User login

Underlying Mental Illness and Risk of Severe Outcomes Associated With COVID-19

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified factors that put patients at a higher risk of severe COVID-19 infection, which include advanced age, obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, lung disease, and immunocompromising conditions. The CDC also acknowledges that mood disorders, including depression and schizophrenia, contribute to the progression to severe COVID-19.1 Antiviral therapies, such as nirmatrelvir and ritonavir combination, remdesivir, and molnupiravir, and monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapies, have been used to prevent hospitalization and mortality from COVID-19 infection for individuals with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 who are at high risk of progressing to severe infection.2 Although antiviral and mAb therapies likely have mitigated many infections, poor prognoses are prevalent. It is important to identify all patients at risk of progressing to severe COVID-19 infection.

Although the CDC considers depression and schizophrenia to be risk factors for severe COVID-19 infection, the Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center (FHCC) in North Chicago, Illinois, does not, making these patients ineligible for antiviral or mAb therapies unless they have another risk factor. As a result, these patients could be at risk of severe COVID-19 infection, but might not be treated appropriately. Psychiatric diagnoses are common among veterans, with 19.7% experiencing a mental illness in 2020.3 It is imperative to determine whether depression or schizophrenia play a role in the progression of COVID-19 to expand access to individuals who are eligible for antiviral or mAb therapies.

Because COVID-19 is a novel virus, there are few studies of psychiatric disorders and COVID-19 prognosis. A 2020 case control study determined that those with a recent mental illness diagnosis were at higher risk of COVID-19 infection with worse outcomes compared with those without psychiatric diagnoses. This effect was most prevalent among individuals with depression and schizophrenia.4 However, these individuals also were found to have additional comorbidities that could have contributed to poorer outcomes. A meta-analysis determined that psychiatric disorders were associated with increased COVID-19-related mortality.5 A 2022 cohort study that included vaccinated US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) patients determined that having a psychiatric diagnosis was associated with increased incidence of breakthrough infections.6 Individuals with psychiatric conditions are thought to be at higher risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes because of poor access to care and higher incidence of untreated underlying health conditions.7 Lifestyle factors also could play a role. Because there is minimal data on COVID-19 prognosis and mental illness, further research is warranted to determine whether psychiatric diagnoses could contribute to more severe COVID-19 infections.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort chart review study at FHCC that compared COVID-19 outcomes in individuals with depression or schizophrenia with those without these diagnoses. FHCC patients with the International Classification of Diseases code for COVID-19 (U07.1) from fiscal years 2020 to 2022 were included. We then selected patients with a depression or schizophrenia diagnosis noted in the electronic health record (EHR). These 2 patient lists were consolidated to identify every individual with a COVID-19 diagnosis and a diagnosis of depression or schizophrenia.

Patients were included if they were aged ≥ 18 years with a positive COVID-19 infection confirmed via polymerase chain reaction or blood test. Patients also had to have mild-to-moderate COVID-19 with ≥ 1 symptom such as fever, cough, sore throat, malaise, headache, muscle pain, loss of taste and smell, or shortness of breath. Patients were excluded if they had an asymptomatic infection, presented with severe COVID-19 infection, or were an FHCC employee. Severe COVID-19 was defined as having oxygen saturation < 94%, a respiratory rate > 30 breaths per minute, or supplemental oxygen requirement.

Patient EHRs were reviewed and analyzed using the VA Computerized Patient Record System and Joint Legacy Viewer. Collected data included age, medical history, use of antiviral or mAb therapy, and admission or death within 30 days of a positive COVID-19 test. The primary outcome of this study was severe COVID-19 outcomes defined as hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit, intubation or mechanical ventilation, or death within 30 days of infection. The primary outcome was analyzed with a student t test; P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

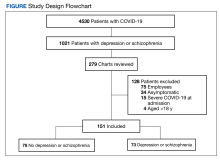

More than 5000 individuals had a COVID-19 diagnosis during the study period. Among these patients, 4530 had no depression or schizophrenia diagnosis; 1021 individuals had COVID-19 and a preexisting diagnosis of depression or schizophrenia. Among these 1021 patients, 279 charts were reviewed due to time constraints; 128 patients met exclusion criteria and 151 patients were included in the study. Of the 151 patients with COVID-19, 78 had no depression or schizophrenia and 73 patients with COVID-19 had a preexisting depression or schizophrenia diagnosis (Figure).

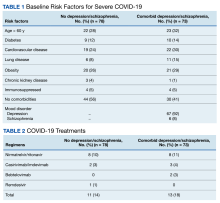

The 2 groups were similar at baseline. The most common risk factors for severe COVID-19 included age > 60 years, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. However, more than half of the individuals analyzed had no risk factors (Table 1). Some patients with risk factors received antiviral or mAb therapy to prevent severe COVID-19 infection; combination nirmatrelvir and ritonavir was the most common agent (Table 2). Of the 73 individuals with a psychiatric diagnosis, 67 had depression (91.8%), and 6 had schizophrenia (8.2%).

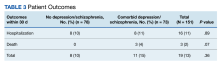

Hospitalization or death within 30 days of COVID-19 infection between patients with depression or schizophrenia and patients without these psychiatric diagnoses was not statistically significant (P = .36). Sixteen individuals were hospitalized, 8 in each group. Three individuals died within 30 days; death only occurred in patients who had depression or schizophrenia (Table 3).

Discussion

This study found that hospitalization or death within 30 days of COVID-19 infection occurred more frequently among individuals with depression or schizophrenia compared with those without these psychiatric comorbidities. However, this difference was not statistically significant.

This study had several limitations. It was a retrospective, chart review study, which relied on accurate documentation. In addition, we reviewed COVID-19 cases from fiscal years 2020 to 2022 and as a result, several viral variants were analyzed. This made it difficult to draw conclusions, especially because the omicron variant is thought to be less deadly, which may have skewed the data. Vaccinations and COVID-19 treatments became available in late 2020, which likely affected the progression to severe disease. Our study did not assess vaccination status, therefore it is unclear whether COVID-19 vaccination played a role in mitigating infection. When the pandemic began, many individuals were afraid to come to the hospital and did not receive care until they progressed to severe COVID-19, which would have excluded them from the study. Many individuals had additional comorbidities that likely impacted their COVID-19 outcomes. It is not possible to conclude if the depression or schizophrenia diagnoses were responsible for hospitalization or death within 30 days of infection or if it was because of other known risk factors. Future research is needed to address these limitations.

