User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

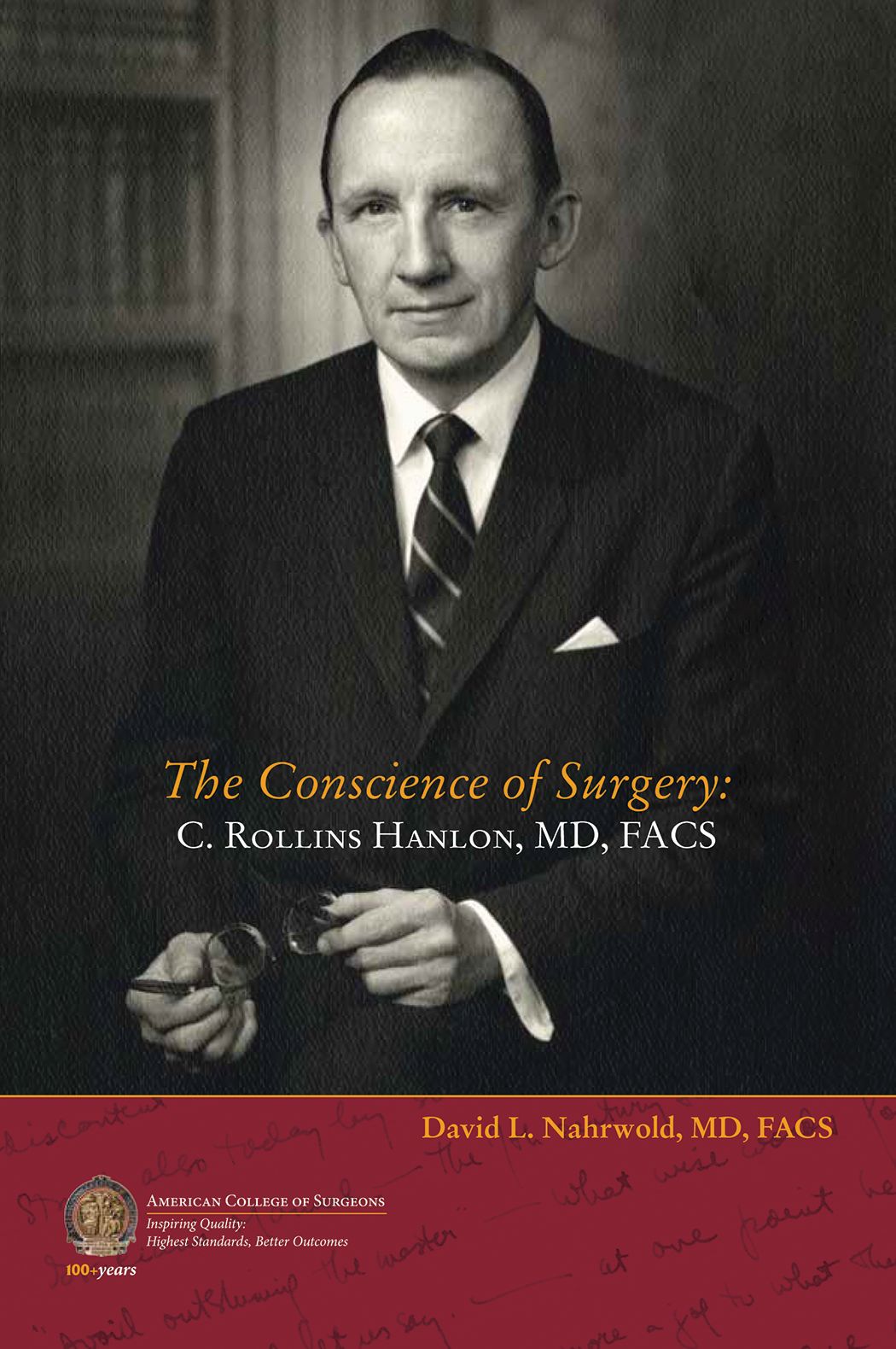

Biography of C. Rollins Hanlon, MD, FACS, Past-Director of the ACS, now available

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) recently published a new biography of C. Rollins Hanlon, MD, FACS, ACS Past-Director, a seminal figure in the history of surgery and the College, titled The Conscience of Surgery: C. Rollins Hanlon, MD, FACS. Written by David L. Nahrwold, MD, FACS, this account examines the life of the erudite, principled cardiothoracic surgeon and innovator, who co-developed the Blalock-Hanlon operation with Alfred P. Blalock, MD, FACS.

The book covers every aspect of Dr. Hanlon’s life—from his boyhood in Baltimore, MD, to his quest to be the best clinician and surgeon-scientist, to his views on the government’s increasing influence on the delivery of surgical care, and to his undying love of the written word. For many surgeons, Dr. Hanlon was the embodiment of what it means to be a Fellow of the ACS.

“I got to know [Dr. Hanlon] as a person and a professional during my stint as the Interim Director of the ACS in 1999 when he was ‘retired’ and serving as Executive Consultant,” Dr. Nahrwold writes in the book’s preface. “He insisted that the mission of the College was to advance the ethical and competent practice of surgery and not to improve the financial well-being of surgeons.”

Throughout his career, Dr. Hanlon’s mentors, colleagues, and students included many eminent surgeons at Johns Hopkins Medical School, Baltimore, MD; Cincinnati General Hospital, OH; and the University of California, San Francisco. He trained under Dean DeWitt Lewis, Walter E. Dandy, Howard C. Naffziger, Warfield “Monty” Firor, and Mont Reid (all MD, FACS). He worked alongside William P. Longmire, MD, FACS; Dr. Blalock; and Mark C. Ravitch, MD, FACS; and his residents and interns at St. Louis University, MO, included Vallee Willman, Theodore Cooper, Theodore Dubuque, and William Stoneman (all MD, FACS), among others.

Dr. Hanlon served in the U.S. Navy in World War II, and followed with a distinguished career at Johns Hopkins and at St. Louis University, where, as chair of surgery, he developed the institution’s cardiac research capabilities, which helped to pioneer early open-heart and heart transplant procedures.

Dr. Hanlon became a Fellow of the College in 1953 and served as the ACS Director for 17 years (1969–1986), making him the longest-serving Director to date. Additionally, he served on the Board of Regents and as the ACS President (1985–1986). After retirement, he stayed on as ACS Executive Consultant, offering his sage advice to his successors, including Paul A. Ebert, MD, FACS; Samuel Wells, MD, FACS; Dr. Nahrwold; Thomas R. Russell, MD, FACS; and David B. Hoyt, MD, FACS. Through these positions, Dr. Hanlon had a profound effect on the direction and philosophy of the College, including in philanthropic endeavors and the establishment of the ACS Archives. He received the first ACS Lifetime Achievement Award in 2010.

“Hanlon’s integrity, faith, hard work, and service to others led him to become a role model for physicians and laypersons alike. These attributes also drove his brilliant career as an innovative surgeon, leadership in academic and organized medicine, and reputation as a humanist and ethicist,” Dr. Narhwold concludes in the preface. “Before he died I knew that I must write his biography to expose his principled life, his goodness, and his devotion to surgery and to surgeons, especially young surgeons, with the hope that they and others will find his life worthy of study and emulation.”

Dr. Nahrwold is Emeritus Professor of Surgery at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, where he was the Loyal and Edith Davis Professor and Chairman, department of surgery, and surgeon-in-chief, Northwestern Memorial Hospital. He is a recipient of the College’s highest honor—the Distinguished Service Award.

Dr. Nahrwold is author of A Mirror Reflecting Surgery, Surgeons, and their College: The Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons, and co-author, with Peter J. Kernahan, MD, PhD, FACS, of A Century of Surgeons and Surgery: The American College of Surgeons 1913–2012.

The Conscience of Surgery: C. Rollins Hanlon, MD, FACS, is available for $15.95 on the ACS E-Store at web4.facs.org/eBusiness/ProductCatalog/Product.aspx?ID=1060 and on amazon.com.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) recently published a new biography of C. Rollins Hanlon, MD, FACS, ACS Past-Director, a seminal figure in the history of surgery and the College, titled The Conscience of Surgery: C. Rollins Hanlon, MD, FACS. Written by David L. Nahrwold, MD, FACS, this account examines the life of the erudite, principled cardiothoracic surgeon and innovator, who co-developed the Blalock-Hanlon operation with Alfred P. Blalock, MD, FACS.

The book covers every aspect of Dr. Hanlon’s life—from his boyhood in Baltimore, MD, to his quest to be the best clinician and surgeon-scientist, to his views on the government’s increasing influence on the delivery of surgical care, and to his undying love of the written word. For many surgeons, Dr. Hanlon was the embodiment of what it means to be a Fellow of the ACS.

