User login

CMS clinical trials raise cardiac mortality

Nearly 2 years ago I speculated in this column that health planners or health economists would attempt to manipulate the patterns of patient care to influence the cost and/or quality of clinical care. At that time I suggested that, in that event, the intervention should be managed as we have with drug or device trials to ensure the authenticity and accuracy and most of all assuring the safety of the patient. Furthermore, the design should be incorporated in the intervention, that equipoise be present in the arms of the trial and that a safety monitoring board be in place to alert investigators when and if patient safety is threatened. Patient consent should also be obtained.

Beginning in 2012, CMS, using claims data from 2008 to 2012, penalized hospitals if they did not achieve acceptable readmission rates. At the same time, the agency established the Hospital Admission Reduction Program to monitor 30-day mortality and standardize readmission data. The recent data indicate that the incentives did achieve some decrease in rehospitalization but this was associated with a 16.5% relative increase in 30-day mortality. It was of particular concern that in the previous decade there had been a progressive decrease in 30-day mortality (Circulation 2014;130:966-75). The increase in 30-day mortality observed in the 4-year observational period appears to have interrupted the progressive decrease in 30-day mortality, which would have decreased to 30% if not impacted by the plan.

My previous concerns with this type of social experimentation and manipulation of health care was carried out, and as far as I can tell, continues without any oversight and little insight into the possible risks of this process. A better designed study would have provided better understanding of these results and might have mitigated the adverse effects and mortality events. It is suggested that some hospitals actually gamed the system to their economic advantage. In addition, no oversight board was or is in place as we have with drug trials to allow monitors to become aware of adverse events before there any further loss of life occurs.

I would agree that a randomized trial in this environment would be difficult to achieve. Obtaining consent from thousands of patients would also be difficult. Nevertheless, .

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

Nearly 2 years ago I speculated in this column that health planners or health economists would attempt to manipulate the patterns of patient care to influence the cost and/or quality of clinical care. At that time I suggested that, in that event, the intervention should be managed as we have with drug or device trials to ensure the authenticity and accuracy and most of all assuring the safety of the patient. Furthermore, the design should be incorporated in the intervention, that equipoise be present in the arms of the trial and that a safety monitoring board be in place to alert investigators when and if patient safety is threatened. Patient consent should also be obtained.

Beginning in 2012, CMS, using claims data from 2008 to 2012, penalized hospitals if they did not achieve acceptable readmission rates. At the same time, the agency established the Hospital Admission Reduction Program to monitor 30-day mortality and standardize readmission data. The recent data indicate that the incentives did achieve some decrease in rehospitalization but this was associated with a 16.5% relative increase in 30-day mortality. It was of particular concern that in the previous decade there had been a progressive decrease in 30-day mortality (Circulation 2014;130:966-75). The increase in 30-day mortality observed in the 4-year observational period appears to have interrupted the progressive decrease in 30-day mortality, which would have decreased to 30% if not impacted by the plan.

My previous concerns with this type of social experimentation and manipulation of health care was carried out, and as far as I can tell, continues without any oversight and little insight into the possible risks of this process. A better designed study would have provided better understanding of these results and might have mitigated the adverse effects and mortality events. It is suggested that some hospitals actually gamed the system to their economic advantage. In addition, no oversight board was or is in place as we have with drug trials to allow monitors to become aware of adverse events before there any further loss of life occurs.

I would agree that a randomized trial in this environment would be difficult to achieve. Obtaining consent from thousands of patients would also be difficult. Nevertheless, .

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

Nearly 2 years ago I speculated in this column that health planners or health economists would attempt to manipulate the patterns of patient care to influence the cost and/or quality of clinical care. At that time I suggested that, in that event, the intervention should be managed as we have with drug or device trials to ensure the authenticity and accuracy and most of all assuring the safety of the patient. Furthermore, the design should be incorporated in the intervention, that equipoise be present in the arms of the trial and that a safety monitoring board be in place to alert investigators when and if patient safety is threatened. Patient consent should also be obtained.

Beginning in 2012, CMS, using claims data from 2008 to 2012, penalized hospitals if they did not achieve acceptable readmission rates. At the same time, the agency established the Hospital Admission Reduction Program to monitor 30-day mortality and standardize readmission data. The recent data indicate that the incentives did achieve some decrease in rehospitalization but this was associated with a 16.5% relative increase in 30-day mortality. It was of particular concern that in the previous decade there had been a progressive decrease in 30-day mortality (Circulation 2014;130:966-75). The increase in 30-day mortality observed in the 4-year observational period appears to have interrupted the progressive decrease in 30-day mortality, which would have decreased to 30% if not impacted by the plan.

My previous concerns with this type of social experimentation and manipulation of health care was carried out, and as far as I can tell, continues without any oversight and little insight into the possible risks of this process. A better designed study would have provided better understanding of these results and might have mitigated the adverse effects and mortality events. It is suggested that some hospitals actually gamed the system to their economic advantage. In addition, no oversight board was or is in place as we have with drug trials to allow monitors to become aware of adverse events before there any further loss of life occurs.

I would agree that a randomized trial in this environment would be difficult to achieve. Obtaining consent from thousands of patients would also be difficult. Nevertheless, .

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

ACC guidance addresses newer HFrEF options

It might be prudent to , according to a new expert consensus document from the American College of Cardiology on managing heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

“While rising natriuretic peptide concentrations are correlated with adverse outcomes, this relationship can be confounded with the use of sacubitril/valsartan. Due to neprilysin inhibition, concentrations of BNP rise in patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan and tend not to return to baseline despite chronic therapy. In contrast, NT-proBNP concentrations typically decrease, as NT-proBNP is not a substrate for neprilysin,” explained authors led by heart failure pathway writing committee chairman Clyde W. Yancy, MD, chief of cardiology at Northwestern University in Chicago (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Dec 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.025).

Treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) “can feel overwhelming, and many opportunities to improve patient outcomes are being missed; hopefully, this Expert Consensus Decision Pathway may streamline care to realize best possible patient outcomes,” the authors wrote.

The 10 issues and their detailed answers address therapeutic options, adherence, treatment barriers, drug costs, special populations, and palliative care. The document is full of tables and figures of treatment algorithms, drug doses, and other matters.

There’s a good deal of advice about using two newer HFrEF options: sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine (Corlanor). Sacubitril/valsartan, an angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ANRI), is a switch agent for patients who tolerate but remain symptomatic on ACE inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB). Moving over to sacubitril/valsartan has been shown to decrease the risk of hospitalization and death.

Switching from an ACEI requires a 36-hour washout period to avoid angdioedema; no washout is needed for ARB switches. Sacubitril/valsartan doses can be increased every 2-4 weeks to allow time for adjustment to vasodilatory effects. In one study, gradual titration over about 6 weeks maximized attainment of target dosages. As with ACEIs and ARBs, titration might require lowering loop diuretic doses, with careful attention paid to potassium concentrations.

“The committee is aware that clinicians may occasionally consider initiating ANRI in patients who have not previously been treated with an ACEI or ARB. To be explicitly clear, no predicate data supports this approach,” but it “might be considered” if patients are well informed of the risks, including angioedema and hypotension, the committee wrote.

Ivabradine is for patients whose resting heart rate is at or above 70 bpm despite maximal beta-blocker treatment. “It is important to emphasize that ivabradine is indicated only for patients in sinus rhythm, not in those with atrial fibrillation, patients who are 100% atrially paced, or unstable patients. From a safety standpoint, patients treated with ivabradine had more bradycardia and developed more atrial fibrillation as well as transient blurring of vision,” according to the consensus document.

Turning to wireless implantable pulmonary artery pressure monitoring, another newer approach, the group noted that, compared with standard care, it reduced hospitalization and led to more frequent adjustment of diuretic doses, suggesting a benefit “in well-selected patients with recurrent congestion. … The impact on mortality is unknown.”

