User login

Research and Reviews for the Practicing Oncologist

Palliative and supportive interventions to improve patient-reported outcomes in rural residents with cancer

People in rural areas have increased rates of advanced cancer and mortality compared with those who live in more affluent and urban areas.1,2 Indeed, a recent report from the Center for Disease Control found that rural residents have higher mortality rates from 5 leading causes of death, including cancer, compared with their urban counterparts.1 Significant challenges facing rural residents are due largely to not having easy access to cancer care and supportive care services.3 In addition, living in a rural area is associated with: a lower socioeconomic status, inadequate health insurance coverage, and less flexible employment that in turn decreases the ability to obtain the full range of supportive oncology services.4 The closest available specialists may be several hours away. Individuals may be unwilling or unable to travel hundreds of miles or more to see a specialist.3 Traveling places financial burdens on patients because of the cost of traveling and loss of work, which can compound the stress and fatigue associated with cancer treatment. People living in rural areas also may have less social support in commuting between their place of living and hospitals.5

Background

Typically, the primary goals of treatment for individuals with advanced cancer are to control the spread of the disease; maintain important patient-reported outcomes (PROs) such as physical, mental, and psychosocial function; and optimize quality of life (QoL). Health-related QoL (ie, the physical and mental health perceptions) are increasingly being used to assess effectiveness of cancer treatment.6 Palliative care and supportive oncology focus on managing physical, social, psychological, and spiritual needs of patients and have been recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology to be integrated into standard oncology care.7

People living in rural areas are less likely to get their care within a single health system. Often, their care is divided across multiple facilities and providers, which increases the chances of miscommunication between providers and can lead to inferior clinical outcomes and decreased patient QoL.8 There is a growing body of research describing the impact of palliative care on people with advanced cancer. Specifically, palliative care has been shown to reduce symptoms, improve QoL, and increase survival.9-11 Differences have been observed in the palliative care needs between people with cancer living in urban and suburban areas.12 It is likely that palliative care needs as well as the impact of palliative care services for people with advanced cancer in rural areas differs from those of their urban and suburban counterparts. Despite the known differences in access to care and impact of cancer between rural and nonrural residents, the impact of palliative care on people with advanced cancer living in rural areas has not been well described in the literature.

The purpose of this systematic review is to examine effect of palliative care and supportive oncology interventions on QoL in people with advanced cancer living in rural areas.

Methods

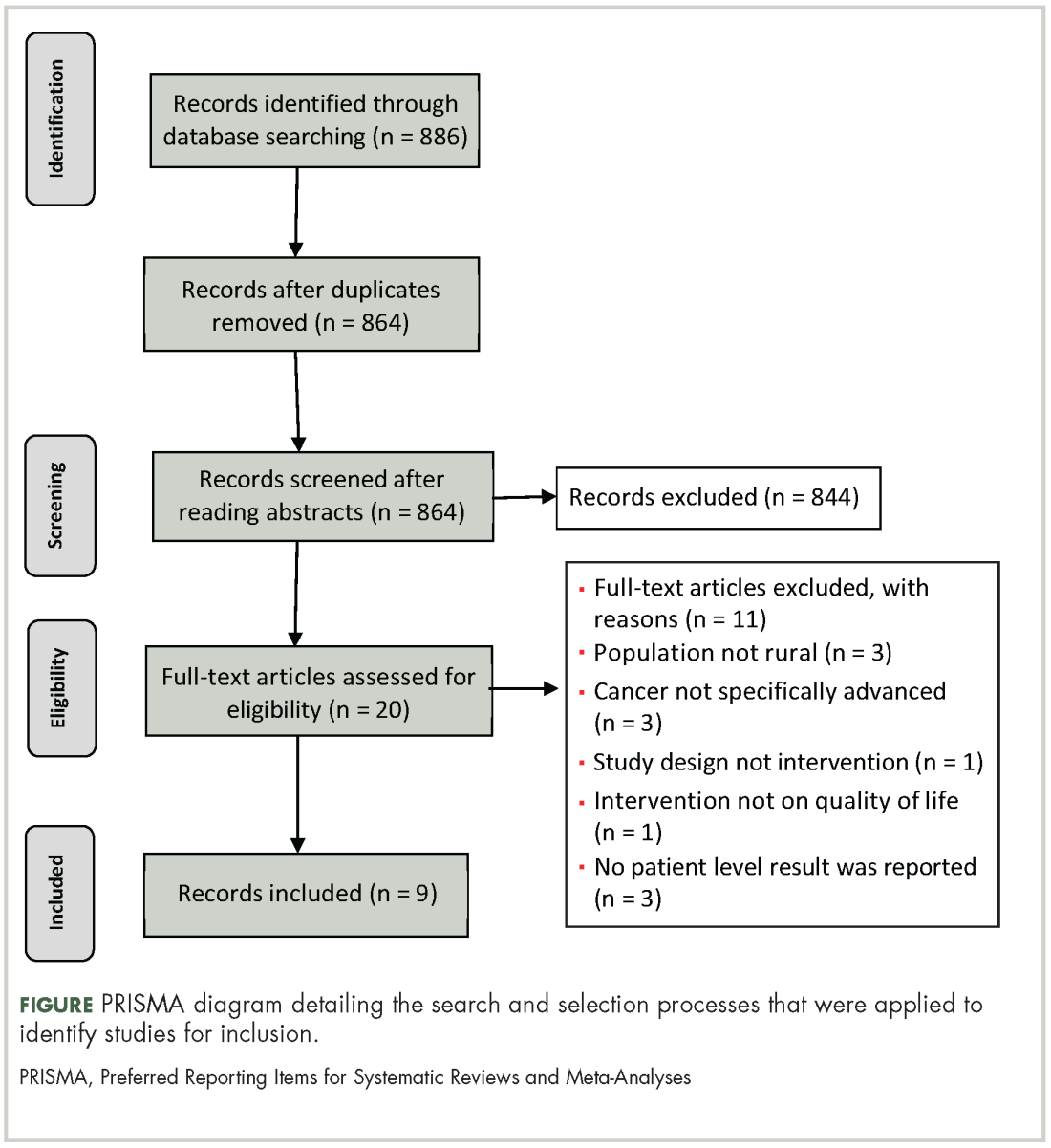

This systematic review was developed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.13

Eligibility criteria

To achieve the objective of a systemic review of studies describing supportive oncology and palliative care interventions in rural communities articles had to meet 4 inclusion criteria:

All research methods were eligible, including mixed-methods and program evaluations, as long as the article met the 4 inclusion criteria. Review articles were ineligible for inclusion as only original research was considered.

Search process

Search terms were developed by the research team with consultation from a medical librarian. Four main search terms were developed and included: palliative care, supportive oncology, rural, and cancer. Synonyms and terms closely related to the main terms were included in the search using the OR command. Examples of closely related search terms include: Palliative care: palliative; Rural: remote; Cancer: neoplasms (Table).

We systematically searched PyschINFO, PubMed, CINHAL, and Scopus for articles that had been published during 1991-2016 and written in English. Databases were chosen to reflect the different subfields that encompass palliative care and supportive oncology: PyschINFO to capture the psychological perspective, CINHAL to capture the nursing perspective, and PubMed to capture the medical perspective. Finally, Scopus was searched to ensure that articles not indexed by the other databases would be included. The search was limited to the past 25 years to capture the most up-to-date literature.

Selection process

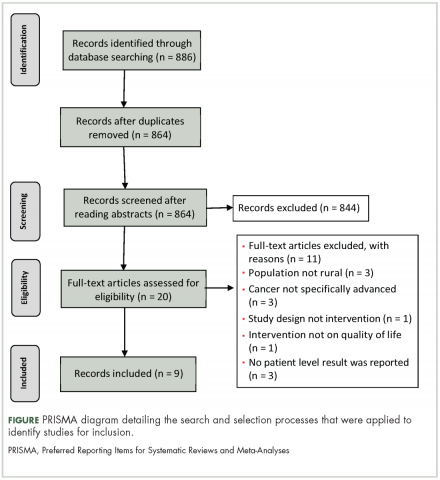

In accordance with PRISMA guidelines, articles underwent an initial screening and an eligibility screening for inclusion in the final review.13 After duplicates were removed, 2 research team members reviewed all abstracts to screen for initial eligibility. Articles that successfully passed the screening process were reviewed in full by 4 research team members. Each member made an independent inclusion decision based on the stated inclusion criteria. Disagreements across team members were resolved through discussion and consensus.

