User login

Asthma-COPD overlap linked to occupational pollutants

The development and worsening of overlapping asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can be affected by pollutants found in rural and urban environments, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“ features,” Jill A. Poole, MD, division chief of allergy and immunology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said in her presentation.

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) first outlined a syndrome in 2015 described as “persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD” and called asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. In 2017, a joint American Thoracic Society/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop outlined knowledge gaps about asthma-COPD overlap, noting it “does not represent a single discrete disease entity.”

“This is not a single disease and should be thought of as being heterogeneous and used as a descriptive label for patients commonly seen in clinical practice,” Dr. Poole said. “Both asthma and COPD definitions are not mutually exclusive because each disease includes several phenotypes with different underlining mechanisms.” An example of how asthma-COPD overlap might present is through a patient with allergic asthma who has a history of smoking who develops airflow obstruction that isn’t fully reversible, or a patient with COPD “with high reversible airflow, obstruction, type 2 inflammation, and perhaps the presence of peripheral blood eosinophils or sputum eosinophils.”

A patient’s interaction with urban, rural, and occupational environments may additionally impact their disease, Dr. Poole explained. “The environmental factors of an urban versus rural environment may not be necessarily mutually exclusive,” she said. “It’s also important to recognize occupational exposures that can be both seen in an urban or rural environment [can] contribute to asthma-COPD overlap.”

In a study of 6,040 men and women with asthma living in Canada, 630 (10.4%) had asthma-COPD overlap, with increased air pollution raising the likelihood of developing asthma-COPD overlap (odds ratio, 2.78; 95% confidence interval, 1.62-4.78). These people experienced later onset asthma, increased emergency department visits before a diagnosis of COPD, and increased mortality. Another study in Canada of women from Ontario in the Breast Cancer Screening Study found 1,705 of 4,051 women with asthma also had COPD. While air pollution did not increase the risk of developing asthma-COPD overlap, there was an association between body mass index, low level of education, living in a rural area, and smoking status.

Among farmers in rural areas, “it has been recognized that there is something called the asthma-like syndrome that’s been reported in adult farming communities,” Dr. Poole said, which includes “some degree of airflow obstruction and reversibility” that can be worsened by smoking and could be an overlap of asthma and COPD. Farmers can also experience asthma exacerbations while working, and “livestock farmers appear more at risk of developing [chronic bronchitis and/or COPD] than do the crop farmers,” she noted.

Occupational environments outside of agriculture exposure can cause incident asthma, with high-molecular-weight antigens such as flour cereal, animal dander, latex, psyllium, crab processing products, and enzymes as well as low-molecular-weight antigens such as isocyanates, woods, antibiotics, glues, epoxies colophony products, and dyes presenting a risk. In food processing, main allergen sources can include raw and processed animal and plant products, additives and preservatives, contaminants from microbes or insects, inhaled dust particles or aerosols, which can be “IgE mediated, mixed IgE-mediated and non-lgE mediated.”

While some studies have been conducted on the prevalence of work-related asthma and asthma-COPD overlap, “in general, the prevalence and clinical features have been scarcely investigated,” Dr. Poole said. One survey of 23,137 patients found 52.9% of adults with work-related asthma also had COPD, compared with 25.6% of participants whose asthma was not work related.

To prevent asthma-COPD overlap, Dr. Poole recommended tobacco cessation, reducing indoor biomass fuel use, medical surveillance programs such as preplacement questionnaires, and considering “reducing exposure to the respiratory sensitizers with ideally monitoring the levels to keep the levels below the permissible limits.”

Dr. Poole noted there is currently no unique treatment for asthma-COPD overlap, but it is “important to fully characterize and phenotype your individual patients, looking for eosinophilia or seeing if they have more neutrophil features and whether or not the allergy features are prevalent and can be treated,” she said. “[A]wareness is really required such that counseling is encouraged for prevention and or interventional strategies as we move forward.”

For patients with features of both asthma and COPD where there is a high likelihood of asthma, treat the disease as if it were asthma, Dr. Poole said, but clinicians should follow GINA GOLD COPD treatment recommendations, adding on long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) when needed, but avoiding LABAs and/or LAMAs without use of inhaled corticosteroids, and avoiding oral corticosteroids entirely. Clinicians should be reviewing the treatments of patients with asthma and COPD features “every 2-3 months to see how their response is to it, and what additional therapies could be used,” she said.

Dr. Poole reports receiving grant support from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and the Central States Center for Agricultural Safety and Health at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

The development and worsening of overlapping asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can be affected by pollutants found in rural and urban environments, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“ features,” Jill A. Poole, MD, division chief of allergy and immunology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said in her presentation.

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) first outlined a syndrome in 2015 described as “persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD” and called asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. In 2017, a joint American Thoracic Society/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop outlined knowledge gaps about asthma-COPD overlap, noting it “does not represent a single discrete disease entity.”

“This is not a single disease and should be thought of as being heterogeneous and used as a descriptive label for patients commonly seen in clinical practice,” Dr. Poole said. “Both asthma and COPD definitions are not mutually exclusive because each disease includes several phenotypes with different underlining mechanisms.” An example of how asthma-COPD overlap might present is through a patient with allergic asthma who has a history of smoking who develops airflow obstruction that isn’t fully reversible, or a patient with COPD “with high reversible airflow, obstruction, type 2 inflammation, and perhaps the presence of peripheral blood eosinophils or sputum eosinophils.”

A patient’s interaction with urban, rural, and occupational environments may additionally impact their disease, Dr. Poole explained. “The environmental factors of an urban versus rural environment may not be necessarily mutually exclusive,” she said. “It’s also important to recognize occupational exposures that can be both seen in an urban or rural environment [can] contribute to asthma-COPD overlap.”

In a study of 6,040 men and women with asthma living in Canada, 630 (10.4%) had asthma-COPD overlap, with increased air pollution raising the likelihood of developing asthma-COPD overlap (odds ratio, 2.78; 95% confidence interval, 1.62-4.78). These people experienced later onset asthma, increased emergency department visits before a diagnosis of COPD, and increased mortality. Another study in Canada of women from Ontario in the Breast Cancer Screening Study found 1,705 of 4,051 women with asthma also had COPD. While air pollution did not increase the risk of developing asthma-COPD overlap, there was an association between body mass index, low level of education, living in a rural area, and smoking status.

Among farmers in rural areas, “it has been recognized that there is something called the asthma-like syndrome that’s been reported in adult farming communities,” Dr. Poole said, which includes “some degree of airflow obstruction and reversibility” that can be worsened by smoking and could be an overlap of asthma and COPD. Farmers can also experience asthma exacerbations while working, and “livestock farmers appear more at risk of developing [chronic bronchitis and/or COPD] than do the crop farmers,” she noted.

Occupational environments outside of agriculture exposure can cause incident asthma, with high-molecular-weight antigens such as flour cereal, animal dander, latex, psyllium, crab processing products, and enzymes as well as low-molecular-weight antigens such as isocyanates, woods, antibiotics, glues, epoxies colophony products, and dyes presenting a risk. In food processing, main allergen sources can include raw and processed animal and plant products, additives and preservatives, contaminants from microbes or insects, inhaled dust particles or aerosols, which can be “IgE mediated, mixed IgE-mediated and non-lgE mediated.”

While some studies have been conducted on the prevalence of work-related asthma and asthma-COPD overlap, “in general, the prevalence and clinical features have been scarcely investigated,” Dr. Poole said. One survey of 23,137 patients found 52.9% of adults with work-related asthma also had COPD, compared with 25.6% of participants whose asthma was not work related.

To prevent asthma-COPD overlap, Dr. Poole recommended tobacco cessation, reducing indoor biomass fuel use, medical surveillance programs such as preplacement questionnaires, and considering “reducing exposure to the respiratory sensitizers with ideally monitoring the levels to keep the levels below the permissible limits.”

