User login

AHA/ACC guidance on ethics, professionalism in cardiovascular care

The American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology have issued a new report on medical ethics and professionalism in cardiovascular medicine.

The report addresses a variety of topics including diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging; racial, ethnic and gender inequities; conflicts of interest; clinician well-being; data privacy; social justice; and modern health care delivery systems.

The 54-page report is based on the proceedings of the joint 2020 Consensus Conference on Professionalism and Ethics, held Oct. 19 and 20, 2020. It was published online May 11 in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology .

The 2020 consensus conference on professionalism and ethics came at a time even more fraught than the eras of the three previous meetings on the same topics, held in 1989, 1997, and 2004, the writing group notes.

“We have seen the COVID-19 pandemic challenge the physical and economic health of the entire country, coupled with a series of national tragedies that have awakened the call for social justice,” conference cochair C. Michael Valentine, MD, said in a news release.

“There is no better time than now to review, evaluate, and take a fresh perspective on medical ethics and professionalism,” said Dr. Valentine, professor of medicine at the Heart and Vascular Center, University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

“We hope this report will provide cardiovascular professionals and health systems with the recommendations and tools they need to address conflicts of interest; racial, ethnic, and gender inequities; and improve diversity, inclusion, and wellness among our workforce,” Dr. Valentine added. “The majority of our members are now employed and must be engaged as the leaders for change in cardiovascular care.”

Road map to improve diversity, achieve allyship

The writing committee was made up of a diverse group of cardiologists, internists, and associated health care professionals and laypeople and was organized into five task forces, each addressing a specific topic: conflicts of interest; diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging; clinician well-being; patient autonomy, privacy, and social justice in health care; and modern health care delivery.

The report serves as a road map to achieve equity, inclusion, and belonging among cardiovascular professionals and calls for ongoing assessment of the professional culture and climate, focused on improving diversity and achieving effective allyship, the writing group says.

The report proposes continuous training to address individual, structural, and systemic racism, sexism, homophobia, classism, and ableism.

It offers recommendations for championing equity in patient care that include an annual review of practice records to look for differences in patient treatment by race, ethnicity, zip code, and primary language.

The report calls for a foundation of training in allyship and antiracism as part of medical school course requirements and experiences: A required course on social justice, race, and racism as part of the first-year curriculum; school programs and professional organizations supporting students, trainees, and members in allyship and antiracism action; and facilitating immersion and partnership with surrounding communities.

“As much as 80% of a person’s health is determined by the social and economic conditions of their environment,” consensus cochair Ivor Benjamin, MD, said in the release.

“To achieve social justice and mitigate health disparities, we must go to the margins and shift our discussions to be inclusive of populations such as rural and marginalized groups from the perspective of health equity lens for all,” said Dr. Benjamin, professor of medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

The report also highlights the need for psychosocial support of the cardiovascular community and recommends that health care organizations prioritize regular assessment of clinicians’ well-being and engagement.

It also recommends addressing the well-being of trainees in postgraduate training programs and calls for an ombudsman program that allows for confidential reporting of mistreatment and access to support.

The report also highlights additional opportunities to:

- improve the efficiency of health information technology, such as electronic health records, and reduce the administrative burden

- identify and assist clinicians who experience mental health conditions, , or

- emphasize patient autonomy using shared decision-making and patient-centered care that is supportive of the individual patient’s values

- increase privacy protections for patient data used in research

- maintain integrity as new ways of delivering care, such as telemedicine, team-based care approaches, and physician-owned specialty centers emerge

- perform routine audits of electronic health records to promote optimal patient care, as well as ethical medical practice

- expand and make mandatory the reporting of intellectual or associational interests in addition to relationships with industry

The report’s details and recommendations will be presented and discussed Saturday, May 15, at 8:00 AM ET, during ACC.21. The session is titled Diversity and Equity: The Means to Expand Inclusion and Belonging.

The AHA will present a live webinar and six-episode podcast series (available on demand) to highlight the report’s details, dialogue, and actionable steps for cardiovascular and health care professionals, researchers, and educators.

This research had no commercial funding. The list of 40 volunteer committee members and coauthors, including their disclosures, are listed in the original report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology have issued a new report on medical ethics and professionalism in cardiovascular medicine.

The report addresses a variety of topics including diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging; racial, ethnic and gender inequities; conflicts of interest; clinician well-being; data privacy; social justice; and modern health care delivery systems.

The 54-page report is based on the proceedings of the joint 2020 Consensus Conference on Professionalism and Ethics, held Oct. 19 and 20, 2020. It was published online May 11 in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology .

The 2020 consensus conference on professionalism and ethics came at a time even more fraught than the eras of the three previous meetings on the same topics, held in 1989, 1997, and 2004, the writing group notes.

“We have seen the COVID-19 pandemic challenge the physical and economic health of the entire country, coupled with a series of national tragedies that have awakened the call for social justice,” conference cochair C. Michael Valentine, MD, said in a news release.

“There is no better time than now to review, evaluate, and take a fresh perspective on medical ethics and professionalism,” said Dr. Valentine, professor of medicine at the Heart and Vascular Center, University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

“We hope this report will provide cardiovascular professionals and health systems with the recommendations and tools they need to address conflicts of interest; racial, ethnic, and gender inequities; and improve diversity, inclusion, and wellness among our workforce,” Dr. Valentine added. “The majority of our members are now employed and must be engaged as the leaders for change in cardiovascular care.”

Road map to improve diversity, achieve allyship

The writing committee was made up of a diverse group of cardiologists, internists, and associated health care professionals and laypeople and was organized into five task forces, each addressing a specific topic: conflicts of interest; diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging; clinician well-being; patient autonomy, privacy, and social justice in health care; and modern health care delivery.

The report serves as a road map to achieve equity, inclusion, and belonging among cardiovascular professionals and calls for ongoing assessment of the professional culture and climate, focused on improving diversity and achieving effective allyship, the writing group says.

The report proposes continuous training to address individual, structural, and systemic racism, sexism, homophobia, classism, and ableism.

It offers recommendations for championing equity in patient care that include an annual review of practice records to look for differences in patient treatment by race, ethnicity, zip code, and primary language.

The report calls for a foundation of training in allyship and antiracism as part of medical school course requirements and experiences: A required course on social justice, race, and racism as part of the first-year curriculum; school programs and professional organizations supporting students, trainees, and members in allyship and antiracism action; and facilitating immersion and partnership with surrounding communities.

“As much as 80% of a person’s health is determined by the social and economic conditions of their environment,” consensus cochair Ivor Benjamin, MD, said in the release.

“To achieve social justice and mitigate health disparities, we must go to the margins and shift our discussions to be inclusive of populations such as rural and marginalized groups from the perspective of health equity lens for all,” said Dr. Benjamin, professor of medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

The report also highlights the need for psychosocial support of the cardiovascular community and recommends that health care organizations prioritize regular assessment of clinicians’ well-being and engagement.

It also recommends addressing the well-being of trainees in postgraduate training programs and calls for an ombudsman program that allows for confidential reporting of mistreatment and access to support.

The report also highlights additional opportunities to:

- improve the efficiency of health information technology, such as electronic health records, and reduce the administrative burden

- identify and assist clinicians who experience mental health conditions, , or

- emphasize patient autonomy using shared decision-making and patient-centered care that is supportive of the individual patient’s values

- increase privacy protections for patient data used in research

- maintain integrity as new ways of delivering care, such as telemedicine, team-based care approaches, and physician-owned specialty centers emerge

- perform routine audits of electronic health records to promote optimal patient care, as well as ethical medical practice

- expand and make mandatory the reporting of intellectual or associational interests in addition to relationships with industry

The report’s details and recommendations will be presented and discussed Saturday, May 15, at 8:00 AM ET, during ACC.21. The session is titled Diversity and Equity: The Means to Expand Inclusion and Belonging.

