User login

How to Prevent and Manage Hospital-Based Infections During Coronavirus Outbreaks: Five Lessons from Taiwan

During the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003, Taiwan reported 346 confirmed cases and 73 deaths.1 Of all known infections, 94% were transmitted inside hospitals. Nine major hospitals were fully or partially shut down, and many doctors and nurses quit for fear of becoming infected. The Taipei Municipal Ho-Ping Hospital was most severely affected. Its index patient, a 42-year-old undocumented hospital laundry worker who interacted with staff and patients for 6 days before being hospitalized, became a superspreader, infecting at least 20 other patients and 10 staff members.2,3 The entire 450-bed hospital was ordered to shut down, and all 930 staff and 240 patients were quarantined within the hospital. The central government appointed the previous Minister of Health as head of the Anti-SARS Taskforce. Ultimately the hospital was evacuated; the outbreak resulted in 26 deaths.2 Events surrounding the hospital’s evacuation offer important lessons for hospitals struggling to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been caused by spread of a similar coronavirus.

LESSON 1: DIAGNOSIS

Flexibility about case definition is important, as is use of clinical criteria for diagnosis when reliable laboratory tests are not available.

The laundry worker of Ho-Ping Hospital was initially misdiagnosed with infectious enteritis, which delayed proper management and, crucially, isolation from other patients. The low index of suspicion for SARS reflected the initial World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for SARS, which included travel to or residence in an area with recent local transmission of SARS within 10 days of symptom onset.4 The laundry worker did not have a recent travel history.3 Additionally, SARS manifested as a lower respiratory tract infection, so many patients were hospitalized for pneumonia before being diagnosed with SARS. Similarly, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission initially issued diagnostic criteria for COVID-19 that, in addition to fever and symptoms of respiratory infections, emphasized direct exposure to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market.5 As a result, many cases of COVID-19 were not identified.

Diagnosing SARS was challenging. Early symptoms such as fever and malaise were nonspecific. Polymerase chain reaction tests, although available, were unreliable especially in early stages of the disease and had a high false-negative rate. As cases of SARS increased rapidly, Taiwan began using fever alone for early detection.6 Patients and hospital staff received temperature measurements twice daily. Despite the late start to SARS screening, the fever criterion identified many suspected patients, which ensured widespread detection and containment.

For COVID-19, symptoms such as fever, dry cough, and shortness of breath can be used as clinical criteria to triage patients for quarantine in endemic areas when reliable diagnostic tests are not readily available, but all frontline clinical staff should receive daily temperature checks and/or COVID-19 tests, if available, to protect their families and the public.

LESSON 2: COORDINATION

Ineffective coordination between central and local governments can delay response, but this can be remedied.

During the SARS outbreak, the Taipei City Government and the Taiwan central government were controlled by opposing political parties. Responses to SARS were initially impeded by political skirmishes, which hindered implementation of policies regarding criteria for diagnosis, tracking of suspected cases and their contacts, duration of quarantine, and allocation of resources and facilities for confirmed cases. To avoid further delays, the central government acted swiftly to create the nonpartisan Anti-SARS Taskforce and appointed leaders who could work cordially with both local and central government agencies. To help to deal with the crisis, the central government also designated a new Minister of Health, an epidemiologist, who became the first nonphysician to hold this position.

LESSON 3: EVACUATION

Treatment in place vs evacuation during hospital infections is a critical decision.

The surge of SARS cases at Ho-Ping Hospital led to confusion and panic among patients and hospital staff. Whether to treat its SARS patients on site or to evacuate the hospital was a complex decision and reflected many concerns, including the following: How many wards had been infected? Was there sufficient equipment (eg, respirators) to monitor or treat infected patients? How many isolation beds were available? How many hospital staff were already infected and quarantined? Were they in different wards? Were there neighboring facilities (eg, hospitals, military camps, dorms) available for quarantine?

If a hospital has sufficient capacity to isolate persons under investigation and to treat confirmed patients, on-site treatment is possible. However, evacuation should be considered when there is widespread infection involving different hospital wards and hospital staff. In such cases, patients should be transferred to different facilities based on clinical severity: Patients with new onset fever or respiratory symptoms but who are relatively healthy should be sent to community or regional hospitals with isolation rooms for monitoring; sicker infected patients should be sent to medical centers; and other hospitalized patients (eg, admitted for heart failure) without infection risk or symptoms should seek care elsewhere.

So far, there has been only one instance of hospital-based COVID-19 infections in Taiwan, and the spread of infection was quickly contained within one ward. All nine confirmed cases (including the index patient, one patient in the same ward but a different room, three nurses, one laundry worker, and three members of patients’ families) and their known contacts were identified, then isolated or quarantined individually. Because the affected hospital is part of a complex with more than 3,000 beds, it was big enough to accommodate all infected patients and no evacuation measures were needed. To further reduce potential nodes in the chain of transmission, interns and many other healthcare workers were temporarily relieved of their duties, elective surgeries were canceled, and hospital visitation was limited to immediate family members. The clear communication of intervention measures ensured rapid cooperation and staved off both social panic and further spread of the disease.

LESSON 4: PATIENT FLOW

Hospitals should establish different flows for different patients.

Having learned from the SARS experience in 2003, hospitals in Taiwan have designated specific pathways to manage patient flow during the COVID-19 outbreak, in addition to checking all patients for travel history and fever: Patients with fever were quickly triaged to a designated fever clinic so they did not mingle with other patients, patients visiting the hospital to obtain chronic disease medications were directed to a “drive-through” lane, patients needing emergent care went through the emergency department, all other regular outpatients were seen in outpatient departments, and visitors of patients were restricted to one visitor per patient at a given time.

LESSON 5: ORGANIZATION

Healthcare providers should be organized into blocks and modular teams to avoid hospital-wide infection.

After SARS, Taiwan learned that one way to reduce the spread of something like COVID-19 among healthcare providers and from providers to patients is to divide providers’ work areas into discrete blocks and organize providers into modular teams. This approach was inspired by the design of watertight compartments in ships: Should the hull be breached, flooding is restricted to the breached compartments. Under this organizational strategy, movements of physicians and nurses would be restricted to their designated locations: They would be routinely exposed only to other staff and patients within their division. Doctors and nurses would be asked to practice in modular teams within their blocked locations, reducing the likelihood that infection in one team would spread to another, which could lead to hospital-wide infections. Movement of senior hospital executives would be similarly restricted. Common areas such as cafeterias where people mingle would be closed. Owing to these stringent initiatives, aside from the hospital-based infection mentioned in Lesson 3, no other hospital-based infections have been reported in Taiwan so far.

CONCLUSION

Lessons from previous hospital-based coronavirus infections can be used to minimize future infections.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Lee Ming-Liang, former Health Minister of Taiwan and director of that central government’s Anti-SARS Taskforce during the 2003 outbreak, for providing valuable recommendations to this work.

1. Hsieh YH, King CC, Chen CWS, et al. Quarantine for SARS, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(2):278-282. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1102.040190.

2. From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome—Taiwan, 2003. JAMA. 2003;289(22):2930-2932. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.22.2930.

3. McNeil DG. The SARS epidemic: the virus; most Taiwan SARS cases spread by one misdiagnosis. New York Times. May 8, 2003. https://www.nytimes.com/2003/05/08/world/the-sars-epidemic-the-virus-most-taiwan-sars-cases-spread-by-one-misdiagnosis.html. Accessed March 28, 2020.

4. Hui DSC, Chan MCH, Wu AK, Ng PC. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): epidemiology and clinical features. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80(945):373-381. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2004.020263.

5. Yang DL. Wuhan officials tried to cover up covid-19 — and sent it careening outward. Washington Post. March 10, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/03/10/wuhan-officials-tried-cover-up-covid-19-sent-it-careening-outward/. Accessed March 28, 2020.

6. Lin EC, Peng YC, Hung Tsai JC. Lessons learned from the anti-SARS quarantine experience in a hospital-based fever screening station in Taiwan. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(4):302-307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2009.09.008.

