User login

MDedge latest news is breaking news from medical conferences, journals, guidelines, the FDA and CDC.

Pfizer’s Withdrawal of SCD Drug Raises Questions

The National Alliance of Sickle Cell Centers issued a statement urging patients not to stop voxelotor abruptly. Instead, they should work out plans with their physicians and medical teams for weaning plans.

“Don’t lose faith. This a step backward, but we will stay on the path to better outcomes for everyone,” said the alliance in a statement to patients and clinicians.

On September 25, Pfizer said it would withdraw all lots of voxelotor in all markets where it is approved. The New York–based drugmaker also said it was discontinuing all active voxelotor clinical trials and expanded access programs worldwide. The cause was data that suggested “an imbalance in vaso-occlusive crises and fatal events which require further assessment.”

Pfizer told this news organization in an email exchange that it is focused on analyzing the data and will share updates in the future about presenting or publishing on this issue.

The withdrawal came amid increased scrutiny of the drug by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). The EMA in July began a review of voxelotor after data from a clinical trial showed that a higher number of deaths occurred with the drug than with placebo and another trial showed the total number of deaths was higher than anticipated.

On September 26, the EMA’s human medicines committee recommended suspending the marketing authorization of voxelotor, citing new safety data that emerged during the review. The drug had received marketing authorization for the European Union in 2022, the agency said.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which first cleared voxelotor for sale in 2019, also said it has been conducting a safety review of the drug. The agency continues to examine post-marketing clinical trial data for voxelotor, the real-world registry studies, and data from the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. At the conclusion of this review, the FDA will communicate any additional findings, if necessary, the agency said.

The FDA said it appeared that more deaths and a higher rate of vaso-occlusive crisis occurred in patients taking voxelotor vs placebo in post-marketing clinical trials.

“Pfizer also observed a higher rate of vaso-occlusive crisis in patients with sickle cell disease receiving Oxbryta in two real-world registry studies,” the FDA said. “Based on the totality of clinical data, Pfizer has determined the benefit of Oxbryta does not outweigh the risk.”

Gene Therapy, Tried-and-True Hydroxyurea (HU)

As a field, SCD has drawn more interest in recent years, with significant gains made lately in cutting-edge projects.

The FDA in December approved two gene-editing treatments for patients aged 12 years or older. These are considered “milestone treatments” for a debilitating and potentially life-threatening blood disorder that affects about 100,000 people in the United States. Exagamglogene autotemcel (Casgevy, Vertex Pharmaceuticals and CRISPR Therapeutics) is the first to use the gene-editing tool CRISPR. And lovotibeglogene autotemcel (Lyfgenia, bluebird bio) uses a different gene-editing tool called a lentiviral vector.

These advances have been covered widely by the news media but are not expected to be widely available, with the cost of these extensive treatments estimated around $2-$3 million per patient.

“Gene therapy is amazing in that it can offer a cure, but it’s very expensive and not all patients are suitable for it. Some have so much existing organ damage that it’s not an option for them,” said John Wood, MD, PhD, director of cardiovascular MRI at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, who does research on SCD.

“So it really is a great treatment for a very few people,” he said in an interview.

The mainstay of treatment for SCD remains a drug that Lydia Pecker, MD, a pediatric hematologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, describes as the “first, oldest, and best”: HU.

The FDA approved this in 1998 for use in SCD. It reduces the frequency of painful crises and acute chest syndrome and other complications of SCD that otherwise could be serious or even lethal, Pecker said.

“Older doctors can tell you that what they experienced with sickle cell disease in the hospitals has been completely transformed because of the high uptake of the drug,” she said, adding that it made a “profound” change. “We just don’t have data for any other agent that’s quite like that.”

Voxelotor had been a good second drug to add for some patients, in addition to HU and blood transfusions, Dr. Pecker noted. It was a first-line drug for those for whom transfusion and HU were not options, which constitutes a relatively small number of patients, she said.

“So we have, in the last 5 years, felt more hopeful because we had something else to offer,” she said.

Alexis A. Thompson, MD, MPH, chief of the Division of Hematology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, said in an interview that her organization also had patients who appeared to benefit from voxelotor, some of whom had been participants in clinical trials.

Dr. Thompson, who has been a top researcher involved in the study of gene therapy, urged the need for companies to keep seeking to expand the options for people with SCD, even after the setback with voxelotor.

“I hope that there’s an appreciation for the need for continued investment in this very serious condition, for which there are insufficient options for treatments,” Dr. Thompson said. “So ongoing investment is really needed if we expect to make progress.”

Dr. Pecker disclosed ties with Novartis, Afimmune, the American Society of Hematology, and the National Institutes of Health. Thompson reported relationships with bluebird bio, Beam, Editas, Novartis, and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The National Alliance of Sickle Cell Centers issued a statement urging patients not to stop voxelotor abruptly. Instead, they should work out plans with their physicians and medical teams for weaning plans.

“Don’t lose faith. This a step backward, but we will stay on the path to better outcomes for everyone,” said the alliance in a statement to patients and clinicians.

On September 25, Pfizer said it would withdraw all lots of voxelotor in all markets where it is approved. The New York–based drugmaker also said it was discontinuing all active voxelotor clinical trials and expanded access programs worldwide. The cause was data that suggested “an imbalance in vaso-occlusive crises and fatal events which require further assessment.”

Pfizer told this news organization in an email exchange that it is focused on analyzing the data and will share updates in the future about presenting or publishing on this issue.

The withdrawal came amid increased scrutiny of the drug by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). The EMA in July began a review of voxelotor after data from a clinical trial showed that a higher number of deaths occurred with the drug than with placebo and another trial showed the total number of deaths was higher than anticipated.

On September 26, the EMA’s human medicines committee recommended suspending the marketing authorization of voxelotor, citing new safety data that emerged during the review. The drug had received marketing authorization for the European Union in 2022, the agency said.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which first cleared voxelotor for sale in 2019, also said it has been conducting a safety review of the drug. The agency continues to examine post-marketing clinical trial data for voxelotor, the real-world registry studies, and data from the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. At the conclusion of this review, the FDA will communicate any additional findings, if necessary, the agency said.

The FDA said it appeared that more deaths and a higher rate of vaso-occlusive crisis occurred in patients taking voxelotor vs placebo in post-marketing clinical trials.

“Pfizer also observed a higher rate of vaso-occlusive crisis in patients with sickle cell disease receiving Oxbryta in two real-world registry studies,” the FDA said. “Based on the totality of clinical data, Pfizer has determined the benefit of Oxbryta does not outweigh the risk.”

Gene Therapy, Tried-and-True Hydroxyurea (HU)

As a field, SCD has drawn more interest in recent years, with significant gains made lately in cutting-edge projects.

The FDA in December approved two gene-editing treatments for patients aged 12 years or older. These are considered “milestone treatments” for a debilitating and potentially life-threatening blood disorder that affects about 100,000 people in the United States. Exagamglogene autotemcel (Casgevy, Vertex Pharmaceuticals and CRISPR Therapeutics) is the first to use the gene-editing tool CRISPR. And lovotibeglogene autotemcel (Lyfgenia, bluebird bio) uses a different gene-editing tool called a lentiviral vector.

These advances have been covered widely by the news media but are not expected to be widely available, with the cost of these extensive treatments estimated around $2-$3 million per patient.

“Gene therapy is amazing in that it can offer a cure, but it’s very expensive and not all patients are suitable for it. Some have so much existing organ damage that it’s not an option for them,” said John Wood, MD, PhD, director of cardiovascular MRI at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, who does research on SCD.

“So it really is a great treatment for a very few people,” he said in an interview.

The mainstay of treatment for SCD remains a drug that Lydia Pecker, MD, a pediatric hematologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, describes as the “first, oldest, and best”: HU.