“I got to know [Dr. Hanlon] as a person and a professional during my stint as the Interim Director of the ACS in 1999 when he was ‘retired’ and serving as Executive Consultant,” Dr. Nahrwold writes in the book’s preface. “He insisted that the mission of the College was to advance the ethical and competent practice of surgery and not to improve the financial well-being of surgeons.”

Throughout his career, Dr. Hanlon’s mentors, colleagues, and students included many eminent surgeons at Johns Hopkins Medical School, Baltimore, MD; Cincinnati General Hospital, OH; and the University of California, San Francisco. He trained under Dean DeWitt Lewis, Walter E. Dandy, Howard C. Naffziger, Warfield “Monty” Firor, and Mont Reid (all MD, FACS). He worked alongside William P. Longmire, MD, FACS; Dr. Blalock; and Mark C. Ravitch, MD, FACS; and his residents and interns at St. Louis University, MO, included Vallee Willman, Theodore Cooper, Theodore Dubuque, and William Stoneman (all MD, FACS), among others.

Dr. Hanlon served in the U.S. Navy in World War II, and followed with a distinguished career at Johns Hopkins and at St. Louis University, where, as chair of surgery, he developed the institution’s cardiac research capabilities, which helped to pioneer early open-heart and heart transplant procedures.

Dr. Hanlon became a Fellow of the College in 1953 and served as the ACS Director for 17 years (1969–1986), making him the longest-serving Director to date. Additionally, he served on the Board of Regents and as the ACS President (1985–1986). After retirement, he stayed on as ACS Executive Consultant, offering his sage advice to his successors, including Paul A. Ebert, MD, FACS; Samuel Wells, MD, FACS; Dr. Nahrwold; Thomas R. Russell, MD, FACS; and David B. Hoyt, MD, FACS. Through these positions, Dr. Hanlon had a profound effect on the direction and philosophy of the College, including in philanthropic endeavors and the establishment of the ACS Archives. He received the first ACS Lifetime Achievement Award in 2010.

“Hanlon’s integrity, faith, hard work, and service to others led him to become a role model for physicians and laypersons alike. These attributes also drove his brilliant career as an innovative surgeon, leadership in academic and organized medicine, and reputation as a humanist and ethicist,” Dr. Narhwold concludes in the preface. “Before he died I knew that I must write his biography to expose his principled life, his goodness, and his devotion to surgery and to surgeons, especially young surgeons, with the hope that they and others will find his life worthy of study and emulation.”

Dr. Nahrwold is Emeritus Professor of Surgery at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, where he was the Loyal and Edith Davis Professor and Chairman, department of surgery, and surgeon-in-chief, Northwestern Memorial Hospital. He is a recipient of the College’s highest honor—the Distinguished Service Award.

Dr. Nahrwold is author of A Mirror Reflecting Surgery, Surgeons, and their College: The Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons, and co-author, with Peter J. Kernahan, MD, PhD, FACS, of A Century of Surgeons and Surgery: The American College of Surgeons 1913–2012.

The Conscience of Surgery: C. Rollins Hanlon, MD, FACS, is available for $15.95 on the ACS E-Store at web4.facs.org/eBusiness/ProductCatalog/Product.aspx?ID=1060 and on amazon.com.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) recently published a new biography of C. Rollins Hanlon, MD, FACS, ACS Past-Director, a seminal figure in the history of surgery and the College, titled The Conscience of Surgery: C. Rollins Hanlon, MD, FACS. Written by David L. Nahrwold, MD, FACS, this account examines the life of the erudite, principled cardiothoracic surgeon and innovator, who co-developed the Blalock-Hanlon operation with Alfred P. Blalock, MD, FACS.

The book covers every aspect of Dr. Hanlon’s life—from his boyhood in Baltimore, MD, to his quest to be the best clinician and surgeon-scientist, to his views on the government’s increasing influence on the delivery of surgical care, and to his undying love of the written word. For many surgeons, Dr. Hanlon was the embodiment of what it means to be a Fellow of the ACS.

“I got to know [Dr. Hanlon] as a person and a professional during my stint as the Interim Director of the ACS in 1999 when he was ‘retired’ and serving as Executive Consultant,” Dr. Nahrwold writes in the book’s preface. “He insisted that the mission of the College was to advance the ethical and competent practice of surgery and not to improve the financial well-being of surgeons.”

Throughout his career, Dr. Hanlon’s mentors, colleagues, and students included many eminent surgeons at Johns Hopkins Medical School, Baltimore, MD; Cincinnati General Hospital, OH; and the University of California, San Francisco. He trained under Dean DeWitt Lewis, Walter E. Dandy, Howard C. Naffziger, Warfield “Monty” Firor, and Mont Reid (all MD, FACS). He worked alongside William P. Longmire, MD, FACS; Dr. Blalock; and Mark C. Ravitch, MD, FACS; and his residents and interns at St. Louis University, MO, included Vallee Willman, Theodore Cooper, Theodore Dubuque, and William Stoneman (all MD, FACS), among others.

Dr. Hanlon served in the U.S. Navy in World War II, and followed with a distinguished career at Johns Hopkins and at St. Louis University, where, as chair of surgery, he developed the institution’s cardiac research capabilities, which helped to pioneer early open-heart and heart transplant procedures.

Dr. Hanlon became a Fellow of the College in 1953 and served as the ACS Director for 17 years (1969–1986), making him the longest-serving Director to date. Additionally, he served on the Board of Regents and as the ACS President (1985–1986). After retirement, he stayed on as ACS Executive Consultant, offering his sage advice to his successors, including Paul A. Ebert, MD, FACS; Samuel Wells, MD, FACS; Dr. Nahrwold; Thomas R. Russell, MD, FACS; and David B. Hoyt, MD, FACS. Through these positions, Dr. Hanlon had a profound effect on the direction and philosophy of the College, including in philanthropic endeavors and the establishment of the ACS Archives. He received the first ACS Lifetime Achievement Award in 2010.

“Hanlon’s integrity, faith, hard work, and service to others led him to become a role model for physicians and laypersons alike. These attributes also drove his brilliant career as an innovative surgeon, leadership in academic and organized medicine, and reputation as a humanist and ethicist,” Dr. Narhwold concludes in the preface. “Before he died I knew that I must write his biography to expose his principled life, his goodness, and his devotion to surgery and to surgeons, especially young surgeons, with the hope that they and others will find his life worthy of study and emulation.”

Dr. Nahrwold is Emeritus Professor of Surgery at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, where he was the Loyal and Edith Davis Professor and Chairman, department of surgery, and surgeon-in-chief, Northwestern Memorial Hospital. He is a recipient of the College’s highest honor—the Distinguished Service Award.

Dr. Nahrwold is author of A Mirror Reflecting Surgery, Surgeons, and their College: The Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons, and co-author, with Peter J. Kernahan, MD, PhD, FACS, of A Century of Surgeons and Surgery: The American College of Surgeons 1913–2012.

The Conscience of Surgery: C. Rollins Hanlon, MD, FACS, is available for $15.95 on the ACS E-Store at web4.facs.org/eBusiness/ProductCatalog/Product.aspx?ID=1060 and on amazon.com.

Heidi Nelson, MD, FACS, named Medical Director of ACS Cancer Programs

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) recently announced that Heidi Nelson, MD, FACS, a colorectal surgeon from Rochester, MN, will be joining the ACS Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care (DROPC) as Medical Director, Cancer Programs, succeeding David P. Winchester, MD, FACS, as he transitions from the position he has served in for more than 30 years. Dr. Nelson comes to the ACS from her position as chair, and vice-chair for research, department of surgery, Mayo Clinic, as well as professor of surgery, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, Rochester. She has master’s faculty privileges in clinical and translation science at the Mayo Clinic Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences and the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science.

Dr. Nelson received a bachelor’s degree from Western Washington University, Bellingham, and her medical degree from the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle. She completed an internship and residency in general surgery at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, where she also served as an American Cancer Society Fellow. She then went to the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, where she was a colon and rectal surgery fellow and completed a research fellowship. Dr. Nelson returned to the University of Washington, where she was a Leo Hirsch Traveling Fellow.

Dr. Nelson has received numerous awards and held membership in many professional organizations, including the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the Mayo Clinic Board of Governors, the Society of Surgical Oncology, and the Association of Women Surgeons, among others.