“For a number of reasons,” hydralazine/isosorbide dinitrate “is often neglected in eligible patients. However, given the benefits of this combination (43% relative reduction in mortality and 33% relative reduction in HF hospitalization), African-American patients should receive these drugs once target or maximally tolerated doses of beta-blocker and ACEI/ ARB/ARNI are achieved. This is especially important for those patients with [New York Heart Association] class III to IV symptoms,” the committee members said.

Regarding treatment adherence, the group noted that “monetary incentives or other rewards for adherence to medications may be cost saving for highly efficacious and inexpensive drugs such as beta-blockers.”

The work was supported by the ACC with no industry funding. Dr. Yancy had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Yancy C et. al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Dec 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.025

It might be prudent to , according to a new expert consensus document from the American College of Cardiology on managing heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

“While rising natriuretic peptide concentrations are correlated with adverse outcomes, this relationship can be confounded with the use of sacubitril/valsartan. Due to neprilysin inhibition, concentrations of BNP rise in patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan and tend not to return to baseline despite chronic therapy. In contrast, NT-proBNP concentrations typically decrease, as NT-proBNP is not a substrate for neprilysin,” explained authors led by heart failure pathway writing committee chairman Clyde W. Yancy, MD, chief of cardiology at Northwestern University in Chicago (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Dec 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.025).

Treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) “can feel overwhelming, and many opportunities to improve patient outcomes are being missed; hopefully, this Expert Consensus Decision Pathway may streamline care to realize best possible patient outcomes,” the authors wrote.

The 10 issues and their detailed answers address therapeutic options, adherence, treatment barriers, drug costs, special populations, and palliative care. The document is full of tables and figures of treatment algorithms, drug doses, and other matters.

There’s a good deal of advice about using two newer HFrEF options: sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine (Corlanor). Sacubitril/valsartan, an angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ANRI), is a switch agent for patients who tolerate but remain symptomatic on ACE inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB). Moving over to sacubitril/valsartan has been shown to decrease the risk of hospitalization and death.

Switching from an ACEI requires a 36-hour washout period to avoid angdioedema; no washout is needed for ARB switches. Sacubitril/valsartan doses can be increased every 2-4 weeks to allow time for adjustment to vasodilatory effects. In one study, gradual titration over about 6 weeks maximized attainment of target dosages. As with ACEIs and ARBs, titration might require lowering loop diuretic doses, with careful attention paid to potassium concentrations.

“The committee is aware that clinicians may occasionally consider initiating ANRI in patients who have not previously been treated with an ACEI or ARB. To be explicitly clear, no predicate data supports this approach,” but it “might be considered” if patients are well informed of the risks, including angioedema and hypotension, the committee wrote.

Ivabradine is for patients whose resting heart rate is at or above 70 bpm despite maximal beta-blocker treatment. “It is important to emphasize that ivabradine is indicated only for patients in sinus rhythm, not in those with atrial fibrillation, patients who are 100% atrially paced, or unstable patients. From a safety standpoint, patients treated with ivabradine had more bradycardia and developed more atrial fibrillation as well as transient blurring of vision,” according to the consensus document.

Turning to wireless implantable pulmonary artery pressure monitoring, another newer approach, the group noted that, compared with standard care, it reduced hospitalization and led to more frequent adjustment of diuretic doses, suggesting a benefit “in well-selected patients with recurrent congestion. … The impact on mortality is unknown.”

“For a number of reasons,” hydralazine/isosorbide dinitrate “is often neglected in eligible patients. However, given the benefits of this combination (43% relative reduction in mortality and 33% relative reduction in HF hospitalization), African-American patients should receive these drugs once target or maximally tolerated doses of beta-blocker and ACEI/ ARB/ARNI are achieved. This is especially important for those patients with [New York Heart Association] class III to IV symptoms,” the committee members said.

Regarding treatment adherence, the group noted that “monetary incentives or other rewards for adherence to medications may be cost saving for highly efficacious and inexpensive drugs such as beta-blockers.”

The work was supported by the ACC with no industry funding. Dr. Yancy had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Yancy C et. al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Dec 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.025

It might be prudent to , according to a new expert consensus document from the American College of Cardiology on managing heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

“While rising natriuretic peptide concentrations are correlated with adverse outcomes, this relationship can be confounded with the use of sacubitril/valsartan. Due to neprilysin inhibition, concentrations of BNP rise in patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan and tend not to return to baseline despite chronic therapy. In contrast, NT-proBNP concentrations typically decrease, as NT-proBNP is not a substrate for neprilysin,” explained authors led by heart failure pathway writing committee chairman Clyde W. Yancy, MD, chief of cardiology at Northwestern University in Chicago (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Dec 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.025).

Treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) “can feel overwhelming, and many opportunities to improve patient outcomes are being missed; hopefully, this Expert Consensus Decision Pathway may streamline care to realize best possible patient outcomes,” the authors wrote.

The 10 issues and their detailed answers address therapeutic options, adherence, treatment barriers, drug costs, special populations, and palliative care. The document is full of tables and figures of treatment algorithms, drug doses, and other matters.

There’s a good deal of advice about using two newer HFrEF options: sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine (Corlanor). Sacubitril/valsartan, an angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ANRI), is a switch agent for patients who tolerate but remain symptomatic on ACE inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB). Moving over to sacubitril/valsartan has been shown to decrease the risk of hospitalization and death.

Switching from an ACEI requires a 36-hour washout period to avoid angdioedema; no washout is needed for ARB switches. Sacubitril/valsartan doses can be increased every 2-4 weeks to allow time for adjustment to vasodilatory effects. In one study, gradual titration over about 6 weeks maximized attainment of target dosages. As with ACEIs and ARBs, titration might require lowering loop diuretic doses, with careful attention paid to potassium concentrations.

“The committee is aware that clinicians may occasionally consider initiating ANRI in patients who have not previously been treated with an ACEI or ARB. To be explicitly clear, no predicate data supports this approach,” but it “might be considered” if patients are well informed of the risks, including angioedema and hypotension, the committee wrote.

Ivabradine is for patients whose resting heart rate is at or above 70 bpm despite maximal beta-blocker treatment. “It is important to emphasize that ivabradine is indicated only for patients in sinus rhythm, not in those with atrial fibrillation, patients who are 100% atrially paced, or unstable patients. From a safety standpoint, patients treated with ivabradine had more bradycardia and developed more atrial fibrillation as well as transient blurring of vision,” according to the consensus document.

Turning to wireless implantable pulmonary artery pressure monitoring, another newer approach, the group noted that, compared with standard care, it reduced hospitalization and led to more frequent adjustment of diuretic doses, suggesting a benefit “in well-selected patients with recurrent congestion. … The impact on mortality is unknown.”

“For a number of reasons,” hydralazine/isosorbide dinitrate “is often neglected in eligible patients. However, given the benefits of this combination (43% relative reduction in mortality and 33% relative reduction in HF hospitalization), African-American patients should receive these drugs once target or maximally tolerated doses of beta-blocker and ACEI/ ARB/ARNI are achieved. This is especially important for those patients with [New York Heart Association] class III to IV symptoms,” the committee members said.

Regarding treatment adherence, the group noted that “monetary incentives or other rewards for adherence to medications may be cost saving for highly efficacious and inexpensive drugs such as beta-blockers.”

The work was supported by the ACC with no industry funding. Dr. Yancy had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Yancy C et. al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Dec 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.025

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Pulmonary hypertension treatment gets under the skin

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) patients with moderate, stable disease can benefit from an implantable drug delivery system, based on data from a review of 60 adults with successful implantations. The findings were published in the December issue of CHEST.

“A fully implanted system offers patients the hope of returning to more normal activities such as bathing, swimming, and reduced risk of infections from externalized central venous catheter contamination or reduced subcutaneous pain from subcutaneous infusion,” wrote Aaron B. Waxman, MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his colleagues (Chest. 2017 June 3. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.04.188).

