User login

Collaborative effort reduces COPD readmissions, costs

Medicare exacts a penalty whenever it deems that hospitals have too many patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who have been re-admitted within 30 days of discharge for care related to the disease. For acute-care hospitals the solution to reducing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) re-admissions has been elusive, but members of a COPD chronic care management collaborative think they have found at least a partial solution.

Among 33 centers participating in the performance improvement program, the aggregated cost avoidance for emergency department (ED) visits was estimated at $351,000, and the savings for hospital re-visits avoided was an estimated $2.6 million, reported Valerie Press, MD, MPH, from the University of Chicago, and co-authors from the health care performance-improvement company Vizient.

The investigators described their chronic care management collaborative in a thematic poster presented during the American Thoracic Society’s virtual international conference (Abstract A1688).

“I’ve been working in the space of COPD re-admissions pretty much since Medicare started its penalty program,” Dr. Press said in an interview.

“At both my own institution and nationally, we’ve been trying to understand the policy that went into place to reduce what was considered to be excessive readmissions after a COPD admission, but there really wasn’t a lot of evidence to suggest how to do this at the time the policy went into place,” she said.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) initiated its Hospital Readmission Reduction Program for COPD in 2014.

“The challenge with COPD is that we have not found really successful interventions to decrease readmissions,” commented Laura C. Myers, MD, MPH, in an interview. Dr. Myers, who studies optimal care delivery models for patients with COPD at Kaiser Permanente Northern California in Oakland, was not involved in the study.

She said that although the aggregate cost savings in the study by Dr. Press and colleagues are relatively modest, “if you extrapolate across the country, then those numbers could potentially be impressive.”

Collaboration details

Dr. Press was a subject matter expert for the collaborative, which included 47 Vizient member sites in the Southeast, Southwest, Midwest, and Northeast and Northwest coasts. Of these centers, 33 completed both parts of the collaboration.

The program included bi-monthly didactic sessions and site report and discussion sessions with peer-to-peer networking for a total of 6 months. During the sessions, meeting participants discussed best practices, received expert coaching, and provided progress updates on performance improvement projects.

“The goal was for them to identify the gaps or needs they had at their hospitals or practices, and then to try to put in place one or more interventions,” Dr. Press said. “This wasn’t a research program. It wasn’t standardized, and not all hospitals had to do the same program.”

The participants submitted reports for baseline and post-collaboration periods on both an intervention’s “reach,” defined as the percentage of patients who received a specified intervention, and on two outcome measures.

The interventions measured included spirometry, follow-up visits scheduled within 7 to 14 days of discharge, patients receiving COPD education, pulmonary referrals, and adherence to the COPD clinical pathway.

The outcome measures were the rate of COPD-related ED visits and hospital readmissions.

Revisits reduced

At the end of the program, 83% of participating sites had reductions in either ED visits or readmissions, and of this group, five sites had decreases in both measures.

Among all sites with improved metrics, the average rate of COPD-related ED revisits declined from 12.7% to 9%, and average inpatient readmissions declined from 20.1% to 15.6%.

As noted, the estimated cost savings in ED revisits avoided was $351,00, and the estimated savings in hospital readmission costs was $2.6 million.

“Although the centers didn’t have to participate in both parts, we did see in our results that the programs that participated fully had better results,” Dr. Press said.

“Historically, we’ve had such difficulty in decreasing COPD readmissions, and it’s nice to see something that actually works, both for patients and for conserving health resources,” Dr. Myers commented.

The study was supported by Vizient. Dr. Press disclosed honoraria from the company in her role as subject matter expert. Dr. Myers reported no conflicts of interest.

Medicare exacts a penalty whenever it deems that hospitals have too many patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who have been re-admitted within 30 days of discharge for care related to the disease. For acute-care hospitals the solution to reducing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) re-admissions has been elusive, but members of a COPD chronic care management collaborative think they have found at least a partial solution.

Among 33 centers participating in the performance improvement program, the aggregated cost avoidance for emergency department (ED) visits was estimated at $351,000, and the savings for hospital re-visits avoided was an estimated $2.6 million, reported Valerie Press, MD, MPH, from the University of Chicago, and co-authors from the health care performance-improvement company Vizient.

The investigators described their chronic care management collaborative in a thematic poster presented during the American Thoracic Society’s virtual international conference (Abstract A1688).

“I’ve been working in the space of COPD re-admissions pretty much since Medicare started its penalty program,” Dr. Press said in an interview.

“At both my own institution and nationally, we’ve been trying to understand the policy that went into place to reduce what was considered to be excessive readmissions after a COPD admission, but there really wasn’t a lot of evidence to suggest how to do this at the time the policy went into place,” she said.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) initiated its Hospital Readmission Reduction Program for COPD in 2014.

“The challenge with COPD is that we have not found really successful interventions to decrease readmissions,” commented Laura C. Myers, MD, MPH, in an interview. Dr. Myers, who studies optimal care delivery models for patients with COPD at Kaiser Permanente Northern California in Oakland, was not involved in the study.

She said that although the aggregate cost savings in the study by Dr. Press and colleagues are relatively modest, “if you extrapolate across the country, then those numbers could potentially be impressive.”

Collaboration details

Dr. Press was a subject matter expert for the collaborative, which included 47 Vizient member sites in the Southeast, Southwest, Midwest, and Northeast and Northwest coasts. Of these centers, 33 completed both parts of the collaboration.

The program included bi-monthly didactic sessions and site report and discussion sessions with peer-to-peer networking for a total of 6 months. During the sessions, meeting participants discussed best practices, received expert coaching, and provided progress updates on performance improvement projects.

“The goal was for them to identify the gaps or needs they had at their hospitals or practices, and then to try to put in place one or more interventions,” Dr. Press said. “This wasn’t a research program. It wasn’t standardized, and not all hospitals had to do the same program.”

The participants submitted reports for baseline and post-collaboration periods on both an intervention’s “reach,” defined as the percentage of patients who received a specified intervention, and on two outcome measures.

The interventions measured included spirometry, follow-up visits scheduled within 7 to 14 days of discharge, patients receiving COPD education, pulmonary referrals, and adherence to the COPD clinical pathway.

The outcome measures were the rate of COPD-related ED visits and hospital readmissions.

Revisits reduced

At the end of the program, 83% of participating sites had reductions in either ED visits or readmissions, and of this group, five sites had decreases in both measures.

Among all sites with improved metrics, the average rate of COPD-related ED revisits declined from 12.7% to 9%, and average inpatient readmissions declined from 20.1% to 15.6%.

As noted, the estimated cost savings in ED revisits avoided was $351,00, and the estimated savings in hospital readmission costs was $2.6 million.

“Although the centers didn’t have to participate in both parts, we did see in our results that the programs that participated fully had better results,” Dr. Press said.

“Historically, we’ve had such difficulty in decreasing COPD readmissions, and it’s nice to see something that actually works, both for patients and for conserving health resources,” Dr. Myers commented.

The study was supported by Vizient. Dr. Press disclosed honoraria from the company in her role as subject matter expert. Dr. Myers reported no conflicts of interest.

Medicare exacts a penalty whenever it deems that hospitals have too many patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who have been re-admitted within 30 days of discharge for care related to the disease. For acute-care hospitals the solution to reducing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) re-admissions has been elusive, but members of a COPD chronic care management collaborative think they have found at least a partial solution.

Among 33 centers participating in the performance improvement program, the aggregated cost avoidance for emergency department (ED) visits was estimated at $351,000, and the savings for hospital re-visits avoided was an estimated $2.6 million, reported Valerie Press, MD, MPH, from the University of Chicago, and co-authors from the health care performance-improvement company Vizient.

The investigators described their chronic care management collaborative in a thematic poster presented during the American Thoracic Society’s virtual international conference (Abstract A1688).

“I’ve been working in the space of COPD re-admissions pretty much since Medicare started its penalty program,” Dr. Press said in an interview.

“At both my own institution and nationally, we’ve been trying to understand the policy that went into place to reduce what was considered to be excessive readmissions after a COPD admission, but there really wasn’t a lot of evidence to suggest how to do this at the time the policy went into place,” she said.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) initiated its Hospital Readmission Reduction Program for COPD in 2014.

