User login

Does screening by primary care providers effectively detect melanoma and other skin cancers?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

No trials have directly assessed skin cancer morbidity associated with physician visual skin screening. A 2018 ecologic cohort study found no difference in melanoma mortality in a population undergoing a national screening program, although screening was associated with 41% more diagnoses of skin cancer.1 A 2012 cohort study found a reduction in melanoma mortality over 7 years associated with a population-based visual skin cancer screening program compared with similar populations that didn’t undergo specific screening.2 At 12-year follow-up, however, there was no longer a difference in mortality.

Primary care visual screening doesn’t decrease melanoma mortality

German researchers trained 1673 non-dermatologists (64% of general practitioners, obstetrician-gynecologists, and urologists in that region of Germany) and 116 dermatologists (98% in the region) to recognize skin cancer through whole-body visual inspection.1 They recruited and screened 360,000 adults (19% of the population older than 20 years; 74% women) and followed age- and sex-adjusted melanoma mortality over the next 10 years. Non-dermatologists performed most screening exams (77%); 37% of screened positive patients were lost to follow-up.

Melanoma mortality ultimately didn’t change in the screened region, compared with populations in other European countries without national screening programs. Screening detected approximately half of melanoma cases (585/1169) in the region and was associated with 41% greater detection of skin cancers compared with other countries.

Researchers recorded age-adjusted increases in incidence per 100,000 of melanoma from 14.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.3-15.1) to 18 (95% CI, 16.6-19.4), melanoma in situ from 5.8 (95% CI, 5.2-6.4) to 8.5 (95% CI, 7.5-9.5), squamous cell carcinoma from 11.2 (95% CI, 10.6-11.8) to 12.9 (95% CI, 12.0-13.8), and basal cell carcinoma from 60.5 (95% CI, 59.0-62.1) to 78.4 (95% CI, 75.9-80.8).

Visual screening by primary care providers vs screening by dermatologists

A cohort study of 16,383 Australian adults found that visual screening by primary care physicians detected melanoma over 3 years with a sensitivity of 40.2% (95% CIs not supplied) and specificity of 86.1% (95% CI, 85.6-86.6%; positive predictive value = 1.4%).3

A second cohort study, enrolling 7436 adults, that evaluated visual screening by dermatologists and plastic surgeons over 2 years found a sensitivity for melanoma of 49% (95% CI, 34.4-63.7%) and a specificity of 97.6% (95% CI, 97.2-97.9%) with a positive predictive value of 11.9% (95% CI, 7.8-17.2%).4

Visual screening more often detects thinner melanomas

A 3-year case-control study (3762 cases, 3824 controls) that examined the association between visual skin screening by a physician (type of physician not specified) and thickness of melanomas detected found that thin melanomas (≤ 0.75 mm) were more common among screened patients compared with unscreened patients (odds ratio [OR] = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.22-1.56) and thicker melanomas (≥ 0.75 mm) were less common (OR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98).5

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review of 8 observational cohort studies with a total of 200,000 patients found a consistent linear increase in melanoma mortality with increasing tumor thickness.6 The largest study (68,495 patients), which compared melanoma mortality for thinner (< 1 mm) and thicker lesions, reported risk ratios of 2.89 for lesion thicknesses of 1.01 to 2 mm (95% CI, 2.62-3.18); 4.69 for thicknesses of 2.01 to 4 mm (95% CI, 4.24-5.02); and 5.71 for thicknesses > 4 mm (95% CI, 5.10-6.39).

The downside of visual screening: False-positives

The 2012 cohort study, which reported outcomes from 16,000 biopsies performed following visual screening exams, found that 28 biopsies were performed for each diagnosis of melanoma and 9 to 10 biopsies for each basal cell carcinoma.2 Diagnosis rates (number of skin biopsies performed for each case of cancer diagnosed) were equal in men and women for both types of cancer. However, researchers observed more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in women than men (56 vs 28 biopsies per case).

Younger patients underwent more biopsies than older patients for each diagnosis of skin cancer. Women 20 to 34 years of age underwent more biopsies than women 65 years or older for each diagnosis of melanoma (19 additional excisions) and basal cell carcinoma (134 additional excisions). Women 35 to 49 years of age underwent 565 more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma than women 65 years or older. Similar patterns applied to men 20 to 34 years of age compared with men 65 years or older (24 additional biopsies per melanoma, 109 per basal cell carcinoma, and 898 per squamous cell carcinoma).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations, based on a systematic review of mostly cohort studies, state that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of clinician visual skin cancer screening.7,8

The American Academy of Dermatology states that skin cancer screening can save lives and supports research on the benefits and harms of screening in the primary care setting.9

Continue to: Editor's Takeaway

Editor’s Takeaway

Skin cancer screening by primary care physicians is associated with increased detection of skin cancers, including melanomas—even though we have no confirmation that it changes melanoma mortality. It is unclear what the appropriate rate of false-positive screening tests should be, but wider adoption of noninvasive diagnostic techniques such as dermoscopy might reduce unwarranted biopsies.

1. Kaiser M, Schiller J, Schreckenberger C. The effectiveness of a population-based skin cancer screening program: evidence from Germany. Eur J Health Econ. 2018:19:355-367.

2. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Weinstock MA, et al. Skin cancer screening participation and impact on melanoma incidence in Germany—an observational study on incidence trends in regions with and without population-based screening. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:970-974.

3. Aitken JF, Janda M, Elwood M, et al. Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006:54:105-114.

4. Fritschi L, Dye SA, Katris P. Validity of melanoma diagnosis in a community-based screening program. Am J Epidemiol. 2006:164:385-390.

5. Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, et al. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010:126:450-458.

6. Wernli KJ, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, et al. Screening for Skin Cancer in Adults: An Updated Systematic Evidence Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016. Evidence Synthesis 137.

7. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Geller AC, et al. Frequency of excisions and yields of malignant skin tumors in a population-based screening intervention of 360,288 whole-body examinations. Arch Dermatol. 2012:148:903-910.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Skin Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

9. Torres A. AAD statement on USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer screening. July 2016. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-statement-on-uspstf 26. Accessed May 2018.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

No trials have directly assessed skin cancer morbidity associated with physician visual skin screening. A 2018 ecologic cohort study found no difference in melanoma mortality in a population undergoing a national screening program, although screening was associated with 41% more diagnoses of skin cancer.1 A 2012 cohort study found a reduction in melanoma mortality over 7 years associated with a population-based visual skin cancer screening program compared with similar populations that didn’t undergo specific screening.2 At 12-year follow-up, however, there was no longer a difference in mortality.

Primary care visual screening doesn’t decrease melanoma mortality

German researchers trained 1673 non-dermatologists (64% of general practitioners, obstetrician-gynecologists, and urologists in that region of Germany) and 116 dermatologists (98% in the region) to recognize skin cancer through whole-body visual inspection.1 They recruited and screened 360,000 adults (19% of the population older than 20 years; 74% women) and followed age- and sex-adjusted melanoma mortality over the next 10 years. Non-dermatologists performed most screening exams (77%); 37% of screened positive patients were lost to follow-up.

Melanoma mortality ultimately didn’t change in the screened region, compared with populations in other European countries without national screening programs. Screening detected approximately half of melanoma cases (585/1169) in the region and was associated with 41% greater detection of skin cancers compared with other countries.

Researchers recorded age-adjusted increases in incidence per 100,000 of melanoma from 14.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.3-15.1) to 18 (95% CI, 16.6-19.4), melanoma in situ from 5.8 (95% CI, 5.2-6.4) to 8.5 (95% CI, 7.5-9.5), squamous cell carcinoma from 11.2 (95% CI, 10.6-11.8) to 12.9 (95% CI, 12.0-13.8), and basal cell carcinoma from 60.5 (95% CI, 59.0-62.1) to 78.4 (95% CI, 75.9-80.8).

