User login

Trial yields evidence that laser resurfacing may prevent NMSC in aged skin

A on treated areas, according to the results of a small, randomized trial.

“Previous research suggests a new model to explain why older patients obtain nonmelanoma skin cancer in areas of ongoing sun exposure,” presenting author Jeffrey Wargo, MD, said during the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “Insulinlike growth factor-1 produced by dermal fibroblasts dictates how overlying skin keratinocytes respond to UVB radiation. The skin of a patient aged in their 20s produces normal levels of healthy fibroblasts, normal levels of insulinlike growth factor 1, and appropriate UVB response via activation of nucleotide excision, repair, and DNA damage checkpoint-signaling systems.”

Older patients, meanwhile, have an increase in senescent fibroblasts, decreased insulinlike growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and an inappropriate UVB response to DNA damage, continued Dr. Wargo, a dermatologist at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus. Previous studies conducted by his mentor, Jeffrey B. Travers, MD, PhD, a dermatologist and pharmacologist at Wright State University, Dayton, showed that fractionated laser resurfacing (FLR) restores UVB response in older patients’ skin by resulting in new fibroblasts and increased levels of IGF 2 years post wounding.

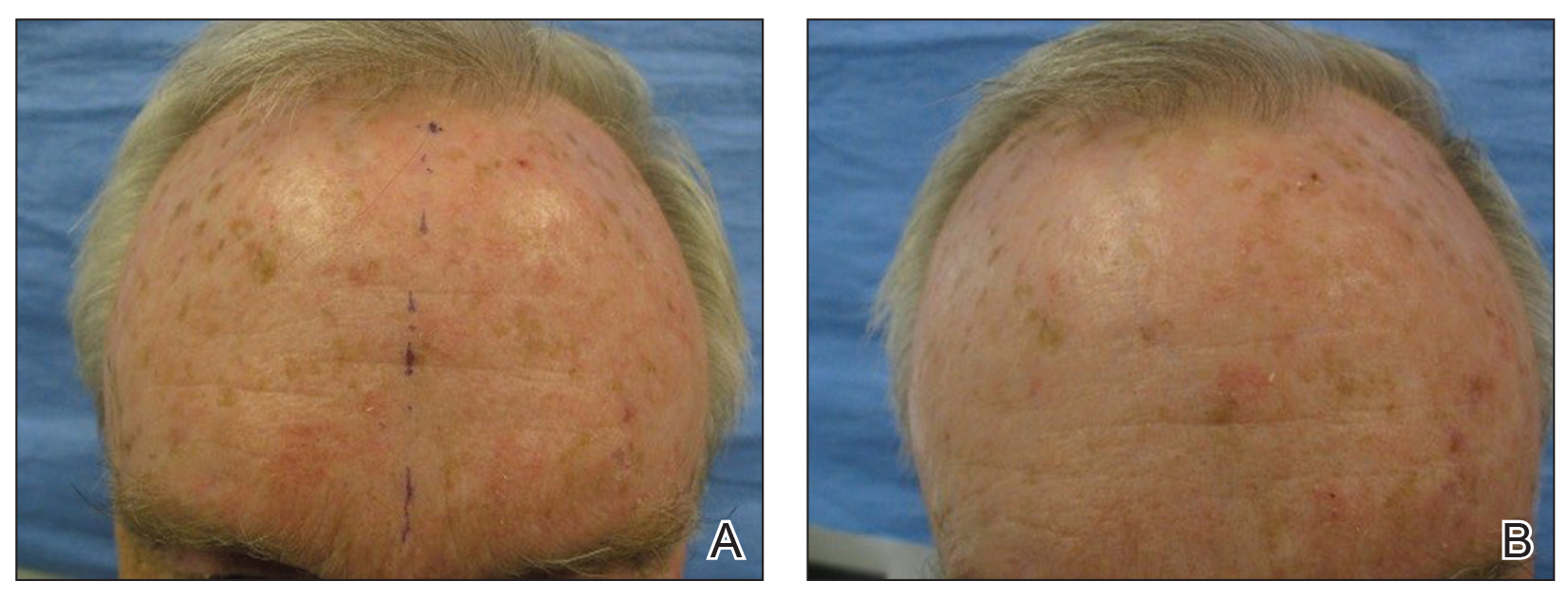

To determine if FLR of aged skin can prevent the development of actinic keratosis (AK) and nonmelanoma skin cancer, Dr. Travers and Dr. Wargo recruited 48 patients at the Dayton VA Medical Center who were 60 years or older and had at least five AKs on each arm that were 3 mm or smaller, with nothing concerning for skin cancer at the screening visit.

Randomization of which arm was treated was based on an odd or even Social Security Number. That arm was treated with the 2,790 nm Erbium:YSSG ablative laser at 120 J/m2 with one pass at 24% coverage from the elbow to hand dorsally. Previously published data reported outcomes for 30 of these patients at 3 and 6 months following treatment. Subsequent to that report, 18 additional subjects have been recruited to the study and follow-up has been extended. Of the 48 patients, 47 were male and their average age was 74, with a range between 61 and 87 years.

At 3 months following FLR, the ratio of AKs on the treated vs. untreated arms was reduced by fourfold, with a P value less than .00001, Dr. Wargo reported. “Throughout the current 30-month follow-up period, this ratio has been maintained,” he said. “In fact, none of the ratios determined at 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, or 30 months post FLR are significantly different. Hence, as described in our first report on this work, these data indicate FLR is an effective treatment for existing AKs. However, our model predicts that FLR treatment will also prevent the occurrence of new AK lesions.”

Among 19 of the study participants who have been followed out to 30 months, untreated arms continued to accumulate increasing number of AKs. In contrast, AKs on treated arms are decreasing with time, indicating the lack of newly initiated lesions.

“A second analysis of the data posits that, if FLR were only removing existing lesions, one would predict the number of AKs that were present at 3 months on both the untreated and FLR-treated [arms] would accumulate at the same rate subsequent to 3 months point in time,” Dr. Wargo said.

He pointed out that 12 patients were removed from the study: two at 12 months, one at 18 months, eight at 24 months, and one at 30 months, as they were found to have 20 or more AKs on their untreated arm and required treatment.

Over the entire study period, “consistent with the notion that FLR was preventing new actinic neoplasia, we noted a dramatic difference in numbers of nonmelanoma skin cancer diagnosed in the untreated areas (22) versus FLR treated areas (2),” Dr. Wargo said. The majority of nonmelanoma skin cancers diagnosed were SCC (17) and 5 basal cell carcinomas on the untreated arms, whereas the 2 diagnosed on the treated arm were SCC. “These studies indicate that a dermal-wounding strategy involving FLR, which upregulates dermal IGF-1 levels, not only treats AKs but prevents nonmelanoma skin cancer,” he said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Travers is the principal investigator. Dr. Wargo reported having no financial disclosures.

A on treated areas, according to the results of a small, randomized trial.

“Previous research suggests a new model to explain why older patients obtain nonmelanoma skin cancer in areas of ongoing sun exposure,” presenting author Jeffrey Wargo, MD, said during the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “Insulinlike growth factor-1 produced by dermal fibroblasts dictates how overlying skin keratinocytes respond to UVB radiation. The skin of a patient aged in their 20s produces normal levels of healthy fibroblasts, normal levels of insulinlike growth factor 1, and appropriate UVB response via activation of nucleotide excision, repair, and DNA damage checkpoint-signaling systems.”

Older patients, meanwhile, have an increase in senescent fibroblasts, decreased insulinlike growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and an inappropriate UVB response to DNA damage, continued Dr. Wargo, a dermatologist at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus. Previous studies conducted by his mentor, Jeffrey B. Travers, MD, PhD, a dermatologist and pharmacologist at Wright State University, Dayton, showed that fractionated laser resurfacing (FLR) restores UVB response in older patients’ skin by resulting in new fibroblasts and increased levels of IGF 2 years post wounding.

To determine if FLR of aged skin can prevent the development of actinic keratosis (AK) and nonmelanoma skin cancer, Dr. Travers and Dr. Wargo recruited 48 patients at the Dayton VA Medical Center who were 60 years or older and had at least five AKs on each arm that were 3 mm or smaller, with nothing concerning for skin cancer at the screening visit.

Randomization of which arm was treated was based on an odd or even Social Security Number. That arm was treated with the 2,790 nm Erbium:YSSG ablative laser at 120 J/m2 with one pass at 24% coverage from the elbow to hand dorsally. Previously published data reported outcomes for 30 of these patients at 3 and 6 months following treatment. Subsequent to that report, 18 additional subjects have been recruited to the study and follow-up has been extended. Of the 48 patients, 47 were male and their average age was 74, with a range between 61 and 87 years.

At 3 months following FLR, the ratio of AKs on the treated vs. untreated arms was reduced by fourfold, with a P value less than .00001, Dr. Wargo reported. “Throughout the current 30-month follow-up period, this ratio has been maintained,” he said. “In fact, none of the ratios determined at 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, or 30 months post FLR are significantly different. Hence, as described in our first report on this work, these data indicate FLR is an effective treatment for existing AKs. However, our model predicts that FLR treatment will also prevent the occurrence of new AK lesions.”

Among 19 of the study participants who have been followed out to 30 months, untreated arms continued to accumulate increasing number of AKs. In contrast, AKs on treated arms are decreasing with time, indicating the lack of newly initiated lesions.

“A second analysis of the data posits that, if FLR were only removing existing lesions, one would predict the number of AKs that were present at 3 months on both the untreated and FLR-treated [arms] would accumulate at the same rate subsequent to 3 months point in time,” Dr. Wargo said.

He pointed out that 12 patients were removed from the study: two at 12 months, one at 18 months, eight at 24 months, and one at 30 months, as they were found to have 20 or more AKs on their untreated arm and required treatment.

