User login

Continuous glucose monitoring might help in managing postoperative hypoglycemia

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) may help curb the severity of hypoglycemia after weight loss operations and even other gastrointestinal procedures, according to recent findings from a small study published in Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism.

Hypoglycemia is a chronic and persistent complication common in patients following bariatric surgery, affecting as many as 30% of people who undergo a sleeve gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

The symptoms of hypoglycemia, including lightheadedness, heart palpitations, difficulty concentrating, and confusion, can mimic anxiety disorders, arrhythmia, and dumping syndrome.

If a postoperative patient experiences these symptoms within a few hours following a meal or exercising, “primary care doctors should consider the possibility that hypoglycemia may be a contributor,” said Mary-Elizabeth Patti, MD, director of the Hypoglycemia Clinic at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston and senior author of the new study.

“In fact, hypoglycemia is a possible diagnosis even among those who underwent [operations other than bariatric, including] fundoplication or other upper gastrointestinal or esophageal surgeries,” she said.

To understand how CGM could benefit patients, Dr. Patti and colleagues recruited 22 participants who had undergone bariatric surgery more than 8 years prior and had postbariatric hypoglycemia. Their mean age was 51 years, 90% were women, 82% were diagnosed with level 3 hypoglycemia, and none had type 1 or 2 diabetes.

All participants experienced neuronal dysfunction with symptoms like fatigue, concentration difficulties, and confusion. More than 90% had received medical nutrition therapy for postbariatric hypoglycemia in the past.

CGM data were collected in the 22 individuals in two sequential phases: masked (no access to sensor glucose or alarms) and unmasked (access to sensor glucose and alarms for low or rapidly declining sensor glucose). Twelve participants wore a CGM (Dexcom G4 device) for a total of 28 days, whereas 10 wore a CGM (the Dexcom G6 device) for a total of 20 days.

The team observed that the percentage of time when the participants’ blood glucose was below 70 mg/dL – the definition of hypoglycemia – was significantly lower during the unmasked phase.

Though CGM devices are not sensitive enough to serve as a diagnostic tool for hypoglycemia, “the alarms on CGM devices can provide some much-needed awareness,” Dr. Patti said. “After a detailed diagnosis, CGM devices can be a helpful tool to assess dietary patterns and make modifications that could reduce the severity of postbariatric hypoglycemia.”

If a patient frequently experiences hypoglycemia, they may not sense when their glucose levels drop, also known as hypoglycemia unawareness, according to Dr. Patti. Studies have found that postbariatric hypoglycemia remains underdiagnosed because most patients are asymptomatic.

the researchers conclude.

Next steps

Patients are more vulnerable to hypoglycemia after a sleeve gastrectomy or gastric bypass surgery because these procedures involve removing the pylorus. This valve plays a crucial role in only allowing small portions of food to enter the intestine and prevents sudden spikes in blood glucose.

Without the pylorus, large amounts of food directly enter the intestine and soon result in large amounts of glucose getting absorbed, according to Sriram Machineni, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, who was not affiliated with the study.

“The pancreas then goes into overdrive and produces a lot of insulin, which continues reducing sugar levels,” Dr. Machineni said. “That is what causes hypoglycemia.”

Dr. Patti and associates are next working on research using CGM-derived data to investigate how different types of meals, physical activities, and other factors could influence glucose metabolism patterns in patients with hypoglycemia.

The study was funded by Dexcom, a manufacturer of continuous glucose monitoring systems. Dr. Patti reported receiving grant funding from the Diabetes Research Center.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) may help curb the severity of hypoglycemia after weight loss operations and even other gastrointestinal procedures, according to recent findings from a small study published in Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism.

Hypoglycemia is a chronic and persistent complication common in patients following bariatric surgery, affecting as many as 30% of people who undergo a sleeve gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

The symptoms of hypoglycemia, including lightheadedness, heart palpitations, difficulty concentrating, and confusion, can mimic anxiety disorders, arrhythmia, and dumping syndrome.

If a postoperative patient experiences these symptoms within a few hours following a meal or exercising, “primary care doctors should consider the possibility that hypoglycemia may be a contributor,” said Mary-Elizabeth Patti, MD, director of the Hypoglycemia Clinic at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston and senior author of the new study.

“In fact, hypoglycemia is a possible diagnosis even among those who underwent [operations other than bariatric, including] fundoplication or other upper gastrointestinal or esophageal surgeries,” she said.

To understand how CGM could benefit patients, Dr. Patti and colleagues recruited 22 participants who had undergone bariatric surgery more than 8 years prior and had postbariatric hypoglycemia. Their mean age was 51 years, 90% were women, 82% were diagnosed with level 3 hypoglycemia, and none had type 1 or 2 diabetes.

All participants experienced neuronal dysfunction with symptoms like fatigue, concentration difficulties, and confusion. More than 90% had received medical nutrition therapy for postbariatric hypoglycemia in the past.

CGM data were collected in the 22 individuals in two sequential phases: masked (no access to sensor glucose or alarms) and unmasked (access to sensor glucose and alarms for low or rapidly declining sensor glucose). Twelve participants wore a CGM (Dexcom G4 device) for a total of 28 days, whereas 10 wore a CGM (the Dexcom G6 device) for a total of 20 days.

The team observed that the percentage of time when the participants’ blood glucose was below 70 mg/dL – the definition of hypoglycemia – was significantly lower during the unmasked phase.

Though CGM devices are not sensitive enough to serve as a diagnostic tool for hypoglycemia, “the alarms on CGM devices can provide some much-needed awareness,” Dr. Patti said. “After a detailed diagnosis, CGM devices can be a helpful tool to assess dietary patterns and make modifications that could reduce the severity of postbariatric hypoglycemia.”

If a patient frequently experiences hypoglycemia, they may not sense when their glucose levels drop, also known as hypoglycemia unawareness, according to Dr. Patti. Studies have found that postbariatric hypoglycemia remains underdiagnosed because most patients are asymptomatic.

the researchers conclude.

Next steps

Patients are more vulnerable to hypoglycemia after a sleeve gastrectomy or gastric bypass surgery because these procedures involve removing the pylorus. This valve plays a crucial role in only allowing small portions of food to enter the intestine and prevents sudden spikes in blood glucose.

Without the pylorus, large amounts of food directly enter the intestine and soon result in large amounts of glucose getting absorbed, according to Sriram Machineni, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, who was not affiliated with the study.

“The pancreas then goes into overdrive and produces a lot of insulin, which continues reducing sugar levels,” Dr. Machineni said. “That is what causes hypoglycemia.”

Dr. Patti and associates are next working on research using CGM-derived data to investigate how different types of meals, physical activities, and other factors could influence glucose metabolism patterns in patients with hypoglycemia.

The study was funded by Dexcom, a manufacturer of continuous glucose monitoring systems. Dr. Patti reported receiving grant funding from the Diabetes Research Center.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) may help curb the severity of hypoglycemia after weight loss operations and even other gastrointestinal procedures, according to recent findings from a small study published in Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism.

Hypoglycemia is a chronic and persistent complication common in patients following bariatric surgery, affecting as many as 30% of people who undergo a sleeve gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

The symptoms of hypoglycemia, including lightheadedness, heart palpitations, difficulty concentrating, and confusion, can mimic anxiety disorders, arrhythmia, and dumping syndrome.

If a postoperative patient experiences these symptoms within a few hours following a meal or exercising, “primary care doctors should consider the possibility that hypoglycemia may be a contributor,” said Mary-Elizabeth Patti, MD, director of the Hypoglycemia Clinic at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston and senior author of the new study.

“In fact, hypoglycemia is a possible diagnosis even among those who underwent [operations other than bariatric, including] fundoplication or other upper gastrointestinal or esophageal surgeries,” she said.

To understand how CGM could benefit patients, Dr. Patti and colleagues recruited 22 participants who had undergone bariatric surgery more than 8 years prior and had postbariatric hypoglycemia. Their mean age was 51 years, 90% were women, 82% were diagnosed with level 3 hypoglycemia, and none had type 1 or 2 diabetes.