Research activities

As the Fred C. Andersen Professor for the Mayo Foundation and a consultant for Mayo Clinic’s division of colon and rectal surgery, Dr. Nelson is internationally renowned for her research in the field of colon and rectal cancer. The goal of her research activities has been to improve the duration and quality of life for these patients. These efforts have helped to reduce the impact of surgery on patients with early-stage disease through the safe introduction of laparoscopic and minimally invasive surgical approaches. Her work also has helped to reduce the cancer burden in patients with locally advanced and recurrent rectal cancer through studies examining the role of complex operations and intraoperative radiation therapy. Dr. Nelson’s work has been funded by the National Institutes of Health, the American Cancer Society, the ASCRS, and many other organizations. In addition to her clinical activities, she has led the Center for Individualized Medicine Microbiome Program at the Mayo Clinic, where she conducts, presents, and publishes research on the human microbiome and its connection to health and disease.

Leadership

Dr. Nelson brings a wealth of experience from leading others and establishing results-oriented teams. She has mentored trainees and investigators and has served as an editor and publisher for high-impact journals. She also has been extensively involved with the ACS throughout her career—Dr. Nelson became an ACS Fellow in 1993 and has served as former Director, ACS Clinical Research Program; former co-chair, ACS Oncology Group; and as a member, Commission on Cancer Executive Committee.

Dr. Nelson started working with the ACS in September on an initial part-time basis, overlapping with Dr. Winchester to ensure a smooth transition and continuity of leadership.

“The American College of Surgeons is excited about Dr. Nelson joining our Executive Leadership Team. Her research acumen and leadership in the cancer care community are well known and widely respected. Her addition to our team will benefit our members, our relationships with cancer care organizations, and the patients whom we serve,” said ACS Executive Director David B. Hoyt, MD, FACS.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) recently announced that Heidi Nelson, MD, FACS, a colorectal surgeon from Rochester, MN, will be joining the ACS Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care (DROPC) as Medical Director, Cancer Programs, succeeding David P. Winchester, MD, FACS, as he transitions from the position he has served in for more than 30 years. Dr. Nelson comes to the ACS from her position as chair, and vice-chair for research, department of surgery, Mayo Clinic, as well as professor of surgery, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, Rochester. She has master’s faculty privileges in clinical and translation science at the Mayo Clinic Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences and the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science.

Dr. Nelson received a bachelor’s degree from Western Washington University, Bellingham, and her medical degree from the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle. She completed an internship and residency in general surgery at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, where she also served as an American Cancer Society Fellow. She then went to the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, where she was a colon and rectal surgery fellow and completed a research fellowship. Dr. Nelson returned to the University of Washington, where she was a Leo Hirsch Traveling Fellow.

Dr. Nelson has received numerous awards and held membership in many professional organizations, including the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the Mayo Clinic Board of Governors, the Society of Surgical Oncology, and the Association of Women Surgeons, among others.

Research activities

As the Fred C. Andersen Professor for the Mayo Foundation and a consultant for Mayo Clinic’s division of colon and rectal surgery, Dr. Nelson is internationally renowned for her research in the field of colon and rectal cancer. The goal of her research activities has been to improve the duration and quality of life for these patients. These efforts have helped to reduce the impact of surgery on patients with early-stage disease through the safe introduction of laparoscopic and minimally invasive surgical approaches. Her work also has helped to reduce the cancer burden in patients with locally advanced and recurrent rectal cancer through studies examining the role of complex operations and intraoperative radiation therapy. Dr. Nelson’s work has been funded by the National Institutes of Health, the American Cancer Society, the ASCRS, and many other organizations. In addition to her clinical activities, she has led the Center for Individualized Medicine Microbiome Program at the Mayo Clinic, where she conducts, presents, and publishes research on the human microbiome and its connection to health and disease.

Leadership

Dr. Nelson brings a wealth of experience from leading others and establishing results-oriented teams. She has mentored trainees and investigators and has served as an editor and publisher for high-impact journals. She also has been extensively involved with the ACS throughout her career—Dr. Nelson became an ACS Fellow in 1993 and has served as former Director, ACS Clinical Research Program; former co-chair, ACS Oncology Group; and as a member, Commission on Cancer Executive Committee.

Dr. Nelson started working with the ACS in September on an initial part-time basis, overlapping with Dr. Winchester to ensure a smooth transition and continuity of leadership.

“The American College of Surgeons is excited about Dr. Nelson joining our Executive Leadership Team. Her research acumen and leadership in the cancer care community are well known and widely respected. Her addition to our team will benefit our members, our relationships with cancer care organizations, and the patients whom we serve,” said ACS Executive Director David B. Hoyt, MD, FACS.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) recently announced that Heidi Nelson, MD, FACS, a colorectal surgeon from Rochester, MN, will be joining the ACS Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care (DROPC) as Medical Director, Cancer Programs, succeeding David P. Winchester, MD, FACS, as he transitions from the position he has served in for more than 30 years. Dr. Nelson comes to the ACS from her position as chair, and vice-chair for research, department of surgery, Mayo Clinic, as well as professor of surgery, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, Rochester. She has master’s faculty privileges in clinical and translation science at the Mayo Clinic Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences and the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science.

Dr. Nelson received a bachelor’s degree from Western Washington University, Bellingham, and her medical degree from the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle. She completed an internship and residency in general surgery at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, where she also served as an American Cancer Society Fellow. She then went to the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, where she was a colon and rectal surgery fellow and completed a research fellowship. Dr. Nelson returned to the University of Washington, where she was a Leo Hirsch Traveling Fellow.

Dr. Nelson has received numerous awards and held membership in many professional organizations, including the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the Mayo Clinic Board of Governors, the Society of Surgical Oncology, and the Association of Women Surgeons, among others.

Research activities

As the Fred C. Andersen Professor for the Mayo Foundation and a consultant for Mayo Clinic’s division of colon and rectal surgery, Dr. Nelson is internationally renowned for her research in the field of colon and rectal cancer. The goal of her research activities has been to improve the duration and quality of life for these patients. These efforts have helped to reduce the impact of surgery on patients with early-stage disease through the safe introduction of laparoscopic and minimally invasive surgical approaches. Her work also has helped to reduce the cancer burden in patients with locally advanced and recurrent rectal cancer through studies examining the role of complex operations and intraoperative radiation therapy. Dr. Nelson’s work has been funded by the National Institutes of Health, the American Cancer Society, the ASCRS, and many other organizations. In addition to her clinical activities, she has led the Center for Individualized Medicine Microbiome Program at the Mayo Clinic, where she conducts, presents, and publishes research on the human microbiome and its connection to health and disease.

Leadership

Dr. Nelson brings a wealth of experience from leading others and establishing results-oriented teams. She has mentored trainees and investigators and has served as an editor and publisher for high-impact journals. She also has been extensively involved with the ACS throughout her career—Dr. Nelson became an ACS Fellow in 1993 and has served as former Director, ACS Clinical Research Program; former co-chair, ACS Oncology Group; and as a member, Commission on Cancer Executive Committee.

Dr. Nelson started working with the ACS in September on an initial part-time basis, overlapping with Dr. Winchester to ensure a smooth transition and continuity of leadership.

“The American College of Surgeons is excited about Dr. Nelson joining our Executive Leadership Team. Her research acumen and leadership in the cancer care community are well known and widely respected. Her addition to our team will benefit our members, our relationships with cancer care organizations, and the patients whom we serve,” said ACS Executive Director David B. Hoyt, MD, FACS.

Ronald V. Maier, MD, FACS, FRCSEd(Hon), FCSHK(Hon) installed as 2018–2019

Ronald. V. Maier, MD, FACS, FRCSEd(Hon), FCSHK(Hon), the Jane and Donald D. Trunkey Endowed Chair in Trauma Surgery; vice-chairman, department of surgery; and professor of surgery, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, was installed as the 99th President of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) at Convocation, October 21, at Clinical Congress 2018 in Boston, MA.

Dr. Maier is highly esteemed for his contributions to trauma surgery, surgical research, and surgical education. In addition to his positions at the University of Washington, he is director, Northwest Regional Trauma Center; and surgeon-in-chief and co-director, surgical intensive care unit (SICU), Harborview Medical Center, Seattle. He also is associate medical staff, University of Washington Medical Center and Seattle Cancer Care Alliance. A Fellow of the College since 1984, Dr. Maier served as First Vice-President of the ACS (2015−2016) and has played an active role on several key committees, most notably the Committee on Trauma (COT).