Over the entire study period, “consistent with the notion that FLR was preventing new actinic neoplasia, we noted a dramatic difference in numbers of nonmelanoma skin cancer diagnosed in the untreated areas (22) versus FLR treated areas (2),” Dr. Wargo said. The majority of nonmelanoma skin cancers diagnosed were SCC (17) and 5 basal cell carcinomas on the untreated arms, whereas the 2 diagnosed on the treated arm were SCC. “These studies indicate that a dermal-wounding strategy involving FLR, which upregulates dermal IGF-1 levels, not only treats AKs but prevents nonmelanoma skin cancer,” he said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Travers is the principal investigator. Dr. Wargo reported having no financial disclosures.

A on treated areas, according to the results of a small, randomized trial.

“Previous research suggests a new model to explain why older patients obtain nonmelanoma skin cancer in areas of ongoing sun exposure,” presenting author Jeffrey Wargo, MD, said during the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “Insulinlike growth factor-1 produced by dermal fibroblasts dictates how overlying skin keratinocytes respond to UVB radiation. The skin of a patient aged in their 20s produces normal levels of healthy fibroblasts, normal levels of insulinlike growth factor 1, and appropriate UVB response via activation of nucleotide excision, repair, and DNA damage checkpoint-signaling systems.”

Older patients, meanwhile, have an increase in senescent fibroblasts, decreased insulinlike growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and an inappropriate UVB response to DNA damage, continued Dr. Wargo, a dermatologist at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus. Previous studies conducted by his mentor, Jeffrey B. Travers, MD, PhD, a dermatologist and pharmacologist at Wright State University, Dayton, showed that fractionated laser resurfacing (FLR) restores UVB response in older patients’ skin by resulting in new fibroblasts and increased levels of IGF 2 years post wounding.

To determine if FLR of aged skin can prevent the development of actinic keratosis (AK) and nonmelanoma skin cancer, Dr. Travers and Dr. Wargo recruited 48 patients at the Dayton VA Medical Center who were 60 years or older and had at least five AKs on each arm that were 3 mm or smaller, with nothing concerning for skin cancer at the screening visit.

Randomization of which arm was treated was based on an odd or even Social Security Number. That arm was treated with the 2,790 nm Erbium:YSSG ablative laser at 120 J/m2 with one pass at 24% coverage from the elbow to hand dorsally. Previously published data reported outcomes for 30 of these patients at 3 and 6 months following treatment. Subsequent to that report, 18 additional subjects have been recruited to the study and follow-up has been extended. Of the 48 patients, 47 were male and their average age was 74, with a range between 61 and 87 years.

At 3 months following FLR, the ratio of AKs on the treated vs. untreated arms was reduced by fourfold, with a P value less than .00001, Dr. Wargo reported. “Throughout the current 30-month follow-up period, this ratio has been maintained,” he said. “In fact, none of the ratios determined at 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, or 30 months post FLR are significantly different. Hence, as described in our first report on this work, these data indicate FLR is an effective treatment for existing AKs. However, our model predicts that FLR treatment will also prevent the occurrence of new AK lesions.”

Among 19 of the study participants who have been followed out to 30 months, untreated arms continued to accumulate increasing number of AKs. In contrast, AKs on treated arms are decreasing with time, indicating the lack of newly initiated lesions.

“A second analysis of the data posits that, if FLR were only removing existing lesions, one would predict the number of AKs that were present at 3 months on both the untreated and FLR-treated [arms] would accumulate at the same rate subsequent to 3 months point in time,” Dr. Wargo said.

He pointed out that 12 patients were removed from the study: two at 12 months, one at 18 months, eight at 24 months, and one at 30 months, as they were found to have 20 or more AKs on their untreated arm and required treatment.

Over the entire study period, “consistent with the notion that FLR was preventing new actinic neoplasia, we noted a dramatic difference in numbers of nonmelanoma skin cancer diagnosed in the untreated areas (22) versus FLR treated areas (2),” Dr. Wargo said. The majority of nonmelanoma skin cancers diagnosed were SCC (17) and 5 basal cell carcinomas on the untreated arms, whereas the 2 diagnosed on the treated arm were SCC. “These studies indicate that a dermal-wounding strategy involving FLR, which upregulates dermal IGF-1 levels, not only treats AKs but prevents nonmelanoma skin cancer,” he said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Travers is the principal investigator. Dr. Wargo reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM ASLMS 2021

AAD unveils new guidelines for actinic keratosis management

. They also conditionally recommend the use of photodynamic therapy (PDT) and diclofenac for the treatment of AK, both individually and as part of combination therapy regimens.

Those are two of 18 recommendations made by 14 members of the multidisciplinary work group that convened to assemble the AAD’s first-ever guidelines on the management of AKs, which were published online April 2 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. The group, cochaired by Daniel B. Eisen, MD, professor of clinical dermatology at the University of California, Davis, and Todd E. Schlesinger, MD, medical director of the Dermatology and Laser Center of Charleston, S.C., conducted a systematic review to address five clinical questions on the management of AKs in adults. The questions were: What are the efficacy, effectiveness, and adverse effects of surgical and chemical peel treatments for AK; of topically applied agents for AK; of energy devices and other miscellaneous treatments for AK; and of combination therapy for the treatment of AK? And what are the special considerations to be taken into account when treating AK in immunocompromised individuals?

Next, the work group applied the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach for assessing the certainty of the evidence and formulating and grading clinical recommendations based on relevant randomized trials in the medical literature.

“As a participant in the work group, I was impressed by the level of care and detail and the involvement of relevant stakeholders, including a patient advocate, as well as having the draft guidelines go out to the AAD membership at large, and evaluating every comment that came in,” Maryam Asgari, MD, MPH, professor of dermatology at Harvard University, Boston, said in an interview. “The academy sought stakeholder and leadership input in revising and revamping the guidelines. The AAD also made sure the work group had minimal conflicts of interest by requiring that the majority of experts convened did not have relevant financial conflicts of interest. That might not be the case in a publication such as a systematic review, where no threshold for financial conflict of interest for coauthorship is set.”

Of the 18 recommendations the work group made for patients with AKs, only four were ranked as “strong” based on the evidence reviewed, while the rest were ranked as “conditional.”

The strong recommendations include the use of UV protection, field treatment with 5-FU, field treatment with imiquimod, and the use of cryosurgery.

The first four conditional recommendations for patients with AKs include the use of diclofenac, treatment with cryosurgery over CO2 laser ablation, aminolevulinic acid (ALA)–red-light PDT, and 1- to 4-hour 5-ALA incubation time to enhance complete clearance with red-light PDT. The work group also conditionally recommends ALA-daylight PDT as less painful than but equally effective as ALA–red-light PDT.

In the clinical experience of Catherine M. DiGiorgio, MD, who was not involved in the guidelines, daylight PDT with ALA is a viable, cost-effective option. “Patients can come into the office, apply the ALA and then they go outside for 2 hours – not in direct sunlight but in a shady area,” Dr. DiGiorgio, a dermatologist who practices at the Boston Center for Facial Rejuvenation, said in an interview. “That’s a cost-effective treatment for patients who perhaps can’t afford some of the chemotherapy creams. I don’t think we’ve adopted ALA-daylight PDT here in the U.S. very much.”

The work group noted that topical 1% tirbanibulin ointment, a novel microtubule inhibitor, was approved for treatment of AKs on the face and scalp by the Food and Drug Administration after the guidelines had been put together.

Several trials of combination therapy were included in the review of evidence, prompting several recommendations. For example, the work group conditionally recommends combined 5-FU cream and cryosurgery over cryosurgery alone, based on moderate-quality evidence and conditionally recommends combined imiquimod and cryosurgery over cryosurgery alone based on low-quality evidence. In addition, the work group conditionally recommends against the use of 3% diclofenac in addition to cryosurgery, favoring cryosurgery alone based on low-quality evidence, and conditionally recommends against the use of imiquimod typically after ALA–blue-light PDT, based on moderate-quality data.

“The additional treatment with imiquimod was thought to add both expense and burden to the patient, which negates much of the perceived convenience of using PDT as a stand-alone treatment modality and which is not mitigated by the modest increase in lesion reduction,” the authors wrote.

The guidelines emphasize the importance of shared decision-making between patients and clinicians on the choice of therapy, a point that resonates with Dr. DiGiorgio. Success of a treatment can depend on whether a patient is willing to go through with it, she said. “Some patients don’t want to do a therapeutic topical like 5-FU. They prefer to come in and have cryotherapy done. Others prefer to not come in and have the cream at home and treat themselves.”

Assembling the guidelines exposed certain gaps in research, according to the work group. Of the 18 recommendations, seven were based on low-quality evidence, and there were not enough data to make guidelines for the treatment of AKs in immunocompromised individuals.

“I can’t tell you the number of times we in the committee sat back and said, ‘we need to have a randomized trial that looks at this, or compares this to that head on,’” Dr. Asgari said. Such limitations “give researchers direction for where the areas of study need to go to help us answer some of these management conundrums.”

She added that the new guidelines “give clinicians a leg to stand on” when an insurer pushes back on a recommended treatment for AK. “It gives you a way to have dialogue with insurers if you’re prescribing some of these treatments.”

The guidelines authors write that there is “strong theoretic rationale for the treatment of AK to prevent skin cancers” but acknowledge that only a few studies in the review “report the incidence of skin cancer as an outcome measure or have sufficient follow-up to viably measure carcinoma development.” In addition, “more long-term research is needed to validate our current understanding of skin cancer progression from AKs to keratinocyte carcinoma.”

Dr. DiGiorgio thinks about this differently. “I think treatment of AKs does prevent skin cancers,” she said. “We call them precancers as we’re treating our patients because we know a certain percentage of them can develop into skin cancers over time.”