Conclusions

More COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths occurred within 30 days of infection among those with depression and schizophrenia compared with individuals without these comorbidities. However, this effect was not statistically significant. Many limitations could have contributed to this finding, which should be addressed in future studies. Because the sample size was small, further research with a larger patient population is warranted to explore the association between psychiatric comorbidities such as depression and schizophrenia and COVID-19 disease progression. Future studies also could include assessment of vaccination status and exclude individuals with other high-risk comorbidities for severe COVID-19 outcomes. These studies could determine if depression and schizophrenia are correlated with worse COVID-19 outcomes and ensure that all high-risk patients are identified and treated appropriately to prevent morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the research committee at the Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center who assisted in the completion of this project, including Shaiza Khan, PharmD, BCPS; Yinka Alaka, PharmD; and Hong-Yen Vi, PharmD, BCPS, BCCCP.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Underlying medical conditions associated with higher risk for severe COVID-19: information for healthcare professionals. Updated February 9, 2023. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/underlyingconditions.html

2. National Institutes of Health. Therapeutic management of nonhospitalized adults with COVID-19. Updated November 2, 2023. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/management/clinical-management-of-adults/nonhospitalized-adults-therapeutic-management

3. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Mental health by the numbers. Updated April 2023. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.nami.org/mhstats

4. Wang Q, Xu R, Volkow ND. Increased risk of COVID-19 infection and mortality in people with mental disorders: analysis from electronic health records in the United States. World Psychiatry . 2021;20(1):124-130. doi:10.1002/wps.20806

5. Fond G, Nemani K, Etchecopar-Etchart D, et al. Association Between Mental Health Disorders and Mortality Among Patients With COVID-19 in 7 Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry . 2021;78(11):1208-1217. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2274

6. Nishimi K, Neylan TC, Bertenthal D, Seal KH, O’Donovan A. Association of Psychiatric Disorders With Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 Breakthrough Infection Among Vaccinated Adults. JAMA Netw Open . 2022;5(4):e227287. Published 2022 Apr 1. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.7287

7. Koyama AK, Koumans EH, Sircar K, et al. Mental Health Conditions and Severe COVID-19 Outcomes after Hospitalization, United States. Emerg Infect Dis . 2022;28(7):1533-1536. doi:10.3201/eid2807.212208

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified factors that put patients at a higher risk of severe COVID-19 infection, which include advanced age, obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, lung disease, and immunocompromising conditions. The CDC also acknowledges that mood disorders, including depression and schizophrenia, contribute to the progression to severe COVID-19.1 Antiviral therapies, such as nirmatrelvir and ritonavir combination, remdesivir, and molnupiravir, and monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapies, have been used to prevent hospitalization and mortality from COVID-19 infection for individuals with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 who are at high risk of progressing to severe infection.2 Although antiviral and mAb therapies likely have mitigated many infections, poor prognoses are prevalent. It is important to identify all patients at risk of progressing to severe COVID-19 infection.

Although the CDC considers depression and schizophrenia to be risk factors for severe COVID-19 infection, the Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center (FHCC) in North Chicago, Illinois, does not, making these patients ineligible for antiviral or mAb therapies unless they have another risk factor. As a result, these patients could be at risk of severe COVID-19 infection, but might not be treated appropriately. Psychiatric diagnoses are common among veterans, with 19.7% experiencing a mental illness in 2020.3 It is imperative to determine whether depression or schizophrenia play a role in the progression of COVID-19 to expand access to individuals who are eligible for antiviral or mAb therapies.

Because COVID-19 is a novel virus, there are few studies of psychiatric disorders and COVID-19 prognosis. A 2020 case control study determined that those with a recent mental illness diagnosis were at higher risk of COVID-19 infection with worse outcomes compared with those without psychiatric diagnoses. This effect was most prevalent among individuals with depression and schizophrenia.4 However, these individuals also were found to have additional comorbidities that could have contributed to poorer outcomes. A meta-analysis determined that psychiatric disorders were associated with increased COVID-19-related mortality.5 A 2022 cohort study that included vaccinated US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) patients determined that having a psychiatric diagnosis was associated with increased incidence of breakthrough infections.6 Individuals with psychiatric conditions are thought to be at higher risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes because of poor access to care and higher incidence of untreated underlying health conditions.7 Lifestyle factors also could play a role. Because there is minimal data on COVID-19 prognosis and mental illness, further research is warranted to determine whether psychiatric diagnoses could contribute to more severe COVID-19 infections.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort chart review study at FHCC that compared COVID-19 outcomes in individuals with depression or schizophrenia with those without these diagnoses. FHCC patients with the International Classification of Diseases code for COVID-19 (U07.1) from fiscal years 2020 to 2022 were included. We then selected patients with a depression or schizophrenia diagnosis noted in the electronic health record (EHR). These 2 patient lists were consolidated to identify every individual with a COVID-19 diagnosis and a diagnosis of depression or schizophrenia.

Patients were included if they were aged ≥ 18 years with a positive COVID-19 infection confirmed via polymerase chain reaction or blood test. Patients also had to have mild-to-moderate COVID-19 with ≥ 1 symptom such as fever, cough, sore throat, malaise, headache, muscle pain, loss of taste and smell, or shortness of breath. Patients were excluded if they had an asymptomatic infection, presented with severe COVID-19 infection, or were an FHCC employee. Severe COVID-19 was defined as having oxygen saturation < 94%, a respiratory rate > 30 breaths per minute, or supplemental oxygen requirement.

Patient EHRs were reviewed and analyzed using the VA Computerized Patient Record System and Joint Legacy Viewer. Collected data included age, medical history, use of antiviral or mAb therapy, and admission or death within 30 days of a positive COVID-19 test. The primary outcome of this study was severe COVID-19 outcomes defined as hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit, intubation or mechanical ventilation, or death within 30 days of infection. The primary outcome was analyzed with a student t test; P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

More than 5000 individuals had a COVID-19 diagnosis during the study period. Among these patients, 4530 had no depression or schizophrenia diagnosis; 1021 individuals had COVID-19 and a preexisting diagnosis of depression or schizophrenia. Among these 1021 patients, 279 charts were reviewed due to time constraints; 128 patients met exclusion criteria and 151 patients were included in the study. Of the 151 patients with COVID-19, 78 had no depression or schizophrenia and 73 patients with COVID-19 had a preexisting depression or schizophrenia diagnosis (Figure).

The 2 groups were similar at baseline. The most common risk factors for severe COVID-19 included age > 60 years, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. However, more than half of the individuals analyzed had no risk factors (Table 1). Some patients with risk factors received antiviral or mAb therapy to prevent severe COVID-19 infection; combination nirmatrelvir and ritonavir was the most common agent (Table 2). Of the 73 individuals with a psychiatric diagnosis, 67 had depression (91.8%), and 6 had schizophrenia (8.2%).

Hospitalization or death within 30 days of COVID-19 infection between patients with depression or schizophrenia and patients without these psychiatric diagnoses was not statistically significant (P = .36). Sixteen individuals were hospitalized, 8 in each group. Three individuals died within 30 days; death only occurred in patients who had depression or schizophrenia (Table 3).

Discussion

This study found that hospitalization or death within 30 days of COVID-19 infection occurred more frequently among individuals with depression or schizophrenia compared with those without these psychiatric comorbidities. However, this difference was not statistically significant.

This study had several limitations. It was a retrospective, chart review study, which relied on accurate documentation. In addition, we reviewed COVID-19 cases from fiscal years 2020 to 2022 and as a result, several viral variants were analyzed. This made it difficult to draw conclusions, especially because the omicron variant is thought to be less deadly, which may have skewed the data. Vaccinations and COVID-19 treatments became available in late 2020, which likely affected the progression to severe disease. Our study did not assess vaccination status, therefore it is unclear whether COVID-19 vaccination played a role in mitigating infection. When the pandemic began, many individuals were afraid to come to the hospital and did not receive care until they progressed to severe COVID-19, which would have excluded them from the study. Many individuals had additional comorbidities that likely impacted their COVID-19 outcomes. It is not possible to conclude if the depression or schizophrenia diagnoses were responsible for hospitalization or death within 30 days of infection or if it was because of other known risk factors. Future research is needed to address these limitations.