Mark C. Weissler, MD, FACS, Past-Chair of the ACS Board of Regents (2014−2015) was installed as the First Vice-President. An otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeon, Dr. Weissler is the Joseph P. Riddle Distinguished Professor, department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery, and chief, division of head and neck surgery, University of North Carolina (UNC) School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. An ACS Fellow since 1989, Dr. Weissler is a former ACS Regent, serving as Vice-Chair of the Board of Regents for two years (2012–2014) and Chair for one year (2014−2015). He has served on the ACS Board of Governors and in other leadership capacities for the College, including the Committee on Ethics, Central Judiciary Committee, Advisory Council for Otolaryngology−Head and Neck Surgery; and President, North Carolina Chapter of the ACS.

The Second Vice-President is Phillip R. Caropreso, MD, FACS, a general surgeon from Keokuk, IA. A committed rural surgeon, Dr. Caropreso has practiced in Mason City, IA; Keokuk, IA; and Carthage, IL. Academic positions have included serving on the teaching faculty, family practice residency, North Iowa Medical Center, Mason City; adjunct clinical professor of surgery, University of Iowa, Iowa City; and director, general surgery rotation, North Iowa Medical Center. A Fellow of the ACS since 1979, Dr. Caropreso has been active at the local and national level. He was Chair, Iowa State COT; President of the Iowa Chapter; and ACS Governor, serving on the Board of Governors Committee on Surgical Practices.

Read more about Dr. Maier, Dr. Weissler, and Dr. Caropreso in the November Bulletin at www.bulletin.facs.org.

Ronald. V. Maier, MD, FACS, FRCSEd(Hon), FCSHK(Hon), the Jane and Donald D. Trunkey Endowed Chair in Trauma Surgery; vice-chairman, department of surgery; and professor of surgery, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, was installed as the 99th President of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) at Convocation, October 21, at Clinical Congress 2018 in Boston, MA.

Dr. Maier is highly esteemed for his contributions to trauma surgery, surgical research, and surgical education. In addition to his positions at the University of Washington, he is director, Northwest Regional Trauma Center; and surgeon-in-chief and co-director, surgical intensive care unit (SICU), Harborview Medical Center, Seattle. He also is associate medical staff, University of Washington Medical Center and Seattle Cancer Care Alliance. A Fellow of the College since 1984, Dr. Maier served as First Vice-President of the ACS (2015−2016) and has played an active role on several key committees, most notably the Committee on Trauma (COT).

Mark C. Weissler, MD, FACS, Past-Chair of the ACS Board of Regents (2014−2015) was installed as the First Vice-President. An otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeon, Dr. Weissler is the Joseph P. Riddle Distinguished Professor, department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery, and chief, division of head and neck surgery, University of North Carolina (UNC) School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. An ACS Fellow since 1989, Dr. Weissler is a former ACS Regent, serving as Vice-Chair of the Board of Regents for two years (2012–2014) and Chair for one year (2014−2015). He has served on the ACS Board of Governors and in other leadership capacities for the College, including the Committee on Ethics, Central Judiciary Committee, Advisory Council for Otolaryngology−Head and Neck Surgery; and President, North Carolina Chapter of the ACS.

The Second Vice-President is Phillip R. Caropreso, MD, FACS, a general surgeon from Keokuk, IA. A committed rural surgeon, Dr. Caropreso has practiced in Mason City, IA; Keokuk, IA; and Carthage, IL. Academic positions have included serving on the teaching faculty, family practice residency, North Iowa Medical Center, Mason City; adjunct clinical professor of surgery, University of Iowa, Iowa City; and director, general surgery rotation, North Iowa Medical Center. A Fellow of the ACS since 1979, Dr. Caropreso has been active at the local and national level. He was Chair, Iowa State COT; President of the Iowa Chapter; and ACS Governor, serving on the Board of Governors Committee on Surgical Practices.

Read more about Dr. Maier, Dr. Weissler, and Dr. Caropreso in the November Bulletin at www.bulletin.facs.org.

Ronald. V. Maier, MD, FACS, FRCSEd(Hon), FCSHK(Hon), the Jane and Donald D. Trunkey Endowed Chair in Trauma Surgery; vice-chairman, department of surgery; and professor of surgery, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, was installed as the 99th President of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) at Convocation, October 21, at Clinical Congress 2018 in Boston, MA.

Dr. Maier is highly esteemed for his contributions to trauma surgery, surgical research, and surgical education. In addition to his positions at the University of Washington, he is director, Northwest Regional Trauma Center; and surgeon-in-chief and co-director, surgical intensive care unit (SICU), Harborview Medical Center, Seattle. He also is associate medical staff, University of Washington Medical Center and Seattle Cancer Care Alliance. A Fellow of the College since 1984, Dr. Maier served as First Vice-President of the ACS (2015−2016) and has played an active role on several key committees, most notably the Committee on Trauma (COT).

Mark C. Weissler, MD, FACS, Past-Chair of the ACS Board of Regents (2014−2015) was installed as the First Vice-President. An otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeon, Dr. Weissler is the Joseph P. Riddle Distinguished Professor, department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery, and chief, division of head and neck surgery, University of North Carolina (UNC) School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. An ACS Fellow since 1989, Dr. Weissler is a former ACS Regent, serving as Vice-Chair of the Board of Regents for two years (2012–2014) and Chair for one year (2014−2015). He has served on the ACS Board of Governors and in other leadership capacities for the College, including the Committee on Ethics, Central Judiciary Committee, Advisory Council for Otolaryngology−Head and Neck Surgery; and President, North Carolina Chapter of the ACS.

The Second Vice-President is Phillip R. Caropreso, MD, FACS, a general surgeon from Keokuk, IA. A committed rural surgeon, Dr. Caropreso has practiced in Mason City, IA; Keokuk, IA; and Carthage, IL. Academic positions have included serving on the teaching faculty, family practice residency, North Iowa Medical Center, Mason City; adjunct clinical professor of surgery, University of Iowa, Iowa City; and director, general surgery rotation, North Iowa Medical Center. A Fellow of the ACS since 1979, Dr. Caropreso has been active at the local and national level. He was Chair, Iowa State COT; President of the Iowa Chapter; and ACS Governor, serving on the Board of Governors Committee on Surgical Practices.

Read more about Dr. Maier, Dr. Weissler, and Dr. Caropreso in the November Bulletin at www.bulletin.facs.org.

Endoscopic vein-graft harvest equals open harvest at 3 years

CHICAGO – Patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting using saphenous veins harvested endoscopically had similar clinical outcomes after nearly 3 years of follow-up as those seen with patients who received vein grafts taken by open harvesting in a multicenter, randomized trial in the United States with 1,150 patients.

As expected, follow-up also showed that endoscopic vein-graft harvesting (EVH) resulted in about half the number of wound infections as did open vein-graft harvesting (OVH). This combination of similar clinical outcomes after a median 2.8 years of follow-up, as well as fewer leg-wound adverse events, makes EVH “the preferred vein-harvesting modality,” Marco A. Zenati, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Although patients far and away prefer EVH because of the reduced pain and faster healing, questions about its clinical efficacy when compared with that of OVH have lingered. That’s because observational data published almost a decade ago taken from the PREVENT IV (Project of Ex-Vivo Vein Graft Engineering via Transfection IV) trial suggested that patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) using vein grafts collected by EVH had more vein-graft failures after 12-18 months and a higher rate of death, MI, or need for revascularization after 3 years, compared with patients treated using OVH (N Engl J Med. 2009 July 16;361[3]:235-44).

The results from the prospective, randomized trial reported by Dr. Zenati “take the cloud away from endovascular vein-graft harvesting that PREVENT IV had made,” commented Timothy J. Gardner, MD, a cardiac surgeon who chaired the session.

“I think this answers the question,” commented Marc Ruel, MD, a professor of surgery and the chief of cardiac surgery at the University of Ottawa. “The results show that endoscopic harvesting of vein grafts is as good as open harvesting for preventing major adverse cardiac events, which is the goal of CABG. This is a definitive trial, with no trend toward more events with endoscopic harvested vein grafts,” said Dr. Ruel, the designated discussant for Dr. Zenati’s report.

However, the study did have some significant limitations, Dr. Ruel added. The new, randomized trial, run at 16 U.S. VA cardiac surgery centers, exclusively used surgeons who were experts in endovascular vein harvesting, which could have meant that they and their surgical teams were not as expert in open vein harvesting, he said. Also, in the broader context of CABG and conduit selection, new evidence suggests the superiority of pedicled vein grafts (Ann Thoracic Surg. 2017 Oct;104[4]1313-17), and “we could also do better by using the radial artery” rather than a saphenous vein graft, Dr. Ruel said. He cited a meta-analysis published in 2018 that showed the superiority of CABG when it combined an internal thoracic artery graft with a radial artery graft rather than with a vein graft (N Engl J Med. 2018 May 31;378[22]:2069-77).