The study was funded by internal funds from the AAD. Dr. Asgari disclosed that she serves as an investigator for Pfizer. Several of the other authors reported having financial disclosures.

Dr. DiGiorgio reported having no financial disclosures.

. They also conditionally recommend the use of photodynamic therapy (PDT) and diclofenac for the treatment of AK, both individually and as part of combination therapy regimens.

Those are two of 18 recommendations made by 14 members of the multidisciplinary work group that convened to assemble the AAD’s first-ever guidelines on the management of AKs, which were published online April 2 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. The group, cochaired by Daniel B. Eisen, MD, professor of clinical dermatology at the University of California, Davis, and Todd E. Schlesinger, MD, medical director of the Dermatology and Laser Center of Charleston, S.C., conducted a systematic review to address five clinical questions on the management of AKs in adults. The questions were: What are the efficacy, effectiveness, and adverse effects of surgical and chemical peel treatments for AK; of topically applied agents for AK; of energy devices and other miscellaneous treatments for AK; and of combination therapy for the treatment of AK? And what are the special considerations to be taken into account when treating AK in immunocompromised individuals?

Next, the work group applied the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach for assessing the certainty of the evidence and formulating and grading clinical recommendations based on relevant randomized trials in the medical literature.

“As a participant in the work group, I was impressed by the level of care and detail and the involvement of relevant stakeholders, including a patient advocate, as well as having the draft guidelines go out to the AAD membership at large, and evaluating every comment that came in,” Maryam Asgari, MD, MPH, professor of dermatology at Harvard University, Boston, said in an interview. “The academy sought stakeholder and leadership input in revising and revamping the guidelines. The AAD also made sure the work group had minimal conflicts of interest by requiring that the majority of experts convened did not have relevant financial conflicts of interest. That might not be the case in a publication such as a systematic review, where no threshold for financial conflict of interest for coauthorship is set.”

Of the 18 recommendations the work group made for patients with AKs, only four were ranked as “strong” based on the evidence reviewed, while the rest were ranked as “conditional.”

The strong recommendations include the use of UV protection, field treatment with 5-FU, field treatment with imiquimod, and the use of cryosurgery.

The first four conditional recommendations for patients with AKs include the use of diclofenac, treatment with cryosurgery over CO2 laser ablation, aminolevulinic acid (ALA)–red-light PDT, and 1- to 4-hour 5-ALA incubation time to enhance complete clearance with red-light PDT. The work group also conditionally recommends ALA-daylight PDT as less painful than but equally effective as ALA–red-light PDT.

In the clinical experience of Catherine M. DiGiorgio, MD, who was not involved in the guidelines, daylight PDT with ALA is a viable, cost-effective option. “Patients can come into the office, apply the ALA and then they go outside for 2 hours – not in direct sunlight but in a shady area,” Dr. DiGiorgio, a dermatologist who practices at the Boston Center for Facial Rejuvenation, said in an interview. “That’s a cost-effective treatment for patients who perhaps can’t afford some of the chemotherapy creams. I don’t think we’ve adopted ALA-daylight PDT here in the U.S. very much.”

The work group noted that topical 1% tirbanibulin ointment, a novel microtubule inhibitor, was approved for treatment of AKs on the face and scalp by the Food and Drug Administration after the guidelines had been put together.

Several trials of combination therapy were included in the review of evidence, prompting several recommendations. For example, the work group conditionally recommends combined 5-FU cream and cryosurgery over cryosurgery alone, based on moderate-quality evidence and conditionally recommends combined imiquimod and cryosurgery over cryosurgery alone based on low-quality evidence. In addition, the work group conditionally recommends against the use of 3% diclofenac in addition to cryosurgery, favoring cryosurgery alone based on low-quality evidence, and conditionally recommends against the use of imiquimod typically after ALA–blue-light PDT, based on moderate-quality data.

“The additional treatment with imiquimod was thought to add both expense and burden to the patient, which negates much of the perceived convenience of using PDT as a stand-alone treatment modality and which is not mitigated by the modest increase in lesion reduction,” the authors wrote.

The guidelines emphasize the importance of shared decision-making between patients and clinicians on the choice of therapy, a point that resonates with Dr. DiGiorgio. Success of a treatment can depend on whether a patient is willing to go through with it, she said. “Some patients don’t want to do a therapeutic topical like 5-FU. They prefer to come in and have cryotherapy done. Others prefer to not come in and have the cream at home and treat themselves.”

Assembling the guidelines exposed certain gaps in research, according to the work group. Of the 18 recommendations, seven were based on low-quality evidence, and there were not enough data to make guidelines for the treatment of AKs in immunocompromised individuals.

“I can’t tell you the number of times we in the committee sat back and said, ‘we need to have a randomized trial that looks at this, or compares this to that head on,’” Dr. Asgari said. Such limitations “give researchers direction for where the areas of study need to go to help us answer some of these management conundrums.”

She added that the new guidelines “give clinicians a leg to stand on” when an insurer pushes back on a recommended treatment for AK. “It gives you a way to have dialogue with insurers if you’re prescribing some of these treatments.”

The guidelines authors write that there is “strong theoretic rationale for the treatment of AK to prevent skin cancers” but acknowledge that only a few studies in the review “report the incidence of skin cancer as an outcome measure or have sufficient follow-up to viably measure carcinoma development.” In addition, “more long-term research is needed to validate our current understanding of skin cancer progression from AKs to keratinocyte carcinoma.”

Dr. DiGiorgio thinks about this differently. “I think treatment of AKs does prevent skin cancers,” she said. “We call them precancers as we’re treating our patients because we know a certain percentage of them can develop into skin cancers over time.”

The study was funded by internal funds from the AAD. Dr. Asgari disclosed that she serves as an investigator for Pfizer. Several of the other authors reported having financial disclosures.

Dr. DiGiorgio reported having no financial disclosures.

. They also conditionally recommend the use of photodynamic therapy (PDT) and diclofenac for the treatment of AK, both individually and as part of combination therapy regimens.

Those are two of 18 recommendations made by 14 members of the multidisciplinary work group that convened to assemble the AAD’s first-ever guidelines on the management of AKs, which were published online April 2 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. The group, cochaired by Daniel B. Eisen, MD, professor of clinical dermatology at the University of California, Davis, and Todd E. Schlesinger, MD, medical director of the Dermatology and Laser Center of Charleston, S.C., conducted a systematic review to address five clinical questions on the management of AKs in adults. The questions were: What are the efficacy, effectiveness, and adverse effects of surgical and chemical peel treatments for AK; of topically applied agents for AK; of energy devices and other miscellaneous treatments for AK; and of combination therapy for the treatment of AK? And what are the special considerations to be taken into account when treating AK in immunocompromised individuals?

Next, the work group applied the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach for assessing the certainty of the evidence and formulating and grading clinical recommendations based on relevant randomized trials in the medical literature.

“As a participant in the work group, I was impressed by the level of care and detail and the involvement of relevant stakeholders, including a patient advocate, as well as having the draft guidelines go out to the AAD membership at large, and evaluating every comment that came in,” Maryam Asgari, MD, MPH, professor of dermatology at Harvard University, Boston, said in an interview. “The academy sought stakeholder and leadership input in revising and revamping the guidelines. The AAD also made sure the work group had minimal conflicts of interest by requiring that the majority of experts convened did not have relevant financial conflicts of interest. That might not be the case in a publication such as a systematic review, where no threshold for financial conflict of interest for coauthorship is set.”

Of the 18 recommendations the work group made for patients with AKs, only four were ranked as “strong” based on the evidence reviewed, while the rest were ranked as “conditional.”

The strong recommendations include the use of UV protection, field treatment with 5-FU, field treatment with imiquimod, and the use of cryosurgery.

The first four conditional recommendations for patients with AKs include the use of diclofenac, treatment with cryosurgery over CO2 laser ablation, aminolevulinic acid (ALA)–red-light PDT, and 1- to 4-hour 5-ALA incubation time to enhance complete clearance with red-light PDT. The work group also conditionally recommends ALA-daylight PDT as less painful than but equally effective as ALA–red-light PDT.

In the clinical experience of Catherine M. DiGiorgio, MD, who was not involved in the guidelines, daylight PDT with ALA is a viable, cost-effective option. “Patients can come into the office, apply the ALA and then they go outside for 2 hours – not in direct sunlight but in a shady area,” Dr. DiGiorgio, a dermatologist who practices at the Boston Center for Facial Rejuvenation, said in an interview. “That’s a cost-effective treatment for patients who perhaps can’t afford some of the chemotherapy creams. I don’t think we’ve adopted ALA-daylight PDT here in the U.S. very much.”

The work group noted that topical 1% tirbanibulin ointment, a novel microtubule inhibitor, was approved for treatment of AKs on the face and scalp by the Food and Drug Administration after the guidelines had been put together.

Several trials of combination therapy were included in the review of evidence, prompting several recommendations. For example, the work group conditionally recommends combined 5-FU cream and cryosurgery over cryosurgery alone, based on moderate-quality evidence and conditionally recommends combined imiquimod and cryosurgery over cryosurgery alone based on low-quality evidence. In addition, the work group conditionally recommends against the use of 3% diclofenac in addition to cryosurgery, favoring cryosurgery alone based on low-quality evidence, and conditionally recommends against the use of imiquimod typically after ALA–blue-light PDT, based on moderate-quality data.

“The additional treatment with imiquimod was thought to add both expense and burden to the patient, which negates much of the perceived convenience of using PDT as a stand-alone treatment modality and which is not mitigated by the modest increase in lesion reduction,” the authors wrote.

The guidelines emphasize the importance of shared decision-making between patients and clinicians on the choice of therapy, a point that resonates with Dr. DiGiorgio. Success of a treatment can depend on whether a patient is willing to go through with it, she said. “Some patients don’t want to do a therapeutic topical like 5-FU. They prefer to come in and have cryotherapy done. Others prefer to not come in and have the cream at home and treat themselves.”

