User login

MD-IQ only

Endometrial Evaluation: Are You Still Relying on a Blind Biopsy?

One-third of patients who visit a gynecologist are there because of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), which is believed to account for more than 70% of gyneco¬logic consults in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulle¬tin on AUB now states that a negative blind endometrial biopsy is not a stopping point in persistent bleeding.

In this supplement, learn about the advantages of diagnosing AUB using a hysteroscope.

- Authors:

- Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP, FACOG

- New York University Medical Center New York, New York

- Ted L. Anderson, MD, PhD

- Vanderbilt University Medical School Nashville, Tennessee

- Click here to read this supplement.

To access the posttest and evaluation, visit

www.worldclasscme.com/endometrialevaluation

One-third of patients who visit a gynecologist are there because of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), which is believed to account for more than 70% of gyneco¬logic consults in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulle¬tin on AUB now states that a negative blind endometrial biopsy is not a stopping point in persistent bleeding.

In this supplement, learn about the advantages of diagnosing AUB using a hysteroscope.

- Authors:

- Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP, FACOG

- New York University Medical Center New York, New York

- Ted L. Anderson, MD, PhD

- Vanderbilt University Medical School Nashville, Tennessee

- Click here to read this supplement.

To access the posttest and evaluation, visit

www.worldclasscme.com/endometrialevaluation

One-third of patients who visit a gynecologist are there because of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), which is believed to account for more than 70% of gyneco¬logic consults in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulle¬tin on AUB now states that a negative blind endometrial biopsy is not a stopping point in persistent bleeding.

In this supplement, learn about the advantages of diagnosing AUB using a hysteroscope.

- Authors:

- Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP, FACOG

- New York University Medical Center New York, New York

- Ted L. Anderson, MD, PhD

- Vanderbilt University Medical School Nashville, Tennessee

- Click here to read this supplement.

To access the posttest and evaluation, visit

www.worldclasscme.com/endometrialevaluation

Endometriomas: Classification and surgical management

Related article:

Endometriosis: Expert answers to 7 crucial questions on diagnosis

Etiology

Endometriomas are extensively described in the literature, and their origin is the subject of several theories. In 1921, Sampson noted luteal membrane and ovarian epithelial tissues within endometriomas and was the first to indicate that endometriomas may result from the invasion of functional cysts by endometrial tissue.2,4,5 In 1979, Czernobilsky and Morris6 found endometrial and oviduct-like epithelium in ovarian endometriosis and concluded that ovarian tissue may be a common histologic precursor. Several other authors subsequently have reported finding different types of tissue within ovarian endometriomas, and not all of these chocolate cysts showed histologic evidence of endometriosis.4,7,8

Read about the classification of endometriomas

Disease classification

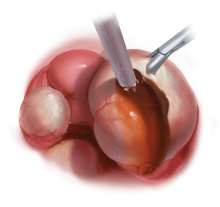

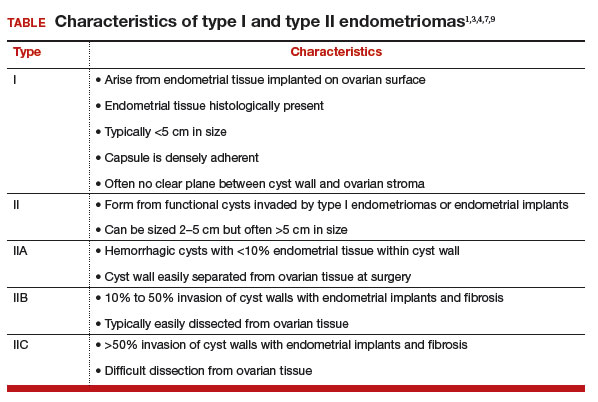

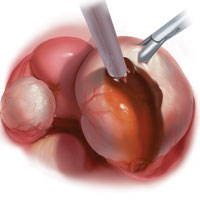

Our classification system identifies 2 types of endometriomas on the basis of their etiologies and characteristics. Type I, which arise from endometrial tissue implanted on the ovarian surface, are also called true endometriomas. Invagination of cortex and subsequent hemorrhage from endometrial tissue result in cyst formation. Endometrial tissue (endometrial stroma and glands) is histologically present in all type I endometriomas.1,4,9 These endometriomas usually are small (<5 cm in diameter) and have a densely adherent fibrous capsule.4 Often, there is no clear plane between cyst wall and ovarian stroma.3

Type II endometriomas arise from functional cysts involved in or invaded by cortical or pelvic side-wall endometrial implants or by type I endometriomas. Type II endometriomas are subclassified by the extent of endometrial implant involvement in the cyst wall. Type IIA endometriomas are hemorrhagic cysts with less than 10% of endometrial tissue within the cyst wall. Similar to the functional cysts from which they originate, type IIA endometriomas have a cyst wall that is separated easily from ovarian tissue during surgery.4,7,9 Although type II endometriomas tend to be larger than their type I counterparts, in some cases they are identified at an early stage of 2 to 5 cm. Endometriomas larger than 5 cm are almost always type II.4

Type IIB and IIC endometriomas have endometrial implants and fibrosis within their cyst walls, with progressively more endometrial invasion in type IIC endometriomas (>50%) than in type IIB (10% to 50%). Consequently, type IIB cysts are relatively easy to dissect from ovarian tissue, except adjacent to an endometriotic area where the cyst densely adheres to the ovarian stroma. In type IIC, endometrial tissue more extensively penetrates the capsule, making dissection of diseased tissue from the ovarian stroma more difficult; in fact, separating type IIC cyst wall from ovarian stroma can be as challenging as excising a type I endometrioma.7 In most cases, a type IIC cyst is attached by adhesions and fibrosis to the pelvic side wall or uterus and ruptures during mobilization (TABLE).

Related article:

Imaging the endometrioma and mature cystic teratoma

Presentation and diagnosis

Almost all patients with an endometrioma concurrently have peritoneal endometriosis, which is characterized by dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, infertility, and, in some cases, gastrointestinal or genitourinary dysfunction.1 Pelvic examination may reveal an adnexal mass that is an endometrioma, or an endometrioma may appear on imaging obtained in a pelvic pain or infertility work-up. Given its 73% sensitivity, 94% specificity, safety, and low cost, transvaginal ultrasonography is the preferred imaging modality for endometrioma.3 The characteristic ultrasonographic appearance is that of a round, homogeneous, fluid-filled mass with low-level echoes.1 Magnetic resonance imaging is appropriate when a more sensitive imaging modality is indicated, as for a patient with risk factors for malignancy.3,10–12

Read about the surgical management of endometriomas

Surgical management

Indications for surgical excision of endometriomas include pelvic pain, infertility, and prevention and diagnosis of malignancy. Endometriomas may be excised prior to use of assisted reproductive technology.13–15 Medical therapy, such as oral contraceptives, can be used to reduce the size of endometriomas but does not improve fertility.3 Certain ovarian cancers are more common in women with endometriosis, and ovarian tumors are thought to develop in about 1% of ovarian endometriosis cases.1,12 Therefore, endometrioma excision may reduce the risk of malignancy. As with other ovarian cysts, large endometriomas may be excised to reduce the risks of rupture and torsion.

