User login

When burnout is moral injury

Several years have passed since I stood among a cohort of eager medical students wearing regalia that signaled a new beginning. Four years of grueling study culminated in a cacophony of unified voices, each reciting a pledge that I had longed to take since early adolescence. Together we celebrated, triumphant despite innumerable exams and various iterations of the Socratic method – all under the guise of assessing knowledge while in truth seeking to insidiously erode the crowd of prospective physicians. Yet our anxiety and uncertainty melted away as names were called, hands firmly clasped, and tassels transposed. For a moment in time, we stood on the precipice of victory, enthusiastic albeit oblivious of the tremendous obstacles that loomed ahead.

Wistfully I reminisce about the unequivocal joy that abounds within the protective shield of naiveté. Specifically, I think about that time when the edict of medicine and the art of being a physician felt congruent. Yet, reality is fickle and often supersedes expectation. Occasionally my thoughts drift to the early days of residency – a time during which the emotional weight of caring for vulnerable patients while learning to master my chosen specialty felt woefully insurmountable. I recall wading blindly through each rotation attempting to emulate the competent and compassionate care so effortlessly demonstrated by senior physicians as they moved through the health care system with apparent ease. They stepped fluidly, as I watched in awe through rose-tinted glasses.

As months passed into years, my perception cleared. What I initially viewed as graceful patient care belied a complex tapestry of health care workers often pressured into arduous decisions, not necessarily in service of a well-constructed treatment plan. Gradually, formidable barriers emerged, guidelines and restrictions embedded within a confining path that suffocated those who dared to cross it. As a result, a field built on the foundations of autonomy, benevolence, and nonmaleficence was slowly engulfed by a system fraught with contrivances. Amid such stressors, physical and psychological health grows tenuous. Classically, this overwhelming feeling of distress is recognized as burnout. Studies reformulated this malady to that which was first described in Vietnam war veterans, a condition known as “moral injury.”

The impact of burnout

To explain the development – and explore the complexities – of moral injury, we must return to 1975 when the term burnout was initially formulated by Herbert Freudenberger, PhD, a psychologist renowned for his work in substance use disorders, psychoanalysis, and clinical education.1 Dr. Freudenberger’s studies noted incidences of heightened emotional and physical distress in his colleagues working in substance abuse and other clinics. He sought to define these experiences as well as understand his own battle with malaise, apathy, and frustration.1 Ultimately, Dr. Freudenberger described burnout as “Becoming exhausted by making excessive demands on energy, strength, or resources in the workplace.”2 Although it characteristically overlaps with depression and anxiety, burnout is conceptualized as a separate entity specifically forged within a context of perfectionism, integrity, and self-sacrifice.2 Such qualities are integral in health care and, as a result, physicians are particularly vulnerable.

Since Dr. Freudenberger published “Burnout: The High Cost of Achievement” in 1980, immense research has assisted in not only identifying critical factors that contribute to its development but also the detrimental effects it has on physiological health.3 These include exhaustion from poor work conditions and extreme commitment to employee responsibilities that in turn precipitate mood destabilization and impaired work performance.3 Furthermore, research has also demonstrated that burnout triggers alterations in neural circuitry via the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, structures critical for emotional regulation.4 To combat the ill effects of burnout while maintaining productivity and maximizing profit, several high-profile corporations instituted changes focusing on self-care, wellness, benefits, and incentives. Although these modifications are effective in decreasing the rate of employee turnover, such strategies are not easily transferable to health care. In fact, the rate of physician burnout has steadily increased over the past two decades as the business of medicine shifts towards longer hours, decreased reimbursement rates, and inexhaustible insurance stipulations.2,5 Consequently, occupational dissatisfaction increases the risk of cynicism, frustration with patients, internalization of failure, and likelihood of early retirement.5 Moreover, burnout may also fracture interpersonal relationships as well as precipitate errors, negative patient outcomes, malpractice, and development of severe mental health conditions associated with high morbidity and mortality.5,8

Although the concept of burnout is critical in understanding the side effects of stereotypical workplace culture, critics of the concept bemoan a suggestion of individual blame.6,8 In essence, they argue that burnout is explained as a side effect of toxic workplace conditions, but covertly represents a lack of resilience, motivation, and ambition to thrive in a physically or emotionally taxing occupational setting.6,8 Thus, the responsibility of acclimation lies upon the impacted individuals rather than the employer. For this reason, many strategies to ameliorate burnout are focused on the individual, including meditation, wellness retreats, creating or adjusting self-care regimens, or in some cases psychotherapy and psychopharmacology.6 Whereas burnout may respond (at least partially) to such interventions, without altering the causal factors, it is unlikely to remit. This is especially the case in health care, where systemic constraints lie beyond the control of an individual physician. Rather than promoting or specifically relying upon personal improvement and recovery, amendments are needed on multiple levels to affect meaningful change.

Moral injury

Similar to burnout, moral injury was not initially conceived within the scope of health care. In the 1990s Jonathan Shay, MD, PhD, identified veterans presenting with symptoms mimicking PTSD that failed to respond to standard, well established and efficacious treatments.9-11 With further analysis he determined that veterans who demonstrated minimal improvement reported similar histories of guilt, shame, and disgust following perceived injustices enacted or abetted by immoral leaders.10,11 Ultimately Shay identified three components of moral injury: 1. A betrayal of what is morally right; 2. By someone who holds legitimate priority; 3. In a high stakes situation.10

This definition was further modified in 2007 by Brett Linz, PhD, and colleagues as: “Perpetuating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”10,11 By expanding this description to include distress experienced by physicians and health care workers, Wendy Dean and Simon Talbot (in 2018 and 2019 respectively) explored how the health care system leads practitioners to deliver what they identify as substandard treatment.6-8 This results in disillusionment and lays the foundation for ethical and moral dilemmas in clinicians.

Themes of moral injury are repeatedly cited in various surveys and studies as a cause for occupational dissatisfaction. As physicians and other health care professionals reel from the aftermath of COVID-19, the effects of reconfiguring medicine into a business-oriented framework are glaringly conspicuous. Vast hospital nursing shortages, high patient census exacerbated by the political misuse and polarization of science, and insufficient availability of psychiatric beds, have culminated in a deluge of psychological strain in emergency medical physicians. Furthermore, pressure from administrators, mandated patient satisfaction measures, tedious electronic medical record systems, and copious licensing and certification requirements, contribute to physician distress as they attempt to navigate a system that challenges the vows which they swore to uphold.8 Because the cost of pursuing a medical degree frequently necessitates acquisition of loans that, without a physician income, may be difficult to repay,9 many doctors feel trapped within a seemingly endless cycle of misgiving that contributes to emotional exhaustion, pessimism, and low morale.

In my next series of The Myth of the Superdoctor columns, we will explore various factors that potentiate risk of moral injury. From medical school and residency training to corporate infrastructure and insurance obstacles, I will seek to discern and deliberate strategies for repair and rehabilitation. It is my hope that together we will illuminate the myriad complexities within the business of medicine, and become advocates and harbingers of change not only for physicians and health care workers but also for the sake of our patients and their families.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with interests in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. Dr. Thomas has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. King N. When a Psychologist Succumbed to Stress, He Coined The Term Burnout. 2016 Dec 8. NPR: All Things Considered.

2. Maslach C and Leiter MP. World Psychiatry. 2016 Jun;15(2):103-11. doi: 10.1002/wps.20311.

3. InformedHealth.org and Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. Depression: What is burnout?. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279286/.

4. Michel A. Burnout and the Brain. Observer. 2016 Jan 29. https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/burnout-and-the-brain.

5. Patel RS et al. Behav Sci. 2018;8(11):98. doi:10.3390/bs8110098.

6. Dean W and Talbot S. Physicians aren’t ‘burning out.’ They’re suffering from moral injury. Stat. 2018 Jul 26. https://www.statnews.com/2018/07/26/physicians-not-burning-out-they-are-suffering-moral-injury/.