“The operation of the future is not necessarily what you saw” in Dr. Zenati’s study, Dr. Ruel cautioned.

The results Dr. Zenati reported came from the REGROUP (Randomized End-Vein Graft Prospective) trial, which enrolled patients who underwent CABG during 2014-2017. All patients received an internal thoracic artery graft and were randomized to receive additional saphenous vein grafts with the conduits collected either by the EVH or OVH method. The study’s primary endpoint of all-cause death, nonfatal MI, or need for repeat revascularization after a median follow-up of 2.8 years occurred in 14% of the patients who received vein grafts with EVH and in 16% of the patients who received grafts with OVH, a difference that was not statistically significant, reported Dr. Zenati, a professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School in Boston and the chief of cardiothoracic surgery for the VA Boston Health System. The incidence of wound infection was 3.1% in the OVH patients and 1.4% in the EVH patients, a difference that came close to but did not reach statistical significance. Concurrently with Dr. Zenati’s report, an article with the results appeared online (N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 11. doi: 0.1056/NEJMoa1812390).

The REGROUP trial did not collect data on vein-graft patency following CABG. The investigators were concerned about having enough patients return for follow-up angiography to produce a meaningful result for this endpoint, and they believed that the clinical endpoint they used sufficed for demonstrating equivalence of the two harvesting methods, Dr. Zenati said during his talk.

“The more arterial conduit used in CABG, the better the durability of the grafts, but often surgeons use vein grafts because there is not enough arterial conduit,” commented Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor and chair of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.* “The recovery from endoscopic vein-graft harvesting is very different from open harvesting. Endoscopic harvesting produces much less pain and infection, and recovery is much easier for patients, so it’s reassuring to see that the quality of the vein is not affected by endoscopic harvesting when done by experts,” he said.

Dr. Zenati, Dr. Gardner, Dr. Ruel, and Dr. Lloyd-Jones had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Zenati M et al. AHA 2018, Abstract 19055.

*Correction, 11/12/18: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of Dr. Donald M. Lloyd-Jones.

This article was updated 11/14/18.

The results from the REGROUP trial are interesting and open the field for additional comparisons of endoscopic and open saphenous vein-graft harvesting, but this trial is not the definitive answer regarding whether these two harvesting approaches produce similar results. Greater reassurance of equivalence would come from studies that included more patients and a more diverse patient population; REGROUP largely enrolled male veterans and patients with multiple comorbidities. Longer follow-up is also needed. A median follow-up of 3 years is too brief for complete reassurance that long-term patency is the same with both approaches. It would also help to have follow-up data on graft patency. Many factors besides patency can lead to differences in clinical outcomes following coronary bypass surgery.

Endoscopic vein harvesting is preferred by patients, and it results in fewer wound infections, as was confirmed in REGROUP. Because of these advantages for endoscopic harvesting, it would be great if we could definitively document that these vein grafts functioned as well as those taken with open harvesting.

Evidence now suggests that the more arterial conduits used during coronary bypass, the better. If I were having triple-vessel bypass surgery, I’d want to get two thoracic-artery bypass grafts and a radial artery graft. But studies like REGROUP are important because a majority of heart surgeons use vein grafts for several reasons including convenience. Surgeons will likely continue to use vein grafts for the foreseeable future, so we need to know whether endoscopic harvesting is an acceptable approach.

Jennifer S. Lawton, MD , is a professor of surgery and chief of cardiac surgery at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore. She had no disclosures. She made these comments in an interview.

The results from the REGROUP trial are interesting and open the field for additional comparisons of endoscopic and open saphenous vein-graft harvesting, but this trial is not the definitive answer regarding whether these two harvesting approaches produce similar results. Greater reassurance of equivalence would come from studies that included more patients and a more diverse patient population; REGROUP largely enrolled male veterans and patients with multiple comorbidities. Longer follow-up is also needed. A median follow-up of 3 years is too brief for complete reassurance that long-term patency is the same with both approaches. It would also help to have follow-up data on graft patency. Many factors besides patency can lead to differences in clinical outcomes following coronary bypass surgery.

Endoscopic vein harvesting is preferred by patients, and it results in fewer wound infections, as was confirmed in REGROUP. Because of these advantages for endoscopic harvesting, it would be great if we could definitively document that these vein grafts functioned as well as those taken with open harvesting.

Evidence now suggests that the more arterial conduits used during coronary bypass, the better. If I were having triple-vessel bypass surgery, I’d want to get two thoracic-artery bypass grafts and a radial artery graft. But studies like REGROUP are important because a majority of heart surgeons use vein grafts for several reasons including convenience. Surgeons will likely continue to use vein grafts for the foreseeable future, so we need to know whether endoscopic harvesting is an acceptable approach.

Jennifer S. Lawton, MD , is a professor of surgery and chief of cardiac surgery at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore. She had no disclosures. She made these comments in an interview.

The results from the REGROUP trial are interesting and open the field for additional comparisons of endoscopic and open saphenous vein-graft harvesting, but this trial is not the definitive answer regarding whether these two harvesting approaches produce similar results. Greater reassurance of equivalence would come from studies that included more patients and a more diverse patient population; REGROUP largely enrolled male veterans and patients with multiple comorbidities. Longer follow-up is also needed. A median follow-up of 3 years is too brief for complete reassurance that long-term patency is the same with both approaches. It would also help to have follow-up data on graft patency. Many factors besides patency can lead to differences in clinical outcomes following coronary bypass surgery.

Endoscopic vein harvesting is preferred by patients, and it results in fewer wound infections, as was confirmed in REGROUP. Because of these advantages for endoscopic harvesting, it would be great if we could definitively document that these vein grafts functioned as well as those taken with open harvesting.

Evidence now suggests that the more arterial conduits used during coronary bypass, the better. If I were having triple-vessel bypass surgery, I’d want to get two thoracic-artery bypass grafts and a radial artery graft. But studies like REGROUP are important because a majority of heart surgeons use vein grafts for several reasons including convenience. Surgeons will likely continue to use vein grafts for the foreseeable future, so we need to know whether endoscopic harvesting is an acceptable approach.

Jennifer S. Lawton, MD , is a professor of surgery and chief of cardiac surgery at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore. She had no disclosures. She made these comments in an interview.

CHICAGO – Patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting using saphenous veins harvested endoscopically had similar clinical outcomes after nearly 3 years of follow-up as those seen with patients who received vein grafts taken by open harvesting in a multicenter, randomized trial in the United States with 1,150 patients.

As expected, follow-up also showed that endoscopic vein-graft harvesting (EVH) resulted in about half the number of wound infections as did open vein-graft harvesting (OVH). This combination of similar clinical outcomes after a median 2.8 years of follow-up, as well as fewer leg-wound adverse events, makes EVH “the preferred vein-harvesting modality,” Marco A. Zenati, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Although patients far and away prefer EVH because of the reduced pain and faster healing, questions about its clinical efficacy when compared with that of OVH have lingered. That’s because observational data published almost a decade ago taken from the PREVENT IV (Project of Ex-Vivo Vein Graft Engineering via Transfection IV) trial suggested that patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) using vein grafts collected by EVH had more vein-graft failures after 12-18 months and a higher rate of death, MI, or need for revascularization after 3 years, compared with patients treated using OVH (N Engl J Med. 2009 July 16;361[3]:235-44).

The results from the prospective, randomized trial reported by Dr. Zenati “take the cloud away from endovascular vein-graft harvesting that PREVENT IV had made,” commented Timothy J. Gardner, MD, a cardiac surgeon who chaired the session.

“I think this answers the question,” commented Marc Ruel, MD, a professor of surgery and the chief of cardiac surgery at the University of Ottawa. “The results show that endoscopic harvesting of vein grafts is as good as open harvesting for preventing major adverse cardiac events, which is the goal of CABG. This is a definitive trial, with no trend toward more events with endoscopic harvested vein grafts,” said Dr. Ruel, the designated discussant for Dr. Zenati’s report.

However, the study did have some significant limitations, Dr. Ruel added. The new, randomized trial, run at 16 U.S. VA cardiac surgery centers, exclusively used surgeons who were experts in endovascular vein harvesting, which could have meant that they and their surgical teams were not as expert in open vein harvesting, he said. Also, in the broader context of CABG and conduit selection, new evidence suggests the superiority of pedicled vein grafts (Ann Thoracic Surg. 2017 Oct;104[4]1313-17), and “we could also do better by using the radial artery” rather than a saphenous vein graft, Dr. Ruel said. He cited a meta-analysis published in 2018 that showed the superiority of CABG when it combined an internal thoracic artery graft with a radial artery graft rather than with a vein graft (N Engl J Med. 2018 May 31;378[22]:2069-77).

