User login

DoD ‘Taking all Necessary Precautions’ Against COVID-19

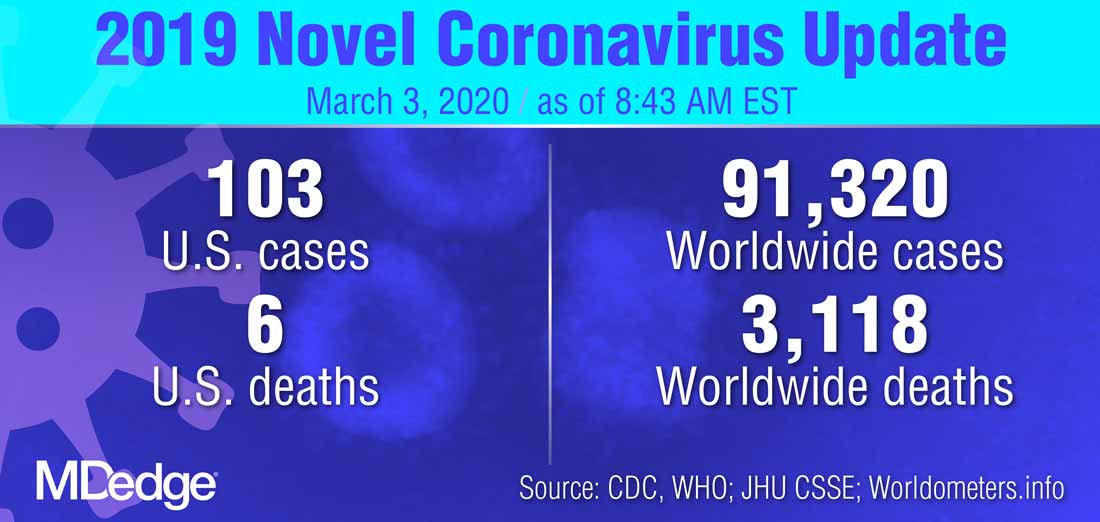

In late February, a soldier stationed at Camp Carroll near Daegu, South Korea, was the first military member to test positive for the coronavirus (COVID-19). Before being diagnosed, he visited other areas, including Camp Walker in Daegu, according to a statement released by US Forces Korea. More than 75,000 troops are stationed in countries with virus outbreaks, including Japan, Italy, and Bahrain.

Military research laboratories are working “feverishly around the horn” to come up with a vaccine, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Gen. Mark A. Milley said in a March 2, 2020, news conference. At the same conference, Defense Secretary Mark T. Esper, MD, said US Department of Defense (DoD) civilian and military leadership are working together to prepare for short-and long-term scenarios.

The US Northern Command is the “global integrator,” Esper said, with the DoD communicating regularly with operational commanders to assess how the virus might impact exercises and ongoing operations around the world. For example, a command post exercise in South Korea has been postponed; Exercise Cobra Gold in Thailand is continuing.

Commanders are taking all necessary precautions because the virus is unique to every situation and every location, Esper said: “We’re relying on them to make good judgments.”

He emphasized that commanders at all levels have the authority and guidance they need to operate. In a late February video teleconference, Esper had told commanders deployed overseas that he wanted them to give him a heads-up before making decisions related to protecting their troops, according to The New York Times.

The New York Times article cited an exchange in which Gen. Robert Abrams, commander of American forces in South Korea, where > 4,000 coronavirus cases have been confirmed, discussed his options to protect American military personnel against the virus. Esper said he wanted advance notice, according to an official briefed on the call and quoted in the Times article. Gen. Abrams said although he would try to give Sec. Esper advance warning, he might have to make urgent health decisions before receiving final approval from Washington.

In a statement responding to the Times article, Jonathan Hoffman, Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs, said the Secretary of Defense has given the Global Combatant Commanders the “clear and unequivocal authority” to take any and all actions necessary to ensure the health and safety of US service members, civilian DoD personnel, families, and dependents.

In the video teleconference, Hoffman said, Secretary Espers “directed commanders to take all force health protection measures, and to notify their chain of command when actions are taken so that DoD leadership can inform the interagency—including US Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Department of Homeland Security, the State Department, and the White House—and the American people.” Esper “explicitly did not direct them to ‘clear’ their force health decisions in advance,” Hoffman said. “[T]hat is a dangerous and inaccurate mischaracterization.”

In January, the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense released a memorandum on force health protection guidance for the coronavirus outbreak. The DoD, it says, will follow the CDC guidance and will “closely coordinate with interagency partners to ensure accurate and timely information is available.”

“An informed, common-sense approach minimizes the chances of getting sick,” military health officials say. But, “due to the dynamic nature of this outbreak,” people should frequently check the CDC website for additional updates. Related Military Health System information and links to the CDC are available at https://www.health.mil/News/In-the-Spotlight/Coronavirus.

The CDC provides a summary of its latest recommendations and DoD health care providers can access COVID-19–specific guidance, including information on evaluating “persons under investigation,” at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/clinical-criteria.html.

Sec. Esper, in the Monday news conference, said, “My number-one priority remains to protect our forces and their families; second is to safeguard our mission capabilities and third [is] to support the interagency whole-of-government’s approach. We will continue to take all necessary precautions to ensure that our people are safe and able to continue their very important mission.”

In late February, a soldier stationed at Camp Carroll near Daegu, South Korea, was the first military member to test positive for the coronavirus (COVID-19). Before being diagnosed, he visited other areas, including Camp Walker in Daegu, according to a statement released by US Forces Korea. More than 75,000 troops are stationed in countries with virus outbreaks, including Japan, Italy, and Bahrain.

Military research laboratories are working “feverishly around the horn” to come up with a vaccine, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Gen. Mark A. Milley said in a March 2, 2020, news conference. At the same conference, Defense Secretary Mark T. Esper, MD, said US Department of Defense (DoD) civilian and military leadership are working together to prepare for short-and long-term scenarios.

The US Northern Command is the “global integrator,” Esper said, with the DoD communicating regularly with operational commanders to assess how the virus might impact exercises and ongoing operations around the world. For example, a command post exercise in South Korea has been postponed; Exercise Cobra Gold in Thailand is continuing.

Commanders are taking all necessary precautions because the virus is unique to every situation and every location, Esper said: “We’re relying on them to make good judgments.”

He emphasized that commanders at all levels have the authority and guidance they need to operate. In a late February video teleconference, Esper had told commanders deployed overseas that he wanted them to give him a heads-up before making decisions related to protecting their troops, according to The New York Times.

The New York Times article cited an exchange in which Gen. Robert Abrams, commander of American forces in South Korea, where > 4,000 coronavirus cases have been confirmed, discussed his options to protect American military personnel against the virus. Esper said he wanted advance notice, according to an official briefed on the call and quoted in the Times article. Gen. Abrams said although he would try to give Sec. Esper advance warning, he might have to make urgent health decisions before receiving final approval from Washington.

In a statement responding to the Times article, Jonathan Hoffman, Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs, said the Secretary of Defense has given the Global Combatant Commanders the “clear and unequivocal authority” to take any and all actions necessary to ensure the health and safety of US service members, civilian DoD personnel, families, and dependents.

In the video teleconference, Hoffman said, Secretary Espers “directed commanders to take all force health protection measures, and to notify their chain of command when actions are taken so that DoD leadership can inform the interagency—including US Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Department of Homeland Security, the State Department, and the White House—and the American people.” Esper “explicitly did not direct them to ‘clear’ their force health decisions in advance,” Hoffman said. “[T]hat is a dangerous and inaccurate mischaracterization.”