In the DelIVery Trial, clinicians at 10 locations in the United States placed a fully implantable delivery system in adults aged 18 years and older with stable PAH who were previously receiving treprostinil via an external pump at an average dose of 71 ng/kg per min.

All 60 patients were successfully implanted with a system consisting of a drug infusion pump placed in an abdominal pocket and an intravascular catheter linking the implanted pump to the superior vena cava.

“The location of the pump pocket was determined in partnership with the patient and was based on consideration of clothing styles, belt line and subcutaneous fat depth,” the researchers noted.

Procedure-related complications deemed clinically significant included one atrial fibrillation, two incidences of pneumothorax, two infections unrelated to catheter placement, and three catheter dislocations (two in the same patient). The most common patient complaints were expected implant site pain in 83% and bruising in 17%.

The findings were limited by the small number of patients, but the researchers identified several factors that contributed to the success of the procedure, including selecting patients who have shown response to treprostinil and are motivated to comply with pump refill visits, performing the procedure at centers with a high volume of PAH patients, keeping the procedure consistent for each patient, and using the same implant team in each case. “The implant procedure was successfully performed with a low complication rate by clinicians with a diverse range of specialty training,” the researchers added.

Patients reported satisfaction with the implant system at 6 weeks and 6 months, and said they spent an average of 75% less time managing their delivery system, according to previously published data on the patients’ perspective (CHEST 2016;150[1]:27-34).

Medtronic sponsored the study. The lead author, Dr. Waxman, had no financial conflicts to disclose; several coauthors reported relationships with companies including Medtronic, Actelion, Bayer, Gilead, Merck, and United Therapeutics.

The development of an implantable therapy for pulmonary hypertension could expand the use of treprostinil, a demonstrated effective treatment for PAH that has been limited in its use because of a range of side effects when given intravenously, orally, subcutaneously, or by inhalation, Joel A. Wirth, MD, FCCP, and Harold I. Palevsky, MD, FCCP, wrote in an editorial.

The use of an intravenous pump and catheter infusion system for stable PAH patients could help them return more quickly to normal activities and curb the risk of catheter-related infections, they said. “Having the potential to remove some of the burden and risk incumbent with an external delivery system may reduce several of the overall barriers to continuous intravenous prostanoid acceptance by both patients and providers,” they noted (Chest. 2017 Dec 6. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.07.006).

Clinicians must be educated to perform the implant procedure itself, and care centers must be trained in identifying patient management issues and refilling the pump reservoir as needed, Dr. Wirth and Dr. Palevsky emphasized. Patients must be educated in what to expect, including how to monitor the pump and track the need for refills, they said. Although the pump is not appropriate for patients with severe PAH, “a planned staged approach of transitioning PAH patients from IV therapy to a less complex system could lend itself to employing prostanoid use earlier and for less severely affected PAH patients,” they said.

Dr. Wirth is affiliated with Tufts University, Boston. Dr. Palevsky is affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Both Dr. Wirth and Dr. Palevsky disclosed serving as consultants and as principal investigators for United Therapeutics.

The development of an implantable therapy for pulmonary hypertension could expand the use of treprostinil, a demonstrated effective treatment for PAH that has been limited in its use because of a range of side effects when given intravenously, orally, subcutaneously, or by inhalation, Joel A. Wirth, MD, FCCP, and Harold I. Palevsky, MD, FCCP, wrote in an editorial.

The use of an intravenous pump and catheter infusion system for stable PAH patients could help them return more quickly to normal activities and curb the risk of catheter-related infections, they said. “Having the potential to remove some of the burden and risk incumbent with an external delivery system may reduce several of the overall barriers to continuous intravenous prostanoid acceptance by both patients and providers,” they noted (Chest. 2017 Dec 6. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.07.006).

Clinicians must be educated to perform the implant procedure itself, and care centers must be trained in identifying patient management issues and refilling the pump reservoir as needed, Dr. Wirth and Dr. Palevsky emphasized. Patients must be educated in what to expect, including how to monitor the pump and track the need for refills, they said. Although the pump is not appropriate for patients with severe PAH, “a planned staged approach of transitioning PAH patients from IV therapy to a less complex system could lend itself to employing prostanoid use earlier and for less severely affected PAH patients,” they said.

Dr. Wirth is affiliated with Tufts University, Boston. Dr. Palevsky is affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Both Dr. Wirth and Dr. Palevsky disclosed serving as consultants and as principal investigators for United Therapeutics.

The development of an implantable therapy for pulmonary hypertension could expand the use of treprostinil, a demonstrated effective treatment for PAH that has been limited in its use because of a range of side effects when given intravenously, orally, subcutaneously, or by inhalation, Joel A. Wirth, MD, FCCP, and Harold I. Palevsky, MD, FCCP, wrote in an editorial.

The use of an intravenous pump and catheter infusion system for stable PAH patients could help them return more quickly to normal activities and curb the risk of catheter-related infections, they said. “Having the potential to remove some of the burden and risk incumbent with an external delivery system may reduce several of the overall barriers to continuous intravenous prostanoid acceptance by both patients and providers,” they noted (Chest. 2017 Dec 6. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.07.006).

Clinicians must be educated to perform the implant procedure itself, and care centers must be trained in identifying patient management issues and refilling the pump reservoir as needed, Dr. Wirth and Dr. Palevsky emphasized. Patients must be educated in what to expect, including how to monitor the pump and track the need for refills, they said. Although the pump is not appropriate for patients with severe PAH, “a planned staged approach of transitioning PAH patients from IV therapy to a less complex system could lend itself to employing prostanoid use earlier and for less severely affected PAH patients,” they said.

Dr. Wirth is affiliated with Tufts University, Boston. Dr. Palevsky is affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Both Dr. Wirth and Dr. Palevsky disclosed serving as consultants and as principal investigators for United Therapeutics.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) patients with moderate, stable disease can benefit from an implantable drug delivery system, based on data from a review of 60 adults with successful implantations. The findings were published in the December issue of CHEST.

“A fully implanted system offers patients the hope of returning to more normal activities such as bathing, swimming, and reduced risk of infections from externalized central venous catheter contamination or reduced subcutaneous pain from subcutaneous infusion,” wrote Aaron B. Waxman, MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his colleagues (Chest. 2017 June 3. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.04.188).

In the DelIVery Trial, clinicians at 10 locations in the United States placed a fully implantable delivery system in adults aged 18 years and older with stable PAH who were previously receiving treprostinil via an external pump at an average dose of 71 ng/kg per min.

All 60 patients were successfully implanted with a system consisting of a drug infusion pump placed in an abdominal pocket and an intravascular catheter linking the implanted pump to the superior vena cava.

“The location of the pump pocket was determined in partnership with the patient and was based on consideration of clothing styles, belt line and subcutaneous fat depth,” the researchers noted.

Procedure-related complications deemed clinically significant included one atrial fibrillation, two incidences of pneumothorax, two infections unrelated to catheter placement, and three catheter dislocations (two in the same patient). The most common patient complaints were expected implant site pain in 83% and bruising in 17%.

The findings were limited by the small number of patients, but the researchers identified several factors that contributed to the success of the procedure, including selecting patients who have shown response to treprostinil and are motivated to comply with pump refill visits, performing the procedure at centers with a high volume of PAH patients, keeping the procedure consistent for each patient, and using the same implant team in each case. “The implant procedure was successfully performed with a low complication rate by clinicians with a diverse range of specialty training,” the researchers added.

Patients reported satisfaction with the implant system at 6 weeks and 6 months, and said they spent an average of 75% less time managing their delivery system, according to previously published data on the patients’ perspective (CHEST 2016;150[1]:27-34).