Dr. Poole noted there is currently no unique treatment for asthma-COPD overlap, but it is “important to fully characterize and phenotype your individual patients, looking for eosinophilia or seeing if they have more neutrophil features and whether or not the allergy features are prevalent and can be treated,” she said. “[A]wareness is really required such that counseling is encouraged for prevention and or interventional strategies as we move forward.”

For patients with features of both asthma and COPD where there is a high likelihood of asthma, treat the disease as if it were asthma, Dr. Poole said, but clinicians should follow GINA GOLD COPD treatment recommendations, adding on long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) when needed, but avoiding LABAs and/or LAMAs without use of inhaled corticosteroids, and avoiding oral corticosteroids entirely. Clinicians should be reviewing the treatments of patients with asthma and COPD features “every 2-3 months to see how their response is to it, and what additional therapies could be used,” she said.

Dr. Poole reports receiving grant support from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and the Central States Center for Agricultural Safety and Health at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

The development and worsening of overlapping asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can be affected by pollutants found in rural and urban environments, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“ features,” Jill A. Poole, MD, division chief of allergy and immunology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said in her presentation.

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) first outlined a syndrome in 2015 described as “persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD” and called asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. In 2017, a joint American Thoracic Society/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop outlined knowledge gaps about asthma-COPD overlap, noting it “does not represent a single discrete disease entity.”

“This is not a single disease and should be thought of as being heterogeneous and used as a descriptive label for patients commonly seen in clinical practice,” Dr. Poole said. “Both asthma and COPD definitions are not mutually exclusive because each disease includes several phenotypes with different underlining mechanisms.” An example of how asthma-COPD overlap might present is through a patient with allergic asthma who has a history of smoking who develops airflow obstruction that isn’t fully reversible, or a patient with COPD “with high reversible airflow, obstruction, type 2 inflammation, and perhaps the presence of peripheral blood eosinophils or sputum eosinophils.”

A patient’s interaction with urban, rural, and occupational environments may additionally impact their disease, Dr. Poole explained. “The environmental factors of an urban versus rural environment may not be necessarily mutually exclusive,” she said. “It’s also important to recognize occupational exposures that can be both seen in an urban or rural environment [can] contribute to asthma-COPD overlap.”

In a study of 6,040 men and women with asthma living in Canada, 630 (10.4%) had asthma-COPD overlap, with increased air pollution raising the likelihood of developing asthma-COPD overlap (odds ratio, 2.78; 95% confidence interval, 1.62-4.78). These people experienced later onset asthma, increased emergency department visits before a diagnosis of COPD, and increased mortality. Another study in Canada of women from Ontario in the Breast Cancer Screening Study found 1,705 of 4,051 women with asthma also had COPD. While air pollution did not increase the risk of developing asthma-COPD overlap, there was an association between body mass index, low level of education, living in a rural area, and smoking status.

Among farmers in rural areas, “it has been recognized that there is something called the asthma-like syndrome that’s been reported in adult farming communities,” Dr. Poole said, which includes “some degree of airflow obstruction and reversibility” that can be worsened by smoking and could be an overlap of asthma and COPD. Farmers can also experience asthma exacerbations while working, and “livestock farmers appear more at risk of developing [chronic bronchitis and/or COPD] than do the crop farmers,” she noted.

Occupational environments outside of agriculture exposure can cause incident asthma, with high-molecular-weight antigens such as flour cereal, animal dander, latex, psyllium, crab processing products, and enzymes as well as low-molecular-weight antigens such as isocyanates, woods, antibiotics, glues, epoxies colophony products, and dyes presenting a risk. In food processing, main allergen sources can include raw and processed animal and plant products, additives and preservatives, contaminants from microbes or insects, inhaled dust particles or aerosols, which can be “IgE mediated, mixed IgE-mediated and non-lgE mediated.”

While some studies have been conducted on the prevalence of work-related asthma and asthma-COPD overlap, “in general, the prevalence and clinical features have been scarcely investigated,” Dr. Poole said. One survey of 23,137 patients found 52.9% of adults with work-related asthma also had COPD, compared with 25.6% of participants whose asthma was not work related.

To prevent asthma-COPD overlap, Dr. Poole recommended tobacco cessation, reducing indoor biomass fuel use, medical surveillance programs such as preplacement questionnaires, and considering “reducing exposure to the respiratory sensitizers with ideally monitoring the levels to keep the levels below the permissible limits.”

Dr. Poole noted there is currently no unique treatment for asthma-COPD overlap, but it is “important to fully characterize and phenotype your individual patients, looking for eosinophilia or seeing if they have more neutrophil features and whether or not the allergy features are prevalent and can be treated,” she said. “[A]wareness is really required such that counseling is encouraged for prevention and or interventional strategies as we move forward.”

For patients with features of both asthma and COPD where there is a high likelihood of asthma, treat the disease as if it were asthma, Dr. Poole said, but clinicians should follow GINA GOLD COPD treatment recommendations, adding on long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) when needed, but avoiding LABAs and/or LAMAs without use of inhaled corticosteroids, and avoiding oral corticosteroids entirely. Clinicians should be reviewing the treatments of patients with asthma and COPD features “every 2-3 months to see how their response is to it, and what additional therapies could be used,” she said.

Dr. Poole reports receiving grant support from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and the Central States Center for Agricultural Safety and Health at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

FROM AAAAI 2021

Novel oral agent effective in teens with atopic dermatitis

Abrocitinib, an investigational drug proven to be a safe and effective treatment for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) in adults 18 years and older, is also safe and effective in patients aged 12-17 years, according to a randomized trial of the oral, once-daily Janus kinase (JAK) 1 selective inhibitor, used in combination with medicated topical therapy.

The results, from the phase 3 JADE TEEN study, were presented during an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“We’re very excited about the introduction of oral JAKs into our armamentarium for atopic dermatitis,” lead author Lawrence Eichenfield, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatrics, University of California, San Diego, and chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, Rady Children’s Hospital, also in San Diego, said in an interview.

AD ranges in severity, and there is a great deal of moderate to severe AD that has a tremendous negative impact on the individual, Dr. Eichenfield said. “Traditionally we have treated it with intermittent topical corticosteroids, but this has left a significant percentage of patients without long-term disease control.”

JAK inhibitors are effective mediators of the inflammation response that occurs in moderate to severe AD. They inhibit the stimulation of the JAK pathway and allow anti-inflammatory effects and therefore have potential, especially in more severe disease, Dr. Eichenfield said.

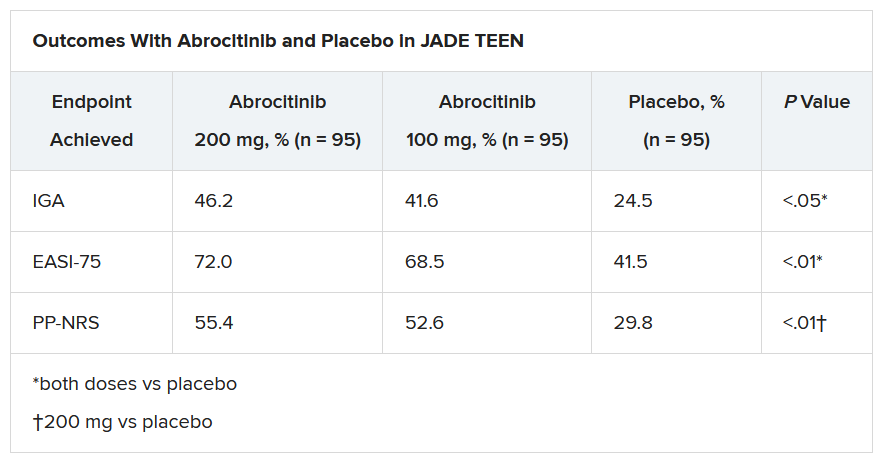

In the current study, which is a spin-off of the original study that looked at abrocitinib in adults, he and his team randomly assigned 285 teens (mean age, 14.9 years; 50.9% male; 56.1% White) with moderate to severe AD to receive one of the following treatments for 12 weeks: abrocitinib 200 mg plus topical therapy (95); abrocitinib 100 mg plus topical therapy (95); or placebo, which consisted of topical therapy alone (95).