In January, the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense released a memorandum on force health protection guidance for the coronavirus outbreak. The DoD, it says, will follow the CDC guidance and will “closely coordinate with interagency partners to ensure accurate and timely information is available.”

“An informed, common-sense approach minimizes the chances of getting sick,” military health officials say. But, “due to the dynamic nature of this outbreak,” people should frequently check the CDC website for additional updates. Related Military Health System information and links to the CDC are available at https://www.health.mil/News/In-the-Spotlight/Coronavirus.

The CDC provides a summary of its latest recommendations and DoD health care providers can access COVID-19–specific guidance, including information on evaluating “persons under investigation,” at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/clinical-criteria.html.

Sec. Esper, in the Monday news conference, said, “My number-one priority remains to protect our forces and their families; second is to safeguard our mission capabilities and third [is] to support the interagency whole-of-government’s approach. We will continue to take all necessary precautions to ensure that our people are safe and able to continue their very important mission.”

In late February, a soldier stationed at Camp Carroll near Daegu, South Korea, was the first military member to test positive for the coronavirus (COVID-19). Before being diagnosed, he visited other areas, including Camp Walker in Daegu, according to a statement released by US Forces Korea. More than 75,000 troops are stationed in countries with virus outbreaks, including Japan, Italy, and Bahrain.

Military research laboratories are working “feverishly around the horn” to come up with a vaccine, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Gen. Mark A. Milley said in a March 2, 2020, news conference. At the same conference, Defense Secretary Mark T. Esper, MD, said US Department of Defense (DoD) civilian and military leadership are working together to prepare for short-and long-term scenarios.

The US Northern Command is the “global integrator,” Esper said, with the DoD communicating regularly with operational commanders to assess how the virus might impact exercises and ongoing operations around the world. For example, a command post exercise in South Korea has been postponed; Exercise Cobra Gold in Thailand is continuing.

Commanders are taking all necessary precautions because the virus is unique to every situation and every location, Esper said: “We’re relying on them to make good judgments.”

He emphasized that commanders at all levels have the authority and guidance they need to operate. In a late February video teleconference, Esper had told commanders deployed overseas that he wanted them to give him a heads-up before making decisions related to protecting their troops, according to The New York Times.

The New York Times article cited an exchange in which Gen. Robert Abrams, commander of American forces in South Korea, where > 4,000 coronavirus cases have been confirmed, discussed his options to protect American military personnel against the virus. Esper said he wanted advance notice, according to an official briefed on the call and quoted in the Times article. Gen. Abrams said although he would try to give Sec. Esper advance warning, he might have to make urgent health decisions before receiving final approval from Washington.

In a statement responding to the Times article, Jonathan Hoffman, Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs, said the Secretary of Defense has given the Global Combatant Commanders the “clear and unequivocal authority” to take any and all actions necessary to ensure the health and safety of US service members, civilian DoD personnel, families, and dependents.

In the video teleconference, Hoffman said, Secretary Espers “directed commanders to take all force health protection measures, and to notify their chain of command when actions are taken so that DoD leadership can inform the interagency—including US Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Department of Homeland Security, the State Department, and the White House—and the American people.” Esper “explicitly did not direct them to ‘clear’ their force health decisions in advance,” Hoffman said. “[T]hat is a dangerous and inaccurate mischaracterization.”

In January, the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense released a memorandum on force health protection guidance for the coronavirus outbreak. The DoD, it says, will follow the CDC guidance and will “closely coordinate with interagency partners to ensure accurate and timely information is available.”

“An informed, common-sense approach minimizes the chances of getting sick,” military health officials say. But, “due to the dynamic nature of this outbreak,” people should frequently check the CDC website for additional updates. Related Military Health System information and links to the CDC are available at https://www.health.mil/News/In-the-Spotlight/Coronavirus.

The CDC provides a summary of its latest recommendations and DoD health care providers can access COVID-19–specific guidance, including information on evaluating “persons under investigation,” at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/clinical-criteria.html.

Sec. Esper, in the Monday news conference, said, “My number-one priority remains to protect our forces and their families; second is to safeguard our mission capabilities and third [is] to support the interagency whole-of-government’s approach. We will continue to take all necessary precautions to ensure that our people are safe and able to continue their very important mission.”

FDA moves to expand coronavirus testing capacity; CDC clarifies testing criteria

The White House Coronavirus Task Force appeared at a press briefing March 2 to provide updates about testing strategies and public health coordination to address the current outbreak of the coronavirus COVID-19. Speaking at the briefing, led by Vice President Mike Pence, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) director Robert Redfield, MD, said, “Working with our public health partners we continue to be able to identify new community cases and use our public health efforts to aggressively confirm, isolate, and do contact tracking.” Calling state, local, tribal, and territorial public health departments “the backbone of the public health system in our country,” Dr. Redfield noted that he expected many more confirmed COVID-19 cases to emerge.

At least some of the expected increase in confirmed cases of COVID-19 will occur because of expanded testing capacity, noted several of the task force members. On Feb. 29, the Food and Drug Administration issued a the virus that is causing the current outbreak of COVID-19.

Highly qualified laboratories, including both those run by public agencies and private labs, are now authorized to begin using their own validated test for the virus as long as they submit an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to the Food and Drug Administration within 15 days of notifying the agency of validation.

“To effectively respond to the COVID-19 outbreak, rapid detection of cases and contacts, appropriate clinical management and infection control, and implementation of community mitigation efforts are critical. This can best be achieved with wide availability of testing capabilities in health care settings, reference and commercial laboratories, and at the point of care,” the agency wrote in a press announcement of the expedited test expansion.

On Feb. 4, the Secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services declared a coronavirus public health emergency. The FDA was then authorized to allow individual laboratories with validated coronavirus tests to begin testing samples immediately. The goal is a more rapid and expanded testing capacity in the United States.

“The global emergence of COVID-19 is concerning, and we appreciate the efforts of the FDA to help bring more testing capability to the U.S.,” Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), said in the press release.

The new guidance that permits the immediate use of clinical tests after individual development and validation, said the FDA, only applies to labs already certified to perform high complexity testing under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments. Many governmental, academic, and private laboratories fall into this category, however.

“Under this policy, we expect certain laboratories who develop validated tests for coronavirus would begin using them right away prior to FDA review,” said Jeffrey Shuren, MD, JD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health. “We believe this action will support laboratories across the country working on this urgent public health situation,” he added in the press release.

“By the end of this week, close to a million tests will be available,” FDA Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, said during the March 2 briefing.*

Updated criteria

The CDC is maintaining updated criteria for the virus testing on its website. Testing criteria are based both on clinical features and epidemiologic risk.

Individuals with less severe clinical features – those who have either fever or signs and symptoms of lower respiratory disease such as cough or shortness of breath, but who don’t require hospitalization – should be tested if they have high epidemiologic risk. “High risk” is defined by the CDC as any individual, including health care workers, who has had close contact with a person with confirmed COVID-19 within the past 2 weeks. For health care workers, testing can be considered even if they have relatively mild respiratory symptoms or have had contact with a person who is suspected, but not yet confirmed, to have coronavirus.

In its testing guidance, the CDC recognizes that defining close contact is difficult. General guidelines are that individuals are considered to have been in close contact with a person who has COVID-19 if they were within about six feet of the person for a prolonged period, or cared for or have spent a prolonged amount of time in the same room or house as a person with confirmed COVID-19.