Visual screening by primary care providers vs screening by dermatologists

A cohort study of 16,383 Australian adults found that visual screening by primary care physicians detected melanoma over 3 years with a sensitivity of 40.2% (95% CIs not supplied) and specificity of 86.1% (95% CI, 85.6-86.6%; positive predictive value = 1.4%).3

A second cohort study, enrolling 7436 adults, that evaluated visual screening by dermatologists and plastic surgeons over 2 years found a sensitivity for melanoma of 49% (95% CI, 34.4-63.7%) and a specificity of 97.6% (95% CI, 97.2-97.9%) with a positive predictive value of 11.9% (95% CI, 7.8-17.2%).4

Visual screening more often detects thinner melanomas

A 3-year case-control study (3762 cases, 3824 controls) that examined the association between visual skin screening by a physician (type of physician not specified) and thickness of melanomas detected found that thin melanomas (≤ 0.75 mm) were more common among screened patients compared with unscreened patients (odds ratio [OR] = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.22-1.56) and thicker melanomas (≥ 0.75 mm) were less common (OR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98).5

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review of 8 observational cohort studies with a total of 200,000 patients found a consistent linear increase in melanoma mortality with increasing tumor thickness.6 The largest study (68,495 patients), which compared melanoma mortality for thinner (< 1 mm) and thicker lesions, reported risk ratios of 2.89 for lesion thicknesses of 1.01 to 2 mm (95% CI, 2.62-3.18); 4.69 for thicknesses of 2.01 to 4 mm (95% CI, 4.24-5.02); and 5.71 for thicknesses > 4 mm (95% CI, 5.10-6.39).

The downside of visual screening: False-positives

The 2012 cohort study, which reported outcomes from 16,000 biopsies performed following visual screening exams, found that 28 biopsies were performed for each diagnosis of melanoma and 9 to 10 biopsies for each basal cell carcinoma.2 Diagnosis rates (number of skin biopsies performed for each case of cancer diagnosed) were equal in men and women for both types of cancer. However, researchers observed more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in women than men (56 vs 28 biopsies per case).

Younger patients underwent more biopsies than older patients for each diagnosis of skin cancer. Women 20 to 34 years of age underwent more biopsies than women 65 years or older for each diagnosis of melanoma (19 additional excisions) and basal cell carcinoma (134 additional excisions). Women 35 to 49 years of age underwent 565 more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma than women 65 years or older. Similar patterns applied to men 20 to 34 years of age compared with men 65 years or older (24 additional biopsies per melanoma, 109 per basal cell carcinoma, and 898 per squamous cell carcinoma).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations, based on a systematic review of mostly cohort studies, state that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of clinician visual skin cancer screening.7,8

The American Academy of Dermatology states that skin cancer screening can save lives and supports research on the benefits and harms of screening in the primary care setting.9

Continue to: Editor's Takeaway

Editor’s Takeaway

Skin cancer screening by primary care physicians is associated with increased detection of skin cancers, including melanomas—even though we have no confirmation that it changes melanoma mortality. It is unclear what the appropriate rate of false-positive screening tests should be, but wider adoption of noninvasive diagnostic techniques such as dermoscopy might reduce unwarranted biopsies.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

No trials have directly assessed skin cancer morbidity associated with physician visual skin screening. A 2018 ecologic cohort study found no difference in melanoma mortality in a population undergoing a national screening program, although screening was associated with 41% more diagnoses of skin cancer.1 A 2012 cohort study found a reduction in melanoma mortality over 7 years associated with a population-based visual skin cancer screening program compared with similar populations that didn’t undergo specific screening.2 At 12-year follow-up, however, there was no longer a difference in mortality.

Primary care visual screening doesn’t decrease melanoma mortality

German researchers trained 1673 non-dermatologists (64% of general practitioners, obstetrician-gynecologists, and urologists in that region of Germany) and 116 dermatologists (98% in the region) to recognize skin cancer through whole-body visual inspection.1 They recruited and screened 360,000 adults (19% of the population older than 20 years; 74% women) and followed age- and sex-adjusted melanoma mortality over the next 10 years. Non-dermatologists performed most screening exams (77%); 37% of screened positive patients were lost to follow-up.

Melanoma mortality ultimately didn’t change in the screened region, compared with populations in other European countries without national screening programs. Screening detected approximately half of melanoma cases (585/1169) in the region and was associated with 41% greater detection of skin cancers compared with other countries.

Researchers recorded age-adjusted increases in incidence per 100,000 of melanoma from 14.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.3-15.1) to 18 (95% CI, 16.6-19.4), melanoma in situ from 5.8 (95% CI, 5.2-6.4) to 8.5 (95% CI, 7.5-9.5), squamous cell carcinoma from 11.2 (95% CI, 10.6-11.8) to 12.9 (95% CI, 12.0-13.8), and basal cell carcinoma from 60.5 (95% CI, 59.0-62.1) to 78.4 (95% CI, 75.9-80.8).

Visual screening by primary care providers vs screening by dermatologists

A cohort study of 16,383 Australian adults found that visual screening by primary care physicians detected melanoma over 3 years with a sensitivity of 40.2% (95% CIs not supplied) and specificity of 86.1% (95% CI, 85.6-86.6%; positive predictive value = 1.4%).3

A second cohort study, enrolling 7436 adults, that evaluated visual screening by dermatologists and plastic surgeons over 2 years found a sensitivity for melanoma of 49% (95% CI, 34.4-63.7%) and a specificity of 97.6% (95% CI, 97.2-97.9%) with a positive predictive value of 11.9% (95% CI, 7.8-17.2%).4

Visual screening more often detects thinner melanomas

A 3-year case-control study (3762 cases, 3824 controls) that examined the association between visual skin screening by a physician (type of physician not specified) and thickness of melanomas detected found that thin melanomas (≤ 0.75 mm) were more common among screened patients compared with unscreened patients (odds ratio [OR] = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.22-1.56) and thicker melanomas (≥ 0.75 mm) were less common (OR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98).5

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review of 8 observational cohort studies with a total of 200,000 patients found a consistent linear increase in melanoma mortality with increasing tumor thickness.6 The largest study (68,495 patients), which compared melanoma mortality for thinner (< 1 mm) and thicker lesions, reported risk ratios of 2.89 for lesion thicknesses of 1.01 to 2 mm (95% CI, 2.62-3.18); 4.69 for thicknesses of 2.01 to 4 mm (95% CI, 4.24-5.02); and 5.71 for thicknesses > 4 mm (95% CI, 5.10-6.39).

The downside of visual screening: False-positives

The 2012 cohort study, which reported outcomes from 16,000 biopsies performed following visual screening exams, found that 28 biopsies were performed for each diagnosis of melanoma and 9 to 10 biopsies for each basal cell carcinoma.2 Diagnosis rates (number of skin biopsies performed for each case of cancer diagnosed) were equal in men and women for both types of cancer. However, researchers observed more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in women than men (56 vs 28 biopsies per case).

Younger patients underwent more biopsies than older patients for each diagnosis of skin cancer. Women 20 to 34 years of age underwent more biopsies than women 65 years or older for each diagnosis of melanoma (19 additional excisions) and basal cell carcinoma (134 additional excisions). Women 35 to 49 years of age underwent 565 more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma than women 65 years or older. Similar patterns applied to men 20 to 34 years of age compared with men 65 years or older (24 additional biopsies per melanoma, 109 per basal cell carcinoma, and 898 per squamous cell carcinoma).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations, based on a systematic review of mostly cohort studies, state that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of clinician visual skin cancer screening.7,8

The American Academy of Dermatology states that skin cancer screening can save lives and supports research on the benefits and harms of screening in the primary care setting.9

Continue to: Editor's Takeaway

Editor’s Takeaway

Skin cancer screening by primary care physicians is associated with increased detection of skin cancers, including melanomas—even though we have no confirmation that it changes melanoma mortality. It is unclear what the appropriate rate of false-positive screening tests should be, but wider adoption of noninvasive diagnostic techniques such as dermoscopy might reduce unwarranted biopsies.

