User login

Poor asthma control during pregnancy trims live birth rate

SAN FRANCISCO – and among the live births had a significantly increased rate of both preterm delivery and neonatal intensive care admissions, according to a review of insurance claims data for more than 1 million American women during 2011-2015.

On the other hand, asthma severity, which the researchers inferred based on the type and amount of treatment patients received, showed essentially no link with the live birth rate, Jennifer Yland said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

“The findings add to the body of evidence that relate poor asthma control to an increased risk for pregnancy complications.” explained Michael X. Schatz, MD, an allergist at Kaiser Permanente of Southern California, in San Diego, and a coauthor of the study.

Results from several prior studies had shown links between asthma and an increased rate of preterm birth, “but the larger, more generalizable population is a strength of the current findings. Results from prior studies have less frequently shown a link between asthma during pregnancy and neonatal ICU admissions,” he added.“The findings strengthen the case for good asthma control during pregnancy.”

For their review, Ms. Yland and her coauthors used insurance claims data from privately-insured American women aged 12-55 years who were pregnant and had drug prescription records during the study period. The database included 996,861 women without an asthma diagnosis and 29,882 women diagnosed with asthma. The analysis excluded women diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at least twice during pregnancy.

To analyze the pregnancy outcomes by asthma severity Ms. Yland and her associates divided the asthma patients into five subgroups based on the drug regimens they were on during pregnancy as a surrogate marker of disease severity. This analysis showed no relationship between disease severity and live birth rate.

The researchers also ran an analysis that divided patients into the quality of their management during pregnancy – either good or poor – based on either of two markers of poor control: filling five or more prescriptions for a short-acting beta-antagonist, or at least one exacerbation episode defined as an asthma-related emergency department visit, hospitalization, or need for oral corticosteroid treatment. By these criteria 7,135 (24%) of the pregnant women with asthma were poorly controlled. The live birth rate was 74% among women without asthma, 71% among those with well-controlled asthma, and 68% among women with poorly-controlled asthma, reported Ms. Yland, a researcher at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for demographic differences and comorbidities, women with poorly-controlled asthma had preterm delivery a statistically significant 30% more often than did women with well-controlled asthma, and the rate of neonatal ICU admissions was a significant 24% higher in women with poorly-controlled asthma, compared with women who had well-controlled asthma. However, the rates of small-for-gestational-age infants and infants with congenital malformations was not significantly different between the well-controlled and poorly-controlled subgroups.

The finding that almost a quarter of the pregnant women in the study were poorly controlled wasn’t surprising, Dr. Schatz said in an interview. In some studies as many as half the asthma patients have poor control.

The 24% rate of poor asthma control during pregnancy in the studied women is “most likely an underestimate of poor control in the general population” because the study used data from women with commercial health insurance, noted Sonia Hernandez-Diaz, MD, lead investigator for the study and professor of epidemiology at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “More disadvantaged populations, such as pregnant women on Medicaid, tend to have worse control.”

Barriers to good asthma control during pregnancy include smoking, weight gain, undertreatment, poor adherence, and viral infection. The overall approach to managing asthma during pregnancy is the same as when women are not pregnant, although certain asthma medications have a better safety record during pregnancy. “The most reassuring data exist for albuterol and inhaled steroids, particularly budesonide and fluticasone. Reassuring data also exist for the long-acting beta agonists salmeterol and formoterol, which are combined with inhaled steroids, and for montelukast,” Dr. Schatz said.

This is the first study to assess the impact of asthma management on pregnancy outcome in such a large population. The large number of women included provided a lot of statistical power and allowed the analyses to control for several potential confounders, Ms. Yland noted in an interview. She plans to expand the analysis with Medicaid data to try to further increase the generalizability and precision of the findings.

The study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline, and a coauthor of the study is a company employee. Ms. Yland had no disclosures. Dr. Schatz has received research funding from ALK, AstraZeneca, Medimmune, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck. Dr. Hernandez-Diaz has been a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, and UCB, and has received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Yland J et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019 Feb;143[2]:AB422.

SAN FRANCISCO – and among the live births had a significantly increased rate of both preterm delivery and neonatal intensive care admissions, according to a review of insurance claims data for more than 1 million American women during 2011-2015.

On the other hand, asthma severity, which the researchers inferred based on the type and amount of treatment patients received, showed essentially no link with the live birth rate, Jennifer Yland said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

“The findings add to the body of evidence that relate poor asthma control to an increased risk for pregnancy complications.” explained Michael X. Schatz, MD, an allergist at Kaiser Permanente of Southern California, in San Diego, and a coauthor of the study.

Results from several prior studies had shown links between asthma and an increased rate of preterm birth, “but the larger, more generalizable population is a strength of the current findings. Results from prior studies have less frequently shown a link between asthma during pregnancy and neonatal ICU admissions,” he added.“The findings strengthen the case for good asthma control during pregnancy.”

For their review, Ms. Yland and her coauthors used insurance claims data from privately-insured American women aged 12-55 years who were pregnant and had drug prescription records during the study period. The database included 996,861 women without an asthma diagnosis and 29,882 women diagnosed with asthma. The analysis excluded women diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at least twice during pregnancy.

To analyze the pregnancy outcomes by asthma severity Ms. Yland and her associates divided the asthma patients into five subgroups based on the drug regimens they were on during pregnancy as a surrogate marker of disease severity. This analysis showed no relationship between disease severity and live birth rate.

The researchers also ran an analysis that divided patients into the quality of their management during pregnancy – either good or poor – based on either of two markers of poor control: filling five or more prescriptions for a short-acting beta-antagonist, or at least one exacerbation episode defined as an asthma-related emergency department visit, hospitalization, or need for oral corticosteroid treatment. By these criteria 7,135 (24%) of the pregnant women with asthma were poorly controlled. The live birth rate was 74% among women without asthma, 71% among those with well-controlled asthma, and 68% among women with poorly-controlled asthma, reported Ms. Yland, a researcher at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for demographic differences and comorbidities, women with poorly-controlled asthma had preterm delivery a statistically significant 30% more often than did women with well-controlled asthma, and the rate of neonatal ICU admissions was a significant 24% higher in women with poorly-controlled asthma, compared with women who had well-controlled asthma. However, the rates of small-for-gestational-age infants and infants with congenital malformations was not significantly different between the well-controlled and poorly-controlled subgroups.

The finding that almost a quarter of the pregnant women in the study were poorly controlled wasn’t surprising, Dr. Schatz said in an interview. In some studies as many as half the asthma patients have poor control.

The 24% rate of poor asthma control during pregnancy in the studied women is “most likely an underestimate of poor control in the general population” because the study used data from women with commercial health insurance, noted Sonia Hernandez-Diaz, MD, lead investigator for the study and professor of epidemiology at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “More disadvantaged populations, such as pregnant women on Medicaid, tend to have worse control.”

Barriers to good asthma control during pregnancy include smoking, weight gain, undertreatment, poor adherence, and viral infection. The overall approach to managing asthma during pregnancy is the same as when women are not pregnant, although certain asthma medications have a better safety record during pregnancy. “The most reassuring data exist for albuterol and inhaled steroids, particularly budesonide and fluticasone. Reassuring data also exist for the long-acting beta agonists salmeterol and formoterol, which are combined with inhaled steroids, and for montelukast,” Dr. Schatz said.

This is the first study to assess the impact of asthma management on pregnancy outcome in such a large population. The large number of women included provided a lot of statistical power and allowed the analyses to control for several potential confounders, Ms. Yland noted in an interview. She plans to expand the analysis with Medicaid data to try to further increase the generalizability and precision of the findings.

The study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline, and a coauthor of the study is a company employee. Ms. Yland had no disclosures. Dr. Schatz has received research funding from ALK, AstraZeneca, Medimmune, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck. Dr. Hernandez-Diaz has been a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, and UCB, and has received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Yland J et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019 Feb;143[2]:AB422.

SAN FRANCISCO – and among the live births had a significantly increased rate of both preterm delivery and neonatal intensive care admissions, according to a review of insurance claims data for more than 1 million American women during 2011-2015.