The FDA approved this in 1998 for use in SCD. It reduces the frequency of painful crises and acute chest syndrome and other complications of SCD that otherwise could be serious or even lethal, Pecker said.

“Older doctors can tell you that what they experienced with sickle cell disease in the hospitals has been completely transformed because of the high uptake of the drug,” she said, adding that it made a “profound” change. “We just don’t have data for any other agent that’s quite like that.”

Voxelotor had been a good second drug to add for some patients, in addition to HU and blood transfusions, Dr. Pecker noted. It was a first-line drug for those for whom transfusion and HU were not options, which constitutes a relatively small number of patients, she said.

“So we have, in the last 5 years, felt more hopeful because we had something else to offer,” she said.

Alexis A. Thompson, MD, MPH, chief of the Division of Hematology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, said in an interview that her organization also had patients who appeared to benefit from voxelotor, some of whom had been participants in clinical trials.

Dr. Thompson, who has been a top researcher involved in the study of gene therapy, urged the need for companies to keep seeking to expand the options for people with SCD, even after the setback with voxelotor.

“I hope that there’s an appreciation for the need for continued investment in this very serious condition, for which there are insufficient options for treatments,” Dr. Thompson said. “So ongoing investment is really needed if we expect to make progress.”

Dr. Pecker disclosed ties with Novartis, Afimmune, the American Society of Hematology, and the National Institutes of Health. Thompson reported relationships with bluebird bio, Beam, Editas, Novartis, and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The National Alliance of Sickle Cell Centers issued a statement urging patients not to stop voxelotor abruptly. Instead, they should work out plans with their physicians and medical teams for weaning plans.

“Don’t lose faith. This a step backward, but we will stay on the path to better outcomes for everyone,” said the alliance in a statement to patients and clinicians.

On September 25, Pfizer said it would withdraw all lots of voxelotor in all markets where it is approved. The New York–based drugmaker also said it was discontinuing all active voxelotor clinical trials and expanded access programs worldwide. The cause was data that suggested “an imbalance in vaso-occlusive crises and fatal events which require further assessment.”

Pfizer told this news organization in an email exchange that it is focused on analyzing the data and will share updates in the future about presenting or publishing on this issue.

The withdrawal came amid increased scrutiny of the drug by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). The EMA in July began a review of voxelotor after data from a clinical trial showed that a higher number of deaths occurred with the drug than with placebo and another trial showed the total number of deaths was higher than anticipated.

On September 26, the EMA’s human medicines committee recommended suspending the marketing authorization of voxelotor, citing new safety data that emerged during the review. The drug had received marketing authorization for the European Union in 2022, the agency said.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which first cleared voxelotor for sale in 2019, also said it has been conducting a safety review of the drug. The agency continues to examine post-marketing clinical trial data for voxelotor, the real-world registry studies, and data from the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. At the conclusion of this review, the FDA will communicate any additional findings, if necessary, the agency said.

The FDA said it appeared that more deaths and a higher rate of vaso-occlusive crisis occurred in patients taking voxelotor vs placebo in post-marketing clinical trials.

“Pfizer also observed a higher rate of vaso-occlusive crisis in patients with sickle cell disease receiving Oxbryta in two real-world registry studies,” the FDA said. “Based on the totality of clinical data, Pfizer has determined the benefit of Oxbryta does not outweigh the risk.”

Gene Therapy, Tried-and-True Hydroxyurea (HU)

As a field, SCD has drawn more interest in recent years, with significant gains made lately in cutting-edge projects.

The FDA in December approved two gene-editing treatments for patients aged 12 years or older. These are considered “milestone treatments” for a debilitating and potentially life-threatening blood disorder that affects about 100,000 people in the United States. Exagamglogene autotemcel (Casgevy, Vertex Pharmaceuticals and CRISPR Therapeutics) is the first to use the gene-editing tool CRISPR. And lovotibeglogene autotemcel (Lyfgenia, bluebird bio) uses a different gene-editing tool called a lentiviral vector.

These advances have been covered widely by the news media but are not expected to be widely available, with the cost of these extensive treatments estimated around $2-$3 million per patient.

“Gene therapy is amazing in that it can offer a cure, but it’s very expensive and not all patients are suitable for it. Some have so much existing organ damage that it’s not an option for them,” said John Wood, MD, PhD, director of cardiovascular MRI at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, who does research on SCD.

“So it really is a great treatment for a very few people,” he said in an interview.

The mainstay of treatment for SCD remains a drug that Lydia Pecker, MD, a pediatric hematologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, describes as the “first, oldest, and best”: HU.

The FDA approved this in 1998 for use in SCD. It reduces the frequency of painful crises and acute chest syndrome and other complications of SCD that otherwise could be serious or even lethal, Pecker said.

“Older doctors can tell you that what they experienced with sickle cell disease in the hospitals has been completely transformed because of the high uptake of the drug,” she said, adding that it made a “profound” change. “We just don’t have data for any other agent that’s quite like that.”

Voxelotor had been a good second drug to add for some patients, in addition to HU and blood transfusions, Dr. Pecker noted. It was a first-line drug for those for whom transfusion and HU were not options, which constitutes a relatively small number of patients, she said.

“So we have, in the last 5 years, felt more hopeful because we had something else to offer,” she said.

Alexis A. Thompson, MD, MPH, chief of the Division of Hematology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, said in an interview that her organization also had patients who appeared to benefit from voxelotor, some of whom had been participants in clinical trials.

Dr. Thompson, who has been a top researcher involved in the study of gene therapy, urged the need for companies to keep seeking to expand the options for people with SCD, even after the setback with voxelotor.

“I hope that there’s an appreciation for the need for continued investment in this very serious condition, for which there are insufficient options for treatments,” Dr. Thompson said. “So ongoing investment is really needed if we expect to make progress.”

Dr. Pecker disclosed ties with Novartis, Afimmune, the American Society of Hematology, and the National Institutes of Health. Thompson reported relationships with bluebird bio, Beam, Editas, Novartis, and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Popular Weight Loss Drugs Now for Patients With Cancer?

Demand for new weight loss drugs has surged over the past few years.

Led by the antiobesity drugs semaglutide (Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Zepbound), these popular medications — more commonly known as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists — have become game changers for shedding excess pounds.

Aside from obesity indications, both drugs have been approved to treat type 2 diabetes under different brand names and have a growing list of other potential benefits, such as reducing inflammation and depression.

While there’s limited data to support the use of GLP-1 agonists for weight loss in cancer, some oncologists have begun carefully integrating the antiobesity agents into care and studying their effects in this patient population.

The reason: Research suggests that obesity can reduce the effectiveness of cancer therapies, especially in patients with breast cancer, and can increase the risk for treatment-related side effects.

The idea is that managing patients’ weight will improve their cancer outcomes, explained Lajos Pusztai, MD, PhD, a breast cancer specialist and professor of medicine at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

Although Dr. Pusztai and his oncology peers at Yale don’t yet use GPL-1 agonists, Neil Iyengar, MD, and colleagues have begun doing so to help some patients with breast cancer manage their weight. Dr. Iyengar estimates that a few hundred — almost 40% — of his patients are on the antiobesity drugs.

“For a patient who has really tried to reduce their weight and who is in the obese range, that’s where I think the use of these medications can be considered,” said Dr. Iyengar, a breast cancer oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

Why GLP-1s in Cancer?

GLP-1 is a hormone that the small intestine releases after eating. GLP-1 agonists work by mimicking GLP-1 to trigger the release of insulin and reduce the production of glucagon — two processes that help regulate blood sugar.

These agents, such as Wegovy (or Ozempic when prescribed for diabetes), also slow gastric emptying and can make people feel fuller longer.