Medtronic sponsored the study. The lead author, Dr. Waxman, had no financial conflicts to disclose; several coauthors reported relationships with companies including Medtronic, Actelion, Bayer, Gilead, Merck, and United Therapeutics.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) patients with moderate, stable disease can benefit from an implantable drug delivery system, based on data from a review of 60 adults with successful implantations. The findings were published in the December issue of CHEST.

“A fully implanted system offers patients the hope of returning to more normal activities such as bathing, swimming, and reduced risk of infections from externalized central venous catheter contamination or reduced subcutaneous pain from subcutaneous infusion,” wrote Aaron B. Waxman, MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his colleagues (Chest. 2017 June 3. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.04.188).

In the DelIVery Trial, clinicians at 10 locations in the United States placed a fully implantable delivery system in adults aged 18 years and older with stable PAH who were previously receiving treprostinil via an external pump at an average dose of 71 ng/kg per min.

All 60 patients were successfully implanted with a system consisting of a drug infusion pump placed in an abdominal pocket and an intravascular catheter linking the implanted pump to the superior vena cava.

“The location of the pump pocket was determined in partnership with the patient and was based on consideration of clothing styles, belt line and subcutaneous fat depth,” the researchers noted.

Procedure-related complications deemed clinically significant included one atrial fibrillation, two incidences of pneumothorax, two infections unrelated to catheter placement, and three catheter dislocations (two in the same patient). The most common patient complaints were expected implant site pain in 83% and bruising in 17%.

The findings were limited by the small number of patients, but the researchers identified several factors that contributed to the success of the procedure, including selecting patients who have shown response to treprostinil and are motivated to comply with pump refill visits, performing the procedure at centers with a high volume of PAH patients, keeping the procedure consistent for each patient, and using the same implant team in each case. “The implant procedure was successfully performed with a low complication rate by clinicians with a diverse range of specialty training,” the researchers added.

Patients reported satisfaction with the implant system at 6 weeks and 6 months, and said they spent an average of 75% less time managing their delivery system, according to previously published data on the patients’ perspective (CHEST 2016;150[1]:27-34).

Medtronic sponsored the study. The lead author, Dr. Waxman, had no financial conflicts to disclose; several coauthors reported relationships with companies including Medtronic, Actelion, Bayer, Gilead, Merck, and United Therapeutics.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: An implantable drug delivery system was successfully placed in 100% of adult PAH patients with no serious complications.

Major finding: The most common complaints among patients who received an implant system to deliver treprostinil were implant site pain (83%) and bruising (17%).

Data source: A multicenter, prospective study of 60 adults with pulmonary arterial hypertension who received implantable pumps to deliver treprostinil.

Disclosures: Medtronic sponsored the study. The lead author, Dr. Waxman, had no financial conflicts to disclose; several coauthors reported relationships with companies including Medtronic, Actelion, Bayer, Gilead, Merck, and United Therapeutics.

Phrenic-nerve stimulator maintains benefits for 18 months

TORONTO – The implanted phrenic-nerve stimulation device that received Food and Drug Administration marketing approval in October 2017 for treating central sleep apnea has now shown safety and efficacy out to 18 months of continuous use in 102 patients.

After 18 months of treatment with the Remede System, patients’ outcomes remained stable and patients continued to see the improvements they had experienced after 6 and 12 months of treatment. These improvements included significant average reductions from baseline in apnea-hypopnea index and central apnea index and significant increases in oxygenation and sleep quality, Andrew C. Kao, MD, said at the CHEST annual meeting.

“We were concerned that there would be a degradation of the benefit [over time]. We are very happy that the benefit was sustained,” said Dr. Kao, a heart failure cardiologist at Saint Luke’s Health System in Kansas City, Mo.

Dr. Kao did not report an 18-month follow-up for the study’s primary endpoint, the percentage of patients after 6 months on treatment who had at least a 50% reduction from baseline in their apnea-hypopnea index. His report focused on the 6-, 12-, and 18-month changes relative to baseline for five secondary outcomes: central sleep apnea index, apnea-hypopnea index, arousal index, oxygen desaturation index, and time spent in REM sleep. For all five of these outcomes, the 102 patients showed an average, statistically significant improvement compared with baseline after 6 months on treatment that persisted virtually unchanged at 12 and 18 months.

For example, average central sleep apnea index fell from 27 events/hour at baseline to 5 per hour at 6, 12, and 18 months. Average apnea-hypopnea index fell from 46 events/hour at baseline to about 25 per hour at 6, 12, and 18 months. The average percentage of sleep spent in REM sleep improved from 12% at baseline to about 15% at 6, 12, and 18 months.

During 18 months of treatment following device implantation, four of the 102 patients had a serious adverse event. One patient required lead repositioning to relieve discomfort and three had an interaction with an implanted cardiac device. The effects resolved in all four patients without long-term impact. An additional 16 patients had discomfort that required an unscheduled medical visit, but these were not classified as serious episodes, and in 14 of these patients the discomfort resolved.

The Remede System phrenic-nerve stimulator received FDA marketing approval for moderate to severe central sleep apnea based on 6-month efficacy and 12-month safety data (Lancet. 2016 Sept 3;388[10048]:974-82). The Pivotal Trial of the Remede System enrolled 151 patients with an apnea-hypopnea index of at least 20 events/hour, about half of whom had heart failure. All patients received a device implant: In the initial intervention group of 73 patients, researchers turned on the device 1 month after implantation, and in the 78 patients randomized to the initial control arm, the device remained off for the first 7 months and then went active. The researchers followed up with 46 patients drawn from both the original treatment arm and 56 patients from the original control arm, at which point the patients had been receiving 18 months of treatment.

The Remede System pivotal trial was sponsored by Respicardia, which markets the phrenic-verse stimulator. Dr. Kao’s institution, Saint Luke’s Health System, received grant support from Respicardia.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

TORONTO – The implanted phrenic-nerve stimulation device that received Food and Drug Administration marketing approval in October 2017 for treating central sleep apnea has now shown safety and efficacy out to 18 months of continuous use in 102 patients.

After 18 months of treatment with the Remede System, patients’ outcomes remained stable and patients continued to see the improvements they had experienced after 6 and 12 months of treatment. These improvements included significant average reductions from baseline in apnea-hypopnea index and central apnea index and significant increases in oxygenation and sleep quality, Andrew C. Kao, MD, said at the CHEST annual meeting.

“We were concerned that there would be a degradation of the benefit [over time]. We are very happy that the benefit was sustained,” said Dr. Kao, a heart failure cardiologist at Saint Luke’s Health System in Kansas City, Mo.

Dr. Kao did not report an 18-month follow-up for the study’s primary endpoint, the percentage of patients after 6 months on treatment who had at least a 50% reduction from baseline in their apnea-hypopnea index. His report focused on the 6-, 12-, and 18-month changes relative to baseline for five secondary outcomes: central sleep apnea index, apnea-hypopnea index, arousal index, oxygen desaturation index, and time spent in REM sleep. For all five of these outcomes, the 102 patients showed an average, statistically significant improvement compared with baseline after 6 months on treatment that persisted virtually unchanged at 12 and 18 months.

For example, average central sleep apnea index fell from 27 events/hour at baseline to 5 per hour at 6, 12, and 18 months. Average apnea-hypopnea index fell from 46 events/hour at baseline to about 25 per hour at 6, 12, and 18 months. The average percentage of sleep spent in REM sleep improved from 12% at baseline to about 15% at 6, 12, and 18 months.

During 18 months of treatment following device implantation, four of the 102 patients had a serious adverse event. One patient required lead repositioning to relieve discomfort and three had an interaction with an implanted cardiac device. The effects resolved in all four patients without long-term impact. An additional 16 patients had discomfort that required an unscheduled medical visit, but these were not classified as serious episodes, and in 14 of these patients the discomfort resolved.