Approach

Laparoscopy is the preferred approach for endometrioma excision. Controversy exists regarding the ideal procedure: complete excision (with stripping of the cyst capsule) or drainage and ablation of the cyst wall. Compared with drainage and ablation, excision reduces recurrence of endometriomas; relieves dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and other symptoms; and improves fertility.13,16 The recurrence rate may be as low as 5.8% with complete excision but is 90% with simple transvaginal aspiration.17,18 If not performed properly, however, cyst capsule stripping may damage nearby ovarian stroma and decrease the ovarian reserve.14 Some authors have advocated combining excision and ablation—performing cystectomy until there is no longer a clear plane between capsule and ovarian stroma and then ablating any remaining endometrial tissue.8

With type I and IIC endometriomas, we have seen the endometrial cyst wall infiltrating the ovarian stroma so deeply there is not always a definable plane. By contrast, type IIA and IIB endometriomas typically have a plane between the cyst wall and the ovarian cortex. In type II endometriomas, endometrial implants on the ovarian cortex infiltrate the plane of the cyst wall such that the juxtaposing lipomatous follicular cyst detaches with minimal intraoperative traction. Portions of type II endometriomas containing fibrosis and adhesions may become more difficult to peel off the cyst wall. For most endometriomas, at least 1 spot is difficult to peel off the ovary, and extra care must be taken at the hilum of ovary to avoid excising healthy ovarian cortex.4,5,7,8

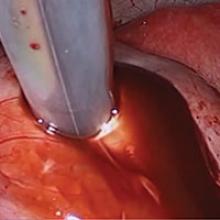

Our surgical approach accounts for the described variations in type I and II endometriomas. Endometrial contents often spill as the endometrioma is dissected off neighboring structures. When possible, endometriomas should be aspirated and irrigated prior to cystectomy to avoid seeding the pelvis and abdomen with spilled endometriotic contents. We use hydrodissection, the injection of dilute vasopressin with a laparoscopic needle, to create a plane between cyst wall and ovarian stroma and strip the cyst capsule with laparoscopic graspers. Type I endometriomas adhere densely to the ovary. Given the presence of fibrosis and adhesions, the cyst is excised in a piecemeal fashion. Care is taken to remove any endometrial implants from the ovary while preserving as much of the ovarian tissue as possible.1

Type II endometriomas are larger cysts originating from the invasion of endometrial implants or type I endometrioma into functional cysts. The difficulty of capsule excision varies according to the extent of endometrial invasion. Type IIA endometriomas contain less than 10% endometrial tissue within the cyst capsule. Thus, the standard ovarian cystectomy stripping technique is successful in removing more than 90% of the cyst capsule. Special care is taken in stripping the residual small portion that involves the endometrial glands and stroma and adheres densely to the ovary.

The larger proportion of endometrial tissue present in type IIB and IIC endometriomas degrades the plane between the cyst capsule and the ovarian stroma, making excision more difficult. Similar to the type I excision, a piecemeal approach is often necessary. If complete stripping of the cyst capsule would result in extensive loss of healthy ovarian tissue, then electrocautery, plasma energy, or laser ablation can be selectively used to destroy focal areas of endometrial invasion. Complete ablation may be difficult, as the endometrioma wall can be up to 5 mm thick.19 For these thick-walled endometriomas, we recommend excision (vs ablation), which lowers the risk of endometrioma recurrence.

Related article:

Endometriosis and pain: Expert answers to 6 questions targeting your management options

- Endometriomas are common adnexal masses in women affected by endometriosis and may exacerbate pelvic pain and impair fertility. Classification of endometriomas into type I and type II,depending on their etiology and characteristics, can guide minimally invasive surgical management.

- Type I endometriomas arise from invagination of endometrial implants on the ovarian cortex, resulting in dense fibrosis and adhesions. These lesions typically require piecemeal excision in order to completely remove the cyst capsule.

- Type II endometriomas result from invasion of endometrial tissue into preexisting functional cysts and are further subclassified by the proportion of cyst capsule containing endometrial tissue (IIA <10%, IIB 10% to 50%, IIC >50%).

- The difficulty of excising type II endometriomas correlates with the degree of endometrial invasion, with type IIA being relatively straightforward and type IIC being as challenging and piecemeal as type I.

- We generally favor complete excision rather than ablation of the cyst capsule, except for when excision would result in an unacceptable loss of healthy ovarian tissue.

Conclusion

Endometriomas, common adnexal masses in women affected by endometriosis, may exacerbate pelvic pain and impair fertility. Gynecologists should be prepared to excise endometriomas completely and exercise care in preserving as much of the ovarian stroma as possible. We classify endometriomas into 2 types: type I, which develop from invagination of endometrial implants in the ovarian cortex, and type II, which stem from invasion of functional cysts by endometrial implants or type I endometrioma. This distinction guides surgical management. We hope this article and its accompanying video will be helpful in guiding laparoscopic excision of type I and II endometriomas.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Nezhat C, Buescher E, Paka C, et al. Video-assisted laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat’s Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013:265–302.

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(3):511–519.

- Keyhan S, Hughes C, Price T, Muasher S. An update on surgical versus expectant management of ovarian endometriomas in infertile women. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:204792.

- Nezhat F, Nezhat C, Allan CJ, Metzger DA, Sears DL. Clinical and histologic classification of endometriomas. Implications for a mechanism of pathogenesis. J Reprod Med. 1992;37(9):771–776.

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. The pathogenesis of endometriosis. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat’s Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013:252–258.

- Czernobilsky B, Morris WJ. A histologic study of ovarian endometriosis with emphasis on hyperplastic and atypical changes. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53(3):318–323.

- Nezhat F, Nezhat C, Nezhat C, Admon D. A fresh look at ovarian endometriomas. Contemp Ob Gyn. 1994;39(11):81–94.

- Donnez J, Lousse JC, Jadoul P, Donnez O, Squifflet J. Laparoscopic management of endometriomas using a combined technique of excisional (cystectomy) and ablative surgery. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(1):28–32.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, Seidman DS. Classification of endometriosis. Improving the classification of endometriotic ovarian cysts. Hum Reprod. 1994;9(12):2212–2213.

- Nezhat FR, Pejovic T, Reis FM, Guo SW. The link between endometriosis and ovarian cancer: clinical implications. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24(4):623–628.

- Nezhat F, Apostol R, Mahmoud M, el Daouk M. Malignant transformation of endometriosis and its clinical significance. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(2):342–344.

- Nezhat FR, Apostal R, Nezhat C, Pejovic T. New insights in the pathophysiology of ovarian cancer and implications for screening and prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(3):262–267.

- Hart RJ, Hickey M, Maouris P, Buckett W. Excisional surgery versus ablative surgery for ovarian endometriomata. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD004992.

- Yates J. Endometriosis and infertility: expert answers to 6 questions to help pinpoint the best route to pregnancy. OBG Manag. 2015;27(6):30–35.

- Littman E, Giudice L, Lathi R, Berker B, Milki A, Nezhat C. Role of laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis in patients with failed in vitro fertilization cycles. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(6):1574–1578.

- Exacoustos C, Zupi E, Amadio A, et al. Laparoscopic removal of endometriomas: sonographic evaluation of residual functioning ovarian tissue. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(1):68–72.

- Gonçalves FC, Andres MP, Passman LJ, Gonçalves MO, Podgaec S. A systematic review of ultrasonography-guided transvaginal aspiration of recurrent ovarian endometrioma. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;134(1):3–7.

- Alborzi S, Momtahan M, Parsanezhad ME, Dehbashi S, Zolghadri J, Alborzi S. A prospective, randomized study comparing laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy versus fenestration and coagulation in patients with endometriomas. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(6):1633–1637.

- Nezhat C, Crowgey SR, Garrison CP. Surgical treatment of endometriosis via laser laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 1986;45(6):778–783.

Related article:

Endometriosis: Expert answers to 7 crucial questions on diagnosis

Etiology

Endometriomas are extensively described in the literature, and their origin is the subject of several theories. In 1921, Sampson noted luteal membrane and ovarian epithelial tissues within endometriomas and was the first to indicate that endometriomas may result from the invasion of functional cysts by endometrial tissue.2,4,5 In 1979, Czernobilsky and Morris6 found endometrial and oviduct-like epithelium in ovarian endometriosis and concluded that ovarian tissue may be a common histologic precursor. Several other authors subsequently have reported finding different types of tissue within ovarian endometriomas, and not all of these chocolate cysts showed histologic evidence of endometriosis.4,7,8

Read about the classification of endometriomas

Disease classification

Our classification system identifies 2 types of endometriomas on the basis of their etiologies and characteristics. Type I, which arise from endometrial tissue implanted on the ovarian surface, are also called true endometriomas. Invagination of cortex and subsequent hemorrhage from endometrial tissue result in cyst formation. Endometrial tissue (endometrial stroma and glands) is histologically present in all type I endometriomas.1,4,9 These endometriomas usually are small (<5 cm in diameter) and have a densely adherent fibrous capsule.4 Often, there is no clear plane between cyst wall and ovarian stroma.3

Type II endometriomas arise from functional cysts involved in or invaded by cortical or pelvic side-wall endometrial implants or by type I endometriomas. Type II endometriomas are subclassified by the extent of endometrial implant involvement in the cyst wall. Type IIA endometriomas are hemorrhagic cysts with less than 10% of endometrial tissue within the cyst wall. Similar to the functional cysts from which they originate, type IIA endometriomas have a cyst wall that is separated easily from ovarian tissue during surgery.4,7,9 Although type II endometriomas tend to be larger than their type I counterparts, in some cases they are identified at an early stage of 2 to 5 cm. Endometriomas larger than 5 cm are almost always type II.4

Type IIB and IIC endometriomas have endometrial implants and fibrosis within their cyst walls, with progressively more endometrial invasion in type IIC endometriomas (>50%) than in type IIB (10% to 50%). Consequently, type IIB cysts are relatively easy to dissect from ovarian tissue, except adjacent to an endometriotic area where the cyst densely adheres to the ovarian stroma. In type IIC, endometrial tissue more extensively penetrates the capsule, making dissection of diseased tissue from the ovarian stroma more difficult; in fact, separating type IIC cyst wall from ovarian stroma can be as challenging as excising a type I endometrioma.7 In most cases, a type IIC cyst is attached by adhesions and fibrosis to the pelvic side wall or uterus and ruptures during mobilization (TABLE).