On the other hand, asthma severity, which the researchers inferred based on the type and amount of treatment patients received, showed essentially no link with the live birth rate, Jennifer Yland said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

“The findings add to the body of evidence that relate poor asthma control to an increased risk for pregnancy complications.” explained Michael X. Schatz, MD, an allergist at Kaiser Permanente of Southern California, in San Diego, and a coauthor of the study.

Results from several prior studies had shown links between asthma and an increased rate of preterm birth, “but the larger, more generalizable population is a strength of the current findings. Results from prior studies have less frequently shown a link between asthma during pregnancy and neonatal ICU admissions,” he added.“The findings strengthen the case for good asthma control during pregnancy.”

For their review, Ms. Yland and her coauthors used insurance claims data from privately-insured American women aged 12-55 years who were pregnant and had drug prescription records during the study period. The database included 996,861 women without an asthma diagnosis and 29,882 women diagnosed with asthma. The analysis excluded women diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at least twice during pregnancy.

To analyze the pregnancy outcomes by asthma severity Ms. Yland and her associates divided the asthma patients into five subgroups based on the drug regimens they were on during pregnancy as a surrogate marker of disease severity. This analysis showed no relationship between disease severity and live birth rate.

The researchers also ran an analysis that divided patients into the quality of their management during pregnancy – either good or poor – based on either of two markers of poor control: filling five or more prescriptions for a short-acting beta-antagonist, or at least one exacerbation episode defined as an asthma-related emergency department visit, hospitalization, or need for oral corticosteroid treatment. By these criteria 7,135 (24%) of the pregnant women with asthma were poorly controlled. The live birth rate was 74% among women without asthma, 71% among those with well-controlled asthma, and 68% among women with poorly-controlled asthma, reported Ms. Yland, a researcher at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for demographic differences and comorbidities, women with poorly-controlled asthma had preterm delivery a statistically significant 30% more often than did women with well-controlled asthma, and the rate of neonatal ICU admissions was a significant 24% higher in women with poorly-controlled asthma, compared with women who had well-controlled asthma. However, the rates of small-for-gestational-age infants and infants with congenital malformations was not significantly different between the well-controlled and poorly-controlled subgroups.

The finding that almost a quarter of the pregnant women in the study were poorly controlled wasn’t surprising, Dr. Schatz said in an interview. In some studies as many as half the asthma patients have poor control.

The 24% rate of poor asthma control during pregnancy in the studied women is “most likely an underestimate of poor control in the general population” because the study used data from women with commercial health insurance, noted Sonia Hernandez-Diaz, MD, lead investigator for the study and professor of epidemiology at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “More disadvantaged populations, such as pregnant women on Medicaid, tend to have worse control.”

Barriers to good asthma control during pregnancy include smoking, weight gain, undertreatment, poor adherence, and viral infection. The overall approach to managing asthma during pregnancy is the same as when women are not pregnant, although certain asthma medications have a better safety record during pregnancy. “The most reassuring data exist for albuterol and inhaled steroids, particularly budesonide and fluticasone. Reassuring data also exist for the long-acting beta agonists salmeterol and formoterol, which are combined with inhaled steroids, and for montelukast,” Dr. Schatz said.

This is the first study to assess the impact of asthma management on pregnancy outcome in such a large population. The large number of women included provided a lot of statistical power and allowed the analyses to control for several potential confounders, Ms. Yland noted in an interview. She plans to expand the analysis with Medicaid data to try to further increase the generalizability and precision of the findings.

The study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline, and a coauthor of the study is a company employee. Ms. Yland had no disclosures. Dr. Schatz has received research funding from ALK, AstraZeneca, Medimmune, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck. Dr. Hernandez-Diaz has been a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, and UCB, and has received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Yland J et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019 Feb;143[2]:AB422.

REPORTING FROM AAAAI 2019

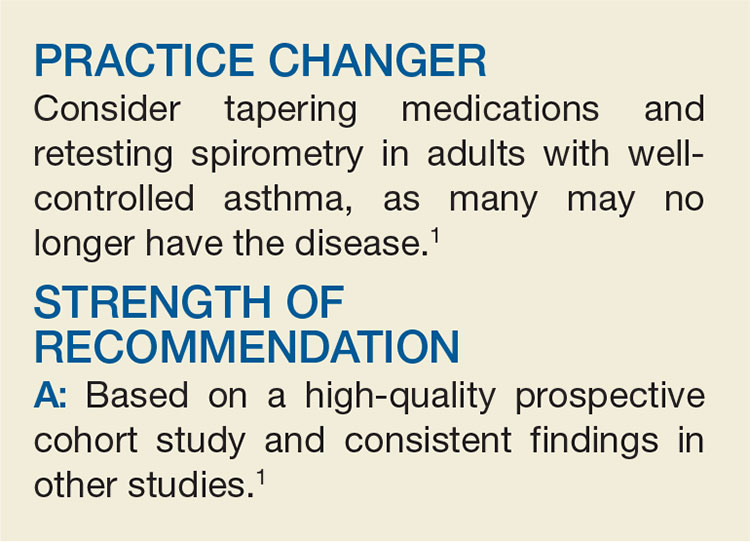

COPD and asthma: Diagnostic accuracy requires spirometry

A study of diagnostic accuracy in the primary care setting showed that among patients receiving inhaled therapies, most had not received an accurate diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma according to international guidelines.1,2 Other studies have shown that up to one-third of patients with a diagnosis of asthma3 or COPD4 may not actually have disease based on subsequent lung function testing.

Diagnostic error in medicine leads to numerous lost opportunities including the opportunity to: identify chronic conditions that are the true sources of patients’ symptoms, prevent morbidity and mortality, reduce unnecessary costs to patients and health systems, and deliver high-quality care.5-7 The reasons for diagnostic error in COPD and asthma are multifactorial, stemming from insufficient knowledge of clinical practice guidelines and underutilization of spirometry testing. Spirometry is recommended as part of the workup for suspected COPD and is the preferred test for diagnosing asthma. Spirometry, combined with clinical findings, can help differentiate between these diseases.

In this article, we review the definitions and characteristics of COPD and asthma, address the potential causes for diagnostic error, and explain how current clinical practice guidelines can steer examinations to the right diagnosis, improve clinical management, and contribute to better patient outcomes and quality of life.8,9

COPD and asthma characteristics

COPD. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) defines COPD as a common lung disease characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow obstruction caused by airway or alveolar abnormalities secondary to significant exposure to noxious particles or gases.10 The most common COPD-risk exposure in the United States is tobacco smoke, chiefly from cigarettes. Risk is also heightened with use of other types of tobacco (pipe, cigar, water pipe), indoor and outdoor air pollution (including second-hand tobacco smoke exposure), and occupational exposures. (Consider testing for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency—a known genetic risk factor for COPD—especially when an individual with COPD is younger and has a limited smoking history.)

The most common symptom of COPD is chronic, progressive dyspnea — an increased effort to breathe, with chest heaviness, air hunger, or gasping. About one-third of people with COPD have a chronic cough with sputum production.10 There may be wheezing and chest tightness. Fatigue, weight loss, and anorexia can be seen in severe COPD. Consider this disorder in any individual older than 40 years of age who has dyspnea and chronic cough with sputum production, as well as a history of risk factors. If COPD is suspected, perform spirometry to determine the presence of fixed airflow limitation and confirm the diagnosis.

Asthma is usually characterized by variable airway hyperresponsiveness and chronic inflammation. A typical clinical presentation is an individual with a history of wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and cough that vary in intensity over time and are coupled with variable expiratory flow limitation. Asthma symptoms are often triggered by allergen or irritant exposure, exercise, weather changes, or viral respiratory infections.2 Symptoms may also be worse at night or first thing in the morning. Once asthma is suspected, document the presence of airflow variability with spirometry to confirm the diagnosis.