Zebound (or Mounjaro for type 2 diabetes) is considered a dual GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide agonist, which may enhance its weight loss benefits.

In practice, however, these drugs can increase nausea and vomiting from chemotherapy, so Dr. Iyengar typically has patients use them afterwards, during maintenance treatment.

Oncologists don’t prescribe the drugs themselves but instead refer patients to endocrinologists or weight management centers that then write the prescriptions. Taking these drugs involves weekly subcutaneous injections patients can administer themselves.

Endocrinologist Emily Gallagher, MD, PhD, of Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City, estimates she has prescribed the antiobesity drugs to a few hundred patients with cancer and, like Dr. Iyengar, uses the drugs during maintenance treatment with hormone therapy for breast cancer. She also has used these agents in patients with prostate and endometrial cancers and has found the drugs can help counter steroid weight gain in multiple myeloma.

But, to date, the evidence for using GPL-1 agonists in cancer remains limited and the practice has not yet become widespread.

Research largely comes down to a few small retrospective studies in patients with breast cancer receiving aromatase inhibitors. Although no safety issues have emerged so far, these initial reports suggest that the drugs lead to significantly less weight loss in patients with cancer compared to the general population.

Dr. Iyengar led one recent study, presented at the 2024 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, in which he and his team assessed outcomes in 75 women with breast cancer who received a GLP-1 agonist. Almost 80% of patients had diabetes, and 60% received hormone therapy, most commonly an aromatase inhibitor. Patients’ median body mass index (BMI) at baseline was 34 kg/m2 (range, 23-50 kg/m2).

From baseline, patients lost 6.2 kg, on average, or about 5% of their total body weight, 12 months after initiating GLP-1 therapy.

In contrast, phase 3 trials show much higher mean weight loss — about two times — in patients without cancer.

Another recent study also reported modest weight loss results in patients with breast cancer undergoing endocrine therapy. The researchers reported that, at 12 months, Wegovy led to 4.34% reduction in BMI, compared with a 14% change reported in the general population. Zebound, however, was associated with a 2.31% BMI increase overall — though some patients did experience a decrease — compared with a 15% reduction in the general population.

“These findings indicate a substantially reduced weight loss efficacy in breast cancer patients on endocrine therapy compared to the general population,” the authors concluded.

It’s unclear why the drugs appear to not work as well in patients with cancer. It’s possible that hormone therapy or metabolic changes interfere with their effectiveness, given that some cancer therapies lead to weight gain. Steroids and hormone therapies, for instance, often increase appetite, and some treatments can slow patients’ metabolism or lead to fatigue, which can make it harder to exercise.

Patients with cancer may need a higher dose of GLP-1 agonists to achieve similar weight loss to the general population, Dr. Iyengar noted.

However, Dr. Gallagher said, in her own experience, she hasn’t found the drugs to be less effective in patients with cancer, especially the newer agents, like Wegovy and Zepbound.

As for safety, Wegovy and Zepbound both carry a black box warning for thyroid C-cell tumors, including medullary thyroid carcinoma. (Recent research, however, has found that GLP-1 agonists do not increase thyroid cancer risk).

These antiobesity agents are also contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma and in patients who have multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2, which is associated with medullary thyroid carcinoma.

Dr. Gallagher hasn’t seen any secondary tumors — thyroid or otherwise — in her patients with cancer, but she follows the labeling contraindications. Dr. Iyengar also noted that more recent and larger data sets have shown no impact on this risk, which may not actually exist, he said

Dr. Gallagher remains cautious about using GPL-1 agonists in patients who have had bariatric surgery because these agents can compound the slower gastric emptying and intestinal transit from surgery, potentially leading to gastrointestinal obstructions.

Looking ahead, GPL-1 manufacturers are interested in adding cancer indications to the drug labeling. Both Dr. Iyengar and Dr. Gallagher said their institutions are in talks with companies to participate in large, multicenter, global phase 3 trials.

Dr. Iyengar welcomes the efforts, not only to test the effectiveness of GPL-1 agonists in oncology but also to “nail down” their safety in cancer.

“I don’t think that there’s mechanistically anything that’s particularly worrisome,” and current observations suggest that these drugs are likely to be safe, Dr. Iyengar said. Even so, “GLP-1 agonists do a lot of things that we don’t fully understand yet.”

The bigger challenge, Dr. Iyengar noted, is that companies will have to show a sizable benefit to using these drugs in patients with cancer to get the Food and Drug Administration’s approval. And to move the needle on cancer-specific outcomes, these antiobesity drugs will need to demonstrate significant, durable weight loss in patients with cancer.

But if these drugs can do that, “I think it’s going to be one of the biggest advances in medicine and oncology given the obesity and cancer epidemic,” Dr. Iyengar said.

Dr. Iyengar has adviser and/or researcher ties with companies that make or are developing GPL-1 agonists, including AstraZeneca, Novartis, Gilead, and Pfizer. Dr. Gallagher is a consultant for Novartis, Flare Therapeutics, Reactive Biosciences, and Seagen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Demand for new weight loss drugs has surged over the past few years.

Led by the antiobesity drugs semaglutide (Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Zepbound), these popular medications — more commonly known as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists — have become game changers for shedding excess pounds.

Aside from obesity indications, both drugs have been approved to treat type 2 diabetes under different brand names and have a growing list of other potential benefits, such as reducing inflammation and depression.

While there’s limited data to support the use of GLP-1 agonists for weight loss in cancer, some oncologists have begun carefully integrating the antiobesity agents into care and studying their effects in this patient population.

The reason: Research suggests that obesity can reduce the effectiveness of cancer therapies, especially in patients with breast cancer, and can increase the risk for treatment-related side effects.

The idea is that managing patients’ weight will improve their cancer outcomes, explained Lajos Pusztai, MD, PhD, a breast cancer specialist and professor of medicine at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

Although Dr. Pusztai and his oncology peers at Yale don’t yet use GPL-1 agonists, Neil Iyengar, MD, and colleagues have begun doing so to help some patients with breast cancer manage their weight. Dr. Iyengar estimates that a few hundred — almost 40% — of his patients are on the antiobesity drugs.

“For a patient who has really tried to reduce their weight and who is in the obese range, that’s where I think the use of these medications can be considered,” said Dr. Iyengar, a breast cancer oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

Why GLP-1s in Cancer?

GLP-1 is a hormone that the small intestine releases after eating. GLP-1 agonists work by mimicking GLP-1 to trigger the release of insulin and reduce the production of glucagon — two processes that help regulate blood sugar.

These agents, such as Wegovy (or Ozempic when prescribed for diabetes), also slow gastric emptying and can make people feel fuller longer.

Zebound (or Mounjaro for type 2 diabetes) is considered a dual GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide agonist, which may enhance its weight loss benefits.

In practice, however, these drugs can increase nausea and vomiting from chemotherapy, so Dr. Iyengar typically has patients use them afterwards, during maintenance treatment.

Oncologists don’t prescribe the drugs themselves but instead refer patients to endocrinologists or weight management centers that then write the prescriptions. Taking these drugs involves weekly subcutaneous injections patients can administer themselves.

Endocrinologist Emily Gallagher, MD, PhD, of Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City, estimates she has prescribed the antiobesity drugs to a few hundred patients with cancer and, like Dr. Iyengar, uses the drugs during maintenance treatment with hormone therapy for breast cancer. She also has used these agents in patients with prostate and endometrial cancers and has found the drugs can help counter steroid weight gain in multiple myeloma.

But, to date, the evidence for using GPL-1 agonists in cancer remains limited and the practice has not yet become widespread.