Related article:

Imaging the endometrioma and mature cystic teratoma

Presentation and diagnosis

Almost all patients with an endometrioma concurrently have peritoneal endometriosis, which is characterized by dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, infertility, and, in some cases, gastrointestinal or genitourinary dysfunction.1 Pelvic examination may reveal an adnexal mass that is an endometrioma, or an endometrioma may appear on imaging obtained in a pelvic pain or infertility work-up. Given its 73% sensitivity, 94% specificity, safety, and low cost, transvaginal ultrasonography is the preferred imaging modality for endometrioma.3 The characteristic ultrasonographic appearance is that of a round, homogeneous, fluid-filled mass with low-level echoes.1 Magnetic resonance imaging is appropriate when a more sensitive imaging modality is indicated, as for a patient with risk factors for malignancy.3,10–12

Read about the surgical management of endometriomas

Surgical management

Indications for surgical excision of endometriomas include pelvic pain, infertility, and prevention and diagnosis of malignancy. Endometriomas may be excised prior to use of assisted reproductive technology.13–15 Medical therapy, such as oral contraceptives, can be used to reduce the size of endometriomas but does not improve fertility.3 Certain ovarian cancers are more common in women with endometriosis, and ovarian tumors are thought to develop in about 1% of ovarian endometriosis cases.1,12 Therefore, endometrioma excision may reduce the risk of malignancy. As with other ovarian cysts, large endometriomas may be excised to reduce the risks of rupture and torsion.

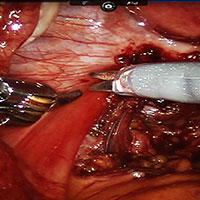

Approach

Laparoscopy is the preferred approach for endometrioma excision. Controversy exists regarding the ideal procedure: complete excision (with stripping of the cyst capsule) or drainage and ablation of the cyst wall. Compared with drainage and ablation, excision reduces recurrence of endometriomas; relieves dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and other symptoms; and improves fertility.13,16 The recurrence rate may be as low as 5.8% with complete excision but is 90% with simple transvaginal aspiration.17,18 If not performed properly, however, cyst capsule stripping may damage nearby ovarian stroma and decrease the ovarian reserve.14 Some authors have advocated combining excision and ablation—performing cystectomy until there is no longer a clear plane between capsule and ovarian stroma and then ablating any remaining endometrial tissue.8

With type I and IIC endometriomas, we have seen the endometrial cyst wall infiltrating the ovarian stroma so deeply there is not always a definable plane. By contrast, type IIA and IIB endometriomas typically have a plane between the cyst wall and the ovarian cortex. In type II endometriomas, endometrial implants on the ovarian cortex infiltrate the plane of the cyst wall such that the juxtaposing lipomatous follicular cyst detaches with minimal intraoperative traction. Portions of type II endometriomas containing fibrosis and adhesions may become more difficult to peel off the cyst wall. For most endometriomas, at least 1 spot is difficult to peel off the ovary, and extra care must be taken at the hilum of ovary to avoid excising healthy ovarian cortex.4,5,7,8

Our surgical approach accounts for the described variations in type I and II endometriomas. Endometrial contents often spill as the endometrioma is dissected off neighboring structures. When possible, endometriomas should be aspirated and irrigated prior to cystectomy to avoid seeding the pelvis and abdomen with spilled endometriotic contents. We use hydrodissection, the injection of dilute vasopressin with a laparoscopic needle, to create a plane between cyst wall and ovarian stroma and strip the cyst capsule with laparoscopic graspers. Type I endometriomas adhere densely to the ovary. Given the presence of fibrosis and adhesions, the cyst is excised in a piecemeal fashion. Care is taken to remove any endometrial implants from the ovary while preserving as much of the ovarian tissue as possible.1

Type II endometriomas are larger cysts originating from the invasion of endometrial implants or type I endometrioma into functional cysts. The difficulty of capsule excision varies according to the extent of endometrial invasion. Type IIA endometriomas contain less than 10% endometrial tissue within the cyst capsule. Thus, the standard ovarian cystectomy stripping technique is successful in removing more than 90% of the cyst capsule. Special care is taken in stripping the residual small portion that involves the endometrial glands and stroma and adheres densely to the ovary.

The larger proportion of endometrial tissue present in type IIB and IIC endometriomas degrades the plane between the cyst capsule and the ovarian stroma, making excision more difficult. Similar to the type I excision, a piecemeal approach is often necessary. If complete stripping of the cyst capsule would result in extensive loss of healthy ovarian tissue, then electrocautery, plasma energy, or laser ablation can be selectively used to destroy focal areas of endometrial invasion. Complete ablation may be difficult, as the endometrioma wall can be up to 5 mm thick.19 For these thick-walled endometriomas, we recommend excision (vs ablation), which lowers the risk of endometrioma recurrence.

Related article:

Endometriosis and pain: Expert answers to 6 questions targeting your management options

- Endometriomas are common adnexal masses in women affected by endometriosis and may exacerbate pelvic pain and impair fertility. Classification of endometriomas into type I and type II,depending on their etiology and characteristics, can guide minimally invasive surgical management.

- Type I endometriomas arise from invagination of endometrial implants on the ovarian cortex, resulting in dense fibrosis and adhesions. These lesions typically require piecemeal excision in order to completely remove the cyst capsule.

- Type II endometriomas result from invasion of endometrial tissue into preexisting functional cysts and are further subclassified by the proportion of cyst capsule containing endometrial tissue (IIA <10%, IIB 10% to 50%, IIC >50%).

- The difficulty of excising type II endometriomas correlates with the degree of endometrial invasion, with type IIA being relatively straightforward and type IIC being as challenging and piecemeal as type I.

- We generally favor complete excision rather than ablation of the cyst capsule, except for when excision would result in an unacceptable loss of healthy ovarian tissue.

Conclusion

Endometriomas, common adnexal masses in women affected by endometriosis, may exacerbate pelvic pain and impair fertility. Gynecologists should be prepared to excise endometriomas completely and exercise care in preserving as much of the ovarian stroma as possible. We classify endometriomas into 2 types: type I, which develop from invagination of endometrial implants in the ovarian cortex, and type II, which stem from invasion of functional cysts by endometrial implants or type I endometrioma. This distinction guides surgical management. We hope this article and its accompanying video will be helpful in guiding laparoscopic excision of type I and II endometriomas.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Related article:

Endometriosis: Expert answers to 7 crucial questions on diagnosis

Etiology

Endometriomas are extensively described in the literature, and their origin is the subject of several theories. In 1921, Sampson noted luteal membrane and ovarian epithelial tissues within endometriomas and was the first to indicate that endometriomas may result from the invasion of functional cysts by endometrial tissue.2,4,5 In 1979, Czernobilsky and Morris6 found endometrial and oviduct-like epithelium in ovarian endometriosis and concluded that ovarian tissue may be a common histologic precursor. Several other authors subsequently have reported finding different types of tissue within ovarian endometriomas, and not all of these chocolate cysts showed histologic evidence of endometriosis.4,7,8

Read about the classification of endometriomas

Disease classification

Our classification system identifies 2 types of endometriomas on the basis of their etiologies and characteristics. Type I, which arise from endometrial tissue implanted on the ovarian surface, are also called true endometriomas. Invagination of cortex and subsequent hemorrhage from endometrial tissue result in cyst formation. Endometrial tissue (endometrial stroma and glands) is histologically present in all type I endometriomas.1,4,9 These endometriomas usually are small (<5 cm in diameter) and have a densely adherent fibrous capsule.4 Often, there is no clear plane between cyst wall and ovarian stroma.3