7. Dean W and Talbot S. Moral injury and burnout in medicine: A year of lessons learned. Stat. 2019 Jul 26. https://www.statnews.com/2019/07/26/moral-injury-burnout-medicine-lessons-learned/.

8. Dean W et al. Reframing Clinician Distress: Moral Injury Not Burnout. Fed Pract. 2019 Sep; 36(9):400-2. https://www.mdedge.com/fedprac/article/207458/mental-health/reframing-clinician-distress-moral-injury-not-burnout.

9. Bailey M. Beyond Burnout: Docs Decry ‘Moral Injury’ From Financial Pressures of Health Care. KHN. 2020 Feb 4. https://khn.org/news/beyond-burnout-docs-decry-moral-injury-from-financial-pressures-of-health-care/.

10. Litz B et al. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009 Dec;29(8):695-706. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003.

11. Norman S and Maguen S. Moral Injury. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/cooccurring/moral_injury.asp.

Several years have passed since I stood among a cohort of eager medical students wearing regalia that signaled a new beginning. Four years of grueling study culminated in a cacophony of unified voices, each reciting a pledge that I had longed to take since early adolescence. Together we celebrated, triumphant despite innumerable exams and various iterations of the Socratic method – all under the guise of assessing knowledge while in truth seeking to insidiously erode the crowd of prospective physicians. Yet our anxiety and uncertainty melted away as names were called, hands firmly clasped, and tassels transposed. For a moment in time, we stood on the precipice of victory, enthusiastic albeit oblivious of the tremendous obstacles that loomed ahead.

Wistfully I reminisce about the unequivocal joy that abounds within the protective shield of naiveté. Specifically, I think about that time when the edict of medicine and the art of being a physician felt congruent. Yet, reality is fickle and often supersedes expectation. Occasionally my thoughts drift to the early days of residency – a time during which the emotional weight of caring for vulnerable patients while learning to master my chosen specialty felt woefully insurmountable. I recall wading blindly through each rotation attempting to emulate the competent and compassionate care so effortlessly demonstrated by senior physicians as they moved through the health care system with apparent ease. They stepped fluidly, as I watched in awe through rose-tinted glasses.

As months passed into years, my perception cleared. What I initially viewed as graceful patient care belied a complex tapestry of health care workers often pressured into arduous decisions, not necessarily in service of a well-constructed treatment plan. Gradually, formidable barriers emerged, guidelines and restrictions embedded within a confining path that suffocated those who dared to cross it. As a result, a field built on the foundations of autonomy, benevolence, and nonmaleficence was slowly engulfed by a system fraught with contrivances. Amid such stressors, physical and psychological health grows tenuous. Classically, this overwhelming feeling of distress is recognized as burnout. Studies reformulated this malady to that which was first described in Vietnam war veterans, a condition known as “moral injury.”

The impact of burnout

To explain the development – and explore the complexities – of moral injury, we must return to 1975 when the term burnout was initially formulated by Herbert Freudenberger, PhD, a psychologist renowned for his work in substance use disorders, psychoanalysis, and clinical education.1 Dr. Freudenberger’s studies noted incidences of heightened emotional and physical distress in his colleagues working in substance abuse and other clinics. He sought to define these experiences as well as understand his own battle with malaise, apathy, and frustration.1 Ultimately, Dr. Freudenberger described burnout as “Becoming exhausted by making excessive demands on energy, strength, or resources in the workplace.”2 Although it characteristically overlaps with depression and anxiety, burnout is conceptualized as a separate entity specifically forged within a context of perfectionism, integrity, and self-sacrifice.2 Such qualities are integral in health care and, as a result, physicians are particularly vulnerable.

Since Dr. Freudenberger published “Burnout: The High Cost of Achievement” in 1980, immense research has assisted in not only identifying critical factors that contribute to its development but also the detrimental effects it has on physiological health.3 These include exhaustion from poor work conditions and extreme commitment to employee responsibilities that in turn precipitate mood destabilization and impaired work performance.3 Furthermore, research has also demonstrated that burnout triggers alterations in neural circuitry via the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, structures critical for emotional regulation.4 To combat the ill effects of burnout while maintaining productivity and maximizing profit, several high-profile corporations instituted changes focusing on self-care, wellness, benefits, and incentives. Although these modifications are effective in decreasing the rate of employee turnover, such strategies are not easily transferable to health care. In fact, the rate of physician burnout has steadily increased over the past two decades as the business of medicine shifts towards longer hours, decreased reimbursement rates, and inexhaustible insurance stipulations.2,5 Consequently, occupational dissatisfaction increases the risk of cynicism, frustration with patients, internalization of failure, and likelihood of early retirement.5 Moreover, burnout may also fracture interpersonal relationships as well as precipitate errors, negative patient outcomes, malpractice, and development of severe mental health conditions associated with high morbidity and mortality.5,8

Although the concept of burnout is critical in understanding the side effects of stereotypical workplace culture, critics of the concept bemoan a suggestion of individual blame.6,8 In essence, they argue that burnout is explained as a side effect of toxic workplace conditions, but covertly represents a lack of resilience, motivation, and ambition to thrive in a physically or emotionally taxing occupational setting.6,8 Thus, the responsibility of acclimation lies upon the impacted individuals rather than the employer. For this reason, many strategies to ameliorate burnout are focused on the individual, including meditation, wellness retreats, creating or adjusting self-care regimens, or in some cases psychotherapy and psychopharmacology.6 Whereas burnout may respond (at least partially) to such interventions, without altering the causal factors, it is unlikely to remit. This is especially the case in health care, where systemic constraints lie beyond the control of an individual physician. Rather than promoting or specifically relying upon personal improvement and recovery, amendments are needed on multiple levels to affect meaningful change.

Moral injury

Similar to burnout, moral injury was not initially conceived within the scope of health care. In the 1990s Jonathan Shay, MD, PhD, identified veterans presenting with symptoms mimicking PTSD that failed to respond to standard, well established and efficacious treatments.9-11 With further analysis he determined that veterans who demonstrated minimal improvement reported similar histories of guilt, shame, and disgust following perceived injustices enacted or abetted by immoral leaders.10,11 Ultimately Shay identified three components of moral injury: 1. A betrayal of what is morally right; 2. By someone who holds legitimate priority; 3. In a high stakes situation.10

This definition was further modified in 2007 by Brett Linz, PhD, and colleagues as: “Perpetuating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”10,11 By expanding this description to include distress experienced by physicians and health care workers, Wendy Dean and Simon Talbot (in 2018 and 2019 respectively) explored how the health care system leads practitioners to deliver what they identify as substandard treatment.6-8 This results in disillusionment and lays the foundation for ethical and moral dilemmas in clinicians.

Themes of moral injury are repeatedly cited in various surveys and studies as a cause for occupational dissatisfaction. As physicians and other health care professionals reel from the aftermath of COVID-19, the effects of reconfiguring medicine into a business-oriented framework are glaringly conspicuous. Vast hospital nursing shortages, high patient census exacerbated by the political misuse and polarization of science, and insufficient availability of psychiatric beds, have culminated in a deluge of psychological strain in emergency medical physicians. Furthermore, pressure from administrators, mandated patient satisfaction measures, tedious electronic medical record systems, and copious licensing and certification requirements, contribute to physician distress as they attempt to navigate a system that challenges the vows which they swore to uphold.8 Because the cost of pursuing a medical degree frequently necessitates acquisition of loans that, without a physician income, may be difficult to repay,9 many doctors feel trapped within a seemingly endless cycle of misgiving that contributes to emotional exhaustion, pessimism, and low morale.