All participants experienced neuronal dysfunction with symptoms like fatigue, concentration difficulties, and confusion. More than 90% had received medical nutrition therapy for postbariatric hypoglycemia in the past.

CGM data were collected in the 22 individuals in two sequential phases: masked (no access to sensor glucose or alarms) and unmasked (access to sensor glucose and alarms for low or rapidly declining sensor glucose). Twelve participants wore a CGM (Dexcom G4 device) for a total of 28 days, whereas 10 wore a CGM (the Dexcom G6 device) for a total of 20 days.

The team observed that the percentage of time when the participants’ blood glucose was below 70 mg/dL – the definition of hypoglycemia – was significantly lower during the unmasked phase.

Though CGM devices are not sensitive enough to serve as a diagnostic tool for hypoglycemia, “the alarms on CGM devices can provide some much-needed awareness,” Dr. Patti said. “After a detailed diagnosis, CGM devices can be a helpful tool to assess dietary patterns and make modifications that could reduce the severity of postbariatric hypoglycemia.”

If a patient frequently experiences hypoglycemia, they may not sense when their glucose levels drop, also known as hypoglycemia unawareness, according to Dr. Patti. Studies have found that postbariatric hypoglycemia remains underdiagnosed because most patients are asymptomatic.

the researchers conclude.

Next steps

Patients are more vulnerable to hypoglycemia after a sleeve gastrectomy or gastric bypass surgery because these procedures involve removing the pylorus. This valve plays a crucial role in only allowing small portions of food to enter the intestine and prevents sudden spikes in blood glucose.

Without the pylorus, large amounts of food directly enter the intestine and soon result in large amounts of glucose getting absorbed, according to Sriram Machineni, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, who was not affiliated with the study.

“The pancreas then goes into overdrive and produces a lot of insulin, which continues reducing sugar levels,” Dr. Machineni said. “That is what causes hypoglycemia.”

Dr. Patti and associates are next working on research using CGM-derived data to investigate how different types of meals, physical activities, and other factors could influence glucose metabolism patterns in patients with hypoglycemia.

The study was funded by Dexcom, a manufacturer of continuous glucose monitoring systems. Dr. Patti reported receiving grant funding from the Diabetes Research Center.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DIABETES, OBESITY, AND METABOLISM

Woman with transplanted uterus gives birth to boy

It’s the first time that a baby has been born to a woman with a transplanted uterus outside of a clinical trial. Officials from University of Alabama–Birmingham Hospital, where the 2-year process took place, said in a statement on July 24 that the birth sets its uterus transplant program on track to perhaps become covered under insurance plans.

The process of uterus transplant, in vitro fertilization, and pregnancy involves 50 medical providers and is open to women who have uterine factor infertility (UFI). The condition may affect up to 5% of reproductive-age women worldwide. Women with UFI cannot carry a pregnancy to term because they were either born without a uterus, had it removed via hysterectomy, or have a uterus that does not function properly.

The woman, whom the hospital identified as Mallory, moved with her family to the Birmingham area to enter the transplant program, which is one of four programs operating in the United States. Mallory learned when she was 17 years old that she was born without a uterus because of Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. Her first child, a daughter, was born after her sister carried the pregnancy as a surrogate.

Mallory received her uterus from a deceased donor. Her son was born in May.

“As with other types of organ transplants, the woman must take immunosuppressive medications to prevent the body from rejecting the transplanted uterus,” the transplant program’s website states. “After the baby is born and if the woman does not want more children, the transplanted uterus is removed with a hysterectomy procedure, and the woman no longer needs to take antirejection medications.”

“There are all different ways to grow your family if you have uterine factor infertility, but this [uterus transplantation] is what I feel like I knew that I was supposed to do,” Mallory said in a statement. “I mean, just hearing the cry at first was just, you know, mind blowing.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

It’s the first time that a baby has been born to a woman with a transplanted uterus outside of a clinical trial. Officials from University of Alabama–Birmingham Hospital, where the 2-year process took place, said in a statement on July 24 that the birth sets its uterus transplant program on track to perhaps become covered under insurance plans.

The process of uterus transplant, in vitro fertilization, and pregnancy involves 50 medical providers and is open to women who have uterine factor infertility (UFI). The condition may affect up to 5% of reproductive-age women worldwide. Women with UFI cannot carry a pregnancy to term because they were either born without a uterus, had it removed via hysterectomy, or have a uterus that does not function properly.

The woman, whom the hospital identified as Mallory, moved with her family to the Birmingham area to enter the transplant program, which is one of four programs operating in the United States. Mallory learned when she was 17 years old that she was born without a uterus because of Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. Her first child, a daughter, was born after her sister carried the pregnancy as a surrogate.

Mallory received her uterus from a deceased donor. Her son was born in May.

“As with other types of organ transplants, the woman must take immunosuppressive medications to prevent the body from rejecting the transplanted uterus,” the transplant program’s website states. “After the baby is born and if the woman does not want more children, the transplanted uterus is removed with a hysterectomy procedure, and the woman no longer needs to take antirejection medications.”

“There are all different ways to grow your family if you have uterine factor infertility, but this [uterus transplantation] is what I feel like I knew that I was supposed to do,” Mallory said in a statement. “I mean, just hearing the cry at first was just, you know, mind blowing.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

It’s the first time that a baby has been born to a woman with a transplanted uterus outside of a clinical trial. Officials from University of Alabama–Birmingham Hospital, where the 2-year process took place, said in a statement on July 24 that the birth sets its uterus transplant program on track to perhaps become covered under insurance plans.

The process of uterus transplant, in vitro fertilization, and pregnancy involves 50 medical providers and is open to women who have uterine factor infertility (UFI). The condition may affect up to 5% of reproductive-age women worldwide. Women with UFI cannot carry a pregnancy to term because they were either born without a uterus, had it removed via hysterectomy, or have a uterus that does not function properly.

The woman, whom the hospital identified as Mallory, moved with her family to the Birmingham area to enter the transplant program, which is one of four programs operating in the United States. Mallory learned when she was 17 years old that she was born without a uterus because of Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. Her first child, a daughter, was born after her sister carried the pregnancy as a surrogate.

Mallory received her uterus from a deceased donor. Her son was born in May.

“As with other types of organ transplants, the woman must take immunosuppressive medications to prevent the body from rejecting the transplanted uterus,” the transplant program’s website states. “After the baby is born and if the woman does not want more children, the transplanted uterus is removed with a hysterectomy procedure, and the woman no longer needs to take antirejection medications.”

“There are all different ways to grow your family if you have uterine factor infertility, but this [uterus transplantation] is what I feel like I knew that I was supposed to do,” Mallory said in a statement. “I mean, just hearing the cry at first was just, you know, mind blowing.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

New guidelines for laser treatment of cutaneous vascular anomalies

A new practice guideline is setting a standard for doctors who use lasers to treat cutaneous vascular anomalies.

Poor treatment has been an issue in this field because no uniform guidelines existed to inform practice, according to a press release from the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

The laser treatment settings can vary based on the type and location of the birthmark and also the patient’s skin type, which has resulted in an inconsistent approach from clinicians, according to the release.

“For decades, I have observed adverse outcomes from the improper laser treatment of vascular birthmarks,” Linda Rozell-Shannon, PhD, president and founder of the Vascular Birthmarks Foundation said in a statement from ASLMS. “As a result of these guidelines, patient outcomes will be improved.”

The guideline, published on the ASLMS website along with supporting videos, was jointly developed by ASLMS, VBF, and an international group of clinicians, marking the first consensus guideline on laser treatments for cutaneous vascular anomalies. It details 32 best practice directives for various scenarios, including advice on safety considerations, additional testing, and when to refer.

“It is important to realize that just because someone is board certified does not mean they are skilled in treating all conditions or using all lasers,” Paul Friedman, MD, a dermatologist in Houston, and former president of ASLMS, said in the ASLMS statement.

Vascular birthmarks are a common condition affecting up to 14% of children, according to VBF. Most are hemangiomas, a buildup of blood vessels that usually appears at birth or within a month after birth. Laser therapy reduces the size and color of the anomalies.

