User login

U.S. fertility rate, teen births are on the decline

The general fertility rate in the United States decreased 2% between 2017 and 2018, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Fertility rates, defined as births per 1,000 women aged 15-44 years, declined for all racial/ethnic groups studied.

Teen birth rates, or births among girls aged 15-19 years, declined from 2017 to 2018 as well.

These data come from the National Vital Statistics System’s Natality Data File, which includes information from birth certificates for all births in the United States.

The data show a decline in the general fertility rate from 60.3 per 1,000 women in 2017 to 59.1 per 1,000 women in 2018, a significant decrease (P less than .05).

Fertility rates declined across the three largest racial/ethnic groups studied, decreasing:

- 3% in Hispanic women, from 67.6 to 65.9 per 1,000.

- 2% in non-Hispanic black women, from 63.1 to 62.0 per 1,000.

- 2% in non-Hispanic white women, from 57.2 to 56.3 per 1,000.

Similarly, teen birth rates declined 7% from 2017 to 2018, decreasing from 18.8 to 17.4 births per 1,000 girls aged 15-19 years (P less than .05). Rates decreased:

- 8% in Hispanic teens, from 28.9 to 26.7 per 1,000.

- 4% in non-Hispanic black teens, from 27.5 to 26.3 per 1,000.

- 8% in non-Hispanic white teens, from 13.2 to 12.1 per 1,000.

The data also show an increase in the rate of vaginal births after previous cesarean (VBAC) delivery. The percentage of VBAC deliveries increased from 12.8% in 2017 to 13.3% in 2018 (P less than .05).

VBAC delivery rates increased across all racial/ethnic groups studied, although the increase among non-Hispanic back women was not significant.

Finally, the report shows an increase in preterm and early term births from 2017 to 2018. Preterm deliveries (less than 37 weeks of gestation) increased from 9.93% to 10.02%, and early term deliveries (37-38 weeks) increased from 26.00% to 26.53% (P less than .05).

At the same time, full-term births (39-40 weeks) decreased from 57.49% to 57.24%, and late- and post-term births (41 weeks or more) decreased from 6.58 % to 6.20% (P less than .05). These findings were consistent across the racial/ethnic groups studied.

SOURCE: Martin JA et al. NCHS Data Brief. 2019 July; no 346.

The general fertility rate in the United States decreased 2% between 2017 and 2018, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Fertility rates, defined as births per 1,000 women aged 15-44 years, declined for all racial/ethnic groups studied.

Teen birth rates, or births among girls aged 15-19 years, declined from 2017 to 2018 as well.

These data come from the National Vital Statistics System’s Natality Data File, which includes information from birth certificates for all births in the United States.

The data show a decline in the general fertility rate from 60.3 per 1,000 women in 2017 to 59.1 per 1,000 women in 2018, a significant decrease (P less than .05).

Fertility rates declined across the three largest racial/ethnic groups studied, decreasing:

- 3% in Hispanic women, from 67.6 to 65.9 per 1,000.

- 2% in non-Hispanic black women, from 63.1 to 62.0 per 1,000.

- 2% in non-Hispanic white women, from 57.2 to 56.3 per 1,000.

Similarly, teen birth rates declined 7% from 2017 to 2018, decreasing from 18.8 to 17.4 births per 1,000 girls aged 15-19 years (P less than .05). Rates decreased:

- 8% in Hispanic teens, from 28.9 to 26.7 per 1,000.

- 4% in non-Hispanic black teens, from 27.5 to 26.3 per 1,000.

- 8% in non-Hispanic white teens, from 13.2 to 12.1 per 1,000.

The data also show an increase in the rate of vaginal births after previous cesarean (VBAC) delivery. The percentage of VBAC deliveries increased from 12.8% in 2017 to 13.3% in 2018 (P less than .05).

VBAC delivery rates increased across all racial/ethnic groups studied, although the increase among non-Hispanic back women was not significant.

Finally, the report shows an increase in preterm and early term births from 2017 to 2018. Preterm deliveries (less than 37 weeks of gestation) increased from 9.93% to 10.02%, and early term deliveries (37-38 weeks) increased from 26.00% to 26.53% (P less than .05).

At the same time, full-term births (39-40 weeks) decreased from 57.49% to 57.24%, and late- and post-term births (41 weeks or more) decreased from 6.58 % to 6.20% (P less than .05). These findings were consistent across the racial/ethnic groups studied.

SOURCE: Martin JA et al. NCHS Data Brief. 2019 July; no 346.

The general fertility rate in the United States decreased 2% between 2017 and 2018, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Fertility rates, defined as births per 1,000 women aged 15-44 years, declined for all racial/ethnic groups studied.

Teen birth rates, or births among girls aged 15-19 years, declined from 2017 to 2018 as well.

These data come from the National Vital Statistics System’s Natality Data File, which includes information from birth certificates for all births in the United States.

The data show a decline in the general fertility rate from 60.3 per 1,000 women in 2017 to 59.1 per 1,000 women in 2018, a significant decrease (P less than .05).

Fertility rates declined across the three largest racial/ethnic groups studied, decreasing:

- 3% in Hispanic women, from 67.6 to 65.9 per 1,000.

- 2% in non-Hispanic black women, from 63.1 to 62.0 per 1,000.

- 2% in non-Hispanic white women, from 57.2 to 56.3 per 1,000.

Similarly, teen birth rates declined 7% from 2017 to 2018, decreasing from 18.8 to 17.4 births per 1,000 girls aged 15-19 years (P less than .05). Rates decreased:

- 8% in Hispanic teens, from 28.9 to 26.7 per 1,000.

- 4% in non-Hispanic black teens, from 27.5 to 26.3 per 1,000.

- 8% in non-Hispanic white teens, from 13.2 to 12.1 per 1,000.

The data also show an increase in the rate of vaginal births after previous cesarean (VBAC) delivery. The percentage of VBAC deliveries increased from 12.8% in 2017 to 13.3% in 2018 (P less than .05).

VBAC delivery rates increased across all racial/ethnic groups studied, although the increase among non-Hispanic back women was not significant.

Finally, the report shows an increase in preterm and early term births from 2017 to 2018. Preterm deliveries (less than 37 weeks of gestation) increased from 9.93% to 10.02%, and early term deliveries (37-38 weeks) increased from 26.00% to 26.53% (P less than .05).

At the same time, full-term births (39-40 weeks) decreased from 57.49% to 57.24%, and late- and post-term births (41 weeks or more) decreased from 6.58 % to 6.20% (P less than .05). These findings were consistent across the racial/ethnic groups studied.

SOURCE: Martin JA et al. NCHS Data Brief. 2019 July; no 346.

Mothers, migraine, colic ... and sleep

In a recent article on this website, Jake Remaly reports on a study suggesting that maternal migraine is associated with infant colic. In a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society, Amy Gelfand, MD, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco, reported the results of a national survey of more than 1,400 parents (827 mothers, 592 fathers) collected via social media. She and her colleagues found that mothers with migraine were more likely to have an infant with colic, with an odds ratio of 1.7 that increased to 2.5 for mothers with more frequent migraine. Fathers with migraine were no more likely to have an infant with colic.

In a video clip included in the article, Dr. Gelfand discusses the possibilities that she and her group considered as they attempted to explain the study’s findings. Are there such things as “migraine genes?” If so, the failure to discover a paternal association might suggest that these would be mitochondrial genes. The researchers wondered if a substance in breast milk was acting as trigger, but they found that the association between colic and migraine was unrelated to whether the baby was fed by breast or bottle.

