User login

Is there a relationship between hypertension and cognitive function in older adults?

Vasectomy not a risk factor for prostate cancer

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Several case-control and cohort studies since the early 1990s have shown conflicting results on a possible association between vasectomy and prostate cancer risk. A recent systematic review failed to show a causal association and suggested several possible mechanisms for inconclusive results. This study addressed some of these limitations.

POPULATION STUDIED: The study included 923 men in New Zealand between the ages of 40 and 74 years with newly diagnosed prostate cancer (cases). All men were on the general electoral roll and had a history of marriage. The control group was randomly selected from the general electoral roll (n = 1224), and frequency matching to cases was performed in 5-year age groups. The mean age for cases and controls was 66.3 and 65.1 years, respectively. All cases and controls had telephone numbers for data collection purposes. Because nearly all study subjects were of European descent (97%), the results may not apply to other ethnic groups.

STUDY DESIGN AND VALIDITY: This national, population-based, case-control study was performed on all newly diagnosed cases of prostate cancer during a specified time (April 1, 1996, to December 31, 1998). Controls were randomly selected from the general electoral roll in which about 95% of adults are listed. Of potential cases and controls, only 12% and 20%, respectively, could not be contacted due to death, doctor or subject refusal, severe illness, inability to trace, or language difficulties.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: The primary outcome measured was the relative risk (RR) of prostate cancer for men who had vasectomies compared with that for men who had not undergone the procedure.

RESULTS: No association between prostate cancer and vasectomy was found (RR = 0.92; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.75–1.14). Even after 25 years since vasectomy, no association was found (RR = 0.92; 95% CI, 0.68–1.23). Adjustments were made for social class, geographic region, religious affiliation, and family history of prostate cancer without any effect on the risk.

This study found that having a vasectomy does not increase a man’s risk of developing prostate cancer, even after 25 or more years of follow-up. Because a previous systematic review also showed no conclusive evidence for an increased risk of prostate cancer after vasectomy, practitioners can confidently advise patients requesting vasectomies of the safety advantages compared with other methods of sterilization.

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Several case-control and cohort studies since the early 1990s have shown conflicting results on a possible association between vasectomy and prostate cancer risk. A recent systematic review failed to show a causal association and suggested several possible mechanisms for inconclusive results. This study addressed some of these limitations.

POPULATION STUDIED: The study included 923 men in New Zealand between the ages of 40 and 74 years with newly diagnosed prostate cancer (cases). All men were on the general electoral roll and had a history of marriage. The control group was randomly selected from the general electoral roll (n = 1224), and frequency matching to cases was performed in 5-year age groups. The mean age for cases and controls was 66.3 and 65.1 years, respectively. All cases and controls had telephone numbers for data collection purposes. Because nearly all study subjects were of European descent (97%), the results may not apply to other ethnic groups.

STUDY DESIGN AND VALIDITY: This national, population-based, case-control study was performed on all newly diagnosed cases of prostate cancer during a specified time (April 1, 1996, to December 31, 1998). Controls were randomly selected from the general electoral roll in which about 95% of adults are listed. Of potential cases and controls, only 12% and 20%, respectively, could not be contacted due to death, doctor or subject refusal, severe illness, inability to trace, or language difficulties.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: The primary outcome measured was the relative risk (RR) of prostate cancer for men who had vasectomies compared with that for men who had not undergone the procedure.

RESULTS: No association between prostate cancer and vasectomy was found (RR = 0.92; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.75–1.14). Even after 25 years since vasectomy, no association was found (RR = 0.92; 95% CI, 0.68–1.23). Adjustments were made for social class, geographic region, religious affiliation, and family history of prostate cancer without any effect on the risk.

This study found that having a vasectomy does not increase a man’s risk of developing prostate cancer, even after 25 or more years of follow-up. Because a previous systematic review also showed no conclusive evidence for an increased risk of prostate cancer after vasectomy, practitioners can confidently advise patients requesting vasectomies of the safety advantages compared with other methods of sterilization.

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Several case-control and cohort studies since the early 1990s have shown conflicting results on a possible association between vasectomy and prostate cancer risk. A recent systematic review failed to show a causal association and suggested several possible mechanisms for inconclusive results. This study addressed some of these limitations.

POPULATION STUDIED: The study included 923 men in New Zealand between the ages of 40 and 74 years with newly diagnosed prostate cancer (cases). All men were on the general electoral roll and had a history of marriage. The control group was randomly selected from the general electoral roll (n = 1224), and frequency matching to cases was performed in 5-year age groups. The mean age for cases and controls was 66.3 and 65.1 years, respectively. All cases and controls had telephone numbers for data collection purposes. Because nearly all study subjects were of European descent (97%), the results may not apply to other ethnic groups.

STUDY DESIGN AND VALIDITY: This national, population-based, case-control study was performed on all newly diagnosed cases of prostate cancer during a specified time (April 1, 1996, to December 31, 1998). Controls were randomly selected from the general electoral roll in which about 95% of adults are listed. Of potential cases and controls, only 12% and 20%, respectively, could not be contacted due to death, doctor or subject refusal, severe illness, inability to trace, or language difficulties.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: The primary outcome measured was the relative risk (RR) of prostate cancer for men who had vasectomies compared with that for men who had not undergone the procedure.

RESULTS: No association between prostate cancer and vasectomy was found (RR = 0.92; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.75–1.14). Even after 25 years since vasectomy, no association was found (RR = 0.92; 95% CI, 0.68–1.23). Adjustments were made for social class, geographic region, religious affiliation, and family history of prostate cancer without any effect on the risk.

This study found that having a vasectomy does not increase a man’s risk of developing prostate cancer, even after 25 or more years of follow-up. Because a previous systematic review also showed no conclusive evidence for an increased risk of prostate cancer after vasectomy, practitioners can confidently advise patients requesting vasectomies of the safety advantages compared with other methods of sterilization.

Inhaled fluticasone superior to montelukast in persistent asthma

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Asthma management guidelines recommend patients with persistent asthma use asthma controller therapy in addition to as-needed short-acting beta-agonist therapy to improve symptom control, maintain pulmonary function, and decrease exacerbations. This study compared 2 asthma controllers, inhaled fluticasone and oral montelukast, with respect to clinical efficacy, patient preference, asthma-specific quality of life, and safety.

POPULATION STUDIED: The patients in this study were men and women aged 15 years and older with asthma recruited from multiple centers across the United States. Nonsmoking patients were included with a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV 1 ) of 50% to 80% of predicted that reversed by at least 15% with bronchodilator use. Patients were then eligible for randomization if, after an 8- to 14-day run-in period, their FEV 1 remained within 15% of initial values, they used albuterol at least 6 of the last 7 days, and they had asthma symptom scores of 2 (on a 0 to 5 scale) for at least 4 of the last 7 days.

STUDY DESIGN AND VALIDITY: This study was a double-blinded, randomized trial sponsored by the makers of fluticasone. Patients meeting initial inclusion criteria underwent an 8- to 14-day run-in period in which only short-acting beta-agonist use was allowed. Patients were then randomized to 1 of 2 treatment groups if they met the secondary inclusion criteria. Personal communication with the lead author confirmed that allocation assignment was concealed. Patients received either fluticasone 88 μg twice daily via metered dose inhaler (MDI) and montelukast placebo, or montelukast 10 mg daily with a placebo MDI. Patients kept daily records and had clinical evaluations at regular intervals for 24 weeks. Seventy-six percent of the patients completed the study.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: The primary outcome was percent change in FEV 1 . Other outcomes included peak flow rate, symptom-free days, daily albuterol use, asthma symptom scores, asthma quality-of-life scores, and patient-rated satisfaction with treatment. Safety was also assessed by reports of clinical adverse events and number of asthma exacerbations.

RESULTS: Using an intent-to-treat analysis, the fluticasone group had a significantly greater sustained change in FEV 1 (22% vs 14%; P < .001). Significant differences were noted after just 2 weeks of treatment. Significant differences favoring fluticasone were also found in all secondary outcomes including the patient-oriented outcomes of change in asthma symptom scores (–0.91 vs –0.57; P < .001), asthma quality-of-life scores (1.3 vs 1.0; P = .004), and patient-rated satisfaction with treatment (83% of fluticasone patients satisfied vs 66% of montelukast patients satisfied; P < .001). No differences were noted in overall incidence of adverse events between treatment groups, but significantly more fluticasone-treated patients reported hoarseness (9 vs 0; P = .002) and oral pharyngeal candidiasis (8 vs 0; P = .008). The incidence of asthma exacerbations was similar (19 fluticasone-treated patients vs 21 montelukast-treated patients).

