User login

Behavioral treatment tied to lower medical, pharmacy costs

Results of a large retrospective study showed that patients newly diagnosed with a BHC who receive OPBHT following diagnosis incur lower medical and pharmacy costs over roughly the next 1 to 2 years, compared with peers who don’t receive OPBHT.

“Our findings suggest that promoting OPBHT as part of a population health strategy is associated with improved overall medical spending, particularly among adults,” the investigators write.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Common, undertreated

Nearly a quarter of adults in the United States have a BHC, and they incur greater medical costs than those without a BHC. However, diagnosis of a BHC is often delayed, and most affected individuals receive little to no treatment.

In their cost analysis, Johanna Bellon, PhD, and colleagues with Evernorth Health, St. Louis, analyzed commercial insurance claims data for 203,401 U.S. individuals newly diagnosed with one or more BHCs between 2017 and 2018.

About half of participants had depression and/or anxiety, 11% had substance use or alcohol use disorder, and 6% had a higher-acuity diagnosis, such as bipolar disorder, severe depression, eating disorder, psychotic disorder, or autism spectrum disorder.

About 1 in 5 (22%) had at least one chronic medical condition along with their BHC.

The researchers found that having at least one OPBHT visit was associated with lower medical and pharmacy costs during 15- and 27-month follow-up periods.

Over 15 months, the adjusted mean per member per month (PMPM) medical/pharmacy cost was $686 with no OPBHT visit, compared with $571 with one or more OPBHT visits.

Over 27 months, the adjusted mean PMPM was $464 with no OPBHT, versus $391 with one or more OPBHT visits.

Dose-response effect

In addition, there was a “dose-response” relationship between OPBHT and medical/pharmacy costs, such that estimated cost savings were significantly lower in the treated versus the untreated groups at almost every level of treatment.

“Our findings were also largely age independent, especially over 15 months, suggesting that OPBHT has favorable effects among children, young adults, and adults,” the researchers report.

“This is promising given that disease etiology and progression, treatment paradigms, presence of comorbid medical conditions, and overall medical and pharmacy costs differ among the three groups,” they say.

Notably, the dataset largely encompassed in-person OPBHT, because the study period preceded the transition into virtual care that occurred in 2020.

However, overall use of OPBHT was low – older adults, adults with lower income, individuals with comorbid medical conditions, and persons of racial and ethnic minorities were less likely to receive OPBHT, they found.

“These findings support the cost-effectiveness of practitioner- and insurance-based interventions to increase OPBHT utilization, which is a critical resource as new BHC diagnoses continue to increase,” the researchers say.

“Future research should validate these findings in other populations, including government-insured individuals, and explore data by chronic disease category, over longer time horizons, by type and quality of OPBHT, by type of medical spending, within subpopulations with BHCs, and including virtual and digital behavioral health services,” they suggest.

The study had no specific funding. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results of a large retrospective study showed that patients newly diagnosed with a BHC who receive OPBHT following diagnosis incur lower medical and pharmacy costs over roughly the next 1 to 2 years, compared with peers who don’t receive OPBHT.

“Our findings suggest that promoting OPBHT as part of a population health strategy is associated with improved overall medical spending, particularly among adults,” the investigators write.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Common, undertreated

Nearly a quarter of adults in the United States have a BHC, and they incur greater medical costs than those without a BHC. However, diagnosis of a BHC is often delayed, and most affected individuals receive little to no treatment.

In their cost analysis, Johanna Bellon, PhD, and colleagues with Evernorth Health, St. Louis, analyzed commercial insurance claims data for 203,401 U.S. individuals newly diagnosed with one or more BHCs between 2017 and 2018.

About half of participants had depression and/or anxiety, 11% had substance use or alcohol use disorder, and 6% had a higher-acuity diagnosis, such as bipolar disorder, severe depression, eating disorder, psychotic disorder, or autism spectrum disorder.

About 1 in 5 (22%) had at least one chronic medical condition along with their BHC.

The researchers found that having at least one OPBHT visit was associated with lower medical and pharmacy costs during 15- and 27-month follow-up periods.

Over 15 months, the adjusted mean per member per month (PMPM) medical/pharmacy cost was $686 with no OPBHT visit, compared with $571 with one or more OPBHT visits.

Over 27 months, the adjusted mean PMPM was $464 with no OPBHT, versus $391 with one or more OPBHT visits.

Dose-response effect

In addition, there was a “dose-response” relationship between OPBHT and medical/pharmacy costs, such that estimated cost savings were significantly lower in the treated versus the untreated groups at almost every level of treatment.

“Our findings were also largely age independent, especially over 15 months, suggesting that OPBHT has favorable effects among children, young adults, and adults,” the researchers report.

“This is promising given that disease etiology and progression, treatment paradigms, presence of comorbid medical conditions, and overall medical and pharmacy costs differ among the three groups,” they say.

Notably, the dataset largely encompassed in-person OPBHT, because the study period preceded the transition into virtual care that occurred in 2020.

However, overall use of OPBHT was low – older adults, adults with lower income, individuals with comorbid medical conditions, and persons of racial and ethnic minorities were less likely to receive OPBHT, they found.

“These findings support the cost-effectiveness of practitioner- and insurance-based interventions to increase OPBHT utilization, which is a critical resource as new BHC diagnoses continue to increase,” the researchers say.

“Future research should validate these findings in other populations, including government-insured individuals, and explore data by chronic disease category, over longer time horizons, by type and quality of OPBHT, by type of medical spending, within subpopulations with BHCs, and including virtual and digital behavioral health services,” they suggest.

The study had no specific funding. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results of a large retrospective study showed that patients newly diagnosed with a BHC who receive OPBHT following diagnosis incur lower medical and pharmacy costs over roughly the next 1 to 2 years, compared with peers who don’t receive OPBHT.

“Our findings suggest that promoting OPBHT as part of a population health strategy is associated with improved overall medical spending, particularly among adults,” the investigators write.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Common, undertreated

Nearly a quarter of adults in the United States have a BHC, and they incur greater medical costs than those without a BHC. However, diagnosis of a BHC is often delayed, and most affected individuals receive little to no treatment.

In their cost analysis, Johanna Bellon, PhD, and colleagues with Evernorth Health, St. Louis, analyzed commercial insurance claims data for 203,401 U.S. individuals newly diagnosed with one or more BHCs between 2017 and 2018.

About half of participants had depression and/or anxiety, 11% had substance use or alcohol use disorder, and 6% had a higher-acuity diagnosis, such as bipolar disorder, severe depression, eating disorder, psychotic disorder, or autism spectrum disorder.

About 1 in 5 (22%) had at least one chronic medical condition along with their BHC.

The researchers found that having at least one OPBHT visit was associated with lower medical and pharmacy costs during 15- and 27-month follow-up periods.

Over 15 months, the adjusted mean per member per month (PMPM) medical/pharmacy cost was $686 with no OPBHT visit, compared with $571 with one or more OPBHT visits.

Over 27 months, the adjusted mean PMPM was $464 with no OPBHT, versus $391 with one or more OPBHT visits.

Dose-response effect

In addition, there was a “dose-response” relationship between OPBHT and medical/pharmacy costs, such that estimated cost savings were significantly lower in the treated versus the untreated groups at almost every level of treatment.

“Our findings were also largely age independent, especially over 15 months, suggesting that OPBHT has favorable effects among children, young adults, and adults,” the researchers report.

“This is promising given that disease etiology and progression, treatment paradigms, presence of comorbid medical conditions, and overall medical and pharmacy costs differ among the three groups,” they say.

Notably, the dataset largely encompassed in-person OPBHT, because the study period preceded the transition into virtual care that occurred in 2020.

However, overall use of OPBHT was low – older adults, adults with lower income, individuals with comorbid medical conditions, and persons of racial and ethnic minorities were less likely to receive OPBHT, they found.

“These findings support the cost-effectiveness of practitioner- and insurance-based interventions to increase OPBHT utilization, which is a critical resource as new BHC diagnoses continue to increase,” the researchers say.

“Future research should validate these findings in other populations, including government-insured individuals, and explore data by chronic disease category, over longer time horizons, by type and quality of OPBHT, by type of medical spending, within subpopulations with BHCs, and including virtual and digital behavioral health services,” they suggest.

The study had no specific funding. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Does dopamine dysregulation cause schizophrenia?

Investigators identified a mechanism on the dopamine receptor, known as the autoreceptor, which regulates how much dopamine is released from the presynaptic neuron. Impairment of this autoreceptor leads to poorly controlled dopamine release and excessive dopamine flow.

The researchers found decreased expression of this autoreceptor accounts for the genetic evidence of schizophrenia risk, and, using a suite of statistical routines, they showed that this relationship is probably causative.

“Our research confirms the scientific hypothesis that too much dopamine plays a likely causative role in psychosis and precisely how this is based on genetic factors,” study investigator Daniel Weinberger, MD, director and CEO of the Lieber Institute for Brain Development, Baltimore, told this news organization.

“Drugs that treat psychosis symptoms by simply blocking dopamine receptors have harsh side effects. ... Theoretically, scientists could now develop therapies that target these malfunctioning autoreceptors to treat this devastating condition with fewer side effects,” he said.

The study was published online in Nature Neuroscience.

‘Privileged spot’

“Large international genetic studies known as genomewide association studies have identified hundreds of regions of the human genome housing potential risk genes for schizophrenia,” Dr. Weinberger said.

“However, these regions are still poorly resolved in terms of specific genes, and treatments and diagnostic techniques are far from what they should be.” Moreover, “treatments for schizophrenia address the symptoms of psychosis but not the cause,” he said.

“For more than 70 years, neuroscientists have suspected that dopamine plays a key role in schizophrenia, but what kind of role, exactly, has remained a mystery,” Dr. Weinberger noted. “It occupied a privileged spot in the principal hypothesis about schizophrenia for over 60 years – the so-called ‘dopamine hypothesis.’ ”

Antipsychotic drugs that reduce dopamine “are the principal medical treatments but they cause serious side effects, including an inability to experience pleasure and joy – a sad reality for patients and their families,” he continued.

The current study “set out to understand how dopamine acts in schizophrenia” using “analysis of the genetic and transcriptional landscape” of the postmortem caudate nucleus from 443 donors (245 neurotypical, 154 with schizophrenia, and 44 with bipolar disorder).

Brain samples were from individuals of diverse ancestry (210 were of African ancestry and 2,233 were of European ancestry).

New treatment target?