In full disclosure, I was not one of the investigators. Neither my wife nor I have migraine, and although our children cried as infants, they wouldn’t have qualified as having colic. However, I spent more than 40 years immersed in more than 300,000 patient encounters and can claim membership in the International Brother/Sisterhood of Anecdotal Observers. And, as such will offer up my explanation for Dr. Gelfand’s findings.

It is clear to me that most, if not all, children with migraine have their headaches when they are sleep deprived. While my sample size is smaller, I believe the same association also is true for many of the adults I know who have migraine. At least in children, restorative sleep ends the migraine much as it does for an epileptic seizure.

Traditionally, colic has been thought to be somehow related to a gastrointestinal phenomenon by many extended family members and some physicians. However, in my experience, it is usually a symptom of sleep deprivation compounded by the failure of those around the children to realize the obvious and take appropriate action. Of course, some babies are reacting to sore tummies, but my guess is that most are having headaches. We may never know. Dr. Gelfand also shares my observation that colicky crying is more likely to occur “at the end of the day,” a time when we are tired and are less tolerant of overstimulation.

However, the presentation varies depending on the age of the patients. Remember, infants can’t talk. It already has been shown that adults with migraine often were more likely to have been colicky infants. (Dr. Gelfand mentions this as well.) These unfortunate individuals probably have inherited a vulnerability to sleep deprivation that manifests itself as a headache. I hope to live long enough to be around when someone discovers the wrinkle in the genome that creates this vulnerability.

So, why did the researchers fail to find an association between fathers and colic? The answer is simple. We fathers are beginning to take on a larger role in parenting of infants and like to complain about how difficult it is. However, it is mothers who still have the lioness’ share of the work. They lose the most sleep and are starting off parenthood with 9 months of less than optimal sleep followed by who knows how many hours of energy-sapping labor. It’s surprising they all don’t have migraines.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

In a recent article on this website, Jake Remaly reports on a study suggesting that maternal migraine is associated with infant colic. In a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society, Amy Gelfand, MD, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco, reported the results of a national survey of more than 1,400 parents (827 mothers, 592 fathers) collected via social media. She and her colleagues found that mothers with migraine were more likely to have an infant with colic, with an odds ratio of 1.7 that increased to 2.5 for mothers with more frequent migraine. Fathers with migraine were no more likely to have an infant with colic.

In a video clip included in the article, Dr. Gelfand discusses the possibilities that she and her group considered as they attempted to explain the study’s findings. Are there such things as “migraine genes?” If so, the failure to discover a paternal association might suggest that these would be mitochondrial genes. The researchers wondered if a substance in breast milk was acting as trigger, but they found that the association between colic and migraine was unrelated to whether the baby was fed by breast or bottle.

In full disclosure, I was not one of the investigators. Neither my wife nor I have migraine, and although our children cried as infants, they wouldn’t have qualified as having colic. However, I spent more than 40 years immersed in more than 300,000 patient encounters and can claim membership in the International Brother/Sisterhood of Anecdotal Observers. And, as such will offer up my explanation for Dr. Gelfand’s findings.

It is clear to me that most, if not all, children with migraine have their headaches when they are sleep deprived. While my sample size is smaller, I believe the same association also is true for many of the adults I know who have migraine. At least in children, restorative sleep ends the migraine much as it does for an epileptic seizure.

Traditionally, colic has been thought to be somehow related to a gastrointestinal phenomenon by many extended family members and some physicians. However, in my experience, it is usually a symptom of sleep deprivation compounded by the failure of those around the children to realize the obvious and take appropriate action. Of course, some babies are reacting to sore tummies, but my guess is that most are having headaches. We may never know. Dr. Gelfand also shares my observation that colicky crying is more likely to occur “at the end of the day,” a time when we are tired and are less tolerant of overstimulation.

However, the presentation varies depending on the age of the patients. Remember, infants can’t talk. It already has been shown that adults with migraine often were more likely to have been colicky infants. (Dr. Gelfand mentions this as well.) These unfortunate individuals probably have inherited a vulnerability to sleep deprivation that manifests itself as a headache. I hope to live long enough to be around when someone discovers the wrinkle in the genome that creates this vulnerability.

So, why did the researchers fail to find an association between fathers and colic? The answer is simple. We fathers are beginning to take on a larger role in parenting of infants and like to complain about how difficult it is. However, it is mothers who still have the lioness’ share of the work. They lose the most sleep and are starting off parenthood with 9 months of less than optimal sleep followed by who knows how many hours of energy-sapping labor. It’s surprising they all don’t have migraines.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

In a recent article on this website, Jake Remaly reports on a study suggesting that maternal migraine is associated with infant colic. In a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society, Amy Gelfand, MD, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco, reported the results of a national survey of more than 1,400 parents (827 mothers, 592 fathers) collected via social media. She and her colleagues found that mothers with migraine were more likely to have an infant with colic, with an odds ratio of 1.7 that increased to 2.5 for mothers with more frequent migraine. Fathers with migraine were no more likely to have an infant with colic.

In a video clip included in the article, Dr. Gelfand discusses the possibilities that she and her group considered as they attempted to explain the study’s findings. Are there such things as “migraine genes?” If so, the failure to discover a paternal association might suggest that these would be mitochondrial genes. The researchers wondered if a substance in breast milk was acting as trigger, but they found that the association between colic and migraine was unrelated to whether the baby was fed by breast or bottle.

In full disclosure, I was not one of the investigators. Neither my wife nor I have migraine, and although our children cried as infants, they wouldn’t have qualified as having colic. However, I spent more than 40 years immersed in more than 300,000 patient encounters and can claim membership in the International Brother/Sisterhood of Anecdotal Observers. And, as such will offer up my explanation for Dr. Gelfand’s findings.

It is clear to me that most, if not all, children with migraine have their headaches when they are sleep deprived. While my sample size is smaller, I believe the same association also is true for many of the adults I know who have migraine. At least in children, restorative sleep ends the migraine much as it does for an epileptic seizure.

Traditionally, colic has been thought to be somehow related to a gastrointestinal phenomenon by many extended family members and some physicians. However, in my experience, it is usually a symptom of sleep deprivation compounded by the failure of those around the children to realize the obvious and take appropriate action. Of course, some babies are reacting to sore tummies, but my guess is that most are having headaches. We may never know. Dr. Gelfand also shares my observation that colicky crying is more likely to occur “at the end of the day,” a time when we are tired and are less tolerant of overstimulation.

However, the presentation varies depending on the age of the patients. Remember, infants can’t talk. It already has been shown that adults with migraine often were more likely to have been colicky infants. (Dr. Gelfand mentions this as well.) These unfortunate individuals probably have inherited a vulnerability to sleep deprivation that manifests itself as a headache. I hope to live long enough to be around when someone discovers the wrinkle in the genome that creates this vulnerability.

So, why did the researchers fail to find an association between fathers and colic? The answer is simple. We fathers are beginning to take on a larger role in parenting of infants and like to complain about how difficult it is. However, it is mothers who still have the lioness’ share of the work. They lose the most sleep and are starting off parenthood with 9 months of less than optimal sleep followed by who knows how many hours of energy-sapping labor. It’s surprising they all don’t have migraines.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

First-time fathers at risk of postnatal depressive symptoms

First-time fathers may be at risk of experiencing depressive symptoms as they transition to parenthood – especially if risk factors such as poor sleep are present, results of a prospective study of more than 600 new fathers show.

