User login

CDC revamps STI treatment guidelines

On July 22, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released updated sexually transmitted infection treatment guidelines to reflect current screening, testing, and treatment recommendations. The guidelines were last updated in 2015.

The new recommendations come at a pivotal moment in the field’s history, Kimberly Workowski, MD, a medical officer at the CDC’s Division of STD Prevention, told this news organization in an email. “The COVID-19 pandemic has caused decreased clinic capacity and drug and diagnostic test kit shortages,” she says. Many of these shortages have been resolved, she added, and it is important that health care professionals use the most current evidence-based recommendations for screening and management of STIs.

Updates to these guidelines were necessary to reflect “continued advances in research in the prevention of STIs, new interventions in terms of STI prevention, and thirdly, changing epidemiology,” Jeffrey Klausner, MD, MPH, an STI specialist with the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said in an interview. “There’s been increased concern about antimicrobial resistance, and that’s really driven some of the key changes in these new STI treatment guidelines.”

Notable updates to the guidelines include the following:

- Updated treatment recommendations for gonorrhea, chlamydia, , and

- Two-step testing for diagnosing genital virus

- Expanded risk factors for testing in pregnant women

- Information on FDA-cleared rectal and oral tests to diagnose chlamydia and gonorrhea

- A recommendation that universal screening be conducted at least once in a lifetime for adults aged 18 years and older

Dr. Workowski emphasized updates to gonorrhea treatment that built on the recommendation published in December 2020 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. The CDC now recommends that gonorrhea be treated with a single 500-mg injection of ceftriaxone, and if chlamydial infection is not ruled out, treating with a regimen of 100 mg of oral doxycycline taken twice daily for 7 days. Other gonorrhea treatment recommendations include retesting patients 3 months after treatment and that a test of cure be conducted for people with pharyngeal gonorrhea 1 to 2 weeks after treatment, using either culture or nucleic-acid amplification tests.

“Effectively treating gonorrhea remains a public health priority,” Dr. Workowski said. “Gonorrhea can rapidly develop antibiotic resistance and is the second most commonly reported bacterial STI in the U.S., increasing 56% from 2015 to 2019.”

The updates to syphilis screening for pregnant women are also important, added Dr. Klausner. “We’ve seen a dramatic and shameful rise in congenital syphilis,” he said. In addition to screening all pregnant women at the first prenatal visit, the CDC recommends retesting for syphilis at 28 weeks’ gestation and at delivery if the mother lives in an area where the prevalence of syphilis is high or if she is at risk of acquiring syphilis during pregnancy. An expectant mother is at higher risk if she has multiple sex partners, has an STI during pregnancy, has a partner with an STI, has a new sex partner, or misuses drugs, the recommendations state.

Dr. Klausner also noted that the updates provide more robust guidelines for treating transgender individuals and incarcerated people.

The treatment guidelines are available online along with a wall chart and a pocket guide that summarizes these updates. The mobile app with the 2015 guidelines will be retired at the end of July 2021, Dr. Workowski said. An app with these updated treatment recommendations is in development and will be available later this year.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On July 22, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released updated sexually transmitted infection treatment guidelines to reflect current screening, testing, and treatment recommendations. The guidelines were last updated in 2015.

The new recommendations come at a pivotal moment in the field’s history, Kimberly Workowski, MD, a medical officer at the CDC’s Division of STD Prevention, told this news organization in an email. “The COVID-19 pandemic has caused decreased clinic capacity and drug and diagnostic test kit shortages,” she says. Many of these shortages have been resolved, she added, and it is important that health care professionals use the most current evidence-based recommendations for screening and management of STIs.

Updates to these guidelines were necessary to reflect “continued advances in research in the prevention of STIs, new interventions in terms of STI prevention, and thirdly, changing epidemiology,” Jeffrey Klausner, MD, MPH, an STI specialist with the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said in an interview. “There’s been increased concern about antimicrobial resistance, and that’s really driven some of the key changes in these new STI treatment guidelines.”

Notable updates to the guidelines include the following:

- Updated treatment recommendations for gonorrhea, chlamydia, , and

- Two-step testing for diagnosing genital virus

- Expanded risk factors for testing in pregnant women

- Information on FDA-cleared rectal and oral tests to diagnose chlamydia and gonorrhea

- A recommendation that universal screening be conducted at least once in a lifetime for adults aged 18 years and older

Dr. Workowski emphasized updates to gonorrhea treatment that built on the recommendation published in December 2020 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. The CDC now recommends that gonorrhea be treated with a single 500-mg injection of ceftriaxone, and if chlamydial infection is not ruled out, treating with a regimen of 100 mg of oral doxycycline taken twice daily for 7 days. Other gonorrhea treatment recommendations include retesting patients 3 months after treatment and that a test of cure be conducted for people with pharyngeal gonorrhea 1 to 2 weeks after treatment, using either culture or nucleic-acid amplification tests.

“Effectively treating gonorrhea remains a public health priority,” Dr. Workowski said. “Gonorrhea can rapidly develop antibiotic resistance and is the second most commonly reported bacterial STI in the U.S., increasing 56% from 2015 to 2019.”

The updates to syphilis screening for pregnant women are also important, added Dr. Klausner. “We’ve seen a dramatic and shameful rise in congenital syphilis,” he said. In addition to screening all pregnant women at the first prenatal visit, the CDC recommends retesting for syphilis at 28 weeks’ gestation and at delivery if the mother lives in an area where the prevalence of syphilis is high or if she is at risk of acquiring syphilis during pregnancy. An expectant mother is at higher risk if she has multiple sex partners, has an STI during pregnancy, has a partner with an STI, has a new sex partner, or misuses drugs, the recommendations state.

Dr. Klausner also noted that the updates provide more robust guidelines for treating transgender individuals and incarcerated people.

The treatment guidelines are available online along with a wall chart and a pocket guide that summarizes these updates. The mobile app with the 2015 guidelines will be retired at the end of July 2021, Dr. Workowski said. An app with these updated treatment recommendations is in development and will be available later this year.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On July 22, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released updated sexually transmitted infection treatment guidelines to reflect current screening, testing, and treatment recommendations. The guidelines were last updated in 2015.

The new recommendations come at a pivotal moment in the field’s history, Kimberly Workowski, MD, a medical officer at the CDC’s Division of STD Prevention, told this news organization in an email. “The COVID-19 pandemic has caused decreased clinic capacity and drug and diagnostic test kit shortages,” she says. Many of these shortages have been resolved, she added, and it is important that health care professionals use the most current evidence-based recommendations for screening and management of STIs.

Updates to these guidelines were necessary to reflect “continued advances in research in the prevention of STIs, new interventions in terms of STI prevention, and thirdly, changing epidemiology,” Jeffrey Klausner, MD, MPH, an STI specialist with the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said in an interview. “There’s been increased concern about antimicrobial resistance, and that’s really driven some of the key changes in these new STI treatment guidelines.”

Notable updates to the guidelines include the following:

- Updated treatment recommendations for gonorrhea, chlamydia, , and

- Two-step testing for diagnosing genital virus

- Expanded risk factors for testing in pregnant women

- Information on FDA-cleared rectal and oral tests to diagnose chlamydia and gonorrhea

- A recommendation that universal screening be conducted at least once in a lifetime for adults aged 18 years and older

Dr. Workowski emphasized updates to gonorrhea treatment that built on the recommendation published in December 2020 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. The CDC now recommends that gonorrhea be treated with a single 500-mg injection of ceftriaxone, and if chlamydial infection is not ruled out, treating with a regimen of 100 mg of oral doxycycline taken twice daily for 7 days. Other gonorrhea treatment recommendations include retesting patients 3 months after treatment and that a test of cure be conducted for people with pharyngeal gonorrhea 1 to 2 weeks after treatment, using either culture or nucleic-acid amplification tests.

“Effectively treating gonorrhea remains a public health priority,” Dr. Workowski said. “Gonorrhea can rapidly develop antibiotic resistance and is the second most commonly reported bacterial STI in the U.S., increasing 56% from 2015 to 2019.”

The updates to syphilis screening for pregnant women are also important, added Dr. Klausner. “We’ve seen a dramatic and shameful rise in congenital syphilis,” he said. In addition to screening all pregnant women at the first prenatal visit, the CDC recommends retesting for syphilis at 28 weeks’ gestation and at delivery if the mother lives in an area where the prevalence of syphilis is high or if she is at risk of acquiring syphilis during pregnancy. An expectant mother is at higher risk if she has multiple sex partners, has an STI during pregnancy, has a partner with an STI, has a new sex partner, or misuses drugs, the recommendations state.