Research largely comes down to a few small retrospective studies in patients with breast cancer receiving aromatase inhibitors. Although no safety issues have emerged so far, these initial reports suggest that the drugs lead to significantly less weight loss in patients with cancer compared to the general population.

Dr. Iyengar led one recent study, presented at the 2024 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, in which he and his team assessed outcomes in 75 women with breast cancer who received a GLP-1 agonist. Almost 80% of patients had diabetes, and 60% received hormone therapy, most commonly an aromatase inhibitor. Patients’ median body mass index (BMI) at baseline was 34 kg/m2 (range, 23-50 kg/m2).

From baseline, patients lost 6.2 kg, on average, or about 5% of their total body weight, 12 months after initiating GLP-1 therapy.

In contrast, phase 3 trials show much higher mean weight loss — about two times — in patients without cancer.

Another recent study also reported modest weight loss results in patients with breast cancer undergoing endocrine therapy. The researchers reported that, at 12 months, Wegovy led to 4.34% reduction in BMI, compared with a 14% change reported in the general population. Zebound, however, was associated with a 2.31% BMI increase overall — though some patients did experience a decrease — compared with a 15% reduction in the general population.

“These findings indicate a substantially reduced weight loss efficacy in breast cancer patients on endocrine therapy compared to the general population,” the authors concluded.

It’s unclear why the drugs appear to not work as well in patients with cancer. It’s possible that hormone therapy or metabolic changes interfere with their effectiveness, given that some cancer therapies lead to weight gain. Steroids and hormone therapies, for instance, often increase appetite, and some treatments can slow patients’ metabolism or lead to fatigue, which can make it harder to exercise.

Patients with cancer may need a higher dose of GLP-1 agonists to achieve similar weight loss to the general population, Dr. Iyengar noted.

However, Dr. Gallagher said, in her own experience, she hasn’t found the drugs to be less effective in patients with cancer, especially the newer agents, like Wegovy and Zepbound.

As for safety, Wegovy and Zepbound both carry a black box warning for thyroid C-cell tumors, including medullary thyroid carcinoma. (Recent research, however, has found that GLP-1 agonists do not increase thyroid cancer risk).

These antiobesity agents are also contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma and in patients who have multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2, which is associated with medullary thyroid carcinoma.

Dr. Gallagher hasn’t seen any secondary tumors — thyroid or otherwise — in her patients with cancer, but she follows the labeling contraindications. Dr. Iyengar also noted that more recent and larger data sets have shown no impact on this risk, which may not actually exist, he said

Dr. Gallagher remains cautious about using GPL-1 agonists in patients who have had bariatric surgery because these agents can compound the slower gastric emptying and intestinal transit from surgery, potentially leading to gastrointestinal obstructions.

Looking ahead, GPL-1 manufacturers are interested in adding cancer indications to the drug labeling. Both Dr. Iyengar and Dr. Gallagher said their institutions are in talks with companies to participate in large, multicenter, global phase 3 trials.

Dr. Iyengar welcomes the efforts, not only to test the effectiveness of GPL-1 agonists in oncology but also to “nail down” their safety in cancer.

“I don’t think that there’s mechanistically anything that’s particularly worrisome,” and current observations suggest that these drugs are likely to be safe, Dr. Iyengar said. Even so, “GLP-1 agonists do a lot of things that we don’t fully understand yet.”

The bigger challenge, Dr. Iyengar noted, is that companies will have to show a sizable benefit to using these drugs in patients with cancer to get the Food and Drug Administration’s approval. And to move the needle on cancer-specific outcomes, these antiobesity drugs will need to demonstrate significant, durable weight loss in patients with cancer.

But if these drugs can do that, “I think it’s going to be one of the biggest advances in medicine and oncology given the obesity and cancer epidemic,” Dr. Iyengar said.

Dr. Iyengar has adviser and/or researcher ties with companies that make or are developing GPL-1 agonists, including AstraZeneca, Novartis, Gilead, and Pfizer. Dr. Gallagher is a consultant for Novartis, Flare Therapeutics, Reactive Biosciences, and Seagen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Demand for new weight loss drugs has surged over the past few years.

Led by the antiobesity drugs semaglutide (Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Zepbound), these popular medications — more commonly known as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists — have become game changers for shedding excess pounds.

Aside from obesity indications, both drugs have been approved to treat type 2 diabetes under different brand names and have a growing list of other potential benefits, such as reducing inflammation and depression.

While there’s limited data to support the use of GLP-1 agonists for weight loss in cancer, some oncologists have begun carefully integrating the antiobesity agents into care and studying their effects in this patient population.

The reason: Research suggests that obesity can reduce the effectiveness of cancer therapies, especially in patients with breast cancer, and can increase the risk for treatment-related side effects.

The idea is that managing patients’ weight will improve their cancer outcomes, explained Lajos Pusztai, MD, PhD, a breast cancer specialist and professor of medicine at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

Although Dr. Pusztai and his oncology peers at Yale don’t yet use GPL-1 agonists, Neil Iyengar, MD, and colleagues have begun doing so to help some patients with breast cancer manage their weight. Dr. Iyengar estimates that a few hundred — almost 40% — of his patients are on the antiobesity drugs.

“For a patient who has really tried to reduce their weight and who is in the obese range, that’s where I think the use of these medications can be considered,” said Dr. Iyengar, a breast cancer oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

Why GLP-1s in Cancer?

GLP-1 is a hormone that the small intestine releases after eating. GLP-1 agonists work by mimicking GLP-1 to trigger the release of insulin and reduce the production of glucagon — two processes that help regulate blood sugar.

These agents, such as Wegovy (or Ozempic when prescribed for diabetes), also slow gastric emptying and can make people feel fuller longer.

Zebound (or Mounjaro for type 2 diabetes) is considered a dual GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide agonist, which may enhance its weight loss benefits.

In practice, however, these drugs can increase nausea and vomiting from chemotherapy, so Dr. Iyengar typically has patients use them afterwards, during maintenance treatment.

Oncologists don’t prescribe the drugs themselves but instead refer patients to endocrinologists or weight management centers that then write the prescriptions. Taking these drugs involves weekly subcutaneous injections patients can administer themselves.

Endocrinologist Emily Gallagher, MD, PhD, of Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City, estimates she has prescribed the antiobesity drugs to a few hundred patients with cancer and, like Dr. Iyengar, uses the drugs during maintenance treatment with hormone therapy for breast cancer. She also has used these agents in patients with prostate and endometrial cancers and has found the drugs can help counter steroid weight gain in multiple myeloma.

But, to date, the evidence for using GPL-1 agonists in cancer remains limited and the practice has not yet become widespread.

Research largely comes down to a few small retrospective studies in patients with breast cancer receiving aromatase inhibitors. Although no safety issues have emerged so far, these initial reports suggest that the drugs lead to significantly less weight loss in patients with cancer compared to the general population.

Dr. Iyengar led one recent study, presented at the 2024 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, in which he and his team assessed outcomes in 75 women with breast cancer who received a GLP-1 agonist. Almost 80% of patients had diabetes, and 60% received hormone therapy, most commonly an aromatase inhibitor. Patients’ median body mass index (BMI) at baseline was 34 kg/m2 (range, 23-50 kg/m2).

From baseline, patients lost 6.2 kg, on average, or about 5% of their total body weight, 12 months after initiating GLP-1 therapy.

In contrast, phase 3 trials show much higher mean weight loss — about two times — in patients without cancer.

Another recent study also reported modest weight loss results in patients with breast cancer undergoing endocrine therapy. The researchers reported that, at 12 months, Wegovy led to 4.34% reduction in BMI, compared with a 14% change reported in the general population. Zebound, however, was associated with a 2.31% BMI increase overall — though some patients did experience a decrease — compared with a 15% reduction in the general population.