The AHA will present a live webinar and six-episode podcast series (available on demand) to highlight the report’s details, dialogue, and actionable steps for cardiovascular and health care professionals, researchers, and educators.

This research had no commercial funding. The list of 40 volunteer committee members and coauthors, including their disclosures, are listed in the original report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology have issued a new report on medical ethics and professionalism in cardiovascular medicine.

The report addresses a variety of topics including diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging; racial, ethnic and gender inequities; conflicts of interest; clinician well-being; data privacy; social justice; and modern health care delivery systems.

The 54-page report is based on the proceedings of the joint 2020 Consensus Conference on Professionalism and Ethics, held Oct. 19 and 20, 2020. It was published online May 11 in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology .

The 2020 consensus conference on professionalism and ethics came at a time even more fraught than the eras of the three previous meetings on the same topics, held in 1989, 1997, and 2004, the writing group notes.

“We have seen the COVID-19 pandemic challenge the physical and economic health of the entire country, coupled with a series of national tragedies that have awakened the call for social justice,” conference cochair C. Michael Valentine, MD, said in a news release.

“There is no better time than now to review, evaluate, and take a fresh perspective on medical ethics and professionalism,” said Dr. Valentine, professor of medicine at the Heart and Vascular Center, University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

“We hope this report will provide cardiovascular professionals and health systems with the recommendations and tools they need to address conflicts of interest; racial, ethnic, and gender inequities; and improve diversity, inclusion, and wellness among our workforce,” Dr. Valentine added. “The majority of our members are now employed and must be engaged as the leaders for change in cardiovascular care.”

Road map to improve diversity, achieve allyship

The writing committee was made up of a diverse group of cardiologists, internists, and associated health care professionals and laypeople and was organized into five task forces, each addressing a specific topic: conflicts of interest; diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging; clinician well-being; patient autonomy, privacy, and social justice in health care; and modern health care delivery.

The report serves as a road map to achieve equity, inclusion, and belonging among cardiovascular professionals and calls for ongoing assessment of the professional culture and climate, focused on improving diversity and achieving effective allyship, the writing group says.

The report proposes continuous training to address individual, structural, and systemic racism, sexism, homophobia, classism, and ableism.

It offers recommendations for championing equity in patient care that include an annual review of practice records to look for differences in patient treatment by race, ethnicity, zip code, and primary language.

The report calls for a foundation of training in allyship and antiracism as part of medical school course requirements and experiences: A required course on social justice, race, and racism as part of the first-year curriculum; school programs and professional organizations supporting students, trainees, and members in allyship and antiracism action; and facilitating immersion and partnership with surrounding communities.

“As much as 80% of a person’s health is determined by the social and economic conditions of their environment,” consensus cochair Ivor Benjamin, MD, said in the release.

“To achieve social justice and mitigate health disparities, we must go to the margins and shift our discussions to be inclusive of populations such as rural and marginalized groups from the perspective of health equity lens for all,” said Dr. Benjamin, professor of medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

The report also highlights the need for psychosocial support of the cardiovascular community and recommends that health care organizations prioritize regular assessment of clinicians’ well-being and engagement.

It also recommends addressing the well-being of trainees in postgraduate training programs and calls for an ombudsman program that allows for confidential reporting of mistreatment and access to support.

The report also highlights additional opportunities to:

- improve the efficiency of health information technology, such as electronic health records, and reduce the administrative burden

- identify and assist clinicians who experience mental health conditions, , or

- emphasize patient autonomy using shared decision-making and patient-centered care that is supportive of the individual patient’s values

- increase privacy protections for patient data used in research

- maintain integrity as new ways of delivering care, such as telemedicine, team-based care approaches, and physician-owned specialty centers emerge

- perform routine audits of electronic health records to promote optimal patient care, as well as ethical medical practice

- expand and make mandatory the reporting of intellectual or associational interests in addition to relationships with industry

The report’s details and recommendations will be presented and discussed Saturday, May 15, at 8:00 AM ET, during ACC.21. The session is titled Diversity and Equity: The Means to Expand Inclusion and Belonging.

The AHA will present a live webinar and six-episode podcast series (available on demand) to highlight the report’s details, dialogue, and actionable steps for cardiovascular and health care professionals, researchers, and educators.

This research had no commercial funding. The list of 40 volunteer committee members and coauthors, including their disclosures, are listed in the original report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FIDELIO-DKD: Finerenone cuts new-onset AFib in patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD

Finerenone treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic kidney disease was linked to a significant drop in the incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation as a prespecified, exploratory endpoint of the FIDELIO-DKD pivotal trial that randomized more than 5,700 patients.

Treatment with finerenone linked with a 29% relative reduction compared with placebo in incident cases of atrial fibrillation (AFib), Gerasimos Filippatos, MD, reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

The absolute reduction was modest, a 1.3% reduction from the 4.5% incidence rate on placebo to a 3.2% rate on finerenone during a median 2.6 years of follow-up. Concurrently with the report, the results appeared online (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 May 17. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.079).

The analyses Dr. Filippatos presented also showed that whether or not patients had a history of AFib, there was no impact on either the primary benefit from finerenone treatment seen in FIDELIO-DKD, which was a significant 18% relative risk reduction compared with placebo in the combined rate of kidney failure, a 40% or greater decline from baseline in estimated glomerular filtration rate, or renal death.

Likewise, prior AFib status had no effect on the study’s key secondary endpoint, a significant 14% relative risk reduction in the combined rate of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure.

The primary results from FIDELIO-DKD (Efficacy and Safety of Finerenone in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetic Kidney Disease) appeared in a 2020 report (N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 3;383[23];2219-29).

‘Side benefits can be very helpful’

“It’s important to know of finerenone’s benefits beyond the primary outcome of a trial because side benefits can be very helpful,” said Anne B. Curtis, MD, an electrophysiologist and professor and chair of medicine at the University of Buffalo (N.Y.) School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. “It’s not a huge benefit, but this could be an added benefit for selected patients,” she said during a press briefing. “Background studies had shown favorable remodeling of the heart [by finerenone] that could affect AFib.”

Possible mitigating effects by finerenone on inflammation and fibrosis might also mediate the drug’s apparent effect on AFib, said Dr. Filippatos, professor of cardiology and director of the Heart Failure and Cardio-Oncology Clinic at Attikon University Hospital and the University of Athens.

He noted that additional data addressing a possible AFib effect of finerenone will emerge soon from the FIGARO-DKD trial, which enrolled patients similar to those in FIDELIO-DKD but with more moderate stages of kidney disease, and from the FINEARTS-HF trial, which is examining the effect of finerenone in patients with heart failure with an ejection fraction of at least 40%.

“Heart failure and AFib go together tightly. It’s worth studying this specifically, so we can see whether there is an impact of finerenone on patients with heart failure who may not necessarily have kidney disease or diabetes,” Dr. Curtis said.

Hypothesis-generating findings

The new findings reported by Dr. Filippatos “should be considered hypothesis generating. Until we have more information, upstream therapies, including mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists [MRAs, the umbrella drug class that includes finerenone], should be used in appropriate patient populations based on defined benefits with the hope they will also reduce the development of AFib and atrial flutter over time,” Gerald V. Naccarelli, MD, and coauthors wrote in an editorial that accompanied the report (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 May 17. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.080).

The FIDELIO-DKD trial randomized 5,734 patients at 913 sites in 48 countries, including 461 patients with a history of AFib. The observed link of finerenone treatment with a reduced incidence of AFib appeared consistent regardless of patients’ age, sex, race, their kidney characteristics at baseline, baseline levels of systolic blood pressure, serum potassium, body mass index, A1c, or use of glucose-lowering medications.

Finerenone belongs to a new class of MRAs that have a nonsteroidal structure, in contrast with the MRAs spironolactone and eplerenone. This means that finerenone does not produce steroidal-associated adverse effects linked with certain other MRAs, such as gynecomastia, and may also differ in other actions.