Type II endometriomas arise from functional cysts involved in or invaded by cortical or pelvic side-wall endometrial implants or by type I endometriomas. Type II endometriomas are subclassified by the extent of endometrial implant involvement in the cyst wall. Type IIA endometriomas are hemorrhagic cysts with less than 10% of endometrial tissue within the cyst wall. Similar to the functional cysts from which they originate, type IIA endometriomas have a cyst wall that is separated easily from ovarian tissue during surgery.4,7,9 Although type II endometriomas tend to be larger than their type I counterparts, in some cases they are identified at an early stage of 2 to 5 cm. Endometriomas larger than 5 cm are almost always type II.4

Type IIB and IIC endometriomas have endometrial implants and fibrosis within their cyst walls, with progressively more endometrial invasion in type IIC endometriomas (>50%) than in type IIB (10% to 50%). Consequently, type IIB cysts are relatively easy to dissect from ovarian tissue, except adjacent to an endometriotic area where the cyst densely adheres to the ovarian stroma. In type IIC, endometrial tissue more extensively penetrates the capsule, making dissection of diseased tissue from the ovarian stroma more difficult; in fact, separating type IIC cyst wall from ovarian stroma can be as challenging as excising a type I endometrioma.7 In most cases, a type IIC cyst is attached by adhesions and fibrosis to the pelvic side wall or uterus and ruptures during mobilization (TABLE).

Related article:

Imaging the endometrioma and mature cystic teratoma

Presentation and diagnosis

Almost all patients with an endometrioma concurrently have peritoneal endometriosis, which is characterized by dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, infertility, and, in some cases, gastrointestinal or genitourinary dysfunction.1 Pelvic examination may reveal an adnexal mass that is an endometrioma, or an endometrioma may appear on imaging obtained in a pelvic pain or infertility work-up. Given its 73% sensitivity, 94% specificity, safety, and low cost, transvaginal ultrasonography is the preferred imaging modality for endometrioma.3 The characteristic ultrasonographic appearance is that of a round, homogeneous, fluid-filled mass with low-level echoes.1 Magnetic resonance imaging is appropriate when a more sensitive imaging modality is indicated, as for a patient with risk factors for malignancy.3,10–12

Read about the surgical management of endometriomas

Surgical management

Indications for surgical excision of endometriomas include pelvic pain, infertility, and prevention and diagnosis of malignancy. Endometriomas may be excised prior to use of assisted reproductive technology.13–15 Medical therapy, such as oral contraceptives, can be used to reduce the size of endometriomas but does not improve fertility.3 Certain ovarian cancers are more common in women with endometriosis, and ovarian tumors are thought to develop in about 1% of ovarian endometriosis cases.1,12 Therefore, endometrioma excision may reduce the risk of malignancy. As with other ovarian cysts, large endometriomas may be excised to reduce the risks of rupture and torsion.

Approach

Laparoscopy is the preferred approach for endometrioma excision. Controversy exists regarding the ideal procedure: complete excision (with stripping of the cyst capsule) or drainage and ablation of the cyst wall. Compared with drainage and ablation, excision reduces recurrence of endometriomas; relieves dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and other symptoms; and improves fertility.13,16 The recurrence rate may be as low as 5.8% with complete excision but is 90% with simple transvaginal aspiration.17,18 If not performed properly, however, cyst capsule stripping may damage nearby ovarian stroma and decrease the ovarian reserve.14 Some authors have advocated combining excision and ablation—performing cystectomy until there is no longer a clear plane between capsule and ovarian stroma and then ablating any remaining endometrial tissue.8

With type I and IIC endometriomas, we have seen the endometrial cyst wall infiltrating the ovarian stroma so deeply there is not always a definable plane. By contrast, type IIA and IIB endometriomas typically have a plane between the cyst wall and the ovarian cortex. In type II endometriomas, endometrial implants on the ovarian cortex infiltrate the plane of the cyst wall such that the juxtaposing lipomatous follicular cyst detaches with minimal intraoperative traction. Portions of type II endometriomas containing fibrosis and adhesions may become more difficult to peel off the cyst wall. For most endometriomas, at least 1 spot is difficult to peel off the ovary, and extra care must be taken at the hilum of ovary to avoid excising healthy ovarian cortex.4,5,7,8

Our surgical approach accounts for the described variations in type I and II endometriomas. Endometrial contents often spill as the endometrioma is dissected off neighboring structures. When possible, endometriomas should be aspirated and irrigated prior to cystectomy to avoid seeding the pelvis and abdomen with spilled endometriotic contents. We use hydrodissection, the injection of dilute vasopressin with a laparoscopic needle, to create a plane between cyst wall and ovarian stroma and strip the cyst capsule with laparoscopic graspers. Type I endometriomas adhere densely to the ovary. Given the presence of fibrosis and adhesions, the cyst is excised in a piecemeal fashion. Care is taken to remove any endometrial implants from the ovary while preserving as much of the ovarian tissue as possible.1

Type II endometriomas are larger cysts originating from the invasion of endometrial implants or type I endometrioma into functional cysts. The difficulty of capsule excision varies according to the extent of endometrial invasion. Type IIA endometriomas contain less than 10% endometrial tissue within the cyst capsule. Thus, the standard ovarian cystectomy stripping technique is successful in removing more than 90% of the cyst capsule. Special care is taken in stripping the residual small portion that involves the endometrial glands and stroma and adheres densely to the ovary.

The larger proportion of endometrial tissue present in type IIB and IIC endometriomas degrades the plane between the cyst capsule and the ovarian stroma, making excision more difficult. Similar to the type I excision, a piecemeal approach is often necessary. If complete stripping of the cyst capsule would result in extensive loss of healthy ovarian tissue, then electrocautery, plasma energy, or laser ablation can be selectively used to destroy focal areas of endometrial invasion. Complete ablation may be difficult, as the endometrioma wall can be up to 5 mm thick.19 For these thick-walled endometriomas, we recommend excision (vs ablation), which lowers the risk of endometrioma recurrence.

Related article:

Endometriosis and pain: Expert answers to 6 questions targeting your management options

- Endometriomas are common adnexal masses in women affected by endometriosis and may exacerbate pelvic pain and impair fertility. Classification of endometriomas into type I and type II,depending on their etiology and characteristics, can guide minimally invasive surgical management.

- Type I endometriomas arise from invagination of endometrial implants on the ovarian cortex, resulting in dense fibrosis and adhesions. These lesions typically require piecemeal excision in order to completely remove the cyst capsule.

- Type II endometriomas result from invasion of endometrial tissue into preexisting functional cysts and are further subclassified by the proportion of cyst capsule containing endometrial tissue (IIA <10%, IIB 10% to 50%, IIC >50%).

- The difficulty of excising type II endometriomas correlates with the degree of endometrial invasion, with type IIA being relatively straightforward and type IIC being as challenging and piecemeal as type I.

- We generally favor complete excision rather than ablation of the cyst capsule, except for when excision would result in an unacceptable loss of healthy ovarian tissue.

Conclusion

Endometriomas, common adnexal masses in women affected by endometriosis, may exacerbate pelvic pain and impair fertility. Gynecologists should be prepared to excise endometriomas completely and exercise care in preserving as much of the ovarian stroma as possible. We classify endometriomas into 2 types: type I, which develop from invagination of endometrial implants in the ovarian cortex, and type II, which stem from invasion of functional cysts by endometrial implants or type I endometrioma. This distinction guides surgical management. We hope this article and its accompanying video will be helpful in guiding laparoscopic excision of type I and II endometriomas.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Nezhat C, Buescher E, Paka C, et al. Video-assisted laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat’s Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013:265–302.

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(3):511–519.

- Keyhan S, Hughes C, Price T, Muasher S. An update on surgical versus expectant management of ovarian endometriomas in infertile women. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:204792.

- Nezhat F, Nezhat C, Allan CJ, Metzger DA, Sears DL. Clinical and histologic classification of endometriomas. Implications for a mechanism of pathogenesis. J Reprod Med. 1992;37(9):771–776.

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. The pathogenesis of endometriosis. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat’s Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013:252–258.

- Czernobilsky B, Morris WJ. A histologic study of ovarian endometriosis with emphasis on hyperplastic and atypical changes. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53(3):318–323.

