User login

Research and Reviews for the Practicing Oncologist

Two cases of possible remission in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) has been shown to generally have a poor prognosis. Within the first 3-5 years of diagnosis, the mortality rate is the highest of all the subtypes of breast cancer, although late relapses are less common.1,2 TNBC is markedly heterogeneous tumor, and the individual prognosis can vary widely.1,3 Metastatic TNBC is generally considered a noncurable disease. The median time from recurrence to death for metastatic disease is about 9 months, compared with 20 months for patients with other subtypes of breast cancers.4,5 The median survival time for patients with metastatic TNBC is about 13 months.3

New targeted therapies are emerging for breast cancer, but there are currently no effective targeted therapies for patients with TNBC. In addition, few reports in the literature that discuss long-term complete remissions in patients who have metastatic TNBC. Here, we describe two cases in which patients with metastatic TNBC achieved sustained complete response on conventional chemotherapy regimens.

Case presentations and summaries

Case 1

A 59-year-old woman (age in 2015) had been diagnosed on biopsy in February 2005 with locally advanced right breast cancer (stage T2N2bM0). She underwent lumpectomy, and the results of her pathology tests revealed a triple-negative invasive ductal carcinoma. She was started on 4 cycles of neoadjuvant doxorubicin (60 mg/m2 IV) and cyclophosphamide (600 mg/m2 IV)

In November 2007, the patient was found to have right chest wall metastasis confirmed by ultrasound-guided needle biopsy, and underwent right-side chest wall and partial sternum resection. In May 2008, she had recurrence in the left axilla, and biopsy results showed that she had TNBC disease. She was started on weekly paclitaxel (90 mg/m2) and bevacizumab (10 mg/kg every 2 weeks) continued until July 2008. Chemotherapy was stopped in July 2008 because of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection of the chest wall and was not resumed after the infection had resolved.

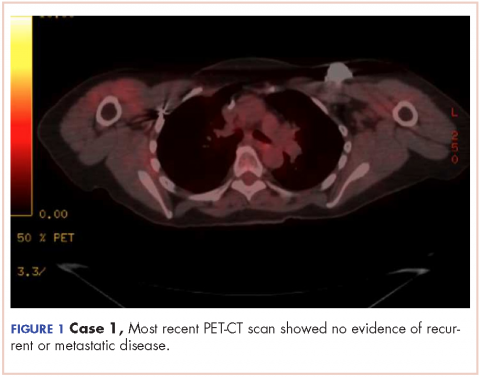

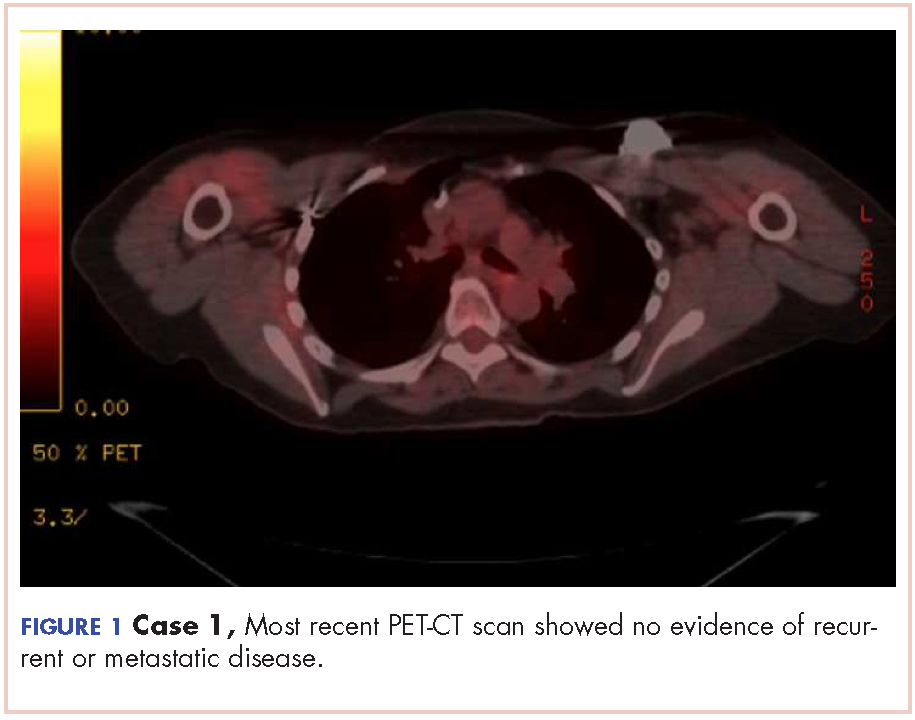

A follow-up positron-emission tomography– computed tomography (PET-CT) scan in June 2009, showed no evidence of disease and the scan was negative for disease in her left axilla. Another PET scan about a year later, in September 2010, was also negative for any disease recurrence.

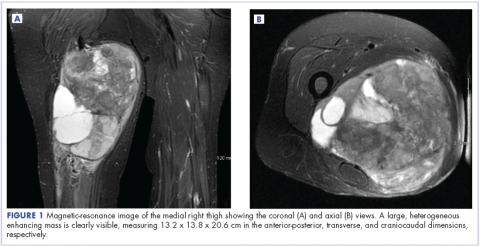

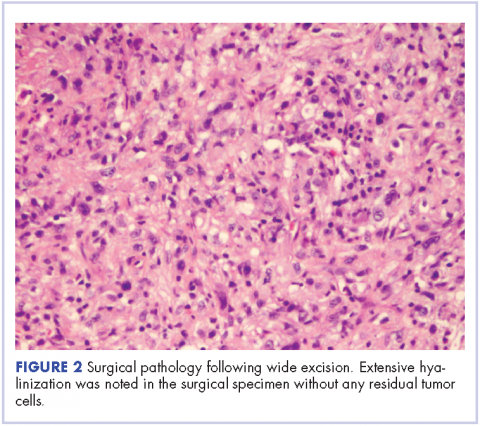

The patient has continued her follow-up with physical examinations and imaging scans. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis (December 2010), an MRI of the breasts (February 2011, August 2015), and a PET-CT scan (April 2015, Figure 1) were all negative for any evidence of disease. In September 2011, she had a CT-guided biopsy of a medial right clavicle and costal junction lesion; and in November 2011 and January 2013, surgical biopsies of the right chest wall and first rib lesions, all negative for any evidence for malignancy. At her last follow-up in January 2017, the patient remained in remission.

Case 2

A 68-year old woman (age in 2015) had been diagnosed in Russia in 2004 with infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the right breast (T4N1M0; receptor status unknown at that time). She underwent a right modified radical mastectomy and received adjuvant chemotherapy with 4 cycles of cyclophosphamide (100 mg/m2 day 1 to day 14), methotrexate (40 mg/m2 IV day 1 and day 8), and fluorouracil (600 mg/m2 IV, day 1 and day 8) followed by 2 cycles of docetaxel (75 mg/m2 IV) and anthracycline adriyamycin (50 mg/m2 IV). The patient later received radiation therapy (radiation dose not known, treatment was received in Russia), and completed her treatment in November 2004.

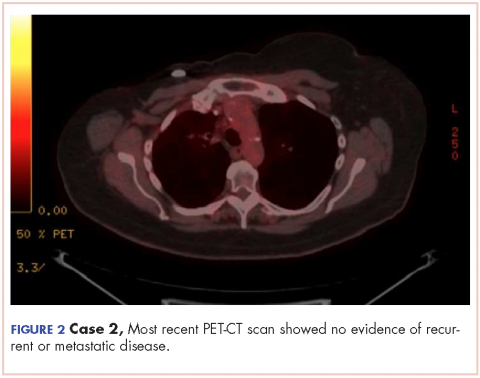

The patient moved to the United States and was started on 25 mg daily exemestane in February 2005. In March 2009, she was diagnosed by biopsy to have recurrence in her internal mammary and hilar lymph nodes and sternum. The cancer was found to be ER- and PR-negative and HER2-neu–negative. The patient was treated with radiation therapy (37.5 Gy in 15 fractions) to sternum and hilar and internal mammary lymph nodes with improvement in pain and shrinkage of lymph nodes size. In May 2009, she was started on 1,500 mg oral twice a day capecitabine (3 cycles). The therapy was started after completion of radiation treatment due to progression of disease. She developed hand-and-foot syndrome as side effect of the capecitabine, so the dose was reduced. She was switched to gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15, every 28-day cycle) as a single-agent therapy and completed 3 cycles. A follow-up PET-CT scan in February 2010 showed no evidence of disease.

In May 2010, the patient had a recurrence in the same metastatic foci as before, and she was again started on gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15, every 28-day cycle). She continued gemcitabine until there was evidence of disease progression on a PET-CT scan in October 2010, which showed new areas of disease in the left parasternal region, left sternum, prevascular mediastinal nodes, and left supraclavicular, hilar and axillary adenopathy, and fourth thoracic vertebra. Gemcitabine was discontinued and patient was started on weekly paclitaxel (90 mg/m2) for 6 cycles. Paclitaxel was discontinued after 6 weeks because she developed a drug-related rash. A follow-up PET-CT scan in December 2010 again showed complete resolution of disease in terms of response.

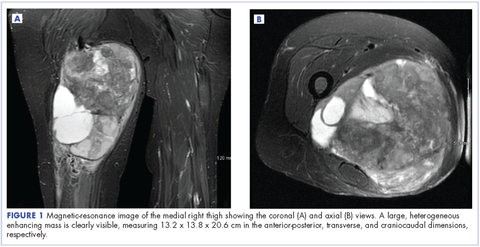

In March 2011, PET imaging showed progression of disease in the left chest wall and axillary lymph nodes, so the patient was started on eribulin therapy (1.4 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 every 21-day cycle) and completed 3 cycles. In May 2011, PET imaging showed complete response to treatment with no evidence of recurrent or metastatic disease. The patient has not had chemotherapy since November 2011, and surveillance PET imaging has not demonstrated any recurrence of disease (Figure 2). Following her last follow-up in November 2016, the patient remains in remission.