Assembling the guidelines exposed certain gaps in research, according to the work group. Of the 18 recommendations, seven were based on low-quality evidence, and there were not enough data to make guidelines for the treatment of AKs in immunocompromised individuals.

“I can’t tell you the number of times we in the committee sat back and said, ‘we need to have a randomized trial that looks at this, or compares this to that head on,’” Dr. Asgari said. Such limitations “give researchers direction for where the areas of study need to go to help us answer some of these management conundrums.”

She added that the new guidelines “give clinicians a leg to stand on” when an insurer pushes back on a recommended treatment for AK. “It gives you a way to have dialogue with insurers if you’re prescribing some of these treatments.”

The guidelines authors write that there is “strong theoretic rationale for the treatment of AK to prevent skin cancers” but acknowledge that only a few studies in the review “report the incidence of skin cancer as an outcome measure or have sufficient follow-up to viably measure carcinoma development.” In addition, “more long-term research is needed to validate our current understanding of skin cancer progression from AKs to keratinocyte carcinoma.”

Dr. DiGiorgio thinks about this differently. “I think treatment of AKs does prevent skin cancers,” she said. “We call them precancers as we’re treating our patients because we know a certain percentage of them can develop into skin cancers over time.”

The study was funded by internal funds from the AAD. Dr. Asgari disclosed that she serves as an investigator for Pfizer. Several of the other authors reported having financial disclosures.

Dr. DiGiorgio reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM JAAD

Less pain, same gain with tirbanibulin for actinic keratosis

“with transient local reactions,” according to the results of two identically designed trials.

However, the results, assessed at day 57 and out to 1 year of follow-up, were associated with recurrence of lesions at 1 year, noted lead author Andrew Blauvelt, MD, president of the Oregon Medical Research Center, Portland, and colleagues.

“The incidence of recurrence with conventional treatment has ranged from 20% to 96%,” they noted. “Among patients who had complete clearance at day 57 in the current trials, the estimated incidence of recurrence of previously cleared lesions was 47% at 1 year.” At 1 year, they added, “the estimated incidence of any lesions (new or recurrent) within the application area was 73%” and the estimate of sustained complete clearance was 27%.

A total of 700 adults completed the two multicenter, double-blind, parallel-group, vehicle-controlled trials, conducted concurrently between September 2017 and April 2019 at 62 U.S. sites. The results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

To be eligible, patients, mostly White men, had to have four to eight clinically typical, visible, and discrete AK lesions on the face or scalp within a contiguous area measuring 25 cm2. They were randomly assigned to treatment with either tirbanibulin 1% ointment or vehicle ointment (containing monoglycerides, diglycerides, and propylene glycol), which they applied once daily to the entire contiguous area for 5 days.

Pooled data across the two trials showed that the primary outcome, complete clearance of all lesions at day 57, occurred in 49% of the tirbanibulin groups versus 9% of the vehicle groups, and partial clearance (the secondary outcome) occurred in 72% versus 18% respectively. For both outcomes, and in both trials, all results were statistically significant.

Of the 174 patients who received tirbanibulin and had complete clearance, 124 had one or more lesions develop within the application area during follow-up, the authors reported. Of these, 58% had recurrences, while 42% had new lesions.

While individual AK lesions are typically treated with cryosurgery, the study authors noted that treatment of multiple lesions involves topical agents, such as fluorouracil, diclofenac, imiquimod, or ingenol mebutate, and photodynamic therapy, some of which have to be administered over periods of weeks or months and “may be associated with local reactions of pain, irritation, erosions, ulcerations, and irreversible skin changes of pigmentation and scarring,” which may reduce adherence.

In contrast, the current studies showed the most common local reactions to tirbanibulin were erythema in 91% of patients and flaking or scaling in 82%, with transient adverse events including application-site pain in 10% and pruritus in 9%.

“Unlike with most topical treatments for actinic keratosis ... severe local reactions, including vesiculation or pustulation and erosion or ulceration, were infrequent with tirbanibulin ointment,” the authors noted. “This could be due to the relatively short, 5-day course of once-daily treatment.”

They concluded that “larger and longer trials are necessary to determine the effects and risks” of treatment with tirbanibulin for treating AK.

Tirbanibulin, a synthetic inhibitor of tubulin polymerization and Src kinase signaling, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in December 2020, for the topical treatment of AK of the face or scalp.

Asked to comment on the findings, Neal Bhatia, MD, a dermatologist and researcher at Therapeutics Dermatology, San Diego, who was not involved with the study, said that “a treatment with a 5-day course and excellent tolerability will make dermatologists rethink the old practice of ‘freeze and go.’ ”

In an interview, he added, “tirbanibulin comes to the U.S. market for treating AKs at a great time, as ingenol mebutate has been withdrawn and the others are not widely supported. The mechanism of promoting apoptosis and inducing cell cycle arrest directly correlates to the local skin reaction profile of less crusting, vesiculation, and overall signs of skin necrosis as compared to [5-fluorouracil] and ingenol mebutate, which work via that pathway. As a result, there is a direct impact on the hyperproliferation of atypical keratinocytes that will treat visible and subclinical disease.”

“The ointment vehicle is also novel as previous therapies have been in either creams or gels,” he said.

The two trials were funded by tirbanibulin manufacturer Athenex. Dr. Blauvelt reported receiving consulting fees from Athenex and other pharmaceutical companies, including Almirall, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dermavant Sciences. Other author disclosures included serving as a consultant to Athenex and other companies. Several authors are Athenex employees. Dr. Bhatia disclosed that he is an adviser and consultant for Almirall and has been an investigator for multiple other AK treatments.

“with transient local reactions,” according to the results of two identically designed trials.

However, the results, assessed at day 57 and out to 1 year of follow-up, were associated with recurrence of lesions at 1 year, noted lead author Andrew Blauvelt, MD, president of the Oregon Medical Research Center, Portland, and colleagues.

“The incidence of recurrence with conventional treatment has ranged from 20% to 96%,” they noted. “Among patients who had complete clearance at day 57 in the current trials, the estimated incidence of recurrence of previously cleared lesions was 47% at 1 year.” At 1 year, they added, “the estimated incidence of any lesions (new or recurrent) within the application area was 73%” and the estimate of sustained complete clearance was 27%.

A total of 700 adults completed the two multicenter, double-blind, parallel-group, vehicle-controlled trials, conducted concurrently between September 2017 and April 2019 at 62 U.S. sites. The results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

To be eligible, patients, mostly White men, had to have four to eight clinically typical, visible, and discrete AK lesions on the face or scalp within a contiguous area measuring 25 cm2. They were randomly assigned to treatment with either tirbanibulin 1% ointment or vehicle ointment (containing monoglycerides, diglycerides, and propylene glycol), which they applied once daily to the entire contiguous area for 5 days.

Pooled data across the two trials showed that the primary outcome, complete clearance of all lesions at day 57, occurred in 49% of the tirbanibulin groups versus 9% of the vehicle groups, and partial clearance (the secondary outcome) occurred in 72% versus 18% respectively. For both outcomes, and in both trials, all results were statistically significant.

Of the 174 patients who received tirbanibulin and had complete clearance, 124 had one or more lesions develop within the application area during follow-up, the authors reported. Of these, 58% had recurrences, while 42% had new lesions.

While individual AK lesions are typically treated with cryosurgery, the study authors noted that treatment of multiple lesions involves topical agents, such as fluorouracil, diclofenac, imiquimod, or ingenol mebutate, and photodynamic therapy, some of which have to be administered over periods of weeks or months and “may be associated with local reactions of pain, irritation, erosions, ulcerations, and irreversible skin changes of pigmentation and scarring,” which may reduce adherence.

In contrast, the current studies showed the most common local reactions to tirbanibulin were erythema in 91% of patients and flaking or scaling in 82%, with transient adverse events including application-site pain in 10% and pruritus in 9%.

“Unlike with most topical treatments for actinic keratosis ... severe local reactions, including vesiculation or pustulation and erosion or ulceration, were infrequent with tirbanibulin ointment,” the authors noted. “This could be due to the relatively short, 5-day course of once-daily treatment.”

They concluded that “larger and longer trials are necessary to determine the effects and risks” of treatment with tirbanibulin for treating AK.

Tirbanibulin, a synthetic inhibitor of tubulin polymerization and Src kinase signaling, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in December 2020, for the topical treatment of AK of the face or scalp.

Asked to comment on the findings, Neal Bhatia, MD, a dermatologist and researcher at Therapeutics Dermatology, San Diego, who was not involved with the study, said that “a treatment with a 5-day course and excellent tolerability will make dermatologists rethink the old practice of ‘freeze and go.’ ”

In an interview, he added, “tirbanibulin comes to the U.S. market for treating AKs at a great time, as ingenol mebutate has been withdrawn and the others are not widely supported. The mechanism of promoting apoptosis and inducing cell cycle arrest directly correlates to the local skin reaction profile of less crusting, vesiculation, and overall signs of skin necrosis as compared to [5-fluorouracil] and ingenol mebutate, which work via that pathway. As a result, there is a direct impact on the hyperproliferation of atypical keratinocytes that will treat visible and subclinical disease.”

“The ointment vehicle is also novel as previous therapies have been in either creams or gels,” he said.

The two trials were funded by tirbanibulin manufacturer Athenex. Dr. Blauvelt reported receiving consulting fees from Athenex and other pharmaceutical companies, including Almirall, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dermavant Sciences. Other author disclosures included serving as a consultant to Athenex and other companies. Several authors are Athenex employees. Dr. Bhatia disclosed that he is an adviser and consultant for Almirall and has been an investigator for multiple other AK treatments.

“with transient local reactions,” according to the results of two identically designed trials.