The researchers performed an analysis of transancestry expression quantitative trait loci, genetic variants that explain variations in gene expression levels, which express in the caudate, annotating “hundreds of caudate-specific cis-eQTLs.”

Then they integrated this analysis with gene expression that emerged from the latest genomewide association study and transcriptome-wide association study, identifying hundreds of genes that “showed a potential causal association with schizophrenia risk in the caudate nucleus,” including a specific isoform of the dopamine D2 receptor, which is upregulated in the caudate nucleus of those with schizophrenia.

“If autoreceptors don’t function properly the flow of dopamine in the brain is poorly controlled and too much dopamine flows for too long,” said Dr. Weinberger.

In particular, they observed “extensive differential gene expression” for schizophrenia in 2,701 genes in those with schizophrenia, compared with those without: glial cell–derived neurotrophic factor antisense RNA was a top-up gene and tyrosine hydroxylase, which is a rate-limiting enzyme in dopamine synthesis, was a down-regulated gene. Dopamine receptors DRD2 and DRD3 were differentially expressed.

Having done this, they looked at the effects of antipsychotic medications that target D2 regions on gene expression in the caudate by testing for differences between individuals with schizophrenia who were taking antipsychotics at the time of death, those not taking antipsychotics at the time of death (n = 104 and 49, respectively), and neurotypical individuals (n = 239).

There were 2,692 differentially expressed genes between individuals taking antipsychotics versus neurotypical individuals (false discovery rate < 0.05). By contrast, there were only 665 differentially expressed genes (FDR < .05) between those not taking antipsychotics and neurotypical individuals.

“We found that antipsychotic medication has an extensive influence on caudate gene expression,” the investigators noted.

They then developed a new approach to “infer gene networks from expression data.” This method is based on deep neural networks, obtaining a “low-dimensional representation of each gene’s expression across individuals.” The representation is then used to build a “gene neighborhood graph and assign genes to modules.”

This method identified “several modules enriched for genes associated with schizophrenia risk.” The expression representations captured in this approach placed genes in “biologically meaningful neighborhoods, which can provide insight into potential interactions if these genes are targeted for therapeutic intervention,” the authors summarized.

“Now that our new research has identified the specific mechanism by which dopamine plays a causative role in schizophrenia, we hope we have opened the door for more targeted drugs or diagnostic tests that could make life better for patients and their families,” Dr. Weinberger said.

No causal link?

Commenting on the study, Rifaat El-Mallakh, MD, director of the mood disorders research program, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, University of Louisville (Ky.), called it an “excellent study performed by an excellent research group” that “fills an important lacuna in our research database.”

However, Dr. El-Mallakh, who was not involved in the research, disagreed that the findings show causality. “The data that can be gleaned from this study is limited and the design has significant limitations. As with all genetic studies, this is an association study. It tells us nothing about the cause-effect relationship between the genes and the illness.

“We do not know why genes are associated with the illness. Genetic overrepresentation can have multiple causes, and more so when the data is a convenience sample. As noted by the authors, much of what they observed was probably related to medication effect. I don’t think this study specifically tells us anything clinically,” he added.

The study was supported by the LIBD, the BrainSeq Consortium, an National Institutes of Health fellowship to two of the authors, and a NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation to one of the authors. Dr. Weinberger has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. El-Mallakh declared no specific financial relationships relevant to the study but has reported being a speaker for several companies that manufacture antipsychotics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators identified a mechanism on the dopamine receptor, known as the autoreceptor, which regulates how much dopamine is released from the presynaptic neuron. Impairment of this autoreceptor leads to poorly controlled dopamine release and excessive dopamine flow.

The researchers found decreased expression of this autoreceptor accounts for the genetic evidence of schizophrenia risk, and, using a suite of statistical routines, they showed that this relationship is probably causative.

“Our research confirms the scientific hypothesis that too much dopamine plays a likely causative role in psychosis and precisely how this is based on genetic factors,” study investigator Daniel Weinberger, MD, director and CEO of the Lieber Institute for Brain Development, Baltimore, told this news organization.

“Drugs that treat psychosis symptoms by simply blocking dopamine receptors have harsh side effects. ... Theoretically, scientists could now develop therapies that target these malfunctioning autoreceptors to treat this devastating condition with fewer side effects,” he said.

The study was published online in Nature Neuroscience.

‘Privileged spot’

“Large international genetic studies known as genomewide association studies have identified hundreds of regions of the human genome housing potential risk genes for schizophrenia,” Dr. Weinberger said.

“However, these regions are still poorly resolved in terms of specific genes, and treatments and diagnostic techniques are far from what they should be.” Moreover, “treatments for schizophrenia address the symptoms of psychosis but not the cause,” he said.

“For more than 70 years, neuroscientists have suspected that dopamine plays a key role in schizophrenia, but what kind of role, exactly, has remained a mystery,” Dr. Weinberger noted. “It occupied a privileged spot in the principal hypothesis about schizophrenia for over 60 years – the so-called ‘dopamine hypothesis.’ ”

Antipsychotic drugs that reduce dopamine “are the principal medical treatments but they cause serious side effects, including an inability to experience pleasure and joy – a sad reality for patients and their families,” he continued.

The current study “set out to understand how dopamine acts in schizophrenia” using “analysis of the genetic and transcriptional landscape” of the postmortem caudate nucleus from 443 donors (245 neurotypical, 154 with schizophrenia, and 44 with bipolar disorder).

Brain samples were from individuals of diverse ancestry (210 were of African ancestry and 2,233 were of European ancestry).

New treatment target?

The researchers performed an analysis of transancestry expression quantitative trait loci, genetic variants that explain variations in gene expression levels, which express in the caudate, annotating “hundreds of caudate-specific cis-eQTLs.”

Then they integrated this analysis with gene expression that emerged from the latest genomewide association study and transcriptome-wide association study, identifying hundreds of genes that “showed a potential causal association with schizophrenia risk in the caudate nucleus,” including a specific isoform of the dopamine D2 receptor, which is upregulated in the caudate nucleus of those with schizophrenia.

“If autoreceptors don’t function properly the flow of dopamine in the brain is poorly controlled and too much dopamine flows for too long,” said Dr. Weinberger.

In particular, they observed “extensive differential gene expression” for schizophrenia in 2,701 genes in those with schizophrenia, compared with those without: glial cell–derived neurotrophic factor antisense RNA was a top-up gene and tyrosine hydroxylase, which is a rate-limiting enzyme in dopamine synthesis, was a down-regulated gene. Dopamine receptors DRD2 and DRD3 were differentially expressed.

Having done this, they looked at the effects of antipsychotic medications that target D2 regions on gene expression in the caudate by testing for differences between individuals with schizophrenia who were taking antipsychotics at the time of death, those not taking antipsychotics at the time of death (n = 104 and 49, respectively), and neurotypical individuals (n = 239).

There were 2,692 differentially expressed genes between individuals taking antipsychotics versus neurotypical individuals (false discovery rate < 0.05). By contrast, there were only 665 differentially expressed genes (FDR < .05) between those not taking antipsychotics and neurotypical individuals.

“We found that antipsychotic medication has an extensive influence on caudate gene expression,” the investigators noted.

They then developed a new approach to “infer gene networks from expression data.” This method is based on deep neural networks, obtaining a “low-dimensional representation of each gene’s expression across individuals.” The representation is then used to build a “gene neighborhood graph and assign genes to modules.”

This method identified “several modules enriched for genes associated with schizophrenia risk.” The expression representations captured in this approach placed genes in “biologically meaningful neighborhoods, which can provide insight into potential interactions if these genes are targeted for therapeutic intervention,” the authors summarized.

“Now that our new research has identified the specific mechanism by which dopamine plays a causative role in schizophrenia, we hope we have opened the door for more targeted drugs or diagnostic tests that could make life better for patients and their families,” Dr. Weinberger said.

No causal link?

Commenting on the study, Rifaat El-Mallakh, MD, director of the mood disorders research program, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, University of Louisville (Ky.), called it an “excellent study performed by an excellent research group” that “fills an important lacuna in our research database.”

However, Dr. El-Mallakh, who was not involved in the research, disagreed that the findings show causality. “The data that can be gleaned from this study is limited and the design has significant limitations. As with all genetic studies, this is an association study. It tells us nothing about the cause-effect relationship between the genes and the illness.

“We do not know why genes are associated with the illness. Genetic overrepresentation can have multiple causes, and more so when the data is a convenience sample. As noted by the authors, much of what they observed was probably related to medication effect. I don’t think this study specifically tells us anything clinically,” he added.

The study was supported by the LIBD, the BrainSeq Consortium, an National Institutes of Health fellowship to two of the authors, and a NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation to one of the authors. Dr. Weinberger has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. El-Mallakh declared no specific financial relationships relevant to the study but has reported being a speaker for several companies that manufacture antipsychotics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators identified a mechanism on the dopamine receptor, known as the autoreceptor, which regulates how much dopamine is released from the presynaptic neuron. Impairment of this autoreceptor leads to poorly controlled dopamine release and excessive dopamine flow.

The researchers found decreased expression of this autoreceptor accounts for the genetic evidence of schizophrenia risk, and, using a suite of statistical routines, they showed that this relationship is probably causative.

“Our research confirms the scientific hypothesis that too much dopamine plays a likely causative role in psychosis and precisely how this is based on genetic factors,” study investigator Daniel Weinberger, MD, director and CEO of the Lieber Institute for Brain Development, Baltimore, told this news organization.

“Drugs that treat psychosis symptoms by simply blocking dopamine receptors have harsh side effects. ... Theoretically, scientists could now develop therapies that target these malfunctioning autoreceptors to treat this devastating condition with fewer side effects,” he said.

The study was published online in Nature Neuroscience.

‘Privileged spot’

“Large international genetic studies known as genomewide association studies have identified hundreds of regions of the human genome housing potential risk genes for schizophrenia,” Dr. Weinberger said.

“However, these regions are still poorly resolved in terms of specific genes, and treatments and diagnostic techniques are far from what they should be.” Moreover, “treatments for schizophrenia address the symptoms of psychosis but not the cause,” he said.

“For more than 70 years, neuroscientists have suspected that dopamine plays a key role in schizophrenia, but what kind of role, exactly, has remained a mystery,” Dr. Weinberger noted. “It occupied a privileged spot in the principal hypothesis about schizophrenia for over 60 years – the so-called ‘dopamine hypothesis.’ ”

Antipsychotic drugs that reduce dopamine “are the principal medical treatments but they cause serious side effects, including an inability to experience pleasure and joy – a sad reality for patients and their families,” he continued.