The primary endpoints were an Investigator’s Global Assessment response of clear or almost clear (scores of 0 and 1, respectively), with an improvement of at least 2 points, and an improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index score of at least 75% at week 12.

Secondary endpoints included an improvement in Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (PP-NRS) response of at least 4 points at week 12.

The teens who received abrocitinib along with medicated topical therapy showed significant improvement in the severity of their AD at the end of the 12-week period, compared with those in the placebo group.

“The percentage of patients achieving essentially no itch, as captured in the fact that more than half of those on the higher dose of abrocitinib made it to no itch, is a new data point and is important to note,” Dr. Eichenfield said. “A lot of the other medicines don’t really get a significant percentage of the population to an itch score of 0 to 1. This drug brought about a rapid and profound itch relief.”

He added: “The results from JADE TEEN extend the drug’s utility in this younger population and show that abrocitinib performs the same with regard to efficacy and safety in the teenagers. Having atopic dermatitis that does not respond to treatment is especially hard for adolescents, but now we know that abrocitinib will be safe and effective and so we now have something to offer these kids.”

“Abrocitinib achieved a good response in this study that was statistically significant, compared to standard treatment,” Jonathan A. Bernstein, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Cincinnati, commented in an interview.

“JAK inhibitors are very promising, and this study adds to that promise. They play an important role in atopic dermatitis, so obviously, teenagers with AD represent an important population,” said Dr. Bernstein, who was not part of the study. “These results are very encouraging, and I think that we will probably see some of these JAK inhibitors approved by the FDA, if not this year, probably next.”

The study was sponsored by Pfizer. Dr. Eichenfield serves as an investigator, speaker, and consultant for Pfizer; and as an investigator, speaker, consultant, and/or is on a data safety monitoring board for AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Arcutis, Asana, Dermavant, Dermira, Forte, Galderma, Ichnos/Glenmark, Incyte, LEO, Lilly, L’Oreal, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Verrica. Dr. Bernstein disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Abrocitinib, an investigational drug proven to be a safe and effective treatment for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) in adults 18 years and older, is also safe and effective in patients aged 12-17 years, according to a randomized trial of the oral, once-daily Janus kinase (JAK) 1 selective inhibitor, used in combination with medicated topical therapy.

The results, from the phase 3 JADE TEEN study, were presented during an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“We’re very excited about the introduction of oral JAKs into our armamentarium for atopic dermatitis,” lead author Lawrence Eichenfield, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatrics, University of California, San Diego, and chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, Rady Children’s Hospital, also in San Diego, said in an interview.

AD ranges in severity, and there is a great deal of moderate to severe AD that has a tremendous negative impact on the individual, Dr. Eichenfield said. “Traditionally we have treated it with intermittent topical corticosteroids, but this has left a significant percentage of patients without long-term disease control.”

JAK inhibitors are effective mediators of the inflammation response that occurs in moderate to severe AD. They inhibit the stimulation of the JAK pathway and allow anti-inflammatory effects and therefore have potential, especially in more severe disease, Dr. Eichenfield said.

In the current study, which is a spin-off of the original study that looked at abrocitinib in adults, he and his team randomly assigned 285 teens (mean age, 14.9 years; 50.9% male; 56.1% White) with moderate to severe AD to receive one of the following treatments for 12 weeks: abrocitinib 200 mg plus topical therapy (95); abrocitinib 100 mg plus topical therapy (95); or placebo, which consisted of topical therapy alone (95).

The primary endpoints were an Investigator’s Global Assessment response of clear or almost clear (scores of 0 and 1, respectively), with an improvement of at least 2 points, and an improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index score of at least 75% at week 12.

Secondary endpoints included an improvement in Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (PP-NRS) response of at least 4 points at week 12.

The teens who received abrocitinib along with medicated topical therapy showed significant improvement in the severity of their AD at the end of the 12-week period, compared with those in the placebo group.

“The percentage of patients achieving essentially no itch, as captured in the fact that more than half of those on the higher dose of abrocitinib made it to no itch, is a new data point and is important to note,” Dr. Eichenfield said. “A lot of the other medicines don’t really get a significant percentage of the population to an itch score of 0 to 1. This drug brought about a rapid and profound itch relief.”

He added: “The results from JADE TEEN extend the drug’s utility in this younger population and show that abrocitinib performs the same with regard to efficacy and safety in the teenagers. Having atopic dermatitis that does not respond to treatment is especially hard for adolescents, but now we know that abrocitinib will be safe and effective and so we now have something to offer these kids.”

“Abrocitinib achieved a good response in this study that was statistically significant, compared to standard treatment,” Jonathan A. Bernstein, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Cincinnati, commented in an interview.

“JAK inhibitors are very promising, and this study adds to that promise. They play an important role in atopic dermatitis, so obviously, teenagers with AD represent an important population,” said Dr. Bernstein, who was not part of the study. “These results are very encouraging, and I think that we will probably see some of these JAK inhibitors approved by the FDA, if not this year, probably next.”

The study was sponsored by Pfizer. Dr. Eichenfield serves as an investigator, speaker, and consultant for Pfizer; and as an investigator, speaker, consultant, and/or is on a data safety monitoring board for AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Arcutis, Asana, Dermavant, Dermira, Forte, Galderma, Ichnos/Glenmark, Incyte, LEO, Lilly, L’Oreal, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Verrica. Dr. Bernstein disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Abrocitinib, an investigational drug proven to be a safe and effective treatment for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) in adults 18 years and older, is also safe and effective in patients aged 12-17 years, according to a randomized trial of the oral, once-daily Janus kinase (JAK) 1 selective inhibitor, used in combination with medicated topical therapy.

The results, from the phase 3 JADE TEEN study, were presented during an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“We’re very excited about the introduction of oral JAKs into our armamentarium for atopic dermatitis,” lead author Lawrence Eichenfield, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatrics, University of California, San Diego, and chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, Rady Children’s Hospital, also in San Diego, said in an interview.

AD ranges in severity, and there is a great deal of moderate to severe AD that has a tremendous negative impact on the individual, Dr. Eichenfield said. “Traditionally we have treated it with intermittent topical corticosteroids, but this has left a significant percentage of patients without long-term disease control.”

JAK inhibitors are effective mediators of the inflammation response that occurs in moderate to severe AD. They inhibit the stimulation of the JAK pathway and allow anti-inflammatory effects and therefore have potential, especially in more severe disease, Dr. Eichenfield said.

In the current study, which is a spin-off of the original study that looked at abrocitinib in adults, he and his team randomly assigned 285 teens (mean age, 14.9 years; 50.9% male; 56.1% White) with moderate to severe AD to receive one of the following treatments for 12 weeks: abrocitinib 200 mg plus topical therapy (95); abrocitinib 100 mg plus topical therapy (95); or placebo, which consisted of topical therapy alone (95).

The primary endpoints were an Investigator’s Global Assessment response of clear or almost clear (scores of 0 and 1, respectively), with an improvement of at least 2 points, and an improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index score of at least 75% at week 12.

Secondary endpoints included an improvement in Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (PP-NRS) response of at least 4 points at week 12.

The teens who received abrocitinib along with medicated topical therapy showed significant improvement in the severity of their AD at the end of the 12-week period, compared with those in the placebo group.

“The percentage of patients achieving essentially no itch, as captured in the fact that more than half of those on the higher dose of abrocitinib made it to no itch, is a new data point and is important to note,” Dr. Eichenfield said. “A lot of the other medicines don’t really get a significant percentage of the population to an itch score of 0 to 1. This drug brought about a rapid and profound itch relief.”