FIDELIO-DKD was sponsored by Bayer, the company developing finerenone. Dr. Filippatos has received lecture fees from or participated in the direction of trials on behalf of Bayer, as well as for Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, Novartis, Servier, and Vifor. Dr. Curtis is an adviser to and receives honoraria from St. Jude Medical, and receives honoraria from Medtronic. Dr. Naccarelli has been a consultant to Acesion, ARCA, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Milestone, Omeicos, and Sanofi. His coauthors had no disclosures.

Finerenone treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic kidney disease was linked to a significant drop in the incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation as a prespecified, exploratory endpoint of the FIDELIO-DKD pivotal trial that randomized more than 5,700 patients.

Treatment with finerenone linked with a 29% relative reduction compared with placebo in incident cases of atrial fibrillation (AFib), Gerasimos Filippatos, MD, reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

The absolute reduction was modest, a 1.3% reduction from the 4.5% incidence rate on placebo to a 3.2% rate on finerenone during a median 2.6 years of follow-up. Concurrently with the report, the results appeared online (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 May 17. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.079).

The analyses Dr. Filippatos presented also showed that whether or not patients had a history of AFib, there was no impact on either the primary benefit from finerenone treatment seen in FIDELIO-DKD, which was a significant 18% relative risk reduction compared with placebo in the combined rate of kidney failure, a 40% or greater decline from baseline in estimated glomerular filtration rate, or renal death.

Likewise, prior AFib status had no effect on the study’s key secondary endpoint, a significant 14% relative risk reduction in the combined rate of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure.

The primary results from FIDELIO-DKD (Efficacy and Safety of Finerenone in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetic Kidney Disease) appeared in a 2020 report (N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 3;383[23];2219-29).

‘Side benefits can be very helpful’

“It’s important to know of finerenone’s benefits beyond the primary outcome of a trial because side benefits can be very helpful,” said Anne B. Curtis, MD, an electrophysiologist and professor and chair of medicine at the University of Buffalo (N.Y.) School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. “It’s not a huge benefit, but this could be an added benefit for selected patients,” she said during a press briefing. “Background studies had shown favorable remodeling of the heart [by finerenone] that could affect AFib.”

Possible mitigating effects by finerenone on inflammation and fibrosis might also mediate the drug’s apparent effect on AFib, said Dr. Filippatos, professor of cardiology and director of the Heart Failure and Cardio-Oncology Clinic at Attikon University Hospital and the University of Athens.

He noted that additional data addressing a possible AFib effect of finerenone will emerge soon from the FIGARO-DKD trial, which enrolled patients similar to those in FIDELIO-DKD but with more moderate stages of kidney disease, and from the FINEARTS-HF trial, which is examining the effect of finerenone in patients with heart failure with an ejection fraction of at least 40%.

“Heart failure and AFib go together tightly. It’s worth studying this specifically, so we can see whether there is an impact of finerenone on patients with heart failure who may not necessarily have kidney disease or diabetes,” Dr. Curtis said.

Hypothesis-generating findings

The new findings reported by Dr. Filippatos “should be considered hypothesis generating. Until we have more information, upstream therapies, including mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists [MRAs, the umbrella drug class that includes finerenone], should be used in appropriate patient populations based on defined benefits with the hope they will also reduce the development of AFib and atrial flutter over time,” Gerald V. Naccarelli, MD, and coauthors wrote in an editorial that accompanied the report (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 May 17. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.080).

The FIDELIO-DKD trial randomized 5,734 patients at 913 sites in 48 countries, including 461 patients with a history of AFib. The observed link of finerenone treatment with a reduced incidence of AFib appeared consistent regardless of patients’ age, sex, race, their kidney characteristics at baseline, baseline levels of systolic blood pressure, serum potassium, body mass index, A1c, or use of glucose-lowering medications.

Finerenone belongs to a new class of MRAs that have a nonsteroidal structure, in contrast with the MRAs spironolactone and eplerenone. This means that finerenone does not produce steroidal-associated adverse effects linked with certain other MRAs, such as gynecomastia, and may also differ in other actions.

FIDELIO-DKD was sponsored by Bayer, the company developing finerenone. Dr. Filippatos has received lecture fees from or participated in the direction of trials on behalf of Bayer, as well as for Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, Novartis, Servier, and Vifor. Dr. Curtis is an adviser to and receives honoraria from St. Jude Medical, and receives honoraria from Medtronic. Dr. Naccarelli has been a consultant to Acesion, ARCA, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Milestone, Omeicos, and Sanofi. His coauthors had no disclosures.

Finerenone treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic kidney disease was linked to a significant drop in the incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation as a prespecified, exploratory endpoint of the FIDELIO-DKD pivotal trial that randomized more than 5,700 patients.

Treatment with finerenone linked with a 29% relative reduction compared with placebo in incident cases of atrial fibrillation (AFib), Gerasimos Filippatos, MD, reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

The absolute reduction was modest, a 1.3% reduction from the 4.5% incidence rate on placebo to a 3.2% rate on finerenone during a median 2.6 years of follow-up. Concurrently with the report, the results appeared online (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 May 17. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.079).

The analyses Dr. Filippatos presented also showed that whether or not patients had a history of AFib, there was no impact on either the primary benefit from finerenone treatment seen in FIDELIO-DKD, which was a significant 18% relative risk reduction compared with placebo in the combined rate of kidney failure, a 40% or greater decline from baseline in estimated glomerular filtration rate, or renal death.

Likewise, prior AFib status had no effect on the study’s key secondary endpoint, a significant 14% relative risk reduction in the combined rate of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure.

The primary results from FIDELIO-DKD (Efficacy and Safety of Finerenone in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetic Kidney Disease) appeared in a 2020 report (N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 3;383[23];2219-29).

‘Side benefits can be very helpful’

“It’s important to know of finerenone’s benefits beyond the primary outcome of a trial because side benefits can be very helpful,” said Anne B. Curtis, MD, an electrophysiologist and professor and chair of medicine at the University of Buffalo (N.Y.) School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. “It’s not a huge benefit, but this could be an added benefit for selected patients,” she said during a press briefing. “Background studies had shown favorable remodeling of the heart [by finerenone] that could affect AFib.”

Possible mitigating effects by finerenone on inflammation and fibrosis might also mediate the drug’s apparent effect on AFib, said Dr. Filippatos, professor of cardiology and director of the Heart Failure and Cardio-Oncology Clinic at Attikon University Hospital and the University of Athens.

He noted that additional data addressing a possible AFib effect of finerenone will emerge soon from the FIGARO-DKD trial, which enrolled patients similar to those in FIDELIO-DKD but with more moderate stages of kidney disease, and from the FINEARTS-HF trial, which is examining the effect of finerenone in patients with heart failure with an ejection fraction of at least 40%.

“Heart failure and AFib go together tightly. It’s worth studying this specifically, so we can see whether there is an impact of finerenone on patients with heart failure who may not necessarily have kidney disease or diabetes,” Dr. Curtis said.

Hypothesis-generating findings

The new findings reported by Dr. Filippatos “should be considered hypothesis generating. Until we have more information, upstream therapies, including mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists [MRAs, the umbrella drug class that includes finerenone], should be used in appropriate patient populations based on defined benefits with the hope they will also reduce the development of AFib and atrial flutter over time,” Gerald V. Naccarelli, MD, and coauthors wrote in an editorial that accompanied the report (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 May 17. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.080).

The FIDELIO-DKD trial randomized 5,734 patients at 913 sites in 48 countries, including 461 patients with a history of AFib. The observed link of finerenone treatment with a reduced incidence of AFib appeared consistent regardless of patients’ age, sex, race, their kidney characteristics at baseline, baseline levels of systolic blood pressure, serum potassium, body mass index, A1c, or use of glucose-lowering medications.

Finerenone belongs to a new class of MRAs that have a nonsteroidal structure, in contrast with the MRAs spironolactone and eplerenone. This means that finerenone does not produce steroidal-associated adverse effects linked with certain other MRAs, such as gynecomastia, and may also differ in other actions.

