) or may reflect an additional superimposed insult (eg, urinary tract infection) on the underlying encephalopathy. Two murmurs in a febrile patient with the multifocal CNS findings suggest endocarditis. The abnormalities on chest examination could indicate a lung infection complicated by hematogenous spread to the brain, such as a lung abscess (secondary to the aspiration event), tuberculosis (TB), or endemic fungal infection.

Serum chemistries were normal, and the serum creatinine was 1.1 mg/dL. White blood cell count was 20,100 per mm3 with 90% neutrophils, 9% lymphocytes, and 1% monocytes. Hemoglobin was 13.7 g/dL, platelet count was 464,000 per mm3. Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) was 6.0 IU/mL (normal, <5.5). International normalized ratio (INR) was 2.2. Urinalysis was normal. Transaminases, bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase were normal. Lactate was 1.9 mmol/L.

Electrocardiogram (EKG) was unchanged from his baseline. ESR was >120 mm/hr (the maximum reportable value); his ESR measurements had been gradually rising during the previous 4 months. Chest x‐ray demonstrated a right upper‐lobe opacity, slightly more pronounced in comparison with chest x‐ray 2 months earlier.

His fever, leukocytosis, elevated ESR, and thrombocytosis all reflect severe inflammation. While infection and then malignancy remain the primary considerations, a third category of inflammatory diseaseautoimmunitywarrants mention. For instance, Wegener's granulomatosis can cause pulmonary and CNS disease in the elderly.

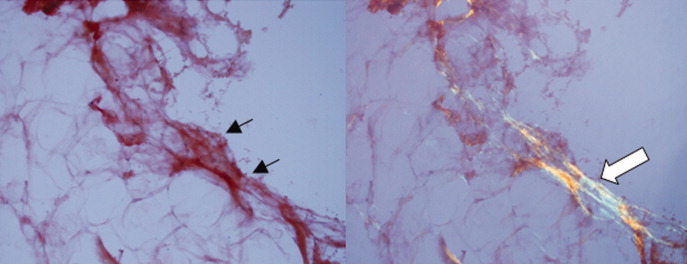

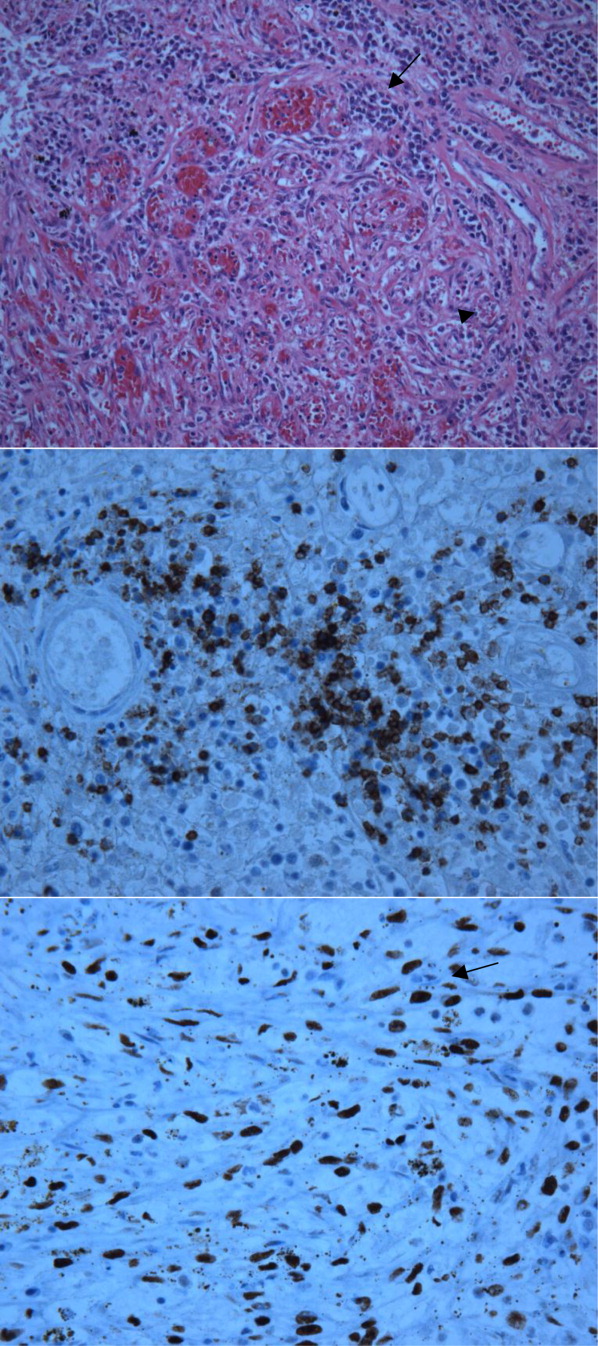

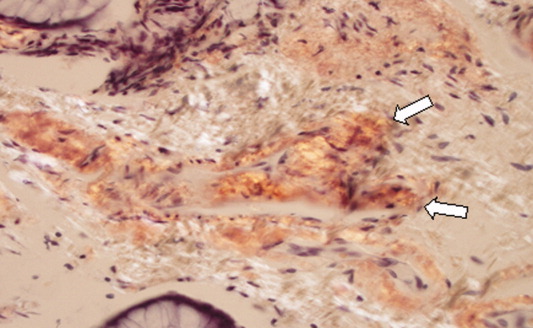

Intravenous ceftriaxone and oral doxycycline were administered. Chest computed tomography (CT) (Figure 1) demonstrated dense right upper‐lobe mass‐like consolidation with associated adenopathy and pleural effusion; in addition, several nodules were present in the left and right lower lobes, the largest of which was 10 mm. CT of the chest 10 months prior to current admission had been normal. CT of the brain, performed without contrast, demonstrated multiple areas of abnormal vasogenic edema with suggestion of underlying masses.