The current study “set out to understand how dopamine acts in schizophrenia” using “analysis of the genetic and transcriptional landscape” of the postmortem caudate nucleus from 443 donors (245 neurotypical, 154 with schizophrenia, and 44 with bipolar disorder).

Brain samples were from individuals of diverse ancestry (210 were of African ancestry and 2,233 were of European ancestry).

New treatment target?

The researchers performed an analysis of transancestry expression quantitative trait loci, genetic variants that explain variations in gene expression levels, which express in the caudate, annotating “hundreds of caudate-specific cis-eQTLs.”

Then they integrated this analysis with gene expression that emerged from the latest genomewide association study and transcriptome-wide association study, identifying hundreds of genes that “showed a potential causal association with schizophrenia risk in the caudate nucleus,” including a specific isoform of the dopamine D2 receptor, which is upregulated in the caudate nucleus of those with schizophrenia.

“If autoreceptors don’t function properly the flow of dopamine in the brain is poorly controlled and too much dopamine flows for too long,” said Dr. Weinberger.

In particular, they observed “extensive differential gene expression” for schizophrenia in 2,701 genes in those with schizophrenia, compared with those without: glial cell–derived neurotrophic factor antisense RNA was a top-up gene and tyrosine hydroxylase, which is a rate-limiting enzyme in dopamine synthesis, was a down-regulated gene. Dopamine receptors DRD2 and DRD3 were differentially expressed.

Having done this, they looked at the effects of antipsychotic medications that target D2 regions on gene expression in the caudate by testing for differences between individuals with schizophrenia who were taking antipsychotics at the time of death, those not taking antipsychotics at the time of death (n = 104 and 49, respectively), and neurotypical individuals (n = 239).

There were 2,692 differentially expressed genes between individuals taking antipsychotics versus neurotypical individuals (false discovery rate < 0.05). By contrast, there were only 665 differentially expressed genes (FDR < .05) between those not taking antipsychotics and neurotypical individuals.

“We found that antipsychotic medication has an extensive influence on caudate gene expression,” the investigators noted.

They then developed a new approach to “infer gene networks from expression data.” This method is based on deep neural networks, obtaining a “low-dimensional representation of each gene’s expression across individuals.” The representation is then used to build a “gene neighborhood graph and assign genes to modules.”

This method identified “several modules enriched for genes associated with schizophrenia risk.” The expression representations captured in this approach placed genes in “biologically meaningful neighborhoods, which can provide insight into potential interactions if these genes are targeted for therapeutic intervention,” the authors summarized.

“Now that our new research has identified the specific mechanism by which dopamine plays a causative role in schizophrenia, we hope we have opened the door for more targeted drugs or diagnostic tests that could make life better for patients and their families,” Dr. Weinberger said.

No causal link?

Commenting on the study, Rifaat El-Mallakh, MD, director of the mood disorders research program, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, University of Louisville (Ky.), called it an “excellent study performed by an excellent research group” that “fills an important lacuna in our research database.”

However, Dr. El-Mallakh, who was not involved in the research, disagreed that the findings show causality. “The data that can be gleaned from this study is limited and the design has significant limitations. As with all genetic studies, this is an association study. It tells us nothing about the cause-effect relationship between the genes and the illness.

“We do not know why genes are associated with the illness. Genetic overrepresentation can have multiple causes, and more so when the data is a convenience sample. As noted by the authors, much of what they observed was probably related to medication effect. I don’t think this study specifically tells us anything clinically,” he added.

The study was supported by the LIBD, the BrainSeq Consortium, an National Institutes of Health fellowship to two of the authors, and a NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation to one of the authors. Dr. Weinberger has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. El-Mallakh declared no specific financial relationships relevant to the study but has reported being a speaker for several companies that manufacture antipsychotics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE NEUROSCIENCE

Clinical factors drive hospitalization after self-harm

Clinicians who assess suicidal patients in the emergency department setting face the challenge of whether to admit the patient to inpatient or outpatient care, and data on predictors of compulsory admission are limited, wrote Laurent Michaud, MD, of the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, and colleagues.

To better identify predictors of hospitalization after self-harm, the researchers reviewed data from 1,832 patients aged 18 years and older admitted to four emergency departments in Switzerland between December 2016 and November 2019 .

Self-harm (SH) was defined in this study as “all nonfatal intentional acts of self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of degree of suicidal intent or other types of motivation,” the researchers noted. The study included 2,142 episodes of self-harm.

The researchers conducted two analyses. They compared episodes followed by any hospitalization and those with outpatient follow-up (1,083 episodes vs. 1,059 episodes) and episodes followed by compulsory hospitalization (357 episodes) with all other episodes followed by either outpatient care or voluntary hospitalization (1,785 episodes).

Overall, women were significantly more likely to be referred to outpatient follow-up compared with men (61.8% vs. 38.1%), and hospitalized patients were significantly older than outpatients (mean age of 41 years vs. 36 years, P < .001 for both).

“Not surprisingly, major psychopathological conditions such as depression, mania, dementia, and schizophrenia were predictive of hospitalization,” the researchers noted.

Other sociodemographic factors associated with hospitalization included living alone, no children, problematic socioeconomic status, and unemployment. Clinical factors associated with hospitalization included physical pain, more lethal suicide attempt method, and clear intent to die.

In a multivariate analysis, independent predictors of any hospitalization included male gender, older age, assessment in the Neuchatel location vs. Lausanne, depression vs. personality disorders, substance use, or anxiety disorder, difficult socioeconomic status, a clear vs. unclear intent to die, and a serious suicide attempt vs. less serious.

Differences in hospitalization based on hospital setting was a striking finding, the researchers wrote in their discussion. These differences may be largely explained by the organization of local mental health services and specific institutional cultures; the workload of staff and availability of beds also may have played a role in decisions to hospitalize, they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the lack of data on the realization level of a self-harm episode and significant events such as a breakup, the researchers explained. Other limitations included missing data, multiple analyses that could increase the risk of false positives, the reliance on clinical diagnosis rather than formal instruments, and the cross-sectional study design, they said.

However, the results have clinical implications, as the clinical factors identified could be used to target subgroups of suicidal populations and refine treatment strategies, they concluded.

The study was supported by institutional funding and the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Clinicians who assess suicidal patients in the emergency department setting face the challenge of whether to admit the patient to inpatient or outpatient care, and data on predictors of compulsory admission are limited, wrote Laurent Michaud, MD, of the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, and colleagues.

To better identify predictors of hospitalization after self-harm, the researchers reviewed data from 1,832 patients aged 18 years and older admitted to four emergency departments in Switzerland between December 2016 and November 2019 .

Self-harm (SH) was defined in this study as “all nonfatal intentional acts of self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of degree of suicidal intent or other types of motivation,” the researchers noted. The study included 2,142 episodes of self-harm.

The researchers conducted two analyses. They compared episodes followed by any hospitalization and those with outpatient follow-up (1,083 episodes vs. 1,059 episodes) and episodes followed by compulsory hospitalization (357 episodes) with all other episodes followed by either outpatient care or voluntary hospitalization (1,785 episodes).

Overall, women were significantly more likely to be referred to outpatient follow-up compared with men (61.8% vs. 38.1%), and hospitalized patients were significantly older than outpatients (mean age of 41 years vs. 36 years, P < .001 for both).

“Not surprisingly, major psychopathological conditions such as depression, mania, dementia, and schizophrenia were predictive of hospitalization,” the researchers noted.

Other sociodemographic factors associated with hospitalization included living alone, no children, problematic socioeconomic status, and unemployment. Clinical factors associated with hospitalization included physical pain, more lethal suicide attempt method, and clear intent to die.

In a multivariate analysis, independent predictors of any hospitalization included male gender, older age, assessment in the Neuchatel location vs. Lausanne, depression vs. personality disorders, substance use, or anxiety disorder, difficult socioeconomic status, a clear vs. unclear intent to die, and a serious suicide attempt vs. less serious.

Differences in hospitalization based on hospital setting was a striking finding, the researchers wrote in their discussion. These differences may be largely explained by the organization of local mental health services and specific institutional cultures; the workload of staff and availability of beds also may have played a role in decisions to hospitalize, they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the lack of data on the realization level of a self-harm episode and significant events such as a breakup, the researchers explained. Other limitations included missing data, multiple analyses that could increase the risk of false positives, the reliance on clinical diagnosis rather than formal instruments, and the cross-sectional study design, they said.

However, the results have clinical implications, as the clinical factors identified could be used to target subgroups of suicidal populations and refine treatment strategies, they concluded.

The study was supported by institutional funding and the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Clinicians who assess suicidal patients in the emergency department setting face the challenge of whether to admit the patient to inpatient or outpatient care, and data on predictors of compulsory admission are limited, wrote Laurent Michaud, MD, of the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, and colleagues.

To better identify predictors of hospitalization after self-harm, the researchers reviewed data from 1,832 patients aged 18 years and older admitted to four emergency departments in Switzerland between December 2016 and November 2019 .

Self-harm (SH) was defined in this study as “all nonfatal intentional acts of self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of degree of suicidal intent or other types of motivation,” the researchers noted. The study included 2,142 episodes of self-harm.

The researchers conducted two analyses. They compared episodes followed by any hospitalization and those with outpatient follow-up (1,083 episodes vs. 1,059 episodes) and episodes followed by compulsory hospitalization (357 episodes) with all other episodes followed by either outpatient care or voluntary hospitalization (1,785 episodes).

Overall, women were significantly more likely to be referred to outpatient follow-up compared with men (61.8% vs. 38.1%), and hospitalized patients were significantly older than outpatients (mean age of 41 years vs. 36 years, P < .001 for both).

“Not surprisingly, major psychopathological conditions such as depression, mania, dementia, and schizophrenia were predictive of hospitalization,” the researchers noted.

Other sociodemographic factors associated with hospitalization included living alone, no children, problematic socioeconomic status, and unemployment. Clinical factors associated with hospitalization included physical pain, more lethal suicide attempt method, and clear intent to die.

In a multivariate analysis, independent predictors of any hospitalization included male gender, older age, assessment in the Neuchatel location vs. Lausanne, depression vs. personality disorders, substance use, or anxiety disorder, difficult socioeconomic status, a clear vs. unclear intent to die, and a serious suicide attempt vs. less serious.

