User login

Five personal finance questions for the young GI

While this article will get you started, these are complex topics, and each could warrant several standalone articles. I strongly encourage you to develop some basic understanding of personal finance through books, websites, and podcasts. If you can manage Barrett’s esophagus, Crohn’s, and cirrhosis, you can understand the basics of personal finance.

1. What should I do about my student loans? Go for public service loan forgiveness or pay them off?

The first step is knowing your debt burden, knowing your options, and developing a plan to pay off student loans. Public service loan forgiveness (PSLF) can be a good option in many situations. For borrowers staying in academic or other 501(c)(3) positions, PSLF is often an obvious move. Importantly, a fall 2022 statement by the U.S. Department of Education clarified that physicians working as contractors for nonprofit hospitals in California and Texas may now qualify for PSLF.1,2

For trainees debating an academic/501(c)(3) position vs. private practice, I would generally not advise making a career choice based purely on PSLF eligibility. However, borrowers with very high federal student loan burdens (e.g., debt to income ratio of > 2:1), or who are very close to the PSLF 10-year requirement may want to consider choosing a qualifying position for a few years to receive PSLF student loan forgiveness. Please see TNG’s 2020 article3 for a deeper discussion. Consultation with a company specializing in student loan advice for physicians may be well worth the upfront cost.

2. Do I need disability insurance? What should I look for?

I would strongly advise getting disability insurance as soon as possible (including while in training). While disability insurance is not cheap, it is one of the first steps you should take and one of the most important ways to protect your financial future. It is essential to look for a specialty-specific own occupation policy. Such a policy will provide disability payments if you are no longer able to work as a gastroenterologist/hepatologist (including an injury which prevents you from doing endoscopies).

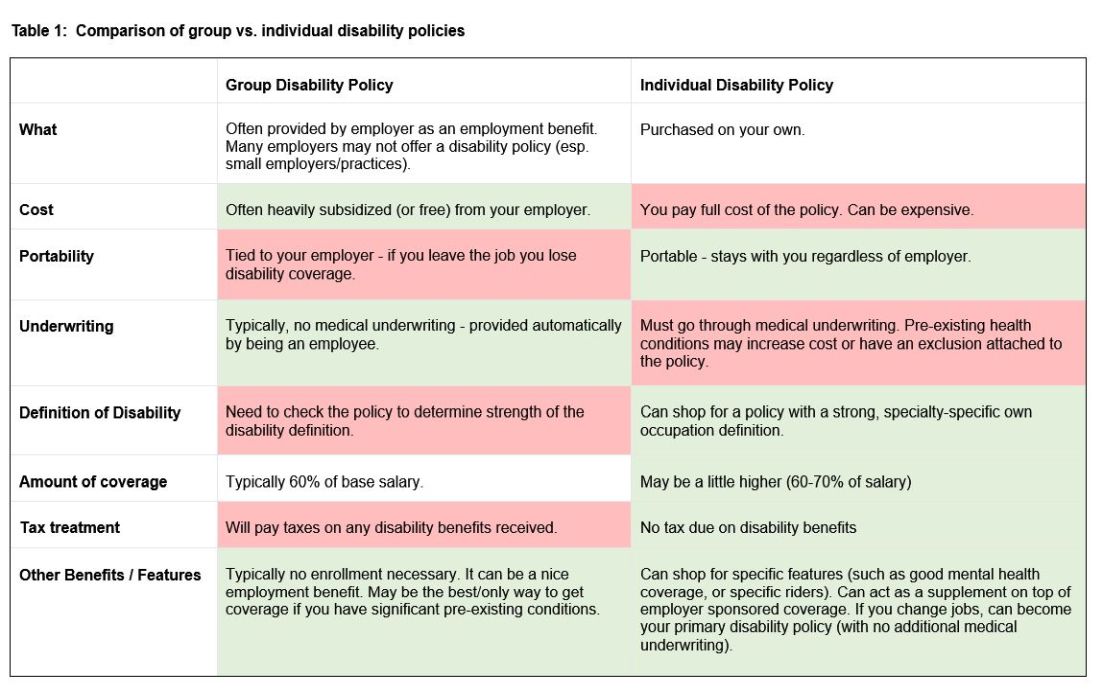

There are two major types of disability policies: group policies and individual policies. See table 1 for a detailed comparison.

Your hospital/employer may provide a group policy at a heavily subsidized rate. Alternatively, you can purchase an individual disability policy, which is independent of your employer and will stay with you even if you change jobs. Currently, the only companies providing high quality own-occupation policies for physicians are Mass Mutual, Principal, Guardian, The Standard, and Ameritas. Because disability insurance is complicated, it is highly advisable to work with an agent experienced in physician disability policies.

Importantly, even if you have a group disability policy, you can purchase an individual policy as a supplement to provide extra coverage. If you leave employers, the individual policy can then become your primary disability policy without any additional medical underwriting.

3. Do I need life insurance? What type should I get?

If anyone is dependent on your income (partner, child, etc.), you should have life insurance. Moreover, if you expect to have dependents in the near future (e.g., children), you could consider getting life insurance now while you are younger and healthier. For a young GI with multiple financial obligations, term life insurance is generally the right product. Term life insurance is a straightforward, affordable product that can be purchased from multiple high-quality insurance carriers. There are two major considerations: The amount of coverage ($2 million, $3 million, etc.) and the length of coverage (20 years, 30 years, etc.). To estimate the appropriate amount of coverage, start with your expected annual household living expenses, and multiply by 25-30. While this is a rule of thumb, it will get you in the ballpark. For many young physicians, a $2-$5 million policy with 20- to 30-year coverage is reasonable.

Many financial advisers may suggest whole life insurance policies. These are typically not the ideal policy for young GIs who are just starting their careers. While whole life insurance may be the right choice in select cases, term life insurance will be the best product for most of TNG’s audience. As an example, a $3 million, 25-year term policy for a healthy, nonsmoking 35-year-old male would cost approximately $175 per month. A similar $3 million whole life policy could cost $2,000 per month or more.