Individuals who have both fever and signs or symptoms of lower respiratory illness who require hospitalization should be tested if they have a history of travel from any affected geographic area within 14 days of the onset of their symptoms. The CDC now defines “affected geographic area” as any country or region that has at least a CDC Level 2 Travel Health Notice for COVID-19, so that the testing criteria themselves don’t need to be updated when new geographic areas are included in these alerts. As of March 3, China, Iran, Italy, Japan, and South Korea all have Level 2 or 3 travel alerts.

The CDC now recommends that any patient who has severe acute lower respiratory illness that requires hospitalization and doesn’t have an alternative diagnosis should be tested, even without any identified source of exposure.

“Despite seeing these new cases, the risk to the American people is low,” said the CDC’s Dr. Redfield. In response to a question from the press about how fast the coronavirus will spread across the United States, Dr. Redfield said, “From the beginning we’ve anticipated seeing community cases pop up.” He added that as these cases arise, testing and public health strategies will focus on unearthing linkages and contacts to learn how the virus is spreading. “We’ll use the public health strategies that we can to limit that transmission,” he said.

*An earlier version of this article misattributed this quote.

The White House Coronavirus Task Force appeared at a press briefing March 2 to provide updates about testing strategies and public health coordination to address the current outbreak of the coronavirus COVID-19. Speaking at the briefing, led by Vice President Mike Pence, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) director Robert Redfield, MD, said, “Working with our public health partners we continue to be able to identify new community cases and use our public health efforts to aggressively confirm, isolate, and do contact tracking.” Calling state, local, tribal, and territorial public health departments “the backbone of the public health system in our country,” Dr. Redfield noted that he expected many more confirmed COVID-19 cases to emerge.

At least some of the expected increase in confirmed cases of COVID-19 will occur because of expanded testing capacity, noted several of the task force members. On Feb. 29, the Food and Drug Administration issued a the virus that is causing the current outbreak of COVID-19.

Highly qualified laboratories, including both those run by public agencies and private labs, are now authorized to begin using their own validated test for the virus as long as they submit an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to the Food and Drug Administration within 15 days of notifying the agency of validation.

“To effectively respond to the COVID-19 outbreak, rapid detection of cases and contacts, appropriate clinical management and infection control, and implementation of community mitigation efforts are critical. This can best be achieved with wide availability of testing capabilities in health care settings, reference and commercial laboratories, and at the point of care,” the agency wrote in a press announcement of the expedited test expansion.

On Feb. 4, the Secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services declared a coronavirus public health emergency. The FDA was then authorized to allow individual laboratories with validated coronavirus tests to begin testing samples immediately. The goal is a more rapid and expanded testing capacity in the United States.

“The global emergence of COVID-19 is concerning, and we appreciate the efforts of the FDA to help bring more testing capability to the U.S.,” Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), said in the press release.

The new guidance that permits the immediate use of clinical tests after individual development and validation, said the FDA, only applies to labs already certified to perform high complexity testing under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments. Many governmental, academic, and private laboratories fall into this category, however.

“Under this policy, we expect certain laboratories who develop validated tests for coronavirus would begin using them right away prior to FDA review,” said Jeffrey Shuren, MD, JD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health. “We believe this action will support laboratories across the country working on this urgent public health situation,” he added in the press release.

“By the end of this week, close to a million tests will be available,” FDA Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, said during the March 2 briefing.*

Updated criteria

The CDC is maintaining updated criteria for the virus testing on its website. Testing criteria are based both on clinical features and epidemiologic risk.

Individuals with less severe clinical features – those who have either fever or signs and symptoms of lower respiratory disease such as cough or shortness of breath, but who don’t require hospitalization – should be tested if they have high epidemiologic risk. “High risk” is defined by the CDC as any individual, including health care workers, who has had close contact with a person with confirmed COVID-19 within the past 2 weeks. For health care workers, testing can be considered even if they have relatively mild respiratory symptoms or have had contact with a person who is suspected, but not yet confirmed, to have coronavirus.

In its testing guidance, the CDC recognizes that defining close contact is difficult. General guidelines are that individuals are considered to have been in close contact with a person who has COVID-19 if they were within about six feet of the person for a prolonged period, or cared for or have spent a prolonged amount of time in the same room or house as a person with confirmed COVID-19.

Individuals who have both fever and signs or symptoms of lower respiratory illness who require hospitalization should be tested if they have a history of travel from any affected geographic area within 14 days of the onset of their symptoms. The CDC now defines “affected geographic area” as any country or region that has at least a CDC Level 2 Travel Health Notice for COVID-19, so that the testing criteria themselves don’t need to be updated when new geographic areas are included in these alerts. As of March 3, China, Iran, Italy, Japan, and South Korea all have Level 2 or 3 travel alerts.

The CDC now recommends that any patient who has severe acute lower respiratory illness that requires hospitalization and doesn’t have an alternative diagnosis should be tested, even without any identified source of exposure.

“Despite seeing these new cases, the risk to the American people is low,” said the CDC’s Dr. Redfield. In response to a question from the press about how fast the coronavirus will spread across the United States, Dr. Redfield said, “From the beginning we’ve anticipated seeing community cases pop up.” He added that as these cases arise, testing and public health strategies will focus on unearthing linkages and contacts to learn how the virus is spreading. “We’ll use the public health strategies that we can to limit that transmission,” he said.

*An earlier version of this article misattributed this quote.

The White House Coronavirus Task Force appeared at a press briefing March 2 to provide updates about testing strategies and public health coordination to address the current outbreak of the coronavirus COVID-19. Speaking at the briefing, led by Vice President Mike Pence, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) director Robert Redfield, MD, said, “Working with our public health partners we continue to be able to identify new community cases and use our public health efforts to aggressively confirm, isolate, and do contact tracking.” Calling state, local, tribal, and territorial public health departments “the backbone of the public health system in our country,” Dr. Redfield noted that he expected many more confirmed COVID-19 cases to emerge.

At least some of the expected increase in confirmed cases of COVID-19 will occur because of expanded testing capacity, noted several of the task force members. On Feb. 29, the Food and Drug Administration issued a the virus that is causing the current outbreak of COVID-19.

Highly qualified laboratories, including both those run by public agencies and private labs, are now authorized to begin using their own validated test for the virus as long as they submit an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to the Food and Drug Administration within 15 days of notifying the agency of validation.

“To effectively respond to the COVID-19 outbreak, rapid detection of cases and contacts, appropriate clinical management and infection control, and implementation of community mitigation efforts are critical. This can best be achieved with wide availability of testing capabilities in health care settings, reference and commercial laboratories, and at the point of care,” the agency wrote in a press announcement of the expedited test expansion.

On Feb. 4, the Secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services declared a coronavirus public health emergency. The FDA was then authorized to allow individual laboratories with validated coronavirus tests to begin testing samples immediately. The goal is a more rapid and expanded testing capacity in the United States.

“The global emergence of COVID-19 is concerning, and we appreciate the efforts of the FDA to help bring more testing capability to the U.S.,” Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), said in the press release.

The new guidance that permits the immediate use of clinical tests after individual development and validation, said the FDA, only applies to labs already certified to perform high complexity testing under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments. Many governmental, academic, and private laboratories fall into this category, however.

“Under this policy, we expect certain laboratories who develop validated tests for coronavirus would begin using them right away prior to FDA review,” said Jeffrey Shuren, MD, JD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health. “We believe this action will support laboratories across the country working on this urgent public health situation,” he added in the press release.