Discussion

Triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs) are defined as tumors that lack expression of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2, and represent about 12%-17% of breast cancer cases.1,6 TNBCs tend to be larger in size at diagnosis than are other subtypes, are usually high-grade (poorly differentiated), and are more likely to be invasive ductal carcinomas.1,7 TNBC and the basal-like breast cancers as a group are associated with an adverse prognosis.1,7 There is no standard preferred chemotherapy and no biologic therapy available for TNBC.1,6-7 A sharp decline in survival outcome during the first 3-5 years after diagnosis initial is observed in TNBC, although the distant relapses after this time are less common.1 Beyond 10 years from diagnosis, the relapses are seen more common among patients with ER-positive cancers than among those with ER-negative subtype cancers. Therefore, although TNBCs are biologically aggressive, many are possibly curable, and this reflects their interesting characteristic heterogeneity.1,6

Chemotherapy is currently the mainstay of systemic medical treatment. Although patients with TNBC have a worse outcome after chemotherapy than patients with breast cancers of other subtypes, it still improves their outcome to a greater extent than in patients with ER-positive subtypes.1,6,7 Considering the heterogeneity of TNBC, it is difficult to predict which patients will benefit more from chemotherapy. The same has been observed in previous studies when subgroups of women with TNBC were extremely sensitive to chemotherapy, whereas in others it was of uncertain benefit.1

Currently, there is no preferred standard form of chemotherapy for TNBC. There are few case reports that demonstrate long-term survival and complete remission in metastatic TNBC. Shakir has reported on a significant clinical response to nab-paclitaxel monotherapy in a patient with triple-negative BRCA1-positive breast cancer, although patient survived a little more than 5 years and died with central nervous system recurrence.8 Montero and Gluck have described a patient with metastatic TNBC who was treated with nab-paclitaxel, gemcitabine, and bevacizumab and who also survived for 5 years after diagnosis.9 Different retrospective analyses have suggested that the addition of docetaxel or paclitaxel to anthracycline-containing adjuvant regimens may be of greater benefit for the treatment of TNBC than for ER-positive tumors.10 A meta-analysis of trials comparing the effects of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF, which was used in Case 2) with anthracycline-containing regimens has suggested that the latter therapy regimen is more effective against TNBC,11 although another retrospective analysis of a separate trial suggested the opposite for basal-like breast cancers. 12 The authors of the latter analysis concluded that anthracycline-containing adjuvant chemotherapy regimens are inferior to adjuvant CMF in women with basal breast cancer.12

Miller and colleagues have shown that the addition of bevacizumab (angiogenesis inhibitor) to paclitaxel (used in Case 1) improved progression-free survival (median PFS, 11.8 vs 5.9 months; hazard ratio [HR] for progression, 0.60; P < .001) in women with TNBC as it did in the overall study group (HR, 0.53 and 0.60, respectively), although the overall survival rate was similar in the two groups (median OS, 26.7 vs 25.2 months; HR, 0.88; P = .16).13

An interesting clinical target in TNBC is the enzyme poly (adenosine diphosphate– ribose) polymerase (PARP), which is involved in base-excision repair after DNA damage. PARP inhibitors have shown encouraging clinical activity in trials of tumors arising in BRCA mutation carriers and in sporadic TNBC cancers.14 Similarly, the use of an oral PARP inhibitor, olaparib, resulted in tumor regression in up to 41% of patients carrying BRCA mutations, most of whom had TNBC.15

Conclusion

TNBC and basal-like breast cancers show aggressive clinical behavior, but a subgroup of these cancers may be markedly sensitive to chemotherapy and associated with a good prognosis when treated with conventional chemotherapy regimens. The two cases presented here show that some patients can get a prolonged disease control from chemotherapy, even after progressing on multiple previous chemotherapy regimens and that after, 5 years or so, these rare patients could be in true long-term remission. Novel approaches, for example PARP inhibitors, have shown encouraging clinical activity in trials of tumors arising in BRCA mutation carriers and as well as sporadic TNBC.

1. Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS, Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1938-1948.

2. Pogoda K, Niwińska A, Murawska M, Pieńkowski T. Analysis of pattern, time and risk factors influencing recurrence in triple-negative breast cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2013;30(1):388.

3. Kassam F, Enright K, Dent R, et al. Survival outcomes for patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: implications for clinical practice and trial design. Clin Breast Cancer. 2009;9(1):29-33.

4. Perou CM. Molecular stratification of triple-negative breast cancers. Oncologist. 2010;15(suppl 5):39-48.

5. Rakha EA, Chan S. Metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2011;23(9):587-600.

6. Williams N, Harris L. Triple-negative breast cancer in the post-genomic era. Oncology (Williston Park). 2013;27(9):859-860, 864.

7. Randhawa SK, Venur VA, Kawsar H, et al. A retrospective comparison of the characteristics and recurrence outcome of triple-negative and triple-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl; abstr 1038).

8. Shakir AR. Strong and sustained response to treatment with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel in a patient with metastatic, triple-negative, BRCA1-positive breast cancer. Case Rep Oncol. 2014;7(1)252-259.

9. Montero A, Glück S. Long-term complete remission with nab-paclitaxel, bevacizumab, and gemcitabine combination therapy in a patient with triple-negative metastatic breast cancer. Case Rep Oncol. 2012;5(3):687-692.

10. Hayes DF, Thor AD, Dressler LG, et al. HER2 and response to paclitaxel in node-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1496-1506.

11. Di Leo A, Isola J, Piette F, et al. A meta- analysis of phase III trials evaluating the predictive value of HER2 and topoisomerase alpha in early breast cancer patients treated with CMF or anthracycline-based adjuvant therapy [SABCS, abstract 705]. http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/69/2_Supplement/705. Published 2008. Accessed May 4, 2017.

12. Cheang M, Chia SK, Tu D, et al. Anthracycline in basal breast cancer: the NCIC-CTG trial MA5 comparing adjuvant CMF to CEF [ASCO; abstract 519]. http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/35150-65. Published 2009. Accessed May 4, 2017.

13. Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, et al. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2666-2676.

14. Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:123-134.

15. Tutt A, Robson M, Garber JE, et al. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376:235-244.

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) has been shown to generally have a poor prognosis. Within the first 3-5 years of diagnosis, the mortality rate is the highest of all the subtypes of breast cancer, although late relapses are less common.1,2 TNBC is markedly heterogeneous tumor, and the individual prognosis can vary widely.1,3 Metastatic TNBC is generally considered a noncurable disease. The median time from recurrence to death for metastatic disease is about 9 months, compared with 20 months for patients with other subtypes of breast cancers.4,5 The median survival time for patients with metastatic TNBC is about 13 months.3

New targeted therapies are emerging for breast cancer, but there are currently no effective targeted therapies for patients with TNBC. In addition, few reports in the literature that discuss long-term complete remissions in patients who have metastatic TNBC. Here, we describe two cases in which patients with metastatic TNBC achieved sustained complete response on conventional chemotherapy regimens.

Case presentations and summaries

Case 1

A 59-year-old woman (age in 2015) had been diagnosed on biopsy in February 2005 with locally advanced right breast cancer (stage T2N2bM0). She underwent lumpectomy, and the results of her pathology tests revealed a triple-negative invasive ductal carcinoma. She was started on 4 cycles of neoadjuvant doxorubicin (60 mg/m2 IV) and cyclophosphamide (600 mg/m2 IV)

In November 2007, the patient was found to have right chest wall metastasis confirmed by ultrasound-guided needle biopsy, and underwent right-side chest wall and partial sternum resection. In May 2008, she had recurrence in the left axilla, and biopsy results showed that she had TNBC disease. She was started on weekly paclitaxel (90 mg/m2) and bevacizumab (10 mg/kg every 2 weeks) continued until July 2008. Chemotherapy was stopped in July 2008 because of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection of the chest wall and was not resumed after the infection had resolved.

A follow-up positron-emission tomography– computed tomography (PET-CT) scan in June 2009, showed no evidence of disease and the scan was negative for disease in her left axilla. Another PET scan about a year later, in September 2010, was also negative for any disease recurrence.

The patient has continued her follow-up with physical examinations and imaging scans. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis (December 2010), an MRI of the breasts (February 2011, August 2015), and a PET-CT scan (April 2015, Figure 1) were all negative for any evidence of disease. In September 2011, she had a CT-guided biopsy of a medial right clavicle and costal junction lesion; and in November 2011 and January 2013, surgical biopsies of the right chest wall and first rib lesions, all negative for any evidence for malignancy. At her last follow-up in January 2017, the patient remained in remission.

Case 2

A 68-year old woman (age in 2015) had been diagnosed in Russia in 2004 with infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the right breast (T4N1M0; receptor status unknown at that time). She underwent a right modified radical mastectomy and received adjuvant chemotherapy with 4 cycles of cyclophosphamide (100 mg/m2 day 1 to day 14), methotrexate (40 mg/m2 IV day 1 and day 8), and fluorouracil (600 mg/m2 IV, day 1 and day 8) followed by 2 cycles of docetaxel (75 mg/m2 IV) and anthracycline adriyamycin (50 mg/m2 IV). The patient later received radiation therapy (radiation dose not known, treatment was received in Russia), and completed her treatment in November 2004.