- Nezhat F, Nezhat C, Nezhat C, Admon D. A fresh look at ovarian endometriomas. Contemp Ob Gyn. 1994;39(11):81–94.

- Donnez J, Lousse JC, Jadoul P, Donnez O, Squifflet J. Laparoscopic management of endometriomas using a combined technique of excisional (cystectomy) and ablative surgery. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(1):28–32.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, Seidman DS. Classification of endometriosis. Improving the classification of endometriotic ovarian cysts. Hum Reprod. 1994;9(12):2212–2213.

- Nezhat FR, Pejovic T, Reis FM, Guo SW. The link between endometriosis and ovarian cancer: clinical implications. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24(4):623–628.

- Nezhat F, Apostol R, Mahmoud M, el Daouk M. Malignant transformation of endometriosis and its clinical significance. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(2):342–344.

- Nezhat FR, Apostal R, Nezhat C, Pejovic T. New insights in the pathophysiology of ovarian cancer and implications for screening and prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(3):262–267.

- Hart RJ, Hickey M, Maouris P, Buckett W. Excisional surgery versus ablative surgery for ovarian endometriomata. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD004992.

- Yates J. Endometriosis and infertility: expert answers to 6 questions to help pinpoint the best route to pregnancy. OBG Manag. 2015;27(6):30–35.

- Littman E, Giudice L, Lathi R, Berker B, Milki A, Nezhat C. Role of laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis in patients with failed in vitro fertilization cycles. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(6):1574–1578.

- Exacoustos C, Zupi E, Amadio A, et al. Laparoscopic removal of endometriomas: sonographic evaluation of residual functioning ovarian tissue. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(1):68–72.

- Gonçalves FC, Andres MP, Passman LJ, Gonçalves MO, Podgaec S. A systematic review of ultrasonography-guided transvaginal aspiration of recurrent ovarian endometrioma. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;134(1):3–7.

- Alborzi S, Momtahan M, Parsanezhad ME, Dehbashi S, Zolghadri J, Alborzi S. A prospective, randomized study comparing laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy versus fenestration and coagulation in patients with endometriomas. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(6):1633–1637.

- Nezhat C, Crowgey SR, Garrison CP. Surgical treatment of endometriosis via laser laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 1986;45(6):778–783.

- Nezhat C, Buescher E, Paka C, et al. Video-assisted laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat’s Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013:265–302.

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(3):511–519.

- Keyhan S, Hughes C, Price T, Muasher S. An update on surgical versus expectant management of ovarian endometriomas in infertile women. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:204792.

- Nezhat F, Nezhat C, Allan CJ, Metzger DA, Sears DL. Clinical and histologic classification of endometriomas. Implications for a mechanism of pathogenesis. J Reprod Med. 1992;37(9):771–776.

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. The pathogenesis of endometriosis. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat’s Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013:252–258.

- Czernobilsky B, Morris WJ. A histologic study of ovarian endometriosis with emphasis on hyperplastic and atypical changes. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53(3):318–323.

- Nezhat F, Nezhat C, Nezhat C, Admon D. A fresh look at ovarian endometriomas. Contemp Ob Gyn. 1994;39(11):81–94.

- Donnez J, Lousse JC, Jadoul P, Donnez O, Squifflet J. Laparoscopic management of endometriomas using a combined technique of excisional (cystectomy) and ablative surgery. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(1):28–32.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, Seidman DS. Classification of endometriosis. Improving the classification of endometriotic ovarian cysts. Hum Reprod. 1994;9(12):2212–2213.

- Nezhat FR, Pejovic T, Reis FM, Guo SW. The link between endometriosis and ovarian cancer: clinical implications. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24(4):623–628.

- Nezhat F, Apostol R, Mahmoud M, el Daouk M. Malignant transformation of endometriosis and its clinical significance. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(2):342–344.

- Nezhat FR, Apostal R, Nezhat C, Pejovic T. New insights in the pathophysiology of ovarian cancer and implications for screening and prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(3):262–267.

- Hart RJ, Hickey M, Maouris P, Buckett W. Excisional surgery versus ablative surgery for ovarian endometriomata. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD004992.

- Yates J. Endometriosis and infertility: expert answers to 6 questions to help pinpoint the best route to pregnancy. OBG Manag. 2015;27(6):30–35.

- Littman E, Giudice L, Lathi R, Berker B, Milki A, Nezhat C. Role of laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis in patients with failed in vitro fertilization cycles. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(6):1574–1578.

- Exacoustos C, Zupi E, Amadio A, et al. Laparoscopic removal of endometriomas: sonographic evaluation of residual functioning ovarian tissue. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(1):68–72.

- Gonçalves FC, Andres MP, Passman LJ, Gonçalves MO, Podgaec S. A systematic review of ultrasonography-guided transvaginal aspiration of recurrent ovarian endometrioma. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;134(1):3–7.

- Alborzi S, Momtahan M, Parsanezhad ME, Dehbashi S, Zolghadri J, Alborzi S. A prospective, randomized study comparing laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy versus fenestration and coagulation in patients with endometriomas. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(6):1633–1637.

- Nezhat C, Crowgey SR, Garrison CP. Surgical treatment of endometriosis via laser laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 1986;45(6):778–783.

IN THIS ARTICLE

Robot-assisted laparoscopic excision of a rectovaginal endometriotic nodule

A rectovaginal endometriosis (RVE) is the most severe form of endometriosis. The gold standard for diagnosis is laparoscopy with histologic confirmation. A review of the literature suggests that surgery improves up to 70% of symptoms with generally favorable outcomes.

In this video, we provide a general introduction to endometriosis and a discussion of disease treatment options, ranging from hormonal suppression to radical bowel resections. We also illustrate the steps in robot-assisted laparoscopic excision of an RVE nodule:

- identify the borders of the rectosigmoid

- dissect the pararectal spaces

- release the rectosigmoid from its attachment to the RVE nodule

- identify and isolate the ureter(s)

- determine the margins of the nodule

- ensure complete resection.

Excision of an RVE nodule is a technically challenging surgical procedure. Use of the robot for resection is safe and feasible when performed by a trained and experienced surgeon.

I am pleased to bring you this video, and I hope that it is helpful to your practice.

>> Arnold P. Advincula, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

A rectovaginal endometriosis (RVE) is the most severe form of endometriosis. The gold standard for diagnosis is laparoscopy with histologic confirmation. A review of the literature suggests that surgery improves up to 70% of symptoms with generally favorable outcomes.

In this video, we provide a general introduction to endometriosis and a discussion of disease treatment options, ranging from hormonal suppression to radical bowel resections. We also illustrate the steps in robot-assisted laparoscopic excision of an RVE nodule:

- identify the borders of the rectosigmoid

- dissect the pararectal spaces

- release the rectosigmoid from its attachment to the RVE nodule

- identify and isolate the ureter(s)

- determine the margins of the nodule

- ensure complete resection.

Excision of an RVE nodule is a technically challenging surgical procedure. Use of the robot for resection is safe and feasible when performed by a trained and experienced surgeon.

I am pleased to bring you this video, and I hope that it is helpful to your practice.

>> Arnold P. Advincula, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

A rectovaginal endometriosis (RVE) is the most severe form of endometriosis. The gold standard for diagnosis is laparoscopy with histologic confirmation. A review of the literature suggests that surgery improves up to 70% of symptoms with generally favorable outcomes.

In this video, we provide a general introduction to endometriosis and a discussion of disease treatment options, ranging from hormonal suppression to radical bowel resections. We also illustrate the steps in robot-assisted laparoscopic excision of an RVE nodule:

- identify the borders of the rectosigmoid

- dissect the pararectal spaces

- release the rectosigmoid from its attachment to the RVE nodule

- identify and isolate the ureter(s)

- determine the margins of the nodule

- ensure complete resection.

Excision of an RVE nodule is a technically challenging surgical procedure. Use of the robot for resection is safe and feasible when performed by a trained and experienced surgeon.

I am pleased to bring you this video, and I hope that it is helpful to your practice.

>> Arnold P. Advincula, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Why are there delays in the diagnosis of endometriosis?

Endometriosis is a common gynecologic problem in adolescents and women. It often presents with pelvic pain, an ovarian endometrioma, and/or subfertility. In a prospective study of 116,678 nurses, the incidence of a new surgical diagnosis of endometriosis was greatest among women aged 25 to 29 years and lowest among women older than age 44.1 Using the incidence data from this study, the calculated prevalence of endometriosis in this large cohort of women of reproductive age was approximately 8%.