“Strategies to promote better sleep, mobilize social support, and strengthen the couple relationship may be important to address in innovative interventions tailored to new fathers at risk for depression during the perinatal period,” wrote Deborah Da Costa, PhD, of McGill University, Montreal, and colleagues. The study was published in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

To determine the prevalence of depressive symptoms in first-time fathers and identify notable risk factors, the researchers surveyed 622 Canadian men during their partner’s third trimester. The same group was surveyed again at 2 and 6 months postpartum. Depression was assessed via the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), and additional variables such as sleep quality, social support, and stress were gathered as well.

Of the initial 622 men surveyed, 487 (78.3%) and 375 (60.3%) completed the questionnaires at 2 and 6 months postpartum, respectively. The prevalence of paternal depressive symptoms was 13.76% (95% confidence interval, 10.70-16.82) at 2 months and 13.6% (95% CI, 10.13-17.07) at 6 months. Of the men who reported depressive symptoms at 2 months postpartum, 40.3% also experienced symptoms during the third trimester. Of the men who reported depressive symptoms at 6 months postpartum, 24% experienced symptoms during the third trimester and after 2 months.

At 2 months, the risk of depressive symptoms increased for men with worse sleep quality (odds ratio, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.10-1.42), poorer couple relationship adjustment (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.94-0.99), and higher parenting stress (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.11). At 6 months, there was a significant association between paternal depressive symptoms and unemployment (OR, 3.75; 95% CI, 1.00-13.72), poorer sleep quality (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.16-1.65), lower social support (OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.84-1.00), poorer couple relationship adjustment (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.92-0.98), and higher financial stress (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.04-1.42).

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including a middling response rate that could affect the accuracy of prevalence estimates and a well-educated, largely middle-class sample that could limit generalizability. In addition, they assessed depressive symptoms by self-report and not diagnostic clinical interviews. However, they also noted that “the EPDS is the most widely used tool to assess depressive symptoms in parents during the perinatal period and was validated in expectant and new fathers.”

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Da Costa D et al. J Affect Disord. 2019 Apr 15;249:371-7.

First-time fathers may be at risk of experiencing depressive symptoms as they transition to parenthood – especially if risk factors such as poor sleep are present, results of a prospective study of more than 600 new fathers show.

“Strategies to promote better sleep, mobilize social support, and strengthen the couple relationship may be important to address in innovative interventions tailored to new fathers at risk for depression during the perinatal period,” wrote Deborah Da Costa, PhD, of McGill University, Montreal, and colleagues. The study was published in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

To determine the prevalence of depressive symptoms in first-time fathers and identify notable risk factors, the researchers surveyed 622 Canadian men during their partner’s third trimester. The same group was surveyed again at 2 and 6 months postpartum. Depression was assessed via the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), and additional variables such as sleep quality, social support, and stress were gathered as well.

Of the initial 622 men surveyed, 487 (78.3%) and 375 (60.3%) completed the questionnaires at 2 and 6 months postpartum, respectively. The prevalence of paternal depressive symptoms was 13.76% (95% confidence interval, 10.70-16.82) at 2 months and 13.6% (95% CI, 10.13-17.07) at 6 months. Of the men who reported depressive symptoms at 2 months postpartum, 40.3% also experienced symptoms during the third trimester. Of the men who reported depressive symptoms at 6 months postpartum, 24% experienced symptoms during the third trimester and after 2 months.

At 2 months, the risk of depressive symptoms increased for men with worse sleep quality (odds ratio, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.10-1.42), poorer couple relationship adjustment (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.94-0.99), and higher parenting stress (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.11). At 6 months, there was a significant association between paternal depressive symptoms and unemployment (OR, 3.75; 95% CI, 1.00-13.72), poorer sleep quality (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.16-1.65), lower social support (OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.84-1.00), poorer couple relationship adjustment (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.92-0.98), and higher financial stress (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.04-1.42).

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including a middling response rate that could affect the accuracy of prevalence estimates and a well-educated, largely middle-class sample that could limit generalizability. In addition, they assessed depressive symptoms by self-report and not diagnostic clinical interviews. However, they also noted that “the EPDS is the most widely used tool to assess depressive symptoms in parents during the perinatal period and was validated in expectant and new fathers.”

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Da Costa D et al. J Affect Disord. 2019 Apr 15;249:371-7.

First-time fathers may be at risk of experiencing depressive symptoms as they transition to parenthood – especially if risk factors such as poor sleep are present, results of a prospective study of more than 600 new fathers show.

“Strategies to promote better sleep, mobilize social support, and strengthen the couple relationship may be important to address in innovative interventions tailored to new fathers at risk for depression during the perinatal period,” wrote Deborah Da Costa, PhD, of McGill University, Montreal, and colleagues. The study was published in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

To determine the prevalence of depressive symptoms in first-time fathers and identify notable risk factors, the researchers surveyed 622 Canadian men during their partner’s third trimester. The same group was surveyed again at 2 and 6 months postpartum. Depression was assessed via the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), and additional variables such as sleep quality, social support, and stress were gathered as well.

Of the initial 622 men surveyed, 487 (78.3%) and 375 (60.3%) completed the questionnaires at 2 and 6 months postpartum, respectively. The prevalence of paternal depressive symptoms was 13.76% (95% confidence interval, 10.70-16.82) at 2 months and 13.6% (95% CI, 10.13-17.07) at 6 months. Of the men who reported depressive symptoms at 2 months postpartum, 40.3% also experienced symptoms during the third trimester. Of the men who reported depressive symptoms at 6 months postpartum, 24% experienced symptoms during the third trimester and after 2 months.

At 2 months, the risk of depressive symptoms increased for men with worse sleep quality (odds ratio, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.10-1.42), poorer couple relationship adjustment (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.94-0.99), and higher parenting stress (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.11). At 6 months, there was a significant association between paternal depressive symptoms and unemployment (OR, 3.75; 95% CI, 1.00-13.72), poorer sleep quality (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.16-1.65), lower social support (OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.84-1.00), poorer couple relationship adjustment (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.92-0.98), and higher financial stress (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.04-1.42).

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including a middling response rate that could affect the accuracy of prevalence estimates and a well-educated, largely middle-class sample that could limit generalizability. In addition, they assessed depressive symptoms by self-report and not diagnostic clinical interviews. However, they also noted that “the EPDS is the most widely used tool to assess depressive symptoms in parents during the perinatal period and was validated in expectant and new fathers.”

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Da Costa D et al. J Affect Disord. 2019 Apr 15;249:371-7.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Maternal migraine is associated with infant colic

PHILADELPHIA – , according to research presented at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society. Fathers with migraine are not more likely to have children with colic, however. These findings may have implications for the care of mothers with migraine and their children, said Amy Gelfand, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco.

Smaller studies have suggested associations between migraine and colic. To examine this relationship in a large, national sample, Dr. Gelfand and her research colleagues conducted a cross-sectional survey of biological parents of 4- to 8-week-olds in the United States. The researchers analyzed data from 1,419 participants – 827 mothers and 592 fathers – who completed online surveys in 2017 and 2018.

Parents provided information about their and their infants’ health. The investigators identified migraineurs using modified International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition criteria and determined infant colic by response to the question, “Has your baby cried for at least 3 hours on at least 3 days in the last week?”

In all, 33.5% of the mothers had migraine or probable migraine, and 20.8% of the fathers had migraine or probable migraine. Maternal migraine was associated with increased odds of infant colic (odds ratio, 1.7). Among mothers with migraine and headache frequency of 15 or more days per month, the likelihood of having an infant with colic was even greater (OR, 2.5).