Differences in hospitalization based on hospital setting was a striking finding, the researchers wrote in their discussion. These differences may be largely explained by the organization of local mental health services and specific institutional cultures; the workload of staff and availability of beds also may have played a role in decisions to hospitalize, they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the lack of data on the realization level of a self-harm episode and significant events such as a breakup, the researchers explained. Other limitations included missing data, multiple analyses that could increase the risk of false positives, the reliance on clinical diagnosis rather than formal instruments, and the cross-sectional study design, they said.

However, the results have clinical implications, as the clinical factors identified could be used to target subgroups of suicidal populations and refine treatment strategies, they concluded.

The study was supported by institutional funding and the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM PSYCHIATRIC RESEARCH

Optimal psychiatric treatment: Target the brain and avoid the body

Pharmacotherapy for psychiatric disorders is a mixed blessing. The advent of psychotropic medications since the 1950s (antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, mood stabilizers) has revolutionized the treatment of serious psychiatric brain disorders, allowing certain patients to be discharged to the community after a lifetime of institutionalization.

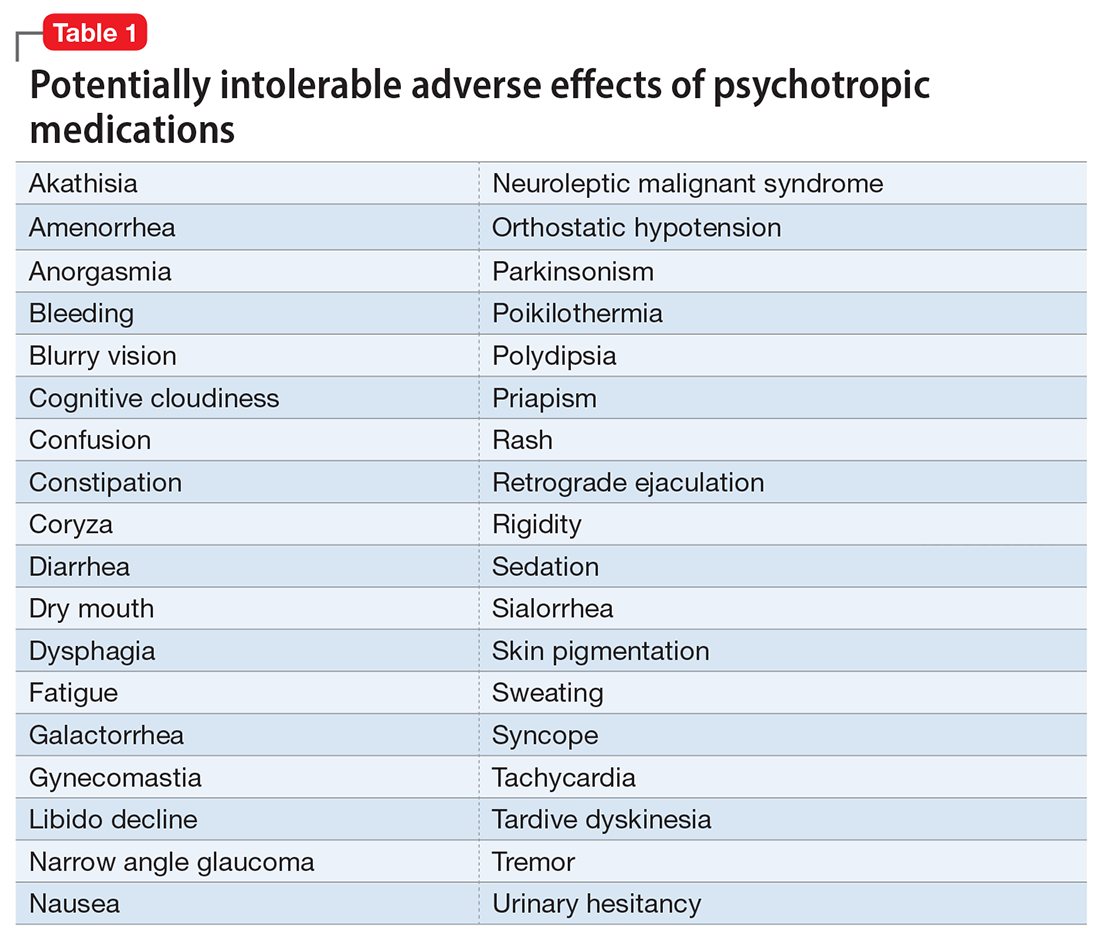

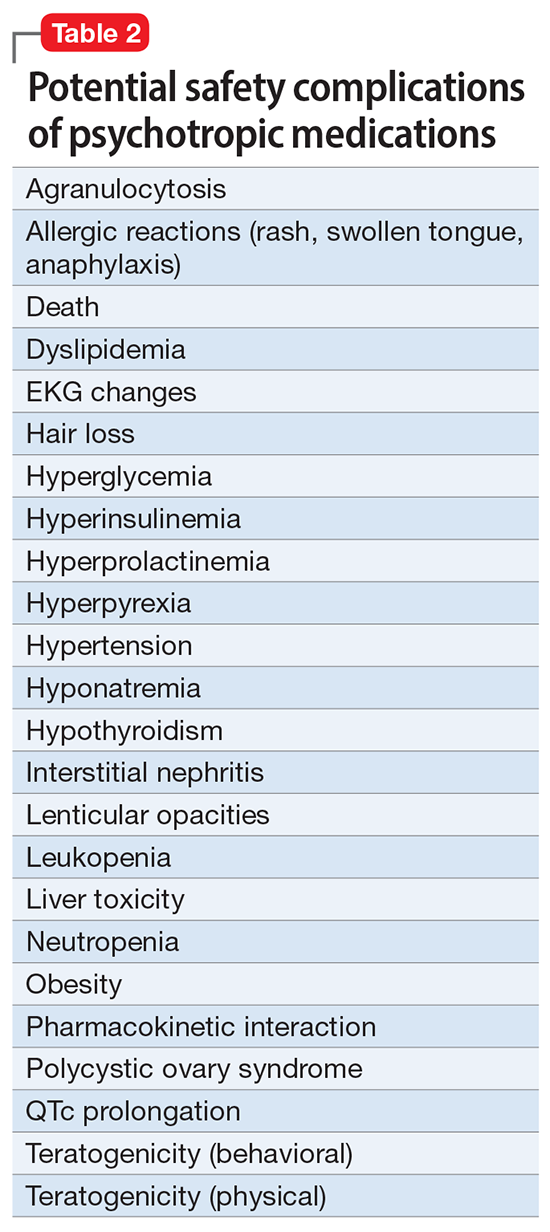

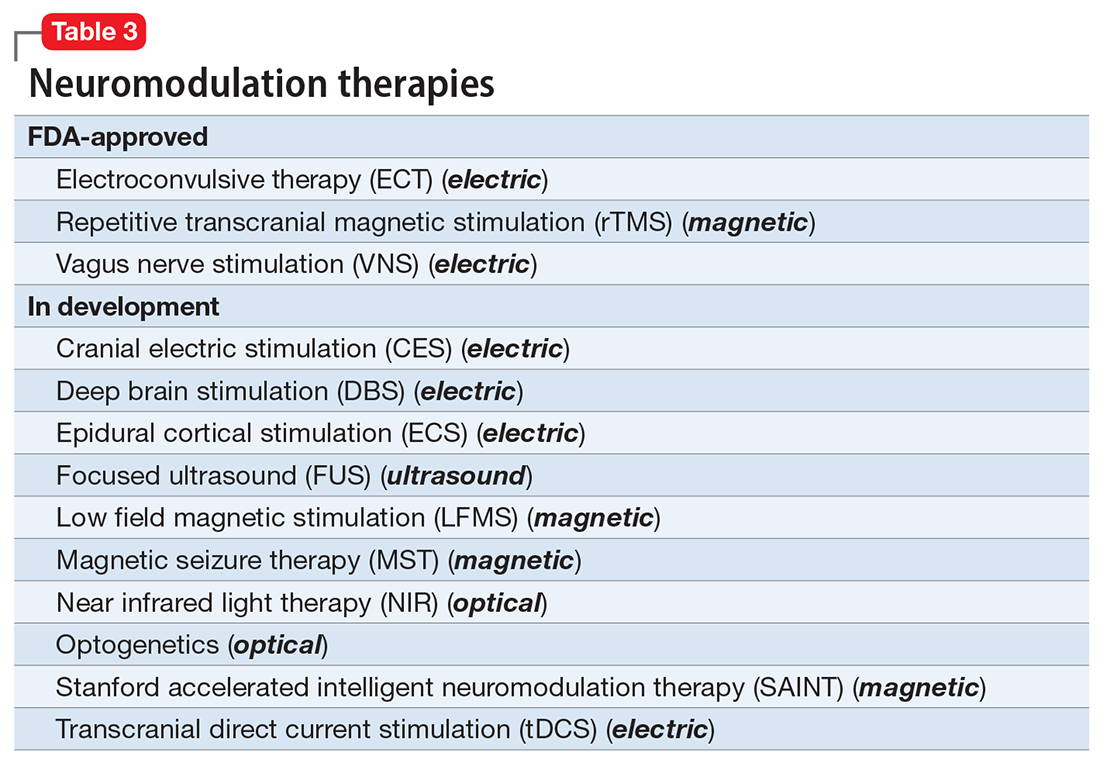

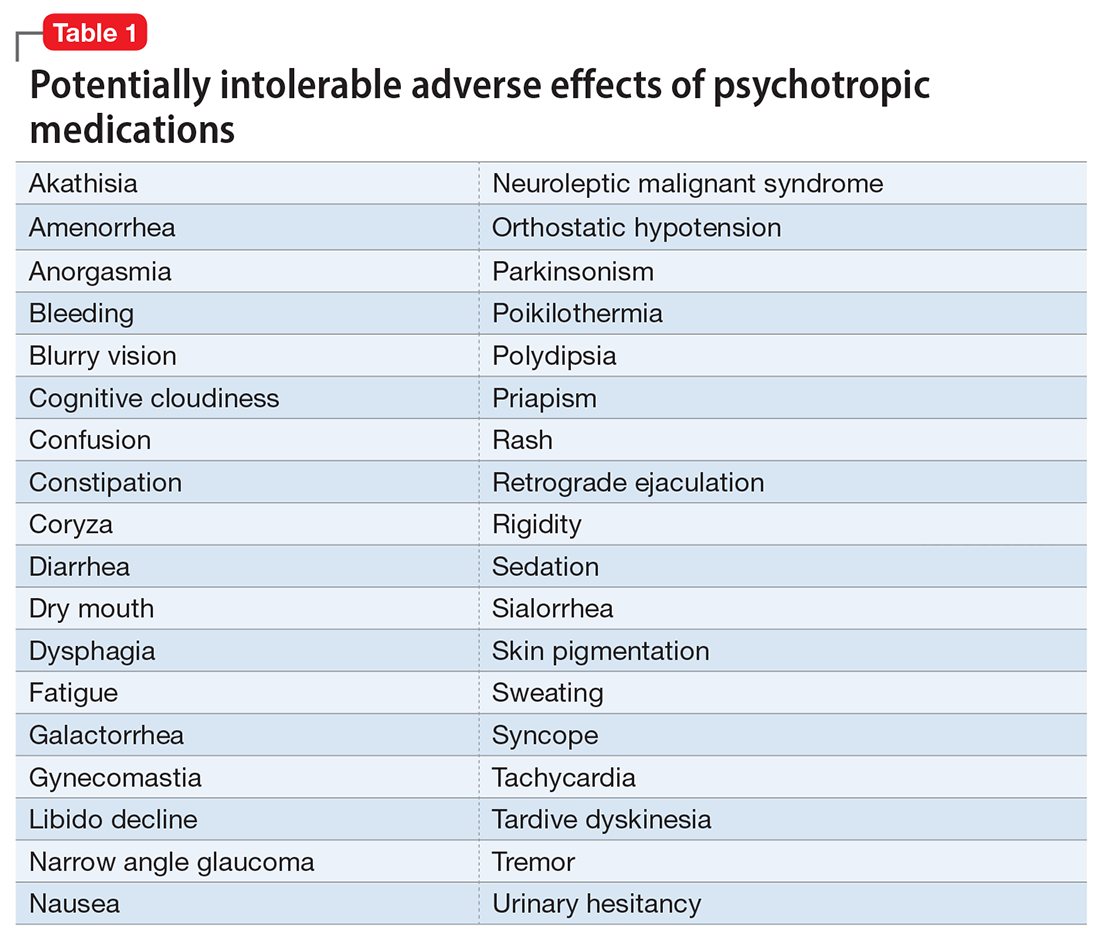

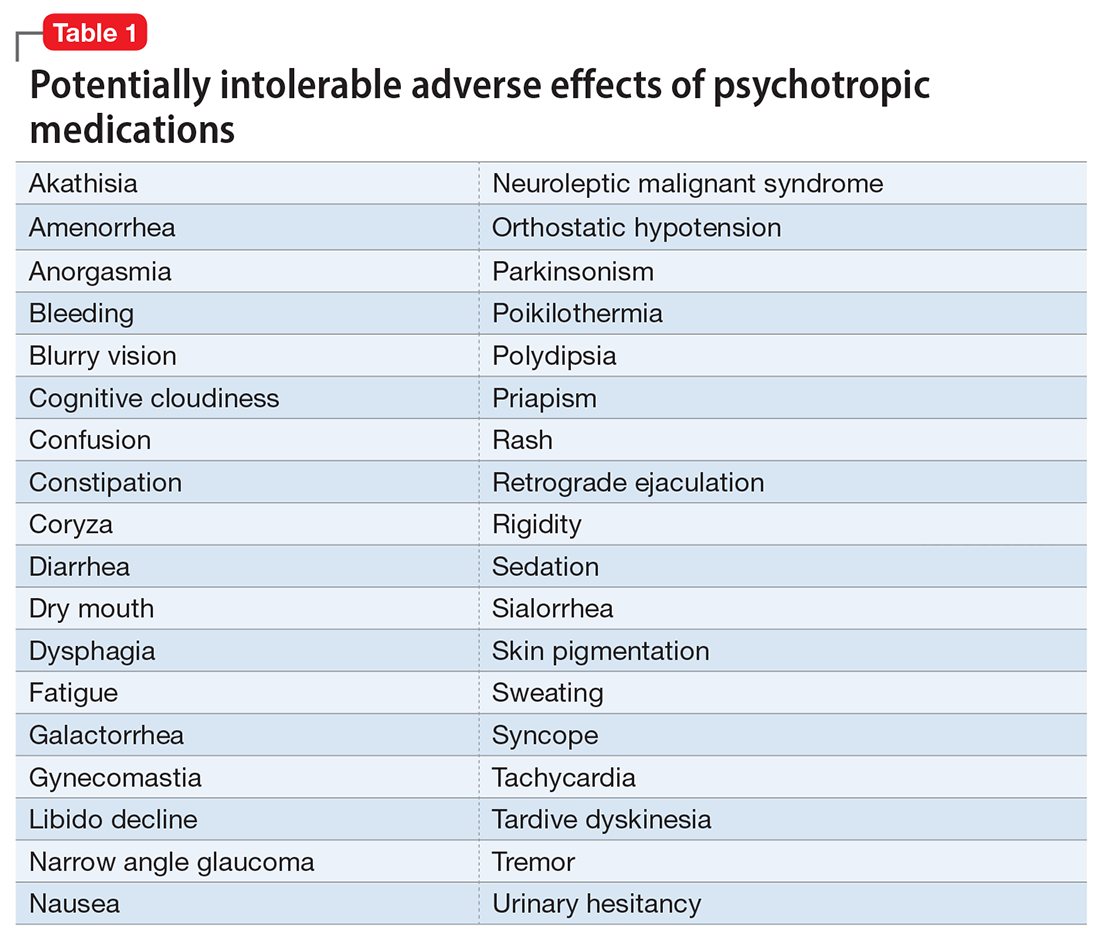

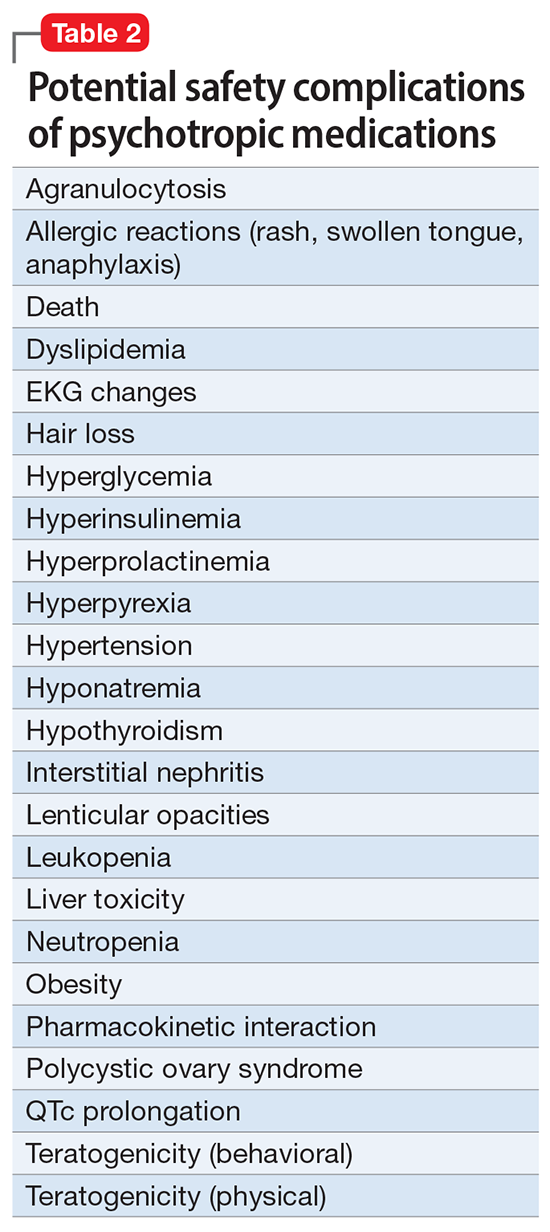

However, like all medications, psychotropic agents are often associated with various potentially intolerable symptoms (Table 1) or safety complications (Table 2) because they interact with every organ in the body besides their intended target, the brain, and its neurochemical circuitry.

