User login

Hospital Ward Adaptation During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey of Academic Medical Centers

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in a surge in hospitalizations of patients with a novel, serious, and highly contagious infectious disease for which there is yet no proven treatment. Currently, much of the focus has been on intensive care unit (ICU) and ventilator capacity for the sickest of these patients who develop respiratory failure. However, most hospitalized patients are being cared for in general medical units.1 Some evidence exists to describe adaptations to capacity needs outside of medical wards,2-4 but few studies have specifically addressed the ward setting. Therefore, there is a pressing need for evidence to describe how to expand capacity and deliver medical ward–based care.

To better understand how inpatient care in the United States is adapting to the COVID-19 pandemic, we surveyed 72 sites participating in the Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN), a national consortium of hospital medicine groups.5 We report results of this survey, carried out between April 3 and April 5, 2020.

METHODS

Sites and Subjects

HOMERuN is a collaborative network of hospitalists from across the United States whose primary goal is to catalyze research and share best practices across hospital medicine groups. Using surveys of Hospital Medicine leaders, targeted medical record review, and other methods, HOMERuN’s funded research interests to date have included care transitions, workforce issues, patient and family engagement, and diagnostic errors. Sites participating in HOMERuN sites are relatively large urban academic medical centers (Appendix).

Survey Development and Deployment

We designed a focused survey that aimed to provide a snapshot of evolving operational and clinical aspects of COVID-19 care (Appendix). Domains included COVID-19 testing turnaround times, personal protective equipment (PPE) stewardship,6 features of respiratory isolation units (RIUs; ie, dedicated units for patients with known or suspected COVID-19), and observed effects on clinical care. We tested the instrument to ensure feasibility and clarity internally, performed brief cognitive testing with several hospital medicine leaders in HOMERuN, then disseminated the survey by email on April 3, with two follow-up emails on 2 subsequent days. Our study was deemed non–human subjects research by the University of California, San Francisco, Committee on Human Research. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize survey responses.

RESULTS

Of 72 hospitals surveyed, 51 (71%) responded. Mean hospital bed count was 940, three were safety-net hospitals, and one was a community-based teaching center; responding and nonresponding hospitals did not differ significantly in terms of bed count (Appendix).