Analysis

The articles that met the inclusion criteria were heterogeneous in design and analytic approach. The set of manuscripts identified, therefore, did not meet the statistical assumptions for meta-analytic data analysis. The analytic plan for this review consisted of sorting the results described in the identified articles into meaningful categories, identifying cross cutting themes, and presenting the results of these themes in narrative forms.

Results

Study selection

The search strategy resulted in 886 articles across the 4 databases. The breakdown for each database is as follows: PsychINFO (n = 286), PubMed (n = 194), CINHAL (n = 334), Scopus (n = 72). After duplicates were removed, 864 articles were left and were initially screened resulting in 844 articles being excluded. The remaining 20 articles were reviewed and 12 articles failed to meet the inclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion included: the population was not rural; no advanced cancer in sample; intervention was not specifically palliative care or supportive oncology. Nine articles representing 8 projects (one project published 2 manuscripts included in this review) were included in the final review (Figure).

After reviewing the articles, 2 clear themes arose: PROs, and overall impact of rural palliative care for people and society. The PRO theme included articles that provided information on how an intervention or program improved the personal lives experience of rural cancer patients. PROs, such as decreased symptomology, were often reported. The “overall impact of rural palliative care for people and society” theme included articles that provided information on how an intervention or program improved the lives of rural people and society as a larger group. An example would include results indicating how a program increased access to supportive oncology care in a rural area.

Study characteristics

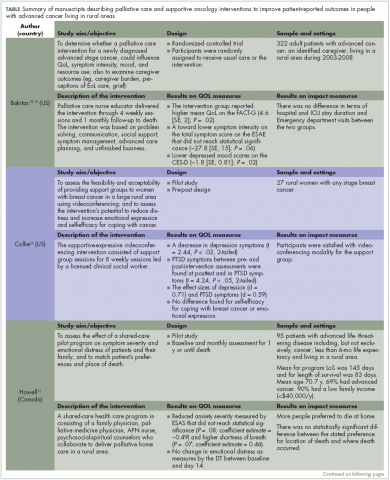

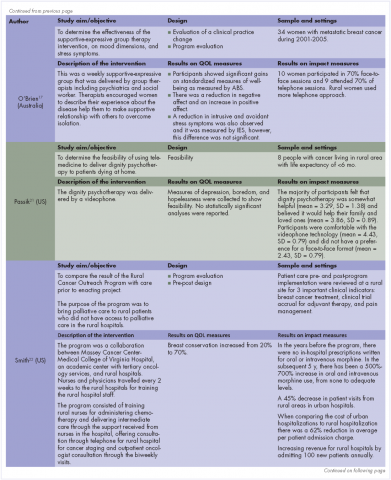

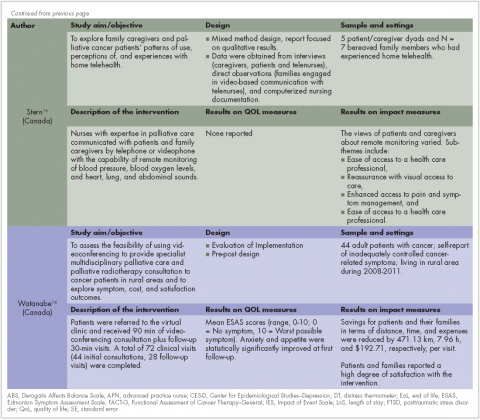

Nine publications, describing 8 projects were included in this review (Table). These projects were conducted in Canada (n = 3)14-16 Australia (n = 1)17 and the United States (n = 5).18-22 All of the the projects used a quantitative approach for the analysis, except 1 that used mixed-methods.16 The studies designs were: 4 feasibilities/pilot studies, 1 randomized control trials (RCT), and 3 program evaluations.

A total of 807 patients participated across the 9 articles. Participants’ age ranged from 20 to 88 years. The average ages for participants ranged from 50.4 to 70.7 years. Overall, there were slightly more men (55%) than women (45%) when all the demographic data were combined across the 9 articles; however, 2 articles exclusively had women as part of the sample.17,20 The cancer types that participants had included: gastrointestinal, genitourinary, breast, lung, brain, kidney, and hematological. Finally, the articles had inconsistent reporting of race/ethnicity data with only 4 studies reporting this information; of the 4 studies, 91% of participants self-identified as white.

The projects targeted multiple PROs, including physical symptoms and psychosocial issues (ie, stress management, grief, mood, emotional distress, coping, self-efficacy, dignity, joy, affection) domains. Publications dates ranged from 1996 to 2013. The sample sizes ranged from 8 to 322; 11.7%-100% of the study population had advanced cancer, and 20%-100% were living in rural area. The duration of the clinical intervention described was 30-120 minutes. The modes of delivery for the palliative intervention were videoconference/videophone (n = 3), telephone/teleconference (n = 3), and in person (n = 2). The interventions were delivered by nurses, psychiatrists, and social workers. In 5 of these studies, participants received palliative care on an individual basis and 2 studies delivered their intervention through groups. The individual basis studies focused on physical aspects of care and the group studies focused on emotional aspects of care.

Patient-reported outcomes

Cancer and its treatments are often associated with physical and emotional sequelae that can have a significant impact on patients and therefore PROs. The interventions reviewed in this article often reported data on the reduction of the physical and/or emotional symptom burden of cancer as well as overall QoL.

Reduction in physical symptoms. Three articles included physical symptoms as an outcome measure. Of those, 2 were pilot or feasibility studies, and 1 was a randomized control trial. Common physical symptoms included: shortness of breath, pain, fatigue, nausea, and appetite change. Across the articles, the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS), a 10-item inventory of common cancer symptoms, was frequently used to measure of symptom scores in these interventions.14,15,19 The ESAS is an empirically validated measure that is used in palliative care research and clinical practice. Individuals are asked to rank 10 common symptoms on an ascending scale from 1 to 10 (0, the symptom is absent; 10, worst possible severity).23

The findings from these 3 research studies were encouraging. In a large randomized control trial of a supportive education program, researchers reported decreased physical symptom intensity after the intervention, however the change did not reach statistical significance.18 Similar findings were reported in a videoconferencing and a home health program to improve access of palliative and supportive oncology health care.14,15 Physical symptoms that had decreasing trends were pain, tiredness, and appetite, however, trends for shortness of breath found increasing severity.14,15 Although these trends were observed, it is important to note that scores on the ESAS did not reach statistical significance for physical symptoms in any of these studies.

Reduction in emotional symptom reduction. In addition to reducing physical symptoms, researchers also sought to understand the impact of programs on the emotional symptoms of cancer including: anxiety, depression, negative affect, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Five articles included emotional symptoms as an outcome measure. Four were pilot or feasibility studies, and 1 was a randomized control trial.

Results across studies indicated an observable decrease in the severity of anxiety and depression for those exposed to an intervention program.14,15,18,19 Again, although trends were found, the results were not statistically significant. Only Watanabe and colleagues14 reported a statistically significant a decrease in anxiety in participants after the implementation of a rural palliative care videoconference consultation program. One report indicated that data on depression severity was collected but was not analyzed because of a small sample size.21

O’Brien and colleagues17 also collected data on negative affect and found that participants who participated in a supportive-expressive therapy group had a reduction in the negative affect as measured by the Derogatis Affects Balance Scale (ABS). Other researchers found no change in emotional distress.15

Finally, Collie and colleagues20 also measured the impact of a videoconference support group of PTSD symptomology for people with breast cancer in rural areas. Their results indicated a statistically significant decrease on the PTSD Checklist-Specific after intervention. Analysis of the data also found a medium effect size. Participants in the intervention group spoke about how participation in the support group allowed them to be generative and share information about breast cancer as well as build an emotional bond with other women with cancer.

Overall quality of life and well-being. Researchers have also looked into impact of intervention on overall QoL. Two articles included QoL or Well-being as an outcome measure. One was a pilot study and 1 was a randomized control trial.

Bakitas and colleagues18,19 found that those enrolled in the intervention arm of their study had higher QoL scores on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) compared with those in the control arm. These results were also found in an analysis of data from participants who subsequently died during the intervention. Improvements in overall well-being were also found by O’Brien and colleagues17 using ABS. They reported that a post hoc comparison of participants’ total positive affect score was significantly higher at the 12-month follow-up. In addition, the authors also noted qualitative improvements in well-being, including increased effort to be at the support group and the low attrition rates.

Overall impact of rural palliative care on individuals and society. In addition to reducing physical and emotional symptoms in patients, several of the articles also addressed other measures of the overall impact of the intervention or program on society as a whole. The authors evaluated patient satisfaction and quality of life, access to health care services, and financial impact on individuals and society at large.