Although endometriosis is known to be a very common gynecologic problem, many studies report that there can be long delays between onset of pelvic pain symptoms and the diagnosis of endometriosis (Figure 1).2−6 Combining the results from 5 studies, involving 1,187 women, the mean age of onset of pelvic pain symptoms was 22.1 years, and the mean age at the diagnosis of endometriosis was 30.7 years. This is a difference of 8.6 years between the age of symptom onset and age at diagnosis.2−6

What factors contribute to the diagnosis delay?

Both patient and physician factors contribute to the reported lengthy delay between symptom onset and endometriosis diagnosis.7,8 Differentiating dysmenorrhea due to primary and secondary causes is difficult for both patients and physicians. Women may conceal the severity of menstrual pain to avoid both the embarrassment of drawing attention to themselves and being stigmatized as unable to cope. Most disappointing is that many women with endometriosis reported that they asked their clinician if endometriosis could be the cause of their severe dysmenorrhea and were told, “No.”7,8

Of interest, the reported delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis is much shorter for women who pre-sent with infertility than for women who present with pelvic pain. In one study from the United States, the delay to diagnosis was 3.13 years for women who presented with infertility and 6.35 years for women who presented with severe pelvic pain.3 This suggests that clinicians and patients more rapidly pursue the diagnosis of endometriosis in women with infertility, but not pelvic pain.

Related article:

Endometriosis: Expert answers to 7 crucial questions on diagnosis

Initial treatment of pelvic pain with NSAIDs and estrogen—progestin contraceptives

Many women with undiagnosed endometriosis present with pelvic pain symptoms including moderate to severe dysmenorrhea. These women are often empirically treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and combination estrogen−progestin contraceptives in either a cyclic or continuous manner.9,10 Since many women with endometriosis will have a reduction in their pelvic pain with NSAID and contraceptive treatment, diagnosis of their endometriosis may be delayed until their disease progresses years after their initial presentation. It is important to gently alert these women to the possibility that they have undiagnosed endometriosis as the cause of their pain symptoms and encourage them to report any worsening pain symptoms in a timely manner.

Sometimes women with pelvic pain are treated with NSAIDs and contraceptives but no significant reduction in pain symptoms occurs. For these women, speedy consideration should be given to offering a laparoscopy to determine the cause of their pain.

Related article:

Avoiding “shotgun” treatment: New thoughts on endometriosis-associated pelvic pain

Diagnosing endometriosis relies on identifying flags in the patient’s history

The gold standard for endometriosis diagnosis is surgical visualization of endometriosis lesions, most often with laparoscopy, plus histologic confirmation of endometriosis on a tissue biopsy.9,10 A key to reducing the time between onset of symptoms and diagnosis of endometriosis is identifying adolescents and women who are at high risk for having the disease. These women should be offered a laparoscopy procedure. In women with moderate to severe pelvic pain of at least 6 months duration, medical history, physical examination, and imaging studies can be helpful in identifying those at increased risk for endometriosis.

Items from the patient history that might raise the likelihood of endometriosis include:

- abdominopelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, subfertility, dyspareunia and/or postcoital bleeding11

- symptoms of dysmenorrhea and/or dyspareunia that are not responsive to NSAIDs or estrogen−progestin contraceptives12

- symptoms of dysmenorrhea and/or dyspareunia associated with absenteeism from school or work13

- multiple visits to the emergency department for severe dysmenorrhea

- endometriosis in the patient’s mother or sister

- subfertility with regular ovulation, patent fallopian tubes, and a partner with a normal semen analysis

- urinary frequency, urgency, and/or pain on urination

- diarrhea, constipation, nausea, dyschezia, bowel cramping, abdominal distention, and early satiety.

A daunting clinical challenge is that symptoms of endometriosis overlap with other gynecologic and nongynecologic problems including pelvic infection, adhesions, ovarian cysts, fibroids, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, interstitial cystitis, myofascial pain, depression, and history of sexual abuse.

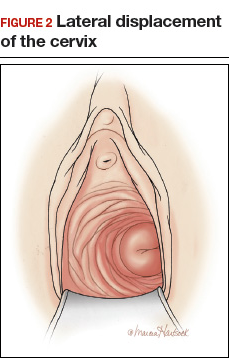

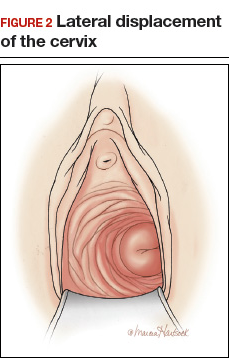

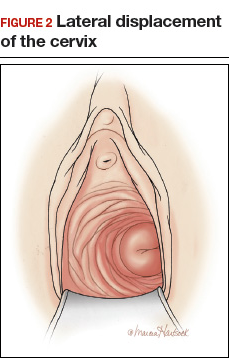

Diagnosing endometriosis relies on identifying flags on physical exam

Physical examination findings that raise the likelihood that the patient has endometriosis include:

- fixed and retroverted uterus

- adnexal mass

- lesions of the cervix or posterior fornix that visually appear to be endometriosis

- uterosacral ligament abnormalities, including tenderness, thickening, and/or nodularity14,15

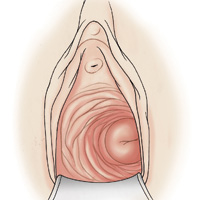

- lateral displacement of the cervix (FIGURE 2)16,17

- severe cervical stenosis.

In one study of 57 women with a surgical diagnosis of endometriosis, uterosacral ligament abnormalities, lateral displacement of the cervix, and cervical stenosis were observed in 47%, 28%, and 19% of the women, respectively.17 In this same study 22 women had none of these findings, but 8 had a complex ovarian mass consistent with endometriosis.

The possibility of endometriosis increases as the number of history and physical examination findings suggestive of endometriosis increase.

Related article:

Endometriosis and pain: Expert answers to 6 questions targeting your management options

When transvaginal ultrasound can aid diagnosis

Most women with endometriosis have normal transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) results because ultrasound cannot detect small isolated peritoneal lesions of endometriosis present in Stage I disease, the most common stage of endometriosis. However, ultrasound is useful in detecting both ovarian endometriomas and nodules of deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE).18 TVUS has excellent sensitivity (>90%) and specificity (>90%) for the detection of ovarian endometriomas because these cysts have characteristic, homogenous, low-level internal echoes.19,20 For the diagnosis of DIE of the uterosacral ligaments and rectovaginal septum, TVUS has fair sensitivity (>50%) and excellent specificity (>90%).21 In most studies, magnetic resonance imaging performs no better than TVUS for imaging ovarian endometriomas and DIE. Hence, TVUS is the preferred imaging modality for detecting endometriosis.22

- Endometriosis is a common gynecologic disease. Approximately 8% of women of reproductive age have the condition.

- Many patients report lengthy delays between the onset of symptoms of pelvic pain and the diagnosis of endometriosis.

- Both patients and clinicians contribute to the delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis: Women are often reluctant to report the severity of their pelvic pain symptoms, and clinicians often under-respond to a patient's report of severe pelvic pain symptoms.

- First-line therapy for the treatment of moderate to severe dysmenorrhea is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and estrogen−progestin contraceptives.

- Increasing vigilance for endometriosis will shorten the time between onset of symptoms and definitive diagnosis.

- Reducing the time between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis of endometriosis will improve the quality of life of women with the disease because they will receive timely treatment.

This is a practice gap we can close

Clinicians take great pride in accurately solving patient problems in a timely and efficient manner. Substantial research indicates that we can improve the timeliness of our diagnosis of endometriosis. By acknowledging patients’ pain symptoms and recognizing the myriad symptoms and physical examination and imaging findings that are associated with endometriosis, we will close the gap and make this diagnosis with greater speed.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Marshall LM, Hunter DJ. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(8):784−796.

- Hadfield R, Mardon H, Barlow D, Kennedy S. Delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a survey of women from the USA and UK. Hum Reprod. 1996;11(4):878−880.

- Dmowski WP, Lesniewicz R, Rana N, Pepping P, Noursalehi M. Changing trends in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a comparative study of women with pelvic endometriosis presenting with chronic pelvic pain or infertility. Fertil Steril. 1997;67(2):238−243.