The patient moved to the United States and was started on 25 mg daily exemestane in February 2005. In March 2009, she was diagnosed by biopsy to have recurrence in her internal mammary and hilar lymph nodes and sternum. The cancer was found to be ER- and PR-negative and HER2-neu–negative. The patient was treated with radiation therapy (37.5 Gy in 15 fractions) to sternum and hilar and internal mammary lymph nodes with improvement in pain and shrinkage of lymph nodes size. In May 2009, she was started on 1,500 mg oral twice a day capecitabine (3 cycles). The therapy was started after completion of radiation treatment due to progression of disease. She developed hand-and-foot syndrome as side effect of the capecitabine, so the dose was reduced. She was switched to gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15, every 28-day cycle) as a single-agent therapy and completed 3 cycles. A follow-up PET-CT scan in February 2010 showed no evidence of disease.

In May 2010, the patient had a recurrence in the same metastatic foci as before, and she was again started on gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15, every 28-day cycle). She continued gemcitabine until there was evidence of disease progression on a PET-CT scan in October 2010, which showed new areas of disease in the left parasternal region, left sternum, prevascular mediastinal nodes, and left supraclavicular, hilar and axillary adenopathy, and fourth thoracic vertebra. Gemcitabine was discontinued and patient was started on weekly paclitaxel (90 mg/m2) for 6 cycles. Paclitaxel was discontinued after 6 weeks because she developed a drug-related rash. A follow-up PET-CT scan in December 2010 again showed complete resolution of disease in terms of response.

In March 2011, PET imaging showed progression of disease in the left chest wall and axillary lymph nodes, so the patient was started on eribulin therapy (1.4 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 every 21-day cycle) and completed 3 cycles. In May 2011, PET imaging showed complete response to treatment with no evidence of recurrent or metastatic disease. The patient has not had chemotherapy since November 2011, and surveillance PET imaging has not demonstrated any recurrence of disease (Figure 2). Following her last follow-up in November 2016, the patient remains in remission.

Discussion

Triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs) are defined as tumors that lack expression of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2, and represent about 12%-17% of breast cancer cases.1,6 TNBCs tend to be larger in size at diagnosis than are other subtypes, are usually high-grade (poorly differentiated), and are more likely to be invasive ductal carcinomas.1,7 TNBC and the basal-like breast cancers as a group are associated with an adverse prognosis.1,7 There is no standard preferred chemotherapy and no biologic therapy available for TNBC.1,6-7 A sharp decline in survival outcome during the first 3-5 years after diagnosis initial is observed in TNBC, although the distant relapses after this time are less common.1 Beyond 10 years from diagnosis, the relapses are seen more common among patients with ER-positive cancers than among those with ER-negative subtype cancers. Therefore, although TNBCs are biologically aggressive, many are possibly curable, and this reflects their interesting characteristic heterogeneity.1,6

Chemotherapy is currently the mainstay of systemic medical treatment. Although patients with TNBC have a worse outcome after chemotherapy than patients with breast cancers of other subtypes, it still improves their outcome to a greater extent than in patients with ER-positive subtypes.1,6,7 Considering the heterogeneity of TNBC, it is difficult to predict which patients will benefit more from chemotherapy. The same has been observed in previous studies when subgroups of women with TNBC were extremely sensitive to chemotherapy, whereas in others it was of uncertain benefit.1

Currently, there is no preferred standard form of chemotherapy for TNBC. There are few case reports that demonstrate long-term survival and complete remission in metastatic TNBC. Shakir has reported on a significant clinical response to nab-paclitaxel monotherapy in a patient with triple-negative BRCA1-positive breast cancer, although patient survived a little more than 5 years and died with central nervous system recurrence.8 Montero and Gluck have described a patient with metastatic TNBC who was treated with nab-paclitaxel, gemcitabine, and bevacizumab and who also survived for 5 years after diagnosis.9 Different retrospective analyses have suggested that the addition of docetaxel or paclitaxel to anthracycline-containing adjuvant regimens may be of greater benefit for the treatment of TNBC than for ER-positive tumors.10 A meta-analysis of trials comparing the effects of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF, which was used in Case 2) with anthracycline-containing regimens has suggested that the latter therapy regimen is more effective against TNBC,11 although another retrospective analysis of a separate trial suggested the opposite for basal-like breast cancers. 12 The authors of the latter analysis concluded that anthracycline-containing adjuvant chemotherapy regimens are inferior to adjuvant CMF in women with basal breast cancer.12

Miller and colleagues have shown that the addition of bevacizumab (angiogenesis inhibitor) to paclitaxel (used in Case 1) improved progression-free survival (median PFS, 11.8 vs 5.9 months; hazard ratio [HR] for progression, 0.60; P < .001) in women with TNBC as it did in the overall study group (HR, 0.53 and 0.60, respectively), although the overall survival rate was similar in the two groups (median OS, 26.7 vs 25.2 months; HR, 0.88; P = .16).13

An interesting clinical target in TNBC is the enzyme poly (adenosine diphosphate– ribose) polymerase (PARP), which is involved in base-excision repair after DNA damage. PARP inhibitors have shown encouraging clinical activity in trials of tumors arising in BRCA mutation carriers and in sporadic TNBC cancers.14 Similarly, the use of an oral PARP inhibitor, olaparib, resulted in tumor regression in up to 41% of patients carrying BRCA mutations, most of whom had TNBC.15

Conclusion

TNBC and basal-like breast cancers show aggressive clinical behavior, but a subgroup of these cancers may be markedly sensitive to chemotherapy and associated with a good prognosis when treated with conventional chemotherapy regimens. The two cases presented here show that some patients can get a prolonged disease control from chemotherapy, even after progressing on multiple previous chemotherapy regimens and that after, 5 years or so, these rare patients could be in true long-term remission. Novel approaches, for example PARP inhibitors, have shown encouraging clinical activity in trials of tumors arising in BRCA mutation carriers and as well as sporadic TNBC.

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) has been shown to generally have a poor prognosis. Within the first 3-5 years of diagnosis, the mortality rate is the highest of all the subtypes of breast cancer, although late relapses are less common.1,2 TNBC is markedly heterogeneous tumor, and the individual prognosis can vary widely.1,3 Metastatic TNBC is generally considered a noncurable disease. The median time from recurrence to death for metastatic disease is about 9 months, compared with 20 months for patients with other subtypes of breast cancers.4,5 The median survival time for patients with metastatic TNBC is about 13 months.3

New targeted therapies are emerging for breast cancer, but there are currently no effective targeted therapies for patients with TNBC. In addition, few reports in the literature that discuss long-term complete remissions in patients who have metastatic TNBC. Here, we describe two cases in which patients with metastatic TNBC achieved sustained complete response on conventional chemotherapy regimens.

Case presentations and summaries

Case 1

A 59-year-old woman (age in 2015) had been diagnosed on biopsy in February 2005 with locally advanced right breast cancer (stage T2N2bM0). She underwent lumpectomy, and the results of her pathology tests revealed a triple-negative invasive ductal carcinoma. She was started on 4 cycles of neoadjuvant doxorubicin (60 mg/m2 IV) and cyclophosphamide (600 mg/m2 IV)

In November 2007, the patient was found to have right chest wall metastasis confirmed by ultrasound-guided needle biopsy, and underwent right-side chest wall and partial sternum resection. In May 2008, she had recurrence in the left axilla, and biopsy results showed that she had TNBC disease. She was started on weekly paclitaxel (90 mg/m2) and bevacizumab (10 mg/kg every 2 weeks) continued until July 2008. Chemotherapy was stopped in July 2008 because of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection of the chest wall and was not resumed after the infection had resolved.

A follow-up positron-emission tomography– computed tomography (PET-CT) scan in June 2009, showed no evidence of disease and the scan was negative for disease in her left axilla. Another PET scan about a year later, in September 2010, was also negative for any disease recurrence.

The patient has continued her follow-up with physical examinations and imaging scans. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis (December 2010), an MRI of the breasts (February 2011, August 2015), and a PET-CT scan (April 2015, Figure 1) were all negative for any evidence of disease. In September 2011, she had a CT-guided biopsy of a medial right clavicle and costal junction lesion; and in November 2011 and January 2013, surgical biopsies of the right chest wall and first rib lesions, all negative for any evidence for malignancy. At her last follow-up in January 2017, the patient remained in remission.

Case 2

A 68-year old woman (age in 2015) had been diagnosed in Russia in 2004 with infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the right breast (T4N1M0; receptor status unknown at that time). She underwent a right modified radical mastectomy and received adjuvant chemotherapy with 4 cycles of cyclophosphamide (100 mg/m2 day 1 to day 14), methotrexate (40 mg/m2 IV day 1 and day 8), and fluorouracil (600 mg/m2 IV, day 1 and day 8) followed by 2 cycles of docetaxel (75 mg/m2 IV) and anthracycline adriyamycin (50 mg/m2 IV). The patient later received radiation therapy (radiation dose not known, treatment was received in Russia), and completed her treatment in November 2004.

The patient moved to the United States and was started on 25 mg daily exemestane in February 2005. In March 2009, she was diagnosed by biopsy to have recurrence in her internal mammary and hilar lymph nodes and sternum. The cancer was found to be ER- and PR-negative and HER2-neu–negative. The patient was treated with radiation therapy (37.5 Gy in 15 fractions) to sternum and hilar and internal mammary lymph nodes with improvement in pain and shrinkage of lymph nodes size. In May 2009, she was started on 1,500 mg oral twice a day capecitabine (3 cycles). The therapy was started after completion of radiation treatment due to progression of disease. She developed hand-and-foot syndrome as side effect of the capecitabine, so the dose was reduced. She was switched to gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15, every 28-day cycle) as a single-agent therapy and completed 3 cycles. A follow-up PET-CT scan in February 2010 showed no evidence of disease.