FIDELIO-DKD was sponsored by Bayer, the company developing finerenone. Dr. Filippatos has received lecture fees from or participated in the direction of trials on behalf of Bayer, as well as for Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, Novartis, Servier, and Vifor. Dr. Curtis is an adviser to and receives honoraria from St. Jude Medical, and receives honoraria from Medtronic. Dr. Naccarelli has been a consultant to Acesion, ARCA, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Milestone, Omeicos, and Sanofi. His coauthors had no disclosures.

FROM ACC 2021

Dapagliflozin misses as treatment for COVID-19 but leaves intriguing signal for benefit

In patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection, the sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin showed a trend for benefit relative to placebo on multiple outcomes, including the primary outcome of time to organ failure or death, according to results from the randomized DARE-19 trial.

Because of the failure to reach statistical significance, these results have no immediate relevance, but the trends support interest in further testing SGLT2 inhibitors in acute diseases posing a high risk for organ failure, according to Mikhail Kosiborod, MD.

In a trial that did not meet its primary endpoint, Dr. Kosiborod acknowledged that positive interpretations are speculative, but he does believe that there is one immediate take-home message.

“Our results do not support discontinuation of SGLT2 inhibitors in the setting of COVID-19 as long as patients are monitored,” said Dr. Kosiborod, director of cardiometabolic research at Saint Luke’s Mid-America Heart Institute, Kansas City, Mo.

At many institutions, it has been common to discontinue SGLT2 inhibitors in patients admitted with COVID-19. One reason was the concern that drugs in this class could exacerbate organ damage, particularly if they were to induced ketoacidosis. However, only 2 (0.003%) of 613 patients treated with dapagliflozin developed ketoacidosis, and the signal for organ protection overall, although not significant, was consistent.

“Numerically, fewer patients treated with dapagliflozin experienced organ failure and death, and this was consistent across systems, including the kidney,” Dr. Kosiborod said in presenting the study at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

Overall, the study suggests that, in the context of COVID-19, dapagliflozin did not show harm and might have potential benefit, he added.

DARE-19 was rapidly conceived, designed, and implemented during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on prior evidence that SGLT2 inhibitors “favorably affect a number of pathophysiologic pathways disrupted during acute illness” and that drugs in this class have provided organ protection in the context of heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and other cardiometabolic conditions, the study was designed to test the hypothesis that this mechanism might improve outcomes in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, Dr. Kosiborod said.

The entry criteria included confirmed or suspected COVID-19 with an onset of 4 days of fewer and one additional risk factor, such as atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, hypertension, or type 2 diabetes. Patients with significant renal impairment or a history of diabetic ketoacidosis were excluded.

On top of standard treatments for COVID-19, patients were randomized to 10 mg dapagliflozin or placebo once daily. There were two primary endpoints. That of prevention was time to criteria for respiratory, cardiovascular, or renal organ failure or death. The second primary outcome, for recovery, was a hierarchical composite for four endpoints: death, organ failure, status at 30 days if hospitalized, and time to discharge if this occurred before day 30.

Of the 1,250 patients randomized at 95 sites in seven countries, 617 in the dapagliflozin group and 620 patients in the placebo group completed the study. Baseline characteristics, which included a mean of age of 62 years; types of comorbidities; and types of treatments were similar.

Results for two primary endpoints

The curves for the primary outcome of prevention had already separated by day 3 and continued to widen over the 30 days in which outcomes were compared. At the end of 30 days, 11.2% of the dapagliflozin group and 13.8% of the placebo group had an event. By hazard ratio, dapagliflozin was linked to 20% nonsignificant relative protection from events (hazard ratio, 0.80; 95% confidence interval, 0.58-1.10).

The trend (P = .168) for the primary endpoint for prevention was reflected in the individual components. For dapagliflozin related to placebo, there were generally similar or greater reductions in new or worsening organ failure (HR, 0.80), cardiac decompensation (HR, 0.81), respiratory decompensation (HR, 0.85), and kidney decompensation (HR, 0.65). None were statistically significant, but the confidence intervals were tight with the upper end never exceeding 1.20.

Moreover, the relative risk reduction for all-cause mortality moved in the same direction (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.52-1.16).

In the hierarchical composite endpoint of recovery, there was no significant difference in the time to discharge, but again many recovery metrics numerically favored dapagliflozin with an overall difference producing a statistical trend (P = .14) similar to organ failure events and death.

In safety analyses, dapagliflozin consistently outperformed placebo across a broad array of safety measure, including any severe adverse event (65% vs. 82%), any adverse event with an outcome of death (32% vs. 48%), discontinuation caused by an adverse event (44% vs. 55%), and acute kidney injury (21% vs. 34%).

Data could fuel related studies

According to Ana Barac, MD, PhD, director of the cardio-oncology program in the Medstar Heart and Vascular Institute, Washington, these data are “thought provoking.” Although this was a negative trial, she said that it generates an “exciting hypothesis” about the potential of SGLT2 inhibitors to provide organ protection. She called for studies to pursue this path of research.

More immediately, Dr. Barac agreed that these data argue against stopping SGLT2 inhibitors in patients admitted to a hospital for COVID-19 infection.

“These data show that these drugs are not going to lead to harm, but they might lead to benefit,” she said.

For James Januzzi, MD, a cardiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, DARE-19 was perhaps most impressive because of its rigorous design and execution in the midst of a pandemic.

Over the past year, “the medical literature was flooded with grossly underpowered, poorly designed, single-center studies” yielding results that have been hard to interpret, Dr. Januzzi said. Despite the fact that this study failed to confirm its hypothesis, he said the investigators deserve praise for the quality of the work.

Dr. Januzzi also believes the study is not without clinically relevant findings, particularly the fact that dapagliflozin was associated with a lower rate of adverse events than placebo. This, at least, provides reassurance about the safety of this drug in the setting of COVID-19 infection.

Dr. Kosiborod reported financial relationships with more than 10 pharmaceutical companies, including AstraZeneca, which provided funding for DARE-19. Dr. Barac reported financial relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb and CTI BioPharma. Dr. Januzzi reported financial relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim, GE Healthcare, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche.

In patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection, the sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin showed a trend for benefit relative to placebo on multiple outcomes, including the primary outcome of time to organ failure or death, according to results from the randomized DARE-19 trial.

Because of the failure to reach statistical significance, these results have no immediate relevance, but the trends support interest in further testing SGLT2 inhibitors in acute diseases posing a high risk for organ failure, according to Mikhail Kosiborod, MD.

In a trial that did not meet its primary endpoint, Dr. Kosiborod acknowledged that positive interpretations are speculative, but he does believe that there is one immediate take-home message.

“Our results do not support discontinuation of SGLT2 inhibitors in the setting of COVID-19 as long as patients are monitored,” said Dr. Kosiborod, director of cardiometabolic research at Saint Luke’s Mid-America Heart Institute, Kansas City, Mo.

At many institutions, it has been common to discontinue SGLT2 inhibitors in patients admitted with COVID-19. One reason was the concern that drugs in this class could exacerbate organ damage, particularly if they were to induced ketoacidosis. However, only 2 (0.003%) of 613 patients treated with dapagliflozin developed ketoacidosis, and the signal for organ protection overall, although not significant, was consistent.

“Numerically, fewer patients treated with dapagliflozin experienced organ failure and death, and this was consistent across systems, including the kidney,” Dr. Kosiborod said in presenting the study at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

Overall, the study suggests that, in the context of COVID-19, dapagliflozin did not show harm and might have potential benefit, he added.

DARE-19 was rapidly conceived, designed, and implemented during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on prior evidence that SGLT2 inhibitors “favorably affect a number of pathophysiologic pathways disrupted during acute illness” and that drugs in this class have provided organ protection in the context of heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and other cardiometabolic conditions, the study was designed to test the hypothesis that this mechanism might improve outcomes in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, Dr. Kosiborod said.