“The challenge with COPD is that we have not found really successful interventions to decrease readmissions,” commented Laura C. Myers, MD, MPH, in an interview. Dr. Myers, who studies optimal care delivery models for patients with COPD at Kaiser Permanente Northern California in Oakland, was not involved in the study.

She said that although the aggregate cost savings in the study by Dr. Press and colleagues are relatively modest, “if you extrapolate across the country, then those numbers could potentially be impressive.”

Collaboration details

Dr. Press was a subject matter expert for the collaborative, which included 47 Vizient member sites in the Southeast, Southwest, Midwest, and Northeast and Northwest coasts. Of these centers, 33 completed both parts of the collaboration.

The program included bi-monthly didactic sessions and site report and discussion sessions with peer-to-peer networking for a total of 6 months. During the sessions, meeting participants discussed best practices, received expert coaching, and provided progress updates on performance improvement projects.

“The goal was for them to identify the gaps or needs they had at their hospitals or practices, and then to try to put in place one or more interventions,” Dr. Press said. “This wasn’t a research program. It wasn’t standardized, and not all hospitals had to do the same program.”

The participants submitted reports for baseline and post-collaboration periods on both an intervention’s “reach,” defined as the percentage of patients who received a specified intervention, and on two outcome measures.

The interventions measured included spirometry, follow-up visits scheduled within 7 to 14 days of discharge, patients receiving COPD education, pulmonary referrals, and adherence to the COPD clinical pathway.

The outcome measures were the rate of COPD-related ED visits and hospital readmissions.

Revisits reduced

At the end of the program, 83% of participating sites had reductions in either ED visits or readmissions, and of this group, five sites had decreases in both measures.

Among all sites with improved metrics, the average rate of COPD-related ED revisits declined from 12.7% to 9%, and average inpatient readmissions declined from 20.1% to 15.6%.

As noted, the estimated cost savings in ED revisits avoided was $351,00, and the estimated savings in hospital readmission costs was $2.6 million.

“Although the centers didn’t have to participate in both parts, we did see in our results that the programs that participated fully had better results,” Dr. Press said.

“Historically, we’ve had such difficulty in decreasing COPD readmissions, and it’s nice to see something that actually works, both for patients and for conserving health resources,” Dr. Myers commented.

The study was supported by Vizient. Dr. Press disclosed honoraria from the company in her role as subject matter expert. Dr. Myers reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM ATS 2021

COPD in younger adults deadlier than expected

Adults in their 30s, 40s and 50s with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) experience significant morbidity and excess mortality from the disease, results of a population-based study show.

Among adults aged 35-55 years with COPD in Ontario in a longitudinal population cohort study, the overall mortality rate was fivefold higher, compared with other adults in the same age range without COPD.

In contrast, the mortality rate among adults 65 years and older with COPD was 2.5-fold higher than that of their peers without COPD, reported Alina J. Blazer, MSc, MD, a clinical and research fellow at the University of Toronto.

“Overall, our study has shown that younger adults with COPD experience significant morbidity, as evidence by their elevated rates of health care use and excess mortality from their disease. This study provides further evidence that so-called ‘early’ COPD is not a benign disease, and suggests that we should focus clinical efforts on identifying COPD in younger patients, in the hopes that earlier intervention may improve their current health, reduce resource utilization, and prevent further disease progression,” she said during a minisymposium at the American Thoracic Society’s virtual international conference (Abstract A1131).

COPD is widely regarded as a disease affecting only older adults, but it can also occur in those younger than 65, and although it is commonly assumed that COPD diagnosed earlier in life will be milder in severity, this assumption has not been fully explored in real-world settings, Dr. Blazer said.

She and her colleagues conducted a study to examine disease burden as measured by health services utilization and mortality among younger adults with COPD, and compared the rates with those of older adults with COPD.

The sample for this study included 194,759 adults with COPD aged 35-55 years in Ontario in 2016. COPD was identified from health administrative data for three or more outpatient claims or one or more hospitalization claims for COPD over a 2-year period.

For context, the data were compared with those for 496,2113 COPD patients aged 65 years and older.

They found that, compared with their peers without the disease, younger adults had a 3.1-fold higher rate of hospitalization for any cause, a 2.2-fold higher rate of all-cause ED visits, and a 1.7-fold higher rate of outpatient visits for any cause.

In contrast, the comparative rates for seniors with versus without COPD were 2.1-fold, 1.8-fold, and 1.4-fold, respectively.

As noted before, the mortality rate for younger adults with COPD was 5-fold higher than for those without COPD, compared with 2.5-fold among older adults with COPD versus those without.

Earlier diagnosis, follow-up

“A very important talk,” commented session comoderator Valerie Press, MD, MPH, from the University of Chicago. “I know that there’s a lot of work to be done in earlier diagnosis in general, and I think starting with the younger population is a really important area.”

She asked Dr. Blazer about the possibility of asthma codiagnosis or misdiagnosis in the younger patients.

“We use a very specific, validated case definition in the study that our group has used before, and the specificity is over 96% for physician-diagnosed COPD, at the expense of sensitivity, so if anything we probably underestimated the rate of COPD in our study,” Dr. Blazer said.

Audience member Sherry Rogers, MD, an allergist and immunologist in private practice in Syracuse, N.Y., asked whether the investigators could determine what proportion of the excess mortality they saw was attributable to COPD.

“This was looking at all-cause mortality, so we don’t know that it’s necessarily all attributable to COPD per se but perhaps also to COPD-attributable comorbidities,” Dr. Blazer said. “It would be important to piece out the actual causes of mortality that are contributing to that elevated [morality] in that population.”

She added that the next step could include examining rates of specialty referrals and pharmacotherapy to see whether younger patients with COPD are receiving appropriate care, and to ascertain how they are being followed.

The study was supported by the University of Toronto and Sunnybrook Research Institute. Dr. Blazer reported no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Adults in their 30s, 40s and 50s with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) experience significant morbidity and excess mortality from the disease, results of a population-based study show.

Among adults aged 35-55 years with COPD in Ontario in a longitudinal population cohort study, the overall mortality rate was fivefold higher, compared with other adults in the same age range without COPD.

In contrast, the mortality rate among adults 65 years and older with COPD was 2.5-fold higher than that of their peers without COPD, reported Alina J. Blazer, MSc, MD, a clinical and research fellow at the University of Toronto.

“Overall, our study has shown that younger adults with COPD experience significant morbidity, as evidence by their elevated rates of health care use and excess mortality from their disease. This study provides further evidence that so-called ‘early’ COPD is not a benign disease, and suggests that we should focus clinical efforts on identifying COPD in younger patients, in the hopes that earlier intervention may improve their current health, reduce resource utilization, and prevent further disease progression,” she said during a minisymposium at the American Thoracic Society’s virtual international conference (Abstract A1131).

COPD is widely regarded as a disease affecting only older adults, but it can also occur in those younger than 65, and although it is commonly assumed that COPD diagnosed earlier in life will be milder in severity, this assumption has not been fully explored in real-world settings, Dr. Blazer said.

She and her colleagues conducted a study to examine disease burden as measured by health services utilization and mortality among younger adults with COPD, and compared the rates with those of older adults with COPD.

The sample for this study included 194,759 adults with COPD aged 35-55 years in Ontario in 2016. COPD was identified from health administrative data for three or more outpatient claims or one or more hospitalization claims for COPD over a 2-year period.

For context, the data were compared with those for 496,2113 COPD patients aged 65 years and older.

They found that, compared with their peers without the disease, younger adults had a 3.1-fold higher rate of hospitalization for any cause, a 2.2-fold higher rate of all-cause ED visits, and a 1.7-fold higher rate of outpatient visits for any cause.

In contrast, the comparative rates for seniors with versus without COPD were 2.1-fold, 1.8-fold, and 1.4-fold, respectively.

As noted before, the mortality rate for younger adults with COPD was 5-fold higher than for those without COPD, compared with 2.5-fold among older adults with COPD versus those without.

Earlier diagnosis, follow-up

“A very important talk,” commented session comoderator Valerie Press, MD, MPH, from the University of Chicago. “I know that there’s a lot of work to be done in earlier diagnosis in general, and I think starting with the younger population is a really important area.”

