User login

The language of AI and its applications in health care

AI is a group of nonhuman techniques that utilize automated learning methods to extract information from datasets through generalization, classification, prediction, and association. In other words, AI is the simulation of human intelligence processes by machines. The branches of AI include natural language processing, speech recognition, machine vision, and expert systems. AI can make clinical care more efficient; however, many find its confusing terminology to be a barrier.1 This article provides concise definitions of AI terms and is intended to help physicians better understand how AI methods can be applied to clinical care. The clinical application of natural language processing and machine vision applications are more clinically intuitive than the roles of machine learning algorithms.

Machine learning and algorithms

Machine learning is a branch of AI that uses data and algorithms to mimic human reasoning through classification, pattern recognition, and prediction. Supervised and unsupervised machine-learning algorithms can analyze data and recognize undetected associations and relationships.

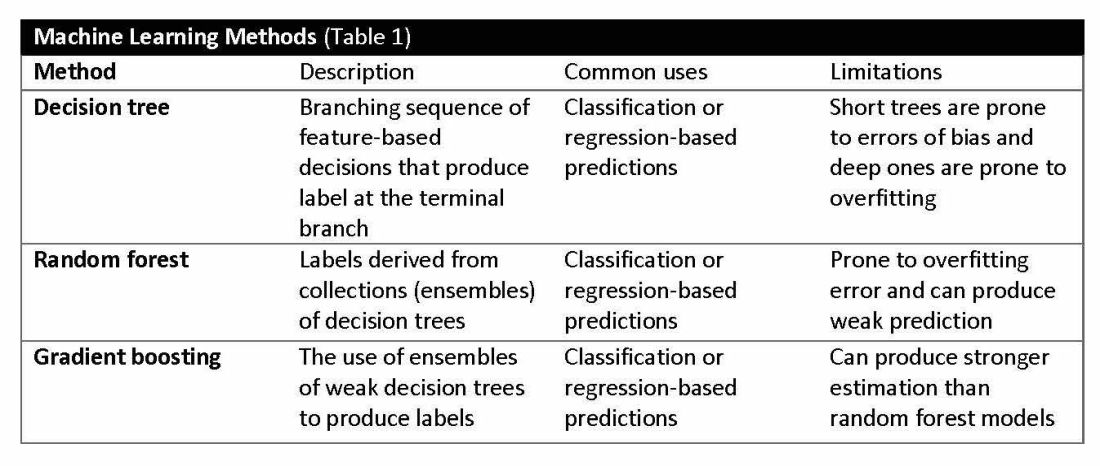

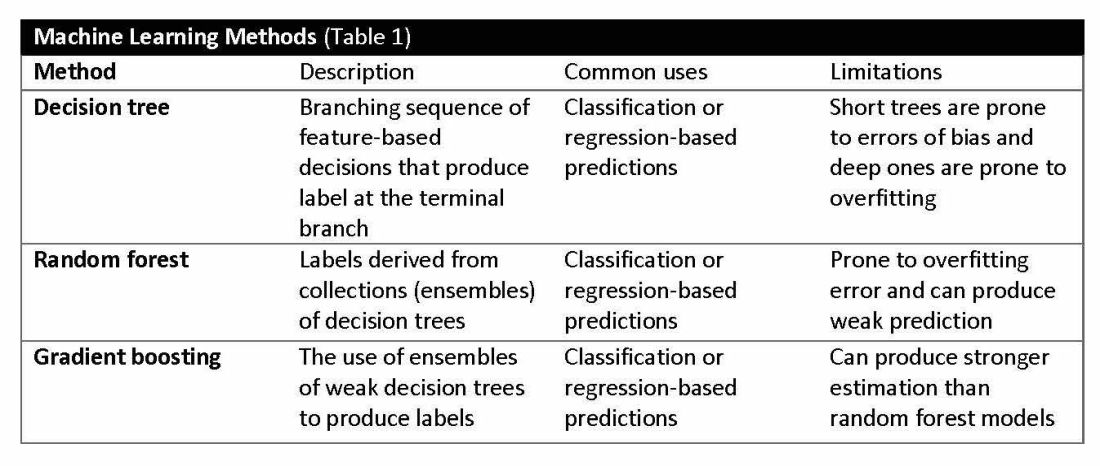

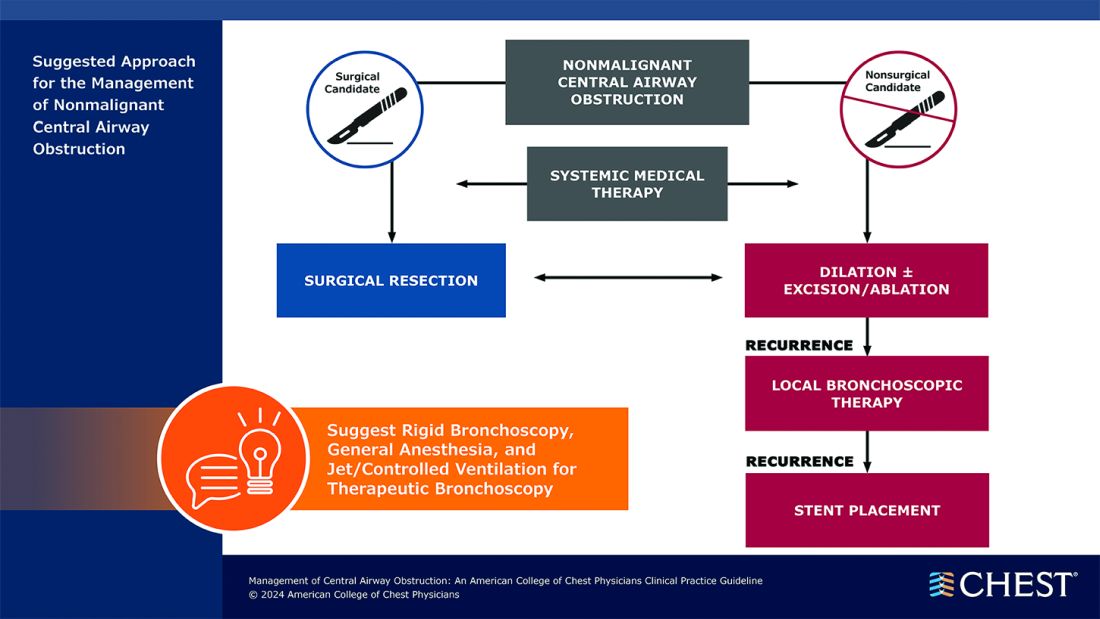

Supervised learning involves training models to make predictions using data sets that have correct outcome parameters called labels using predictive fields called features. Machine learning uses iterative analysis including random forest, decision tree, and gradient boosting methods that minimize predictive error metrics (see Table 1). This approach is widely used to improve diagnoses, predict disease progression or exacerbation, and personalize treatment plan modifications.

Supervised machine learning methods can be particularly effective for processing large volumes of medical information to identify patterns and make accurate predictions. In contrast, unsupervised learning techniques can analyze unlabeled data and help clinicians uncover hidden patterns or undetected groupings. Techniques including clustering, exploratory analysis, and anomaly detection are common applications. Both of these machine-learning approaches can be used to extract novel and helpful insights.

The utility of machine learning analyses depends on the size and accuracy of the available datasets. Small datasets can limit usability, while large datasets require substantial computational power. Predictive models are generated using training datasets and evaluated using separate evaluation datasets. Deep learning models, a subset of machine learning, can automatically readjust themselves to maintain or improve accuracy when analyzing new observations that include accurate labels.

Challenges of algorithms and calibration

Machine learning algorithms vary in complexity and accuracy. For example, a simple logistic regression model using time, date, latitude, and indoor/outdoor location can accurately recommend sunscreen application. This model identifies when solar radiation is high enough to warrant sunscreen use, avoiding unnecessary recommendations during nighttime hours or indoor locations. A more complex model might suffer from model overfitting and inappropriately suggest sunscreen before a tanning salon visit.

Complex machine learning models, like support vector machine (SVM) and decision tree methods, are useful when many features have predictive power. SVMs are useful for small but complex datasets. Features are manipulated in a multidimensional space to maximize the “margins” separating 2 groups. Decision tree analyses are useful when more than 2 groups are being analyzed. SVM and decision tree models can also lose accuracy by data overfitting.

Consider the development of an SVM analysis to predict whether an individual is a fellow or a senior faculty member. One could use high gray hair density feature values to identify senior faculty. When this algorithm is applied to an individual with alopecia, no amount of model adjustment can achieve high levels of discrimination because no hair is present. Rather than overfitting the model by adding more nonpredictive features, individuals with alopecia are analyzed by their own algorithm (tree) that uses the skin wrinkle/solar damage rather than the gray hair density feature.

Decision tree ensemble algorithms like random forest and gradient boosting use feature-based decision trees to process and classify data. Random forests are robust, scalable, and versatile, providing classifications and predictions while protecting against inaccurate data and outliers and have the advantage of being able to handle both categorical and continuous features. Gradient boosting, which uses an ensemble of weak decision trees, often outperforms random forests when individual trees perform only slightly better than random chance. This method incrementally builds the model by optimizing the residual errors of previous trees, leading to more accurate predictions.

In practice, gradient boosting can be used to fine-tune diagnostic models, improving their precision and reliability. A recent example of how gradient boosting of random forest predictions yielded highly accurate predictions for unplanned vasopressor initiation and intubation events 2 to 4 hours before an ICU adult became unstable.2

Assessing the accuracy of algorithms

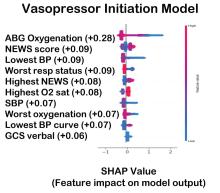

The value of the data set is directly related to the accuracy of its labels. Traditional methods that measure model performance, such as sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values (PPV and NPV), have important limitations. They provide little insight into how a complex model made its prediction. Understanding which individual features drive model accuracy is key to fostering trust in model predictions. This can be done by comparing model output with and without including individual features. The results of all possible combinations are aggregated according to feature importance, which is summarized in the Shapley value for each model feature. Higher values indicate greater relative importance. SHAP plots help identify how much and how often specific features change the model output, presenting values of individual model estimates with and without a specific feature (see Figure 1).

Promoting AI use

AI and machine learning algorithms are coming to patient care. Understanding the language of AI helps caregivers integrate these tools into their practices. The science of AI faces serious challenges. Algorithms must be recalibrated to keep pace as therapies advance, disease prevalence changes, and our population ages. AI must address new challenges as they confront those suffering from respiratory diseases. This resource encourages clinicians with novel approaches by using AI methodologies to advance their development. We can better address future health care needs by promoting the equitable use of AI technologies, especially among socially disadvantaged developers.

References

1. Lilly CM, Soni AV, Dunlap D, et al. Advancing point of care testing by application of machine learning techniques and artificial intelligence. Chest. 2024 (in press).

2. Lilly CM, Kirk D, Pessach IM, et al. Application of machine learning models to biomedical and information system signals from critically ill adults. Chest. 2024;165(5):1139-1148.

AI is a group of nonhuman techniques that utilize automated learning methods to extract information from datasets through generalization, classification, prediction, and association. In other words, AI is the simulation of human intelligence processes by machines. The branches of AI include natural language processing, speech recognition, machine vision, and expert systems. AI can make clinical care more efficient; however, many find its confusing terminology to be a barrier.1 This article provides concise definitions of AI terms and is intended to help physicians better understand how AI methods can be applied to clinical care. The clinical application of natural language processing and machine vision applications are more clinically intuitive than the roles of machine learning algorithms.