The entry criteria included confirmed or suspected COVID-19 with an onset of 4 days of fewer and one additional risk factor, such as atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, hypertension, or type 2 diabetes. Patients with significant renal impairment or a history of diabetic ketoacidosis were excluded.

On top of standard treatments for COVID-19, patients were randomized to 10 mg dapagliflozin or placebo once daily. There were two primary endpoints. That of prevention was time to criteria for respiratory, cardiovascular, or renal organ failure or death. The second primary outcome, for recovery, was a hierarchical composite for four endpoints: death, organ failure, status at 30 days if hospitalized, and time to discharge if this occurred before day 30.

Of the 1,250 patients randomized at 95 sites in seven countries, 617 in the dapagliflozin group and 620 patients in the placebo group completed the study. Baseline characteristics, which included a mean of age of 62 years; types of comorbidities; and types of treatments were similar.

Results for two primary endpoints

The curves for the primary outcome of prevention had already separated by day 3 and continued to widen over the 30 days in which outcomes were compared. At the end of 30 days, 11.2% of the dapagliflozin group and 13.8% of the placebo group had an event. By hazard ratio, dapagliflozin was linked to 20% nonsignificant relative protection from events (hazard ratio, 0.80; 95% confidence interval, 0.58-1.10).

The trend (P = .168) for the primary endpoint for prevention was reflected in the individual components. For dapagliflozin related to placebo, there were generally similar or greater reductions in new or worsening organ failure (HR, 0.80), cardiac decompensation (HR, 0.81), respiratory decompensation (HR, 0.85), and kidney decompensation (HR, 0.65). None were statistically significant, but the confidence intervals were tight with the upper end never exceeding 1.20.

Moreover, the relative risk reduction for all-cause mortality moved in the same direction (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.52-1.16).

In the hierarchical composite endpoint of recovery, there was no significant difference in the time to discharge, but again many recovery metrics numerically favored dapagliflozin with an overall difference producing a statistical trend (P = .14) similar to organ failure events and death.

In safety analyses, dapagliflozin consistently outperformed placebo across a broad array of safety measure, including any severe adverse event (65% vs. 82%), any adverse event with an outcome of death (32% vs. 48%), discontinuation caused by an adverse event (44% vs. 55%), and acute kidney injury (21% vs. 34%).

Data could fuel related studies

According to Ana Barac, MD, PhD, director of the cardio-oncology program in the Medstar Heart and Vascular Institute, Washington, these data are “thought provoking.” Although this was a negative trial, she said that it generates an “exciting hypothesis” about the potential of SGLT2 inhibitors to provide organ protection. She called for studies to pursue this path of research.

More immediately, Dr. Barac agreed that these data argue against stopping SGLT2 inhibitors in patients admitted to a hospital for COVID-19 infection.

“These data show that these drugs are not going to lead to harm, but they might lead to benefit,” she said.

For James Januzzi, MD, a cardiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, DARE-19 was perhaps most impressive because of its rigorous design and execution in the midst of a pandemic.

Over the past year, “the medical literature was flooded with grossly underpowered, poorly designed, single-center studies” yielding results that have been hard to interpret, Dr. Januzzi said. Despite the fact that this study failed to confirm its hypothesis, he said the investigators deserve praise for the quality of the work.

Dr. Januzzi also believes the study is not without clinically relevant findings, particularly the fact that dapagliflozin was associated with a lower rate of adverse events than placebo. This, at least, provides reassurance about the safety of this drug in the setting of COVID-19 infection.

Dr. Kosiborod reported financial relationships with more than 10 pharmaceutical companies, including AstraZeneca, which provided funding for DARE-19. Dr. Barac reported financial relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb and CTI BioPharma. Dr. Januzzi reported financial relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim, GE Healthcare, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche.

In patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection, the sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin showed a trend for benefit relative to placebo on multiple outcomes, including the primary outcome of time to organ failure or death, according to results from the randomized DARE-19 trial.

Because of the failure to reach statistical significance, these results have no immediate relevance, but the trends support interest in further testing SGLT2 inhibitors in acute diseases posing a high risk for organ failure, according to Mikhail Kosiborod, MD.

In a trial that did not meet its primary endpoint, Dr. Kosiborod acknowledged that positive interpretations are speculative, but he does believe that there is one immediate take-home message.

“Our results do not support discontinuation of SGLT2 inhibitors in the setting of COVID-19 as long as patients are monitored,” said Dr. Kosiborod, director of cardiometabolic research at Saint Luke’s Mid-America Heart Institute, Kansas City, Mo.

At many institutions, it has been common to discontinue SGLT2 inhibitors in patients admitted with COVID-19. One reason was the concern that drugs in this class could exacerbate organ damage, particularly if they were to induced ketoacidosis. However, only 2 (0.003%) of 613 patients treated with dapagliflozin developed ketoacidosis, and the signal for organ protection overall, although not significant, was consistent.

“Numerically, fewer patients treated with dapagliflozin experienced organ failure and death, and this was consistent across systems, including the kidney,” Dr. Kosiborod said in presenting the study at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

Overall, the study suggests that, in the context of COVID-19, dapagliflozin did not show harm and might have potential benefit, he added.

DARE-19 was rapidly conceived, designed, and implemented during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on prior evidence that SGLT2 inhibitors “favorably affect a number of pathophysiologic pathways disrupted during acute illness” and that drugs in this class have provided organ protection in the context of heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and other cardiometabolic conditions, the study was designed to test the hypothesis that this mechanism might improve outcomes in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, Dr. Kosiborod said.

The entry criteria included confirmed or suspected COVID-19 with an onset of 4 days of fewer and one additional risk factor, such as atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, hypertension, or type 2 diabetes. Patients with significant renal impairment or a history of diabetic ketoacidosis were excluded.

On top of standard treatments for COVID-19, patients were randomized to 10 mg dapagliflozin or placebo once daily. There were two primary endpoints. That of prevention was time to criteria for respiratory, cardiovascular, or renal organ failure or death. The second primary outcome, for recovery, was a hierarchical composite for four endpoints: death, organ failure, status at 30 days if hospitalized, and time to discharge if this occurred before day 30.

Of the 1,250 patients randomized at 95 sites in seven countries, 617 in the dapagliflozin group and 620 patients in the placebo group completed the study. Baseline characteristics, which included a mean of age of 62 years; types of comorbidities; and types of treatments were similar.

Results for two primary endpoints

The curves for the primary outcome of prevention had already separated by day 3 and continued to widen over the 30 days in which outcomes were compared. At the end of 30 days, 11.2% of the dapagliflozin group and 13.8% of the placebo group had an event. By hazard ratio, dapagliflozin was linked to 20% nonsignificant relative protection from events (hazard ratio, 0.80; 95% confidence interval, 0.58-1.10).

The trend (P = .168) for the primary endpoint for prevention was reflected in the individual components. For dapagliflozin related to placebo, there were generally similar or greater reductions in new or worsening organ failure (HR, 0.80), cardiac decompensation (HR, 0.81), respiratory decompensation (HR, 0.85), and kidney decompensation (HR, 0.65). None were statistically significant, but the confidence intervals were tight with the upper end never exceeding 1.20.

Moreover, the relative risk reduction for all-cause mortality moved in the same direction (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.52-1.16).

In the hierarchical composite endpoint of recovery, there was no significant difference in the time to discharge, but again many recovery metrics numerically favored dapagliflozin with an overall difference producing a statistical trend (P = .14) similar to organ failure events and death.

In safety analyses, dapagliflozin consistently outperformed placebo across a broad array of safety measure, including any severe adverse event (65% vs. 82%), any adverse event with an outcome of death (32% vs. 48%), discontinuation caused by an adverse event (44% vs. 55%), and acute kidney injury (21% vs. 34%).

Data could fuel related studies

According to Ana Barac, MD, PhD, director of the cardio-oncology program in the Medstar Heart and Vascular Institute, Washington, these data are “thought provoking.” Although this was a negative trial, she said that it generates an “exciting hypothesis” about the potential of SGLT2 inhibitors to provide organ protection. She called for studies to pursue this path of research.