The Remede System phrenic-nerve stimulator received FDA marketing approval for moderate to severe central sleep apnea based on 6-month efficacy and 12-month safety data (Lancet. 2016 Sept 3;388[10048]:974-82). The Pivotal Trial of the Remede System enrolled 151 patients with an apnea-hypopnea index of at least 20 events/hour, about half of whom had heart failure. All patients received a device implant: In the initial intervention group of 73 patients, researchers turned on the device 1 month after implantation, and in the 78 patients randomized to the initial control arm, the device remained off for the first 7 months and then went active. The researchers followed up with 46 patients drawn from both the original treatment arm and 56 patients from the original control arm, at which point the patients had been receiving 18 months of treatment.

The Remede System pivotal trial was sponsored by Respicardia, which markets the phrenic-verse stimulator. Dr. Kao’s institution, Saint Luke’s Health System, received grant support from Respicardia.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

TORONTO – The implanted phrenic-nerve stimulation device that received Food and Drug Administration marketing approval in October 2017 for treating central sleep apnea has now shown safety and efficacy out to 18 months of continuous use in 102 patients.

After 18 months of treatment with the Remede System, patients’ outcomes remained stable and patients continued to see the improvements they had experienced after 6 and 12 months of treatment. These improvements included significant average reductions from baseline in apnea-hypopnea index and central apnea index and significant increases in oxygenation and sleep quality, Andrew C. Kao, MD, said at the CHEST annual meeting.

“We were concerned that there would be a degradation of the benefit [over time]. We are very happy that the benefit was sustained,” said Dr. Kao, a heart failure cardiologist at Saint Luke’s Health System in Kansas City, Mo.

Dr. Kao did not report an 18-month follow-up for the study’s primary endpoint, the percentage of patients after 6 months on treatment who had at least a 50% reduction from baseline in their apnea-hypopnea index. His report focused on the 6-, 12-, and 18-month changes relative to baseline for five secondary outcomes: central sleep apnea index, apnea-hypopnea index, arousal index, oxygen desaturation index, and time spent in REM sleep. For all five of these outcomes, the 102 patients showed an average, statistically significant improvement compared with baseline after 6 months on treatment that persisted virtually unchanged at 12 and 18 months.

For example, average central sleep apnea index fell from 27 events/hour at baseline to 5 per hour at 6, 12, and 18 months. Average apnea-hypopnea index fell from 46 events/hour at baseline to about 25 per hour at 6, 12, and 18 months. The average percentage of sleep spent in REM sleep improved from 12% at baseline to about 15% at 6, 12, and 18 months.

During 18 months of treatment following device implantation, four of the 102 patients had a serious adverse event. One patient required lead repositioning to relieve discomfort and three had an interaction with an implanted cardiac device. The effects resolved in all four patients without long-term impact. An additional 16 patients had discomfort that required an unscheduled medical visit, but these were not classified as serious episodes, and in 14 of these patients the discomfort resolved.

The Remede System phrenic-nerve stimulator received FDA marketing approval for moderate to severe central sleep apnea based on 6-month efficacy and 12-month safety data (Lancet. 2016 Sept 3;388[10048]:974-82). The Pivotal Trial of the Remede System enrolled 151 patients with an apnea-hypopnea index of at least 20 events/hour, about half of whom had heart failure. All patients received a device implant: In the initial intervention group of 73 patients, researchers turned on the device 1 month after implantation, and in the 78 patients randomized to the initial control arm, the device remained off for the first 7 months and then went active. The researchers followed up with 46 patients drawn from both the original treatment arm and 56 patients from the original control arm, at which point the patients had been receiving 18 months of treatment.

The Remede System pivotal trial was sponsored by Respicardia, which markets the phrenic-verse stimulator. Dr. Kao’s institution, Saint Luke’s Health System, received grant support from Respicardia.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT CHEST 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Average central apnea index improved from 27 events/hour at baseline to 5 events/hour after 6, 12, and 18 months of treatment.

Data source: 102 patients enrolled in the Pivotal Trial of the remede System were followed for 18 months of treatment.

Disclosures: The remede System pivotal trial was sponsored by Respicardia, which markets the phrenic-verse stimulator. Dr. Kao’s institution, Saint Luke’s Health System, received grant support from Respicardia.

Empagliflozin’s heart failure benefits linked to volume drop

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – When results from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial came out 2 years ago and showed a dramatic decrease in heart failure hospitalizations and deaths linked to treatment with the oral diabetes drug empagliflozin, some experts suggested that a completely hypothetical effect of empagliflozin on reducing fluid volume may have largely caused these unexpected clinical benefits.

New analyses of the trial results show this hypothesis may be at least partially correct.

Results from a post hoc analysis of data collected in Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients (EMPA-REG OUTCOME) suggest that perhaps half the heart failure benefit was attributable to what appears to have been a roughly 7% drop in plasma volume in patients treated with empagliflozin (Jardiance), which began soon after treatment started and continued through the balance of the study, David Fitchett, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Markers of change in plasma volume were important mediators of the reduction in risk of hospitalization for heart failure or death from heart failure,” said Dr Fitchett, a cardiologist at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto and a coinvestigator of EMPA-REG OUTCOME (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2117-28).

The analysis also showed that a “modest” effect from a reduction in uric acid might explain about 20%-25% of the observed heart failure benefit, he reported. In contrast, none of the traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors examined in the analysis – including lipids, blood pressure, obesity, and hemoglobin A1c – appeared to have any relationship to the heart failure effects of empagliflozin.

Dr. Fitchett and his associates assessed the possible impact of a list of potential mediators with a statistical method that performed an unadjusted, univariate analysis of the time-dependent change in each of several variables relative to the observed changes in heart failure outcomes.

This analysis showed that on-treatment changes in two markers of plasma volume, hematocrit and hemoglobin, each showed changes that appeared to mediate about half of the heart failure effects. A third marker of plasma volume, albumin level, appeared to mediate about a quarter of the heart failure effects.

The changes in both hematocrit and hemoglobin first appeared within a few weeks of treatment onset, and soon reached a plateau that remained sustained through the balance of the study. For example, during the first 12 weeks of treatment, the average hematocrit level rose from about 41% at baseline to about 44%. This 3% net rise corresponds to about a 7% drop in plasma volume, Dr. Fitchett said.

In addition to reflecting a potentially beneficial decrease in fluid volume, this effect would also boost the oxygen-carrying capacity of a patient’s blood that could be beneficial for patients with ischemic heart disease and those with reduced left ventricular function, he noted.

The EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly, which jointly market empagliflozin (Jardiance). Dr. Fitchett has received honoraria from those companies and also from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Merck, and Sanofi.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – When results from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial came out 2 years ago and showed a dramatic decrease in heart failure hospitalizations and deaths linked to treatment with the oral diabetes drug empagliflozin, some experts suggested that a completely hypothetical effect of empagliflozin on reducing fluid volume may have largely caused these unexpected clinical benefits.

New analyses of the trial results show this hypothesis may be at least partially correct.

Results from a post hoc analysis of data collected in Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients (EMPA-REG OUTCOME) suggest that perhaps half the heart failure benefit was attributable to what appears to have been a roughly 7% drop in plasma volume in patients treated with empagliflozin (Jardiance), which began soon after treatment started and continued through the balance of the study, David Fitchett, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Markers of change in plasma volume were important mediators of the reduction in risk of hospitalization for heart failure or death from heart failure,” said Dr Fitchett, a cardiologist at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto and a coinvestigator of EMPA-REG OUTCOME (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2117-28).

The analysis also showed that a “modest” effect from a reduction in uric acid might explain about 20%-25% of the observed heart failure benefit, he reported. In contrast, none of the traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors examined in the analysis – including lipids, blood pressure, obesity, and hemoglobin A1c – appeared to have any relationship to the heart failure effects of empagliflozin.