In my next series of The Myth of the Superdoctor columns, we will explore various factors that potentiate risk of moral injury. From medical school and residency training to corporate infrastructure and insurance obstacles, I will seek to discern and deliberate strategies for repair and rehabilitation. It is my hope that together we will illuminate the myriad complexities within the business of medicine, and become advocates and harbingers of change not only for physicians and health care workers but also for the sake of our patients and their families.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with interests in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. Dr. Thomas has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. King N. When a Psychologist Succumbed to Stress, He Coined The Term Burnout. 2016 Dec 8. NPR: All Things Considered.

2. Maslach C and Leiter MP. World Psychiatry. 2016 Jun;15(2):103-11. doi: 10.1002/wps.20311.

3. InformedHealth.org and Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. Depression: What is burnout?. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279286/.

4. Michel A. Burnout and the Brain. Observer. 2016 Jan 29. https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/burnout-and-the-brain.

5. Patel RS et al. Behav Sci. 2018;8(11):98. doi:10.3390/bs8110098.

6. Dean W and Talbot S. Physicians aren’t ‘burning out.’ They’re suffering from moral injury. Stat. 2018 Jul 26. https://www.statnews.com/2018/07/26/physicians-not-burning-out-they-are-suffering-moral-injury/.

7. Dean W and Talbot S. Moral injury and burnout in medicine: A year of lessons learned. Stat. 2019 Jul 26. https://www.statnews.com/2019/07/26/moral-injury-burnout-medicine-lessons-learned/.

8. Dean W et al. Reframing Clinician Distress: Moral Injury Not Burnout. Fed Pract. 2019 Sep; 36(9):400-2. https://www.mdedge.com/fedprac/article/207458/mental-health/reframing-clinician-distress-moral-injury-not-burnout.

9. Bailey M. Beyond Burnout: Docs Decry ‘Moral Injury’ From Financial Pressures of Health Care. KHN. 2020 Feb 4. https://khn.org/news/beyond-burnout-docs-decry-moral-injury-from-financial-pressures-of-health-care/.

10. Litz B et al. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009 Dec;29(8):695-706. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003.

11. Norman S and Maguen S. Moral Injury. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/cooccurring/moral_injury.asp.

Several years have passed since I stood among a cohort of eager medical students wearing regalia that signaled a new beginning. Four years of grueling study culminated in a cacophony of unified voices, each reciting a pledge that I had longed to take since early adolescence. Together we celebrated, triumphant despite innumerable exams and various iterations of the Socratic method – all under the guise of assessing knowledge while in truth seeking to insidiously erode the crowd of prospective physicians. Yet our anxiety and uncertainty melted away as names were called, hands firmly clasped, and tassels transposed. For a moment in time, we stood on the precipice of victory, enthusiastic albeit oblivious of the tremendous obstacles that loomed ahead.

Wistfully I reminisce about the unequivocal joy that abounds within the protective shield of naiveté. Specifically, I think about that time when the edict of medicine and the art of being a physician felt congruent. Yet, reality is fickle and often supersedes expectation. Occasionally my thoughts drift to the early days of residency – a time during which the emotional weight of caring for vulnerable patients while learning to master my chosen specialty felt woefully insurmountable. I recall wading blindly through each rotation attempting to emulate the competent and compassionate care so effortlessly demonstrated by senior physicians as they moved through the health care system with apparent ease. They stepped fluidly, as I watched in awe through rose-tinted glasses.

As months passed into years, my perception cleared. What I initially viewed as graceful patient care belied a complex tapestry of health care workers often pressured into arduous decisions, not necessarily in service of a well-constructed treatment plan. Gradually, formidable barriers emerged, guidelines and restrictions embedded within a confining path that suffocated those who dared to cross it. As a result, a field built on the foundations of autonomy, benevolence, and nonmaleficence was slowly engulfed by a system fraught with contrivances. Amid such stressors, physical and psychological health grows tenuous. Classically, this overwhelming feeling of distress is recognized as burnout. Studies reformulated this malady to that which was first described in Vietnam war veterans, a condition known as “moral injury.”

The impact of burnout

To explain the development – and explore the complexities – of moral injury, we must return to 1975 when the term burnout was initially formulated by Herbert Freudenberger, PhD, a psychologist renowned for his work in substance use disorders, psychoanalysis, and clinical education.1 Dr. Freudenberger’s studies noted incidences of heightened emotional and physical distress in his colleagues working in substance abuse and other clinics. He sought to define these experiences as well as understand his own battle with malaise, apathy, and frustration.1 Ultimately, Dr. Freudenberger described burnout as “Becoming exhausted by making excessive demands on energy, strength, or resources in the workplace.”2 Although it characteristically overlaps with depression and anxiety, burnout is conceptualized as a separate entity specifically forged within a context of perfectionism, integrity, and self-sacrifice.2 Such qualities are integral in health care and, as a result, physicians are particularly vulnerable.

Since Dr. Freudenberger published “Burnout: The High Cost of Achievement” in 1980, immense research has assisted in not only identifying critical factors that contribute to its development but also the detrimental effects it has on physiological health.3 These include exhaustion from poor work conditions and extreme commitment to employee responsibilities that in turn precipitate mood destabilization and impaired work performance.3 Furthermore, research has also demonstrated that burnout triggers alterations in neural circuitry via the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, structures critical for emotional regulation.4 To combat the ill effects of burnout while maintaining productivity and maximizing profit, several high-profile corporations instituted changes focusing on self-care, wellness, benefits, and incentives. Although these modifications are effective in decreasing the rate of employee turnover, such strategies are not easily transferable to health care. In fact, the rate of physician burnout has steadily increased over the past two decades as the business of medicine shifts towards longer hours, decreased reimbursement rates, and inexhaustible insurance stipulations.2,5 Consequently, occupational dissatisfaction increases the risk of cynicism, frustration with patients, internalization of failure, and likelihood of early retirement.5 Moreover, burnout may also fracture interpersonal relationships as well as precipitate errors, negative patient outcomes, malpractice, and development of severe mental health conditions associated with high morbidity and mortality.5,8

Although the concept of burnout is critical in understanding the side effects of stereotypical workplace culture, critics of the concept bemoan a suggestion of individual blame.6,8 In essence, they argue that burnout is explained as a side effect of toxic workplace conditions, but covertly represents a lack of resilience, motivation, and ambition to thrive in a physically or emotionally taxing occupational setting.6,8 Thus, the responsibility of acclimation lies upon the impacted individuals rather than the employer. For this reason, many strategies to ameliorate burnout are focused on the individual, including meditation, wellness retreats, creating or adjusting self-care regimens, or in some cases psychotherapy and psychopharmacology.6 Whereas burnout may respond (at least partially) to such interventions, without altering the causal factors, it is unlikely to remit. This is especially the case in health care, where systemic constraints lie beyond the control of an individual physician. Rather than promoting or specifically relying upon personal improvement and recovery, amendments are needed on multiple levels to affect meaningful change.

Moral injury

Similar to burnout, moral injury was not initially conceived within the scope of health care. In the 1990s Jonathan Shay, MD, PhD, identified veterans presenting with symptoms mimicking PTSD that failed to respond to standard, well established and efficacious treatments.9-11 With further analysis he determined that veterans who demonstrated minimal improvement reported similar histories of guilt, shame, and disgust following perceived injustices enacted or abetted by immoral leaders.10,11 Ultimately Shay identified three components of moral injury: 1. A betrayal of what is morally right; 2. By someone who holds legitimate priority; 3. In a high stakes situation.10

This definition was further modified in 2007 by Brett Linz, PhD, and colleagues as: “Perpetuating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”10,11 By expanding this description to include distress experienced by physicians and health care workers, Wendy Dean and Simon Talbot (in 2018 and 2019 respectively) explored how the health care system leads practitioners to deliver what they identify as substandard treatment.6-8 This results in disillusionment and lays the foundation for ethical and moral dilemmas in clinicians.