He added: “The results from JADE TEEN extend the drug’s utility in this younger population and show that abrocitinib performs the same with regard to efficacy and safety in the teenagers. Having atopic dermatitis that does not respond to treatment is especially hard for adolescents, but now we know that abrocitinib will be safe and effective and so we now have something to offer these kids.”

“Abrocitinib achieved a good response in this study that was statistically significant, compared to standard treatment,” Jonathan A. Bernstein, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Cincinnati, commented in an interview.

“JAK inhibitors are very promising, and this study adds to that promise. They play an important role in atopic dermatitis, so obviously, teenagers with AD represent an important population,” said Dr. Bernstein, who was not part of the study. “These results are very encouraging, and I think that we will probably see some of these JAK inhibitors approved by the FDA, if not this year, probably next.”

The study was sponsored by Pfizer. Dr. Eichenfield serves as an investigator, speaker, and consultant for Pfizer; and as an investigator, speaker, consultant, and/or is on a data safety monitoring board for AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Arcutis, Asana, Dermavant, Dermira, Forte, Galderma, Ichnos/Glenmark, Incyte, LEO, Lilly, L’Oreal, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Verrica. Dr. Bernstein disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Novel agent shows promise against cat allergy

One dose of the novel agent, REGN1908-1909 (Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) resulted in a rapid and durable reduction in cat-allergen-induced bronchoconstriction in cat-allergic subjects with mild asthma.

The finding, from a phase 2 randomized placebo-controlled study, is good news for the millions of people who are plagued by cat allergies, the investigators say.

The study, which was sponsored by Regeneron, was presented in a late breaking oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“REGN1908-1909 contains antibodies against Fel d 1, the major cat allergen, and here we show that it quickly and lastingly reduces acute bronchoconstriction in people with cat allergy,” lead author Frederic J. de Blay, MD, Strasbourg University Hospital, France, said in an interview.

Dr. de Blay admitted he is “quite excited” about the results.

“This study was performed in an environmental exposure chamber, and we clearly demonstrate that these antibodies decrease the asthmatic response to cat allergen within 8 days, and that these effects last 3 months. I never saw that in my life. I was a little bit skeptical at first, so to obtain such robust results after just 8 days, after just one injection, I was very surprised,” he said.

Dr. de Blay and his team screened potential participants to make sure they were cat allergic by exposing them to cat allergen for up to 2 hours while they were in the environmental exposure chamber. To be eligible for the study, participants had to show an early asthmatic response (EAR), defined as a reduction in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of at least 20% from baseline.

The participants were then randomized to receive either single-dose REGN1908-1909, 600 mg, subcutaneously (n = 29 patients) or placebo (n = 27 patients) prior to cat-allergen exposure in the controlled environmental chamber.

Dr. de Blay developed the chamber used in the study: the ALYATEC environmental exposure chamber.

“The chamber is 60 meters square, or 150 cubic meters, and can accommodate 20 patients. We are able to nebulize cat allergen, mice allergen, or whatever we wish to study so we can standardize the exposure. We can control the particle size and the amount so we know the exact amount of allergen that the patient has been exposed to,” he explained.

To test the efficacy of REGN1908-1909 in reducing acute bronchoconstriction, or EAR, the researchers measured FEV1 at baseline, and on days 8, 29, 57, and 85 in both groups. During each exposure, measurements were taken every 10 minutes for periods that lasted up to 4 hours.

They found that the probability of remaining in the chamber with no asthmatic response was substantially elevated in the group treated with REGN1908-1909.

Compared with placebo, REGN1908-1909 significantly increased the median time to EAR, from 51 minutes at baseline to more than 4 hours on day 8, (hazard ratio [HR], 0.36; P < .0083), day 29 (HR, 0.24; P < .0001), day 57 (HR, 0.45; P = .0222), and day 85 (HR, 0.27; P = .0003).

The FEV1 area under the curve (AUC) was also better with REGN1908-1909 than with placebo at day 8 (15.2% vs. 1.6%; P < .001). And a single dose reduced skin-test reactivity to cat allergen at 1 week, which persisted for up to 4 months.

In addition, participants who received REGN1908-1909 were able to tolerate a threefold higher amount of the cat allergen than those who received placebo (P = .003).

“We initially gave 40 nanograms of cat allergen, and then 8 days later they were able to stay longer in the chamber and inhale more of the allergen, to almost triple the amount they had originally been given. That 40 nanograms is very close to real world exposure,” Dr. de Blay noted.

Regeneron plans to start a phase 3 trial soon, he reported.

Promising results

“The study is well designed and shows a reduction in drop of FEV1 in response to cat allergen provocation and a decreased AUC in cat SPT response over 4 months,” Jonathan A. Bernstein, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Cincinnati, said in an interview.

“These are very promising results, which show that REGN1908-1909 can be a novel treatment for cat-induced asthma, which is often the only sensitization patients have. And they love their cats – one-third of the U.S. population has a cat and one-third has a dog, and 50% have both,” noted Dr. Bernstein, who was not involved with the study.

“This novel study used our scientific knowledge of the cat allergen itself to design a targeted antibody-based treatment that demonstrates significant benefit even after the first shot,” added Edwin H. Kim, MD, director of the UNC Food Allergy Initiative at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“This strategy has the potential to revolutionize not only our treatment of common environmental allergies but also other allergic diseases with well-described triggers, such as food and drug allergy,” Dr. Kim, who was not part of the study, said in an interview.

Dr. de Blay reported a financial relationship with Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, which sponsored the study. Dr. Bernstein and Dr. Kim have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One dose of the novel agent, REGN1908-1909 (Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) resulted in a rapid and durable reduction in cat-allergen-induced bronchoconstriction in cat-allergic subjects with mild asthma.

The finding, from a phase 2 randomized placebo-controlled study, is good news for the millions of people who are plagued by cat allergies, the investigators say.

The study, which was sponsored by Regeneron, was presented in a late breaking oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“REGN1908-1909 contains antibodies against Fel d 1, the major cat allergen, and here we show that it quickly and lastingly reduces acute bronchoconstriction in people with cat allergy,” lead author Frederic J. de Blay, MD, Strasbourg University Hospital, France, said in an interview.

Dr. de Blay admitted he is “quite excited” about the results.

“This study was performed in an environmental exposure chamber, and we clearly demonstrate that these antibodies decrease the asthmatic response to cat allergen within 8 days, and that these effects last 3 months. I never saw that in my life. I was a little bit skeptical at first, so to obtain such robust results after just 8 days, after just one injection, I was very surprised,” he said.

Dr. de Blay and his team screened potential participants to make sure they were cat allergic by exposing them to cat allergen for up to 2 hours while they were in the environmental exposure chamber. To be eligible for the study, participants had to show an early asthmatic response (EAR), defined as a reduction in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of at least 20% from baseline.

The participants were then randomized to receive either single-dose REGN1908-1909, 600 mg, subcutaneously (n = 29 patients) or placebo (n = 27 patients) prior to cat-allergen exposure in the controlled environmental chamber.

Dr. de Blay developed the chamber used in the study: the ALYATEC environmental exposure chamber.

“The chamber is 60 meters square, or 150 cubic meters, and can accommodate 20 patients. We are able to nebulize cat allergen, mice allergen, or whatever we wish to study so we can standardize the exposure. We can control the particle size and the amount so we know the exact amount of allergen that the patient has been exposed to,” he explained.

To test the efficacy of REGN1908-1909 in reducing acute bronchoconstriction, or EAR, the researchers measured FEV1 at baseline, and on days 8, 29, 57, and 85 in both groups. During each exposure, measurements were taken every 10 minutes for periods that lasted up to 4 hours.

They found that the probability of remaining in the chamber with no asthmatic response was substantially elevated in the group treated with REGN1908-1909.