Dr. Fitchett and his associates assessed the possible impact of a list of potential mediators with a statistical method that performed an unadjusted, univariate analysis of the time-dependent change in each of several variables relative to the observed changes in heart failure outcomes.

This analysis showed that on-treatment changes in two markers of plasma volume, hematocrit and hemoglobin, each showed changes that appeared to mediate about half of the heart failure effects. A third marker of plasma volume, albumin level, appeared to mediate about a quarter of the heart failure effects.

The changes in both hematocrit and hemoglobin first appeared within a few weeks of treatment onset, and soon reached a plateau that remained sustained through the balance of the study. For example, during the first 12 weeks of treatment, the average hematocrit level rose from about 41% at baseline to about 44%. This 3% net rise corresponds to about a 7% drop in plasma volume, Dr. Fitchett said.

In addition to reflecting a potentially beneficial decrease in fluid volume, this effect would also boost the oxygen-carrying capacity of a patient’s blood that could be beneficial for patients with ischemic heart disease and those with reduced left ventricular function, he noted.

The EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly, which jointly market empagliflozin (Jardiance). Dr. Fitchett has received honoraria from those companies and also from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Merck, and Sanofi.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – When results from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial came out 2 years ago and showed a dramatic decrease in heart failure hospitalizations and deaths linked to treatment with the oral diabetes drug empagliflozin, some experts suggested that a completely hypothetical effect of empagliflozin on reducing fluid volume may have largely caused these unexpected clinical benefits.

New analyses of the trial results show this hypothesis may be at least partially correct.

Results from a post hoc analysis of data collected in Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients (EMPA-REG OUTCOME) suggest that perhaps half the heart failure benefit was attributable to what appears to have been a roughly 7% drop in plasma volume in patients treated with empagliflozin (Jardiance), which began soon after treatment started and continued through the balance of the study, David Fitchett, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Markers of change in plasma volume were important mediators of the reduction in risk of hospitalization for heart failure or death from heart failure,” said Dr Fitchett, a cardiologist at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto and a coinvestigator of EMPA-REG OUTCOME (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2117-28).

The analysis also showed that a “modest” effect from a reduction in uric acid might explain about 20%-25% of the observed heart failure benefit, he reported. In contrast, none of the traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors examined in the analysis – including lipids, blood pressure, obesity, and hemoglobin A1c – appeared to have any relationship to the heart failure effects of empagliflozin.

Dr. Fitchett and his associates assessed the possible impact of a list of potential mediators with a statistical method that performed an unadjusted, univariate analysis of the time-dependent change in each of several variables relative to the observed changes in heart failure outcomes.

This analysis showed that on-treatment changes in two markers of plasma volume, hematocrit and hemoglobin, each showed changes that appeared to mediate about half of the heart failure effects. A third marker of plasma volume, albumin level, appeared to mediate about a quarter of the heart failure effects.

The changes in both hematocrit and hemoglobin first appeared within a few weeks of treatment onset, and soon reached a plateau that remained sustained through the balance of the study. For example, during the first 12 weeks of treatment, the average hematocrit level rose from about 41% at baseline to about 44%. This 3% net rise corresponds to about a 7% drop in plasma volume, Dr. Fitchett said.

In addition to reflecting a potentially beneficial decrease in fluid volume, this effect would also boost the oxygen-carrying capacity of a patient’s blood that could be beneficial for patients with ischemic heart disease and those with reduced left ventricular function, he noted.

The EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly, which jointly market empagliflozin (Jardiance). Dr. Fitchett has received honoraria from those companies and also from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Merck, and Sanofi.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: About according to post hoc analysis of the EMPA-REG OUTCOME study.

Major finding: About half of the observed heart failure benefit was tied to a roughly 3% rise in average hematocrit level.

Data source: Post hoc analysis of data from the 7,028 patients enrolled in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial.

Disclosures: The EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly, the two companies that market empagliflozin (Jardiance). Dr. Fitchett has received honoraria from those companies and also from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Merck, and Sanofi.

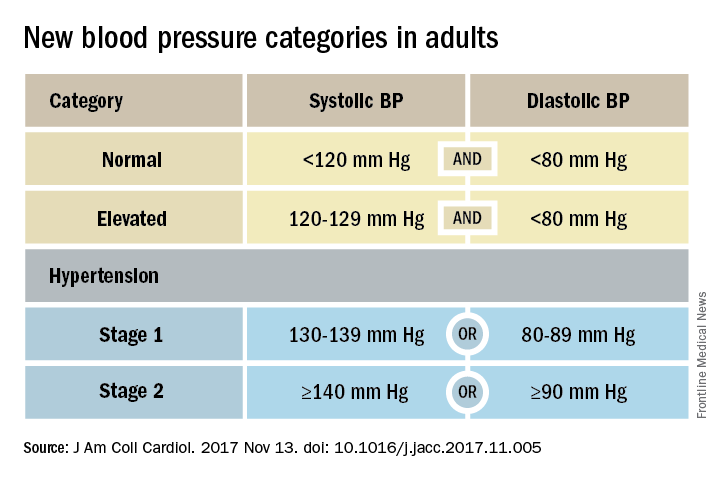

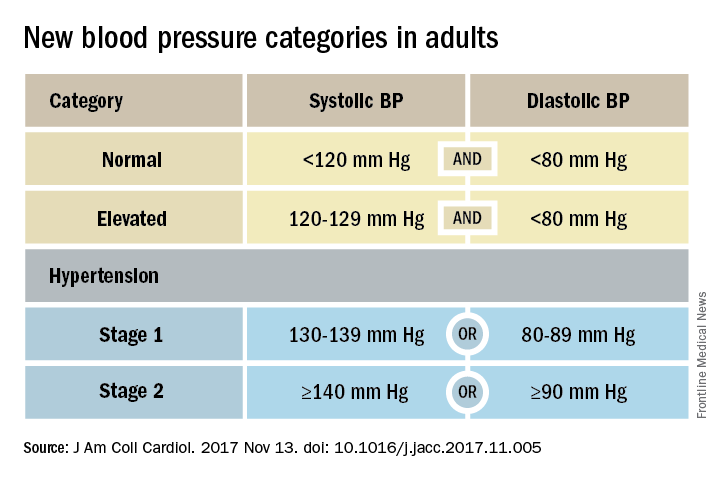

Aim for BP a bit above SPRINT

ANAHEIM – If blood pressure isn’t measured the way it was in the SPRINT trial, it shouldn’t be treated all the way down to the SPRINT target of less than 120 mm Hg; it’s best to aim a little higher, according to investigators from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California.

SPRINT (the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) found that treating hypertension to below 120 mm Hg – as opposed to below 140 mm Hg – reduced the risk of cardiovascular events and death, but blood pressure wasn’t measured the way it usually is in standard practice. Among other differences, SPRINT subjects rested for 5 minutes beforehand, sometimes unobserved, and then three automated measurements were taken and averaged (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2103-16).

In a review of 73,522 hypertensive patients, the Kaiser investigators found that those treated to a mean systolic BP (SBP) of 122 mm Hg – based on standard office measurement – actually had worse outcomes than did those treated to a mean of 132 mm Hg, with a greater incidence of cardiovascular events, hypotension, electrolyte abnormalities, and other problems.

“The way SPRINT measured BP was systematically different than the BPs we rely on to treat patients in clinical practice. We think that, unless you are going to implement a SPRINT-like protocol, aiming for a slightly higher target of around a mean of 130-132 mm Hg will achieve optimal outcomes. You are likely achieving a SPRINT BP of around 120-125 mm Hg,” said Alan Go, MD, director of the comprehensive clinical research unit at Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, Oakland.