Themes of moral injury are repeatedly cited in various surveys and studies as a cause for occupational dissatisfaction. As physicians and other health care professionals reel from the aftermath of COVID-19, the effects of reconfiguring medicine into a business-oriented framework are glaringly conspicuous. Vast hospital nursing shortages, high patient census exacerbated by the political misuse and polarization of science, and insufficient availability of psychiatric beds, have culminated in a deluge of psychological strain in emergency medical physicians. Furthermore, pressure from administrators, mandated patient satisfaction measures, tedious electronic medical record systems, and copious licensing and certification requirements, contribute to physician distress as they attempt to navigate a system that challenges the vows which they swore to uphold.8 Because the cost of pursuing a medical degree frequently necessitates acquisition of loans that, without a physician income, may be difficult to repay,9 many doctors feel trapped within a seemingly endless cycle of misgiving that contributes to emotional exhaustion, pessimism, and low morale.

In my next series of The Myth of the Superdoctor columns, we will explore various factors that potentiate risk of moral injury. From medical school and residency training to corporate infrastructure and insurance obstacles, I will seek to discern and deliberate strategies for repair and rehabilitation. It is my hope that together we will illuminate the myriad complexities within the business of medicine, and become advocates and harbingers of change not only for physicians and health care workers but also for the sake of our patients and their families.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with interests in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. Dr. Thomas has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. King N. When a Psychologist Succumbed to Stress, He Coined The Term Burnout. 2016 Dec 8. NPR: All Things Considered.

2. Maslach C and Leiter MP. World Psychiatry. 2016 Jun;15(2):103-11. doi: 10.1002/wps.20311.

3. InformedHealth.org and Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. Depression: What is burnout?. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279286/.

4. Michel A. Burnout and the Brain. Observer. 2016 Jan 29. https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/burnout-and-the-brain.

5. Patel RS et al. Behav Sci. 2018;8(11):98. doi:10.3390/bs8110098.

6. Dean W and Talbot S. Physicians aren’t ‘burning out.’ They’re suffering from moral injury. Stat. 2018 Jul 26. https://www.statnews.com/2018/07/26/physicians-not-burning-out-they-are-suffering-moral-injury/.

7. Dean W and Talbot S. Moral injury and burnout in medicine: A year of lessons learned. Stat. 2019 Jul 26. https://www.statnews.com/2019/07/26/moral-injury-burnout-medicine-lessons-learned/.

8. Dean W et al. Reframing Clinician Distress: Moral Injury Not Burnout. Fed Pract. 2019 Sep; 36(9):400-2. https://www.mdedge.com/fedprac/article/207458/mental-health/reframing-clinician-distress-moral-injury-not-burnout.

9. Bailey M. Beyond Burnout: Docs Decry ‘Moral Injury’ From Financial Pressures of Health Care. KHN. 2020 Feb 4. https://khn.org/news/beyond-burnout-docs-decry-moral-injury-from-financial-pressures-of-health-care/.

10. Litz B et al. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009 Dec;29(8):695-706. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003.

11. Norman S and Maguen S. Moral Injury. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/cooccurring/moral_injury.asp.

Caregiver Support in a Case of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Lewy Body Dementia

Caregiving for a person with dementia in the community can be extremely difficult work. Much of this work falls on unpaid or informal caregivers. Sixty-three percent of older adults with dementia depend completely on unpaid caregivers, and an additional 26% receive some combination of paid and unpaid support, together comprising nearly 90% of the more than 3 million older Americans with dementia.1 In-home care is preferable for these patients. For veterans, the Caregiver Support Program (CSP) is the only US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) program that exclusively supports caregivers. Although the CSP is not a nursing home diversion or cost savings program, successfully enabling at-home living in lieu of facility living also has the potential to reduce overall cost of care, and most importantly, to enable veterans who desire it to age at home.2,3

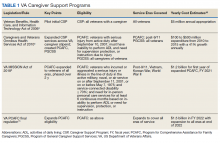

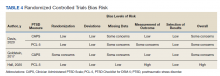

The CSP has 2 unique programs for caregivers of eligible veterans. The Program of General Caregiver Support Services (PGCSS) provides resources, education, and support to caregivers of all veterans enrolled in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). The Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers (PCAFC) provides education and training, access to health care insurance if eligible, mental health counseling, access to a monthly caregiver stipend, enhanced respite care, wellness contacts, and travel compensation for VA health care appointments (Table 1).4,5

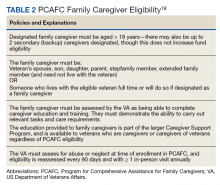

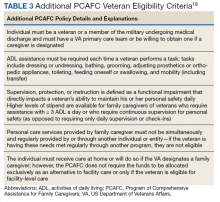

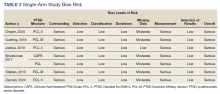

Patients undergo a rigorous assessment and highly specialized and individualized clinical decision-making process to confirm the service is appropriate for the patient. PCAFC was restructured and expanded on October 1, 2020.6 Currently, veterans who incurred or aggravated a serious injury (defined by a single or combined service-connection rating of ≥ 70%) in active military service before May 8, 1975, or after September 10, 2001, are eligible for PCAFC.6 Most notably, these changes opened eligibility in the PCAFC to caregivers of veterans from the Vietnam, Korean, and World War II eras of conflict and veterans with dependence in activities of daily living (ADL) due to a wider variety of illnesses, including dementia.6 The PCAFC is set to further expand to caregivers of otherwise eligible veterans of all eras of service on October 1, 2022, 2 years after the initial expansion, as laid out in the 2018 VA MISSION Act.6 Additional information on the history of the PGCSS and PCAFC and eligibility criteria for veterans and their family caregivers can be found in Tables 2 and 3.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and cognitive impairment are 2 common causes of disability among veterans who receive VHA care. Among older veterans, rates of lifetime development of PTSD reach up to 30%.7 Dementia diagnosis is also more common in older veterans compared with age-matched civilians.8 Furthermore, a prior diagnosis of PTSD has been associated with nearly a 2-fold increase in risk of development of dementia in older age.7 These conditions are also linked to high degrees of service connection. PTSD is the third most prevalent service-connected disability for veterans receiving compensation and cognitive limitation is the third most prevalent category of service-connected disability among veterans.9

We present a case of a Vietnam-era veteran with a history of combat exposure and service-connected PTSD, and a later diagnosis of Lewy body dementia (LBD). Through combination of VHA geriatric services, the CSP, and the expanded PCAFC, the veteran’s primary family caregiver received the materials, support, and financial resources necessary to enable at-home living for the veteran, despite his illness and later complications.

Case Presentation

A male combat veteran presented to his primary care practitioner (PCP) with concerns of several years of progressive changes in gait, forgetfulness, and a gradual decline in the ability to live independently without assistance. At that time, his medical history was notable for PTSD (50% service connection), which had been diagnosed over a decade prior (but for which the veteran had refused medication or therapy on multiple occasions, stating he preferred to “breathe through” his intrusive symptom flare-ups), localized prostate cancer with a radical prostatectomy (100% service connection), multiple kidney stones with persistent left ureteral inflammation, and arteriosclerotic heart disease (10% service connection). A Saint Louis University Mental Status Exam (SLUMS) performed by the PCP was notable for a score of 9/30, in the dementia range. A computed tomography of the brain demonstrated scattered foci of hypoattenuation attributable to normal aging without any other pathology noted.