During the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003, Taiwan reported 346 confirmed cases and 73 deaths.1 Of all known infections, 94% were transmitted inside hospitals. Nine major hospitals were fully or partially shut down, and many doctors and nurses quit for fear of becoming infected. The Taipei Municipal Ho-Ping Hospital was most severely affected. Its index patient, a 42-year-old undocumented hospital laundry worker who interacted with staff and patients for 6 days before being hospitalized, became a superspreader, infecting at least 20 other patients and 10 staff members.2,3 The entire 450-bed hospital was ordered to shut down, and all 930 staff and 240 patients were quarantined within the hospital. The central government appointed the previous Minister of Health as head of the Anti-SARS Taskforce. Ultimately the hospital was evacuated; the outbreak resulted in 26 deaths.2 Events surrounding the hospital’s evacuation offer important lessons for hospitals struggling to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been caused by spread of a similar coronavirus.

LESSON 1: DIAGNOSIS

Flexibility about case definition is important, as is use of clinical criteria for diagnosis when reliable laboratory tests are not available.

The laundry worker of Ho-Ping Hospital was initially misdiagnosed with infectious enteritis, which delayed proper management and, crucially, isolation from other patients. The low index of suspicion for SARS reflected the initial World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for SARS, which included travel to or residence in an area with recent local transmission of SARS within 10 days of symptom onset.4 The laundry worker did not have a recent travel history.3 Additionally, SARS manifested as a lower respiratory tract infection, so many patients were hospitalized for pneumonia before being diagnosed with SARS. Similarly, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission initially issued diagnostic criteria for COVID-19 that, in addition to fever and symptoms of respiratory infections, emphasized direct exposure to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market.5 As a result, many cases of COVID-19 were not identified.

Diagnosing SARS was challenging. Early symptoms such as fever and malaise were nonspecific. Polymerase chain reaction tests, although available, were unreliable especially in early stages of the disease and had a high false-negative rate. As cases of SARS increased rapidly, Taiwan began using fever alone for early detection.6 Patients and hospital staff received temperature measurements twice daily. Despite the late start to SARS screening, the fever criterion identified many suspected patients, which ensured widespread detection and containment.

For COVID-19, symptoms such as fever, dry cough, and shortness of breath can be used as clinical criteria to triage patients for quarantine in endemic areas when reliable diagnostic tests are not readily available, but all frontline clinical staff should receive daily temperature checks and/or COVID-19 tests, if available, to protect their families and the public.

LESSON 2: COORDINATION

Ineffective coordination between central and local governments can delay response, but this can be remedied.

During the SARS outbreak, the Taipei City Government and the Taiwan central government were controlled by opposing political parties. Responses to SARS were initially impeded by political skirmishes, which hindered implementation of policies regarding criteria for diagnosis, tracking of suspected cases and their contacts, duration of quarantine, and allocation of resources and facilities for confirmed cases. To avoid further delays, the central government acted swiftly to create the nonpartisan Anti-SARS Taskforce and appointed leaders who could work cordially with both local and central government agencies. To help to deal with the crisis, the central government also designated a new Minister of Health, an epidemiologist, who became the first nonphysician to hold this position.

LESSON 3: EVACUATION

Treatment in place vs evacuation during hospital infections is a critical decision.

The surge of SARS cases at Ho-Ping Hospital led to confusion and panic among patients and hospital staff. Whether to treat its SARS patients on site or to evacuate the hospital was a complex decision and reflected many concerns, including the following: How many wards had been infected? Was there sufficient equipment (eg, respirators) to monitor or treat infected patients? How many isolation beds were available? How many hospital staff were already infected and quarantined? Were they in different wards? Were there neighboring facilities (eg, hospitals, military camps, dorms) available for quarantine?

If a hospital has sufficient capacity to isolate persons under investigation and to treat confirmed patients, on-site treatment is possible. However, evacuation should be considered when there is widespread infection involving different hospital wards and hospital staff. In such cases, patients should be transferred to different facilities based on clinical severity: Patients with new onset fever or respiratory symptoms but who are relatively healthy should be sent to community or regional hospitals with isolation rooms for monitoring; sicker infected patients should be sent to medical centers; and other hospitalized patients (eg, admitted for heart failure) without infection risk or symptoms should seek care elsewhere.

So far, there has been only one instance of hospital-based COVID-19 infections in Taiwan, and the spread of infection was quickly contained within one ward. All nine confirmed cases (including the index patient, one patient in the same ward but a different room, three nurses, one laundry worker, and three members of patients’ families) and their known contacts were identified, then isolated or quarantined individually. Because the affected hospital is part of a complex with more than 3,000 beds, it was big enough to accommodate all infected patients and no evacuation measures were needed. To further reduce potential nodes in the chain of transmission, interns and many other healthcare workers were temporarily relieved of their duties, elective surgeries were canceled, and hospital visitation was limited to immediate family members. The clear communication of intervention measures ensured rapid cooperation and staved off both social panic and further spread of the disease.

LESSON 4: PATIENT FLOW

Hospitals should establish different flows for different patients.

Having learned from the SARS experience in 2003, hospitals in Taiwan have designated specific pathways to manage patient flow during the COVID-19 outbreak, in addition to checking all patients for travel history and fever: Patients with fever were quickly triaged to a designated fever clinic so they did not mingle with other patients, patients visiting the hospital to obtain chronic disease medications were directed to a “drive-through” lane, patients needing emergent care went through the emergency department, all other regular outpatients were seen in outpatient departments, and visitors of patients were restricted to one visitor per patient at a given time.

LESSON 5: ORGANIZATION

Healthcare providers should be organized into blocks and modular teams to avoid hospital-wide infection.

After SARS, Taiwan learned that one way to reduce the spread of something like COVID-19 among healthcare providers and from providers to patients is to divide providers’ work areas into discrete blocks and organize providers into modular teams. This approach was inspired by the design of watertight compartments in ships: Should the hull be breached, flooding is restricted to the breached compartments. Under this organizational strategy, movements of physicians and nurses would be restricted to their designated locations: They would be routinely exposed only to other staff and patients within their division. Doctors and nurses would be asked to practice in modular teams within their blocked locations, reducing the likelihood that infection in one team would spread to another, which could lead to hospital-wide infections. Movement of senior hospital executives would be similarly restricted. Common areas such as cafeterias where people mingle would be closed. Owing to these stringent initiatives, aside from the hospital-based infection mentioned in Lesson 3, no other hospital-based infections have been reported in Taiwan so far.

CONCLUSION

Lessons from previous hospital-based coronavirus infections can be used to minimize future infections.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Lee Ming-Liang, former Health Minister of Taiwan and director of that central government’s Anti-SARS Taskforce during the 2003 outbreak, for providing valuable recommendations to this work.

During the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003, Taiwan reported 346 confirmed cases and 73 deaths.1 Of all known infections, 94% were transmitted inside hospitals. Nine major hospitals were fully or partially shut down, and many doctors and nurses quit for fear of becoming infected. The Taipei Municipal Ho-Ping Hospital was most severely affected. Its index patient, a 42-year-old undocumented hospital laundry worker who interacted with staff and patients for 6 days before being hospitalized, became a superspreader, infecting at least 20 other patients and 10 staff members.2,3 The entire 450-bed hospital was ordered to shut down, and all 930 staff and 240 patients were quarantined within the hospital. The central government appointed the previous Minister of Health as head of the Anti-SARS Taskforce. Ultimately the hospital was evacuated; the outbreak resulted in 26 deaths.2 Events surrounding the hospital’s evacuation offer important lessons for hospitals struggling to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been caused by spread of a similar coronavirus.

LESSON 1: DIAGNOSIS

Flexibility about case definition is important, as is use of clinical criteria for diagnosis when reliable laboratory tests are not available.

The laundry worker of Ho-Ping Hospital was initially misdiagnosed with infectious enteritis, which delayed proper management and, crucially, isolation from other patients. The low index of suspicion for SARS reflected the initial World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for SARS, which included travel to or residence in an area with recent local transmission of SARS within 10 days of symptom onset.4 The laundry worker did not have a recent travel history.3 Additionally, SARS manifested as a lower respiratory tract infection, so many patients were hospitalized for pneumonia before being diagnosed with SARS. Similarly, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission initially issued diagnostic criteria for COVID-19 that, in addition to fever and symptoms of respiratory infections, emphasized direct exposure to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market.5 As a result, many cases of COVID-19 were not identified.