Machine learning and algorithms

Machine learning is a branch of AI that uses data and algorithms to mimic human reasoning through classification, pattern recognition, and prediction. Supervised and unsupervised machine-learning algorithms can analyze data and recognize undetected associations and relationships.

Supervised learning involves training models to make predictions using data sets that have correct outcome parameters called labels using predictive fields called features. Machine learning uses iterative analysis including random forest, decision tree, and gradient boosting methods that minimize predictive error metrics (see Table 1). This approach is widely used to improve diagnoses, predict disease progression or exacerbation, and personalize treatment plan modifications.

Supervised machine learning methods can be particularly effective for processing large volumes of medical information to identify patterns and make accurate predictions. In contrast, unsupervised learning techniques can analyze unlabeled data and help clinicians uncover hidden patterns or undetected groupings. Techniques including clustering, exploratory analysis, and anomaly detection are common applications. Both of these machine-learning approaches can be used to extract novel and helpful insights.

The utility of machine learning analyses depends on the size and accuracy of the available datasets. Small datasets can limit usability, while large datasets require substantial computational power. Predictive models are generated using training datasets and evaluated using separate evaluation datasets. Deep learning models, a subset of machine learning, can automatically readjust themselves to maintain or improve accuracy when analyzing new observations that include accurate labels.

Challenges of algorithms and calibration

Machine learning algorithms vary in complexity and accuracy. For example, a simple logistic regression model using time, date, latitude, and indoor/outdoor location can accurately recommend sunscreen application. This model identifies when solar radiation is high enough to warrant sunscreen use, avoiding unnecessary recommendations during nighttime hours or indoor locations. A more complex model might suffer from model overfitting and inappropriately suggest sunscreen before a tanning salon visit.

Complex machine learning models, like support vector machine (SVM) and decision tree methods, are useful when many features have predictive power. SVMs are useful for small but complex datasets. Features are manipulated in a multidimensional space to maximize the “margins” separating 2 groups. Decision tree analyses are useful when more than 2 groups are being analyzed. SVM and decision tree models can also lose accuracy by data overfitting.

Consider the development of an SVM analysis to predict whether an individual is a fellow or a senior faculty member. One could use high gray hair density feature values to identify senior faculty. When this algorithm is applied to an individual with alopecia, no amount of model adjustment can achieve high levels of discrimination because no hair is present. Rather than overfitting the model by adding more nonpredictive features, individuals with alopecia are analyzed by their own algorithm (tree) that uses the skin wrinkle/solar damage rather than the gray hair density feature.

Decision tree ensemble algorithms like random forest and gradient boosting use feature-based decision trees to process and classify data. Random forests are robust, scalable, and versatile, providing classifications and predictions while protecting against inaccurate data and outliers and have the advantage of being able to handle both categorical and continuous features. Gradient boosting, which uses an ensemble of weak decision trees, often outperforms random forests when individual trees perform only slightly better than random chance. This method incrementally builds the model by optimizing the residual errors of previous trees, leading to more accurate predictions.

In practice, gradient boosting can be used to fine-tune diagnostic models, improving their precision and reliability. A recent example of how gradient boosting of random forest predictions yielded highly accurate predictions for unplanned vasopressor initiation and intubation events 2 to 4 hours before an ICU adult became unstable.2

Assessing the accuracy of algorithms

The value of the data set is directly related to the accuracy of its labels. Traditional methods that measure model performance, such as sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values (PPV and NPV), have important limitations. They provide little insight into how a complex model made its prediction. Understanding which individual features drive model accuracy is key to fostering trust in model predictions. This can be done by comparing model output with and without including individual features. The results of all possible combinations are aggregated according to feature importance, which is summarized in the Shapley value for each model feature. Higher values indicate greater relative importance. SHAP plots help identify how much and how often specific features change the model output, presenting values of individual model estimates with and without a specific feature (see Figure 1).

Promoting AI use

AI and machine learning algorithms are coming to patient care. Understanding the language of AI helps caregivers integrate these tools into their practices. The science of AI faces serious challenges. Algorithms must be recalibrated to keep pace as therapies advance, disease prevalence changes, and our population ages. AI must address new challenges as they confront those suffering from respiratory diseases. This resource encourages clinicians with novel approaches by using AI methodologies to advance their development. We can better address future health care needs by promoting the equitable use of AI technologies, especially among socially disadvantaged developers.

References

1. Lilly CM, Soni AV, Dunlap D, et al. Advancing point of care testing by application of machine learning techniques and artificial intelligence. Chest. 2024 (in press).

2. Lilly CM, Kirk D, Pessach IM, et al. Application of machine learning models to biomedical and information system signals from critically ill adults. Chest. 2024;165(5):1139-1148.

AI is a group of nonhuman techniques that utilize automated learning methods to extract information from datasets through generalization, classification, prediction, and association. In other words, AI is the simulation of human intelligence processes by machines. The branches of AI include natural language processing, speech recognition, machine vision, and expert systems. AI can make clinical care more efficient; however, many find its confusing terminology to be a barrier.1 This article provides concise definitions of AI terms and is intended to help physicians better understand how AI methods can be applied to clinical care. The clinical application of natural language processing and machine vision applications are more clinically intuitive than the roles of machine learning algorithms.

Machine learning and algorithms

Machine learning is a branch of AI that uses data and algorithms to mimic human reasoning through classification, pattern recognition, and prediction. Supervised and unsupervised machine-learning algorithms can analyze data and recognize undetected associations and relationships.

Supervised learning involves training models to make predictions using data sets that have correct outcome parameters called labels using predictive fields called features. Machine learning uses iterative analysis including random forest, decision tree, and gradient boosting methods that minimize predictive error metrics (see Table 1). This approach is widely used to improve diagnoses, predict disease progression or exacerbation, and personalize treatment plan modifications.

Supervised machine learning methods can be particularly effective for processing large volumes of medical information to identify patterns and make accurate predictions. In contrast, unsupervised learning techniques can analyze unlabeled data and help clinicians uncover hidden patterns or undetected groupings. Techniques including clustering, exploratory analysis, and anomaly detection are common applications. Both of these machine-learning approaches can be used to extract novel and helpful insights.

The utility of machine learning analyses depends on the size and accuracy of the available datasets. Small datasets can limit usability, while large datasets require substantial computational power. Predictive models are generated using training datasets and evaluated using separate evaluation datasets. Deep learning models, a subset of machine learning, can automatically readjust themselves to maintain or improve accuracy when analyzing new observations that include accurate labels.

Challenges of algorithms and calibration

Machine learning algorithms vary in complexity and accuracy. For example, a simple logistic regression model using time, date, latitude, and indoor/outdoor location can accurately recommend sunscreen application. This model identifies when solar radiation is high enough to warrant sunscreen use, avoiding unnecessary recommendations during nighttime hours or indoor locations. A more complex model might suffer from model overfitting and inappropriately suggest sunscreen before a tanning salon visit.

Complex machine learning models, like support vector machine (SVM) and decision tree methods, are useful when many features have predictive power. SVMs are useful for small but complex datasets. Features are manipulated in a multidimensional space to maximize the “margins” separating 2 groups. Decision tree analyses are useful when more than 2 groups are being analyzed. SVM and decision tree models can also lose accuracy by data overfitting.

Consider the development of an SVM analysis to predict whether an individual is a fellow or a senior faculty member. One could use high gray hair density feature values to identify senior faculty. When this algorithm is applied to an individual with alopecia, no amount of model adjustment can achieve high levels of discrimination because no hair is present. Rather than overfitting the model by adding more nonpredictive features, individuals with alopecia are analyzed by their own algorithm (tree) that uses the skin wrinkle/solar damage rather than the gray hair density feature.

Decision tree ensemble algorithms like random forest and gradient boosting use feature-based decision trees to process and classify data. Random forests are robust, scalable, and versatile, providing classifications and predictions while protecting against inaccurate data and outliers and have the advantage of being able to handle both categorical and continuous features. Gradient boosting, which uses an ensemble of weak decision trees, often outperforms random forests when individual trees perform only slightly better than random chance. This method incrementally builds the model by optimizing the residual errors of previous trees, leading to more accurate predictions.

In practice, gradient boosting can be used to fine-tune diagnostic models, improving their precision and reliability. A recent example of how gradient boosting of random forest predictions yielded highly accurate predictions for unplanned vasopressor initiation and intubation events 2 to 4 hours before an ICU adult became unstable.2

Assessing the accuracy of algorithms

The value of the data set is directly related to the accuracy of its labels. Traditional methods that measure model performance, such as sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values (PPV and NPV), have important limitations. They provide little insight into how a complex model made its prediction. Understanding which individual features drive model accuracy is key to fostering trust in model predictions. This can be done by comparing model output with and without including individual features. The results of all possible combinations are aggregated according to feature importance, which is summarized in the Shapley value for each model feature. Higher values indicate greater relative importance. SHAP plots help identify how much and how often specific features change the model output, presenting values of individual model estimates with and without a specific feature (see Figure 1).

Promoting AI use

AI and machine learning algorithms are coming to patient care. Understanding the language of AI helps caregivers integrate these tools into their practices. The science of AI faces serious challenges. Algorithms must be recalibrated to keep pace as therapies advance, disease prevalence changes, and our population ages. AI must address new challenges as they confront those suffering from respiratory diseases. This resource encourages clinicians with novel approaches by using AI methodologies to advance their development. We can better address future health care needs by promoting the equitable use of AI technologies, especially among socially disadvantaged developers.

References

1. Lilly CM, Soni AV, Dunlap D, et al. Advancing point of care testing by application of machine learning techniques and artificial intelligence. Chest. 2024 (in press).

2. Lilly CM, Kirk D, Pessach IM, et al. Application of machine learning models to biomedical and information system signals from critically ill adults. Chest. 2024;165(5):1139-1148.