In May 2010, the patient had a recurrence in the same metastatic foci as before, and she was again started on gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15, every 28-day cycle). She continued gemcitabine until there was evidence of disease progression on a PET-CT scan in October 2010, which showed new areas of disease in the left parasternal region, left sternum, prevascular mediastinal nodes, and left supraclavicular, hilar and axillary adenopathy, and fourth thoracic vertebra. Gemcitabine was discontinued and patient was started on weekly paclitaxel (90 mg/m2) for 6 cycles. Paclitaxel was discontinued after 6 weeks because she developed a drug-related rash. A follow-up PET-CT scan in December 2010 again showed complete resolution of disease in terms of response.

In March 2011, PET imaging showed progression of disease in the left chest wall and axillary lymph nodes, so the patient was started on eribulin therapy (1.4 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 every 21-day cycle) and completed 3 cycles. In May 2011, PET imaging showed complete response to treatment with no evidence of recurrent or metastatic disease. The patient has not had chemotherapy since November 2011, and surveillance PET imaging has not demonstrated any recurrence of disease (Figure 2). Following her last follow-up in November 2016, the patient remains in remission.

Discussion

Triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs) are defined as tumors that lack expression of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2, and represent about 12%-17% of breast cancer cases.1,6 TNBCs tend to be larger in size at diagnosis than are other subtypes, are usually high-grade (poorly differentiated), and are more likely to be invasive ductal carcinomas.1,7 TNBC and the basal-like breast cancers as a group are associated with an adverse prognosis.1,7 There is no standard preferred chemotherapy and no biologic therapy available for TNBC.1,6-7 A sharp decline in survival outcome during the first 3-5 years after diagnosis initial is observed in TNBC, although the distant relapses after this time are less common.1 Beyond 10 years from diagnosis, the relapses are seen more common among patients with ER-positive cancers than among those with ER-negative subtype cancers. Therefore, although TNBCs are biologically aggressive, many are possibly curable, and this reflects their interesting characteristic heterogeneity.1,6

Chemotherapy is currently the mainstay of systemic medical treatment. Although patients with TNBC have a worse outcome after chemotherapy than patients with breast cancers of other subtypes, it still improves their outcome to a greater extent than in patients with ER-positive subtypes.1,6,7 Considering the heterogeneity of TNBC, it is difficult to predict which patients will benefit more from chemotherapy. The same has been observed in previous studies when subgroups of women with TNBC were extremely sensitive to chemotherapy, whereas in others it was of uncertain benefit.1

Currently, there is no preferred standard form of chemotherapy for TNBC. There are few case reports that demonstrate long-term survival and complete remission in metastatic TNBC. Shakir has reported on a significant clinical response to nab-paclitaxel monotherapy in a patient with triple-negative BRCA1-positive breast cancer, although patient survived a little more than 5 years and died with central nervous system recurrence.8 Montero and Gluck have described a patient with metastatic TNBC who was treated with nab-paclitaxel, gemcitabine, and bevacizumab and who also survived for 5 years after diagnosis.9 Different retrospective analyses have suggested that the addition of docetaxel or paclitaxel to anthracycline-containing adjuvant regimens may be of greater benefit for the treatment of TNBC than for ER-positive tumors.10 A meta-analysis of trials comparing the effects of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF, which was used in Case 2) with anthracycline-containing regimens has suggested that the latter therapy regimen is more effective against TNBC,11 although another retrospective analysis of a separate trial suggested the opposite for basal-like breast cancers. 12 The authors of the latter analysis concluded that anthracycline-containing adjuvant chemotherapy regimens are inferior to adjuvant CMF in women with basal breast cancer.12

Miller and colleagues have shown that the addition of bevacizumab (angiogenesis inhibitor) to paclitaxel (used in Case 1) improved progression-free survival (median PFS, 11.8 vs 5.9 months; hazard ratio [HR] for progression, 0.60; P < .001) in women with TNBC as it did in the overall study group (HR, 0.53 and 0.60, respectively), although the overall survival rate was similar in the two groups (median OS, 26.7 vs 25.2 months; HR, 0.88; P = .16).13

An interesting clinical target in TNBC is the enzyme poly (adenosine diphosphate– ribose) polymerase (PARP), which is involved in base-excision repair after DNA damage. PARP inhibitors have shown encouraging clinical activity in trials of tumors arising in BRCA mutation carriers and in sporadic TNBC cancers.14 Similarly, the use of an oral PARP inhibitor, olaparib, resulted in tumor regression in up to 41% of patients carrying BRCA mutations, most of whom had TNBC.15

Conclusion

TNBC and basal-like breast cancers show aggressive clinical behavior, but a subgroup of these cancers may be markedly sensitive to chemotherapy and associated with a good prognosis when treated with conventional chemotherapy regimens. The two cases presented here show that some patients can get a prolonged disease control from chemotherapy, even after progressing on multiple previous chemotherapy regimens and that after, 5 years or so, these rare patients could be in true long-term remission. Novel approaches, for example PARP inhibitors, have shown encouraging clinical activity in trials of tumors arising in BRCA mutation carriers and as well as sporadic TNBC.

1. Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS, Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1938-1948.

2. Pogoda K, Niwińska A, Murawska M, Pieńkowski T. Analysis of pattern, time and risk factors influencing recurrence in triple-negative breast cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2013;30(1):388.

3. Kassam F, Enright K, Dent R, et al. Survival outcomes for patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: implications for clinical practice and trial design. Clin Breast Cancer. 2009;9(1):29-33.

4. Perou CM. Molecular stratification of triple-negative breast cancers. Oncologist. 2010;15(suppl 5):39-48.

5. Rakha EA, Chan S. Metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2011;23(9):587-600.

6. Williams N, Harris L. Triple-negative breast cancer in the post-genomic era. Oncology (Williston Park). 2013;27(9):859-860, 864.

7. Randhawa SK, Venur VA, Kawsar H, et al. A retrospective comparison of the characteristics and recurrence outcome of triple-negative and triple-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl; abstr 1038).

8. Shakir AR. Strong and sustained response to treatment with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel in a patient with metastatic, triple-negative, BRCA1-positive breast cancer. Case Rep Oncol. 2014;7(1)252-259.

9. Montero A, Glück S. Long-term complete remission with nab-paclitaxel, bevacizumab, and gemcitabine combination therapy in a patient with triple-negative metastatic breast cancer. Case Rep Oncol. 2012;5(3):687-692.

10. Hayes DF, Thor AD, Dressler LG, et al. HER2 and response to paclitaxel in node-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1496-1506.

11. Di Leo A, Isola J, Piette F, et al. A meta- analysis of phase III trials evaluating the predictive value of HER2 and topoisomerase alpha in early breast cancer patients treated with CMF or anthracycline-based adjuvant therapy [SABCS, abstract 705]. http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/69/2_Supplement/705. Published 2008. Accessed May 4, 2017.

12. Cheang M, Chia SK, Tu D, et al. Anthracycline in basal breast cancer: the NCIC-CTG trial MA5 comparing adjuvant CMF to CEF [ASCO; abstract 519]. http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/35150-65. Published 2009. Accessed May 4, 2017.

13. Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, et al. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2666-2676.

14. Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:123-134.

15. Tutt A, Robson M, Garber JE, et al. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376:235-244.

1. Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS, Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1938-1948.

2. Pogoda K, Niwińska A, Murawska M, Pieńkowski T. Analysis of pattern, time and risk factors influencing recurrence in triple-negative breast cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2013;30(1):388.

3. Kassam F, Enright K, Dent R, et al. Survival outcomes for patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: implications for clinical practice and trial design. Clin Breast Cancer. 2009;9(1):29-33.

4. Perou CM. Molecular stratification of triple-negative breast cancers. Oncologist. 2010;15(suppl 5):39-48.

5. Rakha EA, Chan S. Metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2011;23(9):587-600.

6. Williams N, Harris L. Triple-negative breast cancer in the post-genomic era. Oncology (Williston Park). 2013;27(9):859-860, 864.

7. Randhawa SK, Venur VA, Kawsar H, et al. A retrospective comparison of the characteristics and recurrence outcome of triple-negative and triple-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl; abstr 1038).

8. Shakir AR. Strong and sustained response to treatment with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel in a patient with metastatic, triple-negative, BRCA1-positive breast cancer. Case Rep Oncol. 2014;7(1)252-259.

9. Montero A, Glück S. Long-term complete remission with nab-paclitaxel, bevacizumab, and gemcitabine combination therapy in a patient with triple-negative metastatic breast cancer. Case Rep Oncol. 2012;5(3):687-692.

10. Hayes DF, Thor AD, Dressler LG, et al. HER2 and response to paclitaxel in node-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1496-1506.

11. Di Leo A, Isola J, Piette F, et al. A meta- analysis of phase III trials evaluating the predictive value of HER2 and topoisomerase alpha in early breast cancer patients treated with CMF or anthracycline-based adjuvant therapy [SABCS, abstract 705]. http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/69/2_Supplement/705. Published 2008. Accessed May 4, 2017.

12. Cheang M, Chia SK, Tu D, et al. Anthracycline in basal breast cancer: the NCIC-CTG trial MA5 comparing adjuvant CMF to CEF [ASCO; abstract 519]. http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/35150-65. Published 2009. Accessed May 4, 2017.

13. Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, et al. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2666-2676.

14. Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:123-134.