Conclusions

More COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths occurred within 30 days of infection among those with depression and schizophrenia compared with individuals without these comorbidities. However, this effect was not statistically significant. Many limitations could have contributed to this finding, which should be addressed in future studies. Because the sample size was small, further research with a larger patient population is warranted to explore the association between psychiatric comorbidities such as depression and schizophrenia and COVID-19 disease progression. Future studies also could include assessment of vaccination status and exclude individuals with other high-risk comorbidities for severe COVID-19 outcomes. These studies could determine if depression and schizophrenia are correlated with worse COVID-19 outcomes and ensure that all high-risk patients are identified and treated appropriately to prevent morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the research committee at the Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center who assisted in the completion of this project, including Shaiza Khan, PharmD, BCPS; Yinka Alaka, PharmD; and Hong-Yen Vi, PharmD, BCPS, BCCCP.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified factors that put patients at a higher risk of severe COVID-19 infection, which include advanced age, obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, lung disease, and immunocompromising conditions. The CDC also acknowledges that mood disorders, including depression and schizophrenia, contribute to the progression to severe COVID-19.1 Antiviral therapies, such as nirmatrelvir and ritonavir combination, remdesivir, and molnupiravir, and monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapies, have been used to prevent hospitalization and mortality from COVID-19 infection for individuals with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 who are at high risk of progressing to severe infection.2 Although antiviral and mAb therapies likely have mitigated many infections, poor prognoses are prevalent. It is important to identify all patients at risk of progressing to severe COVID-19 infection.

Although the CDC considers depression and schizophrenia to be risk factors for severe COVID-19 infection, the Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center (FHCC) in North Chicago, Illinois, does not, making these patients ineligible for antiviral or mAb therapies unless they have another risk factor. As a result, these patients could be at risk of severe COVID-19 infection, but might not be treated appropriately. Psychiatric diagnoses are common among veterans, with 19.7% experiencing a mental illness in 2020.3 It is imperative to determine whether depression or schizophrenia play a role in the progression of COVID-19 to expand access to individuals who are eligible for antiviral or mAb therapies.

Because COVID-19 is a novel virus, there are few studies of psychiatric disorders and COVID-19 prognosis. A 2020 case control study determined that those with a recent mental illness diagnosis were at higher risk of COVID-19 infection with worse outcomes compared with those without psychiatric diagnoses. This effect was most prevalent among individuals with depression and schizophrenia.4 However, these individuals also were found to have additional comorbidities that could have contributed to poorer outcomes. A meta-analysis determined that psychiatric disorders were associated with increased COVID-19-related mortality.5 A 2022 cohort study that included vaccinated US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) patients determined that having a psychiatric diagnosis was associated with increased incidence of breakthrough infections.6 Individuals with psychiatric conditions are thought to be at higher risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes because of poor access to care and higher incidence of untreated underlying health conditions.7 Lifestyle factors also could play a role. Because there is minimal data on COVID-19 prognosis and mental illness, further research is warranted to determine whether psychiatric diagnoses could contribute to more severe COVID-19 infections.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort chart review study at FHCC that compared COVID-19 outcomes in individuals with depression or schizophrenia with those without these diagnoses. FHCC patients with the International Classification of Diseases code for COVID-19 (U07.1) from fiscal years 2020 to 2022 were included. We then selected patients with a depression or schizophrenia diagnosis noted in the electronic health record (EHR). These 2 patient lists were consolidated to identify every individual with a COVID-19 diagnosis and a diagnosis of depression or schizophrenia.

Patients were included if they were aged ≥ 18 years with a positive COVID-19 infection confirmed via polymerase chain reaction or blood test. Patients also had to have mild-to-moderate COVID-19 with ≥ 1 symptom such as fever, cough, sore throat, malaise, headache, muscle pain, loss of taste and smell, or shortness of breath. Patients were excluded if they had an asymptomatic infection, presented with severe COVID-19 infection, or were an FHCC employee. Severe COVID-19 was defined as having oxygen saturation < 94%, a respiratory rate > 30 breaths per minute, or supplemental oxygen requirement.

Patient EHRs were reviewed and analyzed using the VA Computerized Patient Record System and Joint Legacy Viewer. Collected data included age, medical history, use of antiviral or mAb therapy, and admission or death within 30 days of a positive COVID-19 test. The primary outcome of this study was severe COVID-19 outcomes defined as hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit, intubation or mechanical ventilation, or death within 30 days of infection. The primary outcome was analyzed with a student t test; P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

More than 5000 individuals had a COVID-19 diagnosis during the study period. Among these patients, 4530 had no depression or schizophrenia diagnosis; 1021 individuals had COVID-19 and a preexisting diagnosis of depression or schizophrenia. Among these 1021 patients, 279 charts were reviewed due to time constraints; 128 patients met exclusion criteria and 151 patients were included in the study. Of the 151 patients with COVID-19, 78 had no depression or schizophrenia and 73 patients with COVID-19 had a preexisting depression or schizophrenia diagnosis (Figure).

The 2 groups were similar at baseline. The most common risk factors for severe COVID-19 included age > 60 years, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. However, more than half of the individuals analyzed had no risk factors (Table 1). Some patients with risk factors received antiviral or mAb therapy to prevent severe COVID-19 infection; combination nirmatrelvir and ritonavir was the most common agent (Table 2). Of the 73 individuals with a psychiatric diagnosis, 67 had depression (91.8%), and 6 had schizophrenia (8.2%).

Hospitalization or death within 30 days of COVID-19 infection between patients with depression or schizophrenia and patients without these psychiatric diagnoses was not statistically significant (P = .36). Sixteen individuals were hospitalized, 8 in each group. Three individuals died within 30 days; death only occurred in patients who had depression or schizophrenia (Table 3).

Discussion

This study found that hospitalization or death within 30 days of COVID-19 infection occurred more frequently among individuals with depression or schizophrenia compared with those without these psychiatric comorbidities. However, this difference was not statistically significant.

This study had several limitations. It was a retrospective, chart review study, which relied on accurate documentation. In addition, we reviewed COVID-19 cases from fiscal years 2020 to 2022 and as a result, several viral variants were analyzed. This made it difficult to draw conclusions, especially because the omicron variant is thought to be less deadly, which may have skewed the data. Vaccinations and COVID-19 treatments became available in late 2020, which likely affected the progression to severe disease. Our study did not assess vaccination status, therefore it is unclear whether COVID-19 vaccination played a role in mitigating infection. When the pandemic began, many individuals were afraid to come to the hospital and did not receive care until they progressed to severe COVID-19, which would have excluded them from the study. Many individuals had additional comorbidities that likely impacted their COVID-19 outcomes. It is not possible to conclude if the depression or schizophrenia diagnoses were responsible for hospitalization or death within 30 days of infection or if it was because of other known risk factors. Future research is needed to address these limitations.

Conclusions

More COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths occurred within 30 days of infection among those with depression and schizophrenia compared with individuals without these comorbidities. However, this effect was not statistically significant. Many limitations could have contributed to this finding, which should be addressed in future studies. Because the sample size was small, further research with a larger patient population is warranted to explore the association between psychiatric comorbidities such as depression and schizophrenia and COVID-19 disease progression. Future studies also could include assessment of vaccination status and exclude individuals with other high-risk comorbidities for severe COVID-19 outcomes. These studies could determine if depression and schizophrenia are correlated with worse COVID-19 outcomes and ensure that all high-risk patients are identified and treated appropriately to prevent morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the research committee at the Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center who assisted in the completion of this project, including Shaiza Khan, PharmD, BCPS; Yinka Alaka, PharmD; and Hong-Yen Vi, PharmD, BCPS, BCCCP.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Underlying medical conditions associated with higher risk for severe COVID-19: information for healthcare professionals. Updated February 9, 2023. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/underlyingconditions.html

2. National Institutes of Health. Therapeutic management of nonhospitalized adults with COVID-19. Updated November 2, 2023. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/management/clinical-management-of-adults/nonhospitalized-adults-therapeutic-management

3. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Mental health by the numbers. Updated April 2023. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.nami.org/mhstats

4. Wang Q, Xu R, Volkow ND. Increased risk of COVID-19 infection and mortality in people with mental disorders: analysis from electronic health records in the United States. World Psychiatry . 2021;20(1):124-130. doi:10.1002/wps.20806

5. Fond G, Nemani K, Etchecopar-Etchart D, et al. Association Between Mental Health Disorders and Mortality Among Patients With COVID-19 in 7 Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry . 2021;78(11):1208-1217. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2274

6. Nishimi K, Neylan TC, Bertenthal D, Seal KH, O’Donovan A. Association of Psychiatric Disorders With Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 Breakthrough Infection Among Vaccinated Adults. JAMA Netw Open . 2022;5(4):e227287. Published 2022 Apr 1. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.7287

7. Koyama AK, Koumans EH, Sircar K, et al. Mental Health Conditions and Severe COVID-19 Outcomes after Hospitalization, United States. Emerg Infect Dis . 2022;28(7):1533-1536. doi:10.3201/eid2807.212208

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Underlying medical conditions associated with higher risk for severe COVID-19: information for healthcare professionals. Updated February 9, 2023. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/underlyingconditions.html

2. National Institutes of Health. Therapeutic management of nonhospitalized adults with COVID-19. Updated November 2, 2023. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/management/clinical-management-of-adults/nonhospitalized-adults-therapeutic-management

3. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Mental health by the numbers. Updated April 2023. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.nami.org/mhstats

4. Wang Q, Xu R, Volkow ND. Increased risk of COVID-19 infection and mortality in people with mental disorders: analysis from electronic health records in the United States. World Psychiatry . 2021;20(1):124-130. doi:10.1002/wps.20806

5. Fond G, Nemani K, Etchecopar-Etchart D, et al. Association Between Mental Health Disorders and Mortality Among Patients With COVID-19 in 7 Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry . 2021;78(11):1208-1217. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2274

6. Nishimi K, Neylan TC, Bertenthal D, Seal KH, O’Donovan A. Association of Psychiatric Disorders With Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 Breakthrough Infection Among Vaccinated Adults. JAMA Netw Open . 2022;5(4):e227287. Published 2022 Apr 1. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.7287

7. Koyama AK, Koumans EH, Sircar K, et al. Mental Health Conditions and Severe COVID-19 Outcomes after Hospitalization, United States. Emerg Infect Dis . 2022;28(7):1533-1536. doi:10.3201/eid2807.212208

Trauma-Informed Telehealth in the COVID-19 Era and Beyond

COVID-19 has created stressors that are unprecedented in our modern era, prompting health care systems to adapt rapidly. Demand for telehealth has skyrocketed, and clinicians, many of whom had planned to adopt virtual practices in the future, have been pressured to do so immediately.1 In March 2020, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded telehealth services, removing many barriers to virtual care.2 Similar remedy was not necessary for the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) which reported more than 2.6 million episodes of telehealth care in 2019.3 By the time the pandemic was underway in the US, use of telehealth was widespread across the agency. In late March 2020, VHA released a COVID-19 Response Plan, in which telehealth played a critical role in safe, uninterrupted delivery of services.4 While telehealth has been widely used in VHA, the call for replacement of most in-person outpatient visits with telehealth visits was a fundamental paradigm shift for many patients and clinicians.4

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act (HR 748) gave the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) funding to expand coronavirus-related telehealth services, including the purchase of mobile devices and broadband expansion. CARES authorized the agency to expand telemental health services, enter into short-term agreements with telecommunications companies to provide temporary broadband services to veterans, temporarily waived an in-person home visit requirement (accepting video and phone calls as an alternative), and provided means to make telehealth available for homeless veterans and case managers through the HUD-VASH (US Department of Housing and Urban Development-VA Supportive Housing) program.

VHA is a national telehealth exemplar, initiating telehealth by use of closed-circuit televisions as early as 1968, and continuing to expand through 2017 with the implementation of the Veterans Video Connect (VVC) platform.5 VVC has enabled veterans to participate in virtual visits from distant locations, including their homes. VVC was used successfully during hurricanes Sandy, Harvey, Irma, and Maria and is being widely deployed in the current crisis.6-8

While telehealth can take many forms, the current discussion will focus on live (synchronous) videoconferencing: a 2-way audiovisual link between a patient and clinician, such as VVC, which enables patients to maintain a safe and social distance from others while connecting with the health care team and receiving urgent as well as ongoing medical care for both new and established conditions.9 VHA has developed multiple training resources for use of VVC across many settings, including primary care, mental health, and specialties. In this review, we will make the novel case for applying a trauma-informed lens to telehealth care across VHA and beyond to other health care systems.

Trauma-Informed Care

Although our current focus is rightly on mitigating the health effects of a pandemic, we must recognize that stressful phenomena like COVID-19 occur against a backdrop of widespread physical, sexual, psychological, and racial trauma in our communities. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) describes trauma as resulting from “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.”10 Trauma exposure is both ubiquitous worldwide and inequitably distributed, with vulnerable populations disproportionately impacted.11,12

Veterans as a population are often highly trauma exposed, and while VHA routinely screens for experiences of trauma, such as military sexual trauma (MST) and intimate partner violence (IPV), and potential mental health sequelae of trauma, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and suicidality, veterans may experience other forms of trauma or be unwilling or unable to talk about past exposures.13 One common example is that of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which include household dysfunction, neglect, and physical and sexual abuse before the age of 18 years.14 ACEs have been associated with a wide range of risk behaviors and poor health outcomes in adulthood.14 In population-based data, both male and female veterans have reported higher ACE scores.15 In addition, ACE scores are higher overall for those serving in the all-volunteer era (after July 1, 1973).16 Because trauma may be unseen, unmeasured, and unnamed, it is important to deliver all medical care with sensitivity to its potential presence.

It is important to distinguish the concept of trauma-informed care (TIC) from trauma-focused services. Trauma-focused or trauma-specific treatment refers to evidence-based and best practice treatment models that have been proven to facilitate recovery from problems resulting from the experience of trauma, such as PTSD.17 These treatments directly address the emotional, behavioral, and physiologic impact of trauma on an individual’s life and facilitate improvement in related symptoms and functioning: They are designed to treat the consequences of trauma. VHA offers a wide range of trauma-specific treatments, and considerable experience in delivering evidence-based trauma-focused treatment through telehealth exists.18,19 Given the range of possible responses to the experience of trauma, not all veterans with trauma histories need to, chose to, or feel ready to access trauma-specific treatments.20

In contrast, TIC is a global, universal precautions approach to providing quality care that can be applied to all aspects of health care and to all patients.21 TIC is a strengths-based service delivery framework that is grounded in an understanding of, and responsiveness to, the disempowering impact of experiencing trauma. It seeks to maximize physical, psychological, and emotional safety in all health care encounters, not just those that are specifically trauma-focused, and creates opportunities to rebuild a sense of control and empowerment while fostering healing through safe and collaborative patient-clinician relationships.22 TIC is not accomplished through any single technique or checklist but through continuous appraisal of approaches to care delivery. SAMHSA has elucidated 6 fundamental principles of TIC: safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment; voice and choice; and sensitivity to cultural, historical, and gender issues.10

TIC is based on the understanding that often traditional service delivery models of care may trigger, silence, or disempower survivors of trauma, exacerbating physical and mental health symptoms and potentially increasing disengagement from care and poorer outcomes.23 Currier and colleagues aptly noted, “TIC assumes that trustworthiness is not something that an organization creates in a veteran client, but something that he or she will freely grant to an organization.”24 Given the global prevalence of trauma, its well-established and deleterious impact on lifelong health, and the potential for health care itself to be traumatizing, TIC is a fundamental construct to apply universally with any patient at any time, especially in the context of a large-scale community trauma, such as a pandemic.12

Trauma-Informed COVID-19 Care

Catastrophic events, such as natural disasters and pandemics, may serve as both newly traumatic and as potential triggers for survivors who have endured prior trauma.25,26 Increases in depression, PTSD, and substance use disorder (SUD) are common sequalae, occurring during the event, the immediate aftermath, and beyond.25,27 In 2003, quarantine contained the spread of Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) but resulted in a high prevalence of psychological distress, including PTSD and depression.27 Many veterans may have deployed in support of humanitarian assistance/disaster relief missions, which typically do not involve armed combat but may expose service members to warlike situations, including social insecurity and suffering populations.28 COVID-19 may be reminiscent of some of these deployments as well.