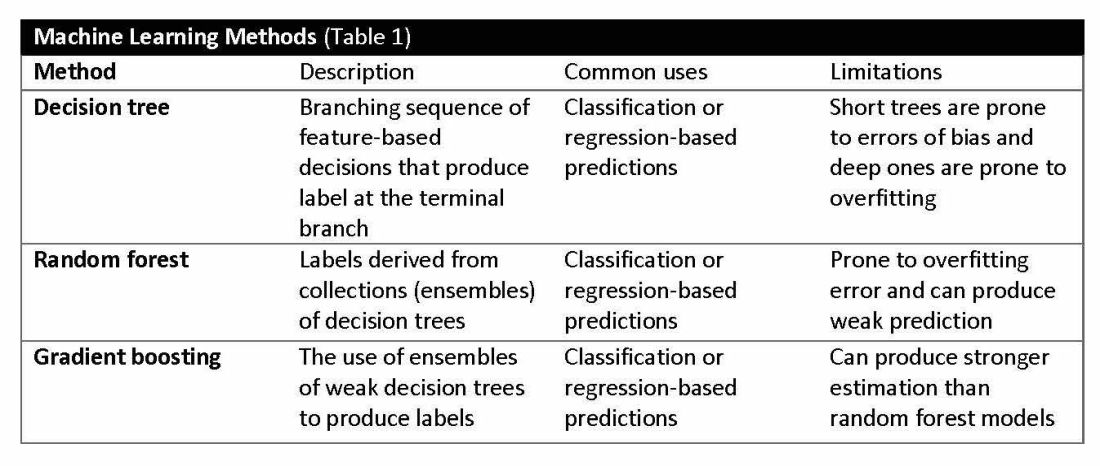

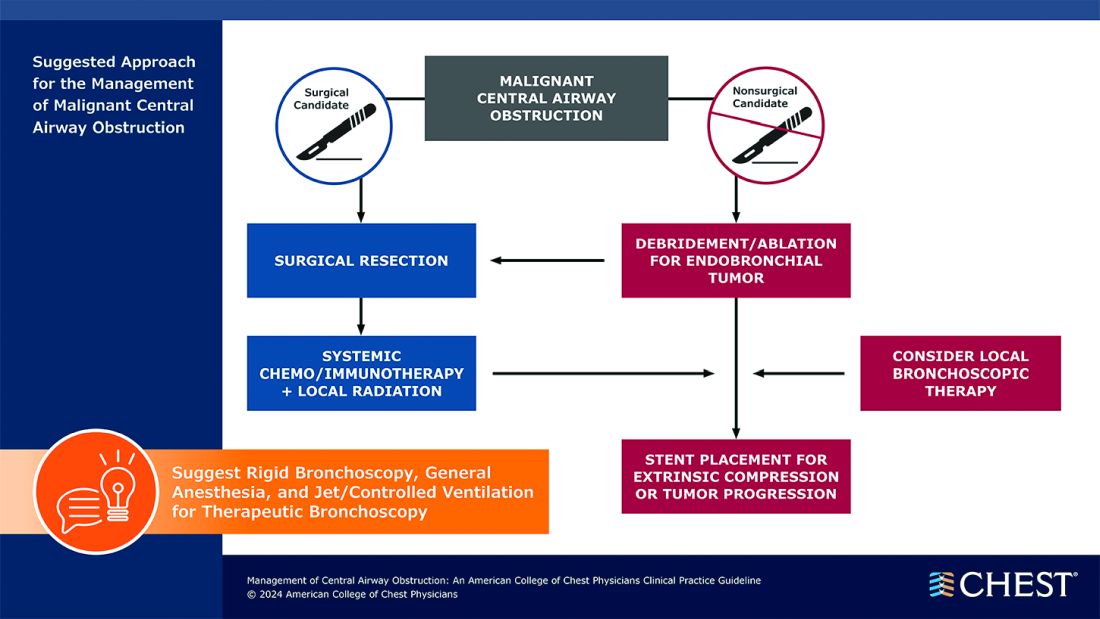

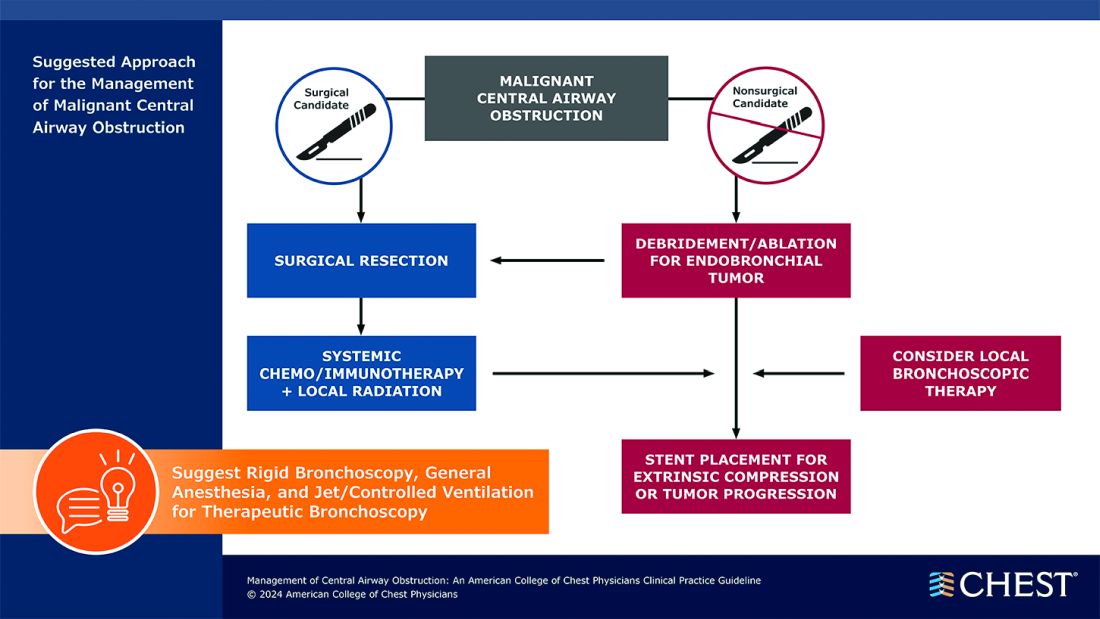

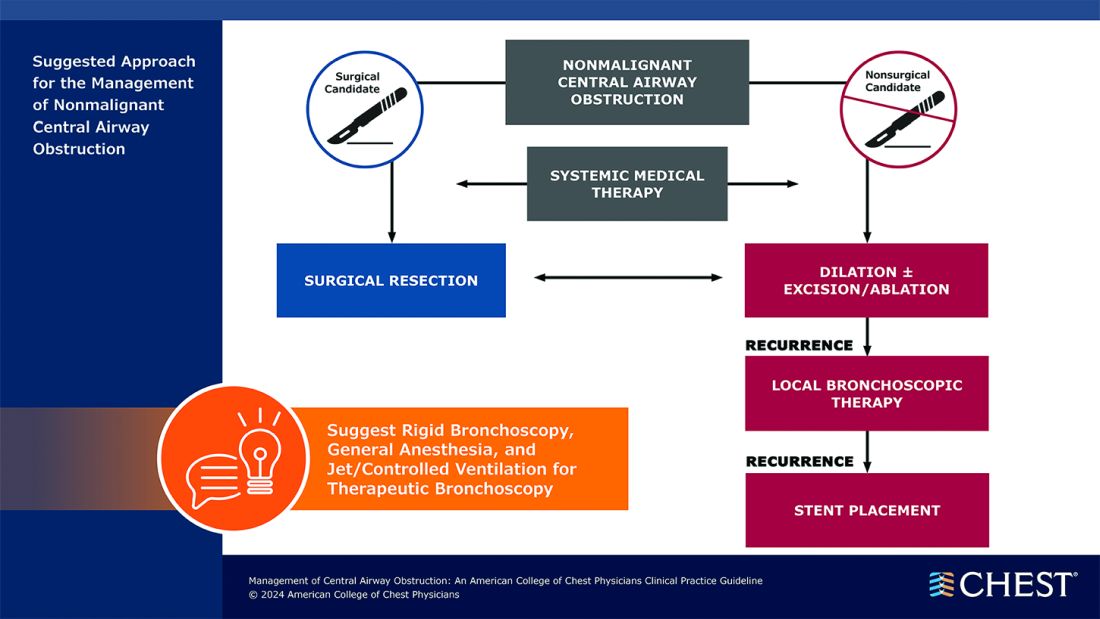

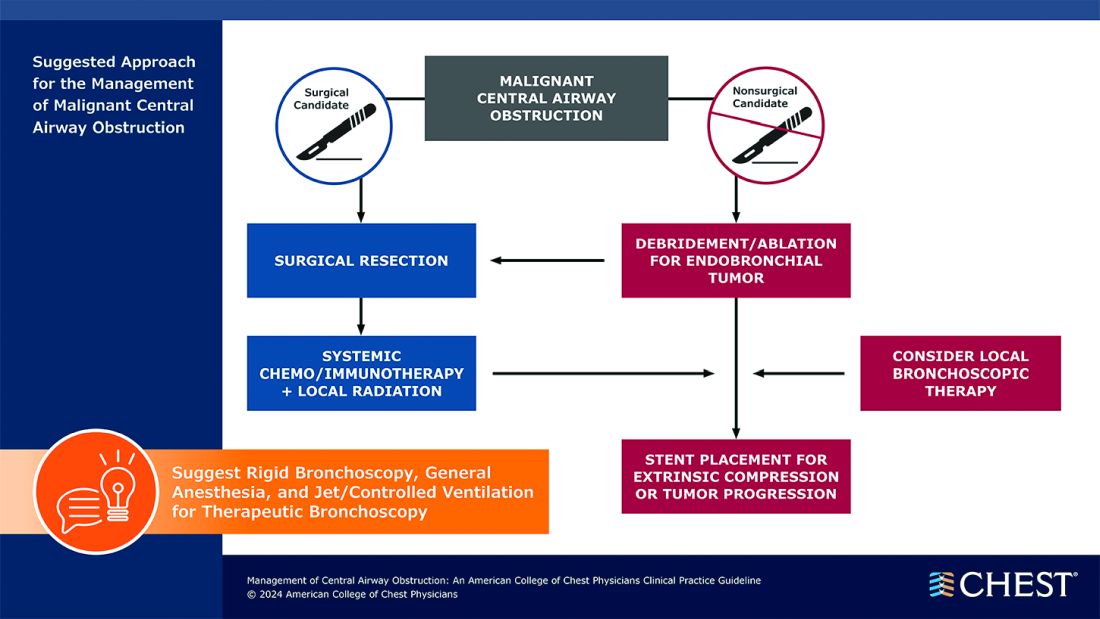

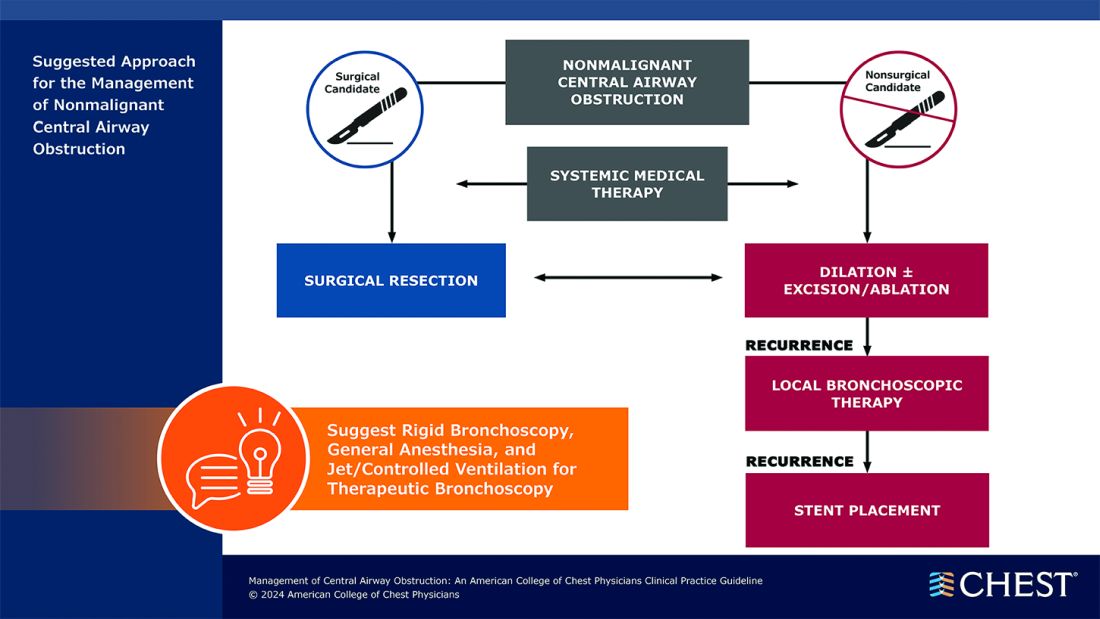

CHEST releases new guideline on management of central airway obstruction

CHEST recently released a new clinical guideline on central airway obstruction (CAO).