[polldaddy:10261486]

Diagnostic error in suspected COPD and asthma

Numerous studies have demonstrated the prevalence of diagnostic error when testing of lung function is neglected.11-14 Using spirometry to confirm a prior clinical diagnosis of COPD, researchers found that:

- 35% to 50% of patients did not have objective evidence of COPD12,13;

- 37% with an asthma-only diagnosis had persistent obstruction, which may indicate COPD or chronic obstructive asthma12; and

- 31% of patients thought to have asthma-COPD overlap did not have a COPD component.12

Continue to: In 2 longitudinal studies...

In 2 longitudinal studies, patients with a diagnosis of asthma were recruited to undergo medication reduction and serial lung function testing. Asthma was excluded in approximately 30% of patients.15,16 Diagnostic error has also been seen in patients hospitalized with exacerbations of COPD and asthma. One study found that only 31% of patients admitted with a diagnosis of COPD exacerbation had undergone a spirometry test prior to hospitalization.17 And of those patients with a diagnosis of COPD who underwent spirometry, 30% had results inconsistent with COPD.17

In another study, 22% of adults hospitalized for COPD or asthma exacerbations had no evidence of obstruction on spirometry at the time of hospitalization.18 This finding refutes a diagnosis of COPD and, in the midst of an exacerbation, challenges an asthma diagnosis as well. Increased awareness of clinical practice guidelines, coupled with the use and accurate interpretation of spirometry are needed for optimal management and treatment of COPD and asthma.

Clinical practice guidelines recommend spirometry for the diagnosis of COPD and asthma and have been issued by GOLD10; the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and the European Respiratory Society19; the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA)2; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.20

When a patient’s symptoms and risk factors suggest COPD, spirometry is needed to show persistent post-bronchodilator airflow obstruction and thereby confirm the diagnosis. However, in the United States, confirmatory spirometry is used only in about one third of patients newly diagnosed with COPD.21,22 Similarly for asthma, in the presence of suggestive symptoms, spirometry is the preferred and most reliable and reproducible test to detect the variable expiratory airflow limitation consistent with this diagnosis.

An alternative to spirometry for the diagnosis of asthma (if needed) is a peak flow meter, a simple tool to measure peak expiratory flow. When compared with spirometry, peak flow measurements are less time consuming, less costly, and not dependent on trained staff to perform.23 However, this option does require that patients perform and document multiple measurements over several days without an objective assessment of their efforts. Unlike spirometry, the peak flow meter has no reference values or reliability and reproducibility standards, and measurements can differ from one peak flow meter to another. Thus, a peak flow meter is less reliable than spirometry for diagnosing asthma. But it can be useful for monitoring asthma control at home and in the clinic setting,24 or for diagnosis if spirometry is unavailable.23

Continue to: Barriers to the use of spirometry...

Barriers to the use of spirometry in the primary care setting exist on several levels. Providers may lack knowledge of clinical practice guidelines that recommend spirometry in the diagnosis of COPD, and they may lack general awareness of the utility of spirometry.25-29 In 2 studies of primary care practices that offered office spirometry, lack of knowledge in conducting and interpreting the test was a barrier to its use.28,30 Primary care physicians also struggle with logistical challenges when clinical visits last just 10 to 15 minutes for patients with multiple comorbidities,27 and maintenance of an office spirometry program may not always be feasible.

Getting to the right diagnosis

Likewise, nonpharmacologic interventions may be misused or go unused when needed if the diagnosis is inaccurate. For patients with COPD, outcomes are improved with pulmonary rehabilitation and supplemental oxygen in the setting of resting hypoxemia, but these resources will not be considered if patients are misdiagnosed as having asthma. A patient with undetected heart failure or obstructive sleep apnea who has been misdiagnosed with COPD or asthma may not receive appropriate diagnostic testing or treatment until asthma or COPD has been ruled out with lung function testing.

Objectively documenting the right diagnosis helps ensure guideline-based management of COPD or asthma. Ruling out these 2 disorders prompts further investigation into other conditions (eg, coronary artery disease, heart failure, gastroesophageal reflux disease, pulmonary hypertension, interstitial lung diseases) that can cause symptoms such as shortness of breath, wheezing, or cough.

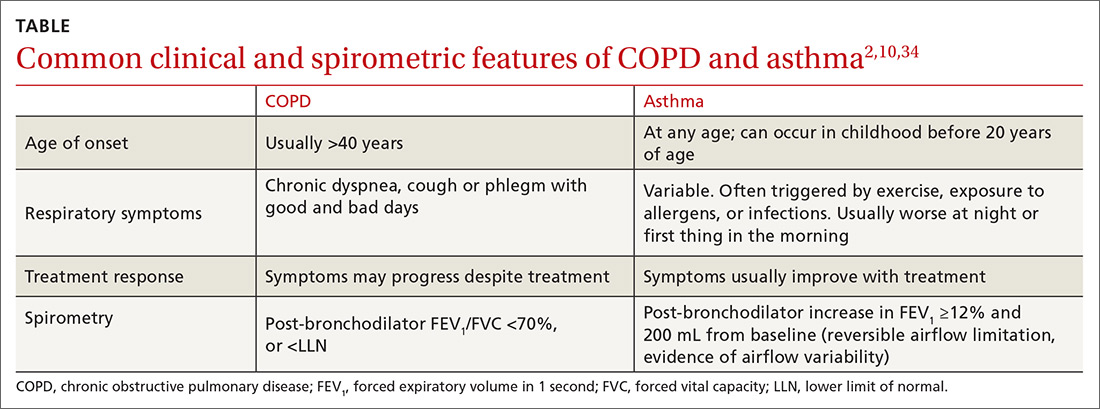

The TABLE2,10,34 summarizes some of the more common clinical and spirometric features of COPD and asthma. Onset of COPD usually occurs in those over age 40. Asthma can present in younger individuals, including children. Tobacco use or exposure to noxious substances is more often associated with COPD. Patients with asthma are more likely to have atopy. Symptoms in COPD usually progress with increasing activity or exertion. Symptoms in asthma may vary with certain activities, such as exercise, and with various triggers. These features represent “typical” cases of COPD or asthma, but some patients may have clinical characteristics

Continue to: The utility of spirometry in measuring lung function

The utility of spirometry in measuring lung function. Spirometry is the most reproducible and objective measurement of airflow limitation,10 and it should precede any treatment decisions. This technique—in which the patient performs maximal inhalation followed by forced exhalation—measures airflow over time and determines the lung volume exhaled at any time point. Because this respiratory exercise is patient dependent, a well-trained technician is needed to ensure reproducibility and reliability of results based on technical standards.

Spirometry measures forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), from which the FEV1/FVC ratio is calculated. FVC is the total amount of air from total lung volume that can be exhaled in one breath. FEV1 is the total amount of air exhaled in the first second after initiation of exhalation. Thus, the FEV1/FVC ratio is the percentage of the total amount of air in a single breath that is exhaled in the first second. On average, an individual with normal lungs can exhale approximately 80% of their FVC in the first second, thereby resulting in a FEV1/FVC ratio of 80%.

Spirometry findings with COPD. A post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio of less than 70% confirms airflow obstruction and is consistent with COPD according to GOLD criteria.10 Post-bronchodilator spirometry is performed after the patient has received a specified dose of an inhaled bronchodilator per lab protocols. In patients with COPD, the FEV1/FVC ratio is persistently low even after administration of a bronchodilator.

Another means of using spirometry to diagnose COPD is referring to age-dependent cutoff values below the lower fifth percentile of the FEV1/FVC ratio (ie, lower limit of normal [LLN]), which differs from the GOLD strategy but is consistent with the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines.35 Because the FEV1/FVC ratio declines with age, older adults may have a normal post-bronchodilator ratio less than 70%. Admittedly, applying GOLD criteria to older adults could result in overdiagnosis, while using the LLN could lead to underdiagnosis. Although there is no consensus on which method to use, the best approach may be the one that most strongly correlates with pretest probability of disease. In a large Canadian study, the approach that most strongly predicted poor patient outcomes was using a FEV1/FVC based on fixed (70%) and/or LLN criteria, and a low FEV134

Spirometry findings with asthma. According to the American Thoracic Society, a post-bronchodilator response is defined as an increase in FEV1 (or FVC) of 12% if that volume is also ≥200 mL. In patients with suspected asthma, an increase in FEV1 ≥12% and 200 mL is consistent with variable airflow limitation2 and supports the diagnosis. Of note, lung function in patients with asthma may be normal when patients are not symptomatic or when they are receiving therapy. Spirometry is therefore ideally performed before initiating therapy and when maintenance therapy is being considered due to symptoms. If therapy is clinically indicated, a short-acting bronchodilator may be prescribed alone and then held 6 to 8 hours before conducting spirometry. If a trial of a maintenance medication is prescribed before spirometry, consider de-escalation of therapy once the patient is more stable and then perform spirometry to confirm the presence of airflow variability consistent with asthma. (In COPD, there can be a positive bronchodilator response; however, the post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio remains low.)