Compared with placebo, REGN1908-1909 significantly increased the median time to EAR, from 51 minutes at baseline to more than 4 hours on day 8, (hazard ratio [HR], 0.36; P < .0083), day 29 (HR, 0.24; P < .0001), day 57 (HR, 0.45; P = .0222), and day 85 (HR, 0.27; P = .0003).

The FEV1 area under the curve (AUC) was also better with REGN1908-1909 than with placebo at day 8 (15.2% vs. 1.6%; P < .001). And a single dose reduced skin-test reactivity to cat allergen at 1 week, which persisted for up to 4 months.

In addition, participants who received REGN1908-1909 were able to tolerate a threefold higher amount of the cat allergen than those who received placebo (P = .003).

“We initially gave 40 nanograms of cat allergen, and then 8 days later they were able to stay longer in the chamber and inhale more of the allergen, to almost triple the amount they had originally been given. That 40 nanograms is very close to real world exposure,” Dr. de Blay noted.

Regeneron plans to start a phase 3 trial soon, he reported.

Promising results

“The study is well designed and shows a reduction in drop of FEV1 in response to cat allergen provocation and a decreased AUC in cat SPT response over 4 months,” Jonathan A. Bernstein, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Cincinnati, said in an interview.

“These are very promising results, which show that REGN1908-1909 can be a novel treatment for cat-induced asthma, which is often the only sensitization patients have. And they love their cats – one-third of the U.S. population has a cat and one-third has a dog, and 50% have both,” noted Dr. Bernstein, who was not involved with the study.

“This novel study used our scientific knowledge of the cat allergen itself to design a targeted antibody-based treatment that demonstrates significant benefit even after the first shot,” added Edwin H. Kim, MD, director of the UNC Food Allergy Initiative at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“This strategy has the potential to revolutionize not only our treatment of common environmental allergies but also other allergic diseases with well-described triggers, such as food and drug allergy,” Dr. Kim, who was not part of the study, said in an interview.

Dr. de Blay reported a financial relationship with Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, which sponsored the study. Dr. Bernstein and Dr. Kim have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One dose of the novel agent, REGN1908-1909 (Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) resulted in a rapid and durable reduction in cat-allergen-induced bronchoconstriction in cat-allergic subjects with mild asthma.

The finding, from a phase 2 randomized placebo-controlled study, is good news for the millions of people who are plagued by cat allergies, the investigators say.

The study, which was sponsored by Regeneron, was presented in a late breaking oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“REGN1908-1909 contains antibodies against Fel d 1, the major cat allergen, and here we show that it quickly and lastingly reduces acute bronchoconstriction in people with cat allergy,” lead author Frederic J. de Blay, MD, Strasbourg University Hospital, France, said in an interview.

Dr. de Blay admitted he is “quite excited” about the results.

“This study was performed in an environmental exposure chamber, and we clearly demonstrate that these antibodies decrease the asthmatic response to cat allergen within 8 days, and that these effects last 3 months. I never saw that in my life. I was a little bit skeptical at first, so to obtain such robust results after just 8 days, after just one injection, I was very surprised,” he said.

Dr. de Blay and his team screened potential participants to make sure they were cat allergic by exposing them to cat allergen for up to 2 hours while they were in the environmental exposure chamber. To be eligible for the study, participants had to show an early asthmatic response (EAR), defined as a reduction in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of at least 20% from baseline.

The participants were then randomized to receive either single-dose REGN1908-1909, 600 mg, subcutaneously (n = 29 patients) or placebo (n = 27 patients) prior to cat-allergen exposure in the controlled environmental chamber.

Dr. de Blay developed the chamber used in the study: the ALYATEC environmental exposure chamber.

“The chamber is 60 meters square, or 150 cubic meters, and can accommodate 20 patients. We are able to nebulize cat allergen, mice allergen, or whatever we wish to study so we can standardize the exposure. We can control the particle size and the amount so we know the exact amount of allergen that the patient has been exposed to,” he explained.

To test the efficacy of REGN1908-1909 in reducing acute bronchoconstriction, or EAR, the researchers measured FEV1 at baseline, and on days 8, 29, 57, and 85 in both groups. During each exposure, measurements were taken every 10 minutes for periods that lasted up to 4 hours.

They found that the probability of remaining in the chamber with no asthmatic response was substantially elevated in the group treated with REGN1908-1909.

Compared with placebo, REGN1908-1909 significantly increased the median time to EAR, from 51 minutes at baseline to more than 4 hours on day 8, (hazard ratio [HR], 0.36; P < .0083), day 29 (HR, 0.24; P < .0001), day 57 (HR, 0.45; P = .0222), and day 85 (HR, 0.27; P = .0003).

The FEV1 area under the curve (AUC) was also better with REGN1908-1909 than with placebo at day 8 (15.2% vs. 1.6%; P < .001). And a single dose reduced skin-test reactivity to cat allergen at 1 week, which persisted for up to 4 months.

In addition, participants who received REGN1908-1909 were able to tolerate a threefold higher amount of the cat allergen than those who received placebo (P = .003).

“We initially gave 40 nanograms of cat allergen, and then 8 days later they were able to stay longer in the chamber and inhale more of the allergen, to almost triple the amount they had originally been given. That 40 nanograms is very close to real world exposure,” Dr. de Blay noted.

Regeneron plans to start a phase 3 trial soon, he reported.

Promising results

“The study is well designed and shows a reduction in drop of FEV1 in response to cat allergen provocation and a decreased AUC in cat SPT response over 4 months,” Jonathan A. Bernstein, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Cincinnati, said in an interview.

“These are very promising results, which show that REGN1908-1909 can be a novel treatment for cat-induced asthma, which is often the only sensitization patients have. And they love their cats – one-third of the U.S. population has a cat and one-third has a dog, and 50% have both,” noted Dr. Bernstein, who was not involved with the study.

“This novel study used our scientific knowledge of the cat allergen itself to design a targeted antibody-based treatment that demonstrates significant benefit even after the first shot,” added Edwin H. Kim, MD, director of the UNC Food Allergy Initiative at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“This strategy has the potential to revolutionize not only our treatment of common environmental allergies but also other allergic diseases with well-described triggers, such as food and drug allergy,” Dr. Kim, who was not part of the study, said in an interview.

Dr. de Blay reported a financial relationship with Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, which sponsored the study. Dr. Bernstein and Dr. Kim have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAAAI

Peanut sublingual immunotherapy feasible and effective in toddlers

Sublingual immunotherapy for the treatment of peanut allergy is safe and effective, even in children as young as age 1 year.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, food challenge (DBPCFC) of some 36 peanut-allergic children (mean age 2.2 years, range 1-4 years), those who were randomly assigned to receive peanut sublingual immunotherapy (PNSLIT) showed significant desensitization compared with those who received placebo.

In addition, there was a “strong potential” for sustained unresponsiveness at 3 months for the toddlers who received the active treatment.

The findings were presented in a late breaking oral abstract session at the 2021 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology virtual annual meeting (Abstract L2).

“A year ago, the Food and Drug Administration approved the oral agent Palforzia (peanut allergen powder) for the treatment of peanut allergy in children 4 and older, and it is a great option, but I think what we have learned over time is that this approach is not for everybody,” Edwin H. Kim, MD, director of the UNC Food Allergy Initiative, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in an interview.

Palforzia is a powder that is mixed in food like yogurt or pudding which the child then eats daily, according to a rigorous schedule. But Palforzia treatment presents some difficulties.

“Palforzia requires getting the powder dose, mixing it with food, like pudding or apple sauce, then eating it, which can take up to 30 minutes depending on age and kids’ cooperation. It tastes and smells like peanut which can cause aversion. Kids have to refrain from exercise or strenuous activity for at least 30 minutes before and after dosing and have to be observed for up to 2 hours post dose for symptoms,” Dr. Kim said.