15. Tutt A, Robson M, Garber JE, et al. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376:235-244.

Making Practice Perfect Download

Please click either of the links below to download your free eBook

Onecount Call To Arms

Bone remodeling associated with CTLA-4 inhibition: an unreported side effect

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) is an important component of the immune checkpoint pathway. CTLA-4 inhibition causes T-cell activation and proliferation, increases T-cell responsiveness, and enhances the anti-tumor immune response. CTLA-4 inhibition also results in immune-related adverse reactions such as colitis, hepatitis, and endocrinopathies. Preclinical investigations have recently shown that CTLA-4 inhibition can cause cytokine-mediated increase in bone remodeling.1,2(p4) Ipilimumab, a recombinant IgG1 kappa antibody against human CTLA-4, has been approved for use in unresectable or metastatic melanoma. We hypothesize that ipilumumab results in increase in bone remodeling manifesting as an autoimmune reaction.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective case-control study of patients with stage III/IV melanoma treated at the University of New Mexico Comprehensive Cancer Center during April 2009-July 2014. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Two cohorts were compared: an ipilumimab cohort receiving ipilumimab at 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks, and a chemotherapy cohort receiving an investigational chemotherapy regimen: carboplatin IV at an area under curve of 5 on day 1, paclitaxel IV at 175 mg/m2 on day 1, and temozolomide orally at 125 mg/m2 daily on days 2 to 6 every 21 days. Patients receiving at least 1 cycle of treatment were included. Those with known hepatic disease or concurrent malignancy were excluded from the study.

Serum ALP level (normal range, 38-150 international units per liter [IU/L]) and patient-reported bone pain measured by the 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS) for pain assessment were recorded before treatment initiation, on each cycle, and upon treatment completion.3 Clinical response was assessed per RECIST guidelines.4 Bone pain was dichotomized into Absent (pain intensity of 0 on the NRS, meaning no pain) or Present (pain intensity of 1-10 on the NRS, with 1 = mild pain and 10 = worst imaginable pain). Patients with a complete or partial response to the therapy were categorized as responders, and those with progressive or stable disease were categorized as nonresponders.

Descriptive statistics were generated for demographic and clinical characteristics. The primary outcome variables of interest were bone pain and mean ALP levels. Generalized linear mixed-effect models for proportion of patients with bone pain (with logit link function) and mean ALP levels (with identify link function) were used to evaluate for a difference in trends between the two cohorts over time. We used the Kenward-Roger approach to adjust for the small size of the degrees of freedom. To assess the significance of difference of the proportions of patients with bone pain and the mean ALP levels between responders and nonresponders in the ipilumimab cohort, the Fisher exact test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test were used, respectively. Statistical analyses were performed with statistical packages R (v3.1.3) and SAS (v9.4).

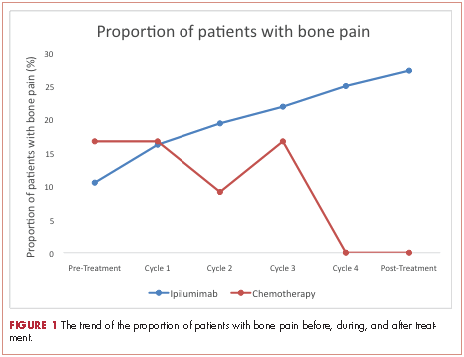

Results

A total of 281 patients were screened, and 51 met the inclusion criteria (39 in the ipilumimab and 12 in chemotherapy cohorts). Baseline parameters were well matched between the cohorts (Table). Of the 39 patients in the ipilimumab cohort, 14 (35.9%) had bone pain during at least one of the treatment cycles, compared with 3 of the 12 patients (25%) in the chemotherapy cohort. At baseline, 4 of 38 ipilimumab patients (10.5%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.9-24.8) and 2 of 12 chemotherapy patients (16.7%; 95% CI, 2.1-48.4) had bone pain. Upon treatment completion, 9 of 33 ipilimumab patients (27.3%; 95% CI, 13.3-45.5) and 0 of 12 chemotherapy patients (0%; 95% CI, 0-26.5) had bone pain. The trend of proportion of patients with bone pain over time was statistically significant between the two cohorts (P = .023, Figure 1). The trends of proportion of patients with bone pain were not statistically significant when stratified by the presence of bone metastasis at inclusion in the study (P = .418) or disease progression at treatment completion (P = .500).

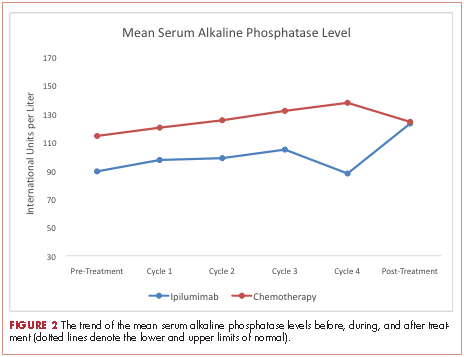

At baseline, the mean ALP level was 89.39 IU/L (95% CI, 81.03-97.75) in the ipilumimab cohort and 114.33 IU/L (95% CI, 69.48-159.19) in the chemotherapy cohort. Upon treatment completion, the mean ALP level was 123.09 IU/L (95% C.I. 80.78-165.41) in the ipilumimab cohort and 124.24 IU/L (95% C.I. 90.88-157.62) in the chemotherapy cohort. The trend of mean ALP level over time was not statistically significant between the 2 cohorts (P = .653, Figure 2).

Discussion

Immune checkpoints are inhibitory pathways that are critical for maintenance of self-tolerance and regulation of appropriate immune response. CTLA-4 is present exclusively on T cells and interacts with its ligands B7.1 and B7.2. CTLA-4 competes with CD28 in binding with B7, leading to dampening of T-cell activation and function.5,6 Development of checkpoint inhibitors such as ipilumimab have heralded a new era of immune targeted therapies for various malignancies including malignant melanoma.

Bone remodeling involves 4 distinct but overlapping phases. The first phase involves detection of loss of bone continuity by osteocytes and activation of osteoclast precursors derived from progenitors of the monocyte-macrophage lineage. The second phase involves osteoclast-medicated bone resorption and concurrent recruitment of mesenchymal stem cells and osteoprogenitors. The third phase involves osteoblast differentiation and osteoid synthesis, and the fourth phase results in mineralization of osteoid and termination of bone remodeling.7,8

The role of T-lymphocytes and cytokines, such as IL-1 and TNF-α, and receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANK-L) in osteoclastogenesis is well studied. RANK-L is considered to be the final downstream effector of this process.9 T-lymphocytes have also been shown to promote osteoblast maturation and function.9,10 These findings suggest a significant interaction between immune system activation and bone remodeling.

The search for a reliable biomarker for immune therapy is ongoing. Although ipilumimab-associated immune-related adverse events have been suggested to predict response to therapy,11 there is considerable debate on the subject. Ipilumimab’s impact on bone remodeling could offer a solution.

In the current study, there was a statistically significant difference in proportion of patients with bone pain in the 2 cohorts. This was preserved with stratification based on bone metastasis at inclusion and disease progression on treatment completion making new or worsening skeletal metastasis. Furthermore, the proportion of patients with bone pain increased with each cycle for ipilumimab cohort. However, we were unable to detect an association between bone pain and response to ipilimumab.

We were not able to detect a difference in trend of mean ALP level with treatment in the two cohorts. Although it is possible that no such association exists, we believe our study was not powered to detect it. Finally, we were not able to study markers for osteoblast (bone-specific ALP) and osteoclasts (N- and C-telopeptides of type 1 collagen, deoxypyridinoline, etc) to better assess this interaction because they are not commonly clinically used.

Regarding the limitations of our study, we chose to dichotomize the patient-reported bone pain because it is a subjective measure and there is a significant variability of the perceived pain intensity among patients. We also excluded patients with hepatitis from receiving the ipilumimab therapy and those with known hepatic disease from the study to reduce the impact of hepatic ALP on total serum ALP levels.

In conclusion, as far as we know, this is the first clinical report suggesting a possible relationship between CTLA-4 inhibition and bone remodeling. Supported by a strong preclinical rationale, this side effect remains under-studied and under-recognized by clinicians. A prospective assessment of this interaction using bone specific markers is planned.

1. Bozec A, Zaiss MM, Kagwiria R, et al. T-cell costimulation molecules CD80/86 inhibit osteoclast differentiation by inducing the IDO/tryptophan pathway. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(235):235ra60.

2. Zhang F, Zhang Z, Sun D, Dong S, Xu J, Dai F. EphB4 promotes osteogenesis of CTLA 4-modified bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells through cross talk with wnt pathway in xenotransplantation. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015;21(17-18):2404-2416.

3. Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94(2):149-158.

4. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228-247.

5. Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):252-264.

6. Sharma P, Allison JP. Immune checkpoint targeting in cancer therapy: toward combination strategies with curative potential. Cell. 2015;161(2):205-214.

7. Clarke B. Normal bone anatomy and physiology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(suppl 3):S131-S139.

8. Feng X, McDonald JM. Disorders of bone remodeling. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:121-145.

9. Gillespie MT. Impact of cytokines and T lymphocytes upon osteoclast differentiation and function. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(2):103.

10. Sims NA, Walsh NC. Intercellular cross-talk among bone cells: new factors and pathways. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2012;10(2):109-117.

11. Downey SG, Klapper JA, Smith FO, et al. Prognostic factors related to clinical response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated by CTL-associated antigen-4 blockade. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(22):6681-6688.

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) is an important component of the immune checkpoint pathway. CTLA-4 inhibition causes T-cell activation and proliferation, increases T-cell responsiveness, and enhances the anti-tumor immune response. CTLA-4 inhibition also results in immune-related adverse reactions such as colitis, hepatitis, and endocrinopathies. Preclinical investigations have recently shown that CTLA-4 inhibition can cause cytokine-mediated increase in bone remodeling.1,2(p4) Ipilimumab, a recombinant IgG1 kappa antibody against human CTLA-4, has been approved for use in unresectable or metastatic melanoma. We hypothesize that ipilumumab results in increase in bone remodeling manifesting as an autoimmune reaction.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective case-control study of patients with stage III/IV melanoma treated at the University of New Mexico Comprehensive Cancer Center during April 2009-July 2014. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Two cohorts were compared: an ipilumimab cohort receiving ipilumimab at 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks, and a chemotherapy cohort receiving an investigational chemotherapy regimen: carboplatin IV at an area under curve of 5 on day 1, paclitaxel IV at 175 mg/m2 on day 1, and temozolomide orally at 125 mg/m2 daily on days 2 to 6 every 21 days. Patients receiving at least 1 cycle of treatment were included. Those with known hepatic disease or concurrent malignancy were excluded from the study.