Continue to: Don't use in isolation

Don’t use in isolation. Use spirometry to support a clinical suspicion of asthma36 or COPD after a thorough history and physical exam, and not in isolation.

Special consideration: Asthma-COPD overlap syndrome

Some patients have features characteristic of both asthma and COPD and are said to have asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS). Between 15% and 20% of patients with COPD may in fact have ACOS.36 While there is no specific definition of ACOS, GOLD and GINA describe ACOS as persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD.2,10,37 ACOS becomes more prevalent with advancing age.

In ACOS, patients with COPD present with increased reversibility or patients with asthma and smoking history develop non-fully reversible airway obstruction at an older age.38 Patients with ACOS have worse lung function, more respiratory symptoms, and lower health-related quality of life than individuals with asthma or COPD alone,39,40 leading to more consumption of medical resources.41 In patients with ACOS, the FEV1/FVC ratio is low and consistent with the diagnosis of COPD. The post-bronchodilator response may be variable, depending on the stage of disease and predominant clinical features. It is still unclear whether ACOS is a separate disease entity, a representation of severe asthma that has morphed into COPD, or not a syndrome but simply 2 separate comorbid disease states.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christina D. Wells, MD, University of Illinois Mile Square Health Center, 1220 S. Wood Street, Chicago, IL 60612; cwells2@uic.edu.

1. Izquierdo JL, Martìn A, de Lucas P, et al. Misdiagnosis of patients receiving inhaled therapies in primary care. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2010;5:241-249.

2. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2018. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/wms-GINA-2018-report-V1.3-002.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2019.

3. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017; 317:269-279.

4. Spero K, Bayasi G, Beaudry L, et al. Overdiagnosis of COPD in hospitalized patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:2417-2423.

5. Singh H, Graber ML. Improving diagnosis in health care—the next imperative for patient safety. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2493-2495.

6. Ball JR, Balogh E. Improving diagnosis in health care: highlights of a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:59-61.

7. Khullar D, Jha AK, Jena AB. Reducing diagnostic errors—why now? N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2491-2493.

8. Lamprecht B, Soriano JB, Studnicka M, et al. Determinants of underdiagnosis of COPD in national and international surveys. Chest. 2015;148:971-985.

9. Yang CL, Simons E, Foty RG, et al. Misdiagnosis of asthma in schoolchildren. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52:293-302.

10. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2019. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/GOLD-2019-v1.7-FINAL-14Nov2018-WMS.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2019.

11. Tinkelman DG, Price DB, Nordyke RJ, et al. Misdiagnosis of COPD and asthma in primary care patients 40 years of age and over. J Asthma. 2006;43:75-80.

12. Abramson MJ, Schattner RL, Sulaiman ND, et al. Accuracy of asthma and COPD diagnosis in Australian general practice: a mixed methods study. Prim Care Respir J. 2012;21:167-173.

13. Sichletidis L, Chloros D, Spyratos D, et al. The validity of the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in general practice. Prim Care Respir J. 2007;16:82-88.

14. Marklund B, Tunsäter A, Bengtsson C. How often is the diagnosis bronchial asthma correct? Fam Pract. 1999;16:112-116.

15. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Boulet LP, et al. Overdiagnosis of asthma in obese and nonobese adults. CMAJ. 2008;179:1121-1131.

16. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM, et al. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017;317:269-279.

17. Damarla M, Celli BR, Mullerova HX, et al. Discrepancy in the use of confirmatory tests in patients hospitalized with the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or congestive heart failure. Respir Care. 2006;51:1120-1124.

18. Prieto Centurion V, Huang F, Naureckus ET, et al. Confirmatory spirometry for adults hospitalized with a diagnosis of asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. BMC Pulm Med. 2012;12:73.

19. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

20. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma-Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007. 120(Suppl):S94-S138.

21. Han MK, Kim MG, Mardon R, et al. Spirometry utilization for COPD: how do we measure up? Chest. 2007;132:403-409.

22. Joo MJ, Lee TA, Weiss KB. Geographic variation of spirometry use in newly diagnosed COPD. Chest. 2008;134:38-45.

23. Thorat YT, Salvi SS, Kodgule RR. Peak flow meter with a questionnaire and mini-spirometer to help detect asthma and COPD in real-life clinical practice: a cross-sectional study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27:32.

24. Kennedy DT, Chang Z, Small RE. Selection of peak flowmeters in ambulatory asthma patients: a review of the literature. Chest. 1998;114:587-592.

25. Walters JA, Hanson E, Mudge P, et al. Barriers to the use of spirometry in general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34:201-203.

26. Barr RG, Celli BR, Martinez FJ, et al. Physician and patient perceptions in COPD: the COPD Resource Network Needs Assessment Survey. Am J Med. 2005;118:1415.

27. Caramori G, Bettoncelli G, Tosatto R, et al. Underuse of spirometry by general practitioners for the diagnosis of COPD in Italy. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2005;63:6-12.

28. Kaminsky DA, Marcy TW, Bachand F, et al. Knowledge and use of office spirometry for the detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by primary care physicians. Respir Care. 2005;50:1639-1648.

29. Foster JA, Yawn BP, Maziar A, et al. Enhancing COPD management in primary care settings. MedGenMed. 2007;9:24.

30. Bolton CE, Ionescu AA, Edwards PH, et al. Attaining a correct diagnosis of COPD in general practice. Respir Med. 2005:99:493-500.

31. Drummond MB, Dasenbrook EC, Pitz MW, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2407-2416.

32. Morales DR. LABA monotherapy in asthma: an avoidable problem. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:627-628.

33. Nelson HS, Weiss ST, Bleecker ER, et al. The Salmeterol Multicenter Asthma Research Trial: a comparison of usual pharmacotherapy for asthma or usual pharmacotherapy plus salmeterol. Chest. 2006;129:15-26.

34. van Dijk W, Tan W, Li P, et al. Clinical relevance of fixed ratio vs lower limit of normal of FEV1/FVC in COPD: patient-reported outcomes from the CanCOLD cohort. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13:41-48.

35. Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319-338.

36. Rogliani P, Ora J, Puxeddu E, et al. Airflow obstruction: is it asthma or is it COPD? Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:3007-3013.

37. Global Initiative for Asthma. Diagnosis and initial treatment of asthma, COPD and asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. 2017. https://ginasthma.org/. Accessed January 12, 2019.

38. Barrecheguren M, Esquinas C, Miravitlles M. The asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome (ACOS): opportunities and challenges. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2015;21:74-79.

39. Kauppi P, Kupiainen H, Lindqvist A, et al. Overlap syndrome of asthma and COPD predicts low quality of life. J Asthma. 2011;48:279-285.

40. Mannino DM, Gagnon RC, Petty TL, et al. Obstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1683-1689.

41. Shaya FT, Dongyi D, Akazawa MO, et al. Burden of concomitant asthma and COPD in a Medicaid population. Chest. 2008;134:14-19.

A study of diagnostic accuracy in the primary care setting showed that among patients receiving inhaled therapies, most had not received an accurate diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma according to international guidelines.1,2 Other studies have shown that up to one-third of patients with a diagnosis of asthma3 or COPD4 may not actually have disease based on subsequent lung function testing.