1. Kaiser M, Schiller J, Schreckenberger C. The effectiveness of a population-based skin cancer screening program: evidence from Germany. Eur J Health Econ. 2018:19:355-367.

2. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Weinstock MA, et al. Skin cancer screening participation and impact on melanoma incidence in Germany—an observational study on incidence trends in regions with and without population-based screening. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:970-974.

3. Aitken JF, Janda M, Elwood M, et al. Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006:54:105-114.

4. Fritschi L, Dye SA, Katris P. Validity of melanoma diagnosis in a community-based screening program. Am J Epidemiol. 2006:164:385-390.

5. Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, et al. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010:126:450-458.

6. Wernli KJ, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, et al. Screening for Skin Cancer in Adults: An Updated Systematic Evidence Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016. Evidence Synthesis 137.

7. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Geller AC, et al. Frequency of excisions and yields of malignant skin tumors in a population-based screening intervention of 360,288 whole-body examinations. Arch Dermatol. 2012:148:903-910.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Skin Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

9. Torres A. AAD statement on USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer screening. July 2016. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-statement-on-uspstf 26. Accessed May 2018.

1. Kaiser M, Schiller J, Schreckenberger C. The effectiveness of a population-based skin cancer screening program: evidence from Germany. Eur J Health Econ. 2018:19:355-367.

2. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Weinstock MA, et al. Skin cancer screening participation and impact on melanoma incidence in Germany—an observational study on incidence trends in regions with and without population-based screening. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:970-974.

3. Aitken JF, Janda M, Elwood M, et al. Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006:54:105-114.

4. Fritschi L, Dye SA, Katris P. Validity of melanoma diagnosis in a community-based screening program. Am J Epidemiol. 2006:164:385-390.

5. Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, et al. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010:126:450-458.

6. Wernli KJ, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, et al. Screening for Skin Cancer in Adults: An Updated Systematic Evidence Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016. Evidence Synthesis 137.

7. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Geller AC, et al. Frequency of excisions and yields of malignant skin tumors in a population-based screening intervention of 360,288 whole-body examinations. Arch Dermatol. 2012:148:903-910.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Skin Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

9. Torres A. AAD statement on USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer screening. July 2016. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-statement-on-uspstf 26. Accessed May 2018.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Possibly. No trials have directly assessed detection of melanoma and other skin cancers by primary care providers.

Training a group comprised largely of primary care physicians to perform skin cancer screening was associated with a 41% increase in skin cancer diagnoses but no change in melanoma mortality.

Visual screening for melanoma by primary care physicians is 40% sensitive and 86% specific (compared with 49% and 98%, respectively, for dermatologists and plastic surgeons).

Melanomas found by visual screening are 38% more likely to be thin (≤ 0.75 mm) than melanomas discovered without screening, which correlates with improved outcomes.

Visual skin cancer screening overall is associated with false-positive rates as follows: 28 biopsies for each melanoma detected, 9 to 10 biopsies for each basal cell carcinoma, and 28 to 56 biopsies for squamous cell carcinoma. False-positive rates are higher for women—as much as double the rate for men—and younger patients—as much as 20-fold the rate for older patients (strength of recommendations for all foregoing statements: B, cohort studies).

Families as Care Partners: Implementing the Better Together Initiative Across a Large Health System

From the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care, Bethesda, MD (Ms. Dokken and Ms. Johnson), and Northwell Health, New Hyde Park, NY (Dr. Barden, Ms. Tuomey, and Ms. Giammarinaro).

Abstract

Objective: To describe the growth of Better Together: Partnering with Families, a campaign launched in 2014 to eliminate restrictive hospital visiting policies and to put in place policies that recognize families as partners in care, and to discuss the processes involved in implementing the initiative in a large, integrated health system.

Methods: Descriptive report.

Results: In June 2014, the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) launched the Better Together campaign to emphasize the importance of family presence and participation to the quality, experience, safety, and outcomes of care. Since then, this initiative has expanded in both the United States and Canada. With support from 2 funders in the United States, special attention was focused on acute care hospitals across New York State. Nearly 50 hospitals participated in 2 separate but related projects. Fifteen of the hospitals are part of Northwell Health, New York State’s largest health system. Over a 10-month period, these hospitals made significant progress in changing policy, practice, and communication to support family presence.

Conclusion: The Better Together initiative was implemented across a health system with strong support from leadership and the involvement of patient and family advisors. An intervention offering structured training, coaching, and resources, like IPFCC’s Better Together initiative, can facilitate the change process.

Keywords: family presence; visiting policies; patient-centered care; family-centered care; patient experience.

The presence of families at the bedside of patients is often restricted by hospital visiting hours. Hospitals that maintain these restrictive policies cite concerns about negative impacts on security, infection control, privacy, and staff workload. But there are no data to support these concerns, and the experience of hospitals that have successfully changed policy and practice to welcome families demonstrates the potential positive impacts of less restrictive policies on patient care and outcomes.1 For example, hospitalization can lead to reduced cognitive function in elderly patients. Family members would recognize the changes and could provide valuable information to hospital staff, potentially improving outcomes.2

In June 2014, the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) launched the campaign Better Together: Partnering with Families.3 The campaign is is grounded in patient- and family- centered care, an approach to care that supports partnerships among health care providers, patients, and families, and, among other core principles, advocates that patients define their “families” and how they will participate in care and decision-making.

Emphasizing the importance of family presence and participation to quality and safety, the Better Together campaign seeks to eliminate restrictive visiting policies and calls upon hospitals to include families as members of the care team and to welcome them 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, according to patient preference. As part of the campaign, IPFCC developed an extensive toolkit of resources that is available to hospitals and other organizations at no cost. The resources include sample policies; profiles of hospitals that have implemented family presence policies; educational materials for staff, patients, and families; and a template for hospital websites. This article, a follow-up to an article published in the January 2015 issue of JCOM,1 discusses the growth of the Better Together initiative as well as the processes involved in implementing the initiative across a large health system.

Growth of the Initiative

Since its launch in 2014, the Better Together initiative has continued to expand in the United States and Canada. In Canada, under the leadership of the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement (CFHI), more than 50 organizations have made a commitment to the Better Together program and family presence.4 Utilizing and adapting IPFCC’s Toolkit, CFHI developed a change package of free resources for Canadian organizations.5 Some of the materials, including the Pocket Guide for Families (Manuel des Familles), were translated into French.6

With support from 2 funders in the United States, the United Hospital Fund and the New York State Health (NYSHealth) Foundation, through a subcontract with the New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG), IPFCC has been able to focus on hospitals in New York City, including public hospitals, and, more broadly, acute care hospitals across New York State. Nearly 50 hospitals participated in these 2 separate but related projects.

Education and Support for New York City Hospitals

Supported by the United Hospital Fund, an 18-month project that focused specifically on New York City hospitals was completed in June 2017. The project began with a 1-day intensive training event with representatives of 21 hospitals. Eighteen of those hospitals were eligible to participate in follow-up consultation provided by IPFCC, and 14 participated in some kind of follow-up. NYC Health + Hospitals (H+H), the system of public hospitals in NYC, participated most fully in these activities.

The outcomes of the Better Together initiative in New York City are summarized in the report Sick, Scared, & Separated From Loved Ones,2 which is based on a pre/post review of hospital visitation/family presence policies and website communications. According to the report, hospitals that participated in the IPFCC training and consultation program performed better, as a group, with respect to improved policy and website scores on post review than those that did not. Of the 10 hospitals whose scores improved during the review period, 8 had participated in the IPFCC training and 1 hospital was part of a hospital network that did so. (Six of these hospitals are part of the H+H public hospital system.) Those 9 hospitals saw an average increase in scores of 4.9 points (out of a possible 11).

A Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State

With support from the NYSHealth Foundation, IPFCC again collaborated with NYPIRG and New Yorkers for Patient & Family Empowerment on a 2-year initiative, completed in November 2019, that involved 26 hospitals: 15 from Northwell Health, New York State’s largest health system, and 11 hospitals from health systems throughout the state (Greater Hudson Valley Health System, now Garnet Health; Mohawk Valley Health System; Rochester Regional Health; and University of Vermont Health Network). An update of the report Sick, Scared, & Separated From Loved Onescompared pre/post reviews of policies and website communications regarding hospital visitation/family presence.7 Its findings confirm that hospitals that participated in the Better Together Learning Community improved both their policy and website scores to a greater degree than hospitals that did not participate and that a planned intervention can help facilitate change.

During the survey period, 28 out of 40 hospitals’ website navigability scores improved. Of those, hospitals that did not participate in the Better Together Learning Community saw an average increase in scores of 1.2 points, out of a possible 11, while the participating hospitals saw an average increase of 2.7 points, with the top 5 largest increases in scores belonging to hospitals that participated in the Better Together Learning Community.7

The Northwell Health Experience

Northwell Health is a large integrated health care organization comprising more than 69,000 employees, 23 hospitals, and more than 750 medical practices, located geographically across New York State. Embracing patient- and family-centered care, Northwell is dedicated to improving the quality, experience, and safety of care for patients and their families. Welcoming and including patients, families, and care partners as members of the health care team has always been a core element of Northwell’s organizational goal of providing world-class patient care and experience.

Four years ago, the organization reorganized and formalized a system-wide Patient & Family Partnership Council (PFPC).8 Representatives on the PFPC include a Northwell patient experience leader and patient/family co-chair from local councils that have been established in nearly all 23 hospitals as well as service lines. Modeling partnership, the PFPC is grounded in listening to the “voice” of patients and families and promoting collaboration, with the goal of driving change across varied aspects and experiences of health care delivery.

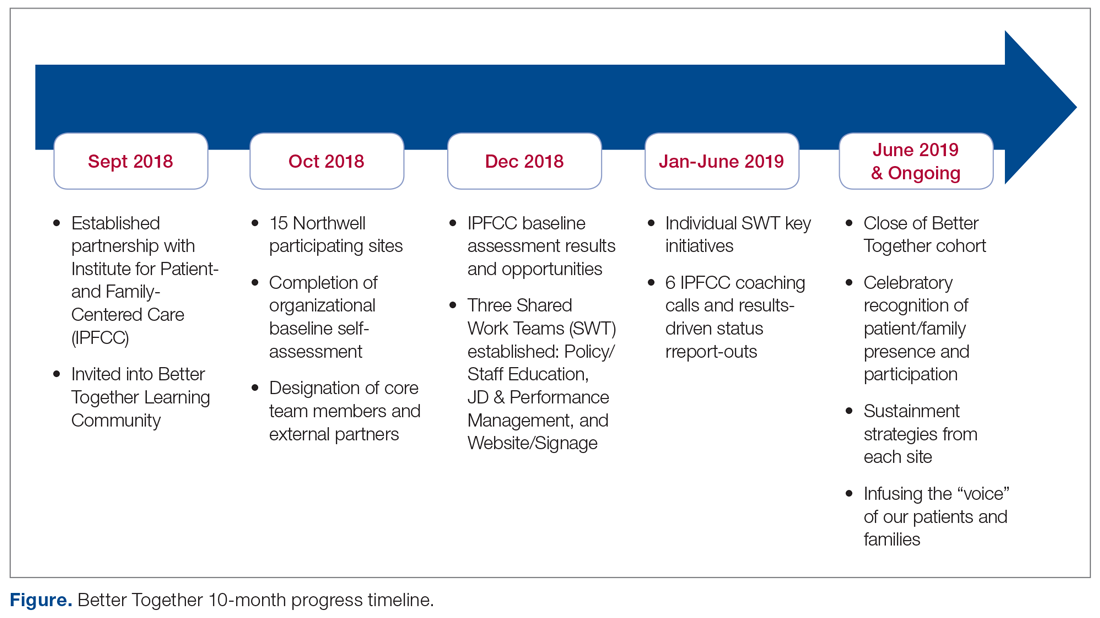

Through the Office of Patient and Customer Experience (OPCE), a partnership with IPFCC and the Better Together Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State was initiated as a fundamental next step in Northwell’s journey to enhance system-wide family presence and participation. Results from Better Together’s Organizational Self-Assessment Tool and process identified opportunities to influence 3 distinct areas: policy/staff education, position descriptions/performance management, and website/signage. Over a 10-month period (September 2018 through June 2019), 15 Northwell hospitals implemened significant patient- and family-centered improvements through multifaceted shared work teams (SWT) that partnered around the common goal of supporting the patient and family experience (Figure). Northwell’s SWT structure allowed teams to meet individually on specific tasks, led by a dedicated staff member of the OPCE to ensure progress, support, and accountability. Six monthly coaching calls or report-out meetings were attended by participating teams, where feedback and recommendations shared by IPFCC were discussed in order to maintain momentum and results.

Policy/Staff Education

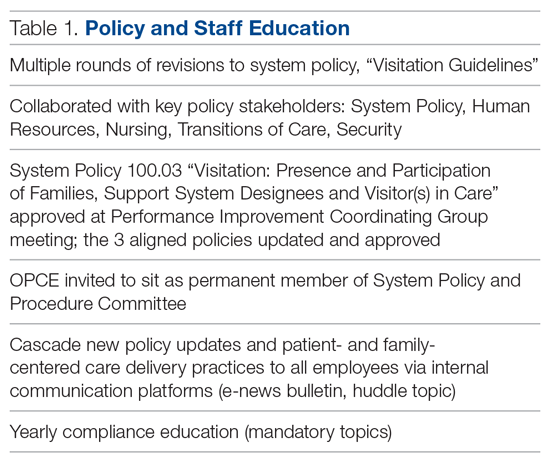

The policy/staff education SWT focused on appraising and updating existing policies to ensure alignment with key patient- and family-centered concepts and Better Together principles (Table 1). By establishing representation on the System Policy and Procedure Committee, OPCE enabled patients and families to have a voice at the decision-making table. OPCE leaders presented the ideology and scope of the transformation to this committee. After reviewing all system-wide policies, 4 were identified as key opportunities for revision. One overarching policy titled “Visitation Guidelines” was reviewed and updated to reflect Northwell’s mission of patient- and family-centered care, retiring the reference to “families” as “visitors” in definitions, incorporating language of inclusion and partnership, and citing other related policies. The policy was vetted through a multilayer process of review and stakeholder feedback and was ultimately approved at a system

Three additional related policies were also updated to reflect core principles of inclusion and partnership. These included system policies focused on discharge planning; identification of health care proxy, agent, support person and caregiver; and standards of behavior not conducive in a health care setting. As a result of this work, OPCE was invited to remain an active member of the System Policy and Procedure Committee, adding meaningful new perspectives to the clinical and administrative policy management process. Once policies were updated and approved, the SWT focused on educating leaders and teams. Using a diversified strategy, education was provided through various modes, including weekly system-wide internal communication channels, patient experience huddle messages, yearly mandatory topics training, and the incorporation of essential concepts in existing educational courses (classroom and e-learning modalities).