Diagnosing SARS was challenging. Early symptoms such as fever and malaise were nonspecific. Polymerase chain reaction tests, although available, were unreliable especially in early stages of the disease and had a high false-negative rate. As cases of SARS increased rapidly, Taiwan began using fever alone for early detection.6 Patients and hospital staff received temperature measurements twice daily. Despite the late start to SARS screening, the fever criterion identified many suspected patients, which ensured widespread detection and containment.

For COVID-19, symptoms such as fever, dry cough, and shortness of breath can be used as clinical criteria to triage patients for quarantine in endemic areas when reliable diagnostic tests are not readily available, but all frontline clinical staff should receive daily temperature checks and/or COVID-19 tests, if available, to protect their families and the public.

LESSON 2: COORDINATION

Ineffective coordination between central and local governments can delay response, but this can be remedied.

During the SARS outbreak, the Taipei City Government and the Taiwan central government were controlled by opposing political parties. Responses to SARS were initially impeded by political skirmishes, which hindered implementation of policies regarding criteria for diagnosis, tracking of suspected cases and their contacts, duration of quarantine, and allocation of resources and facilities for confirmed cases. To avoid further delays, the central government acted swiftly to create the nonpartisan Anti-SARS Taskforce and appointed leaders who could work cordially with both local and central government agencies. To help to deal with the crisis, the central government also designated a new Minister of Health, an epidemiologist, who became the first nonphysician to hold this position.

LESSON 3: EVACUATION

Treatment in place vs evacuation during hospital infections is a critical decision.

The surge of SARS cases at Ho-Ping Hospital led to confusion and panic among patients and hospital staff. Whether to treat its SARS patients on site or to evacuate the hospital was a complex decision and reflected many concerns, including the following: How many wards had been infected? Was there sufficient equipment (eg, respirators) to monitor or treat infected patients? How many isolation beds were available? How many hospital staff were already infected and quarantined? Were they in different wards? Were there neighboring facilities (eg, hospitals, military camps, dorms) available for quarantine?

If a hospital has sufficient capacity to isolate persons under investigation and to treat confirmed patients, on-site treatment is possible. However, evacuation should be considered when there is widespread infection involving different hospital wards and hospital staff. In such cases, patients should be transferred to different facilities based on clinical severity: Patients with new onset fever or respiratory symptoms but who are relatively healthy should be sent to community or regional hospitals with isolation rooms for monitoring; sicker infected patients should be sent to medical centers; and other hospitalized patients (eg, admitted for heart failure) without infection risk or symptoms should seek care elsewhere.

So far, there has been only one instance of hospital-based COVID-19 infections in Taiwan, and the spread of infection was quickly contained within one ward. All nine confirmed cases (including the index patient, one patient in the same ward but a different room, three nurses, one laundry worker, and three members of patients’ families) and their known contacts were identified, then isolated or quarantined individually. Because the affected hospital is part of a complex with more than 3,000 beds, it was big enough to accommodate all infected patients and no evacuation measures were needed. To further reduce potential nodes in the chain of transmission, interns and many other healthcare workers were temporarily relieved of their duties, elective surgeries were canceled, and hospital visitation was limited to immediate family members. The clear communication of intervention measures ensured rapid cooperation and staved off both social panic and further spread of the disease.

LESSON 4: PATIENT FLOW

Hospitals should establish different flows for different patients.

Having learned from the SARS experience in 2003, hospitals in Taiwan have designated specific pathways to manage patient flow during the COVID-19 outbreak, in addition to checking all patients for travel history and fever: Patients with fever were quickly triaged to a designated fever clinic so they did not mingle with other patients, patients visiting the hospital to obtain chronic disease medications were directed to a “drive-through” lane, patients needing emergent care went through the emergency department, all other regular outpatients were seen in outpatient departments, and visitors of patients were restricted to one visitor per patient at a given time.

LESSON 5: ORGANIZATION

Healthcare providers should be organized into blocks and modular teams to avoid hospital-wide infection.

After SARS, Taiwan learned that one way to reduce the spread of something like COVID-19 among healthcare providers and from providers to patients is to divide providers’ work areas into discrete blocks and organize providers into modular teams. This approach was inspired by the design of watertight compartments in ships: Should the hull be breached, flooding is restricted to the breached compartments. Under this organizational strategy, movements of physicians and nurses would be restricted to their designated locations: They would be routinely exposed only to other staff and patients within their division. Doctors and nurses would be asked to practice in modular teams within their blocked locations, reducing the likelihood that infection in one team would spread to another, which could lead to hospital-wide infections. Movement of senior hospital executives would be similarly restricted. Common areas such as cafeterias where people mingle would be closed. Owing to these stringent initiatives, aside from the hospital-based infection mentioned in Lesson 3, no other hospital-based infections have been reported in Taiwan so far.

CONCLUSION

Lessons from previous hospital-based coronavirus infections can be used to minimize future infections.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Lee Ming-Liang, former Health Minister of Taiwan and director of that central government’s Anti-SARS Taskforce during the 2003 outbreak, for providing valuable recommendations to this work.

1. Hsieh YH, King CC, Chen CWS, et al. Quarantine for SARS, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(2):278-282. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1102.040190.

2. From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome—Taiwan, 2003. JAMA. 2003;289(22):2930-2932. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.22.2930.

3. McNeil DG. The SARS epidemic: the virus; most Taiwan SARS cases spread by one misdiagnosis. New York Times. May 8, 2003. https://www.nytimes.com/2003/05/08/world/the-sars-epidemic-the-virus-most-taiwan-sars-cases-spread-by-one-misdiagnosis.html. Accessed March 28, 2020.

4. Hui DSC, Chan MCH, Wu AK, Ng PC. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): epidemiology and clinical features. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80(945):373-381. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2004.020263.

5. Yang DL. Wuhan officials tried to cover up covid-19 — and sent it careening outward. Washington Post. March 10, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/03/10/wuhan-officials-tried-cover-up-covid-19-sent-it-careening-outward/. Accessed March 28, 2020.

6. Lin EC, Peng YC, Hung Tsai JC. Lessons learned from the anti-SARS quarantine experience in a hospital-based fever screening station in Taiwan. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(4):302-307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2009.09.008.

1. Hsieh YH, King CC, Chen CWS, et al. Quarantine for SARS, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(2):278-282. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1102.040190.

2. From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome—Taiwan, 2003. JAMA. 2003;289(22):2930-2932. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.22.2930.

3. McNeil DG. The SARS epidemic: the virus; most Taiwan SARS cases spread by one misdiagnosis. New York Times. May 8, 2003. https://www.nytimes.com/2003/05/08/world/the-sars-epidemic-the-virus-most-taiwan-sars-cases-spread-by-one-misdiagnosis.html. Accessed March 28, 2020.

4. Hui DSC, Chan MCH, Wu AK, Ng PC. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): epidemiology and clinical features. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80(945):373-381. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2004.020263.

5. Yang DL. Wuhan officials tried to cover up covid-19 — and sent it careening outward. Washington Post. March 10, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/03/10/wuhan-officials-tried-cover-up-covid-19-sent-it-careening-outward/. Accessed March 28, 2020.

6. Lin EC, Peng YC, Hung Tsai JC. Lessons learned from the anti-SARS quarantine experience in a hospital-based fever screening station in Taiwan. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(4):302-307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2009.09.008.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

A Transdisciplinary COVID-19 Early Respiratory Intervention Protocol: An Implementation Story

My colleague asked, “Do you remember that patient?” I froze because, like most emergency physicians, this phrase haunts me. It was the early days of the COVID-19 epidemic, and the story that followed was upsetting. A patient who looked comfortable when I admitted him was intubated hours later by the rapid response team who was called to the floor. All I could think was, “But he looked so comfortable when I admitted him; he was just on a couple of liters of oxygen. Why was he intubated?”

In the days after COVID-19 arrived in our region, there were many such stories of patients sent to the floor from the Emergency Department who were intubated shortly after admission. Many of those patients subsequently endured prolonged and complicated courses on the ventilator. While we would typically use noninvasive modalities such as high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) or noninvasive ventilation (NIV) for acute respiratory failure, our quickness to intubate was driven by two factors: (1) early reports that noninvasive modalities posed a high risk of failure and subsequent intubation and (2) fear that HFNC and NIV would aerosolize SARS-CoV-2 and unnecessarily expose the heath care team.1 We would soon find out that our thinking was flawed on both accounts.