4. What do I need to know about retirement accounts and investing?

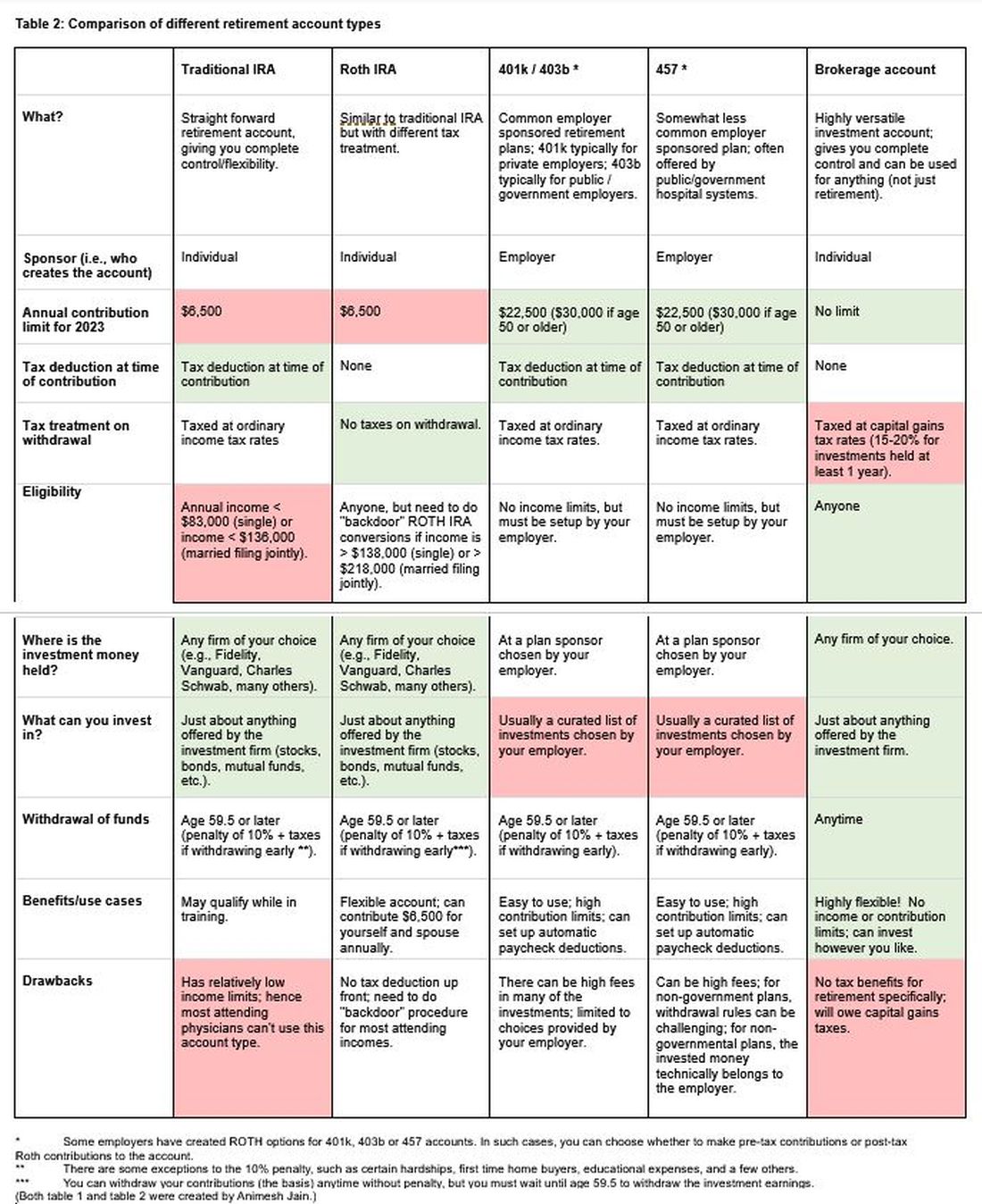

The alphabet soup of retirement accounts can be confusing – IRA, 401k, 457. Retirement accounts provide a tax break to incentivize saving for retirement. Traditional (“non-Roth”) accounts provide a tax break today, but you will pay taxes when withdrawing the money in retirement. Roth accounts provide no tax break now but provide tax-free growth for decades, and no taxes are due when withdrawing money. See table 2 for a detailed comparison of retirement accounts.

Once you place money into a retirement account, you will need to choose specific investments to grow your money. The two most common asset classes are stocks and bonds, though there are many other reasonable assets, such as real estate, commodities, and alternative currencies. It is generally recommended to have a higher proportion of stock-based investments early on (60%-90%) and then increase the ratio of bonds closer to retirement. Using low cost, passive index funds (or exchange traded funds) is a good way to get stock exposure. Target date retirement funds can be a nice tool for beginning investors since they will automatically adjust the stock/bond ratio for you.

Calculating the amount needed for retirement is beyond the scope of this article. However, saving at least 20% of your gross income specifically for retirement is a good starting point and should set you up for a reasonable retirement in about 30 years. For the average GI physician, this would mean saving $4,000 or more per month for retirement. If you aim to retire earlier, consider investing a higher percentage.

5. What do I need to know about buying a house?

The first question to ask is whether it makes sense to rent or buy a house. This is a personal and lifestyle decision, not just a financial decision. Today’s market is difficult with both high home prices and high rent costs. If there is a reasonable chance that you will be moving within 3-5 years, I would consider not buying until your long-term plans are more stable. Moreover, a high proportion of physicians change jobs.4,5,6 If you are just starting a new job, it is often wise to wait at least 6-12 months before buying a house to ensure the new job is a good fit. If you are in a stable long-term situation, it may be reasonable to buy a house. While it is commonly believed that buying a house is a “good financial move,” there are many hidden costs to home ownership, including big ticket repairs, property taxes, and real estate fees when selling a home.

First-time physician home buyers can often secure a physician mortgage with competitive interest rates and a low down payment of 0%-10% instead of the traditional 20% down payment. Moreover, a good physician mortgage should not have private mortgage insurance (PMI). Given the variation between mortgage companies, my most important piece of advice is to shop around for a good mortgage. An independent mortgage broker can be very valuable.

Dr. Jain is associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. He has no conflicts of interest. The information in this article is meant for general educational purposes only. For individualized personal finance advice, please seek your own financial advisor, tax accountant, insurance broker, attorney, or other financial professional. Follow Dr. Jain @AJainMD on X.

References

1. Future of PSLF Fact Sheet

2. The Loophole That Can Get Thousands of Doctors into PSLF

3. Student loan management: An introduction for the young gastroenterologist

4. Study Shows First Job after Medical Residency Often Doesn’t Last

5. More physicians want to leave their jobs as pay rates fall, survey finds

6. Physician turnover rates are climbing as they clamor for better work-life balance

While this article will get you started, these are complex topics, and each could warrant several standalone articles. I strongly encourage you to develop some basic understanding of personal finance through books, websites, and podcasts. If you can manage Barrett’s esophagus, Crohn’s, and cirrhosis, you can understand the basics of personal finance.

1. What should I do about my student loans? Go for public service loan forgiveness or pay them off?

The first step is knowing your debt burden, knowing your options, and developing a plan to pay off student loans. Public service loan forgiveness (PSLF) can be a good option in many situations. For borrowers staying in academic or other 501(c)(3) positions, PSLF is often an obvious move. Importantly, a fall 2022 statement by the U.S. Department of Education clarified that physicians working as contractors for nonprofit hospitals in California and Texas may now qualify for PSLF.1,2

For trainees debating an academic/501(c)(3) position vs. private practice, I would generally not advise making a career choice based purely on PSLF eligibility. However, borrowers with very high federal student loan burdens (e.g., debt to income ratio of > 2:1), or who are very close to the PSLF 10-year requirement may want to consider choosing a qualifying position for a few years to receive PSLF student loan forgiveness. Please see TNG’s 2020 article3 for a deeper discussion. Consultation with a company specializing in student loan advice for physicians may be well worth the upfront cost.

2. Do I need disability insurance? What should I look for?

I would strongly advise getting disability insurance as soon as possible (including while in training). While disability insurance is not cheap, it is one of the first steps you should take and one of the most important ways to protect your financial future. It is essential to look for a specialty-specific own occupation policy. Such a policy will provide disability payments if you are no longer able to work as a gastroenterologist/hepatologist (including an injury which prevents you from doing endoscopies).

There are two major types of disability policies: group policies and individual policies. See table 1 for a detailed comparison.

Your hospital/employer may provide a group policy at a heavily subsidized rate. Alternatively, you can purchase an individual disability policy, which is independent of your employer and will stay with you even if you change jobs. Currently, the only companies providing high quality own-occupation policies for physicians are Mass Mutual, Principal, Guardian, The Standard, and Ameritas. Because disability insurance is complicated, it is highly advisable to work with an agent experienced in physician disability policies.

Importantly, even if you have a group disability policy, you can purchase an individual policy as a supplement to provide extra coverage. If you leave employers, the individual policy can then become your primary disability policy without any additional medical underwriting.

3. Do I need life insurance? What type should I get?

If anyone is dependent on your income (partner, child, etc.), you should have life insurance. Moreover, if you expect to have dependents in the near future (e.g., children), you could consider getting life insurance now while you are younger and healthier. For a young GI with multiple financial obligations, term life insurance is generally the right product. Term life insurance is a straightforward, affordable product that can be purchased from multiple high-quality insurance carriers. There are two major considerations: The amount of coverage ($2 million, $3 million, etc.) and the length of coverage (20 years, 30 years, etc.). To estimate the appropriate amount of coverage, start with your expected annual household living expenses, and multiply by 25-30. While this is a rule of thumb, it will get you in the ballpark. For many young physicians, a $2-$5 million policy with 20- to 30-year coverage is reasonable.

Many financial advisers may suggest whole life insurance policies. These are typically not the ideal policy for young GIs who are just starting their careers. While whole life insurance may be the right choice in select cases, term life insurance will be the best product for most of TNG’s audience. As an example, a $3 million, 25-year term policy for a healthy, nonsmoking 35-year-old male would cost approximately $175 per month. A similar $3 million whole life policy could cost $2,000 per month or more.

4. What do I need to know about retirement accounts and investing?

The alphabet soup of retirement accounts can be confusing – IRA, 401k, 457. Retirement accounts provide a tax break to incentivize saving for retirement. Traditional (“non-Roth”) accounts provide a tax break today, but you will pay taxes when withdrawing the money in retirement. Roth accounts provide no tax break now but provide tax-free growth for decades, and no taxes are due when withdrawing money. See table 2 for a detailed comparison of retirement accounts.