“Central airway obstruction is associated with a poor prognosis, and the management of CAO is highly variable dependent on the provider expertise and local resources. By releasing this guideline, the panel hopes to standardize the definition of CAO and provide guidance for the management of patients to optimize care and improve outcomes,” said Kamran Mahmood, MD, MPH, FCCP, lead author on the guideline. “The guideline recommendations are developed using GRADE methodology and based on thorough evidence review and expert input. But the quality of overall evidence is very low, and the panel calls for well-designed studies and randomized controlled trials for the management of CAO.”

CAO can be caused by a variety of malignant and nonmalignant disorders, and multiple specialists may be involved in the care, including pulmonologists, interventional pulmonologists, radiologists, anesthesiologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, thoracic surgeons and otolaryngologists, etc. The panel recommends shared decision-making with the patients and a multidisciplinary approach to manage CAO.

Below, you’ll find flowcharts outlining the suggested treatments for patients with a malignant or nonmalignant CAO.

Visit www.chestnet.org/CAO-guideline to download the flowcharts and access the complete guideline.

CHEST recently released a new clinical guideline on central airway obstruction (CAO).

“Central airway obstruction is associated with a poor prognosis, and the management of CAO is highly variable dependent on the provider expertise and local resources. By releasing this guideline, the panel hopes to standardize the definition of CAO and provide guidance for the management of patients to optimize care and improve outcomes,” said Kamran Mahmood, MD, MPH, FCCP, lead author on the guideline. “The guideline recommendations are developed using GRADE methodology and based on thorough evidence review and expert input. But the quality of overall evidence is very low, and the panel calls for well-designed studies and randomized controlled trials for the management of CAO.”

CAO can be caused by a variety of malignant and nonmalignant disorders, and multiple specialists may be involved in the care, including pulmonologists, interventional pulmonologists, radiologists, anesthesiologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, thoracic surgeons and otolaryngologists, etc. The panel recommends shared decision-making with the patients and a multidisciplinary approach to manage CAO.

Below, you’ll find flowcharts outlining the suggested treatments for patients with a malignant or nonmalignant CAO.

Visit www.chestnet.org/CAO-guideline to download the flowcharts and access the complete guideline.

CHEST recently released a new clinical guideline on central airway obstruction (CAO).

“Central airway obstruction is associated with a poor prognosis, and the management of CAO is highly variable dependent on the provider expertise and local resources. By releasing this guideline, the panel hopes to standardize the definition of CAO and provide guidance for the management of patients to optimize care and improve outcomes,” said Kamran Mahmood, MD, MPH, FCCP, lead author on the guideline. “The guideline recommendations are developed using GRADE methodology and based on thorough evidence review and expert input. But the quality of overall evidence is very low, and the panel calls for well-designed studies and randomized controlled trials for the management of CAO.”

CAO can be caused by a variety of malignant and nonmalignant disorders, and multiple specialists may be involved in the care, including pulmonologists, interventional pulmonologists, radiologists, anesthesiologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, thoracic surgeons and otolaryngologists, etc. The panel recommends shared decision-making with the patients and a multidisciplinary approach to manage CAO.

Below, you’ll find flowcharts outlining the suggested treatments for patients with a malignant or nonmalignant CAO.

Visit www.chestnet.org/CAO-guideline to download the flowcharts and access the complete guideline.

Obesity Is Not a Moral Failing, GI Physician Says

It takes a long time for some patients with obesity to acknowledge that they need help, said Dr. Laster, a bariatric endoscopist who specializes in gastroenterology, nutrition, and obesity medicine at Gut Theory Total Digestive Care, and Georgetown University Hospital in Washington. “If somebody has high blood pressure or has a cut or has chest pain, you don’t wait for things. You would go seek help immediately. I wish more patients reached out sooner and didn’t struggle.”

Another big challenge is making sure patients have insurance coverage for things like medications, surgery, and bariatric endoscopy, she added.

Her response: education and advocacy. “I’m giving as many talks as I can to fellows, creating courses for residents and fellows and medical students” to change the way physicians talk about obesity and excess weight, she said. Patients need to understand that physicians care about them, that “we’re not judging and we’re changing that perspective.”

Dr. Laster is also working with members of Congress to get bills passed for coverage of obesity medication and procedures. In an interview with GI & Hepatology News, she spoke more about the intersection between nutrition, medicine and bariatric procedures and the importance of offering patients multiple solutions.

Q: Why did you choose GI?

It allowed me a little bit of everything. You have clinic, where you can really interact with patients and get to the root of their problem. You have preventative care with routine colonoscopies and upper endoscopies to prevent for cancer. But then you also have fun stuff — which my mom told me to stop saying out loud — ‘bleeders’ and acute things that you get to fix immediately. So, you get the adrenaline rush too. I like it because you get the best of all worlds and it’s really hard to get bored.

Q: How did you become interested in nutrition and bariatric endoscopy?

My parents had a garden and never let us eat processed foods. In residency, I kept seeing the same medical problems over and over again. Everybody had high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes. Then in GI clinic, everybody had abdominal pain, bloating, constipation, heartburn, and a million GI appointments for these same things. Everyone’s upper endoscopy or colonoscopy was negative. Something else had to be going on.

And that’s sort of where it came from; figuring out the common denominator. It had to be what people were eating. There’s also the prevalence of patients with obesity going up every single year. Correlating all these other medical problems with people’s diets led me down the rabbit hole of: What else can we be doing?

Most people don’t want to undergo surgery. Only 2% of people eligible for surgery actually do it, even though it works. The reasons are because it’s invasive or there’s shame behind it. Bariatric endoscopy is another option that’s out here, that’s less invasive. I’m an endoscopist and gastroenterologist. I should be able to offer all those things and I should know more about nutrition. We don’t talk about it enough.

Q: Do you think more GI doctors should become better educated about nutrition?

100%. Every patient I see has seen a GI doctor before and says, ‘No one has ever told me that if I have carbonated beverages and cheese every day, I’m going to be bloated and constipated.’ And that shouldn’t be the case.

Q: Why do you think that more GI doctors don’t get the education on nutrition during their medical training?

I think it’s our healthcare system. It’s very much focused on secondary treatment rather than preventative care. There’s no emphasis on preventing things from happening.

We’re really good at reactionary medicine. People who have an ulcer, big polyps and colon cancer, esophageal cancer — we do those things really well. But I think because there’s no ICD-10 codes for preventive care via nutrition education, and no good reimbursement, then there’s no incentive for hospital systems to pay for these things. It’s a system based on RVUs (relative value units) and numbers. That’s been our trajectory. We’ve been so focused on reactionary medicine rather than saying, ‘Okay, let’s stop this from happening.’

We just didn’t talk about nutrition in medical school, in residency, or in fellowship. It was looked at as a soft science. When I was in school, people would also say, ‘No one’s going to change. So it’s a waste of your time essentially to talk to people about making dietary changes.’ I feel like if you give people the opportunity, you have to give them the chance. You can’t just write everybody off. Some people won’t change, but that’s okay. They should at least have the opportunity to do so.

Q: How do you determine whether a patient is a good candidate for bariatric surgery?

It’s based on the guidelines: If they meet the BMI requirements, if they have obesity-associated comorbidities, their risk for surgery is low. But it’s also whether they want to do it or not. A patient has to be in the mindset and be ready for it. They need to want to have surgery or bariatric endoscopy, or to use medications, or start to make a change. Some people aren’t there yet — that preemptive stage of making a change. They want the solution, but they’re not ready to do that legwork yet.

And all of it is work. I tell patients, ‘Whether it’s medication or bariatric endoscopy or bariatric surgery, you still have work to do. None of it is going to just magically happen where you could just continue to do the same thing you’re doing now and you’re going to lose weight and keep it off.’

Q: What advances in obesity prevention are you excited about?

I’m excited that bariatric endoscopy came about in the first place, because in every other field there are less invasive approaches that have become available. I’m also excited about the emergence of weight loss medication, like GLP-1s. I think they are a tool that we need.

Q: Do you think the weight loss medications may negate the need for surgery?

I don’t think they necessarily reduce the need for surgery. There’s still a lot we don’t know about why they work in some patients and why they don’t work in others.

Some of our colleagues have come up with phenotypes and blood tests so we can better understand which things will work in different patients. Surgery doesn’t work for some patients. People may need a combination of both after they reach a plateau. I’m excited that people see this as something that we should be researching and putting more effort into — that obesity isn’t a disease of moral failure, that people with excess weight just need to ‘move more’ or ‘eat less’ and it’s their fault. I’m glad people are starting to understand that.

Q: What teacher or mentor had the greatest impact on you?

Probably two. One of them is Andrea E Reid, MD, MPH, a dean of medicine at Harvard. She gives you such motivation to achieve things, no matter how big your idea is or how crazy it may seem. If you have something that you think is important, you go after it. Another person is Christopher C. Thompson, MD, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the father of bariatric endoscopy in a sense. He embodies what Dr. Reid talks about: crazy big ideas. And he goes after them and he succeeds. Having him push me and giving me that type of encouragement was invaluable.

Q: Describe how you would spend a free Saturday afternoon.

Every Saturday is yoga or some type of movement. Spending some time outside doing something, whether it’s messing around with plants that I’m not very good at, or going for a walk.

Lightning Round

Texting or talking?

Text

Favorite city in U.S. besides the one you live in?

New York

Favorite breakfast?

Avocado toast

Place you most want to travel to?

Istanbul

Favorite season?

Fall

Favorite ice cream flavor?

Raspberry sorbet

How many cups of coffee do you drink per day?

One

Best place you ever went on vacation?

Greece

If you weren’t a gastroenterologist, what would you be?

Own a clothing store

Favorite type of music?

Old school R&B

Favorite movie genre?

Romantic comedy or drama

Cat person or dog person?

Dog

Favorite sport?

Football

Favorite holiday?

Christmas

Optimist or pessimist?

Optimist

It takes a long time for some patients with obesity to acknowledge that they need help, said Dr. Laster, a bariatric endoscopist who specializes in gastroenterology, nutrition, and obesity medicine at Gut Theory Total Digestive Care, and Georgetown University Hospital in Washington. “If somebody has high blood pressure or has a cut or has chest pain, you don’t wait for things. You would go seek help immediately. I wish more patients reached out sooner and didn’t struggle.”

Another big challenge is making sure patients have insurance coverage for things like medications, surgery, and bariatric endoscopy, she added.

Her response: education and advocacy. “I’m giving as many talks as I can to fellows, creating courses for residents and fellows and medical students” to change the way physicians talk about obesity and excess weight, she said. Patients need to understand that physicians care about them, that “we’re not judging and we’re changing that perspective.”