“The operation of the future is not necessarily what you saw” in Dr. Zenati’s study, Dr. Ruel cautioned.

The results Dr. Zenati reported came from the REGROUP (Randomized End-Vein Graft Prospective) trial, which enrolled patients who underwent CABG during 2014-2017. All patients received an internal thoracic artery graft and were randomized to receive additional saphenous vein grafts with the conduits collected either by the EVH or OVH method. The study’s primary endpoint of all-cause death, nonfatal MI, or need for repeat revascularization after a median follow-up of 2.8 years occurred in 14% of the patients who received vein grafts with EVH and in 16% of the patients who received grafts with OVH, a difference that was not statistically significant, reported Dr. Zenati, a professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School in Boston and the chief of cardiothoracic surgery for the VA Boston Health System. The incidence of wound infection was 3.1% in the OVH patients and 1.4% in the EVH patients, a difference that came close to but did not reach statistical significance. Concurrently with Dr. Zenati’s report, an article with the results appeared online (N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 11. doi: 0.1056/NEJMoa1812390).

The REGROUP trial did not collect data on vein-graft patency following CABG. The investigators were concerned about having enough patients return for follow-up angiography to produce a meaningful result for this endpoint, and they believed that the clinical endpoint they used sufficed for demonstrating equivalence of the two harvesting methods, Dr. Zenati said during his talk.

“The more arterial conduit used in CABG, the better the durability of the grafts, but often surgeons use vein grafts because there is not enough arterial conduit,” commented Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor and chair of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.* “The recovery from endoscopic vein-graft harvesting is very different from open harvesting. Endoscopic harvesting produces much less pain and infection, and recovery is much easier for patients, so it’s reassuring to see that the quality of the vein is not affected by endoscopic harvesting when done by experts,” he said.

Dr. Zenati, Dr. Gardner, Dr. Ruel, and Dr. Lloyd-Jones had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Zenati M et al. AHA 2018, Abstract 19055.

*Correction, 11/12/18: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of Dr. Donald M. Lloyd-Jones.

This article was updated 11/14/18.

CHICAGO – Patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting using saphenous veins harvested endoscopically had similar clinical outcomes after nearly 3 years of follow-up as those seen with patients who received vein grafts taken by open harvesting in a multicenter, randomized trial in the United States with 1,150 patients.

As expected, follow-up also showed that endoscopic vein-graft harvesting (EVH) resulted in about half the number of wound infections as did open vein-graft harvesting (OVH). This combination of similar clinical outcomes after a median 2.8 years of follow-up, as well as fewer leg-wound adverse events, makes EVH “the preferred vein-harvesting modality,” Marco A. Zenati, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Although patients far and away prefer EVH because of the reduced pain and faster healing, questions about its clinical efficacy when compared with that of OVH have lingered. That’s because observational data published almost a decade ago taken from the PREVENT IV (Project of Ex-Vivo Vein Graft Engineering via Transfection IV) trial suggested that patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) using vein grafts collected by EVH had more vein-graft failures after 12-18 months and a higher rate of death, MI, or need for revascularization after 3 years, compared with patients treated using OVH (N Engl J Med. 2009 July 16;361[3]:235-44).

The results from the prospective, randomized trial reported by Dr. Zenati “take the cloud away from endovascular vein-graft harvesting that PREVENT IV had made,” commented Timothy J. Gardner, MD, a cardiac surgeon who chaired the session.

“I think this answers the question,” commented Marc Ruel, MD, a professor of surgery and the chief of cardiac surgery at the University of Ottawa. “The results show that endoscopic harvesting of vein grafts is as good as open harvesting for preventing major adverse cardiac events, which is the goal of CABG. This is a definitive trial, with no trend toward more events with endoscopic harvested vein grafts,” said Dr. Ruel, the designated discussant for Dr. Zenati’s report.

However, the study did have some significant limitations, Dr. Ruel added. The new, randomized trial, run at 16 U.S. VA cardiac surgery centers, exclusively used surgeons who were experts in endovascular vein harvesting, which could have meant that they and their surgical teams were not as expert in open vein harvesting, he said. Also, in the broader context of CABG and conduit selection, new evidence suggests the superiority of pedicled vein grafts (Ann Thoracic Surg. 2017 Oct;104[4]1313-17), and “we could also do better by using the radial artery” rather than a saphenous vein graft, Dr. Ruel said. He cited a meta-analysis published in 2018 that showed the superiority of CABG when it combined an internal thoracic artery graft with a radial artery graft rather than with a vein graft (N Engl J Med. 2018 May 31;378[22]:2069-77).

“The operation of the future is not necessarily what you saw” in Dr. Zenati’s study, Dr. Ruel cautioned.

The results Dr. Zenati reported came from the REGROUP (Randomized End-Vein Graft Prospective) trial, which enrolled patients who underwent CABG during 2014-2017. All patients received an internal thoracic artery graft and were randomized to receive additional saphenous vein grafts with the conduits collected either by the EVH or OVH method. The study’s primary endpoint of all-cause death, nonfatal MI, or need for repeat revascularization after a median follow-up of 2.8 years occurred in 14% of the patients who received vein grafts with EVH and in 16% of the patients who received grafts with OVH, a difference that was not statistically significant, reported Dr. Zenati, a professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School in Boston and the chief of cardiothoracic surgery for the VA Boston Health System. The incidence of wound infection was 3.1% in the OVH patients and 1.4% in the EVH patients, a difference that came close to but did not reach statistical significance. Concurrently with Dr. Zenati’s report, an article with the results appeared online (N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 11. doi: 0.1056/NEJMoa1812390).

The REGROUP trial did not collect data on vein-graft patency following CABG. The investigators were concerned about having enough patients return for follow-up angiography to produce a meaningful result for this endpoint, and they believed that the clinical endpoint they used sufficed for demonstrating equivalence of the two harvesting methods, Dr. Zenati said during his talk.

“The more arterial conduit used in CABG, the better the durability of the grafts, but often surgeons use vein grafts because there is not enough arterial conduit,” commented Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor and chair of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.* “The recovery from endoscopic vein-graft harvesting is very different from open harvesting. Endoscopic harvesting produces much less pain and infection, and recovery is much easier for patients, so it’s reassuring to see that the quality of the vein is not affected by endoscopic harvesting when done by experts,” he said.

Dr. Zenati, Dr. Gardner, Dr. Ruel, and Dr. Lloyd-Jones had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Zenati M et al. AHA 2018, Abstract 19055.

*Correction, 11/12/18: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of Dr. Donald M. Lloyd-Jones.

This article was updated 11/14/18.

REPORTING FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSION

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Clinical events occurred in 16% of open-harvest vein-graft patients and in 14% who received endoscopically harvested veins.

Study details: REGROUP, a multicenter, randomized trial with 1,150 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Zenati, Dr. Gardner, Dr. Ruel, and Dr. Lloyd-Jones had no disclosures.

Source: Zenati M et al. AHA 2018, Abstract 19055.

‘Organoid technology’ poised to transform cancer care

BOSTON– Imagine being able to .

The implications are nearly endless. To start, chemotherapy and radiation options could be screened in vitro, much like culture and sensitivity testing of bacteria, to find a patient’s best option. Tumor cultures could be banked for mass screening of new cytotoxic candidates.

It’s already beginning to happen in a few research labs around the world, and it might foretell a breakthrough in cancer treatment.

After decades of failure, the trick to growing tumor cells in culture has finally been figured out. When stem cells are fished out of healthy tissue – from the crypts of the gastrointestinal lining, for instance – and put into a three-dimensional matrix culture with growth factors, they grow into little replications of the organs they came from, called “organoids;” when stem cells are pulled from cancers, they replicate the primary tumor, growing into “tumoroids” ready to be tested against cytotoxic drugs and radiation.

Philip B. Paty, MD, FACS, a colorectal surgeon and organoid researcher at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said he is certain that the person who led the team that figured out the right culture condition – Hans Clevers, MD, PhD, a molecular genetics professor at the University of Utrecht (the Netherlands) – is destined for a Nobel Prize.

Dr. Paty took a few minutes at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons to explain in an interview why, and what ‘organoid technology’ will likely mean for cancer treatment in a few years.

“The ability to grow and sustain cancer means that we now can start doing real science on human tissues. We could never do this before. We’ve been treating cancer without being able to grow tumors and study them.” The breakthrough opens the door to “clinical trials in a dish,” and will likely take personalized cancer treatment to a new level, he said.