The imaging provides evidence of a combined pulmonaryCNS syndrome. It is far more common for disease to originate in the lungs (a common portal of entry and environmental exposure) and spread to the brain than vice versa. The list of diseases and pathogens that affect the lungs and spread to the brain includes: primary lung cancer, lymphoma, bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, molds (eg, Aspergillus), Wegener's granulomatosis, and lymphomatoid granulomatosis. Bacterial lung abscess, such as that caused by Streptococcus milleri group, may spread to the brain. Nocardia, a ubiquitous soil organism, infects immunocompromised patients and causes a similar pattern. Actinomycosis is an atypical infection that may mimic cancer, particularly in the lungs; while head and neck disease is characteristic, CNS involvement is less so. Overall, the imaging does not specifically pinpoint 1 entity, but infection remains heavily favored over malignancy, with autoimmunity a distant third.

Respiratory cultures showed normal respiratory flora. Blood cultures grew no organisms. Two samples of induced sputum were negative for acid‐fast bacilli (AFB) on smear examination. Forty‐eight hours after a purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test was placed, there was 0 mm of induration. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain (Figure 2) demonstrated 8 ring‐enhancing supratentorial lesions at the graywhite junction.

Negative blood cultures substantially lower the probability of bacterial endocarditis; there are no epidemiologic risk factors for the rare causes of culture‐negative endocarditis (eg, farm exposure, homelessness). Two negative smears for AFB with dense pulmonary or cavitary disease signify a low probability of tuberculosis.

In the setting of depressed cell‐mediated immunity (eg, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection or chronic prednisone use), multiple ring‐enhancing CNS lesions are a classic appearance of toxoplasmosis, but they also are typical of bacterial brain abscesses and Nocardia. Brain metastases are usually solid, but as central necrosis develops, peripheral enhancement may appear. The diffuse distribution and the localization at the graywhite junction further support a hematogenously disseminated process, but do not differentiate infection from metastases.

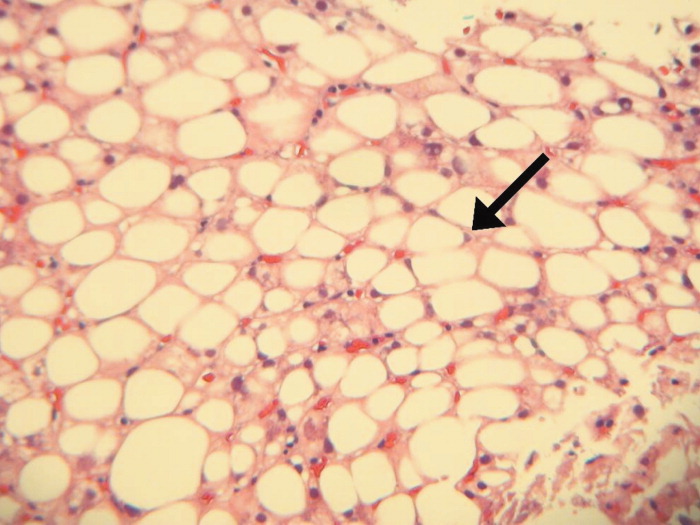

Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated normal left ventricular ejection fraction, clinically insignificant aortic sclerosis and mitral regurgitation, and no evidence of vegetations. Results of a CT‐guided fine‐needle aspiration of the lung were nondiagnostic, showing necropurulent material and benign lung parenchyma with fibrosis. A core biopsy of the lung showed alveolar tissue with patchy mild deposition of fibrinous material and rare scattered acute and chronic inflammatory cells without granulomas. Pleural fluid cytology showed reactive mesothelial cells with mixed inflammatory cells. There were no fungal elements or malignant cells.

The failure to detect malignancy after 2 biopsies and 1 thoracentesis lowers the suspicion of cancer, and thereby bolsters the probability of atypical infections which may elude diagnosis on routine cultures and biopsy. A detailed history, with attention to geographic exposures, is warranted to see which endemic mycosis would put him most at risk. Based on his California residency, disseminated coccidiomycosis or the ubiquitous Cryptococcus are conceivable. Nocardia remains a strong consideration because of his chronic immunosuppression and the lung‐CNS pattern.

Fungal stains and cultures from the biopsies and pleural fluid were negative. Serum antibodies to coccidiomycosis and serum cryptococcal antigen tests were negative. On the eighth hospital day, the microbiology lab reported a few acid‐fast bacilli from a third induced sputum sample. RNA amplification testing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis was negative.

Due to his continued decline, the patient met with the palliative care team and expressed his desire to go home with hospice. While arrangements were being made, he died later that day in the hospital.

There is reasonable evidence that tuberculosis is not the culprit pathogen here: negative PPD, 2 negative sputa in the setting of a massive necrotic lesion, and a negative RNA amplification test. Nontuberculous mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) and M. kansasii may cause disease similar to TB, but they are usually not this difficult to identify. Nocardia is classically a weakly acid‐fast positive bacteria and fits this patient's clinical picture best.

Four colonies of Nocardia (not further speciated) were identified postmortem from the patient's sputum.

DISCUSSION

Nocardia species are ubiquitous soil‐dwelling, Gram‐positive, branching rods which are weakly positive with acid‐fast staining.1 Almost all Nocardia infections occur in patients with immune systems compromised by chronic disease (HIV, malignancy, alcoholism, chronic lung or kidney disease) or by medications. Corticosteroid treatment is the most frequent risk factor. In cases of nocardiosis in patients taking steroids, the median daily prednisone dose was 25 mg (range, 1080 mg) for a median duration of 3 months.2, 3