However, the results, assessed at day 57 and out to 1 year of follow-up, were associated with recurrence of lesions at 1 year, noted lead author Andrew Blauvelt, MD, president of the Oregon Medical Research Center, Portland, and colleagues.

“The incidence of recurrence with conventional treatment has ranged from 20% to 96%,” they noted. “Among patients who had complete clearance at day 57 in the current trials, the estimated incidence of recurrence of previously cleared lesions was 47% at 1 year.” At 1 year, they added, “the estimated incidence of any lesions (new or recurrent) within the application area was 73%” and the estimate of sustained complete clearance was 27%.

A total of 700 adults completed the two multicenter, double-blind, parallel-group, vehicle-controlled trials, conducted concurrently between September 2017 and April 2019 at 62 U.S. sites. The results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

To be eligible, patients, mostly White men, had to have four to eight clinically typical, visible, and discrete AK lesions on the face or scalp within a contiguous area measuring 25 cm2. They were randomly assigned to treatment with either tirbanibulin 1% ointment or vehicle ointment (containing monoglycerides, diglycerides, and propylene glycol), which they applied once daily to the entire contiguous area for 5 days.

Pooled data across the two trials showed that the primary outcome, complete clearance of all lesions at day 57, occurred in 49% of the tirbanibulin groups versus 9% of the vehicle groups, and partial clearance (the secondary outcome) occurred in 72% versus 18% respectively. For both outcomes, and in both trials, all results were statistically significant.

Of the 174 patients who received tirbanibulin and had complete clearance, 124 had one or more lesions develop within the application area during follow-up, the authors reported. Of these, 58% had recurrences, while 42% had new lesions.

While individual AK lesions are typically treated with cryosurgery, the study authors noted that treatment of multiple lesions involves topical agents, such as fluorouracil, diclofenac, imiquimod, or ingenol mebutate, and photodynamic therapy, some of which have to be administered over periods of weeks or months and “may be associated with local reactions of pain, irritation, erosions, ulcerations, and irreversible skin changes of pigmentation and scarring,” which may reduce adherence.

In contrast, the current studies showed the most common local reactions to tirbanibulin were erythema in 91% of patients and flaking or scaling in 82%, with transient adverse events including application-site pain in 10% and pruritus in 9%.

“Unlike with most topical treatments for actinic keratosis ... severe local reactions, including vesiculation or pustulation and erosion or ulceration, were infrequent with tirbanibulin ointment,” the authors noted. “This could be due to the relatively short, 5-day course of once-daily treatment.”

They concluded that “larger and longer trials are necessary to determine the effects and risks” of treatment with tirbanibulin for treating AK.

Tirbanibulin, a synthetic inhibitor of tubulin polymerization and Src kinase signaling, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in December 2020, for the topical treatment of AK of the face or scalp.

Asked to comment on the findings, Neal Bhatia, MD, a dermatologist and researcher at Therapeutics Dermatology, San Diego, who was not involved with the study, said that “a treatment with a 5-day course and excellent tolerability will make dermatologists rethink the old practice of ‘freeze and go.’ ”

In an interview, he added, “tirbanibulin comes to the U.S. market for treating AKs at a great time, as ingenol mebutate has been withdrawn and the others are not widely supported. The mechanism of promoting apoptosis and inducing cell cycle arrest directly correlates to the local skin reaction profile of less crusting, vesiculation, and overall signs of skin necrosis as compared to [5-fluorouracil] and ingenol mebutate, which work via that pathway. As a result, there is a direct impact on the hyperproliferation of atypical keratinocytes that will treat visible and subclinical disease.”

“The ointment vehicle is also novel as previous therapies have been in either creams or gels,” he said.

The two trials were funded by tirbanibulin manufacturer Athenex. Dr. Blauvelt reported receiving consulting fees from Athenex and other pharmaceutical companies, including Almirall, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dermavant Sciences. Other author disclosures included serving as a consultant to Athenex and other companies. Several authors are Athenex employees. Dr. Bhatia disclosed that he is an adviser and consultant for Almirall and has been an investigator for multiple other AK treatments.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Scaly lesion on forearm

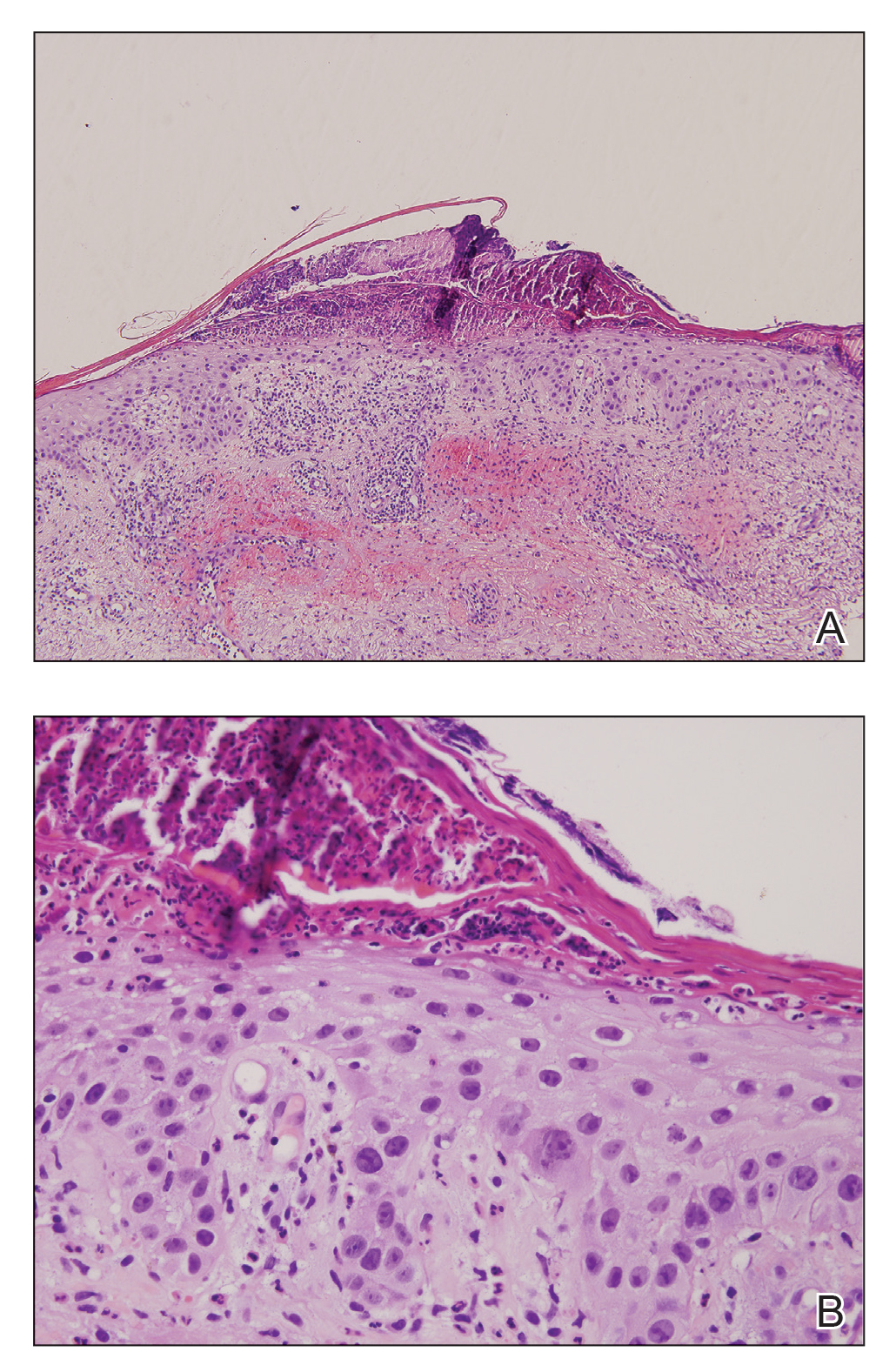

The suspicion raised by the dermoscopy results led to a shave biopsy, which confirmed the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in situ, also known as Bowen disease.

Bowen disease typically manifests as a scaly erythematous patch, often on sun-exposed skin. If untreated, these lesions have the potential to develop into invasive SCCs. Generally, the lesions are preceded by the formation of actinic keratosis (AK). In a 2009 trial performed by the Department of Veterans Affairs, up to 65% of SCCs were found to have previously been diagnosed as AK lesions.1

The selection of treatments includes excision, electrodessication and curettage, cryotherapy, and topical options such as fluorouracil bid for 4 weeks or imiquimod qd for 9 weeks.

After the physician outlined the treatment options, this patient opted for an elliptical excision. At the patient’s next follow-up appointment, she was found to have multiple AKs on her face; they were treated with cryotherapy. Patients with a diagnosis of precancerous or cancerous skin lesions are at high risk for additional AKs and skin cancer, so they should be counseled regarding the use of sun protective measures and the importance of annual screening for new lesions.

Image courtesy of Carlos Cano, MD, and text courtesy of Carlos Cano, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the veterans affairs topical tretinoin chemoprevention trial. Cancer. 2009;115:2523-2530. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24284.

The suspicion raised by the dermoscopy results led to a shave biopsy, which confirmed the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in situ, also known as Bowen disease.

Bowen disease typically manifests as a scaly erythematous patch, often on sun-exposed skin. If untreated, these lesions have the potential to develop into invasive SCCs. Generally, the lesions are preceded by the formation of actinic keratosis (AK). In a 2009 trial performed by the Department of Veterans Affairs, up to 65% of SCCs were found to have previously been diagnosed as AK lesions.1

The selection of treatments includes excision, electrodessication and curettage, cryotherapy, and topical options such as fluorouracil bid for 4 weeks or imiquimod qd for 9 weeks.