Meanwhile, “if you [treat] to 120 mm Hg, you are probably getting around a SPRINT 114 mm Hg. That runs the risk of hypotension, which we did see. There is also the potential for coronary ischemia because you are no longer providing adequate coronary perfusion,” he said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

In their “SPRINT to translation” study, Dr. Go and his team reviewed Kaiser’s electronic medical records to identify patients with baseline BPs of 130-180 mm Hg who met SPRINT criteria and then evaluated how they fared over about 6 years of blood pressure management, with at least one BP taken every 6 months; 7,213 patients were treated to an SBP of 140-149 mm Hg and a mean of 143 mm Hg; 44,847 were treated to an SBP of 126-139 mm Hg and a mean of 132 mm Hg; and 21,462 were treated to 115-125 mm Hg and a mean of 122 mm Hg.

After extensive adjustment for potential confounders, patients treated to 140-149 mm Hg, versus those treated to 126-139 mm Hg, had a 70% increased risk of the composite outcome of acute MI, unstable angina, heart failure, stroke, and cardiovascular death, and a 28% increased risk of all-cause mortality. They also had an increased risk of acute kidney injury, electrolyte abnormalities, and other problems.

More surprisingly, patients treated to 115-125 mm Hg, again versus those treated to 126-139 mm Hg, also had an increased risk of the composite outcome of 9%. They had lower rates of MI and ischemic stroke, but higher rates of heart failure and cardiovascular death. There was also a 17% increased risk of acute kidney injury and a 51% increased risk of hypotension requiring ED or hospital treatment, as well as more electrolyte abnormalities.

The 115-125 mm Hg group also had a 48% increased risk of all-cause mortality. The magnitude of the increase suggests that low blood pressure was a secondary effect of terminal illness in some cases, but Dr. Go didn’t think that was the entire explanation.

The participants had a mean age of 70 years; 63% were women and 75% were white. As in SPRINT, patients with baseline heart failure, stroke, systolic dysfunction, diabetes, end-stage renal disease, and cancer were among those excluded.

There was no external funding for the work, and the investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

ANAHEIM – If blood pressure isn’t measured the way it was in the SPRINT trial, it shouldn’t be treated all the way down to the SPRINT target of less than 120 mm Hg; it’s best to aim a little higher, according to investigators from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California.

SPRINT (the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) found that treating hypertension to below 120 mm Hg – as opposed to below 140 mm Hg – reduced the risk of cardiovascular events and death, but blood pressure wasn’t measured the way it usually is in standard practice. Among other differences, SPRINT subjects rested for 5 minutes beforehand, sometimes unobserved, and then three automated measurements were taken and averaged (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2103-16).

In a review of 73,522 hypertensive patients, the Kaiser investigators found that those treated to a mean systolic BP (SBP) of 122 mm Hg – based on standard office measurement – actually had worse outcomes than did those treated to a mean of 132 mm Hg, with a greater incidence of cardiovascular events, hypotension, electrolyte abnormalities, and other problems.

“The way SPRINT measured BP was systematically different than the BPs we rely on to treat patients in clinical practice. We think that, unless you are going to implement a SPRINT-like protocol, aiming for a slightly higher target of around a mean of 130-132 mm Hg will achieve optimal outcomes. You are likely achieving a SPRINT BP of around 120-125 mm Hg,” said Alan Go, MD, director of the comprehensive clinical research unit at Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, Oakland.

Meanwhile, “if you [treat] to 120 mm Hg, you are probably getting around a SPRINT 114 mm Hg. That runs the risk of hypotension, which we did see. There is also the potential for coronary ischemia because you are no longer providing adequate coronary perfusion,” he said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

In their “SPRINT to translation” study, Dr. Go and his team reviewed Kaiser’s electronic medical records to identify patients with baseline BPs of 130-180 mm Hg who met SPRINT criteria and then evaluated how they fared over about 6 years of blood pressure management, with at least one BP taken every 6 months; 7,213 patients were treated to an SBP of 140-149 mm Hg and a mean of 143 mm Hg; 44,847 were treated to an SBP of 126-139 mm Hg and a mean of 132 mm Hg; and 21,462 were treated to 115-125 mm Hg and a mean of 122 mm Hg.

After extensive adjustment for potential confounders, patients treated to 140-149 mm Hg, versus those treated to 126-139 mm Hg, had a 70% increased risk of the composite outcome of acute MI, unstable angina, heart failure, stroke, and cardiovascular death, and a 28% increased risk of all-cause mortality. They also had an increased risk of acute kidney injury, electrolyte abnormalities, and other problems.

More surprisingly, patients treated to 115-125 mm Hg, again versus those treated to 126-139 mm Hg, also had an increased risk of the composite outcome of 9%. They had lower rates of MI and ischemic stroke, but higher rates of heart failure and cardiovascular death. There was also a 17% increased risk of acute kidney injury and a 51% increased risk of hypotension requiring ED or hospital treatment, as well as more electrolyte abnormalities.

The 115-125 mm Hg group also had a 48% increased risk of all-cause mortality. The magnitude of the increase suggests that low blood pressure was a secondary effect of terminal illness in some cases, but Dr. Go didn’t think that was the entire explanation.

The participants had a mean age of 70 years; 63% were women and 75% were white. As in SPRINT, patients with baseline heart failure, stroke, systolic dysfunction, diabetes, end-stage renal disease, and cancer were among those excluded.

There was no external funding for the work, and the investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

ANAHEIM – If blood pressure isn’t measured the way it was in the SPRINT trial, it shouldn’t be treated all the way down to the SPRINT target of less than 120 mm Hg; it’s best to aim a little higher, according to investigators from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California.

SPRINT (the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) found that treating hypertension to below 120 mm Hg – as opposed to below 140 mm Hg – reduced the risk of cardiovascular events and death, but blood pressure wasn’t measured the way it usually is in standard practice. Among other differences, SPRINT subjects rested for 5 minutes beforehand, sometimes unobserved, and then three automated measurements were taken and averaged (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2103-16).

In a review of 73,522 hypertensive patients, the Kaiser investigators found that those treated to a mean systolic BP (SBP) of 122 mm Hg – based on standard office measurement – actually had worse outcomes than did those treated to a mean of 132 mm Hg, with a greater incidence of cardiovascular events, hypotension, electrolyte abnormalities, and other problems.

“The way SPRINT measured BP was systematically different than the BPs we rely on to treat patients in clinical practice. We think that, unless you are going to implement a SPRINT-like protocol, aiming for a slightly higher target of around a mean of 130-132 mm Hg will achieve optimal outcomes. You are likely achieving a SPRINT BP of around 120-125 mm Hg,” said Alan Go, MD, director of the comprehensive clinical research unit at Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, Oakland.

Meanwhile, “if you [treat] to 120 mm Hg, you are probably getting around a SPRINT 114 mm Hg. That runs the risk of hypotension, which we did see. There is also the potential for coronary ischemia because you are no longer providing adequate coronary perfusion,” he said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

In their “SPRINT to translation” study, Dr. Go and his team reviewed Kaiser’s electronic medical records to identify patients with baseline BPs of 130-180 mm Hg who met SPRINT criteria and then evaluated how they fared over about 6 years of blood pressure management, with at least one BP taken every 6 months; 7,213 patients were treated to an SBP of 140-149 mm Hg and a mean of 143 mm Hg; 44,847 were treated to an SBP of 126-139 mm Hg and a mean of 132 mm Hg; and 21,462 were treated to 115-125 mm Hg and a mean of 122 mm Hg.

After extensive adjustment for potential confounders, patients treated to 140-149 mm Hg, versus those treated to 126-139 mm Hg, had a 70% increased risk of the composite outcome of acute MI, unstable angina, heart failure, stroke, and cardiovascular death, and a 28% increased risk of all-cause mortality. They also had an increased risk of acute kidney injury, electrolyte abnormalities, and other problems.