Once you place money into a retirement account, you will need to choose specific investments to grow your money. The two most common asset classes are stocks and bonds, though there are many other reasonable assets, such as real estate, commodities, and alternative currencies. It is generally recommended to have a higher proportion of stock-based investments early on (60%-90%) and then increase the ratio of bonds closer to retirement. Using low cost, passive index funds (or exchange traded funds) is a good way to get stock exposure. Target date retirement funds can be a nice tool for beginning investors since they will automatically adjust the stock/bond ratio for you.

Calculating the amount needed for retirement is beyond the scope of this article. However, saving at least 20% of your gross income specifically for retirement is a good starting point and should set you up for a reasonable retirement in about 30 years. For the average GI physician, this would mean saving $4,000 or more per month for retirement. If you aim to retire earlier, consider investing a higher percentage.

5. What do I need to know about buying a house?

The first question to ask is whether it makes sense to rent or buy a house. This is a personal and lifestyle decision, not just a financial decision. Today’s market is difficult with both high home prices and high rent costs. If there is a reasonable chance that you will be moving within 3-5 years, I would consider not buying until your long-term plans are more stable. Moreover, a high proportion of physicians change jobs.4,5,6 If you are just starting a new job, it is often wise to wait at least 6-12 months before buying a house to ensure the new job is a good fit. If you are in a stable long-term situation, it may be reasonable to buy a house. While it is commonly believed that buying a house is a “good financial move,” there are many hidden costs to home ownership, including big ticket repairs, property taxes, and real estate fees when selling a home.

First-time physician home buyers can often secure a physician mortgage with competitive interest rates and a low down payment of 0%-10% instead of the traditional 20% down payment. Moreover, a good physician mortgage should not have private mortgage insurance (PMI). Given the variation between mortgage companies, my most important piece of advice is to shop around for a good mortgage. An independent mortgage broker can be very valuable.

Dr. Jain is associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. He has no conflicts of interest. The information in this article is meant for general educational purposes only. For individualized personal finance advice, please seek your own financial advisor, tax accountant, insurance broker, attorney, or other financial professional. Follow Dr. Jain @AJainMD on X.

References

1. Future of PSLF Fact Sheet

2. The Loophole That Can Get Thousands of Doctors into PSLF

3. Student loan management: An introduction for the young gastroenterologist

4. Study Shows First Job after Medical Residency Often Doesn’t Last

5. More physicians want to leave their jobs as pay rates fall, survey finds

6. Physician turnover rates are climbing as they clamor for better work-life balance

While this article will get you started, these are complex topics, and each could warrant several standalone articles. I strongly encourage you to develop some basic understanding of personal finance through books, websites, and podcasts. If you can manage Barrett’s esophagus, Crohn’s, and cirrhosis, you can understand the basics of personal finance.

1. What should I do about my student loans? Go for public service loan forgiveness or pay them off?

The first step is knowing your debt burden, knowing your options, and developing a plan to pay off student loans. Public service loan forgiveness (PSLF) can be a good option in many situations. For borrowers staying in academic or other 501(c)(3) positions, PSLF is often an obvious move. Importantly, a fall 2022 statement by the U.S. Department of Education clarified that physicians working as contractors for nonprofit hospitals in California and Texas may now qualify for PSLF.1,2

For trainees debating an academic/501(c)(3) position vs. private practice, I would generally not advise making a career choice based purely on PSLF eligibility. However, borrowers with very high federal student loan burdens (e.g., debt to income ratio of > 2:1), or who are very close to the PSLF 10-year requirement may want to consider choosing a qualifying position for a few years to receive PSLF student loan forgiveness. Please see TNG’s 2020 article3 for a deeper discussion. Consultation with a company specializing in student loan advice for physicians may be well worth the upfront cost.

2. Do I need disability insurance? What should I look for?

I would strongly advise getting disability insurance as soon as possible (including while in training). While disability insurance is not cheap, it is one of the first steps you should take and one of the most important ways to protect your financial future. It is essential to look for a specialty-specific own occupation policy. Such a policy will provide disability payments if you are no longer able to work as a gastroenterologist/hepatologist (including an injury which prevents you from doing endoscopies).

There are two major types of disability policies: group policies and individual policies. See table 1 for a detailed comparison.

Your hospital/employer may provide a group policy at a heavily subsidized rate. Alternatively, you can purchase an individual disability policy, which is independent of your employer and will stay with you even if you change jobs. Currently, the only companies providing high quality own-occupation policies for physicians are Mass Mutual, Principal, Guardian, The Standard, and Ameritas. Because disability insurance is complicated, it is highly advisable to work with an agent experienced in physician disability policies.

Importantly, even if you have a group disability policy, you can purchase an individual policy as a supplement to provide extra coverage. If you leave employers, the individual policy can then become your primary disability policy without any additional medical underwriting.

3. Do I need life insurance? What type should I get?

If anyone is dependent on your income (partner, child, etc.), you should have life insurance. Moreover, if you expect to have dependents in the near future (e.g., children), you could consider getting life insurance now while you are younger and healthier. For a young GI with multiple financial obligations, term life insurance is generally the right product. Term life insurance is a straightforward, affordable product that can be purchased from multiple high-quality insurance carriers. There are two major considerations: The amount of coverage ($2 million, $3 million, etc.) and the length of coverage (20 years, 30 years, etc.). To estimate the appropriate amount of coverage, start with your expected annual household living expenses, and multiply by 25-30. While this is a rule of thumb, it will get you in the ballpark. For many young physicians, a $2-$5 million policy with 20- to 30-year coverage is reasonable.

Many financial advisers may suggest whole life insurance policies. These are typically not the ideal policy for young GIs who are just starting their careers. While whole life insurance may be the right choice in select cases, term life insurance will be the best product for most of TNG’s audience. As an example, a $3 million, 25-year term policy for a healthy, nonsmoking 35-year-old male would cost approximately $175 per month. A similar $3 million whole life policy could cost $2,000 per month or more.

4. What do I need to know about retirement accounts and investing?

The alphabet soup of retirement accounts can be confusing – IRA, 401k, 457. Retirement accounts provide a tax break to incentivize saving for retirement. Traditional (“non-Roth”) accounts provide a tax break today, but you will pay taxes when withdrawing the money in retirement. Roth accounts provide no tax break now but provide tax-free growth for decades, and no taxes are due when withdrawing money. See table 2 for a detailed comparison of retirement accounts.

Once you place money into a retirement account, you will need to choose specific investments to grow your money. The two most common asset classes are stocks and bonds, though there are many other reasonable assets, such as real estate, commodities, and alternative currencies. It is generally recommended to have a higher proportion of stock-based investments early on (60%-90%) and then increase the ratio of bonds closer to retirement. Using low cost, passive index funds (or exchange traded funds) is a good way to get stock exposure. Target date retirement funds can be a nice tool for beginning investors since they will automatically adjust the stock/bond ratio for you.

Calculating the amount needed for retirement is beyond the scope of this article. However, saving at least 20% of your gross income specifically for retirement is a good starting point and should set you up for a reasonable retirement in about 30 years. For the average GI physician, this would mean saving $4,000 or more per month for retirement. If you aim to retire earlier, consider investing a higher percentage.

5. What do I need to know about buying a house?

The first question to ask is whether it makes sense to rent or buy a house. This is a personal and lifestyle decision, not just a financial decision. Today’s market is difficult with both high home prices and high rent costs. If there is a reasonable chance that you will be moving within 3-5 years, I would consider not buying until your long-term plans are more stable. Moreover, a high proportion of physicians change jobs.4,5,6 If you are just starting a new job, it is often wise to wait at least 6-12 months before buying a house to ensure the new job is a good fit. If you are in a stable long-term situation, it may be reasonable to buy a house. While it is commonly believed that buying a house is a “good financial move,” there are many hidden costs to home ownership, including big ticket repairs, property taxes, and real estate fees when selling a home.

First-time physician home buyers can often secure a physician mortgage with competitive interest rates and a low down payment of 0%-10% instead of the traditional 20% down payment. Moreover, a good physician mortgage should not have private mortgage insurance (PMI). Given the variation between mortgage companies, my most important piece of advice is to shop around for a good mortgage. An independent mortgage broker can be very valuable.