This study confirms earlier studies indicating that inhaled steroids should be first-line treatment for moderate-to-severe persistent asthma. When compared with montelukast, inhaled fluticasone showed greater improvements in clinical measures of asthma, as well as patient-oriented measures such as symptom scores, quality-of-life scores, and patientrated satisfaction. However, moderate-to-severe persistent asthma appears to require more therapeutic measures than just low-dose fluticasone. Despite treatment, patients still used albuterol on more than half of the days, only one third of days were symptom-free, and symptom scores improved by less than 1 point on a 6-point scale.

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Asthma management guidelines recommend patients with persistent asthma use asthma controller therapy in addition to as-needed short-acting beta-agonist therapy to improve symptom control, maintain pulmonary function, and decrease exacerbations. This study compared 2 asthma controllers, inhaled fluticasone and oral montelukast, with respect to clinical efficacy, patient preference, asthma-specific quality of life, and safety.

POPULATION STUDIED: The patients in this study were men and women aged 15 years and older with asthma recruited from multiple centers across the United States. Nonsmoking patients were included with a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV 1 ) of 50% to 80% of predicted that reversed by at least 15% with bronchodilator use. Patients were then eligible for randomization if, after an 8- to 14-day run-in period, their FEV 1 remained within 15% of initial values, they used albuterol at least 6 of the last 7 days, and they had asthma symptom scores of 2 (on a 0 to 5 scale) for at least 4 of the last 7 days.

STUDY DESIGN AND VALIDITY: This study was a double-blinded, randomized trial sponsored by the makers of fluticasone. Patients meeting initial inclusion criteria underwent an 8- to 14-day run-in period in which only short-acting beta-agonist use was allowed. Patients were then randomized to 1 of 2 treatment groups if they met the secondary inclusion criteria. Personal communication with the lead author confirmed that allocation assignment was concealed. Patients received either fluticasone 88 μg twice daily via metered dose inhaler (MDI) and montelukast placebo, or montelukast 10 mg daily with a placebo MDI. Patients kept daily records and had clinical evaluations at regular intervals for 24 weeks. Seventy-six percent of the patients completed the study.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: The primary outcome was percent change in FEV 1 . Other outcomes included peak flow rate, symptom-free days, daily albuterol use, asthma symptom scores, asthma quality-of-life scores, and patient-rated satisfaction with treatment. Safety was also assessed by reports of clinical adverse events and number of asthma exacerbations.

RESULTS: Using an intent-to-treat analysis, the fluticasone group had a significantly greater sustained change in FEV 1 (22% vs 14%; P < .001). Significant differences were noted after just 2 weeks of treatment. Significant differences favoring fluticasone were also found in all secondary outcomes including the patient-oriented outcomes of change in asthma symptom scores (–0.91 vs –0.57; P < .001), asthma quality-of-life scores (1.3 vs 1.0; P = .004), and patient-rated satisfaction with treatment (83% of fluticasone patients satisfied vs 66% of montelukast patients satisfied; P < .001). No differences were noted in overall incidence of adverse events between treatment groups, but significantly more fluticasone-treated patients reported hoarseness (9 vs 0; P = .002) and oral pharyngeal candidiasis (8 vs 0; P = .008). The incidence of asthma exacerbations was similar (19 fluticasone-treated patients vs 21 montelukast-treated patients).

This study confirms earlier studies indicating that inhaled steroids should be first-line treatment for moderate-to-severe persistent asthma. When compared with montelukast, inhaled fluticasone showed greater improvements in clinical measures of asthma, as well as patient-oriented measures such as symptom scores, quality-of-life scores, and patientrated satisfaction. However, moderate-to-severe persistent asthma appears to require more therapeutic measures than just low-dose fluticasone. Despite treatment, patients still used albuterol on more than half of the days, only one third of days were symptom-free, and symptom scores improved by less than 1 point on a 6-point scale.

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Asthma management guidelines recommend patients with persistent asthma use asthma controller therapy in addition to as-needed short-acting beta-agonist therapy to improve symptom control, maintain pulmonary function, and decrease exacerbations. This study compared 2 asthma controllers, inhaled fluticasone and oral montelukast, with respect to clinical efficacy, patient preference, asthma-specific quality of life, and safety.

POPULATION STUDIED: The patients in this study were men and women aged 15 years and older with asthma recruited from multiple centers across the United States. Nonsmoking patients were included with a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV 1 ) of 50% to 80% of predicted that reversed by at least 15% with bronchodilator use. Patients were then eligible for randomization if, after an 8- to 14-day run-in period, their FEV 1 remained within 15% of initial values, they used albuterol at least 6 of the last 7 days, and they had asthma symptom scores of 2 (on a 0 to 5 scale) for at least 4 of the last 7 days.

STUDY DESIGN AND VALIDITY: This study was a double-blinded, randomized trial sponsored by the makers of fluticasone. Patients meeting initial inclusion criteria underwent an 8- to 14-day run-in period in which only short-acting beta-agonist use was allowed. Patients were then randomized to 1 of 2 treatment groups if they met the secondary inclusion criteria. Personal communication with the lead author confirmed that allocation assignment was concealed. Patients received either fluticasone 88 μg twice daily via metered dose inhaler (MDI) and montelukast placebo, or montelukast 10 mg daily with a placebo MDI. Patients kept daily records and had clinical evaluations at regular intervals for 24 weeks. Seventy-six percent of the patients completed the study.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: The primary outcome was percent change in FEV 1 . Other outcomes included peak flow rate, symptom-free days, daily albuterol use, asthma symptom scores, asthma quality-of-life scores, and patient-rated satisfaction with treatment. Safety was also assessed by reports of clinical adverse events and number of asthma exacerbations.

RESULTS: Using an intent-to-treat analysis, the fluticasone group had a significantly greater sustained change in FEV 1 (22% vs 14%; P < .001). Significant differences were noted after just 2 weeks of treatment. Significant differences favoring fluticasone were also found in all secondary outcomes including the patient-oriented outcomes of change in asthma symptom scores (–0.91 vs –0.57; P < .001), asthma quality-of-life scores (1.3 vs 1.0; P = .004), and patient-rated satisfaction with treatment (83% of fluticasone patients satisfied vs 66% of montelukast patients satisfied; P < .001). No differences were noted in overall incidence of adverse events between treatment groups, but significantly more fluticasone-treated patients reported hoarseness (9 vs 0; P = .002) and oral pharyngeal candidiasis (8 vs 0; P = .008). The incidence of asthma exacerbations was similar (19 fluticasone-treated patients vs 21 montelukast-treated patients).

This study confirms earlier studies indicating that inhaled steroids should be first-line treatment for moderate-to-severe persistent asthma. When compared with montelukast, inhaled fluticasone showed greater improvements in clinical measures of asthma, as well as patient-oriented measures such as symptom scores, quality-of-life scores, and patientrated satisfaction. However, moderate-to-severe persistent asthma appears to require more therapeutic measures than just low-dose fluticasone. Despite treatment, patients still used albuterol on more than half of the days, only one third of days were symptom-free, and symptom scores improved by less than 1 point on a 6-point scale.

Is there a role for theophylline in treating patients with asthma?

With adults, oral theophylline may help lower the dosage of inhaled steroids needed to control chronic asthma. It offers no benefit for acute asthma exacerbations. For children, intravenous aminophylline may improve the clinical course of severe asthma attacks. Side effects and toxicity limit use of these medications in most settings. (Grade of recommendation: A, based on systematic reviews and randomized control trials [RCTs]).