RETHINKING INITIAL ASSUMPTIONS

When we dug into the evidence for early intubation, we realized that these recommendations were based on a 12-patient series in which 5 patients were trialed on NIV but ultimately intubated and placed on invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV). As the pandemic progressed, more case series and small studies were published, revealing a different picture.2 Sun and colleagues reported a multifaceted intervention of 610 inpatients, of whom 10% were critically ill, that identified at-risk patients and used NIV or HFNC and awake proning. Reportedly, fewer than 1% required IMV.3 Similarly, a small study found intubation was avoided in 85% of patients with severe acute respiratory failure caused by COVID-19 with use of HFNC and NIV.4 Early findings from New York University in New York, New York, where only 8.5% of patients undergoing IMV were extubated by the time of outcome reporting, suggest early IMV could lead to poor outcomes.5

Still, we had concerns about use of HFNC and NIV because of worries about the health and safety of other patients and particularly that of healthcare workers (HCWs) because they have been disproportionately affected by the disease.6 Fortunately, we identified emerging data that revealed that HFNC is no more aerosolizing than low-flow nasal cannula or a nonrebreather mask and droplet spread is reduced with a surgical mask.7,8 In light of these new studies and our own developing experience with the disease, we felt that there was insufficient evidence to continue following the “early intubation” protocol in patients with COVID-19. It was time for a new paradigm.

GATHERING EVIDENCE AND STAKEHOLDERS

In order to effectively and quickly change our respiratory pathway for these patients, we initially sought out protocols from other institutions through social media. These protocols, supported by early data from those sites, informed our process. We considered data from various sources, including emergency medicine, hospital medicine, and critical care. We then assembled stakeholders within our organization from emergency medicine, hospital medicine, critical care, and respiratory therapy because our protocol would need endorsement from all key players within our organization who cared for these patients across the potential spectrum of care. We made sure that all stakeholders understood that the quality of the evidence for treatment of this novel disease was much lower than our typical threshold to change practice, but that we aimed to reflect the best evidence to date. We also were careful to identify pathways that would be amenable to near-immediate implementation.

UNVEILING A NOVEL PROTOCOL

Our group reached consensus within 48 hours and quickly disseminated our first draft of the protocol (Appendix Figure). Dubbed the “Early Intervention Respiratory Protocol,” it differed from usual management in several ways. First, we had consistently observed (and confirmed from the literature) a phenotype of patients with “silent hypoxemia”9 (that is, a subset of patients who presented with profound hypoxemia but minimally increased work of breathing). The protocol encouraged tolerance of lower oxygen saturations than is usually seen on inpatient units. This required ensuring all stakeholders were comfortable with a target oxygen saturation of 88%. Second, the protocol leveraged early “awake” proning by patients. Historically, proning is used in mechanically ventilated patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) to improve ventilation-perfusion matching, promote more uniform ventilation, and increase end-expiratory lung volume.10 Prior literature was limited to the use of awake proning in small case series of ARDS, but given our limitations in terms of ICU capacity, we agreed to trial awake proning in a sizable proportion of our COVID-19 patients outside the ICU.11,12 Finally, we clarified safe practices regarding the risk of aerosolization with noninvasive modalities. Local infection control determined that HFNC wa not aerosol generating, and use of surgical masks was added for further protection from respiratory droplets. In addition, airborne personal protective equipment was to be worn on the inpatient ward, and we used NIV sparingly and preferentially placed these patients in negative pressure rooms, if available.13