She asked Dr. Blazer about the possibility of asthma codiagnosis or misdiagnosis in the younger patients.

“We use a very specific, validated case definition in the study that our group has used before, and the specificity is over 96% for physician-diagnosed COPD, at the expense of sensitivity, so if anything we probably underestimated the rate of COPD in our study,” Dr. Blazer said.

Audience member Sherry Rogers, MD, an allergist and immunologist in private practice in Syracuse, N.Y., asked whether the investigators could determine what proportion of the excess mortality they saw was attributable to COPD.

“This was looking at all-cause mortality, so we don’t know that it’s necessarily all attributable to COPD per se but perhaps also to COPD-attributable comorbidities,” Dr. Blazer said. “It would be important to piece out the actual causes of mortality that are contributing to that elevated [morality] in that population.”

She added that the next step could include examining rates of specialty referrals and pharmacotherapy to see whether younger patients with COPD are receiving appropriate care, and to ascertain how they are being followed.

The study was supported by the University of Toronto and Sunnybrook Research Institute. Dr. Blazer reported no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Adults in their 30s, 40s and 50s with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) experience significant morbidity and excess mortality from the disease, results of a population-based study show.

Among adults aged 35-55 years with COPD in Ontario in a longitudinal population cohort study, the overall mortality rate was fivefold higher, compared with other adults in the same age range without COPD.

In contrast, the mortality rate among adults 65 years and older with COPD was 2.5-fold higher than that of their peers without COPD, reported Alina J. Blazer, MSc, MD, a clinical and research fellow at the University of Toronto.

“Overall, our study has shown that younger adults with COPD experience significant morbidity, as evidence by their elevated rates of health care use and excess mortality from their disease. This study provides further evidence that so-called ‘early’ COPD is not a benign disease, and suggests that we should focus clinical efforts on identifying COPD in younger patients, in the hopes that earlier intervention may improve their current health, reduce resource utilization, and prevent further disease progression,” she said during a minisymposium at the American Thoracic Society’s virtual international conference (Abstract A1131).

COPD is widely regarded as a disease affecting only older adults, but it can also occur in those younger than 65, and although it is commonly assumed that COPD diagnosed earlier in life will be milder in severity, this assumption has not been fully explored in real-world settings, Dr. Blazer said.

She and her colleagues conducted a study to examine disease burden as measured by health services utilization and mortality among younger adults with COPD, and compared the rates with those of older adults with COPD.

The sample for this study included 194,759 adults with COPD aged 35-55 years in Ontario in 2016. COPD was identified from health administrative data for three or more outpatient claims or one or more hospitalization claims for COPD over a 2-year period.

For context, the data were compared with those for 496,2113 COPD patients aged 65 years and older.

They found that, compared with their peers without the disease, younger adults had a 3.1-fold higher rate of hospitalization for any cause, a 2.2-fold higher rate of all-cause ED visits, and a 1.7-fold higher rate of outpatient visits for any cause.

In contrast, the comparative rates for seniors with versus without COPD were 2.1-fold, 1.8-fold, and 1.4-fold, respectively.

As noted before, the mortality rate for younger adults with COPD was 5-fold higher than for those without COPD, compared with 2.5-fold among older adults with COPD versus those without.

Earlier diagnosis, follow-up

“A very important talk,” commented session comoderator Valerie Press, MD, MPH, from the University of Chicago. “I know that there’s a lot of work to be done in earlier diagnosis in general, and I think starting with the younger population is a really important area.”

She asked Dr. Blazer about the possibility of asthma codiagnosis or misdiagnosis in the younger patients.

“We use a very specific, validated case definition in the study that our group has used before, and the specificity is over 96% for physician-diagnosed COPD, at the expense of sensitivity, so if anything we probably underestimated the rate of COPD in our study,” Dr. Blazer said.

Audience member Sherry Rogers, MD, an allergist and immunologist in private practice in Syracuse, N.Y., asked whether the investigators could determine what proportion of the excess mortality they saw was attributable to COPD.

“This was looking at all-cause mortality, so we don’t know that it’s necessarily all attributable to COPD per se but perhaps also to COPD-attributable comorbidities,” Dr. Blazer said. “It would be important to piece out the actual causes of mortality that are contributing to that elevated [morality] in that population.”

She added that the next step could include examining rates of specialty referrals and pharmacotherapy to see whether younger patients with COPD are receiving appropriate care, and to ascertain how they are being followed.

The study was supported by the University of Toronto and Sunnybrook Research Institute. Dr. Blazer reported no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM ATS 2021

Patients with moderate COPD also benefit from triple therapy

The benefits of a triple fixed-dose inhaled corticosteroid, long-acting muscarinic antagonist, and long-acting beta2 agonist combination extend to patients with moderate as well as severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

That’s according to investigators in the ETHOS (Efficacy and Safety of Triple Therapy in Obstructive Lung Disease) trial (NCT02465567).

In a subanalysis of data on patients with moderate COPD who were enrolled in the comparison trial, the single-inhaler combination of the inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) budesonide, the long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) glycopyrrolate, and the long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA) formoterol fumarate (BGF) showed benefits in terms of COPD exacerbations, lung function, symptoms, and quality-of-life compared with either of two dual therapy combinations (glycopyrrolate or budesonide with formoterol [GFF/BFF]).

“A moderate benefit:risk ratio was demonstrated in patients with moderate COPD, consistent with the results of the overall ETHOS population, indicating the results of the ETHOS study were not driven by patients with severe or very severe COPD,” wrote Gary T. Ferguson, MD, from the Pulmonary Research Institute of Southeast Michigan in Farmington Hills, and colleagues. Their poster was presented during the American Thoracic Society’s virtual international conference. (Abstract A2244).

As reported at ATS 2020, in the overall ETHOS population of 8,509 patients with moderate to very severe COPD the annual rate of moderate or severe COPD exacerbations was 1.08 and 1.07 for the triple combinations with 320-mcg and 160-mcg doses of budesonide, respectively, compared with 1.42 for glycopyrrolate-formoterol, and 1.24 for budesonide-formoterol.

, Klaus F. Rabe, MD, PhD, of LungenClinic Grosshansdorf and Christian-Albrechts University Kiel (Germany), and colleagues found.

Subanalysis details

At the 2021 iteration of ATS, ETHOS investigator Dr. Ferguson and colleagues reported results for 613 patients with moderate COPD assigned to BGF 320 mcg, 604 assigned to BGF 160 mcg, 596 assigned to GFF, and 614 randomized to BFF.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar among the groups, including age, sex, smoking status, mean COPD Assessment Test (CAT) score, mean blood eosinophil count, ICS use at screening, exacerbations in the previous year, mean postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) percentage of predicted, and mean postbronchodilator percentage reversibility.

A modified intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis showed that the rate of moderate or severe exacerbations over 52 weeks with BGF 320 mcg was 21% lower than with GFF (P = .0123), but only 4% lower than with BFF, a difference that was not statistically significant.

The BGF 160-mg dose was associated with a 30% reduction in exacerbations vs. GFF (P = .0002), and with a nonsignificant reduction of 15% compared with BFF.

There was a numerical but not statistically significant improvement from baseline at week 24 in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 between the BGF 320-mcg dose and GFF (difference 47 mL), and a significant improvement (90 mL) with BGF compared with BFF (P = .0006). The BGF 160-mcg dose was associated with a larger improvement (89 mL) compared with BFF (P = .0004) but not with GFF.

The FEV1 area under the curve (AUC) of receiver operating characteristics from 0 to 4 hours was superior with BGF at both doses compared with both GFF and BFF.

Patients who used BGF 320 mcg also used significantly less rescue medication over 24 weeks compared with patients who used GFF (P < .0001) or BFF (P = .0001). There were no significant differences in rescue medication use between the BGF 160-mg dose and either of the dual therapy combinations.

Time to clinically important deterioration – defined as a greater than 100 mL decrease in trough FEV1, or a 4 units increase in St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire total score, or a treatment-emergent moderate/severe COPD exacerbation occurring up to week 52 – was significantly longer with the 320-mcg but not 160-mcg BGF dose compared with GFF (P = .0295) or BFF (P = .0172).