Satisfaction with intervention. In 2 of the articles, individuals or their family members reported to be satisfied with the intervention14,20 and said they would recommend it to others as well.20 Both of those studies used teleconferencing to provide access to the intervention to people in rural communities.

Increasing access to the health care services and quality of care. Four of the articles evaluated the impact of intervention on patient’s access to the health care services.14,16,20,22 Specifically, after the interventions individuals had increased access to palliative care information in rural areas where it had previously been unavailable20 as well as actual delivery of clinical care in their home community, thus eliminating the need to travel to urban areas.14,20,22 This increase of access to health care services in rural area had significant effect on time and distance spent traveling. In 1 study, the amount of saving in terms of distance was 471.13 km and time in, 7.96 hours, for each visit.14

In addition, the quality of overall cancer care in rural area was increased. In an early clinical program, to increase access of palliative care in rural communities, the authors reported an increase in the breast conservation from 20% at the start of the program to 70% 2 years after the program was implemented.22 Breast conservation is not a typical outcome for palliative care studies, but the authors highlighted this practice change because of the improved QoL that is associated with the use of breast conservation therapies. In the same study, the authors reported an increased use of curative therapies for other cancers such as lymphoma as well as an increase use of pain management medication.

Financial impact. Two articles described the financial impact of cancer care costs on the patient and society.14,22 In a study by Watanabe and colleagues in Canada,14 the amount of savings after the intervention in terms of travel expenses was C$192.71 for each visit because patients had previously had to travel from their rural communities to urban tertiary hospitals to receive palliative care. For some patients in that study, the amount of saving for expenses was as high as C$500 a visit. In addition, some individuals were not able to travel and would not have received anything if the intervention had not been available remotely.14 In a study by Smith and colleagues in the United States, there was a 62% decrease in the cost to society for each patient, from US$10,233 to US$3,862.22 The factors contributing to that reduction included increasing outpatient services, engaging nurses and primary care providers instead of specialists, and the lower costs of living in rural areas. In addition, the rural hospitals saw an increase in revenue and profits because of higher admission rates ($500,00 for each hospital annually).22

Discussion

The articles identified in this review provide some evidence of the potential impact that palliative and supportive oncology interventions could have on PROs for rural residents with advanced cancer. Noteworthy results were seen for impact on reducing physical and emotional symptoms, increasing overall QoL and well-being, increasing satisfaction and access to palliative care, and reducing the overall cost of palliative care for individuals and society.14-18,20-22

Although statistical significance was not observed for most of the symptom assessment, trends toward improved symptom reports were observed. A likely explanation for this finding, is the small sample size or inadequate design to evaluate symptoms as an outcome measure. Three studies were pilot or feasibility projects15,20,21 that were not powered to detect the impact of the intervention on symptoms. In contrast, QoL stands out as an outcome that was positively affected by palliative care interventions. Further research is needed to determine if there are important mediating and moderating factors that contribute to improve QoL that are specific to rural residents. Significant outcomes were also reported for participant satisfaction with the interventions, the increase in access to services, and the decrease in costs.

Although there were not enough studies to determine the efficacy of these interventions, these results suggest that palliative and supportive interventions can have an impact on important patient-reported outcomes, such as symptoms and quality of life, and on health care system outcomes, such as cost. Evidence supporting the extent of the effectiveness of palliative care on various PROs in rural people is limited. None of the studies in this review evaluated the different aspects of palliative care specifically in rural residents.

It is interesting to note that all but one of the interventions used a telehealth approach to deliver the intervention. Telehealth interventions seem to be feasible, acceptable to people in rural areas, and show preliminary evidence that they can have an impact on PROs.

Limitations of this review include only inclusion of publications in English. In addition, some studies in this review include populations that were not exclusively rural residents, which makes it difficult for generalization.

Conclusion

Palliative and supportive interventions may improve various PROs in people with advanced cancer living in rural areas. Technologies that support remote access to people in rural areas, such as teleconferencing and videoconferencing, seem particularly promising delivery modalities with their potential to increase access to palliative and supportive interventions in underserved communities. Large-scale studies that are powered to test the impact of palliative care and support oncology interventions on PROs and other aspects of quality care among rural residents with advanced cancer are needed.

The authors thank Jennifer DeBerg, Health Science Librarian at the University of Iowa for her assistance in developing the literature search strategies.

1. Moy E, Garcia MC, Bastian B, et al. Leading causes of death in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan areas – United States, 1999-2014 [published correction at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6603a11.htm]. MMWR Surveillance Summaries [serial online]. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/ss/ss6601a1.htm?s_cid=ss6601a1_w. Published January 13, 2017. Accessed January 20, 2017.

2. Singh GK, Williams SD, Siahpush M, Mulhollen A. Socioeconomic, rural-urban, and racial inequalities in US Cancer Mortality: Part I – All cancers and lung cancer and Part II – Colorectal, prostate, breast, and cervical cancers. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jce/2011/107497/. Published 2011. Accessed April 28, 2017.

3. Charlton M, Schlichting J, Chioreso C, Ward M, Vikas P. Challenges of rural cancer care in the United States. Oncology (Williston Park). 2015;29(9):633-640.

4. Weaver KE, Geiger AM, Lu L, Case LD. Rural‐urban disparities in health status among US cancer survivors. Cancer. 2013;119(5):1050-1057.

5. Fuchsia Howard A, Smillie K, Turnbull K, et al. Access to medical and supportive care for rural and remote cancer survivors in northern British Columbia. J Rural Health. 2014;30(3):311-321.

6. Bottomley A, Aaronson NK. International perspective on health-related quality-of-life research in cancer clinical trials: the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer experience. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5082-5086.

7. Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(8):880-887.

8. Baldwin LM, Cai Y, Larson EH, et al. Access to cancer services for rural colorectal cancer patients. J Rural Health. 2008;24(4):390-399.

9. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742.

10. McCorkle R, Jeon S, Ercolano E, et al. An advanced practice nurse coordinated multidisciplinary intervention for patients with late-stage cancer: a cluster randomized trial. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(11):962-969.

11. Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721-1730.

12. Regn R, Robinson W, Robinson WR. Differences in palliative care needs among cancer survivors in an inner city academic facility versus a suburban community facility. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(29_suppl):61.

13. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;339:b2535.

14. Watanabe SM, Fairchild A, Pituskin E, Borgersen P, Hanson J, Fassbender K. Improving access to specialist multidisciplinary palliative care consultation for rural cancer patients by videoconferencing: report of a pilot project. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(4):1201-1207.

15. Howell D, Marshall D, Brazil K, et al. A shared care model pilot for palliative home care in a rural area: impact on symptoms, distress, and place of death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(1):60-75.

16. Stern A, Valaitis R, Weir R, Jadad AR. Use of home telehealth in palliative cancer care: a case study. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(5):297-300.

17. O’Brien M, Harris J, King R, O’Brien T. Supportive-expressive group therapy for women with metastatic breast cancer: Improving access for Australian women through use of teleconference. Counselling Psychother Res. 2008;8(1):28-35.

18. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial to improve palliative care for rural patients with advanced cancer: baseline findings, methodological challenges, and solutions. Palliat Supportive Care. 2009;7(1):75-86.

19. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741-749.

20. Collie K, Kreshka MA, Ferrier S, et al. Videoconferencing for delivery of breast cancer support groups to women living in rural communities: a pilot study. Psychooncology. 200

21. Passik SD, Kirsh KL, Leibee S, et al. A feasibility study of dignity psychotherapy delivered via telemedicine. Palliat Support Care. 2004;2(2):149-155.

22. Smith TJ, Desch CE, Grasso MA, et al. The Rural Cancer Outreach Program: clinical and financial analysis of palliative and curative care for an underserved population. Cancer Treat Rev. 1996;22(Suppl A):97-101.

23. Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7(2):6-9.