Position Descriptions/Performance Management

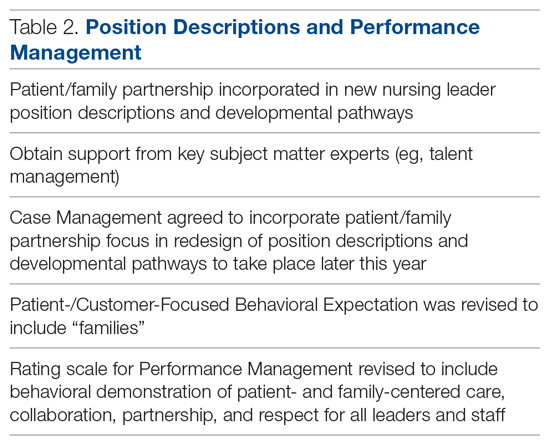

The position descriptions/performance management SWT focused its efforts on incorporating patient- and family-centered concepts and language into position descriptions and the performance appraisal process (Table 2). Due to the complex nature of this work, the process required collaboration from key subject matter experts in human resources, talent management, corporate compensation, and labor management. In 2019, Northwell began an initiative focused on streamlining and standardizing job titles, roles, and developmental pathways across the system. The overarching goal was to create system-wide consistency and standardization. The SWT was successful in advising the leaders overseeing this job architecture initiative on the importance of including language of patient- and family-centered care, like partnership and collaboration, and of highlighting the critical role of family members as part of the care team in subsequent documents.

Northwell has 6 behavioral expectations, standards to which all team members are held accountable: Patient/Customer Focus, Teamwork, Execution, Organizational Awareness, Enable Change, and Develop Self. As a result of the SWT’s work, Patient/Customer Focus was revised to include “families” as essential care partners, demonstrating Northwell’s ongoing commitment to honoring the role of families as members of the care team. It also ensures that all employees are aligned around this priority, as these expectations are utilized to support areas such as recognition and performance. Collaborating with talent management and organizational development, the SWT reviewed yearly performance management and new-hire evaluations. In doing so, they identified an opportunity to refresh the anchored qualitative rating scales to include behavioral demonstrations of patient- and family-centered care, collaboration, respect, and partnership with family members.

Website/Signage

Websites make an important first impression on patients and families looking for information to best prepare for a hospital experience. Therefore, the website/signage SWT worked to redesign hospital websites, enhance digital signage, and perform a baseline assessment of physical signage across facilities. Initial feedback on Northwell’s websites identified opportunities to include more patient- and family-centered, care-partner-infused language; improve navigation; and streamline click levels for easier access. Content for the websites was carefully crafted in collaboration with Northwell’s internal web team, utilizing IPFCC’s best practice standards as a framework and guide.

Next, a multidisciplinary website shared-governance team was established by the OPCE to ensure that key stakeholders were represented and had the opportunity to review and make recommendations for appropriate language and messaging about family presence and participation. This 13-person team was comprised of patient/family partners, patient-experience culture leaders, quality, compliance, human resources, policy, a chief nursing officer, a medical director, and representation from the Institute for Nursing. After careful review and consideration from Northwell’s family partners and teams, all participating hospital websites were enhanced as of June 2019 to include prominent 1-click access from homepages to information for “patients, families and visitors,” as well as “your care partners” information on the important role of families and care partners.

Along with refreshing websites, another step in Northwell’s work to strengthen messaging about family presence and participation was to partner and collaborate with the system’s digital web team as well as local facility councils to understand the capacity to adjust digital signage across facilities. Opportunities were found to make simple yet effective enhancements to the language and imagery of digital signage upon entry, creating a warmer and more welcoming first impression for patients and families. With patient and family partner feedback, the team designed digital signage with inclusive messaging and images that would circulate appropriately based on the facility. Signage specifically welcomes families and refers to them as members of patients’ care teams.

Northwell’s website/signage SWT also directed a 2-phase physical signage assessment to determine ongoing opportunities to alter signs in areas that particularly impact patients and families, such as emergency departments, main lobbies, cafeterias, surgical waiting areas, and intensive care units. Each hospital’s local PFPC did a “walk-about”9 to make enhancements to physical signage, such as removing paper and overcrowded signs, adjusting negative language, ensuring alignment with brand guidelines, and including language that welcomed families. As a result of the team’s efforts around signage, collaboration began with the health system’s signage committee to help standardize signage terminology to reflect family inclusiveness, and to implement the recommendation for a standardized signage shared-governance team to ensure accountability and a patient- and family-centered structure.

Sustainment

Since implementing Better Together, Northwell has been able to infuse a more patient- and family-centered emphasis into its overall patient experience message of “Every role, every person, every moment matters.” As a strategic tool aimed at encouraging leaders, clinicians, and staff to pause and reflect about the “heart” of their work, patient and family stories are now included at the beginning of meetings, forums, and team huddles. Elements of the initiative have been integrated in current Patient and Family Partnership sustainment plans at participating hospitals. Some highlights include continued integration of patient/family partners on committees and councils that impact areas such as way finding, signage, recruitment, new-hire orientation, and community outreach; focus on enhancing partner retention and development programs; and inclusion of patient- and family-centered care and Better Together principles in ongoing leadership meetings.

Factors Contributing to Success

Health care is a complex, regulated, and often bureaucratic world that can be very difficult for patients and families to navigate. The system’s partnership with the Better Together Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State enhanced its efforts to improve family presence and participation and created powerful synergy. The success of this partnership was based on a number of important factors:

A solid foundation of support, structure, and accountability. The OPCE initiated the IPFCC Better Together partnership and established a synergistic collaboration inclusive of leadership, frontline teams, multiple departments, and patient and family partners. As a major strategic component of Northwell’s mission to deliver high-quality, patient- and family-centered care, OPCE was instrumental in connecting key areas and stakeholders and mobilizing the recommendations coming from patients and families.

A visible commitment of leadership at all levels. Partnering with leadership across Northwell’s system required a delineated vision, clear purpose and ownership, and comprehensive implementation and sustainment strategies. The existing format of Northwell’s PFPC provided the structure and framework needed for engaged patient and family input; the OPCE motivated and organized key areas of involvement and led communication efforts across the organization. The IPFCC coaching calls provided the underlying guidance and accountability needed to sustain momentum. As leadership and frontline teams became aware of the vision, they understood the larger connection to the system’s purpose, which ultimately created a clear path for positive change.

Meaningful involvement and input of patient and family partners. Throughout this project, Northwell’s patient/family partners were involved through the PFPC and local councils. For example, patient/family partners attended every IPFCC coaching call; members had a central voice in every decision made within each SWT; and local PFPCs actively participated in physical signage “walk-abouts” across facilities, making key recommendations for improvement. This multifaceted, supportive collaboration created a rejuvenated and purposeful focus for all council members involved. Some of their reactions include, “…I am so happy to be able to help other families in crisis, so that they don’t have to be alone, like I was,” and “I feel how important the patient and family’s voice is … it’s truly a partnership between patients, families, and staff.”

Regular access to IPFCC as a best practice coach and expert resource. Throughout the 10-month process, IPFCC’s Better Together Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State provided ongoing learning interventions for members of the SWT; multiple and varied resources from the Better Together toolkit for adaptation; and opportunities to share and reinforce new, learned expertise with colleagues within the Northwell Health system and beyond through IPFCC’s free online learning community, PFCC.Connect.

Conclusion

Family presence and participation are important to the quality, experience, safety, and outcomes of care. IPFCC’s campaign, Better Together: Partnering with Families, encourages hospitals to change restrictive visiting policies and, instead, to welcome families and caregivers 24 hours a day.

Two projects within Better Together involving almost 50 acute care hospitals in New York State confirm that change in policy, practice, and communication is particularly effective when implemented with strong support from leadership. An intervention like the Better Together Learning Community, offering structured training, coaching, and resources, can facilitate the change process.

Corresponding author: IPFCC, Deborah L. Dokken, 6917 Arlington Rd., Ste. 309, Bethesda, MD 20814; ddokken@ipfcc.org.

Funding disclosures: None.

1. Dokken DL, Kaufman J, Johnson BJ et al. Changing hospital visiting policies: from families as “visitors” to families as partners. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2015; 22:29-36.

2. New York Public Interest Research Group and New Yorkers for Patient & Family Empowerment. Sick, scared and separated from loved ones. third edition: A pathway to improvement in New York City. New York: NYPIRG: 2018. www.nypirg.org/pubs/201801/NYPIRG_SICK_SCARED_FINAL.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2019.

3. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Better Together: Partnering with Families. www.ipfcc.org/bestpractices/better-together.html. Accessed December 12, 2019.

4. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. Better Together. www.cfhi-fcass.ca/WhatWeDo/better-together. Accessed December 12, 2019.

5. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. Better Together: A change package to support the adoption of family presence and participation in acute care hospitals and accelerate healthcare improvement. www.cfhi-fcass.ca/sf-docs/default-source/patient-engagement/better-together-change-package.pdf?sfvrsn=9656d044_4. Accessed December 12, 2019.

6. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. L’Objectif santé: main dans la main avec les familles. www.cfhi-fcass.ca/sf-docs/default-source/patient-engagement/families-pocket-screen_fr.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2019.

7. New York Public Interest Research Group and New Yorkers for Patient & Family Empowerment. Sick, scared and separated from loved ones. fourth edition: A pathway to improvement in New York. New York: NYPIRG: 2019. www.nypirg.org/pubs/201911/Sick_Scared_Separated_2019_web_FINAL.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2019.

8. Northwell Health. Patient and Family Partnership Councils. www.northwell.edu/about/commitment-to-excellence/patient-and-customer-experience/care-delivery-hospitality. Accessed December 12, 2019.

9 . Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. How to conduct a “walk-about” from the patient and family perspective. www.ipfcc.org/resources/How_To_Conduct_A_Walk-About.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2019.

From the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care, Bethesda, MD (Ms. Dokken and Ms. Johnson), and Northwell Health, New Hyde Park, NY (Dr. Barden, Ms. Tuomey, and Ms. Giammarinaro).

Abstract

Objective: To describe the growth of Better Together: Partnering with Families, a campaign launched in 2014 to eliminate restrictive hospital visiting policies and to put in place policies that recognize families as partners in care, and to discuss the processes involved in implementing the initiative in a large, integrated health system.

Methods: Descriptive report.

Results: In June 2014, the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) launched the Better Together campaign to emphasize the importance of family presence and participation to the quality, experience, safety, and outcomes of care. Since then, this initiative has expanded in both the United States and Canada. With support from 2 funders in the United States, special attention was focused on acute care hospitals across New York State. Nearly 50 hospitals participated in 2 separate but related projects. Fifteen of the hospitals are part of Northwell Health, New York State’s largest health system. Over a 10-month period, these hospitals made significant progress in changing policy, practice, and communication to support family presence.

Conclusion: The Better Together initiative was implemented across a health system with strong support from leadership and the involvement of patient and family advisors. An intervention offering structured training, coaching, and resources, like IPFCC’s Better Together initiative, can facilitate the change process.

Keywords: family presence; visiting policies; patient-centered care; family-centered care; patient experience.

The presence of families at the bedside of patients is often restricted by hospital visiting hours. Hospitals that maintain these restrictive policies cite concerns about negative impacts on security, infection control, privacy, and staff workload. But there are no data to support these concerns, and the experience of hospitals that have successfully changed policy and practice to welcome families demonstrates the potential positive impacts of less restrictive policies on patient care and outcomes.1 For example, hospitalization can lead to reduced cognitive function in elderly patients. Family members would recognize the changes and could provide valuable information to hospital staff, potentially improving outcomes.2

In June 2014, the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) launched the campaign Better Together: Partnering with Families.3 The campaign is is grounded in patient- and family- centered care, an approach to care that supports partnerships among health care providers, patients, and families, and, among other core principles, advocates that patients define their “families” and how they will participate in care and decision-making.

Emphasizing the importance of family presence and participation to quality and safety, the Better Together campaign seeks to eliminate restrictive visiting policies and calls upon hospitals to include families as members of the care team and to welcome them 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, according to patient preference. As part of the campaign, IPFCC developed an extensive toolkit of resources that is available to hospitals and other organizations at no cost. The resources include sample policies; profiles of hospitals that have implemented family presence policies; educational materials for staff, patients, and families; and a template for hospital websites. This article, a follow-up to an article published in the January 2015 issue of JCOM,1 discusses the growth of the Better Together initiative as well as the processes involved in implementing the initiative across a large health system.

Growth of the Initiative

Since its launch in 2014, the Better Together initiative has continued to expand in the United States and Canada. In Canada, under the leadership of the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement (CFHI), more than 50 organizations have made a commitment to the Better Together program and family presence.4 Utilizing and adapting IPFCC’s Toolkit, CFHI developed a change package of free resources for Canadian organizations.5 Some of the materials, including the Pocket Guide for Families (Manuel des Familles), were translated into French.6

With support from 2 funders in the United States, the United Hospital Fund and the New York State Health (NYSHealth) Foundation, through a subcontract with the New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG), IPFCC has been able to focus on hospitals in New York City, including public hospitals, and, more broadly, acute care hospitals across New York State. Nearly 50 hospitals participated in these 2 separate but related projects.

Education and Support for New York City Hospitals

Supported by the United Hospital Fund, an 18-month project that focused specifically on New York City hospitals was completed in June 2017. The project began with a 1-day intensive training event with representatives of 21 hospitals. Eighteen of those hospitals were eligible to participate in follow-up consultation provided by IPFCC, and 14 participated in some kind of follow-up. NYC Health + Hospitals (H+H), the system of public hospitals in NYC, participated most fully in these activities.

The outcomes of the Better Together initiative in New York City are summarized in the report Sick, Scared, & Separated From Loved Ones,2 which is based on a pre/post review of hospital visitation/family presence policies and website communications. According to the report, hospitals that participated in the IPFCC training and consultation program performed better, as a group, with respect to improved policy and website scores on post review than those that did not. Of the 10 hospitals whose scores improved during the review period, 8 had participated in the IPFCC training and 1 hospital was part of a hospital network that did so. (Six of these hospitals are part of the H+H public hospital system.) Those 9 hospitals saw an average increase in scores of 4.9 points (out of a possible 11).

A Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State

With support from the NYSHealth Foundation, IPFCC again collaborated with NYPIRG and New Yorkers for Patient & Family Empowerment on a 2-year initiative, completed in November 2019, that involved 26 hospitals: 15 from Northwell Health, New York State’s largest health system, and 11 hospitals from health systems throughout the state (Greater Hudson Valley Health System, now Garnet Health; Mohawk Valley Health System; Rochester Regional Health; and University of Vermont Health Network). An update of the report Sick, Scared, & Separated From Loved Onescompared pre/post reviews of policies and website communications regarding hospital visitation/family presence.7 Its findings confirm that hospitals that participated in the Better Together Learning Community improved both their policy and website scores to a greater degree than hospitals that did not participate and that a planned intervention can help facilitate change.

During the survey period, 28 out of 40 hospitals’ website navigability scores improved. Of those, hospitals that did not participate in the Better Together Learning Community saw an average increase in scores of 1.2 points, out of a possible 11, while the participating hospitals saw an average increase of 2.7 points, with the top 5 largest increases in scores belonging to hospitals that participated in the Better Together Learning Community.7

The Northwell Health Experience

Northwell Health is a large integrated health care organization comprising more than 69,000 employees, 23 hospitals, and more than 750 medical practices, located geographically across New York State. Embracing patient- and family-centered care, Northwell is dedicated to improving the quality, experience, and safety of care for patients and their families. Welcoming and including patients, families, and care partners as members of the health care team has always been a core element of Northwell’s organizational goal of providing world-class patient care and experience.

Four years ago, the organization reorganized and formalized a system-wide Patient & Family Partnership Council (PFPC).8 Representatives on the PFPC include a Northwell patient experience leader and patient/family co-chair from local councils that have been established in nearly all 23 hospitals as well as service lines. Modeling partnership, the PFPC is grounded in listening to the “voice” of patients and families and promoting collaboration, with the goal of driving change across varied aspects and experiences of health care delivery.