“These findings indicate a substantially reduced weight loss efficacy in breast cancer patients on endocrine therapy compared to the general population,” the authors concluded.

It’s unclear why the drugs appear to not work as well in patients with cancer. It’s possible that hormone therapy or metabolic changes interfere with their effectiveness, given that some cancer therapies lead to weight gain. Steroids and hormone therapies, for instance, often increase appetite, and some treatments can slow patients’ metabolism or lead to fatigue, which can make it harder to exercise.

Patients with cancer may need a higher dose of GLP-1 agonists to achieve similar weight loss to the general population, Dr. Iyengar noted.

However, Dr. Gallagher said, in her own experience, she hasn’t found the drugs to be less effective in patients with cancer, especially the newer agents, like Wegovy and Zepbound.

As for safety, Wegovy and Zepbound both carry a black box warning for thyroid C-cell tumors, including medullary thyroid carcinoma. (Recent research, however, has found that GLP-1 agonists do not increase thyroid cancer risk).

These antiobesity agents are also contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma and in patients who have multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2, which is associated with medullary thyroid carcinoma.

Dr. Gallagher hasn’t seen any secondary tumors — thyroid or otherwise — in her patients with cancer, but she follows the labeling contraindications. Dr. Iyengar also noted that more recent and larger data sets have shown no impact on this risk, which may not actually exist, he said

Dr. Gallagher remains cautious about using GPL-1 agonists in patients who have had bariatric surgery because these agents can compound the slower gastric emptying and intestinal transit from surgery, potentially leading to gastrointestinal obstructions.

Looking ahead, GPL-1 manufacturers are interested in adding cancer indications to the drug labeling. Both Dr. Iyengar and Dr. Gallagher said their institutions are in talks with companies to participate in large, multicenter, global phase 3 trials.

Dr. Iyengar welcomes the efforts, not only to test the effectiveness of GPL-1 agonists in oncology but also to “nail down” their safety in cancer.

“I don’t think that there’s mechanistically anything that’s particularly worrisome,” and current observations suggest that these drugs are likely to be safe, Dr. Iyengar said. Even so, “GLP-1 agonists do a lot of things that we don’t fully understand yet.”

The bigger challenge, Dr. Iyengar noted, is that companies will have to show a sizable benefit to using these drugs in patients with cancer to get the Food and Drug Administration’s approval. And to move the needle on cancer-specific outcomes, these antiobesity drugs will need to demonstrate significant, durable weight loss in patients with cancer.

But if these drugs can do that, “I think it’s going to be one of the biggest advances in medicine and oncology given the obesity and cancer epidemic,” Dr. Iyengar said.

Dr. Iyengar has adviser and/or researcher ties with companies that make or are developing GPL-1 agonists, including AstraZeneca, Novartis, Gilead, and Pfizer. Dr. Gallagher is a consultant for Novartis, Flare Therapeutics, Reactive Biosciences, and Seagen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Prominent NIH Neuroscientist Fired Over Alleged Research Misconduct

, the NIH said in a statement.

The misconduct involved “falsification and/or fabrication involving reuse and relabel of figure panels representing different experimental results in two publications,” the NIH said.

The agency said it will notify the two journals of its findings so that appropriate action can be taken.

The NIH reportedly launched its probe into potential research misconduct in May 2023 after it received allegations from the Health and Human Service (HHS) Office of Research Integrity (ORI) that month.

The investigation phase began in December 2023 and concluded on September 15, 2024. The institute subsequently notified HHS ORI of its findings.

Dr. Masliah joined the NIH in the summer of 2016 as director of the Division of Neuroscience at the NIA and an NIH intramural researcher investigating synaptic damage in neurodegenerative disorders, publishing “numerous” papers, the NIH said.

Given the findings of their investigation, the NIH said, Dr. Masliah is no longer serving as director of NIA’s Division of Neuroscience.

NIA deputy director Amy Kelley, MD, is now acting director of NIA’s neuroscience division.

Consistent with NIH policies and procedures, any allegations involving Dr. Masliah’s NIH-supported extramural research prior to joining NIH would be referred to HHS ORI, the NIH said.

The NIH announcement came on the same day that Science magazine published an investigative piece suggesting that Dr. Masliah may have fabricated or falsified images or other information in far more than the two studies NIH cited.

According to the article, “scores” of Dr. Masliah’s lab studies conducted at the NIA and the University of California San Diego are “riddled with apparently falsified Western blots — images used to show the presence of proteins — and micrographs of brain tissue. Numerous images seem to have been inappropriately reused within and across papers, sometimes published years apart in different journals, describing divergent experimental conditions.”

The article noted that a neuroscientist and forensic analysts who had previously worked with Science magazine produced a “300-page dossier revealing a steady stream of suspect images between 1997 and 2023 in 132 of his published research papers.”

They concluded that this “pattern of anomalous data raises a credible concern for research misconduct and calls into question a remarkably large body of scientific work,” the Science article stated.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, the NIH said in a statement.

The misconduct involved “falsification and/or fabrication involving reuse and relabel of figure panels representing different experimental results in two publications,” the NIH said.

The agency said it will notify the two journals of its findings so that appropriate action can be taken.

The NIH reportedly launched its probe into potential research misconduct in May 2023 after it received allegations from the Health and Human Service (HHS) Office of Research Integrity (ORI) that month.

The investigation phase began in December 2023 and concluded on September 15, 2024. The institute subsequently notified HHS ORI of its findings.

Dr. Masliah joined the NIH in the summer of 2016 as director of the Division of Neuroscience at the NIA and an NIH intramural researcher investigating synaptic damage in neurodegenerative disorders, publishing “numerous” papers, the NIH said.

Given the findings of their investigation, the NIH said, Dr. Masliah is no longer serving as director of NIA’s Division of Neuroscience.

NIA deputy director Amy Kelley, MD, is now acting director of NIA’s neuroscience division.

Consistent with NIH policies and procedures, any allegations involving Dr. Masliah’s NIH-supported extramural research prior to joining NIH would be referred to HHS ORI, the NIH said.

The NIH announcement came on the same day that Science magazine published an investigative piece suggesting that Dr. Masliah may have fabricated or falsified images or other information in far more than the two studies NIH cited.

According to the article, “scores” of Dr. Masliah’s lab studies conducted at the NIA and the University of California San Diego are “riddled with apparently falsified Western blots — images used to show the presence of proteins — and micrographs of brain tissue. Numerous images seem to have been inappropriately reused within and across papers, sometimes published years apart in different journals, describing divergent experimental conditions.”

The article noted that a neuroscientist and forensic analysts who had previously worked with Science magazine produced a “300-page dossier revealing a steady stream of suspect images between 1997 and 2023 in 132 of his published research papers.”

They concluded that this “pattern of anomalous data raises a credible concern for research misconduct and calls into question a remarkably large body of scientific work,” the Science article stated.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, the NIH said in a statement.

The misconduct involved “falsification and/or fabrication involving reuse and relabel of figure panels representing different experimental results in two publications,” the NIH said.

The agency said it will notify the two journals of its findings so that appropriate action can be taken.

The NIH reportedly launched its probe into potential research misconduct in May 2023 after it received allegations from the Health and Human Service (HHS) Office of Research Integrity (ORI) that month.

The investigation phase began in December 2023 and concluded on September 15, 2024. The institute subsequently notified HHS ORI of its findings.

Dr. Masliah joined the NIH in the summer of 2016 as director of the Division of Neuroscience at the NIA and an NIH intramural researcher investigating synaptic damage in neurodegenerative disorders, publishing “numerous” papers, the NIH said.

Given the findings of their investigation, the NIH said, Dr. Masliah is no longer serving as director of NIA’s Division of Neuroscience.