The impact of the current COVID-19 pandemic on patients is pervasive. Those with preexisting financial insecurity now face additional economic hardship and health challenges, which are amplified by loneliness and loss of social support networks.26 Widespread unemployment and closures of many businesses add to stress and may exacerbate preexisting mental and physical health concerns for many; some veterans also may be at increased risk.29 While previous postdisaster research suggests that psychopathology in the general population will significantly remit over time, high-risk groups remain vulnerable to PTSD and bear the brunt of social and economic consequences associated with the crisis.25 Veterans with preexisting trauma histories and mental health conditions are at increased risk for being retraumatized by the current pandemic and impacted by isolation and unplanned job or wage loss from it.29 Compounding this, social distancing serves to protect communities but may amplify isolation and danger in abusive relationships or exacerbate underlying mental illness.26,30

Thus, as we expand our use of telehealth, replacing our face-to-face visits with virtual encounters, it is critical for clinicians to be mindful that the pandemic and public health responses to it may result in trauma and retraumatization for veterans and other vulnerable patients, which in turn can impact both access and response to care. The application of trauma-informed principles to our virtual encounters has the potential to mitigate some of these health impacts, increase engagement in care, and provide opportunities for protective, healing connections.

In the setting of the continued fear and uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic, we believe that application of a trauma-informed lens to telehealth efforts is timely. While virtual visits may seem to lack the warmth and immediacy of traditional medical encounters, accumulated experience suggests otherwise.19 Telehealth is fundamentally more patient-focused than traditional encounters, overcomes service delivery barriers, offers a greater range of options for treatment engagement, and can enhance clinician-patient partnerships.6,31,32 Although the rapid transition to telehealth may be challenging for those new to it, experienced clinicians and patients express high degrees of satisfaction with virtual care because direct communication is unhampered by in-office challenges and travel logistics.33

While it may feel daunting to integrate principles of TIC into telehealth during a crisis-driven scale-up, a growing practice and body of research can inform these efforts. To help better understand how trauma-exposed patients respond to telehealth, we reviewed findings from trauma-focused telemental health (TMH) treatment. This research demonstrates that telehealth promotes safety and collaboration—fundamental principles of TIC—that can, in turn, be applied to telehealth visits in primary care and other medical and surgical specialties. When compared with traditional in-person treatment, studies of both individual and group formats of TMH found no significant differences in satisfaction, acceptability, or outcomes (such as reduction in PTSD symptom severity scores34), and TMH did not impede development of rapport.19,35

Although counterintuitive, the virtual space created by the combined physical and psychological distance of videoconferencing has been shown to promote safety and transparency. In TMH, patients have reported greater honesty due to the protection afforded by this virtual space.31 Engaging in telehealth visits from the comfort of one’s home can feel emotionally safer than having to travel to a medical office, resulting in feeling more at ease during encounters.31 In one TMH study, veterans with PTSD described high comfort levels and ability to let their guard down during virtual treatment.19 Similarly, in palliative telehealth care, patients reported that clinicians successfully nurtured an experience of intimacy, expressed empathy verbally and nonverbally, and responded to the patient’s unique situation and emotions.33

Trauma-Informed Telehealth

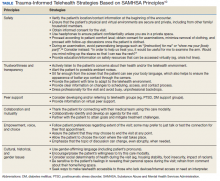

We have discussed how telehealth’s greater flexibility may create an ideal environment in which to implement principles of TIC. It may allow increased collaboration and closeness between patients and clinicians, empowering patients to codesign their care.31,33 The Table reviews 6 core SAMHSA principles of TIC and offers examples of their application to telehealth visits. The following case illustrates the application of trauma-informed telehealth care.

Case Presentation

S is a 45-year-old male veteran of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) who served as a combat medic. He has a history of osteoarthritis and PTSD related to combat experiences like caring for traumatic amputees. Before the pandemic began, he was employed as a server at a local restaurant but was laid off as the business transitioned to takeout orders only. The patient worked near a VA primary care clinic and frequently dropped by to see the staff and to pick up prescriptions. He had never agreed to video visits despite receiving encouragement from his medical team. He was reluctant to try telehealth, but he had developed a painful, itchy rash on his lower leg and was concerned about getting care.

For patients like S who may be reluctant to try telehealth, it is important to understand the cause. Potential barriers to telehealth may include lack of Internet access or familiarity with technology, discomfort with being on video, shame about the appearance of one’s home, or a strong cultural preference for face-to-face medical visits. Some may miss the social support benefit of coming into a clinic, particularly in VHA, which is designed specifically for veteran patients. For these reasons it is important to offer the patient a choice and to begin with a supportive phone call that explores and strives to address the patient’s concerns about videoconferencing.

The clinic nurse called S who agreed to try a VVC visit with gentle encouragement. He shared that he was embarrassed about the appearance of his apartment and fearful about pictures being recorded of his body due to “a bad experience in my past.” The patient was reassured that visits are private and will not be recorded. The nurse also reminded him that he can choose the location in which the visit will take place and can turn his camera off at any time. Importantly, the nurse did not ask him to recount additional details of what happened in his past. Next, the nurse verified his location and contact information and explained why obtaining this information was necessary. Next, she asked his consent to proceed with the visit, reminding him that the visit can end at any point if he feels uncomfortable. After finishing this initial discussion, the nurse told him that his primary care physician (PCP) would join the visit and address his concerns with his leg.

S was happy to see his PCP despite his hesitations about video care. The PCP noticed that he seemed anxious and was avoiding talking about the rash. Knowing that he was anxious about this VVC visit, the PCP was careful to look directly at the camera to make eye contact and to be sure her face was well lit and not in shadows. She gave him some time to acclimate to the virtual environment and thanked him for joining the visit. Knowing that he was a combat veteran, she warned him that there have been sudden, loud construction noises outside her window. Although the PCP was pressed for time, she was aware that S may have had a previous difficult experience around images of his body or even combat-related trauma. She gently brought up the rash and asked for permission to examine it, avoiding commands or personalizing language such as “show me your leg” or “take off your pants for me.”36After some hesitation, the patient revealed his leg that appeared to have multiple excoriations and old scars from picking. After the examination, the PCP waited until the patient’s leg was fully covered before beginning a discussion of the care plan. Together they collaboratively reviewed treatments that would soothe the skin. They decided to virtually consult a social worker to obtain emergency economic assistance and to speak with the patient’s care team psychologist to reduce some of the anxiety that may be leading to his leg scratching.