Dr. Klausner also noted that the updates provide more robust guidelines for treating transgender individuals and incarcerated people.

The treatment guidelines are available online along with a wall chart and a pocket guide that summarizes these updates. The mobile app with the 2015 guidelines will be retired at the end of July 2021, Dr. Workowski said. An app with these updated treatment recommendations is in development and will be available later this year.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Left-Sided Amyand Hernia: Case Report and Review of the Literature

Left-sided Amyand hernia is a rare condition that requires a high degree of clinical suspicion to correctly diagnose.

The presence of the vermiform appendix within an inguinal hernia sac is termed an Amyand hernia. While the incidence of Amyand hernia in the general population is thought to be exceedingly rare, the presence of a left-sided Amyand hernia is even more rare due to the normal anatomical position of the appendix on the right side. Left-sided Amyand hernia presents a novel diagnosis that necessitates a high degree of clinical suspicion and special consideration during patient workup and operative treatment. We describe such a case and provide a review of all reports in the literature of this rare finding.

Case Presentation

A male aged 62 years presented to the emergency department of the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Houston, Texas, in acute distress after experiencing 5 days of nausea and pain in his lower abdomen. The patient’s history was significant for cocaine abuse and a left-sided inguinal hernia that was repaired about 15 years prior to this visit. He reported having no bowel movements for the past 5 days and no other symptoms, including vomiting, hematemesis, and trauma to the abdomen. The patient’s abdominal pain was located in the suprapubic and periumbilical regions. Upon palpation of the lower abdomen, a firm, protruding mass was identified in the left lower quadrant and suspected to be a left-sided inguinal hernia.

A scout film and computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen taken on the same day that the patient presented to the emergency department confirmed the presence of a large left-sided inguinal hernia with possible bowel strangulation involving the colon (Figures 1, 2, and 3). The patient was diagnosed with an incarcerated recurrent left inguinal hernia and was taken emergently to the operating suite. General anesthesia and an ilioinguinal nerve block were performed. An inguinal incision was made on the left side, and the large hernia sac was identified and separated from the scrotum and spermatic cord structures.

On visual inspection, the hernia was identified as both a direct and an indirect inguinal hernia, making it a pantaloon hernia. The hernia sac was opened, and contents of the herniated sac were found to include the omentum, a loop of transverse colon, as well as the entire cecum and appendix, confirming the diagnosis of an Amyand hernia (Figure 4). Though the bowel was initially dusky, all the bowel became pink and appeared to be viable after detorsion of the bowel. Diagnostic laparoscopy through a 5-mm port was performed to assess the remainder of the bowel located intra-abdominally. The remaining intra-abdominal bowel appeared healthy and without obvious signs of ischemia, twisting, or malrotation. The large hernia defect was repaired with a polypropylene mesh.

Discussion

An Amyand hernia is an inguinal hernia in which the vermiform appendix is located within the hernial sac. Named after the French surgeon Claudius Amyand who first documented such a case during an appendectomy in 1735, the Amyand hernia is rare and is thought to occur in < 1% of inguinal hernias.1 Given the normal anatomical position of the appendix on the right side of the body, most Amyand hernias occur in a right-sided inguinal hernia.

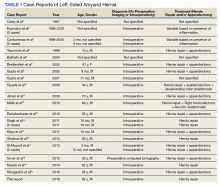

A literature review yielded 25 reported instances of a left-sided Amyand hernia (Table 1) including this report. The true age of incidence of Amyand hernia for each patient is difficult to determine, as many patients do not present until pain or discomfort reaches high levels, often many years after hernia formation. Additionally, some cases of left-sided Amyand hernia described herein, including our case, are recurrent cases of a previous hernia that have been surgically repaired.2-20

Presentation of Amyand hernia often resembles that of a complicated inguinal hernia, acute appendicitis, or both. Hence, clinicians should consider this a possibility when patients present with signs and symptoms that could otherwise be thought to be originating from an incarcerated, strangulated, or recurrent hernia. Specifically, these signs and symptoms include a tender, nonreducible mass in the inguinal region, acute lower abdominal pain, nausea, or signs of intestinal obstruction such as failure to produce bowel movements.4,17 Because of the unusual anatomy in patients presenting with left-sided Amyand hernia, tenderness at the McBurney point usually is absent and not a useful diagnostic tool to rule out acute appendicitis.

A literature review indicates that an Amyand hernia on either side tends to occur in males more often than it does in females. The rate of diagnosis of Amyand hernia also has been reported to be 3 times higher in children than it is in adults due to failure of the processus vaginalis to obliterate during development.21 Our literature review supports this finding, as 16 of the documented 25 cases of left-sided Amyand hernia were reported in males. Additionally, information regarding gender was not found in 6 cases, suggesting a potential for an even higher prevalence in males.

Explanations as to why the appendix is on the left side in these patients include developmental anomalies, such as situs inversus, intestinal rotation, mobile cecum, or an abnormally long appendix.3,8 In our case, the likely causative culprit was a mobile cecum, as there was neither indication of intestinal malformation, rotation, nor of an abnormally long appendix during surgery. Additionally, pre-operative radiologic studies, clinical evaluation, and electrocardiogram did not suggest the presence of situs inversus.

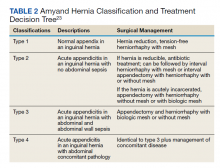

Treatment of Amyand hernia usually follows the landmark classification algorithm set forth in 2007 by Losanoff and Basson (Table 2).22 This system stratifies treatment based on intraoperative findings of the appendix and surrounding structures, ranging from type 1, which involves a normal appendix within the hernia, to type 4, which includes acute appendicitis with additional abdominal pathology. Our patient presented with a type 1 Amyand hernia and appendectomy was foregone as per the guidelines; however, there have been numerous reported cases of surgeons opting for prophylactic appendectomy in the case of a normal appearing appendix and surrounding structures. The decision to act independent of the Losanoff and Basson classification underscores the lack of true standardization, namely, when it comes to a treatment approach for type 1 Amyand hernias. Nonetheless, many contend that indiscriminately performing appendectomies in all cases of left-sided Amyand hernia is useful as a prophylactic measure, as cases of future appendicitis in these patients will have atypical presentations based on the contralateral location of the appendix.6,11,17

Others disagree, citing that prophylactic appendectomy in the case of a normal looking appendix is unnecessary and complicates an otherwise sterile surgery (clean wound classification) with the removal of an appendix containing fecal matter and gut microbiota (converted into a clean contaminated or a contaminated wound classification).17 Additionally, it is thought that in the cases of middle-aged or geriatric patients where the chances of appendicitis are far less, the risks of detriment from prophylactic appendectomy may outweigh the benefits. In these cases, a macroscopic view of the appendix based on visual examination during the operation should guide decision making.4

While the decision to remove a healthy-appearing appendix remains contentious, the decision for or against placement of a heterogenous hernia mesh has proven to be binary, with near universally accepted criteria. If signs of perforation or infection are present in the hernia sac, then surgeons will forego hernioplasty with mesh for simple herniorrhaphy. This contraindication for mesh placement is due to the increased risk of mesh infection, wound infection, and fistulae associated with the introduction of a foreign structure to an active infection site.2

While most cases of Amyand hernia are diagnosed intraoperatively, there have been documented cases of preoperative diagnosis using ultrasonography and CT imaging modalities.19,23,24 In all cases, the presence of the vermiform appendix within the hernia sac can complicate diagnosis and treatment, and preoperative knowledge of this condition may help to guide physician decision making. Identifying Amyand hernia via CT scan is not only useful for alerting physicians of a potentially inflamed appendix within the hernia sac, but also may create opportunities for the use of other treatment modalities. For example, laparoscopic Amyand hernia reduction, an approach that was performed successfully and documented for the first time by Vermillion and colleagues, was made possible by preoperative diagnosis and can potentially result in improved patient outcomes.25

Regardless, while standardization of treatment for Amyand hernia has not yet occurred, it is clear that improved preoperative diagnosis, especially in the case of an unanticipated left-sided Amyand hernia, can allow for better planning and use of a wider variety of treatment modalities. The main impediment to this approach is that suspected cases of appendicitis and inguinal hernias (the most common preoperative diagnoses of Amyand hernia) usually are diagnosed clinically without the need of additional imaging studies like CT or ultrasound. In accordance with the guiding principle of radiation safety of exposing patients to “as low as reasonably achievable” (ALARA) radiation and with consideration of expediency of care and cost efficiency, we recommend physicians continue to screen for and treat cases of potentially emergent appendicitis and/or inguinal hernia as per the conventional methodology. The best approach may involve increasing preoperative diagnoses of left-sided Amyand hernias via physician awareness of this rare finding, as well as evaluating imaging studies that have previously been obtained in order to narrow a broad differential diagnosis.