“By the end of this week, close to a million tests will be available,” FDA Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, said during the March 2 briefing.*

Updated criteria

The CDC is maintaining updated criteria for the virus testing on its website. Testing criteria are based both on clinical features and epidemiologic risk.

Individuals with less severe clinical features – those who have either fever or signs and symptoms of lower respiratory disease such as cough or shortness of breath, but who don’t require hospitalization – should be tested if they have high epidemiologic risk. “High risk” is defined by the CDC as any individual, including health care workers, who has had close contact with a person with confirmed COVID-19 within the past 2 weeks. For health care workers, testing can be considered even if they have relatively mild respiratory symptoms or have had contact with a person who is suspected, but not yet confirmed, to have coronavirus.

In its testing guidance, the CDC recognizes that defining close contact is difficult. General guidelines are that individuals are considered to have been in close contact with a person who has COVID-19 if they were within about six feet of the person for a prolonged period, or cared for or have spent a prolonged amount of time in the same room or house as a person with confirmed COVID-19.

Individuals who have both fever and signs or symptoms of lower respiratory illness who require hospitalization should be tested if they have a history of travel from any affected geographic area within 14 days of the onset of their symptoms. The CDC now defines “affected geographic area” as any country or region that has at least a CDC Level 2 Travel Health Notice for COVID-19, so that the testing criteria themselves don’t need to be updated when new geographic areas are included in these alerts. As of March 3, China, Iran, Italy, Japan, and South Korea all have Level 2 or 3 travel alerts.

The CDC now recommends that any patient who has severe acute lower respiratory illness that requires hospitalization and doesn’t have an alternative diagnosis should be tested, even without any identified source of exposure.

“Despite seeing these new cases, the risk to the American people is low,” said the CDC’s Dr. Redfield. In response to a question from the press about how fast the coronavirus will spread across the United States, Dr. Redfield said, “From the beginning we’ve anticipated seeing community cases pop up.” He added that as these cases arise, testing and public health strategies will focus on unearthing linkages and contacts to learn how the virus is spreading. “We’ll use the public health strategies that we can to limit that transmission,” he said.

*An earlier version of this article misattributed this quote.

FROM A PRESS BRIEFING BY THE WHITE HOUSE CORONAVIRUS TASK FORCE

DoD and VA Release Updated List of Agent Orange Locations

The VA has released an updated list of locations outside of Vietnam where tactical herbicides have been used, tested, or stored by the US military. The list, which includes the “rainbow” herbicides (Agents Orange, Pink, Green, Purple, Blue, and White), comes from the DoD, after a “thorough review” of research, reports, and government publications in response to a November 2018 US Government Accountability Office (GAO) report.

The GAO made 6 recommendations, including that the DoD develop a process for updating the list, and that the DoD and the VA develop a process for coordinating the communication of the information. The DoD concurred with 4 recommendations.

The VA, responding to the GAO report, said it was “concerned that the report conflates the terms commercial herbicides with tactical herbicides, which are distinct from one another.” Certain testing and storage locations (eg, Kelly Air Force Base), it noted, are added to the list based on the presence of commercial herbicides or “mere components” of Agent Orange or other rainbow agents.

The distinction is important for veterans applying for disability benefits. The impetus for creating the list of testing and storage sites, the VA says, was to carry out the administration of providing disability benefits in accordance with the applicable Agent Orange statute and regulations. Exposure to tactical herbicides (herbicides intended for military operations in Vietnam) is required for the VA to grant benefits on a presumptive basis for Agent Orange conditions outside of Vietnam. Thus, the VA concludes in its response, unless the commercial herbicides were the “same composition, forms, and mixtures” as the estimated 20 million gallons of rainbow agents specifically produced for operations in Vietnam, the “discussion is misleading.”

The VA also did not concur with the recommendation that it take the lead on developing “clear and transparent criteria” for what constitutes a location to be included on the list.

The DoD and VA did agree with the recommendation that the DoD should be the lead agency for producing and updating the list, while the VA will be the lead agency in providing information to veterans. The list will be updated as verifiable information becomes available, said Defense Secretary Mark Esper.

The full list of locations is available at https://www.publichealth.va.gov/docs/agentorange/dod_herbicides_outside_vietnam.pdf.

The GAO report is available at https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-19-24.pdf.

The VA has released an updated list of locations outside of Vietnam where tactical herbicides have been used, tested, or stored by the US military. The list, which includes the “rainbow” herbicides (Agents Orange, Pink, Green, Purple, Blue, and White), comes from the DoD, after a “thorough review” of research, reports, and government publications in response to a November 2018 US Government Accountability Office (GAO) report.

The GAO made 6 recommendations, including that the DoD develop a process for updating the list, and that the DoD and the VA develop a process for coordinating the communication of the information. The DoD concurred with 4 recommendations.

The VA, responding to the GAO report, said it was “concerned that the report conflates the terms commercial herbicides with tactical herbicides, which are distinct from one another.” Certain testing and storage locations (eg, Kelly Air Force Base), it noted, are added to the list based on the presence of commercial herbicides or “mere components” of Agent Orange or other rainbow agents.

The distinction is important for veterans applying for disability benefits. The impetus for creating the list of testing and storage sites, the VA says, was to carry out the administration of providing disability benefits in accordance with the applicable Agent Orange statute and regulations. Exposure to tactical herbicides (herbicides intended for military operations in Vietnam) is required for the VA to grant benefits on a presumptive basis for Agent Orange conditions outside of Vietnam. Thus, the VA concludes in its response, unless the commercial herbicides were the “same composition, forms, and mixtures” as the estimated 20 million gallons of rainbow agents specifically produced for operations in Vietnam, the “discussion is misleading.”

The VA also did not concur with the recommendation that it take the lead on developing “clear and transparent criteria” for what constitutes a location to be included on the list.

The DoD and VA did agree with the recommendation that the DoD should be the lead agency for producing and updating the list, while the VA will be the lead agency in providing information to veterans. The list will be updated as verifiable information becomes available, said Defense Secretary Mark Esper.

The full list of locations is available at https://www.publichealth.va.gov/docs/agentorange/dod_herbicides_outside_vietnam.pdf.

The GAO report is available at https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-19-24.pdf.

The VA has released an updated list of locations outside of Vietnam where tactical herbicides have been used, tested, or stored by the US military. The list, which includes the “rainbow” herbicides (Agents Orange, Pink, Green, Purple, Blue, and White), comes from the DoD, after a “thorough review” of research, reports, and government publications in response to a November 2018 US Government Accountability Office (GAO) report.

The GAO made 6 recommendations, including that the DoD develop a process for updating the list, and that the DoD and the VA develop a process for coordinating the communication of the information. The DoD concurred with 4 recommendations.

The VA, responding to the GAO report, said it was “concerned that the report conflates the terms commercial herbicides with tactical herbicides, which are distinct from one another.” Certain testing and storage locations (eg, Kelly Air Force Base), it noted, are added to the list based on the presence of commercial herbicides or “mere components” of Agent Orange or other rainbow agents.

The distinction is important for veterans applying for disability benefits. The impetus for creating the list of testing and storage sites, the VA says, was to carry out the administration of providing disability benefits in accordance with the applicable Agent Orange statute and regulations. Exposure to tactical herbicides (herbicides intended for military operations in Vietnam) is required for the VA to grant benefits on a presumptive basis for Agent Orange conditions outside of Vietnam. Thus, the VA concludes in its response, unless the commercial herbicides were the “same composition, forms, and mixtures” as the estimated 20 million gallons of rainbow agents specifically produced for operations in Vietnam, the “discussion is misleading.”