Dr. Jain is associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. He has no conflicts of interest. The information in this article is meant for general educational purposes only. For individualized personal finance advice, please seek your own financial advisor, tax accountant, insurance broker, attorney, or other financial professional. Follow Dr. Jain @AJainMD on X.

References

1. Future of PSLF Fact Sheet

2. The Loophole That Can Get Thousands of Doctors into PSLF

3. Student loan management: An introduction for the young gastroenterologist

4. Study Shows First Job after Medical Residency Often Doesn’t Last

5. More physicians want to leave their jobs as pay rates fall, survey finds

6. Physician turnover rates are climbing as they clamor for better work-life balance

Stripped privileges: An alarming precedent for community oncologists?

, Alliance Cancer Specialists.

The outcome, some community oncologists say, could set a new precedent in how far large health care organizations will go to take their patients or drive them out of business.

The case

On Sept. 5, Alliance sued Jefferson Health after Jefferson canceled the inpatient oncology/hematology privileges of five Alliance oncologists at three Jefferson Health-Northeast hospitals, primarily alleging that Jefferson was attempting to monopolize cancer care in the area.

Jefferson – one of the largest health care systems in the Philadelphia area that includes the NCI-designated Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center – made the move because it had entered into an exclusive agreement with its own medical group to provide inpatient and outpatient oncology/hematology services at the hospitals.

In its court filings, Jefferson said it entered into the exclusive agreement because doing so was in “the best interest of patients, as it would ensure better integration and availability of care and help ensure that Jefferson consistently provides high-quality medical care in accordance with evidence-based standards.”

Tensions had been building between Alliance and Jefferson for years, ever since, according to Alliance, the community practice declined a buyout offer from Jefferson almost a decade ago.

But the revocation of privileges ultimately tipped the scales for Alliance, sparking the lawsuit.

“For us, that crossed a line,” said Moshe Chasky, MD, one of the five Alliance oncologists and a plaintiff in the suit.

Dr. Chasky and his colleagues had provided care at the hospitals for years, with about 10-15 patients admitted at any one time. The quality of their care is not in dispute. Dr. Chasky, for instance, routinely makes Philadelphia Magazine’s Top Doc List.

Under the new arrangement, the five Alliance oncologists have to hand over care of their admitted patients to Jefferson oncologists or send their patients to another hospital farther away where they do have admitting privileges.

“Without having admitting privileges,” community oncologists “can’t look a patient in the eye and say, ‘No matter what, I’ve got you,’ ” explained Nicolas Ferreyros, managing director of policy, advocacy, and communications at the Community Oncology Alliance, a DC-based lobbying group for independent oncologists.

“A doctor doesn’t want to tell a patient that ‘once you go in the hospital, I have to hand you off.’ ” It undermines their practice, Mr. Ferreyros said.

The situation has caught the attention of other community oncologists who are worried that hospitals canceling admitting privileges might become a new tactic in what they characterize as an ongoing effort to elbow-out independent practitioners and corner the oncology market.

Dr. Chasky said he is getting “calls every day from independent oncologists throughout the country” who “are very concerned. People are watching this for sure.”

Alliance attorney Daniel Frier said that there is nothing unusual about hospitals entering into exclusive contracts with hospital-based practices.

But Mr. Frier said he’s never heard of a hospital entering into an exclusive contract and then terminating the privileges of community oncologists.

“There’s no direct precedent” for the move, he said.

Jefferson Health did not respond to requests for comment.

The ruling

U.S. District Court Judge Kai Scott, who ruled on Alliance’s motion to block the contract and preserve its oncologists’ admitting privileges, ultimately sided with Jefferson and allowed the contract to go forward.

Judge Scott wrote that, “while the court understands the plaintiffs’ concerns and desires to maintain the continuity of care for their own patients,” the court “is not persuaded that either of the two threshold elements for a temporary restraining order or preliminary injunction are met” – first, that Jefferson’s actions violate antitrust laws and second that the plaintiffs “will suffer immediate, irreparable harm” from having their admitting privileges rescinded.

Alliance argued that Jefferson’s contract violated federal antitrust laws and would allow Jefferson to monopolize the local oncology market.

However, Judge Scott called Alliance’s antitrust argument “lifeless” under the strict requirements for antitrust violations, explaining that, among other reasons, a monopoly is unlikely given that Jefferson competes with several high-profile oncology programs in the Philadelphia area, including the Fox Chase Cancer Center.

Judge Scott also expressed doubt that the Jefferson’s actions would cause irreparable harm to Alliance’s business. Alliance employs more than thirty oncologists affiliated with over a dozen hospitals in the greater Philadelphia area, and the inpatient services provided at Jefferson Health-Northeast did not represent a major part of its business.

Despite her ruling, Judge Scott did voice skepticism about some of Jefferson’s arguments.

“The court notes that the Jefferson defendants have briefly argued that Jefferson will be better able to ensure that its own patients receive fully integrated and coordinated care” under the exclusive provider agreement, but “it is unclear how the cooperation of ACS [Alliance Cancer Specialists] and JNE [Jefferson Health-Northeast] hospitalists really caused any problems for the coordinated care of” patients in the many years that they worked together.

It also “does not seem to necessarily serve the community to quickly sever the artery between the services that ACS provides and the services that JNE provides,” Judge Scott wrote.

She added that she would consider another motion from Alliance if the practice makes stronger arguments illustrating antitrust violations and demonstrating irreparable harm.

Currently, Dr. Chasky and Mr. Frier are considering their next steps in the case. The oncologists said they can appeal the judge’s decision or file a new complaint.

Meanwhile, Dr. Chasky and his four colleagues requested and were granted internal medicine privileges at Jefferson Health-Northeast, but given the considerable overlap between oncology and internal medicine, the line between what they can and cannot do remains unclear.

“It’s a mess,” he said.

A familiar story

Large health care entities have increasingly worked to push out or swallow up smaller, independent practices for years.

“What Dr. Chasky and his practice are going through is a little bit more of an aggressive version of what’s going on in the rest of the country,” said Michael Diaz, MD, a community oncologist at Florida Cancer Specialists, the largest independent medical oncology/hematology group in the United States. “The larger institutional hospitals try to make it a closed system so they can keep everything in-house and refer to their own physicians.”

The incentive, Dr. Diaz said, is the financial windfall that Section 340B of the 1992 Public Health Service Act generates for hospital-based oncology services at nonprofit hospitals, such as the Jefferson Health-Northeast facilities.

The 340B program allows nonprofit hospitals to buy primarily outpatient oncology drugs at steep discounts, sometimes 50% or more, and be reimbursed at full price.

When launched in 1992, the program was meant to help a handful of safety-net hospitals cover the cost of charity care, and now approximately more than half of U.S. hospitals participate in the program, particularly after requirements were loosened by the Affordable Care Act. But there’s little transparency on how the money is spent.

Critics say the incentives have created a feeding frenzy among 340B hospitals to either acquire outpatient oncology practices or take their business because of the particularly high margins on oncology drugs. There are similar incentives for hospital-based infusion centers.

In its lawsuit, Alliance alleged that such incentives are what motivated Jefferson’s recent actions.

“It’s all about the money at the end of the day,” said Christian Thomas, MD, a community oncologist with New England Cancer Specialists, Scarborough, Maine, who, like Dr. Diaz, said he’s seen the dynamic play out repeatedly in his career.

The American Hospital Association has been a vigorous defender of 340B in the courts and elsewhere, but the Association’s communications staff had little to say when this news organization reached out about the Jefferson-Alliance situation, except that they do not comment on “specific hospital circumstance.”

Reverberations around the country

Many community oncologists are keeping close tabs on the Jefferson-Alliance situation.

“Our group has been watching Jefferson closely because our [local] hospital is following the same playbook, but they have not yet gone after our privileges,” said Scott Herbert, MD, a community oncologist with the independent Nexus Health system, Sante Fe, N.M.

Dr. Herbert was referring to what has happened since he and his colleagues declined to renew an exclusive provider agreement early this year with St. Vincent Regional Medical Center, a nonprofit hospital in Sante Fe. The agreement allowed the hospital to take advantage of the 340B program because Nexus oncologists acted on its behalf.

St. Vincent’s owner, Christus Health, did not respond to inquiries from this news organization.

Nexus let the contract lapse because its oncologists wanted to provide services at a second, newer hospital in Santa Fe where some of their patients had begun seeking treatment.