Case Discussion

This case illustrates the ways in which TIC can be applied to telehealth for a veteran with combat-related PTSD who may have experienced additional interpersonal trauma. It was not necessary to know more detail about the veteran’s trauma history to conduct the visit in a trauma-informed manner. Connecting to patients at home while considering these principles may thus foster mutuality, mitigate retraumatization, and cultivate enhanced collaboration with health care teams in this era of social distancing.

While a virtual physical examination creates both limitations and opportunity in telehealth, patients may find the greater degree of choice over their clothing and surroundings to be empowering. Telehealth also can allow for a greater portion of time to be dedicated to quality discussion and collaborative planning, with the clinician hearing and responding to the patient’s needs with reduced distraction. This may include opportunities to discuss mental health concerns openly, normalize emotional reactions, and offer connection to mental health and support services available through telehealth, including for patients who have not previously engaged in such care.

Conclusions

1. Wosik J, Fudim M, Cameron B, et al. Telehealth transformation: COVID-19 and the rise of virtual care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(6):957-962. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocaa067

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid programs; policy and regulatory revisions in response to the COVID-19 public health emergency. CMS-1744-IFC. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/covid-final-ifc.pdf. Published March 24, 2020. Accessed April 8, 2020.

3. Eddy N. VA sees a surge in veterans’ use of telehealth services. https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/va-sees-surge-veterans-use-telehealth-services. Published November 25, 2019. Accessed June 17, 2020.

4. Veterans Health Administration, Office of Emergency Management. COVID-19 response plan. Version 1.6. Published March 23, 2020. Accessed June 17, 2020.

5. Caudill RL, Sager Z. Institutionally based videoconferencing. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2015;27(6):496-503. doi:10.3109/09540261.2015.1085369

6. Heyworth L. Sharing Connections [published correction appears in JAMA. 2018 May 8;319(18):1939]. JAMA. 2018;319(13):1323-1324. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.2717

7. Dobalian A. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA’s) response to the 2017 hurricanes. Presented at: American Public Health Association 2019 Annual Meeting and Exposition; November 2-6, 2019; Philadelphia, PA. https://apha.confex.com/apha/2019/meetingapp.cgi/Session/58543. Accessed June 16, 2020.

8. Der-Martirosian C, Griffin AR, Chu K, Dobalian A. Telehealth at the US Department of Veterans Affairs after Hurricane Sandy. J Telemed Telecare. 2019;25(5):310-317. doi:10.1177/1357633X17751005

9. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Telemedicine and telehealth. https://www.healthit.gov/topic/health-it-initiatives/telemedicine-and-telehealth. Updated September 28, 2017. Accessed June 16, 2020.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf. Published July 2014. Accessed June 16, 2020.

11. Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, Friedman MJ. National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(5):537-547. doi:10.1002/jts.21848

12. Kimberg L, Wheeler M. Trauma and Trauma-informed Care. In: Gerber MR, ed. Trauma-informed Healthcare Approaches: A Guide for Primary Care. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2019:25-56.

13. Gerber MR. Trauma-informed care of veterans. In: Gerber MR, ed. Trauma-informed Healthcare Approaches: A Guide for Primary Care. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2019:25-56.

14. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245-258. doi:10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8

15. Katon JG, Lehavot K, Simpson TL, et al. Adverse childhood experiences, Military service, and adult health. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(4):573-582. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.020

16. Blosnich JR, Dichter ME, Cerulli C, Batten SV, Bossarte RM. Disparities in adverse childhood experiences among individuals with a history of military service. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(9):1041-1048. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.724

17. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Treatment improvement protocol (TIP). Series, No. 57. In: SAMHSA, ed. Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. SAMHSA: Rockville, MD; 2014:137-155.

18. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, National Center for PTSD. Trauma, PTSD and treatment. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/PTSD/professional/treat/index.asp. Updated July 5, 2019. Accessed June 17, 2020.

19. Turgoose D, Ashwick R, Murphy D. Systematic review of lessons learned from delivering tele-therapy to veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(9):575-585. doi:10.1177/1357633X17730443

20. Cook JM, Simiola V, Hamblen JL, Bernardy N, Schnurr PP. The influence of patient readiness on implementation of evidence-based PTSD treatments in Veterans Affairs residential programs. Psychol Trauma. 2017;9(suppl 1):51-58. doi:10.1037/tra0000162

21. Raja S, Hasnain M, Hoersch M, Gove-Yin S, Rajagopalan C. Trauma informed care in medicine: current knowledge and future research directions. Fam Community Health. 2015;38(3):216-226. doi:10.1097/FCH.0000000000000071

22. Hopper EK, Bassuk EL, Olivet J. Shelter from the storm: trauma-informed care in homeless service settings. Open Health Serv Policy J. 2009;2:131-151.

23. Kelly U, Boyd MA, Valente SM, Czekanski E. Trauma-informed care: keeping mental health settings safe for veterans [published correction appears in Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2015 Jun;36(6):482]. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2014;35(6):413-419. doi:10.3109/01612840.2014.881941

24. Currier JM, Stefurak T, Carroll TD, Shatto EH. Applying trauma-informed care to community-based mental health services for military veterans. Best Pract Ment Health. 2017;13(1):47-64.

25. Neria Y, Nandi A, Galea S. Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2008;38(4):467-480. doi:10.1017/S0033291707001353

26. Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. the mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the need for prevention and early intervention [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 10]. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562

27. Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(7):1206-1212. doi:10.3201/eid1007.030703

28. Cunha JM, Shen YC, Burke ZR. Contrasting the impacts of combat and humanitarian assistance/disaster relief missions on the mental health of military service members. Def Peace Economics. 2018;29(1):62-77. doi: 10.1080/10242694.2017.1349365

29. Ramchand R, Harrell MC, Berglass N, Lauck M. Veterans and COVID-19: Projecting the Economic, Social and Mental Health Needs of America’s Veterans. New York, NY: The Bob Woodruff Foundation; 2020.

30. van Gelder N, Peterman A, Potts A, et al. COVID-19: reducing the risk of infection might increase the risk of intimate partner violence [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 11]. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;21:100348. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100348

31. Azarang A, Pakyurek M, Giroux C, Nordahl TE, Yellowlees P. Information technologies: an augmentation to post-traumatic stress disorder treatment among trauma survivors. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25(4):263-271. doi:10.1089/tmj.2018.0068.

32. Gilmore AK, Davis MT, Grubaugh A, et al. “Do you expect me to receive PTSD care in a setting where most of the other patients remind me of the perpetrator?”: Home-based telemedicine to address barriers to care unique to military sexual trauma and veterans affairs hospitals. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;48:59-64. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2016.03.004.

33. van Gurp J, van Selm M, Vissers K, van Leeuwen E, Hasselaar J. How outpatient palliative care teleconsultation facilitates empathic patient-professional relationships: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124387. Published 2015 Apr 22. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0124387

34. Morland LA, Mackintosh MA, Glassman LH, et al. Home-based delivery of variable length prolonged exposure therapy: a comparison of clinical efficacy between service modalities. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(4):346-355. doi:10.1002/da.22979

35. Morland LA, Hynes AK, Mackintosh MA, Resick PA, Chard KM. Group cognitive processing therapy delivered to veterans via telehealth: a pilot cohort. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24(4):465-469. doi:10.1002/jts.20661

36. Elisseou S, Puranam S, Nandi M. A novel, trauma-informed physical examination curriculum. Med Educ. 2018;52(5):555-556. doi:10.1111/medu.13569

COVID-19 has created stressors that are unprecedented in our modern era, prompting health care systems to adapt rapidly. Demand for telehealth has skyrocketed, and clinicians, many of whom had planned to adopt virtual practices in the future, have been pressured to do so immediately.1 In March 2020, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded telehealth services, removing many barriers to virtual care.2 Similar remedy was not necessary for the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) which reported more than 2.6 million episodes of telehealth care in 2019.3 By the time the pandemic was underway in the US, use of telehealth was widespread across the agency. In late March 2020, VHA released a COVID-19 Response Plan, in which telehealth played a critical role in safe, uninterrupted delivery of services.4 While telehealth has been widely used in VHA, the call for replacement of most in-person outpatient visits with telehealth visits was a fundamental paradigm shift for many patients and clinicians.4

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act (HR 748) gave the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) funding to expand coronavirus-related telehealth services, including the purchase of mobile devices and broadband expansion. CARES authorized the agency to expand telemental health services, enter into short-term agreements with telecommunications companies to provide temporary broadband services to veterans, temporarily waived an in-person home visit requirement (accepting video and phone calls as an alternative), and provided means to make telehealth available for homeless veterans and case managers through the HUD-VASH (US Department of Housing and Urban Development-VA Supportive Housing) program.