NIA deputy director Amy Kelley, MD, is now acting director of NIA’s neuroscience division.

Consistent with NIH policies and procedures, any allegations involving Dr. Masliah’s NIH-supported extramural research prior to joining NIH would be referred to HHS ORI, the NIH said.

The NIH announcement came on the same day that Science magazine published an investigative piece suggesting that Dr. Masliah may have fabricated or falsified images or other information in far more than the two studies NIH cited.

According to the article, “scores” of Dr. Masliah’s lab studies conducted at the NIA and the University of California San Diego are “riddled with apparently falsified Western blots — images used to show the presence of proteins — and micrographs of brain tissue. Numerous images seem to have been inappropriately reused within and across papers, sometimes published years apart in different journals, describing divergent experimental conditions.”

The article noted that a neuroscientist and forensic analysts who had previously worked with Science magazine produced a “300-page dossier revealing a steady stream of suspect images between 1997 and 2023 in 132 of his published research papers.”

They concluded that this “pattern of anomalous data raises a credible concern for research misconduct and calls into question a remarkably large body of scientific work,” the Science article stated.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Editor's Note: 2024 Rare Neurological Disease Report

EDITOR’S NOTE

This year, we again focus on rare neurological diseases that have new therapies that have been recently approved as well as conditions for which the treatment pipeline is robust. Let’s hope the work of many dedicated researchers adds to the list of rare neurological diseases for which treatment is available.

This year also marks a change of leadership at NORD, our publishing partner in this annual supplement. We here at Neurology Reviews salute the leadership and accomplishments of former NORD CEO Peter Saltonstall and also welcome incoming CEO Pamela Gavin, who has spent many years in NORD leadership roles and was essential in the planning, launch, and early years of this annual supplement. I can think of no one better than Pamela Gavin to continue NORD’s mission into the future.

And finally, a recap of accolades for this annual supplement. For the second year in a row, the Rare Neurological Disease Special Report has won an Azbee award in the category of annual supplement from the American Society of Business Publication Editors. The 2023 issue won a National Gold Award and a Regional Gold Award.

—Glenn Williams, VP, Group Editor, Neurology Reviews and MDedge Neurology

A NOTE FROM NORD

Hello, and Welcome! The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) is pleased to partner with Neurology Reviews to bring you the 2024 edition of the Rare Neurological Disease Report. Through this collaboration, we share cutting-edge research and insights from leading medical experts, including specialists from the NORD Rare Disease Centers of Excellence network, about the latest advances in the treatment of rare neurological conditions.

As healthcare providers, you play a key role in catalyzing advancements and bringing new hope and possibilities to the rare disease community. Your efforts can contribute to shortening the diagnostic odyssey and improving day-to-day care for people living with rare disorders in crucial ways:

Identifying patients: Healthcare providers can recognize the possible signs of a rare disease and initiate further investigation or referral to specialists. Early detection is key as it can lead to a quicker, more accurate diagnosis, better management, and improved outcomes.

Educating other physicians: Many rare diseases are not well-known or understood by the general medical community. Healthcare providers can help bridge this knowledge gap by educating other physicians about rare conditions. They can raise awareness through clinical teaching, seminars, medical literature, or continuing medical education (CME) sessions focused on rare diseases. Raising awareness and providing up-to-date information about rare diseases bolsters diagnostic and treatment capabilities within the medical field.

Providing information to patients: Once a rare disease is identified, healthcare providers can offer valuable support to patients and their families. They can provide potential treatments and management strategies. They can also connect patients with support groups, support programs, educational resources, and specialists with expertise in specific rare conditions. Clear communication and guidance on support resources can positively impact patients’ well-being, empower them to make informed decisions, and help them navigate a complex rare condition.

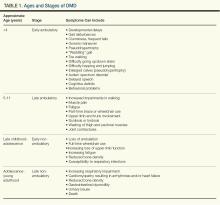

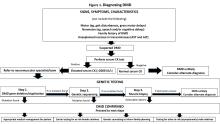

This issue of the Rare Disease Neurological Special Report features articles by rare disease medical experts on specific diseases with updates on clinical management. Topics include the diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, the promise of disease-modifying therapies for Huntington’s disease, patient choices and cultural changes around myasthenia gravis, advances in neuromyelitis optica, and untangling chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. In addition, two online-only articles offer timely insights from key opinion leaders on the pros and cons of genetic testing and what clinicians need to know about newborn screening.

You will also find information about the NORD Rare Diseases and Orphan Products Breakthrough Summit. This annual event convenes thought leaders from patient advocacy organizations, industry, academia, medical and research institutions, and government to discuss critical topics facing the rare disease community.

NORD is deeply appreciative of healthcare professionals like you, who despite long hours and demanding workloads, remain committed to staying up to date on the latest medical advances for the benefit of their patients. Your dedication and hard work make a significant difference to the patients and families we serve, and your commitment does not go unnoticed. Thank you for all that you do.

—Pamela Gavin, NORD Chief Executive Officer

EDITOR’S NOTE

This year, we again focus on rare neurological diseases that have new therapies that have been recently approved as well as conditions for which the treatment pipeline is robust. Let’s hope the work of many dedicated researchers adds to the list of rare neurological diseases for which treatment is available.

This year also marks a change of leadership at NORD, our publishing partner in this annual supplement. We here at Neurology Reviews salute the leadership and accomplishments of former NORD CEO Peter Saltonstall and also welcome incoming CEO Pamela Gavin, who has spent many years in NORD leadership roles and was essential in the planning, launch, and early years of this annual supplement. I can think of no one better than Pamela Gavin to continue NORD’s mission into the future.

And finally, a recap of accolades for this annual supplement. For the second year in a row, the Rare Neurological Disease Special Report has won an Azbee award in the category of annual supplement from the American Society of Business Publication Editors. The 2023 issue won a National Gold Award and a Regional Gold Award.

—Glenn Williams, VP, Group Editor, Neurology Reviews and MDedge Neurology

A NOTE FROM NORD

Hello, and Welcome! The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) is pleased to partner with Neurology Reviews to bring you the 2024 edition of the Rare Neurological Disease Report. Through this collaboration, we share cutting-edge research and insights from leading medical experts, including specialists from the NORD Rare Disease Centers of Excellence network, about the latest advances in the treatment of rare neurological conditions.

As healthcare providers, you play a key role in catalyzing advancements and bringing new hope and possibilities to the rare disease community. Your efforts can contribute to shortening the diagnostic odyssey and improving day-to-day care for people living with rare disorders in crucial ways:

Identifying patients: Healthcare providers can recognize the possible signs of a rare disease and initiate further investigation or referral to specialists. Early detection is key as it can lead to a quicker, more accurate diagnosis, better management, and improved outcomes.

Educating other physicians: Many rare diseases are not well-known or understood by the general medical community. Healthcare providers can help bridge this knowledge gap by educating other physicians about rare conditions. They can raise awareness through clinical teaching, seminars, medical literature, or continuing medical education (CME) sessions focused on rare diseases. Raising awareness and providing up-to-date information about rare diseases bolsters diagnostic and treatment capabilities within the medical field.

Providing information to patients: Once a rare disease is identified, healthcare providers can offer valuable support to patients and their families. They can provide potential treatments and management strategies. They can also connect patients with support groups, support programs, educational resources, and specialists with expertise in specific rare conditions. Clear communication and guidance on support resources can positively impact patients’ well-being, empower them to make informed decisions, and help them navigate a complex rare condition.

This issue of the Rare Disease Neurological Special Report features articles by rare disease medical experts on specific diseases with updates on clinical management. Topics include the diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, the promise of disease-modifying therapies for Huntington’s disease, patient choices and cultural changes around myasthenia gravis, advances in neuromyelitis optica, and untangling chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. In addition, two online-only articles offer timely insights from key opinion leaders on the pros and cons of genetic testing and what clinicians need to know about newborn screening.