Imagine if we could treat our psychiatric patients while bypassing the body and achieve response, remission, and ultimately recovery without any systemic adverse effects. Adherence would dramatically improve, our patients’ quality of life would be enhanced, and the overall effectiveness (defined as the complex package of efficacy, safety, and tolerability) would be superior to current pharmacotherapies. This is important because most psychiatric medications must be taken daily for years, even a lifetime, to avoid a relapse of the illness. Psychiatrists frequently must manage adverse effects or switch the patient to a different medication if a tolerability or safety issue emerges, which is very common in psychiatric practice. A significant part of psychopharmacologic management includes ordering various laboratory tests to monitor adverse reactions in major organs, especially the liver, kidney, and heart. Additionally, psychiatric physicians must be constantly cognizant of medications prescribed by other clinicians for comorbid medical conditions to successfully navigate the turbulent seas of pharmacokinetic interactions.

I am sure you have noticed that whenever you watch a direct-to-consumer commercial for any medication, 90% of the advertisement is a background voice listing the various tolerability and safety complications of the medication as required by the FDA. Interestingly, these ads frequently contain colorful scenery and joyful clips, which I suspect are cleverly designed to distract the audience from focusing on the list of adverse effects.

Benefits of nonpharmacologic treatments

No wonder I am a fan of psychotherapy, a well-established psychiatric treatment modality that completely avoids body tissues. It directly targets the brain without needlessly interacting with any other organ. Psychotherapy’s many benefits (improving insight, enhancing adherence, improving self-esteem, reducing risky behaviors, guiding stress management and coping skills, modifying unhealthy beliefs, and ultimately relieving symptoms such as anxiety and depression) are achieved without any somatic adverse effects! Psychotherapy has also been shown to induce neuroplasticity and reduce inflammatory biomarkers.1 Unlike FDA-approved medications, psychotherapy does not include a “package insert,” 10 to 20 pages (in small print) that mostly focus on warnings, precautions, and sundry physical adverse effects. Even the dosing of psychotherapy is left entirely up to the treating clinician!