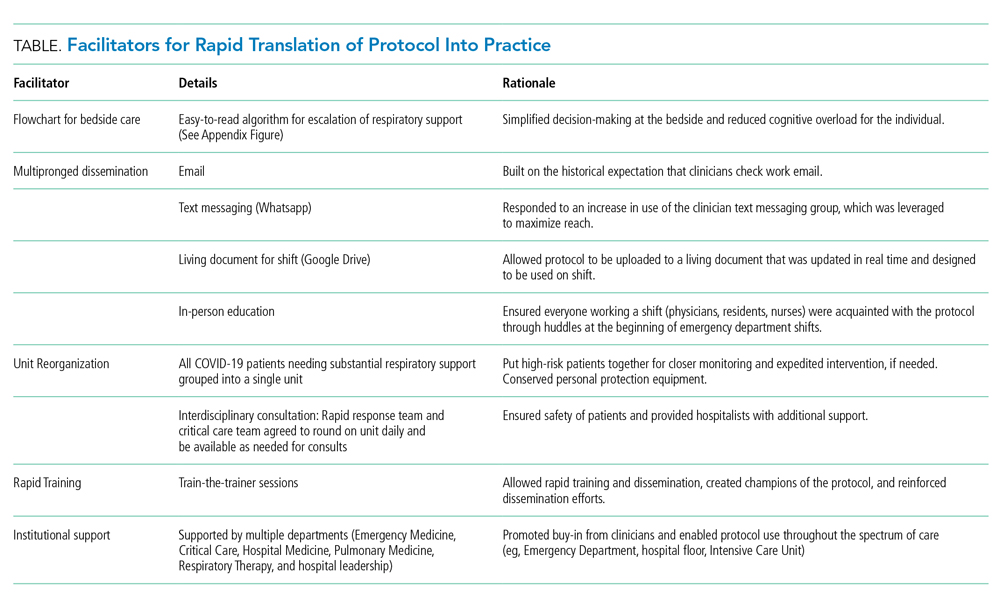

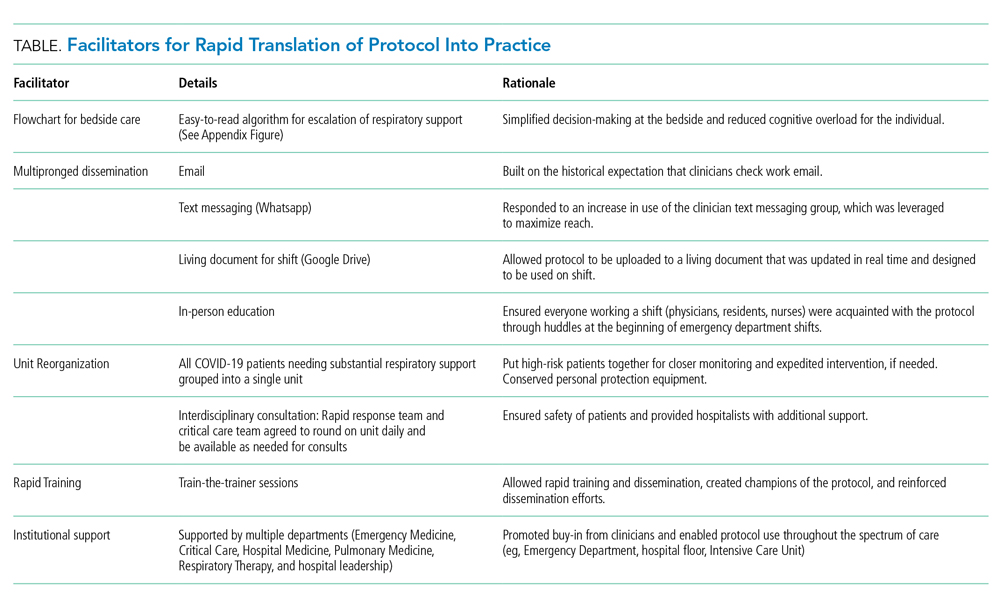

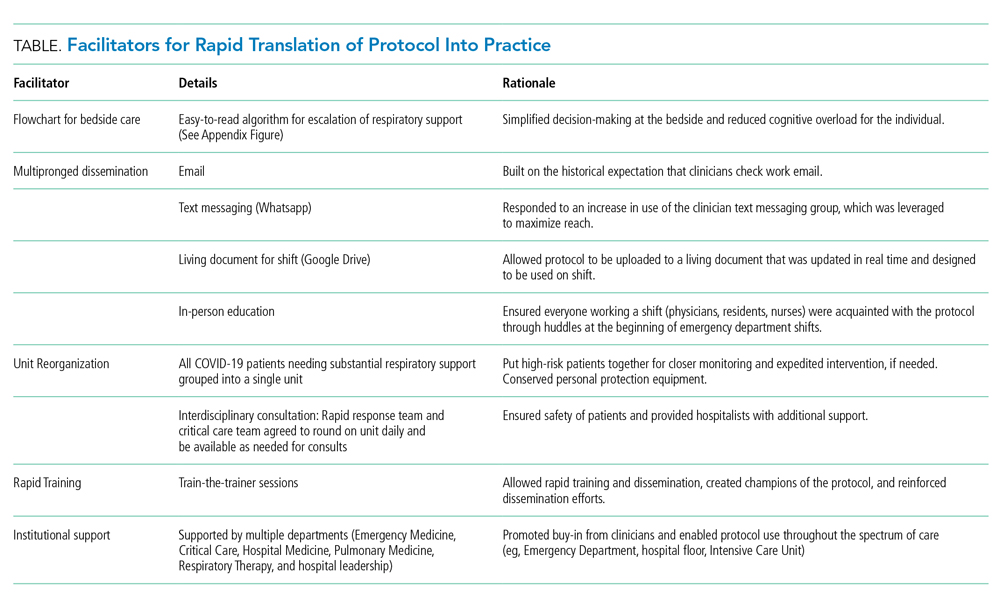

Implementation of the protocol involved aggressive dissemination and education (Table). A single-page protocol was designed for ease of use at the bedside that included anticipatory guidance regarding aerosolization and addressed potential resistance to awake proning because of concerns regarding safety and hassle. Departmental leaders disseminated the protocol throughout the institution with tailored education on the rationale and acknowledgment of a reversal in approach. In addition to email, we used text messaging (WhatsApp) and a comprehensive living document (Google Drive) to reach clinicians.

For ease of monitoring and safety, we designated a COVID-19 intermediate care unit. We partnered with the unit medical director, nurse educator, and a focused group of hospitalists, conducting individual train-the-trainer sessions. This training was carried forward, and all nurses, respiratory therapists, and clinicians were trained on the early aggressive respiratory protocol within 12 hours of protocol approval. In addition, the rapid response and critical care teams agreed to round on the COVID-19 intermediate care unit daily.

As a result of these efforts, adoption of the protocol was essentially immediate across the institution. We had shifted the mindset of a diverse group of clinicians regarding how to support the respiratory status of these patients, but also detected reductions in the proportion of patients undergoing IMV and ICU admission (we are planning to report these results separately).

TRANSLATING KNOWLEDGE INTO PRACTICE

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of having cognitive flexibility when the evidence base is rapidly changing and there is a need for rapid dissemination of knowledge. Even in clinical scenarios with an abundance of high-quality evidence, a gap in knowledge translation on the order of a decade often exists. In contrast, a pandemic involving a novel virus highlights an urgent need for adaptive knowledge translation in the present moment rather than a decade later. In the absence of robust evidence regarding SARS-CoV-2, early management of COVID-19 was based on expert recommendations and experience with other disease processes. Even so, we should anticipate that management paradigms may shift, and we should constantly seek out emerging evidence to adjust our mindset (and protocols like this) accordingly. Our original protocol was based on nearly nonexistent evidence, but we anticipated that, in a pandemic, data would accumulate quickly, so we prioritized rapid translation of new information into practice. In fact, further evidence has emerged regarding the improvement in oxygenation in COVID-19 patients with self-proning.14

The final step is evaluating the success of both clinical and implementation outcomes. We are attempting to identify changes in intubation, length of stay, days on ventilator, and days in ICU. In addition, we will measure feasibility and adaptability. We are also attempting, in real time, to identify barriers to its use, including conducting qualitative interviews to understand whether there were unintended consequences to use of the protocol. This endeavor highlights how the COVID-19 pandemic, for all its tragedy, may represent an important era for implementation science: a time when emerging literature from a variety of sources can be implemented in days rather than years.

1. World Health Organization. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID-19 disease is suspected. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected. Accessed March 25, 2020.

2. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30566-3.

3. Sun Q, Qiu H, Huang M, Yang Y. Lower mortality of COVID-19 by early recognition and intervention: experience from Jiangsu Province. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-020-00650-2.

4. Wang K, Zhao W, Li J, Shu W, Duan J. The experience of high-flow nasal cannula in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in two hospitals of Chongqing, China. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-020-00653-z.

5. Petrilli C, Jones SA, Yang J, Rajagopalan H, et al. Factors associated with hospitalization and critical illness among 4,103 patients with Covid-19 disease in New York City [preprint]. medRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.08.20057794. Accessed April 12, 2020.

6. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061-1069. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1585.

7. Leonard S, Volakis L, DeBellis R, Kahlon A, Mayar S. Transmission Assessment Report: High Velocity Nasal Insufflation (HVNI) Therapy Application in Management of COVID-19. March 25, 2020. Vapotherm Blog. 2020. https://vapotherm.com/blog/transmission-assessment-report/. Accessed March 25, 2020.

8. Iwashyna TJ, Boehman A, Capecelatro J, Cohn A, JM. C. Variation in aerosol production across oxygen delivery devices in 2 spontaneously breathing human subjects [preprint]. medRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.15.20066688. Accessed April 20, 2020.

9. Meng L, Qiu H, Wan L, et al. Intubation and ventilation amid the COVID-19 outbreak [online ahead of print]. Anesthesiology. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000003296.

10. Munshi L, Del Sorbo L, Adhikari NKJ, et al. Prone position for acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(suppl 4):S280-S288. https://doi.org/10.1513/annalsats.201704-343ot.

11. Scaravilli V, Grasselli G, Castagna L, et al. Prone positioning improves oxygenation in spontaneously breathing nonintubated patients with hypoxemic acute respiratory failure: a retrospective study. J Crit Care. 2015;30(6):1390-1394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.07.008

12. Ding L, Wang L, Ma W, He H. Efficacy and safety of early prone positioning combined with HFNC or NIV in moderate to severe ARDS: a multi-center prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-2738-5.

13. Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Intensive Care Med. 2020;1‐34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5.

14. Caputo ND, Strayer RJ, Levitan R. Early self-proning in awake, non-intubated patients in the emergency department: a single ED’s experience during the COVID-19 pandemic [online ahead of print]. Acad Emerg Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13994.

My colleague asked, “Do you remember that patient?” I froze because, like most emergency physicians, this phrase haunts me. It was the early days of the COVID-19 epidemic, and the story that followed was upsetting. A patient who looked comfortable when I admitted him was intubated hours later by the rapid response team who was called to the floor. All I could think was, “But he looked so comfortable when I admitted him; he was just on a couple of liters of oxygen. Why was he intubated?”

In the days after COVID-19 arrived in our region, there were many such stories of patients sent to the floor from the Emergency Department who were intubated shortly after admission. Many of those patients subsequently endured prolonged and complicated courses on the ventilator. While we would typically use noninvasive modalities such as high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) or noninvasive ventilation (NIV) for acute respiratory failure, our quickness to intubate was driven by two factors: (1) early reports that noninvasive modalities posed a high risk of failure and subsequent intubation and (2) fear that HFNC and NIV would aerosolize SARS-CoV-2 and unnecessarily expose the heath care team.1 We would soon find out that our thinking was flawed on both accounts.

RETHINKING INITIAL ASSUMPTIONS

When we dug into the evidence for early intubation, we realized that these recommendations were based on a 12-patient series in which 5 patients were trialed on NIV but ultimately intubated and placed on invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV). As the pandemic progressed, more case series and small studies were published, revealing a different picture.2 Sun and colleagues reported a multifaceted intervention of 610 inpatients, of whom 10% were critically ill, that identified at-risk patients and used NIV or HFNC and awake proning. Reportedly, fewer than 1% required IMV.3 Similarly, a small study found intubation was avoided in 85% of patients with severe acute respiratory failure caused by COVID-19 with use of HFNC and NIV.4 Early findings from New York University in New York, New York, where only 8.5% of patients undergoing IMV were extubated by the time of outcome reporting, suggest early IMV could lead to poor outcomes.5

Still, we had concerns about use of HFNC and NIV because of worries about the health and safety of other patients and particularly that of healthcare workers (HCWs) because they have been disproportionately affected by the disease.6 Fortunately, we identified emerging data that revealed that HFNC is no more aerosolizing than low-flow nasal cannula or a nonrebreather mask and droplet spread is reduced with a surgical mask.7,8 In light of these new studies and our own developing experience with the disease, we felt that there was insufficient evidence to continue following the “early intubation” protocol in patients with COVID-19. It was time for a new paradigm.