The veteran was referred to the Cognitive Care clinic, a local longitudinal multidisciplinary dementia care clinic, along with his spouse/caregiver. Cognitive testing was performed by a licensed clinical psychologist in the clinic and was notable for a Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) score of 18/30, also in the dementia range, and a more robust neuropsychiatric battery demonstrated borderline intact memory and language function but impairments in executive function and visuospatial skills. The patient’s clinical history included functional loss over time, with total dependence in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), or tasks necessary to be fully independent or manage a household, including inability to manage finances, and some need for assistance in ADL, or personal care tasks such as dressing or grooming, including bathing. Physical examination was notable for bradykinesia, a shuffling gait, and rare episodes of speaking to someone who was not in the room, thought to be due to mild nondistressing hallucinations.

A diagnosis of LBD was made. At time of diagnosis, the patient met criteria for probable dementia with Lewy bodies, with 2 of 4 core clinical features (hallucinations and Parkinsonism), and multiple supportive features (gait disturbance, sensory disturbance, and altered mood).10,11 The veteran continued to develop more supportive features for diagnosis of LBD over time, including evidence of autonomic instability.

The veteran and his caregiver were educated on his diagnosis, and longitudinal support was offered. The veteran was no longer driving, and due to the severity of his symptoms, the importance of driving cessation was reinforced by the care team. Over the course of the next year, his illness progressed, with more frequent behaviors and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). He began to exhibit nighttime wandering throughout the house and became more anxious and restless during the day. He lost the ability to make his own health care decisions, and his spouse became his activated health care power of attorney (HCPOA). His BPSD became more disruptive to daily life and was accompanied by a change in the character of his hallucinations, with prior nondistressing visions of other people being replaced with visions of war, burning bodies, and violence, much of it related to combat experiences in Vietnam. The BPSD began to include hiding behind furniture, running out of the house, and shouting and crying in response to hallucinations. At times, his BPSD became violent, lashing out in fear against his hallucinations and caregiver.

The veteran’s change in BPSD was concerning for a new baseline, rather than being clearly related to an underlying unmet physical need, such as pain, hunger, sleep, or discomfort. Multiple hospital admissions during that year involved IV hydration and treatment for urinary tract infections (UTI) for several days of inpatient stay at a time, but these behaviors persisted despite infection treatment and hydration. The patient’s changes in BPSD were thought to be secondary to uncovered and intensified PTSD in the setting of progressive dementia. Due to the clear danger the patient posed to himself and others, potential treatment options for these PTSD-related hallucinations were discussed with his caregiver. The caregiver shared that the patient’s BPSD and hallucinations were so distressing that “he would never want to live like this,” and that things had progressed to the point that “he has no quality of life.”

Oral aripiprazole 2 mg twice daily was prescribed after the risks of infection, cardiac complications, and exacerbation of movement disorder symptoms, such as increased stiffness and falls, were discussed with the caregiver. The caregiver was employed and relied on continued employment for income, but the patient could not be safely left alone. As the patient and his caregiver had reached a crisis point and living at home no longer appeared to be safe, the patient was referred to a VA-contracted skilled nursing facility (SNF) for long-term care. The patient’s caregiver was also referred to CSP for support during this transition. Due to the patient’s level of service connection and personal needs, as well as the patient and caregiver’s preference for the veteran to remain in his home, they were evaluated for the PCAFC for enhanced support to enable home as an alternative to facility living, should the patient respond to the antipsychotic therapy sufficiently, which was evaluated on a regular basis.

After several months, the patient’s BPSD had improved significantly, and he was no longer experiencing distressing hallucinations. However, his mobility also declined, and he became fully dependent in most ADL, including transfers, hygiene, and toileting. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, visitation was limited, which was difficult for both the patient and his caregiver. The veteran and caregiver were approved for PCAFC due to the veteran’s combination of service-connected illnesses > 70%, dependence for most ADLs, and need for continuous supervision. A transfer home from the SNF was arranged.

The PCAFC allowed the veteran’s caregiver and family members to provide in-home full-time caregiving, as an alternative to facility placement. The caregiver received a variety of support, including access to peer support, instruction on ways to assist in his toileting, hygiene, and transfers, and a caregiving stipend. In addition to offsetting lost wages, the stipend also helped offset the cost of care supplies which were not provided or were not readily available from the VA, which at the time included the patient’s preferred nutritional supplement and some supplies for personal care.

The veteran’s care needs continued to escalate. A fall at home resulted in a hip fracture, which was treated with surgical pinning. Postfracture physical therapy in a facility was considered, but ultimately was provided at home. The patient also experienced multiple UTIs and resulting delirium, with accompanying agitation and hallucinations. These episodes improved with IV antibiotics and hydration during short hospital stays. Ultimately, a computed tomography demonstrated overflow incontinence likely related to urologic damage from prior kidney stones and stent placement was recommended.

Visiting skilled nurses for the patient’s area were difficult to coordinate but were eventually arranged. The patient continued residing in his home with the support of his caregiver, the PCAFC, and the local VA medical center geriatric and transitional care services. The patient was also referred to the palliative care outpatient specialty clinic for discussion of goals of care and assistance with advance care planning as his illness progressed. Mental health and geriatric psychiatry consult teams were considered for this case but not utilized.

Discussion

Older adult Americans are at high risk of poor financial wellbeing, with nearly one quarter of Americans aged > 62 years experiencing financial insecurity.12 Even in this case with health care provided by the VA, successful in-home care was challenging and required a dedicated live-in caregiver, care coordination resources, and financial support. As part of its mission of caring for veterans, the VA has instituted CSP, whose mission is to promote the health and well-being of family caregivers through education, support, and services.

PCAFC offers enhanced clinical support for caregivers of eligible veterans who are seriously injured. This includes resources, education, support, financial stipends, health insurance (if eligible), and beneficiary travel (if eligible) to primary caregivers of eligible veterans. PCAFC was originally reserved for veterans who had onset of service-related disability after September 11, 2001, with an associated personal care need. In this population, PCAFC demonstrated an increased usage of clinical resources, likely related to increased ease in accessing care.13

The cohort of post-9/11 veterans is very different from the cohort of veterans and their caregivers who may now qualify for the PCAFC after its October 2020 expansion. Veterans from the Vietnam, Korean, and World War II eras of conflict have rates of service-connected disability 2 to 3 times higher than those of post-9/11 era veterans and are at greater risk for dementia.9 Veterans aged ≥ 75 years who have service connection also report higher rates of difficulty with independent living and self-care compared with their younger peers.9 Since dementia and PTSD are common causes of service connection and disability it is likely that a significant proportion of older veterans will be eligible to apply for the newly expanded PCAFC.

To be eligible for PCAFC, a veteran must have a service-connected disability rating of ≥ 70% and must need in-person care services for ≥ 6 continuous months, based on either an inability to perform an ADL, or a need for supervision, protection, or instruction.

It is not clear how CSP use or increased access to PCAFC will impact costs. However, the PCAFC monthly stipend is scaled to the median wage of a home health aide and to the location of the caregiver, which is considerably less than the cost of recurrent hospitalization or a year of facility-level care.15 The CSP may eventually be a successful long-term investment in cost savings. In order to ensure the process for PCAFC approval is uniform and prompt as the program expands, CSP has restructured, increasing the number of employees, improving the patient review process, and expanding staff training.16 The VA plans to continually re-assess CSP using the infrastructure of the Caregiver Record Management Application as it continues to expand.17

Conclusions

Dementia and PTSD commonly coexist and are a significant source of disability in the service-connected veteran population. This case brings attention to the recent expansion of PCAFC, which now has the potential to support eligible veterans from the World War II, Korean, and Vietnam-era conflicts, in whom these illnesses are more common. In this case, in-home care was preferred by the veteran and primary caregiver but would not have been possible without a complex intervention. There is still more research to be done on the best way to meet the needs of older adults with dementia, the impact of in-home care, and the system-wide implications of PCAFC, especially as the program grows. However, in-home care is preferable to SNF living for many veterans and caregivers, and CSP will continue to be an essential element of providing care for this population.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin. The authors would also like to thank the members of the Veterans Affairs Central Office and National Caregiver Support Program Office, including Elyse Kaplan, Melinda Hogue, Beth Wolfsohn, Colleen Richardson, and Timothy Jobin, for their thorough review of the work and edits to ensure accurate program description.