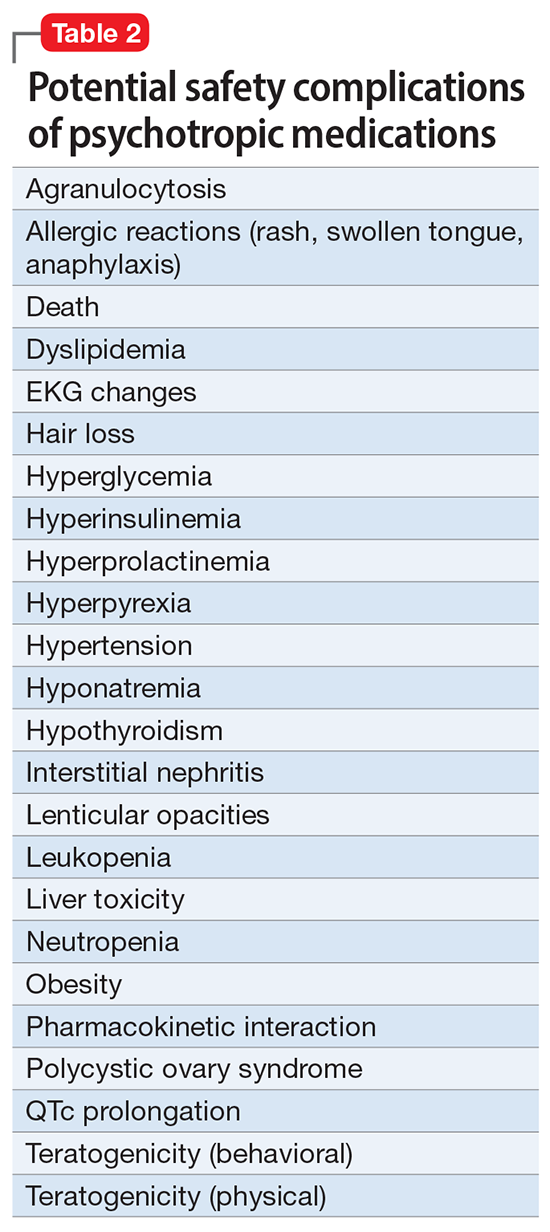

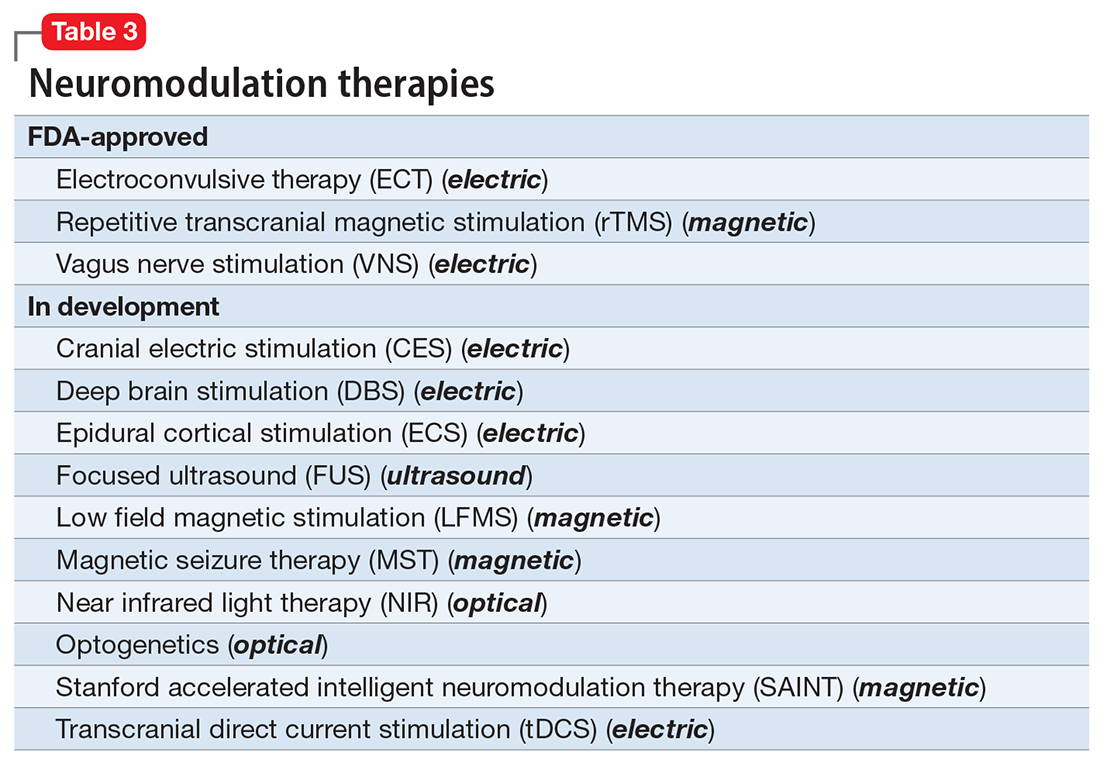

Although I have had many gratifying results with pharmacotherapy in my practice, especially in combination with psychotherapy,2 I also have observed excellent outcomes with nonpharmacologic approaches, especially neuromodulation therapies. The best antidepressant I have ever used since my residency training days is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). My experience is consistent with a large meta-analysis3showing a huge effect size (Cohen d = .91) in contrast to the usual effect size of .3 to .5 for standard antidepressants (except IV ketamine). A recent study showed ECT is even better than the vaunted rapid-acting ketamine,4 which is further evidence of its remarkable efficacy in depression. Neuroimaging studies report that ECT rapidly increases the volume of the hippocampus,5,6 which shrinks in size in patients with unipolar or bipolar depression.

Neuromodulation may very well be the future of psychiatric therapeutics. It targets the brain and avoids the body, thus achieving efficacy with minimal systemic tolerability (ie, patient complaints) (Table 1) or safety (abnormal laboratory test results) issues (Table 2). This sounds ideal, and it is arguably an optimal approach to repairing the brain and healing the mind.

Continue to: ECT is the oldest...

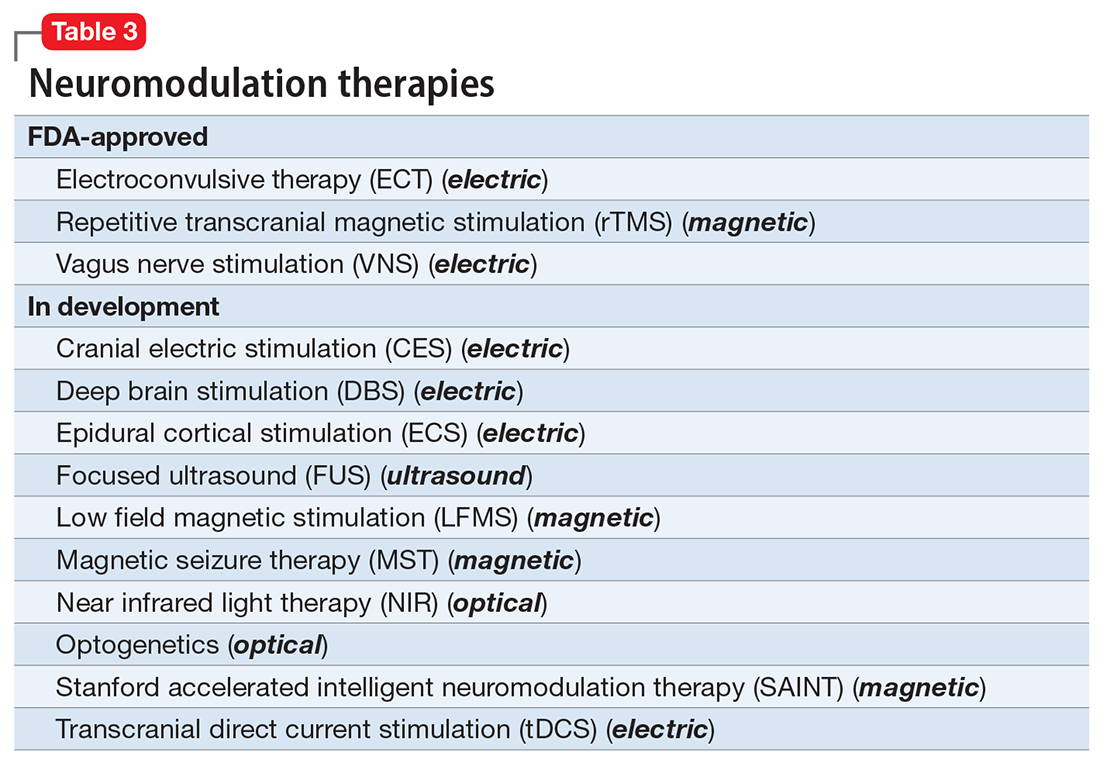

ECT is the oldest neuromodulation technique (developed almost 100 years ago and significantly refined since then). Newer FDA-approved neuromodulation therapies include repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), which was approved for depression in 2013, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in 2018, smoking cessation in 2020, and anxious depression in 2021.7 Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is used for drug-resistant epilepsy and was later approved for treatment-resistant depression,8,9 but some studies report it can be helpful for fear and anxiety in autism spectrum disorder10 and primary insomnia.11

There are many other neuromodulation therapies in development12 that have not yet been FDA approved (Table 3). The most prominent of these is deep brain stimulation (DBS), which is approved for Parkinson disease and has been reported in many studies to improve treatment-resistant depression13,14 and OCD.15 Another promising neuromodulation therapy is transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), which has promising results in schizophrenia16 similar to ECT’s effects in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.17

A particularly exciting neuromodulation approach published by Stanford University researchers is Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy (SAINT),18 which uses intermittent theta-burst stimulation (iTBS) daily for 5 days, targeted at the subgenual anterior cingulate gyrus (Brodman area 25). Remarkably, efficacy was rapid, with a very high remission rate (absence of symptoms) in approximately 90% of patients with severe depression.18

The future is bright for neuromodulation therapies, and for a good reason. Why send a chemical agent to every cell and organ in the body when the brain can be targeted directly? As psychiatric neuroscience advances to a point where we can localize the abnormal neurologic circuit in a specific brain region for each psychiatric disorder, it will be possible to treat almost all psychiatric disorders without burdening patients with the intolerable symptoms or safety adverse effects of medications. Psychiatrists should modulate their perspective about the future of psychiatric treatments. And finally, I propose that psychotherapy should be reclassified as a “verbal neuromodulation” technique.

1. Nasrallah HA. Repositioning psychotherapy as a neurobiological intervention. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):18-19.

2. Nasrallah HA. Bipolar disorder: clinical questions beg for answers. Current Psychiatry. 2006;5(12):11-12.

3. UK ECT Review Group. Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;361(9360):799-808.

4. Rhee TG, Shim SR, Forester BP, et al. Efficacy and safety of ketamine vs electroconvulsive therapy among patients with major depressive episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022:e223352. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.3352

5. Nuninga JO, Mandl RCW, Boks MP, et al. Volume increase in the dentate gyrus after electroconvulsive therapy in depressed patients as measured with 7T. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(7):1559-1568.