GATHERING EVIDENCE AND STAKEHOLDERS

In order to effectively and quickly change our respiratory pathway for these patients, we initially sought out protocols from other institutions through social media. These protocols, supported by early data from those sites, informed our process. We considered data from various sources, including emergency medicine, hospital medicine, and critical care. We then assembled stakeholders within our organization from emergency medicine, hospital medicine, critical care, and respiratory therapy because our protocol would need endorsement from all key players within our organization who cared for these patients across the potential spectrum of care. We made sure that all stakeholders understood that the quality of the evidence for treatment of this novel disease was much lower than our typical threshold to change practice, but that we aimed to reflect the best evidence to date. We also were careful to identify pathways that would be amenable to near-immediate implementation.

UNVEILING A NOVEL PROTOCOL

Our group reached consensus within 48 hours and quickly disseminated our first draft of the protocol (Appendix Figure). Dubbed the “Early Intervention Respiratory Protocol,” it differed from usual management in several ways. First, we had consistently observed (and confirmed from the literature) a phenotype of patients with “silent hypoxemia”9 (that is, a subset of patients who presented with profound hypoxemia but minimally increased work of breathing). The protocol encouraged tolerance of lower oxygen saturations than is usually seen on inpatient units. This required ensuring all stakeholders were comfortable with a target oxygen saturation of 88%. Second, the protocol leveraged early “awake” proning by patients. Historically, proning is used in mechanically ventilated patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) to improve ventilation-perfusion matching, promote more uniform ventilation, and increase end-expiratory lung volume.10 Prior literature was limited to the use of awake proning in small case series of ARDS, but given our limitations in terms of ICU capacity, we agreed to trial awake proning in a sizable proportion of our COVID-19 patients outside the ICU.11,12 Finally, we clarified safe practices regarding the risk of aerosolization with noninvasive modalities. Local infection control determined that HFNC wa not aerosol generating, and use of surgical masks was added for further protection from respiratory droplets. In addition, airborne personal protective equipment was to be worn on the inpatient ward, and we used NIV sparingly and preferentially placed these patients in negative pressure rooms, if available.13

Implementation of the protocol involved aggressive dissemination and education (Table). A single-page protocol was designed for ease of use at the bedside that included anticipatory guidance regarding aerosolization and addressed potential resistance to awake proning because of concerns regarding safety and hassle. Departmental leaders disseminated the protocol throughout the institution with tailored education on the rationale and acknowledgment of a reversal in approach. In addition to email, we used text messaging (WhatsApp) and a comprehensive living document (Google Drive) to reach clinicians.

For ease of monitoring and safety, we designated a COVID-19 intermediate care unit. We partnered with the unit medical director, nurse educator, and a focused group of hospitalists, conducting individual train-the-trainer sessions. This training was carried forward, and all nurses, respiratory therapists, and clinicians were trained on the early aggressive respiratory protocol within 12 hours of protocol approval. In addition, the rapid response and critical care teams agreed to round on the COVID-19 intermediate care unit daily.

As a result of these efforts, adoption of the protocol was essentially immediate across the institution. We had shifted the mindset of a diverse group of clinicians regarding how to support the respiratory status of these patients, but also detected reductions in the proportion of patients undergoing IMV and ICU admission (we are planning to report these results separately).

TRANSLATING KNOWLEDGE INTO PRACTICE

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of having cognitive flexibility when the evidence base is rapidly changing and there is a need for rapid dissemination of knowledge. Even in clinical scenarios with an abundance of high-quality evidence, a gap in knowledge translation on the order of a decade often exists. In contrast, a pandemic involving a novel virus highlights an urgent need for adaptive knowledge translation in the present moment rather than a decade later. In the absence of robust evidence regarding SARS-CoV-2, early management of COVID-19 was based on expert recommendations and experience with other disease processes. Even so, we should anticipate that management paradigms may shift, and we should constantly seek out emerging evidence to adjust our mindset (and protocols like this) accordingly. Our original protocol was based on nearly nonexistent evidence, but we anticipated that, in a pandemic, data would accumulate quickly, so we prioritized rapid translation of new information into practice. In fact, further evidence has emerged regarding the improvement in oxygenation in COVID-19 patients with self-proning.14

The final step is evaluating the success of both clinical and implementation outcomes. We are attempting to identify changes in intubation, length of stay, days on ventilator, and days in ICU. In addition, we will measure feasibility and adaptability. We are also attempting, in real time, to identify barriers to its use, including conducting qualitative interviews to understand whether there were unintended consequences to use of the protocol. This endeavor highlights how the COVID-19 pandemic, for all its tragedy, may represent an important era for implementation science: a time when emerging literature from a variety of sources can be implemented in days rather than years.

My colleague asked, “Do you remember that patient?” I froze because, like most emergency physicians, this phrase haunts me. It was the early days of the COVID-19 epidemic, and the story that followed was upsetting. A patient who looked comfortable when I admitted him was intubated hours later by the rapid response team who was called to the floor. All I could think was, “But he looked so comfortable when I admitted him; he was just on a couple of liters of oxygen. Why was he intubated?”

In the days after COVID-19 arrived in our region, there were many such stories of patients sent to the floor from the Emergency Department who were intubated shortly after admission. Many of those patients subsequently endured prolonged and complicated courses on the ventilator. While we would typically use noninvasive modalities such as high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) or noninvasive ventilation (NIV) for acute respiratory failure, our quickness to intubate was driven by two factors: (1) early reports that noninvasive modalities posed a high risk of failure and subsequent intubation and (2) fear that HFNC and NIV would aerosolize SARS-CoV-2 and unnecessarily expose the heath care team.1 We would soon find out that our thinking was flawed on both accounts.

RETHINKING INITIAL ASSUMPTIONS

When we dug into the evidence for early intubation, we realized that these recommendations were based on a 12-patient series in which 5 patients were trialed on NIV but ultimately intubated and placed on invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV). As the pandemic progressed, more case series and small studies were published, revealing a different picture.2 Sun and colleagues reported a multifaceted intervention of 610 inpatients, of whom 10% were critically ill, that identified at-risk patients and used NIV or HFNC and awake proning. Reportedly, fewer than 1% required IMV.3 Similarly, a small study found intubation was avoided in 85% of patients with severe acute respiratory failure caused by COVID-19 with use of HFNC and NIV.4 Early findings from New York University in New York, New York, where only 8.5% of patients undergoing IMV were extubated by the time of outcome reporting, suggest early IMV could lead to poor outcomes.5

Still, we had concerns about use of HFNC and NIV because of worries about the health and safety of other patients and particularly that of healthcare workers (HCWs) because they have been disproportionately affected by the disease.6 Fortunately, we identified emerging data that revealed that HFNC is no more aerosolizing than low-flow nasal cannula or a nonrebreather mask and droplet spread is reduced with a surgical mask.7,8 In light of these new studies and our own developing experience with the disease, we felt that there was insufficient evidence to continue following the “early intubation” protocol in patients with COVID-19. It was time for a new paradigm.

GATHERING EVIDENCE AND STAKEHOLDERS

In order to effectively and quickly change our respiratory pathway for these patients, we initially sought out protocols from other institutions through social media. These protocols, supported by early data from those sites, informed our process. We considered data from various sources, including emergency medicine, hospital medicine, and critical care. We then assembled stakeholders within our organization from emergency medicine, hospital medicine, critical care, and respiratory therapy because our protocol would need endorsement from all key players within our organization who cared for these patients across the potential spectrum of care. We made sure that all stakeholders understood that the quality of the evidence for treatment of this novel disease was much lower than our typical threshold to change practice, but that we aimed to reflect the best evidence to date. We also were careful to identify pathways that would be amenable to near-immediate implementation.