Diagnostic error in medicine leads to numerous lost opportunities including the opportunity to: identify chronic conditions that are the true sources of patients’ symptoms, prevent morbidity and mortality, reduce unnecessary costs to patients and health systems, and deliver high-quality care.5-7 The reasons for diagnostic error in COPD and asthma are multifactorial, stemming from insufficient knowledge of clinical practice guidelines and underutilization of spirometry testing. Spirometry is recommended as part of the workup for suspected COPD and is the preferred test for diagnosing asthma. Spirometry, combined with clinical findings, can help differentiate between these diseases.

In this article, we review the definitions and characteristics of COPD and asthma, address the potential causes for diagnostic error, and explain how current clinical practice guidelines can steer examinations to the right diagnosis, improve clinical management, and contribute to better patient outcomes and quality of life.8,9

COPD and asthma characteristics

COPD. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) defines COPD as a common lung disease characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow obstruction caused by airway or alveolar abnormalities secondary to significant exposure to noxious particles or gases.10 The most common COPD-risk exposure in the United States is tobacco smoke, chiefly from cigarettes. Risk is also heightened with use of other types of tobacco (pipe, cigar, water pipe), indoor and outdoor air pollution (including second-hand tobacco smoke exposure), and occupational exposures. (Consider testing for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency—a known genetic risk factor for COPD—especially when an individual with COPD is younger and has a limited smoking history.)

The most common symptom of COPD is chronic, progressive dyspnea — an increased effort to breathe, with chest heaviness, air hunger, or gasping. About one-third of people with COPD have a chronic cough with sputum production.10 There may be wheezing and chest tightness. Fatigue, weight loss, and anorexia can be seen in severe COPD. Consider this disorder in any individual older than 40 years of age who has dyspnea and chronic cough with sputum production, as well as a history of risk factors. If COPD is suspected, perform spirometry to determine the presence of fixed airflow limitation and confirm the diagnosis.

Asthma is usually characterized by variable airway hyperresponsiveness and chronic inflammation. A typical clinical presentation is an individual with a history of wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and cough that vary in intensity over time and are coupled with variable expiratory flow limitation. Asthma symptoms are often triggered by allergen or irritant exposure, exercise, weather changes, or viral respiratory infections.2 Symptoms may also be worse at night or first thing in the morning. Once asthma is suspected, document the presence of airflow variability with spirometry to confirm the diagnosis.

[polldaddy:10261486]

Diagnostic error in suspected COPD and asthma

Numerous studies have demonstrated the prevalence of diagnostic error when testing of lung function is neglected.11-14 Using spirometry to confirm a prior clinical diagnosis of COPD, researchers found that:

- 35% to 50% of patients did not have objective evidence of COPD12,13;

- 37% with an asthma-only diagnosis had persistent obstruction, which may indicate COPD or chronic obstructive asthma12; and

- 31% of patients thought to have asthma-COPD overlap did not have a COPD component.12

Continue to: In 2 longitudinal studies...

In 2 longitudinal studies, patients with a diagnosis of asthma were recruited to undergo medication reduction and serial lung function testing. Asthma was excluded in approximately 30% of patients.15,16 Diagnostic error has also been seen in patients hospitalized with exacerbations of COPD and asthma. One study found that only 31% of patients admitted with a diagnosis of COPD exacerbation had undergone a spirometry test prior to hospitalization.17 And of those patients with a diagnosis of COPD who underwent spirometry, 30% had results inconsistent with COPD.17

In another study, 22% of adults hospitalized for COPD or asthma exacerbations had no evidence of obstruction on spirometry at the time of hospitalization.18 This finding refutes a diagnosis of COPD and, in the midst of an exacerbation, challenges an asthma diagnosis as well. Increased awareness of clinical practice guidelines, coupled with the use and accurate interpretation of spirometry are needed for optimal management and treatment of COPD and asthma.

Clinical practice guidelines recommend spirometry for the diagnosis of COPD and asthma and have been issued by GOLD10; the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and the European Respiratory Society19; the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA)2; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.20

When a patient’s symptoms and risk factors suggest COPD, spirometry is needed to show persistent post-bronchodilator airflow obstruction and thereby confirm the diagnosis. However, in the United States, confirmatory spirometry is used only in about one third of patients newly diagnosed with COPD.21,22 Similarly for asthma, in the presence of suggestive symptoms, spirometry is the preferred and most reliable and reproducible test to detect the variable expiratory airflow limitation consistent with this diagnosis.

An alternative to spirometry for the diagnosis of asthma (if needed) is a peak flow meter, a simple tool to measure peak expiratory flow. When compared with spirometry, peak flow measurements are less time consuming, less costly, and not dependent on trained staff to perform.23 However, this option does require that patients perform and document multiple measurements over several days without an objective assessment of their efforts. Unlike spirometry, the peak flow meter has no reference values or reliability and reproducibility standards, and measurements can differ from one peak flow meter to another. Thus, a peak flow meter is less reliable than spirometry for diagnosing asthma. But it can be useful for monitoring asthma control at home and in the clinic setting,24 or for diagnosis if spirometry is unavailable.23

Continue to: Barriers to the use of spirometry...

Barriers to the use of spirometry in the primary care setting exist on several levels. Providers may lack knowledge of clinical practice guidelines that recommend spirometry in the diagnosis of COPD, and they may lack general awareness of the utility of spirometry.25-29 In 2 studies of primary care practices that offered office spirometry, lack of knowledge in conducting and interpreting the test was a barrier to its use.28,30 Primary care physicians also struggle with logistical challenges when clinical visits last just 10 to 15 minutes for patients with multiple comorbidities,27 and maintenance of an office spirometry program may not always be feasible.

Getting to the right diagnosis

Likewise, nonpharmacologic interventions may be misused or go unused when needed if the diagnosis is inaccurate. For patients with COPD, outcomes are improved with pulmonary rehabilitation and supplemental oxygen in the setting of resting hypoxemia, but these resources will not be considered if patients are misdiagnosed as having asthma. A patient with undetected heart failure or obstructive sleep apnea who has been misdiagnosed with COPD or asthma may not receive appropriate diagnostic testing or treatment until asthma or COPD has been ruled out with lung function testing.

Objectively documenting the right diagnosis helps ensure guideline-based management of COPD or asthma. Ruling out these 2 disorders prompts further investigation into other conditions (eg, coronary artery disease, heart failure, gastroesophageal reflux disease, pulmonary hypertension, interstitial lung diseases) that can cause symptoms such as shortness of breath, wheezing, or cough.

The TABLE2,10,34 summarizes some of the more common clinical and spirometric features of COPD and asthma. Onset of COPD usually occurs in those over age 40. Asthma can present in younger individuals, including children. Tobacco use or exposure to noxious substances is more often associated with COPD. Patients with asthma are more likely to have atopy. Symptoms in COPD usually progress with increasing activity or exertion. Symptoms in asthma may vary with certain activities, such as exercise, and with various triggers. These features represent “typical” cases of COPD or asthma, but some patients may have clinical characteristics

Continue to: The utility of spirometry in measuring lung function

The utility of spirometry in measuring lung function. Spirometry is the most reproducible and objective measurement of airflow limitation,10 and it should precede any treatment decisions. This technique—in which the patient performs maximal inhalation followed by forced exhalation—measures airflow over time and determines the lung volume exhaled at any time point. Because this respiratory exercise is patient dependent, a well-trained technician is needed to ensure reproducibility and reliability of results based on technical standards.

Spirometry measures forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), from which the FEV1/FVC ratio is calculated. FVC is the total amount of air from total lung volume that can be exhaled in one breath. FEV1 is the total amount of air exhaled in the first second after initiation of exhalation. Thus, the FEV1/FVC ratio is the percentage of the total amount of air in a single breath that is exhaled in the first second. On average, an individual with normal lungs can exhale approximately 80% of their FVC in the first second, thereby resulting in a FEV1/FVC ratio of 80%.

Spirometry findings with COPD. A post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio of less than 70% confirms airflow obstruction and is consistent with COPD according to GOLD criteria.10 Post-bronchodilator spirometry is performed after the patient has received a specified dose of an inhaled bronchodilator per lab protocols. In patients with COPD, the FEV1/FVC ratio is persistently low even after administration of a bronchodilator.