Dr. Laster is also working with members of Congress to get bills passed for coverage of obesity medication and procedures. In an interview with GI & Hepatology News, she spoke more about the intersection between nutrition, medicine and bariatric procedures and the importance of offering patients multiple solutions.

Q: Why did you choose GI?

It allowed me a little bit of everything. You have clinic, where you can really interact with patients and get to the root of their problem. You have preventative care with routine colonoscopies and upper endoscopies to prevent for cancer. But then you also have fun stuff — which my mom told me to stop saying out loud — ‘bleeders’ and acute things that you get to fix immediately. So, you get the adrenaline rush too. I like it because you get the best of all worlds and it’s really hard to get bored.

Q: How did you become interested in nutrition and bariatric endoscopy?

My parents had a garden and never let us eat processed foods. In residency, I kept seeing the same medical problems over and over again. Everybody had high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes. Then in GI clinic, everybody had abdominal pain, bloating, constipation, heartburn, and a million GI appointments for these same things. Everyone’s upper endoscopy or colonoscopy was negative. Something else had to be going on.

And that’s sort of where it came from; figuring out the common denominator. It had to be what people were eating. There’s also the prevalence of patients with obesity going up every single year. Correlating all these other medical problems with people’s diets led me down the rabbit hole of: What else can we be doing?

Most people don’t want to undergo surgery. Only 2% of people eligible for surgery actually do it, even though it works. The reasons are because it’s invasive or there’s shame behind it. Bariatric endoscopy is another option that’s out here, that’s less invasive. I’m an endoscopist and gastroenterologist. I should be able to offer all those things and I should know more about nutrition. We don’t talk about it enough.

Q: Do you think more GI doctors should become better educated about nutrition?

100%. Every patient I see has seen a GI doctor before and says, ‘No one has ever told me that if I have carbonated beverages and cheese every day, I’m going to be bloated and constipated.’ And that shouldn’t be the case.

Q: Why do you think that more GI doctors don’t get the education on nutrition during their medical training?

I think it’s our healthcare system. It’s very much focused on secondary treatment rather than preventative care. There’s no emphasis on preventing things from happening.

We’re really good at reactionary medicine. People who have an ulcer, big polyps and colon cancer, esophageal cancer — we do those things really well. But I think because there’s no ICD-10 codes for preventive care via nutrition education, and no good reimbursement, then there’s no incentive for hospital systems to pay for these things. It’s a system based on RVUs (relative value units) and numbers. That’s been our trajectory. We’ve been so focused on reactionary medicine rather than saying, ‘Okay, let’s stop this from happening.’

We just didn’t talk about nutrition in medical school, in residency, or in fellowship. It was looked at as a soft science. When I was in school, people would also say, ‘No one’s going to change. So it’s a waste of your time essentially to talk to people about making dietary changes.’ I feel like if you give people the opportunity, you have to give them the chance. You can’t just write everybody off. Some people won’t change, but that’s okay. They should at least have the opportunity to do so.

Q: How do you determine whether a patient is a good candidate for bariatric surgery?

It’s based on the guidelines: If they meet the BMI requirements, if they have obesity-associated comorbidities, their risk for surgery is low. But it’s also whether they want to do it or not. A patient has to be in the mindset and be ready for it. They need to want to have surgery or bariatric endoscopy, or to use medications, or start to make a change. Some people aren’t there yet — that preemptive stage of making a change. They want the solution, but they’re not ready to do that legwork yet.

And all of it is work. I tell patients, ‘Whether it’s medication or bariatric endoscopy or bariatric surgery, you still have work to do. None of it is going to just magically happen where you could just continue to do the same thing you’re doing now and you’re going to lose weight and keep it off.’

Q: What advances in obesity prevention are you excited about?

I’m excited that bariatric endoscopy came about in the first place, because in every other field there are less invasive approaches that have become available. I’m also excited about the emergence of weight loss medication, like GLP-1s. I think they are a tool that we need.

Q: Do you think the weight loss medications may negate the need for surgery?

I don’t think they necessarily reduce the need for surgery. There’s still a lot we don’t know about why they work in some patients and why they don’t work in others.

Some of our colleagues have come up with phenotypes and blood tests so we can better understand which things will work in different patients. Surgery doesn’t work for some patients. People may need a combination of both after they reach a plateau. I’m excited that people see this as something that we should be researching and putting more effort into — that obesity isn’t a disease of moral failure, that people with excess weight just need to ‘move more’ or ‘eat less’ and it’s their fault. I’m glad people are starting to understand that.

Q: What teacher or mentor had the greatest impact on you?

Probably two. One of them is Andrea E Reid, MD, MPH, a dean of medicine at Harvard. She gives you such motivation to achieve things, no matter how big your idea is or how crazy it may seem. If you have something that you think is important, you go after it. Another person is Christopher C. Thompson, MD, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the father of bariatric endoscopy in a sense. He embodies what Dr. Reid talks about: crazy big ideas. And he goes after them and he succeeds. Having him push me and giving me that type of encouragement was invaluable.

Q: Describe how you would spend a free Saturday afternoon.

Every Saturday is yoga or some type of movement. Spending some time outside doing something, whether it’s messing around with plants that I’m not very good at, or going for a walk.

Lightning Round

Texting or talking?

Text

Favorite city in U.S. besides the one you live in?

New York

Favorite breakfast?

Avocado toast

Place you most want to travel to?

Istanbul

Favorite season?

Fall

Favorite ice cream flavor?

Raspberry sorbet

How many cups of coffee do you drink per day?

One

Best place you ever went on vacation?

Greece

If you weren’t a gastroenterologist, what would you be?

Own a clothing store

Favorite type of music?

Old school R&B

Favorite movie genre?

Romantic comedy or drama

Cat person or dog person?

Dog

Favorite sport?

Football

Favorite holiday?

Christmas

Optimist or pessimist?

Optimist

It takes a long time for some patients with obesity to acknowledge that they need help, said Dr. Laster, a bariatric endoscopist who specializes in gastroenterology, nutrition, and obesity medicine at Gut Theory Total Digestive Care, and Georgetown University Hospital in Washington. “If somebody has high blood pressure or has a cut or has chest pain, you don’t wait for things. You would go seek help immediately. I wish more patients reached out sooner and didn’t struggle.”

Another big challenge is making sure patients have insurance coverage for things like medications, surgery, and bariatric endoscopy, she added.

Her response: education and advocacy. “I’m giving as many talks as I can to fellows, creating courses for residents and fellows and medical students” to change the way physicians talk about obesity and excess weight, she said. Patients need to understand that physicians care about them, that “we’re not judging and we’re changing that perspective.”

Dr. Laster is also working with members of Congress to get bills passed for coverage of obesity medication and procedures. In an interview with GI & Hepatology News, she spoke more about the intersection between nutrition, medicine and bariatric procedures and the importance of offering patients multiple solutions.

Q: Why did you choose GI?

It allowed me a little bit of everything. You have clinic, where you can really interact with patients and get to the root of their problem. You have preventative care with routine colonoscopies and upper endoscopies to prevent for cancer. But then you also have fun stuff — which my mom told me to stop saying out loud — ‘bleeders’ and acute things that you get to fix immediately. So, you get the adrenaline rush too. I like it because you get the best of all worlds and it’s really hard to get bored.

Q: How did you become interested in nutrition and bariatric endoscopy?

My parents had a garden and never let us eat processed foods. In residency, I kept seeing the same medical problems over and over again. Everybody had high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes. Then in GI clinic, everybody had abdominal pain, bloating, constipation, heartburn, and a million GI appointments for these same things. Everyone’s upper endoscopy or colonoscopy was negative. Something else had to be going on.

And that’s sort of where it came from; figuring out the common denominator. It had to be what people were eating. There’s also the prevalence of patients with obesity going up every single year. Correlating all these other medical problems with people’s diets led me down the rabbit hole of: What else can we be doing?

Most people don’t want to undergo surgery. Only 2% of people eligible for surgery actually do it, even though it works. The reasons are because it’s invasive or there’s shame behind it. Bariatric endoscopy is another option that’s out here, that’s less invasive. I’m an endoscopist and gastroenterologist. I should be able to offer all those things and I should know more about nutrition. We don’t talk about it enough.

Q: Do you think more GI doctors should become better educated about nutrition?

100%. Every patient I see has seen a GI doctor before and says, ‘No one has ever told me that if I have carbonated beverages and cheese every day, I’m going to be bloated and constipated.’ And that shouldn’t be the case.

Q: Why do you think that more GI doctors don’t get the education on nutrition during their medical training?

I think it’s our healthcare system. It’s very much focused on secondary treatment rather than preventative care. There’s no emphasis on preventing things from happening.

We’re really good at reactionary medicine. People who have an ulcer, big polyps and colon cancer, esophageal cancer — we do those things really well. But I think because there’s no ICD-10 codes for preventive care via nutrition education, and no good reimbursement, then there’s no incentive for hospital systems to pay for these things. It’s a system based on RVUs (relative value units) and numbers. That’s been our trajectory. We’ve been so focused on reactionary medicine rather than saying, ‘Okay, let’s stop this from happening.’

We just didn’t talk about nutrition in medical school, in residency, or in fellowship. It was looked at as a soft science. When I was in school, people would also say, ‘No one’s going to change. So it’s a waste of your time essentially to talk to people about making dietary changes.’ I feel like if you give people the opportunity, you have to give them the chance. You can’t just write everybody off. Some people won’t change, but that’s okay. They should at least have the opportunity to do so.

Q: How do you determine whether a patient is a good candidate for bariatric surgery?

It’s based on the guidelines: If they meet the BMI requirements, if they have obesity-associated comorbidities, their risk for surgery is low. But it’s also whether they want to do it or not. A patient has to be in the mindset and be ready for it. They need to want to have surgery or bariatric endoscopy, or to use medications, or start to make a change. Some people aren’t there yet — that preemptive stage of making a change. They want the solution, but they’re not ready to do that legwork yet.

And all of it is work. I tell patients, ‘Whether it’s medication or bariatric endoscopy or bariatric surgery, you still have work to do. None of it is going to just magically happen where you could just continue to do the same thing you’re doing now and you’re going to lose weight and keep it off.’

Q: What advances in obesity prevention are you excited about?

I’m excited that bariatric endoscopy came about in the first place, because in every other field there are less invasive approaches that have become available. I’m also excited about the emergence of weight loss medication, like GLP-1s. I think they are a tool that we need.

Q: Do you think the weight loss medications may negate the need for surgery?

I don’t think they necessarily reduce the need for surgery. There’s still a lot we don’t know about why they work in some patients and why they don’t work in others.

Some of our colleagues have come up with phenotypes and blood tests so we can better understand which things will work in different patients. Surgery doesn’t work for some patients. People may need a combination of both after they reach a plateau. I’m excited that people see this as something that we should be researching and putting more effort into — that obesity isn’t a disease of moral failure, that people with excess weight just need to ‘move more’ or ‘eat less’ and it’s their fault. I’m glad people are starting to understand that.

Q: What teacher or mentor had the greatest impact on you?