UNVEILING A NOVEL PROTOCOL

Our group reached consensus within 48 hours and quickly disseminated our first draft of the protocol (Appendix Figure). Dubbed the “Early Intervention Respiratory Protocol,” it differed from usual management in several ways. First, we had consistently observed (and confirmed from the literature) a phenotype of patients with “silent hypoxemia”9 (that is, a subset of patients who presented with profound hypoxemia but minimally increased work of breathing). The protocol encouraged tolerance of lower oxygen saturations than is usually seen on inpatient units. This required ensuring all stakeholders were comfortable with a target oxygen saturation of 88%. Second, the protocol leveraged early “awake” proning by patients. Historically, proning is used in mechanically ventilated patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) to improve ventilation-perfusion matching, promote more uniform ventilation, and increase end-expiratory lung volume.10 Prior literature was limited to the use of awake proning in small case series of ARDS, but given our limitations in terms of ICU capacity, we agreed to trial awake proning in a sizable proportion of our COVID-19 patients outside the ICU.11,12 Finally, we clarified safe practices regarding the risk of aerosolization with noninvasive modalities. Local infection control determined that HFNC wa not aerosol generating, and use of surgical masks was added for further protection from respiratory droplets. In addition, airborne personal protective equipment was to be worn on the inpatient ward, and we used NIV sparingly and preferentially placed these patients in negative pressure rooms, if available.13

Implementation of the protocol involved aggressive dissemination and education (Table). A single-page protocol was designed for ease of use at the bedside that included anticipatory guidance regarding aerosolization and addressed potential resistance to awake proning because of concerns regarding safety and hassle. Departmental leaders disseminated the protocol throughout the institution with tailored education on the rationale and acknowledgment of a reversal in approach. In addition to email, we used text messaging (WhatsApp) and a comprehensive living document (Google Drive) to reach clinicians.

For ease of monitoring and safety, we designated a COVID-19 intermediate care unit. We partnered with the unit medical director, nurse educator, and a focused group of hospitalists, conducting individual train-the-trainer sessions. This training was carried forward, and all nurses, respiratory therapists, and clinicians were trained on the early aggressive respiratory protocol within 12 hours of protocol approval. In addition, the rapid response and critical care teams agreed to round on the COVID-19 intermediate care unit daily.

As a result of these efforts, adoption of the protocol was essentially immediate across the institution. We had shifted the mindset of a diverse group of clinicians regarding how to support the respiratory status of these patients, but also detected reductions in the proportion of patients undergoing IMV and ICU admission (we are planning to report these results separately).

TRANSLATING KNOWLEDGE INTO PRACTICE

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of having cognitive flexibility when the evidence base is rapidly changing and there is a need for rapid dissemination of knowledge. Even in clinical scenarios with an abundance of high-quality evidence, a gap in knowledge translation on the order of a decade often exists. In contrast, a pandemic involving a novel virus highlights an urgent need for adaptive knowledge translation in the present moment rather than a decade later. In the absence of robust evidence regarding SARS-CoV-2, early management of COVID-19 was based on expert recommendations and experience with other disease processes. Even so, we should anticipate that management paradigms may shift, and we should constantly seek out emerging evidence to adjust our mindset (and protocols like this) accordingly. Our original protocol was based on nearly nonexistent evidence, but we anticipated that, in a pandemic, data would accumulate quickly, so we prioritized rapid translation of new information into practice. In fact, further evidence has emerged regarding the improvement in oxygenation in COVID-19 patients with self-proning.14

The final step is evaluating the success of both clinical and implementation outcomes. We are attempting to identify changes in intubation, length of stay, days on ventilator, and days in ICU. In addition, we will measure feasibility and adaptability. We are also attempting, in real time, to identify barriers to its use, including conducting qualitative interviews to understand whether there were unintended consequences to use of the protocol. This endeavor highlights how the COVID-19 pandemic, for all its tragedy, may represent an important era for implementation science: a time when emerging literature from a variety of sources can be implemented in days rather than years.

1. World Health Organization. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID-19 disease is suspected. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected. Accessed March 25, 2020.

2. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30566-3.

3. Sun Q, Qiu H, Huang M, Yang Y. Lower mortality of COVID-19 by early recognition and intervention: experience from Jiangsu Province. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-020-00650-2.

4. Wang K, Zhao W, Li J, Shu W, Duan J. The experience of high-flow nasal cannula in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in two hospitals of Chongqing, China. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-020-00653-z.

5. Petrilli C, Jones SA, Yang J, Rajagopalan H, et al. Factors associated with hospitalization and critical illness among 4,103 patients with Covid-19 disease in New York City [preprint]. medRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.08.20057794. Accessed April 12, 2020.

6. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061-1069. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1585.

7. Leonard S, Volakis L, DeBellis R, Kahlon A, Mayar S. Transmission Assessment Report: High Velocity Nasal Insufflation (HVNI) Therapy Application in Management of COVID-19. March 25, 2020. Vapotherm Blog. 2020. https://vapotherm.com/blog/transmission-assessment-report/. Accessed March 25, 2020.

8. Iwashyna TJ, Boehman A, Capecelatro J, Cohn A, JM. C. Variation in aerosol production across oxygen delivery devices in 2 spontaneously breathing human subjects [preprint]. medRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.15.20066688. Accessed April 20, 2020.

9. Meng L, Qiu H, Wan L, et al. Intubation and ventilation amid the COVID-19 outbreak [online ahead of print]. Anesthesiology. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000003296.

10. Munshi L, Del Sorbo L, Adhikari NKJ, et al. Prone position for acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(suppl 4):S280-S288. https://doi.org/10.1513/annalsats.201704-343ot.

11. Scaravilli V, Grasselli G, Castagna L, et al. Prone positioning improves oxygenation in spontaneously breathing nonintubated patients with hypoxemic acute respiratory failure: a retrospective study. J Crit Care. 2015;30(6):1390-1394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.07.008

12. Ding L, Wang L, Ma W, He H. Efficacy and safety of early prone positioning combined with HFNC or NIV in moderate to severe ARDS: a multi-center prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-2738-5.

13. Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Intensive Care Med. 2020;1‐34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5.

14. Caputo ND, Strayer RJ, Levitan R. Early self-proning in awake, non-intubated patients in the emergency department: a single ED’s experience during the COVID-19 pandemic [online ahead of print]. Acad Emerg Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13994.

1. World Health Organization. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID-19 disease is suspected. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected. Accessed March 25, 2020.

2. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30566-3.

3. Sun Q, Qiu H, Huang M, Yang Y. Lower mortality of COVID-19 by early recognition and intervention: experience from Jiangsu Province. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-020-00650-2.

4. Wang K, Zhao W, Li J, Shu W, Duan J. The experience of high-flow nasal cannula in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in two hospitals of Chongqing, China. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-020-00653-z.

5. Petrilli C, Jones SA, Yang J, Rajagopalan H, et al. Factors associated with hospitalization and critical illness among 4,103 patients with Covid-19 disease in New York City [preprint]. medRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.08.20057794. Accessed April 12, 2020.

6. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061-1069. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1585.

7. Leonard S, Volakis L, DeBellis R, Kahlon A, Mayar S. Transmission Assessment Report: High Velocity Nasal Insufflation (HVNI) Therapy Application in Management of COVID-19. March 25, 2020. Vapotherm Blog. 2020. https://vapotherm.com/blog/transmission-assessment-report/. Accessed March 25, 2020.

8. Iwashyna TJ, Boehman A, Capecelatro J, Cohn A, JM. C. Variation in aerosol production across oxygen delivery devices in 2 spontaneously breathing human subjects [preprint]. medRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.15.20066688. Accessed April 20, 2020.

9. Meng L, Qiu H, Wan L, et al. Intubation and ventilation amid the COVID-19 outbreak [online ahead of print]. Anesthesiology. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000003296.

10. Munshi L, Del Sorbo L, Adhikari NKJ, et al. Prone position for acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(suppl 4):S280-S288. https://doi.org/10.1513/annalsats.201704-343ot.

11. Scaravilli V, Grasselli G, Castagna L, et al. Prone positioning improves oxygenation in spontaneously breathing nonintubated patients with hypoxemic acute respiratory failure: a retrospective study. J Crit Care. 2015;30(6):1390-1394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.07.008

12. Ding L, Wang L, Ma W, He H. Efficacy and safety of early prone positioning combined with HFNC or NIV in moderate to severe ARDS: a multi-center prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-2738-5.

13. Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Intensive Care Med. 2020;1‐34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5.