People in rural areas have increased rates of advanced cancer and mortality compared with those who live in more affluent and urban areas.1,2 Indeed, a recent report from the Center for Disease Control found that rural residents have higher mortality rates from 5 leading causes of death, including cancer, compared with their urban counterparts.1 Significant challenges facing rural residents are due largely to not having easy access to cancer care and supportive care services.3 In addition, living in a rural area is associated with: a lower socioeconomic status, inadequate health insurance coverage, and less flexible employment that in turn decreases the ability to obtain the full range of supportive oncology services.4 The closest available specialists may be several hours away. Individuals may be unwilling or unable to travel hundreds of miles or more to see a specialist.3 Traveling places financial burdens on patients because of the cost of traveling and loss of work, which can compound the stress and fatigue associated with cancer treatment. People living in rural areas also may have less social support in commuting between their place of living and hospitals.5

Background

Typically, the primary goals of treatment for individuals with advanced cancer are to control the spread of the disease; maintain important patient-reported outcomes (PROs) such as physical, mental, and psychosocial function; and optimize quality of life (QoL). Health-related QoL (ie, the physical and mental health perceptions) are increasingly being used to assess effectiveness of cancer treatment.6 Palliative care and supportive oncology focus on managing physical, social, psychological, and spiritual needs of patients and have been recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology to be integrated into standard oncology care.7

People living in rural areas are less likely to get their care within a single health system. Often, their care is divided across multiple facilities and providers, which increases the chances of miscommunication between providers and can lead to inferior clinical outcomes and decreased patient QoL.8 There is a growing body of research describing the impact of palliative care on people with advanced cancer. Specifically, palliative care has been shown to reduce symptoms, improve QoL, and increase survival.9-11 Differences have been observed in the palliative care needs between people with cancer living in urban and suburban areas.12 It is likely that palliative care needs as well as the impact of palliative care services for people with advanced cancer in rural areas differs from those of their urban and suburban counterparts. Despite the known differences in access to care and impact of cancer between rural and nonrural residents, the impact of palliative care on people with advanced cancer living in rural areas has not been well described in the literature.

The purpose of this systematic review is to examine effect of palliative care and supportive oncology interventions on QoL in people with advanced cancer living in rural areas.

Methods

This systematic review was developed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.13

Eligibility criteria

To achieve the objective of a systemic review of studies describing supportive oncology and palliative care interventions in rural communities articles had to meet 4 inclusion criteria:

All research methods were eligible, including mixed-methods and program evaluations, as long as the article met the 4 inclusion criteria. Review articles were ineligible for inclusion as only original research was considered.

Search process

Search terms were developed by the research team with consultation from a medical librarian. Four main search terms were developed and included: palliative care, supportive oncology, rural, and cancer. Synonyms and terms closely related to the main terms were included in the search using the OR command. Examples of closely related search terms include: Palliative care: palliative; Rural: remote; Cancer: neoplasms (Table).

We systematically searched PyschINFO, PubMed, CINHAL, and Scopus for articles that had been published during 1991-2016 and written in English. Databases were chosen to reflect the different subfields that encompass palliative care and supportive oncology: PyschINFO to capture the psychological perspective, CINHAL to capture the nursing perspective, and PubMed to capture the medical perspective. Finally, Scopus was searched to ensure that articles not indexed by the other databases would be included. The search was limited to the past 25 years to capture the most up-to-date literature.

Selection process

In accordance with PRISMA guidelines, articles underwent an initial screening and an eligibility screening for inclusion in the final review.13 After duplicates were removed, 2 research team members reviewed all abstracts to screen for initial eligibility. Articles that successfully passed the screening process were reviewed in full by 4 research team members. Each member made an independent inclusion decision based on the stated inclusion criteria. Disagreements across team members were resolved through discussion and consensus.

Analysis

The articles that met the inclusion criteria were heterogeneous in design and analytic approach. The set of manuscripts identified, therefore, did not meet the statistical assumptions for meta-analytic data analysis. The analytic plan for this review consisted of sorting the results described in the identified articles into meaningful categories, identifying cross cutting themes, and presenting the results of these themes in narrative forms.

Results

Study selection

The search strategy resulted in 886 articles across the 4 databases. The breakdown for each database is as follows: PsychINFO (n = 286), PubMed (n = 194), CINHAL (n = 334), Scopus (n = 72). After duplicates were removed, 864 articles were left and were initially screened resulting in 844 articles being excluded. The remaining 20 articles were reviewed and 12 articles failed to meet the inclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion included: the population was not rural; no advanced cancer in sample; intervention was not specifically palliative care or supportive oncology. Nine articles representing 8 projects (one project published 2 manuscripts included in this review) were included in the final review (Figure).

After reviewing the articles, 2 clear themes arose: PROs, and overall impact of rural palliative care for people and society. The PRO theme included articles that provided information on how an intervention or program improved the personal lives experience of rural cancer patients. PROs, such as decreased symptomology, were often reported. The “overall impact of rural palliative care for people and society” theme included articles that provided information on how an intervention or program improved the lives of rural people and society as a larger group. An example would include results indicating how a program increased access to supportive oncology care in a rural area.

Study characteristics

Nine publications, describing 8 projects were included in this review (Table). These projects were conducted in Canada (n = 3)14-16 Australia (n = 1)17 and the United States (n = 5).18-22 All of the the projects used a quantitative approach for the analysis, except 1 that used mixed-methods.16 The studies designs were: 4 feasibilities/pilot studies, 1 randomized control trials (RCT), and 3 program evaluations.

A total of 807 patients participated across the 9 articles. Participants’ age ranged from 20 to 88 years. The average ages for participants ranged from 50.4 to 70.7 years. Overall, there were slightly more men (55%) than women (45%) when all the demographic data were combined across the 9 articles; however, 2 articles exclusively had women as part of the sample.17,20 The cancer types that participants had included: gastrointestinal, genitourinary, breast, lung, brain, kidney, and hematological. Finally, the articles had inconsistent reporting of race/ethnicity data with only 4 studies reporting this information; of the 4 studies, 91% of participants self-identified as white.

The projects targeted multiple PROs, including physical symptoms and psychosocial issues (ie, stress management, grief, mood, emotional distress, coping, self-efficacy, dignity, joy, affection) domains. Publications dates ranged from 1996 to 2013. The sample sizes ranged from 8 to 322; 11.7%-100% of the study population had advanced cancer, and 20%-100% were living in rural area. The duration of the clinical intervention described was 30-120 minutes. The modes of delivery for the palliative intervention were videoconference/videophone (n = 3), telephone/teleconference (n = 3), and in person (n = 2). The interventions were delivered by nurses, psychiatrists, and social workers. In 5 of these studies, participants received palliative care on an individual basis and 2 studies delivered their intervention through groups. The individual basis studies focused on physical aspects of care and the group studies focused on emotional aspects of care.

Patient-reported outcomes

Cancer and its treatments are often associated with physical and emotional sequelae that can have a significant impact on patients and therefore PROs. The interventions reviewed in this article often reported data on the reduction of the physical and/or emotional symptom burden of cancer as well as overall QoL.

Reduction in physical symptoms. Three articles included physical symptoms as an outcome measure. Of those, 2 were pilot or feasibility studies, and 1 was a randomized control trial. Common physical symptoms included: shortness of breath, pain, fatigue, nausea, and appetite change. Across the articles, the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS), a 10-item inventory of common cancer symptoms, was frequently used to measure of symptom scores in these interventions.14,15,19 The ESAS is an empirically validated measure that is used in palliative care research and clinical practice. Individuals are asked to rank 10 common symptoms on an ascending scale from 1 to 10 (0, the symptom is absent; 10, worst possible severity).23

The findings from these 3 research studies were encouraging. In a large randomized control trial of a supportive education program, researchers reported decreased physical symptom intensity after the intervention, however the change did not reach statistical significance.18 Similar findings were reported in a videoconferencing and a home health program to improve access of palliative and supportive oncology health care.14,15 Physical symptoms that had decreasing trends were pain, tiredness, and appetite, however, trends for shortness of breath found increasing severity.14,15 Although these trends were observed, it is important to note that scores on the ESAS did not reach statistical significance for physical symptoms in any of these studies.

Reduction in emotional symptom reduction. In addition to reducing physical symptoms, researchers also sought to understand the impact of programs on the emotional symptoms of cancer including: anxiety, depression, negative affect, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Five articles included emotional symptoms as an outcome measure. Four were pilot or feasibility studies, and 1 was a randomized control trial.

Results across studies indicated an observable decrease in the severity of anxiety and depression for those exposed to an intervention program.14,15,18,19 Again, although trends were found, the results were not statistically significant. Only Watanabe and colleagues14 reported a statistically significant a decrease in anxiety in participants after the implementation of a rural palliative care videoconference consultation program. One report indicated that data on depression severity was collected but was not analyzed because of a small sample size.21

O’Brien and colleagues17 also collected data on negative affect and found that participants who participated in a supportive-expressive therapy group had a reduction in the negative affect as measured by the Derogatis Affects Balance Scale (ABS). Other researchers found no change in emotional distress.15

Finally, Collie and colleagues20 also measured the impact of a videoconference support group of PTSD symptomology for people with breast cancer in rural areas. Their results indicated a statistically significant decrease on the PTSD Checklist-Specific after intervention. Analysis of the data also found a medium effect size. Participants in the intervention group spoke about how participation in the support group allowed them to be generative and share information about breast cancer as well as build an emotional bond with other women with cancer.