Conclusions

Left-sided Amyand hernia is an exceptionally rare condition whose preoperative diagnosis remains difficult to establish but whose treatment decision tree is significantly impacted by the condition.

1. Franko J, Raftopoulos I, Sulkowski R. A rare variation of Amyand’s hernia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(10):2684-2685. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.06060.x

2. Carey LC. Acute appendicitis occurring in hernias: a report of 10 cases. Surgery. 1967;61(2):236-238.

3. Kaymakci A, Akillioglu I, Akkoyun I, Guven S, Ozdemir A, Gulen S. Amyand’s hernia: a series of 30 cases in children. Hernia. 2009;13(6):609-612. doi:10.1007/s10029-009-0528-8

4. Cankorkmaz L, Ozer H, Guney C, Atalar MH, Arslan MS, Koyluoglu G. Amyand’s hernia in the children: a single center experience. Surgery. 2010;147(1):140-143. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2009.09.038

5. Yasumoto R, Kawano M, Kawanishi H, et al. Left acute scrotum associated with appendicitis. Int J Urol. 1998;5(1):108-110. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2042.1998.tb00254.x

6. Bakhshi GD, Bhandarwar AH, Govila AA. Acute appendicitis in left scrotum. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2004;23(5):195.

7. Breitenstein S, Eisenbach C, Wille G, Decurtins M. Incarcerated vermiform appendix in a left-sided inguinal hernia. Hernia. 2005;9(1):100-102. doi:10.1007/s10029-004-0263-0

8. Gupta S, Sharma R, Kaushik R. Left-sided Amyand’s hernia. Singapore Med J. 2005;46(8):424-425.

9. Gupta N, Wilkinson TV, Wilkinson A, Akhtar M. Left-sided incarcerated Amyand’s hernia. Indian J Surg. 2007;69(1):17-18.

10. Tayade, MB, Bakhshi GD, Borisa AD, Deshpande G, Joshi N. A rare combination of left sided Amyand’s and Richter’s hernia. Bombay Hosp J. 2008;50(4): 644-645

11. Johari HG, Paydar S, Davani SZ, Eskandari S, Johari MG. Left-sided Amyand hernia. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29(4):321-322. doi:10.4103/0256-4947.55305

12. Ali SM, Malik KA, Al-Qadhi H. Amyand’s Hernia: Study of four cases and literature review. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2012;12(2):232-236. doi:10.12816/0003119

13. Ravishankaran P, Mohan G, Srinivasan A, Ravindran G, Ramalingam A. Left sided amyand’s hernia, a rare occurrence: A Case Report. Indian J Surg. 2013;75(3):247-248. doi:10.1007/s12262-010-0223-0

14. Singh K, Singh RR, Kaur S. Amyand’s hernia. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2011;16(4):171-172. doi:10.4103/0971-9261.86890

15. Khan TS, Wani ML, Bijli AH, et al. Amyand’s hernia: a rare occurrence. Ann Nigerian Med. 2011;5(2):62-64.doi:10.4103/0331-3131.92955

16. Ghafouri A, Anbara T, Foroutankia R. A rare case report of appendix and cecum in the sac of left inguinal hernia (left Amyand’s hernia). Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2012;26(2):94-95.

17. Al-Mayoof AF, Al-Ani BH. Left-sided amyand hernia: report of two cases with review of literature. European J Pediatr Surg Rep. 2014;2(1):63-66. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1347131

18. Unver M, Ozturk S, Karaman K, Turgut E. Left sided Amyand’s hernia. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;5(10):285-286. doi:10.4240/wjgs.v5.i10.285

19. Maeda K, Kunieda K, Kawai M, et al. Giant left-sided inguinoscrotal hernia containing the cecum and appendix (giant left-sided Amyand’s hernia). Clin Case Rep. 2014;2(6):254-257. doi:10.1002/ccr3.104

20. Mongardini M, Maturo A, De Anna L, et al. Appendiceal abscess in a giant left-sided inguinoscrotal hernia: a rare case of Amyand hernia. Springerplus. 2015;4:378. Published 2015 Jul 26. doi:10.1186/s40064-015-1162-9

21. Ivanschuk G, Cesmebasi A, Sorenson EP, Blaak C, Loukas M, Tubbs SR. Amyand’s hernia: a review. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:140-146. Published 2014 Jan 28. doi:10.12659/MSM.889873

22. Losanoff JE, Basson MD. Amyand hernia: what lies beneath--a proposed classification scheme to determine management. Am Surg. 2007;73(12):1288-1290.

23. Coulier B, Pacary J, Broze B. Sonographic diagnosis of appendicitis within a right inguinal hernia (Amyand’s hernia). J Clin Ultrasound. 2006;34(9):454-457. doi:10.1002/jcu.20266

24. Vehbi H, Agirgun C, Agirgun F, Dogan Y. Preoperative diagnosis of Amyand’s hernia by ultrasound and computed tomography. Turk J Emerg Med. 2016;16(2):72-74. Published 2016 May 8. doi:10.1016/j.tjem.2015.11.014

25. Vermillion JM, Abernathy SW, Snyder SK. Laparoscopic reduction of Amyand’s hernia. Hernia. 1999;3:159-160. doi:10.1007/BF01195318

Left-sided Amyand hernia is a rare condition that requires a high degree of clinical suspicion to correctly diagnose.

Left-sided Amyand hernia is a rare condition that requires a high degree of clinical suspicion to correctly diagnose.

The presence of the vermiform appendix within an inguinal hernia sac is termed an Amyand hernia. While the incidence of Amyand hernia in the general population is thought to be exceedingly rare, the presence of a left-sided Amyand hernia is even more rare due to the normal anatomical position of the appendix on the right side. Left-sided Amyand hernia presents a novel diagnosis that necessitates a high degree of clinical suspicion and special consideration during patient workup and operative treatment. We describe such a case and provide a review of all reports in the literature of this rare finding.

Case Presentation

A male aged 62 years presented to the emergency department of the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Houston, Texas, in acute distress after experiencing 5 days of nausea and pain in his lower abdomen. The patient’s history was significant for cocaine abuse and a left-sided inguinal hernia that was repaired about 15 years prior to this visit. He reported having no bowel movements for the past 5 days and no other symptoms, including vomiting, hematemesis, and trauma to the abdomen. The patient’s abdominal pain was located in the suprapubic and periumbilical regions. Upon palpation of the lower abdomen, a firm, protruding mass was identified in the left lower quadrant and suspected to be a left-sided inguinal hernia.

A scout film and computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen taken on the same day that the patient presented to the emergency department confirmed the presence of a large left-sided inguinal hernia with possible bowel strangulation involving the colon (Figures 1, 2, and 3). The patient was diagnosed with an incarcerated recurrent left inguinal hernia and was taken emergently to the operating suite. General anesthesia and an ilioinguinal nerve block were performed. An inguinal incision was made on the left side, and the large hernia sac was identified and separated from the scrotum and spermatic cord structures.

On visual inspection, the hernia was identified as both a direct and an indirect inguinal hernia, making it a pantaloon hernia. The hernia sac was opened, and contents of the herniated sac were found to include the omentum, a loop of transverse colon, as well as the entire cecum and appendix, confirming the diagnosis of an Amyand hernia (Figure 4). Though the bowel was initially dusky, all the bowel became pink and appeared to be viable after detorsion of the bowel. Diagnostic laparoscopy through a 5-mm port was performed to assess the remainder of the bowel located intra-abdominally. The remaining intra-abdominal bowel appeared healthy and without obvious signs of ischemia, twisting, or malrotation. The large hernia defect was repaired with a polypropylene mesh.

Discussion

An Amyand hernia is an inguinal hernia in which the vermiform appendix is located within the hernial sac. Named after the French surgeon Claudius Amyand who first documented such a case during an appendectomy in 1735, the Amyand hernia is rare and is thought to occur in < 1% of inguinal hernias.1 Given the normal anatomical position of the appendix on the right side of the body, most Amyand hernias occur in a right-sided inguinal hernia.