Support for this initiative was provided by Candela Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new practice guideline is setting a standard for doctors who use lasers to treat cutaneous vascular anomalies.

Poor treatment has been an issue in this field because no uniform guidelines existed to inform practice, according to a press release from the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

The laser treatment settings can vary based on the type and location of the birthmark and also the patient’s skin type, which has resulted in an inconsistent approach from clinicians, according to the release.

“For decades, I have observed adverse outcomes from the improper laser treatment of vascular birthmarks,” Linda Rozell-Shannon, PhD, president and founder of the Vascular Birthmarks Foundation said in a statement from ASLMS. “As a result of these guidelines, patient outcomes will be improved.”

The guideline, published on the ASLMS website along with supporting videos, was jointly developed by ASLMS, VBF, and an international group of clinicians, marking the first consensus guideline on laser treatments for cutaneous vascular anomalies. It details 32 best practice directives for various scenarios, including advice on safety considerations, additional testing, and when to refer.

“It is important to realize that just because someone is board certified does not mean they are skilled in treating all conditions or using all lasers,” Paul Friedman, MD, a dermatologist in Houston, and former president of ASLMS, said in the ASLMS statement.

Vascular birthmarks are a common condition affecting up to 14% of children, according to VBF. Most are hemangiomas, a buildup of blood vessels that usually appears at birth or within a month after birth. Laser therapy reduces the size and color of the anomalies.

Support for this initiative was provided by Candela Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new practice guideline is setting a standard for doctors who use lasers to treat cutaneous vascular anomalies.

Poor treatment has been an issue in this field because no uniform guidelines existed to inform practice, according to a press release from the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

The laser treatment settings can vary based on the type and location of the birthmark and also the patient’s skin type, which has resulted in an inconsistent approach from clinicians, according to the release.

“For decades, I have observed adverse outcomes from the improper laser treatment of vascular birthmarks,” Linda Rozell-Shannon, PhD, president and founder of the Vascular Birthmarks Foundation said in a statement from ASLMS. “As a result of these guidelines, patient outcomes will be improved.”

The guideline, published on the ASLMS website along with supporting videos, was jointly developed by ASLMS, VBF, and an international group of clinicians, marking the first consensus guideline on laser treatments for cutaneous vascular anomalies. It details 32 best practice directives for various scenarios, including advice on safety considerations, additional testing, and when to refer.

“It is important to realize that just because someone is board certified does not mean they are skilled in treating all conditions or using all lasers,” Paul Friedman, MD, a dermatologist in Houston, and former president of ASLMS, said in the ASLMS statement.

Vascular birthmarks are a common condition affecting up to 14% of children, according to VBF. Most are hemangiomas, a buildup of blood vessels that usually appears at birth or within a month after birth. Laser therapy reduces the size and color of the anomalies.

Support for this initiative was provided by Candela Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Surgeon in the C-suite

“If you don’t have a seat at the table, you are probably on the menu.” I first heard this quote in 2013, and it launched my interest in health care leadership and influenced me countless times over the last 10 years.

As Chief of Staff at Cleveland Clinic, I oversee nearly 5,000 physicians and scientists across the globe. I am involved in the physician life cycle: recruiting, hiring, privileging and credentialing, talent development, promotion, professionalism, and career transitions. I also sit at the intersection of medical care and the business of medicine. This means leading 18 clinical service lines responsible for 5.6 million visits, 161,000 surgeries, and billions of dollars in operating revenue per year. How I spend most of my time is a far cry from what I spent 11 years’ training to do—gynecologic surgery. This shift in my career was not because I changed my mind about caring for patients or that I tired of being a full-time surgeon. Nothing could be further from the truth. Women’s health remains my “why,” and my leadership journey has taught me that it is critical to have a seat at the table for the sake of ObGyns and women everywhere.

Women’s health on the menu

I will start with a concrete example of when we, as women and ObGyns, were on the menu. In late 2019, the Ohio state House of Representatives introduced a bill that subjected doctors to potential murder charges if they did not try everything to save the life of a mother and fetus, “including attempting to reimplant an ectopic pregnancy into the woman’s uterus.”1 This bill was based on 2 case reports—one from 1915 and one from 1980—which were both low quality, and the latter case was deemed to be fraudulent.2 How did this happen?

An Ohio state representative developed the bill with help from a lobbyist and without input from physicians or content experts. When asked, the representative shared that “he never researched whether re-implanting an ectopic pregnancy into a woman’s uterus was a viable medical procedure before including it in the bill.”3 He added, “I heard about it over the years. I never questioned it or gave it a lot of thought.”3

This example resonates deeply with many of us; it inspires us to speak up and act. As ObGyns, we clearly understand the consequences of legal and regulatory change in women’s health and how it directly impacts our patients and each of us as physicians. Let’s shift to something that you may feel less passion about, but I believe is equally important. This is where obstetrician-gynecologists sit in the intersection of medical care and business. This is the space where I spend most of my time, and from this vantage point, I worry about our field.

The business of medicine

Starting at the macroeconomic level, let’s think about how we as physicians are reimbursed and who makes these decisions. Looking at the national health care expenditure data, Medicare and Medicaid spending makes up nearly 40% of the total spend, and it is growing.4 Additionally, private health insurance tends to follow Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) decision making, further compounding its influence.4 In simple terms, CMS decides what is covered and how much we are paid. Whether you are in a solo private practice, an employer health care organization, or an academic medical center, physician reimbursement is declining.

In fact, Congress passed its year-end omnibus legislation in the final days of 2022, including a 2% Medicare physician payment cut for 2023,5 at a time when expenses to practice medicine, including nonphysician staff and supplies, are at an all-time high and we are living in a 6% inflationary state. This translates into being asked to serve more patients and cut costs. Our day-to-day feels much tighter, and this is why: Medicare physician pay increased just 11% over the past 20 years6 (2001–2021) in comparison to the cost of running a medical practice, which increased nearly 40% during that time. In other words, adjusting for inflation in practice costs, Medicare physician payment has fallen 22% over the last 20 years.7

Depending on your employment model, you may feel insulated from these changes as increases in reimbursement have occurred in other areas, such as hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers.8 In the short term, these increases help, as organizations will see additional funds. But there are 2 main issues: First, it is not nearly enough when you consider the soaring costs of running a hospital. And second, looking at our national population, we rely tremendously on self-employed doctors to serve our patients.

More than 80% of US counties lack adequate health care infrastructure.9 More than a third of the US population has less-than-adequate access to pharmacies, primary care physicians, hospitals, trauma centers, and low-cost health centers.9 To put things into perspective, more than 20% of counties in the United States are hospital deserts, where most people must drive more than 30 minutes to reach the closest hospital.9

There is good reason for this. Operating a hospital is a challenging endeavor. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic and the most recent health care financial challenges, most health care systems and large hospitals operated with very low operating margins (2%–3%). Businesses with similar margins include grocery stores and car dealerships. These low-margin businesses, including health care, rely on high volume for sustainability. High patient volumes distribute expensive hospital costs over many encounters. If physicians cannot sustain practices across the country, it is challenging to have sufficient admission and surgical volumes to justify the cost base of hospitals.

To tie this together, we have very little influence on what we are paid for our services. Reimbursement is declining, which makes it hard to have financially sustainable practices. As hospitals struggle, there is more pressure to prioritize highly profitable service lines, like orthopedics and urology, which are associated with favorable technical revenue. As hospitals are threatened, health care deserts widen, which leaves our entire health care system in jeopardy. Not surprisingly, this most likely affects those who face additional barriers to access, such as those with lower income, limited internet access, and lack of insurance. Together, these barriers further widen disparities in health care outcomes, including outcomes for women. Additionally, this death by a thousand cuts has eroded morale and increased physician burnout.

Transforming how we practice medicine is the only viable solution. I have good news: You are the leaders you have been waiting for.

Continue to: Physicians make good managers...