After the physician outlined the treatment options, this patient opted for an elliptical excision. At the patient’s next follow-up appointment, she was found to have multiple AKs on her face; they were treated with cryotherapy. Patients with a diagnosis of precancerous or cancerous skin lesions are at high risk for additional AKs and skin cancer, so they should be counseled regarding the use of sun protective measures and the importance of annual screening for new lesions.

Image courtesy of Carlos Cano, MD, and text courtesy of Carlos Cano, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The suspicion raised by the dermoscopy results led to a shave biopsy, which confirmed the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in situ, also known as Bowen disease.

Bowen disease typically manifests as a scaly erythematous patch, often on sun-exposed skin. If untreated, these lesions have the potential to develop into invasive SCCs. Generally, the lesions are preceded by the formation of actinic keratosis (AK). In a 2009 trial performed by the Department of Veterans Affairs, up to 65% of SCCs were found to have previously been diagnosed as AK lesions.1

The selection of treatments includes excision, electrodessication and curettage, cryotherapy, and topical options such as fluorouracil bid for 4 weeks or imiquimod qd for 9 weeks.

After the physician outlined the treatment options, this patient opted for an elliptical excision. At the patient’s next follow-up appointment, she was found to have multiple AKs on her face; they were treated with cryotherapy. Patients with a diagnosis of precancerous or cancerous skin lesions are at high risk for additional AKs and skin cancer, so they should be counseled regarding the use of sun protective measures and the importance of annual screening for new lesions.

Image courtesy of Carlos Cano, MD, and text courtesy of Carlos Cano, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the veterans affairs topical tretinoin chemoprevention trial. Cancer. 2009;115:2523-2530. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24284.

1. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the veterans affairs topical tretinoin chemoprevention trial. Cancer. 2009;115:2523-2530. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24284.

Erythema Ab Igne and Malignant Transformation to Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Case Report

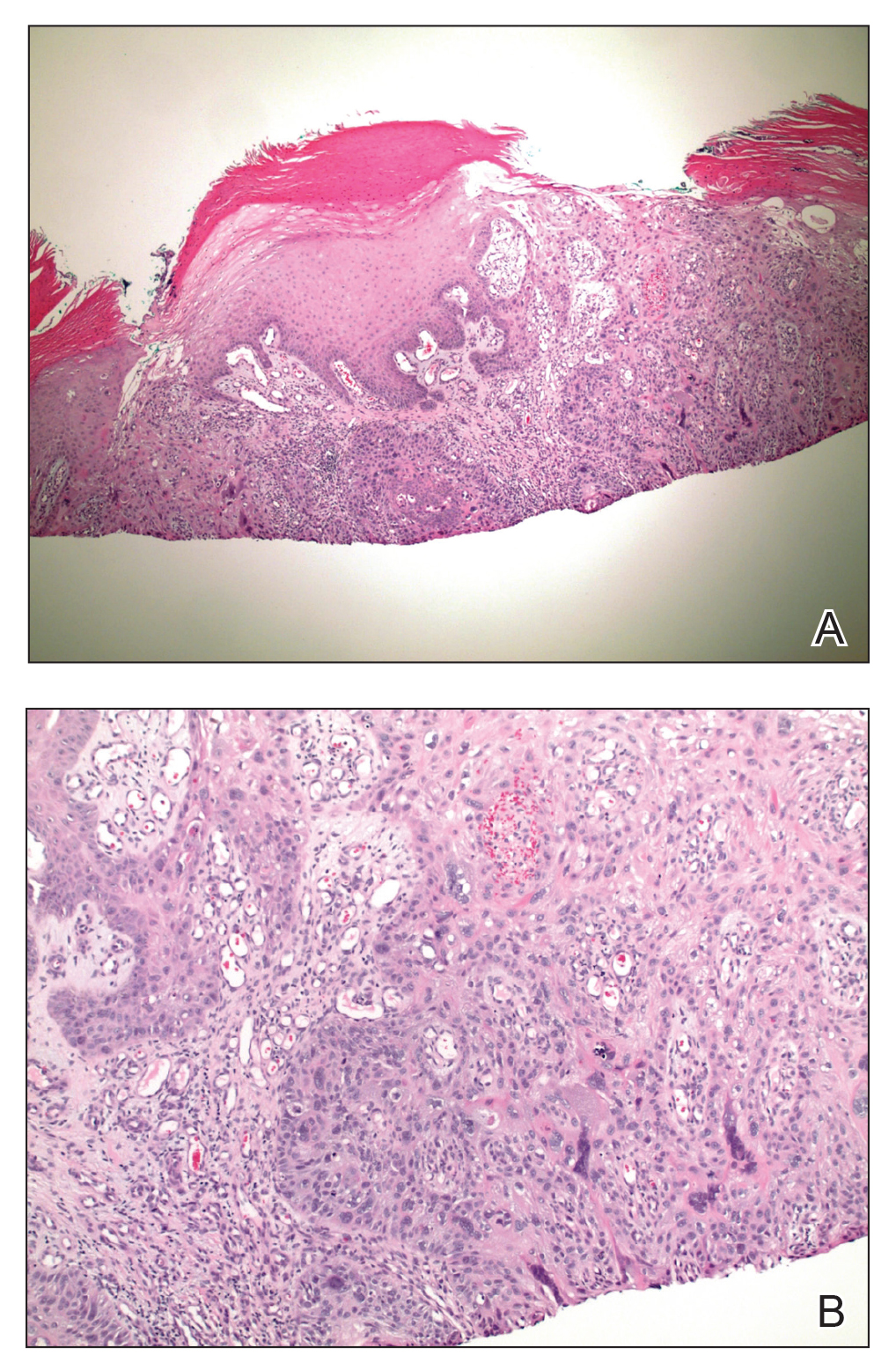

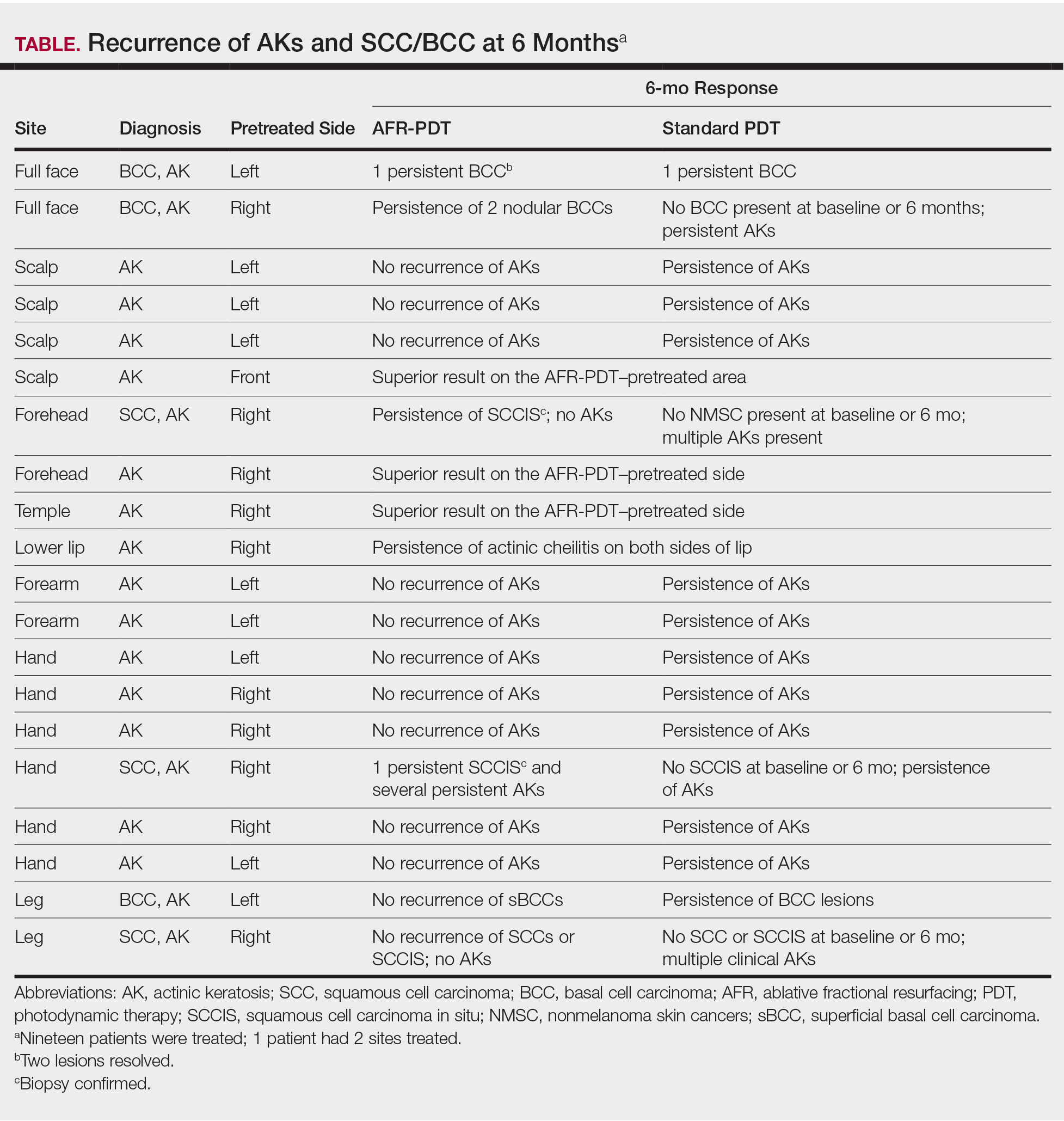

A 67-year-old Black woman presented with a long-standing history of pruritus and “scaly thick bumps” on the lower extremities. Upon further questioning, she reported a 30-year history of placing her feet by an electric space heater and daily baths in “very hot” water. A review of systems and medical history were unremarkable, and the patient was not on any medications. Initial physical examination of the lower extremities demonstrated lichenified plaques and scattered, firm, ulcerated nodules surrounded by mottled postinflammatory hyperpigmentation with sharp demarcation at the midcalf bilaterally (Figure 1).