- Arruda MS, Petta CA, Abrão MS, Benetti-Pinto CL. Time elapsed from onset of symptoms to diagnosis of endometriosis in a cohort study of Brazilian women. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(4):756−759.

- Husby GK, Haugen RS, Moen MH. Diagnostic delay in women with pain and endometriosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(7):649−653.

- Hudelist G, Fritzer N, Thomas A, et al. Diagnostic delay for endometriosis in Austria and Germany: causes and possible consequences. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(12):3412−3416.

- Ballard K, Lowton K, Wright J. What's the delay? A qualitative study of women's experiences of reaching a diagnosis of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(5):1296−1301.

- Seear K. The etiquette of endometriosis: stigmatisation, menstrual concealment and the diagnostic delay. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(8):1220−1227.

- Falcone T, Lebovic DI. Clinical management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):691−705.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 114: Management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):223−236.

- Ballard KD, Seaman HE, de Vries CS, Wright JT. Can symptomatology help in the diagnosis of endometriosis? Findings from a national case-control study--Part 1. BJOG. 2008;115(11):1382−1391.

- Steenberg CK, Tanbo TG, Qvigstad E. Endometriosis in adolescence: predictive markers and management. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92(5):491−495.

- Zannoni L, Giorgi M, Spagnolo E, Montanari G, Villa G, Seracchioli R. Dysmenorrhea, absenteeism from school, and symptoms suspicious for endometriosis in adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2014;27(5):258−265.

- Cheewadhanaraks S, Peeyananjarassri K, Dhanaworavibul K, Liabsuetrakul T. Positive predictive value of clinical diagnosis of endometriosis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87(7):740−744.

- Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Gerada M, Virgilio B, Angioni S, Melis GB. Diagnostic value of transvaginal 'tenderness-guided' ultrasonography for the prediction of location of deep endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(11):2452−2457.

- Propst AM, Storti K, Barbieri RL. Lateral cervical displacement is associated with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1998;70(3):568−570.

- Barbieri RL, Propst AM. Physical examination findings in women with endometriosis: uterosacral ligament abnormalities, lateral cervical displacement and cervical stenosis. J Gynecol Techniques. 1999;5:157−159.

- Guerriero S, Condous G, van den Bosch T, et al. Systematic approach to sonographic evaluation of the pelvis in women with suspected endometriosis, including terms, definitions and measurements: a consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(3):318−332.

- Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PM, Farquhar C, Johnson N, Hull ML. Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009591.

- Somigliana E, Vercellini P, Vigano P, Benaglia L, Crosignani PG, Fedele L. Non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis: the goal or own goal? Hum Reprod. 2010;25(8):1863−1868.

- Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Minguez JA, et al. Accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound for diagnosis of deep endometriosis in uterosacral ligaments, rectovaginal septum, vagina and bladder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46(5):534−545.

- Benacerraf BR, Groszmann Y. Sonography should be the first imaging examination done to evaluate patients with suspected endometriosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(4):651−653.

Endometriosis is a common gynecologic problem in adolescents and women. It often presents with pelvic pain, an ovarian endometrioma, and/or subfertility. In a prospective study of 116,678 nurses, the incidence of a new surgical diagnosis of endometriosis was greatest among women aged 25 to 29 years and lowest among women older than age 44.1 Using the incidence data from this study, the calculated prevalence of endometriosis in this large cohort of women of reproductive age was approximately 8%.

Although endometriosis is known to be a very common gynecologic problem, many studies report that there can be long delays between onset of pelvic pain symptoms and the diagnosis of endometriosis (Figure 1).2−6 Combining the results from 5 studies, involving 1,187 women, the mean age of onset of pelvic pain symptoms was 22.1 years, and the mean age at the diagnosis of endometriosis was 30.7 years. This is a difference of 8.6 years between the age of symptom onset and age at diagnosis.2−6

What factors contribute to the diagnosis delay?

Both patient and physician factors contribute to the reported lengthy delay between symptom onset and endometriosis diagnosis.7,8 Differentiating dysmenorrhea due to primary and secondary causes is difficult for both patients and physicians. Women may conceal the severity of menstrual pain to avoid both the embarrassment of drawing attention to themselves and being stigmatized as unable to cope. Most disappointing is that many women with endometriosis reported that they asked their clinician if endometriosis could be the cause of their severe dysmenorrhea and were told, “No.”7,8

Of interest, the reported delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis is much shorter for women who pre-sent with infertility than for women who present with pelvic pain. In one study from the United States, the delay to diagnosis was 3.13 years for women who presented with infertility and 6.35 years for women who presented with severe pelvic pain.3 This suggests that clinicians and patients more rapidly pursue the diagnosis of endometriosis in women with infertility, but not pelvic pain.

Related article:

Endometriosis: Expert answers to 7 crucial questions on diagnosis

Initial treatment of pelvic pain with NSAIDs and estrogen—progestin contraceptives

Many women with undiagnosed endometriosis present with pelvic pain symptoms including moderate to severe dysmenorrhea. These women are often empirically treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and combination estrogen−progestin contraceptives in either a cyclic or continuous manner.9,10 Since many women with endometriosis will have a reduction in their pelvic pain with NSAID and contraceptive treatment, diagnosis of their endometriosis may be delayed until their disease progresses years after their initial presentation. It is important to gently alert these women to the possibility that they have undiagnosed endometriosis as the cause of their pain symptoms and encourage them to report any worsening pain symptoms in a timely manner.

Sometimes women with pelvic pain are treated with NSAIDs and contraceptives but no significant reduction in pain symptoms occurs. For these women, speedy consideration should be given to offering a laparoscopy to determine the cause of their pain.

Related article:

Avoiding “shotgun” treatment: New thoughts on endometriosis-associated pelvic pain

Diagnosing endometriosis relies on identifying flags in the patient’s history

The gold standard for endometriosis diagnosis is surgical visualization of endometriosis lesions, most often with laparoscopy, plus histologic confirmation of endometriosis on a tissue biopsy.9,10 A key to reducing the time between onset of symptoms and diagnosis of endometriosis is identifying adolescents and women who are at high risk for having the disease. These women should be offered a laparoscopy procedure. In women with moderate to severe pelvic pain of at least 6 months duration, medical history, physical examination, and imaging studies can be helpful in identifying those at increased risk for endometriosis.

Items from the patient history that might raise the likelihood of endometriosis include:

- abdominopelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, subfertility, dyspareunia and/or postcoital bleeding11

- symptoms of dysmenorrhea and/or dyspareunia that are not responsive to NSAIDs or estrogen−progestin contraceptives12

- symptoms of dysmenorrhea and/or dyspareunia associated with absenteeism from school or work13

- multiple visits to the emergency department for severe dysmenorrhea

- endometriosis in the patient’s mother or sister

- subfertility with regular ovulation, patent fallopian tubes, and a partner with a normal semen analysis

- urinary frequency, urgency, and/or pain on urination

- diarrhea, constipation, nausea, dyschezia, bowel cramping, abdominal distention, and early satiety.

A daunting clinical challenge is that symptoms of endometriosis overlap with other gynecologic and nongynecologic problems including pelvic infection, adhesions, ovarian cysts, fibroids, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, interstitial cystitis, myofascial pain, depression, and history of sexual abuse.

Diagnosing endometriosis relies on identifying flags on physical exam

Physical examination findings that raise the likelihood that the patient has endometriosis include:

- fixed and retroverted uterus

- adnexal mass

- lesions of the cervix or posterior fornix that visually appear to be endometriosis

- uterosacral ligament abnormalities, including tenderness, thickening, and/or nodularity14,15

- lateral displacement of the cervix (FIGURE 2)16,17

- severe cervical stenosis.

In one study of 57 women with a surgical diagnosis of endometriosis, uterosacral ligament abnormalities, lateral displacement of the cervix, and cervical stenosis were observed in 47%, 28%, and 19% of the women, respectively.17 In this same study 22 women had none of these findings, but 8 had a complex ovarian mass consistent with endometriosis.

The possibility of endometriosis increases as the number of history and physical examination findings suggestive of endometriosis increase.