Probably two. One of them is Andrea E Reid, MD, MPH, a dean of medicine at Harvard. She gives you such motivation to achieve things, no matter how big your idea is or how crazy it may seem. If you have something that you think is important, you go after it. Another person is Christopher C. Thompson, MD, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the father of bariatric endoscopy in a sense. He embodies what Dr. Reid talks about: crazy big ideas. And he goes after them and he succeeds. Having him push me and giving me that type of encouragement was invaluable.

Q: Describe how you would spend a free Saturday afternoon.

Every Saturday is yoga or some type of movement. Spending some time outside doing something, whether it’s messing around with plants that I’m not very good at, or going for a walk.

Lightning Round

Texting or talking?

Text

Favorite city in U.S. besides the one you live in?

New York

Favorite breakfast?

Avocado toast

Place you most want to travel to?

Istanbul

Favorite season?

Fall

Favorite ice cream flavor?

Raspberry sorbet

How many cups of coffee do you drink per day?

One

Best place you ever went on vacation?

Greece

If you weren’t a gastroenterologist, what would you be?

Own a clothing store

Favorite type of music?

Old school R&B

Favorite movie genre?

Romantic comedy or drama

Cat person or dog person?

Dog

Favorite sport?

Football

Favorite holiday?

Christmas

Optimist or pessimist?

Optimist

Support Researchers with a Donation to the AGA Research Foundation

By joining others in donating to the AGA Research Foundation, you will ensure that researchers have opportunities to continue their lifesaving work.

The AGA Research Foundation remains committed to providing young researchers with unprecedented research opportunities. Each year, we receive a caliber of nominations for AGA research awards. You can help gifted investigators as they work to advance the understanding of digestive diseases through their novel research objectives.

As an AGA member, you can help fund discoveries that will continue to improve GI practice and better patient care.

AGA grants have led to discoveries, including new approaches to down-regulate intestinal inflammation, a test for genetic predisposition to colon cancer and autoimmune liver disease treatments. The importance of these awards is evidenced by the fact that virtually every major advance leading to the understanding, prevention, treatment, and cure of digestive diseases has been made in the research laboratory of a talented young investigator.

Donate to the AGA Research Foundation to ensure that researchers have opportunities to continue their lifesaving work.

Three Easy Ways To Give

Online: Donate at www.foundation.gastro.org.

Through the mail:

AGA Research Foundation

4930 Del Ray Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20814

Over the phone: 301-222-4002

All gifts are tax-deductible to the fullest extent of U.S. law.

By joining others in donating to the AGA Research Foundation, you will ensure that researchers have opportunities to continue their lifesaving work.

The AGA Research Foundation remains committed to providing young researchers with unprecedented research opportunities. Each year, we receive a caliber of nominations for AGA research awards. You can help gifted investigators as they work to advance the understanding of digestive diseases through their novel research objectives.

As an AGA member, you can help fund discoveries that will continue to improve GI practice and better patient care.

AGA grants have led to discoveries, including new approaches to down-regulate intestinal inflammation, a test for genetic predisposition to colon cancer and autoimmune liver disease treatments. The importance of these awards is evidenced by the fact that virtually every major advance leading to the understanding, prevention, treatment, and cure of digestive diseases has been made in the research laboratory of a talented young investigator.

Donate to the AGA Research Foundation to ensure that researchers have opportunities to continue their lifesaving work.

Three Easy Ways To Give

Online: Donate at www.foundation.gastro.org.

Through the mail:

AGA Research Foundation

4930 Del Ray Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20814

Over the phone: 301-222-4002

All gifts are tax-deductible to the fullest extent of U.S. law.

By joining others in donating to the AGA Research Foundation, you will ensure that researchers have opportunities to continue their lifesaving work.

The AGA Research Foundation remains committed to providing young researchers with unprecedented research opportunities. Each year, we receive a caliber of nominations for AGA research awards. You can help gifted investigators as they work to advance the understanding of digestive diseases through their novel research objectives.

As an AGA member, you can help fund discoveries that will continue to improve GI practice and better patient care.

AGA grants have led to discoveries, including new approaches to down-regulate intestinal inflammation, a test for genetic predisposition to colon cancer and autoimmune liver disease treatments. The importance of these awards is evidenced by the fact that virtually every major advance leading to the understanding, prevention, treatment, and cure of digestive diseases has been made in the research laboratory of a talented young investigator.

Donate to the AGA Research Foundation to ensure that researchers have opportunities to continue their lifesaving work.

Three Easy Ways To Give

Online: Donate at www.foundation.gastro.org.

Through the mail:

AGA Research Foundation

4930 Del Ray Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20814

Over the phone: 301-222-4002

All gifts are tax-deductible to the fullest extent of U.S. law.

FDA Approves First Blood Test for Colorectal Cancer

In late July, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first use of a liquid biopsy (blood test) for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. The test, called Shield, launched commercially the first week of August and is the first blood test to be approved by the FDA as a primary screening option for CRC that meets requirements for Medicare reimbursement.

While the convenience of a blood test could potentially encourage more people to get screened, expert consensus is that blood tests can’t prevent CRC and should not be considered a replacement for a colonoscopy. Modeling studies and expert consensus published earlier this year in Gastroenterology and in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology shed light on the perils of liquid biopsy.

“Based on their current characteristics, blood tests should not be recommended to replace established colorectal cancer screening tests, since blood tests are neither as effective nor as cost-effective, and would worsen outcomes,” said David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, chair, AGA CRC Workshop chair and lead author of an expert commentary on liquid biopsy for CRC screening.

Five Key Takeaways

- A blood test for CRC that meets minimal CMS criteria for sensitivity and performed every 3 years would likely result in better outcomes than no screening.

- A blood test for CRC offers a simple process that could encourage more people to participate in screening. Patients who may have declined colonoscopy should understand the need for a colonoscopy if findings are abnormal.

- Because blood tests for CRC are predicted to be less effective and more costly than currently established screening programs, they cannot be recommended to replace established effective screening methods.

- Although blood tests would improve outcomes in currently unscreened people, substituting blood tests for a currently effective test would worsen patient outcomes and increase cost.

- Potential benchmarks that industry might use to assess an effective blood test for CRC going forward would be sensitivity for stage I-III CRC of > 90%, with sensitivity for advanced adenomas of > 40%-50%.

“Unless we have the expectation of high sensitivity and specificity, blood-based colorectal cancer tests could lead to false positive and false negative results, which are both bad for patient outcomes,” said John M. Carethers, MD, AGAF, AGA past president and vice chancellor for health sciences at the University of California San Diego.

In late July, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first use of a liquid biopsy (blood test) for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. The test, called Shield, launched commercially the first week of August and is the first blood test to be approved by the FDA as a primary screening option for CRC that meets requirements for Medicare reimbursement.

While the convenience of a blood test could potentially encourage more people to get screened, expert consensus is that blood tests can’t prevent CRC and should not be considered a replacement for a colonoscopy. Modeling studies and expert consensus published earlier this year in Gastroenterology and in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology shed light on the perils of liquid biopsy.

“Based on their current characteristics, blood tests should not be recommended to replace established colorectal cancer screening tests, since blood tests are neither as effective nor as cost-effective, and would worsen outcomes,” said David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, chair, AGA CRC Workshop chair and lead author of an expert commentary on liquid biopsy for CRC screening.

Five Key Takeaways

- A blood test for CRC that meets minimal CMS criteria for sensitivity and performed every 3 years would likely result in better outcomes than no screening.

- A blood test for CRC offers a simple process that could encourage more people to participate in screening. Patients who may have declined colonoscopy should understand the need for a colonoscopy if findings are abnormal.

- Because blood tests for CRC are predicted to be less effective and more costly than currently established screening programs, they cannot be recommended to replace established effective screening methods.

- Although blood tests would improve outcomes in currently unscreened people, substituting blood tests for a currently effective test would worsen patient outcomes and increase cost.

- Potential benchmarks that industry might use to assess an effective blood test for CRC going forward would be sensitivity for stage I-III CRC of > 90%, with sensitivity for advanced adenomas of > 40%-50%.

“Unless we have the expectation of high sensitivity and specificity, blood-based colorectal cancer tests could lead to false positive and false negative results, which are both bad for patient outcomes,” said John M. Carethers, MD, AGAF, AGA past president and vice chancellor for health sciences at the University of California San Diego.

In late July, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first use of a liquid biopsy (blood test) for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. The test, called Shield, launched commercially the first week of August and is the first blood test to be approved by the FDA as a primary screening option for CRC that meets requirements for Medicare reimbursement.

While the convenience of a blood test could potentially encourage more people to get screened, expert consensus is that blood tests can’t prevent CRC and should not be considered a replacement for a colonoscopy. Modeling studies and expert consensus published earlier this year in Gastroenterology and in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology shed light on the perils of liquid biopsy.

“Based on their current characteristics, blood tests should not be recommended to replace established colorectal cancer screening tests, since blood tests are neither as effective nor as cost-effective, and would worsen outcomes,” said David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, chair, AGA CRC Workshop chair and lead author of an expert commentary on liquid biopsy for CRC screening.

Five Key Takeaways

- A blood test for CRC that meets minimal CMS criteria for sensitivity and performed every 3 years would likely result in better outcomes than no screening.

- A blood test for CRC offers a simple process that could encourage more people to participate in screening. Patients who may have declined colonoscopy should understand the need for a colonoscopy if findings are abnormal.

- Because blood tests for CRC are predicted to be less effective and more costly than currently established screening programs, they cannot be recommended to replace established effective screening methods.

- Although blood tests would improve outcomes in currently unscreened people, substituting blood tests for a currently effective test would worsen patient outcomes and increase cost.

- Potential benchmarks that industry might use to assess an effective blood test for CRC going forward would be sensitivity for stage I-III CRC of > 90%, with sensitivity for advanced adenomas of > 40%-50%.

“Unless we have the expectation of high sensitivity and specificity, blood-based colorectal cancer tests could lead to false positive and false negative results, which are both bad for patient outcomes,” said John M. Carethers, MD, AGAF, AGA past president and vice chancellor for health sciences at the University of California San Diego.

Check Out Our New Irritable Bowel Syndrome Clinician Toolkit

AGA’s new irritable bowel syndrome toolkit gathers all our clinical guidance, continuing education materials, patient education resources, and FAQs in one convenient place. Be sure to check it out and bookmark it for easy access!

Curious about our other toolkits? Visit gastro.org/clinical-guidance to explore our toolkits on ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Keep an eye out for more coming soon!

The toolkit includes clinical guidance on:

- Pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea (IBS-D)

- Pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C)

For more resources for ulcerative colitis patients, visit the Patient Center on the AGA website. The AGA Patient Center has a variety of information that can be shared with your patients, including tips on diet, vaccine recommendations, and information on biosimilars.

AGA’s new irritable bowel syndrome toolkit gathers all our clinical guidance, continuing education materials, patient education resources, and FAQs in one convenient place. Be sure to check it out and bookmark it for easy access!

Curious about our other toolkits? Visit gastro.org/clinical-guidance to explore our toolkits on ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Keep an eye out for more coming soon!

The toolkit includes clinical guidance on:

- Pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea (IBS-D)

- Pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C)

For more resources for ulcerative colitis patients, visit the Patient Center on the AGA website. The AGA Patient Center has a variety of information that can be shared with your patients, including tips on diet, vaccine recommendations, and information on biosimilars.