“The cause of colic is unknown, yet colic is common, and these frequent bouts of intense crying or fussiness can be particularly frustrating for parents, creating family stress and anxiety,” Dr. Gelfand said in a news release. “New moms who are armed with knowledge of the connection between their own history of migraine and infant colic can be better prepared for these often difficult first months of a baby and new mother’s journey.”

PHILADELPHIA – , according to research presented at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society. Fathers with migraine are not more likely to have children with colic, however. These findings may have implications for the care of mothers with migraine and their children, said Amy Gelfand, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco.

Smaller studies have suggested associations between migraine and colic. To examine this relationship in a large, national sample, Dr. Gelfand and her research colleagues conducted a cross-sectional survey of biological parents of 4- to 8-week-olds in the United States. The researchers analyzed data from 1,419 participants – 827 mothers and 592 fathers – who completed online surveys in 2017 and 2018.

Parents provided information about their and their infants’ health. The investigators identified migraineurs using modified International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition criteria and determined infant colic by response to the question, “Has your baby cried for at least 3 hours on at least 3 days in the last week?”

In all, 33.5% of the mothers had migraine or probable migraine, and 20.8% of the fathers had migraine or probable migraine. Maternal migraine was associated with increased odds of infant colic (odds ratio, 1.7). Among mothers with migraine and headache frequency of 15 or more days per month, the likelihood of having an infant with colic was even greater (OR, 2.5).

“The cause of colic is unknown, yet colic is common, and these frequent bouts of intense crying or fussiness can be particularly frustrating for parents, creating family stress and anxiety,” Dr. Gelfand said in a news release. “New moms who are armed with knowledge of the connection between their own history of migraine and infant colic can be better prepared for these often difficult first months of a baby and new mother’s journey.”

PHILADELPHIA – , according to research presented at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society. Fathers with migraine are not more likely to have children with colic, however. These findings may have implications for the care of mothers with migraine and their children, said Amy Gelfand, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco.

Smaller studies have suggested associations between migraine and colic. To examine this relationship in a large, national sample, Dr. Gelfand and her research colleagues conducted a cross-sectional survey of biological parents of 4- to 8-week-olds in the United States. The researchers analyzed data from 1,419 participants – 827 mothers and 592 fathers – who completed online surveys in 2017 and 2018.

Parents provided information about their and their infants’ health. The investigators identified migraineurs using modified International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition criteria and determined infant colic by response to the question, “Has your baby cried for at least 3 hours on at least 3 days in the last week?”

In all, 33.5% of the mothers had migraine or probable migraine, and 20.8% of the fathers had migraine or probable migraine. Maternal migraine was associated with increased odds of infant colic (odds ratio, 1.7). Among mothers with migraine and headache frequency of 15 or more days per month, the likelihood of having an infant with colic was even greater (OR, 2.5).

“The cause of colic is unknown, yet colic is common, and these frequent bouts of intense crying or fussiness can be particularly frustrating for parents, creating family stress and anxiety,” Dr. Gelfand said in a news release. “New moms who are armed with knowledge of the connection between their own history of migraine and infant colic can be better prepared for these often difficult first months of a baby and new mother’s journey.”

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AHS 2019

Neonatal ICU stay found ‘protective’ against risk for developing atopic dermatitis

AUSTIN – The

“While more time in the NICU is associated with a lesser risk of developing atopic dermatitis, we certainly do not want to keep infants in the NICU longer in order to lower their risk of atopic dermatitis,” the study’s first author, Jennifer J. Schoch, MD, said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “Instead, we need to work on understanding the mechanisms behind this relationship. For example, are there certain exposures in the NICU that influence the cutaneous immunity to ultimately reduce the risk of atopic dermatitis?”

According to Dr. Schoch, a pediatric dermatologist at the University of Florida, Gainesville, the medical literature has been conflicted regarding the relationship between prematurity and eczema. A recent meta-analysis of 18 studies found an association between very preterm birth and a decreased risk of eczema, yet the risk became insignificant among children born moderately preterm (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78[6]:1142-8). However, the factors contributing to this relationship are not well understood.

In an effort to explore the infant, maternal, and environmental factors of infants who developed AD, compared with infants who did not, Dr. Schoch and colleagues evaluated infants who were born at University of Florida Health from June 1, 2011, to April 30, 2017; had at least two well-child visits; and had at least one visit at 300 days old or later. The researchers included 4,016 mother-infant dyads in the study. Atopic dermatitis was diagnosed in 26.5% of the infants. Factors significantly associated with the incidence of AD were delivery mode (P = .0127), NICU stay (P = .0001), gestational age (P = .0006), and birth weight (P = .0020). Specifically, infants had a higher risk of developing AD if they were delivered vaginally, did not stay in the NICU, had a higher gestational age, or had a higher birth weight. Extremely preterm (less than 28 weeks’ gestation) and very preterm (28 to less than 32 weeks’ gestation) infants had the lowest rates of AD, at 10.9% and 19%, respectively.

When the researchers adjusted for other variables to their model, only length of stay in the NICU was related to the development of AD. Specifically, infants who spent more time in the NICU had a lower risk of developing atopic dermatitis (P = .0039).

“We were surprised to find that the length of stay in the neonatal intensive care unit was the strongest protective factor against the future development of eczema,” Dr. Schoch said. “Instead of this relationship being mediated by gestational age or birth weight, it was how much time the infants spent in the NICU that seemed to ‘protect’ from future eczema.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design with data gathered from electronic medical records. Also, “diagnosis was determined by ICD-9 or ICD-10 code, and not confirmed by dermatologists,” she said.

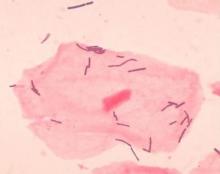

In their abstract, the researchers wrote that the finding highlights “the importance of early life interactions between the microbiome, developing cutaneous immunity, and the evolving skin barrier of the preterm infant. The skin microbiome of premature infants differs from full-term infants, in that the premature infant cutaneous microbiome is dominated by Staphylococcus species” (Microbiome. 2018;6[1]:98). They added that “the early presence of Staphylococcus on the skin may confer protection.”

Dr. Schoch reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Schoch J et al. SPD 2019, Poster 2.

AUSTIN – The

“While more time in the NICU is associated with a lesser risk of developing atopic dermatitis, we certainly do not want to keep infants in the NICU longer in order to lower their risk of atopic dermatitis,” the study’s first author, Jennifer J. Schoch, MD, said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “Instead, we need to work on understanding the mechanisms behind this relationship. For example, are there certain exposures in the NICU that influence the cutaneous immunity to ultimately reduce the risk of atopic dermatitis?”

According to Dr. Schoch, a pediatric dermatologist at the University of Florida, Gainesville, the medical literature has been conflicted regarding the relationship between prematurity and eczema. A recent meta-analysis of 18 studies found an association between very preterm birth and a decreased risk of eczema, yet the risk became insignificant among children born moderately preterm (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78[6]:1142-8). However, the factors contributing to this relationship are not well understood.

In an effort to explore the infant, maternal, and environmental factors of infants who developed AD, compared with infants who did not, Dr. Schoch and colleagues evaluated infants who were born at University of Florida Health from June 1, 2011, to April 30, 2017; had at least two well-child visits; and had at least one visit at 300 days old or later. The researchers included 4,016 mother-infant dyads in the study. Atopic dermatitis was diagnosed in 26.5% of the infants. Factors significantly associated with the incidence of AD were delivery mode (P = .0127), NICU stay (P = .0001), gestational age (P = .0006), and birth weight (P = .0020). Specifically, infants had a higher risk of developing AD if they were delivered vaginally, did not stay in the NICU, had a higher gestational age, or had a higher birth weight. Extremely preterm (less than 28 weeks’ gestation) and very preterm (28 to less than 32 weeks’ gestation) infants had the lowest rates of AD, at 10.9% and 19%, respectively.