Safety

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) occurred in about two-thirds of patients in each trial arm, although TEAEs related to study treatment were more common with the two triple-therapy combinations and with BFF than with GFF.

TEAEs leading to study discontinuation occurred in 5.5% of patients on BGF 320 mcg, 4% on BGF 160 mcg, 4.5% on GFF, and 3.2% on BFF.

Confirmed major adverse cardiovascular events occurred in 0.8% and 1.5% in the BGF 320- and 160-mcg groups, respectively, in 1.8% of patients in the GFF arm, and 1.5% in the BFF arm.

Confirmed pneumonia was seen in 2.6% of patients in each BGF arm, 2.2% in the GFF arm, and 3.6% in the BFF arm.

Selected population

In a comment, David Mannino, MD, medical director of the COPD Foundation, who was not involved in the study, noted that the enrollment criteria for ETHOS tended to skew the population toward patients with severe disease.

In the trial, all patients were receiving at least two inhaled maintenance therapies at the time of screening, and had a postbronchodilator ratio of FEV1 to forced vital capacity of less than 0.7, with a postbronchodilator FEV1 of 25%-65% of the predicted normal value. The patients all had a smoking history of at least 10 pack-years and a documented history of at least one moderate or severe COPD exacerbation in the year before screening.

“The question was whether they would see the same results in people with more moderate impairment, and the answer in this subanalysis is ‘yes.’ The findings weren’t identical between patients with severe and moderate disease, but there were similarities with what was seen in the overall ETHOS study,” he said.

The ETHOS Trial was supported by Pearl Therapeutics. Dr. Ferguson reported grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from AstraZeneca during the conduct of the study; and grants, fees, and nonfinancial support from Pearl and others. Dr. Mannino reports recruitment to an advisory board for AstraZeneca.

The benefits of a triple fixed-dose inhaled corticosteroid, long-acting muscarinic antagonist, and long-acting beta2 agonist combination extend to patients with moderate as well as severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

That’s according to investigators in the ETHOS (Efficacy and Safety of Triple Therapy in Obstructive Lung Disease) trial (NCT02465567).

In a subanalysis of data on patients with moderate COPD who were enrolled in the comparison trial, the single-inhaler combination of the inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) budesonide, the long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) glycopyrrolate, and the long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA) formoterol fumarate (BGF) showed benefits in terms of COPD exacerbations, lung function, symptoms, and quality-of-life compared with either of two dual therapy combinations (glycopyrrolate or budesonide with formoterol [GFF/BFF]).

“A moderate benefit:risk ratio was demonstrated in patients with moderate COPD, consistent with the results of the overall ETHOS population, indicating the results of the ETHOS study were not driven by patients with severe or very severe COPD,” wrote Gary T. Ferguson, MD, from the Pulmonary Research Institute of Southeast Michigan in Farmington Hills, and colleagues. Their poster was presented during the American Thoracic Society’s virtual international conference. (Abstract A2244).

As reported at ATS 2020, in the overall ETHOS population of 8,509 patients with moderate to very severe COPD the annual rate of moderate or severe COPD exacerbations was 1.08 and 1.07 for the triple combinations with 320-mcg and 160-mcg doses of budesonide, respectively, compared with 1.42 for glycopyrrolate-formoterol, and 1.24 for budesonide-formoterol.

, Klaus F. Rabe, MD, PhD, of LungenClinic Grosshansdorf and Christian-Albrechts University Kiel (Germany), and colleagues found.

Subanalysis details

At the 2021 iteration of ATS, ETHOS investigator Dr. Ferguson and colleagues reported results for 613 patients with moderate COPD assigned to BGF 320 mcg, 604 assigned to BGF 160 mcg, 596 assigned to GFF, and 614 randomized to BFF.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar among the groups, including age, sex, smoking status, mean COPD Assessment Test (CAT) score, mean blood eosinophil count, ICS use at screening, exacerbations in the previous year, mean postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) percentage of predicted, and mean postbronchodilator percentage reversibility.

A modified intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis showed that the rate of moderate or severe exacerbations over 52 weeks with BGF 320 mcg was 21% lower than with GFF (P = .0123), but only 4% lower than with BFF, a difference that was not statistically significant.

The BGF 160-mg dose was associated with a 30% reduction in exacerbations vs. GFF (P = .0002), and with a nonsignificant reduction of 15% compared with BFF.

There was a numerical but not statistically significant improvement from baseline at week 24 in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 between the BGF 320-mcg dose and GFF (difference 47 mL), and a significant improvement (90 mL) with BGF compared with BFF (P = .0006). The BGF 160-mcg dose was associated with a larger improvement (89 mL) compared with BFF (P = .0004) but not with GFF.

The FEV1 area under the curve (AUC) of receiver operating characteristics from 0 to 4 hours was superior with BGF at both doses compared with both GFF and BFF.

Patients who used BGF 320 mcg also used significantly less rescue medication over 24 weeks compared with patients who used GFF (P < .0001) or BFF (P = .0001). There were no significant differences in rescue medication use between the BGF 160-mg dose and either of the dual therapy combinations.

Time to clinically important deterioration – defined as a greater than 100 mL decrease in trough FEV1, or a 4 units increase in St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire total score, or a treatment-emergent moderate/severe COPD exacerbation occurring up to week 52 – was significantly longer with the 320-mcg but not 160-mcg BGF dose compared with GFF (P = .0295) or BFF (P = .0172).

Safety

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) occurred in about two-thirds of patients in each trial arm, although TEAEs related to study treatment were more common with the two triple-therapy combinations and with BFF than with GFF.

TEAEs leading to study discontinuation occurred in 5.5% of patients on BGF 320 mcg, 4% on BGF 160 mcg, 4.5% on GFF, and 3.2% on BFF.

Confirmed major adverse cardiovascular events occurred in 0.8% and 1.5% in the BGF 320- and 160-mcg groups, respectively, in 1.8% of patients in the GFF arm, and 1.5% in the BFF arm.

Confirmed pneumonia was seen in 2.6% of patients in each BGF arm, 2.2% in the GFF arm, and 3.6% in the BFF arm.

Selected population

In a comment, David Mannino, MD, medical director of the COPD Foundation, who was not involved in the study, noted that the enrollment criteria for ETHOS tended to skew the population toward patients with severe disease.

In the trial, all patients were receiving at least two inhaled maintenance therapies at the time of screening, and had a postbronchodilator ratio of FEV1 to forced vital capacity of less than 0.7, with a postbronchodilator FEV1 of 25%-65% of the predicted normal value. The patients all had a smoking history of at least 10 pack-years and a documented history of at least one moderate or severe COPD exacerbation in the year before screening.

“The question was whether they would see the same results in people with more moderate impairment, and the answer in this subanalysis is ‘yes.’ The findings weren’t identical between patients with severe and moderate disease, but there were similarities with what was seen in the overall ETHOS study,” he said.

The ETHOS Trial was supported by Pearl Therapeutics. Dr. Ferguson reported grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from AstraZeneca during the conduct of the study; and grants, fees, and nonfinancial support from Pearl and others. Dr. Mannino reports recruitment to an advisory board for AstraZeneca.

The benefits of a triple fixed-dose inhaled corticosteroid, long-acting muscarinic antagonist, and long-acting beta2 agonist combination extend to patients with moderate as well as severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

That’s according to investigators in the ETHOS (Efficacy and Safety of Triple Therapy in Obstructive Lung Disease) trial (NCT02465567).

In a subanalysis of data on patients with moderate COPD who were enrolled in the comparison trial, the single-inhaler combination of the inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) budesonide, the long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) glycopyrrolate, and the long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA) formoterol fumarate (BGF) showed benefits in terms of COPD exacerbations, lung function, symptoms, and quality-of-life compared with either of two dual therapy combinations (glycopyrrolate or budesonide with formoterol [GFF/BFF]).