A literature review yielded 25 reported instances of a left-sided Amyand hernia (Table 1) including this report. The true age of incidence of Amyand hernia for each patient is difficult to determine, as many patients do not present until pain or discomfort reaches high levels, often many years after hernia formation. Additionally, some cases of left-sided Amyand hernia described herein, including our case, are recurrent cases of a previous hernia that have been surgically repaired.2-20

Presentation of Amyand hernia often resembles that of a complicated inguinal hernia, acute appendicitis, or both. Hence, clinicians should consider this a possibility when patients present with signs and symptoms that could otherwise be thought to be originating from an incarcerated, strangulated, or recurrent hernia. Specifically, these signs and symptoms include a tender, nonreducible mass in the inguinal region, acute lower abdominal pain, nausea, or signs of intestinal obstruction such as failure to produce bowel movements.4,17 Because of the unusual anatomy in patients presenting with left-sided Amyand hernia, tenderness at the McBurney point usually is absent and not a useful diagnostic tool to rule out acute appendicitis.

A literature review indicates that an Amyand hernia on either side tends to occur in males more often than it does in females. The rate of diagnosis of Amyand hernia also has been reported to be 3 times higher in children than it is in adults due to failure of the processus vaginalis to obliterate during development.21 Our literature review supports this finding, as 16 of the documented 25 cases of left-sided Amyand hernia were reported in males. Additionally, information regarding gender was not found in 6 cases, suggesting a potential for an even higher prevalence in males.

Explanations as to why the appendix is on the left side in these patients include developmental anomalies, such as situs inversus, intestinal rotation, mobile cecum, or an abnormally long appendix.3,8 In our case, the likely causative culprit was a mobile cecum, as there was neither indication of intestinal malformation, rotation, nor of an abnormally long appendix during surgery. Additionally, pre-operative radiologic studies, clinical evaluation, and electrocardiogram did not suggest the presence of situs inversus.

Treatment of Amyand hernia usually follows the landmark classification algorithm set forth in 2007 by Losanoff and Basson (Table 2).22 This system stratifies treatment based on intraoperative findings of the appendix and surrounding structures, ranging from type 1, which involves a normal appendix within the hernia, to type 4, which includes acute appendicitis with additional abdominal pathology. Our patient presented with a type 1 Amyand hernia and appendectomy was foregone as per the guidelines; however, there have been numerous reported cases of surgeons opting for prophylactic appendectomy in the case of a normal appearing appendix and surrounding structures. The decision to act independent of the Losanoff and Basson classification underscores the lack of true standardization, namely, when it comes to a treatment approach for type 1 Amyand hernias. Nonetheless, many contend that indiscriminately performing appendectomies in all cases of left-sided Amyand hernia is useful as a prophylactic measure, as cases of future appendicitis in these patients will have atypical presentations based on the contralateral location of the appendix.6,11,17

Others disagree, citing that prophylactic appendectomy in the case of a normal looking appendix is unnecessary and complicates an otherwise sterile surgery (clean wound classification) with the removal of an appendix containing fecal matter and gut microbiota (converted into a clean contaminated or a contaminated wound classification).17 Additionally, it is thought that in the cases of middle-aged or geriatric patients where the chances of appendicitis are far less, the risks of detriment from prophylactic appendectomy may outweigh the benefits. In these cases, a macroscopic view of the appendix based on visual examination during the operation should guide decision making.4

While the decision to remove a healthy-appearing appendix remains contentious, the decision for or against placement of a heterogenous hernia mesh has proven to be binary, with near universally accepted criteria. If signs of perforation or infection are present in the hernia sac, then surgeons will forego hernioplasty with mesh for simple herniorrhaphy. This contraindication for mesh placement is due to the increased risk of mesh infection, wound infection, and fistulae associated with the introduction of a foreign structure to an active infection site.2

While most cases of Amyand hernia are diagnosed intraoperatively, there have been documented cases of preoperative diagnosis using ultrasonography and CT imaging modalities.19,23,24 In all cases, the presence of the vermiform appendix within the hernia sac can complicate diagnosis and treatment, and preoperative knowledge of this condition may help to guide physician decision making. Identifying Amyand hernia via CT scan is not only useful for alerting physicians of a potentially inflamed appendix within the hernia sac, but also may create opportunities for the use of other treatment modalities. For example, laparoscopic Amyand hernia reduction, an approach that was performed successfully and documented for the first time by Vermillion and colleagues, was made possible by preoperative diagnosis and can potentially result in improved patient outcomes.25

Regardless, while standardization of treatment for Amyand hernia has not yet occurred, it is clear that improved preoperative diagnosis, especially in the case of an unanticipated left-sided Amyand hernia, can allow for better planning and use of a wider variety of treatment modalities. The main impediment to this approach is that suspected cases of appendicitis and inguinal hernias (the most common preoperative diagnoses of Amyand hernia) usually are diagnosed clinically without the need of additional imaging studies like CT or ultrasound. In accordance with the guiding principle of radiation safety of exposing patients to “as low as reasonably achievable” (ALARA) radiation and with consideration of expediency of care and cost efficiency, we recommend physicians continue to screen for and treat cases of potentially emergent appendicitis and/or inguinal hernia as per the conventional methodology. The best approach may involve increasing preoperative diagnoses of left-sided Amyand hernias via physician awareness of this rare finding, as well as evaluating imaging studies that have previously been obtained in order to narrow a broad differential diagnosis.

Conclusions

Left-sided Amyand hernia is an exceptionally rare condition whose preoperative diagnosis remains difficult to establish but whose treatment decision tree is significantly impacted by the condition.

The presence of the vermiform appendix within an inguinal hernia sac is termed an Amyand hernia. While the incidence of Amyand hernia in the general population is thought to be exceedingly rare, the presence of a left-sided Amyand hernia is even more rare due to the normal anatomical position of the appendix on the right side. Left-sided Amyand hernia presents a novel diagnosis that necessitates a high degree of clinical suspicion and special consideration during patient workup and operative treatment. We describe such a case and provide a review of all reports in the literature of this rare finding.

Case Presentation

A male aged 62 years presented to the emergency department of the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Houston, Texas, in acute distress after experiencing 5 days of nausea and pain in his lower abdomen. The patient’s history was significant for cocaine abuse and a left-sided inguinal hernia that was repaired about 15 years prior to this visit. He reported having no bowel movements for the past 5 days and no other symptoms, including vomiting, hematemesis, and trauma to the abdomen. The patient’s abdominal pain was located in the suprapubic and periumbilical regions. Upon palpation of the lower abdomen, a firm, protruding mass was identified in the left lower quadrant and suspected to be a left-sided inguinal hernia.

A scout film and computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen taken on the same day that the patient presented to the emergency department confirmed the presence of a large left-sided inguinal hernia with possible bowel strangulation involving the colon (Figures 1, 2, and 3). The patient was diagnosed with an incarcerated recurrent left inguinal hernia and was taken emergently to the operating suite. General anesthesia and an ilioinguinal nerve block were performed. An inguinal incision was made on the left side, and the large hernia sac was identified and separated from the scrotum and spermatic cord structures.

On visual inspection, the hernia was identified as both a direct and an indirect inguinal hernia, making it a pantaloon hernia. The hernia sac was opened, and contents of the herniated sac were found to include the omentum, a loop of transverse colon, as well as the entire cecum and appendix, confirming the diagnosis of an Amyand hernia (Figure 4). Though the bowel was initially dusky, all the bowel became pink and appeared to be viable after detorsion of the bowel. Diagnostic laparoscopy through a 5-mm port was performed to assess the remainder of the bowel located intra-abdominally. The remaining intra-abdominal bowel appeared healthy and without obvious signs of ischemia, twisting, or malrotation. The large hernia defect was repaired with a polypropylene mesh.

Discussion

An Amyand hernia is an inguinal hernia in which the vermiform appendix is located within the hernial sac. Named after the French surgeon Claudius Amyand who first documented such a case during an appendectomy in 1735, the Amyand hernia is rare and is thought to occur in < 1% of inguinal hernias.1 Given the normal anatomical position of the appendix on the right side of the body, most Amyand hernias occur in a right-sided inguinal hernia.

A literature review yielded 25 reported instances of a left-sided Amyand hernia (Table 1) including this report. The true age of incidence of Amyand hernia for each patient is difficult to determine, as many patients do not present until pain or discomfort reaches high levels, often many years after hernia formation. Additionally, some cases of left-sided Amyand hernia described herein, including our case, are recurrent cases of a previous hernia that have been surgically repaired.2-20

Presentation of Amyand hernia often resembles that of a complicated inguinal hernia, acute appendicitis, or both. Hence, clinicians should consider this a possibility when patients present with signs and symptoms that could otherwise be thought to be originating from an incarcerated, strangulated, or recurrent hernia. Specifically, these signs and symptoms include a tender, nonreducible mass in the inguinal region, acute lower abdominal pain, nausea, or signs of intestinal obstruction such as failure to produce bowel movements.4,17 Because of the unusual anatomy in patients presenting with left-sided Amyand hernia, tenderness at the McBurney point usually is absent and not a useful diagnostic tool to rule out acute appendicitis.