VHA is a national telehealth exemplar, initiating telehealth by use of closed-circuit televisions as early as 1968, and continuing to expand through 2017 with the implementation of the Veterans Video Connect (VVC) platform.5 VVC has enabled veterans to participate in virtual visits from distant locations, including their homes. VVC was used successfully during hurricanes Sandy, Harvey, Irma, and Maria and is being widely deployed in the current crisis.6-8

While telehealth can take many forms, the current discussion will focus on live (synchronous) videoconferencing: a 2-way audiovisual link between a patient and clinician, such as VVC, which enables patients to maintain a safe and social distance from others while connecting with the health care team and receiving urgent as well as ongoing medical care for both new and established conditions.9 VHA has developed multiple training resources for use of VVC across many settings, including primary care, mental health, and specialties. In this review, we will make the novel case for applying a trauma-informed lens to telehealth care across VHA and beyond to other health care systems.

Trauma-Informed Care

Although our current focus is rightly on mitigating the health effects of a pandemic, we must recognize that stressful phenomena like COVID-19 occur against a backdrop of widespread physical, sexual, psychological, and racial trauma in our communities. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) describes trauma as resulting from “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.”10 Trauma exposure is both ubiquitous worldwide and inequitably distributed, with vulnerable populations disproportionately impacted.11,12

Veterans as a population are often highly trauma exposed, and while VHA routinely screens for experiences of trauma, such as military sexual trauma (MST) and intimate partner violence (IPV), and potential mental health sequelae of trauma, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and suicidality, veterans may experience other forms of trauma or be unwilling or unable to talk about past exposures.13 One common example is that of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which include household dysfunction, neglect, and physical and sexual abuse before the age of 18 years.14 ACEs have been associated with a wide range of risk behaviors and poor health outcomes in adulthood.14 In population-based data, both male and female veterans have reported higher ACE scores.15 In addition, ACE scores are higher overall for those serving in the all-volunteer era (after July 1, 1973).16 Because trauma may be unseen, unmeasured, and unnamed, it is important to deliver all medical care with sensitivity to its potential presence.

It is important to distinguish the concept of trauma-informed care (TIC) from trauma-focused services. Trauma-focused or trauma-specific treatment refers to evidence-based and best practice treatment models that have been proven to facilitate recovery from problems resulting from the experience of trauma, such as PTSD.17 These treatments directly address the emotional, behavioral, and physiologic impact of trauma on an individual’s life and facilitate improvement in related symptoms and functioning: They are designed to treat the consequences of trauma. VHA offers a wide range of trauma-specific treatments, and considerable experience in delivering evidence-based trauma-focused treatment through telehealth exists.18,19 Given the range of possible responses to the experience of trauma, not all veterans with trauma histories need to, chose to, or feel ready to access trauma-specific treatments.20

In contrast, TIC is a global, universal precautions approach to providing quality care that can be applied to all aspects of health care and to all patients.21 TIC is a strengths-based service delivery framework that is grounded in an understanding of, and responsiveness to, the disempowering impact of experiencing trauma. It seeks to maximize physical, psychological, and emotional safety in all health care encounters, not just those that are specifically trauma-focused, and creates opportunities to rebuild a sense of control and empowerment while fostering healing through safe and collaborative patient-clinician relationships.22 TIC is not accomplished through any single technique or checklist but through continuous appraisal of approaches to care delivery. SAMHSA has elucidated 6 fundamental principles of TIC: safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment; voice and choice; and sensitivity to cultural, historical, and gender issues.10

TIC is based on the understanding that often traditional service delivery models of care may trigger, silence, or disempower survivors of trauma, exacerbating physical and mental health symptoms and potentially increasing disengagement from care and poorer outcomes.23 Currier and colleagues aptly noted, “TIC assumes that trustworthiness is not something that an organization creates in a veteran client, but something that he or she will freely grant to an organization.”24 Given the global prevalence of trauma, its well-established and deleterious impact on lifelong health, and the potential for health care itself to be traumatizing, TIC is a fundamental construct to apply universally with any patient at any time, especially in the context of a large-scale community trauma, such as a pandemic.12

Trauma-Informed COVID-19 Care

Catastrophic events, such as natural disasters and pandemics, may serve as both newly traumatic and as potential triggers for survivors who have endured prior trauma.25,26 Increases in depression, PTSD, and substance use disorder (SUD) are common sequalae, occurring during the event, the immediate aftermath, and beyond.25,27 In 2003, quarantine contained the spread of Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) but resulted in a high prevalence of psychological distress, including PTSD and depression.27 Many veterans may have deployed in support of humanitarian assistance/disaster relief missions, which typically do not involve armed combat but may expose service members to warlike situations, including social insecurity and suffering populations.28 COVID-19 may be reminiscent of some of these deployments as well.

The impact of the current COVID-19 pandemic on patients is pervasive. Those with preexisting financial insecurity now face additional economic hardship and health challenges, which are amplified by loneliness and loss of social support networks.26 Widespread unemployment and closures of many businesses add to stress and may exacerbate preexisting mental and physical health concerns for many; some veterans also may be at increased risk.29 While previous postdisaster research suggests that psychopathology in the general population will significantly remit over time, high-risk groups remain vulnerable to PTSD and bear the brunt of social and economic consequences associated with the crisis.25 Veterans with preexisting trauma histories and mental health conditions are at increased risk for being retraumatized by the current pandemic and impacted by isolation and unplanned job or wage loss from it.29 Compounding this, social distancing serves to protect communities but may amplify isolation and danger in abusive relationships or exacerbate underlying mental illness.26,30

Thus, as we expand our use of telehealth, replacing our face-to-face visits with virtual encounters, it is critical for clinicians to be mindful that the pandemic and public health responses to it may result in trauma and retraumatization for veterans and other vulnerable patients, which in turn can impact both access and response to care. The application of trauma-informed principles to our virtual encounters has the potential to mitigate some of these health impacts, increase engagement in care, and provide opportunities for protective, healing connections.