Serum ALP level (normal range, 38-150 international units per liter [IU/L]) and patient-reported bone pain measured by the 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS) for pain assessment were recorded before treatment initiation, on each cycle, and upon treatment completion.3 Clinical response was assessed per RECIST guidelines.4 Bone pain was dichotomized into Absent (pain intensity of 0 on the NRS, meaning no pain) or Present (pain intensity of 1-10 on the NRS, with 1 = mild pain and 10 = worst imaginable pain). Patients with a complete or partial response to the therapy were categorized as responders, and those with progressive or stable disease were categorized as nonresponders.

Descriptive statistics were generated for demographic and clinical characteristics. The primary outcome variables of interest were bone pain and mean ALP levels. Generalized linear mixed-effect models for proportion of patients with bone pain (with logit link function) and mean ALP levels (with identify link function) were used to evaluate for a difference in trends between the two cohorts over time. We used the Kenward-Roger approach to adjust for the small size of the degrees of freedom. To assess the significance of difference of the proportions of patients with bone pain and the mean ALP levels between responders and nonresponders in the ipilumimab cohort, the Fisher exact test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test were used, respectively. Statistical analyses were performed with statistical packages R (v3.1.3) and SAS (v9.4).

Results

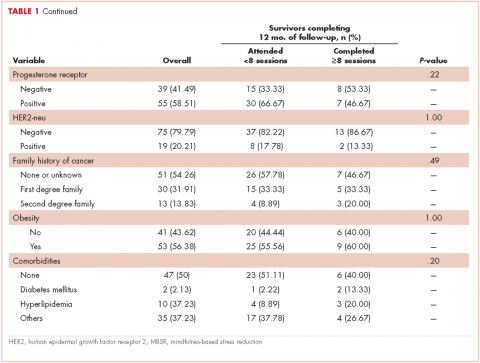

A total of 281 patients were screened, and 51 met the inclusion criteria (39 in the ipilumimab and 12 in chemotherapy cohorts). Baseline parameters were well matched between the cohorts (Table). Of the 39 patients in the ipilimumab cohort, 14 (35.9%) had bone pain during at least one of the treatment cycles, compared with 3 of the 12 patients (25%) in the chemotherapy cohort. At baseline, 4 of 38 ipilimumab patients (10.5%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.9-24.8) and 2 of 12 chemotherapy patients (16.7%; 95% CI, 2.1-48.4) had bone pain. Upon treatment completion, 9 of 33 ipilimumab patients (27.3%; 95% CI, 13.3-45.5) and 0 of 12 chemotherapy patients (0%; 95% CI, 0-26.5) had bone pain. The trend of proportion of patients with bone pain over time was statistically significant between the two cohorts (P = .023, Figure 1). The trends of proportion of patients with bone pain were not statistically significant when stratified by the presence of bone metastasis at inclusion in the study (P = .418) or disease progression at treatment completion (P = .500).

At baseline, the mean ALP level was 89.39 IU/L (95% CI, 81.03-97.75) in the ipilumimab cohort and 114.33 IU/L (95% CI, 69.48-159.19) in the chemotherapy cohort. Upon treatment completion, the mean ALP level was 123.09 IU/L (95% C.I. 80.78-165.41) in the ipilumimab cohort and 124.24 IU/L (95% C.I. 90.88-157.62) in the chemotherapy cohort. The trend of mean ALP level over time was not statistically significant between the 2 cohorts (P = .653, Figure 2).

Discussion

Immune checkpoints are inhibitory pathways that are critical for maintenance of self-tolerance and regulation of appropriate immune response. CTLA-4 is present exclusively on T cells and interacts with its ligands B7.1 and B7.2. CTLA-4 competes with CD28 in binding with B7, leading to dampening of T-cell activation and function.5,6 Development of checkpoint inhibitors such as ipilumimab have heralded a new era of immune targeted therapies for various malignancies including malignant melanoma.

Bone remodeling involves 4 distinct but overlapping phases. The first phase involves detection of loss of bone continuity by osteocytes and activation of osteoclast precursors derived from progenitors of the monocyte-macrophage lineage. The second phase involves osteoclast-medicated bone resorption and concurrent recruitment of mesenchymal stem cells and osteoprogenitors. The third phase involves osteoblast differentiation and osteoid synthesis, and the fourth phase results in mineralization of osteoid and termination of bone remodeling.7,8

The role of T-lymphocytes and cytokines, such as IL-1 and TNF-α, and receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANK-L) in osteoclastogenesis is well studied. RANK-L is considered to be the final downstream effector of this process.9 T-lymphocytes have also been shown to promote osteoblast maturation and function.9,10 These findings suggest a significant interaction between immune system activation and bone remodeling.

The search for a reliable biomarker for immune therapy is ongoing. Although ipilumimab-associated immune-related adverse events have been suggested to predict response to therapy,11 there is considerable debate on the subject. Ipilumimab’s impact on bone remodeling could offer a solution.

In the current study, there was a statistically significant difference in proportion of patients with bone pain in the 2 cohorts. This was preserved with stratification based on bone metastasis at inclusion and disease progression on treatment completion making new or worsening skeletal metastasis. Furthermore, the proportion of patients with bone pain increased with each cycle for ipilumimab cohort. However, we were unable to detect an association between bone pain and response to ipilimumab.

We were not able to detect a difference in trend of mean ALP level with treatment in the two cohorts. Although it is possible that no such association exists, we believe our study was not powered to detect it. Finally, we were not able to study markers for osteoblast (bone-specific ALP) and osteoclasts (N- and C-telopeptides of type 1 collagen, deoxypyridinoline, etc) to better assess this interaction because they are not commonly clinically used.

Regarding the limitations of our study, we chose to dichotomize the patient-reported bone pain because it is a subjective measure and there is a significant variability of the perceived pain intensity among patients. We also excluded patients with hepatitis from receiving the ipilumimab therapy and those with known hepatic disease from the study to reduce the impact of hepatic ALP on total serum ALP levels.

In conclusion, as far as we know, this is the first clinical report suggesting a possible relationship between CTLA-4 inhibition and bone remodeling. Supported by a strong preclinical rationale, this side effect remains under-studied and under-recognized by clinicians. A prospective assessment of this interaction using bone specific markers is planned.

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) is an important component of the immune checkpoint pathway. CTLA-4 inhibition causes T-cell activation and proliferation, increases T-cell responsiveness, and enhances the anti-tumor immune response. CTLA-4 inhibition also results in immune-related adverse reactions such as colitis, hepatitis, and endocrinopathies. Preclinical investigations have recently shown that CTLA-4 inhibition can cause cytokine-mediated increase in bone remodeling.1,2(p4) Ipilimumab, a recombinant IgG1 kappa antibody against human CTLA-4, has been approved for use in unresectable or metastatic melanoma. We hypothesize that ipilumumab results in increase in bone remodeling manifesting as an autoimmune reaction.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective case-control study of patients with stage III/IV melanoma treated at the University of New Mexico Comprehensive Cancer Center during April 2009-July 2014. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Two cohorts were compared: an ipilumimab cohort receiving ipilumimab at 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks, and a chemotherapy cohort receiving an investigational chemotherapy regimen: carboplatin IV at an area under curve of 5 on day 1, paclitaxel IV at 175 mg/m2 on day 1, and temozolomide orally at 125 mg/m2 daily on days 2 to 6 every 21 days. Patients receiving at least 1 cycle of treatment were included. Those with known hepatic disease or concurrent malignancy were excluded from the study.

Serum ALP level (normal range, 38-150 international units per liter [IU/L]) and patient-reported bone pain measured by the 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS) for pain assessment were recorded before treatment initiation, on each cycle, and upon treatment completion.3 Clinical response was assessed per RECIST guidelines.4 Bone pain was dichotomized into Absent (pain intensity of 0 on the NRS, meaning no pain) or Present (pain intensity of 1-10 on the NRS, with 1 = mild pain and 10 = worst imaginable pain). Patients with a complete or partial response to the therapy were categorized as responders, and those with progressive or stable disease were categorized as nonresponders.

Descriptive statistics were generated for demographic and clinical characteristics. The primary outcome variables of interest were bone pain and mean ALP levels. Generalized linear mixed-effect models for proportion of patients with bone pain (with logit link function) and mean ALP levels (with identify link function) were used to evaluate for a difference in trends between the two cohorts over time. We used the Kenward-Roger approach to adjust for the small size of the degrees of freedom. To assess the significance of difference of the proportions of patients with bone pain and the mean ALP levels between responders and nonresponders in the ipilumimab cohort, the Fisher exact test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test were used, respectively. Statistical analyses were performed with statistical packages R (v3.1.3) and SAS (v9.4).