Overall quality of life and well-being. Researchers have also looked into impact of intervention on overall QoL. Two articles included QoL or Well-being as an outcome measure. One was a pilot study and 1 was a randomized control trial.

Bakitas and colleagues18,19 found that those enrolled in the intervention arm of their study had higher QoL scores on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) compared with those in the control arm. These results were also found in an analysis of data from participants who subsequently died during the intervention. Improvements in overall well-being were also found by O’Brien and colleagues17 using ABS. They reported that a post hoc comparison of participants’ total positive affect score was significantly higher at the 12-month follow-up. In addition, the authors also noted qualitative improvements in well-being, including increased effort to be at the support group and the low attrition rates.

Overall impact of rural palliative care on individuals and society. In addition to reducing physical and emotional symptoms in patients, several of the articles also addressed other measures of the overall impact of the intervention or program on society as a whole. The authors evaluated patient satisfaction and quality of life, access to health care services, and financial impact on individuals and society at large.

Satisfaction with intervention. In 2 of the articles, individuals or their family members reported to be satisfied with the intervention14,20 and said they would recommend it to others as well.20 Both of those studies used teleconferencing to provide access to the intervention to people in rural communities.

Increasing access to the health care services and quality of care. Four of the articles evaluated the impact of intervention on patient’s access to the health care services.14,16,20,22 Specifically, after the interventions individuals had increased access to palliative care information in rural areas where it had previously been unavailable20 as well as actual delivery of clinical care in their home community, thus eliminating the need to travel to urban areas.14,20,22 This increase of access to health care services in rural area had significant effect on time and distance spent traveling. In 1 study, the amount of saving in terms of distance was 471.13 km and time in, 7.96 hours, for each visit.14

In addition, the quality of overall cancer care in rural area was increased. In an early clinical program, to increase access of palliative care in rural communities, the authors reported an increase in the breast conservation from 20% at the start of the program to 70% 2 years after the program was implemented.22 Breast conservation is not a typical outcome for palliative care studies, but the authors highlighted this practice change because of the improved QoL that is associated with the use of breast conservation therapies. In the same study, the authors reported an increased use of curative therapies for other cancers such as lymphoma as well as an increase use of pain management medication.

Financial impact. Two articles described the financial impact of cancer care costs on the patient and society.14,22 In a study by Watanabe and colleagues in Canada,14 the amount of savings after the intervention in terms of travel expenses was C$192.71 for each visit because patients had previously had to travel from their rural communities to urban tertiary hospitals to receive palliative care. For some patients in that study, the amount of saving for expenses was as high as C$500 a visit. In addition, some individuals were not able to travel and would not have received anything if the intervention had not been available remotely.14 In a study by Smith and colleagues in the United States, there was a 62% decrease in the cost to society for each patient, from US$10,233 to US$3,862.22 The factors contributing to that reduction included increasing outpatient services, engaging nurses and primary care providers instead of specialists, and the lower costs of living in rural areas. In addition, the rural hospitals saw an increase in revenue and profits because of higher admission rates ($500,00 for each hospital annually).22

Discussion

The articles identified in this review provide some evidence of the potential impact that palliative and supportive oncology interventions could have on PROs for rural residents with advanced cancer. Noteworthy results were seen for impact on reducing physical and emotional symptoms, increasing overall QoL and well-being, increasing satisfaction and access to palliative care, and reducing the overall cost of palliative care for individuals and society.14-18,20-22

Although statistical significance was not observed for most of the symptom assessment, trends toward improved symptom reports were observed. A likely explanation for this finding, is the small sample size or inadequate design to evaluate symptoms as an outcome measure. Three studies were pilot or feasibility projects15,20,21 that were not powered to detect the impact of the intervention on symptoms. In contrast, QoL stands out as an outcome that was positively affected by palliative care interventions. Further research is needed to determine if there are important mediating and moderating factors that contribute to improve QoL that are specific to rural residents. Significant outcomes were also reported for participant satisfaction with the interventions, the increase in access to services, and the decrease in costs.

Although there were not enough studies to determine the efficacy of these interventions, these results suggest that palliative and supportive interventions can have an impact on important patient-reported outcomes, such as symptoms and quality of life, and on health care system outcomes, such as cost. Evidence supporting the extent of the effectiveness of palliative care on various PROs in rural people is limited. None of the studies in this review evaluated the different aspects of palliative care specifically in rural residents.

It is interesting to note that all but one of the interventions used a telehealth approach to deliver the intervention. Telehealth interventions seem to be feasible, acceptable to people in rural areas, and show preliminary evidence that they can have an impact on PROs.

Limitations of this review include only inclusion of publications in English. In addition, some studies in this review include populations that were not exclusively rural residents, which makes it difficult for generalization.

Conclusion

Palliative and supportive interventions may improve various PROs in people with advanced cancer living in rural areas. Technologies that support remote access to people in rural areas, such as teleconferencing and videoconferencing, seem particularly promising delivery modalities with their potential to increase access to palliative and supportive interventions in underserved communities. Large-scale studies that are powered to test the impact of palliative care and support oncology interventions on PROs and other aspects of quality care among rural residents with advanced cancer are needed.

The authors thank Jennifer DeBerg, Health Science Librarian at the University of Iowa for her assistance in developing the literature search strategies.

People in rural areas have increased rates of advanced cancer and mortality compared with those who live in more affluent and urban areas.1,2 Indeed, a recent report from the Center for Disease Control found that rural residents have higher mortality rates from 5 leading causes of death, including cancer, compared with their urban counterparts.1 Significant challenges facing rural residents are due largely to not having easy access to cancer care and supportive care services.3 In addition, living in a rural area is associated with: a lower socioeconomic status, inadequate health insurance coverage, and less flexible employment that in turn decreases the ability to obtain the full range of supportive oncology services.4 The closest available specialists may be several hours away. Individuals may be unwilling or unable to travel hundreds of miles or more to see a specialist.3 Traveling places financial burdens on patients because of the cost of traveling and loss of work, which can compound the stress and fatigue associated with cancer treatment. People living in rural areas also may have less social support in commuting between their place of living and hospitals.5

Background

Typically, the primary goals of treatment for individuals with advanced cancer are to control the spread of the disease; maintain important patient-reported outcomes (PROs) such as physical, mental, and psychosocial function; and optimize quality of life (QoL). Health-related QoL (ie, the physical and mental health perceptions) are increasingly being used to assess effectiveness of cancer treatment.6 Palliative care and supportive oncology focus on managing physical, social, psychological, and spiritual needs of patients and have been recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology to be integrated into standard oncology care.7

People living in rural areas are less likely to get their care within a single health system. Often, their care is divided across multiple facilities and providers, which increases the chances of miscommunication between providers and can lead to inferior clinical outcomes and decreased patient QoL.8 There is a growing body of research describing the impact of palliative care on people with advanced cancer. Specifically, palliative care has been shown to reduce symptoms, improve QoL, and increase survival.9-11 Differences have been observed in the palliative care needs between people with cancer living in urban and suburban areas.12 It is likely that palliative care needs as well as the impact of palliative care services for people with advanced cancer in rural areas differs from those of their urban and suburban counterparts. Despite the known differences in access to care and impact of cancer between rural and nonrural residents, the impact of palliative care on people with advanced cancer living in rural areas has not been well described in the literature.

The purpose of this systematic review is to examine effect of palliative care and supportive oncology interventions on QoL in people with advanced cancer living in rural areas.

Methods

This systematic review was developed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.13

Eligibility criteria

To achieve the objective of a systemic review of studies describing supportive oncology and palliative care interventions in rural communities articles had to meet 4 inclusion criteria:

All research methods were eligible, including mixed-methods and program evaluations, as long as the article met the 4 inclusion criteria. Review articles were ineligible for inclusion as only original research was considered.

Search process

Search terms were developed by the research team with consultation from a medical librarian. Four main search terms were developed and included: palliative care, supportive oncology, rural, and cancer. Synonyms and terms closely related to the main terms were included in the search using the OR command. Examples of closely related search terms include: Palliative care: palliative; Rural: remote; Cancer: neoplasms (Table).