14. Caputo ND, Strayer RJ, Levitan R. Early self-proning in awake, non-intubated patients in the emergency department: a single ED’s experience during the COVID-19 pandemic [online ahead of print]. Acad Emerg Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13994.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

The Role of Hospitalists in Biocontainment Units: A Perspective

In 2015, and in response to the Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa, the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) designated 10 health departments and associated partner hospitals to become regional treatment centers for patients with highly infectious diseases, such as the Ebola virus and other highly infectious special pathogens (HISPs), and reinforce the nation’s infectious disease response capability. These efforts catalyzed the creation and/or expansion of a network of biocontainment units (BCUs) to safely care for patients diagnosed with highly infectious diseases. These units are designed as special care units with environmental/engineering controls, laboratory capabilities, simple imaging testing, and dedicated staff to allow for the uninterrupted care of patients.1,2 The HHS approach closely resembled the tiered structure of trauma center levels familiar to the healthcare system. The regional framework identified four types of facilities (frontline healthcare facilities, assessment hospitals, treatment centers, and regional Ebola and other special pathogens treatment centers [RESPTCs]) with increasing levels of capabilities and responsibilities.

There are over 4,845 frontline healthcare facilities across the United States, which are able to identify and isolate a patient suspected of a HISP infection and inform local and state partners. The facility provides stabilizing treatment while coordinating the transport of the patient to a specialized center. An assessment hospital can identify and isolate a patient with a HISP, inform partnering agencies, and provide care at the facility for up to 96 hours. There are over 217 hospitals with this designation in the United States. Treatment centers are designated as state or jurisdiction treatment centers and have the capacity to care for HISP-infected patients for the entirety of their care plan, as well as serve as a partner in caring for a potential surge in high-risk patients if their partner RESPTC is unable to care for a patient because of capacity limits. Patients may receive care at a treatment center if and when it is determined to be more appropriate (eg, clinical purview, logistics, resources) than sending them to a RESPTC. There are currently 63 designated treatment centers in the United States.

As outlined by HHS, the RESPTCs3 must be ready to receive a HISP-infected patient within their HHS region, domestically, or internationally within 8 hours. RESPTCs provide care for the entirety of the patient care plan. The 10 regional Departments of Public Health representatives are: Massachusetts (Region 1); New York (Region 2); Maryland (Region 3); Georgia (Region 4); Minnesota (Region 5); Texas (Region 6); Nebraska (Region 7); Colorado in partnership with Denver Health Hospital Authority (DHHA; Region 8); California (Region 9); and Washington State (Region 10).

BCU PHYSICIAN STAFFING MODELS

Most RESPCTs BCUs are staffed by a self-selected group of core providers with expertise in infectious diseases (ID) and critical care (CC). Teams are interdisciplinary and committed to a culture of safety.4-7 ID physicians are experts in HISP disease processes and epidemiology, which enables expert guidance on patient care and infection control. CC physicians are trained to provide care to patients requiring life-saving interventions.

DHHA STAFFING MODEL

As specialized units are shifting to include high-risk infectious diseases beyond Ebola, hospitals are developing innovative ways to manage a potential surge of patients with respiratory pathogens, expanding care far beyond the biocontainment unit. With the potential for an influx of HISPs in the healthcare setting, identifying stakeholders uniquely equipped to provide care in all areas of the hospital is ideal. At DHHA, the BCU physician staffing model transitioned from ID and CC physicians to a selected group of ten hospitalists as the primary managing service in 2018.

When DHHA received the RESPTC nomination, it developed a fully voluntary multidisciplinary high-risk infection team (HITeam; Table) with specialized training in personal protective equipment (PPE) donning and doffing, as well as BCU protocols. Our HITeam members participate in every-6-weeks mandatory team drills that involve practicing team dynamics and dexterity while wearing PPE. Team members participate in regular hospital and/or BCU-focused exercises to simulate and practice real-world experiences. They also participate in HISP Journal Club, where members from different disciplines discuss pertinent articles in the field, as well as every-other-month team-building meetings. Our unit’s main challenges included maintaining competencies and staff retention. We developed a unique staffing model aimed at mitigating some of these challenges through a multidisciplinary team approach utilizing different levels of physician involvement. The first group comprises physicians providing primary, direct care to patients, which which consists our specially trained group of 10 hospitalists—including 2 pediatricians, as well as 3 CC and 4 ID consultants. The second group involves consultants from specialties such as nephrology, anesthesia, general surgery, radiology and gynecology; just–in-time training is available for them.

WHY HOSPITALISTS?

Hospitalists are uniquely positioned to care for this distinctive set of patients because they are comfortable with the care of acutely ill patients, many maintain bedside procedural skills, and many have acquired point-of-care-ultrasonography (POCUS) skills. Furthermore, hospitalists usually outnumber available specialists who may be needed to maintain consultative and critical care services for non-BCU patients. We were able to develop a feasible physician staffing model, as described below, and validate hospital medicine’s commitment in addressing institutional needs.

In order to provide ideal unit coverage, 2 hospitalists are scheduled daily and available to respond in case of unit activation. BCU hospitalists are scheduled to cover the BCU when already scheduled to work a clinical shift. In the very infrequent event of BCU activation, BCU hospitalists would move their clinical work to the BCU and a back-up hospitalist would be called in to cover the “other” clinical shift; by overlapping coverage, we ensure BCU hospitalists’ work-life balance and job satisfaction remain intact. Because of expected postexposure monitoring, individual physician’s planned international travel is considered while generating the call schedule. When the unit is activated, the hospital provides payment for extra hours worked by both the BCU hospitalist and the back-up hospitalist, with anticipated revenue recapture through critical care billing by the BCU hospitalist. There are 10 HITeam hospitalists, who are trained and credentialed in bedside procedures and with different levels of POCUS expertise (from literacy to expert level). Team members are expected to attend training in bedside procedures while in PPE 2 times a year. The hospital also provides financial support for hospitalists seeking to further their BCU-related skills and training. It is anticipated that hospitalists will require consultative services from CC and ID in some selected cases to provide a well-rounded care approach to the biocontained patient.

WHAT IT TAKES TO BE A TEAM

Eligibility criteria for HITeam hospitalists include complete initial and quarterly maintenance PPE training; possession of active bedside procedure credentials for at least central line, paracentesis, thoracentesis, and arterial line; demonstration of basic POCUS skills, such as having enough POCUS verbiage literacy to be able to follow a radiologist’s instructions on probe management (ie, a radiologist outside anteroom); and possibility of completing additional training and credentialing on conscious sedation and/or advanced airway management.

Similarly, hospitalists who join the team commit to attendance of at least one National Ebola Training and Education Center (NETEC) provider’s course, representing the Region 8 RESPTC for educational presentations and research at regional and national levels, participation in quarterly HISP multidisciplinary meetings, attendance at quarterly donning and doffing sessions, as well as HITeam training sessions and drills, and active participation in the every-other-month HISP Journal Club/Grand Rounds to maintain competence and knowledge on management of many different pathogens, including Ebola and other filoviruses, MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, Arenaviruses causing hemorrhagic fevers, Hantavirus, and novel influenzas or coronaviruses.

All of these commitments provide HITeam hospitalists with multiple opportunities for professional growth and development, such as augmenting scholarship venues by participating in collaborative national research projects, participating in national topic networks discussion groups and committees, becoming topic experts, and engaging in diversified training such as advanced airway training and conscious sedation. A new bedside ultrasound machine was purchased for the unit and housed within the division of hospital medicine with the intent to provide hospitalists the means necessary to achieve POCUS proficiency. Above all, by fostering a highly motivated and collegial multidisciplinary team, our model helps develop lasting partnerships at an institutional, regional, and national level.

This multidisciplinary team—with its skillfully trained and engaged nurses, physicians, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, infection control and laboratory specialists—works, learns, trains, and thrives collectively with the aim of providing excellent clinical care to our patients while assuring the safety of the team. DHHA has pioneered a RESPTC physician staffing model led by hospitalists.

We live in an ever-changing landscape of emerging diseases with blurred borders of disease geography. Hospitalists are versatile, capable of managing patients of varying acuity, able to perform many bedside procedures and POCUS; they are champions of interdisciplinary and teamwork disposition. By utilizing the resourcefulness of hospital medicine while helping to ease some of the burden that might otherwise be placed on a smaller numbers of physician groups, this approach provides a unique, cost-effective, and viable physician staffing model, which could be implemented in other BCUs in the United States.