When the researchers adjusted for other variables to their model, only length of stay in the NICU was related to the development of AD. Specifically, infants who spent more time in the NICU had a lower risk of developing atopic dermatitis (P = .0039).

“We were surprised to find that the length of stay in the neonatal intensive care unit was the strongest protective factor against the future development of eczema,” Dr. Schoch said. “Instead of this relationship being mediated by gestational age or birth weight, it was how much time the infants spent in the NICU that seemed to ‘protect’ from future eczema.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design with data gathered from electronic medical records. Also, “diagnosis was determined by ICD-9 or ICD-10 code, and not confirmed by dermatologists,” she said.

In their abstract, the researchers wrote that the finding highlights “the importance of early life interactions between the microbiome, developing cutaneous immunity, and the evolving skin barrier of the preterm infant. The skin microbiome of premature infants differs from full-term infants, in that the premature infant cutaneous microbiome is dominated by Staphylococcus species” (Microbiome. 2018;6[1]:98). They added that “the early presence of Staphylococcus on the skin may confer protection.”

Dr. Schoch reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Schoch J et al. SPD 2019, Poster 2.

AUSTIN – The

“While more time in the NICU is associated with a lesser risk of developing atopic dermatitis, we certainly do not want to keep infants in the NICU longer in order to lower their risk of atopic dermatitis,” the study’s first author, Jennifer J. Schoch, MD, said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “Instead, we need to work on understanding the mechanisms behind this relationship. For example, are there certain exposures in the NICU that influence the cutaneous immunity to ultimately reduce the risk of atopic dermatitis?”

According to Dr. Schoch, a pediatric dermatologist at the University of Florida, Gainesville, the medical literature has been conflicted regarding the relationship between prematurity and eczema. A recent meta-analysis of 18 studies found an association between very preterm birth and a decreased risk of eczema, yet the risk became insignificant among children born moderately preterm (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78[6]:1142-8). However, the factors contributing to this relationship are not well understood.

In an effort to explore the infant, maternal, and environmental factors of infants who developed AD, compared with infants who did not, Dr. Schoch and colleagues evaluated infants who were born at University of Florida Health from June 1, 2011, to April 30, 2017; had at least two well-child visits; and had at least one visit at 300 days old or later. The researchers included 4,016 mother-infant dyads in the study. Atopic dermatitis was diagnosed in 26.5% of the infants. Factors significantly associated with the incidence of AD were delivery mode (P = .0127), NICU stay (P = .0001), gestational age (P = .0006), and birth weight (P = .0020). Specifically, infants had a higher risk of developing AD if they were delivered vaginally, did not stay in the NICU, had a higher gestational age, or had a higher birth weight. Extremely preterm (less than 28 weeks’ gestation) and very preterm (28 to less than 32 weeks’ gestation) infants had the lowest rates of AD, at 10.9% and 19%, respectively.

When the researchers adjusted for other variables to their model, only length of stay in the NICU was related to the development of AD. Specifically, infants who spent more time in the NICU had a lower risk of developing atopic dermatitis (P = .0039).

“We were surprised to find that the length of stay in the neonatal intensive care unit was the strongest protective factor against the future development of eczema,” Dr. Schoch said. “Instead of this relationship being mediated by gestational age or birth weight, it was how much time the infants spent in the NICU that seemed to ‘protect’ from future eczema.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design with data gathered from electronic medical records. Also, “diagnosis was determined by ICD-9 or ICD-10 code, and not confirmed by dermatologists,” she said.

In their abstract, the researchers wrote that the finding highlights “the importance of early life interactions between the microbiome, developing cutaneous immunity, and the evolving skin barrier of the preterm infant. The skin microbiome of premature infants differs from full-term infants, in that the premature infant cutaneous microbiome is dominated by Staphylococcus species” (Microbiome. 2018;6[1]:98). They added that “the early presence of Staphylococcus on the skin may confer protection.”

Dr. Schoch reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Schoch J et al. SPD 2019, Poster 2.

REPORTING FROM SPD 2019

Key clinical point: Preterm infants develop atopic dermatitis less often than full term infants.

Major finding: Infants that spent more time in the neonatal ICU had a lower risk of developing atopic dermatitis (P = .0039).

Study details: A single-center study of 4,016 mother-infant dyads.

Disclosures: Dr. Schoch reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Schoch J et al. SPD 2019, Poster 2.

Perinatal depression screening improves screening, treatment for postpartum depression

A policy of universal screening of perinatal depression for women receiving prenatal care at an academic medical center led to more regular screening of depression, and made it more likely that women with postpartum depression would be referred for treatment, according to recent research published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Emily S. Miller, MD, MPH, at Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues performed a retrospective study of 5,127 women receiving prenatal care at the center between 2008 and 2015. They divided the group into those who were at the center before (n = 1,122) and after (n = 4,005) initiation of a policy on universal perinatal depression screening, which consisted of two antenatal screenings at the first prenatal visit and third trimester, and one postpartum screening.

After initiation of the policy, screening increased during the first trimester (0.1% vs. 66%; P less than .001), the third trimester (0% vs. 43%; P less than .001), and at the postpartum visit (70% vs. 90%; P less than .001). Screening continued to increase at both prenatal visits, while screening prevalence remained the same for the postpartum visit. in the post-policy group (30% vs. 65%).

Katrina S. Mark, MD, associate professor of the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, said in an interview that the study “brings attention to an incredibly important topic.

“The researchers in this study found that, after implementation of a new policy regarding antenatal and postpartum depression screening, there was a significant increase in women who were screened during and after pregnancy as well as an increase in those who were appropriately treated,” she said. “Importantly, however, their intervention was not only a policy, but also provided education and resources to providers to increase awareness and knowledge surrounding the subject of depression and how to screen and treat this common condition.”

Dr. Miller and colleagues noted their study was limited because they were unable to determine whether prescriptions were filled or if referrals led to actual provider visits. Other obstacles to mental health care in the perinatal period also exist in the form of logistic barriers to appointments and stigma about mental health treatment.

“Depression is common, and screening and treatment during pregnancy and the postpartum period are extremely important to improve maternal and child health. As the authors point out, there has historically been a hesitation among obstetric providers to screen for depression,” Dr. Mark said. “My suspicion is that this hesitation is not because of a lack of awareness, but rather due to a lack of knowledge of what to do when a woman has a positive screen. In my opinion, the take-home message from this study is that implementation of a policy is possible and can lead to real change if it is accompanied by the appropriate resources and education.”

This study was funded by the Maternal-Fetal Medicine/Lumara Health Policy Award, and grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child and Human Development and from the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Miller ES et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003369.

A policy of universal screening of perinatal depression for women receiving prenatal care at an academic medical center led to more regular screening of depression, and made it more likely that women with postpartum depression would be referred for treatment, according to recent research published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Emily S. Miller, MD, MPH, at Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues performed a retrospective study of 5,127 women receiving prenatal care at the center between 2008 and 2015. They divided the group into those who were at the center before (n = 1,122) and after (n = 4,005) initiation of a policy on universal perinatal depression screening, which consisted of two antenatal screenings at the first prenatal visit and third trimester, and one postpartum screening.