More immediately, Dr. Barac agreed that these data argue against stopping SGLT2 inhibitors in patients admitted to a hospital for COVID-19 infection.

“These data show that these drugs are not going to lead to harm, but they might lead to benefit,” she said.

For James Januzzi, MD, a cardiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, DARE-19 was perhaps most impressive because of its rigorous design and execution in the midst of a pandemic.

Over the past year, “the medical literature was flooded with grossly underpowered, poorly designed, single-center studies” yielding results that have been hard to interpret, Dr. Januzzi said. Despite the fact that this study failed to confirm its hypothesis, he said the investigators deserve praise for the quality of the work.

Dr. Januzzi also believes the study is not without clinically relevant findings, particularly the fact that dapagliflozin was associated with a lower rate of adverse events than placebo. This, at least, provides reassurance about the safety of this drug in the setting of COVID-19 infection.

Dr. Kosiborod reported financial relationships with more than 10 pharmaceutical companies, including AstraZeneca, which provided funding for DARE-19. Dr. Barac reported financial relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb and CTI BioPharma. Dr. Januzzi reported financial relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim, GE Healthcare, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche.

FROM ACC 2021

Novel rehab program fights frailty, boosts capacity in advanced HF

A novel physical rehabilitation program for patients with advanced heart failure that aimed to improve their ability to exercise before focusing on endurance was successful in a randomized trial in ways that seem to have eluded some earlier exercise-training studies in the setting of HF.

The often-frail patients following the training regimen, initiated before discharge from hospitalization for acute decompensation, worked on capabilities such as mobility, balance, and strength deemed necessary if exercises meant to build exercise capacity were to succeed.

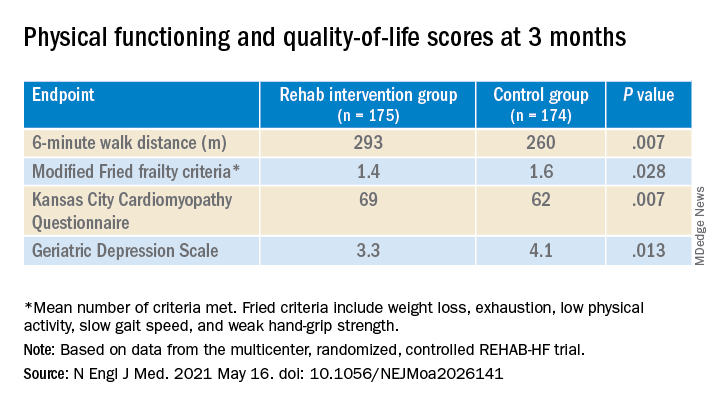

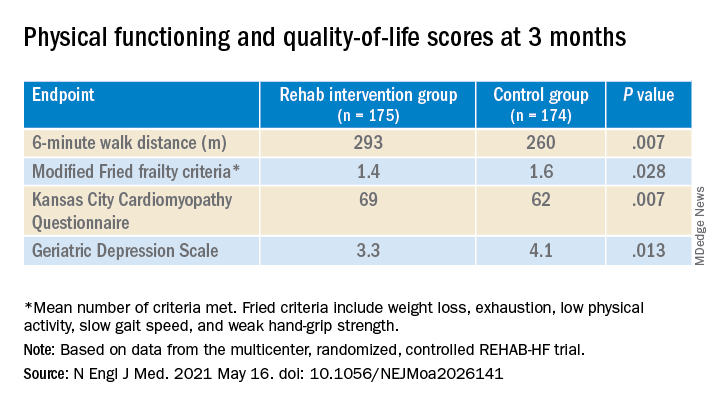

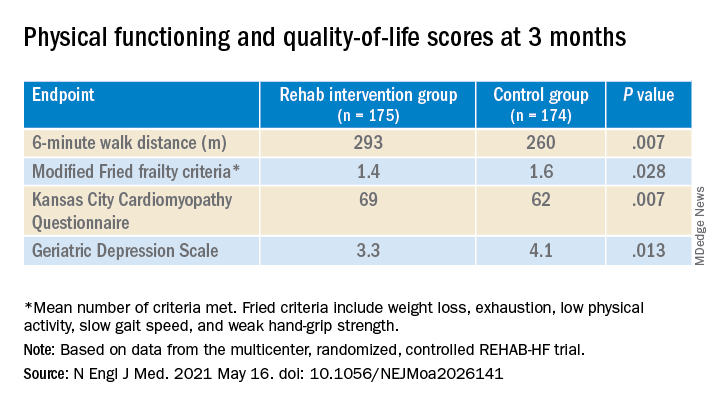

A huge percentage stayed with the 12-week program, which featured personalized, one-on-one training from a physical therapist. The patients benefited, with improvements in balance, walking ability, and strength, which were followed by significant gains in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and measures of physical functioning, frailty, and quality of life. The patients then continued elements of the program at home out to 6 months.

At that time, death and rehospitalizations did not differ between those assigned to the regimen and similar patients who had not participated in the program, although the trial wasn’t powered for clinical events.

The rehab strategy seemed to work across a wide range of patient subgroups. In particular, there was evidence that the benefits were more pronounced in patients with HF and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) than in those with HF and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), observed Dalane W. Kitzman, MD, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Dr. Kitzman presented results from the REHAB-HF (Rehabilitation Therapy in Older Acute Heart Failure Patients) trial at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and is lead author on its same-day publication in the New England Journal of Medicine.

An earlier pilot program unexpectedly showed that such patients recently hospitalized with HF “have significant impairments in mobility and balance,” he explained. If so, “it would be hazardous to subject them to traditional endurance training, such as walking-based treadmill or even bicycle.”

The unusual program, said Dr. Kitzman, looks to those issues before engaging the patients in endurance exercise by addressing mobility, balance, and basic strength – enough to repeatedly stand up from a sitting position, for example. “If you’re not able to stand with confidence, then you’re not able to walk on a treadmill.”

This model of exercise rehab “is used in geriatrics research, and enables them to safely increase endurance. It’s well known from geriatric studies that if you go directly to endurance in these, frail, older patients, you have little improvement and often have injuries and falls,” he added.

Guidance from telemedicine?

The functional outcomes examined in REHAB-HF “are the ones that matter to patients the most,” observed Eileen M. Handberg, PhD, of Shands Hospital at the University of Florida, Gainesville, at a presentation on the trial for the media.

“This is about being able to get out of a chair without assistance, not falling, walking farther, and feeling better as opposed to the more traditional outcome measure that has been used in cardiac rehab trials, which has been the exercise treadmill test – which most patients don’t have the capacity to do very well anyway,” said Dr. Handberg, who is not a part of REHAB-HF.

“This opens up rehab, potentially, to the more sick, who also need a better quality of life,” she said.

However, many patients invited to participate in the trial could not because they lived too far from the program, Dr. Handberg observed. “It would be nice to see if the lessons from COVID-19 might apply to this population” by making participation possible remotely, “perhaps using family members as rehab assistance,” she said.

“I was really very impressed that you had 83% adherence to a home exercise 6 months down the road, which far eclipses what we had in HF-ACTION,” said Vera Bittner, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, as the invited discussant following Dr. Kitzman’s formal presentation of the trial. “And it certainly eclipses what we see in the typical cardiac rehab program.”

Both Dr. Bittner and Dr. Kitzman participated in HF-ACTION, a randomized exercise-training trial for patients with chronic, stable HFrEF who were all-around less sick than those in REHAB-HF.

Four functional domains

Historically, HF exercise or rehab trials have excluded patients hospitalized with acute decompensation, and third-party reimbursement often has not covered such programs because of a lack of supporting evidence and a supposed potential for harm, Dr. Kitzman said.

Entry to REHAB-HF required the patients to be fit enough to walk 4 meters, with or without a walker or other assistant device, and to have been in the hospital for at least 24 hours with a primary diagnosis of acute decompensated HF.