More surprisingly, patients treated to 115-125 mm Hg, again versus those treated to 126-139 mm Hg, also had an increased risk of the composite outcome of 9%. They had lower rates of MI and ischemic stroke, but higher rates of heart failure and cardiovascular death. There was also a 17% increased risk of acute kidney injury and a 51% increased risk of hypotension requiring ED or hospital treatment, as well as more electrolyte abnormalities.

The 115-125 mm Hg group also had a 48% increased risk of all-cause mortality. The magnitude of the increase suggests that low blood pressure was a secondary effect of terminal illness in some cases, but Dr. Go didn’t think that was the entire explanation.

The participants had a mean age of 70 years; 63% were women and 75% were white. As in SPRINT, patients with baseline heart failure, stroke, systolic dysfunction, diabetes, end-stage renal disease, and cancer were among those excluded.

There was no external funding for the work, and the investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Cardiovascular events were 9% more likely in patients treated to 115-125 mm Hg vs. those treated to 126-139 mm Hg.

Data source: Review of 73,522 hypertensive patients at Kaiser Permanente of Northern California

Disclosures: There was no external funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

Heart failure readmission penalties linked with rise in deaths

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Evidence continues to mount that Medicare’s penalization of hospitals with excess heart failure readmissions has cut readmissions but at the apparent price of more deaths.

During the penalty phase of the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP), which started in Oct. 2012, 30-day all-cause mortality following a heart failure hospitalization was 18% higher compared with the adjusted rate during 2006-2010, based on Medicare data from 2006-2014 that underwent “extensive” risk adjustment using prospectively-collected clinical data, Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, and his associates reported in a poster at the American Heart Association scientific sessions. During the same 2012-2014 period with imposed penalties, 30-day all-cause readmissions following an index heart failure hospitalization fell by a risk-adjusted 9% compared to the era just before the HRRP. Both the drop in readmissions and rise in deaths were statistically significant.

A similar pattern existed for the risk-adjusted readmissions and mortality rates during the year following the index hospitalization: readmissions fell by 8% compared with the time before the program but deaths rose by a relative 10%, also statistically significant differences.

“This is urgent and alarming. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services needs to revamp the program to exclude heart failure patients and take steps to mitigate the damage,” Dr. Fonarow said in an interview. He estimated that the uptick in mortality following heart failure hospitalizations is causing 5,000-10,000 excess annual deaths among U.S. heart failure patients that are directly attributable to the HRRP. Similar effects have not been seen for patients with an index hospitalization of pneumonia or acute MI, two other targets of the HRRP, he noted.

The HRRP “currently has penalties for readmissions that are 15-fold higher than for mortality. They need to penalize equally, and they need to get at the gaming that hospitals are doing” to shift outcomes away from readmissions even if it means more patients will die. Heart failure patients “who need hospitalization are being denied admission by hospitals out of fear of the readmissions penalty,” said Dr. Fonarow, professor and co-chief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Seeing increased mortality linked with implementation of the penalty is completely unacceptable.”

Although a prior report used similar Medicare data from 2008-2014 to initially find this inverse association, that analysis relied entirely on administrative data collected in Medicare records to perform risk adjustments (JAMA. 2017 July 17;318[3]:270-8). The new analysis reported by Dr. Fonarow and his associates combined the Medicare data with detailed clinical records for the same patients collected by the Get With the Guidelines--Heart Failure program. The extensive clinical data that the researchers used for risk-adjustment allowed for a more reliable attribution to the HRRP of readmission and mortality differences between the two time periods. Despite the extensive risk adjustment “we see exactly the same result” as initially reported, Dr. Fonarow said.

The findings “remind us that it is very important to look at the unintended consequences” of interventions that might initially seem reasonable, commented Lynne Warner Stevenson, MD, professor and director of cardiomyopathy at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

Concurrent with the presentation at the meeting the results also appeared in an article published online (JAMA Cardiol. 2017 Nov 12;doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2017.4265).

A separate analysis of data collected in the Get With the Guidelines--Heart Failure during 2005-2009 showed that within the past decade the 5-year survival of U.S. hospitalized heart failure patients has remained dismally low, and similar regardless of whether patients had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF, 46% of all heart failure patients in the analysis), heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF, also 46% of patients), or the in-between patients who had heart failure with borderline ejection fraction (HFbEF, an ejection fraction of 41%-49%, in 8% of patients).

The results, from 39,982 patients, showed a 75% mortality rate during 5-years of follow-up, with similar mortality rates regardless of the patient’s ejection-fraction level, reported Dr. Fonarow and his associates in a separate poster. In every age group examined, patients with heart failure had dramatically reduced life expectancies compared with the general population. For example, among heart failure patients aged 65-69 years in the study, median survival was less than 4 years compared with a 19-year expected median survival for people in the general U.S. population in the same age range.

These very low survival rates of heart failure patients initially hospitalized for heart failure during the relatively recent era of 2005-2009 “is a call to action to prevent heart failure,” said Dr. Fonarow.

The poor prognosis most heart failure patients face should also spur aggressive treatment of HFrEF patients with all proven treatments, Dr. Fonarow said. It should also spur more effort to find effective treatments for HFpEF, which currently has no clearly-proven effective treatment.

These results also appeared in a report simultaneously published online (J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 12;doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.074).

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Evidence continues to mount that Medicare’s penalization of hospitals with excess heart failure readmissions has cut readmissions but at the apparent price of more deaths.

During the penalty phase of the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP), which started in Oct. 2012, 30-day all-cause mortality following a heart failure hospitalization was 18% higher compared with the adjusted rate during 2006-2010, based on Medicare data from 2006-2014 that underwent “extensive” risk adjustment using prospectively-collected clinical data, Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, and his associates reported in a poster at the American Heart Association scientific sessions. During the same 2012-2014 period with imposed penalties, 30-day all-cause readmissions following an index heart failure hospitalization fell by a risk-adjusted 9% compared to the era just before the HRRP. Both the drop in readmissions and rise in deaths were statistically significant.

A similar pattern existed for the risk-adjusted readmissions and mortality rates during the year following the index hospitalization: readmissions fell by 8% compared with the time before the program but deaths rose by a relative 10%, also statistically significant differences.

“This is urgent and alarming. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services needs to revamp the program to exclude heart failure patients and take steps to mitigate the damage,” Dr. Fonarow said in an interview. He estimated that the uptick in mortality following heart failure hospitalizations is causing 5,000-10,000 excess annual deaths among U.S. heart failure patients that are directly attributable to the HRRP. Similar effects have not been seen for patients with an index hospitalization of pneumonia or acute MI, two other targets of the HRRP, he noted.

The HRRP “currently has penalties for readmissions that are 15-fold higher than for mortality. They need to penalize equally, and they need to get at the gaming that hospitals are doing” to shift outcomes away from readmissions even if it means more patients will die. Heart failure patients “who need hospitalization are being denied admission by hospitals out of fear of the readmissions penalty,” said Dr. Fonarow, professor and co-chief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Seeing increased mortality linked with implementation of the penalty is completely unacceptable.”

Although a prior report used similar Medicare data from 2008-2014 to initially find this inverse association, that analysis relied entirely on administrative data collected in Medicare records to perform risk adjustments (JAMA. 2017 July 17;318[3]:270-8). The new analysis reported by Dr. Fonarow and his associates combined the Medicare data with detailed clinical records for the same patients collected by the Get With the Guidelines--Heart Failure program. The extensive clinical data that the researchers used for risk-adjustment allowed for a more reliable attribution to the HRRP of readmission and mortality differences between the two time periods. Despite the extensive risk adjustment “we see exactly the same result” as initially reported, Dr. Fonarow said.

The findings “remind us that it is very important to look at the unintended consequences” of interventions that might initially seem reasonable, commented Lynne Warner Stevenson, MD, professor and director of cardiomyopathy at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

Concurrent with the presentation at the meeting the results also appeared in an article published online (JAMA Cardiol. 2017 Nov 12;doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2017.4265).