You will also find information about the NORD Rare Diseases and Orphan Products Breakthrough Summit. This annual event convenes thought leaders from patient advocacy organizations, industry, academia, medical and research institutions, and government to discuss critical topics facing the rare disease community.

NORD is deeply appreciative of healthcare professionals like you, who despite long hours and demanding workloads, remain committed to staying up to date on the latest medical advances for the benefit of their patients. Your dedication and hard work make a significant difference to the patients and families we serve, and your commitment does not go unnoticed. Thank you for all that you do.

—Pamela Gavin, NORD Chief Executive Officer

EDITOR’S NOTE

This year, we again focus on rare neurological diseases that have new therapies that have been recently approved as well as conditions for which the treatment pipeline is robust. Let’s hope the work of many dedicated researchers adds to the list of rare neurological diseases for which treatment is available.

This year also marks a change of leadership at NORD, our publishing partner in this annual supplement. We here at Neurology Reviews salute the leadership and accomplishments of former NORD CEO Peter Saltonstall and also welcome incoming CEO Pamela Gavin, who has spent many years in NORD leadership roles and was essential in the planning, launch, and early years of this annual supplement. I can think of no one better than Pamela Gavin to continue NORD’s mission into the future.

And finally, a recap of accolades for this annual supplement. For the second year in a row, the Rare Neurological Disease Special Report has won an Azbee award in the category of annual supplement from the American Society of Business Publication Editors. The 2023 issue won a National Gold Award and a Regional Gold Award.

—Glenn Williams, VP, Group Editor, Neurology Reviews and MDedge Neurology

A NOTE FROM NORD

Hello, and Welcome! The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) is pleased to partner with Neurology Reviews to bring you the 2024 edition of the Rare Neurological Disease Report. Through this collaboration, we share cutting-edge research and insights from leading medical experts, including specialists from the NORD Rare Disease Centers of Excellence network, about the latest advances in the treatment of rare neurological conditions.

As healthcare providers, you play a key role in catalyzing advancements and bringing new hope and possibilities to the rare disease community. Your efforts can contribute to shortening the diagnostic odyssey and improving day-to-day care for people living with rare disorders in crucial ways:

Identifying patients: Healthcare providers can recognize the possible signs of a rare disease and initiate further investigation or referral to specialists. Early detection is key as it can lead to a quicker, more accurate diagnosis, better management, and improved outcomes.

Educating other physicians: Many rare diseases are not well-known or understood by the general medical community. Healthcare providers can help bridge this knowledge gap by educating other physicians about rare conditions. They can raise awareness through clinical teaching, seminars, medical literature, or continuing medical education (CME) sessions focused on rare diseases. Raising awareness and providing up-to-date information about rare diseases bolsters diagnostic and treatment capabilities within the medical field.

Providing information to patients: Once a rare disease is identified, healthcare providers can offer valuable support to patients and their families. They can provide potential treatments and management strategies. They can also connect patients with support groups, support programs, educational resources, and specialists with expertise in specific rare conditions. Clear communication and guidance on support resources can positively impact patients’ well-being, empower them to make informed decisions, and help them navigate a complex rare condition.

This issue of the Rare Disease Neurological Special Report features articles by rare disease medical experts on specific diseases with updates on clinical management. Topics include the diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, the promise of disease-modifying therapies for Huntington’s disease, patient choices and cultural changes around myasthenia gravis, advances in neuromyelitis optica, and untangling chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. In addition, two online-only articles offer timely insights from key opinion leaders on the pros and cons of genetic testing and what clinicians need to know about newborn screening.

You will also find information about the NORD Rare Diseases and Orphan Products Breakthrough Summit. This annual event convenes thought leaders from patient advocacy organizations, industry, academia, medical and research institutions, and government to discuss critical topics facing the rare disease community.

NORD is deeply appreciative of healthcare professionals like you, who despite long hours and demanding workloads, remain committed to staying up to date on the latest medical advances for the benefit of their patients. Your dedication and hard work make a significant difference to the patients and families we serve, and your commitment does not go unnoticed. Thank you for all that you do.

—Pamela Gavin, NORD Chief Executive Officer

FDA Panel Votes for Limits on Gastric, Esophageal Cancer Immunotherapy

During the meeting, the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) voted in favor of restricting the use of these immunotherapy agents to patients with programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression of 1% or higher.

The agency usually follows the ODAC’s advice.

The FDA had originally approved the two immune checkpoint inhibitors for both indications in combination with chemotherapy, regardless of patients’ PD-L1 status. The FDA had also approved nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab for esophageal cancer, regardless of PD-L1 expression. The approvals were based on overall benefit in intent-to-treat populations, not on specific PD-L1 expression subgroups.

Since then, additional studies — including the agency’s own pooled analyses of the approval trials — have found that overall survival benefits are limited to patients with PD-L1 expression of 1% or higher.

These findings have raised concerns that patients with no or low PD-L1 expression face the risks associated with immunotherapy, which include death, but minimal to no benefits.

In response, the FDA has considered changing the labeling for these indications to require a PD-L1 cutoff point of 1% or higher. The move would mirror guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network that already recommend use with chemotherapy only at certain PD-L1 cutoffs.

Before the agency acts, however, the FDA wanted the advice of the ODAC. It asked the 14-member panel whether the risk-benefit assessment is “favorable for the use of PD-1 inhibitors in first line” for the two indications among patients with PD-L1 expression below 1%.

In two nearly unanimous decisions for each indication, the panel voted that risk-benefit assessment was not favorable. In other words, the risks do outweigh the benefits for this patient population with no or low PD-L1 expression.

The determination also applies to tislelizumab (Tevimbra), an immune checkpoint inhibitor under review by the FDA for the same indications.

Voting came after hours of testimony from FDA scientists and the three drug companies involved in the decisions.

Merck, maker of pembrolizumab, was against any labeling change. Nivolumab’s maker, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), also wanted to stick with the current PD-L1 agnostic indications but said that any indication change should be class-wide to avoid confusion. BeiGene USA, maker of tislelizumab, had no problem with a PD-L1 cutoff of 1% because its approval trial showed benefit only in patients at that level or higher.

In general, Merck and BMS said the drug benefits correspond with higher PD-L1 expression but noted that patients with low or no PD-L1 expression can sometimes benefit from treatment. The companies had several patients testify to the benefits of the agents and noted patients like this would likely lose access. But an ODAC panelist noted that patients who died from immunotherapy complications weren’t there to respond.

The companies also expressed concern about taking treatment decisions out of the hands of oncologists as well as the need for additional biopsies to determine if tumors cross the proposed PD-L1 threshold at some point during treatment. With this potential new restriction, the companies were worried that insurance companies would be even less likely to pay for their checkpoint inhibitors in low or no PD-L1 expressors.

ODAC wasn’t moved. With consistent findings across multiple trials, the strength of the FDA’s data carried the day.

In a pooled analysis of the three companies’ unresectable or metastatic HER2–negative, microsatellite-stable gastric/gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma approval trials across almost 4000 patients, those with PD-L1 levels below 1% did not demonstrate a significant overall survival benefit (hazard ratio [HR], 0.91; 95% CI, 0.75-1.09). The median overall survival with immunotherapy plus chemotherapy was only 1 month more — 13.4 months vs 12.4 months with chemotherapy alone.

FDA’s pooled analysis for unresectable or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma also showed no overall survival benefit (HR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.76-1.58), with a trend suggesting harm. Median overall survival with immunotherapy plus chemotherapy was 14.6 months vs 9.8 months with chemotherapy alone.