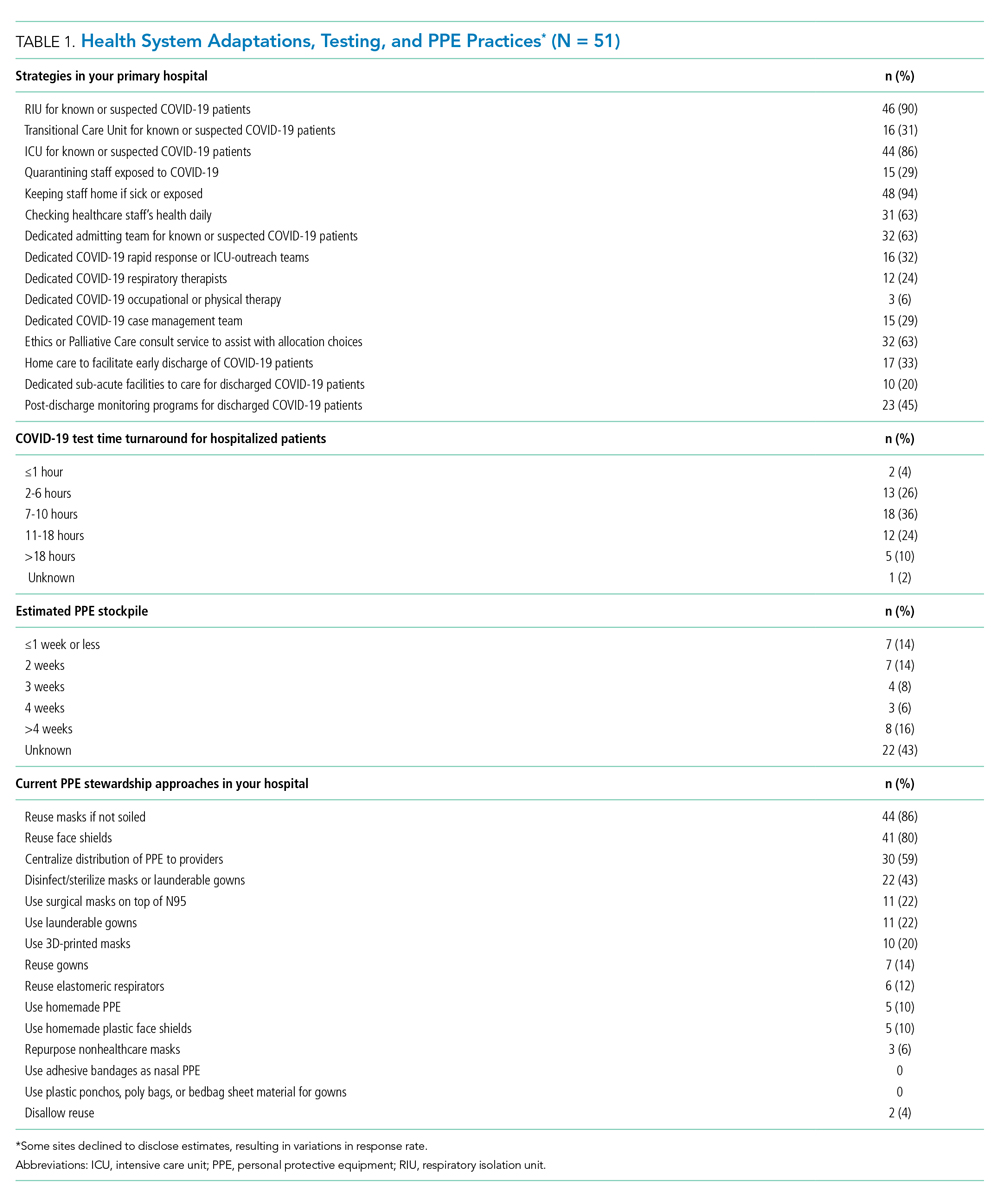

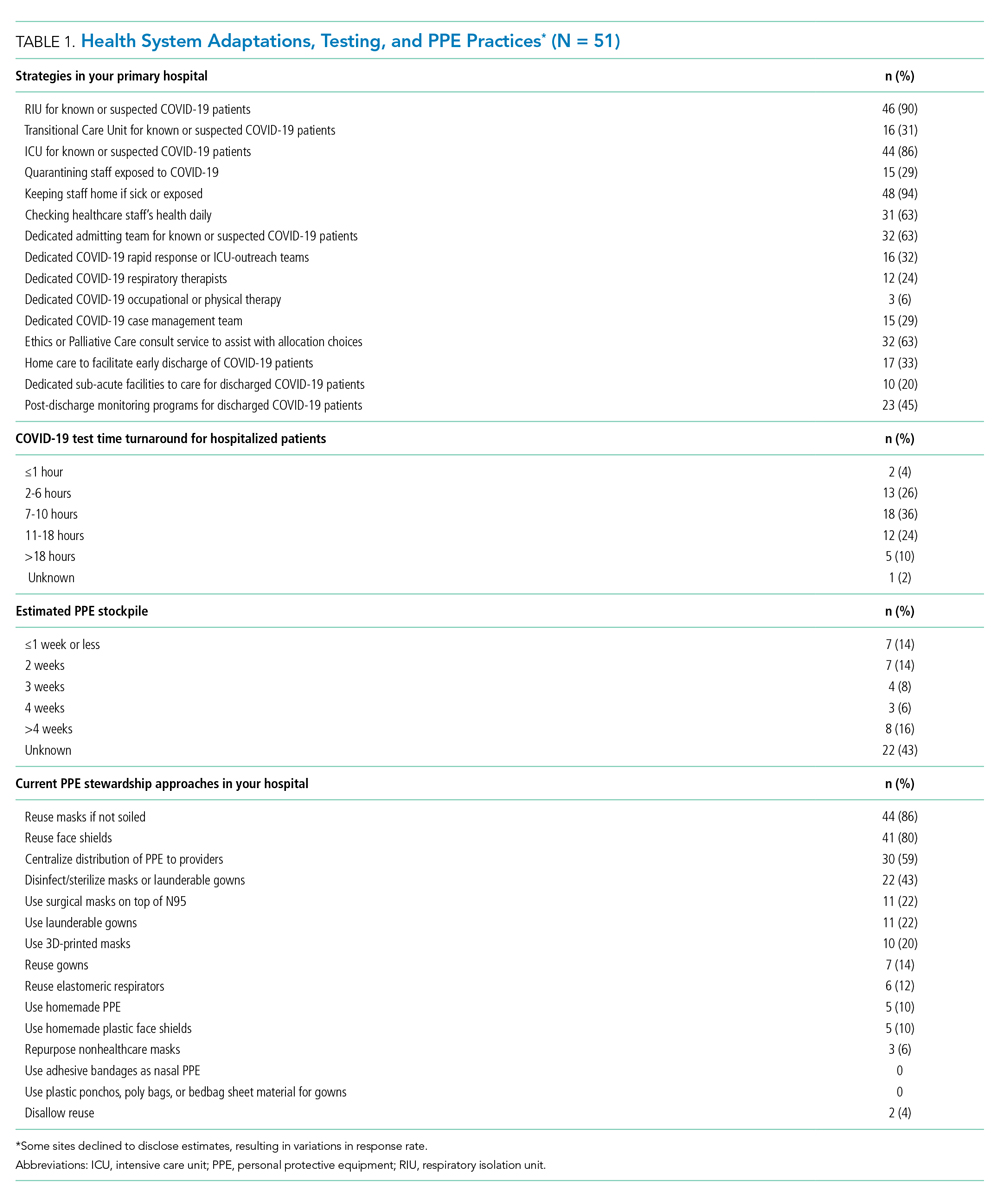

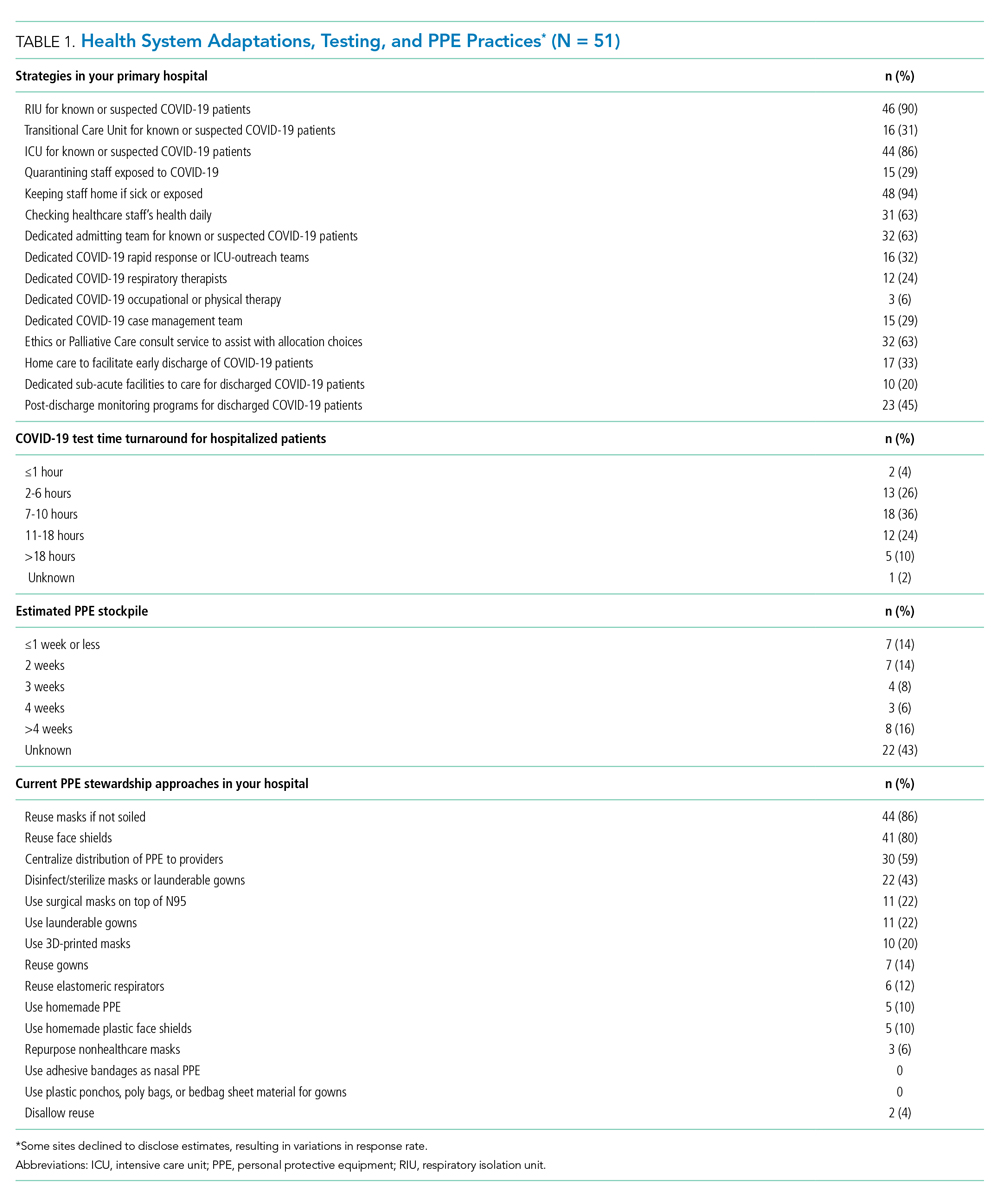

Health System Adaptations, Testing, and PPE Status

Nearly all responding hospitals (46 of 51; 90%) had RIUs for patients with known or suspected COVID-19 (Table 1). Nearly all hospitals took steps to keep potentially sick healthcare providers from infecting others (eg, staying home if sick or exposed). Among respondents, 32% had rapid response teams, 24% had respiratory therapy teams, and 29% had case management teams that were dedicated to COVID-19 care. Thirty-two (63%) had developed models, such as ethics or palliative care consult services, to assist with difficult resource-allocation decisions (eg, how to prioritize ventilator use if demand exceeded supply). Twenty-three (45%) had developed post-acute care monitoring programs dedicated to COVID-19 patients.

At the time of our survey, only 2 sites (4%) reported COVID-19 test time turnaround under 1 hour, and 15 (30%) reported turnaround in less than 6 hours. Of the 29 sites able to provide estimates of PPE stockpile, 14 (48%) reported a supply of 2 weeks or less. The most common approaches to PPE stewardship focused on reuse of masks and face shields if not obviously soiled, centralizing PPE distribution, and disinfecting or sterilizing masks. Ten sites (20%) were utilizing 3-D printed masks, while 10% used homemade face shields or masks.

Characteristics of COVID-19 RIUs

Forty-six hospitals (90% of all respondents) in our cohort had developed RIUs at the time of survey administration. The earliest RIU implementation date was February 10, 2020, and the most recent was launched on the day of our survey. Admission to RIUs was primarily based on clinical factors associated with known or suspected COVID-19 infection (Table 2). The number of non–critical care RIU beds among locations at that time ranged from 10 or less to more than 50. The mean number of hospitalist attendings caring for patients in the RIUs was 10.2, with a mean 4.1 advanced practice providers, 5.5 residents, and 0 medical students. The number of planned patients per attending was typically 5 to 15. Nurses and physicians typically rounded separately. Medical distancing (eg, reducing patient room entry) was accomplished most commonly by grouped timing of medication administration (76% of sites), video links to room outside of rounding times (54% of sites), the use of video or telemedicine during rounds (17%), and clustering of activities such as medication administration or phlebotomy. The most common criteria prompting discharge from the RIU were a negative COVID-19 test (59%) and hospital discharge (57%), though comments from many respondents suggested that discharge criteria were changing rapidly.