Through the Office of Patient and Customer Experience (OPCE), a partnership with IPFCC and the Better Together Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State was initiated as a fundamental next step in Northwell’s journey to enhance system-wide family presence and participation. Results from Better Together’s Organizational Self-Assessment Tool and process identified opportunities to influence 3 distinct areas: policy/staff education, position descriptions/performance management, and website/signage. Over a 10-month period (September 2018 through June 2019), 15 Northwell hospitals implemened significant patient- and family-centered improvements through multifaceted shared work teams (SWT) that partnered around the common goal of supporting the patient and family experience (Figure). Northwell’s SWT structure allowed teams to meet individually on specific tasks, led by a dedicated staff member of the OPCE to ensure progress, support, and accountability. Six monthly coaching calls or report-out meetings were attended by participating teams, where feedback and recommendations shared by IPFCC were discussed in order to maintain momentum and results.

Policy/Staff Education

The policy/staff education SWT focused on appraising and updating existing policies to ensure alignment with key patient- and family-centered concepts and Better Together principles (Table 1). By establishing representation on the System Policy and Procedure Committee, OPCE enabled patients and families to have a voice at the decision-making table. OPCE leaders presented the ideology and scope of the transformation to this committee. After reviewing all system-wide policies, 4 were identified as key opportunities for revision. One overarching policy titled “Visitation Guidelines” was reviewed and updated to reflect Northwell’s mission of patient- and family-centered care, retiring the reference to “families” as “visitors” in definitions, incorporating language of inclusion and partnership, and citing other related policies. The policy was vetted through a multilayer process of review and stakeholder feedback and was ultimately approved at a system

Three additional related policies were also updated to reflect core principles of inclusion and partnership. These included system policies focused on discharge planning; identification of health care proxy, agent, support person and caregiver; and standards of behavior not conducive in a health care setting. As a result of this work, OPCE was invited to remain an active member of the System Policy and Procedure Committee, adding meaningful new perspectives to the clinical and administrative policy management process. Once policies were updated and approved, the SWT focused on educating leaders and teams. Using a diversified strategy, education was provided through various modes, including weekly system-wide internal communication channels, patient experience huddle messages, yearly mandatory topics training, and the incorporation of essential concepts in existing educational courses (classroom and e-learning modalities).

Position Descriptions/Performance Management

The position descriptions/performance management SWT focused its efforts on incorporating patient- and family-centered concepts and language into position descriptions and the performance appraisal process (Table 2). Due to the complex nature of this work, the process required collaboration from key subject matter experts in human resources, talent management, corporate compensation, and labor management. In 2019, Northwell began an initiative focused on streamlining and standardizing job titles, roles, and developmental pathways across the system. The overarching goal was to create system-wide consistency and standardization. The SWT was successful in advising the leaders overseeing this job architecture initiative on the importance of including language of patient- and family-centered care, like partnership and collaboration, and of highlighting the critical role of family members as part of the care team in subsequent documents.

Northwell has 6 behavioral expectations, standards to which all team members are held accountable: Patient/Customer Focus, Teamwork, Execution, Organizational Awareness, Enable Change, and Develop Self. As a result of the SWT’s work, Patient/Customer Focus was revised to include “families” as essential care partners, demonstrating Northwell’s ongoing commitment to honoring the role of families as members of the care team. It also ensures that all employees are aligned around this priority, as these expectations are utilized to support areas such as recognition and performance. Collaborating with talent management and organizational development, the SWT reviewed yearly performance management and new-hire evaluations. In doing so, they identified an opportunity to refresh the anchored qualitative rating scales to include behavioral demonstrations of patient- and family-centered care, collaboration, respect, and partnership with family members.

Website/Signage

Websites make an important first impression on patients and families looking for information to best prepare for a hospital experience. Therefore, the website/signage SWT worked to redesign hospital websites, enhance digital signage, and perform a baseline assessment of physical signage across facilities. Initial feedback on Northwell’s websites identified opportunities to include more patient- and family-centered, care-partner-infused language; improve navigation; and streamline click levels for easier access. Content for the websites was carefully crafted in collaboration with Northwell’s internal web team, utilizing IPFCC’s best practice standards as a framework and guide.

Next, a multidisciplinary website shared-governance team was established by the OPCE to ensure that key stakeholders were represented and had the opportunity to review and make recommendations for appropriate language and messaging about family presence and participation. This 13-person team was comprised of patient/family partners, patient-experience culture leaders, quality, compliance, human resources, policy, a chief nursing officer, a medical director, and representation from the Institute for Nursing. After careful review and consideration from Northwell’s family partners and teams, all participating hospital websites were enhanced as of June 2019 to include prominent 1-click access from homepages to information for “patients, families and visitors,” as well as “your care partners” information on the important role of families and care partners.

Along with refreshing websites, another step in Northwell’s work to strengthen messaging about family presence and participation was to partner and collaborate with the system’s digital web team as well as local facility councils to understand the capacity to adjust digital signage across facilities. Opportunities were found to make simple yet effective enhancements to the language and imagery of digital signage upon entry, creating a warmer and more welcoming first impression for patients and families. With patient and family partner feedback, the team designed digital signage with inclusive messaging and images that would circulate appropriately based on the facility. Signage specifically welcomes families and refers to them as members of patients’ care teams.

Northwell’s website/signage SWT also directed a 2-phase physical signage assessment to determine ongoing opportunities to alter signs in areas that particularly impact patients and families, such as emergency departments, main lobbies, cafeterias, surgical waiting areas, and intensive care units. Each hospital’s local PFPC did a “walk-about”9 to make enhancements to physical signage, such as removing paper and overcrowded signs, adjusting negative language, ensuring alignment with brand guidelines, and including language that welcomed families. As a result of the team’s efforts around signage, collaboration began with the health system’s signage committee to help standardize signage terminology to reflect family inclusiveness, and to implement the recommendation for a standardized signage shared-governance team to ensure accountability and a patient- and family-centered structure.

Sustainment

Since implementing Better Together, Northwell has been able to infuse a more patient- and family-centered emphasis into its overall patient experience message of “Every role, every person, every moment matters.” As a strategic tool aimed at encouraging leaders, clinicians, and staff to pause and reflect about the “heart” of their work, patient and family stories are now included at the beginning of meetings, forums, and team huddles. Elements of the initiative have been integrated in current Patient and Family Partnership sustainment plans at participating hospitals. Some highlights include continued integration of patient/family partners on committees and councils that impact areas such as way finding, signage, recruitment, new-hire orientation, and community outreach; focus on enhancing partner retention and development programs; and inclusion of patient- and family-centered care and Better Together principles in ongoing leadership meetings.

Factors Contributing to Success

Health care is a complex, regulated, and often bureaucratic world that can be very difficult for patients and families to navigate. The system’s partnership with the Better Together Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State enhanced its efforts to improve family presence and participation and created powerful synergy. The success of this partnership was based on a number of important factors:

A solid foundation of support, structure, and accountability. The OPCE initiated the IPFCC Better Together partnership and established a synergistic collaboration inclusive of leadership, frontline teams, multiple departments, and patient and family partners. As a major strategic component of Northwell’s mission to deliver high-quality, patient- and family-centered care, OPCE was instrumental in connecting key areas and stakeholders and mobilizing the recommendations coming from patients and families.

A visible commitment of leadership at all levels. Partnering with leadership across Northwell’s system required a delineated vision, clear purpose and ownership, and comprehensive implementation and sustainment strategies. The existing format of Northwell’s PFPC provided the structure and framework needed for engaged patient and family input; the OPCE motivated and organized key areas of involvement and led communication efforts across the organization. The IPFCC coaching calls provided the underlying guidance and accountability needed to sustain momentum. As leadership and frontline teams became aware of the vision, they understood the larger connection to the system’s purpose, which ultimately created a clear path for positive change.