The VA also did not concur with the recommendation that it take the lead on developing “clear and transparent criteria” for what constitutes a location to be included on the list.

The DoD and VA did agree with the recommendation that the DoD should be the lead agency for producing and updating the list, while the VA will be the lead agency in providing information to veterans. The list will be updated as verifiable information becomes available, said Defense Secretary Mark Esper.

The full list of locations is available at https://www.publichealth.va.gov/docs/agentorange/dod_herbicides_outside_vietnam.pdf.

The GAO report is available at https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-19-24.pdf.

Supreme Court roundup: Latest health care decisions

The Trump administration can move forward with expanding a rule that makes it more difficult for immigrants to remain in the United States if they receive health care assistance, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a 5-4 vote.

The Feb. 21 order allows the administration to broaden the so-called “public charge rule” while legal challenges against the expanded regulation continue in the lower courts. The Supreme Court’s decision, which lifts a preliminary injunction against the expansion, applies to enforcement only in Illinois, where a district court blocked the revised rule from moving forward in October 2019. The Supreme Court’s measure follows another 5-4 order in January, in which justices lifted a nationwide injunction against the revised rule.

Under the long-standing public charge rule, immigration officials can refuse to admit immigrants into the United States or can deny them permanent legal status if they are deemed likely to become a public charge. Previously, immigration officers considered cash aid, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or long-term institutionalized care, as potential public charge reasons for denial.

The revised regulation allows officials to consider previously excluded programs in their determination, including nonemergency Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and several housing programs. Use of these programs for more than 12 months in the aggregate during a 36-month period may result in a “public charge” designation and lead to green card denial.

Eight legal challenges were immediately filed against the rule changes, including a complaint issued by 14 states. At least five trial courts have since blocked the measure, while appeals courts have lifted some of the injunctions and upheld enforcement.

In its Jan. 27 order lifting the nationwide injunction, Associate Justice Neil M. Gorsuch wrote that nationwide injunctions are being overused by trial courts with negative consequences.

“The real problem here is the increasingly common practice of trial courts ordering relief that transcends the cases before them. Whether framed as injunctions of ‘nationwide,’ ‘universal,’ or ‘cosmic’ scope, these orders share the same basic flaw – they direct how the defendant must act toward persons who are not parties to the case,” he wrote. “It has become increasingly apparent that this court must, at some point, confront these important objections to this increasingly widespread practice. As the brief and furious history of the regulation before us illustrates, the routine issuance of universal injunctions is patently unworkable, sowing chaos for litigants, the government, courts, and all those affected by these conflicting decisions.”

In the court’s Feb. 21 order lifting the injunction in Illinois, justices gave no explanation for overturning the lower court’s injunction. However, Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor issued a sharply-worded dissent, criticizing her fellow justices for allowing the rule to proceed.

“In sum, the government’s only claimed hardship is that it must enforce an existing interpretation of an immigration rule in one state – just as it has done for the past 20 years – while an updated version of the rule takes effect in the remaining 49,” she wrote. “The government has not quantified or explained any burdens that would arise from this state of the world.”

ACA cases still in limbo

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court still has not decided whether it will hear Texas v. United States, a case that could effectively dismantle the Affordable Care Act.

The high court was expected to announce whether it would take the high-profile case at a private Feb. 21 conference, but the justices have released no update. The case was relisted for consideration at the court’s Feb. 28 conference.

Texas v. United States stems from a lawsuit by 20 Republican state attorneys general and governors that was filed after Congress zeroed out the ACA’s individual mandate penalty in 2017. The plaintiffs contend the now-valueless mandate is no longer constitutional and thus, the entire ACA should be struck down. Because the Trump administration declined to defend the law, a coalition of Democratic attorneys general and governors intervened in the case as defendants.

In 2018, a Texas district court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and declared the entire health care law invalid. The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals partially affirmed the district court’s decision, ruling that the mandate was unconstitutional, but sending the case back to the lower court for more analysis on severability. The Democratic attorneys general and governors appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court.

If the Supreme Court agrees to hear the challenge, the court could fast-track the case and schedule arguments for the current term or wait until its next term, which starts in October 2020. If justices decline to hear the case, the challenge will remain with the district court for more analysis about the law’s severability.

Another ACA-related case – Maine Community Health Options v. U.S. – also remains in limbo. Justices heard the case, which was consolidated with two similar challenges, on Dec. 10, 2019, but still have not issued a decision.

The consolidated challenges center on whether the federal government owes insurers billions based on an Affordable Care Act provision intended to help health plans mitigate risk under the law. The ACA’s risk corridor program required the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services to collect funds from profitable insurers that offered qualified health plans under the exchanges and distribute the funds to insurers with excessive losses. Collections from profitable insurers under the program fell short in 2014, 2015, and 2016, while losses steadily grew, resulting in the HHS paying about 12 cents on the dollar in payments to insurers. More than 150 insurers now allege they were shortchanged and they want the Supreme Court to force the government to reimburse them to the tune of $12 billion.

The Department of Justice counters that the government is not required to pay the insurers because of appropriations measures passed by Congress in 2014 and in later years that limited the funding available to compensate insurers for their losses.

The federal government and insurers have each experienced wins and losses at the lower court level. Most recently, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit decided in favor of the government, ruling that while the ACA required the government to compensate the insurers for their losses, the appropriations measures repealed or suspended that requirement.

A Supreme Court decision in the case could come as soon as Feb. 26.

Court to hear women’s health cases

Two closely watched reproductive health cases will go before the court this spring.

On March 4, justices will hear oral arguments in June Medical Services v. Russo, regarding the constitutionality of a Louisiana law that requires physicians performing abortions to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital. Doctors who perform abortions without admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles face fines and imprisonment, according to the state law, originally passed in 2014. Clinics that employ such doctors can also have their licenses revoked.

June Medical Services LLC, a women’s health clinic, sued over the law. A district court ruled in favor of the plaintiff, but the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed and upheld Louisiana’s law. The clinic appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Louisiana officials argue the challenge should be dismissed, and the law allowed to proceed, because the plaintiffs lack standing.

The Supreme Court in 2016 heard a similar case – Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt – concerning a comparable law in Texas. In that case, justices struck down the measure as unconstitutional.

And on April 29, justices will hear arguments in Little Sisters of the Poor v. Pennsylvania, a consolidated case about whether the Trump administration acted properly when it expanded exemptions under the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate. Entities that object to providing contraception on the basis of religious beliefs can opt out of complying with the mandate, according to the 2018 regulations. Additionally, nonprofit organizations and small businesses that have nonreligious moral convictions against the mandate can skip compliance. A number of states and entities sued over the new rules.

A federal appeals court temporarily barred the regulations from moving forward, ruling the plaintiffs were likely to succeed in proving the Trump administration did not follow appropriate procedures when it promulgated the new rules and that the regulations were not authorized under the ACA.

Justices will decide whether the parties have standing in the case, whether the Trump administration followed correct rule-making procedures, and if the regulations can stand.

The Trump administration can move forward with expanding a rule that makes it more difficult for immigrants to remain in the United States if they receive health care assistance, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a 5-4 vote.