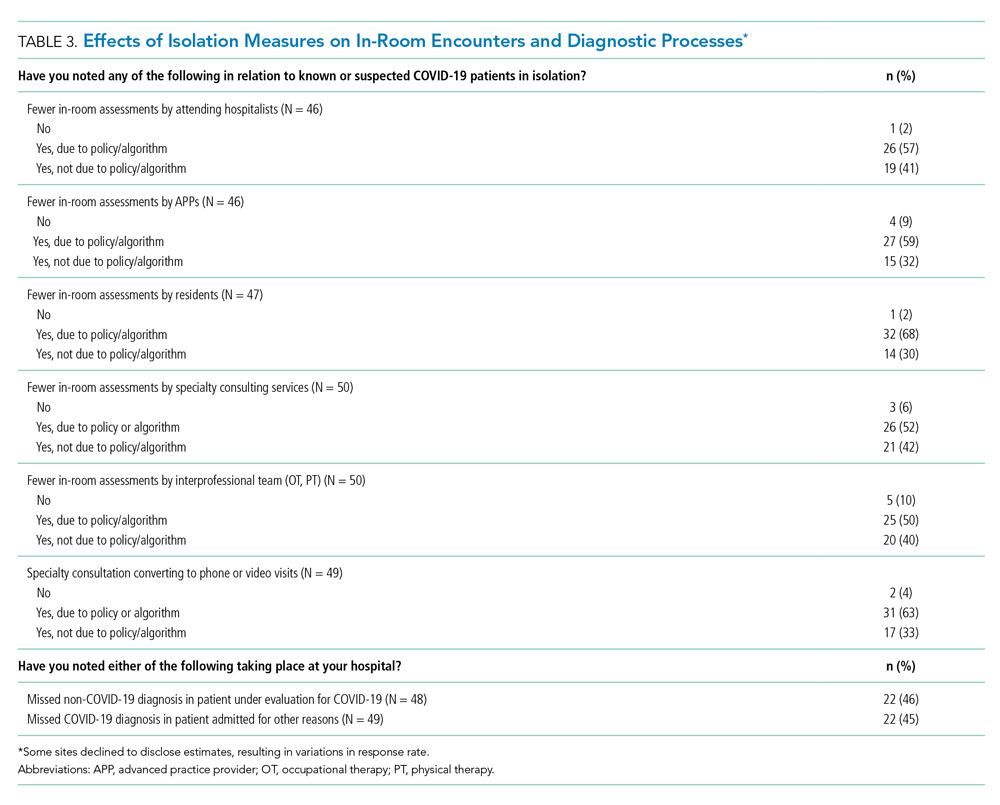

Effects of Isolation Measures on In-Room Encounters and Diagnostic Processes

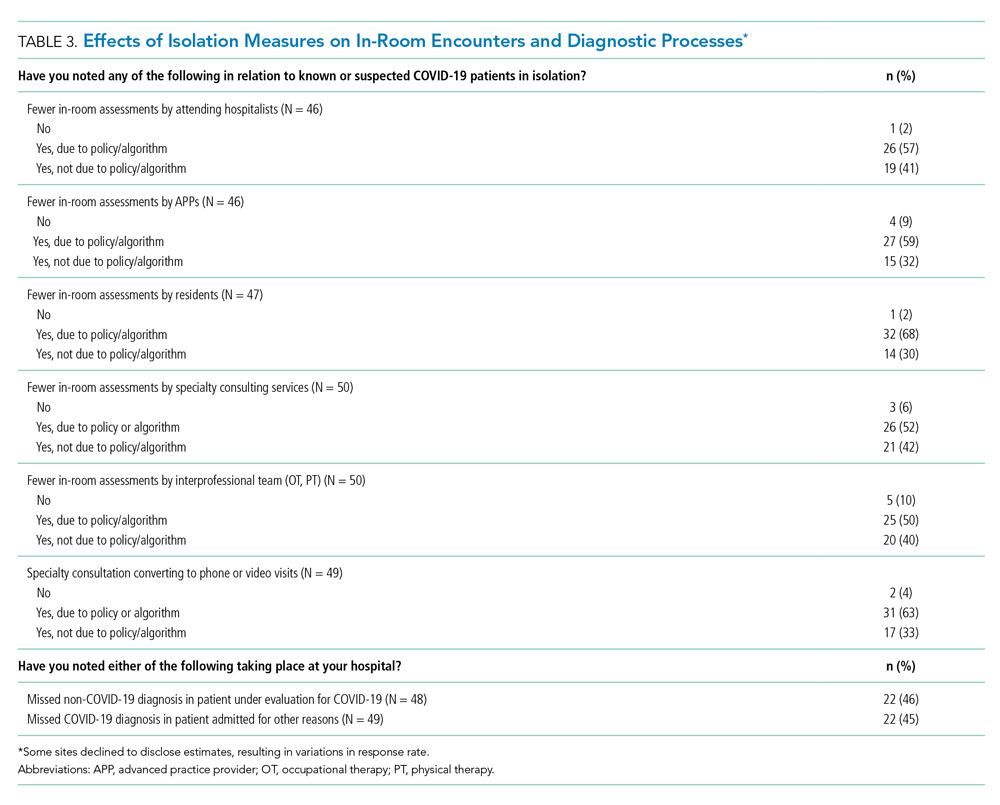

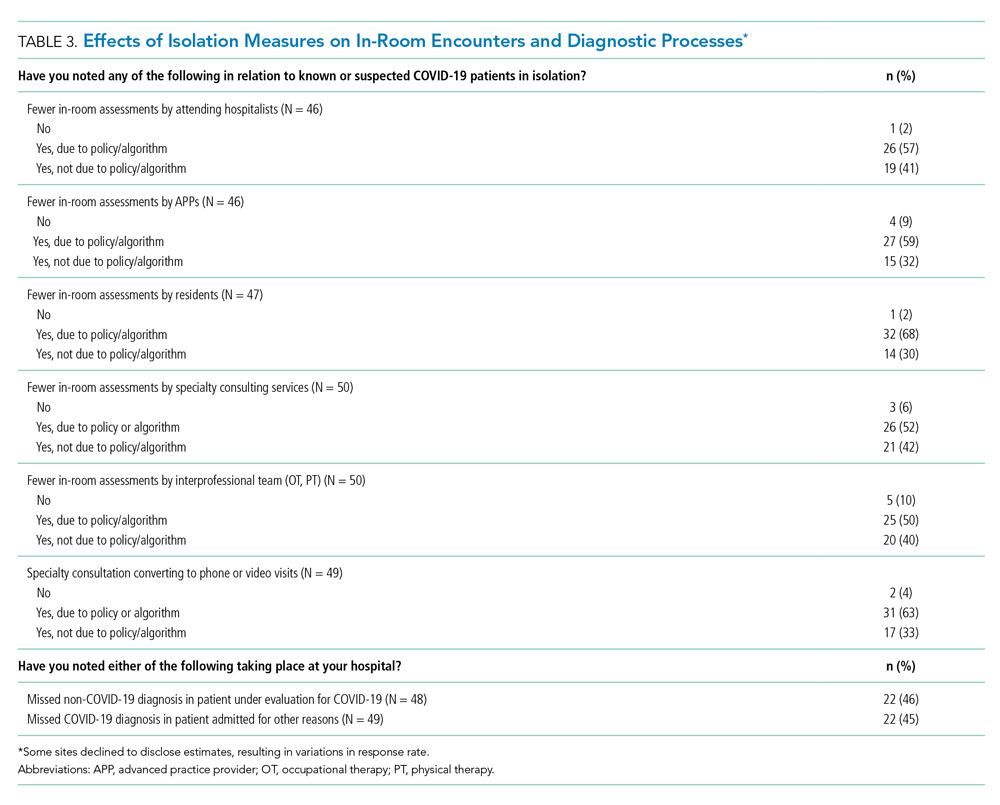

More than 90% of sites reported decreases in in-room encounter frequency across all provider types whether as a result of policies in place or not. Reductions were reported among hospitalists, advanced practice providers, residents, consultants, and therapists (Table 3). Reduced room entry most often resulted from an established or developing policy, but many noted reduced room entry without formal policies in place. Nearly all sites reported moving specialty consultations to phone or video evaluations. Diagnostic error was commonly reported, with missed non–COVID-19 medical diagnoses among COVID-19 infected patients being reported by 22 sites (46%) and missed COVID-19 diagnoses in patients admitted for other reasons by 22 sites (45%).

DISCUSSION

In this study of medical wards at academic medical centers, we found that, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals made several changes in a short period of time to adapt to the crisis. These included implementation and rapid expansion of dedicated RIUs, greatly expanded use of inpatient telehealth for patient assessments and consultation, implementation of other approaches to minimize room entry (such as grouping in-room activities), and deployment of ethics consultation services to help manage issues around potential scarcity of life-saving measures such as ventilators. We also found that availability of PPE and timely testing was limited. Finally, a large proportion of sites reported potential diagnostic problems in the assessment of both patients suspected and those not suspected of having COVID-19.

RIUs are emerging as a primary modality for caring for non-ICU COVID-19 patients, though they never involved medical students; we hope the role of students in particular will increase as new models of training emerge in response to the pandemic.7 In contrast, telemedicine evolved rapidly to hold a substantial role in RIUs, with both ward and specialty teams using video visit technology to communicate with patients. COVID-19 has been viewed as a perfect use case for outpatient telemedicine,8 and a growing number of studies are examining its outpatient use9,10; however, to date, somewhat less attention has been paid to inpatient deployment. Although our data suggest telemedicine has found a prominent place in RIUs, it remains to be seen whether it is associated with differences in patient or provider outcomes. For example, deficiencies in the physical examination, limited face-to-face contact, and lack of physical presence could all affect the patient–provider relationship, patient engagement, and the accuracy of the diagnostic process.

Our data suggest the possibility of missing non–COVID-19 diagnoses in patients suspected of COVID-19 and missing COVID-19 in those admitted for nonrespiratory reasons. The latter may be addressed as routine COVID-19 screening of admitted patients becomes commonplace. For the former, however, it is possible that physicians are “anchoring” their thinking on COVID-19 to the exclusion of other diagnoses, that physicians are not fully aware of complications unique to COVID-19 infection (such as thromboembolism), and/or that the above-mentioned limitations of telemedicine have decreased diagnostic performance.

Although PPE stockpile data were not easily available for some sites, a distressingly large number reported stockpiles of 2 weeks or less, with reuse being the most common approach to extending PPE supply. We also found it concerning that 43% of hospital leaders did not know their stockpile data; we believe this is an important question that hospital leaders need to be asking. Most sites in our study reported test turnaround times of longer than 6 hours; lack of rapid COVID-19 testing further stresses PPE stockpile and may slow patients’ transition out of the RIU or discharge to home.

Our study has several limitations, including the evolving nature of the pandemic and rapid adaptations of care systems in the pandemic’s surge phase. However, we attempted to frame our questions in ways that provided a focused snapshot of care. Furthermore, respondents may not have had exhaustive knowledge of their institution’s COVID-19 response strategies, but most were the directors of their hospitalist services, and we encouraged the respondents to confer with others to gather high-fidelity data. Finally, as a survey of large academic medical centers, our results may not apply to nonacademic centers.

Approaches to caring for non-ICU patients during the COVID-19 pandemic are rapidly evolving. Expansion of RIUs and developing the workforce to support them has been a primary focus, with rapid innovation in use of technology emerging as a critical adaptation while PPE limitations persist and needs for “medical distancing” continue to grow. Although rates of missed COVID-19 diagnoses will likely be reduced with testing and systems improvements, physicians and systems will also need to consider how to utilize emerging technology in ways that can improve clinical care and provider safety while aiding diagnostic thinking. This survey illustrates the rapid adaptations made by our hospitals in response to the pandemic; ongoing adaptation will likely be needed to optimally care for hospitalized patients with COVID-19 while the pandemic continues to evolve.

Acknowledgment

Thanks to members of the HOMERuN COVID-19 Collaborative Group: Baylor Scott & White Medical Center – Temple, Texas - Tresa McNeal MD; Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center - Shani Herzig MD MPH, Joseph Li MD, Julius Yang MD PhD; Brigham and Women’s Hospital - Christopher Roy MD, Jeffrey Schnipper MD MPH; Cedars-Sinai Medical Center - Ed Seferian MD, ; ChristianaCare - Surekha Bhamidipati MD; Cleveland Clinic - Matthew Pappas MD MPH; Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center - Jonathan Lurie MD MS; Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin - Chris Moriates MD, Luci Leykum MD MBA MSc; Denver Health and Hospitals Authority - Diana Mancini MD; Emory University Hospital - Dan Hunt MD; Johns Hopkins Hospital - Daniel J Brotman MD, Zishan K Siddiqui MD, Shaker Eid MD MBA; Maine Medical Center - Daniel A Meyer MD, Robert Trowbridge MD; Massachusetts General Hospital - Melissa Mattison MD; Mayo Clinic Rochester – Caroline Burton MD, Sagar Dugani MD PhD; Medical College of Wisconsin - Sanjay Bhandari MD; Miriam Hospital - Kwame Dapaah-Afriyie MD MBA; Mount Sinai Hospital - Andrew Dunn MD; NorthShore - David Lovinger MD; Northwestern Memorial Hospital - Kevin O’Leary MD MS; Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center - Eric Schumacher DO; Oregon Health & Science University - Angela Alday MD; Penn Medicine - Ryan Greysen MD MHS MA; Rutgers- Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital - Michael Steinberg MD MPH; Stanford University School of Medicine - Neera Ahuja MD; Tulane Hospital and University Medical Center - Geraldine Ménard MD; UC San Diego Health - Ian Jenkins MD; UC Los Angeles Health - Michael Lazarus MD, Magdalena E. Ptaszny, MD; UC San Francisco Health - Bradley A Sharpe, MD, Margaret Fang MD MPH; UK HealthCare - Mark Williams MD MHM, John Romond MD; University of Chicago – David Meltzer MD PhD, Gregory Ruhnke MD; University of Colorado - Marisha Burden MD; University of Florida - Nila Radhakrishnan MD; University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics - Kevin Glenn MD MS; University of Miami - Efren Manjarrez MD; University of Michigan - Vineet Chopra MD MSc, Valerie Vaughn MD MSc; University of Missouri-Columbia Hospital - Hasan Naqvi MD; University of Nebraska Medical Center - Chad Vokoun MD; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill - David Hemsey MD; University of Pittsburgh Medical Center - Gena Marie Walker MD; University of Vermont Medical Center - Steven Grant MD; University of Washington Medical Center - Christopher Kim MD MBA, Andrew White MD; University of Washington-Harborview Medical Center - Maralyssa Bann MD; University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics - David Sterken MD, Farah Kaiksow MD MPP, Ann Sheehy MD MS, Jordan Kenik MD MPH; UW Northwest Campus - Ben Wolpaw MD; Vanderbilt University Medical Center - Sunil Kripalani MD MSc, Eduard E Vasilevskis MD, Kathleene T Wooldridge MD MPH; Wake Forest Baptist Health - Erik Summers MD; Washington University St. Louis - Michael Lin MD; Weill Cornell - Justin Choi MD; Yale New Haven Hospital - William Cushing MA, Chris Sankey MD; Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital - Sumant Ranji MD.

1. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. COVID-19 Projections: United States of America. 2020. Accessed May 5, 2020. https://covid19.healthdata.org/united-states-of-america

2. Iserson KV. Alternative care sites: an option in disasters. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(3):484‐489. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2020.4.47552

3. Paganini M, Conti A, Weinstein E, Della Corte F, Ragazzoni L. Translating COVID-19 pandemic surge theory to practice in the emergency department: how to expand structure [online first]. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020:1-10. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.57

4. Kumaraiah D, Yip N, Ivascu N, Hill L. Innovative ICU Physician Care Models: Covid-19 Pandemic at NewYork-Presbyterian. NEJM: Catalyst. April 28, 2020. Accessed May 5, 2020. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0158

5. Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay JP, et al. The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-420. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000139

6. Livingston E, Desai A, Berkwits M. Sourcing personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic [online first]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5317

7. Bauchner H, Sharfstein J. A bold response to the COVID-19 pandemic: medical students, national service, and public health [online first]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6166

8. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1679‐1681. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2003539

9. Hau YS, Kim JK, Hur J, Chang MC. How about actively using telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Med Syst. 2020;44(6):108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-020-01580-z

10. Smith WR, Atala AJ, Terlecki RP, Kelly EE, Matthews CA. Implementation guide for rapid integration of an outpatient telemedicine program during the COVID-19 pandemic [online first]. J Am Coll Surg. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.04.030

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in a surge in hospitalizations of patients with a novel, serious, and highly contagious infectious disease for which there is yet no proven treatment. Currently, much of the focus has been on intensive care unit (ICU) and ventilator capacity for the sickest of these patients who develop respiratory failure. However, most hospitalized patients are being cared for in general medical units.1 Some evidence exists to describe adaptations to capacity needs outside of medical wards,2-4 but few studies have specifically addressed the ward setting. Therefore, there is a pressing need for evidence to describe how to expand capacity and deliver medical ward–based care.

To better understand how inpatient care in the United States is adapting to the COVID-19 pandemic, we surveyed 72 sites participating in the Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN), a national consortium of hospital medicine groups.5 We report results of this survey, carried out between April 3 and April 5, 2020.