A literature review indicates that an Amyand hernia on either side tends to occur in males more often than it does in females. The rate of diagnosis of Amyand hernia also has been reported to be 3 times higher in children than it is in adults due to failure of the processus vaginalis to obliterate during development.21 Our literature review supports this finding, as 16 of the documented 25 cases of left-sided Amyand hernia were reported in males. Additionally, information regarding gender was not found in 6 cases, suggesting a potential for an even higher prevalence in males.

Explanations as to why the appendix is on the left side in these patients include developmental anomalies, such as situs inversus, intestinal rotation, mobile cecum, or an abnormally long appendix.3,8 In our case, the likely causative culprit was a mobile cecum, as there was neither indication of intestinal malformation, rotation, nor of an abnormally long appendix during surgery. Additionally, pre-operative radiologic studies, clinical evaluation, and electrocardiogram did not suggest the presence of situs inversus.

Treatment of Amyand hernia usually follows the landmark classification algorithm set forth in 2007 by Losanoff and Basson (Table 2).22 This system stratifies treatment based on intraoperative findings of the appendix and surrounding structures, ranging from type 1, which involves a normal appendix within the hernia, to type 4, which includes acute appendicitis with additional abdominal pathology. Our patient presented with a type 1 Amyand hernia and appendectomy was foregone as per the guidelines; however, there have been numerous reported cases of surgeons opting for prophylactic appendectomy in the case of a normal appearing appendix and surrounding structures. The decision to act independent of the Losanoff and Basson classification underscores the lack of true standardization, namely, when it comes to a treatment approach for type 1 Amyand hernias. Nonetheless, many contend that indiscriminately performing appendectomies in all cases of left-sided Amyand hernia is useful as a prophylactic measure, as cases of future appendicitis in these patients will have atypical presentations based on the contralateral location of the appendix.6,11,17

Others disagree, citing that prophylactic appendectomy in the case of a normal looking appendix is unnecessary and complicates an otherwise sterile surgery (clean wound classification) with the removal of an appendix containing fecal matter and gut microbiota (converted into a clean contaminated or a contaminated wound classification).17 Additionally, it is thought that in the cases of middle-aged or geriatric patients where the chances of appendicitis are far less, the risks of detriment from prophylactic appendectomy may outweigh the benefits. In these cases, a macroscopic view of the appendix based on visual examination during the operation should guide decision making.4

While the decision to remove a healthy-appearing appendix remains contentious, the decision for or against placement of a heterogenous hernia mesh has proven to be binary, with near universally accepted criteria. If signs of perforation or infection are present in the hernia sac, then surgeons will forego hernioplasty with mesh for simple herniorrhaphy. This contraindication for mesh placement is due to the increased risk of mesh infection, wound infection, and fistulae associated with the introduction of a foreign structure to an active infection site.2

While most cases of Amyand hernia are diagnosed intraoperatively, there have been documented cases of preoperative diagnosis using ultrasonography and CT imaging modalities.19,23,24 In all cases, the presence of the vermiform appendix within the hernia sac can complicate diagnosis and treatment, and preoperative knowledge of this condition may help to guide physician decision making. Identifying Amyand hernia via CT scan is not only useful for alerting physicians of a potentially inflamed appendix within the hernia sac, but also may create opportunities for the use of other treatment modalities. For example, laparoscopic Amyand hernia reduction, an approach that was performed successfully and documented for the first time by Vermillion and colleagues, was made possible by preoperative diagnosis and can potentially result in improved patient outcomes.25

Regardless, while standardization of treatment for Amyand hernia has not yet occurred, it is clear that improved preoperative diagnosis, especially in the case of an unanticipated left-sided Amyand hernia, can allow for better planning and use of a wider variety of treatment modalities. The main impediment to this approach is that suspected cases of appendicitis and inguinal hernias (the most common preoperative diagnoses of Amyand hernia) usually are diagnosed clinically without the need of additional imaging studies like CT or ultrasound. In accordance with the guiding principle of radiation safety of exposing patients to “as low as reasonably achievable” (ALARA) radiation and with consideration of expediency of care and cost efficiency, we recommend physicians continue to screen for and treat cases of potentially emergent appendicitis and/or inguinal hernia as per the conventional methodology. The best approach may involve increasing preoperative diagnoses of left-sided Amyand hernias via physician awareness of this rare finding, as well as evaluating imaging studies that have previously been obtained in order to narrow a broad differential diagnosis.

Conclusions

Left-sided Amyand hernia is an exceptionally rare condition whose preoperative diagnosis remains difficult to establish but whose treatment decision tree is significantly impacted by the condition.

1. Franko J, Raftopoulos I, Sulkowski R. A rare variation of Amyand’s hernia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(10):2684-2685. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.06060.x

2. Carey LC. Acute appendicitis occurring in hernias: a report of 10 cases. Surgery. 1967;61(2):236-238.

3. Kaymakci A, Akillioglu I, Akkoyun I, Guven S, Ozdemir A, Gulen S. Amyand’s hernia: a series of 30 cases in children. Hernia. 2009;13(6):609-612. doi:10.1007/s10029-009-0528-8

4. Cankorkmaz L, Ozer H, Guney C, Atalar MH, Arslan MS, Koyluoglu G. Amyand’s hernia in the children: a single center experience. Surgery. 2010;147(1):140-143. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2009.09.038

5. Yasumoto R, Kawano M, Kawanishi H, et al. Left acute scrotum associated with appendicitis. Int J Urol. 1998;5(1):108-110. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2042.1998.tb00254.x

6. Bakhshi GD, Bhandarwar AH, Govila AA. Acute appendicitis in left scrotum. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2004;23(5):195.

7. Breitenstein S, Eisenbach C, Wille G, Decurtins M. Incarcerated vermiform appendix in a left-sided inguinal hernia. Hernia. 2005;9(1):100-102. doi:10.1007/s10029-004-0263-0

8. Gupta S, Sharma R, Kaushik R. Left-sided Amyand’s hernia. Singapore Med J. 2005;46(8):424-425.

9. Gupta N, Wilkinson TV, Wilkinson A, Akhtar M. Left-sided incarcerated Amyand’s hernia. Indian J Surg. 2007;69(1):17-18.

10. Tayade, MB, Bakhshi GD, Borisa AD, Deshpande G, Joshi N. A rare combination of left sided Amyand’s and Richter’s hernia. Bombay Hosp J. 2008;50(4): 644-645

11. Johari HG, Paydar S, Davani SZ, Eskandari S, Johari MG. Left-sided Amyand hernia. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29(4):321-322. doi:10.4103/0256-4947.55305

12. Ali SM, Malik KA, Al-Qadhi H. Amyand’s Hernia: Study of four cases and literature review. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2012;12(2):232-236. doi:10.12816/0003119

13. Ravishankaran P, Mohan G, Srinivasan A, Ravindran G, Ramalingam A. Left sided amyand’s hernia, a rare occurrence: A Case Report. Indian J Surg. 2013;75(3):247-248. doi:10.1007/s12262-010-0223-0

14. Singh K, Singh RR, Kaur S. Amyand’s hernia. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2011;16(4):171-172. doi:10.4103/0971-9261.86890

15. Khan TS, Wani ML, Bijli AH, et al. Amyand’s hernia: a rare occurrence. Ann Nigerian Med. 2011;5(2):62-64.doi:10.4103/0331-3131.92955

16. Ghafouri A, Anbara T, Foroutankia R. A rare case report of appendix and cecum in the sac of left inguinal hernia (left Amyand’s hernia). Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2012;26(2):94-95.

17. Al-Mayoof AF, Al-Ani BH. Left-sided amyand hernia: report of two cases with review of literature. European J Pediatr Surg Rep. 2014;2(1):63-66. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1347131

18. Unver M, Ozturk S, Karaman K, Turgut E. Left sided Amyand’s hernia. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;5(10):285-286. doi:10.4240/wjgs.v5.i10.285

19. Maeda K, Kunieda K, Kawai M, et al. Giant left-sided inguinoscrotal hernia containing the cecum and appendix (giant left-sided Amyand’s hernia). Clin Case Rep. 2014;2(6):254-257. doi:10.1002/ccr3.104

20. Mongardini M, Maturo A, De Anna L, et al. Appendiceal abscess in a giant left-sided inguinoscrotal hernia: a rare case of Amyand hernia. Springerplus. 2015;4:378. Published 2015 Jul 26. doi:10.1186/s40064-015-1162-9

21. Ivanschuk G, Cesmebasi A, Sorenson EP, Blaak C, Loukas M, Tubbs SR. Amyand’s hernia: a review. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:140-146. Published 2014 Jan 28. doi:10.12659/MSM.889873

22. Losanoff JE, Basson MD. Amyand hernia: what lies beneath--a proposed classification scheme to determine management. Am Surg. 2007;73(12):1288-1290.