“A moderate benefit:risk ratio was demonstrated in patients with moderate COPD, consistent with the results of the overall ETHOS population, indicating the results of the ETHOS study were not driven by patients with severe or very severe COPD,” wrote Gary T. Ferguson, MD, from the Pulmonary Research Institute of Southeast Michigan in Farmington Hills, and colleagues. Their poster was presented during the American Thoracic Society’s virtual international conference. (Abstract A2244).

As reported at ATS 2020, in the overall ETHOS population of 8,509 patients with moderate to very severe COPD the annual rate of moderate or severe COPD exacerbations was 1.08 and 1.07 for the triple combinations with 320-mcg and 160-mcg doses of budesonide, respectively, compared with 1.42 for glycopyrrolate-formoterol, and 1.24 for budesonide-formoterol.

, Klaus F. Rabe, MD, PhD, of LungenClinic Grosshansdorf and Christian-Albrechts University Kiel (Germany), and colleagues found.

Subanalysis details

At the 2021 iteration of ATS, ETHOS investigator Dr. Ferguson and colleagues reported results for 613 patients with moderate COPD assigned to BGF 320 mcg, 604 assigned to BGF 160 mcg, 596 assigned to GFF, and 614 randomized to BFF.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar among the groups, including age, sex, smoking status, mean COPD Assessment Test (CAT) score, mean blood eosinophil count, ICS use at screening, exacerbations in the previous year, mean postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) percentage of predicted, and mean postbronchodilator percentage reversibility.

A modified intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis showed that the rate of moderate or severe exacerbations over 52 weeks with BGF 320 mcg was 21% lower than with GFF (P = .0123), but only 4% lower than with BFF, a difference that was not statistically significant.

The BGF 160-mg dose was associated with a 30% reduction in exacerbations vs. GFF (P = .0002), and with a nonsignificant reduction of 15% compared with BFF.

There was a numerical but not statistically significant improvement from baseline at week 24 in morning pre-dose trough FEV1 between the BGF 320-mcg dose and GFF (difference 47 mL), and a significant improvement (90 mL) with BGF compared with BFF (P = .0006). The BGF 160-mcg dose was associated with a larger improvement (89 mL) compared with BFF (P = .0004) but not with GFF.

The FEV1 area under the curve (AUC) of receiver operating characteristics from 0 to 4 hours was superior with BGF at both doses compared with both GFF and BFF.

Patients who used BGF 320 mcg also used significantly less rescue medication over 24 weeks compared with patients who used GFF (P < .0001) or BFF (P = .0001). There were no significant differences in rescue medication use between the BGF 160-mg dose and either of the dual therapy combinations.

Time to clinically important deterioration – defined as a greater than 100 mL decrease in trough FEV1, or a 4 units increase in St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire total score, or a treatment-emergent moderate/severe COPD exacerbation occurring up to week 52 – was significantly longer with the 320-mcg but not 160-mcg BGF dose compared with GFF (P = .0295) or BFF (P = .0172).

Safety

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) occurred in about two-thirds of patients in each trial arm, although TEAEs related to study treatment were more common with the two triple-therapy combinations and with BFF than with GFF.

TEAEs leading to study discontinuation occurred in 5.5% of patients on BGF 320 mcg, 4% on BGF 160 mcg, 4.5% on GFF, and 3.2% on BFF.

Confirmed major adverse cardiovascular events occurred in 0.8% and 1.5% in the BGF 320- and 160-mcg groups, respectively, in 1.8% of patients in the GFF arm, and 1.5% in the BFF arm.

Confirmed pneumonia was seen in 2.6% of patients in each BGF arm, 2.2% in the GFF arm, and 3.6% in the BFF arm.

Selected population

In a comment, David Mannino, MD, medical director of the COPD Foundation, who was not involved in the study, noted that the enrollment criteria for ETHOS tended to skew the population toward patients with severe disease.

In the trial, all patients were receiving at least two inhaled maintenance therapies at the time of screening, and had a postbronchodilator ratio of FEV1 to forced vital capacity of less than 0.7, with a postbronchodilator FEV1 of 25%-65% of the predicted normal value. The patients all had a smoking history of at least 10 pack-years and a documented history of at least one moderate or severe COPD exacerbation in the year before screening.

“The question was whether they would see the same results in people with more moderate impairment, and the answer in this subanalysis is ‘yes.’ The findings weren’t identical between patients with severe and moderate disease, but there were similarities with what was seen in the overall ETHOS study,” he said.

The ETHOS Trial was supported by Pearl Therapeutics. Dr. Ferguson reported grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from AstraZeneca during the conduct of the study; and grants, fees, and nonfinancial support from Pearl and others. Dr. Mannino reports recruitment to an advisory board for AstraZeneca.

FROM ATS 2021

Sex differences in COPD symptoms predict cardiac comorbidity

Sex-specific differences in the severity of symptoms and prevalence of comorbidities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) may point to different criteria for diagnosing cardiac comorbidities in women and men, a retrospective analysis suggests.

Among 2,046 patients in the German COSYCONET (COPD and Systemic Consequences–Comorbidities Net) cohort, most functional parameters and comorbidities and several items on the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) differed significantly between men and women.

In addition, there were sex-specific differences in the association between symptoms and cardiac disease, Franziska C. Trudzinski, MD, from the University of Heidelberg (Germany), and colleagues reported.

(Note: Although the authors used the term “gender” to distinguish male from female, this news organization has used the term “sex” in this article to refer to biological attributes of individual patients rather than personal identity.)

“[Sex]-specific differences in COPD comprised not only differences in the level of symptoms, comorbidities, and functional alterations but also differences in their mutual relationships. This was reflected in different sets of predictors for cardiac disease,” they wrote in a thematic poster presented at the American Thoracic Society’s virtual international conference.

GOLD standard

The investigators conducted an analysis of data on 795 women and 1,251 men with GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) class 1-3 disease from the COSYCONET COPD cohort.

They looked at the patients’ clinical history, comorbidities, lung function, CAT scores, and modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea score.

The authors used multivariate regression analysis to model potential sex-related differences in the relationship between symptoms in general and CAT items in particular, and the pattern of comorbidities and functional alterations.

They also performed logistic regression analyses to identify predictors for cardiac disease, defined as myocardial infarction, heart failure, or coronary artery disease. The analyses were controlled for age, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, mMRC, CAT items, and z scores of forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity ratio.

and for CAT items of cough (item 1), phlegm (item 2), and energy (item 8; P < .05 for all comparisons).

In logistic regression analysis, predictors for cardiac disease in men were energy (CAT item 8), mMRC score, smoking status, BMI, age, and spirometric lung function.

In women, however, only age was significantly predictive for cardiac disease.

“Our findings give hints how diagnostic information might be used differently in men and women,” Dr. Trudzinski and colleagues wrote.

Reassuring data

David Mannino, MD, medical director of the COPD Foundation, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview that sex differences in COPD presentation and severity are common.

“In general, men and women report symptoms differently. For example, women don’t report a whole lot of chronic bronchitis and phlegm, although they may have it,” he said, “whereas men may report less dyspnea. It varies, but in general we know that men and women, even with the same type of disease, report symptoms differently.”

Comorbidities also differ between the sexes, he noted. Women more frequently have osteoporosis, and men more frequently have heart disease, as borne out in the study. The prevalence of heart disease among patients in the study was approximately 2.5 times higher in men than women.

“It’s reassuring, because what we’re seeing is similar to what we’ve seen in other [studies] with regards to comorbidities,” he said.

The study was sponsored by Philipps University Marburg Medical Center, Germany. The authors and Dr. Mannino have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of the article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sex-specific differences in the severity of symptoms and prevalence of comorbidities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) may point to different criteria for diagnosing cardiac comorbidities in women and men, a retrospective analysis suggests.

Among 2,046 patients in the German COSYCONET (COPD and Systemic Consequences–Comorbidities Net) cohort, most functional parameters and comorbidities and several items on the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) differed significantly between men and women.

In addition, there were sex-specific differences in the association between symptoms and cardiac disease, Franziska C. Trudzinski, MD, from the University of Heidelberg (Germany), and colleagues reported.

(Note: Although the authors used the term “gender” to distinguish male from female, this news organization has used the term “sex” in this article to refer to biological attributes of individual patients rather than personal identity.)