AGA’s new irritable bowel syndrome toolkit gathers all our clinical guidance, continuing education materials, patient education resources, and FAQs in one convenient place. Be sure to check it out and bookmark it for easy access!

Curious about our other toolkits? Visit gastro.org/clinical-guidance to explore our toolkits on ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Keep an eye out for more coming soon!

The toolkit includes clinical guidance on:

- Pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea (IBS-D)

- Pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C)

For more resources for ulcerative colitis patients, visit the Patient Center on the AGA website. The AGA Patient Center has a variety of information that can be shared with your patients, including tips on diet, vaccine recommendations, and information on biosimilars.

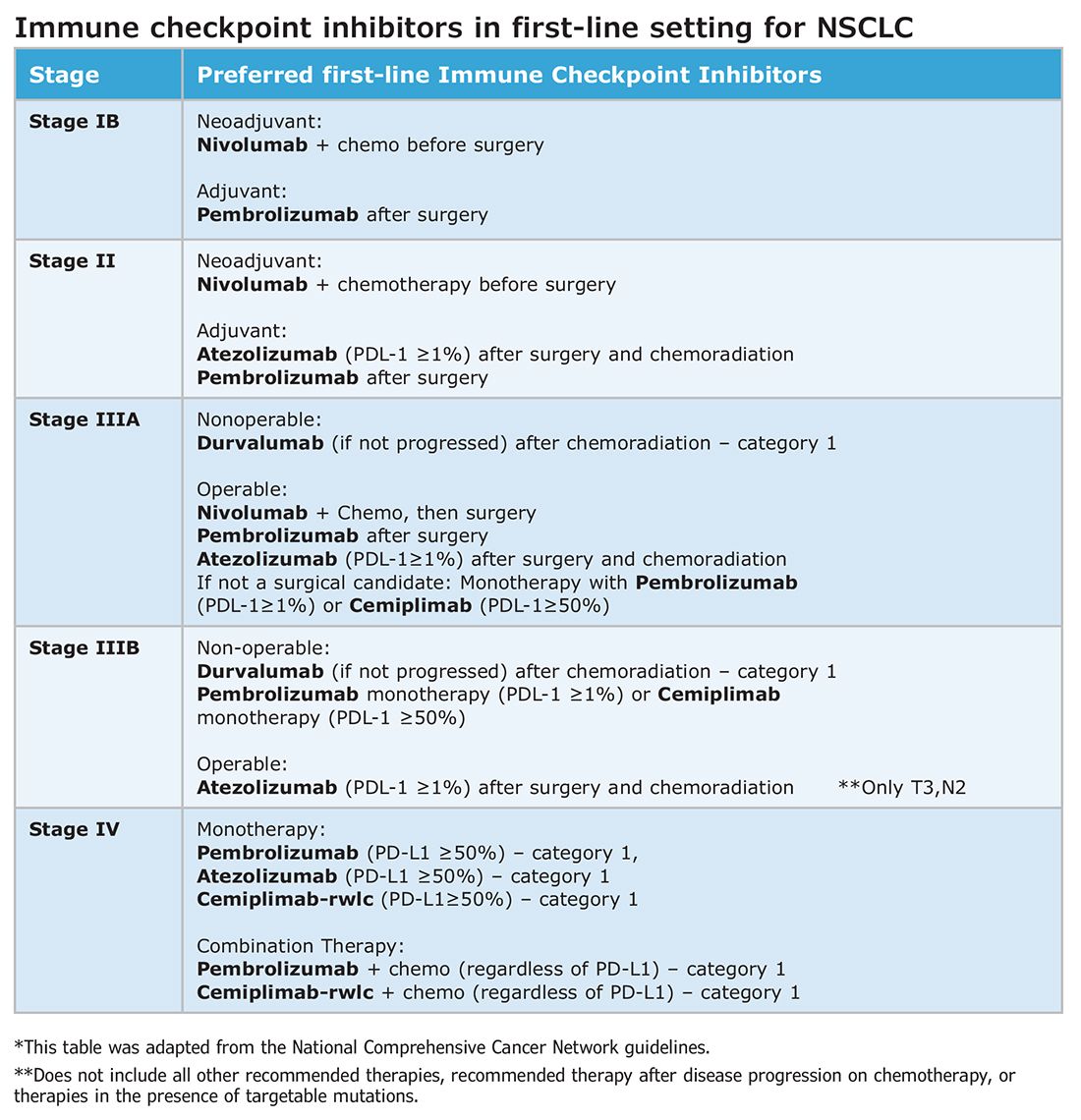

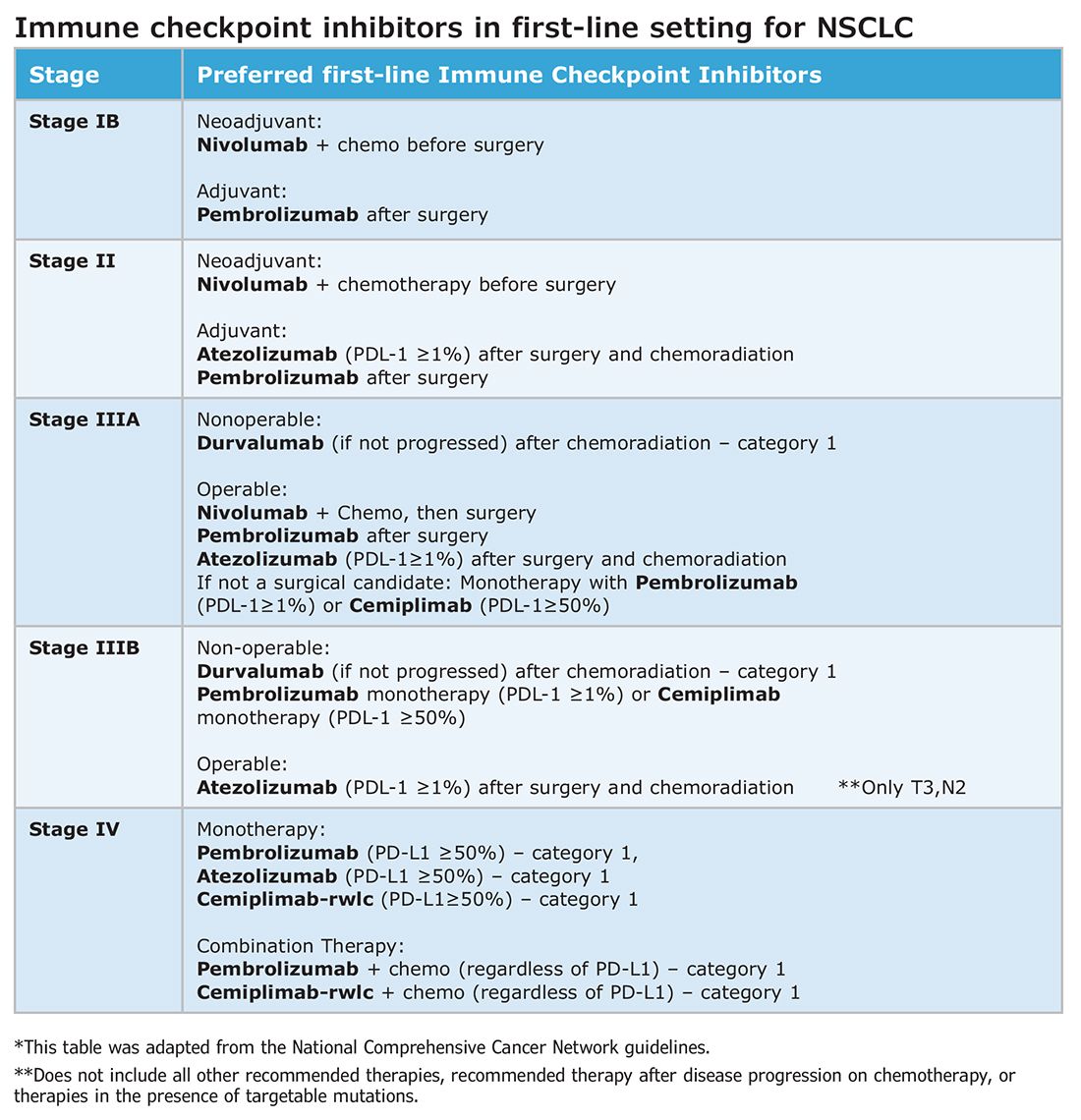

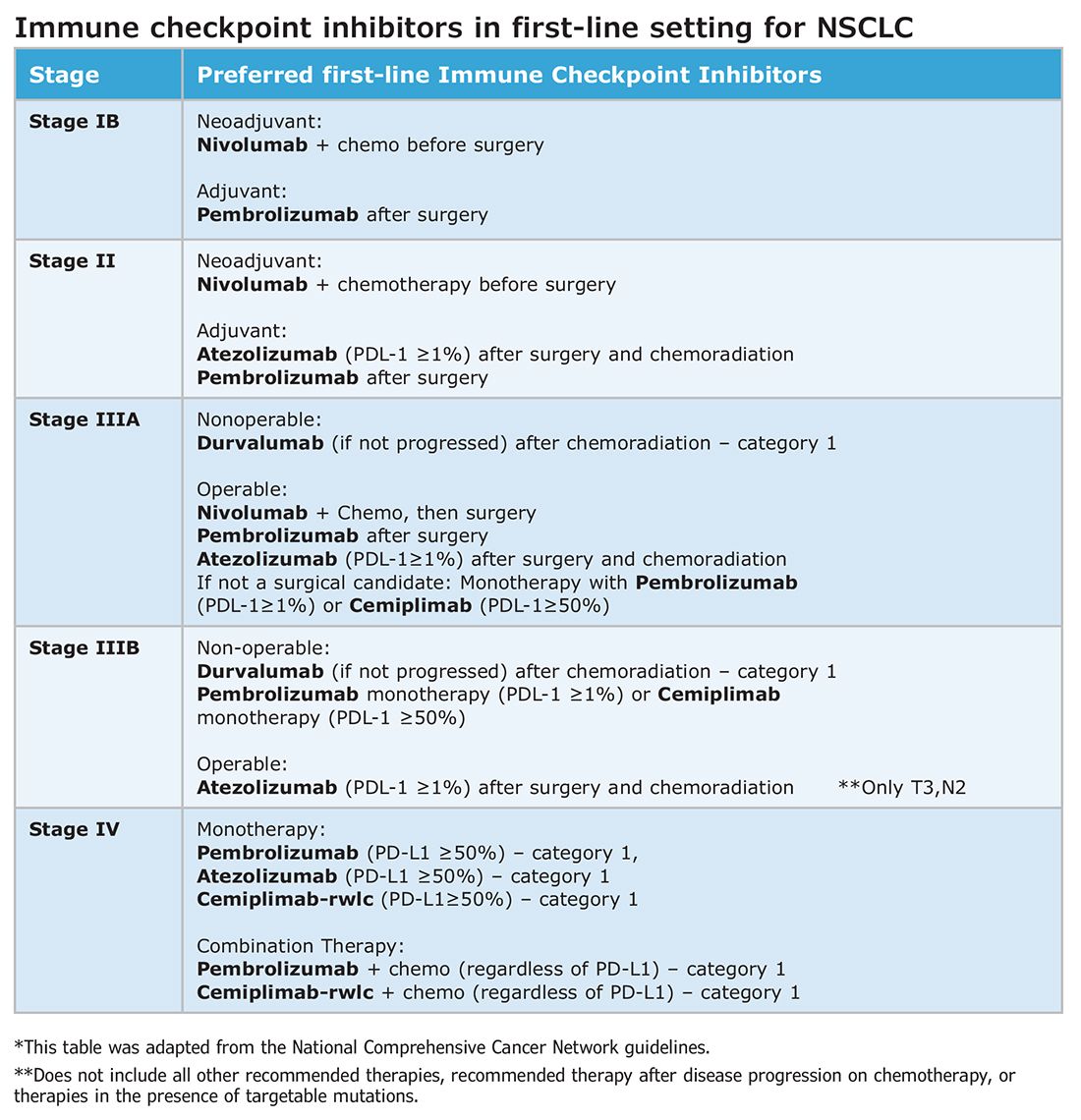

Changing the tumor board conversation: Immunotherapy in resectable NSCLC

Without a doubt, immunotherapy has transformed the treatment landscape of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and enhanced survival rates across the different stages of disease. High recurrence rates following complete surgical resection prompted the study of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) in earlier, operable stages of disease. This shift toward early application of ICI reflects the larger trend toward merging precision oncology with lung cancer staging. The resulting complexity in treatment and decision making creates systemic and logistical challenges that will require health care systems to adapt and improve.