Evidence summary

Several systematic reviews help clarify theophylline’s role in asthma management. When compared with placebo in the management of acute exacerbations, theophylline confers no added benefit to beta-agonist therapy (with or without steroids) in improving pulmonary function or reducing hospitalization rates. Side effects occurred more often in the theophylline group: palpitations/arrhythmias (OR = 2.9; 95% CI: 1.5 to 5.7) and vomiting (OR = 4.2; 95% CI: 2.4 to 7.4).1 For moderately severe asthma in patients already receiving inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), theophylline as maintenance therapy equaled long-acting beta-2-agonists in increasing FEV 1 and PEFR, but was less effective in controlling night time symptoms. Use of long-acting beta-agonists resulted in fewer side effects (RR = 0.38; 95%CI: 0.25-0.57).2 When added to low-dose ICS for maintenance, theophylline was as effective as high-dose ICS alone in improving FEV 1 , decreasing day and night symptoms, and reducing the need for rescue medications and the incidence of attacks. This suggests theophylline has utility as a steroid sparing agent.3

Intravenous aminophylline does appear to be clinically beneficial for children with severe exacerbations, defined as an FEV 1 of 35%-40% of predicted value. Critically ill children receiving aminophylline in addition to usual care exhibited an improved FEV 1 at 24 hours (mean difference = 8.4%; 95% CI: 0.82 to 15.92) and reduced symptom scores at 6 hours.4 The largest RCT of aminophylline in children demonstrated a reduced intubation rate (NNT = 14 CI: 7.8-77).5 Children receiving aminophylline experienced more vomiting (RR = 3.69; 95%CI: 2.15-6.33). Treatment with aminophylline did not reduce length of hospital stay or the number of rescue nebulizers needed (Table).4

TABLE

Theophylline use in asthma

| Adults | Children | |

|---|---|---|

| Acute Treatment | No added benefit to corticosteroids and beta-agonist therapy; increased GI and cardiac side effects. | 24 hours of IV aminophylline improves symptom scores without reducing LOS or nebulizer requirements; may reduce intubation |

| Maintenance Therapy | ||

| Mild | No clinical benefit | Not recommended |

| Moderate | Performs worse than long-acting beta-agonists and has more side effects; may limit the need for high-dose ICS if not using long beta agonists. | No advantage over long-acting beta agonists when added to ICS. More side effects |

| Severe | Same for moderate; does not limit the need for oral corticosteroids in this setting. | Same as moderate |

| LOS = length of stay; ICS = inhaled corticosteroids. | ||

Recommendations from others

Three evidence-supported guidelines concur that theophylline has a limited role as maintenance therapy for moderate-to-severe persistent asthma when symptom control with ICS alone is not adequate. Much stronger evidence supports the use of long-acting beta-2-agonists or leukotriene modifiers in this setting.6-8 The guidelines do not recommend using theophylline to treat acute asthma exacerbations; nor do they address using theophylline in children.

Read a Clinical Commentary by M. Lee Chambliss, MD, MSPH, at www.fpin.org.

1. Wilson AJ, Gibson, PG, Coughlan J. The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2002. Oxford: Update Software.

2. Parameswaran K, Belda J, Rowe BH. The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2002. Oxford: Update Software.

3. Evans DJ, Taylor DA, Zetterstrom O, et al. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1412-8.

4. Mitra A, Bassler D, Ducharme FM. The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2002. Oxford: Update Software.

5. Yung M, South M. Arch Dis Child 1998;79:405-410.

6. Management of Chronic Asthma. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment. Number 44. AHQR Publication Number 01-E043, September 2001.

7. Global Initiative for Asthma, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, (U.S.)/World Health Organization. 1995 Jan (revised 1998).

8. Expert Panel Report 2:Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program/National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (U.S.). 1997 Jul, (reprinted 1998 Apr, 1999 Mar).

With adults, oral theophylline may help lower the dosage of inhaled steroids needed to control chronic asthma. It offers no benefit for acute asthma exacerbations. For children, intravenous aminophylline may improve the clinical course of severe asthma attacks. Side effects and toxicity limit use of these medications in most settings. (Grade of recommendation: A, based on systematic reviews and randomized control trials [RCTs]).

Evidence summary

Several systematic reviews help clarify theophylline’s role in asthma management. When compared with placebo in the management of acute exacerbations, theophylline confers no added benefit to beta-agonist therapy (with or without steroids) in improving pulmonary function or reducing hospitalization rates. Side effects occurred more often in the theophylline group: palpitations/arrhythmias (OR = 2.9; 95% CI: 1.5 to 5.7) and vomiting (OR = 4.2; 95% CI: 2.4 to 7.4).1 For moderately severe asthma in patients already receiving inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), theophylline as maintenance therapy equaled long-acting beta-2-agonists in increasing FEV 1 and PEFR, but was less effective in controlling night time symptoms. Use of long-acting beta-agonists resulted in fewer side effects (RR = 0.38; 95%CI: 0.25-0.57).2 When added to low-dose ICS for maintenance, theophylline was as effective as high-dose ICS alone in improving FEV 1 , decreasing day and night symptoms, and reducing the need for rescue medications and the incidence of attacks. This suggests theophylline has utility as a steroid sparing agent.3

Intravenous aminophylline does appear to be clinically beneficial for children with severe exacerbations, defined as an FEV 1 of 35%-40% of predicted value. Critically ill children receiving aminophylline in addition to usual care exhibited an improved FEV 1 at 24 hours (mean difference = 8.4%; 95% CI: 0.82 to 15.92) and reduced symptom scores at 6 hours.4 The largest RCT of aminophylline in children demonstrated a reduced intubation rate (NNT = 14 CI: 7.8-77).5 Children receiving aminophylline experienced more vomiting (RR = 3.69; 95%CI: 2.15-6.33). Treatment with aminophylline did not reduce length of hospital stay or the number of rescue nebulizers needed (Table).4

TABLE

Theophylline use in asthma

| Adults | Children | |

|---|---|---|

| Acute Treatment | No added benefit to corticosteroids and beta-agonist therapy; increased GI and cardiac side effects. | 24 hours of IV aminophylline improves symptom scores without reducing LOS or nebulizer requirements; may reduce intubation |

| Maintenance Therapy | ||

| Mild | No clinical benefit | Not recommended |

| Moderate | Performs worse than long-acting beta-agonists and has more side effects; may limit the need for high-dose ICS if not using long beta agonists. | No advantage over long-acting beta agonists when added to ICS. More side effects |

| Severe | Same for moderate; does not limit the need for oral corticosteroids in this setting. | Same as moderate |

| LOS = length of stay; ICS = inhaled corticosteroids. | ||

Recommendations from others

Three evidence-supported guidelines concur that theophylline has a limited role as maintenance therapy for moderate-to-severe persistent asthma when symptom control with ICS alone is not adequate. Much stronger evidence supports the use of long-acting beta-2-agonists or leukotriene modifiers in this setting.6-8 The guidelines do not recommend using theophylline to treat acute asthma exacerbations; nor do they address using theophylline in children.

Read a Clinical Commentary by M. Lee Chambliss, MD, MSPH, at www.fpin.org.

With adults, oral theophylline may help lower the dosage of inhaled steroids needed to control chronic asthma. It offers no benefit for acute asthma exacerbations. For children, intravenous aminophylline may improve the clinical course of severe asthma attacks. Side effects and toxicity limit use of these medications in most settings. (Grade of recommendation: A, based on systematic reviews and randomized control trials [RCTs]).

Evidence summary

Several systematic reviews help clarify theophylline’s role in asthma management. When compared with placebo in the management of acute exacerbations, theophylline confers no added benefit to beta-agonist therapy (with or without steroids) in improving pulmonary function or reducing hospitalization rates. Side effects occurred more often in the theophylline group: palpitations/arrhythmias (OR = 2.9; 95% CI: 1.5 to 5.7) and vomiting (OR = 4.2; 95% CI: 2.4 to 7.4).1 For moderately severe asthma in patients already receiving inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), theophylline as maintenance therapy equaled long-acting beta-2-agonists in increasing FEV 1 and PEFR, but was less effective in controlling night time symptoms. Use of long-acting beta-agonists resulted in fewer side effects (RR = 0.38; 95%CI: 0.25-0.57).2 When added to low-dose ICS for maintenance, theophylline was as effective as high-dose ICS alone in improving FEV 1 , decreasing day and night symptoms, and reducing the need for rescue medications and the incidence of attacks. This suggests theophylline has utility as a steroid sparing agent.3

Intravenous aminophylline does appear to be clinically beneficial for children with severe exacerbations, defined as an FEV 1 of 35%-40% of predicted value. Critically ill children receiving aminophylline in addition to usual care exhibited an improved FEV 1 at 24 hours (mean difference = 8.4%; 95% CI: 0.82 to 15.92) and reduced symptom scores at 6 hours.4 The largest RCT of aminophylline in children demonstrated a reduced intubation rate (NNT = 14 CI: 7.8-77).5 Children receiving aminophylline experienced more vomiting (RR = 3.69; 95%CI: 2.15-6.33). Treatment with aminophylline did not reduce length of hospital stay or the number of rescue nebulizers needed (Table).4

TABLE

Theophylline use in asthma

| Adults | Children | |

|---|---|---|

| Acute Treatment | No added benefit to corticosteroids and beta-agonist therapy; increased GI and cardiac side effects. | 24 hours of IV aminophylline improves symptom scores without reducing LOS or nebulizer requirements; may reduce intubation |

| Maintenance Therapy | ||

| Mild | No clinical benefit | Not recommended |

| Moderate | Performs worse than long-acting beta-agonists and has more side effects; may limit the need for high-dose ICS if not using long beta agonists. | No advantage over long-acting beta agonists when added to ICS. More side effects |

| Severe | Same for moderate; does not limit the need for oral corticosteroids in this setting. | Same as moderate |

| LOS = length of stay; ICS = inhaled corticosteroids. | ||

Recommendations from others

Three evidence-supported guidelines concur that theophylline has a limited role as maintenance therapy for moderate-to-severe persistent asthma when symptom control with ICS alone is not adequate. Much stronger evidence supports the use of long-acting beta-2-agonists or leukotriene modifiers in this setting.6-8 The guidelines do not recommend using theophylline to treat acute asthma exacerbations; nor do they address using theophylline in children.