“[Sex]-specific differences in COPD comprised not only differences in the level of symptoms, comorbidities, and functional alterations but also differences in their mutual relationships. This was reflected in different sets of predictors for cardiac disease,” they wrote in a thematic poster presented at the American Thoracic Society’s virtual international conference.

GOLD standard

The investigators conducted an analysis of data on 795 women and 1,251 men with GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) class 1-3 disease from the COSYCONET COPD cohort.

They looked at the patients’ clinical history, comorbidities, lung function, CAT scores, and modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea score.

The authors used multivariate regression analysis to model potential sex-related differences in the relationship between symptoms in general and CAT items in particular, and the pattern of comorbidities and functional alterations.

They also performed logistic regression analyses to identify predictors for cardiac disease, defined as myocardial infarction, heart failure, or coronary artery disease. The analyses were controlled for age, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, mMRC, CAT items, and z scores of forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity ratio.

and for CAT items of cough (item 1), phlegm (item 2), and energy (item 8; P < .05 for all comparisons).

In logistic regression analysis, predictors for cardiac disease in men were energy (CAT item 8), mMRC score, smoking status, BMI, age, and spirometric lung function.

In women, however, only age was significantly predictive for cardiac disease.

“Our findings give hints how diagnostic information might be used differently in men and women,” Dr. Trudzinski and colleagues wrote.

Reassuring data

David Mannino, MD, medical director of the COPD Foundation, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview that sex differences in COPD presentation and severity are common.

“In general, men and women report symptoms differently. For example, women don’t report a whole lot of chronic bronchitis and phlegm, although they may have it,” he said, “whereas men may report less dyspnea. It varies, but in general we know that men and women, even with the same type of disease, report symptoms differently.”

Comorbidities also differ between the sexes, he noted. Women more frequently have osteoporosis, and men more frequently have heart disease, as borne out in the study. The prevalence of heart disease among patients in the study was approximately 2.5 times higher in men than women.

“It’s reassuring, because what we’re seeing is similar to what we’ve seen in other [studies] with regards to comorbidities,” he said.

The study was sponsored by Philipps University Marburg Medical Center, Germany. The authors and Dr. Mannino have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of the article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sex-specific differences in the severity of symptoms and prevalence of comorbidities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) may point to different criteria for diagnosing cardiac comorbidities in women and men, a retrospective analysis suggests.

Among 2,046 patients in the German COSYCONET (COPD and Systemic Consequences–Comorbidities Net) cohort, most functional parameters and comorbidities and several items on the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) differed significantly between men and women.

In addition, there were sex-specific differences in the association between symptoms and cardiac disease, Franziska C. Trudzinski, MD, from the University of Heidelberg (Germany), and colleagues reported.

(Note: Although the authors used the term “gender” to distinguish male from female, this news organization has used the term “sex” in this article to refer to biological attributes of individual patients rather than personal identity.)

“[Sex]-specific differences in COPD comprised not only differences in the level of symptoms, comorbidities, and functional alterations but also differences in their mutual relationships. This was reflected in different sets of predictors for cardiac disease,” they wrote in a thematic poster presented at the American Thoracic Society’s virtual international conference.

GOLD standard

The investigators conducted an analysis of data on 795 women and 1,251 men with GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) class 1-3 disease from the COSYCONET COPD cohort.

They looked at the patients’ clinical history, comorbidities, lung function, CAT scores, and modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea score.

The authors used multivariate regression analysis to model potential sex-related differences in the relationship between symptoms in general and CAT items in particular, and the pattern of comorbidities and functional alterations.

They also performed logistic regression analyses to identify predictors for cardiac disease, defined as myocardial infarction, heart failure, or coronary artery disease. The analyses were controlled for age, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, mMRC, CAT items, and z scores of forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity ratio.

and for CAT items of cough (item 1), phlegm (item 2), and energy (item 8; P < .05 for all comparisons).

In logistic regression analysis, predictors for cardiac disease in men were energy (CAT item 8), mMRC score, smoking status, BMI, age, and spirometric lung function.

In women, however, only age was significantly predictive for cardiac disease.

“Our findings give hints how diagnostic information might be used differently in men and women,” Dr. Trudzinski and colleagues wrote.

Reassuring data

David Mannino, MD, medical director of the COPD Foundation, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview that sex differences in COPD presentation and severity are common.

“In general, men and women report symptoms differently. For example, women don’t report a whole lot of chronic bronchitis and phlegm, although they may have it,” he said, “whereas men may report less dyspnea. It varies, but in general we know that men and women, even with the same type of disease, report symptoms differently.”

Comorbidities also differ between the sexes, he noted. Women more frequently have osteoporosis, and men more frequently have heart disease, as borne out in the study. The prevalence of heart disease among patients in the study was approximately 2.5 times higher in men than women.

“It’s reassuring, because what we’re seeing is similar to what we’ve seen in other [studies] with regards to comorbidities,” he said.

The study was sponsored by Philipps University Marburg Medical Center, Germany. The authors and Dr. Mannino have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of the article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Worse outcomes for patients with COPD and COVID-19

A study of COVID-19 outcomes across the United States bolsters reports from China and Europe that indicate that patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and SARS-CoV-2 infection have worse outcomes than those of patients with COVID-19 who do not have COPD.

Investigators at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Texas, combed through electronic health records from four geographic regions of the United States and identified a cohort of 6,056 patients with COPD among 150,775 patients whose records indicate either a diagnostic code or a positive laboratory test result for COVID-19.

Their findings indicate that patients with both COPD and COVID-19 “have worse outcomes compared to non-COPD COVID-19 patients, including 14-day hospitalization, length of stay, ICU admission, 30-day mortality, and use of mechanical ventilation,” Daniel Puebla Neira, MD, and colleagues from the University of Texas Medical Branch reported in a thematic poster presented during the American Thoracic Society (ATS) 2021 virtual international conference.

A critical care specialist who was not involved in the study said that the results are concerning but not surprising.

“If you already have a lung disease and you develop an additional lung disease on top of that, you don’t have as much reserve and you’re not going to tolerate the acute COVID infection,” said ATS expert Marc Moss, MD, Roger S. Mitchell Professor of Medicine in the division of pulmonary sciences and critical care medicine at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

The evidence shows that “patients with COPD should be even more cautious, because if they get sick and develop, they could do worse,” he said in an interview.

Retrospective analysis

Dr. Neira and colleagues assessed the characteristics and outcomes of patients with COPD who were treated for COVID-19 in the United States from March through August 2020.

Baseline demographics of the patients with and those without COPD were similar except that the mean age was higher among patients with COPD (68.62 vs. 47.08 years).