Results

A total of 281 patients were screened, and 51 met the inclusion criteria (39 in the ipilumimab and 12 in chemotherapy cohorts). Baseline parameters were well matched between the cohorts (Table). Of the 39 patients in the ipilimumab cohort, 14 (35.9%) had bone pain during at least one of the treatment cycles, compared with 3 of the 12 patients (25%) in the chemotherapy cohort. At baseline, 4 of 38 ipilimumab patients (10.5%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.9-24.8) and 2 of 12 chemotherapy patients (16.7%; 95% CI, 2.1-48.4) had bone pain. Upon treatment completion, 9 of 33 ipilimumab patients (27.3%; 95% CI, 13.3-45.5) and 0 of 12 chemotherapy patients (0%; 95% CI, 0-26.5) had bone pain. The trend of proportion of patients with bone pain over time was statistically significant between the two cohorts (P = .023, Figure 1). The trends of proportion of patients with bone pain were not statistically significant when stratified by the presence of bone metastasis at inclusion in the study (P = .418) or disease progression at treatment completion (P = .500).

At baseline, the mean ALP level was 89.39 IU/L (95% CI, 81.03-97.75) in the ipilumimab cohort and 114.33 IU/L (95% CI, 69.48-159.19) in the chemotherapy cohort. Upon treatment completion, the mean ALP level was 123.09 IU/L (95% C.I. 80.78-165.41) in the ipilumimab cohort and 124.24 IU/L (95% C.I. 90.88-157.62) in the chemotherapy cohort. The trend of mean ALP level over time was not statistically significant between the 2 cohorts (P = .653, Figure 2).

Discussion

Immune checkpoints are inhibitory pathways that are critical for maintenance of self-tolerance and regulation of appropriate immune response. CTLA-4 is present exclusively on T cells and interacts with its ligands B7.1 and B7.2. CTLA-4 competes with CD28 in binding with B7, leading to dampening of T-cell activation and function.5,6 Development of checkpoint inhibitors such as ipilumimab have heralded a new era of immune targeted therapies for various malignancies including malignant melanoma.

Bone remodeling involves 4 distinct but overlapping phases. The first phase involves detection of loss of bone continuity by osteocytes and activation of osteoclast precursors derived from progenitors of the monocyte-macrophage lineage. The second phase involves osteoclast-medicated bone resorption and concurrent recruitment of mesenchymal stem cells and osteoprogenitors. The third phase involves osteoblast differentiation and osteoid synthesis, and the fourth phase results in mineralization of osteoid and termination of bone remodeling.7,8

The role of T-lymphocytes and cytokines, such as IL-1 and TNF-α, and receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANK-L) in osteoclastogenesis is well studied. RANK-L is considered to be the final downstream effector of this process.9 T-lymphocytes have also been shown to promote osteoblast maturation and function.9,10 These findings suggest a significant interaction between immune system activation and bone remodeling.

The search for a reliable biomarker for immune therapy is ongoing. Although ipilumimab-associated immune-related adverse events have been suggested to predict response to therapy,11 there is considerable debate on the subject. Ipilumimab’s impact on bone remodeling could offer a solution.

In the current study, there was a statistically significant difference in proportion of patients with bone pain in the 2 cohorts. This was preserved with stratification based on bone metastasis at inclusion and disease progression on treatment completion making new or worsening skeletal metastasis. Furthermore, the proportion of patients with bone pain increased with each cycle for ipilumimab cohort. However, we were unable to detect an association between bone pain and response to ipilimumab.

We were not able to detect a difference in trend of mean ALP level with treatment in the two cohorts. Although it is possible that no such association exists, we believe our study was not powered to detect it. Finally, we were not able to study markers for osteoblast (bone-specific ALP) and osteoclasts (N- and C-telopeptides of type 1 collagen, deoxypyridinoline, etc) to better assess this interaction because they are not commonly clinically used.

Regarding the limitations of our study, we chose to dichotomize the patient-reported bone pain because it is a subjective measure and there is a significant variability of the perceived pain intensity among patients. We also excluded patients with hepatitis from receiving the ipilumimab therapy and those with known hepatic disease from the study to reduce the impact of hepatic ALP on total serum ALP levels.

In conclusion, as far as we know, this is the first clinical report suggesting a possible relationship between CTLA-4 inhibition and bone remodeling. Supported by a strong preclinical rationale, this side effect remains under-studied and under-recognized by clinicians. A prospective assessment of this interaction using bone specific markers is planned.

1. Bozec A, Zaiss MM, Kagwiria R, et al. T-cell costimulation molecules CD80/86 inhibit osteoclast differentiation by inducing the IDO/tryptophan pathway. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(235):235ra60.

2. Zhang F, Zhang Z, Sun D, Dong S, Xu J, Dai F. EphB4 promotes osteogenesis of CTLA 4-modified bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells through cross talk with wnt pathway in xenotransplantation. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015;21(17-18):2404-2416.

3. Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94(2):149-158.

4. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228-247.

5. Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):252-264.

6. Sharma P, Allison JP. Immune checkpoint targeting in cancer therapy: toward combination strategies with curative potential. Cell. 2015;161(2):205-214.

7. Clarke B. Normal bone anatomy and physiology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(suppl 3):S131-S139.

8. Feng X, McDonald JM. Disorders of bone remodeling. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:121-145.

9. Gillespie MT. Impact of cytokines and T lymphocytes upon osteoclast differentiation and function. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(2):103.

10. Sims NA, Walsh NC. Intercellular cross-talk among bone cells: new factors and pathways. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2012;10(2):109-117.

11. Downey SG, Klapper JA, Smith FO, et al. Prognostic factors related to clinical response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated by CTL-associated antigen-4 blockade. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(22):6681-6688.

1. Bozec A, Zaiss MM, Kagwiria R, et al. T-cell costimulation molecules CD80/86 inhibit osteoclast differentiation by inducing the IDO/tryptophan pathway. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(235):235ra60.

2. Zhang F, Zhang Z, Sun D, Dong S, Xu J, Dai F. EphB4 promotes osteogenesis of CTLA 4-modified bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells through cross talk with wnt pathway in xenotransplantation. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015;21(17-18):2404-2416.

3. Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94(2):149-158.

4. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228-247.

5. Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):252-264.

6. Sharma P, Allison JP. Immune checkpoint targeting in cancer therapy: toward combination strategies with curative potential. Cell. 2015;161(2):205-214.

7. Clarke B. Normal bone anatomy and physiology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(suppl 3):S131-S139.

8. Feng X, McDonald JM. Disorders of bone remodeling. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:121-145.

9. Gillespie MT. Impact of cytokines and T lymphocytes upon osteoclast differentiation and function. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(2):103.

10. Sims NA, Walsh NC. Intercellular cross-talk among bone cells: new factors and pathways. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2012;10(2):109-117.

11. Downey SG, Klapper JA, Smith FO, et al. Prognostic factors related to clinical response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated by CTL-associated antigen-4 blockade. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(22):6681-6688.

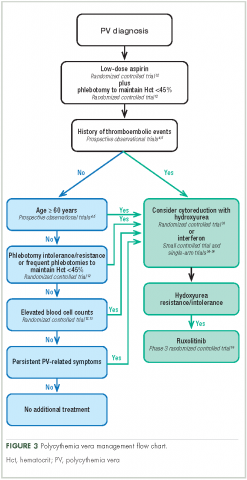

Management of polycythemia vera in the community oncology setting

Polycythemia vera, classified as a myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) and characterized by uncontrolled, clonal, myeloid expansion with predominant erythrocytosis,1 affects about 100,000 individuals in the United States.2 It is a chronic and burdensome disease associated with shortened survival.3 Patients are at an increased risk of cardiovascular events, solid tumors, and transformation to myelofibrosis (MF) and/or acute myeloid leukemia (AML).4,5 Furthermore, patients generally have a reduced quality of life (QoL) stemming from prevalent and occasionally severe polycythemia vera–related signs and symptoms, including fatigue, pruritus, and splenomegaly.6 In general, the classical Philadelphia chromosome-negative MPNs are associated with driver mutations in the following three genes: Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), calreticulin (CALR), and myeloproliferative leukemia virus oncogene (MPL).7 Almost all patients with polycythemia vera have an activating mutation in the cytoplasmic signal transduction protein JAK2.4 Patients with essential thrombocythemia (ET) or MF can have mutations in JAK2, CALR, or MPL. However, CALR and MPL mutations are absent or exceedingly rare in patients with polycythemia vera.7 Diagnosis can be challenging and is currently based on 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) diagnostic criteria.1

Management strategies include the use of aspirin, phlebotomy, and cytoreductive therapy. Ruxolitinib is a newer treatment option available for patients with polycythemia vera who are either resistant to or intolerant of hydroxyurea8,9— a population that previously had few treatment options. It is important for community oncologists and other treating clinicians to understand current diagnostic strategy and management options based on established guidelines, recent clinical evidence, and regulatory updates.

Search and selection process for research sources

In September 2016, we searched PubMed for articles published since 2006 with polycythemia vera included in the abstract or title. The initial 1,730 publications were screened by eye to select 46 key articles that guide current management of polycythemia vera. Four studies published before 2006 were also included based on their continued relevance.

Epidemiology and pathophysiology

Based on a meta-analysis of patients from Europe and the United States, the annual incidence of polycythemia vera estimated to be between 0.7 and 2.6 per 100,000 people.10 The age-adjusted prevalence of polycythemia vera in the United States is about 45-57 per 100,000 people,2 however, the true prevalence might be considerably greater.