1. Chi W, Graf E, Hughes L, et al. Community-dwelling older adults with dementia and their caregivers: key indicators from the National Health and Aging Trends study. Published January 29, 2019. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_files//186501/DemChartbook.pdf

2. Rapaport P, Burton A, Leverton M, et al. “I just keep thinking that I don’t want to rely on people.” A qualitative study of how people living with dementia achieve and maintain independence at home: stakeholder perspectives. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):1-11. doi:10.1186/s12877-019-1406-6

3. Miller EA, Gidmark S, Gadbois E, Rudolph JL, Intrator O. Nursing home referral within the Veterans Health Administration: practice variation by payment source and facility type. Res Aging. 2018;40(7):687-711. doi:10.1177/0164027517730383

4. Veterans Benefits, Health Care, and Information Technology Act of 2006, Pub L No. 109-461, 120 Stat. 3403.

5. Caregivers and Veterans Omnibus Health Services Act of 2010, Pub L No. 111-163, 115 Stat 552.

6. VA MISSION Act of 2018. 38 CFR § 17.

7. Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Lindquist K, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of dementia among US veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):608-613. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.61

8. Krishnan LL, Petersen NJ, Snow AL, et al. Prevalence of dementia among Veterans Affairs medical care system users. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;20(4):245-253. doi:10.1159/000087345

9. Holder, KA. The Disability of Veterans. Social, Economic, and Housing Statistics Division, US Census Bureau; 2014. Accessed February 9, 2022. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2016/demo/Holder-2016-01.pdf

10. Sanford AM. Lewy body dementia. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018;34(4):603-615. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2018.06.007

11. Armstrong MJ. Lewy body dementias. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2019;25(1):128-146. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000685

12. Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection. Financial well-being of older Americans. Published December 2018. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/bcfp_financial-well-being-older-americans_report.pdf

13. Van Houtven CH, Smith VA, Stechuchak KM, et al. Comprehensive support for family caregivers: impact on veteran health care utilization and costs. Med Care Res Rev. 2019;76(1):89-114. doi:10.1177/1077558717697015

14. Boland L, Légaré F, Perez MMB, et al. Impact of home care versus alternative locations of care on elder health outcomes: an overview of systematic reviews. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):20. doi:10.1186/s12877-016-0395-y

15. Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers Improvements and Amendments Under the VA MISSION Act of 2018. 85 FR § 13356.

16. Extension of Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers Eligibility for Legacy Participants and Legacy Applicants. 86 FR § 52614.

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, 2020. Certification of the Implementation of the Caregiver Records Management Application (CARMA). 85 FR § 63358.

18. Sussman, JS. Department of Veterans Affairs: Caregiver Support. Congressional Research Service Report No. R46282. Published March 24, 2020. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20200324_R46282_656f1e8338af12a2a676c471be3b3c13b2fcb0bb.pdf

19. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Affairs Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers Eligibility Criteria Fact Sheet. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2020. Accessed February 9, 2022. https://www.caregiver.va.gov/pdfs/MissionAct/EligibilityCriteriaFactsheet_Chapter2_Launch_Approved_Final_100120.pdf

Caregiving for a person with dementia in the community can be extremely difficult work. Much of this work falls on unpaid or informal caregivers. Sixty-three percent of older adults with dementia depend completely on unpaid caregivers, and an additional 26% receive some combination of paid and unpaid support, together comprising nearly 90% of the more than 3 million older Americans with dementia.1 In-home care is preferable for these patients. For veterans, the Caregiver Support Program (CSP) is the only US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) program that exclusively supports caregivers. Although the CSP is not a nursing home diversion or cost savings program, successfully enabling at-home living in lieu of facility living also has the potential to reduce overall cost of care, and most importantly, to enable veterans who desire it to age at home.2,3

The CSP has 2 unique programs for caregivers of eligible veterans. The Program of General Caregiver Support Services (PGCSS) provides resources, education, and support to caregivers of all veterans enrolled in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). The Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers (PCAFC) provides education and training, access to health care insurance if eligible, mental health counseling, access to a monthly caregiver stipend, enhanced respite care, wellness contacts, and travel compensation for VA health care appointments (Table 1).4,5

Patients undergo a rigorous assessment and highly specialized and individualized clinical decision-making process to confirm the service is appropriate for the patient. PCAFC was restructured and expanded on October 1, 2020.6 Currently, veterans who incurred or aggravated a serious injury (defined by a single or combined service-connection rating of ≥ 70%) in active military service before May 8, 1975, or after September 10, 2001, are eligible for PCAFC.6 Most notably, these changes opened eligibility in the PCAFC to caregivers of veterans from the Vietnam, Korean, and World War II eras of conflict and veterans with dependence in activities of daily living (ADL) due to a wider variety of illnesses, including dementia.6 The PCAFC is set to further expand to caregivers of otherwise eligible veterans of all eras of service on October 1, 2022, 2 years after the initial expansion, as laid out in the 2018 VA MISSION Act.6 Additional information on the history of the PGCSS and PCAFC and eligibility criteria for veterans and their family caregivers can be found in Tables 2 and 3.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and cognitive impairment are 2 common causes of disability among veterans who receive VHA care. Among older veterans, rates of lifetime development of PTSD reach up to 30%.7 Dementia diagnosis is also more common in older veterans compared with age-matched civilians.8 Furthermore, a prior diagnosis of PTSD has been associated with nearly a 2-fold increase in risk of development of dementia in older age.7 These conditions are also linked to high degrees of service connection. PTSD is the third most prevalent service-connected disability for veterans receiving compensation and cognitive limitation is the third most prevalent category of service-connected disability among veterans.9

We present a case of a Vietnam-era veteran with a history of combat exposure and service-connected PTSD, and a later diagnosis of Lewy body dementia (LBD). Through combination of VHA geriatric services, the CSP, and the expanded PCAFC, the veteran’s primary family caregiver received the materials, support, and financial resources necessary to enable at-home living for the veteran, despite his illness and later complications.

Case Presentation

A male combat veteran presented to his primary care practitioner (PCP) with concerns of several years of progressive changes in gait, forgetfulness, and a gradual decline in the ability to live independently without assistance. At that time, his medical history was notable for PTSD (50% service connection), which had been diagnosed over a decade prior (but for which the veteran had refused medication or therapy on multiple occasions, stating he preferred to “breathe through” his intrusive symptom flare-ups), localized prostate cancer with a radical prostatectomy (100% service connection), multiple kidney stones with persistent left ureteral inflammation, and arteriosclerotic heart disease (10% service connection). A Saint Louis University Mental Status Exam (SLUMS) performed by the PCP was notable for a score of 9/30, in the dementia range. A computed tomography of the brain demonstrated scattered foci of hypoattenuation attributable to normal aging without any other pathology noted.

The veteran was referred to the Cognitive Care clinic, a local longitudinal multidisciplinary dementia care clinic, along with his spouse/caregiver. Cognitive testing was performed by a licensed clinical psychologist in the clinic and was notable for a Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) score of 18/30, also in the dementia range, and a more robust neuropsychiatric battery demonstrated borderline intact memory and language function but impairments in executive function and visuospatial skills. The patient’s clinical history included functional loss over time, with total dependence in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), or tasks necessary to be fully independent or manage a household, including inability to manage finances, and some need for assistance in ADL, or personal care tasks such as dressing or grooming, including bathing. Physical examination was notable for bradykinesia, a shuffling gait, and rare episodes of speaking to someone who was not in the room, thought to be due to mild nondistressing hallucinations.