The intervention relied on exercises aimed at improving the four functional domains of strength, balance, mobility, and – when those three were sufficiently developed – endurance, Dr. Kitzman and associates wrote in their published report.

“The intervention was initiated in the hospital when feasible and was subsequently transitioned to an outpatient facility as soon as possible after discharge,” they wrote. Afterward, “a key goal of the intervention during the first 3 months [the outpatient phase] was to prepare the patient to transition to the independent maintenance phase (months 4-6).”

The study’s control patients “received frequent calls from study staff to try to approximate the increased attention received by the intervention group,” Dr. Kitzman said in an interview. “They were allowed to receive all usual care as ordered by their treating physicians. This included, if ordered, standard physical therapy or cardiac rehabilitation” in 43% of the control cohort. Of the trial’s 349 patients, those assigned to the intervention scored significantly higher on the three-component Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) at 12 weeks than those assigned to a usual care approach that included, for some, more conventional cardiac rehabilitation (8.3 vs. 6.9; P < .001).

The SPPB, validated in trials as a proxy for clinical outcomes includes tests of balance while standing, gait speed during a 4-minute walk, and strength. The latter is the test that measures time needed to rise from a chair five times.

They also showed consistent gains in other measures of physical functioning and quality of life by 12 weeks months.

The observed SPPB treatment effect is “impressive” and “compares very favorably with previously reported estimates,” observed an accompanying editorial from Stefan D. Anker, MD, PhD, of the German Center for Cardiovascular Research and Charité Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, and Andrew J.S. Coats, DM, of the University of Warwick, Coventry, England.

“Similarly, the between-group differences seen in 6-minute walk distance (34 m) and gait speed (0.12 m/s) are clinically meaningful and sizable.”

They propose that some of the substantial quality-of-life benefit in the intervention group “may be due to better physical performance, and that part may be due to improvements in psychosocial factors and mood. It appears that exercise also resulted in patients becoming happier, or at least less depressed, as evidenced by the positive results on the Geriatric Depression Scale.”

Similar results across most subgroups

In subgroup analyses, the intervention was successful against the standard-care approach in both men and women at all ages and regardless of ejection fraction; symptom status; and whether the patient had diabetes, ischemic heart disease, or atrial fibrillation, or was obese.

Clinical outcomes were not significantly different at 6 months. The rate of death from any cause was 13% for the intervention group and 10% for the control group. There were 194 and 213 hospitalizations from any cause, respectively.

Not included in the trial’s current publication but soon to be published, Dr. Kitzman said when interviewed, is a comparison of outcomes in patients with HFpEF and HFrEF. “We found at baseline that those with HFpEF had worse impairment in physical function, quality of life, and frailty. After the intervention, there appeared to be consistently larger improvements in all outcomes, including SPPB, 6-minute walk, qualify of life, and frailty, in HFpEF versus HFrEF.”

The signals of potential benefit in HFpEF extended to clinical endpoints, he said. In contrast to similar rates of all-cause rehospitalization in HFrEF, “in patients with HFpEF, rehospitalizations were 17% lower in the intervention group, compared to the control group.” Still, he noted, the interaction P value wasn’t significant.

However, Dr. Kitzman added, mortality in the intervention group, compared with the control group, was reduced by 35% among patients with HFpEF, “but was 250% higher in HFrEF,” with a significant interaction P value.

He was careful to note that, as a phase 2 trial, REHAB-HF was underpowered for clinical events, “and even the results in the HFpEF group should not be seen as adequate evidence to change clinical care.” They were from an exploratory analysis that included relatively few events.

“Because definitive demonstration of improvement in clinical events is critical for altering clinical care guidelines and for third-party payer reimbursement decisions, we believe that a subsequent phase 3 trial is needed and are currently planning toward that,” Dr. Kitzman said.

The study was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Kermit Glenn Phillips II Chair in Cardiovascular Medicine, and the Oristano Family Fund at Wake Forest. Dr. Kitzman disclosed receiving consulting fees or honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bayer Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim, CinRx, Corviamedical, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck; and having an unspecified relationship with Gilead. Dr. Handberg disclosed receiving grants from Aastom Biosciences, Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Amorcyte, AstraZeneca, Biocardia, Boehringer Ingelheim, Capricor, Cytori Therapeutics, Department of Defense, Direct Flow Medical, Everyfit, Gilead, Ionis, Medtronic, Merck, Mesoblast, Relypsa, and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Bittner discloses receiving consulting fees or honoraria from Pfizer and Sanofi; receiving research grants from Amgen and The Medicines Company; and having unspecified relationships with AstraZeneca, DalCor, Esperion, and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Anker reported receiving grants and personal fees from Abbott Vascular and Vifor; personal fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Servier, Cardiac Dimensions, Thermo Fisher Scientific, AstraZeneca, Occlutech, Actimed, and Respicardia. Dr. Coats disclosed receiving personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Menarini, Novartis, Nutricia, Servier, Vifor, Abbott, Actimed, Arena, Cardiac Dimensions, Corvia, CVRx, Enopace, ESN Cleer, Faraday, WL Gore, Impulse Dynamics, and Respicardia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A novel physical rehabilitation program for patients with advanced heart failure that aimed to improve their ability to exercise before focusing on endurance was successful in a randomized trial in ways that seem to have eluded some earlier exercise-training studies in the setting of HF.

The often-frail patients following the training regimen, initiated before discharge from hospitalization for acute decompensation, worked on capabilities such as mobility, balance, and strength deemed necessary if exercises meant to build exercise capacity were to succeed.

A huge percentage stayed with the 12-week program, which featured personalized, one-on-one training from a physical therapist. The patients benefited, with improvements in balance, walking ability, and strength, which were followed by significant gains in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and measures of physical functioning, frailty, and quality of life. The patients then continued elements of the program at home out to 6 months.

At that time, death and rehospitalizations did not differ between those assigned to the regimen and similar patients who had not participated in the program, although the trial wasn’t powered for clinical events.

The rehab strategy seemed to work across a wide range of patient subgroups. In particular, there was evidence that the benefits were more pronounced in patients with HF and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) than in those with HF and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), observed Dalane W. Kitzman, MD, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Dr. Kitzman presented results from the REHAB-HF (Rehabilitation Therapy in Older Acute Heart Failure Patients) trial at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and is lead author on its same-day publication in the New England Journal of Medicine.

An earlier pilot program unexpectedly showed that such patients recently hospitalized with HF “have significant impairments in mobility and balance,” he explained. If so, “it would be hazardous to subject them to traditional endurance training, such as walking-based treadmill or even bicycle.”

The unusual program, said Dr. Kitzman, looks to those issues before engaging the patients in endurance exercise by addressing mobility, balance, and basic strength – enough to repeatedly stand up from a sitting position, for example. “If you’re not able to stand with confidence, then you’re not able to walk on a treadmill.”

This model of exercise rehab “is used in geriatrics research, and enables them to safely increase endurance. It’s well known from geriatric studies that if you go directly to endurance in these, frail, older patients, you have little improvement and often have injuries and falls,” he added.

Guidance from telemedicine?

The functional outcomes examined in REHAB-HF “are the ones that matter to patients the most,” observed Eileen M. Handberg, PhD, of Shands Hospital at the University of Florida, Gainesville, at a presentation on the trial for the media.

“This is about being able to get out of a chair without assistance, not falling, walking farther, and feeling better as opposed to the more traditional outcome measure that has been used in cardiac rehab trials, which has been the exercise treadmill test – which most patients don’t have the capacity to do very well anyway,” said Dr. Handberg, who is not a part of REHAB-HF.

“This opens up rehab, potentially, to the more sick, who also need a better quality of life,” she said.

However, many patients invited to participate in the trial could not because they lived too far from the program, Dr. Handberg observed. “It would be nice to see if the lessons from COVID-19 might apply to this population” by making participation possible remotely, “perhaps using family members as rehab assistance,” she said.