Physicians make good managers

To successfully transform how we practice medicine, it is critical that those leading the transformation deeply understand how medicine is practiced. The level of understanding required can be achieved only through years of medical practice, as a doctor. We understand how medical teams interact and that different sectors of our health care system are interdependent. Also, because physicians drive patient activity and ultimately reimbursement, having a seat at the table is crucial.

Some health care systems are run by businesspeople—people with finance backgrounds—and others are led by physicians. In 2017, Becker’s Hospital Review listed the chief executive officers (CEOs) of 183 nonprofit hospital and health systems.10 Of these, only 25% were led by individuals with an MD. Looking at the 115 largest hospitals in the United States, 30% are physician led.10 Considering the top 10 hospitals ranked by U.S. News & World Report for 2022, 8 of 10 have a physician at the helm.

Beyond raters and rankers, physician-led hospitals do better. Goodall compared CEOs in the top 100 best hospitals in U.S. News & World Report in 3 key medical specialties: cancer, digestive disorders, and cardiac care.11 The study explored the question: “Are hospitals’ quality ranked more highly when they are led by a medically trained doctor or non-MD professional managers?”11 Analysis revealed that hospital quality scores are about 25% higher in physician-run hospitals than in manager-run hospitals.11 Additional research shows that good management practices correlate with hospital performance, and that “the proportion of managers with a clinical degree has the largest positive effect.”12

Several theories exist as to why doctors make good managers in the health care setting.13,14 Doctors may create a more sympathetic and productive work environment for other clinicians because they are one of them. They have peer-to-peer credibility—because they have walked the walk, they have insight and perspective into how medicine is practiced.

Physicians serve as effective change agents for their organizations in several ways:

- First, physicians take a clinical approach in their leadership roles13 and focus on patient care at the center of their decisions. We see the people behind the numbers. Simply put, we humanize the operational side of health care.

- As physicians, we understand the interconnectivity in the practice of medicine. While closing certain service lines may be financially beneficial, these services are often closely linked to profitable service lines.

- Beyond physicians taking a clinical approach to leadership, we emphasize quality.13 Because we all have experienced complications and lived through bad outcomes alongside our patients, we understand deeply how important patient safety and quality is, and we are not willing to sacrifice that for financial gain. For us, this is personal. We don’t see our solution to health care challenges as an “or” situation, instead we view it as an “and” situation.

- Physician leaders often can improve medical staff engagement.13 A 2018 national survey of physicians found that those who are satisfied with their leadership are more engaged at work, have greater job satisfaction, and are less likely to experience signs of burnout.15 Physician administrators add value here.

Continue to: Surgeons as leaders...

Surgeons as leaders

What do we know about surgeons as physician leaders? Looking at the previously mentioned lists of physician leaders, surgeons are relatively absent. In the Becker’s Hospital Review study of nonprofit hospitals, only 9% of CEOs were surgeons.10 In addition, when reviewing data that associated physician leaders and hospital performance, only 3 of the CEOs were surgeons.11 Given that surgeons make up approximately 19% of US physicians, we are underrepresented.

The omission of surgeons as leaders seems inappropriate given that most hospitals are financially reliant on revenue related to surgical care and optimizing this space is an enormous opportunity. Berger and colleagues offered 3 theories as to why there are fewer surgeon leaders16:

- The relative pay of surgeons exceeds that of most other specialties, and there may be less incentive to accept the challenges presented by leadership roles. (I will add that surgeon leadership is more costly to a system.)

- The craftsmanship nature of surgery discourages the development of other career interests beginning at the trainee level.

- Surgeons have been perceived stereotypically to exhibit arrogance, a characteristic that others may not warm to.

This last observation stings. Successful leadership takes social skill and teamwork.14 Although medical care is one of the few disciplines in which lack of teamwork might cost lives, physicians are not trained to be team players. We recognize how our training has led us to be lone wolves or gunners, situations where we as individuals had to beat others to secure our spot. We have been trained in command-and-control environments, in stepping up as a leader in highly stressful situations. This part of surgical culture may handicap surgeons in their quest to be health care leaders.

Other traits, however, make us particularly great leaders in health care. Our desire to succeed, willingness to push ourselves to extremes, ability to laser focus on a task, acceptance of delayed gratification, and aptitude for making timely decisions on limited data help us succeed in leadership roles. Seven years of surgical training helped me develop the grit I use every day in the C-suite.

We need more physician and surgeon leadership to thrive in the challenging health care landscape. Berger and colleagues proposed 3 potential solutions to increase the number of surgeons in hospital leadership positions16:

Nurture future surgical leaders through exposure to management training. Given the contribution to both expense in support services and resources and revenue related to surgical care, each organization needs a content expert to guide these decisions.

Recognize the important contributions that surgeons already make regarding quality, safety, and operational efficiency. An excellent example of this is the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Because surgeons are content experts in this area, we are primed to lead.

Hospitals, medical schools, and academic departments of surgery should recognize administrative efforts as an important part of the overall academic mission. As the adage states, “No margin, no mission.” We need bright minds to preserve and grow our margins so that we can further invest in our missions.

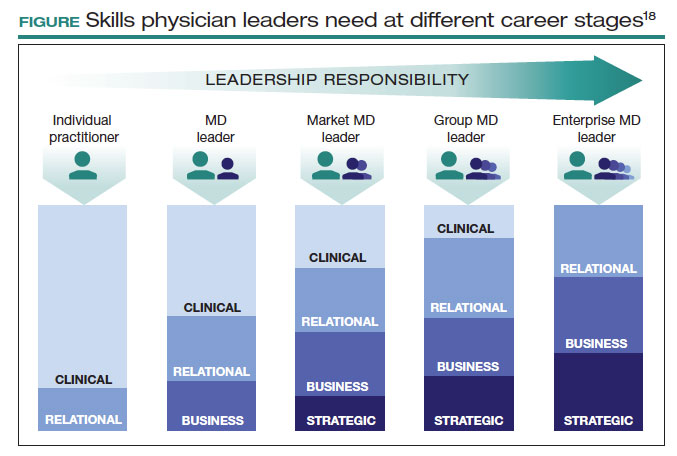

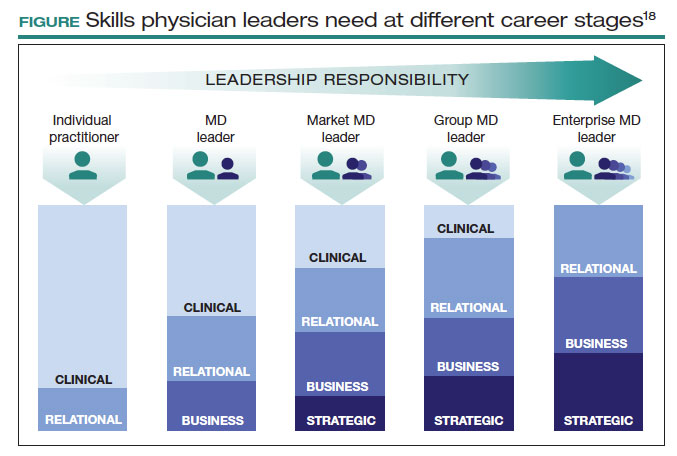

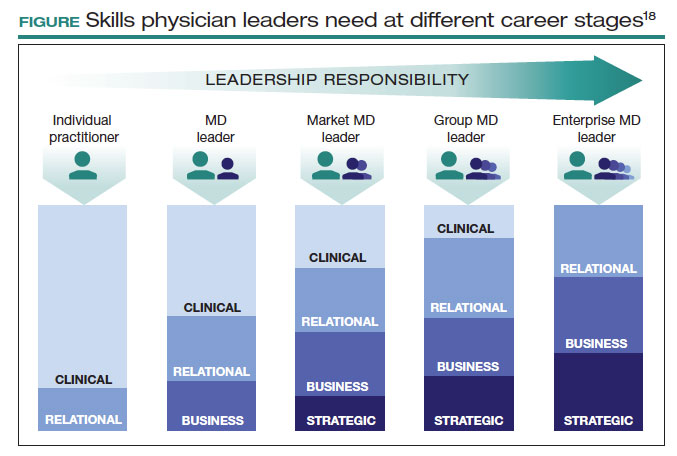

This is not easy. Given the barriers, this will not happen organically. Charan and colleagues provided an outline for a leadership pathway adapted for physicians (FIGURE).17,18 It starts with the individual practitioner who is a practicing physician and spends most of their time focused on patient care. As a physician becomes more interested in leadership, they develop new skills and take on more and more responsibility. As they increase in leadership responsibility, they tend to reduce clinical time and increase time spent on strategic and business management. This framework creates a pipeline so that physicians and surgeons can be developed strategically and given increasing responsibility as they develop their capabilities and expand their skill sets.