“It’s a great drug, but the treatment could be overly difficult for certain families to be able to do, and in some cases the side effects may be more than certain patients are able or willing to handle, so there is a real urgent need for alternative approaches,” Dr. Kim said. “SLIT is several drops under the tongue, held for 2 minutes, swallowed and done.”

In the current placebo-controlled study, he and his group tested the feasibility, efficacy, and safety of the sublingual approach to peanut allergy in children age 4 years and younger.

Both groups were similar with regard to gender, race, ethnicity, atopic history, peanut skin prick test, and qualifying DBPCFC, and all children were previously allergic with positive blood and skin tests, with a positive reaction during baseline food challenge, thus proving the allergy and establishing the baseline threshold.

“We have learned from some studies, for instance the DEVIL and LEAP studies, that strongly suggest that the immune systems in younger patients may be more amenable to change, and there may be some justification for early intervention,” he said.

“Based on both of those ideas, we wanted to take our sublingual approach, which we have shown to have a pretty good efficacy in older children, and bring it down to this younger group and see if it still could have the same efficacy and also maintain what seems to be a very good safety signal.”

The researchers randomly assigned the children to receive PNSLIT at a daily maintenance dose of 4 mg peanut protein (n = 19) or to receive placebo (n = 17) for 36 months.

“There was a 5- to 6-month buildup period where the SLIT dose was increased every 1-2 weeks up to the target dose of 4 mg, and then the final dose of 4 mg was continued through to the end of the study,” Dr. Kim noted.

Over a total of 20,593 potential dosing days, the children took 91.2% of SLIT doses and 93.5% of placebo doses.

At the end of the 3-year study period, the children were challenged by DBPCFC with up to 4,333 mg of peanut protein.

Sustained unresponsiveness was assessed by an identical DBPCFC after discontinuation of the immunotherapy for 3 months.

Cumulative tolerated dose increased from a median of 143 mg to 4,443 mg in the PNSLIT group, compared with a median of 43 mg to 143 mg in the placebo group (P < .0001).

Fourteen of the children receiving PNSLIT, and none of the children receiving placebo, passed the desensitization food challenge. Twelve of the children receiving PNSLIT and two of the children receiving placebo passed the sustained unresponsiveness challenge.

Children who underwent the immunotherapy saw a decrease in their peanut skin prick test from 10 mm to 3.25 mm, compared to an increase from 11.5 mm to 12 mm with placebo (P < .0001).

The most common side effect reported was itching or irritation in the mouth. Most side effects resolved on their own, although some patients used an antihistamine. Getting children as young as 1 to hold the dose under their tongue was a challenge in some instances, but it eventually worked out, Dr. Kim said.

“It took a lot of work from the parents as well as from our research coordinators in trying to train these young kids to, first of all, allow us to put the peanut medication in the mouth and then to try as best as possible to keep it in their mouth for up to 2 minutes, but the families involved in our study were very dedicated and so we were able to get through that,” he said.

Study merits larger numbers

“Among the 36 who completed the 3 years of therapy, the authors report significant rates of desensitization among treated children compared with those receiving placebo. Furthermore, this effect was persistent for at least 3 months after stopping therapy in a subgroup of the children,” said Leonard B. Bacharier, MD, director of the Center for Pediatric Asthma, Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, Nashville, Tenn.

“Overall, these findings suggest the promise of peanut SLIT, which should be studied in larger numbers of preschool children,” Dr. Bacharier, who was not part of the study, said in an interview.

Jonathan A. Bernstein, MD, professor of medicine, University of Cincinnati, agreed.

“It’s a well-designed study, it’s small, but it’s promising,” Dr. Bernstein, who was not involved with the study, said in an interview.

“They did show that most of the patients who got the sublingual therapy were able to get to the target dose and develop tolerance, so I think it’s promising. We know that this stuff works. This is just more data from a well-controlled study in a younger population,” he said.

“We do OIT [oral immunotherapy] and sublingual but we don’t do it in such young children in our practice. The youngest is 3 years old, because they have to understand what is going on and cooperate. If they don’t cooperate it’s not possible.”

Dr. Kim reported financial relationships with DBV Technologies, Kenota Health, Ukko, Aimmune Therapeutics, ALK, AllerGenis, Belhaven Pharma, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Nutricia, NIH/NIAID, NIH/NCCIH, NIH/Immune Tolerance Network, FARE, and the Wallace Foundation. Dr. Bacharier and Dr. Bernstein have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sublingual immunotherapy for the treatment of peanut allergy is safe and effective, even in children as young as age 1 year.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, food challenge (DBPCFC) of some 36 peanut-allergic children (mean age 2.2 years, range 1-4 years), those who were randomly assigned to receive peanut sublingual immunotherapy (PNSLIT) showed significant desensitization compared with those who received placebo.

In addition, there was a “strong potential” for sustained unresponsiveness at 3 months for the toddlers who received the active treatment.

The findings were presented in a late breaking oral abstract session at the 2021 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology virtual annual meeting (Abstract L2).

“A year ago, the Food and Drug Administration approved the oral agent Palforzia (peanut allergen powder) for the treatment of peanut allergy in children 4 and older, and it is a great option, but I think what we have learned over time is that this approach is not for everybody,” Edwin H. Kim, MD, director of the UNC Food Allergy Initiative, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in an interview.

Palforzia is a powder that is mixed in food like yogurt or pudding which the child then eats daily, according to a rigorous schedule. But Palforzia treatment presents some difficulties.

“Palforzia requires getting the powder dose, mixing it with food, like pudding or apple sauce, then eating it, which can take up to 30 minutes depending on age and kids’ cooperation. It tastes and smells like peanut which can cause aversion. Kids have to refrain from exercise or strenuous activity for at least 30 minutes before and after dosing and have to be observed for up to 2 hours post dose for symptoms,” Dr. Kim said.

“It’s a great drug, but the treatment could be overly difficult for certain families to be able to do, and in some cases the side effects may be more than certain patients are able or willing to handle, so there is a real urgent need for alternative approaches,” Dr. Kim said. “SLIT is several drops under the tongue, held for 2 minutes, swallowed and done.”

In the current placebo-controlled study, he and his group tested the feasibility, efficacy, and safety of the sublingual approach to peanut allergy in children age 4 years and younger.

Both groups were similar with regard to gender, race, ethnicity, atopic history, peanut skin prick test, and qualifying DBPCFC, and all children were previously allergic with positive blood and skin tests, with a positive reaction during baseline food challenge, thus proving the allergy and establishing the baseline threshold.

“We have learned from some studies, for instance the DEVIL and LEAP studies, that strongly suggest that the immune systems in younger patients may be more amenable to change, and there may be some justification for early intervention,” he said.

“Based on both of those ideas, we wanted to take our sublingual approach, which we have shown to have a pretty good efficacy in older children, and bring it down to this younger group and see if it still could have the same efficacy and also maintain what seems to be a very good safety signal.”

The researchers randomly assigned the children to receive PNSLIT at a daily maintenance dose of 4 mg peanut protein (n = 19) or to receive placebo (n = 17) for 36 months.

“There was a 5- to 6-month buildup period where the SLIT dose was increased every 1-2 weeks up to the target dose of 4 mg, and then the final dose of 4 mg was continued through to the end of the study,” Dr. Kim noted.

Over a total of 20,593 potential dosing days, the children took 91.2% of SLIT doses and 93.5% of placebo doses.

At the end of the 3-year study period, the children were challenged by DBPCFC with up to 4,333 mg of peanut protein.

Sustained unresponsiveness was assessed by an identical DBPCFC after discontinuation of the immunotherapy for 3 months.

Cumulative tolerated dose increased from a median of 143 mg to 4,443 mg in the PNSLIT group, compared with a median of 43 mg to 143 mg in the placebo group (P < .0001).

Fourteen of the children receiving PNSLIT, and none of the children receiving placebo, passed the desensitization food challenge. Twelve of the children receiving PNSLIT and two of the children receiving placebo passed the sustained unresponsiveness challenge.