Read a Clinical Commentary by M. Lee Chambliss, MD, MSPH, at www.fpin.org.

1. Wilson AJ, Gibson, PG, Coughlan J. The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2002. Oxford: Update Software.

2. Parameswaran K, Belda J, Rowe BH. The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2002. Oxford: Update Software.

3. Evans DJ, Taylor DA, Zetterstrom O, et al. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1412-8.

4. Mitra A, Bassler D, Ducharme FM. The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2002. Oxford: Update Software.

5. Yung M, South M. Arch Dis Child 1998;79:405-410.

6. Management of Chronic Asthma. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment. Number 44. AHQR Publication Number 01-E043, September 2001.

7. Global Initiative for Asthma, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, (U.S.)/World Health Organization. 1995 Jan (revised 1998).

8. Expert Panel Report 2:Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program/National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (U.S.). 1997 Jul, (reprinted 1998 Apr, 1999 Mar).

1. Wilson AJ, Gibson, PG, Coughlan J. The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2002. Oxford: Update Software.

2. Parameswaran K, Belda J, Rowe BH. The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2002. Oxford: Update Software.

3. Evans DJ, Taylor DA, Zetterstrom O, et al. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1412-8.

4. Mitra A, Bassler D, Ducharme FM. The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2002. Oxford: Update Software.

5. Yung M, South M. Arch Dis Child 1998;79:405-410.

6. Management of Chronic Asthma. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment. Number 44. AHQR Publication Number 01-E043, September 2001.

7. Global Initiative for Asthma, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, (U.S.)/World Health Organization. 1995 Jan (revised 1998).

8. Expert Panel Report 2:Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program/National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (U.S.). 1997 Jul, (reprinted 1998 Apr, 1999 Mar).

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Endometriosis: What it is and how it is treated

A 62-year-old man with hypotension and an abnormal chest radiograph

Asymptomatic hyperuricemia: To treat or not to treat

Weight control and antipsychotics: How to tip the scales away from diabetes and heart disease

Weight gain is a potential problem for all patients who require treatment with antipsychotics. Those with schizophrenia face double jeopardy. Both the disorder and the use of virtually any available antipsychotic drug may be associated with weight gain, new-onset glucose intolerance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Because of the cardiovascular risks and other morbidity associated with weight gain and glucose dysregulation,1 the psychiatrist must remain vigilant and manage these complications aggressively. In this article, we offer insights into the prevention and management of metabolic complications associated with the use of antipsychotic agents in patients with schizophrenia.

Weight gain and antipsychotics

Weight change was recognized as a feature of schizophrenia even before antipsychotic drugs were introduced in the 1950s.2 Schizophrenia—independent of drug treatment—also is a risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes. In persons with schizophrenia, serum glucose levels increase more slowly, decline more gradually, and represent higher-than-normal reference values.3

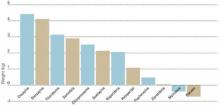

Figure 1 WEIGHT GAIN ASSOCIATED WITH ANTIPSYCHOTIC DRUG ADMINISTRATION

Values represent estimates of drug-induced weight gain after 10 weeks of drug administration.

Source: Allison et al. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1686-96; Brecher et al. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2000;4:287-92.In 1999, Allison et al assessed the effects of conventional and atypical antipsychotics on body weight. Using 81 published articles, they estimated and compared weight changes associated with 10 antipsychotic agents and a placebo when given at standard dosages for 10 weeks.4 Comparative data on quetiapine, which were insufficient in 1999, have since been added (Figure 1).5

Patients who received a placebo lost 0.74 kg across 10 weeks. Weight changes with the conventional agents ranged from a reduction of 0.39 kg with molindone to an increase of 3.19 kg with thioridazine. Weight gains also were seen with all of the newer atypical agents, including clozapine (+4.45 kg), olanzapine (+4.15 kg), risperidone (+2.10 kg), and ziprasidone (+0.04 kg).

Fontaine et al have estimated that weight gain in patients with schizophrenia has its greatest impact on mortality in two scenarios:

- when patients are overweight before they start antipsychotic medication

- with greater degrees of weight gain across 10 years (Figure 2).

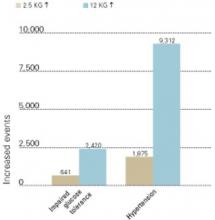

Whatever a patient’s starting weight, substantial weight gain with antipsychotic therapy increases the risk of impaired glucose tolerance and hypertension (Figure 3).6

Schizophrenia and diabetes

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes in patients with schizophrenia increased from 4.2% in 1956 to 17.2% in 1968, related in part to the introduction of phenothiazines.7 A recent study of data collected by the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT)2 found higher rates of diabetes in persons with schizophrenia (lifetime prevalence, 14.9%) than in the general population (approximately 7.3%).1 Most patients in the PORT study were taking older antipsychotics, the use of which has occasionally been associated with carbohydrate dysregulation.

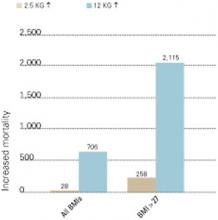

Figure 2 INCREASED MORTALITY ASSOCIATED WITH WEIGHT GAIN

Number of deaths associated with weight gains of 2.5 and 12 kg over 10 years, as related to all body mass index measurements (BMIs) and BMIs >27 (per 100,000 persons in U.S. population).

Source: Fontaine et al. Psychiatry Res 2001;101:277-88.The prevalence of new-onset diabetes with use of specific antipsychotics is unknown. Most information is contained in case reports, and proper epidemiologic studies await publication.

The most detailed report—a pooled study of published cases related to clozapine use—comes from the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.8 In this study, the authors identified 384 reports of diabetes that developed (in 242 patients) or was exacerbated (in 54 patients) in association with clozapine. Patient mean age was 40, and diabetes occurred more commonly in women than in men.

Diabetes developed most commonly within 6 months of starting treatment with clozapine, and one patient developed diabetes after a single 500-mg dose. Metabolic acidosis or ketosis occurred in 80 cases, and 25 subjects died during hyperglycemic episodes. Stopping clozapine or reducing the dosage improved glycemic control in 46 patients.8

Figure 3 INCREASED MORBIDITY ASSOCIATED WITH WEIGHT GAIN

New cases of impaired glucose tolerance and hypertension that developed with weight gains of 2.5 and 12 kg over 10 years (per 100,000 persons in U.S. population).

Source: Fontaine et al. Psychiatry Res 2001;101:277-88.During antipsychotic therapy, it is important to measure patients’ fasting plasma glucose at least annually—and more often for high-risk patients (Table 1). The American Diabetes Association defines diabetes as a fasting serum or plasma glucose 126 mg/dl or a 2-hour postprandial serum or plasma glucose 200 mg/dl. In all patients, these tests should be repeated to confirm the diagnosis. Oral glucose tolerance testing is less convenient than fasting plasma glucose testing but more sensitive in identifying changes in carbohydrate metabolism.

As with weight gain, it is easier to prevent diabetes than to treat it. The psychiatrist can best help the patient with emerging carbohydrate dysregulation by collaborating with an internist, family physician, or endocrinologist.