We systematically searched PyschINFO, PubMed, CINHAL, and Scopus for articles that had been published during 1991-2016 and written in English. Databases were chosen to reflect the different subfields that encompass palliative care and supportive oncology: PyschINFO to capture the psychological perspective, CINHAL to capture the nursing perspective, and PubMed to capture the medical perspective. Finally, Scopus was searched to ensure that articles not indexed by the other databases would be included. The search was limited to the past 25 years to capture the most up-to-date literature.

Selection process

In accordance with PRISMA guidelines, articles underwent an initial screening and an eligibility screening for inclusion in the final review.13 After duplicates were removed, 2 research team members reviewed all abstracts to screen for initial eligibility. Articles that successfully passed the screening process were reviewed in full by 4 research team members. Each member made an independent inclusion decision based on the stated inclusion criteria. Disagreements across team members were resolved through discussion and consensus.

Analysis

The articles that met the inclusion criteria were heterogeneous in design and analytic approach. The set of manuscripts identified, therefore, did not meet the statistical assumptions for meta-analytic data analysis. The analytic plan for this review consisted of sorting the results described in the identified articles into meaningful categories, identifying cross cutting themes, and presenting the results of these themes in narrative forms.

Results

Study selection

The search strategy resulted in 886 articles across the 4 databases. The breakdown for each database is as follows: PsychINFO (n = 286), PubMed (n = 194), CINHAL (n = 334), Scopus (n = 72). After duplicates were removed, 864 articles were left and were initially screened resulting in 844 articles being excluded. The remaining 20 articles were reviewed and 12 articles failed to meet the inclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion included: the population was not rural; no advanced cancer in sample; intervention was not specifically palliative care or supportive oncology. Nine articles representing 8 projects (one project published 2 manuscripts included in this review) were included in the final review (Figure).

After reviewing the articles, 2 clear themes arose: PROs, and overall impact of rural palliative care for people and society. The PRO theme included articles that provided information on how an intervention or program improved the personal lives experience of rural cancer patients. PROs, such as decreased symptomology, were often reported. The “overall impact of rural palliative care for people and society” theme included articles that provided information on how an intervention or program improved the lives of rural people and society as a larger group. An example would include results indicating how a program increased access to supportive oncology care in a rural area.

Study characteristics

Nine publications, describing 8 projects were included in this review (Table). These projects were conducted in Canada (n = 3)14-16 Australia (n = 1)17 and the United States (n = 5).18-22 All of the the projects used a quantitative approach for the analysis, except 1 that used mixed-methods.16 The studies designs were: 4 feasibilities/pilot studies, 1 randomized control trials (RCT), and 3 program evaluations.

A total of 807 patients participated across the 9 articles. Participants’ age ranged from 20 to 88 years. The average ages for participants ranged from 50.4 to 70.7 years. Overall, there were slightly more men (55%) than women (45%) when all the demographic data were combined across the 9 articles; however, 2 articles exclusively had women as part of the sample.17,20 The cancer types that participants had included: gastrointestinal, genitourinary, breast, lung, brain, kidney, and hematological. Finally, the articles had inconsistent reporting of race/ethnicity data with only 4 studies reporting this information; of the 4 studies, 91% of participants self-identified as white.

The projects targeted multiple PROs, including physical symptoms and psychosocial issues (ie, stress management, grief, mood, emotional distress, coping, self-efficacy, dignity, joy, affection) domains. Publications dates ranged from 1996 to 2013. The sample sizes ranged from 8 to 322; 11.7%-100% of the study population had advanced cancer, and 20%-100% were living in rural area. The duration of the clinical intervention described was 30-120 minutes. The modes of delivery for the palliative intervention were videoconference/videophone (n = 3), telephone/teleconference (n = 3), and in person (n = 2). The interventions were delivered by nurses, psychiatrists, and social workers. In 5 of these studies, participants received palliative care on an individual basis and 2 studies delivered their intervention through groups. The individual basis studies focused on physical aspects of care and the group studies focused on emotional aspects of care.

Patient-reported outcomes

Cancer and its treatments are often associated with physical and emotional sequelae that can have a significant impact on patients and therefore PROs. The interventions reviewed in this article often reported data on the reduction of the physical and/or emotional symptom burden of cancer as well as overall QoL.

Reduction in physical symptoms. Three articles included physical symptoms as an outcome measure. Of those, 2 were pilot or feasibility studies, and 1 was a randomized control trial. Common physical symptoms included: shortness of breath, pain, fatigue, nausea, and appetite change. Across the articles, the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS), a 10-item inventory of common cancer symptoms, was frequently used to measure of symptom scores in these interventions.14,15,19 The ESAS is an empirically validated measure that is used in palliative care research and clinical practice. Individuals are asked to rank 10 common symptoms on an ascending scale from 1 to 10 (0, the symptom is absent; 10, worst possible severity).23

The findings from these 3 research studies were encouraging. In a large randomized control trial of a supportive education program, researchers reported decreased physical symptom intensity after the intervention, however the change did not reach statistical significance.18 Similar findings were reported in a videoconferencing and a home health program to improve access of palliative and supportive oncology health care.14,15 Physical symptoms that had decreasing trends were pain, tiredness, and appetite, however, trends for shortness of breath found increasing severity.14,15 Although these trends were observed, it is important to note that scores on the ESAS did not reach statistical significance for physical symptoms in any of these studies.

Reduction in emotional symptom reduction. In addition to reducing physical symptoms, researchers also sought to understand the impact of programs on the emotional symptoms of cancer including: anxiety, depression, negative affect, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Five articles included emotional symptoms as an outcome measure. Four were pilot or feasibility studies, and 1 was a randomized control trial.

Results across studies indicated an observable decrease in the severity of anxiety and depression for those exposed to an intervention program.14,15,18,19 Again, although trends were found, the results were not statistically significant. Only Watanabe and colleagues14 reported a statistically significant a decrease in anxiety in participants after the implementation of a rural palliative care videoconference consultation program. One report indicated that data on depression severity was collected but was not analyzed because of a small sample size.21

O’Brien and colleagues17 also collected data on negative affect and found that participants who participated in a supportive-expressive therapy group had a reduction in the negative affect as measured by the Derogatis Affects Balance Scale (ABS). Other researchers found no change in emotional distress.15

Finally, Collie and colleagues20 also measured the impact of a videoconference support group of PTSD symptomology for people with breast cancer in rural areas. Their results indicated a statistically significant decrease on the PTSD Checklist-Specific after intervention. Analysis of the data also found a medium effect size. Participants in the intervention group spoke about how participation in the support group allowed them to be generative and share information about breast cancer as well as build an emotional bond with other women with cancer.

Overall quality of life and well-being. Researchers have also looked into impact of intervention on overall QoL. Two articles included QoL or Well-being as an outcome measure. One was a pilot study and 1 was a randomized control trial.

Bakitas and colleagues18,19 found that those enrolled in the intervention arm of their study had higher QoL scores on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) compared with those in the control arm. These results were also found in an analysis of data from participants who subsequently died during the intervention. Improvements in overall well-being were also found by O’Brien and colleagues17 using ABS. They reported that a post hoc comparison of participants’ total positive affect score was significantly higher at the 12-month follow-up. In addition, the authors also noted qualitative improvements in well-being, including increased effort to be at the support group and the low attrition rates.

Overall impact of rural palliative care on individuals and society. In addition to reducing physical and emotional symptoms in patients, several of the articles also addressed other measures of the overall impact of the intervention or program on society as a whole. The authors evaluated patient satisfaction and quality of life, access to health care services, and financial impact on individuals and society at large.

Satisfaction with intervention. In 2 of the articles, individuals or their family members reported to be satisfied with the intervention14,20 and said they would recommend it to others as well.20 Both of those studies used teleconferencing to provide access to the intervention to people in rural communities.

Increasing access to the health care services and quality of care. Four of the articles evaluated the impact of intervention on patient’s access to the health care services.14,16,20,22 Specifically, after the interventions individuals had increased access to palliative care information in rural areas where it had previously been unavailable20 as well as actual delivery of clinical care in their home community, thus eliminating the need to travel to urban areas.14,20,22 This increase of access to health care services in rural area had significant effect on time and distance spent traveling. In 1 study, the amount of saving in terms of distance was 471.13 km and time in, 7.96 hours, for each visit.14

In addition, the quality of overall cancer care in rural area was increased. In an early clinical program, to increase access of palliative care in rural communities, the authors reported an increase in the breast conservation from 20% at the start of the program to 70% 2 years after the program was implemented.22 Breast conservation is not a typical outcome for palliative care studies, but the authors highlighted this practice change because of the improved QoL that is associated with the use of breast conservation therapies. In the same study, the authors reported an increased use of curative therapies for other cancers such as lymphoma as well as an increase use of pain management medication.