Children who underwent the immunotherapy saw a decrease in their peanut skin prick test from 10 mm to 3.25 mm, compared to an increase from 11.5 mm to 12 mm with placebo (P < .0001).

The most common side effect reported was itching or irritation in the mouth. Most side effects resolved on their own, although some patients used an antihistamine. Getting children as young as 1 to hold the dose under their tongue was a challenge in some instances, but it eventually worked out, Dr. Kim said.

“It took a lot of work from the parents as well as from our research coordinators in trying to train these young kids to, first of all, allow us to put the peanut medication in the mouth and then to try as best as possible to keep it in their mouth for up to 2 minutes, but the families involved in our study were very dedicated and so we were able to get through that,” he said.

Study merits larger numbers

“Among the 36 who completed the 3 years of therapy, the authors report significant rates of desensitization among treated children compared with those receiving placebo. Furthermore, this effect was persistent for at least 3 months after stopping therapy in a subgroup of the children,” said Leonard B. Bacharier, MD, director of the Center for Pediatric Asthma, Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, Nashville, Tenn.

“Overall, these findings suggest the promise of peanut SLIT, which should be studied in larger numbers of preschool children,” Dr. Bacharier, who was not part of the study, said in an interview.

Jonathan A. Bernstein, MD, professor of medicine, University of Cincinnati, agreed.

“It’s a well-designed study, it’s small, but it’s promising,” Dr. Bernstein, who was not involved with the study, said in an interview.

“They did show that most of the patients who got the sublingual therapy were able to get to the target dose and develop tolerance, so I think it’s promising. We know that this stuff works. This is just more data from a well-controlled study in a younger population,” he said.

“We do OIT [oral immunotherapy] and sublingual but we don’t do it in such young children in our practice. The youngest is 3 years old, because they have to understand what is going on and cooperate. If they don’t cooperate it’s not possible.”

Dr. Kim reported financial relationships with DBV Technologies, Kenota Health, Ukko, Aimmune Therapeutics, ALK, AllerGenis, Belhaven Pharma, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Nutricia, NIH/NIAID, NIH/NCCIH, NIH/Immune Tolerance Network, FARE, and the Wallace Foundation. Dr. Bacharier and Dr. Bernstein have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sublingual immunotherapy for the treatment of peanut allergy is safe and effective, even in children as young as age 1 year.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, food challenge (DBPCFC) of some 36 peanut-allergic children (mean age 2.2 years, range 1-4 years), those who were randomly assigned to receive peanut sublingual immunotherapy (PNSLIT) showed significant desensitization compared with those who received placebo.

In addition, there was a “strong potential” for sustained unresponsiveness at 3 months for the toddlers who received the active treatment.

The findings were presented in a late breaking oral abstract session at the 2021 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology virtual annual meeting (Abstract L2).

“A year ago, the Food and Drug Administration approved the oral agent Palforzia (peanut allergen powder) for the treatment of peanut allergy in children 4 and older, and it is a great option, but I think what we have learned over time is that this approach is not for everybody,” Edwin H. Kim, MD, director of the UNC Food Allergy Initiative, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in an interview.

Palforzia is a powder that is mixed in food like yogurt or pudding which the child then eats daily, according to a rigorous schedule. But Palforzia treatment presents some difficulties.

“Palforzia requires getting the powder dose, mixing it with food, like pudding or apple sauce, then eating it, which can take up to 30 minutes depending on age and kids’ cooperation. It tastes and smells like peanut which can cause aversion. Kids have to refrain from exercise or strenuous activity for at least 30 minutes before and after dosing and have to be observed for up to 2 hours post dose for symptoms,” Dr. Kim said.

“It’s a great drug, but the treatment could be overly difficult for certain families to be able to do, and in some cases the side effects may be more than certain patients are able or willing to handle, so there is a real urgent need for alternative approaches,” Dr. Kim said. “SLIT is several drops under the tongue, held for 2 minutes, swallowed and done.”

In the current placebo-controlled study, he and his group tested the feasibility, efficacy, and safety of the sublingual approach to peanut allergy in children age 4 years and younger.

Both groups were similar with regard to gender, race, ethnicity, atopic history, peanut skin prick test, and qualifying DBPCFC, and all children were previously allergic with positive blood and skin tests, with a positive reaction during baseline food challenge, thus proving the allergy and establishing the baseline threshold.

“We have learned from some studies, for instance the DEVIL and LEAP studies, that strongly suggest that the immune systems in younger patients may be more amenable to change, and there may be some justification for early intervention,” he said.

“Based on both of those ideas, we wanted to take our sublingual approach, which we have shown to have a pretty good efficacy in older children, and bring it down to this younger group and see if it still could have the same efficacy and also maintain what seems to be a very good safety signal.”

The researchers randomly assigned the children to receive PNSLIT at a daily maintenance dose of 4 mg peanut protein (n = 19) or to receive placebo (n = 17) for 36 months.

“There was a 5- to 6-month buildup period where the SLIT dose was increased every 1-2 weeks up to the target dose of 4 mg, and then the final dose of 4 mg was continued through to the end of the study,” Dr. Kim noted.

Over a total of 20,593 potential dosing days, the children took 91.2% of SLIT doses and 93.5% of placebo doses.

At the end of the 3-year study period, the children were challenged by DBPCFC with up to 4,333 mg of peanut protein.

Sustained unresponsiveness was assessed by an identical DBPCFC after discontinuation of the immunotherapy for 3 months.

Cumulative tolerated dose increased from a median of 143 mg to 4,443 mg in the PNSLIT group, compared with a median of 43 mg to 143 mg in the placebo group (P < .0001).

Fourteen of the children receiving PNSLIT, and none of the children receiving placebo, passed the desensitization food challenge. Twelve of the children receiving PNSLIT and two of the children receiving placebo passed the sustained unresponsiveness challenge.

Children who underwent the immunotherapy saw a decrease in their peanut skin prick test from 10 mm to 3.25 mm, compared to an increase from 11.5 mm to 12 mm with placebo (P < .0001).

The most common side effect reported was itching or irritation in the mouth. Most side effects resolved on their own, although some patients used an antihistamine. Getting children as young as 1 to hold the dose under their tongue was a challenge in some instances, but it eventually worked out, Dr. Kim said.

“It took a lot of work from the parents as well as from our research coordinators in trying to train these young kids to, first of all, allow us to put the peanut medication in the mouth and then to try as best as possible to keep it in their mouth for up to 2 minutes, but the families involved in our study were very dedicated and so we were able to get through that,” he said.

Study merits larger numbers

“Among the 36 who completed the 3 years of therapy, the authors report significant rates of desensitization among treated children compared with those receiving placebo. Furthermore, this effect was persistent for at least 3 months after stopping therapy in a subgroup of the children,” said Leonard B. Bacharier, MD, director of the Center for Pediatric Asthma, Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, Nashville, Tenn.

“Overall, these findings suggest the promise of peanut SLIT, which should be studied in larger numbers of preschool children,” Dr. Bacharier, who was not part of the study, said in an interview.

Jonathan A. Bernstein, MD, professor of medicine, University of Cincinnati, agreed.

“It’s a well-designed study, it’s small, but it’s promising,” Dr. Bernstein, who was not involved with the study, said in an interview.

“They did show that most of the patients who got the sublingual therapy were able to get to the target dose and develop tolerance, so I think it’s promising. We know that this stuff works. This is just more data from a well-controlled study in a younger population,” he said.

“We do OIT [oral immunotherapy] and sublingual but we don’t do it in such young children in our practice. The youngest is 3 years old, because they have to understand what is going on and cooperate. If they don’t cooperate it’s not possible.”