The leadership challenge

To thrive, we must transform health care by changing how we practice medicine. As ObGyns, we are the leaders we have been waiting for. As you ponder your future, think of your current career and the opportunities you might have. Do you have a seat at the table? What table is that? How are you using your knowledge, expertise, and privilege to advance health care and medicine? I challenge you to critically evaluate this—and lead. ●

- Law T. Ohio bill suggests doctors who perform abortions could face jail, unless they perform a non-existent treatment. December 1, 2019. Time. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://time.com/5742053 /ectopic-pregnancy-ohio-abortion-bill/

- Grossman D. Ohio abortion, ectopic pregnancy bill: ‘it’s both bad medicine and bad law-making.’ May 21, 2019. Cincinnati.com–The Enquirer. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www .cincinnati.com/story/opinion/2019/05/21/ohio-abortion-bill -john-becker-daniel-grossman-ectopic-pregnancy-false-medicine /3753610002/

- Lobbyist had hand in bill sparking ectopic pregnancy flap. December 11, 2019. Associated Press. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://apnews .com/article/03216e44405fa184ae0ab80fa85089f8

- NHE fact sheet. CMS.gov. Updated February 17, 2023. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and -systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata /nhe-fact-sheet

- Senate passes omnibus spending bill with health provisions. December 23, 2022. American Hospital Association. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.aha.org/special-bulletin/2022-12-20-appropriations -committees-release-omnibus-spending-bill-health-provisions

- Medicare updates compared to inflation (2001-2021). October 2021. American Medical Association. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www .ama-assn.org/system/files/medicare-pay-chart-2021.pdf

- Resneck Jr J. Medicare physician payment reform is long overdue. October 3, 2022. American Medical Association. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/leadership /medicare-physician-payment-reform-long-overdue

- Isenberg M. The stark reality of physician reimbursement. August 24, 2022. Zotec Partners. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://zotecpartners. com/advocacy-zpac/test-1/

- Nguyen A. Mapping healthcare deserts: 80% of the country lacks adequate access to healthcare. September 9, 2021. GoodRx Health. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://www.goodrx.com/healthcare -access/research/healthcare-deserts-80-percent-of-country-lacks -adequate-healthcare-access

- 183 nonprofit hospital and health system CEOs to know–2017. Updated June 20, 2018. Becker’s Hospital Review. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/lists/188-nonprofit -hospital-and-health-system-ceos-to-know-2017.html

- Goodall AH. Physician-leaders and hospital performance: is there an association? Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:535-539. doi:10.1016 /j.socscimed.2011.06.025

- Bloom N, Sadun R, Van Reenen J. Does Management Matter in Healthcare? Center for Economic Performance and Harvard Business School; 2014.

- Turner J. Why healthcare C-suites should include physicians. September 3, 2019. Managed Healthcare Executive. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com /view/why-healthcare-c-suites-should-include-physicians

- Stoller JK, Goodall A, Baker A. Why the best hospitals are managed by doctors. December 27, 2016. Harvard Business Review. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://hbr.org/2016/12/why-the-best-hospitals -are-managed-by-doctors

- Hayhurst C. Data confirms: leaders, physician burnout is on you. April 3, 2019. Aetnahealth. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://www .athenahealth.com/knowledge-hub/practice-management /research-confirms-leaders-burnout-you

- Berger DH, Goodall A, Tsai AY. The importance of increasing surgeon participation in hospital leadership. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:281-282. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.5080

- Charan R, Drotter S, Noel J. The Leadership Pipeline: How to Build the Leadership-Powered Company. Jossey-Bass; 2001.

- Perry J, Mobley F, Brubaker M. Most doctors have little or no management training, and that’s a problem. December 15, 2017. Harvard Business Review. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://hbr.org/2017/12 /most-doctors-have-little-or-no-management-training-and-thats -a-problem

“If you don’t have a seat at the table, you are probably on the menu.” I first heard this quote in 2013, and it launched my interest in health care leadership and influenced me countless times over the last 10 years.

As Chief of Staff at Cleveland Clinic, I oversee nearly 5,000 physicians and scientists across the globe. I am involved in the physician life cycle: recruiting, hiring, privileging and credentialing, talent development, promotion, professionalism, and career transitions. I also sit at the intersection of medical care and the business of medicine. This means leading 18 clinical service lines responsible for 5.6 million visits, 161,000 surgeries, and billions of dollars in operating revenue per year. How I spend most of my time is a far cry from what I spent 11 years’ training to do—gynecologic surgery. This shift in my career was not because I changed my mind about caring for patients or that I tired of being a full-time surgeon. Nothing could be further from the truth. Women’s health remains my “why,” and my leadership journey has taught me that it is critical to have a seat at the table for the sake of ObGyns and women everywhere.

Women’s health on the menu

I will start with a concrete example of when we, as women and ObGyns, were on the menu. In late 2019, the Ohio state House of Representatives introduced a bill that subjected doctors to potential murder charges if they did not try everything to save the life of a mother and fetus, “including attempting to reimplant an ectopic pregnancy into the woman’s uterus.”1 This bill was based on 2 case reports—one from 1915 and one from 1980—which were both low quality, and the latter case was deemed to be fraudulent.2 How did this happen?

An Ohio state representative developed the bill with help from a lobbyist and without input from physicians or content experts. When asked, the representative shared that “he never researched whether re-implanting an ectopic pregnancy into a woman’s uterus was a viable medical procedure before including it in the bill.”3 He added, “I heard about it over the years. I never questioned it or gave it a lot of thought.”3

This example resonates deeply with many of us; it inspires us to speak up and act. As ObGyns, we clearly understand the consequences of legal and regulatory change in women’s health and how it directly impacts our patients and each of us as physicians. Let’s shift to something that you may feel less passion about, but I believe is equally important. This is where obstetrician-gynecologists sit in the intersection of medical care and business. This is the space where I spend most of my time, and from this vantage point, I worry about our field.

The business of medicine

Starting at the macroeconomic level, let’s think about how we as physicians are reimbursed and who makes these decisions. Looking at the national health care expenditure data, Medicare and Medicaid spending makes up nearly 40% of the total spend, and it is growing.4 Additionally, private health insurance tends to follow Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) decision making, further compounding its influence.4 In simple terms, CMS decides what is covered and how much we are paid. Whether you are in a solo private practice, an employer health care organization, or an academic medical center, physician reimbursement is declining.

In fact, Congress passed its year-end omnibus legislation in the final days of 2022, including a 2% Medicare physician payment cut for 2023,5 at a time when expenses to practice medicine, including nonphysician staff and supplies, are at an all-time high and we are living in a 6% inflationary state. This translates into being asked to serve more patients and cut costs. Our day-to-day feels much tighter, and this is why: Medicare physician pay increased just 11% over the past 20 years6 (2001–2021) in comparison to the cost of running a medical practice, which increased nearly 40% during that time. In other words, adjusting for inflation in practice costs, Medicare physician payment has fallen 22% over the last 20 years.7

Depending on your employment model, you may feel insulated from these changes as increases in reimbursement have occurred in other areas, such as hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers.8 In the short term, these increases help, as organizations will see additional funds. But there are 2 main issues: First, it is not nearly enough when you consider the soaring costs of running a hospital. And second, looking at our national population, we rely tremendously on self-employed doctors to serve our patients.