Meaningful involvement and input of patient and family partners. Throughout this project, Northwell’s patient/family partners were involved through the PFPC and local councils. For example, patient/family partners attended every IPFCC coaching call; members had a central voice in every decision made within each SWT; and local PFPCs actively participated in physical signage “walk-abouts” across facilities, making key recommendations for improvement. This multifaceted, supportive collaboration created a rejuvenated and purposeful focus for all council members involved. Some of their reactions include, “…I am so happy to be able to help other families in crisis, so that they don’t have to be alone, like I was,” and “I feel how important the patient and family’s voice is … it’s truly a partnership between patients, families, and staff.”

Regular access to IPFCC as a best practice coach and expert resource. Throughout the 10-month process, IPFCC’s Better Together Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State provided ongoing learning interventions for members of the SWT; multiple and varied resources from the Better Together toolkit for adaptation; and opportunities to share and reinforce new, learned expertise with colleagues within the Northwell Health system and beyond through IPFCC’s free online learning community, PFCC.Connect.

Conclusion

Family presence and participation are important to the quality, experience, safety, and outcomes of care. IPFCC’s campaign, Better Together: Partnering with Families, encourages hospitals to change restrictive visiting policies and, instead, to welcome families and caregivers 24 hours a day.

Two projects within Better Together involving almost 50 acute care hospitals in New York State confirm that change in policy, practice, and communication is particularly effective when implemented with strong support from leadership. An intervention like the Better Together Learning Community, offering structured training, coaching, and resources, can facilitate the change process.

Corresponding author: IPFCC, Deborah L. Dokken, 6917 Arlington Rd., Ste. 309, Bethesda, MD 20814; ddokken@ipfcc.org.

Funding disclosures: None.

From the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care, Bethesda, MD (Ms. Dokken and Ms. Johnson), and Northwell Health, New Hyde Park, NY (Dr. Barden, Ms. Tuomey, and Ms. Giammarinaro).

Abstract

Objective: To describe the growth of Better Together: Partnering with Families, a campaign launched in 2014 to eliminate restrictive hospital visiting policies and to put in place policies that recognize families as partners in care, and to discuss the processes involved in implementing the initiative in a large, integrated health system.

Methods: Descriptive report.

Results: In June 2014, the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) launched the Better Together campaign to emphasize the importance of family presence and participation to the quality, experience, safety, and outcomes of care. Since then, this initiative has expanded in both the United States and Canada. With support from 2 funders in the United States, special attention was focused on acute care hospitals across New York State. Nearly 50 hospitals participated in 2 separate but related projects. Fifteen of the hospitals are part of Northwell Health, New York State’s largest health system. Over a 10-month period, these hospitals made significant progress in changing policy, practice, and communication to support family presence.

Conclusion: The Better Together initiative was implemented across a health system with strong support from leadership and the involvement of patient and family advisors. An intervention offering structured training, coaching, and resources, like IPFCC’s Better Together initiative, can facilitate the change process.

Keywords: family presence; visiting policies; patient-centered care; family-centered care; patient experience.

The presence of families at the bedside of patients is often restricted by hospital visiting hours. Hospitals that maintain these restrictive policies cite concerns about negative impacts on security, infection control, privacy, and staff workload. But there are no data to support these concerns, and the experience of hospitals that have successfully changed policy and practice to welcome families demonstrates the potential positive impacts of less restrictive policies on patient care and outcomes.1 For example, hospitalization can lead to reduced cognitive function in elderly patients. Family members would recognize the changes and could provide valuable information to hospital staff, potentially improving outcomes.2

In June 2014, the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) launched the campaign Better Together: Partnering with Families.3 The campaign is is grounded in patient- and family- centered care, an approach to care that supports partnerships among health care providers, patients, and families, and, among other core principles, advocates that patients define their “families” and how they will participate in care and decision-making.

Emphasizing the importance of family presence and participation to quality and safety, the Better Together campaign seeks to eliminate restrictive visiting policies and calls upon hospitals to include families as members of the care team and to welcome them 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, according to patient preference. As part of the campaign, IPFCC developed an extensive toolkit of resources that is available to hospitals and other organizations at no cost. The resources include sample policies; profiles of hospitals that have implemented family presence policies; educational materials for staff, patients, and families; and a template for hospital websites. This article, a follow-up to an article published in the January 2015 issue of JCOM,1 discusses the growth of the Better Together initiative as well as the processes involved in implementing the initiative across a large health system.

Growth of the Initiative

Since its launch in 2014, the Better Together initiative has continued to expand in the United States and Canada. In Canada, under the leadership of the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement (CFHI), more than 50 organizations have made a commitment to the Better Together program and family presence.4 Utilizing and adapting IPFCC’s Toolkit, CFHI developed a change package of free resources for Canadian organizations.5 Some of the materials, including the Pocket Guide for Families (Manuel des Familles), were translated into French.6

With support from 2 funders in the United States, the United Hospital Fund and the New York State Health (NYSHealth) Foundation, through a subcontract with the New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG), IPFCC has been able to focus on hospitals in New York City, including public hospitals, and, more broadly, acute care hospitals across New York State. Nearly 50 hospitals participated in these 2 separate but related projects.

Education and Support for New York City Hospitals

Supported by the United Hospital Fund, an 18-month project that focused specifically on New York City hospitals was completed in June 2017. The project began with a 1-day intensive training event with representatives of 21 hospitals. Eighteen of those hospitals were eligible to participate in follow-up consultation provided by IPFCC, and 14 participated in some kind of follow-up. NYC Health + Hospitals (H+H), the system of public hospitals in NYC, participated most fully in these activities.

The outcomes of the Better Together initiative in New York City are summarized in the report Sick, Scared, & Separated From Loved Ones,2 which is based on a pre/post review of hospital visitation/family presence policies and website communications. According to the report, hospitals that participated in the IPFCC training and consultation program performed better, as a group, with respect to improved policy and website scores on post review than those that did not. Of the 10 hospitals whose scores improved during the review period, 8 had participated in the IPFCC training and 1 hospital was part of a hospital network that did so. (Six of these hospitals are part of the H+H public hospital system.) Those 9 hospitals saw an average increase in scores of 4.9 points (out of a possible 11).

A Learning Community for Hospitals in New York State

With support from the NYSHealth Foundation, IPFCC again collaborated with NYPIRG and New Yorkers for Patient & Family Empowerment on a 2-year initiative, completed in November 2019, that involved 26 hospitals: 15 from Northwell Health, New York State’s largest health system, and 11 hospitals from health systems throughout the state (Greater Hudson Valley Health System, now Garnet Health; Mohawk Valley Health System; Rochester Regional Health; and University of Vermont Health Network). An update of the report Sick, Scared, & Separated From Loved Onescompared pre/post reviews of policies and website communications regarding hospital visitation/family presence.7 Its findings confirm that hospitals that participated in the Better Together Learning Community improved both their policy and website scores to a greater degree than hospitals that did not participate and that a planned intervention can help facilitate change.

During the survey period, 28 out of 40 hospitals’ website navigability scores improved. Of those, hospitals that did not participate in the Better Together Learning Community saw an average increase in scores of 1.2 points, out of a possible 11, while the participating hospitals saw an average increase of 2.7 points, with the top 5 largest increases in scores belonging to hospitals that participated in the Better Together Learning Community.7

The Northwell Health Experience

Northwell Health is a large integrated health care organization comprising more than 69,000 employees, 23 hospitals, and more than 750 medical practices, located geographically across New York State. Embracing patient- and family-centered care, Northwell is dedicated to improving the quality, experience, and safety of care for patients and their families. Welcoming and including patients, families, and care partners as members of the health care team has always been a core element of Northwell’s organizational goal of providing world-class patient care and experience.

Four years ago, the organization reorganized and formalized a system-wide Patient & Family Partnership Council (PFPC).8 Representatives on the PFPC include a Northwell patient experience leader and patient/family co-chair from local councils that have been established in nearly all 23 hospitals as well as service lines. Modeling partnership, the PFPC is grounded in listening to the “voice” of patients and families and promoting collaboration, with the goal of driving change across varied aspects and experiences of health care delivery.