Dr. Kim reported financial relationships with DBV Technologies, Kenota Health, Ukko, Aimmune Therapeutics, ALK, AllerGenis, Belhaven Pharma, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Nutricia, NIH/NIAID, NIH/NCCIH, NIH/Immune Tolerance Network, FARE, and the Wallace Foundation. Dr. Bacharier and Dr. Bernstein have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAAAI

Asthma not an independent risk factor for severe COVID-19, hospitalization

Asthma is not an independent risk factor for more severe disease or hospitalization due to COVID-19, according to recent research presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“In our cohort of patients tested for SARS-CoV-2 at Stanford between March and September, asthma was not an independent risk factor in and of itself for hospitalization or more severe disease from COVID,” Lauren E. Eggert, MD, of the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in a poster presentation at the meeting. “What’s more, allergic asthma actually decreased the risk of hospitalization by nearly half.”

Dr. Eggert noted that there have been conflicting data on whether comorbid asthma is or is not a risk factor for more severe COVID-19. “The general thought at the beginning of the pandemic was that because COVID-19 is predominantly a viral respiratory illness, and viral illnesses are known to cause asthma exacerbations, that patients with asthma may be at higher risk if they got COVID infection,” she explained. “But some of the data also showed that Th2 inflammation downregulates ACE2 receptor [expression], which has been shown to be the port of entry for the SARS-CoV-2 virus, so maybe allergy might have a protective effect.”

The researchers at Stanford University identified 168,190 patients at Stanford Health Care who had a positive real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test for SARS-CoV-2 between March and September 2020 and collected data from their electronic medical records on their history of asthma, if they were hospitalized, comorbid conditions, and laboratory values. Patients who had no other data available except for a positive SARS-CoV-2 result, or were younger than 28 days, were excluded from the study. Dr. Eggert and colleagues used COVID-19 treatment guidelines from the National Institutes of Health to assess disease severity, which grades COVID-19 severity as asymptomatic or presymptomatic infection, mild illness, moderate illness, severe illness, and critical illness.

In total, the researchers analyzed 5,596 patients who were SARS-CoV-2 positive, with 605 patients (10.8%) hospitalized within 14 days of receiving a positive test. Of these, 100 patients (16.5%) were patients with asthma. There were no significant differences between groups hospitalized and not hospitalized due to COVID-19 in patients with asthma and with no asthma.

Among patients with asthma and COVID-19, 28.0% had asymptomatic illness, 19.0% had moderate disease, 33.0% had severe disease, and 20.0% had critical COVID-19, compared with 36.0% of patients without asthma who had asymptomatic illness, 12.0% with moderate disease, 30.0% with severe disease, and 21.0% with critical COVID-19. Dr. Eggert and colleagues performed a univariate analysis, which showed a significant association between asthma and COVID-19 related hospitalization (odds ratio, 1.53; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-1.93; P < .001), but when adjusting for factors such as diabetes, obesity coronary heart disease, and hypertension, they found there was not a significant association between asthma and hospitalization due to COVID-19 (OR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.86-1.45; P < .40).

In a univariate analysis, asthma was associated with more severe disease in patients hospitalized for COVID-19, but the results were not significant (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.8-1.85; P = .37). When analyzing allergic asthma alone in a univariate analysis, the researchers found a significant association between allergic asthma and lower hospitalization risk, compared with patients who had nonallergic asthma (OR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.31-0.92; P = .029), and this association remained after they performed a multivariate analysis as well.

“When we stratified by allergic asthma versus nonallergic asthma, we found that having a diagnosis of allergic asthma actually conferred a protective effect, and there was almost half the risk of hospitalization in asthmatics with allergic asthma as compared to others, which we thought was very interesting,” Dr. Eggert said.

“Eosinophil levels during hospitalization, even when adjusted for systemic steroid use – and we followed patients out through September, when dexamethasone was standard of care – also correlated with better outcomes,” she explained. “This is independent of asthmatic status.”

The researchers noted that confirmation of these results are needed through large, multicenter cohort studies, particularly with regard to how allergic asthma might have a protective effect against SARS-CoV-2 infection. “I think going forward, these findings are very interesting and need to be looked at further to explain the mechanism behind them better,” Dr. Eggert said.

“I think there is also a lot of interest in how this might affect our patients on biologics, which deplete the eosinophils and get rid of that allergic phenotype,” she added. “Does that have any effect on disease severity? Unfortunately, the number of patents on biologics was very small in our cohort, but I do think this is an interesting area for exploration.”

This study was funded in part by the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy & Asthma Research, Stanford University, Sunshine Foundation, Crown Foundation, and the Parker Foundation.

Asthma is not an independent risk factor for more severe disease or hospitalization due to COVID-19, according to recent research presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“In our cohort of patients tested for SARS-CoV-2 at Stanford between March and September, asthma was not an independent risk factor in and of itself for hospitalization or more severe disease from COVID,” Lauren E. Eggert, MD, of the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in a poster presentation at the meeting. “What’s more, allergic asthma actually decreased the risk of hospitalization by nearly half.”

Dr. Eggert noted that there have been conflicting data on whether comorbid asthma is or is not a risk factor for more severe COVID-19. “The general thought at the beginning of the pandemic was that because COVID-19 is predominantly a viral respiratory illness, and viral illnesses are known to cause asthma exacerbations, that patients with asthma may be at higher risk if they got COVID infection,” she explained. “But some of the data also showed that Th2 inflammation downregulates ACE2 receptor [expression], which has been shown to be the port of entry for the SARS-CoV-2 virus, so maybe allergy might have a protective effect.”

The researchers at Stanford University identified 168,190 patients at Stanford Health Care who had a positive real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test for SARS-CoV-2 between March and September 2020 and collected data from their electronic medical records on their history of asthma, if they were hospitalized, comorbid conditions, and laboratory values. Patients who had no other data available except for a positive SARS-CoV-2 result, or were younger than 28 days, were excluded from the study. Dr. Eggert and colleagues used COVID-19 treatment guidelines from the National Institutes of Health to assess disease severity, which grades COVID-19 severity as asymptomatic or presymptomatic infection, mild illness, moderate illness, severe illness, and critical illness.

In total, the researchers analyzed 5,596 patients who were SARS-CoV-2 positive, with 605 patients (10.8%) hospitalized within 14 days of receiving a positive test. Of these, 100 patients (16.5%) were patients with asthma. There were no significant differences between groups hospitalized and not hospitalized due to COVID-19 in patients with asthma and with no asthma.

Among patients with asthma and COVID-19, 28.0% had asymptomatic illness, 19.0% had moderate disease, 33.0% had severe disease, and 20.0% had critical COVID-19, compared with 36.0% of patients without asthma who had asymptomatic illness, 12.0% with moderate disease, 30.0% with severe disease, and 21.0% with critical COVID-19. Dr. Eggert and colleagues performed a univariate analysis, which showed a significant association between asthma and COVID-19 related hospitalization (odds ratio, 1.53; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-1.93; P < .001), but when adjusting for factors such as diabetes, obesity coronary heart disease, and hypertension, they found there was not a significant association between asthma and hospitalization due to COVID-19 (OR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.86-1.45; P < .40).

In a univariate analysis, asthma was associated with more severe disease in patients hospitalized for COVID-19, but the results were not significant (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.8-1.85; P = .37). When analyzing allergic asthma alone in a univariate analysis, the researchers found a significant association between allergic asthma and lower hospitalization risk, compared with patients who had nonallergic asthma (OR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.31-0.92; P = .029), and this association remained after they performed a multivariate analysis as well.

“When we stratified by allergic asthma versus nonallergic asthma, we found that having a diagnosis of allergic asthma actually conferred a protective effect, and there was almost half the risk of hospitalization in asthmatics with allergic asthma as compared to others, which we thought was very interesting,” Dr. Eggert said.

“Eosinophil levels during hospitalization, even when adjusted for systemic steroid use – and we followed patients out through September, when dexamethasone was standard of care – also correlated with better outcomes,” she explained. “This is independent of asthmatic status.”