“It remains to be proven that “organoid technology “can change outcomes for patients, but those studies are likely coming,” said Dr. Paty, who investigates tumoroid response to radiation in his own lab work.

BOSTON– Imagine being able to .

The implications are nearly endless. To start, chemotherapy and radiation options could be screened in vitro, much like culture and sensitivity testing of bacteria, to find a patient’s best option. Tumor cultures could be banked for mass screening of new cytotoxic candidates.

It’s already beginning to happen in a few research labs around the world, and it might foretell a breakthrough in cancer treatment.

After decades of failure, the trick to growing tumor cells in culture has finally been figured out. When stem cells are fished out of healthy tissue – from the crypts of the gastrointestinal lining, for instance – and put into a three-dimensional matrix culture with growth factors, they grow into little replications of the organs they came from, called “organoids;” when stem cells are pulled from cancers, they replicate the primary tumor, growing into “tumoroids” ready to be tested against cytotoxic drugs and radiation.

Philip B. Paty, MD, FACS, a colorectal surgeon and organoid researcher at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said he is certain that the person who led the team that figured out the right culture condition – Hans Clevers, MD, PhD, a molecular genetics professor at the University of Utrecht (the Netherlands) – is destined for a Nobel Prize.

Dr. Paty took a few minutes at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons to explain in an interview why, and what ‘organoid technology’ will likely mean for cancer treatment in a few years.

“The ability to grow and sustain cancer means that we now can start doing real science on human tissues. We could never do this before. We’ve been treating cancer without being able to grow tumors and study them.” The breakthrough opens the door to “clinical trials in a dish,” and will likely take personalized cancer treatment to a new level, he said.

“It remains to be proven that “organoid technology “can change outcomes for patients, but those studies are likely coming,” said Dr. Paty, who investigates tumoroid response to radiation in his own lab work.

BOSTON– Imagine being able to .

The implications are nearly endless. To start, chemotherapy and radiation options could be screened in vitro, much like culture and sensitivity testing of bacteria, to find a patient’s best option. Tumor cultures could be banked for mass screening of new cytotoxic candidates.

It’s already beginning to happen in a few research labs around the world, and it might foretell a breakthrough in cancer treatment.

After decades of failure, the trick to growing tumor cells in culture has finally been figured out. When stem cells are fished out of healthy tissue – from the crypts of the gastrointestinal lining, for instance – and put into a three-dimensional matrix culture with growth factors, they grow into little replications of the organs they came from, called “organoids;” when stem cells are pulled from cancers, they replicate the primary tumor, growing into “tumoroids” ready to be tested against cytotoxic drugs and radiation.

Philip B. Paty, MD, FACS, a colorectal surgeon and organoid researcher at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said he is certain that the person who led the team that figured out the right culture condition – Hans Clevers, MD, PhD, a molecular genetics professor at the University of Utrecht (the Netherlands) – is destined for a Nobel Prize.

Dr. Paty took a few minutes at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons to explain in an interview why, and what ‘organoid technology’ will likely mean for cancer treatment in a few years.

“The ability to grow and sustain cancer means that we now can start doing real science on human tissues. We could never do this before. We’ve been treating cancer without being able to grow tumors and study them.” The breakthrough opens the door to “clinical trials in a dish,” and will likely take personalized cancer treatment to a new level, he said.

“It remains to be proven that “organoid technology “can change outcomes for patients, but those studies are likely coming,” said Dr. Paty, who investigates tumoroid response to radiation in his own lab work.

REPORTING FROM THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

MIS for cervical cancer: Is it not for anyone or not for everyone?

Shock waves moved through the gynecologic oncology world on Oct. 31, 2018, when the New England Journal of Medicine published two papers on survival outcomes for women undergoing surgery for early stage cervical cancer.

The first was a randomized controlled trial of laparotomy and minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for radical hysterectomy called the LACC trial.1 In the multicenter, international trial of 631 women, the primary objective was disease-specific survival (cervical cancer–related deaths) and was powered to detect noninferiority of the MIS approach when compared with laparotomy. The trial was closed early when investigators noted a lower than expected rate of 3-year, disease-free survival (91% vs. 97%) from cervical cancer in the MIS group, which was made up of 84% laparoscopic and 16% robotic approaches, versus laparotomy. There were 19 deaths in the MIS group observed versus three in the laparotomy group. The conclusions of the trial were that MIS surgery is associated with inferior cervical cancer survival.

In the second study, authors analyzed data from large U.S. databases – the National Cancer Database (NCDB) and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program – to collect all-cause mortality for patients with early-stage cervical cancer who had undergone radical hysterectomy during 2010-2013.2 Among 2,461 observed results, 1,225 had undergone MIS surgery with the majority (79.8%) via robotic-assistance. Women undergoing MIS approaches had smaller, lower grade tumors; were more likely to be white, privately insured, and of a higher income; and had surgery later in the cohort and by nonacademic centers. The researchers adjusted for risk factors with an analytic process called propensity-score weighting, which matched the groups more closely in an attempt to minimize confounders. They identified higher all-cause mortality among women who were treated with an MIS approach, compared with those treated with laparotomy (hazard ratio, 1.65). They also observed a significant decline in the survival from cervical cancer annually that corresponded to the uptake of MIS radical hysterectomies.

In the wake of these publications, many concluded that gynecologic oncologists should no longer offer a minimally invasive approach for radical hysterectomy. Certainly level I evidence published in a highly influential journal is compelling, and the consistency in findings over two studies adds further weight to the results. However, was this the correct conclusion to draw from these results? Surgeons who had been performing MIS radical hysterectomies for many years with favorable outcomes are challenging this and are raising questions about external generalizability and whether these findings were driven by the surgery itself or by the surgeon.

The studies’ authors proposed hypotheses for their results that implicate the surgical route rather than the surgeon; however, these seem ad hoc and not well supported by data, including the authors’ own data. The first was the hypothesis that cervical tumors were being disrupted and disseminated through the use of uterine manipulators in MIS approaches. However, cervical cancers are fairly routinely “disrupted” by preoperative cone biopsies, loop electrosurgical excision procedures (LEEP), and sharp biopsies, which are arguably more invasive than placement of a manipulator. Uterine manipulators routinely are used in endometrial cancer surgeries, in which the manipulator is embedded within the tumor, without an associated negative survival effect in randomized trials.3 Additionally, not all surgeons utilize manipulators for radical hysterectomies, and these studies did not measure or report on their use; therefore, it is impossible to know whether, and by what magnitude, manipulators played a role. Finally, if uterine manipulators are the explanation for inferior survival, surely the recommendation should be to discourage their use, rather than abandon the MIS approach all together.

The other explanation offered was exposure of the tumor to CO2 gas. This seems an even less plausible explanation because CO2 gas is routinely used in MIS cancer surgeries for endometrial, prostate, gastric, and colorectal surgeries and is used as insufflation for malignant interventional endoscopies without a significant deleterious effect. Additionally, the cervix is not exposed to CO2 until colpotomy at the procedure’s end – and only briefly. The in vitro studies implicating a negative effect of simulated CO2 pneumoperitoneum are neither compelling nor consistent.4,5

I would like to propose another hypothesis for the results: surgical proficiency. Surgery, unlike medical interventions, is not a simple variable that is dichotomous – performed or not. Surgeons do not randomly select operative approaches for patients. We select surgical approaches based on patients’ circumstances and surgeon factors, including our own mastery of the various techniques. and any surgeon recognizes this if he or she has observed more than one surgeon or has attempted a procedure via different routes. While some procedures, such as extrafascial hysterectomy for endometrial cancer, are relatively straightforward and surgeon capabilities are more equitable across different approaches, cervical cancer surgery is quite different.

Early-stage cervical cancer primarily exerts radial growth into the cervical stroma and parametria. Curative surgical excision requires broadly negative margins through this tissue, a so called “radical hysterectomy.” The radicality of hysterectomy has been categorized in stages, acknowledging that different sized lesions require different volumes of parametrial resection to achieve adequate clearance from the tumor.6 In doing so, the surgeon must skeletonize and mobilize the distal ureters, cardinal ligament webs, and uterosacral ligaments. These structures are in close proximity to major vascular and neural structures. Hence, the radical hysterectomy is, without dispute, a technically challenging procedure.