More than 80% of US counties lack adequate health care infrastructure.9 More than a third of the US population has less-than-adequate access to pharmacies, primary care physicians, hospitals, trauma centers, and low-cost health centers.9 To put things into perspective, more than 20% of counties in the United States are hospital deserts, where most people must drive more than 30 minutes to reach the closest hospital.9

There is good reason for this. Operating a hospital is a challenging endeavor. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic and the most recent health care financial challenges, most health care systems and large hospitals operated with very low operating margins (2%–3%). Businesses with similar margins include grocery stores and car dealerships. These low-margin businesses, including health care, rely on high volume for sustainability. High patient volumes distribute expensive hospital costs over many encounters. If physicians cannot sustain practices across the country, it is challenging to have sufficient admission and surgical volumes to justify the cost base of hospitals.

To tie this together, we have very little influence on what we are paid for our services. Reimbursement is declining, which makes it hard to have financially sustainable practices. As hospitals struggle, there is more pressure to prioritize highly profitable service lines, like orthopedics and urology, which are associated with favorable technical revenue. As hospitals are threatened, health care deserts widen, which leaves our entire health care system in jeopardy. Not surprisingly, this most likely affects those who face additional barriers to access, such as those with lower income, limited internet access, and lack of insurance. Together, these barriers further widen disparities in health care outcomes, including outcomes for women. Additionally, this death by a thousand cuts has eroded morale and increased physician burnout.

Transforming how we practice medicine is the only viable solution. I have good news: You are the leaders you have been waiting for.

Continue to: Physicians make good managers...

Physicians make good managers

To successfully transform how we practice medicine, it is critical that those leading the transformation deeply understand how medicine is practiced. The level of understanding required can be achieved only through years of medical practice, as a doctor. We understand how medical teams interact and that different sectors of our health care system are interdependent. Also, because physicians drive patient activity and ultimately reimbursement, having a seat at the table is crucial.

Some health care systems are run by businesspeople—people with finance backgrounds—and others are led by physicians. In 2017, Becker’s Hospital Review listed the chief executive officers (CEOs) of 183 nonprofit hospital and health systems.10 Of these, only 25% were led by individuals with an MD. Looking at the 115 largest hospitals in the United States, 30% are physician led.10 Considering the top 10 hospitals ranked by U.S. News & World Report for 2022, 8 of 10 have a physician at the helm.

Beyond raters and rankers, physician-led hospitals do better. Goodall compared CEOs in the top 100 best hospitals in U.S. News & World Report in 3 key medical specialties: cancer, digestive disorders, and cardiac care.11 The study explored the question: “Are hospitals’ quality ranked more highly when they are led by a medically trained doctor or non-MD professional managers?”11 Analysis revealed that hospital quality scores are about 25% higher in physician-run hospitals than in manager-run hospitals.11 Additional research shows that good management practices correlate with hospital performance, and that “the proportion of managers with a clinical degree has the largest positive effect.”12

Several theories exist as to why doctors make good managers in the health care setting.13,14 Doctors may create a more sympathetic and productive work environment for other clinicians because they are one of them. They have peer-to-peer credibility—because they have walked the walk, they have insight and perspective into how medicine is practiced.

Physicians serve as effective change agents for their organizations in several ways:

- First, physicians take a clinical approach in their leadership roles13 and focus on patient care at the center of their decisions. We see the people behind the numbers. Simply put, we humanize the operational side of health care.

- As physicians, we understand the interconnectivity in the practice of medicine. While closing certain service lines may be financially beneficial, these services are often closely linked to profitable service lines.

- Beyond physicians taking a clinical approach to leadership, we emphasize quality.13 Because we all have experienced complications and lived through bad outcomes alongside our patients, we understand deeply how important patient safety and quality is, and we are not willing to sacrifice that for financial gain. For us, this is personal. We don’t see our solution to health care challenges as an “or” situation, instead we view it as an “and” situation.

- Physician leaders often can improve medical staff engagement.13 A 2018 national survey of physicians found that those who are satisfied with their leadership are more engaged at work, have greater job satisfaction, and are less likely to experience signs of burnout.15 Physician administrators add value here.

Continue to: Surgeons as leaders...

Surgeons as leaders

What do we know about surgeons as physician leaders? Looking at the previously mentioned lists of physician leaders, surgeons are relatively absent. In the Becker’s Hospital Review study of nonprofit hospitals, only 9% of CEOs were surgeons.10 In addition, when reviewing data that associated physician leaders and hospital performance, only 3 of the CEOs were surgeons.11 Given that surgeons make up approximately 19% of US physicians, we are underrepresented.

The omission of surgeons as leaders seems inappropriate given that most hospitals are financially reliant on revenue related to surgical care and optimizing this space is an enormous opportunity. Berger and colleagues offered 3 theories as to why there are fewer surgeon leaders16:

- The relative pay of surgeons exceeds that of most other specialties, and there may be less incentive to accept the challenges presented by leadership roles. (I will add that surgeon leadership is more costly to a system.)

- The craftsmanship nature of surgery discourages the development of other career interests beginning at the trainee level.

- Surgeons have been perceived stereotypically to exhibit arrogance, a characteristic that others may not warm to.

This last observation stings. Successful leadership takes social skill and teamwork.14 Although medical care is one of the few disciplines in which lack of teamwork might cost lives, physicians are not trained to be team players. We recognize how our training has led us to be lone wolves or gunners, situations where we as individuals had to beat others to secure our spot. We have been trained in command-and-control environments, in stepping up as a leader in highly stressful situations. This part of surgical culture may handicap surgeons in their quest to be health care leaders.

Other traits, however, make us particularly great leaders in health care. Our desire to succeed, willingness to push ourselves to extremes, ability to laser focus on a task, acceptance of delayed gratification, and aptitude for making timely decisions on limited data help us succeed in leadership roles. Seven years of surgical training helped me develop the grit I use every day in the C-suite.

We need more physician and surgeon leadership to thrive in the challenging health care landscape. Berger and colleagues proposed 3 potential solutions to increase the number of surgeons in hospital leadership positions16:

Nurture future surgical leaders through exposure to management training. Given the contribution to both expense in support services and resources and revenue related to surgical care, each organization needs a content expert to guide these decisions.

Recognize the important contributions that surgeons already make regarding quality, safety, and operational efficiency. An excellent example of this is the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Because surgeons are content experts in this area, we are primed to lead.

Hospitals, medical schools, and academic departments of surgery should recognize administrative efforts as an important part of the overall academic mission. As the adage states, “No margin, no mission.” We need bright minds to preserve and grow our margins so that we can further invest in our missions.

This is not easy. Given the barriers, this will not happen organically. Charan and colleagues provided an outline for a leadership pathway adapted for physicians (FIGURE).17,18 It starts with the individual practitioner who is a practicing physician and spends most of their time focused on patient care. As a physician becomes more interested in leadership, they develop new skills and take on more and more responsibility. As they increase in leadership responsibility, they tend to reduce clinical time and increase time spent on strategic and business management. This framework creates a pipeline so that physicians and surgeons can be developed strategically and given increasing responsibility as they develop their capabilities and expand their skill sets.

The leadership challenge

To thrive, we must transform health care by changing how we practice medicine. As ObGyns, we are the leaders we have been waiting for. As you ponder your future, think of your current career and the opportunities you might have. Do you have a seat at the table? What table is that? How are you using your knowledge, expertise, and privilege to advance health care and medicine? I challenge you to critically evaluate this—and lead. ●

“If you don’t have a seat at the table, you are probably on the menu.” I first heard this quote in 2013, and it launched my interest in health care leadership and influenced me countless times over the last 10 years.

As Chief of Staff at Cleveland Clinic, I oversee nearly 5,000 physicians and scientists across the globe. I am involved in the physician life cycle: recruiting, hiring, privileging and credentialing, talent development, promotion, professionalism, and career transitions. I also sit at the intersection of medical care and the business of medicine. This means leading 18 clinical service lines responsible for 5.6 million visits, 161,000 surgeries, and billions of dollars in operating revenue per year. How I spend most of my time is a far cry from what I spent 11 years’ training to do—gynecologic surgery. This shift in my career was not because I changed my mind about caring for patients or that I tired of being a full-time surgeon. Nothing could be further from the truth. Women’s health remains my “why,” and my leadership journey has taught me that it is critical to have a seat at the table for the sake of ObGyns and women everywhere.