METHODS

Sites and Subjects

HOMERuN is a collaborative network of hospitalists from across the United States whose primary goal is to catalyze research and share best practices across hospital medicine groups. Using surveys of Hospital Medicine leaders, targeted medical record review, and other methods, HOMERuN’s funded research interests to date have included care transitions, workforce issues, patient and family engagement, and diagnostic errors. Sites participating in HOMERuN sites are relatively large urban academic medical centers (Appendix).

Survey Development and Deployment

We designed a focused survey that aimed to provide a snapshot of evolving operational and clinical aspects of COVID-19 care (Appendix). Domains included COVID-19 testing turnaround times, personal protective equipment (PPE) stewardship,6 features of respiratory isolation units (RIUs; ie, dedicated units for patients with known or suspected COVID-19), and observed effects on clinical care. We tested the instrument to ensure feasibility and clarity internally, performed brief cognitive testing with several hospital medicine leaders in HOMERuN, then disseminated the survey by email on April 3, with two follow-up emails on 2 subsequent days. Our study was deemed non–human subjects research by the University of California, San Francisco, Committee on Human Research. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize survey responses.

RESULTS

Of 72 hospitals surveyed, 51 (71%) responded. Mean hospital bed count was 940, three were safety-net hospitals, and one was a community-based teaching center; responding and nonresponding hospitals did not differ significantly in terms of bed count (Appendix).

Health System Adaptations, Testing, and PPE Status

Nearly all responding hospitals (46 of 51; 90%) had RIUs for patients with known or suspected COVID-19 (Table 1). Nearly all hospitals took steps to keep potentially sick healthcare providers from infecting others (eg, staying home if sick or exposed). Among respondents, 32% had rapid response teams, 24% had respiratory therapy teams, and 29% had case management teams that were dedicated to COVID-19 care. Thirty-two (63%) had developed models, such as ethics or palliative care consult services, to assist with difficult resource-allocation decisions (eg, how to prioritize ventilator use if demand exceeded supply). Twenty-three (45%) had developed post-acute care monitoring programs dedicated to COVID-19 patients.

At the time of our survey, only 2 sites (4%) reported COVID-19 test time turnaround under 1 hour, and 15 (30%) reported turnaround in less than 6 hours. Of the 29 sites able to provide estimates of PPE stockpile, 14 (48%) reported a supply of 2 weeks or less. The most common approaches to PPE stewardship focused on reuse of masks and face shields if not obviously soiled, centralizing PPE distribution, and disinfecting or sterilizing masks. Ten sites (20%) were utilizing 3-D printed masks, while 10% used homemade face shields or masks.

Characteristics of COVID-19 RIUs

Forty-six hospitals (90% of all respondents) in our cohort had developed RIUs at the time of survey administration. The earliest RIU implementation date was February 10, 2020, and the most recent was launched on the day of our survey. Admission to RIUs was primarily based on clinical factors associated with known or suspected COVID-19 infection (Table 2). The number of non–critical care RIU beds among locations at that time ranged from 10 or less to more than 50. The mean number of hospitalist attendings caring for patients in the RIUs was 10.2, with a mean 4.1 advanced practice providers, 5.5 residents, and 0 medical students. The number of planned patients per attending was typically 5 to 15. Nurses and physicians typically rounded separately. Medical distancing (eg, reducing patient room entry) was accomplished most commonly by grouped timing of medication administration (76% of sites), video links to room outside of rounding times (54% of sites), the use of video or telemedicine during rounds (17%), and clustering of activities such as medication administration or phlebotomy. The most common criteria prompting discharge from the RIU were a negative COVID-19 test (59%) and hospital discharge (57%), though comments from many respondents suggested that discharge criteria were changing rapidly.

Effects of Isolation Measures on In-Room Encounters and Diagnostic Processes

More than 90% of sites reported decreases in in-room encounter frequency across all provider types whether as a result of policies in place or not. Reductions were reported among hospitalists, advanced practice providers, residents, consultants, and therapists (Table 3). Reduced room entry most often resulted from an established or developing policy, but many noted reduced room entry without formal policies in place. Nearly all sites reported moving specialty consultations to phone or video evaluations. Diagnostic error was commonly reported, with missed non–COVID-19 medical diagnoses among COVID-19 infected patients being reported by 22 sites (46%) and missed COVID-19 diagnoses in patients admitted for other reasons by 22 sites (45%).

DISCUSSION

In this study of medical wards at academic medical centers, we found that, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals made several changes in a short period of time to adapt to the crisis. These included implementation and rapid expansion of dedicated RIUs, greatly expanded use of inpatient telehealth for patient assessments and consultation, implementation of other approaches to minimize room entry (such as grouping in-room activities), and deployment of ethics consultation services to help manage issues around potential scarcity of life-saving measures such as ventilators. We also found that availability of PPE and timely testing was limited. Finally, a large proportion of sites reported potential diagnostic problems in the assessment of both patients suspected and those not suspected of having COVID-19.

RIUs are emerging as a primary modality for caring for non-ICU COVID-19 patients, though they never involved medical students; we hope the role of students in particular will increase as new models of training emerge in response to the pandemic.7 In contrast, telemedicine evolved rapidly to hold a substantial role in RIUs, with both ward and specialty teams using video visit technology to communicate with patients. COVID-19 has been viewed as a perfect use case for outpatient telemedicine,8 and a growing number of studies are examining its outpatient use9,10; however, to date, somewhat less attention has been paid to inpatient deployment. Although our data suggest telemedicine has found a prominent place in RIUs, it remains to be seen whether it is associated with differences in patient or provider outcomes. For example, deficiencies in the physical examination, limited face-to-face contact, and lack of physical presence could all affect the patient–provider relationship, patient engagement, and the accuracy of the diagnostic process.

Our data suggest the possibility of missing non–COVID-19 diagnoses in patients suspected of COVID-19 and missing COVID-19 in those admitted for nonrespiratory reasons. The latter may be addressed as routine COVID-19 screening of admitted patients becomes commonplace. For the former, however, it is possible that physicians are “anchoring” their thinking on COVID-19 to the exclusion of other diagnoses, that physicians are not fully aware of complications unique to COVID-19 infection (such as thromboembolism), and/or that the above-mentioned limitations of telemedicine have decreased diagnostic performance.

Although PPE stockpile data were not easily available for some sites, a distressingly large number reported stockpiles of 2 weeks or less, with reuse being the most common approach to extending PPE supply. We also found it concerning that 43% of hospital leaders did not know their stockpile data; we believe this is an important question that hospital leaders need to be asking. Most sites in our study reported test turnaround times of longer than 6 hours; lack of rapid COVID-19 testing further stresses PPE stockpile and may slow patients’ transition out of the RIU or discharge to home.

Our study has several limitations, including the evolving nature of the pandemic and rapid adaptations of care systems in the pandemic’s surge phase. However, we attempted to frame our questions in ways that provided a focused snapshot of care. Furthermore, respondents may not have had exhaustive knowledge of their institution’s COVID-19 response strategies, but most were the directors of their hospitalist services, and we encouraged the respondents to confer with others to gather high-fidelity data. Finally, as a survey of large academic medical centers, our results may not apply to nonacademic centers.

Approaches to caring for non-ICU patients during the COVID-19 pandemic are rapidly evolving. Expansion of RIUs and developing the workforce to support them has been a primary focus, with rapid innovation in use of technology emerging as a critical adaptation while PPE limitations persist and needs for “medical distancing” continue to grow. Although rates of missed COVID-19 diagnoses will likely be reduced with testing and systems improvements, physicians and systems will also need to consider how to utilize emerging technology in ways that can improve clinical care and provider safety while aiding diagnostic thinking. This survey illustrates the rapid adaptations made by our hospitals in response to the pandemic; ongoing adaptation will likely be needed to optimally care for hospitalized patients with COVID-19 while the pandemic continues to evolve.

Acknowledgment

Thanks to members of the HOMERuN COVID-19 Collaborative Group: Baylor Scott & White Medical Center – Temple, Texas - Tresa McNeal MD; Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center - Shani Herzig MD MPH, Joseph Li MD, Julius Yang MD PhD; Brigham and Women’s Hospital - Christopher Roy MD, Jeffrey Schnipper MD MPH; Cedars-Sinai Medical Center - Ed Seferian MD, ; ChristianaCare - Surekha Bhamidipati MD; Cleveland Clinic - Matthew Pappas MD MPH; Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center - Jonathan Lurie MD MS; Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin - Chris Moriates MD, Luci Leykum MD MBA MSc; Denver Health and Hospitals Authority - Diana Mancini MD; Emory University Hospital - Dan Hunt MD; Johns Hopkins Hospital - Daniel J Brotman MD, Zishan K Siddiqui MD, Shaker Eid MD MBA; Maine Medical Center - Daniel A Meyer MD, Robert Trowbridge MD; Massachusetts General Hospital - Melissa Mattison MD; Mayo Clinic Rochester – Caroline Burton MD, Sagar Dugani MD PhD; Medical College of Wisconsin - Sanjay Bhandari MD; Miriam Hospital - Kwame Dapaah-Afriyie MD MBA; Mount Sinai Hospital - Andrew Dunn MD; NorthShore - David Lovinger MD; Northwestern Memorial Hospital - Kevin O’Leary MD MS; Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center - Eric Schumacher DO; Oregon Health & Science University - Angela Alday MD; Penn Medicine - Ryan Greysen MD MHS MA; Rutgers- Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital - Michael Steinberg MD MPH; Stanford University School of Medicine - Neera Ahuja MD; Tulane Hospital and University Medical Center - Geraldine Ménard MD; UC San Diego Health - Ian Jenkins MD; UC Los Angeles Health - Michael Lazarus MD, Magdalena E. Ptaszny, MD; UC San Francisco Health - Bradley A Sharpe, MD, Margaret Fang MD MPH; UK HealthCare - Mark Williams MD MHM, John Romond MD; University of Chicago – David Meltzer MD PhD, Gregory Ruhnke MD; University of Colorado - Marisha Burden MD; University of Florida - Nila Radhakrishnan MD; University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics - Kevin Glenn MD MS; University of Miami - Efren Manjarrez MD; University of Michigan - Vineet Chopra MD MSc, Valerie Vaughn MD MSc; University of Missouri-Columbia Hospital - Hasan Naqvi MD; University of Nebraska Medical Center - Chad Vokoun MD; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill - David Hemsey MD; University of Pittsburgh Medical Center - Gena Marie Walker MD; University of Vermont Medical Center - Steven Grant MD; University of Washington Medical Center - Christopher Kim MD MBA, Andrew White MD; University of Washington-Harborview Medical Center - Maralyssa Bann MD; University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics - David Sterken MD, Farah Kaiksow MD MPP, Ann Sheehy MD MS, Jordan Kenik MD MPH; UW Northwest Campus - Ben Wolpaw MD; Vanderbilt University Medical Center - Sunil Kripalani MD MSc, Eduard E Vasilevskis MD, Kathleene T Wooldridge MD MPH; Wake Forest Baptist Health - Erik Summers MD; Washington University St. Louis - Michael Lin MD; Weill Cornell - Justin Choi MD; Yale New Haven Hospital - William Cushing MA, Chris Sankey MD; Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital - Sumant Ranji MD.