Patients with polycythemia vera are at increased risk of cardiovascular events, thrombosis, and death.3-5 Risk is highest among patients older than 60 years or with a history of thrombosis.11 Uncontrolled myeloproliferation has also been identified as a risk factor for cardiovascular mortality and thrombosis. This was demonstrated in the prospective Cytoreductive Therapy in Polycythemia Vera (CYTO-PV) trial, which reported more cardiovascular events in patients with hematocrit levels of 45%-50%, compared with those whose hematocrit levels were <45%.12 In addition, retrospective data suggest leukocytosis is a potential risk factor for thromboembolic events and poor outcomes.13

Dysregulated JAK2 signaling is the principal driver of polycythemia vera pathophysiology. About 95% of patients with polycythemia vera will have an identifiable JAK2 V617F exon 14 mutation, with an additional 3%-5% demonstrating a JAK2 exon 12 mutation.4,14 Under physiologic conditions, JAK2 interacts with the STAT family of signal transduction proteins and serves as an important regulator of normal hematopoiesis.15 Mutated, constitutively activated JAK2 signaling promotes the various polycythemia vera disease manifestations, including excessive myeloproliferation, splenomegaly,15 and constitutional symptoms.14,16,17

Burden of disease for the individual

Mortality

Patients with polycythemia vera have an increased risk of mortality compared with an unaffected, age- and gender-matched cohort of the general population.3 A retrospective study of Medicare patients with polycythemia vera (mean age at diagnosis, 76.1 years) reported a median survival of 5.4 years, compared with 8.7 years for a matched cohort.3 A second retrospective study reported a median survival of 13.5 years (median age at diagnosis, 64 years; median follow-up time, 11.8 years).18

Leading causes of death for patients with polycythemia vera include cardiovascular and thrombotic events, the development of secondary solid tumors, and disease transformation to MF and/or AML. In the prospective European Collaboration on Low-Dose Aspirin in Polycythemia Vera (ECLAP) study of 1,638 patients, 45% of deaths (74/164) resulted from cardiovascular causes (1.7 per 100 patient-years).5 Thirteen percent of deaths were related to either leukemic or myelofibrotic transformation, and 20% of deaths were attributed to secondary solid tumors.5 In a retrospective analysis of 1,545 patients with polycythemia vera followed for a median of 6.9 years after diagnosis, 347 had died, primarily from acute leukemia (10%), secondary malignancies (10%), and thrombotic events (9%).4 Arterial and venous thrombotic events occurred in 12% and 9% of patients, respectively, with disease transformation to MF and AML occurring in 9% and 3% of patients. Further support of an increased risk of secondary malignancies comes from a retrospective analysis of a large Swedish cancer registry (1958–2006) that found an increased risk of secondary endocrine, renal, and skin malignancies; MF; and leukemia among patients with polycythemia vera.19

Symptoms and quality of life

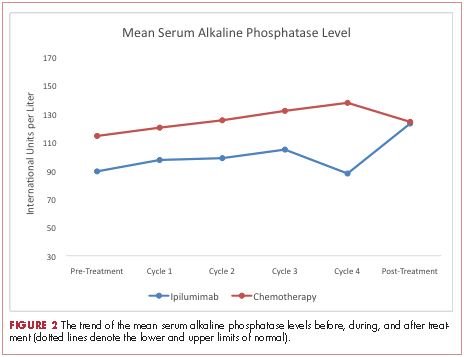

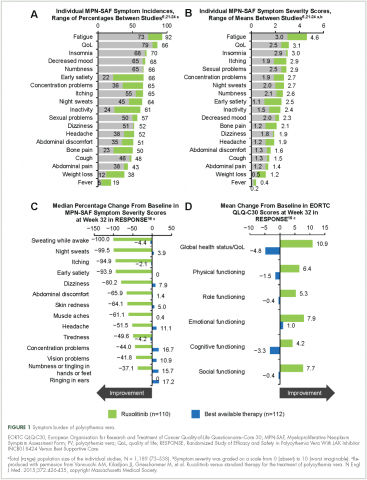

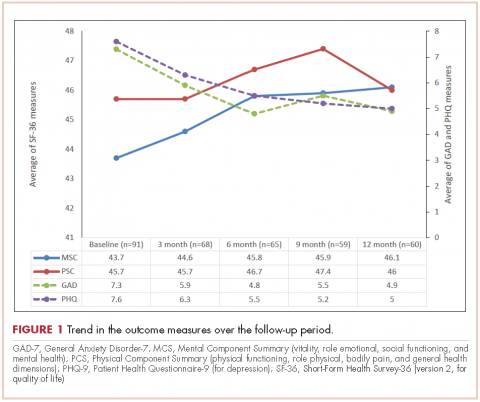

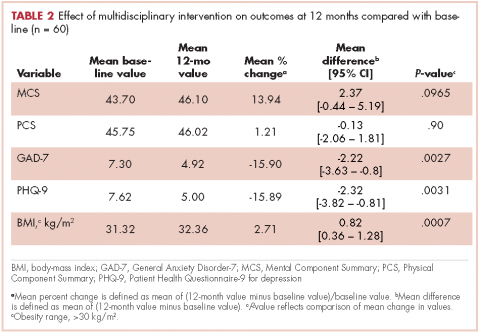

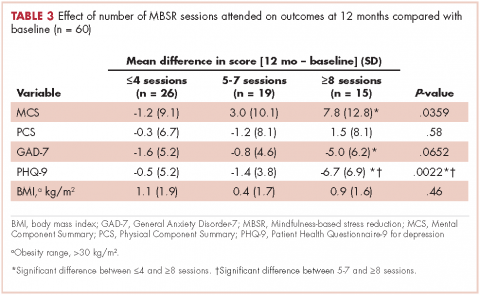

Symptoms of polycythemia vera vary in severity, and patients often fail to attribute symptoms to the disease.20 Moreover, clinicians may underestimate a patient’s true disease burden or the effect it has on QoL.20 Point-of-care metrics, such as the MPN Symptom Assessment Form (MPN-SAF), were developed to aid in identifying and grading symptom burden. Studies using this metric have reported fatigue as the most common and most severe symptom (incidence, 73%-92%), with a variety of other symptoms also affecting a majority of patients (Figure 1).6,21-24 Although fatigue, pruritus, and a higher MPN-SAF total symptom score are significantly correlated with reduced QoL,22,25 the recent MPN Landmark survey suggests that even patients with low symptom severity scores have a reduction in their QoL.6 This study also highlighted that polycythemia vera can adversely affect multiple aspects of daily living: 48% of patients reported disease interfering with daily activities; 63% with family or social life; and 37% with employment, feeling compelled to work reduced hours.6

Splenomegaly is a common feature of polycythemia vera, affecting an estimated one in three patients, which may result in discomfort and early satiety.4

Identification and diagnosis

Most patients diagnosed with polycythemia vera are between the ages of 60 and 76 years,3-5 although about 25% are diagnosed before age 50.4 Tefferi and colleagues reported in a retrospective study that common features at presentation include JAK2 mutations (98%), elevated hemoglobin (73%), endogenous erythroid colony growth (73%), white blood cell count of >10.5 × 109/L (49%), and platelet count of ≥450 × 109/L (53%).4 In that same study, about a third of patients presented with a palpable spleen or polycythemia vera–related symptoms, including pruritus and vasomotor symptoms. However, many patients were asymptomatic at presentation, diagnosed incidentally by abnormal laboratory values.4 Patients can present with vascular thrombosis, occasionally involving atypical sites (eg, Budd-Chiari syndrome, other abdominal blood clots),26 thus, a heightened awareness and testing for JAK2 mutations may be appropriate in the evaluation of such individuals.

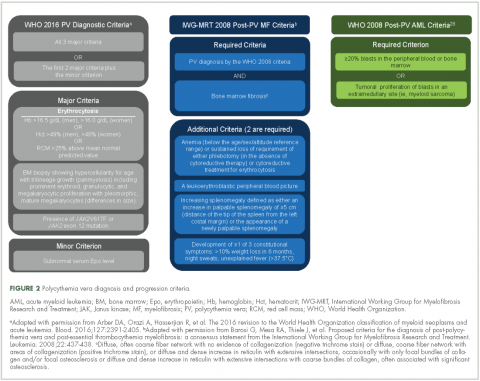

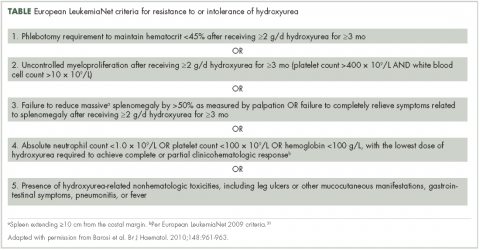

Evidence suggests many clinicians may not rigidly apply the WHO diagnostic criteria to establish a diagnosis.1,27,28 A recent retrospective claims analysis showed that only 40% of 121 patients diagnosed with polycythemia vera met the 2008 WHO diagnostic criteria, and for some patients, the diagnosis was based solely on the presence of the JAK2 V617F mutation.29 One should be aware of individuals with “masked” polycythemia vera, who may present with characteristic polycythemia vera features but have hemoglobin levels below those established by the WHO in 2008, typically owing to iron deficiency and/or a disproportionate expansion of plasma volume.30 To improve polycythemia vera diagnosis, the WHO diagnostic criteria were updated in 2016 with reduced hemoglobin diagnostic thresholds (Figure 2).1

Management strategy

Treatment goals

The primary polycythemia vera–treatment goals are to reduce the risk of cardiovascular, thrombotic, and hemorrhagic events; reduce the risk of fibrotic and/or leukemic transformation; and alleviate polycythemia vera–related symptoms.11,31

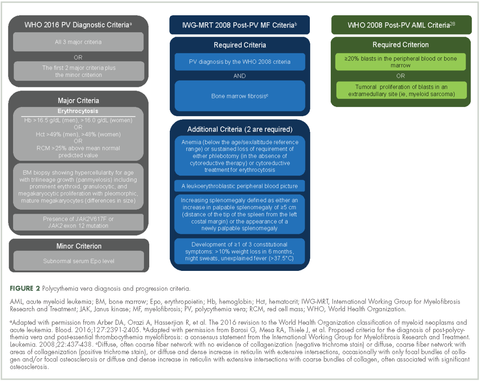

Traditional treatment options