Women’s health on the menu

I will start with a concrete example of when we, as women and ObGyns, were on the menu. In late 2019, the Ohio state House of Representatives introduced a bill that subjected doctors to potential murder charges if they did not try everything to save the life of a mother and fetus, “including attempting to reimplant an ectopic pregnancy into the woman’s uterus.”1 This bill was based on 2 case reports—one from 1915 and one from 1980—which were both low quality, and the latter case was deemed to be fraudulent.2 How did this happen?

An Ohio state representative developed the bill with help from a lobbyist and without input from physicians or content experts. When asked, the representative shared that “he never researched whether re-implanting an ectopic pregnancy into a woman’s uterus was a viable medical procedure before including it in the bill.”3 He added, “I heard about it over the years. I never questioned it or gave it a lot of thought.”3

This example resonates deeply with many of us; it inspires us to speak up and act. As ObGyns, we clearly understand the consequences of legal and regulatory change in women’s health and how it directly impacts our patients and each of us as physicians. Let’s shift to something that you may feel less passion about, but I believe is equally important. This is where obstetrician-gynecologists sit in the intersection of medical care and business. This is the space where I spend most of my time, and from this vantage point, I worry about our field.

The business of medicine

Starting at the macroeconomic level, let’s think about how we as physicians are reimbursed and who makes these decisions. Looking at the national health care expenditure data, Medicare and Medicaid spending makes up nearly 40% of the total spend, and it is growing.4 Additionally, private health insurance tends to follow Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) decision making, further compounding its influence.4 In simple terms, CMS decides what is covered and how much we are paid. Whether you are in a solo private practice, an employer health care organization, or an academic medical center, physician reimbursement is declining.

In fact, Congress passed its year-end omnibus legislation in the final days of 2022, including a 2% Medicare physician payment cut for 2023,5 at a time when expenses to practice medicine, including nonphysician staff and supplies, are at an all-time high and we are living in a 6% inflationary state. This translates into being asked to serve more patients and cut costs. Our day-to-day feels much tighter, and this is why: Medicare physician pay increased just 11% over the past 20 years6 (2001–2021) in comparison to the cost of running a medical practice, which increased nearly 40% during that time. In other words, adjusting for inflation in practice costs, Medicare physician payment has fallen 22% over the last 20 years.7

Depending on your employment model, you may feel insulated from these changes as increases in reimbursement have occurred in other areas, such as hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers.8 In the short term, these increases help, as organizations will see additional funds. But there are 2 main issues: First, it is not nearly enough when you consider the soaring costs of running a hospital. And second, looking at our national population, we rely tremendously on self-employed doctors to serve our patients.

More than 80% of US counties lack adequate health care infrastructure.9 More than a third of the US population has less-than-adequate access to pharmacies, primary care physicians, hospitals, trauma centers, and low-cost health centers.9 To put things into perspective, more than 20% of counties in the United States are hospital deserts, where most people must drive more than 30 minutes to reach the closest hospital.9

There is good reason for this. Operating a hospital is a challenging endeavor. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic and the most recent health care financial challenges, most health care systems and large hospitals operated with very low operating margins (2%–3%). Businesses with similar margins include grocery stores and car dealerships. These low-margin businesses, including health care, rely on high volume for sustainability. High patient volumes distribute expensive hospital costs over many encounters. If physicians cannot sustain practices across the country, it is challenging to have sufficient admission and surgical volumes to justify the cost base of hospitals.

To tie this together, we have very little influence on what we are paid for our services. Reimbursement is declining, which makes it hard to have financially sustainable practices. As hospitals struggle, there is more pressure to prioritize highly profitable service lines, like orthopedics and urology, which are associated with favorable technical revenue. As hospitals are threatened, health care deserts widen, which leaves our entire health care system in jeopardy. Not surprisingly, this most likely affects those who face additional barriers to access, such as those with lower income, limited internet access, and lack of insurance. Together, these barriers further widen disparities in health care outcomes, including outcomes for women. Additionally, this death by a thousand cuts has eroded morale and increased physician burnout.

Transforming how we practice medicine is the only viable solution. I have good news: You are the leaders you have been waiting for.

Continue to: Physicians make good managers...

Physicians make good managers

To successfully transform how we practice medicine, it is critical that those leading the transformation deeply understand how medicine is practiced. The level of understanding required can be achieved only through years of medical practice, as a doctor. We understand how medical teams interact and that different sectors of our health care system are interdependent. Also, because physicians drive patient activity and ultimately reimbursement, having a seat at the table is crucial.

Some health care systems are run by businesspeople—people with finance backgrounds—and others are led by physicians. In 2017, Becker’s Hospital Review listed the chief executive officers (CEOs) of 183 nonprofit hospital and health systems.10 Of these, only 25% were led by individuals with an MD. Looking at the 115 largest hospitals in the United States, 30% are physician led.10 Considering the top 10 hospitals ranked by U.S. News & World Report for 2022, 8 of 10 have a physician at the helm.

Beyond raters and rankers, physician-led hospitals do better. Goodall compared CEOs in the top 100 best hospitals in U.S. News & World Report in 3 key medical specialties: cancer, digestive disorders, and cardiac care.11 The study explored the question: “Are hospitals’ quality ranked more highly when they are led by a medically trained doctor or non-MD professional managers?”11 Analysis revealed that hospital quality scores are about 25% higher in physician-run hospitals than in manager-run hospitals.11 Additional research shows that good management practices correlate with hospital performance, and that “the proportion of managers with a clinical degree has the largest positive effect.”12

Several theories exist as to why doctors make good managers in the health care setting.13,14 Doctors may create a more sympathetic and productive work environment for other clinicians because they are one of them. They have peer-to-peer credibility—because they have walked the walk, they have insight and perspective into how medicine is practiced.

Physicians serve as effective change agents for their organizations in several ways:

- First, physicians take a clinical approach in their leadership roles13 and focus on patient care at the center of their decisions. We see the people behind the numbers. Simply put, we humanize the operational side of health care.

- As physicians, we understand the interconnectivity in the practice of medicine. While closing certain service lines may be financially beneficial, these services are often closely linked to profitable service lines.

- Beyond physicians taking a clinical approach to leadership, we emphasize quality.13 Because we all have experienced complications and lived through bad outcomes alongside our patients, we understand deeply how important patient safety and quality is, and we are not willing to sacrifice that for financial gain. For us, this is personal. We don’t see our solution to health care challenges as an “or” situation, instead we view it as an “and” situation.

- Physician leaders often can improve medical staff engagement.13 A 2018 national survey of physicians found that those who are satisfied with their leadership are more engaged at work, have greater job satisfaction, and are less likely to experience signs of burnout.15 Physician administrators add value here.

Continue to: Surgeons as leaders...

Surgeons as leaders

What do we know about surgeons as physician leaders? Looking at the previously mentioned lists of physician leaders, surgeons are relatively absent. In the Becker’s Hospital Review study of nonprofit hospitals, only 9% of CEOs were surgeons.10 In addition, when reviewing data that associated physician leaders and hospital performance, only 3 of the CEOs were surgeons.11 Given that surgeons make up approximately 19% of US physicians, we are underrepresented.

The omission of surgeons as leaders seems inappropriate given that most hospitals are financially reliant on revenue related to surgical care and optimizing this space is an enormous opportunity. Berger and colleagues offered 3 theories as to why there are fewer surgeon leaders16:

- The relative pay of surgeons exceeds that of most other specialties, and there may be less incentive to accept the challenges presented by leadership roles. (I will add that surgeon leadership is more costly to a system.)

- The craftsmanship nature of surgery discourages the development of other career interests beginning at the trainee level.

- Surgeons have been perceived stereotypically to exhibit arrogance, a characteristic that others may not warm to.