Table 1

FACTORS RELATED TO HIGH RISK OF DEVELOPING TYPE 2 DIABETES

|

| Source: American Diabetes Association |

Weight gain with diabetes drugs Weight gain is associated not only with the use of antipsychotics but also with four classes of oral agents used to treat type 2 diabetes: sulfonylureas, meglitinides, phenylalanine derivatives, and thiazolidinediones. One class—biguanides—contributes to weight reduction, and one—alpha-glucosidase inhibitors—has a variable effect on body weight. These drugs also vary in their effects on serum lipids, including total cholesterol, LDL and HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides (Table 2).9

Many patients with type 2 diabetes require more than one agent to control plasma glucose. With time, insulin deficiency becomes more marked, and insulin therapy is frequently added to the regimen. Hypertension and hyperlipidemia are also very common in patients with type 2 diabetes and require medication to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events.10 As a result, the diabetic patient requiring antipsychotic drugs will likely need polypharmacy, and many of the drugs that might be used may lead to weight gain.

Assessing, managing weight gain

During each visit for the patient with schizophrenia, it is important to routinely weigh those receiving antipsychotics and ask about polydipsia and polyuria, which are early signs of incipient diabetes. A patient who is gaining significant weight (7% of baseline) while taking an antipsychotic and has risk factors for cardiovascular events (e.g., smoking, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia) is a candidate for a change in antipsychotics.

Try to weigh patients at approximately the same time of day at each visit to compensate for possible diurnal weight changes related to polydipsia-hyponatremia syndrome.11 Patients with this syndrome can gain 5 to 10 lbs (or more) per day and excrete the retained fluid at night. It occurs in 5 to 10% of chronically psychotic patients requiring institutional care and in 1 to 2% of outpatients. Patients with schizophrenia complicated by this syndrome may manifest polydipsia and polyuria secondary to psychosis rather than emerging diabetes. Thus, the clinician must be alert to both diabetes and the polydipsia-hyponatremia syndrome in this setting.

Weight-control approaches

Patients who are taking sedating antipsychotics (e.g., clozapine, olanzapine, or low-potency phenothiazines) may gain up to 30 lbs per year if they become physically inactive and do not reduce their food consumption. Thus, it is important to work with such patients to decrease their caloric intake.

A weight-loss program that produces a loss of 0.5 to 1% of body weight per week is considered safe and acceptable.12 Mild to moderate obesity may be managed by reducing food intake by 500 calories and exercising 30 minutes each day.

CBT Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) may help stem weight gain associated with antipsychotic use. Umbricht et al provided CBT to six patients with chronic psychosis who were receiving clozapine or olanzapine. Therapists in group and individual sessions focused on the causes of weight gain, lowcalorie nutrition, weight-loss guidelines, exercise programs, and relaxation strategies. Across 8 weeks, patients’ mean BMI decreased from 29.6 to 25.1 kg/m2

Table 2

METABOLIC EFFECTS OF ORAL ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC DRUGS

| Class | Body weight | Total cholesterol | LDL | HDL | Triglycerides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfonylureas Glipizide Glyburide Glimepiride | ▲ | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► |

| Meglitinides Repaglinide | ▲ | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► |

| Phenylalanine derivatives Nateglinide | ▲ | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► |

| Biguanides Metformin | ▼ | ▼ | ▼ | ▲ | ▼ |

| Thiazolidinediones Pioglitazone Rosiglitazone | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▼ |

| Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors Acarbose Miglitol | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► |

| ▲ Increase ▼ Decrease ◄► Neutral effect/no change | |||||

Weight management program The Weight Watchers weight management program has shown mild success when offered to men and women with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Twenty-one patients who had gained an average of 32 lbs while taking olanzapine were enrolled in a Weight Watchers program at a psychiatric center.14 Mean starting BMI was 32 kg/m2 among the 11 patients who completed the 10-week program. Those 11 lost an average of 5 lbs.

All seven men lost weight. Three of the four women gained weight, and one woman lost 13 lbs. Study subjects remained clinically stable during the 10-week study. Two of the three women who did not lose weight had disabling psychiatric symptoms. Participation rates were similar to those of typical Weight Watchers clientele, suggesting that patients requiring antipsychotics might benefit from treatments used for other obese patients.

Patient education Educating patients about nutrition and exercise may help them control their rate of weight gain during antipsychotic therapy.

Littrell et al provided such an educational program for 1 hour per week for 4 months to six men and six women taking olanzapine for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.15 Patients in the behavioral group gained 0.5 kg, compared with a control group that gained 2.9 kg. Mean increase in BMI was less for the behavioral group (0.3 kg/m2) than for the control patients (0.9 kg/m2). Men in both groups gained more weight than did women.

Pharmacologic approaches

Antiobesity medications are generally reserved for patients with a BMI 30 kg/m2 (threshold for obesity) or for those with a BMI 27 kg/m2 (threshold for overweight is 25 kg/m2) who have additional risk factors for cardiovascular disease, stroke, or diabetes.16

For patients with schizophrenia, who typically have a BMI 27 kg/m2, the presence of these risk factors alone may be enough to warrant consideration of an antiobesity agent. Adding any new drug to a patient’s regimen, however, increases the risk of an adverse interaction.

Antiobesity drugs work by a variety of mechanisms, including decreasing appetite, decreasing fat absorption, and increasing energy expenditure. Drugs may reduce caloric intake by decreasing appetite (anorectic drugs) or increasing satiety (appetite suppressants). Centrally-acting sympathomimetics or serotonergic drugs may suppress appetite.

In studies up to 2 years, the appetite suppressant sibutramine, with mixed serotonergic and noradrenergic reuptake inhibition properties, has been shown to cause more weight loss than a placebo in populations without schizophrenia.17 According to one case report, sibutramine use was associated with new-onset psychosis.18

Common side effects of sibutramine include headache, dry mouth, anorexia, constipation, and insomnia. Regular monitoring of blood pressure is required. Do not prescribe this drug for patients with cardiovascular disease, and avoid co-prescribing with MAO inhibitors and serotonergics.

Orlistat reduces fat absorption from the GI tract.19 Common side effects are largely confined to the GI tract and include oily spotting, flatulence, fecal urgency, fatty/oily stool, and oily evacuation.

Combination therapies

Researchers are studying whether adding adjunctive agents to antipsychotics reduces weight gain.

Clozapine plus quetiapine A group of 65 patients who experienced a mean body weight increase of 6.5 kg while taking clozapine for 6 months were then given clozapine plus quetiapine at chlorpromazine-equivalent dosing during the next 10 months. The patients lost a mean of 4.2 kg, and their glycemic control improved. Elevated glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) became normal in those subjects (20% of participants) who had developed type 2 diabetes while taking clozapine alone. The authors theorized that the weight loss diminished insulin resistance, leading to better control of serum glucose levels.20

Olanzapine plus amantadine A group of 12 outpatients with axis I or II diagnoses had responded well clinically to olanzapine but had gained an average 7.3 kg over 1 to 11 months. In an open-label study, they continued their dosages of olanzapine and also were given amantadine, 100 to 300 mg/d. Amantadine was chosen for this trial because of its possible release of dopamine.

No dietary changes were made, but subjects gained no additional weight after amantadine was added. Over the next 3 to 6 months, they lost a mean 3.5 kg, which was 50% of the weight gain associated with olanzapine administration.21

Clozapine plus topiramate In clinical trials, the anticonvulsant topiramate has been associated with significant weight loss for up to 12 months in patients with seizure disorders.22 This agent, which also has mood-stabilizing effects, may be useful both for mood stabilization and weight loss in tandem with antipsychotic therapy.

In a case study,23 a 29-year-old man with schizophrenia who failed several trials of antipsychotic drugs experienced significant improvement with clozapine, 800 mg/d. Over 2 years, however, he developed myoclonic jerks and gained 45.5 kg (a 49% increase over baseline). When topiramate was added, starting with 25 mg/d and increasing to 125 mg/d, his mood improved and the myoclonic jerks stopped. During 5 months of combination therapy, the patient lost 21 kg without changing his eating habits.

Olanzapine and nizatidine Agents that block histamine (H 2) receptors in the digestive tract may be associated with weight loss when given at high doses, although the mechanism by which they contribute to weight loss is unclear. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study,24 the H 2 blocker nizatidine was given to patients with schizophrenia who were taking olanzapine, 5 to 20 mg/d. In a 16-week trial, 132 patients were randomized to receive adjunctive treatment with low-dose nizatidine (150 mg bid), high-dose nizatidine (300 mg bid), or a placebo.

After 16 weeks, nizatidine demonstrated a dose-response effect when combined with olanzapine. Average weight gain was:

- 5.51 kg with a placebo

- 4.41 kg with low-dose nizatidine

- 2.76 kg with high-dose nizatidine (p =0.02 compared with a placebo).