The Feb. 21 order allows the administration to broaden the so-called “public charge rule” while legal challenges against the expanded regulation continue in the lower courts. The Supreme Court’s decision, which lifts a preliminary injunction against the expansion, applies to enforcement only in Illinois, where a district court blocked the revised rule from moving forward in October 2019. The Supreme Court’s measure follows another 5-4 order in January, in which justices lifted a nationwide injunction against the revised rule.

Under the long-standing public charge rule, immigration officials can refuse to admit immigrants into the United States or can deny them permanent legal status if they are deemed likely to become a public charge. Previously, immigration officers considered cash aid, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or long-term institutionalized care, as potential public charge reasons for denial.

The revised regulation allows officials to consider previously excluded programs in their determination, including nonemergency Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and several housing programs. Use of these programs for more than 12 months in the aggregate during a 36-month period may result in a “public charge” designation and lead to green card denial.

Eight legal challenges were immediately filed against the rule changes, including a complaint issued by 14 states. At least five trial courts have since blocked the measure, while appeals courts have lifted some of the injunctions and upheld enforcement.

In its Jan. 27 order lifting the nationwide injunction, Associate Justice Neil M. Gorsuch wrote that nationwide injunctions are being overused by trial courts with negative consequences.

“The real problem here is the increasingly common practice of trial courts ordering relief that transcends the cases before them. Whether framed as injunctions of ‘nationwide,’ ‘universal,’ or ‘cosmic’ scope, these orders share the same basic flaw – they direct how the defendant must act toward persons who are not parties to the case,” he wrote. “It has become increasingly apparent that this court must, at some point, confront these important objections to this increasingly widespread practice. As the brief and furious history of the regulation before us illustrates, the routine issuance of universal injunctions is patently unworkable, sowing chaos for litigants, the government, courts, and all those affected by these conflicting decisions.”

In the court’s Feb. 21 order lifting the injunction in Illinois, justices gave no explanation for overturning the lower court’s injunction. However, Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor issued a sharply-worded dissent, criticizing her fellow justices for allowing the rule to proceed.

“In sum, the government’s only claimed hardship is that it must enforce an existing interpretation of an immigration rule in one state – just as it has done for the past 20 years – while an updated version of the rule takes effect in the remaining 49,” she wrote. “The government has not quantified or explained any burdens that would arise from this state of the world.”

ACA cases still in limbo

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court still has not decided whether it will hear Texas v. United States, a case that could effectively dismantle the Affordable Care Act.

The high court was expected to announce whether it would take the high-profile case at a private Feb. 21 conference, but the justices have released no update. The case was relisted for consideration at the court’s Feb. 28 conference.

Texas v. United States stems from a lawsuit by 20 Republican state attorneys general and governors that was filed after Congress zeroed out the ACA’s individual mandate penalty in 2017. The plaintiffs contend the now-valueless mandate is no longer constitutional and thus, the entire ACA should be struck down. Because the Trump administration declined to defend the law, a coalition of Democratic attorneys general and governors intervened in the case as defendants.

In 2018, a Texas district court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and declared the entire health care law invalid. The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals partially affirmed the district court’s decision, ruling that the mandate was unconstitutional, but sending the case back to the lower court for more analysis on severability. The Democratic attorneys general and governors appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court.

If the Supreme Court agrees to hear the challenge, the court could fast-track the case and schedule arguments for the current term or wait until its next term, which starts in October 2020. If justices decline to hear the case, the challenge will remain with the district court for more analysis about the law’s severability.

Another ACA-related case – Maine Community Health Options v. U.S. – also remains in limbo. Justices heard the case, which was consolidated with two similar challenges, on Dec. 10, 2019, but still have not issued a decision.

The consolidated challenges center on whether the federal government owes insurers billions based on an Affordable Care Act provision intended to help health plans mitigate risk under the law. The ACA’s risk corridor program required the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services to collect funds from profitable insurers that offered qualified health plans under the exchanges and distribute the funds to insurers with excessive losses. Collections from profitable insurers under the program fell short in 2014, 2015, and 2016, while losses steadily grew, resulting in the HHS paying about 12 cents on the dollar in payments to insurers. More than 150 insurers now allege they were shortchanged and they want the Supreme Court to force the government to reimburse them to the tune of $12 billion.

The Department of Justice counters that the government is not required to pay the insurers because of appropriations measures passed by Congress in 2014 and in later years that limited the funding available to compensate insurers for their losses.

The federal government and insurers have each experienced wins and losses at the lower court level. Most recently, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit decided in favor of the government, ruling that while the ACA required the government to compensate the insurers for their losses, the appropriations measures repealed or suspended that requirement.

A Supreme Court decision in the case could come as soon as Feb. 26.

Court to hear women’s health cases

Two closely watched reproductive health cases will go before the court this spring.

On March 4, justices will hear oral arguments in June Medical Services v. Russo, regarding the constitutionality of a Louisiana law that requires physicians performing abortions to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital. Doctors who perform abortions without admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles face fines and imprisonment, according to the state law, originally passed in 2014. Clinics that employ such doctors can also have their licenses revoked.

June Medical Services LLC, a women’s health clinic, sued over the law. A district court ruled in favor of the plaintiff, but the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed and upheld Louisiana’s law. The clinic appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Louisiana officials argue the challenge should be dismissed, and the law allowed to proceed, because the plaintiffs lack standing.

The Supreme Court in 2016 heard a similar case – Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt – concerning a comparable law in Texas. In that case, justices struck down the measure as unconstitutional.

And on April 29, justices will hear arguments in Little Sisters of the Poor v. Pennsylvania, a consolidated case about whether the Trump administration acted properly when it expanded exemptions under the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate. Entities that object to providing contraception on the basis of religious beliefs can opt out of complying with the mandate, according to the 2018 regulations. Additionally, nonprofit organizations and small businesses that have nonreligious moral convictions against the mandate can skip compliance. A number of states and entities sued over the new rules.

A federal appeals court temporarily barred the regulations from moving forward, ruling the plaintiffs were likely to succeed in proving the Trump administration did not follow appropriate procedures when it promulgated the new rules and that the regulations were not authorized under the ACA.

Justices will decide whether the parties have standing in the case, whether the Trump administration followed correct rule-making procedures, and if the regulations can stand.

The Trump administration can move forward with expanding a rule that makes it more difficult for immigrants to remain in the United States if they receive health care assistance, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a 5-4 vote.

The Feb. 21 order allows the administration to broaden the so-called “public charge rule” while legal challenges against the expanded regulation continue in the lower courts. The Supreme Court’s decision, which lifts a preliminary injunction against the expansion, applies to enforcement only in Illinois, where a district court blocked the revised rule from moving forward in October 2019. The Supreme Court’s measure follows another 5-4 order in January, in which justices lifted a nationwide injunction against the revised rule.

Under the long-standing public charge rule, immigration officials can refuse to admit immigrants into the United States or can deny them permanent legal status if they are deemed likely to become a public charge. Previously, immigration officers considered cash aid, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or long-term institutionalized care, as potential public charge reasons for denial.

The revised regulation allows officials to consider previously excluded programs in their determination, including nonemergency Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and several housing programs. Use of these programs for more than 12 months in the aggregate during a 36-month period may result in a “public charge” designation and lead to green card denial.

Eight legal challenges were immediately filed against the rule changes, including a complaint issued by 14 states. At least five trial courts have since blocked the measure, while appeals courts have lifted some of the injunctions and upheld enforcement.

In its Jan. 27 order lifting the nationwide injunction, Associate Justice Neil M. Gorsuch wrote that nationwide injunctions are being overused by trial courts with negative consequences.