This last observation stings. Successful leadership takes social skill and teamwork.14 Although medical care is one of the few disciplines in which lack of teamwork might cost lives, physicians are not trained to be team players. We recognize how our training has led us to be lone wolves or gunners, situations where we as individuals had to beat others to secure our spot. We have been trained in command-and-control environments, in stepping up as a leader in highly stressful situations. This part of surgical culture may handicap surgeons in their quest to be health care leaders.

Other traits, however, make us particularly great leaders in health care. Our desire to succeed, willingness to push ourselves to extremes, ability to laser focus on a task, acceptance of delayed gratification, and aptitude for making timely decisions on limited data help us succeed in leadership roles. Seven years of surgical training helped me develop the grit I use every day in the C-suite.

We need more physician and surgeon leadership to thrive in the challenging health care landscape. Berger and colleagues proposed 3 potential solutions to increase the number of surgeons in hospital leadership positions16:

Nurture future surgical leaders through exposure to management training. Given the contribution to both expense in support services and resources and revenue related to surgical care, each organization needs a content expert to guide these decisions.

Recognize the important contributions that surgeons already make regarding quality, safety, and operational efficiency. An excellent example of this is the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Because surgeons are content experts in this area, we are primed to lead.

Hospitals, medical schools, and academic departments of surgery should recognize administrative efforts as an important part of the overall academic mission. As the adage states, “No margin, no mission.” We need bright minds to preserve and grow our margins so that we can further invest in our missions.

This is not easy. Given the barriers, this will not happen organically. Charan and colleagues provided an outline for a leadership pathway adapted for physicians (FIGURE).17,18 It starts with the individual practitioner who is a practicing physician and spends most of their time focused on patient care. As a physician becomes more interested in leadership, they develop new skills and take on more and more responsibility. As they increase in leadership responsibility, they tend to reduce clinical time and increase time spent on strategic and business management. This framework creates a pipeline so that physicians and surgeons can be developed strategically and given increasing responsibility as they develop their capabilities and expand their skill sets.

The leadership challenge

To thrive, we must transform health care by changing how we practice medicine. As ObGyns, we are the leaders we have been waiting for. As you ponder your future, think of your current career and the opportunities you might have. Do you have a seat at the table? What table is that? How are you using your knowledge, expertise, and privilege to advance health care and medicine? I challenge you to critically evaluate this—and lead. ●

- Law T. Ohio bill suggests doctors who perform abortions could face jail, unless they perform a non-existent treatment. December 1, 2019. Time. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://time.com/5742053 /ectopic-pregnancy-ohio-abortion-bill/

- Grossman D. Ohio abortion, ectopic pregnancy bill: ‘it’s both bad medicine and bad law-making.’ May 21, 2019. Cincinnati.com–The Enquirer. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www .cincinnati.com/story/opinion/2019/05/21/ohio-abortion-bill -john-becker-daniel-grossman-ectopic-pregnancy-false-medicine /3753610002/

- Lobbyist had hand in bill sparking ectopic pregnancy flap. December 11, 2019. Associated Press. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://apnews .com/article/03216e44405fa184ae0ab80fa85089f8

- NHE fact sheet. CMS.gov. Updated February 17, 2023. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and -systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata /nhe-fact-sheet

- Senate passes omnibus spending bill with health provisions. December 23, 2022. American Hospital Association. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.aha.org/special-bulletin/2022-12-20-appropriations -committees-release-omnibus-spending-bill-health-provisions

- Medicare updates compared to inflation (2001-2021). October 2021. American Medical Association. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www .ama-assn.org/system/files/medicare-pay-chart-2021.pdf

- Resneck Jr J. Medicare physician payment reform is long overdue. October 3, 2022. American Medical Association. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/leadership /medicare-physician-payment-reform-long-overdue

- Isenberg M. The stark reality of physician reimbursement. August 24, 2022. Zotec Partners. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://zotecpartners. com/advocacy-zpac/test-1/

- Nguyen A. Mapping healthcare deserts: 80% of the country lacks adequate access to healthcare. September 9, 2021. GoodRx Health. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://www.goodrx.com/healthcare -access/research/healthcare-deserts-80-percent-of-country-lacks -adequate-healthcare-access

- 183 nonprofit hospital and health system CEOs to know–2017. Updated June 20, 2018. Becker’s Hospital Review. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/lists/188-nonprofit -hospital-and-health-system-ceos-to-know-2017.html

- Goodall AH. Physician-leaders and hospital performance: is there an association? Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:535-539. doi:10.1016 /j.socscimed.2011.06.025

- Bloom N, Sadun R, Van Reenen J. Does Management Matter in Healthcare? Center for Economic Performance and Harvard Business School; 2014.

- Turner J. Why healthcare C-suites should include physicians. September 3, 2019. Managed Healthcare Executive. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com /view/why-healthcare-c-suites-should-include-physicians

- Stoller JK, Goodall A, Baker A. Why the best hospitals are managed by doctors. December 27, 2016. Harvard Business Review. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://hbr.org/2016/12/why-the-best-hospitals -are-managed-by-doctors

- Hayhurst C. Data confirms: leaders, physician burnout is on you. April 3, 2019. Aetnahealth. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://www .athenahealth.com/knowledge-hub/practice-management /research-confirms-leaders-burnout-you

- Berger DH, Goodall A, Tsai AY. The importance of increasing surgeon participation in hospital leadership. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:281-282. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.5080

- Charan R, Drotter S, Noel J. The Leadership Pipeline: How to Build the Leadership-Powered Company. Jossey-Bass; 2001.

- Perry J, Mobley F, Brubaker M. Most doctors have little or no management training, and that’s a problem. December 15, 2017. Harvard Business Review. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://hbr.org/2017/12 /most-doctors-have-little-or-no-management-training-and-thats -a-problem

- Law T. Ohio bill suggests doctors who perform abortions could face jail, unless they perform a non-existent treatment. December 1, 2019. Time. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://time.com/5742053 /ectopic-pregnancy-ohio-abortion-bill/

- Grossman D. Ohio abortion, ectopic pregnancy bill: ‘it’s both bad medicine and bad law-making.’ May 21, 2019. Cincinnati.com–The Enquirer. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www .cincinnati.com/story/opinion/2019/05/21/ohio-abortion-bill -john-becker-daniel-grossman-ectopic-pregnancy-false-medicine /3753610002/

- Lobbyist had hand in bill sparking ectopic pregnancy flap. December 11, 2019. Associated Press. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://apnews .com/article/03216e44405fa184ae0ab80fa85089f8

- NHE fact sheet. CMS.gov. Updated February 17, 2023. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and -systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata /nhe-fact-sheet

- Senate passes omnibus spending bill with health provisions. December 23, 2022. American Hospital Association. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.aha.org/special-bulletin/2022-12-20-appropriations -committees-release-omnibus-spending-bill-health-provisions

- Medicare updates compared to inflation (2001-2021). October 2021. American Medical Association. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www .ama-assn.org/system/files/medicare-pay-chart-2021.pdf

- Resneck Jr J. Medicare physician payment reform is long overdue. October 3, 2022. American Medical Association. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/leadership /medicare-physician-payment-reform-long-overdue

- Isenberg M. The stark reality of physician reimbursement. August 24, 2022. Zotec Partners. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://zotecpartners. com/advocacy-zpac/test-1/

- Nguyen A. Mapping healthcare deserts: 80% of the country lacks adequate access to healthcare. September 9, 2021. GoodRx Health. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://www.goodrx.com/healthcare -access/research/healthcare-deserts-80-percent-of-country-lacks -adequate-healthcare-access

- 183 nonprofit hospital and health system CEOs to know–2017. Updated June 20, 2018. Becker’s Hospital Review. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/lists/188-nonprofit -hospital-and-health-system-ceos-to-know-2017.html

- Goodall AH. Physician-leaders and hospital performance: is there an association? Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:535-539. doi:10.1016 /j.socscimed.2011.06.025

- Bloom N, Sadun R, Van Reenen J. Does Management Matter in Healthcare? Center for Economic Performance and Harvard Business School; 2014.