In the high-dose nizatidine group, only 6% of patients gained more than 10 kg, and weight gain leveled off by week eight. Adverse events and clinical improvements were similar in the three groups.

Related resources

- Weight gain: A growing problem in schizophrenia management. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(suppl 7).

- Weight gain associated with the use of psychotropic medications. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60(suppl 2).

- Effects of atypical antipsychotics on body weight and glucose regulation. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(suppl 23).

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/ob_home.htm

Drug brand names

- Amantadine • Symmetrel

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Nizatidine • Axid

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Orlistat • Xenical

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sibutramine • Meridia

- Topiramate • Topamax

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article.

1. Mokdad AH, Bowman BA, Ford ES, Vinicor F, Marks JS, Koplan JP. The continuing epidemics of obesity and diabetes in the United States. JAMA 2001;286:1195-1200.

2. Dixon L, Weiden P, Delahanty J, et al. Prevalence and correlates of diabetes in national schizophrenia samples. Schizophr Bull 2000;26:903-12.

3. Braceland FJ, Meduna LJ, Vaichulis JA. Delayed action of insulin in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1945;102:108-10.

4. Allison DB, Mentore JL, Heo M, et al. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1686-96.

5. Brecher M, Rak IW, Westhead EK. The long-term effect of quetiapine (“Seroquel’) monotherapy on weight in patients with schizophrenia. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2000;4:287-92.

6. Fontaine KR, Heo M, Harrigan EP, Shear CL, Lakshiminarayanan M. Estimating the consequences of anti-psychotic induced weight gain on health and mortality rate. Psychiatry Res 2001;101:277-88.

7. Theonnard-Neumann E. Phenothiazines and diabetes in hospitalized women. Am J Psychiatry 1968;124:978-82.

8. Koller E, Schneider B, Bennett K, Dubitsky G. Clozapine-associated diabetes. Am J Med 2001;111:716-23.

9. Pendergrass ML. Pathophysiology and management of type 2 diabetes. In: Giles TD, Sowers JR, Weber MA (eds). Diabetes & cardiovascular disease: a practical primer. New Orleans: Institute of Professional Education, 2000;15-40.

10. Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults. Findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA 2002;287:356-9.

11. Vieweg WVR, Leadbetter RA. The polydipsia-hyponatremia syndrome. Epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment. CNS Drugs 1997;7:121-38.

12. Thomas PR. Weighing the options: criteria for evaluating weight management programs. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1995.

13. Umbricht D, Flury H, Bridler R. Cognitive behavioral therapy for weight gain. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:971.-

14. Ball M, Coons V, Buchanan R. A program for treating olanzapine-related weight gain. Psychiatric Services 2001;52:967-9.

15. Littrell KH, Petty RG, Hilligoss NM, Peabody CD, Johnson CG. Educational interventions for the management of antipsychotic-related weight gain. 41st annual meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit, Phoenix, AZ, May 28-31, 2001.

16. Greenberg I, Chan S, Blackburn GL. Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic management of weight gain. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60(suppl 21):31-6.

17. Wirth A, Krause J. Long-term weight loss with sibutramine: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;286:1331-9.

18. Taflinski T, Chojnacka J. Sibutramine-associated psychotic episode. Am J Psychiatry 2001;157:2057-8.

19. Glazer G. Long-term pharmacotherapy of obesity 2000. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:1814-24.

20. Reinstein M, Sirotovskaya L, Jones L. Effect of clozapine-quetiapine combination therapy on weight and glycaemic control. Clin Drug Invest 1999;18:99-104.

21. Floris M, Lejeune J, Deberdt W. Effect of amantadine on weight gain during olanzapine treatment. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2001;11:181-2.

22. Norton J, Potter D, Edwards K. Sustained weight loss associated with topiramate [abstract]. Epilepsia 1997;38(suppl 3):60.-

23. Dursun SM, Devarajan S. Clozapine weight gain, plus topiramate weight loss. Can J Psychiatry 2000;45:198.-

24. Breier A, Tanaka Y, Roychowdhury S, Clark WS. Nizatidine for the prevention of olanzapine-associated weight gain in schizophrenia and related disorders. A randomized controlled double blind study. 41st annual meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit, Phoenix, AZ, May 28-31 2001.

Weight gain is a potential problem for all patients who require treatment with antipsychotics. Those with schizophrenia face double jeopardy. Both the disorder and the use of virtually any available antipsychotic drug may be associated with weight gain, new-onset glucose intolerance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Because of the cardiovascular risks and other morbidity associated with weight gain and glucose dysregulation,1 the psychiatrist must remain vigilant and manage these complications aggressively. In this article, we offer insights into the prevention and management of metabolic complications associated with the use of antipsychotic agents in patients with schizophrenia.

Weight gain and antipsychotics

Weight change was recognized as a feature of schizophrenia even before antipsychotic drugs were introduced in the 1950s.2 Schizophrenia—independent of drug treatment—also is a risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes. In persons with schizophrenia, serum glucose levels increase more slowly, decline more gradually, and represent higher-than-normal reference values.3

Figure 1 WEIGHT GAIN ASSOCIATED WITH ANTIPSYCHOTIC DRUG ADMINISTRATION

Values represent estimates of drug-induced weight gain after 10 weeks of drug administration.

Source: Allison et al. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1686-96; Brecher et al. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2000;4:287-92.In 1999, Allison et al assessed the effects of conventional and atypical antipsychotics on body weight. Using 81 published articles, they estimated and compared weight changes associated with 10 antipsychotic agents and a placebo when given at standard dosages for 10 weeks.4 Comparative data on quetiapine, which were insufficient in 1999, have since been added (Figure 1).5

Patients who received a placebo lost 0.74 kg across 10 weeks. Weight changes with the conventional agents ranged from a reduction of 0.39 kg with molindone to an increase of 3.19 kg with thioridazine. Weight gains also were seen with all of the newer atypical agents, including clozapine (+4.45 kg), olanzapine (+4.15 kg), risperidone (+2.10 kg), and ziprasidone (+0.04 kg).

Fontaine et al have estimated that weight gain in patients with schizophrenia has its greatest impact on mortality in two scenarios:

- when patients are overweight before they start antipsychotic medication

- with greater degrees of weight gain across 10 years (Figure 2).

Whatever a patient’s starting weight, substantial weight gain with antipsychotic therapy increases the risk of impaired glucose tolerance and hypertension (Figure 3).6

Schizophrenia and diabetes

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes in patients with schizophrenia increased from 4.2% in 1956 to 17.2% in 1968, related in part to the introduction of phenothiazines.7 A recent study of data collected by the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT)2 found higher rates of diabetes in persons with schizophrenia (lifetime prevalence, 14.9%) than in the general population (approximately 7.3%).1 Most patients in the PORT study were taking older antipsychotics, the use of which has occasionally been associated with carbohydrate dysregulation.

Figure 2 INCREASED MORTALITY ASSOCIATED WITH WEIGHT GAIN

Number of deaths associated with weight gains of 2.5 and 12 kg over 10 years, as related to all body mass index measurements (BMIs) and BMIs >27 (per 100,000 persons in U.S. population).

Source: Fontaine et al. Psychiatry Res 2001;101:277-88.The prevalence of new-onset diabetes with use of specific antipsychotics is unknown. Most information is contained in case reports, and proper epidemiologic studies await publication.

The most detailed report—a pooled study of published cases related to clozapine use—comes from the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.8 In this study, the authors identified 384 reports of diabetes that developed (in 242 patients) or was exacerbated (in 54 patients) in association with clozapine. Patient mean age was 40, and diabetes occurred more commonly in women than in men.

Diabetes developed most commonly within 6 months of starting treatment with clozapine, and one patient developed diabetes after a single 500-mg dose. Metabolic acidosis or ketosis occurred in 80 cases, and 25 subjects died during hyperglycemic episodes. Stopping clozapine or reducing the dosage improved glycemic control in 46 patients.8

Figure 3 INCREASED MORBIDITY ASSOCIATED WITH WEIGHT GAIN

New cases of impaired glucose tolerance and hypertension that developed with weight gains of 2.5 and 12 kg over 10 years (per 100,000 persons in U.S. population).

Source: Fontaine et al. Psychiatry Res 2001;101:277-88.During antipsychotic therapy, it is important to measure patients’ fasting plasma glucose at least annually—and more often for high-risk patients (Table 1). The American Diabetes Association defines diabetes as a fasting serum or plasma glucose 126 mg/dl or a 2-hour postprandial serum or plasma glucose 200 mg/dl. In all patients, these tests should be repeated to confirm the diagnosis. Oral glucose tolerance testing is less convenient than fasting plasma glucose testing but more sensitive in identifying changes in carbohydrate metabolism.