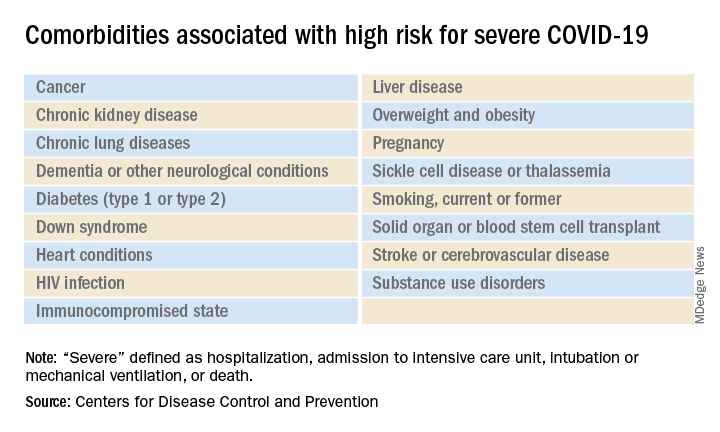

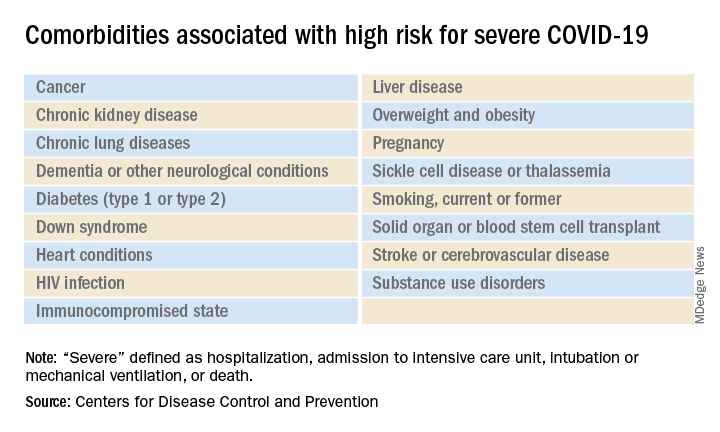

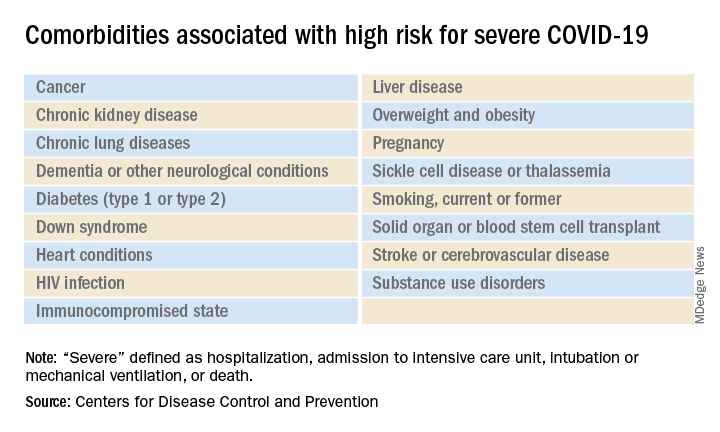

In addition, a significantly higher proportion of patients with COPD had comorbidities compared with those without COPD. Comorbidities included diabetes, hypertension, asthma, chronic kidney disease, end-stage renal disease, stroke, heart failure, cancer, coronary artery disease, and liver disease (P < .0001 for all comparisons).

Among patients with COPD, percentages were higher with respect to the following parameters: 14-day hospitalization for any cause (28.7% vs. 10.4%), COVID-19-related 14-day hospitalization (28.1% vs. 9.9%), ICU use (26.3% vs. 17.9%), mechanical ventilation use (26.3% vs. 16.1%), and 30-day mortality (13.6% vs. 7.2%; P < .0001 for all comparisons).

‘Mechanisms unclear’

“It is unclear what mechanisms drive the association between COPD and mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19,” the investigators wrote. “Several biological factors have been proposed, including chronic lung inflammation, oxidative stress, protease-antiprotease imbalance, and increased airway mediators.”

They recommend use of multivariable logistic regression to tease out the effects of covariates among patients with COPD and COVID-19 and call for research into long-term outcomes for these patients, “as survivors of critical illness are increasingly recognized to have cognitive, psychological, and physical consequences.”

Dr. Moss said that in general, the management of patients with COPD and COVID-19 is similar to that for patients with COVID-19 who do not have COPD, although there may be “subtle” differences, such as ventilator settings for patients with COPD.

No source of funding for the study has been disclosed. The investigators and Dr. Moss have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A study of COVID-19 outcomes across the United States bolsters reports from China and Europe that indicate that patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and SARS-CoV-2 infection have worse outcomes than those of patients with COVID-19 who do not have COPD.

Investigators at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Texas, combed through electronic health records from four geographic regions of the United States and identified a cohort of 6,056 patients with COPD among 150,775 patients whose records indicate either a diagnostic code or a positive laboratory test result for COVID-19.

Their findings indicate that patients with both COPD and COVID-19 “have worse outcomes compared to non-COPD COVID-19 patients, including 14-day hospitalization, length of stay, ICU admission, 30-day mortality, and use of mechanical ventilation,” Daniel Puebla Neira, MD, and colleagues from the University of Texas Medical Branch reported in a thematic poster presented during the American Thoracic Society (ATS) 2021 virtual international conference.

A critical care specialist who was not involved in the study said that the results are concerning but not surprising.

“If you already have a lung disease and you develop an additional lung disease on top of that, you don’t have as much reserve and you’re not going to tolerate the acute COVID infection,” said ATS expert Marc Moss, MD, Roger S. Mitchell Professor of Medicine in the division of pulmonary sciences and critical care medicine at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

The evidence shows that “patients with COPD should be even more cautious, because if they get sick and develop, they could do worse,” he said in an interview.

Retrospective analysis

Dr. Neira and colleagues assessed the characteristics and outcomes of patients with COPD who were treated for COVID-19 in the United States from March through August 2020.

Baseline demographics of the patients with and those without COPD were similar except that the mean age was higher among patients with COPD (68.62 vs. 47.08 years).

In addition, a significantly higher proportion of patients with COPD had comorbidities compared with those without COPD. Comorbidities included diabetes, hypertension, asthma, chronic kidney disease, end-stage renal disease, stroke, heart failure, cancer, coronary artery disease, and liver disease (P < .0001 for all comparisons).

Among patients with COPD, percentages were higher with respect to the following parameters: 14-day hospitalization for any cause (28.7% vs. 10.4%), COVID-19-related 14-day hospitalization (28.1% vs. 9.9%), ICU use (26.3% vs. 17.9%), mechanical ventilation use (26.3% vs. 16.1%), and 30-day mortality (13.6% vs. 7.2%; P < .0001 for all comparisons).

‘Mechanisms unclear’

“It is unclear what mechanisms drive the association between COPD and mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19,” the investigators wrote. “Several biological factors have been proposed, including chronic lung inflammation, oxidative stress, protease-antiprotease imbalance, and increased airway mediators.”

They recommend use of multivariable logistic regression to tease out the effects of covariates among patients with COPD and COVID-19 and call for research into long-term outcomes for these patients, “as survivors of critical illness are increasingly recognized to have cognitive, psychological, and physical consequences.”

Dr. Moss said that in general, the management of patients with COPD and COVID-19 is similar to that for patients with COVID-19 who do not have COPD, although there may be “subtle” differences, such as ventilator settings for patients with COPD.

No source of funding for the study has been disclosed. The investigators and Dr. Moss have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A study of COVID-19 outcomes across the United States bolsters reports from China and Europe that indicate that patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and SARS-CoV-2 infection have worse outcomes than those of patients with COVID-19 who do not have COPD.

Investigators at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Texas, combed through electronic health records from four geographic regions of the United States and identified a cohort of 6,056 patients with COPD among 150,775 patients whose records indicate either a diagnostic code or a positive laboratory test result for COVID-19.

Their findings indicate that patients with both COPD and COVID-19 “have worse outcomes compared to non-COPD COVID-19 patients, including 14-day hospitalization, length of stay, ICU admission, 30-day mortality, and use of mechanical ventilation,” Daniel Puebla Neira, MD, and colleagues from the University of Texas Medical Branch reported in a thematic poster presented during the American Thoracic Society (ATS) 2021 virtual international conference.

A critical care specialist who was not involved in the study said that the results are concerning but not surprising.

“If you already have a lung disease and you develop an additional lung disease on top of that, you don’t have as much reserve and you’re not going to tolerate the acute COVID infection,” said ATS expert Marc Moss, MD, Roger S. Mitchell Professor of Medicine in the division of pulmonary sciences and critical care medicine at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

The evidence shows that “patients with COPD should be even more cautious, because if they get sick and develop, they could do worse,” he said in an interview.

Retrospective analysis

Dr. Neira and colleagues assessed the characteristics and outcomes of patients with COPD who were treated for COVID-19 in the United States from March through August 2020.

Baseline demographics of the patients with and those without COPD were similar except that the mean age was higher among patients with COPD (68.62 vs. 47.08 years).

In addition, a significantly higher proportion of patients with COPD had comorbidities compared with those without COPD. Comorbidities included diabetes, hypertension, asthma, chronic kidney disease, end-stage renal disease, stroke, heart failure, cancer, coronary artery disease, and liver disease (P < .0001 for all comparisons).

Among patients with COPD, percentages were higher with respect to the following parameters: 14-day hospitalization for any cause (28.7% vs. 10.4%), COVID-19-related 14-day hospitalization (28.1% vs. 9.9%), ICU use (26.3% vs. 17.9%), mechanical ventilation use (26.3% vs. 16.1%), and 30-day mortality (13.6% vs. 7.2%; P < .0001 for all comparisons).