“The real problem here is the increasingly common practice of trial courts ordering relief that transcends the cases before them. Whether framed as injunctions of ‘nationwide,’ ‘universal,’ or ‘cosmic’ scope, these orders share the same basic flaw – they direct how the defendant must act toward persons who are not parties to the case,” he wrote. “It has become increasingly apparent that this court must, at some point, confront these important objections to this increasingly widespread practice. As the brief and furious history of the regulation before us illustrates, the routine issuance of universal injunctions is patently unworkable, sowing chaos for litigants, the government, courts, and all those affected by these conflicting decisions.”

In the court’s Feb. 21 order lifting the injunction in Illinois, justices gave no explanation for overturning the lower court’s injunction. However, Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor issued a sharply-worded dissent, criticizing her fellow justices for allowing the rule to proceed.

“In sum, the government’s only claimed hardship is that it must enforce an existing interpretation of an immigration rule in one state – just as it has done for the past 20 years – while an updated version of the rule takes effect in the remaining 49,” she wrote. “The government has not quantified or explained any burdens that would arise from this state of the world.”

ACA cases still in limbo

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court still has not decided whether it will hear Texas v. United States, a case that could effectively dismantle the Affordable Care Act.

The high court was expected to announce whether it would take the high-profile case at a private Feb. 21 conference, but the justices have released no update. The case was relisted for consideration at the court’s Feb. 28 conference.

Texas v. United States stems from a lawsuit by 20 Republican state attorneys general and governors that was filed after Congress zeroed out the ACA’s individual mandate penalty in 2017. The plaintiffs contend the now-valueless mandate is no longer constitutional and thus, the entire ACA should be struck down. Because the Trump administration declined to defend the law, a coalition of Democratic attorneys general and governors intervened in the case as defendants.

In 2018, a Texas district court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and declared the entire health care law invalid. The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals partially affirmed the district court’s decision, ruling that the mandate was unconstitutional, but sending the case back to the lower court for more analysis on severability. The Democratic attorneys general and governors appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court.

If the Supreme Court agrees to hear the challenge, the court could fast-track the case and schedule arguments for the current term or wait until its next term, which starts in October 2020. If justices decline to hear the case, the challenge will remain with the district court for more analysis about the law’s severability.

Another ACA-related case – Maine Community Health Options v. U.S. – also remains in limbo. Justices heard the case, which was consolidated with two similar challenges, on Dec. 10, 2019, but still have not issued a decision.

The consolidated challenges center on whether the federal government owes insurers billions based on an Affordable Care Act provision intended to help health plans mitigate risk under the law. The ACA’s risk corridor program required the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services to collect funds from profitable insurers that offered qualified health plans under the exchanges and distribute the funds to insurers with excessive losses. Collections from profitable insurers under the program fell short in 2014, 2015, and 2016, while losses steadily grew, resulting in the HHS paying about 12 cents on the dollar in payments to insurers. More than 150 insurers now allege they were shortchanged and they want the Supreme Court to force the government to reimburse them to the tune of $12 billion.

The Department of Justice counters that the government is not required to pay the insurers because of appropriations measures passed by Congress in 2014 and in later years that limited the funding available to compensate insurers for their losses.

The federal government and insurers have each experienced wins and losses at the lower court level. Most recently, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit decided in favor of the government, ruling that while the ACA required the government to compensate the insurers for their losses, the appropriations measures repealed or suspended that requirement.

A Supreme Court decision in the case could come as soon as Feb. 26.

Court to hear women’s health cases

Two closely watched reproductive health cases will go before the court this spring.

On March 4, justices will hear oral arguments in June Medical Services v. Russo, regarding the constitutionality of a Louisiana law that requires physicians performing abortions to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital. Doctors who perform abortions without admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles face fines and imprisonment, according to the state law, originally passed in 2014. Clinics that employ such doctors can also have their licenses revoked.

June Medical Services LLC, a women’s health clinic, sued over the law. A district court ruled in favor of the plaintiff, but the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed and upheld Louisiana’s law. The clinic appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Louisiana officials argue the challenge should be dismissed, and the law allowed to proceed, because the plaintiffs lack standing.

The Supreme Court in 2016 heard a similar case – Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt – concerning a comparable law in Texas. In that case, justices struck down the measure as unconstitutional.

And on April 29, justices will hear arguments in Little Sisters of the Poor v. Pennsylvania, a consolidated case about whether the Trump administration acted properly when it expanded exemptions under the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate. Entities that object to providing contraception on the basis of religious beliefs can opt out of complying with the mandate, according to the 2018 regulations. Additionally, nonprofit organizations and small businesses that have nonreligious moral convictions against the mandate can skip compliance. A number of states and entities sued over the new rules.

A federal appeals court temporarily barred the regulations from moving forward, ruling the plaintiffs were likely to succeed in proving the Trump administration did not follow appropriate procedures when it promulgated the new rules and that the regulations were not authorized under the ACA.

Justices will decide whether the parties have standing in the case, whether the Trump administration followed correct rule-making procedures, and if the regulations can stand.

June Medical Services v. Russo: Understanding this high-stakes abortion case

On March 4, 2020, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) will hear opening arguments for June Medical Services v. Russo. (Please note that this case was originally referred to as June Medical Services v. Gee. However, Secretary Rebekah Gee resigned from her position on January 31, 2020, and was replaced by Interim Secretary Stephen Russo.) The case will examine a Louisiana law (Louisiana Act 620, or LA 620), originally passed in 2014, that requires physicians to have hospital admitting privileges within 30 miles of where they provide abortion services.1 When LA 620 was signed into law in 2014, 5 of Louisiana’s 6 abortion clinics would not have met the standards created by this legislation and would have been forced to close, potentially leaving the vast majority of women in Louisiana without access to an abortion provider, and disproportionately impacting poor and rural women. Prior to enactment of this law, physicians at these 5 clinics attempted to obtain admitting privileges, and all were denied. The denials occurred due to two main reasons—because the providers admitted too few patients each year to qualify for hospital privileges or simply because they provided abortion care.2 Shortly after this legislation was signed into law, the Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR) challenged the law, citing the undue burden it created for patients attempting to access abortion care.

Prior case also considered question of hospital privileges for abortion providers

Interestingly, SCOTUS already has ruled on this very question. In 1992, the Court ruled in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey that it is unconstitutional for a state to create an “undue burden” on a woman’s right to abortion prior to fetal viability.3 And in 2016, when considering whether or not requiring abortion providers to obtain hospital privileges creates an undue burden in Whole Women’s Health (WWH) v. Hellerstedt, the Supreme Court’s answer was yes, it does. WWH, with legal aid from CRR, challenged Texas House Bill 2 (H.B. 2), which similar to LA 620, required abortion providers to have local admitting privileges. Based largely on the precedent set in Casey, SCOTUS ruled 5-3 in favor of WWH.

The Louisiana law currently in question was written and challenged in district court simultaneous to the Supreme Court’s review of WWH. The district court declared LA 620 invalid and permanently enjoined its enforcement, finding the law would “drastically burden women’s right to choose abortions.”4 However, the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit reviewed the case and overturned the district court decision, finding the lower court’s analysis erroneous and stating, “no clinics will likely be forced to close on account of [LA 620].” The Fifth Circuit panel ruled that, despite the precedent of WWH, LA 620 did not create an undue burden because of state-level differences in admitting privileges, demographics, and geography. They also found that only 30% of the 2 million women living in Louisiana would be impacted by the law, predominantly via longer wait times, and argued that this does not represent significant burden. The plaintiffs filed for an emergency stay with SCOTUS, who granted the stay pending a full hearing. On March 4, the Supreme Court will hear arguments to determine if the Fifth Circuit was correct in drawing a distinction between LA 620 and the SCOTUS verdict in WWH.