23. Coulier B, Pacary J, Broze B. Sonographic diagnosis of appendicitis within a right inguinal hernia (Amyand’s hernia). J Clin Ultrasound. 2006;34(9):454-457. doi:10.1002/jcu.20266

24. Vehbi H, Agirgun C, Agirgun F, Dogan Y. Preoperative diagnosis of Amyand’s hernia by ultrasound and computed tomography. Turk J Emerg Med. 2016;16(2):72-74. Published 2016 May 8. doi:10.1016/j.tjem.2015.11.014

25. Vermillion JM, Abernathy SW, Snyder SK. Laparoscopic reduction of Amyand’s hernia. Hernia. 1999;3:159-160. doi:10.1007/BF01195318

1. Franko J, Raftopoulos I, Sulkowski R. A rare variation of Amyand’s hernia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(10):2684-2685. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.06060.x

2. Carey LC. Acute appendicitis occurring in hernias: a report of 10 cases. Surgery. 1967;61(2):236-238.

3. Kaymakci A, Akillioglu I, Akkoyun I, Guven S, Ozdemir A, Gulen S. Amyand’s hernia: a series of 30 cases in children. Hernia. 2009;13(6):609-612. doi:10.1007/s10029-009-0528-8

4. Cankorkmaz L, Ozer H, Guney C, Atalar MH, Arslan MS, Koyluoglu G. Amyand’s hernia in the children: a single center experience. Surgery. 2010;147(1):140-143. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2009.09.038

5. Yasumoto R, Kawano M, Kawanishi H, et al. Left acute scrotum associated with appendicitis. Int J Urol. 1998;5(1):108-110. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2042.1998.tb00254.x

6. Bakhshi GD, Bhandarwar AH, Govila AA. Acute appendicitis in left scrotum. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2004;23(5):195.

7. Breitenstein S, Eisenbach C, Wille G, Decurtins M. Incarcerated vermiform appendix in a left-sided inguinal hernia. Hernia. 2005;9(1):100-102. doi:10.1007/s10029-004-0263-0

8. Gupta S, Sharma R, Kaushik R. Left-sided Amyand’s hernia. Singapore Med J. 2005;46(8):424-425.

9. Gupta N, Wilkinson TV, Wilkinson A, Akhtar M. Left-sided incarcerated Amyand’s hernia. Indian J Surg. 2007;69(1):17-18.

10. Tayade, MB, Bakhshi GD, Borisa AD, Deshpande G, Joshi N. A rare combination of left sided Amyand’s and Richter’s hernia. Bombay Hosp J. 2008;50(4): 644-645

11. Johari HG, Paydar S, Davani SZ, Eskandari S, Johari MG. Left-sided Amyand hernia. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29(4):321-322. doi:10.4103/0256-4947.55305

12. Ali SM, Malik KA, Al-Qadhi H. Amyand’s Hernia: Study of four cases and literature review. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2012;12(2):232-236. doi:10.12816/0003119

13. Ravishankaran P, Mohan G, Srinivasan A, Ravindran G, Ramalingam A. Left sided amyand’s hernia, a rare occurrence: A Case Report. Indian J Surg. 2013;75(3):247-248. doi:10.1007/s12262-010-0223-0

14. Singh K, Singh RR, Kaur S. Amyand’s hernia. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2011;16(4):171-172. doi:10.4103/0971-9261.86890

15. Khan TS, Wani ML, Bijli AH, et al. Amyand’s hernia: a rare occurrence. Ann Nigerian Med. 2011;5(2):62-64.doi:10.4103/0331-3131.92955

16. Ghafouri A, Anbara T, Foroutankia R. A rare case report of appendix and cecum in the sac of left inguinal hernia (left Amyand’s hernia). Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2012;26(2):94-95.

17. Al-Mayoof AF, Al-Ani BH. Left-sided amyand hernia: report of two cases with review of literature. European J Pediatr Surg Rep. 2014;2(1):63-66. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1347131

18. Unver M, Ozturk S, Karaman K, Turgut E. Left sided Amyand’s hernia. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;5(10):285-286. doi:10.4240/wjgs.v5.i10.285

19. Maeda K, Kunieda K, Kawai M, et al. Giant left-sided inguinoscrotal hernia containing the cecum and appendix (giant left-sided Amyand’s hernia). Clin Case Rep. 2014;2(6):254-257. doi:10.1002/ccr3.104

20. Mongardini M, Maturo A, De Anna L, et al. Appendiceal abscess in a giant left-sided inguinoscrotal hernia: a rare case of Amyand hernia. Springerplus. 2015;4:378. Published 2015 Jul 26. doi:10.1186/s40064-015-1162-9

21. Ivanschuk G, Cesmebasi A, Sorenson EP, Blaak C, Loukas M, Tubbs SR. Amyand’s hernia: a review. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:140-146. Published 2014 Jan 28. doi:10.12659/MSM.889873

22. Losanoff JE, Basson MD. Amyand hernia: what lies beneath--a proposed classification scheme to determine management. Am Surg. 2007;73(12):1288-1290.

23. Coulier B, Pacary J, Broze B. Sonographic diagnosis of appendicitis within a right inguinal hernia (Amyand’s hernia). J Clin Ultrasound. 2006;34(9):454-457. doi:10.1002/jcu.20266

24. Vehbi H, Agirgun C, Agirgun F, Dogan Y. Preoperative diagnosis of Amyand’s hernia by ultrasound and computed tomography. Turk J Emerg Med. 2016;16(2):72-74. Published 2016 May 8. doi:10.1016/j.tjem.2015.11.014

25. Vermillion JM, Abernathy SW, Snyder SK. Laparoscopic reduction of Amyand’s hernia. Hernia. 1999;3:159-160. doi:10.1007/BF01195318

Success in LGBTQ+ medicine requires awareness of risk

Patients who are transgender, for instance, are nine times more likely to commit suicide than the general population (2015 U.S. Transgender Survey (USTS). Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. 2019 May 22. doi: 10.3886/ICPSR37229.v1), and those who are also Black have an estimated HIV prevalence of 62%, demonstrating the cumulative, negative health effects of intersectionality (www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/hiv-prevalence.html).

“Experiences with marginalization and stigma directly relate to some of the poor physical and mental health outcomes that these patients experience,” Megan McNamara, MD, said during a presentation at the American College of Physicians annual Internal Medicine meeting.

Dr. McNamara, who is director of the Gender Identity Veteran’s Experience (GIVE) Clinic, Veterans Affairs Northeast Ohio Healthcare System, Cleveland, offered a brief guide to managing LGBTQ+ patients. She emphasized increased rates of psychological distress and substance abuse, and encouraged familiarity with specific risks associated with three subgroups: men who have sex with men (MSM), women who have sex with women (WSW), and those who are transgender.

Men who have sex with men

According to Dr. McNamara, preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) should be offered based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention eligibility criteria, which require that the patient is HIV negative, has had a male sex partner in the past 6 months, is not in a monogamous relationship, and has had anal sex or a bacterial sexually transmitted infection in the past 6 months. The two PrEP options, emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, are equally effective and have similar safety profiles, Dr. McNamara said, but patients with impaired renal function should receive the alafenamide formulation.

Dr. McNamara also advised screening gay men for extragenital STIs, noting a 13.3% increased risk. When asked about anal Pap testing for HPV, Dr. McNamara called the subject “very controversial,” and ultimately recommended against it, citing a lack of data linking anal HPV infection and dysplasia with later development of rectal carcinoma, as well as the nonactionable impact of a positive result.

“For me, the issue is ... if [a positive anal Pap test] is not going to change my management, if I don’t know that the anal HPV that I diagnose will result in cancer, should I continue to monitor it?” Dr. McNamara said.

Women who have sex with women

Beyond higher rates of psychological distress and substance abuse among lesbian and bisexual women, Dr. McNamara described increased risks of overweight and obesity, higher rates of smoking, and lower rates of Pap testing, all of which should prompt clinicians to advise accordingly, with cervical cancer screening in alignment with guidelines. Clinicians should also discuss HPV vaccination with patients, taking care to weigh benefits and risks, as “catch-up” HPV vaccination is not unilaterally recommended for adults older than 26 years.