Despite the vote on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, panelists had reservations about making decisions based on just over 160 patients with PD-L1 levels below 1% in the three esophageal squamous cell carcinoma trials.

Still, one panelist said, it’s likely “the best dataset we will get.”

The companies all used different methods to test PD-L1 levels, and attendees called for a single standardized PD-L1 test. Richard Pazdur, MD, head of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, said the agency has been working with companies for years to get them to agree to such a test, with no luck.

If the FDA ultimately decides to restrict immunotherapy use in this patient population based on PD-L1 levels, insurance company coverage may become more limited. Pazdur asked the companies if they would be willing to expand their patient assistance programs to provide free coverage of immune checkpoint blockers to patients with low or no PD-L1 expression.

BeiGene and BMS seemed open to the idea. Merck said, “We’ll have to ... think about it.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

During the meeting, the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) voted in favor of restricting the use of these immunotherapy agents to patients with programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression of 1% or higher.

The agency usually follows the ODAC’s advice.

The FDA had originally approved the two immune checkpoint inhibitors for both indications in combination with chemotherapy, regardless of patients’ PD-L1 status. The FDA had also approved nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab for esophageal cancer, regardless of PD-L1 expression. The approvals were based on overall benefit in intent-to-treat populations, not on specific PD-L1 expression subgroups.

Since then, additional studies — including the agency’s own pooled analyses of the approval trials — have found that overall survival benefits are limited to patients with PD-L1 expression of 1% or higher.

These findings have raised concerns that patients with no or low PD-L1 expression face the risks associated with immunotherapy, which include death, but minimal to no benefits.

In response, the FDA has considered changing the labeling for these indications to require a PD-L1 cutoff point of 1% or higher. The move would mirror guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network that already recommend use with chemotherapy only at certain PD-L1 cutoffs.

Before the agency acts, however, the FDA wanted the advice of the ODAC. It asked the 14-member panel whether the risk-benefit assessment is “favorable for the use of PD-1 inhibitors in first line” for the two indications among patients with PD-L1 expression below 1%.

In two nearly unanimous decisions for each indication, the panel voted that risk-benefit assessment was not favorable. In other words, the risks do outweigh the benefits for this patient population with no or low PD-L1 expression.

The determination also applies to tislelizumab (Tevimbra), an immune checkpoint inhibitor under review by the FDA for the same indications.

Voting came after hours of testimony from FDA scientists and the three drug companies involved in the decisions.

Merck, maker of pembrolizumab, was against any labeling change. Nivolumab’s maker, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), also wanted to stick with the current PD-L1 agnostic indications but said that any indication change should be class-wide to avoid confusion. BeiGene USA, maker of tislelizumab, had no problem with a PD-L1 cutoff of 1% because its approval trial showed benefit only in patients at that level or higher.

In general, Merck and BMS said the drug benefits correspond with higher PD-L1 expression but noted that patients with low or no PD-L1 expression can sometimes benefit from treatment. The companies had several patients testify to the benefits of the agents and noted patients like this would likely lose access. But an ODAC panelist noted that patients who died from immunotherapy complications weren’t there to respond.

The companies also expressed concern about taking treatment decisions out of the hands of oncologists as well as the need for additional biopsies to determine if tumors cross the proposed PD-L1 threshold at some point during treatment. With this potential new restriction, the companies were worried that insurance companies would be even less likely to pay for their checkpoint inhibitors in low or no PD-L1 expressors.

ODAC wasn’t moved. With consistent findings across multiple trials, the strength of the FDA’s data carried the day.

In a pooled analysis of the three companies’ unresectable or metastatic HER2–negative, microsatellite-stable gastric/gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma approval trials across almost 4000 patients, those with PD-L1 levels below 1% did not demonstrate a significant overall survival benefit (hazard ratio [HR], 0.91; 95% CI, 0.75-1.09). The median overall survival with immunotherapy plus chemotherapy was only 1 month more — 13.4 months vs 12.4 months with chemotherapy alone.

FDA’s pooled analysis for unresectable or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma also showed no overall survival benefit (HR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.76-1.58), with a trend suggesting harm. Median overall survival with immunotherapy plus chemotherapy was 14.6 months vs 9.8 months with chemotherapy alone.

Despite the vote on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, panelists had reservations about making decisions based on just over 160 patients with PD-L1 levels below 1% in the three esophageal squamous cell carcinoma trials.

Still, one panelist said, it’s likely “the best dataset we will get.”

The companies all used different methods to test PD-L1 levels, and attendees called for a single standardized PD-L1 test. Richard Pazdur, MD, head of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, said the agency has been working with companies for years to get them to agree to such a test, with no luck.

If the FDA ultimately decides to restrict immunotherapy use in this patient population based on PD-L1 levels, insurance company coverage may become more limited. Pazdur asked the companies if they would be willing to expand their patient assistance programs to provide free coverage of immune checkpoint blockers to patients with low or no PD-L1 expression.

BeiGene and BMS seemed open to the idea. Merck said, “We’ll have to ... think about it.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

During the meeting, the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) voted in favor of restricting the use of these immunotherapy agents to patients with programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression of 1% or higher.

The agency usually follows the ODAC’s advice.

The FDA had originally approved the two immune checkpoint inhibitors for both indications in combination with chemotherapy, regardless of patients’ PD-L1 status. The FDA had also approved nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab for esophageal cancer, regardless of PD-L1 expression. The approvals were based on overall benefit in intent-to-treat populations, not on specific PD-L1 expression subgroups.

Since then, additional studies — including the agency’s own pooled analyses of the approval trials — have found that overall survival benefits are limited to patients with PD-L1 expression of 1% or higher.

These findings have raised concerns that patients with no or low PD-L1 expression face the risks associated with immunotherapy, which include death, but minimal to no benefits.

In response, the FDA has considered changing the labeling for these indications to require a PD-L1 cutoff point of 1% or higher. The move would mirror guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network that already recommend use with chemotherapy only at certain PD-L1 cutoffs.

Before the agency acts, however, the FDA wanted the advice of the ODAC. It asked the 14-member panel whether the risk-benefit assessment is “favorable for the use of PD-1 inhibitors in first line” for the two indications among patients with PD-L1 expression below 1%.

In two nearly unanimous decisions for each indication, the panel voted that risk-benefit assessment was not favorable. In other words, the risks do outweigh the benefits for this patient population with no or low PD-L1 expression.

The determination also applies to tislelizumab (Tevimbra), an immune checkpoint inhibitor under review by the FDA for the same indications.

Voting came after hours of testimony from FDA scientists and the three drug companies involved in the decisions.

Merck, maker of pembrolizumab, was against any labeling change. Nivolumab’s maker, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), also wanted to stick with the current PD-L1 agnostic indications but said that any indication change should be class-wide to avoid confusion. BeiGene USA, maker of tislelizumab, had no problem with a PD-L1 cutoff of 1% because its approval trial showed benefit only in patients at that level or higher.

In general, Merck and BMS said the drug benefits correspond with higher PD-L1 expression but noted that patients with low or no PD-L1 expression can sometimes benefit from treatment. The companies had several patients testify to the benefits of the agents and noted patients like this would likely lose access. But an ODAC panelist noted that patients who died from immunotherapy complications weren’t there to respond.

The companies also expressed concern about taking treatment decisions out of the hands of oncologists as well as the need for additional biopsies to determine if tumors cross the proposed PD-L1 threshold at some point during treatment. With this potential new restriction, the companies were worried that insurance companies would be even less likely to pay for their checkpoint inhibitors in low or no PD-L1 expressors.

ODAC wasn’t moved. With consistent findings across multiple trials, the strength of the FDA’s data carried the day.