After initiation of the policy, screening increased during the first trimester (0.1% vs. 66%; P less than .001), the third trimester (0% vs. 43%; P less than .001), and at the postpartum visit (70% vs. 90%; P less than .001). Screening continued to increase at both prenatal visits, while screening prevalence remained the same for the postpartum visit. in the post-policy group (30% vs. 65%).

Katrina S. Mark, MD, associate professor of the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, said in an interview that the study “brings attention to an incredibly important topic.

“The researchers in this study found that, after implementation of a new policy regarding antenatal and postpartum depression screening, there was a significant increase in women who were screened during and after pregnancy as well as an increase in those who were appropriately treated,” she said. “Importantly, however, their intervention was not only a policy, but also provided education and resources to providers to increase awareness and knowledge surrounding the subject of depression and how to screen and treat this common condition.”

Dr. Miller and colleagues noted their study was limited because they were unable to determine whether prescriptions were filled or if referrals led to actual provider visits. Other obstacles to mental health care in the perinatal period also exist in the form of logistic barriers to appointments and stigma about mental health treatment.

“Depression is common, and screening and treatment during pregnancy and the postpartum period are extremely important to improve maternal and child health. As the authors point out, there has historically been a hesitation among obstetric providers to screen for depression,” Dr. Mark said. “My suspicion is that this hesitation is not because of a lack of awareness, but rather due to a lack of knowledge of what to do when a woman has a positive screen. In my opinion, the take-home message from this study is that implementation of a policy is possible and can lead to real change if it is accompanied by the appropriate resources and education.”

This study was funded by the Maternal-Fetal Medicine/Lumara Health Policy Award, and grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child and Human Development and from the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Miller ES et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003369.

A policy of universal screening of perinatal depression for women receiving prenatal care at an academic medical center led to more regular screening of depression, and made it more likely that women with postpartum depression would be referred for treatment, according to recent research published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Emily S. Miller, MD, MPH, at Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues performed a retrospective study of 5,127 women receiving prenatal care at the center between 2008 and 2015. They divided the group into those who were at the center before (n = 1,122) and after (n = 4,005) initiation of a policy on universal perinatal depression screening, which consisted of two antenatal screenings at the first prenatal visit and third trimester, and one postpartum screening.

After initiation of the policy, screening increased during the first trimester (0.1% vs. 66%; P less than .001), the third trimester (0% vs. 43%; P less than .001), and at the postpartum visit (70% vs. 90%; P less than .001). Screening continued to increase at both prenatal visits, while screening prevalence remained the same for the postpartum visit. in the post-policy group (30% vs. 65%).

Katrina S. Mark, MD, associate professor of the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, said in an interview that the study “brings attention to an incredibly important topic.

“The researchers in this study found that, after implementation of a new policy regarding antenatal and postpartum depression screening, there was a significant increase in women who were screened during and after pregnancy as well as an increase in those who were appropriately treated,” she said. “Importantly, however, their intervention was not only a policy, but also provided education and resources to providers to increase awareness and knowledge surrounding the subject of depression and how to screen and treat this common condition.”

Dr. Miller and colleagues noted their study was limited because they were unable to determine whether prescriptions were filled or if referrals led to actual provider visits. Other obstacles to mental health care in the perinatal period also exist in the form of logistic barriers to appointments and stigma about mental health treatment.

“Depression is common, and screening and treatment during pregnancy and the postpartum period are extremely important to improve maternal and child health. As the authors point out, there has historically been a hesitation among obstetric providers to screen for depression,” Dr. Mark said. “My suspicion is that this hesitation is not because of a lack of awareness, but rather due to a lack of knowledge of what to do when a woman has a positive screen. In my opinion, the take-home message from this study is that implementation of a policy is possible and can lead to real change if it is accompanied by the appropriate resources and education.”

This study was funded by the Maternal-Fetal Medicine/Lumara Health Policy Award, and grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child and Human Development and from the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Miller ES et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003369.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: A policy of universal perinatal screening improved adherence to screening and treatment for women with postpartum depression.

Major finding: After initiation of the policy, screening increased during the first prenatal visit (0.1% vs. 66%), the third trimester (0% vs. 43%), and at a postpartum visit (70% vs. 90%). Women who had a positive result after postpartum depression screening were more than twice as likely to receive treatment or a referral for their depression in the post-policy group (30% vs. 65%).

Study details: A retrospective cohort study of 5,127 women at a single academic center undergoing perinatal care before and after an institutional policy for perinatal depression screening between 2008 and 2015.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Maternal-Fetal Medicine/Lumara Health Policy Award, and grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child and Human Development and from the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Miller ES et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003369.

Opioid exposure leads to poor perinatal and postnatal outcomes

according to data from more than 8,000 children.

Previous studies have shown the increased risk of a range of health problems associated with maternal opioid use, including neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), but data on the long-term consequences of in utero opioid exposure are limited, wrote Romuladus E. Azuine, DrPH, MPH, of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, Md., and colleagues.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed data from 8,509 mother/newborn pairs in the Boston Birth Cohort, a database that included a large urban, low-income, multiethnic population of women who had singleton births at the Boston Medical Center starting in 1998.

A total of 454 infants (5%) experienced prenatal opioid exposure. Mothers were interviewed 48-72 hours after delivery about sociodemographic factors, drug use, smoking, and alcohol use.

The risk of small for gestational age and preterm birth were significantly higher in babies exposed to opioids (OR 1.87 and OR 1.49, respectively), compared with unexposed newborns.

Children’s developmental outcomes were collected starting in 2003 based on electronic medical records. A total of 3,153 mother-newborn pairs were enrolled in a postnatal follow-up study. For preschoolers, prenatal opioid exposure was associated with increased risk of lack of expected physiological development and conduct disorder/emotional disturbance (OR 1.80 and OR 2.13, respectively), compared with unexposed children. School-aged children with prenatal opioid exposure had an increased risk of ADHD (OR 2.55).

The incidence of NAS in the study population was at least 24 per 1,000 hospital births starting in 2004, and peaked at 61 per 1,000 hospital births in 2008, but remained higher than 32 per 1,000 through 2016.

The study findings were limited by several factors including potential misclassification of opioid exposure, confounding from other pregnancy exposures, loss of many participants to follow-up, and a lack of generalizability, but the results support the need for additional research, and show that the prevalence of NAS was approximately 10 times the national average in a subset of low-income, urban, minority women, the researchers said.

“However, the effect of opioids is still difficult to disentangle from effects of other childhood exposures. Policy and programmatic efforts to prevent NAS and mitigate its health consequences require more comprehensive longitudinal and intergenerational research,” they concluded.

The study findings contribute to and support the evidence of poor neurodevelopmental and emotional/behavioral outcomes for children with prenatal exposure to opioids or a history of NAS, Susan Brogly, PhD, MSc, noted in an accompanying editorial. Other studies have shown increased risks for visual impairments including strabismus, reduced visual acuity, and delayed visual maturation.

Dr. Brogly, of Queen’s University, Kingston Health Science Center, Ontario, nonetheless noted that a child’s home environment may modify the impact of prenatal opioid exposure or NAS, as evidence has shown that children with in utero heroin exposure have improved outcomes in healthy home environments.

Although the mechanism for how opioid exposure affects development remains uncertain, she suggested that future research should address “interventions to improve health outcomes in this rapidly growing population of children, regardless of the causal mechanism of impairment.”