Transgender patients

Discussing transgender patients, Dr. McNamara focused on cross-sex hormone therapy (CSHT), first noting the significant psychological benefits, including improvements in depression, somatization, interpersonal sensitivity, hostility, anxiety, phobic anxiety/agoraphobia, and quality of life.

According to Dr. McNamara, CSHT is relatively simple and may be safely administered by primary care providers. For transmasculine patients, testosterone supplementation is all that is needed, whereas transfeminine patients will require spironolactone or GnRH agonists to reduce testosterone and estradiol to increase feminizing hormones to pubertal levels.

CSHT is not without risks, Dr. McNamara said, including “very high” risks of erythrocytosis among transmasculine patients and venous thromboembolic disease among transfeminine patients; but these risks need to be considered in the context of an approximate 40% suicide rate among transgender individuals.

“I can tell you in my own practice that these [suicide] data ring true,” Dr. McNamara said. “Many, many of my patients have attempted suicide, so [CSHT] is something that you really want to think about right away.”

Even when additional risk factors are present, such as preexisting cardiovascular disease, Dr. McNamara suggested that “there are very few absolute contraindications to CSHT,” and described it as a “life-sustaining treatment” that should be viewed analogously with any other long-term management strategy, such as therapy for diabetes or hypertension.

Fostering a transgender-friendly practice

In an interview, Nicole Nisly, MD, codirector of the LGBTQ+ Clinic at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, reflected upon Dr. McNamara’s presentation, noting that primary care providers – with a little education – are the best candidates to care for transgender patients.

“I think [primary care providers] do a better job [caring for transgender patients] than endocrinologists, honestly, because they can provide care for the whole person,” Dr. Nisly said. “They can do a Pap, they can do STI screening, they can assess mood, they can [evaluate] safety, and the whole person, as opposed to endocrinologists, who do hormone therapy, but somebody else does everything else.”

Dr. Nisly emphasized the importance of personalizing care for transgender individuals, which depends upon a welcoming practice environment, with careful attention to language.

Foremost, Dr. Nisly recommended asking patients for their preferred name, sexual orientation, and gender identity.

“One of the most difficult things [for transgender patients] is to see notes with the wrong name – the name that makes them feel uncomfortable – or the wrong pronoun,” Dr. Nisly said. “That’s very important to the community.”

Dr. Nisly also recommended an alternative term for cross-sex hormone therapy.

“I hate cross-sex hormone therapy terminology, honestly,” Dr. Nisly said. “I just think it’s so unwelcoming, and I think most of our patients don’t like the terminology, so we use ‘gender-affirming hormone therapy.’”

Dr. Nisly explained that the term “cross-sex” assumes a conventional definition of sex, which is inherently flawed.

When discussing certain medical risk factors, such as pregnancy or HIV, it is helpful to know “sex assigned at birth” for both patients and their sexual partners, Dr. Nisly said. It’s best to ask in this way, instead of using terms like “boyfriend” or “girlfriend,” as “sex assigned at birth” is “terminology the community recognizes, affirms, and feels comfortable with.”

Concerning management of medical risk factors, Dr. Nisly offered some additional perspectives.

For one, she recommended giving PrEP to any patient who has a desire to be on PrEP, noting that this desire can indicate a change in future sexual practices, which the CDC criteria do not anticipate. She also advised in-hospital self-swabbing for extragenital STIs, as this can increase patient comfort and adherence. And, in contrast with Dr. McNamara, Dr. Nisly recommended anal Pap screening for any man that has sex with men and anyone with HIV of any gender. She noted that rates of anal dysplasia are “pretty high” among men who have sex with men, and that detection may reduce cancer risk.

For clinicians who would like to learn more about caring for transgender patients, Dr. Nisly recommended that they start by reading the World Professional Association for Transgender Health guidelines.

“It’s about 300 pages,” Dr. Nisly said, “but it is great.”

Dr. McNamara and Dr. Nisly reported no conflicts of interest.

Patients who are transgender, for instance, are nine times more likely to commit suicide than the general population (2015 U.S. Transgender Survey (USTS). Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. 2019 May 22. doi: 10.3886/ICPSR37229.v1), and those who are also Black have an estimated HIV prevalence of 62%, demonstrating the cumulative, negative health effects of intersectionality (www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/hiv-prevalence.html).

“Experiences with marginalization and stigma directly relate to some of the poor physical and mental health outcomes that these patients experience,” Megan McNamara, MD, said during a presentation at the American College of Physicians annual Internal Medicine meeting.

Dr. McNamara, who is director of the Gender Identity Veteran’s Experience (GIVE) Clinic, Veterans Affairs Northeast Ohio Healthcare System, Cleveland, offered a brief guide to managing LGBTQ+ patients. She emphasized increased rates of psychological distress and substance abuse, and encouraged familiarity with specific risks associated with three subgroups: men who have sex with men (MSM), women who have sex with women (WSW), and those who are transgender.

Men who have sex with men

According to Dr. McNamara, preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) should be offered based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention eligibility criteria, which require that the patient is HIV negative, has had a male sex partner in the past 6 months, is not in a monogamous relationship, and has had anal sex or a bacterial sexually transmitted infection in the past 6 months. The two PrEP options, emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, are equally effective and have similar safety profiles, Dr. McNamara said, but patients with impaired renal function should receive the alafenamide formulation.

Dr. McNamara also advised screening gay men for extragenital STIs, noting a 13.3% increased risk. When asked about anal Pap testing for HPV, Dr. McNamara called the subject “very controversial,” and ultimately recommended against it, citing a lack of data linking anal HPV infection and dysplasia with later development of rectal carcinoma, as well as the nonactionable impact of a positive result.

“For me, the issue is ... if [a positive anal Pap test] is not going to change my management, if I don’t know that the anal HPV that I diagnose will result in cancer, should I continue to monitor it?” Dr. McNamara said.

Women who have sex with women

Beyond higher rates of psychological distress and substance abuse among lesbian and bisexual women, Dr. McNamara described increased risks of overweight and obesity, higher rates of smoking, and lower rates of Pap testing, all of which should prompt clinicians to advise accordingly, with cervical cancer screening in alignment with guidelines. Clinicians should also discuss HPV vaccination with patients, taking care to weigh benefits and risks, as “catch-up” HPV vaccination is not unilaterally recommended for adults older than 26 years.

Transgender patients

Discussing transgender patients, Dr. McNamara focused on cross-sex hormone therapy (CSHT), first noting the significant psychological benefits, including improvements in depression, somatization, interpersonal sensitivity, hostility, anxiety, phobic anxiety/agoraphobia, and quality of life.

According to Dr. McNamara, CSHT is relatively simple and may be safely administered by primary care providers. For transmasculine patients, testosterone supplementation is all that is needed, whereas transfeminine patients will require spironolactone or GnRH agonists to reduce testosterone and estradiol to increase feminizing hormones to pubertal levels.

CSHT is not without risks, Dr. McNamara said, including “very high” risks of erythrocytosis among transmasculine patients and venous thromboembolic disease among transfeminine patients; but these risks need to be considered in the context of an approximate 40% suicide rate among transgender individuals.

“I can tell you in my own practice that these [suicide] data ring true,” Dr. McNamara said. “Many, many of my patients have attempted suicide, so [CSHT] is something that you really want to think about right away.”

Even when additional risk factors are present, such as preexisting cardiovascular disease, Dr. McNamara suggested that “there are very few absolute contraindications to CSHT,” and described it as a “life-sustaining treatment” that should be viewed analogously with any other long-term management strategy, such as therapy for diabetes or hypertension.

Fostering a transgender-friendly practice

In an interview, Nicole Nisly, MD, codirector of the LGBTQ+ Clinic at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, reflected upon Dr. McNamara’s presentation, noting that primary care providers – with a little education – are the best candidates to care for transgender patients.

“I think [primary care providers] do a better job [caring for transgender patients] than endocrinologists, honestly, because they can provide care for the whole person,” Dr. Nisly said. “They can do a Pap, they can do STI screening, they can assess mood, they can [evaluate] safety, and the whole person, as opposed to endocrinologists, who do hormone therapy, but somebody else does everything else.”

Dr. Nisly emphasized the importance of personalizing care for transgender individuals, which depends upon a welcoming practice environment, with careful attention to language.

Foremost, Dr. Nisly recommended asking patients for their preferred name, sexual orientation, and gender identity.

“One of the most difficult things [for transgender patients] is to see notes with the wrong name – the name that makes them feel uncomfortable – or the wrong pronoun,” Dr. Nisly said. “That’s very important to the community.”