Targeted restrictions on abortion providers

LA 620 joins a long series of laws meant to enact targeted restrictions on abortion providers, or “TRAP” laws. TRAP laws are written to limit access to abortion under the guise of improving patient safety, despite ample evidence to the contrary, and include such various regulations as admitting privileges, facilities requirements, waiting periods, and parental or partner notification. Many such laws have been enacted in the last decade, and many struck down based on judicial precedent.

How the Supreme Court has ruled in the past

When a case is appealed to the Supreme Court, the court can either decline to hear the case, thereby leaving the lower courts’ ruling in place, or choose to hear the case in full and either affirm or overturn the lower court’s decision. After issuing a ruling in WWH, the 2016-2017 Roberts Court declined to hear challenges from other states with similarly overturned laws, leaving the laws struck down. In electing to hear June Medical Services v. Russo, the court has the opportunity to uphold or overturn the Fifth Circuit Court’s decision. However, today’s Supreme Court differs greatly from the Supreme Court in 2016.

In 2016, the court ruled 5-3 to overturn H.B. 2 in WWH shortly after the death of Justice Antonin Scalia. Scalia was replaced by Justice Neil Gorsuch, a Constitutional originalist who has never directly ruled on an abortion case.5 In 2018, Justice Anthony Kennedy, who authored the court’s majority opinion on Casey and was among the majority on WWH, retired, and was replaced by Justice Brett Kavanaugh. Kavanaugh has ruled once on the right to abortion in Garza v. Hargan in 2017, where he argued that precedent states that the government has “permissible interests in favoring fetal life…and refraining from facilitating abortion,” and that significant delay in care did not constitute undue burden.6 In regard to the 5-4 stay issued by the court in June Medical Services, Kavanaugh joined Gorsuch in voting to deny the application for stay, and was the only justice to issue an opinion alongside the ruling, arguing that because the doctors in question had not applied for and been denied admitting privileges since the WWH ruling, the case hinges on theoretical rather than demonstrable undue burden.7 Appointed by President Donald Trump, both Gorsuch and Kavanaugh are widely considered to be conservative judges, and while neither has a strong judicial record on abortion rights, both are anticipated to side with the conservative majority on the court.

The Supreme Court rarely overturns its own precedent, but concerns are high

The question of precedent will be central in SCOTUS hearing June Medical Services v. Russo so quickly after the WWH decision. Additionally, in hearing this case, the court will have the opportunity to reexamine all relevant precedent, including the Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey decision and even Roe v. Wade. With a conservative court and an increasingly charged political environment, reproductive rights advocates fear that the June Medical Services v. Russo ruling may be the first step toward dismantling judicial protection of abortion rights in the United States.

If SCOTUS rules against June Medical Services, stating that admitting privileges do not cause an undue burden for women seeking to access abortion care, other states likely will introduce and enact similar legislation. These TRAP laws have the potential to limit or eliminate access to abortion for 25 million people of reproductive age. Numerous studies have demonstrated that limiting access to abortion care does not decrease the number of abortions but can result in patients using unsafe means to obtain an abortion.8

The medical community recognizes the danger of enacting restrictive legislation. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), along with the American Medical Association, the Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, the Association for Sexual and Reproductive Medicine, the American Association of Family Practitioners, and many others, filed an amicus curiae in support of the June Medical Services plaintiffs.9 These brief filings are critical to ensuring the courts hear physician voices in this important legal decision, and ACOG’s briefs have been quoted in several previous Supreme Court opinions, concurrences, and dissents.

Action items

- Although June Medical Services v. Russo’s decision will not be made until early summer 2020, we can continue to use our voices and expertise to speak out against laws designed to limit access to abortion—at the state and federal levels. As women’s health clinicians, we see the impact abortion restrictions have on our patients, especially our low income and rural patients. Sharing these stories with our legislators, testifying for or against legislation, and speaking out in our communities can have a powerful impact. Check with your local ACOG chapter or with ACOG’s state and government affairs office for more information.

- Follow along with this case at SCOTUS Blog.

- Lastly, make sure you are registered to vote. We are in an election year, and using our voices in and out of the ballot box is critical. You can register here.

- HB338. Louisiana State Legislature. 2014. http://www.legis.la.gov/legis/BillInfo.aspx?s=14RS&b=ACT620&sbi=y. Accessed February 19, 2020.

- Nash E, Donovan MK. Admitting priveleges are back at the U.S. Supreme Court with serious implications for abortion access. Guttmacher Institute. Updated December 3, 2019.

- Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey. Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/505/833. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- June Medical Services LLC v Gee. Oyez. www.oyez.org/cases/2019/18-1323. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- Neil Gorsuch. Oyez. https://www.oyez.org/justices/neil_gorsuch. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- Judge Kavanaugh’s Judicial Record on the Right to Abortion. Center for Reproductive Rights. https://www.reproductiverights.org/sites/crr.civicactions.net/files/documents/factsheets/Judge-Kavanaugh-Judicial-Record-on-the-Right-to-Abortion2.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- Kavanaugh B. (2019, February 7). June Medical Services, L.L.C, v. Gee, 586 U.S. ____ (2019). Supreme Court of the United States. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/18pdf/18a774_3ebh.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- Cohen SA. Facts and consequences: Legality, incidence and safety of abortion worldwide. November 20, 2009.

- June Medical Services, LLC v. Russo. SCOTUSblog. February 6, 2020. https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/june-medical-services-llc-v-russo/. Accessed February 20, 2020.

On March 4, 2020, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) will hear opening arguments for June Medical Services v. Russo. (Please note that this case was originally referred to as June Medical Services v. Gee. However, Secretary Rebekah Gee resigned from her position on January 31, 2020, and was replaced by Interim Secretary Stephen Russo.) The case will examine a Louisiana law (Louisiana Act 620, or LA 620), originally passed in 2014, that requires physicians to have hospital admitting privileges within 30 miles of where they provide abortion services.1 When LA 620 was signed into law in 2014, 5 of Louisiana’s 6 abortion clinics would not have met the standards created by this legislation and would have been forced to close, potentially leaving the vast majority of women in Louisiana without access to an abortion provider, and disproportionately impacting poor and rural women. Prior to enactment of this law, physicians at these 5 clinics attempted to obtain admitting privileges, and all were denied. The denials occurred due to two main reasons—because the providers admitted too few patients each year to qualify for hospital privileges or simply because they provided abortion care.2 Shortly after this legislation was signed into law, the Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR) challenged the law, citing the undue burden it created for patients attempting to access abortion care.

Prior case also considered question of hospital privileges for abortion providers

Interestingly, SCOTUS already has ruled on this very question. In 1992, the Court ruled in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey that it is unconstitutional for a state to create an “undue burden” on a woman’s right to abortion prior to fetal viability.3 And in 2016, when considering whether or not requiring abortion providers to obtain hospital privileges creates an undue burden in Whole Women’s Health (WWH) v. Hellerstedt, the Supreme Court’s answer was yes, it does. WWH, with legal aid from CRR, challenged Texas House Bill 2 (H.B. 2), which similar to LA 620, required abortion providers to have local admitting privileges. Based largely on the precedent set in Casey, SCOTUS ruled 5-3 in favor of WWH.