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in a surge in hospitalizations of patients with a novel, serious, and highly contagious infectious disease for which there is yet no proven treatment. Currently, much of the focus has been on intensive care unit (ICU) and ventilator capacity for the sickest of these patients who develop respiratory failure. However, most hospitalized patients are being cared for in general medical units.1 Some evidence exists to describe adaptations to capacity needs outside of medical wards,2-4 but few studies have specifically addressed the ward setting. Therefore, there is a pressing need for evidence to describe how to expand capacity and deliver medical ward–based care.

To better understand how inpatient care in the United States is adapting to the COVID-19 pandemic, we surveyed 72 sites participating in the Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN), a national consortium of hospital medicine groups.5 We report results of this survey, carried out between April 3 and April 5, 2020.

METHODS

Sites and Subjects

HOMERuN is a collaborative network of hospitalists from across the United States whose primary goal is to catalyze research and share best practices across hospital medicine groups. Using surveys of Hospital Medicine leaders, targeted medical record review, and other methods, HOMERuN’s funded research interests to date have included care transitions, workforce issues, patient and family engagement, and diagnostic errors. Sites participating in HOMERuN sites are relatively large urban academic medical centers (Appendix).

Survey Development and Deployment

We designed a focused survey that aimed to provide a snapshot of evolving operational and clinical aspects of COVID-19 care (Appendix). Domains included COVID-19 testing turnaround times, personal protective equipment (PPE) stewardship,6 features of respiratory isolation units (RIUs; ie, dedicated units for patients with known or suspected COVID-19), and observed effects on clinical care. We tested the instrument to ensure feasibility and clarity internally, performed brief cognitive testing with several hospital medicine leaders in HOMERuN, then disseminated the survey by email on April 3, with two follow-up emails on 2 subsequent days. Our study was deemed non–human subjects research by the University of California, San Francisco, Committee on Human Research. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize survey responses.

RESULTS

Of 72 hospitals surveyed, 51 (71%) responded. Mean hospital bed count was 940, three were safety-net hospitals, and one was a community-based teaching center; responding and nonresponding hospitals did not differ significantly in terms of bed count (Appendix).

Health System Adaptations, Testing, and PPE Status

Nearly all responding hospitals (46 of 51; 90%) had RIUs for patients with known or suspected COVID-19 (Table 1). Nearly all hospitals took steps to keep potentially sick healthcare providers from infecting others (eg, staying home if sick or exposed). Among respondents, 32% had rapid response teams, 24% had respiratory therapy teams, and 29% had case management teams that were dedicated to COVID-19 care. Thirty-two (63%) had developed models, such as ethics or palliative care consult services, to assist with difficult resource-allocation decisions (eg, how to prioritize ventilator use if demand exceeded supply). Twenty-three (45%) had developed post-acute care monitoring programs dedicated to COVID-19 patients.

At the time of our survey, only 2 sites (4%) reported COVID-19 test time turnaround under 1 hour, and 15 (30%) reported turnaround in less than 6 hours. Of the 29 sites able to provide estimates of PPE stockpile, 14 (48%) reported a supply of 2 weeks or less. The most common approaches to PPE stewardship focused on reuse of masks and face shields if not obviously soiled, centralizing PPE distribution, and disinfecting or sterilizing masks. Ten sites (20%) were utilizing 3-D printed masks, while 10% used homemade face shields or masks.

Characteristics of COVID-19 RIUs

Forty-six hospitals (90% of all respondents) in our cohort had developed RIUs at the time of survey administration. The earliest RIU implementation date was February 10, 2020, and the most recent was launched on the day of our survey. Admission to RIUs was primarily based on clinical factors associated with known or suspected COVID-19 infection (Table 2). The number of non–critical care RIU beds among locations at that time ranged from 10 or less to more than 50. The mean number of hospitalist attendings caring for patients in the RIUs was 10.2, with a mean 4.1 advanced practice providers, 5.5 residents, and 0 medical students. The number of planned patients per attending was typically 5 to 15. Nurses and physicians typically rounded separately. Medical distancing (eg, reducing patient room entry) was accomplished most commonly by grouped timing of medication administration (76% of sites), video links to room outside of rounding times (54% of sites), the use of video or telemedicine during rounds (17%), and clustering of activities such as medication administration or phlebotomy. The most common criteria prompting discharge from the RIU were a negative COVID-19 test (59%) and hospital discharge (57%), though comments from many respondents suggested that discharge criteria were changing rapidly.

Effects of Isolation Measures on In-Room Encounters and Diagnostic Processes

More than 90% of sites reported decreases in in-room encounter frequency across all provider types whether as a result of policies in place or not. Reductions were reported among hospitalists, advanced practice providers, residents, consultants, and therapists (Table 3). Reduced room entry most often resulted from an established or developing policy, but many noted reduced room entry without formal policies in place. Nearly all sites reported moving specialty consultations to phone or video evaluations. Diagnostic error was commonly reported, with missed non–COVID-19 medical diagnoses among COVID-19 infected patients being reported by 22 sites (46%) and missed COVID-19 diagnoses in patients admitted for other reasons by 22 sites (45%).

DISCUSSION

In this study of medical wards at academic medical centers, we found that, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals made several changes in a short period of time to adapt to the crisis. These included implementation and rapid expansion of dedicated RIUs, greatly expanded use of inpatient telehealth for patient assessments and consultation, implementation of other approaches to minimize room entry (such as grouping in-room activities), and deployment of ethics consultation services to help manage issues around potential scarcity of life-saving measures such as ventilators. We also found that availability of PPE and timely testing was limited. Finally, a large proportion of sites reported potential diagnostic problems in the assessment of both patients suspected and those not suspected of having COVID-19.

RIUs are emerging as a primary modality for caring for non-ICU COVID-19 patients, though they never involved medical students; we hope the role of students in particular will increase as new models of training emerge in response to the pandemic.7 In contrast, telemedicine evolved rapidly to hold a substantial role in RIUs, with both ward and specialty teams using video visit technology to communicate with patients. COVID-19 has been viewed as a perfect use case for outpatient telemedicine,8 and a growing number of studies are examining its outpatient use9,10; however, to date, somewhat less attention has been paid to inpatient deployment. Although our data suggest telemedicine has found a prominent place in RIUs, it remains to be seen whether it is associated with differences in patient or provider outcomes. For example, deficiencies in the physical examination, limited face-to-face contact, and lack of physical presence could all affect the patient–provider relationship, patient engagement, and the accuracy of the diagnostic process.

Our data suggest the possibility of missing non–COVID-19 diagnoses in patients suspected of COVID-19 and missing COVID-19 in those admitted for nonrespiratory reasons. The latter may be addressed as routine COVID-19 screening of admitted patients becomes commonplace. For the former, however, it is possible that physicians are “anchoring” their thinking on COVID-19 to the exclusion of other diagnoses, that physicians are not fully aware of complications unique to COVID-19 infection (such as thromboembolism), and/or that the above-mentioned limitations of telemedicine have decreased diagnostic performance.

Although PPE stockpile data were not easily available for some sites, a distressingly large number reported stockpiles of 2 weeks or less, with reuse being the most common approach to extending PPE supply. We also found it concerning that 43% of hospital leaders did not know their stockpile data; we believe this is an important question that hospital leaders need to be asking. Most sites in our study reported test turnaround times of longer than 6 hours; lack of rapid COVID-19 testing further stresses PPE stockpile and may slow patients’ transition out of the RIU or discharge to home.

Our study has several limitations, including the evolving nature of the pandemic and rapid adaptations of care systems in the pandemic’s surge phase. However, we attempted to frame our questions in ways that provided a focused snapshot of care. Furthermore, respondents may not have had exhaustive knowledge of their institution’s COVID-19 response strategies, but most were the directors of their hospitalist services, and we encouraged the respondents to confer with others to gather high-fidelity data. Finally, as a survey of large academic medical centers, our results may not apply to nonacademic centers.

Approaches to caring for non-ICU patients during the COVID-19 pandemic are rapidly evolving. Expansion of RIUs and developing the workforce to support them has been a primary focus, with rapid innovation in use of technology emerging as a critical adaptation while PPE limitations persist and needs for “medical distancing” continue to grow. Although rates of missed COVID-19 diagnoses will likely be reduced with testing and systems improvements, physicians and systems will also need to consider how to utilize emerging technology in ways that can improve clinical care and provider safety while aiding diagnostic thinking. This survey illustrates the rapid adaptations made by our hospitals in response to the pandemic; ongoing adaptation will likely be needed to optimally care for hospitalized patients with COVID-19 while the pandemic continues to evolve.

Acknowledgment

Thanks to members of the HOMERuN COVID-19 Collaborative Group: Baylor Scott & White Medical Center – Temple, Texas - Tresa McNeal MD; Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center - Shani Herzig MD MPH, Joseph Li MD, Julius Yang MD PhD; Brigham and Women’s Hospital - Christopher Roy MD, Jeffrey Schnipper MD MPH; Cedars-Sinai Medical Center - Ed Seferian MD, ; ChristianaCare - Surekha Bhamidipati MD; Cleveland Clinic - Matthew Pappas MD MPH; Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center - Jonathan Lurie MD MS; Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin - Chris Moriates MD, Luci Leykum MD MBA MSc; Denver Health and Hospitals Authority - Diana Mancini MD; Emory University Hospital - Dan Hunt MD; Johns Hopkins Hospital - Daniel J Brotman MD, Zishan K Siddiqui MD, Shaker Eid MD MBA; Maine Medical Center - Daniel A Meyer MD, Robert Trowbridge MD; Massachusetts General Hospital - Melissa Mattison MD; Mayo Clinic Rochester – Caroline Burton MD, Sagar Dugani MD PhD; Medical College of Wisconsin - Sanjay Bhandari MD; Miriam Hospital - Kwame Dapaah-Afriyie MD MBA; Mount Sinai Hospital - Andrew Dunn MD; NorthShore - David Lovinger MD; Northwestern Memorial Hospital - Kevin O’Leary MD MS; Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center - Eric Schumacher DO; Oregon Health & Science University - Angela Alday MD; Penn Medicine - Ryan Greysen MD MHS MA; Rutgers- Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital - Michael Steinberg MD MPH; Stanford University School of Medicine - Neera Ahuja MD; Tulane Hospital and University Medical Center - Geraldine Ménard MD; UC San Diego Health - Ian Jenkins MD; UC Los Angeles Health - Michael Lazarus MD, Magdalena E. Ptaszny, MD; UC San Francisco Health - Bradley A Sharpe, MD, Margaret Fang MD MPH; UK HealthCare - Mark Williams MD MHM, John Romond MD; University of Chicago – David Meltzer MD PhD, Gregory Ruhnke MD; University of Colorado - Marisha Burden MD; University of Florida - Nila Radhakrishnan MD; University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics - Kevin Glenn MD MS; University of Miami - Efren Manjarrez MD; University of Michigan - Vineet Chopra MD MSc, Valerie Vaughn MD MSc; University of Missouri-Columbia Hospital - Hasan Naqvi MD; University of Nebraska Medical Center - Chad Vokoun MD; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill - David Hemsey MD; University of Pittsburgh Medical Center - Gena Marie Walker MD; University of Vermont Medical Center - Steven Grant MD; University of Washington Medical Center - Christopher Kim MD MBA, Andrew White MD; University of Washington-Harborview Medical Center - Maralyssa Bann MD; University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics - David Sterken MD, Farah Kaiksow MD MPP, Ann Sheehy MD MS, Jordan Kenik MD MPH; UW Northwest Campus - Ben Wolpaw MD; Vanderbilt University Medical Center - Sunil Kripalani MD MSc, Eduard E Vasilevskis MD, Kathleene T Wooldridge MD MPH; Wake Forest Baptist Health - Erik Summers MD; Washington University St. Louis - Michael Lin MD; Weill Cornell - Justin Choi MD; Yale New Haven Hospital - William Cushing MA, Chris Sankey MD; Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital - Sumant Ranji MD.

1. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. COVID-19 Projections: United States of America. 2020. Accessed May 5, 2020. https://covid19.healthdata.org/united-states-of-america

2. Iserson KV. Alternative care sites: an option in disasters. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(3):484‐489. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2020.4.47552

3. Paganini M, Conti A, Weinstein E, Della Corte F, Ragazzoni L. Translating COVID-19 pandemic surge theory to practice in the emergency department: how to expand structure [online first]. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020:1-10. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.57

4. Kumaraiah D, Yip N, Ivascu N, Hill L. Innovative ICU Physician Care Models: Covid-19 Pandemic at NewYork-Presbyterian. NEJM: Catalyst. April 28, 2020. Accessed May 5, 2020. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0158

5. Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay JP, et al. The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-420. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000139

6. Livingston E, Desai A, Berkwits M. Sourcing personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic [online first]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5317

7. Bauchner H, Sharfstein J. A bold response to the COVID-19 pandemic: medical students, national service, and public health [online first]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6166

8. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1679‐1681. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2003539

9. Hau YS, Kim JK, Hur J, Chang MC. How about actively using telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Med Syst. 2020;44(6):108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-020-01580-z

10. Smith WR, Atala AJ, Terlecki RP, Kelly EE, Matthews CA. Implementation guide for rapid integration of an outpatient telemedicine program during the COVID-19 pandemic [online first]. J Am Coll Surg. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.04.030

1. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. COVID-19 Projections: United States of America. 2020. Accessed May 5, 2020. https://covid19.healthdata.org/united-states-of-america

2. Iserson KV. Alternative care sites: an option in disasters. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(3):484‐489. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2020.4.47552

3. Paganini M, Conti A, Weinstein E, Della Corte F, Ragazzoni L. Translating COVID-19 pandemic surge theory to practice in the emergency department: how to expand structure [online first]. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020:1-10. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.57

4. Kumaraiah D, Yip N, Ivascu N, Hill L. Innovative ICU Physician Care Models: Covid-19 Pandemic at NewYork-Presbyterian. NEJM: Catalyst. April 28, 2020. Accessed May 5, 2020. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0158

5. Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay JP, et al. The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-420. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000139

6. Livingston E, Desai A, Berkwits M. Sourcing personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic [online first]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5317

7. Bauchner H, Sharfstein J. A bold response to the COVID-19 pandemic: medical students, national service, and public health [online first]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6166

8. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1679‐1681. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2003539

9. Hau YS, Kim JK, Hur J, Chang MC. How about actively using telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Med Syst. 2020;44(6):108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-020-01580-z

10. Smith WR, Atala AJ, Terlecki RP, Kelly EE, Matthews CA. Implementation guide for rapid integration of an outpatient telemedicine program during the COVID-19 pandemic [online first]. J Am Coll Surg. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.04.030

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Developing a Patient- and Family-Centered Research Agenda for Hospital Medicine: The Improving Hospital Outcomes through Patient Engagement (i-HOPE) Study

Thirty-six million people are hospitalized annually in the United States,1 and a significant proportion of these patients are rehospitalized within 30 days.2 Gaps in hospital care are many and well documented, including high rates of adverse events, hospital-acquired conditions, and suboptimal care transitions.3-5 Despite significant efforts to improve the care of hospitalized patients and some incremental improvement in the safety of hospital care, hospital care remains suboptimal.6-9 Importantly, hospitalization remains a challenging and vulnerable time for patients and caregivers.

Despite research efforts to improve hospital care, there remains very little data regarding what patients, caregivers, and other stakeholders believe are the most important priorities for improving hospital care, experiences, and outcomes. Small studies described in brief reports provide limited insights into what aspects of hospital care are most important to patients and to their families.10-13 These small studies suggest that communication and the comfort of caregivers and of patient family members are important priorities, as are the provision of adequate sleeping arrangements, food choices, and psychosocial support. However, the limited nature of these studies precludes the possibility of larger conclusions regarding patient priorities.10-13

The evolution of patient-centered care has led to increasing efforts to engage, and partner, with patients, caregivers, and other stakeholders to obtain their input on healthcare, research, and improvement efforts.14 The guiding principle of this engagement is that patients and their caregivers are uniquely positioned to share their lived experiences of care and that their involvement ensures their voices are represented.15-17 Therefore to obtain greater insight into priority areas from the perspectives of patients, caregivers, and other healthcare stakeholders, we undertook a systematic engagement process to create a patient-partnered and stakeholder-partnered research agenda for improving the care of hospitalized adult patients.

METHODS

Guiding Frameworks for Study Methods

We used two established, validated methods to guide our collaborative, inclusive, and consultative approach to patient and stakeholder engagement and research prioritization:

- The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) standards for formulating patient-centered research questions,18 which includes methods for stakeholder engagement that ensures the representativeness of engaged groups and dissemination of study results.18

- The James Lind Alliance (JLA) approach to “priority setting partnerships,” through which patients, caregivers, and clinicians partner to identify and prioritize unanswered questions.19

The Improving Hospital Outcomes through Patient Engagement (i-HOPE) study included eight stepwise phases to formulate and prioritize a set of patient-centered research questions to improve the care and experiences of hospitalized patients and their families.20 Our process is described below and summarized in Table 1.

Phases of Question Development

Phase 1: Steering Committee Formation

Nine clinical researchers, nine patients and/or caregivers, and two administrators from eight academic and community hospitals from across the United States formed a steering committee to participate in teleconferences every other week to manage all stages of the project including design, implementation, and dissemination. At the time of the project conceptualization, the researchers were a subgroup of the Society of Hospital Medicine Research Committee.21 Patient partners on the steering committee were identified from local patient and family advisory councils (PFACs) of the researchers’ institutions. Patients partners had previously participated in research or improvement initiatives with their hospitalist partners. Patient partners received stipends throughout the project in recognition of their participation and expertise. Included in the committee was a representative from the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM)—our supporting and dissemination partner.

Phase 2: Stakeholder Identification

We created a list of potential stakeholder organizations to participate in the study based on the following:

- Organizations with which SHM has worked on initiatives related to the care of hospitalized adult patients

- Organizations with which steering committee members had worked

- Internet searches of organizations participating in similar PCORI-funded projects and of other professional societies that represented patients or providers who work in hospital or post-acute care settings

- Suggestions from stakeholders identified through the first two approaches as described above

We intended to have a broad representation of stakeholders to ensure diverse perspectives were included in the study. Stakeholder organizations included patient advocacy groups, providers, researchers, payers, policy makers and funding agencies.

Phase 3: Stakeholder Engagement and Awareness Training

Representatives from 39 stakeholder organizations who agreed to participate in the study were further orientated to the study rationale and methods via a series of interactive online webinars. This included reminding organziations that everyone’s input and perspective were valued and that we had a flat organization structure that ensured all stakeholders were equal.

Phase 4: Survey Development and Administration

We chose a survey approach to solicit input on identifying gaps in patient care and to generate research questions. The steering committee developed an online survey collaboratively with stakeholder organization representatives. We used survey pretesting with patient and researcher members from the steering committee. The goal of pretesting was to ensure accessibility and comprehension for all potential respondents, particularly patients and caregivers. The final survey asked respondents to record up to three questions that they thought would improve the care of hospitalized adult patients and their families. The specific wording of the survey is shown in the Figure and the entire survey in Appendix Document 1.

We chose three questions because that is the number of entries per participant that is recommended by JLA; it also minimizes responder burden.19 We asked respondents to identify the stakeholder group they represented (eg, patient, caregiver, healthcare provider, researcher) and for providers to identify where they primarily worked (eg, acute care hospital, post-acute care, advocacy group).

Survey Administration. We administered the survey electronically using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a secure web-based application used for collecting research data.22 Stakeholders were asked to disseminate the survey broadly using whatever methods that they felt was appropriate to their leadership or members.

Phase 5: Initial Question Categorization Using Qualitative Content Analysis

Six members of the steering committee independently performed qualitative content analysis to categorize all submitted questions.23,24 This analytic approach identifies, analyzes, and reports patterns within the data.23,24 We hypothesized that some of the submitted questions would relate to already-known problems with hospitalization. Therefore the steering committee developed an a priori codebook of 48 categories using common systems-based issues and diseases related to the care of hospitalized patients based on the hospitalist core competency topics developed by hospitalists and the SHM Education Committee,25 personal and clinical knowledge and experience related to the care of hospitalized adult patients, and published literature on the topic. These a priori categories and their definitions are shown in Appendix Document 2 and were the basis for our initial theory-driven (deductive) approach to data analysis.23

Once coding began, we identified 32 new and additional categories based on our review of the submitted questions, and these were the basis of our data-driven (inductive) approach to analysis.23 All proposed new codes and definitions were discussed with and approved by the entire steering committee prior to being added to the codebook (Appendix Document 2).

While coding categories were mutually exclusive, multiple codes could be attributed to a question depending on the content and meaning of a question. To ensure methodological rigor, reviewers met regularly via teleconference or communicated via email throughout the analysis to iteratively refine and define coding categories. All questions were reviewed independently, and then discussed, by at least two members of the analysis team. Any coding disparities were discussed and resolved by negotiated consensus.26 Analysis was conducted using Dedoose V8.0.35 (Sociocultural Research Consultants, Los Angeles, California).

Phase 6: Initial Question Identification Using Quantitative Content Analysis

Following thematic categorization, all steering committee members then reviewed each category to identify and quantify the most commonly submitted questions.27 A question was determined to be a commonly submitted question when it appeared at least 10 times.

Phase 7: Interim Priority Setting

We sent the list of the most commonly submitted questions (Appendix Document 3) to stakeholder organizations and patient partner networks for review and evaluation. Each organization was asked to engage with their constituents and leaders to collectively decide on which of these questions resonated and was most important. These preferences would then be used during the in-person meeting (Phase 8). We did not provide stakeholder organizations with information about how many times each question was submitted by respondents because we felt this could potentially bias their decision-making processes such that true importance and relevance would not obtained.