In the setting of the continued fear and uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic, we believe that application of a trauma-informed lens to telehealth efforts is timely. While virtual visits may seem to lack the warmth and immediacy of traditional medical encounters, accumulated experience suggests otherwise.19 Telehealth is fundamentally more patient-focused than traditional encounters, overcomes service delivery barriers, offers a greater range of options for treatment engagement, and can enhance clinician-patient partnerships.6,31,32 Although the rapid transition to telehealth may be challenging for those new to it, experienced clinicians and patients express high degrees of satisfaction with virtual care because direct communication is unhampered by in-office challenges and travel logistics.33

While it may feel daunting to integrate principles of TIC into telehealth during a crisis-driven scale-up, a growing practice and body of research can inform these efforts. To help better understand how trauma-exposed patients respond to telehealth, we reviewed findings from trauma-focused telemental health (TMH) treatment. This research demonstrates that telehealth promotes safety and collaboration—fundamental principles of TIC—that can, in turn, be applied to telehealth visits in primary care and other medical and surgical specialties. When compared with traditional in-person treatment, studies of both individual and group formats of TMH found no significant differences in satisfaction, acceptability, or outcomes (such as reduction in PTSD symptom severity scores34), and TMH did not impede development of rapport.19,35

Although counterintuitive, the virtual space created by the combined physical and psychological distance of videoconferencing has been shown to promote safety and transparency. In TMH, patients have reported greater honesty due to the protection afforded by this virtual space.31 Engaging in telehealth visits from the comfort of one’s home can feel emotionally safer than having to travel to a medical office, resulting in feeling more at ease during encounters.31 In one TMH study, veterans with PTSD described high comfort levels and ability to let their guard down during virtual treatment.19 Similarly, in palliative telehealth care, patients reported that clinicians successfully nurtured an experience of intimacy, expressed empathy verbally and nonverbally, and responded to the patient’s unique situation and emotions.33

Trauma-Informed Telehealth

We have discussed how telehealth’s greater flexibility may create an ideal environment in which to implement principles of TIC. It may allow increased collaboration and closeness between patients and clinicians, empowering patients to codesign their care.31,33 The Table reviews 6 core SAMHSA principles of TIC and offers examples of their application to telehealth visits. The following case illustrates the application of trauma-informed telehealth care.

Case Presentation

S is a 45-year-old male veteran of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) who served as a combat medic. He has a history of osteoarthritis and PTSD related to combat experiences like caring for traumatic amputees. Before the pandemic began, he was employed as a server at a local restaurant but was laid off as the business transitioned to takeout orders only. The patient worked near a VA primary care clinic and frequently dropped by to see the staff and to pick up prescriptions. He had never agreed to video visits despite receiving encouragement from his medical team. He was reluctant to try telehealth, but he had developed a painful, itchy rash on his lower leg and was concerned about getting care.

For patients like S who may be reluctant to try telehealth, it is important to understand the cause. Potential barriers to telehealth may include lack of Internet access or familiarity with technology, discomfort with being on video, shame about the appearance of one’s home, or a strong cultural preference for face-to-face medical visits. Some may miss the social support benefit of coming into a clinic, particularly in VHA, which is designed specifically for veteran patients. For these reasons it is important to offer the patient a choice and to begin with a supportive phone call that explores and strives to address the patient’s concerns about videoconferencing.

The clinic nurse called S who agreed to try a VVC visit with gentle encouragement. He shared that he was embarrassed about the appearance of his apartment and fearful about pictures being recorded of his body due to “a bad experience in my past.” The patient was reassured that visits are private and will not be recorded. The nurse also reminded him that he can choose the location in which the visit will take place and can turn his camera off at any time. Importantly, the nurse did not ask him to recount additional details of what happened in his past. Next, the nurse verified his location and contact information and explained why obtaining this information was necessary. Next, she asked his consent to proceed with the visit, reminding him that the visit can end at any point if he feels uncomfortable. After finishing this initial discussion, the nurse told him that his primary care physician (PCP) would join the visit and address his concerns with his leg.

S was happy to see his PCP despite his hesitations about video care. The PCP noticed that he seemed anxious and was avoiding talking about the rash. Knowing that he was anxious about this VVC visit, the PCP was careful to look directly at the camera to make eye contact and to be sure her face was well lit and not in shadows. She gave him some time to acclimate to the virtual environment and thanked him for joining the visit. Knowing that he was a combat veteran, she warned him that there have been sudden, loud construction noises outside her window. Although the PCP was pressed for time, she was aware that S may have had a previous difficult experience around images of his body or even combat-related trauma. She gently brought up the rash and asked for permission to examine it, avoiding commands or personalizing language such as “show me your leg” or “take off your pants for me.”36After some hesitation, the patient revealed his leg that appeared to have multiple excoriations and old scars from picking. After the examination, the PCP waited until the patient’s leg was fully covered before beginning a discussion of the care plan. Together they collaboratively reviewed treatments that would soothe the skin. They decided to virtually consult a social worker to obtain emergency economic assistance and to speak with the patient’s care team psychologist to reduce some of the anxiety that may be leading to his leg scratching.

Case Discussion

This case illustrates the ways in which TIC can be applied to telehealth for a veteran with combat-related PTSD who may have experienced additional interpersonal trauma. It was not necessary to know more detail about the veteran’s trauma history to conduct the visit in a trauma-informed manner. Connecting to patients at home while considering these principles may thus foster mutuality, mitigate retraumatization, and cultivate enhanced collaboration with health care teams in this era of social distancing.

While a virtual physical examination creates both limitations and opportunity in telehealth, patients may find the greater degree of choice over their clothing and surroundings to be empowering. Telehealth also can allow for a greater portion of time to be dedicated to quality discussion and collaborative planning, with the clinician hearing and responding to the patient’s needs with reduced distraction. This may include opportunities to discuss mental health concerns openly, normalize emotional reactions, and offer connection to mental health and support services available through telehealth, including for patients who have not previously engaged in such care.

Conclusions

COVID-19 has created stressors that are unprecedented in our modern era, prompting health care systems to adapt rapidly. Demand for telehealth has skyrocketed, and clinicians, many of whom had planned to adopt virtual practices in the future, have been pressured to do so immediately.1 In March 2020, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded telehealth services, removing many barriers to virtual care.2 Similar remedy was not necessary for the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) which reported more than 2.6 million episodes of telehealth care in 2019.3 By the time the pandemic was underway in the US, use of telehealth was widespread across the agency. In late March 2020, VHA released a COVID-19 Response Plan, in which telehealth played a critical role in safe, uninterrupted delivery of services.4 While telehealth has been widely used in VHA, the call for replacement of most in-person outpatient visits with telehealth visits was a fundamental paradigm shift for many patients and clinicians.4

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act (HR 748) gave the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) funding to expand coronavirus-related telehealth services, including the purchase of mobile devices and broadband expansion. CARES authorized the agency to expand telemental health services, enter into short-term agreements with telecommunications companies to provide temporary broadband services to veterans, temporarily waived an in-person home visit requirement (accepting video and phone calls as an alternative), and provided means to make telehealth available for homeless veterans and case managers through the HUD-VASH (US Department of Housing and Urban Development-VA Supportive Housing) program.

VHA is a national telehealth exemplar, initiating telehealth by use of closed-circuit televisions as early as 1968, and continuing to expand through 2017 with the implementation of the Veterans Video Connect (VVC) platform.5 VVC has enabled veterans to participate in virtual visits from distant locations, including their homes. VVC was used successfully during hurricanes Sandy, Harvey, Irma, and Maria and is being widely deployed in the current crisis.6-8

While telehealth can take many forms, the current discussion will focus on live (synchronous) videoconferencing: a 2-way audiovisual link between a patient and clinician, such as VVC, which enables patients to maintain a safe and social distance from others while connecting with the health care team and receiving urgent as well as ongoing medical care for both new and established conditions.9 VHA has developed multiple training resources for use of VVC across many settings, including primary care, mental health, and specialties. In this review, we will make the novel case for applying a trauma-informed lens to telehealth care across VHA and beyond to other health care systems.

Trauma-Informed Care