As with weight gain, it is easier to prevent diabetes than to treat it. The psychiatrist can best help the patient with emerging carbohydrate dysregulation by collaborating with an internist, family physician, or endocrinologist.

Table 1

FACTORS RELATED TO HIGH RISK OF DEVELOPING TYPE 2 DIABETES

|

| Source: American Diabetes Association |

Weight gain with diabetes drugs Weight gain is associated not only with the use of antipsychotics but also with four classes of oral agents used to treat type 2 diabetes: sulfonylureas, meglitinides, phenylalanine derivatives, and thiazolidinediones. One class—biguanides—contributes to weight reduction, and one—alpha-glucosidase inhibitors—has a variable effect on body weight. These drugs also vary in their effects on serum lipids, including total cholesterol, LDL and HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides (Table 2).9

Many patients with type 2 diabetes require more than one agent to control plasma glucose. With time, insulin deficiency becomes more marked, and insulin therapy is frequently added to the regimen. Hypertension and hyperlipidemia are also very common in patients with type 2 diabetes and require medication to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events.10 As a result, the diabetic patient requiring antipsychotic drugs will likely need polypharmacy, and many of the drugs that might be used may lead to weight gain.

Assessing, managing weight gain

During each visit for the patient with schizophrenia, it is important to routinely weigh those receiving antipsychotics and ask about polydipsia and polyuria, which are early signs of incipient diabetes. A patient who is gaining significant weight (7% of baseline) while taking an antipsychotic and has risk factors for cardiovascular events (e.g., smoking, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia) is a candidate for a change in antipsychotics.

Try to weigh patients at approximately the same time of day at each visit to compensate for possible diurnal weight changes related to polydipsia-hyponatremia syndrome.11 Patients with this syndrome can gain 5 to 10 lbs (or more) per day and excrete the retained fluid at night. It occurs in 5 to 10% of chronically psychotic patients requiring institutional care and in 1 to 2% of outpatients. Patients with schizophrenia complicated by this syndrome may manifest polydipsia and polyuria secondary to psychosis rather than emerging diabetes. Thus, the clinician must be alert to both diabetes and the polydipsia-hyponatremia syndrome in this setting.

Weight-control approaches

Patients who are taking sedating antipsychotics (e.g., clozapine, olanzapine, or low-potency phenothiazines) may gain up to 30 lbs per year if they become physically inactive and do not reduce their food consumption. Thus, it is important to work with such patients to decrease their caloric intake.

A weight-loss program that produces a loss of 0.5 to 1% of body weight per week is considered safe and acceptable.12 Mild to moderate obesity may be managed by reducing food intake by 500 calories and exercising 30 minutes each day.

CBT Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) may help stem weight gain associated with antipsychotic use. Umbricht et al provided CBT to six patients with chronic psychosis who were receiving clozapine or olanzapine. Therapists in group and individual sessions focused on the causes of weight gain, lowcalorie nutrition, weight-loss guidelines, exercise programs, and relaxation strategies. Across 8 weeks, patients’ mean BMI decreased from 29.6 to 25.1 kg/m2

Table 2

METABOLIC EFFECTS OF ORAL ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC DRUGS

| Class | Body weight | Total cholesterol | LDL | HDL | Triglycerides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfonylureas Glipizide Glyburide Glimepiride | ▲ | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► |

| Meglitinides Repaglinide | ▲ | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► |

| Phenylalanine derivatives Nateglinide | ▲ | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► |

| Biguanides Metformin | ▼ | ▼ | ▼ | ▲ | ▼ |

| Thiazolidinediones Pioglitazone Rosiglitazone | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▼ |

| Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors Acarbose Miglitol | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► | ◄► |

| ▲ Increase ▼ Decrease ◄► Neutral effect/no change | |||||

Weight management program The Weight Watchers weight management program has shown mild success when offered to men and women with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Twenty-one patients who had gained an average of 32 lbs while taking olanzapine were enrolled in a Weight Watchers program at a psychiatric center.14 Mean starting BMI was 32 kg/m2 among the 11 patients who completed the 10-week program. Those 11 lost an average of 5 lbs.

All seven men lost weight. Three of the four women gained weight, and one woman lost 13 lbs. Study subjects remained clinically stable during the 10-week study. Two of the three women who did not lose weight had disabling psychiatric symptoms. Participation rates were similar to those of typical Weight Watchers clientele, suggesting that patients requiring antipsychotics might benefit from treatments used for other obese patients.

Patient education Educating patients about nutrition and exercise may help them control their rate of weight gain during antipsychotic therapy.

Littrell et al provided such an educational program for 1 hour per week for 4 months to six men and six women taking olanzapine for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.15 Patients in the behavioral group gained 0.5 kg, compared with a control group that gained 2.9 kg. Mean increase in BMI was less for the behavioral group (0.3 kg/m2) than for the control patients (0.9 kg/m2). Men in both groups gained more weight than did women.

Pharmacologic approaches

Antiobesity medications are generally reserved for patients with a BMI 30 kg/m2 (threshold for obesity) or for those with a BMI 27 kg/m2 (threshold for overweight is 25 kg/m2) who have additional risk factors for cardiovascular disease, stroke, or diabetes.16

For patients with schizophrenia, who typically have a BMI 27 kg/m2, the presence of these risk factors alone may be enough to warrant consideration of an antiobesity agent. Adding any new drug to a patient’s regimen, however, increases the risk of an adverse interaction.

Antiobesity drugs work by a variety of mechanisms, including decreasing appetite, decreasing fat absorption, and increasing energy expenditure. Drugs may reduce caloric intake by decreasing appetite (anorectic drugs) or increasing satiety (appetite suppressants). Centrally-acting sympathomimetics or serotonergic drugs may suppress appetite.

In studies up to 2 years, the appetite suppressant sibutramine, with mixed serotonergic and noradrenergic reuptake inhibition properties, has been shown to cause more weight loss than a placebo in populations without schizophrenia.17 According to one case report, sibutramine use was associated with new-onset psychosis.18

Common side effects of sibutramine include headache, dry mouth, anorexia, constipation, and insomnia. Regular monitoring of blood pressure is required. Do not prescribe this drug for patients with cardiovascular disease, and avoid co-prescribing with MAO inhibitors and serotonergics.

Orlistat reduces fat absorption from the GI tract.19 Common side effects are largely confined to the GI tract and include oily spotting, flatulence, fecal urgency, fatty/oily stool, and oily evacuation.

Combination therapies

Researchers are studying whether adding adjunctive agents to antipsychotics reduces weight gain.

Clozapine plus quetiapine A group of 65 patients who experienced a mean body weight increase of 6.5 kg while taking clozapine for 6 months were then given clozapine plus quetiapine at chlorpromazine-equivalent dosing during the next 10 months. The patients lost a mean of 4.2 kg, and their glycemic control improved. Elevated glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) became normal in those subjects (20% of participants) who had developed type 2 diabetes while taking clozapine alone. The authors theorized that the weight loss diminished insulin resistance, leading to better control of serum glucose levels.20

Olanzapine plus amantadine A group of 12 outpatients with axis I or II diagnoses had responded well clinically to olanzapine but had gained an average 7.3 kg over 1 to 11 months. In an open-label study, they continued their dosages of olanzapine and also were given amantadine, 100 to 300 mg/d. Amantadine was chosen for this trial because of its possible release of dopamine.

No dietary changes were made, but subjects gained no additional weight after amantadine was added. Over the next 3 to 6 months, they lost a mean 3.5 kg, which was 50% of the weight gain associated with olanzapine administration.21

Clozapine plus topiramate In clinical trials, the anticonvulsant topiramate has been associated with significant weight loss for up to 12 months in patients with seizure disorders.22 This agent, which also has mood-stabilizing effects, may be useful both for mood stabilization and weight loss in tandem with antipsychotic therapy.

In a case study,23 a 29-year-old man with schizophrenia who failed several trials of antipsychotic drugs experienced significant improvement with clozapine, 800 mg/d. Over 2 years, however, he developed myoclonic jerks and gained 45.5 kg (a 49% increase over baseline). When topiramate was added, starting with 25 mg/d and increasing to 125 mg/d, his mood improved and the myoclonic jerks stopped. During 5 months of combination therapy, the patient lost 21 kg without changing his eating habits.