Phase 8: In-person Meeting for Final Question Prioritization and Refinement

Representatives from all 39 participating stakeholder organizations were invited to participate in a 2-day, in-person meeting to create a final prioritized list of questions to be used to guide patient-centered research seeking to improve the care of hospitalized adult patients and their caregivers. This meeting was attended by 43 stakeholders (26 stakeholder organization representatives and 17 steering committee members) from 37 unique stakeholder organizations. To facilitate the inclusiveness and to ensure a consensus-driven process, we used nominal group technique (NGT) to allow all of the meeting participants to discuss the list of prioritized questions in small groups.28 NGT allows participants to comprehend each other’s point of view to ensure no perpsectives are excluded.28 The NGT was followed by two rounds of individual voting. Stakeholders were then asked to frame their discussions and their votes based on the perspectives of their organizations or PFACs that they represent. The voting process required participants to make choices regarding the relative importance of all of the questions, which therefore makes the resulting list a true prioritized list. In the first round of voting, participants voted for up to five questions for inclusion on the prioritized list. Based on the distribution of votes, where one vote equals one point, each of the 36 questions was then ranked in order of the assigned points. The rank-ordering process resulted in a natural cut point or delineated point, resulting in the 11 questions considered to be the highest prioritized questions. Following this, a second round of voting took place with the same parameters as the first round and allowed us to rank order questions by order of importance and priority. Finally, during small and large group discussions, the original text of each question was edited, refined, and reformatted into questions that could drive a research agenda.

Ethical Oversight

This study was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and deemed not to be human subject research (UT Health San Antonio IRB Protocol Number: HSC20170058N).

RESULTS

In total, 499 respondents from 39 unique stakeholder organizations responded to our survey. Respondents self-identified into multiple categorizes resulting in 267 healthcare providers, 244 patients and caregivers, and 63 researchers. Characteristics of respondents to the survey are shown in Table 2.

An overview of study results is shown in Table 1. Respondents submitted a total of 782 questions related to improving the care of hospitalized patients. These questions were categorized during thematic analysis into 70 distinct categories—52 that were health system related and 18 that were disease specific (Appendix 2). The most frequently used health system–related categories were related to discharge care transitions, medications, patient understanding, and patient-family-care team communication (Appendix 2).

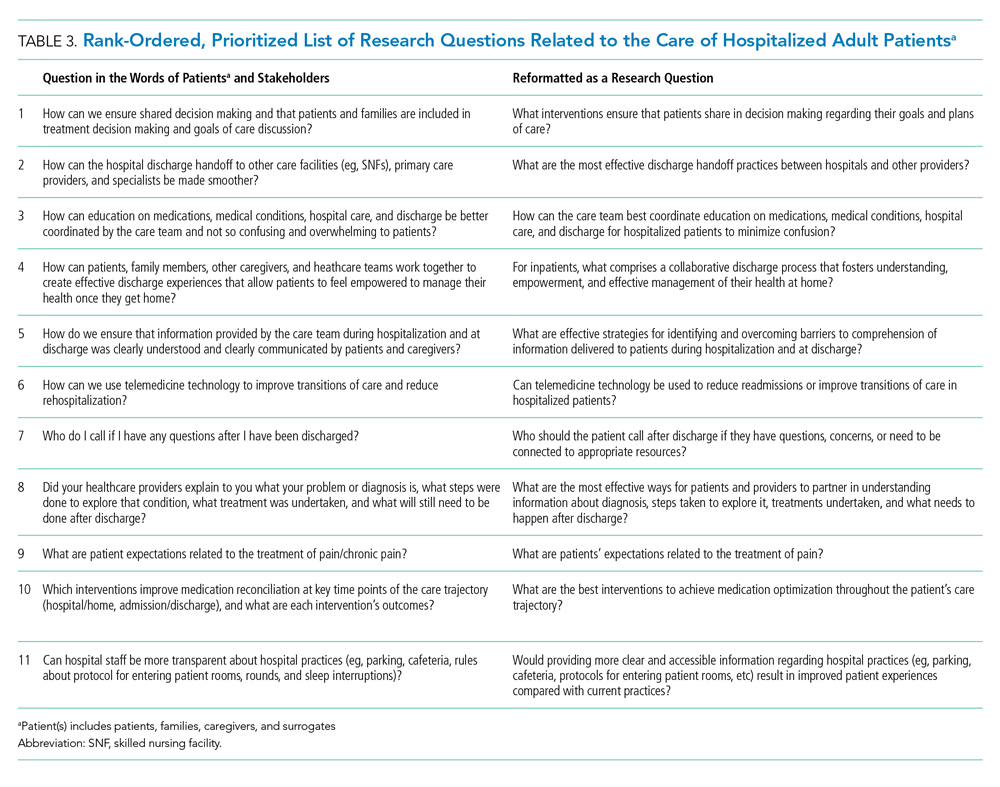

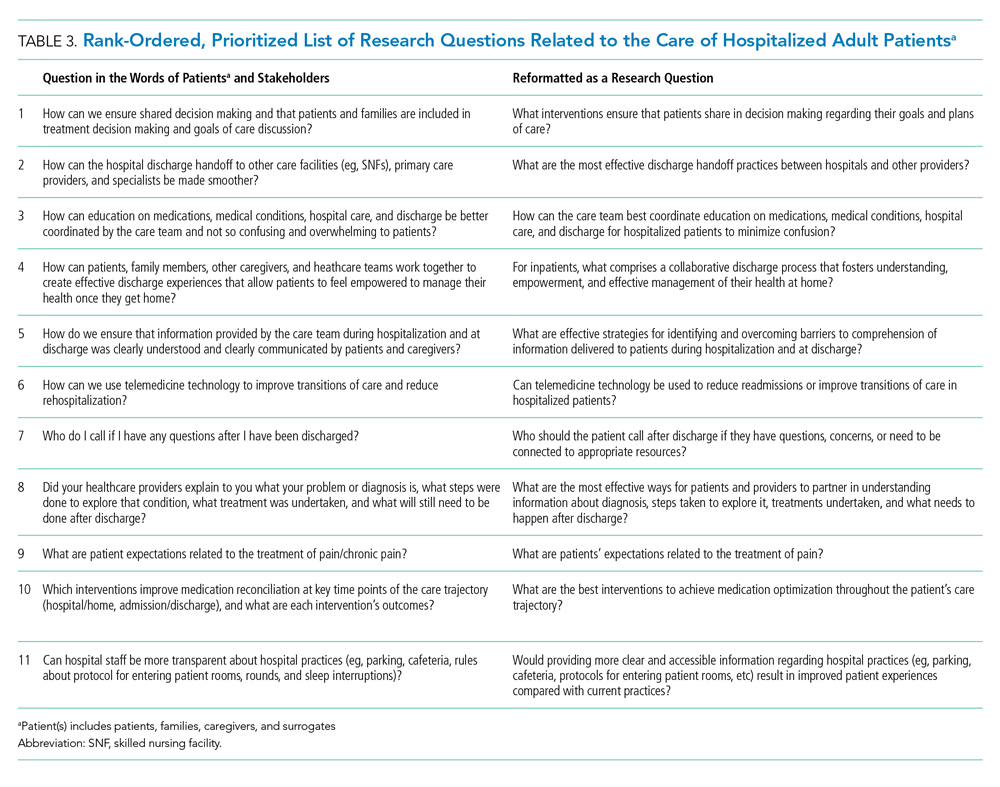

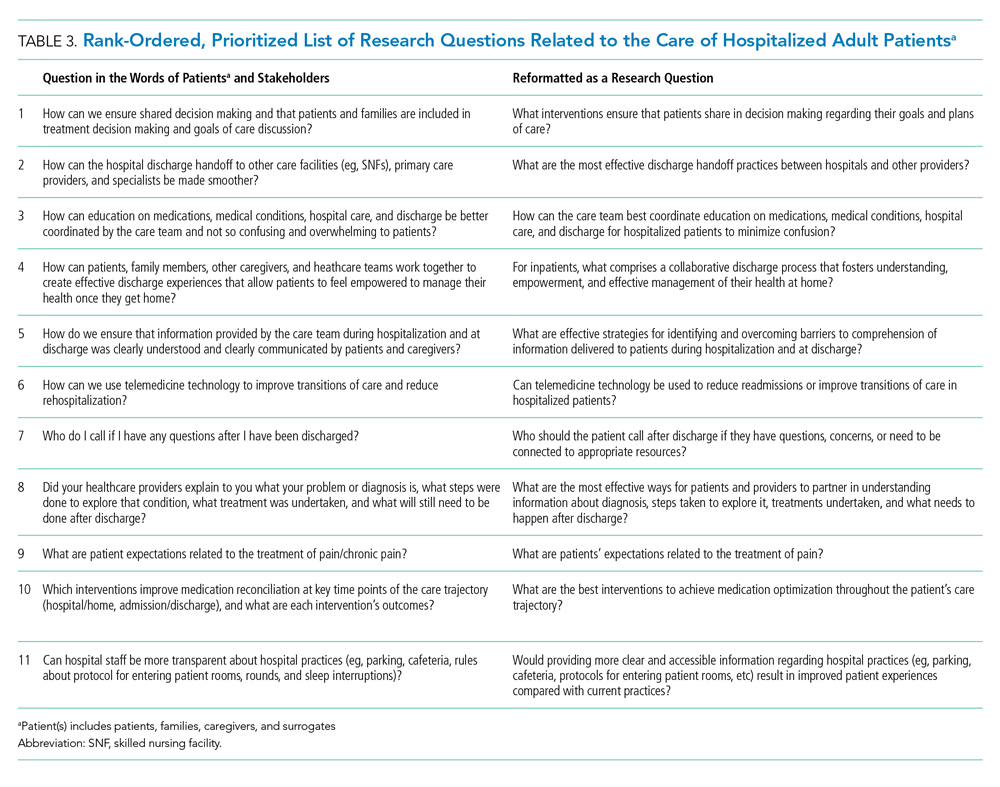

From these categories, 36 questions met our criteria for “commonly identified,” ie, submitted at least 10 times (Appendix Document 3). Notably, these 36 questions were derived from 67 different coding categories, of which 24 (36%) were a priori (theory-driven) categories23 created by the Steering Committee before analysis began and 43 (64%) categories were created as a result of this study’s stakeholder-engaged process and a data-driven approach23 to analysis (Appendix Document 3). These groups of questions were then presented during the 2-day, in-person meeting and reduced to a final 11 questions that were identified in rank order as top priorities (Table 3). The questions considered highest priority related to ensuring shared treatment and goals of care decision making, improving hospital discharge handoff to other care facilities and providers, and reducing the confusion related to education on medications, conditions, hospital care, and discharge.

DISCUSSION

Using a dynamic and collaborative stakeholder engagement process, we identified 11 questions prioritized in order of importance by patients, caregivers, and other healthcare stakeholders to improve the care of hospitalized adult patients. While some of the topics identified are already well-known topics in need of research and improvement, our findings frame these topics according to the perspectives of patients, caregivers, and stakeholders. This unique perspective adds a level of richness and nuance that provides insight into how to better address these topics and ultimately inform research and quality improvement efforts.