6. Joshi SH, Espinoza RT, Pirnia T, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

7. Rhee TG, Olfson M, Nierenberg AA, et al. 20-year trends in the pharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder by psychiatrists in outpatient care settings. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):706-715.

8. Hilz MJ. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation - a brief introduction and overview. Auton Neurosci. 2022;243:103038. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2022.103038

9. Pigato G, Rosson S, Bresolin N, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation in treatment-resistant depression: a case series of long-term follow-up. J ECT. 2022. doi:10.1097/YCT.0000000000000869

10. Shivaswamy T, Souza RR, Engineer CT, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation as a treatment for fear and anxiety in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J Psychiatr Brain Sci. 2022;7(4):e220007. doi:10.20900/jpbs.20220007

11. Wu Y, Song L, Wang X, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation could improve the effective rate on the quality of sleep in the treatment of primary insomnia: a randomized control trial. Brain Sci. 2022;12(10):1296. doi:10.3390/brainsci12101296

12. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

13. Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45(5):651-660.

14. Choi KS, Mayberg H. Connectomic DBS in major depression. In: Horn A, ed. Connectomic Deep Brain Stimulation. Academic Press; 2022:433-447.

15. Cruz S, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, González-Domenech P, et al. Deep brain stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114869. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114869

16. Lisoni J, Baldacci G, Nibbio G, et al. Effects of bilateral, bipolar-nonbalanced, frontal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on negative symptoms and neurocognition in a sample of patients living with schizophrenia: results of a randomized double-blind sham-controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;155:430-442.

17. Sinclair DJ, Zhao S, Qi F, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):CD011847. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011847.pub2

18. Cole EJ, Stimpson KH, Bentzley BS, et al. Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy for treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):716-726.

Pharmacotherapy for psychiatric disorders is a mixed blessing. The advent of psychotropic medications since the 1950s (antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, mood stabilizers) has revolutionized the treatment of serious psychiatric brain disorders, allowing certain patients to be discharged to the community after a lifetime of institutionalization.

However, like all medications, psychotropic agents are often associated with various potentially intolerable symptoms (Table 1) or safety complications (Table 2) because they interact with every organ in the body besides their intended target, the brain, and its neurochemical circuitry.

Imagine if we could treat our psychiatric patients while bypassing the body and achieve response, remission, and ultimately recovery without any systemic adverse effects. Adherence would dramatically improve, our patients’ quality of life would be enhanced, and the overall effectiveness (defined as the complex package of efficacy, safety, and tolerability) would be superior to current pharmacotherapies. This is important because most psychiatric medications must be taken daily for years, even a lifetime, to avoid a relapse of the illness. Psychiatrists frequently must manage adverse effects or switch the patient to a different medication if a tolerability or safety issue emerges, which is very common in psychiatric practice. A significant part of psychopharmacologic management includes ordering various laboratory tests to monitor adverse reactions in major organs, especially the liver, kidney, and heart. Additionally, psychiatric physicians must be constantly cognizant of medications prescribed by other clinicians for comorbid medical conditions to successfully navigate the turbulent seas of pharmacokinetic interactions.

I am sure you have noticed that whenever you watch a direct-to-consumer commercial for any medication, 90% of the advertisement is a background voice listing the various tolerability and safety complications of the medication as required by the FDA. Interestingly, these ads frequently contain colorful scenery and joyful clips, which I suspect are cleverly designed to distract the audience from focusing on the list of adverse effects.

Benefits of nonpharmacologic treatments

No wonder I am a fan of psychotherapy, a well-established psychiatric treatment modality that completely avoids body tissues. It directly targets the brain without needlessly interacting with any other organ. Psychotherapy’s many benefits (improving insight, enhancing adherence, improving self-esteem, reducing risky behaviors, guiding stress management and coping skills, modifying unhealthy beliefs, and ultimately relieving symptoms such as anxiety and depression) are achieved without any somatic adverse effects! Psychotherapy has also been shown to induce neuroplasticity and reduce inflammatory biomarkers.1 Unlike FDA-approved medications, psychotherapy does not include a “package insert,” 10 to 20 pages (in small print) that mostly focus on warnings, precautions, and sundry physical adverse effects. Even the dosing of psychotherapy is left entirely up to the treating clinician!

Although I have had many gratifying results with pharmacotherapy in my practice, especially in combination with psychotherapy,2 I also have observed excellent outcomes with nonpharmacologic approaches, especially neuromodulation therapies. The best antidepressant I have ever used since my residency training days is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). My experience is consistent with a large meta-analysis3showing a huge effect size (Cohen d = .91) in contrast to the usual effect size of .3 to .5 for standard antidepressants (except IV ketamine). A recent study showed ECT is even better than the vaunted rapid-acting ketamine,4 which is further evidence of its remarkable efficacy in depression. Neuroimaging studies report that ECT rapidly increases the volume of the hippocampus,5,6 which shrinks in size in patients with unipolar or bipolar depression.

Neuromodulation may very well be the future of psychiatric therapeutics. It targets the brain and avoids the body, thus achieving efficacy with minimal systemic tolerability (ie, patient complaints) (Table 1) or safety (abnormal laboratory test results) issues (Table 2). This sounds ideal, and it is arguably an optimal approach to repairing the brain and healing the mind.

Continue to: ECT is the oldest...

ECT is the oldest neuromodulation technique (developed almost 100 years ago and significantly refined since then). Newer FDA-approved neuromodulation therapies include repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), which was approved for depression in 2013, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in 2018, smoking cessation in 2020, and anxious depression in 2021.7 Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is used for drug-resistant epilepsy and was later approved for treatment-resistant depression,8,9 but some studies report it can be helpful for fear and anxiety in autism spectrum disorder10 and primary insomnia.11

There are many other neuromodulation therapies in development12 that have not yet been FDA approved (Table 3). The most prominent of these is deep brain stimulation (DBS), which is approved for Parkinson disease and has been reported in many studies to improve treatment-resistant depression13,14 and OCD.15 Another promising neuromodulation therapy is transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), which has promising results in schizophrenia16 similar to ECT’s effects in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.17

A particularly exciting neuromodulation approach published by Stanford University researchers is Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy (SAINT),18 which uses intermittent theta-burst stimulation (iTBS) daily for 5 days, targeted at the subgenual anterior cingulate gyrus (Brodman area 25). Remarkably, efficacy was rapid, with a very high remission rate (absence of symptoms) in approximately 90% of patients with severe depression.18

The future is bright for neuromodulation therapies, and for a good reason. Why send a chemical agent to every cell and organ in the body when the brain can be targeted directly? As psychiatric neuroscience advances to a point where we can localize the abnormal neurologic circuit in a specific brain region for each psychiatric disorder, it will be possible to treat almost all psychiatric disorders without burdening patients with the intolerable symptoms or safety adverse effects of medications. Psychiatrists should modulate their perspective about the future of psychiatric treatments. And finally, I propose that psychotherapy should be reclassified as a “verbal neuromodulation” technique.

Pharmacotherapy for psychiatric disorders is a mixed blessing. The advent of psychotropic medications since the 1950s (antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, mood stabilizers) has revolutionized the treatment of serious psychiatric brain disorders, allowing certain patients to be discharged to the community after a lifetime of institutionalization.

However, like all medications, psychotropic agents are often associated with various potentially intolerable symptoms (Table 1) or safety complications (Table 2) because they interact with every organ in the body besides their intended target, the brain, and its neurochemical circuitry.

Imagine if we could treat our psychiatric patients while bypassing the body and achieve response, remission, and ultimately recovery without any systemic adverse effects. Adherence would dramatically improve, our patients’ quality of life would be enhanced, and the overall effectiveness (defined as the complex package of efficacy, safety, and tolerability) would be superior to current pharmacotherapies. This is important because most psychiatric medications must be taken daily for years, even a lifetime, to avoid a relapse of the illness. Psychiatrists frequently must manage adverse effects or switch the patient to a different medication if a tolerability or safety issue emerges, which is very common in psychiatric practice. A significant part of psychopharmacologic management includes ordering various laboratory tests to monitor adverse reactions in major organs, especially the liver, kidney, and heart. Additionally, psychiatric physicians must be constantly cognizant of medications prescribed by other clinicians for comorbid medical conditions to successfully navigate the turbulent seas of pharmacokinetic interactions.

I am sure you have noticed that whenever you watch a direct-to-consumer commercial for any medication, 90% of the advertisement is a background voice listing the various tolerability and safety complications of the medication as required by the FDA. Interestingly, these ads frequently contain colorful scenery and joyful clips, which I suspect are cleverly designed to distract the audience from focusing on the list of adverse effects.

Benefits of nonpharmacologic treatments

No wonder I am a fan of psychotherapy, a well-established psychiatric treatment modality that completely avoids body tissues. It directly targets the brain without needlessly interacting with any other organ. Psychotherapy’s many benefits (improving insight, enhancing adherence, improving self-esteem, reducing risky behaviors, guiding stress management and coping skills, modifying unhealthy beliefs, and ultimately relieving symptoms such as anxiety and depression) are achieved without any somatic adverse effects! Psychotherapy has also been shown to induce neuroplasticity and reduce inflammatory biomarkers.1 Unlike FDA-approved medications, psychotherapy does not include a “package insert,” 10 to 20 pages (in small print) that mostly focus on warnings, precautions, and sundry physical adverse effects. Even the dosing of psychotherapy is left entirely up to the treating clinician!

Although I have had many gratifying results with pharmacotherapy in my practice, especially in combination with psychotherapy,2 I also have observed excellent outcomes with nonpharmacologic approaches, especially neuromodulation therapies. The best antidepressant I have ever used since my residency training days is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). My experience is consistent with a large meta-analysis3showing a huge effect size (Cohen d = .91) in contrast to the usual effect size of .3 to .5 for standard antidepressants (except IV ketamine). A recent study showed ECT is even better than the vaunted rapid-acting ketamine,4 which is further evidence of its remarkable efficacy in depression. Neuroimaging studies report that ECT rapidly increases the volume of the hippocampus,5,6 which shrinks in size in patients with unipolar or bipolar depression.

Neuromodulation may very well be the future of psychiatric therapeutics. It targets the brain and avoids the body, thus achieving efficacy with minimal systemic tolerability (ie, patient complaints) (Table 1) or safety (abnormal laboratory test results) issues (Table 2). This sounds ideal, and it is arguably an optimal approach to repairing the brain and healing the mind.