Minimally invasive surgery further handicaps the surgeon by eliminating manual contact with tissue, and relying on complex instrumentation, electrosurgical modalities, and loss of haptics. The learning curve for MIS radical hysterectomy is further attenuated by their relative infrequency. Therefore, it makes sense that, when the MIS approach is randomly assigned to surgeons (such as in the LACC trial) or broadly and independently applied (as in the retrospective series), one might see variations in skill, quality, and outcomes, including oncologic outcomes.

The retrospective study by Melamed et al. acknowledged that surgeon skill and volume may contribute to their findings but stated that, because of the nature of their source data, they were unable to explain why they observed their results. The LACC trial attempted to overcome the issue of surgeon skill by ensuring all surgeons were from high-volume sites and had videos reviewed of their cases. However, the videos were chosen by the surgeons themselves and not available for audit in the study’s supplemental material. The LACC trial was conducted over a 9-year period across 33 sites and enrolled a total of 631 subjects. This equates to an enrollment of approximately two patients per site per year and either reflects extremely low-volume sites or highly selective patient enrollment. If the latter, what was different about the unenrolled patients and what was the preferred chosen route of surgery for them?

All 34 recurrences occurred in patients from just 14 of the 33 sites in the LACC trial. That means that less than half of the sites contributed to all of the recurrences. The authors provided no details on the specific sites, surgeons, or accrual rates in their manuscript or supplemental materials. Therefore, readers are unable to know what was different about those sites; whether they contributed the most patients and, therefore, the most recurrences; or whether they were low-volume sites with lower quality.

While margin status, positive or negative, was reported, there was no data captured regarding volume of resected parametrial tissue, or relative distance from tumor to margin, both of which might provide the reader with a better appraisal of surgeon proficiency and consistency in radicality of the two approaches. The incidence of locoregional (pelvic) recurrences were higher in the MIS arm, which is expected if there were inadequate margins around the laparoscopically resected tumors.

Finally, the authors of the LACC trial observed equivalent rates of postoperative complications between the laparotomy and MIS groups. The main virtue for MIS approaches is the reduction in perioperative morbidity. To observe no perioperative morbidity benefit in the MIS group is a red flag suggesting that these surgeons may not have achieved proficiency with the MIS approach.

Despite these arguments, the results of these studies should be taken seriously. Clearly, it is apparent that preservation of oncologic outcomes is not guaranteed with MIS radical hysterectomy, and it should not be the chosen approach for all patients and all surgeons. However, rather than entirely abandoning this less morbid approach, I would argue that it is a call to arms for gynecologic oncologists to self-evaluate. We should know our own data with respect to case volumes, perioperative complications, and cancer-related recurrence and death.

Perhaps MIS radical hysterectomies should be consolidated among high-volume surgeons with demonstrated good outcomes? Just as has been done for rectal cancer surgery with positive effect, we should establish accredited centers of excellence.7 We also need to improve the training of surgeons in novel, difficult techniques, as well as enhance the sophistication of MIS equipment such as improved instrumentation, haptics, and vision-guided surgery (for example, real-time intraoperative assessment of the tumor margins).

Let’s not take a wholesale step backwards to the surgical approaches of a 100 years ago just because they are more straightforward. Let’s do a better job of advancing the quality of what we do for our patients in the future.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She said she had no conflicts of interest. Email Dr. Rossi at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806395.

2. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804923.

3. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Mar 1;30(7):695-700.

4. Med Sci Monit. 2014 Dec 1;20:2497-503.

5. Surg Endosc. 2006 Oct;20(10):1556-9.

6. Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122(2):264-8.

7. Surgery. 2016 Mar;159(3):736-48.

Shock waves moved through the gynecologic oncology world on Oct. 31, 2018, when the New England Journal of Medicine published two papers on survival outcomes for women undergoing surgery for early stage cervical cancer.

The first was a randomized controlled trial of laparotomy and minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for radical hysterectomy called the LACC trial.1 In the multicenter, international trial of 631 women, the primary objective was disease-specific survival (cervical cancer–related deaths) and was powered to detect noninferiority of the MIS approach when compared with laparotomy. The trial was closed early when investigators noted a lower than expected rate of 3-year, disease-free survival (91% vs. 97%) from cervical cancer in the MIS group, which was made up of 84% laparoscopic and 16% robotic approaches, versus laparotomy. There were 19 deaths in the MIS group observed versus three in the laparotomy group. The conclusions of the trial were that MIS surgery is associated with inferior cervical cancer survival.

In the second study, authors analyzed data from large U.S. databases – the National Cancer Database (NCDB) and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program – to collect all-cause mortality for patients with early-stage cervical cancer who had undergone radical hysterectomy during 2010-2013.2 Among 2,461 observed results, 1,225 had undergone MIS surgery with the majority (79.8%) via robotic-assistance. Women undergoing MIS approaches had smaller, lower grade tumors; were more likely to be white, privately insured, and of a higher income; and had surgery later in the cohort and by nonacademic centers. The researchers adjusted for risk factors with an analytic process called propensity-score weighting, which matched the groups more closely in an attempt to minimize confounders. They identified higher all-cause mortality among women who were treated with an MIS approach, compared with those treated with laparotomy (hazard ratio, 1.65). They also observed a significant decline in the survival from cervical cancer annually that corresponded to the uptake of MIS radical hysterectomies.

In the wake of these publications, many concluded that gynecologic oncologists should no longer offer a minimally invasive approach for radical hysterectomy. Certainly level I evidence published in a highly influential journal is compelling, and the consistency in findings over two studies adds further weight to the results. However, was this the correct conclusion to draw from these results? Surgeons who had been performing MIS radical hysterectomies for many years with favorable outcomes are challenging this and are raising questions about external generalizability and whether these findings were driven by the surgery itself or by the surgeon.

The studies’ authors proposed hypotheses for their results that implicate the surgical route rather than the surgeon; however, these seem ad hoc and not well supported by data, including the authors’ own data. The first was the hypothesis that cervical tumors were being disrupted and disseminated through the use of uterine manipulators in MIS approaches. However, cervical cancers are fairly routinely “disrupted” by preoperative cone biopsies, loop electrosurgical excision procedures (LEEP), and sharp biopsies, which are arguably more invasive than placement of a manipulator. Uterine manipulators routinely are used in endometrial cancer surgeries, in which the manipulator is embedded within the tumor, without an associated negative survival effect in randomized trials.3 Additionally, not all surgeons utilize manipulators for radical hysterectomies, and these studies did not measure or report on their use; therefore, it is impossible to know whether, and by what magnitude, manipulators played a role. Finally, if uterine manipulators are the explanation for inferior survival, surely the recommendation should be to discourage their use, rather than abandon the MIS approach all together.

The other explanation offered was exposure of the tumor to CO2 gas. This seems an even less plausible explanation because CO2 gas is routinely used in MIS cancer surgeries for endometrial, prostate, gastric, and colorectal surgeries and is used as insufflation for malignant interventional endoscopies without a significant deleterious effect. Additionally, the cervix is not exposed to CO2 until colpotomy at the procedure’s end – and only briefly. The in vitro studies implicating a negative effect of simulated CO2 pneumoperitoneum are neither compelling nor consistent.4,5

I would like to propose another hypothesis for the results: surgical proficiency. Surgery, unlike medical interventions, is not a simple variable that is dichotomous – performed or not. Surgeons do not randomly select operative approaches for patients. We select surgical approaches based on patients’ circumstances and surgeon factors, including our own mastery of the various techniques. and any surgeon recognizes this if he or she has observed more than one surgeon or has attempted a procedure via different routes. While some procedures, such as extrafascial hysterectomy for endometrial cancer, are relatively straightforward and surgeon capabilities are more equitable across different approaches, cervical cancer surgery is quite different.

Early-stage cervical cancer primarily exerts radial growth into the cervical stroma and parametria. Curative surgical excision requires broadly negative margins through this tissue, a so called “radical hysterectomy.” The radicality of hysterectomy has been categorized in stages, acknowledging that different sized lesions require different volumes of parametrial resection to achieve adequate clearance from the tumor.6 In doing so, the surgeon must skeletonize and mobilize the distal ureters, cardinal ligament webs, and uterosacral ligaments. These structures are in close proximity to major vascular and neural structures. Hence, the radical hysterectomy is, without dispute, a technically challenging procedure.

Minimally invasive surgery further handicaps the surgeon by eliminating manual contact with tissue, and relying on complex instrumentation, electrosurgical modalities, and loss of haptics. The learning curve for MIS radical hysterectomy is further attenuated by their relative infrequency. Therefore, it makes sense that, when the MIS approach is randomly assigned to surgeons (such as in the LACC trial) or broadly and independently applied (as in the retrospective series), one might see variations in skill, quality, and outcomes, including oncologic outcomes.