Subsequently, the patient was shown to have multiple actinic keratoses and SCCs, both in situ and invasive, within the areas of EAI (Figure 2). The patient had no actinic keratoses or other cutaneous malignant neoplasms elsewhere on the skin. Management of actinic keratoses, SCC in situ, and invasive SCC on the lower extremities included numerous excisions, treatment with liquid nitrogen, and topical 5-fluorouracil under occlusion. The patient continues to be monitored frequently.

Comment

Presentation of EAI

Erythema ab igne is a cutaneous reaction resulting from prolonged exposure to an infrared heat source at temperatures insufficient to cause a burn (37 °F to 11

Histopathology of EAI

Histologically, later stages of EAI can demonstrate focal hyperkeratosis with dyskeratosis and increased dermal elastosis, similar to actinic damage, with a predisposition to develop SCC.2 Notably, early reports document various heat-induced carcinomas, including kangri-burn cancers among Kashmiris, kang thermal cancers in China, and kairo cancers in Japan.2,4,5 More recent reports identify cutaneous carcinomas arising specifically in the setting of EAI, most commonly SCC3; Merkel cell carcinoma and cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma are less commonly reported malignancies.6,7 Given the frequency of malignant transformation within sites of thermal exposure, chronic heat exposure may share a common pathophysiology with SCC and other neoplasms, including Merkel cell carcinoma and cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.

SCC in Black Individuals

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in Black individuals, with a notably higher incidence in high-risk subpopulations (immunosuppressed patients). Unlike White individuals, SCCs frequently occur in non–sun-exposed areas in Black individuals and are associated with unique risk factors, such as human papillomavirus, as demonstrated in Black transplant patients.8 A retrospective study examining the characteristics of SCC on the legs of Black individuals documented atypical hyperkeratotic neoplasms surrounded by abnormal pigmentation and mottling of surrounding skin.9 Morphologic skin changes could be the result of chronic thermal damage: Numerous patients reported a history of leg warming from an open heat source. Other patients had an actual diagnosis of EAI. The predilection for less-exposed skin suggests UV radiation (UVR) might be a less important predisposing risk factor for this racial group, and the increased mortality associated with SCC in Black individuals might represent a more aggressive nature to this subset of SCCs.9 Furthermore, infrared radiation (IRR), such as fires and coal stoves, might have the potential to stimulate skin changes similar to those associated with UVR and ultimately malignant changes.

Infrared Radiation

Compared to UVR, little is known about the biological effects of IRR (wavelength, 760 nm to 1 mm), to which human skin is constantly exposed from natural and artificial light sources. Early studies have demonstrated the carcinogenic potential of IRR, observing an augmentation of UVR-induced tumorigenesis in the presence of heat. More recently, IRR was observed to stimulate increased collagenase production from dermal fibroblasts and influence pathways (extracellular signal-related kinases 1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases) in a similar fashion to UVB and UVA.10,11 Therefore, IRR might be capable of eliciting molecular responses comparable to those caused by UVR.

Conclusion

Although SCC in association with EAI is uncommon, historical reports of thermal cancers and scientific observations of IRR-induced biological and molecular effects support EAI as a predisposing risk factor for SCC and the important need for close monitoring by physicians. Studies are needed to further elucidate the pathologic effects of IRR, with more promotion of caution relating to thermal exposure.

- Milchak M, Smucker J, Chung CG, et al. Erythema ab igne due to heating pad use: a case report and review of clinical presentation, prevention, and complications. Case Rep Med. 2016;2016:1862480.

- Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28. Accessed December 10, 2020. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/47z4v01z

- Wharton JB, Sheehan DJ, Lesher JL Jr. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:488-489.

- Neve EF. Kangri-burn cancer. Br Med J. 1923;2:1255-1256.

- Laycock HT. The kang cancer of North-West China. Br Med J. 1948;1:982.

- Wharton J, Roffwarg D, Miller J, et al. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1080-1081.

- Jones CS, Tyring SK, Lee PC, et al. Development of neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma mixed with squamous cell carcinoma in erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:110-113.

- Pritchett EN, Doyle A, Shaver CM, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer in nonwhite organ transplant recipients. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1348-1353.

- McCall CO, Chen SC. Squamous cell carcinoma of the legs in African Americans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:524-529.

- Freeman RG, Knox JM. Influence of temperature on ultraviolet injury. Arch Dermatol. 1964;89:858-864.

- Schieke SM, Schroeder P, Krutmann J. Cutaneous effects of infrared radiation: from clinical observations to molecular response mechanisms. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2003;19:228-234.

Case Report

A 67-year-old Black woman presented with a long-standing history of pruritus and “scaly thick bumps” on the lower extremities. Upon further questioning, she reported a 30-year history of placing her feet by an electric space heater and daily baths in “very hot” water. A review of systems and medical history were unremarkable, and the patient was not on any medications. Initial physical examination of the lower extremities demonstrated lichenified plaques and scattered, firm, ulcerated nodules surrounded by mottled postinflammatory hyperpigmentation with sharp demarcation at the midcalf bilaterally (Figure 1).

Subsequently, the patient was shown to have multiple actinic keratoses and SCCs, both in situ and invasive, within the areas of EAI (Figure 2). The patient had no actinic keratoses or other cutaneous malignant neoplasms elsewhere on the skin. Management of actinic keratoses, SCC in situ, and invasive SCC on the lower extremities included numerous excisions, treatment with liquid nitrogen, and topical 5-fluorouracil under occlusion. The patient continues to be monitored frequently.

Comment

Presentation of EAI

Erythema ab igne is a cutaneous reaction resulting from prolonged exposure to an infrared heat source at temperatures insufficient to cause a burn (37 °F to 11

Histopathology of EAI

Histologically, later stages of EAI can demonstrate focal hyperkeratosis with dyskeratosis and increased dermal elastosis, similar to actinic damage, with a predisposition to develop SCC.2 Notably, early reports document various heat-induced carcinomas, including kangri-burn cancers among Kashmiris, kang thermal cancers in China, and kairo cancers in Japan.2,4,5 More recent reports identify cutaneous carcinomas arising specifically in the setting of EAI, most commonly SCC3; Merkel cell carcinoma and cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma are less commonly reported malignancies.6,7 Given the frequency of malignant transformation within sites of thermal exposure, chronic heat exposure may share a common pathophysiology with SCC and other neoplasms, including Merkel cell carcinoma and cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.

SCC in Black Individuals

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in Black individuals, with a notably higher incidence in high-risk subpopulations (immunosuppressed patients). Unlike White individuals, SCCs frequently occur in non–sun-exposed areas in Black individuals and are associated with unique risk factors, such as human papillomavirus, as demonstrated in Black transplant patients.8 A retrospective study examining the characteristics of SCC on the legs of Black individuals documented atypical hyperkeratotic neoplasms surrounded by abnormal pigmentation and mottling of surrounding skin.9 Morphologic skin changes could be the result of chronic thermal damage: Numerous patients reported a history of leg warming from an open heat source. Other patients had an actual diagnosis of EAI. The predilection for less-exposed skin suggests UV radiation (UVR) might be a less important predisposing risk factor for this racial group, and the increased mortality associated with SCC in Black individuals might represent a more aggressive nature to this subset of SCCs.9 Furthermore, infrared radiation (IRR), such as fires and coal stoves, might have the potential to stimulate skin changes similar to those associated with UVR and ultimately malignant changes.

Infrared Radiation

Compared to UVR, little is known about the biological effects of IRR (wavelength, 760 nm to 1 mm), to which human skin is constantly exposed from natural and artificial light sources. Early studies have demonstrated the carcinogenic potential of IRR, observing an augmentation of UVR-induced tumorigenesis in the presence of heat. More recently, IRR was observed to stimulate increased collagenase production from dermal fibroblasts and influence pathways (extracellular signal-related kinases 1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases) in a similar fashion to UVB and UVA.10,11 Therefore, IRR might be capable of eliciting molecular responses comparable to those caused by UVR.

Conclusion

Although SCC in association with EAI is uncommon, historical reports of thermal cancers and scientific observations of IRR-induced biological and molecular effects support EAI as a predisposing risk factor for SCC and the important need for close monitoring by physicians. Studies are needed to further elucidate the pathologic effects of IRR, with more promotion of caution relating to thermal exposure.

Case Report

A 67-year-old Black woman presented with a long-standing history of pruritus and “scaly thick bumps” on the lower extremities. Upon further questioning, she reported a 30-year history of placing her feet by an electric space heater and daily baths in “very hot” water. A review of systems and medical history were unremarkable, and the patient was not on any medications. Initial physical examination of the lower extremities demonstrated lichenified plaques and scattered, firm, ulcerated nodules surrounded by mottled postinflammatory hyperpigmentation with sharp demarcation at the midcalf bilaterally (Figure 1).

Subsequently, the patient was shown to have multiple actinic keratoses and SCCs, both in situ and invasive, within the areas of EAI (Figure 2). The patient had no actinic keratoses or other cutaneous malignant neoplasms elsewhere on the skin. Management of actinic keratoses, SCC in situ, and invasive SCC on the lower extremities included numerous excisions, treatment with liquid nitrogen, and topical 5-fluorouracil under occlusion. The patient continues to be monitored frequently.