Olanzapine and nizatidine Agents that block histamine (H 2) receptors in the digestive tract may be associated with weight loss when given at high doses, although the mechanism by which they contribute to weight loss is unclear. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study,24 the H 2 blocker nizatidine was given to patients with schizophrenia who were taking olanzapine, 5 to 20 mg/d. In a 16-week trial, 132 patients were randomized to receive adjunctive treatment with low-dose nizatidine (150 mg bid), high-dose nizatidine (300 mg bid), or a placebo.

After 16 weeks, nizatidine demonstrated a dose-response effect when combined with olanzapine. Average weight gain was:

- 5.51 kg with a placebo

- 4.41 kg with low-dose nizatidine

- 2.76 kg with high-dose nizatidine (p =0.02 compared with a placebo).

In the high-dose nizatidine group, only 6% of patients gained more than 10 kg, and weight gain leveled off by week eight. Adverse events and clinical improvements were similar in the three groups.

Related resources

- Weight gain: A growing problem in schizophrenia management. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(suppl 7).

- Weight gain associated with the use of psychotropic medications. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60(suppl 2).

- Effects of atypical antipsychotics on body weight and glucose regulation. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(suppl 23).

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/ob_home.htm

Drug brand names

- Amantadine • Symmetrel

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Nizatidine • Axid

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Orlistat • Xenical

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sibutramine • Meridia

- Topiramate • Topamax

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article.

Weight gain is a potential problem for all patients who require treatment with antipsychotics. Those with schizophrenia face double jeopardy. Both the disorder and the use of virtually any available antipsychotic drug may be associated with weight gain, new-onset glucose intolerance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Because of the cardiovascular risks and other morbidity associated with weight gain and glucose dysregulation,1 the psychiatrist must remain vigilant and manage these complications aggressively. In this article, we offer insights into the prevention and management of metabolic complications associated with the use of antipsychotic agents in patients with schizophrenia.

Weight gain and antipsychotics

Weight change was recognized as a feature of schizophrenia even before antipsychotic drugs were introduced in the 1950s.2 Schizophrenia—independent of drug treatment—also is a risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes. In persons with schizophrenia, serum glucose levels increase more slowly, decline more gradually, and represent higher-than-normal reference values.3

Figure 1 WEIGHT GAIN ASSOCIATED WITH ANTIPSYCHOTIC DRUG ADMINISTRATION

Values represent estimates of drug-induced weight gain after 10 weeks of drug administration.

Source: Allison et al. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1686-96; Brecher et al. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2000;4:287-92.In 1999, Allison et al assessed the effects of conventional and atypical antipsychotics on body weight. Using 81 published articles, they estimated and compared weight changes associated with 10 antipsychotic agents and a placebo when given at standard dosages for 10 weeks.4 Comparative data on quetiapine, which were insufficient in 1999, have since been added (Figure 1).5

Patients who received a placebo lost 0.74 kg across 10 weeks. Weight changes with the conventional agents ranged from a reduction of 0.39 kg with molindone to an increase of 3.19 kg with thioridazine. Weight gains also were seen with all of the newer atypical agents, including clozapine (+4.45 kg), olanzapine (+4.15 kg), risperidone (+2.10 kg), and ziprasidone (+0.04 kg).

Fontaine et al have estimated that weight gain in patients with schizophrenia has its greatest impact on mortality in two scenarios:

- when patients are overweight before they start antipsychotic medication

- with greater degrees of weight gain across 10 years (Figure 2).

Whatever a patient’s starting weight, substantial weight gain with antipsychotic therapy increases the risk of impaired glucose tolerance and hypertension (Figure 3).6

Schizophrenia and diabetes

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes in patients with schizophrenia increased from 4.2% in 1956 to 17.2% in 1968, related in part to the introduction of phenothiazines.7 A recent study of data collected by the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT)2 found higher rates of diabetes in persons with schizophrenia (lifetime prevalence, 14.9%) than in the general population (approximately 7.3%).1 Most patients in the PORT study were taking older antipsychotics, the use of which has occasionally been associated with carbohydrate dysregulation.

Figure 2 INCREASED MORTALITY ASSOCIATED WITH WEIGHT GAIN

Number of deaths associated with weight gains of 2.5 and 12 kg over 10 years, as related to all body mass index measurements (BMIs) and BMIs >27 (per 100,000 persons in U.S. population).

Source: Fontaine et al. Psychiatry Res 2001;101:277-88.The prevalence of new-onset diabetes with use of specific antipsychotics is unknown. Most information is contained in case reports, and proper epidemiologic studies await publication.

The most detailed report—a pooled study of published cases related to clozapine use—comes from the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.8 In this study, the authors identified 384 reports of diabetes that developed (in 242 patients) or was exacerbated (in 54 patients) in association with clozapine. Patient mean age was 40, and diabetes occurred more commonly in women than in men.

Diabetes developed most commonly within 6 months of starting treatment with clozapine, and one patient developed diabetes after a single 500-mg dose. Metabolic acidosis or ketosis occurred in 80 cases, and 25 subjects died during hyperglycemic episodes. Stopping clozapine or reducing the dosage improved glycemic control in 46 patients.8

Figure 3 INCREASED MORBIDITY ASSOCIATED WITH WEIGHT GAIN

New cases of impaired glucose tolerance and hypertension that developed with weight gains of 2.5 and 12 kg over 10 years (per 100,000 persons in U.S. population).

Source: Fontaine et al. Psychiatry Res 2001;101:277-88.During antipsychotic therapy, it is important to measure patients’ fasting plasma glucose at least annually—and more often for high-risk patients (Table 1). The American Diabetes Association defines diabetes as a fasting serum or plasma glucose 126 mg/dl or a 2-hour postprandial serum or plasma glucose 200 mg/dl. In all patients, these tests should be repeated to confirm the diagnosis. Oral glucose tolerance testing is less convenient than fasting plasma glucose testing but more sensitive in identifying changes in carbohydrate metabolism.

As with weight gain, it is easier to prevent diabetes than to treat it. The psychiatrist can best help the patient with emerging carbohydrate dysregulation by collaborating with an internist, family physician, or endocrinologist.

Table 1

FACTORS RELATED TO HIGH RISK OF DEVELOPING TYPE 2 DIABETES

|

| Source: American Diabetes Association |

Weight gain with diabetes drugs Weight gain is associated not only with the use of antipsychotics but also with four classes of oral agents used to treat type 2 diabetes: sulfonylureas, meglitinides, phenylalanine derivatives, and thiazolidinediones. One class—biguanides—contributes to weight reduction, and one—alpha-glucosidase inhibitors—has a variable effect on body weight. These drugs also vary in their effects on serum lipids, including total cholesterol, LDL and HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides (Table 2).9

Many patients with type 2 diabetes require more than one agent to control plasma glucose. With time, insulin deficiency becomes more marked, and insulin therapy is frequently added to the regimen. Hypertension and hyperlipidemia are also very common in patients with type 2 diabetes and require medication to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events.10 As a result, the diabetic patient requiring antipsychotic drugs will likely need polypharmacy, and many of the drugs that might be used may lead to weight gain.

Assessing, managing weight gain

During each visit for the patient with schizophrenia, it is important to routinely weigh those receiving antipsychotics and ask about polydipsia and polyuria, which are early signs of incipient diabetes. A patient who is gaining significant weight (7% of baseline) while taking an antipsychotic and has risk factors for cardiovascular events (e.g., smoking, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia) is a candidate for a change in antipsychotics.

Try to weigh patients at approximately the same time of day at each visit to compensate for possible diurnal weight changes related to polydipsia-hyponatremia syndrome.11 Patients with this syndrome can gain 5 to 10 lbs (or more) per day and excrete the retained fluid at night. It occurs in 5 to 10% of chronically psychotic patients requiring institutional care and in 1 to 2% of outpatients. Patients with schizophrenia complicated by this syndrome may manifest polydipsia and polyuria secondary to psychosis rather than emerging diabetes. Thus, the clinician must be alert to both diabetes and the polydipsia-hyponatremia syndrome in this setting.

Weight-control approaches

Patients who are taking sedating antipsychotics (e.g., clozapine, olanzapine, or low-potency phenothiazines) may gain up to 30 lbs per year if they become physically inactive and do not reduce their food consumption. Thus, it is important to work with such patients to decrease their caloric intake.

A weight-loss program that produces a loss of 0.5 to 1% of body weight per week is considered safe and acceptable.12 Mild to moderate obesity may be managed by reducing food intake by 500 calories and exercising 30 minutes each day.