A diagnosis of LBD was made. At time of diagnosis, the patient met criteria for probable dementia with Lewy bodies, with 2 of 4 core clinical features (hallucinations and Parkinsonism), and multiple supportive features (gait disturbance, sensory disturbance, and altered mood).10,11 The veteran continued to develop more supportive features for diagnosis of LBD over time, including evidence of autonomic instability.

The veteran and his caregiver were educated on his diagnosis, and longitudinal support was offered. The veteran was no longer driving, and due to the severity of his symptoms, the importance of driving cessation was reinforced by the care team. Over the course of the next year, his illness progressed, with more frequent behaviors and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). He began to exhibit nighttime wandering throughout the house and became more anxious and restless during the day. He lost the ability to make his own health care decisions, and his spouse became his activated health care power of attorney (HCPOA). His BPSD became more disruptive to daily life and was accompanied by a change in the character of his hallucinations, with prior nondistressing visions of other people being replaced with visions of war, burning bodies, and violence, much of it related to combat experiences in Vietnam. The BPSD began to include hiding behind furniture, running out of the house, and shouting and crying in response to hallucinations. At times, his BPSD became violent, lashing out in fear against his hallucinations and caregiver.

The veteran’s change in BPSD was concerning for a new baseline, rather than being clearly related to an underlying unmet physical need, such as pain, hunger, sleep, or discomfort. Multiple hospital admissions during that year involved IV hydration and treatment for urinary tract infections (UTI) for several days of inpatient stay at a time, but these behaviors persisted despite infection treatment and hydration. The patient’s changes in BPSD were thought to be secondary to uncovered and intensified PTSD in the setting of progressive dementia. Due to the clear danger the patient posed to himself and others, potential treatment options for these PTSD-related hallucinations were discussed with his caregiver. The caregiver shared that the patient’s BPSD and hallucinations were so distressing that “he would never want to live like this,” and that things had progressed to the point that “he has no quality of life.”

Oral aripiprazole 2 mg twice daily was prescribed after the risks of infection, cardiac complications, and exacerbation of movement disorder symptoms, such as increased stiffness and falls, were discussed with the caregiver. The caregiver was employed and relied on continued employment for income, but the patient could not be safely left alone. As the patient and his caregiver had reached a crisis point and living at home no longer appeared to be safe, the patient was referred to a VA-contracted skilled nursing facility (SNF) for long-term care. The patient’s caregiver was also referred to CSP for support during this transition. Due to the patient’s level of service connection and personal needs, as well as the patient and caregiver’s preference for the veteran to remain in his home, they were evaluated for the PCAFC for enhanced support to enable home as an alternative to facility living, should the patient respond to the antipsychotic therapy sufficiently, which was evaluated on a regular basis.

After several months, the patient’s BPSD had improved significantly, and he was no longer experiencing distressing hallucinations. However, his mobility also declined, and he became fully dependent in most ADL, including transfers, hygiene, and toileting. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, visitation was limited, which was difficult for both the patient and his caregiver. The veteran and caregiver were approved for PCAFC due to the veteran’s combination of service-connected illnesses > 70%, dependence for most ADLs, and need for continuous supervision. A transfer home from the SNF was arranged.

The PCAFC allowed the veteran’s caregiver and family members to provide in-home full-time caregiving, as an alternative to facility placement. The caregiver received a variety of support, including access to peer support, instruction on ways to assist in his toileting, hygiene, and transfers, and a caregiving stipend. In addition to offsetting lost wages, the stipend also helped offset the cost of care supplies which were not provided or were not readily available from the VA, which at the time included the patient’s preferred nutritional supplement and some supplies for personal care.

The veteran’s care needs continued to escalate. A fall at home resulted in a hip fracture, which was treated with surgical pinning. Postfracture physical therapy in a facility was considered, but ultimately was provided at home. The patient also experienced multiple UTIs and resulting delirium, with accompanying agitation and hallucinations. These episodes improved with IV antibiotics and hydration during short hospital stays. Ultimately, a computed tomography demonstrated overflow incontinence likely related to urologic damage from prior kidney stones and stent placement was recommended.

Visiting skilled nurses for the patient’s area were difficult to coordinate but were eventually arranged. The patient continued residing in his home with the support of his caregiver, the PCAFC, and the local VA medical center geriatric and transitional care services. The patient was also referred to the palliative care outpatient specialty clinic for discussion of goals of care and assistance with advance care planning as his illness progressed. Mental health and geriatric psychiatry consult teams were considered for this case but not utilized.

Discussion

Older adult Americans are at high risk of poor financial wellbeing, with nearly one quarter of Americans aged > 62 years experiencing financial insecurity.12 Even in this case with health care provided by the VA, successful in-home care was challenging and required a dedicated live-in caregiver, care coordination resources, and financial support. As part of its mission of caring for veterans, the VA has instituted CSP, whose mission is to promote the health and well-being of family caregivers through education, support, and services.

PCAFC offers enhanced clinical support for caregivers of eligible veterans who are seriously injured. This includes resources, education, support, financial stipends, health insurance (if eligible), and beneficiary travel (if eligible) to primary caregivers of eligible veterans. PCAFC was originally reserved for veterans who had onset of service-related disability after September 11, 2001, with an associated personal care need. In this population, PCAFC demonstrated an increased usage of clinical resources, likely related to increased ease in accessing care.13

The cohort of post-9/11 veterans is very different from the cohort of veterans and their caregivers who may now qualify for the PCAFC after its October 2020 expansion. Veterans from the Vietnam, Korean, and World War II eras of conflict have rates of service-connected disability 2 to 3 times higher than those of post-9/11 era veterans and are at greater risk for dementia.9 Veterans aged ≥ 75 years who have service connection also report higher rates of difficulty with independent living and self-care compared with their younger peers.9 Since dementia and PTSD are common causes of service connection and disability it is likely that a significant proportion of older veterans will be eligible to apply for the newly expanded PCAFC.

To be eligible for PCAFC, a veteran must have a service-connected disability rating of ≥ 70% and must need in-person care services for ≥ 6 continuous months, based on either an inability to perform an ADL, or a need for supervision, protection, or instruction.

It is not clear how CSP use or increased access to PCAFC will impact costs. However, the PCAFC monthly stipend is scaled to the median wage of a home health aide and to the location of the caregiver, which is considerably less than the cost of recurrent hospitalization or a year of facility-level care.15 The CSP may eventually be a successful long-term investment in cost savings. In order to ensure the process for PCAFC approval is uniform and prompt as the program expands, CSP has restructured, increasing the number of employees, improving the patient review process, and expanding staff training.16 The VA plans to continually re-assess CSP using the infrastructure of the Caregiver Record Management Application as it continues to expand.17

Conclusions

Dementia and PTSD commonly coexist and are a significant source of disability in the service-connected veteran population. This case brings attention to the recent expansion of PCAFC, which now has the potential to support eligible veterans from the World War II, Korean, and Vietnam-era conflicts, in whom these illnesses are more common. In this case, in-home care was preferred by the veteran and primary caregiver but would not have been possible without a complex intervention. There is still more research to be done on the best way to meet the needs of older adults with dementia, the impact of in-home care, and the system-wide implications of PCAFC, especially as the program grows. However, in-home care is preferable to SNF living for many veterans and caregivers, and CSP will continue to be an essential element of providing care for this population.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin. The authors would also like to thank the members of the Veterans Affairs Central Office and National Caregiver Support Program Office, including Elyse Kaplan, Melinda Hogue, Beth Wolfsohn, Colleen Richardson, and Timothy Jobin, for their thorough review of the work and edits to ensure accurate program description.