The question considered to be the highest priority area for future research and improvement surmised how it may be possible to implement interventions that engage patients in shared decision making. Shared decision making involves patients and their care team working together to make decisions about treatment, and other aspects of care based on sound clinical evidence that balances the risks and outcomes with patient preferences and values. Although considered critically important,29 a recent evaluation of shared decision making practices in over 250 inpatient encounters identified significant gaps in physicians’ abilities to perform key elements of a shared decision making approach and reinforced the need to identify what strategies can best promote widespread shared decision making.30 While there has been considerable effort to faciliate shared decision making in practice, there remains mixed evidence regarding the sustainability and impact of tools seeking to support shared decision making, such as decision aids, question prompt lists, and coaches.31 This suggests that new approaches to shared decision making may be required and likely explains why this question was rated as a top priority by stakeholders in the current study.

Respondents frequently framed their questions in terms of their lived experiences, providing stories and scenarios to illustrate the importance of the questions they submitted. This personal framing highlighted to us the need to think about improving care delivery from the end-user perspective. For example, respondents framed questions about care transitions not with regard to early appointments, instructions, or medication lists, but rather in terms of whom to call with questions or how best to reach their physician, nurse, or other identified provider. These perspectives suggest that strategies and approaches to improvement that start with patient and caregiver experiences, such as design thinking,32 may be important to continued efforts to improve hospital care. Additionally, the focus on the interpersonal aspects of care delivery highlights the need to focus on the patient-provider relationship and communication.

Questions submitted by respondents demonstrated a stark difference between “patient education” and “patient understanding,” which suggests that being provided with education or education materials regarding care did not necessarily lead to a clear patient understanding. The potential for lack of understanding was particularly prominent in the context of care plan development and during times of care transition—topics that were encompassed in 9 out of 11 of our prioritized research questions. This may suggest that approaches that improve the ability for healthcare providers to deliver information may not be sufficient to meet the needs of patients and caregivers. Rather, partnering to develop a shared understanding—whether about prognosis, medications, hospital, or discharge care plans—is critical. Improved communication practices are not an endpoint for information delivery, but rather a starting point leading to a shared understanding.

Several of the priority areas identified in our study reflect the immensely complex intersections among patients, caregivers, clinicians, and the healthcare delivery system. Addressing these gaps in order to reach the goal of ideal hospital care and an improved patient experience will likely require coordinated approaches and strong involvement and buy-in from multiple stakeholders including the voices of patients and caregivers. Creating patient-centered and stakeholder-driven research has been an increasing priority nationally.33 Yet to realize this, we must continue to understand the foundations and best practices of authentic stakeholder engagement so that it can be achieved in practice.34 We intend for this prioritized list of questions to galvanize funders, researchers, clinicians, professional societies, and patient and caregiver advocacy groups to work together to address these topics through the creation of new research evidence or the sustainable implementation of existing evidence.

Our findings provide a foundation for stakeholder groups to work in partnership to find research and improvement solutions to the problems identified. Our efforts demonstrate the value and importance of a systematic and broad engagement process to ensure that the voices of patients, caregivers, and other healthcare stakeholders are included in guiding hospital research and quality improvement efforts. This is highlighted by the fact our results of prioritized category areas for research were largely only uncovered following the creation of coding categories during the analysis process and were not captured using a priori catgeories that were expected by the steering committee.

The strengths of this study include our attempts to systematically identify and engage a wide range of perspectives in hospital medicine, including perspectives from patients and their caregivers. There are also acknowledged limitations in our study. While we included patients and PFACs from across the country, the opinions of the people we included may not be representative of all patients. Similarly, the perspectives of the other participants may not have completely represented their stakeholder organizations. While we attempted to include a broad range of organizations, there may be other relevant groups who were not represented in our sample.

In summary, our findings provide direction for the multiple stakeholders involved in improving hospital care. The results will allow the research community to focus on questions that are most important to patients, caregivers, and other stakeholders, reframing them in ways that are more relevant to patients’ lived experiences and that reflect the complexity of the issues. Our findings can also be used by healthcare providers and delivery organizations to target local improvement efforts. We hope that patients and caregivers will use our results to advocate for research and improvement in areas that matter the most to them. We hope that policy makers and funding agencies use our results to promote work in these areas and drive a national conversation about how to most effectively improve hospital care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all patients, caregivers, and stakeholders who completed the survey. The authors also would like to acknowledge the organizations and individuals who participated in this study (see Appendix Document 4 for full list). At SHM, the authors would like to specifically thank Claudia Stahl, Jenna Goldstein, Kevin Vuernick, Dr Brad Sharpe, and Dr Larry Wellikson for their support.

Disclaimer

The statements presented in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee.

1. American Hospital Association. 2019 American Hospital Association Hospital Statistics. Chicago, Illinois: American Hospital Association; 2019.

2. Alper E, O’Malley T, Greenwald J. UptoDate: Hospital discharge and readmission. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/hospital-discharge-and-readmission. Accessed August 8, 2019.

3. de Vries EN, Ramrattan MA, Smorenburg SM, Gouma DJ, Boermeester MA. The incidence and nature of in-hospital adverse events: a systematic review. Qual Saf Heal Care. 2008;17(3):216-223. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2007.023622.

4. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Readmissions and Adverse Events After Discharge. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/11/Readmissions-and-Adverse-Events-After-Discharge. Accessed August 8, 2019.

5. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC; National Academies Press; 2001. https://doi.org/10.17226/10027.

6. Trivedi AN, Nsa W, Hausmann LRM, et al. Quality and equity of care in U.S. hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(24):2298-2308. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1405003.

7. National Patient Safety Foundation. Free from Harm: Accelerating Patient Safety Improvement Fifteen Years after To Err Is Human. Boston: National Patient Safety Foundation; 2015.

8. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ National Scorecard on Hospital-Acquired Conditions Updated Baseline Rates and Preliminary Results 2014–2017. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/quality-patient-safety/pfp/hacreport-2019.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2019.

9. Hansen LO, Greenwald JL, Budnitz T, et al. Project BOOST: effectiveness of a multihospital effort to reduce rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(8):421-427. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2054.

10. Snyder HJ, Fletcher KE. The hospital experience through the patients’ eyes. J Patient Exp. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/2374373519843056.

11. Kebede S, Shihab HM, Berger ZD, Shah NG, Yeh H-C, Brotman DJ. Patients’ understanding of their hospitalizations and association with satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1698-1700. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3765.

12. Shoeb M, Merel SE, Jackson MB, Anawalt BD. “Can we just stop and talk?” patients value verbal communication about discharge care plans. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(6):504-507. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1937.

13. Neeman N, Quinn K, Shoeb M, Mourad M, Sehgal NL, Sliwka D. Postdischarge focus groups to improve the hospital experience. Am J Med Qual. 2013;28(6):536-538. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860613488623.

14. Duffett L. Patient engagement: what partnering with patients in research is all about. Thromb Res. 2017;150:113-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2016.10.029.

15. Pomey M, Hihat H, Khalifa M, Lebel P, Neron A, Dumez V. Patient partnership in quality improvement of healthcare services: patients’ inputs and challenges faced. Patient Exp J. 2015;2:29-42. https://doi.org/10.35680/2372-0247.1064.

16. Robbins M, Tufte J, Hsu C. Learning to “swim” with the experts: experiences of two patient co-investigators for a project funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Perm J. 2016;20(2):85-88. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/15-162.

17. Tai-Seale M, Sullivan G, Cheney A, Thomas K, Frosch D. The language of engagement: “aha!” moments from engaging patients and community partners in two pilot projects of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Perm J. 2016;20(2):89-92. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/15-123.

18. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). PCORI Methodology Standards: Standards for Formulating Research Questions. https://www.pcori.org/research-results/about-our-research/research-methodology/pcori-methodology-standards#Formulating Research Questions. Accessed August 8, 2019.

19. James Lind Alliance. The James Lind Alliance Guidebook. Version 8. Southampton, England: James Lind Alliance; 2018.

20. Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM). Improving Hospital Outcomes through Patient Engagement: The i-HOPE Study. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/clinical-topics/i-hope-study/. Accessed August 8, 2019.

21. Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM). Committees. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/membership/committees/. Accessed August 8, 2019.

22. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) - a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

23. Schreier M. Qualitative content analysis in practice. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications; 2012.

24. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107-115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x.

25. Nichani S, Crocker J, Fitterman N, Lukela M. Updating the core competencies in hospital medicine—2017 revision: introduction and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(4):283-287. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2715.

26. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758-1772. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x.

27. Coe K, Scacco JM. Content analysis, quantitative. Int Encycl Commun Res Methods. 2017:1-11. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118901731.iecrm0045.

28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evaluation Briefs: Gaining Consensus Among Stakeholders Through the Nominal Group Technique. Atlanta, GA; 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/evaluation/pdf/brief7.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2019.

29. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(5):681-692. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3.

30. Blankenburg R, Hilton JF, Yuan P, et al. Shared decision-making during inpatient rounds: opportunities for improvement in patient engagement and communication. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(7):453-461. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2909.

31. Legare F, Adekpedjou R, Stacey D, et al. Interventions for increasing the use of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7):CD006732. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub4.

32. Roberts JP, Fisher TR, Trowbridge MJ, Bent C. A design thinking framework for healthcare management and innovation. Healthc (Amst). 2016;4(1):11-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.12.002.

33. Selby JV, Beal AC, Frank L. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) national priorities for research and initial research agenda. JAMA. 2012;307(15):1583-1584. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.500.

34. Harrison J, Auerbach A, Anderson W, et al. Patient stakeholder engagement in research: a narrative review to describe foundational principles and best practice activities. Health Expect. 2019;22(3):307-316. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12873.

Thirty-six million people are hospitalized annually in the United States,1 and a significant proportion of these patients are rehospitalized within 30 days.2 Gaps in hospital care are many and well documented, including high rates of adverse events, hospital-acquired conditions, and suboptimal care transitions.3-5 Despite significant efforts to improve the care of hospitalized patients and some incremental improvement in the safety of hospital care, hospital care remains suboptimal.6-9 Importantly, hospitalization remains a challenging and vulnerable time for patients and caregivers.

Despite research efforts to improve hospital care, there remains very little data regarding what patients, caregivers, and other stakeholders believe are the most important priorities for improving hospital care, experiences, and outcomes. Small studies described in brief reports provide limited insights into what aspects of hospital care are most important to patients and to their families.10-13 These small studies suggest that communication and the comfort of caregivers and of patient family members are important priorities, as are the provision of adequate sleeping arrangements, food choices, and psychosocial support. However, the limited nature of these studies precludes the possibility of larger conclusions regarding patient priorities.10-13

The evolution of patient-centered care has led to increasing efforts to engage, and partner, with patients, caregivers, and other stakeholders to obtain their input on healthcare, research, and improvement efforts.14 The guiding principle of this engagement is that patients and their caregivers are uniquely positioned to share their lived experiences of care and that their involvement ensures their voices are represented.15-17 Therefore to obtain greater insight into priority areas from the perspectives of patients, caregivers, and other healthcare stakeholders, we undertook a systematic engagement process to create a patient-partnered and stakeholder-partnered research agenda for improving the care of hospitalized adult patients.

METHODS

Guiding Frameworks for Study Methods