Comment

Presentation of EAI

Erythema ab igne is a cutaneous reaction resulting from prolonged exposure to an infrared heat source at temperatures insufficient to cause a burn (37 °F to 11

Histopathology of EAI

Histologically, later stages of EAI can demonstrate focal hyperkeratosis with dyskeratosis and increased dermal elastosis, similar to actinic damage, with a predisposition to develop SCC.2 Notably, early reports document various heat-induced carcinomas, including kangri-burn cancers among Kashmiris, kang thermal cancers in China, and kairo cancers in Japan.2,4,5 More recent reports identify cutaneous carcinomas arising specifically in the setting of EAI, most commonly SCC3; Merkel cell carcinoma and cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma are less commonly reported malignancies.6,7 Given the frequency of malignant transformation within sites of thermal exposure, chronic heat exposure may share a common pathophysiology with SCC and other neoplasms, including Merkel cell carcinoma and cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.

SCC in Black Individuals

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in Black individuals, with a notably higher incidence in high-risk subpopulations (immunosuppressed patients). Unlike White individuals, SCCs frequently occur in non–sun-exposed areas in Black individuals and are associated with unique risk factors, such as human papillomavirus, as demonstrated in Black transplant patients.8 A retrospective study examining the characteristics of SCC on the legs of Black individuals documented atypical hyperkeratotic neoplasms surrounded by abnormal pigmentation and mottling of surrounding skin.9 Morphologic skin changes could be the result of chronic thermal damage: Numerous patients reported a history of leg warming from an open heat source. Other patients had an actual diagnosis of EAI. The predilection for less-exposed skin suggests UV radiation (UVR) might be a less important predisposing risk factor for this racial group, and the increased mortality associated with SCC in Black individuals might represent a more aggressive nature to this subset of SCCs.9 Furthermore, infrared radiation (IRR), such as fires and coal stoves, might have the potential to stimulate skin changes similar to those associated with UVR and ultimately malignant changes.

Infrared Radiation

Compared to UVR, little is known about the biological effects of IRR (wavelength, 760 nm to 1 mm), to which human skin is constantly exposed from natural and artificial light sources. Early studies have demonstrated the carcinogenic potential of IRR, observing an augmentation of UVR-induced tumorigenesis in the presence of heat. More recently, IRR was observed to stimulate increased collagenase production from dermal fibroblasts and influence pathways (extracellular signal-related kinases 1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases) in a similar fashion to UVB and UVA.10,11 Therefore, IRR might be capable of eliciting molecular responses comparable to those caused by UVR.

Conclusion

Although SCC in association with EAI is uncommon, historical reports of thermal cancers and scientific observations of IRR-induced biological and molecular effects support EAI as a predisposing risk factor for SCC and the important need for close monitoring by physicians. Studies are needed to further elucidate the pathologic effects of IRR, with more promotion of caution relating to thermal exposure.

- Milchak M, Smucker J, Chung CG, et al. Erythema ab igne due to heating pad use: a case report and review of clinical presentation, prevention, and complications. Case Rep Med. 2016;2016:1862480.

- Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28. Accessed December 10, 2020. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/47z4v01z

- Wharton JB, Sheehan DJ, Lesher JL Jr. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:488-489.

- Neve EF. Kangri-burn cancer. Br Med J. 1923;2:1255-1256.

- Laycock HT. The kang cancer of North-West China. Br Med J. 1948;1:982.

- Wharton J, Roffwarg D, Miller J, et al. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1080-1081.

- Jones CS, Tyring SK, Lee PC, et al. Development of neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma mixed with squamous cell carcinoma in erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:110-113.

- Pritchett EN, Doyle A, Shaver CM, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer in nonwhite organ transplant recipients. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1348-1353.

- McCall CO, Chen SC. Squamous cell carcinoma of the legs in African Americans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:524-529.

- Freeman RG, Knox JM. Influence of temperature on ultraviolet injury. Arch Dermatol. 1964;89:858-864.

- Schieke SM, Schroeder P, Krutmann J. Cutaneous effects of infrared radiation: from clinical observations to molecular response mechanisms. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2003;19:228-234.

- Milchak M, Smucker J, Chung CG, et al. Erythema ab igne due to heating pad use: a case report and review of clinical presentation, prevention, and complications. Case Rep Med. 2016;2016:1862480.

- Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28. Accessed December 10, 2020. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/47z4v01z

- Wharton JB, Sheehan DJ, Lesher JL Jr. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:488-489.

- Neve EF. Kangri-burn cancer. Br Med J. 1923;2:1255-1256.

- Laycock HT. The kang cancer of North-West China. Br Med J. 1948;1:982.

- Wharton J, Roffwarg D, Miller J, et al. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1080-1081.

- Jones CS, Tyring SK, Lee PC, et al. Development of neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma mixed with squamous cell carcinoma in erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:110-113.

- Pritchett EN, Doyle A, Shaver CM, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer in nonwhite organ transplant recipients. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1348-1353.

- McCall CO, Chen SC. Squamous cell carcinoma of the legs in African Americans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:524-529.

- Freeman RG, Knox JM. Influence of temperature on ultraviolet injury. Arch Dermatol. 1964;89:858-864.

- Schieke SM, Schroeder P, Krutmann J. Cutaneous effects of infrared radiation: from clinical observations to molecular response mechanisms. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2003;19:228-234.

Practice Points

- Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a cutaneous reaction in response to prolonged exposure to infrared heat sources at temperatures insufficient to induce a burn.

- Common infrared heat sources include open fires, coal stoves, heating pads, laptop computers, and electric space heaters.

- Although considered a chronic pigmentary disorder, EAI rarely can progress to malignant transformation, including squamous cell carcinoma. Patients with EAI should be monitored long-term for malignant transformation.

New AK treatments: Local reactions are the price for greater clearance rates

, according to an expert speaking at the annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium, held virtually.

This relationship is not new. In a review of treatments for AKs, Neal Bhatia, MD, a dermatologist and researcher at Therapeutics Dermatology, San Diego, advised that most effective agents trade a higher risk of inflammatory reactions – including erythema, flaking, and scaling – for greater therapeutic gain. In many cases, local skin reactions are an inevitable consequence of their mechanism of action.

Data from the completed phase 3 trials of tirbanibulin 1% ointment (KX01-AK-003 and KX01-AK-004), are illustrative. (Tirbanibulin 1% ointment was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in mid-December, after the Coastal Derm meeting was held.)

In the phase 3 trials, which have not yet been published, tirbanibulin, an inhibitor of Src kinase, which has an antiproliferative action, was four to five times more effective than vehicle by day 57 for overall complete clearance (P < .0001) of AKs and complete clearance of the face (P < .0001), but rates of local skin reactions were generally two to three times higher, according to Dr. Bhatia.

In the KX01-AK-004 trial, for example, 61% of patients had complete clearance of the face, versus 14% of those randomized to vehicle. The difference for overall partial clearance (76% vs. 20%; P < .0001), partial clearance of the face (80% vs. 22%; P < .0001), and partial clearance of the scalp (69% vs. 15%; P < .0001) was even greater. When compared with placebo, tirbanibulin was also associated with greater rates of erythema (90% vs. 31%), crusting (45% vs. 8%), flaking (84% vs. 35%), swelling (38% vs. 2%) and erosions or ulcers (12% vs. 1%).

Although these events might be a challenge with regard to tolerability for some patients, they might best be described as evidence that the drug is working.

“Local skin reactions are anticipated. They are not adverse events. They are not side effects,” Dr. Bhatia said at the meeting, jointly presented by the University of Louisville and Global Academy for Medical Education. “Patients are going to get red, and you need to counsel patients about the 5 days when they can expected to be red. It is a sign of the civil war, if you will, that your skin is taking on with the actinic keratoses.”

Both 3- and 5-day courses of the drug were tested in the clinical trials. (The approved prescribing information recommends treatment on the face or scalp once a day for 5 consecutive days).

Other studies evaluating treatments for AKs have also associated an increased risk of local skin reactions with greater efficacy, Dr. Bhatia noted. As an example, he cited a phase 4 study comparing 0.015% ingenol mebutate gel to diclofenac sodium 3% gel in people with facial and scalp AK lesions.

At the end of the 3-month study, complete clearance was higher among those on ingenol mebutate, which was applied for 3 days, when compared with diclofenac sodium gel, which was applied daily for 3 months (34% vs. 23%; P = .006). However, patients randomized to ingenol mebutate gel had to first weather a higher rate of application-site erythema (19% vs. 12%) before achieving a greater level of clearance.

The correlation between efficacy and local reactions at the site of treatment application emphasizes the importance of educating patients about this relationship and in engaging in shared decision-making, Dr. Bhatia said.

“It is basically a tradeoff between local skin reactions, between frequency [of applications], compliance, and, of course, duration of therapy, even though both drugs served their purposes well,” said Dr. Bhatia, referring to the comparison of the ingenol mebutate and diclofenac gels.

Although not absolute, efficacy and tolerability were also generally inversely related in a recent four-treatment comparison of four commonly used field-directed therapies. In that trial, the primary endpoint was at least a 75% reduction from baseline in the number of AKs to 12 months after treatment ended.

For that outcome, 5% fluorouracil (5-FU) cream (74.7%) was significantly more effective than 5% imiquimod cream (53.9%), methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy (37.7%), and 0.015% ingenol mebutate gel (28.9%). Also, 5-FU treatment was associated with the moderate or severe erythema (81.5%), severe pain (16.%), and a severe burning sensation (21.5%).

Other therapies on the horizon, some of which are already available in Europe or Canada, show a relationship between efficacy and local skin reactions. Of two that Dr. Bhatia cited, 5-FU and salicylic acid combined in a solution and 5-FU and calcipotriene combined in an ointment have demonstrated high rates of efficacy but at the cost of substantial rates of erythema and flaking.

Transient skin reactions can be made acceptable to patients who are informed of the goals of clearing AKs, which includes lowering the risk of cancer, as well as cosmetic improvement. In the phase 4 study comparing ingenol mebutate gel to diclofenac sodium gel, the end-of-study global satisfaction rates were higher (P < .001) for those randomized to the most effective therapy despite the local skin reactions.