Related article:

Endometriosis and pain: Expert answers to 6 questions targeting your management options

When transvaginal ultrasound can aid diagnosis

Most women with endometriosis have normal transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) results because ultrasound cannot detect small isolated peritoneal lesions of endometriosis present in Stage I disease, the most common stage of endometriosis. However, ultrasound is useful in detecting both ovarian endometriomas and nodules of deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE).18 TVUS has excellent sensitivity (>90%) and specificity (>90%) for the detection of ovarian endometriomas because these cysts have characteristic, homogenous, low-level internal echoes.19,20 For the diagnosis of DIE of the uterosacral ligaments and rectovaginal septum, TVUS has fair sensitivity (>50%) and excellent specificity (>90%).21 In most studies, magnetic resonance imaging performs no better than TVUS for imaging ovarian endometriomas and DIE. Hence, TVUS is the preferred imaging modality for detecting endometriosis.22

- Endometriosis is a common gynecologic disease. Approximately 8% of women of reproductive age have the condition.

- Many patients report lengthy delays between the onset of symptoms of pelvic pain and the diagnosis of endometriosis.

- Both patients and clinicians contribute to the delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis: Women are often reluctant to report the severity of their pelvic pain symptoms, and clinicians often under-respond to a patient's report of severe pelvic pain symptoms.

- First-line therapy for the treatment of moderate to severe dysmenorrhea is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and estrogen−progestin contraceptives.

- Increasing vigilance for endometriosis will shorten the time between onset of symptoms and definitive diagnosis.

- Reducing the time between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis of endometriosis will improve the quality of life of women with the disease because they will receive timely treatment.

This is a practice gap we can close

Clinicians take great pride in accurately solving patient problems in a timely and efficient manner. Substantial research indicates that we can improve the timeliness of our diagnosis of endometriosis. By acknowledging patients’ pain symptoms and recognizing the myriad symptoms and physical examination and imaging findings that are associated with endometriosis, we will close the gap and make this diagnosis with greater speed.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Endometriosis is a common gynecologic problem in adolescents and women. It often presents with pelvic pain, an ovarian endometrioma, and/or subfertility. In a prospective study of 116,678 nurses, the incidence of a new surgical diagnosis of endometriosis was greatest among women aged 25 to 29 years and lowest among women older than age 44.1 Using the incidence data from this study, the calculated prevalence of endometriosis in this large cohort of women of reproductive age was approximately 8%.

Although endometriosis is known to be a very common gynecologic problem, many studies report that there can be long delays between onset of pelvic pain symptoms and the diagnosis of endometriosis (Figure 1).2−6 Combining the results from 5 studies, involving 1,187 women, the mean age of onset of pelvic pain symptoms was 22.1 years, and the mean age at the diagnosis of endometriosis was 30.7 years. This is a difference of 8.6 years between the age of symptom onset and age at diagnosis.2−6

What factors contribute to the diagnosis delay?

Both patient and physician factors contribute to the reported lengthy delay between symptom onset and endometriosis diagnosis.7,8 Differentiating dysmenorrhea due to primary and secondary causes is difficult for both patients and physicians. Women may conceal the severity of menstrual pain to avoid both the embarrassment of drawing attention to themselves and being stigmatized as unable to cope. Most disappointing is that many women with endometriosis reported that they asked their clinician if endometriosis could be the cause of their severe dysmenorrhea and were told, “No.”7,8

Of interest, the reported delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis is much shorter for women who pre-sent with infertility than for women who present with pelvic pain. In one study from the United States, the delay to diagnosis was 3.13 years for women who presented with infertility and 6.35 years for women who presented with severe pelvic pain.3 This suggests that clinicians and patients more rapidly pursue the diagnosis of endometriosis in women with infertility, but not pelvic pain.

Related article:

Endometriosis: Expert answers to 7 crucial questions on diagnosis

Initial treatment of pelvic pain with NSAIDs and estrogen—progestin contraceptives

Many women with undiagnosed endometriosis present with pelvic pain symptoms including moderate to severe dysmenorrhea. These women are often empirically treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and combination estrogen−progestin contraceptives in either a cyclic or continuous manner.9,10 Since many women with endometriosis will have a reduction in their pelvic pain with NSAID and contraceptive treatment, diagnosis of their endometriosis may be delayed until their disease progresses years after their initial presentation. It is important to gently alert these women to the possibility that they have undiagnosed endometriosis as the cause of their pain symptoms and encourage them to report any worsening pain symptoms in a timely manner.

Sometimes women with pelvic pain are treated with NSAIDs and contraceptives but no significant reduction in pain symptoms occurs. For these women, speedy consideration should be given to offering a laparoscopy to determine the cause of their pain.

Related article:

Avoiding “shotgun” treatment: New thoughts on endometriosis-associated pelvic pain

Diagnosing endometriosis relies on identifying flags in the patient’s history

The gold standard for endometriosis diagnosis is surgical visualization of endometriosis lesions, most often with laparoscopy, plus histologic confirmation of endometriosis on a tissue biopsy.9,10 A key to reducing the time between onset of symptoms and diagnosis of endometriosis is identifying adolescents and women who are at high risk for having the disease. These women should be offered a laparoscopy procedure. In women with moderate to severe pelvic pain of at least 6 months duration, medical history, physical examination, and imaging studies can be helpful in identifying those at increased risk for endometriosis.

Items from the patient history that might raise the likelihood of endometriosis include:

- abdominopelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, subfertility, dyspareunia and/or postcoital bleeding11

- symptoms of dysmenorrhea and/or dyspareunia that are not responsive to NSAIDs or estrogen−progestin contraceptives12

- symptoms of dysmenorrhea and/or dyspareunia associated with absenteeism from school or work13

- multiple visits to the emergency department for severe dysmenorrhea

- endometriosis in the patient’s mother or sister

- subfertility with regular ovulation, patent fallopian tubes, and a partner with a normal semen analysis

- urinary frequency, urgency, and/or pain on urination

- diarrhea, constipation, nausea, dyschezia, bowel cramping, abdominal distention, and early satiety.

A daunting clinical challenge is that symptoms of endometriosis overlap with other gynecologic and nongynecologic problems including pelvic infection, adhesions, ovarian cysts, fibroids, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, interstitial cystitis, myofascial pain, depression, and history of sexual abuse.

Diagnosing endometriosis relies on identifying flags on physical exam

Physical examination findings that raise the likelihood that the patient has endometriosis include:

- fixed and retroverted uterus

- adnexal mass

- lesions of the cervix or posterior fornix that visually appear to be endometriosis

- uterosacral ligament abnormalities, including tenderness, thickening, and/or nodularity14,15

- lateral displacement of the cervix (FIGURE 2)16,17

- severe cervical stenosis.

In one study of 57 women with a surgical diagnosis of endometriosis, uterosacral ligament abnormalities, lateral displacement of the cervix, and cervical stenosis were observed in 47%, 28%, and 19% of the women, respectively.17 In this same study 22 women had none of these findings, but 8 had a complex ovarian mass consistent with endometriosis.

The possibility of endometriosis increases as the number of history and physical examination findings suggestive of endometriosis increase.

Related article:

Endometriosis and pain: Expert answers to 6 questions targeting your management options

When transvaginal ultrasound can aid diagnosis

Most women with endometriosis have normal transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) results because ultrasound cannot detect small isolated peritoneal lesions of endometriosis present in Stage I disease, the most common stage of endometriosis. However, ultrasound is useful in detecting both ovarian endometriomas and nodules of deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE).18 TVUS has excellent sensitivity (>90%) and specificity (>90%) for the detection of ovarian endometriomas because these cysts have characteristic, homogenous, low-level internal echoes.19,20 For the diagnosis of DIE of the uterosacral ligaments and rectovaginal septum, TVUS has fair sensitivity (>50%) and excellent specificity (>90%).21 In most studies, magnetic resonance imaging performs no better than TVUS for imaging ovarian endometriomas and DIE. Hence, TVUS is the preferred imaging modality for detecting endometriosis.22

- Endometriosis is a common gynecologic disease. Approximately 8% of women of reproductive age have the condition.

- Many patients report lengthy delays between the onset of symptoms of pelvic pain and the diagnosis of endometriosis.

- Both patients and clinicians contribute to the delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis: Women are often reluctant to report the severity of their pelvic pain symptoms, and clinicians often under-respond to a patient's report of severe pelvic pain symptoms.

- First-line therapy for the treatment of moderate to severe dysmenorrhea is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and estrogen−progestin contraceptives.

- Increasing vigilance for endometriosis will shorten the time between onset of symptoms and definitive diagnosis.