Dr. Brogly noted that most of the opioid-using mothers in the study by Azuine et al. were unmarried, non-Hispanic white, and multiparous, and had histories of other substance abuse. She emphasized the need for supportive communities for women at risk of opioid use, who also are more likely to have unstable housing situations and histories of sexual and physical abuse.

“The risks of poor pregnancy and child outcomes in cases of maternal opioid exposure are not because of prenatal opioid exposure alone; ongoing difficult social and environmental circumstances have an important role,” and future interventions should address these circumstances to improve long-term health of high-risk women and their children, she emphasized.

The Boston Birth Cohort study is supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. None of the authors had financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Brogly disclosed grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development outside the submitted work.

SOURCE: Azuine RE et al. JAMA Network Open. 2019 Jun 28. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6405; Brogly S. JAMA Network Open. 2019 Jun 28. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6428.

according to data from more than 8,000 children.

Previous studies have shown the increased risk of a range of health problems associated with maternal opioid use, including neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), but data on the long-term consequences of in utero opioid exposure are limited, wrote Romuladus E. Azuine, DrPH, MPH, of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, Md., and colleagues.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed data from 8,509 mother/newborn pairs in the Boston Birth Cohort, a database that included a large urban, low-income, multiethnic population of women who had singleton births at the Boston Medical Center starting in 1998.

A total of 454 infants (5%) experienced prenatal opioid exposure. Mothers were interviewed 48-72 hours after delivery about sociodemographic factors, drug use, smoking, and alcohol use.

The risk of small for gestational age and preterm birth were significantly higher in babies exposed to opioids (OR 1.87 and OR 1.49, respectively), compared with unexposed newborns.

Children’s developmental outcomes were collected starting in 2003 based on electronic medical records. A total of 3,153 mother-newborn pairs were enrolled in a postnatal follow-up study. For preschoolers, prenatal opioid exposure was associated with increased risk of lack of expected physiological development and conduct disorder/emotional disturbance (OR 1.80 and OR 2.13, respectively), compared with unexposed children. School-aged children with prenatal opioid exposure had an increased risk of ADHD (OR 2.55).

The incidence of NAS in the study population was at least 24 per 1,000 hospital births starting in 2004, and peaked at 61 per 1,000 hospital births in 2008, but remained higher than 32 per 1,000 through 2016.

The study findings were limited by several factors including potential misclassification of opioid exposure, confounding from other pregnancy exposures, loss of many participants to follow-up, and a lack of generalizability, but the results support the need for additional research, and show that the prevalence of NAS was approximately 10 times the national average in a subset of low-income, urban, minority women, the researchers said.

“However, the effect of opioids is still difficult to disentangle from effects of other childhood exposures. Policy and programmatic efforts to prevent NAS and mitigate its health consequences require more comprehensive longitudinal and intergenerational research,” they concluded.

The study findings contribute to and support the evidence of poor neurodevelopmental and emotional/behavioral outcomes for children with prenatal exposure to opioids or a history of NAS, Susan Brogly, PhD, MSc, noted in an accompanying editorial. Other studies have shown increased risks for visual impairments including strabismus, reduced visual acuity, and delayed visual maturation.

Dr. Brogly, of Queen’s University, Kingston Health Science Center, Ontario, nonetheless noted that a child’s home environment may modify the impact of prenatal opioid exposure or NAS, as evidence has shown that children with in utero heroin exposure have improved outcomes in healthy home environments.

Although the mechanism for how opioid exposure affects development remains uncertain, she suggested that future research should address “interventions to improve health outcomes in this rapidly growing population of children, regardless of the causal mechanism of impairment.”

Dr. Brogly noted that most of the opioid-using mothers in the study by Azuine et al. were unmarried, non-Hispanic white, and multiparous, and had histories of other substance abuse. She emphasized the need for supportive communities for women at risk of opioid use, who also are more likely to have unstable housing situations and histories of sexual and physical abuse.

“The risks of poor pregnancy and child outcomes in cases of maternal opioid exposure are not because of prenatal opioid exposure alone; ongoing difficult social and environmental circumstances have an important role,” and future interventions should address these circumstances to improve long-term health of high-risk women and their children, she emphasized.

The Boston Birth Cohort study is supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. None of the authors had financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Brogly disclosed grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development outside the submitted work.

SOURCE: Azuine RE et al. JAMA Network Open. 2019 Jun 28. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6405; Brogly S. JAMA Network Open. 2019 Jun 28. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6428.

according to data from more than 8,000 children.

Previous studies have shown the increased risk of a range of health problems associated with maternal opioid use, including neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), but data on the long-term consequences of in utero opioid exposure are limited, wrote Romuladus E. Azuine, DrPH, MPH, of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, Md., and colleagues.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed data from 8,509 mother/newborn pairs in the Boston Birth Cohort, a database that included a large urban, low-income, multiethnic population of women who had singleton births at the Boston Medical Center starting in 1998.

A total of 454 infants (5%) experienced prenatal opioid exposure. Mothers were interviewed 48-72 hours after delivery about sociodemographic factors, drug use, smoking, and alcohol use.

The risk of small for gestational age and preterm birth were significantly higher in babies exposed to opioids (OR 1.87 and OR 1.49, respectively), compared with unexposed newborns.

Children’s developmental outcomes were collected starting in 2003 based on electronic medical records. A total of 3,153 mother-newborn pairs were enrolled in a postnatal follow-up study. For preschoolers, prenatal opioid exposure was associated with increased risk of lack of expected physiological development and conduct disorder/emotional disturbance (OR 1.80 and OR 2.13, respectively), compared with unexposed children. School-aged children with prenatal opioid exposure had an increased risk of ADHD (OR 2.55).

The incidence of NAS in the study population was at least 24 per 1,000 hospital births starting in 2004, and peaked at 61 per 1,000 hospital births in 2008, but remained higher than 32 per 1,000 through 2016.

The study findings were limited by several factors including potential misclassification of opioid exposure, confounding from other pregnancy exposures, loss of many participants to follow-up, and a lack of generalizability, but the results support the need for additional research, and show that the prevalence of NAS was approximately 10 times the national average in a subset of low-income, urban, minority women, the researchers said.

“However, the effect of opioids is still difficult to disentangle from effects of other childhood exposures. Policy and programmatic efforts to prevent NAS and mitigate its health consequences require more comprehensive longitudinal and intergenerational research,” they concluded.

The study findings contribute to and support the evidence of poor neurodevelopmental and emotional/behavioral outcomes for children with prenatal exposure to opioids or a history of NAS, Susan Brogly, PhD, MSc, noted in an accompanying editorial. Other studies have shown increased risks for visual impairments including strabismus, reduced visual acuity, and delayed visual maturation.

Dr. Brogly, of Queen’s University, Kingston Health Science Center, Ontario, nonetheless noted that a child’s home environment may modify the impact of prenatal opioid exposure or NAS, as evidence has shown that children with in utero heroin exposure have improved outcomes in healthy home environments.

Although the mechanism for how opioid exposure affects development remains uncertain, she suggested that future research should address “interventions to improve health outcomes in this rapidly growing population of children, regardless of the causal mechanism of impairment.”

Dr. Brogly noted that most of the opioid-using mothers in the study by Azuine et al. were unmarried, non-Hispanic white, and multiparous, and had histories of other substance abuse. She emphasized the need for supportive communities for women at risk of opioid use, who also are more likely to have unstable housing situations and histories of sexual and physical abuse.