‘Mechanisms unclear’

“It is unclear what mechanisms drive the association between COPD and mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19,” the investigators wrote. “Several biological factors have been proposed, including chronic lung inflammation, oxidative stress, protease-antiprotease imbalance, and increased airway mediators.”

They recommend use of multivariable logistic regression to tease out the effects of covariates among patients with COPD and COVID-19 and call for research into long-term outcomes for these patients, “as survivors of critical illness are increasingly recognized to have cognitive, psychological, and physical consequences.”

Dr. Moss said that in general, the management of patients with COPD and COVID-19 is similar to that for patients with COVID-19 who do not have COPD, although there may be “subtle” differences, such as ventilator settings for patients with COPD.

No source of funding for the study has been disclosed. The investigators and Dr. Moss have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Carbon monoxide diffusion with COPD declines more in women

Single breath diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide shows greater decline over time in COPD patients compared with controls, but declines significantly more in women compared with men, according to data from 602 adults with a history of smoking.

In previous studies, diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLco) has been associated with decreased exercise capacity and poor health status in patients with COPD, but its association as a measure of disease progression has not been well studied, wrote Ciro Casanova, MD, of Hospital Universitario La Candelaria, Spain, and colleagues.

In a study published in the journal CHEST®, the researchers identified 506 adult smokers with COPD and 96 adult smoker controls without COPD. Lung function based on single breath DLco was measured each year for 5 years. The study population was part of the COPH History Assessment in SpaiN (CHAIN), an ongoing observational study of adults with COPD. COPD was defined as a history of at least 10 pack-years of smoking and a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC greater than 0.7 after 400 micrograms of albuterol, the researchers said.

During the 5-year period, the average overall annual decline in DLco was 1.34% in COPD patients, compared with .04% in non-COPD controls (P = .004). Among COPD patients, age, body mass index, FEV1%, and active smoking were not associated with longitudinal change in DLco values, the researchers said.

Notably, women with COPD at baseline had lower baseline DLco values compared with men (11.37%) and a significantly steeper decline in DLco (.89%) compared with men (P = .039). “Being a woman was the only factor that related to the annual rate of change in DLco,” the researchers said.

In a subgroup analysis, the researchers identified 305 COPD patients and 69 non-COPD controls who had at least 3 DLco measurements over the 5-year study period. In this group, 16.4% patients with COPD and 4.3% smokers without COPD showed significant yearly declines in DLco of –4.139% and –4.440%, respectively. Among COPD patients, significantly more women than men showed significant DLco declines (26% vs. 14%, P = .005). No significant differences were observed in mortality or hospitalizations per patient-year for COPD patients with and without DLco decline, the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of annual measurements of DLco among some patients, potential variability in the instruments used to measure DLco, and the absence of computerized tomography data for the chest, the researchers noted. However, the results support the value of the test for COPD progression when conducted at 3- to 4-year intervals, given the slow pace of the decline, they said. More research is needed, but “women seem to have a different susceptibility to cigarette smoke in the alveolar or pulmonary vascular domains,” they added.

DLco remains a valuable marker

The study is important because the usual longitudinal decline of diffusion capacity, an important physiological parameter in patients with COPD, was unknown, Juan P. de Torres, MD, of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., said in an interview.

“The finding of a different longitudinal decline of DLco in women was a surprise,” said Dr. de Torres, who was a coauthor on the study. “We knew from previous works from our group that COPD has a different clinical and prognostic behavior in women with COPD, but this specific finding is novel and important,” he said.

“These results provide information about the testing frequency (3-4 years) needed to use DLco as a marker of COPD progression in clinical practice,” Dr. de Torres added.

“What is the driving cause of this sex difference is unknown. We speculate that different causes of low DLco in COPD such as degree of emphysema, interstitial lung abnormalities, and pulmonary hypertension, may have a different prevalence and progression in women with COPD,” he said.

Looking ahead, “Large studies including an adequate sample of women with COPD is urgently needed because they will be the main face of COPD in the near future,” said Dr. de Torres. “Sex difference in their physiological characteristics, the reason to explain those differences and how they behave longitudinally is also urgently needed,” he added.

The study was supported in part by AstraZeneca and by the COPD research program of the Spanish Respiratory Society. The researchers and Dr. de Torres had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Single breath diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide shows greater decline over time in COPD patients compared with controls, but declines significantly more in women compared with men, according to data from 602 adults with a history of smoking.

In previous studies, diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLco) has been associated with decreased exercise capacity and poor health status in patients with COPD, but its association as a measure of disease progression has not been well studied, wrote Ciro Casanova, MD, of Hospital Universitario La Candelaria, Spain, and colleagues.

In a study published in the journal CHEST®, the researchers identified 506 adult smokers with COPD and 96 adult smoker controls without COPD. Lung function based on single breath DLco was measured each year for 5 years. The study population was part of the COPH History Assessment in SpaiN (CHAIN), an ongoing observational study of adults with COPD. COPD was defined as a history of at least 10 pack-years of smoking and a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC greater than 0.7 after 400 micrograms of albuterol, the researchers said.

During the 5-year period, the average overall annual decline in DLco was 1.34% in COPD patients, compared with .04% in non-COPD controls (P = .004). Among COPD patients, age, body mass index, FEV1%, and active smoking were not associated with longitudinal change in DLco values, the researchers said.

Notably, women with COPD at baseline had lower baseline DLco values compared with men (11.37%) and a significantly steeper decline in DLco (.89%) compared with men (P = .039). “Being a woman was the only factor that related to the annual rate of change in DLco,” the researchers said.

In a subgroup analysis, the researchers identified 305 COPD patients and 69 non-COPD controls who had at least 3 DLco measurements over the 5-year study period. In this group, 16.4% patients with COPD and 4.3% smokers without COPD showed significant yearly declines in DLco of –4.139% and –4.440%, respectively. Among COPD patients, significantly more women than men showed significant DLco declines (26% vs. 14%, P = .005). No significant differences were observed in mortality or hospitalizations per patient-year for COPD patients with and without DLco decline, the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of annual measurements of DLco among some patients, potential variability in the instruments used to measure DLco, and the absence of computerized tomography data for the chest, the researchers noted. However, the results support the value of the test for COPD progression when conducted at 3- to 4-year intervals, given the slow pace of the decline, they said. More research is needed, but “women seem to have a different susceptibility to cigarette smoke in the alveolar or pulmonary vascular domains,” they added.

DLco remains a valuable marker

The study is important because the usual longitudinal decline of diffusion capacity, an important physiological parameter in patients with COPD, was unknown, Juan P. de Torres, MD, of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., said in an interview.

“The finding of a different longitudinal decline of DLco in women was a surprise,” said Dr. de Torres, who was a coauthor on the study. “We knew from previous works from our group that COPD has a different clinical and prognostic behavior in women with COPD, but this specific finding is novel and important,” he said.

“These results provide information about the testing frequency (3-4 years) needed to use DLco as a marker of COPD progression in clinical practice,” Dr. de Torres added.

“What is the driving cause of this sex difference is unknown. We speculate that different causes of low DLco in COPD such as degree of emphysema, interstitial lung abnormalities, and pulmonary hypertension, may have a different prevalence and progression in women with COPD,” he said.

Looking ahead, “Large studies including an adequate sample of women with COPD is urgently needed because they will be the main face of COPD in the near future,” said Dr. de Torres. “Sex difference in their physiological characteristics, the reason to explain those differences and how they behave longitudinally is also urgently needed,” he added.

The study was supported in part by AstraZeneca and by the COPD research program of the Spanish Respiratory Society. The researchers and Dr. de Torres had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Single breath diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide shows greater decline over time in COPD patients compared with controls, but declines significantly more in women compared with men, according to data from 602 adults with a history of smoking.

In previous studies, diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLco) has been associated with decreased exercise capacity and poor health status in patients with COPD, but its association as a measure of disease progression has not been well studied, wrote Ciro Casanova, MD, of Hospital Universitario La Candelaria, Spain, and colleagues.