The nonprofit hospital in Sante Fe is now building its own oncology practice. Similar to Dr. Chasky’s experience in Philadelphia, Dr. Herbert said his group has seen referrals from the hospital dry up and existing patients rechanneled to the hospital’s oncologists.

“We found over 109 patients in January and February that were referred to one of our docs that got rerouted to one of their docs,” he said.

Dr. Herbert has sent cease-and-desist letters, but “after we saw what Jefferson did, my group said, ‘You better back off of the hospital, or it’s going to take our privileges.’ ”

The Jefferson situation “is sending a message,” he said. “Frankly, we’ve been terrified” at the thought of losing privileges there. “It’s the busiest hospital in our area.”

The future of community oncology

Despite the challenges, Mr. Ferreyros at the Community Oncology Alliance remains optimistic about the future of independent oncology.

Under the competitive pressures, a lot of independent oncology practices have folded in recent years, but the ones that remain are strong. Payers are also increasingly noticing that community oncology practices are less expensive than hospital-based practices for comparable care, he said.

Relationships with hospitals aren’t always adversarial, either. “A lot of practices have collaborative agreements with local hospitals” that work out well, Mr. Ferreyros said, adding that sometimes hospitals even hand over oncology care to local independents after finding that starting and maintaining an oncology service is harder than they imagined.

“The last two decades have been difficult,” but the remaining community oncology practices “are going strong,” he said, and “we’ve never seen more engagement on our issues,” particularly around the issue of cost savings.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, Alliance Cancer Specialists.

The outcome, some community oncologists say, could set a new precedent in how far large health care organizations will go to take their patients or drive them out of business.

The case

On Sept. 5, Alliance sued Jefferson Health after Jefferson canceled the inpatient oncology/hematology privileges of five Alliance oncologists at three Jefferson Health-Northeast hospitals, primarily alleging that Jefferson was attempting to monopolize cancer care in the area.

Jefferson – one of the largest health care systems in the Philadelphia area that includes the NCI-designated Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center – made the move because it had entered into an exclusive agreement with its own medical group to provide inpatient and outpatient oncology/hematology services at the hospitals.

In its court filings, Jefferson said it entered into the exclusive agreement because doing so was in “the best interest of patients, as it would ensure better integration and availability of care and help ensure that Jefferson consistently provides high-quality medical care in accordance with evidence-based standards.”

Tensions had been building between Alliance and Jefferson for years, ever since, according to Alliance, the community practice declined a buyout offer from Jefferson almost a decade ago.

But the revocation of privileges ultimately tipped the scales for Alliance, sparking the lawsuit.

“For us, that crossed a line,” said Moshe Chasky, MD, one of the five Alliance oncologists and a plaintiff in the suit.

Dr. Chasky and his colleagues had provided care at the hospitals for years, with about 10-15 patients admitted at any one time. The quality of their care is not in dispute. Dr. Chasky, for instance, routinely makes Philadelphia Magazine’s Top Doc List.

Under the new arrangement, the five Alliance oncologists have to hand over care of their admitted patients to Jefferson oncologists or send their patients to another hospital farther away where they do have admitting privileges.

“Without having admitting privileges,” community oncologists “can’t look a patient in the eye and say, ‘No matter what, I’ve got you,’ ” explained Nicolas Ferreyros, managing director of policy, advocacy, and communications at the Community Oncology Alliance, a DC-based lobbying group for independent oncologists.

“A doctor doesn’t want to tell a patient that ‘once you go in the hospital, I have to hand you off.’ ” It undermines their practice, Mr. Ferreyros said.

The situation has caught the attention of other community oncologists who are worried that hospitals canceling admitting privileges might become a new tactic in what they characterize as an ongoing effort to elbow-out independent practitioners and corner the oncology market.

Dr. Chasky said he is getting “calls every day from independent oncologists throughout the country” who “are very concerned. People are watching this for sure.”

Alliance attorney Daniel Frier said that there is nothing unusual about hospitals entering into exclusive contracts with hospital-based practices.

But Mr. Frier said he’s never heard of a hospital entering into an exclusive contract and then terminating the privileges of community oncologists.

“There’s no direct precedent” for the move, he said.

Jefferson Health did not respond to requests for comment.

The ruling

U.S. District Court Judge Kai Scott, who ruled on Alliance’s motion to block the contract and preserve its oncologists’ admitting privileges, ultimately sided with Jefferson and allowed the contract to go forward.

Judge Scott wrote that, “while the court understands the plaintiffs’ concerns and desires to maintain the continuity of care for their own patients,” the court “is not persuaded that either of the two threshold elements for a temporary restraining order or preliminary injunction are met” – first, that Jefferson’s actions violate antitrust laws and second that the plaintiffs “will suffer immediate, irreparable harm” from having their admitting privileges rescinded.

Alliance argued that Jefferson’s contract violated federal antitrust laws and would allow Jefferson to monopolize the local oncology market.

However, Judge Scott called Alliance’s antitrust argument “lifeless” under the strict requirements for antitrust violations, explaining that, among other reasons, a monopoly is unlikely given that Jefferson competes with several high-profile oncology programs in the Philadelphia area, including the Fox Chase Cancer Center.

Judge Scott also expressed doubt that the Jefferson’s actions would cause irreparable harm to Alliance’s business. Alliance employs more than thirty oncologists affiliated with over a dozen hospitals in the greater Philadelphia area, and the inpatient services provided at Jefferson Health-Northeast did not represent a major part of its business.

Despite her ruling, Judge Scott did voice skepticism about some of Jefferson’s arguments.

“The court notes that the Jefferson defendants have briefly argued that Jefferson will be better able to ensure that its own patients receive fully integrated and coordinated care” under the exclusive provider agreement, but “it is unclear how the cooperation of ACS [Alliance Cancer Specialists] and JNE [Jefferson Health-Northeast] hospitalists really caused any problems for the coordinated care of” patients in the many years that they worked together.

It also “does not seem to necessarily serve the community to quickly sever the artery between the services that ACS provides and the services that JNE provides,” Judge Scott wrote.

She added that she would consider another motion from Alliance if the practice makes stronger arguments illustrating antitrust violations and demonstrating irreparable harm.

Currently, Dr. Chasky and Mr. Frier are considering their next steps in the case. The oncologists said they can appeal the judge’s decision or file a new complaint.

Meanwhile, Dr. Chasky and his four colleagues requested and were granted internal medicine privileges at Jefferson Health-Northeast, but given the considerable overlap between oncology and internal medicine, the line between what they can and cannot do remains unclear.

“It’s a mess,” he said.

A familiar story

Large health care entities have increasingly worked to push out or swallow up smaller, independent practices for years.

“What Dr. Chasky and his practice are going through is a little bit more of an aggressive version of what’s going on in the rest of the country,” said Michael Diaz, MD, a community oncologist at Florida Cancer Specialists, the largest independent medical oncology/hematology group in the United States. “The larger institutional hospitals try to make it a closed system so they can keep everything in-house and refer to their own physicians.”

The incentive, Dr. Diaz said, is the financial windfall that Section 340B of the 1992 Public Health Service Act generates for hospital-based oncology services at nonprofit hospitals, such as the Jefferson Health-Northeast facilities.

The 340B program allows nonprofit hospitals to buy primarily outpatient oncology drugs at steep discounts, sometimes 50% or more, and be reimbursed at full price.

When launched in 1992, the program was meant to help a handful of safety-net hospitals cover the cost of charity care, and now approximately more than half of U.S. hospitals participate in the program, particularly after requirements were loosened by the Affordable Care Act. But there’s little transparency on how the money is spent.

Critics say the incentives have created a feeding frenzy among 340B hospitals to either acquire outpatient oncology practices or take their business because of the particularly high margins on oncology drugs. There are similar incentives for hospital-based infusion centers.

In its lawsuit, Alliance alleged that such incentives are what motivated Jefferson’s recent actions.

“It’s all about the money at the end of the day,” said Christian Thomas, MD, a community oncologist with New England Cancer Specialists, Scarborough, Maine, who, like Dr. Diaz, said he’s seen the dynamic play out repeatedly in his career.

The American Hospital Association has been a vigorous defender of 340B in the courts and elsewhere, but the Association’s communications staff had little to say when this news organization reached out about the Jefferson-Alliance situation, except that they do not comment on “specific hospital circumstance.”