Another means of using spirometry to diagnose COPD is referring to age-dependent cutoff values below the lower fifth percentile of the FEV1/FVC ratio (ie, lower limit of normal [LLN]), which differs from the GOLD strategy but is consistent with the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines.35 Because the FEV1/FVC ratio declines with age, older adults may have a normal post-bronchodilator ratio less than 70%. Admittedly, applying GOLD criteria to older adults could result in overdiagnosis, while using the LLN could lead to underdiagnosis. Although there is no consensus on which method to use, the best approach may be the one that most strongly correlates with pretest probability of disease. In a large Canadian study, the approach that most strongly predicted poor patient outcomes was using a FEV1/FVC based on fixed (70%) and/or LLN criteria, and a low FEV134

Spirometry findings with asthma. According to the American Thoracic Society, a post-bronchodilator response is defined as an increase in FEV1 (or FVC) of 12% if that volume is also ≥200 mL. In patients with suspected asthma, an increase in FEV1 ≥12% and 200 mL is consistent with variable airflow limitation2 and supports the diagnosis. Of note, lung function in patients with asthma may be normal when patients are not symptomatic or when they are receiving therapy. Spirometry is therefore ideally performed before initiating therapy and when maintenance therapy is being considered due to symptoms. If therapy is clinically indicated, a short-acting bronchodilator may be prescribed alone and then held 6 to 8 hours before conducting spirometry. If a trial of a maintenance medication is prescribed before spirometry, consider de-escalation of therapy once the patient is more stable and then perform spirometry to confirm the presence of airflow variability consistent with asthma. (In COPD, there can be a positive bronchodilator response; however, the post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio remains low.)

Continue to: Don't use in isolation

Don’t use in isolation. Use spirometry to support a clinical suspicion of asthma36 or COPD after a thorough history and physical exam, and not in isolation.

Special consideration: Asthma-COPD overlap syndrome

Some patients have features characteristic of both asthma and COPD and are said to have asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS). Between 15% and 20% of patients with COPD may in fact have ACOS.36 While there is no specific definition of ACOS, GOLD and GINA describe ACOS as persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD.2,10,37 ACOS becomes more prevalent with advancing age.

In ACOS, patients with COPD present with increased reversibility or patients with asthma and smoking history develop non-fully reversible airway obstruction at an older age.38 Patients with ACOS have worse lung function, more respiratory symptoms, and lower health-related quality of life than individuals with asthma or COPD alone,39,40 leading to more consumption of medical resources.41 In patients with ACOS, the FEV1/FVC ratio is low and consistent with the diagnosis of COPD. The post-bronchodilator response may be variable, depending on the stage of disease and predominant clinical features. It is still unclear whether ACOS is a separate disease entity, a representation of severe asthma that has morphed into COPD, or not a syndrome but simply 2 separate comorbid disease states.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christina D. Wells, MD, University of Illinois Mile Square Health Center, 1220 S. Wood Street, Chicago, IL 60612; cwells2@uic.edu.

A study of diagnostic accuracy in the primary care setting showed that among patients receiving inhaled therapies, most had not received an accurate diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma according to international guidelines.1,2 Other studies have shown that up to one-third of patients with a diagnosis of asthma3 or COPD4 may not actually have disease based on subsequent lung function testing.

Diagnostic error in medicine leads to numerous lost opportunities including the opportunity to: identify chronic conditions that are the true sources of patients’ symptoms, prevent morbidity and mortality, reduce unnecessary costs to patients and health systems, and deliver high-quality care.5-7 The reasons for diagnostic error in COPD and asthma are multifactorial, stemming from insufficient knowledge of clinical practice guidelines and underutilization of spirometry testing. Spirometry is recommended as part of the workup for suspected COPD and is the preferred test for diagnosing asthma. Spirometry, combined with clinical findings, can help differentiate between these diseases.

In this article, we review the definitions and characteristics of COPD and asthma, address the potential causes for diagnostic error, and explain how current clinical practice guidelines can steer examinations to the right diagnosis, improve clinical management, and contribute to better patient outcomes and quality of life.8,9

COPD and asthma characteristics

COPD. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) defines COPD as a common lung disease characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow obstruction caused by airway or alveolar abnormalities secondary to significant exposure to noxious particles or gases.10 The most common COPD-risk exposure in the United States is tobacco smoke, chiefly from cigarettes. Risk is also heightened with use of other types of tobacco (pipe, cigar, water pipe), indoor and outdoor air pollution (including second-hand tobacco smoke exposure), and occupational exposures. (Consider testing for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency—a known genetic risk factor for COPD—especially when an individual with COPD is younger and has a limited smoking history.)

The most common symptom of COPD is chronic, progressive dyspnea — an increased effort to breathe, with chest heaviness, air hunger, or gasping. About one-third of people with COPD have a chronic cough with sputum production.10 There may be wheezing and chest tightness. Fatigue, weight loss, and anorexia can be seen in severe COPD. Consider this disorder in any individual older than 40 years of age who has dyspnea and chronic cough with sputum production, as well as a history of risk factors. If COPD is suspected, perform spirometry to determine the presence of fixed airflow limitation and confirm the diagnosis.

Asthma is usually characterized by variable airway hyperresponsiveness and chronic inflammation. A typical clinical presentation is an individual with a history of wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and cough that vary in intensity over time and are coupled with variable expiratory flow limitation. Asthma symptoms are often triggered by allergen or irritant exposure, exercise, weather changes, or viral respiratory infections.2 Symptoms may also be worse at night or first thing in the morning. Once asthma is suspected, document the presence of airflow variability with spirometry to confirm the diagnosis.

[polldaddy:10261486]

Diagnostic error in suspected COPD and asthma

Numerous studies have demonstrated the prevalence of diagnostic error when testing of lung function is neglected.11-14 Using spirometry to confirm a prior clinical diagnosis of COPD, researchers found that:

- 35% to 50% of patients did not have objective evidence of COPD12,13;

- 37% with an asthma-only diagnosis had persistent obstruction, which may indicate COPD or chronic obstructive asthma12; and

- 31% of patients thought to have asthma-COPD overlap did not have a COPD component.12

Continue to: In 2 longitudinal studies...

In 2 longitudinal studies, patients with a diagnosis of asthma were recruited to undergo medication reduction and serial lung function testing. Asthma was excluded in approximately 30% of patients.15,16 Diagnostic error has also been seen in patients hospitalized with exacerbations of COPD and asthma. One study found that only 31% of patients admitted with a diagnosis of COPD exacerbation had undergone a spirometry test prior to hospitalization.17 And of those patients with a diagnosis of COPD who underwent spirometry, 30% had results inconsistent with COPD.17

In another study, 22% of adults hospitalized for COPD or asthma exacerbations had no evidence of obstruction on spirometry at the time of hospitalization.18 This finding refutes a diagnosis of COPD and, in the midst of an exacerbation, challenges an asthma diagnosis as well. Increased awareness of clinical practice guidelines, coupled with the use and accurate interpretation of spirometry are needed for optimal management and treatment of COPD and asthma.

Clinical practice guidelines recommend spirometry for the diagnosis of COPD and asthma and have been issued by GOLD10; the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and the European Respiratory Society19; the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA)2; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.20

When a patient’s symptoms and risk factors suggest COPD, spirometry is needed to show persistent post-bronchodilator airflow obstruction and thereby confirm the diagnosis. However, in the United States, confirmatory spirometry is used only in about one third of patients newly diagnosed with COPD.21,22 Similarly for asthma, in the presence of suggestive symptoms, spirometry is the preferred and most reliable and reproducible test to detect the variable expiratory airflow limitation consistent with this diagnosis.

An alternative to spirometry for the diagnosis of asthma (if needed) is a peak flow meter, a simple tool to measure peak expiratory flow. When compared with spirometry, peak flow measurements are less time consuming, less costly, and not dependent on trained staff to perform.23 However, this option does require that patients perform and document multiple measurements over several days without an objective assessment of their efforts. Unlike spirometry, the peak flow meter has no reference values or reliability and reproducibility standards, and measurements can differ from one peak flow meter to another. Thus, a peak flow meter is less reliable than spirometry for diagnosing asthma. But it can be useful for monitoring asthma control at home and in the clinic setting,24 or for diagnosis if spirometry is unavailable.23

Continue to: Barriers to the use of spirometry...