“The risks of poor pregnancy and child outcomes in cases of maternal opioid exposure are not because of prenatal opioid exposure alone; ongoing difficult social and environmental circumstances have an important role,” and future interventions should address these circumstances to improve long-term health of high-risk women and their children, she emphasized.

The Boston Birth Cohort study is supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. None of the authors had financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Brogly disclosed grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development outside the submitted work.

SOURCE: Azuine RE et al. JAMA Network Open. 2019 Jun 28. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6405; Brogly S. JAMA Network Open. 2019 Jun 28. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6428.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Diverse vaginal microbiome may signal risk for preterm birth

in an analysis of approximately 12,000 samples, according to a study published in Nature Medicine.

Preterm births, defined as less than 37 weeks’ gestation, remain the second most common cause of neonatal death worldwide, but few strategies exist to prevent and predict preterm birth (PTB) wrote Jennifer M. Fettweis, MD, of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and her colleagues. In the United States, women of African ancestry are at significantly greater risk for PTB.

A highly diverse vaginal microbiome is thought to be associated with an increased risk of inflammation, infection, and PTB, “however, many asymptomatic healthy women have diverse vaginal microbiota,” the researchers said.

To identify vaginal microbiota distinct to women who experienced PTB, the researchers analyzed data from the Multi-Omic Microbiome Study: Pregnancy Initiative (MOMS-PI), part of the National Institutes of Health–sponsored Integrative Human Microbiome Project. The MOMS-PI study included 12,039 samples of vaginal flora from 597 pregnancies; the analysis included 45 singleton pregnancies that met the criteria for spontaneous PTB (23-36 weeks, 6 days of gestation) and 90 case-matched full-term singleton pregnancies (greater than or equal to 39 weeks). Approximately 78% of the women were of African descent in both groups, and their average age was 26 years in both groups.

Overall, the diversity of the vaginal microbiome was greater among women who experienced PTB, compared with term birth (TB). Women who experienced PTB had less Lactobacillus crispatus, but more bacterial vaginosis–associated bacterium-1 (BVAB1), Prevotella cluster 2, and Sneathia amnii, compared with TB women.

Of note, vaginal cytokine data showed that proinflammatory cytokines, which may be associated with the induction of labor, may be prompted by inflammation in the vaginal microbiome, Dr. Fettweis and her associates said. “We observed that vaginal IP-10/CXCL10 levels were inversely correlated with BVAB1 in PTB, inversely correlated with L. crispatus in TB, and positively correlated with L. iners in TB, suggesting complex host-microbiome interactions in pregnancy,” they said.

“Further studies are needed to determine whether the signatures of PTB reported in the present study replicate in other cohorts of women of African ancestry, to examine whether the observed differences in vaginal microbiome composition between women of different ancestries has a direct causal link to the ethnic and racial disparities in PTB rates, and to establish whether population-specific microbial markers can be ultimately integrated into a generalizable spectrum of vaginal microbiome states linked to the risk for PTB,” Dr. Fettweis and her associates said.

In a companion study also published in Nature Medicine, Myrna G. Serrano, MD, also of Virginia Commonwealth University, and her colleagues as part of the MOMS-PI initially determined that vaginal microbiome profiles varied between 613 pregnant and 1,969 nonpregnant women in that “pregnant women had significantly higher prevalence of the four most common Lactobacillus vagitypes (L. crispatus, L. iners, L. gasseri, and L. jensenii) and a commensurately lower prevalence of vagitypes dominated by other taxa.” The primary driver of the differences was L. iners.

They then compared vaginal microbiome data from 300 pregnant and 300 nonpregnant case-matched women of African, Hispanic, or European ancestry, as well as 90 pregnant women (49 of African ancestry and 41 of European) ancestry.

In the subset of 300 pregnant and 300 nonpregnant women, the vaginal microbiome of the pregnant women overall became more dominated by Lactobacillus early in pregnancy. Further stratification by race showed that pregnant women of African and Hispanic ancestry had significantly higher levels of four types of Lactobacillus than their nonpregnant counterparts, but no significant difference was seen between pregnant and nonpregnant women of European ancestry.

“It appears that changes occurring during pregnancy may render the reproductive tracts of women of all racial backgrounds more hospitable to taxa of Lactobacillus and less favorable for Gardnerella vaginalis and other taxa associated with BV [bacterial vaginosis] and dysbiosis,” the researchers said.

“Interestingly, BVAB1, which has been associated with dysbiotic vaginal conditions and risk of PTB, and which is present as a major vagitype largely in women of African ancestry, is not noticeably decreased in prevalence in pregnancy,” Dr. Serrano and her associates said. “Thus, BVAB1, for reasons yet to be determined, is apparently resistant to factors sculpting the microbiome in pregnant women, possibly explaining in part the enhanced risk for PTB experienced by women of African ancestry.”

In a look at the 49 pregnant women of African ancestry and 41 of European ancestry, those of African ancestry had “significantly lower representation of the L. crispatus, L. gasseri and L. jensenii vagitypes, and higher representation of L. iners and BVAB1 vagitypes. Variability in women of African ancestry was driven by BVAB1 and L. iners, whereas variability in women of non-African ancestry was driven by L. crispatus and L. iners. Again, pregnancy had no significant effect on prevalence of the BVAB1 vagitype. Prevalence of Lactobacillus-dominated profiles in women of African ancestry was lower in the first than in later trimesters, whereas women of European ancestry had a higher prevalence of Lactobacillus vagitypes throughout pregnancy.”

The presence of vaginal microbiome profiles associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes highlights the need for further studies that take advantage of this information, Dr. Serrano and her associates said. “That the vaginal microbiomes known to confer higher risk of poor health and adverse outcomes of pregnancy are more highly associated with women of African and Hispanic ancestry, but that pregnancy tends to drive these microbiomes toward more favorable microbiota, suggests that an external intervention that favors this trend might be beneficial for these populations,” they concluded. “What remains is to verify the most favorable microbiome and the most effective strategy for intervention.”

Dr. Fettweis had no financial conflicts to disclose; two coauthors are full-time employees at Pacific Biosciences. Dr. Serrano and her coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Serrano’s study received grants from the National Institutes of Health and other sources, as well as support from the Common Fund, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, the Office of Research on Women’s Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

SOURCES: Fettweis J et al. Nature Medicine 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0450-2; Serrano M et al. Nature Medicine. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0465-8.

in an analysis of approximately 12,000 samples, according to a study published in Nature Medicine.

Preterm births, defined as less than 37 weeks’ gestation, remain the second most common cause of neonatal death worldwide, but few strategies exist to prevent and predict preterm birth (PTB) wrote Jennifer M. Fettweis, MD, of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and her colleagues. In the United States, women of African ancestry are at significantly greater risk for PTB.

A highly diverse vaginal microbiome is thought to be associated with an increased risk of inflammation, infection, and PTB, “however, many asymptomatic healthy women have diverse vaginal microbiota,” the researchers said.

To identify vaginal microbiota distinct to women who experienced PTB, the researchers analyzed data from the Multi-Omic Microbiome Study: Pregnancy Initiative (MOMS-PI), part of the National Institutes of Health–sponsored Integrative Human Microbiome Project. The MOMS-PI study included 12,039 samples of vaginal flora from 597 pregnancies; the analysis included 45 singleton pregnancies that met the criteria for spontaneous PTB (23-36 weeks, 6 days of gestation) and 90 case-matched full-term singleton pregnancies (greater than or equal to 39 weeks). Approximately 78% of the women were of African descent in both groups, and their average age was 26 years in both groups.