Caregiving for a person with dementia in the community can be extremely difficult work. Much of this work falls on unpaid or informal caregivers. Sixty-three percent of older adults with dementia depend completely on unpaid caregivers, and an additional 26% receive some combination of paid and unpaid support, together comprising nearly 90% of the more than 3 million older Americans with dementia.1 In-home care is preferable for these patients. For veterans, the Caregiver Support Program (CSP) is the only US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) program that exclusively supports caregivers. Although the CSP is not a nursing home diversion or cost savings program, successfully enabling at-home living in lieu of facility living also has the potential to reduce overall cost of care, and most importantly, to enable veterans who desire it to age at home.2,3

The CSP has 2 unique programs for caregivers of eligible veterans. The Program of General Caregiver Support Services (PGCSS) provides resources, education, and support to caregivers of all veterans enrolled in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). The Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers (PCAFC) provides education and training, access to health care insurance if eligible, mental health counseling, access to a monthly caregiver stipend, enhanced respite care, wellness contacts, and travel compensation for VA health care appointments (Table 1).4,5

Patients undergo a rigorous assessment and highly specialized and individualized clinical decision-making process to confirm the service is appropriate for the patient. PCAFC was restructured and expanded on October 1, 2020.6 Currently, veterans who incurred or aggravated a serious injury (defined by a single or combined service-connection rating of ≥ 70%) in active military service before May 8, 1975, or after September 10, 2001, are eligible for PCAFC.6 Most notably, these changes opened eligibility in the PCAFC to caregivers of veterans from the Vietnam, Korean, and World War II eras of conflict and veterans with dependence in activities of daily living (ADL) due to a wider variety of illnesses, including dementia.6 The PCAFC is set to further expand to caregivers of otherwise eligible veterans of all eras of service on October 1, 2022, 2 years after the initial expansion, as laid out in the 2018 VA MISSION Act.6 Additional information on the history of the PGCSS and PCAFC and eligibility criteria for veterans and their family caregivers can be found in Tables 2 and 3.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and cognitive impairment are 2 common causes of disability among veterans who receive VHA care. Among older veterans, rates of lifetime development of PTSD reach up to 30%.7 Dementia diagnosis is also more common in older veterans compared with age-matched civilians.8 Furthermore, a prior diagnosis of PTSD has been associated with nearly a 2-fold increase in risk of development of dementia in older age.7 These conditions are also linked to high degrees of service connection. PTSD is the third most prevalent service-connected disability for veterans receiving compensation and cognitive limitation is the third most prevalent category of service-connected disability among veterans.9

We present a case of a Vietnam-era veteran with a history of combat exposure and service-connected PTSD, and a later diagnosis of Lewy body dementia (LBD). Through combination of VHA geriatric services, the CSP, and the expanded PCAFC, the veteran’s primary family caregiver received the materials, support, and financial resources necessary to enable at-home living for the veteran, despite his illness and later complications.

Case Presentation

A male combat veteran presented to his primary care practitioner (PCP) with concerns of several years of progressive changes in gait, forgetfulness, and a gradual decline in the ability to live independently without assistance. At that time, his medical history was notable for PTSD (50% service connection), which had been diagnosed over a decade prior (but for which the veteran had refused medication or therapy on multiple occasions, stating he preferred to “breathe through” his intrusive symptom flare-ups), localized prostate cancer with a radical prostatectomy (100% service connection), multiple kidney stones with persistent left ureteral inflammation, and arteriosclerotic heart disease (10% service connection). A Saint Louis University Mental Status Exam (SLUMS) performed by the PCP was notable for a score of 9/30, in the dementia range. A computed tomography of the brain demonstrated scattered foci of hypoattenuation attributable to normal aging without any other pathology noted.

The veteran was referred to the Cognitive Care clinic, a local longitudinal multidisciplinary dementia care clinic, along with his spouse/caregiver. Cognitive testing was performed by a licensed clinical psychologist in the clinic and was notable for a Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) score of 18/30, also in the dementia range, and a more robust neuropsychiatric battery demonstrated borderline intact memory and language function but impairments in executive function and visuospatial skills. The patient’s clinical history included functional loss over time, with total dependence in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), or tasks necessary to be fully independent or manage a household, including inability to manage finances, and some need for assistance in ADL, or personal care tasks such as dressing or grooming, including bathing. Physical examination was notable for bradykinesia, a shuffling gait, and rare episodes of speaking to someone who was not in the room, thought to be due to mild nondistressing hallucinations.

A diagnosis of LBD was made. At time of diagnosis, the patient met criteria for probable dementia with Lewy bodies, with 2 of 4 core clinical features (hallucinations and Parkinsonism), and multiple supportive features (gait disturbance, sensory disturbance, and altered mood).10,11 The veteran continued to develop more supportive features for diagnosis of LBD over time, including evidence of autonomic instability.

The veteran and his caregiver were educated on his diagnosis, and longitudinal support was offered. The veteran was no longer driving, and due to the severity of his symptoms, the importance of driving cessation was reinforced by the care team. Over the course of the next year, his illness progressed, with more frequent behaviors and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). He began to exhibit nighttime wandering throughout the house and became more anxious and restless during the day. He lost the ability to make his own health care decisions, and his spouse became his activated health care power of attorney (HCPOA). His BPSD became more disruptive to daily life and was accompanied by a change in the character of his hallucinations, with prior nondistressing visions of other people being replaced with visions of war, burning bodies, and violence, much of it related to combat experiences in Vietnam. The BPSD began to include hiding behind furniture, running out of the house, and shouting and crying in response to hallucinations. At times, his BPSD became violent, lashing out in fear against his hallucinations and caregiver.

The veteran’s change in BPSD was concerning for a new baseline, rather than being clearly related to an underlying unmet physical need, such as pain, hunger, sleep, or discomfort. Multiple hospital admissions during that year involved IV hydration and treatment for urinary tract infections (UTI) for several days of inpatient stay at a time, but these behaviors persisted despite infection treatment and hydration. The patient’s changes in BPSD were thought to be secondary to uncovered and intensified PTSD in the setting of progressive dementia. Due to the clear danger the patient posed to himself and others, potential treatment options for these PTSD-related hallucinations were discussed with his caregiver. The caregiver shared that the patient’s BPSD and hallucinations were so distressing that “he would never want to live like this,” and that things had progressed to the point that “he has no quality of life.”

Oral aripiprazole 2 mg twice daily was prescribed after the risks of infection, cardiac complications, and exacerbation of movement disorder symptoms, such as increased stiffness and falls, were discussed with the caregiver. The caregiver was employed and relied on continued employment for income, but the patient could not be safely left alone. As the patient and his caregiver had reached a crisis point and living at home no longer appeared to be safe, the patient was referred to a VA-contracted skilled nursing facility (SNF) for long-term care. The patient’s caregiver was also referred to CSP for support during this transition. Due to the patient’s level of service connection and personal needs, as well as the patient and caregiver’s preference for the veteran to remain in his home, they were evaluated for the PCAFC for enhanced support to enable home as an alternative to facility living, should the patient respond to the antipsychotic therapy sufficiently, which was evaluated on a regular basis.

After several months, the patient’s BPSD had improved significantly, and he was no longer experiencing distressing hallucinations. However, his mobility also declined, and he became fully dependent in most ADL, including transfers, hygiene, and toileting. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, visitation was limited, which was difficult for both the patient and his caregiver. The veteran and caregiver were approved for PCAFC due to the veteran’s combination of service-connected illnesses > 70%, dependence for most ADLs, and need for continuous supervision. A transfer home from the SNF was arranged.

The PCAFC allowed the veteran’s caregiver and family members to provide in-home full-time caregiving, as an alternative to facility placement. The caregiver received a variety of support, including access to peer support, instruction on ways to assist in his toileting, hygiene, and transfers, and a caregiving stipend. In addition to offsetting lost wages, the stipend also helped offset the cost of care supplies which were not provided or were not readily available from the VA, which at the time included the patient’s preferred nutritional supplement and some supplies for personal care.