Adjuvant immunotherapy for NSCLC

Prior to recent approvals for adjuvant immunotherapy, it was standard to give chemotherapy following resection of stage IB-IIIA disease, which offered a statistically nonsignificant survival gain. Recurrence in these patients is believed to be related to postsurgical micrometastasis. The utilization of alternative mechanisms to prevent recurrence is increasingly more common.

Atezolizumab, a PD-L1 inhibitor, is currently approved as first-line adjuvant treatment following chemotherapy in post-NSCLC resection patients with PD-L1 scores ≥1%. This category one recommendation by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) is based on results from the IMpower010 trial, which randomized patients to Atezolizumab vs best supportive care. All were early-stage NSCLC, stage IB-IIIA, who underwent resection followed by platinum-based chemotherapy. Statistically significant benefits were found in disease-free survival (DFS) with a trend toward overall survival.1

The PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091 trial evaluated another PD-L1 inhibitor, Pembrolizumab, as adjuvant therapy. Its design largely mirrored the IMPower010 study, but it differed in that the ICI was administered with or without chemotherapy following resection in patients with stage IB-IIIA NSCLC. Improvements in DFS were found in the overall population, leading to FDA approval for adjuvant therapy in 2023.2

These approvals require changes to the management of operable NSCLC. Until recently, it was not routine to send surgical specimens for additional testing because adjuvant treatment meant chemotherapy only. However, it is now essential that all surgically resected malignant tissue be sent for genomic sequencing and PD-L1 testing. Selecting the next form of therapy, whether it is an ICI or targeted drug therapy, depends on it.

From a surgical perspective, quality surgery with accurate nodal staging is crucial. The surgical findings can determine and identify those who are candidates for adjuvant immunotherapy. For these same reasons, it is helpful to advise surgeons preoperatively that targeted adjuvant therapy is being considered after resection.

Neoadjuvant immunotherapy for NSCLC

ICIs have also been used as neoadjuvant treatment for operable NSCLC. In 2021, the Checkmate-816 trial evaluated Nivolumab with platinum doublet chemotherapy prior to resection of stage IB-IIIa NSCLC. When compared with chemotherapy alone, there were significant improvements in EFS, MPR, and time to death or distant metastasis (TTDM) out to 3 years. At a median follow-up time of 41.4 months, only 28% in the nivolumab group had recurrence postsurgery compared with 42% in the chemotherapy-alone group.3 As a result, certain patients who are likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy may additionally receive neoadjuvant immunotherapy with chemotherapy before surgical resection. In 2023, the KEYNOTE-671 study demonstrated that neoadjuvant Pembrolizumab and chemotherapy in patients with resectable stage II-IIIb (N2 stage) NSCLC improved EFS. At a median follow-up of 25.2 months, the EFS was 62.4% in the Pembrolizumab group vs 40.6% in the placebo group (P < .001).4

Such changes in treatment options mean patients should be discussed first and simultaneous referrals to oncology and surgery should occur in early-stage NSCLC. Up-front genomic phenotyping and PD-L1 testing may assist in decision making. High PD-L1 levels correlate better with response.

When an ICI-chemotherapy combination is given up front for newly diagnosed NSCLC, there is the potential for large reductions in tumor size and lymph node burden. Although the NCCN does not recommend ICIs to induce resectability, a patient originally deemed inoperable could theoretically become a surgical candidate with neoadjuvant ICI treatment. There is also the potential for toxicity, which could increase the risk of surgery when it does occur. Such scenarios will require frequent tumor board discussions so plans can be adjusted in real time to optimize outcomes as clinical circumstances change.

Perioperative immunotherapy for NSCLC

It is clear that both neoadjuvant and adjuvant immunotherapy can improve outcomes for patients with resectable NSCLC. The combination of neoadjuvant with adjuvant immunotherapy/chemotherapy is currently being studied. Two recent phase III clinical trials, NEOTORCH and AEGAEN, have found statistical improvements in EFS and MPR with this approach.5,6 These studies have not found their way into the NCCN guidelines yet but are sure to be considered in future iterations. Once adopted, the tumor board at each institution will have more options to choose from but many more decisions to make.

References

1. Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10308):1344-1357. [Published correction appears in Lancet. 2021 Nov 6;398(10312):1686.]

2. O’Brien M, Paz-Ares L, Marreaud S, et al. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy for completely resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091): an interim analysis of a randomised, triple-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(10):1274-1286.

3. Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(21):1973-1985.

4. Wakelee H, Liberman M, Kato T, et al. Perioperative pembrolizumab for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(6):491-503.

5. Lu S, Zhang W, Wu L, et al. Perioperative toripalimab plus chemotherapy for patients with resectable non-small cell lung cancer: the neotorch randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2024;331(3):201-211.

6. Heymach JV, Harpole D, Mitsudomi T, et al. Perioperative durvalumab for resectable non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(18):1672-1684.

Without a doubt, immunotherapy has transformed the treatment landscape of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and enhanced survival rates across the different stages of disease. High recurrence rates following complete surgical resection prompted the study of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) in earlier, operable stages of disease. This shift toward early application of ICI reflects the larger trend toward merging precision oncology with lung cancer staging. The resulting complexity in treatment and decision making creates systemic and logistical challenges that will require health care systems to adapt and improve.

Adjuvant immunotherapy for NSCLC

Prior to recent approvals for adjuvant immunotherapy, it was standard to give chemotherapy following resection of stage IB-IIIA disease, which offered a statistically nonsignificant survival gain. Recurrence in these patients is believed to be related to postsurgical micrometastasis. The utilization of alternative mechanisms to prevent recurrence is increasingly more common.

Atezolizumab, a PD-L1 inhibitor, is currently approved as first-line adjuvant treatment following chemotherapy in post-NSCLC resection patients with PD-L1 scores ≥1%. This category one recommendation by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) is based on results from the IMpower010 trial, which randomized patients to Atezolizumab vs best supportive care. All were early-stage NSCLC, stage IB-IIIA, who underwent resection followed by platinum-based chemotherapy. Statistically significant benefits were found in disease-free survival (DFS) with a trend toward overall survival.1

The PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091 trial evaluated another PD-L1 inhibitor, Pembrolizumab, as adjuvant therapy. Its design largely mirrored the IMPower010 study, but it differed in that the ICI was administered with or without chemotherapy following resection in patients with stage IB-IIIA NSCLC. Improvements in DFS were found in the overall population, leading to FDA approval for adjuvant therapy in 2023.2

These approvals require changes to the management of operable NSCLC. Until recently, it was not routine to send surgical specimens for additional testing because adjuvant treatment meant chemotherapy only. However, it is now essential that all surgically resected malignant tissue be sent for genomic sequencing and PD-L1 testing. Selecting the next form of therapy, whether it is an ICI or targeted drug therapy, depends on it.

From a surgical perspective, quality surgery with accurate nodal staging is crucial. The surgical findings can determine and identify those who are candidates for adjuvant immunotherapy. For these same reasons, it is helpful to advise surgeons preoperatively that targeted adjuvant therapy is being considered after resection.

Neoadjuvant immunotherapy for NSCLC

ICIs have also been used as neoadjuvant treatment for operable NSCLC. In 2021, the Checkmate-816 trial evaluated Nivolumab with platinum doublet chemotherapy prior to resection of stage IB-IIIa NSCLC. When compared with chemotherapy alone, there were significant improvements in EFS, MPR, and time to death or distant metastasis (TTDM) out to 3 years. At a median follow-up time of 41.4 months, only 28% in the nivolumab group had recurrence postsurgery compared with 42% in the chemotherapy-alone group.3 As a result, certain patients who are likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy may additionally receive neoadjuvant immunotherapy with chemotherapy before surgical resection. In 2023, the KEYNOTE-671 study demonstrated that neoadjuvant Pembrolizumab and chemotherapy in patients with resectable stage II-IIIb (N2 stage) NSCLC improved EFS. At a median follow-up of 25.2 months, the EFS was 62.4% in the Pembrolizumab group vs 40.6% in the placebo group (P < .001).4

Such changes in treatment options mean patients should be discussed first and simultaneous referrals to oncology and surgery should occur in early-stage NSCLC. Up-front genomic phenotyping and PD-L1 testing may assist in decision making. High PD-L1 levels correlate better with response.

When an ICI-chemotherapy combination is given up front for newly diagnosed NSCLC, there is the potential for large reductions in tumor size and lymph node burden. Although the NCCN does not recommend ICIs to induce resectability, a patient originally deemed inoperable could theoretically become a surgical candidate with neoadjuvant ICI treatment. There is also the potential for toxicity, which could increase the risk of surgery when it does occur. Such scenarios will require frequent tumor board discussions so plans can be adjusted in real time to optimize outcomes as clinical circumstances change.

Perioperative immunotherapy for NSCLC

It is clear that both neoadjuvant and adjuvant immunotherapy can improve outcomes for patients with resectable NSCLC. The combination of neoadjuvant with adjuvant immunotherapy/chemotherapy is currently being studied. Two recent phase III clinical trials, NEOTORCH and AEGAEN, have found statistical improvements in EFS and MPR with this approach.5,6 These studies have not found their way into the NCCN guidelines yet but are sure to be considered in future iterations. Once adopted, the tumor board at each institution will have more options to choose from but many more decisions to make.

References

1. Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10308):1344-1357. [Published correction appears in Lancet. 2021 Nov 6;398(10312):1686.]

2. O’Brien M, Paz-Ares L, Marreaud S, et al. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy for completely resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091): an interim analysis of a randomised, triple-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(10):1274-1286.

3. Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(21):1973-1985.

4. Wakelee H, Liberman M, Kato T, et al. Perioperative pembrolizumab for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(6):491-503.

5. Lu S, Zhang W, Wu L, et al. Perioperative toripalimab plus chemotherapy for patients with resectable non-small cell lung cancer: the neotorch randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2024;331(3):201-211.