Reverberations around the country

Many community oncologists are keeping close tabs on the Jefferson-Alliance situation.

“Our group has been watching Jefferson closely because our [local] hospital is following the same playbook, but they have not yet gone after our privileges,” said Scott Herbert, MD, a community oncologist with the independent Nexus Health system, Sante Fe, N.M.

Dr. Herbert was referring to what has happened since he and his colleagues declined to renew an exclusive provider agreement early this year with St. Vincent Regional Medical Center, a nonprofit hospital in Sante Fe. The agreement allowed the hospital to take advantage of the 340B program because Nexus oncologists acted on its behalf.

St. Vincent’s owner, Christus Health, did not respond to inquiries from this news organization.

Nexus let the contract lapse because its oncologists wanted to provide services at a second, newer hospital in Santa Fe where some of their patients had begun seeking treatment.

The nonprofit hospital in Sante Fe is now building its own oncology practice. Similar to Dr. Chasky’s experience in Philadelphia, Dr. Herbert said his group has seen referrals from the hospital dry up and existing patients rechanneled to the hospital’s oncologists.

“We found over 109 patients in January and February that were referred to one of our docs that got rerouted to one of their docs,” he said.

Dr. Herbert has sent cease-and-desist letters, but “after we saw what Jefferson did, my group said, ‘You better back off of the hospital, or it’s going to take our privileges.’ ”

The Jefferson situation “is sending a message,” he said. “Frankly, we’ve been terrified” at the thought of losing privileges there. “It’s the busiest hospital in our area.”

The future of community oncology

Despite the challenges, Mr. Ferreyros at the Community Oncology Alliance remains optimistic about the future of independent oncology.

Under the competitive pressures, a lot of independent oncology practices have folded in recent years, but the ones that remain are strong. Payers are also increasingly noticing that community oncology practices are less expensive than hospital-based practices for comparable care, he said.

Relationships with hospitals aren’t always adversarial, either. “A lot of practices have collaborative agreements with local hospitals” that work out well, Mr. Ferreyros said, adding that sometimes hospitals even hand over oncology care to local independents after finding that starting and maintaining an oncology service is harder than they imagined.

“The last two decades have been difficult,” but the remaining community oncology practices “are going strong,” he said, and “we’ve never seen more engagement on our issues,” particularly around the issue of cost savings.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, Alliance Cancer Specialists.

The outcome, some community oncologists say, could set a new precedent in how far large health care organizations will go to take their patients or drive them out of business.

The case

On Sept. 5, Alliance sued Jefferson Health after Jefferson canceled the inpatient oncology/hematology privileges of five Alliance oncologists at three Jefferson Health-Northeast hospitals, primarily alleging that Jefferson was attempting to monopolize cancer care in the area.

Jefferson – one of the largest health care systems in the Philadelphia area that includes the NCI-designated Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center – made the move because it had entered into an exclusive agreement with its own medical group to provide inpatient and outpatient oncology/hematology services at the hospitals.

In its court filings, Jefferson said it entered into the exclusive agreement because doing so was in “the best interest of patients, as it would ensure better integration and availability of care and help ensure that Jefferson consistently provides high-quality medical care in accordance with evidence-based standards.”

Tensions had been building between Alliance and Jefferson for years, ever since, according to Alliance, the community practice declined a buyout offer from Jefferson almost a decade ago.

But the revocation of privileges ultimately tipped the scales for Alliance, sparking the lawsuit.

“For us, that crossed a line,” said Moshe Chasky, MD, one of the five Alliance oncologists and a plaintiff in the suit.

Dr. Chasky and his colleagues had provided care at the hospitals for years, with about 10-15 patients admitted at any one time. The quality of their care is not in dispute. Dr. Chasky, for instance, routinely makes Philadelphia Magazine’s Top Doc List.

Under the new arrangement, the five Alliance oncologists have to hand over care of their admitted patients to Jefferson oncologists or send their patients to another hospital farther away where they do have admitting privileges.

“Without having admitting privileges,” community oncologists “can’t look a patient in the eye and say, ‘No matter what, I’ve got you,’ ” explained Nicolas Ferreyros, managing director of policy, advocacy, and communications at the Community Oncology Alliance, a DC-based lobbying group for independent oncologists.

“A doctor doesn’t want to tell a patient that ‘once you go in the hospital, I have to hand you off.’ ” It undermines their practice, Mr. Ferreyros said.

The situation has caught the attention of other community oncologists who are worried that hospitals canceling admitting privileges might become a new tactic in what they characterize as an ongoing effort to elbow-out independent practitioners and corner the oncology market.

Dr. Chasky said he is getting “calls every day from independent oncologists throughout the country” who “are very concerned. People are watching this for sure.”

Alliance attorney Daniel Frier said that there is nothing unusual about hospitals entering into exclusive contracts with hospital-based practices.

But Mr. Frier said he’s never heard of a hospital entering into an exclusive contract and then terminating the privileges of community oncologists.

“There’s no direct precedent” for the move, he said.

Jefferson Health did not respond to requests for comment.

The ruling

U.S. District Court Judge Kai Scott, who ruled on Alliance’s motion to block the contract and preserve its oncologists’ admitting privileges, ultimately sided with Jefferson and allowed the contract to go forward.

Judge Scott wrote that, “while the court understands the plaintiffs’ concerns and desires to maintain the continuity of care for their own patients,” the court “is not persuaded that either of the two threshold elements for a temporary restraining order or preliminary injunction are met” – first, that Jefferson’s actions violate antitrust laws and second that the plaintiffs “will suffer immediate, irreparable harm” from having their admitting privileges rescinded.

Alliance argued that Jefferson’s contract violated federal antitrust laws and would allow Jefferson to monopolize the local oncology market.

However, Judge Scott called Alliance’s antitrust argument “lifeless” under the strict requirements for antitrust violations, explaining that, among other reasons, a monopoly is unlikely given that Jefferson competes with several high-profile oncology programs in the Philadelphia area, including the Fox Chase Cancer Center.

Judge Scott also expressed doubt that the Jefferson’s actions would cause irreparable harm to Alliance’s business. Alliance employs more than thirty oncologists affiliated with over a dozen hospitals in the greater Philadelphia area, and the inpatient services provided at Jefferson Health-Northeast did not represent a major part of its business.

Despite her ruling, Judge Scott did voice skepticism about some of Jefferson’s arguments.

“The court notes that the Jefferson defendants have briefly argued that Jefferson will be better able to ensure that its own patients receive fully integrated and coordinated care” under the exclusive provider agreement, but “it is unclear how the cooperation of ACS [Alliance Cancer Specialists] and JNE [Jefferson Health-Northeast] hospitalists really caused any problems for the coordinated care of” patients in the many years that they worked together.

It also “does not seem to necessarily serve the community to quickly sever the artery between the services that ACS provides and the services that JNE provides,” Judge Scott wrote.

She added that she would consider another motion from Alliance if the practice makes stronger arguments illustrating antitrust violations and demonstrating irreparable harm.

Currently, Dr. Chasky and Mr. Frier are considering their next steps in the case. The oncologists said they can appeal the judge’s decision or file a new complaint.

Meanwhile, Dr. Chasky and his four colleagues requested and were granted internal medicine privileges at Jefferson Health-Northeast, but given the considerable overlap between oncology and internal medicine, the line between what they can and cannot do remains unclear.

“It’s a mess,” he said.

A familiar story

Large health care entities have increasingly worked to push out or swallow up smaller, independent practices for years.

“What Dr. Chasky and his practice are going through is a little bit more of an aggressive version of what’s going on in the rest of the country,” said Michael Diaz, MD, a community oncologist at Florida Cancer Specialists, the largest independent medical oncology/hematology group in the United States. “The larger institutional hospitals try to make it a closed system so they can keep everything in-house and refer to their own physicians.”

The incentive, Dr. Diaz said, is the financial windfall that Section 340B of the 1992 Public Health Service Act generates for hospital-based oncology services at nonprofit hospitals, such as the Jefferson Health-Northeast facilities.

The 340B program allows nonprofit hospitals to buy primarily outpatient oncology drugs at steep discounts, sometimes 50% or more, and be reimbursed at full price.

When launched in 1992, the program was meant to help a handful of safety-net hospitals cover the cost of charity care, and now approximately more than half of U.S. hospitals participate in the program, particularly after requirements were loosened by the Affordable Care Act. But there’s little transparency on how the money is spent.