Barriers to the use of spirometry in the primary care setting exist on several levels. Providers may lack knowledge of clinical practice guidelines that recommend spirometry in the diagnosis of COPD, and they may lack general awareness of the utility of spirometry.25-29 In 2 studies of primary care practices that offered office spirometry, lack of knowledge in conducting and interpreting the test was a barrier to its use.28,30 Primary care physicians also struggle with logistical challenges when clinical visits last just 10 to 15 minutes for patients with multiple comorbidities,27 and maintenance of an office spirometry program may not always be feasible.

Getting to the right diagnosis

Likewise, nonpharmacologic interventions may be misused or go unused when needed if the diagnosis is inaccurate. For patients with COPD, outcomes are improved with pulmonary rehabilitation and supplemental oxygen in the setting of resting hypoxemia, but these resources will not be considered if patients are misdiagnosed as having asthma. A patient with undetected heart failure or obstructive sleep apnea who has been misdiagnosed with COPD or asthma may not receive appropriate diagnostic testing or treatment until asthma or COPD has been ruled out with lung function testing.

Objectively documenting the right diagnosis helps ensure guideline-based management of COPD or asthma. Ruling out these 2 disorders prompts further investigation into other conditions (eg, coronary artery disease, heart failure, gastroesophageal reflux disease, pulmonary hypertension, interstitial lung diseases) that can cause symptoms such as shortness of breath, wheezing, or cough.

The TABLE2,10,34 summarizes some of the more common clinical and spirometric features of COPD and asthma. Onset of COPD usually occurs in those over age 40. Asthma can present in younger individuals, including children. Tobacco use or exposure to noxious substances is more often associated with COPD. Patients with asthma are more likely to have atopy. Symptoms in COPD usually progress with increasing activity or exertion. Symptoms in asthma may vary with certain activities, such as exercise, and with various triggers. These features represent “typical” cases of COPD or asthma, but some patients may have clinical characteristics

Continue to: The utility of spirometry in measuring lung function

The utility of spirometry in measuring lung function. Spirometry is the most reproducible and objective measurement of airflow limitation,10 and it should precede any treatment decisions. This technique—in which the patient performs maximal inhalation followed by forced exhalation—measures airflow over time and determines the lung volume exhaled at any time point. Because this respiratory exercise is patient dependent, a well-trained technician is needed to ensure reproducibility and reliability of results based on technical standards.

Spirometry measures forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), from which the FEV1/FVC ratio is calculated. FVC is the total amount of air from total lung volume that can be exhaled in one breath. FEV1 is the total amount of air exhaled in the first second after initiation of exhalation. Thus, the FEV1/FVC ratio is the percentage of the total amount of air in a single breath that is exhaled in the first second. On average, an individual with normal lungs can exhale approximately 80% of their FVC in the first second, thereby resulting in a FEV1/FVC ratio of 80%.

Spirometry findings with COPD. A post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio of less than 70% confirms airflow obstruction and is consistent with COPD according to GOLD criteria.10 Post-bronchodilator spirometry is performed after the patient has received a specified dose of an inhaled bronchodilator per lab protocols. In patients with COPD, the FEV1/FVC ratio is persistently low even after administration of a bronchodilator.

Another means of using spirometry to diagnose COPD is referring to age-dependent cutoff values below the lower fifth percentile of the FEV1/FVC ratio (ie, lower limit of normal [LLN]), which differs from the GOLD strategy but is consistent with the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines.35 Because the FEV1/FVC ratio declines with age, older adults may have a normal post-bronchodilator ratio less than 70%. Admittedly, applying GOLD criteria to older adults could result in overdiagnosis, while using the LLN could lead to underdiagnosis. Although there is no consensus on which method to use, the best approach may be the one that most strongly correlates with pretest probability of disease. In a large Canadian study, the approach that most strongly predicted poor patient outcomes was using a FEV1/FVC based on fixed (70%) and/or LLN criteria, and a low FEV134

Spirometry findings with asthma. According to the American Thoracic Society, a post-bronchodilator response is defined as an increase in FEV1 (or FVC) of 12% if that volume is also ≥200 mL. In patients with suspected asthma, an increase in FEV1 ≥12% and 200 mL is consistent with variable airflow limitation2 and supports the diagnosis. Of note, lung function in patients with asthma may be normal when patients are not symptomatic or when they are receiving therapy. Spirometry is therefore ideally performed before initiating therapy and when maintenance therapy is being considered due to symptoms. If therapy is clinically indicated, a short-acting bronchodilator may be prescribed alone and then held 6 to 8 hours before conducting spirometry. If a trial of a maintenance medication is prescribed before spirometry, consider de-escalation of therapy once the patient is more stable and then perform spirometry to confirm the presence of airflow variability consistent with asthma. (In COPD, there can be a positive bronchodilator response; however, the post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio remains low.)

Continue to: Don't use in isolation

Don’t use in isolation. Use spirometry to support a clinical suspicion of asthma36 or COPD after a thorough history and physical exam, and not in isolation.

Special consideration: Asthma-COPD overlap syndrome

Some patients have features characteristic of both asthma and COPD and are said to have asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS). Between 15% and 20% of patients with COPD may in fact have ACOS.36 While there is no specific definition of ACOS, GOLD and GINA describe ACOS as persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD.2,10,37 ACOS becomes more prevalent with advancing age.

In ACOS, patients with COPD present with increased reversibility or patients with asthma and smoking history develop non-fully reversible airway obstruction at an older age.38 Patients with ACOS have worse lung function, more respiratory symptoms, and lower health-related quality of life than individuals with asthma or COPD alone,39,40 leading to more consumption of medical resources.41 In patients with ACOS, the FEV1/FVC ratio is low and consistent with the diagnosis of COPD. The post-bronchodilator response may be variable, depending on the stage of disease and predominant clinical features. It is still unclear whether ACOS is a separate disease entity, a representation of severe asthma that has morphed into COPD, or not a syndrome but simply 2 separate comorbid disease states.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christina D. Wells, MD, University of Illinois Mile Square Health Center, 1220 S. Wood Street, Chicago, IL 60612; cwells2@uic.edu.

1. Izquierdo JL, Martìn A, de Lucas P, et al. Misdiagnosis of patients receiving inhaled therapies in primary care. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2010;5:241-249.

2. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2018. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/wms-GINA-2018-report-V1.3-002.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2019.

3. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017; 317:269-279.

4. Spero K, Bayasi G, Beaudry L, et al. Overdiagnosis of COPD in hospitalized patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:2417-2423.

5. Singh H, Graber ML. Improving diagnosis in health care—the next imperative for patient safety. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2493-2495.

6. Ball JR, Balogh E. Improving diagnosis in health care: highlights of a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:59-61.

7. Khullar D, Jha AK, Jena AB. Reducing diagnostic errors—why now? N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2491-2493.

8. Lamprecht B, Soriano JB, Studnicka M, et al. Determinants of underdiagnosis of COPD in national and international surveys. Chest. 2015;148:971-985.

9. Yang CL, Simons E, Foty RG, et al. Misdiagnosis of asthma in schoolchildren. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52:293-302.

10. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2019. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/GOLD-2019-v1.7-FINAL-14Nov2018-WMS.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2019.

11. Tinkelman DG, Price DB, Nordyke RJ, et al. Misdiagnosis of COPD and asthma in primary care patients 40 years of age and over. J Asthma. 2006;43:75-80.

12. Abramson MJ, Schattner RL, Sulaiman ND, et al. Accuracy of asthma and COPD diagnosis in Australian general practice: a mixed methods study. Prim Care Respir J. 2012;21:167-173.

13. Sichletidis L, Chloros D, Spyratos D, et al. The validity of the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in general practice. Prim Care Respir J. 2007;16:82-88.