Financial impact. Two articles described the financial impact of cancer care costs on the patient and society.14,22 In a study by Watanabe and colleagues in Canada,14 the amount of savings after the intervention in terms of travel expenses was C$192.71 for each visit because patients had previously had to travel from their rural communities to urban tertiary hospitals to receive palliative care. For some patients in that study, the amount of saving for expenses was as high as C$500 a visit. In addition, some individuals were not able to travel and would not have received anything if the intervention had not been available remotely.14 In a study by Smith and colleagues in the United States, there was a 62% decrease in the cost to society for each patient, from US$10,233 to US$3,862.22 The factors contributing to that reduction included increasing outpatient services, engaging nurses and primary care providers instead of specialists, and the lower costs of living in rural areas. In addition, the rural hospitals saw an increase in revenue and profits because of higher admission rates ($500,00 for each hospital annually).22

Discussion

The articles identified in this review provide some evidence of the potential impact that palliative and supportive oncology interventions could have on PROs for rural residents with advanced cancer. Noteworthy results were seen for impact on reducing physical and emotional symptoms, increasing overall QoL and well-being, increasing satisfaction and access to palliative care, and reducing the overall cost of palliative care for individuals and society.14-18,20-22

Although statistical significance was not observed for most of the symptom assessment, trends toward improved symptom reports were observed. A likely explanation for this finding, is the small sample size or inadequate design to evaluate symptoms as an outcome measure. Three studies were pilot or feasibility projects15,20,21 that were not powered to detect the impact of the intervention on symptoms. In contrast, QoL stands out as an outcome that was positively affected by palliative care interventions. Further research is needed to determine if there are important mediating and moderating factors that contribute to improve QoL that are specific to rural residents. Significant outcomes were also reported for participant satisfaction with the interventions, the increase in access to services, and the decrease in costs.

Although there were not enough studies to determine the efficacy of these interventions, these results suggest that palliative and supportive interventions can have an impact on important patient-reported outcomes, such as symptoms and quality of life, and on health care system outcomes, such as cost. Evidence supporting the extent of the effectiveness of palliative care on various PROs in rural people is limited. None of the studies in this review evaluated the different aspects of palliative care specifically in rural residents.

It is interesting to note that all but one of the interventions used a telehealth approach to deliver the intervention. Telehealth interventions seem to be feasible, acceptable to people in rural areas, and show preliminary evidence that they can have an impact on PROs.

Limitations of this review include only inclusion of publications in English. In addition, some studies in this review include populations that were not exclusively rural residents, which makes it difficult for generalization.

Conclusion

Palliative and supportive interventions may improve various PROs in people with advanced cancer living in rural areas. Technologies that support remote access to people in rural areas, such as teleconferencing and videoconferencing, seem particularly promising delivery modalities with their potential to increase access to palliative and supportive interventions in underserved communities. Large-scale studies that are powered to test the impact of palliative care and support oncology interventions on PROs and other aspects of quality care among rural residents with advanced cancer are needed.

The authors thank Jennifer DeBerg, Health Science Librarian at the University of Iowa for her assistance in developing the literature search strategies.

1. Moy E, Garcia MC, Bastian B, et al. Leading causes of death in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan areas – United States, 1999-2014 [published correction at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6603a11.htm]. MMWR Surveillance Summaries [serial online]. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/ss/ss6601a1.htm?s_cid=ss6601a1_w. Published January 13, 2017. Accessed January 20, 2017.

2. Singh GK, Williams SD, Siahpush M, Mulhollen A. Socioeconomic, rural-urban, and racial inequalities in US Cancer Mortality: Part I – All cancers and lung cancer and Part II – Colorectal, prostate, breast, and cervical cancers. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jce/2011/107497/. Published 2011. Accessed April 28, 2017.

3. Charlton M, Schlichting J, Chioreso C, Ward M, Vikas P. Challenges of rural cancer care in the United States. Oncology (Williston Park). 2015;29(9):633-640.

4. Weaver KE, Geiger AM, Lu L, Case LD. Rural‐urban disparities in health status among US cancer survivors. Cancer. 2013;119(5):1050-1057.

5. Fuchsia Howard A, Smillie K, Turnbull K, et al. Access to medical and supportive care for rural and remote cancer survivors in northern British Columbia. J Rural Health. 2014;30(3):311-321.

6. Bottomley A, Aaronson NK. International perspective on health-related quality-of-life research in cancer clinical trials: the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer experience. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5082-5086.

7. Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(8):880-887.

8. Baldwin LM, Cai Y, Larson EH, et al. Access to cancer services for rural colorectal cancer patients. J Rural Health. 2008;24(4):390-399.

9. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742.

10. McCorkle R, Jeon S, Ercolano E, et al. An advanced practice nurse coordinated multidisciplinary intervention for patients with late-stage cancer: a cluster randomized trial. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(11):962-969.

11. Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721-1730.

12. Regn R, Robinson W, Robinson WR. Differences in palliative care needs among cancer survivors in an inner city academic facility versus a suburban community facility. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(29_suppl):61.

13. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;339:b2535.

14. Watanabe SM, Fairchild A, Pituskin E, Borgersen P, Hanson J, Fassbender K. Improving access to specialist multidisciplinary palliative care consultation for rural cancer patients by videoconferencing: report of a pilot project. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(4):1201-1207.

15. Howell D, Marshall D, Brazil K, et al. A shared care model pilot for palliative home care in a rural area: impact on symptoms, distress, and place of death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(1):60-75.

16. Stern A, Valaitis R, Weir R, Jadad AR. Use of home telehealth in palliative cancer care: a case study. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(5):297-300.

17. O’Brien M, Harris J, King R, O’Brien T. Supportive-expressive group therapy for women with metastatic breast cancer: Improving access for Australian women through use of teleconference. Counselling Psychother Res. 2008;8(1):28-35.

18. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial to improve palliative care for rural patients with advanced cancer: baseline findings, methodological challenges, and solutions. Palliat Supportive Care. 2009;7(1):75-86.

19. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741-749.

20. Collie K, Kreshka MA, Ferrier S, et al. Videoconferencing for delivery of breast cancer support groups to women living in rural communities: a pilot study. Psychooncology. 200

21. Passik SD, Kirsh KL, Leibee S, et al. A feasibility study of dignity psychotherapy delivered via telemedicine. Palliat Support Care. 2004;2(2):149-155.

22. Smith TJ, Desch CE, Grasso MA, et al. The Rural Cancer Outreach Program: clinical and financial analysis of palliative and curative care for an underserved population. Cancer Treat Rev. 1996;22(Suppl A):97-101.

23. Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7(2):6-9.

1. Moy E, Garcia MC, Bastian B, et al. Leading causes of death in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan areas – United States, 1999-2014 [published correction at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6603a11.htm]. MMWR Surveillance Summaries [serial online]. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/ss/ss6601a1.htm?s_cid=ss6601a1_w. Published January 13, 2017. Accessed January 20, 2017.

2. Singh GK, Williams SD, Siahpush M, Mulhollen A. Socioeconomic, rural-urban, and racial inequalities in US Cancer Mortality: Part I – All cancers and lung cancer and Part II – Colorectal, prostate, breast, and cervical cancers. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jce/2011/107497/. Published 2011. Accessed April 28, 2017.

3. Charlton M, Schlichting J, Chioreso C, Ward M, Vikas P. Challenges of rural cancer care in the United States. Oncology (Williston Park). 2015;29(9):633-640.

4. Weaver KE, Geiger AM, Lu L, Case LD. Rural‐urban disparities in health status among US cancer survivors. Cancer. 2013;119(5):1050-1057.

5. Fuchsia Howard A, Smillie K, Turnbull K, et al. Access to medical and supportive care for rural and remote cancer survivors in northern British Columbia. J Rural Health. 2014;30(3):311-321.

6. Bottomley A, Aaronson NK. International perspective on health-related quality-of-life research in cancer clinical trials: the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer experience. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5082-5086.

7. Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(8):880-887.

8. Baldwin LM, Cai Y, Larson EH, et al. Access to cancer services for rural colorectal cancer patients. J Rural Health. 2008;24(4):390-399.

9. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742.