Continue to: ECT is the oldest...

ECT is the oldest neuromodulation technique (developed almost 100 years ago and significantly refined since then). Newer FDA-approved neuromodulation therapies include repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), which was approved for depression in 2013, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in 2018, smoking cessation in 2020, and anxious depression in 2021.7 Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is used for drug-resistant epilepsy and was later approved for treatment-resistant depression,8,9 but some studies report it can be helpful for fear and anxiety in autism spectrum disorder10 and primary insomnia.11

There are many other neuromodulation therapies in development12 that have not yet been FDA approved (Table 3). The most prominent of these is deep brain stimulation (DBS), which is approved for Parkinson disease and has been reported in many studies to improve treatment-resistant depression13,14 and OCD.15 Another promising neuromodulation therapy is transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), which has promising results in schizophrenia16 similar to ECT’s effects in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.17

A particularly exciting neuromodulation approach published by Stanford University researchers is Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy (SAINT),18 which uses intermittent theta-burst stimulation (iTBS) daily for 5 days, targeted at the subgenual anterior cingulate gyrus (Brodman area 25). Remarkably, efficacy was rapid, with a very high remission rate (absence of symptoms) in approximately 90% of patients with severe depression.18

The future is bright for neuromodulation therapies, and for a good reason. Why send a chemical agent to every cell and organ in the body when the brain can be targeted directly? As psychiatric neuroscience advances to a point where we can localize the abnormal neurologic circuit in a specific brain region for each psychiatric disorder, it will be possible to treat almost all psychiatric disorders without burdening patients with the intolerable symptoms or safety adverse effects of medications. Psychiatrists should modulate their perspective about the future of psychiatric treatments. And finally, I propose that psychotherapy should be reclassified as a “verbal neuromodulation” technique.

1. Nasrallah HA. Repositioning psychotherapy as a neurobiological intervention. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):18-19.

2. Nasrallah HA. Bipolar disorder: clinical questions beg for answers. Current Psychiatry. 2006;5(12):11-12.

3. UK ECT Review Group. Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;361(9360):799-808.

4. Rhee TG, Shim SR, Forester BP, et al. Efficacy and safety of ketamine vs electroconvulsive therapy among patients with major depressive episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022:e223352. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.3352

5. Nuninga JO, Mandl RCW, Boks MP, et al. Volume increase in the dentate gyrus after electroconvulsive therapy in depressed patients as measured with 7T. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(7):1559-1568.

6. Joshi SH, Espinoza RT, Pirnia T, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

7. Rhee TG, Olfson M, Nierenberg AA, et al. 20-year trends in the pharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder by psychiatrists in outpatient care settings. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):706-715.

8. Hilz MJ. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation - a brief introduction and overview. Auton Neurosci. 2022;243:103038. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2022.103038

9. Pigato G, Rosson S, Bresolin N, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation in treatment-resistant depression: a case series of long-term follow-up. J ECT. 2022. doi:10.1097/YCT.0000000000000869

10. Shivaswamy T, Souza RR, Engineer CT, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation as a treatment for fear and anxiety in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J Psychiatr Brain Sci. 2022;7(4):e220007. doi:10.20900/jpbs.20220007

11. Wu Y, Song L, Wang X, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation could improve the effective rate on the quality of sleep in the treatment of primary insomnia: a randomized control trial. Brain Sci. 2022;12(10):1296. doi:10.3390/brainsci12101296

12. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

13. Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45(5):651-660.

14. Choi KS, Mayberg H. Connectomic DBS in major depression. In: Horn A, ed. Connectomic Deep Brain Stimulation. Academic Press; 2022:433-447.

15. Cruz S, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, González-Domenech P, et al. Deep brain stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114869. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114869

16. Lisoni J, Baldacci G, Nibbio G, et al. Effects of bilateral, bipolar-nonbalanced, frontal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on negative symptoms and neurocognition in a sample of patients living with schizophrenia: results of a randomized double-blind sham-controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;155:430-442.

17. Sinclair DJ, Zhao S, Qi F, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):CD011847. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011847.pub2

18. Cole EJ, Stimpson KH, Bentzley BS, et al. Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy for treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):716-726.

1. Nasrallah HA. Repositioning psychotherapy as a neurobiological intervention. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):18-19.

2. Nasrallah HA. Bipolar disorder: clinical questions beg for answers. Current Psychiatry. 2006;5(12):11-12.

3. UK ECT Review Group. Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;361(9360):799-808.

4. Rhee TG, Shim SR, Forester BP, et al. Efficacy and safety of ketamine vs electroconvulsive therapy among patients with major depressive episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022:e223352. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.3352

5. Nuninga JO, Mandl RCW, Boks MP, et al. Volume increase in the dentate gyrus after electroconvulsive therapy in depressed patients as measured with 7T. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(7):1559-1568.

6. Joshi SH, Espinoza RT, Pirnia T, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

7. Rhee TG, Olfson M, Nierenberg AA, et al. 20-year trends in the pharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder by psychiatrists in outpatient care settings. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):706-715.

8. Hilz MJ. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation - a brief introduction and overview. Auton Neurosci. 2022;243:103038. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2022.103038

9. Pigato G, Rosson S, Bresolin N, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation in treatment-resistant depression: a case series of long-term follow-up. J ECT. 2022. doi:10.1097/YCT.0000000000000869

10. Shivaswamy T, Souza RR, Engineer CT, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation as a treatment for fear and anxiety in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J Psychiatr Brain Sci. 2022;7(4):e220007. doi:10.20900/jpbs.20220007

11. Wu Y, Song L, Wang X, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation could improve the effective rate on the quality of sleep in the treatment of primary insomnia: a randomized control trial. Brain Sci. 2022;12(10):1296. doi:10.3390/brainsci12101296

12. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

13. Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45(5):651-660.

14. Choi KS, Mayberg H. Connectomic DBS in major depression. In: Horn A, ed. Connectomic Deep Brain Stimulation. Academic Press; 2022:433-447.

15. Cruz S, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, González-Domenech P, et al. Deep brain stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114869. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114869

16. Lisoni J, Baldacci G, Nibbio G, et al. Effects of bilateral, bipolar-nonbalanced, frontal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on negative symptoms and neurocognition in a sample of patients living with schizophrenia: results of a randomized double-blind sham-controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;155:430-442.

17. Sinclair DJ, Zhao S, Qi F, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):CD011847. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011847.pub2

18. Cole EJ, Stimpson KH, Bentzley BS, et al. Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy for treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):716-726.

Breast cancer screening in women receiving antipsychotics

Women with severe mental illness (SMI) are more likely to develop breast cancer and often have more advanced stages of breast cancer when it is detected.1 Antipsychotics have a wide variety of FDA-approved indications and many important life-saving properties. However, patients treated with antipsychotic medications that increase prolactin levels require special consideration with regards to referral for breast cancer screening. Although no clear causal link between antipsychotic use and breast cancer has been established, antipsychotics that raise serum prolactin levels (haloperidol, iloperidone, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, risperidone) are associated with a higher risk of breast cancer than antipsychotics that produce smaller increases in prolactin levels (aripiprazole, asenapine, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, clozapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone).2,3 Risperidone and paliperidone have the highest propensities to increase prolactin (45 to >100 ng/mL), whereas other second-generation antipsychotics are associated with only modest elevations.4 Prolonged exposure to high serum prolactin levels should be avoided in women due to the increased risk for breast cancer.2,3 Although there are no clear rules regarding which number or cluster of personal risk factors necessitates a further risk assessment for breast cancer, women receiving antipsychotics (especially those age ≥40) can be referred for further assessment. An individualized, patient-centered approach should be used.

Recognize risk factors

Patients with SMI often need to take a regimen of medications, including antipsychotics, for weeks or months to stabilize their symptoms. Once a woman with SMI is stabilized, consider referral to a clinic that can comprehensively assess for breast cancer risk. Nonmodifiable risk factors include older age, certain genetic mutations (BRCA1 and BRCA2), early menarche, late menopause, high breast tissue density as detected by mammography, a family history of breast cancer, and exposure to radiation.5,6 Modifiable risk factors include physical inactivity, being overweight or obese, hormonal exposure, drinking alcohol, and the presence of certain factors in the patient’s reproductive history (first pregnancy after age 30, not breastfeeding, and never having a full-term pregnancy).2,3 When making such referrals, it is important to avoid making the patient feel alarmed or frightened of antipsychotics. Instead, explain that a referral for breast cancer screening is routine.

When to refer

All women age ≥40 should be offered a referral to a clinic that can provide screening mammography. If a woman has pain, detects a lump in her breast, has a bloody discharge from the nipple, or has changes in the shape or texture of the nipple or breast, a more urgent referral should be made.4 The most important thing to remember is that early breast lesion detection can be life-saving and can avert the need for more invasive surgeries as well as exposure to chemotherapy and radiation.

What to do when prolactin is elevated

Ongoing monitoring of serum prolactin levels can help ensure that the patient’s levels remain in a normal range (<25 ng/mL).2,3,5,6 If hyperprolactinemia is detected, consider switching to an antipsychotic less likely to increase prolactin. Alternatively, the addition of aripiprazole/brexpiprazole or a dopamine agonist as combination therapy can be considered to rapidly restore normal prolactin levels.2 Such changes should be carefully considered because patients may decompensate if antipsychotics are abruptly switched. An individualized risk vs benefit analysis is necessary for any patient in this situation. Risks include not only the recurrence of psychiatric symptoms but also a potential loss of their current level of functioning. Patients may need to continue to take an antipsychotic that is more likely to increase prolactin, in which case close monitoring is advised as well as collaboration with other physicians and members of the patient’s care team. Involving the patient’s support system is helpful.

1. Weinstein LC, Stefancic A, Cunningham AT, et al. Cancer screening, prevention, and treatment in people with mental illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):134-151.

2. Rahman T, Sahrmann JM, Olsen MA, et al. Risk of breast cancer with prolactin elevating antipsychotic drugs: an observational study of US women (ages 18–64 years). J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;42(1):7-16.

3. Rahman T, Clevenger CV, Kaklamani V, et al. Antipsychotic treatment in breast cancer patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(6):616-621.

4. Peuskens J, Pani L, Detraux J, et al. The effects of novel and newly approved antipsychotics on serum prolactin levels: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(5):421-453.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. Breast cancer. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/index.htm

6. Steiner E, Klubert D, Knutson D. Assessing breast cancer risk in women. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(12):1361-1366.