Critics say the incentives have created a feeding frenzy among 340B hospitals to either acquire outpatient oncology practices or take their business because of the particularly high margins on oncology drugs. There are similar incentives for hospital-based infusion centers.

In its lawsuit, Alliance alleged that such incentives are what motivated Jefferson’s recent actions.

“It’s all about the money at the end of the day,” said Christian Thomas, MD, a community oncologist with New England Cancer Specialists, Scarborough, Maine, who, like Dr. Diaz, said he’s seen the dynamic play out repeatedly in his career.

The American Hospital Association has been a vigorous defender of 340B in the courts and elsewhere, but the Association’s communications staff had little to say when this news organization reached out about the Jefferson-Alliance situation, except that they do not comment on “specific hospital circumstance.”

Reverberations around the country

Many community oncologists are keeping close tabs on the Jefferson-Alliance situation.

“Our group has been watching Jefferson closely because our [local] hospital is following the same playbook, but they have not yet gone after our privileges,” said Scott Herbert, MD, a community oncologist with the independent Nexus Health system, Sante Fe, N.M.

Dr. Herbert was referring to what has happened since he and his colleagues declined to renew an exclusive provider agreement early this year with St. Vincent Regional Medical Center, a nonprofit hospital in Sante Fe. The agreement allowed the hospital to take advantage of the 340B program because Nexus oncologists acted on its behalf.

St. Vincent’s owner, Christus Health, did not respond to inquiries from this news organization.

Nexus let the contract lapse because its oncologists wanted to provide services at a second, newer hospital in Santa Fe where some of their patients had begun seeking treatment.

The nonprofit hospital in Sante Fe is now building its own oncology practice. Similar to Dr. Chasky’s experience in Philadelphia, Dr. Herbert said his group has seen referrals from the hospital dry up and existing patients rechanneled to the hospital’s oncologists.

“We found over 109 patients in January and February that were referred to one of our docs that got rerouted to one of their docs,” he said.

Dr. Herbert has sent cease-and-desist letters, but “after we saw what Jefferson did, my group said, ‘You better back off of the hospital, or it’s going to take our privileges.’ ”

The Jefferson situation “is sending a message,” he said. “Frankly, we’ve been terrified” at the thought of losing privileges there. “It’s the busiest hospital in our area.”

The future of community oncology

Despite the challenges, Mr. Ferreyros at the Community Oncology Alliance remains optimistic about the future of independent oncology.

Under the competitive pressures, a lot of independent oncology practices have folded in recent years, but the ones that remain are strong. Payers are also increasingly noticing that community oncology practices are less expensive than hospital-based practices for comparable care, he said.

Relationships with hospitals aren’t always adversarial, either. “A lot of practices have collaborative agreements with local hospitals” that work out well, Mr. Ferreyros said, adding that sometimes hospitals even hand over oncology care to local independents after finding that starting and maintaining an oncology service is harder than they imagined.

“The last two decades have been difficult,” but the remaining community oncology practices “are going strong,” he said, and “we’ve never seen more engagement on our issues,” particularly around the issue of cost savings.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Early career considerations for gastroenterologists interested in diversity, equity, and inclusion roles

Highlighting the importance of DEI across all aspects of medicine is long overdue, and the field of gastroenterology is no exception. Diversity in the gastroenterology workforce still has significant room for improvement with only 12% of all gastroenterology fellows in 2018 identifying as Black, Latino/a/x, American Indian or Alaskan Native, or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.1 Moreover, only 4.4% of practicing gastroenterologists identify as Black, 6.7% identify as Latino/a/x, 0.1% as American Indian or Alaskan Native, and 0.003% as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.2

The intensified focus on diversity in GI is welcomed, but increasing physician workforce diversity is only one of the necessary steps. If our ultimate goal is to improve health outcomes and achieve health equity for historically marginalized racial, ethnic, and socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, we must critically evaluate the path beyond just enhancing workforce diversity.

Black and Latino/a/x physicians are more likely to care for historically marginalized communities,3 which has been shown to improve all-cause mortality and reduce racial disparities.4 Additionally, diverse work teams are more innovative and productive.5 Therefore, expanding diversity must include 1) providing equitable policies and access to opportunities and promotions; 2) building inclusive environments in our institutions and practices; and 3) providing space for all people to feel like they can belong, feel respected at work, and genuinely have their opinions and ideas valued. What diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging provide for us and our patients are avenues to thrive, solve complex problems, and tackle prominent issues within our institutions, workplaces, and communities.

To this end, many academic centers, hospitals, and private practice entities have produced a flurry of new DEI initiatives coupled with titles and roles. Some of these roles have thankfully brought recognition and economic compensation to the people doing this work. Still, as an early career gastroenterologist, you may be offered or are considering taking on a DEI role during your early career. As two underrepresented minority women in medicine who took on DEI roles with their first jobs, we wanted to highlight a few aspects to think about during your early career:

Does the DEI role come with resources?

Historically, DEI efforts were treated as “extra work,” or an activity that was done using one’s own personal time. In addition, this work called upon the small number of physicians underrepresented in medicine, largely uncompensated and with an exorbitant minority tax during a critical moment in establishing their early careers. DEI should no longer be seen as an extracurricular activity but as a vital component of an institution’s success.

If you are considering a DEI role, the first question to ask is, “Does this role come with extra compensation or protected time?” We highly recommend not taking on the role if the answer is no. If your institution or employer is only offering increased minority tax, you are being set up to either fail, burn out, or both. Your employer or institution does not appear to value your time or effort in DEI, and you should interpret their lack of compensation or protected time as such.

If the answer is yes, then here are a few other things to consider: Is there institutional support for you to be successful in your new role? As DEI work challenges you to come up with solutions to combat years of historic marginalization for racial and ethnic minorities, this work can sometimes feel overwhelming and isolating. The importance of the DEI community and mentorship within and outside your institution is critical. You should consider joining DEI working groups or committees through GI national societies, the Association of American Medical Colleges, or the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. You can also connect with a fantastic network of people engaged in this work via social media and lean on friends and colleagues leading similar initiatives across the country.

Other critical logistical questions are if your role will come with administrative support, whether there is a budget for programs or events, and whether your institution/employer will support you in seeking continued professional development for your DEI role.6

Make sure to understand the “ask” from your division, department, or company.

Before confirming you are willing to take on this role, get a clear vision of what you are being asked to accomplish. There are so many opportunities to improve the DEI landscape. Therefore, knowing what you are specifically being asked to do will be critical to your success.

Are you being asked to work on diversity?

Does your institution want you to focus on and improve the recruitment and retention of trainees, physicians, or staff underrepresented in medicine? If so, you will need to have access to all the prior work and statistics. Capture the landscape before your interventions (% underrepresented in medicine [URiM] trainees, % URiM faculty at each level, % of URiM trainees retained as faculty, % of URiM faculty being promoted each year, etc.) This will allow you to determine the outcomes of your proposed improvements or programs.

Is your employer focused on equity?

Are you being asked to think about ways to operationalize improved patient health equity, or are you being asked to build equitable opportunities/programs for career advancement for URiMs at your institution? For either equity issue, you first need to understand the scope of the problem to ask for the necessary resources for a potential solution. Discuss timeline expectations, as equity work is a marathon and may take years to move the needle on any particular issue. This timeline is also critical for your employer to be aware of and support, as unrealistic timelines and expectations will also set you up for failure.

Or, are you being asked to concentrate on inclusion?

Does your institution need an assessment of how inclusive the climate is for trainees, staff, or physicians? Does this assessment align with your division or department’s impression, and how do you plan to work toward potential solutions for improvement?

Although diversity, equity, and inclusion are interconnected entities, they all have distinct objectives and solutions. It is essential to understand your vision and your employer’s vision for this role. If they are not aligned, having early and in-depth conversations about aligning your visions will set you on a path to success in your early career.

Know your why or more importantly, your who?

Early career physicians who are considering taking on DEI work do so for a reason. Being passionate about this type of work is usually born from a personal experience or your deep-rooted values. For us, experiencing and witnessing health disparities for our family members and people who look like us are what initially fueled our passion for this work. Additional experiences with trainees and patients keep us invigorated to continue highlighting the importance of DEI and encourage others to be passionate about DEI’s huge value added. As DEI work can come with challenges, remembering and re-centering on why you are passionate about this work or who you are engaging in this work for can keep you going.