10. McCorkle R, Jeon S, Ercolano E, et al. An advanced practice nurse coordinated multidisciplinary intervention for patients with late-stage cancer: a cluster randomized trial. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(11):962-969.

11. Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721-1730.

12. Regn R, Robinson W, Robinson WR. Differences in palliative care needs among cancer survivors in an inner city academic facility versus a suburban community facility. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(29_suppl):61.

13. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;339:b2535.

14. Watanabe SM, Fairchild A, Pituskin E, Borgersen P, Hanson J, Fassbender K. Improving access to specialist multidisciplinary palliative care consultation for rural cancer patients by videoconferencing: report of a pilot project. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(4):1201-1207.

15. Howell D, Marshall D, Brazil K, et al. A shared care model pilot for palliative home care in a rural area: impact on symptoms, distress, and place of death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(1):60-75.

16. Stern A, Valaitis R, Weir R, Jadad AR. Use of home telehealth in palliative cancer care: a case study. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(5):297-300.

17. O’Brien M, Harris J, King R, O’Brien T. Supportive-expressive group therapy for women with metastatic breast cancer: Improving access for Australian women through use of teleconference. Counselling Psychother Res. 2008;8(1):28-35.

18. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial to improve palliative care for rural patients with advanced cancer: baseline findings, methodological challenges, and solutions. Palliat Supportive Care. 2009;7(1):75-86.

19. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741-749.

20. Collie K, Kreshka MA, Ferrier S, et al. Videoconferencing for delivery of breast cancer support groups to women living in rural communities: a pilot study. Psychooncology. 200

21. Passik SD, Kirsh KL, Leibee S, et al. A feasibility study of dignity psychotherapy delivered via telemedicine. Palliat Support Care. 2004;2(2):149-155.

22. Smith TJ, Desch CE, Grasso MA, et al. The Rural Cancer Outreach Program: clinical and financial analysis of palliative and curative care for an underserved population. Cancer Treat Rev. 1996;22(Suppl A):97-101.

23. Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7(2):6-9.

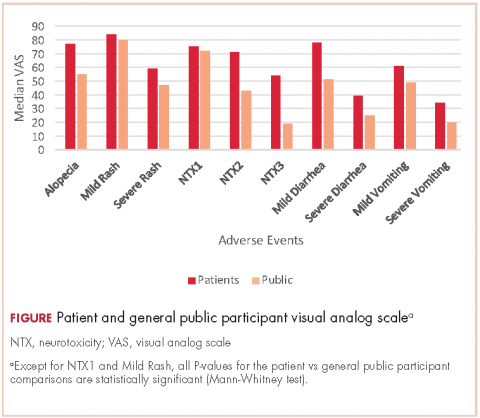

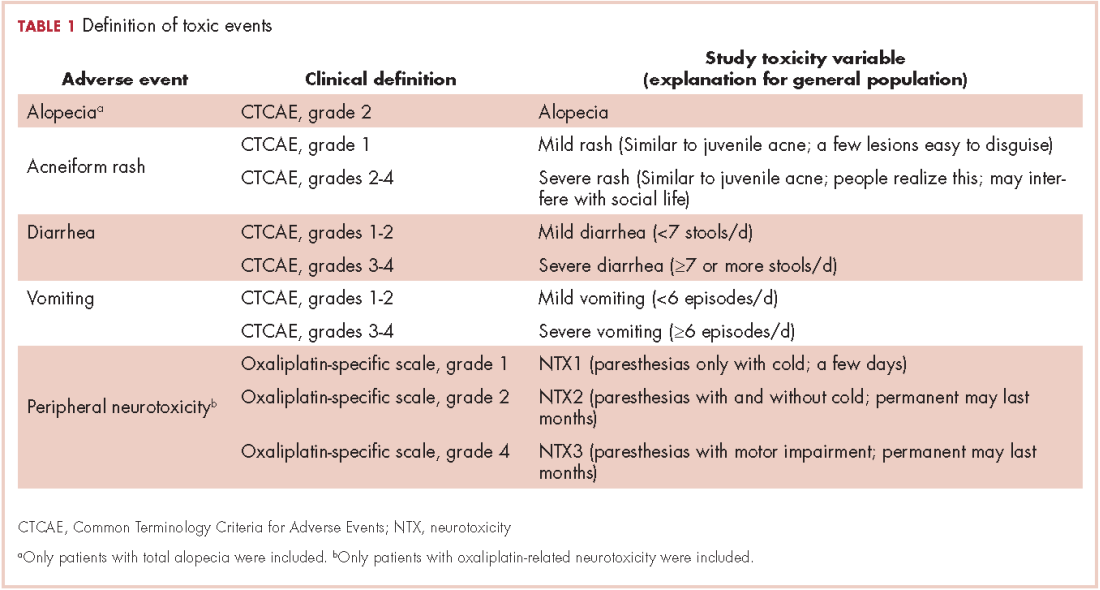

Adverse events from systemic treatment of cancer and patient-reported quality of life

Adverse events (AEs) from systemic treatment of cancer have a negative impact on patient quality of life (QoL). The extent of this impact is difficult to ascertain, particularly in patients undergoing palliative treatment because of variations in QoL resulting from antitumor effect.1 Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are the best tool for elicitation of patient preferences, therefore helping cancer patients, oncologists, and health care managers to make better choices. Indeed, analysis of self-reported QoL during cancer chemotherapy provides new insights that are missed by other efficacy outcomes,2 although patient-reported AEs correlate well with AEs reported by clinicians.3 Self-reported symptoms provide better control during cancer treatment.4 However, there are other instruments to measure the impact of treatments on QoL that are based on preferences of members of the general public. Use of that strategy has been strongly debated. The most obvious problem is the difficulty that persons from the general public may have in putting themselves in the patient position.5 In addition, there is evidence that compared with the general public, patients adapt to their illness5,6 and then tend to downplay severity when rating values of health states.7 Therefore, a systematic discrepancy is observed between actual patients and the general public. It is not clear if it reflects the inability of members of the general public to fully grasp the relative severity of health problems or to the adaptation process of patients. This fact may obscure a negative impact on QoL which, in turn, could be detected using the general public as a surrogate. A combination of both approaches has been recommended for rating QoL when the ultimate purpose is making decisions on resource allocation.5 This debate is prolonging in time and it is far from over.8,9

Based on this background, this study investigates the impact of AEs on QoL of cancer patients from the perspective of cancer patients who had experienced the AEs of interest (ex post population) and the perspective of members of the general public. The second group comprised participants imagining themselves as hypothetical cancer patients experiencing the AEs (ex ante population). Previous studies with this dual approach allowing for comparisons between these two populations are small or centered on a few AEs.10 Therefore, a large and comprehensive study on the impact of AEs on QoL is lacking. Supported by previous literature, the investigational hypothesis was that ex post impact would be significantly lower than that imagined in an ex ante setting. The secondary objective is to study the potential use of the EuroQol (EQ-5D) instrument for health-related QoL in the measurement of the impact of AEs in cancer patients. This generic instrument is based on interviews with members of the general public. We tried to investigate to what extent those values relate to the cancer patients’ evaluation of their own health during treatment. The ultimate goal of the study is to assist in increasing the utility that patients derive from the benefits associated with cancer treatment.

Methods

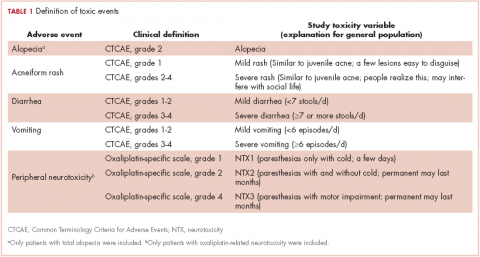

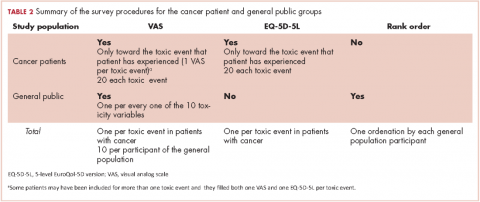

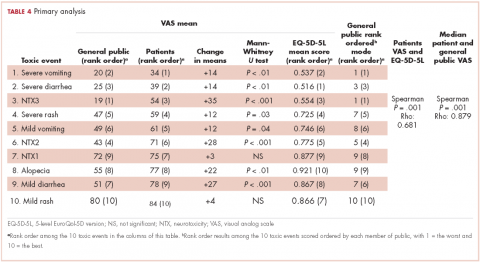

Selection of AEs