Dr. Nisly also recommended an alternative term for cross-sex hormone therapy.

“I hate cross-sex hormone therapy terminology, honestly,” Dr. Nisly said. “I just think it’s so unwelcoming, and I think most of our patients don’t like the terminology, so we use ‘gender-affirming hormone therapy.’”

Dr. Nisly explained that the term “cross-sex” assumes a conventional definition of sex, which is inherently flawed.

When discussing certain medical risk factors, such as pregnancy or HIV, it is helpful to know “sex assigned at birth” for both patients and their sexual partners, Dr. Nisly said. It’s best to ask in this way, instead of using terms like “boyfriend” or “girlfriend,” as “sex assigned at birth” is “terminology the community recognizes, affirms, and feels comfortable with.”

Concerning management of medical risk factors, Dr. Nisly offered some additional perspectives.

For one, she recommended giving PrEP to any patient who has a desire to be on PrEP, noting that this desire can indicate a change in future sexual practices, which the CDC criteria do not anticipate. She also advised in-hospital self-swabbing for extragenital STIs, as this can increase patient comfort and adherence. And, in contrast with Dr. McNamara, Dr. Nisly recommended anal Pap screening for any man that has sex with men and anyone with HIV of any gender. She noted that rates of anal dysplasia are “pretty high” among men who have sex with men, and that detection may reduce cancer risk.

For clinicians who would like to learn more about caring for transgender patients, Dr. Nisly recommended that they start by reading the World Professional Association for Transgender Health guidelines.

“It’s about 300 pages,” Dr. Nisly said, “but it is great.”

Dr. McNamara and Dr. Nisly reported no conflicts of interest.

Patients who are transgender, for instance, are nine times more likely to commit suicide than the general population (2015 U.S. Transgender Survey (USTS). Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. 2019 May 22. doi: 10.3886/ICPSR37229.v1), and those who are also Black have an estimated HIV prevalence of 62%, demonstrating the cumulative, negative health effects of intersectionality (www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/hiv-prevalence.html).

“Experiences with marginalization and stigma directly relate to some of the poor physical and mental health outcomes that these patients experience,” Megan McNamara, MD, said during a presentation at the American College of Physicians annual Internal Medicine meeting.

Dr. McNamara, who is director of the Gender Identity Veteran’s Experience (GIVE) Clinic, Veterans Affairs Northeast Ohio Healthcare System, Cleveland, offered a brief guide to managing LGBTQ+ patients. She emphasized increased rates of psychological distress and substance abuse, and encouraged familiarity with specific risks associated with three subgroups: men who have sex with men (MSM), women who have sex with women (WSW), and those who are transgender.

Men who have sex with men

According to Dr. McNamara, preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) should be offered based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention eligibility criteria, which require that the patient is HIV negative, has had a male sex partner in the past 6 months, is not in a monogamous relationship, and has had anal sex or a bacterial sexually transmitted infection in the past 6 months. The two PrEP options, emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, are equally effective and have similar safety profiles, Dr. McNamara said, but patients with impaired renal function should receive the alafenamide formulation.

Dr. McNamara also advised screening gay men for extragenital STIs, noting a 13.3% increased risk. When asked about anal Pap testing for HPV, Dr. McNamara called the subject “very controversial,” and ultimately recommended against it, citing a lack of data linking anal HPV infection and dysplasia with later development of rectal carcinoma, as well as the nonactionable impact of a positive result.

“For me, the issue is ... if [a positive anal Pap test] is not going to change my management, if I don’t know that the anal HPV that I diagnose will result in cancer, should I continue to monitor it?” Dr. McNamara said.

Women who have sex with women

Beyond higher rates of psychological distress and substance abuse among lesbian and bisexual women, Dr. McNamara described increased risks of overweight and obesity, higher rates of smoking, and lower rates of Pap testing, all of which should prompt clinicians to advise accordingly, with cervical cancer screening in alignment with guidelines. Clinicians should also discuss HPV vaccination with patients, taking care to weigh benefits and risks, as “catch-up” HPV vaccination is not unilaterally recommended for adults older than 26 years.

Transgender patients

Discussing transgender patients, Dr. McNamara focused on cross-sex hormone therapy (CSHT), first noting the significant psychological benefits, including improvements in depression, somatization, interpersonal sensitivity, hostility, anxiety, phobic anxiety/agoraphobia, and quality of life.

According to Dr. McNamara, CSHT is relatively simple and may be safely administered by primary care providers. For transmasculine patients, testosterone supplementation is all that is needed, whereas transfeminine patients will require spironolactone or GnRH agonists to reduce testosterone and estradiol to increase feminizing hormones to pubertal levels.

CSHT is not without risks, Dr. McNamara said, including “very high” risks of erythrocytosis among transmasculine patients and venous thromboembolic disease among transfeminine patients; but these risks need to be considered in the context of an approximate 40% suicide rate among transgender individuals.

“I can tell you in my own practice that these [suicide] data ring true,” Dr. McNamara said. “Many, many of my patients have attempted suicide, so [CSHT] is something that you really want to think about right away.”

Even when additional risk factors are present, such as preexisting cardiovascular disease, Dr. McNamara suggested that “there are very few absolute contraindications to CSHT,” and described it as a “life-sustaining treatment” that should be viewed analogously with any other long-term management strategy, such as therapy for diabetes or hypertension.

Fostering a transgender-friendly practice

In an interview, Nicole Nisly, MD, codirector of the LGBTQ+ Clinic at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, reflected upon Dr. McNamara’s presentation, noting that primary care providers – with a little education – are the best candidates to care for transgender patients.

“I think [primary care providers] do a better job [caring for transgender patients] than endocrinologists, honestly, because they can provide care for the whole person,” Dr. Nisly said. “They can do a Pap, they can do STI screening, they can assess mood, they can [evaluate] safety, and the whole person, as opposed to endocrinologists, who do hormone therapy, but somebody else does everything else.”

Dr. Nisly emphasized the importance of personalizing care for transgender individuals, which depends upon a welcoming practice environment, with careful attention to language.

Foremost, Dr. Nisly recommended asking patients for their preferred name, sexual orientation, and gender identity.

“One of the most difficult things [for transgender patients] is to see notes with the wrong name – the name that makes them feel uncomfortable – or the wrong pronoun,” Dr. Nisly said. “That’s very important to the community.”

Dr. Nisly also recommended an alternative term for cross-sex hormone therapy.

“I hate cross-sex hormone therapy terminology, honestly,” Dr. Nisly said. “I just think it’s so unwelcoming, and I think most of our patients don’t like the terminology, so we use ‘gender-affirming hormone therapy.’”

Dr. Nisly explained that the term “cross-sex” assumes a conventional definition of sex, which is inherently flawed.

When discussing certain medical risk factors, such as pregnancy or HIV, it is helpful to know “sex assigned at birth” for both patients and their sexual partners, Dr. Nisly said. It’s best to ask in this way, instead of using terms like “boyfriend” or “girlfriend,” as “sex assigned at birth” is “terminology the community recognizes, affirms, and feels comfortable with.”

Concerning management of medical risk factors, Dr. Nisly offered some additional perspectives.

For one, she recommended giving PrEP to any patient who has a desire to be on PrEP, noting that this desire can indicate a change in future sexual practices, which the CDC criteria do not anticipate. She also advised in-hospital self-swabbing for extragenital STIs, as this can increase patient comfort and adherence. And, in contrast with Dr. McNamara, Dr. Nisly recommended anal Pap screening for any man that has sex with men and anyone with HIV of any gender. She noted that rates of anal dysplasia are “pretty high” among men who have sex with men, and that detection may reduce cancer risk.

For clinicians who would like to learn more about caring for transgender patients, Dr. Nisly recommended that they start by reading the World Professional Association for Transgender Health guidelines.

“It’s about 300 pages,” Dr. Nisly said, “but it is great.”

Dr. McNamara and Dr. Nisly reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM INTERNAL MEDICINE 2021

HPV vaccination rates continue to climb among young adults in U.S.

Although vaccination rates against the human papillomavirus remain low for young adults across the United States, the number of self-reported HPV vaccinations among women and men aged between 18 and 21 years has markedly increased since 2010, according to new research findings.

The findings were published online April 27, 2021, as a research letter in JAMA.

In 2006, the Food and Drug Administration approved the HPV vaccine for the prevention of cervical cancer and genital warts in female patients. Three years later, the FDA approved the vaccine for the prevention of anogenital cancer and warts in male patients.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend two doses of the HPV vaccine for children aged 11-12 years. Adolescents and young adults may need three doses over the course of 6 months if they start their vaccine series on or following their 15th birthday.