There are several aspects to consider before taking on a DEI role, but overall, the work is rewarding and can be a great addition to the building blocks of your early career. In the short term, you build a DEI community network of peers, mentors, colleagues, and friends beyond your immediate institution and specialty. You also can demonstrate your leadership skills and potential early on in your career. In the long-term, engaging in these types of roles helps build a climate and culture that is conducive to enacting change for our patients and communities, including advancing healthcare equity and working toward recruitment, retention, and expansion efforts for our trainees and faculty. Overall, we think this type of work in your early career can be an integral part of your personal and professional development, while also having an impact that ripples beyond the walls of the endoscopy suite.

Dr. Fritz is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. Dr. Rodriguez is a gastroenterologist with Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Neither Dr. Rodriguez nor Dr. Fritz disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Santhosh L,Babik JM. Trends in racial and ethnic diversity in internal medicine subspecialty fellowships from 2006 to 2018. JAMA Network Open 2020;3:e1920482-e1920482.

2. Colleges AoAM. Physician Specialty Data Report/Active physicians who identified as Black or African-American, 2021. 2022.

3. Komaromy M et al. The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. New England Journal of Medicine 1996;334:1305-10.

4. Snyder JE et al. Black representation in the primary care physician workforce and its association with population life expectancy and mortality rates in the US. JAMA Network Open 2023;6:e236687-e236687.

5. Page S. Diversity bonuses and the business case. The Diversity Bonus: Princeton University Press, 2017:184-208.

6. Vela MB et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion officer position available: Proceed with caution. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 2021;13:771-3.

Helpful resources

Diversity and Inclusion Toolkit Resources, AAMC

Blackinggastro.org, The Association of Black Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists (ABGH)

Podcast: Clinical Problem Solvers: Anti-Racism in Medicine

Highlighting the importance of DEI across all aspects of medicine is long overdue, and the field of gastroenterology is no exception. Diversity in the gastroenterology workforce still has significant room for improvement with only 12% of all gastroenterology fellows in 2018 identifying as Black, Latino/a/x, American Indian or Alaskan Native, or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.1 Moreover, only 4.4% of practicing gastroenterologists identify as Black, 6.7% identify as Latino/a/x, 0.1% as American Indian or Alaskan Native, and 0.003% as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.2

The intensified focus on diversity in GI is welcomed, but increasing physician workforce diversity is only one of the necessary steps. If our ultimate goal is to improve health outcomes and achieve health equity for historically marginalized racial, ethnic, and socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, we must critically evaluate the path beyond just enhancing workforce diversity.

Black and Latino/a/x physicians are more likely to care for historically marginalized communities,3 which has been shown to improve all-cause mortality and reduce racial disparities.4 Additionally, diverse work teams are more innovative and productive.5 Therefore, expanding diversity must include 1) providing equitable policies and access to opportunities and promotions; 2) building inclusive environments in our institutions and practices; and 3) providing space for all people to feel like they can belong, feel respected at work, and genuinely have their opinions and ideas valued. What diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging provide for us and our patients are avenues to thrive, solve complex problems, and tackle prominent issues within our institutions, workplaces, and communities.

To this end, many academic centers, hospitals, and private practice entities have produced a flurry of new DEI initiatives coupled with titles and roles. Some of these roles have thankfully brought recognition and economic compensation to the people doing this work. Still, as an early career gastroenterologist, you may be offered or are considering taking on a DEI role during your early career. As two underrepresented minority women in medicine who took on DEI roles with their first jobs, we wanted to highlight a few aspects to think about during your early career:

Does the DEI role come with resources?

Historically, DEI efforts were treated as “extra work,” or an activity that was done using one’s own personal time. In addition, this work called upon the small number of physicians underrepresented in medicine, largely uncompensated and with an exorbitant minority tax during a critical moment in establishing their early careers. DEI should no longer be seen as an extracurricular activity but as a vital component of an institution’s success.

If you are considering a DEI role, the first question to ask is, “Does this role come with extra compensation or protected time?” We highly recommend not taking on the role if the answer is no. If your institution or employer is only offering increased minority tax, you are being set up to either fail, burn out, or both. Your employer or institution does not appear to value your time or effort in DEI, and you should interpret their lack of compensation or protected time as such.

If the answer is yes, then here are a few other things to consider: Is there institutional support for you to be successful in your new role? As DEI work challenges you to come up with solutions to combat years of historic marginalization for racial and ethnic minorities, this work can sometimes feel overwhelming and isolating. The importance of the DEI community and mentorship within and outside your institution is critical. You should consider joining DEI working groups or committees through GI national societies, the Association of American Medical Colleges, or the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. You can also connect with a fantastic network of people engaged in this work via social media and lean on friends and colleagues leading similar initiatives across the country.

Other critical logistical questions are if your role will come with administrative support, whether there is a budget for programs or events, and whether your institution/employer will support you in seeking continued professional development for your DEI role.6

Make sure to understand the “ask” from your division, department, or company.

Before confirming you are willing to take on this role, get a clear vision of what you are being asked to accomplish. There are so many opportunities to improve the DEI landscape. Therefore, knowing what you are specifically being asked to do will be critical to your success.

Are you being asked to work on diversity?

Does your institution want you to focus on and improve the recruitment and retention of trainees, physicians, or staff underrepresented in medicine? If so, you will need to have access to all the prior work and statistics. Capture the landscape before your interventions (% underrepresented in medicine [URiM] trainees, % URiM faculty at each level, % of URiM trainees retained as faculty, % of URiM faculty being promoted each year, etc.) This will allow you to determine the outcomes of your proposed improvements or programs.

Is your employer focused on equity?

Are you being asked to think about ways to operationalize improved patient health equity, or are you being asked to build equitable opportunities/programs for career advancement for URiMs at your institution? For either equity issue, you first need to understand the scope of the problem to ask for the necessary resources for a potential solution. Discuss timeline expectations, as equity work is a marathon and may take years to move the needle on any particular issue. This timeline is also critical for your employer to be aware of and support, as unrealistic timelines and expectations will also set you up for failure.

Or, are you being asked to concentrate on inclusion?

Does your institution need an assessment of how inclusive the climate is for trainees, staff, or physicians? Does this assessment align with your division or department’s impression, and how do you plan to work toward potential solutions for improvement?

Although diversity, equity, and inclusion are interconnected entities, they all have distinct objectives and solutions. It is essential to understand your vision and your employer’s vision for this role. If they are not aligned, having early and in-depth conversations about aligning your visions will set you on a path to success in your early career.

Know your why or more importantly, your who?

Early career physicians who are considering taking on DEI work do so for a reason. Being passionate about this type of work is usually born from a personal experience or your deep-rooted values. For us, experiencing and witnessing health disparities for our family members and people who look like us are what initially fueled our passion for this work. Additional experiences with trainees and patients keep us invigorated to continue highlighting the importance of DEI and encourage others to be passionate about DEI’s huge value added. As DEI work can come with challenges, remembering and re-centering on why you are passionate about this work or who you are engaging in this work for can keep you going.

There are several aspects to consider before taking on a DEI role, but overall, the work is rewarding and can be a great addition to the building blocks of your early career. In the short term, you build a DEI community network of peers, mentors, colleagues, and friends beyond your immediate institution and specialty. You also can demonstrate your leadership skills and potential early on in your career. In the long-term, engaging in these types of roles helps build a climate and culture that is conducive to enacting change for our patients and communities, including advancing healthcare equity and working toward recruitment, retention, and expansion efforts for our trainees and faculty. Overall, we think this type of work in your early career can be an integral part of your personal and professional development, while also having an impact that ripples beyond the walls of the endoscopy suite.

Dr. Fritz is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. Dr. Rodriguez is a gastroenterologist with Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Neither Dr. Rodriguez nor Dr. Fritz disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Santhosh L,Babik JM. Trends in racial and ethnic diversity in internal medicine subspecialty fellowships from 2006 to 2018. JAMA Network Open 2020;3:e1920482-e1920482.

2. Colleges AoAM. Physician Specialty Data Report/Active physicians who identified as Black or African-American, 2021. 2022.

3. Komaromy M et al. The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. New England Journal of Medicine 1996;334:1305-10.