14. Marklund B, Tunsäter A, Bengtsson C. How often is the diagnosis bronchial asthma correct? Fam Pract. 1999;16:112-116.

15. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Boulet LP, et al. Overdiagnosis of asthma in obese and nonobese adults. CMAJ. 2008;179:1121-1131.

16. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM, et al. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017;317:269-279.

17. Damarla M, Celli BR, Mullerova HX, et al. Discrepancy in the use of confirmatory tests in patients hospitalized with the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or congestive heart failure. Respir Care. 2006;51:1120-1124.

18. Prieto Centurion V, Huang F, Naureckus ET, et al. Confirmatory spirometry for adults hospitalized with a diagnosis of asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. BMC Pulm Med. 2012;12:73.

19. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

20. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma-Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007. 120(Suppl):S94-S138.

21. Han MK, Kim MG, Mardon R, et al. Spirometry utilization for COPD: how do we measure up? Chest. 2007;132:403-409.

22. Joo MJ, Lee TA, Weiss KB. Geographic variation of spirometry use in newly diagnosed COPD. Chest. 2008;134:38-45.

23. Thorat YT, Salvi SS, Kodgule RR. Peak flow meter with a questionnaire and mini-spirometer to help detect asthma and COPD in real-life clinical practice: a cross-sectional study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27:32.

24. Kennedy DT, Chang Z, Small RE. Selection of peak flowmeters in ambulatory asthma patients: a review of the literature. Chest. 1998;114:587-592.

25. Walters JA, Hanson E, Mudge P, et al. Barriers to the use of spirometry in general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34:201-203.

26. Barr RG, Celli BR, Martinez FJ, et al. Physician and patient perceptions in COPD: the COPD Resource Network Needs Assessment Survey. Am J Med. 2005;118:1415.

27. Caramori G, Bettoncelli G, Tosatto R, et al. Underuse of spirometry by general practitioners for the diagnosis of COPD in Italy. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2005;63:6-12.

28. Kaminsky DA, Marcy TW, Bachand F, et al. Knowledge and use of office spirometry for the detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by primary care physicians. Respir Care. 2005;50:1639-1648.

29. Foster JA, Yawn BP, Maziar A, et al. Enhancing COPD management in primary care settings. MedGenMed. 2007;9:24.

30. Bolton CE, Ionescu AA, Edwards PH, et al. Attaining a correct diagnosis of COPD in general practice. Respir Med. 2005:99:493-500.

31. Drummond MB, Dasenbrook EC, Pitz MW, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2407-2416.

32. Morales DR. LABA monotherapy in asthma: an avoidable problem. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:627-628.

33. Nelson HS, Weiss ST, Bleecker ER, et al. The Salmeterol Multicenter Asthma Research Trial: a comparison of usual pharmacotherapy for asthma or usual pharmacotherapy plus salmeterol. Chest. 2006;129:15-26.

34. van Dijk W, Tan W, Li P, et al. Clinical relevance of fixed ratio vs lower limit of normal of FEV1/FVC in COPD: patient-reported outcomes from the CanCOLD cohort. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13:41-48.

35. Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319-338.

36. Rogliani P, Ora J, Puxeddu E, et al. Airflow obstruction: is it asthma or is it COPD? Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:3007-3013.

37. Global Initiative for Asthma. Diagnosis and initial treatment of asthma, COPD and asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. 2017. https://ginasthma.org/. Accessed January 12, 2019.

38. Barrecheguren M, Esquinas C, Miravitlles M. The asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome (ACOS): opportunities and challenges. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2015;21:74-79.

39. Kauppi P, Kupiainen H, Lindqvist A, et al. Overlap syndrome of asthma and COPD predicts low quality of life. J Asthma. 2011;48:279-285.

40. Mannino DM, Gagnon RC, Petty TL, et al. Obstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1683-1689.

41. Shaya FT, Dongyi D, Akazawa MO, et al. Burden of concomitant asthma and COPD in a Medicaid population. Chest. 2008;134:14-19.

1. Izquierdo JL, Martìn A, de Lucas P, et al. Misdiagnosis of patients receiving inhaled therapies in primary care. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2010;5:241-249.

2. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2018. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/wms-GINA-2018-report-V1.3-002.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2019.

3. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017; 317:269-279.

4. Spero K, Bayasi G, Beaudry L, et al. Overdiagnosis of COPD in hospitalized patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:2417-2423.

5. Singh H, Graber ML. Improving diagnosis in health care—the next imperative for patient safety. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2493-2495.

6. Ball JR, Balogh E. Improving diagnosis in health care: highlights of a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:59-61.

7. Khullar D, Jha AK, Jena AB. Reducing diagnostic errors—why now? N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2491-2493.

8. Lamprecht B, Soriano JB, Studnicka M, et al. Determinants of underdiagnosis of COPD in national and international surveys. Chest. 2015;148:971-985.

9. Yang CL, Simons E, Foty RG, et al. Misdiagnosis of asthma in schoolchildren. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52:293-302.

10. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2019. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/GOLD-2019-v1.7-FINAL-14Nov2018-WMS.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2019.

11. Tinkelman DG, Price DB, Nordyke RJ, et al. Misdiagnosis of COPD and asthma in primary care patients 40 years of age and over. J Asthma. 2006;43:75-80.

12. Abramson MJ, Schattner RL, Sulaiman ND, et al. Accuracy of asthma and COPD diagnosis in Australian general practice: a mixed methods study. Prim Care Respir J. 2012;21:167-173.

13. Sichletidis L, Chloros D, Spyratos D, et al. The validity of the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in general practice. Prim Care Respir J. 2007;16:82-88.

14. Marklund B, Tunsäter A, Bengtsson C. How often is the diagnosis bronchial asthma correct? Fam Pract. 1999;16:112-116.

15. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Boulet LP, et al. Overdiagnosis of asthma in obese and nonobese adults. CMAJ. 2008;179:1121-1131.

16. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM, et al. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017;317:269-279.

17. Damarla M, Celli BR, Mullerova HX, et al. Discrepancy in the use of confirmatory tests in patients hospitalized with the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or congestive heart failure. Respir Care. 2006;51:1120-1124.

18. Prieto Centurion V, Huang F, Naureckus ET, et al. Confirmatory spirometry for adults hospitalized with a diagnosis of asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. BMC Pulm Med. 2012;12:73.

19. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

20. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma-Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007. 120(Suppl):S94-S138.

21. Han MK, Kim MG, Mardon R, et al. Spirometry utilization for COPD: how do we measure up? Chest. 2007;132:403-409.

22. Joo MJ, Lee TA, Weiss KB. Geographic variation of spirometry use in newly diagnosed COPD. Chest. 2008;134:38-45.

23. Thorat YT, Salvi SS, Kodgule RR. Peak flow meter with a questionnaire and mini-spirometer to help detect asthma and COPD in real-life clinical practice: a cross-sectional study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27:32.

24. Kennedy DT, Chang Z, Small RE. Selection of peak flowmeters in ambulatory asthma patients: a review of the literature. Chest. 1998;114:587-592.

25. Walters JA, Hanson E, Mudge P, et al. Barriers to the use of spirometry in general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34:201-203.

26. Barr RG, Celli BR, Martinez FJ, et al. Physician and patient perceptions in COPD: the COPD Resource Network Needs Assessment Survey. Am J Med. 2005;118:1415.

27. Caramori G, Bettoncelli G, Tosatto R, et al. Underuse of spirometry by general practitioners for the diagnosis of COPD in Italy. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2005;63:6-12.

28. Kaminsky DA, Marcy TW, Bachand F, et al. Knowledge and use of office spirometry for the detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by primary care physicians. Respir Care. 2005;50:1639-1648.

29. Foster JA, Yawn BP, Maziar A, et al. Enhancing COPD management in primary care settings. MedGenMed. 2007;9:24.

30. Bolton CE, Ionescu AA, Edwards PH, et al. Attaining a correct diagnosis of COPD in general practice. Respir Med. 2005:99:493-500.

31. Drummond MB, Dasenbrook EC, Pitz MW, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2407-2416.