“I was really very impressed that you had 83% adherence to a home exercise 6 months down the road, which far eclipses what we had in HF-ACTION,” said Vera Bittner, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, as the invited discussant following Dr. Kitzman’s formal presentation of the trial. “And it certainly eclipses what we see in the typical cardiac rehab program.”

Both Dr. Bittner and Dr. Kitzman participated in HF-ACTION, a randomized exercise-training trial for patients with chronic, stable HFrEF who were all-around less sick than those in REHAB-HF.

Four functional domains

Historically, HF exercise or rehab trials have excluded patients hospitalized with acute decompensation, and third-party reimbursement often has not covered such programs because of a lack of supporting evidence and a supposed potential for harm, Dr. Kitzman said.

Entry to REHAB-HF required the patients to be fit enough to walk 4 meters, with or without a walker or other assistant device, and to have been in the hospital for at least 24 hours with a primary diagnosis of acute decompensated HF.

The intervention relied on exercises aimed at improving the four functional domains of strength, balance, mobility, and – when those three were sufficiently developed – endurance, Dr. Kitzman and associates wrote in their published report.

“The intervention was initiated in the hospital when feasible and was subsequently transitioned to an outpatient facility as soon as possible after discharge,” they wrote. Afterward, “a key goal of the intervention during the first 3 months [the outpatient phase] was to prepare the patient to transition to the independent maintenance phase (months 4-6).”

The study’s control patients “received frequent calls from study staff to try to approximate the increased attention received by the intervention group,” Dr. Kitzman said in an interview. “They were allowed to receive all usual care as ordered by their treating physicians. This included, if ordered, standard physical therapy or cardiac rehabilitation” in 43% of the control cohort. Of the trial’s 349 patients, those assigned to the intervention scored significantly higher on the three-component Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) at 12 weeks than those assigned to a usual care approach that included, for some, more conventional cardiac rehabilitation (8.3 vs. 6.9; P < .001).

The SPPB, validated in trials as a proxy for clinical outcomes includes tests of balance while standing, gait speed during a 4-minute walk, and strength. The latter is the test that measures time needed to rise from a chair five times.

They also showed consistent gains in other measures of physical functioning and quality of life by 12 weeks months.

The observed SPPB treatment effect is “impressive” and “compares very favorably with previously reported estimates,” observed an accompanying editorial from Stefan D. Anker, MD, PhD, of the German Center for Cardiovascular Research and Charité Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, and Andrew J.S. Coats, DM, of the University of Warwick, Coventry, England.

“Similarly, the between-group differences seen in 6-minute walk distance (34 m) and gait speed (0.12 m/s) are clinically meaningful and sizable.”

They propose that some of the substantial quality-of-life benefit in the intervention group “may be due to better physical performance, and that part may be due to improvements in psychosocial factors and mood. It appears that exercise also resulted in patients becoming happier, or at least less depressed, as evidenced by the positive results on the Geriatric Depression Scale.”

Similar results across most subgroups

In subgroup analyses, the intervention was successful against the standard-care approach in both men and women at all ages and regardless of ejection fraction; symptom status; and whether the patient had diabetes, ischemic heart disease, or atrial fibrillation, or was obese.

Clinical outcomes were not significantly different at 6 months. The rate of death from any cause was 13% for the intervention group and 10% for the control group. There were 194 and 213 hospitalizations from any cause, respectively.

Not included in the trial’s current publication but soon to be published, Dr. Kitzman said when interviewed, is a comparison of outcomes in patients with HFpEF and HFrEF. “We found at baseline that those with HFpEF had worse impairment in physical function, quality of life, and frailty. After the intervention, there appeared to be consistently larger improvements in all outcomes, including SPPB, 6-minute walk, qualify of life, and frailty, in HFpEF versus HFrEF.”

The signals of potential benefit in HFpEF extended to clinical endpoints, he said. In contrast to similar rates of all-cause rehospitalization in HFrEF, “in patients with HFpEF, rehospitalizations were 17% lower in the intervention group, compared to the control group.” Still, he noted, the interaction P value wasn’t significant.

However, Dr. Kitzman added, mortality in the intervention group, compared with the control group, was reduced by 35% among patients with HFpEF, “but was 250% higher in HFrEF,” with a significant interaction P value.

He was careful to note that, as a phase 2 trial, REHAB-HF was underpowered for clinical events, “and even the results in the HFpEF group should not be seen as adequate evidence to change clinical care.” They were from an exploratory analysis that included relatively few events.

“Because definitive demonstration of improvement in clinical events is critical for altering clinical care guidelines and for third-party payer reimbursement decisions, we believe that a subsequent phase 3 trial is needed and are currently planning toward that,” Dr. Kitzman said.

The study was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Kermit Glenn Phillips II Chair in Cardiovascular Medicine, and the Oristano Family Fund at Wake Forest. Dr. Kitzman disclosed receiving consulting fees or honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bayer Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim, CinRx, Corviamedical, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck; and having an unspecified relationship with Gilead. Dr. Handberg disclosed receiving grants from Aastom Biosciences, Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Amorcyte, AstraZeneca, Biocardia, Boehringer Ingelheim, Capricor, Cytori Therapeutics, Department of Defense, Direct Flow Medical, Everyfit, Gilead, Ionis, Medtronic, Merck, Mesoblast, Relypsa, and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Bittner discloses receiving consulting fees or honoraria from Pfizer and Sanofi; receiving research grants from Amgen and The Medicines Company; and having unspecified relationships with AstraZeneca, DalCor, Esperion, and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Anker reported receiving grants and personal fees from Abbott Vascular and Vifor; personal fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Servier, Cardiac Dimensions, Thermo Fisher Scientific, AstraZeneca, Occlutech, Actimed, and Respicardia. Dr. Coats disclosed receiving personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Menarini, Novartis, Nutricia, Servier, Vifor, Abbott, Actimed, Arena, Cardiac Dimensions, Corvia, CVRx, Enopace, ESN Cleer, Faraday, WL Gore, Impulse Dynamics, and Respicardia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A novel physical rehabilitation program for patients with advanced heart failure that aimed to improve their ability to exercise before focusing on endurance was successful in a randomized trial in ways that seem to have eluded some earlier exercise-training studies in the setting of HF.

The often-frail patients following the training regimen, initiated before discharge from hospitalization for acute decompensation, worked on capabilities such as mobility, balance, and strength deemed necessary if exercises meant to build exercise capacity were to succeed.

A huge percentage stayed with the 12-week program, which featured personalized, one-on-one training from a physical therapist. The patients benefited, with improvements in balance, walking ability, and strength, which were followed by significant gains in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and measures of physical functioning, frailty, and quality of life. The patients then continued elements of the program at home out to 6 months.

At that time, death and rehospitalizations did not differ between those assigned to the regimen and similar patients who had not participated in the program, although the trial wasn’t powered for clinical events.

The rehab strategy seemed to work across a wide range of patient subgroups. In particular, there was evidence that the benefits were more pronounced in patients with HF and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) than in those with HF and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), observed Dalane W. Kitzman, MD, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Dr. Kitzman presented results from the REHAB-HF (Rehabilitation Therapy in Older Acute Heart Failure Patients) trial at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and is lead author on its same-day publication in the New England Journal of Medicine.

An earlier pilot program unexpectedly showed that such patients recently hospitalized with HF “have significant impairments in mobility and balance,” he explained. If so, “it would be hazardous to subject them to traditional endurance training, such as walking-based treadmill or even bicycle.”

The unusual program, said Dr. Kitzman, looks to those issues before engaging the patients in endurance exercise by addressing mobility, balance, and basic strength – enough to repeatedly stand up from a sitting position, for example. “If you’re not able to stand with confidence, then you’re not able to walk on a treadmill.”

This model of exercise rehab “is used in geriatrics research, and enables them to safely increase endurance. It’s well known from geriatric studies that if you go directly to endurance in these, frail, older patients, you have little improvement and often have injuries and falls,” he added.